18 Africa in the World

18 Africa in the World

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

Africa’s development depends, in part, upon a facilitating global environment. In this theme, we review global trends and then present four global scenarios, examining how a Sustainable World, a Divided World, a World at War, and a Growth World impact Africa's development.

For more information about the International Futures modelling platform we use for the forecasts and scenarios, please see the Technical page.

Summary

This theme begins with an overview of trends in power and influence, drawing on various indices to understand the likely future evolution of a business-as-usual (Current Path) forecast. The analysis reveals incremental improvements in Africa's material power, but these do not keep pace with the continent's rapidly growing population.

Globally, economic and political heft is shifting towards Asia. Around 2043, China is expected to surpass the US as the world's most powerful country, with its economy already larger than the US's from 2034 onward. We examine its ambitions. Although the West remains dominant in wealth, technology and power for the remainder of the 21st century, discord between the US and Europe means that the North Atlantic partners' ability to shape and maintain the liberal international order to their benefit is rapidly declining.

Historically and currently, Africa is a small player on the global stage. Its status has been elevated at times due to East-West competition, its role in providing fossil fuels during the War on Terror, and the focus on development with the crafting of the Millennium and Sustainable Development Goals. Lately, Africa has again become a focal point of competition among the West, China and Russia. Its importance will increase given the sheer number of African states participating in various global fora, Africa's role as a source of critical minerals powering the transition to a sustainable future, and its growing population, which has fueled fears in Europe and elsewhere about a significant outflow of migrants from Africa.

Building on these trends, we frame Africa’s development through four alternative global scenarios: a Sustainable World, a Growth World, a Divided World, and a World at War. Each scenario examines the potential implications for Africa, focusing on how globalisation, sustainability and geopolitical shifts could shape the continent’s future.

Until recently, the current trajectory most closely aligned with the Divided World scenario, reflecting disaffection with the Western rules-based system. This scenario illustrates the acceleration of current trends toward a more fragmented global order and China's inexorable rise to great-power status toward the end of the forecast horizon.

The US withdrawal from multilateralism and its shift to a transactional approach toward others could lead to the unfolding of a Growth World scenario. The Growth World scenario is also characterised by increased corporate concentration, which yields better economic results than the Divided or World at War scenarios, but at the expense of equality and efforts to mitigate global greenhouse gas emissions, leading to negative climate change impacts. Trade competition between the US and the EU intensifies, while the economic complementarity between the US and China, the G2, drives global growth.

The Sustainable World scenario maximises Africa's economic potential, including improvements in income and poverty reduction. The international community acts in concert to balance growth and distribution by reducing overall consumption and constraining greenhouse gas emissions. The Sustainable World implies the evolution of the current rules-based system towards greater equity and balance. It is, however, the most difficult scenario to attain and most likely to emerge from a crisis, such as the World at War scenario or catastrophic climate change events.

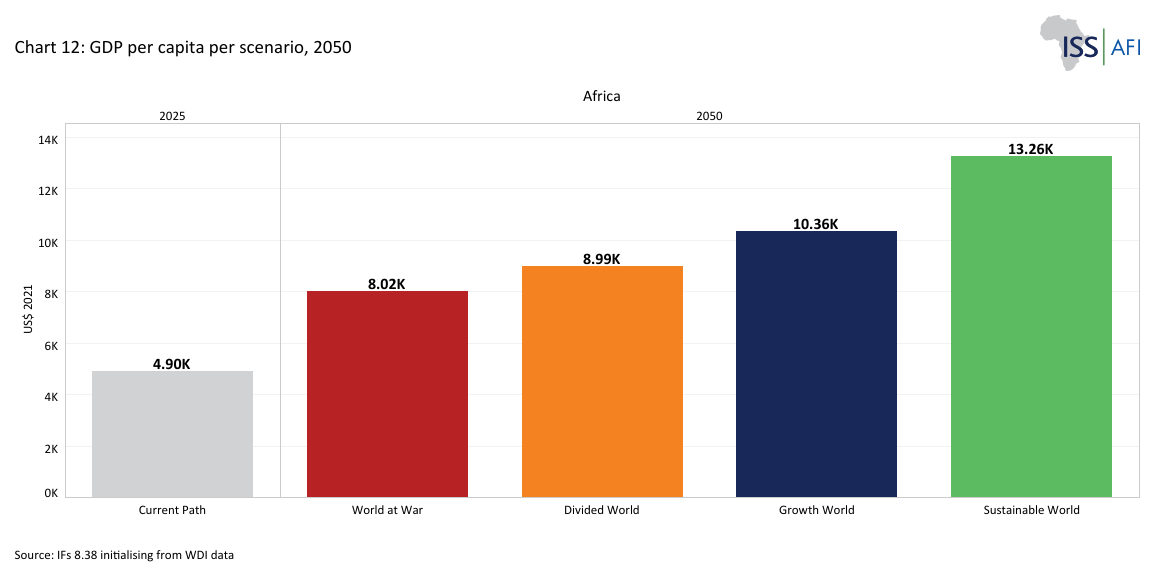

The World at War scenario is the worst-case for everyone, as overall gains are lower than in any other. War in Europe and the Middle East is followed by war in Asia. The scenario could originate from the war in Ukraine or from conflict in the Middle East, or, much later, in Asia as China and India come to blows. Military expenditures and inequality increase. Due to population growth, Africa continues to experience economic growth, albeit at a slow pace, but trends in GDP per capita and poverty reduction are flat or negative. The scenario facilitates China's earlier global dominance than in any other scenario.

Africa is complex and diverse, and the effects of the scenarios differ markedly between countries. Expectedly, Africa does best in the Sustainable World and worst in the World at War scenario. Regional integration, or the lack thereof, plays a crucial role in shaping the associated outcomes; however, even in the Sustainable World scenario, Africa will still struggle with extreme poverty across the forecast horizon.

Beyond Africa's development needs, two megatrends underpin the analysis: the accelerating impacts of climate change and technological advancements, particularly artificial intelligence. Only much deeper economic and political integration in Africa, complemented by more rapid and sustained economic growth, could offset the continent's limited role in shaping global orientations.

The analysis also considers the disruptive potential of various low-probability but high-impact wildcards, such as great-power implosion (in China or the US), expansion or contraction in the EU, and the impacts of artificial intelligence.

The theme concludes with a set of policy recommendations. Seen from an African perspective, the headline requirement is clear: geopolitical stability that provides space for Africa's development and avoids renewed efforts to instrumentalise the continent and its member states in the ongoing rivalry between China, Russia, the US and others. Alternatively, Africa should partner with the EU, India and others in pursuit of an equitable rules-based system.

All charts for Africa in the World

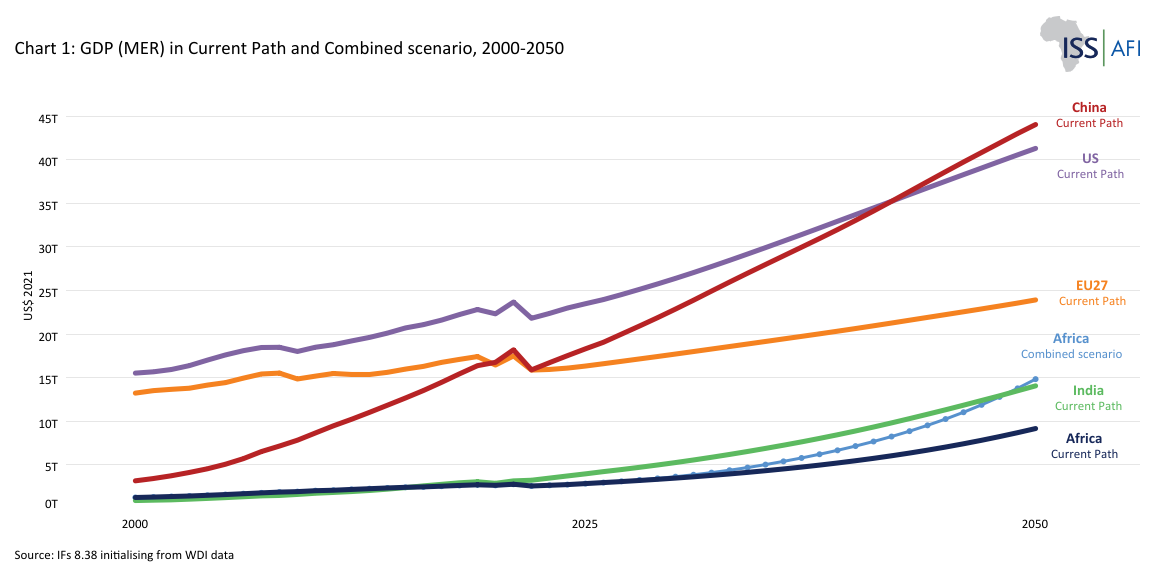

- Chart 1: GDP (MER) in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2000-2050

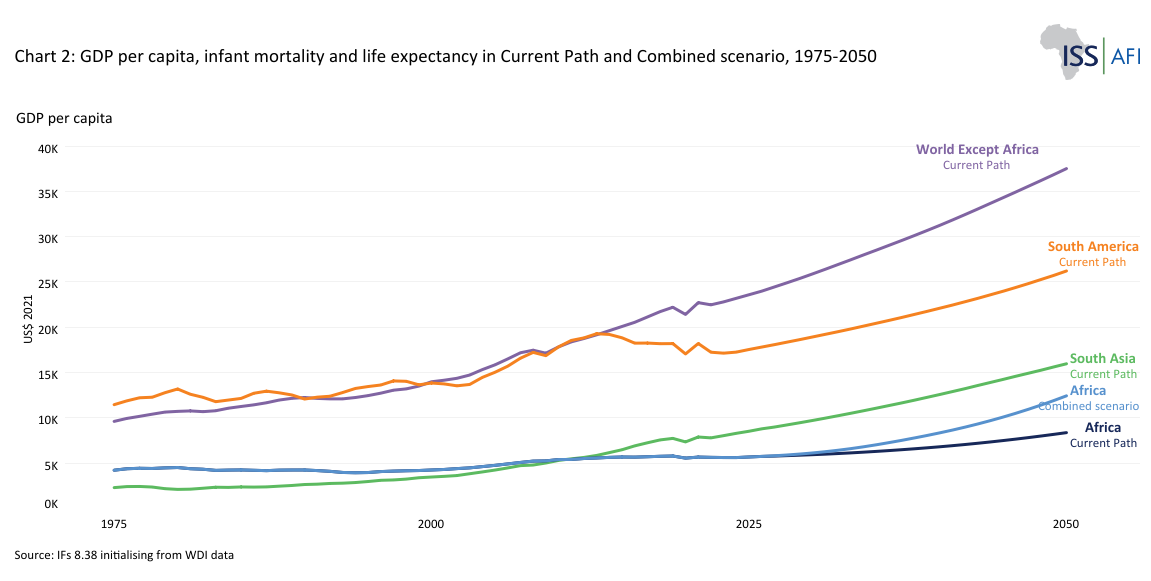

- Chart 2: GDP per capita, infant mortality and life expectancy in Current Path and Combined scenario, 1975 to 2050

