Development pathways for the DRC to 2050

Summary

- Despite its huge natural resources, the DRC ranks near the bottom in various development indicators and poverty is widespread. Jump link to Introduction

- Bad governance, cronyism and corruption are holding back developmental progress. Jump link to Governance

- The average income is about 40% of its value at independence in 1960. On the current development trajectory, the projected income per capita by 2050 is almost the same as its value in the 1970s. Jump link to Economy

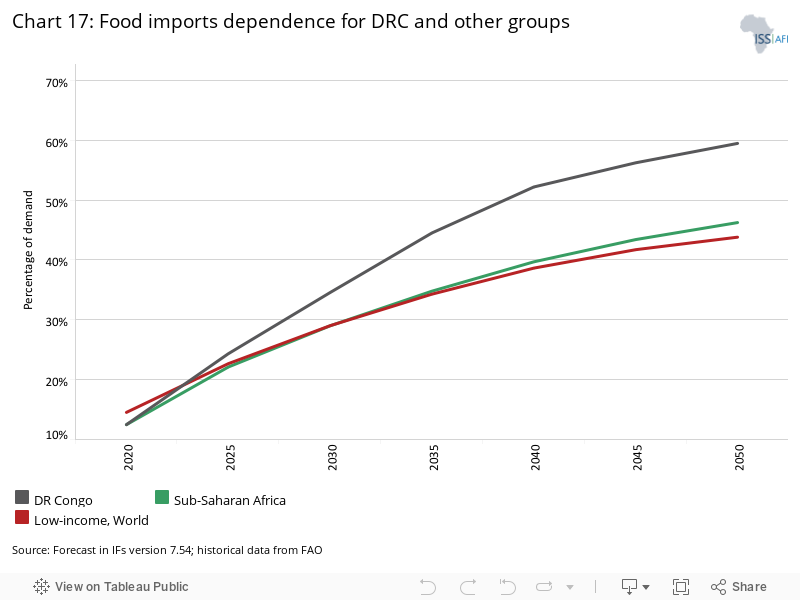

- Despite being the country with the largest available farmland in Africa, the DRC has not achieved food independence and malnutrition is widespread. Jump link to Agriculture and climate change

- The huge infrastructure deficit, especially transport infrastructure and electricity supply, is impeding higher productivity and growth. Jump link to Infrastructure

- Low completion rates and quality are some of the challenges facing the education system. There is a disconnect between this system and the needs of the labour market. Jump link to Education

- Congolese have little access to basic healthcare, mainly due to lack of funding of the sector, mismanagement, shortage of qualified medical staff and high cost of healthcare. Jump link to Health

- The high fertility rate is constraining the prospects for human development. Jump link to Demographics

- The DRC has not made progress in transforming its economy. Exports are poorly diversified and almost exclusively consist of primary products that remain subject to volatile global commodity markets. Jump link to International trade

All charts for Development pathways for the DRC to 2050

- Chart 1: Governance indicators

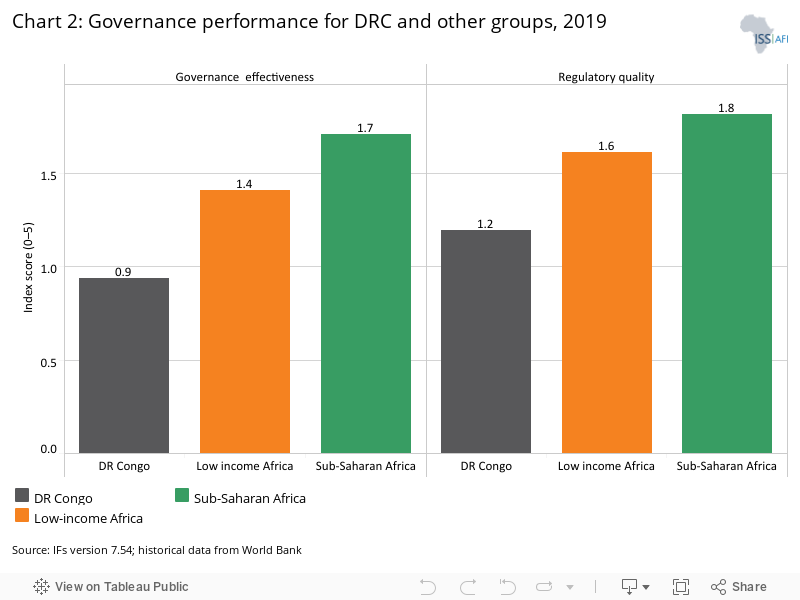

- Chart 2: Governance performance for DR Congo and other groups, 2019

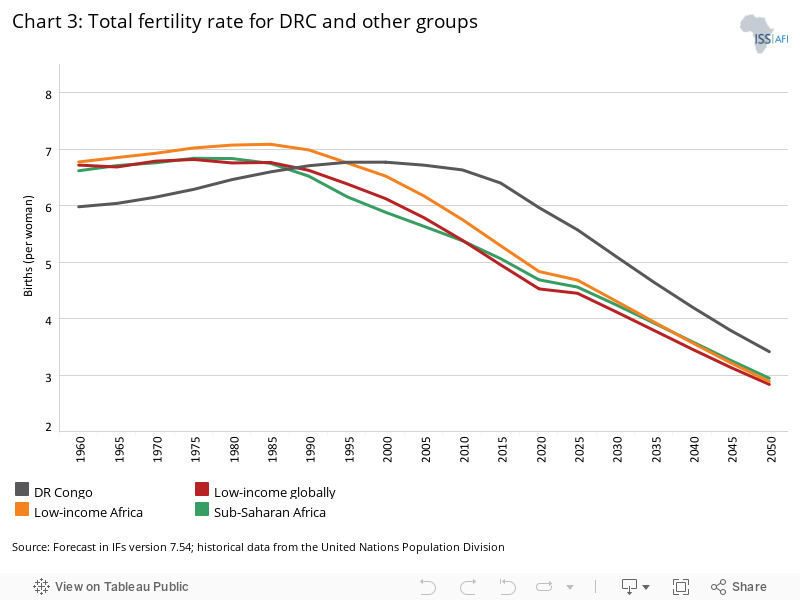

- Chart 3: Total fertility rate for DR Congo and other groups

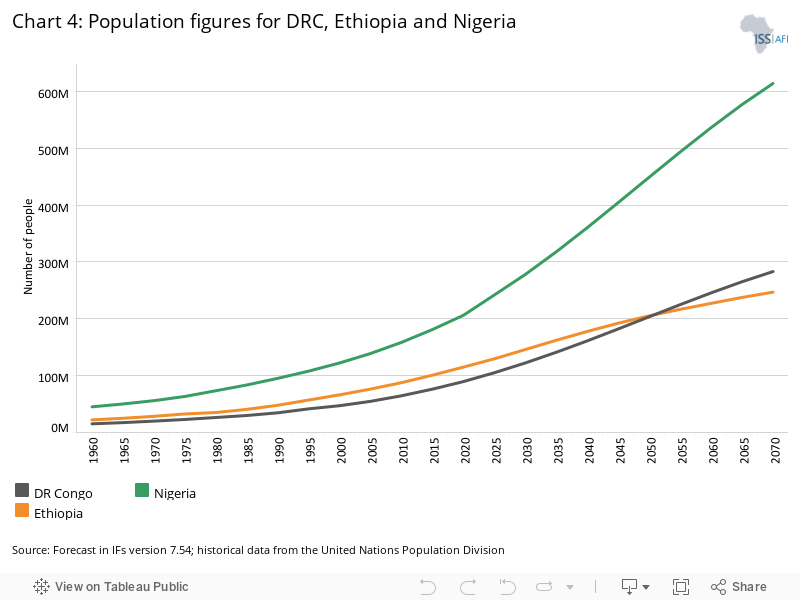

- Chart 4: Population figures for DR Congo, Ethiopia and Nigeria

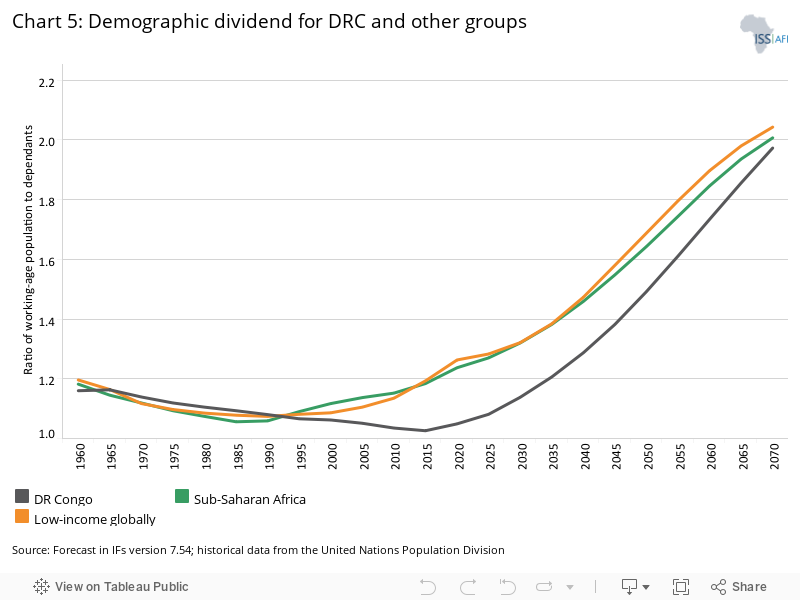

- Chart 5: Demographic dividend for DR Congo and other groups

- Chart 6: Trends in income poverty in DR Congo (<US$1.90 per day)

- Chart 7: Selected educational indicators

- Chart 8: Education outcomes, 2019

- Chart 9: Life expectancy for DR Congo and other groups

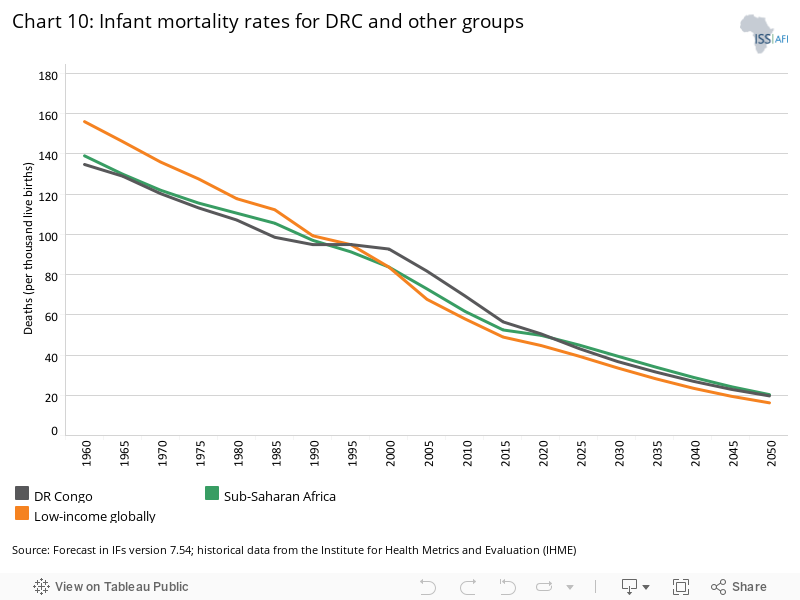

- Chart 10: Infant mortality rates for DR Congo and other groups

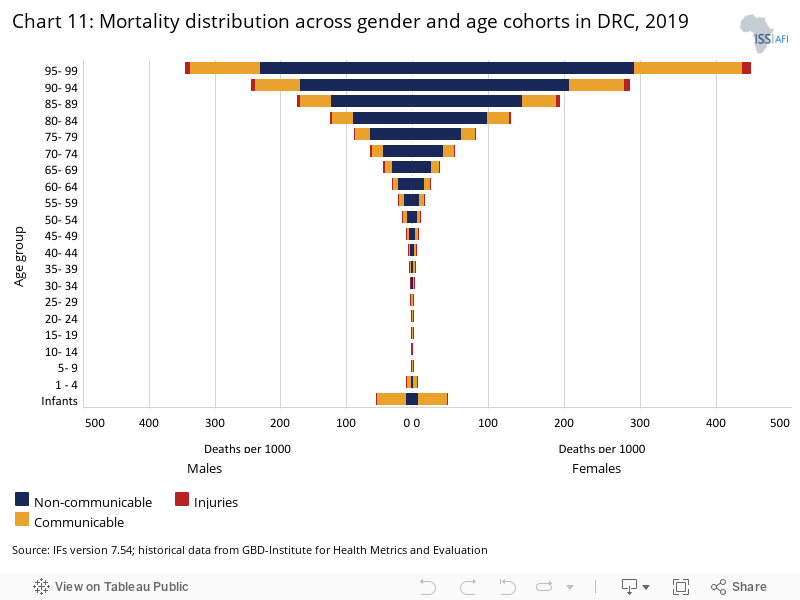

- Chart 11: Mortality distribution across gender and age cohorts in DR Congo, 2019

