Africa’s uncomfortable future: insights from the T20 Policy Dialogue

The recent T20 Africa High-Level Policy Dialogue laid bare an inconvenient truth: African agency cannot exist without disrupting the status quo.

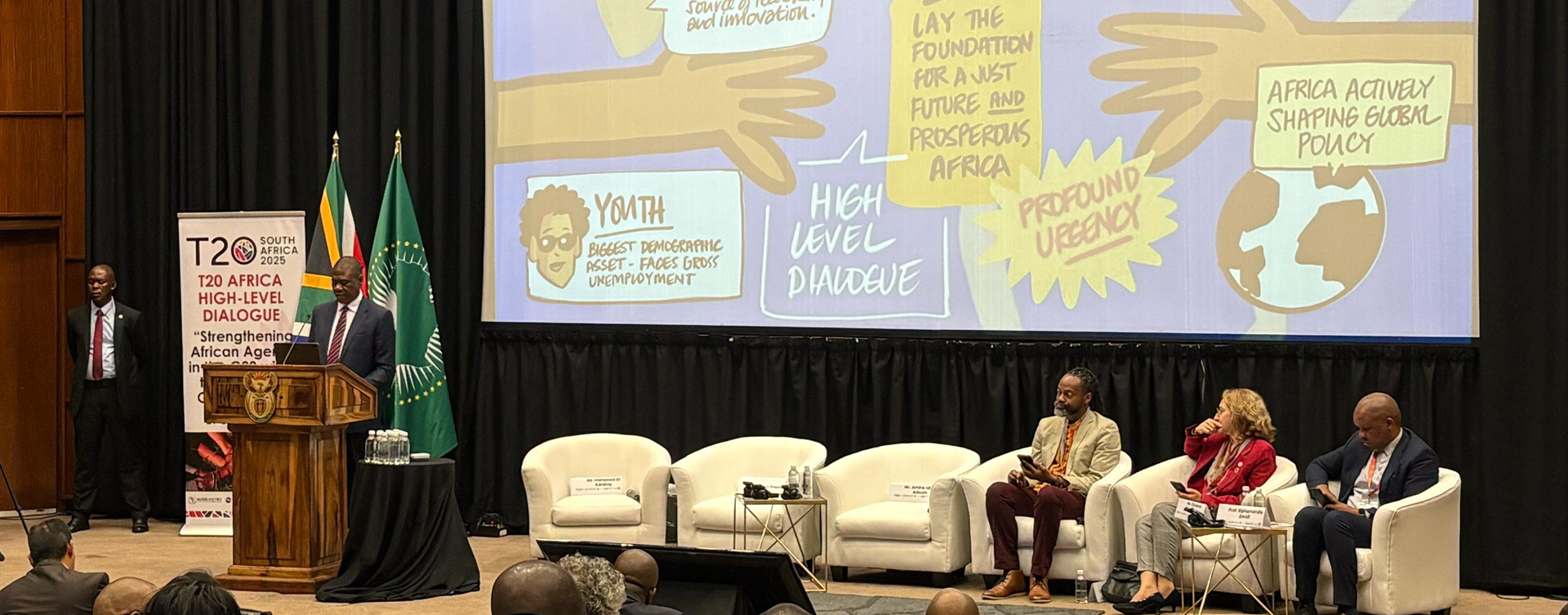

The T20 Africa High-Level Policy Dialogue, held on 29–30 April, brought together African policymakers, leading think tanks and global experts to strengthen African agency in the G20 and the emerging global order. The event formed part of South Africa’s G20 presidency and followed the African Union’s long-awaited admission to the G20—both widely hailed as milestones in advancing African agency. But symbolism alone will not shift the deeper, long-standing structural discomforts. Meaningful agency means more than a seat at global tables. Our systems need rethinking, our institutions reform and our slogans substance. Africa’s struggle with its present is as urgent as its ambition for the future.

Africa’s struggle with its present is as urgent as its ambition for the future

The most pressing call is for introspection. A central theme that emerged was the necessity to “get our house in order.” The so-called elephant in the room, our own governance failures, was openly acknowledged. Entrenched systems, fragile institutions, weak accountability and disconnected leaders have created a governance vacuum that no amount of multilateral positioning can remedy. As one participant bluntly stated, ‘We cannot influence the world if we cannot govern ourselves.’ Another compelling argument was made that before we address the "how" of making progress, we must confront the "why" behind persistent failure, despite extensive knowledge of Africa's challenges and opportunities. This is not merely a question of capability, but of will. Why, despite decades of research, insights and donor interventions, do we keep circling the same issues, poor infrastructure, youth unemployment and extractive politics, without any significant change?

