7 Manufacturing

7 Manufacturing

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

In this study, we explore the current state of industrialisation in Africa and the effect of stagnating and early deindustrialisation on the continent. We then present a manufacturing scenario that shows the powerful potential of industrialisation to drive economic development and improve the livelihoods of African people.

Summary

- Industrialisation is crucial to the productive transformation of a country’s economy towards sustained high growth, employment creation and improved prosperity.

- Many African economies have experienced structural transformation but very slowly. The gradual shift away from the agriculture sector has not been towards manufacturing but rather towards low-end services.

- The Current Path is for a steady increase in the size of Africa’s service sector to 58% in 2043, with manufacturing increasing to 22% and agriculture declining to 6%.

- North Africa is the most industrialised region in Africa, with a manufacturing sector contributing 18% to GDP in 2019. On average, the contribution of manufacturing to most sub-Saharan African economies has steadily declined since the 1980s.

- In Africa’s manufacturing sector, jobs are not being created at the pace required to match rapid population growth. In many African countries, the share of manufacturing employment in total employment has also declined.

- Africa’s under-industrialisation can be explained by various causes, such as the absence of clear industrial development planning, lack of commitment and poor leadership, among others.

- A number of factors, such as the growing demand for processed goods and other products such as motor vehicles, manufactures of metals and industrial machinery on the continent, provide confidence in the potential for Africa’s future industrialisation.

- A future in which knowledge flows are more distributed offers opportunities for Africa but requires investment in information and communication technologies and large-scale provision of essential enablers such as electricity.

- When countries embark on a manufacturing transition, inequality may initially increase.

- With a determined effort to embark on a manufacturing pathway and by taking active steps to cushion the immediate costs of pushing a manufacturing agenda, solid improvements in the livelihoods of a large portion of the African population are possible.

- To transform African economies to become more productive and to enable more rapid income growth will require stable and facilitating policy frameworks, government support and incentives, as well as a sufficiently large private sector to drive the innovation agenda.

All charts for Theme 7

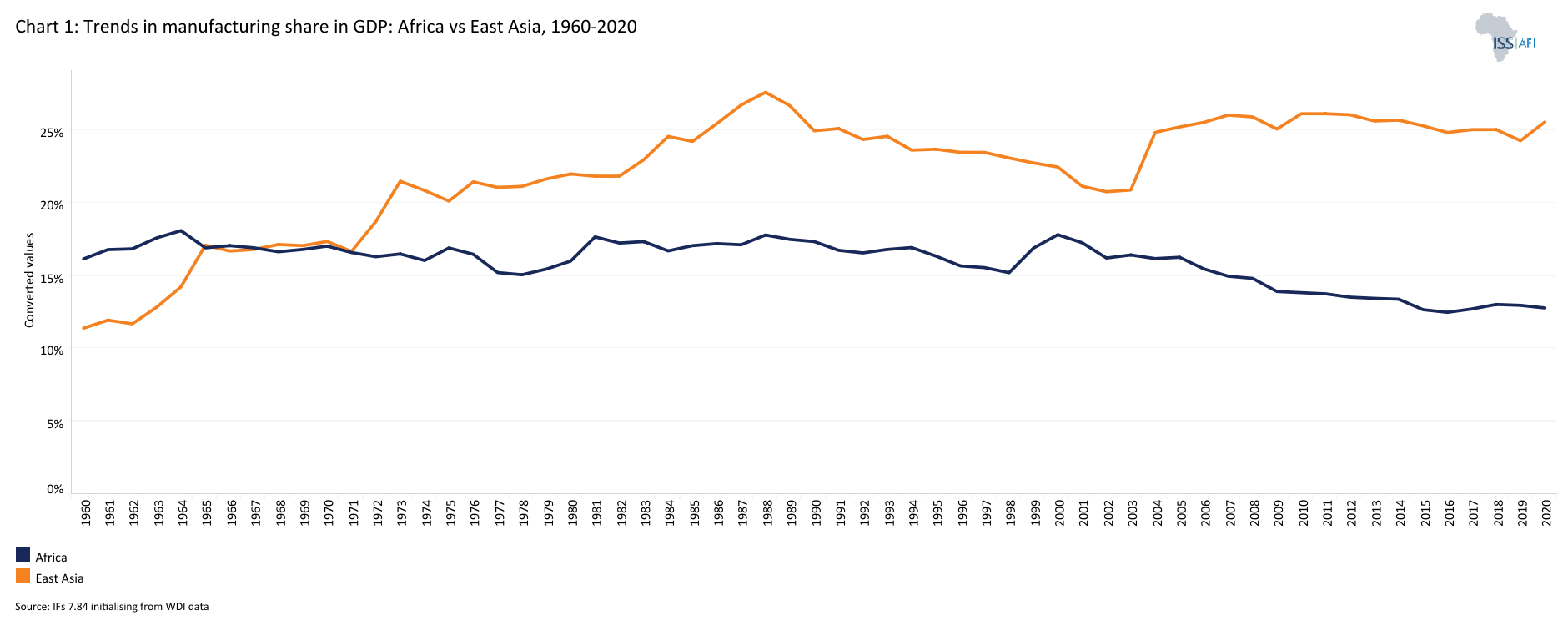

- Chart 1: Trends in manufacturing share in GDP: Africa vs East Asia, 1960–2020

- Chart 2: Kaldor’s growth laws

- Chart 3: Sectoral composition of global economies by income groups, 2019

- Chart 4: Shares of agriculture, manufacturing and services in Africa’s GDP, 1960–2020

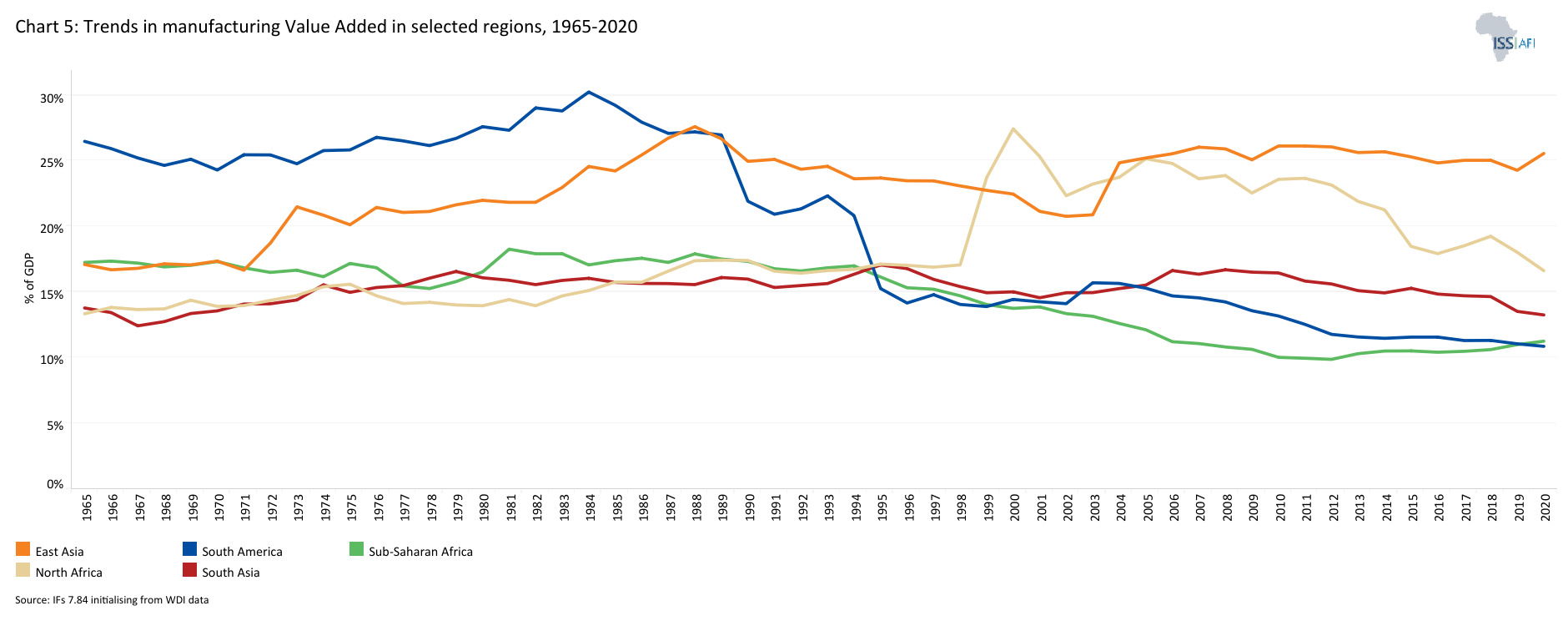

- Chart 5: Trends in manufacturing value added in selected regions, 1965–2020

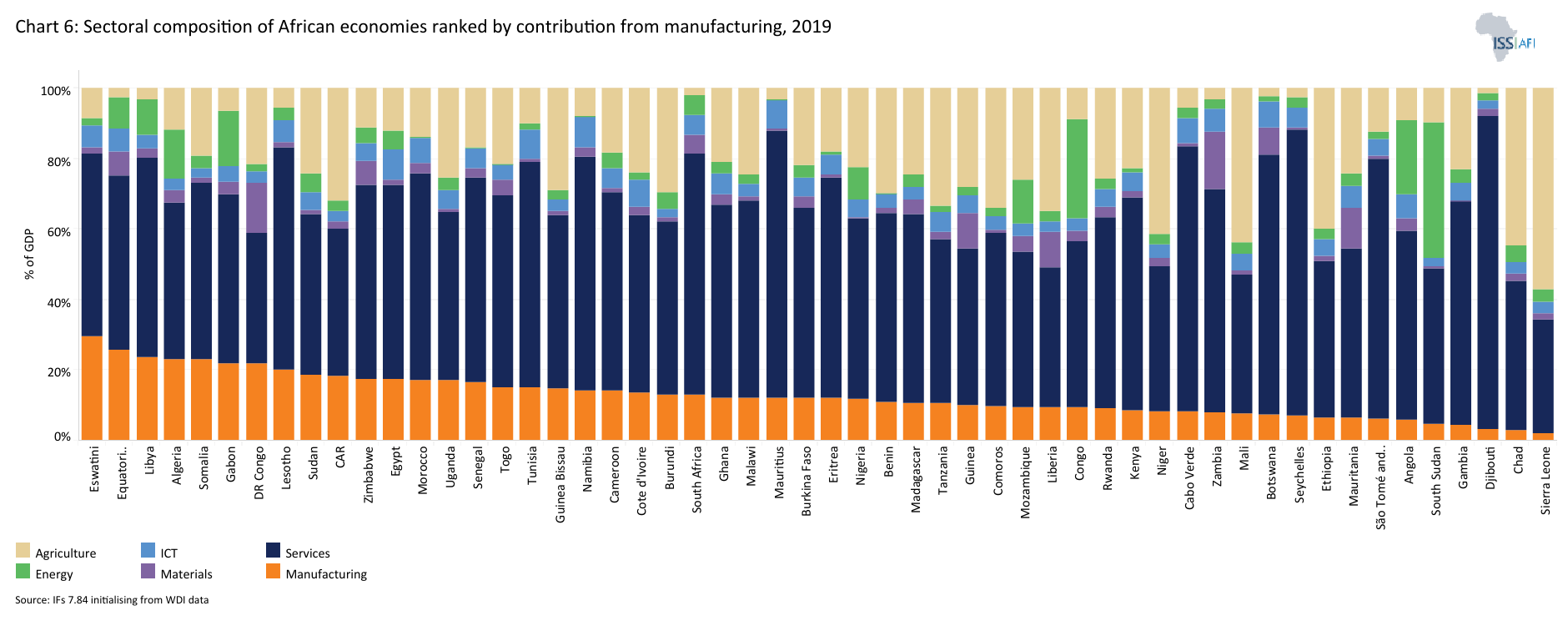

- Chart 6: Sectoral composition of African economies ranked by contribution from manufacturing, 2019

- Chart 7: Manufacturing share (%) in total employment in selected African countries, 2018

