Ghana

Ghana

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

This page presents a comprehensive analysis of Ghana. The analysis outlines the nation's extensive socio-economic challenges and opportunities, examining various developmental paths through 2043. It discusses the significant economic growth potential from its rich natural resources while noting the country's persistent issues with poverty, inequality, governance and reliance on commodity export. Various scenarios consider the impacts of improvements in sectors like agriculture, education and manufacturing. The analysis aims to provide policymakers and researchers with insights to guide Ghana towards a more prosperous future.

For more information about the International Futures modelling platform we use to develop the various scenarios, please see About this Site.

Summary

We begin this page with an introduction and context to Ghana.

Ghana is one of the lower-middle-income countries in Africa. It is located in West Africa along the Gulf of Guinea, bordering Burkina Faso in the north, Côte d’Ivoire in the west and Togo in the east, all of which are members of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). The national capital, Accra, is located in the Greater Accra Region of southern Ghana. The country has a total area of 238 535 km² and a tropical climate with two major seasons consisting of a rainy season and a dry season. Ghana is divided into six ecological zones, namely: Sudan savannah, Guinea savannah, Coastal savannah, forest/savannah transitional zone, deciduous forest zone, and the rain forest zone. Jump to Chart 1

The introductory section is followed by an analysis of the Current Path for Ghana which informs the region’s likely current development trajectory to 2043, mostly comparing Ghana with its income peers in Africa. It is based on current geopolitical trends and assumes that no major shocks would occur in a ‘business as usual’ future.

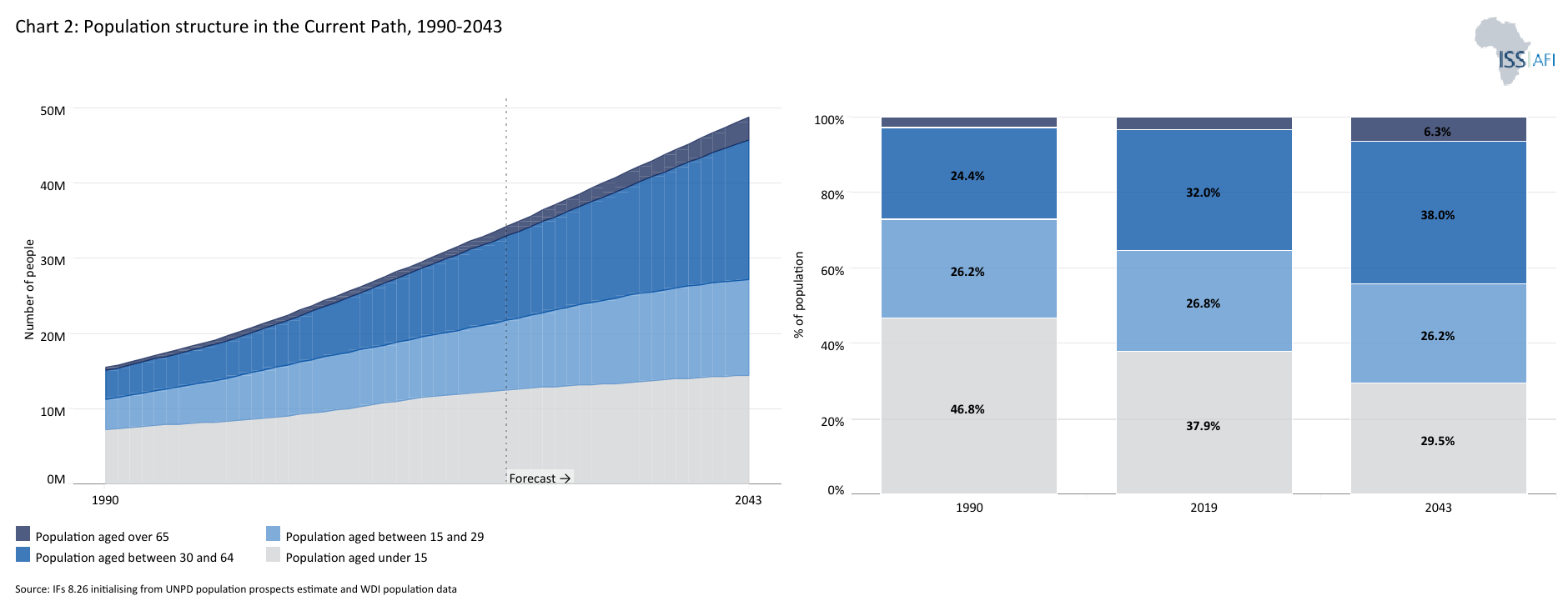

- Ghana is the second most populous country in West Africa after Nigeria and the 13th most populous country in Africa. The total population increased from 15.5 million in 1990 to 34.3 million in 2023 and by 2043, it will be 48.8 million. In terms of population structure, 36.5% of Ghanaians were under the age of 15, 59.7% were in the 15–64 age group (working age), and 3.8% were 65 years and older. Jump to Chart 2

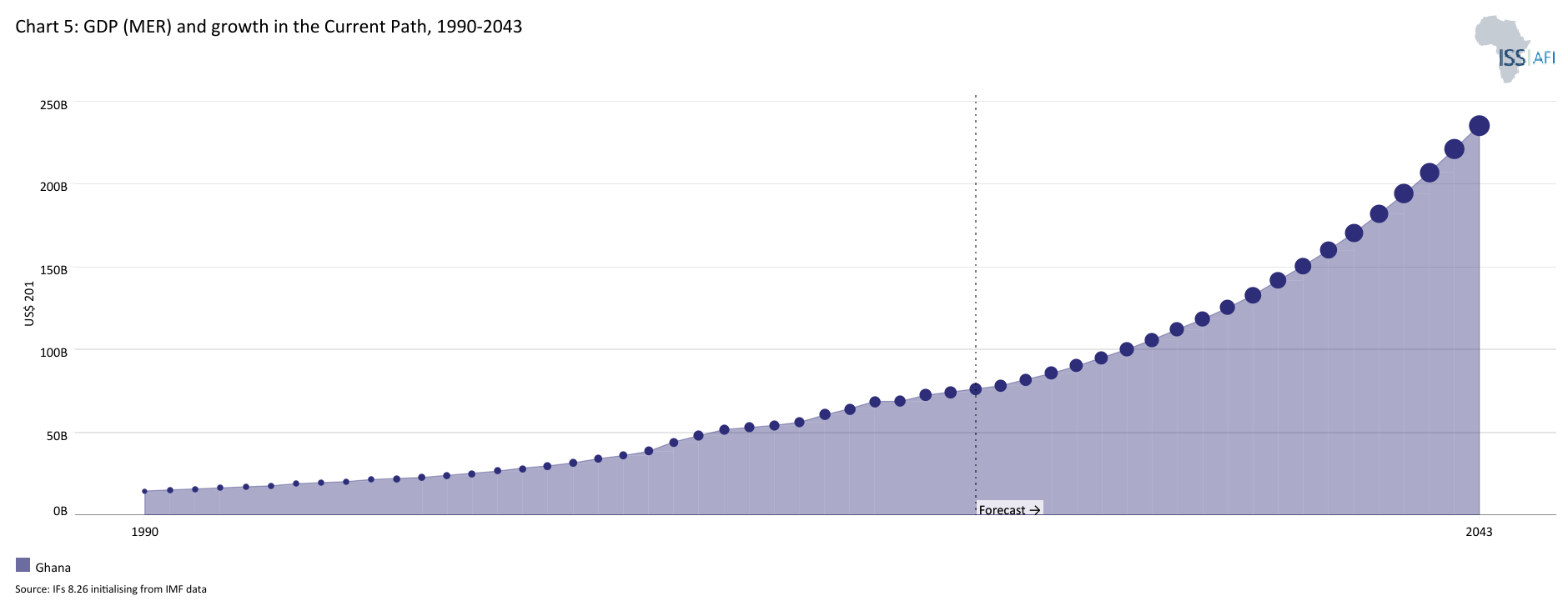

- The country’s GDP, measured in market exchange rates (MER), grew from US$14.4 billion in 1990 to US$76.1 billion in 2023, making it the second largest in West Africa. The average GDP growth rate during this period stood at 5.1% per annum, above the average of 3.9% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. By 2043, GDP will more than double to US$235.4 billion. Jump to Chart 5

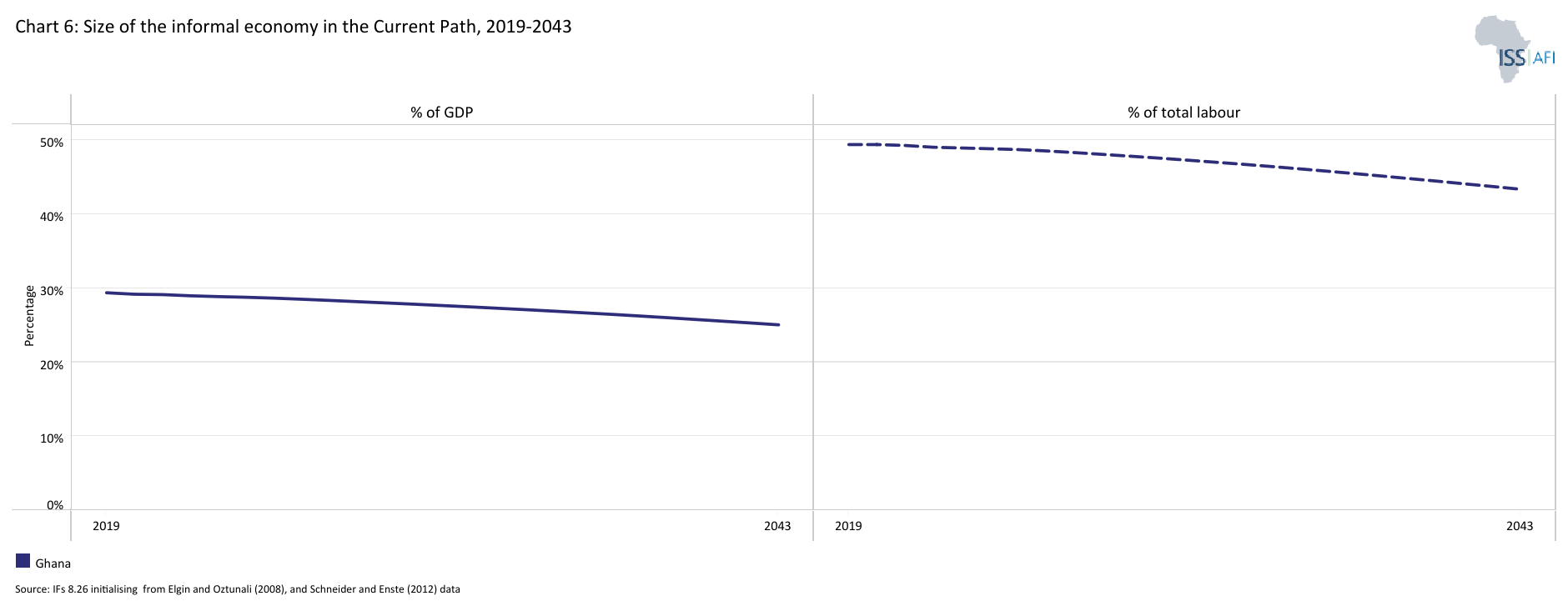

- Ghana has a large informal sector that is vital to its economy. In 2023, the size of the informal sector in Ghana was approximately 28.9% of GDP, almost at par with the average of 29.5% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. On the Current Path, the size of the informal sector will decline slightly to 25.1% of GDP by 2043, at which point it will be below the average for its income-peers in Africa at 26.8% of GDP. Jump to Chart 6

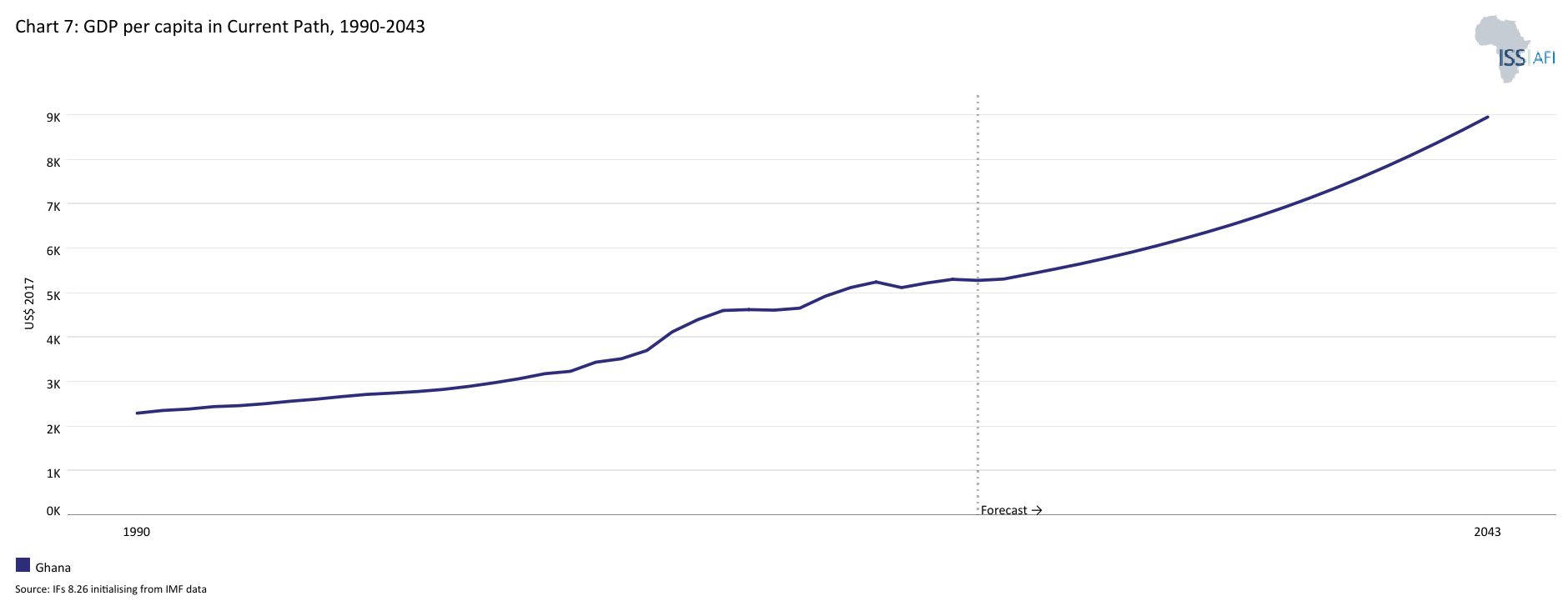

- Ghana has the eighth-highest GDP per capita among the 24 lower–middle-income countries in Africa. Using the purchasing power parity (PPP) measure for this analysis, its GDP per capita of US$5 286 in 2023 was 10.3% lower than the group average of US$5 830. By 2043, Ghana will still have the largest GDP per capita, which will rise to US$8 960. Jump to Chart 7

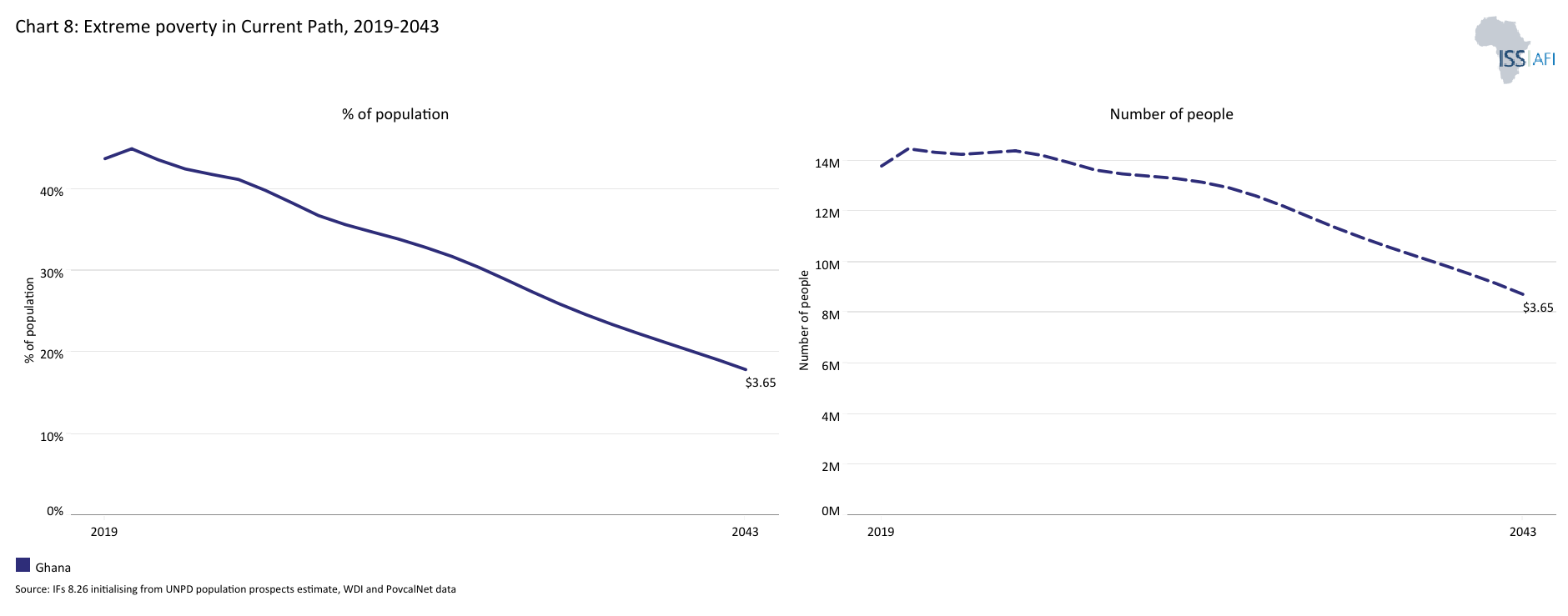

- Ghana currently ranked 145th on the United Nation’s World Human Development Index and 16th in Africa with a score of 0.602. In 2023, 14.3 million Ghanaians, representing 41.8% of the population, lived below the poverty line of US$3.65, far below the average of 49.0% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. By 2043, the poverty rate of 15.6% (equivalent to 8.7 million Ghanaians) will be less than half the average rate of 32.5% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. Jump to Chart 8

- Ghana’s Vision 2057 is the country’s Long-Term National Development Perspective Framework which reflects the development aspirations of the Ghanaian people. Its Vision is to aspire to ”A free, just, prosperous, and self-reliant nation which secures the welfare and happiness of its citizens, while playing a leading role in international affairs”. The overall goal is to improve the living standards of Ghanaians and attain an upper-middle-income country status. Jump to Chart 9

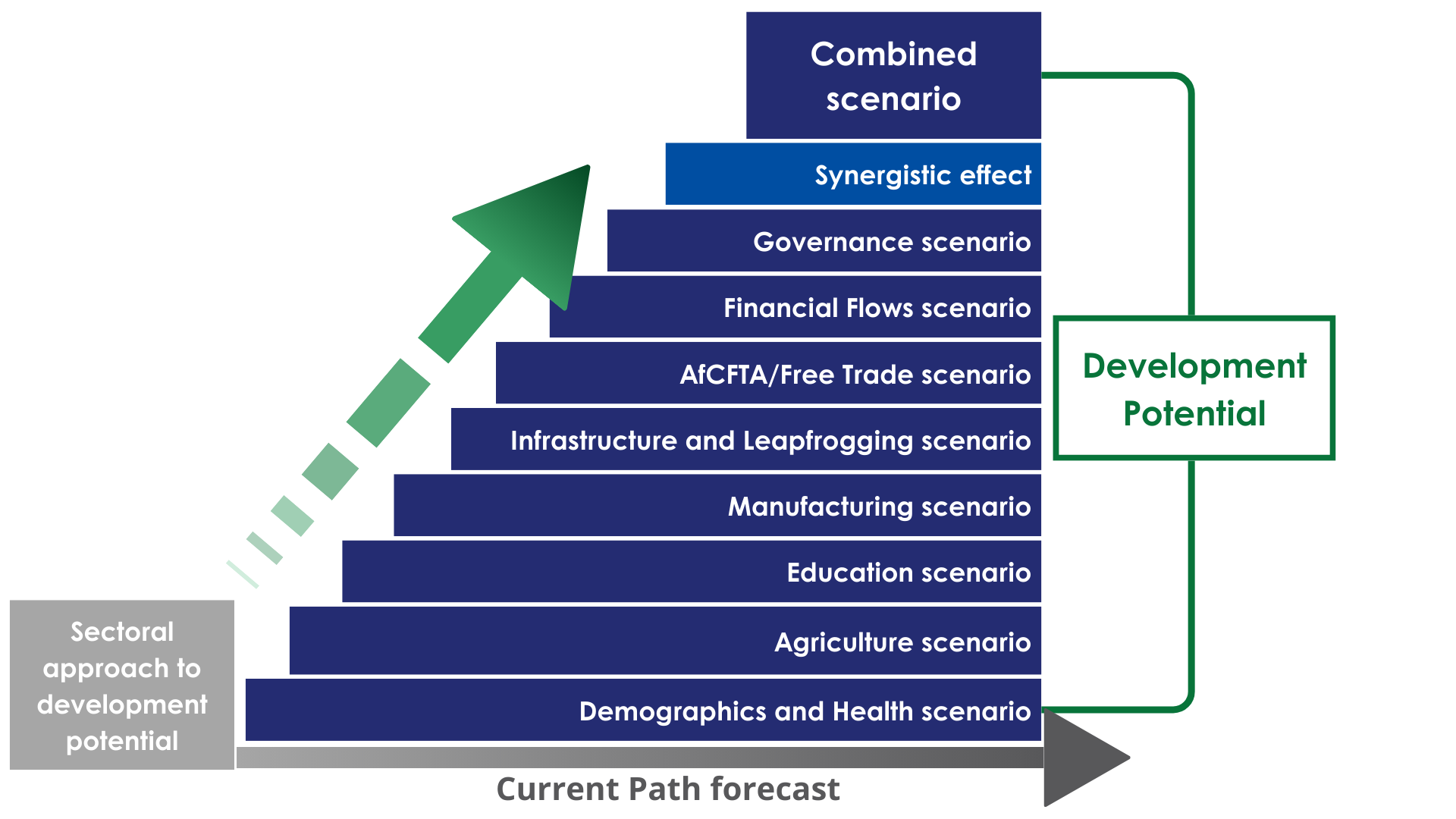

The next section compares progress on the Current Path with eight sectoral scenarios. These are Demographics and Health; Agriculture; Education; Manufacturing; the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA); Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging; Financial Flows; and Governance. Each scenario is benchmarked to present an ambitious but reasonable aspiration in that sector.

