17 Combined scenario

17 Combined scenario

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

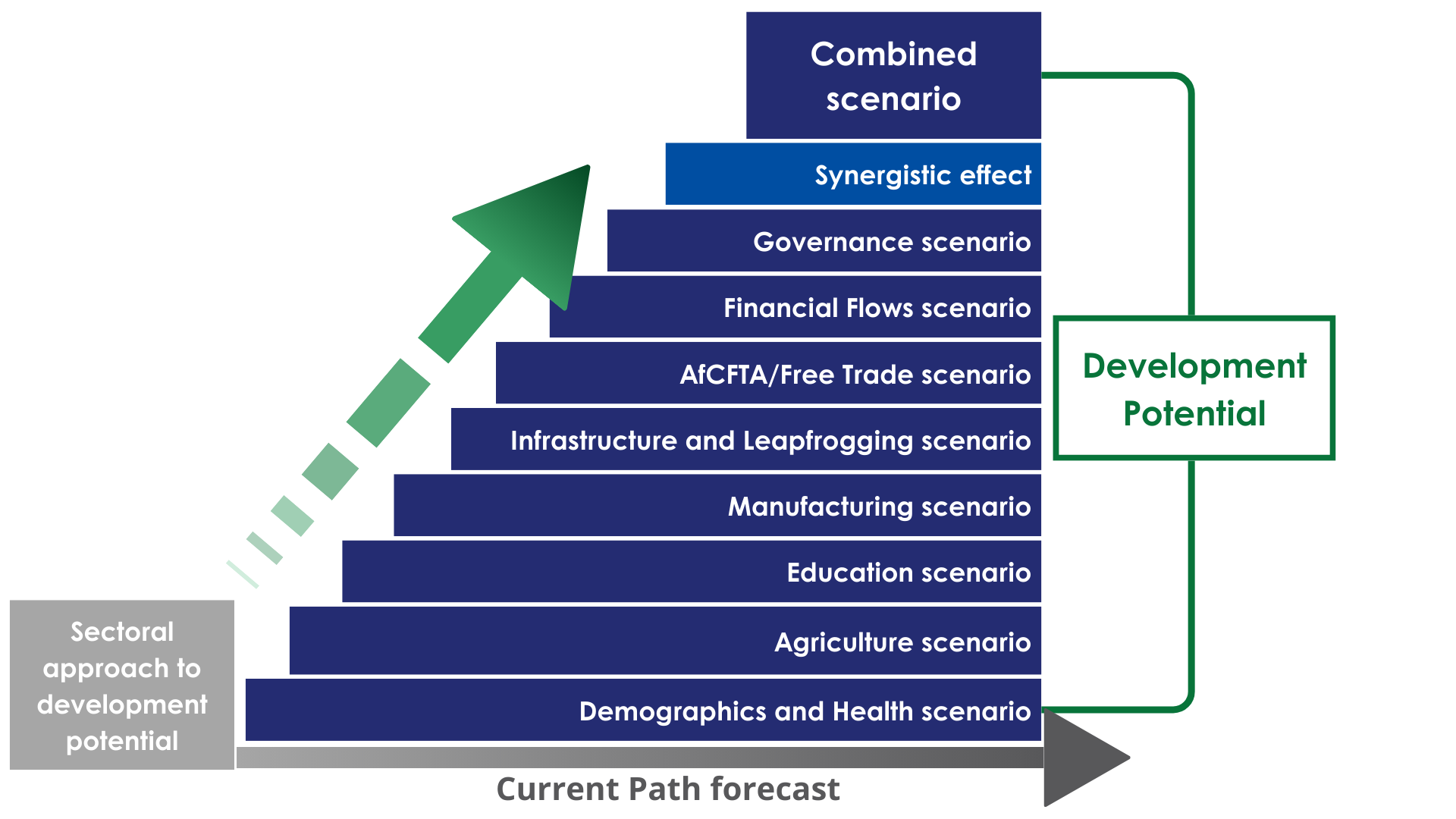

The Combined scenario reflects the integrated impact of eight transformative sectoral interventions across Africa, offering a realistic, benchmarked vision of what coordinated development could achieve by 2043. These sectors are demographics and health, education, agriculture, manufacturing, trade integration (AfCFTA), infrastructure and leapfrogging, financial flows, and governance, as well as the synergistic contribution that comes from combining them. It presents the progress that is possible towards achieving the African Union’s Agenda 2063 by the end of the third, ten-year implementation plan, by 2043. The theme also presents the associated changes in Africa's economic structure, employment, the informal sector and urbanisation and concludes with a set of high-level policy recommendations.

Please see the Technical page for more information about the International Futures modelling platform we use for our forecasts and scenarios.

Summary

The theme begins with an introductory section. Africa’s development presents a global challenge. The Combined scenario offers a strategic, integrated roadmap for Africa’s development by 2043, aligning eight transformative sectors to demonstrate how coordinated action can contribute to the development goals articulated in the African Union’s Agenda 2063.

The Combined scenario's vision is rooted in interlinked reforms across health, education, agriculture, manufacturing, infrastructure, trade integration, finance, and governance. Rather than treating sectors in isolation, the Combined scenario leverages their interdependence — for example, how improvements in health and education enable higher labour productivity, which in turn supports industrialisation and financial mobilisation.

We then explore Africa’s growth. A growth-accounting approach reveals the contribution that labour, capital and multifactor productivity (MFP) or technical progress make to Africa’s slow growth during and after colonialism. When looking to the future, it is evident that most growth will come from the contribution of MFP.

Subsequent sections examine the specific impacts on economic size, GDP per capita, and poverty reduction. The development transformation in the Combined scenario is broad-based and far-reaching. In aggregate terms, Africa’s economy is projected to grow by 233% over two decades, compared to just 139% on a business-as-usual trajectory (the Current Path). Africa’s share of the global economy would increase from 2.8% in 2023 to 5.3% in 2043.

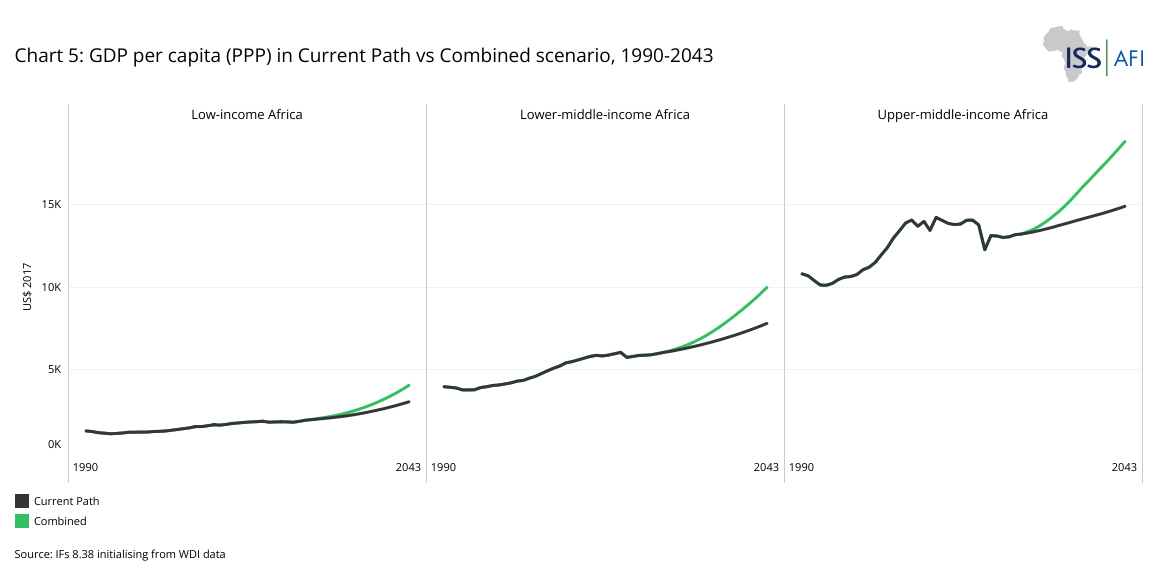

GDP per capita (in purchasing power parity, or PPP, terms) would increase by 147% from 2023 levels. This compares favourably to just a 98% increase in the Current Path. As a result, Africa would reverse the declining trend in income convergence, raising its average per capita income to 28% of the average of the rest of the world (i.e. the world except Africa), up from 25% in 2023.

