Tanzania

Tanzania

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

The page provides an in-depth analysis of Tanzania's current and projected future development, examining various sectoral scenarios and their potential impacts on the country's growth. It explores the individual and combined impact of eight sectors including demographic, economic, and infrastructure-related outcomes for Tanzania to 2043. The analysis offers insights into policy actions that could enhance Tanzania's developmental trajectory.

Please see the Technical Site for more information about the International Futures (IFs) modelling platform we use to develop the various scenarios.

Charts: Tanzania Tableau Workbook.

Note: The charts presented in each section are hyperlinked to the corresponding visualisations in the Tanzania Tableau Workbook for easy reference and deeper exploration of the underlying data.

Summary

We begin this page with an introductory assessment of the country’s context by looking at current population distribution, social structure, climate and topography.

- Tanzania is situated in East Africa, bordered by eight countries: Kenya and Uganda to the north, Rwanda, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo) to the west, Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique to the south. The country’s coastline stretches over 1 400 km along the Indian Ocean, providing access to important ports such as Dar es Salaam, which acts as the main maritime gateway for the country and several landlocked neighbours.

- Tanzania’s landscape is strikingly diverse, encompassing a coastal plain, an extensive central plateau, the Great Rift Valley and several highland zones. In the north-east rises Mount Kilimanjaro, Africa’s highest peak. The country also borders three of Africa’s Great Lakes: Lake Victoria, the continent’s largest; Lake Tanganyika, its deepest; and Lake Malawi, shared with Mozambique and Malawi to the south.

- With a total land size of 947 303 km2, the United Republic of Tanzania is the 13th-largest country in Africa, with the 8th-largest economy in terms of GDP and 5th-largest population. However, the country ranks at only 31st when comparing GDP per capita in PPP. According to the World Bank country income classification, Tanzania is a lower-middle-income country (LMIC) with a Gross National Income (GNI) of US$4 120 in 2024.

This section is followed by an analysis of the Current Path for Tanzania, which informs the country’s likely current development trajectory to 2043. It is based on current geopolitical trends and assumes that no major shocks would occur in a ‘business-as-usual’ future.

- Tanzania has one of the youngest and fastest-growing populations in Africa, with a median age of 18.4 and 43% under 15. Fertility is declining slowly, from 4.6 children per woman in 2023 to a projected 3.3 by 2043, meaning growth will continue. The population will rise from 66.5 million in 2023 to 110.5 million by 2043. The working-age share is expanding, but Tanzania is not expected to reach the demographic dividend threshold until after 2050. Realising this potential will depend on sustained investment in education, job creation and healthcare to harness its large youth population productively. Tanzania’s urbanisation remains relatively slow. The urban population rose from 22% in 2000 to just 38% in 2023—still well below the lower-middle-income Africa average of 49.2%. While urbanisation is projected to reach 51% by 2043, this slower-than-average pace constrains the country’s ability to benefit from the economic agglomeration effects typically associated with urban growth. Without more proactive planning and infrastructure investment, urban centres risk becoming overwhelmed by informal growth and inadequate service provision.

- Tanzania’s economy has expanded rapidly, averaging around 6% annual growth over the past two decades. GDP tripled between 2004 and 2023 to US$69.5 billion and is projected to reach US$230.6 billion by 2043, driven by agriculture, services and industry alongside stable macroeconomic management and growing exports. However, Tanzania also has the second-largest informal sector in Africa, accounting for 46% of GDP and 76% of employment in 2023—constraining productivity, fiscal revenues and structural transformation.

- Despite strong economic performance, growth has not translated into equivalent gains in individual incomes, ranking 31st on the continent. GDP per capita remains low at US$2 582 in 2023 and is projected to reach only US$4 306 by 2043, among the lowest in Africa’s lower-middle-income group. To achieve Vision 2050’s ambition of upper-middle-income status, Tanzania must shift from stability-driven to transformation-led growth by diversifying its economy, expanding formal employment and investing in human capital, innovation and climate resilience.

- Poverty remains widespread despite Tanzania’s strong growth trajectory. At the lower-middle-income poverty line of US$3.65, 71% of Tanzanians (47.5 million) lived in poverty in 2023, falling to 37% by 2043, though rapid population growth means the absolute number of poor people will remain high. Using the international extreme poverty line of US$2.15 a day, 40% of Tanzanians—around 26.8 million people—were extremely poor in 2023. On the Current Path, this will decline to 12% (13.2 million) by 2043.

- Tanzania’s national planning evolved from early post-independence socialist strategies to more market-oriented approaches from the 1990s. Vision 2025 marked a strategic pivot, aiming for middle-income status by 2025 through improved governance, economic competitiveness and social development. While Tanzania made steady progress, including GDP growth of 6% over two decades, it did not reach its middle-income target, with poverty reduction and structural transformation falling short. Successive Five-Year Development Plans (FYDPs) supported Vision 2025, with growing emphasis on industrialisation, infrastructure and human capital. Building on this, the draft Vision 2050 sets a more ambitious course towards an inclusive, resilient and upper-middle-income economy by mid-century. The Vision rests on a foundation of good governance, peace, security and stability, emphasising democracy, human rights and social cohesion. Implementation is structured around three pillars: a strong, inclusive and competitive economy, human capabilities and environmental integrity and climate resilience. These are supported by transformative sectors such as logistics, science and technology, research and development and digital transformation, aimed at driving long-term socio-economic transformation.

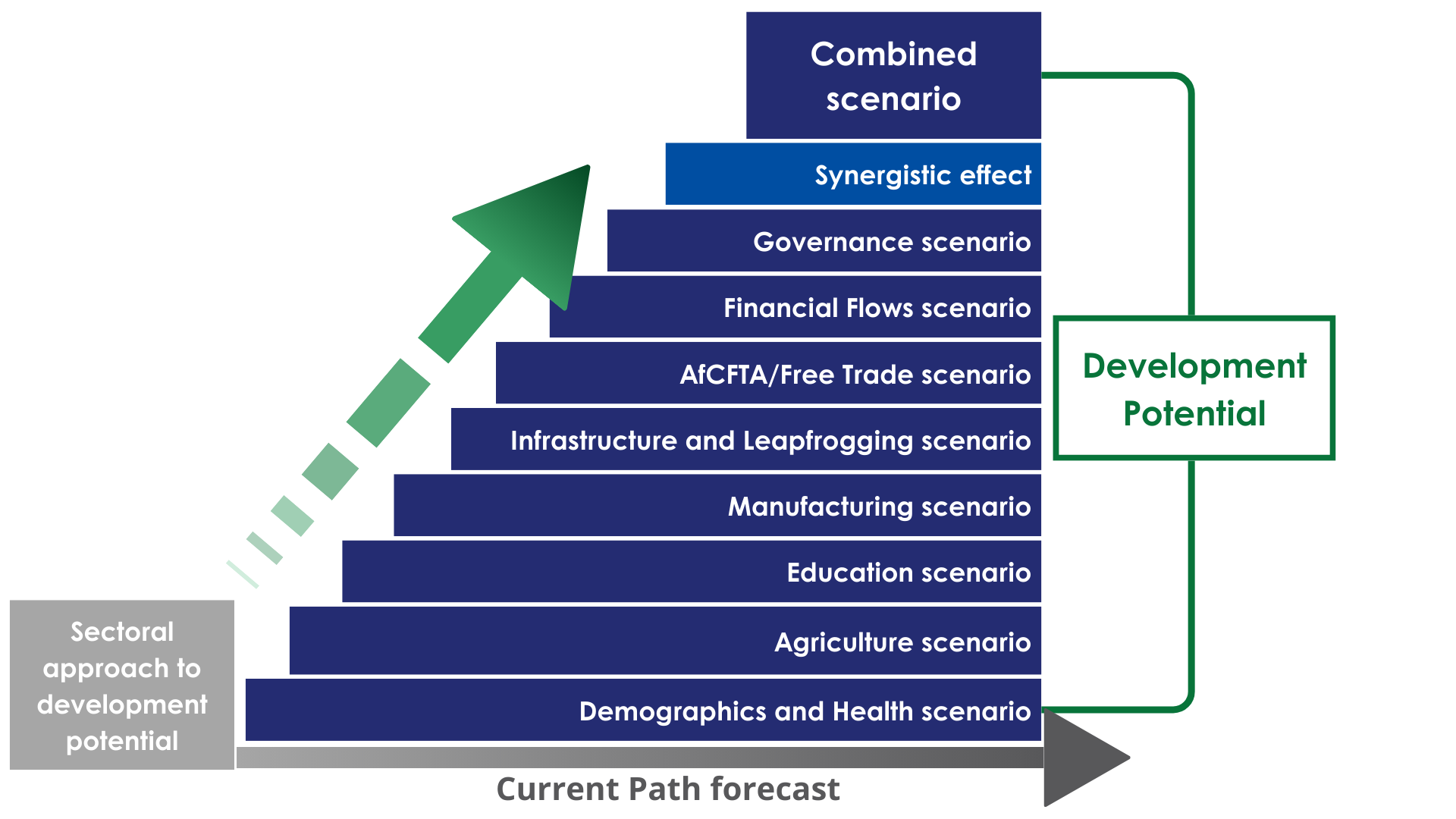

The next section compares progress on the Current Path with eight sectoral scenarios. These are Demographics and Health; Agriculture; Education; Manufacturing; the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA); Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging; Financial Flows; and Governance. Each scenario is benchmarked to present an ambitious but reasonable aspiration in that sector.

- Tanzania has made steady progress in public health, with declining maternal and child mortality rates and increased access to healthcare. However, challenges persist, including a 66% health workforce gap, high fertility and limited access to safe water and sanitation. In the Demographics and Health scenario, stronger investment in health systems, family planning and WaSH services accelerates demographic change and improves survival outcomes. Infant mortality declines to 17.3 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2043, compared to 22.4 on the Current Path, while fertility falls to 2.7 births per woman, down from 3.3. These shifts lower population growth and bring forward Tanzania’s demographic dividend to 2043, seven years earlier than on the Current Path, unlocking the potential for faster, more inclusive growth if accompanied by sufficient job creation and investment in education and human capital.

- The Agriculture scenario models a revitalised and climate-resilient agricultural sector driven by modern farming techniques, wider irrigation uptake and improved supply chains. By 2043, agricultural crop import dependence declines to 13.5%, compared to 25.4% on the Current Path, reflecting stronger domestic production. Increased yields, better water access and reduced post-harvest losses raise productivity and improve rural incomes. Access to rural roads enhances market linkages, while a focus on meeting domestic food demand boosts per capita calorie availability. Forest protection efforts reinforce long-term sustainability. Together, these interventions reduce food insecurity, strengthen climate resilience and support more inclusive, sustainable economic growth.

- Tanzania has achieved near-universal access to primary education, with gross enrolment reaching 98% in 2023. However, quality, equity and progression beyond primary school remain persistent challenges. Transition to lower secondary remains weak—only 35% complete this level, though this is projected to rise to 54% by 2043. Participation in upper-secondary and tertiary education is even more limited, at 9% and 7% respectively in 2023, underscoring the steep drop-off in the education pipeline. The TVET sector has expanded rapidly, enrolling more than half a million students, yet still faces low coverage, fragmented oversight and poor alignment with labour market needs. The Education scenario models ambitious but achievable improvements in access, completion and learning outcomes across all levels, alongside progress towards gender parity and strengthened vocational training. The mean years of education among youth aged 15-24 have risen to 8.1 in 2023 and are projected to reach 9.3 by 2043. Under the Education scenario, this increases further to 9.7 years.

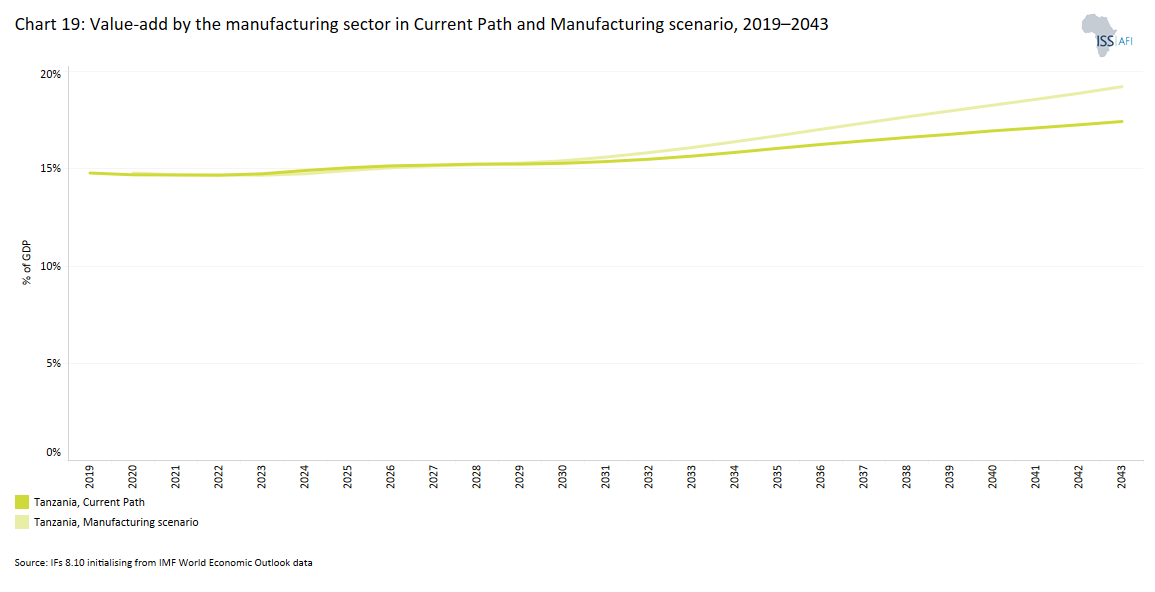

- The Manufacturing scenario envisions a more dynamic and competitive industrial base driven by greater investment, innovation and labour participation. By 2043, the manufacturing sector’s share of GDP rises to 17.3%, compared to 15.2% on the Current Path. Increased investment, government expenditure on R&D, improved business regulation and improved labour participation enhance productivity and competitiveness, while expanded formal employment opportunities boost incomes and job quality.

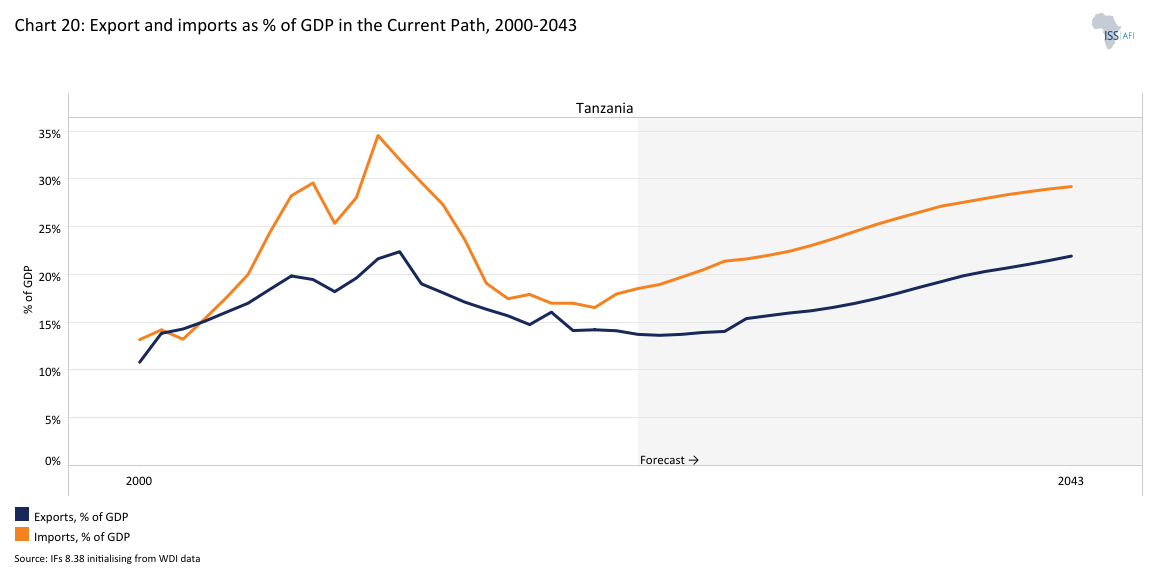

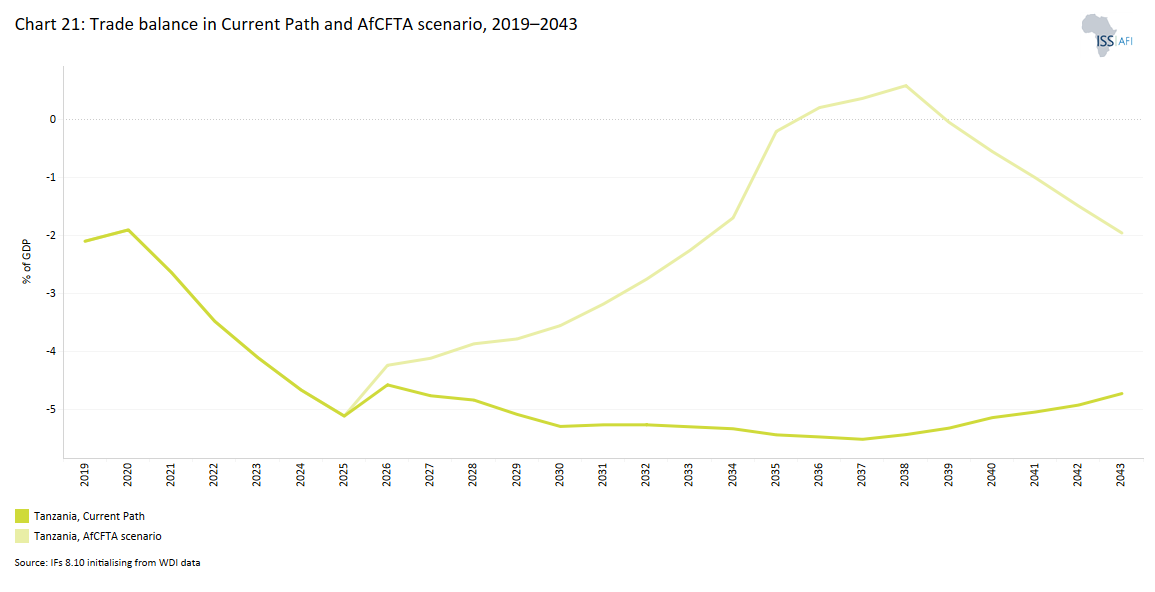

- The AfCFTA scenario models deeper regional integration through tariff reductions, productivity gains and export diversification. By 2043, Tanzania’s exports rise to 24.1% of GDP, compared to 21.9% on the Current Path, while the trade deficit narrows slightly to -5.5% from -7.3%. Increased imports of capital and intermediate goods, improved logistics and reduced non-tariff barriers enhance competitiveness and boost overall trade. Although imports remain high, the scenario demonstrates modest but meaningful progress toward a more diversified economy aligned with continental integration goals.

