4 Agriculture

4 Agriculture

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

This entry describes the evolution and dominant characteristics of agriculture in Africa and how the sector can impact the continent’s development trajectory. Without a revolution in agriculture, Africa will struggle to improve its development outcomes. This entry also presents an Agriculture scenario, showing how farming with a growth mindset can improve food security and incomes, reduce poverty and benefit Africa’s development outlook.

Summary

- Many efforts have been made to improve agricultural production in Africa, but it is still dominated by millions of smallholder farms, low productivity and traditional farming practices. Since farming is the bedrock of human development, slow progress in this domain generally helps explain slow growth. Historically, geography and climate translated into a high disease burden and low population densities, meaning farming in sub-Saharan Africa emerged later and differently than elsewhere.

- Slavery meant that African societies remained more dispersed and mobile, including denuding the continent of its most productive labour. With colonialism, indigenous crops were replaced with commodities to feed demand and factories in Europe, and most Africans were dispossessed of their land, undermining food security at home.

- The green revolution of the 1950s and 1960s effectively passed Africa by, and little changed after independence. African leaders did not pursue food self-sufficiency, and the continent continues to lag behind other regions concerning agrarian productivity. Extended periods of conflict in countries such as Angola and DR Congo were particularly destructive. Despite its massive agriculture potential, Africa is steadily becoming more dependent on food imports, with agriculture production increasing due to increased land area under cultivation rather than productivity improvements.

- African countries with large agricultural sectors mainly export raw commodities such as cocoa, coffee and cashew nuts with little value addition. In contrast, successive efforts such as the Comprehensive Africa Agricultural Development Programme (CAADP) have had limited impact. In the Current Path, Africa’s agricultural import bill will likely grow from US$114 billion in 2019 to US$510 billion in 2043. Low agricultural productivity and high levels of inequality in Africa amidst rapid population growth contribute to the slow rate of poverty reduction.

- Transforming agriculture in Africa will require access to finance and technology and secure land tenure rather than ill-considered land redistribution programmes, such as in Zimbabwe. Agriculture should be pursued with the primary purpose of ensuring national food security before opportunities for foreign exchange, although the two are, of course, closely related.

- Africa can learn valuable lessons from models in China and Brazil. The proliferation of mobile phones and better connectivity means that agricultural technologies (AgTech) can help farmers overcome market barriers and enhance farm productivity and sustainability.

- In an Agriculture scenario, improved yields, putting more land under irrigation, increasing water availability, focusing on ecosystem restoration, improving supply chains, increasing rural accessibility and increasing per capita caloric consumption results in greater food security and reduced import dependence.

- The Agriculture scenario is expected to have significant economic and development impacts in Africa, particularly for low and lower-middle-income countries. In the scenario, Africa’s agriculture production volumes more than double. By 2043, Africa will produce 486 million metric tons of additional food compared to the Current Path. The continent can reduce its agricultural import bill by US$212 billion while increasing its export earnings from agriculture by US$227.6 billion.

- African governments must recognise that agriculture is a foundation for sustained economic development. Modern technology can assist but needs to be part of an overall strategy on food self-sufficiency and shifting value-addition to Africa.

All charts for Theme 4

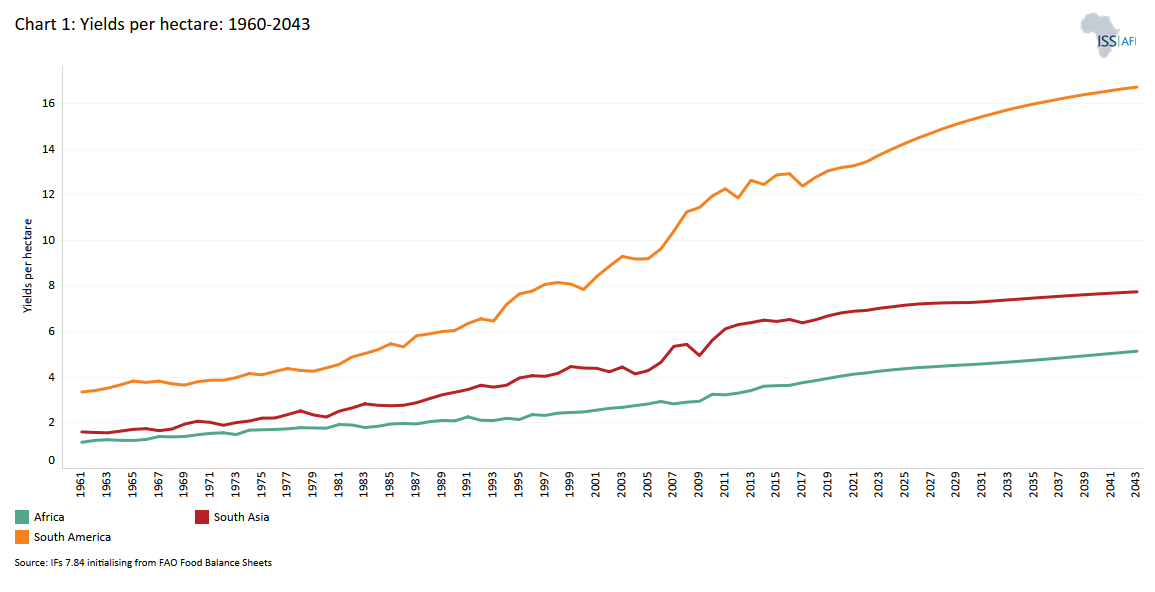

- Chart 1: Yield per hectare: Africa vs World except for Africa and other regions, 1960–2043

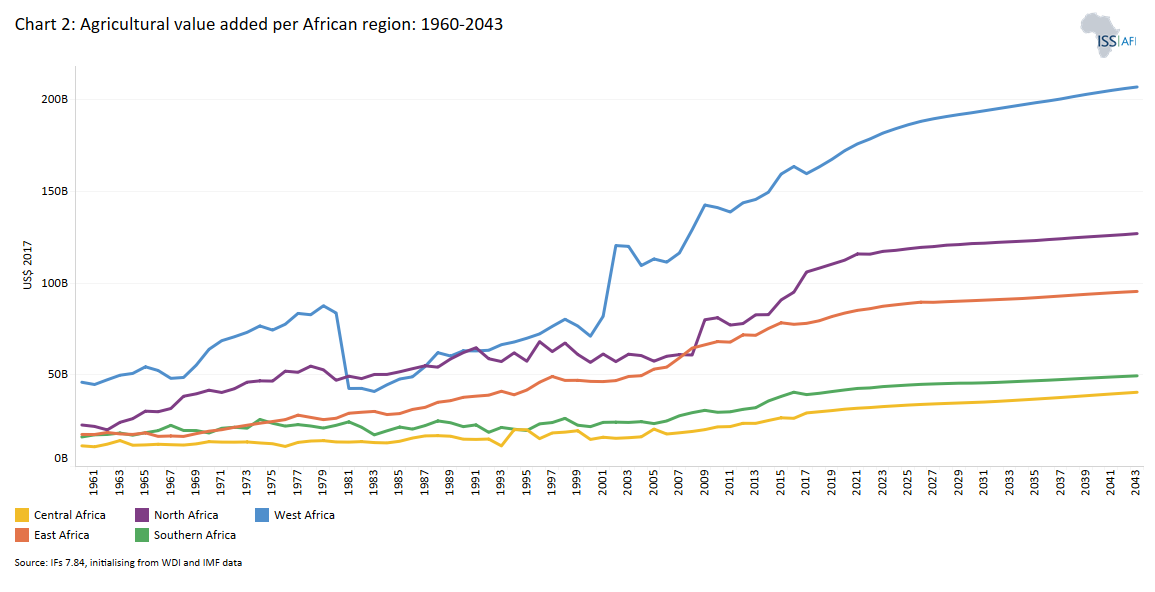

- Chart 2: Agricultural value added per African region: 1960–2043

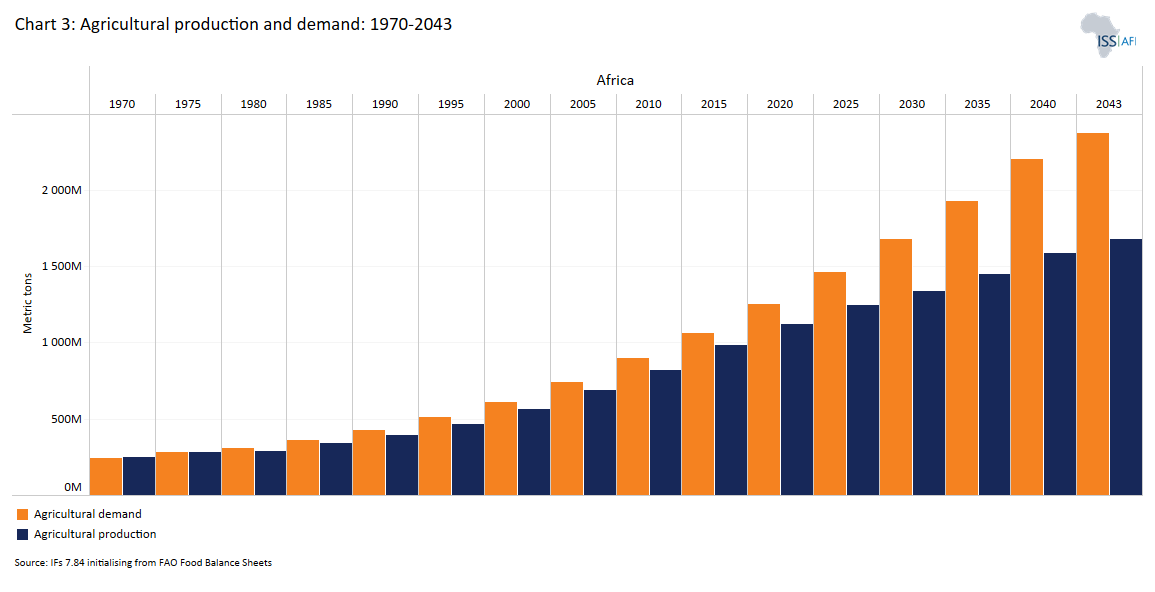

- Chart 3: Agricultural production and demand: 1970–2043

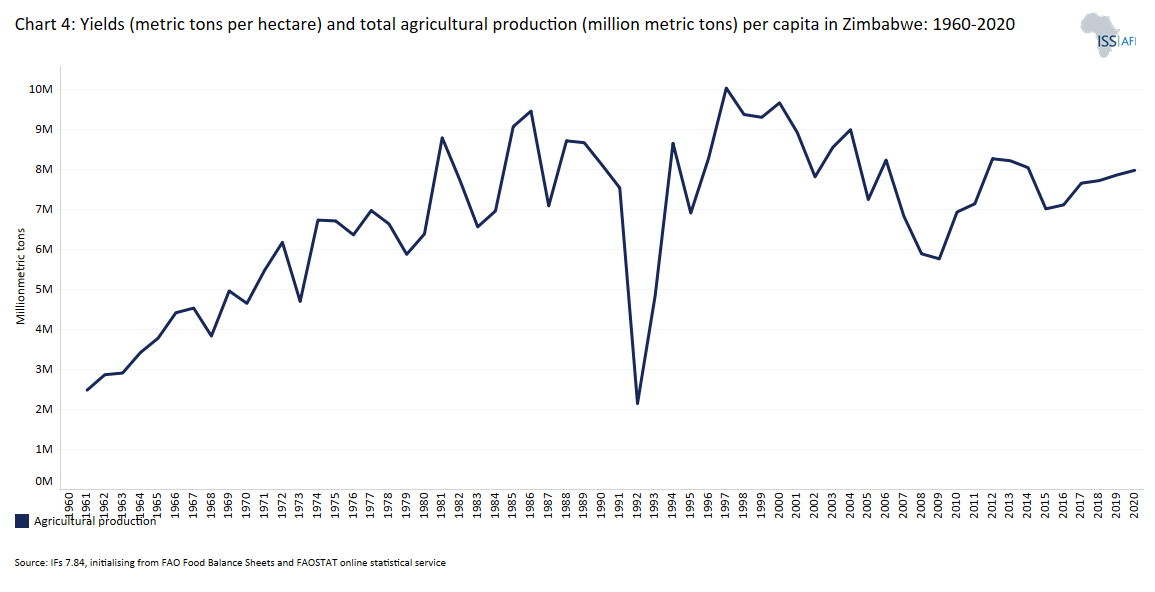

- Chart 4: Yield (metric tons per hectare) and total agricultural production (million metric tons) per capita in Zimbabwe: 1960–2020