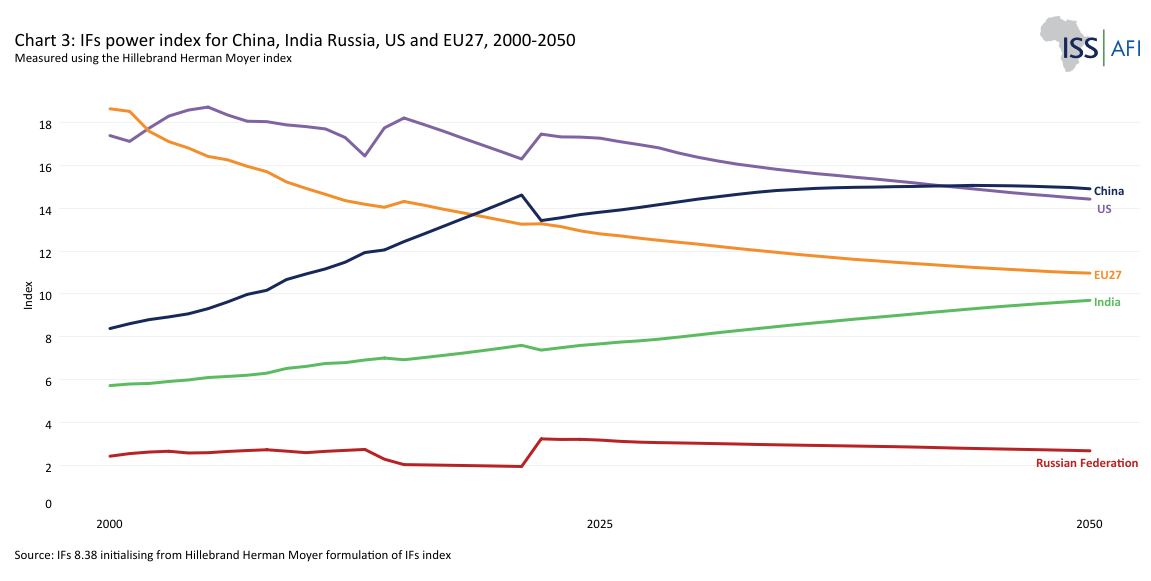

- Chart 3: IFs power index for China, India, Russia, US and EU27, 2000 to 2050

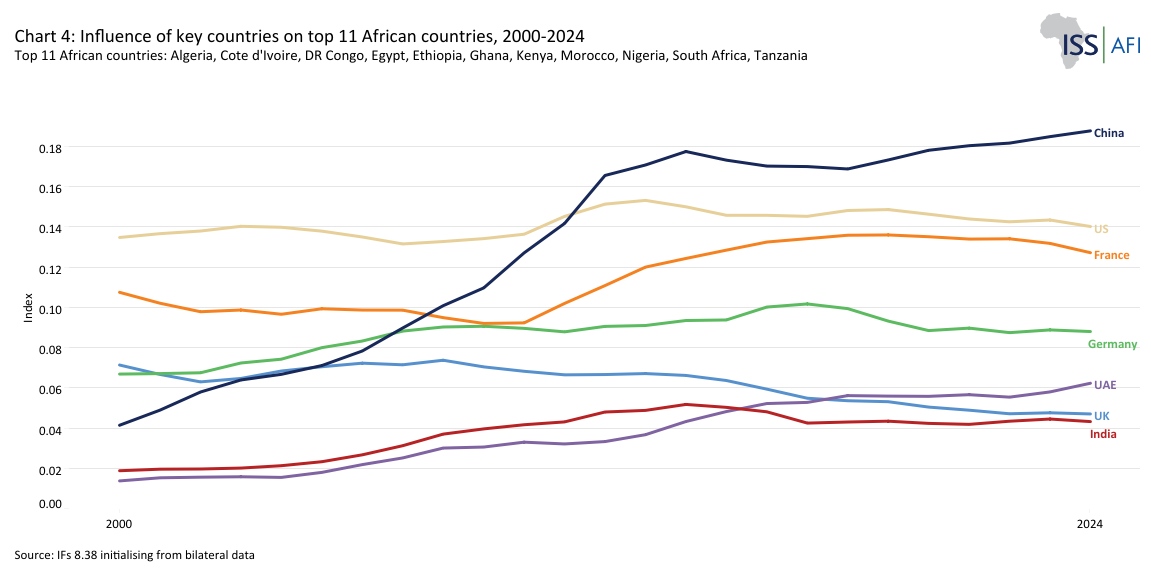

- Chart 4: Influence of key countries on top 11 African countries, 2000-2024

- Chart 5: Scenario framework

- Chart 6: Summary feature of four global scenarios

- Chart 7: GDP (MER) per scenario, 2025 and 2050

- Chart 8: Global military expenditure per scenario, 2025 and 2050

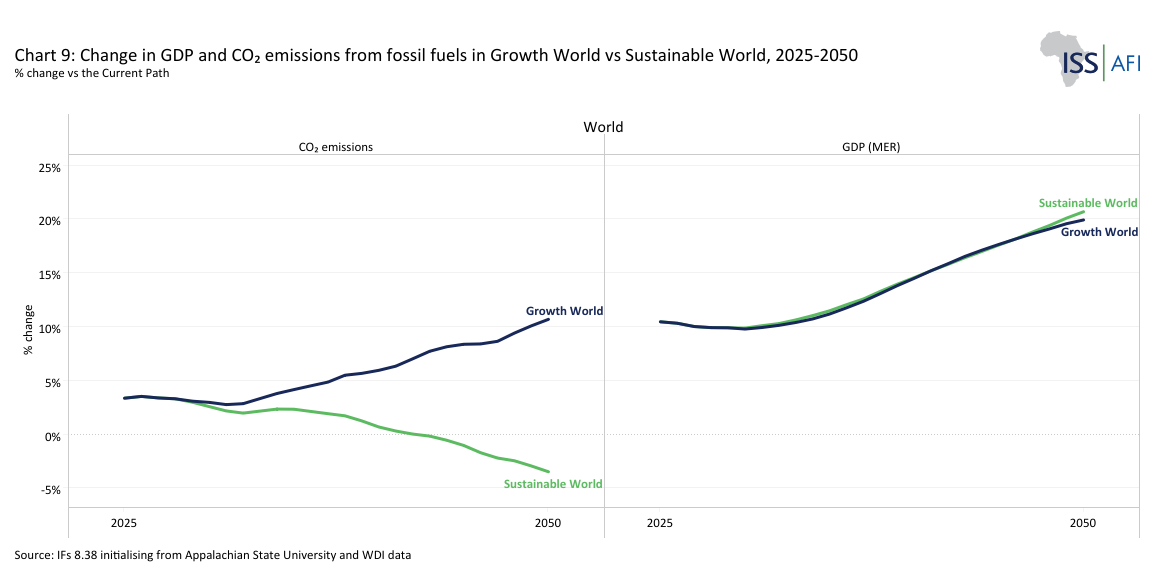

- Chart 9: Change in GDP and CO2 emissions from fossil fuels in Growth World vs Sustainable World, 2025-2050

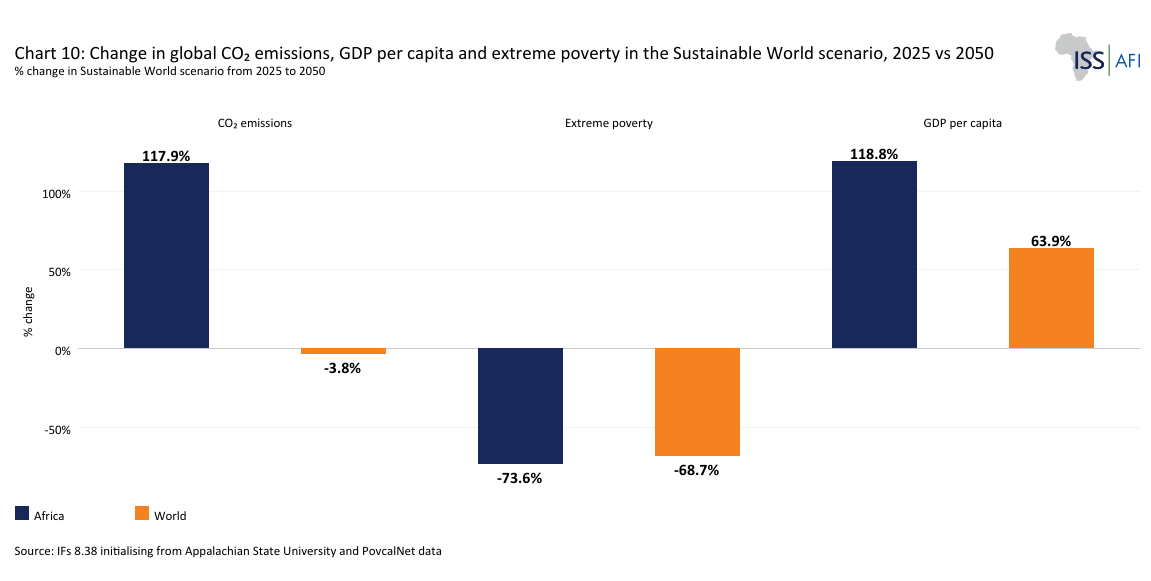

- Chart 10: Change in global CO2 emissions, GDP per capita and extreme poverty in the Sustainable World scenario, 2025-2050

- Chart 11: African scenario characteristics associated with each global scenario

