19 UN Security Council

19 UN Security Council

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

This theme examines the need and content of reforming the UN Security Council (UNSC) to make it fit for a changed world. The proposals involve a comprehensive reconfiguration of the Council, including the automatic inclusion of a new category of Global Powers (with additional votes but no veto) and the expansion of the number of elected members who serve for three-year terms. Other elements include provision for regions such as Europe and the African Union to act as one in the reformed Council and various measures to overcome deadlock. The analysis draws on forecasts of changes in the global distribution of power examined in the theme on Africa in the World.

Summary

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is fundamental to upholding a rules-based global order and the maintenance of global peace and security, which is a prerequisite for Africa’s development. However, at a time of rapid global change, the Council is losing legitimacy and effectiveness. The world needs a more legitimate, representative and effective UNSC to manage a crowded and interconnected 21st century, different from the situation today, where five permanent members with veto power dominate decision-making. This imbalance is the key source of the Council’s dysfunction.

Beyond a potential nuclear conflagration and the enduring challenge of interstate conflict, future global security challenges include the increasing impact of climate change and the threat of pandemics, nuclear terrorism and cybercrime. History also speaks to the risks inherent in shifting power relations between global powers, such as between the United States and China, at a time of significant changes in their influence and economic size. Multipolarity without sufficient multilateralism is a dangerous trend.

The reform of the UNSC has been on the agenda of the United Nations General Assembly for several decades. Yet, there is no prospect of progress in the current deadlocked intergovernmental negotiations at the UN in New York. Various groups have sought incremental change to the system and have been engaged in this process for successive generations without results.

A political and intellectual leap is required to overcome the frustrating impasse between the various negotiating positions and groups. This theme outlines such a different approach. It is based on clear and realistic first principles, such as electoral fairness, and does not seek a compromise between the various reform coalitions that have evolved as part of the fruitless quest towards this end.

A reformed UNSC needs to be grounded in much greater equity among states. However, given the disparities in economic size, population and influence, it cannot consist of countries elected through only a direct proportional system. An enlarged Council needs to recognise and accommodate emerging geopolitical realities at regional and global levels.

The proposals end the veto and permanent UNSC membership in favour of a new “Global Power” category defined by three objective criteria, namely a set proportion of the global population, economy and contribution to the UN budget. The proposal also provides for coalitions of countries that collectively qualify for Global Power status - that choose to act in concert within the Council instead of being represented by individual member states. These Global Powers or coalitions of states will have enhanced voting rights (i.e. their votes will each count for three) but no veto.

All other UNSC members would be elected for a three-year tenure to the enlarged and reformed Council, with all members subject to four technical criteria for candidacy. Electoral regions may designate one seat to stand for immediate re-election should they consider the importance of ongoing representation of a regional power in the Council. The increase in the term of elected members from two to three years will, in conjunction with the various other proposals that follow, bring greater stability and predictability to the Council and its proceedings.

All UNSC decisions will require an affirmative two-thirds majority of votes cast.

To unlock resistance to change and to accommodate some of the world’s more intractable and long-running disputes, the outgoing UNSC will be requested to draw up a list of issues that, for up to 30 years, may not be subject to an additional Chapter VII UNSC resolution beyond updates, removal or maintenance.

A mandatory review of the UNSC will occur every 30 years, to be concluded within three years.

The proposals should be contained in a single amendment to the UN Charter.

All charts for UN Security Council

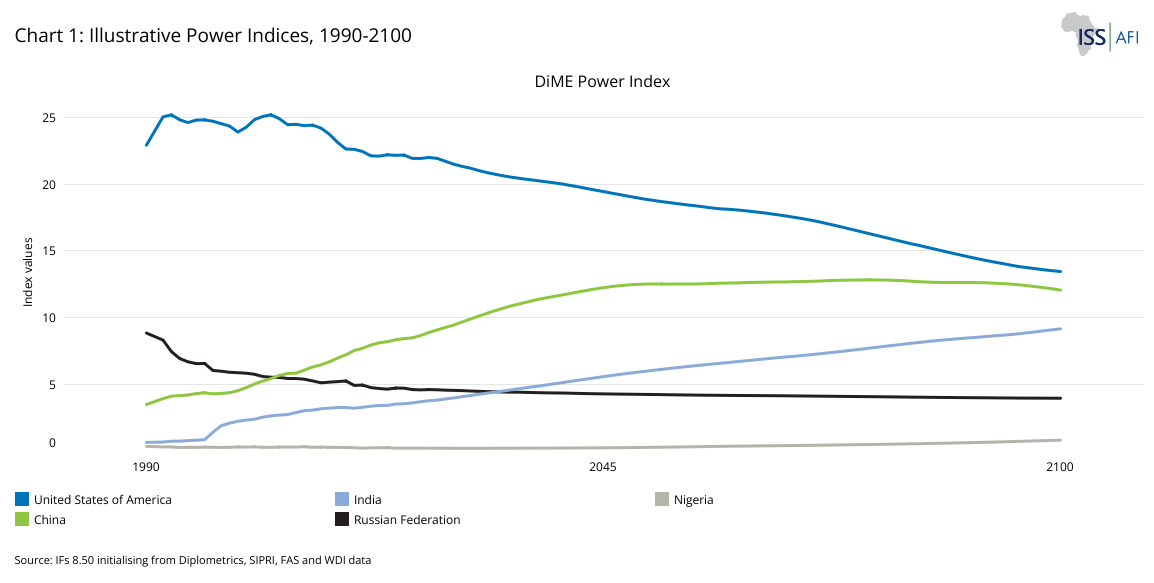

- Chart 1: Illustrative Power Indices from 1990 to 2100

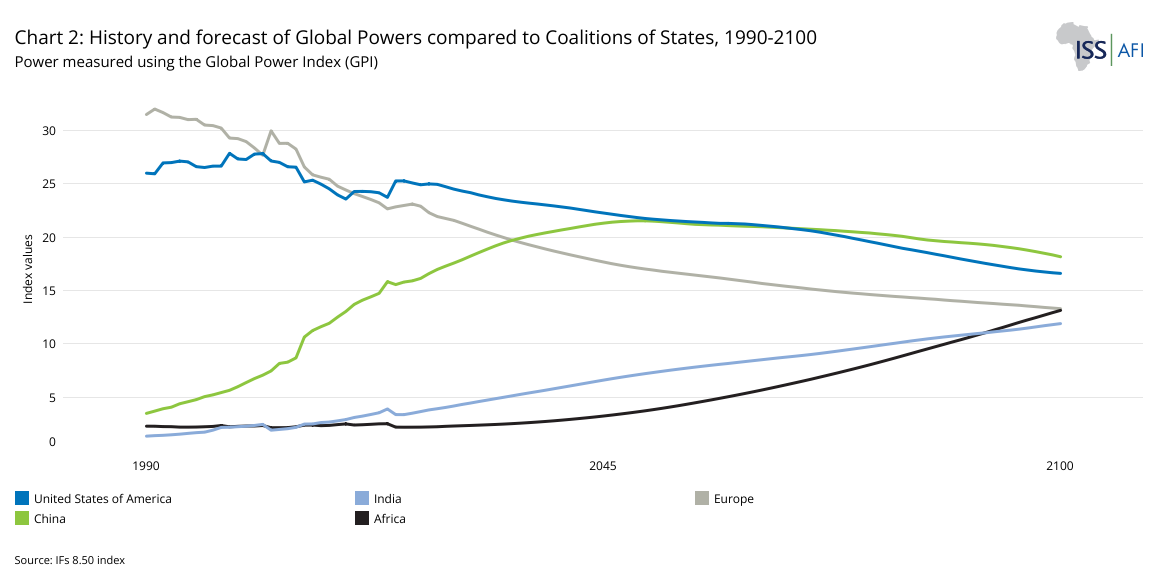

- Chart 2: History and forecast of Global Powers compared to Coalitions of States, 1990 to 2100

