12 Governance

12 Governance

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

In this entry, we describe and forecast the development of governance in Africa and its impact on the continent’s development trajectory, consisting of the quest for stability, capacity and inclusion.

Please see the Technical page for more information about the International Futures modelling platform we use for our forecasts and scenarios.

Summary

- In much of the world, three sequential transitions delivered a functioning state: a legitimate monopoly of the use of force, the extension of government capacity and broader, deeper inclusion.

- The section on governance in Africa looks at the origins of state-formation in Africa and the disruptive impact of slavery, colonialism and the Cold War. It then reflects on the period during which democracy advanced globally, and African partners focussed on it as a prerequisite for support.

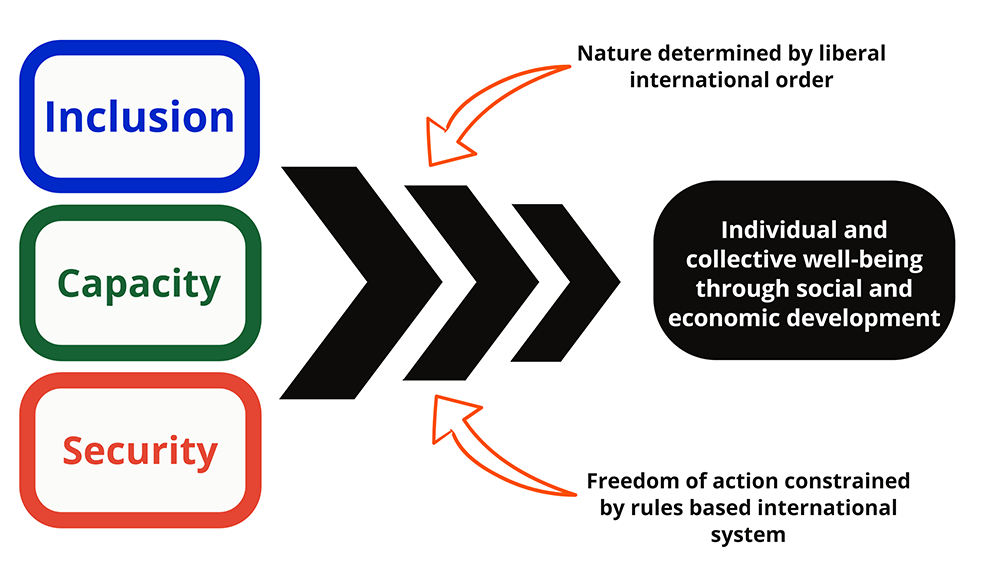

- Today, African states must simultaneously pursue security, capacity and inclusion in a rules-based global order that is often quite different to the historical experience elsewhere.

- Security is the bedrock of state-formation and the section on security and governance summarises general conflict trends.

- Recent years have seen fatalities from armed conflict in Africa decline in line with global conflict trends but African states do not rest on a secure footing and remain vulnerable to numerous drivers of conflict including external influences.

- Violent political Islam, originally most evident in Algeria, has gained a foothold in countries such as Somalia and Nigeria and in the Sahel, with recent upsurges in the eastern DR Congo and northern Mozambique. Africa has become the global epicentre of terrorism.

- In contrast to the gradual decline in fatalities from armed violence, the number of protests and riots is increasing though associated fatalities are low.

- Sub-Saharan Africa does particularly poorly when measuring government capacity which is weakened by the extent of neo-patrimonialism. North Africa has a particularly large democratic deficit.

- Generally the extent of electoral (or thin) democracy in sub-Saharan Africa is extensive, but few African states evidence deeper, liberal democracy that advances good governance and accountability.

- The relationship between democracy and economic growth is complex. Although democracies evidence sustained higher economic growth in the long term and are able to absorb high levels of social turbulence, there is little evidence of a positive relationship at low levels of development and in the shorter term.

- The sum impression is that governance in Africa is thin, particularly because stability is absent. There is also limited capacity in sub-Saharan Africa and low levels of inclusion in North Africa.

- The Governance scenario models the impact of improvements in stability, capacity and inclusion in Africa and measures its impact on measures such as GDP per capita and extreme poverty.

- Better governance will make an important contribution to improved development outcomes in Africa, but on its own, more inclusion (or democracy) cannot compensate for the lack of security or capacity.

All charts for Governance

- Chart 1: The sequential evolution of governance transitions globally

- Chart 2: Trends in the development of electoral and liberal democracies in the world and Africa

- Chart 3: Governance transitions in post-colonial Africa

- Chart 4: Number of armed conflict events vs population in the world, 1960 to 2021

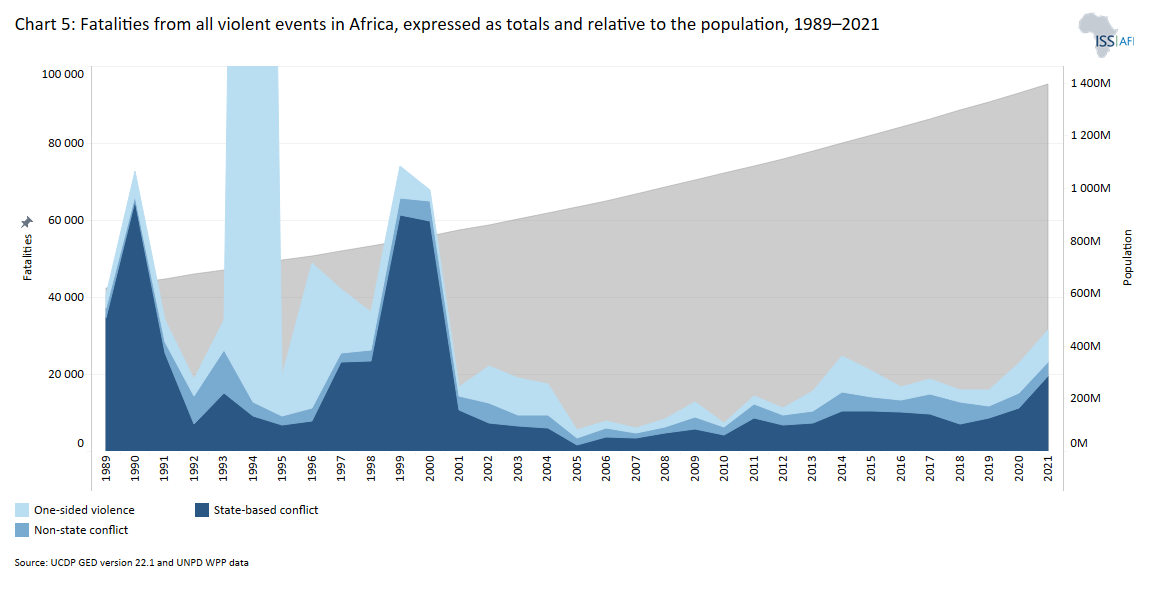

- Chart 5: Fatalities from all violent events in Africa, expressed as totals and relative to the population, 1989–2019

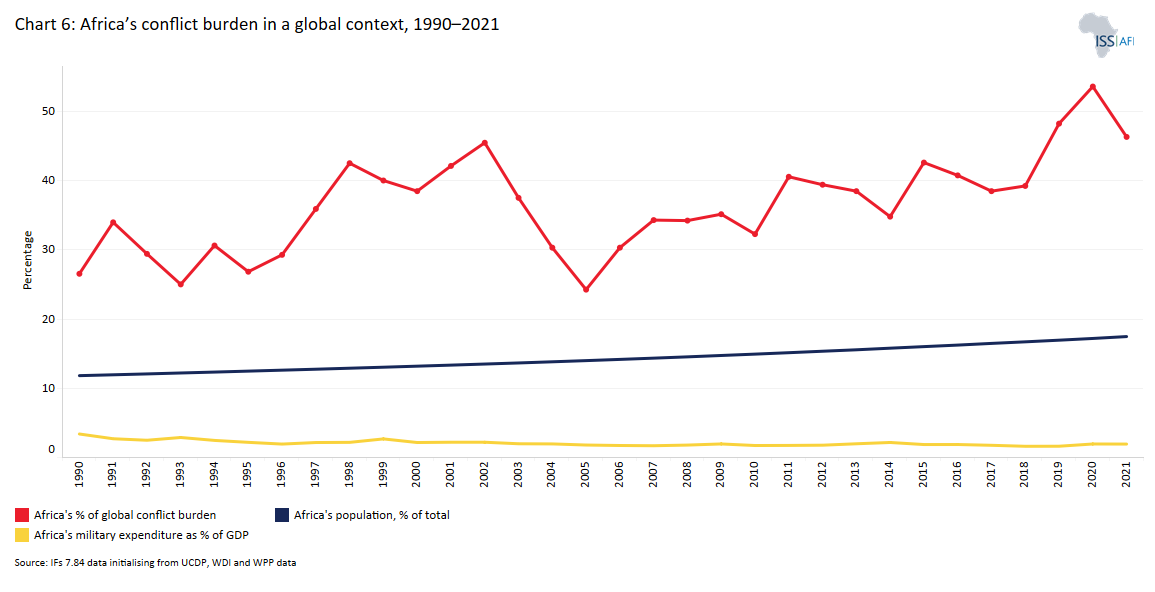

- Chart 6: Africa’s conflict burden in a global context

- Chart 7: Drivers of intrastate conflict

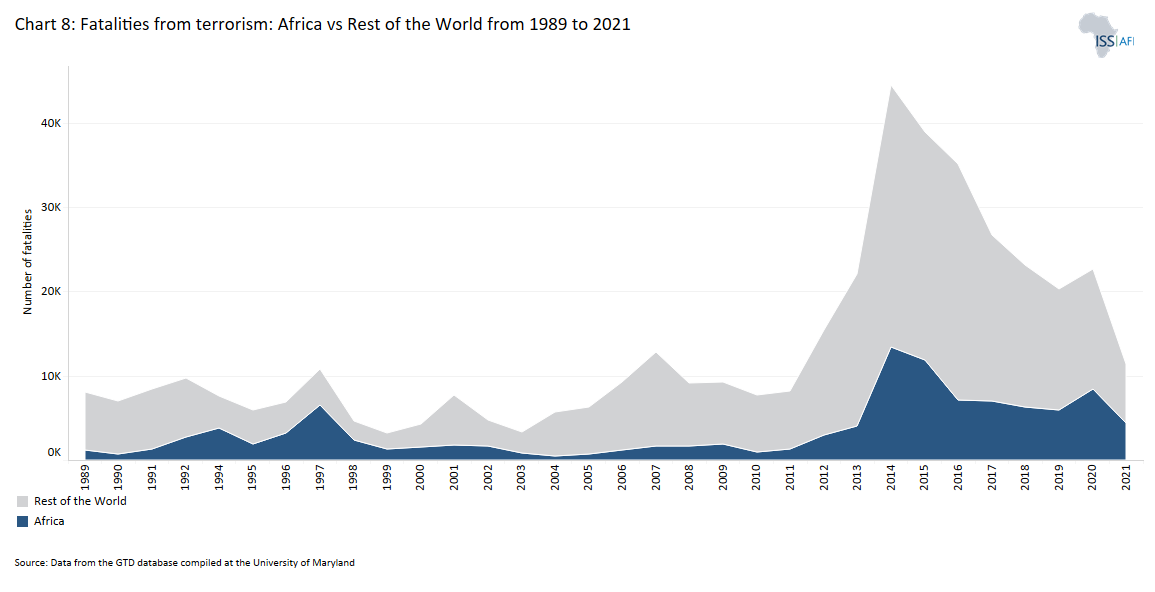

- Chart 8: Fatalities from terrorism: Africa vs Rest of the World, 1989 to 2021

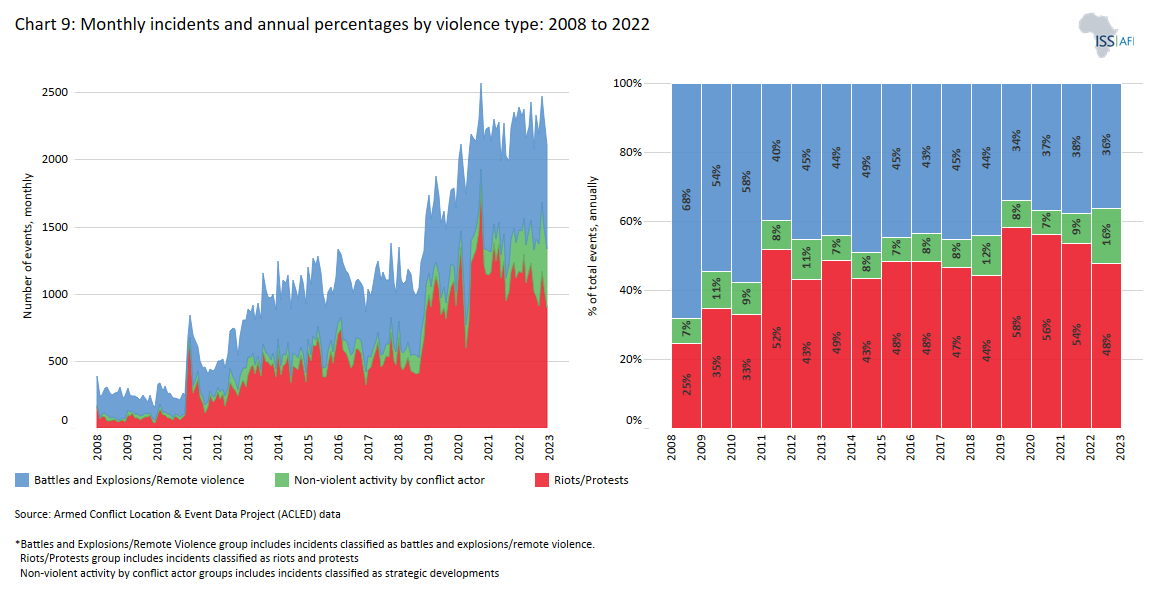

- Chart 9: Monthly incidents and annual percentages by violence type: 2008 to 2022

