The US-China trade war and Africa’s manufacturing crossroads

Trump’s tariff resurgence may hit China hard, but Africa’s fragile path to industrialisation could suffer the most.

The intensifying US-China trade war—most recently marked by sweeping US tariffs on Chinese imports—has global ripple effects that extend far beyond Washington and Beijing. While headlines tend to centre on geopolitical rivalry and Trump-era protectionism, the trade conflict has quietly, yet significantly, undermined Africa’s industrial development prospects. As China looks to reroute its exports toward new markets, particularly in the Global South, African countries are facing a surge of cheap, subsidised imports. This heightened competition threatens already vulnerable domestic manufacturing sectors. At this critical juncture, Africa must move beyond passive observation and undertake strategic recalibration. The continent faces a defining question: How can it avoid becoming collateral damage in a conflict between two industrial titans?

At first glance, President Trump’s tariff escalation may appear as an extension of his combative, egocentric political style. However, when viewed through the lens of international trade and development, this protectionist turn serves deeper strategic purposes—chief among them, correcting persistent trade imbalances and reviving domestic manufacturing.

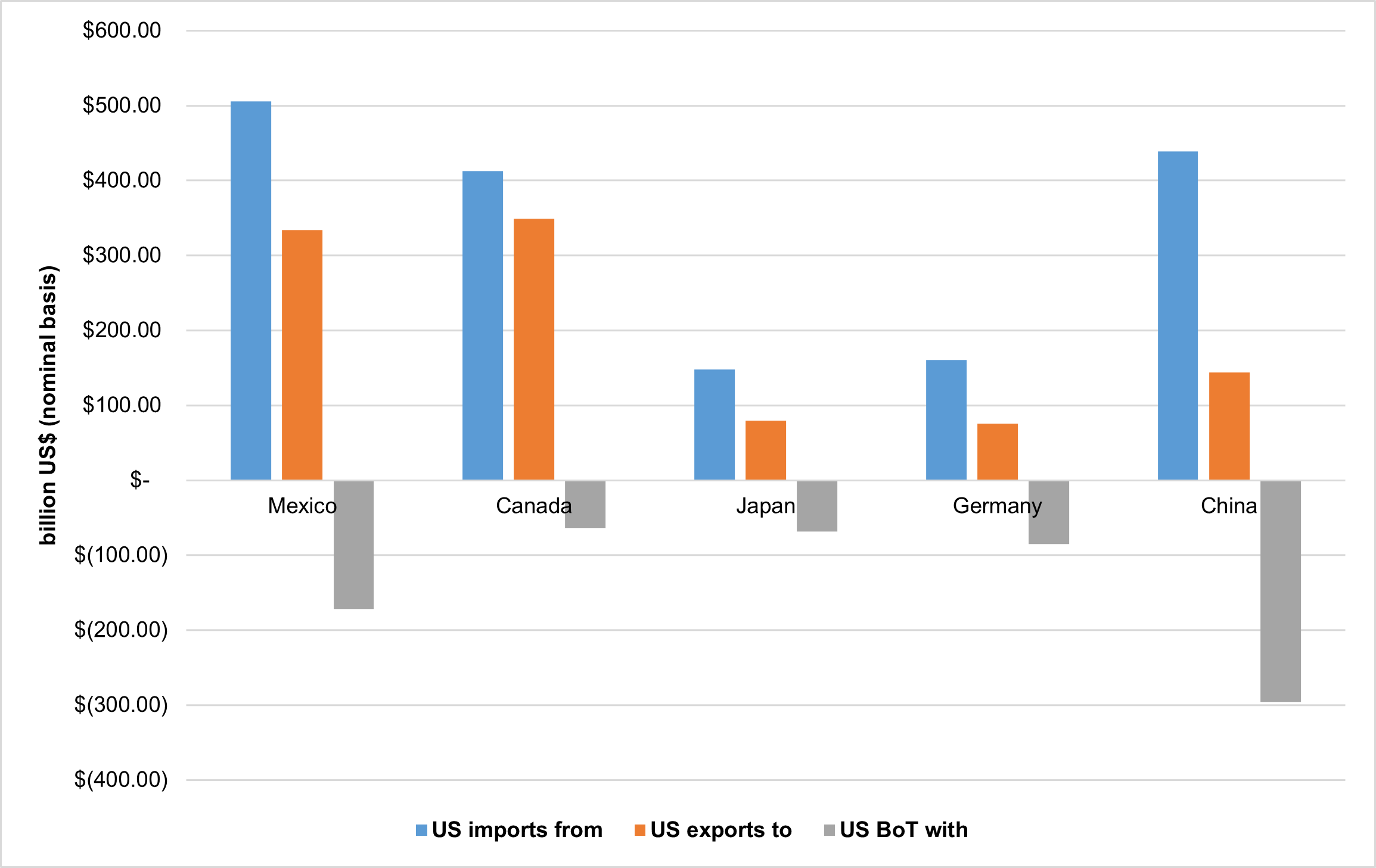

In 2024, the US recorded a trade deficit with all five of its top trading partners, with China remaining the most significant contributor (Figure 1).

