Botswana

Botswana

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

This report analyses Botswana’s current development path and prospects, examining how various sectoral interventions could shape the country’s economic and social landscape through to 2043, the end of the third ten-year implementation plan of the African Union's Agenda 2063. The analysis is grounded in scenario modelling and explores eight key sectors: Demographics and Health, Agriculture, Education, Manufacturing, Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), Financial Flows, and Governance. In addition to evaluating the effects of each sectoral scenario individually, the report assesses the combined impact of these interventions on Botswana’s long-term growth and development trajectory. The report concludes by summarising the key findings and offering policy insights to support Botswana in pursuing a more inclusive, resilient, and sustainable development path. It underscores the importance of coordinated, multi-sectoral reforms to unlock the country’s long-term economic and social potential.

Visit the Technical section for additional information on the International Futures (IFs) modelling platform, which serves as the analytical foundation for this report's scenario simulations.

Summary

This page begins with an introductory assessment of the country’s context, examining current population distribution, social structure, climate and topography.

- Botswana is a semi-arid, landlocked country in Southern Africa that is bordered by Namibia, Zimbabwe, Zambia and South Africa. It has transitioned from one of the world’s poorest countries at independence in 1966 to a stable multiparty democracy with upper-middle-income status. It now faces a strategic imperative to deepen structural transformation and achieve inclusive, high-income growth by 2036 under its national development blueprint, Vision 2036.

The introduction is followed by an analysis of the Current Path for Botswana, which informs the country’s likely current development trajectory to 2043. It is based on current geopolitical trends and assumes that no major shocks would occur in a ‘business-as-usual’ future.

- Botswana’s population will grow from 2.46 million in 2023 to 3.08 million by 2043, with a steadily improving working-age ratio that supports a demographic dividend but requires complementary investments in health, education and job creation.

- Botswana’s urban population share almost doubled from about 43% in 1990 to approximately 80% in 2023, and will reach nearly 89% by 2043 under the Current Path. This trend underscores the importance of inclusive urban planning and infrastructure investment in managing rapid urban growth.

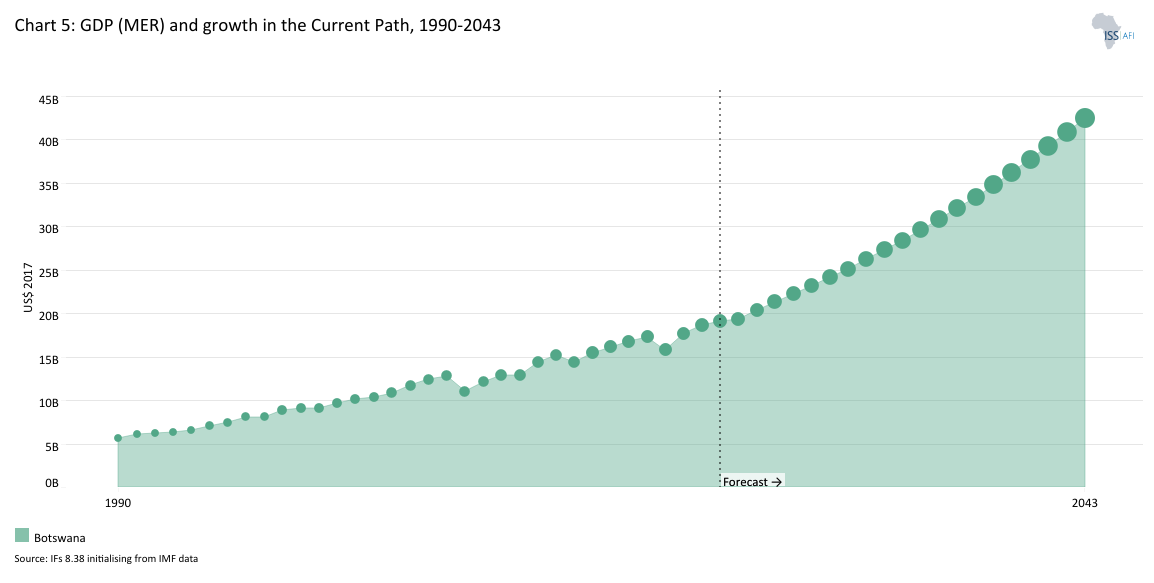

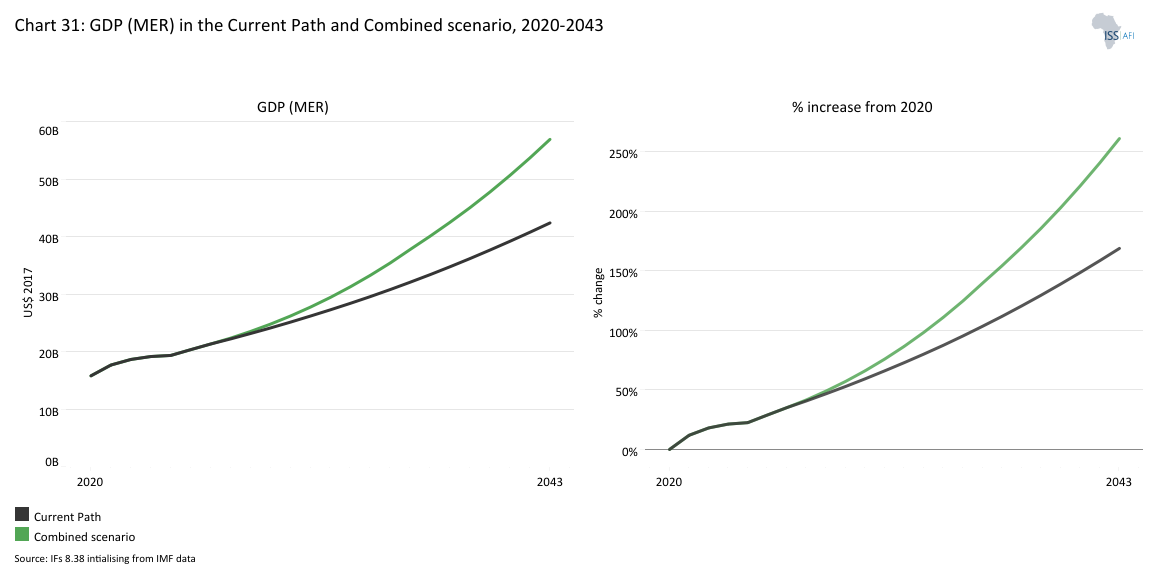

- In the Current Path, Botswana’s gross domestic product (GDP) at market exchange rates (MER) will grow from US$19.14 billion in 2023 to US$42.39 billion by 2043, reflecting a moderate average annual growth rate of 4.1% driven primarily by services and consumption.

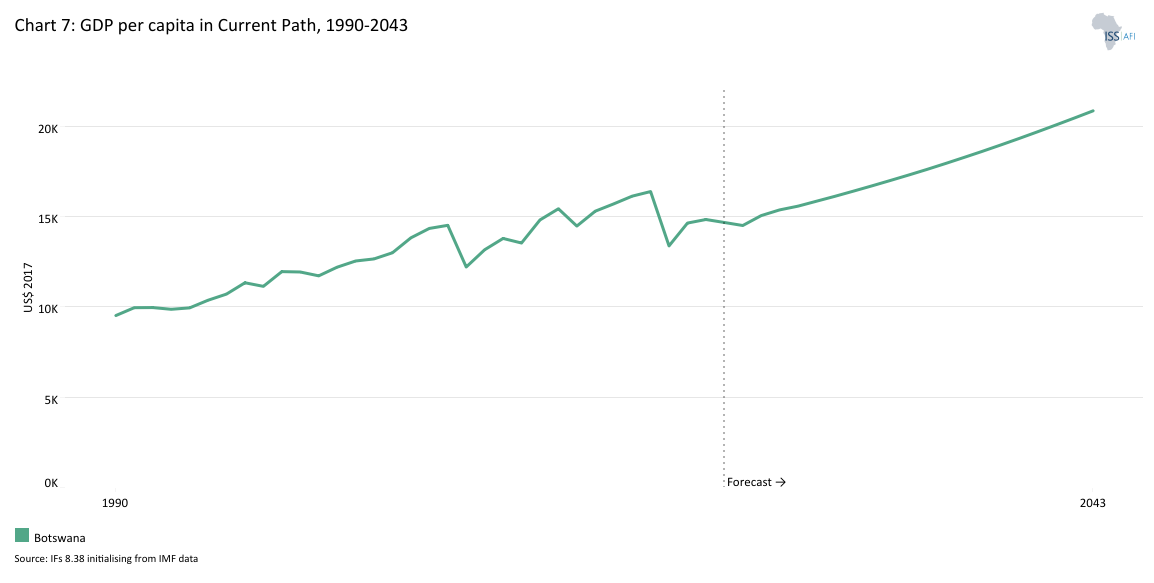

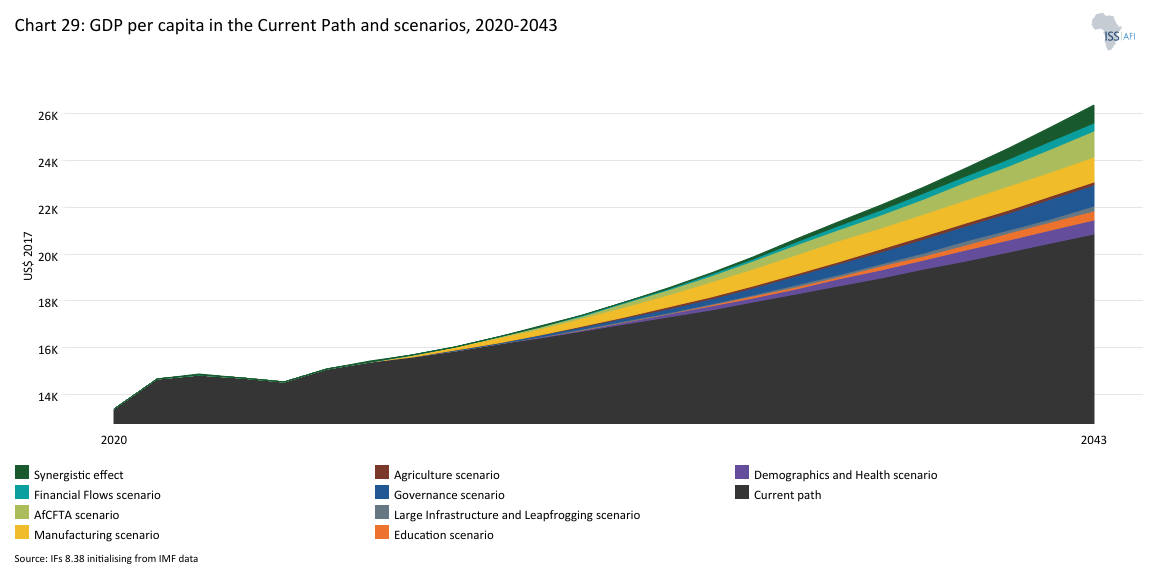

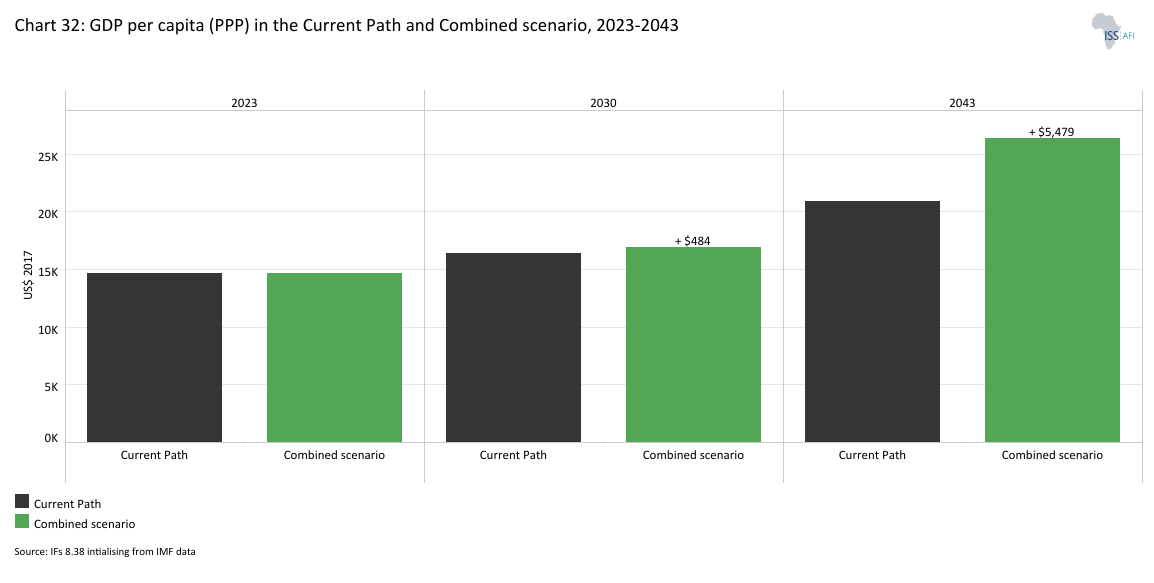

- Botswana’s GDP per capita in purchasing power parity (PPP) will increase from US$14 670 in 2023 to US$20 850 in 2043 under the Current Path. This indicates gradual improvements in living standards but falling short of the standard for high-income status, if compared with countries like Seychelles.

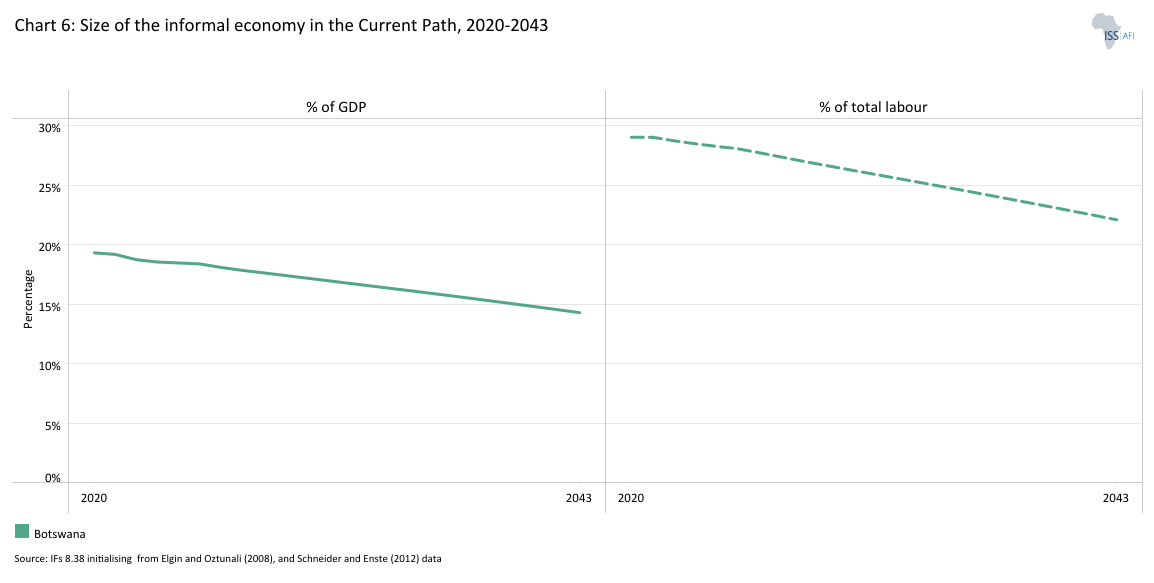

- The informal sector’s share of GDP will remain above 14% and informal employment above 22% by 2043, signalling persistent labour market informality and limited economic structural transformation.

