How the war in Ukraine ends, and the implications for Africa

To reach its growth potential, Africa needs a rapprochement between the West and China.

The war in Ukraine and the intensified competition between the United States (US) and China loom over every international relations discussion. How does the war end, and what are the implications for Africa?

Although Africa represents only 3% of the global economy, its large and poor population (17% of the world’s total) means the continent is deeply affected by the war. It’s already affected food and fertiliser supplies and prices. And as it continues, the war will divert resources away from Africa, including aid and investment. Humanitarian relief efforts will suffer.

Already the International Monetary Fund and World Bank regularly revise their growth and poverty alleviation estimations downwards, now referring to the potential of a lost decade. Instead of heading towards a sustainable world, lower global growth will seriously affect income growth and poverty reduction in Africa.

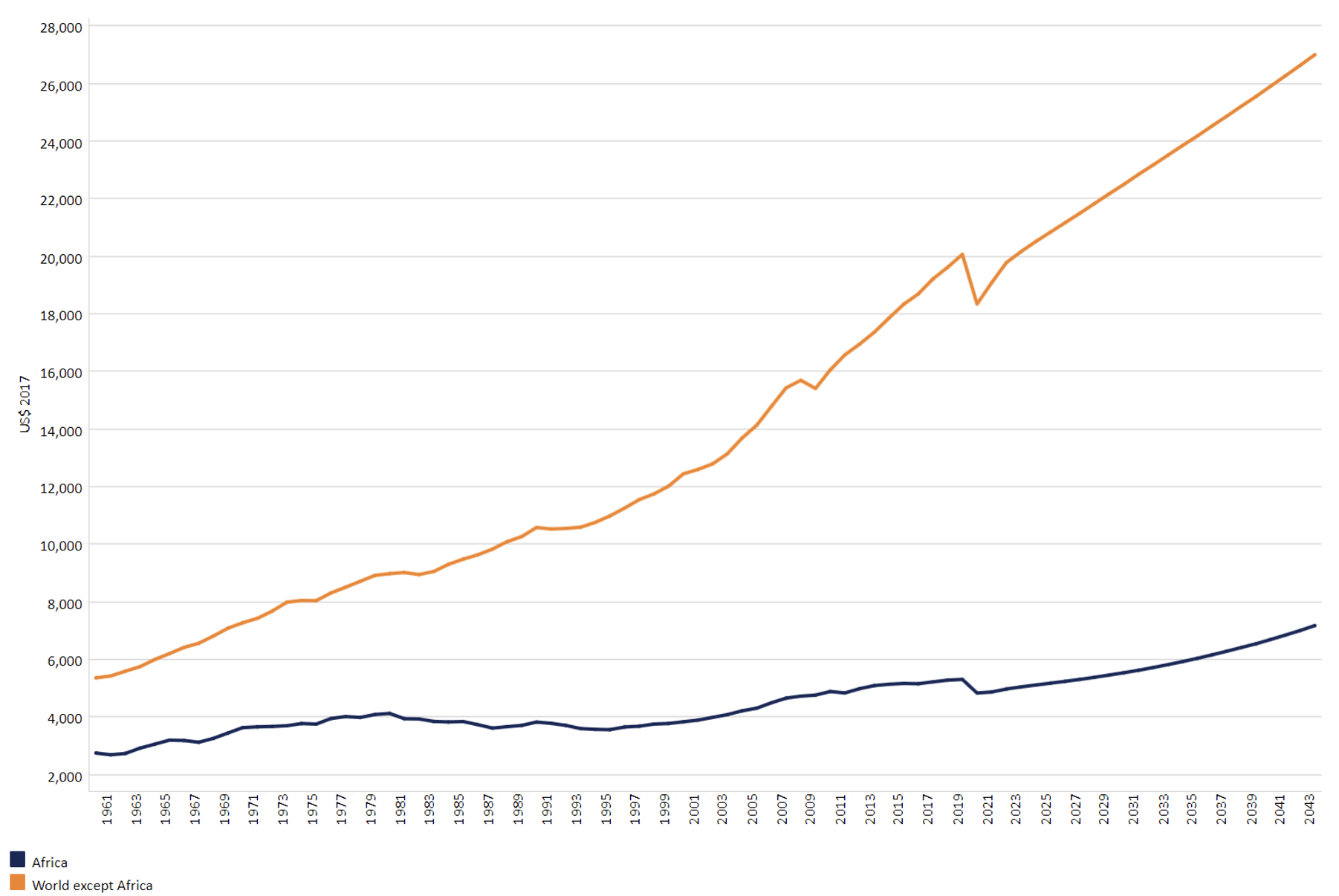

Africa needs to grow rapidly if it is to stem and then close the growing gap in average incomes compared to the rest of the world. Chart 1 includes the history and a forecast of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita for Africa compared to the average for the rest of the world by 2043.

The war in Ukraine has already affected food and fertiliser supplies and prices in Africa

From 1963 to 2022, Africa’s economy grew at an average rate of 3.5%. Because Africa has a young and rapidly expanding population, the 3.5% translated into less than 1% average improvement in GDP per capita. Meanwhile, average economic growth rates in the rest of the world were slightly lower, at 3.3%, but lower population growth translated into more than double the GDP per capita growth rate.

Chart 1: History and forecast of GDP per capita for Africa and the rest of the world, 1963 to 2043