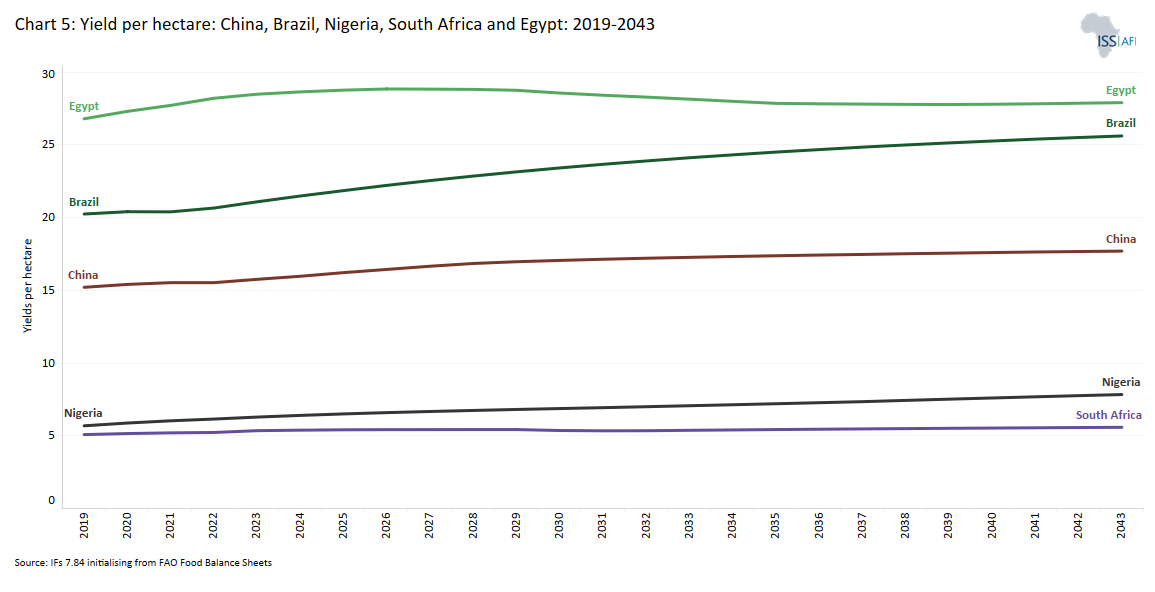

- Chart 5: Yield per hectare: China, Brazil, Nigeria, South Africa and Egypt: 2019–2043

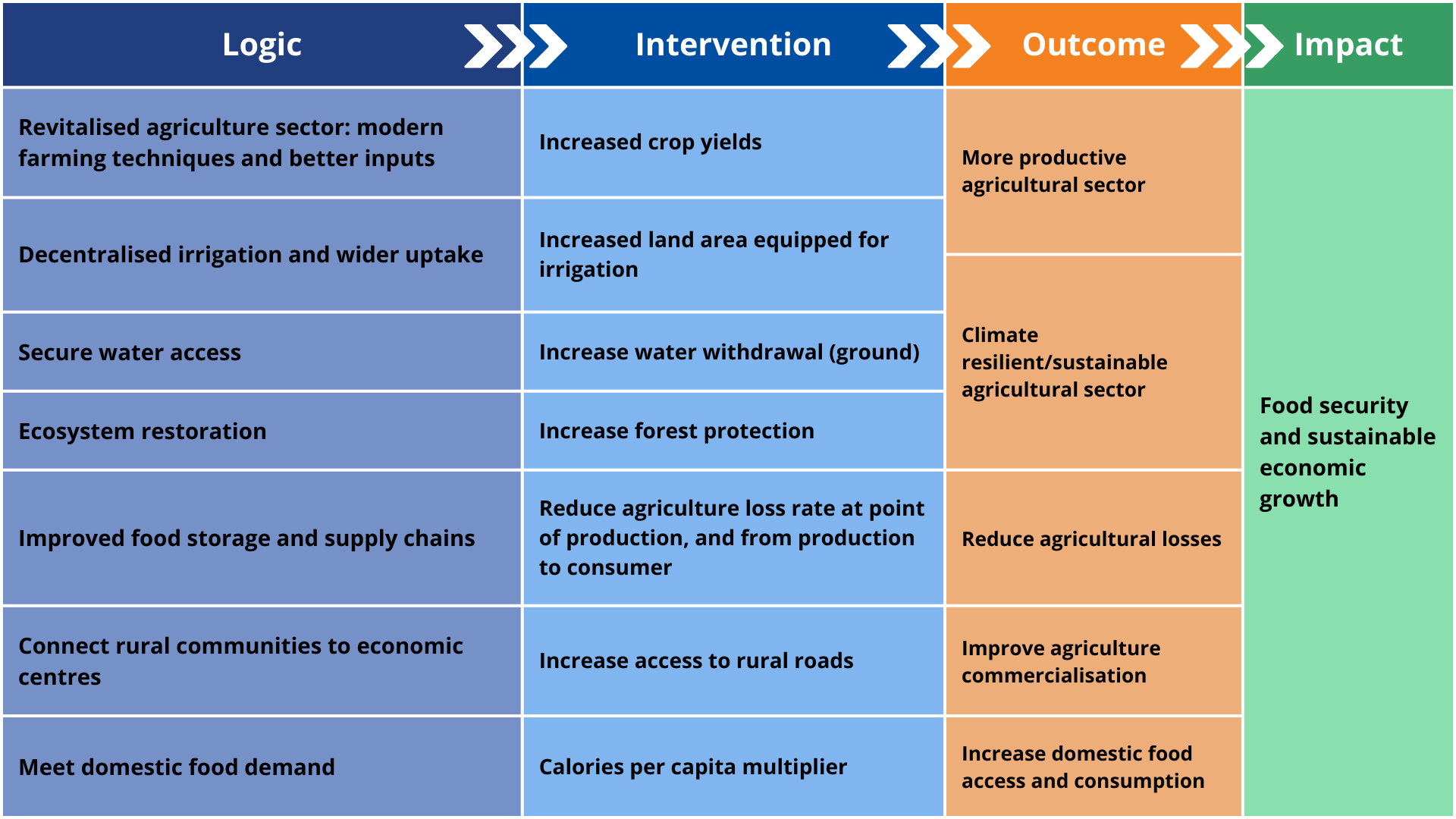

- Chart 6: The Agriculture scenario

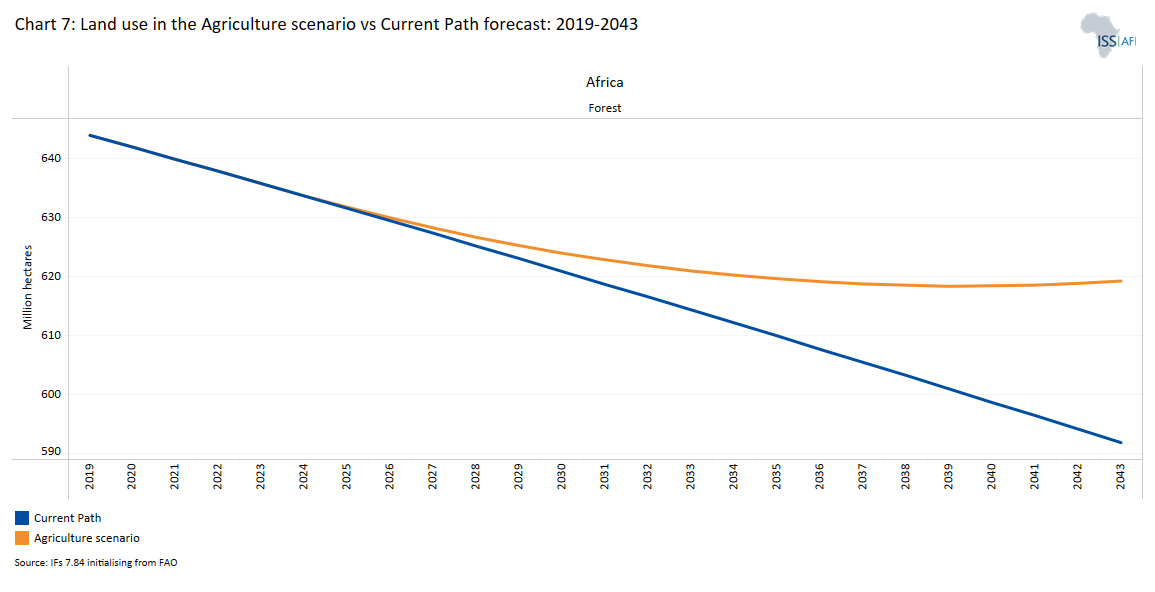

- Chart 7: Land use in the Agriculture scenario vs Current Path forecast: 2019-2043

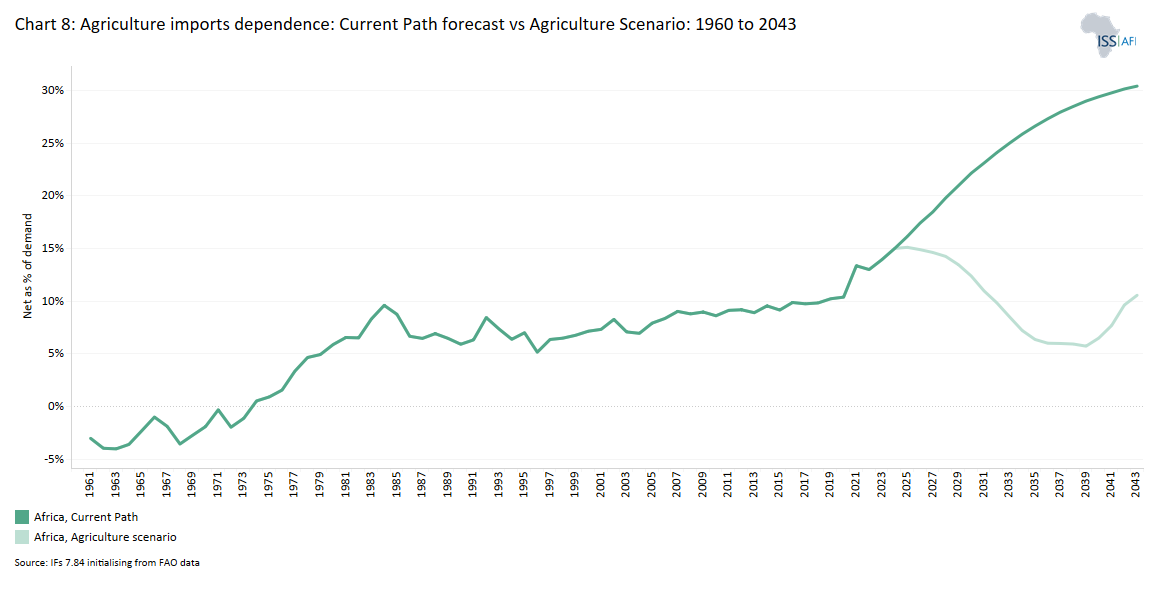

- Chart 8: Agriculture imports dependence: Current Path forecast vs Agriculture scenario: 1960–2043