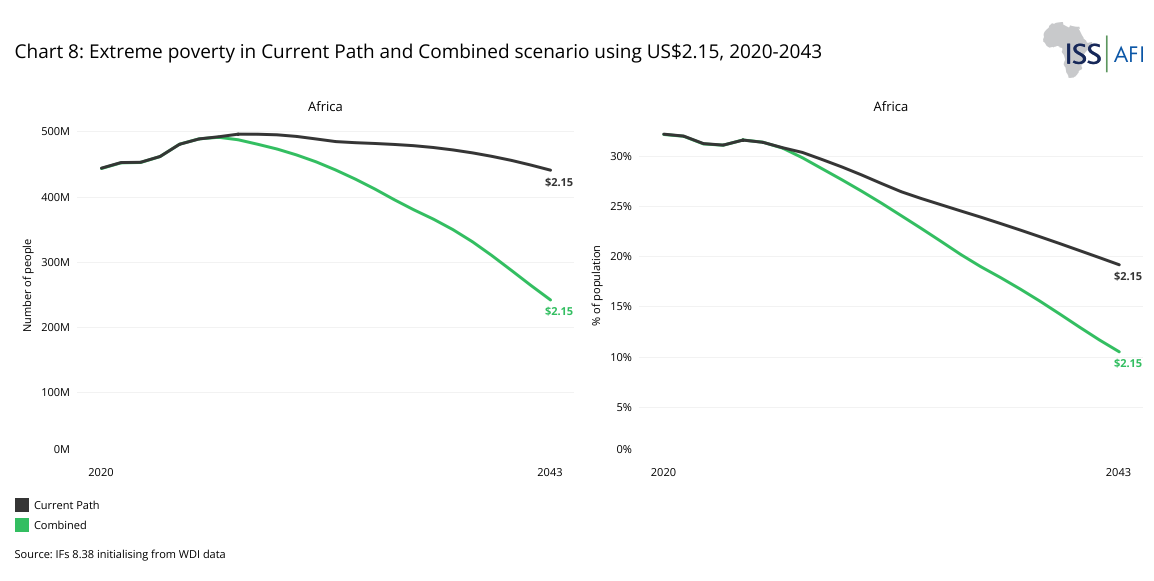

Extreme poverty in Africa drops from a Current Path forecast of 31% in 2043 to 10% in the Combined scenario, thanks to targeted interventions that improve equity and inclusion. Investments in education, healthcare and rural infrastructure drive inclusive growth, especially in low-income countries.

We then explore how Africa's economic structure shifts toward greater diversification, value addition and technological integration. The Combined scenario supports a labour market transformation, with informal employment declining significantly as manufacturing and high-value services expand. It positions urbanisation and technology as development levers, supporting smarter cities, e-governance and digital inclusion. Realising the Combined scenario vision depends on capable leadership and institutions, grounded in inclusive governance and pragmatic reform.

The final section outlines the conditions for success: political will, national ownership, strategic prioritisation, and adaptive capacity. Africa’s development is not predetermined — it is a matter of choice, strategy and collective action.

All charts for Combined scenario

- Chart 1: Scenario structure

- Chart 2: Growth accounting: contribution of labour, capital and MFP to GDP growth in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020-2043

- Chart 3: Africa’s GDP in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020-2043

- Chart 4: GDP and GDP growth rate by group or country, 2023 to 2043

- Chart 5: GDP per capita (PPP) in Current Path vs Combined scenario, 1990-2043

- Chart 6: GDP per capita in the Current Path and impact by scenario, 2020-2043

- Chart 7: Top four scenarios by impact on increase in GDP per capita, 2033 vs 2043

- Chart 8: Extreme poverty using US$2.15, 2020-2043

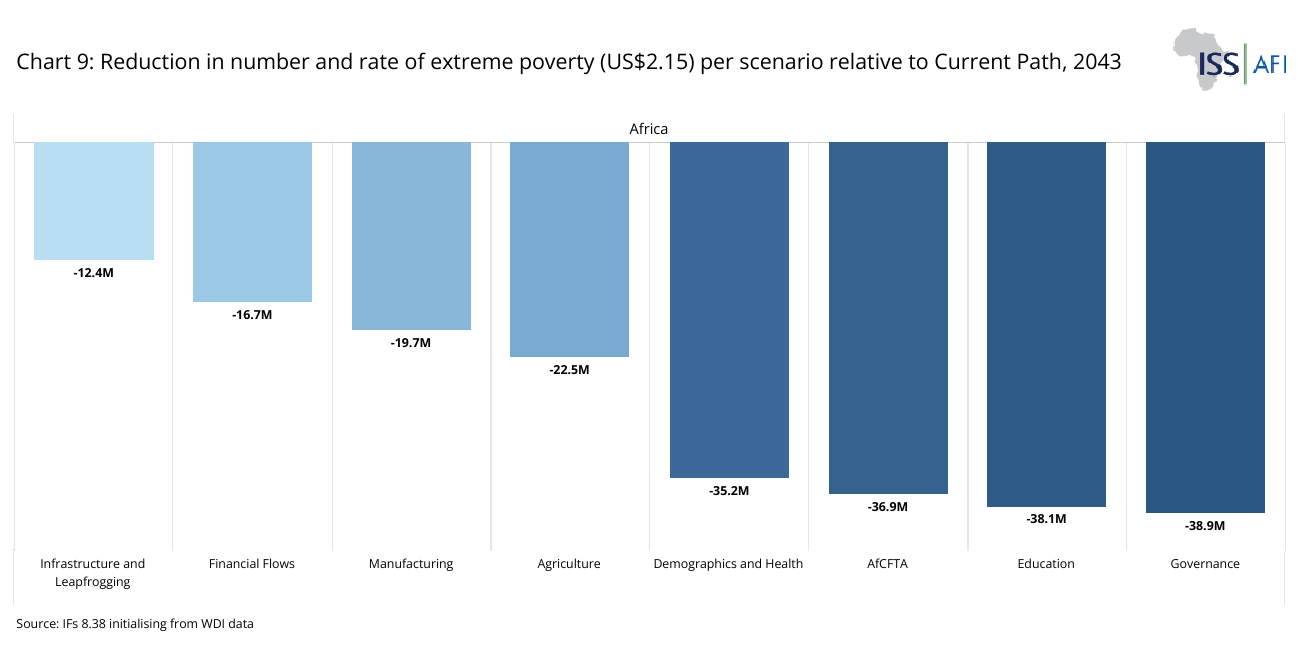

- Chart 9: Reduction in number and rate of extreme poverty (US$2.15) per scenario relative to Current Path, 2033 vs 2043

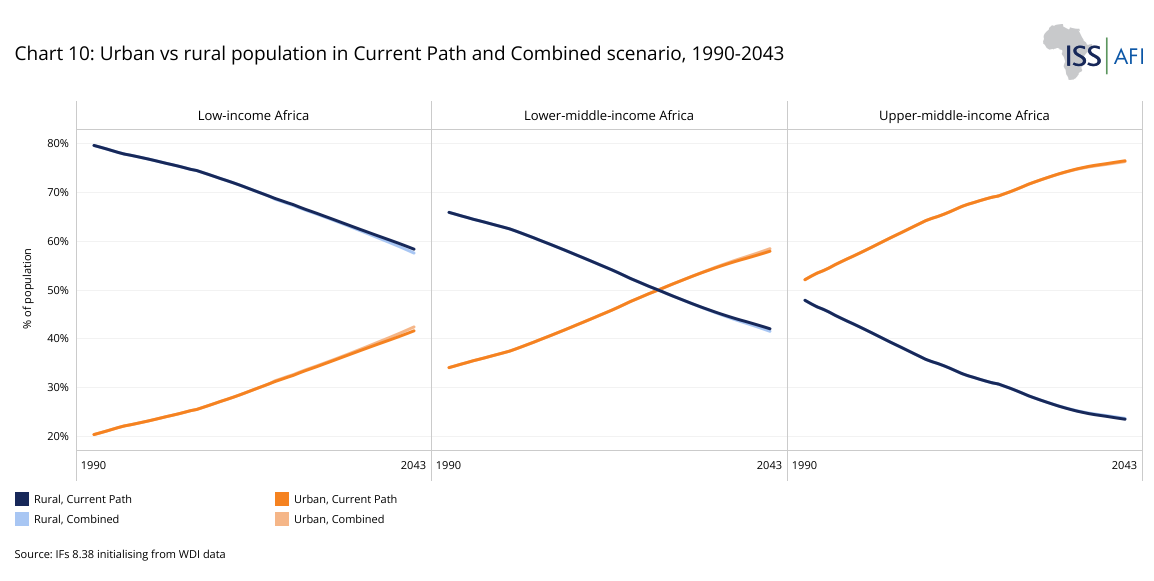

- Chart 10: Urban vs rural population in Current Path and Combined scenario, 1990-2043