- The Demographics and Health scenario will reduce the infant mortality rate from 34.4 deaths per 1 000 births in 2023 to 12.8 deaths by 2043, 6.4 deaths fewer than in the Current Path. The scenario pushes the ratio of the working-age population to dependants to 2.0-to-1 by 2043, far above the ratio of 1.7-to-1 that is required to enter a potential demographic window of opportunity.

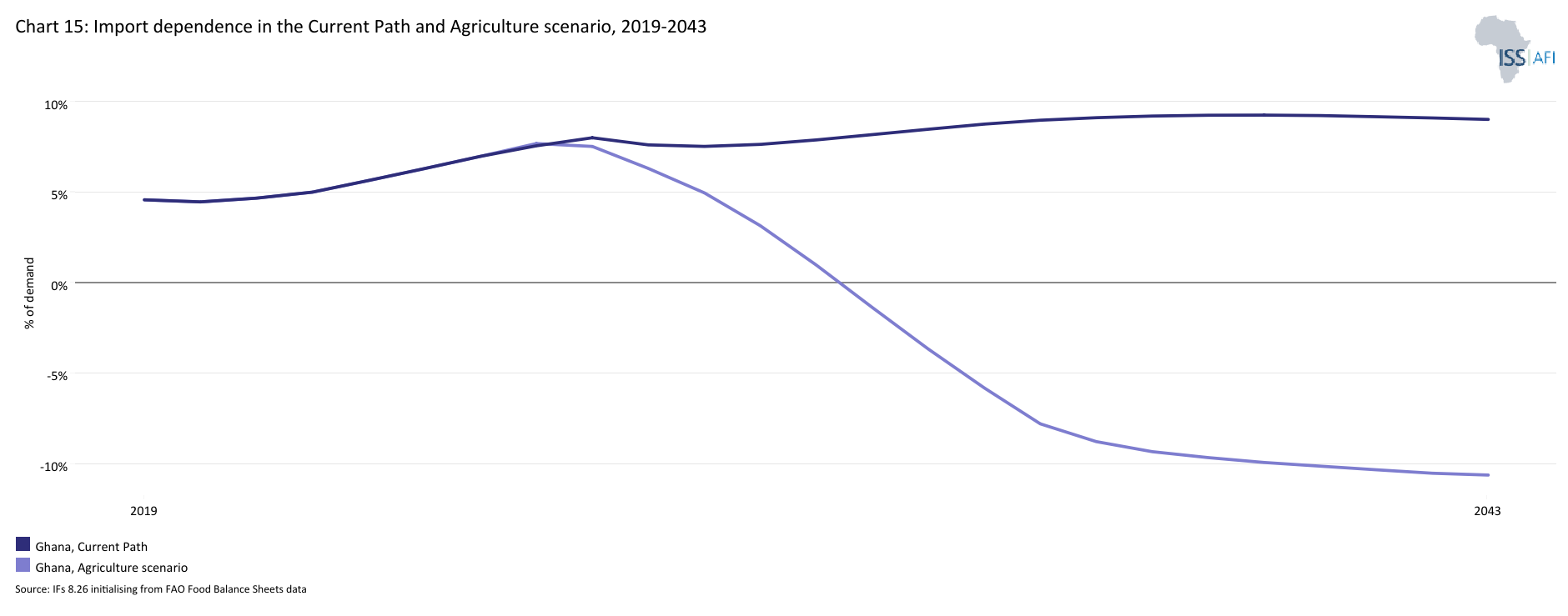

- In 2023, Ghana’s net import of crops stood at 5.6% of total crop demand, which was lower than the average of 11.8% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. Ghana will become a net exporter of crops under the scenario so that by 2043, the net export of crops will reach 10.6% in the Agriculture scenario.

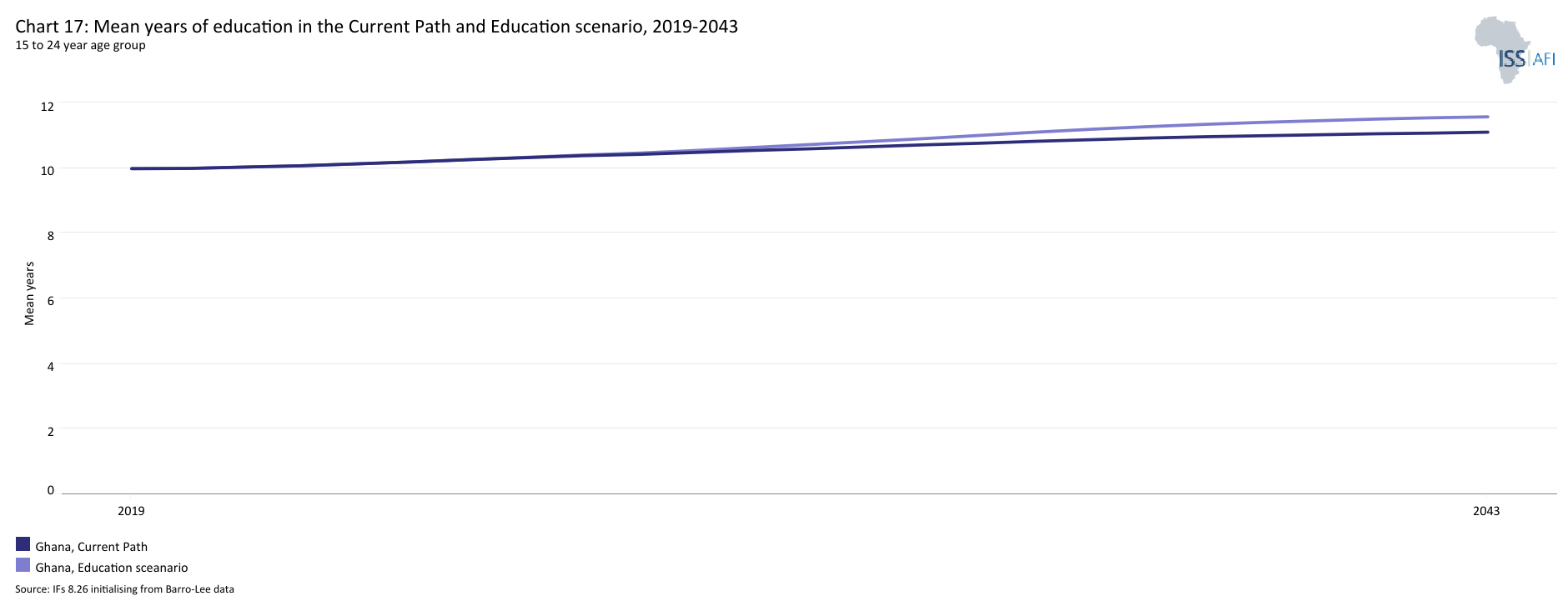

- In 2023, the mean years of education attained by adults between 15 and 24 years in Ghana stood at 10.1 years — below the average of 7.8 years for lower-middle-income countries on the continent. In the Education scenario, the mean years of adult education in Ghana will increase to 11.6 by 2043, 0.5 years more than the Current Path and higher than the average for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. By 2043, the scenario further increases average test scores for primary and secondary school students by 44.4% and 44.6%, respectively.

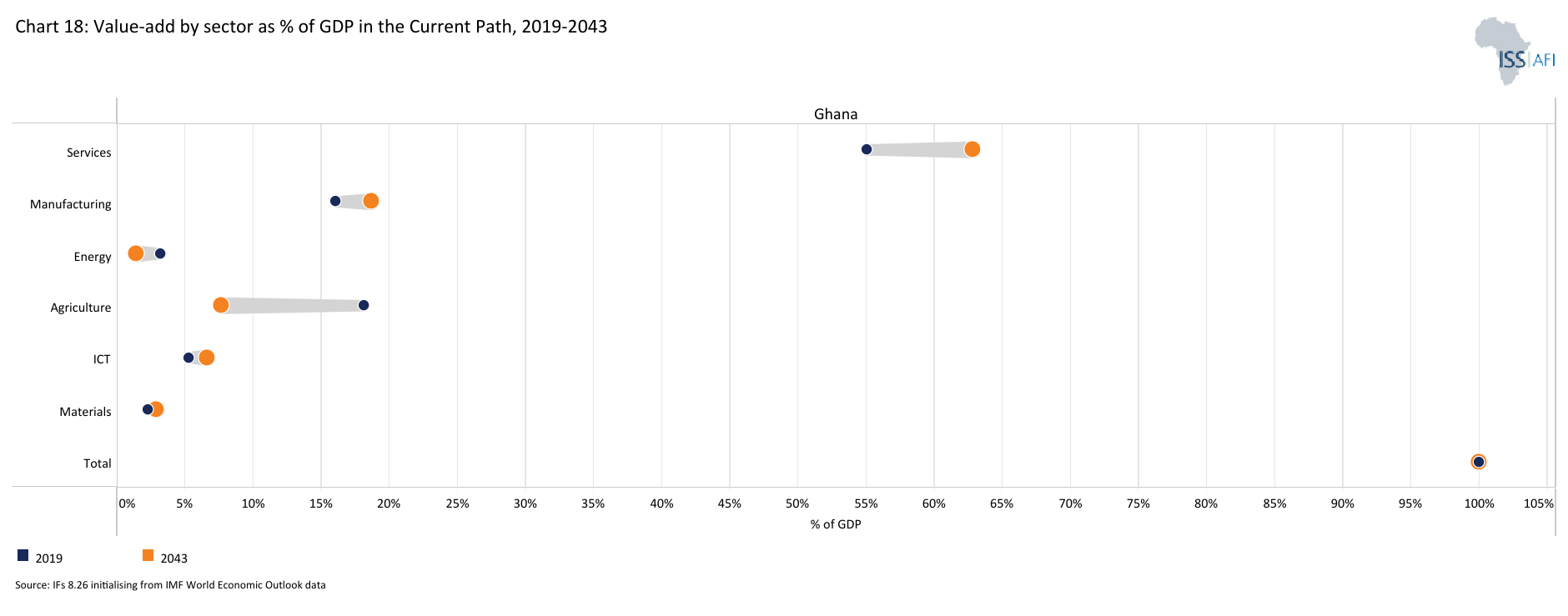

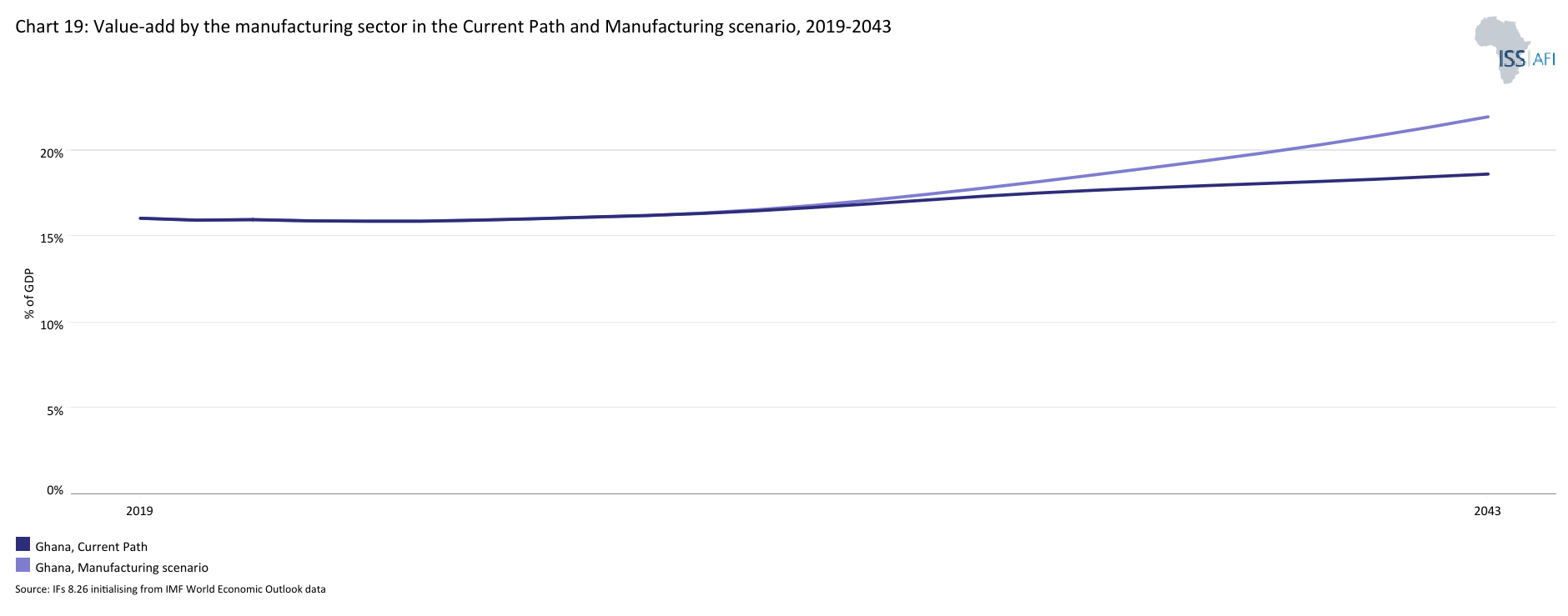

- In the Manufacturing scenario, Ghana makes substantial progress in industrialisation such that, by 2043, the share of the manufacturing sector in GDP is about 22% equivalent to US$55.4 billion. This will be about 3.3 percentage points of GDP above the Current Path valued at US$12 billion.

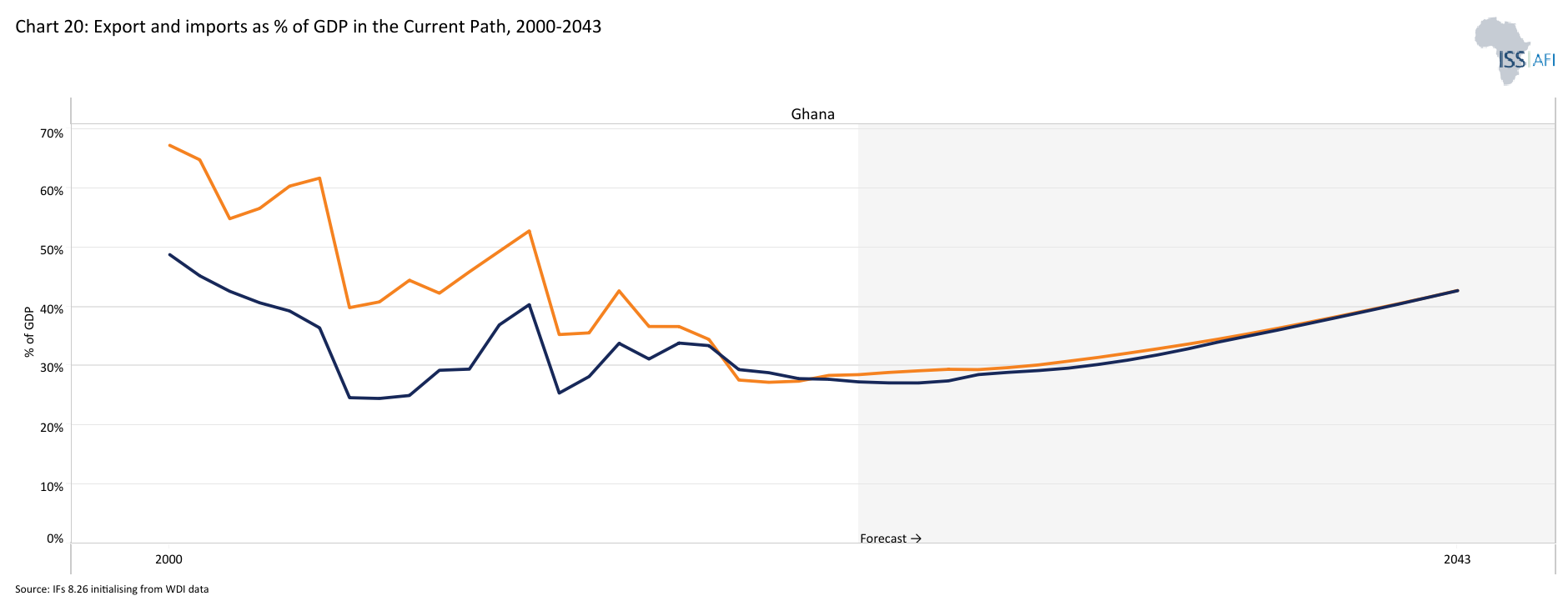

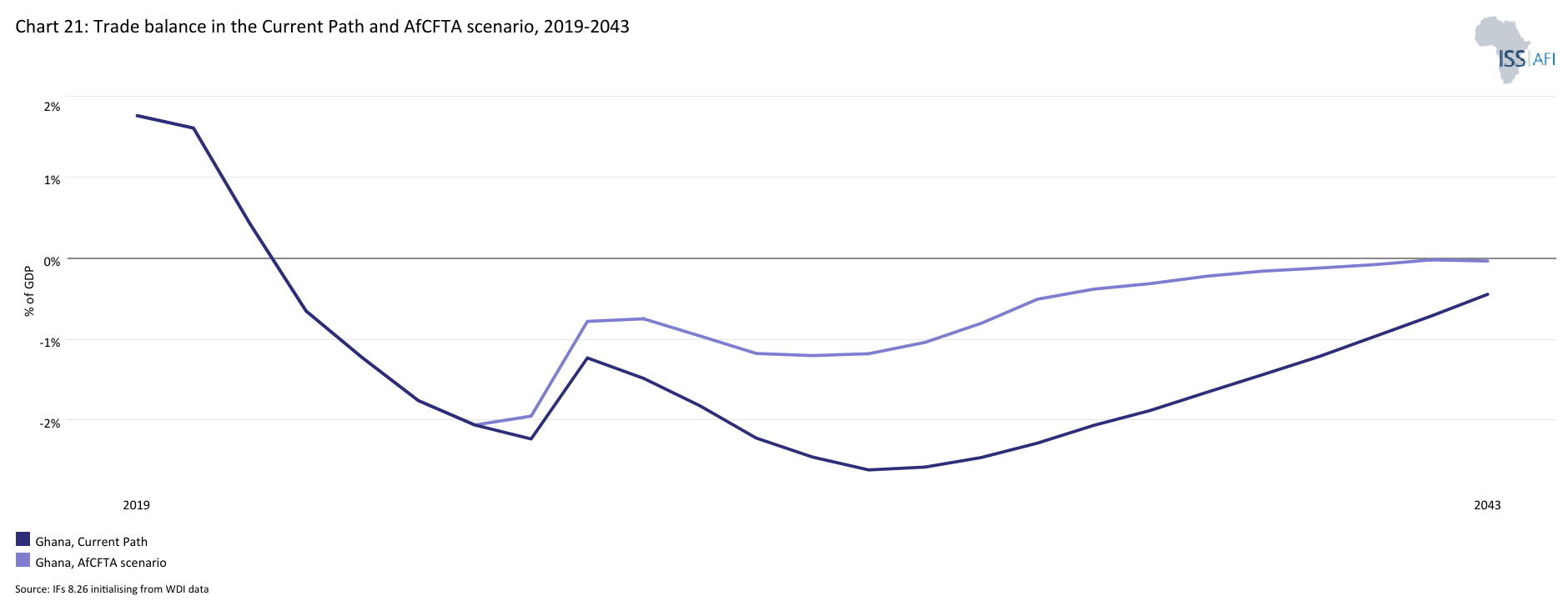

- In the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) scenario, Ghana’s trade deficit will constitute about 0.02% of GDP by 2043 instead of the 0.4% of GDP on the Current Path. Also, the sum of Ghana's exports and imports as a percentage of GDP will reach 85.5% by 2043. This will be about 13.3 percentage points above the Current Path and 33.4 percentage points below the average of lower-middle-income African countries.