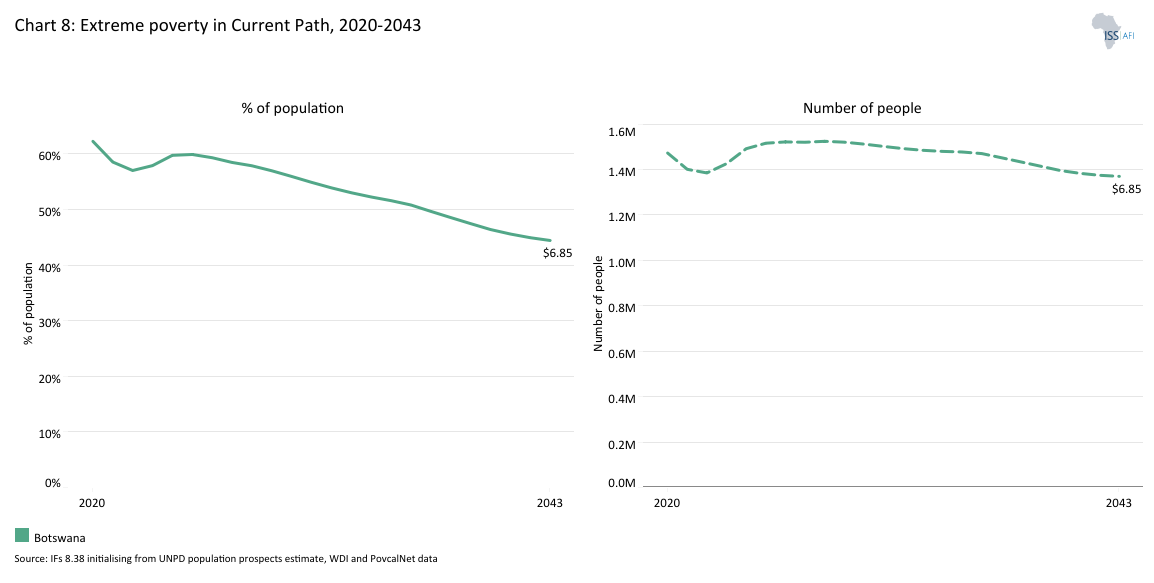

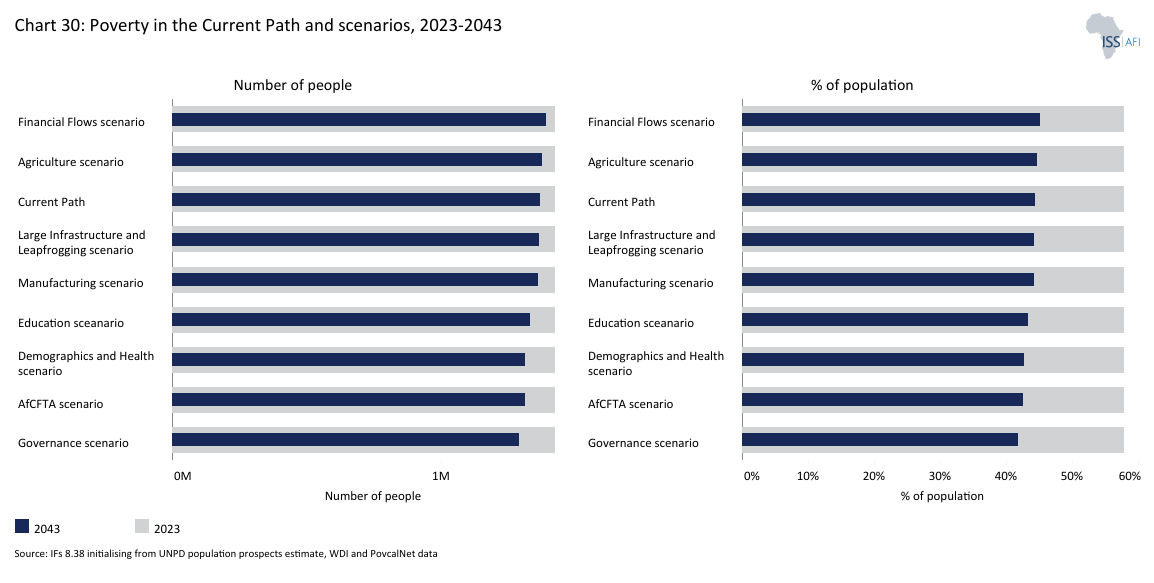

- Under the Current Path, poverty will decline from 57.9% in 2023 to 44.4% in 2043, reflecting modest progress in income distribution and service access but insufficient to meet national poverty reduction goals.

- Vision 2036 and successive National Development Plans (NDPs) guide Botswana's development trajectory. These strategies outline inclusive growth, human capital development and economic diversification. Yet, high dependence on the diamond sector and persistent implementation gaps, especially in tackling labour market informality, income inequality and poverty, remain key obstacles to reaching high-income status within the Vision 2036 timeframe.

The next section compares progress on the Current Path with eight sectoral scenarios. These are Demographics and Health; Agriculture; Education; Manufacturing; the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA); Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging; Financial Flows; and Governance. Each scenario is benchmarked to present an ambitious but reasonable aspiration in that sector, comparing Botswana with other countries at similar levels of development and characteristics.

- The Demographics and Health scenario places Botswana on track to meet the African Union’s Agenda 2063 life expectancy target of 75 years and achieve Sustainable Development Goal 3.2 on neonatal mortality before 2043. Life expectancy reaches 73.7 years, and infant mortality falls to 11 per 1 000 live births by 2043, reflecting sustained investment in maternal health, adolescent services, non-communicable diseases (NCD) prevention and universal healthcare access.

- The Agriculture scenario moderates Botswana’s crop import dependence to 65% of total demand by 2043, down from almost 72% forecast under the Current Path, reflecting gains in domestic production and food system resilience. However, to translate this into significant poverty reduction, there is a need to better integrate smallholder farmers, scale agro-processing and strengthen climate resilience, particularly in rural areas.

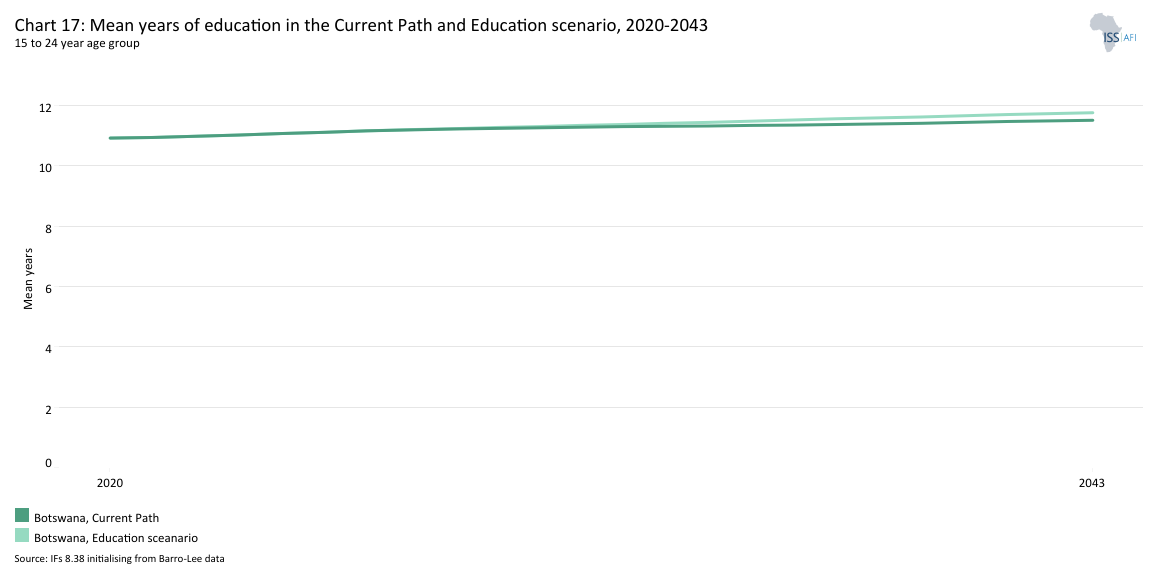

- Under the Education scenario, average schooling among youth aged 14-24 years increases to 11.8 years by 2043, with narrowing gender gaps and improved learning outcomes. These gains enhance human capital and productivity, while contributing to moderate poverty reduction, reinforcing the role of education reform and digital inclusion in long-term growth.

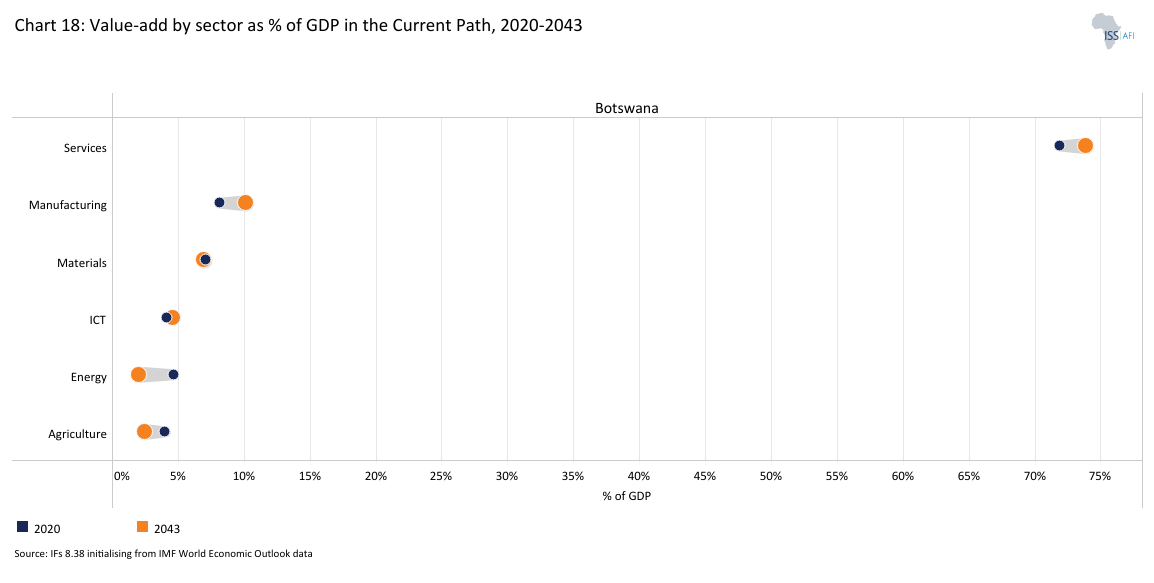

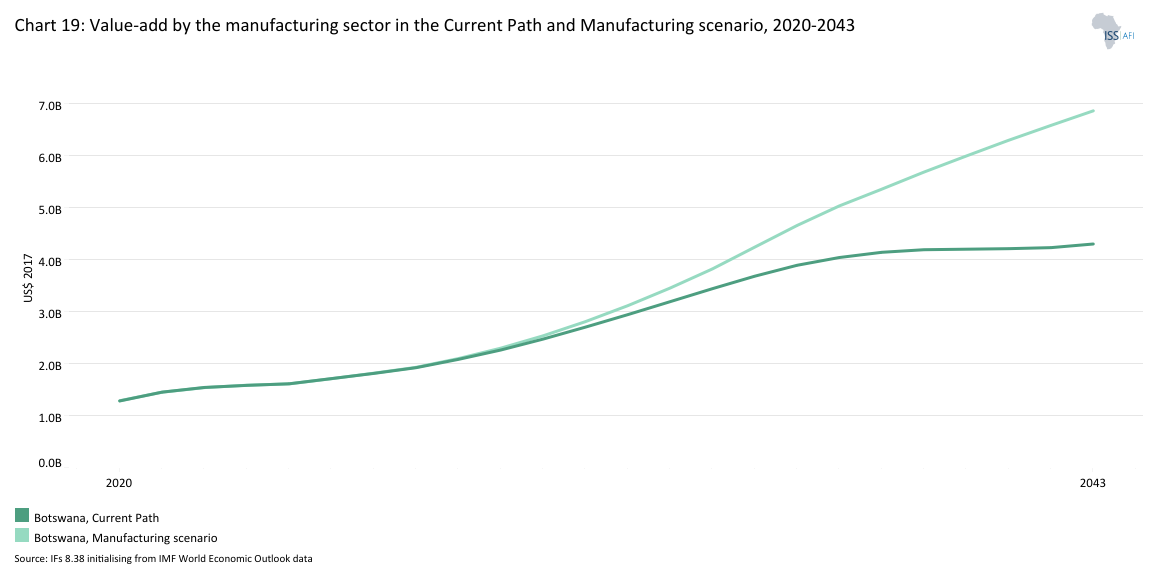

- The Manufacturing scenario drives a revitalised industrial base, with manufacturing value-added exceeding 15% of GDP by 2043, catalysing job creation and income growth, especially in the medium term. It affirms industrial policy, infrastructure and small to medium enterprise (SME) support as critical to Botswana’s structural transformation.

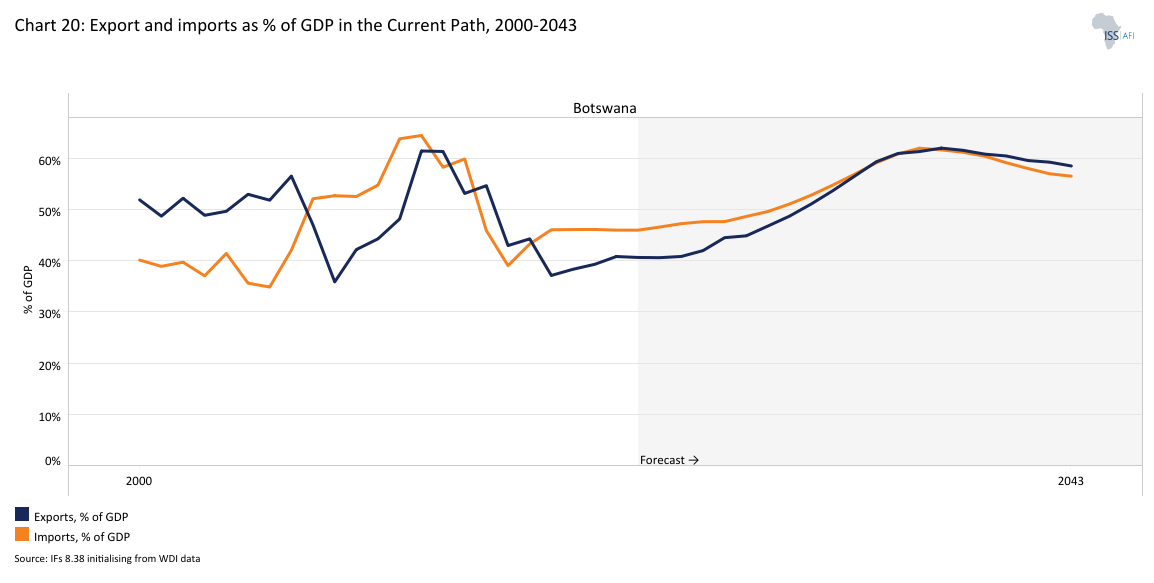

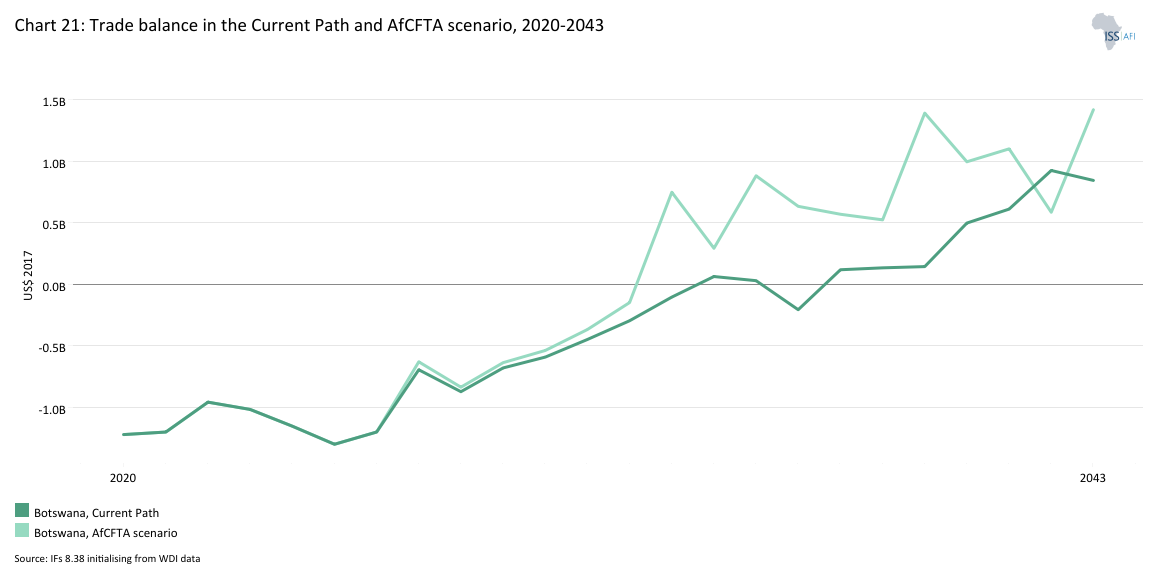

- Under the AfCFTA scenario, Botswana’s share of trade balance in GDP shifts from a 5.3% deficit in 2023 to a 3.1% surplus by 2043, as AfCFTA implementation boosts exports and market access. The scenario delivers the highest gains in per capita income by 2043 and accelerates export diversification, confirming regional integration as a key lever for long-term competitiveness.

