Algeria

Algeria

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

This page presents a comprehensive analysis of Algeria. It outlines the country's extensive socio-economic challenges and opportunities, examining various developmental paths through 2043. It discusses the substantial economic growth potential from its human capital and natural resource wealth, particularly its significant reserves of oil and natural gas. Algeria faces persistent issues with economic diversification and unemployment, infrastructure, governance, education and healthcare. Various scenarios consider the impacts of improvements in these sectors. The analysis aims to provide policymakers with recommendations to guide Algeria towards a more prosperous future.

For more information about the International Futures modelling platform that we use for the development of the various scenarios, please see About this Site.

Summary

We begin this page with an introductory assessment of Algeria’s context looking at the current population distribution and structure, climate and topography.

- Algeria has the largest land area in Africa and the 10th largest in the world. The country is bordered by Tunisia to the north-east, Libya to the east, Morocco to the west and shares borders with Niger, Mali, Mauritania and the disputed region of Western Sahara in the south-west.

This section is followed by an analysis of the Current Path forecast for Algeria which informs the country’s likely current development trajectory to 2043. It is based on current geopolitical trends and assumes that no major shocks would occur in a ‘business as usual’ future. We also provide an overview of the national development plan.

- On the Current Path, Algeria’s population will increase from 44.2 million in 2021 to 58.6 million in 2043. With a working-age population accounting for 66.1% of its total population by 2043, Algeria will find itself in a favourable window of demographic opportunity contributing to steady growth.

- Algeria is a big player on the African continent, not only because of its substantial land area but also because of its sizable GDP, in 2019, its GDP was the fourth largest in Africa at US$266.5 billion. The size of the economy will grow to US$453.5 billion in 2043.

- Algeria’s GDP per capita will improve by nearly a thousand dollars from US$15 200 in 2019 to US$16 400 in 2043. Its GDP per capita income will remain above the projected average of lower-middle-income African countries by 2043.

- In 2021, about 0.3% of Algeria’s population lived below the poverty line of US$1.90 per day. About 962 000 Algerian people lived on less than US$3.20 per day in 2021. By 2043, the share of people living below the US$3.20 poverty line will decline to 494 000.

- National Development Plan was carried out with the objective of supporting the establishment of Algeria’s National Vision 2030.

The next section compares progress on the Current Path with eight sectoral scenarios. The eight sectoral scenarios are Demographics and Health; Agriculture; Education; Manufacturing; the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA); Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging; Financial Flows; and Governance. Each scenario is benchmarked to present an ambitious but reasonable aspiration in that sector.

- The Demographics and Health scenario will reduce Algeria’s population by 0.4% relative to the Current Path. The total fertility rate will decrease from 2.1 births per fertile woman (Current Path) to 2.0 births in 2043.

- The Agriculture scenario will increase Algeria’s crop production by 11 million metric tons relative to the Current Path, reducing the import bill by about US$6.6 billion in 2043.

- The Education scenario will increase Algeria’s mean years of education for adults (15–24 years) to 10.4 - an improvement of about 0.6 years relative to the Current Path in 2043.

- The Manufacturing scenario will increase value added by about US$18.3 billion (or 2.4% of GDP) relative to the Current Path to about US$132.8 billion in 2043, highlighting the expected growth and changing dynamics in the manufacturing sector.

- Algeria’s export composition is dominated by hydrocarbons (98% of total exports), and it is heavily dependent on imports (70% of the country’s needs are imported). In the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) scenario, Algeria’s total trade deficit will continue to be dominated by its manufacturing sector. The energy sector trade surplus will account for 16.6% of GDP.

- The Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario will increase mobile broadband subscriptions by just 0.8 subscription per 100 people relative to the Current Path.

- In the Financial Flows scenario, FDI inflows as a percentage of GDP will increase from 1.7% (Current Path) to 3.3% of GDP in 2043.

- Generally, governance in Algeria does better compared to the average of lower-middle-income countries in Africa. In the Governance scenario, its inclusion index score will increase by 0.11 (or 22.1%) reaching an overall score of 0.59.

The third section compares the impact of each of the eight sectoral scenarios with one another and with a Combined scenario (the sum effect of all eight scenarios).

Progress is measured on various dimensions such as economic size (in Market Exchange Rates), Gross Domestic Product per Capita (in Purchasing Power Power Parity), extreme poverty, carbon emissions, the changes in the structure of the economy, and selected sectoral dimensions such as progress with mean years of education, life expectancy, the Gini coefficient or reductions in mortality rates.

- Algeria’s GDP per capita will increase to about US$22 727 by 2043, 38.3% higher than the US$16 437 in the Current Path. The AfCFTA scenario will have the greatest impact on GDP per capita in 2043.

- 391 000 Algerian people will be lifted out of extreme poverty at US$3.20 per person per day.

- Algeria’s economy will be US$271.3 billion (or 59.8%) larger than when compared to the Current Path in 2043.

- The share of the informal economy as a per cent of GDP will drop by about 8.2% relative to the Current Path by 2043.

We end this page with a summarising conclusion offering key recommendations for decision-making.

All charts for Algeria

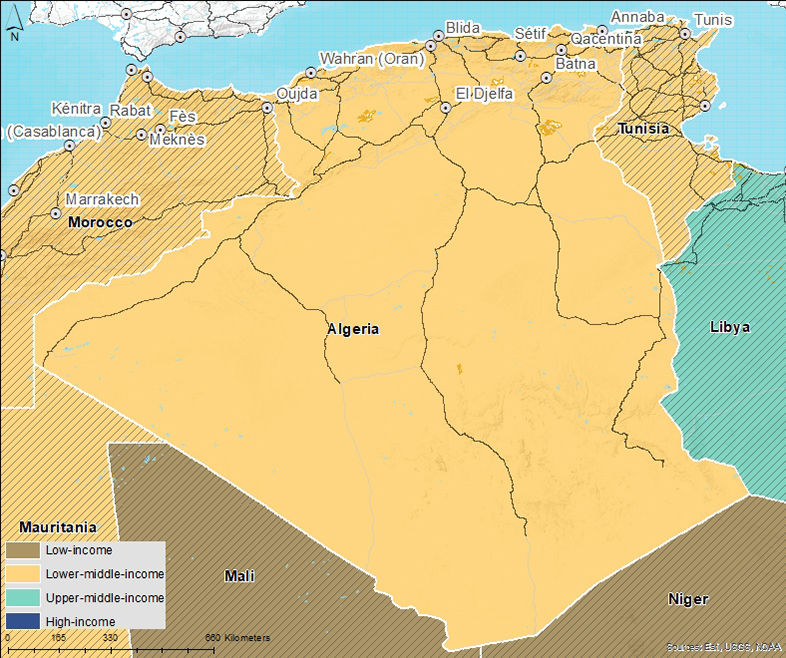

- Chart 1: Political map of Algeria

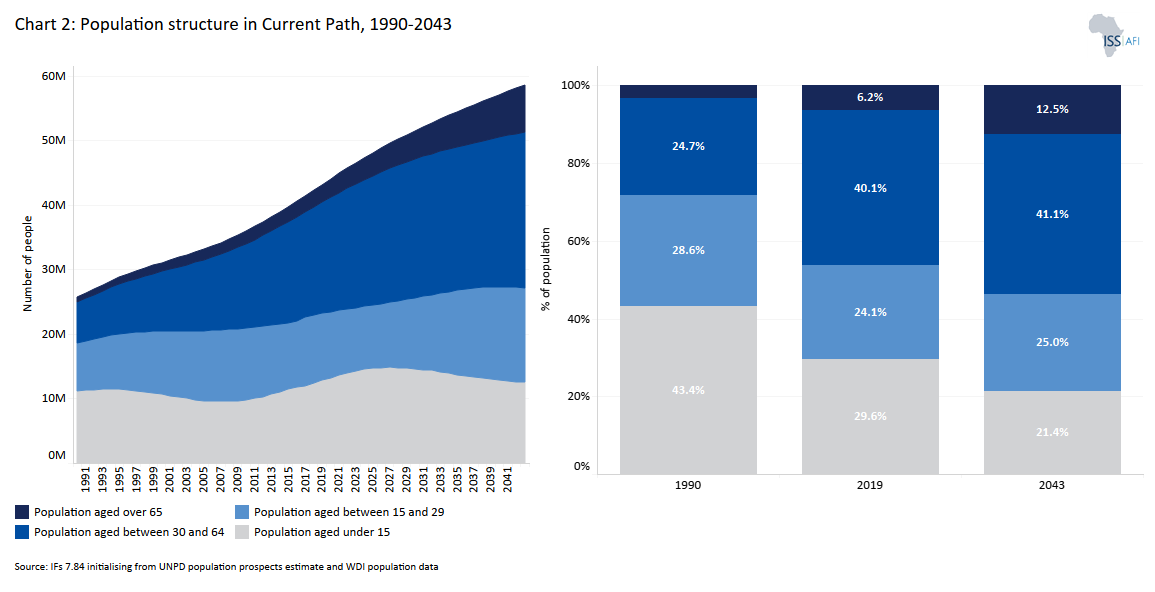

- Chart 2: Population structure in Current Path, 2019–2043

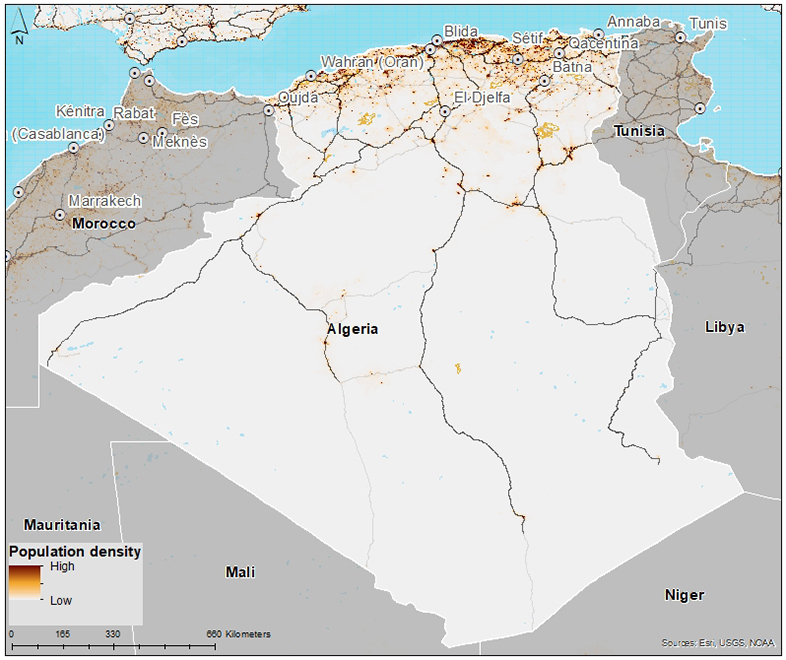

- Chart 3: Population distribution map, 2022

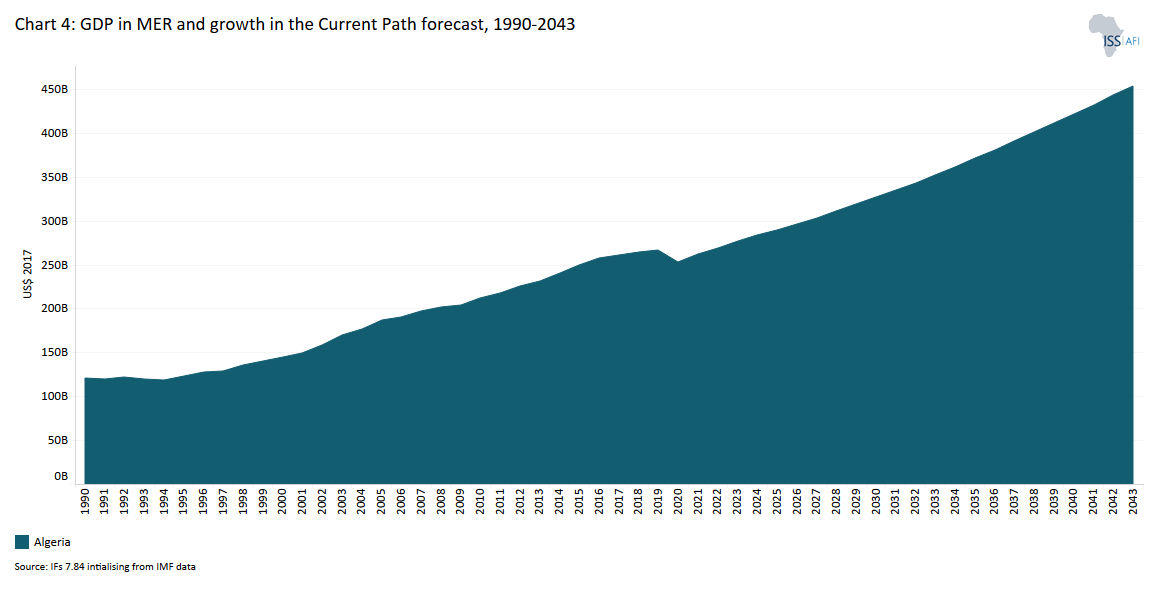

- Chart 4: GDP in MER and growth in Current Path, 1990–2043

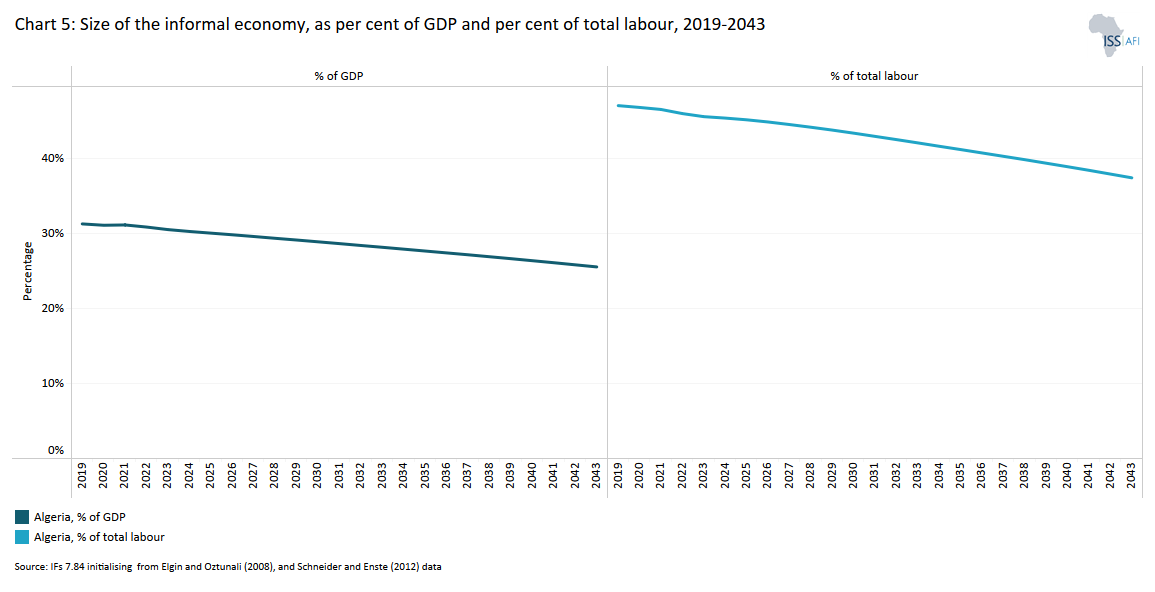

- Chart 5: Size of the informal economy as percentage of GDP and of total labour, 2019-2043

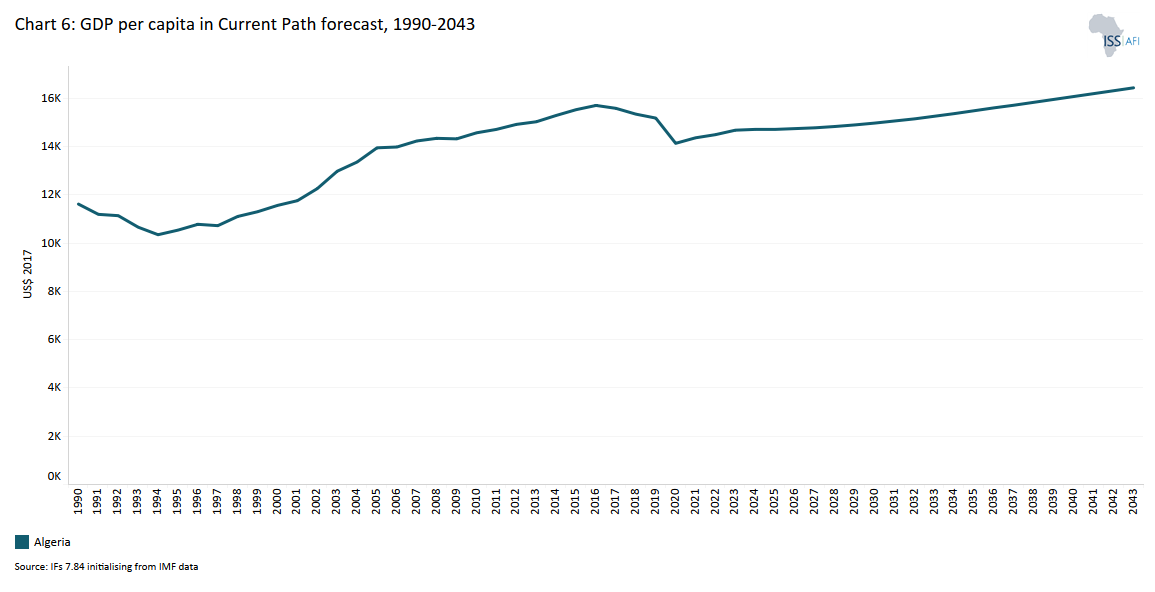

- Chart 6: GDP per capita in Current Path, 1990–2043

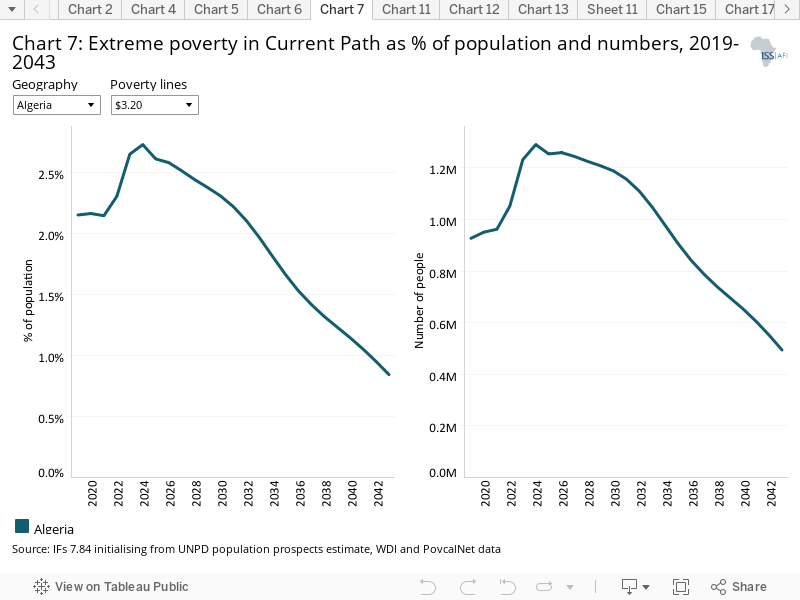

- Chart 7: Extreme poverty in Current Path as percentage of population and numbers, 2019–2043