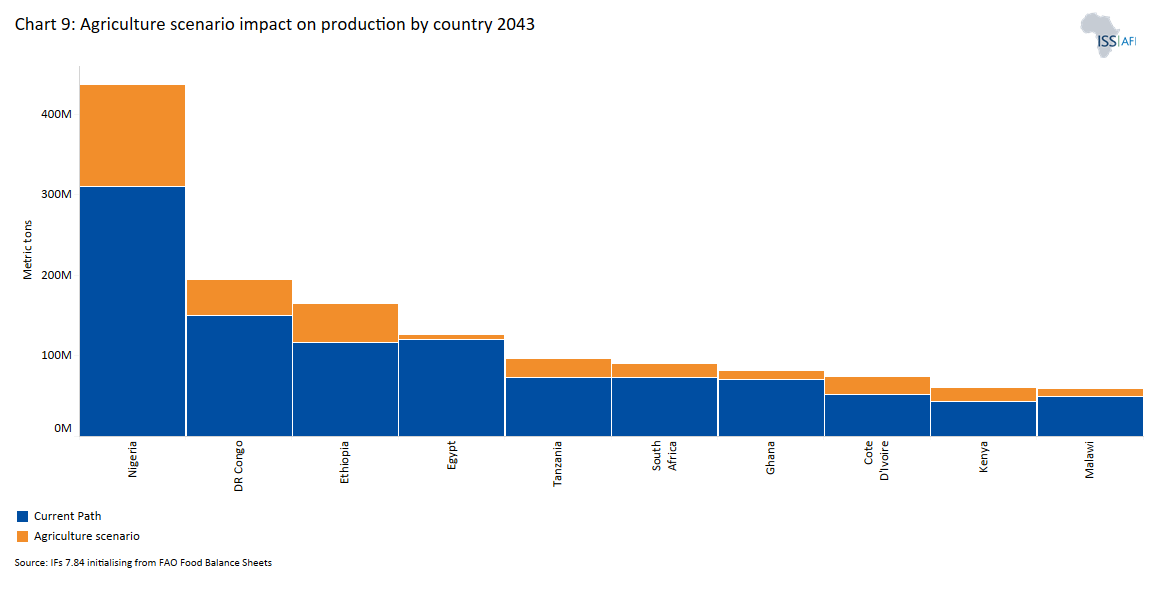

- Chart 9: Agriculture scenario impact on production by country 2043

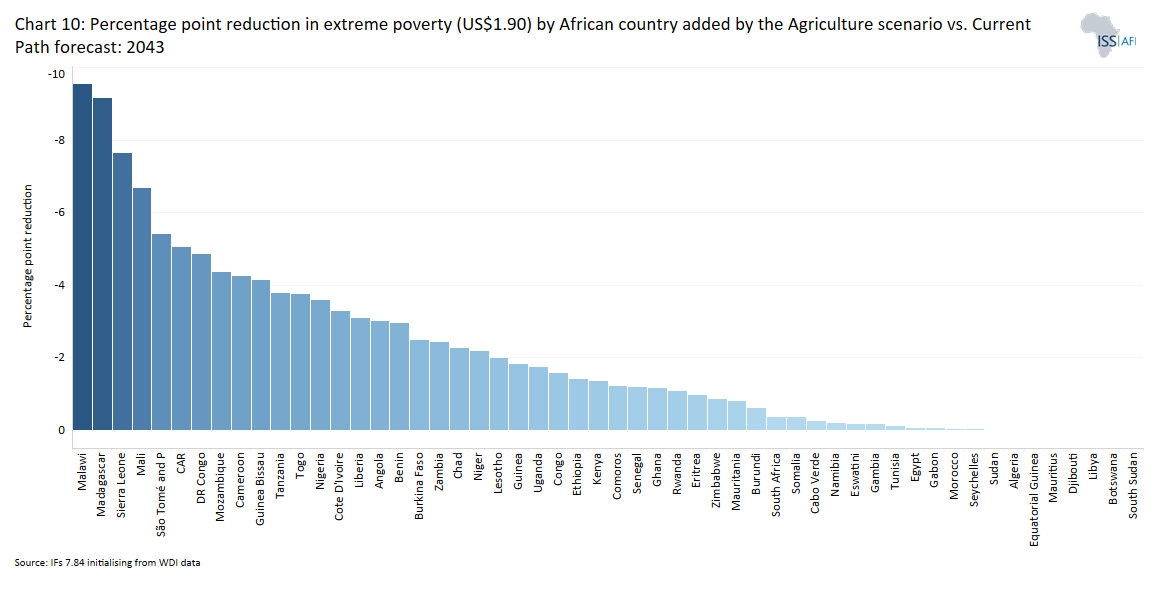

- Chart 10: Percentage point reduction in extreme poverty (US$1.90) by African country added by the Agriculture scenario vs Current Path forecast: 2043

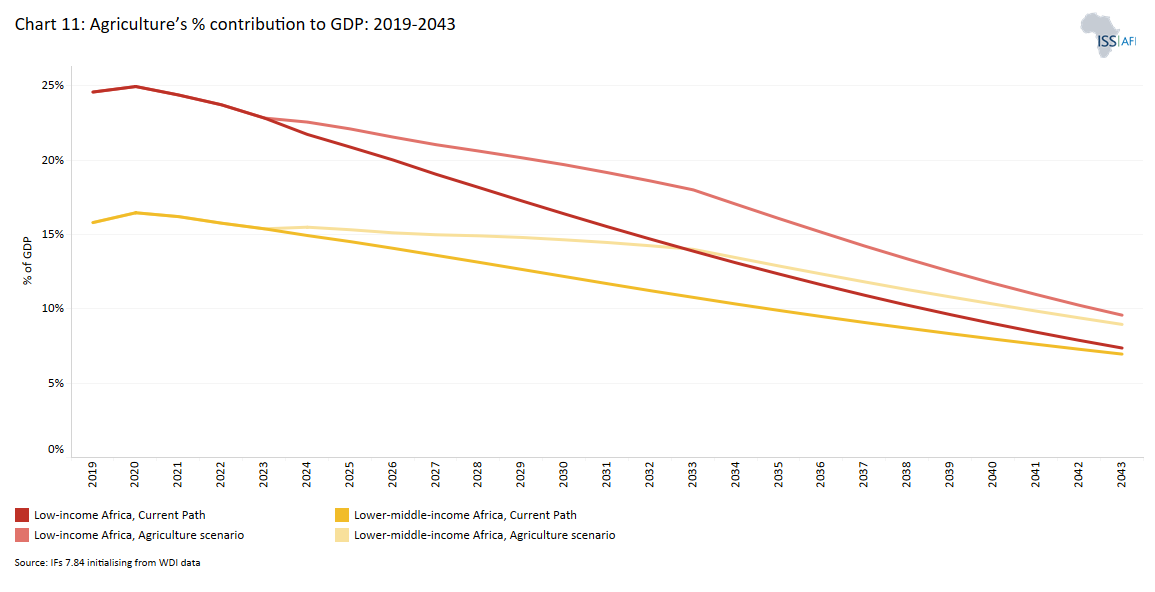

- Chart 11: Agriculture’s % contribution to GDP: 2019-2043

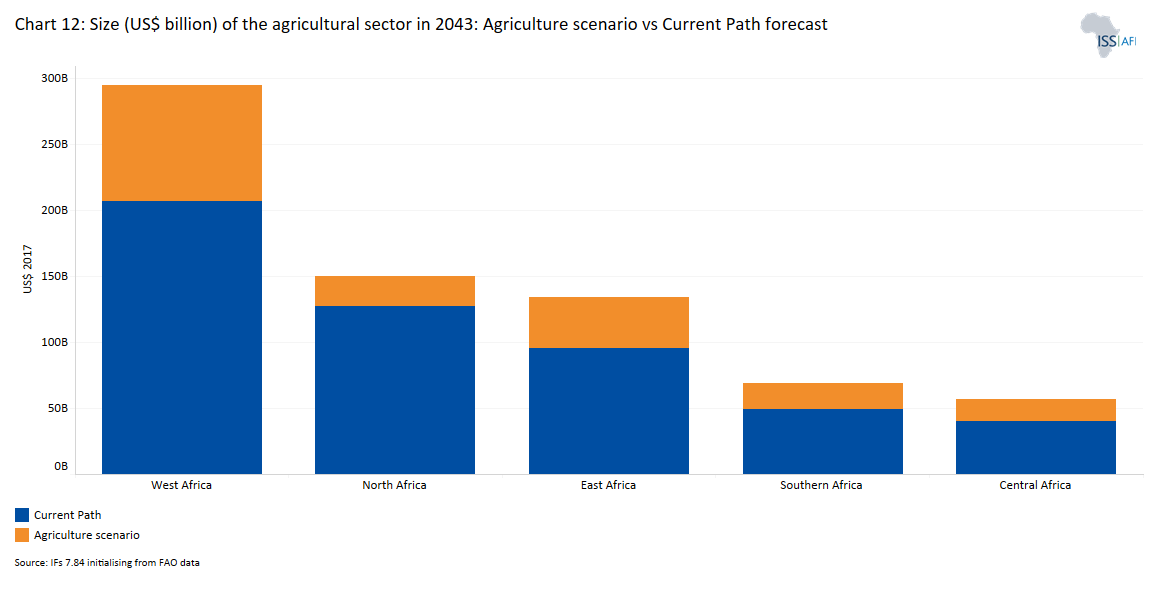

- Chart 12: Size (US$ billion) of the agricultural sector in 2043: Agriculture scenario vs Current Path forecast