The Institute for Security Studies’ African Futures and Innovation team’s Current Path forecast is that Africa’s economy will expand by a healthy 4.5% from 2024 to 2043 compared to a 2.3% average for the rest of the world. Because of rapid population growth, 4.5% will translate into GDP per capita growth of only about 1.5% annually in Africa and marginally less in the rest of the world.

The main reason for the big difference is that while Africa’s population will expand by 2.2% annually, in the rest of the world, population growth will be below 0.5%. Once we fully factor in the impact of the war in Ukraine, the forecasts will become significantly more pessimistic.

In June 2022, we released our modelling on Africa’s growth potential should the continent make a series of targeted interventions in multiple sectors. The forecasts comprise up to 11 sectoral scenarios for each African country ranging from an agricultural revolution to the impact of industrialisation and leapfrogging. Once combined, the sectoral scenarios reasonably estimate Africa’s development potential in a facilitating world environment.

We term this global facilitating context a Sustainable World, reflecting the successful pursuit of the broad objectives of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. In this ideal, sustainable, high-growth world, Africa’s economy grows at what we consider its maximum rate of 7.5%.

Fully implementing the African Continental Free Trade Area can unlock more rapid growth than any other scenario

To be clear, Africa would have to grow at an average rate of 15% annually to close the income gap with the average for the rest of the world in two decades, around 13% to do so by 2053, and roughly 11% by 2063. This is the end year of the African Union’s long-term development plan for the continent. No country, not even China, has achieved such rates, never mind a group of 54 highly diverse countries.

The Ukraine war makes the chance of a Sustainable World materialising even more doubtful. Indeed, no one knows how the conflict will end, which has encouraged us to turn to scenarios to explore the implications of alternatives.