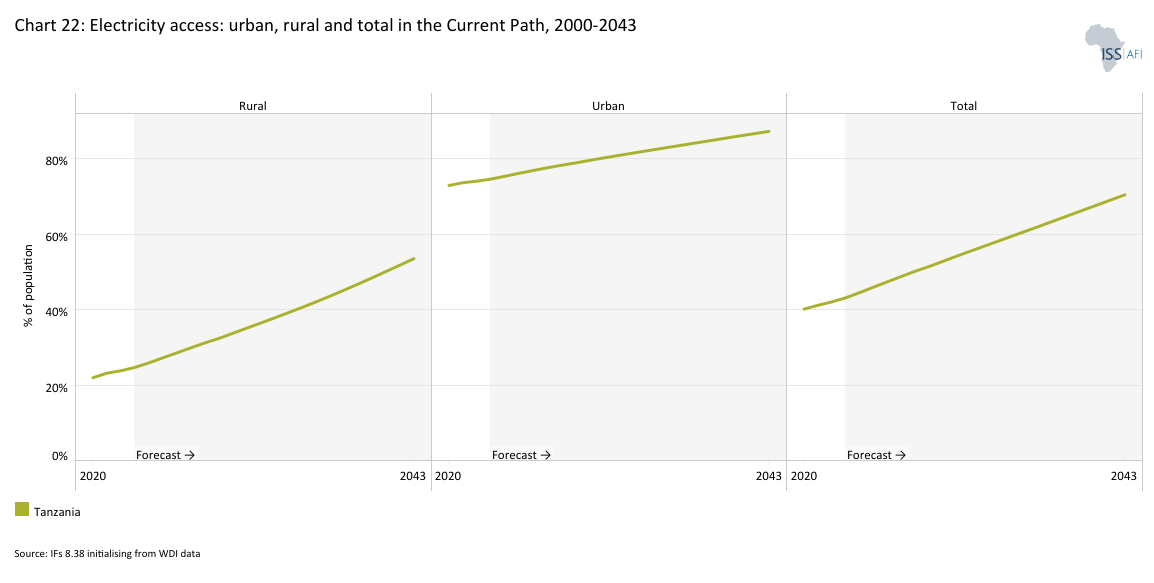

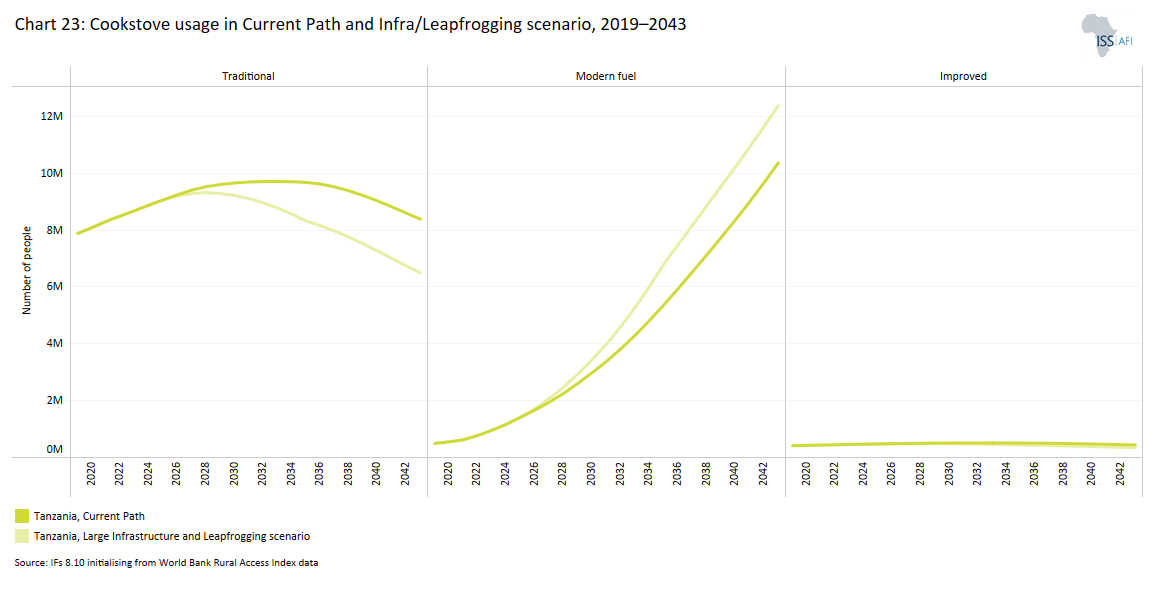

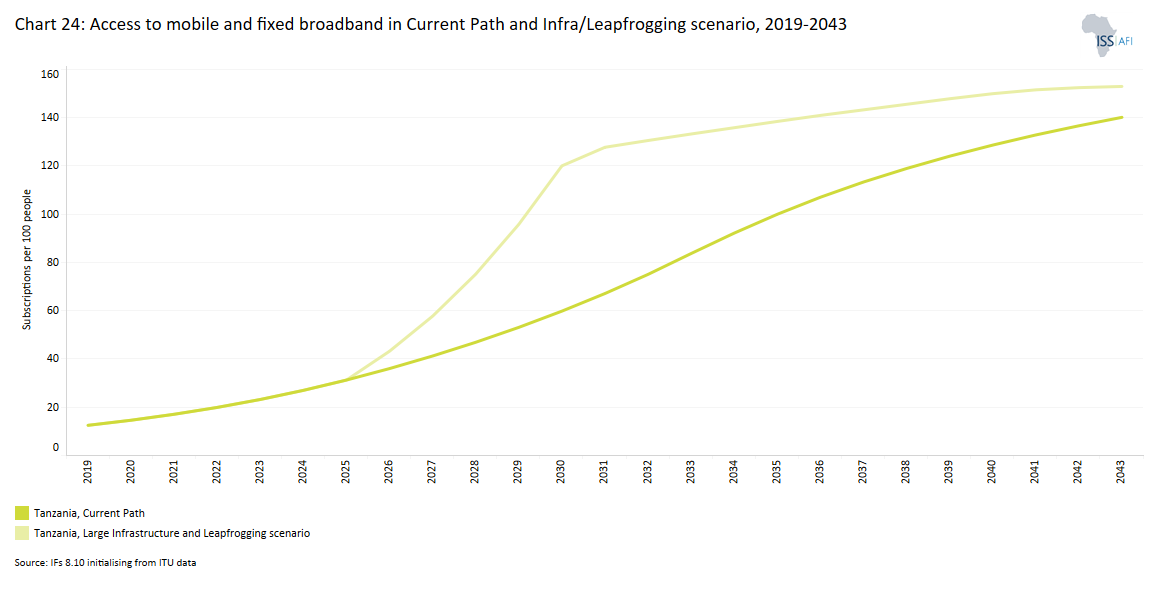

- Tanzania’s infrastructure gap remains a major constraint on inclusive development, with limited access to electricity, modern energy and digital connectivity curbing productivity and opportunity. Reliance on traditional cookstoves is widespread, used by 87% of households in 2023, exposing women and children to severe health risks and driving deforestation. Under the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario, this share declines sharply to 36% by 2043, while households using modern fuels rise to 62%, improving both health and environmental outcomes. Digital connectivity also accelerates. Fixed broadband access, currently 2.6 subscriptions per 100 people expands to 23 per 100 by 2043, exceeding the 19 per 100 projected on the Current Path. These advances in infrastructure and connectivity would strengthen economic inclusion and support Tanzania’s transition toward a more resilient, modern economy.

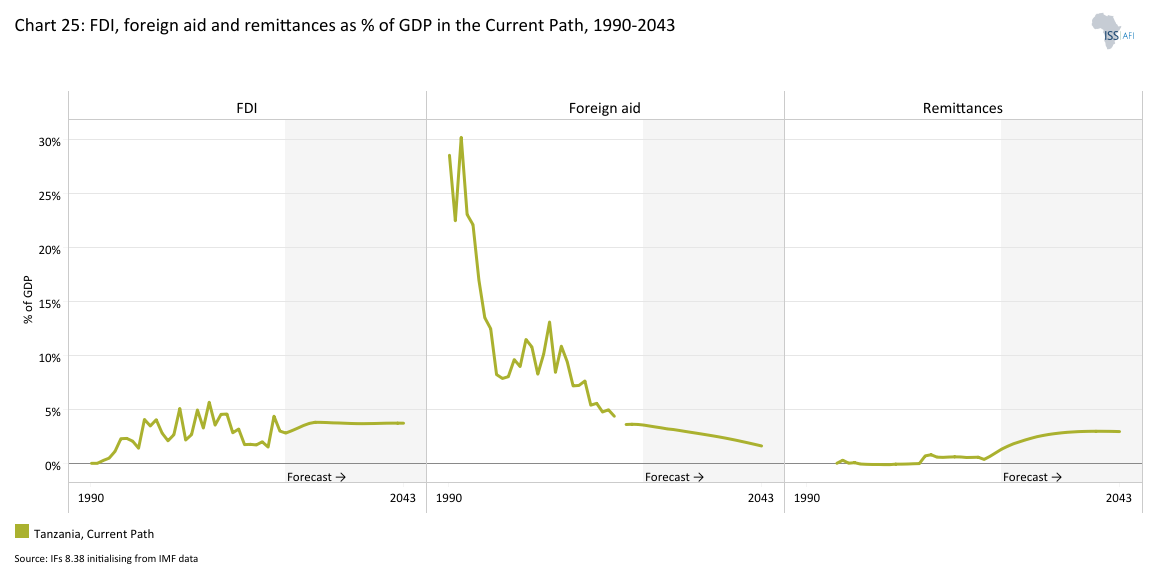

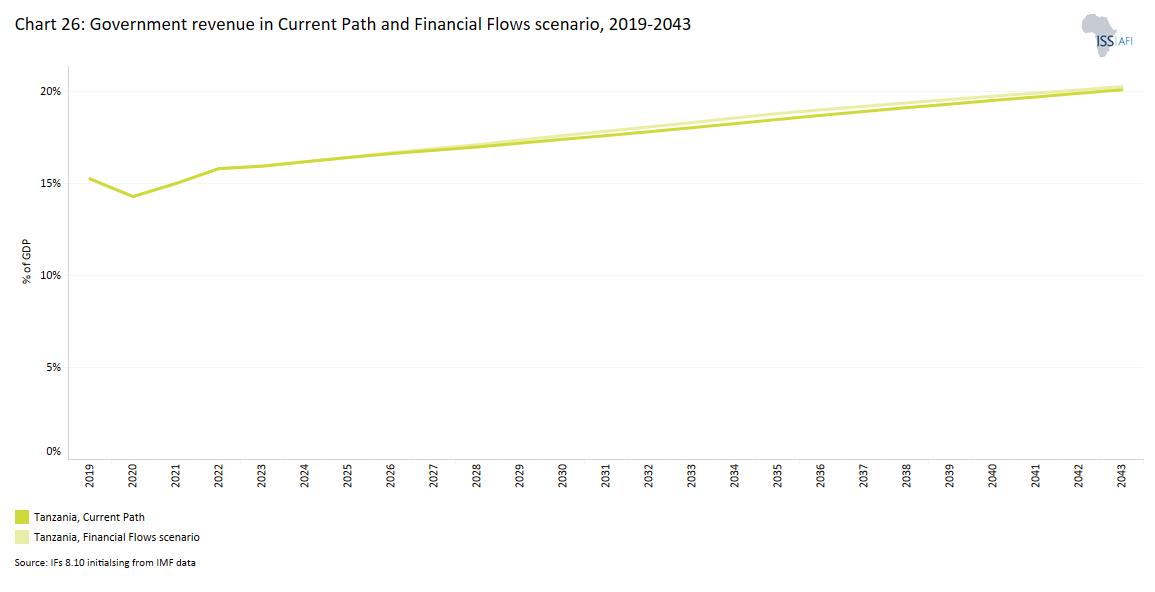

- Tanzania remains fiscally dependent on external financing, with aid still accounting for 23% of government revenue in 2023—among the highest in its peer group. Although its relative weight is declining, the Financial Flows scenario projects cumulative aid inflows US$2.7 billion higher than the baseline by 2043, with aid representing 9% of revenue that year. Remittances, though modest at 1.3% of GDP (US$415 million) in 2023, are expected to rise to nearly 3% of GDP by 2043 as the diaspora expands and transfer systems improve. Foreign direct investment (FDI) has recovered strongly since the pandemic, reaching 3% of GDP in 2023, above the peer average, driven by mining, manufacturing and financial services, mainly from China, India and the UK. Under the scenario, FDI grows to 4.8% of GDP by 2043, raising the investment stock from 38.2% to 48.2% of GDP, an additional US$24.2 billion. Government revenue remains low at 15.5% of GDP in 2023, reflecting a narrow tax base, evasion and inefficient administration. Under the scenario, revenues rise slightly by 0.2 percentage points of GDP, adding US$7.5 billion cumulatively by 2043. While stronger aid, FDI and remittance inflows improve fiscal space, Tanzania’s long-term resilience will depend on expanding its domestic tax base and reducing reliance on external flows.

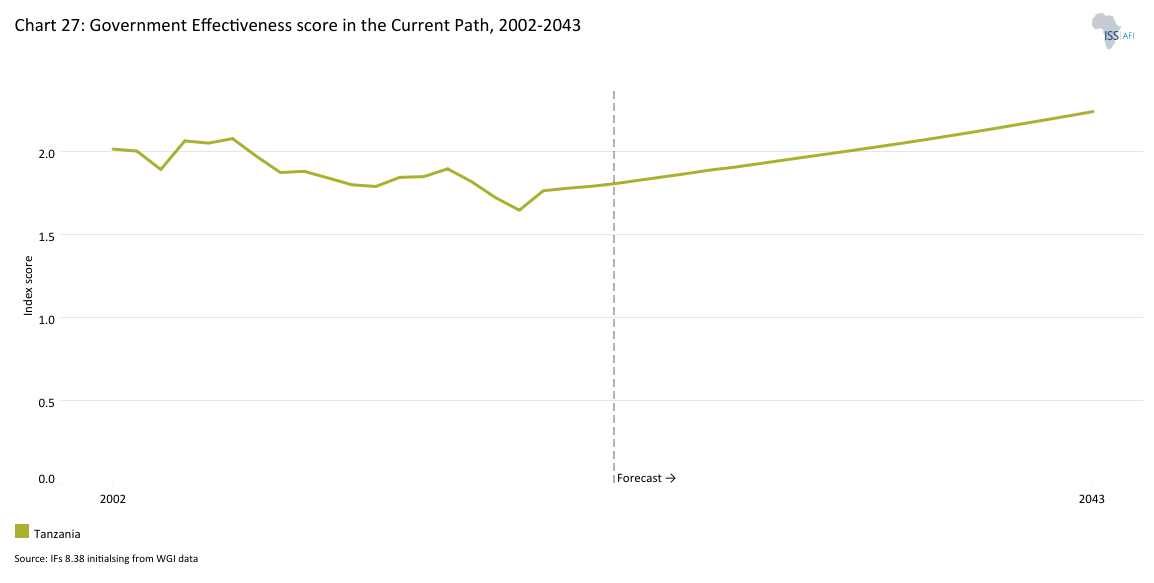

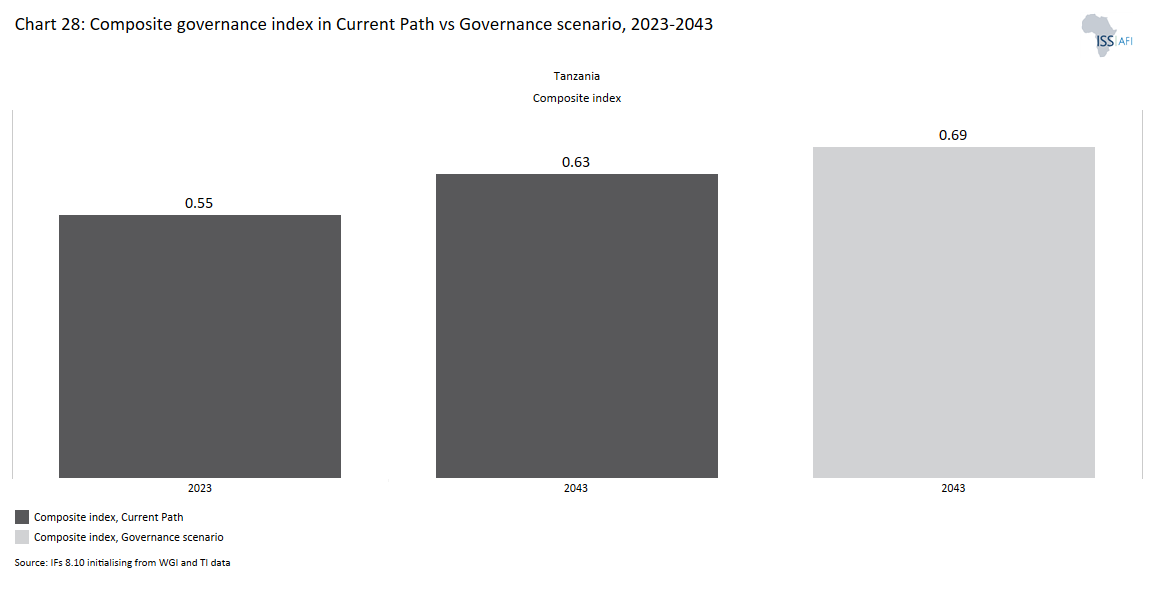

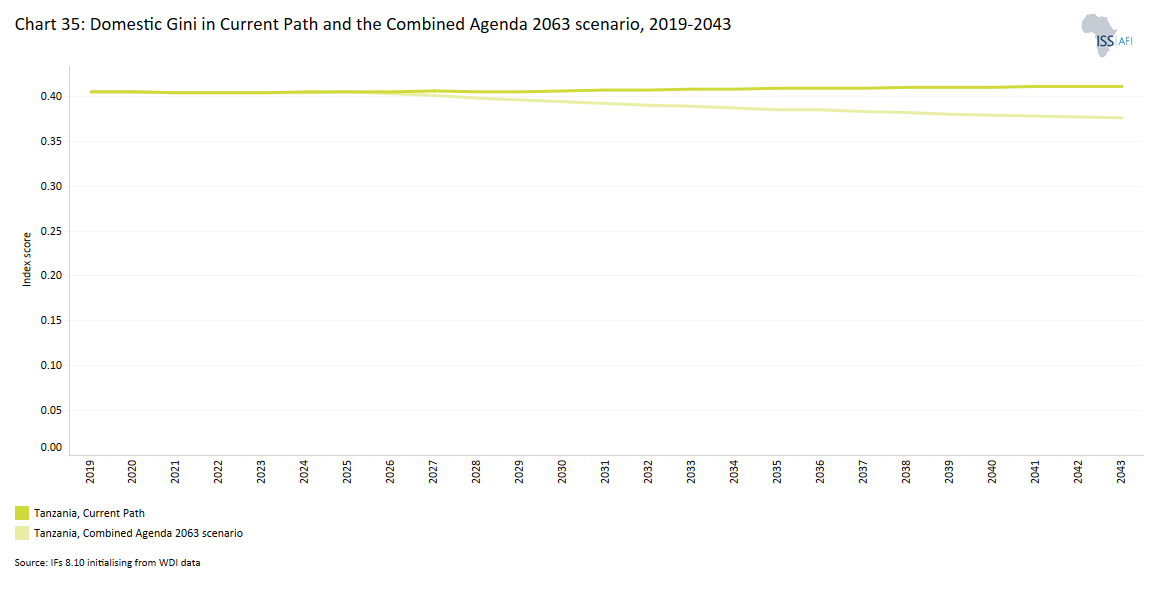

- By 2043, Tanzania’s composite governance score improves from 0.69 on the Current Path to 0.76 in the Governance scenario, lifting it from 7th to 3rd among Africa’s lower-middle-income countries. The largest gains occur in security and inclusion, supported by more effective public administration, stronger fiscal management and reduced corruption. Enhanced transparency and accountability improve service delivery, while expanded welfare transfers reduce inequality and strengthen resilience. Together, these reforms make growth more efficient, equitable and politically stable, positioning governance as a key driver of Tanzania’s long-term transformation.