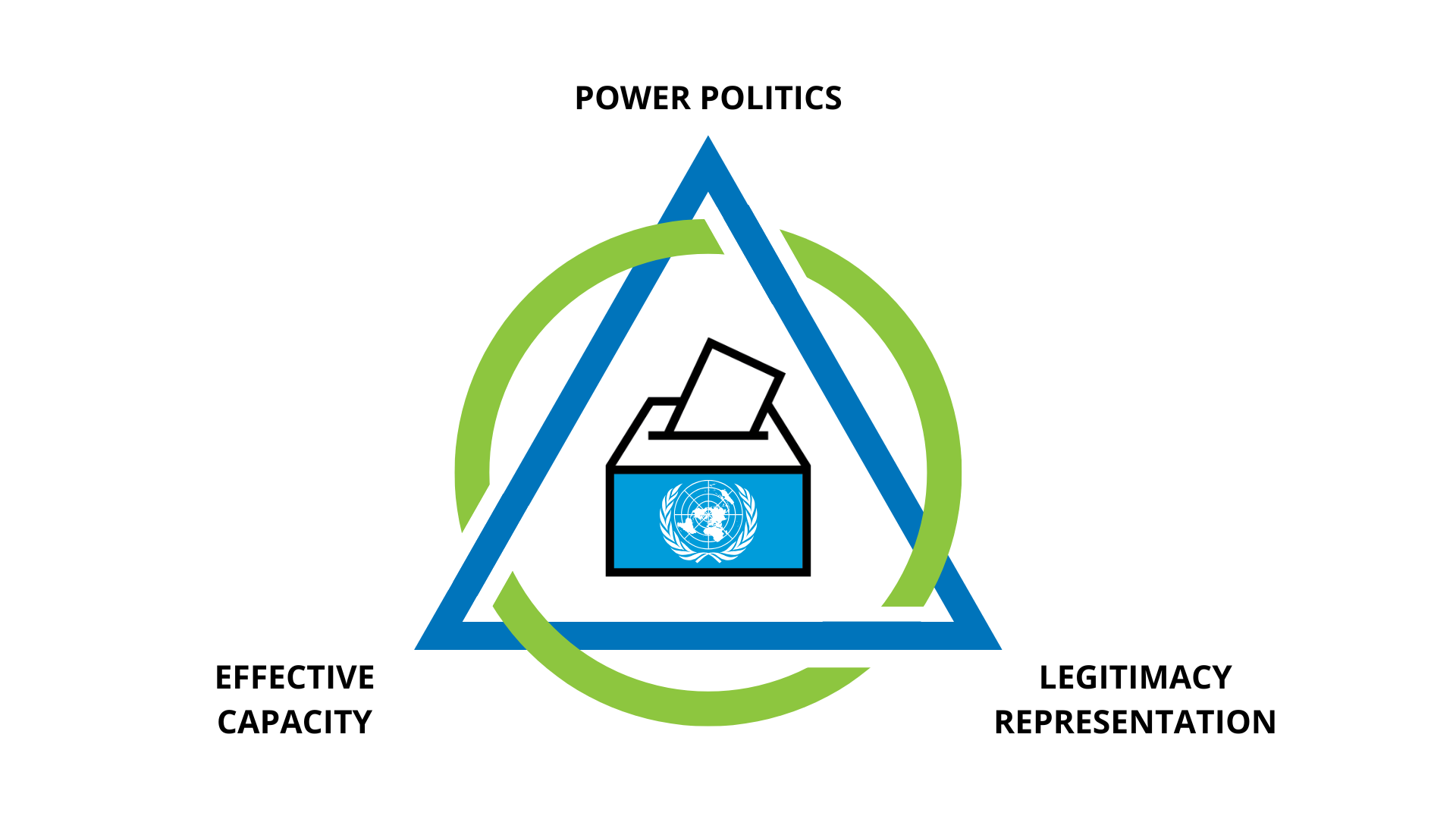

- Chart 3: Primary principles for reform

- Chart 4: Conclusions to inform reform proposals

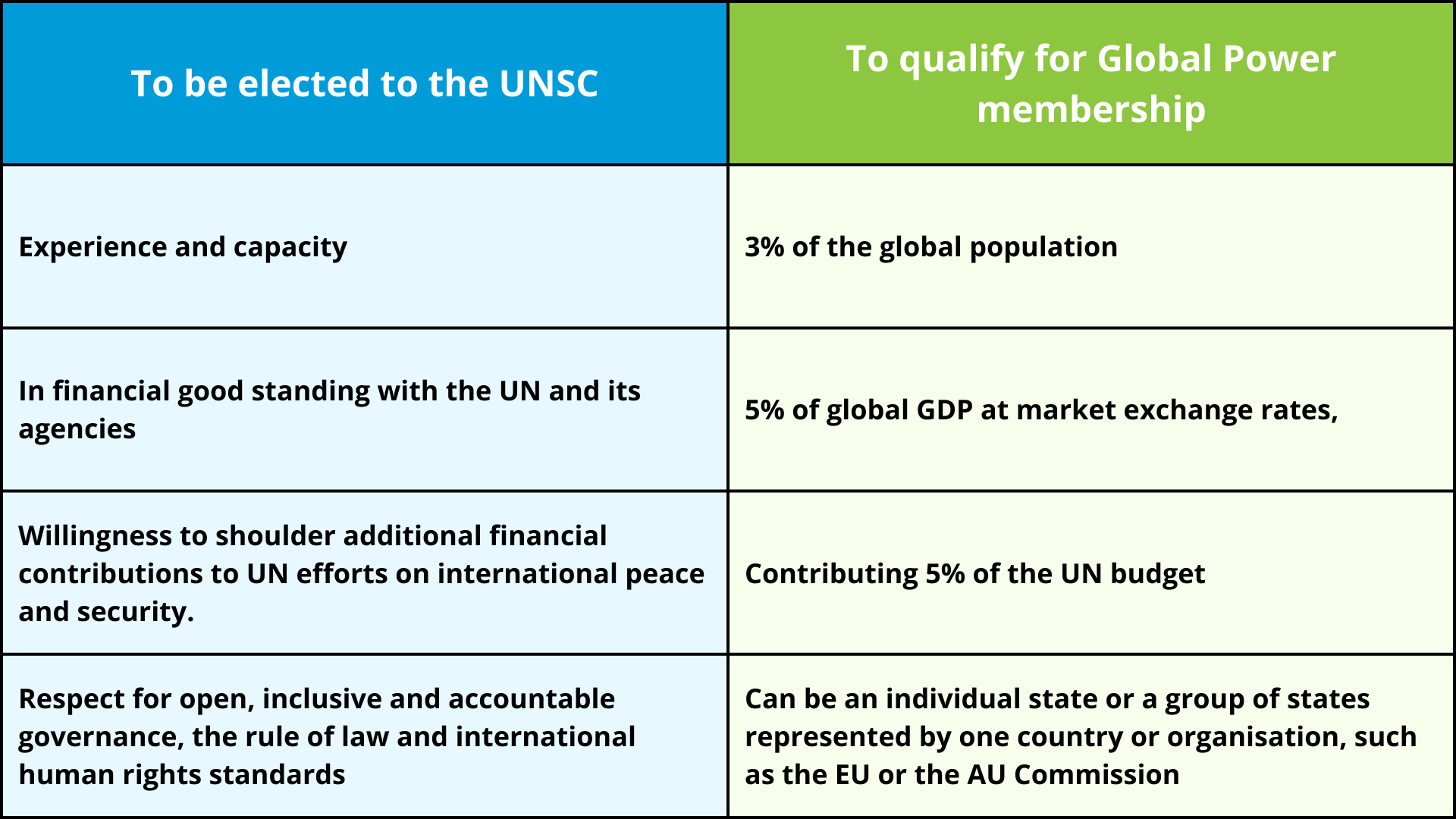

- Chart 5: Membership requirements

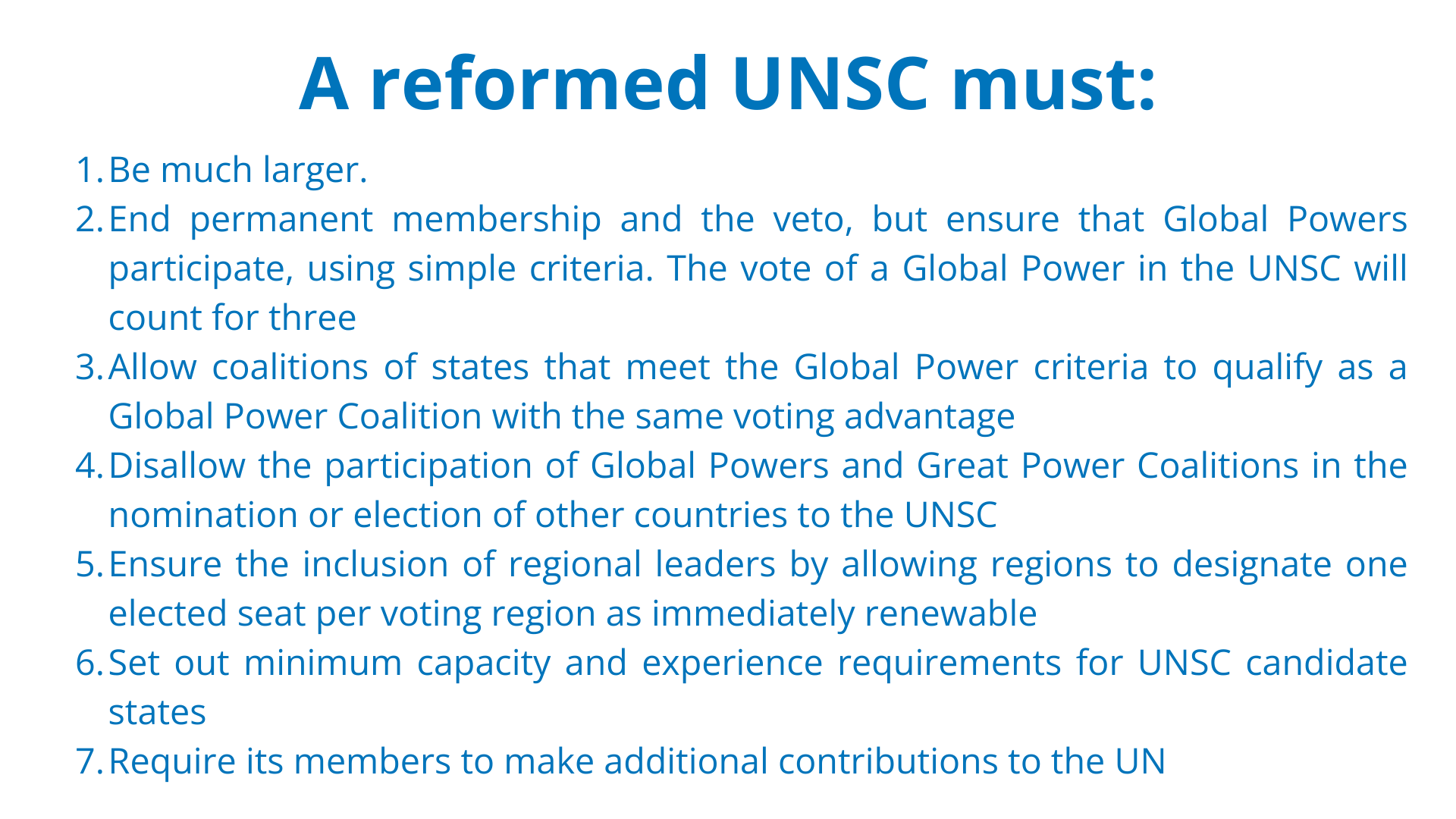

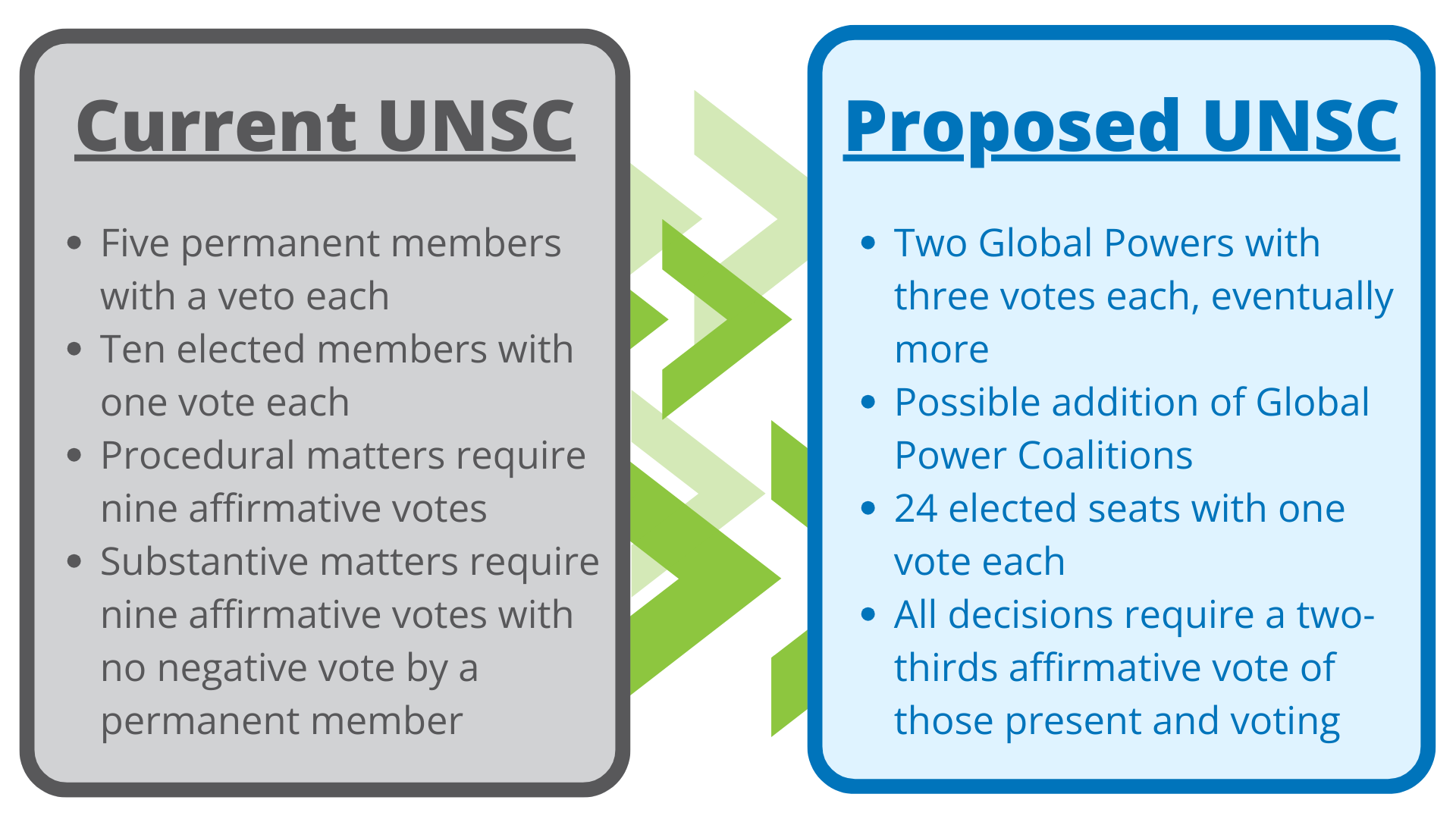

- Chart 6: Current vs proposed UNSC

The UN system has, for eight decades, driven substantial improvements to the daily lives of the world’s people. Established in the wake of the most devastating war in modern history, the UN Security Council (UNSC) has contributed immeasurably to the management of global conflict. UN peacekeepers and observer missions have stabilised dozens of conflict situations and helped to establish the foundations for peace and development in numerous fragile and conflict-torn countries. Efforts at peacemaking and conflict prevention have also defused potential conflicts. Despite frequent rumblings of discontent, no country has felt strongly enough about its treatment at the hands of the UNSC to leave the UN, despite being placed under sanction or subjected to armed action authorised by the council. The Council has established a system and practice of the rule of law, but it is fraying.

For years, wealthy states, the US in particular, have been frustrated by the waste and inefficiency within the UN system, while poor states complain about their lack of representation on the UNSC and the dominance of the five permanent members (P5) interests. Stalled reforms of the Council cause the whole UN system to suffer, with deep political divides spilling over into other UN processes and leading to vote-buying.

In an era of growing global interdependence and renewed great power competition, the world needs a credible and responsive forum to pre-empt and address international crises. The UNSC remains central to this requirement, yet its current structure is increasingly out of step with today’s geopolitical realities, and it is steadily losing legitimacy and effectiveness. Today, the five permanent members with veto power continue to dominate decision-making and are a key source of dysfunction and growing mistrust in the Council’s role.

