20 State Futures in the Global South

20 State Futures in the Global South

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

This theme on State Futures in the Global South explores how emerging global trends such as demographic shifts, climate change, digital disruption and geopolitical realignment are reshaping the state's role, capacity and legitimacy. The analysis draws on governance indicators, horizon scanning and regional consultations to assess key challenges and opportunities across political, economic, social, technological and environmental domains. Four scenarios are developed to examine how state governance might evolve under different global conditions, providing a toolkit for anticipatory policy planning and strategic resilience.

Summary

This report begins with an introductory overview of its purpose and conceptual framework. It lays out a foresight-driven inquiry into how state governance in the Global South may evolve over the next two decades. Adopting a state-centric lens combined with a Global South perspective, it highlights how colonial legacies, hybrid political systems and emerging global trends shape diverse governance trajectories across regions.

The following section outlines the research design and methodology. It explains how the application of futures thinking and strategic foresight tools, such as scenario planning, horizon scanning and expert consultations. Quantitative analysis using the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) is complemented by regional workshops and the International Futures model, producing an integrated understanding of governance drivers and trajectories.

In the third part, the report reviews the historical and current governance context. It traces the evolution of state systems in the Global South, from post-independence reforms to current challenges such as institutional fragility, elite capture and democratic backsliding. The section highlights regional variations in governance performance, with some states improving regulatory quality and government effectiveness, while others face stagnation in voice and accountability.

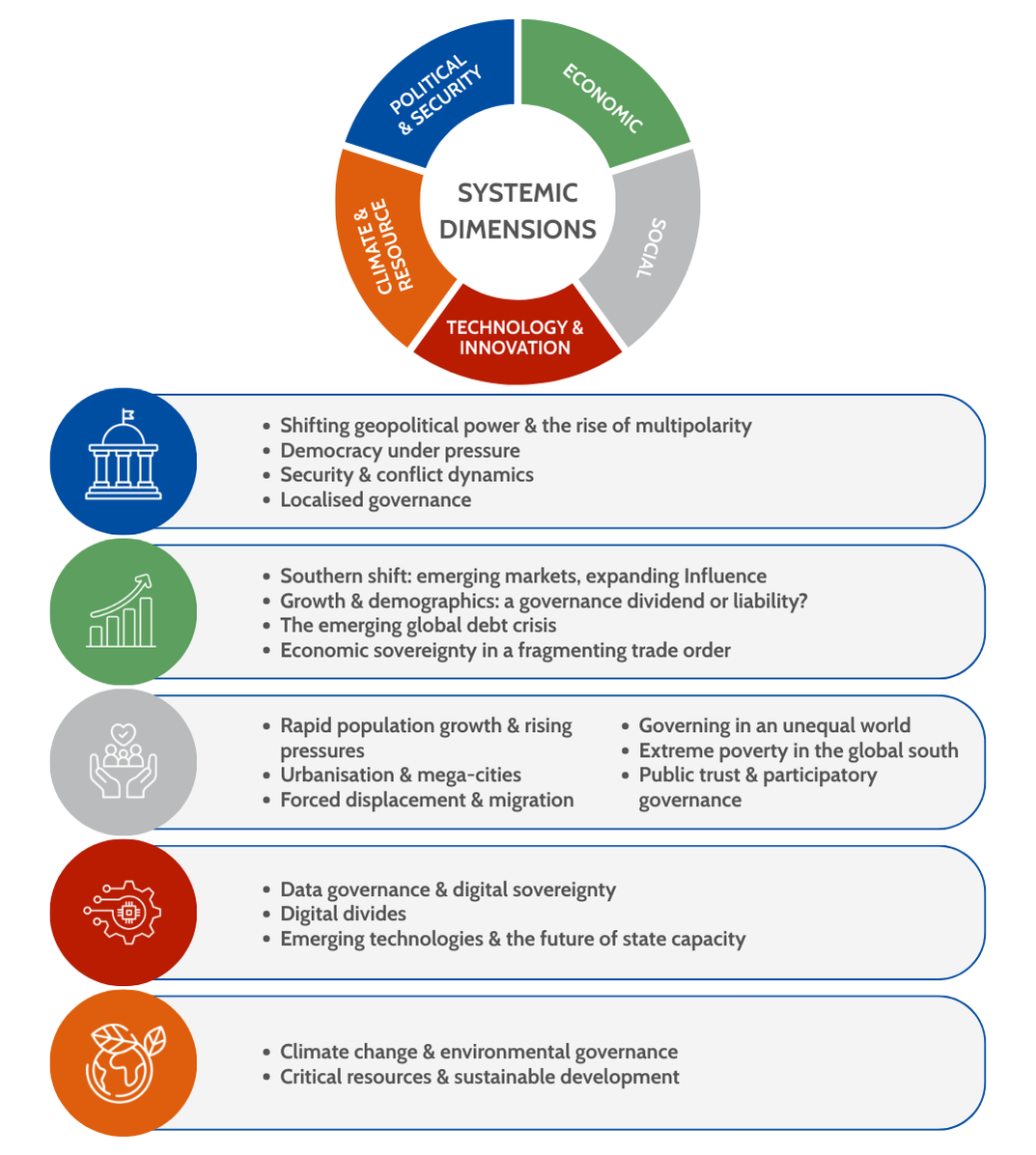

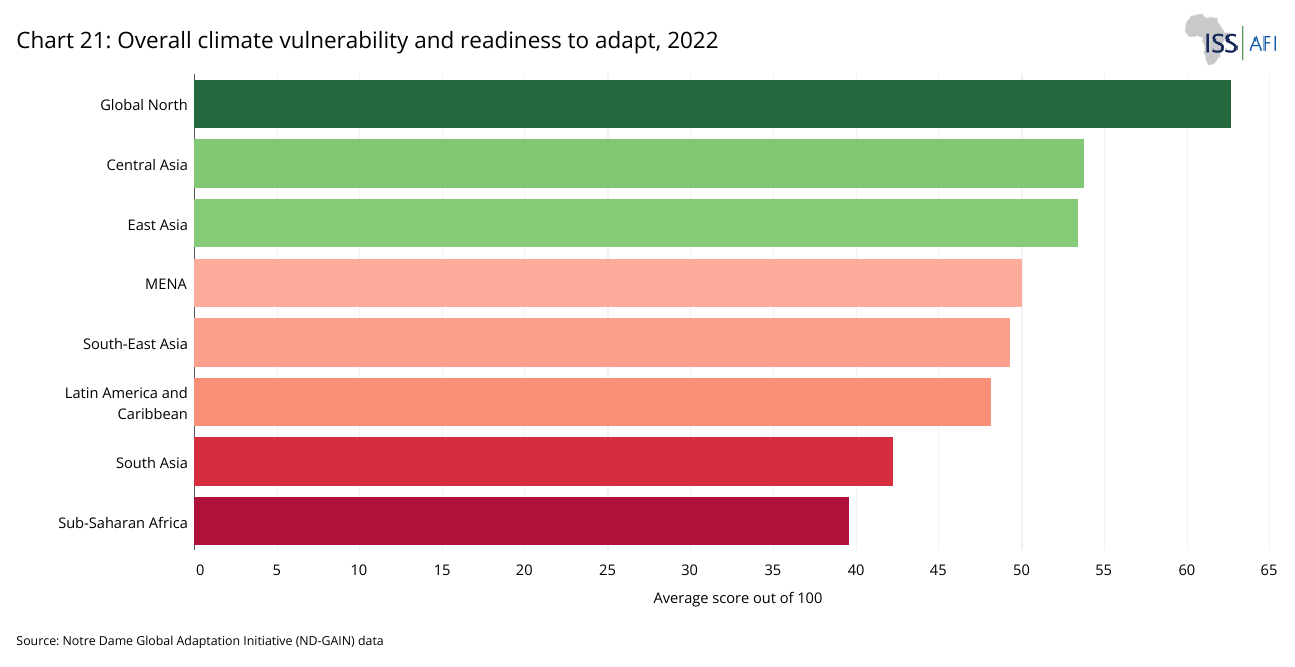

The fourth section presents a systemic horizon scan across five domains: political/security, economic, social, technological and environmental. It identifies key trends including rising authoritarianism, digital control, demographic pressures, debt constraints, urbanisation, inequality and climate vulnerability. These factors are not isolated; they interact to reshape how authority is contested and governance is delivered.

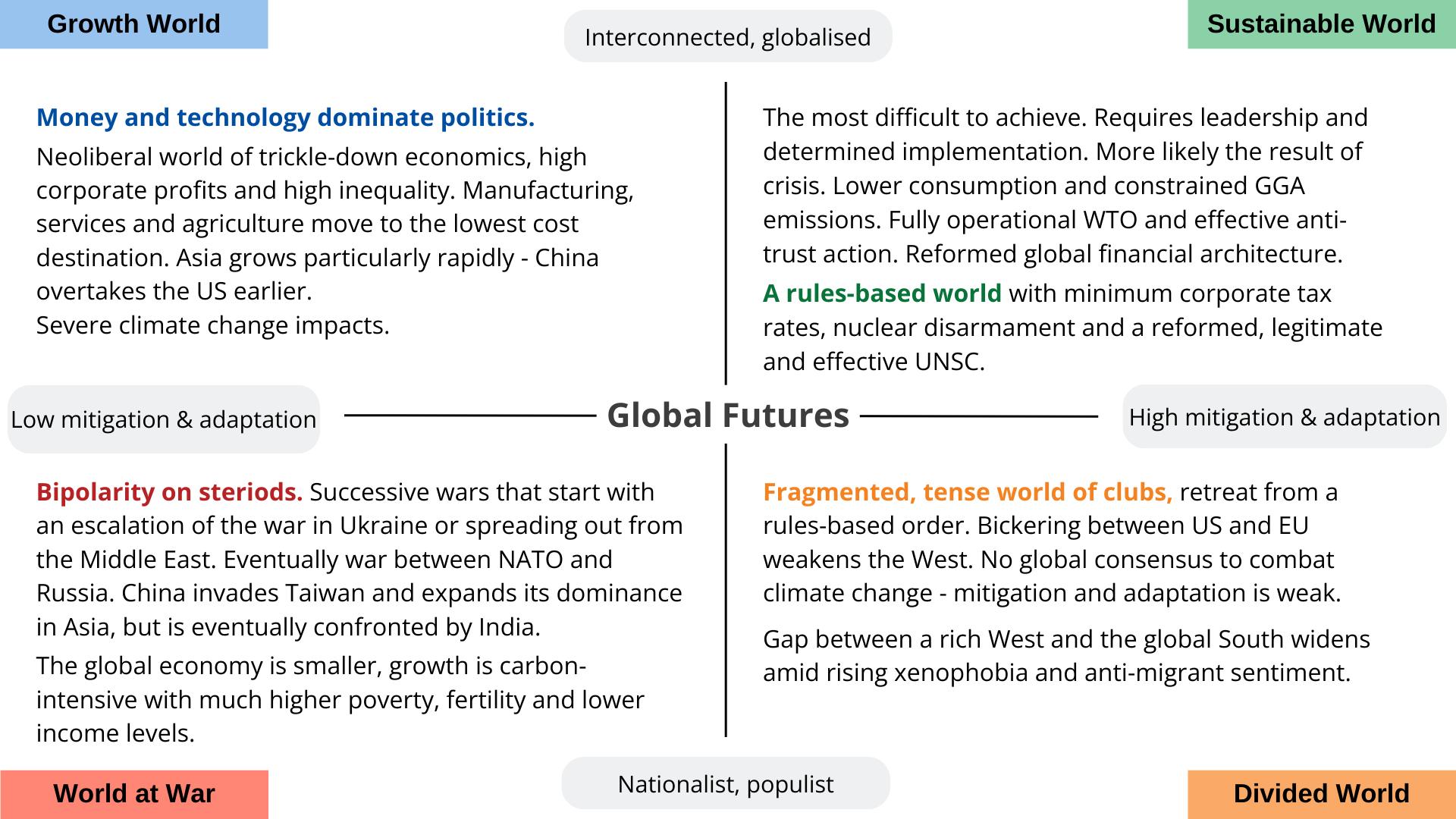

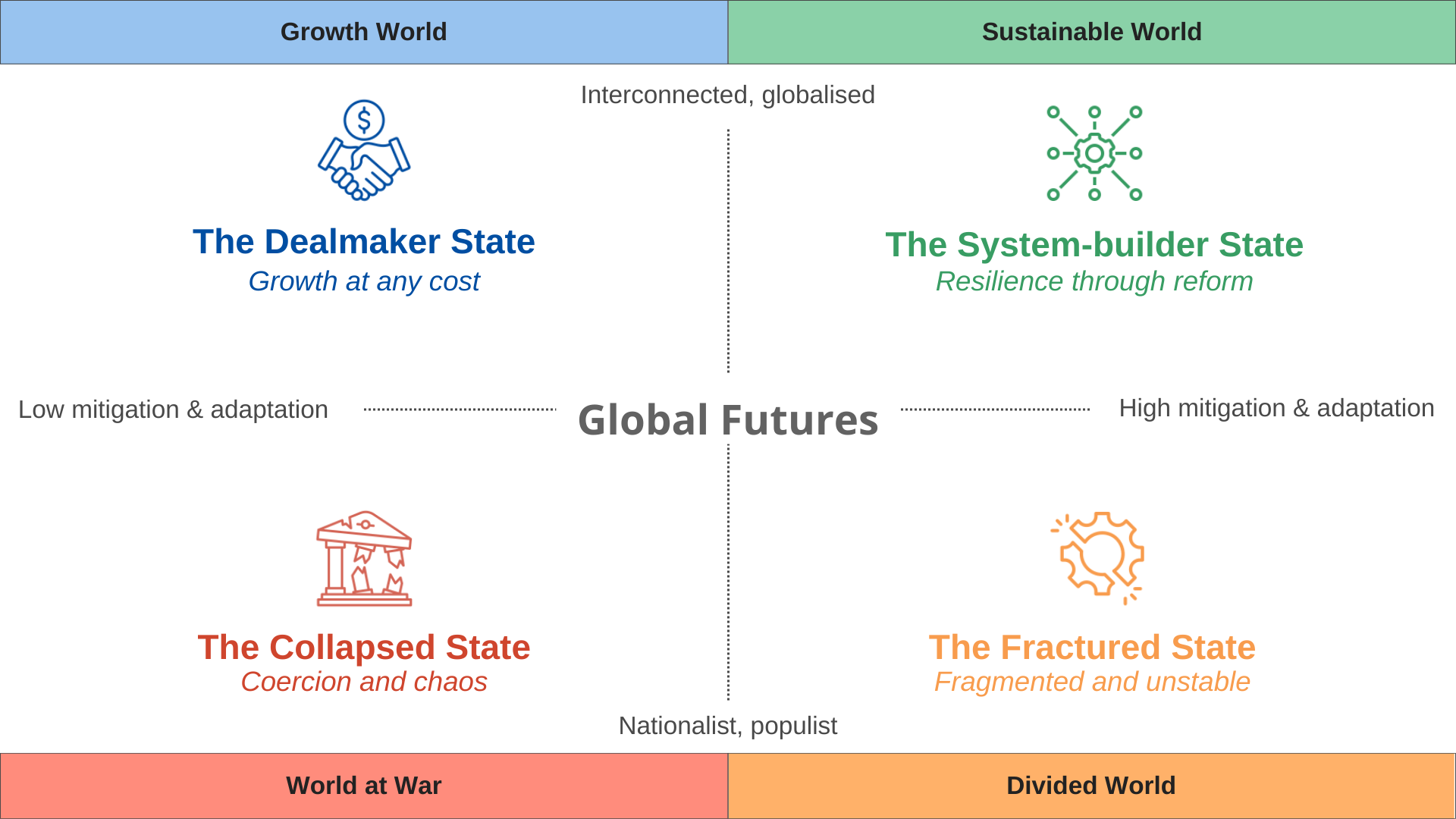

The fifth section introduces four alternative scenarios for the future of governance: the Growth World, the Sustainable World, the Divided World, and the World at War. Each scenario explores different configurations of state roles, legitimacy and institutional capacity under varying global conditions. They highlight how states might evolve as dealmakers, system-builders, fractured authorities or survivalist regimes.

