Beyond control: letting markets and communities build Africa’s cities

A pragmatic case for devolved, rules-based urbanism that trusts people, and prices, over plans

The most persistent colonial legacy in African urbanism is not the geometry of old colonial street grids. It is the habit of central control: through capital budgets held in national treasuries, one-size-fits-all planning laws and a presumption that officials know best. That legacy has survived independence, donor cycles and legislative rewrites. The result is a planning culture that manages compliance rather than enabling commerce, housing supply and infrastructure investment.

If cities are to become engines of growth, the centre must loosen its grip, and local government must act less like regulators of utopias and more like stewards of functioning markets. Effective decentralisation implies minimising the role of the state. It means refocusing it: from direct control to setting transparent frameworks for resolving disputes and protecting equity as local markets and communities do the heavy lifting of building functional cities.

The consequences of that colonial legacy of control are felt in everyday governance. Across the continent, the decisive constraints on urban development are not cultural. Irrespective of British, French, Portuguese and Italian colonial pasts, they remain institutional and fiscal. Land is rationed by rigid, centrally authored rules through minimum plot sizes, use segregation, height caps and approval chains that stretch from local desks to national ministries. Formal compliance is costly, slow and uncertain, so most households and firms do what markets always do when rules misprice formality: they exit without permits or approvals, as informality grows. Incremental, community-led development fills the gap, delivering shelter and micro-enterprise at speed while the formal system debates standards it cannot enforce. UN-Habitat’s World Cities Report 2022 describes the downstream effect plainly: infrastructure and governance deficits, not population growth per se, explain why urbanisation has not reliably translated into productivity. The evidence aligns with the World Bank’s Africa’s Cities thesis: our cities are “crowded, disconnected and costly” because policy closes land and service markets rather than opening them.

Central control also distorts capital formation. National ministries prioritise visible projects and spread funding thinly, while municipal plans lack enforceable links to budgets, property rights or user charges. The OECD/Sahel and West Africa Club’s Africa’s Urbanisation Dynamics 2022 shows that productivity follows connected market size. Yet, too many corridors remain underserved because approvals, tariffs and rights-of-way are locked in slow, centralised processes. When prices cannot signal scarcity and permissions do not arrive on time, investment stalls and informality becomes the default production system.

The counterevidence is instructive. Wherever rules make it easy to hold and trade rights, connect to infrastructure at predictable cost and start firms without discretionary approvals, urban markets deepen. Elinor Ostrom’s Nobel Prize lecture on polycentric governance supplies the institutional logic: complex systems perform better when decision rights are distributed, monitoring is local, and overlapping authorities learn and compete. In cities, that means devolving powers to municipalities and communities, clarifying who owns or controls what, and letting multiple providers (public, private and community) solve problems within common-sense safety rules.

Building such a system requires an enabling-state playbook: one that shifts from command to coordination, from prescriptive rules to performance-based governance. A genuinely enabling state remains indispensable, however: capable national oversight and accountable local governments must enforce safety, fairness and environmental standards. Should one reach the complicated and often unthinkable point where governments are prepared to relinquish control and let markets and communities build Africa’s cities themselves, several fundamental and very logical events must take place.

Building such a system requires an enabling-state playbook: one that shifts from command to coordination, from prescriptive rules to performance-based governance

The starting point is always to address property and access to property through secure ownership. Secure, tradeable rights (formal titles where feasible, lawful use rights where not) are the precondition for investment. Hernando de Soto’s argument remains relevant: the poor are not asset-poor; they are paper-poor, unable to convert what they already own or control into capital. The policy implication is not a crusade for universal titling that triggers displacement; it is a pragmatic mix of tenure recognition, streamlined subdivision and registries that record reality at low cost. Where paper matches practice, collateral emerges, transaction costs fall and small builders scale up.

In a property secure environment, it is necessary to legalise what works and price what matters. Minimum plot sizes, single-use zoning and prescriptive building codes should give way to performance-based rules that allow incremental housing and mixed-use on small lots. If a structure meets basic health and safety thresholds, it should be lawful, full stop. On the infrastructure side, tariffs must reflect cost, with targeted lifeline support for the poor rather than broad cross-subsidies that quietly bankrupt utilities and municipalities. Where regulation permits open access, such as wheeling in electricity or wholesale access in water, competition and contracting can discipline cost and improve reliability. The point is not ideological privatisation, but rather to let prices carry information and choice, within clear safety and environmental limits. The World Cities Report and Africa’s Cities both emphasise that predictable rules plus serviced land, not new master plans, are what reduce the “crowded, disconnected, costly” trap.

Cities should concentrate scarce capital where markets already signal demand rather than through political pet projects. Employment-rich corridors and nodes that link housing, logistics and services will identify themselves. Utilise corridor or nodal-level special rating areas, betterment levies or voluntary land readjustment to recycle a share of uplift into bulk networks. Do fewer things, properly, where they unlock private follow-on spend. The OECD/SWAC analytics on connected market size support this sequencing: connectivity is a growth policy, not an afterthought in transport planning.

Trust communities with budgets and boundaries. Where residents co-produce services, neighbourhood road surfacing, standpipes, solid-waste collection and delivery accelerate and accountability improves. Polycentric arrangements work because proximity reduces monitoring costs and increases feedback. The enabling state sets the rules, publishes the data, enforces safety and buys outcomes; it does not prescribe inputs from the centre. Ostrom’s polycentric framework is not a slogan here; it is an operating model for urban Africa.

Finally, align plans with money and responsibility. A plan that cannot change a budget, a tariff or a permit is political theatre. Tie spatial strategies to municipal delegations that include approvals, borrowing limits, tariff policy within national bands and the right to contract. Publish annual “plan-to-budget” tables that show what was funded, built and connected, and by whom. In this world, planning becomes a platform for investment, not a blueprint for aspiration.

When rights are unlocked, services are priced honestly, decision-making is devolved and multiple providers are allowed to compete under clear safety rules, African cities can grow in productivity

Taken together, these principles outline a pragmatic path toward urban systems that grow by design and incentives rather than decree. When rights are unlocked, services are priced honestly, decision-making is devolved and multiple providers are allowed to compete under clear safety rules, African cities can grow in productivity—not by decree, but by design and incentives. Informality, rather than a problem to be eradicated, is a rational response to mis-priced formality. The institutional remedy lies in dismantling centralised control, trusting markets and communities, and equipping urban governments to enable rather than police urban life. That is how the colonial reflex of control can give way to a civic habit of consent, contract, accountability and investment.

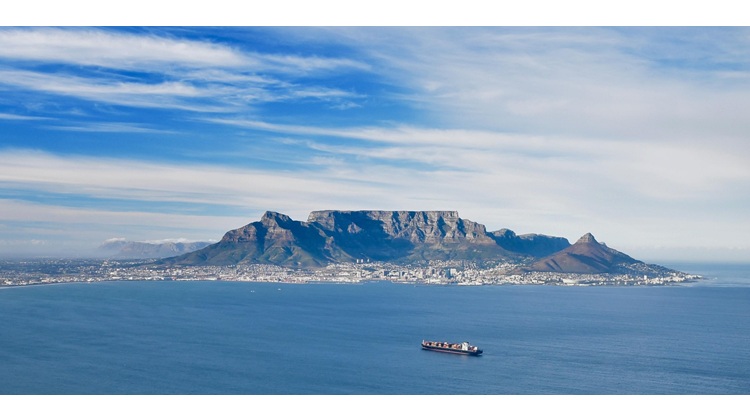

Image: Goldenwabbit/Wikimedia Commons

Republication of our Africa Tomorrow articles only with permission. Contact us for any enquiries.