- Chart 8: National Development Plan of Algeria

- Chart 9: Current Path and scenarios

- Chart 10: Demographics and Health scenario

- Chart 11: Urban and rural population in Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 1990–2043

- Chart 12: Infant mortality rate in Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 2019–2043

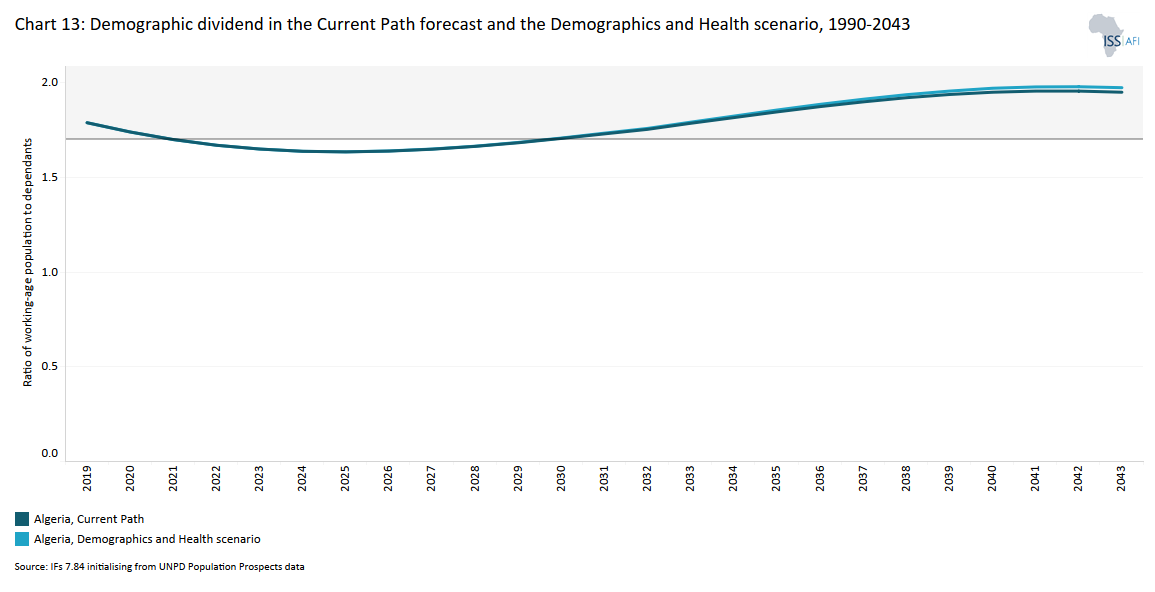

- Chart 13: Demographic dividend in Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 2019–2043

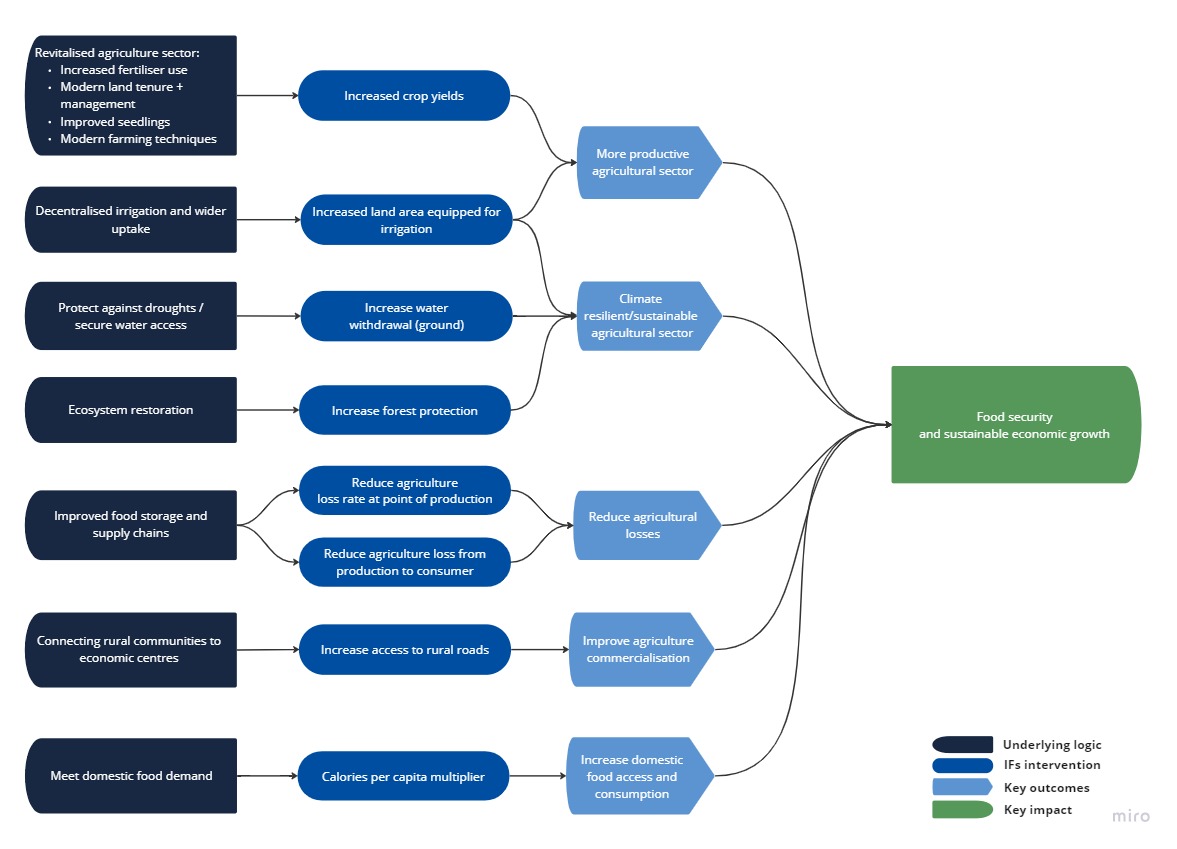

- Chart 14: Agriculture scenario

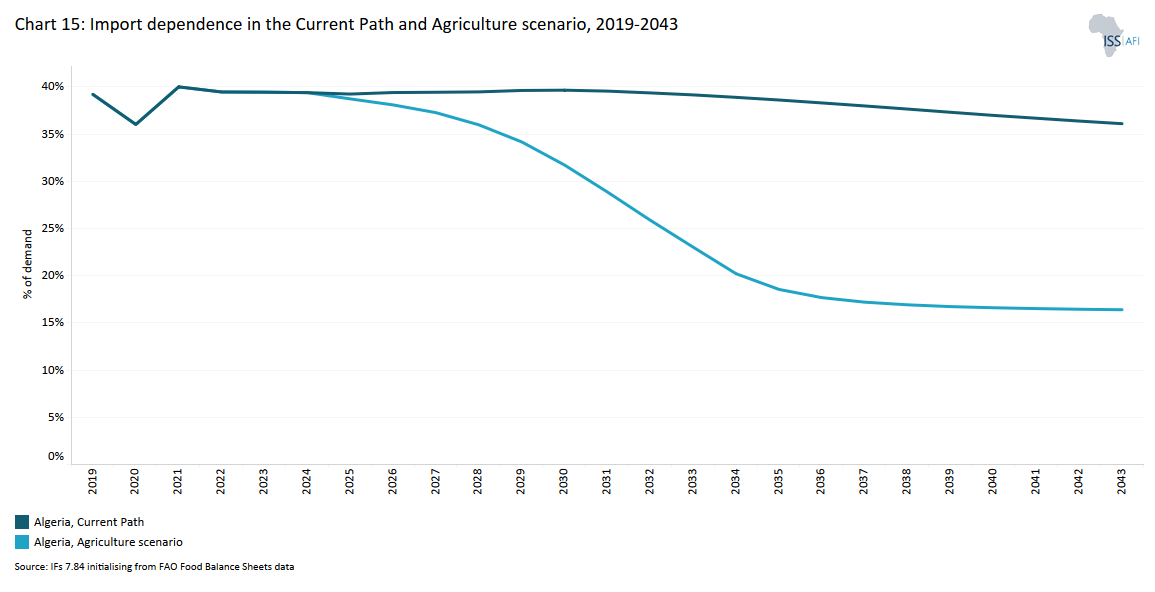

- Chart 15: Import dependence in Current Patht and Agriculture scenario, 2019–2043

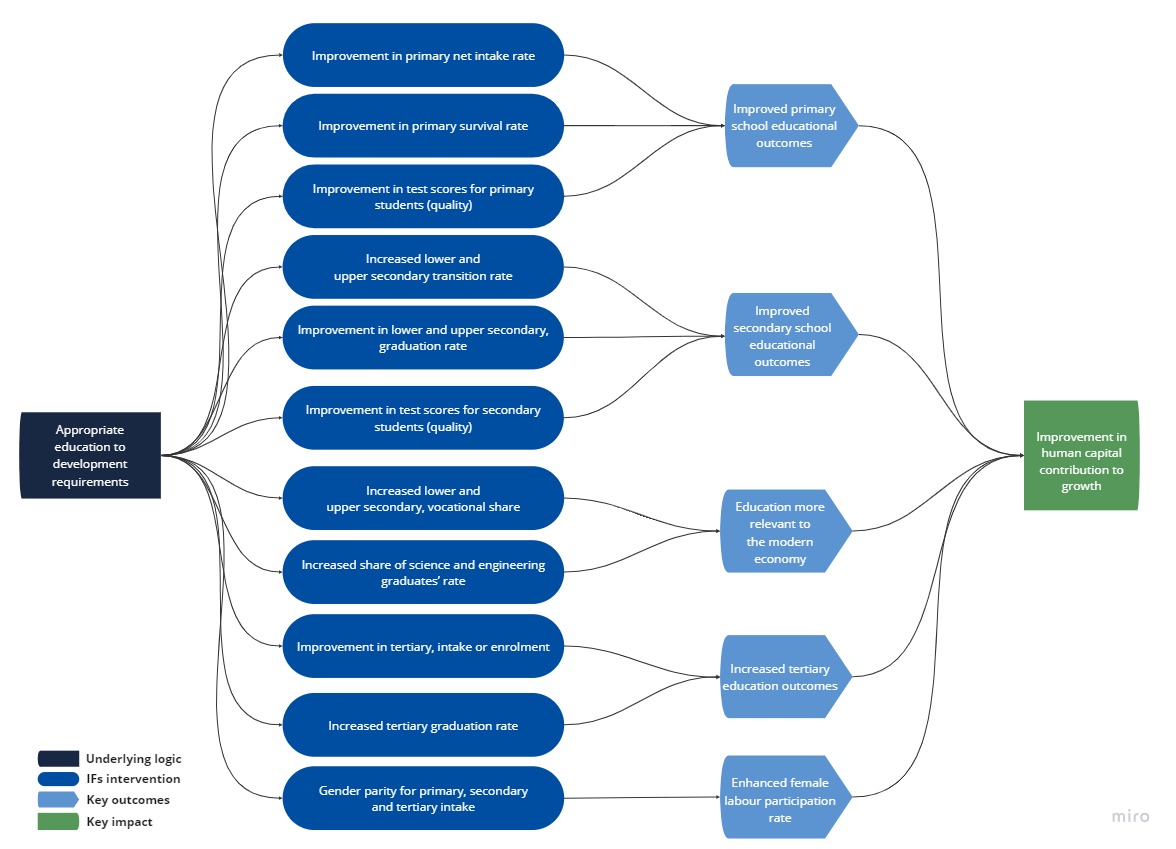

- Chart 16: Education scenario

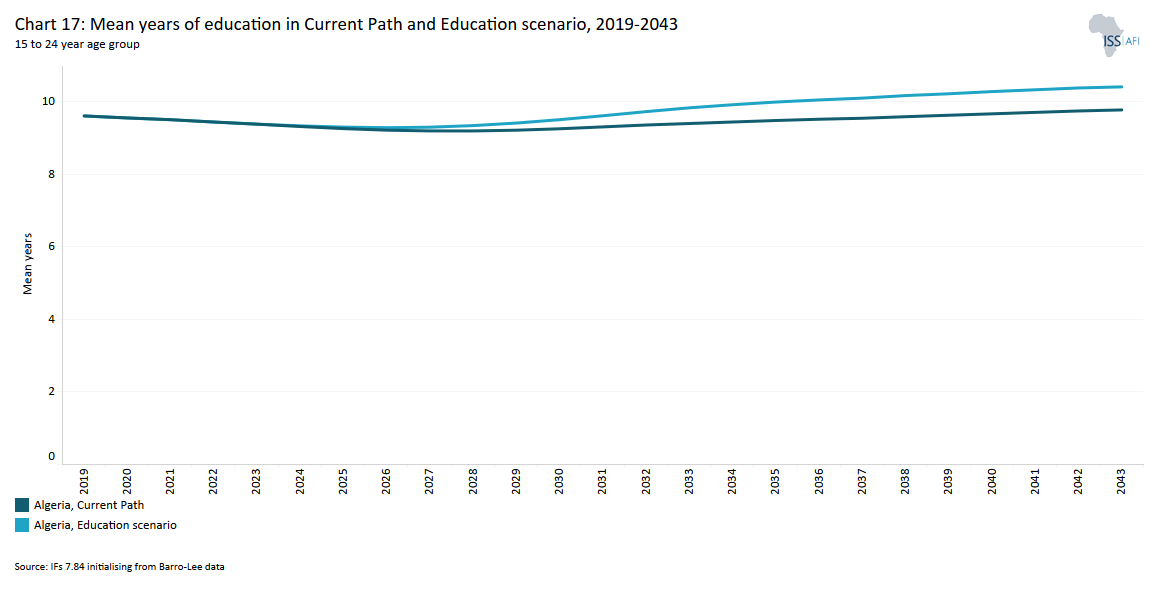

- Chart 17: Mean years of education in Current Path and Education scenario, 2019–2043

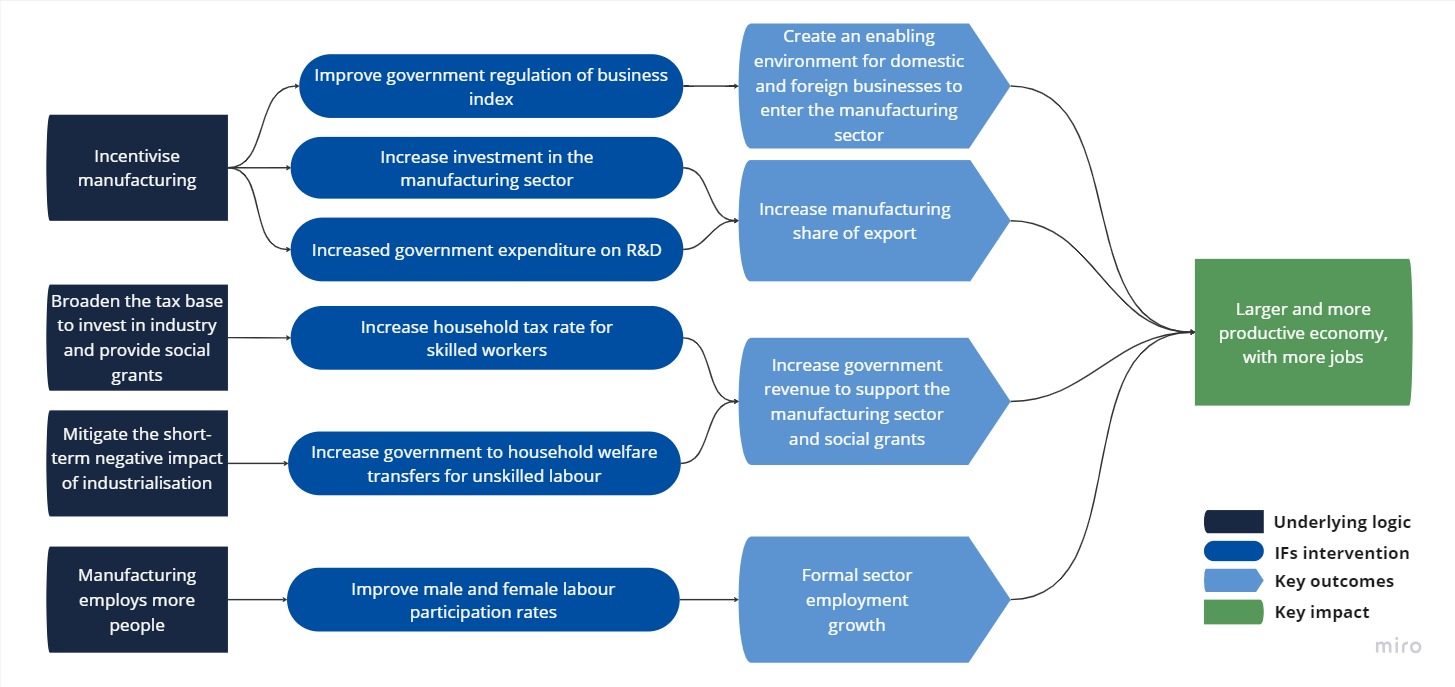

- Chart 18: Manufacturing scenario

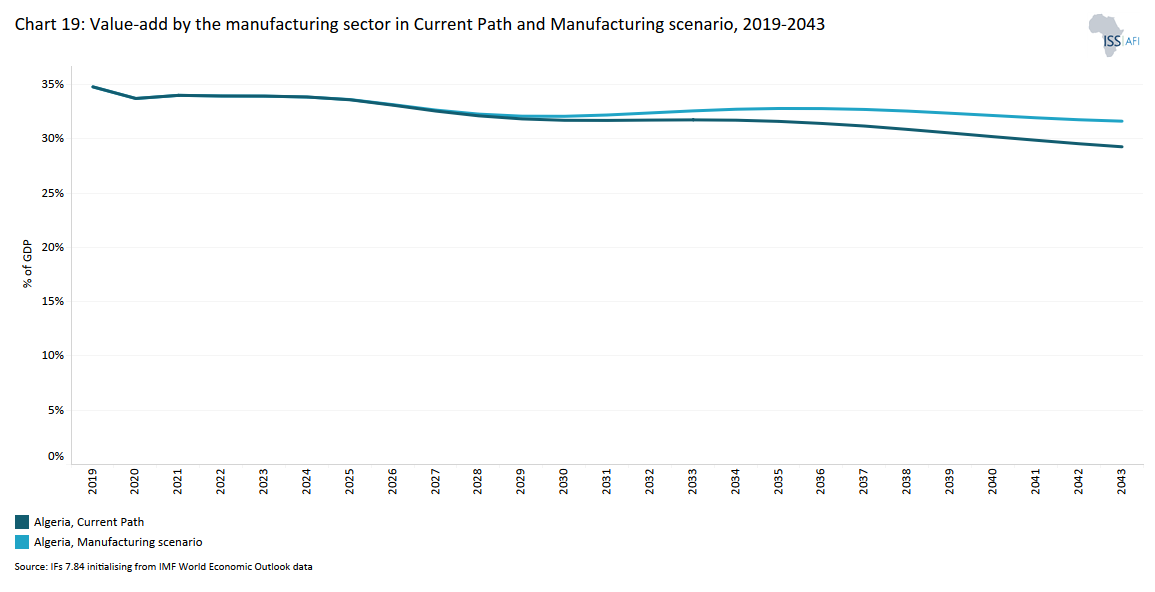

- Chart 19: Value-add by the manufacturing sector in Current Path and Manufacturing scenario, 2019–2043 US$ 2017 and % of GDP