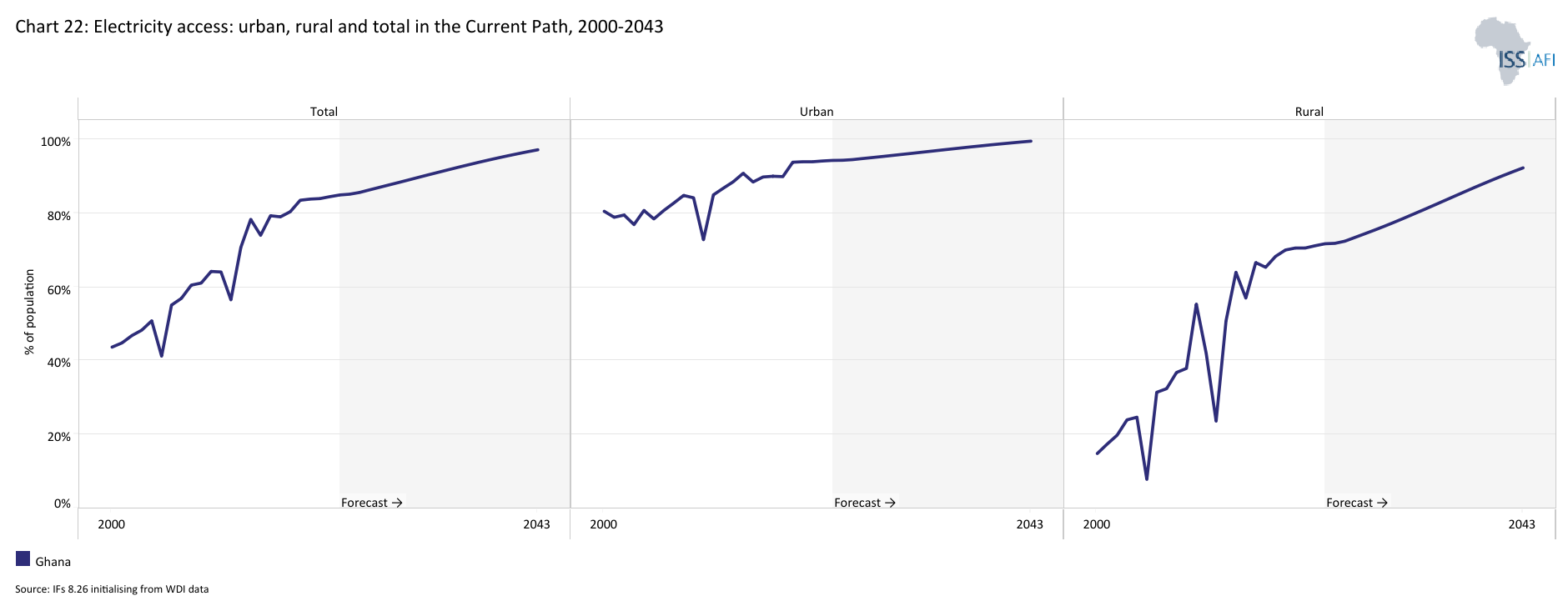

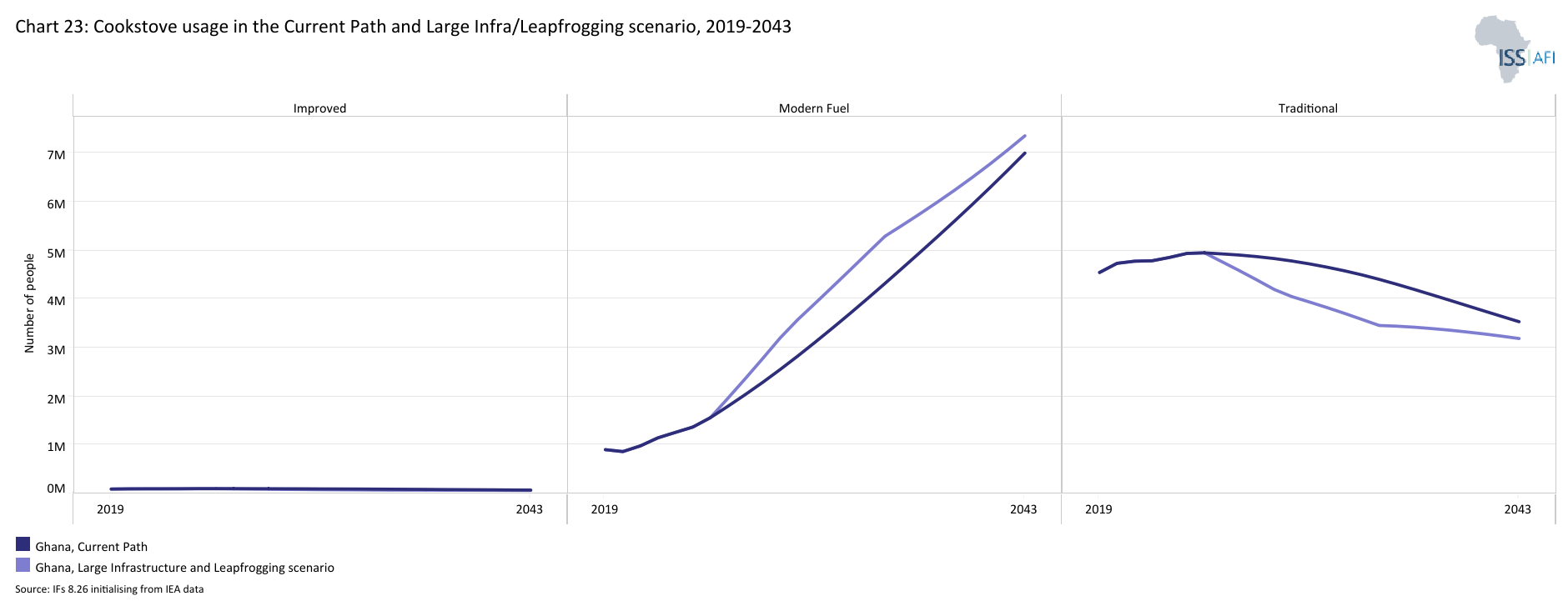

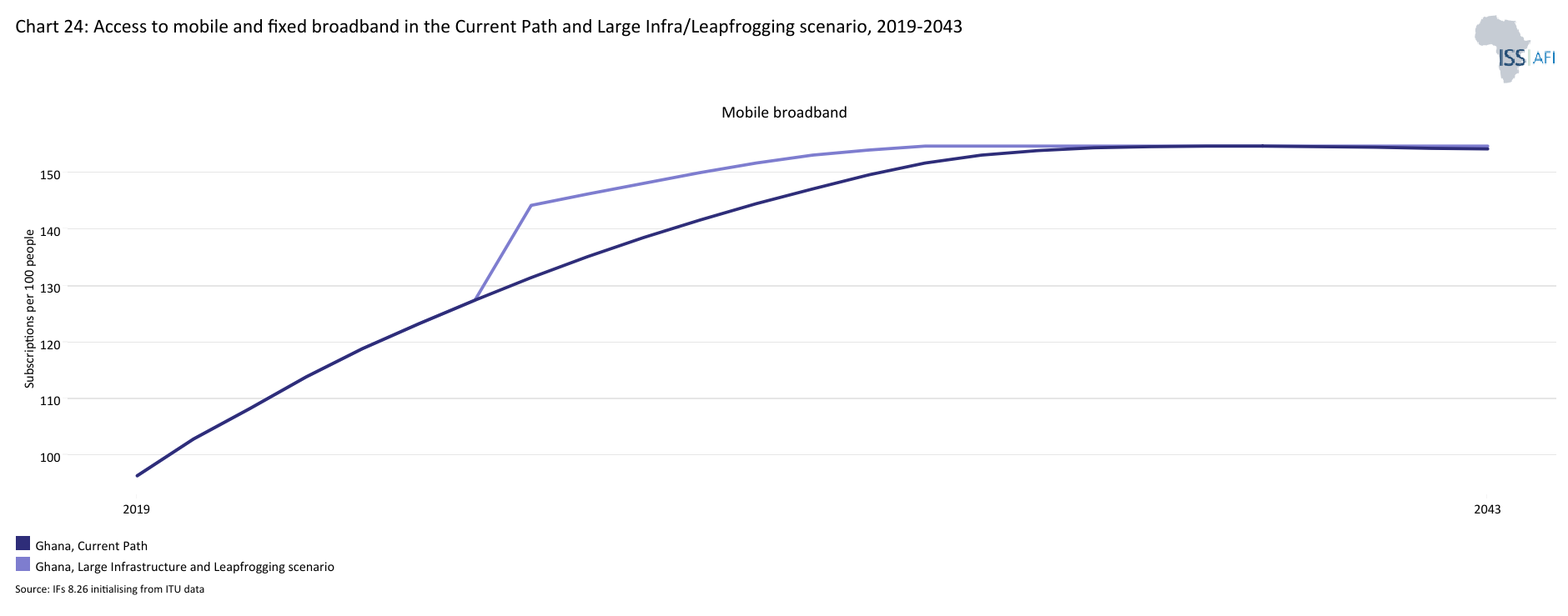

- Based on the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario, Ghana will attain a universal electricity access rate by 2035. As a result, 69.3% of households in Ghana will use modern fuel for cooking in the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario. The scenario will further lead to a larger increase in fixed broadband access, so that, by 2043, subscriptions will likely be at 30 per 100 people compared to 19.8 subscriptions on the Current Path.

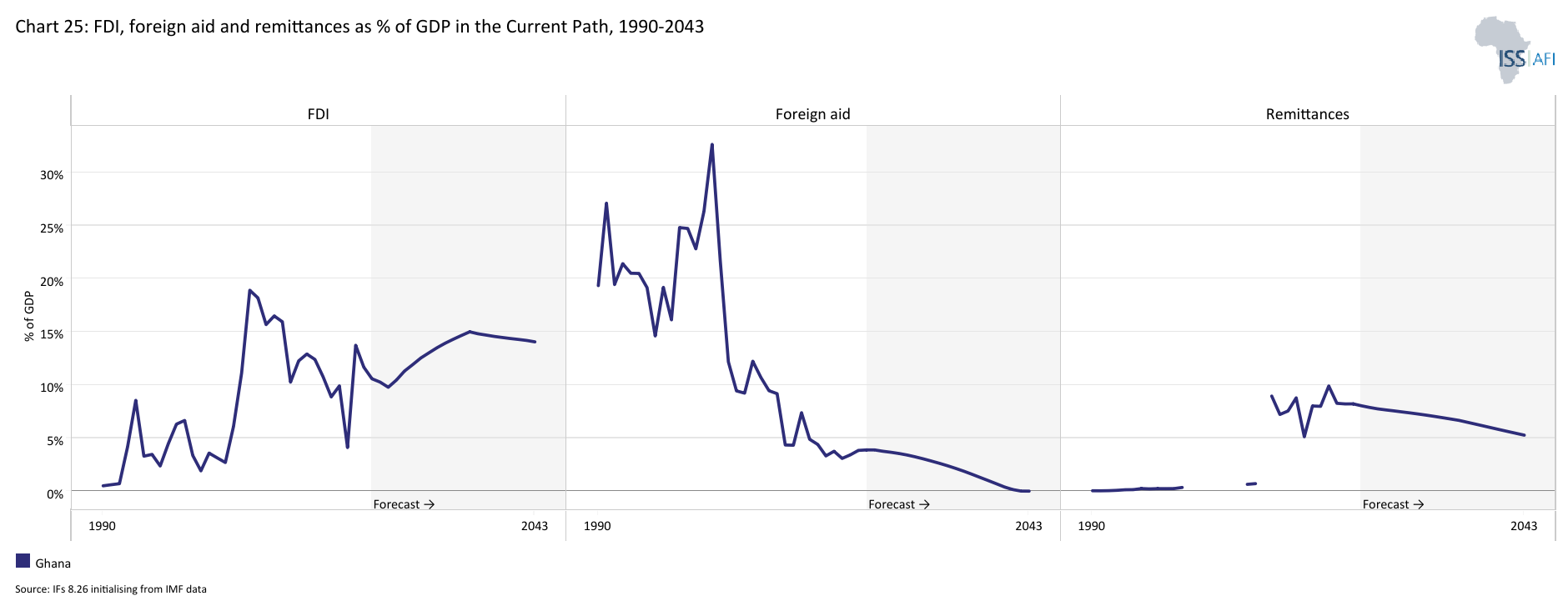

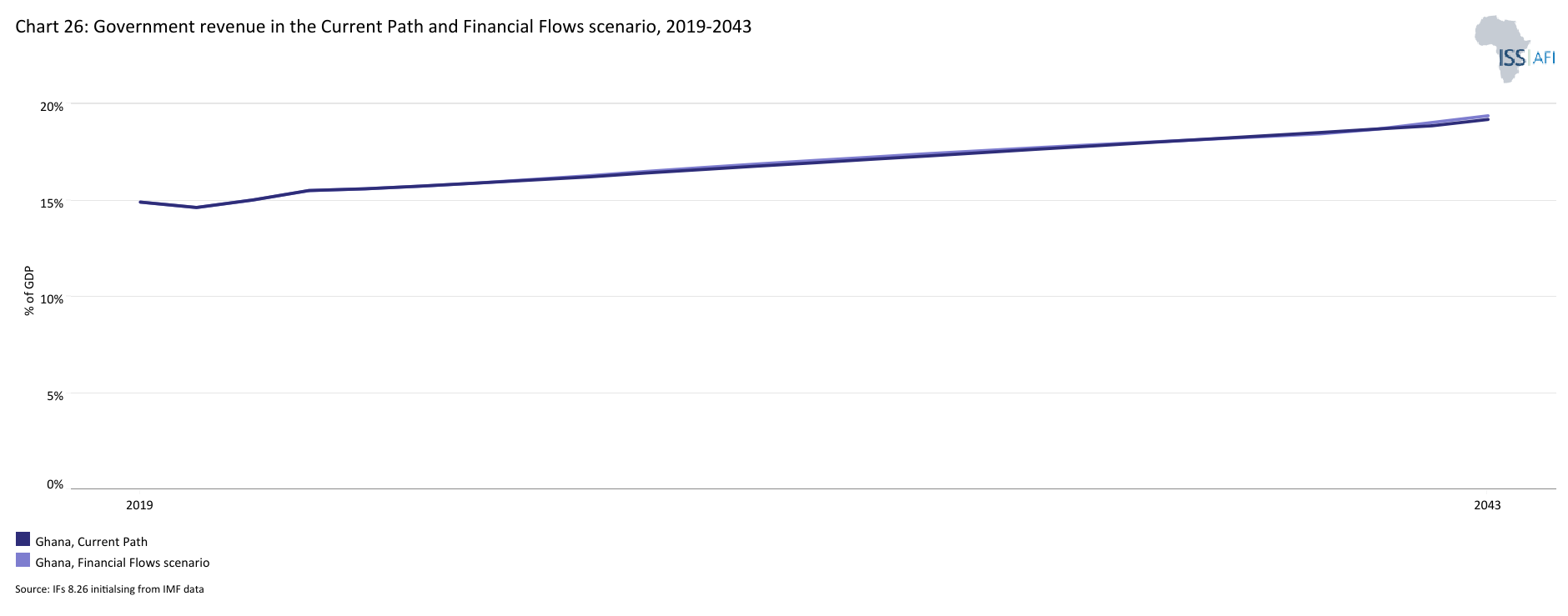

- In 2023, the government’s total revenue in Ghana amounted to US$11.9 billion, equivalent to 15.6% of GDP — slightly below the average of its income-group peers in Africa. Compared to the Current Path, the Financial Flows scenario will improve government revenue in Ghana by an additional US$3.4 billion by 2043.

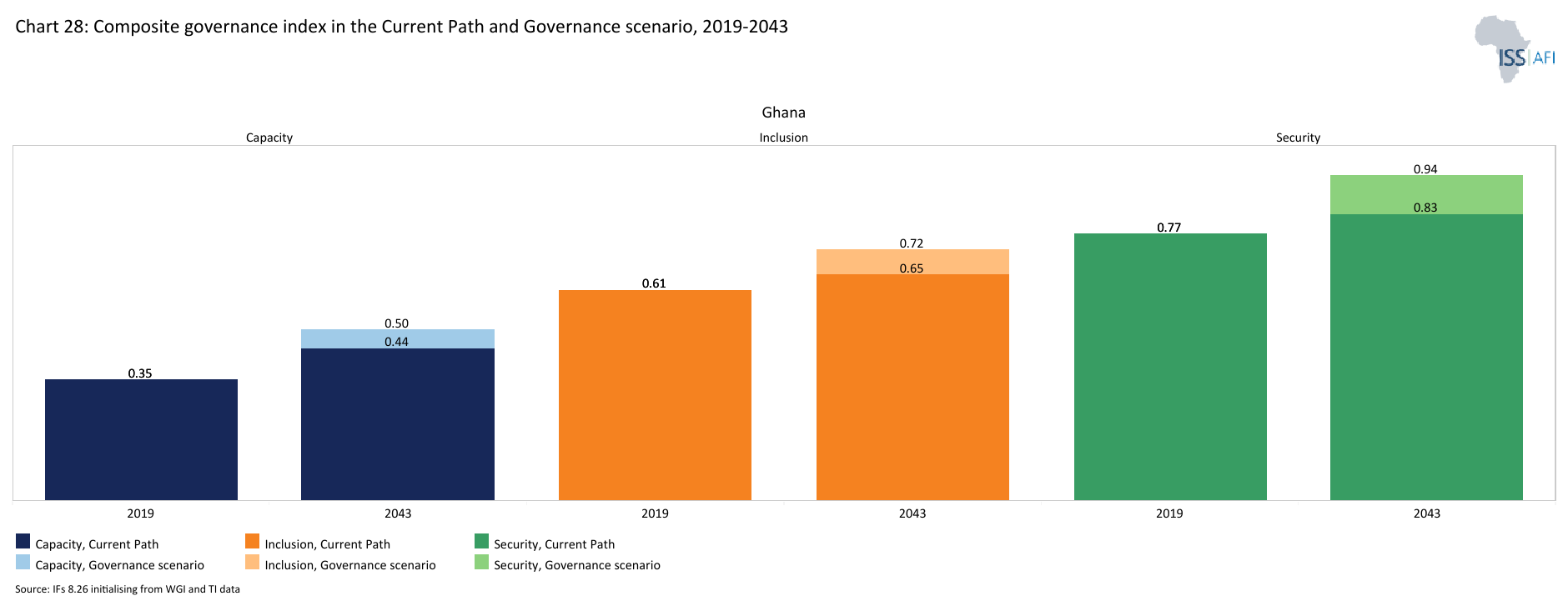

- Generally, Ghana performs better on governance indices than most African countries. Ghana’s score on the composite governance index of 0.58 in 2023 was 16.2% higher than the average for its income peers in Africa. In the Governance scenario, Ghana's score on the composite governance index will improve to 0.72, which is about 12.5% above the Current Path by 2043 and about 30.9% above the Current Path average of lower-middle-income Africa in the same year.

In the third section, we compare the impact of each of these eight sectoral scenarios with one another and subsequently with a Combined scenario (the integrated effect of all eight scenarios). In our forecasts, we measure progress on various dimensions such as economic size (in market exchange rates), gross domestic product per capita (in purchasing power parity), extreme poverty, carbon emissions, the changes in the structure of the economy, and selected sectoral dimensions such as progress with mean years of education, life expectancy, the Gini coefficient or reductions in mortality rates.