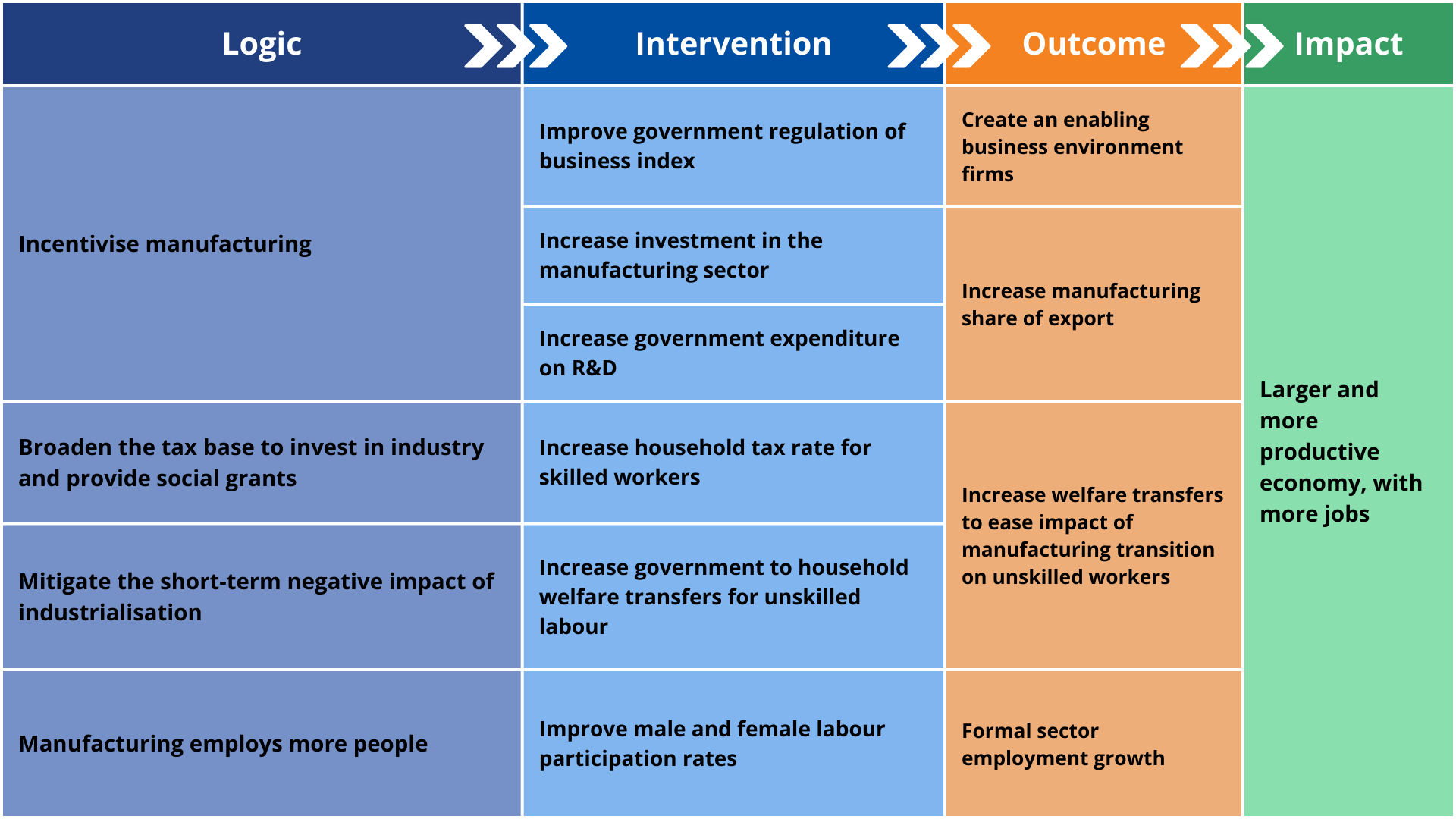

- Chart 8: Manufacturing scenario

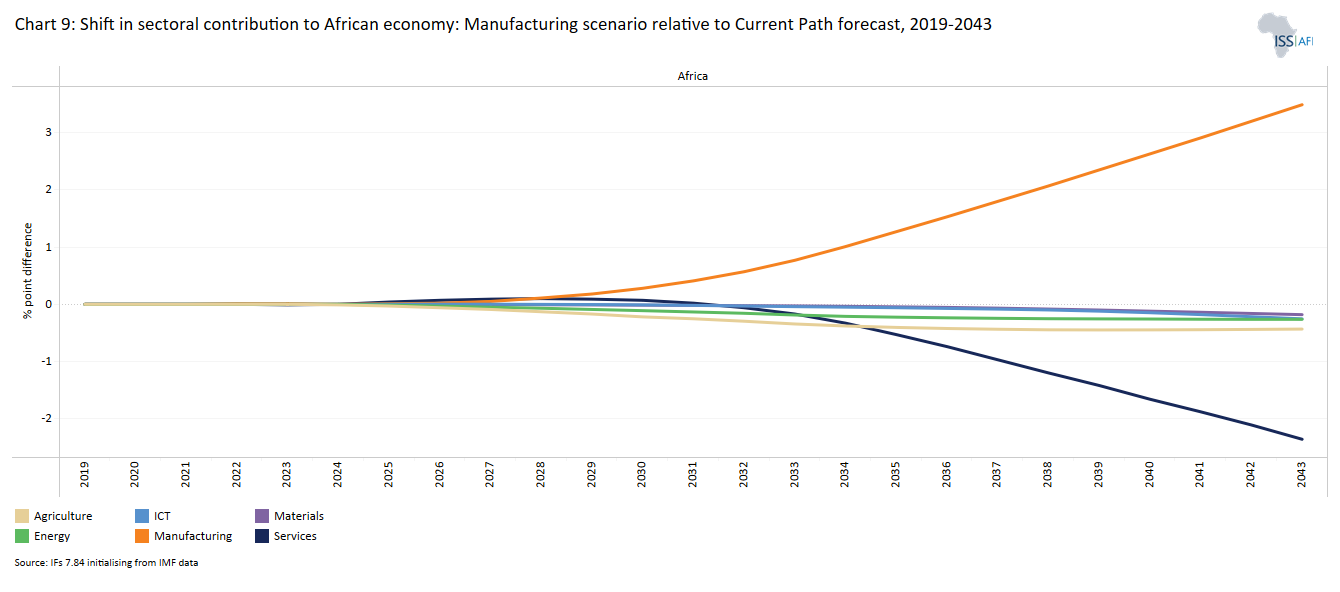

- Chart 9: Shift in sectoral contribution to African economy: Manufacturing scenario relative to Current Path forecast

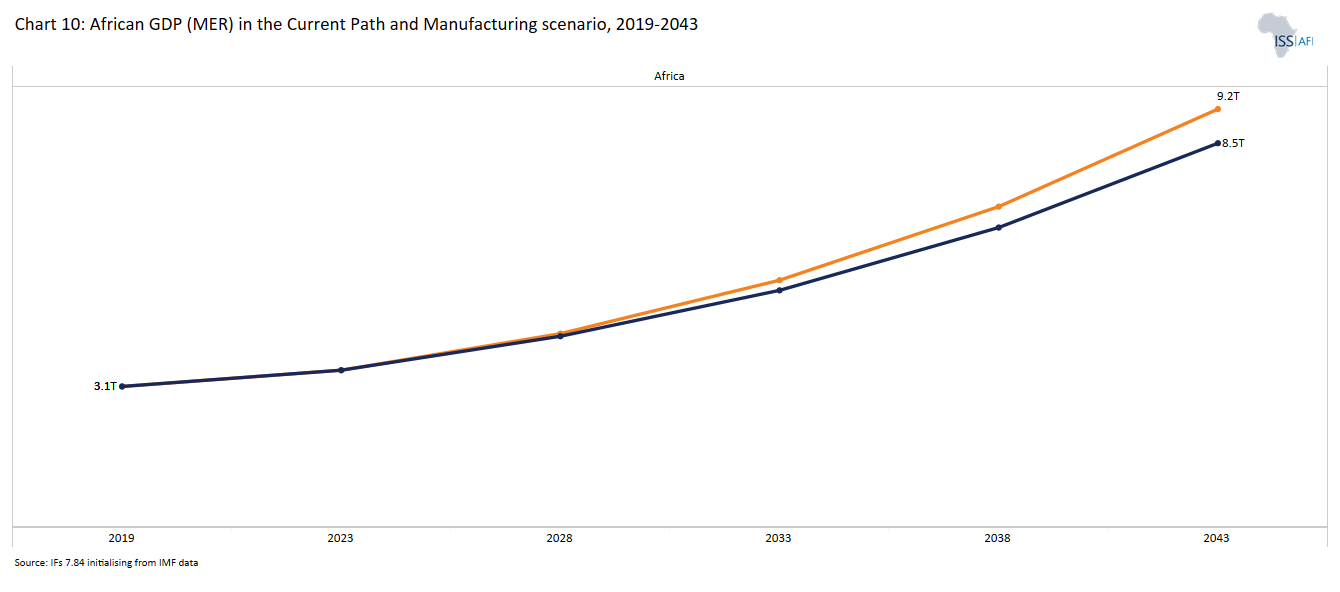

- Chart 10: African GDP in the Current Path and Manufacturing scenario in 2043 (MER)

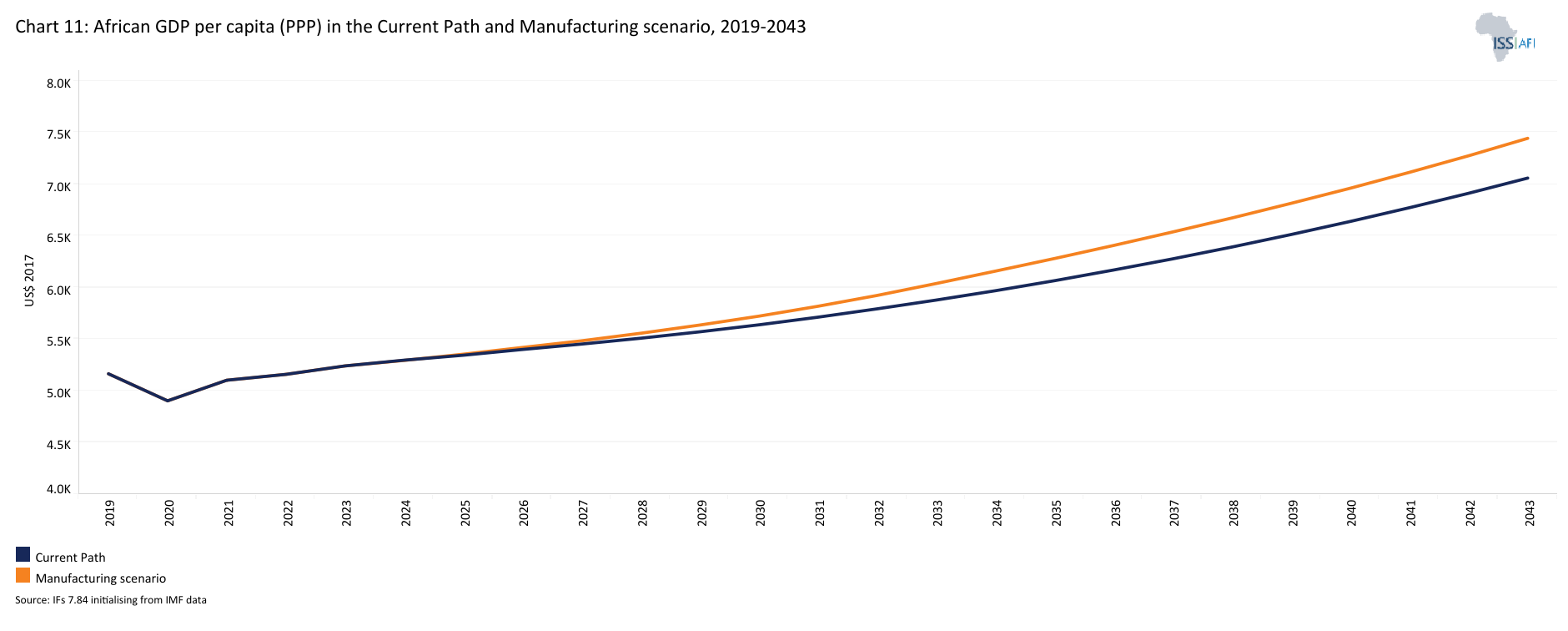

- Chart 11: African GDP per capita (PPP) in the Current Path and Manufacturing scenario

