6 Education

6 Education

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

In this entry, we describe the context of education in Africa and how improving both the level and quality of education can impact the continent’s development trajectory. We then present an Education scenario that targets every level of the formal education flow and shows the potential of education as a development accelerator.

Summary

-

- Better education is fundamental to economic development. Investments in education increase the talent in the labour pool, raise productivity and boost economic growth and incomes.

- However, improvements in education in Africa are progressing slower than elsewhere in the world both in terms of its level and quality. Africa’s educational funnel is leaking. Despite fairly high enrolment figures at the primary level, few students complete the full educational journey to graduate from upper secondary school to enter tertiary education or vocational training with confidence.

- Students in sub-Saharan Africa consistently perform more poorly than the rest of the world, with little foreseeable improvement. The quality of education in the public schooling system is hampered by children being unprepared for learning because of poverty and malnutrition, teachers’ lack of skills, limited resources and facilities, and poor management.

- In sub-Saharan Africa, gender parity in education has improved over time but still trails the world’s average and regions such as North Africa and South America.

- The COVID-19 pandemic had a devastating impact on education in Africa. The restrictions and protocols associated with the pandemic caused many schools to shut down and learning was temporarily suspended, thereby worsening education outcomes.

- The Education scenario modelled here targets every level of the formal education flow from primary education enrolment to tertiary graduation.

- The Education scenario has a transformative impact on African economies and societies. As the level and quality of education improve, Africa’s economies start to grow, translating into increased GDP per capita and declining poverty levels. An improvement in education also leads to improvement in key health outcomes such as infant mortality, life expectancy and fertility rates.

- However, improving education outcomes will require concerted effort, new ways of thinking, rapid uptake of technology and committed governance.

All charts for Theme 6

- Chart 1: Progress through the education funnel in sub-Saharan Africa compared with other regions (gross percentages), 2019

- Chart 2: Definitions/terminology in education

- Chart 3: Current Path forecast of mean years of education among 15–25-year-olds, 2019 and 2043

- Chart 4: Current Path forecast of mean years of education among adults 25 years and older, 2019 and 2043

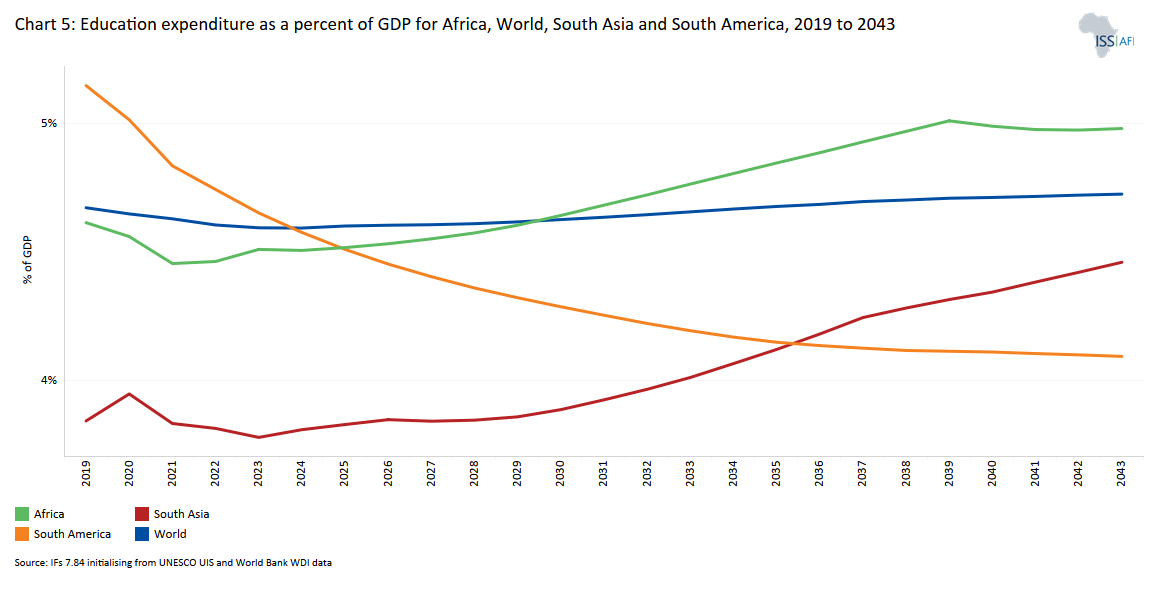

- Chart 5: Education expenditure as a per cent of GDP for Africa, World, South Asia and South America, 2019–2043

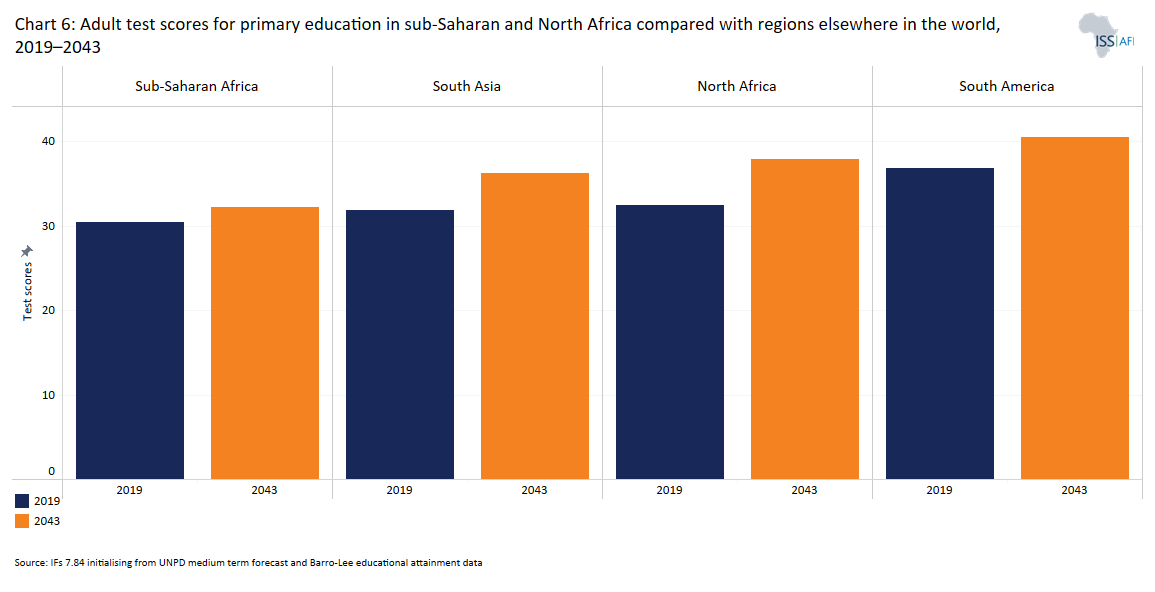

- Chart 6: Adult test scores for primary education in sub-Saharan and North Africa compared with regions elsewhere in the world, 2019–2043

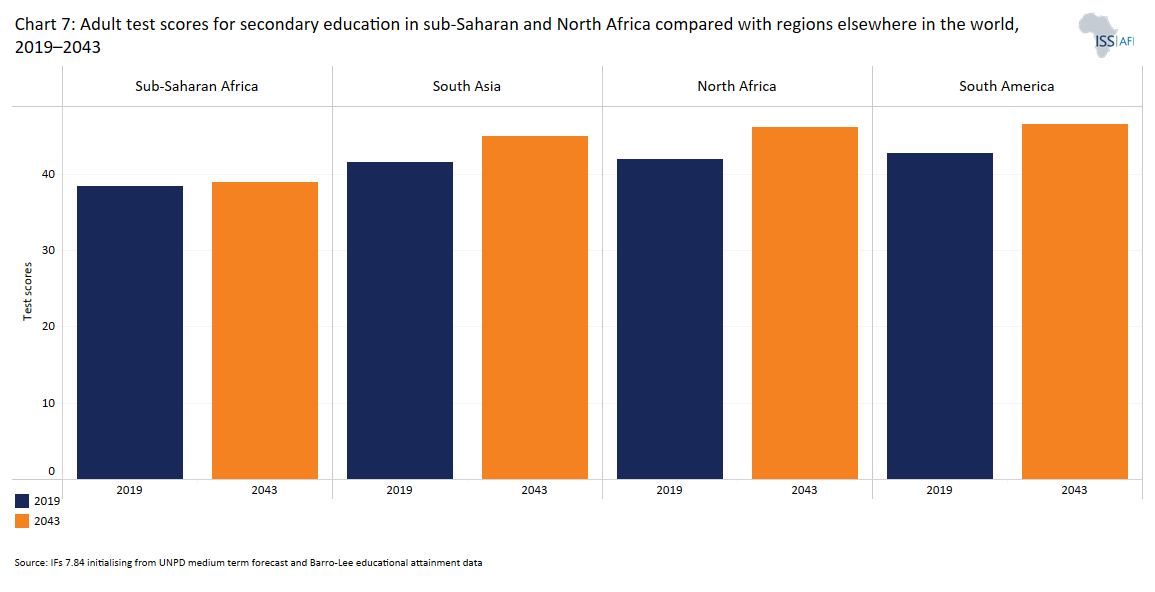

- Chart 7: Adult test scores for secondary education in sub-Saharan and North Africa compared with regions elsewhere in the world, 2019–2043