Governance failures are undeniably part of Africa’s development challenge, but they are not the whole story. As AFI’s Jakkie Cilliers rightly noted, structural constraints, especially demographics, are just as critical. With some of the world’s highest dependency ratios, the continent faces a demographic drag that cannot be fixed by institutional reform alone.

Unlocking the long-promised demographic dividend, expected only after 2050, requires bold and early action. That means scaling labour-intensive sectors like agriculture, enhancing quality education and developing industries capable of absorbing the millions of young people entering the job market each year. Initiatives like the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) are essential, but without real traction in productivity and economic transformation, they risk becoming yet another hollow framework. Africa’s future depends on aligning institutional change with a strategic response to its demographic reality.

We cannot redesign broken systems without first shifting the mindsets that built them. That shift demands more than policy—it demands coalitions across sectors, and above all, the authentic inclusion of Africa’s youth. At the T20 Dialogue, youth participants did not just speak, they challenged. They disrupted stale narratives, called out disconnected leadership and pushed for action rooted in lived realities. One voice cut through the formalities, pressing leaders to stop repeating challenges and start closing the gaps.

ISS’s Ottilia Maunganidze captured this generational disconnect with stark clarity: while Africa’s median age is 19, its leaders' average is 63. The continent’s future is being shaped by those with the least stake in its long-term outcomes. Africa’s future must be shaped by those who will live it, not inherited from those who will not.True transformation will not come from the top down. It will require transferring power, not just consulting youth. It will mean challenging existing hierarchies and co-creating systems that reflect the realities, aspirations and agency of the next generation.

Africa’s future must be shaped by those who will live it, not inherited from those who will not

If African agency is to mean anything, it must also be rooted in execution, not just aspiration. Africa has mastered the choreography of planning, but not the discipline of doing. The gap between what is promised and what is delivered continues to erode public trust. Too many plans are long on aspiration, short on financing, timelines or enforcement mechanisms. A clear example is the Yamoussoukro Decision of 1988, which aimed to liberalise air transport across Africa. More than 30 years later, delayed by inertia and fragmented commitments, most states still restrict their airspace and enforce visa barriers. A follow-up agreement, the 2018 Single African Air Transport Market, was launched to reignite progress, but has delivered little.

Even well-intentioned dialogues, like the T20 itself, risk becoming echo chambers if not grounded in concrete next steps. Africa does not need more blueprints, it needs action plans that are financed, grounded and built to outlast political cycles. As amplified in recent media and again at the T20 Dialogue: ‘Turn off the microphone and put on the power.’ This is starkly illustrated by the continent’s persistent energy poverty. Despite decades of plans and promises, the region still accounts for the majority of people worldwide without electricity, and is projected to remain so through 2043.

Africa’s agency cannot be built on the illusion of uniformity. Pan-African unity is often used as a rhetorical shield, masking deep divergences in institutional capacity, political will and economic strategy. But there is no real agency in pretending alignment where it does not exist. If we are serious about building futures that are both inclusive and actionable, we must recognise that complexity is not a constraint—it is the condition for legitimacy and long-term impact. It requires a shift from consensus to coordination: investing in mechanisms that allow countries to move at different speeds and through different models, yet still pursue shared visions and measurable outcomes. Some states will lead, others will follow. Progress will be uneven. But that does not undermine collective agency. What matters is being strategic about alignment, and having the resolve to move — deliberately and together.

The African Futures Combined Agenda 2063 Scenario demonstrates how national efforts, varying in pace and approach, can deliver continent-wide impact. The scenario models the cumulative impact of country-specific interventions on poverty reduction in Africa. In 2023, 455 million Africans (31%) lived in extreme poverty. On the Current Path, that number falls only slightly, to 386 million (17%) by 2043. But under the Combined Scenario, extreme poverty drops dramatically, to just 169 million (8%). This sharp decline is not the result of uniform action, but of coordinated, context-aware interventions—states moving at different speeds toward a future that delivers for all.

Think tanks are essential to bridge high-level dialogues to grounded, evidence-based transformation. Their value lies not only in analysis, but in their ability to convene: to connect policy with people, ambition with action and institutions with each other. To meet this moment, think tanks must move from the margins to the centre of policy influence. This will require sustained investment in African knowledge ecosystems, the generation of disaggregated, decision-ready data and the building of cross-sector coalitions. It also means creating space for meaningful collaboration between government, the private sector and civil society — anchored in strategic priorities, shared accountability and deliverable outcomes.

Africa’s future will not shift until its present is disrupted—deliberately, uncomfortably and without delay.

Image: Alize le Roux/AFI