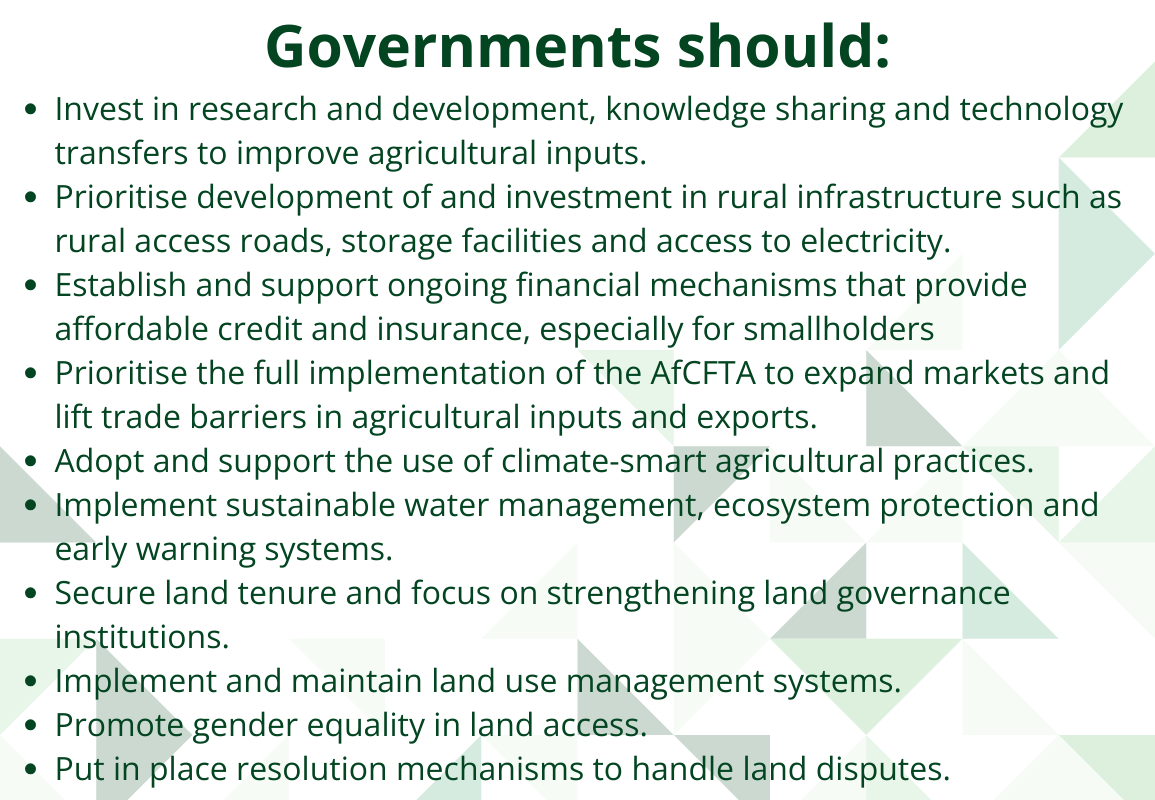

- Chart 13: Key policy recommendations

Although there are promising developments in several African countries, the continent has yet to have a modern revolution in agricultural production. The lack of progress is disheartening, for it follows several decades of efforts to implement improvements, much of which was initially led by the World Bank, the African Union's Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) and the Alliance for a Green Revolution (AGRA) that sought to introduce technologies like high-yielding seed hybrids, agrochemicals, mechanisation, and irrigation to Africa, based on the success achieved in improving agricultural productivity in parts of Asia and Latin America.

Fostering growth in Africa’s agricultural sector hinges on the millions of smallholder farmers that constitute the sector. Generally, low levels of investment in agriculture, lack of land reform, the continued use of traditional farming methods and ineffective agricultural policies have left Africa with the lowest agricultural yields in the world. Yet farming is the bedrock of human development, and slow progress in this domain, historically and recently, generally helps explain poor progress with development in Africa.

With the noteworthy exceptions of the Nile River, modern-day Ethiopia, some parts of West Africa and the Sahel, the agricultural development pathway in Africa followed a somewhat unique trajectory compared to other regions. The continent’s high disease burden (discussed in the theme on Health/WaSH) constrained population growth in large parts even as humanity expanded rapidly elsewhere. It also inhibited the spread of domesticated livestock southward, as did the poor soil quality in most of the continent, except areas along great rivers such as the Nile and the length of the Great Rift Valley in East and Central Africa.[1J Reader, Africa: A biography of the continent, New York: Penguin, 1998, 99; also see: J Diamond, Guns, germs and steel: The fates of human societies, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1997; R Tignor et al, Worlds together, worlds apart: A history of the world — Beginnings through the fifteenth century, 3rd ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2010. A 1997 study by the US Department of Agriculture calculates that 55% of the land in Africa is unsuitable for any kind of agriculture except nomadic grazing. See: H Eswaran et al, Soil Quality and Soil Productivity in Africa, Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 10:4, 1997, 75–90.]

Free from most diseases, the fertile highlands of Ethiopia were the only regions where Africans developed intensive agriculture, while the open savannah south of the Sahara and north of the tropical rain forests allowed for relatively small-scale settlements. Cattle were important, and the crop plants included sorghum and millet. But as far as technology was concerned, writes Cyril Aydon, the peoples of sub-Saharan Africa still lived in the Stone Age at the time of the Bronze Age, which had passed them by.[2C Aydon, The story of man, Constable, London, 2007, 78.]

Crop plants in sub-Saharan Africa, such as sorghum and pearl millet, were not as nutrient-rich as wheat, barley, rye, oats, rice and maise — the common staple foods that emerged in the rest of the world — nor were they well suited to the prevailing climatic conditions in southern and eastern regions of the continent.[3J Diamond, Guns, germs and steel: The fates of human societies, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997] However, the cultivation of yams (perennial herbaceous vines native to Africa) in West Africa around 3 000 BC allowed for more significant surpluses, eventually setting off migration southward and eastward. Grains such wheat, barley, rice, and maise are all members of the grass family that produce small, hard seeds meaning they had low moisture content and were durable once harvasted and thus easy to store. Their high energy density (calories per kilogram) makes them attractive to transport to distant markets and can be handled at scale to sow, maintain and harvest. As a result these cerial grains, as they are generally known, and the associated production methods that emerged, enabled the emergence of denser settlements, cities and eventually, states.

Maise, which produced much higher yields than sorghum and millet; was introduced into Africa around 1600 but is not drought-resistant. Also, because the continent covers numerous climatic zones from north to south, the richer staple foods prevalent elsewhere could not readily be transplanted across the humid equatorial regions southward.

With farming in sub-Saharan Africa emerging much later than elsewhere, together with the high disease burden in the tropics, the subsequent lower population pressure and competition translated into lower levels of technology. It is reflected in the relatively short lifespans of Africa’s numerous empires that either collapsed when the central authority found it unable to maintain control over the extended lands, or were forcibly dismantled by outsiders. Even before the Arab and Atlantic slave trades, most wars on the continent were fought to capture labour rather than to occupy land to the extent that indigenous African slavery was widespread.

Collectively, the indigenous, Arab, European and Transatlantic slave trades, from the mid-7th century to the 19th century, had a devastating impact on the African continent. Slavery meant that African societies remained more dispersed and mobile than others. On top of a high disease burden, poor soils and lack of access to technology, farming was challenging in a situation of low population density, lawlessness and violence. People constantly moved to avoid capture, often avoiding areas that offered easy access, such as along larger rivers. Once slaves had been captured and violently removed, it was the young, elderly or disabled who were left behind. Large parts of Africa were denuded of a productive labour force. Farming and herding could, therefore, not develop systematically, nor could social, political and economic systems mature to allow for technological and productivity improvements to track development seen in other regions of the world.

Despite the continuous drain of labour formally ending with the abolition of slavery by the mid-19th century, other forced labour schemes under the guise of imperialism and colonialism soon followed. In the decades that followed the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, where Africa was formally divided between various European states, the continent became an increasingly important source of raw agricultural products to feed the factories in Great Britain, Germany, Belgium, France, Italy, Portugal and Spain.

In addition, introducing foreign crops such as peanuts and sesame oriented to the export market replaced dietary staples such as millet and sorghum and reduced domestic food security. Population densities were low, and in many colonies settlers often designated large areas terra nullius (unoccupied land) and formal property rights were reserved for them and their European firms. European settlers steadily established themselves and the land was subsequently dispossessed. Much of the rest of the agricultural land was given ‘customary’ tenure, meaning it could be used but not owned, and that it was subject to seizure by the state.

Investment in road and rail infrastructure followed to allow raw materials to be transported from productive areas to the coast, from where products were shipped to Europe. Consequently, the rural and domestic agricultural sectors and regional trade were either destroyed or remained economically marginal. In this way, slavery, imperialism and colonialism fundamentally altered the development of agriculture on the continent. They effectively destroyed Africa’s burgeoning trade in food and displaced indigenous crops with commodities beneficial for the industrialising economies in Europe, which undermined food security at home.

Although African independence brought many political benefits, few accrued to agriculture. With limited exceptions, rural and agrarian development received little resource and budgetary allocation after independence; leaders sought rapid industrialisation or vanity projects instead. Most African governments also retained the bifurcated system of land ownership, with customary property rights in so-called tribal lands and legal property rights reserved for a limited few and in some urban areas. Effectively, the urban elites that shared the ethnic orientation of the governing party replaced colonists in state institutions and land ownership. The notion of formalising land ownership gained wider recognition only towards the end of the 20th century when population growth had significantly complicated efforts at tenure reform.

Substantive yield-enhancing shifts were seen in agriculture elsewhere in the world, including mechanisation and the introduction of new crop varieties and agricultural chemicals in the green revolution of the 1950s and 1960s. However, the focus was on political rather than economic emancipation in Africa. Without tenure reform and being locked into an inequitable supply chain that effectively penalised efforts towards food self-sufficiency and disincentivised domestic value addition to its agricultural commodities, Africa continued to lag behind other regions concerning agrarian productivity.

By the early 1960s, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimated that average yields in Africa were approximately 1.1 tons per hectare, roughly 1.3 tons per hectare below the average for the rest of the world. It took 30 years for yields to double to 2.2 metric tons by the early 1990s. By 2020, yields in Africa had increased to about 4 tons per hectare yet were still 3.7 tons below the average of the rest of the world. Thus, for successive generations, agricultural yields in Africa have remained at about half that in the rest of the world, with little prospect of catching up in the Current Path forecast to 2043 (Chart 1).

Chart 1 also compares the average yields per hectare with two global comparative regions, South Asia and South America. Because food is cheaper on the international market than domestically and because the quality of diets changes with income, Africa is becoming more, rather than less, dependent on food imports despite the continent having millions of hectares of arable land with massive untapped agricultural potential.

Despite isolated success stories, the agricultural sector in Africa still needs to be significantly more productive than in other regions and is likely to remain so into the future. The most recent FAO data (2021) shows that 16 of the 20 countries with the lowest average cereal yields per hectare globally were in Africa. At the same time, only one African country — Egypt, with its large Nile river and delta — is among the top 15 most productive cereal producers. The next African state on the list, South Africa, is ranked 44th, followed by Ethiopia in the 97th position.

Lengthy periods of conflict have also negatively affected agriculture. For example, Angola is one of Africa’s most fertile countries and was, before independence in 1975, self-sufficient in all main food crops except wheat. It was the fourth largest coffee producer globally, but successive wars, which lasted until 2002, destroyed much of that. Most of its population fled to urban areas (generally to the capital Luanda). Today, nearly seven out of ten Angolans reside in urban areas, and there is still limited infrastructure to connect the capital city to the rest of the country. However, the government is working hard to correct this deficit. As a result, Angola ranked close to the bottom (160th of 167 countries globally) on the World Bank’s 2018 Logistics Performance Index (LPI).

Next door to Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo) has been host to the largest peacekeeping mission in the world for many years, yet it is still wracked by instability. The DR Congo is ranked 143rd on the LPI. Despite being a country with the agricultural potential to feed the entire continent, it has yet to achieve food independence, and malnutrition is widespread. With only 10% of its 80 million hectares of arable land cultivated, the country has the potential to become a global agricultural powerhouse, and the sector provides about 60% of jobs. However, most of these only provide for subsistence needs.

However, like Angola, violent conflicts have severely affected the DR Congo’s agriculture sector. For example, by 2006, agricultural productivity had fallen to 60% of its level at independence in 1960. The DR Congo's current food trade deficit (the difference between the value of exports and imports) is US$1.5 billion annually. It will increase over time, given the lack of transport infrastructure such as roads and railways, which require lengthy and costly investment, continuing to make the country a net food importer.

Africa’s progress has, therefore, been slow, despite the World Bank noting that Africa has approximately 45% of the global total surface area suitable for sustainable production expansion and that low labour costs could encourage labour-intensive agricultural production.