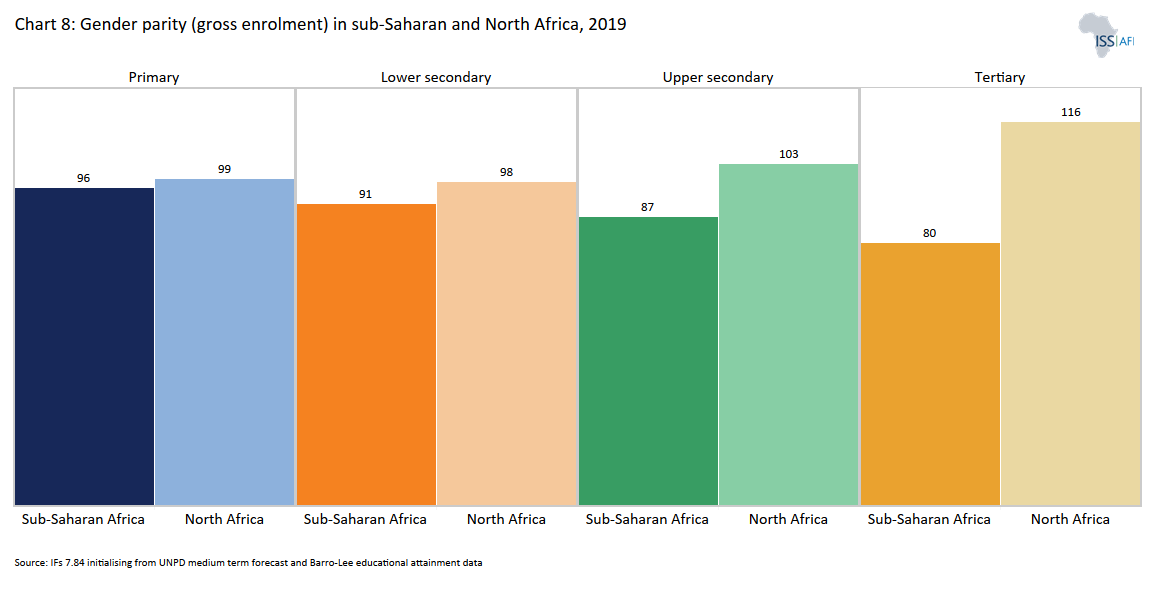

- Chart 8: Gender parity (gross enrolment) in sub-Saharan and North Africa, 2019

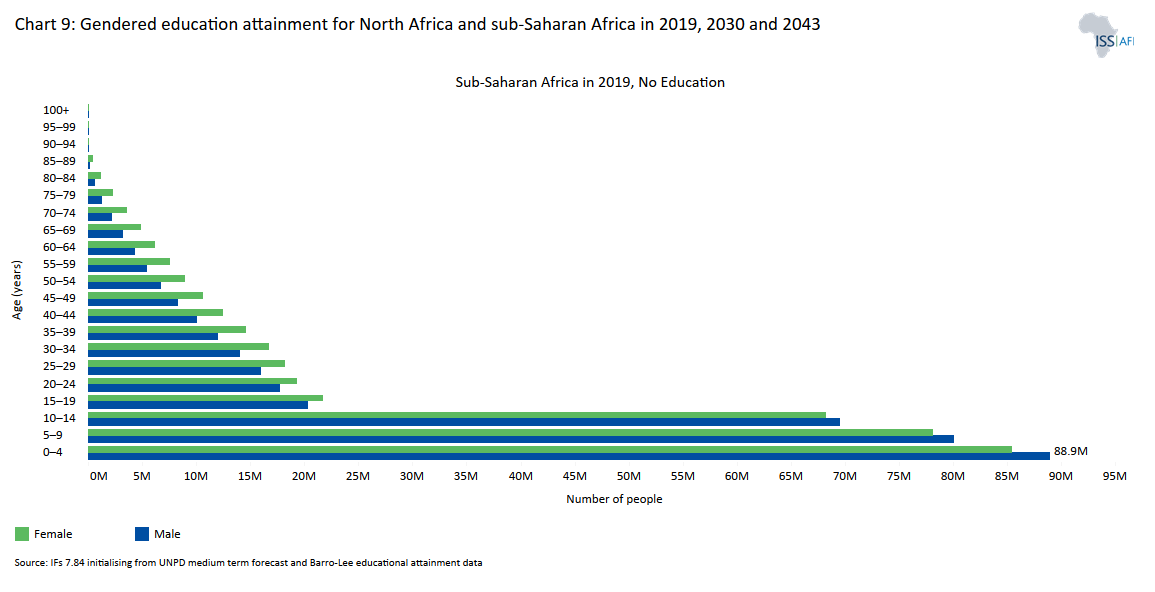

- Chart 9: Gendered education attainment for North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa in 2019, 2030 and 2043

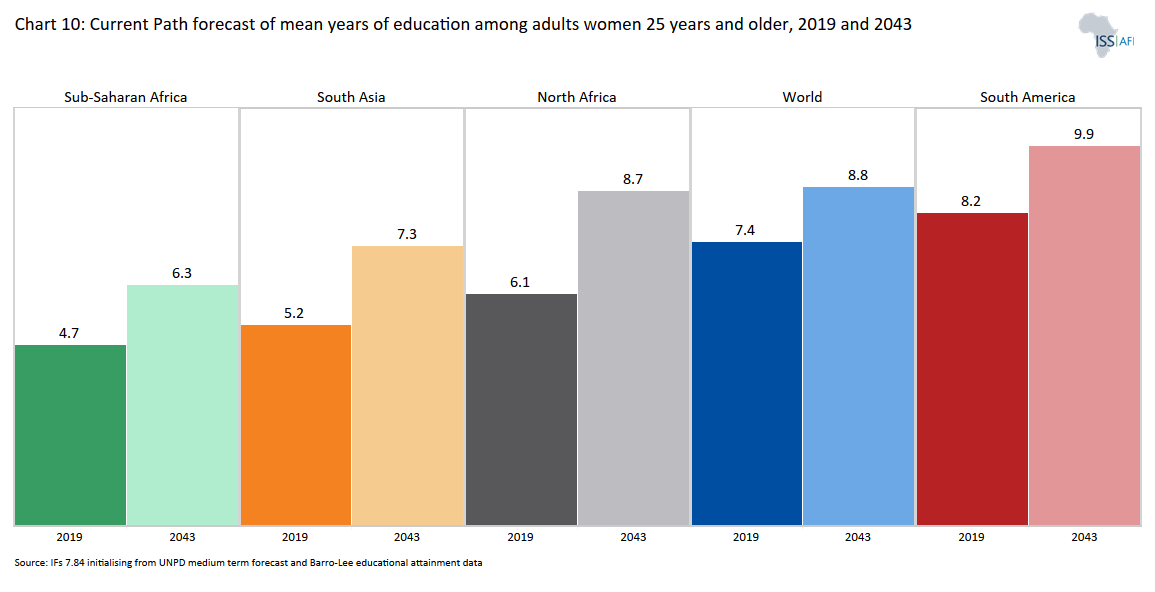

- Chart 10: Current Path forecast of mean years of education among adult females 25 years and older, 2019 and 2043

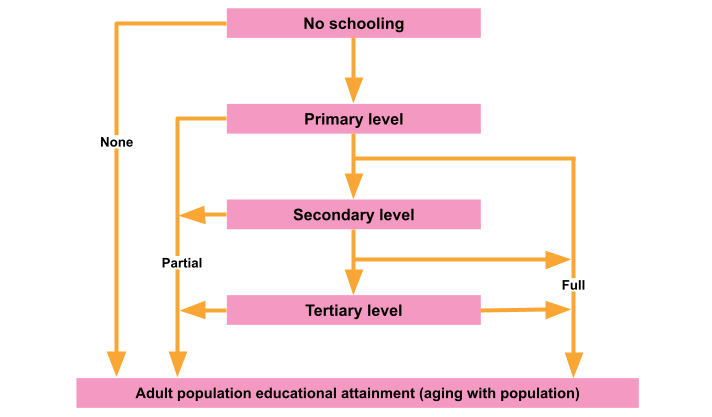

- Chart 11: Education flows and stocks

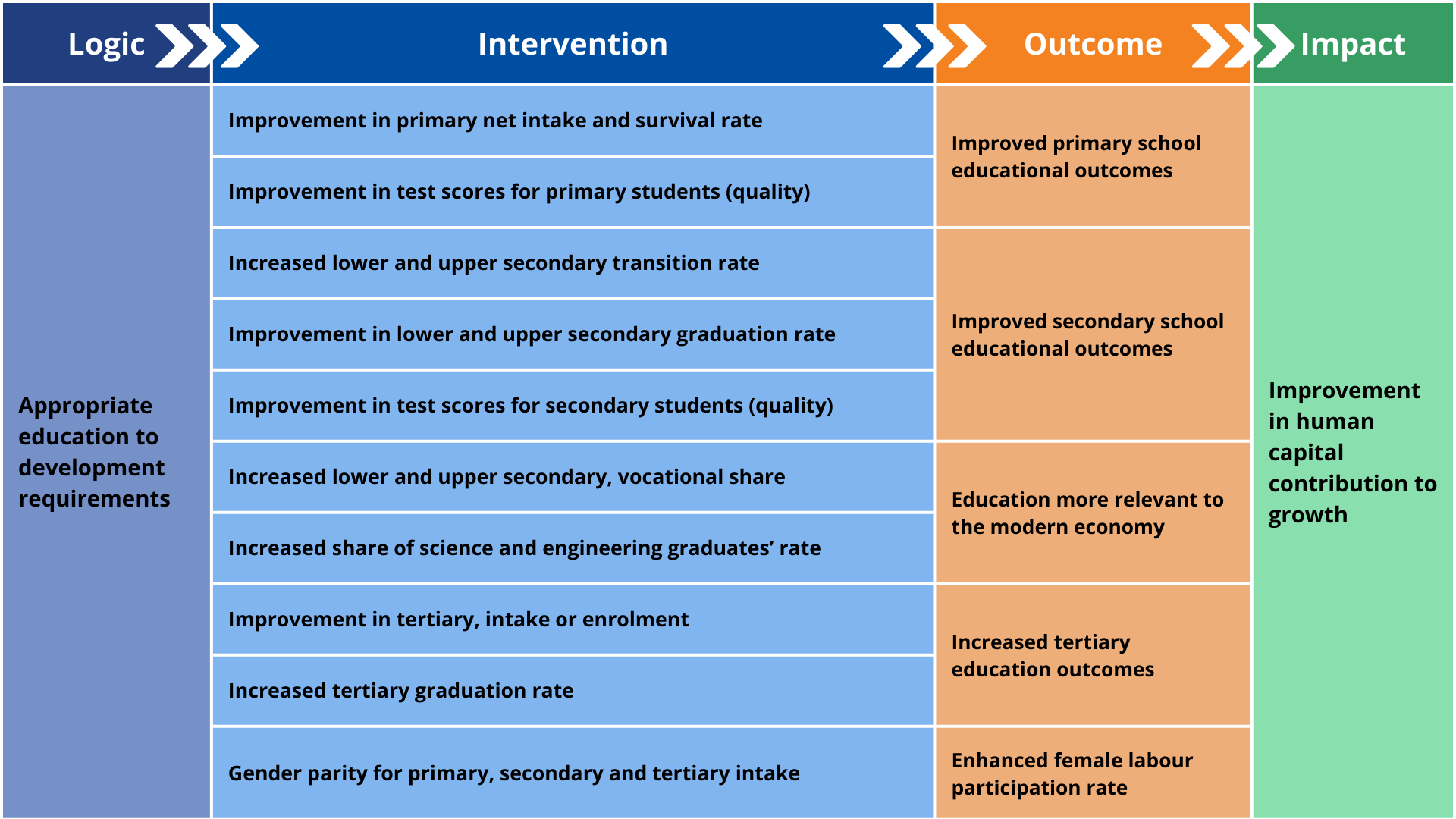

- Chart 12: The Education scenario

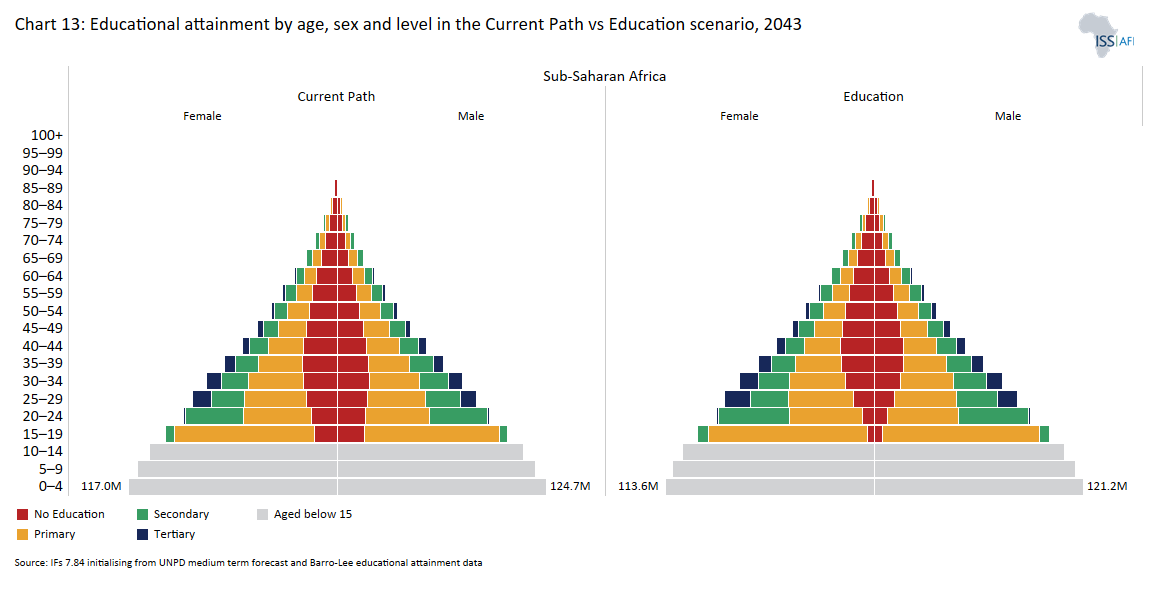

- Chart 13: Educational attainment by age, sex and level in the Education scenario, 2043