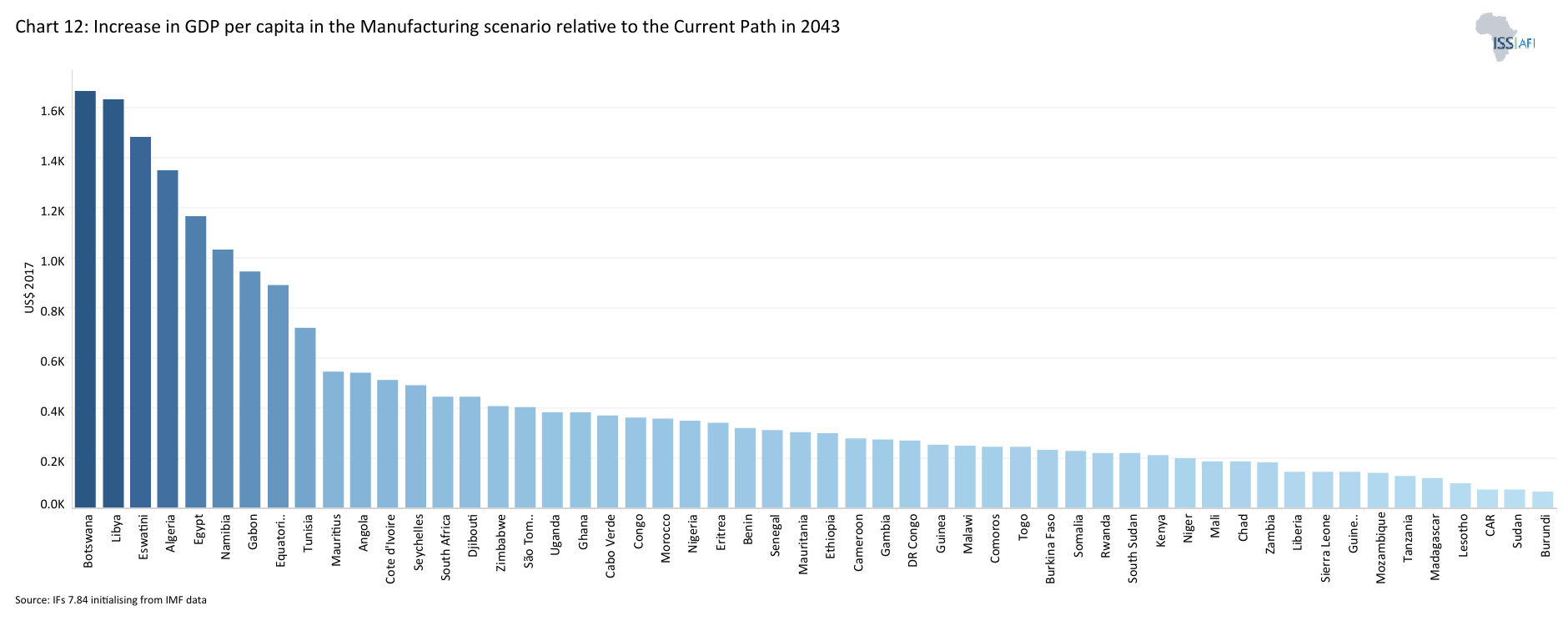

- Chart 12: Increase in GDP per capita in the Manufacturing scenario relative to the Current Path in 2043

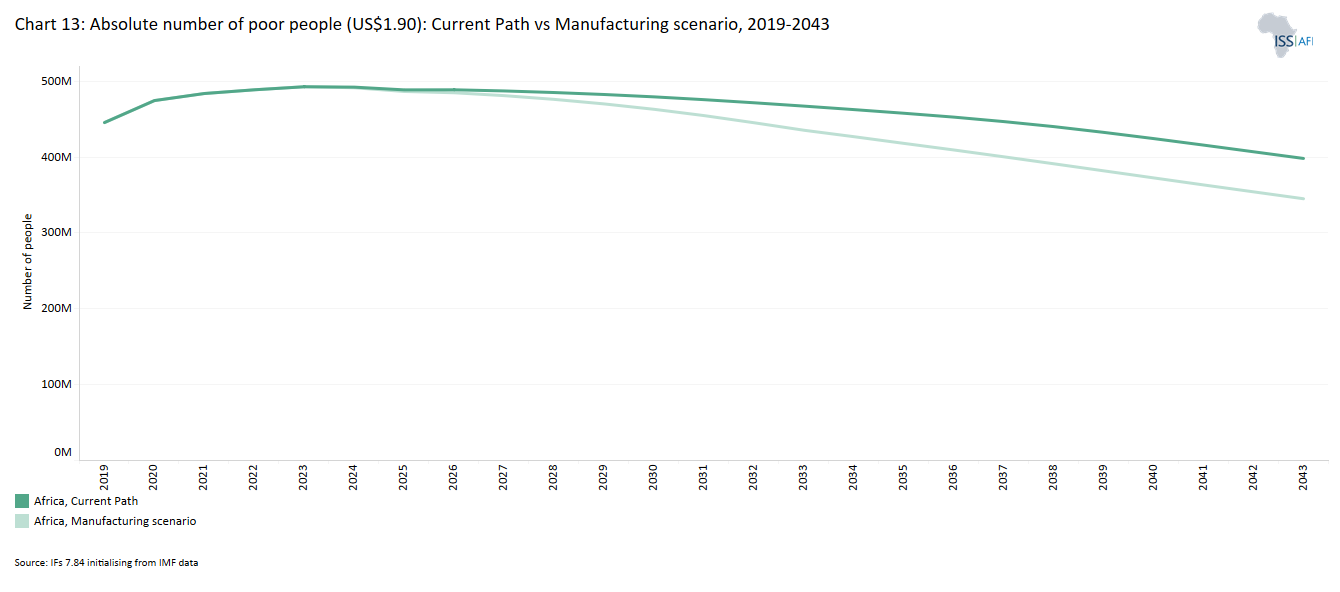

- Chart 13: Absolute number of poor people (US$1.90): Current Path vs Manufacturing scenario

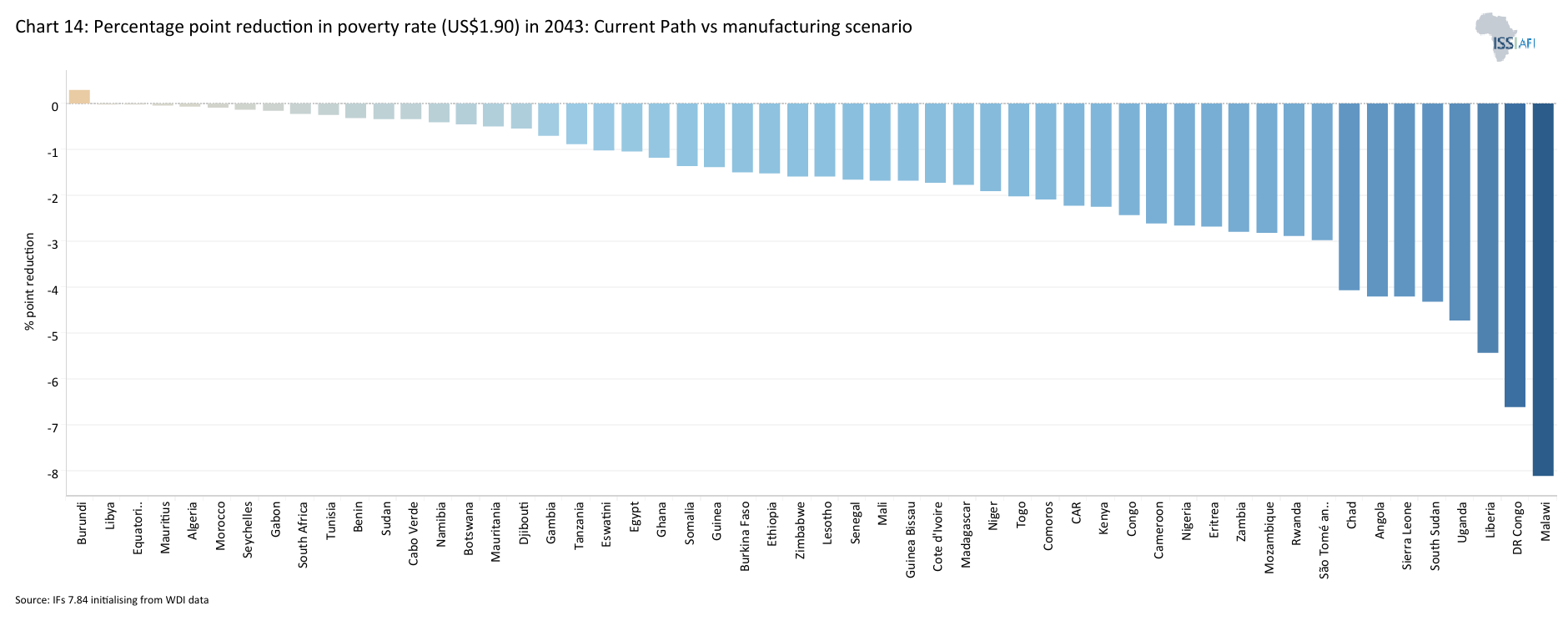

- Chart 14: Percentage point reduction in poverty rate (US$1.90) in 2043: Current Path vs Manufacturing scenario

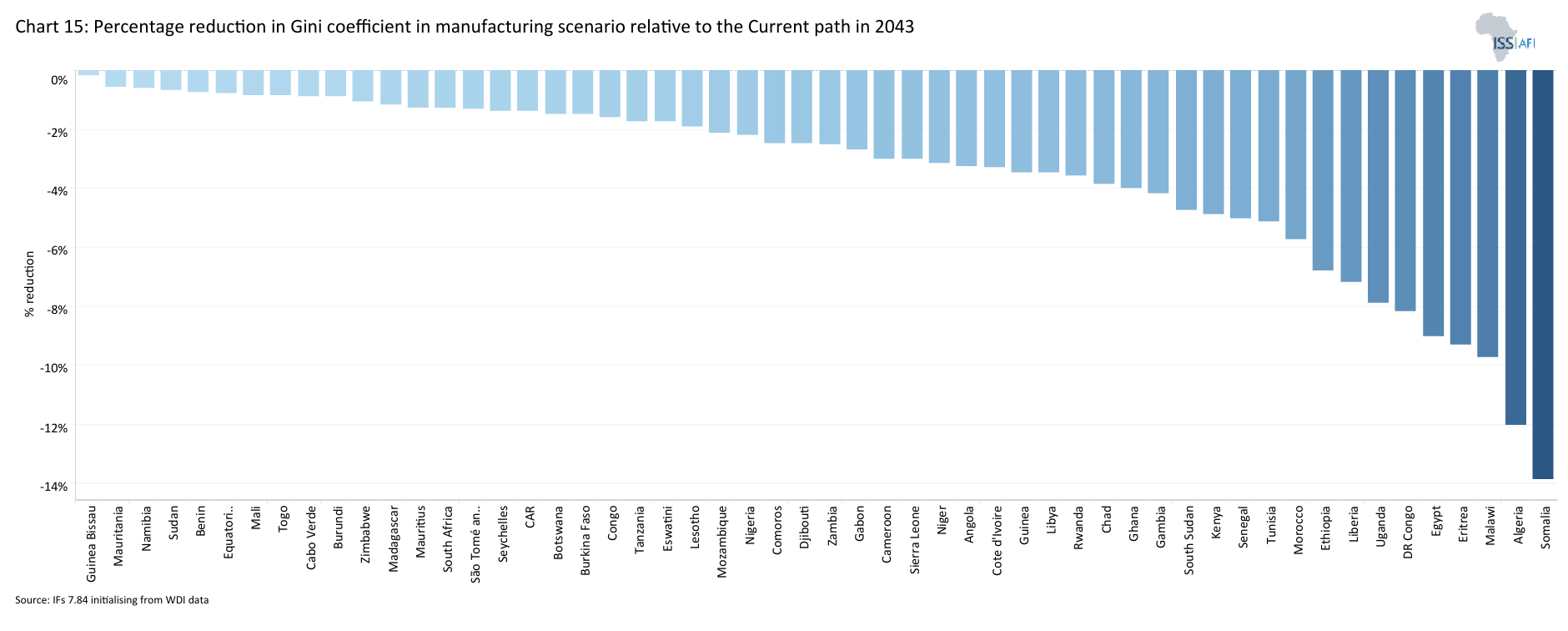

- Chart 15: Percentage reduction in Gini coefficient in Manufacturing scenario relative to the Current Path in 2043

- Chart 16: Summary of key recommendations

Since the Industrial Revolution, rapid and sustained economic growth that alleviates poverty and reduces unemployment has generally been associated with the size and productivity of the manufacturing sector. Industrialisation has transformed countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States, France, Germany and Japan into some of the world’s wealthiest nations. Most recently, it has helped the Asian Tigers — Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore and Taiwan — catch up with advanced countries. Industralisation has turned China, which accounts for about 30% of global manufacturing output, into one of the world’s fastest growing economies globally.