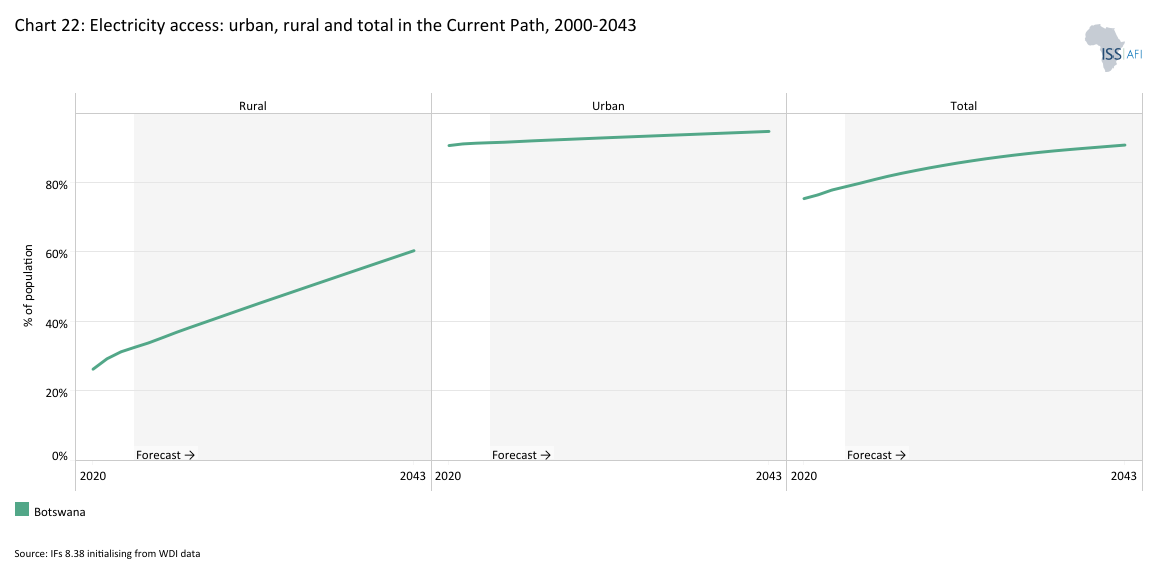

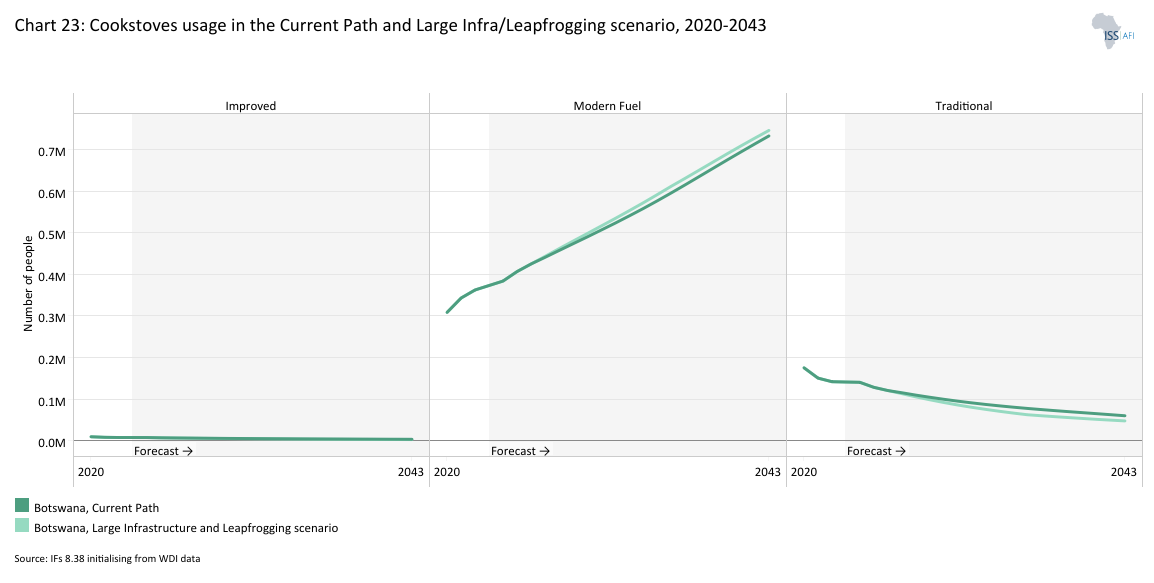

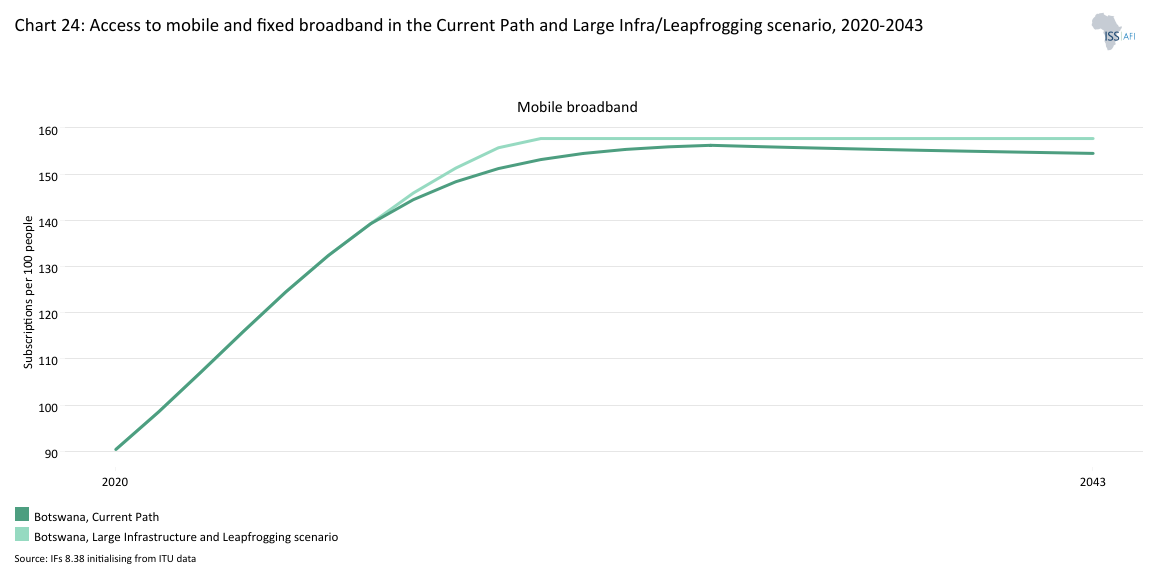

- The Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario accelerates the transition to clean cooking, with almost 94% of households using modern fuel cookstoves by 2043, significantly reducing emissions and expanding renewable energy production. It also boosts growth in digital services, though rural access gaps remain and require targeted infrastructure and affordability measures.

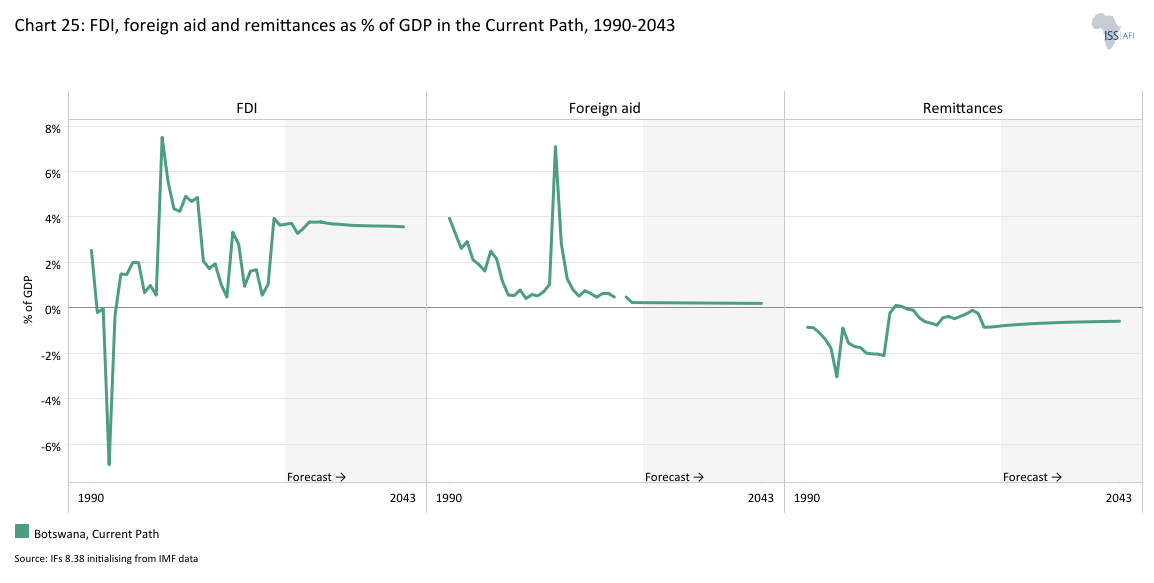

- In the Financial Flows scenario, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows rise to 5.2% of GDP by 2043, peaking at 6% in 2036, enabling Botswana to meet its medium-term sustainable financing strategy target. While this drives growth, the impact on poverty and inequality is limited, highlighting the need for policies that align capital inflows with inclusive employment and local enterprise development.

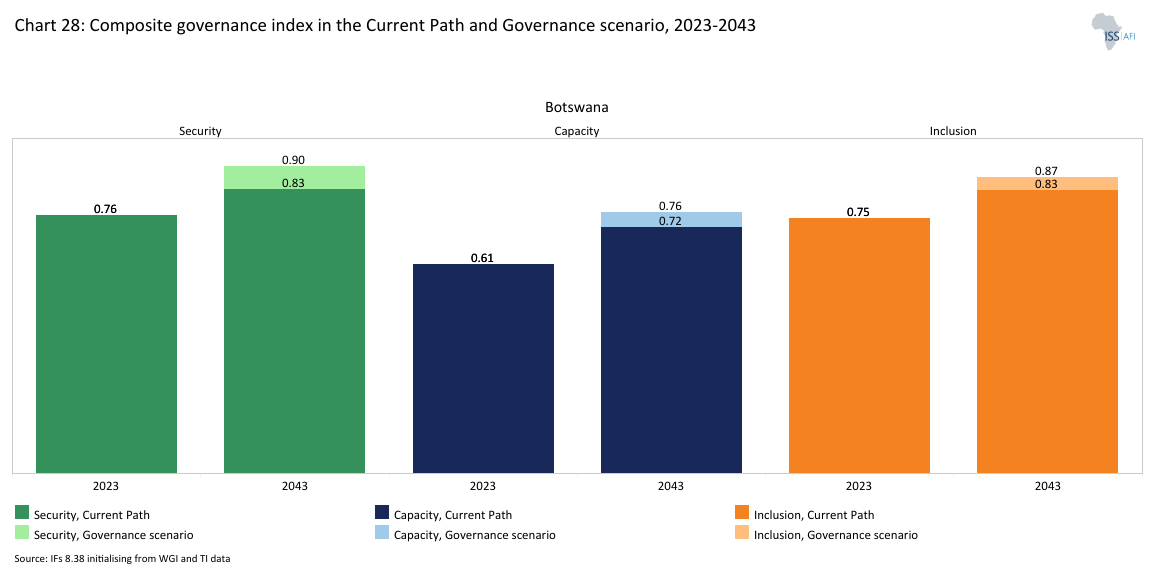

- Improved government effectiveness, accountability and public service delivery under the Governance scenario yield the largest reductions in poverty and boost fiscal efficiency. It reinforces governance reform as a foundational enabler of inclusive, sustainable development across all sectors.

The fourth section compares the impact of each of these eight sectoral scenarios with one another and subsequently with a Combined scenario (the integrated effect of all eight scenarios). The forecasts measure progress on various dimensions such as economic size (in market exchange rates), gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (in purchasing power parity), extreme poverty, carbon emissions, the changes in the structure of the economy, and selected sectoral dimensions such as progress with mean years of education, life expectancy, the Gini coefficient or reductions in mortality rates.

- In the Combined Scenario, Botswana’s GDP (MER) reaches US$56.93 billion by 2043, compared to US$42.39 billion under the Current Path, driven by broad-based productivity gains, structural transformation and improved institutional effectiveness. The average annual growth rate rises to 5.6% from 2024 to 2043, compared to 4.1% on the baseline, reflecting the compounding impact of coordinated, cross-sectoral reforms.

- GDP per capita increases to US$26 330 by 2043, nearly US$5 500 higher than in the Current Path, indicating more inclusive and sustained improvements in living standards. These gains reflect stronger labour market performance, export competitiveness and human capital development.

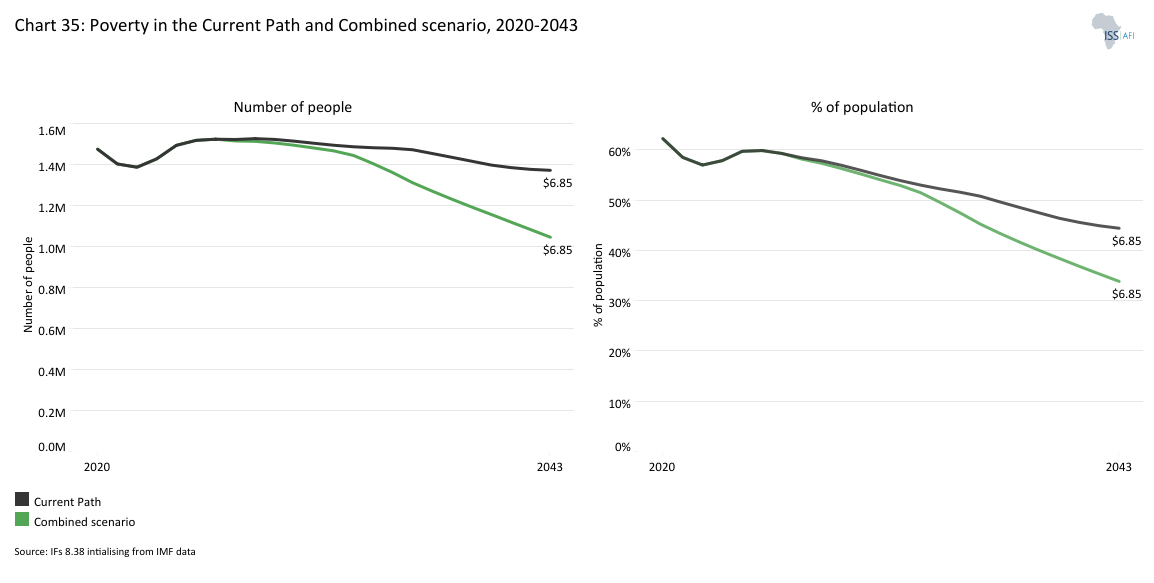

- Poverty (at less US$6.85/day) declines to 34.7% by 2043 under the Combined scenario, nearly 10 percentage points below the Current Path, due to faster income growth, expanded service delivery and more equitable distribution of development outcomes. Progress is further reinforced by improvements in governance, education and rural infrastructure development.

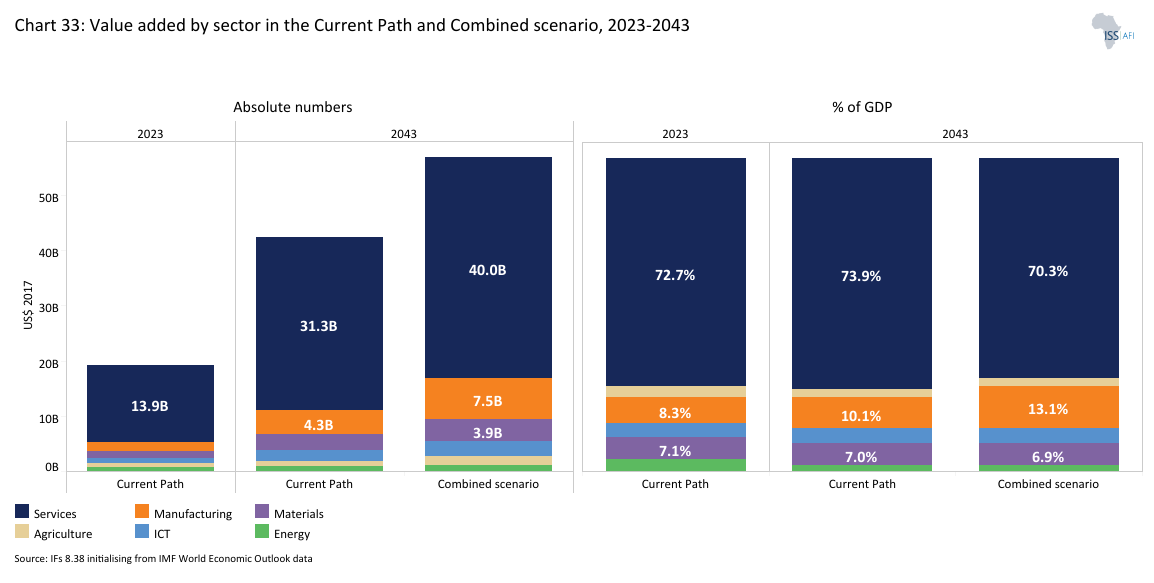

- The Combined scenario drives a more balanced economic structure, with manufacturing’s share of GDP rising to over 13% by 2043, 3 percentage points above the baseline. Gains in ICT (+0.37 percentage points) and agriculture (+0.22) complement this shift, while all sectors expand in absolute terms, signalling broad-based growth and deeper diversification.