- Chart 12: GDP per capita per scenario, 2025 and 2050

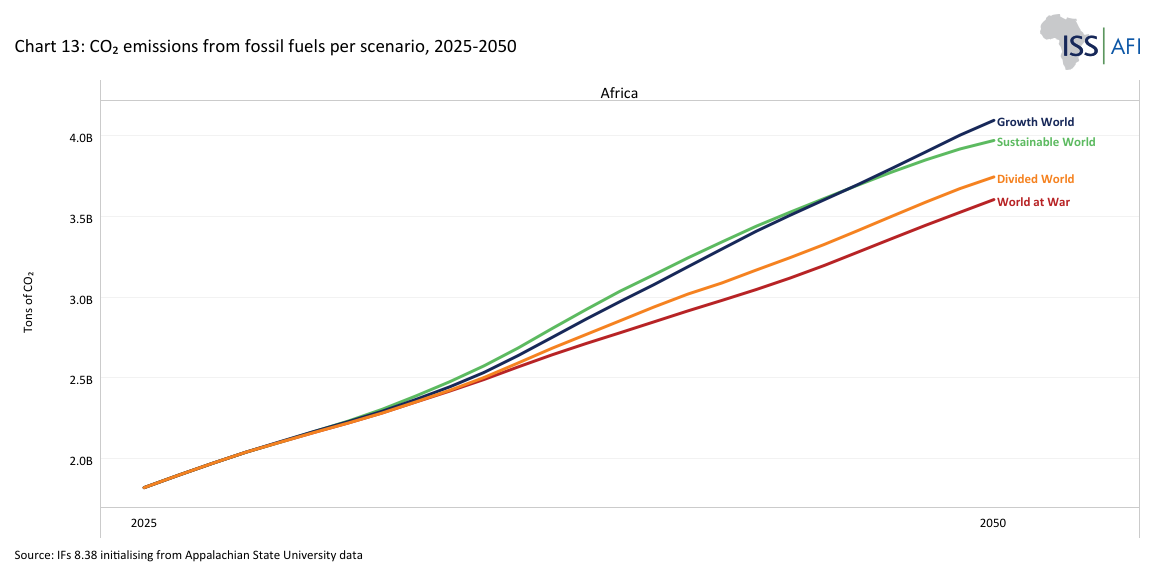

- Chart 13: CO₂emissions from fossil fuels per scenario, 2025-2050

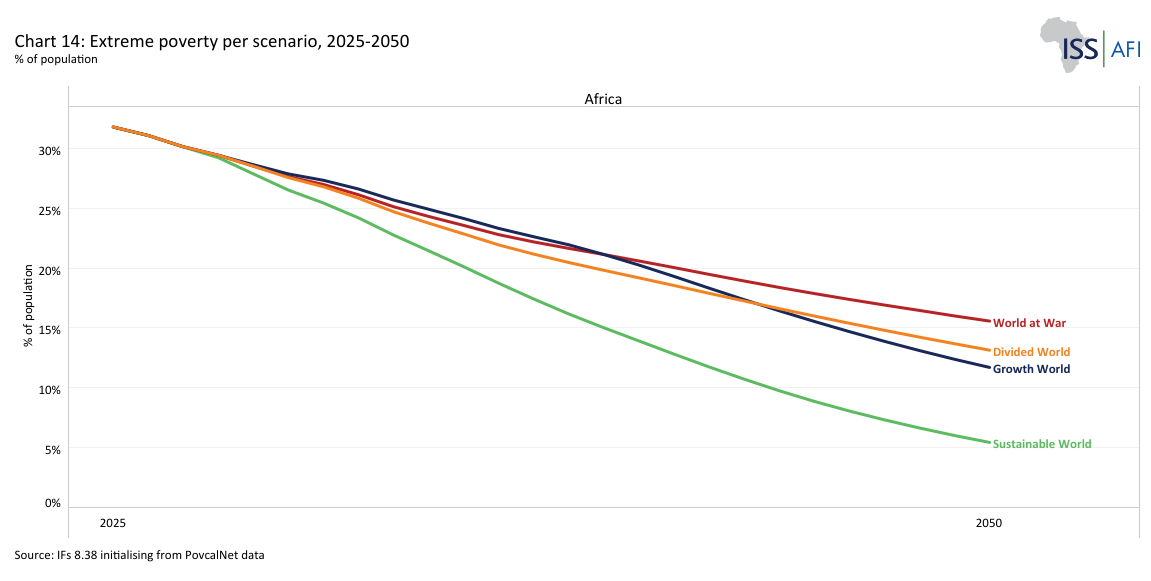

- Chart 14: Extreme poverty per scenario, 2025-2050

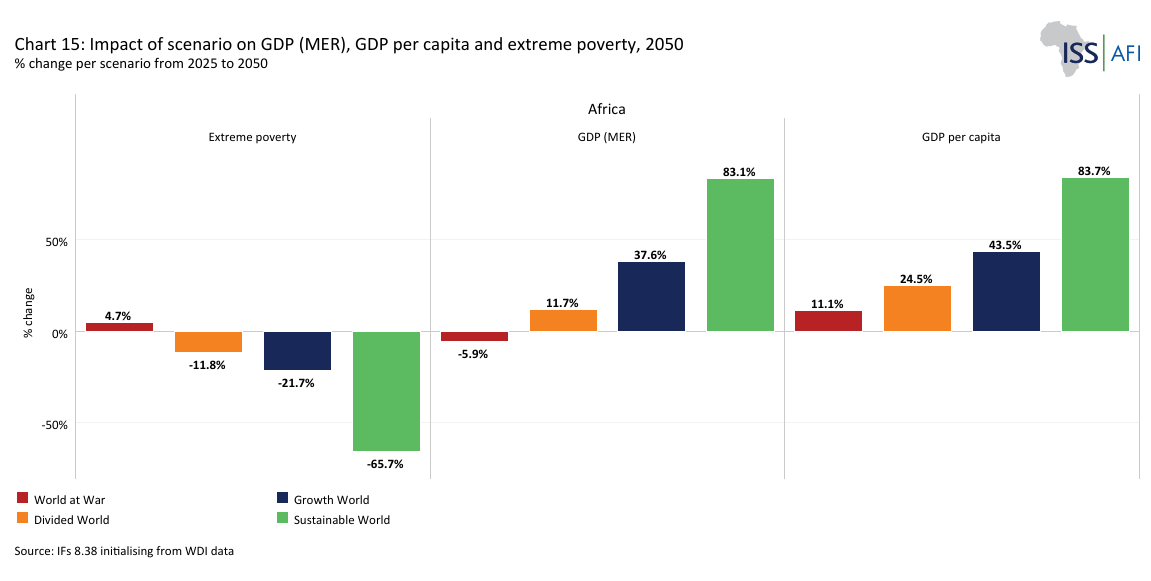

- Chart 15: Impact of scenario GDP (MER), GDP per capita and extreme poverty, 2050

- Chart 16: Recommendations from Africa

Africa’s development trajectory is deeply intertwined with global dynamics. This theme examines how shifts in global power and influence would shape Africa’s development prospects. The analysis incorporates results from modelling the global distribution of power and influence, drawing on various indices embedded in the International Futures forecasting platform (University of Denver) to help understand the likely evolution of a business-as-usual forecast (Current Path). The Technical page on this website provides details on IFs. The Global Power Index (GPI) provides a comprehensive, quantitative assessment of a country’s broad power capabilities relative to those of other states across the international system. The Diplomacy, Military and Economy (DiME) Index focuses on core capability components. The Formal Bilateral Influence Capacity (FBIC) Index assesses influence between country pairs.

Building on these insights, we frame Africa’s development within four alternative global scenarios: a Sustainable World, a Growth World, a Divided World, and a World at War. Each scenario explores the implications for Africa, highlighting how globalisation, sustainability and geopolitical shifts might shape the continent’s future. The analysis also considers the disruptive potential of wildcards, including a great-power implosion in the US or China, major regional developments in Europe or Asia, extreme impacts from climate change and the unintended effects of rapidly advancing artificial intelligence.

In assessing Africa's position in the world, it is useful to draw on the forecasts on Africa’s current development trajectory, the Current Path, and the continent's development potential, the Combined scenario. In 2025, Africa's economy accounted for 3% of the global economy. On the Current Path, it will increase to 5% of the world economy by mid-century, but could get to 7.3% in the high-growth Combined scenario. Rates of growth in African economies are steadily rising, and even under the Current Path forecast, the region is set to grow faster than any other region for much of the 21st Century because of rapid population growth.

On the Current Path, the combined size of the African economy should, before the end of the 21st Century, have overtaken the EU27 and India, and may even approach that of China and the US. But that is comparing the combined economic size of 55 countries with a single country, such as India or China, and only makes sense if Africa has, by then, achieved meaningful economic and political integration. Mid-century prospects are more modest.

Within Africa, Nigeria's economy accounts for 16% of the continent's total. By mid-century, Egypt and Nigeria are likely to have the largest economies on the continent, then comparable to Vietnam, Saudi Arabia and the Netherlands, placing these two African countries in the top 20% of global economies. By 2050, more than 25% of the world’s population will be African, and Nigeria will be the country with the third-largest population, overtaking the US shortly after 2040.

Much can happen in the intervening years. Various themes on the website model the impact of efforts to advance growth and development across different economic sectors, such as through improved education and a manufacturing transition. In the Combined scenario, the African economy will be roughly 60% larger by mid-century compared to the Current Path. The top three African economies (Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa) would be among the top 15% of global economies by size, rather than the top 20%, and the total African economy would have surpassed India in size by mid-century.

Since 2000, African countries such as the Seychelles, Mauritius and Botswana have performed well, with Ethiopia and Rwanda experiencing some of the fastest economic expansions in the world, averaging more than 7.5% per year in recent decades. However, with some exceptions since independence, Africa has not been able to narrow the gap with the rest of the world on key well-being indicators, such as infant mortality rates and life expectancy. Measures of income have done even worse. Using a crude measure, such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita in purchasing power parity (PPP), the gap between Africa and the average for the rest of the world (i.e., the world excluding Africa) has steadily increased, even when comparing Africa with other developing regions such as South Asia and South America. Chart 2 illustrates the recent history of the growing gap in average GDP per capita between Africa, South Asia and South America from 2000 and includes a forecast to 2050.

In recent years, seven successive shocks have accelerated the trend of increasing divergence in development indicators across Africa and other regions. These are: (1) the impact of the 2008/09 global financial crisis, (2) the COVID-19 pandemic, (3) Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and associated tensions, (4) the deteriorating relations between China and the West, (5) the resurgence of hostilities in the Middle East following events in Israel and Gaza, (6) the rise of populism in the US with the second presidency of Donald Trump and the subsequent disruption of trade and aid, and finally (7) populist trends in Europe with the resurgence of right-wing parties, leading to anti-migrant sentiments and reductions in development aid.

The world is entering uncharted territory, with the accelerated effects of climate change and the disruptive impact of generative artificial intelligence. Climate change could be particularly impactful, given Africa's reliance on imported food and its limited infrastructure. Among other climate-related risks is the growing threat of simultaneous harvest failures across the six global breadbaskets, which produce 60% of the world’s corn, rice, soy and wheat. Thus, the UN Secretary-General’s report, Our Common Agenda, notes that ‘we are at an inflexion point in history’ facing a stark choice between ‘breakdown’ and ‘breakthrough’.

On the one hand, one can ask to what extent the growing divergence between averages for Africa and the rest of the world will impact global sustainability and stability, including the demand for critical minerals and increased migration to Europe and within the continent. Is it possible to envisage a stable world so starkly divided between Europe and Africa in wealth and quality of life? For example, the average GDP per capita in Africa is only 11% of that in the European Union (EU), and there is a 14-year gap in average life expectancy. We expect these differences to only reduce marginally over the next two decades.

On the other hand, global disruptions mean that growth paths are diverging, and trade and financial systems no longer hold as strongly. What we are witnessing is not a temporary disruption but a reality shock: a moment when inherited narratives collide with a world that is fragmenting, competing and reshaping itself in real time. African resilience will require more robust, capacitated states with fit-for-purpose institutions, enhanced security and improvements across various economic and human development sectors, many of which are within Africa’s domestic policy space. We examine many of these considerations in separate pages on this as part of our geographic and thematic analyses.

Rapid development in Africa will also require a facilitating global environment—the subject of this theme. Therefore, we ask what the impact of geopolitics on Africa's development is. To explore the potential implications, we model Africa's development across four future global scenarios, outlined below.

The shift of the global centre of economic gravity from the North Atlantic eastward to Asia is well established and widely reported. The result is a commensurate reduction in the West's relative economic and political weight, now increasingly divided between the US and its former North Atlantic partners, accompanied by the rise of additional sources of capital and influence, such as those from the Middle East (particularly the UAE and Saudi Arabia). The result is a clear trend towards regionalism that reinforces global fracturing. At the height of globalisation, global trade grew more rapidly than global GDP. It is now stable as a percentage of GDP, with trade within politically aligned blocs now growing faster than trade between them, reflecting a splintering into more deeply integrated blocks. For example, today, Asia’s economy is less dependent on trade with other regions and is increasingly more integrated and self-sufficient.

For over a century, the US has been the most powerful country in the world (both in hard and soft power terms). It has successfully presented a narrative that equates global development, stability and progress with American interests. The close connection it has established between democracy, the free market and so-called Western values, however, is starting to fray and accelerating as US President Donald Trump rails against friend and foe alike. Matters came to a head with the publication of the US National Security Strategy in November 2025, which calls for political change in Europe, its purported ally, and the subsequent withdrawal of the US from 66 international organisations early in 2026. The focus on bilateral relations and direct economic benefits rather than democracy, human rights and good governance is a stark departure from the policies pursued by previous administrations.

The US has derived considerable advantage from its dominant global position. Globalisation allowed it to attract investment and allowed the US (and Europe) to manipulate the international system to its benefit. The status of the US dollar as the global reserve currency enabled the US to consistently run a larger current account deficit than most other countries. That advantage will fade in the years ahead as the use of national currencies between regions and countries, such as between individual African countries and China, gains momentum.

The fracking revolution in the US, together with the fallout from the war in Ukraine, means that China has become the most significant fossil energy market for the billions of dollars of oil exports from the Middle East, Russia, Venezuela and others. A new world energy order is emerging that will eventually transact in various currencies, not just the dollar. That shift will set the stage for the steady diminution of the dollar-based financial system and the benefits it brought to the US. While China powers ahead, expanding its regional relations through the Belt and Road Initiative and other initiatives, the US now regularly flouts key norms such as the use of force only in self-defence. The reaction to globalisation across rural America and the rise of domestic populism have led to a resurgence of nationalism and isolationism, detracting from US soft power. Trust in the US is declining amid divergent approaches by successive presidents (Obama, Trump, Biden and Trump again) on Ukraine, North Korea, Russia and Taiwan.

Given the economic growth in Asia and elsewhere, the sum effect is that the US's soft power advantages are declining. More recently, the impunity that the US has provided to Israel for the war that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu pursued in Gaza in the wake of the terror attacks by Hamas of 7 October 2023 has reinforced views in the Global South that different standards apply for people generally considered part of the 'civilised West' versus the rest.

