Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

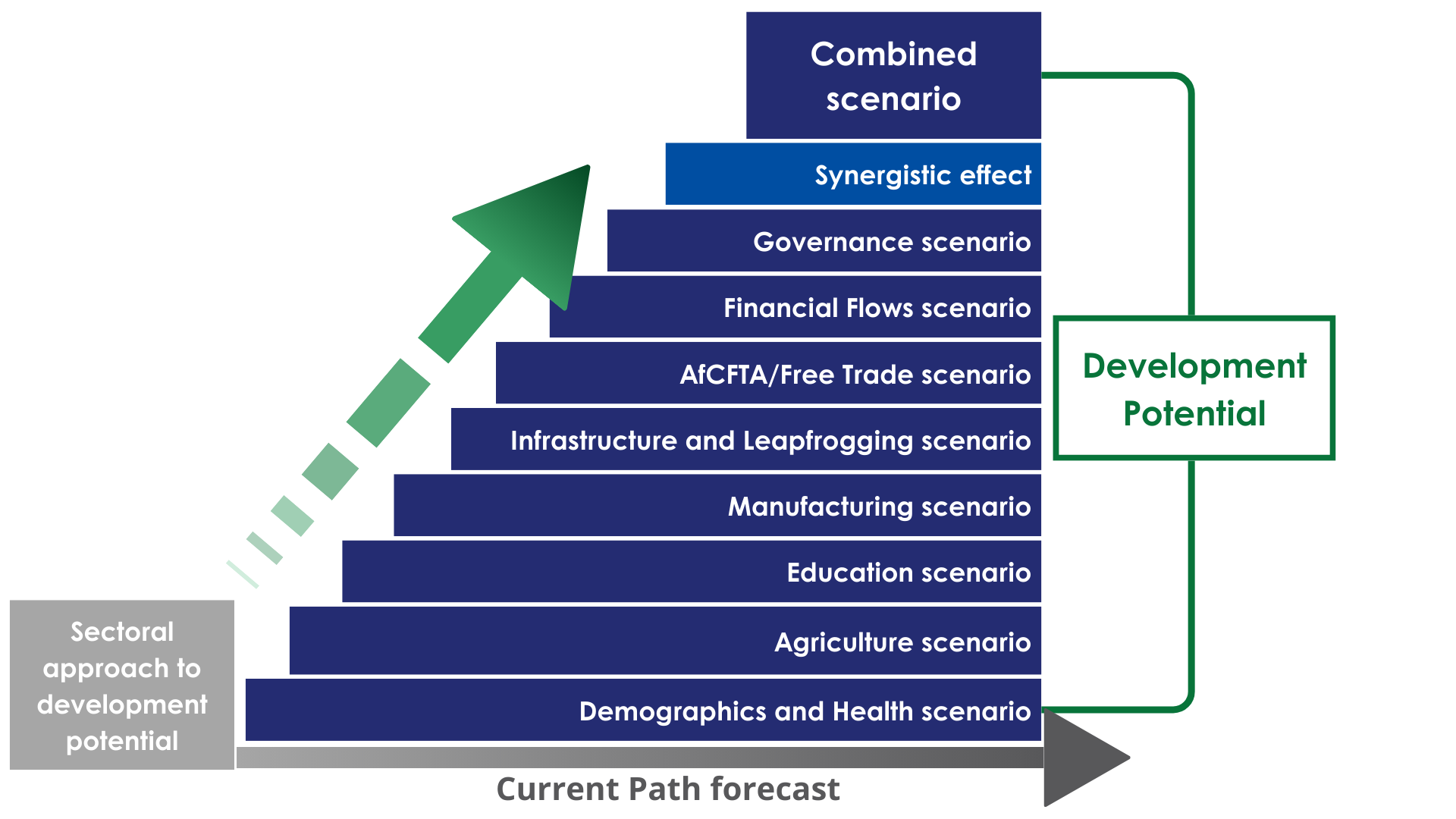

This page explores Zimbabwe's current and projected future development, examining various sectoral scenarios and their potential impacts on the country's growth and development. It explores eight individual sectoral scenarios: demographics and health, agriculture, education, manufacturing, infrastructure and leapfrogging, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), financial flows and governance. Additionally, it evaluates the combined impact of these scenarios on Zimbabwe’s economic growth and development up to 2043, marking the conclusion of the third ten-year implementation plan for the African Union Agenda 2063. The analysis provides insights into policy measures that could strengthen the country's development path.

The report is divided into five sections. The first section introduces the country by providing its geographical location, social structure and political history. The second section outlines the Current Path for Zimbabwe, which unfolds through 2043. This Current Path is based on country-level data sourced from various reputable data sources, focusing on prioritising data from national sources. It covers key growth and development factors, including demographics, real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in market exchange rates (MER), informal economy, real GDP per capita, poverty levels, and the National Development Plan (NDP). The third section presents individual sectorial scenarios outlining potential improvements in the eight key sectors mentioned above. The fourth section is divided into two parts. The first part analyses the impact of individual and combined scenarios on economic growth, specifically real GDP in purchasing power parity (PPP) and poverty alleviation. The second part examines the impact of the combined scenario on various factors, including real GDP per capita at MER, value-add by sector, the informal economy, life expectancy, income inequality, carbon emissions, and energy distribution. The report concludes in the final section.

For more information about the International Futures modelling platform we use to develop the various scenarios, please see About this Site.

Summary

We begin this page with an introductory assessment of the country’s context by looking at current population distribution, social structure, climate and topography.

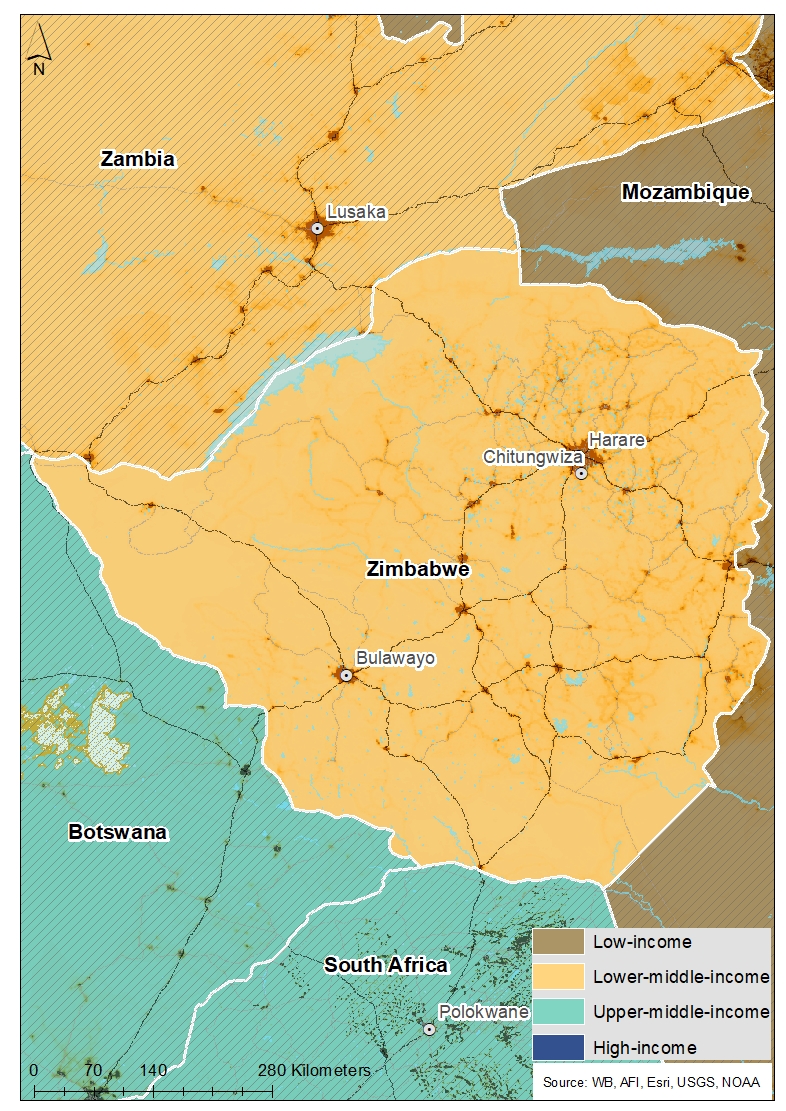

- Zimbabwe is a landlocked country in Southern Africa, classified as a lower-middle-income country, with a total land area of 390 757 square kilometres (km²). It shares borders with Zambia to the northwest, Mozambique to the east and northeast, South Africa to the south, and Botswana to the southwest. The country possesses abundant natural resources and fertile land suitable for agriculture. As of 2024, the agricultural sector employed 70% of the population, making it the largest employer, particularly in rural areas. This sector plays a crucial role in poverty alleviation and rural development. Besides agriculture, Zimbabwe's economy also relies on mining and the informal sector. However, to fully capitalise on these economic sectors and drive structural transformation, the country must enhance beneficiation and governance reforms.

This section is followed by an analysis of the Current Path for Zimbabwe, which informs the country’s likely current development trajectory to 2043. It is based on current geopolitical trends and assumes that no major shocks would occur in a ‘business-as-usual’ future.

- Zimbabwe’s population structure is characterised by a youthful and growing population, with a high proportion of children (under 15 years) and a gradually increasing working-age population (15-64 years). By 2023, the total population was estimated at 16 million, with 41% under the age of 15 and 56% in the working-age category. Around 33% of the population resided in urban areas, while the remaining 67% lived in rural areas. In the Current Path (business-as-usual) scenario, the population will grow at an average annual rate of 2%, reaching approximately 24 million by 2043. This trajectory will be mainly driven by declining fertility rates and increasing life expectancy.

- Zimbabwe's economy has undergone significant fluctuations, shifting between periods of prosperity, crisis and recovery. Following its recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, the country's GDP reached US$19 billion in 2023. The Current Path presents a cautiously optimistic outlook, projecting an average annual GDP growth rate of 5% between 2023 and 2030, which will raise GDP to US$27 billion by 2030. If the growth rate accelerates to 7% annually between 2031 and 2043, GDP will potentially reach US$68 billion by 2043. However, this projection indicates that Zimbabwe is unlikely to achieve its Vision 2030 target of an annual GDP growth rate between 7% and 10% unless the interventions outlined in this report are effectively implemented.

- On the Current Path, Zimbabwe’s GDP in purchasing power parity (PPP) will increase from US$2 190 in 2023 to approximately US$2 580 by 2030 and further rise to around US$4 400 by 2043. These forecasts are based on an annual average growth rate of about 2.3% between 2023 and 2030, followed by a growth rate of 4.2% per year from 2031 to 2043.

- In 2023, the informal sector accounted for 40% of employment and 54% of GDP. Though its share of both employment and GDP will decline to 35% by 2043 on the Current Path, it will remain a critical component of the economy and a key source of livelihood.

- On the Current Path, extreme poverty affected 35% of the population (5.6 million people) in 2023. While absolute numbers may rise slightly to 5.7 million by 2030, representing 30% of the population, improvements are projected by 2043, with extreme poverty affecting 18% (4.3 million people). These statistics are concerning, especially when considering that in 1998, only 0.96 million people lived in extreme poverty, accounting for just 8% of the population.

- The National Development Strategy 1 (NDS1) aims to build on the achievements of the Transitional Stabilization Programme (TSP) and guide Zimbabwe toward achieving Vision 2030, transforming the country into an upper-middle-income economy. Beyond 2030, the focus will shift to economic modernisation and long-term prosperity by 2043.

The next section compares progress on the Current Path with eight sectoral scenarios. These are Demographics and Health; Agriculture; Education; Manufacturing; the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA); Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging; Financial Flows; and Governance. Each scenario is benchmarked to present an ambitious but reasonable aspiration in that sector.

- Sustained policy focus and increased investment in Demographics and Health scenario will reduce the infant mortality rate from 37 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2023 to 27 and 15 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2030 and 2043, respectively. This trend suggests that the country will achieve the Sustainable Development Goal 3.2 target of reducing infant mortality to below 25 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2032. However, if Zimbabwe remains on the Current Path, this milestone would be delayed until 2040.

- Enhancing domestic crop production capacity through targeted interventions in the Agriculture scenario can boost crop yields, strengthening the resilience of Zimbabwe’s agricultural sector. As a result, in this scenario, agriculture import dependence will decrease to 31% by 2043, a significant drop from the 53% on the Current Path.

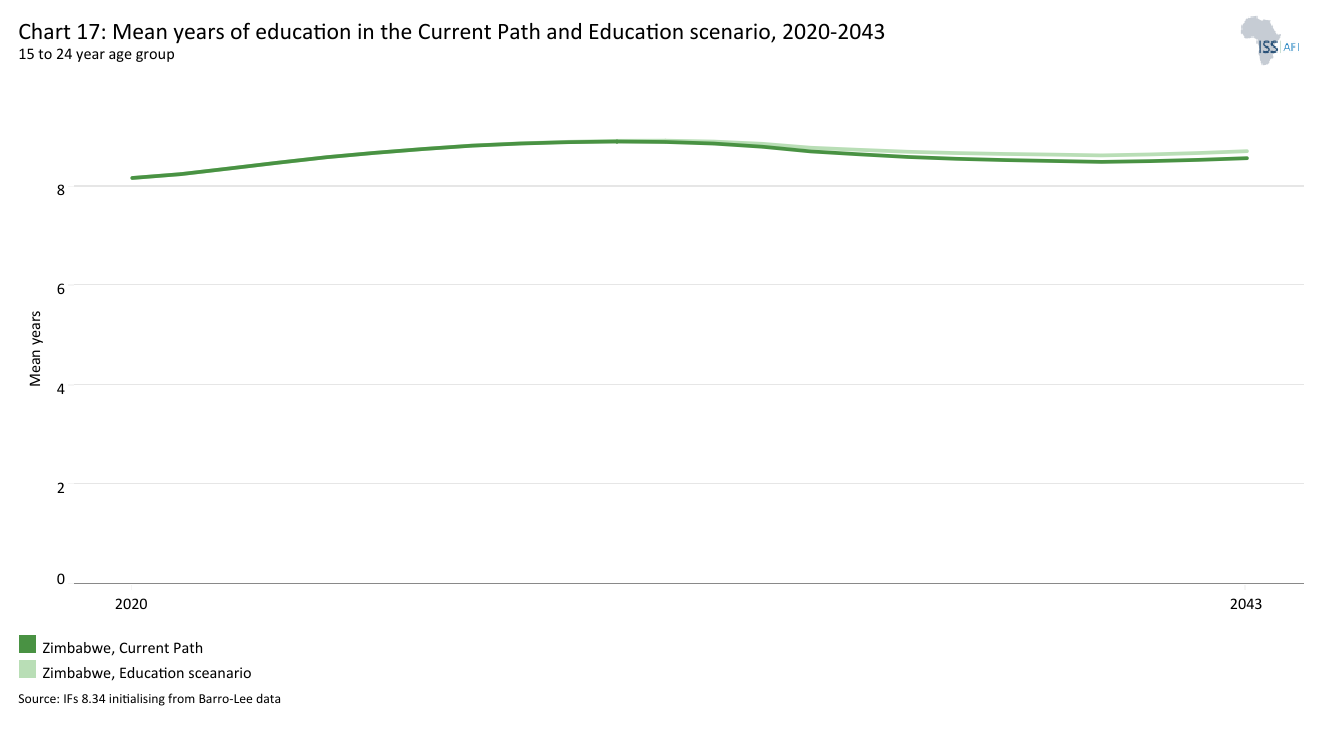

- The country's education sector faces several significant challenges, including inadequate infrastructure (both hard and soft), a shortage of teachers and insufficient funding, all of which stem from political and economic instability. The interventions proposed in the Education scenario aim to address these issues. Consequently, under this scenario, the average educational attainment for the lower youth age group (15-24 years) will reach 8.7 years, slightly higher than the 8.6 years on the Current Path. The average educational attainment for adults aged 15 and older will increase to 11.4 years by 2043 in the Education scenario, compared to 11.3 years on the Current Path.

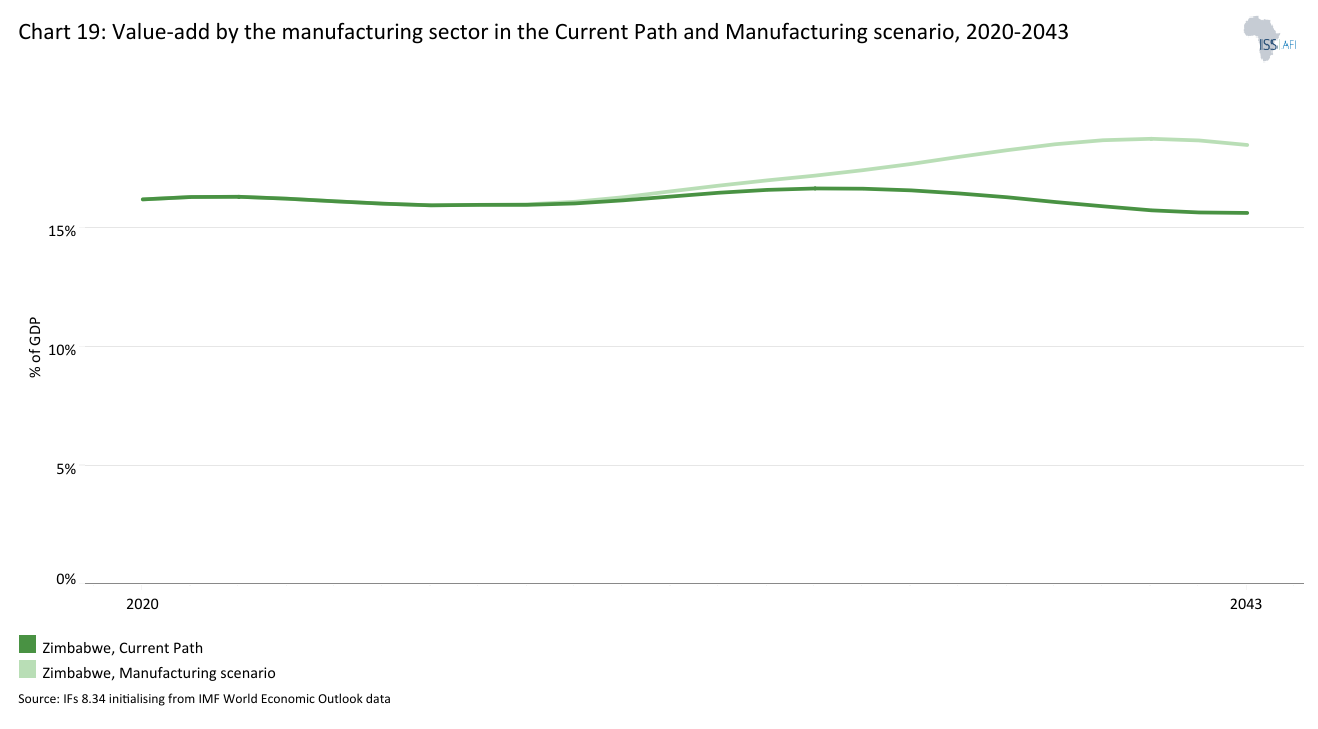

- Zimbabwe's business regulatory environment and industrial development outlook indicate substantial potential for growth in the manufacturing sector. This growth is dependent on factors such as political stability, institutional reforms, investment in research and development (R&D), and initiatives in beneficiation. By implementing these measures, Zimbabwe's manufacturing sector will experience a revitalisation, with its contribution to GDP increasing from 15.6% on the Current Path to 18.5% by 2043 in the Manufacturing scenario. The Manufacturing scenario, thus, places Zimbabwe's manufacturing sector share above the average of 17.2% for lower-middle-income African countries by 2043.