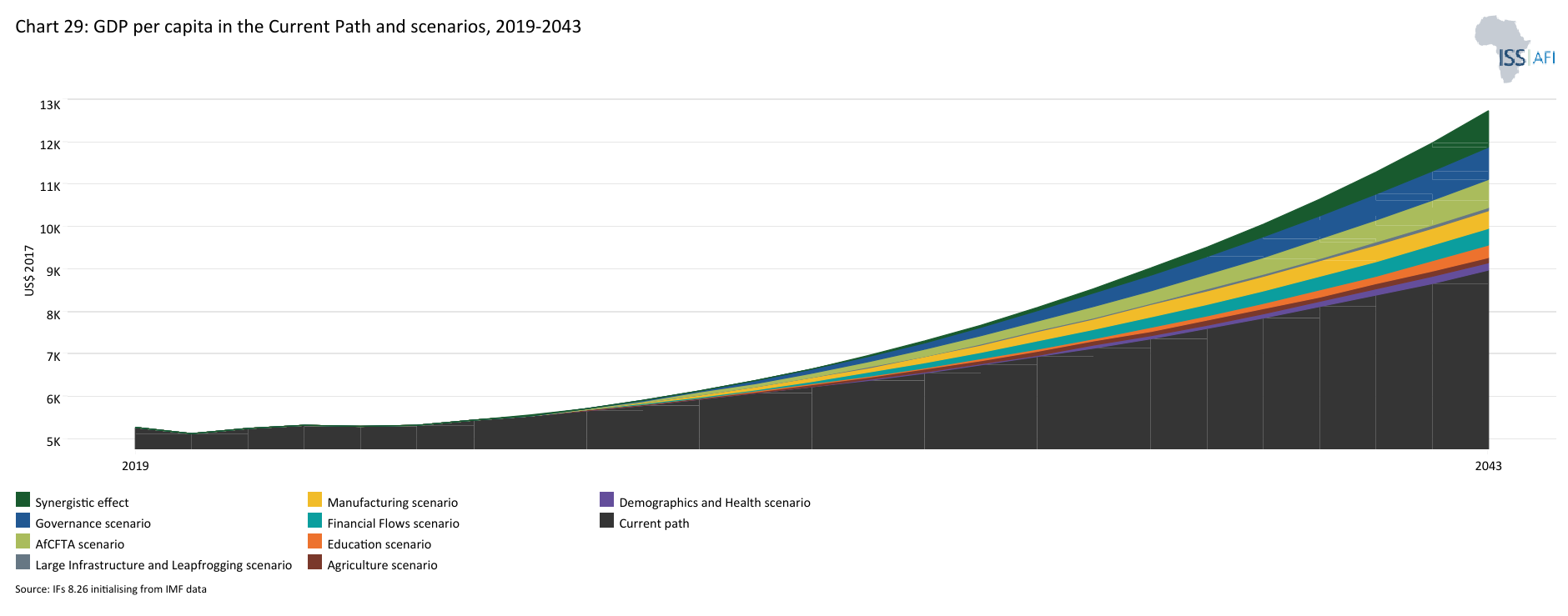

- The scenario with the greatest impact on GDP per capita in Ghana by 2043 is the Governance scenario, followed by the AfCFTA and the Manufacturing scenarios. In the Governance scenario, Ghana’s GDP per capita will witness an increase of US$768 or 8.6% more than the Current Path. The AfCFTA and Manufacturing scenarios further raise GDP per capita for Ghana by an additional US$659 and US$432 by 2043.

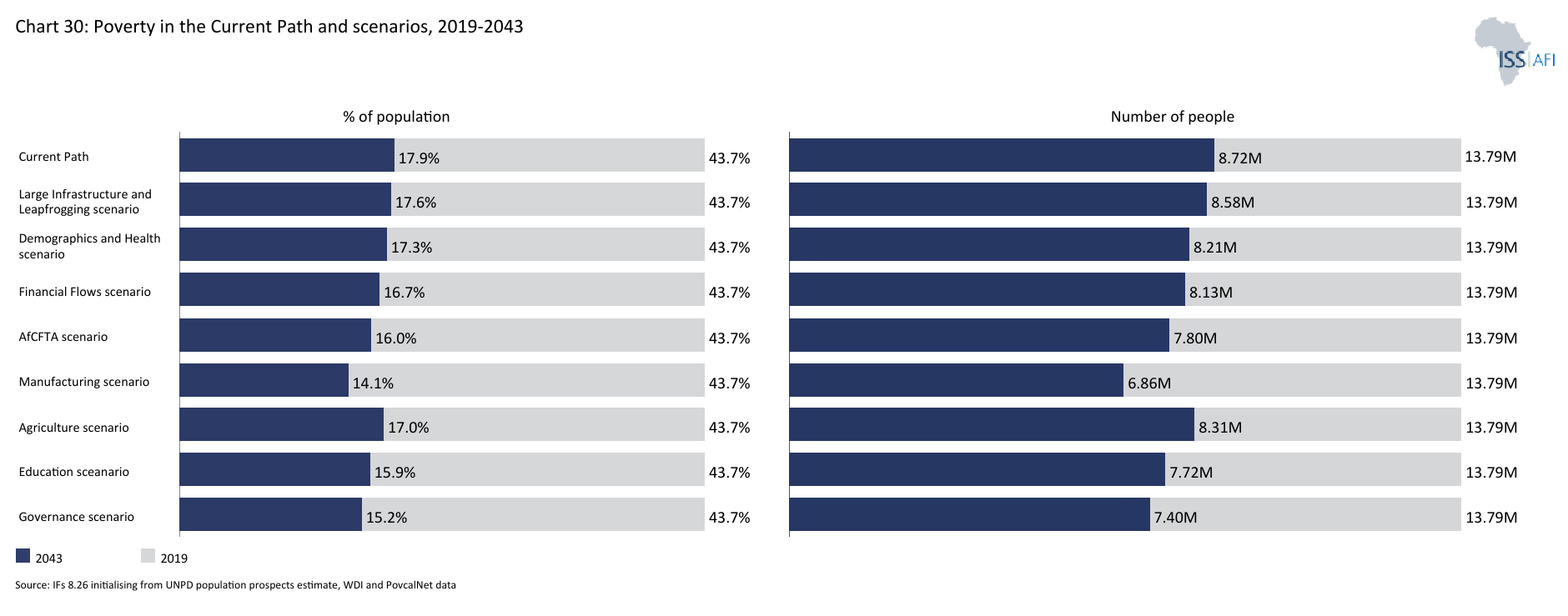

- The Manufacturing scenario also has the largest potential to reduce extreme poverty, followed by the Governance and Education scenarios. The Manufacturing scenario has the potential to reduce extreme poverty in Ghana by an additional 1.9 million people. Similarly, the Governance and Education scenarios can lift about 1.3 and 1.0 million people out of extreme poverty, respectively.

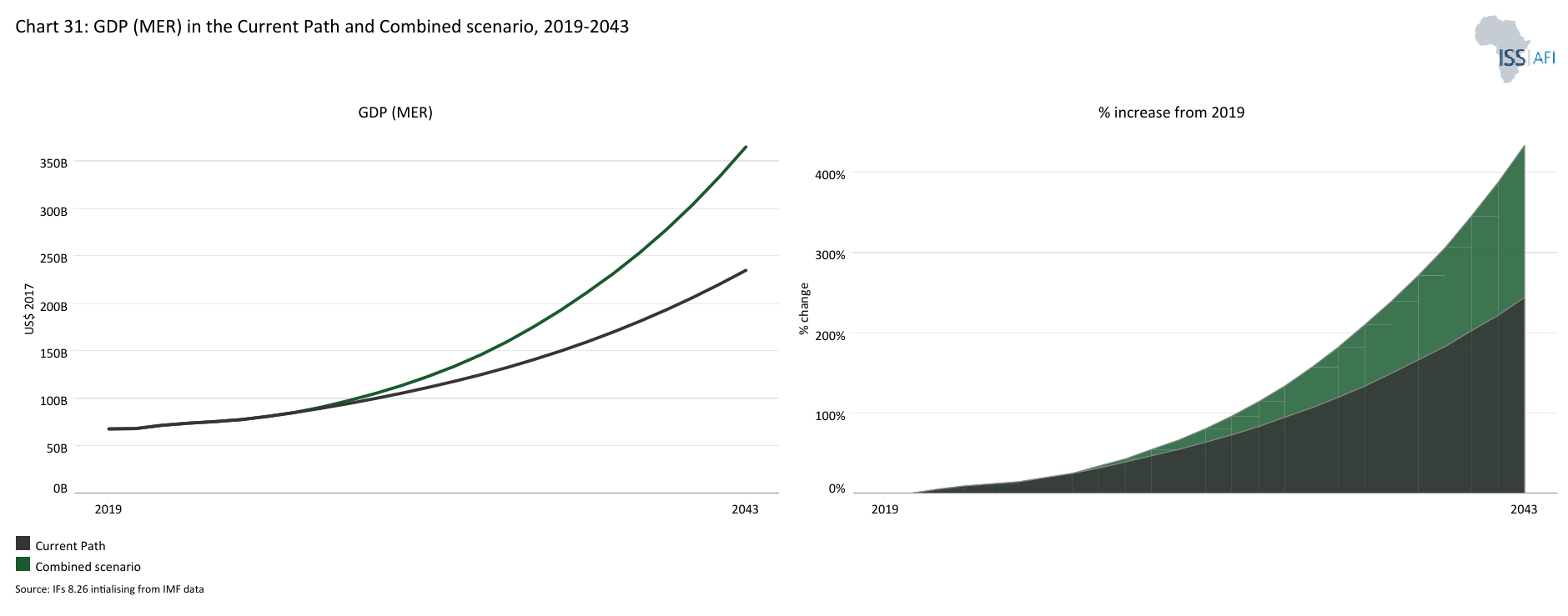

- In the Combined scenario, Ghana’s GDP will rise to US$365 billion exceeding the Current Path of US$235 billion. Similarly, in the Combined scenario, GDP per capita for Ghana will increase to US$12 720 by 2043. This will be US$3 760 more than the US$8 960 on the Current Path.

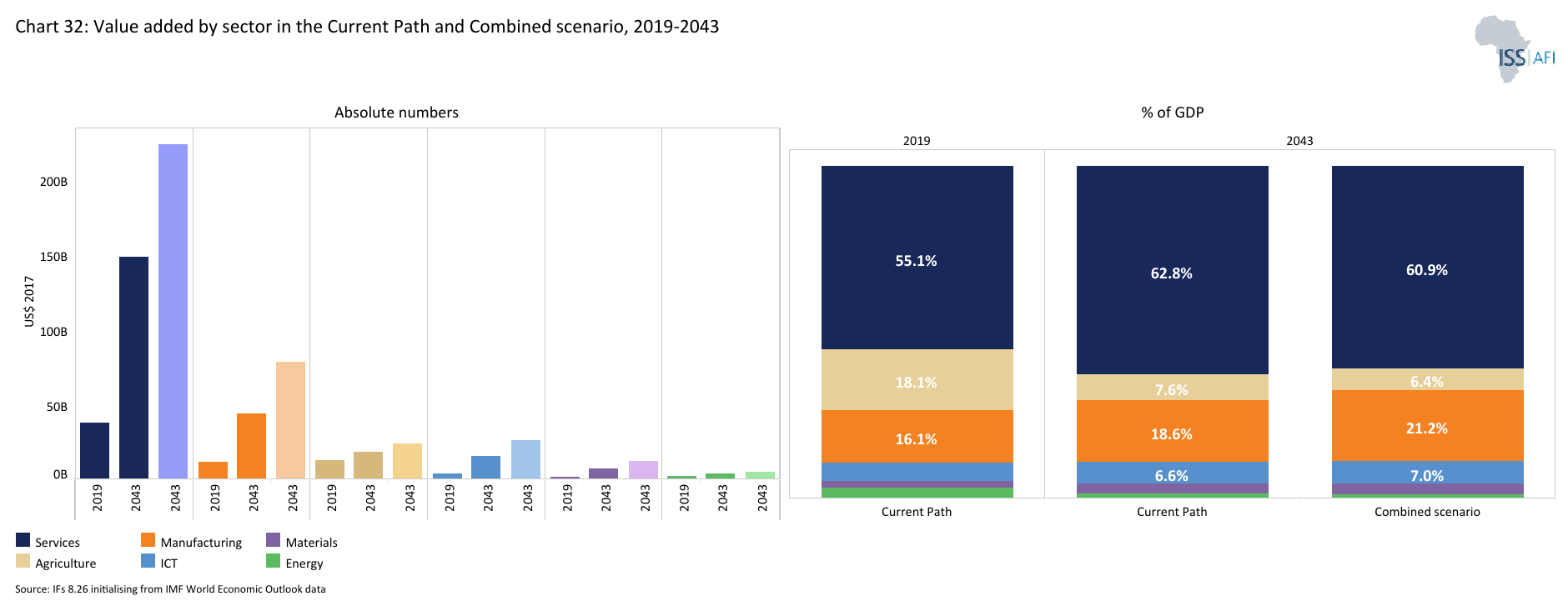

- By 2043, the service sector will still be the largest contributor to GDP at 60.5%. The manufacturing sector will be the second-largest contributor to GDP in the scenario by 2043 with a share of 21.%. The share of the agriculture sector will decline to 7.2% while the share of ICT will rise 7.0%.

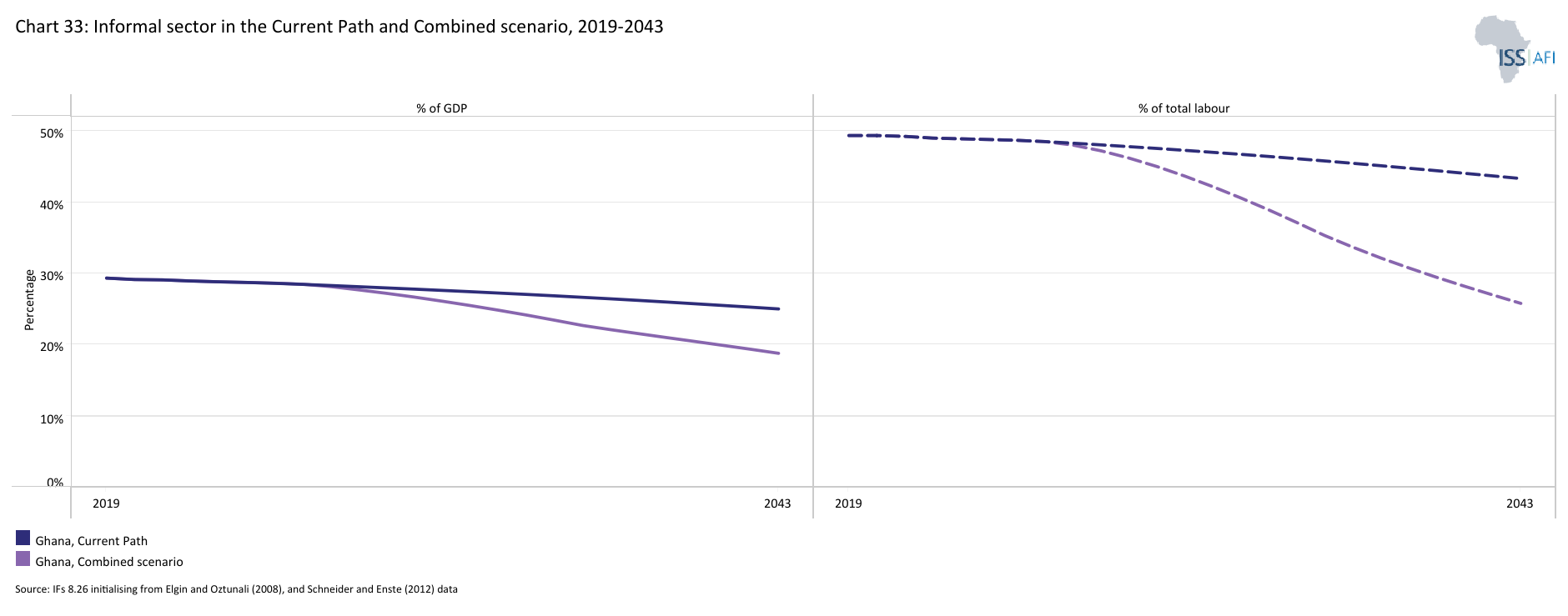

- By 2043, the size of the informal sector in Ghana will decline to 18.8% of GDP, valued at US$68.8 billion. At this rate, the contribution of the informal economy will be lower than the Current Path at 25.1% (valued at US$59.0 billion). Likewise, the size of the informal labour sector will be about 3.7 million by 2043, constituting 25.8% of the total labour force instead of 43.4% in the Current Path.

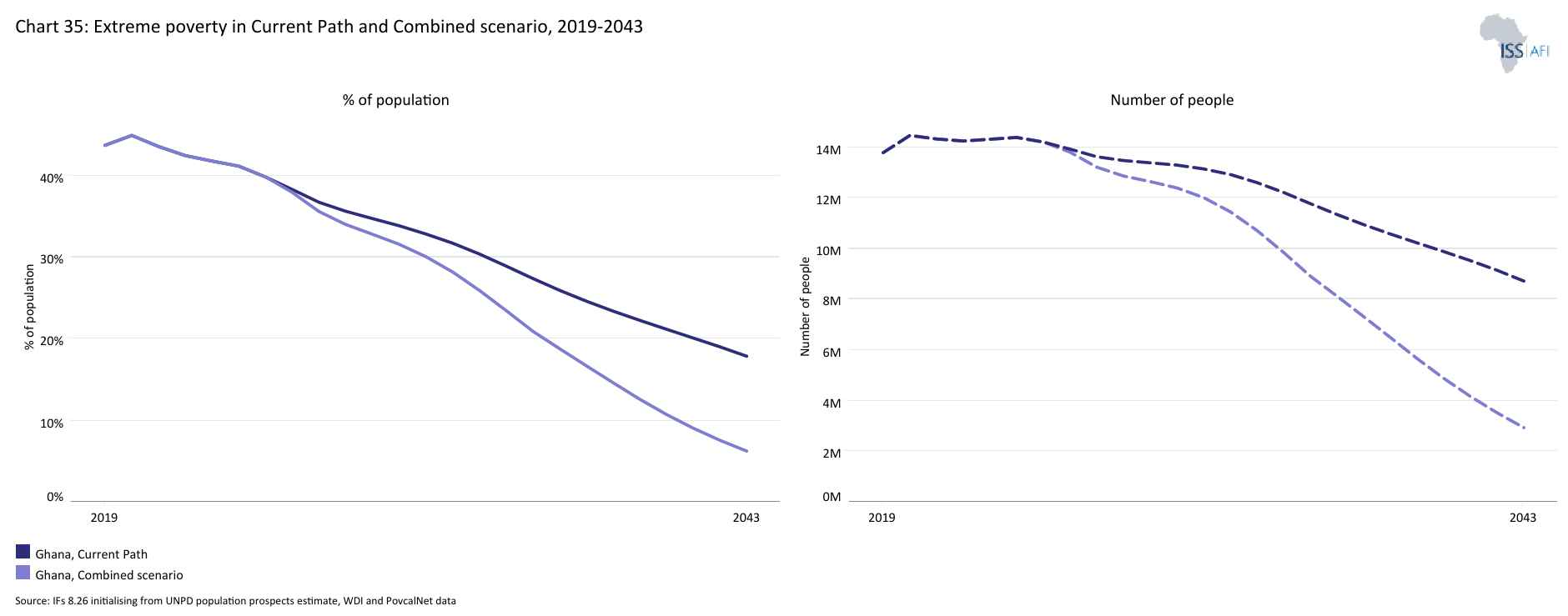

- In the Combined scenario, both the number and portion of poor people will significantly decline. By 2043, only about 6.3% of Ghanaians equivalent to 2.9 million people will be living in extreme poverty, meaning 5.8 million more people could be lifted out of poverty.

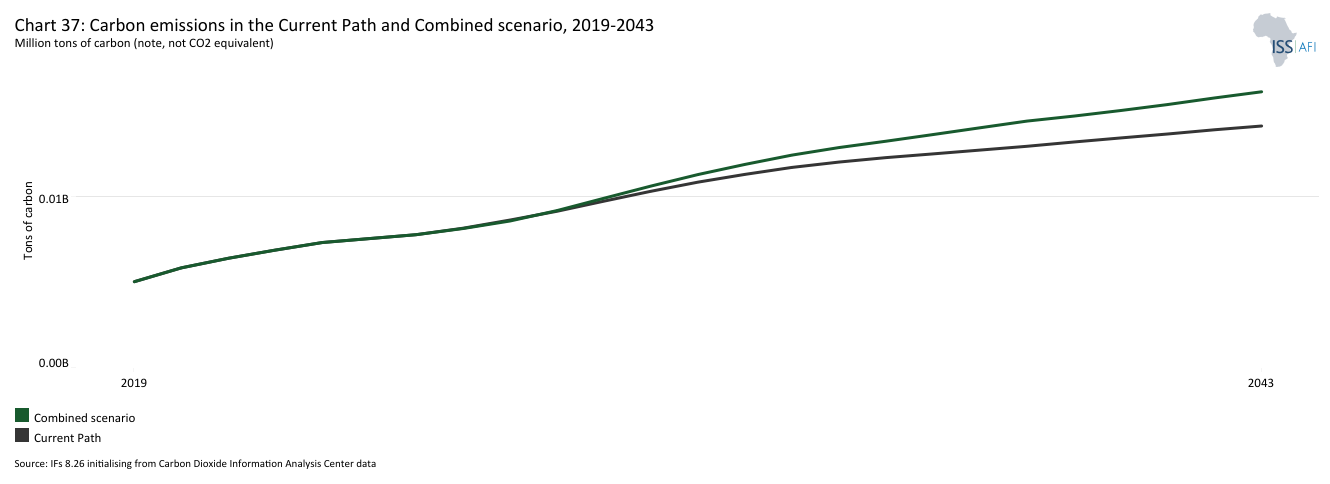

- In 2023, Ghana released about 7 million tons of carbon from fossil fuel use. In the Combined scenario, Ghana’s total carbon emissions will rise to 16 million tons — 14.3% higher than what is estimated in the Current Path in the same year.