Industrialisation is central to development; hence, building a productive manufacturing sector is one of the most promising strategies for creating formal jobs at scale, promoting sustained, inclusive growth and modern development.

However, despite its manufacturing potential (exemplified by its fast growing internal markets, abundant raw materials and large labour force), Africa’s experience with industrialisation has been disappointing. Agriculture still plays a central role in many African economies, accounting for more than 60% of the labour force, although its contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) has declined. In fact, the slow growth of manufacturing in Africa has given way to the notion that Africa is deindustrialising as the manufacturing sector’s contribution to Africa’s GDP is either stagnant or declining (shown in Chart 1). In 2019, only 12 African countries had a manufacturing sector worth over US$10 billion. Africa’s share of global manufacturing has declined from about 3% in the 1970s to less than 2% currently. Manufacturing production on the continent is also heavily concentrated in low-technology products such as food, textiles, clothing and footwear.

Today, fostering industrialisation is high on the list of priorities for African policymakers. The importance of manufacturing to unlock the continent’s development potential is clearly articulated in the African Union’s 2011 Action Plan for the Accelerated Industrial Development of Africa and reaffirmed in Agenda 2063. Industrialisation is also one of the ‘High 5’ priority areas of the African Development Bank. Under its Industrialize Africa strategy, the Bank is committed to helping African countries to accelerate their industrialisation and unlock their economic potential.

This theme presents an overview of industrialisation in Africa and a manufacturing push scenario that shows the powerful potential of industrialisation to drive economic development and improve African populations’ livelihoods.

Industrialisation typically involves a shift from agriculture to manufacturing as the primary source of employment and output, leading to increased productivity, sometimes to higher wages and a more diversified economy.

Several theories have been proposed to explain the relationship between industrialisation and economic growth. The traditional ‘structural change’ theory suggests that industrialisation typically involves shifting labour and capital from low-productivity to high-productivity sectors. Countries that manage to escape from poverty and grow incomes are those that are able to diversify away from agriculture into manufacturing. As labour and other resources move from agriculture into modern activities, overall productivity rises and employment expands. Industrialisation is, therefore, unique in its forward and backward linkages to other sectors.

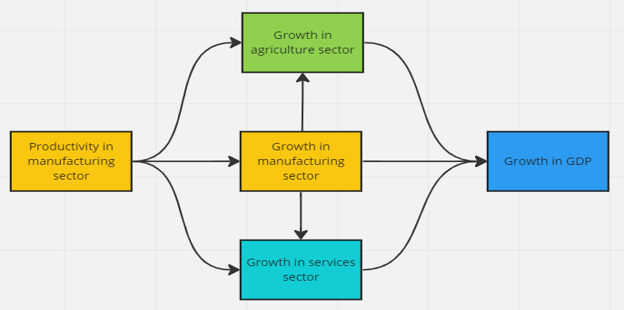

According to Nicholas Kaldor and others, the manufacturing industry enjoys higher productivity growth rates and stimulates productivity growth in non-manufacturing sectors such as services and agriculture. Kaldor’s three growth laws can be summarised as follows:

- Productivity drives the growth of the manufacturing sector, which has important spillover effects.

- The faster the growth of the manufacturing sector, the faster the productivity of the non-manufacturing sector.

- The faster the growth of the manufacturing industry, the faster the total GDP growth.

For Kaldor, the manufacturing sector is the breeding ground of productivity growth, and causality runs from growth in the manufacturing sector to the other sectors, as outlined in Chart 2.

Manufacturing is generally recognised as a powerful driver of economic development because it can increase productivity faster than the service sector. The transformation of the agriculture sector assisted many countries in Asia in alleviating poverty and improving general well-being in the early stages of development. Once economies had gained some momentum and basic education and literacy had made sufficient progress, these countries pursued a manufacturing transition that was facilitated by favourable demographics and determined leadership. This eventually led to unprecedented economic growth rates and improved incomes in countries such as Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and, recently, China.

Countries such as Brazil, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Philippines, South Africa and Turkey also experienced substantive growth for several years due to industrialisation, but generally not at the rates of and not for the extended period seen in Asia.

In his best-selling book Kicking away the ladder, the South Korean author and academic Ha-Joon Chang[1H-J Chang, Kicking away the ladder: Development strategy in historical perspective, London: Anthem Press, 2003, 43.] described the view that developing countries could largely skip industrialisation and enter the post-industrial phase where services increasingly drive employment and productivity growth as ‘a fantasy’. This is because the manufacturing sector has ‘an inherently faster productivity growth than the services sector,’ he argues.

The extent to which industrialisation leads to improved wages and better living conditions for the working class, is, however, contested and context specific. For example, while a scarcity of skilled labour meant that industrial employment in the United States during its Industrial Revolution (resulting in the so-called American System of Manufacturing) focussed on technological improvements to raise productivity and was accompanied by higher wages for successive decades, that was not the case in Europe. Here a surplus of sufficiently skilled labour would see employment increase but not wages until new opportunities, such as with railways, changed the balance of power between investors and labour.[2D Acemoglu & S Johnson, Power and Progress - Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity, Basic Books, London, 2023, chapters 4 to 6]

Early industrialisation is therefore an important development driver, with governments required to act as enablers to unlock private sector capital and innovation. Increased productivity in industry, with a simultaneous transformation out of agriculture, accounted for about half of the catch-up by developing countries to advanced economies’ output per worker between 1950 and 2006. Industry is, therefore, the pre-eminent destination sector at early stages of development because it is a better paid sector than subsistence agriculture that can absorb large numbers of moderately skilled workers.

Beyond a basic, subsistence level of development, industrialisation also determines agricultural efficiency and expansion, and even the development of high-value services. Large-scale commercial agriculture in Africa, for example, is dependent on a large and diversified manufacturing base, as the processes involved are similar.

More recently, Carol Newman and colleagues find that the manufacturing sector in Africa is six times more productive than agriculture. Also, some recent studies find that ‘rumours of the demise of industrialisation as the engine of development are greatly exaggerated.’

The arguments for a special role of industrialisation in the process of economic growth can be summarised as follows:

- Manufacturing typically contributes more to productivity growth than other sectors. The transfer of resources from low-productivity sectors, such as traditional agriculture or informal services, to high-productivity and dynamic sectors, such as manufacturing, provides a structural change bonus.

- Compared to agriculture, the manufacturing sector offers special opportunities for capital accumulation. Capital accumulation can be more easily realised in spatially concentrated manufacturing than in spatially dispersed agriculture. Returns to capital (in terms of labour productivity or total factor productivity) are higher than in other sectors. Productive investment opportunities in manufacturing encourage high savings rates, characteristic of East Asian development.

- The manufacturing sector also offers opportunities for economies of scale, which are less available in agriculture or services.[3N Kaldor, Strategic factors in economic development. New York: Cornell University Press, 1967.] Technological advancement is concentrated in the manufacturing sector and diffuses from there to other economic sectors.

- Manufacturing industries produce tradable goods and can be rapidly integrated into global production networks, facilitating technology transfer and absorption. Even when they produce just for the home market, they operate under competitive threat from efficient suppliers from abroad, requiring that they constantly upgrade their operations to remain efficient. Traditional agriculture, many non-tradable services and especially informal economic activities do not share these characteristics. As a result, manufacturing attracts more research and development (R&D) investment than other sectors in a virtuous cycle.

- Linkage and spillover effects are stronger in manufacturing than in other economic sectors. The linkage effects refer to the direct forward and backward relations between different sectors and subsectors.[4AO Hirschman, The strategy of economic development, Boulder and London: Westview Press, 1958.]

- As per capita incomes rise, the share of agricultural expenditures in total (consumption) expenditures declines and the share of expenditures on manufactured goods increases. This is in line with the so-called Engel’s law that postulates that as household incomes increase, the percentage of income spent on food will decline. Therefore, countries specialising in agricultural and primary production will face a demand-side constraint to growth unless they industrialise.

The idea that manufacturing is the pioneering driver of economic growth has also been the subject of numerous empirical studies. The majority of them find that manufacturing is a key engine of economic growth, especially for developing countries. However, some studies reveal an ambiguity in the direction of causality between manufacturing and other sectors. Furthermore, they show that manufacturing may not be the most important sector influencing economic growth in the long-term future.

Some argue that the service sector, combined with ICT technologies could become the new engine of economic growth in developing economies. With the decline in mass employment in manufacturing, the contribution of the service sector to growth has become important — a trend accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic that saw the rapid modernisation of services akin to the establishment of complex supply chains in manufacturing some decades previously. An important consideration here is that the reduction in manufacturing employment as a portion of total employment inevitably means that its general economic effects are reduced. The nature of services is also changing, permeating all aspects of production as information and communication technologies (ICT) have become more important as a source of productivity growth.

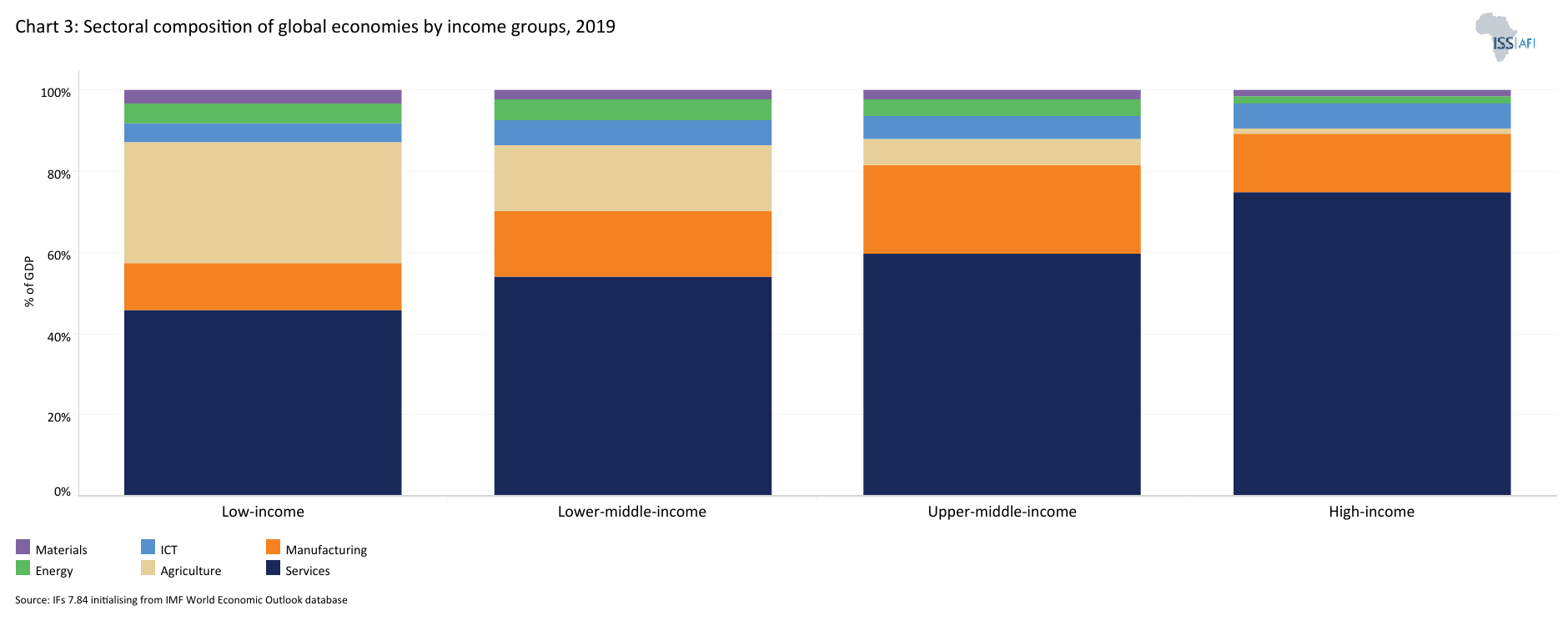

Chart 3 presents the average sectoral composition of low-, low-middle-, upper-middle- and high-income countries’ economies as modelled in IFs for 2019. The forecast initialises from the World Development Indicators and IMF data and may differ slightly from other datasets. This is because IFs use Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) data to categorise forecasts of economic value into six sectors instead of the standard threefold distinction between agriculture, services and manufacturing. In IFs, energy, materials and ICT constitute additional aggregated sectors.