Beyond the need to address the emerging security threats of the 21st century, such as the potential for nuclear terrorism, Africa and the Middle East are the two regions with the largest armed conflict and terrorist burden globally, and will very likely need sustained UNSC support in the future. Also, conflict between states has recently increased in tandem with greater turbulence within states, although fatalities from armed conflict are still below levels seen at the end of the Cold War.

The 21st-century world is vastly more interconnected, and the surge in physical and digital communication has created new global security risks, particularly regarding organised crime and cybercrime and the power of Artificial Intelligence. The result is a turbulent and brittle global system.

There are innumerable ways in which the Council can be reformed. What follows is a principled yet practical model of reform that serves to highlight the need and complexity of the challenge.

The UNSC was established in 1945 after six years of unprecedented global conflict, but today, the Council struggles to fulfil its primary function of preventing another global conflict, this time between nuclear-armed states. The challenge is acute since the UN Charter does not include a mechanism to account for shifts in global power, effectively freezing the 1945 status quo when a mere 51 states signed the UN Charter.

The Council is one of the six principal organs of the UN and bears primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security. It has the authority to make decisions that member states are obligated to implement under the UN Charter, including the imposition of sanctions, the authorisation of the use of force and the establishment of peacekeeping operations.

The UNSC is composed of fifteen members. Five are permanent members (P5) comprising China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States. Each member holds one vote, but the P5 possess the veto: the ability to block the adoption of any substantive resolution, regardless of the number of votes in favour. The Council’s current structure reflects the post-World War II balance of power, with five permanent members from North America, Europe, and Asia—but none from Africa or Latin America, despite their global significance and size.

The ten non-permanent members are elected by the General Assembly for two-year terms according to a geographic rotation system that allocates seats among regional groups: three for Africa, two for Asia-Pacific, two for Latin America and the Caribbean, two for Western Europe and Others, and one for Eastern Europe. These seats provide limited influence over agenda-setting or enforcement decisions, which remain heavily shaped by the positions and vetoes of the P5.

The Council derives its binding authority primarily from Chapter VII of the UN Charter that empowers the Council to determine the existence of any threat to peace, breach of the peace or act of aggression, and to take military or non-military action to restore international peace and security. Chapter VII decisions (such as imposing sanctions, authorising military force or mandating peacekeeping missions) are legally binding on all member states. This enforcement power makes the UNSC uniquely authoritative among UN bodies, but also heightens the impact of P5 vetoes, which can block action even in the face of widespread consensus.

The last reform of the UNSC occurred in 1965, when the number of non-permanent seats was increased from six to 10. More substantial reform has been on the agenda of the UN General Assembly (UNGA) since 1979, with no progress despite multiple initiatives. Vested interests and national rivalries have helped to ensure that meaningful reform keeps stalling. Regional blocs battle each other to a stalemate, and the reform process is effectively moribund. After several decades, countries have been unable to even agree on a negotiating text despite the best efforts of the world’s top diplomats.