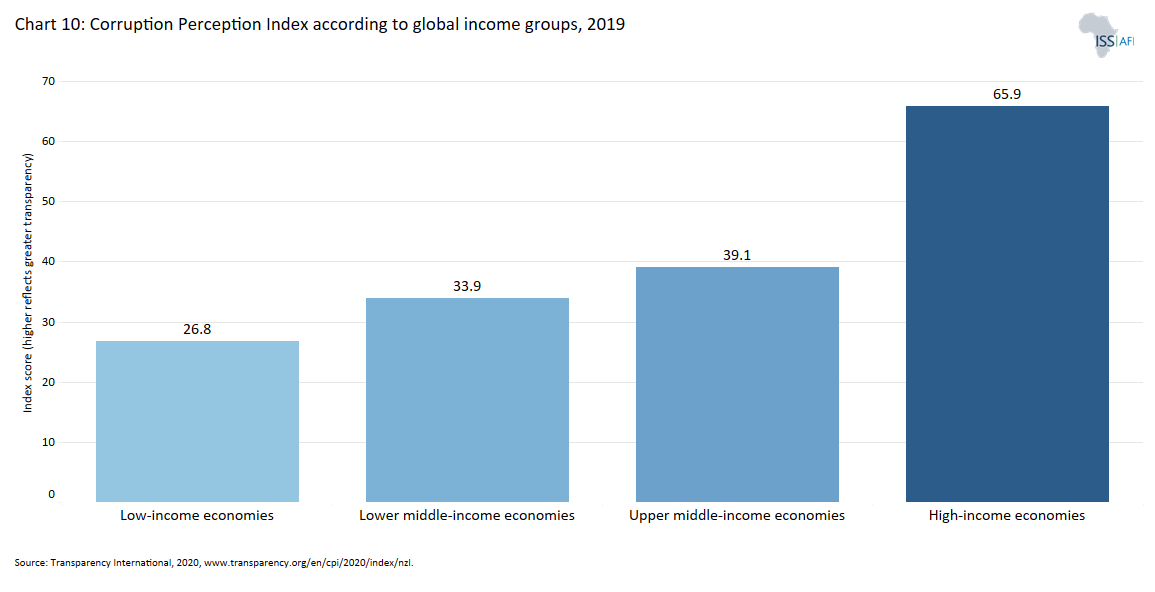

- Chart 10: Corruption Perception Index according to global income groups, 2019

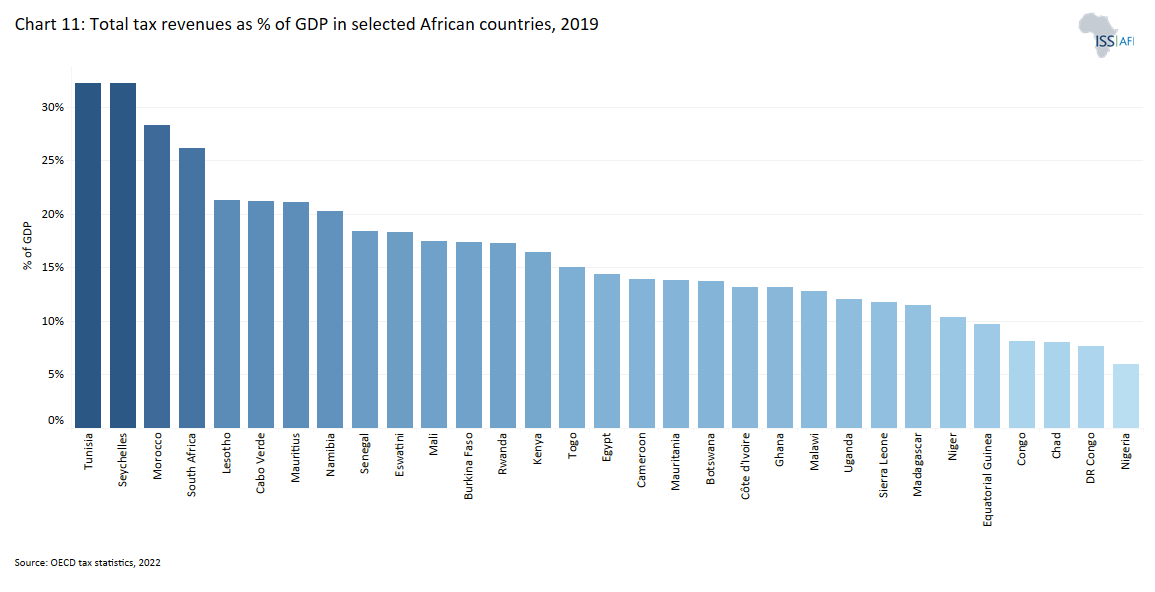

- Chart 11: Total tax revenues as % of GDP in selected African countries, 2019

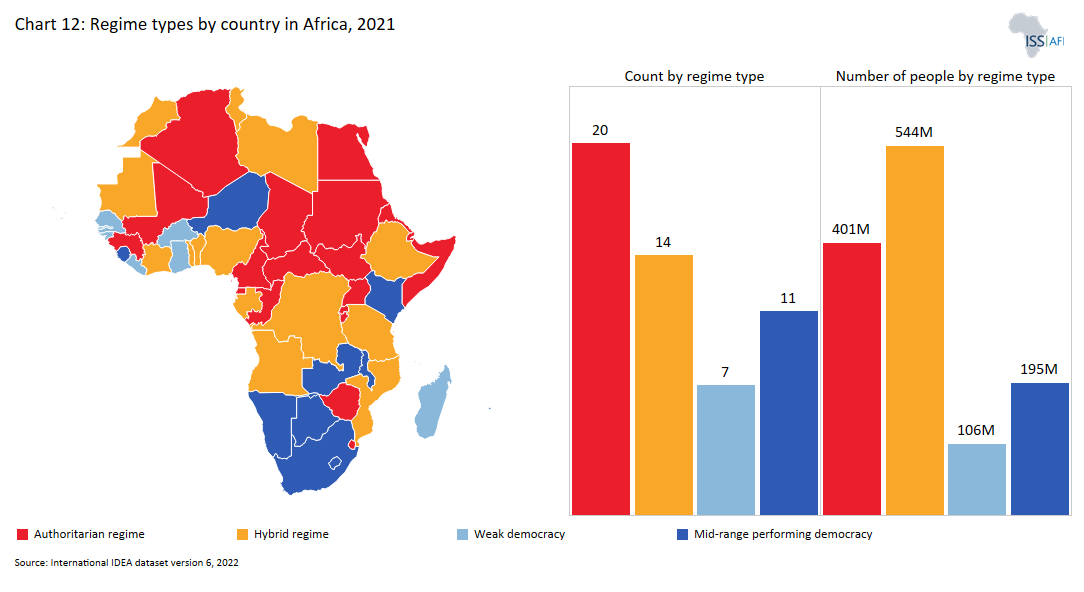

- Chart 12: Regime types by country in Africa, 2021 from International IDEA

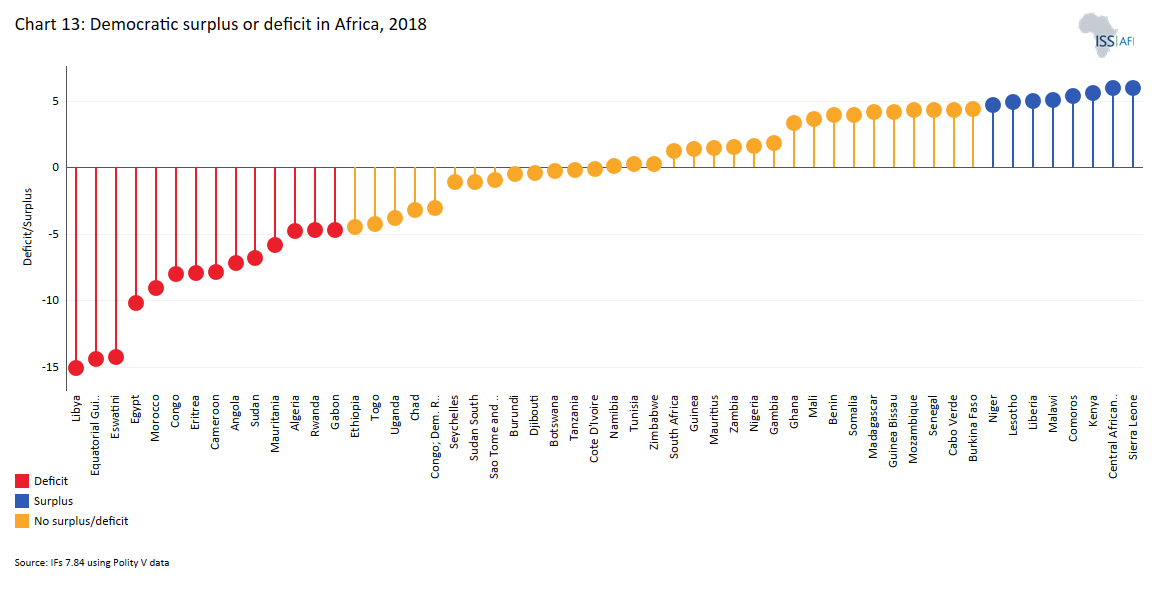

- Chart 13: Democratic surplus or deficit in Africa, 2018

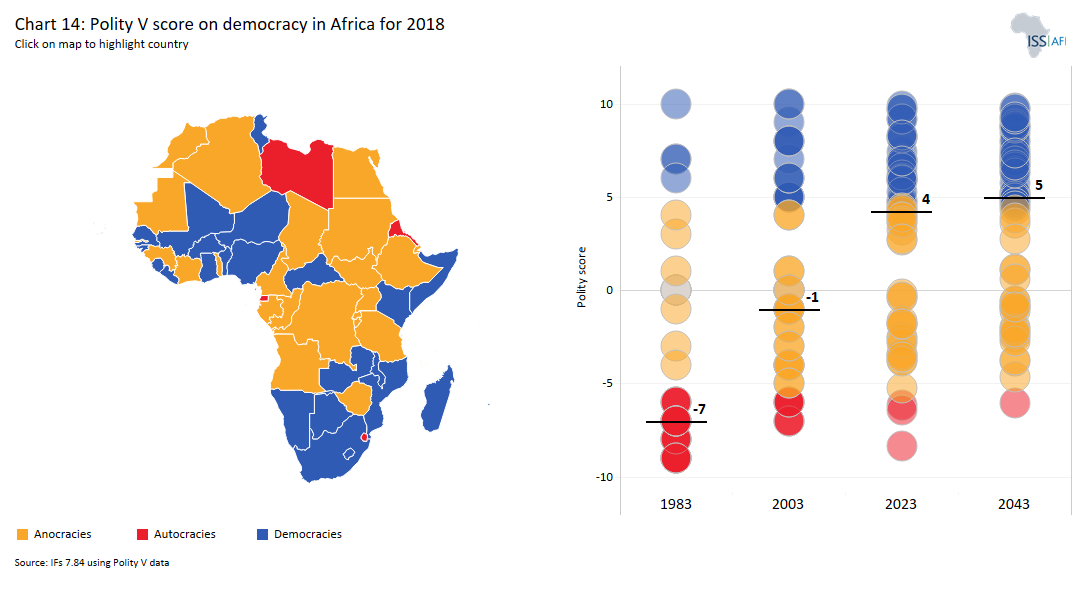

- Chart 14: Polity V score on democracy in Africa for 2018

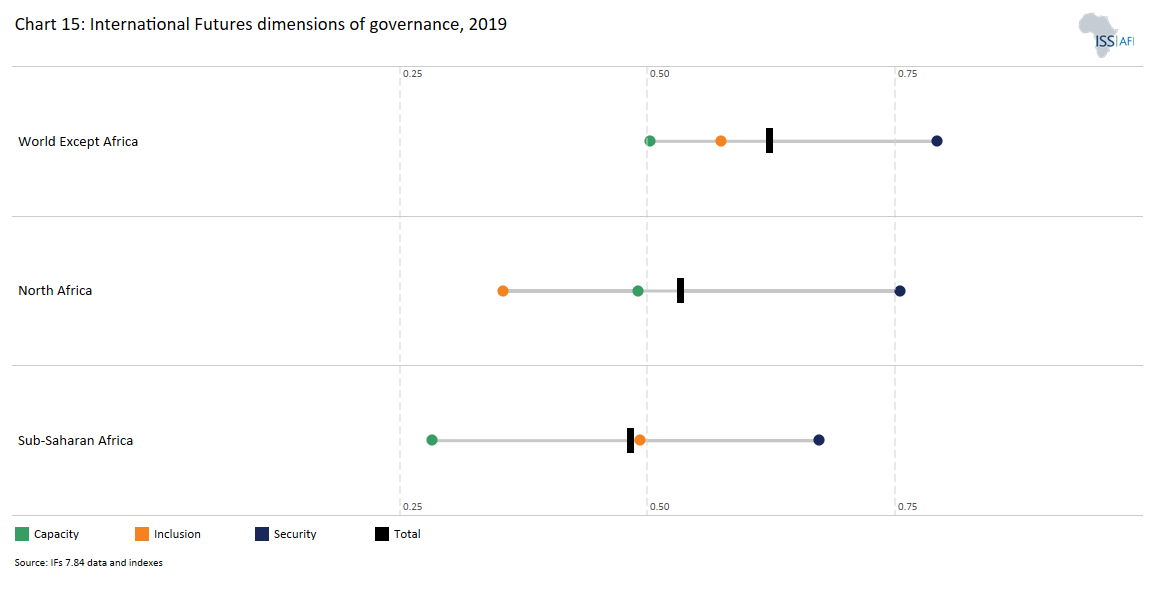

- Chart 15: International Futures dimensions of governance; African regions compared to the Rest of the World, 2019