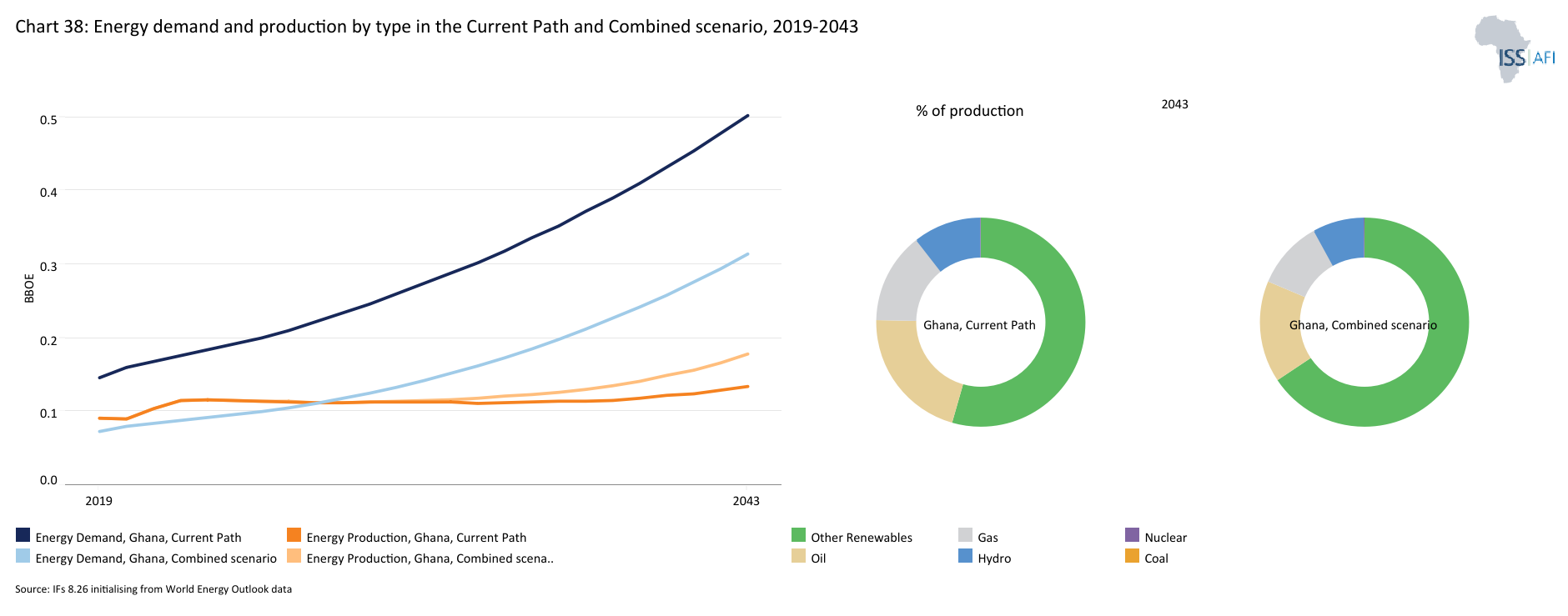

- The Combined scenario shows an increase in energy demand, creating a larger energy deficit, with renewable energy becoming the dominant energy source, surpassing oil and gas. By 2043, the excess demand for energy in the scenario of 133 million BOE will be 13.7% higher than the Current Path. The share of other renewable energy in total energy production in the country will rise significantly to constitute 66% and to become the leading contributor.

We end this page with a summarising conclusion offering key recommendations for decision-making.

Ghana has made significant progress in advancing human development and its economic growth prospect is higher than many of its African income peers. However, it will still lag behind its developmental targets if it does not accelerate its development potential and harness its manifold economic opportunities. Therefore, a comprehensive and targeted set of socio-economic policy interventions across demographics, health, education, agriculture, infrastructure, manufacturing, trade, financial flows, and governance is necessary to redirect the country’s current development trajectory towards a more sustainable and inclusive path.

All charts for Ghana

- Chart 1: Political map of Ghana

- Chart 2: Population structure in the Current Path, 1990–2043

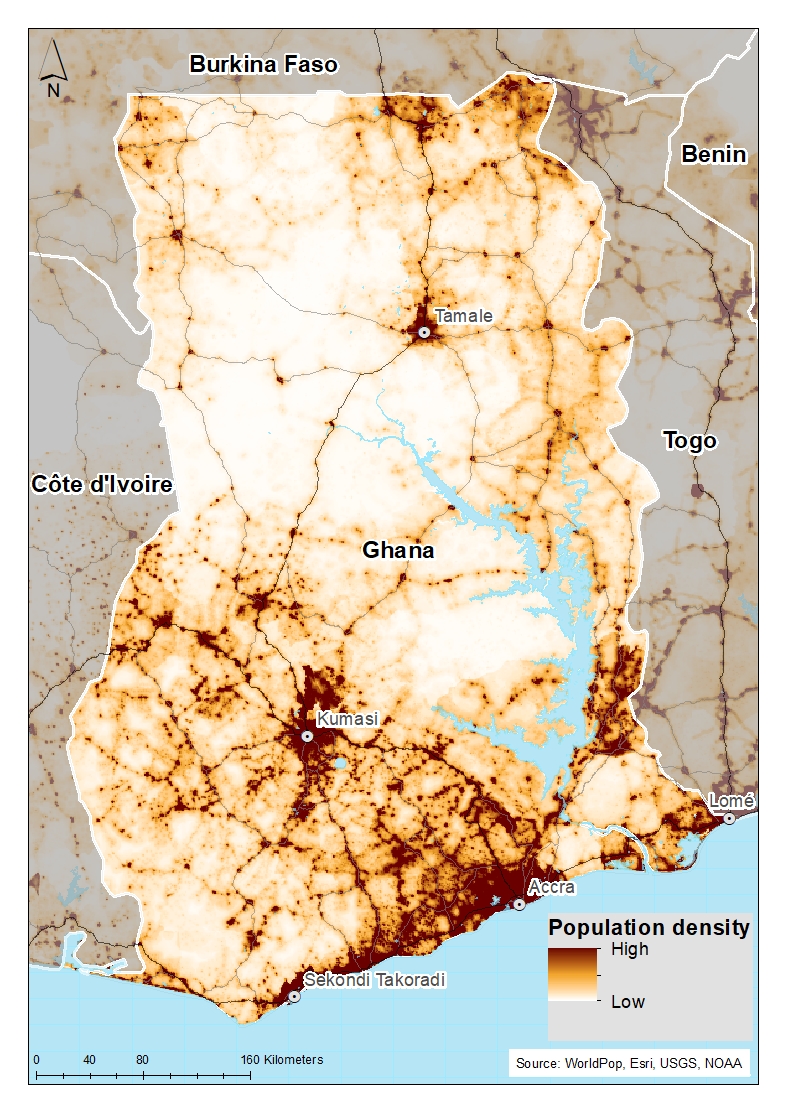

- Chart 3: Population distribution map, 2023

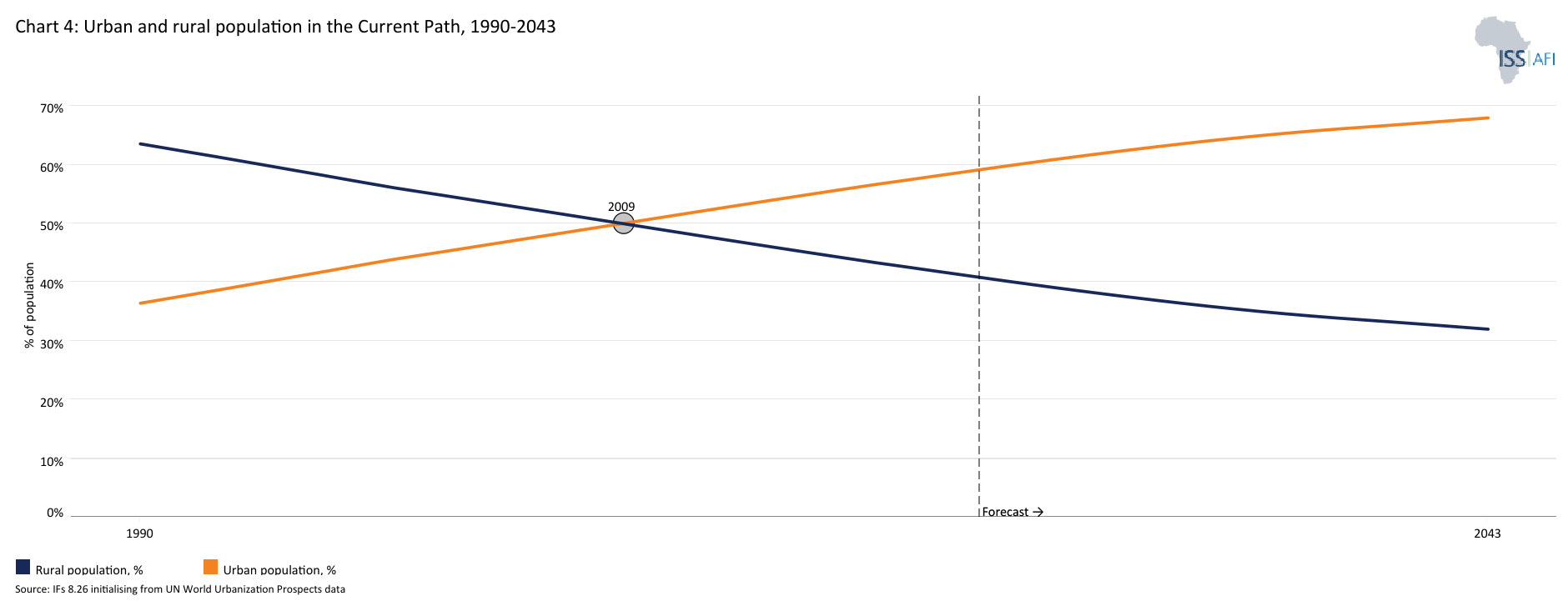

- Chart 4: Urban and rural population in the Current Path, 1990-2043

- Chart 5: GDP (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, 1990–2043

- Chart 6: Size of the informal economy in the Current Path, 2019-2043

- Chart 7: GDP per capita in Current Path, 1990–2043

- Chart 8: Extreme poverty in the Current Path, 2019–2043

- Chart 9: National Development Plan of Ghana

- Chart 10: Relationship between Current Path and scenario

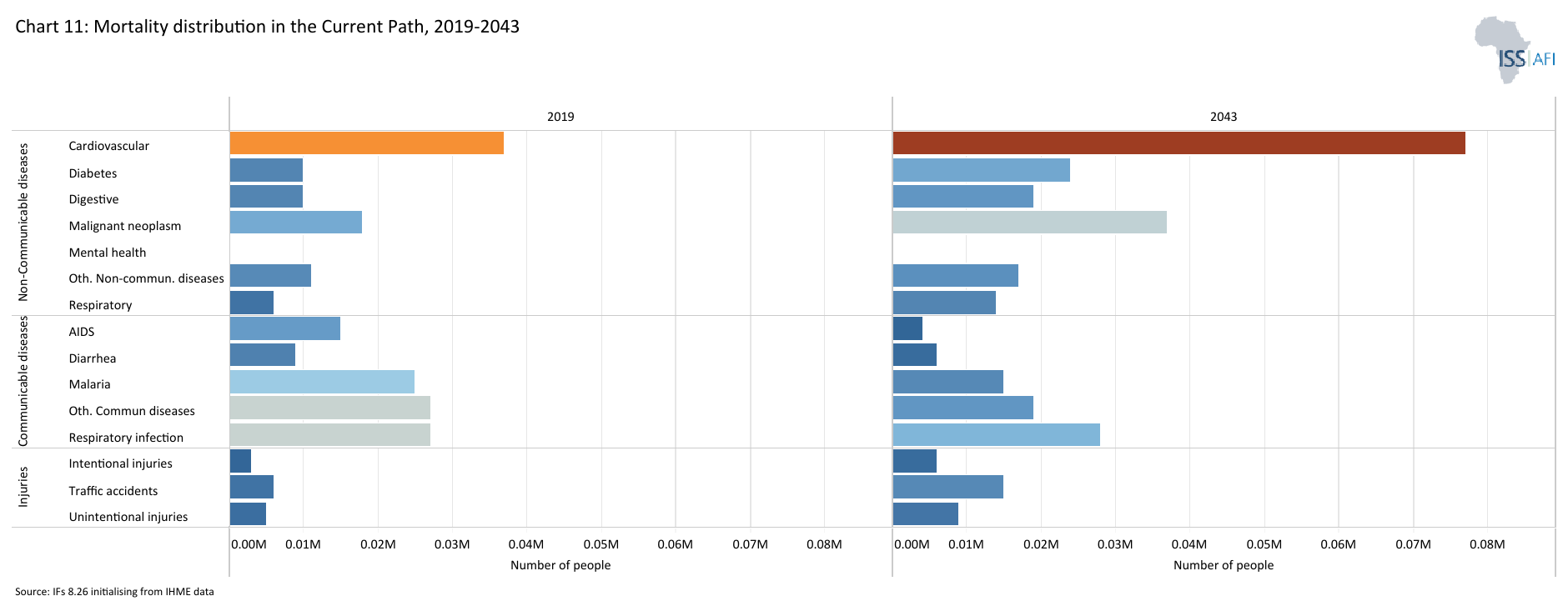

- Chart 11: Mortality distribution in the Current Path, 2019-2043

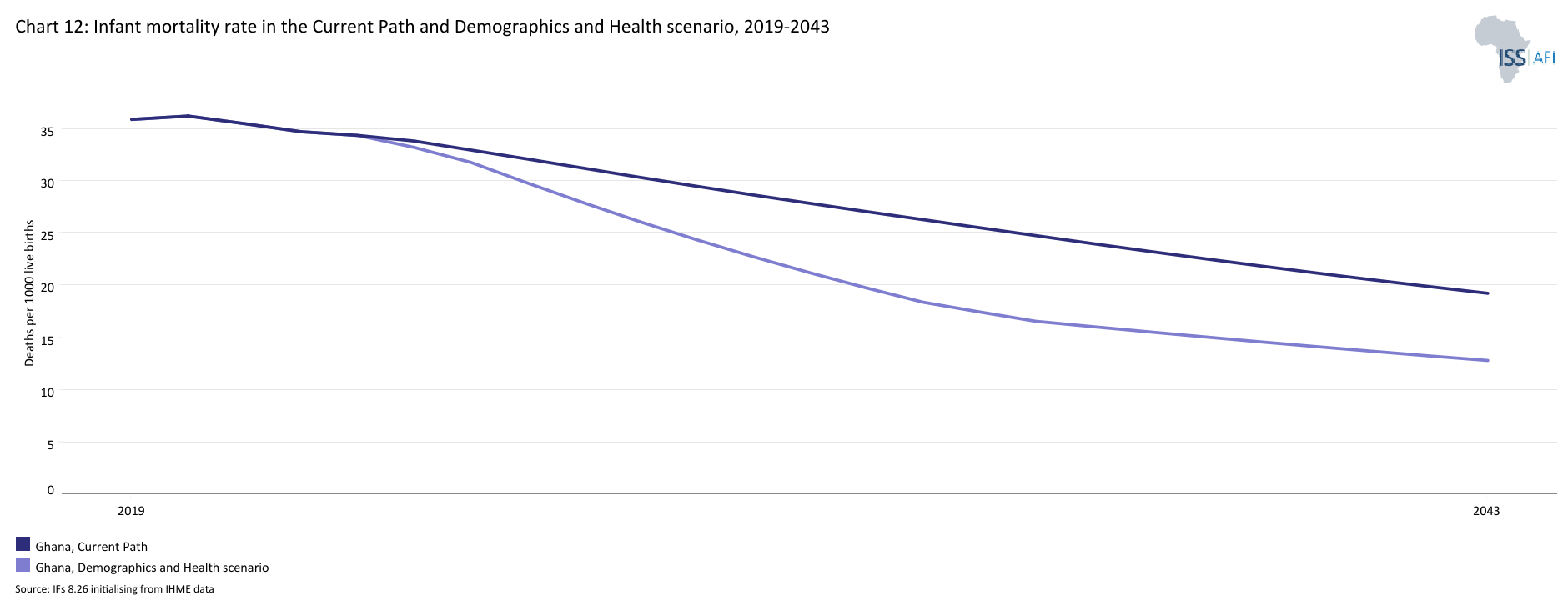

- Chart 12: Infant mortality rate in Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 2019–2043

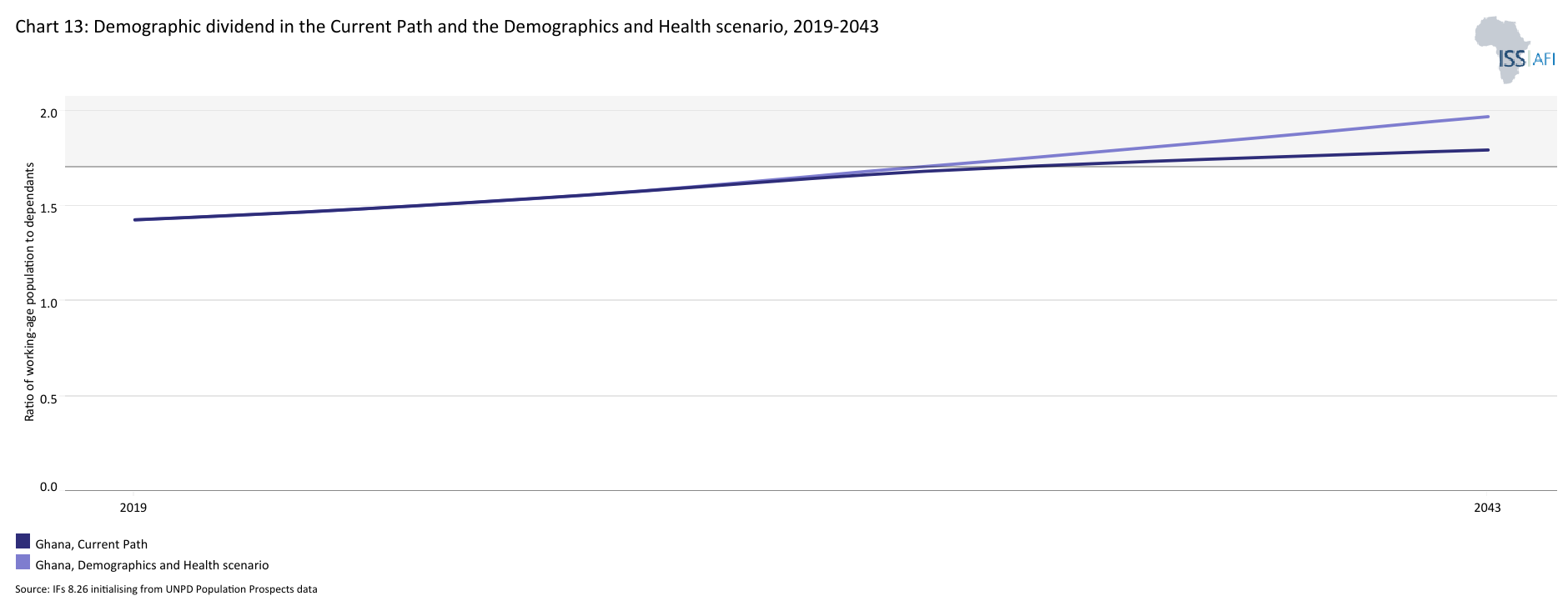

- Chart 13: Demographic dividend in the Current Path and the Demographics and Health scenario, 2019–2043