- Chart 20: AfCFTA scenario

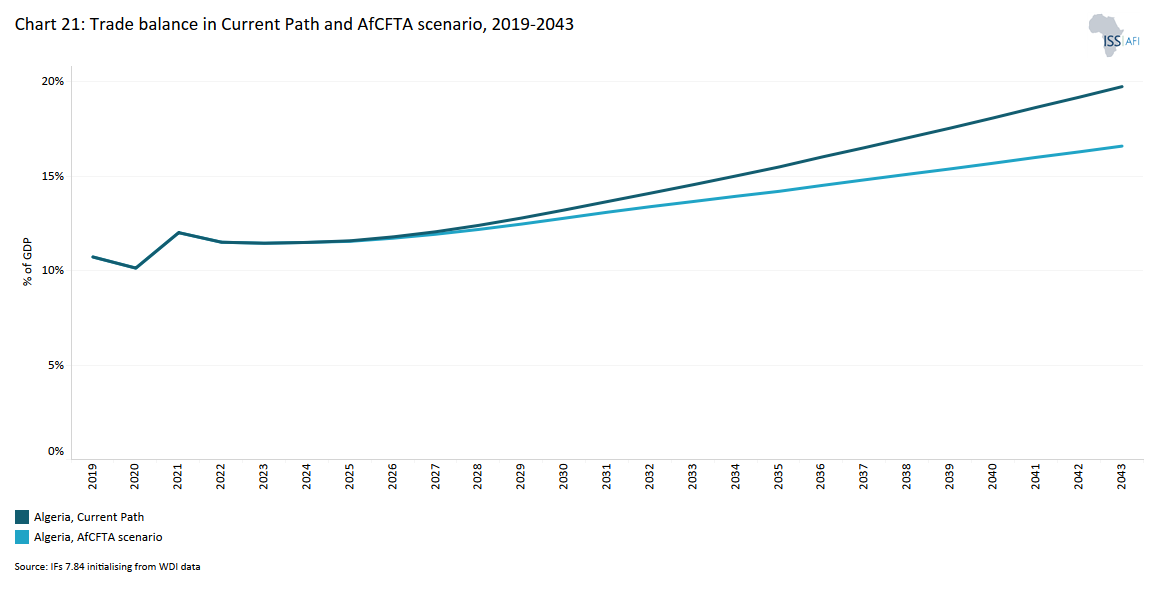

- Chart 21: Trade balance in Current Path and AfCFTA scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 22: Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario

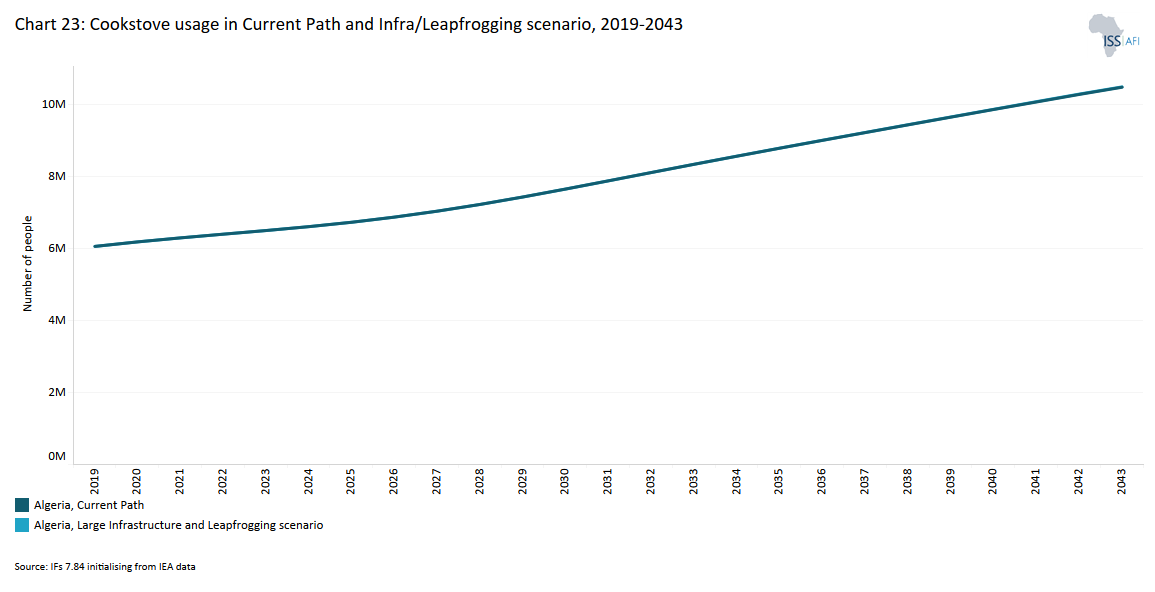

- Chart 23: Cookstove usage in Current Path and Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

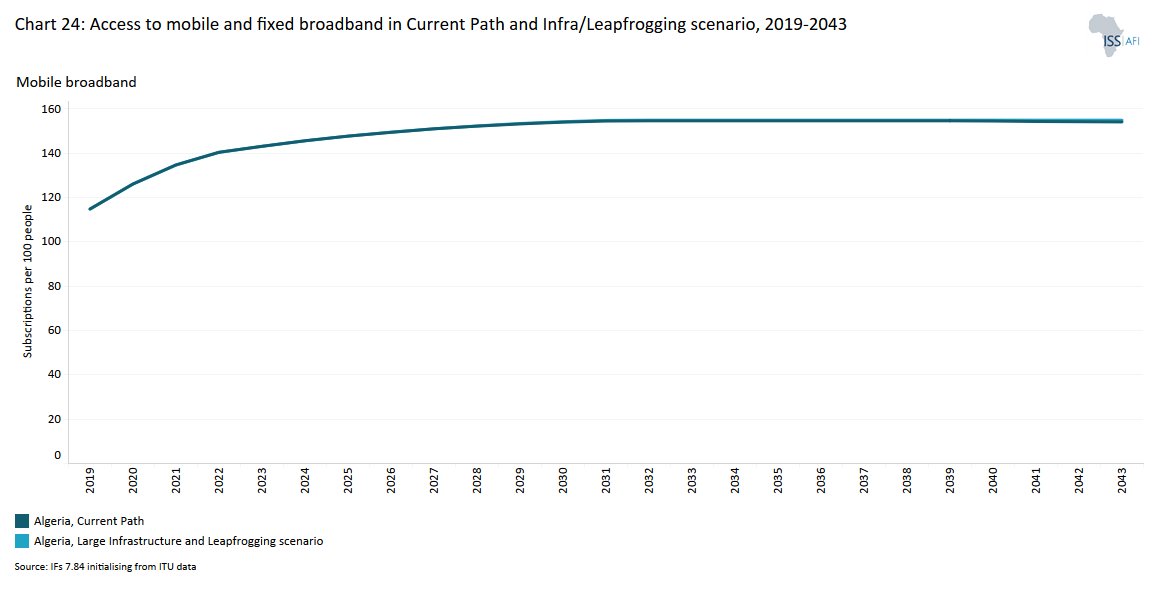

- Chart 24: Access to mobile and fixed broadband in Current Path and Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

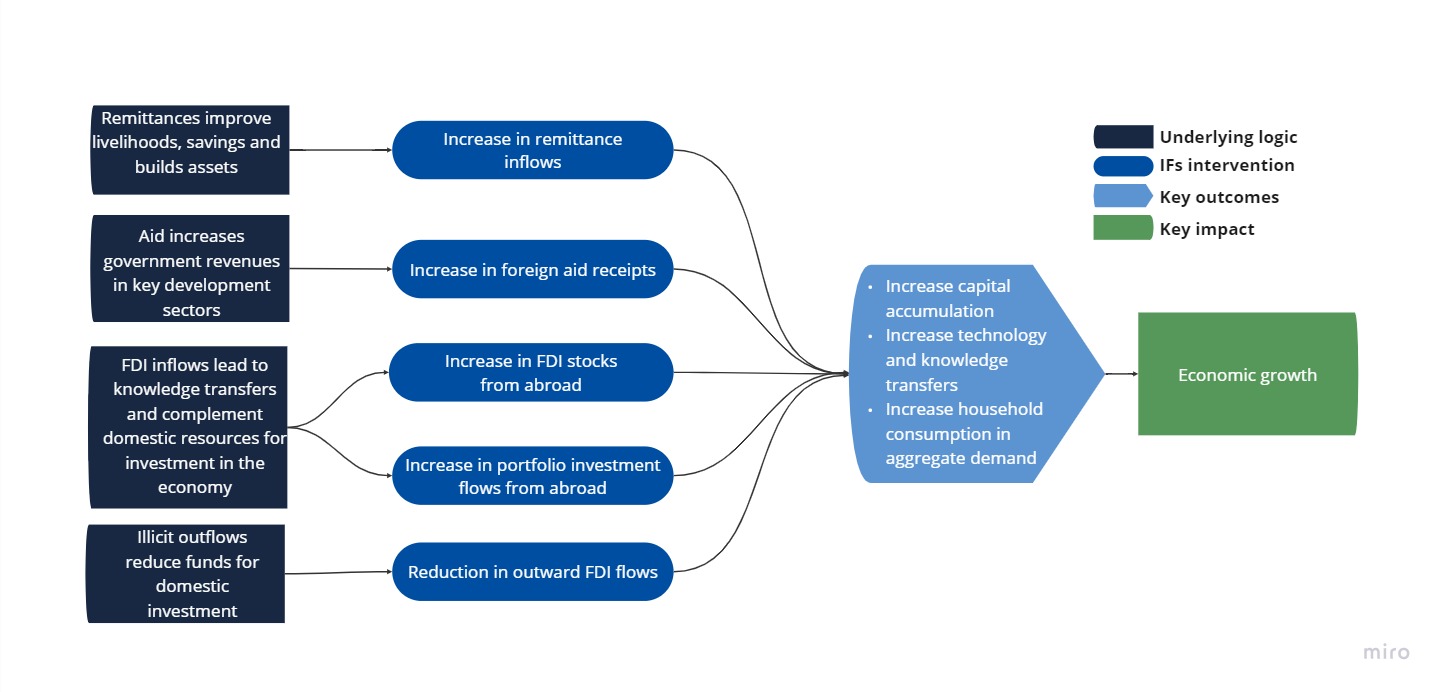

- Chart 25: Financial Flows scenario

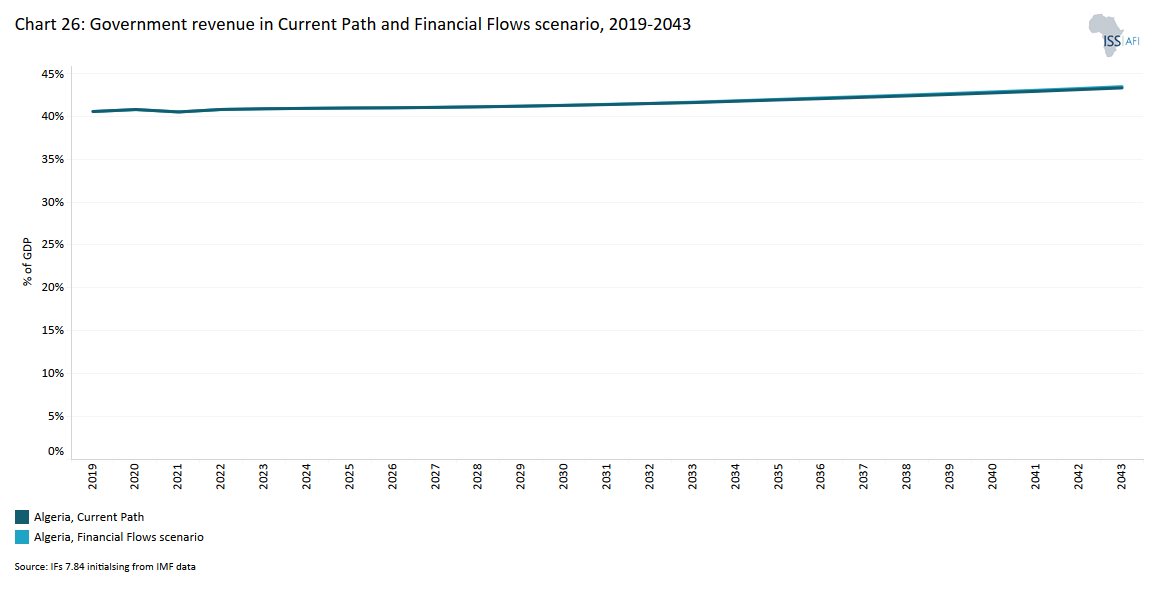

- Chart 26: Government revenue in Current Path and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

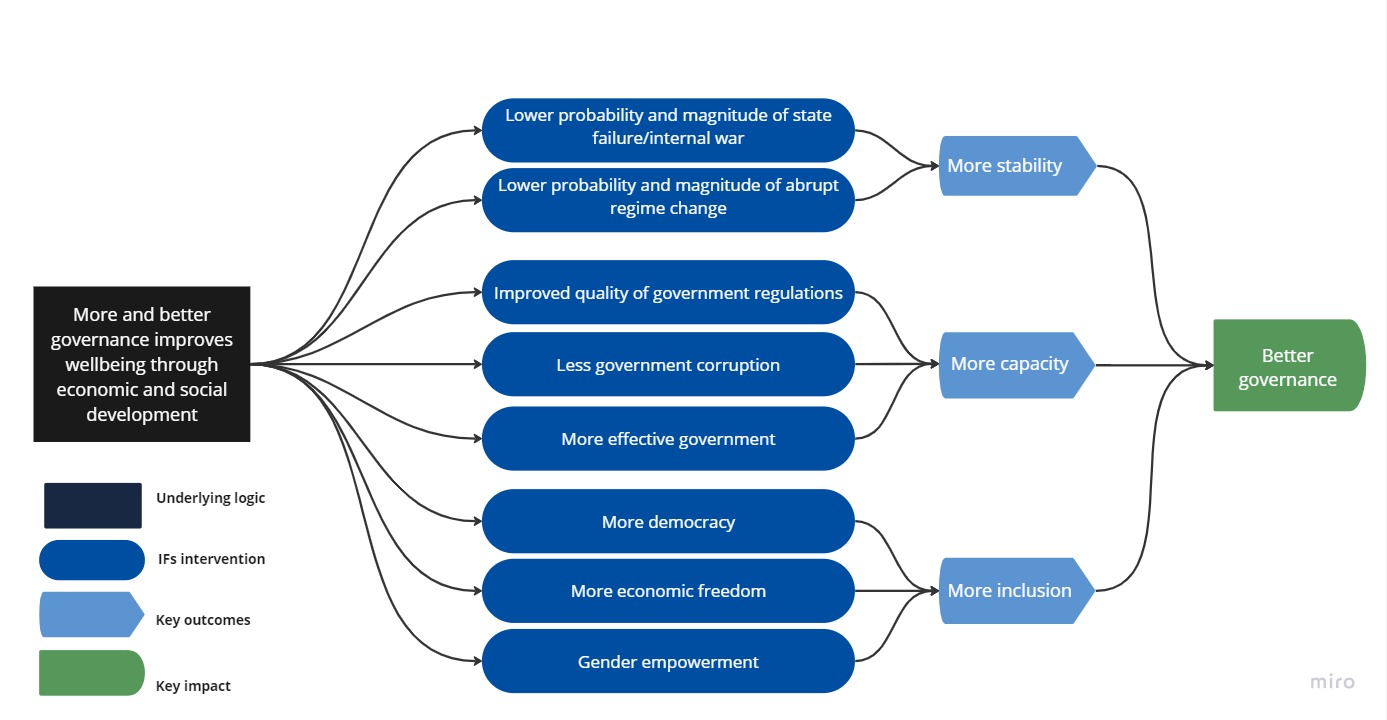

- Chart 27: Governance scenario

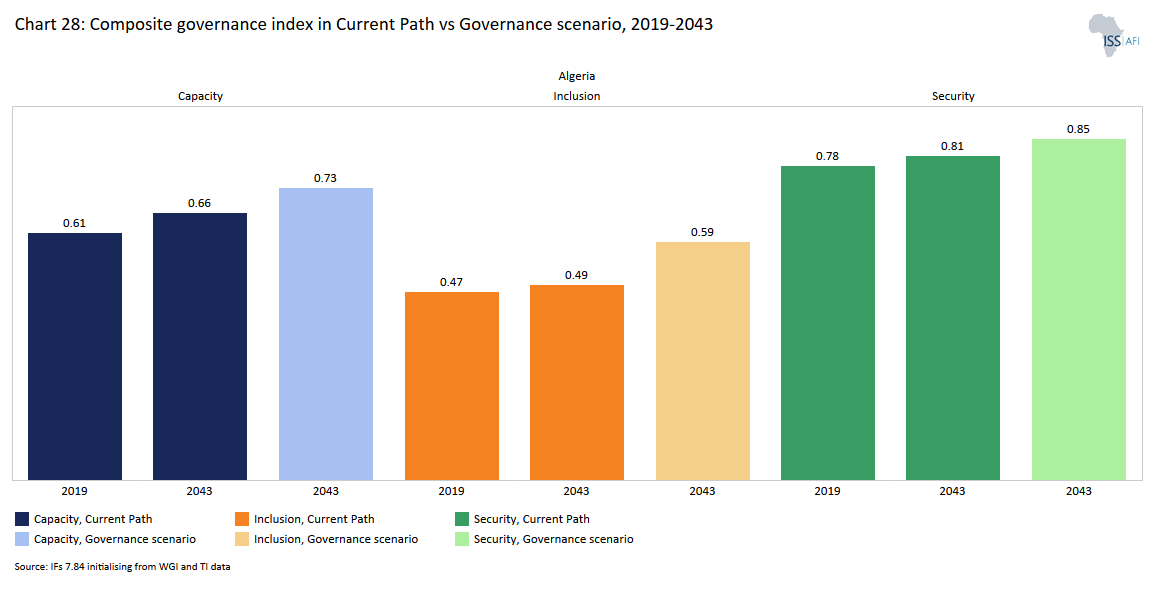

- Chart 28: Composite governance index in Current Path vs Governance scenario, 2019–2043