Chart 3 shows that:

- the contribution of the service sector grows as countries’ populations become wealthier, with a concomitant decline in the contribution from agriculture,

- the manufacturing sector expands until countries achieve upper-middle-income status; however, once countries graduate to high-income status its role reduces, with high-end services then becoming the driver of growth,

- the energy and materials sectors decline in their contribution to GDP as income status increases, and

- the contribution from ICT remains steady (approximately 5–6%).

There are, of course, large variations in this general trend, with some high-income countries (such as Taiwan) having a manufacturing sector above 50% of GDP, whereas the sector contributes only about 1.2% to GDP in the Bahamas.

Over the last two decades, the contribution of ICT to global GDP has overtaken that of agriculture at around 6% of GDP globally, and it has become particularly important in high-income economies. Despite its relatively small contribution to added value, ICT is a growth multiplier as countries go up the GDP per capita ladder because it facilitates knowledge exchanges, including the effective functioning of regional and multinational value chains, which include goods and services. Looking at the changed nature and structure of modern economies, the question is if ICT can leverage the same productivity improvements in combination with the service sector at low levels of development that previously came from manufacturing.

A number of African countries have experienced very rapid economic growth in the last two decades. But that growth came mainly from high commodity prices. Further, high commodity prices have attracted more investment in extractive industries with limited linkages to the rest of the economy and away from manufacturing, limiting economic diversification and rendering Africa vulnerable to external shocks.

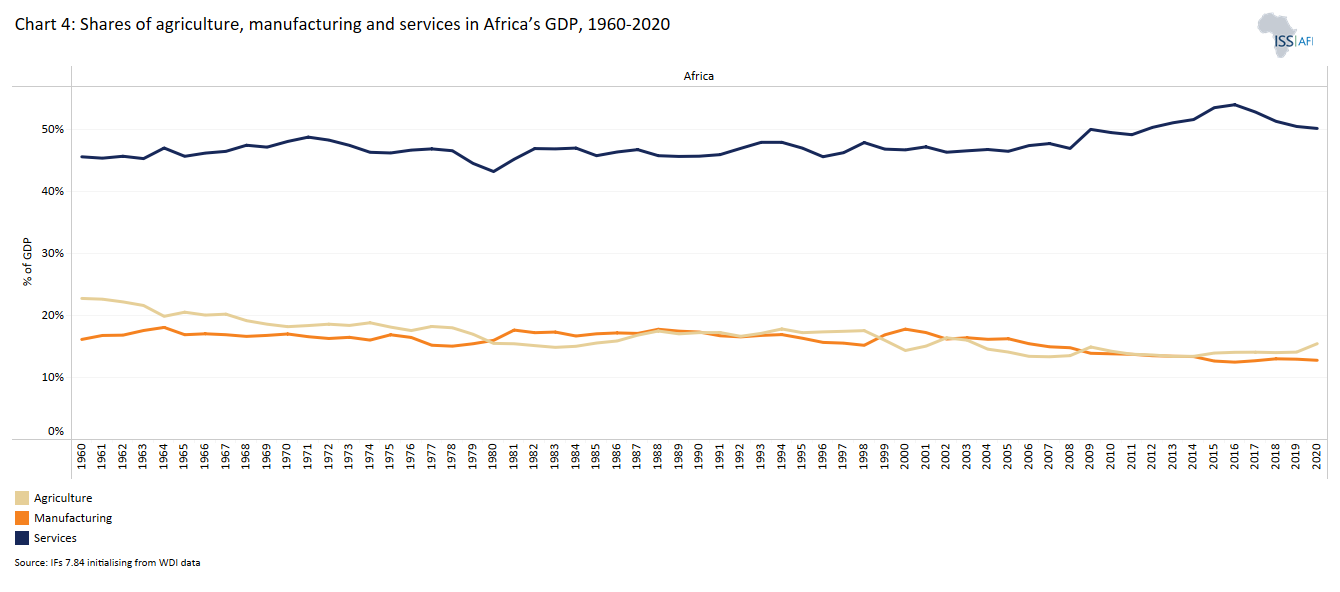

Using the standard threefold categorisation of the economy into agriculture, manufacturing and services, Chart 4 shows that the service sector has the largest contribution to GDP in Africa, having increased from 43.3% in 1980 to a peak of 54% in 2016 before declining slightly to 50% in 2020. At high levels of development, financial services, computer and software services, and transport and distribution services are dynamic requirements for continued growth. But high-value services constitute only a very small segment of the large and growing service sector in Africa, much of which is in the informal retail sector.

The agriculture sector’s share of Africa’s GDP is decreasing but at a slower pace, from 23% in 1960 to 16% in 2020. The share of the manufacturing sector declined from 18% in 2000 to 13% in 2020. The gradual shift from the agriculture sector has not been towards manufacturing as in the classic pattern of structural economic transformation experienced by most advanced countries. The service sector has absorbed most of the shift away from agriculture, becoming the most significant contributor to GDP for most African countries.

The slow structural transformation and industrialisation in Africa come with high economic and social costs, preventing large segments of the population from benefiting from economic growth and subsequent improved livelihoods.

The Current Path forecast is for a steady increase in the size of Africa’s service sector, to 58% in 2043, with manufacturing increasing to 22% and agriculture declining to 6%.

On its Current Path, Africa is following in India’s footsteps. India is an example of a country that, until recently, pursued a services-led growth strategy. The contribution of the service sector to GDP overtook that of agriculture in 1975, but the contribution of manufacturing to GDP only overtook agriculture three decades later. India’s developmental model has been unique among major economies, shifting from low-end agriculture to low-end services without major industrial expansion.

The early growth in services and fairly recent entrance into a favourable demographic window are two important reasons for India’s lower-than-expected growth over several decades. Since 1991, economic liberalisation has partly unshackled an economy stifled by over-regulation, corruption and lack of competition. However, the recent improvement in the ratio of working-age persons to dependants, better education, the prioritisation of investment in infrastructure and greater emphasis being placed on expanding the manufacturing sector offers prospects for more rapid future growth.

The counter-example to India is China, which focused on manufacturing and, together with a much lower population dependency ratio, had significantly higher sustained growth and employment generation.

Chart 5 shows trends in manufacturing value added as a percentage of GDP across different regions. Deindustrialisation is evident in North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa and South America. Sub-Saharan Africa has significantly lower levels of manufacturing compared to other developing regions. On average, since independence, the contribution of manufacturing to sub-Saharan Africa’s GDP is either stagnant or declining and has never reached the peak share of 20–35% of GDP as was seen in Europe and North America. North Africa is the most industrialised region on the continent, with a manufacturing sector contributing 18% to GDP in 2019.

While deindustrialisation in developed countries with higher income levels is expected due to structural changes in their economies, deindustrialisation in low-income countries is alarming and worrisome. The Economist, in its 7 November 2015 issue, summarised the challenge thus: ‘Many African countries are deindustrialising while they are still poor, raising the worrying prospect that they will miss out on the chance to grow rich by shifting workers from farms to higher-paying factory jobs.’

Growth in the manufacturing sector drove wage increases in the West, and after they peaked, employment and output in that sector declined. In an environment of a stagnant but skilled labour force, growth in high-end services and industrial agriculture compensated for stagnant manufacturing growth. As countries develop, the manufacturing compensation premium — the additional pay a manufacturing worker traditionally earns relative to a comparable non-manufacturing worker at the same educational level — has also declined.

Chart 6 presents the sectoral composition of all African economies as modelled in IFs, with countries ranked according to the contribution of manufacturing to GDP in 2019. With a few exceptions, African economies are dominated by large, low-productivity service sectors and subsistence farming. Evidence has shown that countries that specialise in supplying raw materials, unprocessed agricultural products or low-end services yield a progressively smaller return for every unit of capital or labour compared with those that provide value-added goods. ‘German’ coffee, ‘Swiss’ chocolate or ‘Italian’ handbags or shoes all demand high prices. Yet, the raw materials all originate in Africa, which receives little of the associated value-added profits. Instead, the manufacturing sector in Africa has been dominated by low-value production of food, beverages, tobacco, textile, clothing and wood, shifting to more durable and capital goods in only a few countries, such as South Africa.

Chart 6 shows that only two African countries, Algeria and Eswatini, have a manufacturing share in GDP higher than 25%, and it has been so for these two countries for the last 30 years. Manufacturing’s share of GDP fluctuated around 15% for many African countries, with most of them recording a decline in the last ten years.

The African Industrialization Index from the African Development Bank tracks African progress on industrialisation. The results of the first edition in 2022 show that a handful of countries in Africa have already developed sophisticated manufacturing capabilities. The top quintile in the African Industrialization Index ranking includes South Africa, three North African countries (Morocco, Tunisia and Egypt), along with Mauritius and Eswatini. Encouragingly, the index also shows that some African countries are making steady progress in industrial development.

With appropriate policies, Ethiopia, for instance, did well in growing its manufacturing sector (though from a very low base) by attracting manufacturing foreign direct investment (FDI) from China and elsewhere. The Ethiopian government has determinedly pursued policies to develop its manufacturing sector. For example, over the period 2005 to 2017, on average, output in Ethiopia’s manufacturing sector grew by 11% annually, and manufacturing for export gained a foothold until the civil war in Tigrey ended Ethiopia’s remarkable growth trajectory. Industrial parks and factories emerged, many dedicated to making the textiles and clothing that often represent the first rung on the industrialisation ladder. Apparel giants like H&M and Primark began sourcing products from Ethiopian plants, and the value of clothing exports rose more than sixfold from 2009 to 2019. FDI in Ethiopia roughly quadrupled from 2011 to 2017, with about 80% in the manufacturing sector. However, the manufacturing sector is still at the embryonic stage, and its contribution to job creation and output is far from being an engine for growth and economic transformation. With the end of the conflict in the Tigray region, Ethiopia now needs to work hard to regain investors’ confidence.

Tanzania also has built a more resource-intensive manufacturing sector focused on serving domestic and regional markets. The manufacturing output in Tanzania increased by more than 7% annually from 1997 to 2017.

Chart 6 also illustrates a number of other trends and counter-factual observations:

- The contribution from agriculture is generally lowest among upper-middle-income countries and highest among low-income countries in Africa.

- South Africa is among the countries with the smallest contribution of agriculture to GDP (just over 2%). Yet, South Africa, which has an efficient commercial farming sector, is one of the few African countries that are largely self-sufficient with regard to the food supply, reflecting the dichotomy that famine typically occurs in countries with large, low-technology agriculture sectors and that the size of the agriculture sector does not necessarily relate to food security.

- Countries such as Sierra Leone, Burundi, Central African Republic, Mali and Nigeria all have large agriculture sectors as a portion of their economy but are all net food importers, and their import dependency is set to expand significantly in the future.

- Low-income countries generally have small energy and manufacturing sectors.

- Countries where the energy sector made up a large portion of the national economy in 2019 were South Sudan, Republic of Congo, Angola, Algeria and Gabon. All are oil exporters.