Finally, the report concludes with eight strategic reflections. These emphasise the need to rethink governance beyond the state, address the participation-performance gap, invest in anticipatory capacity and embed foresight into policy planning. A central message emerges: governance futures are not predetermined; they depend on how states, societies and international actors respond to accelerating complexity.

All charts for State Futures in the Global South

- Chart 1: Global North versus Global South in WGI, 1996-2023

- Chart 2: Worldwide Governance Indicators - group averages, 1996-2023

- Chart 3: Systemic factors shaping the future of state governance in the Global South

- Chart 4: Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) global democracy index, 1994-2024

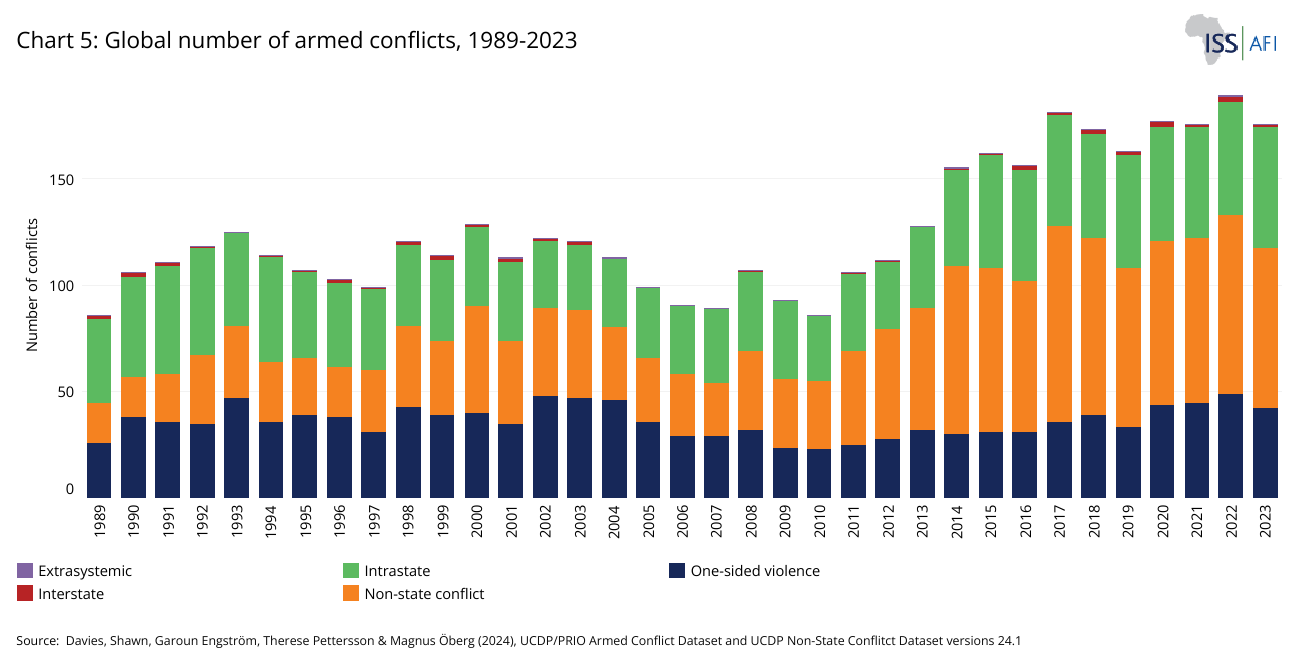

- Chart 5: Global number of armed conflicts, 1989-2023

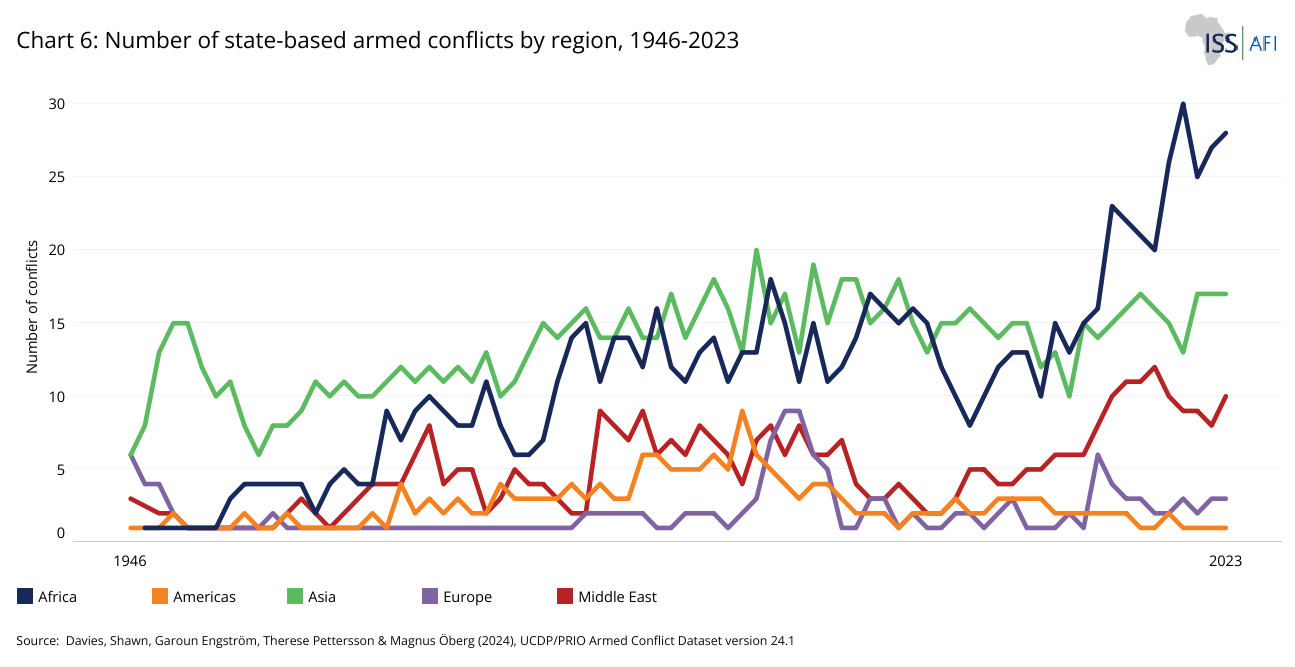

- Chart 6: Number of state-based armed conflicts by region, 1946-2023