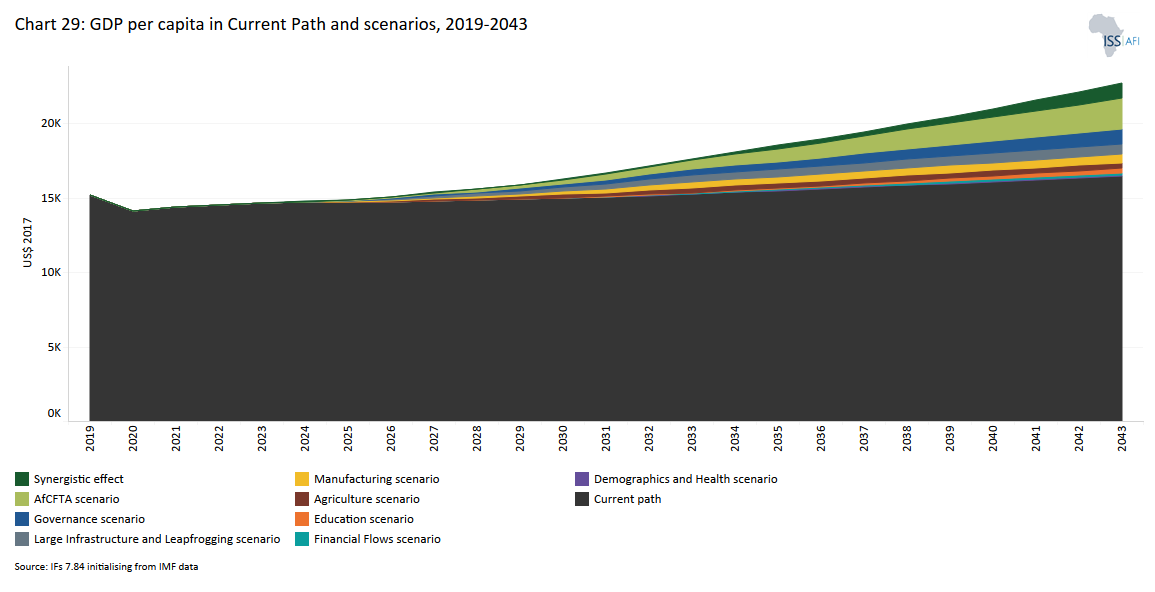

- Chart 29: GDP per capita in Current Path and scenarios, 2019–2043

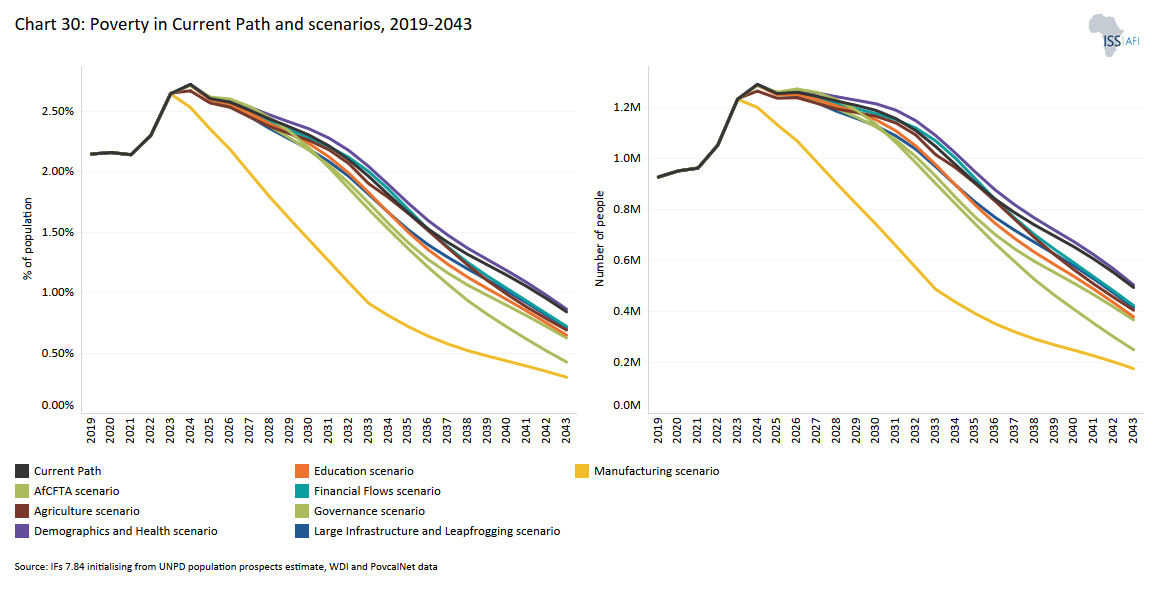

- Chart 30: Poverty in Current Path and scenarios, 2019–2043

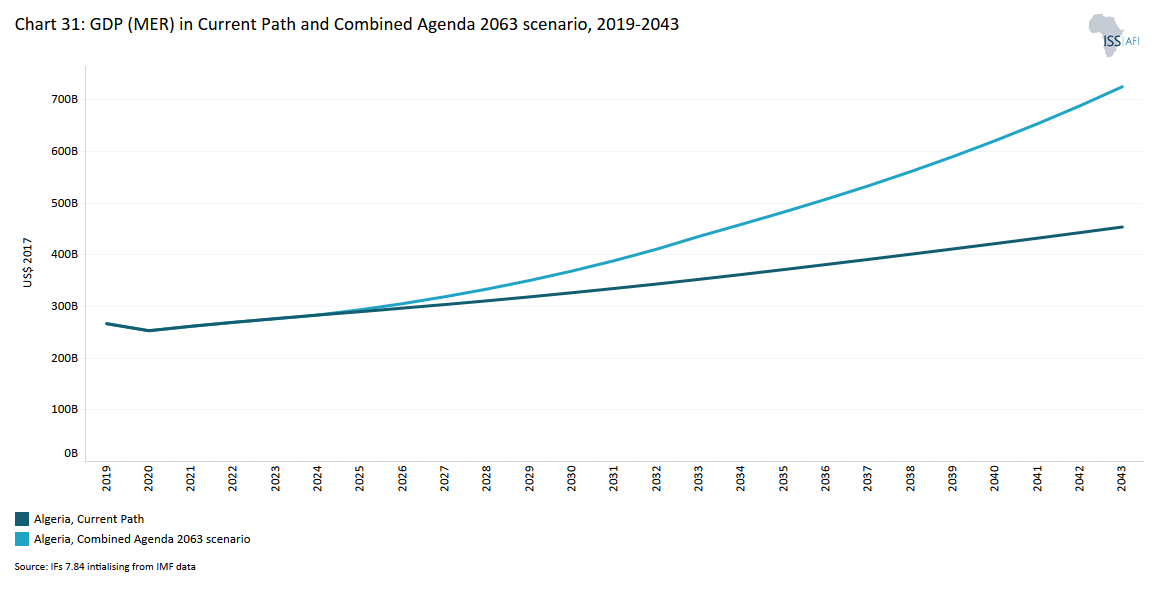

- Chart 31: GDP (MER) in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

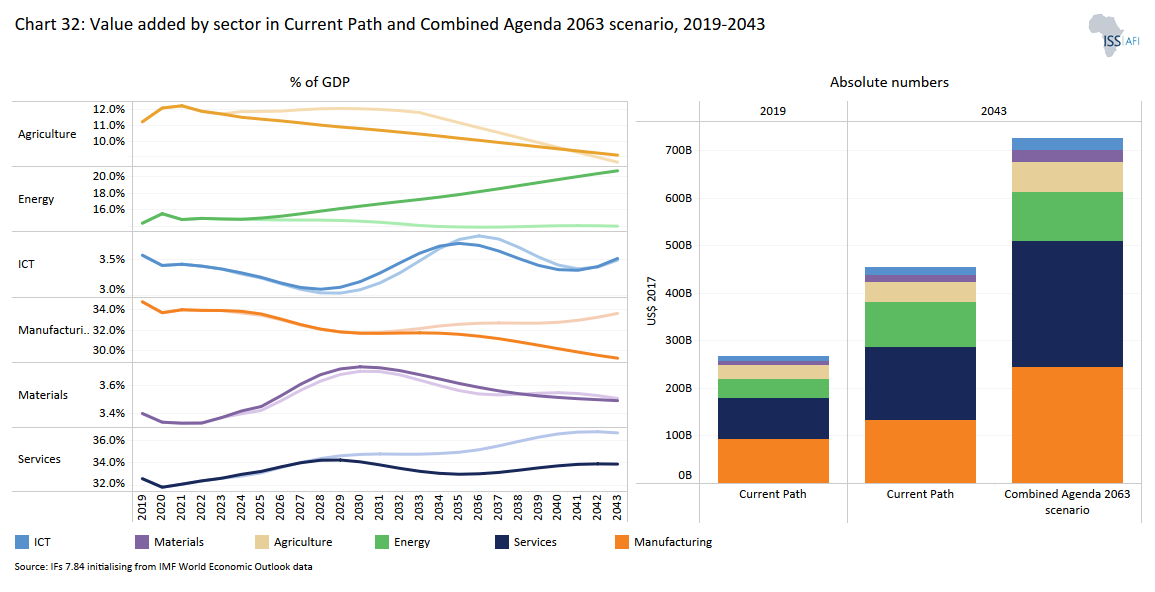

- Chart 32: Value added by sector in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

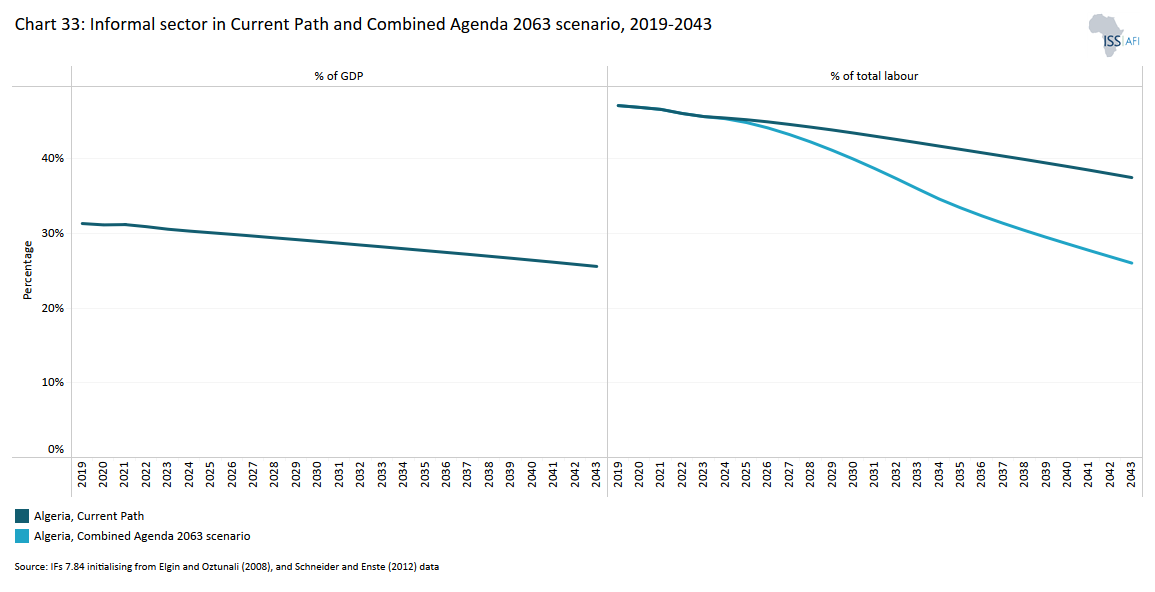

- Chart 33: Informal sector as % of total economy in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

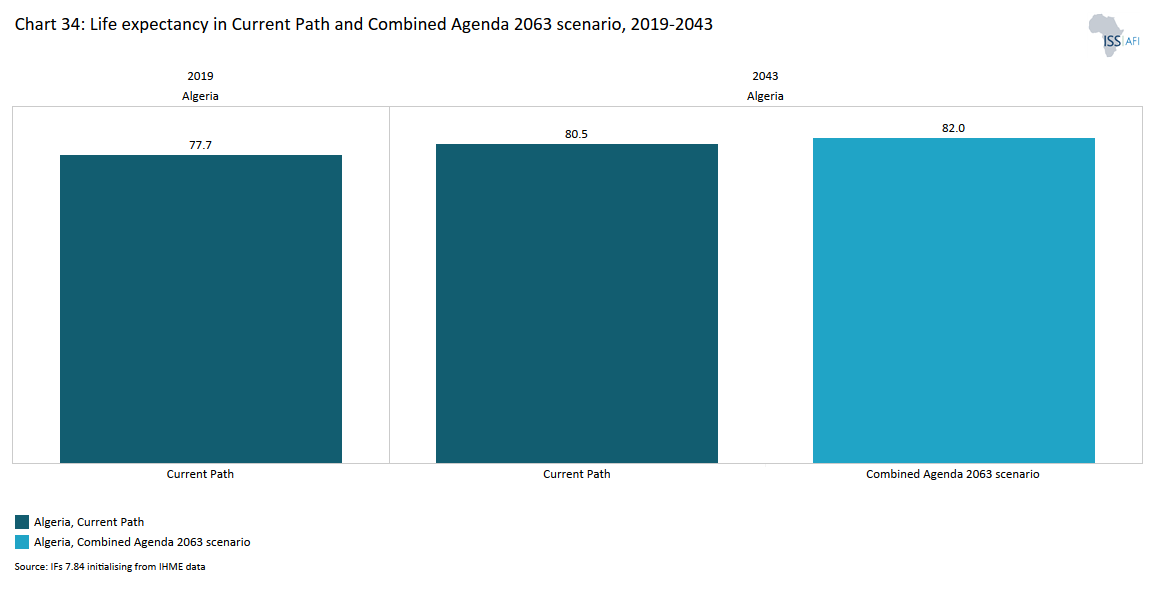

- Chart 34: Life expectancy in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

