Saudi Arabia in Africa: the Kingdom courts the Continent

The Kingdom’s late entry into Africa reflects its wider shift from religious outreach to strategic, state-led engagement.

As Saudi Arabia seeks to reposition itself in an evolving global order, one strategic truth is becoming increasingly clear in Riyadh: no global actor can shape international affairs without a clear and coherent Africa strategy. Although a latecomer, Saudi Arabia is beginning to develop a structured African engagement that combines geopolitical ambition, commercial interests and soft power projection. The critical question, however, is whether it can carve out a distinctive role and achieve relevance in a crowded and competitive space. As traditional Western partners retreat, China recalibrates, and middle powers like the UAE and Türkiye deepen their African footprints, Saudi Arabia needs to outline its comparative advantage and long-term intent clearly.

While Saudi Arabia’s Africa approach is still nascent, the contours of a strategy are emerging. Geopolitically, Africa is central to Riyadh’s effort to move beyond hydrocarbons and diversify ties. The old model of religious outreach and Wahhabi export is starting to make way for a more pragmatic playbook, focused less on ideology and more on infrastructure, investment and influence.

In Africa, Saudi Arabia is advancing a more pragmatic model: less about ideology, more about infrastructure, investment and influence

There are a number of factors driving this outward pivot. Internally, the push stems from the need to sustain momentum behind domestic economic reform and unlock new avenues for growth beyond oil. Externally, the pull lies in Africa’s untapped markets, including renewable potential and strategic geography. Yet, it is also a response to shifting regional dynamics. Countering Iran’s influence remains a lingering concern. Then there is Riyadh’s rivalry with the United Arab Emirates (UAE), its Gulf neighbour, which has been quicker and more agile in embedding itself across African political and commercial networks.

Now, as Riyadh charts its path on the continent, four strategic vectors are shaping the nature of its engagement: critical minerals, agriculture, talent and soft power. Each of these areas reflects the effort to match Africa’s development needs with its own diversification goals.

Critical minerals as a foundation for long-term Saudi-Africa partnerships

Minerals are at the heart of Saudi Arabia’s push for economic transformation, and Africa has become a key partner in securing critical resources. Riyadh is prioritising mining partnerships as part of a broader drive to enhance its energy security and ensure a reliable supply of minerals essential to future industries such as Artificial Intelligence (AI). This comes at a time when many African governments are shifting away from the traditional extract-and-export model, seeking greater beneficiation, local processing and in-country value addition.

Saudi Arabia's long-term success in this space will depend on its ability to approach things differently. Unlike traditional and other emerging players, the Kingdom must use its late entry, deep pockets and developmental approach in its favour. A sustainable investment-led approach, rather than one based on aid or short-term wins, is likely to resonate strongly. It would not only provide African states with an alternative source of capital but also offer leverage in an increasingly multipolar funding landscape.

As Semafor’s Prashant Rao notes, the Public Investment Fund (PIF), which is spearheading many of these efforts, is less constrained by market sentiment than publicly listed firms. This enables long-term investments, crucial for transformative partnerships. With limited colonial baggage and military entanglement, the Kingdom is less encumbered than other powers—something not lost on African governments. Evidence of growing appetite on both sides was visible in the strong African presence at the Future Minerals Forum hosted in Riyadh.

Agriculture as a tool for food security, resilience and regional influence

Food security represents another important dimension of Saudi-Africa cooperation. The Kingdom is increasingly investing in African agriculture to ensure long-term food and water security, diversify its economic base and simultaneously support agricultural development across the continent. This “agricultural diplomacy” aims to serve multiple goals: meeting domestic needs, fostering economic resilience and contributing to regional stability.

A number of investments are already materialising. Notably, Saudi Arabia and the UAE jointly committed over US$400 million to Sudan’s agricultural sector, with an additional US$3 billion allocated to an investment fund.

Linked to this is a focus on climate and environmental sustainability. As noted by the European Council on Foreign Relations, sub-Saharan Africa, with its abundant solar and wind resources, presents an ideal landscape for Gulf countries to test and scale renewable energy technologies. For Riyadh, Africa offers both a platform to develop exportable green technology and a proving ground for new energy models. The Horn of Africa, though politically fragile, remains central to these ambitions. As a strategic maritime corridor, potential food basket and emerging energy frontier, the sub-region sits at the nexus of trade, resource politics and growth opportunities. Saudi investment in solar and wind infrastructure across East Africa could both advance Africa’s energy access and position Riyadh as a credible player in the global green economy.

Talent and labour mobility as an untapped opportunity for mutual benefit

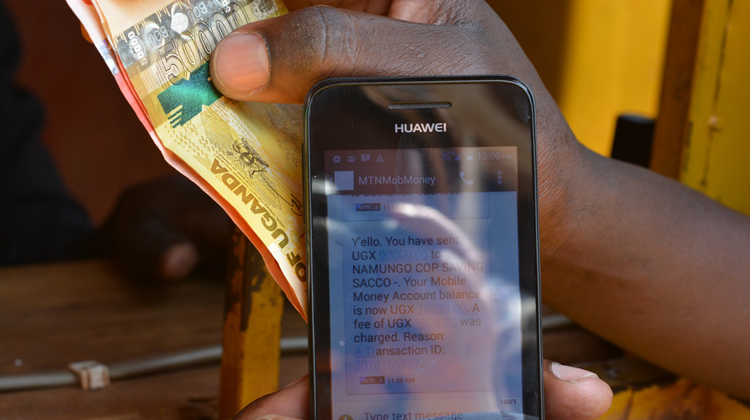

Another underexplored dimension is labour mobility. As Saudi Arabia drives towards ambitious economic growth, it faces a structural talent shortage at home. Africa, by contrast, has a growing young population and limited domestic employment options. If approached strategically, labour migration could become a mutually beneficial dynamic—enabling skills transfer, income flows and stronger people-to-people ties.

