Malawi

Malawi

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

The page provides an in-depth analysis of Malawi's current and projected future development, examining various sectoral scenarios and their potential impacts on the country's growth. It explores eight sectors, including demographic, economic and infrastructure-related outcomes for Malawi up to 2043. The analysis also considers the implications of the Agenda 2063 goals, aiming to offer insights into policy actions that could enhance Malawi's developmental trajectory.

For more information about the International Futures modelling platform we use to develop the various scenarios, please see About this Site.

Summary

We begin this page with an introductory assessment of the country’s context by looking at current population distribution, social structure, climate and topography.

- Malawi, a low-income, landlocked country in Southern Africa, faces persistent economic and developmental challenges despite political stability and democratic governance. Over 70% of the population lives below the poverty line, and GDP per capita remains below US$1 500. Ranking 172nd on the Human Development Index (HDI), Malawi lags behind regional peers due to structural weaknesses such as corruption, inadequate infrastructure and an undiversified economy heavily reliant on agriculture. Climate shocks have further strained food security, with acute food insecurity affecting nearly 6 million people in 2024. Agriculture is the backbone of Malawi’s economy, employing over two-thirds of the population and contributing nearly a quarter of the country’s GDP. The sector is dominated by smallholder farmers, with 76% cultivating plots smaller than one hectare. Fiscal pressures have escalated, with a current account deficit of 18.7% of GDP and official reserves dwindling to just 0.5 months of import cover. The 2025 suspension of US aid has disrupted essential services, compounding an already precarious economic situation. With the highest fiscal deficit in sub-Saharan Africa (10.2% of GDP), urgent fiscal consolidation and debt restructuring are crucial to restoring stability and unlocking sustainable growth. Despite these challenges, Malawi has the potential for transformation. Targeted policy interventions, economic diversification and resilience-building measures could drive sustainable progress. As Malawi nears its 2025 general elections, the nation faces a volatile political and economic landscape, where potential policy shifts could reshape its development trajectory, impacting economic stability, governance priorities and long-term growth prospects.

This section is followed by an analysis of the Current Path for Malawi which informs the country’s likely current development trajectory to 2043. It is based on current geopolitical trends and assumes that no major shocks would occur in a ‘business-as-usual’ future.

- Malawi has one of the youngest populations in Africa, with a median age of 16.4 years in 2000, among the continent's lowest. However, the past decade has seen a gradual rise, reaching 18.4 years in 2023, aligning with the average for low-income African nations. This demographic shift is marked by a declining proportion of the population under 15 and a growing working-age group (15–64 years), projected to increase from 55.6% in 2023 to 63% by 2043 and 68.5% by 2063. If Malawi capitalises on this expanding workforce through strategic investments in education, employment and economic diversification, it could enter a demographic window of opportunity by 2041.

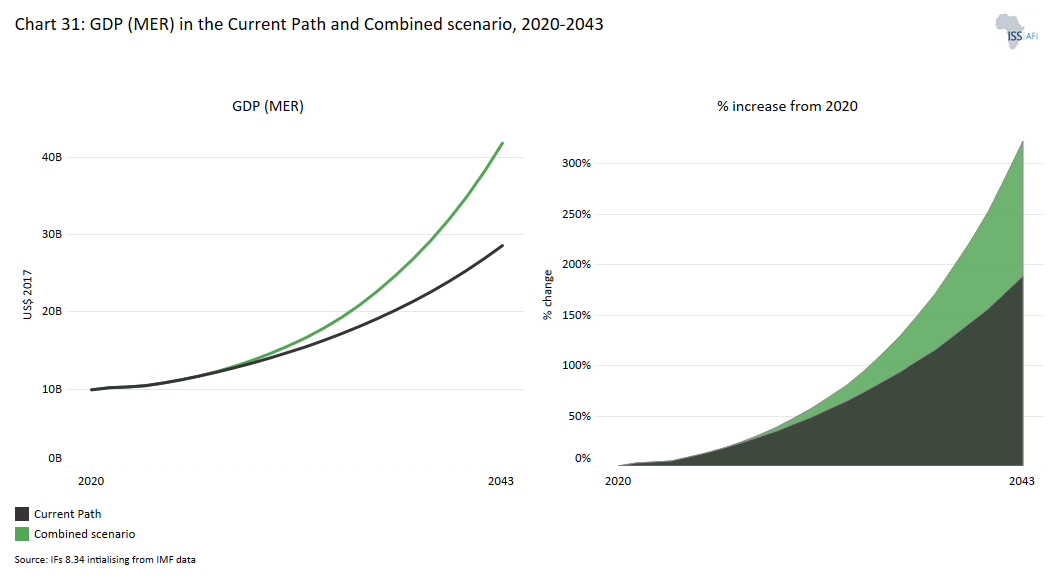

- Malawi's economy faces significant fiscal and structural challenges despite projected GDP growth from US$10.5 billion in 2023 to US$28.6 billion by 2043. The abrupt withdrawal of over US$350 million in USAID funding, which constituted more than 13% of the national budget, has deepened fiscal deficits, strained essential services and worsened foreign exchange shortages. Economic growth remains hindered by recurrent climate shocks, macroeconomic instability and a heavy reliance on foreign aid. The country's public debt has surged to 93% of GDP as of March 2024, constraining investment in critical sectors, with 42% of government revenue in 2024–25 earmarked for debt servicing. Informality remains a dominant feature of the economy, with 68.1% of employment in the informal sector in 2023, projected to decline to 62% by 2043.

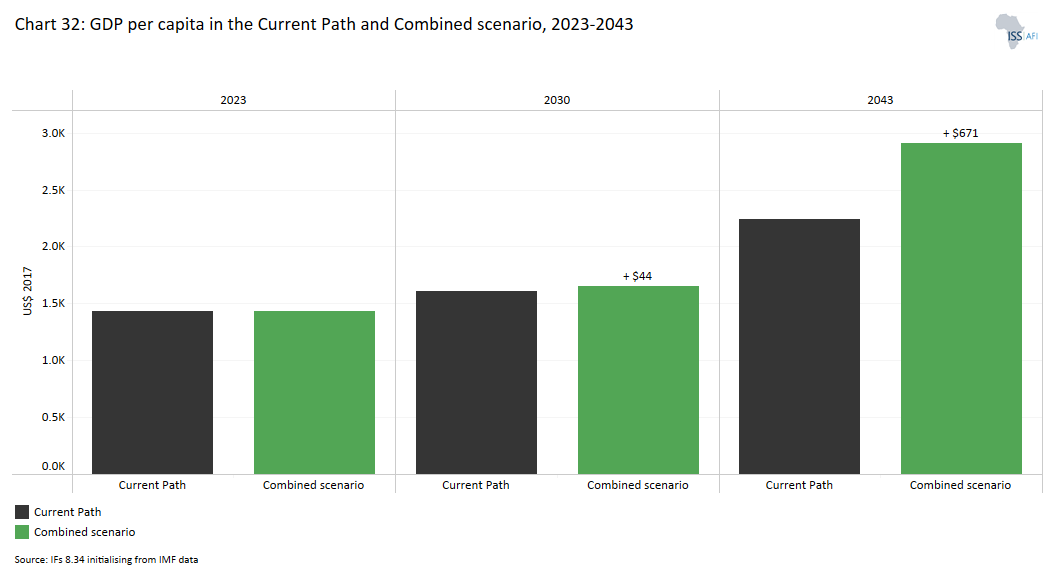

- Malawi's GDP per capita (PPP) stood at US$1 436 in 2023, well below the US$1 814 average for low-income African nations, and will remain below its peers through 2043, reaching US$2 242 compared to the projected US$2 986 average. Heavy reliance on agriculture, limited industrialisation and rapid population growth continue to strain resources and dilute economic gains. Additionally, high dependency on foreign aid has increased economic vulnerability, with recent funding cuts exacerbating fiscal deficits. While some economic progress is expected, achieving parity with similar economies will require sustained, inclusive growth strategies, structural reforms and economic diversification.

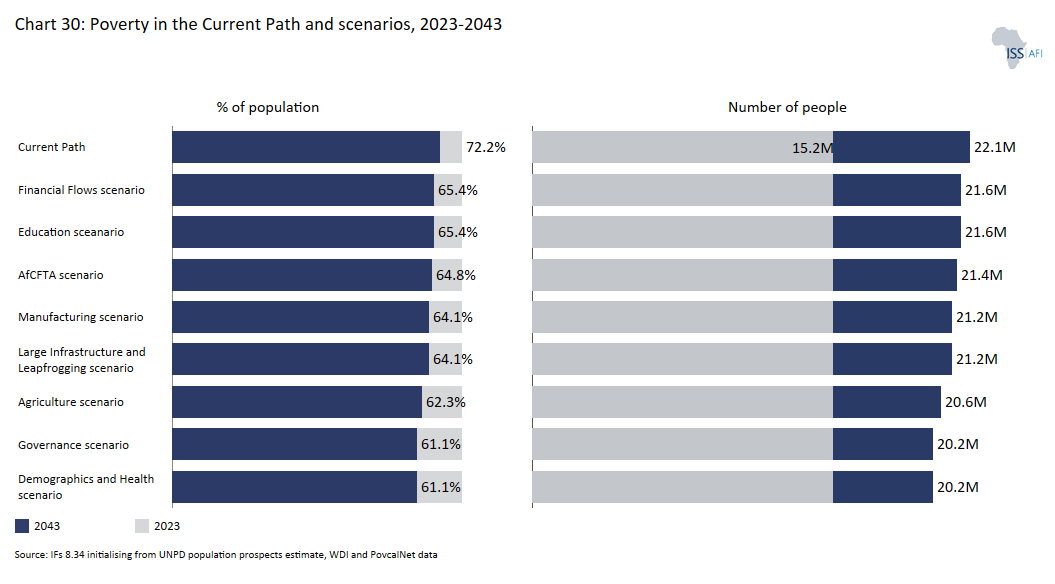

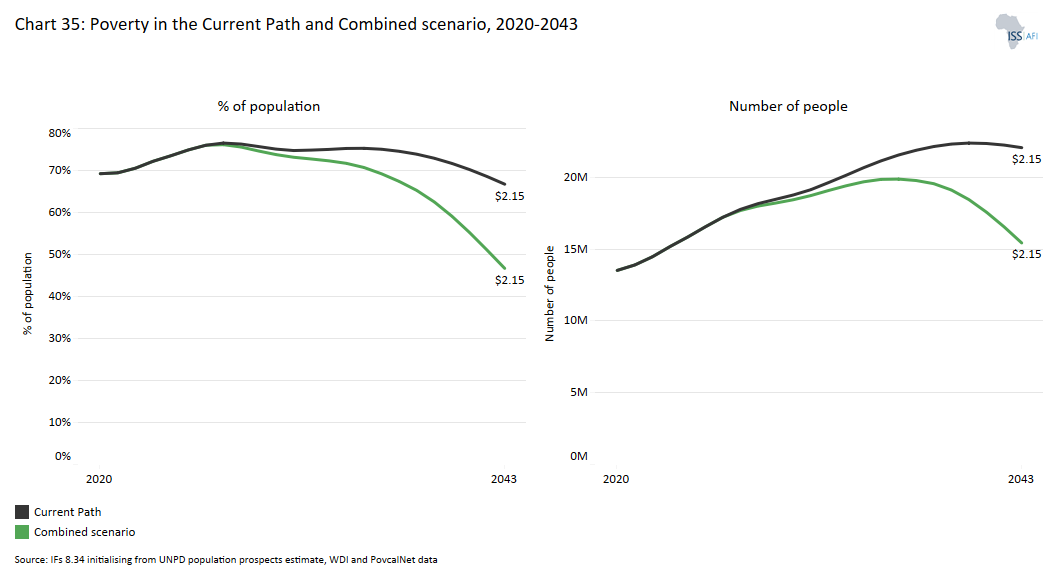

- Poverty in Malawi remains a major challenge, driven by economic vulnerabilities, rapid population growth and limited fiscal capacity. A narrow tax base and high debt burden constrain public investment in essential services, while structural issues such as low agricultural productivity and climate shocks hinder progress. Although the poverty rate is projected to decline from 72% in 2023 to 21% by 2063, high population growth will increase the absolute number of people in poverty until the 2040s. Addressing these challenges will require economic diversification, job creation, strengthened social protection systems and expanded access to family planning to manage demographic pressures.

- Malawi 2063 (MW2063), launched in 2021, is a strategic blueprint aimed at transforming Malawi into an inclusive, self-reliant and industrialised upper-middle-income country by 2063. It builds on and improves upon Vision 2020, which fell short due to the absence of clear mid-term goals and effective monitoring mechanisms. MW2063 addresses these shortcomings with a phased implementation plan, beginning with MIP-1 (2021–2030), which targets lower-middle-income status and progress on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. The vision is structured around three key pillars—agricultural productivity and commercialisation, industrialisation and urbanisation—supported by seven enablers, including governance reforms, human capital development, private sector growth and sustainable infrastructure, ensuring a comprehensive approach to economic transformation.

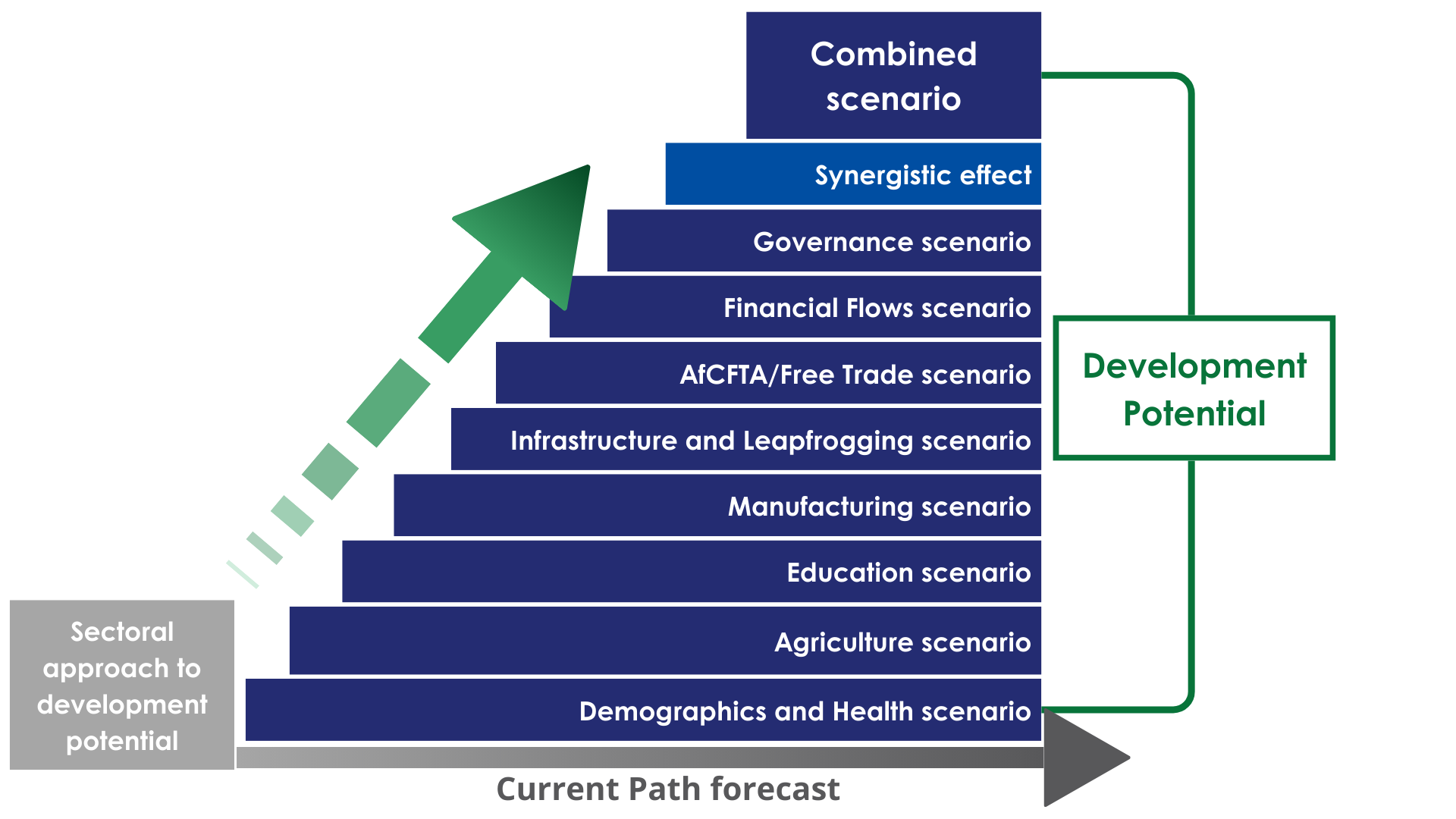

The next section compares progress on the Current Path with eight sectoral scenarios . These are Demographics and Health; Agriculture; Education; Manufacturing; the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA); Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging; Financial Flows; and Governance. Each scenario is benchmarked to present an ambitious but reasonable aspiration in that sector.