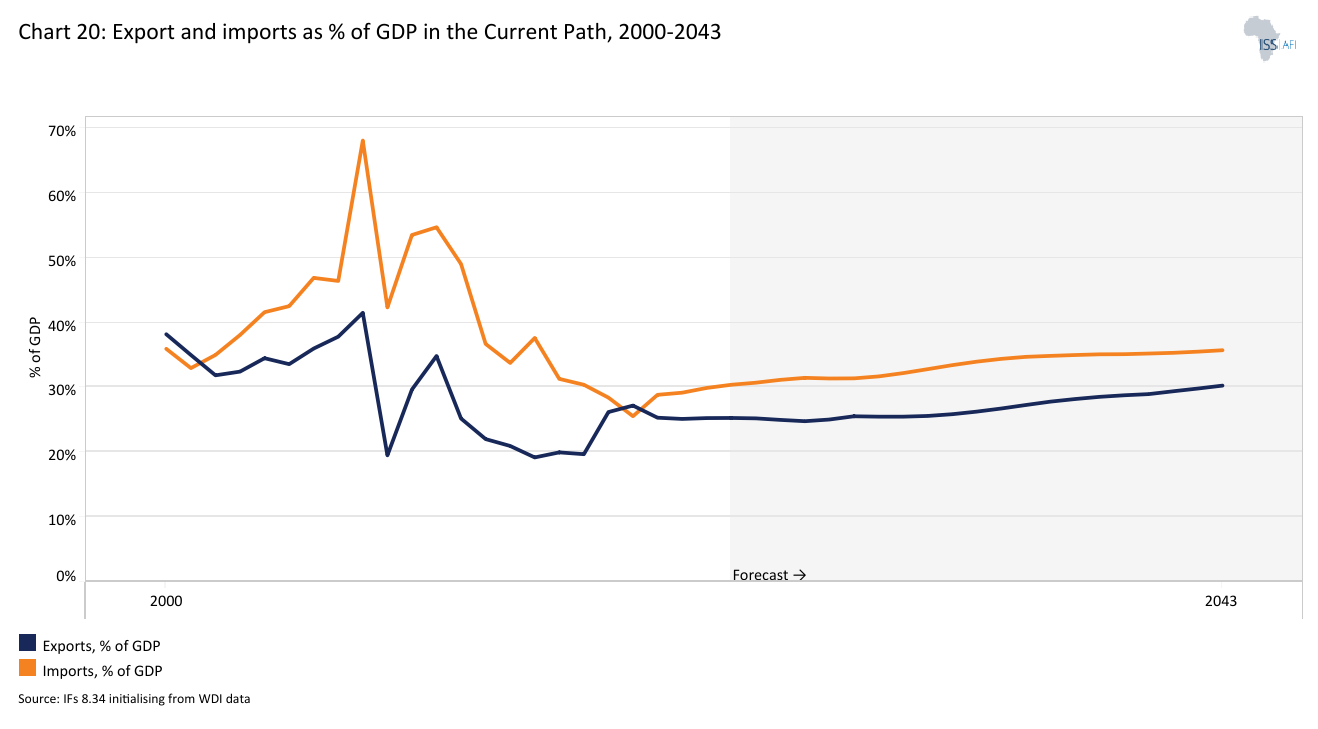

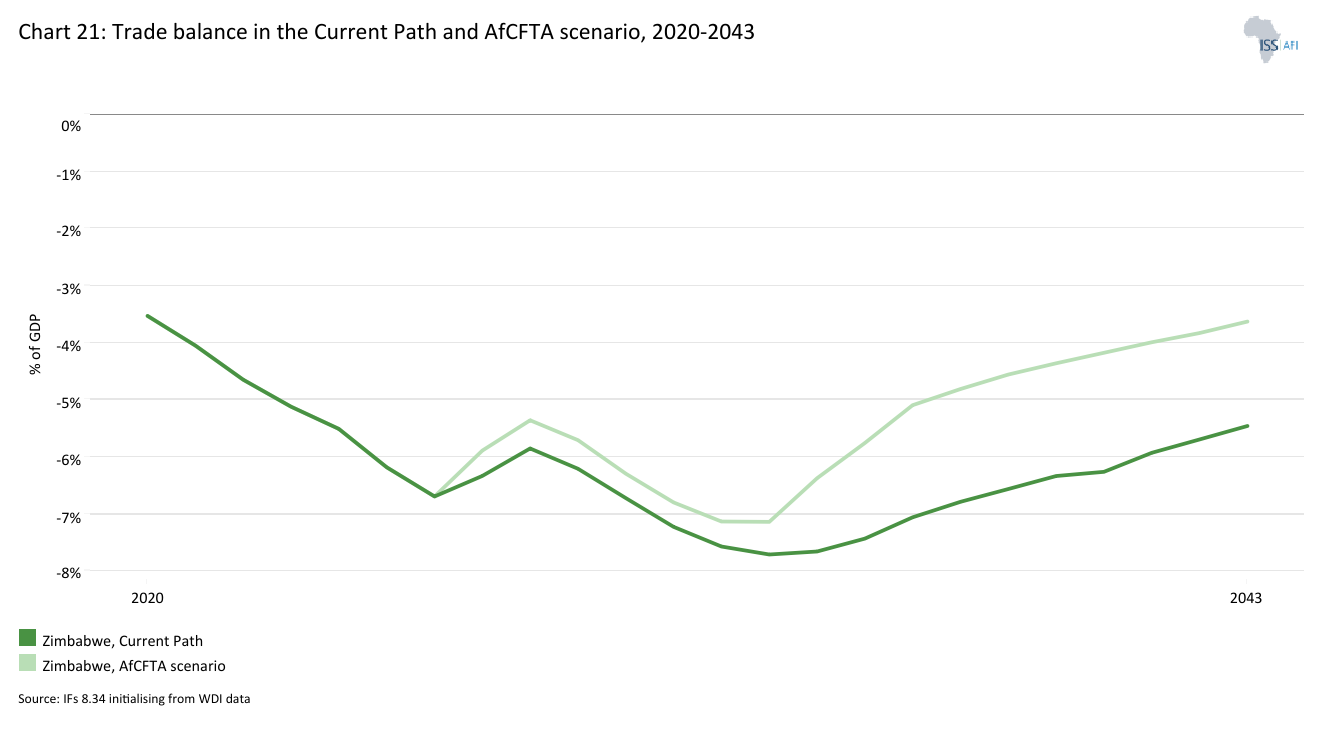

- Interventions in the AfCFTA scenario aim to ensure that export growth matches the increase in imports, helping to maintain a favourable trade balance. If these interventions are effectively implemented, Zimbabwe's trade deficit could decrease to 3.6% of GDP by 2043 in the AfCFTA scenario, compared to 5.5% on the Current Path. In terms of sectoral impact, these interventions will significantly boost export growth in materials, followed by services, agriculture, ICT and energy. However, manufacturing exports will be adversely impacted, indicating a crowding-out effect.

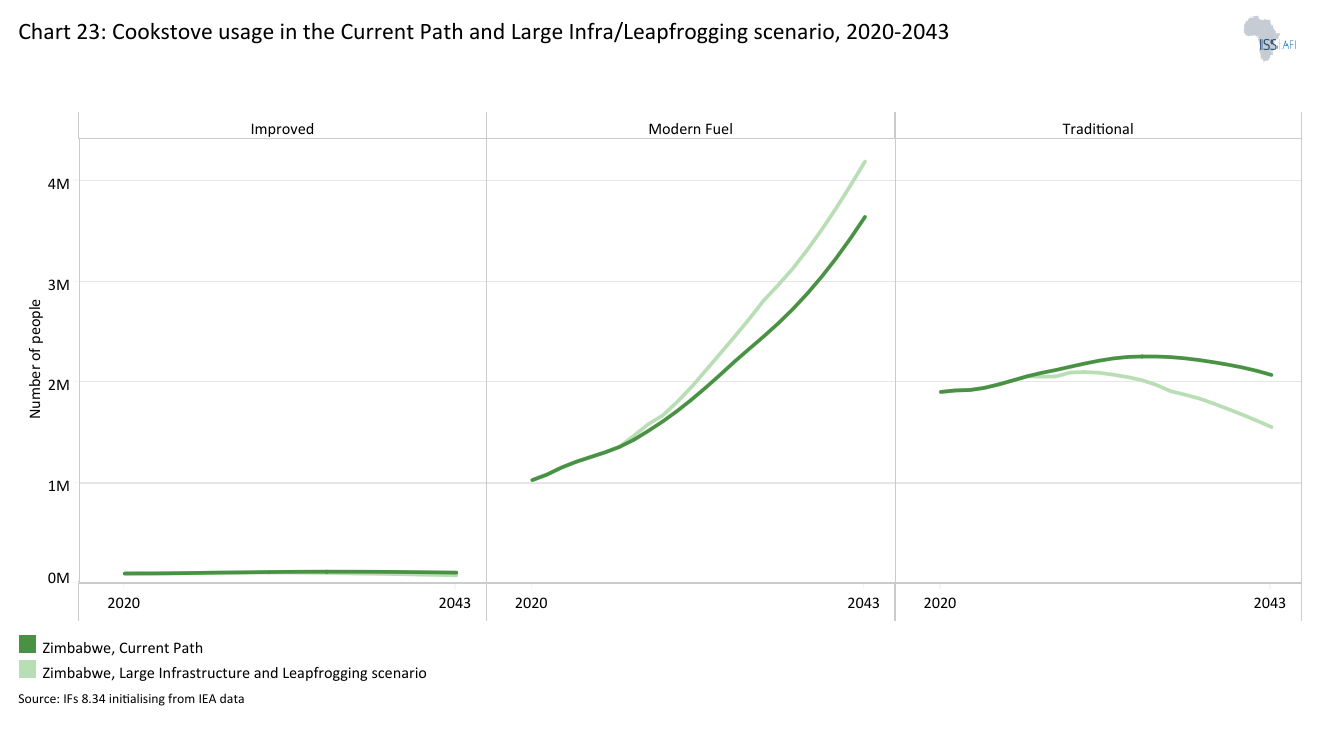

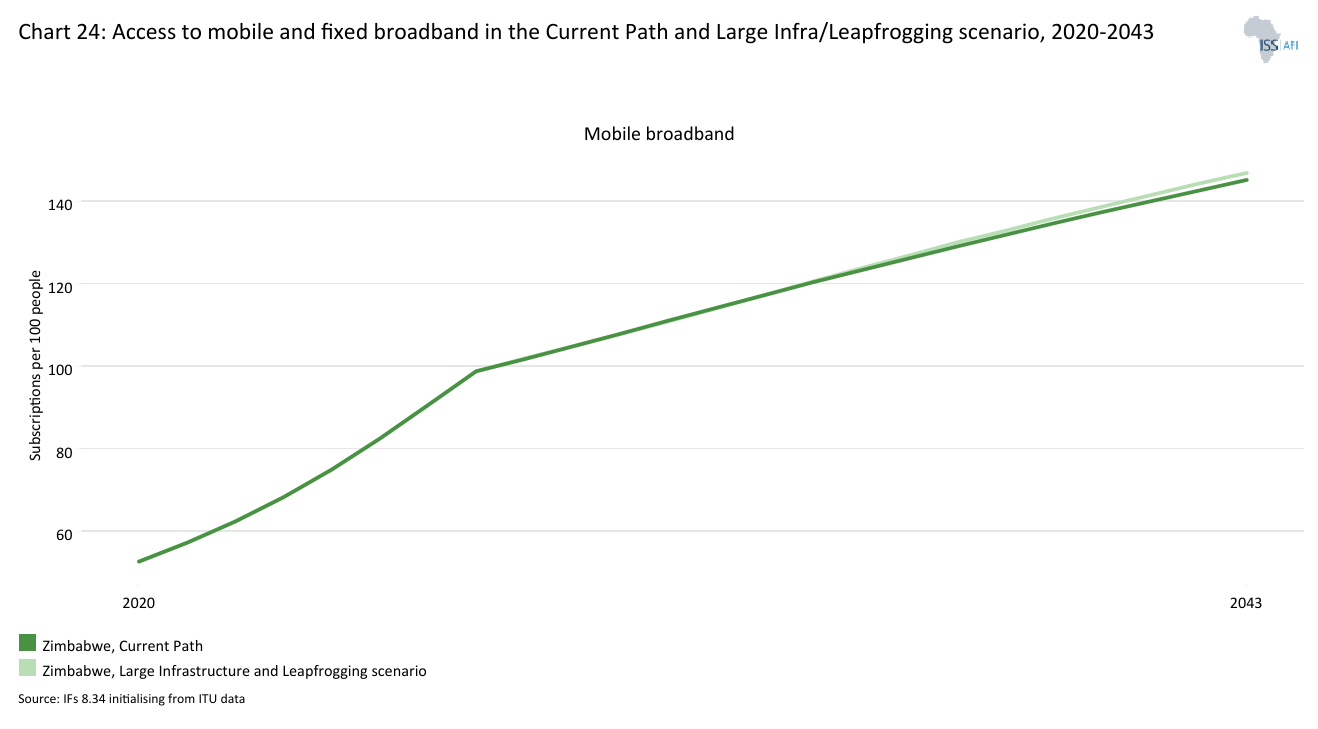

- Zimbabwe’s advancements in energy, transportation, clean cooking technologies and digital connectivity highlight its steady progress toward sustainable development and modernisation. With government incentives and global sustainability efforts promoting clean cooking, Zimbabwe will achieve near-universal access to clean and efficient cookstoves by 2043, with approximately 72% of households (4.2 million people) using modern fuel-powered cookstoves in the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario, compared to 63% (3.7 million people) on the Current Path. Additionally, interventions in the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario will boost mobile and fixed broadband subscriptions to 147 and 6 per 100 people, respectively, in 2043. This compares to 145.3 mobile and 28.7 fixed broadband subscriptions per 100 people on the Current Path by 2043.

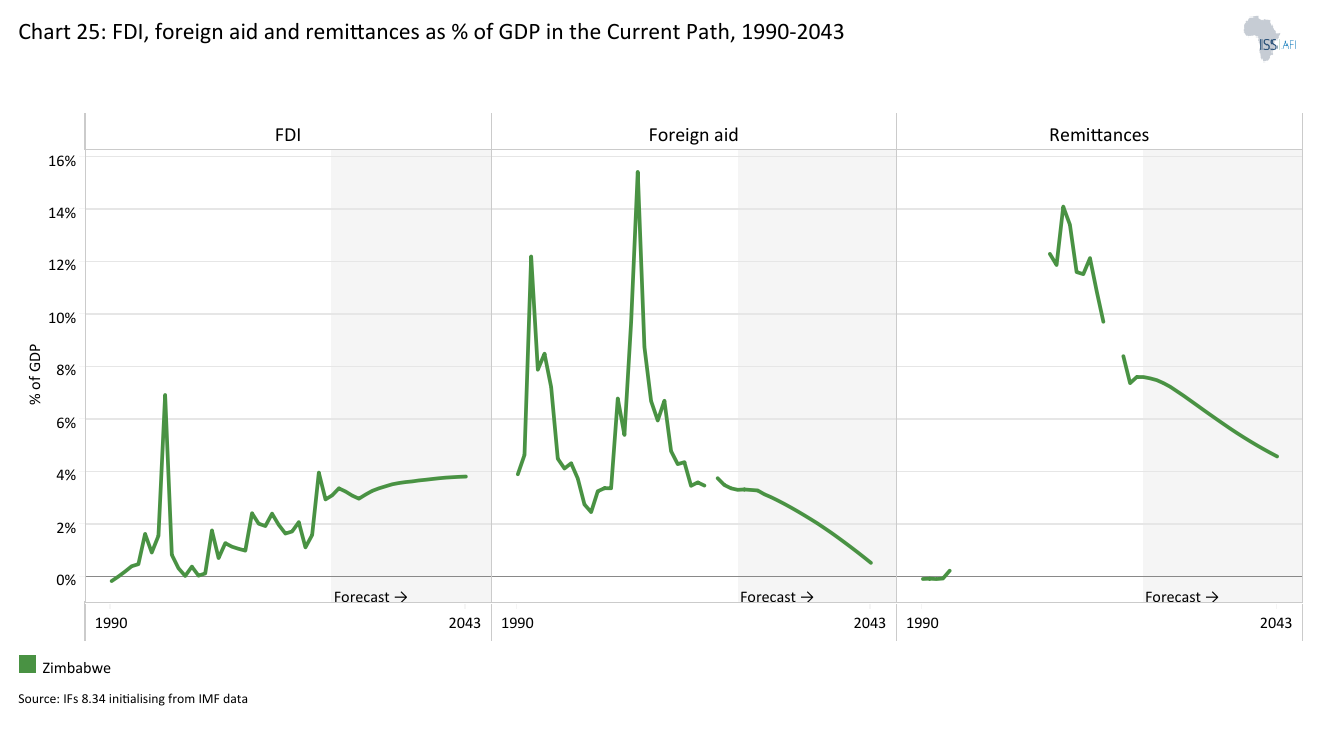

- Zimbabwe's economic outlook remains cautiously optimistic, with significant progress expected in debt reduction, government revenue collection, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and decreased reliance on financial aid. In the Financial Flows scenario, FDI will increase from 3.1% of GDP in 2023 to approximately 5% by 2043, compared to just 3.8% on the Current Path. These measures will also play a crucial role in reducing Zimbabwe's dependence on financial aid, with aid receipts as a share of GDP dropping from 3% in 2023 to 0.5% by 2043 in the Financial Flows scenario, slightly lower than the 0.6% on the Current Path.

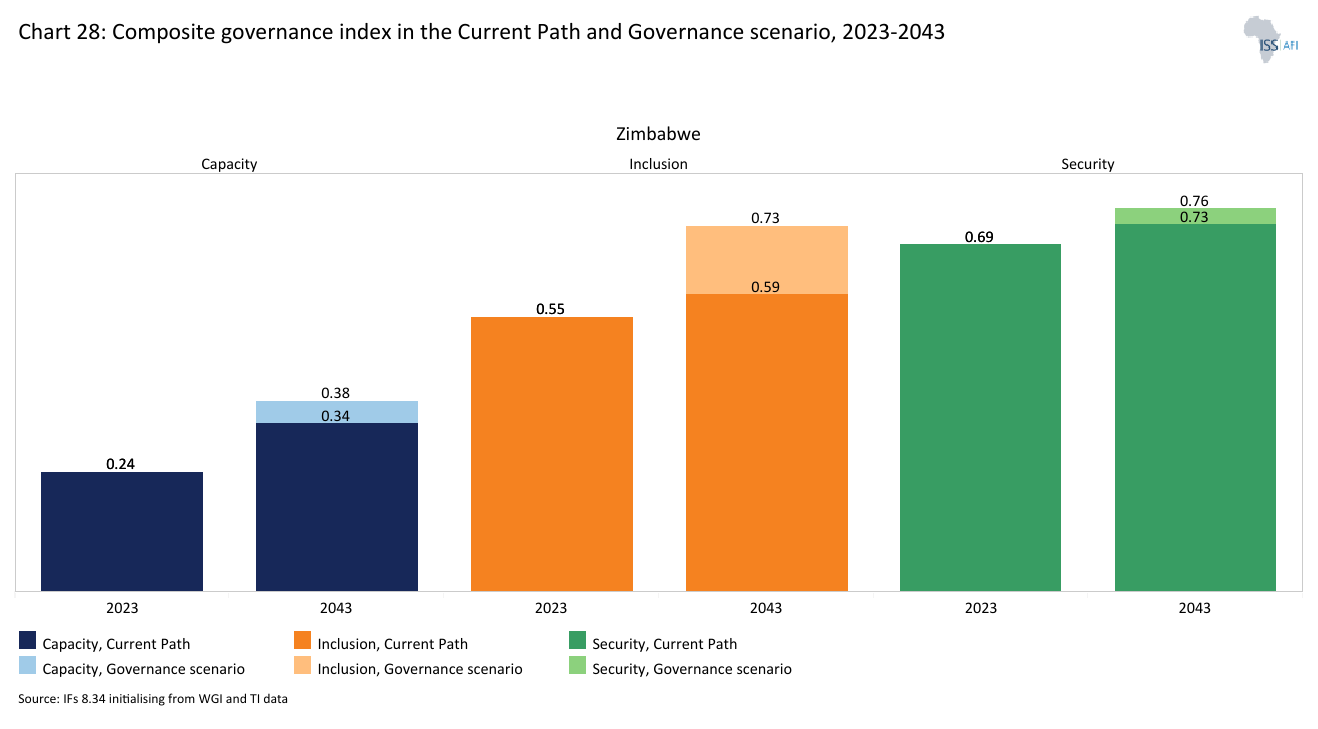

- Zimbabwe’s governance system has undergone significant evolution over time, shaped by various internal and external factors that have influenced its legal and political frameworks. By 2023, the country’s composite governance index stood at 0.49. Interventions in the Governance scenario have the potential to significantly improve governance, positioning Zimbabwe above the average for lower-middle-income African countries. As a result, the composite governance index will increase to 0.62 by 2043 in this scenario, compared to 0.55 on the Current Path.

In the third section, we compare the impact of each of these eight sectoral scenarios with one another and subsequently with a Combined scenario (the integrated effect of all eight scenarios). In our forecasts, we measure progress on various dimensions such as economic size (in market exchange rates), gross domestic product per capita (in purchasing power parity), extreme poverty, carbon emissions, the changes in the structure of the economy, and selected sectoral dimensions such as progress with mean years of education, life expectancy, the Gini coefficient or reductions in mortality rates.

