Under pressure: governance futures in the Global South

Foresight analysis maps four scenarios showing how global forces may reshape the role, capacity and legitimacy of the state.

Global South states face mounting pressure as climate change, demographic shifts, technology and geopolitical tensions reshape their legitimacy, capacity and democracy. Governments must deliver more with fewer resources, while authority diffuses to non-state actors. This diffusion could strengthen resilience or deepen fragility.

To explore what this means, a new AFI-ISS study, funded by IDRC, State Futures in the Global South, applies strategic foresight to examine how governance could evolve. The study draws on a set of illustrative, long-term global scenarios developed initially for the Africa in the World theme (Figure 1).

In a region as diverse and complex as the Global South, reducing the future to a narrow set of trajectories would be misguided. This exploratory foresight approach instead seeks to engage systematically with the uncertainties and complexities shaping how states may evolve. It challenges assumptions, exposes the interconnections between drivers of change and uncovers patterns often overlooked. The goal is to open up space for more critical, futures-oriented thinking about what governance could become — and what it might take to shape it differently.

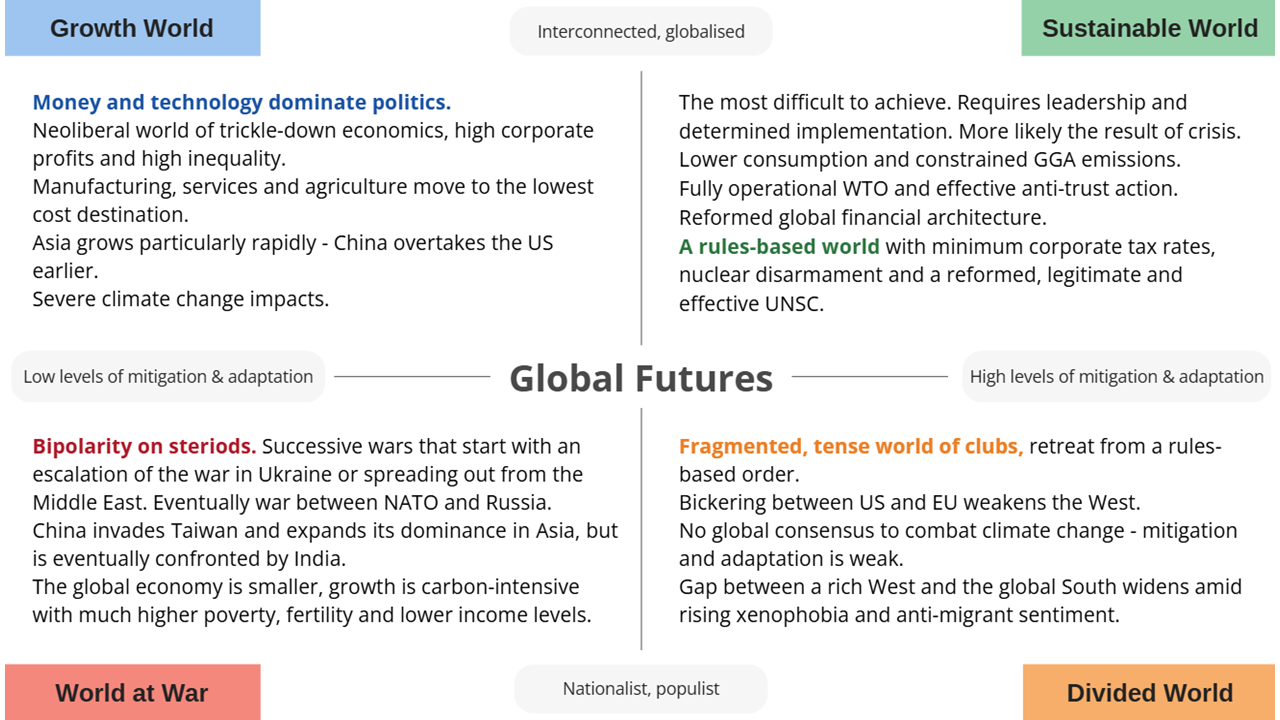

Chart 1: Global scenarios descriptions

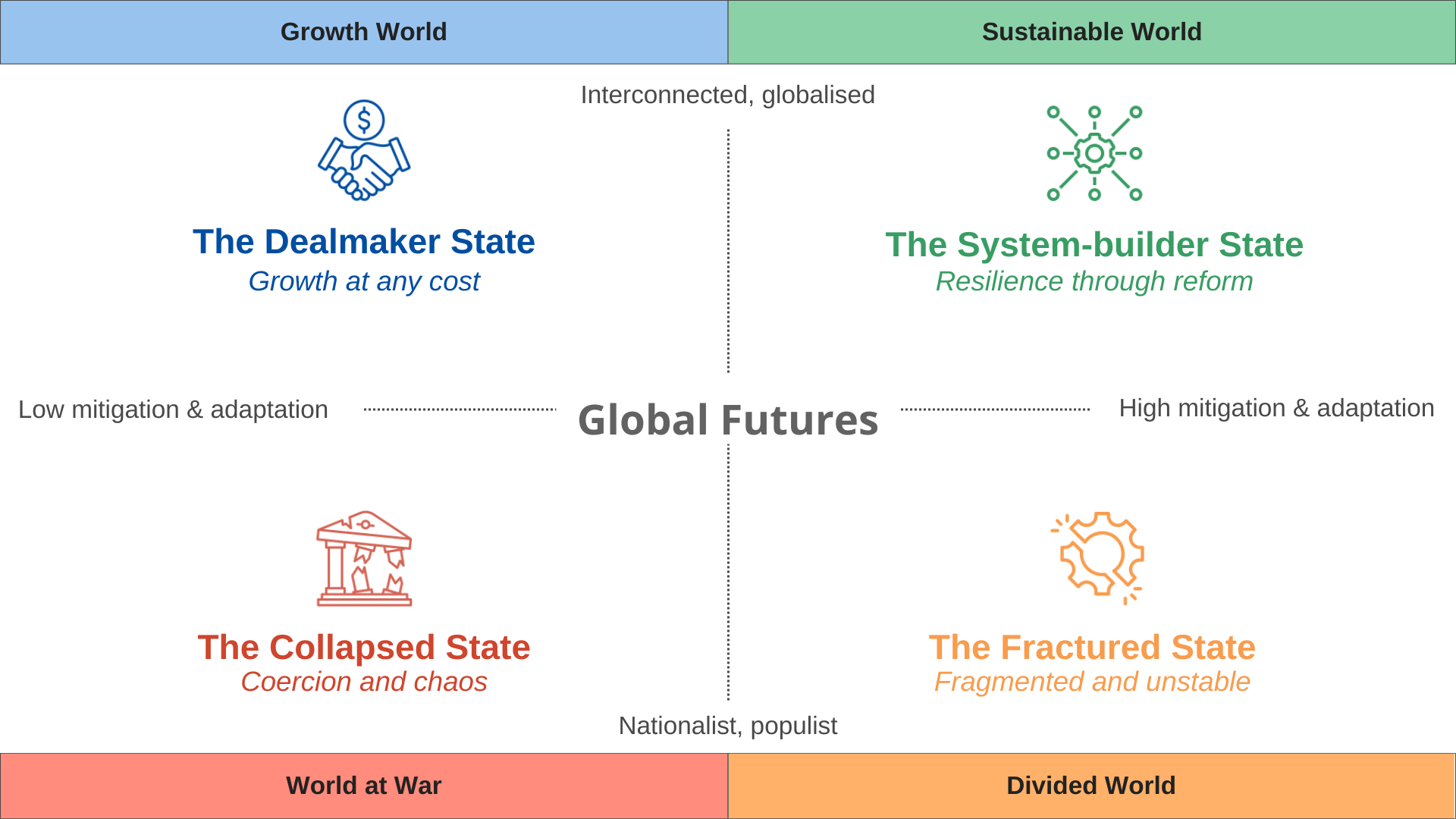

Taken together, the global forces point to why governance in the Global South cannot be assumed to follow a linear path. Different mixes of external shocks and domestic choices will push states in very different directions, and the foresight analysis distils these dynamics into four archetypes: the dealmaker, the system-builder, the fractured and the collapsed state. These capture four distinct pathways in which states could evolve in the decades ahead (Figure 2).

Chart 2: Four futures of the state

In the Growth World, governments shift from planners of development to dealmakers, brokering access to markets, labour, data and natural resources. External capital flows, US-China realignments and intensifying technological dependencies accelerate this shift.