- Sustained policy focus and increased investment in the Demographics and Health scenario will significantly improve health outcomes. The infant mortality rate will decline from 40 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2023 to 19 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2043, while the maternal mortality ratio is set to decrease from 157 deaths per 100 000 live births in 2023 to 76 deaths per 100 000 live births by 2043.

- Targeted interventions in the Agriculture scenario can boost crop yields and strengthen Malawi’s agricultural resilience. Yields per hectare will rise from 8.1 million to 10.5 million tons in the Current Path and 11.8 million tons in the Agriculture scenario by 2043. Without intervention, reliance on agricultural imports will reach 21.6% of domestic demand, increasing vulnerability to global market fluctuations. However, the Agriculture scenario reduces import dependency to 11.3%, promoting greater self-sufficiency.

- Malawi faces a learning crisis, marked by low secondary and tertiary enrolment, high dropout rates and poor foundational skills—only 19% of children aged 7 to 14 demonstrate basic reading abilities, while just 13% achieve foundational numeracy. Contributing factors include low Early Childhood Education (ECE) attendance (34% in 2023) and urban-rural disparities in teacher quality, infrastructure and school access. As a result, Malawi’s mean years of education stood at 5.5 years in 2023, below the 5.9-year average for low-income African nations and significantly lower than the continental average of 7.2 years. Under the Current Path, gradual improvement is expected, reaching 6.1 years by 2043, while the Education scenario presents a more optimistic rise to 6.8 years, emphasising the need for targeted educational reforms.

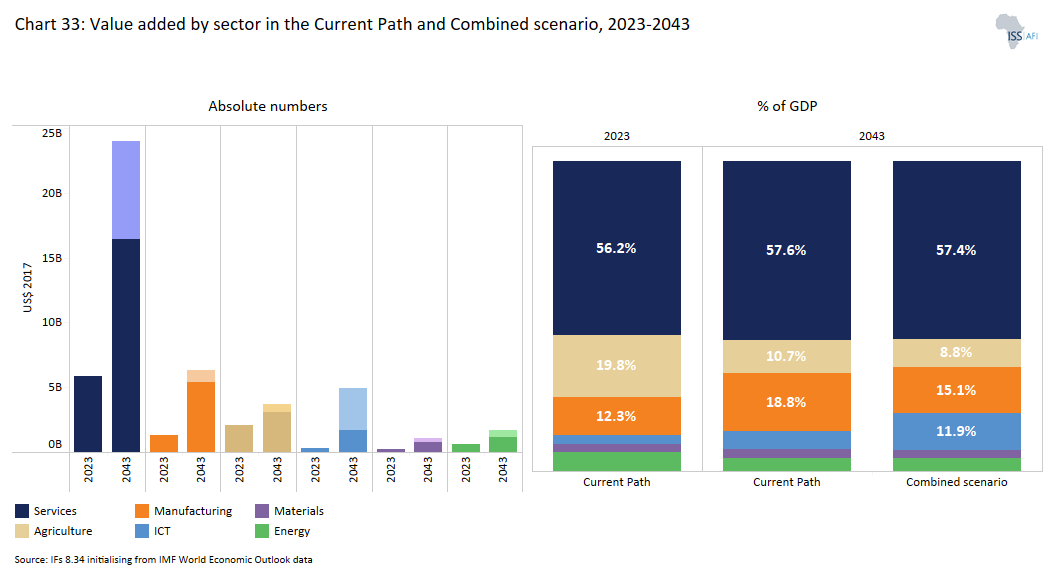

- Malawi’s economy remains service-driven, with the sector projected to account for 57.6% of GDP by 2043, while agriculture’s share declines from 19.8% in 2023 to 10.7% in 2043 and 4.2% by 2063. The digital economy will grow, with ICT contributing 5.9% of GDP by 2043. Manufacturing, despite past declines, is set to rise from 12.3% to 18.8% under the Current Path and 20.4% in the Manufacturing scenario, nearing but not fully meeting MW2063’s 20% target by 2042. Recent policies, including the Investment and Export Promotion Act (2024) and the Special Economic Zones (SEZ) Act (2024), aim to attract investment and boost industrialisation. However, success depends on addressing infrastructure gaps, energy reliability and workforce skills. The National Export Strategy II (2021–2026) and ongoing National Industrial Policy (NIP) reforms further emphasise industrial growth and economic diversification.

- Malawi’s economy remains heavily reliant on raw agricultural exports while importing manufactured goods, making it vulnerable to global price fluctuations and climate risks. In 2023, the country recorded a trade deficit of US$2.2 billion, with imports at US$4.6 billion and exports at US$2.4 billion. By 2043, exports will grow to US$13.8 billion, narrowing but not eliminating the trade gap. Malawi actively engages in regional trade blocs like COMESA, SADC, TFTA and AfCFTA, which enhance market access and support industrialisation efforts. However, high transport costs, limited infrastructure and an underdeveloped manufacturing sector continue to constrain trade competitiveness. The AfCFTA scenario offers only a modest improvement in the trade balance, highlighting the structural challenges Malawi faces in achieving economic diversification.

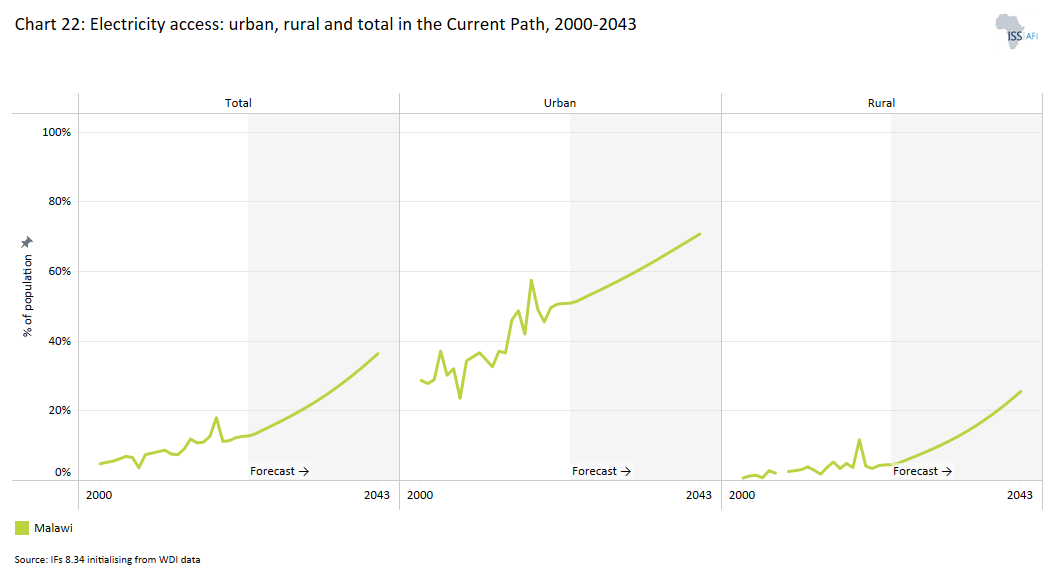

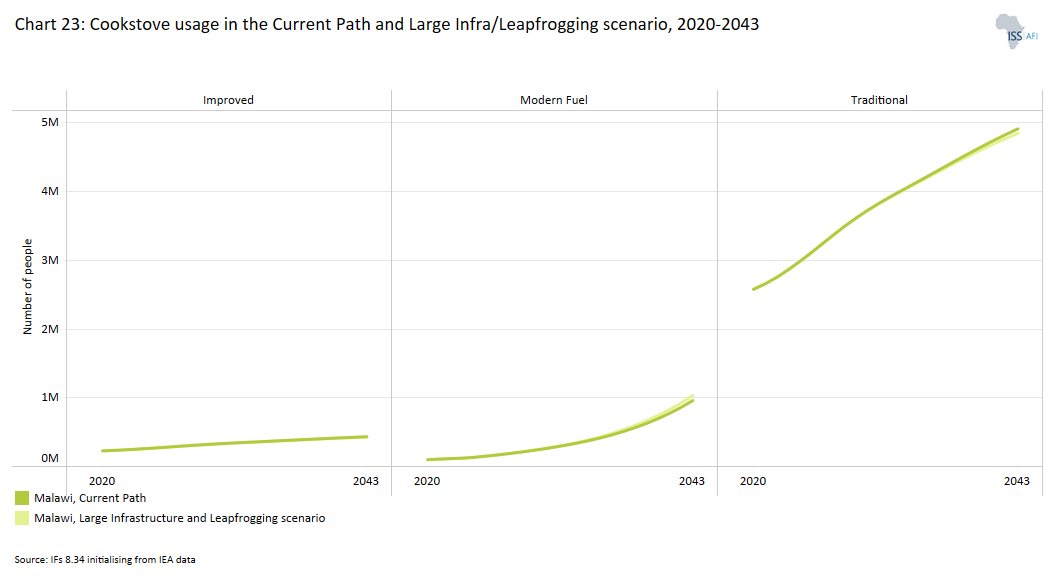

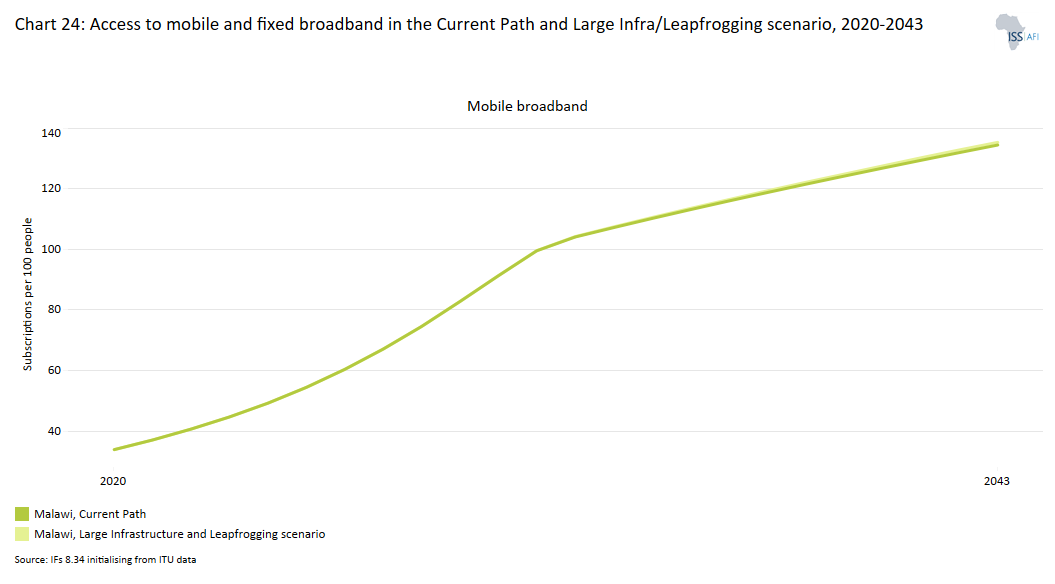

- Targeted investments in renewable energy, infrastructure and digital connectivity can significantly accelerate Malawi’s development trajectory. In the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario, electricity access expands to 45% by 2043, compared to 36% in the Current Path, with rural access increasing to 34% instead of 26%, driven by solar, wind and regional integration. Clean cooking solutions also see faster progress, with reliance on traditional fuels dropping to 73%, while modern fuel adoption rises to 21%, compared to 78% and 15% in the Current Path. In ICT, mobile subscriptions show little difference, but fixed broadband access expands more rapidly, reaching 23 per 100 people compared to 15 per 100 in the Current Path, improving digital inclusion and economic opportunities. These improvements highlight the potential of strategic investments to drive faster, more inclusive growth and enhance Malawi’s resilience to future challenges.

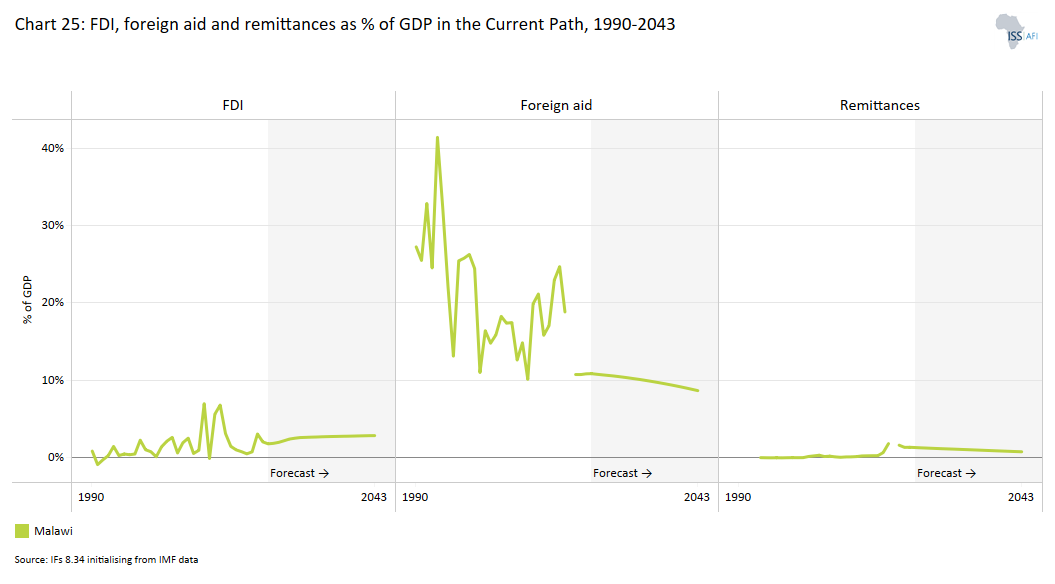

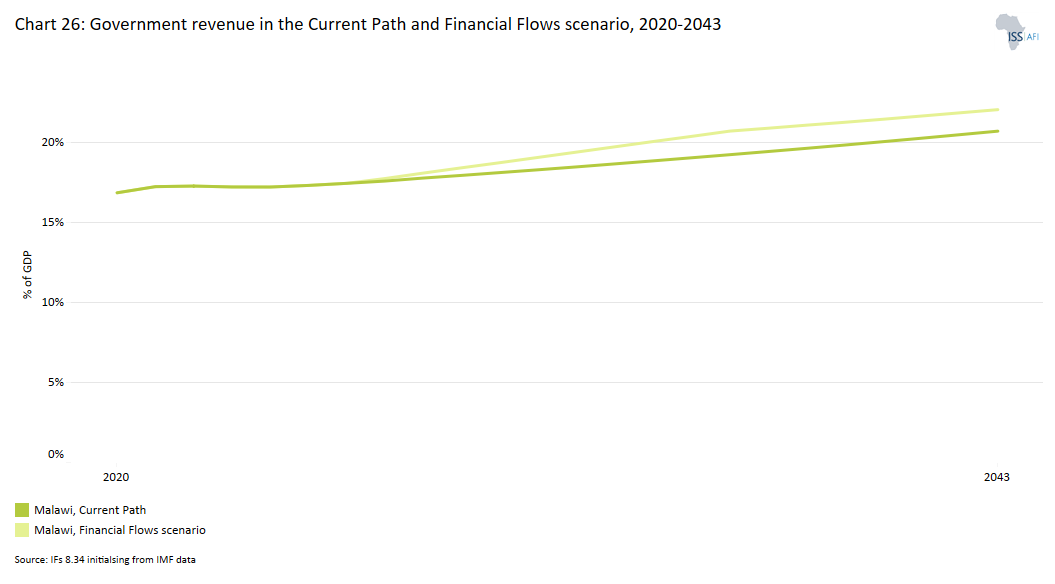

- Malawi has historically relied heavily on foreign aid, which exceeded 20% of GDP in the 1990s but declined to around 11% in 2023. However, the abrupt withdrawal of USAID support in 2025—which accounted for 13% of Malawi’s budget—highlights the country’s vulnerability to shifts in donor funding. This underscores the urgent need for economic self-sufficiency and stronger domestic revenue generation. Remittances have grown significantly, rising from 0.2% of GDP in 2013 to 1.3% in 2023, with South Africa as the top destination for Malawian migrants. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) remains modest, projected to rise from 1.8% of GDP in 2023 to 2.9% in 2043 in the Current Path and 3.5% in the Financial Flows scenario, which assumes improved governance and investment conditions. Government revenue will grow from 17.2% of GDP in 2023 to 22% by 2043 in the Financial Flows scenario, aided by stronger tax compliance and external investments. However, tax revenue remains low, with a 12.5% tax-to-GDP ratio in 2023, well below the 15% minimum recommended by the World Bank. Expanding the tax base, strengthening tax administration and formalising the informal sector will be key to boosting domestic resource mobilisation and reducing reliance on external aid.