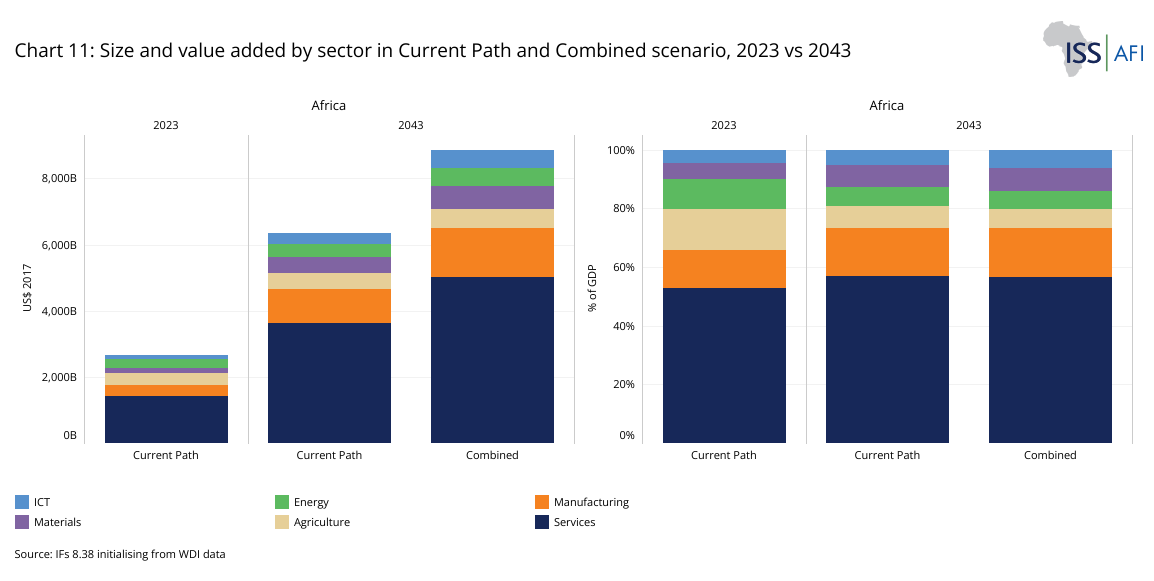

- Chart 11: Size and value added by sector in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 vs 2043

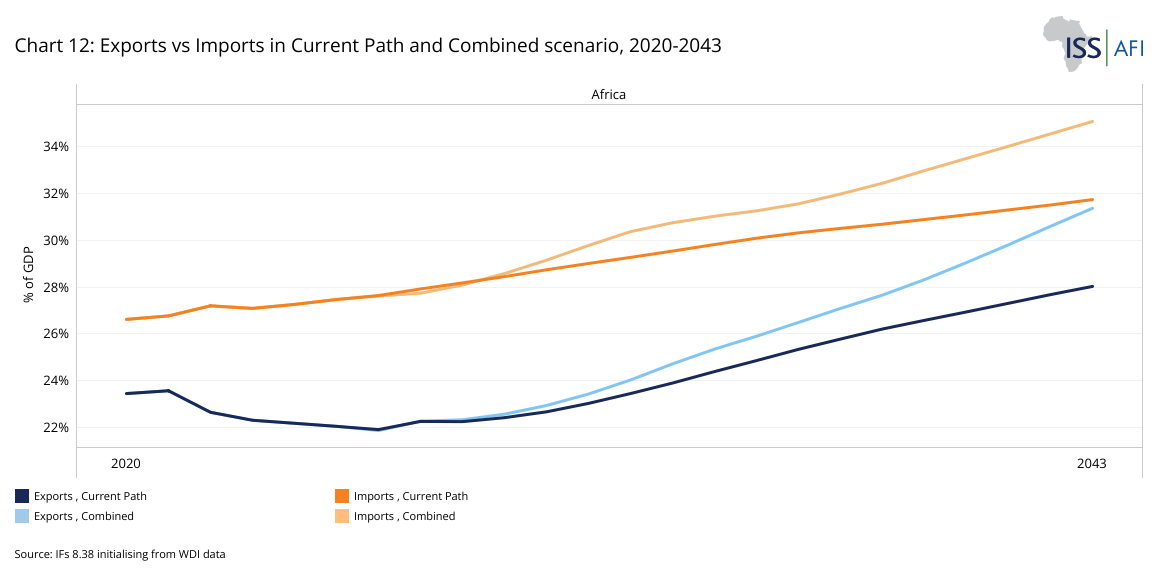

- Chart 12: Exports vs Imports in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020-2043

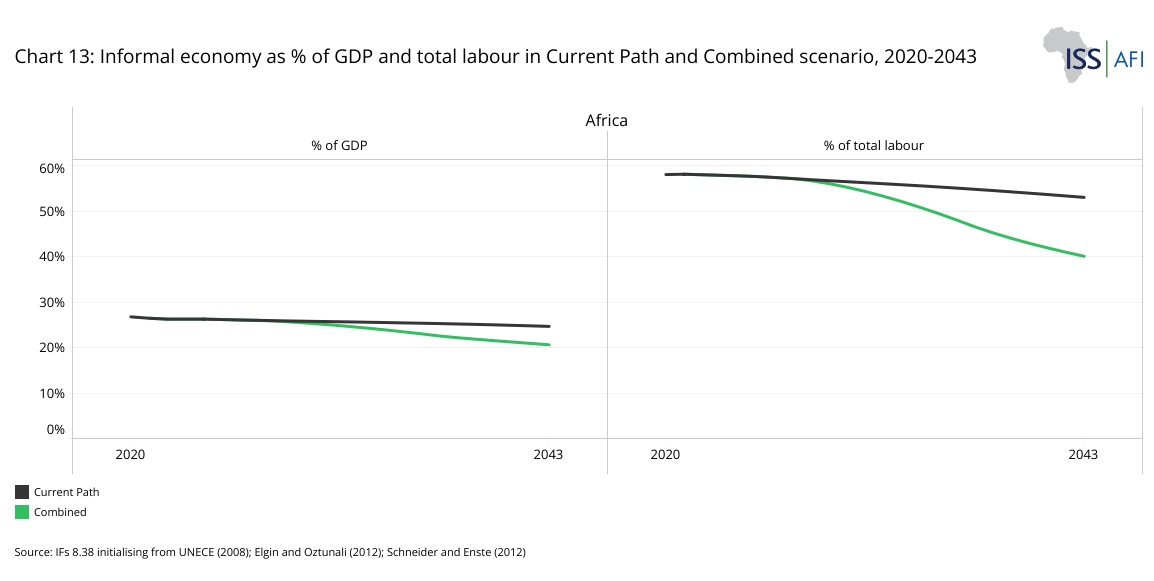

- Chart 13: Informal economy as % of GDP and total labour in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020-2043

- Chart 14: Recommendations

Africa’s development remains one of the most consequential global challenges of the 21st century.

The continent’s path to development unfolds amid complex and interlinked global and domestic pressures. For example, Africa faces the simultaneous challenge of expanding energy access for hundreds of millions who remain without electricity while responding to calls for a low-carbon transition. Rapid digitalisation offers new opportunities for inclusion, yet deep connectivity gaps persist between and within countries. Mounting debt burdens, volatile aid flows and growing geopolitical fragmentation further constrain fiscal space and policy autonomy. These tensions underscore that Africa’s transformation will not occur in a vacuum: progress depends on how effectively countries navigate the trade-offs between growth, equity, sustainability and sovereignty in a shifting global order.

Despite steady progress in some domains, the continent continues to grapple with persistent poverty, rapid population growth, structural economic vulnerabilities and governance challenges. Yet Africa holds significant untapped potential: vast natural resources, a youthful and rapidly expanding population, a burgeoning middle class and the promise of increasing regional cooperation driven by ambitious initiatives such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) that will, in time, unlock additional growth and opportunity, if fully implemented.