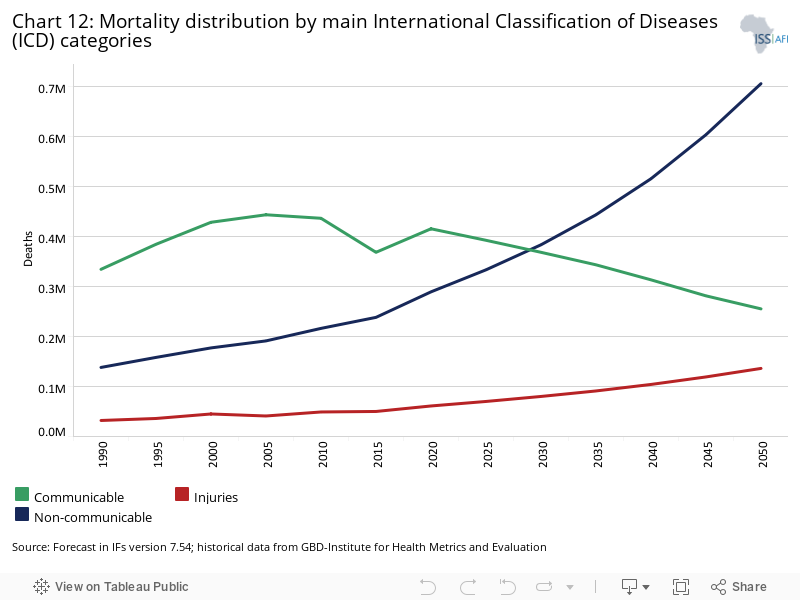

- Chart 12: Mortality distribution by main International Classification of Diseases (ICD) categories

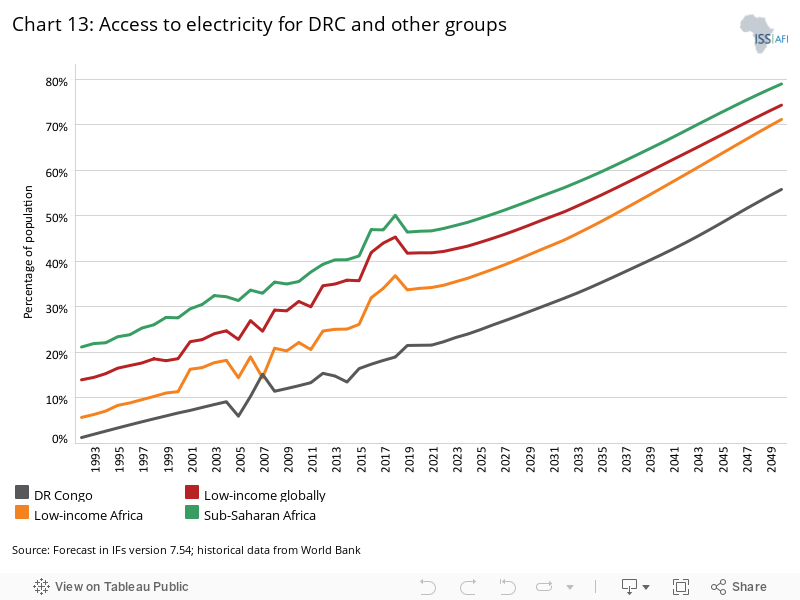

- Chart 13: Access to electricity for DR Congo and other groups

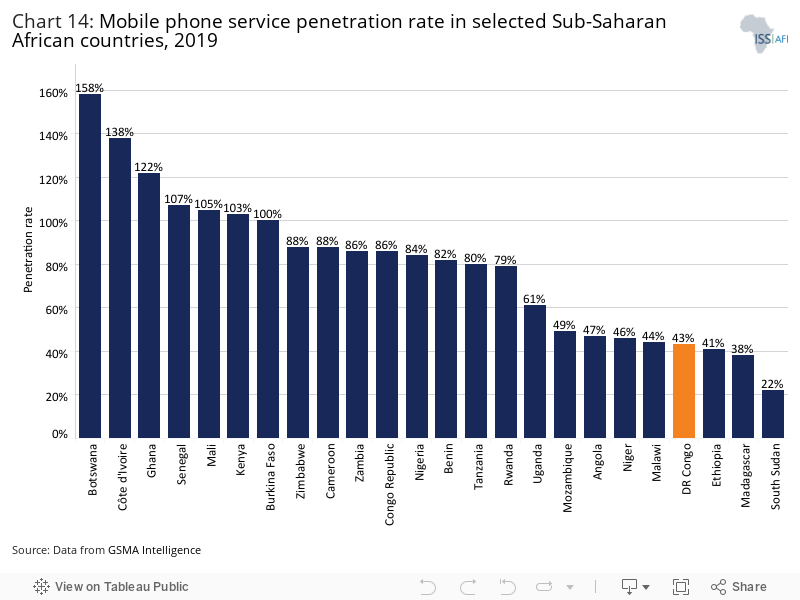

- Chart 14: Mobile phone service penetration rate in selected sub-Saharan African countries, 2019

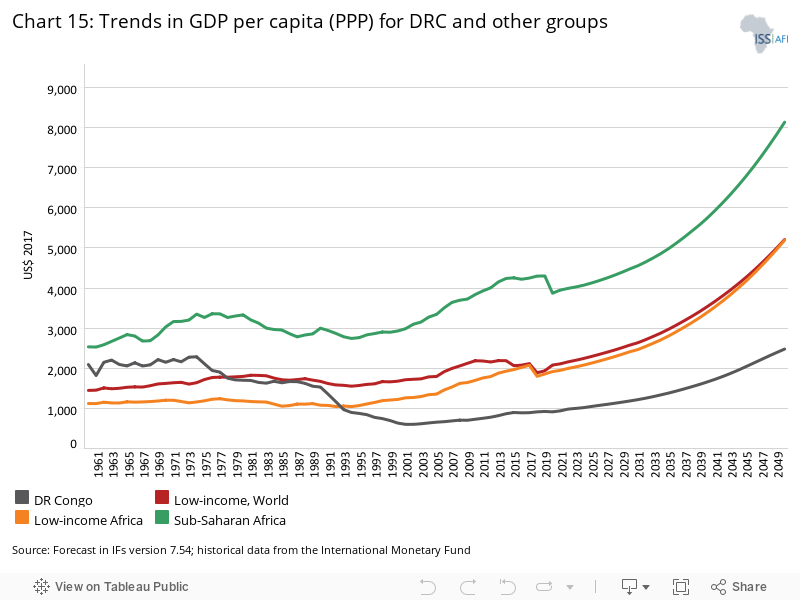

- Chart 15: Trends in GDP per capita (PPP) for DR Congo and other groups

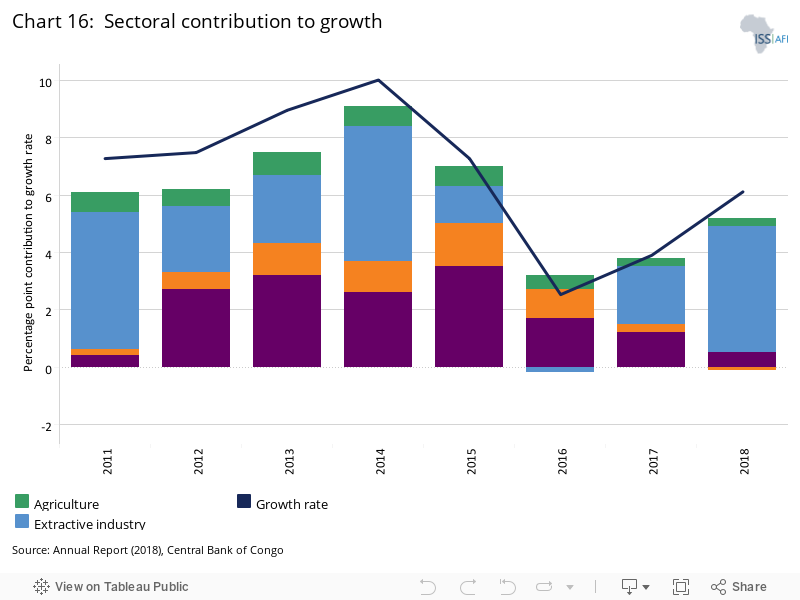

- Chart 16: Sectoral contribution to growth

- Chart 17: Food imports dependence for DR Congo and other groups

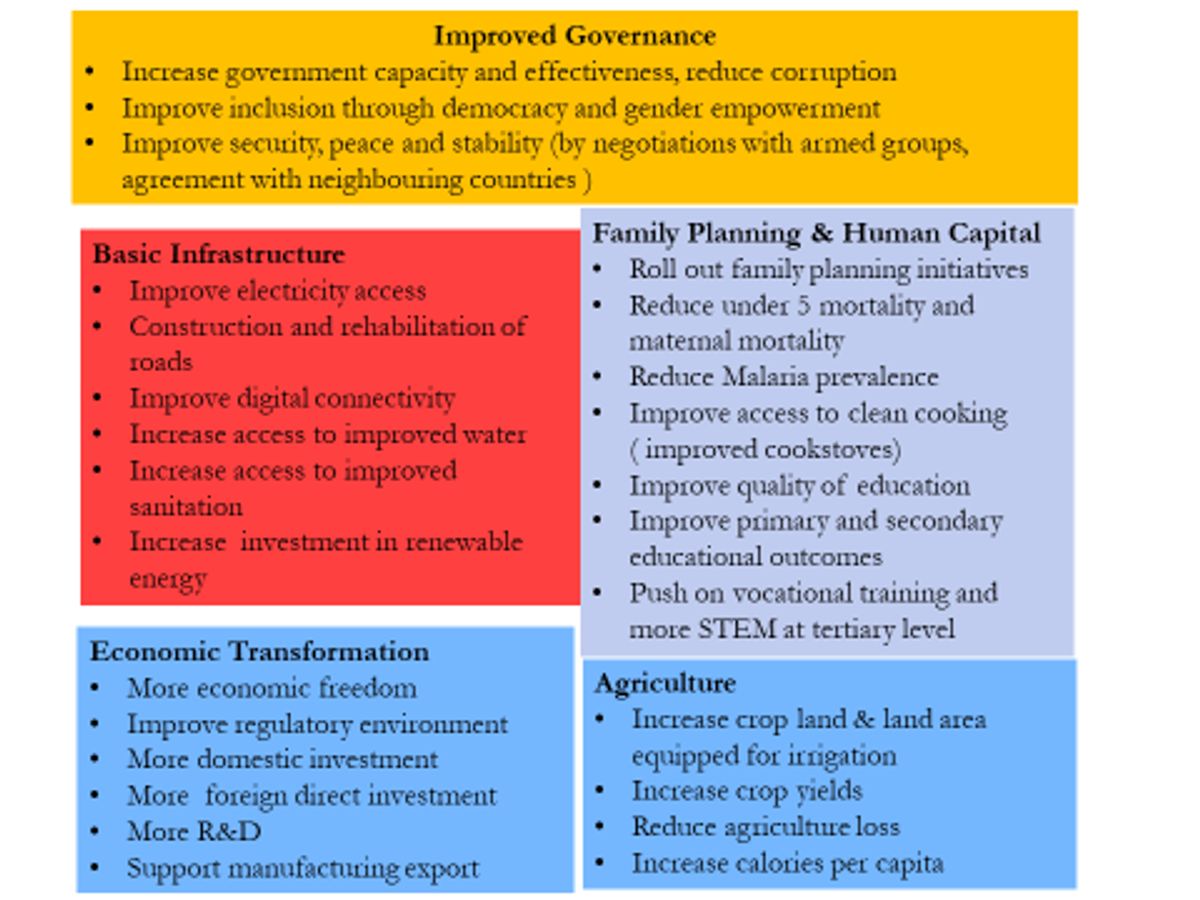

- Chart 18: Intervention clusters

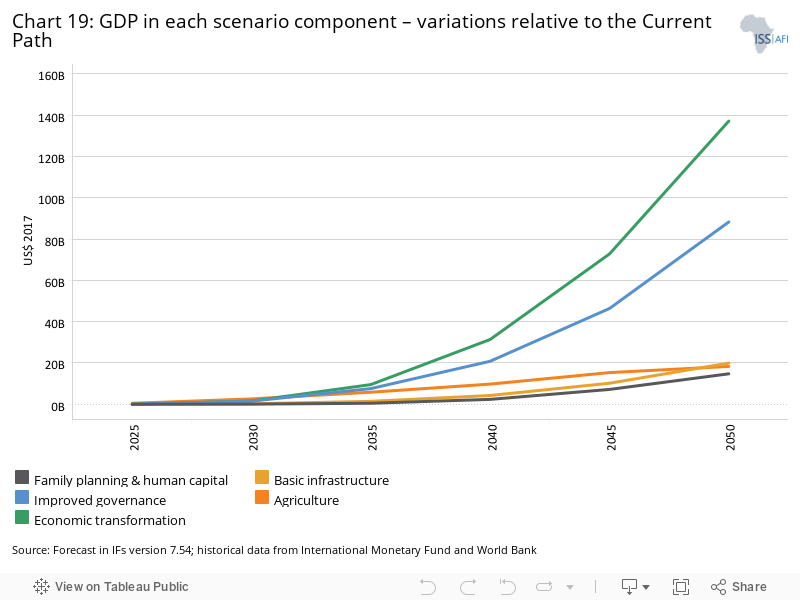

- Chart 19: GDP in each scenario component — variations relative to the Current Path