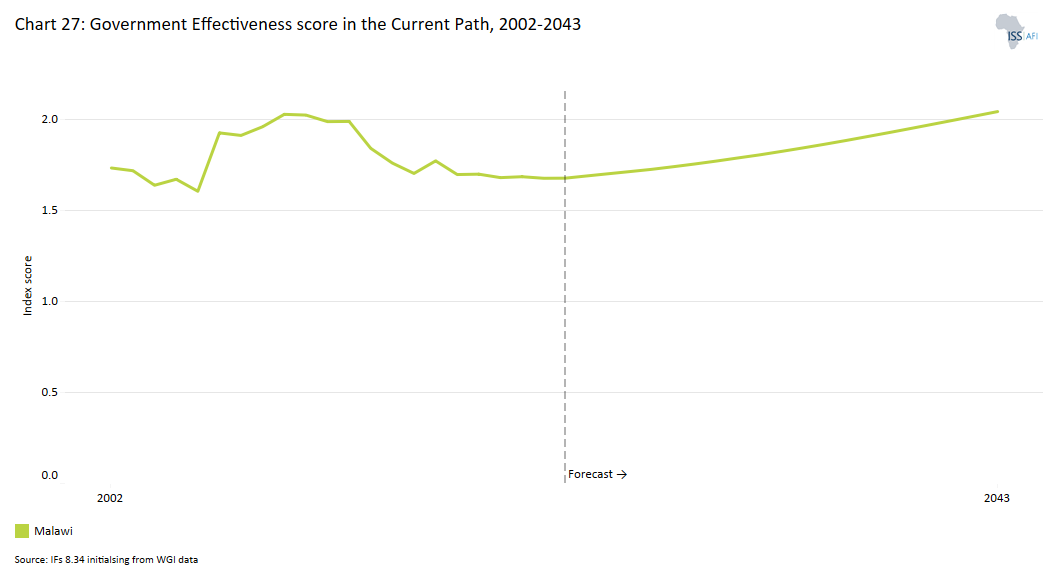

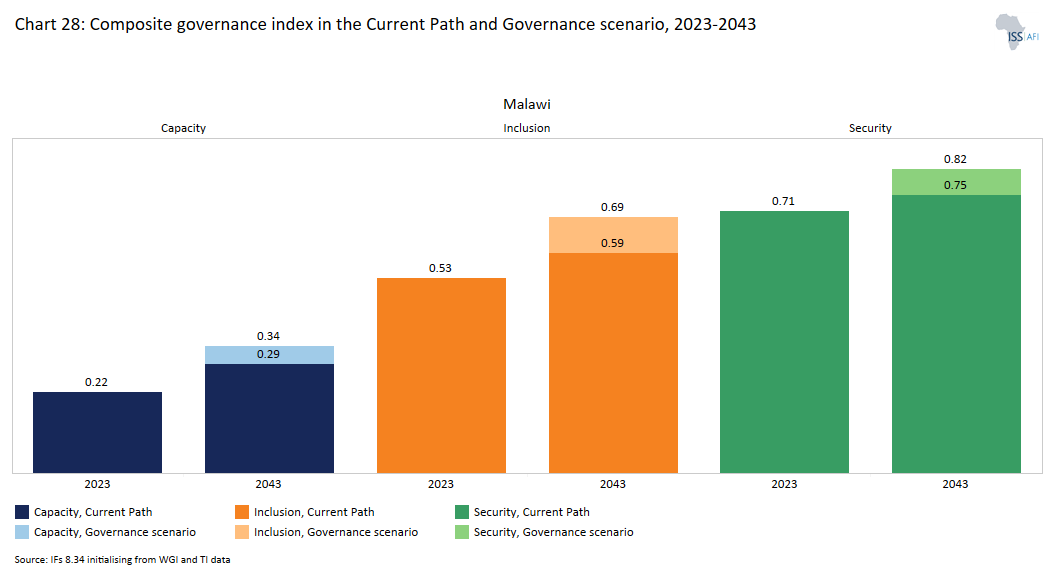

- While the country has historically ranked above its peers, challenges such as corruption, weak institutional capacity and bureaucratic inefficiencies persist. In the Current Path, Malawi’s overall governance score will rise from 0.48 in 2023 to 0.55 by 2043, but in the Governance scenario, where institutional reforms are prioritised, it could improve to 0.62. Security is projected to strengthen from 0.74 to 0.82, inclusion from 0.59 to 0.69, and governance capacity—while still a challenge—from 0.29 to 0.34. Corruption remains a major obstacle, with Malawi ranking 107th in Transparency International’s 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index despite ongoing reforms.

In the third section, we compare the impact of each of these eight sectoral scenarios with one another and subsequently with a Combined scenario (the integrated effect of all eight scenarios). In our forecasts, we measure progress on various dimensions such as economic size (in market exchange rates), gross domestic product per capita (in purchasing power parity), extreme poverty, carbon emissions, the changes in the structure of the economy, and selected sectoral dimensions such as progress with mean years of education, life expectancy, the Gini coefficient or reductions in mortality rates.

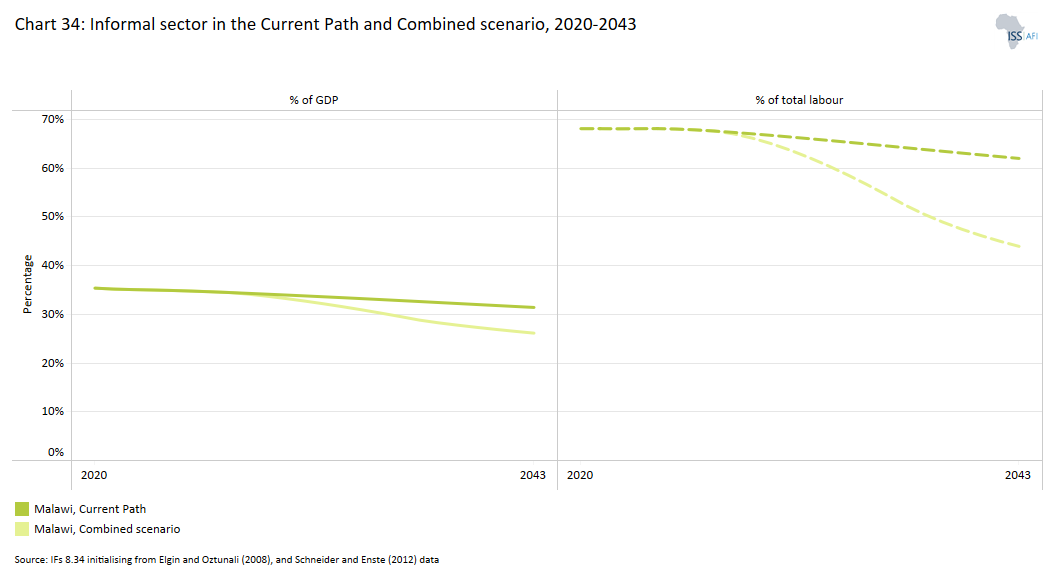

- The Combined scenario delivers the most transformative impact, lifting 6.7 million people out of poverty by 2043 and reducing extreme poverty by 20 percentage points (from 67% to 47%). GDP per capita increases by US$671 (30%), reaching US$2 913 by 2043, compared to US$2 242 in the Current Path. The Combined scenario increases GDP from US$10.5 billion in 2023 to US$41.9 billion by 2043, compared to US$28.6 billion in the Current Path, demonstrating the power of multisectoral interventions. Informality shrinks significantly, with the informal labour force falling from 68.1% to 44%, compared to 62% in the Current Path, improving tax revenues and worker protections.

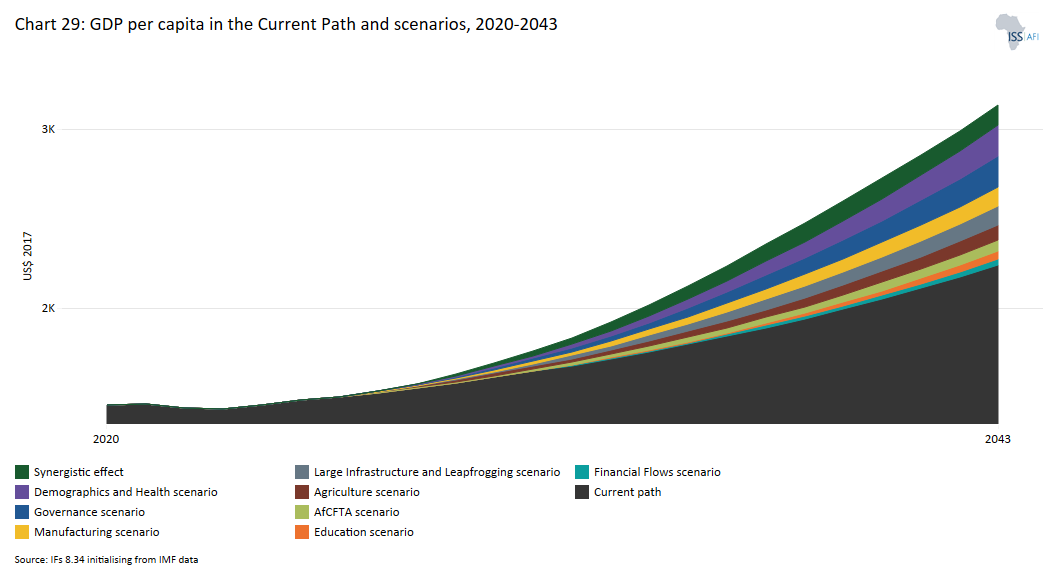

- The Governance scenario has the highest single-sector impact on GDP per capita, increasing it by US$175 to US$2 417 by 2043 while also delivering the largest percentage reduction in poverty, decreasing it by 5.6 percentage points.

- The Demographics and Health scenario achieves the greatest absolute poverty reduction, lifting 2.5 million people out of extreme poverty by 2043 by improving workforce productivity and slowing population growth.

- The Manufacturing scenario adds US$959 million to GDP by 2043 but results in a smaller poverty reduction of 0.9 million people.

- Agricultural interventions reduce poverty by 4.4 percentage points (1.4 million people) but cause short-term disruptions, with poverty peaking at 76% in 2028 before eventually declining.

- The AfCFTA, Education, and Financial Flows scenarios have slower but long-term impacts due to structural barriers. Education takes time to improve workforce productivity, while trade and financial flows require stronger infrastructure, governance and institutional capacity to be fully effective.

We end this page with a summarising conclusion offering key recommendations for decision-making. While governance reforms, demographic management and industrialisation present the most immediate opportunities for economic growth and poverty reduction, the country’s long-term resilience will be shaped by improvements in infrastructure, trade and financial flows. The Combined scenario demonstrates the transformative potential of multisectoral interventions, with GDP nearly quadrupling and poverty declining by 20 percentage points by 2043. However, energy security, economic diversification and institutional capacity building remain key challenges that must be addressed to sustain progress. Strengthening domestic resource mobilisation, formalising the economy and investing in human capital will be essential for Malawi to break out of aid dependency and achieve inclusive, self-sustaining growth.