Perceptions of hard power are also shifting. Clearly, no other country can match the US's military sophistication and hard power capability, but its engagements in semi-conventional operations, such as in Afghanistan and against ISIS, are less impressive. The declining efficacy of US weaponry on the Ukrainian battlefield has not gone unnoticed, despite the skill and expertise demonstrated with the capture of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro on 3 January 2026. Without a commensurate manufacturing base, such as China's, the US will struggle to sustain extended conventional combat.

The inevitable power transition between the US and China is confirmed by work published early in 2022 by our colleagues at the Frederick S Pardee Institute for International Futures. Using 29 alternative scenarios in its Diplomacy, Military and Economy (DiME) Index about the future diplomatic, military and economic capabilities of the US and China (including forecasts of nuclear weapon stockpiles), the Pardee Institute concludes that Chinese capabilities surpass the US's in 26 scenarios before 2060, with the most frequent period of power transition being the early 2040s. Chart 3 presents one scenario result, showing the percentage of global power held by the EU27, the US, India and China from 2000 to 2050, using the Hillebrand Herman Moyer Index (IFs index). The key question is whether the US will pursue its traditional partnerships in the West, particularly with the EU, or whether it will eventually seek what is effectively a grand bargain with China to consolidate its dominance of the Western Hemisphere.

The picture for the US is bound to change rapidly following the disbandment of USAID in 2025, which was previously the largest provider of humanitarian aid to Africa. US interest in Africa has waned over many years, reflected in declining investment, and will be accelerated by the shrinking of its diplomatic corps and by the limited focus evident in its 2025 National Security Strategy and 2026 National Defence Strategy.

Much depends upon the EU. With an economy currently roughly comparable in size to those of China and the US, though declining, the EU is the most important advocate of a rules-based system and its domestic policies evidence efforts at a balance between the power of the market, technology and government, reflected in antitrust activities to Internet privacy, membership in international organisations, the pursuit of democracy and support for human rights. Still, it suffers from an acute deficit in hard power capabilities compared to the US and China. Its social-democratic or more egalitarian model of development, particularly that of the Nordic countries, stands in sharp contrast to the raw capitalism in the US and the denial of individual rights in China, although that model is steadily in question with the rise of populist parties in key member states, including Germany, France, Italy, Sweden and others.

Given colonialism, it is not surprising that the EU group had significantly more influence in Africa than even the combined influence of China and Russia. However, it is declining.[x] Similar to the US, nationalist populism is driving politics in Europe, and it will negatively affect its relations with Africa, particularly regarding concerns around migration, culture and religion.

Western countries evidence a trend of power diffusion away from the state, which is today less central in many people’s lives as additional patterns of interaction emerge. The decline in manufacturing, new technologies, the internet and lately artificial intelligence, all detract from social cohesion, infusing hate speech, extremism and conspiracy theories into echo chambers on social media that serve to divide rather than cohere society. These technologies detract from the ability of democracies to offer freedom of speech and access to information in a balanced and unbiased manner, which are now increasingly manipulated by commercial interests (social media in particular) and foreign actors such as Russia, while strengthening the ability of centralised systems in authoritarian countries, such as China, to monitor and control their populations.

A range of non-state actors, including those from the private sector, civil society and social media influencers, now serve as alternative sources of authority and reference, complicating and crowding the space previously occupied by traditional media, bureaucracies and elected representatives. Their influence is particularly significant through Big Tech, with companies such as Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, Meta (formerly Facebook), Microsoft and Nvidia, which, due to their substantial market influence and size, wield considerable political and market power in the US and globally, facilitated by an open door at the White House.

In the meantime, the flow of materials from Africa to China, along with Beijing's investments in infrastructure and trade with the continent, is altering Africa's external relationships. Using an index measuring influence (see Chart 4), China has steadily increased its influence over the top 11 largest economies in Africa, while the UK has seen the largest decline. These 11 countries are Nigeria, Egypt, South Africa, Algeria, Morocco, Ethiopia, Kenya, Ghana, Cote d’Ivoire, Tanzania and DR Congo. The UAE has also increased its influence, surpassing that of the UK and India. The recent surge in anti-French sentiment in its former African colonies speaks for itself, as it has been ejected by military governments from Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso and Chad, as well as by the democratic government of Senegal.

The trend with Russia is dissimilar. Following a decline in Russian influence for much of the 1990s, Moscow has made a concerted effort to benefit from the waning support for the West in the Sahel by providing security and arms to several military governments in West Africa in the wake of its invasion of Ukraine. With limited economic leverage, however, Russia's proxy war with the West in Africa has its limits. With an economy that is the size of Brazil, Russia lags significantly behind great powers such as the US and China

In considering these findings, it is essential to recognise the benefits that accrue to the US (and Europe) as the historical ‘system makers’ and, therefore, ‘privilege takers’ of the current global order. This group of industrialised, rich countries share several core values (such as a market-based economy, democracy and human rights) and various cultural traits. The North Atlantic powers have dominated world affairs since the Industrial Revolution, shaping today's rules, norms and values to determine interstate relations in their interests.

Should we consider these countries as a single group and juxtapose them with countries aligned with China, the relative power and influence of the West remains dominant globally. The wealth and technology of its citizens and states significantly outpace those of others. Despite the rise of China and Asia, the GDP per capita gap between North America, Europe and Japan, compared to China, has remained relatively constant and is likely to increase. Thus, the comparative advantage of citizens and countries in the West versus China and its few true partners, such as North Korea, Cambodia and others, remains large across the forecast horizon. All of this, of course, is undermined by the growing divisions between the US and its erstwhile partners that erode the West's advantage.

As a single country, China will become hugely influential within our forecast period. Its material or hard power capabilities eventually surpass those of any other country, including the US. With its focus on multilateralism and non-intervention, norms that are popular in the Global South, China will also steadily close the soft power gap with the US and others. Its rise, however, does not translate into globally dominant power capabilities unless the fractures emerging within the West deepen considerably.

Thus, the global trend is toward a complex, multipolar global power configuration. In these times of upheaval and change, the past is not an inevitable guide to the future. Thus, the risk of a new bipolar order dominated by the US and China looms large unless countries and groups such as Europe, Africa, India and others can cohere to establish a third alternative, rooted in a revised and reformed rules-based system. The US and China together account for 43% of the global economy, and both are growing much faster than the EU, although the US regularly runs a much larger trade deficit with China than with the EU.

The rise of China could shift the geopolitical orientation of Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand in its favour as leaders position themselves to benefit from it. New alliances may also emerge, such as between India and Japan. On the other hand, a Chinese decision to incorporate Taiwan and continued internal repression and human rights issues concerning communities such as the Uyghurs in China could exacerbate current regional divisions. The unification of the two Koreas would likely shift that country into a non-aligned grouping or China's orbit, given the proximity impact and the accompanying trade-offs. Similar to the problematic history of the US's relations with Central and South America, China's growing influence is encouraging efforts to resist its domination in Asia, particularly by the six or so countries that have territorial disputes with it.

Views on China's global ambitions differ. On the one side are views that China’s primary interests are ‘foreign resources and markets, not foreign colonies.’ Thus, its grand strategy of building global infrastructure and engaging in regions such as Africa aims to reduce its dependence on the West, bind its neighbourhood more closely together, and reduce its reliance on foreign suppliers, including minerals from Australia and high technology from the US. In this view, China’s ambition is regional, not global dominance, but it does require a facilitating international context. Students of Xi Jinping, such as Steve Tsang and Olivia Cheung, hold differing views. Their book, The Political Thought of Xi Jinping, makes a compelling case for huge ambition, to 'make China great again'. The successive release by President Xi of China's proposal on Building a Community with a Shared Future for Humanity, its Global Development Initiative, a Global Security Initiative, its Global Civilisation Initiative and proposals on Reform and Development of Global Governance, present a comprehensive alternative framework to the Western rules-based system including on views on national sovereignty, national development, human rights, climate change, green and low-carbon development, globalisation, the role of the private sector, and more. It presents a model of domestic and foreign relations where regional powers are likely to dominate, free from interference from elsewhere, and where governments pursue national policies without the constraints of a free media, foreign interference or the need to balance the executive, judiciary and legislature—all subject to the requirement to pay due homage in a Sino-centric world. Many countries in the Global South, including those in Africa, support this approach, even as their populations remain enthusiastic about democracy and the protection of human rights.

While the West will continue to dominate in many aspects of material and soft power calculations, a growing divide is emerging between the Global South and within the Global North, as bickering and trade friction between the US and the EU intensify.

Africa: A Pawn rather than a Player?

Download to pdfAgainst the background outlined above, we next consider Africa’s place and power in the international arena.

After independence, Africa’s standing was elevated, with East and West competing for influence until the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989, which diminished its strategic value. Until then, important states on the continent were courted with money and arms as part of the Cold War competition between Washington and the Soviet Union. Democracy and human rights considerations were generally trumped by loyalty, although sections within the development assistance community in some Western countries pushed back against this crude division.

After that, Africa’s oil exports and location in the US war against terrorism briefly elevated its status at different times. Violent, political Islam spread from Afghanistan and Syria to North-West Africa and East Africa, primarily driven by the displacement effect of US military interventions in Asia and the Middle East. The period coincided with a brief unipolar moment during which the US achieved peak power and influence in the absence of a rival.

Africa’s importance again dissipated thereafter, allowing for a brief period during which development priorities rose in international prominence. That period culminated with the agreement on the Millennium Development Goals in 2000 and, in 2015, on the Sustainable Development Goals. The boom in hydraulic fracturing for oil and gas in the US that started in these years effectively ended its dependence on imported fossil fuels and, hence, its concerns about stability in the Middle East as well as in key African states such as Angola and Nigeria, and the support that the US had provided to oil-rich autocracies.

European–African relations have been deeper and more enduring than those with the US, not surprisingly, given the legacy of colonialism. Europe shares the same time zones and key languages, and the two are geographically proximate. As a group, Europe is Africa’s largest trading partner, although China is the continent's largest single trade partner. Europe also has the most extensive stock of foreign direct investment in Africa. However, the growing popularity of right-wing parties in the UK, Sweden, Germany, France and Italy is the single most consequential domestic trend in several decades and is increasingly shaping Europe's foreign and international relations with Africa. At its extreme were responses by the UK and Italy that planned to send African asylum seekers to Rwanda and Albania on a one-way ticket. Other measures include the hardening of borders, such as those implemented by Spain, and large grants and loans to countries such as Egypt, in return for efforts by the government of President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi to clamp down on migrant transit to Europe. Structurally, the tensions are fuelled by globalisation, the shift of blue-collar manufacturing jobs to Asia, and rural-urban political divides in rich countries. These tensions also feed off deep-seated historical, religious, and cultural divisions and fears that date back centuries.

In contrast to the declining relations with the US and Europe, China’s footprint and influence in Africa have become more important each year. ‘No other country comes near the breadth and depth of China’s engagement in Africa,’ wrote The Economist in an in-depth study of the relationship in May 2022.

During the 1960s and 1970s, as the Cold War intensified, China–Africa relations were marked by strong political and ideological ties. In 1971, when the UN voted to replace Taiwan with China, 26 African countries voted in favour. Itself a poverty-stricken country, China provided military support and aid to the African continent. The construction of the Tazara railway line in support of the frontline states in their conflict with apartheid South Africa, then primarily supported by the West, serves as the most prominent showpiece.

China’s relationship with Africa underwent significant changes during the 1990s, as it grew in both economic and political importance. A booming China needed oil and metals, and eventually found an outlet for its sizable current account surplus, as well as work for its construction companies that had built its roads, railway lines, and ports, perfectly matching Africa’s need for investment and infrastructure. China’s annual loans to Africa decreased with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic but have since rebounded. Trade and return on investment are now more critical for China, even as it continues to buy favours in Africa, such as the recent gift of a building (and bugging) the tower block that hosts the offices of the African Union Commission in Addis Ababa, and building modern parliament buildings for Zimbabwe and Malawi. Zimbabwe, which has an external debt of US$21 billion, is heavily indebted to China, the only country willing to extend loans to Harare due to its deficient domestic investment environment, poor governance, and dismal repayment record.