In the fourth section, we compare the impact of each of these eight sectoral scenarios with one another and subsequently with a Combined scenario (the integrated effect of all eight scenarios). In our forecasts, we measure progress on various dimensions such as economic size (in market exchange rates), gross domestic product per capita (in purchasing power parity), extreme poverty, carbon emissions, the changes in the structure of the economy, and selected sectoral dimensions such as progress with mean years of education, life expectancy, the Gini coefficient or reductions in mortality rates.

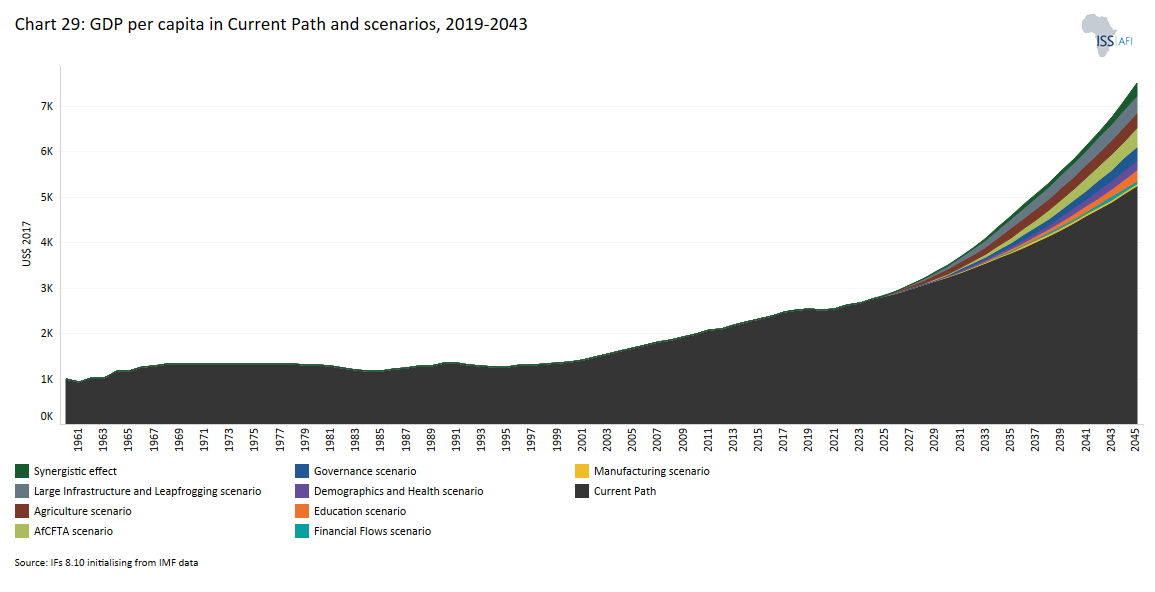

- Across all eight sectoral scenarios, GDP per capita rises above the Current Path by 2043. The Governance and the AfCFTA scenarios generate the largest gains, US$211 and US$203 per person higher, respectively, demonstrating the power of regional integration and institutional reform to drive productivity and inclusive growth. The Agriculture scenario follows, adding US$128 per person through higher yields, improved water use and rural income growth. Education and financial reforms have smaller but vital long-term impacts, strengthening human capital and investment capacity.

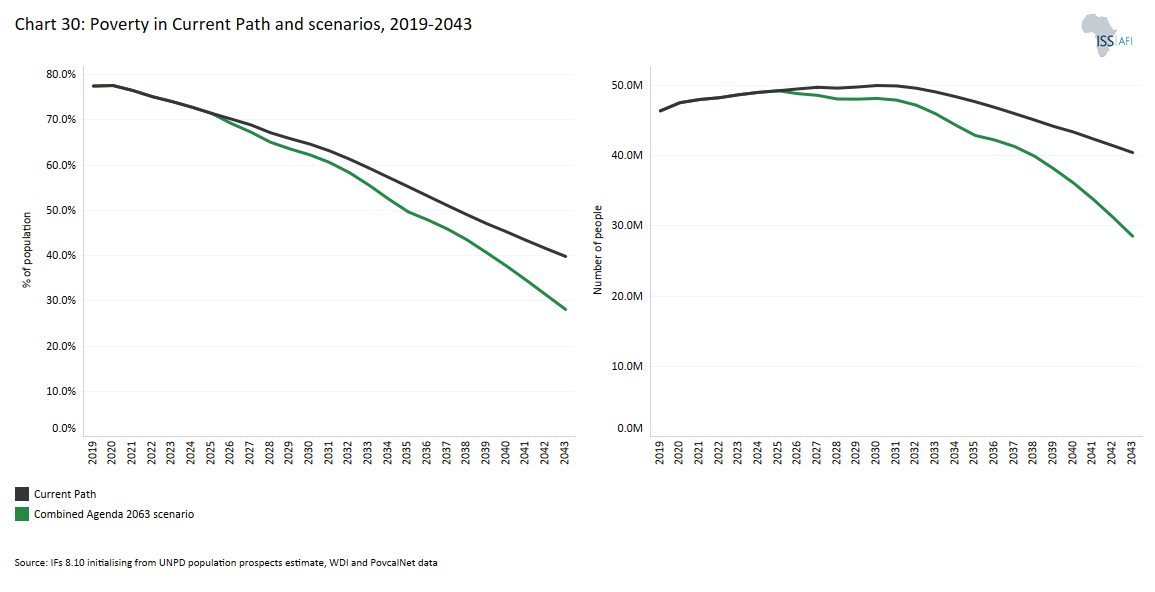

- All scenarios also lead to a reduction in poverty. The Governance and Education scenarios deliver the strongest poverty reduction effects. Governance reforms enhance both the efficiency and equity of resource allocation by expanding fiscal space, strengthening tax systems and curbing corruption, ensuring that public funds reach those most in need. The Education scenario has a strong and multidimensional influence on poverty reduction in Tanzania. By enhancing skills, employability and productivity, it raises household incomes and resilience while lowering fertility and dependency ratios—mechanisms that have immediate welfare effects.

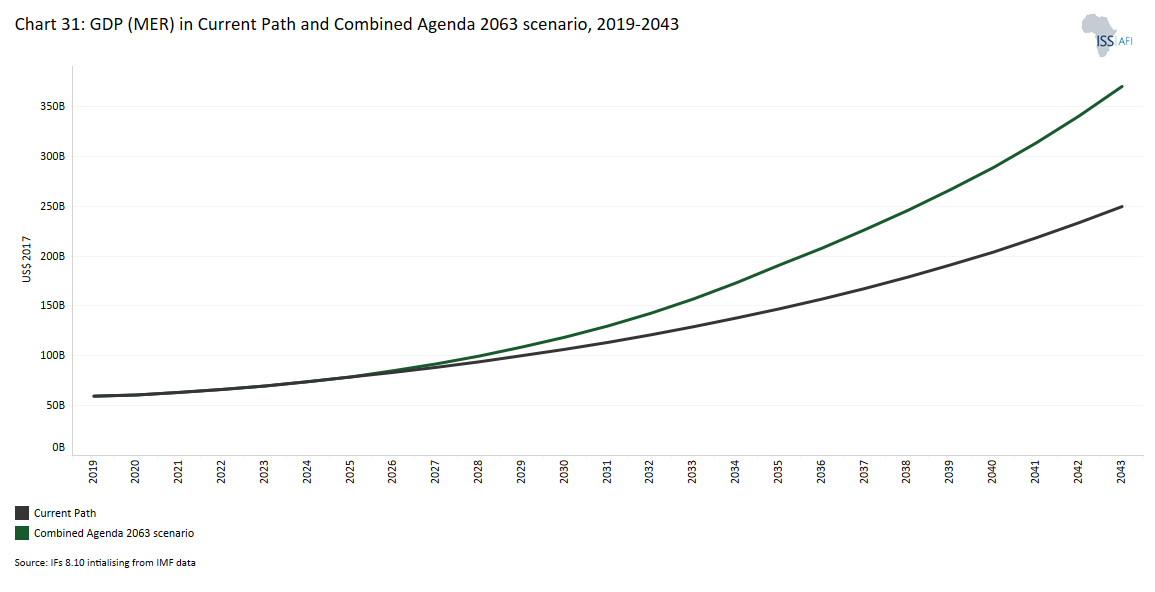

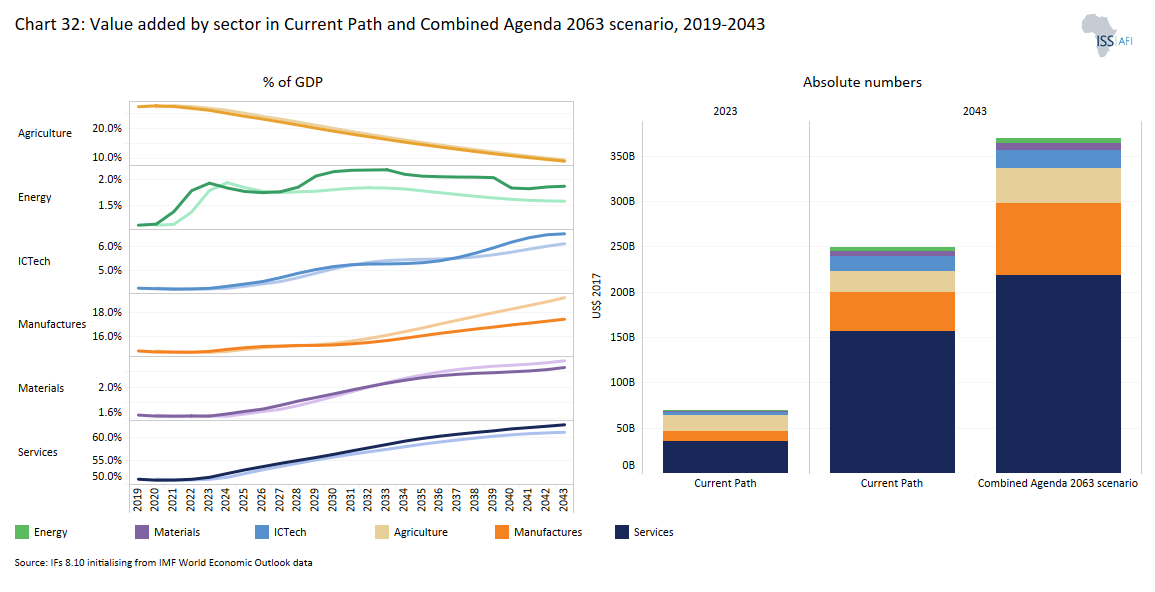

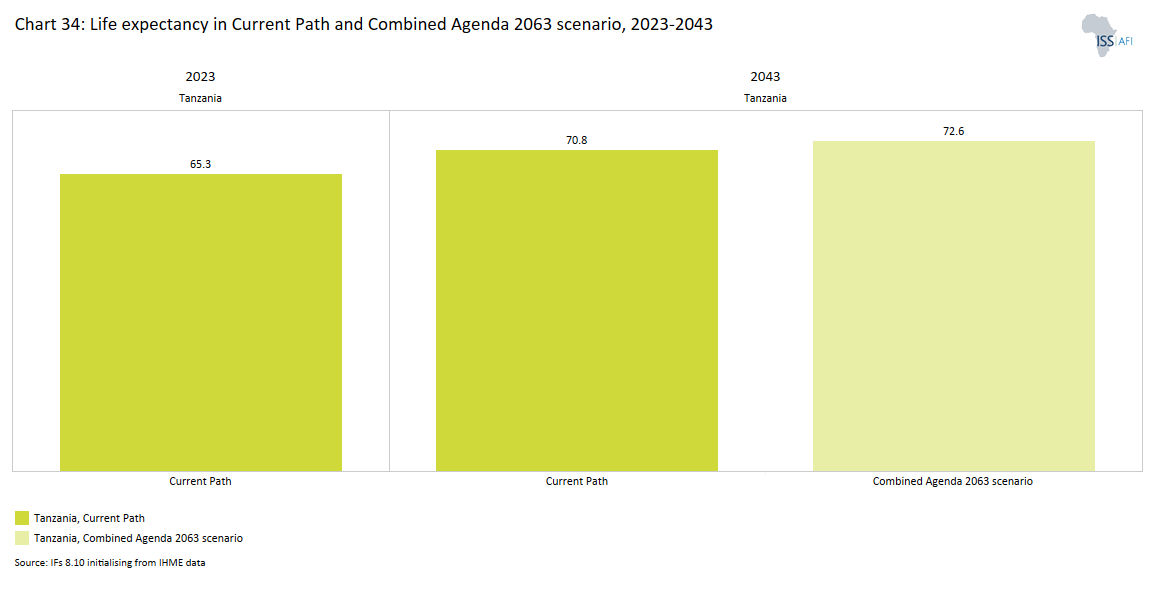

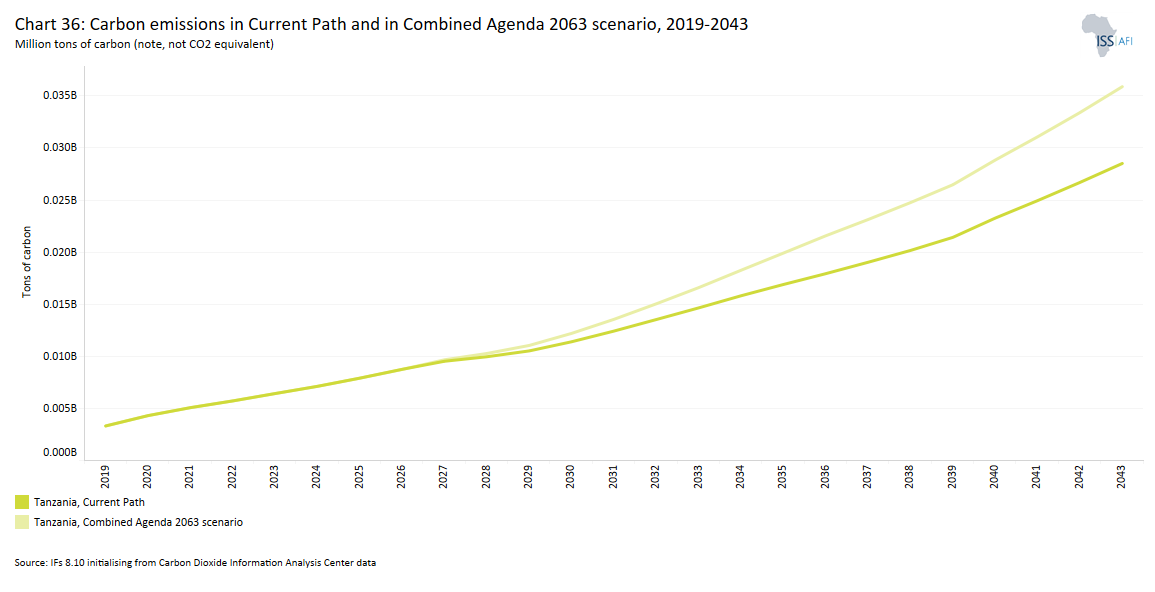

- When combined, these reforms yield transformative results. By 2043, GDP per capita (PPP) is US$1 059 higher than the Current Path, and GDP (MER) reaches US$305.2 billion, lifting Tanzania to the 6th-largest economy in Africa. Under the Combined scenario, Tanzania achieves a far greater reduction in poverty than on the Current Path. Using the lower-middle-income poverty line of US$3.65 per day (2017 PPP), the poverty rate falls from 71% in 2023 to 26% in 2043, compared to 37% on the Current Path—an 11 percentage-point improvement, equivalent to around 15 million fewer people living in poverty. Extreme poverty at US$2.15 per day also declines more sharply, from 12% on the Current Path to 6% in the Combined scenario by 2043, translating to about 7.2 million fewer Tanzanians living in extreme poverty. The Combined scenario shows that Tanzania’s transformation depends on sustained, coordinated reforms across all sectors. Growth must become more productive, employment-intensive and inclusive to align with Vision 2050’s goal of a resilient, upper-middle-income economy.