The modest increases in agricultural production in Africa since independence were generally the result of the increased land area under cultivation rather than improved productivity, leading to Africa being described in 2013 as ‘the only developing region in which the percentage of area expansion exceeded growth in yield over the period 1990–2007.’

Land rotation practices in Africa have traditionally used slash-and-burn techniques, with farmers clearing new lands and leaving the old field fallow for a year or two to recover. Although this worked well while population densities were low, shortages of arable land due to increasing population numbers forced farmers to cultivate the same fields season after season. For example, rapid population growth and urbanisation in Kenya and Ethiopia have increased land prices and swallowed some of the best farmland, sometimes leading to violent protests. Soil erosion, deforestation and unsustainable agricultural practices have also contributed to floods and soil losses.

Only those farmlands near urban areas generally had roads good enough for products to be transported to the market. The lack of paved roads and other infrastructure in prime agricultural areas far from major population centres means that large parts of the available arable land are not used for large-scale production. Closer to population centres, unsustainable cultivation practices in these high-density areas contribute to substantial soil degradation as average farm sizes shrink and decrease soil fertility.

The impact of extreme weather-related events has also been profoundly felt across the continent, particularly in the agricultural sector. Droughts, in particular, cause crop failures and lower yield outputs, leading to significant food crises and, in some cases, famine. Over the last 100 years, the continent has battled over 350 extreme drought events, with nearly half leading to food shortages or famines. Flooding is also a regular occurrence in Africa, leading to infrastructure damage, soil erosion, crop damage, and nutrient-depleted soils. Tropical storms and cyclones impact soil salinity, contribute to soil loss and damage critical infrastructure, leaving many rural communities unable to utilise land resources. Since 95% of the continent's cultivation depends on rains and not irrigation, the impact of climate change contributes to inconsistent agricultural productivity.

Deforestation, in addition to causing soil degradation, also significantly impacts water availability. Deforestation releases stored carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, contributing to increased temperatures and varied rainfall patterns that change crop growth and yields. Forests are vital to regulating water cycles through water storage and subsequent transpiration. Deforestation also contributes to biodiversity loss, which disrupts ecological balance. An estimated 4 million hectares of forest land are cut down yearly in Africa. Many forests are converted into low-yield agricultural cropland, but the negative impacts of deforestation outweigh the yields achieved. Since 1990, Africa has decreased forest land from 722 million hectares to 642 million hectares in 2020. As deforestation continues, it will directly contribute to increased flooding, impacting the sector's productivity and giving rise to food insecurity.

In response to these challenges, the African Union launched the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) in 2001, which emphasises agriculture as a critical driver of economic growth and poverty reduction. Success has been mixed, however.

On average, Africa spends only 5–7% of national budgets on agriculture. However, a 2018 study found that 11 African countries have allocated 10% or more of their budgets to agriculture in some years since 2005, with Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique and Sierra Leone achieving 6% agricultural growth in most of these years. Agriculture employs about half of the workforce, with smallholder farmers contributing to 80% of agriculture production in sub-Saharan Africa. However, smallholder farmers continue to face numerous challenges stemming from fragmented agricultural supply chains, lack of access to fair markets, affordable inputs, modern equipment, financial services, and essential information like market prices, weather predictions, and pest risk, ultimately resulting in reduced profit margins. Poor market infrastructure and lack of processing facilities lead to lower prices for farmers. Inadequate access to harvesting equipment, irrigation systems, cold storage, and agricultural inputs such as fertilisers hampers production.

Today, Africa is the most food-insecure region globally. According to the 2022 Food Security and Nutrition report, about 278 million Africans faced undernutrition in 2021. The continent has seen an alarming backsliding in the prevalence of undernourishment since 2015, amplified by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. While the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target of achieving zero hunger is noble, it is unlikely to be met anytime soon on the continent. In 2021, moderate and severe food insecurity prevalence stood at 58%. East and Central Africa are particularly struggling with undernourishment rates measuring as high as 30% and 33%, respectively, in 2021.

African countries with large agricultural sectors mainly export raw products without value addition and need help to go up the value chain. For example:

- Africa produces about 45% of the world’s cashew nuts, with 90% of the crop exported for processing overseas but with little benefit to the 2.5 million farmers involved in the industry. The African Cashew Alliance estimates that a 25% increase in raw cashew nut processing in Africa would generate more than US$100 million in household income. As it is, a recent report noted that Tanzania’s farmers get rock-bottom prices, and the country imports its nuts back after processing to meet buoyant domestic demand.

- Africa also produces 70% of the global total of cocoa, with much of that from Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, the two largest producers globally. Yet these two countries only receive 5% to 6% of the revenue from an annual market estimated to be worth US$130bn annually.

Many efforts have been made to address such unequal relationships. Recently, the March 2018 Abidjan Declaration by the presidents of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana again seeks a common sustainable cocoa strategy that would increase the prices received by cocoa farmers. The subsequent Côte d’Ivoire-Ghana Cocoa Initiative (CIGCI) announced that from October 2020, the two countries would charge a fixed premium of US$400 a ton over the benchmark futures price plus a country premium linked to quality. The Living Income Differential (LID) initiative is intended to guarantee producers a minimum price in a market that some describe as a quasi-oligopoly with a small number of buyers and sellers who have to sell goods that cannot be easily stored.

These measures will only succeed with simultaneous better management and control of domestic production. This remains a challenge, and many countries across the continent need help to implement these measures and policies. The LID, for instance, while yielding short-term benefits, has since struggled in practice. A combination of the COVID-19 pandemic, corruption, opposition from significant purchasing companies, pressure from environmental lobbyists and the lack of regulation in the production sector all contributed to limited adherence to the LID. The sector faces additional pressures as Ecuador and Brazil emerge as non-African cocoa-production competitors.

Beyond commodity-specific efforts regarding cocoa and cashew nut production, there have also been many public and private initiatives on the continent to boost agriculture production and food security. Some of these include:

- The Comprehensive Africa Agricultural Development Programme (CAADP) led by the African Union encourages countries to invest 10% of national budgets in agriculture.

- The Green Revolution Programme involves public and private initiatives to produce and distribute improved seeds, fertilisers and pesticides.

- The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) can give access to a more extensive consumer base while promoting the trade of various agricultural inputs (e.g. access to better seedlings, fertiliser, modern technologies, farming knowledge and climate-smart practices). The AfCFTA will also aid in removing trade barriers and diversifying access to a larger agricultural market and is discussed and modelled in the AfCFTA theme.

Given the continent’s massive geographic extent and diverse topography and climate, agriculture potential and production differ vastly from region to region and country. Chart 2 presents the contribution from the agricultural sector for each African region and country from 1960 and includes a forecast for 2043.

- In 2019, the agricultural sector in West Africa was the largest at US$168 billion. The sector has seen astonishing growth over the past two decades, recording a 118% increase between 1999 and 2019. According to the Current Path forecast, it is expected to grow to US$207 billion by 2043 (a 23% increase).

- North Africa has also seen strong agricultural growth, growing by 80% between 1999 and 2019. The 2019 value of US$110 billion is Africa’s second most significant agricultural region. Growth is expected to be lower in the next two decades at US$127 billion by 2043.

- Agricultural growth in East Africa is expected to be minimal, with a forecasted 17% increase over the forecast horizon, representing an agricultural sector worth US$96 billion by 2043.

- At US$41 billion in 2019, the agricultural sector in Southern Africa is the second smallest on the continent; it is expected to grow by 22% to US$50 billion by 2043. Central Africa’s small agricultural sector has only recently (in the past decade) seen noticeable growth. Strong growth, at 32%, is forecasted between 2019 and 2043, with an expected agricultural sector worth US$41 billion by 2043.

The uninspiring improvement in agricultural productivity and high levels of inequality in Africa amidst rapid population growth contributes to the slow rate of poverty reduction. Evolving dietary preferences also contribute to food insecurity because African countries import more food yearly as Africans turn to non-African foodstuffs.

In 2019, 1 007 million metric tons of crops were produced in Africa — a significant increase from the 365 million metric tons produced in 1990. In the Current Path forecast, crop production will increase to 1 213 million metric tons by 2030 and an estimated 1 473 million metric tons by 2043. Agricultural crop demand is set to increase from 1 125 million metric tons in 2019 to about 1 537 million metric tons by 2030 and to 2 126 million metric tons by 2043. This illustrates a growing demand for foodstuff that will be unmet by local production, as shown in Chart 3.

In the Current Path forecast, Africa’s agricultural import bill will likely grow from US$114 billion in 2019 to US$510 billion in 2043. Food imports are forecast to increase from 174 million metric tons in 2019 to 754 million metric tons by 2043, leaving the continent extremely vulnerable to fluctuations in international food prices. Chart 3 allows the user to view and select total agriculture production and demand for any African country or group from 1970 with a forecast to 2043.

Generally, agricultural reform must start by unlocking access to credit, enabling farmers to advance towards higher productivity. That is only possible by making land a bankable asset, yet the potential for property rights to unlock capital remains unrealised, in part because the average smallholder farmer cultivates less than two hectares of land:

- An estimated 90% of rural land in Africa is not formally documented.

- Just 4% of African countries have mapped and titled the private land in their capital cities.

- Less than 20% of occupied land in sub-Saharan Africa is registered; the rest is undocumented, informally administered and, as a result, vulnerable to land grabbing and expropriation without adequate compensation.

- Up to 60% of national land in sub-Saharan Africa is held under customary or traditional forms of land ownership.

A myriad of factors affects whether land titles are useful, such as custom, other laws and the capacity of the state to enforce people’s legal property rights. Additionally, vested interests, such as traditional leaders and urban elites, obstruct reform.

With few exceptions, agriculture in Africa has low levels of technological advancement, seen in limited irrigation, low levels of mechanisation (as labour is cheap and farmers need more capital) and minor (or no) fertiliser use. All of these require access to credit. The continent also sees limited use of genetically modified seeds, which are more resilient to disease, slow progress in organic farming and little cultivation of indigenous crops better suited to the continent.

Credit requires secure and transferable land ownership, indicating the need to formalise, regulate and modernise land ownership. With clarity on ownership, farmers can access finance, transfer land or protect themselves against encroachment.

Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto noted that farmers inevitably need help to leverage their resources and assets to create wealth. Legally protected property rights are the key source of the developed world’s prosperity, he argued, and the lack thereof is the reason why many nations remain mired in poverty by the ‘tragedy of the commons’, where their unregistered assets can be stolen by powerful interests, hurting individuals and broader economic development.

It is, therefore, somewhat ironic that a comprehensive ‘land grab’ was recently evident across Africa, particularly in the Nile River Basin, which covers an area of 3.18 million km2 (from Uganda to Egypt). Companies from several developed nations have acquired fertile Nile-irrigated land for growing food crops, flowers, tobacco and biofuels, rearing livestock and logging trees. Most of these deals are agricultural leases and forest concessions, though the recent wars in South Sudan and Sudan have disrupted this trend. Although some industrial-type farms have brought positive benefits to local economies, in most cases, the local people suffer because governments prioritise foreign investment and export earnings above pursuing local livelihoods.

The World Bank has found ‘little evidence of a relationship between increased commercialisation and improved nutritional status.’ Low- and lower-middle-income African countries should prioritise food production for domestic consumption before pursuing cash crops for the export market, it argues.

To capitalise on the benefits of having an educated and healthy labour force, governments need an unwavering emphasis on achieving food security with an apparent effort to support the consumption of domestic crops suited to the local climatic conditions. Agriculture should be pursued with the primary purpose of ensuring national food security before opportunities for foreign exchange although the two are, of course, closely related.