After a COVID-19-induced decline in 2020, trade between China and Africa rose by 35% to US$245 billion in 2021 and to US$295 billion by 2024. China is Africa’s largest bilateral creditor (as a group, Western private banks have a larger share) and a crucial source of infrastructure construction and investment. Its projects are also concluded more rapidly. The average infrastructure project in the Belt and Road Initiative takes 2.8 years, roughly a third of the time needed by the World Bank or the African Development Bank, in part because environmental impact studies and other regulations are sometimes bypassed. Whereas the West provides aid and, through various agencies, concessional loans, Chinese development finance generally takes the form of near-market-rate loans, much of it for infrastructure.

China’s hard-nosed practice is quite different from its benevolent ‘win-win’ rhetoric. Contracts include strict confidentiality clauses, requirements that China be repaid ahead of others, the use of escrow accounts and specific identification of which revenues would be required to repay loans. Because Chinese creditors are numerous and fragmented, keeping track is complex. More than one newly elected African leader (most recently, President Hakainde Hichilema of Zambia) has found that the amounts his country owed to China were much higher than initially thought, once so-called hidden debts were also counted.

China’s role in Africa is expanding beyond trade and loans. Already, Chinese firms account for an estimated one-eighth of the continent's industrial output. Its digital infrastructure is critical to Africa’s communication, much of which was built by Huawei, a company under US sanctions. The result is that political, military and cultural ties are all becoming closer. African views about China are evolving and are now more favourable than those of the US. However, a majority of Africans still list the US significantly ahead of China as a preferred future model, given its more open system of governance.

Relations between China and Africa have, therefore, deepened. In July 2024, Tanzania hosted the largest-ever Chinese military deployment to sub-Saharan Africa for Exercise Peace Unity-2024, which included troops from neighbouring Mozambique.

The response in the West to China’s growing influence in Africa has been alarmist, with recent efforts to counter the Belt and Road Initiative in Africa and elsewhere. In 2021, the Biden administration launched Build Back Better World, and the EU launched Global Gateway; in 2022, the G7 club announced its Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) to mobilise US$600 billion in infrastructure projects over the next five years, with a particular focus on Africa. And for a brief few years under the Biden presidency, senior US and European diplomats visited the continent.

Despite its large population, Africa is a small global player, with its combined influence diminished by the number of its constituent countries and its current lack of economic and political integration. Without a supranational authority such as the EU Commission and its various structures and much deeper economic integration, the calculation of Africa’s power potential is inevitably less than the sum of its more than 50 members, which, using the IFs power index, constituted less than 10% of global power in 2025. By 2050, Africa would increase its portion of global power to 13%. Unlike the EU, the Commission of the AU is essentially an intergovernmental secretariat with limited and circumscribed policy latitude. The continent still has to register practical progress on trade integration through the early signs with the African Free Trade Area are promising.

However, there is also a flip side to Africa’s large number of constituent states, illustrated by Russia’s recent charm offensive that followed its invasion of Ukraine and subsequent sanctions and ostracism from the West. Russia accounts for almost half of Africa’s arms imports. It is a major supplier (along with Ukraine) of Africa’s cereal imports, which was severely disrupted by the war between the two. Russia accounts for only 1% of the continent's stock of foreign direct investment (FDI). This is minute compared to the 36% stock of Europe's FDI in Africa, and recent FDI flows from China, Africa’s largest trading partner.

The large number of African states and their relative weakness mean that they offer numerous opportunities for Russia (and others) to pursue a proxy war with the West. For example, they could provide military support (through the Wagner group, now known as the Africa Corps) and protection to coup makers in the Sahel, leading to the ouster of French and US forces from the region.

Africa’s economic growth and population increase will steadily increase its power potential but more slowly than most analysts think.

An important reason is that Africa’s labour force is relatively small in relation to its dependants (children and the elderly), although it is increasing rapidly, while workers suffer from low levels of education, with some exceptions, and poor health. Africa is rapidly approaching a double burden of disease as the rates of non-communicable diseases are increasing rapidly. The result is that Africa’s labour productivity is about one-fifth the average of the rest of the world, and together with high poverty levels and low incomes, the capital per working-age person is even less.

Although it receives relatively large amounts of capital through remittance inflows and aid, Africa loses substantial amounts due to corruption and illicit financial outflows. Because of extreme poverty levels, unemployment, high levels of inequality and limited government revenues to improve basic services delivery, key African countries, including Nigeria, South Africa and others, experience high crime levels and poor governance. However, perceptions of instability are often generalised, not distinguishing between developing and stable countries and those in conflict. Finally, much of Africa’s physical capital, such as roads, rail, water, electricity and other essential infrastructures, is still of a colonial-era vintage. Still, it is being improved mainly due to recent investments by African governments and China in railways, ports, and associated infrastructure.

Manufacturing and services will expand rapidly on the continent – although much of this growth will initially be at the lower end of the value-add curve due to Africa's dependence on commodity exports. Until recently, the evolution of complex global supply chains meant that the location of least-cost manufacturing tended to gravitate towards the region with the cheapest labour, domestic stability, policy certainty, and access to a large market, typically Asia. Given reductions in input costs, the push towards reshoring and diversification and the need to reduce carbon emissions provide incentives to locate manufacturers closer to the future market in which Africa features prominently. Sub-Saharan Africa will increasingly feature as a location where industry can thrive. However, this depends upon the rapid integration of its fragmented markets, infrastructure provision, investment in improving its human capital endowment and better governance.

Eventually, regional economic communities with common currencies, freedom of movement of labour and capital across borders, and standard import and export tariffs will increase Africa’s attraction as a location for manufacturing. Indeed, Africa took a big step towards this goal when its members ratified the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA).

These prospects do not hide that Africa has effectively been an instrument of global power competition since independence, reflected in the preceding analysis, although health and humanitarian relief considerations have also been prominent. Its limited influence is hardly surprising since Africa's entire economy is only 3% of the world economy. On the Current Path, it will increase to 5% of the world economy by mid-century but could get to 7.3% in the high-growth Combined scenario. The increase largely results from the continent’s rapidly growing population in addition to improvements in productivity, although from a low base. Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, constitutes a mere 0.5% of the global economy and will increase that portion by only 0.1 percentage points to 0.6% by 2050,(or 0.9% in the Combined scenario). Within Africa, its economy accounts for 16% of the continent's total.

Against that background, the following section presents four global scenarios and then examines their impact on Africa.

