7 Manufacturing

7 Manufacturing

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

This theme evaluates the state of industrialisation in Africa, highlighting the causes and effects of stagnation and premature deindustrialisation. It then presents a forward-looking Manufacturing scenario that models the potential benefits of scaled-up investment in manufacturing, research and development (R&D), labour participation and reforms in the business regulatory environment. The analysis underscores industrialisation’s transformative power to accelerate economic development and improve livelihoods across the continent. For more information about the International Futures (IFs) modelling platform used for the forecasts and scenarios, please visit the Technical page.

Summary

This theme begins with an introductory overview of the historical and current context of manufacturing in Africa.

- Industrialisation is pivotal to economic transformation. It drives sustained growth, job creation, productivity gains and sustainable economic development. For Africa, this pathway remains essential to inclusive and resilient economic development.

The subsequent sections discuss industrialisation theories, Africa’s manufacturing landscape, the sectoral composition of economies, de-industrialisation as well as Africa’s potential.

- Africa’s manufacturing sector is at a strategic turning point. Large youthful demographics, rising intra- and extra-African demand for processed goods and industrial inputs, abundant raw materials, enabling policy frameworks (such as AfCFTA) and investments in infrastructure and Special Economic Zones (SEZs) are aligning to reignite industrial momentum.

- Unlike successful industrialised economies, Africa’s structural transformation has largely bypassed manufacturing, transitioning directly from agriculture into low-value services. This deviation limits the continent’s ability to realise the productivity gains typically associated with industrialisation.

- Manufacturing has not kept pace with the continent’s rapidly expanding working-age population. Without a concerted push to industrialise and modernise agriculture, Africa, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, risks entrenching a dual economy: rural subsistence farming coexisting with urban informal service sectors marked by low productivity.

- The continent's struggle to industrialise stems from a mix of historical factors, policy inconsistencies, infrastructure deficits, skills and technology gaps, capital constraints, an unfavourable business climate and external shocks from global market dynamics.

The second half of this report proceeds with modelling a positive Manufacturing scenario and analysing its impacts on the economy and poverty.

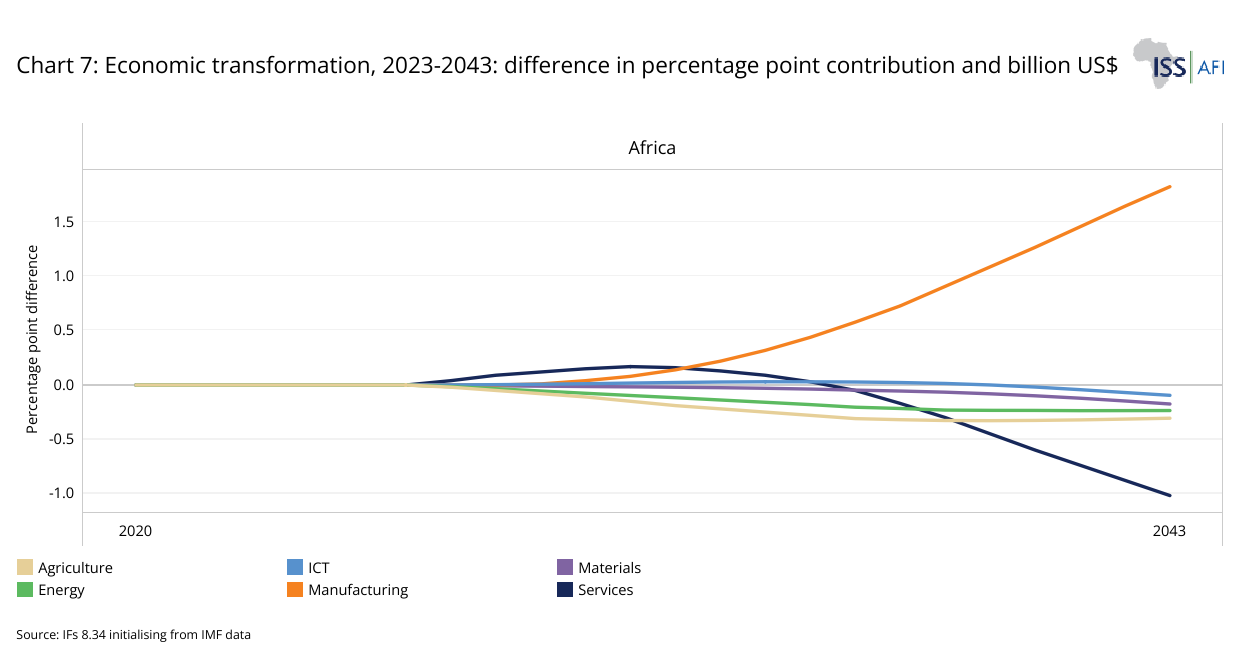

- Under a business-as-usual (the Current Path) scenario, Africa’s manufacturing sector will grow from 13% of GDP in 2023 to 16% by 2043, with services rising from 53% to 57%. Agriculture’s share will almost halve, declining from 15% to 8%. The Manufacturing scenario envisions a 1.8 percentage point increase in manufacturing's share of GDP above the Current Path, which translates to an additional US$168.2 billion by 2043. Overall, all sectors will grow beyond their Current Path in absolute terms by 2043, highlighting the positive spillover effects of manufacturing and the potential for significant re-industrialisation.