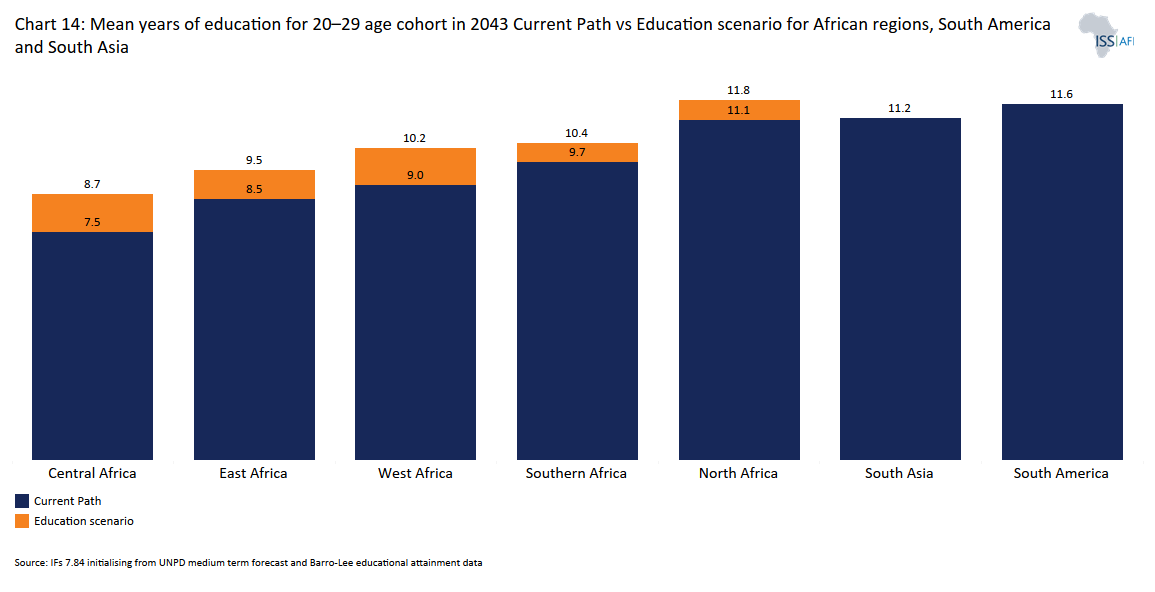

- Chart 14: Mean years of education for 20–29 age cohort in 2043 Current Path vs Education scenario for African regions, South America and South Asia

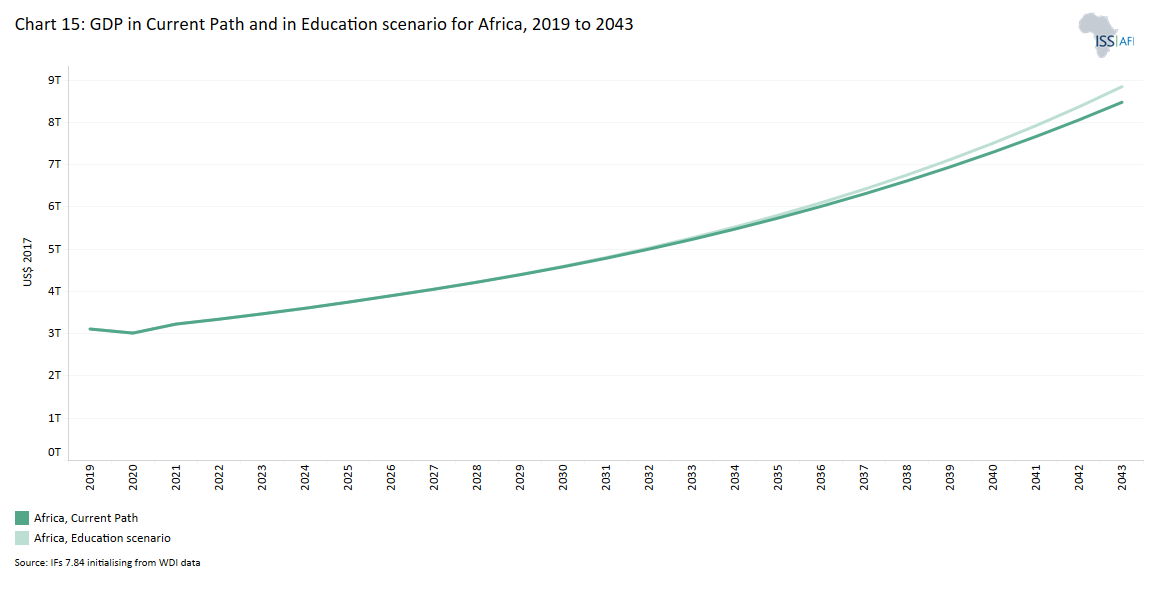

- Chart 15: GDP in Current Path and in Education scenario for Africa, 2019–2043

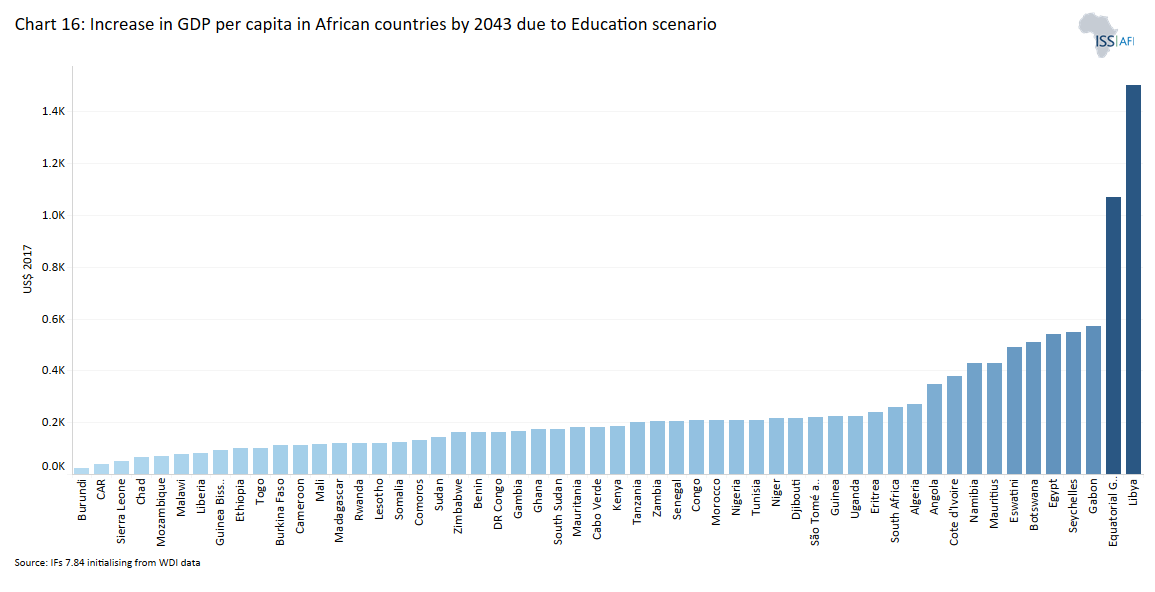

- Chart 16: Increase in GDP per capita in African countries by 2043 due to Education scenario

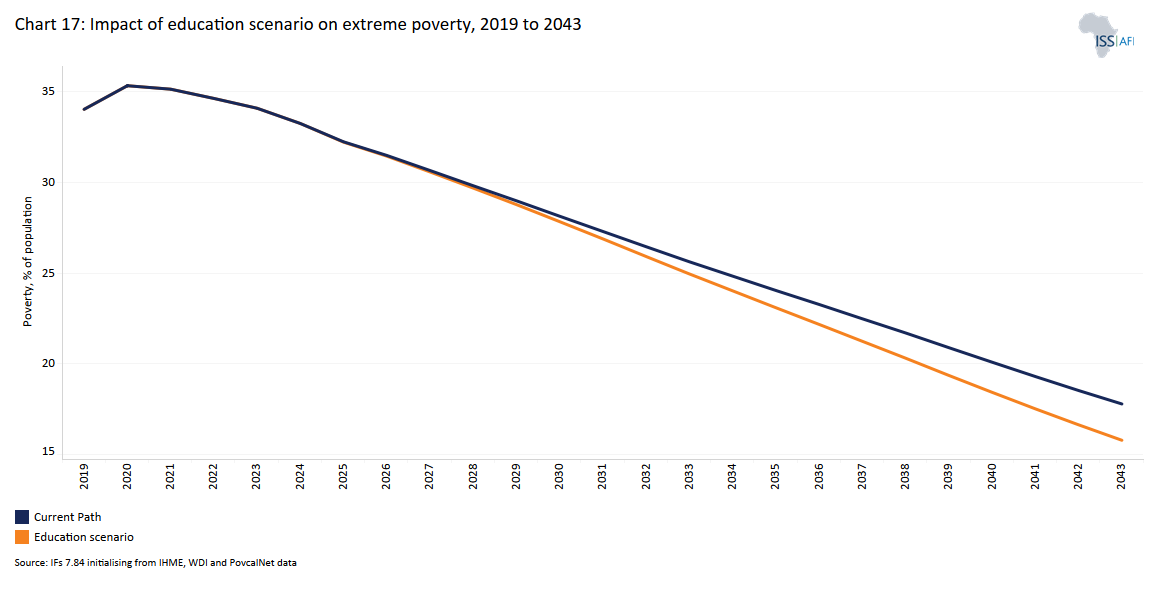

- Chart 17: Impact of Education scenario on extreme poverty, 2019 to 2043

- Chart 18: Key recommendations

Education is the foundation of human development and self-actualisation. It enables us to lead a self-determined existence, increase professional performance and improve our health. Investments in education increase the talent in the labour pool, raise productivity and boost economic growth and incomes.

Beyond a certain basic education level, a growing economy requires and, therefore, incentivises education of various sorts to meet the demand for productivity enhancements. This works best if the focus on education is accompanied by industrialisation or a shift to work that is more knowledge-intensive, such as in higher-end services, as demand then drives improved education outcomes. To this end, as countries graduate to middle-income status, the education system needs to provide additional skills and knowledge that respond to anticipated future demands.

Education and prosperity go hand in hand, with the demand for unskilled labour decreasing and that for semi-skilled and skilled labour increasing worldwide. Generally, basic literacy and primary school education are a requirement for countries to graduate from low- to middle-income status. Research shows that each additional year of schooling is associated with an increase of nearly 0.6% in long-term gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates, although the economic payoff is often only seen long after the initial investment in education.

However, whereas in Europe and the US rising levels of education foreshadowed development, in Asia improvements in education beyond primary school levels generally accompanied rather than preceded more rapid economic growth. Between 1960 and 1980, the average amount of education among the adult population in the East Asia and Pacific region increased by about 80%, and growth in GDP per capita tracked closely at about 85%. However, from 1980 to 2000, GDP per capita more than doubled, from about US$3 800 per person in 1980 to about US$8 400 per person in 2000, although the number of average years of education in the adult population in this period increased only by a third.[1When coming off a higher base, it is not as easy to maintain the previous momentum of improved education as levels approach saturation.] Since the 1950s, it has taken around 13 years to add one year of education to the cohort aged 15 to 24 years of age.

Improving the general level of education takes time and reaping the economic returns takes even longer. A study by the Education Policy and Data Center found that it could take up to 150 years, or seven generations, to move from 10% adult primary school completion to 90% secondary school completion. The average length of the transition for the countries in the group was nearly 90 years.

