Rethinking remittances: the overlooked billions sustaining African households

FinTech, migration policy and AfCFTA must align to unlock the development potential of remittances in Africa.

In just over a decade, remittance inflows to Africa have surged from approximately US$53 billion in 2010 to roughly US$95 billion in 2024. This reflects an increase in their share of the continent’s GDP from 3.6% to 5.1% over the same period, making remittances one of Africa’s largest and most stable sources of external finance. Despite their scale and stability, they remain overlooked in Africa’s economic development debates.

Remittances to Africa have matched or exceeded the value of official development assistance (ODA) and foreign direct investment (FDI) in recent years, underscoring their growing macroeconomic significance. For instance, in 2024, FDI inflows to the continent reached US$97 billion, roughly in line with remittances (around 36% of this FDI was concentrated in a single urban development project in Egypt, making the remaining continent’s 2024 FDI about US$62 billion).

In recent years, remittances to Africa have matched or exceeded the value of ODA and FDI, underscoring their growing macroeconomic significance

Egypt, Nigeria and Morocco accounted for the largest shares of Africa’s remittance inflows in 2024. By contrast, several countries, including Angola, Seychelles and São Tomé and Príncipe, received less than 1% of total inflows, highlighting stark disparities in remittance dependence. Regionally, North and West Africa attracted the highest overall remittance volumes.

Remittances are pivotal in sustaining household livelihoods, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Unlike ODA or FDI, remittances are sent directly to households to cover essential expenses, mostly bypassing bureaucratic channels. Therefore, they have a direct impact on a family’s food security, healthcare, housing and education. Recipients spend most of these funds locally, stimulating trade and services, and sometimes investing in community infrastructure.

In 2019, for instance, approximately 65% of Kenya's population and almost half of Gambia's population relied on remittances as a key source of household income. These statistics reinforce the argument for including estimates in national poverty alleviation strategies, especially where formal employment and social protection systems are fragile or underdeveloped.

On a broader scale, remittances provide a stable source of foreign exchange, which helps bolster national reserves and reduce external vulnerabilities. In several African countries, including the Gambia, Lesotho, Comoros, South Sudan, Liberia and Somalia, remittances account for more than 10% of GDP (Figure 1).

Discussions on development tend to focus on big-ticket investment, trade deals or aid flows. This neglect persists even though remittance flows are typically more stable and countercyclical, providing a critical buffer in times of crisis, as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic when ODA and FDI declined.

A substantial share of Africa’s remittance flows continues to move through informal channels, such as hand-carried cash or unregistered transfer systems, particularly evident in the DR Congo, Libya, Zimbabwe, Somalia and Nigeria (Figure 2). This persistent reliance on unregulated intermediaries undermines financial inclusion, masks the full scale of diaspora contributions and weakens data for policymaking.

Closing the gap between remittances’ potential and their current use requires action on three fronts: lowering costs and formalising flows, integrating them into national financial systems and creating incentives for diaspora investment.

Lowering transfer costs and formalising remittance channels is the first essential step. The average cost of sending money through mobile applications to Africa was around 5% of the amount transferred in 2023, far above the UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target of reducing transfer costs to 3% by 2030. Addressing these bottlenecks will require both regulatory innovation and investment in inclusive financial ecosystems.