We end this page with a summarising conclusion offering key recommendations for decision-making.

The analysis concludes that Tanzania has achieved strong economic growth over the past two decades, yet this progress has not translated into corresponding gains in income or poverty reduction. The Combined scenario shows that coordinated investments across governance, regional integration, education, infrastructure, energy and agriculture can unlock transformative and inclusive growth. Under this pathway, GDP rises by US$80.4 billion above the Current Path by 2043, advancing Tanzania to the 6th-largest economy in Africa while reducing poverty from 71% to 24%. To realise this potential, Tanzania must prioritise AfCFTA implementation, governance reform, human capital development, industrialisation and agricultural transformation, supported by digital infrastructure, clean energy and climate resilience. With strategic execution, Tanzania can transition from steady growth to a diversified, high-productivity and inclusive development path.

All charts for Tanzania

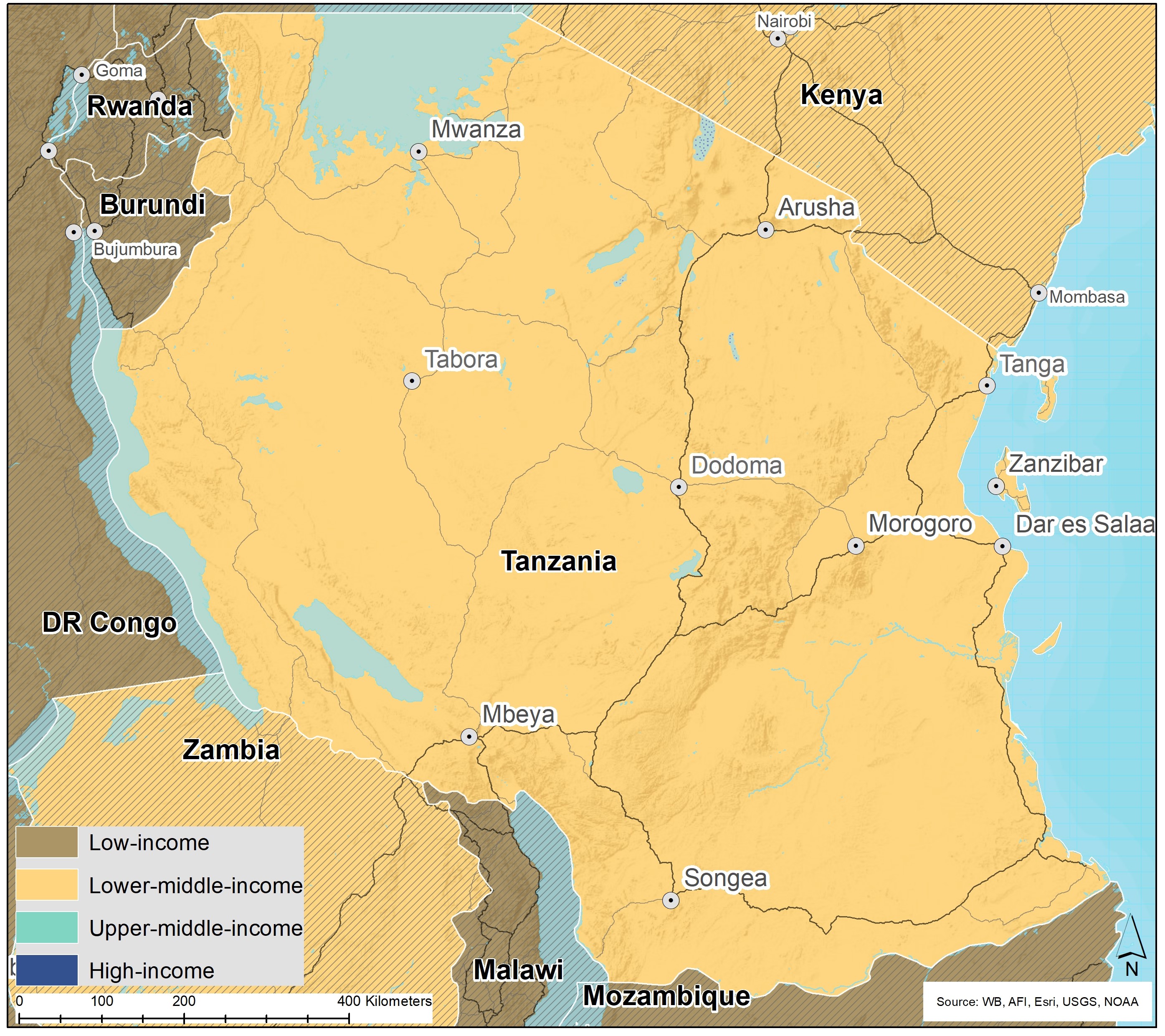

- Chart 1: Political map of Tanzania

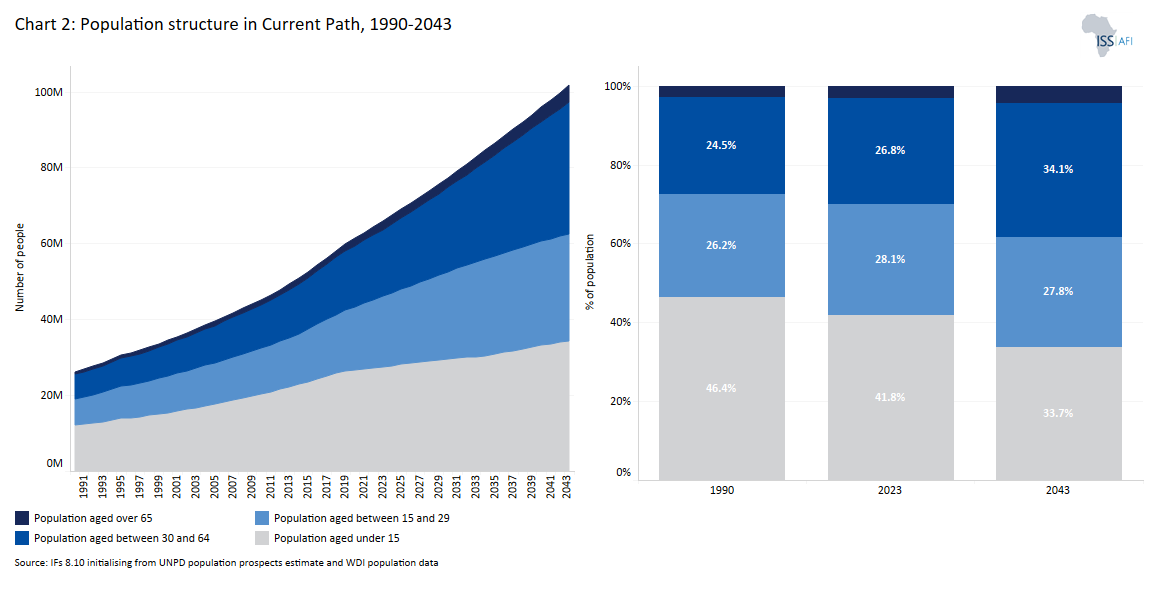

- Chart 2: Population structure in the Current Path, 1990–2043

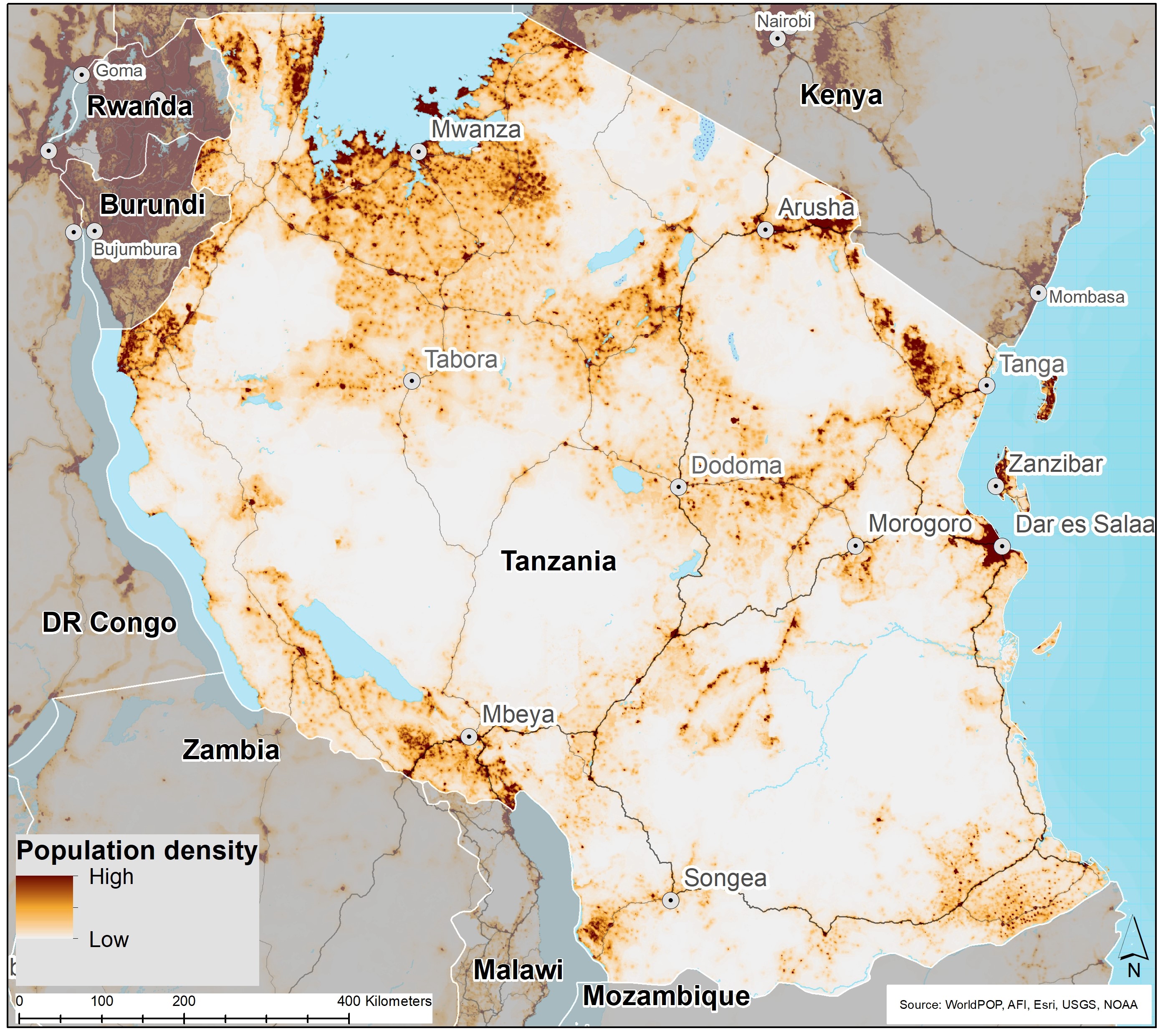

- Chart 3: Population distribution map, 2023

- Chart 4: Urban and rural population in the Current Path, 1990-2043

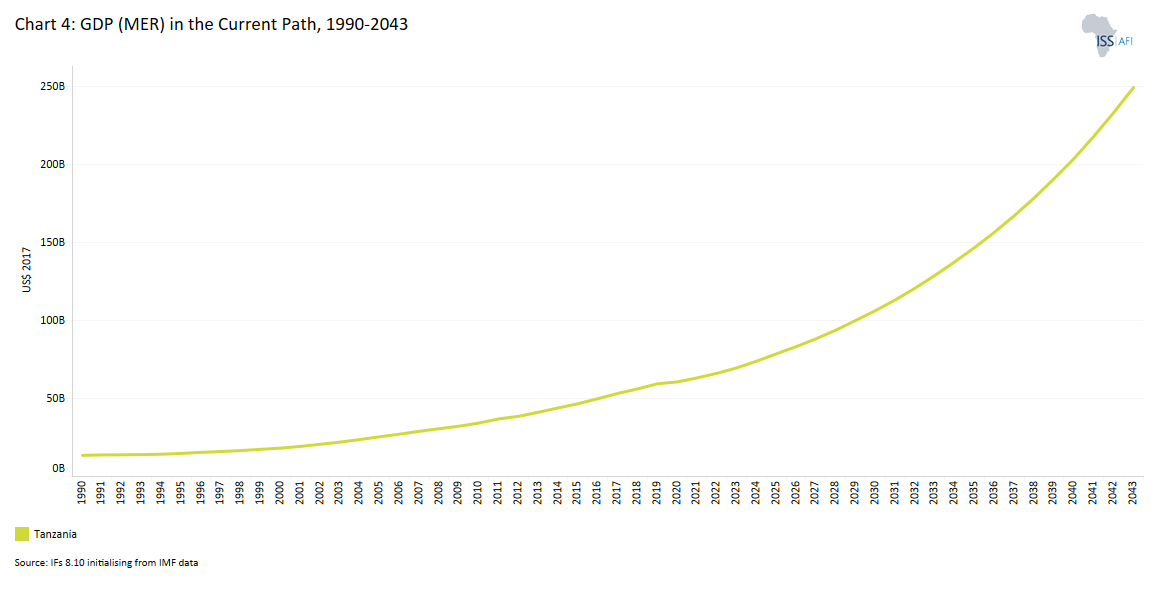

- Chart 5: GDP (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, 1990–2043

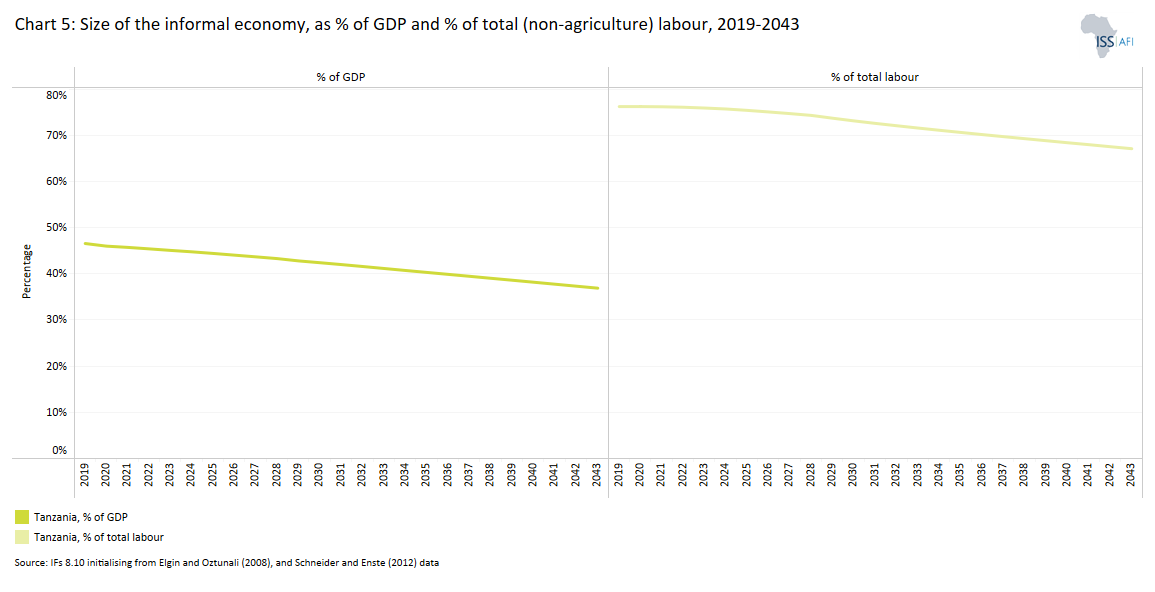

- Chart 6: Size of the informal economy in the Current Path, 2020-2043