Africa’s leadership is often responsible for land grabs at an even larger scale. Zimbabwe’s disastrous land redistribution programme (from 1992 to 2010), which eventually destroyed its most productive sector, illustrates the importance of security of ownership that can unlock land as a bankable asset and the implications of land expropriation without due process.

When Rhodesia declared itself a republic, a few years after independence in 1965, most of the black population had been relegated to so-called tribal trust lands, generally in the lowlands — areas significantly less productive and often disease-ridden.

After a violent struggle involving liberation forces operating from several neighbouring countries, Zimbabwe was born in 1979. The Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF), led by Robert Mugabe, subsequently won the first elections in 1980 and embarked upon a land reform programme that steadily became more chaotic and violent.

Between 1960 and 1990, Zimbabwe exported about 10% more food than it consumed and consistently outproduced China per capita. However, production per capita dropped rapidly in the early 1990s (Chart 4). Although agricultural output recovered later that decade, the country has never regained previous production levels.

In the early 2000s, Mugabe evicted more than 4 000 white commercial farmers from their land. Later his party embarked upon centralised ‘command agriculture’, which dealt a further blow to Zimbabwe’s agricultural sector. By 2010, yields per hectare in Zimbabwe were below the levels seen at the time of its Unilateral Declaration of Independence in 1965, although, due to the expansion of land under cultivation, total production was significantly higher.

Despite President Emmerson Mnangagwa initially appearing to embark on a different approach after deposing Mugabe in a military coup in November 2017, he soon reverted to the same policies that had brought disaster in the first place. By 2019, Zimbabwe imported nearly 22% of its total food demand. When Mnangagwa half-heartedly sought to reverse course in 2020, fewer than 300 white commercial farmers (mostly dairy farmers) were estimated to be left in the country. Much of the land violently acquired had, in the meanwhile, been handed to party officials. In 2000, 10% of Zimbabweans lived in extreme poverty. In 2020 that number had increased to 37% of the population living on less than US$1.90 daily. Ham-fisted efforts at land and agricultural reform in Zimbabwe have worsened the situation.

A different approach in Zimbabwe would have yielded very different outcomes. The World Bank finds that agricultural markets regularly fail African farmers, generally because ‘the pattern of market failures is general and structural, and not related to the head-of-household’s gender, or geographic characteristics such as distance to roads or large population centres.’ African farms are less productive because farmers are chronically unable to access the finances (or credit) that would allow them to purchase critical inputs that could improve yields, such as fertiliser and seed.

The first 20 years of China’s agricultural revolution, which improved productivity on smallholder farms through institutional incentivisation and access to better seeds and farming practices, hold many lessons for Africa.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Deng Xiaoping used the household responsibility approach to transform the domestic agricultural sector in China. The reforms contracted individual households instead of collectives to farm. This new responsibility and other market-related reforms improved productivity by 20% above collective era output.

The average yield nearly tripled between 1970 and 2013 and was a catalyst in the economic growth enjoyed by the country during those decades. The available calories per person increased by almost 70%, and there were fewer than 2 million malnourished children in 2015, compared to more than 22 million in 1987.

The African experience is that different families farm small patches of land, relying on unproductive, often traditional, practices. This is similar to the situation in China several decades ago. By working with the individual farmer and focusing on improved smallholder productivity, China transformed its agricultural sector and fed its rapidly growing population. Today, electronic land-use transfer systems contribute to continued productivity, with farmers able to lease their land to others, creating larger and potentially more productive farms.

Brazil also enjoyed rapid improvements in agricultural production in the decade between 2000 and 2010. Although the country has traditionally been a net food exporter, it has improved that position by nearly seven percentage points. Between 1980 and 2000, Brazil doubled average yields per hectare despite crop land decreasing by about 4 million hectares.

Brazil’s agricultural sector has grown in absolute terms and diversified but, like China, only achieved that progress once it had graduated to an upper middle-income status. Today, Brazil is the world’s largest exporter of sugar and coffee, second only to the United States in soybean exports and third to the United States and Argentina in maize exports. The genetic tailoring of seeds and plants had an essential role in these changes.

Brazil is now at a stage in development where it is moving beyond agricultural production for food security. The country exported approximately 12% more food than it consumed in 2018. It has begun to embrace a ‘forest, agriculture and livestock integration’ approach to farming that is widely acknowledged to benefit both agricultural production and environmental sustainability. But it is achieving many of these goals at the much greater cost of environmental degradation, as farmland steadily encroaches on the vast Amazon forests that serve as a significant global carbon sink.

In Africa, Egypt also managed to double yields between 1970 and 2000. A series of targeted strategies and policies, including large-scale land reclamation projects, expansion of the Nile irrigation system, the introduction of high-yield crop varieties, improved fertiliser use, the uptake of modern farming technologies and increased investment in agricultural research, contributed to the growth and improved yields. Chart 5 compares yields per hectare for China and Brazil and Africa’s top three crop producers, Nigeria, South Africa and Egypt.

Chart 3 forecasts Africa's steady increase in total agriculture production to 2043. However, because of its rapid population growth, agricultural production per capita will slowly decline by 2043. This is in contrast to China’s yields, which continue to rise while South America sustains higher production after an impressive decade-long sprint to improve productivity. Africa is condemned to food insecurity and expensive agricultural imports without an agricultural revolution.

Agricultural technologies (AgTech) can help farmers overcome market barriers and enhance agricultural productivity and sustainability. AgTech can improve access to financial services, inputs (such as seeds, fertilisers, and agrochemicals), markets, and information, as well as give access to shared assets such as tractors. It can reduce input costs associated with herbicides, pesticides and fertilisers through greater application precision and smart sensors. In its 2019 report on the state of climatic conditions in Africa, for example, the World Meteorological Association notes that solar-powered micro-irrigation has the potential not only to offset carbon emissions but also to increase farm-level incomes five to ten times, improve yields by up to 300% and reduce water usage by up to 90%.

The last decade has seen many innovations in agricultural technologies. The proliferation of mobile phones and the growing availability of connectivity can allow companies to offer credit to unbanked smallholder farmers and insurance to safeguard their livelihoods. It can provide these farmers with direct market access, information about weather events, advice, crop monitoring, and access to shared assets through equipment rentals for tractors and other mechanised farming equipment. African farmers have fewer than two tractors per thousand hectares of cropland, compared to an average of ten tractors in South Asia and South America. The mobile platform Hello Tractor connects tractor owners and operators with farmers needing tractor services to make tractor ownership more profitable and tractor use more affordable.

Real-time data can allow farmers to adapt farming practices to changing weather conditions while monitoring soils can help farmers make informed decisions about irrigation and fertiliser use. The global phosphate and fertiliser giant OCP, majority owned by the Moroccan state, has partnered with Microsoft to leverage artificial intelligence for its African digital agriculture platform. The partnership uses OCP's data on soil mapping, soil samples, and demonstration trails to customise fertiliser solutions and provide farmers with decision-informing data. Similarly, the US company Atmo employs artificial intelligence in weather forecasting. It has partnered with COMESA to offer governments meteorology and supercomputing technologies to help make informed decisions based on accurate weather prediction. That, in turn, enhances country-level crop insurance, optimises input allocation, and bolsters preparedness for natural disasters. In Kenya, FarmDrive uses machine learning and various data sources to unlock access to credit for smallholder farmers. Once the exact location of the smallholder farm is confirmed, often concerning a known point such as the location of a nearby primary school, the system accesses geospatial information to determine soil quality, weather conditions and market accessibility. Then, it uses an algorithm to determine a credit score. The associated decision-making tool enables financial institutions to develop small-scale agriculture loan products.

In Ghana, Kenya and Uganda, over 20 000 farmers have access to affordable insurance contracts (such as against crop failure or the loss of expensive breeding stock) via their smartphones, using blockchain technology. The system uses high-resolution satellite images to detect rainfall and plant growth data. It advises what, when and where to plant and directs farmers to suitable packaging and distribution centres.[4In most of rural Africa, the precise location of a farm is objectively unknown so the location is determined via a series of SMS questions (e.g. time to walk to different primary schools). The more schools a farmer is familiar with in their area, the easier it is to hone in on their specific location.]

Applications such as DigiFarm in Kenya help farmers access low-cost seed and fertiliser, loans, insurance and bulk purchases.

In Ghana, a voice service and SMS platform, Farmerline, has helped about a million farmers with advice on market prices, financial tips and weather forecasts.

Over the last decade, the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) has invested hundreds of millions of dollars in improved seeds. It has doubled maise yields in the 18 countries where it works (although detractors oppose these Green Revolution programmes and call them efforts to promote industrial agriculture).

These examples reflect some of the many emerging African solutions that can help the continent’s estimated 50 million smallholder farmers change a traditional farming mindset to one focused on practising agriculture as a business. However, a lack of access to electricity in rural areas and low Internet penetration are significant obstacles to applying modern technology in agriculture (see the theme on Leapfrogging).

Improving soil fertility is another critical aspect of improved agricultural production. The use of organic or human-made fertilisers has significantly boosted yields. Usage in Africa is generally lower than elsewhere in the world despite the soil being poorer than in most other continents. Sub-Saharan Africa has shallow fertiliser use of 22 kg per hectare, whereas the world average is 146 kg per hectare. Countries such as China are closer to 400 kilograms per hectare.

With the limited use of fertiliser, soil fertility depletion generally continues unabated. The challenge is that the manufacturing and application of fertilisers (generally in the form of ammonia as a nitrogen supplement) have a heavy carbon emissions toll. Africa produces approximately 30 million metric tons of fertiliser annually, twice as much as it consumes. Yet approximately 90% of fertiliser consumed in sub-Saharan Africa is imported, primarily from outside the continent and at enormous cost. The low domestic fertiliser use in Africa is due to prices being far higher than elsewhere. Although the delivery cost at the port is similar to that for other importing countries, the cost of distribution in Africa is higher, reflecting the continent’s poor transport infrastructure, the lack of competition and inappropriate regulations.

Despite a strong lobby against more intensive fertiliser use, various efforts are underway to increase the production, access, affordability and appropriate use of fertilisers on the continent.

- The Africa Fertilizer Financing Mechanisms (AFFM) supports improving smallholders' access to fertiliser. The African Development Bank reports that by the end of 2022, 97 small and medium enterprises gained access to finance, 138 fertiliser suppliers and just shy of 21 000 smallholder farmers benefited from capacity-building through the AFFM.

- The Indorama Eleme public-private fertiliser plant, completed in 2016, advertises itself as the largest single-line fertiliser plant in the world and was built to turn Nigeria from a large fertiliser importer to a self-sufficient producer and eventually a net exporter. In 2017, Nigeria exported 700 000 metric tons of urea fertiliser. The plant produces 1.5 million metric tons annually, of which 40% are used in the Nigerian farming sector.

- Morocco’s OCP Group, which holds 75% of the world’s phosphate reserves (an essential ingredient for phosphate-based fertilisers), signed an agreement in 2021 that will see the actualisation of a US$1.5 billion plant with an estimated operational starting date in 2025.

-

At the African Union (AU) Fertilizer & Soil Health Summit in Nairobi on 7-9 May 2024, African leaders unveiled the new 10-year Fertilizer and Soil Health Action Plan 2023-2033. Designed to maintain soil fertility and ensure soil health across the continent, the roadmap adopts an approach that combines both chemical and organic fertilisers with improved seeds and agrochemicals. The plan aims to 'significantly increase investments in the local manufacturing and distribution of mineral and organic fertilisers, bio fertilisers and biostimulants' and 'triple fertiliser use from 18 kg/ha in 2020 nutrients to 54 kg/ha in 2033'.

