Africa’s US trade surplus at risk

US tariff chaos risks undermining AGOA’s gains, hitting African exporters hard and highlighting the urgent need for market diversification.

On 2 April 2025, United States (US) President Donald Trump announced a 10% baseline tariff on nearly all imports, effective 5 April, along with additional “reciprocal” tariffs on goods from 57 countries, including 20 African nations (Figure 1)—originally set for 9 April but now paused for 90 days. A limited number of product categories such as pharmaceutical, minerals, natural gas and petroleum oils were exempted. Trump cited trade deficits as reasons for targeting those countries.

These tariff measures have sparked numerous questions across Africa: What are the implications for the continent’s export-driven growth, its entrepreneurs and consumers and the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA)? What strategies are needed to counter and cushion the effects of the tariff pressure?

Since the 2000s, the US has consistently recorded a merchandised trade deficit with Africa, with the exception of 2014 and 2015. This imbalance has been primarily driven by substantial imports of mineral fuels from Nigeria, Angola and Algeria, along with mineral resources from South Africa. In 2023, the US registered a trade deficit with the continent of US$11.3 billion—about 3.6% of its global trade deficit. South Africa and Nigeria accounted for approximately 63% and 29% of the deficit, respectively (Figure 2).

Given the relatively low levels of industrial development across many African countries, their imports from the US tend to be dominated by capital goods. These are essential inputs for infrastructure, industry and services, reflecting Africa’s dependence on external sources for advanced technologies and equipment. This structural dependence means that any increase in US tariffs or tightening of trade conditions can significantly raise costs and slow down development efforts on the continent.

Figure 2: US bilateral trade balance with the target 20 African countries, 2023. Source: Author’s calculations based on data from Trade Map, 2025.

In an increasingly interconnected global economy, the US trade deficit with Africa may reflect deep supply chain integration, where American firms depend on African inputs to produce medium- and high-technology goods for domestic use and export.

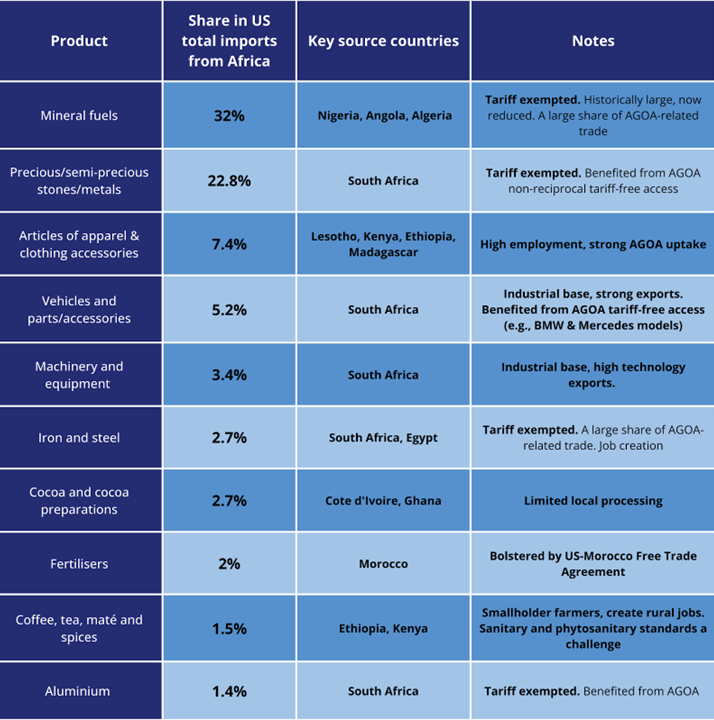

Mineral fuels and metals, which account for over 50% of US imports from Africa, are vital to the energy, manufacturing and defence sectors. The US importation of competitively priced primary and intermediate goods from Africa boosts its domestic production. Moreover, imports of capital goods such as machinery and equipment (which represented just 3.4% of its imports from Africa in 2023) foster long-term growth by enhancing productivity and driving innovation across both primary and manufacturing industries.