Agenda 2063, the African Union (AU)'s strategic framework for the continent's long-term socio-economic transformation, represents Africa's collective aspiration towards an integrated, prosperous and peaceful continent, driven by its citizens and playing a significant role in the global arena. However, achieving this ambitious vision requires a significant shift from current trends, substantial investment, policy coherence, regional collaboration and visionary leadership. The Combined scenario presents such a detailed and integrated vision, illustrating how deliberate and coordinated efforts across multiple development sectors could dramatically transform Africa's trajectory by 2043, the end of the third ten-year implementation plan of Agenda 2063.

Africa is diverse, young and rapidly urbanising, and its population and economy will grow quite quickly. But will this growth be sufficient to improve well-being?

At first glance, the energy levels on the continent resemble those of the Asian Tigers and China several decades ago, but with significant differences. Emulating countries like South Korea and China in Africa may only be possible in some respects. Still, there is much to learn from them in the determined manner in which their governments focused on poverty alleviation, structural economic transformation and growth, and building their human capital by investing heavily in education and healthcare and eventually pursuing an open, export-oriented manufacturing growth path.

Today, Africa’s challenge is to navigate its own path through intersecting transitions — demographic, digital, urban and green — in a turbulent global order.

It is best to view societies as living organisms that thrive on balance. To grow, an organism needs a combination of different nutrients. For societies, progress in one area alone quickly encounters limits: education without jobs or trade without manufacturing; only focusing on one provides rapidly diminishing or even negative returns. Sustainable development, therefore, requires integrated action, where gains in one sector reinforce and unlock progress in others.

Societies become productive by linking different factors of production and eventually being able to do more with them, although not necessarily in equal amounts. That is why this website has taken a comprehensive approach to development, examining all aspects and sectors, enabled by the highly integrated nature of the International Futures forecasting platform (IFs).

The various interventions in the Combined scenario reinforce one another. For example, investments in education enhance workforce productivity, but these investments yield greater benefits when complemented by improvements in health, infrastructure and governance. Similarly, advancements in agricultural productivity require and are accelerated by concurrent improvements in rural infrastructure, access to markets and better governance structures.

The Combined scenario fundamentally reimagines Africa’s development path by integrating strategic interventions across eight critical sectors: demographics and health, agriculture, education, manufacturing, infrastructure and leapfrogging, financial flows, governance, and regional trade integration via the AfCFTA. Each sector is explored separately as a theme on this website and compared to the business-as-usual trajectory (the Current Path ). This approach is schematically presented in Chart 1.

Details on the specific interventions in each sector are outlined on the Technical page.

Each sector addresses a structural constraint on development, and together, they represent the full suite of policy levers through which Africa can transition from slow to rapid, sustainable growth.

Better health, more and better education, urbanisation, female empowerment, and the formalisation of economies reinforce one another to reduce the number of children that need to be educated (and therefore increase the money available for those already in school). As fertility declines, public expenditure per child increases, leading to better-equipped schools, smaller class sizes and improved teaching quality. Over time, education systems produce a more skilled and flexible labour force, capable of adopting and creating new technologies and driving innovation. Yet it only happens if governments focus on implementation.

The next section below presents a growth-accounting approach to Africa’s development, aiming to determine the most significant contributors and drags on economic growth.

A subsequent section presents the impact of the Combined scenario on economic size (gross domestic product (GDP) at market exchange rates), GDP per capita (in purchasing power parity (PPP)) and poverty rates. These three indicators are imperfect and incomplete measures of development, but they remain helpful in gauging Africa’s general direction and correlate with numerous other welfare indices.

Africa’s geographic location, straddling the equator, meant that this was where humanity evolved. However, due to its close relationship with nature, the continent’s population has the highest disease burden globally, resulting in low population densities and a unique development trajectory. Skip forward several hundred thousand years, and while populations outside of Africa grew rapidly, requiring organised farming practices and pressures leading to technological advances and often war, Africa’s empires and kingdoms were relatively isolated from these events, including the plagues and diseases of denser settlements, but also from the pressures and demands that fueled rapid progress, the industrial revolution in particular.

Following the Industrial Revolution, declining death rates (accompanied by continued high fertility rates) led to steady population growth in most European and North American societies for successive generations, only recently beginning to experience ageing. Although it had similar fertility rates, Africa’s population growth was much slower due to higher maternal and child mortality rates; however, it is now accelerating rapidly.

Instead, since the mid-15th century, slavery from the West and East denuded Africa of much of its labour, historically the primary source of economic growth. Unable to resist the technologically advanced intrusion from elsewhere, subsequent colonialism left the populations of sub-Saharan Africa poorly educated and with little or no ability or infrastructure to participate in global trade, which drove prosperity after the end of the Second World War. Even independence in the 1960s made little difference, given the straitjacket effects of the subsequent Cold War and the generally low levels of education, health and infrastructure in much of Africa at the end of colonialism.

The theme of agriculture underscores the importance of food security and agricultural progress as the foundation for overall development. Despite the continent’s vast potential, agriculture in Africa has contributed little to national development.

Colonial administrations primarily structured African economies to serve the interests of the colonisers, focusing on the extraction of raw materials, the supply of cheap labour and the cultivation of cash crops for export. This orientation disrupted indigenous agricultural practices and food systems. Post-independence, many African nations inherited and often perpetuated these skewed economic structures, which continued to prioritise export-oriented agriculture over food self-sufficiency.

Programs like Ghana's Operation Feed Yourself aimed to boost domestic food production but were marred by mismanagement, corruption and inadequate support for smallholder farmers, and eventually failed or were abandoned. Instead, African governments often pursued rapid industrialisation, as seen in the efforts of Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana, Shehu Shagari in Nigeria, Thomas Sankara in Burkina Faso, Ahmed Sékou Touré in Guinea, and Félix Houphouët-Boigny in the former Ivory Coast. However, without the foundational importance of agriculture, Africa’s post-independence efforts at industrialisation failed. Indeed, the efforts to effectively create islands of technological sophistication and prestige projects in a sea of informal, subsistence farming and low-technology economies were a recipe bound to fail. Without forward and backwards linkages to the domestic economy, these projects relied heavily on development aid, government subsidies, and handouts in terms of access to foreign markets, and ultimately came to nothing.

Furthermore, the adoption of Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) in the 1980s, under the guidance of international financial institutions, led to reduced public spending on agriculture, the removal of subsidies and liberalisation of markets. These measures often disadvantaged local farmers who could not compete with imported goods and lacked access to necessary inputs.

In the meantime, determined leadership and demographics would unlock growth in the Asian tigers and China, while in Africa, the ratio of dependents to the labour force steadily increased until the mid-eighties, as examined in the theme on demographics . Instead of productivity from a larger, healthier and better educated labour force relative to dependents, the ratio of working-age persons to dependents declined. Thus, it was generally the export of commodities such as oil and gas, later followed by cocoa and coffee, that contributed most to growth, reflected in the year-on-year increase in the high levels of dependence on commodity exports, with deleterious effects on the productive structures of many African economies.

That situation has now started to change, such that the continent may enter a demographic window of opportunity by mid-century. Already, by 2023, the ratio of working-age persons to dependents had improved to 1.3 to one, and will steadily improve to 1.6 to one by 2043. At a ratio of 1.7 to one, a potential window of rapid labour-fueled growth beckons in the second half of the century, a ratio that has currently only been achieved by a handful of North African countries and some of Africa’s island states.

