The potential of digitisation in Ghana

Ghana’s digital push, from smart IDs to AI hubs, offers a real chance to fast-track growth and close the gap with global peers.

Ghana’s developmental trajectory is often compared to that of South Korea, with both countries gaining independence around the same period, in 1957 and 1948, respectively. While South Korea was initially the poorer of the two, it has made stellar progress and now has an income level nearly nine times that of Ghana. This contrast came to the fore during the African Futures and Innovation programme country analysis, prompting reflection on the divergent paths the two nations took.

At independence, South Korea had few natural resources and, in 1950, suffered the Korean War that lasted until 1953. In contrast, Ghana has, for five centuries, been part of a region known as the Gold Coast, and the mineral is still Ghana’s most valuable export. Only Ghana’s role as the centre of the British slave trade potentially eclipses, negatively, the importance of gold. The Gold Coast was a British Crown colony on the Gulf of Guinea from 1821 until its independence as Ghana in 1957, while the entire Korean peninsula was colonised by Japan and formally annexed in 1910.

Suffice it to say that both countries have a troubled colonial history. What then explains the subsequent diverse development outcomes?

With the end of the war in 1953, poverty-stricken South Korea placed its focus on food self-sufficiency, basic education, family planning and the provision of basic healthcare. Because it managed to reduce its fertility rates rapidly, it experienced a steady increase in the number of working-age persons to dependants. Thanks to this demographic dividend, the ratio of working-age persons to dependants (children and the elderly) increased from around 1.2 in the 1950s to almost 2.8 in 2016, an extraordinarily high ratio, achieved only by China and the other Asian Tiger economies in recent history. Since labour is the most important contributor to growth for low-income countries, the South Korean economy grew rapidly, and the result helped transform its economy into a manufacturing one. With fewer mouths to feed and schools to build, South Korea could invest in improving the human capital endowment of its existing youthful population to contribute to increased productivity.

By contrast, high population growth and limited technological advancement have contributed to Ghana’s slow development over the years.

By African standards, Ghana has a medium-sized population (around 33.9 million people in 2023). It is more urbanised than most African countries (about 60% – a rate that South Korea achieved in 1982), allowing for a more rapid transition to digital services and also making it easier to provide water, sanitation and other services. By 2043, 69% of Ghanaians will reside in urban areas. This demographic shift will accelerate economic growth and potentially enable Ghana to graduate from its current lower-middle-income status to become an upper-middle-income country.

Ghana’s relatively high rate of urbanisation has contributed to a sharp decline in fertility, with the total fertility rate now at 3.4 children per woman. As a result, Ghana is forecast to enter its demographic dividend window of opportunity by 2033, earlier than most other West African countries, though significantly later than South Korea. This transition presents a critical opportunity for accelerated growth. However, labour is only one contributor to economic growth, but with the right policies and technology, Ghana, too, may now be poised for take-off.

This take-off hinges on how Ghana harnesses digital technologies to modernise governance, services and economic systems. To fully capitalise on the demographic shift, Ghana must strengthen inclusive democratic governance and digital systems, offering a more participatory alternative to the authoritarian model once used by South Korea and replacing South Korean industrial smokestacks with modern services.

If Ghana can stay its course, that may just be possible.

Ghana’s take-off hinges on how the country harnesses digital technologies to modernise governance, services and economic systems

In 2008, the country officially launched a smart national identification system (dubbed the Ghana Card), which uses biometrics, following the passage of the National Identification Authority (NIA) Act 2006 (Act 707). Despite various contributions by successive governments to implement this vision, the card was rolled out free of charge from 2018. The process will provide each Ghanaian with a unique personal identification number (PIN). This is a huge leap forward, as Ghana has, until recently, had no comprehensive identity system, and the pace of roll-out is proceeding much more rapidly than in China and Western countries, where such systems were originally rolled out manually and with great effort over several decades. According to the NIA, 18.7 million Ghanaians have been enrolled, and 17.6 million cards have been issued as of May 2025. The Card has now become the primary source document for its biometric voter register, which it introduced in 2012.

The Ghana Card enables the owner to open a bank account, apply for a passport or driver’s licence, register a SIM card, buy property, register a business or even enrol children in school (children are linked to their parents’ identification cards).

With its paperless port system, exports or imports are directly linked to the PIN to eliminate fraud and theft in the shipping and clearing of goods at ports and harbours. Already, the number of agencies required to inspect a container in Ghana has been reduced from 16 to just three, which cuts a lot of red tape.

Furthermore, the PIN will be used to verify a person’s identity during job searches and applications, for e-tickets at airports, at border crossings, police checkpoints and the like. It will eventually become mandatory for the validation of payments, particularly electronic payments.

