5 Health and WaSH

5 Health and WaSH

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

This theme examines the evolution of Africa’s health and water, sanitation and hygiene (WaSH) systems and their central role in shaping the continent’s long-term development prospects. The report explores how investments in health, clean water and sanitation can reduce preventable deaths, strengthen resilience and unlock productivity gains. The Demographics and Health scenario (also used in the Demographics theme) assesses how faster progress in these sectors could accelerate Africa’s demographic transition, expand human capital and advance inclusive, sustainable growth across diverse country contexts.

Please visit the Technical page for more information about the International Futures (IFs) modelling platform used for the forecasts and scenarios.

Summary

This theme begins with an introduction and an overview of the historical and current context of health, including Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WaSH) in Africa.

Health and WaSH systems are foundational to human development. They underpin progress in education, productivity, gender equality and resilience. Yet, decades of uneven investment, weak infrastructure and structural inequities have left significant gaps in access and outcomes. Africa continues to bear a high burden of communicable diseases, even as non-communicable diseases are rising with urbanisation and lifestyle changes. Persistent shortfalls in clean water, sanitation and hygiene services amplify these health risks and constrain the continent’s human capital potential.

Demographic pressures, climate variability and shifting global aid dynamics expose Africa’s health and WaSH vulnerabilities and create opportunities for reform and innovation. Expanding community health systems, digital health tools, local pharmaceutical production, and climate-resilient sanitation solutions could dramatically improve outcomes if supported by stronger governance and sustainable financing.

The second half of this report presents the Demographics and Health scenario, which models how accelerated progress in advancing Africa’s demographic window of opportunity and improved health and WaSH could improve life expectancy, reduce disease burden and boost productivity. It shows that sustained investment in preventive healthcare, clean water and sanitation can yield significant social and economic returns: lowering poverty, strengthening resilience and advancing Africa’s demographic transition.

The subsequent section discusses the impacts of the Demographics and Health scenario. Across all indicators, the scenario delivers marked improvements over the Current Path. Access to safe water and sanitation expands significantly, communicable and non-communicable disease burdens decline, and both infant mortality and life expectancy show major gains by 2043. These health improvements translate into measurable economic benefits: higher GDP per capita, a larger overall economy and tens of millions fewer people living in extreme poverty. Together, the results illustrate how accelerated investment in health and WaSH could generate wide-ranging social and economic returns, reinforcing the foundations of Africa’s long-term development.

The theme concludes with differentiated policy options for countries at different levels of development and capacity. It outlines three overarching priorities: investing in resilient community systems, strengthening regional self-reliance and aligning health and WaSH strategies with Africa’s green and demographic transitions. If Africa acts decisively, it can transform the current drag of health and WaSH on productivity improvements and persistent vulnerabilities into positive contributors to inclusive growth, human security and sustainable development by 2043.