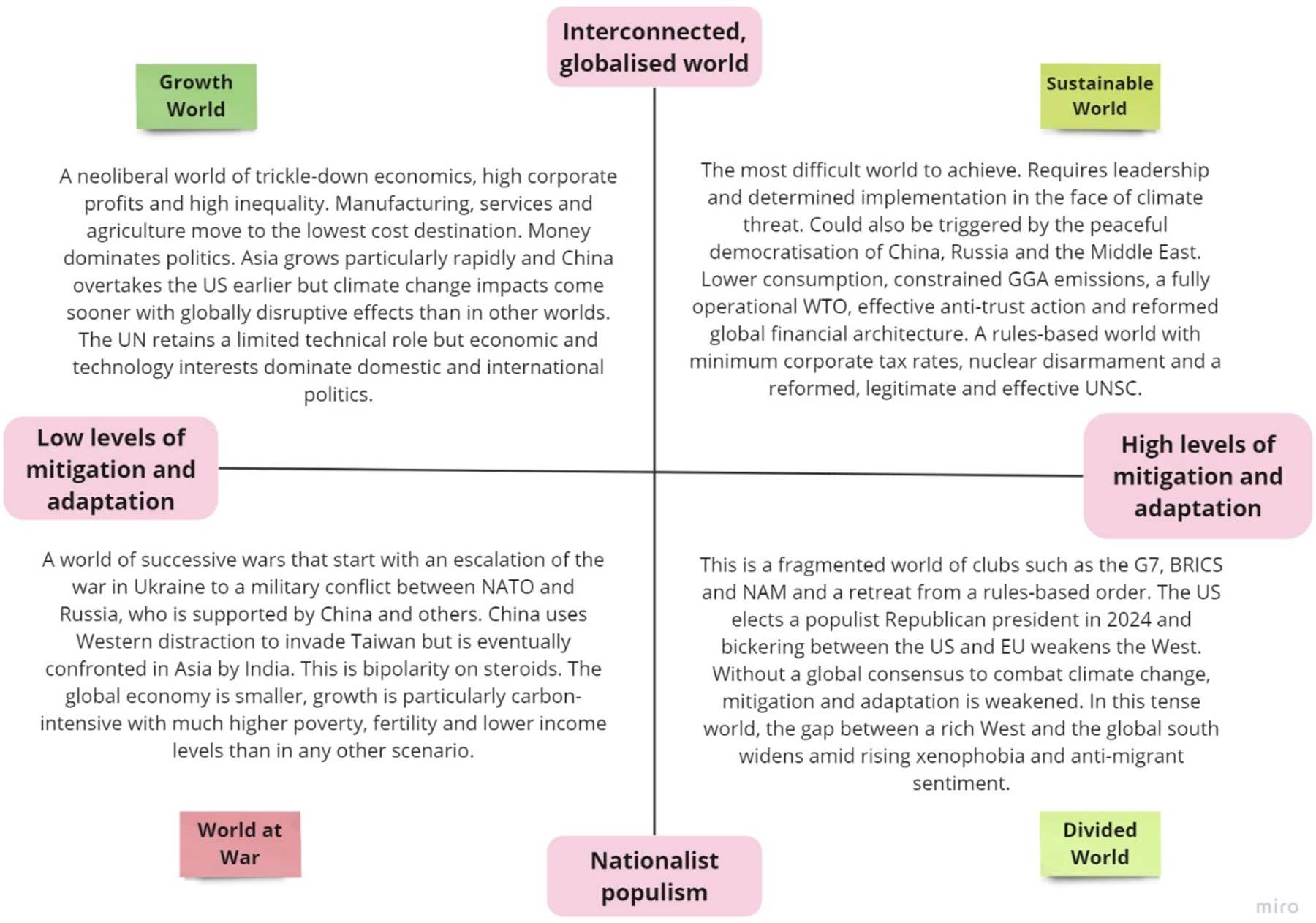

In addition to the best-of-world Sustainable World scenario, we add three global scenarios to our forecasting to capture all reasonable long-term outcomes. Chart 2 presents the framing and conceptual approach and includes the key characteristics of each global scenario. We use globalisation and sustainability as the two axes to frame our scenarios.

Chart 2: Global scenarios

In a Growth World scenario, countries focus on the rapid improvements in income and returns on investment, eschewing environmental concerns, but do so still within a global, rules-based context. The third scenario is of a Divided World, perhaps closest to our current trajectory, characterised by a sense of global fracturing, populism, nationalism and a retreat from globalisation.

A Divided World reflects the fraying of the rules-based system as we know it, with its complex lattice of norms and institutions. The final scenario is a World at War, where competition between the West and its competitors, led by China, dominates all aspects of the global economy, politics and relations with violent outcomes. Shut out of the prospects for more rapid development, Africans suffer.

As the war continues, it will divert resources away from Africa, including aid and investment

An African scenario complements each global scenario, premised on the extent of regional economic integration and Africa’s relations with countries and regions such as China, the European Union (EU) and the US. The details of each scenario and the associated forecasts are in the theme on Africa in the World on the African Futures website.