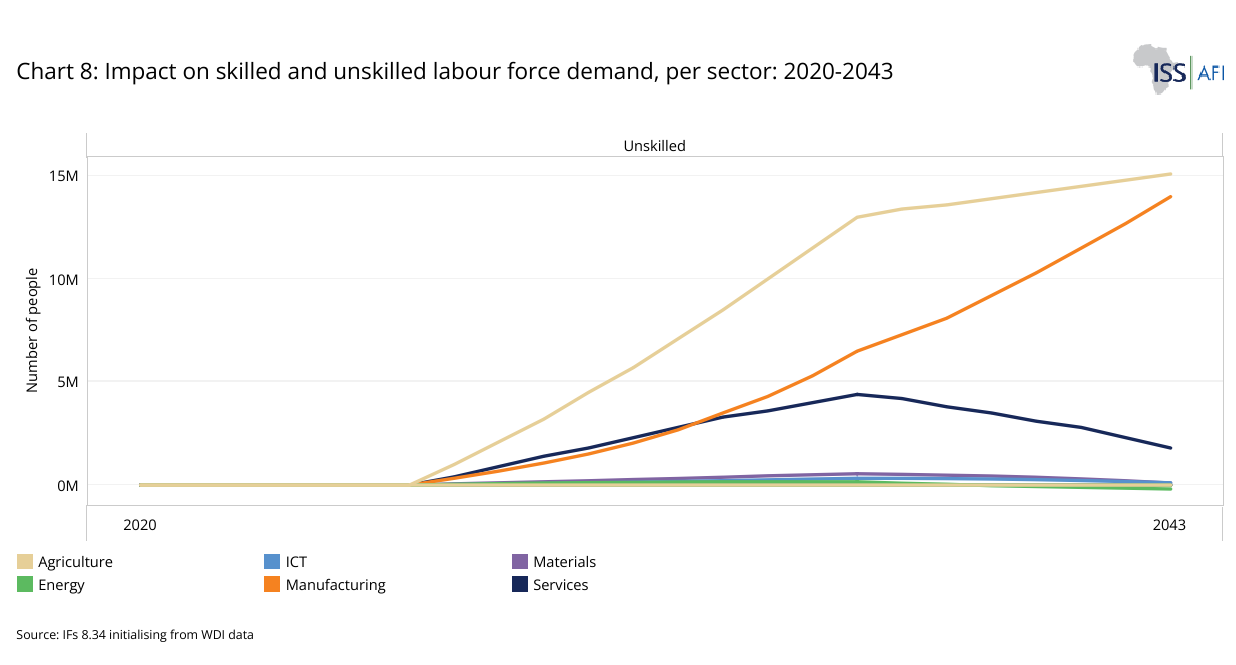

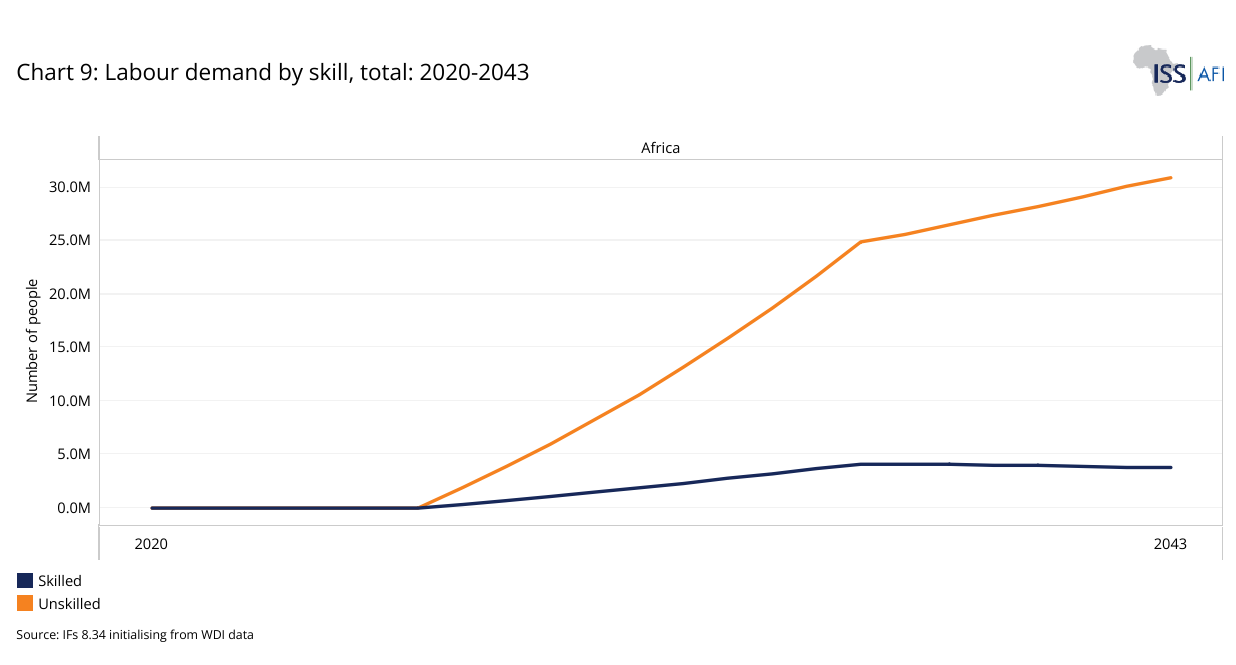

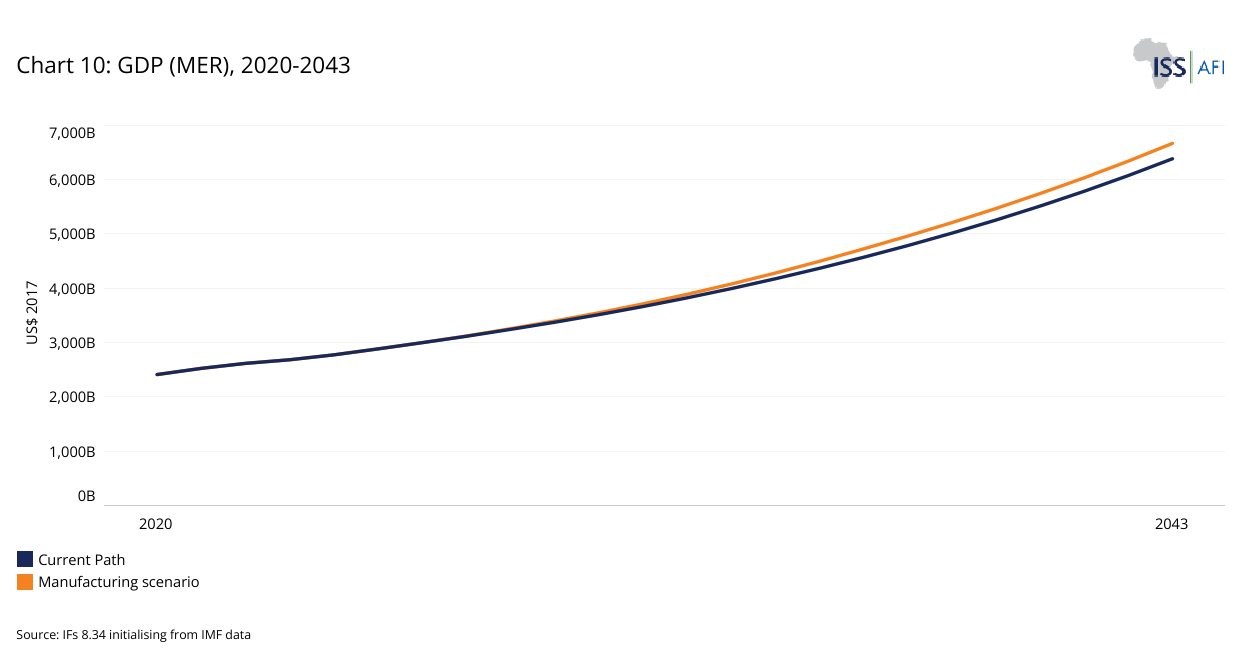

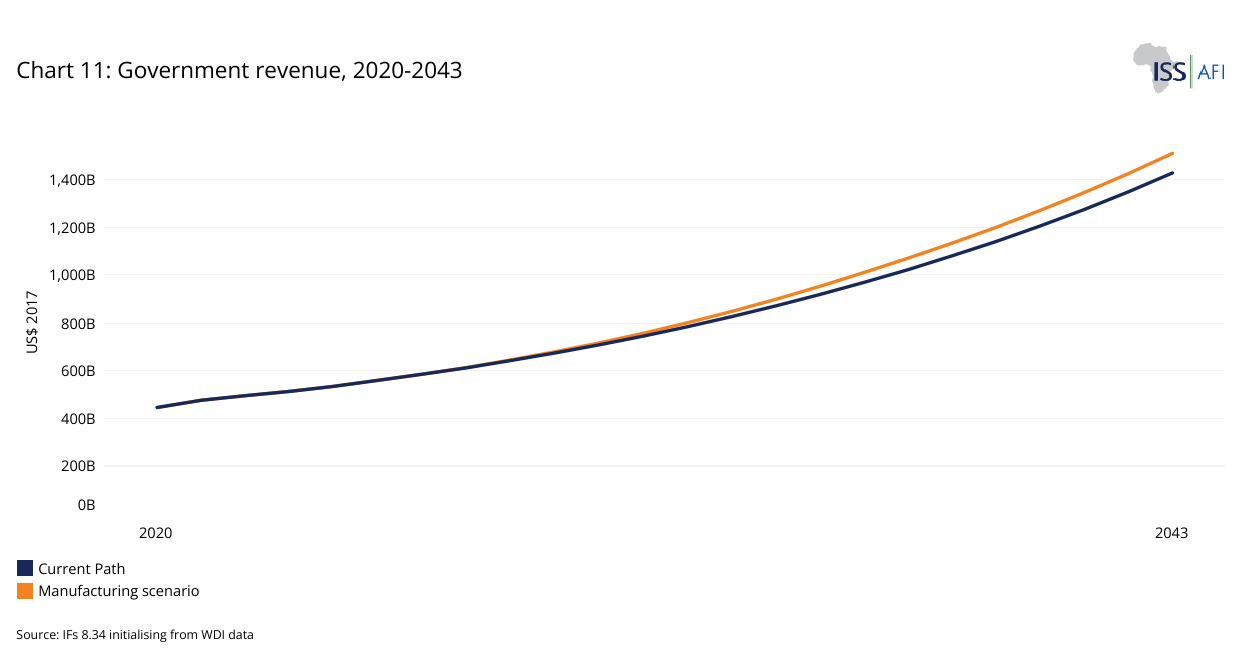

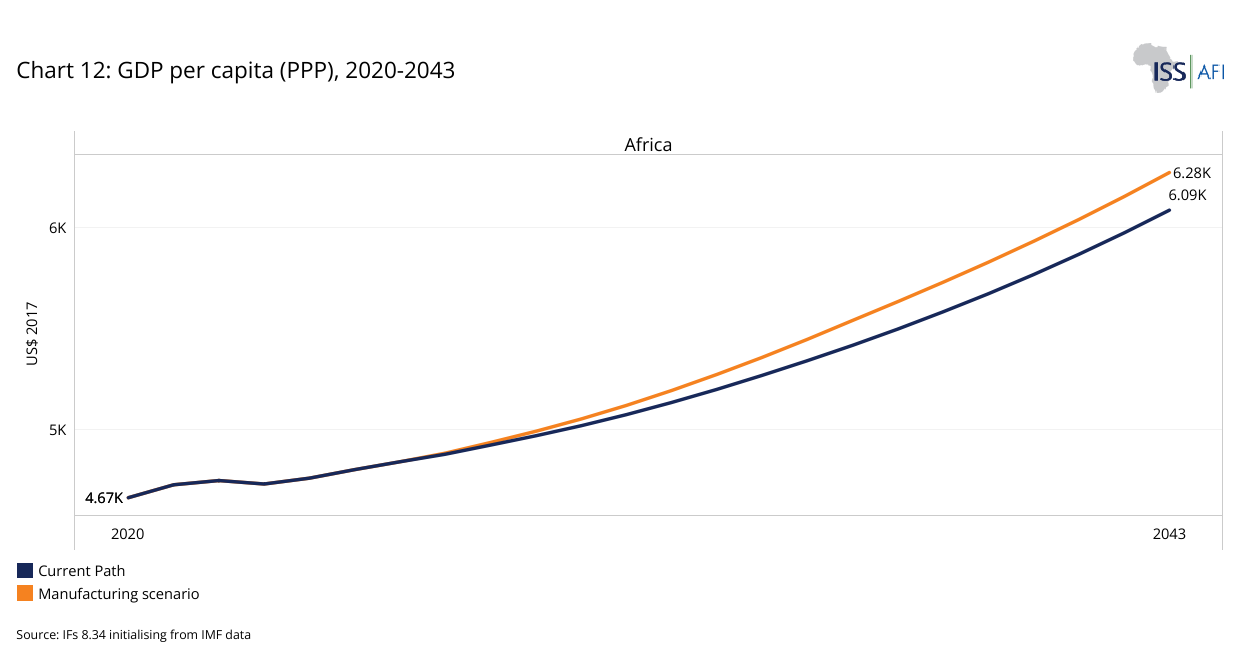

- This scenario will generate an additional 3.7 million skilled jobs and 30.9 million unskilled jobs by 2043, compared to the Current Path. It will also inject US$282.8 billion more into the continent’s economy, raise government revenues by US$81.6 billion , and boost GDP per capita by US$190 relative to the respective Current Path forecasts for 2043. Most importantly, it will lift 19.1 million more people out of poverty by 2043 than the Current Path suggests.

The theme ends with a conclusion discussing the key findings, offering recommendations to African policymakers.

If Africa decisively pursues industrialisation, it could by 2043 realise a significantly larger and more diversified economy, millions of new jobs, reduced poverty, improved public revenues and improved standards of living across the continent.

All charts for Manufacturing

- Chart 1: Manufacturing value-added % in GDP, 2000-2023

- Chart 2: Kaldor’s growth laws

- Chart 3: Sectoral composition of global economies by income groups, 2023

- Chart 4: Trends in manufacturing, services and agriculture value-add as % of GDP, 1960-2043

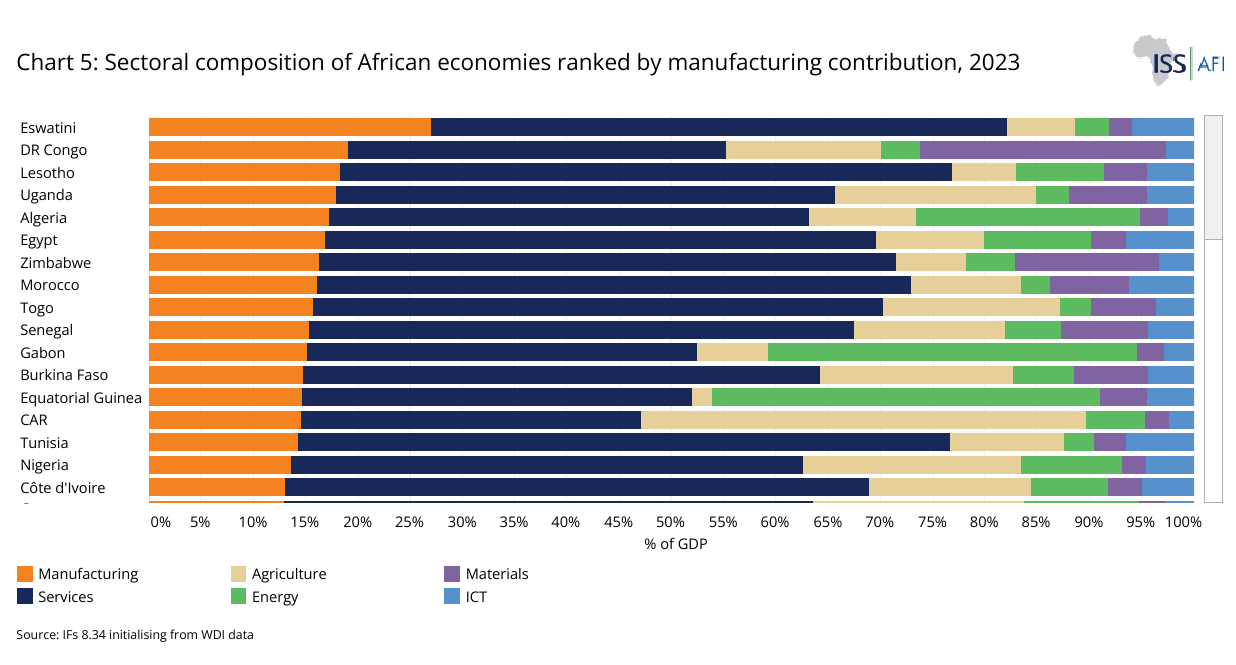

- Chart 5: Sectoral composition of African economies ranked by manufacturing contribution, 2023

- Chart 6: Manufacturing scenario

- Chart 7: Economic transformation, 2023-2043: difference in percentage point contribution and billion US$

- Chart 8: Impact on skilled and unskilled labour force demand, per sector: 2020-2043

- Chart 9: Labour demand by skill, total: 2020-2043

- Chart 10: GDP (MER), 2020-2043

- Chart 11: Government Revenue, 2020-2043

- Chart 12: GDP per capita (PPP), 2020-2043

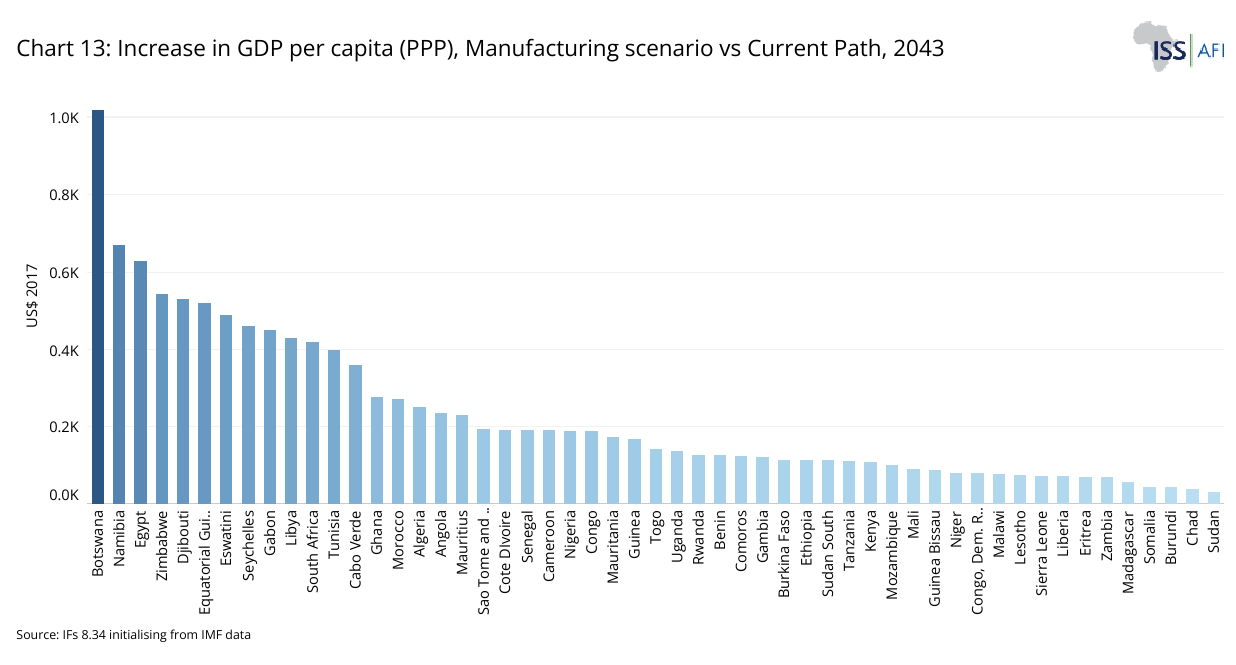

- Chart 13: Increase in GDP per capita (PPP), Manufacturing scenario vs Current Path, 2043