- Zambia (copper), DR Congo (copper, cobalt), Liberia (gold) and Mauritania (mostly iron ore and phosphate) have the largest contribution from raw materials.

- The service sector is highest in Djibouti, São Tomé and Príncipe and Seychelles, contributing more than 70% of GDP in all three in 2019. Seychelles is also Africa’s only high-income country.

A final, important observation not evident from Chart 6 is that Chinese companies play an increasing role in growing manufacturing in Africa. Chinese investors seem to have early recognised the potential and future demand in African markets as Africa’s population grows rapidly.

- China has recently built the largest ceramic tile factory in Africa in Ethiopia.

- Nearly a third of the more than 10 000 Chinese companies that McKinsey estimates are active in Africa are involved in manufacturing. Together they are responsible for more than 12% of Africa’s industrial production.

- Most of the Chinese manufacturers are small and privately owned rather than state-owned behemoths, and their focus is mostly on serving the needs of Africa’s fast-growing market rather than on exports.

The dominance of Chinese firms is even more pronounced in infrastructure projects, claiming nearly 50% of Africa’s internationally contracted construction market. Most of these companies are oriented at serving the domestic market, not at exports and appear to ‘represent a long-term commitment to Africa rather than [focusing on] trading or contracting activities.’ Furthermore, nearly two-thirds of Chinese employers provide some kind of skills training through introducing a new product, service or technology to the local market. In some cases, Chinese firms had lowered prices for existing products and services by up to 40% through improved technology and efficiencies of scale. The report by McKinsey upon which these findings draw indicates that Chinese firms’ efficient cost structures and speedy delivery were noted as major value-adds by government officials in Africa.

If Chinese companies can enter and grow the manufacturing sector in Africa, why can’t Africans? Aliko Dangote, Africa’s wealthiest individual and a Nigerian businessman, provides an example by investing in oil refining, food processing and cement manufacturing across the continent.

Traditionally, manufacturing has been viewed as a labour-absorbing sector during the process of economic development. As manufacturing industries with higher productivity emerge, labour moves from farming to manufacturing jobs (and associated services) in urban areas. There is no better example of this than China, where formal-sector manufacturing employed around 50 million workers in 2014. With 50 million jobs, a country like Nigeria could employ more than 80% of its current labour force, estimated at about 60 million.

However, in Africa’s manufacturing sector, jobs are not being created at the pace required to match rapid population growth, even though Chinese-owned manufacturing firms have employed several million Africans. The latest available data shows that the number of workers employed in manufacturing in Africa is low (see Chart 7). In many African countries, the share of manufacturing employment in total employment has even declined. In South Africa, for instance, manufacturing accounted, on average, for about 13% of total employment over the period 2001 to 2010 compared to 10% for the period 2011 to 2018.

According to Diao and colleagues, the low employment performance of the formal African manufacturing sector might be explained by the nature of technologies available to African firms. Using the case of Tanzania and Ethiopia, they show that the relatively large manufacturing firms that are supposed to employ more workers are significantly more capital-intensive than what would be expected on the basis of the countries’ income levels or relative factor endowments (abundant labour). In other words, adopting capital-intensive modes of production is one of the important reasons behind poor employment performance.

Why would manufacturing firms in Africa adopt capital-intensive modes of production while labour is abundant on the continent? According to Diao and colleagues, two things have happened in recent decades that push firms in that direction:

First, manufacturing has experienced significant technological change in advanced economies. Naturally, innovation has taken a direction that responds to relative factor prices in the settings where it has taken place. So, it has been markedly labour-saving. Secondly, globalization and the spread of global value chains have had a homogenizing effect on technology adoption around the world. This means that the range of substitution between capital and low-skill labour has likely shrunk. The imperative of competing with production in much richer countries at similar quality levels makes it difficult to undertake large shifts in technique. Unlike earlier waves of developing nations, many African countries joined the world economy at a point where these two trends were already well established. Meanwhile, they are still poor and have very low relative capital endowments. This creates a conundrum: competing with established producers on world markets is only possible by adopting technologies that make it virtually impossible to generate significant amounts of employment to be generated.

If these trends continue (capital-biased manufacturing), it will get harder for African firms to create jobs in the same numbers that Asian ones did from the 1970s onwards. In other words, it will be challenging for Africa to use manufacturing or industrialisation to absorb its expanding labour force productively and to reduce poverty.

This is not to say that Africa should not adopt the industrialisation path for its development. Manufacturing offers African countries a chance to increase resilience to economic shocks. Also, productivity growth in manufacturing firms could create jobs indirectly. For example, if the agro-processing industry is capital intensive, it may increase employment in smallholder farming which is labour-intensive.

The growth of low-end services in informal urban areas and subsistence farming in rural areas does not notably improve productive structure. Without concomitant revolutions in industrialisation and agriculture, much of sub-Saharan Africa’s economic future will be shaped by a large subsistence agriculture sector in rural areas and low-end, informal services in urban areas that generally consist of wholesale and retail trade.

Initial attempts at developing manufacturing in African countries were through import-substitution industrialisation strategies in the immediate post-colonial period of the 1960s and 1970s. Efforts were made to substitute imported manufactured goods with locally produced goods in domestic markets by first manufacturing intermediate inputs with the aim of upgrading to capital goods. Many African countries achieved modest levels of industrialisation by manufacturing low-value consumer and intermediate goods.

However, this early wave of industrialisation was derailed by various internal and external factors, such as the absence of clear industrial development planning, lack of commitment, poor leadership, debt crisis and the subsequent structural adjustment programmes. In the 1980s, many African states lost interest in industrial policy; factories closed as the IMF and World Bank pressed governments to focus on what they already had an ‘advantage’ in — often commodities — and to open their markets to foreign competition.

-

The reasons for Africa’s under-industrialisation mentioned in the literature can be summarised as follows: It is widely believed that the initial conditions for industrial development did not exist in Africa, including core infrastructure (such as roads and rail) and an educated, productive workforce. Bureaucracy and a seemingly small and unsophisticated financial sector were seen as barriers to entry. Without greater financial depth, many African countries have struggled to attract larger investments.

However, these initial conditions did not exist at the beginning of industrialisation in Japan, the so-called Asian Tigers (Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan) or China. Greater financial depth, core infrastructure and a better-educated workforce developed in response to incentives, policies and effort. Governments are responsible for creating the right incentives to allow physical, human, social and knowledge capital to develop. That, in turn, requires a governing elite committed to economic growth and sufficient government capacity to formulate and implement policy. Many African leaders govern in the interests of their tribe, ethnic group or region and struggle to keep broad interests and coalitions together. The result is that they either have to extend huge resources to their small band of followers or need a vast system of patronage spread over multiple power brokers to stay in power.

-

Few African countries set out and implemented a concerted package of public investments, appropriate policy and institutional reforms to increase the share of industrial exports in GDP (Mauritius is a rare exception). In most African countries, little or no consistent effort was made to boost non-traditional exports, which still mostly consist of commodities.

-

Providing improved social services and infrastructure in a contained physical area attracts foreign companies and high-quality staff. In low-income countries, the domestic industry generally benefits from positive knowledge spillovers from foreign-owned firms, especially if it is part of the same value chain. Because African governments did not pursue the establishment of local value chains, African firms did not benefit from the few special economic zones (SEZs) that were set up. Instead, manufacturing firms have been dispersed across urban areas (instead of located close to one another), with limited requirements or incentives to source locally, train locals and establish local value chains. Ghana has gone as far as establishing a ‘one district, one factory’ initiative, with little apparent recognition of the associated requirements or benefits of locating factories closer together.

-

African governments also did not invest in high-quality SEZ infrastructure, promote these zones or bring in professional management. Weak infrastructure drives up the costs of making things. Electricity, a high cost for most manufacturers, costs three times more on average in Africa than it does even in South Asia. Poor roads and congested ports also drive up the cost of moving raw materials about and shipping out finished goods. African SEZs are generally not connected to domestic value chains since the practice (if not policy) of governments has been to treat them as stand-alone enclaves.

-

There is no real commitment and implementation support for FDI. For this reason, most African countries linger at the bottom of various indices concerning the ease of doing business and attracting foreign investment.

-

Several African countries (e.g. Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal and Tanzania) have embarked on investment reforms in an effort to improve the physical, institutional and regulatory environments in which firms operate. However, concerted efforts to improve the competitiveness of domestic industries or practical measures to reduce trade friction costs resulting from poor trade logistics have not accompanied these reforms.

-

It is also argued that East Asia’s string of successes happened under the ‘flying geese’ development model, where a ‘lead’ country creates a slipstream for others to follow. This happened first in the 1970s, when Japan moved labour-intensive manufacturing to Taiwan and South Korea. Similarly, light manufacturing is leaving China for neighbouring Bangladesh and Vietnam. Africa seems to have missed the flock. ‘We don’t have a leading goose, a Japan,’ says Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Nigeria’s former finance minister.

-

Bad luck has also played a part. When African economies spluttered back into life at the end of the 20th century after decades of poor growth, they not only had to compete with the industrial North but also with a number of countries in East Asia, including China. Import tariffs and nontariff barriers, including import quotas, local content requirements and export subsidies, were often used by the currently industrialised countries during their industrialisation process to protect their ‘infant industry’. However, the current global trading regime restricts these instruments. The result was so-called ‘premature deindustrialisation’ because of employment in the manufacturing sector and manufacturing’s share of GDP falling in Africa. For many commentators, the structural constraints on industrialisation were simply too large.

In summary, contrary to successes achieved elsewhere, most African governments have paid little to no attention to making SEZs work, nor have they integrated their approaches to SEZs into a comprehensive policy framework. SEZs have played a large part in the successful industrialisation in Asia. They allowed export-oriented industrial agglomerations to benefit from the advantages of being close to knowledge-intensive institutions, including foreign and domestic companies, research institutes and universities.

ICT-led globalisation and associated knowledge flows are undermining the previous competitive advantage of industrialised countries and are changing the outlook for global value chains. The result is that an increased number of jobs in the developed world are now in direct competition with jobs in emerging economies. The cross-border flow of data and knowledge has broken the monopoly that workers in wealthy nations had on using advanced manufacturing-specific intellectual property, giving rise to the notion of ‘new globalisation’. In theory, individuals can directly participate in globalisation by using digital platforms to study, find jobs, showcase their talent and build networks. In practice, this opportunity is limited to those who have electricity, are connected to the Internet and have the inclination, knowledge and interest to pursue it.

Although globalisation has had a disruptive impact in much of North America and Europe, fuelling populist politics, the phenomenon has had a cohesive impact on emerging Asia, where the middle class has flourished and millions of people have been lifted out of poverty.

In an interconnected and globalised world, knowledge flows inevitably undermine the concept of country comparative advantage — even in countries that are part of integrated trade blocs[5Examples are the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA), the European Union, and East and Southeast Asia.] where regional value chains are well established. Financial flows are already generally deregulated and now knowledge is also flowing more freely across boundaries; it is only labour mobility that remains restricted.

In response to the impact of this ‘new globalisation’, industrialised countries have embraced policies to protect their knowledge, for example, through excessive use of patent protection and instituting requirements for minimum labour standards and the amount of carbon generated in production. Conversely, emerging factory economies have embraced policies that foster knowledge sharing and creation. It is for this reason that China champions globalisation (despite having significant domestic barriers to foreign companies), whereas the US seeks to protect its domestic manufacturing sector from foreign competition by withdrawing or renegotiating trade agreements to now include much higher domestic and labour content requirements.

The problem for the US and other high-income economies is that the ICT revolution has broken industrialised nations’ monopoly on knowledge. As a result, barriers faced by manufacturers and specific industries and services in emerging countries, including in Africa, are constantly being lowered, often quite dramatically.

Trends in robotics, automation, computerised manufacturing and artificial intelligence (AI) all appear to reduce the advantage of locations with low labour costs. But this is not necessarily to the detriment of Africa. Originally, companies sought to locate manufacturers in countries with the cheapest labour and rapid growth in multinationals and consumers occurring in emerging rather than developed economies today. According to one estimate, almost half of the world’s largest companies will have headquarters in emerging markets and closer to consumer growth by 2025. These trends will first benefit economies of Asia but are beginning to be seen in Africa too.