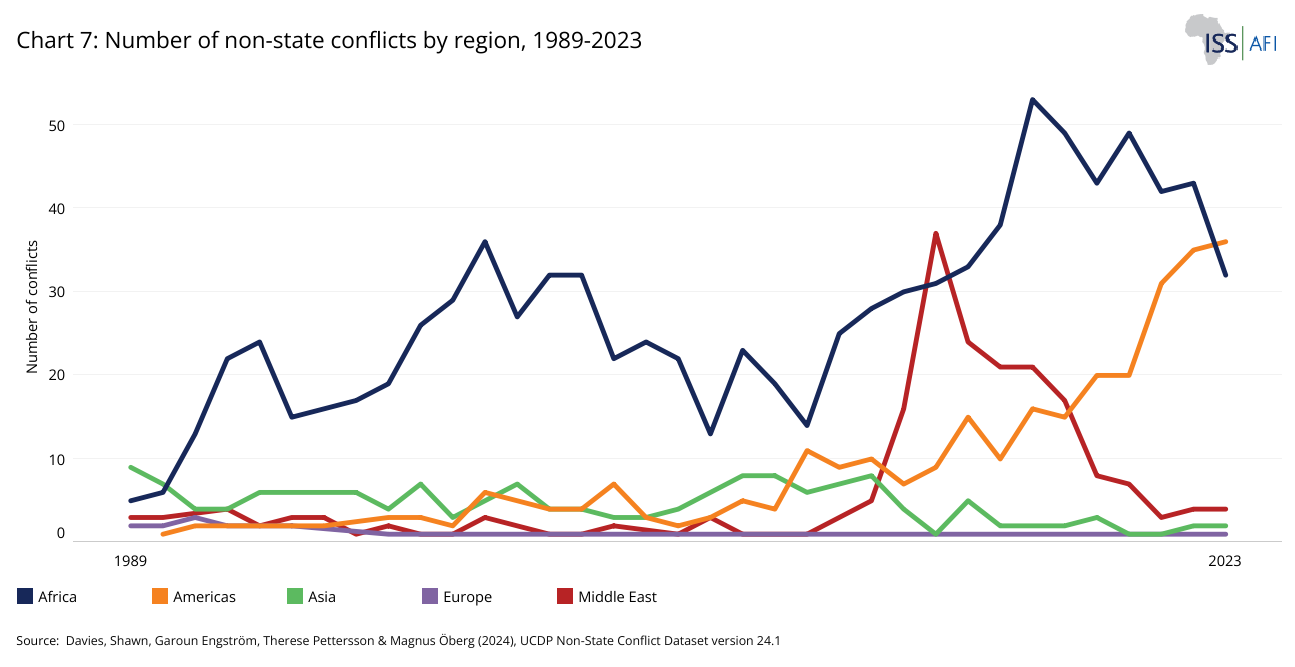

- Chart 7: Number of non-state conflicts by region, 1989-2023

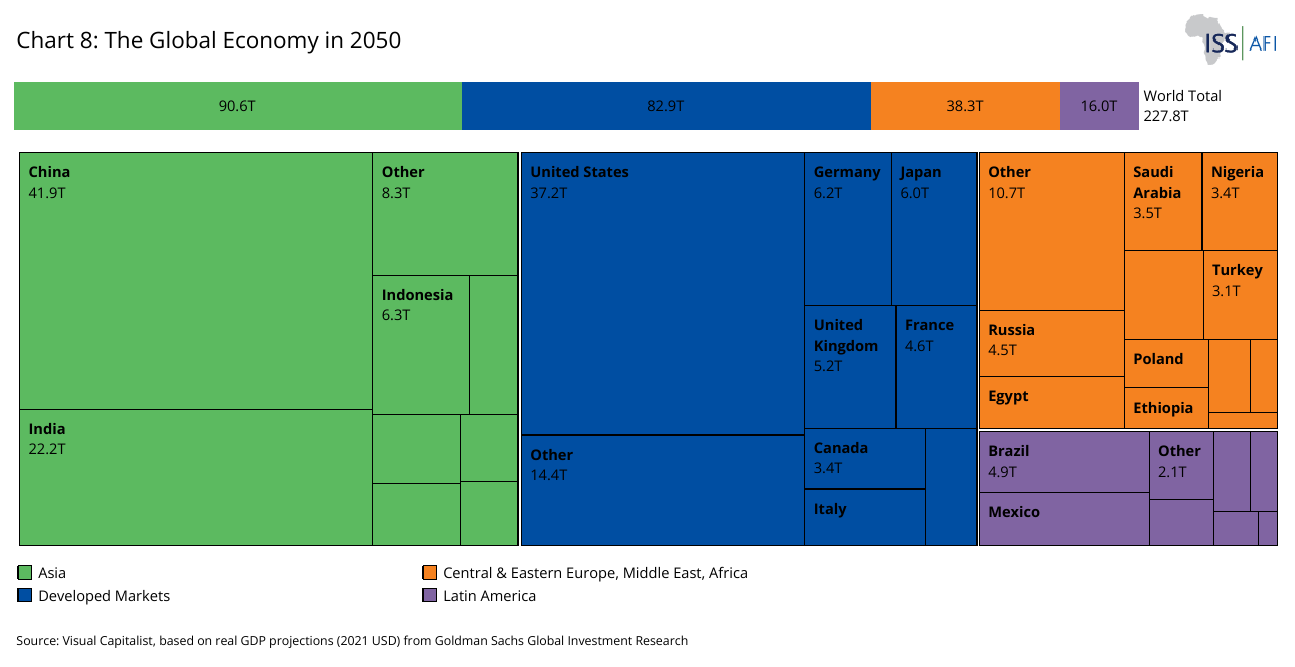

- Chart 8: The Global Economy in 2050

- Chart 9: GDP growth rate forecast by region, 2025-2050

- Chart 10: GDP per capita (PPP) in regions, 1960-2050

- Chart 11: Demographic dividend in Global South regions, 1960-2050

- Chart 12: The emerging Global Debt Crisis

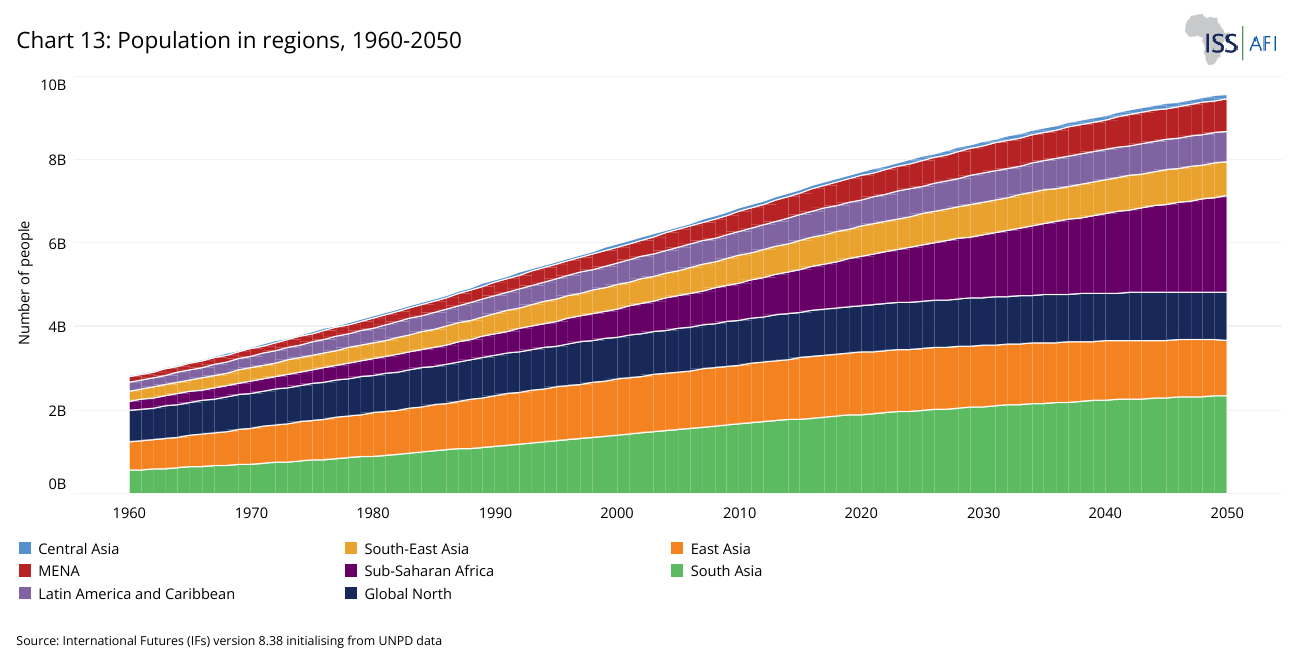

- Chart 13: Population in regions, 1960-2050

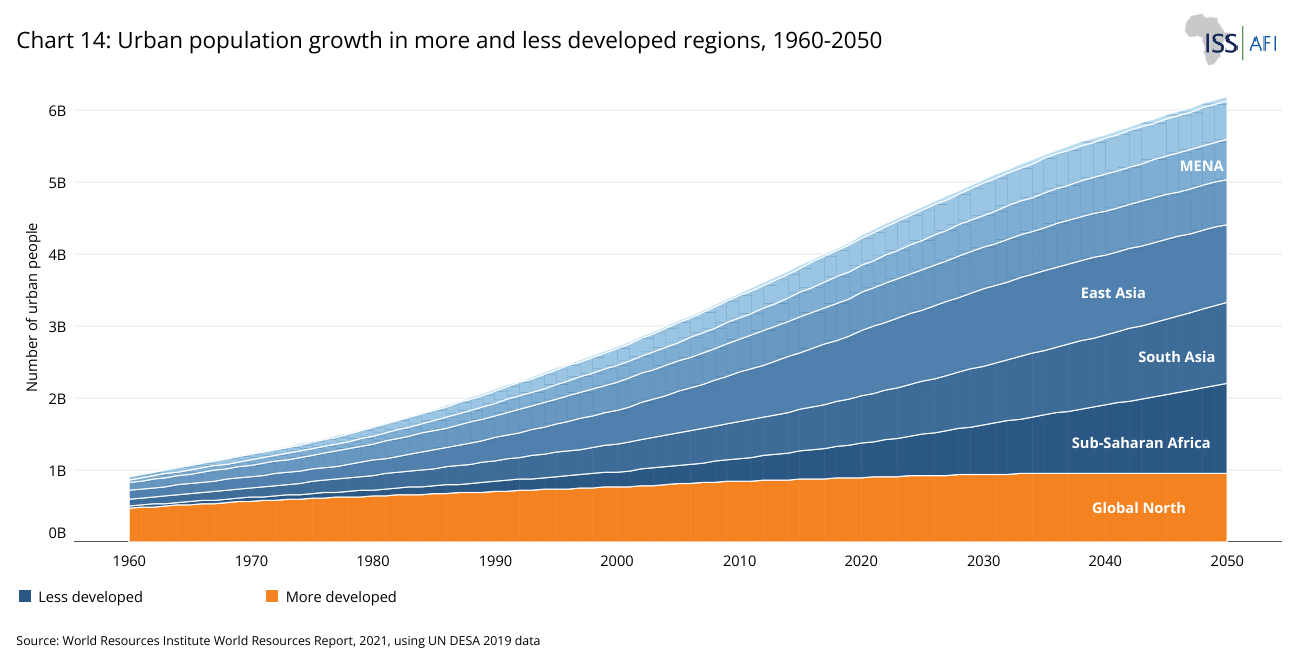

- Chart 14: Urban population growth in more and less developed regions, 1960-2050

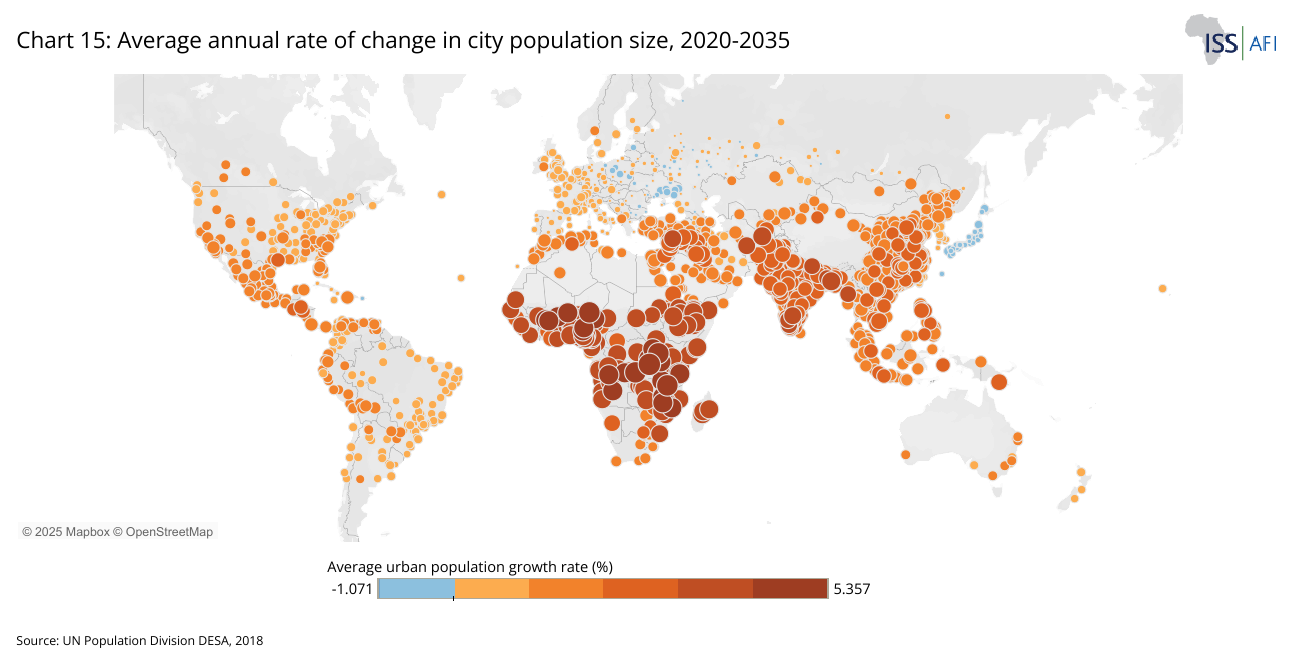

- Chart 15: Average annual rate of change in city population size, 2020-2035

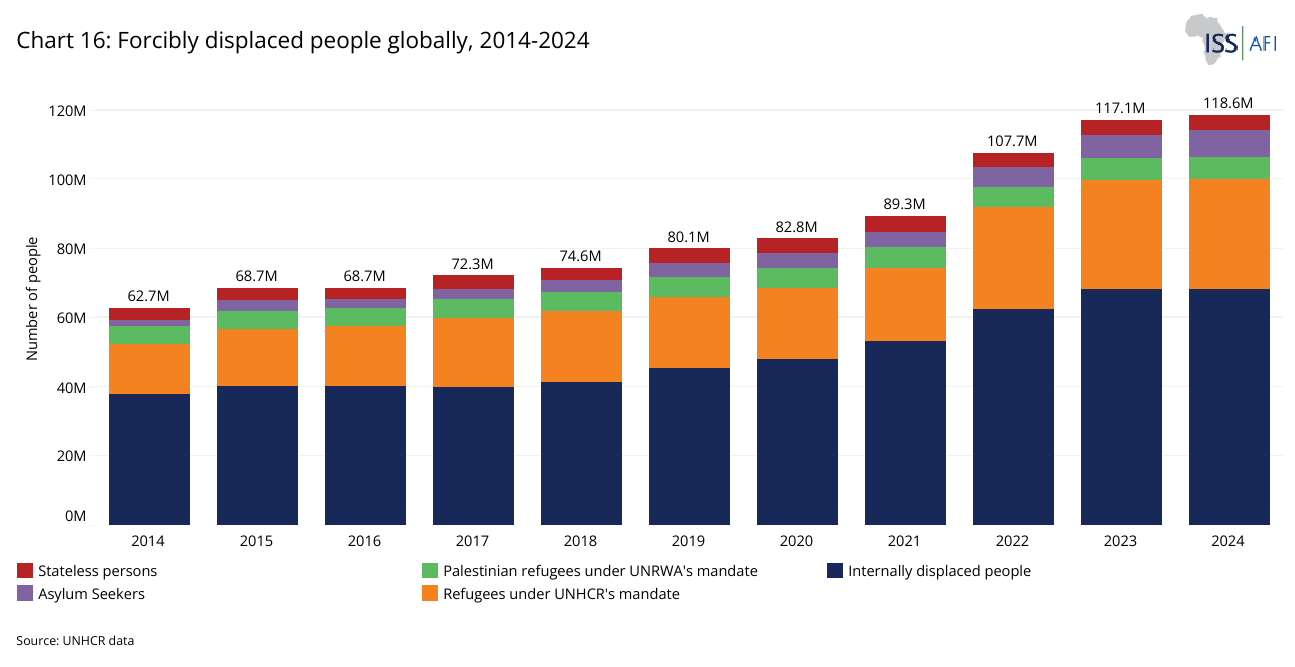

- Chart 16: Forcibly displaced people globally, 2014-2024

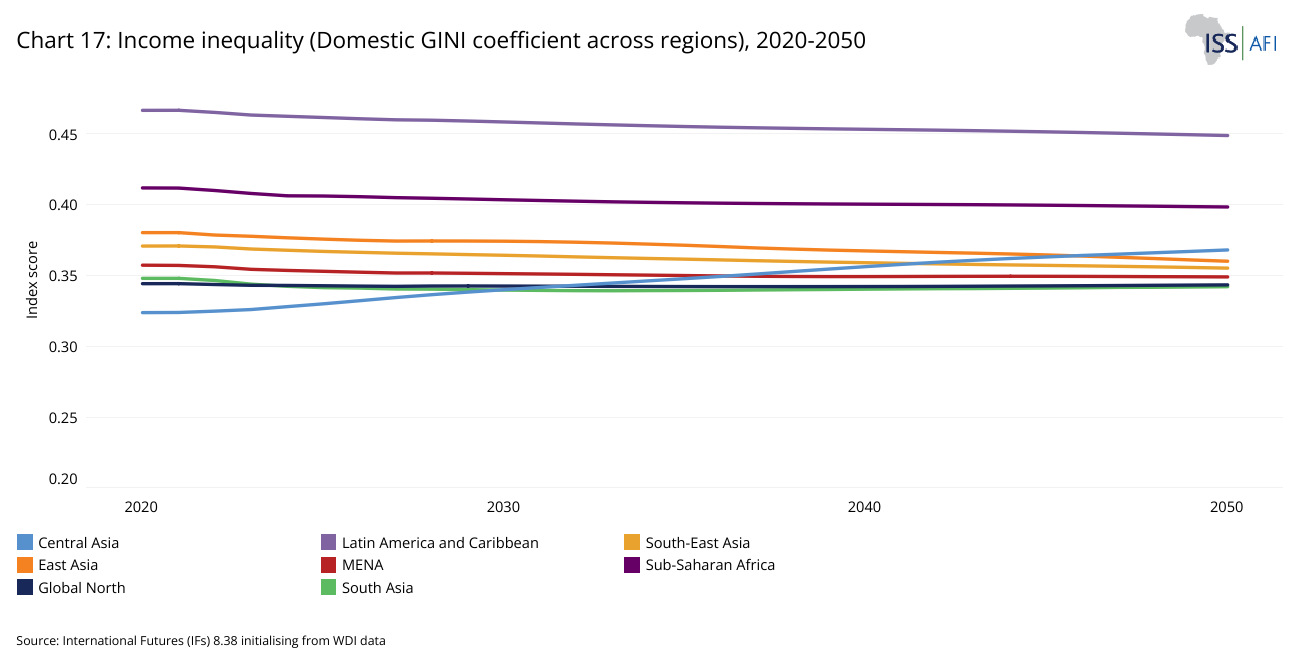

- Chart 17: Income inequality (Domestic GNI coefficient across regions), 2020-2050