However, quick progress is possible, as shown in South Korea. In a period of rapid economic growth in South Korea after the Korean War (the so-called Miracle on the Han River), the mean number of education years tripled in 55 years (from four years in 1960 to 12 years in 2015). By 2015, South Korea had caught up with established Western democracies (e.g. the UK) and surpassed others (e.g. Sweden). It also achieved exceptional primary enrolment rates for 42 consecutive years, affirming the importance of getting the foundation right as part of an investment in the future.

In practice, the demand for appropriate levels and types of education to meet market demands shapes educational outcomes. Decision-makers’ investments in core knowledge and competencies (traditionally termed reading, writing and arithmetic) have to be complemented by strategies that anticipate future demands and envisioned opportunities.

Unfortunately, the challenge for many poor countries is that they have to contend with the migration of their skilled labour to richer countries. This is part of the story of the African brain drain, where highly skilled African workers, such as nurses, doctors and engineers, often seek employment in higher-income countries. Recent data from AfroBarometer confirms that sub-Saharan African nations account for eight out of the ten fastest-growing international migrant populations since 2010. With this steady exodus, the education system in origin countries needs to work twice as hard.[2This is the view advanced by Swedish economist and Nobel Laureate Gunnar Myrdal. His work preempted that of John Maynard Keynes.]

To explore the trends in education in Africa, the following aspects should be considered:

- the massive annual influx children into educational infrastructure and systems that are already struggling to deal with overcrowding and inefficient use of resources,

- the inability of many African countries to retain students in the education system,

- the quality of education,

- private education,

- trends in gender parity, and

- vocational versus academic teaching

The education system can be viewed as a long funnel, with various cracks along the way. Many children enter the system at the mouth of the funnel but few complete the entire journey — from primary to secondary school and then university — to eventually graduate with a tertiary or equivalent education at the other end. To improve the level of education in a country, the goal is to increase successful completion rates along each segment of the funnel. A perfect system would be one where the previous narrowing funnel has changed to a straight pipeline without ‘leaks’, with the full complement of age-appropriate students entering at one end and progressing to relevant higher education at the other end, and one that provides for appropriate academic and practical skills training.

In Finland, generally considered the country with the best education system globally, the gross intake ratio to the last grade of primary school and lower secondary education is close to 100%. The completion rate in the lower secondary phase is 100% and almost 90% for upper secondary education. All Finns therefore complete at least lower secondary education, with a loss of only 10% by the end of the upper secondary phase. The numbers drop off substantially only by tertiary education stage. By this standard, Africa will require successive generations of rapid progress.

In sub-Saharan Africa, more than 20% of children between the ages of 6 and 11 years are out of school, and over 33% of young people between the ages of 12 and 14 years are out of school. The situation is even worse for young people between the ages of 15 and 17 years, with an estimated 60% not in school.

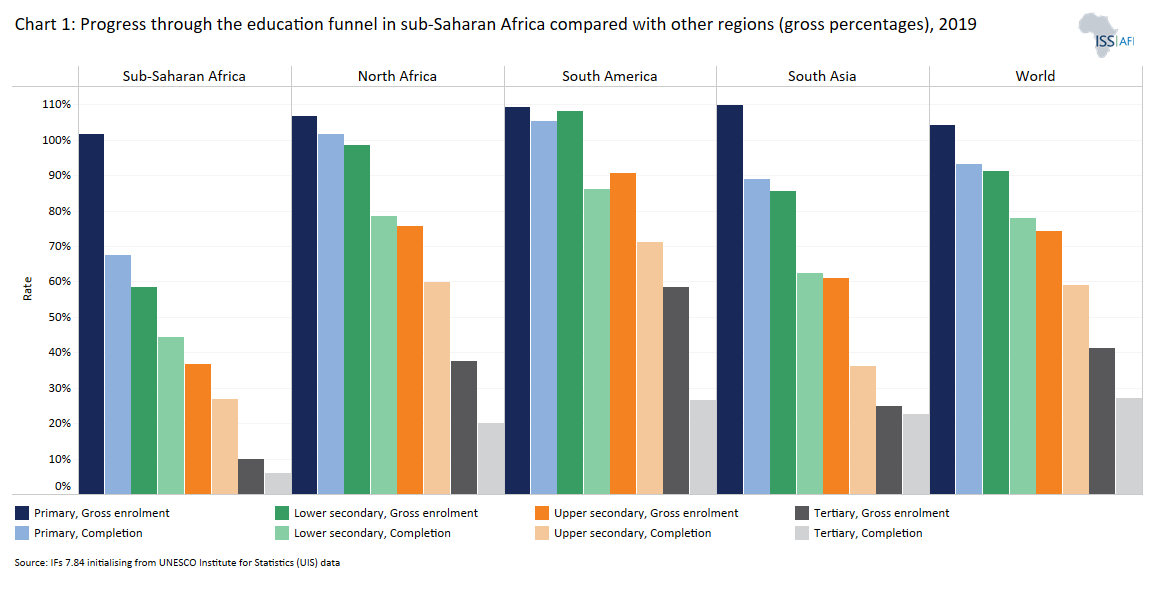

Chart 1 shows that educational throughput in sub-Saharan Africa is very different from that in North Africa, South Asia and South America (the latter two being the regions most comparable to Africa used in this website) and is consistently below world averages. Poor outcomes at either enrolment or completion are shown in orange or red, given the severity of the situation compared to other regions.

The gross enrolment rate for primary school in sub-Saharan Africa was 101.7% in 2019 but the net primary enrolment rate was only 78.9%. This indicates that a large number of children who are supposed to be in school are in fact not and that many classes are likely crowded by older children. Crowded classrooms can manifest in several forms including a higher student-to-teacher ratio, and insufficient availability of desks, books and equipment. The consequence is lower contact time per student, higher workload for teachers as well as lower instructional quality. The primary completion rate was 67.5% in 2019, almost 26 percentage points below the world’s average. It lags behind other regions, particularly North Africa with a completion rate of 102% and South America at 105%.

Of those who complete the primary level, some will transition immediately to the lower secondary level, some will enrol in the lower secondary level after some years out of school, and some will never enter the lower secondary level — and so on through the upper secondary and tertiary levels. In 2019, gross enrolment for lower and upper secondary levels in sub-Saharan Africa stood at 58.4% and 36.6, respectively, while that of North Africa was 98.6% and 75.7% in the same period. Completion rates drop acutely from 44% in the lower secondary phase to a mere 27% in the upper secondary phase in sub-Saharan Africa, indicative of a rapid contraction in the educational funnel. This contrasts markedly with the situation in North Africa, where lower and upper secondary completion rates were at 78.6% and 60%, respectively.

The situation at the tertiary level is even worse. In 2019, gross tertiary enrolment in sub-Saharan Africa was below 10%. This is just one-quarter of the world average, less than one-third of North Africa and almost one-sixth of the rates in South America. Even with this, only about 6% of the relevant age group in sub-Saharan Africa graduated from a tertiary institution with at least a first degree in 2019. Comparing the average of 20% in North Africa and 26.6% in South America reveals the depth of the educational crisis in sub-Saharan Africa and the rapid contraction along the educational funnel.

Moreover, enrolment does not always translate into attendance. In the majority of poor countries, enrolment rates are significantly higher than attendance rates as many children who are officially enrolled do not regularly attend school.

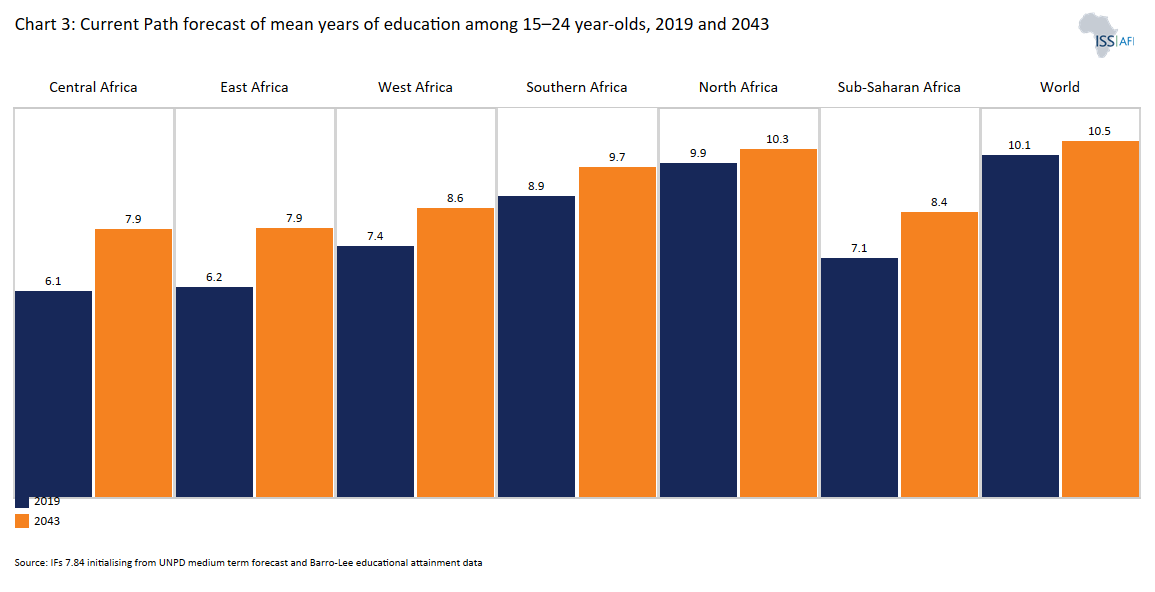

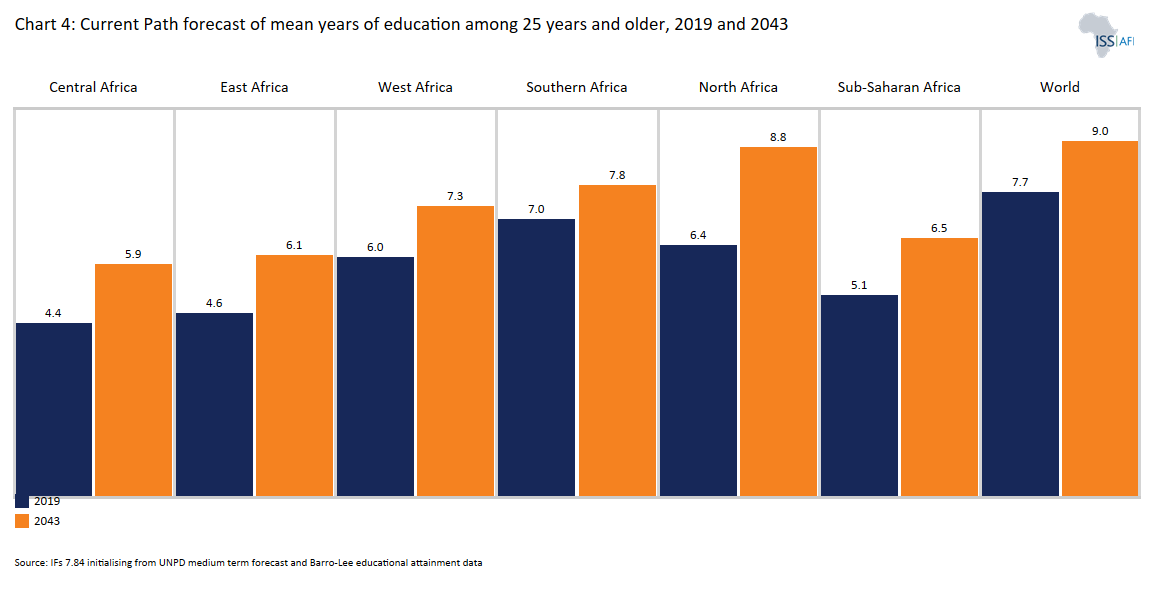

Another way of measuring the general level of education in a country is to look at the mean level of adult education. The mean years of education for the five regions in Africa, as well as the global averages, are shown for the age group 15–24 years in Chart 3 and for adults 25 years and older in Chart 4.