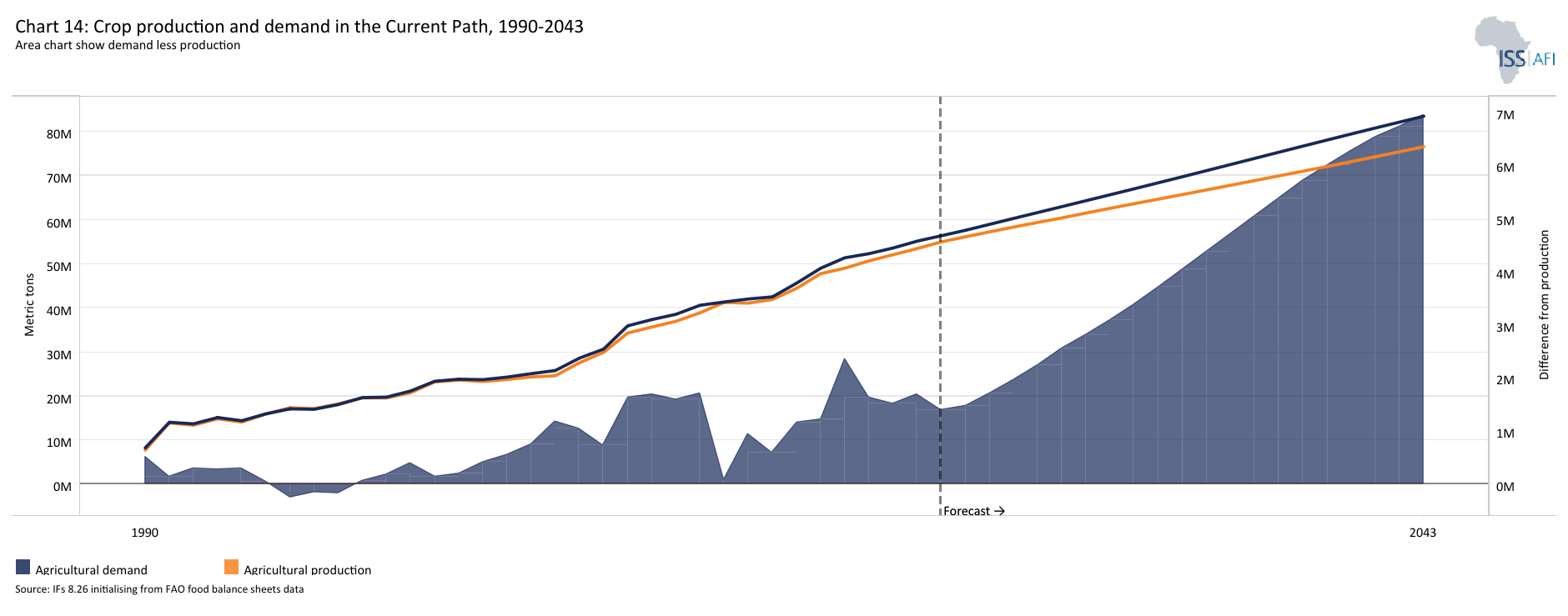

- Chart 14: Crop production and demand in the Current Path, 1990-2043

- Chart 15: Import dependence in the Current Path and Agriculture scenario, 2019–2043

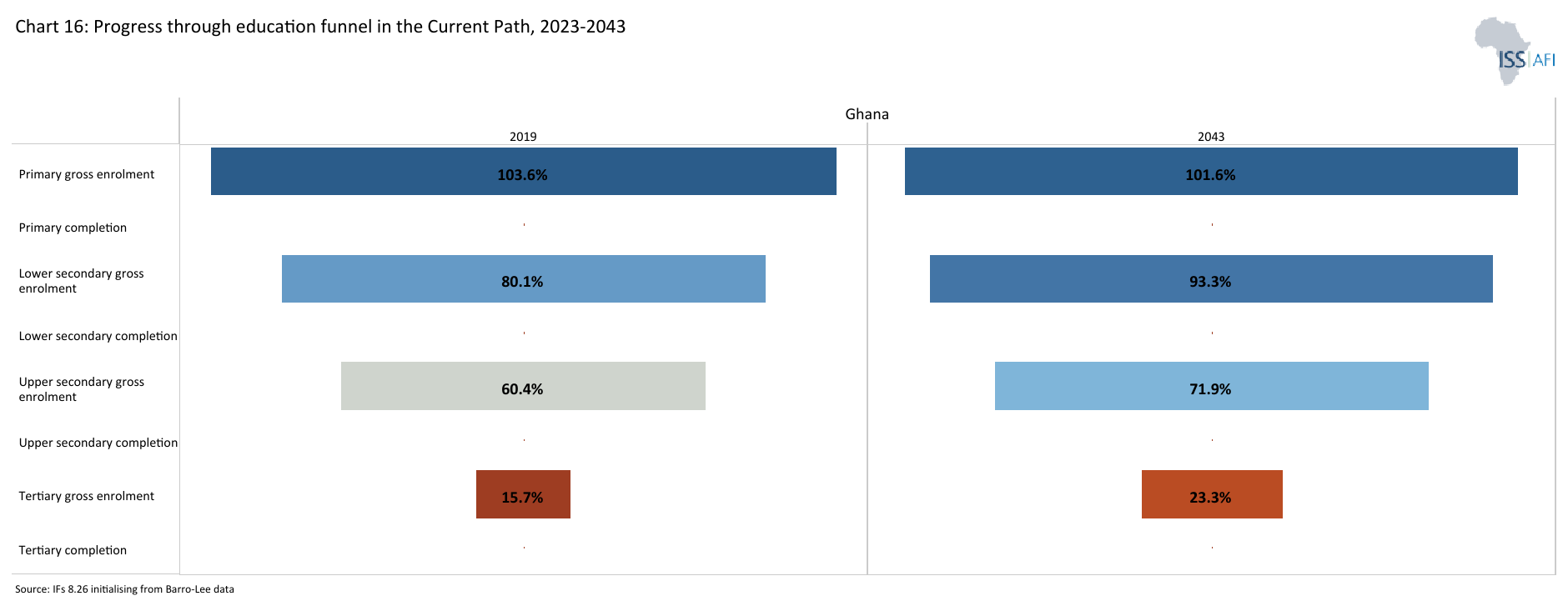

- Chart 16: Progress through the education funnel in the Current Path, 2019-2043

- Chart 17: Mean years of education in the Current Path and Education scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 18: Value-add by sector as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2019-2043

- Chart 19: Value-add by the manufacturing sector in the Current Path and Manufacturing scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 20: Exports and imports as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2000-2043

- Chart 21: Trade balance in the Current Path and AfCFTA scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 22: Electricity access: urban, rural and total in the Current Path, 2000-2043

- Chart 23: Cookstove usage in the Current Path and Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 24: Access to mobile and fixed broadband in the Current Path and the Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 25: FDI, foreign aid and remittances as % of GDP in the Current Path, 1990-2043

- Chart 26: Government revenue in the Current Path and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

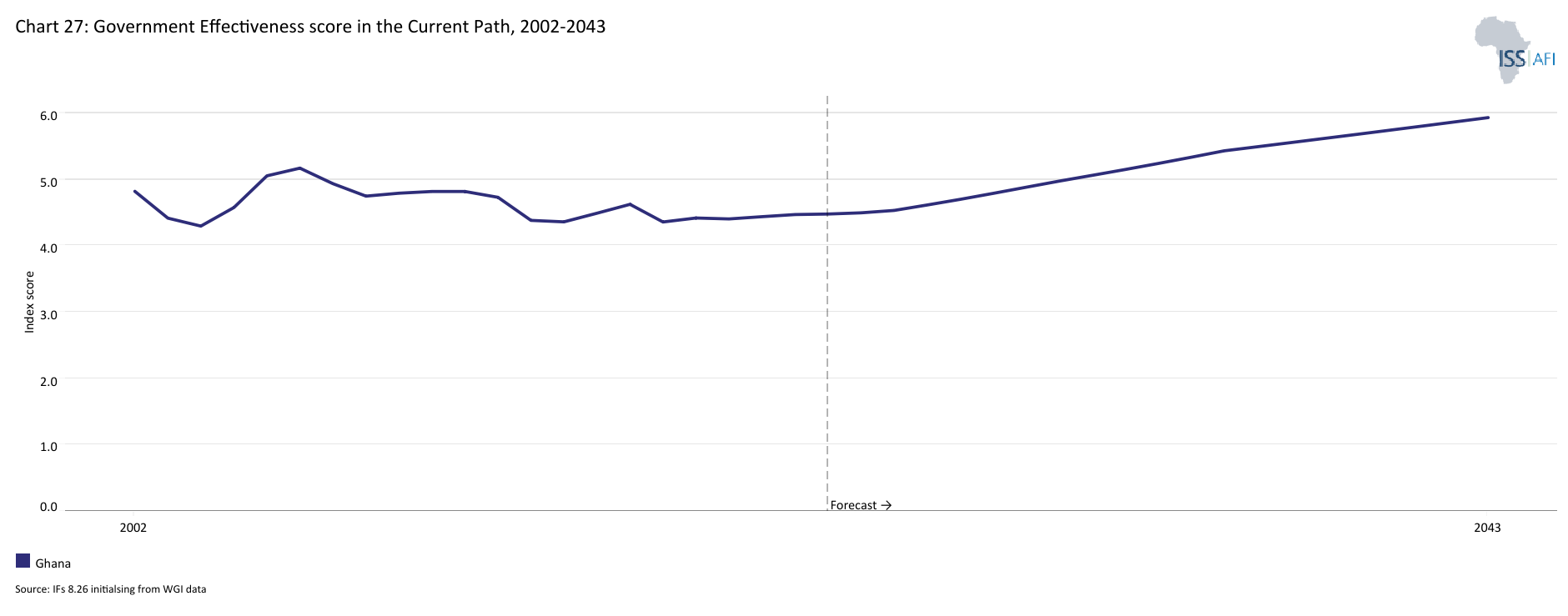

- Chart 27: Government effectiveness score in the Current Path, 2002-2043

- Chart 28: Composite governance index in the Current Path and Governance scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 29: GDP per capita in the Current Path and scenarios, 2019–2043

- Chart 30: Poverty in the Current Path and scenarios, 2019–2043

- Chart 31: GDP (MER) in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 32: Value added by sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 33: Informal sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

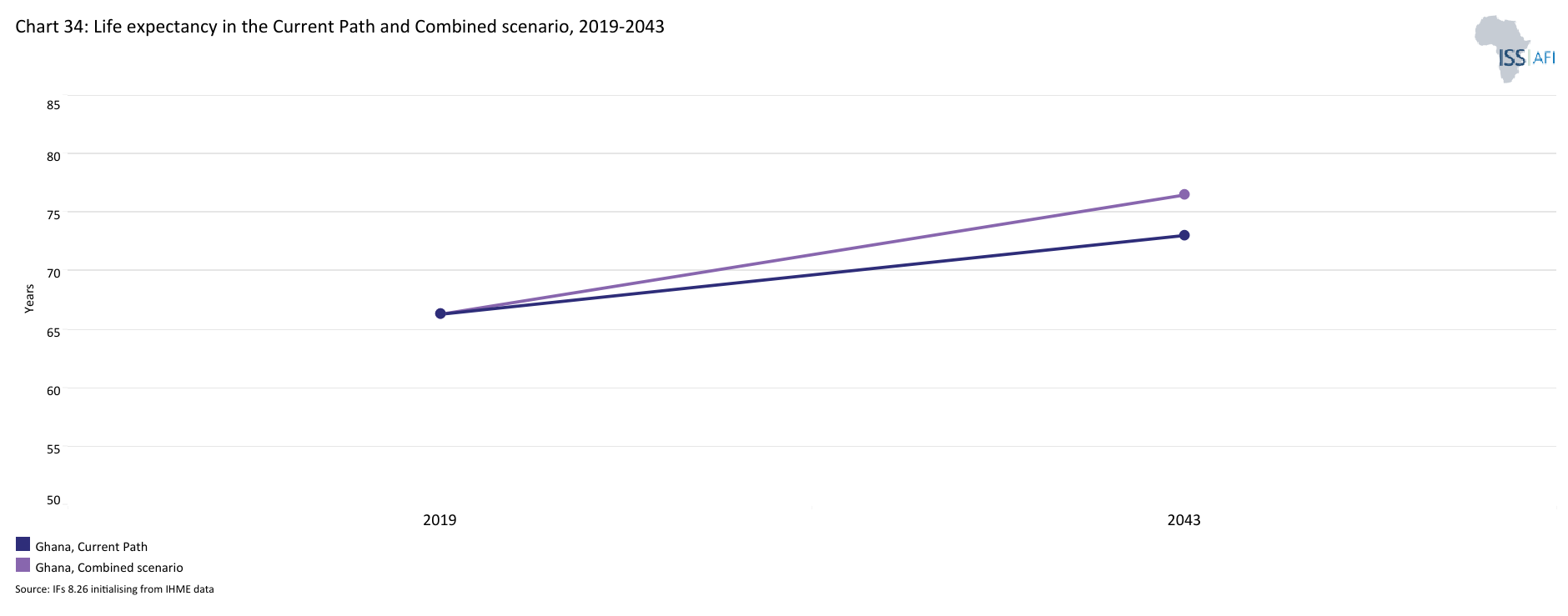

- Chart 34: Life expectancy in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 35: Poverty in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

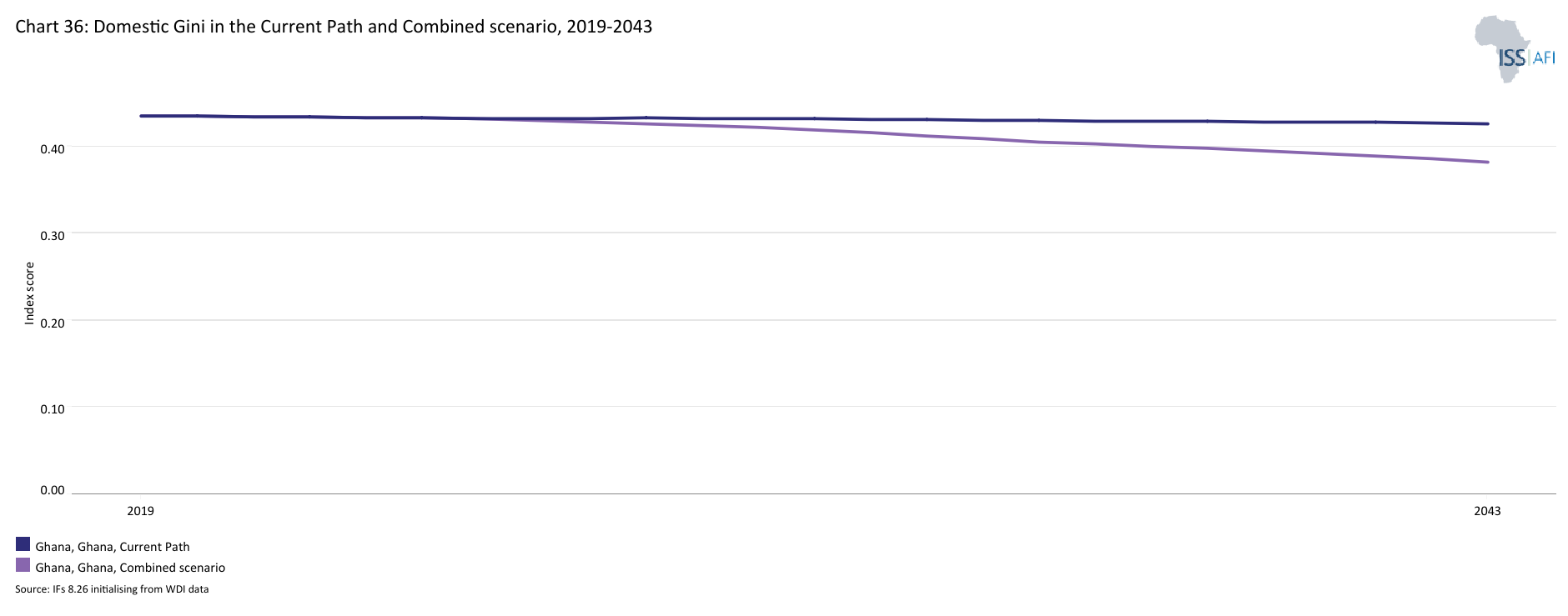

- Chart 36: Domestic Gini in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 37: Carbon emissions in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 38: Energy demand and production by type in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019-2043

- Chart 39: Policy recommendations

Chart 1 is a political map of Ghana.

Ghana is one of the lower-middle-income countries in Africa. It is located in West Africa along the Gulf of Guinea, bordering Burkina Faso in the north, Côte d’Ivoire in the west and Togo in the east, all of which are members of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). The national capital, Accra, is located in the Greater Accra Region of southern Ghana. The country has a total area of 238 535 km² and a tropical climate with two major seasons consisting of a rainy season and a dry season. Ghana is divided into six ecological zones, namely: Sudan savannah, Guinea savannah, Coastal savannah, forest/savannah transitional zone, deciduous forest zone, and the rain forest zone. Ghana has abundant natural resources such as gold, bauxite, diamonds, timber, manganese and oil, and it is the second-largest producer of cocoa in the world. The country is divided into 16 administrative regions, after a 2019 referendum which increased the number from 10 to 16, consisting of 261 districts.

Since Ghana gained independence from the British in 1957, it has oscillated between military rule and democratic governance, experiencing four successful military coups and numerous attempted coups. After independence, Kwame Nkrumah who led the country to attain independence assumed the role of Prime Minister on the ticket of his party, the Convention People’s Party while the Queen of England remained the Head of State. Three years after that, the country officially became a republican state in 1960, which made Kwame Nkrumah both the head of state and the head of government. Nkrumah’s rule as president only lasted for 6 years after he was overthrown in a military coup on 24 February 1966 leading to the truncation of the First Republic. This coup was led by military officers Colonel E.K. Kotoka, Major A.A. Afrifa, Lieutenant General (retired) J.A. Ankrah, and Police Inspector General J.W.K. Harlley. Following the coup, the National Liberation Council (NLC), the resulting military junta, assumed control of the country with Joseph Ankrah as the President of Ghana.

The NLC ruled for three years and facilitated a transition to democratic rule through the August 1969 general elections. The Progress Party (PP) won the elections establishing the Second Republic with its leader Kofi Abrefa Busia as the prime minister and Edward Akufo Addo as president. On 13 January 1972, the PP government was overthrown in a military coup led by Colonel Ignatius Kutu Acheampong. Following the coup, the newly established National Redemption Council (NRC) assumed control of Ghana, with Colonel Acheampong appointed as both the head of state and the head of the NRC. By 1975, the NRC was transformed into the Supreme Military Council (SMC), and the palace coup in July 1978 replaced General Acheampong with General F.W.K. Akuffo as the leader of the SMC. On 4 June 1979, an uprising by young military officers overthrew the SMC and established the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC) with Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings as its leader.

The AFRC supervised the 1979 general election which was won by the People's National Party (PNP) establishing the Third Republic with its leader Hillia Limann as President. The reign of Limann was cut short when on 31 December 1981 his administration was overthrown in a military coup led by Flight Lieutenant Rawling who had earlier relinquished power to him. After the coup, Rawlings established the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) with himself as the Chairman marking the beginning of the longest military rule in the country. By 1991, Rawlings agreed to implement a new constitution and hold elections.

A new constitution was enacted in 1992, introducing multiparty democracy and general elections to establish the Fourth Republic thereby returning the country to constitutional rule in 1993. Since the 1992 election, the country has fully embraced liberal multiparty democracy and has successfully organised eight successive presidential and parliamentary elections every four years. These elections have led to the alternation of power between the two dominant political parties in the country, that is, the New Patriotic Party (NPP) and the National Democratic Congress (NDC) – a feat which has been highly acclaimed both locally and globally. So far, Ghana has had five presidents under this republic, namely, Jerry John Rawlings of NDC (1993-2000), John Agyekum Kuffour of NPP (2001-2008), John Evans Atta-Mills of NDC (2009-2012)[1who died in office on July 2012 before completing his tenure in January 2013. ], John Dramani Mahama of NDC (2012-2016), and Nana Addo Danquah Akuffo-Addo of NPP (2017-2024). This has made the Fourth Republic the most enduring, longest and stable republic in the country’s history. Since 1992, the party that wins the presidential elections also wins majority in parliament with the only exception occurring during the 2020 general elections. For the first time, both the NDC and NPP secured 137 members of parliament each with one independent candidate leading to a hung or split parliament. Ghana is scheduled to organise another presidential and parliamentary on 7th December 2024 to choose a leader that will replace the incumbent President Akuffo Addo whose tenure will expire on 6 January 2025. The two leading candidates are the main opposition NDC’s candidate, former president John Dramani Mahama, and Mahamudu Bawumia, vice president and candidate for the governing NPP.

Chart 2 presents the Current Path of the population structure, from 2019 to 2043.

Ghana is the second most populous country in West Africa after Nigeria and the 13th most populous country in Africa. In 1990, Ghana’s population stood at 15.5 million people. By 2023, the population had more than doubled to 34.3 million people. This growth can be attributed to the high fertility rate coupled with a declining death rate in the country. Such rapid population growth has costly repercussions for the economy and human development prospects as it inevitably contributes to the deterioration of quality of life in terms of health, nutrition, access to employment and other basic amenities.

However, population growth has slowed in recent years owing to the slowing fertility rate due to the increased use of modern contraceptives. Consequently, Ghana’s population growth rate of 2.0% made it the 18th lowest in Africa and second lowest in West Africa after Cabo Verde. This was below the average of 2.6% for Africa and a decline from the 2.8% it recorded in 1990. Likewise, in 2023, the total fertility rate among women of childbearing age in Ghana of 3.5 births per woman was below Africa’s average of 4.3 births per woman and was the second lowest in West Africa after Cabo Verde. The declining total fertility and the associated population growth among other things can be attributed to the rising female participation in the labour force which was estimated to be 64% in 2023.

In terms of population structure, 36.5% of Ghanaians were under the age of 15, 59.7% were in the 15–64 age group (working age), and 3.8% were 65 years and older. Comparing this with the structure in 1990 reveals that Ghana’s population has fundamentally changed over the past three decades. This means Ghana has a relatively high active population part compared to its dependent or vulnerable population part. Therefore, if well-trained and a sufficient number of jobs and opportunities are created, the active population part can be a potential source of growth. However, with limited opportunities and training, it can become a drag on growth.