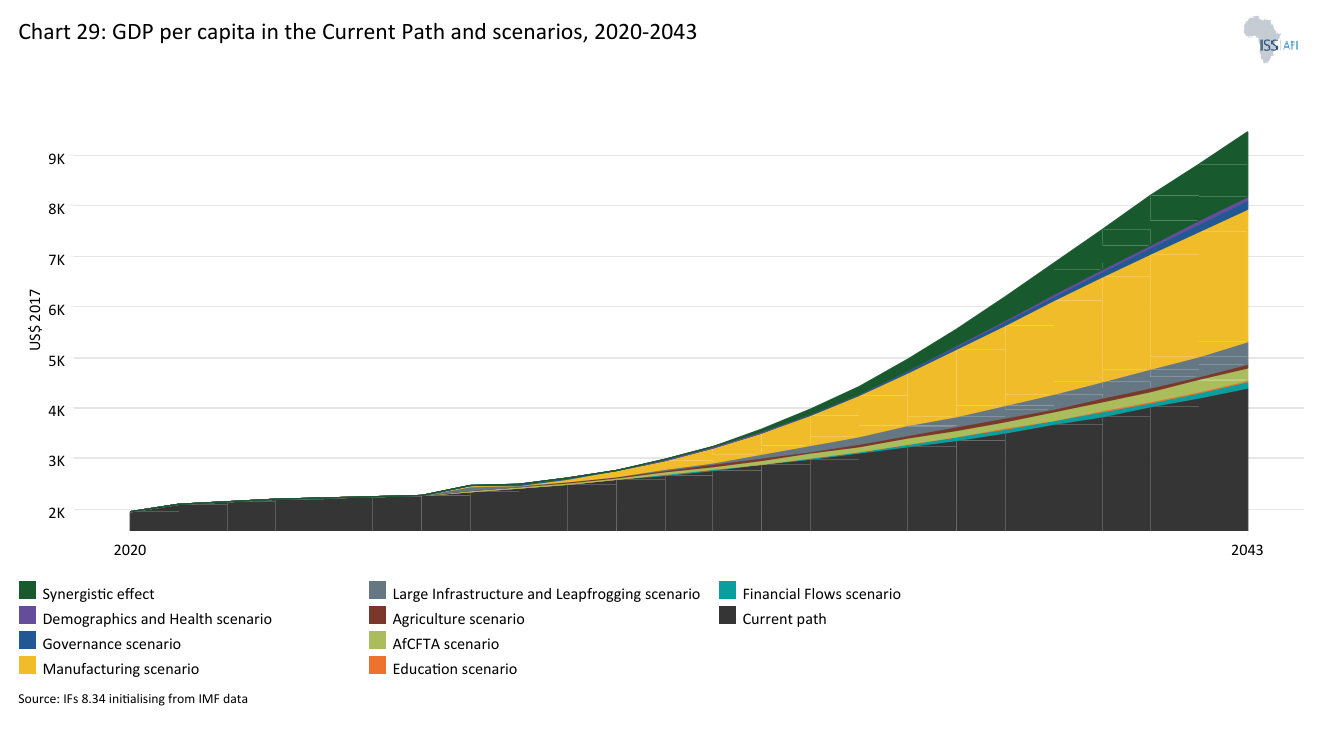

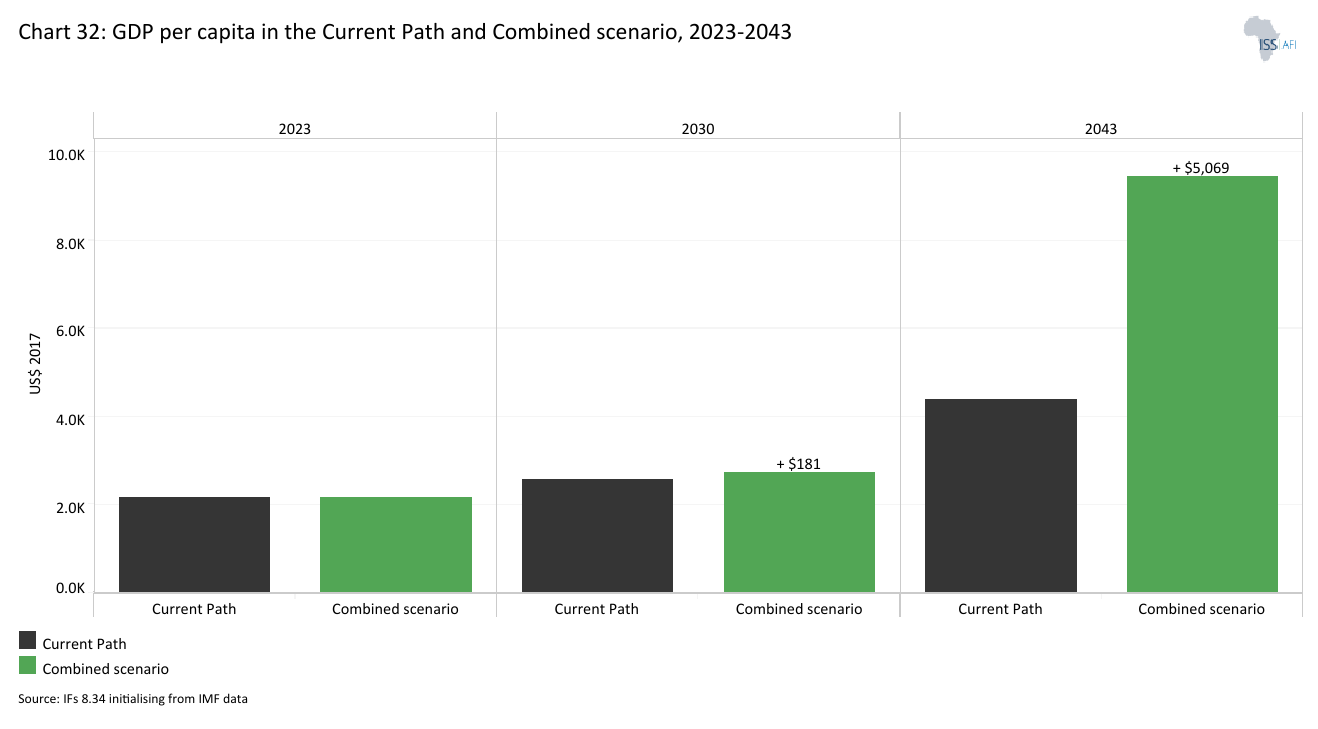

- The Combined scenario can push Zimbabwe’s GDP per capita in PPP to US$9 470 by 2043, exceeding the Current Path by US$5 070 (115%). Among individual scenarios, Manufacturing will have the most substantial impact on GDP per capita both in the short and long run, raising it to US$7 040 by 2043, followed by Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging (US$4 830), AfCFTA (US$4 660), Governance (US$4 570), Financial Flows (US$4 510), Agriculture (US$4 470), Demographics and Health (US$4 460) and Education (US$4 440).

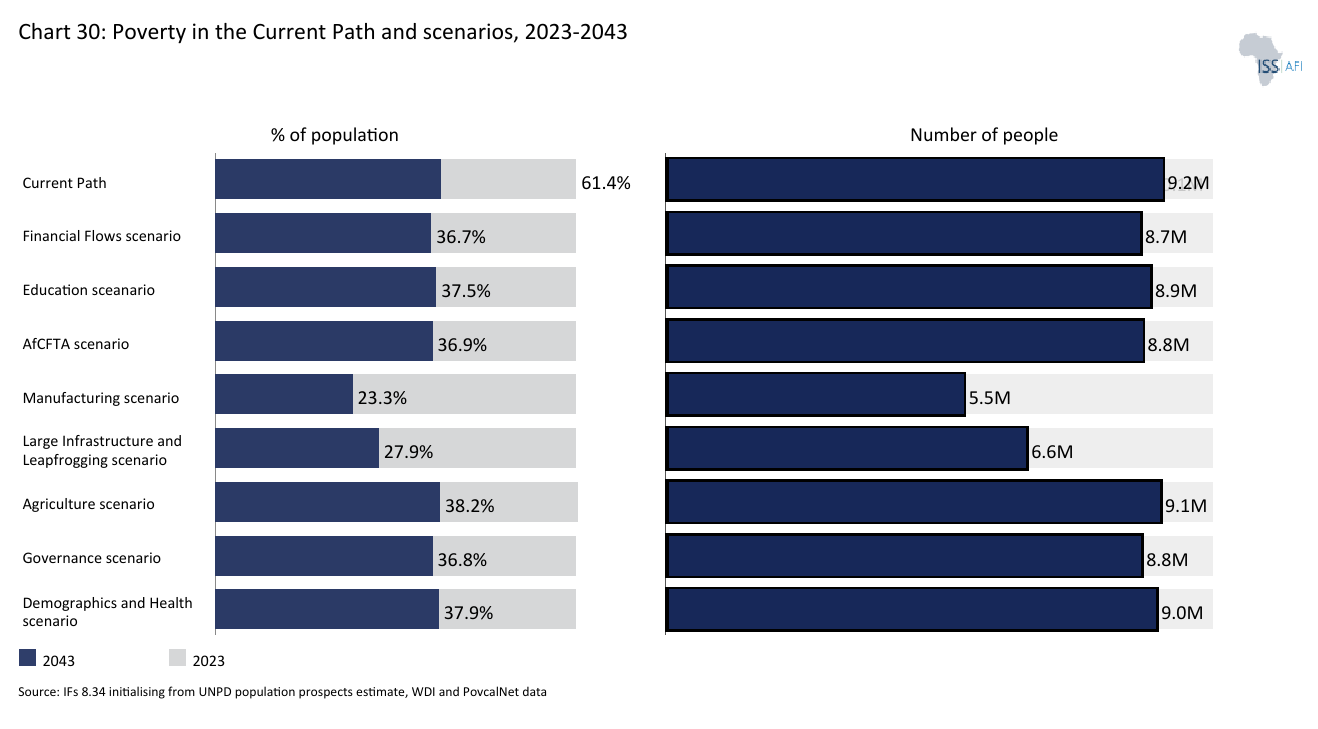

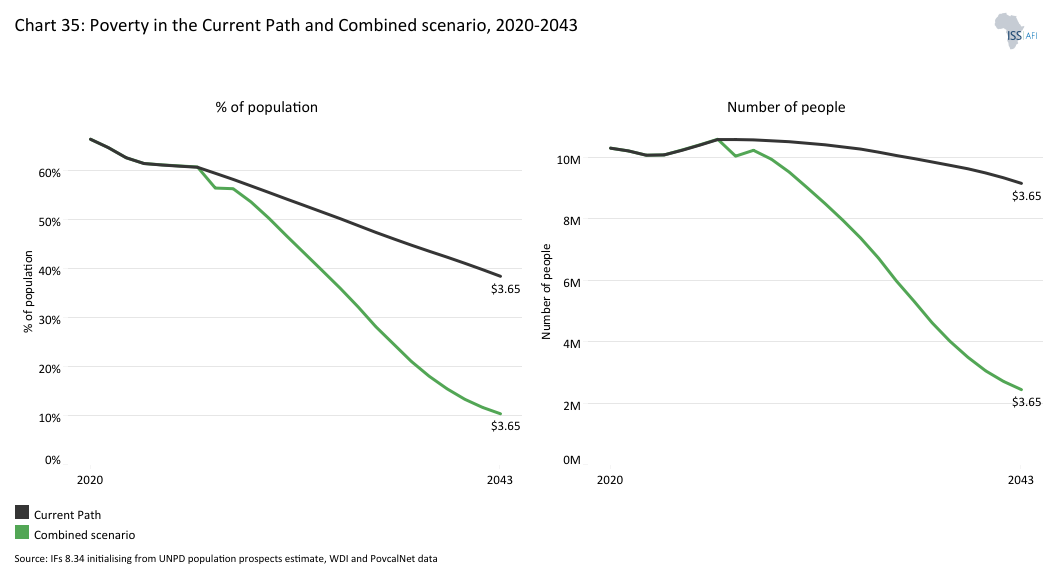

- With effective implementation of interventions in the Combined scenario, Zimbabwe’s extreme poverty rate can significantly fall to 3% (610 000 people) by 2043, compared to 18% (4.2 million) on the Current Path. Among individual scenarios, the Manufacturing scenario shows the greatest potential for reducing extreme poverty, bringing the rate down to 9% (2 million people) by 2043. This is followed by the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario at 11% (2.7 million) and Financial Flows at 16% (3.9 million). Other sectoral scenarios would result in an extreme poverty level of about 17% (approximately 4 million people).

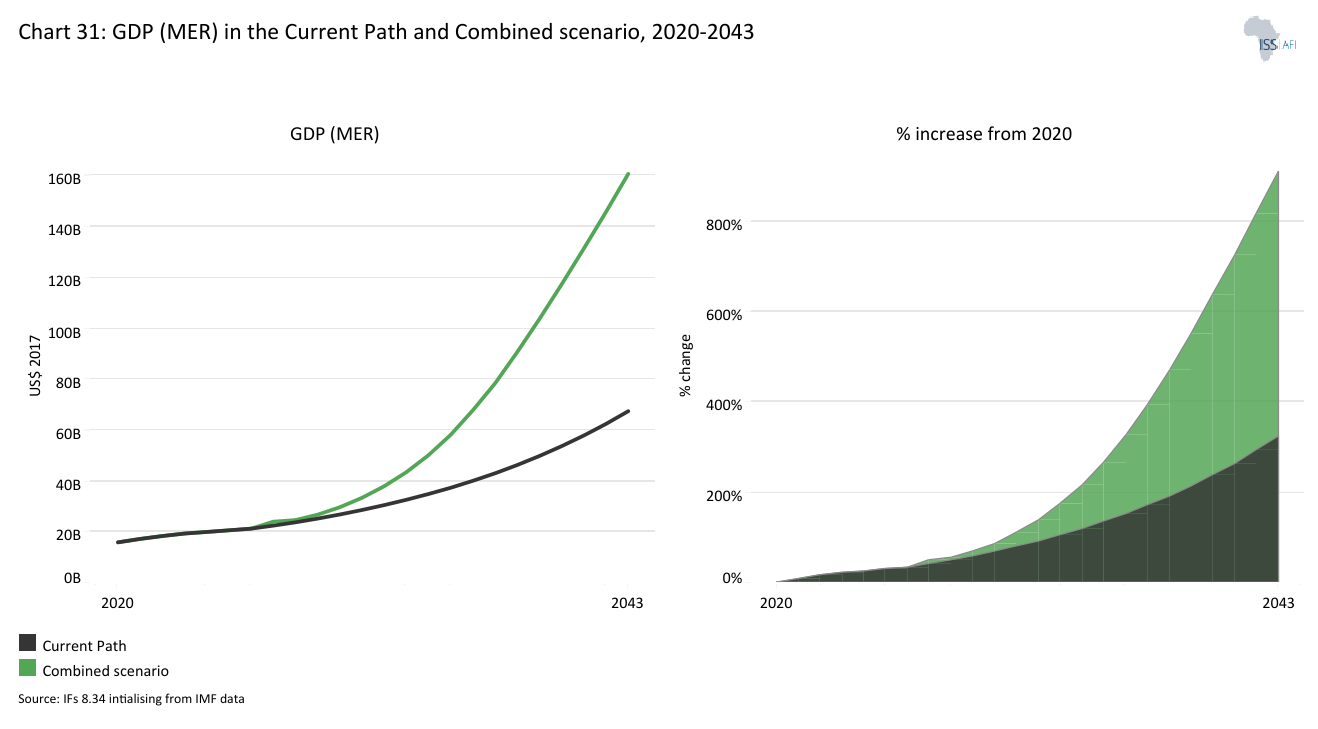

- If Zimbabwe adopts the interventions proposed in the Combined scenario, the country will achieve significant economic growth, with an average annual growth rate of 8% from 2026 to 2030, compared to 5% on the Current Path. These measures are essential for supporting Zimbabwe's Vision 2030, which aims for GDP growth rates between 7% and 10% by 2030. Looking ahead, from 2026 to 2043, the average annual growth rate will reach 12% in the Combined scenario, surpassing the 9% growth rate on the Current Path by 3 percentage points. Consequently, Zimbabwe's GDP (MER) will be approximately US$2.6 billion larger than the Current Path by 2030 and US$93 billion larger by 2043.

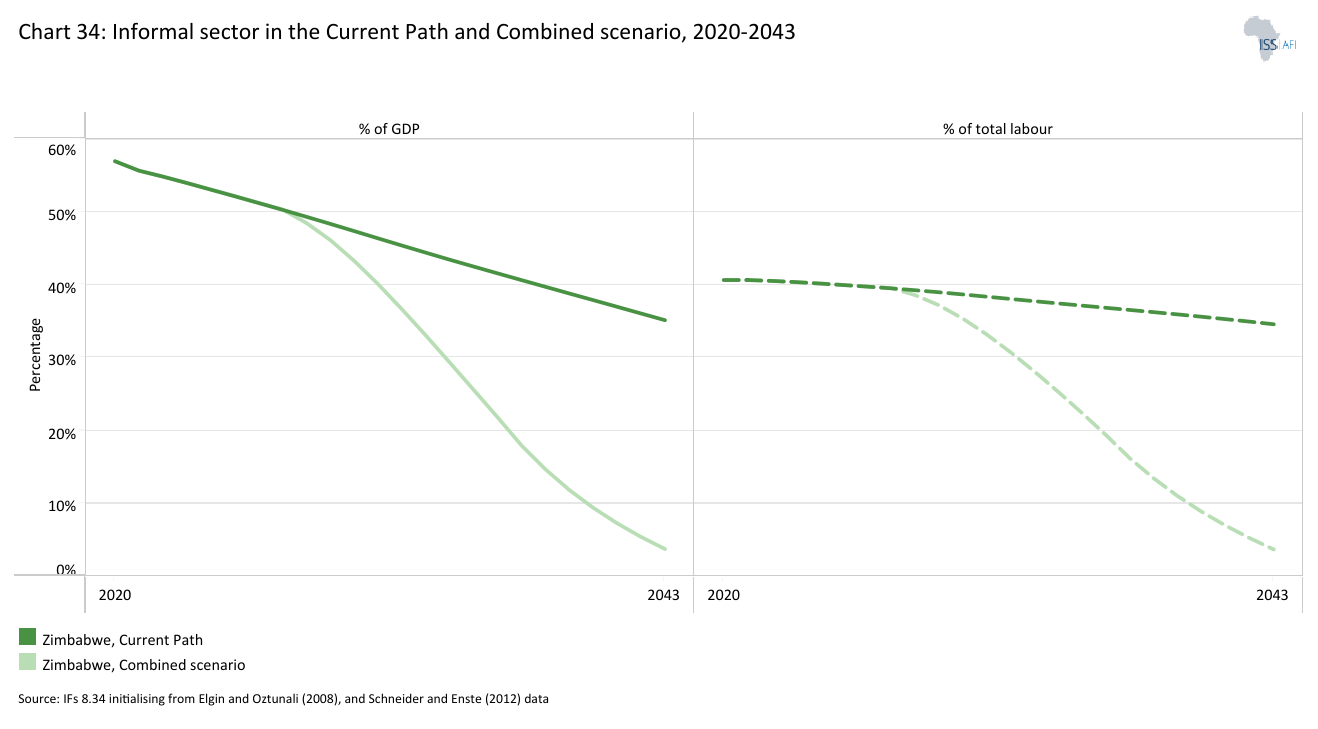

- The Combined scenario will shift 31% of the informal sector’s GDP and employment contribution to the formal economy by 2043, enhancing overall economic resilience and national development.

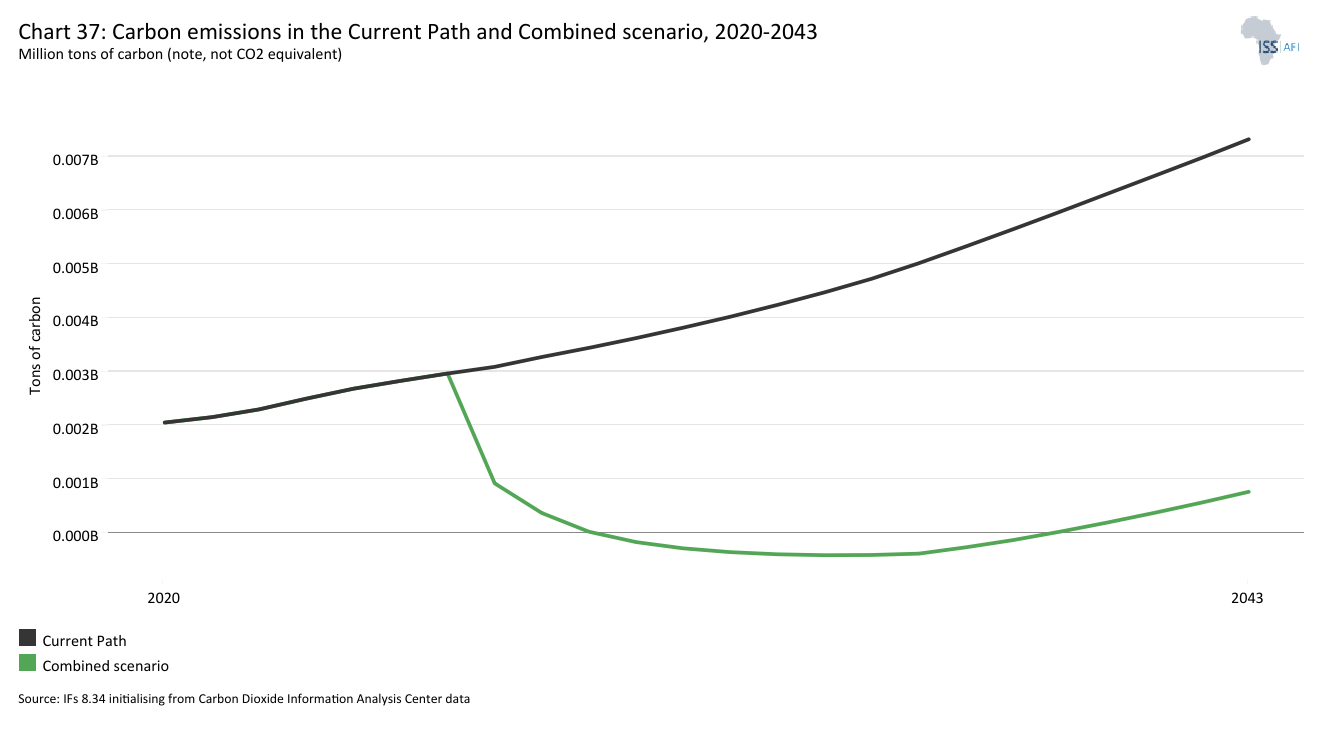

- A successful shift to cleaner energy, driven by technological leapfrogging and sustainability-focused policies, can significantly reduce carbon emissions from 2.5 million tons in 2023 to approximately 760 000 tons by 2043 under the Combine scenario. In contrast, emissions are forecasted to reach 7.3 million tons on the Current Path.

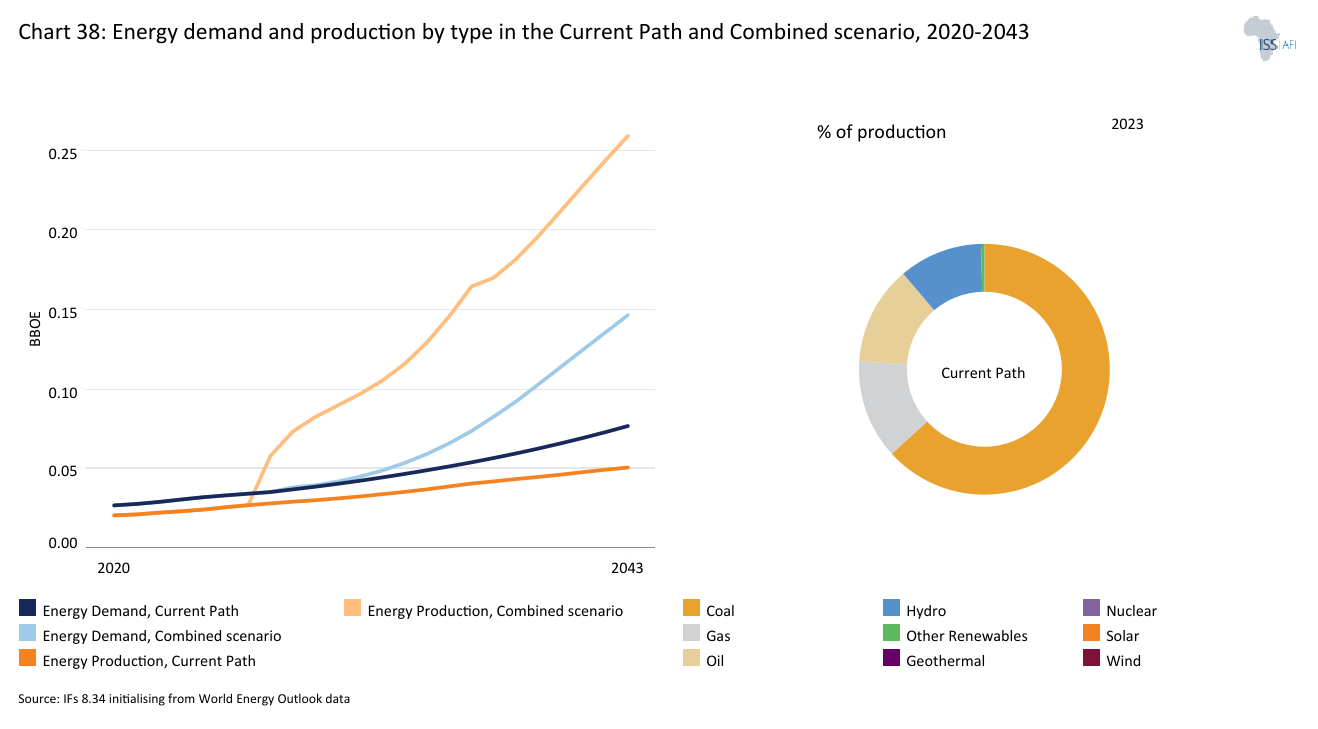

- If Zimbabwe successfully implements interventions in the Combined Scenario, total energy production will reach 259.1 million barrels of oil equivalent, surpassing the Current Path by 407 percentage points. This would result in an energy surplus of approximately 112.6 million barrels of oil equivalent, enabling Zimbabwe to meet growing energy needs while reducing reliance on hydro and fossil fuels, fostering sustainable energy production, and building a more resilient energy system for the future.