Average levels of education in North Africa are substantially higher than in other regions. Education levels in East Africa are expected to improve more than in Central Africa by 2043, with Kenya doing particularly well. Progress in education levels in Africa is reflected by young people (15–24 years) often being better educated than their parents. Africa, therefore, also has a large intergenerational gap when it comes to education. The literacy and education rates for the youngest population group in poor countries can be up to three times higher than those for the oldest population group. These large differences in outlook and expectation inevitably translate into frustration and even violence.[3A prime example is the event known as the Arab Spring in North Africa in 2010/11, where the protests were generally led by younger, well-educated people, many of whom were unable to find formal-sector jobs in economies stifled by state bureaucracy and corruption. At the time, the 15–24-year cohort had been educated for two years more than those aged 25 and older.]

In 2019, the mean years of education for the 25-years and older age group in North and Southern Africa was almost similar at 6.7 years. Looking to 2043, North Africa will continue to improve its education endowment on the Current Path (to 8.9 years), while the improvement in Southern Africa will only be to 7.6 years. By 2043, West Africa (with a mean of 6 years in 2019) will almost close the gap by 2043, progressing to 7.3 years. The main reason for Southern Africa’s slow improvement is that the adult education level in South Africa, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Madagascar will improve very slowly. This is an alarming forecast for South Africa, as it finds itself in a demographic sweet spot for growth given its favourable demographic dividend (see the theme on demographics ). Botswana will perform best in this region (and indeed on the continent), reaching 11.3 years by 2043. Mozambique, the country with the lowest average in the region, improves from 2.8 years in 2019 to 5.2 years in 2043.

The Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 focuses on quality education and is closely related to Goal 5 on gender equality. In the Current Path forecast, Africa is set to miss its targets by 2030:

- At a gross primary enrolment rate of 107%, the continent will achieve only indicator 4.1.1a of this SDG (however, it will fall short of its net enrolment target by 12 percentage points, reminding us of the misleading nature of gross enrolment figures).

- Enrolment rates at secondary level and completion rates for both primary and secondary education will also remain well below the targets.

- Upper secondary graduation rates will fall short of the SDG target by almost 60 percentage points (at 38% with a target of 97%).

- Gender parity rates will improve but will also fall short of the 2030 targets.

Although getting primary education right remains the top priority, Africa needs to attack all aspects of the educational funnel to ensure that it not only retains students at every level but also increases the progression rate to expand the pool of students at each successive level. This is generally the most cost-effective way to increase general levels of education throughout society and improve skills and potential as part of a comprehensive development strategy. However, African countries often do not take a systematic approach. In a number of countries, a lot of funds and too much attention are spent on improving later education phases (e.g. upper secondary or even tertiary) without prioritising throughput at primary and lower secondary school levels.

In summary, the gap in adult educational attainment between Africa and other developing regions is forecast to widen, especially at higher levels. By 2030, citizens in South Asia and South America could expect to receive about seven to eight full years of education, respectively, whereas citizens in sub-Saharan Africa will only obtain about six years. The second continental report on the implementation of the African Union Agenda 2063 reveals that the continent fell short of meeting all the targets relating to Goal 2 (on education) of the Agenda with an overall performance score of 44%. The divergence in education between sub-Saharan Africa and other regions is driven by factors that relate to rates of economic growth, the policy to use non-African languages as the medium of instruction and low or skewed government expenditure on education.

Spending on education remains one of the most significant public expenditures in Africa. Conventionally, education all over the world is financed mainly by the government although there has been increased privatisation over the years. The African Union’s Dakar Framework for Action: Education for All enjoins member countries to allocate at least 20% of their national budgets to education. In reality though, most African countries spend above this target averaging almost 25% of national budgets on education.

Government spending priorities on education differs. With the limited revenue and competing priorities, governments have to decide whether to invest in expanding access vis-à-vis improving quality. Beyond these, choosing between building more schools and providing textbooks compared with raising teacher salaries are also hard choices that policymakers face.

In many African countries, government funding is complemented by donor support in the form of aid. Between 2002 and 2015, donor support for education ranged from 0.86% of GDP to 0.45% of GDP. Beyond this, there are also local councils and parent–teacher associations that provide support for funding public schools. Households in Africa spend 4.2% of their annual total expenditure on education. In addition, almost 30% of national expenditure on education is provided by households.

Chart 5 illustrates education expenditure as a per cent of GDP for Africa, World, South Asia and South America. In 2019, total education expenditure in Africa amounted to US$131.7 billion, equivalent to 4.6% of GDP. At this rate, Africa’s expenditure on education is higher than the average for the world except for Africa (4.6% of GDP) and South Asia (3.8% of GDP) but below that of South America (5.1% of GDP). On the Current Path, Africa’s total expenditure on education is projected to reach 5% of GDP by 2043. At the regional level, Southern Africa has the highest expenditure on education estimated at 5.6% of GDP, followed by North Africa at 5% of GDP. Central and West Africa have the least expenditure on education on the continent at 3.1% and 3.7% of GDP, respectively. At the country level, education expenditure ranges from 10.5% of GDP in Botswana to 1.8% of GDP in South Sudan. These variations can be explained by the fact that the level of development in the country or region strongly influences its budget for education. Typically, wealthy countries spend more on education than poor countries.

A large proportion of the 44% of total expenditure on education in Africa is spent on primary level, 22.6% on tertiary level and the remainder on lower and upper secondary. The high expenditure on primary level education reflects the high enrolment rates at that level compared to other levels. On the other hand, although there are relatively fewer students at the tertiary level, the cost of training a child at the tertiary level is significantly higher than at other levels, especially for science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) courses, accounting for the enormous expenditure at that level. Generally, as students move through the educational funnel, it becomes more expensive to educate them. In 2019, the average amount spent on tertiary students was US$1 775. This is almost three times what was spent on upper secondary students, 4.4 times the cost of educating a child at the lower secondary and 6.5 times more than it cost to educate a primary student. Indeed, it is estimated that most sub-Saharan African countries spend over ten times more on their university students than they do on their primary students.

There are significant variations in expenditure per student across the continent. While Southern Africa spent US$3 079 per tertiary student in 2019, West Africa spent only US$648 at the same level. Southern Africa has the highest per-student expenditure at all levels of education, with upper secondary being the only exception. In the case of upper secondary, North Africa has the highest expenditure per student.

Despite the high education expenditure, it is still inadequate to meet the needs of the continent. In recent times, the rise of free secondary education on the continent, in particular in sub-Saharan Africa, has increased the funding needs of most countries. Countries such as Ghana, Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania all offer free secondary education, which is affecting their budget for education.

At the same time, as African governments require greater funding needs, diverse sources of funding are set to decline. International assistance and donor support towards funding education have been decreasing. Aid for education in 2022 declined by US$2 billion, meaning that African governments have had to finance more of their education budgets from domestic resources.

The COVID-19 pandemic also posed a significant challenge to financing education globally. The financing gap needed to meet SDG 4 has increased by almost one-third since the pandemic. In its 2020 Global Education Monitoring Report, UNESCO estimated a shortage of about 33.3% of annual funding required to meet SDG 4 on education. There is also high inequality in allocation and spending on education. Most public schools, especially in rural areas, have poor infrastructure, are underfunded and also understaffed. It is estimated that children from wealthy families benefit as much as 12 times more than their counterparts from poorer households.

Furthermore, there is also the issue of efficiency in expenditure. Generally, greater educational funding is expected to lead to improved educational quality and performance through its effect on increased, better infrastructure and teaching and learning materials. Thus, investment in education is critical to providing quality education and expanding access to all citizens. However, this impact is not automatic and requires efficiency in expenditure. It is estimated that efficient use of education funds can raise primary completion rates by 42% and those of secondary by 41%.

In the case of Africa, research has shown that high expenditure does not always translate into improved educational performance.[4See Hanushek (2006)] The disconnect between education funding and education performance on the continent can be attributed to inefficiency in spending. Although Africa has the second highest spender on education after the EU, its spending on education is the least efficient globally and 20 percentage points below the last but one Latin America. In most African countries, the majority of the education budget is spent on recurrent expenditures such as salaries, barely leaving room for other essential capital expenditures and learning materials that have a direct bearing on learning outcomes. As a matter of fact, in some African countries, almost all the monies allocated to the education sector is spent on salaries.

Research suggests that there is a stronger correlation between educational quality and economic growth than between educational quantity and growth.[5EA Hanushek and L Wößmann, Education Quality and Economic Growth, Washington DC: World Bank, 2007.] Although comparisons of quality are difficult to make across different cultural, economic and linguistic contexts, a number of international standardised tests have been developed in recent years to measure systemically, albeit imperfectly, learning outcomes at the primary and secondary school levels across countries. Using the results from these scores in IFs, charts 6 and 7 show that sub-Saharan Africa is consistently performing worse than the rest of the world, with little foreseeable improvement.

In 2019, the average test score for primary and secondary students in sub-Saharan Africa stood at 30.4 and 38.4 out of 100, respectively. In sub-Saharan Africa, primary test scores ranged from 39.1% in Madagascar to 22.6% in Burkina Faso, while secondary test scores ranged from 47.8% in Seychelles to 31.9% in Niger. In North Africa, test scores are slightly better averaging 32.4% and 42.0% for primary and secondary students, respectively. The most comparable region, South Asia, had primary and secondary test scores of 32.4% and 42.0%, respectively, in 2019. However, in the Current Path forecast, it is likely to leave sub-Saharan Africa behind and join South America, which is closer to the world average by 2043.

It is trite that learning starts slowly in low-income countries, where pre-schooling is mostly non-existent, and even students who make it to the end of primary school often do not master basic competencies. In fact, research shows that the average primary school student from a low-income country would be singled out for remedial attention based on being below standard should they attend primary school in a high-income country. Recent attention has shifted to the importance of early childhood development (ECD) in laying a foundation for cognitive functioning, physical health, and developing behavioural social and self-regulatory capacities. Proper nutrition forms part of this approach, as it supports cognitive development. At the pre-primary level, appropriate education and curricula, complemented by feeding programmes, lay the foundation for developing cognitive, behavioural, physical and social skills.

However, many young African students cannot solve mathematical or reading problems appropriate for their grades, yet complete schooling and, eventually, enter tertiary education. Children who may have received good ECD education but end up in a public school offering primary education that is largely characterised by overcrowding and a low teacher-to-student ratio (which speaks to a range of other problems in teacher training and attendance) will likely not excel. The main importance of ECD is to ensure that students get appropriate cognitive preparation to produce quality learning outcomes at each level of schooling, which is not fully captured by quantitative measures such as completion rates and test scores.

In sub-Saharan Africa, less than half of students meet the minimum proficiency threshold that is used in the standardised testing, whereas the mean for developed countries is 86%. To put that in comparative context: when it comes to learning outcomes, ‘the top-performing country in sub-Saharan Africa has a lower average score than the lowest-performing country in Western Europe.’ Similarly, the State of Global Education Update estimates that about 90% of people in Africa cannot write and understand simple text by the age of 10 compared to the global level of 70%.

A 2017 report by the World Bank warned of a ‘learning crisis in global education’ following an analysis of reading, mathematics and science outcomes, with disheartening results for sub-Saharan Africa. According to the World Bank, the immediate causes of poor-quality education are fourfold:

- Although school attendance is generally good in sub-Saharan Africa, many children arrive unprepared to learn because of illness, malnutrition or income deprivation (generally children from poor households learn much less).

- Teachers often lack the skills or motivation to teach effectively. Absenteeism among teachers is also widespread and even those present at school do not attend the class they are supposed to teach. Some engage in a second (or third) job to support themselves and their families. Moreover, as schools are understaffed, some teachers are inundated with administrative tasks.