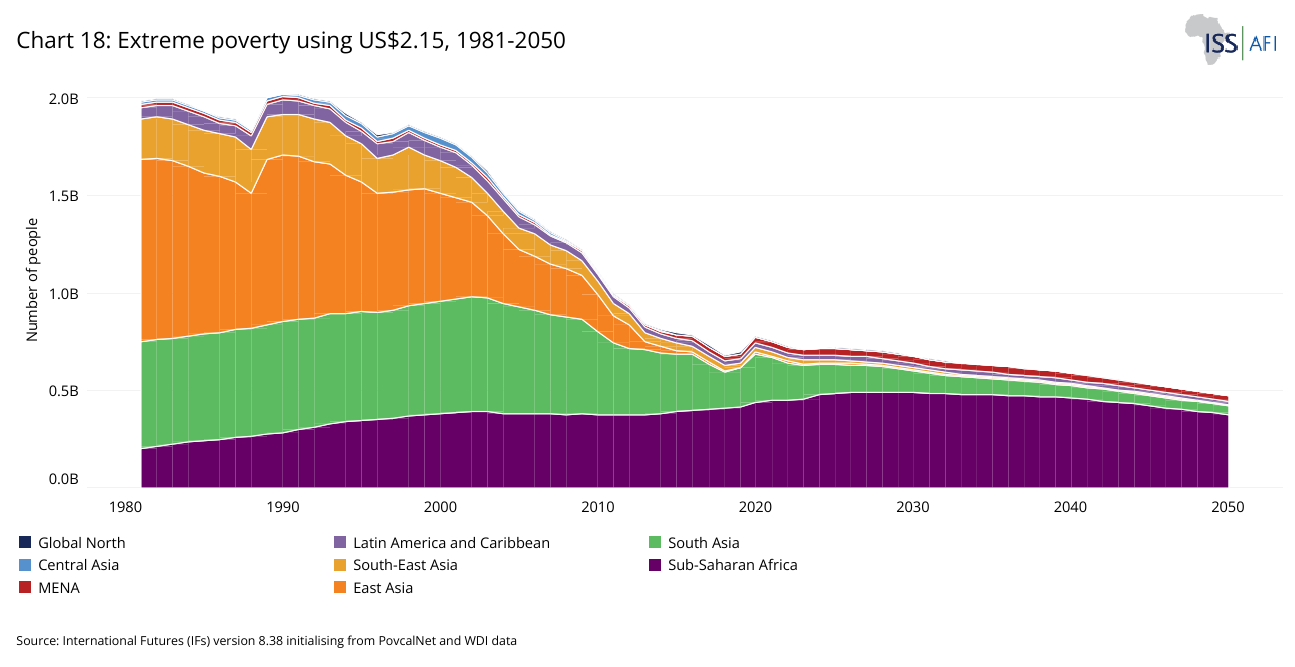

- Chart 18: Extreme poverty using US$2.15, 1981-2050

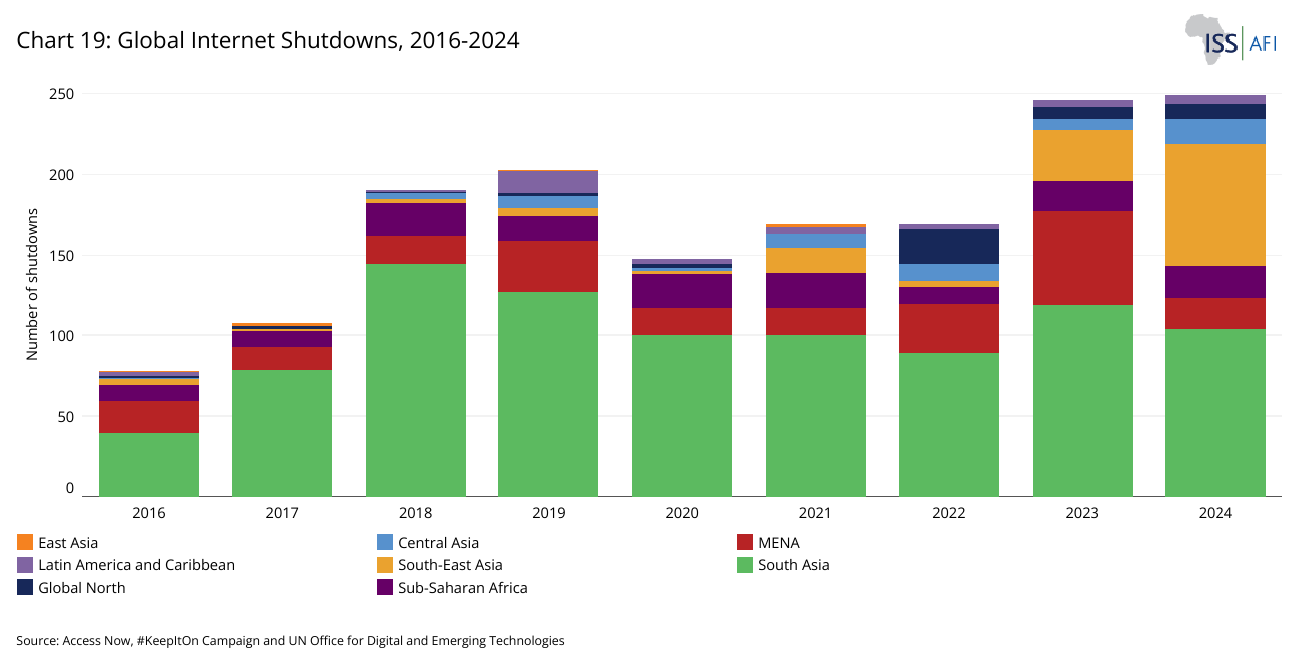

- Chart 19: Global Internet Shutdowns, 2016-2024

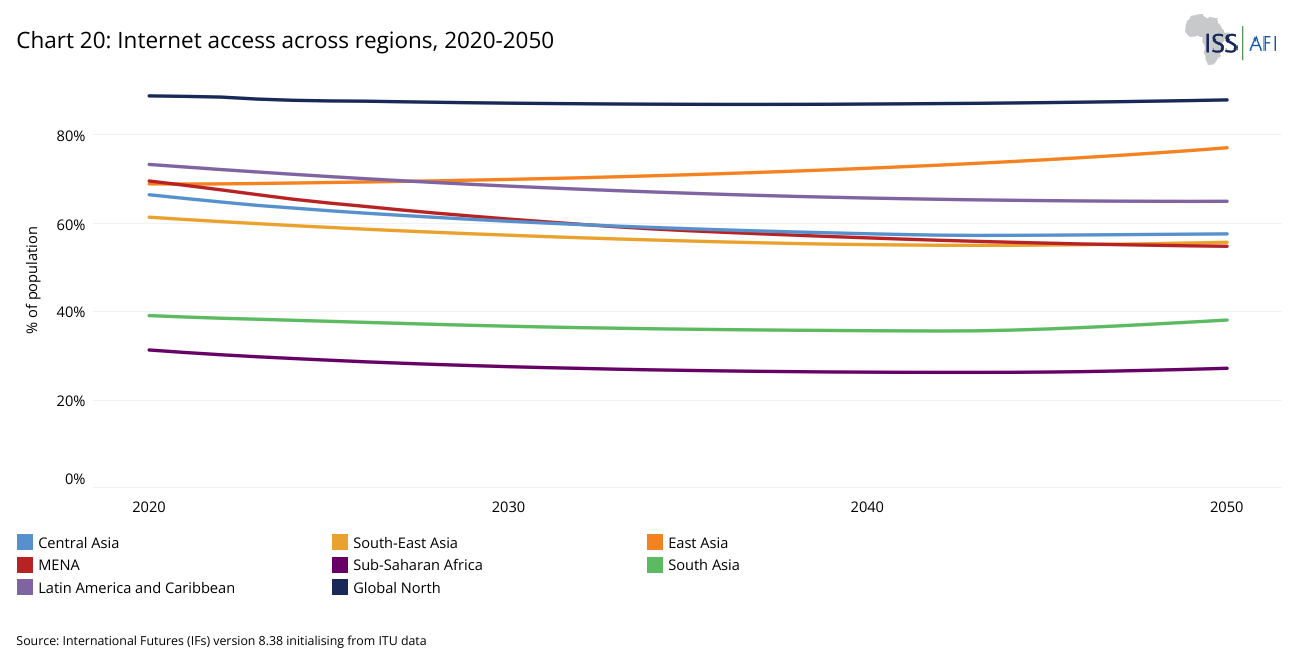

- Chart 20: Internet access across regions, 2020-2050

- Chart 21: Overall climate vulnerability and readiness to adapt, 2022

- Chart 22: Global scenario descriptions

- Chart 23: Four Futures of the State

Introduction

Download to pdfThis theme uses a foresight-driven approach to explore the trajectory of state governance in the Global South over the next two decades. State governance refers to the structures, processes and practices through which states exercise authority, make decisions and manage resources to achieve societal objectives.

By applying a futures lens, the theme identifies emerging trends, innovations and strategic adaptations that could shape how states respond to complex and evolving challenges. The analysis is forward-looking but grounded in current dynamics, with the goal of informing more effective, inclusive and responsive governance models in a rapidly changing global context.

The theme seeks to answer the following:

- What are the key forces shaping the future of state governance in the Global South, and how can policymakers anticipate and respond to these transformations?

- What roles do technology, economic transitions, geopolitical shifts and non-state actors play in reshaping governance models, and how can states harness these forces for sustainable development?

- What scenarios best illustrate the potential governance trajectories for the Global South, and what policy pathways can help states navigate toward equitable, stable and future-ready governance structures?

- How can governments and institutions in the Global South build more resilient, adaptive and inclusive governance systems in the face of accelerating global disruptions?

- How can futures thinking and strategic foresight be leveraged to inform governance strategies, ensuring that decision-making remains proactive rather than reactive in an uncertain world?

These questions position the theme as a forward-looking, strategic exploration rather than an analysis of current trends. Seeking to answer these questions emphasises the core role that anticipation, adaptation and transformation will play in Global South governance.

Note: The theme links to an interactive display in the software tool Tableau, which is available here. It allows for easy data visualisation and disaggregated views (i.e., by country within each Global South group).

The analysis adopts two key approaches: a state-centric perspective and a Global South-focused lens. These complementary approaches allow for a nuanced examination of governance structures, state functions and their evolving role in response to global and regional transformations.

State Governance

At the core of this framework is the concept of state governance: the structures and processes through which a state organises, regulates and adapts its political, social and economic systems. Governance involves the distribution of power and decision-making authority among both state institutions and non-state actors, such as multilateral organisations, businesses and civil society groups. Beyond formal structures, it is also influenced by historical contexts, social norms and shared values, all of which affect a state’s long-term development and stability.

The evolution of governance is non-linear and varied. Seen from the perspective of the Global North, state governance is essentially viewed as a progression from non-democratic to democratic systems with the associated institutionalisation. That view often does not acknowledge the indigenous and historically unique governance systems that have evolved in many countries in the Global South, much of which has been hidden (or suppressed) by the dominant impact of imperialism, colonialism and more recently through a bipolar or unipolar system. As that overarching dominance declines with the rise of the Global South in population numbers and in economic size, new challenges and historical (or deep) drivers emerge that challenge the dominant development and governance discourse emanating from the Global North. Instead of democracy, the preferred destination for many countries in the Global South is accountable governance and structures that can strengthen this responsible governance.

Global South Perspective

The Global South-focused lens ensures that governance analysis remains grounded in the socio-economic, political and historical realities of these regions. Historical legacies such as colonial rule, structural adjustment programmes and geopolitical shifts have all influenced state-building processes, governance capacities and institutional effectiveness. This perspective accounts for the diversity of governance models across the Global South while recognising shared challenges, including economic dependency, legitimacy struggles and governance capacity constraints. It also recognises the enduring relevance of indigenous governance systems, which continue to shape localised governance practices and offer valuable insights into resilience and legitimacy.

For the purposes of this theme, the Global South consists of seven regions namely Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Latin America and the Caribbean, Central Asia (with Russia at its core), South Asia (with India at its core), Southeast Asia and East Asia (including China).

The Global North typically refers to high-income, industrialised countries, such as Canada, the United States (US), all EU countries, the United Kingdom (UK), Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand.

|

Sub-Saharan Africa: Angola, Cameroon, Benin, Botswana, Congo, Kenya, Côte d'Ivoire, Equatorial Guinea, Sudan, Uganda, Niger, Guinea, Burkina Faso, Zambia, Malawi, Madagascar, Ghana, Mauritania, Togo, Gabon, Namibia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Zimbabwe, DR Congo, Somalia, South Africa, Tanzania, South Sudan, Burundi, Cabo Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea Bissau, Lesotho, Liberia, Mali, Mozambique, Sao Tome and Principe, Seychelles, Sierra Leone. |

|

Middle East and North Africa (MENA): Algeria, Egypt, Bahrain, Djibouti, Iran, Tunisia, Jordan, Kuwait, UAE, Yemen, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Syria, Libya, Turkey, Oman, Lebanon, Palestine, Morocco. |

|

Central Asia: Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Russia. |

|

South Asia: Bangladesh, Maldives, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. |

|

Southeast Asia: Brunei, Laos, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Timor Leste, Vietnam, Thailand. |

|

East Asia: China, Mongolia, Hong Kong, DR Korea, Taiwan. |

|

Latin America and the Caribbean: Argentina, Brazil, Bahamas, Bolivia, Chile, El Salvador, Colombia, Costa Rica, Barbados, Belize, Cuba, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Guatemala, Ecuador, Jamaica, Mexico, Dominican, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, St Lucia, St Vincent, Surinam, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay, Venezuela, Grenada. |

|

Global North: Australia, Bulgaria, Austria, Belgium, Canada, France, Croatia, Czechoslovakia, Slovakia, Poland, Sweden, Slovenia, Spain, Portugal, Greece, Germany, Finland, Hungary, New Zealand, Denmark, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Lithuania, Romania, South Korea, United Kingdom, Luxembourg, Netherlands, USA, Iceland, Israel, Latvia, Switzerland, Malta. |

Research Design

Download to pdfThe theme employs a multi-method research design that integrates, expert workshops and foresight methodologies to assess state governance trends and future trajectories in the Global South.

Comparing state governance

The World Bank's Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) measure perceptions of state governance across six key dimensions, allowing for meaningful comparisons:

- Voice and Accountability which can be considered a rough proxy for democracy

- Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism

- Government Effectiveness

- Regulatory Quality

- Rule of Law

- Control of Corruption.

Their comparability across countries enables benchmarking governance performance, while longitudinal insights allow tracking governance trends over time. The indicators were used to compare governance performance across the four alternative future scenarios and assess policy implications.

Expert Workshops

Several expert workshops, conducted virtually, brought together scholars, policymakers and practitioners. Experts were identified based on their backgrounds in governance and democracy across different regions. The recruitment process combined several approaches: leveraging team networks, acting on expert referrals and conducting targeted online research.

- Firstly, 40 experts participated in the methodology workshop in March 2024, which contributed to initially framing this theme's approach.

- Secondly, a Global North workshop was held in June 2024 to contrast insights from the Global South, with 13 experts attending.

- Thirdly, the Global South regional workshops were conducted in four groupings: Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and Asia. Between 7 and 19 experts participated in each workshop.

- Finally, in March 2025, an internal workshop within the Institute for Security Studies explored the evolution of state governance in the four alternative global futures examined further below in this theme.

These workshops provided regional perspectives on governance challenges, helped to validate scenario assumptions and highlighted emerging governance trends. By engaging regional experts and incorporating workshop insights into the analysis, the theme captures governance challenges and opportunities from multiple perspectives, ensuring a more nuanced understanding of governance dynamics.

Horizon Scan

To identify and systematically analyse the key forces shaping governance trajectories in the Global South over the coming decades. This systemic approach explores political, social, technological, economic and environmental trends influencing the future of state governance.

Alternative Scenarios

- Scenario Framework: The AFI-ISS developed four global scenarios initially to explore Africa's potential development paths. In this theme, they serve as a structural framework for analysing how state governance in the Global South may evolve under different global conditions. Each scenario presents a distinct combination of geopolitical, economic and social forces, shaping governance outcomes differently.

- Scenario Narratives: Building on these four global scenarios, this theme integrates insights from the horizon scan to enhance depth and relevance, grounding governance futures in contextual, interconnected development pathways.

Governance Outcomes Across Scenarios

Comparing WGI scores across alternative futures illustrates how measures of voice, capacity and control could evolve along divergent pathways. This approach highlights not only institutional strengths and weaknesses, but also the potential for deeper shifts in the nature and role of the state under different global conditions.

Strategic Conclusions

By integrating the above methodology elements, the theme offers a forward-looking analysis linking global trends to governance outcomes. It provides a structured framework for exploring uncertainty, challenging assumptions and identifying options in the face of accelerating change. Governments, civil society, donors and regional actors in the Global South can use this theme to understand emerging risks better, identify new possibilities and strengthen institutional responses to complexity.

Historical Overview and Current Governance Context

Download to pdfGovernance in the Global South has been shaped by a complex interplay of colonial legacies and post-independence challenges, institutional evolution and global economic and political forces. Understanding this trajectory provides a critical context for assessing contemporary governance challenges and anticipating future developments.

The modern state structures in many Global South countries were primarily influenced by colonial rule, such as parliamentary or presidential systems, which imposed administrative frameworks that often disregarded indigenous governance systems. The post-independence period saw newly formed states grappling with the challenges of nation-building, economic restructuring and institutional development since these structures required significant adaptation to align with diverse domestic political, social and economic conditions. Some states successfully reformed their institutions to enhance political stability and public sector capacity, while others experienced governance challenges, including institutional fragility, political polarisation and difficulty in managing diverse interests. These experiences highlight an essential principle: governance structures must be responsive, inclusive and adaptable to national contexts to ensure long-term effectiveness.

During the Cold War, geopolitical alignments influenced state governance, with many Global South countries caught between competing ideological blocs. This period saw increased foreign intervention, often reinforcing authoritarian regimes or undermining state sovereignty.

Subsequently, the 1980s and 1990s introduced structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) led by international financial institutions, which mandated economic liberalisation and state downsizing. While these reforms aimed to stimulate economic growth, they often weakened state capacity, exacerbated inequalities, and fueled social discontent.

The turn of the 21st Century ushered in an era of globalisation, intensifying state interdependencies. Economic integration, digital transformation and the rise of regional governance structures have redefined the state's role. While globalisation has created new opportunities, it has also exposed states to external shocks, from financial crises to pandemics, highlighting the need for adaptive governance models.

Beyond institutional design, political stability has remained a defining governance challenge. Many states have faced military coups, single-party rule or hybrid governance models that blend democratic institutions with centralised control. Political transitions, contested elections and civic unrest continue to test the resilience of institutions, underscoring the importance of legal frameworks, judicial independence and mechanisms for political accountability. External influences have also shaped governance trajectories, from Cold War-era interventions to contemporary economic partnerships that present both opportunities and governance considerations.