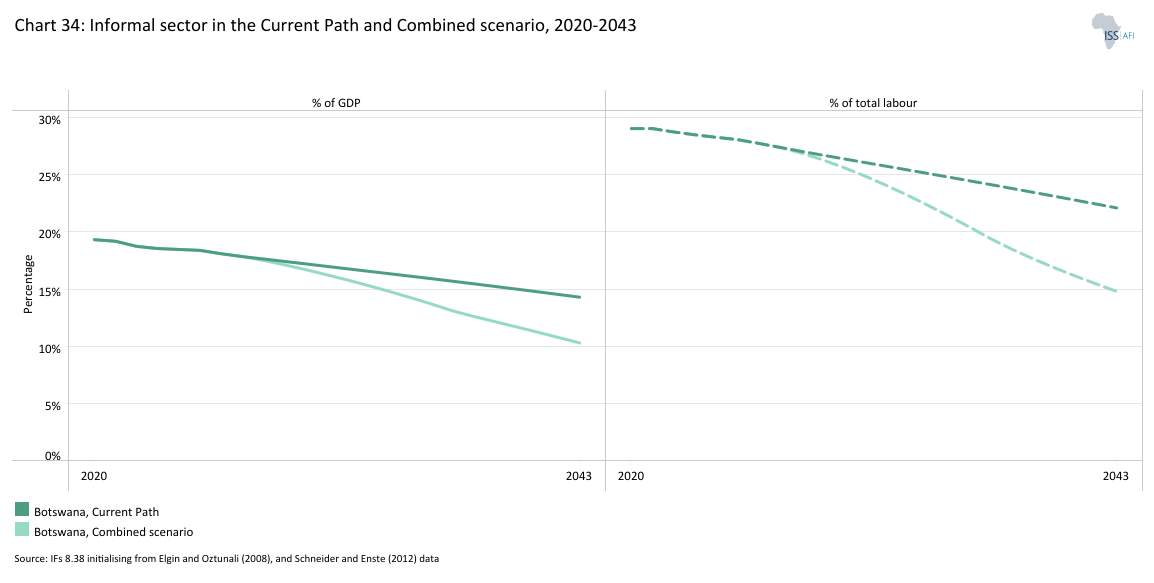

- Informality declines significantly, with the informal sector’s GDP share falling to 10.3% and informal employment dropping to 14.8% by 2043, compared to over 14% and 22% in the Current Path. These changes reflect labour market formalisation, skills development and SME integration into formal value chains.

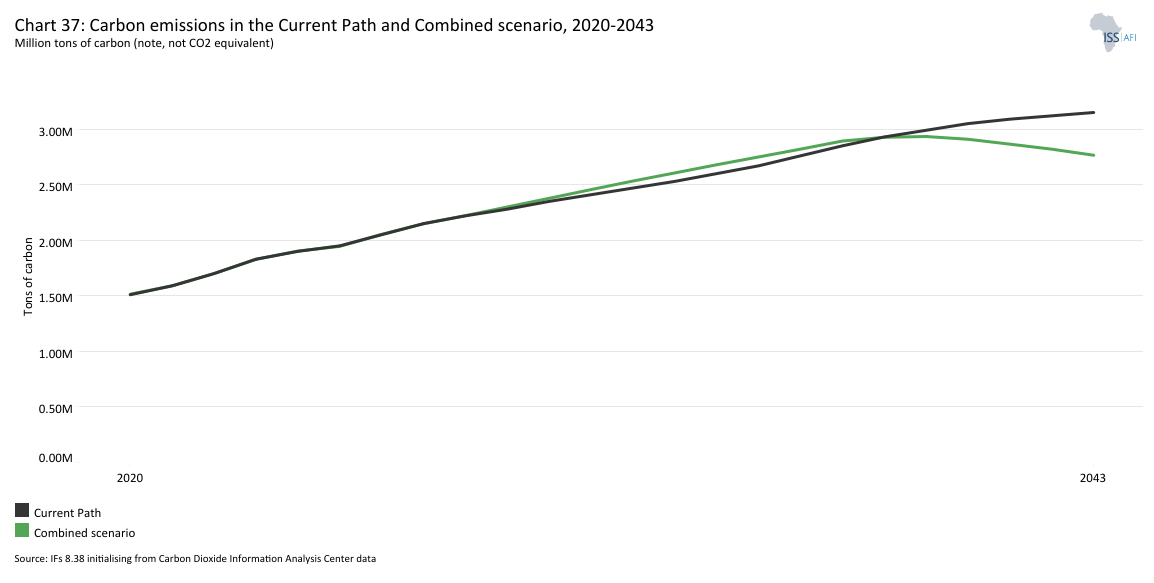

- Despite faster economic growth, total carbon emissions under the Combined scenario are 400 000 tons lower than in the Current Path by 2043, reaching 2.8 million tons. Emission reductions stem from accelerated adoption of clean energy, energy efficiency and sustainable infrastructure planning.

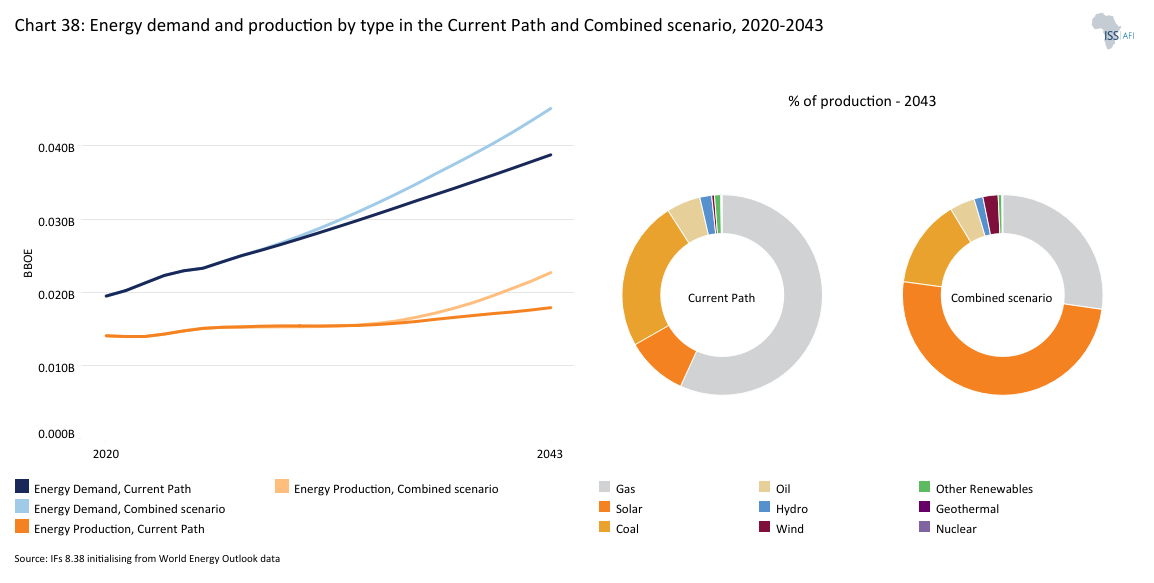

- Domestic energy production rises from 14 million barrels of oil equivalent (BOE) in 2023 to 23 million BOE by 2043 under the Combined scenario, 5 million BOE higher than the Current Path forecast, driven primarily by a surge in solar and wind generation. However, energy demand outpaces supply, growing to over 45 million BOE, resulting in a continued but manageable energy deficit that underscores the need for regional integration and efficiency measures.

The analysis concludes with a summarising section offering recommendations. Botswana has made significant socio-economic progress since independence, but its current development trajectory under the Current Path is not sufficient to achieve the country’s Vision 2036 goal of high-income, inclusive growth. The Combined scenario demonstrates that coordinated investments across governance, human capital, infrastructure, trade and energy can yield transformative results, raising GDP per capita, reducing poverty and accelerating structural change. It also shows that inclusive development is compatible with environmental sustainability, with lower carbon emissions and increased renewable energy generation. To realise this potential, Botswana must prioritise industrial policy, educational reform, digital infrastructure and climate-smart agriculture, while deepening regional integration through AfCFTA. Strengthening public financial management, reducing informality and expanding social protection are equally critical to ensure broad-based and equitable growth. With strategic implementation, Botswana can shift from incremental progress to a dynamic, diversified and inclusive development path.

All charts for Botswana

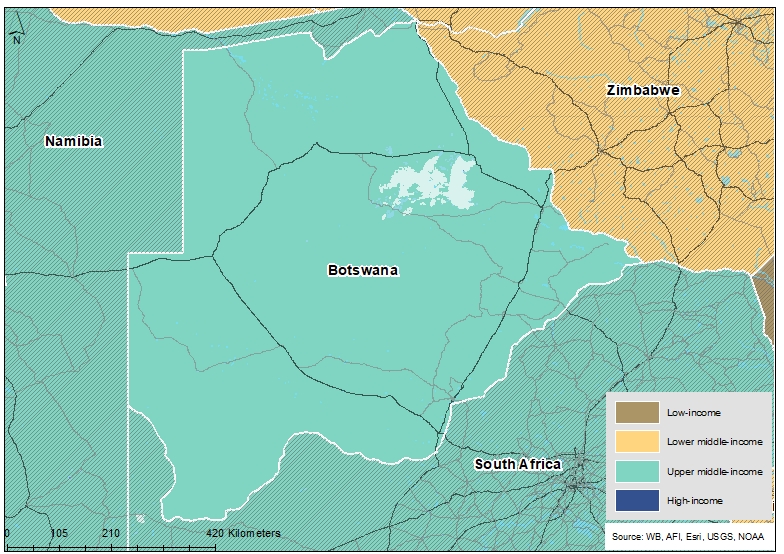

- Chart 1: Political map of Botswana

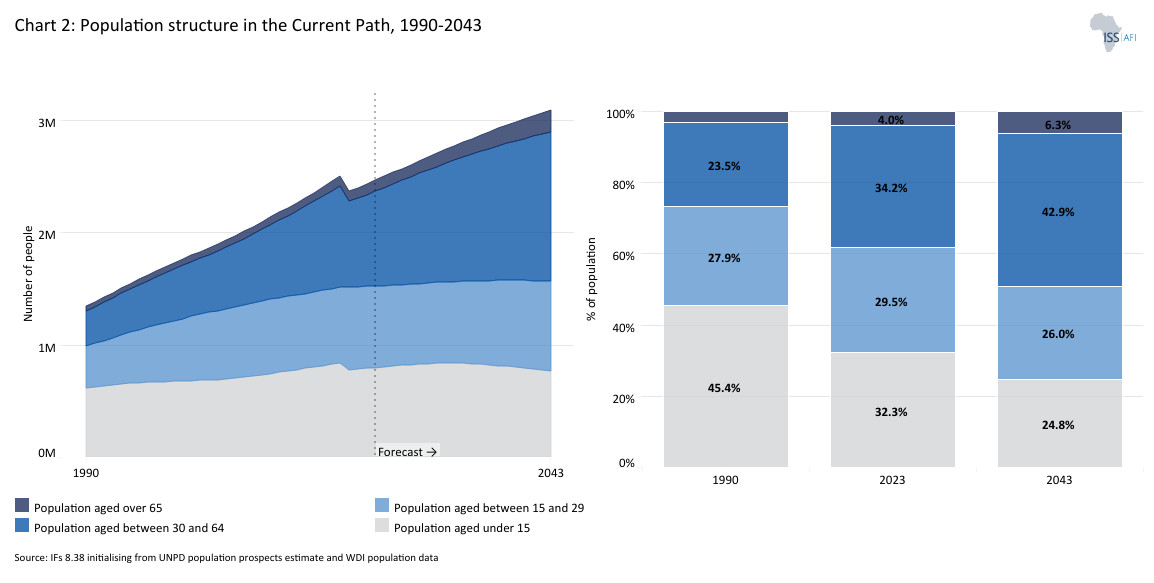

- Chart 2: Population structure in the Current Path, 1990–2043

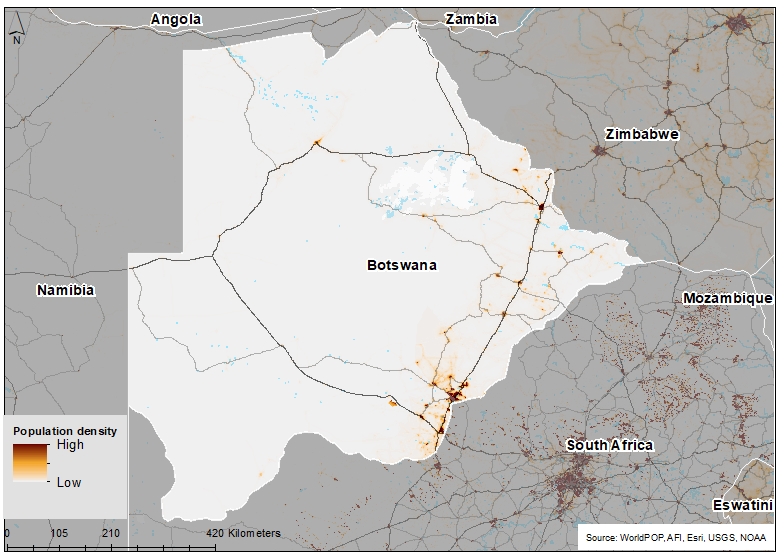

- Chart 3: Population distribution map, 2023

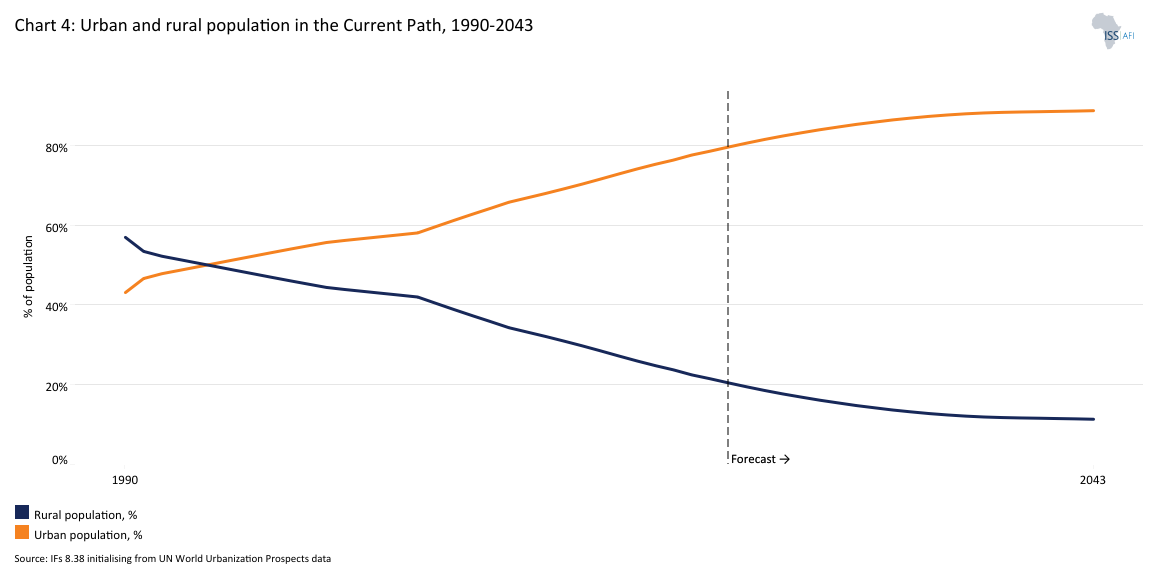

- Chart 4: Urban and rural population in the Current Path, 1990-2043

- Chart 5: GDP (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, 1990–2043

- Chart 6: Size of the informal economy in the Current Path, 2020-2043

- Chart 7: GDP per capita in Current Path, 1990–2043

- Chart 8: Extreme poverty in the Current Path, 2020–2043

- Chart 9: National Development Plan of Botswana

- Chart 10: Relationship between Current Path and Scenarios

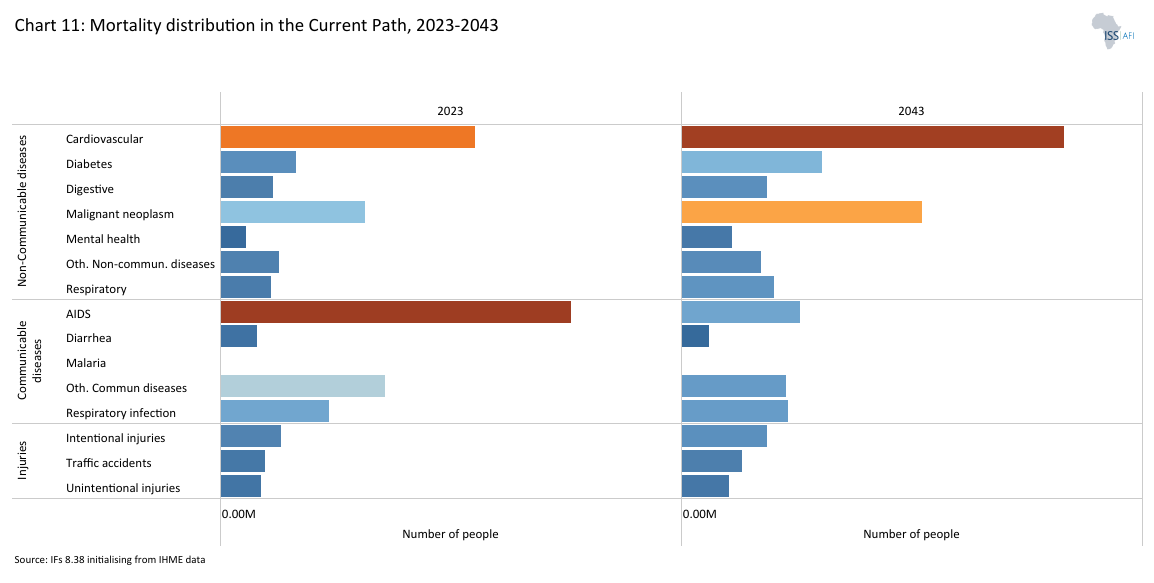

- Chart 11: Mortality distribution in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