- Teaching and learning materials such as books often fail to reach classrooms at the right time or to affect learning.

- Poor management and governance often undermine schooling quality. Turning this around will require substantial effort from governments and policymakers on the continent.

Against the concerning background outlined in the previous sections, the rise of private education in Africa has become a source of hope for some and controversy for others. Historically, private schools were often purely charitable undertakings, with mission schools providing education of a quality far higher than the colonial or segregated public school system at the time. However, today, the proliferation of private schools is associated less with charity, and more with government failures, commodification and profit-seeking. Due to the poor quality of education at public schools, many parents, especially in urban areas, send their children to private schools if they can afford to. However, a significant proportion of the population still relies on public/government schools.

The number of students in private schooling in Africa, in both aggregate and proportional terms, has been growing rapidly since the 1990s. Enrolments in private primary schools approximately doubled during the 1990s, while public school enrolments grew at approximately half that rate. By 2017, 19 sub-Saharan African countries had 20% or more of their primary and secondary school students being taught in non-state facilities. In Equatorial Guinea, 54% of its primary school students are in private schools. At 60%, Liberia has the largest proportion of secondary school students in private schools, followed closely by Mauritius (57%).

Much of the growth in the number of private educational institutions has been driven by foreign investors and also by the World Bank’s active promotion of private education through advice and lending. The argument in favour of private education is that it fulfils a need which African governments have failed to meet, with respect to both the quantity and the quality of education across much of Africa. In some cases, private education appears to be providing a much needed quality service. In Kenya, for example, private education (previously viewed as an unnecessary extravagance) has become highly sought after. This is particularly so in the context of overcrowded public schools, where 40% of Grade 2 students were found to be illiterate or innumerate and where teachers can sometimes be expected to teach classes of up to 100 students. Top schools in many countries, especially at the basic level, including in Ghana and South Africa, are usually private schools, although they serve a very small proportion of the population.

However, there is considerable criticism of and opposition to the mass roll-out of private education in Africa, as private education is seen to serve only a small proportion of the population, exacerbates inequality and diverts resources from the public education sector. The widening gap in achievement between wealthy and poor people is not only driven by improvements in quality education by private schools but also by a simultaneous drop in standards in public schools, as (better) teachers and resources are drawn to better pay and working conditions.

Although many private schools in Africa consistently achieve high rankings in school achievement indices, there are also many that fail to provide a better education than the public sector, while costing more. This can generally be ascribed to the loosening of regulations of private schools, which allow profit-seeking investors to run schools at extremely low cost, translating to inadequate resources and facilities and poorly qualified, underpaid teachers.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on education in Africa. The restrictions and protocols associated with the pandemic caused many schools to shut down and learning temporarily suspended. At the peak of the pandemic, more than 90% of African students had their studies interrupted as a result of school closures. Even in South Africa, where the education sector is relatively well-resourced and information and communication technologies (ICT) infrastructure is better developed than in many other countries, UNICEF estimates that the average student lost between three-quarters and a full year of schooling, and up to half a million children dropped out of school entirely since the beginning of the pandemic.

Countries with larger rural and extremely poor populations seem to have suffered the most. In many countries, children received no education at all during the COVID-19 pandemic, either because schools without facilities to teach remotely closed entirely or because of inadequate ICT infrastructure to allow students and teachers to log in to classes. Economic inequalities have again become decisive, with wealthy students who have access to well-resourced schools and homes equipped with high-speed Internet having experienced minimal disruption to their programmes, while many rural and poor students without such resources lost access to school entirely.

Even when they were able to access lessons, the sudden shift undermined learning as students struggled to focus in a home setting or received inadequate personal attention through online classes, with resulting mental health consequences of lockdowns that, in some instances, lasted up to two years. Outside school, children were also more susceptible to exploitation of child labour, particularly girls with respect to unpaid domestic work, further distracting them from their studies and undermining their fundamental rights.

Although students around the world have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, the higher levels of poverty as well as the significant digital divide in Africa have rendered Africans particularly vulnerable. Internet access rates are very low in Africa compared to the rest of the world, with studies estimating that 60% to 85% of African university students did not have the necessary devices or Internet access to continue online education. This highlights the need for a greatly expanded roll-out of quality and affordable ICT infrastructure (see the theme on leapfrogging) and integrating these technologies into education, including reskilling teachers.

Changing gender parity in education[6Gender parity refers to the number of female students participating in a given level of education relative to the number of male students at the same level.] is another important priority for improved education. In sub-Saharan Africa, gender parity in education has improved over time but still trails regions such as North Africa, notwithstanding the bad reputation of the latter when it comes to the rights of girls and women. It is estimated that 9 million girls in Africa between the ages of 6 and 11 years never go to school, as opposed to 6 million boys in the same age category.

Chart 8 provides a snapshot of the male-to-female ratio in education in 2019. At the primary level, 96 girls were enrolled in school for every 100 boys in sub-Saharan Africa compared to almost 99 girls to 100 boys in North Africa in the same period. In sub-Saharan Africa, Central Africa performs significantly worse than other regions at enrolling girls in primary school (93 girls to 100 boys), whereas Southern Africa does best at 99 girls to 100 boys.

The situation is the same at lower secondary levels. In 2019, there were only 91 girls enrolled in lower secondary school for every 100 boys in sub-Saharan Africa as opposed to 98 girls for every 100 boys in North Africa. This performance is boosted by the high female enrolment rate at this level in East Africa, averaging 97 girls enrolled for every 100 boys. Central Africa lags behind significantly in closing the gender gap at this level with only 77 girls enrolled for every 100 boys in the region.

The ratio worsens notably at higher levels of education. At upper secondary level, there are only 87 girls for every 100 boys in sub-Saharan Africa compared to 103 girls to 100 boys in North Africa in 2019. Again, Central Africa is the worst performer in the region with only 68 girls enrolled for every 100 boys, while Southern Africa tops the region with almost 101 girls to 100 boys in 2019. At tertiary level, there are 80 female students for every 100 male students as compared to 116 female students for every 100 male students in North Africa. Southern Africa was the only region in sub-Saharan Africa with female enrolment at the tertiary level higher than males (119 females to 100 males).

In 2019, the average woman of 25 years or older in sub-Saharan Africa received about 1.5 years less education than men in the same age group (see Chart 9 and 10). The gap is slightly lower (0.6 years) when looking at the 15–24 years age cohort. In North Africa, female adults of 25 or older have more than six years of education, around 1.2 years less than their male counterparts. However, the situation is the reverse when looking at those aged 15–24 as females have about 0.5 more years of education than their male counterparts. In 2019, female adults 25 years or older had three years less education than males in Somalia, the worst-performing country in sub-Saharan Africa. Only in Namibia, Lesotho, Gabon, Rwanda, Mali and Libya did female adults in this age group have more education than males.

In contrast, females 25 years or older in South America had, on average, slightly more education than their male counterparts, whereas in East Asia, Central Asia and Europe the gap between the mean years for males’ and females’ levels of education varies between about 0.06 and 0.93 years. Although females still get less education than males in these regions, levels are rapidly approaching equality. Only in South Asia do females face higher barriers to educational attainment than in sub-Saharan Africa (with a gap of 2.4 years between the mean for males and females in 2019), although South Asia will likely outperform sub-Saharan Africa in this respect by 2043. Given the link between female education and fertility, this difference explains, to a large degree, Africa’s high fertility rates (see the theme on demographics).

Improving levels of educational attainment is a slow process. For instance, it took sub-Saharan Africa a decade (from 2000 to 2010) to increase the average number of years of education of females by one year. The global mean length of adult female education stood at 8.4 years in 2019 — a goal sub-Saharan Africa will achieve only in the second half of this century on the Current Path, at which point the global average will likely have increased to about 10 years. Although Africa is improving, there is no indication of the continent closing this gap with the rest of the world in the Current Path forecast without aggressive interventions.

Future job requirements differ from country to country and defy easy generalisation. The modern trend appears to be towards broader sectoral training, which includes a set of generic business and life skills rather than preparing an individual for a specific job such as being an accountant, welder, carpenter or chef. This allows the individual to move from an entry-level job to a longer-term career more readily. A report from the Global Commission on the Future of Work confirms this analysis and refers to ‘a universal entitlement to lifelong learning that enables people to acquire skills and to reskill and upskill.’

A study from the African Development Bank found three main factors that constrain rapid job creation in Africa. First, job creation has not kept pace with the number of graduates from secondary and tertiary institutions. Also, those who finish school are not equipped with the skills required by the available jobs. Finally, young people generally lack the soft skills, social networks and professional experience to compete with older job applicants. The African Center for Economic Transformation specifically also noted that there is too little emphasis on relevant training in science, technology, engineering and maths, on technical and vocational education and training, and on higher-order cognitive and analytical skills. This leads to a considerable mismatch between job seekers’ actual skills and those that employers require.[7African Center for Economic Transformation, The future of work in Africa — The impact of the Fourth Industrial Revolution on job creation and skill development in Africa, Accra: African Center for Economic Transformation, 2018, 2.]

In 2019, only 8.5% of upper secondary school students were enrolled in vocational programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. This is less than one-quarter of North Africa’s average and less than half of the world’s average and South America’s. Angola has performed well in this regard with more than half of upper secondary students enrolled in vocational programmes. Additionally, other countries had at least 30% of upper secondary school students enrolled in vocational programmes in 2019. However, countries such as Comoros, Kenya, Tanzania, Equatorial Guinea, Sudan and Mauritania all had less than 3% of upper secondary students enrolled in vocational programmes.

At the tertiary level, in 2019 merely 14.2% of tertiary graduates in sub-Saharan Africa had a science and engineering background, which is considered key to the future of work. Although this is a little close to the averages in North Africa (16.7%) and South America (16.1%), it lags behind South Asia’s average of 24.3% in the same period. Djibouti has the highest share of science and engineering graduates, constituting close to 40% of total graduates, followed by Eritrea, Algeria, Sudan and Tunisia, respectively, with shares close to 30%. Uganda, The Gambia, Sierra Leone and Eswatini are the worst performers with less than 5% of graduates with backgrounds in science and engineering.

In the light of this evidence, African educators should balance the need for academic education with vocational and technical training. Education in Africa needs to respond to the demand for expanding small-holder farming and agribusinesses (see the theme on agriculture), allowing countries to enter low-end manufacturing (see the theme on manufacturing). This will prepare for the rapid expanded use of modern systems and technologies (see the theme on leapfrogging) as digitisation and the Fourth Industrial Revolution present new opportunities and risks for the future. The trend is away from low-skilled, and even semi-skilled, labour towards skilled labour.

In addition to advocating for technical and vocational training as a parallel education stream from secondary school onwards, the World Bank advocates for workplace training and short-term job training programmes. It finds that informal apprenticeships are most common in sub-Saharan Africa, supported by examples in Benin, Cameroon, Côte d'Ivoire and Senegal where these programmes account for almost 90% of the training that prepares workers for crafts jobs and employment in some trades.

Valuable examples of technical teaching innovation come from modern Germany. One of the most widely acclaimed German practices is its vocational training system at secondary level schooling and the partnership that has been established, in law, between publicly funded vocational schools and small and medium-sized companies. The system culminates in providing a student with a certificate issued by a competent body (e.g. a chamber of industry and commerce or a chamber of crafts and trades) in around 330 occupations requiring formal training in Germany.

However, what works in a highly formalised and developed economy such as Germany will not work in most of Africa. In addition to many other challenges, the low quality of education in most sub-Saharan countries means that students may not have fully mastered the foundational skills of reading, writing, numeracy, critical thinking and problem-solving that are required for entering the vocational training stream. The World Bank refers to this as ‘not just a lack of trained workers; it is a lack of readily trainable workers.’ Regardless of the continent’s preparedness, digitisation and the Fourth Industrial Revolution will require a large cadre of technical skills, and the poor quality of general schooling in Africa implies that great care must be taken to ensure that students who do choose this vocational line of education have sufficient grounding.