As a result, it was only in December 1992 that UNSC reform was added to the UNGA agenda. In 1993, this resulted in the establishment of the Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG), and the provisional agenda of the 49th UNGA session included the item ‘Question of equitable representation on and increase in the membership of the Security Council and related matters’.[1A/RES/48/26 of 3 December 1993. The UNSG report dated 20 July 1993 set out the comments received from 75 member states on UNSC reform. See Doc A/48/264 of 20 July 1993.]

Subsequent decades would see numerous efforts at reform that have all come to nought, to the extent that the 2000 Millennium Summit, in its final document, could only commit ‘to intensify … efforts to achieve comprehensive reform of the Council in all its aspects.’ Ahead of the 2005 Summit, the UN Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, subsequently submitted two reform options in 2004 as part of the report from the High-Level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change – A more secure world: our shared responsibility. The two options contained in the 2005 In Larger Freedom report[2Plan A calls for creating six new permanent seats plus three new non-permanent seats, for a total of 24 seats in the council. Plan B calls for creating eight new seats in a new class of members, which would serve for four years, subject to renewal, plus one non-permanent seat, also for a total of 24. Former UN secretary-general Kofi Annan favoured making the decision quickly, and argued for a decision at the September 2005 Millennium+5 Summit.] advocated for an increase in membership from the current 15 to 24 members.[3Model A provides for six new permanent seats, with no veto being created, and three new two-year non-permanent seats. Model B provides for no new permanent seats but creates a new category of eight four-year renewable seats and one new two-year non-permanent (and non-renewable) seat. The composition of the UNSC would also be reviewed in 2020.]

Progress proved impossible, and the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document again limply committed leaders to ‘early reform of the Security Council … to make it more broadly representative, efficient and transparent and thus to further enhance its effectiveness and the legitimacy and implementation of its decisions’.[4UNGA, 2005 World Summit Outcome Document, par 153.]

In September 2007, it was agreed to start intergovernmental negotiations, the details of which were only finalised a year later in Decision 62/557. Part of this decision is the requirement for a solution that ‘can garner the widest possible political acceptance by Member States’.

Negotiations officially started early in 2009. Subsequent years saw the promising development of a 30-page ‘negotiation text’ based on submissions from member states, but that too led to an impasse.

In April 2015, after several months of consultations, the then chairperson of the intergovernmental committee on UNSC reform, Jamaican Ambassador E Courtenay Rattray, embarked on a clean slate approach. Instead of trying to end the impasse, he circulated a one-page ‘framework’ consisting of various headings that member states were requested to populate with their suggestions on reform, subsequently summarised in a 24-page consolidated framework document. The response to Rattray’s initiative was impressive, but opposition remained strong and the text was eventually abandoned. More recent efforts suffered the same fate despite widespread frustration with the frequent use of the veto by Russia after it invaded Ukraine.

In September 2024, heads of state adopted the UN’s Pact for the Future that again endorsed Security Council reform given the urgent need to make it ‘more representative, inclusive, transparent, efficient, effective, democratic and accountable’ as central to underpinning a ‘just, democratic, equitable, and representative’ multilateral system—particularly emphasising Africa’s historical underrepresentation whilst also pointing to that of Asia-Pacific and Latin America and the Caribbean. The Pact does not mention the removal of the veto, but refers to ‘limiting its scope and use’.

Over time, several negotiating groups have emerged, with some countries being active in two or more of these groups. These are as follows:

- Africa: Building on its previous position, as outlined in the Harare Declaration, the African Union (AU) presented its proposal, commonly referred to as the Ezulwini Consensus, in July 2005. The position calls for 11 additional members on the UNSC, taking it to 26, with Africa gaining two permanent seats and five non-permanent seats that would rotate between African states. The AU position is that new seats gain all existing privileges, including veto powers, and that the AU would determine the criteria for African members serving on the UNSC.

- G4 (Germany, Brazil, Japan and India): Delivered at the Intergovernmental Negotiations (IGN) on 15 April 2025, India's Permanent Representative reaffirmed the G4's core reform model: expand the Council from 15 to 25-26 members, comprising 11 permanent and 14-15 non-permanent seats. The six new permanent seats would consist of two for Africa, two for Asia-Pacific, one for Latin America and the Caribbean, and one for Western Europe and Others. The new permanent members would only gain veto powers after a review period (10-15 years post-reform) and be elected in the General Assembly.

- Uniting for Consensus (UfC): The grouping consists of 12-14 states, but its views are shared by 20-30 others that also do not want additional permanent seats, especially if it would include the veto. The group is generally led by Italy, and includes Spain, Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, Pakistan, South Korea, Turkey, Indonesia and others. During the March 2024 Intergovernmental Negotiations (IGN), the UfC introduced expanding rotating seats and an updated comprehensive model that maintains their opposition to new permanent seats, introduces longer and shorter regional seats, veto reform, more transparency, reviews and accountability and greater representation for Africa and the Small Island and Developing States (SIDS).

- The Small Islands and Developing States (SIDS)[5As of 2025, there are 38 UN member states and 20 non-UN members or associate members recognized as SIDS, grouped into three geographic regions: Caribbean (16 countries) namely Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Haiti, Jamaicam Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, Belize, Guyana. Pacific (12 countries) namely Fiji, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Micronesia (Federated States of), Nauru, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Timor-Leste, Tonga, Tuvalu. Atlantic, Indian Ocean and South China Sea (10 countries) namely Bahrain, Cabo Verde, Comoros, Guinea-Bissau, Maldives, Mauritius, São Tomé and Príncipe, Seychelles, Singapore, Sri Lanka. Non-UN Members and Associate Members (20 territories) including American Samoa, Anguilla, Aruba, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Cook Islands, French Polynesia, Guam, Montserrat, New Caledonia, Niue, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, Sint Maarten, Tokelau, Turks and Caicos Islands, U.S. Virgin Islands, Wallis and Futuna

These territories participate in regional SIDS coordination and often in forums such as the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) and the UN SIDS programme, even if they are not full UN member states.] actively advocate for an exclusive seat, given their shared climate and ocean matters, and have cross-cutting members serving on various other groups. - Groups such as the Small Five (S5), consisting of Costa Rica, Jordan, Liechtenstein, Singapore and Switzerland, and its successor, the 25-27-member ACT grouping (to improve Accountability, Coherence and Transparency), take a different approach. ACT avoids involvement in the debate on reforming and extending the membership of the Council, but rather on improving the working methods of the Council. In New York, Switzerland serves as the coordinating mission for the group.

The unsuccessful reform efforts have proven that there is no ‘sweet spot’ or consensus possible in the entrenched positions of the various negotiating blocks. Currently, a P5 member can prevent the adoption of any non-procedural UNSC resolution not to its liking. Even the threat of a veto may lead to changes in a resolution or to a resolution’s being withheld altogether. The result is frequently a rush to the lowest common denominator, with efforts to keep the P5 on board taking precedence over other considerations. These inefficiencies serve the interests of the P5 by enabling them to block action within the Council and giving them the freedom to act outside it in their national interests. The result is a dysfunctional and increasingly illegitimate system, with declining relevance and impact.