Figure 1: US bilateral trade with its top five partners in 2024. Source: Author’s computation using the US Census Bureau dataset.

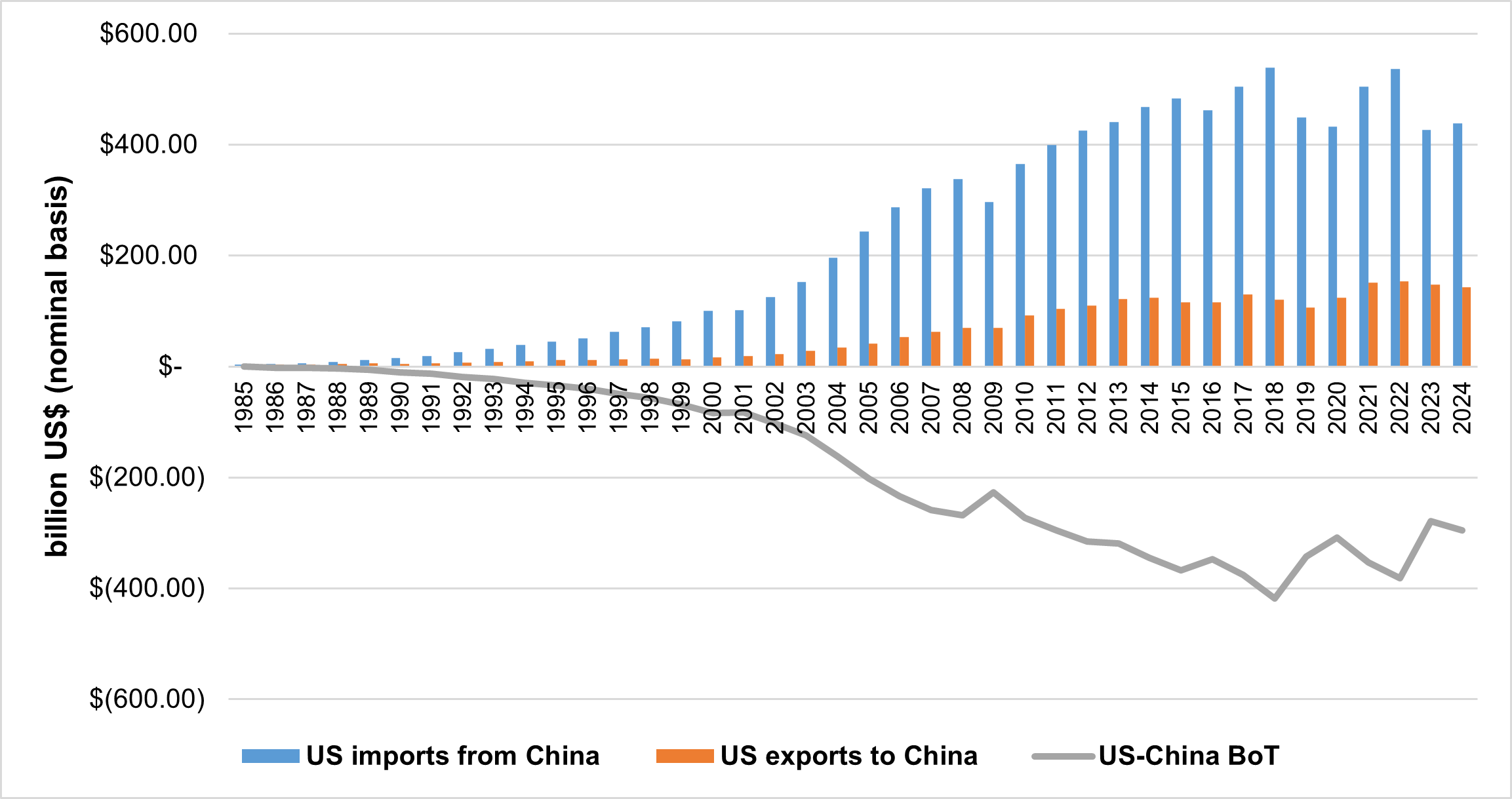

This deficit with China has grown from just US$10 million in 1985 to US$295.4 billion in 2024, with a historical peak of US$418.23 billion in 2018 (Figure 2). These persistent imbalances set the stage for Trump’s revived protectionist agenda.