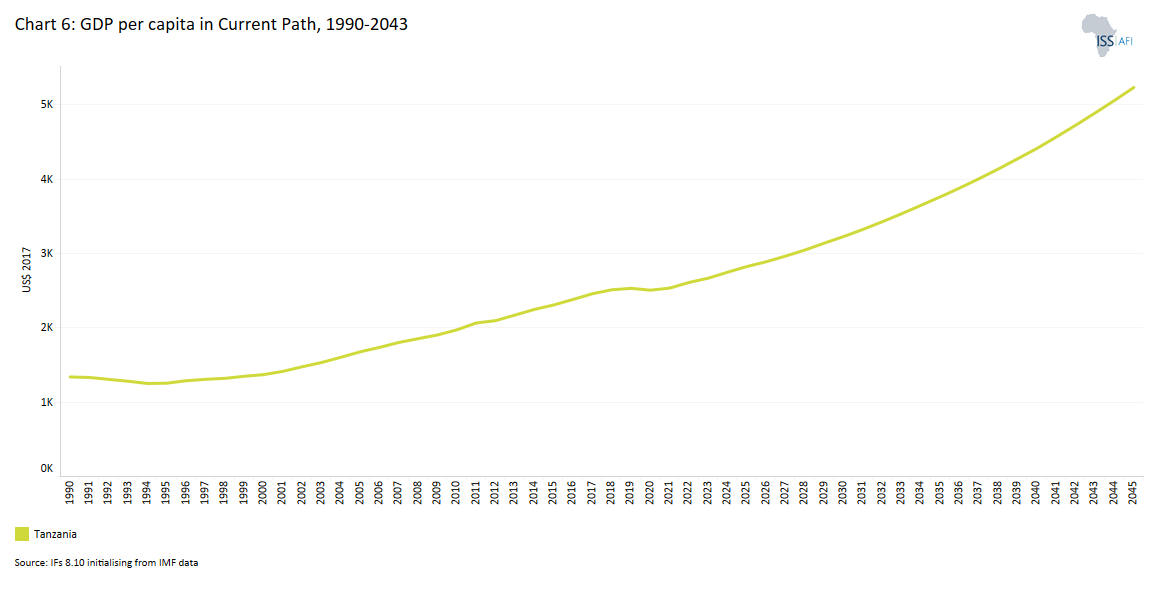

- Chart 7: GDP per capita in Current Path, 1990–2043

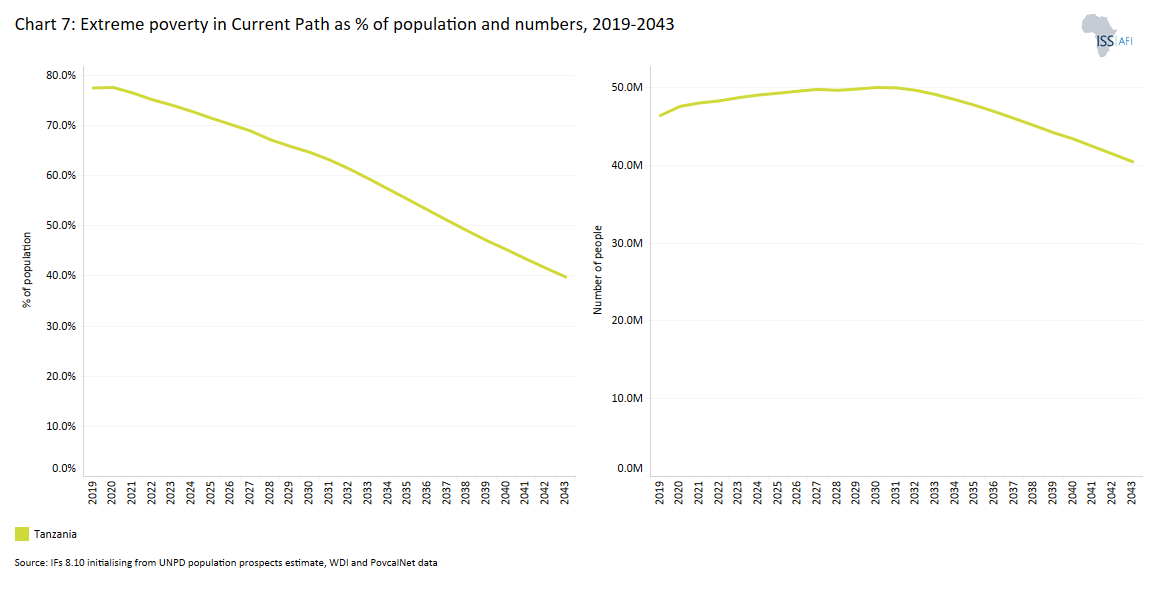

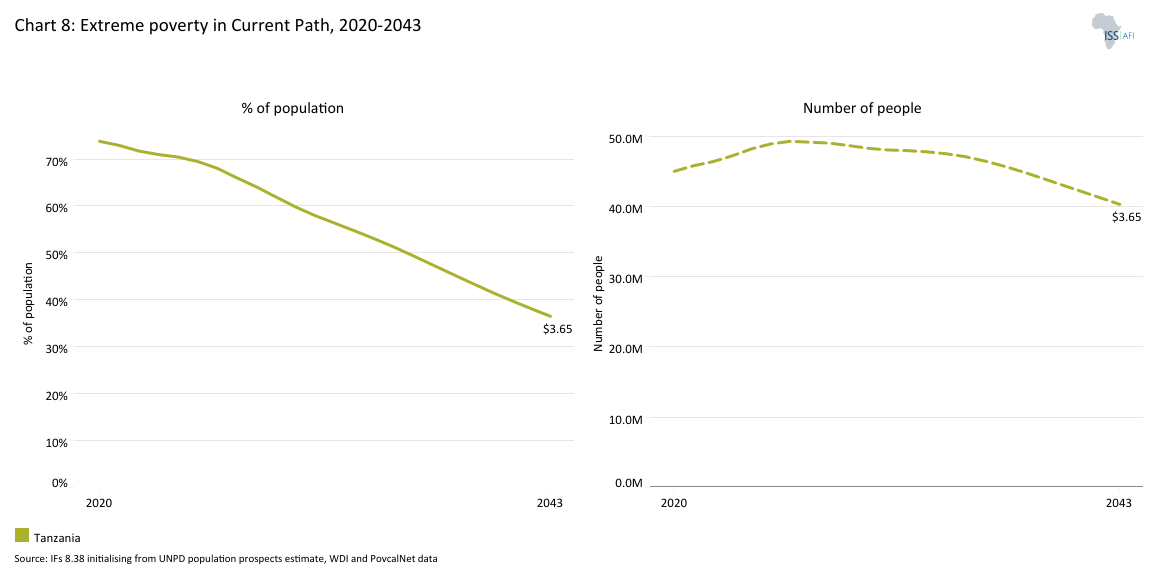

- Chart 8: Extreme poverty in the Current Path, 2020–2043

- Chart 9: National Development Plan of Tanzania

- Chart 10: Relationship between Current Path and scenarios

- Chart 11: Mortality distribution in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

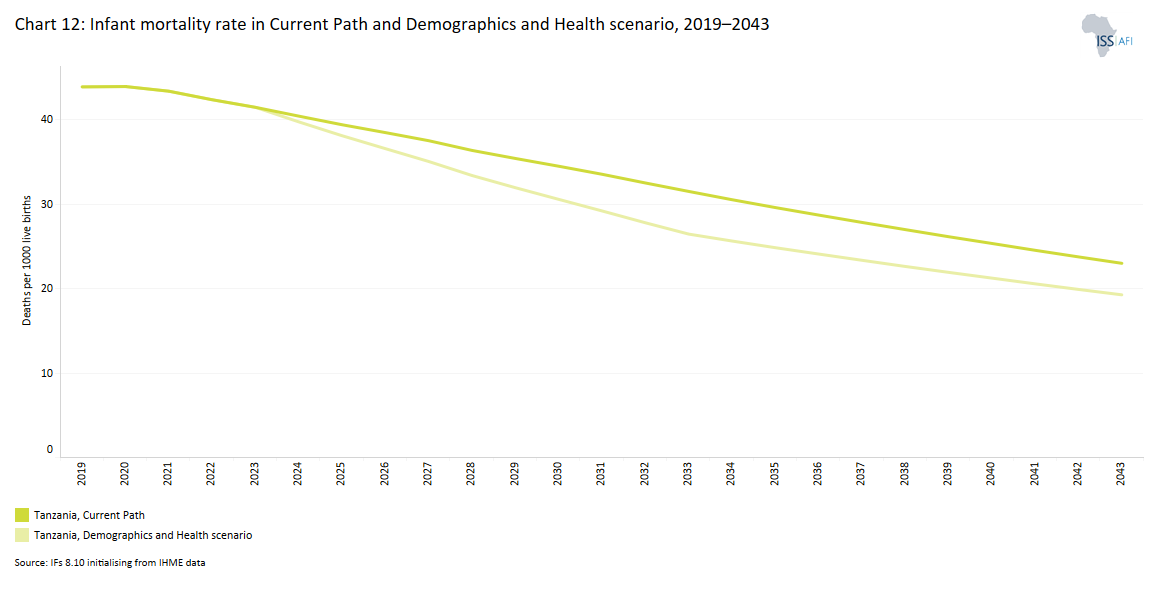

- Chart 12: Infant mortality rate in Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 2020–2043

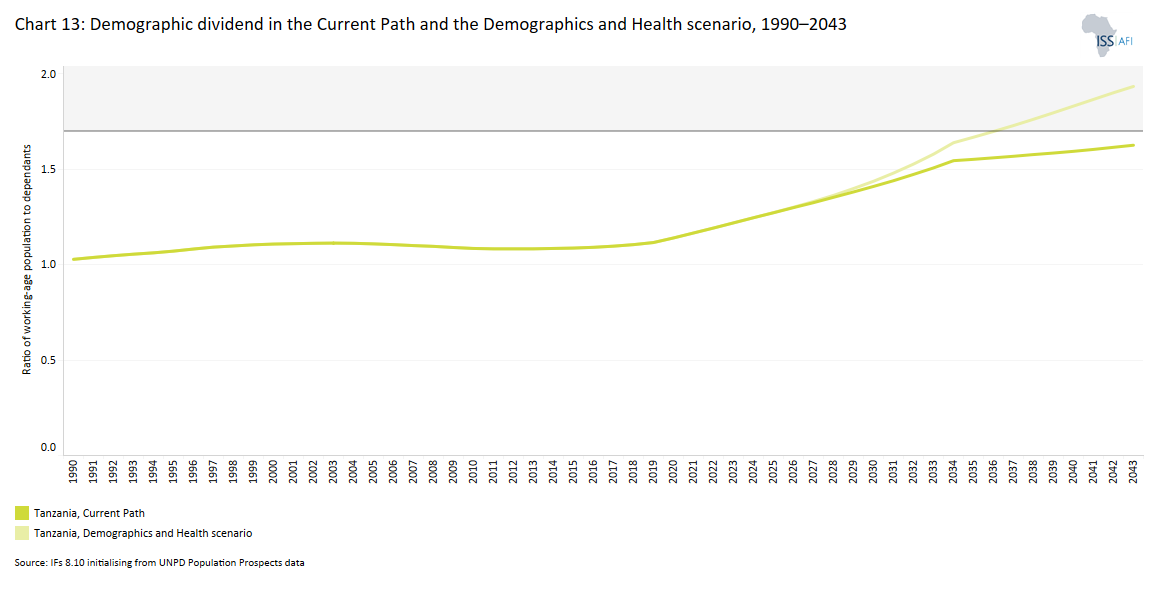

- Chart 13: Demographic dividend in the Current Path and the Demographics and Health scenario, 2020–2043

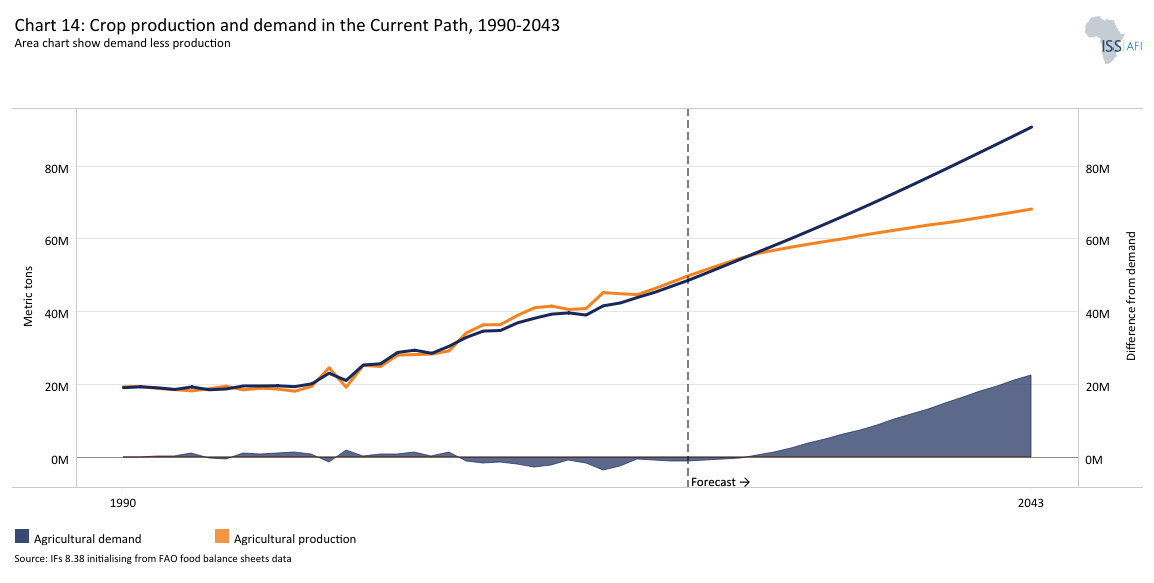

- Chart 14: Crop production and demand in the Current Path, 1990-2043

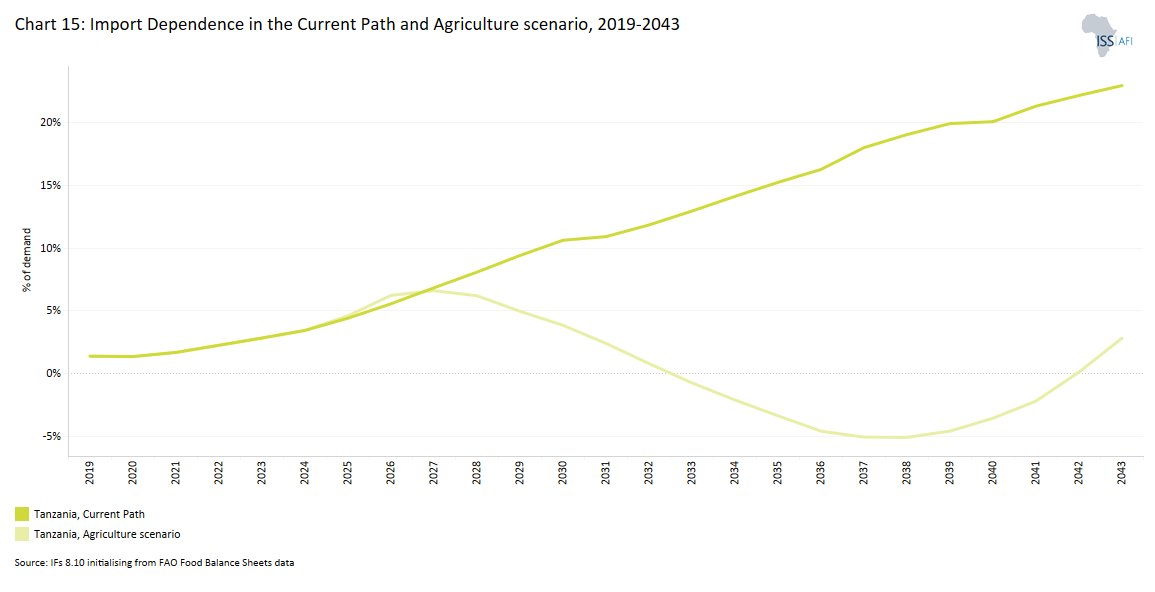

- Chart 15: Import dependence in the Current Path and Agriculture scenario, 2020–2043

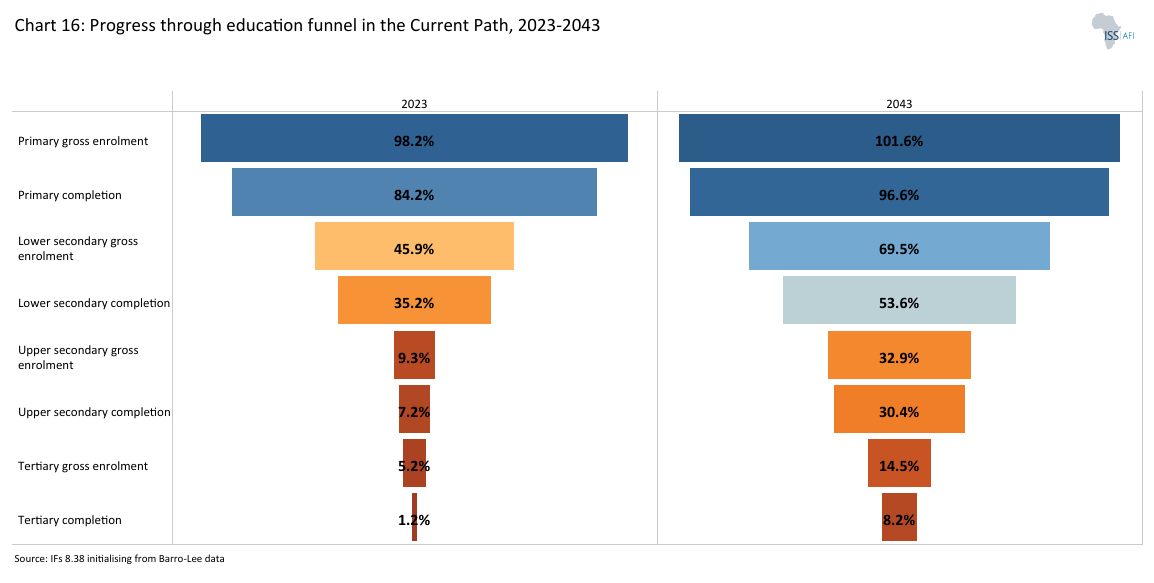

- Chart 16: Progress through the education funnel in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

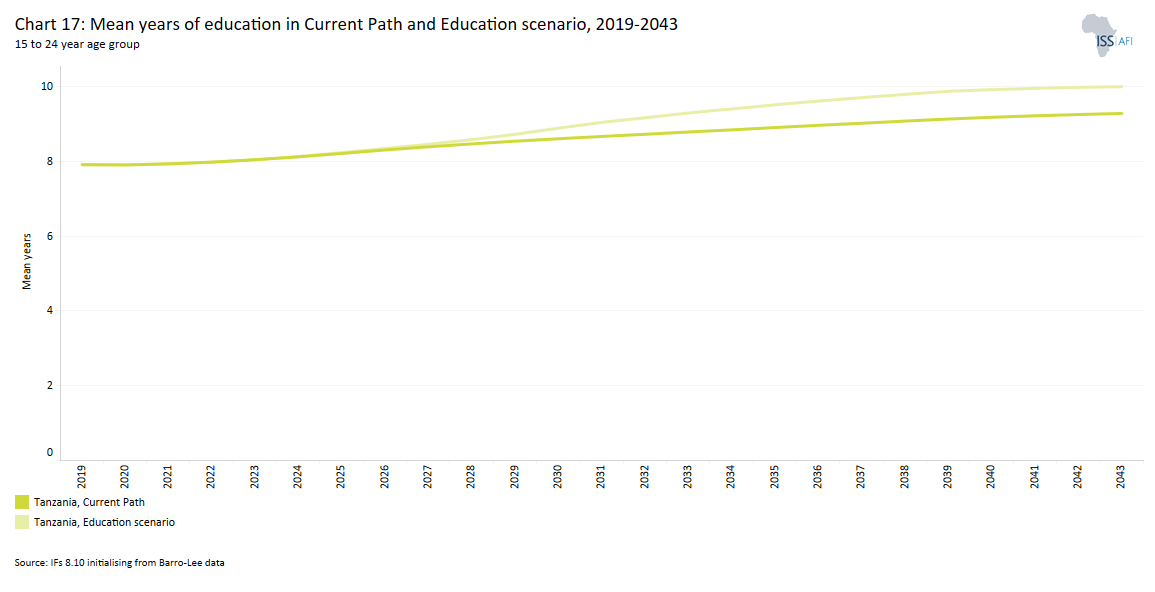

- Chart 17: Mean years of education in the Current Path and Education scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 18: Value-add by sector as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 19: Value-add by the manufacturing sector in the Current Path and Manufacturing scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 20: Exports and imports as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2000-2043