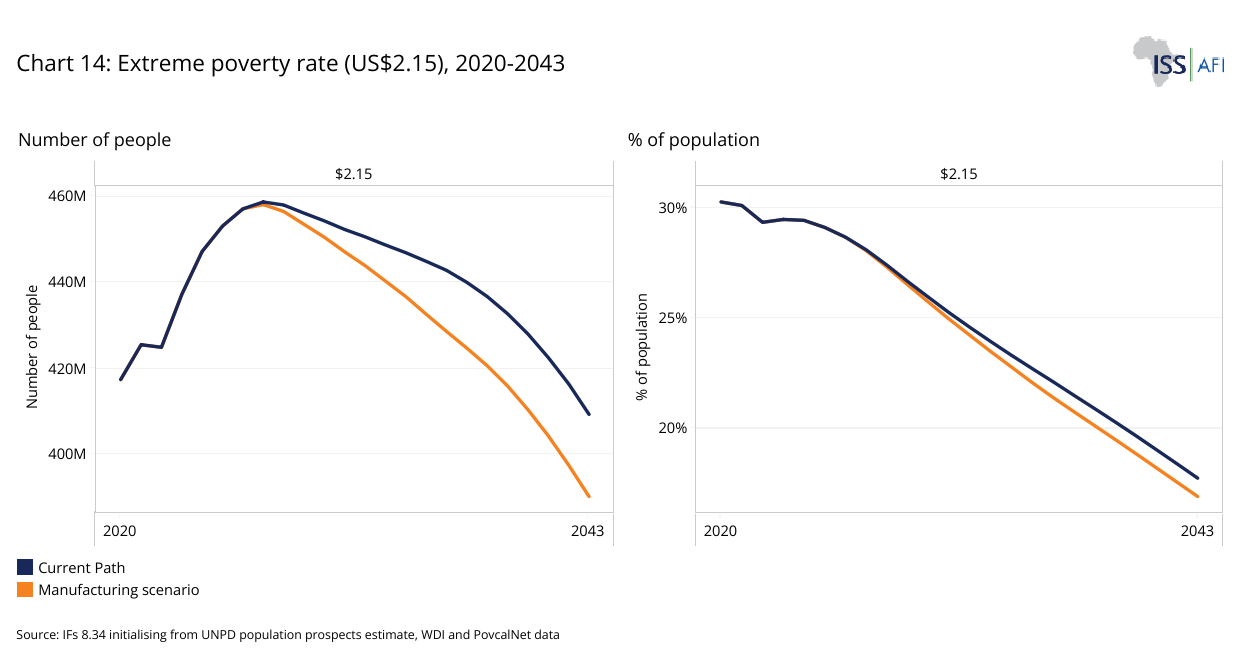

- Chart 14: Extreme poverty rate (US$2.15), 2020-2043

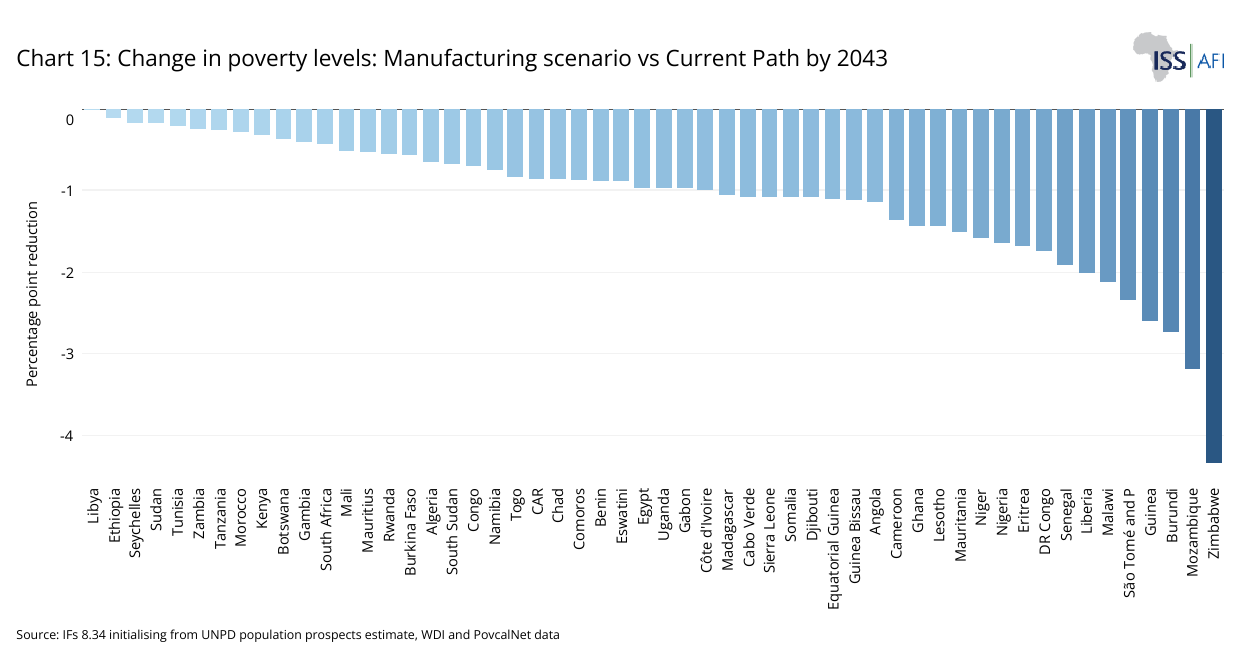

- Chart 15: Changes in poverty levels: Manufacturing scenario vs Current Path by 2043

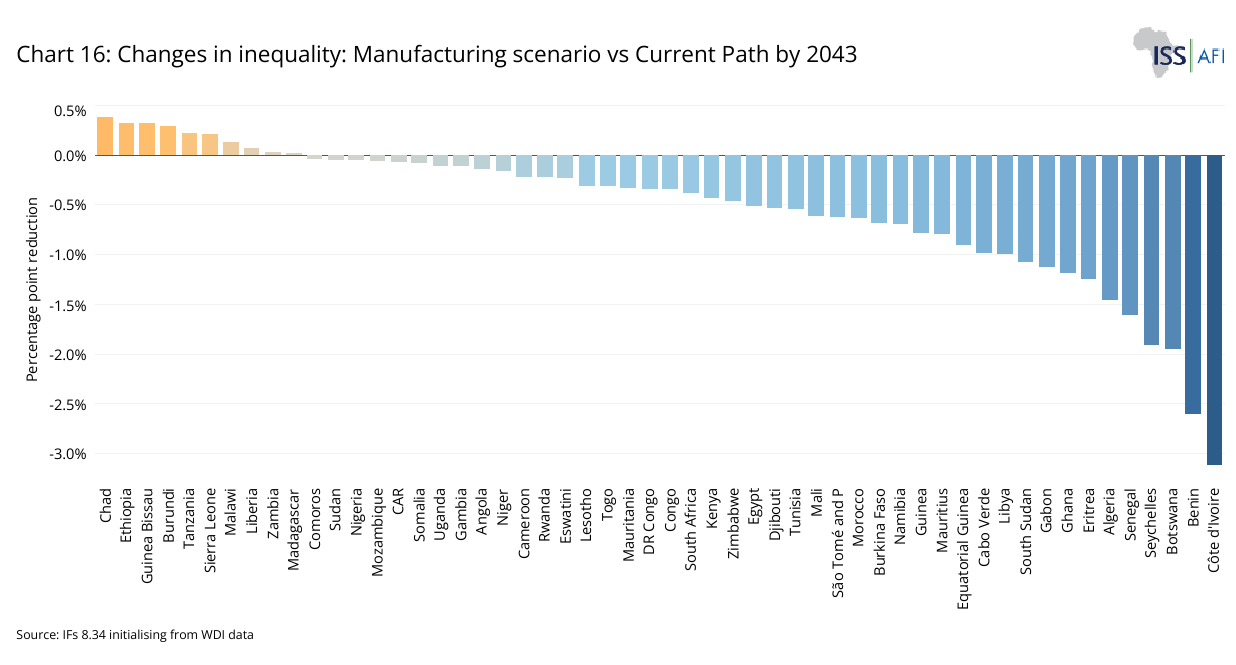

- Chart 16: Changes in inequality: Manufacturing scenario vs Current Path by 2043

- Chart 17: Summary of key recommendations

Since the Industrial Revolution, rapid and sustained economic growth has typically been linked to the size and productivity of the manufacturing sector. Industrialisation has transformed countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States (US), France, Germany and Japan into some of the wealthiest nations in the world. More recently, it has enabled the Asian Tigers (Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore and Taiwan) to catch up with advanced economies. Industrialisation has also fuelled China’s growth to the extent that, in 2010, it surpassed the United States to become the world’s largest manufacturer. By 2023, China accounted for 29% of global manufacturing output, 12 percentage points ahead of the US. Industrialisation is central to modernisation: a vibrant manufacturing base creates employment at scale, drives technological progress and fosters broad-based, inclusive growth.

However, despite its manufacturing potential, including fast-growing internal markets, abundant raw materials and a large labour force, Africa’s experience with industrialisation has been disappointing. Low-end services and subsistence agriculture still play a central role in many African economies, employing approximately 60% of Africa's labour force and contributing 20% to gross domestic product (GDP). The share of manufacturing value added in the continent’s GDP has stagnated under 13% since 2020, leading to concerns of premature deindustrialisation. In 2023, only five African countries (Nigeria, Egypt, South Africa, Algeria and Morocco) had a manufacturing value added over US$10 billion.

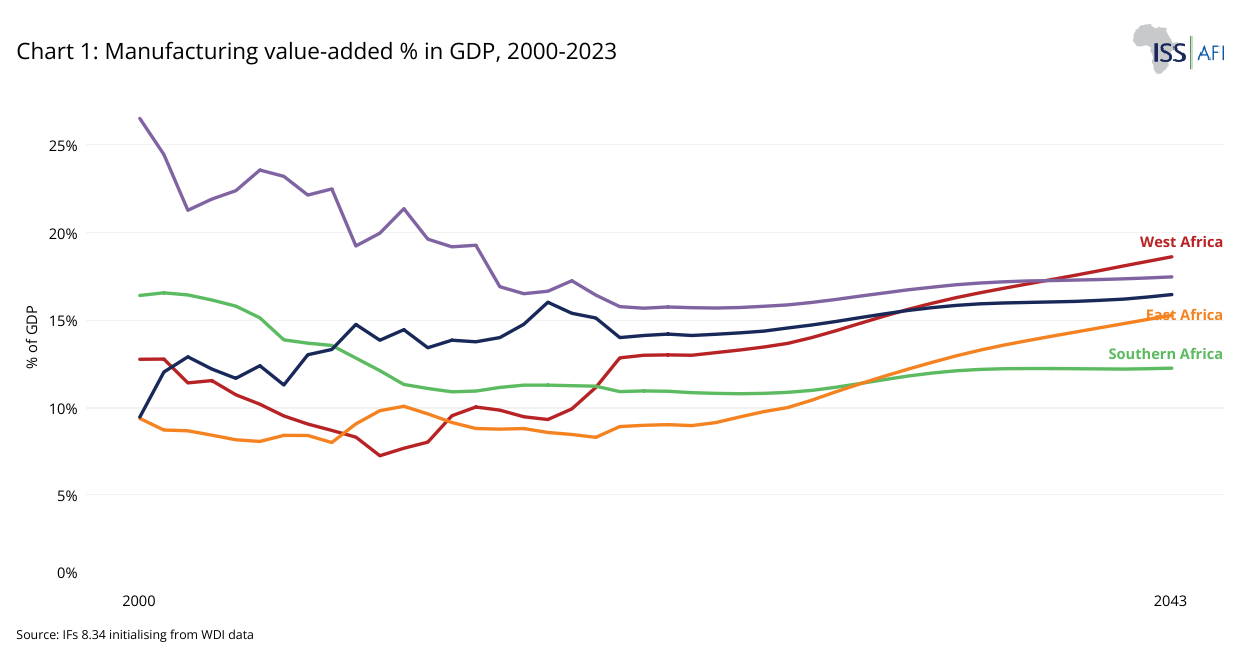

Chart 1 depicts Africa’s manufacturing value-added share in GDP from 2000 to 2043. Africa’s share of global manufacturing has declined from about 3% in the 1970s to less than 2% in 2023. This contribution is significantly below other regions, placing the continent at the bottom of the global value chain. North Africa contributes the largest share of manufacturing value added on the continent, followed by Central and West Africa, which have experienced significant improvements over the past decade. In contrast, Southern Africa's share has been declining, while East Africa consistently has the lowest share of manufacturing value added across the continent.

African industry is primarily focused on low-technology products such as food, beverages, textiles, clothing and wood. There is a limited presence in higher-value manufacturing. This slow growth in the manufacturing sector, combined with an early transition to services, has led to concerns that Africa is de-industrialising before it has a chance to industrialise. In other words, the continent risks missing out on the traditional manufacturing-led pathway to prosperity.

Fostering industrialisation is currently high on the list of priorities for African policymakers. The importance of manufacturing to unlock the continent’s development potential is clearly articulated in the African Union’s 2011 Action Plan for the Accelerated Industrial Development of Africa and reaffirmed in Agenda 2063. Industrialisation is also one of the ‘Top 5’ priority areas of the African Development Bank (AfDB), as reflected in its Industrialise Africa strategy.