However, Riyadh’s labour practices are under growing scrutiny, with well-documented concerns around exploitation and human rights violations. For any partnership in this space to be sustainable, the Kingdom will need to address these reputational risks and offer a more dignified model of labour engagement. Done right, this could drive soft power and shared human capital.

Soft power redefined: from religious outreach to economic diplomacy

Alongside its economic and geopolitical overtures, Saudi Arabia is recalibrating its soft power approach in Africa. Historically, Riyadh’s influence was largely religious, centred on the export of Wahhabi Islam and framed as a counter to Iranian efforts to spread Shia influence on the continent. This approach involved religious institutions, philanthropic aid and mosque construction, all of which sought to position the Kingdom as the spiritual centre of the Islamic world.

Under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, however, that model has shifted. The embrace of “moderate Islam” as part of the Vision 2030 agenda has marked a deliberate move away from religious proselytisation. Instead, Saudi soft power is increasingly being expressed through economic engagement, summit diplomacy and cultural exports such as sport.

One of the clearest examples of this is the Saudi-Arab-African Economic Conference, held in Riyadh in 2023, which brought together leaders from over 50 Middle Eastern and African countries. The summit aimed to deepen political ties, expand trade cooperation and support the African Union’s accession to the G20. This was followed by the New Africa Summit in 2024, reinforcing the Kingdom’s desire to be seen as a credible partner and political stakeholder across the continent. In another arena, Saudi Arabia is using “sports diplomacy” through football investments, event bids and infrastructure projects across Africa.

Moreover, Riyadh has demonstrated increasing sensitivity to global political sentiment. In an age of rising demand for more equitable representation in global governance, the Kingdom publicly supported the African Union’s bid to join the G20. As Foreign Policy notes, Saudi Arabia is also positioning itself as a potential broker and development partner on the continent. Recent moves on debt, infrastructure and conflict mediation reflect the Kingdom’s evolving role.

African strategy to harness Saudi engagement

For African states, the timing is opportune. As the West turns inward and faces domestic dysfunction, and as China recalibrates its approach, African capitals are increasingly open to new relationships—especially those backed by green industrial transformation, patient capital, long-term commitment and fewer political strings. Within this shifting landscape, the broader rebranding of Saudi Arabia’s role in Africa (from religious patron to strategic partner) is opportune.

That said, for Saudi Arabia to realise the full potential of this pivot, several factors merit consideration. Its late entry into the African arena, while often seen as a disadvantage, may prove to be an asset. Arriving after others, Riyadh has the benefit of hindsight. It can learn from the missteps of earlier entrants, such as China, and the overreach of other actors. There is now an opportunity to craft a cleaner, more strategic partnership which avoids extraction and transactional models and instead emphasises sustainability, long-term value addition, as well as mutual and transparent collaboration.

A key strength Saudi Arabia brings is its preference for relationship-driven diplomacy, which aligns well with how African states value engagement. As the Kingdom looks to strengthen its global image, investing in people, showing respect and offering financing with fewer conditions could prove highly effective in winning hearts and minds across the continent. But if Riyadh is serious about taking this relationship to the next level, it must institutionalise its approach. Currently, its Africa engagement remains ad hoc and loosely coordinated. Establishing a dedicated Africa Strategy Unit, similar to efforts by Türkiye, would enhance its coherence and credibility.

In parallel, Saudi Arabia should sharpen the articulation of its unique value proposition. State-led transformation resonates with African governments, which view Saudi development as a model. At the heart of the Kingdom’s engagement is a broader recalibration of its foreign policy posture, which aligns with its internal transformation under Vision 2030. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 parallels the African Agenda 2063 as they both strive to make structural transformations to their respective economies. In Saudi Arabia’s case, it hopes to diversify the economy away from oil reliance.

Riyadh’s capacity to mobilise state resources around a central vision—be it in infrastructure, energy or digital innovation—is a powerful example of how strategic state-led growth can drive rapid development. Creating co-creation platforms in areas such as green energy, fintech, smart agriculture and climate resilience could become the next frontier of meaningful collaboration.

For African governments, the renewed Saudi interest is undeniably welcome. It offers both diversification of partnerships and access to new streams of investment. Here, understanding the Saudi operating model is crucial. Riyadh tends to operate at scale and prefers structured, high-impact investments. Therefore, African sovereigns would do well to align their offerings with sectors that resonate with Saudi priorities—most notably those which cut across agriculture, infrastructure and energy—and consider pooling projects across countries or regions to create scale and investment appeal.

For African governments, the renewed Saudi interest offers partnership and investment opportunities, if they understand its high-impact, scale-driven operating model

Moreover, African states should actively leverage Saudi influence in multilateral forums to advocate for continental priorities. Doing so would enhance Africa’s voice and align both parties’ interests on the global stage. This requires doing homework: detailed mapping of opportunities to Vision 2030, understanding cultural nuances and adapting business environments to suit Riyadh’s style of engagement. African governments must do the work to make themselves compelling partners.

In the broader context, Saudi Arabia’s shift towards relationship-based diplomacy offers African countries another international partner. As traditional donors retreat and the global aid architecture fractures, Riyadh may well emerge as a key player in filling the gap—provided it can match ambition with delivery, and African states can respond in kind.

Image: GDJ/Pixabay

Republication of our Africa Tomorrow articles only with permission. Contact us for any enquiries.