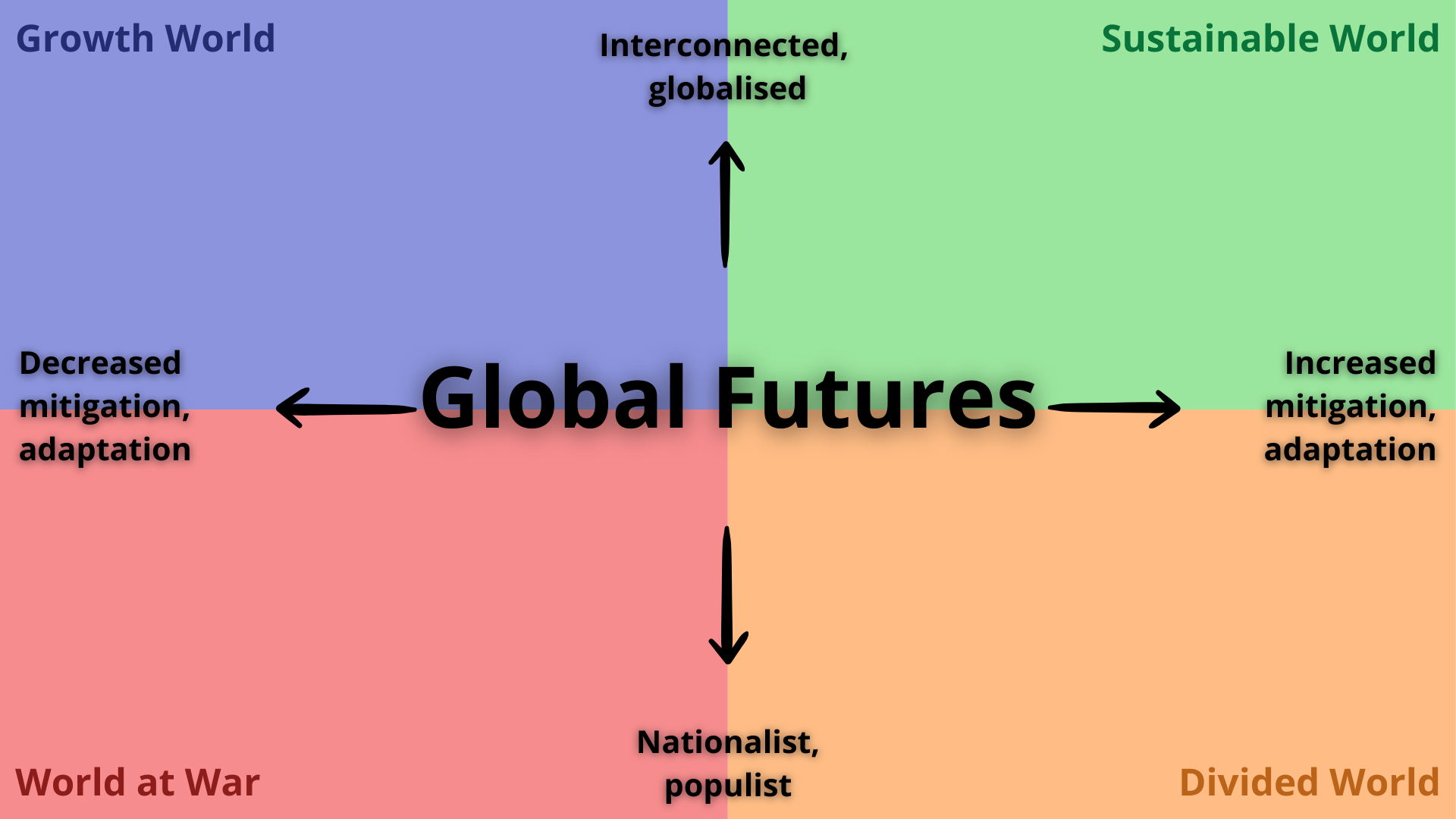

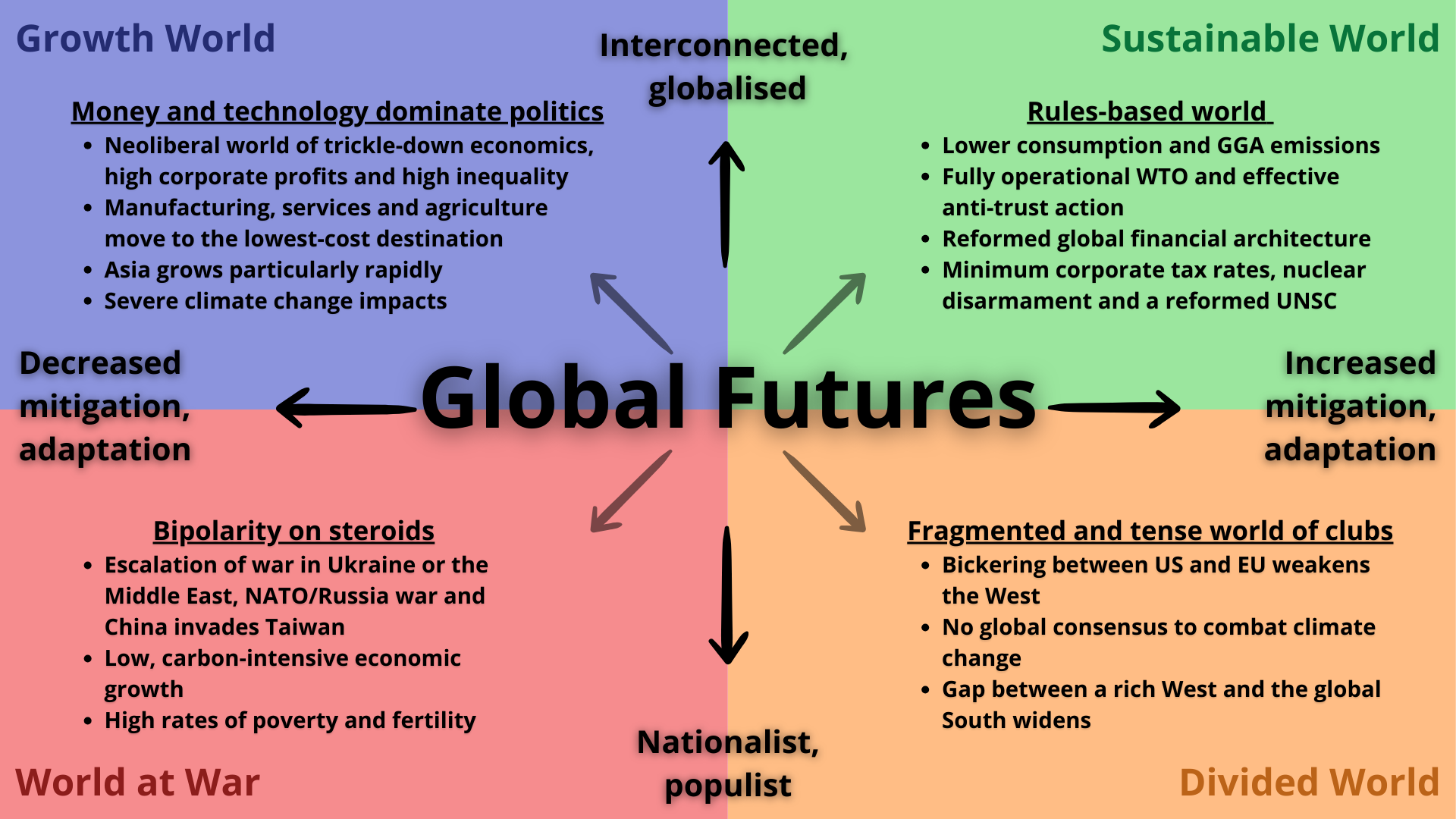

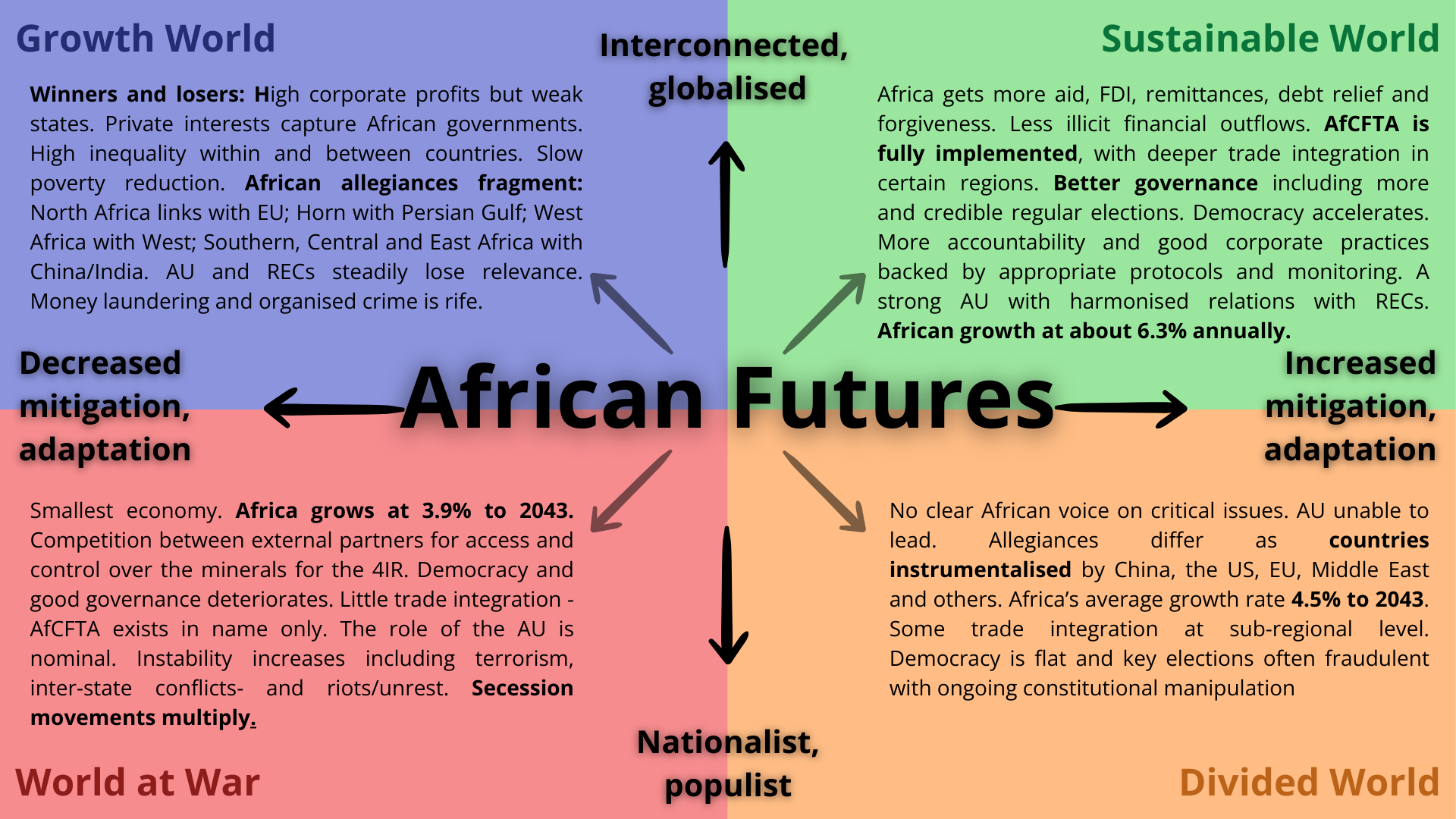

We frame Africa’s development within four alternative global scenarios based on the above-mentioned trends and measurements. We use two key dimensions that represent fundamental, highly uncertain forces shaping the international system, each with significant implications for development, geopolitics, and environmental resilience, depicted in Chart 5. The extent of globalisation (vertical axis) captures the degree to which countries and regions remain interconnected through trade, technology and cooperation—or shift towards fragmentation and regionalism. The pursuit of sustainability (horizontal axis) prioritises equitable growth, environmental stewardship, and long-term resource management over unchecked exploitation and short-term gains.

These dimensions form a framework with four quadrants, each representing a possible future scenario based on how these uncertainties might unfold: a Sustainable World, a Divided World, a World at War and a Growth World.

No scenario seeks to present the current global trajectory, which would inevitably fall somewhere between these ideal types but is currently most akin to the Divided World scenario, with potential to morph towards a Growth World.

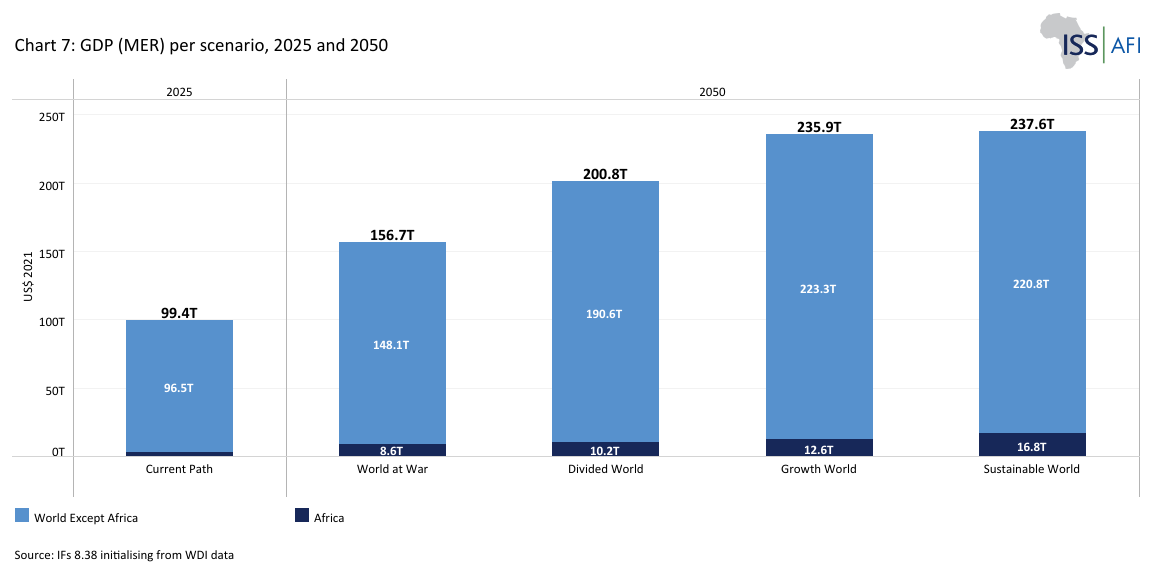

The first scenario, a Sustainable World scenario, prioritises sustainability, equity and achieving the objectives set out in the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Rapid and ambitious regional integration lies at the heart of this scenario, progressing from an African continental free trade area, then a customs union and eventually a common market that allows the free movement of capital, labour, and services across most countries. In this world, Africa progresses as outlined in the Combined scenario on this website, marked by steady gains in productivity, accountability, democracy, and stability. The Sustainable World maximises economic growth with a 2050 global economy of US$237 trillion (compared to US$110 trillion in 2025), improves income, and reduces poverty. However, it is the most difficult to attain given its focus on multilateralism, environmental sustainability and equity.

In a second Growth World scenario, countries focus on rapid improvements in income and returns on investment, eschewing environmental concerns, within the context of a grand bargain between the US and China. Commercial and trade interests dominate, and by 2050, the world economy will be roughly the same size as forecast in the Sustainable World scenario. Still, the Growth World will release 13% less CO2 from fossil fuels, one indicator of the differences between these two futures. The Growth World leads to impressive economic results, but at the expense of equality and efforts to contain global greenhouse gas emissions, resulting in negative climate change impacts, slower reductions in extreme poverty, and increased inequality.

Instead of the continental integration characteristic of the Sustainable World, in the Growth World, African countries and regions link up with external partners in Europe, the Persian Gulf, the US, and China, signing preferential agreements. Different rules apply with each partnership, and considerations regarding human rights and democracy play a relatively minor role. The AU is eventually marginal, with countries and groups of countries pursuing the advantages of partnering with Europe (North Africa), the Persian Gulf (the Horn), the US (West Africa), and China (Southern, East, and Central Africa). More importantly, the Growth World will have 173 million more extremely poor people than the Sustainable World, most of whom will be in sub-Saharan Africa.

The third indicative scenario is a Divided World, with a future characterised by global fracturing, populism, nationalism, and a retreat from globalisation — effectively, the fraying of the rules-based system as we know it, with its complex lattice of norms and institutions. Everyone seems to be angry, selfish and unhappy and xenophobia and anti-migrant sentiment increase as rates of migration accelerate. National and competitive interests dominate in Africa as bickering and beggar-thy-neighbour policies escalate, although there is some trade integration at the sub-regional level. Economic growth is tepid, and poverty reduction is slow. In addition to constant interference in the domestic affairs of their neighbours and domestic oppression, Africans again allow themselves to be instrumentalised by external partners, although governance and development improve in a number of countries. By 2050, the size of the world economy is US$200 trillion, roughly 15% smaller than in the Growth and Sustainable World scenarios

The fourth scenario is a World at War, where competition within and between the US and China dominates all aspects of the global economy, politics and relations with violent outcomes. In addition to fragmentation in Libya, Sudan and the Sahel, more African states fracture as competing armed groups vie for power, including large countries such as the DR Congo. Shut out of the prospects for more rapid development, Africans suffer. Poverty increases as economic growth is insufficient to improve incomes, given more rapid population growth typically associated with instability.