- Chart 21: Trade balance in the Current Path and AfCFTA scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 22: Electricity access: urban, rural and total in the Current Path, 2000-2043

- Chart 23: Cookstove usage in the Current Path and Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 24: Access to mobile and fixed broadband in the Current Path and the Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 25: FDI, foreign aid and remittances as % of GDP in the Current Path, 1990-2043

- Chart 26: Government revenue in the Current Path and Financial Flows scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 27: Government effectiveness score in the Current Path, 2002-2043

- Chart 28: Composite governance index in the Current Path and Governance scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 29: GDP per capita in the Current Path and scenarios, 2020–2043

- Chart 30: Poverty in the Current Path and scenarios, 2020–2043

- Chart 31: GDP (MER) in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 32: GDP per capita in the Current Path and the Combined scenario, 2020-2043

- Chart 33: Value added by sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 34: Informal sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 35: Poverty in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 36: Life expectancy in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

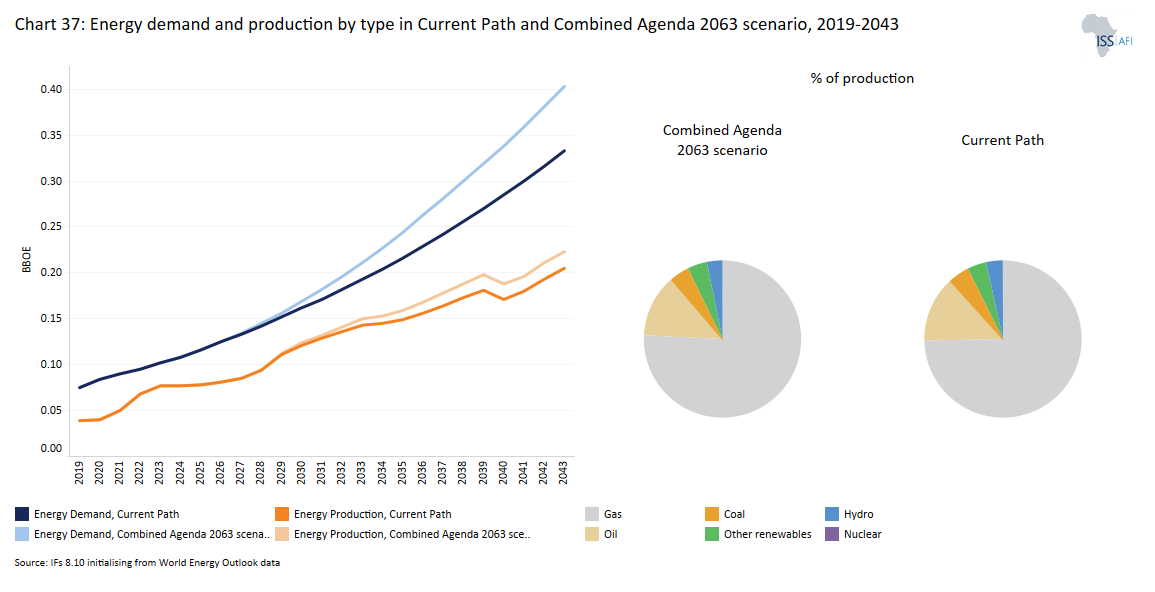

- Chart 37: Carbon emissions in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

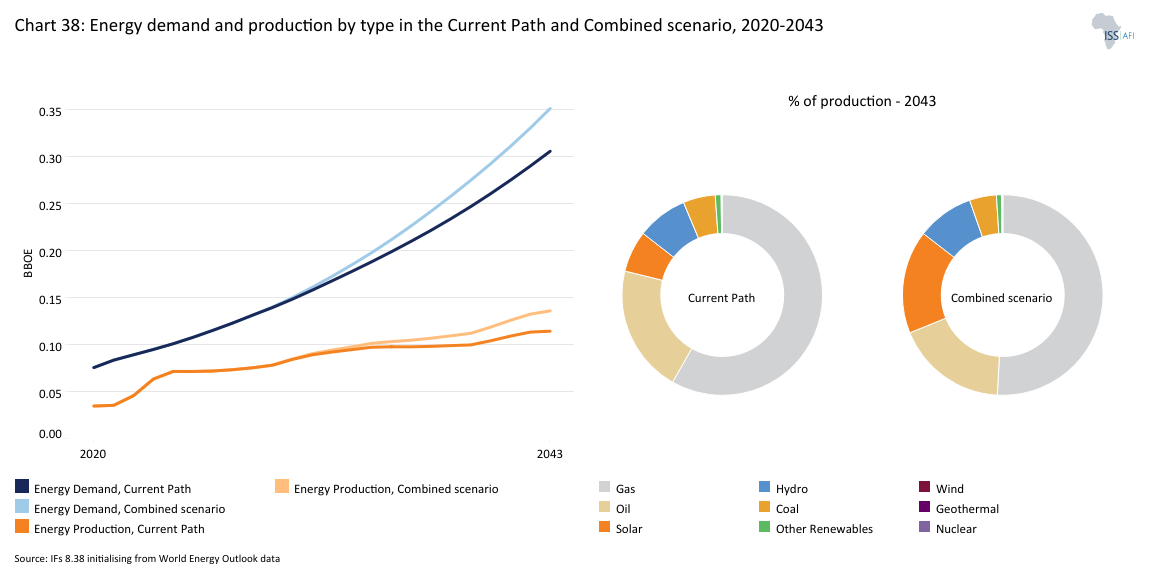

- Chart 38: Energy demand and production by type in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020-2043

- Chart 39: Policy recommendations

Chart 1 is a political map of Tanzania.

With a total land size of 947 303 km2, the United Republic of Tanzania is the 13th-largest country in Africa, with the 8th-largest economy in terms of GDP and 5th-largest population. However, it still ranks at only 31st when comparing GDP per capita in PPP. According to the World Bank country income classification, Tanzania is a lower-middle-income country (LMIC) with a Gross National Income (GNI) of US$4 120 in 2024.

Tanzania is situated in East Africa, bordered by Kenya and Uganda to the north, Rwanda, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo) to the west, Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique to the south and the Indian Ocean to the east. The country’s coastline stretches over 1 400 km along the Indian Ocean, providing access to important ports such as Dar es Salaam, which acts as the main maritime gateway for the country and several landlocked neighbours. The landscape is diverse, featuring the coastal plain, central plateau, the Great Rift Valley and highland zones. Mount Kilimanjaro, Africa's highest mountain, is in the mountainous and densely forested north-east of Tanzania. Three of Africa's Great Lakes are partly within Tanzania: Lake Victoria, Africa’s largest lake; Lake Tanganyika, the continent's deepest lake; and Lake Malawi.

The coastal region and islands experience a humid, tropical climate, while the interior has a more temperate or arid environment. Rainfall is unevenly distributed, with bimodal patterns in the north and unimodal patterns in the south and west, leading to periodic droughts and localised flooding. Environmental challenges include deforestation, soil erosion and land degradation, particularly in over-cultivated or densely settled areas.

Tanzania’s political system has evolved through several stages since the 1964 union of Tanganyika and Zanzibar. The country operated under an interim constitution until 1977, when a permanent charter was adopted and later amended to include a bill of rights. Zanzibar maintains its own constitution and governing institutions, with autonomy over domestic matters, though tensions over the balance of power between the mainland and the islands have periodically resurfaced.

For decades, politics was shaped by a one-party system dominated by the Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM), itself born from the merger of Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) on the mainland and the Afro-Shirazi Party in Zanzibar. This framework enshrined national unity and stability, often equating dissent with disloyalty. Multiparty politics was only introduced in 1992, and although Tanzania has held regular competitive elections since 1995, CCM has never lost power. Its dominance rests not only on access to state resources but also on its ability to absorb internal divisions and project itself as the custodian of unity and order.

The political opening of the early 1990s allowed for the emergence of opposition parties, but they remain weak. The 2025 elections unfolded in a contested environment. President Samia Suluhu Hassan, in office since 2021, initially signalled a more open political climate, permitting opposition rallies and easing restrictions on the press. However, these moves have been offset by renewed repression, including the disqualification of the main opposition party Chama cha Demokrasia na Maendeleo (CHADEMA), the arrest of its leader Tundu Lissu and restrictions on civic space. Analysts argue this reflects a long-standing consensus model: while Tanzania has avoided ethnic conflict and maintained stability, its political culture continues to prioritise cohesion and discipline over adversarial contestation.

Human rights concerns remain pressing. Reports of arbitrary arrests, violent crackdowns on protests, censorship and the forced eviction of Indigenous Maasai communities illustrate a persistent pattern of repression alongside official narratives of order and unity.

Following the October 2025 general elections, the contrast between institutional continuity and restricted political pluralism has sharpened, underscoring the fragility of Tanzania’s democratic trajectory. The polls, which returned President Samia Suluhu Hassan and the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) to power with an overwhelming majority (98%), were marred by serious irregularities, an internet shutdown and widespread reports of violence. In the days that followed, nationwide protests erupted across major cities as demonstrators, many of them young Tanzanians, denounced the results and the exclusion of opposition parties from the contest. Security forces responded with force, deploying live ammunition and imposing curfews amid a near-total blackout of communication. Human rights organisations and international media reported numerous deaths and injuries, though the full scale of casualties remains contested. Independent monitors documented arbitrary arrests and alleged instances of unlawful killings.

The African Union’s election observer mission concluded that the polls did not meet democratic standards and that the electoral environment was neither free nor fair. Condemnation from the AU, the UN and international partners has intensified scrutiny of the government’s legitimacy.

These events have reshaped Tanzania’s political landscape. Long regarded as a model of stability, the country now illustrates the limits of controlled pluralism—one that maintains order through coercion rather than legitimacy. The suppression of dissent and erosion of civic freedoms signal a deepening governance crisis and a fraying social contract. As Tanzania enters a new political cycle, the evolving relationship between state and citizen will determine whether stability in the coming years is rooted in consent or sustained by force.

Tanzania’s economy has been on a steady upward trajectory for more than two decades, with GDP growth averaging around 6% annually and total output projected to more than triple by 2043. This performance has underpinned the country’s transition to LMIC in 2020 and reflects relative macroeconomic stability, expanding exports, and investment in infrastructure. Yet these aggregate gains have not translated into commensurate improvements in individual incomes: in 2023, Tanzania ranked 31st among African countries in GDP per capita. The disconnect is driven by rapid population growth, low-productivity agriculture and a large informal economy that limits wages, productivity and fiscal revenues. Extreme poverty remains widespread, while persistent gaps in health, education and nutrition reinforce deprivation, particularly in rural areas.

In 2023, Tanzania ranked 165th out of 191 countries in the UNDP Human Development Report, placing it in the medium human development category. This position reflects slower progress compared to most of its East African neighbours.

Looking ahead, the government’s Third Five-Year Development Plan (FYDP III) and the draft Vision 2050 both acknowledge that sustaining high GDP growth will not be enough. The focus must shift towards structural transformation, job creation and human capital investment if growth is to raise living standards, reduce poverty and capture the demographic dividend.

Chart 2 presents the Current Path of the population structure, from 1990 to 2043.

Tanzania has a young and rapidly expanding population, with a median age of just 18.4 years. At independence in 1963, Tanzania’s population stood at around 11 million. By 2000, it had more than tripled to 34.5 million, and by 2023, it had nearly doubled again to reach 65.5 million. On the Current Path trajectory, the population will reach 110.5 million by 2043.

Although fertility rates are gradually declining, the pace remains slow. In 2023, the fertility rate was 4.6 children per woman, and by 2043, it is expected to fall to 3.3. This remains consistently higher than the average for African lower-middle-income countries, indicating that rapid population growth will continue to shape Tanzania’s development outlook. Various factors contribute to Tanzania’s high fertility and rapid population growth, including its large informal economy (46% of GDP in 2023), low levels of urbanisation (38% in 2023) and education (an average of 7.8 years of schooling among adults over 15) also contribute, as does the relatively early age of marriage—two years below the average of its peer group. These structural characteristics are such that they outweigh the fact that Tanzania has slightly higher access to modern contraceptives (at 40% in 2023) than the average for lower-middle-income Africa (at 37%).

Like many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the population of Tanzania is predominantly young, with 43% under the age of 15 in 2023, gradually declining to 36% in 2043. About 54% of the Tanzanian population is in the 15-64 working-age group, and this will increase to 60% by 2043. The proportion aged 65 and older was 3% in 2023, slightly increasing to 4% in 2043. This gradual shift means the number of working-age Tanzanians will grow faster than the number of dependants. If the economy can absorb these new workers productively, the country can reap what is known as the demographic dividend: a period when a high ratio of workers (15-64 years) to dependants (0-14 years of age and 65+) accelerates economic growth. In practice, this tends to occur once the ratio exceeds about 1.7 workers per dependant, but the dividend is never automatic. It requires heavy, sustained investment in quality education, accessible healthcare, decent job creation and women’s full economic participation. In 2023, Tanzania’s ratio of working-age population to dependants was estimated at 1.2:1, meaning there were 1.2 individuals of working age for every one dependant. It is projected to enter this window only after 2050 under the Current Path. Yet the groundwork must be laid now if the potential of its youthful population is to be unlocked.

Tanzania also has a large youth bulge at 48.9% in 2023, defined as the ratio of the population between 15 and 29 years to the total adult population (15+ years of age). A large number of young adults can lead to positive political change in a country through youth activism, but they can also carry the seeds for socio-political instability in the absence of economic opportunities. On the Current Path, Tanzania’s youth bulge will decline to 43.6% by 2043.

Chart 3 presents a population distribution map for 2023.

Tanzania’s population density is shaped by geographic, economic and demographic factors. As of 2023, Tanzania had an overall average population density of approximately 0.75 persons per hectare, while urban areas recorded a significantly higher average density of 28.3 persons per hectare. Tanzania’s population density remains low compared to the average for LMICs in Africa.

The country is divided into a total of 31 administrative regions, with 26 located on the mainland and 5 in the Zanzibar archipelago. Located on the Swahili coast, Dar es Salaam is the most populous urban region in East Africa, with over 5 million residents (about 8% of the national total), which serves as the economic and former administrative capital. Beyond Dar es Salaam, the only regions with populations above three million are Mwanza, Tabora, Morogoro and Dodoma. Dodoma was designated as Tanzania’s new capital in 1974 by President Julius Kambarage Nyerere, with the goal of fostering more centralised governance and balanced national development due to its strategic central location within the country. However, the relocation process was slow and gradual, with significant progress only happening decades later. Between 2012 and 2022, the population of Dodoma Region increased by just over 1 million people. Other major cities include Arusha, Mbeya and Tanga.

Although Dar es Salaam and Dodoma often attract more attention due to their political and economic significance, it is Geita’s rapid regional demographic expansion that stands out most clearly in the 2022 census results. Between 2012 and 2022, Tanzania’s fastest-growing region in absolute population terms was Geita, which added over 1.2 million people, rising from 1.74 million to nearly 3 million residents. Tabora followed closely, expanding by about 1.1 million people, while Dar es Salaam and Dodoma each grew by just over one million. The Geita region’s population growth is driven largely by the gold mining sector, which directly and indirectly employs over 100 000 people. It has also been fuelled by productive agricultural land supporting surplus crop and livestock output. Yet this expansion has outpaced urban management capacity, as Geita Town has spread into surrounding rural villages that lack basic services. Despite its rich resources, the town remains heavily dependent on agriculture, while mining and agro-processing are not fully leveraged to improve local livelihoods or strengthen value chains. The Geita Town Master Plan (2017–2037) outlines a coordinated strategy to harness the region’s mining and agricultural potential by promoting value addition, strengthening local governance, and guiding sustainable urban development.

The least densely populated areas are Iringa (1.2 million), Katavi (1.2 million) and Njombe (0.9 million).

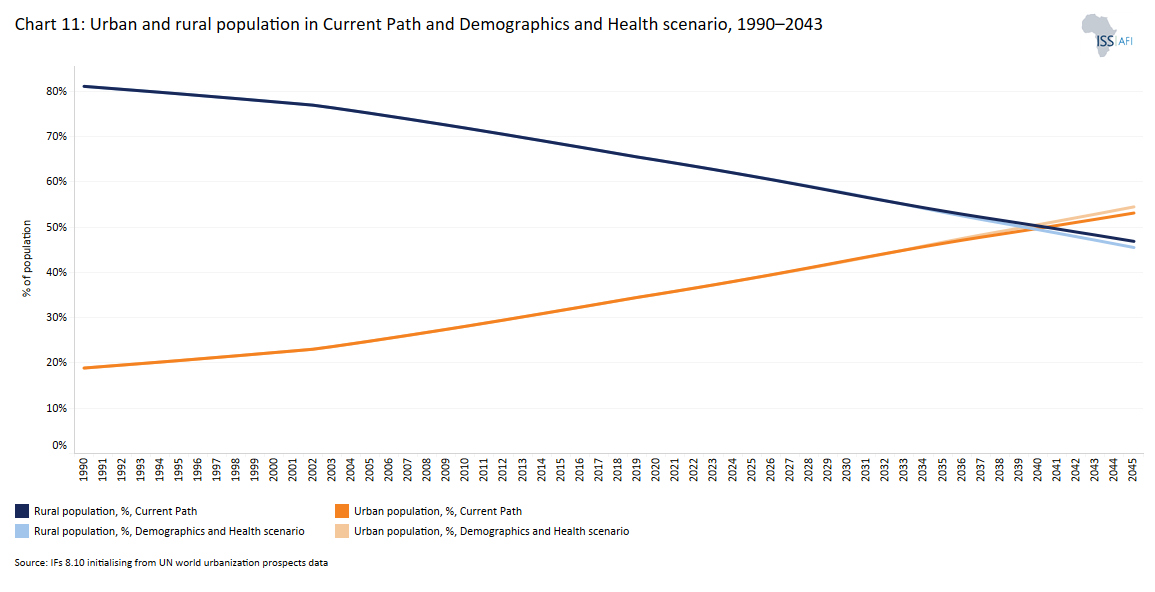

Chart 4 presents the urban and rural population in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

Tanzania’s urban population rose from 22% in 2000 to 38% in 2023 and will reach 51% by 2043. Its urbanisation rate remains below the lower-middle-income Africa average (about 49.2% in 2023).