Indeed, the first wave of tariffs in 2018 yielded a measurable impact, reducing the US trade deficit with China by 18% in 2019 and an estimated 29% by 2024, holding pandemic-related disruptions constant. While controversial, these measures partially succeeded in reshaping trade flows and stimulating domestic manufacturing in targeted sectors.

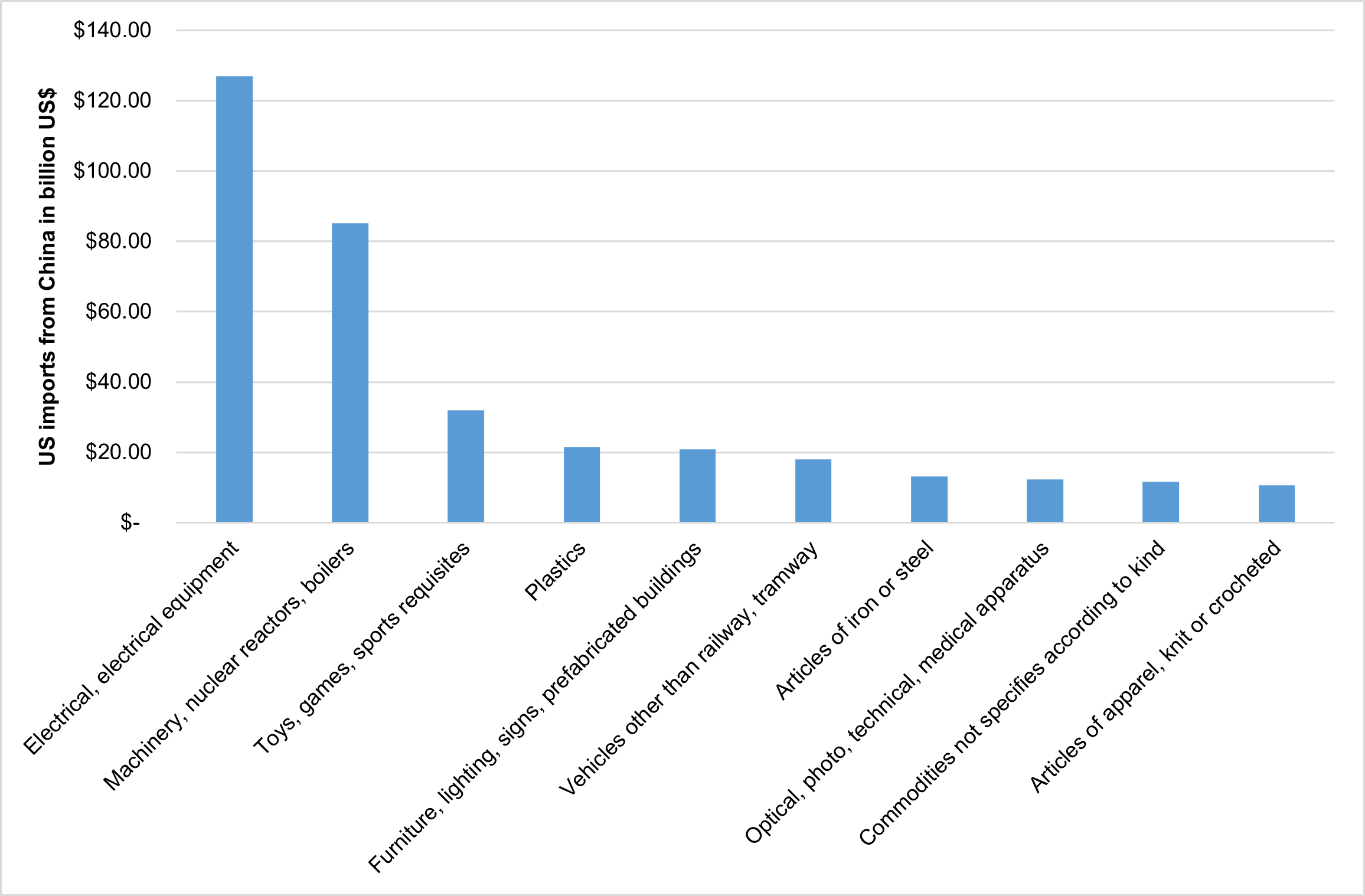

Figure 2: US-China bilateral trade. Source: Author’s computation using the US Census Bureau dataset.

A closer look at the composition of US imports from China reveals why these sectors matter. US imports from China are heavily dominated by finished goods, particularly consumer electronics and electrical equipment, which alone made up 29% of total imports in 2024 (Figure 3). These are industries in which US firms still possess latent competitive advantages, suggesting that with the right policy support, reindustrialisation remains plausible. As such, the tariffs are framed not merely as economic retaliation but as a broader strategy to restore manufacturing competitiveness and protect technological sovereignty.