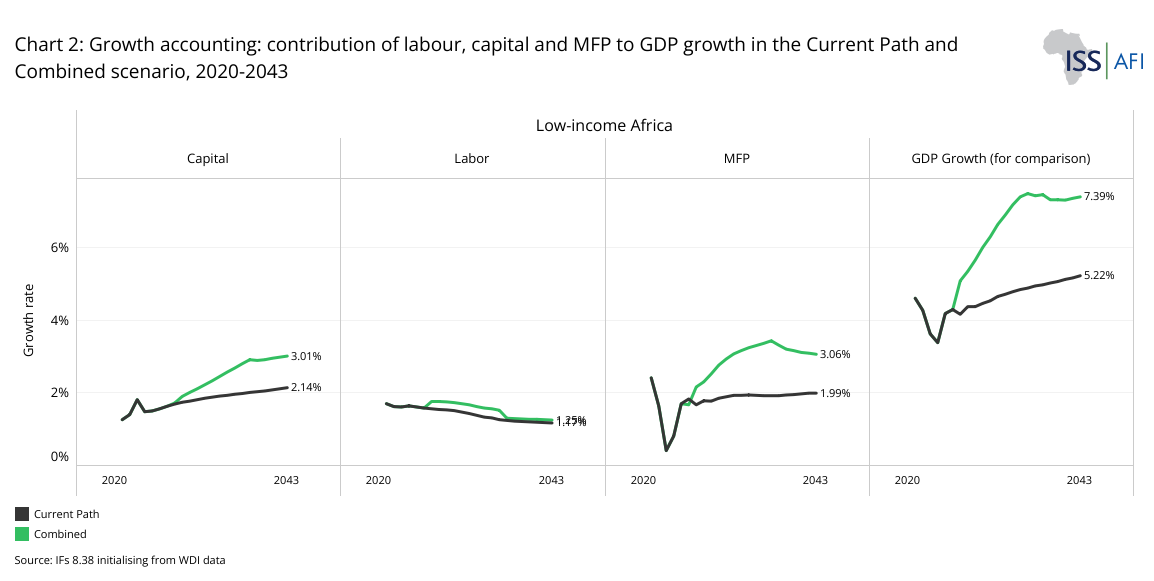

According to neoclassical growth theory, per capita income growth in Africa requires more labour, capital and technological progress (also known as total or multifactor productivity). But given the late onset of Africa’s demographic dividend, it is unlikely that the continent can emulate the labour-fueled growth that powered other regions. As a result, over the next two decades or so, economic growth will need to come primarily from increased investment (physical capital accumulation) and technological gains, that is, improvements in MFP.

Adopting this growth-accounting approach, Chart 2 presents the contributions of labour, capital, and MFP to growth, and includes the GDP growth rate forecast (i.e., the sum of labour, capital, and MFP) for comparative purposes. The default forecast applies to lower-middle-income Africa, but the user can select any African country or region and toggle between the Current Path and Combined scenarios. Given the continent's diversity, it is essential to recognise that Africa’s growth is inevitably heterogeneous in its sources. The brief explanation below uses the average interpretation of the various income groups.

In line with the preceding discussion, and given the high dependency ratios in Africa’s low- and lower-middle-income countries, labour contributes least to sustainable growth in both low- and lower-middle-income countries, either in the Current Path or in the Combined scenario. Instead, most economic growth comes from the contribution of MFP.

At first glance, this appears counterintuitive, given Africa’s large and growing labour force, but is explained when considering the continent’s high dependency ratios, low growth in employment and skills and high levels of informality. Employment per capita in much of sub-Saharan Africa has barely risen and contributes little to output growth. Instead, much of the expansion in output per capita stems from other sources, mostly improvements in capital accumulation.

In our modelling, MFP is further divided into physical capital[1Modelling draws on traditional infrastructure, ICT infrastructure, other infrastructure spending level, and the price of energy.] (or infrastructure investment), human capital[2Modelling draws on educational spending, the years of adult education, the quality of adult education, life expectancy, stunting/undernutrition of children, disability, and extent of vocational education.] (health and education), social capital[3Modelling draws on economic freedom, government effectiveness, corruption, democracy, freedom and levels of conflict.] (governance) and knowledge capital[4Modelling draws on research and development spending, global economic integration and tertiary graduation rates in science and engineering.]. In both low- and lower-middle-income groups, poor physical capital is the largest drag on growth; hence, improvements in Africa’s infrastructure deficit contribute most. For upper-middle-income countries, it is poor human capital, i.e. education and health outcomes that constrain growth.

Long-run output growth is driven by capital accumulation, labour force growth and MPF (or technological progress), of which MFP is the primary driver of sustained economic growth. Building on this insight, endogenous growth theorists argue that continual investment in human capital and innovation can generate positive spillovers that maintain growth.

In summary, a growth-accounting analysis underpins the importance of industrialisation through physical capital accumulation, skills development, R&D, governance reforms and trade openness. Technology and efficiency gains drive long-term growth and reinforce why productivity enhancements are paramount for Africa’s future, while investing in people and innovation can sustain these gains over time.

Africa’s Development Potential in the Combined Scenario

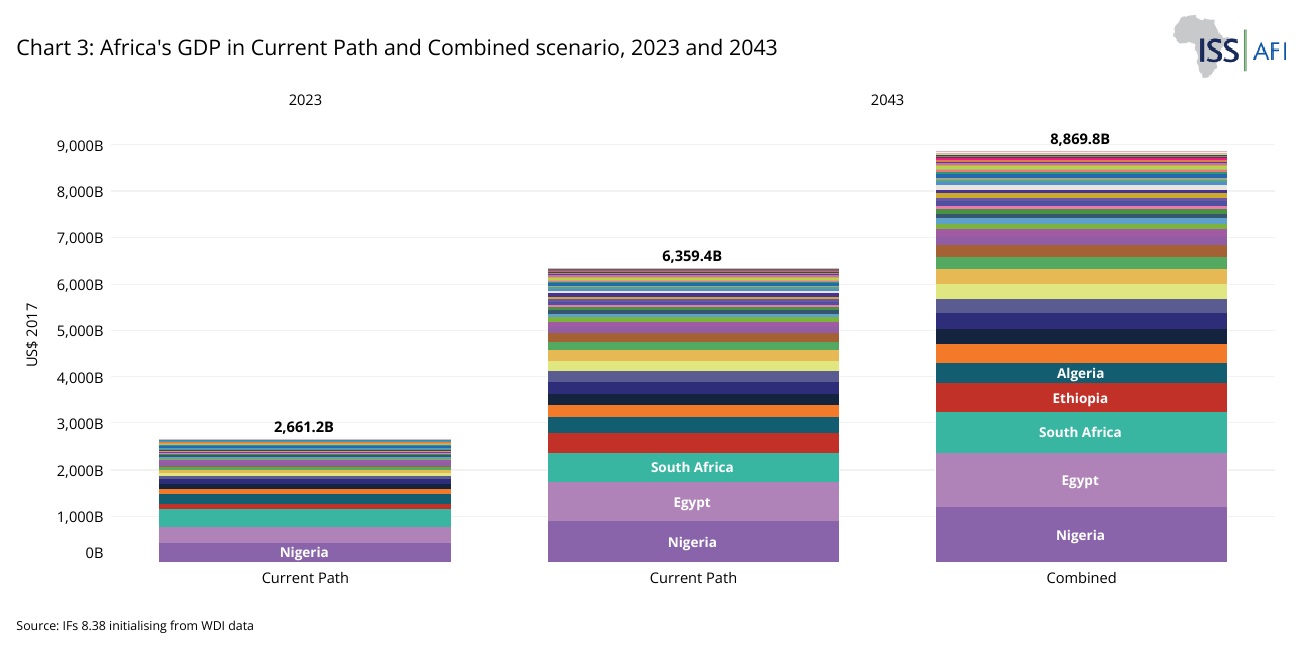

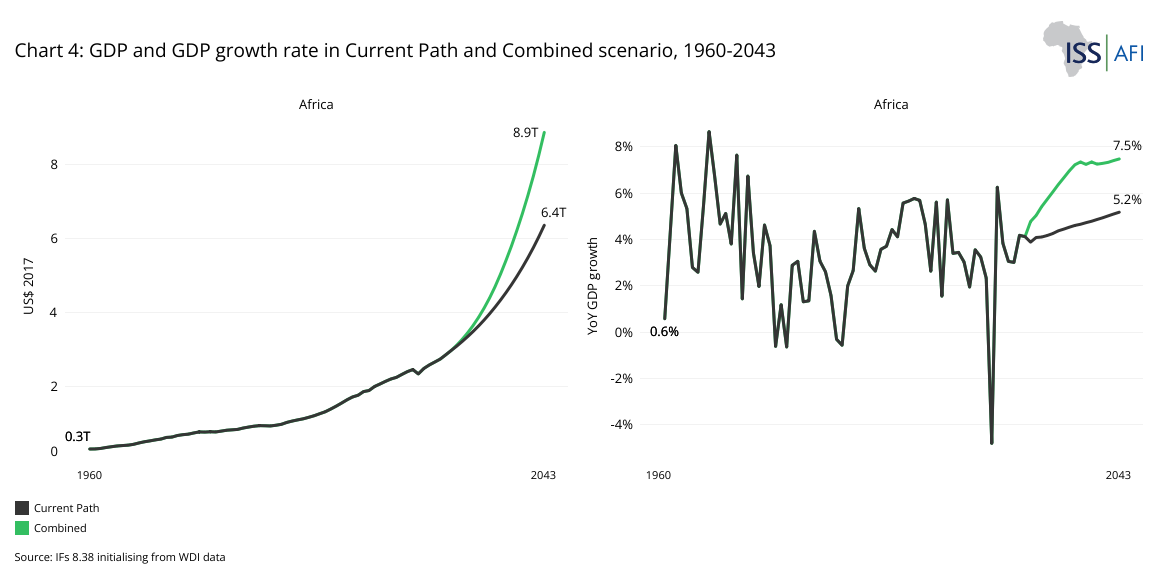

Download to pdfUnder the Combined scenario, Africa's economy is projected to grow to approximately US$8.9 trillion by 2043, at an average annual growth rate of 6.2%, compared to US$6.4 trillion on the Current Path, with a growth rate of 4.5%.