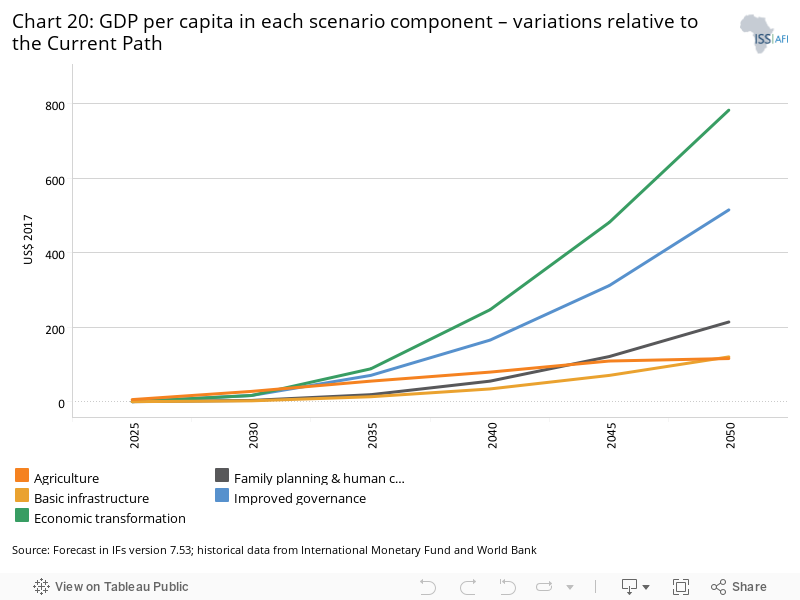

- Chart 20: GDP per capita in each scenario component — variations relative to the Current Path

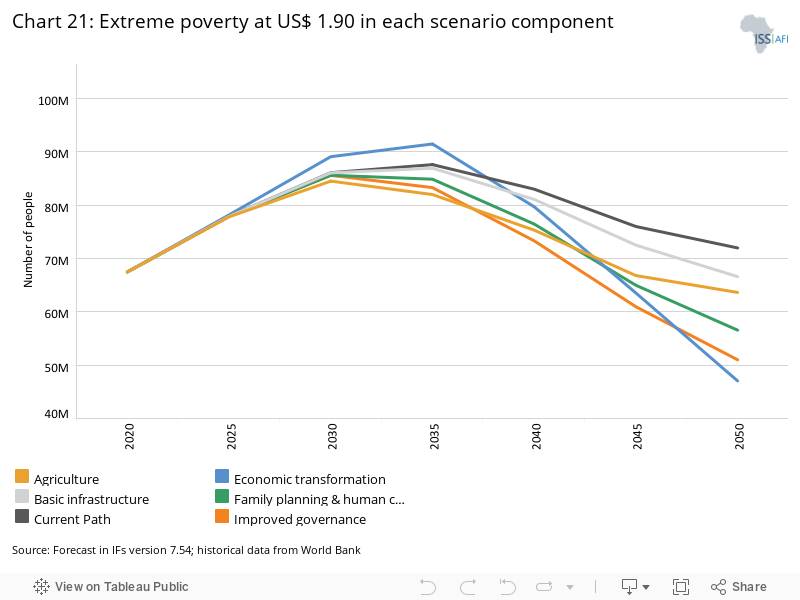

- Chart 21: Extreme poverty at US$ 1.90 in each scenario component

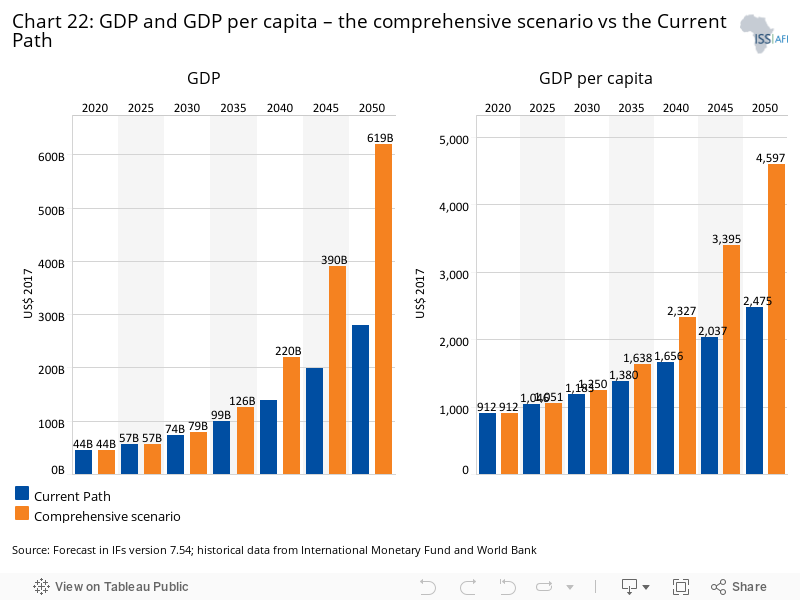

- Chart 22: GDP and GDP per capita — the comprehensive scenario vs the Current Path

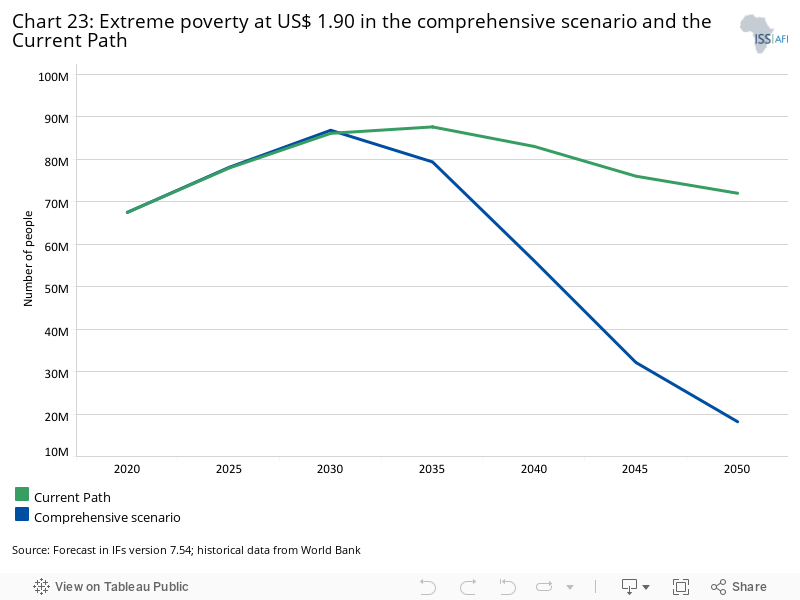

- Chart 23: Extreme poverty at US$ 1.90 in the comprehensive scenario and the Current Path

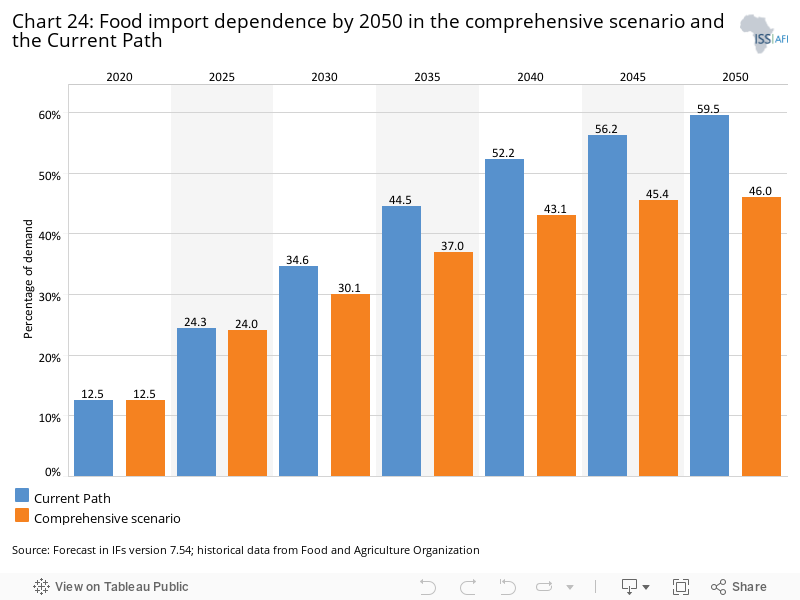

- Chart 24: Food import dependence by 2050 in the comprehensive scenario and the Current Path

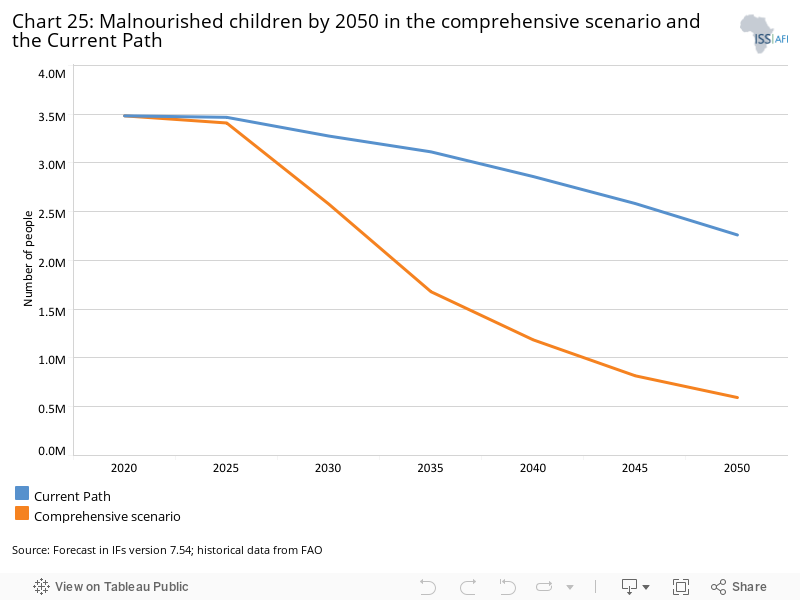

- Chart 25: Malnourished children by 2050 in the comprehensive scenario and the Current Path

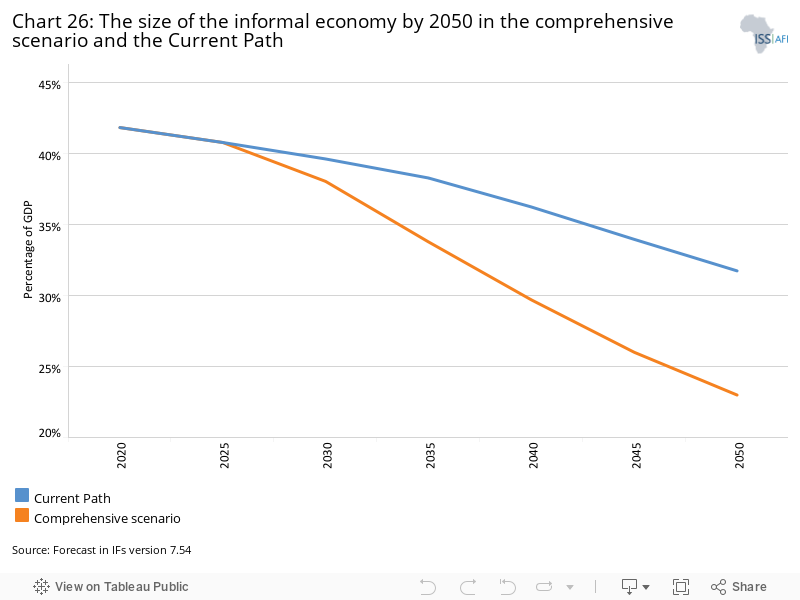

- Chart 26: The size of the informal economy by 2050 in the comprehensive scenario and the Current Path

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo) is the second largest country in Africa after Algeria in terms of territory and the third most populous country in Africa after Nigeria and Ethiopia. It has a surface area of 2.3 million km² and a population of more than 85 million.[1The demographic figures in the DRC are not very solid; the last census was organised in 1984.] The country is particularly known for its abundant and diverse mineral resources, extensive navigable waterways, vast hydroelectric potential and its arable land estimated at 80 million hectares. It possesses about 50% of the global reserves of cobalt, 25% of the world's diamond reserves and large reserves of coltan.[2The Sentry, Country briefs: Democratic Republic of Congo, July 2015]

With these immense and enviable natural resources, one would expect the DR Congo to be among the richest economies and even one of the locomotives of economic growth in Africa. However, the reality is quite different. The country is a classic case of what is called the 'paradox of plenty'. Indeed, the DR Congo ranks near the bottom in various human and economic development indicators.