Since the UNSC is at the apex of the UN system, the power granted to the P5 cascades through every level of the organisation and its structures. Instead of protecting the weak against the strong, the anachronistic privilege of the veto undermines principled consensus. The veto regularly prevents the Council from acting on pressing international issues. It affords the P5 inordinate influence within the UN system as a whole, including the appointment of the UN Secretary-General and amendments to the UN Charter. It detracts from the legitimacy and effectiveness of the entire UN system and has hamstrung effective reform of the UN Human Rights Council, ECOSOC and the multitude of UN agencies and bodies.

Since it is largely the veto that makes the UNSC dysfunctional, it is difficult to argue for an increase in the number of states with this power.

Publicly, the P5 members keep a low profile on reform, given their preference for maintaining the status quo. They seek reform that will not dilute their privilege, and a global system that does not constrain their freedom of action. Thus, China and Russia profess support for reform, but practically undermine proposals that could dilute their privilege. The US, UK and France (the P3) typically emphasise the burden of responsibility and the need for adequate resources (diplomatic, military and other) required to fulfil their self-appropriated duties, although there have recently been some changes in the stance of the UK and France. For its part, the US administration under President Donald Trump has little but disdain for the UN and multilateralism generally.

Aspirant middle powers to permanent seats, such as Germany, India, Brazil and Japan, find their ambitions blocked by regional competitors (the Uniting for Consensus group in particular) and, in the case of Japan, by virulent opposition from China. Germany remains committed to a proposal that would see additional permanent European representation on a Council that already has two permanent seats from that region. Then there is the lack of agreement on a formula for expanding the Council to achieve greater regional balance, particularly for Africa and Latin America.

Most developing countries, including the African Group’s starting position, are that the veto should be abolished, but if it is retained, they insist that new permanent members should be accorded the same rights and privileges as existing permanent members.

This fragmentation in global security governance brings great uncertainty to an already fragile and divided world. It is a dangerous and unnecessary risk.

The UNSC’s inability to respond decisively to ongoing crises, from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to the war in Gaza and escalating climate-related threats, underscores its eroding authority and the urgent need for structural reform.

Currently, the UN has 193 member states that coexist, compete and cooperate in a world that is very different from the one that had emerged at the end of the Second World War. The world’s population has increased threefold. Regions such as Africa have evolved from colonies to independent states. Today, only the US and China occupy a global leadership role, and the current P5 no longer represent the primacy of economic and military power, population size or technological leadership.

The 21st century is also characterised by a diffusion of power away from states and a shift in material power and influence from countries bordering the North Atlantic to the Pacific and Indian oceans, also known as the ‘rise of the rest’. Some of these evolving trends are examined in the Africa in the World theme.

Chart 1 allows the user to view a forecast taken from the International Futures (IFs) forecasting platform using three different calculations of global power, essentially a measure of the percentage of the global total that accrues to any single country. The first two, the Global Power Index and the Hillebrand, Herman, Moyer index, measure the potential of material (or hard) power. The third, the Diplomatic, Military and Economic Power Index (DiME) includes soft power in its calculations. The visualisation starts in 1990, following the demise of the Soviet Union.

Irrespective of the weightings and exact composition of the indices in Chart 1, all three reflect the disproportionate power and influence of the US, China and eventually India towards the end of the century.

If these forecasts are generally reasonable, a reformed UNSC that does not include the US, China and eventually India will struggle to gain legitimacy and assert global leadership—but reform should not repeat the mistake made previously to give these countries a permanent seat and veto, as there is no guarantee of that future. Rather, reform should identify clear, verifiable criteria that separate Global Powers with inordinate material power and influence from others.

Currently, Article 4 of the UN Charter confines membership of the UN to states. It is, however, also possible that coalitions of states (such as Africa or Europe) may wish to have their engagement with the UNSC reflect deeper regional integration and the desire to act in concert at a global level. By way of illustration, Chart 2 depicts the history and forecast of the Global Power Index, also used in Chart 1, to compare the EU28 and Africa with China, India and the US from 1990 to 2100.

UNSC reform faces numerous obstacles. First is the challenge of accommodating the two Global Powers of the first part of the 21st century—the US and China, both of which are very comfortable with the veto power. Then there is the question of what happens to the UK, France and Russia, none of which are Global Powers.

Third is the challenge of eventually accommodating additional Global Powers (the previous section indicates that, on current forecasts, India is most likely to aspire to that status), and the practical need to bring regional leaders onto the Council, given the ongoing diffusion of power to regions such as Asia and Africa.

Given the increase in UN member states since 1945, a reformed council needs to be much larger. In the interests of effectiveness, responses from UN member states to the successive reform efforts over the years would indicate that an expanded Council should not exceed 27 members.

A reformed UNSC thus needs to balance three competing needs: legitimacy (representation and equity), functionality (size and efficiency) and realism (power matters), as reflected in Chart 3.

The three primary principles for reform imply that UNSC reform needs to balance geopolitical representation with the significant discrepancies between the power and influence of UN member states and do so in a manner that improves the capacity and effectiveness of the Council. This leads to difficult discussions about the criteria for elections to the UNSC. Some states resist any minimum criteria that could bar a country from standing as a candidate, insisting on the right of all states to contest for UNSC membership. Yet, more than 60 UN member states have never been on the UNSC, and many have never contested for membership, indicating a limited ambition in this regard, and perhaps a recognition of the limited capacity of small and micro states to contribute to international peace and security.

Various groups engaged in reform are concerned that a Council composed of only larger states will not serve their interests. It is nevertheless important to recognise the large disparities in population and economic size among UN members. For example, it is theoretically possible for 129 states (many of which are island states or micro states like Tuvalu, Nauru, St. Kitts and Nevis and Bhutan) with a combined 8% of the global population to command a two-thirds vote in the UNGA—or for 65 states with less than 1% of the global population to block a substantive vote requiring a two-thirds majority in the UNGA. The disparities in economic size (and income levels) are even larger. These differences in population and economic size would be a huge obstacle to reform if all states were part of a single electoral college. However, the potential dictatorship of minorities is constrained by the system in which states are currently grouped in five regions for UNSC electoral purposes.

If the UNSC is supposed to respond to international peace and security matters, its composition requires membership from states with commensurate capacity, implying minimum criteria for UNSC membership—and the importance of ensuring that Global Powers (and countries that in future may wish to act in concert) are included.

The diffusion of power from the countries bordering the North Atlantic to regions such as Asia and Africa, and the increase in UN member states, greater complexity and larger populations require a means to ensure that regional powers (however they are defined) also to be considered, though the latter inevitably requires the consent of the majority of countries in that region. This can be done by allowing a limited number of seats to be immediately renewable.

From this context, six key conclusions inform proposals for a UNSC fit for the future:

- The need for a much larger UNSC.

- The UNSC must include behemoths such as the US and China and incentivise their inclusion. These powerful countries bear a disproportionate responsibility in global affairs, and their votes should count for more than one, but no country should have a veto.