All charts for Malawi

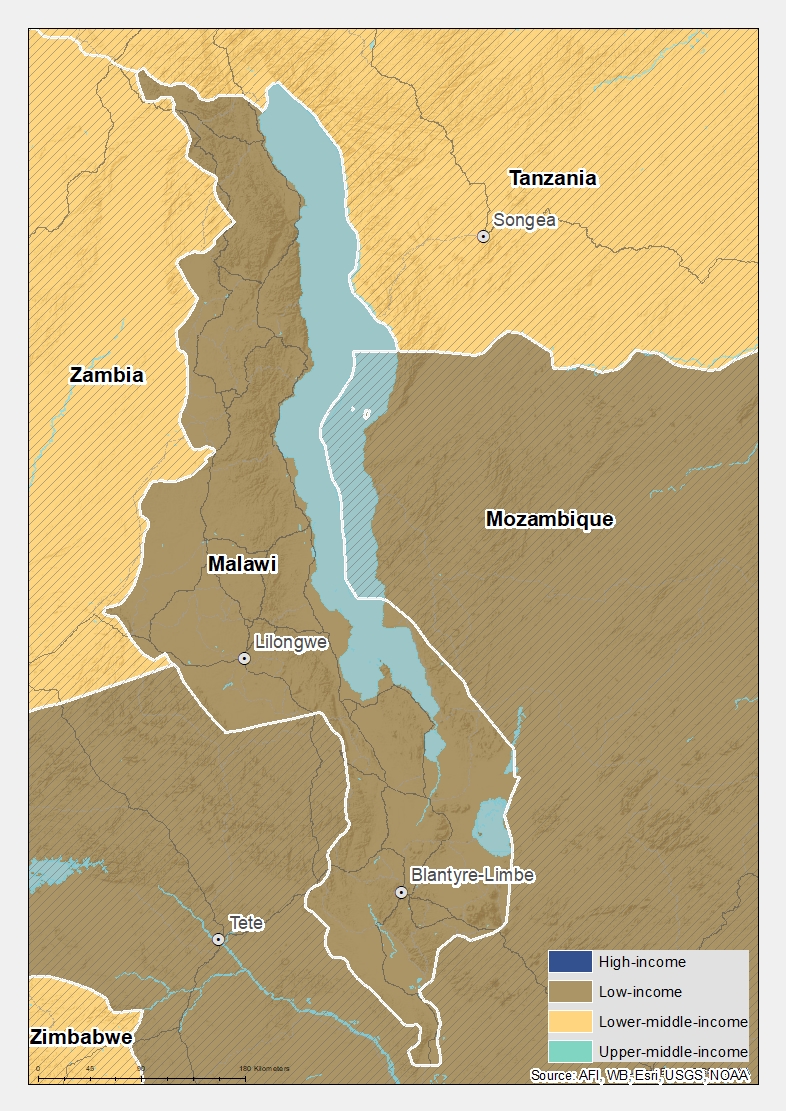

- Chart 1: Political map of Malawi

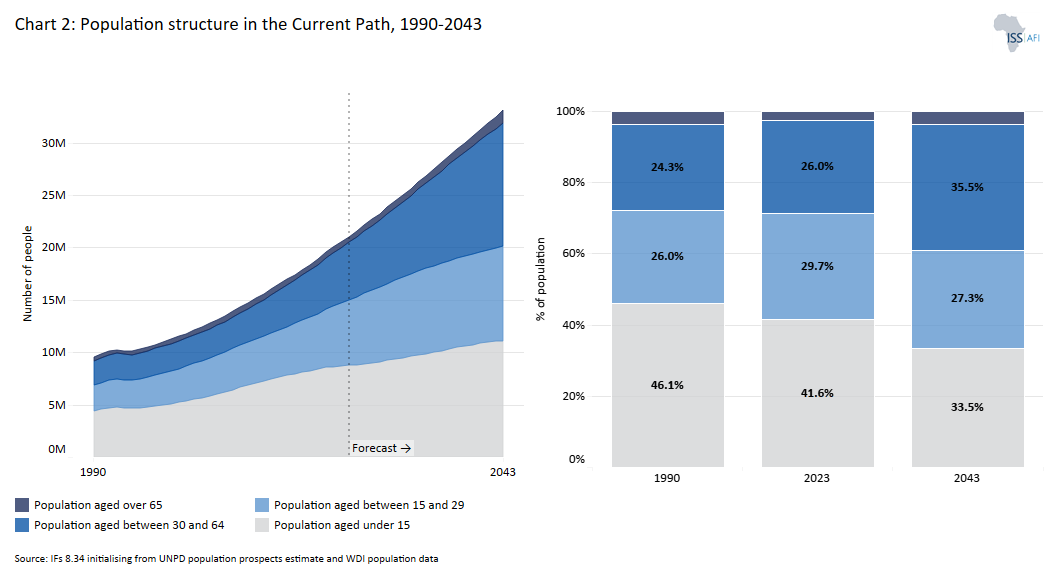

- Chart 2: Population structure in the Current Path, 1990–2043

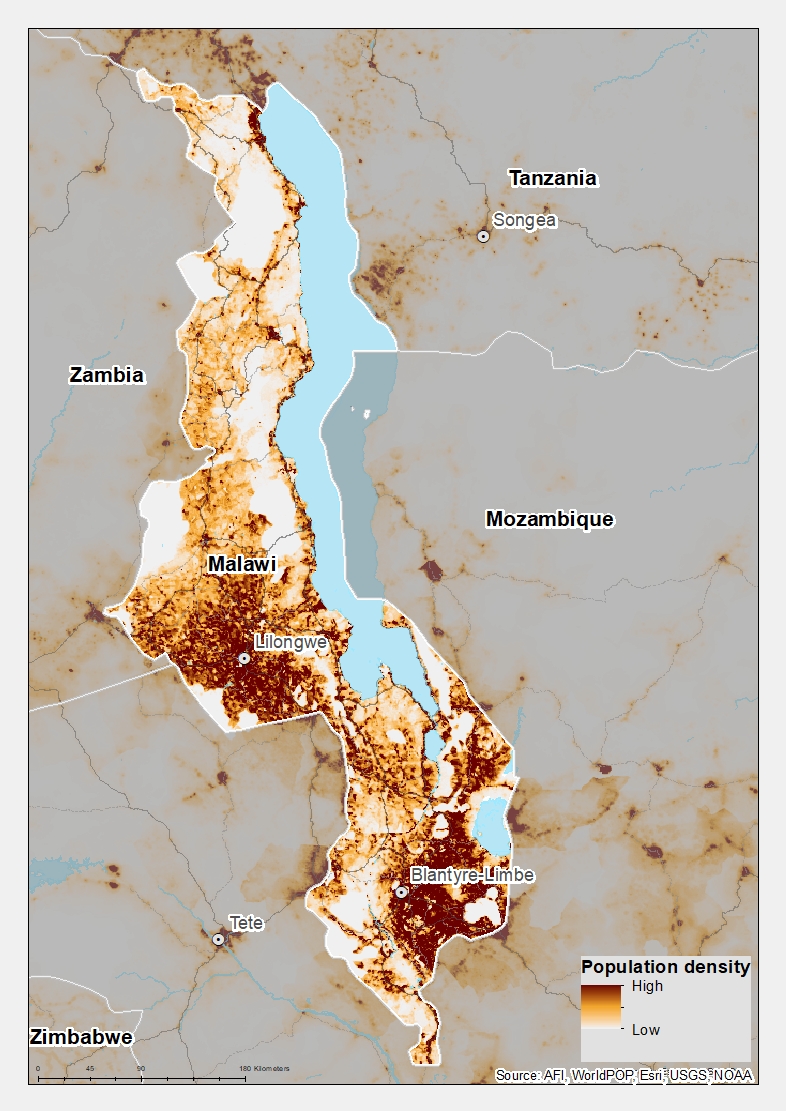

- Chart 3: Population distribution map, 2023

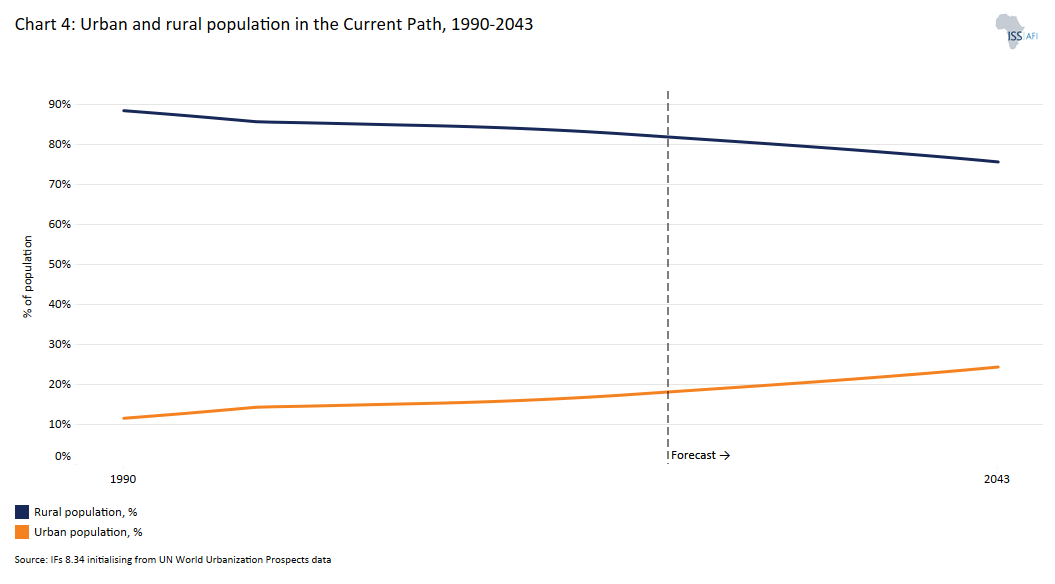

- Chart 4: Urban and rural population in the Current Path, 1990-2043

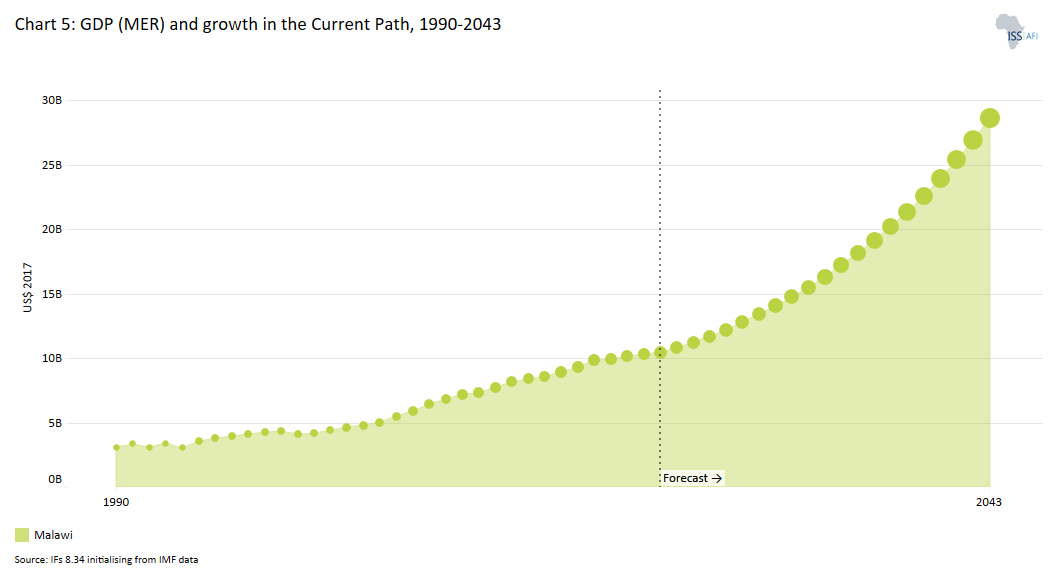

- Chart 5: GDP (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, 1990–2043

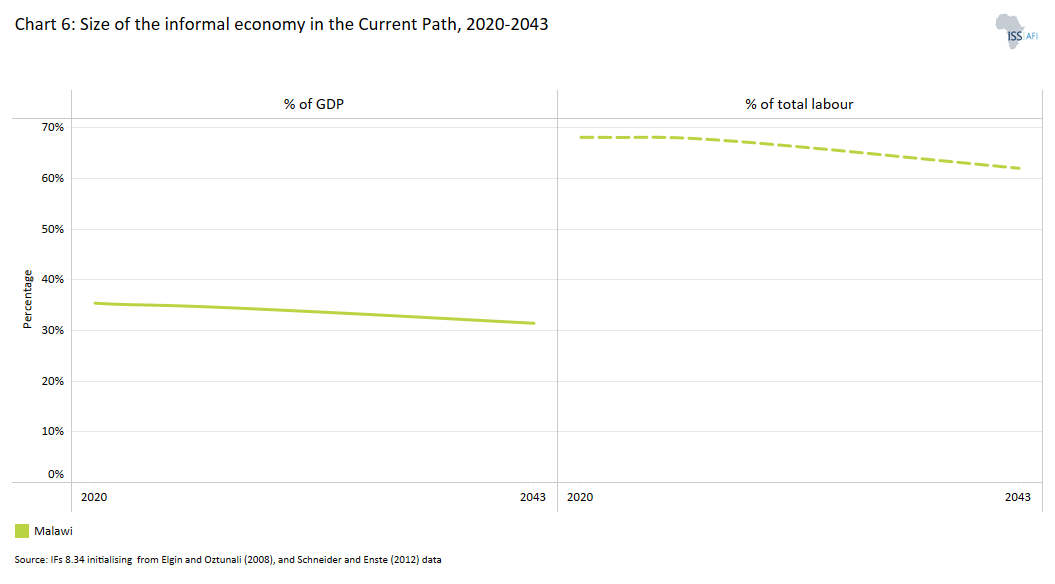

- Chart 6: Size of the informal economy in the Current Path, 2020-2043

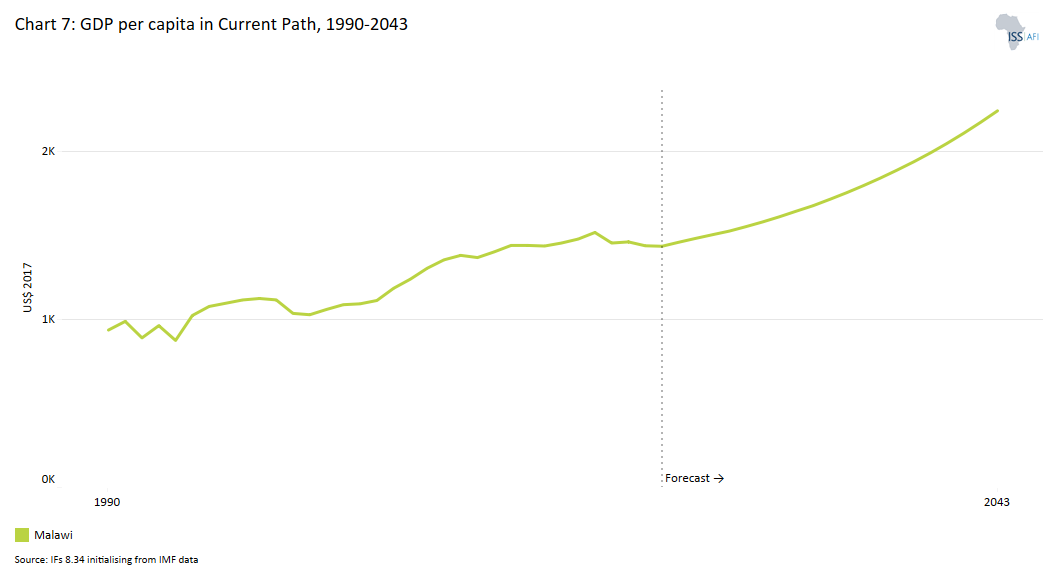

- Chart 7: GDP per capita in Current Path, 1990–2043

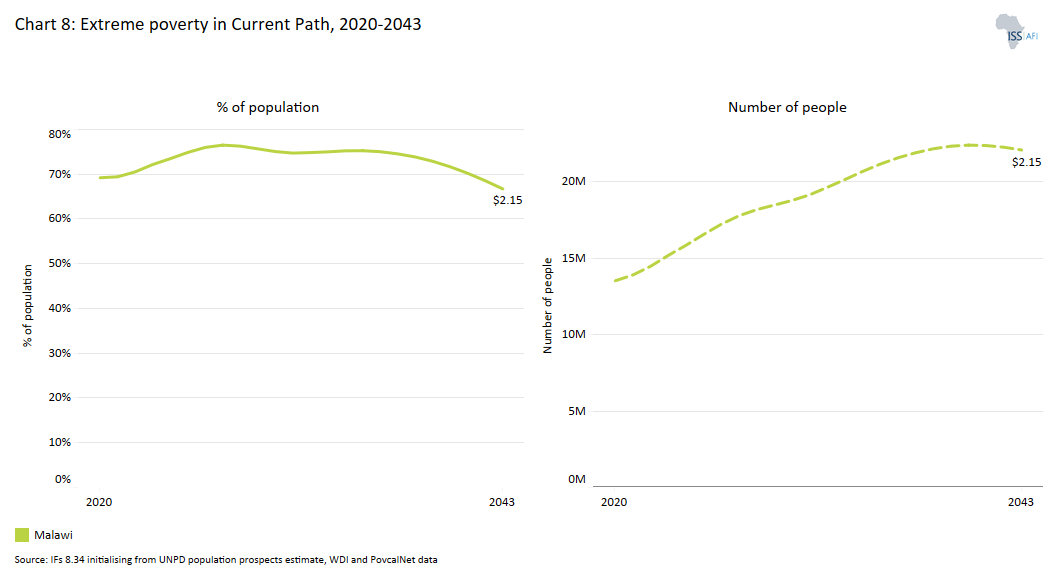

- Chart 8: Extreme poverty in the Current Path, 2020–2043

- Chart 9: National Development Plan of Malawi

- Chart 10: Relationship between Current Path and scenarios

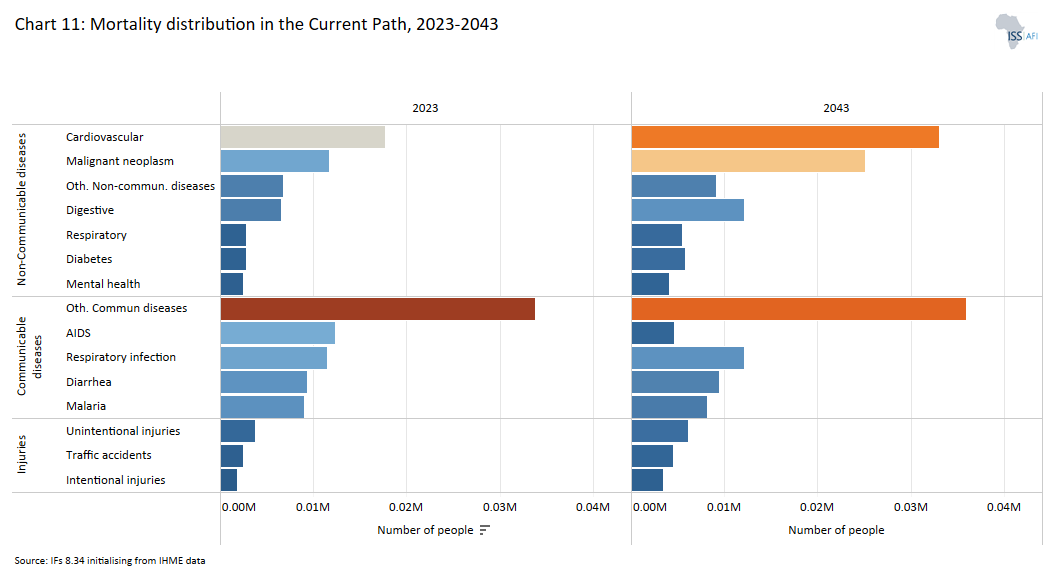

- Chart 11: Mortality distribution in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

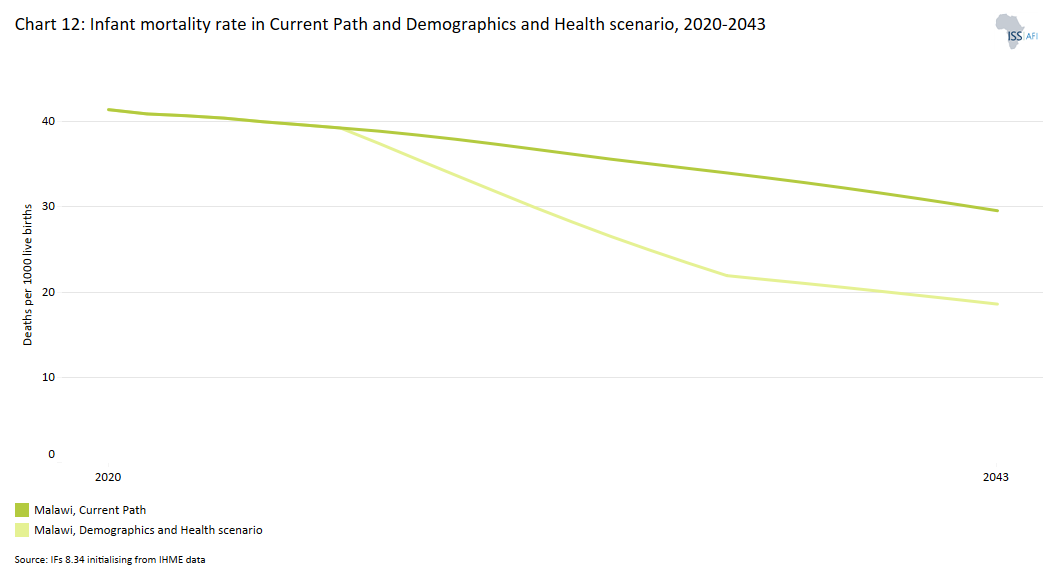

- Chart 12: Infant mortality rate in Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 2020–2043

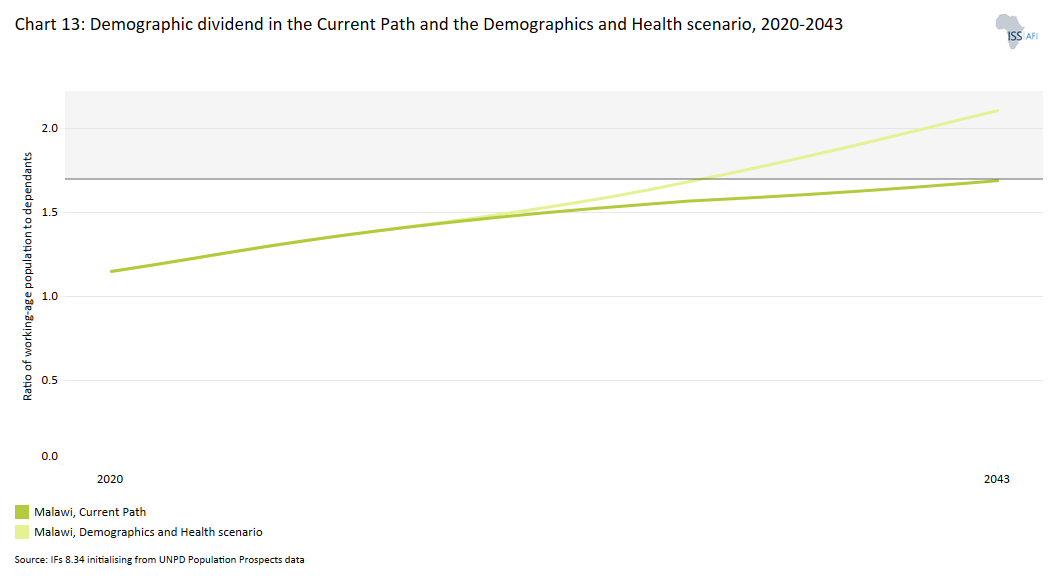

- Chart 13: Demographic dividend in the Current Path and the Demographics and Health scenario, 2020–2043