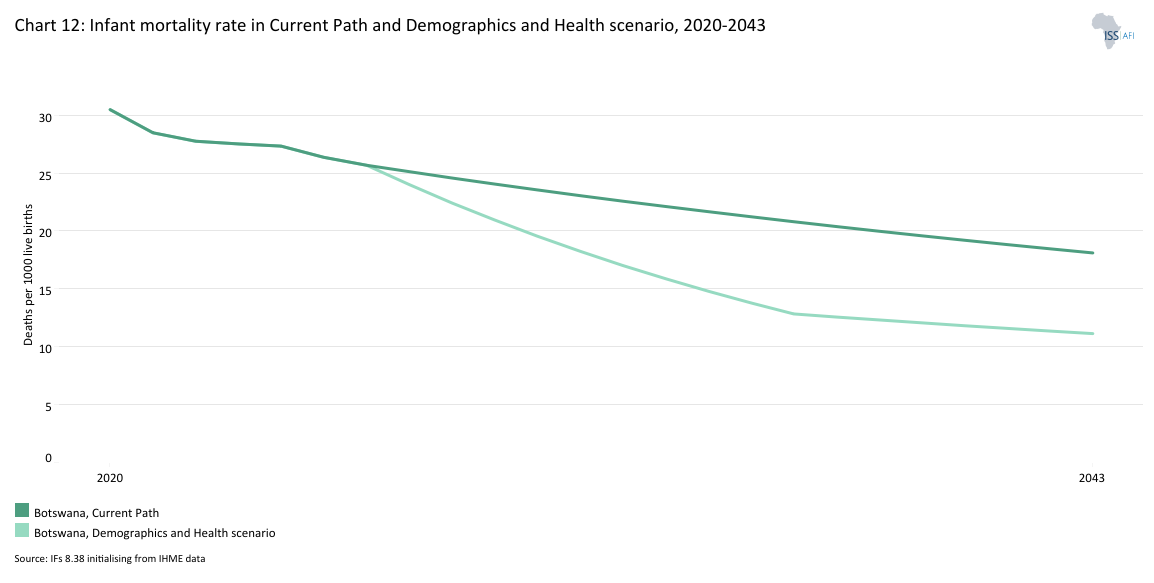

- Chart 12: Infant mortality rate in Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 2020–2043

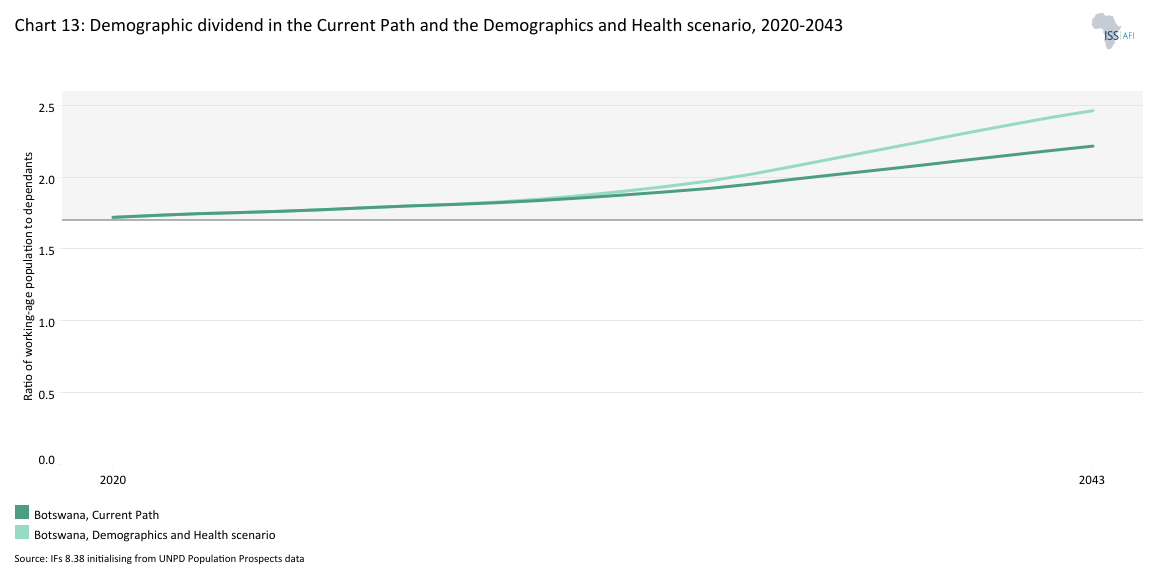

- Chart 13: Demographic dividend in the Current Path and the Demographics and Health scenario, 2020–2043

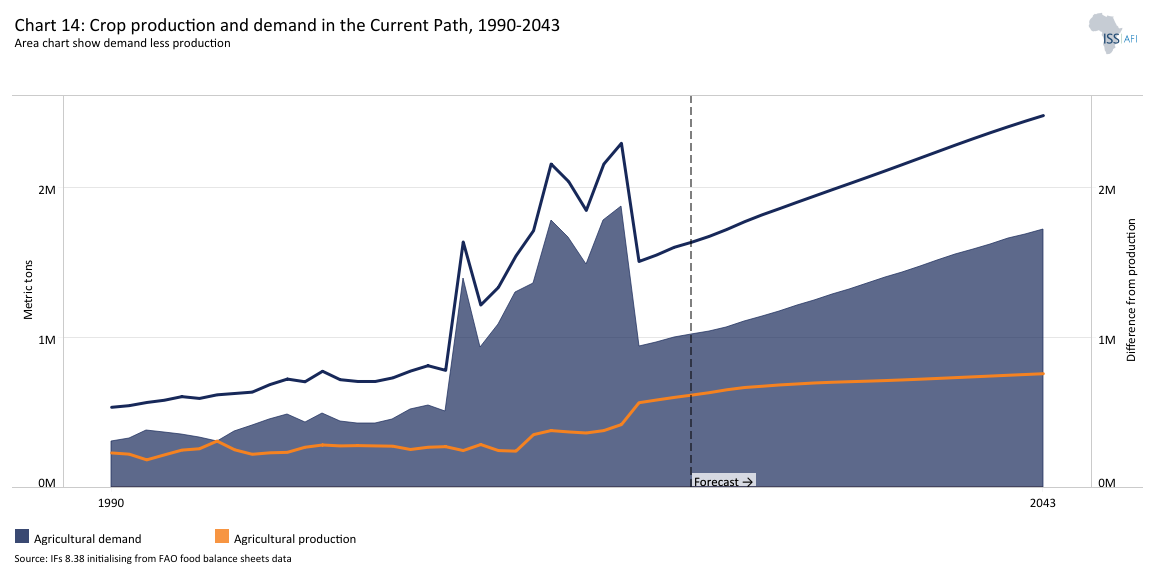

- Chart 14: Crop production and demand in the Current Path, 1990-2043

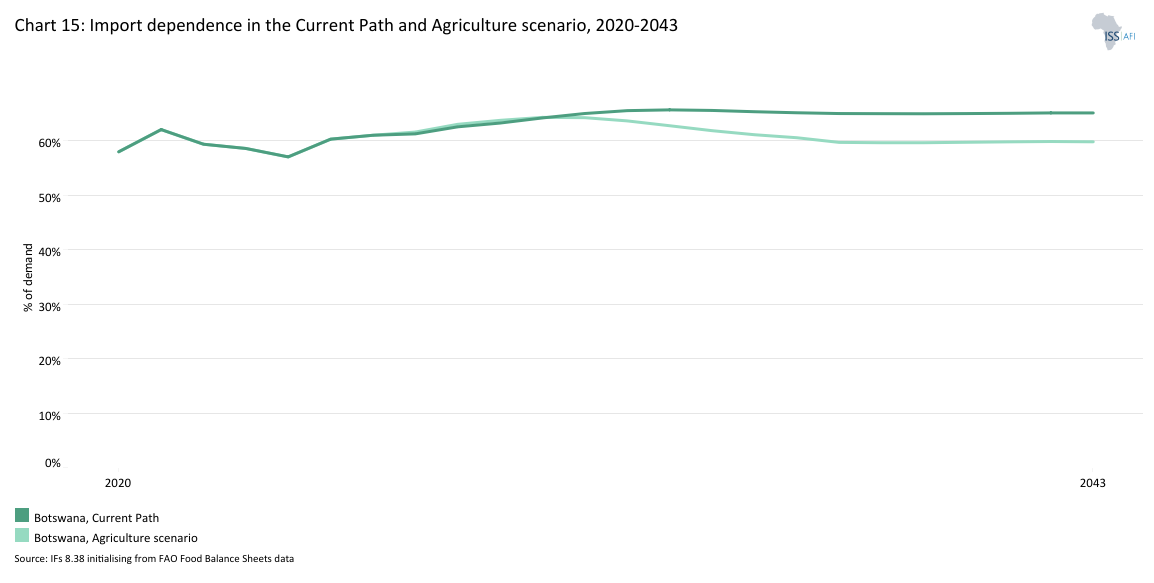

- Chart 15: Import dependence in the Current Path and Agriculture scenario, 2020–2043

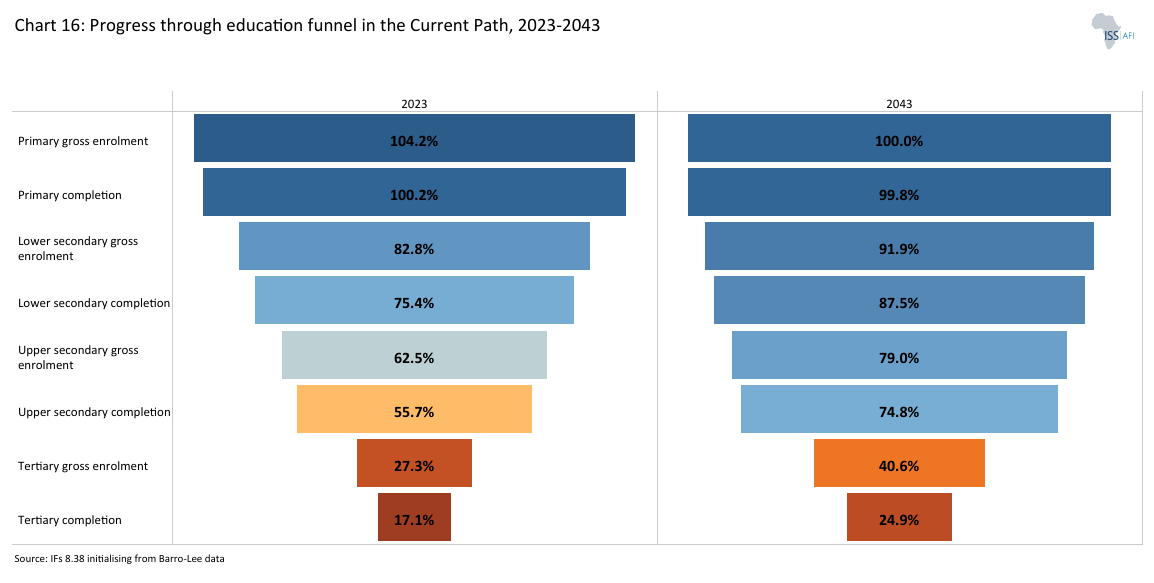

- Chart 16: Progress through the education funnel in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 17: Mean years of education in the Current Path and Education scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 18: Value-add by sector as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 19: Value-add by the manufacturing sector in the Current Path and Manufacturing scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 20: Exports and imports as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2000-2043

- Chart 21: Trade balance in the Current Path and AfCFTA scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 22: Electricity access: urban, rural and total in the Current Path, 2000-2043

- Chart 23: Cookstove usage in the Current Path and Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 24: Access to mobile and fixed broadband in the Current Path and the Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 25: FDI, foreign aid and remittances as % of GDP in the Current Path and in the Financial Flows scenario, 1990-2043

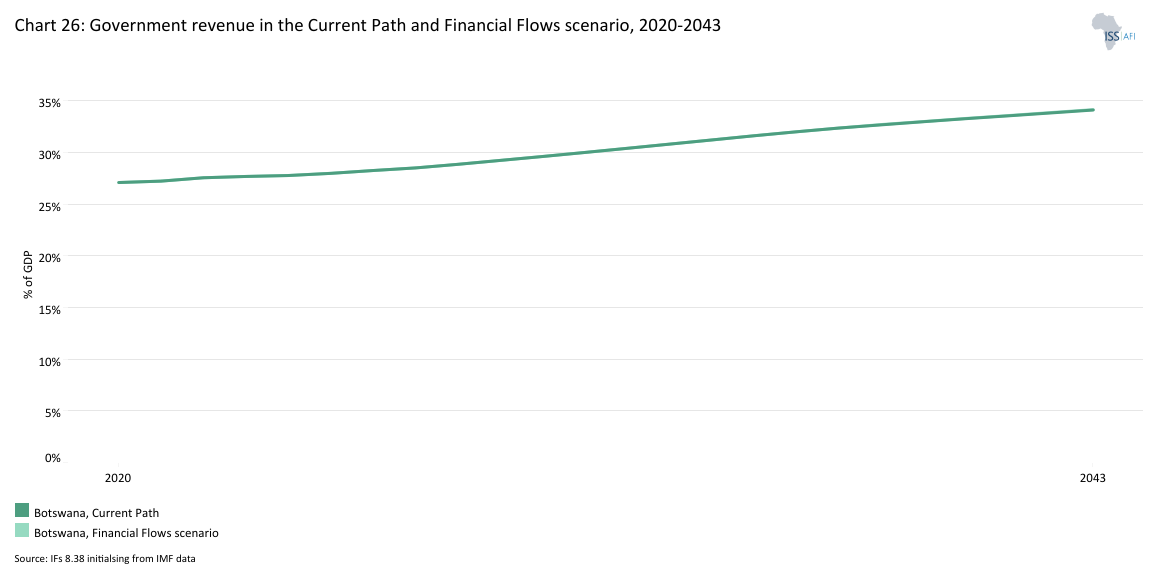

- Chart 26: Government revenue in the Current Path and Financial Flows scenario, 2020–2043

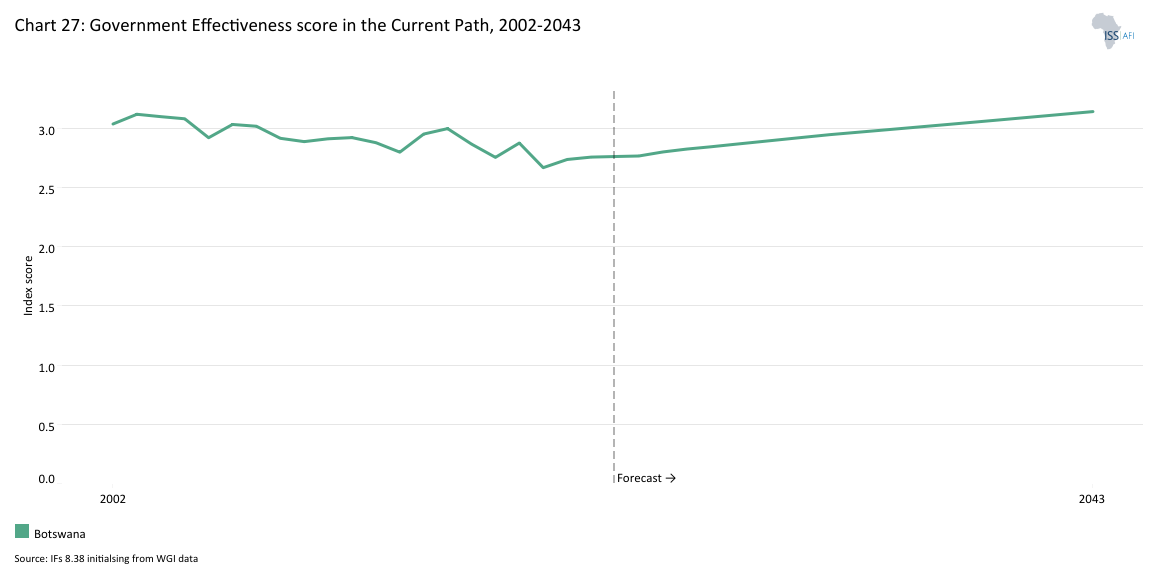

- Chart 27: Government effectiveness score in the Current Path, 2002-2043

- Chart 28: Composite governance index in the Current Path and Governance scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 29: GDP per capita in the Current Path and scenarios, 2020–2043