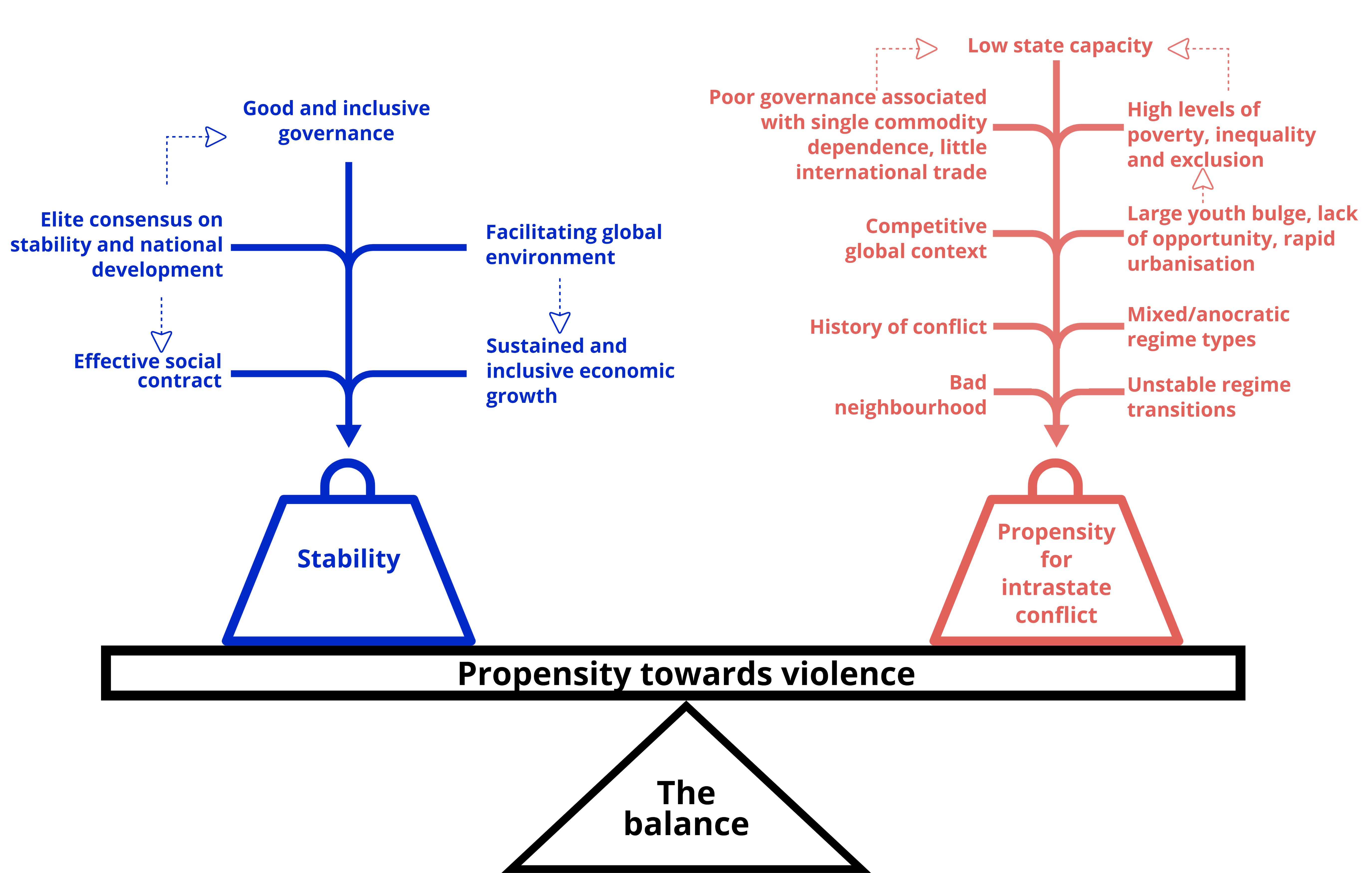

- Chart 16: The stability balance

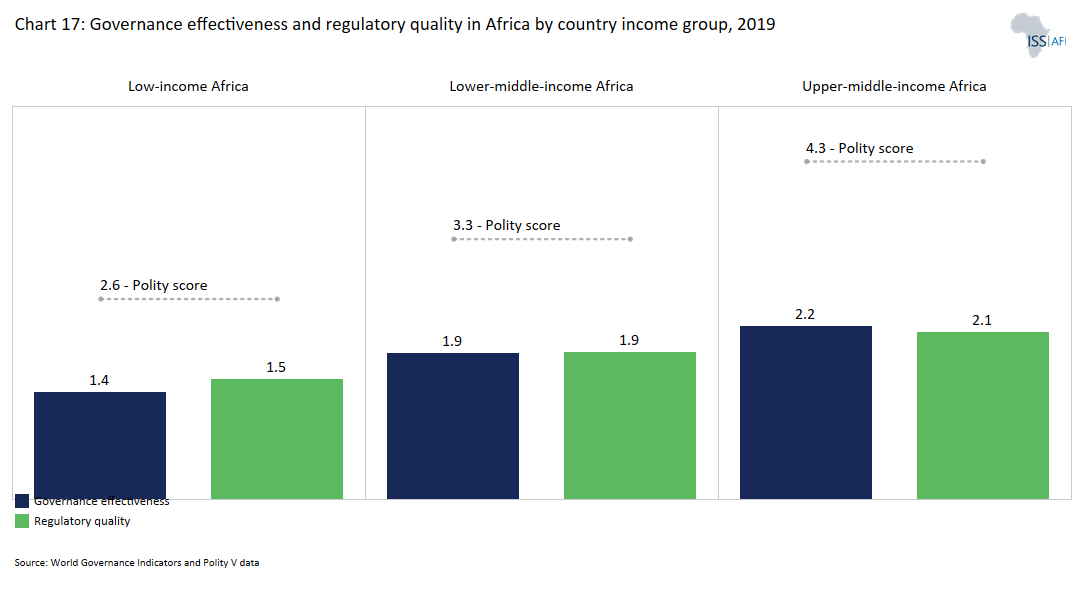

- Chart 17: Government effectiveness and regulatory quality in the context of democracy according to income groupings in Africa, 1996–2019

- Chart 18: The Governance scenario

- Chart 19: Improvement on the IFs Governance index by 2043: Governance scenario compared to the Current Path forecast

- Chart 20: Difference in GDP per capita in Governance scenario compared with Current Path in 2043

- Chart 21: Reduction in extreme poverty in Governance scenario compared with Current Path in 2043