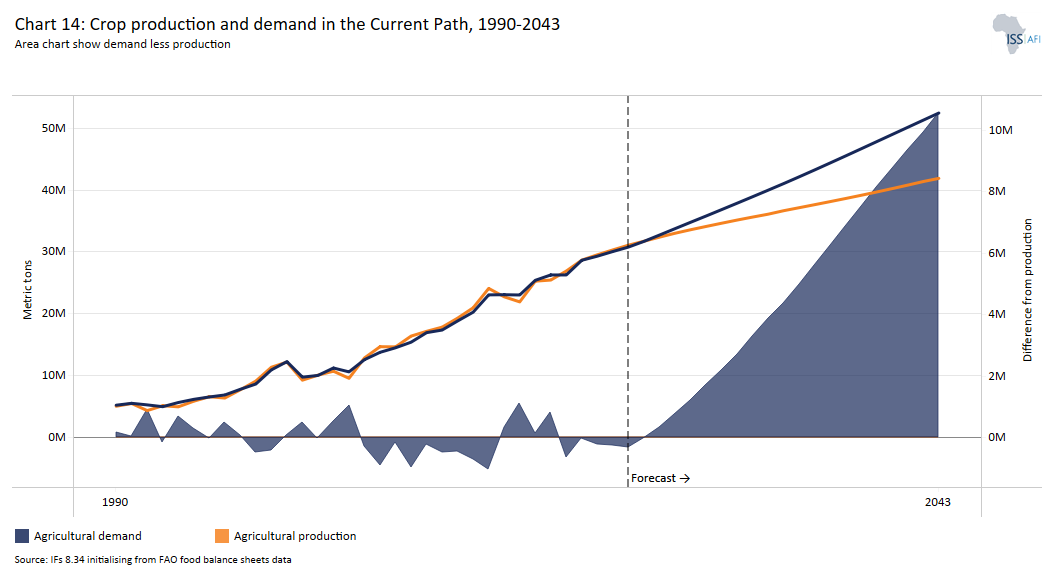

- Chart 14: Crop production and demand in the Current Path, 1990-2043

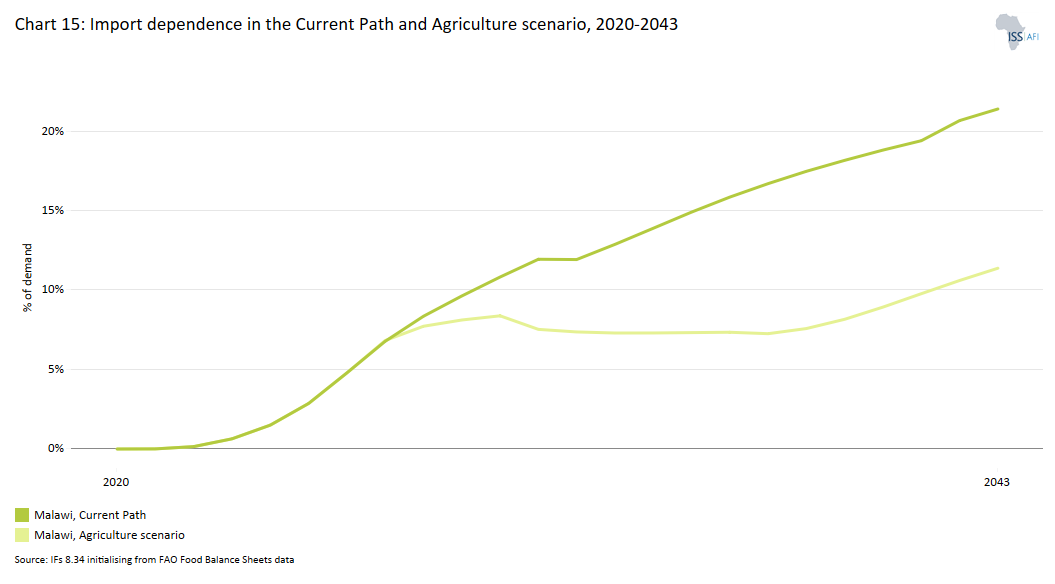

- Chart 15: Import dependence in the Current Path and Agriculture scenario, 2020–2043

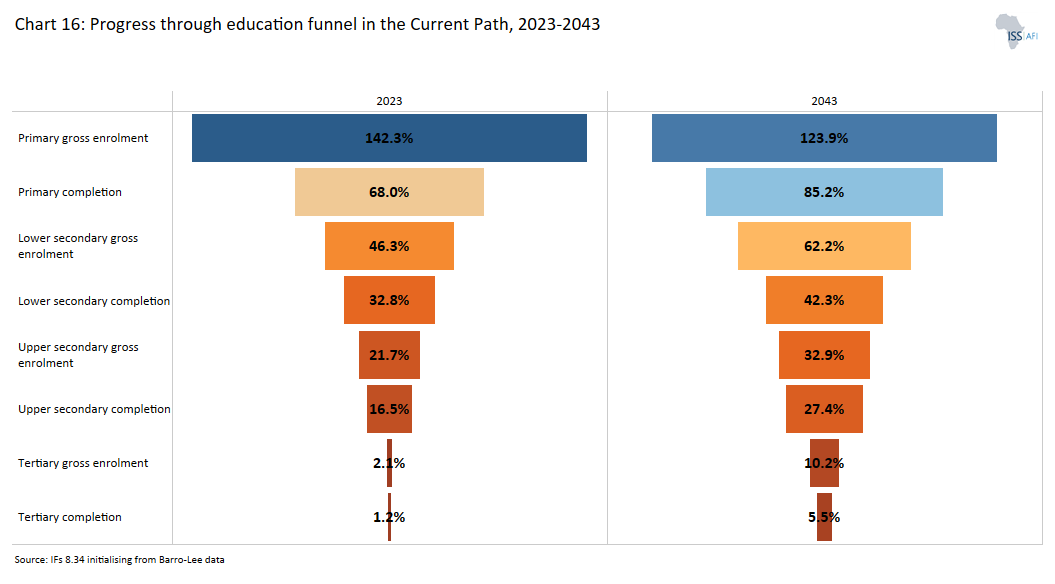

- Chart 16: Progress through the education funnel in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

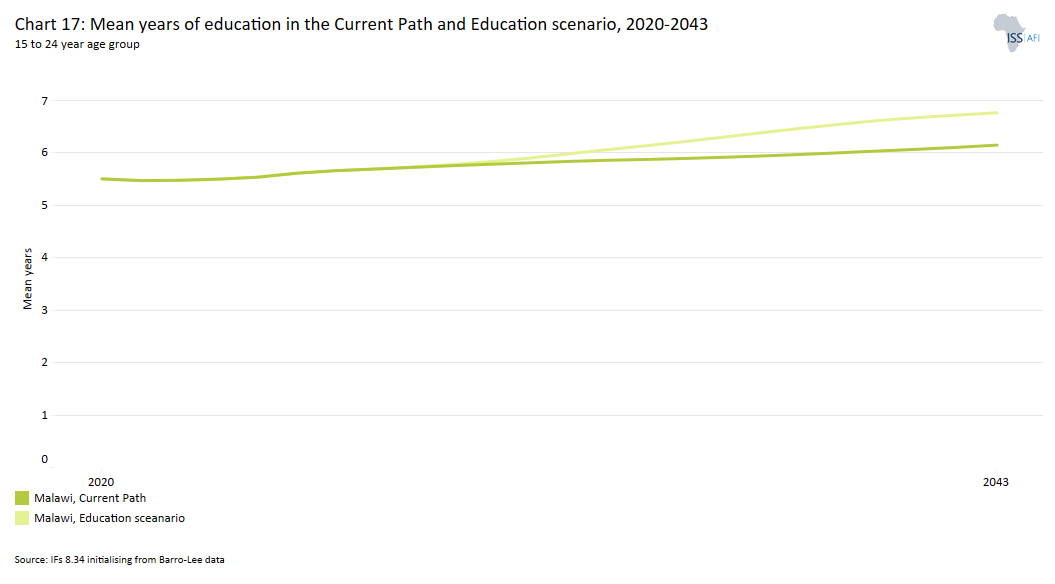

- Chart 17: Mean years of education in the Current Path and Education scenario, 2020–2043

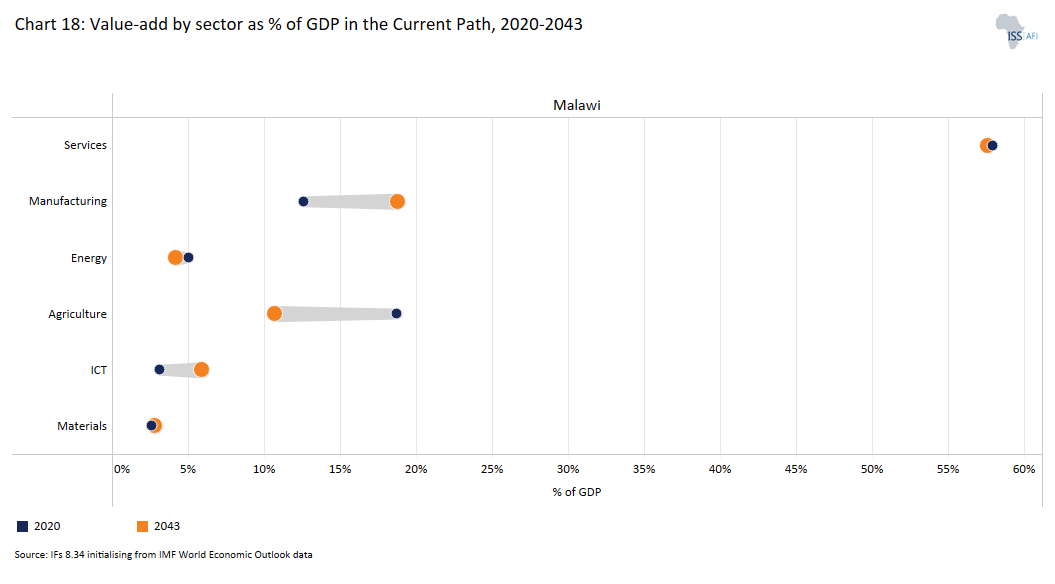

- Chart 18: Value-add by sector as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

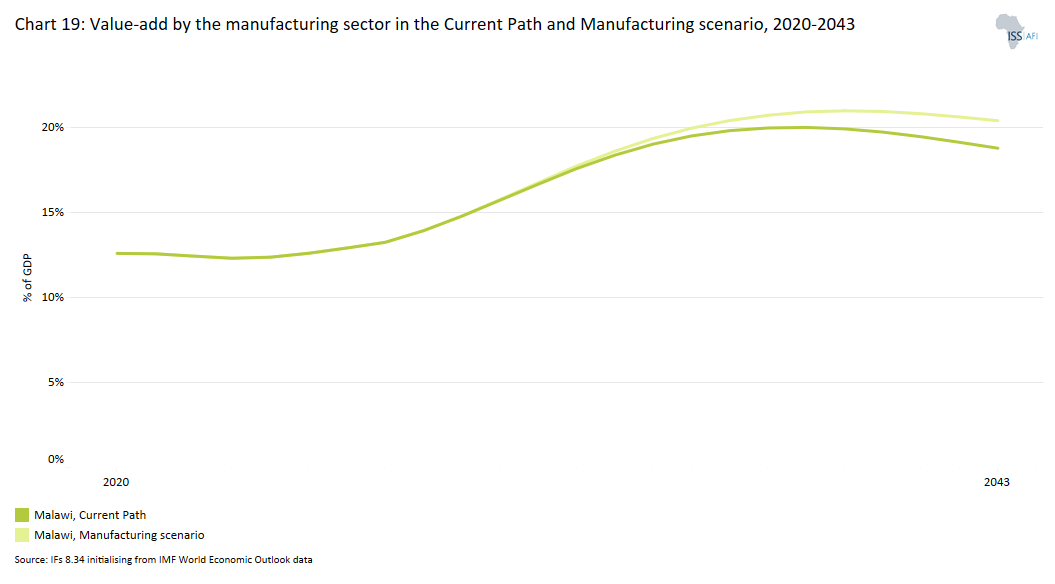

- Chart 19: Value-add by the manufacturing sector in the Current Path and Manufacturing scenario, 2020–2043

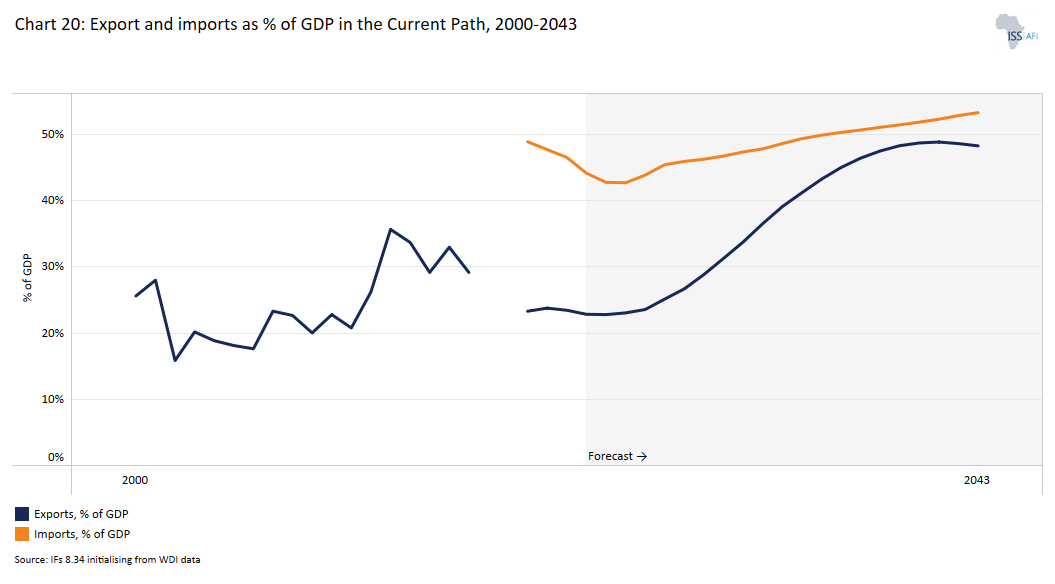

- Chart 20: Exports and imports as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2000-2043

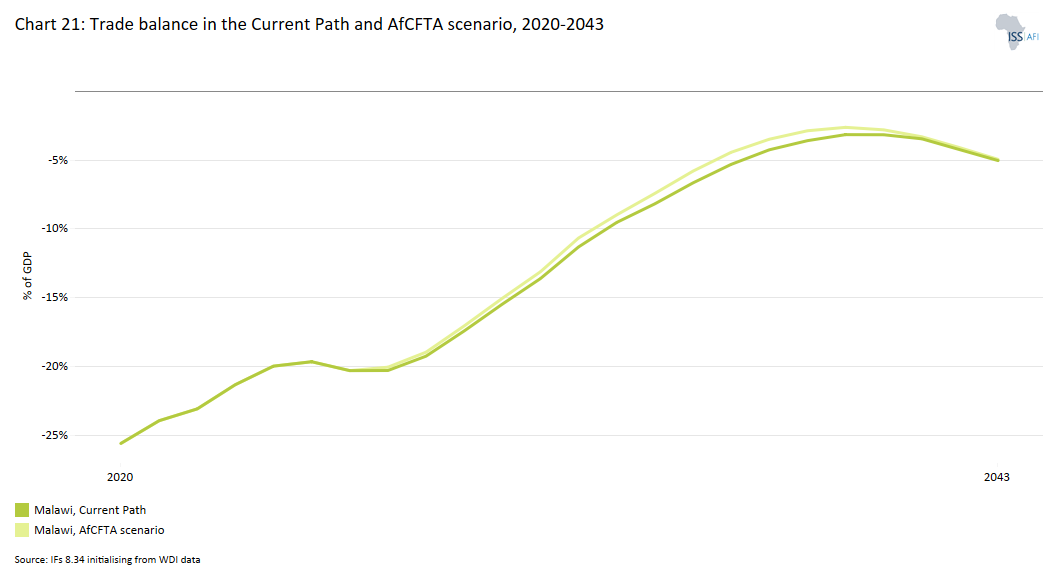

- Chart 21: Trade balance in the Current Path and AfCFTA scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 22: Electricity access: urban, rural and total in the Current Path, 2000-2043

- Chart 23: Cookstove usage in the Current Path and Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 24: Access to mobile and fixed broadband in the Current Path and the Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 25: FDI, foreign aid and remittances as % of GDP in the Current Path and in the Financial Flows scenario, 1990-2043

- Chart 26: Government revenue in the Current Path and Financial Flows scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 27: Government effectiveness score in the Current Path, 2002-2043

- Chart 28: Composite governance index in the Current Path and Governance scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 29: GDP per capita in the Current Path and scenarios, 2020–2043