- Chart 30: Poverty in the Current Path and Scenarios, 2020–2043

- Chart 31: GDP (MER) in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 32: GDP per capita in the Current Path and the Combined scenario, 2020-2043

- Chart 33: Value added by sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 34: Informal sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 35: Poverty in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

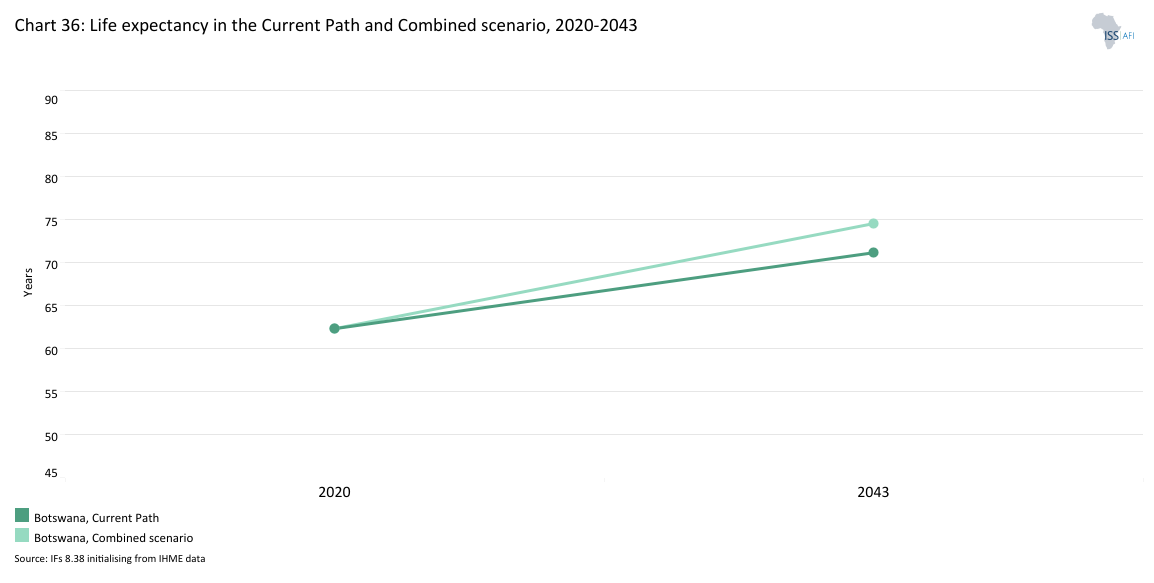

- Chart 36: Life expectancy in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 37: Carbon emissions in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 38: Energy demand and production by type in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020-2043

- Chart 39: Policy recommendations

Chart 1 is a political map of Botswana.

Botswana is a landlocked country in Southern Africa, bordered by Namibia to the west and north, Zimbabwe to the northeast, South Africa to the south and southeast, and a narrow crossing to Zambia at the Kazungula Bridge in the north. It covers about 566 730 km², slightly bigger than France (547 557 km²), and has a relatively flat terrain dominated by the Kalahari Desert in the central and southern regions.

In the north, the famed Okavango Delta and Makgadikgadi salt pans provide unique wetlands amid the arid landscape. The climate is semi-arid, with erratic summer rainfall varying from approximately 576 mm in the northeast to under 280 mm in the southwest. Recurrent droughts pose challenges like desertification and water scarcity, forcing reliance on groundwater. Despite the dry climate, Botswana sustains rich wildlife in well-protected parks, making it a popular eco-tourism destination.

Politically, Botswana is a stable multiparty parliamentary republic that achieved independence from British colonial rule on 30 September 1966, transitioning from the Bechuanaland Protectorate to the Republic of Botswana. Since gaining independence, Botswana has developed into one of Africa’s most stable democratic institutions, which helped transform it from one of the poorest countries at independence into an upper-middle-income economy. Led initially by Seretse Khama, the country established strong democratic institutions and achieved steady economic growth. His successors, Quett Masire (1980–1998), Festus Mogae (1998–2008) and Ian Khama (2008–2018), maintained political continuity and pursued economic reforms, though Khama’s tenure drew criticism for undermining press freedom. In 2018, Mokgweetsi Masisi took office, pledging democratic renewal amid internal party rifts. A historic shift occurred in 2024 when the opposition, Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC), a centre-left to left-wing alliance of political parties in Botswana, led by Duma Boko, won the general election. This ended the Botswana Democratic Party’s 58-year rule and marked a peaceful transfer of power that reaffirmed the country's democratic credentials.

The capital city is Gaborone, and English is the official language. The majority of the population speaks Setswana (Tswana), the national language, along with other indigenous languages such as Kalanga and Sekgalagadi.

Botswana is a member of regional bodies like the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the Southern African Customs Union (SACU). Its long-standing political stability, sound macroeconomic policies and effective governance have enabled it to avoid the resource curse that has afflicted many other mineral-rich African countries. Despite its heavy reliance on diamond exports, which account for approximately 80% of export earnings and about 25% of GDP, Botswana has maintained prudent fiscal discipline, accumulated substantial foreign reserves and achieved sustained economic growth over the decades.

A cornerstone of Botswana's success is its joint venture with De Beers, known as Debswana, which manages major diamond mines including Jwaneng and Orapa. This partnership has not only generated substantial revenue but also facilitated investments in infrastructure, education and healthcare, contributing to the nation's development.

In 2025, Botswana renegotiated its agreement with De Beers, increasing its share of diamond sales from 25% to 30%, with plans to reach a 50-50 split in the coming years. This move aims to ensure greater national benefit from diamond revenues and reflects the country's proactive approach to resource management.

However, the country faces challenges due to fluctuations in the global diamond market. In 2024, diamond exports declined by 50% compared to the previous year, highlighting the vulnerability associated with heavy reliance on a single commodity. In response, Botswana is actively pursuing economic diversification strategies, focusing on sectors like tourism, agriculture and manufacturing to build a more resilient economy.

Chart 2 presents the Current Path of the population structure from 1990 to 2043.

Botswana’s population has grown steadily, from approximately 1.31 million in 1990 to 2.46 million in 2023. The Current Path suggests that it will reach 3.08 million by 2043. However, this growth has not been uniform across regions or demographic groups. Spatial and socio-economic disparities in population dynamics underscore the need for regionally targeted policies that address uneven development and ensure equitable access to services and opportunities nationwide.

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, the country faced a significant slowdown in population growth, primarily due to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. At its peak, Botswana had one of the highest HIV prevalence rates globally, with nearly 39% of adults living with the virus. This health crisis led to increased AIDS-related mortality rates and a decline in life expectancy, which dropped from about 61 years in 1990 to a historical record low of 45 years in 2002.

Despite these challenges, Botswana has made significant strides in addressing the HIV/AIDS epidemic and improving public health. The country has implemented comprehensive prevention and treatment programs, leading to a reduction in new HIV infections and improvements in life expectancy. These efforts have contributed to the resumption of population growth, albeit at a slower pace compared to earlier decades.

In addition to the impact of HIV/AIDS, Botswana experienced a sharp decline in fertility rates during the 1990-2023 period. The total fertility rate decreased from 4.5 children per woman in 1990 to 2.7 in 2023. This decline was influenced by factors such as increased use of modern contraceptives and integration of family planning services into maternal and child health programs.

The country’s demographic landscape has also undergone significant changes over the past three decades, marked by shifts in age group distributions that underscore the country's ongoing transition from a youthful to a more balanced age structure.

In 1990, approximately 46.5% of the population were children under the age of 15 years. This youthful demographic posed challenges for the country, particularly in providing adequate education and health services to meet the needs of a large dependent population. By 2023, children under 15 had declined to 32.3% of the population, reflecting a demographic transition influenced by factors such as declining fertility rates and improved child survival. In contrast, the share of the working-age population (15-64 years) increased from 52.9% in 1990 to 63.7% by 2023. This implies that Botswana is at an advanced stage of the demographic transition, with a large working-age population and relatively fewer dependents.

The working-age population share will rise to 68.9%, while children under 15 will decline to 24.8% by 2043 under the Current Path. This shift has implications for Botswana's socioeconomic planning, as a decreasing youth population may reduce the strain on educational and healthcare systems, while an increasing working-age population can potentially boost economic productivity. However, to fully capitalise on the potential economic benefits of a larger working-age population, Botswana must invest in education, job creation and skills development to ensure that this segment of the population is effectively integrated into the economy.

The proportion of the elderly (above 65 years) population, though small, will increase by two percentage points from roughly 4% in 2023 to 6.3% by 2043. Life expectancy will also increase from roughly 64 years in 2023 to about 71 years by 2043. This development highlights a growing need for policies and programs that address the health and social care requirements of the elderly population.

Botswana officially entered its demographic dividend phase in 2018, when the ratio of the working-age population (15–64 years) to dependants (children under 15 and adults over 64) reached 1.7. This ratio will improve to 2.2 by 2043 in the Current Path, meaning there will be more than two working-age individuals for every dependant. As the dependency ratio rises above 2.0, countries begin to fully realise the economic gains from demographic change, provided complementary policies are in place. Economically, this shift presents a unique opportunity for accelerated growth: a larger, healthier and better-educated labour force, if gainfully employed, can drive productivity, boost savings and increase per capita income.

However, the dividend is not automatic. For Botswana to convert this demographic window into sustained economic growth, strategic investments are essential, particularly in job creation, quality education and healthcare. This includes aligning the education system with labour market needs, expanding vocational training, and supporting innovation and entrepreneurship to absorb new entrants into the workforce. Without these interventions, the expanding youth population could instead become a source of social and economic strain, manifesting in higher unemployment, underemployment and inequality. The challenge for Botswana lies in seizing this demographic moment through bold reforms in education, economic policy and governance, transforming its youth into a powerful engine of inclusive growth.

Chart 3 presents a population distribution map for 2023.

Botswana is one of Africa’s least populated countries, with a population density of 4 people per km² (equivalent to 0.04 people per hectare) as of 2023. The majority of the population is concentrated in the eastern and south-eastern regions of the country, while the western interior, much of which is the Kalahari Desert and nature reserves, is nearly empty.

The capital, Gaborone and its surrounding areas in the southeast hold a particularly large inhabitant share. More than 10% of the country’s people live in Gaborone alone, and nearly 50% live within 100 km of Gaborone. The second-largest city, Francistown in the far northeast, is another population centre, though much smaller than the capital. Outside these urban nodes and the eastern corridor, settlement is very sparse. Protected areas like national parks in the northwest and central Kalahari have virtually no permanent population.

This uneven distribution means that population density varies widely across Botswana. Densities range from over 1 200 people per km² (equivalent to 12 people per hectare) in Gaborone, which is the most densely populated district, to essentially zero people per km² in the desert interior. Overall, 87% of Batswana live in the eastern hydrological catchment of the Limpopo River, which underscores the eastward concentration. This pattern reflects historical factors such as the colonial-era development of the east, better water availability and transport links like the railway along the east.

Policymakers recognise this imbalance and have, in development plans, noted the need for more spatially balanced development, but the east-west divide in population remains pronounced. The 2022 census reported a total population of 2 359 609, confirming continued moderate growth, concentrated in existing urban centres. The government uses this data for infrastructure and service planning, focusing on high-growth districts in the east while ensuring remote communities (many in the west) also receive the necessary support.

Chart 4 presents the urban and rural population in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

Botswana has undergone a dramatic urbanisation transition since the 1990s. In 1990, 43.1% of the population lived in urban areas, but by 2023 the urban share had risen to about 79.5% and it will continue to rise gradually. This transformation places Botswana as the second most urbanised upper-middle-income country in Africa, trailing only Gabon, and well above the continental average of 44.2%.

Under the Current Path, about 88.7% of Batswana will be living in urban areas by 2043. This means rural inhabitants will shrink to less than 12% of the population, down from 57% in 1990. In absolute terms, the urban population will grow from roughly 2 million people in 2023 to 2.7 million by 2043, as cities expand and new towns develop, while the rural population declines from 504 050 to 349 700 people during the same period. This trajectory will keep Botswana above the African average urbanisation.

Urban settlement patterns in Botswana are characterised by a network of small to medium-sized towns rather than megacities. Apart from Gaborone and Francistown, which had about 270 000 and 100 000 residents in 2023, respectively, most other towns had fewer than 70 000 people. As urbanisation continues, these towns are growing and some are beginning to merge into larger conurbations, for example, Gaborone and surrounding villages form a growing metro region. Meanwhile, rural communities, often small villages, face challenges of youth outmigration and limited services.

Botswana’s rapid urbanisation reflects a structural transition in its economy from a predominantly rural, subsistence-based society to one increasingly oriented around urban-centric sectors such as services, mining and public administration. However, urbanisation has brought both opportunities and challenges. While cities like Gaborone and Francistown have become hubs of economic activity and infrastructure investment, the pace of urban growth has also strained housing, public services and employment capacity. The government’s planning must, therefore, manage the strain on urban infrastructure (housing, transport, utilities) as cities grow, while also attending to rural development to prevent excessive urban drift.

From an economic development perspective, high urbanisation rates can support agglomeration economies, enhancing productivity, innovation and access to markets and services. However, to fully leverage the benefits of urbanisation, Botswana must invest in inclusive urban planning, affordable housing, efficient transportation networks and sustainable service delivery. Without these, urban growth may deepen spatial inequalities and environmental pressures, especially in peri-urban and informal settlements.

Chart 5 presents GDP in market exchange rates (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

Botswana’s economic trajectory is one of Africa’s most notable development success stories. At independence in 1966, it was among the world’s poorest countries, with minimal infrastructure and a largely agrarian economy. However, through prudent fiscal management, good governance and effective use of diamond revenues, Botswana achieved remarkable growth. In 2007, it was formally classified as an upper-middle-income country by the World Bank, a status it has retained since. As of 2022, Botswana’s Gross National Income (GNI) per capita stood at US$6 940, according to the World Bank’s Atlas method, reaffirming its position among Africa’s more economically advanced countries.

Between 1966 and 1989, Botswana emerged as one of the world's fastest-growing economies, with an average annual GDP growth rate of approximately 13%. Peak growth rates exceeded 25% in the early 1970s. This robust expansion was primarily driven by the discovery and exploitation of diamond resources, particularly the opening of the Orapa mine in 1971, and later the Jwaneng mine in 1982. The government's prudent fiscal management, strategic partnerships, such as the 50:50 joint venture with De Beers, and investments in infrastructure and education further bolstered economic performance.

However, post-1989, Botswana's economic growth moderated, averaging around 4% annually from a GDP of US$5.62 billion in 1990 to US$19.14 billion in 2023. This deceleration reflects a natural maturation of the economy but also stems from several domestic and external headwinds. These include volatile global diamond demand, periodic global economic shocks, the COVID-19 pandemic and persistent structural challenges such as high unemployment and income inequality.

In 1998/99, the Asian financial crisis significantly dampened global demand for diamonds, leading to reduced export revenues. The 2008/09 global financial crisis further disrupted trade and investment flows, triggering another downturn. In 2014/15, a temporary drop in diamond production, compounded by falling global prices, again weighed heavily on the economy. More recently, the sharp output decline in 2019/20 was driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused a severe domestic recession. Nationwide lockdowns brought tourism to a standstill, disrupted global supply chains and sharply curtailed demand for diamonds. The country’s economy rebounded in 2021/22 as international commodity markets began to recover and economic activity resumed both domestically and abroad.

In addition, the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the late 1990s and early 2000s imposed a heavy toll on Botswana’s human capital and government budget. At its peak, the epidemic reduced life expectancy and weakened labour productivity while straining the national healthcare system and fiscal resources. Botswana’s effective public health interventions, including the rollout of one of Africa’s earliest and most comprehensive antiretroviral therapy (ART) programs, helped mitigate long-term economic damage.

Despite these periodic setbacks, Botswana has maintained relative economic stability through sound macroeconomic policies, governance reforms and efforts to diversify its economy beyond diamond mining. The government’s Vision 2036 envisions an export-led, labour-intensive, private-sector-driven model to reduce heavy reliance on diamonds. Central to this transformation is diversification through strategic investments in tourism, manufacturing, financial services and the digital economy, alongside regulatory reforms to foster a more competitive and innovative business environment.

Looking ahead, Botswana’s economy is expected to maintain a positive growth trajectory. Under the Current Path, GDP will reach US$42.39 billion by 2043, implying an average annual growth rate of approximately 4.1% from 2024 to 2043. This growth rate is 1.5 percentage points higher than the average of Africa’s upper-middle-income countries. While growth may not match the explosive double-digit rates of the 1970s and 1980s, it will remain robust, barring major external shocks, driven by continued sound macroeconomic management and reforms to stimulate new industries. Achieving high-income country status in the coming decades will depend on Botswana’s ability to deepen economic diversification, reduce inequality and harness its demographic and technological potential.