The country’s youth bulge (the ratio of its population aged between 15 and 29 to the total adult population) stood at about 42.2% in 2023 — a fall from 49.3% in 1990. This was below the average of 45.4% for Africa. The median age for Ghana in 2023 was 21.8 years — an increase from 15.4 years recorded in 1990 and Africa’s median age of 20.4 years. The implication of a large youth bulge as in the case of Ghana is that it can usher in youth activism and positive political changes in the country, it can also increase the likelihood of criminal violence, conflicts and instability, mainly when the needs of the youth, such as employment, cannot be met. The large youth bulge in the country raises concerns about youth unemployment and underemployment. According to the 2023 Ghana Human Development Report, 65% of Ghanaian youth between ages 15-24 are unemployed. Likewise, the World Bank reports that more than half of Ghanaian youth are unemployed. With such high levels of unemployment, it is not surprising that the country has witnessed several protests in recent years among the youth. The Fix-the-Country-Movement was one such protest which, among other things, demanded that the government fix the rising unemployment and cost of living in Ghana.

In the forecast horizon, the structure of the Ghanaian population will modestly change as the share of the youth population slightly declines. With the country’s population growth rate declining to 1.4% by 2043, the total population will rise steadily reaching 48.8 million in 2043 by which it will be the 14th largest in Africa. By then, the median age will increase to 30.0 years, and the youth bulge will slightly fall to 33.6%. The proportion of people under the age of 15 will decline to 29.5%, while the share of the working-age population and the population aged 65 and older will increase to 64.2% and 6.3%, respectively, by 2043. This rapid decline in population growth will follow the drastic fall in the total fertility rate to 2.5 births per woman. This can facilitate Ghana’s development and improve average incomes much quicker as the demands on the fiscus to cater to its youthful population will reduce.

Chart 3 presents a population distribution map for 2023.

Ghana’s total land area is approximately 238 533 km². In 2023, Ghana was the 4th most densely populated country in West Africa and the 12th most densely populated country in Africa. Ghana's population density is estimated to be about 1.5 people per hectare, which is three times the average of 0.49 for Africa. The concentration of Ghana’s population has been around the southern part of the country, mainly the Accra-Kumasi-Takoradi triangle along the south of the Kwahu Plateau. The Northern Region is the largest in size, but the Greater Accra Region, where the national capital is located, is the most populous region and city, followed by Kumasi in the Ashanti Region. This is mainly due to the economic productivity of the region. Indeed, the south of Kwahu Plateau contains all the country’s mining centres, timber-producing deciduous forests and cocoa-growing lands. The area is also linked to the coast through rail and road networks, thereby important for investment and labour movement. The south is also populated partly due to the influx of refugees from Liberia during the war, and many Togolese people who fled political violence settled along the Volta River Basin. By 2043, Ghana’s population density will reach 2.1 people per hectare, far above the average of 0.812 for Africa.

Chart 4 presents the urban and rural population in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

Over the years, Ghana has rapidly urbanised, achieving parity in urban-rural settlement as far back as 2009. In 1990, 36.4% of Ghanaians lived in urban areas, above the average of 30.5% for Africa and 33.4% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. As a result of the rapid urbanisation, by 2023, 59.1% of the population resided in urban centres, which is ten percentage points above the average for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. This places Ghana as the 16th most urbanised country on the continent, the 9th most urbanised country among Africa’s lower-middle-income countries and the third most urbanised country in West Africa, after Cabo Verde and Gambia.

Generally, urbanisation can occur either from the development of more towns to the status of urban centres or as a result of rural-urban migration. Post-independence, urbanisation in Ghana was largely influenced by its development strategy through industrialisation, modernisation and economic diversification. As a result, the country witnessed the emergence of industrial core cities such as Kumasi, Accra and Sekondi-Takoradi which accounted for 86% of industries in Ghana. Beyond this, the introduction of cocoa centres coupled with decentralisation also led to the proliferation of urban centres across the country. However, the rapid urbanisation witnessed in recent years stems from three main sources: natural increase, rural-urban migration and reclassification of towns into urban centres after attaining the threshold of 5 000 people.

Among these, the prominent contributing factor is rural-urban migration, mainly by young people in search of employment and better opportunities in major cities like Accra and Kumasi. It is therefore not surprising that the Greater Accra Region, despite its relatively smaller size, is now the most populated region. The effects of this rapid urbanisation as evident in the national capital of Accra are problems such as the development of slums, congestion, pressure on social amenities, expensive housing, poor sanitation and large youth unemployment, among other issues.

On the Current Path, about 68% of Ghanaians will reside in urban centres by 2043, far above the average for its income peers at 58.5% and Africa’s average of 52.8%.

Chart 5 presents GDP in market exchange rates (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

Ghana’s economy is highly dependent on commodity exports. It is presently the second largest in West Africa after Nigeria and the 9th largest in Africa. The country’s GDP, measured in market exchange rates (MER), grew from US$14.4 billion in 1990 to US$76.1 billion in 2023. The average GDP growth rate during this period stood at 5.1% per annum, above the average of 3.9% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. This partly reflects the political stability of the Fourth Republic which, unlike previous republics, has endured since 1992. Another factor that can explain this growth is the implementation of various internationally assisted economic reform programmes aimed at enhancing economic development and improving quality of life. These include the Structural Adjustment Programmes, Aid Effectiveness, the Highly Indebted Poor Country (HIPC), Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and the African Union Agenda 2063.

In addition, the country has implemented several medium-term plans, visions and strategies such as the Ghana Poverty Reduction Strategy (GPRS, 2003-2009) I&II, Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda (GSGDA, 2010-2017) I&II, and the Agenda for Jobs: Creating Prosperity and Equal Opportunity for All (2018-2021) I&II. Another important factor that bolstered the economy of Ghana was the discovery and production of oil in commercial quantities. For instance, in 2011, which marked the beginning of oil production in the country, the economy grew by a whopping 14%. The impact of these initiatives and policies has resulted in relatively higher economic growth over the past two decades, attaining a middle-income status in November 2010. Indeed, in 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic, Ghana’s economy was projected by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to be the fastest-growing economy in the world.

Despite these gains, the fundamentals of the economy remain weak and the economic structure is still agrarian and untransformed. The economy still revolves around the export of major traditional raw materials such as cocoa and gold while relying heavily on imported processed or finished goods with no major attempt to (apart, perhaps, from the 1960s) restructure the economy to support more beneficial industrialisation. Over the past three decades, the country has witnessed several economic crises mainly driven by domestic vulnerability and worsened by global or external shocks. These include the 2007/2009 global financial crisis which caused economic growth to dip. Also, between 2014/16, the global commodity crisis worsened the already challenging domestic crisis of unstable electricity supply (Dumsor), leading to a fall in economic growth to a paltry 2.1% in 2015 and worsening economic conditions.

In recent years, the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic coupled with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine worsened the domestic economic vulnerabilities. What started as a debt crisis in the beginning of 2022, with a debt-to-GDP ratio of above 80% and projected by the World Bank to reach 104% by the end of 2022, later resulted in a full-blown economic recession. The woes of the country began when international credit rating agencies downgraded Ghana to junk status due to its unsustainable and growing debt levels, which denied the government access to the global capital markets. Moody downgraded Ghana from B3 to Caa1 and further to Caa2, the worst ever. Similarly, Fitch also downgraded Ghana from B early that year to CCC and later to CC. These resulted in a free fall of the Ghana cedi and in the process it was ranked the worst-performing currency globally, after losing 45% of its value relative to the US Dollar in 2022. Inflation rose sharply from 13.9% in January 2022 to a 22-year high of 54.1% in December 2022, mainly driven by food inflation which ranked the highest food prices in sub-Saharan Africa. Similarly, the country’s interest rate of 30% and lending rate of 35% were the highest on the continent.

As the economic woes deepened, the country sought the support of the IMF as has been the case previously. In December 2022, the government signed a US$3 billion Extended Credit Facility staff-level agreement with the IMF, making it the 17th time Ghana has had its support. As a result, the government embarked on stringent measures such as debt restructuring (both domestic and external) and introduced additional taxes, including the electronic transaction levy (e-levy) which was vehemently opposed by many Ghanaians. Since then, the economy has seen relative stability with marginal improvement in growth rates. The debt-to-GDP ratio has also slightly declined to 86.1% mainly due to the debt restructuring. Inflation slowed down to 22.1% as of October 2024 and the Ghana cedi gained relative stability compared to 2022.

However, the structural macroeconomic vulnerability of the economy remains. The lingering challenges of high public debt often due to large fiscal deficits, subdued growth, high inflation, exchange rate volatility and rising interest rates continue to undermine the development potential of the country. Also, the financial sector stands at major risk due to the financial sector clean-up which collapsed several financial institutions and the recent domestic debt exchange programme which has reduced confidence in the financial sector. These notwithstanding, the World Bank projects that the growth rate will rebound to 5% by 2026 with improved macroeconomic fundamentals. On the Current Path, Ghana’s GDP will more than triple to US235.4 billion by 2043. The increase in GDP reflects the higher rate of economic growth expected to occur within the next 20 years.

Chart 6 presents the size of the informal economy as per cent of GDP and per cent of total labour (non-agriculture), from 2019 to 2043. The data in our modelling are largely estimates and therefore may differ from other sources.

The informal sector serves as a lifeline to many people, especially unskilled labourers, who cannot secure employment in the formal sector. According to the International Labour Organization, informal employment is often associated with income insecurity, unsafe work conditions, and limited access to the rights and benefits accorded to the formal sector. The lack of workplace safeguards can impact workforce participation rates and limit the contribution to the economy by lower-waged workers.

Ghana has a large informal sector that is vital to its economy. The sector constitutes about 62% of all commercial enterprises in the country and accounts for 90% of all businesses registered in the country. The informal economy in Ghana includes rural agriculture, small-scale gold and diamond mining, garage operators, shoe-manufacturing businesses, private lotto operators, private arms manufacturers, petty traders, commuter services, private taxi services, and small-time loan and saving scheme operators. The informal sector is dominated by the retail sector, demonstrating the extent and depth of the informal economy in the country. It often relies on low-technology and family labour, casual labour, apprenticeships, and communal labour. People in the informal sector are mostly self-employed and work from home, with some using any accessible public space (also known as 'no man's land').

In 2023, the size of the informal sector in Ghana was approximately 28.9% of GDP, almost at par with the average of 29.5% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. The large size of the informal sector also signals a huge potential for increasing government revenue by monitoring and regulating the activities of the sector. In terms of the labour force, close to half (48.9%) of the total labour force in Ghana was employed in the informal sector in 2023. Although this was high, it was below the 57.2% average for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. Other sources estimate that the informal sector employs 65.3% of the active labour force in Ghana. Indeed, the private informal sector accounts for 70-80% of the workforce in the country. The sector is often characterised by illiterate or semi-illiterate people and persons with no formal training. Their skills are usually acquired through apprenticeships and from family. Among these people are mostly women, followed by men and children. Most of the employees in the informal sector are paid below the national minimum wage with no social security benefits. This is mainly due to excess labour supply and a lack of skills that may attract higher wages.

To formalise the sector, the government is implementing several policies by removing impediments to business registration and access to financial services. Some of these efforts include the digitisation drive of the economy through various initiatives such as a digital property addressing system, a paperless port system, a mobile payment interoperability platform and the issuance of national ID cards. Also, the government has enhanced access to financial services through mobile money services and mobile money interoperability to promote the financial inclusion of people in the informal sector. Another policy is the government reducing bureaucratic barriers for businesses to attract informal sector business owners to register their businesses. On the Current Path, the size of the informal sector will decline slightly to 25.1% of GDP by 2043, at which point it will be below the average for its income-peers in Africa at 26.8% of GDP. Likewise, the informal labour share of the total labour force will fall to 43.4% by 2043. This projected reduction in the size of the informal economy augurs well for government revenue.

Chart 7 presents GDP per capita in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

Despite its limitations, GDP per capita is generally used to measure the standard of living and is the most widely used and accepted indicator to compare welfare among countries. Ghana has the eighth-highest GDP per capita among the 24 lower-middle-income countries in Africa. Using the purchasing power parity (PPP) measure for this analysis, its GDP per capita of US$5 286 in 2023 was 10.3% lower than the group average of US$5 830. This figure represents more than double the US$2 300 it recorded in 1990. This GDP per capita is due to Ghana’s relatively high economic growth and slower population growth which ensures that gains from economic growth translate into higher income per person. On the Current Path, Ghana’s GDP per capita will rise to US$8 960 by 2043. At this rate, the country’s GDP per capita will overtake the average of US$7 757 for its income-group peers in Africa.

Chart 8 presents the rate and numbers of extremely poor people in the Current Path, from 2019 to 2043.

In 2015, the World Bank adopted US$1.90 per person per day (in 2011 prices using GNI), also used to measure progress towards achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 1 of eradicating extreme poverty. In 2022, the World Bank updated the poverty lines to 2017 constant dollar values as follows:

- The previous US$1.90 extreme poverty line is now set at US$2.15, also for use with low-income countries.

- US$3.20 for lower-middle-income countries, now US$3.65 in 2017 values.

- US$5.50 for upper-middle-income countries, now US$6.85 in 2017 values.

- US$22.70 for high-income countries. The Bank has not yet announced the new poverty line in 2017 US$ prices for high-income countries.

Monetary poverty only tells part of the story, however. In addition, the global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) measures acute multidimensional poverty by measuring each person’s overlapping deprivations across 10 indicators in three equally weighted dimensions: health, education and standard of living. The MPI complements the international $2.15 a day poverty rate by identifying who is multidimensionally poor and also shows the composition of multidimensional poverty. The headcount or incidence of multidimensional poverty is often several percentage points higher than that of monetary poverty. This implies that individuals living above the monetary poverty line may still suffer deprivations in health, education and/or standard of living.[2The 2010 Human Development Report introduced the MPI and since 2018 the Human Development Report Office (HDRO) and the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative jointly produce and publish the MPI estimates. Multidimensional Poverty Index 2023 Unstacking global poverty: data for high impact action Briefing note for countries on the 2023 Multidimensional Poverty Index]

Ghana’s impressive growth rate over the last two decades has not translated into the expected reduction in poverty levels. The country is currently ranked 145th on the United Nations World Human Development Index and 16th in Africa with a score of 0.602.

In 2023, 14.3 million Ghanaians, representing 41.8% of the population, lived below the poverty line of US$3.65, far below the average of 49.0% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. It means that over the past decades, the country’s effort at poverty eradication through the implementation of several programmes has yielded some results as the poverty rate declined below the average for its income peers in Africa. These efforts include the implementation of the Ghana Poverty Reduction Strategy (GPRS) through which the government introduced free basic compulsory education, a National Health Insurance Scheme, and free maternal healthcare among others. Another important initiative is the Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty, a cash-transfer programme for extremely poor and vulnerable households that began in 2008 which ameliorates the plight of poor people.

Aside from the governmental ones, there are other initiatives by private organisations and NGOs aimed at combating poverty. For instance, Opportunity International undertakes initiatives to alleviate poverty through agricultural loans and education financing. They offer loans to farmers to increase crop yields, notably in cocoa growing, where women play an important role in local livelihoods. Training in agricultural practices helps farmers diversify their revenue streams, while mobile banking connects rural communities to financial services. Also, the Edu-Finance initiative supports affordable private schools, enabling parents to pay school fees and improving educational quality, leading to increased student enrollment and better learning outcomes. These efforts collectively aim to empower families and break the cycle of poverty in Ghana.

Despite this relative progress, poverty eradication has slowed down in recent years and there are still many Ghanaians who are multidimensionally poor. The yearly rate of poverty reduction has reduced considerably from 1.8 percentage points per annum during the 1990s to 1.1 percentage points per annum since 2006. According to the Ghana Statistical Service Report, about 7.3 million Ghanaians representing 24.3% of the population are multidimensionally poor and are mostly without basic education, health insurance coverage, and proper or sufficient nutrition. The most contributing factors to multidimensional poverty in the country are employment, health and education. Almost 44% of people who are multidimesionally poor experience severe poverty. Studies have established that lack of access to high-quality education, lack of access to high-quality healthcare, unemployment and sociocultural issues are factors contributing to poverty.

The 2022 economic crisis also worsened poverty levels and pushed more Ghanaians into extreme poverty. According to the World Bank, about 850 000 Ghanaians were pushed into poverty in 2022 due to rising prices of goods and services, leading to a worsening standard of living and food insecurity among households. On the Current Path, Ghana’s progress in reducing poverty rates will be more rapid compared to the average of its income-group peers in Africa such that by 2043, the poverty rate of 15.6% (equivalent to 8.7 million Ghanaians) will be less than half the average rate of 32.5% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa.

Chart 9 depicts the National Development Plan of Ghana.

Ghana has developed several long-term national development plans which are usually implemented through 4-year medium-term plans. Previously, Ghana implemented the Vision 2020 strategy which was to be guiding a framework for national development and was implemented through several medium-term plans. However, after the expiration of the First Medium-Term National Development Plan, the country abandoned Vision 2020 in favour of the poverty reduction strategies after entering the Highly Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) status. As a result, Ghana developed and implemented the Ghana Poverty Reduction Strategy 1&2 as its medium-term plans for 2003-2005 and 2006-2009, respectively. Since, the country has developed four medium-term plans:

- The Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda (GSGDA I, 2010-2013)

- The Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda (GSGDA II, 2014-2017)

- Agenda for Jobs: Creating Prosperity and Equal Opportunity For All I, 2018-2021

- Agenda for Jobs: Creating Prosperity and Equal Opportunity For All II, 2012-2025

Currently, Ghana’s Vision 2057 is the country’s Long-Term National Development Perspective Framework which reflects the development aspirations of the Ghanaian people. It stipulates the vision of Ghana regarding its social, economic and environmental development by 2057 which will mark the 100th anniversary of Ghana’s independence in 1957. The development of Vision 2057 was guided by several previous frameworks and documents such as the Black Star Rising: Long-Term National Development Plan (2018-2057) also referred to as the 40-year plan, Ghana @100 and the National Development Policy Framework (Vision 2020). It was also developed in line with global and regional frameworks and aspirations like the African Union Agenda 2063 and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. The document also takes into account lessons from global shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change and the geopolitical challenges that are confronting the world. Vision 2057 is to be implemented through various medium-term plans by successive governments and therefore give flexibility regarding specific actions, programmes and projects which are to be determined.

The Vision is to aspire to ”A free, just, prosperous, and self-reliant nation which secures the welfare and happiness of its citizens, while playing a leading role in international affairs”. The overall goal is to improve the living standards of Ghanaians and attain an upper-middle-income country status. This vision and goal is anchored on the following drivers of transformation:

- Achieving and maintaining macroeconomic stability

- Enabling attitudinal culture for sustainable social cohesion

- Peace and security

- Effective and efficient public service and institutional strengthening

- Human capital development for improved productivity

- Science and technology and innovation

- Effective land reforms

- Sustainable infrastructure development and

- Clean, affordable and sustainable energy transitional trajectory

To effectively measure success towards achieving the overall goals, the Vision 2057 is clustered around five main dimensions. These include economic development, social development, natural and built environment, governance and emergency preparedness and resilience. Each of these dimensions have well outlined objectives, goals and the strategies for achieving the goals.

The eight sectoral scenarios as well as their relationship to the Current Path and the Combined scenario are explained in the About Page. Chart 10 summarises the approach.

Chart 11 presents the mortality distribution in the Current Path from 2019 to 2043.

The Demographics and Health scenario envisions ambitious improvements in child and maternal mortality rates, enhanced access to modern contraception, and decreased mortality from communicable diseases (e.g., AIDS, diarrhoea, malaria, respiratory infections) and non-communicable diseases (e.g., diabetes), alongside advancements in safe water access and sanitation. This scenario assumes a swift demographic transition supported by heightened investments in health and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WaSH) infrastructure.

Visit the themes on Demographics and Health/WaSH for more detail on the scenario structure and interventions.

Ghana has made significant strides in improving access to healthcare in the past decade. Overall, there has been an expansion of healthcare facility coverage and the number of doctors and nurses per capita has risen. The government has also promoted community-based Health Planning and Services to support community-based primary healthcare. In 2003, the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) was established to provide financial access to quality basic healthcare for Ghanaian residents. The scheme expanded to include free maternal care in 2008 and free mental healthcare services in 2012. Since its introduction, the NHIS has significantly increased healthcare service utilization and outpatient visits per capita.