- Chart 30: Poverty in the Current Path and scenarios, 2020–2043

- Chart 31: GDP (MER) in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 32: GDP per capita in the Current Path and the Combined scenario, 2020-2043

- Chart 33: Value added by sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 34: Informal sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 35: Poverty in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

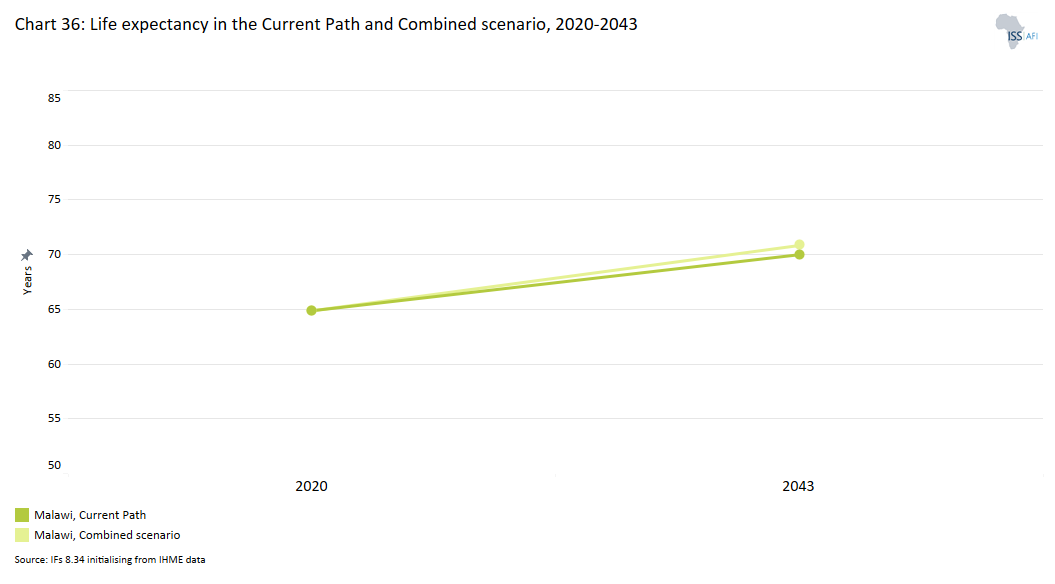

- Chart 36: Life expectancy in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

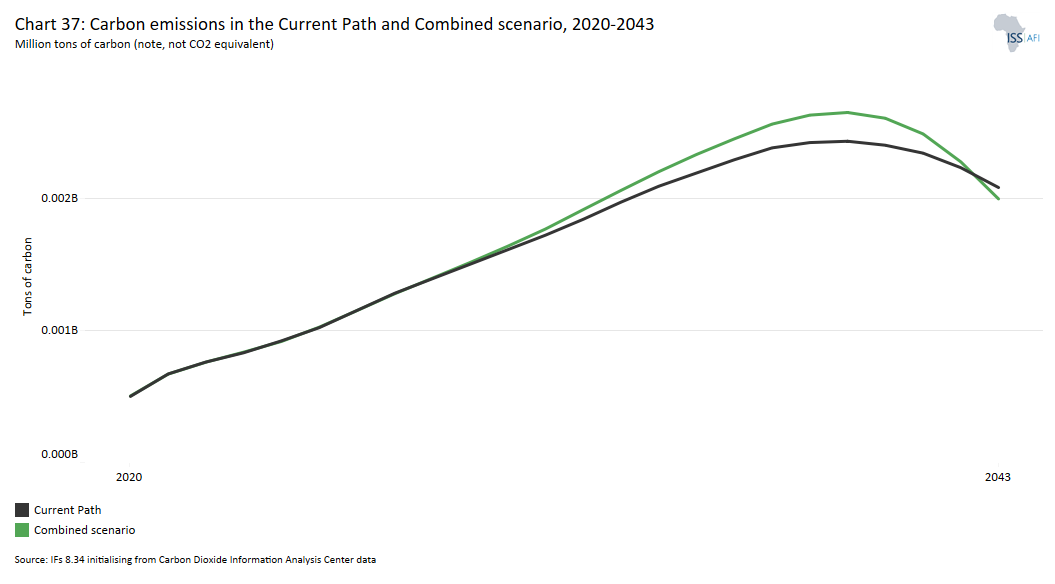

- Chart 37: Carbon emissions in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

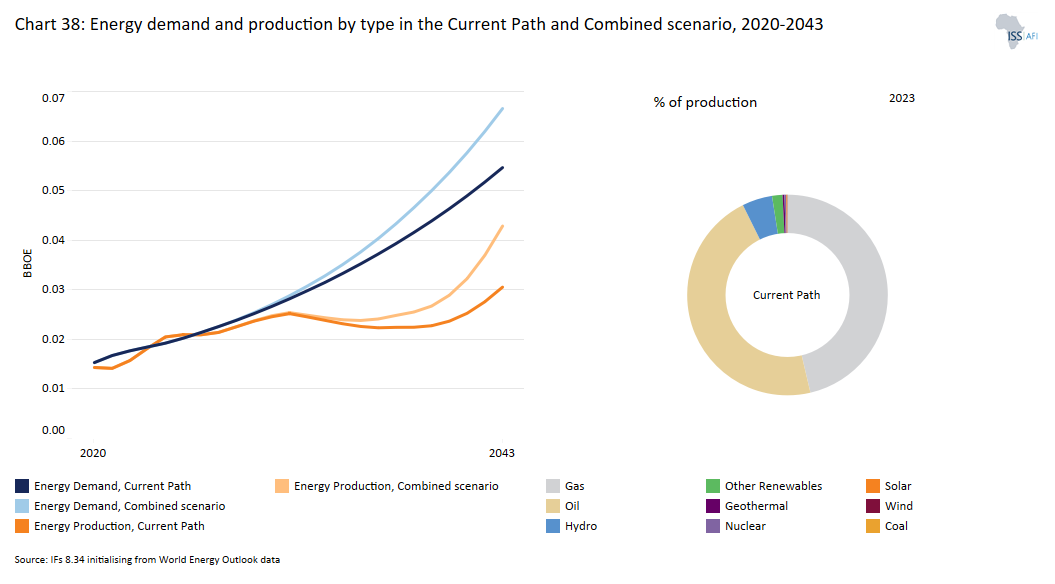

- Chart 38: Energy demand and production by type in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020-2043

- Chart 39: Policy recommendations

Chart 1 is a political map of Malawi.

Malawi, a landlocked country in Southern Africa, is bordered by Mozambique, Zambia and Tanzania. It is one of the 22 low-income countries in Africa, with an estimated population of 21.1 million in 2023.

In January 2021, the Malawian government introduced Malawi Vision 2063 (MW2063). This long-term development blueprint envisions transforming Malawi into an inclusive, wealthy and self-reliant industrialised upper-middle-income country by 2063. The operationalisation is structured into 10-year implementation phases, starting with the Malawi Implementation Plan I (MIP-1), which runs from 2021 to 2030. MIP-1 aims to achieve two key milestones: elevating Malawi to lower-middle-income status by 2030 and meeting most of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by the same year.

Generally considered a peaceful nation, Malawi has experienced stable governance since gaining independence in 1964. The era of one-party rule ended in 1993, leading to the establishment of multiparty presidential and parliamentary elections held every five years. Malawi continues to uphold its democratic processes. Following the tragic death of Vice President Saulos Chilima in a plane crash on 10 June 2024, President Lazarus Chakwera appointed Michael Usi as the new Vice President in late June 2024. The next general election is scheduled for 16 September 2025.

Despite making progress in improving socio-economic indicators like health and education and reducing child and maternal mortality rates, Malawi continues to face significant developmental challenges. As of 2023, over 70% of Malawians live below the international poverty line of US$2.15 per day, with a GDP per capita averaging below US$1 500 over the past decade. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) ranked Malawi as a country with low human development in its 2023 report, scoring 0.51 on the Human Development Index (HDI). Malawi ranks 172nd globally, trailing behind its neighbours Tanzania (167th) and Zambia (153rd) but faring better than Mozambique (183rd). Malawi ranks 5th out of 22 countries in the African low-income group.

Persistent structural issues hinder Malawi's development, including corruption, poor infrastructure, weak human capital, policy inconsistencies and a challenging business environment. The economy relies heavily on agriculture, contributing around 25% of GDP and employing 64% of the labour force. Efforts to diversify the economy and expand irrigation systems have progressed slowly, increasing the country's vulnerability to economic and climatic shocks while intensifying existing socio-economic challenges. Malawi's 2023/24 rainy season, influenced by El Niño, was marked by a delayed start and prolonged dry spells, especially in central and southern areas. Some dry periods exceeded four weeks during the key January–February growing season, severely damaging crops and reducing food production. In March 2024, President Lazarus Chakwera declared a State of Disaster in 23 out of 28 districts due to the crisis. Between May and September 2024, around 6 million people experienced acute food insecurity.

Recent challenges, including the COVID-19 pandemic, geopolitical tensions, economic shocks and increased weather-related disasters, have exacerbated fiscal pressures. These factors have resulted in soaring budgetary deficits. The freezing of USAID funds by the US administration in early 2025 has severely impacted Malawi, halting essential medical supplies and educational support. The US previously contributed over US$350 million annually, constituting more than 13% of Malawi's budget.

Malawi's current account deficit reached 18.7% of GDP in 2024, further straining official reserves, which stood at US$119.9 million (0.5 months of import cover) as of August 2024. The country recorded the highest fiscal deficit in sub-Saharan Africa at 10.2% of GDP, partly due to fiscal slippages and the recapitalisation of the Reserve Bank of Malawi to cover exchange rate losses. This severely limits resources available for productive investments and social programs. To achieve fiscal and external sustainability, it will be necessary to implement fiscal consolidation measures and negotiate a carefully structured debt restructuring process.

In summary, Malawi’s development path remains complex, but with strategic reforms and targeted interventions, the country can make meaningful progress toward its long-term goals. This report outlines key policy actions that, if effectively implemented, could help Malawi navigate its challenges, strengthen resilience and move closer to realising its full development potential by 2043.

Chart 2 presents the Current Path of the population structure, from 2020 to 2043.

Throughout much of the 1970s, Malawi’s annual population growth rates were well above the average for African countries, and in the latter half of the 1980s, growth rates in Malawi were among the highest globally. In the first half of the 1990s, growth rates plummeted as HIV/AIDS-related deaths coincided with the mass repatriation of refugees back to Mozambique after the civil war there ended.

Since 2000, Malawi has maintained a high population growth rate, averaging 2.3% per year. The population has significantly increased from 3.6 million people in 1960 to an estimated 21.1 million in 2023. On the Current Path, Malawi’s population will reach 33 million by 2043. By mid-century, it is likely that Malawi will be home to 37 million people, and by 2063, the population is expected to reach 43 million.

The total fertility rate in Malawi peaked in 1980 when the country recorded 7.8 births per woman — the third highest in Africa. Since then, the government of Malawi has made significant strides in reducing fertility rates, and the decline in fertility rates between 2010 and 2019 was among the three fastest reductions globally. This decline, in part, can be attributed to a significant push to provide access to modern contraceptives, with numerous government and donor plans and programs active within the family planning domain. Significant attention to this sector has led to an estimated 66% prevalence rate of modern contraception use in 2023 among women aged 15 to 49 years. This is the second-highest prevalence rate among low-income Africa and is well above the estimated 36% average rate for the continent.

Despite this promising trend, the current fertility rate of 3.7 births per woman in 2023, while below the average for Africa and its low-income countries, remains unfavourably high. The government has reiterated that population growth management remains a critical priority in meeting the country’s social and economic development goals. This is currently prioritised as a focus area in the first MW2063 10-year Implementation Plan (MIP–1). The targets, as set out in the outcomes indicators, are to improve family planning and access to modern contraceptives to reduce fertility rates further to 3.4 births per woman by 2030. The Current Path shows that Malawi is on track to meet its fertility rate targets, reaching a marginally higher 3.5 in 2030. However, the country will fall significantly short of reaching 100% of modern contraceptive use, reaching only 71% in 2030.

Several studies show that the prevalence rate of contraceptive use is lowest among the younger and poorer population cohorts. Political and community leadership and raising awareness among this population cohort must address this challenge and meet the MIP–1 target. Interventions targeting the youth must be mainstreamed within the current policies and programs.

Life expectancy in Malawi has seen significant fluctuations over the decades. It improved from 37.8 years in 1960 to 48.4 years in 1990 but declined sharply to 44.7 years by the turn of the century due to the devastating impact of the HIV/AIDS pandemic in the 1990s. While the past few decades have brought gradual improvements, with life expectancy reaching 65.7 years in 2023, it remains slightly below the average for low-income African countries (66.4 years). In the Current Path, life expectancy is projected to reach 70 years by 2043 and 74.1 years by 2063—still falling short of the MW2063 target of 80 years.

High fertility rates coupled with persistent low life expectancies resulted in Malawi having one of the most youthful age structures in Africa at the turn of the century. The median age in 2000 was 16.4 years, the seventh lowest in Africa, a figure that stagnated for years. The past decade, however, has seen the start of a slow transition in Malawi’s age structures, with the median age climbing to 18.4 in 2023. This is on par with the average for low-income African countries, with half of the population below the age of 18.

The Current Path shows that the median age in 2043 is likely to be 23.7 years and by 2063 will have improved to 30.3 years (3.5 years more than the average for low-income Africa). This gradual ageing of the population is most noticeable in the decline in the population below 15 years, with associated growth in the economically active age group. In 2023, 42% of the population was below the age of 15 years. On the Current Path, with an expected drop in fertility rates, it is forecast that by 2043, 33.5% of the population will be below 15 years, and 24% by 2063. This large cohort of children below 15 years of age requires huge and ongoing investments in education and healthcare.

An increase in life expectancy is also evident in the growing elderly dependant population group (aged above 64, which will increase from 2.6% in 2023 to 3.7% in 2043 and to 7.5% by 2063.

The working-age population cohort (between 15 and 64 years) will increase from 55.6% in 2023 to 63% in 2043 and to 68.5% by 2063. This growing workforce could allow Malawi to enter a potential demographic window of opportunity by 2041. This shift creates an opportunity for increased productivity and economic development, provided it is supported by investments in education, health, job creation and effective economic policies.

Chart 3 presents a population distribution map for 2023.

Malawi is divided into three regions: Northern, Central and Southern, which are further subdivided into 28 districts. The capital and largest city, Lilongwe, located in the Central Region, has a population of 1 115 815. Other major urban centres include Blantyre (902 588), Mzuzu (249 564) and Zomba (118 440).

The country’s population size relative to its geographic size makes it one of the ten most densely populated countries in Africa. In 2023, Malawi's population density was 223 persons per square kilometre. The Southern Region is the most densely populated, followed by the Central and Northern Regions.

Population densities are projected to more than double over the next four decades, reaching 458 persons per square kilometre by 2063, placing significant pressure on land use planning and resource management.

Chart 4 presents the urban and rural population in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

Together with population growth and structural demographic changes, Malawi is also expected to see a dramatic shift towards urban areas. Malawi is a predominantly rural country and one of the least urbanised in the world. In 2023, still only 18% of the population resided in urban areas, accounting for 3.8 million people. This slow urbanisation trend is the result of pro-rural policies such as the very aggressive integrated rural development plan contained in the 2006 Malawi Growth and Development Strategy.

Urbanisation is critical to economic growth and development as it fosters entrepreneurship and increases productivity. Cities in Africa generate between 55% and 60% of the continent’s GDP. Urban development in Malawi has gained traction with the government, and the need to accelerate urbanisation is supported as pillar 3 in MW2063. The government launched the Malawi Secondary Cities Plan (MSCP) in 2022 — a new spatial master plan that aims to decongest the existing cities through the development of eight additional secondary cities. These catalytic locations aim to be centres of government, industry, agriculture, tourism, mining activities and investment. The secondary cities are expected to provide economic opportunities, easy commuting and close connectivity to social amenities while playing a vital role in the decongestion of current cities.

On the Current Path, urbanisation rates will continue to increase but at a much lower rate compared to the objectives set out by the government of Malawi. The Current Path is that the urbanisation rate for Malawi will be 24% in 2043, below the government’s desired target of 36%. By 2063, in the Current Path, Malawi’s cities and towns will be home to 35% of the population, significantly below the 60% target of MW2063.

This is very likely the result of the urbanisation lag that followed historical pro-rural policies and underinvestment in urban spaces. While new plans, such as the MSCP, will support the transition, it will take some time for urbanisation to gain critical momentum. To align with MW2063 targets, strategic interventions such as increased investment in secondary cities, improved rural-to-urban migration policies and the development of essential infrastructure will be required. However, without comprehensive urban planning, these efforts could also lead to increased urban poverty, informality and unstructured development. Ensuring that urban growth is well-managed through proactive policies and investments in sustainable city planning will be crucial for Malawi’s long-term development.

Chart 5 presents GDP in market exchange rates (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

In 2023, GDP (MER) was US$10.5 billion and is forecast to reach US$28.6 billion in 2043.