Chart 3 presents the size of the African economy in the Current Path and Combined scenario.

Chart 4 enables the user to select the size of individual African economies (or groups) and their associated growth rates in both the Current Path and Combined scenarios. The Combined scenario gains are not uniform across countries or regions. Much of Africa's young and rapidly growing population is in West, East, and Central Africa, and rates of urbanisation, education, access to healthcare, and informality differ within and between these regions.

North Africa has the highest levels of development in Africa (and hence the slowest rate of population growth), followed by Southern Africa, while Central Africa is more challenged than other regions. Among other reasons, Central Africa lacks a locomotive state (such as Nigeria or South Africa), where the size of a single national economy provides a sufficiently large market that could boost the region as a whole. Instead, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo), which lies at the heart of the region, is beset by challenges around development, stability and governance.

Low-income countries such as the DR Congo, Uganda and Mozambique would experience particularly rapid economic growth in the Combined scenario — above 8% annually — driven by improvements in agricultural productivity, health and education. In contrast, upper-middle-income countries such as South Africa, Algeria and Tunisia would grow more modestly, reflecting the diminishing returns on investment at higher income levels and their inability to escape the notorious middle-income trap.

For all its well-known limitations, GDP per capita is a powerful, simple metric that reflects both the economic productivity of an economy and the number of people among whom that product must be divided. In the Combined scenario, GDP per capita (in PPP terms) would increase from US$4 850 in 2023 to US$6 758 by 2043, representing an increase of 147% from 2023 levels. This compares favourably to the 98% increase in the Current Path. As a result, Africa would reverse the declining trend in income convergence compared to the average for the rest of the world (i.e., the world excluding Africa), raising its average per capita income to 28% of the average of the rest of the world, up from 25% in 2023.

Chart 5 compares GDP per capita in the Current Path with the Combined scenario.

Ultimately, an integrated approach provides a roadmap for African nations to harness their demographic dividends, leverage regional integration through initiatives such as the AfCFTA, and strategically position themselves in a rapidly evolving global economic landscape. The separate themes on this website provide actionable insights and clear benchmarks for policymakers committed to realising Agenda 2063.

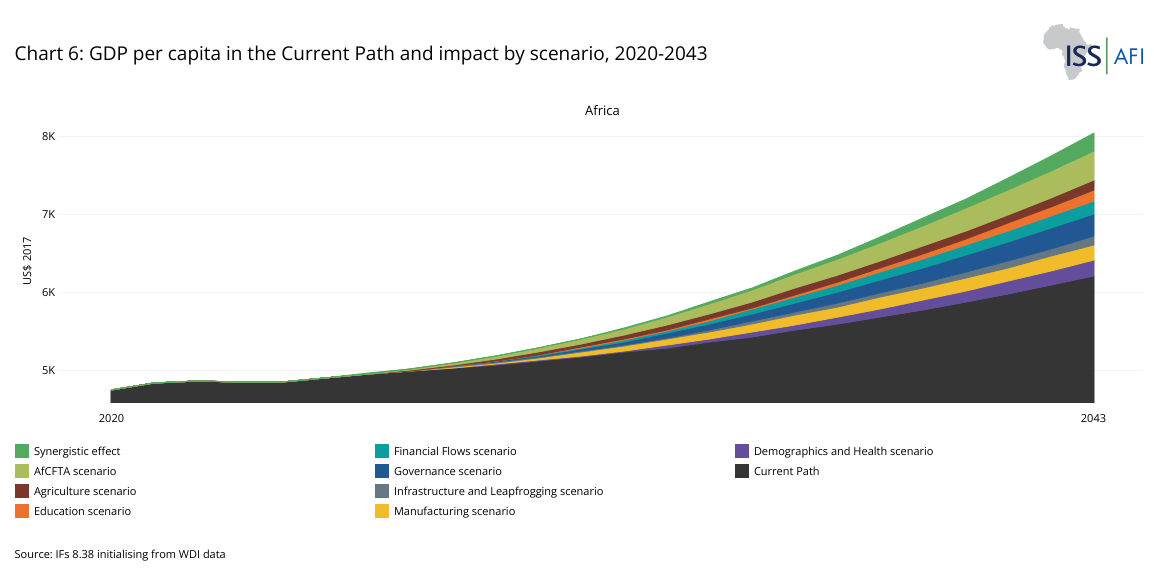

The GDP per capita contribution of each sectoral scenario for the various African geographies is presented in Chart 6.

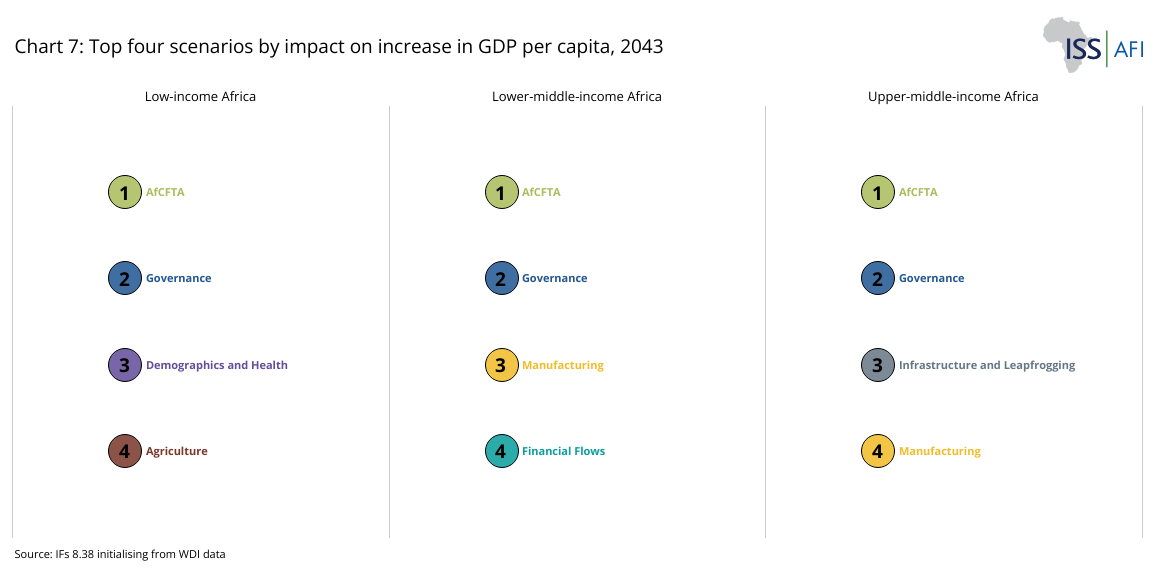

Chart 7 ranks the four scenarios that are expected to provide the largest change in GDP per capita in purchasing power parity by 2043. The default display compares low-, lower-middle-, and upper-middle-income country groups, but the user can select any three African countries or groups.

The visualisation in Chart 7 does not imply that policymakers should choose one set of interventions above another. Development is organic and context-specific: eventually, a carefully crafted and coordinated effort across dimensions produces significantly better progress than pushing on any single sector to the exclusion of another.

By 2043, the AfCFTA scenario will do best for all country income groups, followed by the Governance scenario. For this reason, the African Development Bank, the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), the World Bank, and development economists are all excited about the AfCFTA's potential.

Poverty reduction in the Combined scenario accelerates dramatically compared to the Current Path.