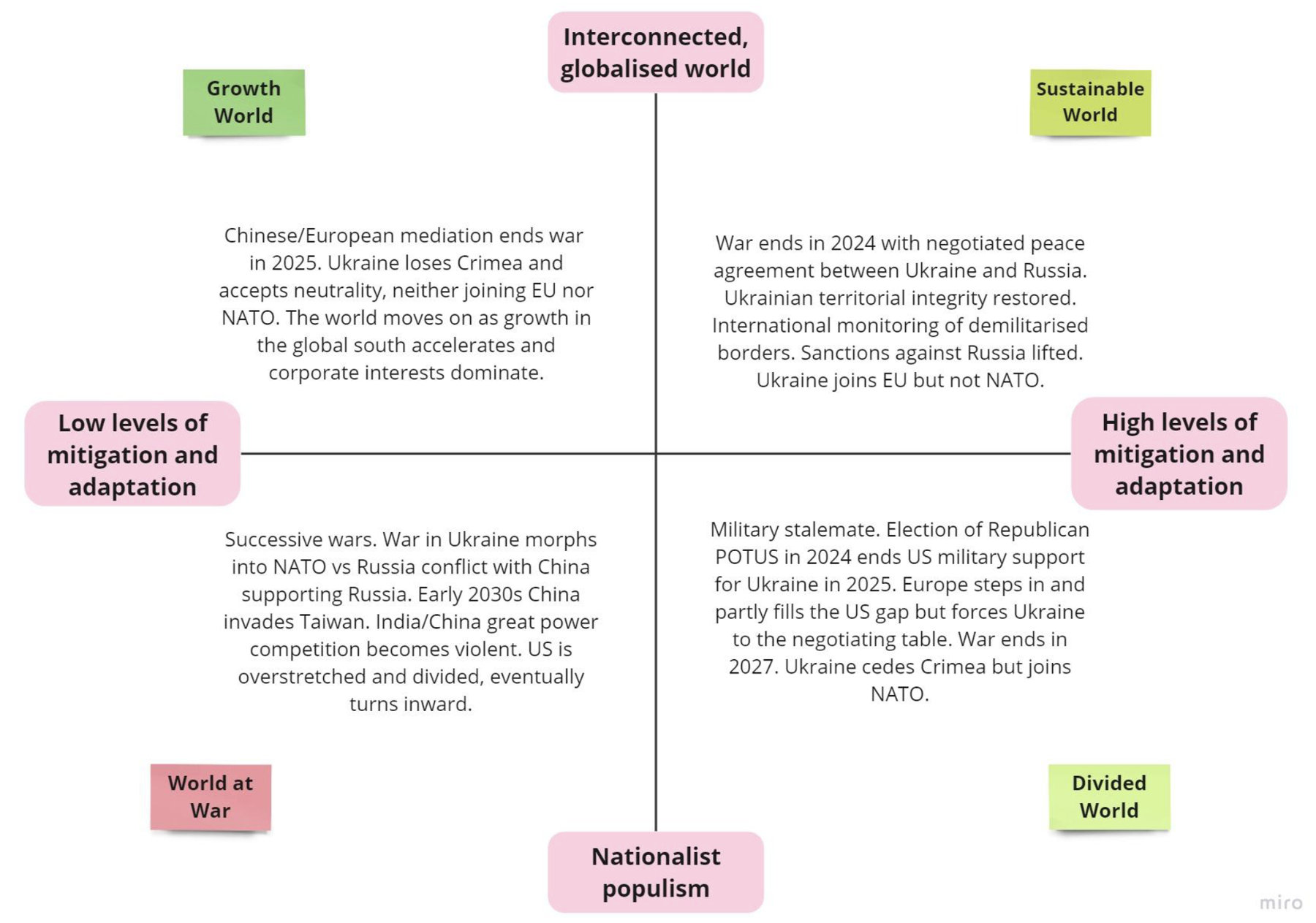

Chart 3 presents four ways the war in Ukraine could end, associated with the four global scenarios. In the Sustainable World, the war ends in 2024 or 2025 after a palace revolt in the Kremlin followed by a negotiated peace agreement brokered by China and others. The territorial integrity of Ukraine is restored to its pre-2014 borders which are demarcated, demilitarised and internationally monitored. In time most sanctions against Russia are lifted, and it rejoins the international community of nations, although its stature is significantly diminished.