- Should coalitions of states (such as Africa or Europe) wish to have their engagement with the UNSC reflect their desire for deeper regional integration and to act in concert at a global level, they should be allowed to consolidate their representation on the Council by also being able to qualify for global power status. One country (or an organisation such as the EU or AU Commission) would then represent that group.

- Global powers (or coalition members) should not participate in elections for other UNSC members in the General Assembly to avoid undue extension of their influence.

- A distinction may need to be made between regional leaders and other states from the same region desiring to serve on the UNSC to encourage a more cooperative approach to relations, candidacy and in supporting subsequent action by the Council. Such recognition reflects the extent to which regional cooperation and agency have become characteristic of changes in international relations and could consist of a limited, renewable membership category.

- States that serve on the UNSC should have a minimum capacity (such as the number of embassies, particularly in conflict-affected areas) and a track record if they are to contribute to global peace and security issues.

- Similar to states that are elected to the UNSC, Global Powers (or coalitions) would be expected to make additional contributions to the UN peace and security budget.

Outside of the UNSC, most modern treaty-based arrangements are based on ‘one country, one vote’. This is a general electoral and representative norm that is far more widely established today than in 1945, when the UN Charter was signed. Thus, except for the new category of Global Powers, all UNSC members would be elected in the General Assembly, with the following four technical requirements for candidacy:

- Experience (i.e. peacekeeping deployment, engagement in humanitarian support, conflict resolution and participation in peacebuilding) and capacity (i.e. resources such as diplomatic missions globally and in conflict-affected regions);

- In financial good standing with the UN and its agencies;

- Willingness to shoulder additional financial contributions to UN efforts on international peace and security;[6Peace operations are funded by assessments, using a formula derived from the regular funding scale that includes a weighted surcharge for the P5 members, which must approve all peacekeeping operations. This surcharge serves to offset discounted peacekeeping assessment rates for less developed states. for the period 2025 to 2027 the scales are contained in the addendum to the report of the Secretary-General (A/79/318/Add.1, annex), and adopted by the Assembly in its resolution 79/250 of 24 December 2024.]

- Respect for open, inclusive and accountable governance, the rule of law and international human rights standards.

The current five electoral regions would be expected to identify candidates from their region using whichever practices they deem suitable, such as rotation, competition, additional regional criteria, etc. and then present the candidates to the UNGA for election by simple majority, in line with current practice.[7The formula for regional groups for the purposes of election to the UNSC is set out in UN General Assembly (UNGA) Resolution 1991 (XVIII), which was adopted in 1963 and took effect in 1965. Under that resolution, the five seats originally corresponding to the African and Asia-Pacific states were combined. In reality, the candidates for election to the African seats (three) and Asia-Pacific seats (two) operate separately. The current non-permanent seats allocate one seat for the GRULAC group; two seats every even calendar year for the WEOG (competition is open between various subgroups consisting of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden), the CANZ (Canada, Australia and New Zealand) and Benelux (Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands); one seat for the EEG every odd calendar year; three seats for the African Group with its five subregions; and two seats for the Asia-Pacific Group/Group of Asia and the Pacific Small Island Developing States. An Arab swing seat is based on an informal agreement whereby the Asia Pacific and Africa groups take turns every two years in providing a suitable candidate from the Arab League.] An important consideration to be borne in mind is that the current electoral regions differ in size, ranging from 54 (in the Africa group) to 23 members (in the Eastern European Group), which requires agreements between groups to share seats as well as the associated inter-regional voting arrangements during elections. An additional complication is the demand for acknowledgement of cross-regional interest groups such as the SIDS and the Arab Group. These complications may imply that UN member states may wish to consider revising the membership of the current five voting regions.

Three proportional measurements (such as 3% of the global population, 5% of global GDP at market exchange rates and contributing 5% of the UN budget) would suffice in distinguishing Global Powers and coalitions vying for global power status from other influential states. They would automatically qualify for an UNSC seat whilst meeting all three criteria. Each of their votes in the Council would count for three, but they would not have a veto. Chart 5 depicts a summary of membership requirements.

States or state groupings that qualify for membership in terms of the Global Powers criteria would be excluded from participating in the election of other states to the UNSC. For example, assuming China and the US qualify for automatic membership, the 191 remaining UNGA countries may decide to elect one state to the UNSC for every 8 countries, translating into 24 elected seats but necessitating complex inter-regional arrangements in the interests of equity. Regions may further decide that some of these seats (say one per region) may be immediately re-electable or rotate on an agreed internal arrangement in the interest of long-term stability in regional representation.

The UNSC would then consist of around 24 states elected on a proportional basis, plus the two states that qualify as great powers due to their size and influence, translating into 30 votes (24 individual votes plus six votes from the two great powers). Chart 6 shows the current versus proposed UNSC characteristics.

Both substantive and procedural decisions within the UNSC would require a two-thirds affirmative majority. A two-thirds affirmative vote with all members present and voting would therefore require 20 votes.

Similar to current provisions, parties to a conflict serving on the UNSC would have the right to be heard but may not vote.

There are several intractable issues (such as Israel/Palestine) that could block any proposed UNSC reforms. The outgoing UNSC should therefore be asked to compile a list of intractable issues that, for a period of up to 30 years, would not be subject to an additional Chapter VII UNSC resolution beyond the renewal and revision of existing mandates.

Chapter VII governs UNSC action on threats to peace and acts of aggression. It empowers the Council to make recommendations and decisions to maintain or restore international peace and security, and may call upon UN members to apply economic sanctions, interruption of communications or severance of diplomatic relations. Should these measures be inadequate, the UNSC may take action in terms of Chapter VII by air, sea or land forces as necessary to maintain or restore international peace and security.

The UNGA should undertake a mandatory review of the functions, role, composition and rules of procedure of the UNSC every 30 years. This review should be concluded within three years and would be done based on a self-reflective report and recommendations prepared and finalised by the UNSC. The report would be adopted through the normal voting procedures of the UNSC and then submitted for consideration, comment, discussion and possibly remedial action by the UNGA.

Should this process not reach a conclusion within three years (including approval of changes to the UN Charter, if required), the matter under contention would be subject to binding arbitration by the International Court of Justice, which would be required to resolve the matter within one year. If the results of the arbitration required an amendment to the UN Charter, that amendment would be passed by a simple majority of the members of the UNGA and at the national level by more than half of UN members.

Article 30 of the UN Charter stipulates that the UNSC shall adopt its own rules of procedure. The Council did so in 1946 when it adopted its Provisional Rules of Procedure (S/96), which continue to be provisional although they have been amended several times.

The UNSC should provisionally adopt and recommend by a two-thirds majority the draft rules of procedure to the UNGA, doing so within one year of the enabling UNGA resolution. The UNGA would be required to approve these rules of procedure by a two-thirds majority vote of member states within one year after receipt of the draft. Pending such approval, the UNSC should be allowed to operate based on the draft rules of procedure. Should the UNSC be unwilling or unable to submit draft rules of procedure to the UNGA, the latter should finalise and adopt, by a simple majority, its version of the rules to which the UNSC shall adhere.

