The geopolitics of imagination

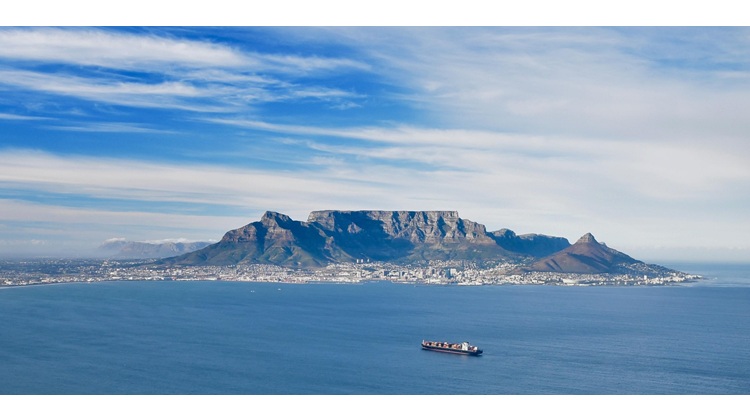

Geopolitical power now operates through narratives, with Africa a key arena where stories shape investment, policy and long-term development.

Power, politics and influence are about far more than boots on the ground, drones in the air and tariffs on trade routes in the current geopolitical landscape. These dynamics matter everywhere, but they are particularly consequential for Africa, where struggles over narratives and imagined futures increasingly shape development choices and trajectories that are still being actively formed.

In Africa, struggles over narratives and imagined futures increasingly shape development choices and trajectories

As human society has become more globalised, and as technology and financial markets are a reminder that physical borders cannot control innovation, inflation or ideas, the “4M” model of power, developed by Flux Trends as a geopolitical sense-making tool, offers a framework for shaping the future.

The 4M model of power describes how “muscle”, i.e. physical power including control over geography and commodities (and people), has become untethered from other borderless critical sources or layers of power, namely money, medium and message.

“Money” no longer neatly respects national monetary policy and flows where it wishes (via crypto, cash and grey-market channels). For instance, Nigeria’s failed attempts to control USD-based stablecoins are a case in point.

“Medium” refers to how much of the invisible infrastructure that controls the “software” layer of human society, specifically social media platforms, censorship-resistant Signal messaging services and privately owned satellite networks, refuse to comply with national interests, aided by VPNs and onion routers.

Lastly, but perhaps most interestingly, “message” refers to soft and cultural power and explains how the stories people share with and about each other, online and offline, privately and publicly, interact with and influence the other three layers of power, and prove to be the most resistant to official state and government (and even private platform interest) attempts to control and contain them.

Ideas, and the power of imagination to resist physical and financial power, and indeed exert control over more traditional sources of power and control, are therefore critical to understanding, anticipating and influencing the future.

People are shaped by the narratives they believe about themselves and what their future looks like. If they are told to expect a recession, they save rather than invest, anticipating bad times ahead, and their pessimism starves them of progress and development, perpetuating the same recession they feared.

This is why forward guidance, or setting expectations, is a key monetary policy lever employed by finance ministers and central banks to encourage spending and investment or saving and prudence to avoid recessions or overexuberance, respectively.

The same principles apply in a more qualitative, soft power sense. If The Economist magazine calls Africa “the Hopeless Continent” or the Financial Times casts doubt on African governance, Africans and non-Africans alike lose confidence in investing in the continent's future. Capital responds to the market’s common understanding of risk, whether that risk is based on figures or fears and feelings.

If a few years later, the same magazines change their cover story to “Africa Rising”, risk-averse capital follows suit and creates virtuous instead of vicious confidence and investment cycles.

Stories are powerful. Forecasts, whether numerical or narrative, influence the futures they attempt to predict.

Yes, this is an oversimplification; no amount of forward guidance, no matter how credible, can substitute the necessity of institutional credibility and individual and collective action towards shared goals, but the truth remains: how futures are framed influences how they unfold.

Indeed, stories can move people and change self-limiting beliefs. This makes them effective tools that can be wielded to forge social cohesion and direction through turbulent times (‘Each of us is as intimately attached to the soil of this beautiful country as are the famous jacaranda trees of Pretoria and the mimosa trees of the bushveld—a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world.’ Nelson Mandela, 1994), or as a weapon to exploit societal divisions to consolidate power (‘Together, we will make America strong again. We will make America wealthy again. We will make America proud again. We will make America safe again. And, yes, together, we will make America great again.’ Donald Trump, 2025).

As such, striving for good stories that inspire positive action can be a powerful policy lever.

These good stories have three critical factors in common. Firstly, they are plausible. If a story is not credible enough to feel possible, people will not really believe in it, and a belief in the possible is key to forward momentum and behaviour change. This is most clearly demonstrated by the extent to which the credibility of central banks affects policy efficacy by up to 69%.

Secondly, the stories are positive; that is, they speak of a desirable future that all people and stakeholders involved want to be part of. If people do not want to be a part of a proposed future, they will not support its progress. Here, emotive stories are proven to be particularly powerful at galvanising social movements and shifting public sentiment away from the undesirable towards what is necessary for the preferred alternative.

And, thirdly, the future imagined must be inclusive if people hope to unify. That is, it must show each and every person expected to participate that they have a personal part to play in it, that there is a valued and valuable role for them within it. Futures that do not leave space for people do not inspire collective action; they inspire apathy, resistance and even revolution.

Commonly shared stories that “colonise” the global popular imagination about the African continent, however, sorely lack these three critical elements. The portrayals of the world’s most youthful and resource-rich continent focus on dependency, fatalism or fantasy. They are “owned” by foreign creditors and capitalised on by Hollywood producers, instead of being directed by the content’s own citizens. Foreign interests cast Africans as supporting actors rather than leaders and directors of their own destiny, and prevalent “Afro-pessimism” narratives have a real influence on not only biases but also international investor behaviour.

Foreign interests cast Africans as supporting actors rather than leaders and directors of their own destiny

Yet Africa does not have to accept imported stories. African citizens can write their own.

When it comes to the future of Africa, the continent needs better stories to move public (and institutional) imagination, and mobilise funding and effort towards them, if Africa is to break out of the (very modest) expected, forecast trajectories, which, based on present trends, predict the gap between Africa and the rest of the developed world growing rather than shrinking.

Research shows that emotive stories can influence policymakers’ decisions as well as citizens’ behaviour. However, once again, due to their ability to influence decision-makers, the kinds of stories selected and showcased to policymakers matter.

These dynamics are already being actively tested through African-led futures initiatives. The Afrofutures2050 project, and likewise the Young Changemakers Visions for Africa, showcased at the ISS African Futures Conference 2025, are designed to do just that: encourage young Africans to envision their own healthy, preferred possible future for the Africa they want to live in. Futures dreamed by those who will have to live in—and build—that future. The very act of dreaming and sharing the desired way forward puts society one step closer to accomplishing it and policymakers one step closer to supporting it.

The very act of dreaming and sharing the desired way forward puts society one step closer to accomplishing it

By defining what Africans want and what Africa could be, policymakers and citizens alike can “backcast” the required transformations as a plausible path from the present to the preferred, shared future.

Image: geralt/Pixabay

Republication of our Africa Tomorrow articles is only with permission. Contact us for any enquiries.