Given its constitutionally embedded neutral status, Ukraine eventually joins the EU but not the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Its security is, instead, guaranteed through a number of bilateral agreements. This would represent the best possible scenario for Africa’s development and cause the least disruption to the continent’s growth potential and development needs.

Chart 3: How the war in Ukraine ends

In the Divided World, the election of a Republican president in the US in 2024 means that US military support for Ukraine starts to taper down as from 2025. Europe steps in and partly fills the US gap, but the loss of US war materials and supplies weakens Ukraine’s war effort significantly, and the war grinds to a punishing stalemate.

After considerable bickering that threatens to split the EU and NATO, France and Germany lead in forcing Ukraine to negotiate, with tacit support from the US. The war eventually comes to an exhausting end. Ukraine is forced to cede Crimea to Russia, but as a guarantee for its security, it joins NATO and, some years later, the EU.

The World at War comprises a series of overlapping wars. The war in Ukraine morphs into a conflict between NATO and Russia, possibly involving tactical nuclear weapons. China provides sufficient direct logistic and armament support to Russia to avert a military and institutional collapse in Russia. With NATO focused on its war with Russia, China invades and eventually invades Taiwan even as the conflict drags in the US, Japan and Australia.

Africa must grow rapidly to close the growing gap in average incomes compared to the rest of the world

Several years later an assertive China is ultimately confronted by India as the two Asian giants collide. The conventional conflict between China and India escalates into a limited nuclear exchange before settling down. In this scenario, the US is overstretched and divided, suffering significant military losses in Europe and during efforts to defend Taiwan. It eventually turns inward to fortress America and leaves NATO. Its stature as a great power is severely eroded.

In the Growth World, the war in Ukraine ends in 2025 through Chinese/UN mediation. Ukraine loses Crimea and is forced to accept neutrality entrenched in a new constitution, joining neither the EU nor NATO. The world moves on as growth in the global south accelerates.

Russia is now an effective economic subordinate of China, increasingly concerned about the threat of Chinese encroachment into its vast and poorly populated eastern spaces. Rather than politics and geopolitical positioning, the focus is on economic growth until the accelerated impact of climate change forces humanity to confront an even larger foe.