In 2023, approximately 462 million Africans lived in extreme poverty. In the Current Path, this number will fall only slightly to 441 million by 2043, due to rapid population growth and modest income gains. However, under the Combined scenario, extreme poverty declines to 242 million people, equivalent to 10% of Africa’s much larger 2043 population — nearly half the number projected under the Current Path. These gains reflect a comprehensive approach that leverages policy coherence, effective governance, strategic investments in infrastructure and human capital, and a robust industrialisation agenda. Chart 8 depicts extreme poverty from 2020 to 2043 in the Current Path and the Combined scenario.

Progress in the Combined scenario is also apparent in various non-income dimensions of human development, such as longer life expectancy, reductions in malnutrition, and more and better-educated children. Gender disparities narrow, especially in education and labour force participation. Health systems are better equipped to manage epidemics and chronic diseases, thereby reducing disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and enhancing human capital.

The reasons for the dramatic improvements are that the Combined scenario reflects interventions that address the structural drivers of poverty — low education, poor health, weak infrastructure, lack of productive employment — through coordinated investment and policy reform.

Poverty reduction is most pronounced in low-income countries, where improvements in agriculture, demographics and governance have the largest impact. For example, in countries like Liberia, Mozambique and Rwanda, per capita incomes increase by more than 40% above the Current Path, significantly lowering poverty rates. In upper-middle-income countries, targeted social transfers help reduce inequality and ensure that growth is broadly shared.

Chart 9 compares the impact of the various sectoral scenarios on poverty reduction with the Current Path.

At the continental level, the Governance scenario is the most effective in reducing extreme poverty by 2043, followed by the Education, AfCFTA, and Demographics/Health scenarios. It is important to note that the Governance scenario includes additional social transfers (welfare payments) to unskilled workers, which is particularly effective in reducing extreme poverty and also reducing inequality. To fund these transfers, the scenario increases taxes on skilled households.

Market forces alone will not alleviate extreme poverty. As noted by the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), doing so requires a capable state committed to harnessing and regulating all resources for poverty alleviation, monitoring needs, and directly empowering those most vulnerable, particularly by supporting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), the primary wealth and job creators of the 21st century. Governments need to offer an enabling hand that shapes the market in a pro-poor manner while alleviating extreme poverty through grants, work schemes, education, housing and other measures for those who cannot adequately provide for themselves. It requires the precise allocation of poverty alleviation resources, seeking to help families and communities in ways that address their immediate needs and enable them to ultimately overcome poverty.

Structural transformation — the shift from low-productivity to high-productivity sectors — is the hallmark of economic development. It reflects changes in the composition of output, employment, and trade, and signals deeper transitions in technology, skills, and institutions. In Africa, this transformation has long been elusive, in part because of the small size of the most productive manufacturing sector. Many countries remain locked into a pattern of exporting raw commodities while importing high-value manufactured goods. Agriculture dominates employment but contributes a declining share to GDP, and informal and low-value activities often predominate in the service sector.

In this vein, the African Growth Initiative at the Brookings Institution popularised the potential of “industries without smokestacks,” pointing to the productivity improvement effects of tourism, agro-processing, and other tradable services in a modernising economy, comparable to traditional industrialisation. Others are more sceptical and argue that services such as tourism are “quick wins”, but cannot serve as a pathway for long-term growth. Although it generates export earnings, growth and employment, specialisation in tourism tends to yield limited growth benefits. To generate growth through tourism, a country must attract more tourists annually, placing a higher strain on public services such as security and utilities. Additionally, tourism encompasses low-productivity activities, including hotels and restaurants. Thus, a study by the IMF shows that to achieve a 6% annual growth rate, it would need to increase tourism receipts as a share of exports by more than 70%, which is unlikely to occur in most African countries.

The Combined scenario models a gradual but significant transformation of Africa’s economic structure toward a more diversified, resilient and knowledge-based economy; however, the exact policy mix depends on the national context. This transformation is already visible in several African economies. Morocco’s automotive industry has surpassed phosphates as the country’s leading export, supported by strategic infrastructure investment and trade agreements. In East Africa, Kenya’s ICT sector and digital finance ecosystem continue to expand regional value chains and improve productivity. Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire are adding value to cocoa through local processing, while Namibia and South Africa are positioning themselves in emerging green hydrogen and battery mineral value chains. These examples demonstrate how deliberate industrial and trade policies can translate the principles of the Combined scenario into tangible economic outcomes. Resource-rich countries like Nigeria, Angola and Zambia must diversify away from hydrocarbons and minerals, using extractive revenues to build industrial and human capital. Small island economies, such as Mauritius, Cape Verde and Seychelles, can leverage tourism, services and innovation to achieve high-income status. Fragile states make slower progress, but often benefit from targeted interventions in agriculture.

Urbanisation should be viewed as a catalyst for industrialisation and economic growth, as it concentrates labour and resources, fosters innovation, and necessitates the development of infrastructure. In 2023, about 44% of Africa’s population lived in urban areas. By 2043, this is projected to increase to over 55%, adding hundreds of millions of people to cities.

The benefits of urbanisation are not automatic. If cities grow without adequate services, they become poverty traps rather than engines of growth. African governments need to invest in urban resilience — building infrastructure that can withstand climate shocks, planning for inclusive housing and prioritising investments in clean energy, public transport and waste management.

If not planned, urbanisation can detract from productivity as cities sprawl further, characterised by low density that increases the cost of providing additional infrastructure, often at the expense of prime agricultural land. Consequently, instead of increasing productivity and access to services, one of the main advantages of urbanisation starts to decrease. Some African countries (e.g. Tunisia) are already predominantly urban, but East Africa is the most rural region in the world. Here, the growth of a city such as Addis Ababa has become a significant source of tension as urban sprawl encroaches on surrounding Oromo farmland, eventually contributing to violent riots from 2014 to 2016.

Chart 10 enables users to view the population numbers for Africa’s urban and rural areas.

Digital solutions can contribute to providing essential services in low-income urban communities through pay-as-you-go models that allow customers to make small, incremental payments towards otherwise unaffordable goods and services, including clean water, electricity, and sanitation. The result is a sustainable business model that can respond to the challenges of urban poverty and its associated traps.

By 2043, all major sectors in Africa will be larger in absolute terms than in 2023, as reflected in Chart 11, which presents the size and changes in the growth of the six economic sectors modelled in the Current Path and Combined scenario: agriculture, energy, materials, manufacturing, services and ICT for African countries and groups.

While services remain the largest sector — growing from 53% of GDP in 2023 to 56% in 2043 — manufacturing gains ground, reversing the recent trend of premature deindustrialisation. By 2043, its share of GDP increases modestly but representing a strategic rebalancing of most African economies. This is achieved through targeted policies that support value addition, technology adoption, industrial clusters and export competitiveness. Countries like Ethiopia, Rwanda, Ghana, and Tanzania show strong gains, while more advanced economies, such as South Africa and Egypt, consolidate higher-end manufacturing niches.

In the Combined scenario, agriculture’s share of GDP declines from 14% to 7% by 2043, consistent with global trends. However, this does not reflect stagnation or collapse. On the contrary, agricultural output and productivity rise sharply due to investments in smallholder farming, irrigation, extension services and rural infrastructure. The sector becomes more commercialised and integrated into national and regional value chains. It continues to employ a large share of the workforce in many countries, but now as a dynamic and productive sector.

Information and communication technology (ICT) becomes a key enabler of structural change. Though its share of GDP remains modest, it underpins transformation in virtually every sector — from digital agriculture and online education to e-commerce and mobile financial services.

The energy sector is also evolving, with significant investment in renewables, decentralised systems, and clean technologies. Africa’s energy mix is becoming more diversified, reducing reliance on fossil fuels and improving access in underserved areas, thus providing a platform for industrialisation and digital inclusion.

These structural shifts reflect a transition from consumption-driven to investment- and export-led growth. They also point to increased complexity and diversification in African economies, with stronger forward and backwards linkages across sectors. Over time, these trends contribute to greater resilience, job creation and fiscal sustainability.

Africa’s structural transformation has important implications for trade. The continent shifts from being an exporter of raw commodities to a more balanced trade profile, including manufactured goods, processed agricultural products and services. The Combined scenario assumes deeper regional integration through AfCFTA, enabling the development of regional value chains and intra-African specialisation. Export earnings become more stable and inclusive, and African economies become more resilient to global commodity shocks.

Africa’s changed economic structure will inevitably deepen trade integration within Africa and globally. Chart 12 presents a line graph of the change in export and import values as a percentage of GDP and in billions of US dollars.