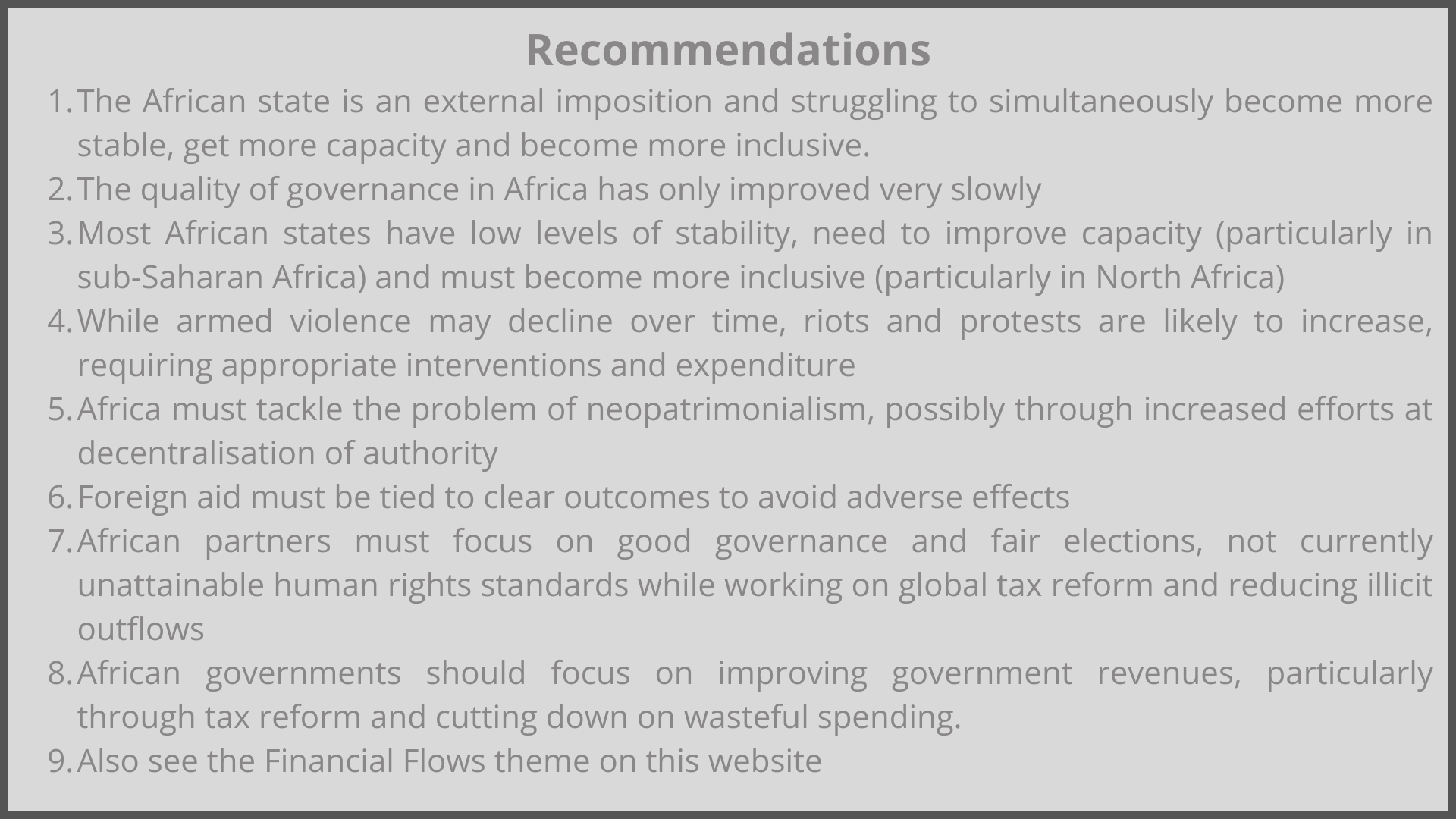

- Chart 22: Key recommendations

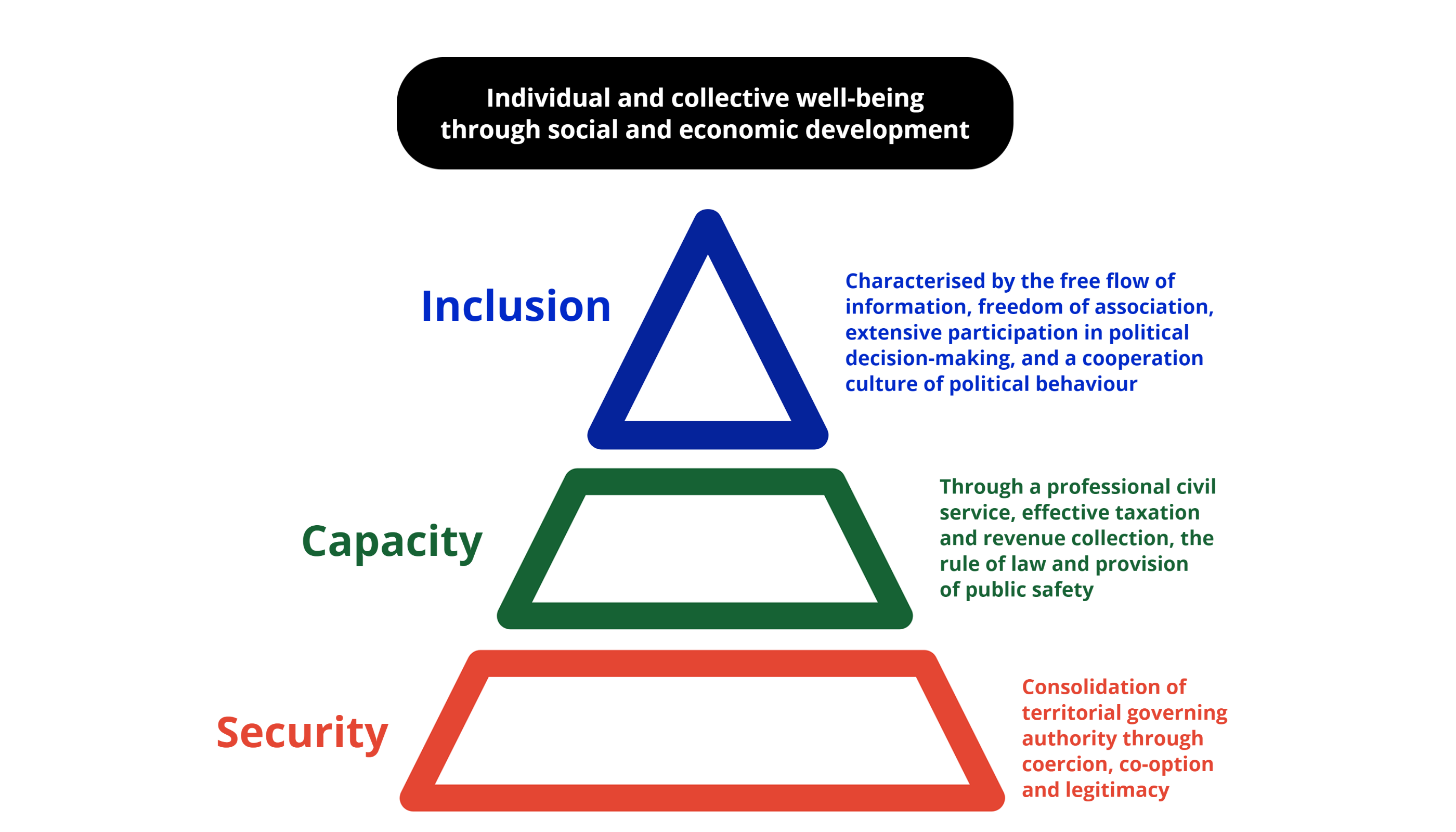

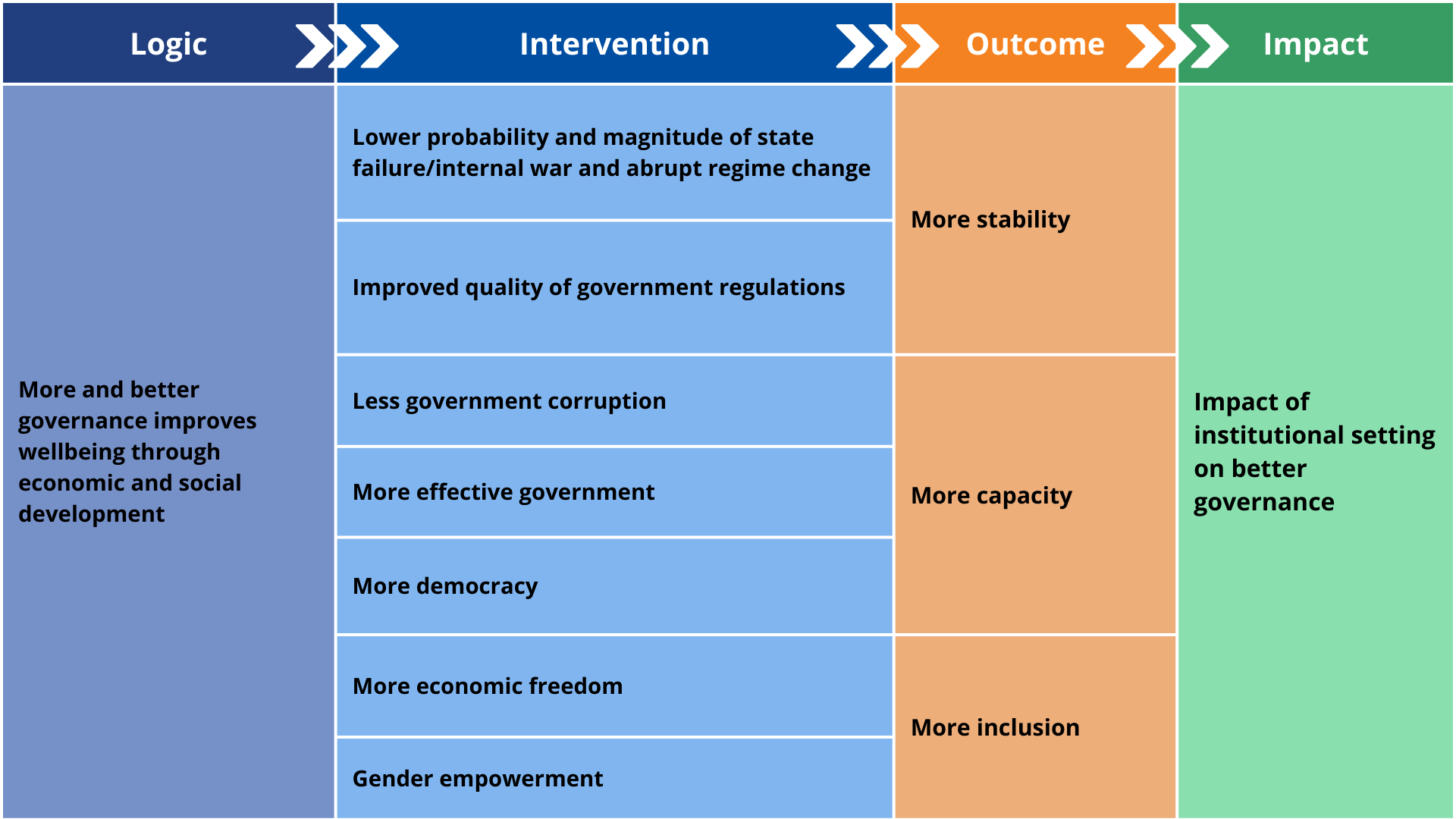

Leadership matters. It can be transformational. This theme focuses on the three fundamental transitions that, given good leadership, deliver a functioning, well-governed state: the development of a legitimate monopoly of the use of force within a territory (the security transition[1In IFs, security is driven by a performance and risk index and state failure from internal event occurrence. Each is in turn driven by a variety of other indicators. For example, state failure from an internal event occurrence depends on levels of development (poor countries evidence more conflict), infant mortality (often used as a proxy for government capacity), size of the youth bulge (a larger youth bulge indicates greater propensity for turbulence), nature of the governance system (mixed regime types are more prone to instability), levels of education and integration into the global system (relationship of exports to GDP).]), the expansion and extension of government capacity,[2The IFs capacity index combines data on tax collection from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the World Bank’s World Development Indicators project, and uses the Corruption Perception Index from Transparency International as a proxy for capacity to manage those resources.] and broader and deeper inclusion[3Once governments achieve a minimum degree of security and have developed appropriate capacity, pressure mounts for greater inclusion in political and economic structures and processes as part of an emerging social contract between a government and its citizens. The IFs model forecasts its inclusion index based on regime type (using Polity V data) and a measure for gender empowerment as a proxy for horizontal inclusion.] as part of the subsequent social contract. The analysis is necessarily presented in broad brushstrokes, given the diversity of Africa. The approach is in accordance with that adopted by Barry Hughes and others at the Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures, which developed and hosts the International Futures (IFs) forecasting platform that is extensively used for forecasting on this website.[4See BB Hughes et al, Strengthening governance globally: Forecasting the next 50 years, Patterns of Potential Human Progress, volume 5, Boulder: Oxford University Press, 2014, 6–18.]

These three transitions — security, capacity and inclusion — have historically occurred sequentially and over extended periods, meaning that the establishment of security was a prerequisite for the extension of capacity, which eventually saw the demand for greater inclusion as a condition for further development. It is inevitably the product of successive leaders and leadership making the right choices over extended periods of time.

In much of the world, ‘war’, in the classic framing by Charles Tilly, ‘made the state, and the state made war.’[5C Tilly, Reflections on the history of European state-making, in C Tilly (ed.), The formation of national states in Western Europe, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1975, 3–89.] As population density in favourable locations increased, families and tribes competed over limited resources, as well as opportunities elsewhere. Competition meant that tribes eventually were required to stand together if they were to survive against external enemies. These developments characterised the city-states of Greece and the Roman, Gallic and Frankish empires as much as the civilisations that had already started to emerge in what we today know as China and India. Development was a bloody and messy affair, but less so in sub-Saharan Africa, where nature was humanity’s main protagonist.

This process of inward–outward state formation took different forms in different regions. Larger populations, competition and expansion drove development, which was periodically constrained and even reversed by plagues, drought and other calamities. It is depicted in Chart 1. In this way, nationalism came to accompany and generally precede development.

Thinking of governance in terms of security, capacity, and inclusion provides a useful lens for examining how countries have progressed over time, comparing the state of governance between countries and groups of countries, and forecasting its likely future evolution. To this end, IFs include an index (0 to 1) for each dimension, with higher scores indicating improved outcomes. A composite governance index is a simple average of the three.[6BB Hughes et al, Strengthening governance globally: Forecasting the next 50 years, Patterns of Potential Human Progress, volume 5, Boulder: Oxford University Press, 2014, 6. IFs also forecasts several indices related to governance, including the World Bank measurement of government effectiveness and regulatory quality, but these do not drive the forecasts.]

This section summarises the history and impact of Africa’s imposed state formation process.

Africa experienced a unique trajectory in the evolution of governance. The fixed territorial state with a single jurisdiction and government, then already well established elsewhere, was essentially a late colonial imposition on the continent during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Whereas in Asia and Europe, the process of territorial state formation was shaped by conflict over resources, land, animals, slaves and trade, the African experience for thousands of years was that of shifting tribes that moved seasonally with their animals, providing a more fluid progression. Socially, many of sub-Saharan Africa’s societies came to be characterised by an age-grade system that established male gerontocracy as the dominant form of political organisation, still evident in numerous countries today.[7Each age group was allocated a standard set of social and political duties and produced a conservative, consensual system where respect for the (surviving) elders and their way of doing things was a core tenant of the social structure. J Reader, Africa: A biography of the continent, Penguin, London, 1998, 258–262.]

For centuries, even before the large south- and eastward drift of the Bantu-speaking people from West Africa, sub-Saharan Africa’s general low population density meant tribal wars were not fought over land but over labour — to capture slaves. Enrichment and social elevation depended on the possibility of large herds and cultivating a maximum surface area; hence the interest of heads of families to have a large workforce. The more slaves and women a man owned, the more land he could cultivate and the richer he was. Only ancient Egypt, later the Ethiopian highlands around Aksum (or Axum), and development along the Niger river in West Africa would buck this general trend.

Africa’s high disease burden also meant that military innovations, often the driver of progress, such as the war horse, chariots, widespread use of bronze and later, weapons made from iron, were not required.[8C Aydon, The story of man, Constable, London, 2007, 60–62; J Reader, Africa: A biography of the continent, Penguin, 1998, 123–330.] Conflicts in Africa were small-scale compared to what was happening in Europe and Asia. And they were not required for survival among early African societies that traditionally lived in relatively small groups scattered across large distances, eking out an existence in harsh environments. In the words of John Reader, ‘like everything else in human evolutionary history, small peaceful communities in Africa were an ecological expedience; ensuring survival in a hostile environment of impoverished soils, fickle climate, hordes of pests, and a more numerous variety of disease-bearing parasites than anywhere else on earth.’[9J Reader, Africa: A biography of the continent, Penguin, London, 1998, 242.]

In time, sub-Saharan Africa changed socially and politically, although more slowly than other regions, with large, relatively complex social formations evolving and succeeding one another in the Sahelian region of West Africa and elsewhere, but never rivalling the density and size of cities and most emerging states outside of Africa.[10J Reader, Africa: A biography of the continent, Penguin, London, 1998, 276–278.]

From the early seventh century, the Arab and, from the 15th century, the transatlantic slave trades had a particularly destructive effect on Africa’s governance and development. During the Arab slave trade between 11 million to 17 million Africans were transported, mostly across the Sahara desert, from sub-Saharan Africa to North Africa for onward sale. A further 12.5 million men, women and children were captured and shipped to North America in exchange for imported goods that brought wealth and power to a small group of traders, chiefs and kings at the expense of immeasurable suffering. Many more Africans died in the process. As a result of slavery, sub-Saharan Africa’s population stagnated in absolute numbers, as did progress towards greater security, capacity and inclusion.[11J Reader, Africa: A biography of the continent, Penguin, London, 1998, 404. Domestic and Arab slavery increased when the transatlantic slave trade ended.]

Ironically, the demand for slaves was legitimised in the eyes of many African traders and leaders by widespread domestic slavery and forced labour practices.

Constantly denuded of sufficient, productive human capital, parts of West and Central Africa were almost in perpetual turmoil, and development here took a different route to that in Europe and Asia until the imposition of rigid colonial borders established nominal order.

Already a late starter, colonialism compounded the impact of slavery and further hampered the sequential state-formation process in much of Africa. The colonial state was an external imposition — created by outsiders to provide access to Africa’s labour, minerals and commodities — to fuel development elsewhere. Formally, colonialism lasted for only around 75 years, but slavery and imperialism had a much longer footprint. To compound matters, once released from the straitjacket of colonialism in the 1960s, Africa’s freedom of action, domestic and international, was constrained by the bipolar Cold War until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989.

The collapse of the Soviet Union ended a series of proxy wars in Africa, where the West and the Soviet bloc had each supported or propped up their client states. The West had triumphed, or so it appeared, and with the subsequent concerns for elections, human rights, and accountability (rather than ideological orientation) came the closely associated global belief in liberal capitalism. Whereas, during the post-colonial period, African states were trapped and held hostage to a bipolar world order that effectively rewarded loyalty rather than democracy or effective governance, the collapse of the Soviet Union allowed a brief post-Cold War peace dividend that saw levels of conflict decline and levels of democracy improve.