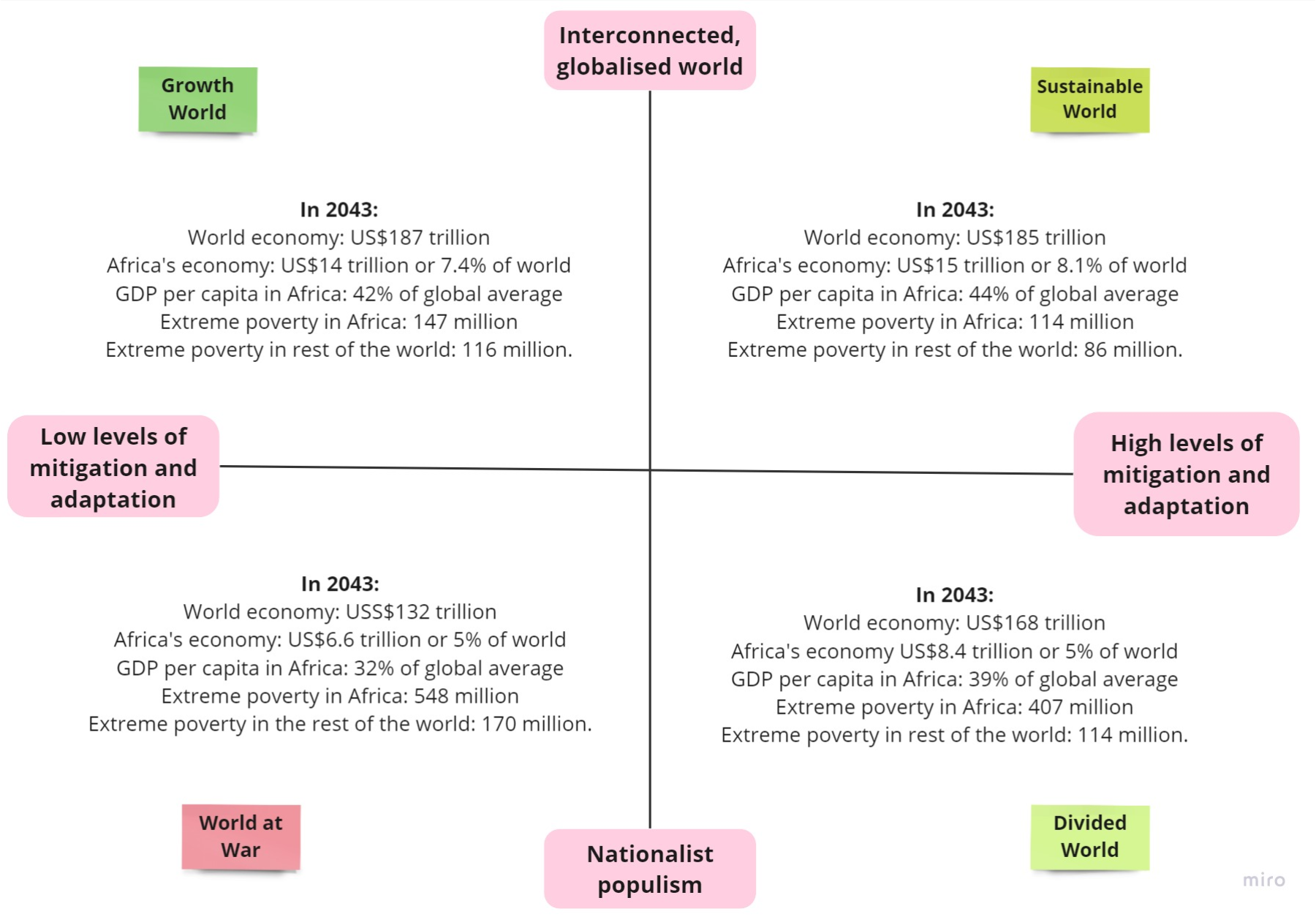

Our modelling would suggest that even in the Sustainable World scenario, Africa would still have 400 million people living in extreme poverty by 2030 and 127 million by 2043. The 2043 total for the rest of the world is 85 million. Whereas GDP per capita in the rest of the world is 75% larger than in Africa in 2023, by 2043, the gap would have declined to 62%.

The results for the four scenarios are presented in Chart 4, which clearly highlights the stark consequences of a World at War scenario. The chart compares the outcomes for the Divided World, World at War and Growth World with the achievements possible in the Sustainable World.

Chart 4: Summary impact of different worlds

Scenarios are not predictions. They are tools that help to frame alternative futures systematically and to enable a coherent discussion of different outcomes. Scenarios done using the traditional two-dimension analysis, in this case, the extent of global fracturing versus efforts at sustainability, present four divergent alternatives that assist in the associated modelling and conceptualisation.

Reality will be much more complex and typically ends up somewhere in between. Done well, however, scenarios surface structural trends and the outcomes or effects of different pathways or trends.

Africa has come a long way but faces an uphill struggle to fully realise its potential. Since independence in the 1960s, African countries have gained less than other regions from globalisation and the associated expansion of trade, knowledge and financial flows.

Eventually, the commodities boom, not the Lagos Plan of Action (1980) or the Abuja Treaty (1991), changed Africa’s prospects. From 1994 until 2008 (when the financial crisis hit), Africa experienced its most sustained growth. The average growth rate was 4.6% annually, and per capita income increased by 35%. However, high levels of inequality and rapid population growth meant that the share of Africans living in extreme poverty decreased by only about five percentage points.

Looking to the future, Africa needs global stability. It needs a rapprochement between the West and China, and it needs to take control of its growth agenda. It will suffer if the current efforts at instrumentalising Africans in this Divided World continue.

Africa needs debt relief, Chinese trade and investment, expanded relations with the EU, capital from the US and more trade with the rest of the global south. It needs an agricultural revolution to ensure food security and accelerate its trade integration agenda to provide a larger and more attractive domestic and foreign capital market.

In the long term, fully implementing the African Continental Free Trade Area can unlock more rapid growth than any other scenario.

Meanwhile, as the elephants fight, the grass suffers.

Originally published on 13 April 2023. Updated on 18 April 2024

Image: ©BarksJapan / Alamy Stock Photo (adapted)