All charts for Health and WaSH

- Chart 1: Journey of Homo sapiens from Africa

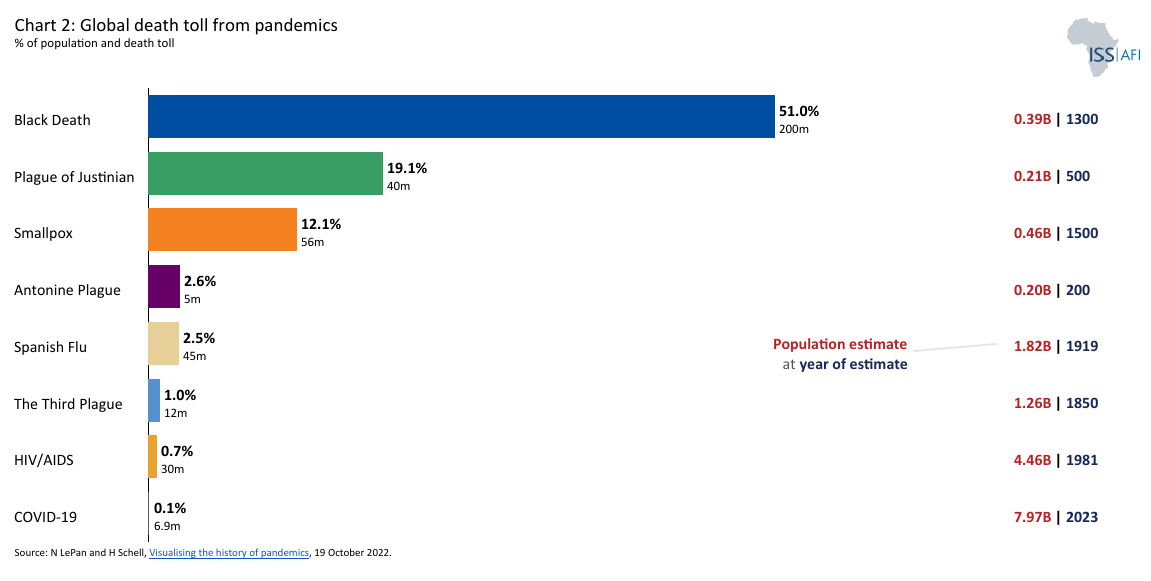

- Chart 2: Global death toll from pandemics

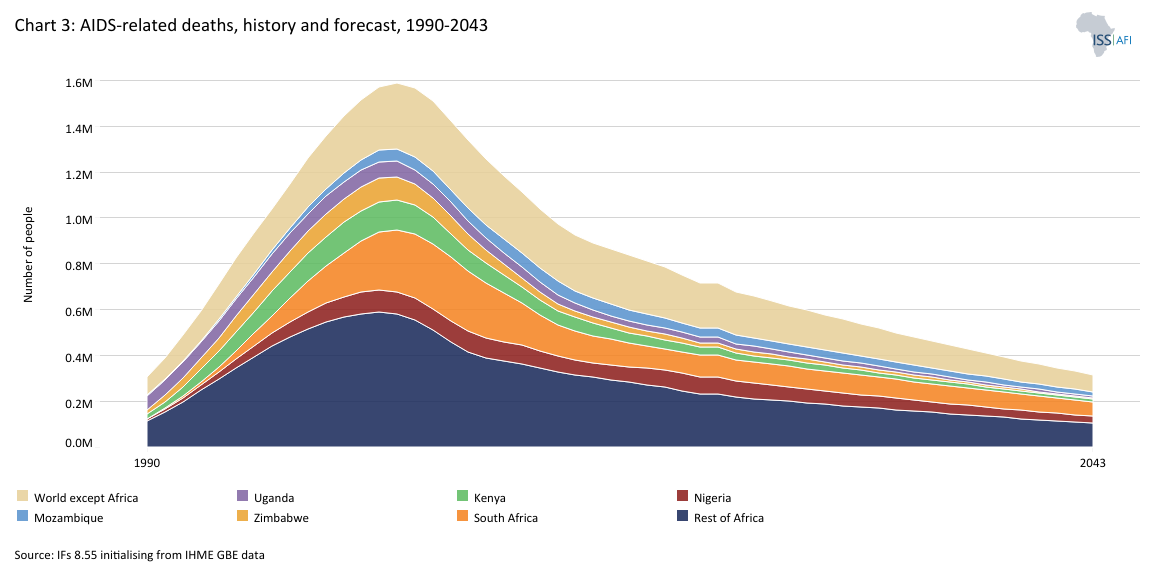

- Chart 3: AIDS-related deaths, history and forecast

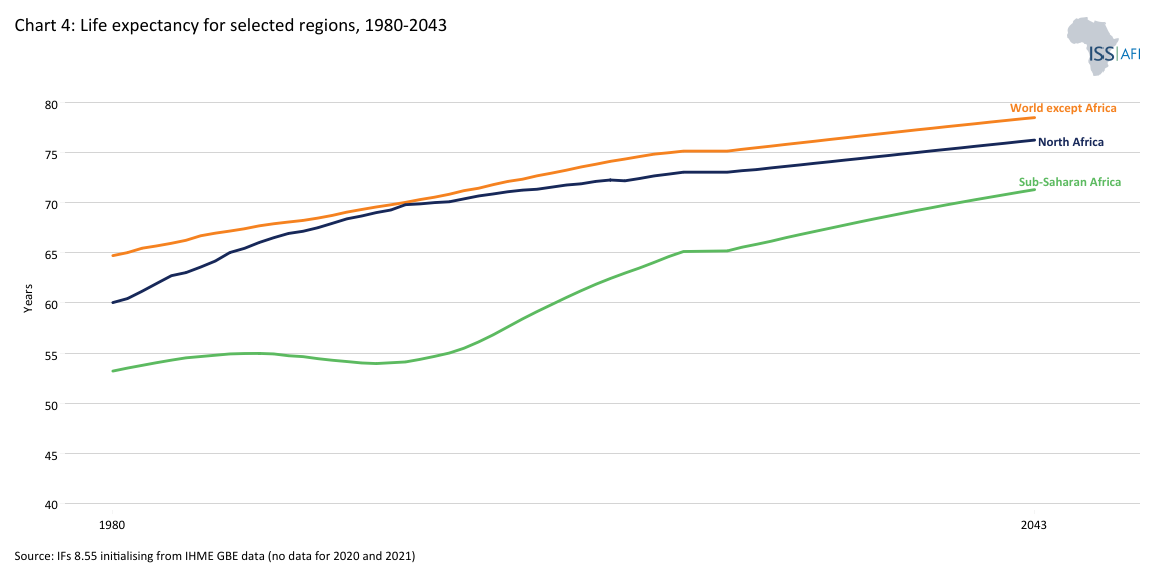

- Chart 4: Life expectancy for selected regions

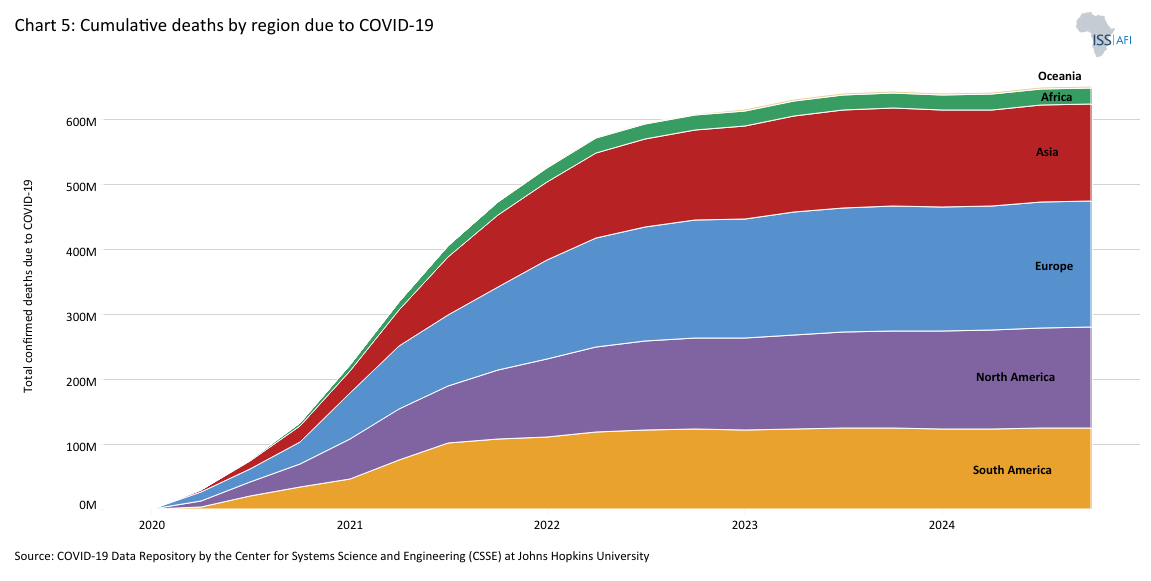

- Chart 5: Cumulative deaths by region due to COVID-19

- Chart 6: Impact of COVID-19 on extreme poverty

- Chart 7: Deaths by major ICD categories, per cent of total, 2023-2043

- Deaths rates for communicable and non-communicable diseases for selected countries and regions, 2023-2043

- Chart 9: Proportional access to WaSH facilities on the Current Path, 2023-2043

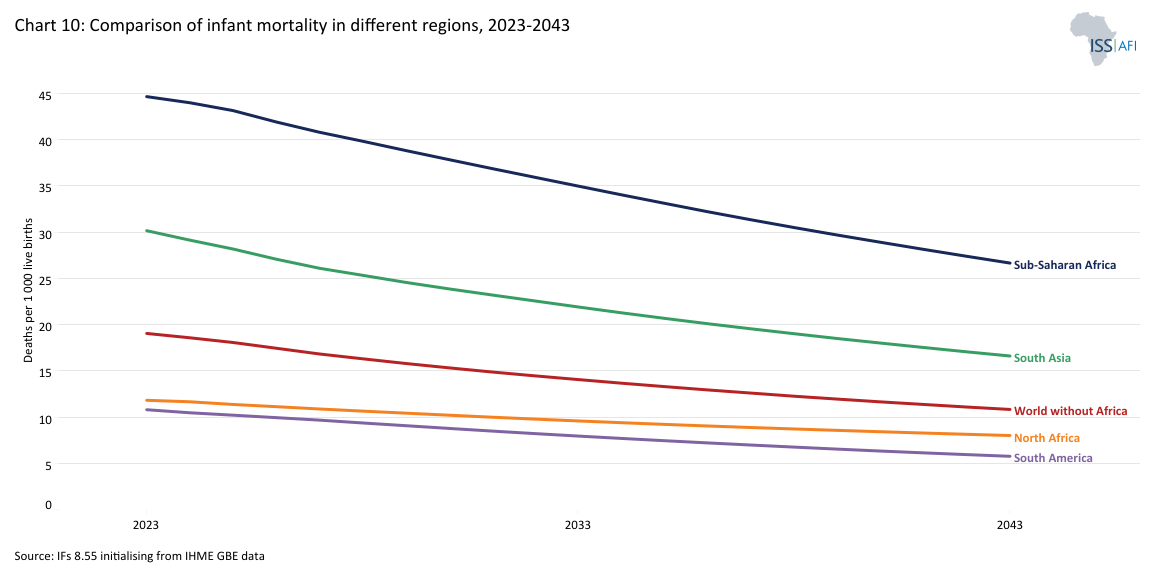

- Chart 10: Comparison of infant mortality in different regions

- Chart 11: Demographics and Health Scenario

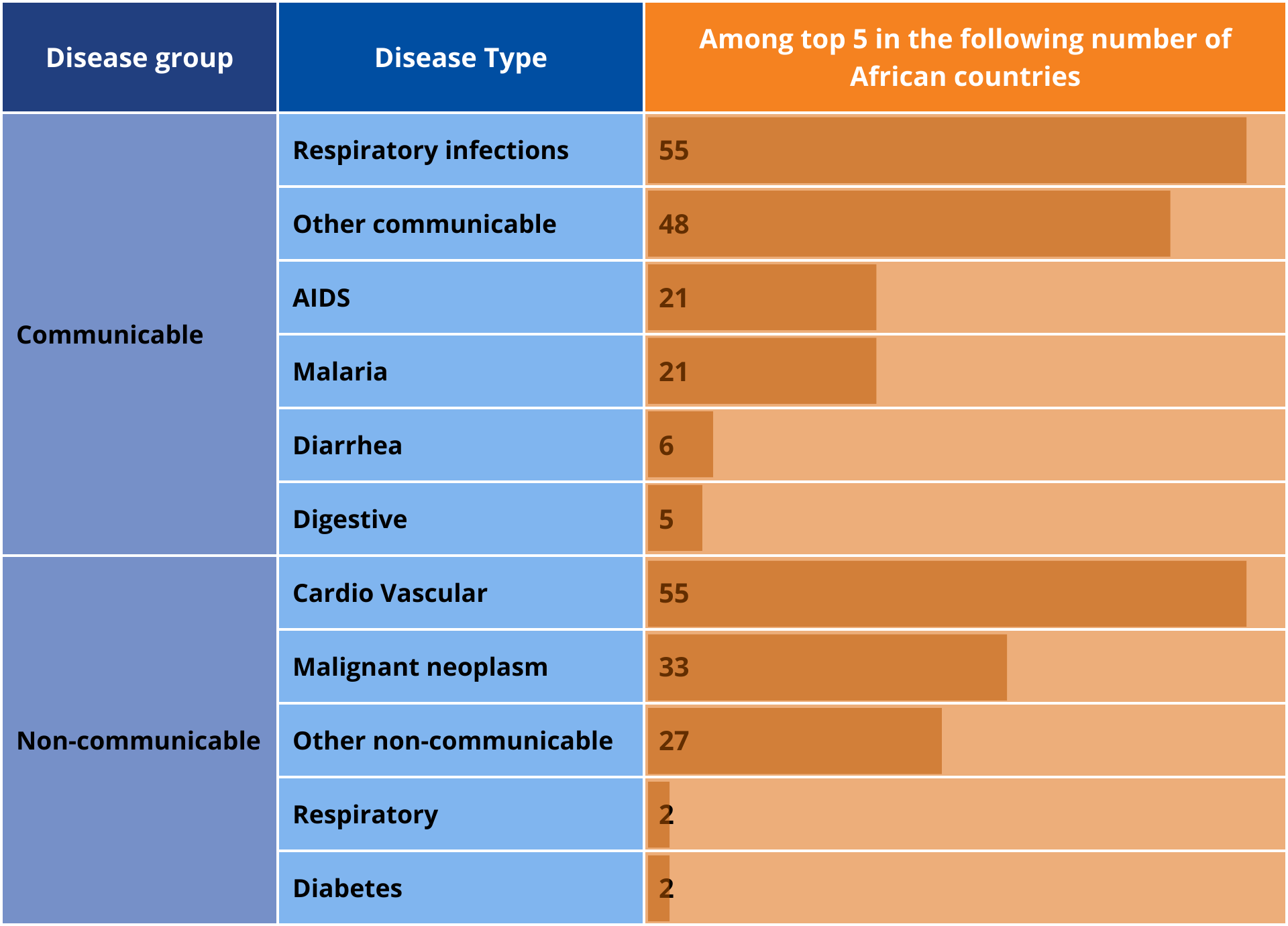

- Chart 12: Number of African countries in which the disease type was among the top five, 2022