Figure 3: Top ten US imports from China in 2024. Source: Author’s computation based on the Trading Economics dataset.

The tariffs have largely spared critical raw materials, especially those exported by African countries such as South Africa. Key mineral exports, including platinum group metals (PGMs), coal, gold, manganese and chrome, which are essential to the US manufacturing value chain, were notably exempt. This selective approach reveals a calculated strategy: punish industrial competitors while preserving access to vital raw inputs.

Meanwhile, China’s retaliatory tariffs, despite its already steep average import rate of 67% on US goods, are driven more by political signalling rather than economic rationale. In response, the US counter-retaliation has seen tariff rates on some Chinese imports soar from an initial 34% to as high as 245%. What began as a trade dispute has now escalated into a broader economic Cold War—no longer confined to goods and services, but encompassing technology, supply chains and geopolitical influence.

Collateral damage: Africa’s manufacturing sector

In this clash of titans, smaller economies may bear the brunt. As China redirects its trade focus toward the Global South, Africa is increasingly at risk of becoming a dumping ground for Chinese-manufactured goods.

Between 2002 and 2023, Africa’s trade deficit with China ballooned from US$2.31 billion to US$82.68 billion, with South Africa alone accounting for nearly 12% of this figure. This growing imbalance reflects the surge in Chinese imports in Africa, ranging from consumer electronics and vehicles to office equipment, apparel and household appliances, which have steadily displaced local industries. The ongoing trade war threatens to exacerbate this trend, further undermining Africa’s manufacturing base and constraining its industrial development. In contrast, Africa’s trade relationship with the US has evolved more positively over the same period, shifting from a deficit of US$450 million to a surplus of US$11.24 billion, underscoring the potential benefits of preferential trade frameworks such as the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA).

Where giants clash, smaller economies are often trampled—Africa must act now or risk becoming a dumping ground for displaced industrial overcapacity

Africa’s exposure stems from two enduring vulnerabilities: a narrow and underdeveloped industrial base as well as weak coordination of trade and industrial policies. Without decisive intervention, the continent could find itself locked into a neo-mercantilist structure, dependent on imported consumer goods and stripped of productive capacity.

To reverse this trajectory, African governments must urgently adopt coherent and ambitious industrial policies that go beyond rhetoric. These strategies should centre on nurturing infant industries through targeted subsidies, access to finance, public procurement and selective import substitution. Prioritising sectors such as agro-processing, textiles, green technologies and electronics can help establish a more resilient and diversified manufacturing base.

At the continental level, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) offers a unique opportunity to build regional value chains, expand intra-African trade and reduce reliance on external markets. Realising this vision will require investment in cross-border infrastructure, harmonisation of trade regulations and the creation of regional industrial clusters that can achieve economies of scale.

Complementing these efforts is the need for stronger enforcement of customs regulations and product standards. The influx of under-invoiced and substandard imports, especially from China, weakens local industry and drains government revenues. Modernising customs systems and enhancing quality control can help level the playing field for African producers.

Rethinking trade partnerships

In parallel, African countries must take a more assertive approach to trade negotiations with both the US and China. These arrangements must prioritise long-term structural transformation over short-term consumer access. Trade policy must serve as a lever for industrial development, not merely consumption.

Trade must be a lever for structural transformation, not just a pipeline for consumer goods

For the US, renewing and modernising the AGOA could be a vital step. The updated framework should incorporate stronger incentives for local value addition, for example, offering preferential access for goods produced through joint ventures or domestic assembly. Sectors with high employment potential, such as pharmaceuticals, renewable energy and digital manufacturing, should receive special attention.

China, for its part, must recalibrate its trade and investment approach. Rather than perpetuating dependence through mass export of cheap goods and import of raw materials, Beijing should promote joint manufacturing ventures, support local assembly operations and invest in skills development. Such a pivot would not only foster African job creation but also cultivate long-term goodwill and market stability.

Concrete steps are also needed to address the widening trade deficit between China and Africa. Tools such as import quotas, sourcing targets and subsidised procurement of African products could help balance the relationship. China’s continued growth must not come at the cost of Africa’s industrial future.

Equally important, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) must closely align with Africa’s development priorities, particularly those articulated in the African Union’s Agenda 2063. Infrastructure projects under the BRI should support industrial zones, logistics hubs and power infrastructure that underpin industrialisation, rather than simply facilitating the flow of Chinese exports and African raw materials.

The US-China trade war is not just a bilateral spat—it represents a fundamental reshaping of global trade, production and power. For Africa, this disruption carries both peril and promise. With strategic foresight and collective action, the continent can shield its manufacturing sector, reshape its trade relationships and position itself not as collateral damage, but as an emerging industrial force. Realising this vision will require courage, coordination and a decisive break from business-as-usual.

Image: Mohamed_hassan/Pixabay