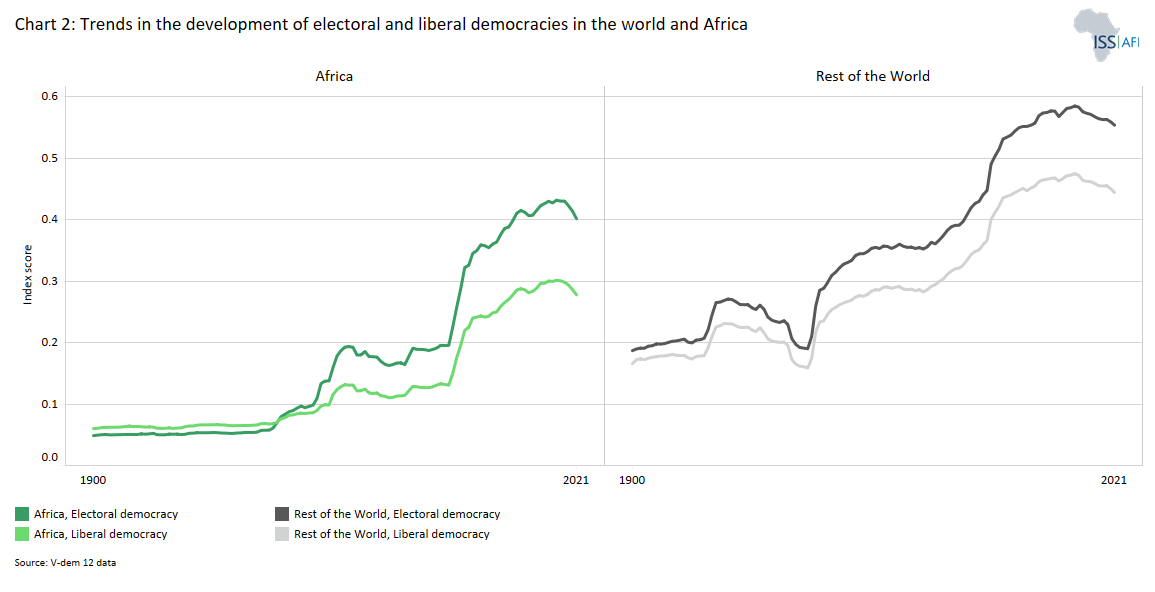

The broad positive trend towards democracy is presented in Chart 2, which shows the evolution of two types of democracy coded by the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, namely electoral (nominal or thin democracy) and liberal (substantive or thick democracy). The global averages are shown from 1900 and for Africa from 1960, covering its independence period. The index on the y-axis ranges from 0 (complete absence of democracy) to 1 (full liberal or electoral democracy in all countries). In the five years from 1989 to 1993, levels of electoral and liberal democracy in Africa and globally increased sharply, although the increase in electoral democracy is more pronounced than for liberal democracy.

In the lexicon of most academics and development practitioners, good governance and democracy are often used interchangeably as they share many characteristics, such as adherence to the rule of law, the importance of institutions and a separation of powers, but there are important differences. Good governance is essentially a broader concept that focuses on the outcomes of governing a country, including effectiveness and efficient public institutions, whereas democracy is about the process of governing. Democracy is generally seen as a crucial component of good governance, and the latter strengthens democratic institutions and processes, but a democratic system can also suffer from poor governance.

Over the past two centuries, democracy has advanced in three global waves, reflected in Chart 2, with much of Africa gaining independence as part of the second. With each wave, the quality, depth and reach of democracy have peaked higher before the subsequent trough and changed our understanding of what it means to be governed. Each peak has raised the high-water mark left by its predecessor, granting momentum to an apparent tide of democracy as it envelops increasingly more significant shares of the world’s population and more countries. Only China and some oil-rich Gulf states seem immune to its global allure, supported by its recent negative trend, which has given rise to much analysis and commentary on the apparent increase in authoritarianism.

A peaceful electoral transition of power from a governing party to an opposition party, or the defeat of an incumbent president during elections, is an essential benchmark of democracy. By this standard, democracy in Africa is relatively recent. After independence, the first peaceful transfer of power occurred in Somalia in 1967 when Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke defeated incumbent President Aden Abdullah Osman Daar. A quarter of a century later, the second occurred in November 1991 when trade union leader Frederick Chiluba defeated incumbent president Kenneth Kaunda in Zambia's first multiparty elections. Popular sentiment was important, but so was external pressure, with governments forced into accepting political liberalisation as part of a set of conditions for the balance of payment support. The latter formed part of the structural adjustment policies initiated in the mid-1980s and followed Africa's debt crisis. In effect, African leaders traded democracy for debt forgiveness and aid. By 2016, African opposition leaders had defeated incumbents in 20 different elections, yet with one or two exceptions.

Many analysts hailed the Arab Spring of 2010 as either the start of a fourth wave of democratisation — as it originated in the region with the lowest levels of political and economic inclusion globally — or proof that the third wave had not yet entirely run its course. Libya, Egypt and several countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) have subsequently suffered devastating blows to peace and stability — and democracy. To date, only Tunisia has emerged from this turmoil with substantially higher scores on the various measures of democracy. However, its democratic transition is increasingly shaky, given the lack of economic opportunity and emancipation.

In 2018 and 2019, a new wave of popular protests swept first across North Africa, starting in Ethiopia and then spilling over into Sudan and Algeria as citizens challenged long-standing parties and rulers. This suggested that before the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on societies, democratisation in Africa was still on an upward trajectory, despite the absence of many of the supposed pre-conditions for democratic consolidation, described as ‘a coherent national identity, strong and autonomous political institutions, a developed and autonomous civil society, the rule of law, and a strong and well-performing economy.’

Overall, democracy in Africa improved significantly with the end of the Cold War in 1989. However, its pre- and post-COVID-19 trajectory was flat and recently negative following a spate of coups in Francophone West Africa.

Globally, levels of electoral democracy are higher than those of liberal democracy, and the gap has grown over time. This gap is much more significant in Africa than elsewhere, reflecting the low quality of democracy, poverty and limited capacity on the continent. In many countries, elections were initially held to respond to external demands, although this is changing with demands now coming from Africa's growing young population. Still, the lived experience of political liberties, the rule of law and separation of powers is often absent as elderly elites maintain their grip on power in a continent where the median age of its leadership is higher than in other regions. Regular elections are changing this, but practically, although many African countries have the essential elements of electoral democracy, the incidence of liberal democracy is much less pronounced, given the associated requirements of institutionalisation and resources that it requires.

From the 1970s, Africa’s Western development partners invested in civil service reform and efforts to improve public financial management and helped to set up anti-corruption watchdogs and public audit bodies. Multiparty elections, democratic decentralisation and other methods of achieving citizen participation were equally popular. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund were at the forefront of these efforts to ensure governments’ withdrawal from productive sectors, limiting their role to policymaking and regulatory functions. The focus on good governance as an apparent prerequisite for development in Africa steadily gained traction in the 1980s as international development institutions sought to respond to the challenge of slow growth and high levels of indebtedness and corruption in Africa. In the absence of other means to respond to Africa’s slow pace of development, the focus on good governance is essentially a technocratic response from donors and others to bad policies and, especially, bad politics in many African countries.

The mantra of Africa’s Western development partners is often that Africa needs to adopt liberal democracy as a prerequisite for development. Democracy, Africans are told, will lead to better governance, which, in turn, will improve development outcomes. However, transformative spurts of economic development do not necessarily require a democratic state (although desirable) but a developmental state in which leaders are genuinely committed to development and have the capacity to make it work.[12A Leftwich, Governance, democracy and development in the third world, Third World Quarterly, 14:3, 1993, 620.] Also, it is debateable if democracy can compensate for deficiencies in stability and capacity.

In this post-colonial and post-Cold War world, the original sequenced processes of consolidation of security, building capacity and expanded inclusion in Africa now occur simultaneously, reflected in Chart 3. Instead of security serving as a solid footing and enabler for extending the capacity of the state, weak and incomplete security has meant limited capacity. Instead of citizens demanding more inclusion in exchange for fealty to a central government, inclusion was often imposed in the form of demands for democracy and good governance by the West. The result has been the early democratisation of Africa, meaning that many countries on the continent have higher levels of democracy compared to other countries globally at similarly low levels of education and income.

Generally, political power in much of Africa is now decided at the ballot box and not through the barrel of the gun, although the quality of elections is often low, and incumbents resort to various manoeuvres (legal and illegal) to extend their stay in power.

Each dimension, security, capacity and inclusion, is discussed separately below.

Security and Governance

Download to pdfThis section summarises general conflict trends, the drivers of intrastate violence, the impact of terrorism and the rising incidence of protests and riots.

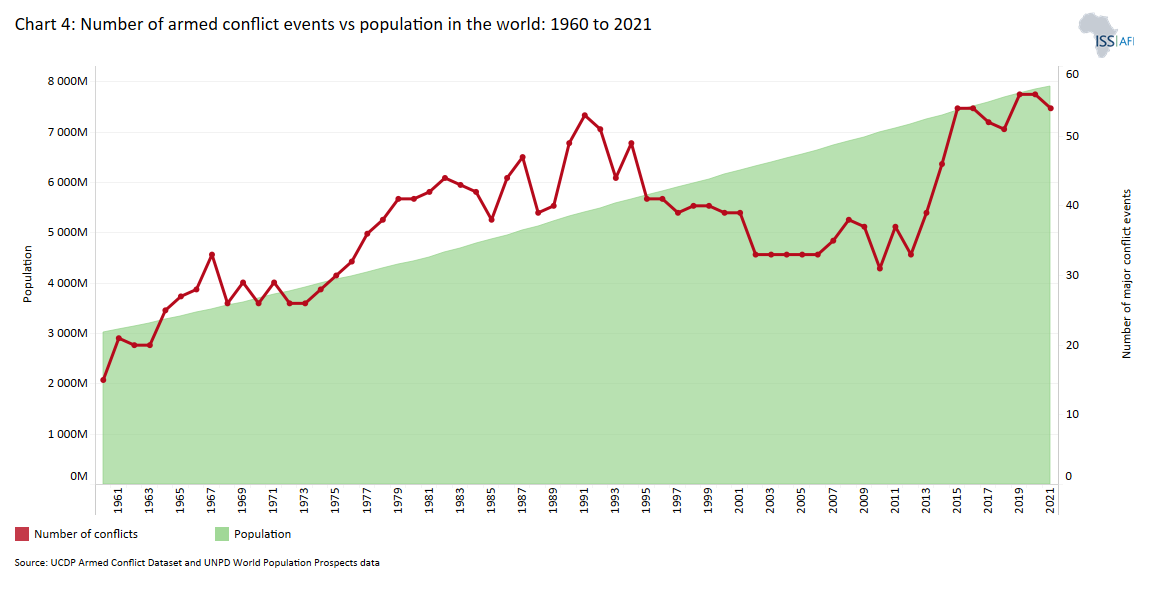

Chart 4 is an overlay of the number of armed conflicts (as measured by the Uppsala Conflict Data Program UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset) and the increase in global population from 1960 to 2022.[13UCDP captures minimum casualties of between 25 and 999 and 1 000 or more battle-related deaths per year, which are coded at intensity levels 1 and 2, respectively. UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset Codebook, Version 4-2015, Uppsala Conflict Data Program: 8.]

In line with global trends, reflected in Chart 4, Africa’s most violent period since independence in the 1960s occurred shortly before the end of the Cold War in 1989. Levels of organised, armed violence in Africa increased faster than the global average during the 1970s and 1980s, even as death rates declined. The reason was self-evident — the continent served as a proxy battleground between the former Soviet Union and the United States of America (US) and their allies, each backing particular clients. As tension between the East and the West mounted, the burden of armed conflict increased. The collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989 then removed competitive bipolarity, a significant source of conflict from the international system, with the period from 2004 to 2006 being more peaceful than any other in Africa’s recent history.

The reduction in Africa’s strategic relevance with the end of the Cold War, and subsequently, the end of US demand for oil and gas, the continent was now more reliant on its domestic resources to ensure stability and, inevitably, Africa’s incomplete security transition that continues to manifests itself in various violent ways.

Chart 5 presents fatalities[14Data on fatalities is from UCDP, which defines an event as ‘an incident where armed force was used by an organised actor against another organised actor, or against civilians, resulting in at least 1 direct death at a specific location and a specific date’ (H Stina, UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset Codebook Version 20.1, Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala: Uppsala University, 2020). However, events are only included in the UCDP data when fatalities amount to 25 deaths per year and per group. In this way, the dataset tries to exclude individual murders and deaths from crime but includes most organised, armed actors such as rebel groups.] relative to population growth in Africa from 1989 to 2022, including the 1994 genocide in Rwanda.[15Population data is from the UN Population Division, reflecting an increase from 621 million people in 1989 to 1.328 billion in 2019.] The chart distinguishes between state-based conflict (involving a government), non-state conflict (no involvement of government armed forces) and one-sided violence (the deliberate use of armed force by the government of a state or by a formally organised group against civilians). High levels of non-state conflict reflect the absence of effective government control and the inability of a government to exert its authority, collect taxes, enforce compliance or provide services.

In 2023-24 concerns are mounting that the continent is again a proxy battlefield between Russia and the West, through disinformation and the deployment of the Wagner military group (since rebranded as the Africa Corps and now part of its military).

Generally, a government’s ability to ensure law and order, police its territory effectively, monitor borders and suppress dissent is the most important reflection of a country’s stability, or the lack thereof. Many African governments, particularly in Central Africa and the Sahel, do not fully control their territories, cannot police their borders and, in extreme cases such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo), Mali or Burkina Faso, may be battling terrorists or rebel groups that effectively control parts of their territories.

Three distinct periods seem to emerge from the data, namely a period of extremely high numbers of fatalities between 1990 and 2000, a sharp decline until 2005 and then increasing again, with an acceleration seen after the Arab Spring in late 2010. After 2005, the ratio of conflict-related fatalities (deaths to number of people) declined (excluding a peak in 2014). At this level of analysis, stability in Africa is improving, although slowly.

With states’ limited capacity to impose order and often balancing numerous factions across borderlands, Africa’s conflict burden (measured as fatalities per thousand or million inhabitants) has declined more slowly than the global average. The African state is clearly not really in control, often because it was never established and consolidated in the first place.

Chart 6 presents Africa’s population as a percentage of global population and Africa’s armed conflict burden as a percentage of the global armed conflict burden (using UCDP data) and military expenditure as a per cent of the total. From this, it is clear that Africa’s conflict burden is significantly higher than the global average but the continent spends limited amounts on defence, although it is only one element of total security expenditure.