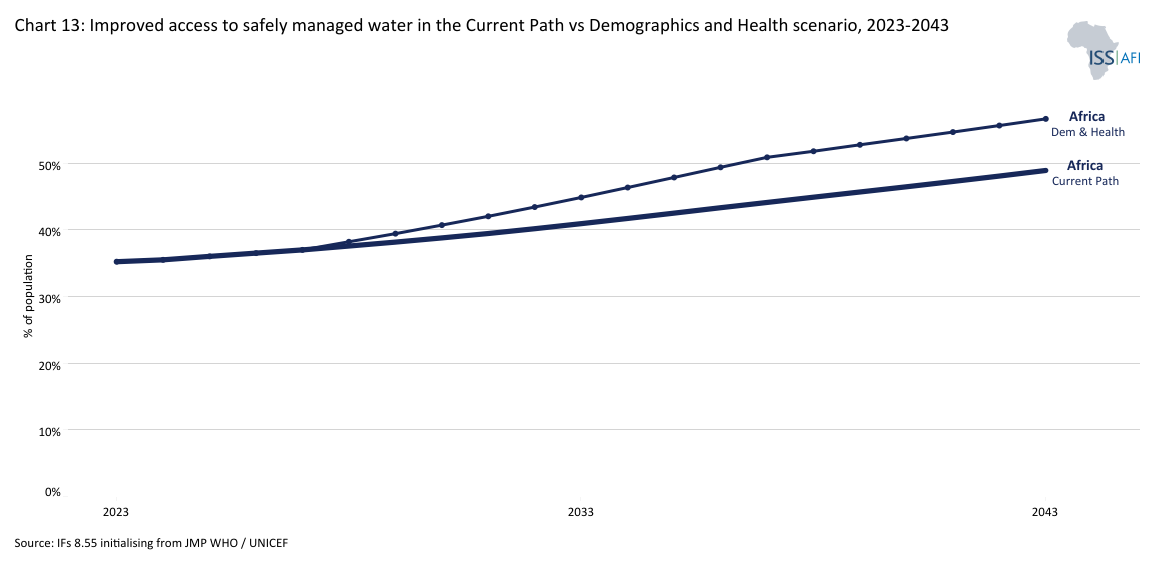

- Chart 13: Improved access to safely managed water in the Current Path vs Demographics and Health scenario, 2023-2043

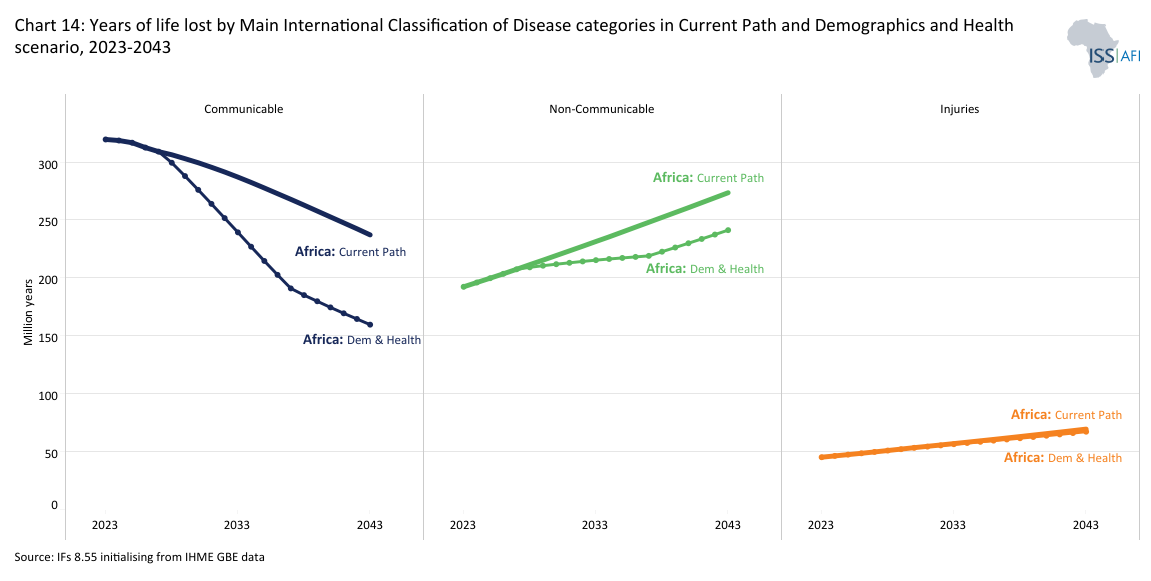

- Chart 14: Years of life lost by Main International Classification of Diseases categories in Africa: million years

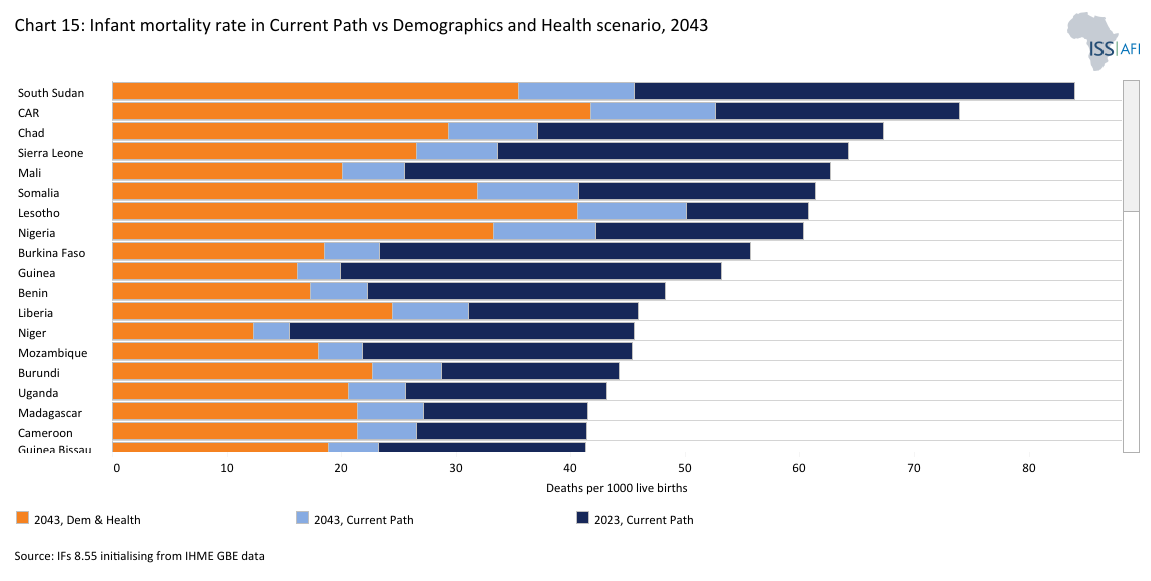

- Chart 15: Infant mortality rate in Current Path vs Demographics and Health scenario, 2043

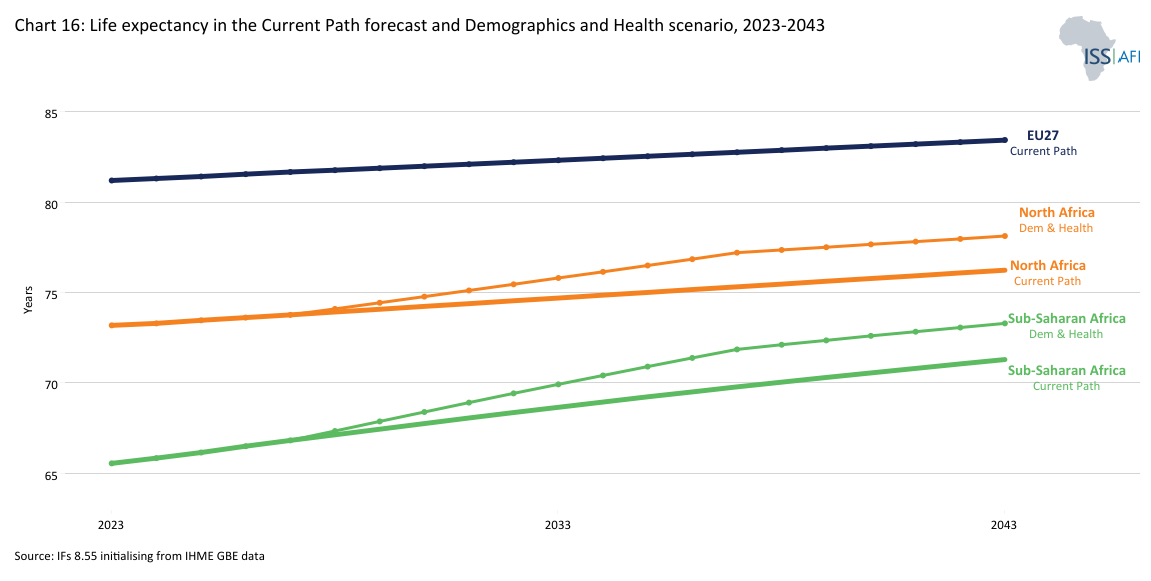

- Chart 16: Life expectancy in the Current Path forecast and Demographics and Health scenario, 2023-2043