Chart 6 presents the size of the informal economy as per cent of GDP and per cent of total labour (non-agriculture), from 2020 to 2043. The data in our modelling are largely estimates and therefore may differ from other sources.

Botswana’s informal sector, the part of the economy not registered or regulated by the government, is relatively small by African standards, reflecting the country’s more formalised economic base. In 2023, the informal economy was estimated at 18.5% of GDP (equivalent to US$3.55 billion). This share is lower than in many African countries, though slightly higher than the average for upper-middle-income African countries. In comparison to its income group peers in Africa, the share of Botswana's informal sector in GDP is relatively higher, ranking second only to Gabon.

Approximately 28.5% of Botswana’s labour force was employed in the informal sector in 2023. This share is roughly half the African average, but slightly above the average for upper-middle-income African countries. Many of these jobs are in small-scale retail, street vending, subsistence agriculture, hair salons, liquor stores and informal transport or services. The relatively modest size of the informal sector can be attributed to Botswana’s strong mining industry, a formal sector activity and extensive public sector employment, which together absorb many workers who in other African countries might be informal.

Looking ahead, the Current Path indicates a gradual decline in the informal sector’s role as the economy grows and formal job opportunities increase. The informal sector will account for about 14.3% of GDP by 2043, narrowing its gap with the average for upper-middle-income African countries from 3.8 percentage points in 2023 to just 0.5 percentage points. Additionally, the proportion of workers in informal employment will fall below the average for upper-middle-income African countries by 2040, reaching 22.1% by 2043.

These trends depict progress towards formalisation, indicating more efficient, taxable economic activity, better-quality jobs and job security. Such developments are consistent with the objectives of Vision 2036, which aspires to transition Botswana into a high-income economy. In high-income countries, the informal sector typically constitutes only a small share of total employment and GDP, as formal job creation and sustained economic growth are driven by investments in manufacturing, high-value services such as tourism, finance and information and communication technology (ICT), and by policies that actively promote business formalisation. For Botswana, continued efforts to diversify the economy and support small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) will be essential in enabling informal businesses to scale up and integrate into the formal sector.

While Botswana’s informal sector is relatively small, it remains a critical component of the economy, particularly in supporting rural livelihoods and providing income opportunities for urban youth who are not formally employed. During economic shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, informal activity functioned as a vital safety net for many households. Recognising its role, the government has implemented initiatives to assist informal entrepreneurs, including entrepreneurship training, micro-credit schemes and small business development programs. If effectively expanded and integrated with broader economic reform, these efforts could accelerate formalisation and enhance inclusive growth.

Chart 7 presents GDP per capita in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043, compared with the average for the African income group.

Botswana’s GDP per capita (in purchasing power parity terms) rose from approximately US$9 270 in 1990 to US$14 670 in 2023, an average annual growth rate of 1.6%. This sustained upward trend is the result of a combination of prudent macroeconomic management, strategic investment of mineral revenues and sound governance. At the core of this trajectory is a stable political environment, underpinned by democratic institutions and the rule of law. Botswana has consistently ranked among Africa’s best-governed and least corrupt countries, ensuring effective policy implementation and fostering investor confidence. This institutional strength created the necessary conditions for long-term planning and efficient public service delivery.

Macroeconomic stability has also played a critical role. The government maintained conservative fiscal policies, often running budget surpluses during boom years and saving excess revenue in the Pula Fund, Botswana’s sovereign wealth fund. These savings provided a crucial buffer during economic downturns and helped to maintain investment in public services. Simultaneously, the Bank of Botswana ensured low and stable inflation through prudent monetary policy, maintaining a relatively stable currency and keeping inflation in check. These policies shielded the economy from external shocks and created a predictable environment for business and investment.

Diamond wealth has been central to Botswana’s development, but unlike many other resource-rich countries, it successfully avoided the resource curse. Through a strategic partnership with De Beers, Botswana developed a robust diamond industry that at its peak accounted for more than 70% of export earnings and approximately one-third of the country’s GDP. Rather than squander this windfall, the government reinvested mineral revenues into physical infrastructure, health and education. Major improvements in road networks, electricity supply and public administration laid the foundation for a more diversified economy. Botswana made significant progress in expanding access to education and health services, particularly through its early and comprehensive response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, which had severely affected the country in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

While diamond mining remains dominant, Botswana has made modest but important strides in economic diversification. Tourism, especially high-value ecotourism in the Okavango Delta and Chobe region, has emerged as a key growth sector, generating jobs and foreign exchange. Financial services and manufacturing are also gradually gaining traction, supported by government-led initiatives such as Special Economic Zones (SEZs) and public-private partnerships aimed at stimulating investment outside the mineral sector. Although diversification is still limited, these efforts have started to build alternative sources of income and employment.

Demographic and spatial transformations have further supported GDP per capita growth. Since 1990, the urban share of the population has surged from approximately 43% to nearly 80% in 2023, improving access to infrastructure, markets and services. Botswana began to enter its demographic dividend phase around 2018, with a growing working-age population relative to dependants. While the full economic benefit of this shift has yet to be realised, it offers a window of opportunity to accelerate growth if accompanied by job creation and skills development.

Botswana’s ability to withstand and recover from external shocks has been critical. The economy suffered contractions during the 1998 Asian financial crisis, the 2008 global financial crisis, the 2014 decline in diamond prices and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. However, due to fiscal buffers, policy agility and the rapid recovery of commodity markets, Botswana rebounded strongly, particularly in 2021 and 2022. The government’s crisis management capacity and forward-looking development planning, as outlined in Vision 2036, continue to support sustainable growth.

By 2023, Botswana’s GDP per capita was already more than US$1 600 above the average for Africa’s upper-middle-income countries. Looking ahead, the Current Path indicates that this gap will widen to over US$5 900 by 2043 as the country’s GDP per capita rises to US$20 850, reflecting an average annual increase of 1.8% from 2024 to 2043. If this trajectory holds, Botswana is poised to overtake Libya by 2040, becoming the second-highest-ranked upper-middle-income African country in GDP per capita terms, second only to Mauritius.

This performance underscores the importance of continued structural reforms, especially those aimed at deepening economic diversification, enhancing human capital and fostering private-sector dynamism. Botswana’s long-term competitiveness will depend not only on sustaining macroeconomic stability but also on unlocking productivity in non-mineral sectors such as tourism, manufacturing, financial services and ICT. Doing so will be critical to achieving the goals of Vision 2036 and transitioning toward a high-income country status in the coming decades.

However, challenges remain, including high unemployment rates, poverty and income inequality. Addressing these issues will require targeted policies and continued investment in education and social services to ensure inclusive growth.

Chart 8 presents the rate and number of extremely poor people in the Current Path from 2020 to 2043.

In 2022, the World Bank updated its poverty lines to 2017 constant dollar values, now using US$2.15 per person for extreme poverty and US$6.85 as the poverty line for upper-middle-income countries (UMICs) such as Botswana.

Monetary poverty only tells part of the story, however. In addition, the global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) measures acute multidimensional poverty by measuring each person’s overlapping deprivations across 10 indicators in three equally weighted dimensions: health, education and standard of living. The MPI complements the international US$2.15 a day poverty rate by identifying who is multidimensionally poor and also shows the composition of multidimensional poverty. The headcount or incidence of multidimensional poverty is often several percentage points higher than that of monetary poverty. This implies that individuals living above the monetary poverty line may still suffer deprivations in health, education and/or standard of living.[x]

According to the 2023 UNDP MPI Report, an estimated 17.2% of Botswana’s population (approximately 446 000 individuals) were living in multidimensional poverty as of 2021. These individuals faced overlapping deprivations across critical dimensions such as health, education and living standards. A further 19.7% (around 509 000 people) were classified as vulnerable to multidimensional poverty, indicating a high risk of falling into acute deprivation. These figures underscore the persistent socio-economic inequalities that endure despite Botswana’s upper-middle-income status, highlighting the need for targeted and inclusive development policies.

Income poverty in Botswana has declined over time, but a substantial proportion of the population remains poor when assessed against the World Bank’s poverty line for UMICs of US$6.85 per day. In the early 2000s, Botswana had very high poverty rates by this benchmark. The proportion of people living below US$6.85/day was estimated to be well above 60%. The country made progress in reducing poverty in the 2000s and 2010s through the Poverty Eradication Program (PEP) and other socio-economic programs which were key in alleviating poverty with better access to safety net income, education, health and services. Accordingly, the share of people living below the US$2.15/day extreme poverty line fell from 29% in 2002 to 15.4% in 2015. At the UMICs’ line (at less than US$6.85/day), poverty also fell in the 2000s, but rose again slightly between 2009 and 2015, from 60.4% to 63.5%. This setback was attributed to slower job creation as many new jobs were in capital-intensive mining rather than labour-intensive sectors, and recurring droughts that hurt rural livelihoods. Essentially, while Botswana’s average income grew, many rural and less-skilled households did not see proportional improvements, and income inequality remained high.

The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 likely caused another spike in poverty due to income losses in tourism and informal trade, and higher inflation in 2022 further eroded purchasing power. In 2020, approximately 62.2% of the population lived on less than US$6.85 a day, positioning Botswana, along with South Africa, as one of the African upper-middle-income countries with the highest poverty rates. This rate improved modestly to 57.9% in 2023, underscoring that a majority of Batswana are still economically vulnerable by this benchmark, even though extreme poverty (at US$2.15/day) is relatively low (around 11.5% in 2023). Many households earn incomes slightly above the national poverty line, but less than US$6.85 per day. This means they are above subsistence level, yet still not financially secure.

Looking forward, the Current Path indicates that Botswana's poverty rate (at US$6.85/day) will gradually decline to 44.4% by 2043. This represents a significant narrowing of the gap with the average poverty rate for Africa’s upper-middle-income countries, from nearly 13 percentage points in 2023 to just four percentage points by 2043. Extreme poverty (at US$2.15/day) will halve from 11.5%, affecting approximately 283 000 people, to 5.2% (about 160 000 people) by 2043. Under this trajectory, Botswana’s extreme poverty rate will fall below the average for Africa’s upper-middle-income countries by 2027. These are meaningful improvements, yet they still imply that roughly 1.37 million out of an estimated 3.08 million people in Botswana will remain below the US$6.85/day threshold by 2043.

To accelerate poverty reduction, Botswana has implemented various programs focused on youth employment, education quality and rural development. While these efforts are commendable, achieving the ambitions of Vision 2036, which aspires to transform Botswana into a high-income country and eradicate extreme poverty and inequality, will require a more comprehensive and inclusive growth strategy. This includes not only creating quality jobs for a growing youth population entering the labour market but also sustaining targeted social welfare investments and addressing the structural drivers of income inequality.

Vision 2036 sets out a bold goal of prosperity for all, which entails eliminating extreme poverty and substantially reducing moderate poverty levels by the 2030s. The current trajectory is encouraging, yet sustaining momentum will demand policy vigilance and institutional agility, particularly in the face of external risks such as commodity price volatility, climate-related shocks or regional instability, all of which could adversely affect household incomes and undermine progress.

Chart 9 depicts the National Development Plan (NDP).

Botswana’s development agenda is shaped by a combination of long-term strategic visions and medium-term National Development Plans (NDPs). The most recent plan, NDP 11, covered the period from April 2017 to March 2023. Adopted in late 2016, NDP 11 coincided with the country’s 50th independence anniversary and marked the official launch of Vision 2036, Botswana’s twenty-year blueprint for transforming into a high-income, inclusive and knowledge-based economy by 2036.

In alignment with Vision 2036, NDP 11’s theme was “Inclusive Growth for the Realisation of Sustainable Employment Creation and Poverty Eradication.” This encapsulated the plan’s focus on economic diversification, job creation and reducing poverty. NDP 11 identified six broad national priorities:

- Developing diversified sources of economic growth;

- Human capital development;

- Social development;

- Sustainable use of natural resources;

- Consolidation of good governance and national security; and

- Implementation of an effective monitoring and evaluation system.

These priorities meant investing in new industries beyond diamonds (like tourism, agriculture, manufacturing and ICT), improving education and skills, strengthening social services and safety nets, managing the environment and water resources sustainably, upholding Botswana’s reputation for good governance and security, and improving government performance through monitoring and evaluation. In essence, NDP 11 was about transitioning the economy to be more private-sector-led and export-driven, creating jobs especially for youth and women and ensuring growth is sustainable and inclusive.

As NDP 11 drew to a close in 2023, Botswana underwent a planning transition. NDP 11’s legacy has been establishing the foundations for diversification and inclusive growth.

The next six-year strategy, NDP 12, was initially expected to start in April 2023. However, the government decided to defer NDP 12’s start to 2025 to better align it with needed reforms and the national electoral cycle. To bridge the gap, a Two-Year Transitional National Development Plan (TNDP) was implemented for the fiscal years 2023/24 and 2024/25, maintaining momentum on ongoing initiatives and high-priority projects while NDP 12 is finalised.

The TNDP is due in October 2025 and focuses on high-impact projects and continuing programs from NDP 11, especially those delayed by COVID-19, to ensure no major development gap occurs during the pause. It also allowed the newly established National Planning Commission (NPC) to incorporate structural reforms into the planning process, such as aligning national plans with district plans and the political cycle and strengthening project appraisal and implementation frameworks.

NDP 12’s preparation has involved broad consultations to gather input for a truly inclusive plan. It is scheduled to commence in the fiscal year 2025/26 and will probably run for five years instead of six, to sync with the election timetable. This adjustment will enable each elected government to have a say in the national plan during its term, addressing a past issue where planning and electoral cycles were misaligned. Key areas likely to feature in NDP 12 include: accelerating private sector growth (reducing reliance on government spending), tackling unemployment, improving the quality of education and health outcomes and climate resilience.

As Botswana moves into NDP 12, the emphasis will be on fully realising the targets of Vision 2036, eradicating extreme poverty, creating decent jobs, and achieving high-income status inclusively and sustainably. The planning process itself is being strengthened to be more responsive and results-oriented, which bodes well for execution.

Chart 11 presents the mortality distribution in the Current Path for 2023 and 2043.

The Demographics and Health scenario envisions ambitious improvements in child and maternal mortality rates, enhanced access to modern contraception, and decreased mortality from communicable diseases (e.g., AIDS, diarrhoea, malaria, respiratory infections) and non-communicable diseases (e.g., diabetes), alongside advancements in safe water access and sanitation. This scenario assumes a swift demographic transition supported by heightened investments in health and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WaSH) infrastructure.

Visit the themes on Demographics and Health/WaSH for more details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Botswana’s present disease burden is marked by a double burden of persistent HIV/AIDS and rising non-communicable diseases (NCDs). HIV/AIDS remains a leading cause of death. For instance, in 2021, nearly 15% of deaths in Botswana were AIDS-related. At the same time, nearly one-third of deaths (29%) were from NCDs, reflecting the growing impact of chronic conditions. Key NCDs such as cardiovascular diseases and malignant neoplasms are now major contributors to mortality.

Beyond HIV, lower respiratory infections and other communicable diseases (CDs) also exert pressure on the health system. In 2021, about 4.3% of deaths in Botswana were from lower respiratory infections. This epidemiological profile underscores the challenge for Botswana’s health sector: tackling AIDS and infections while simultaneously addressing a surge in chronic diseases. National policies recognise this challenge; Botswana’s National Health Policy and Vision 2036 strategy explicitly call for combating both communicable diseases and NCDs to ensure Batswana “live long and healthy lives”. The country’s commitment to healthcare is evident: Botswana is one of the few African countries that has consistently met the Abuja Declaration target of allocating at least 15% of the government budget to health, providing a strong foundation to confront its health burden.

Under the Current Path, Botswana will witness a sharp rise in NCD-related mortality over the next two decades. Annual deaths from cardiovascular diseases will increase from roughly 3 490 in 2023 to about 5 230 by 2043, while deaths from malignant neoplasms will climb from around 1 980 to 3 290 in the same period. This steep increase is largely driven by an ageing population and lifestyle risk factors. As development gains and HIV treatment allow more Batswana to live longer, more people survive into age ranges where heart disease, stroke, diabetes and cancer become prevalent.

Moreover, lifestyle changes, such as diets high in sugar and fats, tobacco and alcohol use and physical inactivity, are contributing to higher NCD incidence. Unfortunately, gaps in prevention and early detection exacerbate the problem: studies indicate that many NCD cases in Botswana go undiagnosed until late stages. For example, about 70% of cancers nationally are only detected at an advanced stage, severely limiting treatment success.

These trends mirror the broader African shift in disease burden as projected by the World Health Organisation (WHO), that by 2030, NCDs will become the leading cause of death in sub-Saharan Africa, overtaking communicable diseases like HIV/AIDS. To address this looming crisis, Botswana has developed a Multi-Sectoral Strategy for NCD Prevention and Control and is aligning with global targets, the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3.4, which aims to reduce premature NCD mortality by one-third by 2030. Implementing stronger tobacco and alcohol controls, promoting healthy diets and exercise, and bolstering screening, for example for hypertension and cancers, are key policy priorities to curb NCD mortality. International partners such as the WHO and NCD Alliance are supporting Botswana’s efforts through technical assistance and the dissemination of “best buy” interventions for NCD prevention.