It was unable to fulfil any of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) by 2015[3Nations Unies, Commission Economique pour l’Afrique, Profile de pays: République démocratique du Congo 2017, Addis Ababa: NU.CEA, 2018–03] and remains a low-income country with one of the lowest GDP per capita in the world. More than 70% of the population lives in extreme poverty and the country ranks 179th of 189 countries on the Human Development Index. [4The score of the DRC on human development index, which measures the 'basic achievement levels in human development such as knowledge and understanding, a long and healthy life, and an acceptable standard of living', experienced only a marginal increase from 0.37 in 1990 to 0.45 in 2018. For more details, see Human Development

Report 2019.] For most of its recent history, the country has been plagued by persistent political instability, violent conflict involving foreign and local armed groups, and poor governance.

Even though the DR Congo is portrayed as a post-conflict country, considerable parts of the country and millions of Congolese are still coping with violent conflict daily, including large parts of North Kivu, South Kivu, Ituri, Haut-Uele and Tanganyika provinces. Consequently, the country continues to face an acute and complex humanitarian crisis.

According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the DR Congo is currently home to five million internally displaced people, the largest in Africa. It also hosts 538 000 refugees from neighbouring countries and has the second largest number of people in acute food insecurity in the world with 15.6 million people affected while 4.7 million people suffer from acute malnutrition.[5OCHA, Aperçu des besoins humanitaires, République démocratique du Congo, Cycle de programme humanitaire 2020, 2019]

In sum, the DR Congo faces numerous development challenges. There are, however, reasons to expect a better future. The first peaceful transfer of power in the country's history offers hope for national and regional stability — a key condition for inclusive sustained growth and development.

The new president, Félix Tshisekedi, has promised major reforms and policies to transform the country's image of poverty, conflicts and diseases into a flourishing economy and a conducive place for investment. In his speech during the 'Makutano Forum' that took place in September 2019 in Kinshasa, President Tshisekedi promised to set the country on a path of sustained economic growth. He pointed out that, 'DRC has for a long time been termed as a giant with clay feet, however, the country is now standing and ready to move forward.'[6Edith Mutethya, DR Congo aims for economic growth, China Daily, 12 September 2019

]

This report first presents the likely human and economic development prospects of the DR Congo to 2050 on its current trajectory. The analysis of the Current Path is followed by a set of complementary scenario interventions that explore the impact of sectoral improvements on the future of the country that may help the authorities to achieve their long-term development targets.

The report uses the International Futures (IFs) forecasting platform (see Box 1) to compare progress with three main country groups (global low-income, Africa low-income and sub-Saharan Africa). The DR Congo is excluded from these groups.

Box 1: Tool for forecasting: The International Futures (IFs) modelling platform

The IFs modelling platform is a global long-term forecasting tool that integrates various development systems, including demography, economy, education, health, agriculture, environment, energy, infrastructure, technology and governance. It blends different modelling techniques to form a series of relationships based on academic literature to generate its forecasts.

IFs uses historical data from 1960 (where available) to identify trends and produce a ‘Current Path’ scenario from 2015 (the current base year). The Current Path is a dynamic scenario representing current policy choices and technological advancements and assumes no significant shocks or catastrophes. However, it moves beyond a linear extrapolation of past and current trends by leveraging our available knowledge about how systems interact to produce a dynamic forecast.

The data series within IFs comes from a range of international sources like the World Bank, World Health Organization (WHO) and various UN bodies like the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNPF). The model is an open-source tool and can be downloaded for free at www.pardee.du.edu.

This project uses IFs version 7.63 for its analysis.

Note that all gross domestic product (GDP) and GDP per capita figures in this report are in 2017 constant US$.

The history of the DR Congo, since its independence, has been characterised by recurrent conflicts and political instability, poor governance and ineffective economic policies. Almost immediately after the country gained independence in 1960, it experienced social and political upheavals. The army mutinied one week after independence and the provinces of Kasaï and Katanga, respectively rich in diamond and copper, attempted to secede in the following weeks.[7World Bank, Democratic Republic of Congo, Systematic Country Diagnostic, Report No. 112733-ZR, 2018.] Eventually, United Nations and Congolese government forces managed to reconquer Kasaï (in December 1961) and Katanga (in January 1963).

The first republic, between 1960 and 1965, was marked by armed conflicts that claimed the lives of nearly two million Congolese and ended in a military coup led by Colonel Joseph-Désiré Mobutu on 24 November 1965. Mobutu declared himself president for five years and was elected as such but without opposition in 1970.[8World Bank, Democratic Republic of Congo, Systematic Country Diagnostic, Report No. 112733-ZR, 2018.]

Amongst many measures, Mobutu rolled back the imposition of a federal state as set out in the 1964 Luluabourg Constitution that had divided the country into 21 provinces. Henceforth, the country was divided into nine provinces with limited provincial autonomy. The impetus towards greater regional autonomy did not disappear, however. In 1982, the parliament embarked on a series of reforms, including administrative decentralisation but the legal text was never implemented. Mobutu was eventually forced from power in 1997 having effectively mismanaged his country for more than three decades.[9DP Zongwe, Decentralization in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Autonomy Arrangements in the World, March 2019, 9, DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.20028.08321.]

Efforts at economic reform on the back of high copper prices did see a brief period of economic expansion between 1967 and 1973 that came to an abrupt end with the two oil crises (1973 and 1979) and the fall in the price of copper (1975). The impact of the 1973 oil crisis was exacerbated by the introduction of Mobutu’s Zairianisation policy in 1973 (a form of indigenisation of the economy) that was followed by the radicalisation policy which saw an increase in the role of the state in the economy.

These policies along with poor public financial management and wanton corruption led to hyperinflation, mounting debt, capital flight, increased poverty, and low agricultural production, among other problems.[10DR Congo, Agence nationale pour la promotion des investissements, 2020] By 1975, the country could no longer service its debt and requested the assistance of the IMF to extricate it from its economic crisis.

From 1983 to 1989, the DR Congo partnered with the IMF and the World Bank in a structural adjustment programme that contributed to economic recovery. However, with the return of a more favourable external environment, the government ceased its efforts at policy and governance reforms only to again experience a marked deterioration in its financial performance.[11B Akitoby and M Cinyabuguma, Sources of Growth in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: A Cointegration Approach, IMF Working Paper WP/04/114, July 2004, 5–7.]

The end of the Cold War in 1989 effectively robbed the DR Congo of its strategic importance and coincided with a drawn-out political transition, hyperinflation, currency depreciation and the increasing use of the United States dollar in the economy. The weak state and the impact of the Rwandan genocide of 1994 that saw some 1.2 million Rwandese Hutus flee to the eastern part of the country, set the stage for the start of the 1996/97 war.

By 1996, the DR Congo faced a crisis while Mobutu's international support had almost completely vanished.[12G Prunier, Africa's World War: Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Making of a Continental Catastrophe, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.] Successive efforts by the IMF and the World Bank to provide support had also come to naught.

In May 1997, Mobutu was driven from power by the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (AFDL), a coalition of rebel groups backed by Rwanda and Uganda. Laurent-Désiré Kabila proclaimed himself president and changed the name of the country from Zaïre to the DR Congo. He inherited a dysfunctional country and attempted to carry out limited economic and financial reforms, notably a monetary reform that instituted a new currency, the Franc Congolais. He also reduced the decentralised entities (provinces) to four.

However, his fall-out with his old supporters led to a second war — often called the Great African War or the African World War — in August 1998 that involved a number of neighbouring states. The conflict was eventually brought to an end with the signing of the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement in July 1999 between the DR Congo, Angola, Namibia, Rwanda, Uganda and Zimbabwe and the establishment of the United Nations Organisation Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUC).

MONUC’s initial mandate was to observe the ceasefire and the disengagement of state and non-state armed forces but its mandate was substantially expanded over time. According to some studies, the war claimed the lives of millions of people, a large part of which were children under the age of five.[13World Bank, Democratic Republic of Congo, Systematic Country Diagnostic, Report No. 112733-ZR, 2018.]

In 2001, President Laurent-Désiré Kabila was assassinated and succeeded by his son, Joseph Kabila Kabange. The result was a re-engagement with the international community, allowing MONUC to deploy across the country. In 2002, talks among Congolese actors led to the signing of a peace agreement — the Accord Global et Inclusif. This paved the way for the 2003 Transition Constitution, three years of transition, and the holding of the first free and fair elections in the country in 2006, which Joseph Kabila won.

The Accord and the Transition Constitution tasked the Senate with the drafting of the new Constitution that benefited from the work of a constituent assembly, provincial consultations and the input of foreign and Congolese legal experts. The subsequent (and still current) Constitution was adopted in December 2005 by popular referendum and promulgated by President Kabila in February 2006 against a backdrop of ongoing political and security crises. The subsequent 2008 organic law on the territorial-administrative organisation of the state set out the structure of provinces, decentralised territorial entities and deconcentrated territorial entities.

However, little has come of these intentions. The central government failed to meet the 2010 deadline for the establishment of the 26 provinces envisioned in the Constitution, only completing that task five years later.[14The breakdown of the Katanga province into several smaller provinces also aimed at stripping the former Katanga governor and then-presidential hopeful Moise Katumbi of a potential electoral base. DP Zongwe, Decentralization in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Autonomy Arrangements in the World, March 2019, 10–14, DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.20028.08321.]

In the meanwhile, in 2010, MONUC became the United Nations Organisation Stabilisation Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO), now acting in support of an elected government. Joseph Kabila was re-elected in the 2011 presidential election although the event was marred by accusations of corruption and fraud.

Subsequent ambiguity about whether or not Kabila intended to stand for a third term — from which he was constitutionally barred — coupled with a two-year delay in holding the elections, sparked sustained and widespread protests and created significant instability. Following pressure from continental, regional and international actors, Kabila announced, in mid-2018, that he would not stand again and national and provincial elections were eventually held in December 2018. The election results were heavily disputed by the opposition and civil society.

According to domestic election observers, opposition leader Martin Fayulu won the presidential contest. President Félix Tshisekedi's arrival in power is widely perceived as the result of a political deal struck by outgoing President Kabila, whose party lost but who maintains a significant grip on power as a result of a substantial majority in parliament.

Tshisekedi’s Union pour la Démocratie et le Progrès Social (UDPS), Kabila's Front Commun pour le Congo (FCC), and Tshisekedi’s running mate, Vital Kamerhe's Union pour la Nation Congolaise (UNC) now govern the country through a rickety coalition government but which might soon change with the recent shift in power that has come with the ouster of the speaker of its parliament — a perceived Kabila loyalist.

Governance in the DR Congo is characterised by networks of rent-seeking political, military and economic elites that direct and organise the abundant natural resources of the country to serve their ethnic and regional allegiances rather than for sustainable development.[15K Kaiser and S Wolters, Fragile states, elites, and rents in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), in D North et al, (eds.), In the Shadow of Violence: Politics, Economics, and the Problems of Development, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.] Key positions in the administration are typically allocated based on a system of political patronage (prebendalism) rather than on merit.[16K Kaiser and S Wolters, Fragile states, elites, and rents in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), in D North et al, (eds.), In the Shadow of Violence: Politics, Economics, and the Problems of Development, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.]

Despite its vast size, the DR Congo has been a highly centralised state until, in terms of the 2006 Constitution, the former 11 provinces were divided into 26 new territorial units. The subsequent implementation of decentralisation has been fraught, however. As stated by Zongwe:

The rolling out of the decentralisation policy and its timing have been significantly driven by political calculations more than resource constraints, most recently by an attempt by the ruling government to divide provinces into smaller ones in order to prolong its rule. Even after the effective partition of the 11 former provinces [into 26], the process still suffers further complications, like delays and logistic problems in electing new governors, which in turn led to litigation before the Constitutional Court in September 2018. These difficulties take place in a broader context of even greater challenges. The latter include insufficient capacity of provincial administrators, fiscal decentralisation, the questionable economic viability of most provinces, and repeated internal wrangling that has already culminated in the removal or resignation of governors in several provinces.[17DP Zongwe, Decentralization in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Autonomy Arrangements in the World, March 2019, DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.20028.08321.]