The recent withdrawal of more than US$350 million in USAID funding, which accounted for over 13% of Malawi’s national budget, has had a profound effect on the economy. This sudden decline in financial support has created budget deficits in essential sectors like healthcare and education, worsening the country's fiscal challenges and slowing down development initiatives. Additionally, the reduction in aid has aggravated foreign exchange shortages, putting further pressure on the already struggling economy.

Malawi’s economic growth continues to face significant challenges from recurrent climate shocks and persistent macroeconomic instability. These factors disrupt development progress and threaten the country’s long-term economic aspirations.

The goal of MW2063 is to graduate Malawi to a low-middle-income country by 2030 and to an upper-middle-income country by 2063. For Malawi to transition into the lower-middle-income bracket, it must achieve a gross national income (GNI) per capita of US$1 086. Between 2018 and 2023, the GNI per capita rose by 25%, increasing from US$500 to US$623. In 2021, GNI per capita reached a record high of US$648 before declining in 2022 and 2023, primarily due to external shocks. For Malawi to remain on track to achieve middle-income status by 2030, it would require adopting aggressive reform strategies and achieving an unlikely annual GDP growth rate exceeding 10%. The projected average economic growth rate between 2023 and 2043 is about 5%, and across the forecast horizon, the maximum economic growth rate in Malawi is 6.1%.

Malawi is confronting significant fiscal challenges that jeopardise its aspirations to achieve middle-income status by 2030. As of March 2024, the country's total public debt reached MK 14.71 trillion (approximately US$8.49 billion), representing 93% of its GDP. This marks a substantial increase from 60% of GDP in the 2019/20 financial year.

The escalating debt has led to unsustainable debt servicing costs, with projections indicating that 42% of total government revenue for the 2024/25 financial year will be allocated to debt repayments.

This heavy debt burden constrains the government's capacity to invest in critical sectors such as infrastructure, education and healthcare, which are essential for long-term economic growth. An example is the Nacala Logistics Corridor, a major regional infrastructure network to connect the inland mining and agricultural hinterland in Malawi and Moatize in Tete Province, Mozambique, to the deep-water port of Nacala in Northern Mozambique.

Chart 6 presents the size of the informal economy as per cent of GDP and per cent of total labour (non-agriculture), from 2020 to 2043. The data in our modelling are largely estimates and therefore may differ from other sources.

The informal economy comprises activities that have market value and would add to tax revenue and GDP if they were recorded. Countries with high informality face a host of development challenges, such as low revenue mobilisation. Economic growth tends to be below potential in these countries.

However, the informal sector is the lifeblood of the growing population of young Malawians. In the absence of formal sector opportunities, around 68.1% of total employment was estimated to be in the informal sector in Malawi. On the Current Path, informality is expected to decline to 62% by 2043.

The size of the informal sector in Malawi was equivalent to 35% of GDP in 2023. On the Current Path, the level of informality will slowly decline to 31.4% of GDP by 2043 and to 27.3% of GDP by 2063.

The Malawian government has recently introduced several initiatives to formalise small businesses and enhance financial inclusion. The Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSME) Bill 2024 established the Small and Medium Enterprises Development Corporation (SMEDCO) to regulate and support MSMEs. Additionally, the Malawi Revenue Authority (MRA) has encouraged small businesses to register for the revamped Presumptive Tax, which applies a tiered tax system to businesses earning under MWK 12.5 million annually. On financial inclusion, the National Financial Literacy and Capability Strategy (2024-2030) aims to improve financial literacy and decision-making across the country. Meanwhile, the National Strategy for Financial Inclusion III (2024-2028) seeks to ensure that 95% of adults have access to at least one formal financial service by 2028. Additionally, the Financial Inclusion and Entrepreneurship Scaling (FInES) Project, supported by the World Bank, is addressing capital access issues for MSMEs. These initiatives reflect Malawi’s ongoing efforts to create a more structured business environment and increase access to financial services.

Addressing informality is essential to promote inclusive wealth creation in Malawi. Gradual formalisation of Malawi’s informal sector is essential for inclusive economic growth. Instead of abrupt enforcement, policies should focus on reducing business registration costs and bureaucracy to ease the transition. Tax incentives can encourage small enterprises to formalise, while vocational training and entrepreneurship programs will equip individuals with skills to sustain formal businesses. Expanding access to financial services through initiatives like the National Strategy for Financial Inclusion III (2024-2028) and the FInES Project is also crucial. Additionally, investments in job creation and quality education will ensure formalisation supports long-term economic stability.

Chart 7 presents GDP per capita in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043, compared with the average for the Africa income group.

In 2023, Malawi had the 35th largest GDP in Africa. However, it ranked 48th out of Africa's 54 countries in terms of GDP per capita. Malawi’s heavy reliance on agriculture, limited industrialisation and rapid population growth continue to strain resources and dilute GDP gains. Additionally, high dependency on foreign aid has created economic vulnerability, with recent aid cuts worsening fiscal deficits.

Malawi’s GDP per capita (PPP) was US$1 436 in 2023, well below the average of US$1 814 for low-income African countries. Projections suggest that Malawi's GDP per capita will remain below the average of its income peers on the Current Path. By 2043, the country will achieve a real GDP per capita of US$2 242, still below the average of low-income African countries projected to reach US$2,986. While these figures indicate gradual improvement, they reflect the persistent challenge of achieving parity with similar economies, highlighting the need for sustained and inclusive economic growth strategies.

Chart 8 presents the rate and numbers of extremely poor people in the Current Path from 2020 to 2043.

In 2022, the World Bank updated the poverty lines to 2017 constant dollar values as follows:

- The previous US$1.90 extreme poverty line is now set at US$2.15, also for use with low-income countries.

- US$3.20 for lower-middle-income countries, now US$3.65 in 2017 values.

- US$5.50 for upper-middle-income countries, now US$6.85 in 2017 values.

- US$22.70 for high-income countries. The Bank has not yet announced the new poverty line in 2017 US$ prices for high-income countries.

Monetary poverty only tells part of the story, however. In addition, the global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) measures acute multidimensional poverty by measuring each person’s overlapping deprivations across 10 indicators in three equally weighted dimensions: health, education and standard of living. The MPI complements the international US$2.15 a day poverty rate by identifying who is multidimensionally poor and also shows the composition of multidimensional poverty. The headcount or incidence of multidimensional poverty is often several percentage points higher than that of monetary poverty. This implies that individuals living above the monetary poverty line may still suffer deprivations in health, education and/or standard of living.

Poverty in Malawi remains a significant and persistent challenge, shaped by a confluence of demographic trends and economic pressures that complicate efforts to reduce poverty levels over the coming decades. Structural poverty in the country stems from several interrelated factors, including low agricultural productivity, volatile economic growth, rapid population growth, poor human capital development, limited access to financial services, the increased frequency of climate-related shocks and underperforming safety net programs.

Malawi’s narrow tax base, underpinned by a predominantly informal economy and low income levels, severely limits the government’s capacity to generate revenue. This fiscal constraint hampers critical investments in public services such as education, healthcare and infrastructure—essential drivers of poverty alleviation and sustainable economic growth. Additionally, the high poverty rate compounds these fiscal challenges, as a substantial share of the population earns below taxable thresholds. This creates a vicious cycle wherein limited fiscal resources curtail meaningful poverty reduction and economic expansion. Exacerbating the situation is Malawi’s substantial debt burden, which diminishes public investment, slows income growth and reduces fiscal space for social spending due to the high costs of debt servicing.

While the proportion of the population living below the international poverty line of $2.15 per day is expected to decline from 72% in 2023 to 67% in 2043 and further to 21% by 2063, the absolute number of people living in poverty will continue to rise due to high population growth. From 15.2 million in 2023, the number of people living in poverty will rise throughout the 2040s, reaching 22.1 million by 2043 before gradually declining to 8.9 million by 2063.

The forecast highlights the critical need for Malawi to adopt accelerated poverty reduction strategies, focusing on economic diversification, job creation and strengthening social protection systems. Additionally, addressing high population growth will be crucial to ensure that development gains are not offset by demographic pressures.

Chart 9 depicts the National Development Plan of Malawi.

Launched in 2000, Vision 2020 aimed to transform Malawi into a technologically advanced middle-income nation by 2020. However, its implementation fell short of expectations. Persistent challenges, including slow economic growth, widespread poverty and inadequate infrastructure hindered progress. Additionally, Vision 2020 was criticised for its lack of mid-term benchmarks and specific short-term goals, which made it difficult to track progress effectively.

On 19 January 2021, the Malawian government introduced Malawi 2063 (MW2063) as a successor to Vision 2020. This long-term development blueprint envisions transforming Malawi into an inclusive, wealthy and self-reliant industrialised upper-middle-income country by the year 2063. The new vision addresses the shortcomings of its predecessor by adopting a phased implementation plan with clear milestones. The operationalisation is structured into 10-year implementation phases, starting with the Malawi Implementation Plan I (MIP-1), which runs from 2021 to 2030. MIP-1 aims to achieve two key milestones: elevating Malawi to lower-middle-income status by 2030 and meeting most of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by the same year.

MW2063 is anchored on three key pillars that are essential for achieving its vision:

- Agricultural productivity and commercialisation: This pillar emphasises enhancing agricultural output and integrating commercial practices to boost food security and economic growth.

- Industrialisation: Focused on developing new industries and adding value to local products, this pillar aims to reduce import dependency and increase exports through enhanced manufacturing capabilities.

- Urbanisation: This pillar promotes sustainable urban development and improves living standards by creating vibrant urban centres, supporting a growing population.

To support these pillars, MW2063 identifies seven enablers crucial for fostering an environment conducive to development:

- Mindset change: Encouraging a shift in citizens' attitudes towards innovation and productivity.

- Effective governance systems and institutions: Establishing transparent and accountable governance structures to facilitate development initiatives.

- Enhanced public sector performance: Improving efficiency and effectiveness within government services to better meet citizens' needs.

- Private sector dynamism: Promoting entrepreneurship and private sector growth as drivers of economic development.

- Human capital development: Investing in education and skills training to build a knowledgeable workforce supporting industrialisation efforts.

- Economic infrastructure: Developing robust infrastructure such as roads, energy supply and communication networks to support economic activities.

- Environmental sustainability: Ensuring development initiatives are environmentally friendly and promote sustainable resource management.

The eight sectoral scenarios as well as their relationship to the Current Path and the Combined scenario are explained in the About Page. Chart 10 summarises the approach.

Chart 11 presents the mortality distribution in the Current Path for 2023 and 2043.

The Demographics and Health scenario envisions ambitious improvements in child and maternal mortality rates, enhanced access to modern contraception, and decreased mortality from communicable diseases (e.g., AIDS, diarrhoea, malaria, respiratory infections) and non-communicable diseases (e.g., diabetes) alongside advancements in safe water access and sanitation. This scenario assumes a swift demographic transition supported by heightened investments in health and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WaSH) infrastructure.

Visit the themes on Demographics and Health/WaSH for more detail on the scenario structure and interventions.

Malawi's health sector has faced significant challenges that hinder human capital development. Persistent malnutrition has negatively impacted cognitive and physical growth, while poor infrastructure and limited access to quality healthcare have worsened disease burdens. Although progress has been made, these issues continue to affect health outcomes, labour productivity and educational achievements, slowing socio-economic advancement.

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Malawi has encountered a series of crises that have further strained its health sector. The most severe cholera outbreak in its history occurred between 2022 and 2023, placing immense pressure on already limited healthcare resources and exposing the vulnerability of the country’s health infrastructure to external shocks.

Despite substantial investments in Malawi’s health sector, the country consistently falls short of the Abuja Declaration's target of allocating 15% of the budget to health. In 2023, the country’s health expenditure measured 8.5% of the National budget (MK 328 billion). In 2024, the government allocated 9.2% of the national budget (MK 550 billion), the second-largest budget after education (14.6%).

In 2024/25, per capita health spending was estimated at US$16, rising to US$40 with donor and private contributions. However, this remains far below the Health Sector Strategic Plan (HSSP III) target of US$78.7 and the WHO-recommended minimum of US$86. Persistent funding gaps, fiscal deficits and debt continue to hinder health sector improvements, progress towards achieving universal health coverage and broader economic growth.

Malawi is projected to undergo its epidemiological transition in 2037, the point at which deaths from non-communicable diseases (NCDs) surpass those from communicable diseases. The country will face a double burden of disease, as an increasing prevalence of NCDs demands more complex and costly care, further straining the national health budget.

In 2023, NCDs accounted for 38% of all deaths in Malawi. This share is expected to rise significantly, reaching 53% by 2043. Meanwhile, communicable diseases, which were responsible for 56% of deaths in 2023, are projected to decline to 39% over the same period.

Among the leading causes of death, cardiovascular diseases ranked second in 2023, accounting for 13% of all deaths. By 2043, they are expected to become the leading cause, rising to 18% of total deaths. Malignant neoplasms, which relate to deaths caused by cancers, were responsible for 9% of deaths in 2023 and are forecast to increase to 14% by 2043, making them the second leading cause of death.

These trends highlight the urgent need for Malawi to adapt its health systems and policies to address the growing challenge of chronic diseases alongside persistent infectious disease burdens.

Chart 12 presents the infant mortality rate in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

The infant mortality rate is the probability of a child born in a specific year dying before reaching the age of one. It measures the child-born survival rate and reflects the social, economic and environmental conditions in which children live, including their health care. It is measured as the number of infant deaths per 1 000 live births and is an important marker of the overall quality of the health system in a country.

The infant mortality rate remains a significant concern, with 40 deaths per 1 000 live births. Neonatal mortality accounts for 21 deaths per 1 000 live births. In the Demographics and Health scenario, improvements in basic healthcare will reduce infant mortality to 19 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2043, in contrast to the 30 deaths forecasted under the Current Path. Additionally, neonatal mortality is expected to decrease from 16 to 10 deaths per 1 000 live births in the Demographics and Health scenario.

Maternal health outcomes are similarly alarming, with the maternal mortality ratio at 157 deaths per 100 000 live births—well above the Southern African Development Community (SADC) average of 305 and far from the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target of fewer than 70 deaths per 100 000 by 2030. In the Demographics and Health scenario, this number is reduced to 76 deaths per 100 000 live births. Compounding these challenges is Malawi’s high fertility rate of 3.7 children per fertile woman, which exceeds the replacement rate of 2.1 and further strains healthcare resources. Addressing these persistent issues requires a coordinated, multisectoral approach to tackle the underlying social, economic and structural determinants of poor health outcomes.

Chart 13 presents the demographic dividend in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

The dividend is the window of economic growth opportunity that opens when the ratio of working-age persons to dependants increases to 1.7 to 1 and higher.

An increase in the working-age population relative to dependants (children and elderly people) can generate economic growth due to the resultant demographic dividend. When there are fewer dependants to take care of, it frees up resources for investment in both physical and human capital formation and eventually increases female labour force participation. Studies have shown that about one-third of economic growth during the East Asia economic miracle can be attributed to the large worker bulge and the relatively small number of dependants. However, the growth in the working-age population relative to dependants does not automatically translate into rapid economic growth unless the labour force acquires the needed skills and is absorbed by the labour market. Without sufficient education and employment generation to successfully harness their productive power, the growing labour force (very likely in urban areas) could result in the emergence of civil instability as many people of working age may remain unemployed and in poverty, potentially creating frustration, social tension and conflict.

Generally, the demographic dividend materialises when a country reaches a ratio of at least 1.7 working-age people for each dependant (children and elderly people). The projected increase in Malawi’s working-age population cohort (between 15 and 64 years) could allow Malawi to reach its demographic dividend by 2041. Health and population interventions in the Demographics and Health scenario allow Malawi to benefit from this potential dividend by as early as 2035.

Malawi needs to sustain its momentum in reducing fertility rates and invest in education to empower this future workforce with appropriate skills. Without sufficient employment opportunities and a responsive governance system, Malawi’s large youth bulge could threaten stability.

Chart 14 presents crop production and demand in the Current Path from 1990 to 2043.

The Agriculture scenario envisions an agricultural revolution that ensures food security through ambitious yet feasible increases in yields per hectare, thanks to improved management, seed, fertiliser technology, and expanded irrigation. Efforts to reduce food loss and waste are emphasised, with increased calorie consumption as an indicator of self-sufficiency and prioritising it over food exports. Additionally, enhanced forest protection signifies a commitment to sustainable land use practices.

Visit the theme on Agriculture for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Agriculture is the backbone of Malawi’s economy, employing over two-thirds of the population and contributing nearly a quarter of the country’s GDP. The sector is dominated by smallholder farmers, with 76% cultivating plots smaller than one hectare.

The government has introduced several initiatives to modernise agriculture and enhance resilience, including crop diversification, climate-smart agriculture techniques and irrigation expansion to reduce dependence on rain-fed farming. Smallholder farmers have received support through improved access to credit, modern seeds, fertilisers and extension services. While these interventions have led to some productivity gains, major obstacles persist. Many farmers still rely on outdated farming techniques and lack access to modern technology, mechanisation and well-developed markets. Poor rural infrastructure further restricts access to supply chains, limiting the sector’s growth potential.

