Ecologies of wealth in the Congo Basin

Indigenous value systems reveal how prosperity and resilience are rooted in Africa’s ecological and cultural foundations.

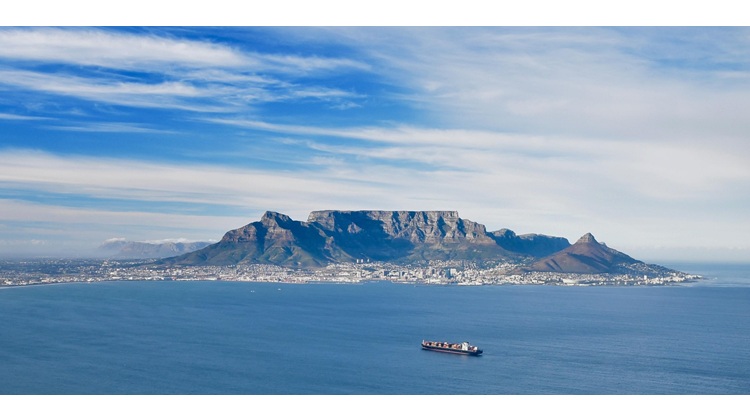

The minerals that power the world’s green transition are extracted from one of its most fragile ecosystems, the Congo Basin rainforest. Stretching across six countries, this vast landscape stores immense carbon, regulates regional rainfall and sustains millions whose lives depend on its forests and rivers. Yet, its mineral abundance exposes deep inequalities in how global transitions are financed and resources governed. Here, the promise of a cleaner planet collides with the local reality of mining.

The current scramble for critical minerals again poses a security and governance challenge for Africa. Without careful regulation and local oversight, it risks replicating the destructive patterns of the past, in which industrialised nations and transnational corporations—through forms of “technocolonialism” that bypass local governance and community rights—profit from cheap resources while local populations bear the socio-environmental and political costs. Moreover, as demand for these minerals skyrockets, traditional understanding of wealth fails to capture the full picture of value and loss in mineral-rich communities. Can Africa define wealth on its own terms?

As the demand for critical minerals skyrockets, the traditional understanding of wealth fails to capture the full picture of value and loss in mineral-rich communities

In southern DR Congo’s cobalt belt, for instance, artisanal miners work beside industrial concessions that export billions in raw ore while local children face an education crisis and illegal child labour, and while critical infrastructure such as clinics remains underfunded. These contrasts highlight why GDP growth alone cannot measure real prosperity.

The minerals race forces a defining question for Africa: Is the continent entering yet another cycle of extractive dependency, or will it harness the moment as a turning point toward self-determined development? Extractive dependency, weak governance and a narrow notion of value have deepened insecurity in the Congo Basin, Africa’s ecological heartland. Yet, Indigenous value systems offer a different perspective on development and resilience.

A re-evaluation of wealth through the lens of “ecologies of value”, rather than purely economic metrics, is essential. Ecologies of value is a concept that embeds wealth as emerging from the socio-ecological relationships among people, ecosystems and culture, grounded in Indigenous understandings of prosperity. Recognising that prosperity arises from intertwined systems—natural, social, cultural and spiritual—is a critical perspective for building a more secure, equitable and sustainable African future.

Meanwhile, extractive dependency channels wealth outward, erodes trust in institutions and degrades the ecosystems that sustain livelihoods. When revenues from critical minerals are captured by elites or armed groups, they finance conflict and corruption rather than community development. Weak regulatory oversight allows environmental destruction to undermine food and water security, while social exclusion amplifies local grievances and displacement. Conventional measures of value in resource economies, focused on export revenue and GDP growth, largely overlook the local social, cultural and ecological dimensions that sustain long-term security and well-being. This narrow valuation of wealth perpetuates extractive dependence and masks real losses to community resilience and ecosystem health, transforming resource wealth into a structural source of instability across the Congo Basin.

At the root of this instability lies a deeper governance pathology. The failure to translate mineral wealth into sustainable development reflects entrenched corruption, lack of transparency and the state's limited capacity to enforce its own mining codes. These weaknesses enable illegal operations to thrive, leading to the collapse of the social contract. Revenues meant for public services and infrastructure instead enrich a small, connected elite and criminal networks. In many areas, communities are excluded from decision-making processes, leading to the forced displacement of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands. True development cannot be measured solely by national economic growth; it must be judged by the tangible improvements in the lives of those most affected by resource extraction.