While many states in the Global South share common governance challenges, their trajectories have also been shaped by unique historical, political and economic circumstances. For example, China pursued a state-led economic development model, combining centralised governance with market-oriented reforms to achieve rapid industrialisation and global economic integration. This contrasts with countries in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, where governance has often been influenced by democratic transitions, external financial dependencies and fluctuating political stability.

Similarly, Southeast Asia has seen varied governance models, with states such as Singapore and Vietnam leveraging strong state capacity to drive economic growth. In contrast, others have faced constraints linked to political fragmentation and policy instability. These diverse paths highlight that governance in the Global South is far from monolithic, and understanding these differences is essential in assessing both challenges and opportunities.

As governance structures continue to evolve, states in the Global South face a rapidly changing landscape influenced by globalisation, economic transformation, technology and environmental challenges. Economic governance remains a critical factor in state capacity and institutional resilience. Many states have pursued industrialisation and economic diversification with varying degrees of success, navigating both domestic and global constraints. Key factors such as infrastructure development, access to capital, policy consistency and human capital investment have influenced economic trajectories. While some countries have integrated into global value chains and high-growth sectors, others continue to face structural challenges, including economic volatility, limited diversification and reliance on commodity exports. Demographic trends, including rapid population growth and urbanisation, add further complexity, requiring governments to create employment opportunities, strengthen public services and develop infrastructure that supports sustainable economic development.

Therefore, the evolution of governance in the Global South reflects a continuous process of adaptation, shaped by historical legacies and contemporary global shifts. Political instability, external influences, economic transitions, technological advancements and environmental challenges have all played a role in defining governance trajectories. The central challenge remains the ability of states to build resilient, inclusive and adaptive institutions—ones that can navigate complex political and economic pressures while fostering long-term stability, accountability and development.

Governance across the Global South is characterised by diverse models that reflect historical legacies and contemporary adaptations. States vary in their institutional design, ranging from presidential to parliamentary systems, from highly centralised authorities to increasingly decentralised arrangements. Many function in practice as hybrid regimes, combining formal governance structures with informal power dynamics, traditional authorities or customary law. These models often evolve in response to shifting internal needs and external pressures, rather than following a uniform trajectory toward liberal democratic norms.

Ongoing tensions accompany this diversity. On the one hand, states must maintain legitimacy and deliver public goods in contexts marked by limited resources, demographic pressures and contested authority. On the other hand, they must adapt to emerging transnational challenges such as climate change, technological disruption and insecurity. In many cases, legitimacy is grounded less in procedural norms, such as electoral cycles, and more in performance-based measures: the capacity of the state to deliver services, maintain order and foster economic inclusion.

Institutional resilience varies widely across the region. Some states have demonstrated adaptability and innovation in the face of shocks, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic or economic crises, while others struggle with weak institutional capacity and eroding trust. These challenges are compounded by growing demands for accountability and transparency from increasingly vocal citizenries.

Non-state actors are also reshaping the governance landscape. Civil society organisations, traditional leaders, private sector actors and regional institutions play more prominent roles in shaping policy, delivering services and holding governments accountable. This reflects a broader shift toward multilevel and networked governance, where authority is distributed across overlapping systems rather than concentrated solely in central governments. In some contexts, non-state armed actors—such as criminal organisations, gangs, rebel groups and militias— challenge formal governance through less conventional and often coercive means.

Taken together, these trends point to a dynamic and contested governance terrain. While institutional fragmentation remains a risk in some contexts, others show signs of innovation and transformation. This complexity underscores the need for context-specific analysis of governance performance, explored in the following section.

This section analyses and compares the current context of global state governance through the six World Bank Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI). Derived from multiple data sources, including surveys and expert assessments, WGI ensure a broad and balanced representation of governance realities. The indicators align with global development frameworks such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goal 16 to promote peaceful and inclusive societies, reinforcing their relevance for policy formulation. Given the unique governance challenges of many Global South states—such as institutional fragility, external dependencies and informal power structures—WGI serve as a crucial tool for context-specific governance reforms, risk assessments and strategic investment decisions. These six indicators are:

- Voice and Accountability, which can be considered a rough proxy for democracy,

- Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism (aka Stability),

- Government Effectiveness,

- Regulatory Quality,

- Rule of Law,

- Control of Corruption.

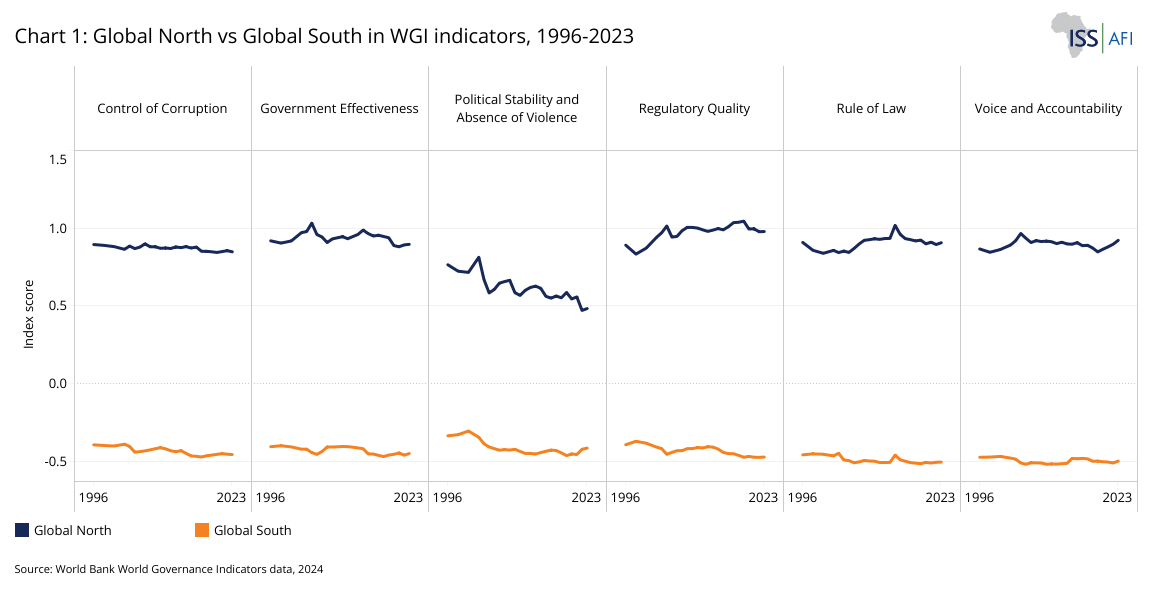

The general picture until 2023 is one of stagnation and regression globally, with a sharp deterioration in stability in the Global North. Chart 1 depicts the WGI for the Global North versus the South. Stability also declines in the Global South, but less sharply. The data reveals a consistent gap between the Global North and South across key governance dimensions. Many regimes in the Global South can be classified as "hybrid regimes” - countries that hold regular elections but do not fully conform to democratic principles. Hybrid regimes are typically more unstable than full autocracies or liberal democracies.

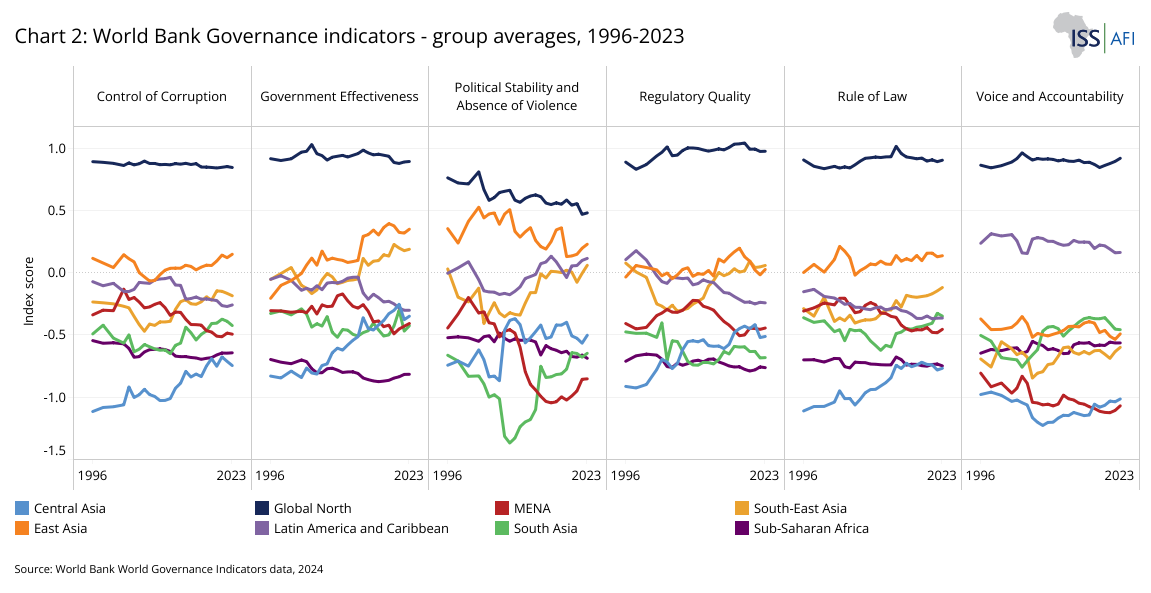

Trends within the Global South are diverse, reflecting the varying historical, political and economic trajectories of different regions. The general trend across the seven groups in the Global South is no change in Control of Corruption, with four regions seeing improvements in Government Effectiveness. Generally, there is a slight improvement in Regulatory Quality and Rule of Law, and no improvement/decline in Voice and Accountability (except for Southeast Asia). Chart 2 shows group averages for the WGI from 1996 to 2023.

A key insight from the data is the disconnect between political participation and governance capacity. While some lower-income regions, such as Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, score relatively high on Voice and Accountability, these gains have not translated into stronger governance outcomes as reflected in low scores on Government Effectiveness and Regulatory Quality. This suggests a phenomenon sometimes referred to as premature democratisation in these regions, where political participation expands faster than institutional capacity, contributing to weak institutions, corruption and limited state effectiveness. In a region such as Sub-Saharan Africa, conditional development aid and structural adjustment programmes are some of the drivers of relatively high levels of democracy at low levels of development. In 2025, it raises the question of whether significant reductions in aid by partners such as USAID and the UK could result in a decline in the levels of democracy currently enjoyed in the region.

In contrast, regions with lower democratic participation, such as East Asia and parts of Central Asia, tend to score lower on Voice and Accountability but have demonstrated notable improvements in Government Effectiveness and Regulatory Quality. This indicates that while political freedoms remain constrained, state capacity in these regions has improved, leading to better development outcomes, although accompanied by lower levels of respect for human rights and democracy.

The governance models that have shaped the Global South are now at an inflection point. The historical legacies of colonial administration, structural adjustment programmes and regional governance patterns will continue to influence future state trajectories. However, as global uncertainties mount, governance trajectories will increasingly be determined by a different set of drivers of change. The following section explores these key forces—ranging from technological disruption to demographic shifts—that will shape the governance models of the future.

The following horizon scan outlines the critical drivers and trends shaping the future of state governance in the Global South. Using a systemic lens, it examines interlinked developments across five domains: political and security governance, economic governance, social governance, technology and innovation, and climate and resource governance. Together, these forces reshape how states govern, how authority is exercised and contested, and how states engage with citizens, markets and international systems. The scan aims to illuminate key pressures and possibilities that will influence governance trajectories over the coming decades. These dynamics not only present risks but also open up opportunities to reimagine and redesign governance models in ways that are more inclusive, resilient and tailored to the diverse contexts of the Global South.

Chart 3 illustrates the systemic domains explored in the horizon scan, depicting the interconnected forces shaping the future of state governance in the Global South. It also provides a consolidated list of all factors within each systemic category.

Shifting Geopolitical Power and the Rise of Multipolarity

The global order is undergoing a significant transformation, as the unipolar dominance of the post-Cold War era gives way to a more diffuse and contested landscape. States are increasingly navigating various partnerships, development models and geopolitical alignments. In this context, multipolarity is not simply the redistribution of influence but the reconfiguration of agency, expanding the range of strategic options while also introducing new complexities and risks.

A key driver of this realignment is the erosion of trust in the Western-led order. The Trump administration's aggressive retreat from multilateralism—via aid cuts, tariff wars and transactional diplomacy—is a leading example exposing the fragility of long-standing alliances and intensified uncertainty. Although felt globally, many states in the Global South were especially affected due to their historical reliance on Western-led financing and trade relationships. As a result, longstanding questions about the reliability of traditional alliances and economic frameworks have resurfaced with greater urgency, prompting states to accelerate or deepen efforts to reassess their development and security strategies in an increasingly unpredictable global environment.

This evolving landscape is not driven by abstract shifts alone; it is being actively reshaped by ambitious initiatives from emerging powers. Chief among them is China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which exemplifies how infrastructure can serve as a vehicle for geopolitical influence. It operates as a grand strategic lever: redrawing trade routes, embedding Chinese standards and expanding diplomatic influence across more than 140 countries. The proliferation of large-scale projects—often opaque, debt-financed and strategically located—poses difficult questions for states trying to balance developmental needs with long-term sovereignty.

Alongside China’s bilateral efforts, a broader rebalancing is taking place through coalitions that are positioning themselves as alternative centres of global decision-making and financial governance. The recent expansion of BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) to include Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Argentina, the United Arab Emirates, Iran and Ethiopia further signals the rising weight of non-Western blocs in global decision-making. The New Development Bank (NDB), initially founded by the five BRICS nations, has likewise grown its membership. Although full-scale de-dollarisation or the advent of a digital BRICS currency remains unlikely in the near term, both China and Russia have signalled strong interest in forging an alternative financial system outside the US dollar’s dominance. If these efforts mature, they could blunt the force of dollar-based sanctions and increase the appeal of alternative monetary regimes, particularly for heavily indebted countries in the Global South.

Regional frameworks like AfCFTA and ASEAN offer promising platforms for building collective agency and reducing vulnerability to great-power competition. AfCFTA, for instance, could boost intra-African trade by over 45% by 2045, if long-standing implementation hurdles can be overcome. Similarly, ASEAN’s emerging digital governance frameworks, including coordinated efforts on data, cybersecurity and e-commerce, illustrate how regional cooperation can enhance sovereignty in critical technological sectors. Still, the success of these mechanisms depends on the ability of member states to reconcile divergent political systems, economic priorities and levels of institutional capacity.

The intensifying multipolarity in the Global South is not confined to economic or diplomatic arenas. It is increasingly shaped by complex security dynamics, particularly in strategically contested maritime spaces. Along the Red Sea and Indian Ocean, littoral states (countries bordering these waters, such as Djibouti, Sudan and Kenya) face growing challenges as military competition escalates. The Houthi missile and drone attacks on commercial shipping have prompted retaliatory naval interventions, including the US-led Operation Prosperity Guardian, a multinational coalition established in December 2023 to ensure freedom of navigation and regional security. Despite the coalition's efforts, Houthi attacks have persisted, leading to significant disruptions in maritime traffic. Reports indicate that the Houthis have adapted their tactics, utilizing low-cost, high-impact weapons that strain the defensive systems of their adversaries. These tensions intersect with China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which has financed dual-use infrastructure such as the Djibouti port and logistical hubs in Kenya, and the expansion of BRICS to include Egypt, Ethiopia and Saudi Arabia (countries with direct stakes in Red Sea security).