Additionally, the high dependence on rain-fed agriculture makes the sector increasingly susceptible to climate shocks, exacerbating food insecurity. Malawi's susceptibility to climate change is highlighted by the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) Index in 2021, scoring 37.6 out of 100 and ranking 161st out of 185 countries globally. Between 2010 and 2023, Malawi faced 17 significant floods, a landslide triggered by heavy rainfall, five major storms and three intense droughts. In March 2023, Cyclone Freddy caused extensive damage, destroying homes and infrastructure and leading to substantial losses of crops and livestock. The cyclone resulted in widespread flooding, 1 200 fatalities, and the displacement of over 600 000 people nationwide. This disaster severely impacted the agricultural sector, with more than 2 million farmers losing over 170 000 hectares of land and an estimated 1.4 million livestock lost. In 2024, the situation was exacerbated by an El Niño-induced drought, which led to a significant decline in maize production. The drought resulted in a forecasted 22.9% decrease in maize harvests compared to the five-year average, intensifying food insecurity in the region. These consecutive climatic shocks have highlighted Malawi's vulnerability to climate change, underscoring the need for enhanced resilience and adaptive strategies within the agricultural sector.

Malawi’s heavy reliance on agricultural imports also increases vulnerability to global supply chain disruptions and price volatility, further exacerbating domestic food insecurity. Rapid population growth and accelerating urbanisation are placing additional pressure on agricultural production and food systems.

Between May and September 2024, approximately 6 million people in Malawi faced acute food insecurity, classified by Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) Phase 3 or above (‘crisis’). An additional 6.7 million people were in IPC Phase 2 (‘stressed’). Although Malawi's crop production significantly increased from 5 million metric tons in 1990, future projections indicate that food demand will continue to outpace supply.

The Current Path projects agricultural crop demand to grow from 30.1 million metric tons in 2023 to 52.4 million by 2043.

In the Current Path, Yield per Hectare increased from 8.1 million tons per hectare to 10.5 million tons per hectare. Meanwhile, target interventions lead to 11.8 million tons per hectare in 2043 in the Agriculture scenario.

Chart 15 presents the import dependence in the Current Path and the Agriculture scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

Malawi’s agricultural sector heavily depends on imports, particularly for essential inputs such as fertilisers, seeds, pesticides and machinery. This dependence arises from limited domestic manufacturing capacity and the dominance of smallholder farming, which often lacks the economies of scale and infrastructure needed to support local production of agricultural inputs. High costs associated with importing these essential inputs place a significant financial burden on farmers and the government, further amplifying challenges in improving farm productivity and food security. Structural inefficiencies, lack of investment in local production capabilities and environmental vulnerabilities have compounded this reliance, making it a persistent issue for Malawi’s agricultural sector.

The Farm Input Subsidy Programme (FISP) was introduced in 2005/06 to boost food security, enabling smallholder farmers to purchase fertilisers and seeds at subsidised rates, significantly raising maize yields. Its early success in reducing hunger was offset by criticisms regarding high fiscal costs, administrative inefficiencies and dependence on imported inputs. To streamline the programme and extend subsidised inputs to a broader population segment, the government launched the Affordable Inputs Programme (AIP) in the 2020/21 season. Much like its predecessor, AIP aims to reduce the cost of fertilisers and seeds for smallholder farmers—still the backbone of Malawi’s agricultural sector. Nonetheless, it faces similar hurdles, including reliance on foreign fertiliser supplies, logistical challenges in voucher distribution and fluctuating budgetary allocations. Recent policy discussions and research continue to assess whether further reforms could improve the programmes’ cost-effectiveness.

The Current Path indicates that Malawi’s reliance on agricultural imports will increase to 21.6% of domestic demand by 2043, reflecting growing exposure to global market fluctuations, supply chain disruptions and price volatility. In contrast, the Agriculture scenario, which prioritises enhanced domestic production and self-sufficiency, substantially reduces import reliance to just 11.3% of domestic demand.

Chart 16 depicts the progress through the educational system in the Current Path, for 2023 and 2043.

The Education scenario represents reasonable but ambitious improvements in intake, transition, and graduation rates from primary to tertiary levels and better quality of education at primary and secondary levels. It also models substantive progress towards gender parity at all levels, additional vocational training at the secondary school level, and increases in the share of science and engineering graduates.

Visit the theme on Education for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Malawi faces persistent challenges in education enrolment, particularly beyond the primary level. While primary school enrolment has improved, transitioning to secondary and tertiary education remains a major obstacle due to widespread poverty and geographical disparities in access to quality education. Gender disparities persist, with higher dropout rates among female students driven by socio-economic pressures and cultural expectations.

Underfunding remains a major barrier to education sector reform. According to the 2024 Education Sector Report, Malawi allocated 4% of its GDP to education, falling below the regional average of 4.6%, while Official Development Assistance (ODA) dropped by 9% between 2023 and 2024. These funding constraints limit efforts to improve infrastructure, access and overall education quality, underscoring the need for greater investment and policy commitment from the government and development partners.

Malawi’s primary education system is predominantly public, with 83% of schools government-run. The total number of schools grew by 10% between 2020 and 2024, reaching 7 117 in 2024, with most growth driven by private institutions. However, 34% (4 718 schools) remain inaccessible during the rainy season, highlighting infrastructure deficits. Additionally, digital education remains extremely limited, with only 2% of schools offering ICT lessons and 3% having internet connectivity.

Despite these challenges, education efficiency is improving. The gross enrolment rate will decline from 142.3% in 2023 to 123.9% in 2043, while the net enrolment rate will increase from 88.1% to 93%. These shifts indicate a reduction in over-age and under-age enrolments and improved access for school-age children. Primary school completion rates will rise from 68% in 2023 to 85.2% in 2043, marking a significant improvement in student retention.

Secondary education has expanded, but accessibility and completion rates remain major concerns. By 2024, 75% of secondary schools were public, while 25% were private, with the total number increasing to 1 916 schools. However, rural accessibility remains a challenge, with 263 schools inaccessible during the rainy season, compared to only 3 in urban areas and 46 in semi-urban areas.

Although secondary enrolment has increased, low completion rates, particularly at the upper-secondary level, highlight barriers such as poverty, inadequate infrastructure and socio-economic disparities. In 2024, 3.2% of secondary school students repeated classes, while the overall dropout rate was 4.3%. Female students were disproportionately affected, accounting for 60% of dropouts compared to 40% for males. Financial barriers, early marriages and long travel distances to schools remain the primary causes of dropout.

Higher education remains one of the weakest areas of Malawi’s education system. With a gross enrolment rate of just 2.1% in 2023, projected to rise to 10.2% by 2043, access remains among the lowest globally and regionally. Completion rates are similarly low, increasing modestly from 1.2% in 2023 to 5.5% in 2043.

Despite improvements in enrolment, the quality of education remains a significant concern, particularly in rural areas, where inadequate infrastructure, teacher shortages and limited learning materials hinder student progress. Malawi faces a learning crisis, with only 19% of children aged 7 to 14 demonstrating foundational reading skills and 13% achieving foundational numeracy skills. A key contributor to this challenge is the low attendance rate in Early Childhood Education (ECE), which stood at just 34% in 2023 and urban-rural disparities in teacher quality, infrastructure and access to schools.

Chart 17 presents the mean years of education in the Current Path and in the Education scenario, from 2020 to 2043, for the 15 to 24 age group.

The average years of education in the adult population aged 15 to 24 is a good first indicator of how the stock of knowledge in society is changing.

Malawi’s mean years of education stood at 5.5 years in 2023, falling slightly below the 5.9-year average for low-income African countries and nearly two years below the continental average of 7.2 years. Under the Current Path, gradual progress is anticipated, with the mean years of education projected to increase to 6.1 years by 2043. In comparison, the Education scenario presents a more optimistic outlook, with the mean years of education expected to reach 6.8 years over the same period.

Despite these projections, significant challenges persist due to longstanding deficits in basic education. In 2023, the literacy rate for individuals aged 15 and older was only 64%, reflecting foundational gaps that extend into adulthood. These issues are further exacerbated by disparities in access to quality education, particularly in rural areas, where shortages of qualified teachers and inadequate infrastructure are most pronounced.

While teacher qualifications have improved, gaps remain in pedagogical skills and subject-specific expertise, particularly in underserved regions. Professional development programmes are not yet scaled to adequately address these deficiencies, and limited access to ICT resources hampers digital literacy, a critical skill for Malawi’s future workforce. Expanding and enhancing these areas is essential to bridging educational inequalities.

Efforts to strengthen education funding have shown progress, including a 33% increase in government funding for student loans between 2022 and 2024.

New technical colleges have expanded access to vocational training, an essential step towards addressing skills gaps. However, aligning education with labour market demands remains a pressing challenge. As of 2024, only 19% of graduates from Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TEVET) programs were employed, highlighting a significant disconnect between the skills provided by training programs and the needs of the labour market. Enrolment in technical colleges increased significantly from 5 599 in 2023 to 9 707 in 2024. Still, this growth has been undermined by resource constraints, including a student-to-qualified-instructor ratio of 40:1—twice the target of 20:1. To close this gap, substantial investments in training infrastructure, curriculum reform and stronger partnerships with industry are essential.

Chart 18 presents the value-add by sector as share of GDP in the Current Path, for 2023 and 2043.

In the Manufacturing scenario, reasonable but ambitious growth in manufacturing is envisaged through increased investment in the sector, research and development (R&D), and improved government regulation of businesses. This aims to enhance total labour

Visit the theme on Manufacturing for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

On the Current Path, the service sector will continue to have the largest share of GDP in 2043, accounting for 57.6%. Strengthening the digital economy is also essential for Malawi to boost growth and achieve its development objectives. Within this sector, the digital economy could be a significant growth driver by enhancing service delivery, streamlining manufacturing processes and fostering innovation. To realise this potential, Malawi will need to invest in robust digital infrastructure, expand connectivity in both urban and rural areas, and develop a digitally skilled workforce. Additionally, establishing an enabling regulatory framework and encouraging public-private partnerships will be essential to spur innovation and attract further investment in the digital space. Current Path forecasts that the ICT sector will account for 5.9% of GDP by 2043 and rise to 6.8% by 2063, making it the third-largest contributor after services and manufacturing.

Agriculture remains a vital pillar of Malawi’s economic development, underpinning the livelihoods of the majority of the labour force and supplying essential inputs to drive manufacturing growth. In doing so, agriculture stimulates demand in both the services and manufacturing sectors, serving as a cornerstone for broader economic progress. However, as Malawi advances towards a more diversified and industrialised economy, the agriculture sector’s share of GDP is expected to decline markedly—from 19.8% in 2023 to 10.7% by 2043 and further to 4.2% by 2063 (outpacing the set target of 8% in 2063).

The manufacturing sector, however, has experienced a steady decline in its GDP share since peaking at 19% in 1992, signalling deindustrialisation while the country remains in poverty. Despite various government initiatives aimed at revitalising industrial growth, the sector continues to perform poorly, as elaborated on in the subsequent section.

Chart 19 presents the contribution of the manufacturing sector to GDP in the Current Path and in the Manufacturing scenario, from 2020 to 2043. The data is in US$ and % of GDP.

Malawi has long sought to industrialise and transform its economy from one reliant on agriculture and raw material exports to one driven by manufacturing and value addition. However, despite various policy interventions and development strategies, the country has struggled to achieve meaningful industrial growth due to structural constraints such as corruption, poor infrastructure, an unstable macroeconomic environment, lack of appropriate skills and limited export access. And while agro-processing remains a key priority, diversification into other emerging manufacturing sectors is crucial for reducing economic vulnerability.

The National Export Strategy II (NES II) 2021-2026 builds upon previous initiatives by prioritising export-oriented manufacturing, agro-processing and new cash crops such as industrial hemp and medical cannabis. This strategy is designed to shift Malawi from a factor-driven economy to an efficiency-driven one, reducing reliance on tobacco exports, which have declined in recent years. The National Industrial Policy (NIP) 2017-2021 aimed to stimulate manufacturing growth, encourage value addition and reduce dependence on raw material exports. However, its impact has been limited, with many underlying constraints—such as infrastructure gaps and weak investment—remaining unaddressed. To address these shortcomings, the NIP is currently undergoing a review to incorporate necessary reforms that align with Malawi’s long-term industrialisation and economic diversification goals.

On 2 February 2024, Malawi enacted the Investment and Export Promotion Act, which formally established the Malawi Investment and Trade Centre (MITC) to support investment and export activities in the country. The Act outlines the Centre's mandate, responsibilities and authority, including its role in registering investors and exporters, issuing investment certificates and providing facilitation services to businesses. Another major development in 2024 was the enactment of the Special Economic Zones (SEZ) Act, which aims to attract investment into dedicated industrial zones. SEZs are expected to provide tax incentives, improved infrastructure and streamlined regulations to enhance industrial production and exports. While this initiative holds promise, its success depends on the government's ability to provide reliable energy, transport and skilled labour—areas where Malawi still faces significant shortcomings.

In 2023, manufacturing contributed 12.3% to GDP, and while it will grow to 18.8% by 2043 in Current Path and will reach 20.4% in the Manufacturing scenario—exceeding the projected low-income African country average of 16.2%—it is still expected to fall short of the MW2063 target of 20% by 2042. The sector’s contribution to GDP will grow significantly, rising from US$1.3 billion in 2023 to US$5.4 billion by 2043 under the current trajectory. Under the Manufacturing scenario, which assumes targeted reforms and enhanced industrial growth, this figure could reach US$6.2 billion by 2043, representing 20.4% of GDP.

Chart 20 depicts exports and imports as a percentage of GDP, from 2000 to 2043, in the Current Path and in the AfCFTA scenario.

The AfCFTA scenario represents the impact of fully implementing the African Continental Free Trade Agreement by 2034. The scenario increases exports in manufacturing, agriculture, services, ICT, materials and energy exports. It also includes improved multifactor productivity growth from trade and reduced tariffs for all sectors.

Visit the theme on AfCFTA for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Like many African countries, Malawi primarily exports raw agricultural products while importing manufactured goods. Limited progress in diversifying its export base has left the economy vulnerable to global commodity price fluctuations, destabilising government revenue and foreign exchange reserves and constraining inclusive growth and development. This reliance on agricultural exports also amplifies exposure to climate-related risks.

In 2023, tobacco dominated exports, contributing over 47% of total export revenue, followed by oil seeds and oleaginous fruits (11%), edible vegetables (10%), and coffee, tea and spices (8%). Belgium was Malawi’s export partner, accounting for 16% of exports, followed by Tanzania (11%), China (6%) and South Africa (5%).

On the import side, Malawi relies heavily on mineral fuels and refined oils, which accounted for 19% of total imports in 2023, reflecting the country’s significant energy needs. Fertilisers, essential to Malawi’s agriculture-driven economy, represented 11%, while machinery constituted 7%. Import partners include China (17%), South Africa (16%), the UAE (12%), India (7%) and Tanzania (7%).

In 2023, Malawi recorded a significant trade imbalance, with imports totalling US$4.6 billion and exports at US$2.4 billion. Projections along the Current Path indicate that, by 2043, imports will reach US$15.2 billion while exports are expected to grow to US$13.8 billion, narrowing but not eliminating the trade deficit.

Chart 21 presents the trade balance in the Current Path and in the AfCFTA scenario, from 2020 to 2043 as a percentage of GDP.

At the regional level, Malawi actively participates in integration initiatives through the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC), the Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). These arrangements provide reciprocal market access based on specific rules of origin, enabling Malawi to expand its export footprint. Beyond market access, the RECs support collaborative regional projects in industrialisation, transport, energy, trade facilitation and other developmental infrastructure, addressing challenges typically faced by landlocked countries like Malawi.

Malawi maintains an open trade policy with relatively low tariffs and minimal non-tariff barriers, which aims to boost exports' contribution to Malawi’s economic and social transformation. In FY2023/24, the simple average applied Most Favored Nation (MFN) tariff was 12.7%, a rate that has remained stable since 2016.

The trade balance, measured as a percentage of GDP, shows a gradual improvement under both the Current Path and the AfCFTA scenario. In 2023, Malawi’s trade deficit stood at -21.3% of GDP, and by 2043, the deficit will narrow to -5% in the Current Path. The AfCFTA scenario shows only a slight improvement, with the deficit projected to reach -4.9% in 2043, an increase of just 0.09 percentage points. The modest impact of the AfCFTA scenario on Malawi’s trade balance reflects several structural challenges. As a landlocked country, high transportation costs and limited connectivity constrain its ability to compete in regional and global markets. The economy’s reliance on primary agricultural exports, vulnerability to price volatility and climate risks, underdeveloped manufacturing base and inadequate infrastructure further restrict diversification.

Chart 22 presents the Current Path of access to electricity for urban, rural and the total population from 2000 to 2043.

The Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario involves ambitious investments in road and renewable energy infrastructure, improved electricity access and accelerated broadband connectivity. It emphasises adopting modern technologies to enhance government efficiency and incorporates significant investments in major infrastructure projects like rail, ports, and airports (other infra) while highlighting the positive impacts of renewables and ICT.

Visit the themes on Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.