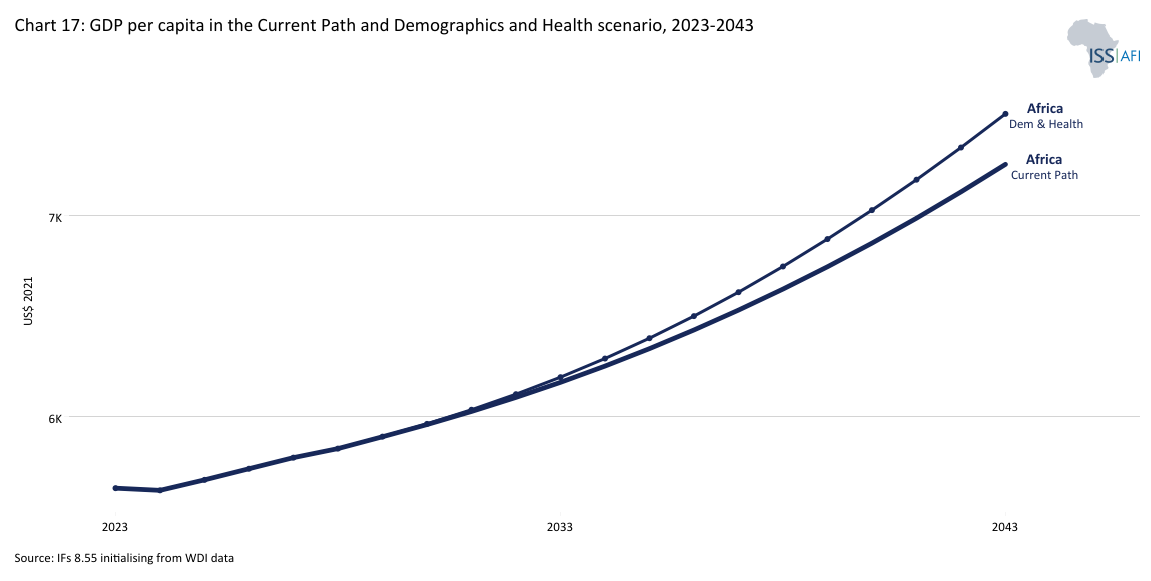

- Chart 17: GDP per capita in the Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 2023-2043

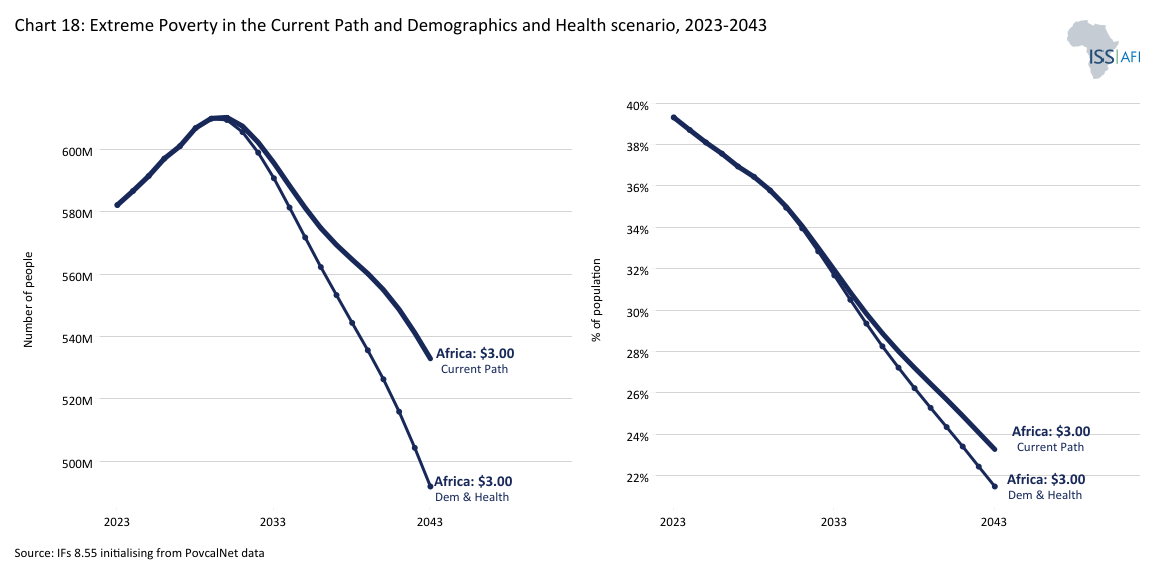

- Chart 18: Extreme poverty headcount for Africa in Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 2020-2050

- Chart 18: Recommendations

Health and WaSH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) are foundational for human development. Improved access to healthcare and sanitation underpins potential gains in education, economic productivity and gender equality. The Health and WaSH sector encompasses many services and systems essential to human well-being, including healthcare delivery, disease prevention, access to clean water, sanitation and hygiene. In Africa, these sectors are particularly intertwined: inadequate water and sanitation are major contributors to the continent’s high burden of communicable diseases. At the same time, weak health systems often struggle to respond effectively. Health and WaSH form the foundation for public health, resilience and inclusive development. They are critical for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the African Union Agenda 2063.

Despite progress, Africa still faces high rates of child and maternal mortality, inadequate health financing and uneven access to safe water and safely managed sanitation services.

Africa’s health systems and WaSH infrastructure reflect decades of uneven development, underinvestment and structural inequities. Colonial legacies, demographic dynamics and global dependency patterns profoundly shape them. While there have been notable gains, including reductions in child mortality, expanded vaccine coverage and increased access to safe drinking water and safely managed sanitation services, overall progress remains unbalanced, fragile and insufficient to meet current and future needs of the continent’s citizens.

Health systems: progress and persistent fragilities

Since 2000, many African countries have made measurable improvements in public health indicators. For example, mortality rates from malaria and vaccine-preventable diseases have declined, maternal care services have expanded and regional cooperation has strengthened through platforms like Africa CDC (Centres for Disease Control and Prevention). However, several core barriers and limitations constrain these gains.

First, Africa has low per capita health spending. Most countries spend well below the thresholds recommended by the WHO and the Abuja Declaration on public health.

Second, Africa’s health systems have severe infrastructure and staffing shortfalls. Health worker density, hospital beds and clinical facilities remain far below global averages, limiting the reach and quality of care, particularly in rural and underserved areas.

Third, urban–rural disparities continue to shape health and WaSH outcomes across the continent. Service delivery is heavily concentrated in urban centres, leaving rural populations with significant access gaps in basic care and essential infrastructure.

Fourth, many African health systems remain heavily dependent on external donor funding. Critical services such as HIV treatment, immunisation campaigns, and disease surveillance are often sustained by international development assistance, raising concerns about long-term sustainability and domestic ownership. The closure of USAID in 2025 cruelly exposed the associated vulnerabilities, then the largest external provider of aid to Africa’s health sector. According to The Lancet, the effect of the defunding translates into roughly 1.8 to 2.5 million extra deaths per year between 2025 and 2030.

In many countries, health financing mechanisms are fragmented and regressive, with high out-of-pocket payments limiting access, especially for persons experiencing poverty. The reduction in US support to Africa’s health sector came shortly after the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, which exposed the vulnerability of African health systems, including the lack of domestic vaccine production and diagnostics, intensive care, and supply chain coordination.

WaSH infrastructure: critical enabler but major bottleneck

Access to clean water, basic sanitation and hygiene services is a central barrier to health gains across Africa. In 2023, 959 million lacked access to safely managed water and more than a billion to safely managed sanitation, where households do not share sanitation, there is safe disposal of excreta and handwashing facilities with soap and water. These shortfalls are especially acute in rural areas and informal urban settlements, where investment in infrastructure has not kept pace with population growth.

This infrastructure gap drives high rates of diarrhoeal diseases, cholera outbreaks and parasitic infections, particularly among children under five, who are most vulnerable to waterborne illness and undernutrition. Poor WaSH conditions also increase the burden on health facilities and reduce the effectiveness of public health interventions. In schools and healthcare settings, inadequate hygiene infrastructure undermines learning outcomes and infection control. It also limits the ability of women and girls to manage menstrual hygiene, contributing to absenteeism and school dropouts. As climate change intensifies water stress and flooding, the resilience of WaSH systems will become even more critical for protecting health and advancing the SDGs.

Why these systems matter for Africa’s future

The quality, reach and resilience of Africa’s health and WaSH systems are key determinants of human development, economic growth and social stability across the continent. These systems are foundational to reducing preventable mortality and the burden of both communicable and non-communicable diseases, enabling healthier, longer lives. They are essential to improving educational outcomes and workforce productivity, as healthy children are more likely to attend school and adults are better able to work and contribute economically. Robust health and sanitation systems also allow countries to capitalise on their demographic transitions by equipping growing young populations with the health foundations needed to drive inclusive growth. Moreover, resilient systems are critical for withstanding future shocks, including pandemics, climate-related disasters and disease outbreaks linked to environmental and social stressors.

Yet, current systems across much of the continent are not on track to meet the SDG 2030 goals and targets. Health and WaSH disparities will likely deepen without a concerted effort to accelerate investment, strengthen institutions and scale innovation. The continent risks missing a pivotal opportunity to transform well-being and development outcomes for the next generation.