In 1989, Africa had 12% of the world’s population and 39% of its armed-conflict incidents. By 2014 Africa had 16% of the world’s population and 52% of the world’s armed-conflict incidents, a hefty increase from just 40% the previous year.

Given its high conflict burden but low levels of defence expenditure African countries need to consider what would be 'appropriate' levels of security expenditure, as well as optimise the use and allocation of such monies.

Political violence is pervasive in Africa but not to the extent that many people believe. In January 2023, the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) released its Conflict Severity Index, using four key indicators to map out how and where severe conflict occurs. The findings reflect the large category of political violence that receives little public attention given the focus of the media on armed conflict and terrorism.

At the start of 2023, 46 countries and territories globally met at least one of the four severity indicators used by ACLED. Of these, only 17 were in Africa. The four indicators are:

- deadliness (the fatality rate from political violence)

- the danger of political violence to civilians (the rate of violent events affecting civilians)

- the geographic distribution of events at subnational level, and

- the extent of fragmentation represented by a count of active armed, organised non-state political groups.

The 17 African countries include Mali (extreme severity); Burkina Faso, DR Congo, Nigeria, Somalia and South Sudan (high severity); Cameroon, Ethiopia, Libya, Mozambique, Niger and Sudan (moderate severity); Burundi, the Central African Republic (CAR), Egypt, Eswatini and Kenya (limited severity).

The associated trend analysis indicates that most countries are experiencing sustained or escalating levels of violence, except for the DR Congo, South Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia, Sudan and Libya, all of which have experienced a modest decline in the severity index since 2018. Violence in all of these countries comes from a very high level, of course, and is driven by state weakness and violent competition for state resources and power.

Finally, those countries most affected by political violence:

- are home to multiple conflicts, often with limited overlap

- involve many active groups that often are fighting each other as frequently as they clash with state security forces

- have militias playing a leading role in the violence

- have generally failed to fully resolve or at least reduce violence (though peace agreements and post-conflict arrangements have changed the nature of the violence), and

- are lower-middle rather than in low-income countries.

Historically, territories with a single government, defined borders and a shared, central administration experience only a quarter of the average death rate as states without a national government. The trends in the ACLED index confirm this general conclusion. A continent consisting of countries whose governments ensure law and order across their territories will inevitably be more peaceful and experience lower mortality of all types. For this reason it is of utmost importance for Africa’s development that stability is brought to Somalia, the Sahel, the eastern provinces of the DR Congo, north-eastern Nigeria and Libya, to list a few. At the same time, it is clear that conflict in Africa is becoming more complicated (and hence more difficult to contain) with multiple insurgent groups, militias and criminal groups fighting one another and the government.

Sustained violence in several African countries in Chart 6 reflects deep (or structural) drivers of conflict, presented schematically in Chart 7, including:

- a bad neighbourhood (and the risk of spill-over or external interference)

- a history of armed conflict[16Recurring conflicts are a massive problem in Africa and cycles of war tend to repeat themselves in the same countries, such as Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia and Somalia. As a result, the best predictor of future instability is past instability.] (that has created a legacy of grievances)

- a youthful population (particularly a large cohort of 15- to 29-year-olds)

- high levels of poverty (poor countries do not have the means to invest in security or provide social services)

- inequality and exclusion (particularly if combined with improved education that does not translate into employment opportunities)

- unstable regime transitions (demonstrating regime weakness)

- mixed or anocratic (or semi-democratic) regime types (that are particularly vulnerable to violence), and

- poor governance (often associated with single commodity dependence and low levels of participation in international trade).[17Being heavily involved in international trade requires respect for the rule of law and low levels of corruption. Low participation levels in international trade likely see groups distorting trade and other economic activity for their benefit, making internal conflicts more likely.]

By implication, lasting peace, or at least more stability, requires that these grievances are addressed and a government that is committed to development, which takes time, commitment and resources. But even then the proliferation of multiple conflict actors means that negotiations and peacebuilding efforts have mostly limited effect. Once violence becomes endemic, efforts at negotiating an end to it or stabilising a situation through the deployment of peacekeepers, such as in South Sudan or CAR, often need to be measured in decades rather than years.

In Southern Africa, the extraordinarily high level of inequality in countries such as Namibia, Botswana and South Africa presents a potential threat to stability. In addition to the legacy of colonialism and apartheid, the informal sectors in these countries are relatively small compared to those in other countries at similar levels of development, meaning its ability to soak up unemployment and provide a means for survival is low. The extent of autocratic repression in countries such as Equatorial Guinea and Eswatini also presents a problem if left unattended, and these countries experience recurring bouts of violence. Efforts by leaders such as Obiang Nguema Mbasogo (Equatorial Guinea), Mswati III (Eswatini), Paul Biya (Cameroon), Yoweri Museveni (Uganda), Alpha Conde (Guinea) and Alassane Ouattara (Côte d’Ivoire) to extend their terms in office or effect dynastic succession present obvious challenges as pressure mounts without the prospects for either democratic change or generational succession.

Perceptions about the distribution of wealth between groups and levels of equity in society play an important role and fuel discontent. In Central Africa and a country such as Kenya, governments are unable to deliver the most basic services outside of the capital city, yet the political elite has been exceptionally creative in designing strategies to retain access to government revenues.

The “centre of gravity” for the Islamic State (IS) group has moved from the Middle East to Africa. Most of the countries with the largest increase in terrorism (Burkina Faso, Mozambique, DR Congo, Mali, Niger, Cameroon and Ethiopia) are in sub-Saharan Africa. Whereas in 2010, only five African countries experienced sustained activity from violent Islamist extremism (Algeria, Mali, Niger, Nigeria and Somalia), that number increased to 12 countries by 2019, with Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Egypt, Kenya, Libya and Tunisia added to the list.

Definitions of terrorism are notoriously subjective, given the political nature generally ascribed to its motivations. With that caveat, Chart 8 presents data from the University of Maryland which hosts the largest global dataset on terrorism. It presents fatalities from terrorism, distinguishing between those in Africa and the rest of the World.

The contribution of Islamic terror to Africa’s conflict burden has waxed and waned since the 1960s, but it is generally accepted to have its origins in Algeria’s bloody independence struggle with France, to have gone through various stages and name changes, and to have shifted allegiances until the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (Groupe Salafiste pour la Prédication et le Combat, GSPC), which had spread to Chad, Sudan, Libya, Mali and Mauritania, changed its name to al-Qaeda in the land of the Islamic Maghreb in 2007.

Together with the impact of the Arab Spring (which weakened state capacity in North Africa to combat terror), the 2003 US intervention in Iraq revitalised Islamic terror globally and facilitated the growth of the Islamic State of Iraq (ISIS).[18ISIS later changed its name to the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant.] US troops left Iraq in 2011, even as the impact of the Arab Spring washed across the MENA region, which eventually forced President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali of Tunisia to flee, initiated changes in the Egyptian regime and led to the deposition of Muammar Gaddafi in Libya. However, the momentum of the Arab Spring was insufficient to replace the pre-existing order in key authoritarian states. Instead, it effectively facilitated the Islamic State’s expansion from Iraq to Syria and destabilised large parts of the Maghreb, particularly the Sahel.

The intervention of NATO in Libya led to the collapse of central authority and provided a space for Syrian combatants from al-Qaeda and the Islamic State to relocate. It also facilitated the looting of the giant arms supplies that Gaddafi’s regime had built up over the years, serving as the primary source of arms in the region. The weapons and Tuareg fighters from Libya subsequently stoked conflict in Mali and Nigeria, igniting a war in the Sahel. French military intervention (Operation Serval in 2013) narrowly averted the capture of Bamako, but neither a subsequent UN peacekeeping mission nor regional efforts have been able to restore stability.

In addition, developments in Africa’s largest economy and most populous country, Nigeria, are particularly worrisome. Although not initially linked to violent Islam, successive bouts of widespread and intense instability have plagued Nigeria since independence from Britain in 1960, including the effort at secession by the Eastern Region as the Republic of Biafra (1967–1970) and ethnic violence for control over the oil-producing Niger Delta from 1992 to 2009.

Recent violence in Nigeria’s north-east has, however, been closely linked to politically violent Islam. The dominant narrative remains that a Christian government in the south caused deprivation and poverty in the north. Most victims are Muslim, however, as the first priority is to consolidate its power base. In 2015, a faction of Boko Haram (which means Western education is forbidden), named itself the Islamic State West Africa Province.

Beyond Egypt and Algeria, terrorism in Africa is also generally associated with Somalia, where it spread after the collapse of the Siad Barre regime in 1991, allowing Al-Itihaad al-Islamiya (AIAI) to spread its influence. Members of AIAI fought with the mujahideen in Afghanistan in the late 1990s and subsequently planned and conducted both the US embassy bombings in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam in 1998 and attacked an Israeli hotel and an airliner in Mombasa in 2002.[19A Weber, Al-Shabaab: Youth without God, in G Steinberg and A Weber (eds.), Jihadism in Africa: Local causes, regional expansion, international alliances, Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2015.]

Hardliners in the AIAI eventually joined forces with an alliance of sharia courts, known as the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), and gained control over the Somali capital, Mogadishu. That event triggered intervention by Ethiopia in December 2006, eventually driving al-Shabaab and the ICU from Mogadishu.

Kenyan troops crossed into Somalia in 2011 to fight al-Shabaab and, like the Ethiopians, later joined the African Union (AU) peacekeeping force in its mission in Somalia. In subsequent years, a string of ruthless and high-profile attacks, mostly in neighbouring Kenya, continued to keep al-Shabaab in the news, even as a rival organisation, the Islamic State in Somalia, mounted regular well-publicised operations.

Domestic grievances primarily drive terrorism, which is then contextualised and animated within a broader religious or political framing. This remains valid even as several copycat insurgencies have recently emerged, such as in the eastern DR Congo and northern Mozambique. Although people’s decisions to join armed jihadist groups reflect marginalisation, poverty and poor governance, the decision to engage in violence is typically related to personal experiences at the hands of authorities rather than ideology such as radical Islam. Eventually, a specific incident mobilises locals and leaders, who then frame the reasons for the situation and the need for action within a broader political, ideological or religious context.

Similar to terrorism, and in sharp contrast to the gradual decline of armed violence (if viewed over long time horizons), Africa is experiencing increased anti-government riots and violent protests. Protests have become a more acceptable public behaviour in many countries, initially associated with democratisation and, since 2020, the hardships that followed lock-down measures to combat COVID-19.

According to ACLED, non-violent protests and violent riots in Africa have increased elevenfold in the decade since the start of the Arab Spring, compared with the population increasing only by a factor of 1.3.[20ACLED and UCDP are the largest publicly available data providers that comprehensively cover Africa. ACLED defines a protest as follows: ‘A non-violent, group public demonstration, often against a government institution. Rioting is a violent form of demonstration’ (ACLED, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Codebook, Oslo: International Peace Research Institute, 2019).]

The continent generally seems to be becoming more politically aware and restless (although better reporting and access to social media probably accentuate the increase), reflected in Chart 9. The increase in the number of riots and protests also reflects the impact of increased levels of education on Africa’s youth amidst limited job opportunities, slow growth in recent years, together with rapid urbanisation and the impact of social media and Internet access. In Kenya, youth protests were triggered by the government's attempts to introduce punitive tax increases, while those in Mozambique in 2024/5 followed elections in October 2024. In Nigeria calls to disband the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) that were accused of police brutality subsequently widened to raise citizen concerns relating to corruption, maladministration, and inequality.

However, riots and protests appear to have become less deadly over time, with fewer fatalities per event. For example, while Africa experienced an average of eight deaths per event between 2001 and 2003, the average declined to three between 2015 and 2017. Widespread access to the Internet, smartphones and the subsequent public reporting of abuses by security forces may also have contributed to the decline.

As sub-Saharan Africa is less urbanised than other regions in the world, more rapid urbanisation in the future could prove to be politically destabilising in the region, especially as riots and protests may increase because of democratisation and changes in regime type being experienced here. With many people living in towns and cities, population density can facilitate the kind of crowd and mass dynamics that eventually ejected Ben Ali from his presidency in Tunisia, forcing a rotation in the governing elite in Egypt and culminating in a civil war in Libya. Democracy can absorb much of this turbulence, but only if it is substantive.

Government capacity is reflected in the mobilisation and effective use of government revenues. Wagner’s law reflects the well-established tendency of states to mobilise and use a progressively higher share of the gross domestic product (GDP) as they develop economically and build professional public administrations. As a result, the share of public expenditure increases relative to national income.[21See, for example, RE Wagner and WE Weber, Wagner's law, fiscal institutions, and the growth of government, National Tax Journal, 30:1, 1977, 59–68.]. The World Bank calculates that a tax-to-GDP ratio of 15% is a rough minimum level to help countries generate sufficient domestic resources to invest in health, education, and infrastructure. The unweighted average tax-to-GDP ratio for the 33 African countries for which the OECD had data in 2021 was 15.6% in 2021, and recorded no change relative to 2020. The average of15.6% for countries with data in Africa is below the averages of Asian and Pacific economies (19.8%), Latin America and the Caribbean (21.7%), and the OECD (34.1%), reflecting low government capacity.

The effective use of government revenues is, of course, undermined by corruption, which can be used as a proxy to reflect the capacity to manage these resources. The best-known public index that compares levels of corruption between countries is the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) from Transparency International.

Chart 10 presents the average CPI score for each global country income group. Results are normalised to a scale of 0–100, where 0 equals the highest level of perceived corruption (and the lowest level of transparency), and 100 equals the lowest level of perceived corruption (and the highest level of transparency). Low-income countries invariably score poorly since public services, institutions and systems function poorly. Rich countries, with ample resources, inevitably score well.