The considerations relating to the quantity and quality of education mean that it is highly unlikely that Africa will meet the education targets of SDG 4, with Target 4.1 aimed at all children having access to ‘free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education’, as measured by a minimum proficiency in mathematics and reading. Accordingly, this section sets out the interventions in the IFs modelling platform that represent ambitious but reasonable improvements in the quantity, quality and nature of education in Africa. We then compare the impact of the scenario with education outcomes on the Current Path, including on growth rates, size of economies, average incomes and inequality.

Our approach is systematic and comprehensive. The interventions target every level of the formal education flow, from primary education enrolment to tertiary graduation. Some aspects — such as with regard to ECD, adult education and informal education — are, however, not not yet included in the IFs forecasting platform. Informal education in particular remains hard to measure and compare across African countries. These elements all deserve further investigation.

Chart 11 presents a simple schematic for flows and stocks within the education system. We use the standard UNESCO categorisation of primary, lower and upper secondary, and tertiary levels.

Chart 12 indicates the logic of the interventions across 11 sets of variables, which target intake, survival and graduation rates, as well as quality from primary to tertiary level. We also target gender parity, particularly at the primary and secondary level, and the proportion of students enrolled in key skill programmes, including vocational studies and courses focused on STEM at higher levels.

Improving Primary Access

The first intervention is improving net primary intake to increase net enrolment at the primary school level. Although gross enrolment is high in most African countries, net enrolment remains low at 81.8% in 2019 compared to 89% in South Asia and 96% in South America. Nonetheless, some countries in Africa, particularly North Africa, have advanced in net enrolment with the region close to saturation levels. This intervention is done only for countries where the Current Path fails to reach 100% by 2043. As a result, net enrolment increases from 81.8% in 2019 to 96.3% in 2043 in the scenario, which is almost at the same level as South America and South Asia and 6% above the Current Path forecast in 2043.

The next intervention at the primary level is an improvement in survival rate. The dropout rate in Africa is very high even at the primary level. In 2019, Africa’s primary school survival rate was 68.3%, compared to 85% in South Asia and 90.3% in South America. This intervention pushes the primary school survival rate to 90.2% instead of 82.5% on the Current Path, thereby closing the gap between Africa and South Asia. The impact is such that rates for gross primary school completion in Africa improve from 76% at primary level in 2019 to 110% by 2043, instead of only 90% on the Current Path. This is an aggressive intervention but without a huge effort to improve this foundational aspect of Africa’s development, subsequent progress on most other dimensions is virtually impossible. In the process, Africa overtakes South Asia in primary school completion rates by 2029 and catches up to South America’s rate by 2030.

Improving secondary access

At the lower secondary level, we improve the transition rates from primary to lower secondary, which addresses the high dropout rates in these levels. The intervention improves transition rates from primary to lower secondary from 86.6% in 2019 to 98.7% in 2043, on par with South America and South Asia, instead of 94% on the Current Path. Another intervention at the lower secondary level is an improvement in lower graduation rates to increase the proportion of students who complete the last level of lower secondary. The intervention raises the lower secondary completion rate from 49.6% in 2019 to 74% in 2043 in the scenario compared to 63% in the Current Path forecast.

The same set of interventions are repeated at the upper secondary levels (i.e. improvement in upper secondary transition and graduation rates). As a result, the transition rate from lower to upper secondary in the scenario increases from 83.6% in 2019 to 94.7% by 2043, slightly below South Asia and South America, compared to 87.2% in the Current Path forecast. Likewise, upper secondary completion rates rise from 31.9% in 2019 to 54.8% in the scenario as opposed to 46.1% in the Current Path forecast. Although the intervention improves completion rates in the scenario, they will still lag behind South Asia and South America by 2043.

Improving tertiary access

With respect to tertiary education, our interventions are less aggressive as improvements in tertiary education output will rely decisively on gains at lower levels first. The interventions consist of an improvement in net enrolment as well as improvement in tertiary graduation. In this scenario, tertiary enrolment improves from 14% in 2019 to 39.4% in 2043, compared to the forecast of 23.4% on the Current Path. This reduces the gap in tertiary enrolment with South Asia at 44.5% and South America at 58.3% quicker than the Current Path. Similarly, the tertiary graduation rate rises from a low base of 8% in 2019 to almost 18% in 2043 — 3.3 percentage points higher than the Current Path forecast. Africa will continue to lag behind South Asia’s and South America’s rates of over 30% graduation rate in 2043, however, demonstrating the size of the gap and the long time frames required to improve the education system.

Education relevant to modern economy

To improve the supply of relevant skills for future demand, we improve the lower and upper secondary vocational share and the share of science and engineering graduates. Consequently, the percentage of lower secondary students enrolling for vocational training in 2043 is 5.6% instead of 1.6%. The percentage of upper secondary school students pursuing vocational studies is boosted from the 2043 Current Path forecast of 17.8% to 22.8%. In viewing these numbers, it is important to bear in mind that these percentages are accompanied by very rapid population growth rates. The share of science and engineering graduates at the tertiary level increases from 14.6% in 2019 to 24% by 2043.

Improving gender parity

The Education scenario creates a more aggressive gradient and pushes gender parity rates closer to the 1:1 female-to-male ratio goal on almost every indicator. In the Education scenario, gender parity in net primary enrolment is achieved as early as 2028 and maintained until 2043. Although gender parity in net secondary enrolment occurs much later by 2035 in the Education scenario, it is a significant improvement over the Current Path given that gender parity is not possible in the latter even by 2043. Gender parity at the tertiary level is likely to follow the general global trend of reaching a 1:1 ratio and then surpassing it (as female students often tend to be higher achievers at tertiary education levels) both in the Current Path forecast and in the Education scenario.

Improving the quality of education and skills

This set of interventions improves the quality of education at primary and secondary levels.

At the primary level, Africa does not currently lag far behind South Asia, although composite test scores (including for maths, reading and science) are lower. However, while South Asia’s education scores are likely to rise by about five percentage points (a 14% improvement), Africa is set to stagnate on the Current Path, seeing an improvement of only two percentage points (or 7%) by 2043 compared to scores in 2019.

In the Education scenario, our interventions instead point to Africa achieving slightly higher levels of quality than South Asia by 2043 (about a 26.7% improvement from 2019 value), although both regions will still fall slightly behind South America’s scores. The trend is similar at the secondary level, with the interventions boosting quality across maths, reading and science to keep up with progress in South Asia and South America. By 2043, Africa’s test score of 45.5 at the secondary level will marginally surpass the score of 45.2 in South Asia while catching up with the quality levels in South America at 46.5.

Meeting SDG targets

The interventions in the Education scenario would also be good news for Africa’s SDG ambitions. In the Education scenario, Africa will get significantly closer to attaining SDG 4.1 of achieving equitable and quality universal primary and secondary education.

The scenario raises primary net enrolment from 82% of-age children in 2019 to 92% by 2030, and the primary gross completion rate from 73% to 100% in the same period. Also, the Education scenario also improves gross lower secondary enrolment from 59% in 2019 to 92% in 2030 and gross upper secondary enrolment to 66% from 43% in 2019. Similar improvements can be seen across the other indicators although, like on the Current Path, Africa will only meet its enrolment and completion goals by 2030 if this aggressive scenario were to be fully realised.

The impact of the Education scenario can be measured in different ways, outlined below.

Chart 13 presents education by age, sex and level for sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa in 2043 in the Current Path forecast and Education scenario.

A simple way to measure impact is to look at mean years of education. Chart 14 compares the mean years of education for adults aged 20–29 years with the 2043 forecast for South America and South Asia. By using a youthful age cohort (20–29 years), the findings reflect the improvements modelled in the Education scenario.

In the Education scenario and when using this age cohort as a lens to measure progress, all five regions start closing the gap relative to the rest of the world, yet only North Africa surpasses the 2019 mean for the world, and South Asia and South America by 2043. Central Africa, which generally lags in improvements, performs best with regard to increasing mean years of education, seeing an improvement of 56.4% between 2019 and 2043 (from 5.9 years to 9.2 years). However, coming from a much lower base, it remains the worst-performing region. East Africa also sees an aggressive increase of 49%. Because it already does much better than sub-Saharan Africa, the least improvement occurs in North Africa with an increase of about 20%, though it is still the best performing region.

The Education scenario increases expenditure on education in Africa from US$143.7 billion in 2019 (representing 4.5% of GDP) to US$490.5 billion (5.6% of GDP) by 2043. This is equivalent to US$67.9 billion (0.56% of GDP) of additional funds in that year, i.e. on top of the US$423.1 billion that Africa is forecast to spend on education on the Current Path in 2043. Although this is a substantial amount, these additional costs produce an African economy that is US$368 billion larger. Cumulatively, Africa will have invested an additional US$461 billion in education from 2024 to 2043. The result is, however, a cumulative addition to the African economy equivalent to US$1 872 billion. This is a huge return on investment, and it reflects that education is essentially a multiplier on the contribution that labour makes to growth. As the level of skills improves, Africa’s economies start to grow, slowly at first and then accelerating over time, and improvements to GDP snowball beyond the 2043 time horizon. It is this return on investment that results in the mantra about better education lifting all boats as improved education reduces fertility, improves productivity and raises the quality of democracy and governance to make countries more stable.

By 2043, the difference in the GDP growth rate between the Education scenario and the Current Path forecast is 0.5 percentage points and, as a result, the African economy will be US$368.4 billion (equivalent to 4.3%) larger in 2043 in the Education scenario than in the Current Path forecast.

Using the purchasing power parity (PPP) measure, Africa’s average GDP per capita in the Education scenario will rise to US$7 302 by 2043 from US$5 194 recorded in 2019. This translates into additional gains of about US$240 per person over the Current Path forecast by 2043. The benefits inevitably accrue disproportionately to more developed countries, which already have higher productivity levels and, thus, benefit most from this multiplicative effect. By 2043, average levels of GDP per capita (in PPP) will increase by:

- US$149 per person in low-income Africa,

- US$283 per person for lower-middle-income Africa,

- US$458 per person in upper-middle-income countries, and

- US$600 per person in the Seychelles, Africa’s only high-income country.

By country (Chart 16), the impact of the Education scenario on the GDP per capita by 2043, i.e. above the Current Path forecast, differs for that year. Libya and Equatorial Guinea gain the most (US$1 632 and US$1 190, respectively) and Burundi, Central African Republic and Sierra Leone gain the least (US$28, US$44 and US$57, respectively).

If Africa could simultaneously reduce the size of the annual influx of primary school children by means of appropriate family planning interventions as set out in the theme on demographics , the effect of improved education could be even greater. The result of having fewer children who enter primary school will soon cascade through the entire education system (on top of the decline in fertility associated with better education), meaning more funds could be spent on the smaller cohort of children as they progress from primary to secondary and, eventually, tertiary levels. In this manner, the Demographics and the Education scenarios reinforce each other in a powerful way.

The Education scenario would also reduce extreme poverty (Chart 17) by more than two percentage points across the continent, about 47 million fewer extremely poor people compared to the Current Path forecast, in 2043.[8Using US$1.90 per person per day as the threshold of extreme poverty.] In this case, low- and lower-middle-income countries in Africa benefit the most with projected 24.4 million and 22 million fewer extremely poor people, respectively, than the Current Path forecast by 2043. Improved levels and quality of education have a small but positive effect in reducing inequality[9Using the Gini coefficient measure of inequality.] with low- and lower-middle-income countries benefiting the most.