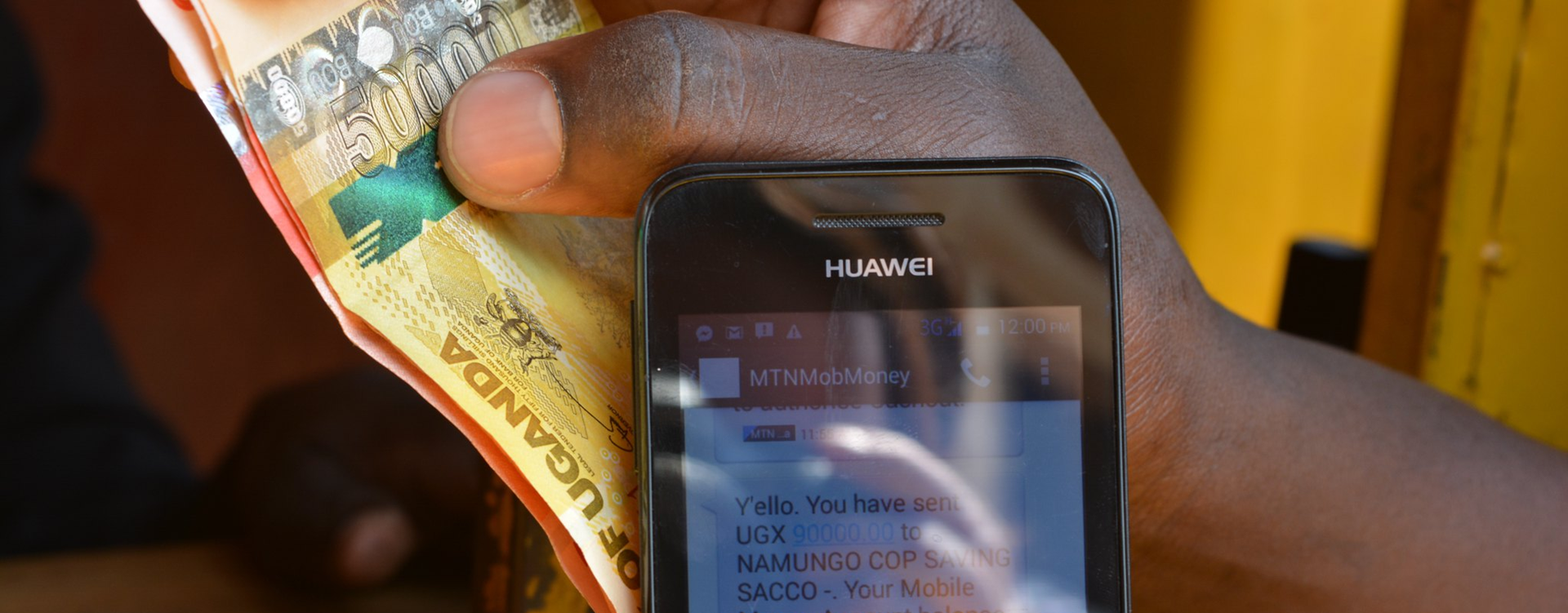

Technological advancement is starting to break some of these barriers. The recent expansion of financial technology (FinTech) platforms has been instrumental in facilitating faster, cheaper and more secure cross-border payments. Mobile money platforms, blockchain-based transfers and peer-to-peer (P2P) apps can enable simple payments and cut costs drastically, such as M-Pesa, MTN MoMo and Airtel Money. This transformation is largely driven by the rising intra- and extra-African migration, which is reshaping financial flows in the continent and reflects a broader shift toward the need for more formalised channels. The AfCFTA Protocol on Digital Trade and cross-border payment systems like Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS) offer a framework for harmonising rules, lowering costs and expanding formal remittance corridors.

A second priority is to link remittance inflows more effectively with national financial systems. The growing use of FinTech-enabled remittance transfers is not uniform across the continent, and a missed integration with broader financial systems persists. Few African countries have robust frameworks to link remittance inflows with savings, insurance or productive investment, so their potential as an overarching development lever remains largely untapped. Stronger policy frameworks are needed to connect remittances with financial products and domestic capital mobilisation.

Finally, creating incentives for diaspora investment can turn remittances into a long-term source of development finance. If better harnessed, remittances could support structured savings, investment products or diaspora bonds, providing a sustainable source of capital for national development. However, increased reliance on remittances also carries risks. Economic shocks in host countries can reduce flows, heavy dependence on inflows may disincentivise structural reforms in-country, and digital channels bring cybersecurity and fraud concerns. Clear incentives, balanced with safeguards, are needed to channel diaspora capital productively while avoiding overdependence.

Another underexplored frontier is that while the bulk of Africa’s remittance inflows traditionally originates from the Gulf States, North America and Europe, there is a growing trend of intra-continental remittance flows. Approximately one-fifth of total remittances stems from transfers within Africa. In 2023, this accounted for about US$20 billion of remittances originating from within Africa.

A notable example is Zimbabwe, where in 2021, approximately 37% of its remittance inflows came from neighbouring South Africa (Figure 3), which hosts over 690 000 Zimbabwean migrants. This reflects regional migration patterns and highlights the importance of FinTech platforms such as Mukuru, a key provider of low-cost cross-border transactions in Southern Africa. During the COVID-19 lockdown, when physical movement was restricted, Mukuru sustained household support by channelling remittances through regulated digital pathways.

With globalisation intensifying and migration on the rise, remittances will remain a steadily growing pillar of Africa’s financial inflows. A recent AFI–ISS study finds that if robust financial reforms are pursued, Africa’s net remittances will reach approximately US$168.2 billion by 2043, compared to US$137.2 billion under the baseline trajectory.

There are valuable policy lessons from other Global South economies, which have pioneered successful models for transforming remittance flows into broad-based growth. These show that remittances can shift from mere consumption support to productive investments in small enterprises, rural infrastructure, health systems, education, and more.

In Bangladesh, targeted measures include a 2.5% cash incentive for transfers via official channels, expansion of digital banking infrastructure and the creation of diaspora bonds and migrant-focused financial products. These reforms have reduced informality, deepened financial access and enhanced macroeconomic stability.

The Philippines offers another example. Through the Overseas Workers Welfare Administration (OWWA) and the Philippine Development Plan (PDP) for Overseas Filipinos, the government has institutionalised financial literacy programs and promoted remittance-backed savings and microenterprise development. These have strengthened formal diaspora engagement and local development ownership.

In Mexico, remittances have been integrated into national development strategies through innovative instruments. The 3x1 Program for Migrants scheme, for instance, matches every dollar sent for community projects with three dollars from federal, state and municipal governments. The initiative has financed schools, health facilities, roads and water systems, especially in rural areas with limited public funding.

Bangladesh, Philippines and Mexico models demonstrate that remittances can be redirected from mere household support to engines of inclusive development

Deliberate efforts to promote financial literacy, reduce transaction costs, incentivise formal remittance flows and align diaspora finance with local development needs can turn remittances into engines of inclusive economic development. As Africa navigates debt stress, climate pressures, economic transformation and global power shifts, the time to rethink remittances is now. They are a strategic asset for Africa’s financial future.

Image: World Remit Comms/Flickr

Republication of our Africa Tomorrow articles only with permission. Contact us for any enquiries.