Chart 11 presents government revenue as a percentage of GDP for each African country in 2019.

Although tax revenue mobilisation performance varies widely across African countries, Africa's average tax-to-GDP ratio of 16.5% is lower than other regions such as Asia and the Pacific (19.1%), Latin America and the Caribbean (21.9%), and Organisation for Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries (33.5%).

Important countries such as Nigeria and the DR Congo do very poorly, meaning that governments there have limited resources to spend on education, infrastructure and other social services. In terms of development and stability, larger countries struggle more than smaller ones.

Tax revenue has progressed in African countries, but most remain below their tax potential, the maximum tax a country can collect given its economic structure and institutions. A new IMF study suggests that there is still a significant unmet tax potential, especially in low-income countries, implying that a further increase in domestic revenue is achievable with appropriate policies. Higher domestic revenue will improve public finances and help reduce new borrowing while providing fiscal space for well-targeted spending to revive growth.

The emerging picture is concerning. Poor countries score badly because they do not have mature systems and institutions characteristic of rich countries (i.e. they have limited capacity). Furthermore, African states, large countries in particular, are often characterised as neo-patrimonial, reflecting the extent to which patrons use state resources to purchase support.

The third dimension of governance is inclusion, and two indices can be used to analyse and develop a reasonable forecast in this regard: levels of democracy and gender. Since a separate theme on this website is devoted to gender, we focus on democracy. We also add a third component, namely the implementation of social grants (or welfare) as an important component in Africa, given widespread poverty and the absence of formal employment opportunities.

To review the state of democracy in Africa, various sources track trends and provide extensive datasets, particularly the annual Global State of Democracy published by International IDEA, the V-Dem project and Polity. In addition, Afrobarometer runs regular surveys on attitudes to democracy, on average now across 39 African countries. The Afrobarometer findings indicate that support for democracy remains robust in the face of a global democratic recession, but has declined by seven percentage points from 2011 to 2023. Afrobarometer notes, however, that the widening gap between citizens' expectations and the actual delivery of democratic governance is fuelling disillusionment and instability. Large numbers of Africans call for government accountability and the rule of law. Opposition to military rule has also weakened. More than half of Africans (53% across 39 countries) were willing, in 2023, to accept a military takeover if elected leaders 'abuse power for their own ends'. Fewer than half (45%) of Africans think their countries are mostly or completely democratic, and only 37% say they are satisfied with the way democracy works in their countries.

V-Dem’s Democracy Report 2024 (including data up to 2023) notes the steep global decline in democracy in Eastern Europe and South and Central Asia since 2010, concluding that ‘the level of democracy enjoyed by the average person in the world in 2023 is down to 1985-levels; by country-based averages, it is back to 1998.' A much larger portion of the world's population, 71%, lives in autocracies - an increase from 48% ten years ago. The trend in Africa has recently followed the wave of autocratization, although there are also signs of improvement in selected countries.

Focusing on the electoral component of democracy, International IDEA has adopted a threefold regime typology, namely democracies (of varying performance), hybrid regimes and non-democracies. Democracy is based on five attributes: representative government, fundamental rights, checks on government, impartial administration, and participatory engagement. Each has several sub-attributes, and for a country to be classified as a democracy, it needs to hold minimally competitive multiparty elections. Depending on how they score on the five core democratic attributes, countries are categorised as high-performing democracies, mid-range performing democracies or weak/low-performing democracies.

The situation in Africa in 2021, with these criteria applied, is summarised in Chart 12.

The IFs forecasting platform uses the Polity index from the Center for Systemic Peace with a similar threefold regime classification. The index ranks countries from −10 (hereditary monarchy) to +10 (consolidated multiparty democracy). Countries that score from −5 to +5 are considered anocratic (or mixed/hybrid) regimes that display elements of democracy (e.g. regular elections) that coexist with autocratic behaviour and institutions (e.g. limited legislative oversight).

Analysis of the Polity data within IFs provides two interesting insights. The first is that it allows a comparison of the level of autocracy/democracy in a country with the average for countries with similar levels of education and GDP per capita. It reveals countries that have particularly high levels of democracy compared to other countries at similar levels of development (a democratic ‘surplus’) or low levels (a democratic ‘deficit’), as shown in Chart 13. A difference of five points from zero in either direction is taken as indicative of a surplus or deficit. The chart is for 2018, the last year of available data in Polity V.

According to this interpretation, Niger, Sierra Leone, CAR, Kenya and Comoros have constitutions and democratic practices that are considered more democratic when compared with other countries at the same levels of development. In contrast, in Libya, Equatorial Guinea, Eswatini, Egypt, Morocco, the Republic of the Congo, Eritrea, Cameroon, Sudan, The Gambia, Angola and Mauritania, the levels of democracy are substantially lower than in other countries at similar levels of income and education.

The nature and the point at which inclusion becomes excessive (and what that means) remain unclear, however. It likely depends on the context and may wax and wane over time.

Historically, the reason for early or premature democratisation in a number of African states is likely the dominance, until recently, of the liberal democratic West, which provided significant amounts of conditional development assistance to Africa. Furthermore, in an interconnected world, citizens can compare their domestic conditions to those in other countries. This has steadily led to the conviction among the majority of Africans that democracy is the most desirable regime type, given their lived experience of decades of brutal post-independence authoritarianism. Although electoral democracy has hardly delivered better developmental results in Africa, the process of being consulted and having the power to affect changes in leadership has reshaped the dynamics of power and the perception of accountability.

Based on survey data, Afrobarometer reports that ‘on average across the continent, Africans support democracy as a preferred type of political regime. Large majorities also reject alternative authoritarian regimes such as presidential dictatorship, military rule, and one-party government.’ This trend is confirmed in subsequent surveys, even as Africans’ positive view of authoritarian China has overtaken that of the democratic US. The most notable examples of ‘excessive inclusion’ are governments of national unity or where there are power-sharing arrangements. This is a common approach to papering over divisions in a society, typically producing a measure of political stability but engendering paralysis in governance and economic performance. Lack of development, in turn, leads to social instability, and in these circumstances, a government of national unity sometimes unwittingly plants the seeds for the next crisis since it is often unable to sustain or promote economic growth.

A second insight relates to countries with a Polity score of −5 to +5, so-called anocracies, versus autocracies and full democracies (roughly similar to the hybrid regime type used by International IDEA). The 2018 Polity data presented in Chart 14 indicates which African countries could be considered autocratically stable (such as Eswatini and Eritrea), countries with mixed regime types (ranging from Cameroon to Zimbabwe) and countries that could be considered largely democratic and stable (ranging from Burkina Faso to Mauritius). Subsequent to the last data update from Polity, things have deteriorated in Burkina Faso, following a severe drought and the growing threat of an Islamic insurgency that, in 2022, saw a military coup.

The group of anocracies in the middle band across the chart in 2018 (Cameroon to Somalia) are those with mixed/hybrid regimes. According to Persson and Rothstein, ‘hybrid regimes are comparatively more clientelistic and corrupt than both full-fledged democracies or outright dictatorships … and tend not only to perform worse than consolidated democracies but also than authoritarian regimes on a large variety of public goods indicators, including population health, education, access to clean water and sanitation, as well as to basic infrastructure such as roads and electricity.’[22AL Persson and B Rothstein, Lost in Transition: A bottom-up perspective on hybrid regimes, Annals of Comparative Democratization, 17:3, 2019, 10.]

Generally, liberal democracies are more stable and peaceful than other regime types. The reason is linked to the ‘primacy of institutions’ that set the game's rules rather than the whims of personalities when considering long-term economic success. Inclusive economic institutions typically feature ‘secure private property, an unbiased system of law, and a provision of public services that provides a level playing field in which people can exchange and contract; it also must permit the entry of new businesses and allow people to choose their careers.’[23D Acemoglu and J Robinson, Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity and poverty. New York: Crown Business, 2013.] Institutions are, of course, expensive and require leadership and resources to establish, meaning that they are typically associated with high-income countries.

Being more inclusive has not compensated for a lack of security or capacity, though. For example, as the number of conflict actors increases, resolving conflict in countries such as Sudan, South Sudan, the DR Congo and CAR becomes more complex.[24UCDP measures and codes these as conflict dyads consisting of two conflicting primary parties.] Rebel (and extremist) groups that split into smaller groups complicate efforts at mediation or reconciliation. Although commentators and interest groups readily agitate for maximum inclusion as part of agreements, the problem with most peace agreements is a lack of implementation rather than inclusivity.[25M Joshi and JM Quinn, Implementing the peace: The aggregate implementation of comprehensive peace agreements and peace duration after intrastate armed conflict, British Journal of Political Science, 47:4, 2017, 869–92.] No sooner do mediators persuade the warring parties to sign an agreement than a group splits off and a new faction emerges, and additional demands follow.

Similarly, political inclusion, such as having a broadly representative cabinet, contributes less to peace than most suspect — a finding underlined by data on the composition of cabinets for several countries collected by the African Cabinet and Political Elite Dataset. Most African leaders are involved in complex, dangerous and costly games of ‘elite management’ in the interest of remaining in power, thereby severely constraining their ability to undertake economic or other reforms.

More inclusivity generally only matters if it improves security and capacity. However, the transition from autocracy to democracy is often turbulent, and mixed regime types (so-called anocracies or hybrid regimes) are volatile. For example, of the 16 African countries that experienced sustained armed violence in 2021, none are fully democratic. Many African governments include elements of both autocracy and democracy and function as anocracies according to the Polity definition for 2018,[26On the Polity score, a mixed/intermediate regime type has a score from +5 to −5 in an index that ranges from +10 to −10. V-Dem distinguishes between different types of democracy, each with its own index. Its Electoral Democracy Index is closest to the Polity IV index.] namely Côte d’Ivoire, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Algeria, Burundi and The Gambia. The 2021 list of hybrid regimes from International IDEA is longer: Angola, Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, DR Congo, Ethiopia, Gabon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Mozambique, Nigeria, Tanzania, Togo and Tunisia. Despite regular competitive elections in these intermediate regimes, the legislature has little practical control over the executive branch of government and political elites are often focused on ensuring their own continuity rather than on governance.

Intermediate regimes (anocracies or hybrid regimes) are six times more likely to experience new outbreaks of civil conflict than democracies and 2.5 times more likely than autocracies. More than half of them experience a significant regime change within five years, and 70% within ten years. Recent years have seen imaginative efforts by incumbents to amend the rules in their own favour. From 2000 to 2019, for example, there were 25 attempted constitutional amendments to favour presidential third-term projects. Of these, only seven failed; 18 were successfully implemented or enforced.

Recent coups in Chad, Mali, Guinea, Burkina Faso and Sudan do not mean that democracy in Africa is failing. The evidence suggests that while the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and recently the fallout of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is inevitably placing downward pressure on democracy, a robust democratic culture is, in fact, growing in many parts of the continent.

The relationship between economic growth and democracy is complex and contested. It is clearly affected by the development level and the time horizon adopted for the associated analysis, as well as the actions of local elites. In respect of the former, Acemoglu et al. found that there is a ‘robust and sizable effect of democracy on economic growth’ and that a country that switches from non-democracy to democracy achieves about 20% higher GDP per capita in the long run.’ They argue that the global rise of democracy over the preceding half-century yielded a roughly 6% higher world GDP. Democracy also positively affects economic reform, private investment, the size and capacity of government, and reduced social conflict. For them, democracy is necessary for the formation of good corporate management, civil and political rights, solid institutional structures, property rights, social satisfaction and political stability, meaning that there is a solid and close link between economic growth and democracy — but this positive relationship is only evident with a long-term perspective where democracy creates a large, educated and articulate middle class of people and, second, transforms people’s values and motivations.

In respect of agency, it is also important to recognise the extent to which ruling elites in many African countries have been able to game the democratic system when external partners in the West started demanding political reform in exchange for debt forgiveness and aid. Rather than a response to domestic pressure, adopting the rhetoric of democracy was also a response to external conditionality. The effect is often that democracy in Africa is more procedural than substantive and has undermined the social contract between the ruling elite and citizens that lies at the root of substantive democracy.

Almost all high-income countries are democracies, reflecting the relationship between democracy and economic growth. However, the extent to which democracy causes economic growth at all income levels, as claimed by Acemoglu and others, remains contested. A lot depends upon the level of development, the nature of that democracy, how substantive it is and the extent to which local elites respond or manipulate the democratic intent.

Substantive democracy (which can perhaps be best described as liberal, constitutional democracy, including a clear separation of powers, credible and regular elections, etc.) contributes to growth by increasing investment, encouraging economic reforms, improving the provision of schooling and healthcare, and reducing social unrest. On the other hand, only rich countries have the means to affect the institutions associated with a liberal democracy.

Over longer periods, democracies invest more in broad-based public goods and are more likely to enact economic reforms that politically powerful actors would otherwise resist. Through credible elections, democracy provides a mechanism to hold the power of the elite or special interest groups in check; if imperfectly so, it ensures the separation of state powers into discrete branches of government and protects human rights and the rule of law. In this manner, democracies engender confidence to pursue long-term investments, encouraging domestic and foreign investors. Non-democracies are less likely to do so.

The evidence over shorter time horizons and at low levels of development is less compelling and somewhat contradictory. As democracy in low-income countries is invariably of a low, procedural type, it contributes little to improvements in well-being or how the country is governed. Because the quality of democracy in Africa is poor, ‘more’ democracy in poor countries does not necessarily translate into better governance or more rapid development.

The introduction of competitive politics and economic liberalisation in fragile settings such as post-conflict societies, for instance, in Somalia or South Sudan, may even undo much of the progress previously made in ending the conflict, as politicians invariably mobilise support along ethnic or sectarian lines and soon reopen the wounds that the peace process sought to resolve.[27Consider, for example, fragile post-conflict states such as South Sudan, Somalia, CAR, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, and the DR Congo.]