Better education reduces infant mortality by an average of 1.8 fewer deaths per 1 000 live births over the Current Path in 2043 for Africa, although the reduction is much larger for lower-middle-income countries (by five fewer deaths). Likewise, the Education scenario reduces total fertility (by 0.121 births per woman in 2043) and increases life expectancy by about five months by 2043. The result is an African population of 12 million people fewer by 2043 than it would have been on the Current Path forecast.

The power of education is such that some commentators argue that education and health, rather than age structure, bring about the demographic dividend . It is investments in these aspects of human capital, they argue, that serve as the trigger of both a demographic transition and economic growth; declining youth dependency ratios show negative impacts on income growth when combined with low education. Thus, ‘the true demographic dividend is a human capital dividend’ and policymakers are urged to focus on strengthening the human resource base for sustainable development.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic stimulated changes in education, it also caused many students to lose considerable education in 2020 and 2021. In the wake of the pandemic, teachers and policymakers are busy reassessing education, particularly the current limits with distance learning in a situation where broadband Internet access in much of Africa is still limited. After the pandemic, a new model could catalyse systemic improvements to education, particularly for children in distant and under-resourced districts, but only provided the necessary infrastructure is available.

The potential comes in various forms. On the one hand, augmented reality (AR) may soon become accessible as a practical teaching mode, with billions of dollars already being spent on research and development. The application of new technologies could replace a teacher in front of a whiteboard (or chalkboard) with apps, gameplay and entirely new ways of teaching. If the promise of 5G speeds and connectivity examined in the leapfrogging theme comes to Africa, students can consume lectures much more effectively. Using an AR headset, students studing biology can dissect virtual animals and view their organs. Medical students will be able to do the same with the human body, and trainee nurses will be able to track blood flow, explore the digestive system and see how muscles work.

AR will make learning more immersive, exciting and effective. It could enable students in the most isolated and disadvantaged rural areas to see and do things they would otherwise never have the opportunity to do. It is a powerful way of providing individual and flexible learning, connecting theory with the real world. In tomorrow’s world, understanding technology and coding will be crucial. AR and artificial intelligence can help students get to grips with concepts of computation, sensors, networks, digital printing, genetic engineering and robotics, to name a few.[10For example: Winners of the 2019 XPRIZE (aimed at eliminating adult illiteracy in the US, retooling tomorrow’s workforce and encouraging lifelong learning) included Learning Upgrade, which has developed an app that helps students learn English and mathematics through videos, songs and gamification from pre-school to adult education, and PeopleForWords, which offers an immersive virtual environment and gamification to improve vocabulary and comprehension.]

On the other hand new technology also helps with basic literacy and in areas with limited broadband access. An example is the use of an app such as Daariz which has, according to its user data, taught over 410 000 people in the Horn of Affrica to read and write. Different to the connection speeds required by AR, Daariz is an education-entertainment app that, once downloaded, allows off-line use on a smartphone. Daariz was developed by Ismail Ahmed and his Sahamiye Foundation who previously developed the World Remit app that allows cheap money transfers. Want to get a child to learn a foreign language or to understand computer coding? Get them to play a game in that language or to experiment with coding. On its website the Foundation claims that it reduces the time to become functionally literate in one's mother tongue from 450 to just 50 hours.

Education systems are notoriously slow-moving, and in most African countries particularly so. African countries will not close the gap in average levels of education compared to the rest of the world by using current systems and practices. Technology can fundamentally change the nature of teaching and enable the move away from brick-and-mortar campuses to virtual campuses that will facilitate much broader access for both students and teachers. Much of that is already possible in so-called point learning, where the curious African can use the Internet to make, disassemble, repair, cook or understand almost anything by watching videos. You do not need to be an accredited technician with years of formal training to repair or replace smartphone parts; you need the Internet and a set of tiny screwdrivers. But this is only possible with electricity and broadband access, and getting these basics in place will largely determine the extent to which Africa can leapfrog in education.

Education can provide improved opportunities to poor people and the relationship between better education and improved income levels is strong. The Education scenario would have a transformative impact on African economies and societies, but the results will not be achieved without great effort and new ways of thinking. Africa not only needs to get the basics right but should also ensure very rapid uptake of modern technology to help compensate for deficits in teaching capacity and for governments to invest appropriately.

Beyond basic levels of (primary) education and literacy, an education system must evolve to respond to many requirements, including changing education demands to help prepare students for the job requirements of the future. By 2030, about 230 million jobs in Africa will require digital skills. The world of work requires more skilled and fewer semi- and unskilled workers.

There is clearly a powerful relationship between citizens’ level of education and the prosperity of nations, but it is also quite complicated, as the example by Ricardo Hausmann shows:

In 1998, Ghana’s workforce had an average of about seven years of education and its per capita income was about $1 000. When Mexico’s workforce first achieved an average of seven years of education — in 1993 — its income was over $10 000, while France’s per capita income when its workforce first got to an average of seven years of education (in 1985), was over $20 000. These figures tell us that rich countries are rich not just because of education, and, conversely, that investing in education alone won’t make you rich.

Hausmann attributes the ability to translate education and technology into growth to the ability to apply knowledge. That, he argues, comes through imitation and repetition of tasks — learning by doing. For a country to develop and grow, it needs to provide the opportunity for learning while doing. What he does not examine, however, is the matter of the quality of the education provided in Ghana, Mexico and France, pointing to the need to dig deep when considering key relationships.

Because of colonialism, most African countries still adhere to the outdated Prussian model of rote education. It has often, and rightly so, been criticised for being overly rigid and inflexible. In Africa, overcrowded classrooms, poorly educated teachers and limited educational facilities are the norm. Many children are poor, undernourished and have to walk far to attend school every day. Looking at the rather dismal state of education in Africa, the continent could clearly do with much greater order and a sense of educational purpose. This is particularly important when it comes to improving children’s reading, writing and arithmetic skills, ensuring teachers’ attendance, and in finding ways to manage the large classes that are typical in so many schools.

Effective education requires students who are sufficiently nourished, stimulated and cared for, capable teaching, skilled management and a government and education system that pulls all of this together. Many countries in sub-Saharan Africa do not have these four key components in place and face a crisis in education that the World Bank describes as a low-learning trap. It is possible to escape this trap, as is demonstrated by the advances made in South Korea, China and Vietnam, but it requires a tremendous effort, political leadership, societal engagement and the use of modern technology.

With the right kind of education and skills formation, the large young population can be a powerful contributor to growth in Africa. However, it can also be a drag on growth and cause social and political upheaval if the continent does not create the right opportunities to realise their potential. By 2050, 40% of all children (one billion people) and adolescents below the age of 18 years will be in Africa. This is an opportunity for Africa to build the largest human capital in the world and leverage it for growth. Achieving this requires significant investment in the education and training of children and adolescents on the continent to acquire the relevant knowledge and skills that can drive the development agenda of the continent and achieve a demographic dividend.

As a starter, governments need to fix education systematically, working their way through the education funnel from the starting point: by investing in ECD, ensuring primary school enrolment and completion, developing literacy and using modern technology in the process. Once progress is achieved in primary education, the priority should shift to improving enrolment and completion in lower secondary schools, then to fixing upper secondary and, eventually, tertiary education.

Specifically, the government must pay special attention to pre-schools to improve foundational learning for basic reading and mathematics at early stages of pre-primary and primary levels. In this regard, school authorities can dedicate extra hours to numeracy and literacy at pre-primary and primary levels. Also, there is the need for greater inclusion of and critical attention paid to dropouts in the educational funnel. Governments need to eliminate barriers to higher education starting from secondary school levels. Policies such as free secondary education and school feeding programmes targeting needy and vulnerable households can increase enrolments and survival rates among school children.

The quality of education is important, together with offering vocational and technical training as opposed to the singular focus on academic teaching so evident across many African countries. Simply pushing children through school is not a solution if their education does not comprehensively and fundamentally address the basics of reading, writing and arithmetic, and then allowing them to build the skills required for the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Thus, governments need to recognise and prioritise technical and vocational education especially at the lower secondary levels. This is to ensure that students who choose technical and vocational lines of education at higher levels have the sufficient grounding to excel. It is also imperative to find ways to channel many more students towards vocational training programmes that benefit from broader integration into the educational system and enable informal, virtual self-empowerment.

African states cannot abdicate their responsibility to provide an essential public good to millions of poor citizens in favour of a profit-seeking private sector. However, this is not to say that private schools should not play a role. The development of carefully crafted regulations to prevent predatory practices by the private sector, as well as the continued need for states to properly fund, manage and regulate their public education systems, are needed in parallel. With the decline in donor support coupled with governments’ competing spending priorities, there is a need to raise additional funding through innovative financing. Particularly, governments need to rope in the private sector to finance technical, vocational and higher education that has a direct link with industries and private sector growth.

As discussed earlier, digital connectivity is critical for learning and skills development. New teaching technologies and methods must be exploited to help meet the challenges of the future, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic. There is the need to partner with telecommunication firms and Internet service providers to bring down the cost of broadband services and mobile data that impede virtual learning. This will facilitate innovation in teaching and learning methods and expand virtual learning platforms. Furthermore, capacity building, skills upgrading and further training for teachers is essential to building a quality educational system. Accordingly, countries need to periodically redesign their teacher development programmes to cater for new teaching and learning skills including digital education.

Each African country faces different challenges, but more parental involvement, upskilling teachers and designing teaching and learning methods that are sensitive to local conditions are central to creating functioning education systems throughout Africa. Not all of this requires sophisticated technology,[11Already a number of schooling projects require teachers to post a selfie by 8 a.m. every day to prove they are in class and teaching.] but once the basics are in place, technology in the forms of 5G and AR could be a key facilitator to drive the progress modelled in the Education scenario. Clearly, strategic planning, innovation, investment and, most of all, leadership are required to address the continent’s education backlog. Africa’s likely prospects in the Current Path forecast are depressing. If the continent fails in this dimension it will fail in all others.

Endnotes

When coming off a higher base, it is not as easy to maintain the previous momentum of improved education as levels approach saturation.

This is the view advanced by Swedish economist and Nobel Laureate Gunnar Myrdal. His work preempted that of John Maynard Keynes.

A prime example is the event known as the Arab Spring in North Africa in 2010/11, where the protests were generally led by younger, well-educated people, many of whom were unable to find formal-sector jobs in economies stifled by state bureaucracy and corruption. At the time, the 15–24-year cohort had been educated for two years more than those aged 25 and older.

See Hanushek (2006)

EA Hanushek and L Wößmann, Education Quality and Economic Growth, Washington DC: World Bank, 2007.

Gender parity refers to the number of female students participating in a given level of education relative to the number of male students at the same level.

African Center for Economic Transformation, The future of work in Africa — The impact of the Fourth Industrial Revolution on job creation and skill development in Africa, Accra: African Center for Economic Transformation, 2018, 2.

Using US$1.90 per person per day as the threshold of extreme poverty.

Using the Gini coefficient measure of inequality.

For example: Winners of the 2019 XPRIZE (aimed at eliminating adult illiteracy in the US, retooling tomorrow’s workforce and encouraging lifelong learning) included Learning Upgrade, which has developed an app that helps students learn English and mathematics through videos, songs and gamification from pre-school to adult education, and PeopleForWords, which offers an immersive virtual environment and gamification to improve vocabulary and comprehension.

Already a number of schooling projects require teachers to post a selfie by 8 a.m. every day to prove they are in class and teaching.

Page information

Contact at AFI team is Enoch Randy Aikins and Jakkie Cilliers

This entry was last updated on 11 October 2024 using IFs 7.84.

Reuse our work

- All visualizations, data, and text produced by African Futures are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

- The data produced by third parties and made available by African Futures is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

- All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Cite this research

Enoch Randy Aikins and Jakkie Cilliers (2025) Education. Published online at futures.issafrica.org. Retrieved from https://futures.issafrica.org/thematic/06-education/ [Online Resource] Updated 11 October 2024.