We end this page with a summarising conclusion offering key recommendations for decision-making.

Zimbabwe faces major growth and development challenges, including food insecurity, limited economic diversification and beneficiation, low agricultural productivity, an unfavourable business climate, inadequate infrastructure and insufficient skills development. These issues stem from over three decades of political and economic instability. While addressing these challenges is essential for achieving inclusive and sustainable growth, prioritising the manufacturing sector is critical. By 2043, manufacturing will play a key role in driving sustainable economic growth and improving living standards. Focusing on this sector will help Zimbabwe diversify its economy, create jobs, reduce poverty and enhance resilience against external economic shocks. To fully unlock its potential, the country must invest strategically in skills development, infrastructure, innovation and governance reforms that foster a supportive environment for value-add and beneficiation investments. These initiatives are essential for Zimbabwe’s Vision 2030, which aims for a GDP expansion of 7-10% by 2030.

All charts for Zimbabwe

- Chart 1: Political map of Zimbabwe

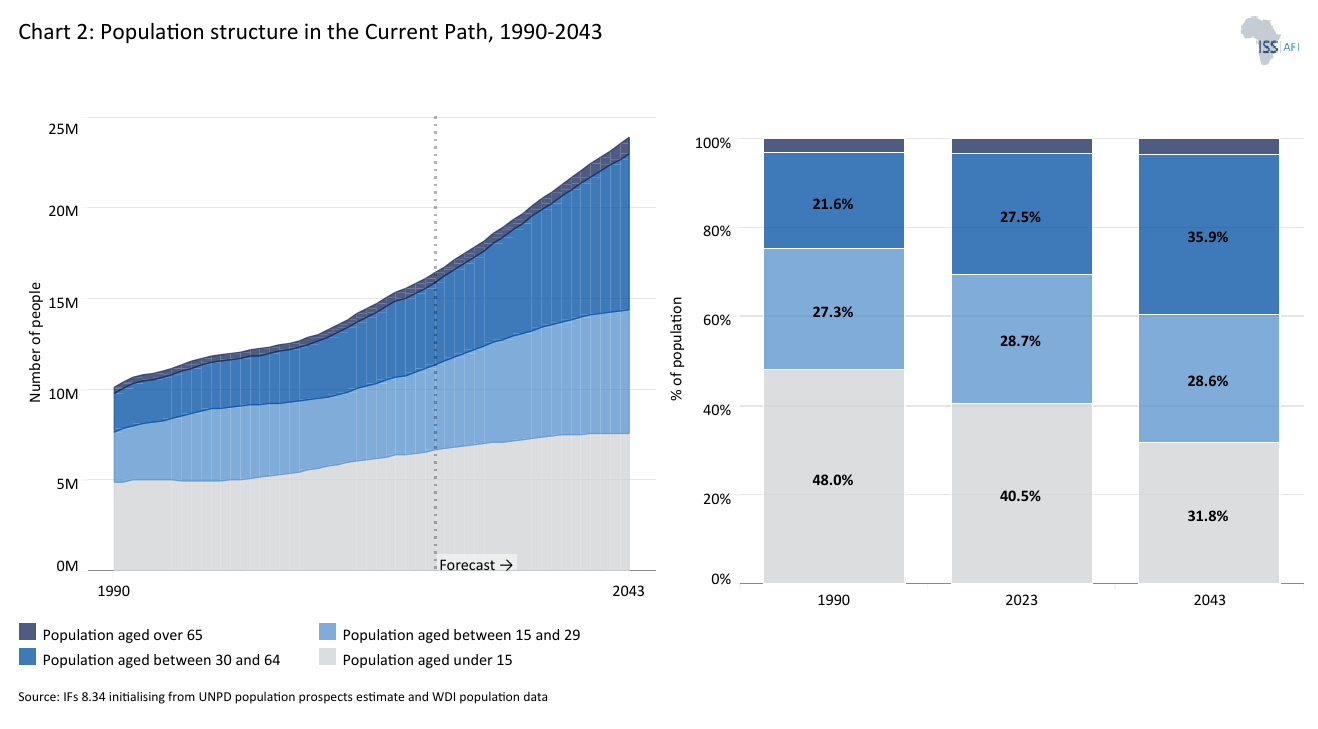

- Chart 2: Population structure in the Current Path, 1990–2043

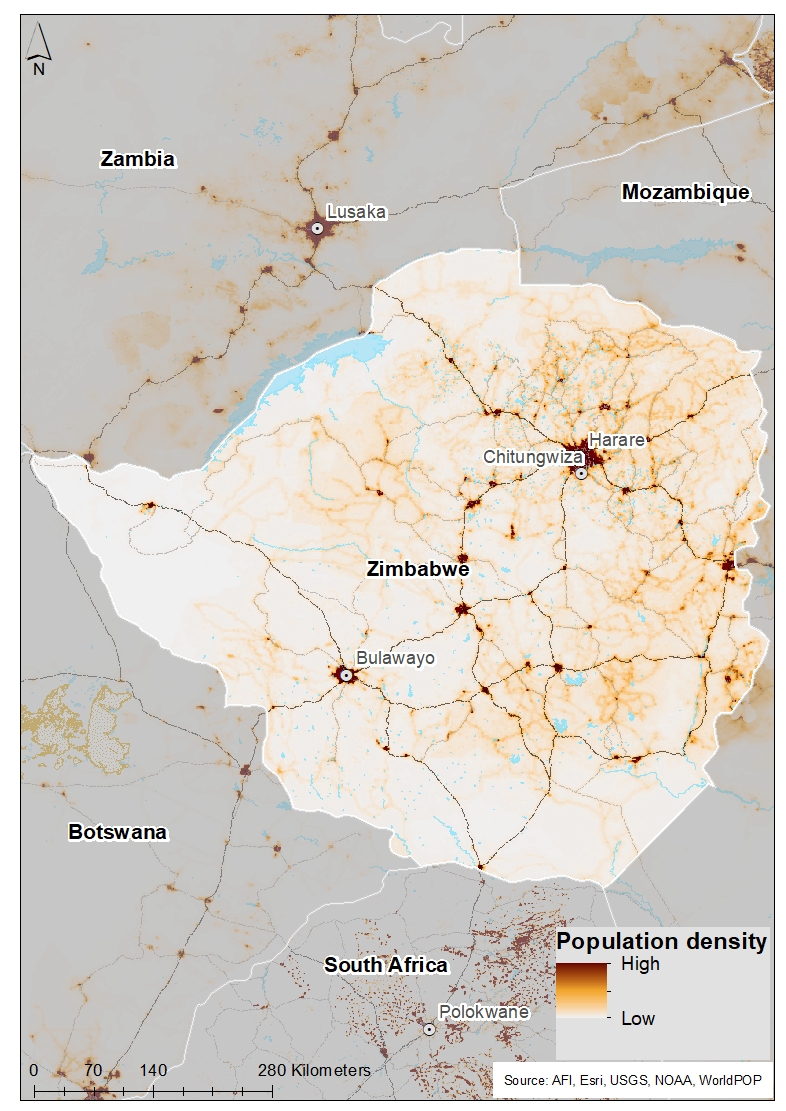

- Chart 3: Population distribution map, 2023

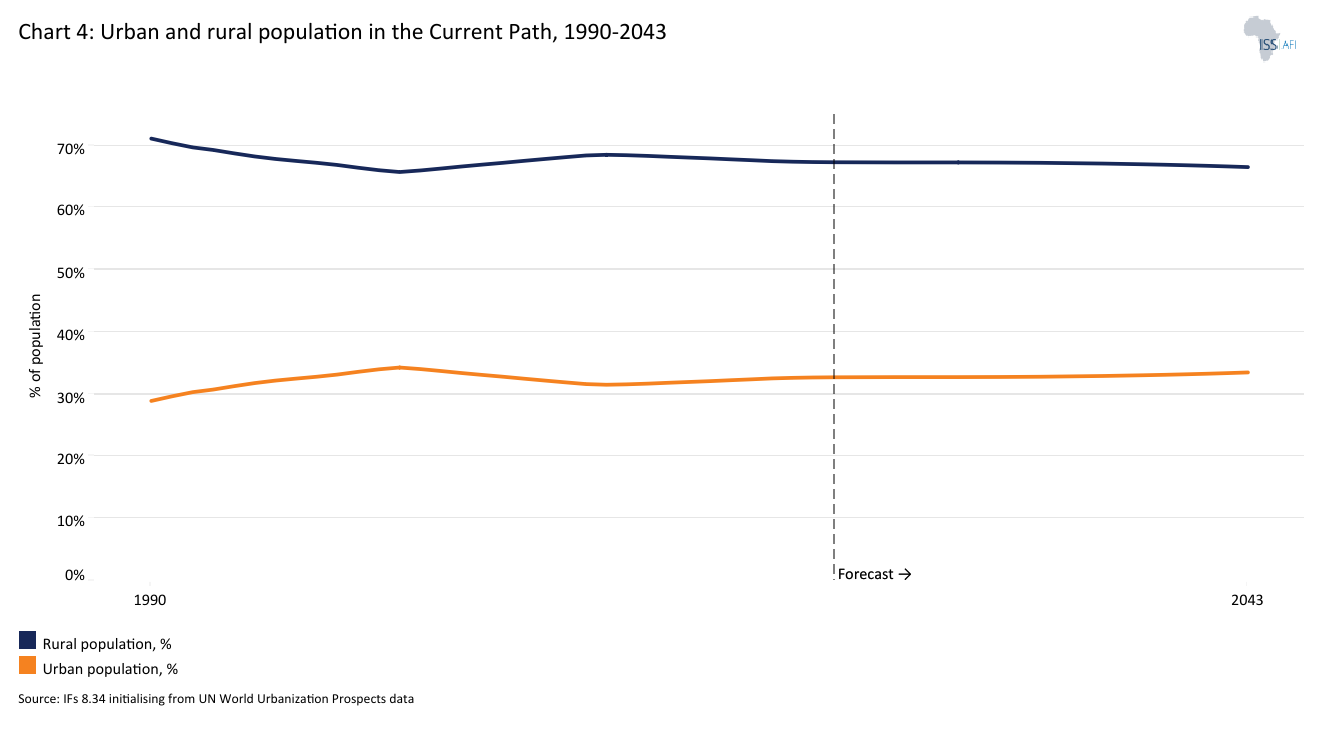

- Chart 4: Urban and rural population in the Current Path, 1990-2043

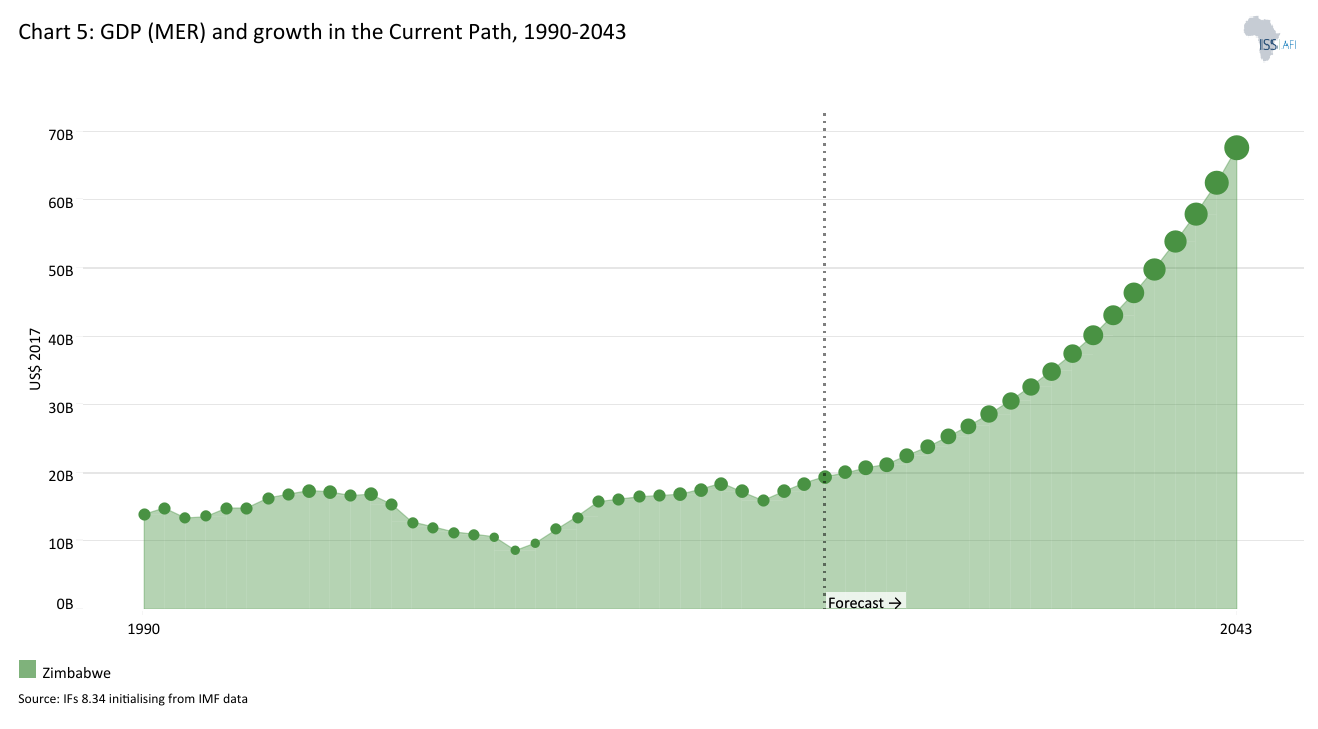

- Chart 5: GDP (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, 1990–2043

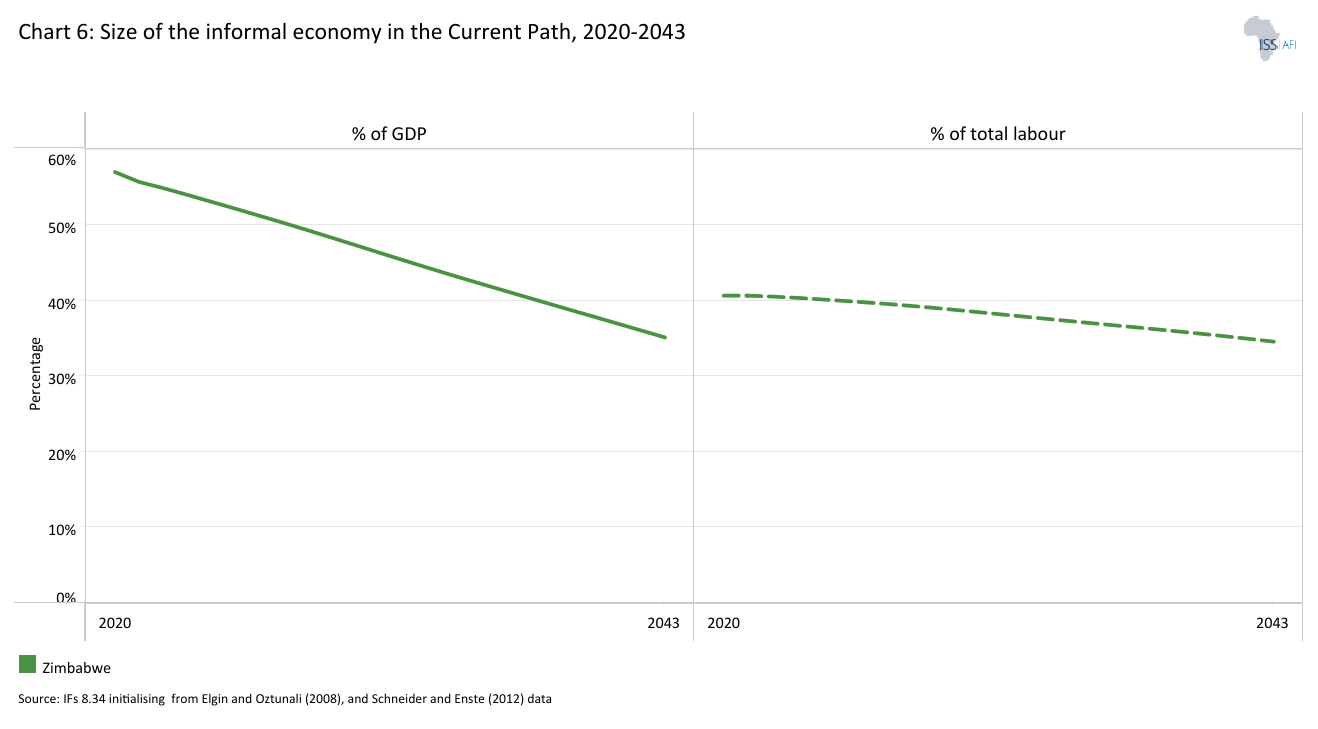

- Chart 6: Size of the informal economy in the Current Path, 2020-2043

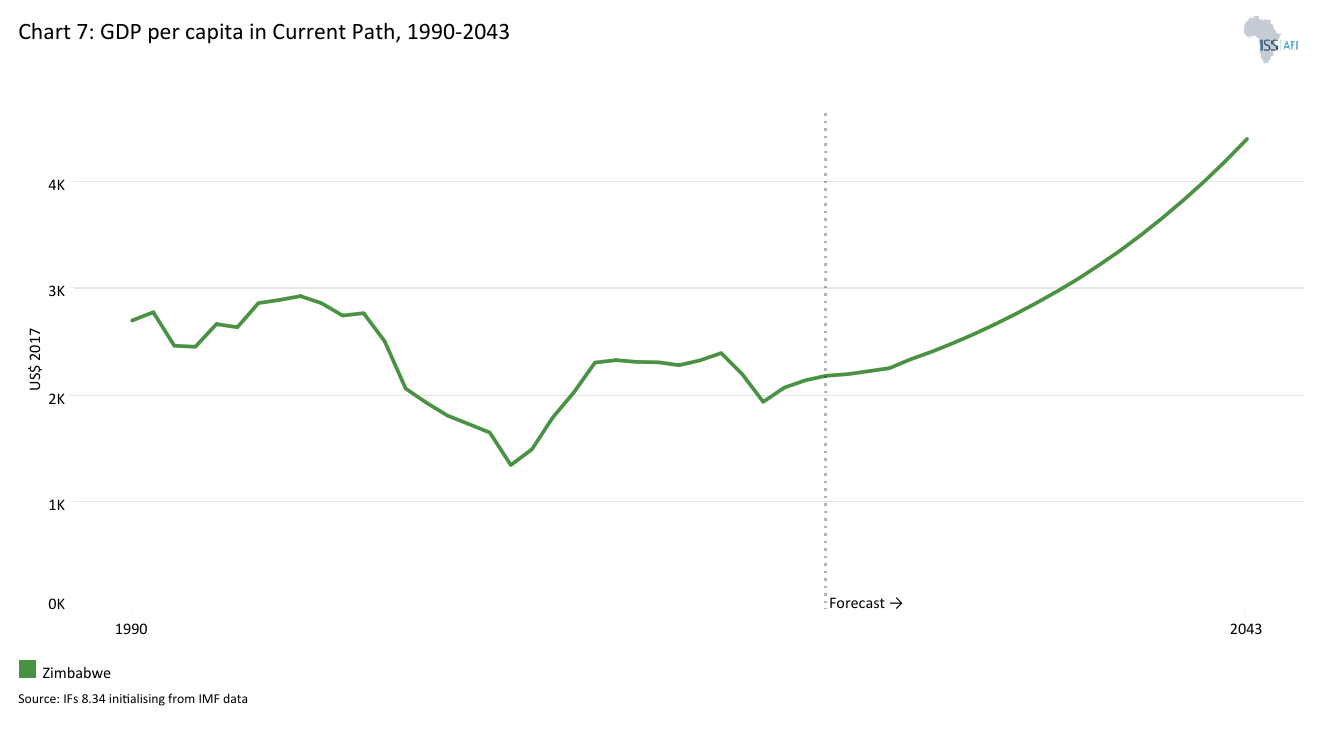

- Chart 7: GDP per capita in Current Path, 1990–2043

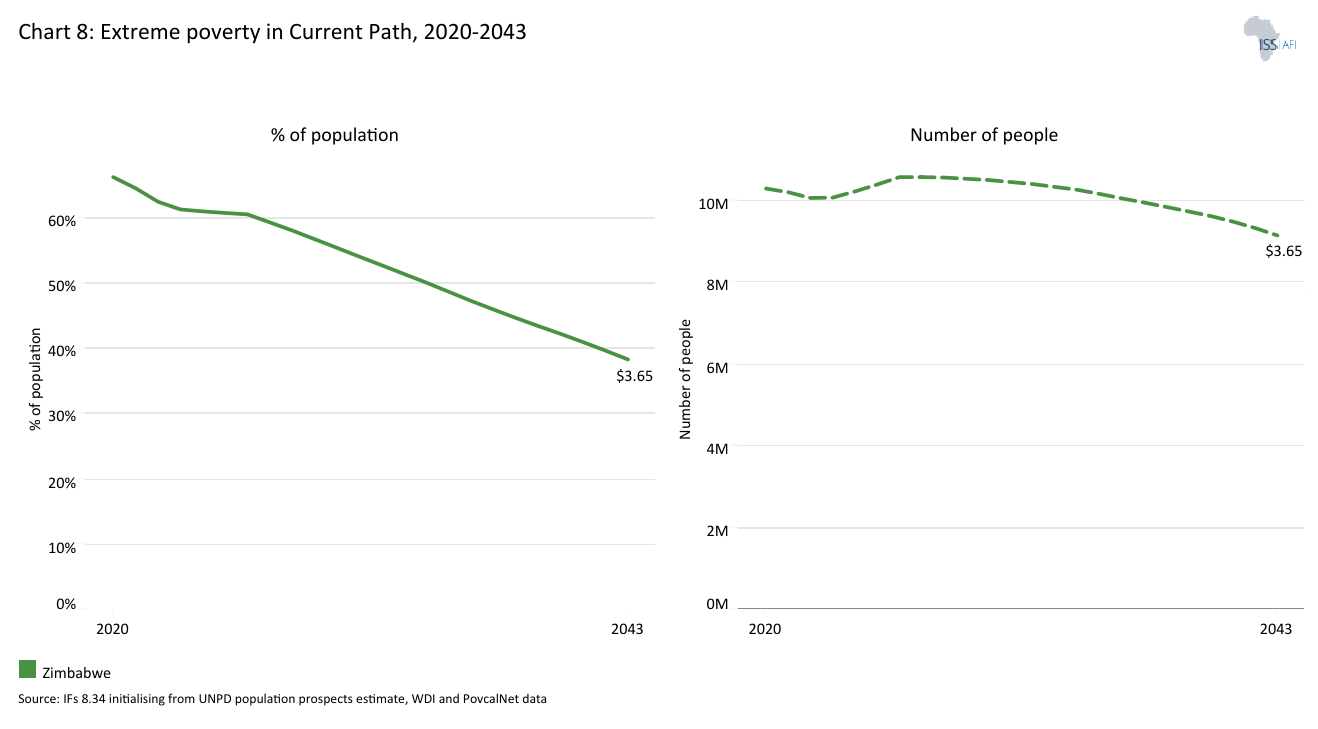

- Chart 8: Extreme poverty in the Current Path, 2020–2043

- Chart 9: National Development Plan of Zimbabwe

- Chart 10: Relationship between Current Path and scenario

- Chart 11: Mortality distribution in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 12: Infant mortality rate in Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 2020–2043