By starving the provinces of money, Kinshasa effectively manages the country from the centre. Between 2007 and 2013, for example, the central government only transferred 6%–7% of taxes to the provinces instead of the 40% prescribed in the Constitution.[18DP Zongwe, Decentralization in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Autonomy Arrangements in the World, March 2019, DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.20028.08321.]

A report by Transparency International[19Transparency International, Overview of corruption and anti-corruption in the DRC, 2010, ] points out that, ‘clientelism, rent-seeking and patronage have decimated fair competition, particularly in the sectors of public procurement and extractive industries in DR Congo.’ The report notes that, ‘the ruling elite has a direct stake in the country's economy, and often steer economic activities in accordance [with] their own personal opportunities.’ Often these same state officials present themselves as private entrepreneurs or resort to their parents (or other family members) to obtain state contracts.[20See for example: B Akitoby and M Cinyabuguma, Sources of Growth in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: A Cointegration Approach, IMF Working Paper WP/04/114, July 2004; International Monetary Fund, Democratic Republic of the Congo: Staff-monitored program and request for disbursement under the rapid credit facility, Press Release, Staff Report and Statement by the Executive Director for the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 23 December 2019,]

Corruption is endemic in the DR Congo and permeates all sectors. It ranges from basic bureaucratic and administrative corruption to grand forms of corruption involving high-ranking members of the government and defence and security forces. The extractive (oil and mining) sector, tax and customs administrations, and the state-run enterprises are among the most affected. Significant amounts of mining revenues and taxes that are collected are not channelled to the treasury and end up in the pockets of individuals and public officials. Gécamines, the largest state-run company in the mining sector, is often cited as the main facilitator in the diversion of the mining revenue from the government budget.[21Global Witness, Regime cash machine: How the Democratic Republic of Congo's booming mining exports are failing to benefit its people, 21 July 2017]

Poor government effectiveness and the absence of strong institutional and legal mechanisms to ensure accountability hamper economic progress and further deepen corruption. In 2019, the DR Congo ranked 168th of 180 countries on the Transparency International corruption perceptions index. This high level of corruption significantly affects domestic revenue mobilisation, and hence compromises the badly needed investment in basic socio-economic infrastructure in the country.

Following pressure from the international community, a legal framework to combat corruption was established under Joseph Kabila’s regime but remains ineffective. It often serves more as a political weapon than an actual indication of political will to tackle corruption. As pointed out by Matti,[22SA Matti, The Democratic Republic of Congo: Corruption, Patronage and Competitive Authoritarianism in the DRC, Africa Today, 56:4, Summer 2010, 42–61.] ‘the rent-seeking elites in DR Congo generally lack the incentives and political will to build strong institutions to curb corruption.’

However, the new president has made a strong commitment to deviate from the inefficiency, corruption and political patronage that have characterised governance since Mobutu’s era. Thus, a new commission to combat corruption has been created — l'Agence de prévention et de lutte contre la corruption (APLC) — and some high-level arrests have been made, such as the president’s chief of staff, Vital Kamerhe, who was found guilty of embezzlement. However, Vital Kamerhe's supporters and some observers perceive his arrest as politically motivated given his presidential ambitions for 2023 rather than a step towards the establishment of the rule of law in the country.

The institutional characteristics echo this telling feature of the institutional environment. The Polity V composite index from the Centre for Systemic Peace (CSP) categorises countries according to their regime characteristics. According to this index, the DR Congo has transitioned from an authoritarian governance model to an anocracy (reflecting its current unstable hybrid regime type). It is neither authoritarian nor fully democratic; it goes through the motions of elections, for example, but they are not substantively free and fair with all the attendant challenges associated with such hybrid systems.

In its most recent data update for 2018, the CSP allocated the DR Congo a score of -3 on its scale of -10 (full autocracy) to +10 (consolidated democracy). This is compared to the average for low-income countries of 1.36, indicating that the country has significantly more authoritarian governance characteristics than its peers.[23Center for Systemic Peace, Polity5 Annual Time Series 1946–2018]

The V-Dem dataset, which compares different types of democracy, scores the DR Congo as 0.327 out of 1 on its electoral democracy index but only 0.139 on its liberal democracy index. This reflects the extent to which the nominal practices of democracy are not accompanied by substantive democracy. To compound these challenges, the gap between the two types of democracy has increased, reflecting the extent to which the DR Congo’s institutions and elections lack legitimacy and that many of its core structures are not independent.

The characteristics of a country's population can shape its long-term social, economic, and political foundations; thus, understanding a nation’s demographic profile indicates its development prospects.

The population of the DR Congo is made up of 40 ethnic groups and a wide variety of sub-groups.[24The number of ethnic groups varies according to sources. Demographic data in the DRC should be taken with caution. The first and so far only census conducted in the country dates from 1984.] This diversity is an important factor in political, social and cultural terms and has evolved into an important source of tensions and conflicts in the country. The population is predominantly animist and Christian while French is the official language. The other major recognised and spoken national languages are Kikongo (in the west), Lingala (in Kinshasa and the northwest), Swahili (in the east) and Tshiluba (in the south centre).[25DR Congo, Deuxieme Enquete Demographique et de Santé (EDS-RDC II 2013–2014), Ministère du Plan et Suivi de la Mise en oeuvre de la Révolution de la Modernité, Septembre 2014]

The fertility rate in the DR Congo was 5.9 children per woman in 2019, down from its average level of 6.7 in the 1990s. With one of the highest fertility rates in the world — it is currently ranked third globally after Niger (6.9) and Somalia (6.1) — the DR Congo’s population is rapidly growing. The growth rate in 2019 was about 3.2%, making it the fifth highest in terms of population growth in Africa. Its total population was estimated at 89.5 million in 2020, and the country ranks third in Africa after Nigeria and Ethiopia in population size.

The fertility rate is not homogenous across the country. According to the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) 2013/2014, Kinshasa has the lowest fertility rate with 4.2 children per woman. The highest fertility rate is recorded in Kasaï Occidental with 8.2 children per woman. The urban areas have a lower fertility rate (5.4) compared to the rural areas (7.3).

The fertility rate also varies according to the level of education and wealth of the mother. The average number of children per woman with at least a secondary education is 2.9, and 7.4 for a woman with no education. The average number of children per woman in the poorest households is 7.6 while it is 4.9 in the wealthiest households. [26DR Congo, Deuxieme Enquete Demographique et de Santé (EDS-RDC II 2013–2014), Ministère du Plan et Suivi de la Mise en oeuvre de la Révolution de la Modernité, Septembre 2014] Modern contraception use is about 20% and varies according to the level of education. For instance, it is 19% among women with at least secondary education while it is only 4% among women with no education.[27DR Congo, Deuxieme Enquete Demographique et de Santé (EDS-RDC II 2013–2014), Ministère du Plan et Suivi de la Mise en oeuvre de la Révolution de la Modernité, Septembre 2014]

On the Current Path, the total fertility rate in the DR Congo is expected to be 3.4 in 2050. This will be above the averages for sub-Saharan Africa (2.9) and low-income countries globally (2.8) in 2050 (Chart 3). The country will then have the sixth highest fertility rate in the world.

On the Current Path, the total population of the DR Congo is estimated to double by 2045 and overtake Ethiopia from 2050 to become the second most populous country in Africa after Nigeria (Chart 4).

The high population growth in the DR Congo goes hand-in-hand with rapid urbanisation. In 2019, 45% of the population was living in urban areas and it is projected to reach 64% in 2050.[28United Nations, World Urbanisation Prospects: the 2018 revision, New York: UN, 2019, ] As a result of this rapid urbanisation, Kinshasa, the capital city with its population estimated at 12 million in 2016 and an annual growth rate of about 5.1%, is projected to be home to 24 million people by 2030. It will become the most populous city in Africa, ahead of Cairo and Lagos.[29World Bank, Democratic Republic of Congo Urbanization Review: Productive and Inclusive Cities for an Emerging Congo, Directions in Development: Environment and Sustainable Development, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2018.]

This is likely to pose huge challenges without proper urban planning and management and if the creation of employment opportunities for urban youth is not achieved. Nearly 75% of the urban population in the DR Congo live in slums. This is 15 percentage points higher than the average for sub-Saharan Africa.[30World Bank, Democratic Republic of Congo Urbanization Review: Productive and Inclusive Cities for an Emerging Congo, Directions in Development: Environment and Sustainable Development, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2018.]

One of the important aspects of a nation’s population is the age structure because it can contribute to or delay economic growth and progress in human development. The share of the working-age population (15 to 64 years) is currently 51% of the total population, and it is projected to be 60% in 2050.

About 46% of the country’s population is under the age of 15. This means that a large portion of the population is dependent on the small workforce to provide for its needs. The population under 15 years is expected to decline but will still constitute about 36% of the population in 2050. The share of the elderly (65 and above) has been stable over time — it is about 3% — and it is projected to reach 3.6% in 2050.

When the ratio of the working-age population to dependent is 1.7:1 or more, countries often experience more rapid growth provided the growing number of workers can be absorbed by the labour market. This is an easy way in which to measure a country’s demographic dividend.

On the Current Path, the ratio of the working-age population to dependents will only be at 1.2:1 in 2030 and 1.5:1 in 2050, below the threshold ratio of 1.7:1 that a country needs to reap the demographic dividend. The DR Congo only gets to this positive ratio at around 2060, implying that it will achieve its demographic dividend almost a decade later than the average for low-income countries globally.

Empirical studies have shown that the demographic dividend contributed significantly to the East Asian countries' economic miracle, however, the demographic change was not something that happened automatically but rather the result of demographic policies. For instance, these countries improved access to contraceptive services and encouraged couples to have fewer children through incentives.[31A Mason (ed.), Population Policies and Programs in East Asia, Population and Health Series No. 123, Honolulu: East-West Centre, 2001] Therefore, appropriate policies need to be implemented by DR Congo authorities to stimulate the demographic transition and to reap the demographic dividend.

The DR Congo also has a large youth bulge at 49%. A youth bulge is defined as the percentage of the population between 15 and 29 years old relative to the population aged 15 and above. In addition to the requirement for more spending on education, health services and job creation, large numbers of young adults can positively influence change in a country.

Events such as the Arab Spring and social unrest in Chile and Sudan have shown that large numbers of young adults, particularly males without employment or job prospects, can carry the seeds for socio-political instability but they also have the potential of youth activism leading to positive political changes in a country.

Without the design and implementation of sound demographic policies aimed at bringing down the current high fertility rate, the rapidly growing population in the DR Congo is a significant obstacle to the country’s progress towards economic prosperity and decent human development.

The DR Congo is among the world’s poorest countries with a GDP per capita of US$837 in 2019. In 2005, 94% of the Congolese were surviving on less than US$1.90 a day, the international threshold of extreme poverty for low-income countries. It declined to about 77% in 2012. The latest estimation by the World Bank put the extreme poverty rate at 73% in 2018.[32World Bank, Country profile, DR Congo, 2019.]

Despite this modest decline, extreme poverty in the DR Congo is exceptionally high and above that of sub-Saharan Africa which is at about 41.1%.[33World Bank, Piecing together the poverty puzzle, Poverty and shared prosperity, 2018] With about 60 million people living in extreme poverty, DR Congo is the country with the highest number of poor people in sub-Saharan Africa after Nigeria which has about 83 million people in extreme poverty. According to the World Bank, DR Congo, India, Nigeria, Ethiopia and Bangladesh are home to 50% of the people that are extremely poor in the world.

The poverty incidence varies across provinces. For instance, Equateur, Kivu and the former Orientale provinces experienced a significant decline in extreme poverty from 2005 to 2012, (-16% to -21%) while Maniema and the Kasaï provinces recorded an increased incidence of poverty (+8.6% to +23.3%).[34World Bank, Democratic Republic of Congo, Systematic Country Diagnostic, Report No. 112733-ZR, 2018.]

Poverty seems to have become more an urban phenomenon in the country as the poverty rate has declined faster in rural areas than in urban areas. The latest data from the World Bank indicates that, in 2012, the national poverty rate was 64.9% in rural areas compared to 66.8% in urban areas (excluding Kinshasa). Between 2005 and 2012, the poverty rate in rural areas declined by 5.6 percentage points compared to 5.1 in urban areas (excluding Kinshasa). The poverty rate in Kinshasa is lower than the national average, although it has decreased slower than in rural and other urban areas.[35World Bank, Democratic Republic of Congo Urbanization Review: Productive and Inclusive Cities for an Emerging Congo, Directions in Development: Environment and Sustainable Development, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2018.]