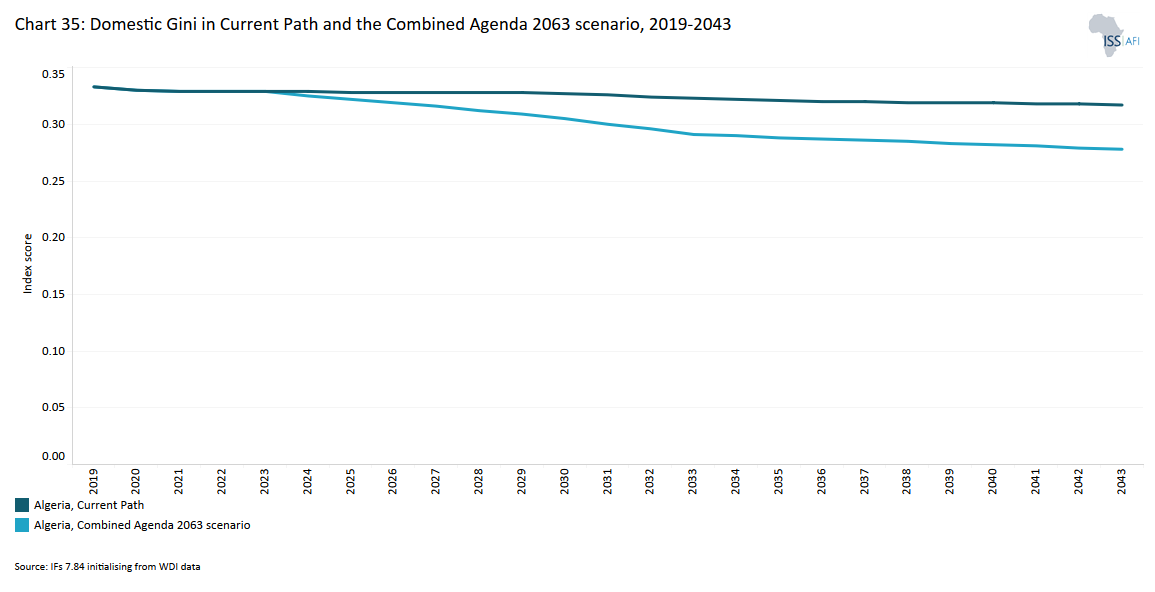

- Chart 35: Domestic Gini in Current Path and the Combined scenario, 2019–2043

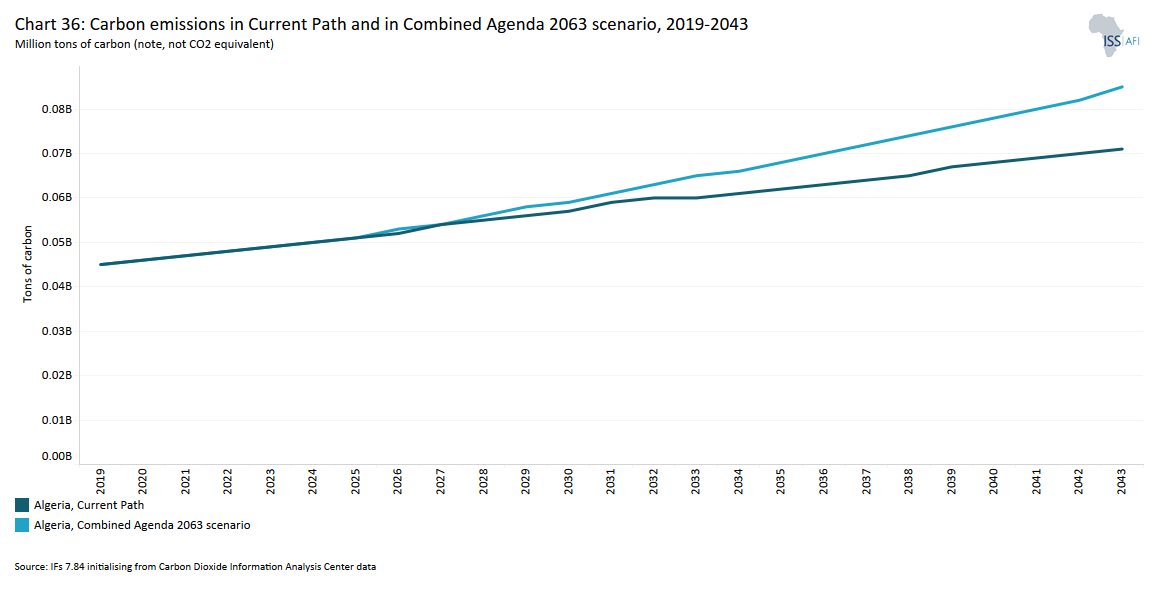

- Chart 36: Carbon emissions in Current Path and in Combined scenario, 2019–2043

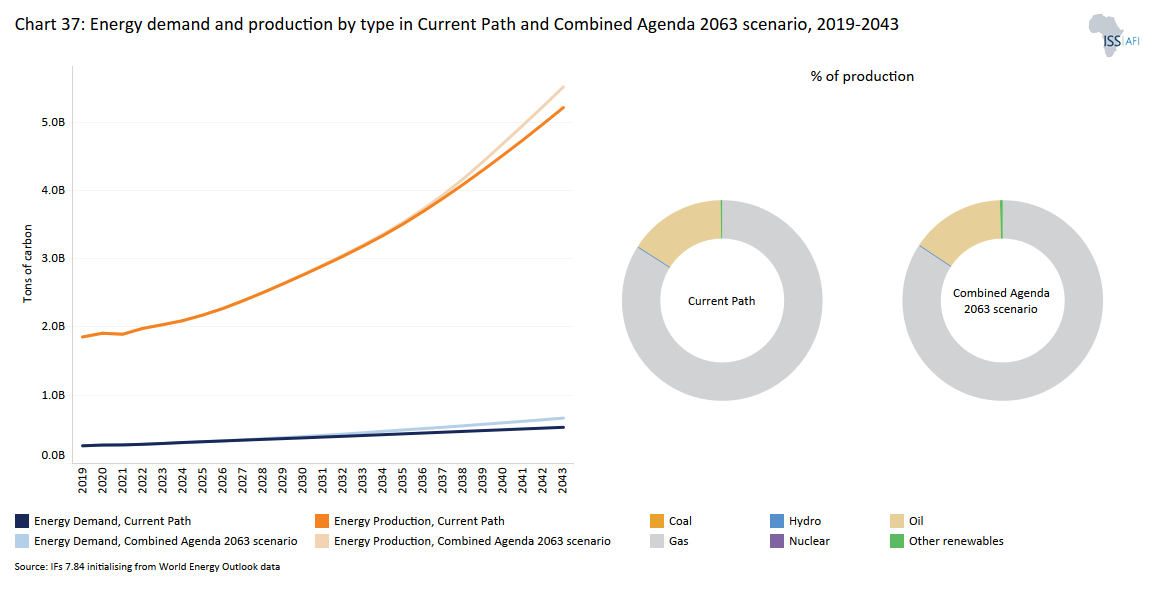

- Chart 37: Energy production by type in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019-2043

- Chart 38: Policy recommendations

Chart 1 is a political map of Algeria.

Algeria has the largest land area in Africa and the 10th largest in the world, covering an area of 2 381 741 square kilometres, but 80% desert. In terms of income classification level, until early 2020, it was classified as an upper-middle-income country before it was downgraded to lower-middle-income country status.

The country is bordered by Tunisia to the north-east, Libya to the east, Morocco to the west and shares borders with Niger, Mali, Mauritania and the disputed region of Western Sahara in the south-west. Much of the interior is arid and most people are concentrated in the fertile coastal plain along its thousand-kilometre coastline of the Mediterranean Sea.

An important gas and oil producer, Algeria’s main oil and gas fields are located on the mainland of the country since offshore exploration of fields has been limited. A well-developed pipeline chain connects Algeria’s main oil and gas fields with terminals, refineries and liquefied natural gas export terminals along the coast. In addition to domestic pipelines, three transcontinental natural gas pipelines connect Algeria with Europe. There are two supply gas pipelines to Spain and Italy.

Algeria is a member of the Arab Maghreb Union (comprising Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia), but the Union has long been stagnant largely due to differences with Morocco over the status of Western Sahara. In 2024 President Tebboune announced that Algeria would explore the establishment of free trade zones with neighbours Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Tunisia and Libya, in spite of the instability evident in some of these countries. Algeria has been a member of the Organization of Oil Exporting Countries (OPEC) since 1969 and is also a member state of the Arab League.

The country gained its independence from France in 1962 after a long and bloody struggle, with Ahmed Ben Bella becoming the first prime minister (1962–1963) and later the first elected president (1963–1965).

Algiers is the capital and largest city of Algeria. It is found along the Mediterranean Sea and in the north-central part of the country. Oran is the second largest and major coastal city, located in the north-west of the country.

Chart 2 presents the population structure to 2043 in the Current Path.

Algeria is the most populous country in the Maghreb and the 10th most populated economy in Africa. The country’s population more than doubled between 1980 and 2021, increasing from 19.2 million people to 44.2 million, with an average population growth rate of 2.3% over the period.

In the Current Path, the population of Algeria will continue to grow steadily, increasing to about 58.6 million people by 2043 — an increase of 32.7% compared to 2021. The country’s working-age population (15–64 years of age) will account for 66.1% of its total population by 2043 meaning that Algeria finds itself in a favourable window of demographic opportunity. The lowest proportion of the population will comprise adults aged 65 years and older.

The median age population will increase from 28.4 to 32.4 years by 2043 on the Current Path. Unemployment is high among the youth and women, and it is therefore critical that the government focuses on providing economic opportunities for this large working-age population group.

Overall, Algeria’s population growth is significantly below the average of the Middle East, North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa as the country’s population growth rate has been falling since the 1960s. This is due to the declining fertility rates and the impact of government investments in healthcare and education, particularly for women, which have led to improved maternal and child health and increased female literacy. Combined with urbanisation, access to modern contraceptives and changing societal norms, Algeria’s total fertility rate declined to approximately 4.5 children per woman by the end of the 20th century.

In 2019, Algeria’s total fertility rate ranked 44th in Africa at 2.99 births per fertile woman. The country’s total fertility rate will reach the replacement level of 2.1 births per fertile woman by 2045 and then drop below two children per woman after 2048. This will significantly affect Algeria’s demographic profile. Its population will age and likely present the country with several challenges, including increased health spending on non-communicable diseases, which are inherently more expensive to diagnose and treat. Additionally, there's a risk of a shrinking economy and declining per capita incomes unless the country improves its economic productivity through better use of technology and more investment.

One contributing factor to Algeria’s modest improvements in income per capita is its larger pool of labour (15–64 years of age) relative to dependants (less than 15 years old and 65+ years old). This ratio peaked in 2002, reaching a ratio of 1.7 working-age persons for every one dependant, which means that on average, for every dependant in Algeria, there were only 1.7 persons of working age.

Generally, countries experience more rapid economic growth if the ratio of working-age persons to dependants is greater than or equal to 1.7. Most European and North American countries have not experienced the high ratios of China and the Asian Tigers (peaking at 2.8). However, they have kept the ratio of working-age people to dependants above 1.7 over an extended period — a ratio that Algeria has achieved over the period 2002 to 2019.

Nevertheless, on the Current Path, Algeria will lose its minimum ratio of 1.7-to-1 for a potential demographic dividend from 2022 up to 2029. It will peak again to 1.7 working-age persons for every dependant in 2030, in line with the shifts in fertility rates discussed previously.

Although Algeria has a favourable ratio of working-age population to dependants, unemployment remains high. In 2019, female labour participation in the country was estimated at 19.7%, which is 19.4 percentage points lower than the average for lower-middle-income African countries. This gap will persist well beyond 2043; therefore, the government must find a mechanism to include this large and relatively youthful working-age proportion of the population in the economy.

In the second half of the century, the country will face a declining working-age population. Algeria will need to invest in technologies that allow for improvements in productivity as its labour force, as a proportion of the total population, shrinks. It will also need to attract significantly higher levels of investment to offset the decline in the contribution that labour makes to growth.

Chart 3 presents a population density map from 2022.

With a total land area of over 2 million km2, Algeria is one of the least densely populated countries in Africa, ranking 44th in 2020. The vast majority of Algerians live along the Mediterranean coast, particularly in the Algiers metropolis. The capital, Algiers is the largest city in the country with an estimated population of nearly two million people.

Chart 4 presents the size of Algeria’s economy from 1990 to 2043, including the associated growth rate.

Algeria is a big player on the African continent, not only because of its substantial land area but also because of its sizable GDP and activism regarding developing countries. In 2019, Algeria’s GDP was the fourth largest in Africa (after South Africa, Nigeria and Egypt), at US$266.5 billion.

Algeria is heavily reliant on hydrocarbons revenues to fuel its economy. The country has experienced a persistent decline of its manufacturing sector following the 1986 oil counter-shock. The service sector dominates in its contribution to GDP.

The country is also characterised by low competitiveness and productivity. In an effort to regain control over its natural resources and economy, the Algerian government has halted the privatisation of state-owned industries and imposed restrictions on imports and foreign involvement in its economy.

Oil and gas account for nearly 30% of GDP, 65% of budget revenues, more than 85% of exports and an estimated 95% of Algeria’s foreign currency receipts. The state-owned company Sonatrach owns almost 80% of the country's total fossil fuel production, making it the largest oil and gas company in Africa.

Because of this hydrocarbon dependence, Algeria recorded multiple bouts of negative growth rates from 1986 to 1994 linked to fluctuating oil prices and periods of domestic instability. Since 2014, low oil prices, political instability, unemployment and widening fiscal and external deficits have undermined the economy.

In 2017, the government designed a fiscal consolidation policy to reduce public spending in light of its budget deficit. Its reversal in the second half of the year has since led to an even higher-than-expected current account deficit of 8.2% of GDP, particularly because of subsidies and transfers, wages and depletion of foreign exchange and savings. Continued spending at the current level, along with low oil prices, is expected to deplete official foreign exchange reserves by 2024 and lead to rapidly increasing public debt.

The country’s economic challenges are worsened by its closed and state-controlled economy, in spite of efforts to grow the private sector and economic liberalisation in the early 1990s. It is characterised by a lack of competition, high barriers to entry in the most productive and labour-intensive sectors, a weak legal and judicial system and cronyism. Other issues are social exclusion, high public employment and universal[1Meaning there is a single subsidised price with no restrictions on consumption.] consumer subsidies that draw resources away from effective and diversified sustained growth.

In 2022, Algeria recorded an annual GDP growth of 2.9%, supported by the acceleration of non-hydrocarbon GDP. In addition, night-light data suggest continued, cross-regional growth in non-hydrocarbon activity in the first quarter of 2023. Algeria will achieve an average growth of about 2.5% between 2024 and 2043, about 2.1 percentage points below the average for lower-middle-income African countries. The size of the economy was estimated at US$269.2 billion in 2022, and will grow to US$453.5 billion in 2043. This is a nearly 68.5% improvement from 2022.

The high dependence on hydrocarbons, stifling bureaucracy and the closed nature of the country’s economy reflect the lack of economic diversification. However, there have been recent improvements. The economic and social development indicators show that Algeria has so far achieved notable economic growth. Nevertheless, it requires a sustainable growth-driver through industrial diversification and reform in the areas of government responsibility and equal opportunity.

Prerequisites for Algeria’s industrial diversification include the emergence of a sizable number of private enterprises and reform of small and medium enterprises. The dominance of small and medium enterprises in Algeria is a crucial obstacle to private sector development for industrial diversification. To promote private sector growth, the government should enact policies that provide clear guidance to private investors and build trust in these policies by creating a fair environment for all investors. This means removing obstacles, both formal and informal, that limit competition and improving access to credit. For example, the Atlas of Economic Complexity Index indicates that the country has the potential for diversification in industrial machinery and plastics.

Chart 5 shows the size of the informal economy as a percentage of GDP and in absolute terms, as well as the percentage of total non-agriculture labour involved in the informal economy. Also see Chart 33 that presents the impact of the Combined scenario on the informal sector.

Estimations and data on the informal sector are often unreliable and must be treated carefully. Researchers generally distinguish between the shadow and informal economy. According to the ILO: ‘The informal economy refers to all economic activities by workers and economic units that are — in law or in practice — not covered or insufficiently covered by formal arrangements. Where data is not available, our modelling estimates the size. Note that the ILO definition of employment in the informal economy excludes the agricultural sector.

The informal economy acts as a safety valve to reduce unemployment and to provide basic livelihood for many Algerians. Between 2000 and 2017, it was estimated that the informal economy reduced unemployment from 30% to 12%. In 2018, the informal economy constituted about 31.4% of Algeria’s economy (US$82.5 billion). By 2043, the country’s share of informal economy contribution to GDP will modestly decline to 25.6%.

In addition to ongoing efforts to grow its manufacturing base and to expand the role of the private sector, it is important for Algeria to find ways to gradually integrate the informal economy into the formal sector with the least friction possible. This can be done through policies and legislation that reduce barriers to entry and embrace localised and flexible procedures. Critical to this integration is the decriminalisation of parts of the informal economy by distinguishing between illicit and informal activities.

In the long term, a large informal sector is, however, detrimental to the overall functioning of the economy, given its limited contribution to taxes and low levels of productivity compared to the formal sector.

Chart 6 presents the average GDP per capita from 1990 to 2043 in the Current Path.

In 2019, Algeria had the second highest GDP per capita among North African countries after Libya and did slightly better than Tunisia and Egypt. It also had the highest GDP per capita among Africa’s 23 lower-middle-income countries.

Algeria’s per capita income will improve by nearly a thousand dollars from US$15 200 in 2019 to US$16 400 in 2043. Its GDP per capita income will remain above the average of lower-middle-income African countries by 2043. From 2028, Algeria’s GDP per capita will be below the average of upper-middle-income African countries.

Chart 7 presents the number of people living in extreme poverty, also expressed as a percentage of the population, 2019 to 2043.

In 2015, the World Bank adopted US$1.90 per person per day (in 2011 prices using GNI), also used to measure progress towards achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 1 of eradicating extreme poverty. In 2022, the World Bank updated the US$1.90 to US$2.15 in 2017 constant dollars. They are:

- US$3.20 for lower-middle-income countries, now US$3.65 in 2017 values.

- US$5.50 for upper-middle-income countries, now US$6.85 in 2017 values.

- US$22.70 for high-income countries. The Bank has not yet announced the new poverty line in 2017 US$ prices for high-income countries.

This page still uses US$1.90 and US$3.20.

Algeria has significantly reduced extreme poverty in the last two decades. In terms of human development, it is among the 20 countries on the continent to have achieved the most substantial decrease in Human Development Index deficit between 1990 and 2015.

The country now has inclusive, albeit low-quality, social services (universal education and healthcare, and subsidised food, housing and public transportation). These policies have lessened inequality, although subnational and regional differences remain significant.

Although Algeria’s subsidies and transfers have reduced poverty, they have also created other social and regional inequalities owing to inefficient and poor targeting of subsidy items. These disparities manifest in significant inequalities in consumption rates with a gap of nearly 28% between rich and poor people.

In 2021,128 000 people (0.3% of Algeria’s population) lived on less than US$1.90 per day. Using the US$3.20 benchmark for lower-middle-income countries, about 962 000 Algerian people lived on less than US$3.20 per day in 2021. The figure will decrease to 494 000 people by 2043.

The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) shows that only 1.4% of Algerians (600 000 people) in 2020 were multidimensionally poor. The intensity of deprivation in the country, which is the average deprivation score among people living in multidimensional poverty, was 39.2%. Deprivation in education contributes the most to the index (49.3%), followed by health (31.2%) and standard of living (19.5%). Unemployment, coupled with declining oil prices, will however make tackling poverty and inequality a serious challenge in the future.

In 2012, the Knowledge Sharing Program (KSP) with Algeria was carried out with the objective of supporting the establishment of Algeria’s National Vision 2030. The vision includes five priority areas:

-

Restructuring Algerian industries through industrial diversification,

-

National reform in the governance structure,

-

Improvement of human capital through education reform,

-

National land development for growth and equality, and

- Enhanced quality of life for Algerians through reform in the public health sector.

Representative in Algeria: ‘The implementation of Government Action Plan measures to increase mobilization of tax revenues, more efficiently use public resources, and promote private sector investment is essential to navigating the global challenges safely and put Algeria on the path of a sustainable and inclusive growth.’