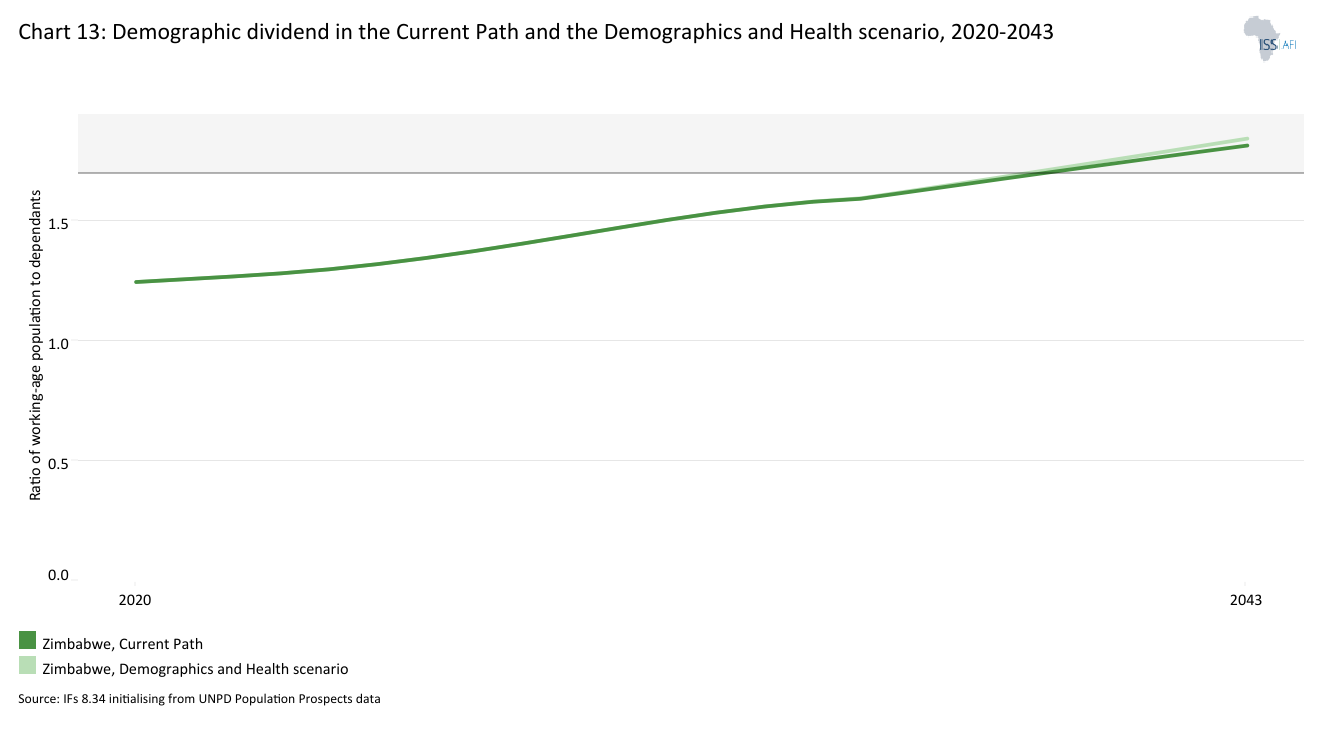

- Chart 13: Demographic dividend in the Current Path and the Demographics and Health scenario, 2020–2043

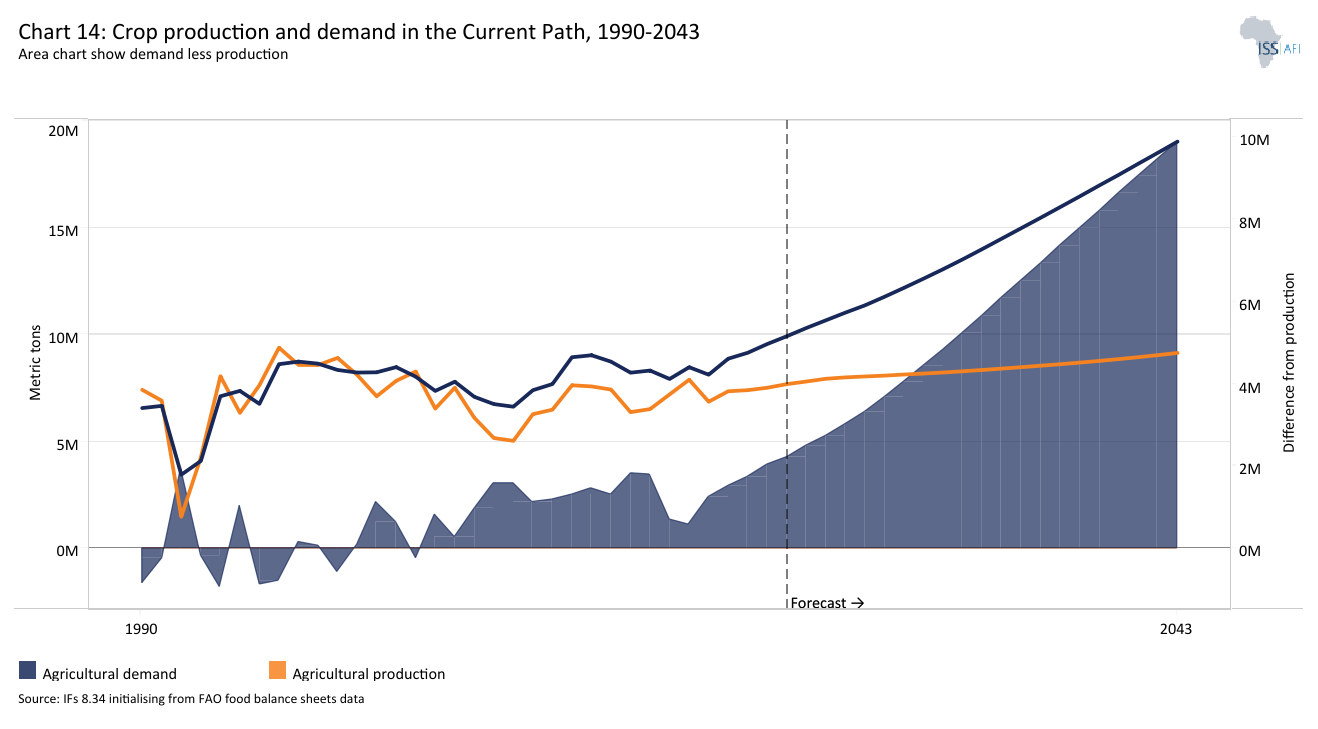

- Chart 14: Crop production and demand in the Current Path, 1990-2043

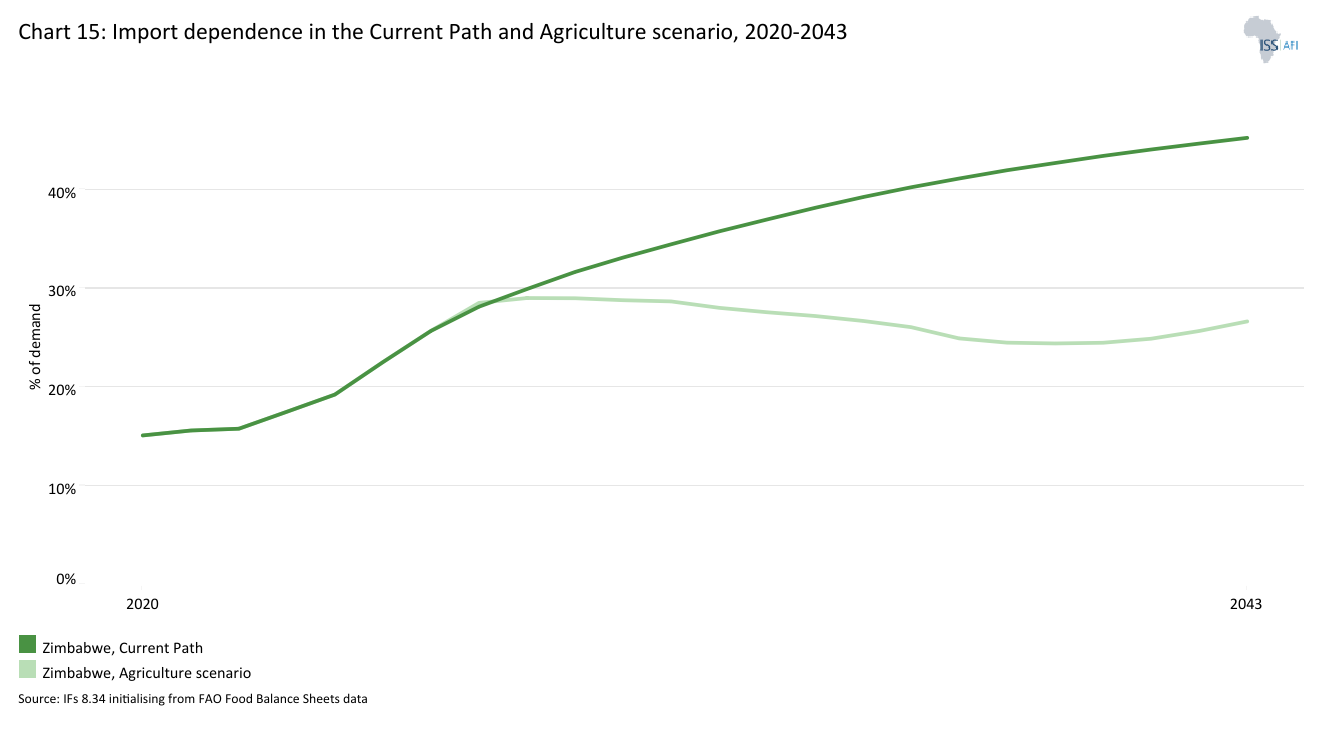

- Chart 15: Import dependence in the Current Path and Agriculture scenario, 2020–2043

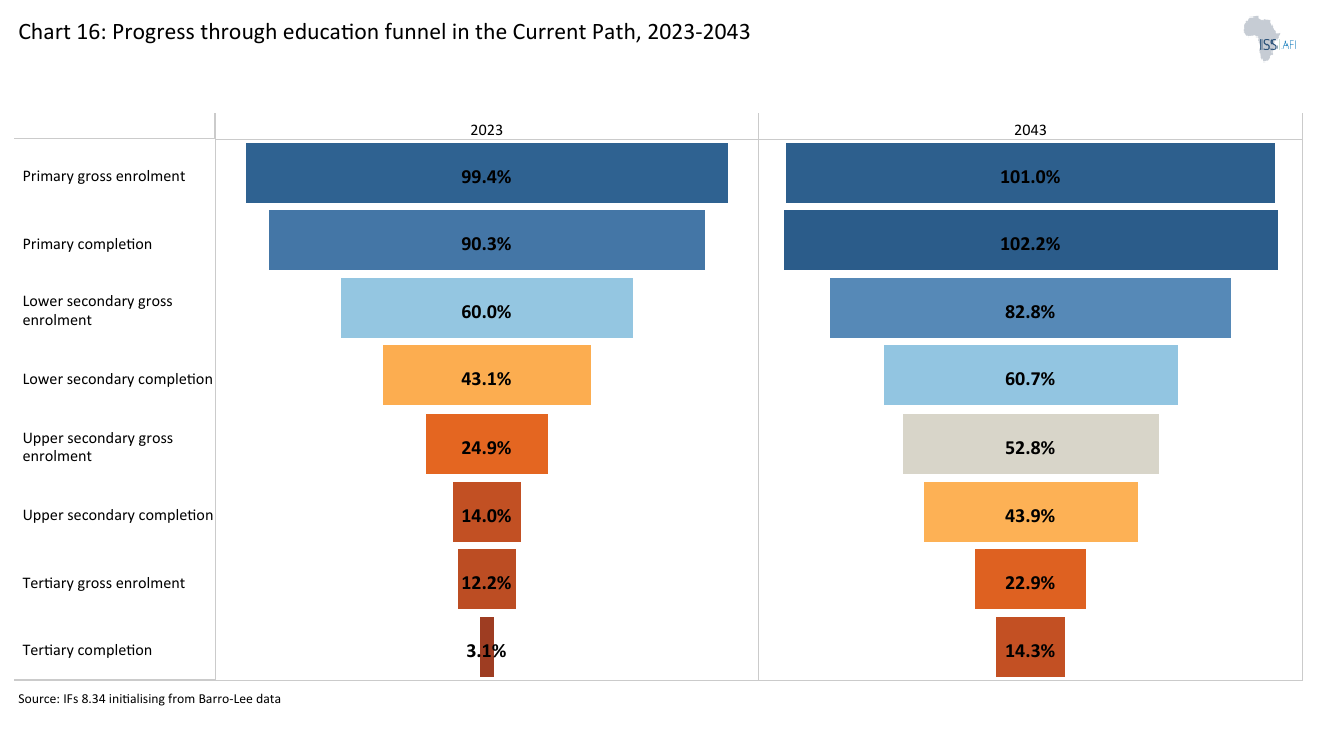

- Chart 16: Progress through the education funnel in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043 Per cent of-age children

- Chart 17: Mean years of education in the Current Path and Education scenario, 2020–2043 15 to 24 age group

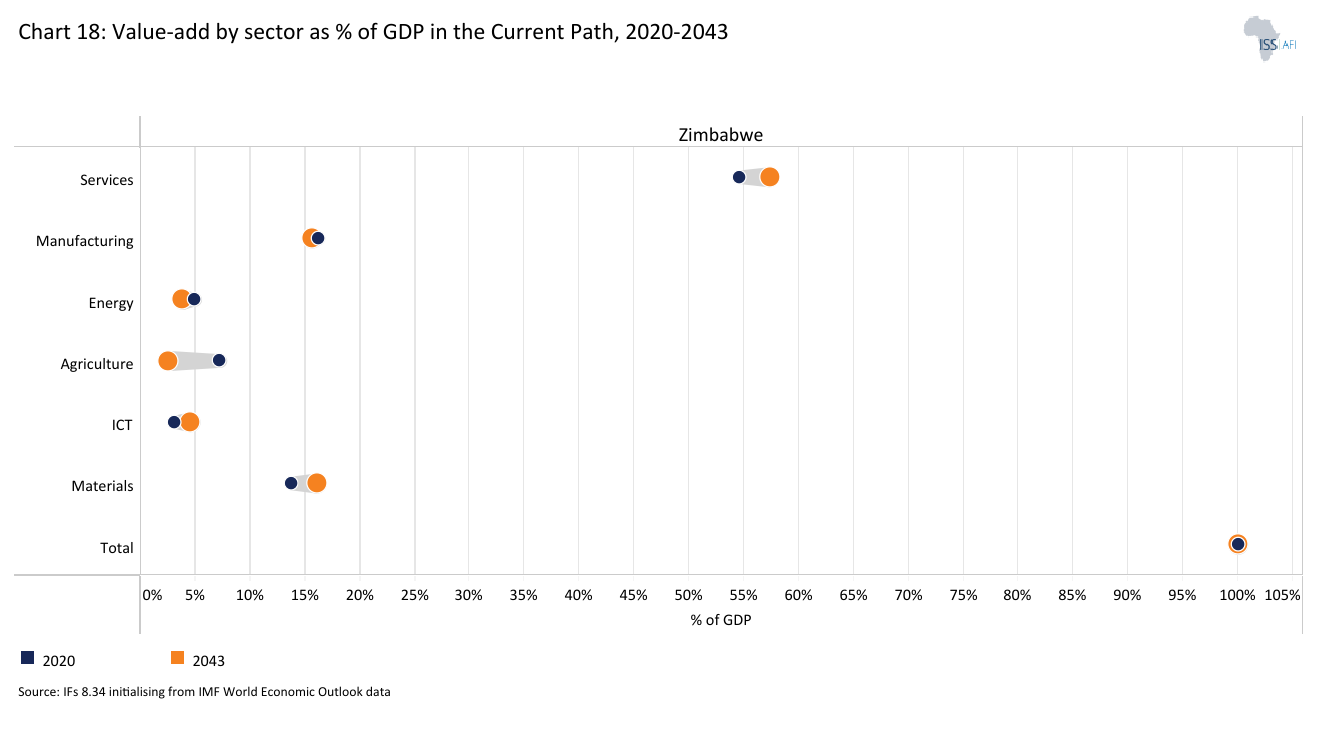

- Chart 18: Value-add by sector as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 19: Value-add by the manufacturing sector in the Current Path and Manufacturing scenario, 2020–2043 US$ 2017 and % of GDP

- Chart 20: Exports and imports as % of GDP in the Current Path and the AfCFTA scenario, 2000-2043

- Chart 21: Trade balance in the Current Path and AfCFTA scenario, 2020–2043 % of GDP

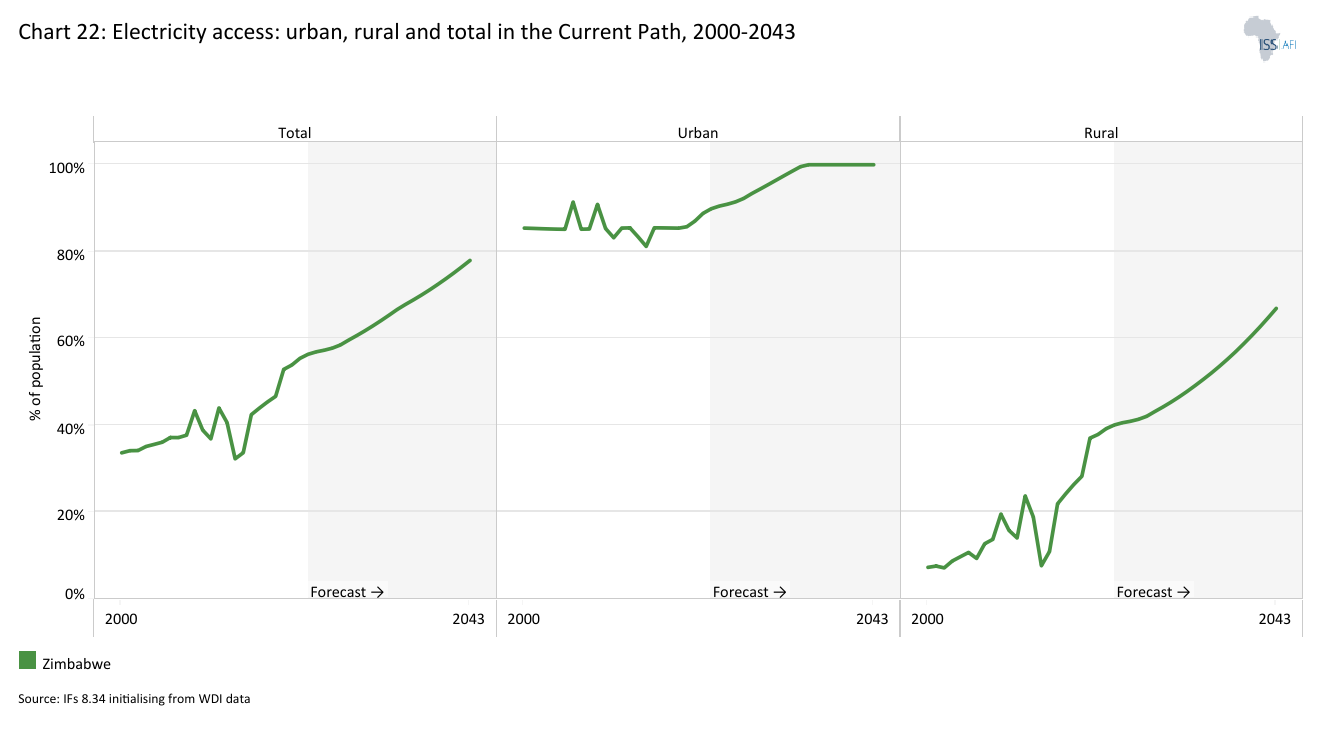

- Chart 22: Electricity access: urban, rural and total in the Current Path, 2000-2043