If no agreement could be reached within the UNGA within an additional year, the issue should be referred to the International Court of Justice for a final and binding decision on appropriate Rules of Procedure.

A member of the UNSC could be suspended from membership by a supermajority of 80% of votes if considered in flagrant violation of the UN Charter. Such suspensions should be reviewed annually.

The recommendations listed in this theme imply amendments to Articles 23 to 32, and Article 109 of the UN Charter.

Chapter XVIII details two methods to amend the Charter:

- Article 108: This is the more direct route for individual amendments. An amendment is adopted by a vote of two-thirds of the members of the General Assembly. However, for the amendment to enter into force, it must be ratified by two-thirds of the UN member states, including all five permanent members of the Security Council.

- Article 109 provides for the convening of a General Conference to review the Charter. Such a conference can be called by a two-thirds vote of the General Assembly and a vote of any nine members of the Security Council. Any alterations to the Charter proposed by the conference would then require ratification by two-thirds of the member states, again including all five permanent members of the Security Council. While this mechanism was envisioned for broader revisions, it has never been utilised.

Whichever model the member states agree on, the bar to reform as set out in Chapter XVIII makes it extremely difficult to envision progress, given the required ratification by each of the P5 members. However, without reform of the Council, the entire UN system becomes increasingly irrelevant, with potentially disastrous consequences for regions such as Africa, Latin America and the Middle East. The impasse on UNSC reform also blocks reform at many other levels, including the Secretariat, the UN General Assembly (UNGA), the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) and the Human Rights Council. It also threatens the legitimacy and efficacy of other important global institutions, such as the International Criminal Court (ICC). The result is an organisation divided between the power of the majority, the veto and the power of the purse.

In the absence of reform, a country such as India may eventually decide to cease support and collaboration with the UNSC or for non-permanent members to walk out of the Council.

There can be no real UN reform without changes to the UNSC. The Council is at the apex of UN functionality; thus, a reformed Council will unlock many other gains in the organisation and its associated structures and agencies. Secretary-General António Guterres has been forthright about this. In June 2025, his views were echoed by Ban Ki-moon and Helen Clark, who wrote: ‘Largely due to its veto-wielding five permanent members, the council has failed to prevent many conflicts over the decades. Worse still, its permanent members have been directly involved in several of these conflicts …’

The current UNSC still has significant legitimacy and serves as a primary shock absorber through which the international community can confront shared challenges and responsibilities. It remains the only executive body on international peace and security issues, and its decisions are binding. But one cannot assume that this situation will continue indefinitely.

An interdependent yet increasingly divided world needs a new and different approach that prioritises global concerns over national interests. The current deadlock in intergovernmental negotiations underscores the need for a bold departure from past efforts.

There will never be a perfect moment to change the UNSC. Reform is long overdue, and the need becomes greater as global interdependence (and tensions) accumulate. The longer it takes, the more difficult it will become to implement change in an increasingly turbulent, interconnected and dynamic world characterised by rapid shifts in power. A Council based on principle and electoral mechanisms, reflecting today’s power and population dynamics, could provide such an approach. It will likely result in a more cautious UNSC than one dominated by Western powers, but one whose authority and decisions will carry far greater force and legitimacy.

Endnotes

A/RES/48/26 of 3 December 1993. The UNSG report dated 20 July 1993 set out the comments received from 75 member states on UNSC reform. See Doc A/48/264 of 20 July 1993.

Plan A calls for creating six new permanent seats plus three new non-permanent seats, for a total of 24 seats in the council. Plan B calls for creating eight new seats in a new class of members, which would serve for four years, subject to renewal, plus one non-permanent seat, also for a total of 24. Former UN secretary-general Kofi Annan favoured making the decision quickly, and argued for a decision at the September 2005 Millennium+5 Summit.

Model A provides for six new permanent seats, with no veto being created, and three new two-year non-permanent seats. Model B provides for no new permanent seats but creates a new category of eight four-year renewable seats and one new two-year non-permanent (and non-renewable) seat. The composition of the UNSC would also be reviewed in 2020.

UNGA, 2005 World Summit Outcome Document, par 153.

As of 2025, there are 38 UN member states and 20 non-UN members or associate members recognized as SIDS, grouped into three geographic regions: Caribbean (16 countries) namely Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Haiti, Jamaicam Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, Belize, Guyana. Pacific (12 countries) namely Fiji, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Micronesia (Federated States of), Nauru, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Timor-Leste, Tonga, Tuvalu. Atlantic, Indian Ocean and South China Sea (10 countries) namely Bahrain, Cabo Verde, Comoros, Guinea-Bissau, Maldives, Mauritius, São Tomé and Príncipe, Seychelles, Singapore, Sri Lanka. Non-UN Members and Associate Members (20 territories) including American Samoa, Anguilla, Aruba, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Cook Islands, French Polynesia, Guam, Montserrat, New Caledonia, Niue, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, Sint Maarten, Tokelau, Turks and Caicos Islands, U.S. Virgin Islands, Wallis and Futuna

These territories participate in regional SIDS coordination and often in forums such as the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) and the UN SIDS programme, even if they are not full UN member states.

Peace operations are funded by assessments, using a formula derived from the regular funding scale that includes a weighted surcharge for the P5 members, which must approve all peacekeeping operations. This surcharge serves to offset discounted peacekeeping assessment rates for less developed states. for the period 2025 to 2027 the scales are contained in the addendum to the report of the Secretary-General (A/79/318/Add.1, annex), and adopted by the Assembly in its resolution 79/250 of 24 December 2024.

The formula for regional groups for the purposes of election to the UNSC is set out in UN General Assembly (UNGA) Resolution 1991 (XVIII), which was adopted in 1963 and took effect in 1965. Under that resolution, the five seats originally corresponding to the African and Asia-Pacific states were combined. In reality, the candidates for election to the African seats (three) and Asia-Pacific seats (two) operate separately. The current non-permanent seats allocate one seat for the GRULAC group; two seats every even calendar year for the WEOG (competition is open between various subgroups consisting of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden), the CANZ (Canada, Australia and New Zealand) and Benelux (Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands); one seat for the EEG every odd calendar year; three seats for the African Group with its five subregions; and two seats for the Asia-Pacific Group/Group of Asia and the Pacific Small Island Developing States. An Arab swing seat is based on an informal agreement whereby the Asia Pacific and Africa groups take turns every two years in providing a suitable candidate from the Arab League.

Page information

Contact at AFI team is Jakkie Cilliers

This entry was last updated on 29 November 2025 using IFs v8.38.

Reuse our work

- All visualizations, data, and text produced by African Futures are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

- The data produced by third parties and made available by African Futures is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

- All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Cite this research

Jakkie Cilliers (2026) UN Security Council. Published online at futures.issafrica.org. Retrieved from https://futures.issafrica.org/thematic/19-un-security-council/ [Online Resource] Updated 29 November 2025.