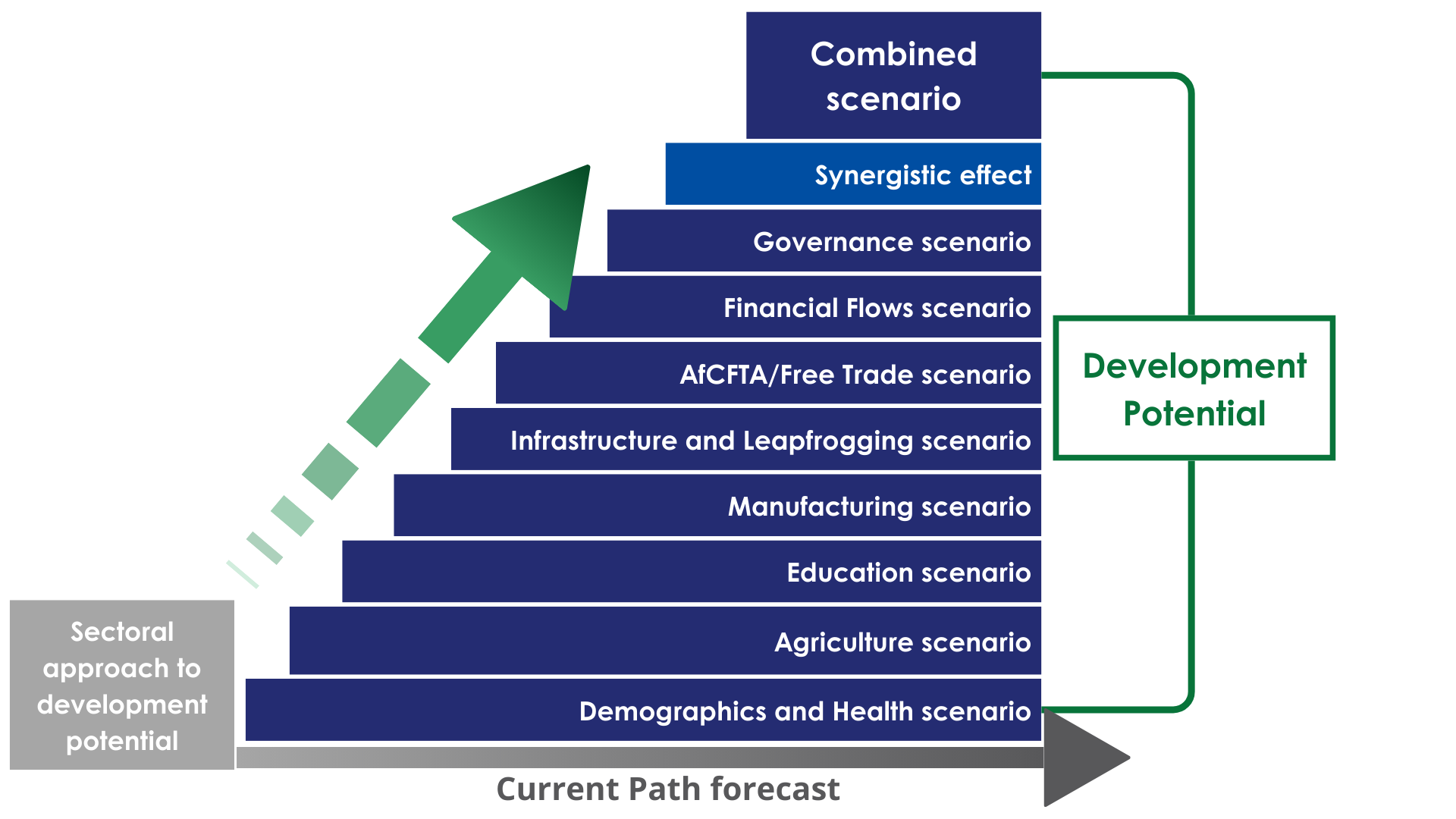

Chart 9 depicts the relationship between the Current Path, the various sectoral scenarios and the Combined scenario.

The Current Path is a dynamic scenario in our modelling that imitates continuing current policies and environmental conditions.

The eight sectoral scenarios are each explained in the various themes on the website and the impact on each is compared with the Current Path and a Combined scenario. The eight scenarios are:

- A more rapid demographic transition and investments in better health and water, sanitation and hygiene (WaSH) infrastructure,

- Better and more education (looking at quantity, quality and relevance),

- Large infrastructure and leapfrogging (the impact of renewables, ICT and the more rapid formalisation of the informal sector),

- Food security and an agricultural revolution,

- A low-end manufacturing transition,

- The full implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA),

- More inward financial flows (consisting of aid, foreign direct investment, remittances and illicit financial flows), and

- Better governance (consisting of stability, capacity and inclusion).

The Combined scenario is a combination of all eight sectoral scenarios.

The impact of these scenarios on jobs/employment and greenhouse gas emissions and energy are presented in separate themes.

A final theme models the effect of alternative global scenarios on Africa’s development potential.

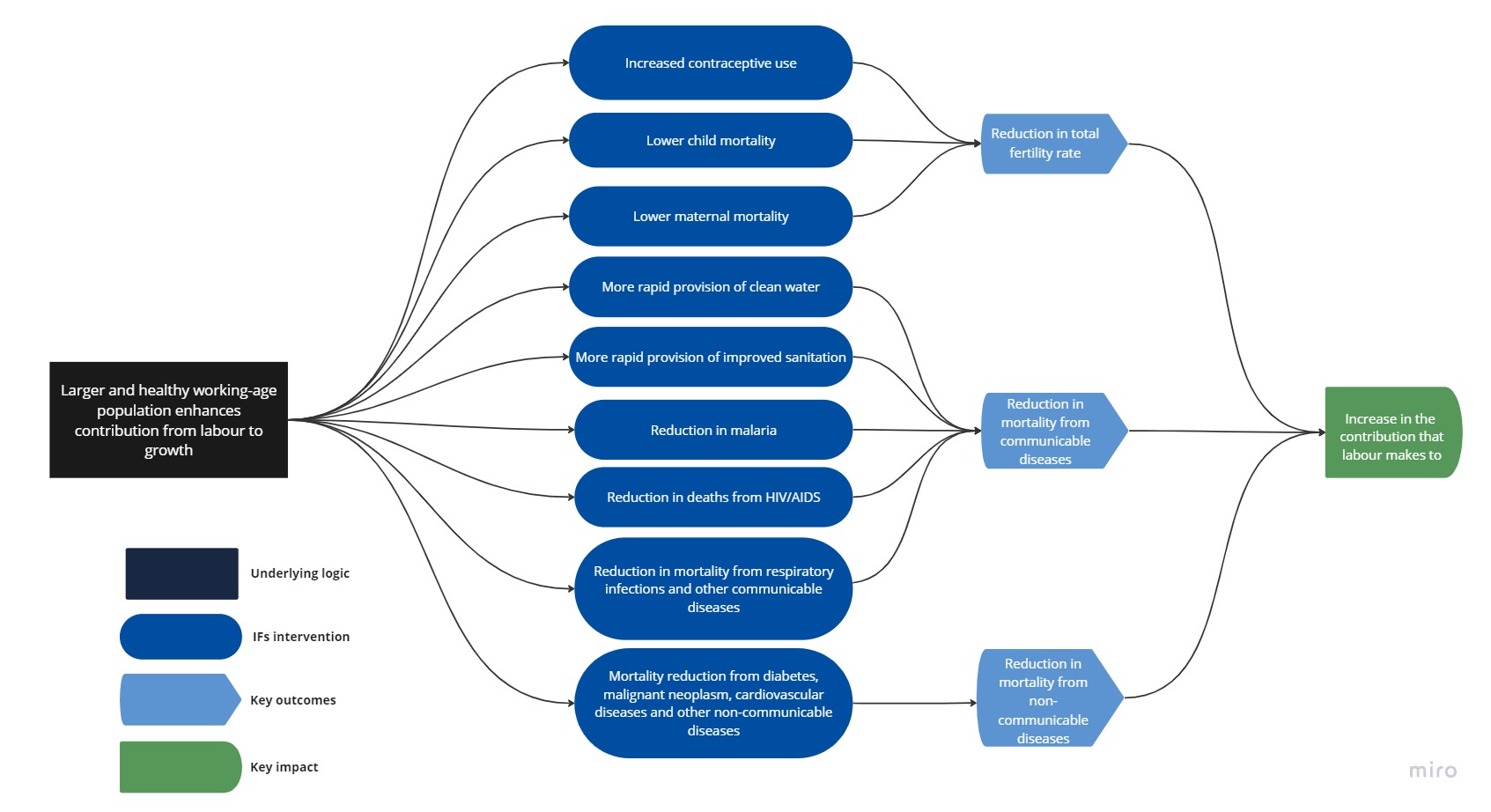

Chart 10 presents the structure of the Demographics and Health scenario that advances the demographic dividend and improves health.

The Demographics and Health scenario consists of reasonable but ambitious reductions in child and maternal mortality ratio, increased access to modern contraception and reductions in the mortality rates associated with both communicable diseases (e.g., AIDS, diarrhoea, malaria and respiratory infections) and non-communicable diseases (e.g. diabetes), as well as improvements in access to safe water and better sanitation.

Visit the themes on Demographics and Health/WaSH for more detail on the scenario structure and interventions.

Free healthcare was introduced in Algeria in 1974. In 1984, the government introduced reforms that shifted the health system from a curative to a preventive one more suited to its then youthful population with high levels of communicable diseases. The results were impressive. For example, compared to 1970, when the infant mortality rate was 106 deaths per 1 000 live births, by 1990 it had fallen to just 41. In 2020, Algeria’s infant mortality rate was estimated at roughly 22 deaths per 1 000 live births and by 2040 it will drop to 17. However, under current policies, Algeria will not achieve the aspirational objective of the SDGs to end preventable deaths of newborns and children under five by 2030.

Algeria’s maternal mortality ratio was estimated at 106.4 deaths per 100 000 live births in 2019. The country is on track to achieve the SDG target of fewer than 70 deaths per 100 000 live births in around 2028.

Although the country has continued to invest in its health sector, it faces considerable pressure as its ageing population needs inherently more expensive care for non-communicable diseases. This is complicated by a shortage of healthcare professionals and social inequalities in the country. Deaths from communicable diseases are low when compared to sub-Saharan Africa. Other communicable diseases[2Catch phrase for other communicable diseases that are not prevalent enough to be categorised on their own.] are more common among infants, while respiratory infections are more prevalent in the older cohorts.

In 2019, life expectancy at birth in Algeria was estimated at 77.7 years. By 2034, it will reach 80, which is significantly higher than that for lower-middle-income and upper-middle-income African countries.

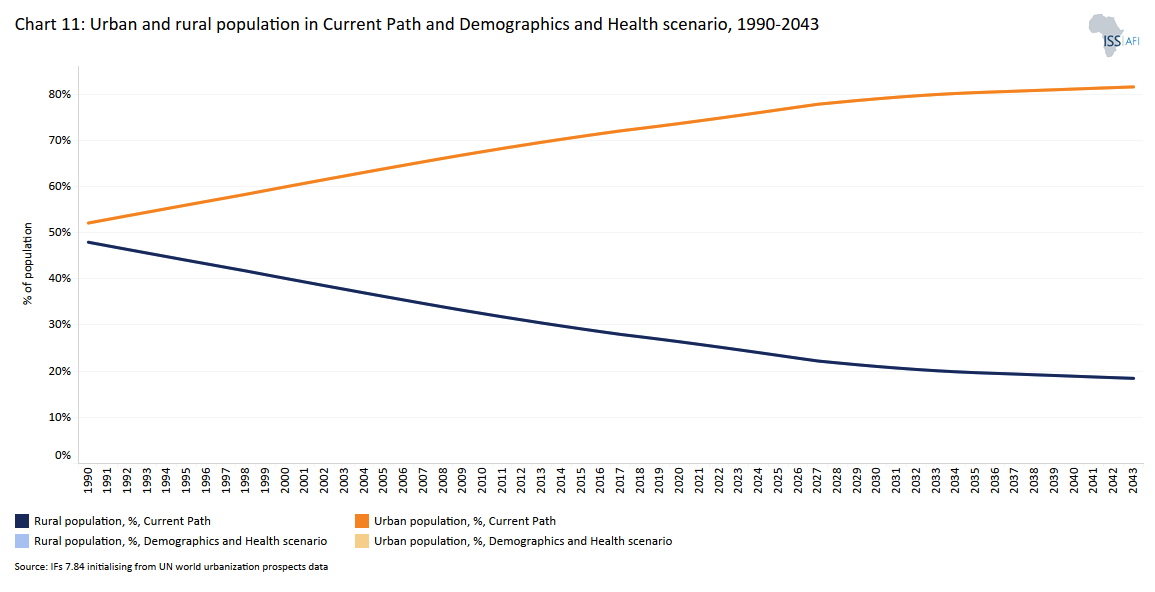

Chart 11 compares urban and rural populations in the Current Path and the Demographics and Health scenario from 1990 to 2043. The reader can toggle between Current Path and scenario.

The Demographics and Health scenario will slightly reduce Algeria's 2043 population, affecting rural and urban areas. In the scenario, Algeria’s total population will reduce by 0.4% relative to the Current Path in 2043 — from about 58.6 million to nearly 58.4 million people. The rural population will decline by about 0.5%, while the urban population will decrease by 0.4%.

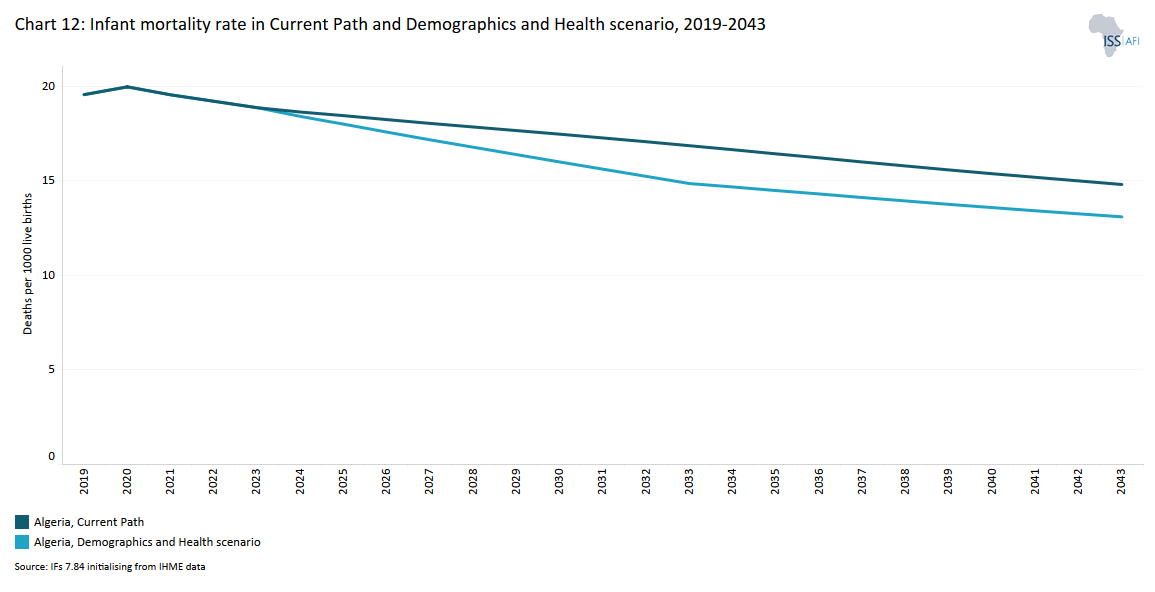

Chart 12 presents the infant mortality rate in the Current Path and the Demographics and Health scenario from 2019 to 2043.

Infant mortality rate is the probability of a child born in a specific year or period dying before reaching the age of one. It measures the child-born survival rate and reflects the social, economic and environmental conditions in which children live, including their healthcare. It is measured as the number of infant deaths per 1 000 live births and is an important marker of the overall quality of the health system in a country.

In 2019, the infant mortality rate in Algeria was 20.1 deaths per 1 000 live births — a remarkable decline from an average of nearly 65.5 deaths per 1 000 live births in the 1980s. This threefold decline has placed Algeria’s infant mortality rate far below the average of 44.8 deaths for other lower-middle-income African countries in 2019.

The Demographics and Health scenario will reduce Algeria’s infant mortality rate from 14.8 deaths per 1 000 births (Current Path) to 13.1 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2043. This is a reduction of about 1.7 deaths per 1 000 births. The country would achieve the SDG target of 12 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2051 — 12 years earlier than in the Current Path.

In addition, in the Demographics and Health scenario, the total fertility rate will decrease from 2.1 births per fertile woman (Current Path) to 2.0 births in 2043. Life expectancy will increase to 81.1 years — an increase of 0.6 years relative to the Current Path and about 8.4 years more than the projected average for Africa-OLMICs in 2043.

Chart 13 presents the demographic dividend in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario from 2019 to 2043.

The demographic dividend is the economic growth opportunity that opens up by having a proportionally larger working-age population relative to dependants. When a family has a larger number of people with decent jobs, and fewer children and elderly persons (65+ years) they need to take care of, the family can save and invest more in the economy. When this happens on a large scale, a country can benefit from a boost in its growth.

This study uses the ratio of working-age persons to dependants, i.e. the size of the labour force (between 15 and 64 years of age) relative to dependants (children below 15 years and elderly people above 64 years) as set out in the Demographics theme. In Algeria, the age group between 15 and 64 years old accounted for approximately 63% of the total population in 2021.

A window of opportunity opens when the ratio of the working-age population to dependants is at least 1.7-to-1, meaning that for every dependant, there are 1.7 workers. When there are fewer dependants to take care of, it frees up resources for investment in both physical and human capital formation. Studies have shown that about one-third of economic growth during the East Asia economic ‘miracle’ can be attributed to the large worker bulge and a relatively small number of dependants.

However, the growth in the working-age population relative to dependants does not automatically translate into rapid economic growth unless the labour force acquires the needed skills and is absorbed by the labour market. Without sufficient education and employment generation to successfully harness their productive power, the growing labour force (especially those in urban areas) could increasingly become frustrated with the lack of job opportunities leading to social tension and even civil instability.

The interventions in the Demographics and Health scenario have a marginal impact on Algeria’s demographic dividend. In the scenario, by 2043, the ratio of the working-age population to dependants in Algeria will slightly increase from 1.95-to-1 (Current Path) to 1.97-to-1. This translates into a GDP per capita gain of US$76.3 relative to the Current Path. The focus on family planning, education and investments in the health sector can benefit Algeria.

Chart 14 sets out the composition of the Agriculture scenario to advance food security.

The Agriculture scenario represents reasonable but ambitious increases in yields per hectare (reflecting better management and seed and fertiliser technology), increased land equipped and under irrigation and reductions in food loss and waste. We use increased calorie consumption as a proxy for food self-sufficiency above food exports as a desirable policy objective.

The increase in forest protection reflects sustainable land use practices.

Visit the theme on Agriculture for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Owing to the vast expanse of the Sahara Desert, Algeria has only about 8.4 million hectares of arable land, which is less than 4% of its total land area. Just over 50% of arable land is dedicated to cultivating crops, mostly cereals and pulses. As Algeria is heavily reliant on oil and gas exports (aka the Dutch disease), an oil price boom may lead to a significant appreciation of its currency that will cause a contraction of its non-resource sectors, particularly agriculture and manufacturing sectors. Moreover, global warming is causing serious drought concerns in the region, such as below-average rainfall, with pockets of drought constraining yields in 2020.

Since there is limited scope to increase land under cultivation, intensification is the most viable pathway to improve efficiency in agriculture. This involves increasing land under irrigation, using better seeds and fertilisers and introducing modern farming practices. Additionally, reductions in loss and waste from production to consumption could help to meet food demand.