- Chart 23: Cookstove usage in the Current Path and Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2020–2043 Number of people

- Chart 24: Access to mobile and fixed broadband in the Current Path and the Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2020–2043 % of population, toggle between mobile and fixed broadband

- Chart 25: FDI, foreign aid and remittances as % of GDP in the Current Path and in the Financial Flows scenario, 1990-2043

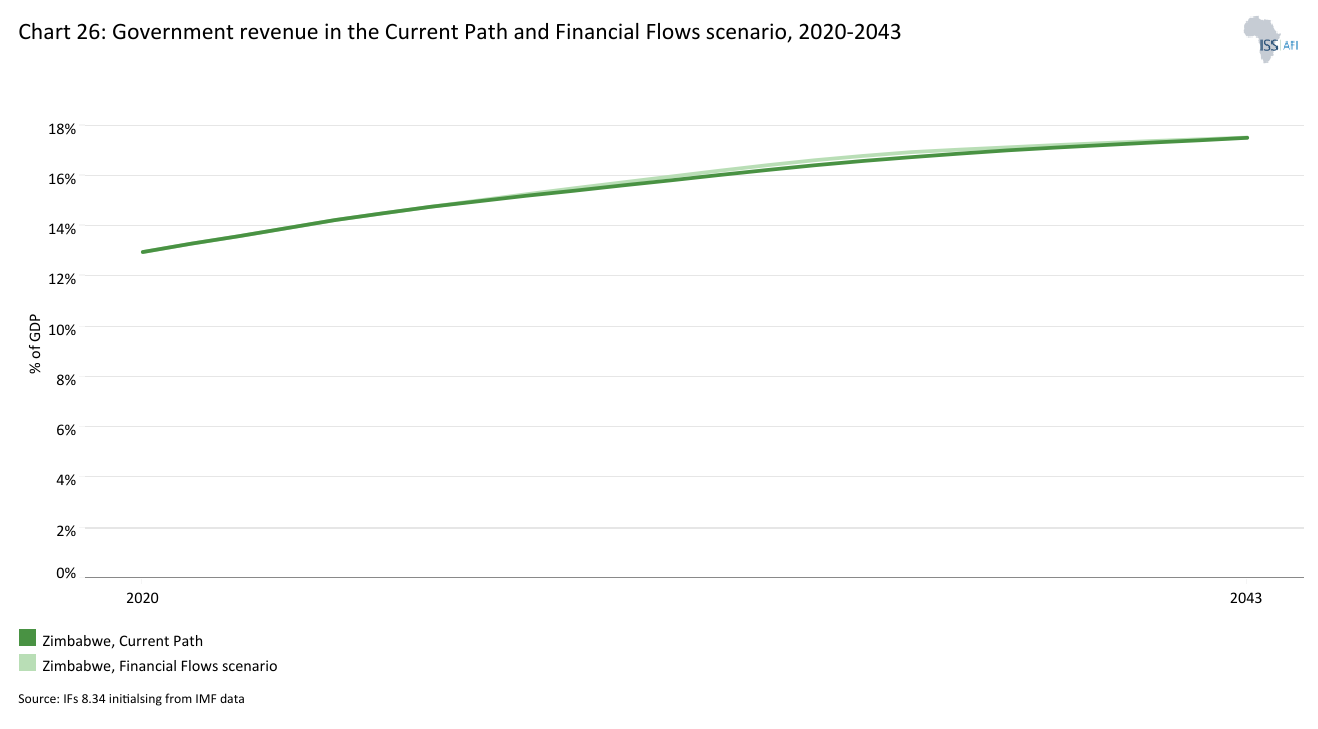

- Chart 26: Government revenue in the Current Path and Financial Flows scenario, 2020–2043 US$ 2017 and % of GDP

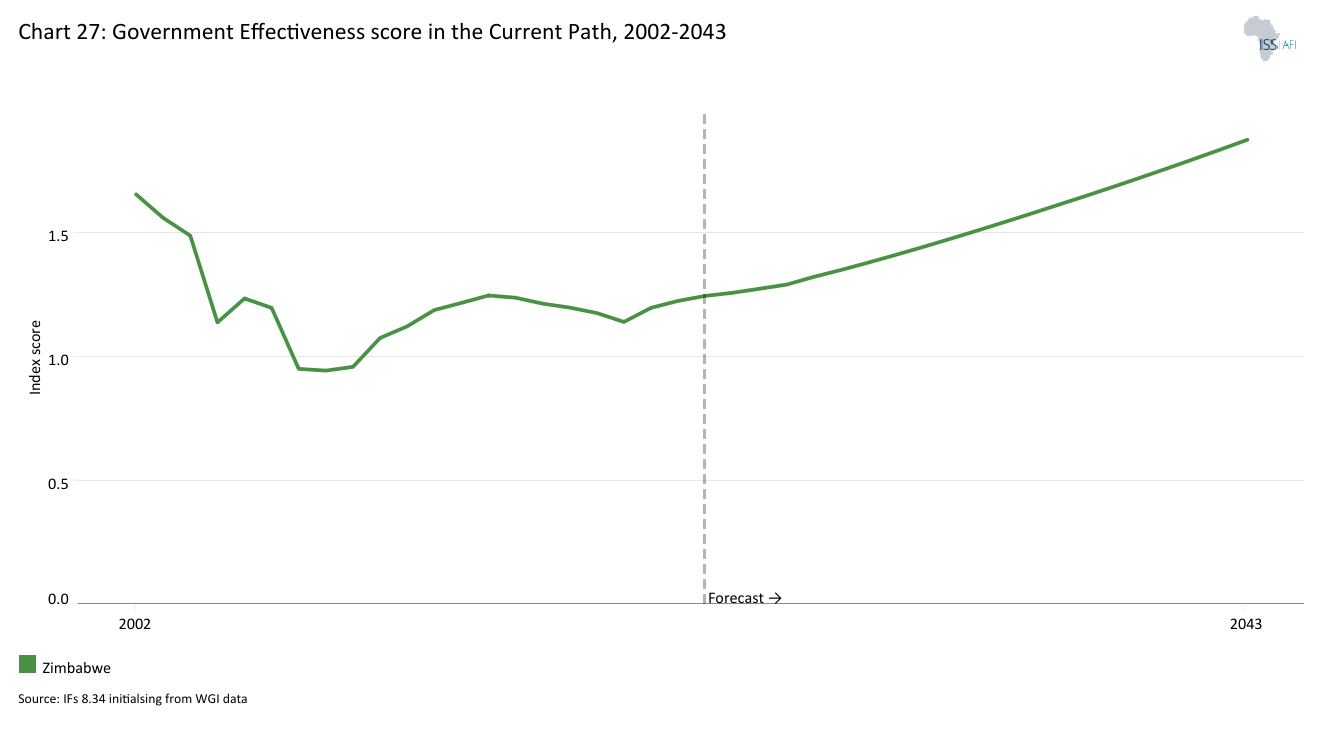

- Chart 27: Government effectiveness score in the Current Path, 2002-2043

- Chart 28: Composite governance index in the Current Path and Governance scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 29: GDP per capita in the Current Path and scenarios, 2020–2043

- Chart 30: Poverty in the Current Path and scenarios, 2020–2043

- Chart 31: GDP (MER) in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 32: GDP per capita in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023-2043

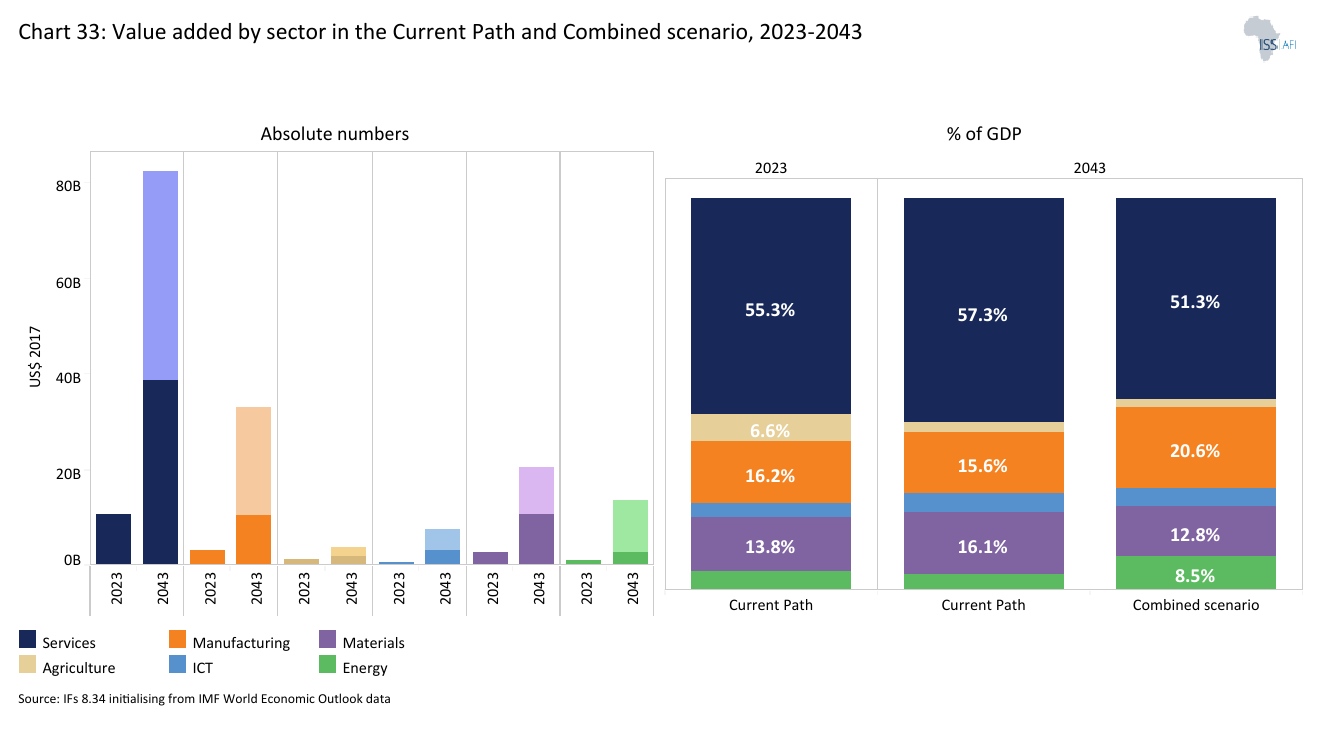

- Chart 33: Value-add by sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 34: Informal sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 35: Life expectancy in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

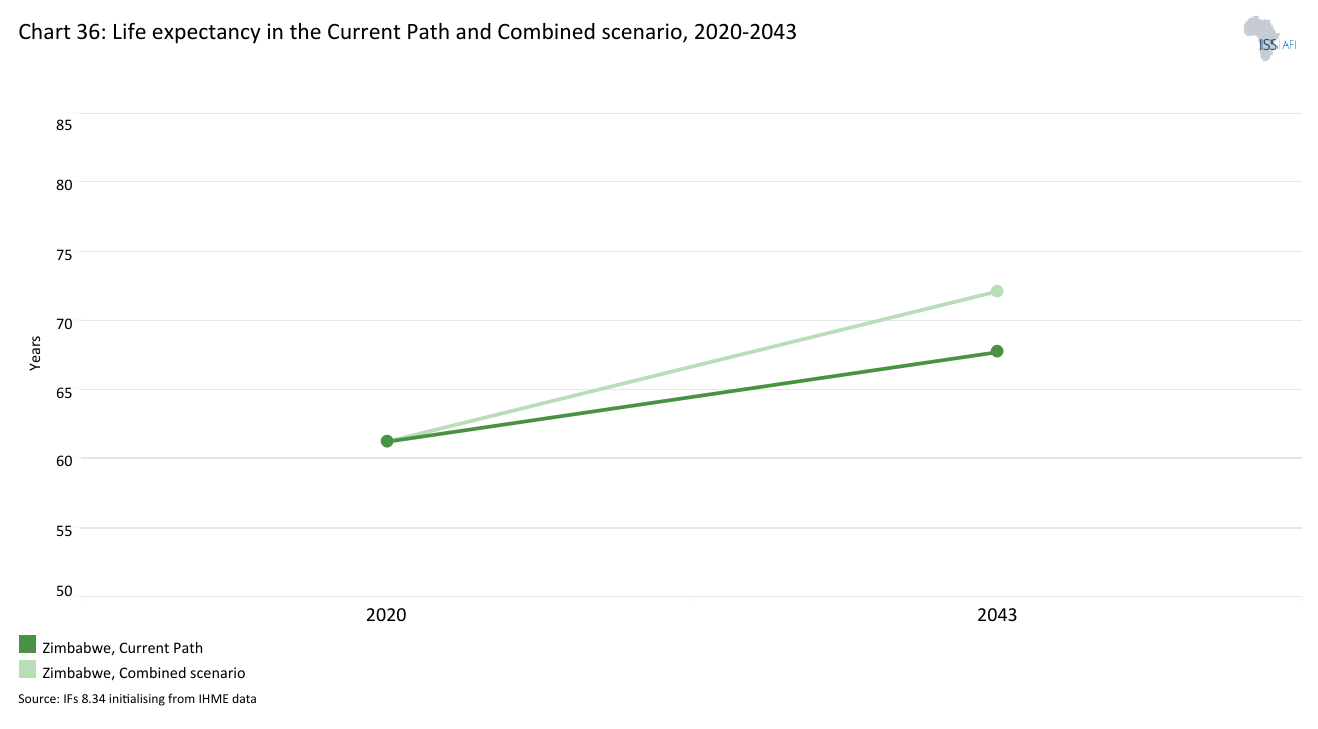

- Chart 36: Domestic Gini in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 37: Carbon emissions in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 38: Energy demand and production by type in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020-2043

- Chart 39: Policy recommendations

Chart 1 is a political map of Zimbabwe.

Zimbabwe is a landlocked, lower-middle-income country in Southern Africa, with a total land area of 390 757 square kilometres (km²). It shares borders with Zambia to the northwest, Mozambique to the east and northeast, South Africa to the south, and Botswana to the southwest. The country has a centralised government based in its capital, Harare, and is divided into eight provinces and two cities holding provincial administrative status. Each province has its provincial capital, from which government administration is typically conducted.

Zimbabwe is a member of several regional economic and political organisations, including the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) and the African Union (AU).

Zimbabwe gained independence from Britain on 18 April 1980, following a prolonged liberation war. The late President Robert Mugabe served as Prime Minister from 1980 to 1987 and then as President from 1987 until his controversial retirement in November 2017. He was succeeded by Mr Emmerson Mnangagwa.

The ethnic composition of Zimbabwe is primarily made up of the Shona people, who represent approximately 81% of the population. The Ndebele follow, accounting for about 12% of the population. There are also smaller ethnic groups, including the Ndau (3%), Tonga (2%), Shangani (0.8%), Venda (0.5%), Kalanga (0.4%), official English (0.3%), and others, including Xhosa, Tswana, Sotho, Nambya, Chewa, Chibarwe and Khoisan (1.2%). Additionally, Zimbabwe has a small but noteworthy population of people of European, Indian, Coloured descent, and East Asians, particularly Chinese. Over the years, these populations have declined, especially the European population and British, largely due to emigration following independence in 1980 and during the land reform program in the early 2000s.

Zimbabwe features a diverse topography that supports unique ecosystems, including grasslands, woodlands and mountainous forests. In the east, Zimbabwe features rugged mountain ranges, such as the Eastern Highlands, which include peaks like Mount Nyangani. To the west and southwest, the terrain transitions into lower, drier areas like the Kalahari Basin. Key rivers such as the Zambezi (north) and the Limpopo (south) form natural boundaries, contributing to diverse landscapes from lush valleys to arid savannas.

Despite its abundant natural resources (e.g., gold, diamonds, platinum, chrome and lithium), fertile agricultural land and strategic location in southern Africa, Zimbabwe has faced challenges related to governance, economic and political instability, and human development since gaining independence.

Chart 2 presents the Current Path of the population structure, from 1990 to 2043.

The population structure of Zimbabwe from 1990 to 2023 was characterised by a youthful and growing population, with a high proportion of children (under 15 years) and a gradually increasing working-age population (15-64 years). This structure is forecast to remain the same by 2043. When compared to other lower-middle-income African countries such as Angola, Ghana, Nigeria and Kenya, Zimbabwe shares similar demographic patterns but faces unique challenges, particularly in the areas of economic growth and healthcare. Common trends across these countries include declining fertility rates, longer life expectancy and an increasing proportion of the working population.

Since 1990, Zimbabwe’s population structure has undergone notable changes driven by demographic trends, migration, and the country’s political and economic landscape. These factors have reshaped age distribution, urbanisation patterns and population growth rates. The population was estimated at 10 million in 1990, growing to 12 million by 2000. However, factors like HIV/AIDS, declining fertility and emigration slowed this growth during this period.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic significantly impacted Zimbabwe’s population structure, especially in the 1990s and early 2000s. The number of HIV/AIDS-related deaths rose sharply, increasing from 12 000 in 1990 to a peak of about 109 360 in 2003, reflecting an annual growth rate of approximately 25%. However, these numbers have since dropped to 17 620 in 2023. This epidemic also influenced the gender ratio, as higher mortality rates among men widened the gender gap in favour of women.

Zimbabwe’s total fertility rate dropped from 4.88 births per woman in 1990 to 3.64 in 2006, with a modest rebound to 3.72 by 2023. This decline was largely due to improvements in access to family planning, healthcare and education, especially for women.

Economic and political instability since the 1990s has fueled significant emigration, with net migration shifting from a surplus of 4 900 people in 1990 to a deficit of 108 700 in 2010 and 57 230 in 2023. Many Zimbabweans, particularly young people, sought opportunities abroad, migrating to neighbouring countries like South Africa, Botswana and Namibia, as well as to the Global North. This migration contributed to a shrinking youth demographic, often referred to as a youth bulge, particularly in the 2000s when economic difficulties intensified. Youth bulge dropped from a peak of 58% in 2002 to 48% in 2023 and will decrease further to 42% by 2043 on the Current Path. Be that as it may, inward migration from neighbouring countries like Mozambique, Malawi and Zambia, and more recently from China, has also played a role in shaping population dynamics.

Despite these challenges, Zimbabwe’s population has continued to grow, reaching 13 million in 2010 and 16 million by 2023. The Current Path suggests that it will climb to 19 million in 2030 and 24 million by 2043. Declining fertility rates, which are forecast to fall from 3.65 births per woman in 2023 to 2.45 by 2043, will play a key role in this trend. This decrease will be driven by improved education for women, greater access to family planning and ongoing urbanisation.

On the Current Path, an additional 3 million people projected by 2030 and 8 million by 2043, compared to 2023 levels, exert substantial pressure on the country's public infrastructure and services, necessitating urgent and strategic investments in several key areas such as investments in healthcare, food production, services for an aging population, job creation and sustainable urban development. These areas of focus will be essential for mitigating the challenges associated with demographic growth and ensuring that Zimbabwe can develop sustainably and inclusively.

The HIV/AIDS pandemic, along with ongoing political and economic challenges, has led to a significant decline in life expectancy and increased adult mortality in Zimbabwe. Life expectancy sharply decreased from 62 years in 1990 to 46 years in 2004. However, it has since improved, returning to 62 years in 2023, with women averaging 65 years and men 59 years. This progress is largely due to improved access to antiretroviral treatment (ART). Despite these developments, economic and political instability continue to drive outward migration.

Looking ahead, the Current Path shows that the proportion of children under 15 will decline from 41% in 2023 to 38% in 2030 and 31% by 2043. Conversely, the working-age population (15–64) will rise steadily from 56% in 2023 to 60% in 2030 and 64% by 2043. The elderly population (65+) will grow modestly, increasing from 3% in 2023 to 4% by 2043. These trends align with those observed in average lower-middle-income African countries.

While the growing working-age population presents economic challenges, as generating sufficient employment to accommodate this expansion will require substantial policy measures, it also offers the potential for a demographic dividend if the working population is absorbed into the economy. The Current Path indicates that Zimbabwe could enter a demographic window of opportunity around 2039 when the working-age population-to-dependant ratio will reach the 1.7:1 threshold necessary to realise a demographic dividend. To maximise the potential benefits of this demographic dividend, Zimbabwe will need to invest in education, healthcare and job creation to ensure that the growing working-age population is equipped with the necessary skills and can be absorbed into the labour market.

Chart 3 presents a population distribution map for 2023.

As of 2023, Zimbabwe's average population density was approximately 0.42 people per hectare, based on a total land area of 390 757 km² (39 075 700 hectares). This density is unevenly distributed, with higher concentrations in major urban areas like Harare and Bulawayo, which are pivotal as the country's economic and political centres.

Due to its urban opportunities and capital status, Harare attracts many migrants from rural areas and other cities. Despite economic challenges, Bulawayo remains a key industrial and trade hub, though its growth has been slower than Harare's, which has been influenced by factors like deindustrialisation, emigration and political-related issues. Bulawayo is seen as an opposition stronghold, often reflecting broader societal frustrations with government policies and economic conditions.

In terms of rural and urban distribution, as of 2023, approximately 33% of the population lived in urban areas, while the remaining 67% was rural. Rural areas are predominantly engaged in agriculture, but they face challenges such as limited access to basic services and infrastructure.

The population is also characterised by a youthful demographic, with a significant proportion of children under the age of 15 years (41% in 2023) and working-age population (56% in 2023), which presents both opportunities and challenges for job creation and social services. Overall, the distribution underscores the need for balanced development between urban and rural areas to address disparities and ensure sustainable growth.