Baseline Trends and Current State

Download to pdf- Briefly

- Deep roots of a continent’s burden

- Colonial legacies and infrastructure gaps

- The enduring impact of HIV/AIDS in Africa

- COVID-19 and emerging pandemic risk in Africa

- Sub-Saharan Africa’s double burden of disease and malnutrition on the continent

- Access to WaSH infrastructure and human development impacts

- Health financing

- Health system capacity and preparedness

- Regional variation and country typologies

Africa’s health and WaSH systems are shaped by gradual trends and systemic risks that cut across sectors and borders. These challenges often interact in complex ways, amplifying vulnerabilities and constraining resilience. From pandemic threats to climate-health feedback loops, the continent faces growing exposure to global health risks. At the same time, deeply rooted structural issues, such as persistent disparities in service access between urban and rural areas, and the acute fragility of health systems in conflict-affected states, continue to undermine stability and long-term development. Strengthening preparedness and resilience requires integrated strategies beyond the health sector, addressing governance, infrastructure and equity gaps.

The following sub-sections explore several of these interlinked challenges in more detail. They also provide forecasts based on a business-as-usual scenario, the Current Path. The Current Path presents the development path up to 2043, assuming no major shocks would occur, such as a global pandemic. It provides for the steady expansion and improvements of health and WaSH systems as economic growth and incomes improve over time.

Africa’s high disease burden has deep ecological and historical roots. Chart 1 depicts the journey of Homo sapiens from Africa across the world. Unlike temperate regions, where annual climate variation disrupted the life cycles of disease vectors, sub-Saharan Africa’s tropical and subtropical zones allowed parasites, viruses, bacteria and insects such as mosquitoes and ticks to thrive year-round. This contributed to a long-standing burden of vector-borne diseases such as malaria, yellow fever and sleeping sickness.

Malaria is particularly prevalent in Africa, with around 90% of cases and deaths still occurring here. The continent also accounts for 34 of the 47 countries prone to yellow fever outbreaks and about 40% of the global burden of lymphatic filariasis (elephantiasis), both being diseases spread by mosquitoes in tropical areas. Today, 16 of the 30 countries listed by the World Health Organization (WHO) as having a high burden of tuberculosis are in Africa, although none are in the top five.

Thus, early humans gained an initial health reprieve when, many thousands of years ago, their ancestors moved out of Africa into cooler regions with fewer insect-borne diseases and ‘the many parasites and disease organisms that had evolved in parallel with the human species.’[1J Reader, Africa: A Biography of the Continent, New York: Penguin, 1998, 234] As a result, humanity multiplied rapidly in these new areas, and eventually, the large number of people required a more organised way of food production, giving rise to the first agricultural (or Neolithic) revolution that allowed humans, approximately 12 000 years ago, to slowly change from hunter-gatherer lifestyles into permanent settlements.

Diseases affected humans and livestock, limiting the domestication of animals like oxen and horses in much of the continent, which constrained agricultural productivity and technological diffusion for centuries.

By 1 000 BCE, dense populations had emerged in only a few parts of Africa, such as the Nile Valley—one of the few regions with reliable irrigation and fertile soils. The interior remained sparsely populated, partially due to the high health risks, reflected in hunter-gatherer rather than agrarian lifestyles since relatively low population densities did not require more productive agricultural systems.

Over millennia, the continent’s sparse densities and relative isolation from global pandemics like the Black Death spared it some devastation. It also limited the push for the agricultural, industrial and technological revolutions that transformed Europe and Asia. Chart 2 depicts global death tolls from pandemics.

These deep historical and ecological patterns continued to shape Africa’s demographic and infrastructure trajectory into the modern era. When independence arrived in the 1960s, health and WaSH systems still reflected centuries of geographic dispersion, high disease exposure, and colonial neglect. Infrastructure remained fragmented and unevenly distributed—a legacy that continues to influence health outcomes today. Understanding these systemic roots is essential when envisioning futures for health and sanitation across the continent.

In industrialising regions such as Western Europe and later North America, the rise of dense cities before the discovery of antibiotics and modern medical practices necessitated investment in health infrastructure, from sewage systems to clean water supply, to combat infectious disease outbreaks. In contrast, when urbanisation began accelerating in Africa in the late 19th Century, colonial administrations primarily relied on imported biomedical solutions (like vaccines and antibiotics) to control disease rather than investing in permanent urban infrastructure. Unlike in other regions, this allowed denser settlements to grow without the sanitation and planning necessary to contain outbreaks.

Even today, many African countries have poor sanitation, making people more susceptible to infectious diseases, although access to safe water is steadily improving. The simple but essential act of washing one’s hands is difficult without consistent and reliable access to clean water. The situation is dire in rural areas, where more than half of Africa’s population lives.

In 2023, only 36% of Africans had access to a safely managed water supply, compared to 79% of the people in the rest of the world. Cholera, an acute diarrhoeal infection primarily caused by contaminated water, has, for example, become endemic in Africa. Over the past four decades, Africa has recorded more than 70% of global outbreaks, which have significantly strained healthcare facilities across the continent.

This situation will, however, slowly improve. By 2030, access to safely managed water services in Africa will increase to approximately 39% and 49% by 2043.

The 2030 SDG target is universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water, adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all, and an end to open defecation. By 2030, 12% of Africa’s total population is still likely to practice open defecation (down from 14% in 2023), while only about one in three Africans has reliable, safe, on-premises water.

Low levels of urbanisation drag the provision of bulk infrastructure and limit the potential for rapid improvement. On the other hand, it likely constrains the spread of infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS and COVID-19.

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) originated from the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), a virus found in African monkeys that spread to chimpanzees and eventually to humans. Although such interspecies transmission is not uncommon, early outbreaks of SIV did not result in widespread epidemics due to low human population densities. As populations grew, however, the virus was able to mutate and survive, eventually evolving into HIV in what is now Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo). From there, it spread across Africa along transport routes.

HIV’s long asymptomatic incubation period and association with diverse opportunistic infections complicated early detection. While the virus reached epidemic proportions by the mid-1970s, AIDS was only recognised as a new disease in 1981, and HIV-1 was identified later, in 1983. In Africa, weak health systems, limited diagnostics and poor infrastructure allowed the virus to spread silently for years. Even after its recognition, government responses were often inadequate, hindered by fear, stigma, limited capacity, and in some cases, denialism. In South Africa, for example, President Thabo Mbeki’s rejection of the scientific consensus on HIV/AIDS significantly delayed life-saving interventions, contributing to thousands of avoidable deaths.

AIDS is not the first modern pandemic[2Spanish influenza killed 40 million to 50 million people in 1918, Asian flu killed 2 million people in 1957, and Hong Kong influenza killed 1 million people in 1968.], yet it has left a devastating legacy. Chart 3 shows the history and forecast of AIDS-related deaths. Between 1998 and 2009, more than a million Africans died annually from AIDS-related illnesses, peaking at over 1.3 million in 2003/4. By 2023, nearly 28 million people on the continent had died. Life expectancy plummeted, particularly in Southern and Eastern Africa, disrupting families, economies and public services. Countries including South Africa, Nigeria, Uganda, Kenya, Zimbabwe and Mozambique were among the most brutally hit.

The region's life expectancy dropped below that of other African sub-regions during the crisis and, despite treatment rollouts, has yet to recover fully. Chart 4 depicts life expectancy for selected regions. In 2023, sub-Saharan Africa’s life expectancy stood at 66.6 years—nearly eight years below the global average. The delay in access to antiretrovirals, sometimes referred to as “vaccine apartheid,” prolonged the crisis, exposing stark inequities in global health governance.

HIV/AIDS hit just as many African economies were beginning to emerge from the impact of the 2007/8 financial crisis. The resulting increase in dependency ratios weakened labour productivity and compounded demographic challenges. While AIDS death rates have declined by more than 66% since their peak in 2004, Africa still accounted for an estimated 72% of global AIDS-related deaths in 2023. The disease strains health systems, exacerbates vulnerabilities, and undermines progress in related sectors such as maternal health and WaSH.

COVID-19, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, was first detected in the Wuhan Seafood Wholesale Market in China’s Hubei province in December 2019. It spread rapidly across the globe, becoming what the United Nations called ‘the greatest test that we have faced since the formation of the United Nations. The International Monetary Fund labelled it ‘the worst economic fallout since the Great Depression.’ Globally, trillions of US dollars have been committed to fighting both the direct and indirect effects of the pandemic. By September 2021, the US alone had spent and allocated more than US$8 trillion and, by some estimates, much more.

Unlike HIV/AIDS, which drastically affected mortality in Africa, the direct health toll of COVID-19 was comparatively lower. Chart 5 shows the cumulative deaths by global region due to COVID-19. Recorded infections and deaths in Africa were five times lower than in the Americas and Europe, partly attributed to the continent’s younger age profile, lower rates of comorbidities such as obesity and diabetes and potential cross-immunity from other coronaviruses or past BCG (tuberculosis) vaccination campaigns. However, the data were incomplete: later research found that COVID-19 cases and deaths in Africa were likely under-reported by a factor of 8.5 due to weak health systems and limited surveillance capacity.

COVID-19 spread fastest in middle-income and urbanised parts of Africa—mainly South Africa, Tunisia, Egypt and Morocco—where comorbidities and urban density intensified health outcomes. The broader continent faced delayed vaccine access, reviving accusations of “vaccine apartheid,” as African nations were left waiting while wealthier countries prioritised their national needs.