Poverty is not just a lack of money. Poverty is multidimensional, thus, measuring poverty by focusing only on the monetary aspect can be misleading. For instance, malnutrition, lack of clean water, health services, electricity or education are examples of poverty that go beyond the income considerations. The global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI)[5] which takes into account the multidimensional aspect of poverty shows that 64.5% of Congolese are multidimensionally poor with 36.8% of them in severe multidimensional poverty.[36The MPI has three dimensions and 10 indicators: health (nutrition and child mortality); education (years of schooling and school attendance); and living standards (cooking fuel, sanitation, drinking water, electricity, housing, assets).]

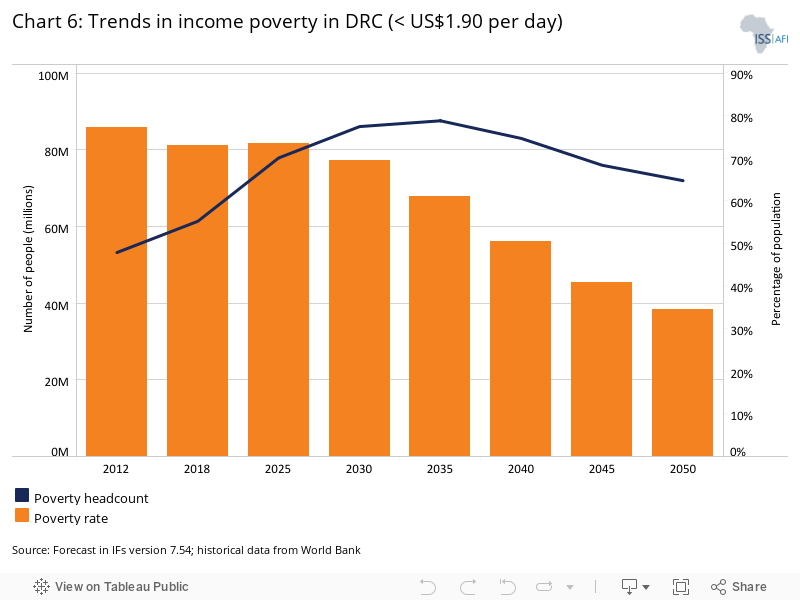

In the Current Path forecast, about 69% of the population will live on less than US$1.90 per day (extreme poverty) by 2030, and 34.5% in 2050 (Chart 6). This would imply that, on the current development trajectory, the DR Congo will not be able to achieve the headline goal of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) concerning the eradication of extreme poverty.

On the Current Path, about 86 million people will still be living in extreme poverty by 2030, and nearly 72 million by 2050. This is in line with the 2018 Goalkeepers report by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.[37B Gates and M French Gates, Goalkeepers, The stories behind the data, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, 2018,

] According to this report, by 2050, sub-Saharan Africa will be home to 86% of the people living in extreme poverty in the world, and this will be mainly driven by the large number of poor people in Nigeria and DR Congo. The report stated that by 2050, these two countries will be home to more than 40% of the world's poorest people.

The DR Congo had a relatively high level of income inequality (measured by the Gini index) at 42.1 in 2012 that might have contributed to the low elasticity of poverty to economic growth. The Current Path forecast in IFs puts the Gini index at 42.4 in 2019, below the average income inequality level for sub-Saharan Africa (43), and above the average for low-income countries globally (39.7) in the same year.

Overall, poverty is massive in the DR Congo regardless of the measures used (national or international standards). Factors such as armed conflicts, poor governance, high fertility rate, infrastructure shortage and low schooling, among others, are some of the root causes of the misery of millions of Congolese. Urgent action by all stakeholders is required to curb this alarming poverty trend.

The Congolese education system is a hybrid. It is made up of public secular schools and religiously affiliated schools. The Catholic Church is by far the most important actor in the DR Congo’s education system and this was so from the very early stages of the colonial period. The Church organises most of the education and the state provides (at least in theory) the funding.

The duration of compulsory basic education is six years for children between six and eleven years old. Although there is a three-year pre-primary education, it is only available in a few urban areas.

Secondary education has two components (cycle long and cycle court). The cycle long consists of the first stage of two years of general studies called tronc commun or cycle d’orientation. The second stage of four years of specialisation ends with a certificate called the Diplôme d'Etat for those who pass the terminal examination called the Examen d'Etat which grants access to tertiary education. The cycle court concerns vocational education and consists of a four-year course starting immediately after primary education, or a three-year course after the first stage of the cycle long.[38World Bank, Education in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Priorities and Options for Regeneration, World Bank Country Study, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2005]

The regular age for lower secondary education is 12 to 13 years and 14 to 17 years for upper secondary education. Repetition is permitted only once in each stage.[39World Bank, Education in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Priorities and Options for Regeneration, World Bank Country Study, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2005]

The DR Congo has recorded a notable improvement in indicators related to education over the past 15 years. The adult literacy rate (population aged 15 years and older) experienced an improvement from 61.2% in 2007 to 79.5% in 2019. Higher literacy rates improve employment prospects for the poor, and hence, an opportunity to get themselves out of extreme poverty. IFs forecasts the literacy rate in the DR Congo at 98% by 2050, well above the average for low-income Africa (91%).

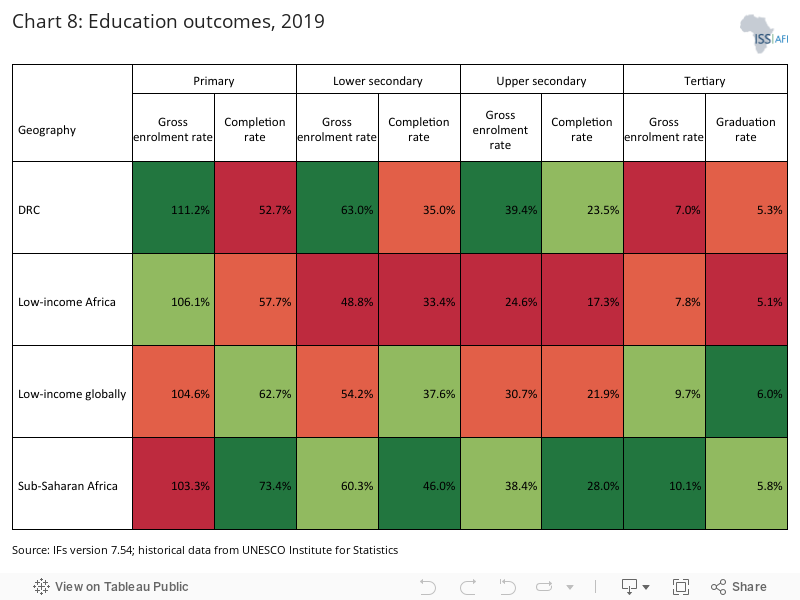

Generally, the DR Congo is on par with its peers in terms of primary and secondary school participation rates (Chart 8).

The education completion rate is very low regardless of the level. Because of low completion and transition rates right from the primary level, fewer students are eligible for subsequent education levels and the resultant outcomes get poorer. It is estimated that half of the students who enrol at universities drop out before their third year. Some of the root causes of low educational outcomes in the country are widespread malnutrition, the difficulty for the students to switch from their mother tongue to learning in French, and especially, financial constraints. In a survey conducted in 2018, about 64% of households mentioned that financial constraints were the main obstacle to their children’s education.[40World Bank, 'When I grow up, I'll be a teacher.' The new ambitions of Congolese schoolchildren now that school is free, World Bank, 16 June 2020]

Although free primary education in public schools is enshrined in the 2006 Constitution and included in the education law adopted in 2014, it was not applied until September 2019 after a decision by the newly-elected President Tshisekedi. This gives an additional 2.5 million children access to primary education.[41World Bank, 'When I grow up, I'll be a teacher.' The new ambitions of Congolese schoolchildren now that school is free, World Bank, 16 June 2020] Previously parents had to pay two-thirds of school costs which most households were unable to afford and often had to choose between feeding their children or keeping them in school.[42World Bank, 'When I grow up, I'll be a teacher.' The new ambitions of Congolese schoolchildren now that school is free, World Bank, 16 June 2020]

The free primary education programme is widely supported, but the decision to implement it raises concerns about the government's capacity to shoulder the associated cost (teachers’ salaries, etc.) estimated at more than US$1 billion annually, and the material capacity of the educational system to absorb such a massive influx of learners.

Female education in the DR Congo has experienced some improvements, but more needs to be done to close the gap between female and male education, especially at secondary and tertiary levels. The improvement is more significant in primary education. For instance, the parity ratio in primary education increased from 0.81 in 2007 to 0.90 in 2015 and was estimated at 0.99 in 2019. The parity ratio in secondary education was 0.70 in 2019, up from 0.5 in 2007. The parity ratio at tertiary level improved from 0.35 in 2007 to roughly 0.60 in 2019.[43UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2020]

This improvement in gender equality in education augurs well for productivity and growth in the DR Congo. Educating girls improves not only the average level of human capital in a country but also generates female-specific effects such as decreasing fertility and child mortality rates, as well as benefits on children’s health and education that contribute to economic growth.[44World Bank, World Development Report 2012: Gender Equality and Development, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2012.]

Although the DR Congo has made significant progress in getting more children into school, the quality of education they receive is poor and not well suited to the needs of the job market. This remains a major challenge facing the education system. Learners in the DR Congo score 318 out of 625 on the Harmonised Test Scores while the average African learner scores 374; 625 represents advanced attainment while 300 represents minimum attainment. The country ranked 40th out of 44 African countries on educational quality.[45African Economic Outlook, Developing Africa’s workforce for the future, African Development Bank, 2020.]

The main factors explaining this low quality of education are the shortage of teaching staff with the required skills, obsolete equipment and overcrowded classrooms.[46World Bank, Democratic Republic of Congo, Systematic Country Diagnostic, Report No. 112733-ZR, 2018.] The education sector is underfunded; the government spending on education was about 2.5% of GDP in 2019 while the sub-Saharan African average was 4.3% of GDP.

There are promising efforts towards the improvement in the quality and quantity of education and hence human capital in the DR Congo. On 16 June 2020, the World Bank approved US$1 billion in loans and grants to support the education and health sectors in the DR Congo. Specifically, US$800 million will be used to roll out the free primary education programme in the poorest provinces such as the Centre, East and Kinshasa. The funds will also be used to strengthen governance in the education system as well as to improve the quality of education.

According to the World Bank, the programme will provide more than one million poor children, currently excluded from the education system, with access to education, while US$200 million will be used to respond to health emergencies in 14 provinces, particularly for mothers and children.[47Agence France-Presse, The World Bank earmarks US$1bn for DR Congo health, education, MNA International, 17 June 2020

]

At independence, the DR Congo had a relatively well-organised and efficient health system as a result of the mutual efforts of the government, multilateral cooperation and secular and religiously affiliated NGOs. However, subsequent lack of investment, mismanagement and decades of conflict have led to a near-collapse of the system. There is a high presence of non-state actors, such as faith-based organisations, in the country’s health system. For instance, in 2013, 45% of hospitals in the country were managed by religious organisations, 44% by the government and 11% by private firms.[48B Naughton et al, DRC survey: An overview of demographics, health, and financial services in the Democratic Republic of Congo, START Center, University of Washington, March 2017, ]

Congolese have little access to basic healthcare, mainly due to lack of funding of the sector, mismanagement and corruption, lack of qualified medical staff, and high cost of healthcare, among others. For example, healthcare costs are 60%–70% funded by direct contributions from households, compared to a world average of 46%. Also, because there are a limited number of health centres, around 74% of the population live more than 5 km from such centres.[49LS Ho et al, Effects of a community scorecard on improving the local health system in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo: Qualitative evidence using the most significant change technique, Conflict and Health, 9:27, 2015]

Since the mid-2000s, the country has, however, undertaken several reforms in the health sector reflected in multiple strategies. In 2010, the government adopted the National Health Development Plan 2011–2015 to provide effective solutions to the health problems of the population. This was followed by a second plan for 2016–2020, in 2015.

With the technical and financial assistance of the international community, the health system has registered some recent improvements, reflected in changes in indicators such as life expectancy, infant mortality and maternal mortality rates. The DR Congo has made some progress in these areas, although it still lags behind its peers.