Chart 4 presents the urban and rural population in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

The urbanisation rate in Zimbabwe has been increasing steadily, though it remains lower than in many other lower-middle-income African countries. In 1990, Zimbabwe was predominantly a rural society, with approximately 71% of the population living in rural areas and the remaining 29% in urban centres. However, by 2002, the rural population had decreased to around 66%. This decline reflects a trend of urbanisation that has been ongoing since the 1950s, driven by rural-to-urban migration and a growing youth population seeking employment and tertiary education opportunities. Major urban and industrial centres such as Harare, Bulawayo, Mutare, Gweru, Masvingo, Kadoma and Kwekwe experienced population growth, often at the expense of rural areas.

After 2002, the rural population began to increase again, rising to 68% by 2014. This shift suggests a reverse trend of urban-to-rural migration, which is likely attributed to the difficult economic conditions that affected the country during this period, causing significant hardship for the urban population. Many elderly individuals have been forced to migrate to their rural retirement homes due to the high cost of living in urban areas and a significant decline in basic urban amenities. For instance, access to essential water services for the urban population decreased from 31% in 2000 to 27% in 2023, with the Current Path indicating a further decline to 20% by 2043. Furthermore, dwindling economic opportunities compelled some of the working-age population to leave the cities and return to their rural homes.

Despite ongoing economic challenges, there has been a small increase in urbanisation beginning in 2014, which has reduced the rural population to 67% in 2023. This slight increase in the urban population can be attributed to the youth who are seeking employment opportunities in urban areas.

The Current Path suggests that the rural population will stay around 67%, with a consistent population gap between rural and urban areas until 2043. This consistent gap can be attributed to the limited urban and industrial development that is typically associated with rural-to-urban migration.

Rural areas in Zimbabwe have often been neglected regarding socio-economic development despite making up a significant portion of the population. Based on the Current Path, it is essential for the government and stakeholders to implement policies that promote sustainable development in both urban and rural areas. This will ensure that the basic needs of populations in both settings are adequately addressed.

Chart 5 presents GDP in market exchange rates (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

Since 1990, Zimbabwe's economy has experienced significant fluctuations, moving from prosperity to crisis and attempts at recovery. Initially, during the decade after independence, Zimbabwe thrived with a diverse agricultural sector and strong mining and manufacturing, leading to GDP growth from US$9 billion to US$14 billion.

In the 1990s, the introduction of Structural Adjustment Programs (SAP) aimed at liberalising the economy brought some growth, with GDP reaching around US$17 billion in 1999, but also led to fiscal imbalances and unrest due to contentious land reforms that resulted in economic chaos and food shortages.

By 2008, Zimbabwe's economy collapsed, with GDP falling to US$9 billion amid rampant hyperinflation. The adoption of a multi-currency system in 2009 temporarily stabilised the economy, and by 2018, GDP had risen to approximately US$18 billion, although challenges like corruption and poor infrastructure persisted. From 2019 onward, the abolition of the multi-currency system reintroduced hyperinflation, and by 2020, GDP had dropped to US$16 billion, further worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, by 2023, a recovery was noticeable, with GDP rising to about US$19 billion, supported by rebounds in agriculture and mining. The Current Path is cautiously optimistic, with an average GDP growth rate of 5% annually between 2023 and 2030, potentially elevating GDP to US$27 billion by 2030 and an even more ambitious reach of US$68 billion by 2043, if the average growth rate accelerates to 7% annually between 2031 and 2043. The Current Path GDP growth rate of approximately 6% by 2030 suggests that Zimbabwe will not meet its Vision 2030 goal of achieving an annual GDP growth rate between 7% and 10%.

For sustainable growth, Zimbabwe must focus on comprehensive reforms in several key areas: enhancing agricultural productivity, developing its mining sector through beneficiation, improving infrastructure, revitalising tourism and embracing digital innovation. Achieving these goals will require stabilising the currency, enhancing governance, reducing external debt and fostering better international relationships to restore investor confidence.

Chart 6 presents the size of the informal economy as per cent of GDP and per cent of total labour (non-agriculture), from 2020 to 2043. The data in our modelling are largely estimates and therefore may differ from other sources.

In the early 1990s, Zimbabwe implemented economic reforms as part of SAPs, which included privatisation, austerity measures and cuts in government spending. These changes resulted in rising unemployment and a reduction in formal sector jobs. Consequently, many Zimbabweans were pushed into the informal sector, engaging in activities such as street vending, small-scale farming and other informal enterprises to make ends meet. The growth of informal businesses continued to expand from the early 2000s due to the economic challenges (mentioned above) as people sought alternative sources of income.

Beginning in 2000, many industries faced collapse or downsizing, resulting in significant job losses. During this time, street vending became increasingly common, while cross-border trading, informal foreign exchange dealing, informal retail and artisanal mining activities also gained prominence as people sought alternatives to the dwindling formal job market. After the introduction of the multi-currency regime in 2009, many informal businesses began transitioning into more structured, semi-formal operations. However, the complete formalisation of these businesses has been slow, hindered by ongoing regulatory challenges and the continued reliance on informal practices.

In the 2010s, Zimbabwe faced ongoing policy inconsistencies characterised by frequent changes in regulations and tax laws that affected informal sector operators. As a result, many small businesses found themselves operating in a grey area, with limited access to formal banking services, government support and infrastructure. Despite these challenges, the informal sector demonstrated remarkable resilience. Smallholder farmers, informal foreign exchange dealers, cross-border traders, artisans and others continued to make significant contributions to the economy, particularly in terms of employment and local consumption.

The global COVID-19 pandemic put additional pressure on the Zimbabwean economy, particularly impacting the informal sector. Movement restrictions and lockdowns severely affected street vending, small-scale trade and informal mining activities. Despite these challenges, the informal sector demonstrated remarkable adaptability by embracing innovation. The pandemic led to a rise in digital platforms and online businesses, as many individuals turned to e-commerce and delivery services in response to the disruption of physical markets.

As of 2023, the informal sector in Zimbabwe played a vital role in the economy, employing around 40% of the total labour force and contributing approximately 54% to the country's GDP. Although the Current Path suggests that this sector's share of employment and GDP may decline to 35% by 2043, it is expected to remain essential for the Zimbabwean economy and the livelihoods of many citizens over the next two decades.

To effectively transition the informal sector towards formalisation and improve productivity, a comprehensive strategy is needed. Key approaches include access to finance, infrastructure development, reform of business regulatory framework, capacity building and support, public-private partnerships, political stability, anti-corruption measures, and monitoring and evaluation. By pursuing these strategies, policymakers can foster an inclusive economic environment that empowers informal businesses and contributes to economic growth. This could lead to the informal sector becoming a more organised part of the economy by 2043, promoting innovation, job creation and national development.

Chart 7 presents GDP per capita in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043, compared with the average for the Africa income group.

Zimbabwe's GDP per capita displayed relative stability in the early 1990s, averaging around US$2 730, with a peak of US$2 930 in 1998—a level last seen in 1974. This stability was supported by a strong agricultural sector and mineral exports. However, challenges emerged toward the end of the decade, including political instability and rising external debt, which contributed to slower growth.

The early 2000s marked a significant decline in GDP per capita, which fell from approximately US$2 750 in 2000 to a record low of US$1 350 in 2008. This drop was largely a result of the land reform program that destabilised agriculture, compounded by political turmoil and rampant corruption, culminating in a hyperinflation crisis.

After the adoption of a multi-currency system in 2009, GDP per capita saw a moderate recovery, rising to about US$2 400 by 2018. Nonetheless, issues like low productivity, high unemployment and external debt persisted. In 2020, GDP per capita decreased to around US$1 940 due to currency instability following the end of the multi-currency system in early 2019. Moreover, negative impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with domestic instability and natural disasters, further hindered growth, leading to a contraction in GDP per capita.

By 2023, signs of recovery emerged, particularly in the mining and agriculture sectors, with GDP per capita rising to about US$2 190. Despite this progress, Zimbabwe's GDP per capita remained significantly lower than the average GDP per capita of lower-middle-income African countries, which stood at US$5 780 in 2023.

On the Current Path, GDP per capita will grow to approximately US$2 580 by 2030 and then reach around US$4 400 by 2043, assuming annual average growth rates of approximately 2.3% and 4.2%, respectively. At this growth rate, Zimbabwe's economic development, as measured by GDP per capita, will continue to lag behind the average growth of lower-middle-income African countries, which will reach US$7 710 by 2043 from US$6 240 in 2030 on the Current Path.

Relatively higher growth rates are achievable if key factors such as political stability, institutional reforms, efficient natural resource management, infrastructure investment, debt management and currency stability are addressed. Successfully overcoming these challenges could enable Zimbabwe to experience significant economic growth and improve its attractiveness as an investment destination by 2043.

Chart 8 presents the rate and numbers of extremely poor people in the Current Path from 2020 to 2043.

In 2022, the World Bank updated the poverty lines to 2017 constant dollar values as follows:

- The previous US$1.90 extreme poverty line is now set at US$2.15, also for use with low-income countries.

- US$3.20 for lower-middle-income countries, now US$3.65 in 2017 values.

- US$5.50 for upper-middle-income countries, now US$6.85 in 2017 values.

- US$22.70 for high-income countries. The Bank has not yet announced the new poverty line in 2017 US$ prices for high-income countries.

Zimbabwe has experienced significant fluctuations in poverty levels over recent decades despite various efforts to stabilise the economy. In the 1980s, following independence, about 13% of the population lived on less than $2.15 per day, with rural poverty affecting over 60% of the population. The 1990s saw a decline in poverty, dropping from 11% in 1990 to a record low of 8% in 1998. However, the situation worsened in the 2000s due to severe economic challenges, with extreme poverty rising dramatically to 41% by 2008, a significant increase driven by factors such as land reform disruptions and political instability.

The adoption of a multi-currency system in 2009 led to a notable recovery, reducing the proportion of people living in extreme poverty by nearly half by 2012. However, ongoing economic fragility meant poverty remained a significant issue, especially in rural areas suffering from high unemployment and underemployment. From 2012 to 2018, weak GDP growth and a high formal unemployment rate contributed to persistent extreme poverty. The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 exacerbated the poverty crisis, leading to economic disruptions and job losses, particularly in rural regions.

On the Current Path, extreme poverty (at less than US$2.15 per day) affected 35% of the population (5.8 million people) in 2023. While absolute numbers may drop slightly to 5.6 million by 2030, representing 30% of the population, significant improvements are projected by 2043, with extreme poverty affecting only 18% (4.2 million people). These forecasts are concerning, especially when considering that in 1998, only 0.96 million people lived in extreme poverty, accounting for just 8% of the population. Furthermore, these forecasts suggest that the country is unlikely to meet Sustainable Development Goal 1 (SDG 1), which aims to end extreme poverty and ensure that less than 3% of the global population lives below the extreme poverty line (at less than US$2.15 per day) by 2030.

To have a better chance of achieving SDG 1, Zimbabwe would need focused interventions aimed at fostering economic growth, creating jobs, ensuring effective governance, and enhancing access to education and health services. This includes leveraging its natural resources responsibly, investing in human capital, and establishing a predictable and stable political environment conducive to investment. Without significant policy changes and investments in these areas, the likelihood of achieving the target of reducing extreme poverty below 3% by 2030 remains slim.

Chart 9 depicts the National Development Plan of Zimbabwe.

Zimbabwe's national development plan has evolved over several decades to address shifting economic, political and social challenges. In the early 1990s, the country initiated SAP, guided by the Growth with Equity Strategy of 1991. This plan was influenced by a global shift toward neoliberal economic policies, aiming for: (i) economic liberalisation to reduce government intervention in the market, (ii) market-based reforms that focused on the privatisation of state-owned enterprises, trade liberalisation and cuts to subsidies, and (iii) economic growth with equity, which sought to diminish poverty and inequalities while promoting economic development. However, this era was also characterised by significant challenges, including rising inflation, high unemployment and a declining industrial sector, which prompted a reevaluation of these policies in the late 1990s.

During the hyperinflation crisis, the government did not present a formal long-term development plan. However, following the political and economic upheaval, a power-sharing government was established in 2009 between the ruling party Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) and the main opposition party Movement for Democratic Change (MDC). This coalition government implemented the Short-Term Economic Recovery Programme (STERP) which aimed to stabilise the economy through a series of strategic measures, including currency stabilisation (the country transitioned from its currency to a multi-currency system, primarily using the US$ and South African rand), restoring growth (with a major focus on rebuilding essential sectors such as agriculture, mining and manufacturing) and infrastructure rehabilitation of key infrastructure projects that deteriorated during the crisis years.

While these efforts led to some economic stabilisation, challenges such as high unemployment, poverty and political instability remained. In 2013, Zimbabwe launched the Zimbabwe Agenda for Sustainable Socio-Economic Transformation (ZIM-ASSET), which spanned from 2013 to 2018. This plan aimed at achieving economic transformation through several key objectives:

- Natural Resource Management: Leveraging the country's mineral wealth for industrialis

- Agriculture and Food Security: Enhancing agricultural production to ensure food self-sufficiency.

- Infrastructure Development: Focusing on road improvements, energy and water systems to enhance the business environment.

- Employment Creation: Promoting industrialisation and the development of small-scale enterprises to reduce unemployment.

While ZIM-ASSET outlined ambitious goals, its implementation was often hindered by the country's economic challenges, including a lack of financing and pressures from external debt. The Transitional Stabilization Programme (TSP) was introduced in 2018 following the ousting of former President Robert Mugabe. It aimed to guide Zimbabwe through a period of economic transition and stabilisation. The key objectives of the TSP included:

- Economic Stabilization: Stabilizing the currency and managing inflation.

- Fiscal Consolidation: Reducing the budget deficit and controlling government expenditure.

- Reform and Modernization: Reforming the state-owned enterprises sector, implementing anti-corruption measures and enhancing governance.

- Infrastructure Development: Continuing infrastructure projects, particularly in energy and transport.

The TSP was expected to pave the way for the long-term goals outlined in the National Development Strategy 1 (NDS1). The NDS1, covering the period from 2021 to 2025, serves as Zimbabwe’s mid-term development plan. It aims to build on the achievements of the TSP and lay the groundwork for the country to become an upper-middle-income economy by 2030. Key priorities of the NDS1 include:

- Economic Diversification: Moving away from reliance on agriculture and mining to incorporate manufacturing and services.

- Infrastructure Development: Expanding roads, power generation and social services like health and education.

- Human Capital Development: Improving education and healthcare systems to create a skilled and healthy workforce.

- Digital Transformation: Promoting the use of technology in both the public and private sectors.

- Environmental Sustainability: Encouraging green initiatives and sustainable land use.

Zimbabwe's Vision 2030 represents the long-term national development goal of transforming the country into an upper-middle-income economy by 2030. This vision emphasises:

- Economic Growth: Achieving an annual GDP growth rate of around 7% to 10%.

- Industrialization and Value Addition: Shifting away from exporting raw materials to focusing on manufacturing and value-added exports.

- Poverty Reduction: Significantly lowering poverty levels by improving living standards.

- Sustainable Development: Ensuring that economic progress is environmentally sustainable and inclusive.

Zimbabwe’s development goals aim to achieve economic modernisation and create a more prosperous country. This plan builds on the groundwork laid in the Vision 2030 framework. Key long-term objectives may include:

- Technological Innovation: Promoting research and development while integrating emerging technologies across all sectors.

- Global Competitiveness: Positioning Zimbabwe as a competitive economy in regional and global markets.

- Social Inclusion: Ensuring that the benefits of economic growth reach all segments of society, particularly marginalised groups.

- Institutional Development: Strengthening transparent institutions that promote governance, peace and development.

The national development plans from 1990 reflect the evolution of Zimbabwe's economic and development strategies, moving from addressing immediate crises to setting ambitious long-term growth goals. While progress has been uneven, Zimbabwe remains focused on structural transformation, poverty reduction and sustainable development as it works toward these objectives.

The eight sectoral scenarios as well as their relationship to the Current Path and the Combined scenario are explained in the About Page. Chart 10 summarises the approach.

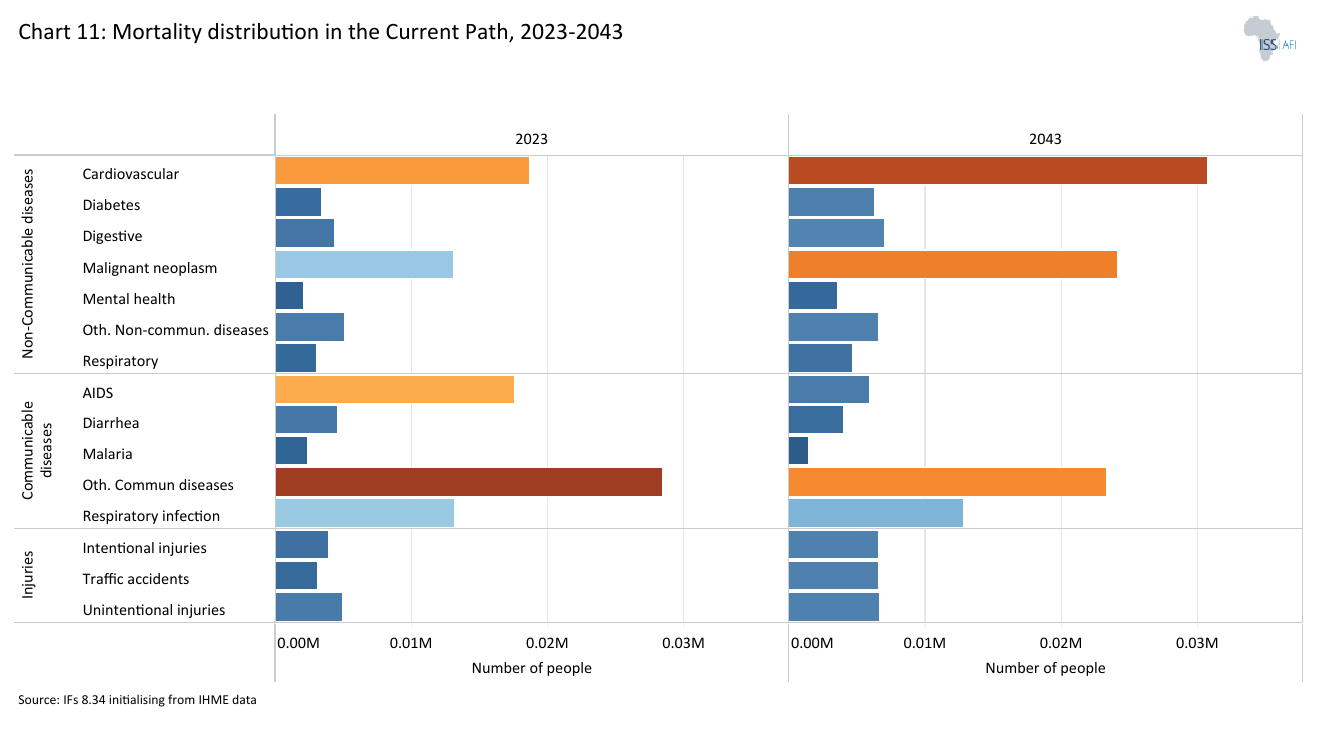

Chart 11 presents the mortality distribution in the Current Path for 2023 and 2043.

The Demographics and Health scenario envisions ambitious improvements in child and maternal mortality rates, enhanced access to modern contraception, and decreased mortality from communicable diseases (e.g., AIDS, diarrhoea, malaria, respiratory infections) and non-communicable diseases (e.g., diabetes) alongside advancements in safe water access and sanitation. This scenario assumes a swift demographic transition supported by heightened investments in health and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WaSH) infrastructure.

Visit the themes on Demographics and Health/WaSH for more detail on the scenario structure and interventions.

Zimbabwe's mortality distribution is characterised by a combination of factors, including communicable diseases (CDs) and non-communicable diseases (NCDs). CDs include HIV/AIDS, respiratory infections and others. NCDs include cardiovascular and malignant neoplasm. Lack of safe water access and sanitation is a significant contributor to the country's health challenges as it increases the risk of waterborne and sanitation-related diseases.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic in Zimbabwe has been a significant health challenge since the 1980s, but the country has made remarkable progress in reducing infection and death rates. The AIDS-related deaths dropped from a peak of 109 390 in 2003 to 17 620 in 2023 due to the widespread rollout of antiretroviral therapy (ART) starting in the 2000s, supported by initiatives like the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Global Fund. Moreover, Zimbabwe adopted a universal test-and-treat policy in 2010 and now has over 1 million individuals on ART, achieving substantial progress toward global "90-90-90" targets.

Expanding access to testing and ART, addressing stigma, improving healthcare infrastructure and providing targeted support for vulnerable populations can further reduce AIDS-related deaths to 5 960 by 2043 on the Current Path. Furthermore, by integrating HIV care into broader health systems and leveraging education, technology and sustainable funding, Zimbabwe can eliminate mother-to-child transmission, maintain high viral suppression rates and achieve long-term health outcomes.

Although HIV/AIDS remains a major concern, respiratory infections and other CDs continue to affect the population. On the Current Path, deaths from respiratory infections and other CDs will decline from 13 190 and 28 410 in 2023 to 12 860 and 23 340 by 2043, respectively. These figures highlight the persistent burden of CDs, which has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, further straining healthcare resources and increasing mortality rates. However, progress can be made through preventive measures, enhancements in healthcare infrastructure, increased education and awareness and tackling social determinants of health.

On the other hand, the Current Path indicates an increase in deaths from NCDs, with fatalities due to malignant neoplasms (MagligNeoPi) and cardiovascular diseases (Cardio Vasc) rising from 13 120 and 18 680 in 2023 to 24 110 and 30 760 by 2043, respectively. This surge is driven by demographic shifts, lifestyle changes and healthcare challenges. As a result, effectively addressing NCDs in Zimbabwe will require a stronger emphasis on prevention, early diagnosis and strategic resource allocation to meet the growing healthcare demands.

With a decline in deaths related to CDs and an increase in deaths from NCDs, the Current Path indicates that Zimbabwe will experience its epidemiological transition by 2031. This transition marks the point when NCD-related death rates surpass those of CDs.