Leaders across Africa, informed by the delayed access to antiretrovirals during the HIV/AIDS crisis, called for the waiver of intellectual property restrictions to expand vaccine production in developing countries. While the US eventually supported such a move, it was blocked by opposition from several European nations where many of the large pharmaceutical companies are based, reflecting the ongoing geopolitical inequalities in global health governance and the general poor state of the health industry in Africa.

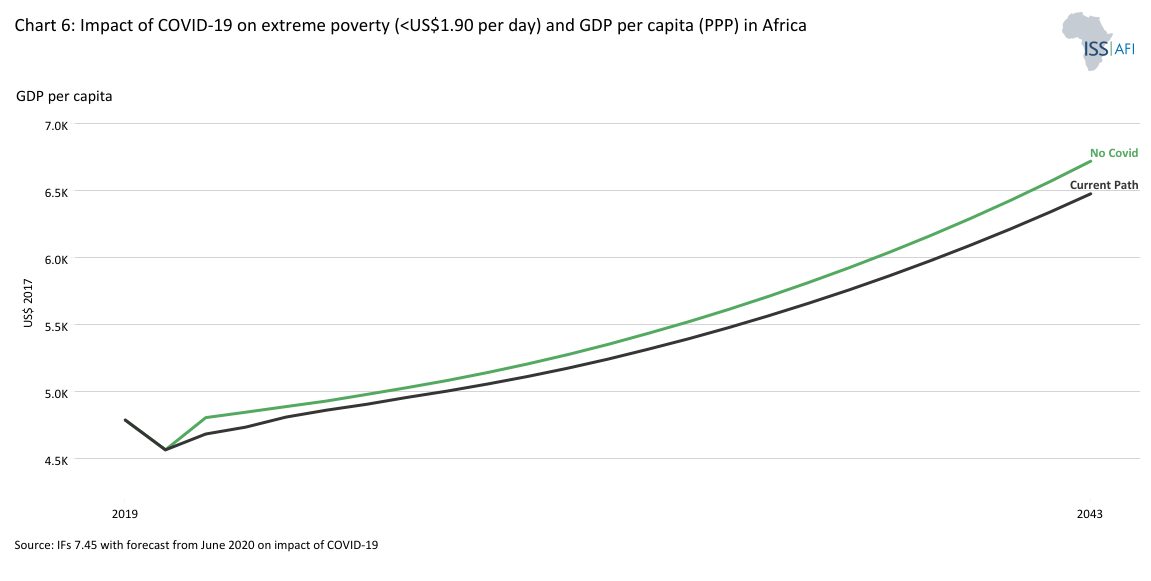

Economically, the pandemic hit Africa hard. Lockdowns, disrupted trade and supply chains, and plummeting commodity demand pushed an additional 24 to 25 million people into extreme poverty in 2020-2021. Chart 6 depicts the impact of COVID-19 on extreme poverty, still using US$1.90 as it is from an earlier study that we did on its impact.

GDP per capita only recovered to 2019 levels in 2023. Reduced government revenues—estimated at US$73 billion in 2020 alone—limited public spending on infrastructure, health and security, contributing to increased instability, food insecurity and protest activity across the continent.

Perhaps more Africans will ultimately suffer from the indirect effects of COVID-19—including reduced access to treatment for other diseases, malnutrition and disrupted education—than from the virus itself. These shocks also diverted resources away from WaSH investments. They exposed the fragility of health systems, especially in informal urban and rural areas where people’s access to clean water and sanitation was already limited.

COVID-19 also raised alarm about future pandemics. Increased human activity, deforestation, livestock expansion and wildlife trade make zoonotic spillover events more likely, particularly in West Africa, where human-animal interfaces are dense. Estimates now place the likelihood of another pandemic on the scale of COVID-19 at 22-28% within the next 10 years, and 47-57% over the next 25 years.

The world is adjusting to living with COVID-19, as it has with HIV/AIDS. Still, the pandemic has also accelerated transitions: toward remote work, digitalisation, food security concerns and new awareness of global health interdependence.

Africa is undergoing a profound shift in its disease profile. The typical evolution of disease burden in countries begins with the gradual decline of infectious (communicable) diseases, followed by the rise of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer. This epidemiological transition is closely associated with the younger age profile of developing versus the older profile of higher-income countries. In the latter, it follows improvements in public health, vaccination, food security and living standards in wealthier countries, and it comes with higher health care costs and service complexity.

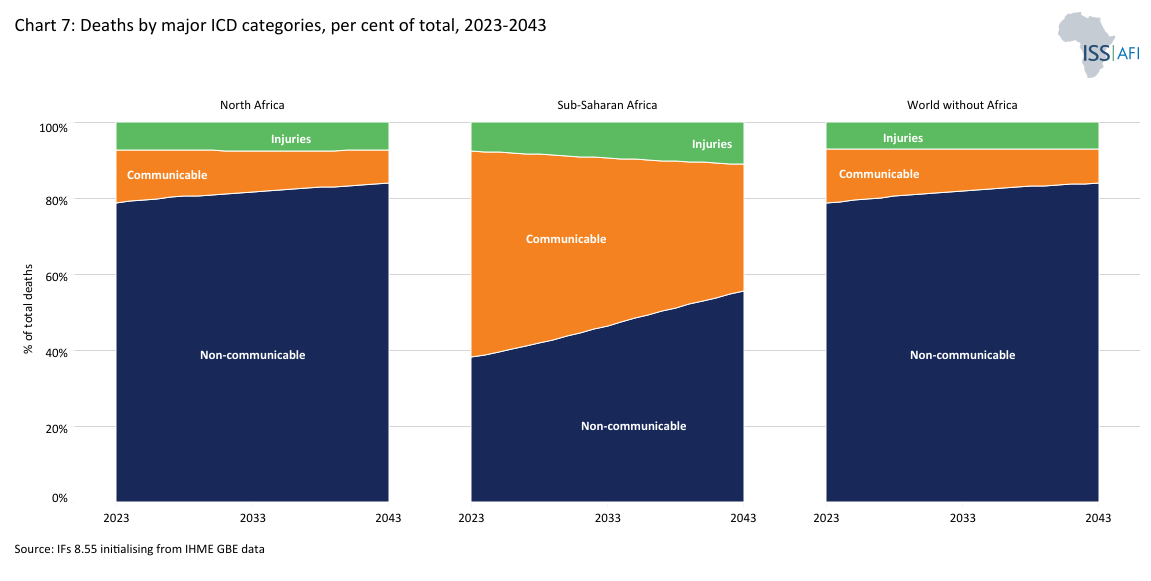

Chart 7 presents death rates in Africa as a percentage of total deaths for the three major categories used in the Global Burden of Disease database, namely communicable diseases[3Includes HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis together with maternal deaths, neonatal deaths and deaths from malnutrition.], non-communicable diseases[4These are often chronic, long-term illnesses and include cardiovascular diseases (including stroke), cancers, diabetes and chronic respiratory diseases (such as chronic pulmonary disease and asthma, but excluding infectious respiratory diseases such as tuberculosis and influenza).] and injuries[5Injuries are caused by road accidents, homicides, conflict deaths, drowning, fire-related accidents, natural disasters and suicides.], compared to the rates for the rest of the world for the period 2019 to 2043. In 2023, Africa accounted for 47% of all infectious disease deaths worldwide, despite making up just 18% of the global population. While progress in combating communicable diseases will narrow the gap in life expectancy between Africa and the rest of the world, from 7 years in 2023 to 4.9 years in 2043, the continent is now also facing a surge in chronic illnesses. This double burden of disease requires strategic health planning to manage overlapping challenges.

In sub-Saharan Africa, this transition occurs at a lower income level, urbanisation and institutional capacity than in most other global regions. The increasing prevalence of chronic non-communicable diseases such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes and heart diseases comes on top of the battle to deal with infectious diseases such as flu, termed a “double burden of disease”. The transition will present health systems with higher costs as they navigate increasingly complex public health landscapes. Sub-Saharan Africa’s low average incomes translate into limited state budgets and capacity to provide the necessary healthcare to treat non-communicable diseases.