In 2019, this sector employed approximately 9.6% of the working-age population and accounted for 12% of the country's GDP, marking a rise from its 8.5% contribution in 2010. Its significance had waned after independence as governments prioritised industrialisation.[3Tin Hinane El Kadi, Peer reviewer, London School of Economics, 15 June 2020. After independence Algeria’s industrial policy was based on an import substitution industrialisation (ISI) strategy and focused on the promotion of unbalanced growth, favouring heavy manufacturing over agriculture and investment over consumption.]

Lack of investment, years of government restructuring, limited water resources and dependence on rainwater, and state-controlled land ownership policies have constrained improvements in agricultural production.

In 2019, Algeria’s agriculture sector accounted for 12.3% of GDP, which was about 3.3 percentage points below the average for lower-middle-income African countries. The contribution of the sector to GDP will decline to about 9.1% of GDP by 2043 in the Current Path.

Through various National Agricultural Development Plans (PNDAs) since 2000, agricultural yields have improved although the sector is generally less productive compared to Algeria’s income-group peers. Algeria’s average crop yield of 3 metric tons per hectare is closer to the average for low-income African countries (2.6 tons per hectare).

Because of poor yields, agricultural demand has outstripped supply since the 1970s (see Chart 15), making Algeria heavily dependent on food imports. This dependence makes the nation susceptible to inflationary pressures in the global market, with approximately US$12.8 billion worth of agricultural products imported in 2019.

Chart 15 presents the import dependence in the Current Path and the Agriculture scenario from 2019 to 2043.

The data on agricultural production and demand in our modelling initialises from data provided on food balances by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The model contains data on numerous types of agriculture but aggregate its forecast into crops, meat and fish, presented in million metric tons. Chart 15 shows agricultural production and demand as a total of all three categories.

In the Current Path, Algeria’s crop produced was estimated at 26.7 million metric tons in 2019 — a significant increase from the 5.4 million metric tons produced in 1990. Algeria’s 2019 crop demand was estimated at 41.8 million metric tons, creating an unmet demand of 15.1 million metric tons. The Current Path crop demand will increase to about 55.3 million metric tons, while production will increase to just 33.2 million metric tons by 2043. This illustrates a growing demand for foodstuff that will be unmet by local production.

The Agriculture scenario reduces the gap between million metric tons of demand and production from 62% in 2019 to 8% in 2043, instead of 55% in the Current Path. Key parameters in the Agriculture scenario are a 2.1 ton per hectare increase in crop yields and adding 54 000 hectares of irrigated land by 2043.

Although Algeria’s crop yields in the Agriculture scenario will improve by 6.2 tons in 2043, they will still be significantly below the average for Africa’s lower-middle-income countries, then at 6.4 tons per hectare.

In the Agriculture scenario, Algeria’s crop production will increase to 44.2 million metric tons in 2043 — an increase of 11 million metric tons relative to the Current Path. A reduction in reliance on food imports is crucial because heavy import dependence can expose the country to supply chain disruptions, price fluctuations and related risks, as observed during the COVID-19 crisis when foreign reserves were depleted.

Food price fluctuations in imports can severely impact Algeria’s food security. The Agriculture scenario will reduce the country’s agriculture crop import dependence from 40.5% in the Current Path to 17.5% in the scenario and reduce its growing crop import bill from US$15.4 billion (Current Path) to US$8.8 billion in 2043.

Water stress is a critical issue in Algeria, particularly in the context of its agricultural sector, which accounts for a significant portion of total water demand. Algeria faces challenges related to water sustainability, including the use of non-renewable fossil water and expensive desalination methods, leading to anticipated increases in water prices by 2043. The region's harsh agricultural conditions and vulnerability to climate change further threaten water resources and food security, potentially impacting regional stability.

Agriculture alone used 66% of total water demand in 2019 (5.6 km3 of total water demand of 8.4 km3). Algeria withdrew around 20% of its water demand from non-renewable fossil water (about 1.7 km3) in 2019, while an additional 10% of its water supply was from expensive desalination plants. The Current Path is that water prices will increase until 2043. In addition, water demand from other sectors, such as municipal and industrial, will also increase.

North Africa faces challenges due to its harsh agricultural conditions and heightened vulnerability to the effects of climate change. These factors are likely to disrupt water resources and food security, posing a risk to regional stability.

In 2019, groundwater withdrawal stood at 4.5 km3 per annum; it will decline to 3.5 km3 in 2043. In the Agriculture scenario, groundwater withdrawal increases to 4.7 km3 in 2043. The increase in supply offsets the 0.5 km3 demand increase for irrigation by 2043 and would see Algeria’s total water supply increase to 9.44 km3 in 2043, compared to the 8.76 km3 in the Current Path. Additional work is required to determine if this increase is possible.

Chart 16 presents the structure of the Education scenario. This scenario improves the quantity and quality of education and its relevance to job requirements.

The Education scenario represents reasonable but ambitious improved intake, transition and graduation rates from primary to tertiary levels and better quality of education at primary and secondary levels. It also models substantive progress towards gender parity at all levels, additional vocational training at the secondary school level and increases in the share of science and engineering graduates.

Visit the theme on Education for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

After independence from France in 1962, Algeria embarked on a concerted effort of Arabisation and Islamisation that sought to displace the dominant role of the French language and culture in the country. Compulsory basic education was introduced in the 1970s and the country’s enrolment levels have improved significantly since then.

The government invested heavily in expanding access to education. In 1990, for example, the education sector received almost 30% of the national budget. As a result, the country’s literacy rate stood at 82% in 2019, compared to under 50% in the 1980s.

Algeria is also considered to have achieved universal primary education with a 97% net enrolment rate in 2009. Today, Arabic is the language of instruction from primary to secondary school. At tertiary level, hard sciences are taught in French.

Chart 17 presents mean years of education in the Current Path and the Education scenario for the 15 to 24-year age group, 2019 to 2043.

The average years of education in the adult population aged 15 to 24 is a good first indicator of how the stock of knowledge in society is changing.

Although Algeria has achieved universal primary education and generally records good educational outcomes, there are significant leakages in its secondary system, particularly in upper secondary. The mean years of education (15–24 years) for Algeria stood at 9.6 years in 2019. This is more than a year above the average for lower-middle-income African countries and it will modestly improve to 9.8 years by 2043 in the Current Path. In the Education scenario, Algeria’s mean years of education for adults aged 15–24 years will increase to 10.4 — an improvement of about 0.6 years relative to the Current Path in 2043.

The total quality of education in Algeria is slightly above the average for lower-middle-income African countries, but male education quality slightly lags behind. The challenges faced by Algeria’s education system include shortages in educational resources such as teachers, issues with the language of instruction and poor infrastructure.

Reforms to improve the quality of education were introduced in 2003, comprising new teaching methods, restructuring of the curriculum and an ongoing switch in the language of instruction from French to Arabic. Despite these reforms, the UN special rapporteur reported in 2015 that the quality of education in Algeria was low, citing inadequate teacher training and classroom overcrowding as key factors.

In 2008, private higher institutions were authorised to operate. There has been a significant shift towards these institutions since 2018 to alleviate some of the pressure on the free government-sponsored public education system.

Female education in Algeria is improving rapidly. For example, in 2019, female education in the 15 to 24-year age cohort was 1.4 years higher than that of males. In time, Algeria’s total adult female population will be better educated than its adult male population. These improvements are, however, largely wasted when considering that the labour force participation rate for women in 2019 was 52 percentage points below men. In the Current Path, the difference will only reduce to a 39 percentage point difference by 2043.

The situation is inevitably different in rural areas and the obstacles often cited include socio-cultural limitations on girls’ potential, remote schools and domestic chores.

The reason for the rapid improvement in female education is that beyond age 16, which is the age up to which education is compulsory, girls stay in school longer than boys and do better in getting high school diplomas and proceeding on to higher education. The ratio of females to males is more than 1.5-to-1 at the tertiary level.

Like other countries, Algeria seems to be experiencing a disconnect between the current demands of the job market, prospects for the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) and the education system. To prepare for the 4IR, countries must invest in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) and commit to life-long learning and education that encourages entrepreneurship. An encouraging trend in Algeria is that the number of learners enrolling in vocational training has risen in the recent past.

Furthermore, in 2018, women accounted for 41% of STEM graduates. This mismatch between the (female) skills of the labour force that is dominated by males is one of the reasons for the high unemployment rates in the country.[4Tin Hinane El Kadi, Peer reviewer, London School of Economics, 15 June 2020.]

Chart 18 depicts the structure of the Manufacturing scenario.

The manufacturing sector is important to create jobs and increase the rate of employment, to improve productivity, change the structure of an economy and ultimately reduce poverty. Thus, the sector is the base of economic power. However, Algeria’s heavy reliance on commodity exports (aka the Dutch disease) makes manufacturing less competitive.[5Tin Hinane El Kadi, Peer reviewer, London School of Economics, 15 June 2020.]

The Manufacturing scenario represents reasonable but ambitious manufacturing growth through greater investment in the manufacturing sector, in research and development (R&D) as well as improvement in government regulation of businesses. It increases total labour participation rates with a larger increase in female participation rates where appropriate. It is accompanied by increased welfare transfers (social grants) to unskilled workers to moderate the initial increases in inequality typically associated with a manufacturing transition.

Visit the theme on Manufacturing for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Chart 19 presents the contribution of the manufacturing sector to GDP in the Current Path and the Manufacturing scenario. Our modelling uses data from the Global Trade and Analysis Project (GTAP) to classify economic activity into six sectors: agriculture, energy, materials (including mining), manufacturing, services and information and communication technologies (ICT). Most other sources use a threefold distinction between only agriculture, industry and services, with the result that data may differ.

By comparative African standards, Algeria has a large manufacturing sector, which was significantly bigger than the average for lower-middle-income African countries in 2019.

In 2019, Algeria’s manufacturing sector contributed US$63.5 billion to its GDP, equivalent to 23.9%. The manufacturing sector was the second-largest contributor to GDP in that year after the service sector. The service sector contributed about 46.4% of GDP in 2019, equivalent to about US$123.5 billion. The energy sector contributed US$38.4 billion, constituting 14.4% of GDP, and the contributions of the agriculture and materials sectors in 2019 were valued at US$29.9 billion (11.2% of GDP) and US$9.1 billion (3.4% of GDP), respectively.

In the Current Path, the contribution of the manufacturing sector will increase to 29.3% of GDP in 2043 as the contribution of the agriculture and service sector will decrease to 9.1%. and 33.9%, respectively.

Manufacturing value added will increase by about US$18.3 billion (or 2.4% of GDP) relative to the Current Path to about US$132.8 billion in 2043, highlighting the expected growth and changing dynamics in the manufacturing sector.

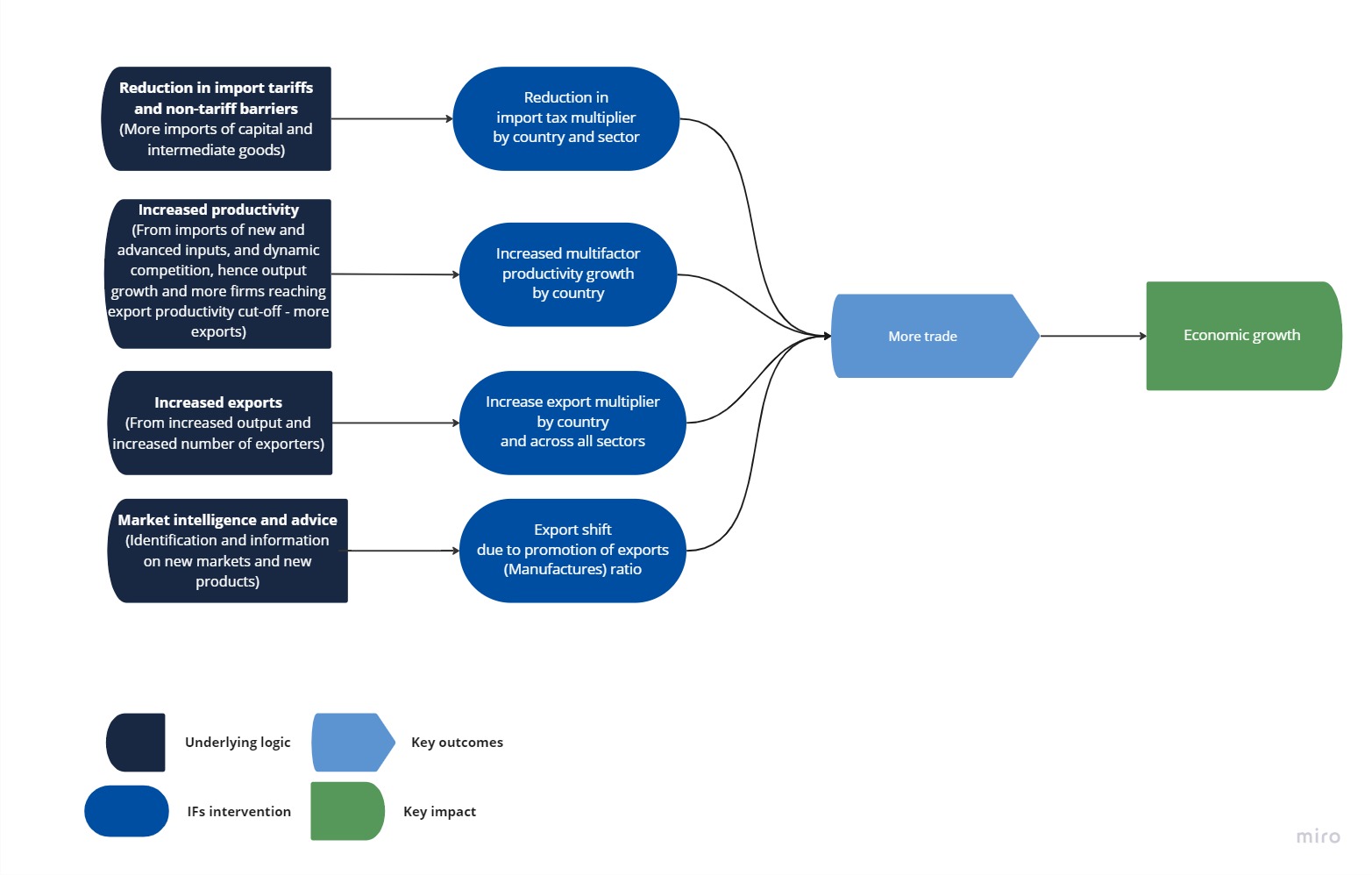

Chart 20 presents the structure of the AfCFTA scenario. This scenario represents the impact of fully implementing the continental free trade agreement by 2043. It increases exports in manufacturing, agriculture, services, ICT, materials and energy. It also includes an improvement in multifactor productivity growth emanating from trade and a reduction in tariffs for all sectors.

Visit the theme on AfCFTA for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Algeria’s export composition is dominated by hydrocarbons (98% of total exports), and it is heavily dependent on imports (70% of the country’s needs are imported). According to the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), in 2021 the country’s total merchandised exports were valued at US$35.4 billion, while total imports amounted to US$34.3 billion. Thus, there was a surplus trade balance of about US$100 million in that year.

Algeria’s top five exports in 2021 were petroleum gas (US14.3 billion), crude petroleum (US$10.7 billion), refined petroleum (US$6.2 billion), nitrogenous fertilisers (US$1.21 billion) and ammonia (US$714 million), mostly exported to Italy, Spain, France, South Korea and the United States. The country’s top five imports in 2021 were wheat (US$2.2 billion), concentrated milk (US$1.3 billion), cars (US$800 million), soybean oil (US$798 million) and corn (US$795), mostly imported from China, France, Spain, Germany and Italy.

Chart 21 compares the trade balance in the Current Path with the AfCFTA scenario from 2019 to 2043.

From 1996 to 2013, Algeria’s trade balance was generally positive (a surplus). It then slumped to a deficit of US$3.5 billion (1.4% of GDP) in 2014, and further to US$19.4 billion (7.3% of GDP) in 2019.

The deficit in 2019 was mostly dominated by the deficit in its manufacturing sector, at 8.1% of GDP. Algeria’s trade deficit is projected to continue to be dominated by its manufacturing sector with the sector accounting for about 10.9% by 2043. The AfCFTA scenario would increase the deficit by 0.7 percentage points relative to the Current Path in 2043.

Algeria has had a trade surplus in the energy sector. In 2019, the sector trade surplus accounted for 10.7% of its GDP. In the Current Path, the trade surplus is projected to increase to 19.7% of GDP in 2043. In the AfCFTA scenario, Algeria’s energy trade surplus accounts for 16.6% of GDP — a decrease of 3.1 percentage points relative to the Current Path in 2043.

Beyond the impact of global developments such as the COVID-19 pandemic, it appears that Algeria’s imports are largely controlled by politically connected corporate barons who enjoy tax holidays, energy subsidies and credit from state-owned banks to expand their businesses. Because they are entrenched and incentivised to import, they effectively prevent the industrialisation of Algeria.

In 2018, the government of Algeria imposed temporary import restrictions to protect foreign currency reserves and incentivise local production and diversification. In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, the government introduced additional import restrictions in 2020 and committed to reducing imports by US$6 billion. The aim was to cap imports at US$30 billion in 2020. However, the imports value in 2020 exceeded the targeted value by US$40.3 billion.

Trade within the North African region is limited and Algeria’s poor export performance reflects this. The Maghreb is the least economically integrated bloc in the world with a share of intra-regional trade of only around 5% of total trade. This lack of regional integration is a significant obstacle to diversification and growth for countries in the region. A mere 4% of Algeria’s trade is within the Maghreb. The 1 600 km border between Algeria and Morocco has been closed since 1994, reflecting the extent to which fraught political relations in the region determine economics.

In a 2019 IMF report on how economic integration could accelerate growth in the Maghreb, the authors point to the lack of regional considerations on trade and the restrictions on trade and capital flows that constrain regional integration. The report lists the myriad economic benefits that would flow from such integration. These include attracting foreign direct investment (FDI), easing the movement of capital and labour, ensuring more efficient resource allocation and making the region more resilient to external shocks and market volatility. However, except for Morocco, instead of increasing, the trade openness of countries in the region has steadily declined and traders face significant hurdles.

Despite (and perhaps because of) the limited formal trade within North Africa, there is evidence of significant volumes of informal trade with Tunisia and Mali. This informal trade is facilitated by the associated topography — mountains and deserts that offer plenty of opportunities for illicit activities. Gasoline is ten times cheaper in Algeria than in Tunisia and informal traders benefit from this disparity at the expense of tax revenues. Tax and subsidy differentials are the main drivers of the considerable unregulated and informal trade between Algeria and its neighbours.