Looking to the future, much hope is centred on the impact of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). Launched in 2021, the AfCFTA is a flagship initiative aimed at overcoming the small domestic markets that previously hindered industrial growth. By unifying Africa into the world’s largest free trade area when counting participating countries and geographical areas, the AfCFTA is expected to create economies of scale for African firms and incentivise investments in cross-border value chains. Estimates published by the UN Economic Commision for Africa (UNECA) in The Economic Report on Africa (ERA), , indicate that successful AfCFTA implementation could increase Africa’s combined GDP by US$141 billion and intra-African trade by 45% by 2045. In the short term, AfCFTA also hedges against external shocks: for instance, African industries like automotive assembly and fertiliser production can shift to regional markets to bypass global trade disputes and tariffs.

Equally important is leveraging technology and sustainable practices to leapfrog traditional industrialisation stages. The diffusion of digital manufacturing techniques, such as automation, 3D printing and AI-driven processes, provides opportunities for African firms to boost productivity and join global supply chains in ways not possible before. There is also a growing emphasis on green industrialisation, using renewable energy and circular economy models to ensure industrial growth is environmentally sustainable. African governments and partners are investing in the enablers of modern industry, from Information and Communications Technology (ICT) infrastructure to reliable electricity. For example, Africa’s Industrialisation Week 2024 was held under the theme “Leveraging Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Green Industrialisation,” highlighting the push to integrate advanced technologies and clean energy into manufacturing.

Significant investments in infrastructure and industrial zones are also underway. New highways, rail links, ports and power plants across Africa aim to reduce the high transport and energy costs that have hampered competitiveness. Dozens of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) and industrial parks have been established to attract investors with better facilities and incentives. Ethiopia’s government-led industrial parks, for instance, have been pivotal in attracting foreign investment into light manufacturing like textiles and apparel. Other countries are following suit: Nigeria opened the new Lekki Deep Sea Port in 2023, which now handles about 25% of the country’s container traffic and is expected to improve logistics efficiency for manufacturers. In Central Africa, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo) broke ground in March 2025 on the Musompo SEZ in cobalt-rich Lualaba province, a 900-hectare zone dedicated to battery and electric vehicle production, developed in partnership with Zambia and international investors. Projects like these seek to move African countries up the value chain, for example, from mining and exporting raw minerals to producing battery precursors and assembling electric vehicles locally.

Current developments therefore signal a renewed commitment across Africa to harness manufacturing as a driver of inclusive growth. The theoretical foundations laid by development economists, from structural change models to Kaldor’s growth laws, remain highly relevant to Africa’s situation. All suggest that shifting resources into manufacturing and higher value-added activities is essential for sustained growth.

The following sections explore these concepts and Africa’s progress in more detail, before presenting a scenario analysis of a manufacturing push. The Manufacturing scenario illustrates the potential outcomes by 2043 if Africa pursues aggressive industrialisation policies, as well as the impacts on jobs, incomes and broader development goals.

Industrialisation, Economic Growth and Development

Download to pdfIndustrialisation is widely recognised as a critical engine of structural transformation, skills and economic development. It typically entails a shift from an economy reliant on agriculture and raw material exports to one centred on manufacturing, processing and value-added industries. This transition also includes the expansion of complementary sectors such as construction, energy, technology and services, laying the foundation for a more diverse, resilient and self-sustaining economy.

Several theoretical frameworks have been developed to explain the relationship between industrialisation and economic growth. Chief among them is the structural change theory, which argues that economic progress is driven by the reallocation of labour and capital from low-productivity sectors (like subsistence agriculture, informal trade and artisanal mining) to high-productivity sectors (manufacturing and modern services). This reallocation enhances overall productivity, stimulates job creation and broadens the tax and export base.

Countries that have succeeded in raising their incomes and reducing poverty are typically those that have managed to diversify away from primary commodities toward industrial and knowledge-intensive activities. Industrialisation is particularly significant due to its strong forward and backward linkages: it drives demand for upstream inputs and raw materials while also supplying critical inputs and components to downstream industries and consumers.

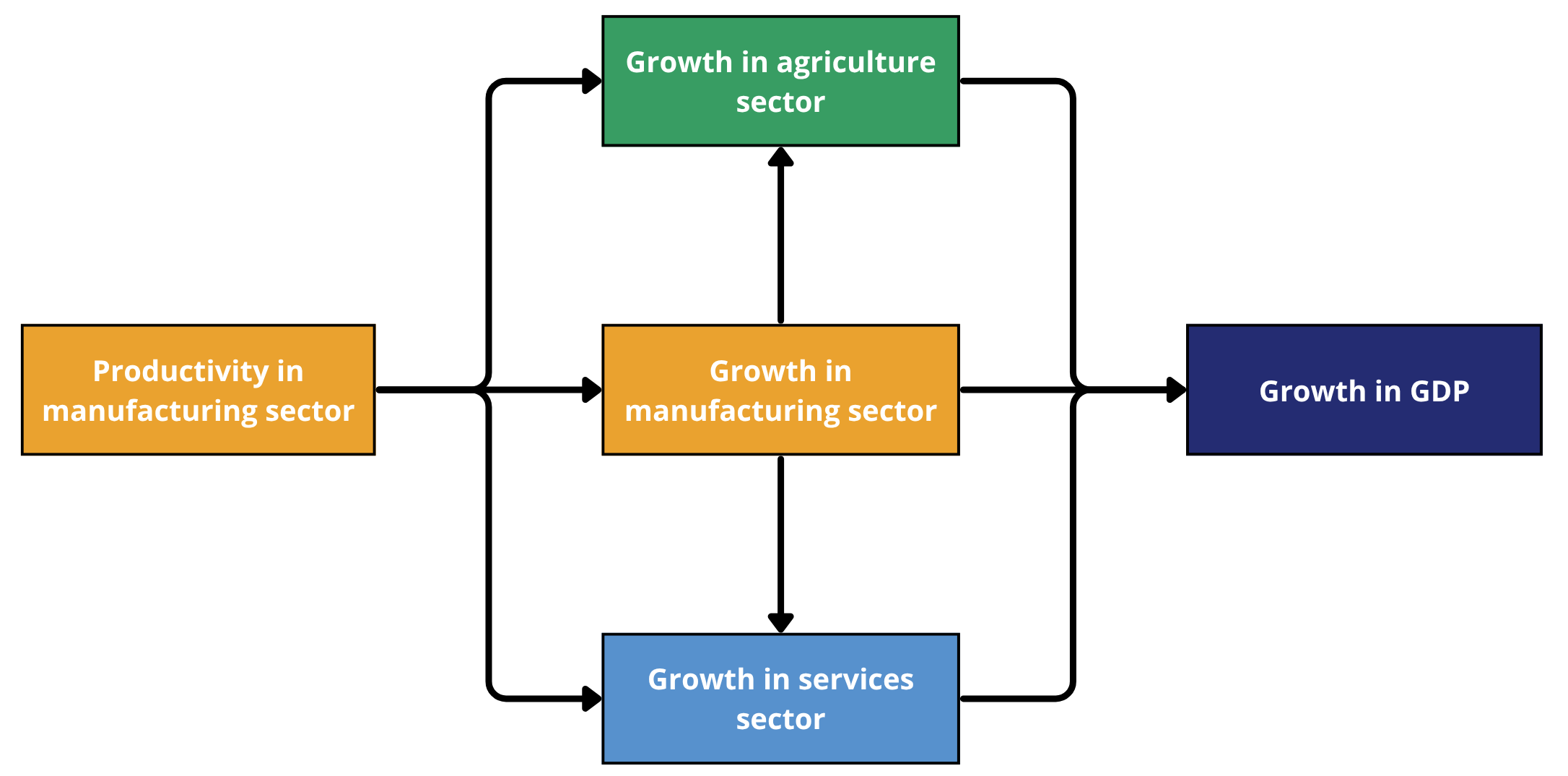

Nicholas Kaldor’s growth laws provide further theoretical grounding for manufacturing’s role in economic growth. Chart 2 shows the concept of Kaldor’s laws. The first law observes that growth in manufacturing output tends to drive productivity gains economy-wide, due to increasing returns to scale, learning-by-doing and rapid technological diffusion in industry. His second law notes that productivity in non-manufacturing sectors (agriculture, services) is enhanced by manufacturing growth, through demand and efficiency spillovers. The third law finds a strong positive correlation between a country’s overall GDP growth and its manufacturing growth. In essence, Kaldor viewed manufacturing as the “engine of growth”: as industry expands, it pulls along other sectors and lifts the entire economy’s performance. This perspective is supported by historical experience; few economies have achieved high incomes without a period of robust industrialisation.

It is important to note that manufacturing-led development usually goes hand-in-hand with improvements in agriculture and human capital, especially in early stages. Many Asian countries first invested in transforming their agricultural sectors, which boosted food security and rural incomes, creating the conditions for labour to shift into industry. These countries also expanded basic education and skills development, yielding a more capable workforce ready for factory jobs. Favourable demographics (a growing working-age population) and strategic, visionary leadership were crucial additional ingredients enabling the transition to manufacturing.

Asian economies pursued deliberate industrial policies to accelerate this transition. Export-oriented manufacturing was often a focus, supported by infrastructure development, technology upgrading and integration into global markets. As a result, countries such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong and, more recently, China, have achieved unprecedented growth, rapid urbanisation and rising living standards by riding the manufacturing wave. Their experience underscores how industrialisation, if well-managed, can lead to transformative development. Countries such as Brazil, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Philippines, South Africa and Turkey also experienced substantive growth for several years due to industrialisation, but generally not at the rates of Asia and not for the extended period seen there.

In his best-selling book Kicking Away the Ladder, the South Korean author and academic Ha-Joon Chang described the view that developing countries could largely skip industrialisation and enter the post-industrial phase where services increasingly drive employment and productivity growth as ‘a fantasy’. This is because the manufacturing sector has ‘an inherently faster productivity growth than the services sector,’ he argues.

The extent to which industrialisation leads to improved wages and better living conditions for the working class is, however, contested and context-specific. For example, while a scarcity of skilled labour meant that industrial employment in the US during its Industrial Revolution (resulting in the so-called American System of Manufacturing) focused on technological improvements to raise productivity and was accompanied by higher wages for successive decades, that was not the case in Europe. Here, a surplus of sufficiently skilled labour would see employment increase but not wages until new opportunities, such as with railways, changed the balance of power between investors and labour.[x]

Early industrialisation is therefore an important development driver, with governments required to act as enablers to unlock private sector capital and innovation. Increased productivity in industry, with a simultaneous transformation out of agriculture, accounted for about half of the catch-up by developing countries to advanced economies’ output per worker between 1950 and 2006. Industry is, therefore, the pre-eminent destination sector at early stages of development because it is a better-paid sector than subsistence agriculture that can absorb large numbers of moderately skilled workers.

Beyond a basic, subsistence level of development, industrialisation also determines agricultural efficiency and expansion, and even the development of high-value services. Large-scale commercial agriculture in Africa, for example, is dependent on a large and diversified manufacturing base, as the processes involved are similar.

More recently, Carol Newman and colleagues found that the manufacturing sector in Africa is six times more productive than agriculture. Also, some recent studies find that ‘rumours of the demise of industrialisation as the engine of development are greatly exaggerated.’

The case for prioritising industrialisation in Africa’s growth strategy rests on several compelling economic foundations. Chief among these is manufacturing's superior contribution to productivity growth. Structural transformation, which is shifting labour and resources from low-productivity sectors such as subsistence agriculture or informal services to high-productivity sectors like manufacturing, yields a significant productivity bonus. This transformation not only enhances overall economic efficiency but also lays the foundation for sustained growth.

Manufacturing also presents unique advantages for capital accumulation. Unlike agriculture, which is spatially dispersed, manufacturing activities are typically concentrated in specific zones or clusters, allowing for more effective investment and infrastructure deployment. The sector also yields higher returns on capital, both in terms of labour productivity and total factor productivity, making it an attractive destination for investment. These dynamics have historically driven high savings and investment rates in successful industrialising economies, such as those in East Asia.

Moreover, the manufacturing sector is characterised by economies of scale and intensive technological advancement. It serves as a conduit for innovation, with new technologies typically emerging in manufacturing before diffusing to other parts of the economy. The scale and scope of these technological gains are rarely matched by agriculture or traditional services sectors, thus reinforcing manufacturing’s central role in driving productivity and competitiveness.

Another critical advantage of manufacturing is its integration into global value chains. Manufacturing industries not only produce goods for domestic consumption but are also highly exportable, facilitating foreign exchange earnings, technology transfer and exposure to international best practices. Even when focused on the domestic market, manufacturers operate under competitive pressure from global suppliers, incentivising continual upgrading of processes and products. In contrast, traditional agriculture and informal services lack this exposure and competitive discipline.

Furthermore, manufacturing generates strong linkage and spillover effects within the economy. It creates robust forward and backward linkages across multiple sectors, stimulating demand for raw materials, logistics, services and consumer goods. These interconnections amplify industrialisation’s impact on job creation, enterprise development and value chain expansion.

Finally, demand dynamics support the case of industrialisation. As per capita incomes rise, the share of income spent on food declines while demand for manufactured goods increases, a phenomenon explained by Engel’s Law. This means countries overly reliant on agriculture and primary commodities face inherent demand-side constraints on growth. Without industrialisation, they risk stagnating in low-income, low-productivity equilibria.