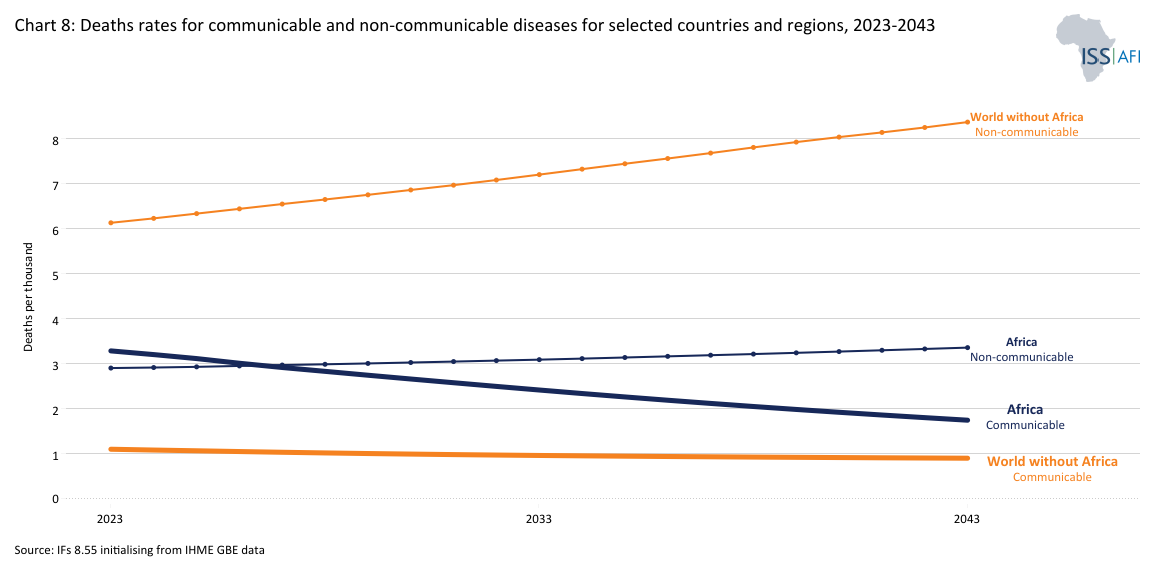

At some point, as populations age and the nature of illnesses changes, deaths from infectious diseases are overtaken by deaths from non-communicable diseases. The transition occurred more than a century ago in Europe and North America. In Latin America and the Caribbean, and in South Asia it happened around the start of the current century. It is currently happening in North Africa and will only occur in the next decade in sub-Saharan Africa with its very young population. Chart 8 shows death rates for communicable and non-communicable diseases across regions.

The result of sub-Saharan Africa’s approaching double burden of disease will be more sick adults, requiring more resources to prevent and treat non-communicable conditions, as well as present a more complex problem. Pollution and tobacco are also proving to be a challenge, as tobacco companies are now actively targeting the next generation of smokers, all of whom are in the developing world.

Sub-Saharan Africa is particularly vulnerable. With a median age just above 19, the region still experiences a high burden of child illnesses such as malaria and diarrhoeal disease, exacerbated by poor WaSH infrastructure, unsafe water and overcrowding. At the same time, adult populations in urban centres rely on processed foods, often lead sedentary lifestyles and are targeted by tobacco marketing, fuelling obesity, diabetes and hypertension—often before income levels or healthcare access can support early diagnosis and treatment.

Health expenditure per person in North Africa is already nearly four times higher than in sub-Saharan Africa. As the burden of chronic illness rises, budget shortfalls, staff shortages and uneven access to health facilities will become more critical. The nutrition transition adds another layer of complexity: undernutrition in children coexists with obesity and overnutrition in adults, creating a double burden of malnutrition.

These transitions represent a significant shift in future health spending needs, health workforce training, pharmaceutical priorities and prevention strategies. Policymakers must respond with integrated strategies that bridge communicable disease control, NCD management and food systems reform while maintaining momentum on universal access to safely managed water and sanitation.

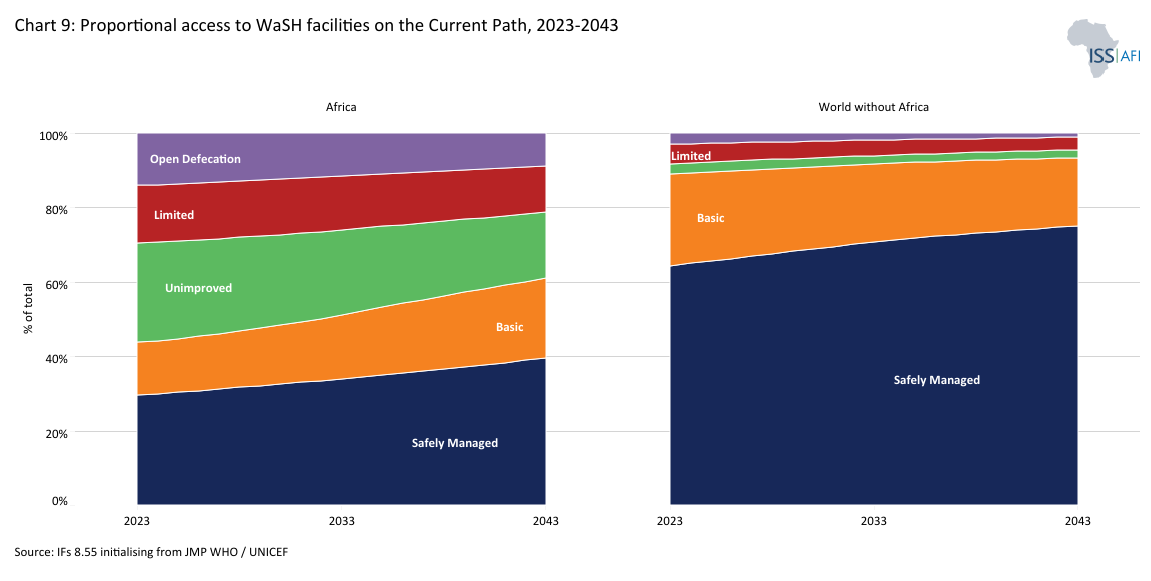

Sub-Saharan Africa is entering its epidemiological transition with significant deficits in foundational infrastructure for clean water and sanitation. This gap increases health risks from infectious disease and undernutrition and constrains long-term human capital development and economic growth. Chart 9 depicts proportional access to WaSH facilities on the Current Path from 2023 to 2043.

In 2023, 76 million people in the DR Congo, Ethiopia and Nigeria alone still had to practice open defecation. This number will actually have increased in the DR Congo and Nigeria by the time the SDGs are meant to be achieved (2030). The situation will only improve in Ethiopia. Nigeria’s rapid population growth will continue to pressure basic infrastructure, as it will have 40 million people without sanitation in 2043 compared to 42 million in 2030. Despite their massive economic potential, these large populations seem likely to suffer from a lack of proper sanitation for the foreseeable future; even Ethiopians will have to wait several decades for their material improvement.

The picture is similar to nearly any other measure of access to infrastructure or services. For example, in 2023, almost 99% of the population outside of Africa had access to electricity, whereas in Africa, the figure was approximately 60% (and 53% in sub-Saharan Africa). Using solid fuels instead of electricity for cooking and heating is also a significant source of indoor air pollution, with associated health complications. This lack of access to physical infrastructure and basic services constrains Africa’s ability to develop its human potential fully and thus capitalise on its future demographic dividend.

WaSH infrastructure supports the development of broader human potential through its strong forward linkages to other vital aspects of the SDGs, such as poverty, education and gender equality. Improved WaSH infrastructure generally translates into sizable gains in a country's overall development as it improves the human capital contribution to economic growth.

For example, children who do not have adequate access to WaSH facilities are more vulnerable to undernutrition. Malnourished children are not only highly susceptible to infectious diseases, with diarrhoeal diseases being among the most frequent and severe examples. Still, they may also suffer lifelong effects, such as stunting (low height for age).

Stunting impairs both physical and cognitive development. According to the WHO, stunted individuals suffer from ‘poor cognition and educational performance, low adult wages, lost productivity and, when accompanied by excessive weight gain later in childhood, an increased risk of nutrition-related chronic diseases in adult life.’ Put bluntly, stunting is an irreversible condition that inhibits the potential of the affected individual or community for life and is particularly prevalent in children below five years of age. However, the overall stunting rate in sub-Saharan Africa is “only” about one-fifth (with a modest decline forecast to 2043).

A driving force behind the shift from undernutrition in childhood to overnutrition in adulthood in low- and middle-income countries. These factors led to tremendous changes in lifestyle marked predominantly by changes in diet and physical activity. As a result, under- and overnutrition co-occur among different population groups.

Insufficient WaSH access leaves all children vulnerable, but as they mature, the negative impacts disproportionately affect girls and women. Poorly maintained or non-existent WaSH facilities are one of the leading causes of the high rate of school dropout among teenage girls, who lack menstrual hygiene services, for example. The absence of these facilities, in turn, could lead to a significant disparity in educational attainment between men and women and significantly diminish the economic opportunities for women, translating to lower growth for society as a whole.

Given the extent of rural populations that make the provision of bulk infrastructure expensive in sub-Saharan Africa, advancing access to WaSH infrastructure presents immense challenges. Even upper-middle-income countries in Africa are struggling to expand access to WaSH infrastructure. Of Africa’s eight upper-middle-income countries, only Mauritius, Botswana, and South Africa have more than half of their populations with safely managed sanitation services.

Infant mortality rates[6Infant mortality is the death of an infant before its first birthday. Rates are typically expressed as the number of infant deaths for every 1 000 live births.] illustrate the exceptional situation in Africa. Chart 10 shows a comparison of infant mortality in different regions from 2023 to 2043. At 42 infant deaths per 1 000 live births in 2023, infant mortality in Africa recorded more than double the average for the rest of the world (i.e. the world without Africa), which was at 19, and is more than three times higher than in South America, which was at 13.

Health financing in Africa consistently faces underinvestment and remains insufficient, fragmented, and heavily reliant on external aid that poses a fundamental constraint to delivering universal, equitable, and resilient healthcare services. While many African governments have formally committed to increasing domestic spending, few have implemented this ambition.

According to the WHO’s African Region Health Expenditure Atlas 2023, just eight out of 47 countries in sub-Saharan Africa met the recommended threshold of US$249 per capita between 2012 and 2020, to support essential health services and progress towards Universal Health Coverage (UHC). Only five countries (Botswana, Mauritius, Namibia, Seychelles and South Africa) reached that level. Per capita spending in most low-income African countries is under US$100.