Similarly, there is evidence of significant informal trade between Algeria. As a result of the cross-border trade between southern Algeria and northern Mali, the area benefits from lower prices than if goods came from the south of Mali. This phenomenon partially explains the lower poverty levels in the north of Mali, particularly in and around Kidal.

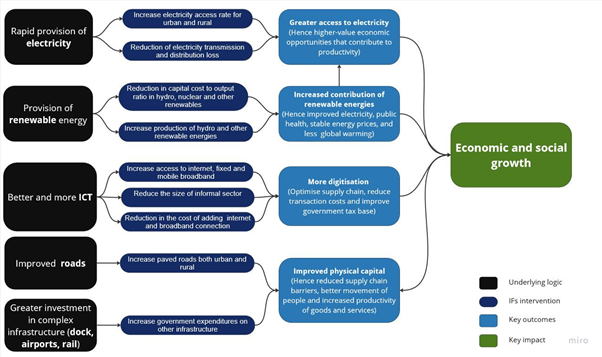

Chart 22 presents the structure of the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario.

The Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario represents a reasonable but ambitious investment in road infrastructure, renewable energy technologies and improved access to electricity in urban and rural areas. The scenario includes accelerated access to mobile and fixed broadband and the adoption of modern technology that improves government efficiency and allows for the more rapid formalisation of the informal sector. A final intervention emulates investments in large infrastructure such as rail, port and airports.

Visit the themes on Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Modern infrastructure can improve productivity, augment healthy lifestyles, boost educational outcomes and facilitate government effectiveness. Infrastructure development is positioned as a key enabler in Algeria’s National Vision 2030 strategy.

Physical infrastructure, such as roads and railways, is a critical driver of economic growth and an important component of development. It facilitates the movement of people, goods and services, promotes inter and intra-country trade and serves as an enabler of social service provision such as education and health.

Algeria has excellent all-season road access, comparable to Egypt and Libya in North Africa. In 2019, 86.7% of the rural population had access within 2 km of an all-weather road, while the average for lower-middle-income African countries was only 66.7%. The Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario will increase all-season rural road access of the rural population in Algeria to 92.1% in 2043, compared to 91.6% in the Current Path. Paved roads increase by 8.2 percentage points, or 21 023 km, above the Current Path in 2043.

Chart 23 shows cookstove usage in the Current Path and the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario from 2019 to 2043.

In 2019, about 42.8 million Algerians (99.5% of the population) had access to electricity. This was above the average of 64.9% and 83.7% for lower-middle-income and upper-middle-income countries in Africa, respectively. In the Current Path, Algeria’s access to rural electricity will reach 100% of the population by 2022, while urban electricity access by 2020.

As access to electricity in urban and rural areas increases, more households switch from traditional cookstoves, such as wood-burning or coal stoves, to improved and modern fuel stoves, such as electric or gas cookers. Our modelling distinguishes between three types of cookstoves: traditional, improved and modern. In 2019, 0.01% of households in Algeria used traditional stoves for cooking, while 99.99% used modern cookstoves.

Chart 24 presents access to mobile and fixed broadband in the Current Path and the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario as % of population, 2019 to 2043. The reader can toggle between mobile and fixed broadband.

Mobile broadband in Africa is expanding rapidly but fixed broadband lags. In 2019, Algeria had a mobile broadband subscription rate of 114.8 subscriptions per 100 people, which was significantly greater than the average of 42.0 and 84.8 for lower-middle-income and upper-middle-income African countries, respectively.

Because Algeria is already performing well in terms of access to mobile broadband, with the Current Path reaching 154.1 subscriptions per 100 people by 2043, the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario has only a marginal impact. The scenario gets to 154.9 subscriptions per 100 people by 2043, an increase of 0.8 subscriptions per 100 people relative to the Current Path.

In 2019, fixed broadband subscriptions in Algeria were estimated at about 9.9 subscriptions per 100 people. This was above the average for lower-middle-income and upper-middle-income African countries, with averages of 3.3 and 3.9 subscriptions per 100 people, respectively.

In the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario, fixed broadband subscription in Algeria will increase to 49.7 subscriptions per 100 people in 2033 — an increase of 11.7 subscriptions per 100 people relative to the Current Path. The Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario will have no impact by 2043. The number of subscriptions will be equal to the Current Path, at 50 subscriptions per 100 people.

Chart 25 presents the structure of the Financial Flows scenario.

The Financial Flows scenario represents a reasonable but ambitious increase in inward flows of worker remittances, aid to poor countries and an increase in the stock of foreign direct investment (FDI) and additional portfolio investment inflows. We reduce outward financial flows to emulate a reduction in illicit financial outflows.

Visit the theme on Financial Flows for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Algeria attracts significantly lower levels of FDI as a per cent of GDP compared to the average of lower-middle-income African countries; this gap has steadily widened. In 2019, Algeria’s FDI stock was 17.4% of GDP, about two times lower than the average of lower-middle-income African countries.

Since the Arab Spring, FDI from Europe into Algeria and the region has dropped, although Gulf investors have shown greater interest. China has also increased its investments in Algeria over the past two decades, recently taking over France's historical position as the largest investor, mainly in the construction and mining sectors. Algeria is a close ally of Beijing and the two countries have a strategic partnership.[6Tin Hinane El Kadi, Peer reviewer, London School of Economics,15 June 2020.]

According to UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2023, Algeria’s FDI inflows fell from about US$1.5 billion in 2014 to US$585 million in 2015 but improved to US$870 million after a rebound in 2021. However, Algeria’s FDI inflow fell by 89.8% in 2022 to US$89 million, due mainly to overlapping global crises — soaring public debt, the war in Ukraine and high food and energy prices.

The World Bank ranked Algeria 157th out of 190 countries in its Doing Business 2020 report, which measures aspects of business regulation and their implications for firm establishment and operations.

Numerous regulatory and practical hurdles constrain FDI in Algeria. The World Economic Forum lists impenetrable markets, protectionism, corruption, weak and overregulated digital and e-commerce economy, weak intellectual property laws and bureaucracy as obstacles to investment.

Algeria has also been protecting and promoting small and medium enterprises, which generally lack managerial independence, efficiency and accountability and place a burden on the national budget through contingent liabilities. A shakeup of small and medium enterprises and promotion of the private sector are key requirements if Algeria is to grow faster.

There are signs of progress: improved investment laws and plans for diversification are outlined in the Complementary Finance Law of 2020. This law removes the application of the 51/49 investment rule on domestic ownership of foreign business and cuts corporate taxes for investment in certain locations. It also provides for concession of land by mutual agreement and tax exemptions throughout the life of exporting projects.

Algeria can also take advantage of ICT to promote efficiency and direct less effort at the speculative economy and more at the productive economy.

Remittance flows to Algeria were valued at US$1.760 billion in 2022. This is a decline in remittance inflow by 1.8% when compared to 2021. Remittance outflows were estimated at US$82 million in 2022 — a decline from US$83 million in 2021.

Chart 26 presents government revenues in the Current Path and Financial Flows scenario, from 2019 to 2043 and in US$ 2017 values or % of GDP.

Wagner's law, or the law of increasing state activity, is the observation that public expenditure increases as national income rises. It is, therefore, reasonable to expect that government revenues will increase as a per cent of GDP in the Financial Flows scenario compared to the Current Path.

The increase in FDI inflows, aid and remittances have a significant positive impact on Algeria’s government revenue. In 2019, Algeria’s FDI inflow as a percentage of its GDP was 0.8%. The Financial Flows scenario will contribute to attracting higher FDI inflows. By 2043, Algeria’s FDI inflows as a percentage of GDP will increase from 1.7% (Current Path) to 3.3% of GDP in the Financial Flows scenario. This will be about 1.6 percentage points above the Current Path for that year. This increase is, however, below the projected Current Path average of 3.5% for lower-middle-income countries and above the average of 3.2% for upper-middle-income countries on the continent.

In 2019, government revenue for Algeria was US$107.7 billion. In the Current Path, it will increase to US$185.5 billion by 2043, growing at an average annual rate of 2.2% (in the period 2019 to 2043). In the Financial Flows scenario, government revenue of Algeria will rise to US$187.2 billion — an increase of US$1.6 billion (or 0.9%) relative to the Current Path in 2043.

Chart 27 depicts the composition of the Governance scenario. Thinking of governance in terms of security, capacity and inclusion provides a useful lens to compare how countries progressed over time, as well as compare the state of governance between countries and groups of countries.

Visit the theme on Governance for a full conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

In brief, the stability dimension uses data from the Political Instability Task Force on:

- the probability and magnitude of state failure/internal war,

- the probability and magnitude of abrupt regime change, and

- social violence consisting of reductions in conflict and terror and police conflict.

Capacity is enhanced by improving the quality of government regulation, government effectiveness (both from the Worldwide Governance Indicators) and reductions in corruption using data from Transparency International.

Inclusion improves as a result of:

- an improvement in levels of democracy using the Polity IV index applied to those countries that evidence a democratic deficit,

- an improvement in gender empowerment using the gender empowerment measure (GEM) from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and

- more economic freedom (using the associated index from the Fraser Institute).

These indices compare well with the results from others, although our modelling adopts a more structural/long term approach. For example, Worldwide Governance Indicators published by the World Bank measures six dimensions of governance, many of which overlap with the three indices. These are: voice and accountability; political stability and absence of violence/terrorism; government effectiveness; regulatory quality; rule of law; and control of corruption.

In addition to the scars of the brutal civil conflict in Algeria (from December 1991 to February 2002), Algeria’s political system has become increasingly lethargic and its economic framework is performing poorly. The economy has been bedevilled by overregulation, cronyism, corruption, lack of innovation and dependence on a rapidly declining hydrocarbon industry.

Like many other societies in North Africa, Algerians show increasing disenchantment with a political system that prevents many from participating in gainful economic activities. This widespread dissatisfaction, coupled with an economic environment that offers few opportunities, previously triggered the formation of Islamist fundamentalist and extremist groupings in the country. More recently, the impact has been on limited political and economic reform

In response to the first wave of the Arab Spring, the government instituted a set of political reforms in 2011 in an attempt to undercut the rising tide of discontent. It ended a 19-year-old state of emergency, increased female representation in elective posts and expanded subsidies.

However, later that year Algeria’s eastern neighbour, Libya, descended into civil war in a region characterised by poor border control and rampant organised crime and smuggling. It was only the size and efficiency of its large security establishment that allowed Algeria to contain the destabilising impact of the spread of weapons and the influx of terrorism.

Oil rents have allowed the regime to promote social stability and co-opt several opposition groups. The drop in oil prices since 2014 constrained the ability of the state to implement social programmes and so dampen the impact of rising popular discontent. This disaffection is the product of years of economic stagnation, high unemployment, extreme labour market segmentation and chronic corruption.

Discontent peaked in February 2019 when then-president Abdelaziz Bouteflika announced his intention to stand for a fifth presidential term in the April 2019 elections.[7Bouteflika had, in 2016, engineered a constitutional amendment that limits presidential terms to two, but since it was not retroactive it allowed him to stand for a fifth term.] Incapacitated and presiding over a government considered corrupt and elitist, his announcement triggered weekly protests by millions of Algerians in what became known as the Hirak movement.

With no signs of the protests abating, Bouteflika eventually announced that he would not seek re-election and then postponed the elections. This did not quell the protests and eventually the military forced his resignation.

For over a year, Algerians protested twice a week and promised to keep doing so until the country achieved what they considered to be ‘genuine reform’. This included the promise of an overhaul of the regime and free and fair elections. The establishment of a new electoral authority also failed to halt the protests.

The election that took place on 12 December 2019 was a dismal and widely boycotted affair. The candidates were all perceived to be part of the same political establishment that gave rise to protestors’ discontent. Former Prime Minister Abdelmadjid Tebboune, a perceived loyalist of the ousted president, won the presidential vote with the lowest voter turnout in the country’s history.

The Hirak protest movement in 2019 put pressure on the regime to reform but a crackdown on dissent since the COVID-19 pandemic has prevented large-scale demonstrations from continuing.

In 2021, the High Security Council designated the Rachad — an organization that includes former Islamic Salvation Front members — and the Movement for the Self-Determination of Kabylie (MAK) as terrorist organisations. Numerous people accused of affiliation with the groups have since faced arrest. In November 2022, exiled MAK leader Ferhat Mehenni was sentenced in absentia to life in prison on terrorism-related charges.

Regardless of the domestic situation, it is clear that governance in Algeria is out of step with its peers globally. Better governance ensures the efficient allocation and distribution of state resources and encourages FDI inflows.

Within our modelling, governance consists of three dimensions, namely security, capacity and inclusion. Each is constructed out of a series of subsidiary data and indices. In 2019, Algeria did well compared to the averages of lower-middle-income and upper-middle-income countries in Africa in the security and capacity dimension. However, it trails upper-middle-income African countries in terms of inclusion, which consists of broad elements of democracy, gender empowerment and youth participation.

Chart 28 presents progress with each of the three governance dimensions by 2043 in the Current Path and Governance scenario compared to 2019. It shows the time series (line) and each aspect separately (bar).

Generally, governance in Algeria does better compared to the average of lower-middle-income countries in Africa. In the total governance index, its score of 0.62 in 2019 was 21.4% higher than the average of lower-middle-income countries in Africa and just 8.2% lower than the average of upper-middle-income countries.

Algeria does well and will continue performing better compared to the average of upper-middle-income African countries in the security and capacity dimension. It will continue to trail behind the average of upper-middle-income African countries in terms of inclusion by 2043. On the Current Path, Algeria’s inclusion index will reach 0.49 by 2043. In the Governance scenario, the score will increase by 0.11 (or 22.1%) reaching an overall score of 0.59.

Chart 29 presents a stacked area graph on the contribution of each scenario to GDP per capita from 2019 to 2043.

The cumulative impact of better education, health, infrastructure, leapfrogging, etc. means an additional benefit in our modelling that we refer to as the synergistic effect.

In the Combined scenario, Algeria’s GDP per capita will increase to US$22 727 by 2043. This will be US$6 293 (or 38.3%) higher than the US$16 437 in the Current Path.

The scenarios with the greatest impact on GDP per capita in Algeria by 2043 will be the AfCFTA, followed by the Governance scenario and Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario. In the AfCFTA scenario, Algeria’s GDP per capita will increase by US$1 711 (or 10.4%) relative to the Current Path by 2043. The Governance and Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenarios will increase Algeria’s GDP per capita by US$981 (6.0%) and US$676 (4.1%) relative to the Current Path by 2043. These scenarios illustrate the potential economic growth and improvements in living standards under different development paths.

Chart 30 presents the impact of each scenario on extreme poverty by 2043. The user can select the number of extremely poor people or percentage of the population.

The Combined scenario impacts on poverty in Algeria, where 3 000 Algerian people will be living in extreme poverty at US$3.20 per day in 2043. Thus, 391 000 Algerian people will be lifted out of extreme poverty at US$3.20 per person per day relative to the Current Path of 394 000 Algerian people in 2043. This is equivalent to a decline of 99.2 percentage points compared to the Current Path of about 394 000 people (or 0.7% of the 58 million in the Algerian population) in 2043.

Extreme poverty at the US$3.20 per person per day threshold is reduced most significantly by the Manufacturing scenario, followed by the AfCFTA scenario. In the Manufacturing scenario, 288 000 Algerians will be lifted out of extreme poverty relative to the Current Path by 2043. The AfCFTA scenario will reduce extreme poverty in Algeria by 52.5% (or 187 000 people) relative to the Current Path.

Chart 31 compares the size of the economy in the Current Path with the Combined scenario at market exchange rates (MER).

The Combined scenario consists of the combination of all eight sectoral scenarios, namely Governance, Demographics and Health, Education, Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging, Agriculture, Manufacturing, AfCFTA and Financial Flows.

In the Combined scenario, Algeria’s economy will be US$271.3 billion (or 59.8%) larger than when compared to the Current Path of about US$453.5 billion in 2043. The AfCFTA scenario will have the largest impact on Algeria’s economy by 2043 as it will increase Algeria’s GDP by US$71.3 billion (or 15.7%) relative to the Current Path.

Chart 32 presents the change in the economy's structure, comparing the Current Path with the Combined scenario from 2019 to 2043, in US$ 2017 and % of GDP.

Our modelling uses data from GTAP to classify economic activity into six sectors: agriculture, energy, materials (including mining), manufacturing, services and information and communication technologies (ICT). Most other sources use a threefold distinction between only agriculture, industry and services, with the result that data may differ.

The Combined scenario anticipates notable growth in Algeria's economy, with the service and manufacturing sectors playing prominent roles in this economic expansion. By 2043, total value added by all sectors will increase from about US$453.5 billion in the Current Path to US$724.9 billion in the Combined scenario.

The service sector will make the largest contribution to the economy of Algeria relative to the Current Path and will continue to have the largest share contribution to the GDP of Algeria. The service sector will contribute about US$111.8 billion to the economy of Algeria relative to the Current Path in 2043. This will increase the sector’s contribution to GDP from 33.9% (Current Path) to 36.6% in the scenario.

The service sector will be followed by the manufacturing sector, which will contribute US$111.2 billion relative to the Current Path in 2043. This will increase the manufacturing sector contribution to 33.7% of GDP, about 4.4 percentage points increase relative to the Current Path.

Chart 33 presents the size of the informal sector as a % of GDP or % labour force. Data on the contribution of the informal sector is often estimated and should be treated with care.

The Combined scenario will also have a positive impact on the size of the informal sector in Algeria. By 2043, the share of the informal economy as a percentage of GDP will drop by about 8.2% relative to the Current Path of 25.6%. This shows that greater economic freedom, gradually diversifying away from hydrocarbons, good governance and access to opportunities in the overall economic system can encourage formalisation. This in turn expands the revenue base of Algeria.

Chart 34 compares life expectancy in the Current Path with the Combined scenario from 2019 to 2043.

In the Combined scenario, life expectancy at birth in Algeria will increase to about 82 years by 2043, which will be about 1.5 years higher than the country’s Current Path in the same year.

Chart 35 compares the Gini coefficient in the Current Path with the Combined scenario from 2019 to 2043.

The benefits of economic growth may not be evenly distributed in a country due to inequality. High levels of inequality have many negative effects including a breakdown of social structure and cohesion which can result in instability. The Gini coefficient is the standard measure of the level of inequality in a country. A higher score depicts greater inequality while a lower score shows a more equal country.