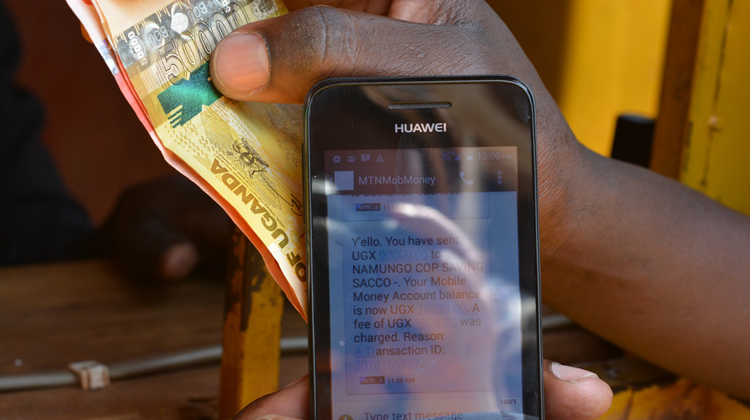

Most importantly, an identification number allows large portions of the informal sector to be brought into the formal economy, especially given the country’s advancement in mobile banking.

In addition to the smart personal identification system, the GhanaPostGPS provides a unique digital address for each 5m2 of the land areas in a country that previously had no formal system of finding a specific location without local knowledge. Armed with a digital address, small and informal businesses can now register for a bank account, access credit and get deliveries by drone. Drone delivery of emergency medical supplies and COVID-19 vaccines has already started with the company Zipline.

Besides many other benefits, these innovations will improve tax collection, as both informal and formal businesses will steadily be forced to use electronic payment systems, crowding the former into the latter. The 2019 report on Africa by the United Nations Commission for Africa (UNECA) finds that in the long term, government revenue on the continent can be increased by 12–20% of GDP through the rigorous pursuit of tax and non-tax income collection, which is possible through digitisation such as already the norm in Rwanda and South Africa.

Ghana also has a fully digital platform to pay for all government services (Ghana.GOV), including driver’s licences and car registrations. The digitisation of land ownership (as part of the Ghana Enterprise Land Information System project) is also progressing. The aim is for a new base map survey to use blockchain technology to secure and verify the ownership of all land. Furthermore, with the support of the World Bank, the Ghanaian Ministry of Education is adopting modern technology for e-learning.

Technology also enables the documentation of important personal events (e.g., births, adoptions, legitimations and recognitions, deaths, marriages, divorces, separations and annulments), which are fundamental to having a legal identity and access to public services. It can provide access to finance and information about health, and offer a way to educate and connect people. The new government also launched the One Million Coders initiative to train one million Ghanaians, especially the teeming youth, in essential digital skills to empower them for the future.

In recognition of these efforts, Google opened its first African artificial intelligence research centre in Accra (Google Research Africa), bringing together top machine learning researchers and engineers. Ghana has also signed a US$1 billion memorandum of understanding with the UAE to build an AI and tech hub hosting Microsoft and Meta by 2027.

Modern technology also allows for better policing of issues like mining licences, for example. In many African countries, including in South Africa and DR Congo, illegal mining is rife, often practised by desperate illegal migrants who mine in extremely dangerous conditions. Some 150 drone pilots have already been trained to monitor illegal mining across Ghana in an initiative spearheaded by the Minerals Commission of Ghana.

Many challenges remain, most notably the tendency to rush into spending public money ahead of elections on projects that are never completed. Ghana continues to grapple with numerous incomplete public infrastructure projects, but Ghana’s National Development Planning Commission and the Ghana Statistical Service teamed up with the Copenhagen Consensus to create Ghana Priorities, which aims to steer the government away from pork-belly politics by using evidence to assess the return on each cedi spent. The partnership assessed more than 400 ideas, narrowed them down to 79 and identified several high-impact interventions in nutrition, health, education, digitisation and rural electrification. An example is a pilot scheme for the early diagnosis of tuberculosis, which could prevent more than 3 000 deaths in six years. Benefits outweigh costs more than 100 times.

The Ghana Priorities research partnership narrowed development solutions down to 79, and identified several high-impact interventions in nutrition, health, education, digitisation and rural electrification

There have also been many mistakes. Ghana announced its One District One Factory (1D1F) initiative in 2017 as it sought to change the nature of its economy from one dependent on the export of raw materials to one focused on manufacturing, value addition and export of processed goods. Eventually, in March 2025, the new government terminated the 1D1F in validation of traditional approaches, which aim to attract foreign companies and cluster infrastructure and incentives in specialised industrial zones rather than seeking to spread factories out across large geographies without the necessary infrastructure and other support.

Looking ahead, Ghana's economic prospects for 2026 appear cautiously optimistic. Continued investment in key sectors, coupled with governance reforms and prudent fiscal management, is essential for sustaining growth. Closing the gap with South Korea may still take decades, but Ghana now has the demographic trends, digital infrastructure and innovation momentum to begin shifting the trajectory.

Image: Mohamed_hassan/Pixabay

Read the full country analysis of Ghana here.