The World at War scenario is the worst case for everyone, as overall gains are lower than in any other scenario with successive wars between major powers. Autocracy is spreading everywhere, and those African countries that avoid fracturing grow slowly, constrained by their small domestic markets and without the advantages of trade integration. The World at War scenario results in a much smaller world economy at US$156 trillion in 2050, with Africa growing particularly slowly despite its much larger population.

Chart 6 summarises the key characteristics of the four scenarios.

The scenario closest to the global trajectory is the Divided World scenario, with 411 million extremely poor people in 2050, significantly more than in the Sustainable (196 million) or Growth World (369 million) scenarios. Extreme poverty in the World at War scenario will be 492 million, most of them in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Divided World scenario reflects the acceleration of current trends towards a more fragmented global order, an associated retreat from the Western rules-based system, and China's rapid rise to great power status towards the end of the forecast horizon. Having overtaken the EU27 in economic size in 2021China overtakes the US in 2034.

Populist party successes in Germany, France, Italy, Finland, the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark and Austria followed the election of Donald Trump as US president in November 2024. Instead of pulling together, pursuing narrow national interests rather than a common approach to China, and on matters such as support for Ukraine, is to the detriment of the West. Nationalist populism eventually undermines the Western rules-based system, which is, by 2050, hardly recognisable from its current form, with the US and the EU constantly bickering and pulling in different directions, providing the opportunity for others, most prominently China, Russia and countries in the Middle East, to exploit these differences to their advantage.

Driven closer by European sanctions on Russian oil and gas, the rapprochement between China and Russia proceeded apace. The latter eventually becomes entirely dependent on China for oil and gas exports, in addition to its exports of agricultural products and minerals to countries in the Global South.

Although the EU avoids another Brexit moment, it is consumed by bickering in the wake of the end of the war in Ukraine in 2027, with the ceding of Crimea and some eastern provinces to Russia.

On this trajectory, the steady loss in legitimacy, influence and salience of the UN proceeds apace. Non-permanent members eventually stop attending Security Council sessions in protest against the right of veto still held by permanent members and the lack of structural reform. Local solutions, including industrial subsidies and hard border control, dominate. The free movement of labour, knowledge and eventually capital is restricted. Uncertainty and insecurity mean that the number of nuclear-armed states increases as efforts to contain proliferation have long collapsed.

Nominally, an isolationist US, a bickering EU, China, India and others are constantly at odds with one another. Smaller countries in Africa, South America, and Asia try to stay out of the fight. Globally, efforts to forge new alliances and partnerships regularly emerge as countries seek the best partners to advance their interests, but none last.

India pursues its interests and alliances, including with Africa, while continuing to challenge China in Asia. Still, it struggles to gain traction for its traditional independent stance, given its worsening relations with Pakistan after New Delhi’s unilateral decision in 2019 to alter Kashmir’s constitutional status. In this scenario, armed confrontation along their shared borders becomes endemic.

The Asian region is particularly tense, with the Chinese invasion of Taiwan more likely given public pronouncements by US President Trump in 2026 that US soldiers would not die in defence of the island. As a result, China's subsequent occupation of Taiwan proceeds relatively quickly and with relatively limited damage, although extensive financial and other sanctions follow.

The degree to which Russia disregarded the UN Charter with its invasion of Ukraine and Israeli defiance of the UN Security Council in 2024/5 in its war on Gaza emboldens others. In addition to the US, countries such as Turkey, Iran, India, Pakistan, Myanmar, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Malaysia, Rwanda, Egypt and others regularly violate previously sacrosanct international norms of behaviour. Domestic priorities regularly trump the global good, including the fraying of humanitarian practices, regressive legislation and practices in respect of the widespread reintroduction of the death penalty, rolling back of progress with women's rights and even the reintroduction of practices such as female genital mutilation in Africa. The Gambia first proposed a bill to this effect in 2024, and it was subsequently also legislated in Uganda, Somalia, and several other countries.

Perceptions in this scenario reinforce long-standing caricatures of Africa (corrupt, poor, suffering) and the West (unequal, selfish, exploitative). Chinese efforts towards an alternative set of global rules (non-interference, mutual respect, and social order based on domestic surveillance and control) gain traction. Rather than pulling together, the African Union is divided, and an African voice is generally absent from discussions about global futures. Some countries try to remain non-aligned; others align with the West or China. There is no clear African voice or position on crucial issues ranging from peace and security to climate change and development, and more countries pursue their own autocratic development futures. A lack of coherence in decision-making on crucial development policies means that Africa continues to fall behind global averages in development indicators.

Attitudes harden. This world is more crowded, angry and fearful, with slow growth in the Global South propelling a substantial illegal migrant movement that drives populist politics and xenophobia in Europe and North America, reducing the ability of these countries and regions to play a positive role in international politics. Africa’s colonial legacy transforms into a decidedly anti-Western sentiment, and the continent is again a theatre for proxy wars between Russia and the West, and between the EU, the US and China. By 2026, France, the UK, and the US have effectively been ejected from Africa, losing access to all their previous military bases and some embassies. Whereas the US had 29 military bases in 15 African countries in 2019, by 2026, it is down to five, and by 2030, only Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti will remain. Illegal migration to the EU becomes a big problem and regularly overwhelms border arrangements with violent clashes and many deaths.

In the Divided World, relations between most African and European countries deteriorate significantly, and the once close partnership between the EU and the AU is eventually a distant memory. China gains the most in this scenario through Xi Jinping's determined pursuit of his ambitions and vision to 'make China great again', becoming a globally respected leader in high-tech manufacturing, particularly in the green economy.

There is little appetite for follow-on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in a Divided World. Sustainable development solutions are regional and scattered. Efforts to contain carbon emissions and combat climate change proceed apace, but they are weaker and less effective than the Sustainable World scenario, given the lack of coordinated international action. China powers ahead, however, and within a decade it emerges as the undisputed global leader in the sustainable economy, cementing its role as the dominant supplier of batteries, wind and solar solutions, and associated technologies.

However, African countries are adept at playing China, Europe, and the US off against one another, as they have done for several decades. African subregions, such as the Southern African Development Community (SADC), deepen existing levels of economic integration, but progress with the AfCFTA stalls. Conflicts are complex, with the number of actors involved constantly increasing, frustrating African efforts at mediation. The effects of climate change are evident across Africa, but most visible in the Sahel and the Horn of Africa. With its large, youthful, and poor population, instability in Africa is increasing.

In summary, the Divided World scenario predicts a future marked by global fragmentation, where rising populism and geopolitical tensions diminish Western influence and pave the way for China's dominance. This division undermines global cooperation and international norms, leading to a world where regional interests trump collective efforts, exacerbating geopolitical tensions, particularly in Asia, and increasing nuclear proliferation that sees Australia, Japan, Iran, South Korea, Ukraine, Poland and Germany all develop national nuclear forces. It is this balance of terror that eventually staves off mutually assured destruction at the global level. Sustainable development is sidelined in a Divided World, global governance weakens, and Africa faces heightened instability and challenges in economic integration, reflecting the broader global shift towards prioritising national over collective interests.

Hard power competition dominates in the World at War scenario, which consists of successive large-scale wars and numerous smaller conflicts that eventually engulf all leading and regional economies. On several occasions, the use of nuclear weapons is only averted at the last minute in a context that has seen a degree of proliferation. Efforts to review the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) collapsed, and in 2026, the New START treaty finally lapsed, having been on life support since Russian President Vladimir Putin's February 2023 State of the Nation address, in which he announced his country's suspension of participation.

The first large-scale conflict is the escalation of Russia’s war on Ukraine into a broader military confrontation with NATO. To stave off a Ukrainian defeat and to counter the deployment of more significant numbers of troops from North Korea, France, Germany and the UK deployed combat troops into the country. Russian retaliation included attacks on logistic bases in Poland and elsewhere, setting the scene for the geographic expansion of the conflict. The war in Ukraine has already pushed Russia closer to China as the primary destination for its oil and gas exports. In April 2024, the two countries pledged to cooperate more closely to maintain international industrial supply chain stability. 'China and Russia will be more active in pursuing the convergence of their interests . . . and work together to maintain international industrial supply chain stability,' a ministry statement quoted Chinese Foreign Ministry Wang Yi as saying. Under full sanctions from the West, Russia has no other outlet for its fossil fuel exports, on which its economy depends.

Others that extend the China–Russia military cooperation include Iran (which has a long-standing grievance with the West), North Korea, Pakistan, and eventually Vietnam and Cambodia. For China, importing gas and oil from Russia bolsters its efforts to reduce its reliance on strategic resources from Western suppliers. Still, it remains dependent on oil and gas from the Middle East.

Russia and China do not enter a formal military alliance to oppose NATO. Still, military cooperation is close, building on the February 2022 statement by Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin that their partnership has ‘no limits’, as the two vowed to deepen cooperation across various fronts. Already, in 2022, NATO added China to its perceived threat environment.

China bides its time and readies for an invasion of Taiwan, but eventually desists following the announcement that the renegade island had developed its own nuclear capacity. Previous efforts towards such a capacity in the 1970s and 1980s were halted by the US, but a third attempt now succeeds, this time with covert US support.

A second trigger for the World at War scenario originates in the Middle East. Following the horrific terror attacks by Hamas on Israel on 7 October 2023, the Jewish state lashed out in Gaza, the West Bank, Lebanon, Syria, Yemen, the Red Sea, the Arabian Sea and eventually Iran. The US, which had tried to resist the growing regional conflagration, going so far as to support UN Security Council decisions that sought to constrain and eventually condemn Israel, is drawn into steady escalating military support for its ally, eventually alienating long-standing partners such as Saudi Arabia and Egypt, where popular sentiment forces regimes in both countries to abandon their efforts at moderation.

The first indication of what is to come is the collapse of the Abraham Accords of 2020, which briefly normalised relations between Israel, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain. Eventually, it is separate deadly attacks by Houthis and the Islamic State in the region, including clear evidence of the extent of military support to Iran from Russia, that tip the scales into a bloody confrontation - opening up a front extending from Ukraine to the Middle East, with the US too stretched to ensure Israel's security. After a decade of war and with a weakened US, Israel eventually agrees to a two-state solution along the lines of the 1967 delimitations, having become perilously close to the use of its nuclear arsenal on several occasions.

A third trigger (or successive regional war) is border conflict, which eventually leads to a conventional war between India and China. Although India will continue to have significantly fewer power capabilities than China across the forecast horizon, the two are increasingly regional and global power competitors with a shared long border. The significant disparities in their material power capabilities make this unlikely before the end of our forecast horizon.

In addition to direct conflict, the often violent rivalry between Chinese-supported, nuclear-armed Pakistan and India over Kashmir could also trigger conflict between China and India, particularly if the two look to balance their relations with Washington and Beijing. India already fought a brief war with China in 1962, and India and Pakistan have had numerous border skirmishes and military stand-offs.

In this world, India’s alarm at Chinese assertions and aggression, particularly in the South China Sea, leads it to align more closely with the West to balance Islamabad’s close relations with Beijing. In a starkly bipolar world, there would be less space for India’s traditional non-aligned orientation.

Complicating matters is New Delhi’s cordial but guarded relations with Russia, from which it buys most of its weapons. The defining characteristic of the World at War scenario is the division of the globe into two poles with little space for others — a return of global relations to a bipolar era reminiscent of the height of the Cold War but on steroids. The US House of Representatives passed the Countering Malign Russian Activities in Africa Act on 27 April 2022 as a clear sign of where things could go. After Senate approval, President Trump signed it into law in 2026, imposing sanctions on African countries that trade with Russia and are perceived to have close relations with it, such as South Africa. China is in a different league from the former USSR, however. In 2024, China was already the largest trading partner for more than 120 countries and regions, including the US and the EU. Its economy is already more significant than the US’s, using purchasing power parity, and in this scenario, the Chinese economy surpasses the US in 2033 at market exchange rates. By 2050, the Chinese economy will be 26% larger than the US economy.