As a result, in poor countries, the nature and orientation of the governing elite appear to be much more critical for positive developmental outcomes than the institutional setting (democratic or not). The reason is that these countries typically lack the associated institutions and extensive codification in law and regulations to embed accountability in practice.

It is in this vein that Gerring et al. find that the relationship between electoral democracy and human development is maximised when:

- elections are relatively free and fair,

- the chief executive of a country is selected (directly or indirectly) through elections,

- suffrage is extensive,

- political and civil society organisations operate freely, and

- people have freedom of expression, including access to alternative information.

These five components lie at the heart of substantive or liberal democracy. Separating the powers of the executive, judiciary, and legislature, establishing a genuinely competitive political environment, and allowing for the development of free media and independent oversight mechanisms that have some teeth require adequate resources. Building these norms and institutions takes time and money, which is an essential reason for their close association with high-income levels. Governments can quickly adopt the trappings of electoral democracy (reflecting a hybrid/mixed system) by going through the motions of regular elections. Still, without capacitated systems and institutions, elected authorities cannot hold their executive to account.

In summary, the finding by Gerring et al. is that democracy will likely only have a positive impact on governance and development in Africa if it is substantive. That requires minimum levels of stability and capacity, implying minimum levels of development and confirming the limited contribution of democracy to growth in low- and lower-middle-income countries.

If one now compares the average ‘thickness’ of governance (consisting of the average for security, capacity and inclusion) in Africa with the Rest of the World (RoW), Africa has about a quarter ‘less’ governance. Since the state is particularly important for the provision of basic services at early stages of development, providing law and order and basic services, the poor state of governance in much of Africa is an important explanation for slower-than-expected development.

Chart 15 compares the results for each of Africa’s geographic regions for the three dimensions with the average for the Rest of the World (or the World without Africa). It reflects the fact that African averages are lower across the board, with Central Africa particularly poor. North Africa does best in capacity but does poorly in inclusion, as mentioned previously. It is because of its capacity constraints that foreign donors support Africa through development assistance, as discussed in the theme on financial flows.

Seen from a social control perspective, the potential for violence/instability in Africa stems from governments that have not invested (or cannot invest) in appropriate early warning systems, police and military responses, and institutions that institutionalise conflict mediation, management, and resolution. Instability, therefore, reflects an incomplete security and capacity transition, although the international context also plays a role. More inclusion or attempts to institute the trappings of substantive democracy typically translate into corruption rather than into accountability. Developing countries also have fewer resources to devote to either security or development. In that sense, Africa is trapped in a vicious circle: many countries are unstable because they are poor, and because they are poor, they are unstable.

Collectively, the absence of sufficient social control mechanisms provides an opportunity for violence and instability. Against this background, democracy and associated systems (part of the inclusive transition) play an important role as an effective shock absorber, evident in a country such as South Africa with its extraordinarily high levels of democracy, inequality and turbulence. By providing a sense of accountability, transparency and recourse, South Africa’s liberal constitution, separation of powers, free media and independent courts mediate and dampen the momentum towards the violent displacement of a corrupt and self-serving governing party.

The balance between accelerating and mediating factors is depicted graphically in Chart 16.

Rwanda and Ethiopia had made particularly rapid developmental progress. In both countries, a national trauma has driven the burning desire to develop — the genocide of the Red Terror in Ethiopia under Mengistu Haile Mariam, which lasted until 1978, and the Rwandan genocide of 1994.

In the wake of those traumas, governing elites in Ethiopia and Rwanda intervened decisively in the society and the economy in favour of national development and improved productivity, often exerting considerable short-term pain for the sake of achieving long-term gain — policy choices that are much easier to implement in an autocratic than in a democratic setting. Both made clear pro-growth policies and stuck to them, united behind a visionary leader (under Meles Zenawi in Ethiopia and still Paul Kagame in Rwanda) intent on escaping debilitating poverty and underdevelopment.

Dependence on a single key figure readily undoes progress once that leadership clings to power or is replaced by a flawed successor, as it has in Uganda, Angola, Zimbabwe, Egypt, Sudan, South Sudan, Equatorial Guinea, Libya, Algeria, as well as in Ethiopia following the death of Zenawi. As a result, sustained growth in an autocracy is more brittle and volatile than in a democracy, and it seems inevitable that, unless the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) invests substantively in succession planning, Rwanda will face challenges once Paul Kagame steps down, or unexpectedly vacates his position for whatever reason.

Other indices, such as the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI)[28The reason for the slight divergence between the two indices is likely statistical. WGI ranks country scores annually and any improvements in trends in governance in Africa is outpaced by larger improvements in the rest of the world. As a result, the gap tends to increase. However, when dimensions of governance are measured year-on-year, independent of global trends (essentially what IIAG does), modest improvements are seen.] and the Mo Ibrahim Foundation Index of African Governance (IIAG), also measure changes in the quality of governance over time, and their conclusions appear to validate the analysis presented above.

For example, indices of the quality of governance inevitably correlate with levels of development, which, in turn, largely accord with the extent of democracy. Chart 17 compares the two WGI subindices of government effectiveness and regulatory quality with levels of democracy from the Polity IV dataset. In low-income countries, government effectiveness and regulatory quality are poor, and they have electoral democracy compared to middle-income countries. Government effectiveness and regulatory quality improve in tandem with higher levels of average income.

Chart 18 presents the logic that underpins the Governance scenario, divided into the three dimensions of governance, more stability/security, capacity and inclusion.

In the Governance scenario, more stability uses data from the Political Instability Task Force [29Previously known as the State Failure Task Force.] to model:

- a reduction in the probability and magnitude of state failure/internal war, and

- a reduction in the probability and magnitude of abrupt regime change.

Capacity is enhanced by improving the quality of government regulation, government effectiveness (both from the WGI) and reductions in corruption using the ICG from Transparency International.

Inclusion improves as a result of:

- an improvement in levels of democracy using the Polity IV index

- an improvement in gender empowerment using the gender empowerment measure (GEM) from the UNDP[30GEM has subsequently been replaced with the Gender Development Index (GDI) and the Gender Inequality Index (GII).]

- more economic freedom, using the associated index from the Fraser Institute, and

- the roll-out of a cash grant program to benefit poor people, which is briefly discussed below (this intervention was recently added and may not be included in all geographic reports).

Modern technology makes it possible to set up social grant systems without the inefficiencies and corruption of the past and is often associated with a push to provide Africans with secure identity systems and the establishment of a national population register.

The traditional forms of social grant systems consisted of old-age pensions, disability grants, child support grants and foster care grants. In this theme, the focus is on a government program that provides financial assistance (cash) to poor people. The advances in digital technology, with biometrics and its incorporation into identification systems, mean that a social grant system can be set up rapidly and relatively cheaply, although the political and practical challenges should not be underestimated. Previously, government efforts often focused on subsidies, particularly for fuel (such as in Nigeria), bread and basic foodstuffs (in many North African countries), but the benefits did not always reach the intended beneficiaries, were prone to abuse and were dependent upon the availability of sufficient foreign exchange.

Direct cash transfers have many advantages, such as transactions in local currency (as opposed to subsidising fuel imports that are bought using foreign exchange), although, if provided over extended periods, they can lead to dependency and reduce the incentive to undertake or seek employment.

In Egypt, for example, the Takaful (Solidarity) and Karama (Dignity) cash transfer programme was launched in 2015 and covers 3.69 million households — approximately 12.84 million individuals, or 13% of Egypt’s population. The programme was originally introduced to cushion the impact of Egypt’s ambitious 2014 economic reform programme, which included the removal of energy subsidies, the adoption of a flexible exchange rate and the introduction of a new value-added tax. The government has also scaled up its social protection programmes. The Takaful (Solidarity) part of the programme provides modest, unconditional monthly pensions to the elderly and disabled citizens, while the Karama (Dignity) part provides conditional income support aimed at increasing families’ food consumption, reducing poverty, encouraging families to keep children in school and providing them with healthcare.

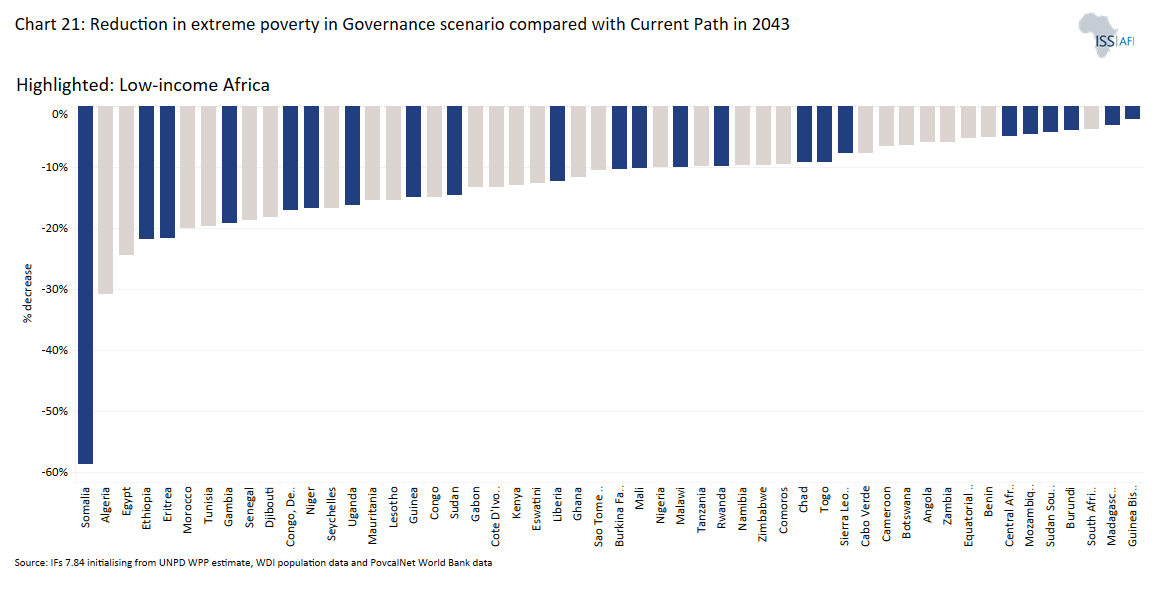

The impact of the scenario on the combined government index (the average of improvements in security, capacity and inclusion) is presented in Chart 19. The data is presented as the per cent increase in governance for each African country in 2043 compared to the Current Path forecast for that year. Unsurprisingly, the countries that gain the most include the Central African Republic, Somalia, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Togo, the DR Congo and Chad, whereas Comoros, Seychelles, Kenya, Botswana, Cape Verde, Mauritius and South Africa gain the least.

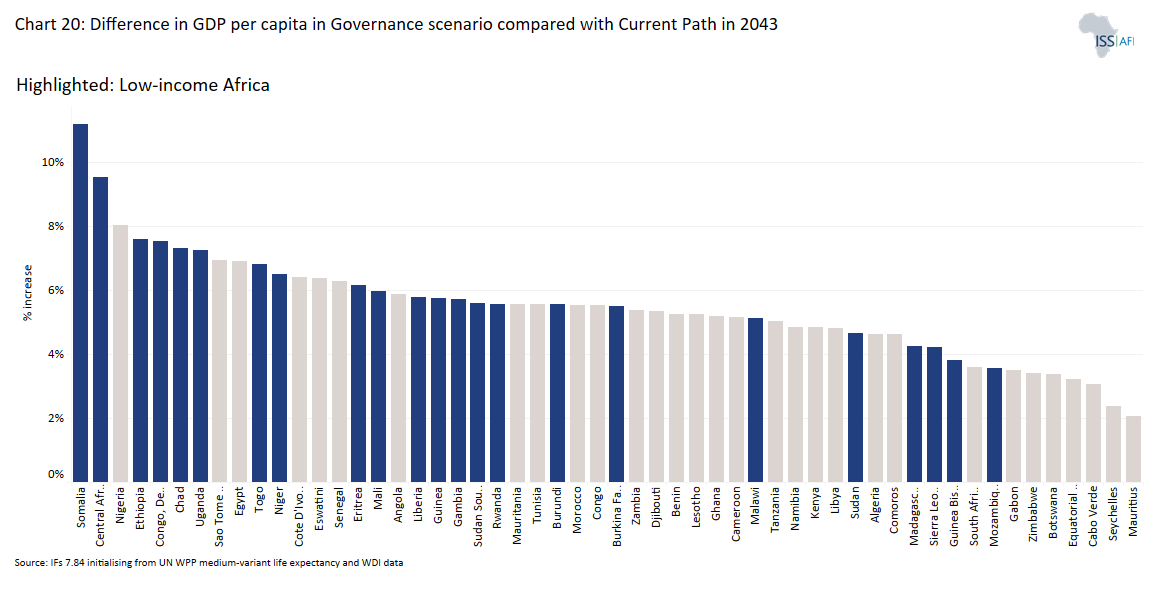

The scenario shows that more stability, capacity and inclusion would translate into more rapid economic growth in Africa. In the Governance scenario, the size of the African economy by 2043 will be US$972.5 billion larger than in the Current Path forecast (in market exchange rates). This is equivalent to an 11.5% improvement. Given its large economy, Nigeria would gain the most (US$208 billion or 14% larger), followed by Egypt (US$130 billion or 13% larger), South Africa (US$872 billion or 11% larger) and Ethiopia (US$51 billion or 14% larger) and. Expressed as a per cent improvement, the economy of Uganda gains most from the Governance scenario with a 2043 economy that is 16.4% larger than in the Current Path forecast, followed by Namibia with a 15% improvement. South Sudan gains the least, only 7%.