The idea that manufacturing is the pioneering driver of economic growth has also been the subject of numerous empirical studies. The majority of them find that manufacturing is a key engine of economic growth, especially for developing countries. However, some studies reveal an ambiguity in the direction of causality between manufacturing and other sectors and show that manufacturing may not be the most important sector influencing sustainable economic growth.

According to these views, the service sector, combined with ICT technologies, could become the new engine of economic growth in developing economies. With the decline in mass employment in manufacturing, the contribution of the service sector to growth has become important, a trend accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic that saw the rapid modernisation of services akin to the establishment of complex supply chains in manufacturing some decades previously. An important consideration here is that the reduction in manufacturing employment as a portion of total employment inevitably means that its general economic effects are reduced. The nature of services is also changing, permeating all aspects of production as ICT has become more important as a source of productivity growth.

The next sections assess how the manufacturing-led growth hypothesis advanced by Kaldor and others is playing out in the African context, examining structural transformation trends, the current state of African manufacturing and the barriers that have held back industrial growth on the continent.

In recent years, African countries have increasingly embraced the view that industrialisation should be at the centre of their economic development strategies. Several trends, including policy renewals and strategic planning, the establishment of the AfCFTA, digital and green industrialisation, investment in infrastructure and SEZs, and the potential of Africa’s demographic dividend, reflect this shift.

Many governments have adopted industrialisation strategies aligned with the African Union’s Agenda 2063 and its action plans, such as the Accelerated Industrial Development of Africa (AIDA) initiative. National strategies in countries like Ghana, Nigeria, Ethiopia and Kenya have launched ambitious initiatives to enhance manufacturing growth and downstream beneficiation. For example, Nigeria’s current development agenda emphasises local value addition in solid minerals (like lithium) to support an emerging electric vehicle and battery industry. Examples of policy errors also abound, such as Ghana’s ill-considered One District, One Factory initiative, which aimed to establish industries across the country (and not benefiting from the agglomoration effect) to diversify the economy until basic economics forced its abandonment.

Overall, there is a stronger commitment to locating industrial development at the forefront of economic planning, and the initiative that has the most potential in this regard is the 2021 launch of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) which is examined in a separate theme. Once fully operational, the AfCFTA can build regional value chains, deepen intra-African trade and boost demand for locally manufactured goods. A larger unified market can support competitive industrial production that no single small economy can sustain. Progress in AfCFTA implementation continues: as of mid-2025, 48 countries have ratified the agreement, and additional protocols on investment, competition policy and digital trade have been concluded.

By dismantling intra-African tariffs and simplifying customs, AfCFTA is already fostering cross-border industrial value chains. For instance, automobile assembly is poised to benefit; components made in one country can be shipped tariff-free for vehicle production in another, serving the entire continent. If fully implemented, our modelling suggests that the AfCFTA could raise Africa’s GDP by US$592 billion above the Current Path by 2043.

In the short run, the AfCFTA also provides alternatives for African manufacturers facing external trade hurdles. Automotive and fertiliser producers, for example, can target regional consumers to mitigate the impact of global trade tensions and tariff wars. AfCFTA promises to deepen intra-African trade, where manufactured goods already account for the bulk of exports and create a virtuous cycle of increased investment and industrial output across Africa.

The adoption of digital technologies and smart manufacturing is helping some African countries leapfrog traditional stages of industrialisation. Meanwhile, there is a growing emphasis on sustainable, green industrial practices, supported by renewable energy transitions and circular economy models. Automation, robotics, CAD/CAM design and e-commerce are increasingly being used by firms in sectors from apparel to auto parts. For example, South African and Kenyan companies are using 3D printing for prototyping and spare parts production, reducing costs and lead times.

There is also a growing emphasis on a sustainable, green industry. Many African countries are integrating renewable energy into industry, such as solar-powered industrial parks, and exploring circular economy models (recycling and reusing waste in production). These efforts not only reduce carbon footprints but also offer cost advantages in the long run. The African Union has highlighted these themes, with the 2024 Africa Industrialisation Week focusing on harnessing artificial intelligence and green manufacturing innovations to accelerate industrial growth. The goal is to ensure Africa’s industrialisation in the 21st century is both technologically up-to-date and environmentally responsible.

These promising efforts and examples aside, infrastructure bottlenecks, from unreliable electricity to poor transport networks, have long constrained African industry. Recognising this, governments and development partners are investing heavily in industrial infrastructure. Power generation and distribution are being expanded in many countries. For instance, Egypt and Ethiopia have added significant electricity capacity, while South Africa is opening the grid to independent power producers to ease its energy crisis. Transportation corridors are also improving: new ports (such as Nigeria’s Lekki Port and Kenya’s Lamu Port), modernised railways (the Standard Gauge Railway in East Africa), and upgraded highways are facilitating the movement of inputs and finished goods.

SEZs have become a popular tool for creating industry-friendly enclaves with ready infrastructure and policy incentives. Ethiopia’s network of industrial parks is often cited. Hawassa Industrial Park, for example, provides world-class facilities for textile and garment manufacturers and has attracted numerous foreign investors. Egypt has established large economic zones along the Suez Canal and elsewhere, drawing manufacturing investment in sectors like automotive and chemicals. In West Africa, Togo’s Adétikopé Industrial Platform (PIA) and Ghana’s Tema Export Processing Zone are creating hubs for processing agricultural commodities and assembling goods. A recent landmark project is the DRC–Zambia Battery Valley initiative: in 2025, the DRC launched the development of the Musompo SEZ, a 900-hectare zone to produce battery precursors and potentially assemble electric vehicles using locally mined cobalt. Zambia is also planning a complementary zone as part of this cross-border project, with backing from the African Export-Import Bank and Africa Finance Corporation.

These infrastructures and SEZ investments, while at varying stages, are laying the groundwork for accelerated industrial activity. They aim to reduce operating costs and risks for manufacturers, making African locations more competitive for production.

Finally, Africa’s young population and rapid urbanisation present both a challenge and an opportunity for industrialisation. We expand on demographics in a separate theme. Each year, millions of African youth enter the labour market, often with limited prospects in agrarian or informal sectors. Manufacturing could absorb many of these workers if it expands. A large, youthful workforce can be a source of lower-cost labour that attracts labour-intensive industries (much as East and Southeast Asia benefited from demographic dividends). Urbanisation is creating burgeoning consumer markets in African cities, which can stimulate demand for domestically made products from food to furniture to appliances. However, to harness this demographic dividend, investments in education and technical and vocational training are crucial so that the labour force has the skills needed in modern factories and industrial enterprises. If properly skilled and utilised, Africa’s human capital could be a key asset powering industrial growth through to mid-century. In the theme on employment, we explain and view the effect of various scenarios on the future of work in Africa, noting that by 2029, Africa would have a larger working-age population than China and, by 2032, larger than India. This underscores the urgency of creating productive jobs – industrialisation will be central to achieving that at scale.

In a nutshell, Africa’s manufacturing landscape is at an inflexion point. Structural factors like demographics and demand are aligning with policy momentum – at the continental and national levels – and investments on the ground (like infrastructure, SEZs) to potentially kick-start a new era of industrial growth.

The following sections delve into the specifics of Africa’s industrial performance and the challenges that need to be addressed. Later, the theme explores what the future could hold under a more aggressive but realistic industrialisation scenario.

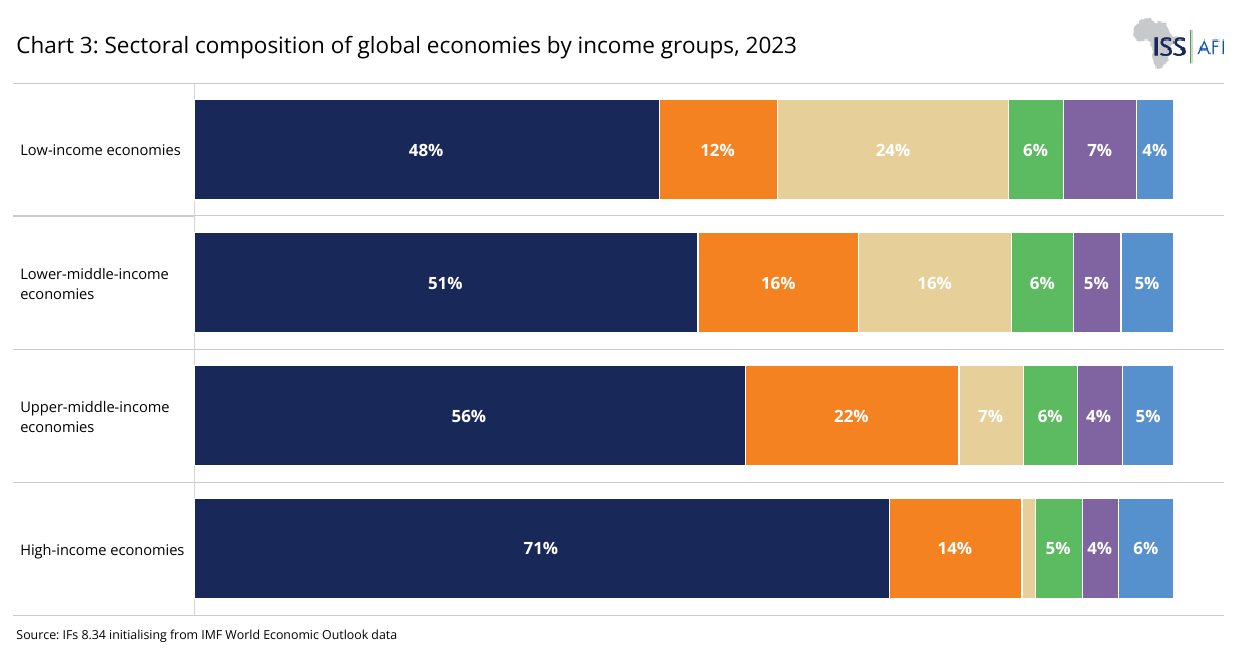

Chart 3 presents the average sectoral composition of low-, lower-middle-, upper-middle- and high-income countries’ economies globally for 2023. The forecast is initialised from the World Development Indicators and IMF data and may differ slightly from other datasets. This is because the International Futures forecasting platform uses Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) data to categorise forecasts of economic value into six sectors instead of the standard threefold distinction between agriculture, services and manufacturing. Energy, materials and ICT constitute additional sectors that allow for more granular forecasting.

Chart 3 illustrates how the sectoral composition of GDP evolves as countries advance economically through the reallocation of economic activity from low-productivity sectors to high-productivity ones. As populations grow wealthier, the contribution of the services sector increases significantly, while the share of agriculture and materials declines. The manufacturing sector plays a growing role during the transition to upper-middle-income status, but its relative importance diminishes once countries attain high-income levels, at which point high-end services become the primary engine of growth. Notably, the contribution of the energy sector declines steadily as income rises, whereas the ICT sector maintains a consistent contribution of approximately 4% in low-income countries and two to three percentage points higher in other income groups.

In recent decades, the contribution of ICT has become particularly important in high-income economies. Despite its relatively small contribution to added value, ICT is a growth multiplier as countries go up the GDP per capita ladder. It facilitates knowledge exchanges, including the effective functioning of regional and multinational value chains, which include goods and services. Looking at the changed nature and structure of modern economies, the question is whether ICT can leverage the same productivity improvements in combination with the service sector at low levels of development that previously came from manufacturing.

Although a number of African countries have experienced very rapid economic growth in the last two decades, that growth came mainly from high commodity prices that have attracted more investment in extractive industries with limited linkages to the rest of the economy and away from manufacturing, limiting economic diversification and rendering Africa vulnerable to external shocks.

Across all income groups, agro-processing is often the entry point for industrialisation, with the potential for exports and to benefit from regional trade agreements. The associated strategies are often SEZs and industrial parks but with mixed success. Regional integration such as the AfCFTA offers an opportunity to scale manufacturing markets beyond small domestic bases, as discussed previously.

There are, of course, large variations in this general trend, with some high-income countries globally (such as Taiwan) having a manufacturing sector above 50% of GDP, whereas the sector contributes only about 1.2% to GDP in the Bahamas.