With around 41 million people still living in rural areas (about 62% of the population), migration to towns and cities is set to remain robust, especially among young people seeking jobs and services. On the Current Path, Tanzania must accommodate more than 30 million additional urban residents by 2043, concentrated in Dar es Salaam and fast-growing secondary cities such as Mwanza, Dodoma, Arusha and Morogoro, alongside extensive peri-urban expansion.

While urbanisation can raise productivity through agglomeration and scale effects, the payoff is not automatic: early, sustained investment in serviced land, affordable housing, public transport, water and sanitation, and policies that expand formal jobs and integrate informal settlements will be essential to realise the benefits.

Tanzania’s updated National Land Policy recognises that rapid urbanisation must be matched with stronger land governance. The 2023 reforms make land registration in planned areas mandatory, aiming to reduce informal transactions, strengthen tenure security and expand the tax base. A new national geospatial system and online geo-portal will integrate maps, surveys and land data, improving planning for urban expansion. The policy also opens space for foreign and diaspora investment in housing, with safeguards to protect citizen interests, and designates land banks to encourage more structured real estate development. In parallel, the reforms tackle weak inheritance rights for women and promote fairer access to land, helping to address gender imbalances that often worsen in urban contexts. By modernising registration systems, streamlining data and clarifying ownership, the policy seeks to guide urban growth more sustainably and inclusively.

Chart 5 presents GDP in market exchange rates (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

Tanzania’s economy is relatively diversified, with the agriculture sector accounting for about 23% of total value addition, industry around 26% and services nearly 51%. Agriculture continues to be Tanzania's primary source of employment, with two in three Tanzanians working in the sector.

Over the past two decades, Tanzania has built a track record of macroeconomic stability, even amid serious economic shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Economic growth has been robust, with an annual average growth of around 6% between 2004 and 2023. Tanzania’s GDP tripled, from US$23.7 billion to around US$69.5 billion during the period. Fiscal balances have generally remained under control, inflation has stayed within single digits, and the investment climate has benefited from improvements in the business environment. This stability, combined with abundant natural resources and favourable demographics, has underpinned high levels of investment and rising productive capacity. Exports of gold, agricultural commodities and tourism services have further boosted growth by improving the country’s terms of trade.

Looking ahead, Tanzania’s economy is projected to expand from about US$69.5 billion in 2023 to roughly US$230.6 billion by 2043—an average annual growth rate of 6.1%. Yet the quality of this growth matters as much as the quantity. According to the World Bank, Tanzania’s progress to date has not translated into the depth of structural transformation or poverty reduction needed to meet its development ambitions. Public sector-led growth has delivered stability but is constrained in its capacity to drive broad-based development. To achieve the objectives outlined in Vision 2050, Tanzania will need to transition toward more inclusive, private sector-driven growth that generates productive jobs, especially for its rapidly expanding youthful workforce. This requires moving labour out of subsistence agriculture and informal activities into higher-value sectors, backed by sustained investment in education, health and infrastructure. Ensuring women and girls have equal access to opportunities will be central to unlocking human capital and capturing the demographic dividend. At the same time, building resilience to climate change will be essential to safeguard gains and prevent economic setbacks.

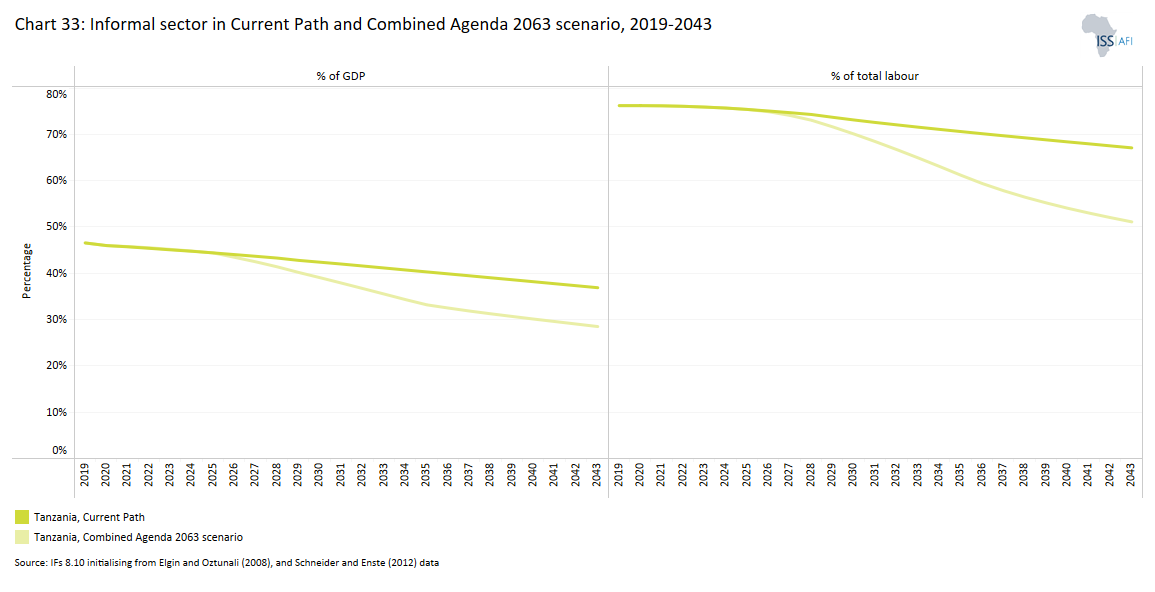

Chart 6 presents the size of the informal economy as per cent of GDP and per cent of total labour (non-agriculture), from 2020 to 2043. The data in our modelling are largely estimates and therefore may differ from other sources.

Informality in poorer countries stems not only from burdensome regulations or weak enforcement but also from broader conditions of underdevelopment. In wealthier economies, advanced technologies and favourable economic environments encourage workers to pursue formal wage employment, largely due to higher earnings. Likewise, managers are more inclined to register and operate within the formal sector, since the greater income opportunities in developed markets outweigh the costs of taxes and regulations. As economies progress, the informal sector generally contracts. According to a World Bank study, roughly 30% of aggregate output growth driven by productivity gains is associated with about a 25% decline in the average size of informal enterprises.

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), ‘the informal economy refers to all economic activities by workers and economic units that are–in law or practice–not covered or insufficiently covered by formal arrangements’. The ILO definition of employment in the informal economy excludes the agricultural sector.

Despite ongoing policy initiatives, high informality persists in Tanzania. In recent years, the government has revised its National Employment Policy to expand formal jobs, updated the SME Development Policy to help small businesses move from the informal to the formal sector, strengthened the PPP framework to boost private sector-led employment, and introduced tax and registration reforms to lower barriers for businesses. While these measures aim to promote formalisation, their impact has so far been limited. The informal sector dominates Tanzania’s economy, accounting for 46% of GDP in 2023. This was the second-highest share in Africa, surpassed only by Zimbabwe at 54%. This means that a significant portion of Tanzanians are not registered or taxed. On the Current Path, Tanzania’s informal economy as a percentage of GDP will gradually decline to 39% in 2043.

The informal economy as a percentage of total labour stood at 76% in 2023, more than any African LMIC and ranked 4th highest when compared to all LMICs. Tanzania is expected to remain far above peer levels in the coming decades, declining only to 69% by 2043 compared to an African LMIC average of 54%.

Informality in Tanzania endures because of deep structural and institutional barriers. The economy remains dominated by smallholder agriculture and low-capital enterprises such as petty trade, small services, informal construction and home-based processing—activities that require little investment but yield low productivity. Formal job creation has not kept pace with rapid population growth, leaving the informal sector to absorb the roughly new workers who enter the labour market annually, which was estimated to be about 800 000 annually in 2022.

Complex registration and tax systems, weak enforcement capacity and fragmented policies further discourage formalisation. At the same time, low skills, limited access to finance and the cultural acceptance of informal work—especially among youth and women—sustain its appeal. Rapid urbanisation, combined with external shocks such as climate stress and COVID-19, has only reinforced the role of the informal economy as Tanzania’s shock absorber by providing livelihoods where the formal sector cannot, and making it the default rather than the exception in the country’s labour market.

Chart 7 presents GDP per capita in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043, compared with the average for the Africa income group.

After two decades of sustained economic growth, Tanzania was reclassified by the World Bank from low-income to lower-middle-income status in July 2020. The shift occurred when its GNI per capita reached US$1 080, surpassing the LMICs threshold of US$1 036 at the time, with a GDP per capita (PPP) of US$2 565 in 2019. Despite this milestone, Tanzania’s GDP per capita remains among the lowest of Africa’s LMICs, higher only than that of Lesotho and Zimbabwe, and is likely to stay at the lower end of the group across many development indicators on the Current Path.

However, this has not translated into improved livelihoods. In 2023, Tanzania’s GDP per capita (PPP) was US$2 582, the third lowest amongst its peer grouping of Africa’s LMICs (ahead of Lesotho and Zimbabwe), and ranking 31st in Africa. By 2043, it will reach US$4 306, maintaining a pattern of underperformance relative to both its peer group (US$7 805) and the continental average (US$6 207).

The persistence of low per capita incomes reflects a pattern of growth that has been narrow, uneven and weakly transformative. Tanzania’s draft Vision 2050 acknowledges that, despite two decades of stable growth averaging 5-7% annually, the impact on poverty reduction has been limited. Growth has not been underpinned by sufficient diversification, productivity or export competitiveness. Much of the labour force remains in low-value agriculture or shifts into informal urban trade rather than higher-productivity manufacturing and services. Women, young people and people with disabilities are disproportionately concentrated in these low-paid informal jobs. Rapid population growth further dilutes output per head, while high levels of informality limit productivity, wages and fiscal revenues. Moreover, Tanzania has underutilised opportunities for value addition, regional integration and global value chains, leaving it vulnerable to shocks and reliant on low-productivity sectors.

Looking ahead, Vision 2050 sets an ambitious aspiration: to reach upper-middle-income status by 2050, which would require sustained annual growth of at least 10%. Achieving this will demand a decisive break from past growth patterns by building a more diversified, inclusive and globally competitive economy. The Vision stresses the importance of strengthening human capital, expanding productive employment and creating a predictable and enabling policy and regulatory environment to attract investment. In short, raising GDP per capita will depend not only on sustaining high growth, but on ensuring that growth is structurally transformative, inclusive and resilient.

Chart 8 presents the rate and numbers of extremely poor people in the Current Path from 2020 to 2043.

In 2022, the World Bank updated the poverty lines to 2017 constant dollar values as follows:

- The previous US$1.90 extreme poverty line is now set at US$2.15, also for use with low-income countries.

- US$3.20 for lower-middle-income countries, now US$3.65 in 2017 values.

- US$5.50 for upper-middle-income countries, now US$6.85 in 2017 values.

- US$22.70 for high-income countries. The Bank has not yet announced the new poverty line in 2017 US$ prices for high-income countries.

Starting with monetary poverty, using US$2.15, 40% of Tanzania’s population was considered extremely poor in 2023, equivalent to 26.8 million people. As a percentage of its total population, only Zambia, DR Congo and Lesotho had higher monetary poverty rates among Africa’s LMICs in 2023. On the Current Path, Tanzania’s extreme poverty rate will decline to 12% (or 13.2 million people) in 2043. Tanzania will still have a sizable extreme poverty burden but rank 10th instead of fourth in the portion of extremely poor people among Africa’s lower-middle-income countries.

While the US$2.15 extreme poverty line is used to monitor progress towards achieving Goal 1 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) towards eliminating extreme poverty by 2030, Tanzania is now categorised as a lower-middle-income country. The World Bank and others consider US$3.65 a more appropriate monetary poverty line than US$2.15 for these countries.

Using the US$3.65 per day poverty line, Tanzania had the second-highest poverty rate among its peer group in 2023, just behind Zambia. At this threshold, around 71% of Tanzanians (or 47.5 million people) were classified as poor. On the Current Path, this share will decline to 37% by 2043. However, due to rapid population growth, that still translates to 41.1 million people living in poverty.

Tanzania’s national basic needs poverty line was set at 49,320 Tanzanian shillings per adult per month in 2018 (about US$21.2, or roughly US$1.35 per person per day in PPP terms). Using this benchmark—which captures the minimum income required to cover both food and essential non-food needs—the poverty headcount declined from 38.6% of the population in 1991 to 26.4% in 2018, representing around 14 million people.

However, monetary poverty only tells part of the story. The global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) measures acute multidimensional poverty by measuring each person’s overlapping deprivations across 10 indicators in three equally weighted dimensions: health, education and standard of living. The MPI complements the international US$2.15-a-day poverty extreme rate by identifying who is multidimensionally poor and also shows the composition of multidimensional poverty. The headcount or incidence of multidimensional poverty is often several percentage points higher than that of monetary poverty. This implies that individuals living above the monetary poverty line may still suffer deprivations in health, education and/or standard of living.

According to the 2024 Global MPI report, 47.2% of the population in Tanzania is multidimensionally poor, about eight percentage points higher than the monetary extreme poverty rate. An additional 23.1% of the population is also classified as vulnerable to multidimensional poverty. Multidimensional poverty is primarily concentrated on children aged 0-17 years, about 60%.

High poverty levels in Tanzania are shaped not only by the structure of growth, but also by the everyday vulnerabilities households face. Limited access to quality education, healthcare, clean water and electricity constrains human capital and locks many families into low-income trajectories. Rural households are particularly disadvantaged, relying heavily on rain-fed agriculture that is highly exposed to climate variability. Rapid population growth adds pressure on land and services. The government has introduced a range of initiatives to address these challenges, including the Productive Social Safety Net programme (PSSN), agricultural transformation strategies, and investments in health and education, yet coverage and impact remain uneven relative to need.

Chart 9 depicts the National Development Plan of Tanzania.

Tanzania has a long history of national development plans, dating back to the country's independence in 1961. The first five-year development plan was launched in 1964, and it was followed by a series of plans, each of which has been informed by the country's changing development priorities.

The early development plans in Tanzania were focused on achieving economic growth and self-reliance. The Arusha Declaration of 1967, a policy statement issued by the ruling party at the time, enshrined the principles of ujamaa (socialism) and self-reliance as the basis for the country's development. The development plans of the 1970s and 1980s focused on implementing these principles through policies such as the collectivisation of agriculture and the promotion of village industries.

In the early 1990s, Tanzania started to move towards a more market-oriented approach to development. The development plans of this period were therefore focused on promoting economic growth through private-sector investment and trade liberalisation. The National Development Vision 2025, launched in 1999, set a long-term goal for Tanzania to become a middle-income country by 2025. Vision 2025 was built around three pillars: ensuring a high quality of life for all Tanzanians, consolidating good governance and the rule of law, and creating a strong and competitive economy capable of withstanding global pressures.

To operationalise Vision 2025, Tanzania adopted successive Five-Year Development Plans (FYDPs). The First FYDP (2011/12–2015/16) emphasised infrastructure development and industrialisation; the Second FYDP (2016/17–2020/21) focused on advancing an industrial economy; and the Third FYDP (2021/22–2025/26), currently in effect, seeks to consolidate lower-middle-income status by accelerating economic transformation, strengthening human capital and promoting competitiveness.

Most recently, Tanzania has drafted the development Vision 2050, which extends the horizon of national planning and builds on the lessons of Vision 2025. It is built around three pillars supported by good governance, peace and stability:

- a strong, inclusive and competitive economy;

- human capabilities and social development;

- and environmental integrity and climate resilience.

Its six goals prioritise:

- Diversified, resilient, inclusive upper-middle-income economy.

- Eradicate poverty (with focus on women, youth, persons with disabilities) and balanced regional development.

- High quality of life: strong social services, human security, cohesion, cultural diversity, and national unity.

- Human capability maximised: harness women and a growing youth population for national development and global citizenship.

- Inclusive, transparent, accountable governance ensuring lasting peace, freedoms, and citizen security.

- Sustainable management of ecosystems and resources, with climate resilience.

Vision 2050 aspires to achieve upper-middle-income status by mid-century, requiring sustained double-digit growth rates. It diagnoses the limits of past growth—highlighting that while GDP expanded by 5-7% annually over two decades, poverty reduction has been modest and structural transformation limited. The Vision therefore emphasises diversification, productivity and global competitiveness, underpinned by human capital development, social inclusion and resilience to climate and external shocks. Together, Vision 2050 and the FYDP III frame Tanzania’s long-term path towards an inclusive and transformative growth model.

Chart 11 presents the mortality distribution in the Current Path for 2023 and 2043.

Visit the themes on Demographics and Health/WaSH for more details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Tanzania’s health sector has recorded important gains over the past two decades, notably in reducing maternal and under-five mortality and steadily expanding the health workforce. Recent recruitment drives have prioritised rural areas, while new legislation, the Universal Health Insurance (UHI) Act of 2023, establishes a framework for mandatory coverage and subsidised premiums for low-income households. These measures reflect the government’s commitment to universal health coverage and are complemented by plans to train over 100 000 community health workers to strengthen service delivery at the community level.

Despite these advances, the sector continues to face serious systemic constraints. The workforce shortage remains acute: current estimates suggest that closing the 66% human resources gap would require hiring around 200 000 additional health workers, particularly at the primary care level. Infrastructure and supply deficits also persist, with shortages of health facilities, medical equipment and essential drugs undermining service quality. High fertility rates add to the pressure by generating sustained demand for maternal and child health services.

Financing is another weak spot. Tanzania spends less on health than its East African Community peers, translating into fewer doctors, health workers and hospital beds per capita, although life expectancy is slightly higher. Recent increases in government health expenditure—and the gradual reduction in donor dependence—mark a positive shift, but out-of-pocket payments remain significant, leaving many households vulnerable to catastrophic costs.

Nutrition challenges, with stunting rates above 30% in some regions, further compound the picture. Recognising these pressures, Tanzania has embraced digital health innovations, including telemedicine, electronic hospital management systems and the m-mama emergency transport programme to reduce maternal deaths. Yet gaps in ICT infrastructure, electricity supply and health worker skills still constrain their full impact.