This section models an Agriculture scenario that emulates the impact of an agricultural revolution on the continent. The scenario is built on eight interventions within the IFs forecasting platform to address the pressing issues of low productivity, high climate vulnerability, high agricultural losses, weak access to agricultural markets and high malnutrition rates. Each intervention initialises from individual country data, and the improvements are benchmarked to ambitious rates of progress in countries at similar levels of development. Addressing the challenges outlined in the previous section will boost farmers’ income, helping to stimulate public demand for goods and services in rural areas, which will establish new enterprises and contribute to the broader process of structural economic transformation and diversification. Collectively the interventions promise improvements in food security and income growth for Africa and its large subsistence farming population.

The underlying logic to the interventions and their key outcomes and eventual impacts is summarised in Chart 6 below.

The first IFs intervention is on improving crop yields. Most African countries can improve yield outputs by improving inputs. This intervention assumes that governments prioritise agricultural productivity improvements through:

- Adopting modern farming techniques: Precision and mechanised farming equipment, satellite monitoring, early warning systems, sensors, access to information and crop rotation are all potent ways of improving productivity and efficiency.

- Improving the use of and access to improved seedlings: Farmers, particularly subsistence farmers, require access to drought-tolerant, disease-resistant, high-yielding seeds.

- Improving tenure security and transferability: Many African countries have recently started overhauling communal land rights, creating a middle ground between individual freehold and the customary colonial model. The result is progress on land administration at a reasonable cost. It is being pursued in countries as diverse as Ethiopia, Rwanda, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Benin, Burkina Faso and Tanzania.

- Increasing fertiliser use: Fertilisers are critical to improving soil fertility, an essential component of boosting yields. While this has improved in many African countries, limited access to and sporadic use and low uptake of fertilisers are still noticeable in most.

In the Agriculture scenario, Africa’s average crop yields improve to 7 tons per hectare by 2043, representing a 37% improvement compared to the Current Path forecast of 5.1 tons per hectare. The intervention brings yields per hectare closer to South Asia’s 7.7 tons per hectare by 2043 but is still to be less than half that of South America’s 16.7 tons. The improvements are particularly potent for Central and East Africa, where yields will increase by 41% above the Current Path forecast by 2043. Yields will improve by 40% and 35% compared to the Current Path forecast for Central and Southern Africa. Even with modest interventions in North Africa, yields can increase by 14% above the Current Path by 2043, indicating the importance of improving agricultural inputs.

Access to irrigation was one of the three key components that underpin Asia’s green revolution. However, most African countries’ stock of land currently under irrigation is meagre, with about 5% of cropland under irrigation, compared to the global average of 21%. Most of the cropland in sub-Saharan countries is rain-fed, dependent on predictable seasonal rainfall, which is increasingly becoming irregular due to climate change and desertification. This intervention is a critical adaptation response to climate change. Irrigation allows farmers to grow crops year-round, diversifying production and increasing crop yields, but is costly and not applied in countries with more predictable and consistent rainfall that experiences fewer meteorological droughts. These include the lower band countries of West Africa and western equator countries such as Nigeria, Benin, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Central African Republic and Congo, where ample water makes rain-fed agriculture still viable. However, this is a critical adaptation measure in Southern Africa, the Sahel and the Horn of Africa.

In 2019, Africa had roughly 14.2 million hectares of land under irrigation. In the Current Path forecast, the amount of irrigated land decreases such that by 2043 only 13.8 million hectares are under irrigation. In the Agriculture scenario, irrigated land will increase by 3.6 million hectares to 17.4 million hectares by 2043 — a 26% increase above the Current Path. The intervention has the following impact on Africa’s various regions:

- Central Africa sees an increase of 159% compared to the Current Path forecast by 2043, but equivalent to only 145 000 hectares. Central Africa remains the region with the lowest irrigation use due to rain-fed agriculture remaining a viable option given higher annual rainfall levels and a tropical climate.

- East Africa sees a 34% increase compared to the Current Path forecast, pushing irrigated land to 5 million hectares by 2043.

- In Southern Africa, irrigated land is pushed up to 3.6 million hectares by 2043 — a 71% increase from the Current Path forecast in the same year.

- West Africa sees a 49% increase compared to the Current Path forecast in 2043, but this comes off a low base and the intervention only adds 471 000 hectares of irrigated land, pushing irrigated land to 1.4 million hectares in 2043. The majority will be in the northern belt of West Africa, where the semi-arid climate and frequent droughts necessitate irrigation.

- North Africa is already well developed in terms of irrigated land. Currently, it boasts around 7.1 million hectares of irrigated land and the scenario sees an increase of only 3.3% for this region.

Increasing agriculture production inevitably increases the water demand, particularly for irrigation but expanding irrigation in many countries is made difficult by limited access to water resources. Excluding South Africa, Africa also has the world’s lowest water storage capacity: 43 m3 per person compared to 6 150 m3 per person in North America. (South Africa’s storage capacity is 750 m3 per person.) As a result, much of the continent has little ability to control water flow and conserve it during periods of abundance for use during periods of scarcity. Dryland conditions, variable rainfall and non-perennial rivers necessitate access to sustainable water resources such as groundwater. High rainfall bands (in lower West Africa and western equator countries) with fewer meteorological droughts can utilise either rainwater harvests or surface water sources. The intervention increases the total water supply in Africa by 14% compared to the Current Path forecast in 2043 (309 instead of 267 cubic kilometers). Higher interventions are applied in countries with dryland conditions (in steppe and desert climates) and savanna areas faced with repeated and severe rainfall variability and meteorological droughts. Groundwater extraction should, however, be carefully managed to ensure the sustainability of resources, but it remains an underutilised water resource across much of sub-Saharan Africa.

Many subsistence farming practices in rural areas across Africa significantly strain land resources, and increased land degradation and deforestation threaten agricultural productivity and sustainability. Historically, increased agriculture production in Africa came from expanding land use. Estimates suggest that Africa has 480 to 840 million hectares of untapped agricultural land. However, much of this land is heavily forested or currently unreachable, implying the need to balance land use with afforestation. The IFs Current Path forecast already includes an expansion of crop land from 279.7 million hectares in 2023 to 298.8 million hectares in 2043. The intervention emulates a reduction in the deforestation rate through environmental conservation and protection, reflecting the protection of forests in critical areas. Reforestation is applied in a select few countries to restore ecosystem services. The result reduces the rapid deforestation rate currently observed on the continent and slows it down such that by 2036 deforestation is stopped and forest land is slowly reintroduced, restoring forest land by 2043 to levels observed in 2029. This scenario therefore assumes an ecosystem-based approach that focuses on sustainable land management practices and ecosystem restoration and protection by increasing forest protection to protect rural communities against floods, soil erosion and other negative impacts of climate change.

In the Agriculture scenario (Chart 7):

- Forest land is forecast to decrease from 644 million hectares in 2019 to 592 million hectares by 2043 in the Current Path forecast. The Agriculture scenario limits this decline to 622 million hectares by 2043, saving 30 million hectares of forest land. While much more aggressive interventions are needed on the continent, it would come at the cost of agricultural land expansion and food security.

- The protection of forests reduces the availability of cropland. In the Current Path forecast, cropland expands from 279 million hectares in 2019 to 312 million in 2043. However, in the Agriculture scenario, cropland only expands to 300 million hectares in 2043 — a difference of 12 million hectares.

- The same holds for grazing land: in the Agriculture scenario, it equates to 903 million hectares in 2043, whereas in the Current Path forecast, it will be 920 million hectares by 2043.

- The intervention has the biggest impact in Central Africa, adding 2.3 million hectares of forest to this critical ecosystem between 2019 and 2043.

Reduced post-harvest losses will increase food availability. Whereas the average loss and waste of agricultural produce in the rest of the world is roughly 14%, it is at 24% in Africa and up to 30% in West Africa. Unlike in Europe and North America, where most food reaches the consumer and is discarded or wasted, almost a third of the food loss in Africa happens in the production stage. Modern technology can play a big role here as, according to FAO, one-third of the world’s food — approximately 1.3 billion tons and worth US$1.2 trillion a year — is wasted. Technology can help track inventory and reduce food waste along the distribution chain. One African example is InspiraFarms, which produces affordable, energy-efficient cold storage and processing equipment for on- or off-grid use. Reduced post-production losses and increased yields can increase food availability for local consumption and export (or at least reduce import dependency).

In the Current Path forecast, agricultural loss and waste (as a share of production) will increase from 24.3% in 2019 to 26.3% by 2043, more than 8% above South Asia and double that of South America. In the Agriculture scenario, food loss and waste fall quickly to 19.4% by 2033, followed by a slight upward trend towards 2043.

Farmers need to sell their products to obtain an income, making access to markets essential. Given the large rural population in Africa, investing in rural access roads will promote positive economic impacts such as improved rural incomes, better agricultural productivity and increased economic participation. Improved rural mobility and connectivity will promote positive social impacts such as reducing poverty, addressing the exceptionally high maternal mortality rate and improving paediatric health through easier access to healthcare facilities.

Africa has less than half the kilometres of roads per capita compared to the world's average. Likewise, the percentage of the African rural population with access to an all-weather road was 56% in 2019, compared to a world average of 77%. The Agriculture scenario pushes the percentage of rural accessibility up to 69% compared to the Current Path forecast at 62%. The scenario’s impact is largest in Central Africa, where accessibility increases from 47% in the Current Path forecast to 57% in 2043 (a 23% increase).

Calories per capita is used in the Agriculture scenario as a proxy to ensure that the additional agriculture produce that flows from the various interventions in the scenario is not all exported but that some are domestically consumed, thus reducing the food import bill and improving food security. The vast majority of African countries have more than 2 000 calories per person per day, as recommended by the World Health Organisation. Africa has therefore made good progress, although the positive national numbers obscure very large sub-national and local differences in per capita calory access. In 2019 it was only low-income Somalia, Burundi, Madagascar, Central African Republic and the DR Congo that had less than 2 000 calories per person per day, although all are forecast to progress above the minimum within the next decade on the Current Path forecast.

To emulate an increase in domestic food security before prioritising exports, the intervention increases average calories per person per day by 4.4% in 2043 compared to the Current Path forecast. Africa climbs to 2936 calories per capita per day, compared to a world average (that excludes Africa) at 3272 in 2043. The intervention has the biggest impact in Central Africa, improving calories available by 9% compared to the Current Path forecast by 2043. North Africa continues to outperform the region throughout the forecast horizon, although the intervention only increases calorie availability by 2.2%.

The impact of the Agriculture scenario is impressive, with Africa’s agriculture production volumes more than doubling in the next two decades. With the interventions in the Agriculture scenario, Africa can produce around 2 167 million metric tons of agricultural produce in 2043, surpassing South Asia’s production in 2038 and edging closer to South America’s production of 2273 million metric tons. By 2043, Africa will produce 486 million metric tons of additional food (crops, meat and fish) in the Agricultural scenario, compared to the Current Path forecast for 2043.

With increased domestic food production in the Agriculture scenario, Africa’s agricultural import bill can be reduced by US$212 billion in 2043 compared to the Current Path forecast. Likewise, the continent’s export earnings from agriculture can increase from US$48.4 billion in the Current Path forecast to US$276 billion in 2043, while still prioritising domestic consumption.

The increase in available food energy (calories) in the Agriculture scenario reduces the number of children suffering from malnourishment by more than 1.7 million in 2043 compared to the Current Path forecast. The scenario also reduces infant mortality by nearly a million children deaths per 1 000 live births in 2043.