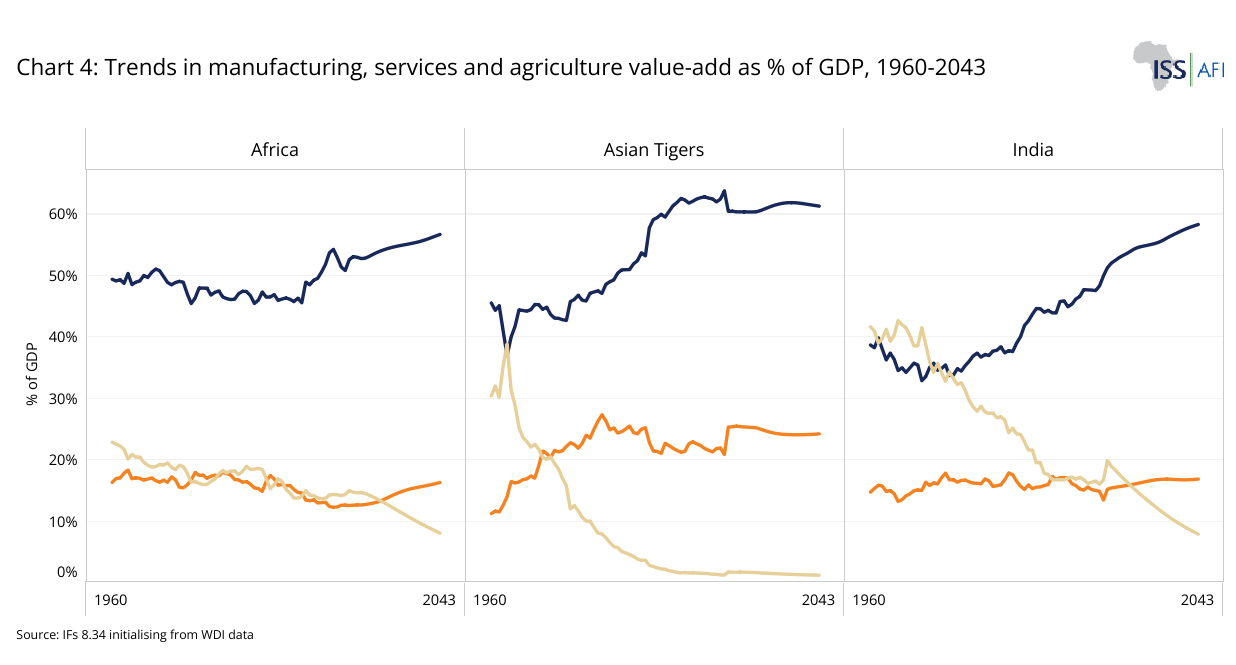

Chart 4 compares trends in manufacturing, services and agriculture in contribution to GDP in Africa, the Asian Tigers and India from 1960 to 2043. Historically, Africa appeared to be a mirror of India’s recent development path, particularly in the extent to which services dominate African economies. In India, the contribution of the service sector to GDP overtook agriculture's contribution to GDP as early as 1975, yet it took another three decades for manufacturing to do the same, highlighting the subdued role of industrialisation in India’s economic structure.

India’s model, while distinctive, has come with trade-offs. The premature growth of the service sector, without a broad-based industrial foundation, alongside a delayed demographic dividend (India entered its demographic window of opportunity in 2008), contributed to slower-than-anticipated growth and job creation over several decades. Furthermore, systemic challenges such as bureaucratic overregulation, corruption and limited market competition stifled economic dynamism until the landmark economic liberalisation reforms of 1991. These reforms initiated a process of deregulation and market opening, but structural weaknesses remained.

India’s recent demographic dividend, combined with improvements in education, increased infrastructure investment and a renewed policy focus on expanding the manufacturing base, as reflected in initiatives like Make in India, suggests a potential pivot toward more rapid and employment-intensive growth in the future. Examined in the theme on demographics, Africa should get to its demographic window of opportunity at around 2051, much later than other regions, and this is an important reason for its relatively slow improvements in income.

In contrast to India, China (and previously Japan and the Asian Tigers) followed a manufacturing-led strategy, underpinned by deliberate state planning, export-oriented industrialisation and aggressive investment in infrastructure and human capital. With a lower dependency ratio and a strong manufacturing base, China achieved sustained high growth rates and generated mass employment across rural and urban areas. Its development path underscores the critical role of industrialisation in facilitating broad-based structural transformation.

The nature and value contribution of Africa’s manufacturing sector differ widely across African countries depending on income level, structural transformation and integration with global markets. Thus, in low-income African countries such as Chad, Malawi, Burundi and DR Congo, manufacturing represents small, informal and micro-enterprises. These often are family-based enterprises that make furniture, textiles and garments, process food and beverages and make handicrafts with no or limited capital investment, using outdated technology. In lower-middle-income countries such as Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal, agro-processing of cocoa, coffee, cashew, maize, oil palm, as well as production of construction material, is characteristic of the manufacturing sector. Growth in manufacturing in these countries is often constrained by high energy costs, unreliable energy supply, weak infrastructure deficit, skills shortages and import competition compared to the more mature and globally integrated sectors such as automotive and component manufacturing, chemicals and petrochemicals, metals and machinery found in upper-middle-income African countries such as South Africa, Mauritius, Botswana and Nambia. These countries face intense competition from Asia.

For Africa, these contrasting models offer important insights. Africa’s youthful population, expanding infrastructure networks and regional integration through the AfCFTA offer a strategic opportunity to craft a hybrid model, one that combines the dynamism of services, especially in digital finance, telecommunications and logistics, with the transformative power of manufacturing and value addition.

Since the mid-1990s, sub-Saharan Africa’s manufacturing share of GDP has hovered around or below 12%, significantly lower than in other developing regions and never approaching the 20–30% levels reached by East Asia or Latin America at their industrial peaks. North Africa is the most industrialised region in Africa, with a manufacturing sector contributing 15% to GDP in 2023. These numbers underline that Africa as a whole remains an outlier – no region other than Africa has urbanised and grown so much with so little manufacturing.

While deindustrialisation in upper-middle-income and high-income countries is normal due to structural transformation (a post-industrial shift to services), deindustrialisation in low-income and lower-middle-income countries in Africa is alarming and worrisome. As The Economist noted, many African countries are ‘deindustrialising while still poor,’ missing out on the classic path of moving workers from farms into better-paying factory jobs. This premature deindustrialisation could imply forfeiting some potential growth and employment gains.

One aspect behind this trend is the wage and productivity dynamics. In the Global North, manufacturing booms eventually led to wage increases that made manufacturing less competitive, and thus output and employment in that sector later declined, compensated by growth in services and high-tech industries. As countries develop, the manufacturing compensation premium, which is the additional pay a manufacturing worker traditionally earns relative to a comparable non-manufacturing worker at the same educational level, has also declined. In Africa, a different story unfolded: manufacturing never became dominant. Instead, some countries saw early stagnation or a drop in manufacturing jobs due to limited industrial competitiveness and the availability of low-end service opportunities absorbing labour. Furthermore, as global manufacturing became more skill- and capital-intensive, African firms struggled to compete, given a relatively small pool of skilled labour and cheaper competition from abroad. The result has been that manufacturing’s traditional role as a large employer has not materialised.

Chart 5 ranks all African economies by their share of manufacturing value added in GDP for 2023. The United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO)’s industrial development goals suggest that for manufacturing to be a meaningful driver of structural transformation, manufacturing value added should reach at least 20% of GDP. Achieving this level is linked to fostering sustainable industrial growth and progressing toward upper-middle-income status. Only one low-middle-income African country, Eswatini, exceeds the 20% threshold, with manufacturing value added of 27% of GDP in 2023. This is partly due to its successful textiles and sugar processing industries, bolstered by trade access to the large US market through the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which in 2025 came under threat from US President Donald Trump. Even Africa’s largest economies fall short of that benchmark: for instance, South Africa, the continent’s most industrialised economy by absolute output, has around 13% of GDP in manufacturing, Nigeria approximately 8% and Kenya roughly 12%. A few North African countries, including Tunisia, Morocco, Egypt and Algeria, have manufacturing shares between 10% and 20%, but many others are below 10%.

Chart 5 highlights several important trends and counterfactual insights regarding sectoral contributions to GDP across African countries. Agriculture’s share of GDP is highest in low-income countries and lowest in upper-middle-income economies, with South Africa standing out for its minimal agricultural contribution (just over 2%), yet it remains largely food self-sufficient due to a highly efficient commercial farming sector. This underscores a critical distinction: famine and food insecurity are more common in countries with large, low-technology agricultural sectors, and the size of the agricultural sector does not necessarily correlate with food security. Paradoxically, countries such as Sierra Leone, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Mali and Nigeria have sizable agricultural sectors but remain net food importers, a dependency expected to deepen in the coming years.

Low-income countries also tend to have limited energy and manufacturing sectors. Conversely, in 2023, oil-exporting countries like Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, the Republic of Congo, Angola and Chad had energy sectors that accounted for a substantial portion of their economies. Meanwhile, mineral-rich countries such as Zambia, DR Congo, Mauritania, Guinea and Zimbabwe derive significant GDP contributions from raw materials like copper, cobalt, iron ore, aluminium ore, gold, lithium and diamonds. On the other end of the spectrum, the services sector dominates in economies like Djibouti, Seychelles, Cabo Verde, Botswana and Mauritius, each with services contributing more than 70% of GDP. Notably, in Seychelles, Africa’s only high-income country, the contribution of the services sector to GDP stood at 23%, further reflecting the strong link between services-led growth and higher income levels.

An important yet less visible trend is the growing footprint of Chinese companies in Africa’s expanding manufacturing sector. Chinese investors appear to have anticipated the continent’s demographic and market potential early, positioning themselves to meet the rising domestic demand driven by Africa’s rapid population growth.

According to McKinsey, nearly one-third of the more than 10 000 Chinese companies operating in Africa are engaged in manufacturing, collectively accounting for over 12% of Africa’s industrial output. Unlike the state-owned giants often associated with Chinese overseas investment, most of these firms are small, privately owned enterprises focused primarily on meeting the growing domestic consumption needs within African markets, rather than pursuing export-oriented strategies. There are, of course, also larger examples. Thus, China established the biggest ceramic tile factory in Africa, located in Ethiopia, and in 2024, the Dinson Iron and Steel Company (Disco), a Chinese investor, completed the Manhize steel plant in Zimbabwe, now one of the continent’s largest producers. This shift underscores China’s evolving role in shaping Africa’s industrial landscape through localised, demand-driven investment.

The dominance of Chinese firms is even more pronounced in debt-financed infrastructure projects, claiming nearly 50% of Africa’s internationally contracted construction market. Most of these companies are oriented at serving the domestic market, not at exports and appear to ‘represent a long-term commitment to Africa rather than [focusing on] trading or contracting activities.’ Furthermore, nearly two-thirds of Chinese employers provide some kind of skills training by introducing a new product, service or technology to the local market. In some cases, Chinese firms had lowered prices for existing products and services by up to 40% through improved technology and economies of scale. The report by McKinsey, upon which these findings draw, indicates that Chinese firms’ efficient cost structures and speedy delivery were noted as major value additions by government officials in Africa.

If Chinese companies can enter and expand Africa's manufacturing sector, why can Africans not do the same? Aliko Dangote, Africa’s richest individual and a Nigerian entrepreneur, sets an example by investing in oil refining, food processing and cement manufacturing across the continent.

For most African countries, the manufacturing value-added share has remained under 15%, and the majority have experienced a decline since 1990, implying limited industrialisation and high vulnerability to commodity and/or informal sector dependence.

This underscores that only a handful of African countries have built even a modest industrial base. The Africa Industrialisation Index 2022 echoes this point, indicating that the top performers are limited to a few countries with relatively advanced manufacturing and diversification. South Africa, Eswatini, Mauritius and North African economies (like Morocco, Egypt, Tunisia and Algeria) occupy the top tier of the index, while the vast majority of countries trail with low levels of industrial competitiveness. Broadly, Africa’s exports remain dominated by raw materials and commodities, and high-tech manufactured exports are minimal. A classic example: Africa produces raw cocoa but exports mostly unprocessed beans, while Europe imports them and sells “Swiss chocolate” or “Belgian chocolate” for far higher value. The same pattern repeats with African crude oil versus imported fuels and petrochemicals, or cotton versus imported apparel. The continent captures only a tiny fraction of the value chain in many industries.

The challenge for Africa is to redirect some of the structural shift towards manufacturing and higher value addition so that economic growth comes with commensurate gains in productivity and incomes.

Encouragingly, several countries have either maintained or increased their shares in manufacturing through intentional efforts. For example, Eswatini has utilised trade preferences to support its apparel industry, while Rwanda has gradually expanded its small manufacturing sector, particularly in construction materials and agro-processing, by implementing business-friendly reforms and investing in infrastructure. Ethiopia managed to increase its share of manufacturing in GDP in the 2010s by attracting garment and leather factories (though from a very low base, and progress stalled due to recent conflict and macroeconomic issues). These examples show that policy choices and investments can influence outcomes, even within global constraints. Tanzania also has built a more resource-intensive manufacturing sector focused on serving domestic and regional markets. The manufacturing output in Tanzania increased by more than 7% annually from 1997 to 2017.

In summary, Africa’s structural transformation thus far has been atypical and suboptimal from an industrialisation standpoint.

Africa’s struggle to industrialise stems from a confluence of historical and structural factors, policy inconsistencies and lack of industrial strategy, hard infrastructure gaps, skills and technology gaps, capital constraints, unfavourable business and investment climate, and external shocks emanating primarily from global market dynamics. Understanding these challenges is essential before proceeding with modelling an increase in manufacturing.