Despite significant progress, Ghana still faces challenges in ensuring equitable access to healthcare. Disparities in the distribution of human resources and health facilities exist between regions and within communities. Urban and wealthier populations have better access to the NHIS than rural and poorer populations. As a result, pregnant women from poorer households usually deliver their babies outside healthcare facilities, and under-five mortality rates are higher among the poorest. Limited government support and delayed reimbursements have led to illegal charges and disruptions in service delivery, further straining the NHIS. Additionally, the quality of care remains a major concern, with issues such as ineffective administrative structures, inadequate equipment, and non-adherence to protocols impacting patient outcomes. Ghana's heavy reliance on imported pharmaceuticals and medical equipment exacerbates these challenges, leading to shortages of essential supplies, particularly in public facilities. These factors collectively contribute to the persistent disparities in healthcare access and outcomes in Ghana. Since the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, the country has witnessed a large-scale brain drain in the health sector, with many nurses and doctors migrating to the UK, US and Canada. For instance, in 2022 alone, more than 1 200 Ghanaian nurses joined the UK nursing register. This large-scale emigration of critical health workers is affecting quality healthcare delivery.

As part of efforts to address these challenges, the government aims to allocate a larger portion of the national budget to healthcare to address infrastructure and workforce shortages. Ghana has initiated a roadmap for achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) by 2030, emphasising primary healthcare and community-based services. This has led to the introduction of Community-Based Health Planning and Services (CHPS), which aims to shift primary healthcare services from subdistrict health facilities to more accessible community settings. Over 6 500 CHPS compounds are currently operational, which has improved access to healthcare in rural areas, enhanced equity, fostered intersectoral collaboration, and improved service delivery efficiency. The government has also commenced the Agenda 111 project which aims to construct 101 district hospitals, 7 regional hospitals, 2 psychiatric hospitals and redevelopment of the Accra Psychiatric Hospital. This will ensure access to quality healthcare delivery in every district and region in Ghana.

Our modelling uses the International Classification of Disease (ICD) to differentiate between three broad categories: communicable diseases, non-communicable diseases and injuries, as well as 15 subcategories of mortality and morbidity. In 1990, communicable diseases caused about 90 000 deaths, constituting about 62.8% of total deaths in that year. This was followed by non-communicable diseases that caused 45 000 deaths (32% of total deaths) and injuries that caused 8 000 deaths (5.5% of total deaths). By 2023, deaths from non-communicable diseases had risen to constitute 47.3% almost half of all deaths (105 000) while deaths from communicable diseases had steadily risen to 101 000, representing 42% of all deaths. This means that the country has achieved its epidemiological transition (a point where deaths from non-communicable diseases outweigh deaths from communicable diseases). Deaths from injuries also rose to 8 000 (equivalent to 7.5% of all deaths). According to the WHO, the top causes of death in Ghana include stroke, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, lower respiratory infections, heart diseases, malaria, preterm birth complications, diarrhoeal diseases, road injury and kidney diseases. The activities of illegal mining (galamsey) are also leading to further public health crises. Research has linked the pollution of water from galamsey to chronic diseases such as Kidney failures, birth defects and cancers as evident in many mining communities in the country. On the Current Path, by 2043, non-communicable diseases will continue to be the highest cause of death in Ghana causing 188 000 deaths, representing about 64.8% of all deaths in the country. The transition to deaths from non-communicable diseases as the main cause of mortality will inevitably increase health sector costs as they are more expensive to treat. By then, deaths from communicable diseases will rapidly decline to 73 000, constituting 25% of all deaths, while deaths from injuries will rise to 30 000, constituting the remaining 10.2%.

Access to improved, safe, treated water, such as piped water, is an important means of preventing the spread of communicable diseases. The country has carried out initiatives to provide access to hygienic facilities and clean water, notably in metropolitan areas. Ghana has made significant advancements towards the attainment of SDG goal 6.1 of universal access to safe drinking water. In 2023, 23.7 million people in Ghana (constituting 92.2% of the population) had access to improved water supply. This represents a significant improvement from the 73.8% in 2000. Out of this, 10.5 million people (representing about 36.4% of the population) had access to a piped water supply in the country, far below the average of lower-middle-income countries in Africa. However, improvement will slow on the Current Path so that at the end of the SDG implementation, 92.4% of people in Ghana will have access to improved water. In recent years, the activities of illegal mining also threaten safe drinking water in the country.

The use of heavy equipment, such as excavators, bulldozers and chanfans has destroyed major river bodies in the country. Major rivers in the country like Pra, Ankobra, Pra, Oti, Offin and Birim which are source water have all been polluted. The Ghana Water Company Limited has already warned of severe water shortage in Ghana if the activities of galamsey are not curbed. It has stated that it is presently recording water turbidity levels of 14 000 NTU (Nephelometric Turbidity Units) far above the 2 000 NTU required for adequate treatment. Experts have warned that the country risks importing water by 2030. By 2043, it is projected that access to improved water will increase to about 95.1% of which piped water will constitute almost 58% connections.

Sanitation is a huge problem in Ghana, especially in the nation's capital. According to the UN, only 57% of Ghanaians use shared or public toilet facilities while 18% still relies defecate in open defecation. This poses a major health risk to the country with many people dying from WASH-related diseases. The WHO estimates show that 21 people die every day from preventable WASH-related diseases. A study by the World Bank also shows that Ghana loses US$290 million annually due to poor sanitation. The country loses US$79 million due to open defection. In 2023, only about 27.3% of the population (4.8 million people) had access to improved sanitation, which was about half of the average of 52.5% for its income-group peers in Africa. The share of the population with access to shared sanitation at 45% is below Africa’s lower-middle-income group average of 17.3% while populations with access to unimproved sanitation constitute the rest. On the Current Path, the proportion of the population with improved access to sanitation will rise to 48.6% by 2043, above the average of 62.5% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. By this time, the share of the population with access to shared sanitation will decline to 32.5% above the average for its income-group peers.

Chart 12 presents the infant mortality rate in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 1990 to 2043.

The infant mortality rate is the probability of a child born in a specific year dying before reaching the age of one. It measures the child-born survival rate and reflects the social, economic and environmental conditions in which children live, including their health care. It is measured as the number of infant deaths per 1 000 live births and is an important marker of the overall quality of the health system in a country.

The infant mortality rate is an important marker of the overall quality of a country’s health system. In 2023, the infant mortality rate in Ghana was 34.4 deaths per 1 000 live births — a drop of more than half of the 70 deaths per 1 000 live births in 1990. This was 9.4 deaths fewer than the average of 43.8 deaths for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. On the Current Path, the infant mortality rate will decline further, reaching 19.3 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2043, which is 11.7 fewer deaths than the average for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. It means that Ghana will not achieve the SDG target of 12 deaths per 1 000 live births even by 2043 and can only be achieved by 2058 in the Current Path.

The Demographics and Health scenario will reduce the infant mortality rate in Ghana further to 12.8 deaths per 1 000 births by 2043. This is 6.4 deaths fewer than in the Current Path and almost a third of the Current Path average of lower-middle-income countries in Africa. This also means that the country can also meet the SDG goal by 2043 if rapid interventions are implemented.

Chart 13 presents the demographic dividend in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2019 to 2043.

The dividend is the window of economic growth opportunity that opens when the ratio of working-age persons to dependents increases to 1.7 to 1 and higher.

Demographers typically differentiate between a first, second and even third demographic dividend. Given Ghana’s youthful population structure and the strides made in the past two decades, the study focuses on the first dividend. There are different ways to conceptualise the first demographic dividend. For example, studies have shown that a promising demographic window occurs when less than 30% of the population falls within the ages 0–14 years (children) while those above the age of 65 years and above (elderly) make up less than 15%. Alternatively, a demographic dividend opens when a country attains an average median age of between 26 and 41 years. We generally use the ratio of working-age persons to dependants, i.e. the size of the labour force (between 15 and 64 years of age) relative to dependants (children and elderly people).

The demographic dividend is the economic growth generated by changes in the population structure. It generally materialises when the ratio of the working-age population to dependants is at least 1.7-to-1, meaning that for every dependant, there are 1.7 workers. When there are fewer dependants to take care of, it frees up resources for investment in both physical and human capital formation. Studies have shown that about one-third of economic growth during the East Asia economic ‘miracle’ can be attributed to the large worker bulge and a relatively small number of dependants. However, the growth in the working-age population relative to dependants does not automatically translate into rapid economic growth unless the labour force acquires the needed skills and is absorbed by the labour market. Without sufficient education and employment generation to successfully harness their productive power, the growing labour force (especially those in urban areas) could increasingly become frustrated with the lack of job opportunities leading to social tension and even the emergence of civil instability.

In 2023, the ratio of the working-age population to dependants in Ghana was 1.48-to-1 which means that on average, there were only 1.5 persons of working age (15–64 years of age) for every dependant in Ghana. This represents an improvement from the ratio of 1-to-0 in 1990 and above the 1.3-to-1 average for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. On the Current Path, Ghana will achieve the minimum ratio of 1.7 working-age persons for each dependant required for the materialisation of the demographic dividend or demographic gift by 2035.

The Demographics and Health scenario pushes the country above this target such that by 2043, the ratio of the working-age population to dependants is projected to be 2.0-to-1 in the scenario instead of the 1.8-to-1 as in the Current Path and above the average of 1.6-to-1 for the country’s income-group peers in Africa by 2043. Increasing the size of the working-age population in Ghana can be a catalyst for growth if they are educated and employment opportunities are generated to successfully harness their productive power. Otherwise, it could turn into a demographic ’bomb’, as many people of working age may remain unemployed and in poverty, potentially creating frustration, social tension and conflict.

Chart 14 presents crop production and demand in the Current Path from 1990 to 2043.

The Agriculture scenario envisions an agricultural revolution that ensures food security through ambitious yet feasible increases in yields per hectare, thanks to improved management, seed, fertiliser technology, and expanded irrigation and equipped land. Efforts to reduce food loss and waste are emphasised, with increased calorie consumption as an indicator of self-sufficiency and prioritising it over food exports. Additionally, enhanced forest protection signifies a commitment to sustainable land use practices.

Visit the theme on Agriculture for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Agriculture is the primary activity and source of income and employment for Ghana's inhabitants, particularly in the northern regions whose output potential is virtually untapped. The agriculture sector in Ghana employs over half of the workforce and provides a primary source of livelihood for most of the country's poorest households. Ghana has introduced several policies to improve agricultural productivity. In 2017, the government launched the "Planting for Food and Jobs" initiative, which aims to increase food security and farmer income by providing improved seeds and fertilizers. The PFJ programme offers subsidies for fertilisers and improved seeds, addressing soil fertility and climate resilience, which is crucial for small-scale farmers. The "Ghana Feed the Future Agriculture Policy Support Project" also focuses on data-driven policy reforms to encourage private-sector agricultural investment, which is crucial for job creation and economic stability. Moreover, through the Ghana Agricultural Investment, the government supports sustainable practices through various laws and frameworks. Furthermore, the Modernizing Agriculture in Ghana Programme (MAG), a CAD$135 million initiative, aims to increase productivity by providing agricultural extension services and developing value chains, benefiting millions of farmers. Likewise, programmes like BRIDGE-in Agriculture empower youth with finance and technical support, fostering sustainable agricultural practices.

Aside from the government, there are other non-governmental organisations that also support agricultural activities in the country. The USAID's Feed the Future initiative employs a behaviour-change approach to assist Ghana in achieving self-sufficiency by enhancing agricultural productivity and profitability, strengthening market systems, improving access to finance, promoting resilience, optimising economic inclusion, and improving nutrition. This is accomplished through evidence-based interventions such as targeting food security initiatives in northern Ghana, protecting marine fisheries, promoting diverse and nutrient-rich crops, improving processing and storage, and partnering with private firms to expand their businesses and meet national and global standards. These combined efforts aim to modernise agriculture, increase productivity and ensure food security

Despite its huge potential, the sector is confronted with several challenges that impede its growth. Some of the challenges faced are related to the poor state of infrastructure and the effects of climate change, with irregular rains leading to annual flooding and a protracted dry season. Many large, medium and small dams for various purposes, including irrigation, remain underdeveloped. The government, in 2017, under its flagship project of one village, one dam, promised to construct dams in the northern region to promote all-year farming. However, this initiative received limited funding and most of the dams constructed dried up during the dry season. As a result, water scarcity during the extended dry season harms output, household income and living standards. Limited technological adoption, poor soils, dependency on rainfed systems, and insufficient infrastructure further hampered low yields. In recent years, the activities of galamsey have caused the destruction of farmlands, particularly cocoa. Data from the COCOBOD shows that cocoa production, currently at 429 323 metric tons, is less than 55% of its seasonal output, mainly due to illegal mining activities. In the Mankurom community alone, over 100,000 acres of cocoa have been destroyed due to galamsey.

In 1990, Ghana’s average crop yield of 2.0 metric tons per hectare was below the average of 2.5 metric per hectare for its income-group peers in Africa. Over the years, the country has witnessed an improvement in agriculture yields such that by 2023, the average crop yield per hectare of 8.0 metric tons was above the average of 5.3 metric tons per hectare for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. This means that compared to its income-group peers, Ghana has been able to adopt improved technology and mechanised agriculture that significantly increased its yield per hectare over the years. On the Current Path, yield per hectare will rise to 10.0 metric tons per hectare by 2043, which will be 53.4% higher than the average of lower-middle-income African countries. Sustaining Ghana’s agricultural yields will prove challenging in the face of increased population growth, increasing galamsey (illegal mining) and limited and declining agricultural land.

Total agriculture production in 1990 stood at about 8.4 million metric tons. Of this, 7.8 million metric tons, representing 93.1%, were crops, with the remainder constituting meat production. By 2023, total agricultural production in Ghana had grown to 56.1 million metric tons. Of this, crop production constituted 98.1%, equivalent to 55.1 million metric tons, meat production and fish production constituted the remainder of the total production. Ghana's principal agricultural commodities include maize, roots, vegetables and fruits, cassava (tubers), oil palm, rubber, rice, cashew nuts and cocoa. For instance, Ghana is the world's second-largest cocoa producer and exporter after the Ivory Coast.

Ghana faces huge crop loss and waste estimated at 19.3% of total production. This is largely due to post-harvest losses for crops, estimated at 7.5% of production, and transmission losses for crops, at 8.5%. Such losses can be a result of pest and disease infections, spoilage and the lack of adequate and effective storage facilities. Fish and meat also witnessed loss and waste accounting for 29.7% and 20% of total production respectively. As such, enhancing roads, storage facilities, and market access is crucial for reducing post-harvest losses and boosting farmer incomes

In terms of demand, the total demand for agricultural products in Ghana has always been more than the total production. Total demand stood at about 8.9 million metric tons in 1990, of which 8.3 million metric tons, equivalent to 93% of total demand, were for crops. The remaining demand was for meat (232 000 tons) and for fish (393 000 tons). Since then, domestic demand has rapidly outgrown production, and by 2023, agricultural demand had reached 58.2 million tons. Of the total demand, 97.0% is for crops (56.4 million tons). The remaining demand is for meat (764 000 tons) and for fish (1.0 million tons).

Despite the increase in domestic production, reaching 78.7 million metric tons in 2043, it will not be enough to meet domestic demand that will rapidly grow to 88.7 million metric tons. As a result, excess demand for agricultural products will reach 10 million by 2043. This indicates that Ghana faces the risk of food shortages in the future if drastic measures are not taken to revamp the agriculture sector to increase domestic production.

With total agricultural demand outgrowing domestic production, Ghana will have to rely on imports to meet its domestic demand. In 2023, Ghana’s net import of crops stood at 5.6% of total crop demand, which was lower than the average of 11.8% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. Also, the net import of fish stood at 41.8% of total fish demand, while the net import of meat was estimated at 40.6% of total meat demand all far above the average for lower middle-income countries. Reliance on food imports has grown, even for essential items like rice, poultry, sugar and vegetable oils.

In light of its huge population, shrinking agricultural land, water scarcity and other effects of climate change, Ghana remains food insecure and vulnerable to international price shocks and disruptions in supply chains. In the Current Path, net crop imports will grow in Ghana to 9% of total crop demand by 2043 while that of meat and fish will be 37.7% and 79% of their respective demands respectively. This suggests a growing level of national food insecurity; however, it can also be a result of changes in dietary preferences. Greater import dependence makes Ghana more vulnerable to international price shocks and accompanying risks of disruptions in the global supply chains as seen during COVID-19. Thus, while Ghana has increased agricultural production, the sector needs major reform to focus and incentivise the production of goods like vegetables and fruits in which Ghana has a comparative advantage.

Chart 15 presents the import dependence in the Current Path and the Agriculture scenario, from 2019 to 2043.

In the Agriculture scenario, yield per hectare will increase to 11.9 metric tons by 2043 — a 19.0% improvement compared to the Current Path and almost twice the average of lower-middle-income countries in Africa. The improvement in yields will lead to an improvement in total agricultural production. By 2043, in the Agriculture scenario, total production will increase to 90.1 million tons, almost 11.5 million metric tons, or 14.6%, more than the Current Path by 2043. Annual crop production in Ghana will rise by 15% over the Current Path to 88.1 million tons in the Agriculture scenario by 2043. The increases in crop production in the Agriculture scenario reduce the import dependency of crops in the country compared to the Current Path. Indeed, Ghana will become a net exporter of crops under the scenario so that by 2043, the net export of crops will reach 10.6% in the Agriculture scenario. This means that Ghana has the potential to be food sufficient and export to other countries in the longer term if agriculture is revolutionalised.

Chart 16 depicts the progress through the educational system in the Current Path, from 2019 to 2043.

The Education scenario represents reasonable but ambitious improvements in intake, transition, and graduation rates from primary to tertiary levels and better quality of education at primary and secondary levels. It also models substantive progress towards gender parity at all levels, additional vocational training at the secondary school level, and increases in the share of science and engineering graduates.

Visit the theme on Education for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Ghana's education system has a 6-3-4-4 structure: six years of elementary school, three years of junior secondary school, and three years of senior secondary school, followed by four years of university study. Over the years, Ghana's education system has been characterised by low funding, which is reflected in inadequate educational infrastructure and learning materials, especially at the basic level, where public schools constitute the majority. In 2023, Ghana spent US$3.1 billion on its education system — this amount is equivalent to 4.0% of the country’s GDP. At this rate, Ghana’s spending on education was below the average of 4.5% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. On the Current Path, Ghana’s total expenditure on education will reach US$9.1 billion, constituting 3.9% of GDP, by 2043.

About 38.0% of spending on education in Ghana is on the upper-secondary level making it the largest educational expenditure in the country. This departs from the trend observed in most African countries where much of the spending is done at the primary or lower-secondary level. The high spending at the upper-secondary levels is mainly due to the implementation of the free senior high school programme that commenced in 2017 which has increased enrolment significantly at the secondary level. With the government absorbing almost all the cost of secondary schools including academic user, boarding and feeding fees, it is therefore not surprising that more of the country’s education budget is spent at this level. On average, it costs US$666 to educate a student at the tertiary level. This is almost 2.6 times what was spent on lower-secondary students, 4.4 times the cost of educating a child at the primary level. However, it is less than the US$1 189 that is spent on educating a tertiary-level student. While this has expanded access at the secondary levels, it has also crippled the other levels especially the basic levels as it leaves little resources available. Nonetheless, spending at the primary level constitutes 16.2% while spending on lower secondary and tertiary levels constitutes 16.4% and 19.4%, respectively.

The education system can be viewed as a long funnel where children enter at the primary level and exit after completing tertiary-level education. Many children enter the system at the wide mouth of the funnel, but few complete the entire journey — from primary to secondary school and then university — to eventually graduate with a tertiary or equivalent education at the other end. However, the education funnel in Ghana largely mirrors funnel leakages and cracks along the way.

Ghana has implemented several policies to enhance its education system and improve access, notably through the Education Strategic Plan (ESP) 2018-2030. These policies include the Free Senior High School (SHS) initiative, launched in 2017, which aims to eliminate tuition fees and improve access for all students. Additionally, the government has expanded physical school infrastructure and facilities to accommodate increased enrollment, improved quality through the provision of core textbooks and supplementary readers, and rationalised teacher deployment. To improve equity, the government has implemented a policy reserving 30% of places in elite senior secondary schools for students from public junior secondary schools.

In 2023, the gross enrolment rate for primary school students in Ghana was 106.0%, an increase from 71.4% in 1990 higher than the average of 101% of lower-middle-income countries in Africa. Comparing this to the net enrolment rate of almost 90.3% in the same period leads to two important conclusions. First, a number of children in Ghana who are of school-going age are not in school. Secondly, many classrooms in Ghana are likely to be crowded by older students as is the case in many African countries. On the Current Path, Ghana's gross and net enrolment rates will almost converge at 100% meaning by then classrooms will be filled with students of appropriate age.

The gross primary completion rate stood at 88.7% in 2023, indicating that a number of children who enrolled did not complete the last grade of primary school in Ghana as is the trend in most low- and lower-middle-income countries in Africa. On the Current Path, Ghana’s progress in ensuring more children complete primary school will be maintained throughout the forecast period such that, by 2043, almost every primary school student will complete the last grade. This progress in Ghana ensures that its educational system will mirror that of a developed country an advanced educational system where access at the basic level is universal and an older population is highly educated. Of those who complete primary-level education, some will transition immediately to the lower-secondary level, some will enrol in the lower-secondary level after some years out of school and some will never enter the lower-secondary level, and so on, through the upper-secondary and tertiary levels.