Ultimately, the shift in economic structure envisioned in the Combined scenario represents a movement up the productivity ladder. African economies become more productive, with considerable growth in the service sector, in line with global trends. However, none of this will happen on its own. It requires appropriate policies that support local industry, determined implementation and productive investment.

While the continent has experienced moderate economic growth in recent decades, this has not been accompanied by significant job creation. Most Africans remain trapped in low-productivity, informal employment. In 2023, more than 85% of all employment in Africa was informal, with many working in subsistence agriculture, petty trade and unregulated services. Nearly one-third of the employed population earned less than US$2.15 per day, placing them among the “working poor.”

In the Combined scenario, the share of informal employment in Africa declines from 58% in 2023 to 40% in 2043 (compared to 53% in the 2043 Current Path forecast), a substantial improvement with far-reaching implications for economic growth, government revenues and household well-being.

Chart 13 presents the size of the informal economy as a percentage of GDP and informal labour as a percentage of total labour in the Current Path and Combined scenario.

Historically, manufacturing has provided pathways out of poverty for many countries due to its impact on other sectors. The Combined scenario envisions a resurgence of manufacturing through investments in infrastructure, industrial parks, trade integration and workforce skills. Industries such as food processing, textiles, assembly and agro-processing flourish, offering opportunities for both urban and rural populations. Across the continent, early signs of labour-market transformation are emerging. Ethiopia’s industrial parks have created tens of thousands of jobs in textiles and footwear, linking rural labour to export markets, although the civil war did much damage. Nigeria’s creative industries and fintech sector illustrate how digital innovation can generate youth employment and spill over into traditional services. In Rwanda, investment in tourism, logistics, and ICT is formalising work opportunities for young professionals. These country experiences demonstrate that inclusive employment growth is achievable when infrastructure, education and targeted industrial support are aligned.

Digital technologies, automation and artificial intelligence have the potential to transform the nature of employment. Digital literacy, broadband expansion, and support for digital platforms that enable microenterprises to access markets, manage transactions, and build business networks are all essential tools in this process.

The shift in employment patterns also transforms the nature of work itself. As formality increases, workers gain access to social protection, legal rights and the ability to organise. Governments are better able to collect taxes, regulate labour conditions and invest in public services. Informal workers benefit from improved infrastructure, access to finance, and the gradual extension of regulatory frameworks that enhance working conditions.

Overall, the employment transformation projected under the Combined scenario reshapes the structure, security and dignity of work across the continent, offering a path toward more inclusive and sustainable development.

Sustained and rapid growth is difficult to achieve. Each African country needs to develop organic practices tailored to that country's domestic conditions. Countries become successful, argues Lant Pritchett, through an ugly, messy, contested hard slog that takes decades. And then, once successful, they create myths about how wonderful the journey was, when in reality it was just a hard slog.

Development also seldom follows the smooth forecasts on this website. Instead, in their 2020 book African Economic Development, Cramer, Sender and Oqubay note that it is inevitably characterised by ‘persistent failure, wastage, exploitation and misery.’ Africa is hugely diverse, and the future, as in the past, will reflect significant variations in the development trajectories of its constituent countries. It is also doubtful that Africa will simultaneously advance on all the transitions assessed in the various scenarios modelled on this website. Some countries may make progress in certain areas, while others may stagnate or even regress.

Eventually, the transformation of Africa is less about grand schemes and ambitions (of which there have been many) and more about the mundane functions of improving food security through land reform and support of small-scale farming, ensuring a hassle-free and facilitative investment environment, holding one another to account, and facilitating foreign investment in clear terms. It requires a detailed, technical and bureaucratic process, where governments meticulously go through every impediment that deters or inhibits innovation, entrepreneurship and doing business. It is about governments that get behind success, offering support and helping to facilitate growth in a sector already showing potential, rather than merely shovelling money in that direction.

Perhaps the only constant is for African governments to consistently invest in knowledge creation. The Norwegian scholar and economic philosopher Erik Reinert concurs with others such as Joseph Stiglitz and Bruce Greenwald in describing what lies at the heart of development: ‘The global economy,’ Reinert writes, ‘can in many ways be seen as a pyramid scheme of sorts — a hierarchy of knowledge — where those who continually invest in innovation remain at the apex of welfare.’ Reinert points to the importance of ‘going up the productivity and technology curve’, generally a function of investments in research, development and expanding the manufacturing sector more than others.

In a different context, the McKinsey Global Institute argues that ‘all global value chains are becoming more knowledge-intensive’.

Coordinated action across sectors yields far greater benefits than piecemeal reforms. Synergy between health, education, infrastructure, governance and trade can unlock productivity, reduce poverty and create jobs. Africa’s demographic dividend, natural endowments and youthful energy can serve as the foundations for a continental transformation.

Such a transformation presumes a social contract between citizens and the state. Governments must deliver, but citizens must also engage. Taxes must be paid, laws respected, and civic duties fulfilled. This mutual accountability — between leaders and people, between generations, between states and markets — is the foundation of development.

Realising that vision firstly requires leadership with vision and resolve. The experience of successful development stories — from East Asia to Latin America to parts of Africa — shows that progress is enabled by committed governments that mobilise their societies around shared goals, resist short-term pressures and focus relentlessly on delivery. Leadership must be accountable, strategic, inclusive and decisive.

Second, it requires national ownership. Development cannot be outsourced to donors, consultants or multilateral institutions. The most effective policies are those rooted in local realities, designed through national dialogue and driven by domestic constituencies. The AU Agenda 2063 provides a continental framework, but it must be realised through national plans, budgets and political choices.

Third, it requires strategic prioritisation. Countries cannot do everything at once. The Combined scenario helps identify catalytic interventions — such as agriculture in low-income settings, or digital infrastructure in urbanising regions — that can trigger broader change. Sequencing matters: early wins in basic services build trust and legitimacy, paving the way for more complex reforms.

Fourth, it requires capacity for implementation. Policy is not what governments say but what they do. Policy only matters if it is implemented. This demands capable civil services, empowered local governments, effective procurement systems and robust monitoring and evaluation. Donors and development partners can support capacity-building efforts, but they must be led from within.

Fifth, it requires a developmental state, not in the ideological sense, but in the practical one: a state that plans, coordinates, learns and adapts. A state that enables markets, not replaces them; that regulates for the public good, not for private capture. A state that sees its citizens not as clients, but as co-creators of development.

Sixth, it requires managing the political economy. Reforms that disrupt rents or redistribute power will face resistance. To sustain change, coalitions must be built across classes, sectors, and regions. Civil society, business associations, youth networks, and traditional leaders all have roles to play. Development is technocratic, political, contested, and negotiated.

Seventh, it requires resilience and patience. Progress is seldom linear. Shocks will come — pandemics, conflicts, climate events, global downturns. What matters is the capacity to recover, learn, and continue. Africa’s development is an intergenerational marathon that requires persistence, adaptability and shared purpose.

Finally, it requires a belief in Africa’s potential, in its people, in a better future that does not ignore complexity or hardship. With smart choices and collective effort, Africa can become a place of prosperity, justice and leadership in the world.

The Combined scenario is a benchmark of Africa’s potential if leadership commits to an integrated, long-term vision. It challenges governments to make tough choices, citizens to demand accountability and development partners to align with African priorities.

Above all, it requires Africans to take ownership of their development paths, embrace the hard work of reform, and build states that empower.

Africa’s future is not a matter of fate, but of strategy, action and solidarity. The journey will be long, but the direction is clear — towards a continent that is integrated, prosperous and peaceful; driven by its citizens; and a dynamic force in the global arena.

Endnotes

Modelling draws on traditional infrastructure, ICT infrastructure, other infrastructure spending level, and the price of energy.

Modelling draws on educational spending, the years of adult education, the quality of adult education, life expectancy, stunting/undernutrition of children, disability, and extent of vocational education.

Modelling draws on economic freedom, government effectiveness, corruption, democracy, freedom and levels of conflict.

Modelling draws on research and development spending, global economic integration and tertiary graduation rates in science and engineering.

Page information

Contact at AFI team is Jakkie Cilliers

This entry was last updated on 11 February 2026 using IFs v8.38.

Reuse our work

- All visualizations, data, and text produced by African Futures are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

- The data produced by third parties and made available by African Futures is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

- All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Cite this research

Jakkie Cilliers (2026) Combined scenario. Published online at futures.issafrica.org. Retrieved from https://futures.issafrica.org/thematic/17-combined-agenda-2063/ [Online Resource] Updated 11 February 2026.