The intense competition and even conflict between a declining US and rising China in this scenario will affect every country and region in the world, even as struggles for self-determination and independence intensify, such as efforts by the Kurds to establish their homeland, the ongoing struggle of the Palestinians to escape the yoke of Israeli repression and occupation, and in regions such as the Sahel in Africa.

Africa becomes a key area of strategic, and sometimes violent, competition for control of its mineral resources in the World at War scenario. Still, it remains unable to benefit from its beneficiation. China has been a first mover in securing supplies of the strategic minerals required to transition to a renewables-based future, including lithium, nickel, cobalt, manganese, and palladium. Chinese companies were the only ones willing to invest in the DR Congo for years. As a result, by 2021, Chinese companies controlled 60% of global cobalt reserves and 80% of the world’s cobalt refining capacity, which helped China secure a significant lead as an electronic vehicle battery maker to the extent that a single Chinese company, Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited (CATL), then already controlled one-third of the entire global battery market.

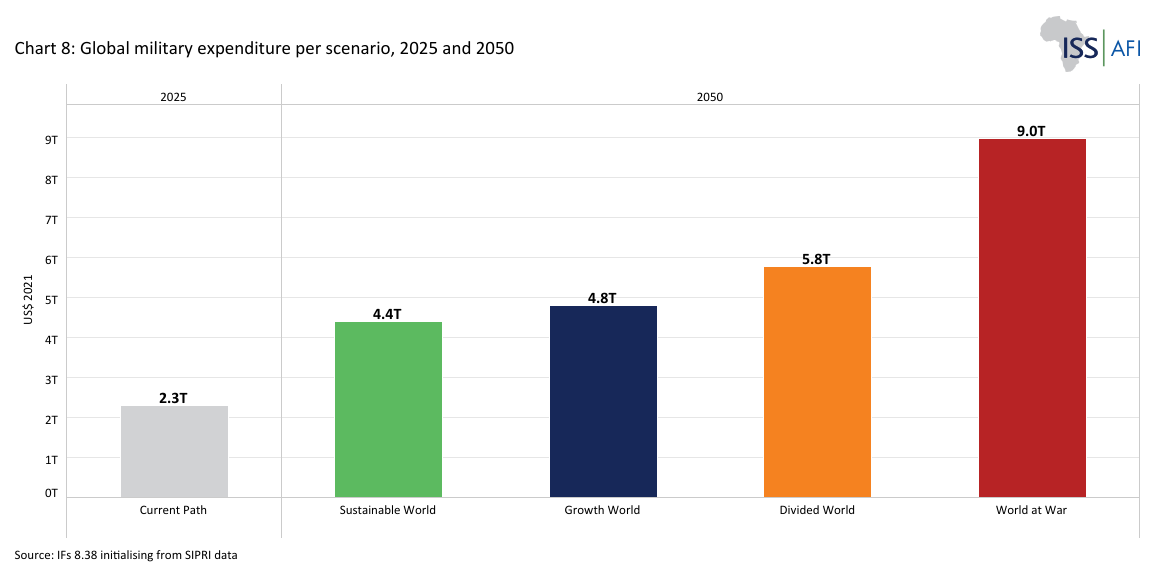

Chart 8 depicts world military expenditure, keeping in mind that the global economy is significantly smaller in the World at War scenario than in the Growth and Sustainable Worlds. Instead of spending US$4.4 trillion on the military in 2050 (in the Sustainable World scenario), the world will spend more than double that amount. From a low base, military expenditure in Africa increases more than fivefold from 2025 to 2050.

As arms purchases and the number of arms increase, Africa is again flooded by surplus weaponry, older stocks are replaced with more modern armaments, and countries upgrade and replace their systems, as happened at the end of the Cold War. The ready supply of weapons threatens the rupture of several additional African countries on top of the divisions in Libya, Sudan, Nigeria, Ethiopia and Cameroon.

Democracy is declining globally, and Africans are pressured to choose sides to the point that Internet interoperability is breaking down, with the Internet now segmented into regional fiefdoms. The momentum towards the AfCFTA and trade integration falters. Each country does the best that it can, on its own.

Instead of African states being able to secure their territories and borders, in the World at War scenario, the Islamic State and its affiliated networks further spread their influence to establish the caliphate's future after previously being defeated and driven out of Syria and Iraq. By 2030, IS/ISIS is active in at least 20 countries, with more than 20 others used for logistics and to mobilise funds and other resources. In this scenario, Iran and Russia play an important role in funding, supporting and expanding terror in Western-aligned African countries.

In summary, the World at War scenario predicts a future defined by intensified global military conflicts, including significant wars among major economies and nuclear exchanges. The breakdown of nuclear non-proliferation treaties and escalating tensions, particularly between NATO and Russia and between China and India, underscores a shift towards a bipolar global division reminiscent of the Cold War but much more intense. This era of hard power competition sees the US and China as central figures, with Africa becoming a strategic battleground for mineral resources and military influence, leading to a dramatic increase in military expenditures and armament. The scenario highlights the dire consequences of global divisions, emphasising the need for strategic alliances and the significant impact of leadership decisions on global stability and regional conflicts.

Neoliberalism, trickle-down economics, and increased corporate concentration characterise the Growth World, with little care for the environment and a transactional approach to international relations. This high-growth, unequal world would see slow reductions in extreme poverty, accompanied by a rise in the power and influence of private capital and of rich countries such as the US, which actively support the growth of large firms. The rich get richer, and the poor suffer. Efforts to introduce minimum tax rates for corporations, which began in 2021 when 136 countries agreed to implement a 15% global minimum rate, have not gained traction. Instead, large corporations increase their power and profits everywhere, including in the EU, which was previously a bastion of anti-trust legislation. All profits flow back to the corporate head offices of a handful of global behemoths.

The US and the EU both step back from antitrust efforts that could rein in anticompetitive behaviour, while major industries consolidate their presence in the services, finance, and manufacturing sectors through mergers. A lack of competitiveness allows companies to lower wages, increase prices, and dilute the quality of their products. The practice of tax avoidance through profit shifting to low-tax jurisdictions effectively leads to a race to the bottom as countries compete to attract foreign direct investment. Developing countries suffer, as funds are drained away to tax havens and low-cost locations. Unemployment reaches unprecedented high levels in poor countries with large pools of low-skilled labour.

Chart 9 illustrates the rapid growth in global GDP in the Growth World scenario, surpassing US$235 trillion by 2050, and the concurrent rise in carbon emissions to the end of the forecast horizon. In contrast to the Sustainable World scenario, income growth comes at the cost of a rapidly deteriorating environment and growing inequality.

Competition between China, the US, and Europe changes in this scenario. In retrospect, the subsequent G2 world had its origins in the meeting on 30 October 2025 between US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping in Busan, South Korea, on the sidelines of the APEC summit. It was followed by two state visits: Trump's to China in April 2026 and Xi's to the US later in the year. The unexpected death of Chinese President Xi Jinping at the end of that year accelerated the partnership, reversing the harsh clampdown on economic and political freedoms that had characterised Xi's third five-year term as president. China is rewarded by massive inward investment when the US enters into a Grand Bargain with its former foe in the final year of the second Trump presidency. The restrictions on ownership and investment in Western countries disappear almost overnight as business leaders scramble to cash in on the largest global market. Instead of contracting, global value chains expand, and the period of reshoring and friendshoring manufacturing is soon a distant memory. The lowest-cost considerations again drive factory and manufacturing location. Instead of moving to surrounding countries with lower labour costs, China's extensive state subsidies, excellent infrastructure, and numerous incentives enable it to strengthen its position as the world's high-technology factory, most prominently in the field of generative artificial intelligence.

Skilled migration to China resumes, and other countries that offer a high quality of life, security for investment, and the required information technology attract the best and brightest. Companies now compete in an unregulated global market to provide high-end services without establishing a legal presence or paying taxes in other countries. The Chinese economy grows more rapidly in the Growth World than in any other scenario. However, as incomes rise, domestic pressure for more freedom and growing inequality make China’s future more unpredictable.

With a focus on maximising profit and extracting rents, the saliency of the United Nations, its Security Council, and various agencies rapidly declines in this scenario. Rich countries adapt to the impact of climate change, but the developing world suffers. Instead of the AfCFTA, African subregions are forming external partnerships, such as North Africa with the EU, several West African countries entering into agreements with the US, countries in the Horn of Africa with the Middle East, and those in East and Southern Africa with China. Central Africa trails behind. More significant migration flows inevitably follow. Peacekeeping is a lucrative business in this world, now outsourced to private companies and developing countries with large populations. Instead of through the UN, peacekeeping is funded bilaterally with richer countries keen to secure their investments in unstable areas.

In summary, in the Growth World scenario, the focus on financial rewards and associated corporate dominance leads to substantial global GDP growth, but also to environmental degradation. Large corporations can circumvent efforts to implement global minimum tax rates and antitrust legislation, thereby exacerbating inequality and unemployment. The Growth World scenario envisions China's economic and political landscape transforming following Xi Jinping's unexpected death, leading to massive inward investment and a shift toward less regulated global markets. In contrast, the developing world, including Africa, faces the increased effects of rapid climate change and external economic dependencies.

In the Sustainable World scenario, the international community balances growth and distribution by reducing overall consumption and constraining greenhouse gas emissions, amongst other measures, through a differentiated global carbon tax (examined in our theme on Energy) that contributes to Africa's energy transition. Collaboration and norm development extend across multiple sectors, including a resurgence in the role of the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the introduction and steady increase of a global minimum corporate tax rate, which stands at 20% by 2043.

This future is most likely to emerge from a crisis, such as the impact of the World at War scenario, the rapid acceleration of climate change, and repeated global pandemics that force a reluctant world to adopt a collective response. Already, in June 2023, UN Secretary-General Guterres warned that the world would reach 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming above preindustrial levels by early 2030 and that the Earth was on a trajectory towards 2 to 3 degrees Celsius by 2100.

A Sustainable World could even originate in the US due to the corporate profiteering and excesses evident during the second Trump presidency. In this scenario, US politics swing violently against the corrosive power of money during the 2029 presidential elections with the election of a progressive independent who restores democracy. In subsequent years, the US pursued aggressive antitrust policies to increase competition and rein in the damaging effects of private money on domestic politics.

In terms of great power competition, a Sustainable World scenario is likely to be associated with an expanded and more influential EU, as well as constraints on the role of money in US politics. Unlike the US and China, the EU has limited hard power and prioritises its role as an advocate of a global rules-based system, reflected in its approach to digital sovereignty, harmonised rules on the fair access and use of data that protect individual rights and democratic freedoms, amongst others.

The Sustainable World scenario is the most difficult to achieve. Unlike the other three scenarios, leaders with little in common must take bold steps to realise a better world that will inevitably run into significant domestic resistance. It is only possible with the realisation within the EU and the US, working with countries such as China and India, that global sustainability requires rethinking key aspects of global collaboration and governance, including the role and decisions at the International Financial Institutions and an overhaul of the UN Charter, including the composition and workings of the UN Security Council.

Under the auspices of the UN, this scenario would see countries craft and agree on an ambitious set of follow-on Sustainable Development Goals to eliminate extreme poverty in the most affected region, sub-Saharan Africa, which is also under significant threat from climate change. These follow-on goals and targets merge climate mitigation and adaptation ambitions into an overarching, comprehensive Global Sustainability Framework 2050 (GSF). Part and parcel of the GSF 2050 is a new push for aid to low and low-middle-income African countries. Whereas net aid to Africa amounted to US$73 billion in 2025 (2.3% of Africa’s GDP), by 2050, it had increased to US$156 billion, accounting for only 0.9% of Africa’s much larger GDP. Commitments of this nature mean the world can sustainably pursue poverty alleviation, reduce carbon emissions and advance environmental protection. Chart 10 shows the dual impact of the Sustainable World scenario on global poverty and carbon emissions from fossil fuels. Extreme poverty in Africa falls from 491 million (32% of the population) in 2025 to 130 million (5%) in 2050. Globally, CO2 emissions from fossil fuels peak in 2038 and, by 2050, are back to 2025 levels.