Many African economies emerged from colonial rule with a focus on extractive industries and commodity exports, not manufacturing. The infrastructure and institutions left behind were often geared towards mining or plantation agriculture, with a limited industrial base. This path-dependency meant that post-independence industrial growth had to start almost from scratch in many places. Additionally, relatively small domestic markets due to low incomes and fragmented borders made it hard for nascent industries to achieve economies of scale. Where East Asian countries could scale up by exporting to global markets, African firms often struggled to compete internationally in manufactured goods given their small domestic markets and faced stiff competition from established producers in Asia and the West.

Compounding its colonial legacy, several African countries attempted import substitution industries through state-owned enterprises after independence. Many of these efforts faltered due to inefficiencies, corruption or external shocks, and were later reversed under structural adjustment programs in the 1980s and 1990s. The liberalisation era often led to deindustrialisation, as protective tariffs were removed and local industries collapsed under import competition. In the 2000s, countries like Nigeria, Ethiopia, Kenya, Morocco and Rwanda reconsidered and crafted new industrial policies. However, implementation has varied. In some cases, lack of clear planning, inconsistent commitment and poor governance undermined industrial initiatives. Frequent changes in policies, such as sudden tax hikes, import bans or forex restrictions, created uncertainty for investors. Countries that sustained a focused industrial strategy tend to have better outcomes than those that oscillated or treated industrialisation as a slogan more than a plan. Examples are (Ethiopia’s push in light manufacturing during the 2010s) or Morocco’s deliberate development of automotive and aerospace clusters.

A fundamental barrier to industrialisation in much of Africa has been the cost and reliability of inputs like power, transport and Information and Communication Technology (ICT). Reliable power supply and efficient transport networks are not merely infrastructure issues; they are central to any viable industrialisation strategy. Yet, many African manufacturers continue to grapple with chronic electricity shortages and logistical bottlenecks, severely limiting their competitiveness and growth potential. In Nigeria, for example, approximately 90% of manufacturers depend on diesel generators due to the chronic instability of the national power grid. The government estimates that its manufacturers lose approximately US$27 billion annually as a result of power outages, an economic burden that significantly hampers industrial growth. Consequently, Nigeria's manufacturing sector has stagnated, contributing around 13% to GDP since 2020. Similarly, in South Africa, load-shedding (rolling blackouts) by utility Eskom has forced regular plant shutdowns from late 2007 to early 2024, undercutting manufacturing output.

Inadequate transport infrastructure is another significant obstacle to industrial development in Africa, driving up logistics costs and causing long lead times. The continent’s roads, railways and ports have failed to keep pace with growing economic demands, making the movement of goods both slow and expensive. In 2018, sub-Saharan Africa, despite comprising 17% of the world’s land mass, accounted for just 6% of global road networks, a stark contrast to South Asia’s 17% share. According to the Africa Finance Corporation’s 2024 report, Africa’s total paved road network spans only about 680 000 kilometres, roughly one-sixth the size of India’s, despite the two regions having roughly equal population sizes. Africa is, of course, more than nine times the size of India, meaning that its few roads have to service much larger geographic areas. This infrastructure gap leaves vast areas poorly connected and creates severe logistical challenges for manufacturers across the continent.

Moving goods across African countries can be slow and expensive due to poor roads, congested ports and cumbersome border procedures. For example, it can cost more (and take longer) to ship goods from one West African country to a neighbouring one than from China to Africa. This lack of connectivity and high internal trade costs have dissuaded investment in regional value chains. World Bank estimates suggest that sub-Saharan Africa’s infrastructure deficit reduces annual economic growth by roughly two percentage points and that it lowers business productivity by up to 40% in some countries.

The AfCFTA is intended to tackle some of these issues by improving trade facilitation, but the need for hard infrastructure requires sustained investment. Encouragingly, as noted earlier, there are major projects in progress: from new ports and railways to hydroelectric schemes and renewable energy farms that could power industries. Until these deficits are substantially addressed, though, they remain a drag on industrial competitiveness.

Many African manufacturers face a shortage of skilled technicians, engineers and managers needed to run modern industries. Educational systems in many countries have not produced enough graduates with technical and vocational skills relevant to manufacturing. This often forces firms to either invest heavily in training new hires or bring in expatriate expertise, both of which raise costs. Additionally, limited access to cutting-edge technology and know-how has been an issue. African firms typically invest less in research and development (R&D) than firms in other regions. Technology transfer through foreign direct investment has been happening. For instance, Japanese car makers are training workers in South Africa, or Chinese textile firms in Ethiopia are introducing new machinery. However, not all investments come with significant skills transfer, and there is still a gap in local technological capacity. Closing this gap will require investments in education, particularly in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) and vocational training, as well as stronger industry-academia linkages and incentives for innovation. Initiatives like Ghana’s Skills Development Fund and Kenya’s technical institutes are steps in the right direction, but much more needs to be done to equip the workforce for industrial jobs.

Manufacturing enterprises often require substantial capital to purchase equipment, build factories and weather initial losses. In Africa, access to long-term finance at reasonable interest rates is limited. Banks often consider manufacturing too risky compared to commerce or resource deals and interest rates can be very high, making loans for industrial investment prohibitive. Capital markets are shallow in most of Africa, so raising equity or bond financing is also tough. Development finance institutions like the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the African Development Bank (AfDB) and national development banks have been important in funding industrial projects on a concessional basis, but overall, the financing constraint remains. Without affordable finance, local entrepreneurs struggle to establish or expand manufacturing businesses. This often leaves the field to foreign investors or limits industries to those with quick turnover. Improving the financial ecosystem through reforms, guarantees and innovative financing models (like blended finance or industrial venture funds) could help channel more capital into manufacturing ventures.

Beyond finance, general ease-of-doing-business factors play a role. Red tape, slow bureaucratic procedures and regulatory uncertainty can deter industrial investment. However, some countries have made strides in streamlining business registration and customs procedures. Rwanda is a notable example of creating a business-friendly environment. Others still have notorious hurdles, like difficulty in getting land title deeds or complex import-export licensing that can delay inputs for factories. Corruption is another challenge that raises costs and uncertainty. Moreover, political instability or security issues in certain regions (the Sahel, parts of Central Africa) naturally scare off potential industrial investors who seek stability. The countries that have attracted manufacturing FDI tend to be those that assure investors of stability, protection and a workable business climate. For example, Morocco has special arrangements and one-stop shops for investors in its Tanger Automotive City. Additionally, Egypt has reformed investment laws to allow full foreign ownership in many sectors and created industrial zones with dedicated governance. Improving the overall business environment across Africa is key to both domestic industrial growth and to luring foreign manufacturers seeking new low-cost locations.

Africa’s industrialisation is also happening in a different global context than earlier industrialisers. Global value chains are now well established, and Asia, particularly China, but also Vietnam, Bangladesh and other have entrenched positions in many manufacturing segments. Africa is essentially trying to break into markets that are already very competitive. For instance, making textiles or electronics to export means going up against Asia’s efficient producers.

Additionally, the rise of automation and robotics globally means low-wage labour is not as critical an advantage as it once was; some manufacturing is being restored to developed countries as automation cuts labour costs. That said, global supply chain shifts due to trade tensions and the pandemic have opened some opportunities. Companies are increasingly pursuing a ‘China+1’ strategy or seeking regional diversification for resilience, which provides a potential benefit if Africa manages to position itself as a viable alternative location for certain industries. There are early signs: global apparel brands have started sourcing from Ethiopia and Egypt; automobile companies like Volkswagen and Nissan have set up assembly in countries such as Kenya, Ghana and Nigeria to serve regional markets; and manufacturers of generic pharmaceuticals were eyeing African hubs in the wake of COVID-19 to shorten supply chains. However, capturing these opportunities requires a proactive industrial policy to market Africa’s advantages, like abundant labour and raw materials and mitigate its disadvantages (costs and risks).

Africa’s under-industrialisation is, therefore, not due to any single factor but the result of a web of interrelated challenges. Overcoming them will require holistic efforts, from hard infrastructure upgrades to soft reforms and capacity-building. The good news is that these issues are increasingly recognised by African governments, researchers and policymakers, and there is growing continental cooperation to address common obstacles, for instance, through the Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA), and skills mobility initiatives under the African Union.

Against this background, there are reasons to be optimistic that Africa can industrialise more robustly in the coming years. The long decline in manufacturing’s GDP share appears to have bottomed out, and in a few African economies, it is inching upward. For instance, Ethiopia increased manufacturing value added from approximately 3.4% of GDP in 2012 to 7.4% in 2023 (though the trajectory was disrupted by conflict). Rwanda has seen a small uptick in manufacturing contribution as it focuses on Made in Rwanda import substitution. Senegal and Ghana have ambitions to raise their manufacturing share through their development plans. For example, Ghana’s target is to become a regional manufacturing hub under its Ghana Beyond Aid policy.

While Africa as a whole is not yet on a clear upward industrial trend, these pockets show it is possible to reverse the decline with consistent policy support. Even in aggregate, the manufacturing share of Africa’s GDP has increased from 12.2% in 2016 to 12.7% in 2023, rather than falling further, which could indicate a turning point if growth accelerates, particularly as a result of the rapid diffusion of knowledge and technology which could be a game-changer for Africa’s industrial prospects. In addition, the tide could turn if the continent can diversify its investors’ portfolio, prioritise manufacturing investment, leverage domestic demand, invest in new and expanding sectors, expedite AfCFTA implementation and reform its governance structures.

In an era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, characterised by digitalisation, automation and interconnected value chains, geographic barriers are less prohibitive than before. Technology transfer and knowledge flows are more distributed globally, offering new entrants a chance to catch up faster than was historically possible, but it requires active government support and upstream enablers.

African countries can potentially leverage technologies like the internet, mobile connectivity, cloud computing and AI-powered tools to accelerate industrial learning. For instance, an African startup can download advanced machine designs or participate in online training to acquire manufacturing skills that took earlier industrialisers years to develop domestically. Open-source designs for machinery or 3D printing of spare parts are already helping some local manufacturers solve problems without waiting for foreign experts. The proliferation of smartphones and connectivity means that even small entrepreneurs can access market information, technical tutorials on YouTube or join networks of makers and engineers.

Calestous Juma is among many who believed that the digital revolution lowers entry barriers for Africa to participate in value chains from which it was previously excluded and that latecomer countries can harness new technologies to leapfrog in certain industries. For example, an African firm can provide outsourced services like CAD design, coding for Computer Numverical Control (CNC) machines and more to global manufacturers without having a fully developed domestic industry. A small enterprise can also use e-commerce platforms to sell handicrafts or artisanally manufactured products worldwide. These avenues were not available in the analogue era.

However, the diffusion of knowledge does not automatically translate to industrial development; it requires investment in human capital and infrastructure to absorb and use that knowledge. Countries need widespread ICT access, reliable internet and digital skills training to take advantage of these opportunities. Many parts of Africa still lack broadband connectivity or affordable data, which can limit participation in the digital economy, although a number of initiatives are underway to improve this. For example, Google and Meta have laid subsea internet cables around Africa, while Starlink is available to provide broadband internet access across the continent. Across the continent, countries are expanding 4G/5G networks and investing in tech hubs.

Beyond digital tech, the diffusion of industrial knowledge often comes through partnerships and foreign investments. When a multinational builds a factory in Africa, it brings technical know-how that can spill over to local workers and firms. This is happening with automotive assembly training programs. For example, recognising the need for knowledge transfer, the AfCFTA’s automotive strategy, developed with support from the African Association of Automotive Manufacturers and Afreximbank, launched an Industrial Policy Executive Course in 2025 to train African officials in developing automotive value chains. Such efforts aim to ensure that when industries are set up, Africans increasingly manage and innovate within them.

Another aspect of knowledge diffusion is the role of the African diaspora and reverse engineering. Skilled Africans abroad bring expertise home. For example, Nigerian engineers from Silicon Valley are starting hardware companies in Lagos, or Ethiopian researchers in biotech are returning to Addis to start pharmaceutical labs. Similarly, local tinkerers often reverse-engineer imported machinery to create cheaper versions. There are anecdotes of ingenious mechanics in West Africa building small-scale processing machines from scrap parts by observing how imported ones work.

All of these point to opportunities: a future in which knowledge flows are more open and accessible can help Africa overcome some traditional disadvantages. However, to capitalise on that, large-scale provision of essential enablers like electricity, quality education and internet access is required. Without power, one cannot run modern machines; without skilled technicians, advanced equipment sits idle; without connectivity, knowledge cannot flow efficiently.

It is also worth noting that the diffusion of knowledge can have a disruptive side. Automation and AI are spreading worldwide, which might reduce the window for labour-intensive manufacturing as a development strategy. If robots become cheaper, companies may prefer to automate rather than hire thousands of low-skilled workers, and this is a concern often raised about Africa’s prospects of following Asia’s labour-driven model. However, most analysts believe there is still room for labour-intensive industry in Africa in the coming decades, given the sheer wage differentials and the fact that not everything can or will be automated immediately, especially in sectors like garments, some assembly tasks and more. New industries like digital services or creative industries can also provide further employment.