Meanwhile, in the South China Sea, disputes involving China, Vietnam and the Philippines have intensified, with militarised maritime confrontations and coercive strategies eroding regional stability. These developments expose how military competition is entangled with economic multipolarity, amplifying governance challenges for states caught between great power rivalries. Diversifying resources into military build-ups, securitisation of state functions and heightened external alignment pressures risk weakening domestic institutions, eroding social contracts and undermining inclusive governance across the Global South.

Faced with this increasingly complex terrain, many states are adopting hedging strategies, balancing rival powers in an attempt to preserve autonomy and extract value from competing spheres of influence. For instance, Vietnam courts both China and the US, and Kenya has renegotiated Chinese-financed infrastructure projects under public pressure, whilst simultaneously engaging with the US on a bilateral trade agreement. These are often cited as cases of successful strategic autonomy. However, such manoeuvres demand high levels of institutional coherence, policy agility and political consensus. Absent these, hedging can devolve into policy drift, elite capture or renewed forms of clientelism under new banners.

Debt remains a key instrument of influence. Although Chinese lending has slowed since 2020, the aftershocks of earlier loans continue to shape fiscal trajectories. Sri Lanka’s 2017 signature of a 99-year lease agreement with China for the Hambantota Port is a cautionary tale in this regard. Zambia’s protracted restructuring of its US$17 billion debt shows the complexity of managing diverse creditors, including China, multilateral banks and private bondholders. These are not uniquely Chinese dilemmas: any poorly structured borrowing, regardless of source, can either unlock development or compromise sovereignty, depending on the transparency, competence and strategic foresight of borrower governments.

Some states assert control through economic policy, reviving protectionist tools to shield domestic industries and reduce exposure to volatile global markets. Indonesia’s ban on unprocessed nickel exports and India’s “Atmanirbhar Bharat” strategy reflect a broader trend toward economic nationalism. These measures aim to build domestic capacity and increase resilience, but they also risk disrupting supply chains, triggering retaliation and undermining regional cooperation.

Yet, the rise of multipolarity is not confined to interstate competition. Increasingly, power is being wielded by actors outside the formal state system, especially multinational tech firms, whose influence over critical infrastructure rivals that of governments. Firms like Amazon, Tencent, Meta and Huawei influence commerce, speech, data flows and even public infrastructure. Their platforms often outpace national regulation, leaving states scrambling to assert control over digital spaces. This shift represents a direct challenge to traditional state authority, particularly in regions with limited regulatory capacity.

The next decade will test whether multipolarity enables a more equitable and pluralistic international order or merely recasts old hierarchies in a new form. What emerges will depend less on structural shifts than on the strength, agility and foresight of state institutions facing a world in flux.

|

Critical considerations for state governance in the future:

|

Democracy Under Pressure

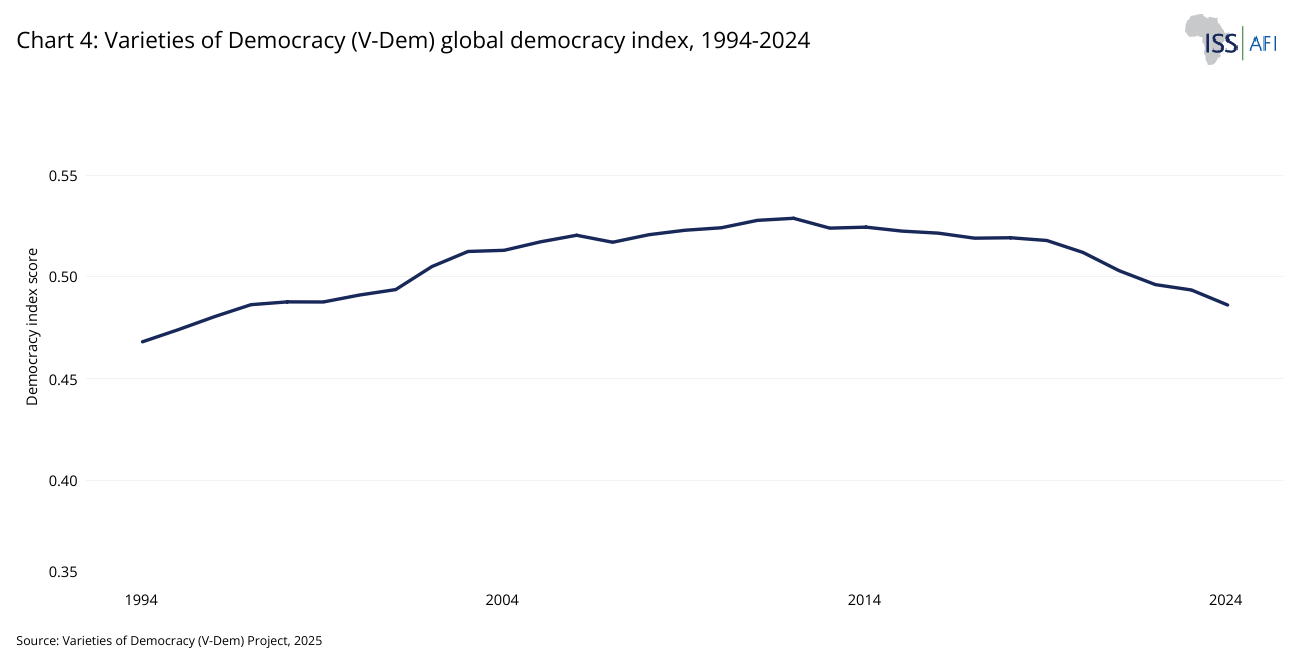

The global average of democratic rights and freedoms has regressed to levels last seen in the 1980s, with over a third of the world’s population now living under authoritarian rule. This shift is reshaping governance worldwide, especially in the Global South, where many states are navigating a fragile space between autocracy and liberal democracy. These developments are prompting a deeper examination of how democratic systems function in practice and what they can realistically deliver. Chart 4 depicts the global democracy index (by Varieties of Democracy Project) from 1994 to 2024.

Since the Industrial Revolution, core countries of the Global North have defined dominant models of development and governance, first through imperialism and colonialism, later through globalisation. As these states became wealthy and democratic, they exported their institutional frameworks and political ideals through influence or imposition. In doing so, they embedded the belief that liberal democracy is the ultimate outcome of development and a key enabler of accountable governance, particularly across the Global South and within the international development agenda.

While democracy is often assumed to lead to good governance, history shows it does not guarantee it. The advance of democracy in Latin America and the Caribbean, Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia has not delivered on the promise of development or equity. These regions have achieved relatively high democratic scores, yet remain among the most unequal in the world. Meanwhile, authoritarian regimes in East Asia and the Gulf have significantly improved infrastructure, income and basic services. This divergence has seriously undercut the once-dominant assumption that democracy and development naturally go hand in hand.

In much of the Global South, formal democratic structures have often failed to overcome deeply entrenched inequalities and vested interests. Many transitions stall in hybrid regimes, where elections coexist with patronage politics, elite control of media and resources and limited civic agency. These systems are often vulnerable to both internal disruptions (such as citizen protests or economic shocks) and external interference, particularly when governance is weak or extractive institutions remain intact. Despite this, demand for accountable governance remains strong, which is evident in anti-corruption campaigns, social justice protests and calls for transparency across Africa, Asia and Latin America.

The challenge is not a lack of democratic aspiration, but the absence of political structures capable of delivering on those aspirations in equitable, durable and inclusive ways.

The pressures on democracy are increasingly shaping public policy. A resurgence of nationalism and a renewed focus on national identity drive shifts toward stricter immigration controls and the reassertion of state sovereignty. Across Europe, the Americas and Asia, political parties are harnessing public anxieties over economic insecurity, cultural change and perceived threats to national cohesion. Many deploy rhetoric that challenges progressive norms on diversity, gender and identity, often framed as resistance to so-called “woke” politics. This polarisation influences legislative agendas, weakening institutional safeguards and eroding democratic consensus. Crucially, this climate has triggered a growing backlash against rights defenders like journalists, activists and civil society leaders who now face escalating harassment, surveillance and criminalisation.

This disconnect is unfolding amid what many describe as a global democratic recession. The "rise of the rest" has coincided with the erosion of democratic norms, not only in emerging powers but within the Global North itself. Elections worldwide have exposed profound voter disillusionment and fractured mandates. Populist parties on both the left and right are entering the mainstream, attacking elites, undermining institutions and deepening societal division.

|

Critical considerations for state governance in the future:

|

Security and Conflict Dynamics

Over the past five years, the number of conflict events worldwide has almost doubled, marking a stark escalation in global insecurity. Chart 5 presents the global number of armed conflicts from 1989 to 2023. This surge reflects both the eruption of new large-scale wars and the intensification of protracted crises. High-impact conflicts in Ukraine, Gaza and Myanmar have driven much of the recent violence, while entrenched instability in places like Sudan, Mexico, Yemen and across the Sahel continues unabated.

State-Based Conflict

According to the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), 2023 recorded 59 state-based conflicts in 34 countries, the highest number since 1946. This marks a significant reversal of the post-Cold War decline in armed conflict. For the past eight consecutive years, more than 50 such conflicts have occurred annually, signalling a sustained and systemic deterioration in global peace and security. Chart 6 shows the number of state-based armed conflicts by region from 1946 to 2023.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the Global South. Africa has seen its number of state-based conflicts nearly double in the past decade, from 15 in 2013 to 28 in 2023. Countries such as Sudan, Ethiopia, Mali and Burkina Faso continue to face armed uprisings, often intensified by jihadist groups and political fragmentation. Meanwhile, the Middle East, previously on a downward trajectory, has seen a resurgence, most notably in the deadly Israel-Palestine war, which caused over 23 000 fatalities in just three months.

These conflicts increasingly occur in middle-income and partially democratic states, challenging the long-held assumption that economic development and electoral democratisation naturally lead to stability. Without inclusive, accountable governance, these states often become flashpoints for grievances, competition and violent contestation.

States as Perpetrators of Violence

The governance crisis deepens when the state is not merely unable to protect its citizens, but is itself a source of violence. In 2023, over 10 200 civilian deaths were attributed to one-sided violence, with more than 2 000 caused by state actors. While slightly lower than recent peaks, state-perpetrated violence remains a disturbing trend. In countries such as Myanmar, Syria, Sudan and Russia (in Ukraine), government forces have been implicated in widespread human rights abuses, often targeting civilians directly.

This shift, where states actively undermine their protective role, profoundly erodes the social contract, intensifies societal division and complicates peacebuilding efforts. It also exposes a structural weakness in global governance: the lack of effective accountability mechanisms when sovereign states violate the rights of their own populations.

Rise of Non-State Actors

Alongside these developments, non-state conflicts have surged and stabilised at historically high levels. In 2023, 75 non-state conflicts were recorded, mostly involving criminal organisations, terrorist groups or militias. The UCDP classifies these actors into:

- Formally organised groups, with identifiable names and structures;

- Informal political groups, such as party-affiliated mobs; and

- Communal groups, rooted in ethnic, religious or tribal identity.

Organised groups primarily drive the rise in non-state violence, while communal conflicts have also grown steadily. Conflicts involving informal political groups remain relatively rare. Chart 7 presents the number of non-state conflicts by region from 1989 to 2023.

Regional patterns vary significantly. Notably, the Americas surpassed Africa for the first time, becoming the region with the highest number of non-state conflicts, driven by violence linked to powerful drug cartels in Mexico and Brazil. Mexico alone accounted for nearly 14 000 battle-related deaths in 2023, underscoring the severity and complexity of non-state violence in the region. In contrast, Africa has seen a notable decline in non-state conflicts over the past six years, despite historically being the most affected region.

While both Africa and the Americas have recorded high numbers of non-state conflicts, the nature of these conflicts differs considerably. In the Americas, violence is primarily driven by highly structured and well-armed groups such as organised crime syndicates and drug cartels. In Africa, non-state violence more often stems from communal conflicts, rooted in ethnic, religious or local identity divisions. Meanwhile, the Middle East, which saw a significant rise in non-state conflicts during the 2010s, has experienced a sharp downturn in such incidents in recent years.

By contrast, Europe and Asia continue to experience relatively low levels of non-state conflict, both in terms of frequency and intensity. This regional variation highlights the importance of context-specific approaches to understanding and addressing non-state violence across the Global South.

The evolving nature of conflict presents a fundamental challenge to state governance in the Global South. As conflicts become more fragmented, involving multiple actors and overlapping grievances, states must navigate a complex security environment where they are both responders to and, at times, instigators of violence. Reclaiming legitimacy will require not only restoring civilian trust and accountability but also adopting flexible, inclusive and context-specific approaches to security governance. Strengthening institutions, ensuring human rights protections and confronting the structural roots of violence are essential for moving from crisis response to long-term stability.

|

Critical considerations for state governance in the future:

|

Localised Governance

Localised governance is emerging as a frontline issue in the reconfiguration of state legitimacy across the Global South. Often described in terms of decentralisation, it is more than a technical redistribution of powers; it is a profoundly political process that redefines who governs, where and how. It determines whether state authority feels accessible or remote, whether services are delivered equitably and whether diverse communities see themselves reflected in national institutions.

This trend is not driven by policy preference alone but by mounting systemic pressures. Rapid urbanisation has stretched megacities like Lagos, Dhaka and Mumbai to their limits, forcing subnational authorities to take on more governance responsibilities, often without corresponding authority or resources. Simultaneously, localised governance is being propelled from below as Indigenous movements, grassroots organisations and informal authorities demand greater recognition and autonomy. In many cases, governance is not devolved by design but delegated out of necessity.

In fragile or rural contexts, informal and traditional institutions often act as the default governance systems. In countries like Nigeria, Somalia and Afghanistan, tribal courts, clan elders and customary authorities regularly mediate justice and manage community affairs, particularly in areas where formal institutions lack legitimacy or reach. Traditional leaders are often viewed as more trustworthy than elected officials or police forces, especially in rural areas. These dynamics are not relics of the past; they are operational, embedded forms of local governance, though their effectiveness varies across contexts.

Around the world, decentralisation efforts that build on such culturally grounded systems tend to generate more durable legitimacy. In Bali, the subak system, a centuries-old, community-managed irrigation model, has been formally integrated into environmental governance, aligning spiritual, ecological and institutional logics. In Brazil’s Amazon, Indigenous communities now co-manage forests with federal agencies, blending traditional environmental knowledge with satellite monitoring technologies. Similarly, in Colombia, the formal recognition of Indigenous Cabildos has empowered communities to act as official local governments with administrative powers and public budgets, enhancing both environmental stewardship and cultural identity. In Mexico’s Ixtlán de Juárez, Indigenous-led forest management has transformed local economies and ecosystems, reducing poverty and ecological degradation through collective governance. Across Africa, Indigenous knowledge systems, including pastoralist conflict resolution and resource management, continue to shape local governance, offering adaptive and resilient models rooted in generations of ecological understanding.

While outside the Global South in this theme, Australia offers a telling case of the challenges surrounding formal Indigenous inclusion. In October 2023, a national referendum to enshrine an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to Parliament was defeated, revealing deep societal divisions over Indigenous participation in governance. This underscores a broader truth: genuine Indigenous engagement requires more than symbolic recognition; it demands structural reform, political will and durable institutions rooted in Indigenous knowledge systems.