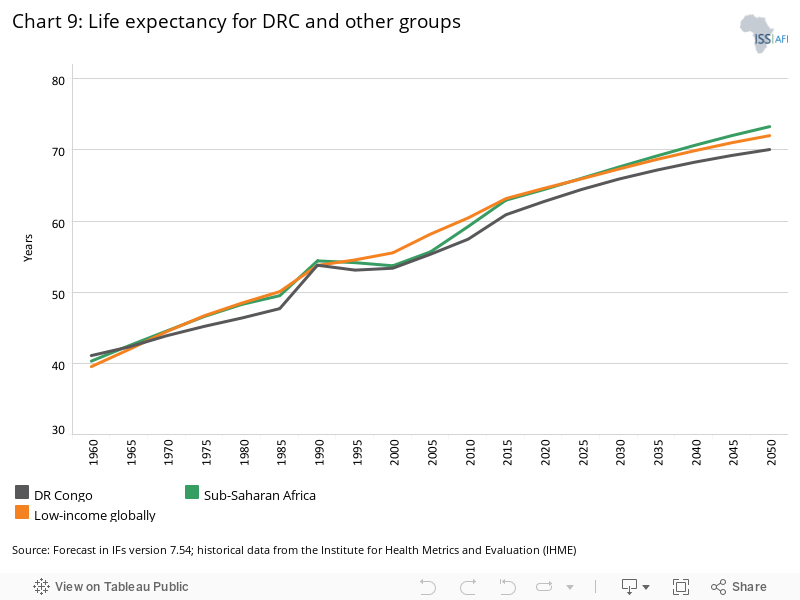

Life expectancy has increased from 53.7 years in 1990 to 62.5 in 2019. The sub-Saharan African average was 64.2 and 64.3 for low-income countries globally in the same year. Life expectancy in the DR Congo is projected to be about 70 years by 2050, with the gap between the average for low-income countries globally having modestly increased over time. Instead of catching up, the DR Congo seems to be falling further behind (Chart 9).

The infant mortality rate declined from 95 deaths per 1 000 live births in 1990 to about 51 deaths in 2019, slightly above the average for low-income countries globally (45) in the same year. As for the maternal mortality rate, it declined to 426 deaths per 100 000 live births in 2019 compared to 879 in 1990, above the average for low-income countries globally (384) in 2019.

On the Current Path, IFs estimates the infant mortality rate at 37 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2030 and 20 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2050. The maternal mortality rate is projected to be 307 deaths per 100 000 live births in 2030 and 74 in 2050. The DR Congo has made progress in combating infant and (to a lesser degree) maternal mortality, however, on the Current Path, it will fail to achieve the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals regarding these indicators.[50The target by 2030 is fewer than 70 per 100 000 live births for maternal mortality and 25 per 1 000 births for infant mortality.]

However, the country has not made much progress concerning child malnutrition. The situation remains difficult where 43% of children under five suffer from chronic malnutrition (more than six million children). One child in ten suffers from acute malnutrition while being underweight affects 23% of children under the age of five and 16% of children in school.[51Republique Democratique du Congo, Ministère de la santé publique, Plan national de développement sanitaire 2016–2020, 2016] As a result of malnutrition, 43% of children under the age of five are stunted, while global and African averages are respectively 21.9% and 30%.[52UNICEF, WHO and World Bank, Levels and trends in child malnutrition: Key findings of the 2019 edition, 2019]

Policymakers in the DR Congo should be highly concerned by the negative effects of malnutrition as stunted children experience diminished intellectual capacity, academic performance and future productivity. A high rate of stunted children implies, therefore, a significant loss of human capital for the country and compromises its long-term development objectives.

The epidemiological profile of the DR Congo is marked by the emergence and re-emergence of several communicable diseases with epidemic potential.[53Republique Democratique du Congo, Ministère de la santé publique, Plan national de développement sanitaire 2016–2020, 2016] The country has experienced several epidemic outbreaks such as cholera, yellow fever, measles, Ebola virus and the recent COVID-19. These diseases lead to increased morbidity and mortality among the vulnerable populations, in particular children, women and populations living in isolated areas with poor access to healthcare.

Communicable diseases are currently the leading causes of death among children under the age of five and the youth (Chart 11). Malaria is reported to be responsible for 80% of deaths among children under five in DR Congo. Non-communicable diseases are the dominant causes of death among the elderly cohort, although deaths from communicable diseases are also still high among this group.

Because of its more youthful population, the DR Congo will only experience its epidemiological transition, a point at which death rates from non-communicable diseases exceed that of communicable diseases, in 2030. This is roughly five years later than the average for low-income countries in Africa and a decade later than low-income countries globally.

By 2050, the number of deaths caused by non-communicable diseases will be twice as high as the number of deaths caused by communicable diseases. This has implications for DR Congo’s healthcare system which will need to invest in the capacities for dealing with the double burden of disease.

Overall, despite some improvements mostly due to peace consolidation, the DR Congo’s health system is still facing many challenges. Like many other African countries, the DR Congo has not yet complied with the Abuja Declaration that African countries spend 15% of their GDP on health. Government expenditure on healthcare in the DR Congo is among the lowest in the world. In 2017, government expenditure on healthcare was about US$2.00 per capita and less than 4% of GDP.[54World Bank, Word Development Indicators, 2019]

Quality infrastructure not only enables business and industry development but also increases efficiency in the delivery of social services. Important basic infrastructure, such as water and sanitation facilities, roads, electricity, Internet and telecommunications, among others, plays a vital role in achieving sustainable and inclusive economic growth. Infrastructure shortage is considered as one of the key factors that are impeding higher productivity and growth in the DR Congo.

Water, sanitation and hygiene (WaSH)

The DR Congo is considered to be Africa’s most water-rich country with more than 50% of the African continent’s water reserves, however, millions of Congolese do not have access to safe water.[55UNICEF, Democratic Republic of Congo, Water, sanitation and hygiene] Water and sanitation infrastructure is extremely dilapidated and inadequate, even in the capital city, Kinshasa. Between 1990 and the early 2000s, water and sanitation infrastructure collapsed and access to drinking water declined significantly due to conflicts and political crises.[56Water and Sanitation Program, Water supply and sanitation in the Democratic Republic of Congo, AMCOW Country Status Overview, 2011]

As a result of the relative stability, especially in the western provinces, since the mid-2000s, the water and sanitation sector in the DR Congo has been recovering, albeit slowly. The proportion of the population having access to improved water sources increased from 44.6% in 2000 to 57.6% in 2019 which is significantly below its peer groups. In 2019, 21.2% of the population had access to improved sanitation facilities, almost 10 percentage points below the average for low-income countries globally.

Water and sanitation infrastructure is chronically lacking in rural areas in the DR Congo. As of 2017, only 8.2% of the population had access to piped water in rural areas, up from its level of 3.4% in 2000. In rural areas, 24.2% of the population use non-piped sources while 52.8% of them use unimproved water sources. This dire situation is compounded by the lack of adequate sanitary facilities with 51.5% of the population in rural areas using unimproved sanitation.[57WHO/UNICEF, Joint Monitoring Programme, 2019.]

Access to adequate hygienic services is critical to prevent many diseases such as diarrhoeal and respiratory infections. According to the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), children can reduce their risk of getting diarrhoea by more than 40% by handwashing with soap and water. As of 2017, only 4.5% of the population, with 2.2% in rural areas and 7.4% in urban areas, had access to basic handwashing facilities including soap and water in the DR Congo.[58WHO/UNICEF, Joint Monitoring Programme, 2019, ]

The High-Quality Technical Assistance for Results (HEART) programme, funded by the United Kingdom, has provided £164.8 million over seven years (2013–2020) to improve water and sanitation infrastructure in the country.[59High-Quality Technical Assistance for Results (HEART), Increasing sustainable access to water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Annual review 2018

]

Overall, access to clean water and adequate sanitation has been increasing in the DR Congo, but the IFs forecast is that the country will trail further behind its peer groupings. More needs to be done to eliminate bottlenecks, such as lack of qualified technicians, that undermine progress in the sector. IFs estimates the proportion of the Congolese population with access to improved water sources at 92% and 47.8% for improved sanitation by 2050.

Energy and electricity

The DR Congo has abundant and varied energy resources such as hydroelectricity, biomass, solar, wind and fossil fuels, among others. For instance, the country possesses a huge potential of hydroelectric power estimated at 100 GW, which represents about 13% of the world's hydroelectric potential.[60Nations Unies, Commission Economique pour l’Afrique, Profile de pays: République démocratique du Congo 2017, Addis Ababa: NU.CEA, 2018–03, ] The country also has potential in other sources of energy, estimated at 70 GW for solar and 15 GW for wind power. In sum, the DR Congo has the potential to become a leading exporter of electricity in Africa.[61PricewaterhouseCoopers, Africa gearing up, 2013]

Paradoxically, the DR Congo has one of the largest deficits in energy access in the world. The energy supply is largely insufficient for the country's needs and energy consumption comes mainly from biomass. Only 3% is generated by hydroelectric power, the rest is from charcoal and firewood.[62B Naughton et al, DRC survey: an overview of demographics, health, and financial services in the Democratic Republic of Congo, START Center, University of Washington, March 2017] Although progress has been made, the DR Congo still has one of the lowest rates of electrification globally.

The share of the population with access to electricity increased from 6% in 2005 to 19% in 2018. IFs estimated electricity access at 21% in 2019, far below the averages for low-income countries globally and for sub-Saharan Africa which were respectively 41.7% and 46.4% in the same year (Chart 13). The country ranks 48th lowest of 54 countries in Africa in terms of electricity access rate.

On the Current Path, 25% of the population will have access to electricity by 2025, about 30% in 2030, and 55.7% by 2050. Unfortunately, the government's ambitious target to increase the proportion of the population that has access to electricity to 60% by 2025[63PricewaterhouseCoopers, Africa gearing up, 2013, ] is out of reach.

Access to electricity is heavily biased in favour of the urban and mining areas, notably Lualaba and Haut Katanga provinces where the copper and cobalt industry is concentrated. In rural areas, electricity is almost non-existent; only 1% of the rural population has access to electricity against 42% in urban areas. Access is also uneven across the provinces, ranging from 44% in Kinshasa to 0.5% in Kasaï Occidental.[64African Development Bank, DRC Green Mini-Grid Program, 2019, www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Project-and-Operations/ DRC_-_PAR_GREEN_MINI-GRID_PSN.pdf.]

The energy used by households in rural areas comes mainly from firewood (traditional cookstoves) which poses a risk to the environment with the acceleration of deforestation. It also affects the health of infants and children by causing respiratory problems. Also, cookstoves limit study hours for learners because the daily collection of firewood, which sometimes involves young girls, may deprive them of time that could be devoted to education. It is therefore very concerning that the IFs forecast for the percentage of households that use traditional cookstoves is still at 59% by 2050.

The existing and very limited power supply is also unstable, and electricity shortages and power blackouts are recurrent. For instance, it is estimated that, in Kinshasa, about 21% of those who have access to electricity receive less than four hours of power per day, and on average, electricity shortages occur 10 days per month in the country.[3] Due to this unreliable electricity supply, about 60% of firms in the DR Congo have back-up generators against 43%, on average, in sub-Saharan Africa.[65World Bank, Increasing access to electricity in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Opportunities and challenges, 2020, ] These frequent electricity shortages penalise the productive sectors of the economy and hamper productivity and growth.

Out of 100 GW hydroelectric potential, only about 2 677 MW have been installed, and only 1 100 MW are exploited. This power is mainly generated by the Inga I and Inga II dams. These two dams currently operate at around 50% of their capacity due to lack of maintenance. The World Bank has been leading efforts to rehabilitate turbines at Inga I and Inga II but the project is not yet complete.

In addition, the state power utility, Societe Nationale d'Electricite (SNEL), in charge of electricity production, transportation and distribution is highly inefficient. Almost half of the electricity produced is lost during transmission and distribution due to the obsolescence of the equipment and the absence of an adequate maintenance system.[66V Foster and DA Benitez, The Democratic Republic of Congo's Infrastructure: A Continental Perspective, Washington DC: World Bank, 2011]

Aside from the national grid, there are some mini-grids, albeit very limited. For instance, Synoki, Hydroforce and Virunga operate mini-grid hydroelectric projects, and their market share of the electricity sector is estimated at 6%.[67African Development Bank, DRC Green Mini-Grid Program, 2019] According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), only 3.66 MW of solar photovoltaics (PV) had been installed by the end of 2017. Off-grid systems are usually easier and less costly to implement and could be one of the solutions to the growing unmet electricity demand in the country.

There are some promising actions to resolve the problem of access to electricity in the country. The Grand Inga Dam is a proposed giant hydroelectric scheme with an expected capacity of 44 000 MW of electricity. According to projections, the Grand Inga Hydroelectric Project could meet the entire need of the DR Congo and even supply half of the African continent with electricity. The project will cost US$80 billion and is scheduled for completion in seven phases.[68M Mateso, RD-Congo: la construction d’Inga, le plus grand barrage du monde, peine à démarrer, Geopolis, 16 March 2015.]