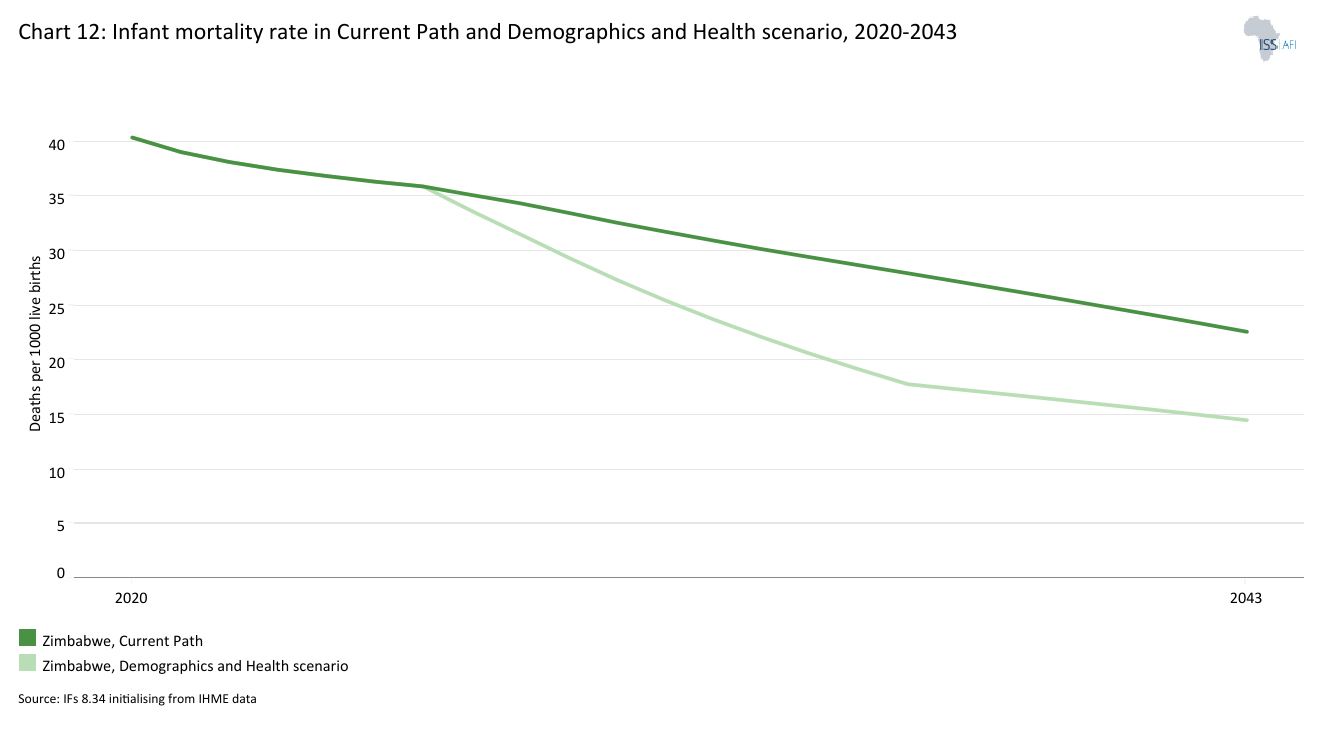

Chart 12 presents the infant mortality rate in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

The infant mortality rate is the probability of a child born in a specific year dying before reaching the age of one. It measures the child-born survival rate and reflects the social, economic and environmental conditions in which children live, including their health care. It is measured as the number of infant deaths per 1 000 live births and is an important marker of the overall quality of the health system in a country.

Zimbabwe’s infant mortality rates have fluctuated over the years due to a combination of social, political and economic factors. In 1990, the rate stood at around 47 deaths per 1 000 live births, increasing to 54 by 1999 as a result of economic hardships and the HIV/AIDS crisis. The early 2000s saw further deterioration, peaking at 58 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2009. However, starting in 2010, enhanced healthcare efforts, supported by foreign aid and public health initiatives, began to reverse this trend. By 2020, the rate had dropped to approximately 40 deaths per 1 000 live births, further decreasing to 37 by 2023. With continued improvements in healthcare access, sanitation and economic stability, this figure will further decrease to 33 in 2030 and 23 deaths per 1000 live births by 2043 on the Current Path.

Sustained policy focus and increased investment in public health interventions in the Demographics and Health scenario will drive even greater progress, potentially reducing the infant mortality rate to 27 and 15 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2030 and 2043, respectively. However, this trajectory indicates that Zimbabwe will not meet the SDG 3.2 target of reducing the infant mortality rate to less than 25 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2030. The target could potentially be reached by 2032 in the Demographics and Health scenario while remaining on the Current Path would delay the achievement until 2040.

Severe acute malnutrition (SAM) remains a significant challenge for children in Zimbabwe, fueled by food insecurity, poverty and gaps in healthcare services. SAM prevalence among children under five rose sharply from 0.4% in 1988 to 4.2% in 1999 during a period of economic and health crises. Although international aid in the 2010s contributed to treatment advancements, SAM rates have remained a concern, with an estimated 0.7% prevalence by 2023. This rate will remain unchanged until 2043 on the Current Path. However, it can decline slightly to 0.6% with interventions in the Demographics and Health scenario. These interventions focus on sustained improvements in food security and access to healthcare.

Similarly, Zimbabwe’s maternal mortality ratio (MMR) has experienced dramatic shifts. It peaked at 685 deaths per 100 000 live births in 2008 due to economic instability and the impact of HIV/AIDS. Efforts to enhance maternal healthcare in the early 2010s led to a steady decline, with the MMR dropping to 357 by 2020 and further to 323 in 2023. With sustained investment in healthcare systems and addressing underlying social issues like poverty and education as part of the interventions in the Demographics and Health scenario, the MMR will drop to 76 by 2043 compared to 101 deaths per 100 000 live births on the Current Path. Despite this progress, Zimbabwe will not reach the 2030 international health target of reducing the MMR to below 70 deaths per 100 000 live births until 2043.

Overall, while strides have been made in improving health outcomes in Zimbabwe, challenges remain due to economic instability, food insecurity and healthcare access. Continued focus on maternal and child health, nutrition and healthcare infrastructure will be critical for achieving sustainable reductions in infant mortality, SAM and maternal mortality rates by 2043.

Chart 13 presents the demographic dividend in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

The dividend is the window of economic growth opportunity that opens when the ratio of working-age persons to dependants increases to 1.7 to 1 and higher.

Zimbabwe’s fertility rates have shown a consistent decline since 1990, decreasing from approximately 5 births per woman to approximately 4 by 2023. This trend will continue, with the Current Path suggesting a decrease to 2.4 births per woman by 2043. The reduction in fertility rates will result in a smaller dependent population (children) and a larger working-age population, which has significant implications for economic development.

As fertility rates decline, the demographic composition of Zimbabwe's population is expected to shift. On the Current Path, the proportion of the population aged 65 and above will gradually increase but is projected to remain relatively low, around 4% by 2043. Conversely, the working-age population (ages 15-64) will grow significantly, potentially making up 64% of the total population by 2043, compared to 56% in 2023. This demographic transition creates a potential for what is known as a "demographic dividend."

By 2023, Zimbabwe's ratio of working-age population to dependants was 1.3:1, which is below the 1.7:1 threshold required to achieve a demographic dividend. Both the Current Path and the proposed Demographics and Health scenario suggest that Zimbabwe will enter a demographic window of opportunity by 2039, with dependency ratios of 1.71 and 1.72, respectively. Until that time, the country will not benefit from a demographic dividend, which could have sped up economic growth.

To maximise the potential benefits of this demographic dividend, Zimbabwe will need to invest in education, healthcare and job creation to ensure that the growing working-age population is healthy, equipped with the necessary skills and can be absorbed into the labour market.

Chart 14 presents crop production and demand in the Current Path from 1990 to 2043.

The Agriculture scenario envisions an agricultural revolution that ensures food security through ambitious yet feasible increases in yields per hectare, thanks to improved management, seed, fertiliser technology, and expanded irrigation and equipped land. Efforts to reduce food loss and waste are emphasised, with increased calorie consumption as an indicator of self-sufficiency and prioritising it over food exports. Additionally, enhanced forest protection signifies a commitment to sustainable land use practices.

Visit the theme on Agriculture for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Zimbabwe's agriculture sector is predominantly crop-based and is vital to the economy and livelihoods, serving as a key pillar of food security, particularly for rural communities. Over the years, food security has fluctuated due to economic policies, land reforms, climate conditions and international trade dynamics. Total agricultural production and demand have both increased, reaching 9.3 and 11.6 million metric tons in 2023 from 8.11 and 7.76 million metric tons in 1990, respectively. However, since 2001, demand has consistently exceeded production, widening the food deficit to 2.3 million metric tons by 2023.

In the 1990s, the country was recognised for having some of the highest crop production levels in sub-Saharan Africa. Crop production increased from 7.4 million metric tons in 1990 to 8.7 million metric tons in 1999, primarily driven by staple crops such as maize and tobacco. During the same period, overall agricultural crop production rose from 6.6 million to 8.4 million metric tons.

However, severe droughts, particularly during the 1992/1993 season, led to a sharp decline in yields. In 1992, crop yields plummeted to a record low of 1.5 million metric tons, significantly below the national demand of 3.5 million metric tons. Total agricultural production also fell to a record low of 2.15 million metric tons, compared to the national demand of 4.09 million metric tons in that same year. Recovery efforts allowed crop production to rebound to 9.4 million metric tons by 1999, while domestic demand increased to 8.6 million metric tons.

The land reform program of the early 2000s, which aimed to redistribute commercial farmland to local farmers, significantly reduced agricultural productivity. The displacement of skilled commercial farmers led to a drastic decline in crop yields, which dropped from 8.9 million metric tons in 2000 to 5.1 million metric tons by 2009. This situation marked the beginning of food shortages as crop demand consistently remained above production, even as it decreased from 8.3 million metric tons to 6.7 million metric tons during the same period.

From 2010 onwards, recovery efforts increased crop production again to 7.9 million metric tons in 2018. However, yields still fell short of pre-reform levels, while demand rose to 8.5 million metric tons in the same period. The land reform led to ongoing food insecurity, widening the food deficit from 2001 onward, and caused economic instability due to decreased financial inflows from agricultural exports.

Ongoing economic challenges, erratic rainfall due to climate change events such as the 2023/2043 El Niño and insufficient investment in agricultural technology have further strained the agricultural sector. As a result, crop yields declined again to 7.7 million metric tons in 2023, while demand increased to 9.9 million metric tons. This situation resulted in a crop production deficit of 2.2 million metric tons in 2023.

On the Current Path, the crop production deficit will increase nearly fivefold to 9.9 million metric tons by 2043, with demand reaching 19.1 million metric tons against production of 9.2 million metric tons. This suggests that the country is straying from the SDG 2 goal of eradicating hunger, ensuring food security and enhancing nutrition by 2030.

Land reform also negatively affected agricultural losses (both post-harvest losses and food waste), irrigation development and rural road access, particularly in farming regions. Equipped irrigated land is crucial, especially as Zimbabwe has experienced inconsistent rainfall for over two decades. Additionally, rural road access is essential for improving agricultural efficiency, production and market access. Reducing agricultural losses is necessary to mitigate food shortages and prevent food price hikes, as production and distribution losses often result in higher costs for consumers.

Although crop production losses due to storage and distribution challenges will decrease slightly from 10.3% in 2023 to 9.7% in 2043 on the Current Path, they remain higher than the averages of lower-middle-income African countries. Before the land reform, equipped-irrigated land expanded from 109 000 hectares in 1990 to 174 000 hectares by 1999. However, growth stalled during the land reform crisis, only beginning to recover in 2017 through investments in large-scale and smallholder irrigation systems. By 2023, equipped-irrigated land had reached approximately 190 000 hectares. The Current Path shows a decline to 167 000 hectares by 2043.

Rural road access, once relatively strong before land reform, has deteriorated since the early 2000s. The proportion of the rural population with access to all-season roads declined from 65% in 2002 to 56% in 2020. Recent infrastructure investments have begun reversing this trend, increasing access to 57% by 2023. Consistent investments in road development could raise this figure to about 62% by 2023 on the Current Path.

In summary, Zimbabwe’s agricultural sector faces a complex array of challenges, including unstable crop yields, high production losses, dependence on rain-fed farming and deteriorating infrastructure. A comprehensive strategy involving major investments in irrigation, modern agricultural practices, rural road networks, and effective land reform policies could revitalise the sector. Without addressing these pressing issues, Zimbabwe’s agricultural performance will likely continue to lag behind regional peers, impacting long-term food security and economic stability.

Chart 15 presents the import dependence in the Current Path and the Agriculture scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

In the 1990s, Zimbabwe's agricultural sector was highly productive and diversified, enabling the country to achieve self-sufficiency in key commodities. Zimbabwe was a net exporter of agricultural products such as tobacco, maize, cotton and sugar, with tobacco being the largest contributor to foreign currency earnings. The highest dependence on imports occurred during the 1992 drought. However, by 1994, the country had significantly enhanced its self-sufficiency. While the country was largely self-reliant in food and cash crop production, it still imported a small portion of agricultural inputs, including fertilisers, machinery and seeds. Moreover, climatic risks, particularly for rain-fed farming, posed challenges as droughts occasionally necessitated imports of staple foods.

The early 2000s marked a dramatic shift in Zimbabwe’s agricultural landscape. The Land Reform Program, coupled with political instability and economic collapse, caused a sharp decline in agricultural output. The redistribution of commercial farms significantly reduced production as new farm owners often lacked resources and expertise, leading to widespread food insecurity. Zimbabwe became heavily reliant on imported food staples such as maize, wheat and rice to meet domestic demand. Shortages of essential inputs like fertilisers and seeds, compounded by a foreign exchange crisis, further exacerbated the situation. Tobacco and cotton production, once major exports, also declined, reducing the country’s capacity to earn foreign exchange. Since the 2001/2002 season, the country has shifted from self-sufficiency to import dependency.

During the 2010s, Zimbabwe began efforts to rebuild its agricultural sector, but challenges in achieving self-sufficiency persisted. While tobacco production recovered, overall agricultural output remained low, and import dependency on staples like maize, wheat and rice continued. Limited access to irrigation systems, unpredictable weather and rural infrastructure issues hindered productivity. Imported fertilisers, pesticides and equipment were critical to maintaining production, but high costs and limited foreign currency made these inputs inaccessible to many farmers. Periodic droughts and floods disrupted agriculture, increasing reliance on food imports to ensure food security.

By the 2020s, Zimbabwe's economic stability had improved, yet the agricultural sector continued to struggle with reducing import dependency which stood at 20% in 2023, up from 7% in 2002. Crop exports were approximately US$50 million, while imports were US$468 million. As a result, the crop trade deficit stood at roughly US$418 million in 2023.

The country remained reliant on imported agricultural inputs such as fertilisers, seeds and machinery to sustain productivity. Additionally, disease outbreaks highlighted ongoing challenges. While tobacco remained a major export crop and efforts were made to revive cotton and horticulture exports, overall export capacity was constrained by high input costs and low production levels. Furthermore, Zimbabwe's dependence on rain-fed agriculture and limited irrigation infrastructure left it vulnerable to climate variability, leading to inconsistent domestic production.

Looking ahead, the Current Path suggests that Zimbabwe's dependence on agriculture imports will worsen, reaching 53% by 2043. At the same time, agricultural imports will increase to US$2.03 billion while exports will drop significantly to US$1.2 million.

Zimbabwe's agricultural future relies on climate adaptation, technological investment, infrastructure development, economic stability and effective policy implementation. If these issues are not addressed, increasing agricultural output will remain a challenge. Hence, interventions in the Agriculture scenario focus on substantial investments in small-scale and large-scale irrigation systems, agricultural technology, climate-adaptive agricultural practices, infrastructure, agro-processing and nutrition. Strengthening domestic production capacity through these measures can lead to improved exports of tobacco and horticultural products, ultimately fostering a more resilient agricultural sector.

In the Agriculture scenario, dependence on agricultural imports will increase to 31% by 2043, compared to 53% on the Current Path. At the same time, agriculture exports will rise to US$180 million by 2043, far above the US$1.2 million on the Current Path, while import growth will be limited to US$1.5 billion, which is lower than the US$2.03 billion on the Current Path.

Chart 16 depicts the progress through the educational system in the Current Path, for 2023 and 2043.

The Education scenario represents reasonable but ambitious improvements in intake, transition, and graduation rates from primary to tertiary levels, as well as better quality of education at primary and secondary levels. It also models substantive progress towards gender parity at all levels, additional vocational training at the secondary school level, and increases in the share of science and engineering graduates.

Visit the theme on Education for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

The educational landscape in Zimbabwe, particularly since the 1990s, has been shaped by various socio-economic and political factors that have impacted access, quality and gender parity across different education levels. Despite these challenges, the literacy rate among individuals aged 15 and older has steadily risen, from around 80% in 1990 to 90% in 2023. In 2024, Zimbabwe ranked among the top 10 African countries with the highest education levels, securing the 4th position. This ranking is based on literacy rates and years of schooling. The Current Path indicates that Zimbabwe’s literacy rate will reach 91% by 2030 and 96% by 2043. As a result, Zimbabwe aligns with SDG 4.6, which aims to ensure that all youth and a significant proportion of adults, regardless of gender, attain literacy and numeracy by 2030.

In the 1990s, Zimbabwe was a notable leader in educational attainment within sub-Saharan Africa, achieving near-universal primary education and substantial gender parity at both primary and secondary levels. The government's proactive investment in educational infrastructure and policies effectively reduced the gender gap, providing equal opportunities for boys and girls. Despite the robust enrollment figures, challenges loomed for secondary education where access was limited and many families could not afford associated costs.

The early 2000s brought a significant downturn as Zimbabwe experienced a severe economic crisis characterised by hyperinflation and declining governmental support for education. This crisis severely impacted secondary and tertiary education enrollment rates, particularly affecting girls due to economic pressures leading to higher dropout rates from schools and increased risks of early marriages and pregnancies.

International aid initiatives were instrumental in advancing gender parity and increasing girls' enrollment in both primary and secondary education during this challenging period. However, challenges persisted for women in tertiary education.

Following the dollarisation of the economy in 2009, Zimbabwe's education system began to show signs of recovery. Primary education net enrollment remained high and secondary school net enrollment gradually improved, although it was accompanied by issues such as overcrowded classrooms and inadequate infrastructure. Enhancements in gender parity continued, with an increasing presence of female students in tertiary institutions by the 2010s, reflecting a growing commitment to higher educational attainment regardless of gender.

The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 accelerated the implementation of online learning but the country's previously established digital infrastructure issues highlighted the uneven access to technology between urban and rural areas. Nevertheless, initiatives aimed at promoting gender equality and removing barriers for female students continued.

Looking ahead, the Current Path indicates that Zimbabwe will achieve the SDG 4 2030 target of at least 97% net primary enrollment and gender parity in primary education by 2043. Girls’ net enrollment rates will rise from 93% in 2023 to 100% by 2043, while boys' enrollment will increase from 80% to 94% during the same period.

In secondary education, the gender gap in net enrollment will close entirely by 2034 on the Current Path, with a net enrollment rate of 52%, up from 35% for females and 39% for males in 2023. This rate will rise to 56% by 2043. There is potential for improvement through initiatives like scholarships, mentorship programs and community-based efforts aimed at overcoming socio-cultural barriers such as early marriage and teenage pregnancies. These measures are crucial since the country's net secondary school enrollment rates are still lower than the average for lower-middle-income African countries. By 2043, this average will reach 63% after achieving gender parity at 60% in 2038 on the Current Path.

In tertiary education, the gender gap in gross enrollment closed at approximately 12% in 2023. However, the Current Path shows that it reopened in 2024, this time favouring females. Despite this shift, the gap will remain small as enrollment rates rise to about 26% for females and 23% for males by 2043. This trend is consistent with the average observed in lower-middle-income African countries, with marginal variations.

Zimbabwe has made significant progress toward gender parity in education, implementing policies to increase girls' enrollment in secondary education and tackle barriers like teenage pregnancy. By 2023, gender parity across all education levels was nearly 1:1, with almost equal gross enrollment rates for both genders. The Current Path indicates that parity levels will be maintained across all education levels through 2043.

The country's primary focus must be on enhancing the quality of tertiary education and equipping both male and female graduates with the skills needed to compete in a global economy. Future policies and reforms must also continue prioritising access to education and funding, especially in rural areas, while addressing gender disparities. As digital education gains prominence worldwide, Zimbabwe may further integrate online learning platforms; however, access to technology will remain a challenge unless significant infrastructure improvements are made.

Economic recovery and growth will be crucial in shaping the quality of education in the coming decades. A strong economy will enable better funding and accessibility for education. By 2043, gender parity in education is expected to be more firmly established, with more girls staying in school longer and entering traditionally male-dominated fields such as Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM). Additionally, the education system may see notable improvements in the transition from secondary to tertiary education, particularly in response to the growing global demand for skilled labour.

Chart 17 presents the mean years of education in the Current Path and in the Education scenario, from 2020 to 2043, for the 15 to 24 age group.

The average years of education in the adult population aged 15 to 24 is a good first indicator of how the stock of knowledge in society is changing.

Zimbabwe’s education system continues to face challenges, including inadequate infrastructure, teacher shortages and economic instability. Despite these obstacles, the country’s educational attainment remains competitive within the region.

In general, on the Current Path, the average years of educational attainment for adults aged 15 and older will increase, reaching 11.3 years for both males and females by 2040, remaining stable through 2043. This convergence marks a shift from the 2023 figures, which were 11.4 years for males and 11 years for females (11.2 years total).

Zimbabwe's Current Path trend on average years of adult educational attainment from 2023 to 2043 surpasses that of economically stable African countries such as Botswana, South Africa and Mauritius. However, these countries have achieved significantly higher average years of educational attainment among the lower youth age group (15–24 years) due to their stable economies and consequently well-funded education systems. The lower youth age group serves as a key indicator of a country's human capital stock.