On paper, regulatory quality and government effectiveness improve, yet these gains are deceptive and rest on technocratic delivery rather than democratic inclusion. Legitimacy rests on GDP growth and investor confidence, not improved social outcomes. States compete to appear ‘business-friendly’ by cutting taxes and easing labour and environmental standards — a short-term magnet for investment that weakens revenues and social protections over time. Spatial inequality deepens and governance becomes increasingly urban-centred, fuelling exclusion, resentment and long-term fragility.

What emerges is a governance model that looks efficient but is brittle. Stability is maintained at the macro level, but social unrest, environmental displacement and localised instability simmer beneath the surface.

Anchored in the Sustainable World, the system-builder state is the hardest trajectory to achieve and likely emerges from a crisis. Climate disasters, social unrest and economic shocks push governments to shift from dealmakers to stewards. Legitimacy is rebuilt through delivery and co-creation, redistribution and long-term planning.

The model balances structured authority with flexibility. States invest in rebuilding equitable systems, aligning with reformed global institutions and stronger regional blocs, while integrating local and Indigenous practices that ground legitimacy in context. Gains in rule of law, corruption control and participation come slowly: government effectiveness may falter during disruptive reforms, but later strengthens as institutions adapt.

Regional cooperation and fairer trade norms strengthen resilience to systemic shocks such as climate disasters and supply chain disruptions. Civil society and media scrutiny help curb elite capture, while expanded social protections build citizen trust. Yet the benefits are uneven and some South-South partnerships could reproduce hierarchies or extractive practices. States with weaker institutions, low technological readiness or limited inclusivity risk being sidelined, left dependent on stronger regional players or excluded from decision-making arenas.