Participatory budgeting, pioneered in Porto Alegre, Brazil, has been adopted in cities like Buenos Aires and Jakarta, enabling citizens to influence budget allocations directly. While these initiatives create new avenues for transparency and inclusion, in low-capacity settings, they can reinforce centralisation, especially when local authorities lack the legal or technical leverage to control digital platforms or safeguard citizen data. In such cases, digital governance risks becoming a new form of top-down control rather than a driver of local empowerment.

The trajectory of local governance will significantly shape state legitimacy, cohesion and institutional resilience in the Global South. However, the outcomes of decentralisation remain uneven. Where reforms are limited to symbolic gestures, without absolute autonomy, resources or accountability, they risk reinforcing inequality and public distrust. Where supported by political commitment and institutional capacity, decentralisation can enable more locally grounded responses to governance challenges. Looking ahead, a key uncertainty is whether these evolving models will lead to genuine power-sharing or reconfigure centralised control through more fragmented or technologically mediated forms.

Ultimately, legitimacy and trust in state institutions are deeply intertwined with the effectiveness of local governance. When communities see their values, knowledge systems and leadership reflected in governance structures, trust is strengthened and legitimacy is reinforced. Recognising and integrating Indigenous governance models not only honours cultural heritage but also builds more resilient and inclusive states.

|

Critical considerations for state governance in the future:

|

Southern Shift: Emerging Markets, Expanding Influence

The centre of global economic gravity is shifting, measurably and irreversibly, from the industrialised North to the emerging South. Over the past two decades, much of global GDP growth has come not from Europe or North America, but from Asia, Africa and Latin America. By 2040, more than half of global GDP is expected to be generated by countries currently classified as “emerging markets,” with Asia alone accounting for over 40%. This is not merely a geopolitical transition; it is an economic realignment that is reshaping the foundations of global development. Chart 8 illustrates the global economy in 2050.

At the heart of this transformation is the rise of new middle classes across the Global South, particularly in Asia. In 2020, over two billion people in Asia-Pacific were classified as middle-income; a number projected to reach 3.5 billion by 2030. In Africa, a demographic surge is fueling similar momentum: with over 70% of the population under 30, the continent is becoming a hub of urbanisation, innovation and rising demands. Cities like Lagos, Nairobi and Accra are emerging as consumption engines and economic dynamism.

India, now the world’s most populous country, is on track to become the third-largest economy by the end of the decade. Its growing domestic market, digital infrastructure and demographic edge position it as a global engine of demand and innovation. China, despite facing population decline, remains an economic heavyweight, driving investment, production and capital flows across the Global South. Together, these regions are not just catching up; they are becoming the global marketplace of the future.

With this demographic and economic growth comes bargaining power. The Global South is no longer just a supplier of raw materials or low-cost labour. It is a fast-growing consumer base capable of shaping production standards, influencing trade flows and setting norms around technology, sustainability and labour. As consumption patterns shift towards meat, mobility, digital goods and higher energy use, so too do expectations around regulation, climate governance and social protections. States that can effectively represent and align these interests at the global level will play a pivotal role in redesigning 21st-century markets.

But growth brings pressure. Expanding middle classes increase demand for water, food, energy and housing, amplifying resource constraints and environmental risk. Without adequate urban planning, infrastructure investment and sustainability strategies, states risk being overwhelmed by congestion, pollution and inequality. Informality remains high in many economies, limiting tax capacity and social insurance coverage. Rising aspirations must be matched by institutional capability, or they may become political volatility.

Meanwhile, the global production map is also shifting. Countries like Vietnam, Bangladesh, Mexico and Ethiopia are becoming competitive alternatives to China in manufacturing and logistics. However, to sustain this advantage, states must go beyond low wages; they must invest in labour standards, digital connectivity, logistics systems and green compliance.

As Global South economies gain weight, regional integration and South-South cooperation will become even more essential tools of strategic leverage. By coordinating policy, pooling resources and negotiating as blocs, states can amplify their influence in global rule-setting, from trade and digital governance to climate finance and debt negotiations. The ability to shape, not just absorb, global markets will depend on how well emerging economies build coalitions, institutional resilience and common developmental agendas across regions.

|

Critical considerations for state governance in the future:

|

Growth and Demographics: A Governance Dividend or Liability?

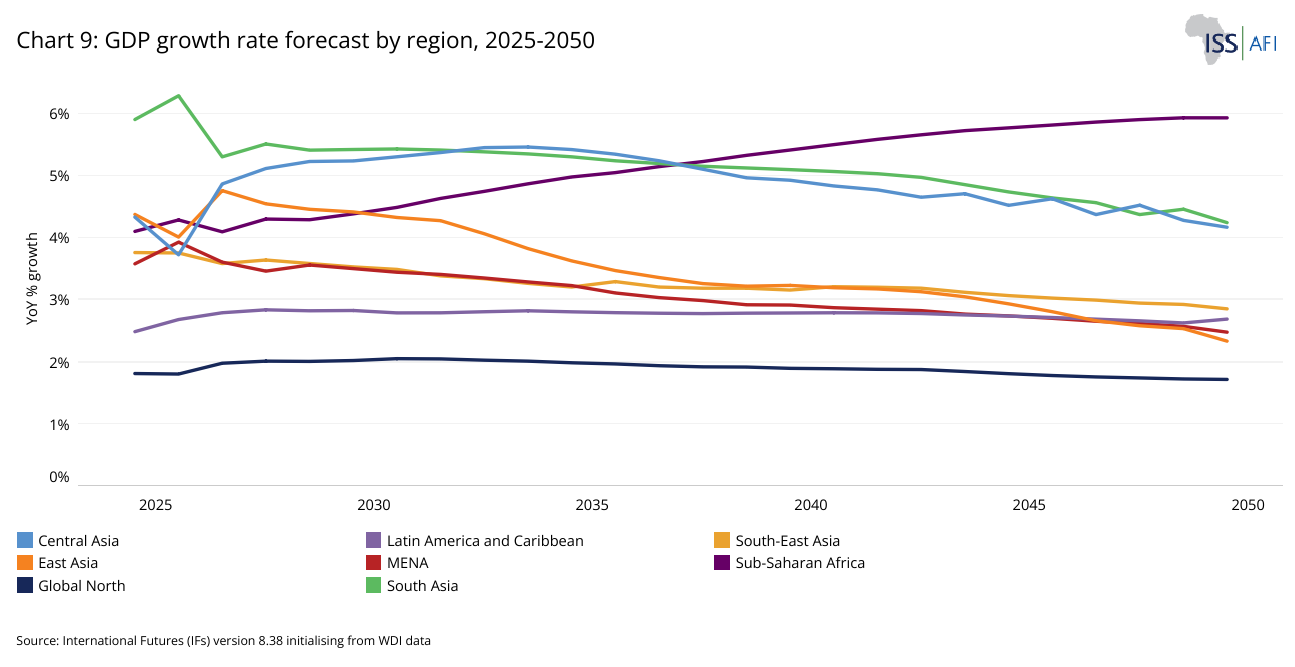

Economic development will be a defining force shaping governance futures in the Global South, especially where it intersects with rapid demographic transformation. Chart 9 presents the GDP growth rate forecast by region from 2025 to 2050. Over the next 25 years, the Global South is expected to be the primary engine of global economic growth. Yet, this growth will be uneven, and its developmental impact is far from guaranteed. What matters is not how fast economies grow, but how well that growth is governed through inclusive institutions, accountable public investment and forward-looking policy choices.

Chart 9 shows that South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa are forecast to record the highest GDP growth rates globally between 2025 and 2050. This is primarily driven by their youthful populations and expanding labour forces. However, this headline growth risks being misleading. Without strong economic governance, including capable institutions, inclusive fiscal policy and long-term investment strategies, rapid growth may exacerbate inequality, strain public services and deepen instability.

By contrast, the Global North is approaching the end of its demographic dividend, with ageing populations slowing workforce growth. Average annual GDP growth is projected at just 1.6%. In these regions, maintaining economic performance will depend on governance that promotes innovation, automation and capital investment to offset labour shortages.

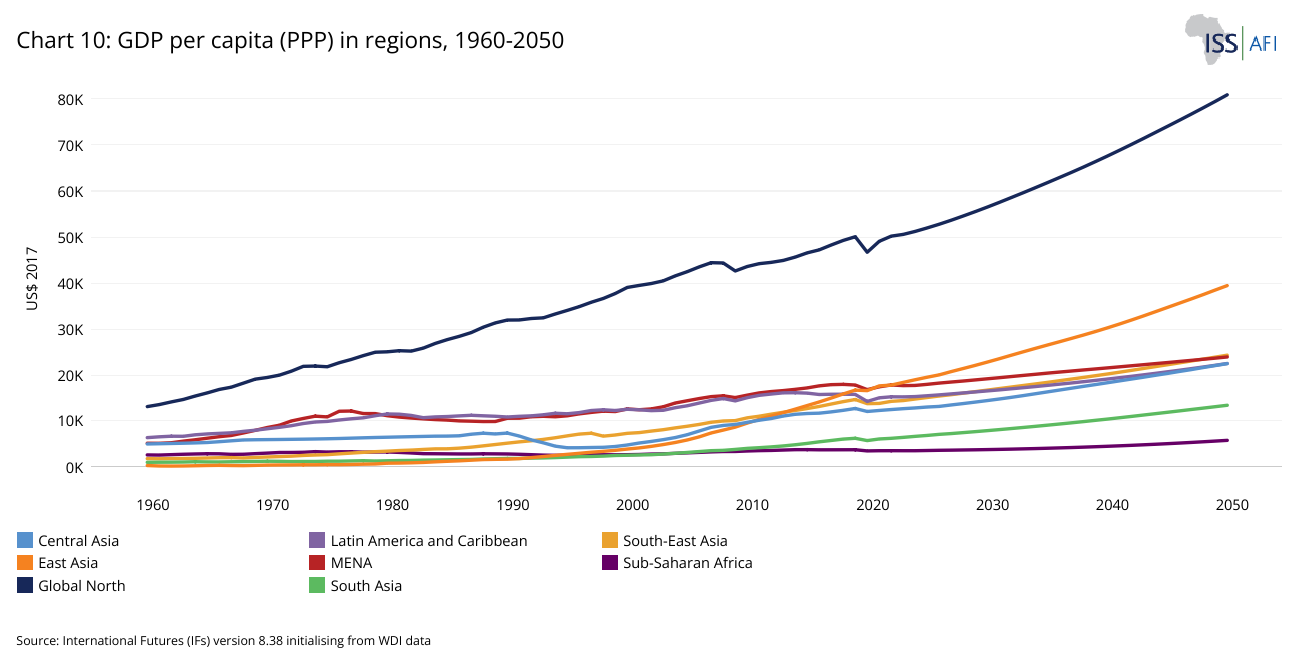

Chart 10 depicts the development of GDP per capita by region from 1960 to 2050. It reveals a stark disconnect: despite high projected growth, Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia remain at the bottom in terms of GDP per capita, lagging far behind the Global North. Sub-Saharan Africa’s average income level is forecast to stay under 10% of the Global North’s by 2050. This points to a deeper development gap, one that will not be closed by growth alone. Structural deficits in governance, from weak revenue mobilisation to limited policy coherence, continue to constrain the region’s capacity to convert growth into prosperity.

In contrast, East Asia offers a gostory of vernance success sIts manufacturing-led growth, underpinned by active state intervention, has translated into major gains in GDP per capita. By 2050, East Asia’s income levels are projected to reach nearly half those of the Global North; a remarkable convergence by Global South standards.

For the Global South, the coming decades will be defined not just by how fast economies grow but also by how well states manage that growth through inclusive, accountable and forward-looking governance systems.

Demographic Transitions

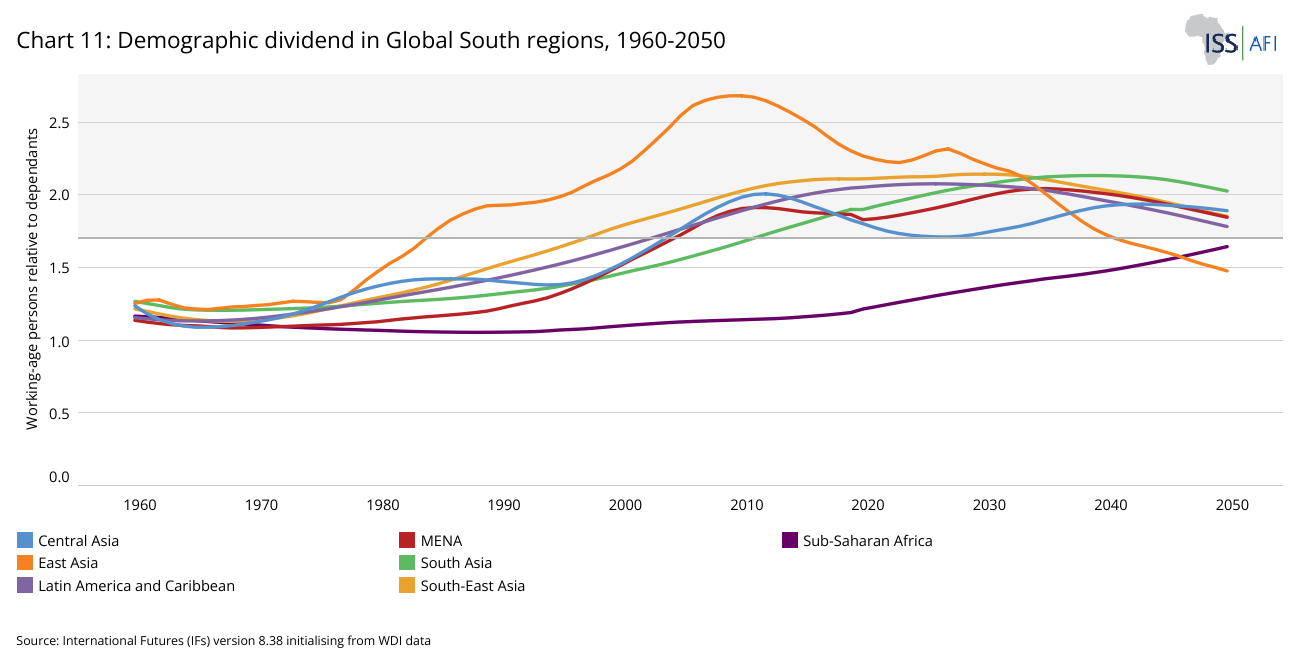

A demographic dividend refers to the potential economic boost that arises when a country’s working-age population grows larger relative to its dependents (children and the elderly). This period, when most people are economically active, enables governments to shift resources from basic services like schooling and childcare toward investments that fuel economic growth.

A widely accepted measure of this opportunity is the ratio of working-age individuals (aged 15–64) to dependents. When this ratio reaches around 1.7 to one, a country typically enters its first demographic dividend phase. Yet, this numeric threshold is only part of the story. Realising the full potential of a demographic dividend depends crucially on a state’s ability to provide high-quality education, accessible healthcare and robust employment opportunities.

Chart 11 maps the demographic dividend timelines across major regions in the Global South from 1960 to 2050. It shows that East Asia is currently at the peak of its demographic window, benefiting from a high ratio of working-age individuals. However, this window is closing rapidly; it is projected to exit the dividend period by the early 2040s—a shift that will be reflected in declining economic growth rates.