A variety of digital technologies (particularly in the media), new materials (such as bio- or nano-based materials) and new processes (such as 3D printing, AI and robotics) threaten to disrupt existing manufacturing patterns. The future will likely see the development of a more distributed global economy, where manufacturing and services are closely linked and value chains are shorter and closer to markets. All offer opportunities for Africa. Generally, new technology decreases the required input costs of manufacturing, particularly for smaller production runs. Technologies such as 3D printing may eventually end the smokestack factory model of production and perhaps the world could even see the evolution of something akin to a cottage-industry model.

Lower barriers to entry allow companies to venture into areas outside their traditional specialisation. Start-ups can quickly go up the productivity curve to threaten established businesses. It is even evident in something as established as car manufacturing, with a company such as BYD in China threatening to outflank traditional manufacturers in Germany, the US, Japan and South Korea by investing heavily in electric vehicle technologies.

Instead of an ownership economy, digital platforms also allow and facilitate the development of a sharing economy (where individuals rent or borrow goods and services for a specific time or task rather than buy and own them). Production is therefore experiencing a shift towards customisation consisting of smaller production runs closer to the end markets and greater flexibility. The local manufacturer of, say, a spare part for a car or a replacement gear in a machine will be able to purchase the plan from the cloud and print locally. That means there is no more need for international shipping, tracking or customs.

Ghanaian entrepreneur Bright Simons refers to this as the rise of ‘Alibaba industrialisation’. He refers to an ‘unsung industrial revolution’ in several African countries powered by ‘a worldwide revolution in modular design, multi-purpose machinery, efficient small-batch production, global SME–SME [small and medium enterprise] engagement, new forex transfer practices, and the growing strategic transformation of China’s late-phase industrial players.’ This is a world where small and medium-sized Chinese suppliers provide large chunks of the industrial jigsaw and ‘African hustlers and unconventional industrialists act as shuttle-brokers of the various factors of production between China and Africa.’ According to him, the Fourth Industrial Revolution (digitisation) makes it easier for African states to become part of value chains from which they were previously excluded.

There are many things that raise hope in Africa’s industrialisation:

- A recent analysis shows that FDI flows to Africa are diversifying into manufacturing and other non-mining sectors.

- Also, the decline in manufacturing’s share of Africa’s GDP seems to have bottomed out in some African countries.

- According to the 2019 Africa’s Development Dynamics Report by the African Union and the OECD, Africa’s domestic demand, anchored on a young and growing population, is now shifting towards more processed goods and is growing 1.5 times faster than the global average. The publication also shows that demand for many other products such as motor vehicles, manufactures of metals and industrial machinery is also expanding faster than the global average.

- The continent’s auto industry, valued at US$30.44 billion in 2021, is expected to grow to US$42.06 billion by 2027 — a nearly 40% increase in value. Across the continent, there is an average annual demand for 2.4 million motor cars and 300 000 commercial vehicles. This rising domestic demand — due to the continent-wide increase in disposable income, strong growth of the middle class and rapid urbanisation — is currently being met primarily by imported used vehicles. However, domestic production has also been growing by an average of 7% annually over the past few years. Today, Morocco and South Africa are leading the way as major players in the automotive sector, making up 80% of African exports, with Algeria also experiencing rapid growth.

- Africa is endowed with essential raw materials for electric vehicles and new technologies required to reach the net-zero carbon emissions. There is also a huge market for motorcycles in Africa — especially in West, East and North Africa — as well as electric two-wheelers.

- Pharmaceuticals also offer a great opportunity for Africa to enhance manufacturing given the high product complexity, which can lead to greater opportunities for high local value-added production. The pharmaceutical industry is projected to grow at about 5% annually between 2022 and 2027 in Africa. Within pharmaceuticals, packaged medicines make up the largest import shares for Africa (65% of the US$17 billion pharmaceutical imports) and present a big opportunity, given their high percentage of imports and the sourcing and manufacturing stages that constitute the value chain.

- China and other countries in East Asia are restructuring their economies to meet growing domestic demand, which will create space for Africa to compete with countries such as Bangladesh as the low-end manufacturing market of choice for future relocation.

However, the biggest opportunity to grow domestic manufacturing is with intra-Africa trade. Manufactured products dominate intra-Africa trade, and evidence suggests that there is considerable room to grow intra-Africa manufactured exports through trade liberalisation. For instance, the German auto giant Volkswagen, already a key player on the continent, has recognised the potential of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) to catalyse local production of automotives and meet local demand.

Close to 60% of African imports are manufactured goods, while exports are dominated by energy commodities such as oil, coal and gas. Many of the imported goods can be manufactured locally and can boost the value of regional trade. There is great potential to increase intra-Africa trade in a host of foodstuffs, beverages and cigarettes, rubber and plastics, electronics, motor cars, non-metallic mineral products and pharmaceuticals. Processed and semi-processed goods constitute 61% of intra-Africa trade, and intra-Africa exports are more diversified and technologically advanced than those to other regions. The full implementation of the AfCFTA will help to overcome the challenge of narrow domestic markets and create a positive cycle of increased regional manufacturing. Small and isolated markets made it impossible for African countries to compete with Asian manufacturers. The continental market will help sustain greater economies of scale.

Replacing imported manufactured goods with locally produced goods will not be easy and will start with low-value goods. This is because global value chains have higher efficiencies and reduced prices, making it difficult for new entrants to compete. Still, it remains a crucial step in transforming African economies, and the evolution of global value chains could harbour opportunities for Africa.

The entry point for manufacturing traditionally involved labour-intensive segments of regional manufacturing value chains, meaning that labour costs need to be competitive. Given that Africa suffers from various disadvantages, such as poor physical infrastructure, a high disease burden, poor rule of law, low regulatory and policy quality, and a lack of policy certainty, the general view is that African labour costs need to be cheap enough to compensate for these deficits. However, a 2017 study on Africa’s manufacturing labour costs concluded that poor African countries have higher labour costs than their average income levels would suggest. The study compared 12 African countries to 17 non-African countries. Only Ethiopia compared favourably. In all other African countries reviewed, labour costs were higher than those of their non-African peers. In this regard, South Africa stands out as a middle-income country with particularly high labour costs and a very capital-intensive industrial sector — partly explaining its extraordinarily large burden of unemployment and high levels of inequality. Manufacturing labour costs in low- and low-middle-income countries such as Kenya, Tanzania and Senegal — three relatively stable coastal countries with strong business sectors — are higher than in Bangladesh, a country with a comparable World Economic Forum competitiveness rating and income levels.

However, with the advent of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the importance of labour costs in the location of industry is declining. In addition, current trends point to manufacturing preferentially being located closer to end markets.

For these reasons, industrialisation in Africa remains possible, although its nature will differ from that in other regions. Newman and colleagues describe three considerations:

First, economic changes are taking place in Asia that create a window of opportunity for late industrializers elsewhere to gain a toehold in global markets. Second, the nature of manufactured exports themselves is changing. A growing share of global trade in the industry is made up of stages of vertical value chains – or tasks – rather than finished products. Trade in tasks offers late industrializers an opportunity to enter global markets in areas suited to their factor costs and endowments of skills and capabilities. Third, trade in services and agro-industry is growing faster. These ‘industries without smokestacks’ broaden the range of products in which Africa can compete, and a number of them are intensive in locations specific factors abundant in Africa.

Typically when countries embark on a manufacturing transition, inequality and poverty may initially increase. This is because resources and investments are diverted to more capital and knowledge-intensive sectors, which leads to an initial crunch in consumption. However, in the long term, these efforts stimulate inclusive growth with a greater impact on poverty and inequality reduction.

Policies aimed at industrialisation, therefore, need to be accompanied by measures to mitigate these effects. These could include efforts to directly support extremely poor families through social programmes (e.g. distributing cash grants) and investing in education, job creation and providing basic services.

The Manufacturing scenario

Download to pdfThis section briefly presents a set of interventions modelled in the IFs platform to emulate a manufacturing push in Africa with a time horizon to 2043, the end of the third ten-year implementation of the African Union’s Agenda 2063, and compares its impact to the Current Path forecast. The conceptualisation is set out in Chart 8.

Clear industrial policy and determined government leadership and action are critical if African economies are to grow more rapidly. For this reason, the first set of interventions increases government revenue to allow for investment in manufacturing and the roll-out of a social grants programme. It reflects the determined efforts by forward-looking African governments to set the agenda for industrial development and to reduce the short-term impact of these measures, which often initially increase poverty and inequality until more rapid economic growth is able to reduce both.

In addition to low rates, complex and antiquated systems and inefficiencies in revenue collection mean that African governments forgo large amounts of tax revenue. There are also lucrative new tax opportunities for taxing big tech companies. With millions of Internet users in Africa (including 255 million using Facebook alone) in 2022, taxing the digital economy could contribute to the fiscal demands of many African economies.

Implementing such policies is not easy or straightforward as they require significant political determination. In Ethiopia, efforts launched in 2006 to expand the tax base made steady progress. Total taxes collected nearly tripled in seven years, from US$1.3 billion in 2007 to US$3.8 billion in 2013, but then stalled for several years after the death of Prime Minister Meles Zenawi. However, as a share of total government revenue, the contribution from tax grew from 48% in 2007 to 82% in 2016. Zenawi had personally championed the reforms and insulated them from political interference.

At 16.5% of GDP, Africa’s average tax-to-GDP ratio is lower than other regions, such as Asia and the Pacific (19.1%), Latin America and the Caribbean (21.9%) and Organization for Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries (33.5%).

Without sufficient revenues, governments cannot deliver on improved education, infrastructure or healthcare, provide security or democracy, or, as is modelled here, invest in a more productive economy.

In the Manufacturing scenario, African governments are expected to raise US$260 billion more in taxes by 2043 compared to the Current Path forecast. Government-to-household transfers increase from 7.5% of GDP in 2043 (in the Current Path forecast) to 9.3% (in the Manufacturing scenario), translating to US$163 billion in additional transfers. Rapid structural transformation may entail a trade-off between growth and inequality. Progressive taxation and welfare spending are important to mitigate this effect. Generally, cash transfers are better than fuel or other government subsidies such as those used in Nigeria, Tunisia, Algeria and Egypt. Subsidies that lock governments into foreign exchange-linked expenditure (such as bread subsidies in Egypt, which are linked to wheat imports, or fuel subsidies in Nigeria) are particularly problematic. Large fluctuations in the exchange rate or a deterioration of rates create an external financial obligation that may escalate beyond the means to service the associated costs, which is domestically difficult to scale down or remove.

In the Manufacturing scenario, government expenditure in research and development (R&D) also increases by about US$1.3 billion by 2043 relative to the Current Path forecast — a particularly powerful driver of improvements in productivity. Technology upgrading through R&D is crucial for a robust manufacturing sector. It stimulates innovation, increases productivity and improves the quality of products.

The Manufacturing scenario improves the quality of business regulation and investment in the manufacturing sector.

Finally, increasing manufacturing should lead to direct and indirect employment in the sector. Therefore, the scenario includes a modest increase in labour participation rates equivalent to 1.5 percentage points above the Current Path forecast by 2043. Generally, the employment intensity of the manufacturing sector is declining globally when seen relative to the period when Asia experienced its most rapid manufacturing growth.

Chart 9 presents the shift in the sectoral composition that would occur at the continental level due to the Manufacturing scenario. The manufacturing sector’s share of GDP is, by 2043, 3.5 percentage points of GDP larger than it would have been on the Current Path, while the shares of other sectors in GDP decline compared to the Current Path forecast. The service sector accounts for 55% of the total African economy by 2043 — 2.4 percentage points of GDP lower than the Current Path forecast. The manufacturing sector has absorbed the shift away from agriculture, and other sectors becoming the second most significant contributor to Africa’s GDP at just over 25% in 2043.

In absolute terms, all sectors are larger by 2043 than in the Current Path forecast for that year, reflecting the growth spillover effect from the manufacturing industry to the other sectors. The contribution of the manufacturing sector to GDP has the biggest improvement (an increase of US$463.4 billion) compared to the Current Path forecast in 2043. The manufacturing sector is followed by the service sector with an increase of US$163 billion above the Current Path in 2043. ICT comes in third position and is US$16.5 billion larger than the Current Path forecast in 2043.