Tanzania also needs to improve on various indices of basic infrastructure. For example, among Africa’s 23 LMICs, it had the second-largest population still dependent on unimproved sanitation services and the seventh-largest population dependent on unimproved water supply, at 35% and 14%, respectively, in 2023.

Communicable diseases (CDs) remain the leading cause of illness and death in Tanzania, with lower respiratory infections being a major contributor. In 2023, the country recorded an estimated 37 100 lower respiratory-related deaths. The most common respiratory conditions in the country are pneumonia, tuberculosis and HIV-associated respiratory illnesses. Since 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has driven a sharp rise in lower respiratory illness and emerged as a leading cause of respiratory morbidity and mortality in Tanzania.

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs), particularly cardiovascular conditions and malignant neoplasms, remain the leading causes of death among the elderly. At the same time, Tanzania has made notable progress in recent years on key health outcomes. The stunting rate among children under five has fallen sharply, from about 49% in the 1990s to 29.1% in 2023, just 2.7 percentage points above the African LMICs average of 26.5%. On its Current Path, Tanzania is projected to meet the SDG target of 25% by 2030, with stunting expected to decline further to 24.1% by 2030 and 16.3% by 2043.

Maternal mortality has declined from 997 deaths per 100 000 live births in 1990 to 213.9 in 2023, compared with an average of 494.2 for LMICs in Africa. The reduction in maternal mortality can be attributed to various factors, including improvements in healthcare systems, policies and community engagement. On the Current Path, Tanzania's maternal mortality rate will decline further, reaching 159 deaths per 100 000 live births by 2030—significantly above the SDG target of fewer than 70 deaths per 100 000 live births—and 68.7 deaths per 100 000 live births by 2043.

Child (under five) mortality has also declined from 198 deaths per 1 000 live births in 1990 to about 100 deaths in 2023, while life expectancy has increased from 50.7 years to 68 years over the same period.

With a declining trend in deaths from CDs and a rising trend in deaths from NCDs, Tanzania is forecast to undergo its epidemiologic transition in 2029, when NCD-related death rates will surpass those from CDs. This transformation is driven by demographic shifts, urbanisation, changing lifestyles and improved access to healthcare. The growing burden of NCDs poses significant challenges for Tanzania's healthcare system, given the higher costs associated with treating NCDs, requiring substantial investments to build the capacity needed to address this evolving health landscape. NCD care is lifelong and monitoring-intensive; without stronger prevention and primary care, the transition will strain an already constrained health budget.

Both Vision 2025 and the draft Vision 2050 place human capital and health at the centre of Tanzania’s development strategy. The emphasis is on universal healthcare, maternal and child survival, prevention and tackling NCDs, alongside systemic reforms to ensure that the health sector can deliver inclusive, resilient and high-quality services.

The Demographics and Health scenario envisions ambitious improvements in child and maternal mortality rates, enhanced access to modern contraception, and decreased mortality from communicable diseases (e.g., AIDS, diarrhoea, malaria, respiratory infections) and non-communicable diseases (e.g., diabetes), alongside advancements in safe water access and sanitation. This scenario assumes a swift demographic transition supported by heightened investments in health and water, sanitation and hygiene (WaSH) infrastructure.

Chart 12 presents the infant mortality rate in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

The infant mortality rate is the probability of a child born in a specific year dying before reaching the age of one. It measures the child-born survival rate and reflects the social, economic and environmental conditions in which children live, including their health care. It is measured as the number of infant deaths per 1 000 live births and is an important marker of the overall quality of the health system in a country.

Infant mortality in Tanzania is relatively high compared to the average of its peer group, although it has improved drastically since 1990, when it stood at 100.8. This positive trend is expected to continue, with infant mortality estimated at 39 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2023. The contributors to high infant mortality rates in Tanzania include poverty, malnutrition, infectious diseases such as malaria and pneumonia and limited health care access. On the Current Path, it will decline further to around 22.4 by 2043.

In the Demographics and Health scenario, which assumes more ambitious investments in health, Tanzania’s rate could fall even further to 17 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2043, which will be six deaths per 1 000 below the Current Path in the same year.

Chart 13 presents the demographic dividend in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

The dividend is the window of economic growth opportunity that opens when the ratio of working-age persons to dependants increases to 1.7 or higher.

Greater access to modern contraception, combined with appropriate education and information, will significantly reduce Tanzania’s total fertility rate, which stood at 4.6 births per woman in 2023. Modern contraceptive use is projected to rise from 40.1% in 2023 to 56.6% by 2043.

In the Demographics and Health scenario, fertility declines more rapidly, reaching 2.7 births per woman by 2043, compared to 3.3 on the Current Path. A lower fertility rate will slow population growth, resulting in four million fewer people by 2043 (107 million instead of 111 million). As a result, Tanzania would enter its demographic window of opportunity by 2043, in line with the average for its LMIC peers and seven years earlier than on the Current Path, where this threshold is only reached by 2050.

While entering a demographic window of opportunity is a critical milestone, the demographic dividend is not automatic. Reaping its full benefits depends on the extent to which Tanzania can create the right enabling conditions, such as quality education, accessible healthcare, sufficient job creation, higher labour productivity and strong institutions. Without these foundations, a larger working-age population may translate into rising unemployment and growing inequality, rather than economic gains. It is therefore essential that Tanzania invests in these areas now, well before the window opens, to ensure the workforce is healthy, skilled and productively employed when the opportunity arises.

Chart 14 presents crop production and demand from 1990 to 2043.

The Agriculture scenario envisions an agricultural revolution that ensures food security through ambitious yet feasible increases in yields per hectare, thanks to improved management, seed, fertiliser technology and expanded irrigation. Efforts to reduce food loss and waste are emphasised, with increased calorie consumption as an indicator of self-sufficiency and prioritising it over food exports. Additionally, enhanced forest protection signifies a commitment to sustainable land use practices.

Visit the theme on Agriculture for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Agriculture forms the backbone of Tanzania’s economy, providing employment, food security and foreign exchange earnings. The country’s diverse agro-climatic conditions allow for the cultivation of a wide range of crops, from subsistence staples to commercial cash crops for export. Alongside agriculture, mineral resources, particularly gold, also play a pivotal role in shaping the nation’s export profile.

Tanzania possesses around 44 million hectares of arable land, yet only about a quarter, roughly 10.8 million hectares, is currently cultivated. The country has vast irrigation potential, estimated at 29.4 million hectares, of which 2.3 million are rated high potential and 4.8 million moderate. Despite this resource base, agriculture remains dominated by smallholders, most cultivating less than five hectares under rain-fed conditions, with limited use of fertiliser, improved seed or mechanisation. High post-harvest losses, volatile prices and weak market access continue to suppress productivity and profitability, reinforcing rural poverty and food insecurity. According to the 2022 Population and Housing Census, about 5.1 million households, roughly 40 million people or 65.6% of the population, are engaged primarily in agriculture. Smallholders account for about 80% of cultivated land and produce most of the country’s food supply, though their output fluctuates widely with rainfall variability.

To promote agricultural transformation, Tanzania is expanding the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor (SAGCOT) model into a nationwide framework, the Agricultural Growth Corridors of Tanzania (AGCOT), covering the Southern, Northern, Lake Zone and Mtwara corridors. The initiative seeks to attract investment, strengthen logistics and align production with regional agro-ecological advantages. While the corridor approach has catalysed investment and export diversification in targeted zones, the benefits remain spatially uneven, with limited spillovers to rain-dependent and food-deficient regions.

Tanzania’s food self-sufficiency ratio (SSR) rose to 128% in 2023/24, up from 124% the previous year, suggesting that national food production exceeded domestic consumption. This surplus was supported by good rainfall, the rollout of fertiliser and seed subsidies and improved management practices. However, the national figure conceals localised food insecurity. The IPC Tanzania Acute Food Insecurity Report found that around 900 000 people (13%) were in crisis (phase 3) and 2.2 million (31%) in stressed (phase 2) conditions during the same period. Such regional disparities reflect systemic weaknesses: the predominance of rain-fed smallholder farming, inadequate irrigation coverage, poor storage and transport infrastructure, and weak market integration that prevents surplus regions from offsetting deficits elsewhere.

At the same time, agricultural exports surged to USD 3.54 billion in 2023/24, up from USD 2.33 billion the year before, driven by strong global demand and high prices for cash crops such as cashew nuts, coffee, tobacco and cotton. These export gains underscore the success of commercial agriculture policies and input support programs but highlight a growing duality within the agricultural sector. Export-oriented crops are concentrated in high-potential regions and produced by better-capitalised farmers, while staple foods, maize, rice, cassava and beans, remain smallholder-dominated and vulnerable to climatic and market volatility. As a result, Tanzania can simultaneously record a rising SSR and booming exports while millions still face food insecurity.

This dual-track agricultural economy, commercial and export-driven on one side, subsistence and fragile on the other, reveals a pattern of progress laced with persistent structural imbalance. National food availability and export earnings are improving, yet household food access and nutritional security lag behind. Addressing this divide will require targeted investment in irrigation, rural infrastructure and storage, together with policies that integrate smallholders into value chains and strengthen resilience to climate shocks. Only then can Tanzania’s agricultural growth become both competitive and inclusive.

In 1990, crop demand stood at 19.1 million metric tons while crop production was slightly higher at 19.3 million metric tons, indicating near parity between the two indicators. This balance persisted through the early and mid-1990s, with both demand and production exhibiting modest fluctuations. Between 2010 and 2020, Tanzania sustained a moderate surplus. In 2023, crop demand stood at 48.6 million metric tons while crop production was slightly higher at 49.9 million metric tons. Agriculture demand will outpace production at an accelerating pace from 2028 onwards. By 2043, demand will reach 90.7 million metric tons compared to 68.2 million metric tons of production. The forecasted deficit of 22.5 million metric tons by 2043 highlights the need for sustained investment in agricultural modernisation, climate-resilient practices and value chain development.

This gap mirrors that of the broader lower-middle-income Africa group, where production has never outpaced demand and the deficit has grown from 14 million metric tons in 1990 to 340 million metric tons by 2043. Both the national and regional trajectories reveal that achieving food security will require not only scaling up aggregate production but addressing the systemic barriers that limit productivity, resilience and inclusive sectoral growth.

Chart 15 presents the import dependence in the Current Path and the Agriculture scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

Despite recent progress in boosting local production, Tanzania remains heavily dependent on agricultural imports for key inputs. In 2023/24, over a fifth of national seed availability came from imports, with particularly high reliance on vegetable seeds (73.5%) and soybeans (70.3%), while even strategic staples such as maize and wheat still required significant external sourcing. Fertiliser dependence is even more pronounced: although domestic output has expanded nearly fourfold in five years, imports continue to account for around 60% of the national supply. The country also faces a structural deficit in edible oil production, with a 350 000-ton annual shortfall met largely through imports of palm oil. This reliance on imported inputs exposes Tanzania’s agriculture to global price shocks and supply disruptions, underscoring the need to accelerate investment in local seed systems, fertiliser production and oilseed processing to strengthen food system resilience.

In 2023, Tanzania’s agricultural crop net import dependence as a percentage of demand was -0.9%—a crop trade surplus. On the Current Path, it will reach a deficit of 25.4% by 2043. The Agriculture scenario will reduce agriculture crop import dependence by 11.9 percentage points compared to the Current Path, to 13.5% in 2043.

Chart 16 depicts the progress through the educational system in the Current Path, for 2023 and 2043.

The Education scenario represents reasonable but ambitious improvements in intake, transition, and graduation rates from primary to tertiary levels and better quality of education at primary and secondary levels. It also models substantive progress towards gender parity at all levels, additional vocational training at the secondary school level, and increases in the share of science and engineering graduates.

Visit the theme on Education for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Tanzania has made significant strides in expanding access across pre-primary, primary and secondary education, but continues to wrestle with quality, equity and outcomes. The newly launched Education Sector Development Plan (ESDP 2025/26–2029/30) seeks to consolidate gains and tackle these challenges with targeted reforms.

The country has made significant progress in primary school enrolment, with gross enrolment increasing from 34% in 1970 to 98% in 2023, slightly below the average of 101% for Africa’s lower-middle-income countries.

Gross enrolment refers to the total number of students enrolled at a given education level, regardless of age, while net enrolment counts only those within the official age group—making net enrolment a better measure of age-appropriate access to education. Tanzania’s net enrollment in primary schools increased substantially from 51% in 1993 to 90% in 2023.

Primary school enrolment increased from 485 470 in 1961 to 11.4 million in 2023. Despite major national progress, enrolment declined in half of Tanzania’s regions between 2022 and 2023, highlighting persistent regional inequalities in access to education. According to the 2022 Population and Housing Census (PHC), the regions with the lowest primary net enrolment were Rukwa, Katavi and Tabora. The highest net enrolment was observed in Mjini Magharibi, Kusini Unguja and Dar es Salaam.

Despite high primary enrolment, the transition to and completion of lower-secondary education remains a major challenge. In 2023, gross enrolment was 46% and the completion rate was just 35%. On the Current Path, completion will reach 54% by 2043, but rural children, especially girls, continue to face barriers such as distance to schools, affordability and cultural norms. Urban areas outperform rural ones across both access and completion, while gender gaps persist: girls are more likely to drop out due to early marriage, pregnancy or household responsibilities.

At the upper-secondary stage, participation is even more limited. Upper-secondary gross enrolment stood at 9% in 2023 and will increase to 33% by 2043, with completion rates at 7% and 30%, respectively. Tanzania lags behind its peer group of lower-middle-income countries that had an average completion rate of 35% and 48% in 2023 and 2043, respectively.

In 2023, tertiary gross enrolment stood at 5%, well below the average of 16% for lower-middle-income African countries and placing it last (23rd) in the group. On the Current Path, tertiary gross enrolment will increase to 15% in 2043, compared to the group average of 23%. This means Tanzania moves up one spot to 22nd out of the 23 lower-middle-income African countries, ahead only of Mauritania. The average tertiary completion for the group was 16% in 2023 and will increase to 23% in 2043.

Tanzania’s technical and vocational education and training (TVET) sector has expanded quickly, with enrolment now exceeding half a million students across more than 1 300 institutions—almost triple the size of the higher education sector. Access has widened through Folk Development Colleges and Vocational Training Centres, which particularly serve rural youth, girls and school dropouts, but overall coverage is far from adequate.

Despite this expansion, participation remains extremely limited: the gross enrolment ratio was only 2.5% in 2020/21, one of the lowest in the region. Training quality and labour market alignment remain weak. Completion rates in critical technical fields such as engineering, petrol and gas are below 50%, and tracer studies show that many graduates struggle to find formal employment, often relying on informal networks rather than structured employer linkages. At the same time, employers tend to value diploma and certificate holders. However, there is strong potential for further development as TVET becomes more established as an important complement to academic education.

Governance and financing challenges further constrain the sector. Oversight is fragmented across multiple ministries. While reforms are underway, structural constraints in financing, institutional authority and alignment with labour market demands continue to limit TVET’s capacity to drive industrialisation and meaningful employment.

Chart 17 presents the mean years of education in the Current Path and in the Education scenario, from 2020 to 2043, for the 15 to 24-year age group.

The average years of education in the adult population aged 15 to 24 is a good first indicator of how the stock of knowledge in society is changing.

Another way of measuring the general level of education in a country is to look at the mean level of adult education. Tanzania’s mean years of education have increased rapidly since 1990, rising from 5 to 8.1 by 2023. In 2023, Tanzania ranked 18th on the continent and 9th among African LMICs for mean years of education in this youth cohort.

This progress reflects sustained policy momentum and a renewed government drive to improve the quality, relevance and inclusivity of education. Tanzania is implementing a comprehensive reform of the 2014 Education and Training Policy, anchored in a new curriculum introduced in 2023, with full execution expected by 2027. At the core of this reform is a restructured education system (1+6+4+2/3+3), comprising one year of kindergarten, six years of primary schooling, four years of lower secondary, two to three years of upper secondary, and three years of tertiary education. Under the new framework, compulsory education will extend from seven to ten years, ensuring that all children complete both primary and lower-secondary levels.

The reform represents a decisive shift from a purely academic orientation to a skills-based learning model, better aligned with labour market demands and the country’s development priorities. To modernise learning content, the curriculum introduces vocational training from the first year of secondary school and expands subject offerings to include business studies, tailoring, performing arts, home economics, food and nutrition, religious education, ICT, languages and life skills. Kiswahili will serve as the medium of instruction for Tanzanian history and ethics, reinforcing cultural identity and national cohesion.

On the Current Path, mean years of education for youth aged 15-24 will rise to 9.3 years by 2043, reaching 9.5 years for females and 9.1 years for males. Under the Education scenario, this increases slightly to 9.7 years for the total cohort, with females averaging 9.8 years and males 9.5 years, reflecting accelerated investment and reform in the education sector.

Chart 18 presents the value-add by sector as share of GDP in the Current Path, for 2023 and 2043.

Tanzania’s economy is undergoing a gradual structural shift, with services already established as the dominant sector. In 2023, services accounted for just over half of GDP (50.8%) and will expand their share to 60.4% by 2043, reflecting the growing role of trade, finance, transport and other service industries in driving growth. Agriculture, by contrast, contributed just under a quarter (23%) of GDP in 2023 but is expected to decline sharply to 9% by 2043, consistent with the long-term transition away from subsistence farming as productivity rises in other parts of the economy.

Industry is set to play an increasing role. Manufacturing was the third-largest contributor in 2023 at 12% of GDP and will rise steadily to 15.2% by 2043, supported by industrialisation strategies and regional integration. The materials sector, which includes mining, is also projected to expand, increasing from 6.5% in 2023 to 8.6% by 2043, reflecting Tanzania’s mineral endowments and rising global demand. Smaller but fast-growing sectors will also gain ground: information and communication technologies (ICTech) are projected to rise from 3.8% to 5.2% of GDP, while energy decreases from 3.8% to 1.7% over the same period.

Chart 19 presents the contribution of the manufacturing sector to GDP in the Current Path and in the Manufacturing scenario, from 2020 to 2043. The data is in US$ and % of GDP.

The manufacturing sector in Tanzania is at a developing stage but has demonstrated significant potential to drive economic growth, diversification and job creation. While the sector currently contributes a modest share to the national GDP compared to agriculture and mining, it is increasingly recognised by policymakers as a cornerstone for industrial transformation under initiatives such as Tanzania’s Industrialization Development Strategy 2025.