Nowhere is this tension more acute than in the Congo Basin, home to the world’s second-largest rainforest and a significant portion of strategic minerals, from cobalt and coltan to gold and 3Ts (tin, tungsten and tantalum); and critical minerals (lithium, rare earth elements and manganese). The link between natural resources and conflict in the Congo Basin is well-documented: the trade in conflict minerals fuels ongoing violence as armed groups compete for control of lucrative mining territories. Efforts to disrupt this financing through international disclosure rules have had limited success, while the proliferation of small-scale, difficult-to-trace mining operations, particularly for gold, has widened the geography of conflict. Weak institutions and the absence of the rule of law allow this exploitation to persist, trapping communities in a cycle of poverty and insecurity.

At the same time, the global race for green transition minerals, viewed by the international community as a solution to climate change, is generating a new set of environmental and human security crises on the ground. Mining has led to severe water contamination, soil degradation and deforestation, directly impacting the health, food security and livelihoods of Indigenous communities. The reliance on informal mining, often using hazardous and unregulated methods, further exposes workers to toxic chemicals and unsafe conditions.

This dynamic reveals a significant paradox that lies at the heart of the Congo Basin crisis: the resources needed for technologies designed to save the planet from climate disaster cause profound environmental and health damage in the very communities that have historically acted as guardians of this ecosystem.

The challenge for international criminal justice is to extend its reach beyond high-profile cases to hold both corporate entities and individuals accountable for complicity in these crimes. The illicit trade in minerals is a transnational crime that requires a coordinated, global response to dismantle the networks that sustain conflict and human rights abuses.

As international markets fixate on the monetary value of these subterranean resources, a profound clash of values is underway. For the Indigenous and local communities of the region, wealth is not measured solely by GDP. Values such as secure land tenure, forest health, community reciprocity, cultural continuity and the ability to maintain livelihoods across generations are rarely captured in conventional economic metrics but are critical for resilience and justice in the face of climate and resource crises.

For the Indigenous and local communities of the region, wealth is not measured solely by GDP but by values such as secure land tenure, forest health and cultural continuity

These values extend beyond traditional indicators and shape governance and security. Natural capital is life, not merely a stock of resources, but the foundation of survival and cultural continuity. The forest is not a warehouse of resources but kin; for example, among Baka communities in Cameroon, livelihood practices regulate hunting and logging to ensure natural regeneration. Its intact state ensures clean water, regulates climate and maintains biodiversity. It is simultaneously a source of food, medicine and sacred grounding, with its value defined by relational and sustainable use rather than extractive transactions. This benefit is erased by GDP, which only records the timber felled or minerals extracted, counting the loss of natural capital as economic gain.

Social capital is currency, a stabilising force where wealth is measured by the strength of social networks, mutual aid, social cohesion, intergenerational knowledge transfer and community resilience. This reduces vulnerability to conflict and displacement. It is the bedrock of a prosperous community where obligations are met and conflicts are resolved through kinship structures. The influx of industrial mining disrupts this fabric, creating wage labour dependencies and eroding traditional governance.

Cultural and spiritual capital are foundation. Rooted in language, ceremony, ancestral land and cultural practices tied to the ecosystem, it provides the legitimacy necessary for cohesive governance. The destruction of a forest for a mine is not just an environmental loss; it is a spiritual and cultural catastrophe, severing a people’s connection to their history and identity.

This holistic conception of wealth stands in stark opposition to the extractive model, which externalises these forms of capital as irrelevant to the bottom line. The GEP (Gross Ecosystem Product) framework offers progress. It treats ecological integrity as a foundational asset that contributes to wealth and integrates natural capital into its approach to measuring long-term economic sustainability—rather than treating environmental protection as a trade-off against economic growth. Even as an expanded accounting framework, GEP remains bound to economic quantification and monetises ecosystem services to make them “visible” in policy and planning. Indigenous and local conceptions of wealth extend beyond and resist the reduction of nature to purely monetary value. Recognising these alternative forms opens the door to a deeper understanding of security: not merely as control of territory, but as continuity of life, knowledge and balance. Integrating this living perspective into policy requires new indicators and new ways of thinking, anchored in foresight, adaptability and inclusive learning. This requires courageous governance and innovative policy informed by Indigenous Data Sovereignty (IDS). True security is impossible without this foundational rethinking of what it means to be wealthy.

Recognising alternative forms of value opens the door to a deeper understanding of security: not merely as control of territory, but as continuity of life, knowledge and balance

The path to sustainable peace in the Congo Basin lies in recognising that the greatest value may not lie in what is taken from the ground, but in what is left standing. By embracing the sophisticated ecologies of value held by its Indigenous communities, Africa can redefine the very meaning of development.

Image: jbdodane/Flickr

Part I of the series: Rethinking wealth and security in the Congo Basin

Republication of our Africa Tomorrow articles only with permission. Contact us for any enquiries.