The first phase (Inga III), which is estimated to cost US$14 billion, will generate 4 800 MW of electricity and its entry into service was initially scheduled for 2024 or 2025.[69M Mateso, RD-Congo: la construction d’Inga, le plus grand barrage du monde, peine à démarrer, Geopolis, 16 March 2015.] However, the execution of the project has been significantly delayed. In 2016, the World Bank suspended its funding towards the construction of the Inga III phase because the then president, Joseph Kabila, decided to bring the project oversight committee into his presidency, and it, therefore, lacked transparency. The project is still ongoing, albeit at a very slow pace. The Inga III Project is now estimated to come on stream in 2030 at the earliest, dependent upon a partnership between South Africa and the DR Congo.[70Congo Research Group, I need you, I don't need You: South Africa and Inga III, March 2020, Congo Research Group and Phuzumoya Consulting.]

In March 2019, to speed up access to renewable energy, the board of the African Development Bank approved a US$20 million financing package to back renewable-based mini-grid projects in the DR Congo. The Green Mini-Grid Programme will supply electricity to 21 200 households, and 2 100 buildings and small and medium-sized firms.[71African Development Bank, DR Congo Green Mini-Grid Program, 2019]

Roads

The DR Congo has very poor transport infrastructure. About half of the country is inaccessible by road including the capital city Kinshasa which cannot be reached by road from much of the rest of the country. Only a few provincial capitals are connected to Kinshasa. The country is effectively an 'archipelago' state; the only effective means to travel and trade internally is by air — which is costly — or via the Congo River.

The few existing roads and railways are also generally dilapidated. As of 2015, the DR Congo had a total road network of 152 373 km, with only 3 047 km paved (2%). The total urban and non-urban road networks were respectively 7 400 km and 144 973 km. The country also has 4 007 km of railways but an impressive 15 000 km of waterways.[72Central Intelligence Agency, The world factbook, 2020] Armed conflict has however significantly damaged road and rail networks in the DR Congo and both operate at about 10% and 20% of their levels in 1960.

According to the World Bank, the DR Congo is among the countries with the highest deficit of transport infrastructure in Africa, and without vigorous actions to curb this trend, it will take more than a century to close this infrastructure gap.[12] According to the IMF, ‘Difficulties in transportation constitute a major obstacle to the realisation of the DR Congo’s immense agroindustrial and mining potential.’[73B Akitoby and M Cinyabuguma, Sources of Growth in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: A Cointegration Approach, IMF Working Paper WP/04/114, July 2004, 10.] It is also one of the main stumbling blocks in the physical integration of the country and the extension of state authority.

Information and communication technology (ICT)

The mobile phone sector is perhaps the most dynamic and reliable infrastructure sector in the DR Congo. The country is considered as one of the top ten African countries with a very promising market for mobile phones.[74B Frégist, Téléphonie mobile: la RDC parmi les 10 marchés du mobile les plus prometteurs d'Afrique, Digital Business Africa, 2014] Currently, six mobile phone companies operate in the sector, namely, Airtel, Vodacom, Orange, Africell, Supercell and Tatem Telecom. Mobile cellular subscriptions have grown rapidly over the past decade. As of 2018, there were 36.47 million mobile cellular subscriptions against only 1.25 million in 2003.[75See: Number of mobile cellular subscriptions in the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 2000 to 2020] This translates to about 43 subscriptions per 100 people in 2018, reflected in Chart 14.

There is a disparity between rural and urban areas in terms of access to mobile phone service in the DR Congo. According to the latest Demographic and Health Survey 2013/2014, about 80% of households in urban areas have access to mobile phone services compared to 20% of households in rural areas. In 2019, subscriptions to mobile Internet services increased by 18.5% to reach 15.1 million people while Mobile Money service subscriptions increased by nearly 14% to reach nearly seven million people.[76E Mboyo, RDC: sociétés: la rédaction, 2019]

Despite this improvement, the country lags behind many of its peers in Africa in terms of Internet access and mobile phone services. Poor infrastructure, such as the frequent power shortages and high taxation, as well as complex regulations, are some of the bottlenecks that retard the expansion of the sector.[77Deloitte, Digital inclusion and mobile sector taxation in the Democratic Republic of Congo, 2015]

Although there have been some improvements in infrastructure in the DR Congo since the mid-2000s, the country is still at the bottom of the ranking for almost all measures of access to infrastructure. The infrastructure deficit is particularly severe in road transport, electricity supply and access to improved water sources.

Improving the connectivity between provinces through quality roads will inevitably promote trade and inclusive growth. Initiatives, such as the infrastructure-for-minerals deal with China, could improve infrastructure development in the country if well managed.

In the latest version of the contract, Chinese companies would spend US$3 billion on infrastructure rehabilitation and construction, including roads, railways and hydroelectric structures, among others. However, the agreement is skewed towards China. The roads are mostly towards mining areas and mining concessions are believed to be worth much more than the amount dedicated to infrastructure projects in the country. Also, a decade after the agreement, the DR Congo does not seem to have obtained the promised beneficial socio-economic outcome as the infrastructure construction has incurred significant delays.[78AM Larrarte and GC Quiroga, The Impact of Sicomines on Development in the Democratic Republic of Congo, International Affairs, 95:2, 2019, 423–446.]

Growth and composition of GDP

The Congolese economy was particularly hard hit by the series of violent conflicts in the 1990s. For instance, over the period 1990–2003, the size of the economy shrank by about 40% while the GDP per capita declined to nearly 30% of its level at independence in 1960. The mining sector which was the mainstay of the economy collapsed.

Following the signing of an all-inclusive peace agreement in 2002, the transition government led by Joseph Kabila reengaged with international financial institutions leading to a resumption in support from the World Bank and the IMF, which had been suspended in the early 1990s. Several reforms and policies, such as the government's Economic Programme (PEG 2002–2005) and the First Strategy Paper for Growth and Poverty Reduction (GPRSP1 2006–2010) were implemented under the auspices of the Bretton Woods Institutions. These were aimed at creating an economic environment conducive to private investment and growth.

These reforms and policies, in conjunction with a rebound in post-war economic activity, served to control hyperinflation and revived economic growth. Indeed, the inflation rate, which stood at 513.9% in 2000, fell to 4% by 2004.[79World Bank, World Development Indicators, 2014.] In 2002, after a recession that had lasted a decade, the country returned to growth. In July 2010, the DR Congo obtained debt relief of US$12.3 billion, the largest in the history of the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative.[80BBC, DR Congo to get billions in debt relief from the IMF, 2010] As of 2018, the stock of external public debt was 13.7% of GDP and 6.5% of GDP for domestic debt.[81African Development Bank, African economic outlook, 2020.]

The latest sustainability analysis by the World Bank indicates that the country’s debt risk remains moderate. However, this is likely to deteriorate significantly amid the multiple shocks associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, the budget deficit in the first half of 2020 was 886 billion Congolese Franc against a deficit of 455 billion for the whole of the year 2019.[82RFI, Afrique economie]

Buoyed by rising commodity prices, the DR Congo recorded an average growth rate of 7.7% from 2010 to 2015 compared to an average of 4.3% for sub-Saharan Africa over the same period. However, the subsequent cyclical fluctuations in commodity prices have slowed growth dynamics to 4.1% from 2016 to 2019 and revealed the country’s high exposure to commodity price shocks.

According to the IMF forecast released in October 2020, the GDP of the DR Congo will have shrunk by 2.2% in 2020 amid the COVID-19 pandemic — the first economic recession since 2002. To mitigate the negative effect of COVID-19 on the economy, the Central Bank lowered its interest rate from 9% to 7.5%. However, this monetary easing has resulted in excess liquidity in the economy, rising inflation and the depreciation of the Congolese Franc, which further weakens the purchasing power of consumers amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

To combat inflation and currency depreciation, the Central Bank has recently increased its interest rate from 7.5% to 18.5%.[83RFI, Afrique economie] Although necessary, this high interest rate is more likely to impact negatively on domestic investment and delay economic recovery once the pandemic abates.

After a sustained decline, the GDP of DR Congo has almost tripled as compared to its level in 2001. It was about US$13.4 billion in 2001 against US$39.5 billion in 2019. In 2019, the country had the 16th largest GDP in Africa. However, it ranked near the bottom in terms of GDP per capita at US$923 in 2019, which is about 40% of its level in 1960.

This is far below the average for sub-Saharan Africa and low-income countries (Chart 15). With this level of GDP per capita, the DR Congo ranks 51st of 54 countries in Africa. It is only ahead of the Central African Republic, Burundi and Somalia.

Instead of catching up, the DR Congo has seemed to be falling further behind its group peers since 1990. Before that year, the GDP per capita of DR Congo was well above the average for low-income Africa.

The persistent high population growth outpaces economic growth in the DR Congo and is constraining its GDP per capita growth, and thus undermining the efforts to improve the well-being of the population. On the Current Path, the GDP per capita (PPP) is projected to only come to US$1 184 in 2030, and US$2 478 in 2050, by then almost the same as its value in 1974 (US$2 284).

Whereas the mining sector accounted for 25% of GDP in the mid-1980s, it declined to 9% by 2003.[84IMF, Democratic Republic of the Congo: Selected issues and statistical appendix, Country Report No.05/373, 2005.] However, it rebounded after the war to become the second largest contributor to GDP since 2011. On average, the value added of the extractive industry increased by 19.6% over the period 2010–2014. According to the data from the Central Bank of Congo, the share of the extractive sector in GDP increased from 23.2% in 2011 to 28.7% in 2018.

On average, the contribution of the manufacturing industry was about 18% and agriculture about 20% over the period 2010–2018.[85Central Bank of Congo, Annual report, 2018.] The share of the services sector to GDP was 37% in the mid-1980s and 43% in 2003 before dropping to around 35% in 2018. Looking at the structure of the country’s GDP, it is clear that the growth rebound to 2014 largely occurred on the back of the contribution of the extractive sector to GDP (Chart 16).

The current growth model of the DR Congo is fragile and holds little promise for improvements in livelihoods; without a significant structural transformation of the economy, economic growth will continue to be at the mercy of commodity price shocks.

The preponderance of the extractive sector in economic growth is one of the reasons why the growth elasticity of poverty is so low. For instance, in the DR Congo, 1% growth of GDP is associated with a 1.1% decline in the poverty rate, against 7.3% in the Republic of Congo or 4.6% in Uganda.[86IMF, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Country Report No. 15/281, ]

Unlike artisanal and small-scale mining which are labour intensive, the large-scale mining operations are capital intensive and offer very few job opportunities. The agricultural sector continues to be the reservoir of jobs with 65% of total employment while the extractive industry accounts for only 11% of employment.[87Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2018] Investing in the agriculture and manufacturing sector would be a promising approach to offer future generations better living conditions.

Natural resources

The DR Congo has immense natural wealth. Virtually every kind of precious natural resource can be found in the country but this richness has brought only suffering and misery to the population as the exploitation of the resources is often associated with violent conflicts and human rights abuses.

The DR Congo has extensive forest resources. The country possesses about 60% of the Congo Basin rainforest making it the second largest tropical forested country globally with more than 100 million hectares. Its potential for timber exploitation is estimated at 10 million m3/year. These forest resources are overall in good condition as the national deforestation rate remains relatively low, at 0.2%.[88Interfaith Rainforest Initiative, DR Congo]

The country also has large reserves of crude oil and gas which represent significant economic potential. The discovery of oil and gas in the eastern part of the DR Congo has put the country in the second position in terms of crude oil reserves in Central and Southern Africa after Angola.[89Privacy Shield Framework, Country Commercial Guide, Democratic Republic of Congo] However, the exploitation of these reserves is controversial as it would affect the Virunga National Park which is home to the mountain gorilla.

The find of oil has drawn the attention of numerous players in the sector and may factor in the future treatment of the DR Congo's request, made in 2019, to join the East African Community. It is already a member of the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) and the Economic Community of the Great Lakes Countries (ECGLC).

The proven reserves of the country are 180 million barrels, but estimates put the total oil reserves above 5 billion barrels. Currently, oil production in the country is estimated at 25 000 barrels per day. In 2018, oil production increased by 11.4% to reach about 8.4 million barrels.[90Central Bank of Congo, BCC Annual Report, 2018, Kinshasa: BCC, 2018.]

In addition, the DR Congo could reasonably gain access to the rich off-shore oil and gas fields currently exploited by Angola. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) governs which strips of sea belong to which countries. The oil fields are responsible for about half of Angola’s production implying that the DR Congo could become one of Africa’s largest oil producers overnight. Instead, because successive regimes have been beholden to Angola for their security in terms of the Joint Interest Zone (JIZ), the DR Congo has very limited access and rights to these fields.[91For a useful summary see P Edmond, K Titeca and E Kennes, Angola’s oil could actually be the DR Congo’s: Here’s why it isn’t, African Arguments, 3 October 2019]

In addition to its oil reserves, the country may hold as much as 30 billion m3 of methane and natural gas in its three main petroleum deposits. The Lake Kivu field has methane reserves estimated at 60 billion m3 which are shared with Rwanda.[92Embassy of the DRC, Invest in DRC, Hydrocarbon]