Figure 3: Top 10 US Imports from Africa and their share in its total imports from the continent, 2023. Source: Author’s calculations based on data from Trade Map, 2025.

Exports contribute significantly to income generation and employment across Africa. In 2023, the continent’s exports were equivalent to 23.8% of its GDP, significantly below the global average of around 37%. Exports to the US accounted for nearly 1.5% of Africa’s GDP. However, a relatively small proportion of these exports comprised manufactured or high-value-added goods (Figure 3), which typically provide more stable and substantial contributions to economic output. Instead, many African economies remain heavily dependent on a limited range of primary and commodity goods, making them particularly vulnerable to fluctuations in global market prices and geopolitical tensions.

With the largest economy in the world at close to US$30 trillion and a population of over 345 million, the US represents a significant export market highly attractive to competitive African exporters seeking growth and market diversification. However, the imposition of higher reciprocal tariffs will erode the competitiveness of African exports in the US market, with particularly adverse effects on low-income economies like Lesotho, Madagascar and Mozambique, where most exporting firms are still in the early stages of development—exporting labour-intensive goods such as agriculture, and textiles and apparel. The significant impact on such sectors effectively nullifies the benefits of the AGOA, which was intended to help kickstart light manufacturing in sub-Saharan Africa and presents a significant risk of firms’ closures and job losses.

The significant tariff impact effectively nullifies the benefits of the AGOA, which was intended to help kickstart manufacturing in sub-Saharan Africa

This additional cost imposed by the tariffs will lead to a decline in demand in the US market, potentially negatively impacting these economies, particularly those that had previously benefited from preferential free access under AGOA.

Textiles and apparel imported into the US from Lesotho will now face an additional 50% import duty, potentially impacting exports worth around US$173 million—representing about 75% of Lesotho’s total exports to the US in 2023.

Reciprocal tariffs on Africa’s automotive exports will potentially reduce foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows that are driven by export opportunities in the US market. The tariffs will increase the cost of African-made vehicles in the US market, making African production less attractive to investors targeting American consumers.

Over the past two decades, US imports from Africa have declined (Figure 4) from approximately US$68 billion in 2005 to around US$40 billion in 2023. During these years, the US share in Africa’s total exports fell sharply from 36% to roughly 6%, while China’s share rose from 11% to 17%. The introduction of reciprocal tariffs will further reduce Africa’s export share in the US market, diminishing an already shrinking flow.

Given Africa’s relatively small share of total exports to the US, the impact of the new tariffs is best assessed at the country level rather than continent-wide. The effects will be more pronounced for those that export heavily to the US in targeted sectors (agriculture, automotive, textiles and apparel), particularly under the AGOA.

The tariff effects will be pronounced for countries that export heavily to the US in targeted sectors

South Africa is the continent’s leading exporter of vehicles and parts to the US, accounting for 13% of its total exports to the US and 92% of all African automotive and parts exports to the US in 2023. It also exports a significant volume of agricultural products, machinery and equipment to the US. The imposed “reciprocal” tariffs present considerable challenges that may reshape its future trade patterns.

Conversely, Lesotho is highly reliant on textile and apparel exports, which make up roughly 75% of its total exports to the US. A 50% tariff on garments will severely impact employment and manufacturing operations in the country.

The impact will be minimal on the 35 other African countries whose exports to the US will be subject to just the 10% baseline tariff.

Trump’s tariffs and foreign policy signal the need for Africa to diversify its exports and export markets, reduce over-dependence on a single partner or region, and deepen regional integration through customs unions, regional economic communities (RECs) and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). Following the 9 April announcement of a 90-day pause on these high tariffs for all countries except China, African governments must coordinate their efforts in negotiating revisions to the harsh tariff measures.

Image: geralt/Pixabay