This pathway demands hard political choices, axing elites, curbing carbon-intensive industries and enforcing sustainability standards: reforms that will inevitably face resistance. It also requires change from multilateral institutions to loosen rigid conditionalities and embed sustainability and equity into global rules and financing frameworks.

The fractured state emerges in a Divided World defined by fragmentation, resurgent nationalism, transactional partnerships and diverging development pathways. Multilateral systems erode as protectionist, populist and sovereignty-first movements take hold.

Authority becomes hybrid and contested, shared or fought over by governments, regional actors, private firms and informal networks. Decision-making is reactive and crisis-driven, focused on short-term stability rather than long-term resilience or inclusion. Formal participation weakens, replaced by symbolic or performative gestures that further alienate marginalised groups. Rising inequality, exclusion and corruption fuel unrest and distrust, while resource competition intensifies conflict and elite capture of policy.

Yet this is not a story of collapse everywhere. Some states reclaim policy space through selective trade barriers or industrial support, fostering pockets of resilience. Advanced economies develop competitive green industries and regional blocs experiment with localised adaptation, but progress is uneven. Lower-income states remain locked into fossil-fuel dependency, and without coherent global coordination, overall progress falls short of what is needed for sustainability.

In the World at War, the most volatile future, the state is no longer a provider or planner: it becomes a fortress. Governance is reduced to coercion, focused on territorial control, elite protection and security at all costs.

The social contract is shattered. Participation and accountability vanish, replaced by fear and force. Resistance is violently suppressed or driven underground. Where the state disappears entirely, opportunistic actors — warlords, militias and criminal networks — fill the vacuum with fragmented and predatory forms of rule.

Globally, cooperation collapses. Power becomes transactional and opportunistic. Proxy wars, resource seizures and military blocs replace diplomacy. Resource-rich zones in the Global South become battlegrounds, while strategic corridors are militarised. States lacking geopolitical value are left behind — abandoned to chaos, displacement and humanitarian breakdown.

These four archetypes reveal divergent governance trajectories shaping plausible futures of state legitimacy and authority in the Global South. The dealmaker state delivers growth and short-term improvements in development indicators, but at the cost of long-term inclusivity. The system-builder state demands the greatest sacrifices up front, but offers the strongest foundation for sustainable, legitimate and equitable governance in the long run. The fractured state creates space for experimentation with alternatives to global dependence, but leaves the most vulnerable dangerously exposed. The collapsed state is the worst-case scenario: authority endures only through force, while governance, the ability to provide, protect and plan, disappears.

Across all four plausible futures, shared drivers and vulnerabilities become visible, pointing to underlying dynamics.

Firstly, governance is increasingly hybrid: shaped by states, non-state actors and informal networks. Yet hybrid systems are not inherently democratic or inclusive; they are contested spaces. Without coordination and meaningful inclusion, they risk reinforcing elite capture and mistrust. Where power is genuinely shared, they can foster resilience and renewal.

Secondly, inequality undermines all futures. It is not just a variable to be managed but the terrain on which governance succeeds or fails — the force that shapes legitimacy, distorts participation and amplifies fragility.

Inequality undermines all futures and is the terrain on which governance succeeds or fails

Thirdly, the participation-performance gap further unsettles long-held assumptions. Participation without delivery breeds disillusionment and populist backlash; in authoritarian contexts, it often becomes controlled dissent. Inclusion without impact is hollow; performance without trust is brittle.

The pivotal question, then, is whether delivery-based legitimacy can coexist with democratic renewal, or whether the drive for visible results will erode deeper accountability. The answer lies not in choosing one over the other, but in recognising their interdependence. The most resilient states will be those that align competence with connection — treating performance not as a substitute for democracy, but as the platform on which it is rebuilt.

The most resilient states will be those that align competence with connection — not treating performance as a substitute for democracy

Geopolitics adds another layer. South-South cooperation, once grounded in solidarity, is shifting toward strategic alignment. Regional blocs, infrastructure corridors and new financial institutions signal a move from rhetorical unity to institutional leverage — but whether this delivers equity or replicates old hierarchies remains uncertain.

In conclusion, the future of governance in the Global South will be shaped by how effectively states confront inequality, negotiate legitimacy and navigate strategic alliances in an increasingly complex world.

A long-term, systemic lens brings into focus the difficult trade-offs ahead: between efficiency and inclusion, control and adaptability, sovereignty and interdependence. It exposes the often-overlooked tension between immediate governance demands and long-term imperatives. Ultimately, state resilience will depend on visionary leadership that anticipates complexity, adapts with purpose and stays committed to sustainable, equitable progress. As change accelerates, the real test will be making deliberate, and often uncomfortable, choices about what to prioritise, what to reform and what to leave behind.

Image: AFI

Read the full new theme report State Futures in the Global South here.

Republication of our Africa Tomorrow articles only with permission. Contact us for any enquiries.