Chart 10 presents the size of the African economy in 2043 on the Current Path and in the Manufacturing scenario in market exchange rate (MER).

In 2019, Africa’s GDP was just over US$3 trillion. In the Current Path forecast, it will increase to US$8.5 trillion by 2043, at an average growth rate of 4.4% per annum. In the Manufacturing scenario, the 2043 African economy is substantially larger: US$9 trillion with an average growth rate of 4.8% — a difference of 0.4 percentage points. The result of the Manufacturing scenario is an African economy that is US$658 billion (or 8%) larger in 2043 than expected in the Current Path forecast. The 23 lower-middle-income countries in Africa gain more (in a relative increase in the size of their economies) than low- or upper-middle-income countries.

By 2043, the average African is forecast to have an income of US$7 445, which is US$383 more than the Current Path forecast of US$7 062, with the largest increases in the upper-middle-income group (at US$660 in PPP).

The impact of the scenario on GDP per capita also differs by country. The DR Congo experiences the largest increase in its GDP per capita (at 10%) compared to the Current Path in 2043, followed by Malawi. The countries that gain the least are Seychelles and Sudan. However, in absolute value, Botswana sees the largest increase in GDP per capita (at US$1 671) compared to the Current Path in 2043, followed by Libya. The countries that gain the least are the Central African Republic and Burundi (Chart 12). The manufacturing sector in Burundi is weak; almost all manufactured consumer goods are imported. In 2021, Burundi ranked 51st of 52 countries on the African Development Bank's African Industrialization Index.

Considering progress towards the SDG headline goal of eliminating extreme poverty by 2030, using US$1.90 as the extreme poverty line, the Manufacturing scenario could lift about 16 million Africans out of poverty by 2030 and 53 million people (a 2.4 percentage point reduction in the poverty rate) by 2043.

The magnitude of the impact of the scenario on poverty reduction differs between African countries. Chart 14 presents the percentage point reduction in poverty rate (US$1.90) in 2043 in the Manufacturing scenario compared to the Current Path. Malawi, the DR Congo and Liberia are set to experience the largest decline in poverty rates. However, in considering the absolute number of poor people, the DR Congo sees the biggest poverty reduction by 2043 (11.3 million fewer poor people compared to the Current Path forecast), followed by Nigeria (10.5 million fewer poor people). The extreme poverty rate at US$1.90 is already eliminated in countries such as Seychelles, Mauritius and in North Africa. As a result, the number of people lifted out of poverty by 2043 is marginal in these countries.

The scenario also contributes to income inequality reduction as measured by the Gini coefficient (index) in all the countries. As shown in Chart 15, Somalia and Algeria gain the most from the Manufacturing scenario, whereas Guinea-Bissau, Sudan and Cabo Verde gain the least. In sum, with determined efforts to embark on a manufacturing pathway and taking active steps to cushion the immediate costs of pushing a manufacturing agenda, solid improvements in the well-being of a large portion of the African population are possible.

Today, industrialisation has become one of the most talked about issues among African policymakers. The question of how to make African economies more productive and inclusive is gaining new urgency amid the long lasting effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine and the increase in tensions between China and the West.

This analysis has sought to unpack the current state of industrialisation in Africa and to simulate the impact of a manufacturing push scenario on Africa’s socio-economic development prospects.

The analysis reveals that since the 1970s, African economies have experienced a limited — as well as limiting — form of structural transformation from low-productivity agriculture to low-end services. Manufacturing and industrial development have never taken off. The continent appears to be de-industrialising at low levels of income. Also, in the majority of African countries, the shares of manufacturing in total employment are very low. The same is true with the shares of manufacturing in the export baskets of most of the countries on the continent.

Africa tends to export unprocessed commodities (e.g. coffee, cocoa, etc.) and to import processed products and finished goods. This trend will likely continue, reflecting the limited value-addition characteristic of most African production and exports.

Economic growth based on increasing commodity exports rather than exports of value-added products cannot induce structural economic transformation. Instead, it has led to economic enclaves in several African countries with few linkages to the rest of the economy. Examples include the oil-producing parts of Angola off the coast of Cabinda, parts of oil-producing Nigeria (in the Niger Delta), sections of Equatorial Guinea and soon the Cabo Delgado province in northern Mozambique with its rich natural gas endowment.

Compare this with the experience of rapidly developed Asian countries such as Japan, the Asian Tigers and Vietnam, where activist governments actively pursued industrialisation, encouraging growth in the manufacturing sector and their entry into global value chains that improved the quality and productivity of the associated goods. They did so deliberately and targetted, working closely with the private sector and adopting an iterative and learning approach. In this manner, these countries steadily upgraded their technical capabilities to meet international standards, often by inviting and partnering with multinational companies to transfer technology, skills and knowledge. Instead, Africa has relied on exporting primary commodities, which has long been conceptually and empirically linked with underdevelopment. A thicket of complex regulations, corruption, and poor infrastructure often hinder foreign manufacturing sector investment.

Today, global value chains are shifting closer to the market and, in some instances, becoming more regional. These developments offer opportunities for Africa, which generally forms only a peripheral part of these chains. Modern technology provides significant opportunities for industrial latecomers to skip over the brick-and-mortar institutions of yesteryear into a world where banking and sourcing of inputs occur remotely while benefiting from a decline in the financial investment required to embark on manufacturing. New technologies enable greater flexibility and customisation, shifting production closer to the consumer.

The most important driver of shifting value chains in the 21st century is the signs of increased manufacturing nationalism and diversification away from the global factory in China. In the US and Europe, the push for energy independence, China’s trade surplus and xenophobia led to the election of Donald Trump as president, who routinely scapegoated China for apparent unfair trade practices. The result was that the US imposed tariffs and restrictions on Chinese imports before settling on an uncomfortable trade deal early in 2020. Later that year, the European Union (EU) also released a new industrial strategy for Europe, which set out its ambitions towards reinforcing the EU’s industrial and strategic autonomy to delink from China for ‘critical materials and technologies, food, infrastructure, security and other strategic areas.’ Shortly after assuming office, President Biden's administration launched a comprehensive US industrial strategy - the first explicit effort at federal level in several decades.

The increased global geopolitical tensions associated with tension between the US and China and the Russian–Ukraine war have given impetus to the trend towards. Many firms and policymakers are seeking to make their supply chains more resilient by moving production home or to geopolitically aligned countries (friend-shoring).

These developments are all to Africa’s potential advantage. With its large and growing population, the continent offers a sizeable future market and labour force and facilitates geography — provided it can unlock the potential of its segmented market, currently divided into 55 national geographies.

Declining agriculture and manufacturing sectors and an increase in the relative contribution of the low-end service sector on the Current Path will likely bring only modest reductions in poverty, with a significantly more significant proportion of the working poor found in services and agriculture. Rapid poverty reduction in Africa is intimately associated with changes to and within the agricultural and manufacturing sectors. The IFs Current Path forecast suggests that most African countries will make only slow progress to reduce extreme poverty, with the bulk of impoverished people increasingly concentrated in countries such as Nigeria, the DR Congo and Madagascar. However, more rapid progress is possible with the right policies and dedicated effort.

To develop, Africa needs to transform its economies to become more productive and to enable more rapid income growth. Traditionally, that has been achieved through industrialisation, although the breakthroughs in improvements in productivity in services also mean that services-led growth can translate more rapidly into improvements in other sectors. Many authors suggest that key manufacturing characteristics, such as tradability, scale, innovation and learning by doing, are becoming features of modern services too. An IMF study indicates that two types of services — transport and communications and financial intermediation and business services (rentals of machinery and equipment, software and data processing, R&D and professional services) — tend to exhibit labour productivity growth similar to or higher than manufacturing.

Starting from a low base, where most workers engage in subsistence farming or informal services, Africa has more to gain from structural economic transformation than other developing regions. But it has yet to manage to achieve this. Industrialisation in Africa will create more formal direct and indirect jobs because it will change the productive structures of African economies and unlock more rapid growth. The continent needs to invest in lowering transport and infrastructure costs, ensure policy certainty and work towards a low regulatory burden to compensate for Africa’s relatively high labour costs. It must also ensure the success of trade integration to provide larger markets and rapid digitisation. Collectively, this will attract and grow manufacturing. All of this requires an explicit industrial policy, the deliberate steering of industry 'to capture learning and innovation externalities', in the words of Harvard economist Dani Rodrik.

In a future where more goods will be produced and consumed in regional rather than global markets, and possibly in a much more distributed manner, Africa has considerable opportunities for industrialisation and regional trade. However, this will happen only if Africa embarks on a deliberate effort to go up the manufacturing curve and establish and support SEZs, sets clear industrial policies, provides relevant education and invests in the necessary digital backbone. Digital production will play a role in this journey, highlighting the importance of investing in ICT.

The Manufacturing scenario modelled in this theme shows that an industrialisation push in Africa has the potential to unlock more rapid economic growth rates, increase jobs in the formal sector, and reduce poverty.

However, industrialisation takes time and effort. It requires deliberate policies and visionary and determined leadership to embark on this journey, especially in resource-rich countries where the abundance of petrodollars makes importing various goods and services easier. Industrialisation requires constructive relationships between the state and the private sector, which it encourages and supports. Firms need a state with solid capabilities in setting an overall economic vision and strategy, efficiently providing supportive infrastructure and services, maintaining a regulatory environment conducive to entrepreneurial activity, and making it easier to acquire new technology and enter new economic activities and markets.

African leaders should learn from the Asian countries where governments played a significant role in their industrialisation. The leading ‘hand of the state’ steered labour and capital into activities the market would not necessarily undertake. For instance, in the 1960s, South Korea exported rice, silk, wigs and tungsten. With the ambition to industrialise hard and intelligent work, the country embarked on developing shipbuilding, electronics and car industries. South Korea has today a dynamic industrial base with flagship products like televisions, cellphones and, among others, motor vehicles. South Korea’s path would have been quite different without its developmentally oriented leaders with an appetite for risk-taking.

This is not impossible for Africa which needs to learn from experience elsewhere. There is a need to re-galvanise political leadership for accelerated inclusive and sustainable industrialisation in Africa. Reforms should be undertaken to boost manufacturing to capture a large part of the growing demand for processed goods and other products such as motor vehicles, manufactures of metals and industrial machinery on the continent. Africa’s natural comparative advantage in agro-business, solid minerals and metals, and oil and gas could be leveraged through commodity-based manufacturing.

To this end, African authorities should continue their reform efforts to improve the business climate and economic freedom to attract domestic and foreign investment to the manufacturing industry. Public procurement should be used strategically to patronise domestically produced goods.

Also, African countries should develop their people's skills to produce intermediate and final goods of high quality. To this end, partnerships with the private sector should address the vast skills mismatch and promote productivity in manufacturing processes. Investing in good ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ infrastructure and energy and developing a continental financing platform that supports industrialisation is also necessary. They should equally ensure macroeconomic stability and the success of the African continental free trade agreement (trade integration) to provide larger markets and create economies of scale.

Finally, domestic revenue mobilisation should be prioritised with a particular emphasis on fighting illicit financial flows, depriving the continent of approximately US$90 billion annually that could advance industrialisation through more investment.

Endnotes

H-J Chang, Kicking away the ladder: Development strategy in historical perspective, London: Anthem Press, 2003, 43.

D Acemoglu & S Johnson, Power and Progress - Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity, Basic Books, London, 2023, chapters 4 to 6

N Kaldor, Strategic factors in economic development. New York: Cornell University Press, 1967.

AO Hirschman, The strategy of economic development, Boulder and London: Westview Press, 1958.

Examples are the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA), the European Union, and East and Southeast Asia.

Page information

Contact at AFI team is Kouassi Yeboua

This entry was last updated on 14 January 2025 using IFs 7.84.

Reuse our work

- All visualizations, data, and text produced by African Futures are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

- The data produced by third parties and made available by African Futures is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

- All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Cite this research

Kouassi Yeboua (2025) Manufacturing. Published online at futures.issafrica.org. Retrieved from https://futures.issafrica.org/thematic/07-manufacturing/ [Online Resource] Updated 14 January 2025.