Despite these gains, Chart 8 presents Africa’s growing food import dependence over time, a trend driven by a rapidly growing population. In 2019, the continent imported 10.2% of its agriculture demand, including staple foods such as rice and maize, which are cheaper to procure internationally than domestically. In the Current Path forecast, net agriculture import dependence will reach an alarming 30.4% of demand by 2043, whereas the Agriculture scenario can reduce the continent’s food import dependence to 10.6%.

The averages conceal huge differences between countries and regions (Chart 9). Countries that achieve the most spectacular increases in production volumes (Nigeria, Ethiopia, the DR Congo, Cote D’Ivoire, Tanzania, South Africa and Kenya) are well known for their agricultural potential. In contrast, arid and small island states (many of which have reached saturation levels) gain the least. With its rich and fertile soils, Nigeria could increase from the 2043 Current Path volumes of 311 million metric tons of agricultural products to 438 million in 2043 if the associated reforms are implemented. This will cement Nigeria’s position as Africa’s most significant agricultural producer.

Egypt, one of the continent’s most agriculturally productive countries, is already close to its full agricultural potential and, thus, the Agriculture scenario only increases total production by 5 million metric tons above the Current Path forecast, becoming Africa’s fourth largest agricultural producer in 2043. The Agriculture scenario bodes well for Ethiopia, the DR Congo, Cote D’Ivoire, and Tanzania, with respective gains of 48 million, 45 million and 23 million metric tons above the Current Path forecast in 2043. Although coming off a low base, the Agriculture scenario also benefits countries such as Madagascar, Gabon and Mozambique, which can expect significant increases of 46%, 45% and 42% above the Current Path forecast in 2043.

The Agriculture scenario has significant developmental and economic impacts on Africa, as shown in Chart 10:

- Levels of poverty (using US$1.90 as a benchmark) in the Agriculture scenario are expected to decline from 34% in 2019 to 27% by 2030. While this is more promising than the Current Path forecast at 28%, both fall significantly short of the SDG target of eliminating extreme poverty by 2030. By 2043, the Agriculture scenario is expected to reduce the number of extremely poor Africans to 339 million (15%) instead of 398 million people (18%) in the Current Path forecast.

- Africa’s low- and lower-middle-income, agriculture-dependent countries will benefit most from poverty alleviation in this scenario.

- Malawi, Madagascar and Sierra Leone will see an additional 10, 9 and 8 percentage point reduction in poverty rates compared to the Current Path forecast in 2043.

- Mali, São Tomé and Príncipe, Central African Republic and the DR Congo Príncipe will all see more than a five percentage point additional reduction in poverty rates.

- In absolute numbers, it will be Nigeria, the DR Congo, Madagascar, Tanzania, Malawi and Ethiopia that will benefit most from poverty reduction in the Agriculture

By 2043, Africa’s total economy, under the Agriculture scenario, will be US$354 billion larger (using MER) than in the Current Path forecast. The Agriculture scenario will increase the average GDP per person (in PPP) in Africa by US$ 204 in 2043 — a 3% improvement on the Current Path figure forecast for that year. Agriculture tends to be particularly effective in boosting GDP growth in the short term. In Africa, low- and middle-income countries also gain the most in GDP per capita income from the Agriculture scenario. Regional breakdowns suggest that by 2043:

- Because of a well-established agricultural sector, North Africa will benefit least from improving its GDP per capita through the Agriculture scenario. The region’s per capita income will increase by 1.2% compared to the Current Path forecast, representing an increase of US$179 in GDP per person.

- Proportionally, West Africa will benefit most at a 5% increase above the Current Path (equivalent to US$292

- East Africa will likely expect a 3.9% increase above the Current Path forecast.

- Southern Africa has a well-established agriculture sector and can expect an additional 2.6% increase in income levels above the Current Path forecast.

- Income in Central Africa will be US$97 per capita more in 2043 than in the Current Path forecast, representing a 4.3% increase.

The contribution of agriculture to the economy generally declines as countries graduate from low- to middle- and eventually to high-income status. For example, in Africa’s 23 low-income countries, the agricultural sector contributed about 25% to GDP in 2019 — about 16% in the 23 lower-middle-income countries and less than 3% in the upper-middle-income countries. By 2043, according to Africa’s Current Path forecast, these portions will likely have declined to 7.4%, 7% and 1.6% for low-, lower-middle- and upper-middle-income Africa, respectively, showing a slowly changing economic structure. In the Agriculture scenario, these numbers would be 9.6%, 9% and 2%, respectively.

Chart 11 shows the impact of the Agriculture scenario on the average size of the agricultural sector (as a percentage of GDP) for the two most affected income groups. These two groups comprise 46 of Africa’s 54 member states, including in our modelling. For low-income Africa, the interventions will raise the agricultural sector's contribution to GDP to 9.6% instead of the Current Path’s 7.4%. For lower-middle-income countries, the agricultural sector's contribution to GDP will likely be 9% instead of the Current Path’s 7%.

A different expression of the same metric is that in the Agriculture scenario, the sector would contribute 8.8% of the economy of the DR Congo by 2043 (down from 29% in 2019), compared to an even more rapid decline to 6.3% in the Current Path forecast. In addition, the economy of the DR Congo will be more significant in 2043 in the Agriculture scenario, with the agricultural sector contributing an additional US$7.97 billion above the Current Path forecast.

In 2019, the agricultural sector was the largest, as a percentage of GDP, in East Africa (22%) compared to only 4.9% in Southern Africa. Chart 12 shows the increase in the size of the agricultural sector in the Agriculture scenario relative to the Current Path forecast for each region and country by 2043. The regional differences are:

- US$17.6 billion in Southern Africa

- US$14.7 billion in Central Africa

- US$21 billion in North Africa

- US$35.6 billion in East Africa

- US$80 billion in West Africa

However, these improvements are not a given, as they would depend on factors such as the amount of water available for irrigation, the effect of carbon fertilisation due to climate change on crop growth, as well as the impact of new cultivars and genetically modified plants that are more temperature tolerant.

More than half of Africa’s labour force is engaged in the agricultural sector. The Agriculture scenario accelerates the rate at which employment in the sector declines even as productivity improves and total output increases. However, jobs will be created downstream in the much larger agro-processing sector, ensuring increased food security. Productivity improvements could come from upgrading value-chain activities such as logistics, input services, storage and other off-farm activities — all of which will require improved connectivity and basic infrastructure.[5Some of these constraints can be overcome through technology, such as the use of precision irrigation and application of precise amounts of fertiliser exactly where they are required. Then there is also the potential of vertical farming, which could produce 180 million tons of food globally, according to some analysts.] As Africa moves up the agricultural value chain, growth in the sector will expand employment opportunities in downstream agro-processing, with much of that in urban centres.

Europe is often blamed for Africa’s lack of access to its agricultural market. Yet, African leaders fail to recognise the need to focus comprehensively on the production of staple foodstuffs for domestic consumption, advancing regional rather than international trade in agriculture, investing in agriculture research, advancing rural property rights, in schooling for agriculture and generally focusing attention on rural poverty rather than on urban elites. If African countries prioritise growing staple foods while actively encouraging intensive smallholder farming and sustainable practices, they could increase rural incomes, reduce poverty and eventually open up the potential of agribusiness and large-scale exports that earn foreign exchange. The much-needed Agriculture scenario modelled here will reduce Africa’s agricultural import dependence, improve food security and contribute to growth.

Raising agricultural productivity serves as a foundation for broader sustained economic development. Eventually, agriculture ‘is central to securing foreign exchange earnings that can allow for the expansion of imports, thereby fuelling investment and growth.’

There is much that Africa can do to improve agriculture, even as it inevitably declines as a share of national economies. To this end, the AGRA calls for a holistic land management strategy that includes raising the organic matter, moisture retention and other forms of soil rehabilitation, and using inorganic fertilisers. In South Africa, for example, primary agriculture contributes very little to GDP. However, it provides food security on the back of a highly productive private agricultural sector and significant agro-processing industry. As a result, the country had a secure food supply system when it went into a six-month lockdown in March 2020 to curb the spread of COVID-19, while many other countries on the continent suffered.

Modern technology in the form or AgTech can play an important role in this regard and offer cost-effective means for private sector companies to reach smallholder farmers by offering nontraditional credit-assessment methods to purchase seeds and fertilisers as well as insurance to safeguard their livelihoods. Currently, less than 4% of total commercial-bank lending goes into the agricultural sector, with financial institutions often citing the lack of collateral, high transaction costs, lag between investment and return on revenue, poor infrastructure, and high risk as a result of variable rainfall and price spikes. Investing in irrigation and dams is just one of many additional requirements while insurance penetration in African farming is also very low and the share of spending by sub-Saharan African countries on agricultural research development close to zero. Digital platforms can connect farmers directly with vendors seeking products, offer last-mile distribution while offering vendors loans to pay for products over time. Since most agriculture in Africa is rainfed, timely and precise weather forecasts increases the efficient use of inputs and reduces the vulnerability of climate change-related risks while mobile platforms can allow farmers to share tractors and other productivity-enhancing mechanisation.

The impact of climate change on African agricultural yields is a significant uncertainty. A recent long-term forecast on the future of five Sahel countries (Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, Chad and Mauritania) highlighted the impact climate change has already had and will continue to have in this region. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change soberly notes that the Sahel, where agriculture accounts for more than 75% of total employment, has ‘experienced the most substantial and sustained decline in rainfall recorded anywhere in the world within the period of instrumental measurements.’

The climate change/energy theme examines climate change's impact on Africa’s future. It varies across the continent, given changes in temperature and rainfall and the increased variability of weather with many more extreme events such as floods, wildfires and droughts. The IFs forecasting platform includes some of these effects in its agriculture yield forecast but may underestimate the impact vastly. Significant uncertainties exist, particularly the potential for technology to increase agricultural production — not through the traditional route of expanding land under cultivation, but through more precise and sustainable farming methods. Eventually, solar-powered cold storage, accurate weather forecasts, monitoring of soil conditions and access to market information can all have an important role, as could greater efficiencies to reduce food waste. However, this will require current practices to change.

Without food security, developing countries cannot escape from hunger, poverty and the variances of nature. With food security, meaningful advancement is possible, if not impossible, to sustain. It is increasingly evident that the effects of climate change are likely to hold significant negative consequences for agriculture in much of Africa.

Africa’s economy has not been able to benefit from the agricultural sector. However, the continent has enormous potential, and it is agriculture upon which the most significant portion of Africans depend for survival. Subsistence and smallholder agriculture, which primarily cater for household consumption, need to be targeted and receive coordinated support from governments. This is quite different from the private-sector growth model of medium- and large-scale commercial farming, although that, too, has its place. Clumsy interventions by African governments to set minimum prices for commodities such as cocoa, coffee and cashew nuts without considering the broader impact often have unintended consequences. For example, it could encourage an increase in production by many more poor farmers, causing the commodity's price to fall. The result is that more poor people will be trapped in subsistence farming, unable to escape. Low- and lower-middle-income African countries should emphasise food self-sufficiency first and then focus on the massive export potential of agricultural products.

Despite some progress, World Bank President Robert McNamara’s prognosis in 1973 that a long-term solution to the food problem would not be possible without rapid progress in smallholder agriculture remains valid today in much of Africa.

For a successful agricultural transition, it is imperative to focus on growing indigenous crops, such as cassava, cowpea, soybeans and yam, on using indigenous practices and ensuring that these practices are sustainable and preserving ecosystems. Once that is achieved, steady progress up the agro-processing value chain will unlock improvements rather than efforts to enter the global food export market without sufficient domestic reform.