Evidence should shape South Africa's housing policy

With the energy crisis receding, funding Solar Home Systems through housing grants creates a policy misalignment that reduces delivery impact.

Until recently, blackouts dictated the rhythm of national life in South Africa; and in certain years, with at least one stage of loadshedding every single day. Entire communities were forced to organise their activities around blackout schedules. For some, it was rather an inconvenience. For millions of low-income South Africans, however, it was a daily crisis that amplified structural inequality. In homes that rely on monthly social grants and bulk food purchases, prolonged power cuts meant spoiled food in fridges and additional financial pressure. For small-scale entrepreneurs relying on basic tools, it meant the abrupt suspension of livelihoods. Load shedding was not an equal opportunity disruptor. It exposed the sharp edges of poverty in ways that were visible and painful - a typical South African story of inequality.

The government’s response was shaped by the urgency of the moment. In 2023, the country endured its most severe power cuts with more than 6 700 hours of load shedding, roughly 335 out of 365 days. Faced with widespread frustration and the need to offer relief to vulnerable communities, it was against this backdrop that former Minister of Human Settlements, Mmamoloko Kubayi, announced that Solar Home Systems (SHS) would be included in the minimum norms and standards for all new subsidy houses. Each unit, comprising a small solar panel, an inverter and a battery, was to be provided at approximately ZAR20 300. The rationale was threefold: to cushion households during outages, reduce demand on the national grid and offer some relief from energy poverty.

While the urgency was understandable, the funding mechanism was not. The SHS intervention was financed not through energy-sector budgets, but through the Human Settlements Development Grant (HSDG). This grant exists for a singular, noble purpose: to deliver housing opportunities for low-income households. Every rand allocated to SHS was, in effect, a rand diverted from bricks, roofs and serviced sites. In policy terms, this was an emergency measure layered onto a housing grant without a clear evidence base or a long-term sustainability plan.

Funding Solar Home Systems was an emergency measure layered onto a housing grant without a clear evidence base or a long-term sustainability plan

Two years later, the context has shifted. Eskom, under new leadership, has made a significant recovery. The utility has added thousands of megawatts to the grid, increased its Energy Availability Factor and stabilised its generation capacity. In its 2025 annual financial year (announced on 30 September 2025), Eskom posted its first positive balance sheet in over a decade, with a profit before tax of ZAR23.9 billion. For more than four months, the country has experienced no load shedding at all. Transmission infrastructure is being modernised, municipalities are procuring power from Independent Power Producers, and the grid is more stable than at any point over the past several years.

Despite this, the SHS policy remains firmly in place. Housing funds continue to be diverted to address an energy crisis that has, at least for now, been brought under control. This is not simply an administrative oversight. It raises fundamental questions about how state resources are utilised, how policy is adapted to changing circumstances and whether government is willing to sunset interventions that have outlived their relevance.

Using a combination of technical performance assessments, cost modelling and interviews with energy specialists, a recent study by the Western Cape Department of Infrastructure examined the SHS intervention through a rigorous, evidence-based lens. The study offers a realistic picture of how SHS operates in practice by assessing capital and operational costs, its contribution to reducing household energy poverty, its impact on national electricity demand and the sustainability of the model for both the state and households.

The findings were clear. Across every parameter, the costs outweighed the benefits. SHS units make little difference to grid demand because low-income households already consume very low levels of electricity. Their contribution to alleviating energy poverty is marginal, as the systems cannot power high-demand appliances such as stoves and fridges. Given the frequency of loading at the time and the capacity of the envisaged SHS, systems could not recharge to deliver their modest energy benefits, such as lighting and recharging cellphones. Maintenance, particularly battery replacement, is unaffordable for the households in question, often exceeding a month’s income. Once batteries fail, systems will likely be discarded. Critically, their core value, as a backup during outages, has diminished in the wake of Eskom’s recovery.

The opportunity cost is significant. At roughly ZAR20 300 per unit, the cumulative expenditure on SHS runs into hundreds of millions of rand that could otherwise have been spent on constructing additional housing units, upgrading serviced sites or improving settlement infrastructure. In a context where the housing backlog remains vast and budgets are constrained, such diversions have real human consequences: families wait longer for houses, informal settlements remain under-serviced and delivery targets slip further out of reach.

Policies must evolve with evidence and context. Crisis measures introduced in moments of urgency cannot become permanent line items by default. Where the intervention does not effectively address the identified problem, resources should be redirected to where they can deliver the greatest impact.

At its core, this is a question of fiscal discipline and institutional integrity. Public funds are limited, and their allocation reflects state priorities. The HSDG was never intended to subsidise domestic energy systems. Its purpose is to deliver adequate housing, a constitutional obligation and a critical component of social stability. Using it to compensate for failures in another sector blurs accountability lines and undermines the credibility of government budgeting. This reflects a recurring challenge in South Africa’s governance culture: crisis measures are introduced quickly, often justifiably, but they are rarely reviewed rigorously once the crisis abates. Policies that were once necessary can become entrenched, consuming resources long after their justification has faded. This is not unique to SHS. It speaks to the importance of institutionalising review mechanisms and creating incentives for departments to wind down or redesign interventions when circumstances change.

Institutionalising review mechanisms and creating incentives to redesign interventions when circumstances change is crucial

Energy poverty should not be ignored; it remains a pressing issue, particularly in informal settlements and overcrowded dwellings. However, the solutions lie in structural, system-level interventions - expanding utility-scale renewable generation and storage, reforming tariffs to make electricity more affordable for low-income users, enhancing municipal utilities and strengthening the Free Basic Electricity programme for vulnerable households. These are the levers that can shift the energy landscape sustainably; housing grants cannot and should not bear this burden.

South Africa faces difficult fiscal choices. The state must do more with less while confronting persistent social backlogs. In this context, evidence-based policymaking is essential. The SHS case provides a clear lesson: evidence must trump habit, and fiscal integrity must guide how we adapt policies over time. The National Department of Human Settlements and Minister Nkadimeng should prioritise the constitutional mandate and optimise the use of limited resources by raising the issue at MINMEC and reversing the SHS decision. Doing so would restore the HSDG to its original purpose: funding housing opportunities, not energy stopgaps.

As the lights remain on and the energy sector stabilises, it is time to exorcise the ghost of load shedding from the housing budget. Redirecting these funds back to their original purpose would not only accelerate delivery but also signal a shift towards a more disciplined, evidence-led state, one that allocates resources where they are most needed and withdraws interventions when their time has passed.

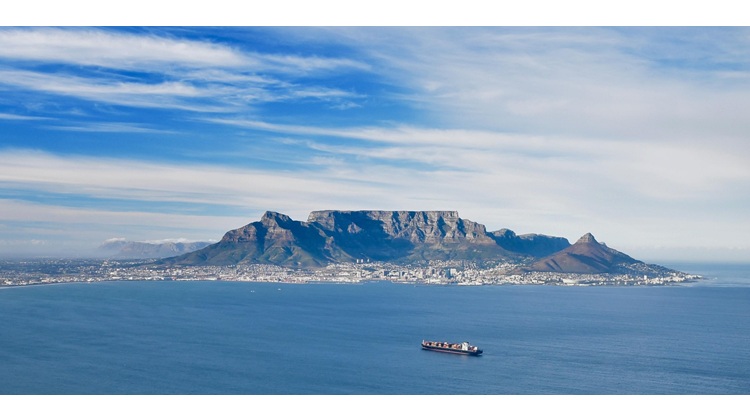

Image: Olga Ernst/Wikimedia Commons

Republication of our Africa Tomorrow articles only with permission. Contact us for any enquiries.