In the Middle East and North Africa, a favourable age structure has not yet translated into significant economic gains. Political and institutional constraints, ranging from rigid labour markets to state-dominated economic frameworks and persistent challenges in gender equity and education quality, continue to hamper progress.

Sub-Saharan Africa remains in a pre-dividend stage. With the youngest population globally, only five countries in the region (Mauritius, Cabo Verde, Seychelles, South Africa and Botswana) have entered a demographic dividend window. In many other nations, the persistently high dependency ratio, where children and the elderly far outnumber the working-age population, has slowed economic growth. This imbalance places tremendous pressure on public resources, as governments must allocate a significant share of their budgets to fundamental services like healthcare and education rather than investing in growth-enhancing sectors. While these challenges have constrained productivity and limited labour force participation, they also underscore the region’s tremendous future potential. If Sub-Saharan African countries can build robust governance frameworks to better manage this transition, they stand to unlock significant long-term economic and social dividends.

Demographics set the stage, governance writes the story

A large working-age population is not a dividend by default. Without the right conditions like jobs, education, healthcare and public investment, the demographic shift can lead to economic stagnation, rising inequality and social unrest.

Governments must play an enabling role, particularly in:

- Expanding access to quality education and vocational skills,

- Creating inclusive labour markets that absorb young workers,

- Facilitating urban development to support growing populations, and

- Maintaining macroeconomic and political stability.

These goals are often the hardest to achieve in fragile or highly unequal contexts. If left unaddressed, the demographic dividend can quickly turn into a demographic liability, placing unsustainable strain on public systems and increasing vulnerability to instability.

Ultimately, the demographic dividend is a governance opportunity. Countries that anticipate the shift and plan accordingly can unlock significant improvements in economic performance and human development. Others may miss the window, or worse, face the destabilising consequences of inaction.

|

Critical considerations for state governance in the future:

|

The Emerging Global Debt Crisis

The global debt crisis is not merely an economic problem; it is a structural threat to the fiscal sovereignty, developmental capacity and political legitimacy of states in the Global South.

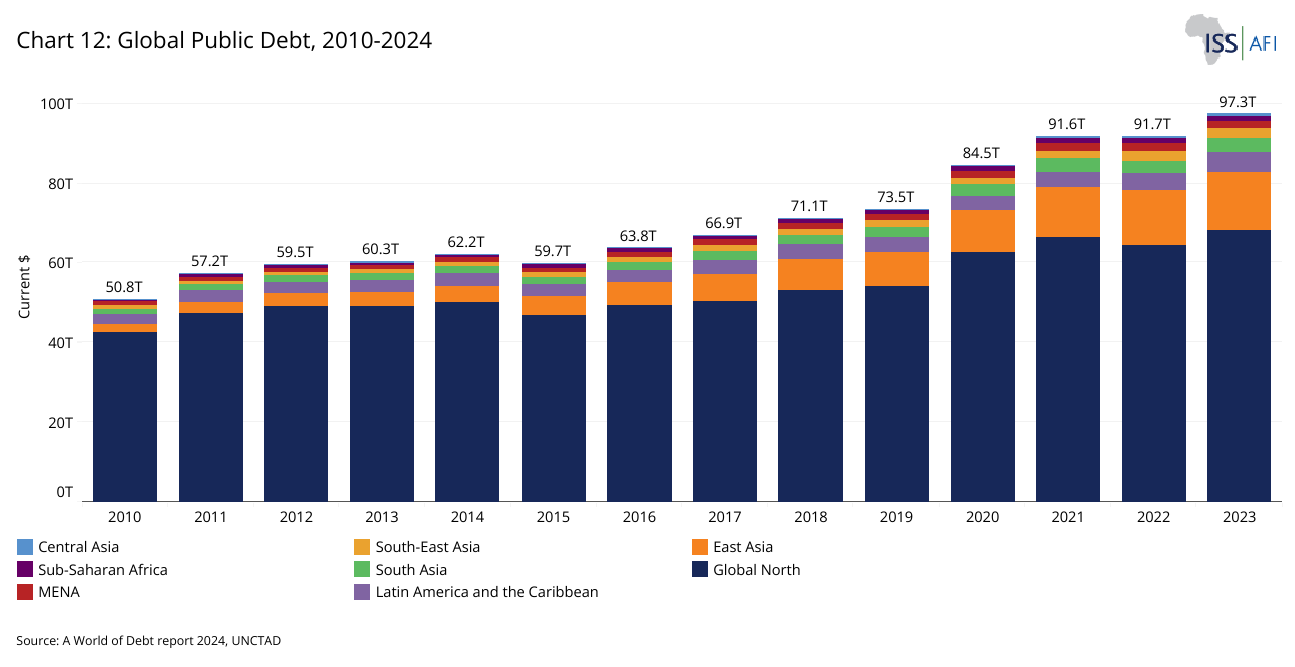

Chart 12 illustrates global public debt from 2010 to 2024. In 2023, global public debt soared to a record US$97 trillion, with over 40% of the world’s population living in countries where interest payments consume more funds than investments in education or health. Although developing countries account for just under one-third of this debt, around US$29 trillion, their borrowing has grown at twice the pace of that in developed economies since 2010.

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are at the heart of this crisis. In 2023, LMICs outside China spent about US$971 billion on debt servicing, double the amount from a decade ago, with interest payments rising by 33% to US$406 billion. The poorest nations have faced even steeper increases, with interest costs quadrupling to US$34.6 billion since 2013. These pressures stem from pandemic-induced borrowing, soaring global interest rates, currency devaluations and escalating climate adaptation costs.

A significant factor exacerbating these issues is the structure of external debt. Over half of the long-term debt owed by LMICs (excluding China) and 40% of the debt in the poorest nations is linked to variable interest rates that mirror the high rates in the Global North. In addition, more than 80% of LMIC debt is denominated in US dollars, increasing costs further as the dollar strengthens. As governments are forced to spend more on debt servicing, they have less available to invest in essential infrastructure, healthcare and long-term development—actions that stifle economic growth and erode public trust.

Compounding external pressures is the persistent challenge of domestic revenue mobilisation. Many Global South countries struggle with weak tax systems, large informal sectors and political resistance to progressive taxation. Corruption, widespread tax avoidance and exploitable loopholes further reduce fiscal resources, forcing these governments to rely on expensive and often restrictive external financing. This fiscal fragility not only limits policy options but also exposes states to external geopolitical pressures.

The stakes are high. As debt servicing increasingly crowds out vital investments in public goods, countries risk falling into a vicious cycle of stagnation, widening inequality and institutional decay. Addressing these challenges will require a dual approach: overhauling domestic revenue systems to build fiscal resilience and exploring alternative financing mechanisms that protect transparency and accountability.

Reclaiming fiscal sovereignty is increasingly recognised as a foundational condition for sustainable governance. Addressing this challenge will require a two-pronged approach. First, domestic revenue systems should be strengthened to improve equity, effectiveness and resilience. This includes broadening the tax base, addressing weaknesses in tax administration, enhancing compliance and tackling illicit financial flows. Ensuring fair taxation, both across income groups and economic sectors, remains central to restoring state legitimacy and funding long-term development goals. Second, financing mechanisms should be diversified to reduce over-reliance on external debt and expand access to development finance on terms that safeguard national autonomy. This involves rethinking the architecture of public borrowing, exploring instruments such as sovereign wealth funds, climate-related finance, diaspora bonds and regional development pools, while ensuring transparency and public accountability in all financing strategies.

|

Critical considerations for state governance in the future:

|

Economic Sovereignty in a Fragmenting Trade Order

The Global South has long navigated a trading system shaped by post-World War II institutions like the WTO, IMF and World Bank. While economic liberalisation has benefited some, it often constrained the policy space of developing nations, locking many into roles as raw material exporters with limited access to technology or value-added markets.

In response, regional trade alliances are gaining momentum. Initiatives like the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and Latin America's MERCOSUR aim to strengthen intra-regional trade, harmonise regulations and reduce dependence on external actors. These frameworks offer pathways toward economic coordination, but their success hinges on overcoming internal fragmentation and aligning national interests.

Meanwhile, global trade patterns are undergoing a fundamental shift. The rise of “friendshoring” (the reconfiguration of supply chains to favour politically aligned or strategically located partners) is creating new winners and losers in the Global South. Countries like Vietnam and Mexico have emerged as key beneficiaries, offering geopolitical alignment, cost-competitive manufacturing and trade proximity to major markets (e.g., the US and East Asia). Others, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, Central Asia and smaller island economies, risk marginalisation due to infrastructure gaps, perceived instability or lack of integration into global production networks.

As both a major trading partner and geopolitical rival to the West, China is central to Global South economies, providing investment, market access and alternative financing through initiatives like the Belt and Road. Yet, efforts by Western powers to “de-risk” from China are reshaping where capital flows and factories land, adding a layer of strategic tension for states caught between major powers.

Legal frameworks like Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) continue to challenge national sovereignty, allowing corporations to sue governments over public-interest regulations. At the same time, new trade frontiers such as digital services, environmental standards and carbon border taxes risk entrenching old inequalities in new ways. Looking ahead, economic sovereignty will be a contested and strategic domain. The choices states make today—about alliances, industrial policy and negotiation leverage—will shape their ability to govern effectively in a world of fractured globalisation.

|

Critical considerations for state governance in the future:

|

Rapid Population Growth and Rising Pressures

State governance is inextricably linked to demographic dynamics. The size and age structure of a population shape the breadth and urgency of state responsibilities; whether it is building schools, expanding healthcare systems or managing urbanisation.

Chart 13 depicts population development by region from 1960 to 2050. It highlights the extraordinary pace of population growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. In 2020, its population, at 1.15 billion, was on par with the Global North. By 2050, it is projected to double, reaching 2.3 billion and matching South Asia. This expansion spans a highly diverse group of 48 countries, led by Nigeria, Ethiopia and the DR Congo in absolute numbers. All other countries in the group have much smaller populations, although many are growing rapidly. For example, populations in the DR Congo, Chad, Niger, Equatorial Guinea, Mauritania, Angola, Somalia and Uganda are growing at more than 3% per annum.

With an average growth rate of 2.3% per year from 2025 to 2050, Sub-Saharan Africa stands apart from regions like East Asia and the Global North, where populations are set to decline. South Asia, led by India, has substantial population growth but shows signs of slowing towards mid-century, maintaining considerable pressures on governance systems. Latin America and MENA, by contrast, are approaching demographic plateaus, but even minimal increases risk straining already fragile and unequal governance structures.

For governments across the Global South, the challenge is not just managing numbers; it is about expanding state capacity fast enough to meet rising demands for housing, education, healthcare and jobs. How effectively states respond will play a defining role in shaping the region’s development path.

|

Critical considerations for state governance in the future:

|

Urbanisation and Mega-Cities

Urbanisation is reshaping the world, with more than half of the global population now living in cities and towns. By 2050, nearly 70% of people are projected to reside in urban areas, with Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa contributing to around 90% of this growth. Chart 14 shows urban population growth in more or less developed regions from 1960 to 2050.

The number of cities with populations exceeding 10 million, known as megacities, is also expected to rise, increasing from 33 in 2018 to 43 by 2030, with all new additions occurring in the Global South. Chart 15 depicts the average annual rate of change in city population size from 2020 to 2035.

Some of the challenges to governance include:

- The swift expansion of urban populations often outpaces the development of essential infrastructure and services, leading to inadequate housing, transportation and sanitation. This strain challenges local governments to provide for their citizens effectively.

- A significant portion of urban dwellers reside in informal settlements without secure tenure or access to basic services. The proliferation of these areas complicates urban planning and governance, necessitating inclusive policies that address the needs of all residents.

- Megacities contribute substantially to carbon emissions and face heightened risks from climate change-related disasters. Governance structures must integrate environmental considerations into urban planning to mitigate these impacts.

The complexity of managing megacities has prompted many countries to decentralise authority, empowering local governments to make decisions tailored to their unique contexts. This shift can lead to more responsive and effective governance. Engaging citizens in planning and decision-making processes fosters transparency and ensures that urban development aligns with the needs of the population. Initiatives like participatory budgeting have been successfully implemented in various cities to involve residents directly. Projects like Tatu City in Kenya exemplify new approaches to urban development, aiming to create well-planned, sustainable urban spaces that address common challenges associated with rapid urbanisation.

Addressing the multifaceted challenges posed by rapid urbanisation and the rise of megacities requires adaptive governance structures that prioritise inclusivity, sustainability and resilience. By embracing innovative approaches and fostering collaborative partnerships, cities in the Global South can navigate the complexities of urban growth and enhance the well-being of their inhabitants. Mega-cities act as economic engines yet simultaneously strain infrastructure, exacerbate inequalities and generate complex socio-political challenges. Effective urban governance will increasingly define state legitimacy and capability, requiring states to adopt innovative governance models, invest in sustainable infrastructure and address urban inequalities proactively.

|

Critical considerations for state governance in the future:

|

Forced Displacement and Migration

The global displacement crisis has reached historic levels, posing one of the most urgent and complex governance challenges of the 21st Century. Chart 16 illustrates forcibly displaced people globally from 2014 to 2024. By the end of 2023, an estimated 117.3 million people were forcibly displaced due to conflict, persecution, human rights violations or events that severely disrupted public order. This marks an 8% increase from the previous year and continues a 12-year trend of year-on-year growth. Early 2024 estimates suggest the number may already have exceeded 120 million.

Displacement remains heavily concentrated in the Global South. Three-quarters of forcibly displaced people are hosted in low- and middle-income countries, and 69% remain in neighbouring countries, placing immense strain on host states with limited financial and institutional capacity. In smaller countries like Lebanon and Aruba, displaced populations make up as much as one-fifth of the total population, reshaping demographics and stretching basic services.

Climate change is rapidly compounding this crisis. By the end of 2023, nearly 75% of displaced people were living in countries with high or extreme climate-related risks, such as droughts, floods or extreme heat. Nearly half lived in countries exposed to both climate hazards and ongoing conflict. These converging pressures, particularly in countries like Sudan, Somalia and the DR Congo, are destabilising livelihoods, fuelling local tensions and weakening governance systems, especially in already fragile regions.

Internal displacement continues to rise sharply. In 2023 alone, there were 13.7 million new instances of people being forced to flee their homes due to violence, without crossing borders. This brought the total number of internally displaced people (IDPs) to 63.3 million by year’s end. The majority of new displacements occurred in just five countries, including Sudan, DR Congo and Syria. While some eventually return home, the number of people able to do so dropped significantly, with only 5.1 million returns reported, 39% fewer than in the previous year.

Statelessness compounds displacement. At the end of 2023, at least 4.4 million people lacked legal nationality. Some, like the Rohingya, are both stateless and forcibly displaced. Without recognised citizenship, they face serious barriers to accessing services, exercising rights or rebuilding their lives. In contexts of displacement, statelessness amplifies exclusion and presents significant governance challenges, particularly around legal protection and long-term integration.

These intersecting crises (protracted conflict, climate stress, internal displacement and statelessness) are shifting the nature of displacement. What was once treated as a temporary humanitarian issue is increasingly becoming a long-term governance reality. States must adapt to a future in which managing human mobility, protecting rights and ensuring cohesion will be core to resilience and legitimacy.

|

Critical considerations for state governance in the future:

|

Governing in an Unequal World