The accelerating diffusion of global knowledge and technology, therefore, offers both opportunities and challenges for Africa’s industrial future. It lowers barriers to entry and allows faster learning, potentially enabling Africa to jump into new industries without reinventing every wheel. However, it also means African industries must be agile and continually upgrade, as the technological frontier is a moving target. If African countries invest wisely in education, ICT and innovation, they can turn the information revolution to their advantage, fostering tech-savvy manufacturing and even leading in niche areas (for example, Kenya is a leader in mobile financial tech, Rwanda in drone logistics for medical supplies).

After a period of stagnation, foreign direct investment (FDI) into Africa is showing signs of diversification into manufacturing and other non-extractive sectors. We examine these trends in the theme of Financial Flows. For example, the 2024 EY Africa Attractiveness Report confirms that FDI to Africa rebounded by about 7% in 2023, recovering from the pandemic dip. Notably, this growth was driven by significant projects in renewable energy, software and IT services and business services, moving beyond the traditional focus on mining and hydrocarbons. Manufacturing FDI is also rising in certain niches. For example, Morocco and Egypt have attracted FDI into automobile and aeronautics production; Ethiopia and Kenya are seeing investments in textiles and apparel; and Ghana has new investments in steel and vehicle assembly. Intra-African investment is increasing too, with South African, Kenyan, Moroccan and Nigerian companies investing around the continent, which often goes into consumer goods manufacturing, agri-processing, and cement. These trends suggest a slowly broadening industrial base. If Africa continues to improve its business climate, implement AfCFTA and maintain political stability, investor confidence could further increase, bringing in capital and expertise for industrial ventures.

Africa’s growing domestic market is a powerful engine for industrialisation. The 2019 African Union and OECD’s Africa’s Development Dynamics report noted that Africa’s domestic consumer demand is growing 1.5 times faster than the global average, and it is shifting towards more processed and manufactured goods as incomes rise. For example, demand for products like packaged foods, building materials, household appliances and automobiles is expanding rapidly. The continent’s auto market, valued at around US$30 billion in 2021, is projected to grow to over $42 billion by 2027, a nearly 40% increase. Africa already buys about 2.4 million cars (mostly pre-owned) and 300 000 new commercial vehicles per year. As urbanisation and middle-class growth continue, these numbers will rise. If African manufacturers can capture even a fraction of this growing demand, it would be a huge boost. There are encouraging signs: Morocco and South Africa are leading in automotive assembly and together account for 80% of Africa’s vehicle exports. Algeria has also grown its local assembly industry recently, mostly for its domestic market.

In cement and construction materials, Nigerian and Moroccan firms now dominate West African markets, largely displacing imports. In food processing, companies like Ethiopia’s emerging agro-processors are tapping into local markets that were previously served by imports. In short, Africa’s market is large and getting bigger and local firms are slowly stepping up to meet that demand, which bodes well for the future.

As Africa industrialises, it does not have to rely solely on old industries. There are new frontiers where it can establish leadership. Automotive is one such sector that is getting a continental push. The AfCFTA has prioritised an African Automotive Value Chain, under a common policy, countries are coordinating to attract vehicle assembly and component manufacturing. Major carmakers, including Volkswagen, Toyota, Nissan and Peugeot, have either started or announced assembly operations in about a dozen African countries. While many are small knock-down kit assembly plants now, the vision is to progressively increase local content and production scale. In 2025, the African Association of Automotive Manufacturers, Afreximbank and the AfCFTA Secretariat even launched a policy course to train officials in developing the automotive industry, highlighting the strategic focus. Additionally, the rise of electric vehicles (EVs) presents a fresh opportunity. Africa is rich in key EV minerals (cobalt, lithium, manganese) and is now striving to move up the chain to produce batteries and even EVs. DR Congo and Zambia’s battery initiative is one example. Nigeria is also entering this space: in 2023–2025, it partnered with Chinese investors to plan local lithium processing and EV assembly, aiming to become West Africa’s EV manufacturing hub. Meanwhile, startups like Spiro are setting up e-motorcycle assemblies in countries such as Nigeria and Benin to electrify Africa’s two-wheeler market.

Pharmaceuticals offer another high-growth manufacturing opportunity. Africa's pharmaceutical market is projected to grow at about 5% annually between 2022 and 2027, driven by population growth and health needs. The continent’s demand for packaged pharmaceuticals amounts to roughly US$18 billion annually, with 61% imported. This reliance became important during COVID-19, prompting strong moves toward local vaccine and drug manufacturing. By 2025, initiatives in countries like Senegal, South Africa, Rwanda, Ghana and Egypt are underway to establish vaccine production lines and pharmaceutical plants. For instance, Senegal’s Institut Pasteur de Dakar is expanding to produce vaccines against COVID-19 and others, South Africa’s Aspen Pharmacare is producing vaccines and other treatments, and a consortium backed by the African Union and partners launched a US$1.2 billion fund to accelerate African vaccine manufacturing. These efforts, if successful, will build significant pharma manufacturing capacity on the continent, creating skilled jobs and reducing import dependency.

Green technologies are also part of Africa’s future industrial portfolio. Many African countries are investing in renewable energy hardware assembly, such as solar panel assembly plants in Kenya, South Africa and Egypt, and are exploring green hydrogen production. Namibia, South Africa and Mauritania have projects to use solar/wind to produce hydrogen for export. The push for climate-friendly solutions means new industries like electric batteries, solar components and e-mobility products are in growing demand. With its mineral wealth and ample renewable resources, Africa could capture a niche in manufacturing the inputs for clean energy globally, for example, localising part of the battery supply chain (as DR Congo and Zambia are attempting) or producing electrolysers for hydrogen. These are early-stage opportunities but are being actively explored.

Perhaps the most decisive factor for the future of manufacturing in Africa is regional integration. African countries have small economies, but together, Africa is a US$3.4 trillion market. The AfCFTA, by creating a single market, can fundamentally change the calculus for industrial investors. Instead of 54 separate markets with different standards and tiny scales, a company can produce in one African location and sell across the continent. For instance, German automaker Volkswagen has indicated that the success of its Africa strategy depends on AfCFTA enabling it to treat Africa as one market.

The AfCFTA not only reduces tariffs but is working on harmonising regulations, standards and investment rules. A unified African market facilitates economies of scale and could make industries like vehicle manufacturing, chemicals or heavy equipment viable where they were not before. Moreover, regional infrastructure projects, like trans-African highways and power pools, will further support industrial corridors spanning multiple countries.

The political will behind AfCFTA remains strong and as technical protocols get implemented in the coming years, businesses are expected to respond. There are already early wins: a handful of trading under AfCFTA’s pilot initiative has occurred, and companies are adjusting strategies to leverage regional supply chains. For example, an apparel maker in Mauritius might source cotton fabric from Benin instead of China to qualify for AfCFTA preferences. Over the next decade, as intra-African trade costs drop, it should become much easier to source inputs within Africa and target neighbouring markets, giving local manufacturers a leg up. This integration is arguably the single most important “game changer” for Africa’s industrial prospects.

Continued governance reforms will play a role. Many countries are working to improve their ease of doing business, setting up industrial development agencies and crafting incentives for priority sectors. There is also a trend of peer learning, with countries copying successful policies from each other. For example, after seeing Morocco’s booming car industry, Ghana and Kenya introduced automotive policies of their own, offering tax breaks for assemblers, restricting used car imports over a certain age to encourage demand for newer vehicles and more. Similarly, Ethiopia’s industrial parks model is being emulated in some form in countries from Senegal to Rwanda. If governance keeps improving, with more transparency, better infrastructure governance and reduced conflict, it will create a conducive environment for industry to flourish. Africa’s political and economic institutions are maturing in many places, which gives hope that the next 20 years will not repeat the mistakes of the past 20.

The next section models an ambitious but reasonable Manufacturing scenario that illustrates the potential benefits and why those benefits outweigh the transitional challenges. It is a blueprint showing how, with the right investments and reforms, Africa’s economies could be transformed by 2043, and how issues like inequality and poverty could benefit in the process.

This section presents a set of interventions modelled to emulate a manufacturing push in Africa, looking ahead to 2043. The modelling and benchmarking are done at an individual country level. The Manufacturing scenario asks how Africa’s development outcomes would change if strong policies and investments were implemented to boost industrialisation, compared to a business-as-usual (the Current Path) scenario. The goal is to quantify the potential impact of a successful manufacturing drive on economic growth, employment, income and other indicators.

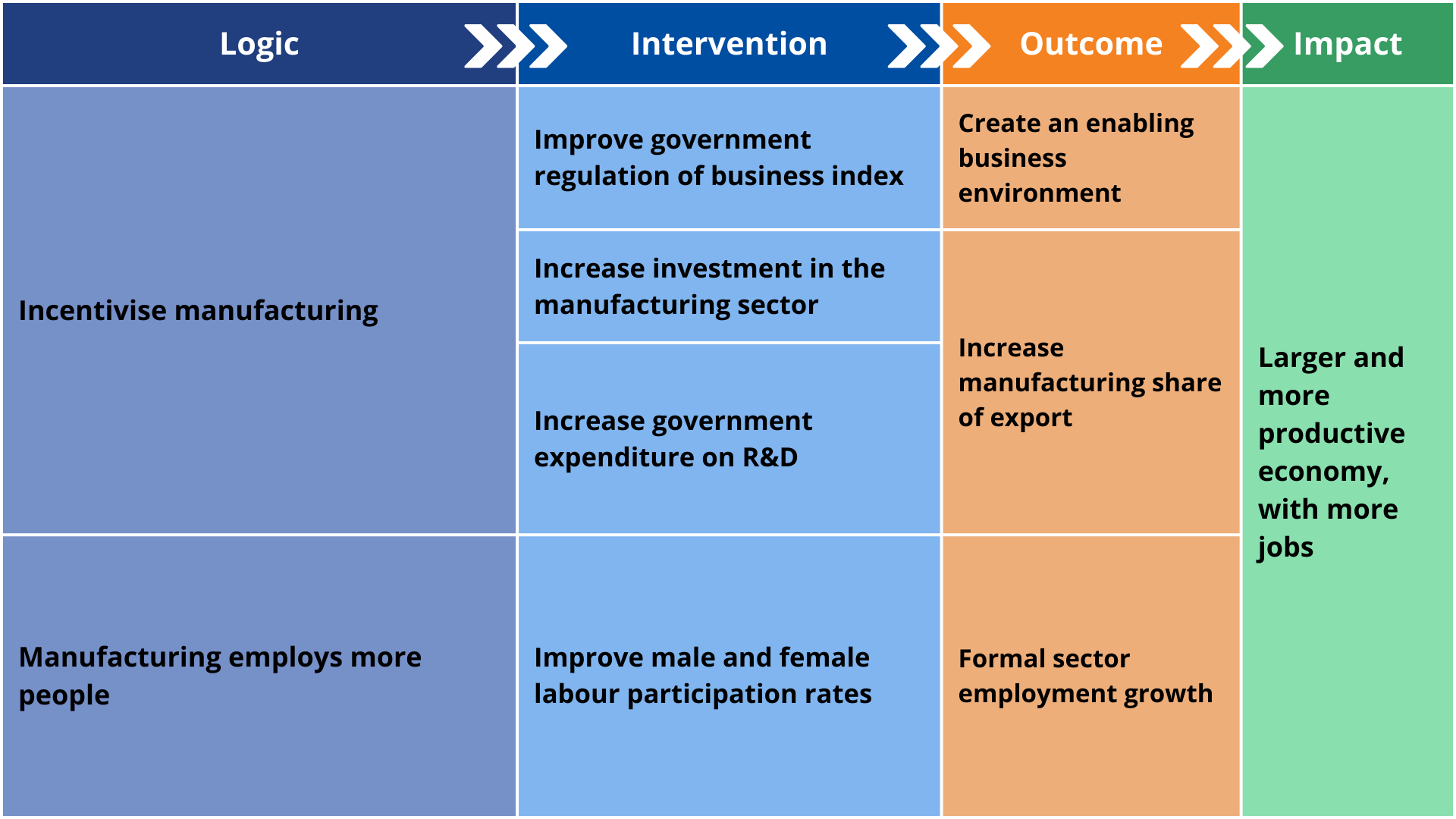

The scenario is based on a series of ambitious yet achievable and realistic interventions that start in 2027, gradually increasing over a period of 10 years and then maintained at that level thereafter. Key elements include investments in manufacturing, technological advancement through research and development (R&D), reforms to business regulations and increased labour participation. Chart 6 presents the structure of the Manufacturing scenario.

In the Current Path, Africa’s ratio of manufacturing investment to GDP will increase from 3.5 (equivalent to US$93 billion) in 2023 to 4.4 (equivalent to US$281 billion) in 2043. This trajectory envisions African governments increasing capital spending on power, transport and industrial parks. Moreover, FDI inflows into domestic investment in the manufacturing sector rise as countries improve the ease of doing business and target strategic sectors. In the Manufacturing scenario, however, Africa’s ratio of manufacturing investment to GDP will be 1.6 points (equivalent to US$120 billion) higher by 2043 than on the Current Path.