In contrast to the rising NCD burden, Botswana is making remarkable progress in reducing communicable-disease mortality. The Current Path suggests a significant decrease in AIDS-related deaths from roughly 4 800 deaths in 2023 to about 1 620 by 2043. This trajectory reflects Botswana’s successful HIV/AIDS programs and its commitment to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030. Botswana has essentially achieved the UNAIDS “95-95-95” targets for HIV treatment ahead of schedule: as of 2021, an estimated 95% of people living with HIV know their status, 98% of those are on antiretroviral therapy and 98% of those on treatment are virally suppressed. Achieving these targets, which Botswana did four years early, has led to steep declines in AIDS mortality and new infections. National initiatives such as the “Treat All” policy (universal free ART), nearly universal antenatal HIV screening and community-based prevention have been fundamental to this success. Botswana’s achievement is internationally recognised; it is one of a handful of high-prevalence countries to reach the 95-95-95 milestone, demonstrating that an AIDS-free generation is possible.

Beyond HIV, deaths from other communicable diseases are also set to decline. For example, annual fatalities from respiratory infections will drop from about 2 260 in 2023 to 1 440 by 2043, and deaths from other communicable diseases in general will likewise decrease from approximately 1 490 to roughly 1 460. These improvements can be attributed to sustained investments in infectious disease control, such as childhood immunisation programs, TB detection and treatment, improved water and sanitation (reducing diarrheal disease) and strong pandemic responses. Botswana’s national health plans align with regional initiatives like the African Union’s Catalytic Framework to End AIDS, TB and Malaria by 2030, and the country has nearly achieved the goal of ending AIDS by 2030 in line with global SDG 3.3.

Continued vigilance is needed, for example to maintain high HIV treatment coverage and to address emerging challenges like antimicrobial resistance, but the overall trend in communicable disease burden is very positive. Botswana’s experience underscores the impact of robust health funding and partnerships (PEPFAR, Global Fund, etc.), strong political leadership and donor support have together put the country on a path to virtually eliminate AIDS and drastically reduce other communicable diseases within the next decade.

In general, Botswana demonstrates strong health performance in terms of overall mortality compared to many peers. Total annual deaths from all causes will increase only slightly, from around 20 000 in 2023 to roughly 22 000 by 2043, a modest rise given population growth and ageing. In relative terms, this is a much slower increase than the average for Africa’s upper-middle-income countries, which collectively will see total deaths jump from about 917 000 in 2023 to approximately 1.3 million by 2043 under the Current Path.

Botswana’s ability to nearly stabilise its mortality count reflects effective disease control, especially of HIV and improvements in healthcare. Consequently, life expectancy in the country is on an upward trajectory. It will rise from about 64.1 years in 2023 to approximately 71.1 years by 2043. This gain of 7 years in two decades signals continued progress in health outcomes and living conditions. Notably, Botswana had suffered a significant hit to life expectancy during the worst of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. For context, life expectancy fell below 50 years from the late 90s to early 2000s, but has since rebounded strongly with the expansion of antiretroviral treatment. By 2019, life expectancy had recovered to approximately 65 years, though the COVID-19 pandemic caused a temporary dip to about 61 years in 2021.

The long-term outlook is positive, with the country’s life expectancy reaching 71 years by 2043 under the Current Path. However, this figure will remain lower than that of some comparable upper-middle-income countries, especially outside sub-Saharan Africa. For example, Algeria already had a life expectancy of about 76 years in 2021, and the average life expectancy across all upper-middle-income countries globally stands around 76 years as of 2023. This indicates that, despite improvements, Botswana still faces a gap in longevity that it aims to close. The relatively lower life expectancy is largely a legacy of the HIV/AIDS era and the ongoing burden of NCDs. It highlights the importance of continued health investments to catch up with global peers.

Female life expectancy in Botswana will continue to be higher than male life expectancy, which is consistent with global trends. In the Current Path, by 2043, females will live about 75.1 years on average, versus 67.1 years for males. This 8-year gender gap (female advantage) has widened slightly from 2023 (when female life expectancy was about 67.6 versus 60.5 for males). The phenomenon of women outliving men is seen worldwide. In 2021, the global life expectancy was 73.8 years for women compared to 68.4 for men (a 5-year gap), often attributed to a mix of biological factors and behavioural differences (men face higher rates of heart disease, injuries and risk-taking behaviours, for example).

In Botswana, the persistence of a male disadvantage in longevity suggests a need for targeted health interventions for men (such as improving men’s health-seeking behaviour, addressing occupational health risks and reducing alcohol and tobacco use among men). Overall, rising life expectancy for both genders is a positive sign that Botswana is recovering from past health crises and making steady progress toward the longevity levels of its income-group counterparts.

Chart 12 presents the infant mortality rate in the Current Path and the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

The infant mortality rate is the probability of a child born in a specific year dying before reaching the age of one. It measures the child-born survival rate and reflects the social, economic and environmental conditions in which children live, including their health care. It is measured as the number of infant deaths per 1 000 live births and is an important marker of the overall quality of the health system in a country.

Botswana has already achieved part of the SDG 3.2 target of reducing under-five mortality to at least 25 deaths per 1 000 live births. In 2023, the country recorded a notably low rate of just seven deaths per 1 000 children under five, a figure forecasted to decline further to 3 deaths under the Demographics and Health scenario. This represents an improvement of 2 deaths per 1 000 compared to the Current Path forecast.

However, Botswana is not on track to meet the other part of the SDG 3.2 target: reducing neonatal mortality to at least 12 deaths per 1 000 live births. Under the Current Path, the infant mortality rate will remain above this threshold, declining from approximately 28 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2023 to 18 by 2043. With this trajectory, Botswana will continue to lag slightly behind the average for Africa’s upper-middle-income countries until around 2033. This underscores the need for intensified short-term investments in primary healthcare, immunisation programs and maternal and child health services, priorities already reflected in the strategic objectives of Botswana’s National Health Policy and Vision 2036 (specifically under Pillar 3).

In contrast, the Demographics and Health scenario offers more promising outcomes. It forecasts a reduction in infant mortality to below 12 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2040, reaching approximately 11 by 2043. Under this scenario, Botswana will surpass the average infant mortality rate of its African income peer group as early as 2027/2028 and become the third-best performing upper-middle-income African country in reducing infant mortality by 2043, ranking just behind Libya and Mauritius. These improvements reflect the compounded benefits of enhanced neonatal care, expanded antenatal and postnatal service coverage and broader socio-economic development. They are also in alignment with global frameworks such as the WHO and UNICEF's Every Newborn Action Plan, which emphasise integrated strategies to improve maternal and newborn health outcomes.

Life expectancy also improves substantially in the Demographics and Health scenario, reaching 73.7 years by 2043, compared to 71.1 years under the Current Path. This trajectory would position Botswana among the top five upper-middle-income African countries in terms of life expectancy, and just 0.4 years below the African upper-middle-income average of 74.1 years. Such progress reflects a significant narrowing of historical health disparities, particularly those rooted in the country's past HIV/AIDS burden.

Importantly, the scenario places Botswana on track to meet the African Union’s Agenda 2063 health target of a minimum life expectancy of 75 years by 2063. However, despite this progress, Botswana is unlikely to attain its more ambitious national target of ranking within the global top 15% of countries for life expectancy by 2036. This underscores the need for sustained investments in public health, improved healthcare delivery and strengthened disease prevention strategies to accelerate gains in longevity and close the remaining gap with global benchmarks.

Gender gaps persist but narrow. Female life expectancy rises 2.5 years above the Current Path, while male life expectancy improves by 2.7 years, reaching 77.6 and 69.8 years, respectively, by 2043. These trends underscore the transformative potential of comprehensive demographic and health investments, especially in preventive care and equitable health service delivery.

Chart 13 presents the demographic dividend in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

The dividend is the window of economic growth opportunity that opens when the ratio of working-age persons to dependants increases to 1.7 to 1 and higher.

Demographers typically distinguish between the first, second and, in some cases, even a third demographic dividend. This analysis focuses on Botswana’s first demographic dividend, which is the economic growth potential that stems from shifts in the population's age structure. Specifically, this occurs when the proportion of the working-age population (15–64 years) increases relative to the dependent population, those under 15 and over 64 years of age. A dependency ratio below 0.59 or, equivalently, a working-age to dependent ratio greater than 1.7, is often used as a benchmark to identify the opening of a demographic window of opportunity.

This transition reduces the dependency burden on the economically active population, creating an opportunity to boost savings, investment and labour productivity, all of which can enhance per capita income. However, this dividend is not automatic; it must be supported by targeted investments in education, healthcare, employment creation and governance to realise its full potential.

Botswana formally entered its demographic window of opportunity in 2018, when the working-age to dependent population ratio reached the critical threshold of 1.7, a widely accepted benchmark for the onset of the first demographic dividend. By 2023, this ratio had modestly improved to 1.75, indicating that the country remains in the early stages of this potential high-growth phase. If effectively harnessed through sound investments and governance, this window could remain open for two to three decades, offering Botswana a rare chance to boost economic growth and reduce poverty.

Under the Current Path, Botswana’s ratio of working-age population to dependants will rise steadily, reaching 2.22 by 2043. Notably, the country will surpass the average ratio for Africa’s upper-middle-income countries by 2037, reflecting its ongoing fertility decline, rising child survival rates and gains in educational attainment. This trend aligns with national development objectives articulated in Vision 2036 Pillar 3 and the Revised National Population Policy, which prioritise human capital development, family well-being and inclusive growth.

The Demographics and Health scenario, which envisions enhanced investments in health, education and family planning, yields even more favourable outcomes. The working-age to dependant ratio will reach 2.46 by 2043, representing a 0.24-point increase above the Current Path forecast. This evolving age structure underscores a critical policy opportunity. To fully capitalise on the dividend, Botswana must complement demographic shifts with economic reforms, including expanded access to quality education, productive job creation (especially for youth), gender-inclusive labour policies and fiscal strategies that channel savings into productive investment. These imperatives are aligned with SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth) and the African Union’s Demographic Dividend Roadmap.

Without targeted investments, the demographic dividend could remain untapped. With the right reforms, however, Botswana is well-positioned to translate this population shift into sustainable and inclusive development gains by the mid-21st century.

Chart 14 presents crop production and demand in the Current Path from 1990 to 2043.

The Agriculture scenario envisions an agricultural revolution that ensures food security through ambitious yet feasible increases in yields per hectare, due to improved management, seed, fertiliser technology, and expanded irrigation. Efforts to reduce food loss and waste are emphasised, with increased calorie consumption as an indicator of self-sufficiency and prioritising it over food exports. Additionally, enhanced forest protection signifies a commitment to sustainable land use practices.

Visit the theme on Agriculture for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Botswana’s agricultural sector has undergone steady transformation over the past three decades, with both crop production and domestic demand increasing significantly. Between 1990 and 2023, total agricultural output expanded from approximately 420 000 metric tons to 1.06 million metric tons, while domestic food demand rose from 790 000 to 2.26 million metric tons. This persistent imbalance has resulted in a widening food production deficit, which reached an estimated 1.2 million metric tons by 2023.

The Current Path suggests a worsening agriculture production-demand gap by 2043. Total demand will rise to 3.54 million metric tons, while production will increase modestly to 1.51 million metric tons, leaving Botswana with a food deficit of over 2 million metric tons. This growing disparity underscores the country's increasing dependence on food imports and exposes its vulnerability to external supply shocks and global food price volatility, challenges that are expected to intensify under climate change.

While Botswana’s agricultural economy is traditionally dominated by extensive cattle ranching, crop production plays an increasingly strategic role in advancing food security, rural employment and import substitution. Particularly in rural and remote regions, crop farming remains a critical livelihood source and buffer against extreme poverty.

Crop yields have experienced modest but sustained growth, rising from 0.6 metric tons per hectare in 1990 to 2.06 metric tons per hectare in 2023. During this period, total crop production more than doubled, reaching approximately 615 350 metric tons in 2023. However, yield improvements have been uneven and highly sensitive to recurring droughts, erratic rainfall and limited access to irrigation and agricultural inputs. The slow adoption of modern technologies, including improved seed varieties, conservation agriculture and mechanisation, has further constrained potential productivity gains.

Looking ahead to 2043, the Current Path indicates continued, though moderate, progress. Crop yields will reach 2.51 metric tons per hectare, raising total crop production to approximately 757 690 metric tons. However, this increase will remain outpaced by population growth and consumption patterns, unless complemented by productivity-enhancing policies and resilient farming systems.

Addressing Botswana’s widening food production deficit requires a strategic policy shift toward productive, diversified and climate-resilient agricultural systems. This includes scaling up research and innovation through institutions such as the National Agricultural Research and Development Institute (NARDI), and improving access to climate-resilient seeds, fertilisers and mechanisation, particularly for smallholder farmers. The promotion of public-private partnerships across priority value chains (such as sorghum, maize and horticulture) will be essential to modernise production and improve market integration. In parallel, strengthening early warning systems and expanding weather-indexed insurance schemes will help buffer farmers against growing climate variability. These measures align with Botswana’s Vision 2036 and the Revised National Agricultural Policy (2021), both of which emphasise transforming the sector into a commercially viable, export-oriented industry, while enhancing national food security and reducing reliance on imports.

It is important to note that Botswana has made notable strides in expanding irrigation capacity, a key pillar of climate-resilient agriculture. The total area equipped for irrigation increased from just 1 380 hectares in 1992 to a peak of 4 030 hectares in 2022 and 2023. Despite this progress, water scarcity, exacerbated by prolonged dry spells and groundwater dependency, remains a critical constraint. As a result, irrigated area will decline slightly to 3 910 hectares by 2043 under the Current Path, underscoring the fragile sustainability of current water-use patterns.

The Current Path trajectory contrasts starkly with Botswana’s estimated irrigation potential of 13 000 hectares, based on land suitability and surface water assessments. Closing this gap will require targeted investment in irrigation infrastructure, institutional support for smallholder farmers and implementation of efficient water-use practices, including drip irrigation, rainwater harvesting and wastewater reuse. These priorities are echoed in the National Agricultural Investment Plan (NAIP), which highlights the need to enhance climate-smart agriculture and water resource management.

Chart 15 presents the import dependence in the Current Path and the Agriculture scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

Botswana’s heavy reliance on food imports remains a structural vulnerability in its agri-food system, exposing the country to global market volatility, currency fluctuations and external supply shocks. In 2023, approximately 63.2% of total crop demand was met through imports, a reflection of constrained domestic production capacity, climatic challenges and underutilisation of irrigation infrastructure.

The Agriculture scenario illustrates a more ambitious trajectory aligned with Botswana’s national goals to enhance food self-sufficiency and reduce dependency on imports. In this scenario, irrigated land expands from 3 840 hectares in 2023 to 9 110 hectares by 2043, an increase of 5 390 hectares over the Current Path forecast. This significant expansion brings Botswana within reach of its estimated national irrigation potential of 13 000 hectares.

As a result of increased irrigation and improved productivity, crop production will reach roughly 920 000 metric tons by 2043, about 160 000 metric tons more than in the Current Path. This yield-driven growth translates into a corresponding reduction in the national agricultural production gap, which narrows to 1.87 million metric tons in 2043, down from 2.03 million under the Current Path.

Importantly, this progress contributes to moderating Botswana’s dependence on imported crops. Under the Agriculture scenario, the crop import share declines to 65% of total demand by 2043, which is 6.7 percentage points lower than the 71.7% under the Current Path. While this still reflects a high level of dependence, it signals meaningful gains in domestic supply capacity and resilience.

However, even with these improvements, Botswana will remain vulnerable to international food system disruptions for the foreseeable future. The country’s semi-arid climate, limited arable land and water scarcity pose enduring constraints. Therefore, the success of the Agriculture Scenario hinges not only on expanding irrigation infrastructure, but also on sustained investment in extension services, input supply chains and climate-smart agriculture. Enhancing the resilience of domestic production systems is essential to ensure food affordability and security, especially for low-income and rural households.

Botswana’s Vision 2036, NAIP, and the SADC Regional Agricultural Policy all emphasise the imperative of reducing import dependence through sustainable intensification, smart irrigation and improved market integration. The Agriculture Scenario illustrates that these ambitions are feasible, but will require effective policy coordination, robust financing mechanisms and strong public-private partnerships to translate potential into food system transformation.

Chart 16 depicts the progress through the educational system in the Current Path, for 2023 and 2043.

The Education scenario represents reasonable but ambitious improvements in intake, transition and graduation rates from primary to tertiary levels and better quality of education at primary and secondary levels. It also models substantive progress towards gender parity at all levels, additional vocational training at the secondary school level, and increases in the share of science and engineering graduates.

Visit the theme on Education for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.