Compounding this is the high proportion of out-of-pocket spending, which exceeds 35% of total health expenditures in many countries and undermines access for low-income populations, contributing to catastrophic health costs for millions of households.

Moreover, many African health systems remain donor-dependent, suffering significant damage from the 2025 decision to close USAID. External assistance remains a crucial source of funding, often focused on disease-specific vertical programs such as HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis. It accounts for a substantial share of health financing in low-income countries, including the funding of current health expenditure. While these programs have delivered critical gains, they also contribute to fragmented service delivery and underinvestment in core system-building.

Efforts to expand health insurance coverage and risk pooling remain limited and uneven. Only a handful of countries, such as Rwanda, Ghana and Kenya, have made meaningful strides toward universal health coverage (UHC) through public or community-based schemes.

In sum, despite the region’s growing disease burden, health systems continue to suffer from chronic underfunding, high out-of-pocket costs, and donor dependency. Financing health systems that can respond to the double disease burden, ageing populations and pandemic threats will require core reforms.

First, focus needs to be on increasing and sustaining domestic investment. Second, there should be an emphasis on more strategic and pooled donor support. Third, Africa must enable and harness innovative financing mechanisms, including diaspora bonds, sin taxes and public-private partnerships.

Without such structural reforms and more equitable financing models, Africa risks continued underperformance in health outcomes. It may miss the opportunity to capitalise on health gains as a driver of inclusive growth and resilience.

Despite improvements in health outcomes across Africa since 2000, systemic weaknesses in health system capacity continue to undermine resilience, responsiveness and equity in service delivery. These gaps are particularly evident in health workforce density, investment priorities and supply chain logistics, and limit the continent’s ability to address existing disease burdens and emerging threats such as pandemics or climate-related health shocks.

Health Workforce: Shortages and Distributional Imbalances Africa faces a critical shortfall in health workers, with the continent home to 24% of the global disease burden but only 3% of the global health workforce. According to the WHO, the average health worker density in sub-Saharan Africa is 1.55 per 1 000 people, well below the SDG minimum threshold of 4.45 per 1 000 required to achieve universal health coverage. The shortage is particularly acute in rural areas and in conflict-affected countries, where training institutions are under-resourced and retention rates are low. Even where workforce numbers are growing, skill mix and quality vary considerably.

Primary versus Tertiary Care Imbalance Many African health systems are disproportionately skewed toward tertiary care, likely reflecting the demands of their elderly governing elites. Public investment tends to concentrate in capital city hospitals, often at the expense of primary and community health systems, which are more cost-effective and better aligned with Africa’s disease profile. As a result, preventable and treatable conditions, from diarrhoeal diseases to maternal complications, frequently go unaddressed at the local level. Strengthening frontline health systems is critical for improving health outcomes and realising the broader demographic dividend.

Supply Chains and Logistics Health supply chains across the continent remain fragmented, underfunded and vulnerable to shocks. Many countries rely heavily on international procurement and donations for essential medicines, vaccines and equipment. Inconsistent cold chain infrastructure, customs delays and lack of last-mile delivery systems regularly lead to stockouts, even for high-priority items. Regional harmonisation efforts, such as pooled procurement initiatives by the Africa CDC and the African Union, are underway but remain in early stages.

Local Production and Pharmaceutical Sovereignty The COVID-19 pandemic exposed Africa’s overreliance on global suppliers for critical health commodities. As of 2023, the continent imported roughly two-thirds or more of its medicines, despite efforts to promote local manufacturing. Only a few countries, such as South Africa, Egypt and Morocco, have significant production capacity. Following the pandemic, investment in local manufacturing of vaccines, diagnostics, personal protective equipment and generic medicines is considered a strategic priority for both health sovereignty and economic development. The African Medicines Agency (AMA), operationalised in 2021, offers a potential platform for regulatory harmonisation and regional production scale-up.

Climate Intersections Climate change is increasingly testing the resilience of Africa’s health systems. Rising temperatures, erratic rainfall and more frequent extreme weather events disrupt supply chains, damage health infrastructure and exacerbate disease outbreaks such as cholera, malaria and dengue. Flooding and drought also affect water availability and sanitation systems, undermining public health efforts. Health systems in many countries are not yet climate-adaptive, lacking the infrastructure and planning mechanisms to anticipate or respond to climate-related shocks. Integrating climate resilience into health system design, especially at the primary care and community level, is becoming an urgent priority.

Improving health system capacity in Africa will require rebalancing investment toward primary care, expanding the health workforce, and developing resilient, locally grounded supply systems. These efforts are critical for achieving health-related SDGs and the African Union Agenda 2063.

Health and WaSH outcomes vary widely across Africa’s diverse regions and country contexts, reflecting differences in resource levels, governance capacity, infrastructure development, urbanisation and conflict exposure. No single African health profile exists; the continent exhibits a complex mosaic of progress and persistent gaps.

North Africa: Countries like Algeria, Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia typically perform above the continental average on most health indicators. These countries have higher health expenditures, stronger public health infrastructure and better access to clean water and sanitation, especially in urban areas. Non-communicable diseases are already the dominant health challenge, and most countries have entered the later stages of the epidemiological transition.

Southern Africa: Despite relatively high GDP per capita and stronger health infrastructure in countries like South Africa and Botswana, Southern Africa faces a disproportionately high burden of HIV/AIDS, along with growing non-communicable disease prevalence. Health inequality, urban-rural divides and political mismanagement have also shaped divergent national outcomes.

East Africa: East African countries such as Kenya, Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Rwanda have made considerable progress in expanding basic health coverage, reducing child mortality, and scaling community health systems. However, health financing remains low, and sanitation access in rural areas lags significantly. In countries like Ethiopia and Uganda, service delivery continues to strain.

West Africa: This region faces persistent challenges from fragile governance, conflict and high fertility rates. Countries like Nigeria, while economically influential, have large populations that still lack access to WaSH services and basic healthcare. Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, affected by the 2014–2016 Ebola epidemic, illustrate the region’s vulnerability to health shocks.

Central Africa: Home to some of the lowest-performing health systems globally. Countries like the Central African Republic, DR Congo and Chad struggle with protracted insecurity, underfunded health systems and minimal WaSH coverage. Conflict and weak state capacity are major drivers of poor outcomes.

In comparative health systems research, such as Tashobya et al. (2014), African countries have been grouped into typologies (or clusters) reflecting shared traits. The authors argue that while many global frameworks focus on service delivery and health outcomes, the underlying governance structures, institutional accountability, and financing mechanisms determine whether reforms translate into better health, especially in low-income countries.

Performance differences across African countries often stem from funding gaps and variations in institutional strength, management efficiency, and policy coherence. Differences in health governance mean that two countries with similar resources may achieve very different results. However, it can still help tailor policy responses to broadly group African countries into functional typologies that reflect shared structural realities.

- Low-income fragile states (e.g. Central African Republic, South Sudan, Somalia): These countries often face overlapping challenges of protracted conflict, state fragility and extremely weak health and WaSH infrastructure. External humanitarian assistance usually dominates health service provision, with limited national coordination. Chronic underinvestment and insecurity severely limit long-term health planning or infrastructure development prospects.

- Middle-income reformers (e.g. Kenya, Ghana, Rwanda): These are policy-active states that have made notable gains in health outcomes despite limited fiscal space. They experiment with innovative financing, community-based health insurance and digital health systems, and often serve as continental models for scalable primary care strategies. Continued progress depends on sustained investment, equity-focused policies, and the management of demographic pressures.

- Resource-rich but underperforming states (e.g. Nigeria, Angola, DR Congo): These countries possess substantial natural wealth but face persistent governance, equity and service delivery challenges. Health outcomes remain poor due to underfunded systems, corruption, urban bias and weak public accountability. WaSH access in rural areas is particularly low, and fragmented infrastructure hinders long-term planning. Unlocking their potential requires structural reforms and better revenue management.

- Small, high-performing states (e.g. Mauritius, Seychelles, Cabo Verde): These are outliers on the continent with strong public health systems, near-universal WaSH access and longer life expectancy. Their small populations allow for greater system coherence, and many have invested strategically in tourism-aligned health infrastructure or regional medical services. While their challenges differ, they offer valuable lessons for efficiency, prevention and long-term health planning.

The four clusters below mirror long-established governance and health-system performance patterns observed across the WHO, World Bank and AFI datasets. This fragile–reformer–resource-rich–small high-performer distinction aligns with typologies used in comparative development analyses such as the African Development Bank’s African Economic Outlook (AfDB, 2023), the World Bank’s Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (World Bank, 2024) and governance groupings in the Ibrahim Index of African Governance (Mo Ibrahim Foundation, 2024).

Many countries exhibit features of more than one group. Also, there are often challenges of within-country inequality. National typologies inevitably mask subnational divergence. Nigeria, for instance, has pockets of reformist innovation (e.g. Lagos digital health) within a generally underperforming system.

Recognising such a typological approach can enable a pragmatic entry point for governments, donors, and analysts to design more context-specific interventions and model differentiated scenario pathways. It also highlights that progress is possible across income groups, provided policy alignment, leadership and investment frameworks are in place.

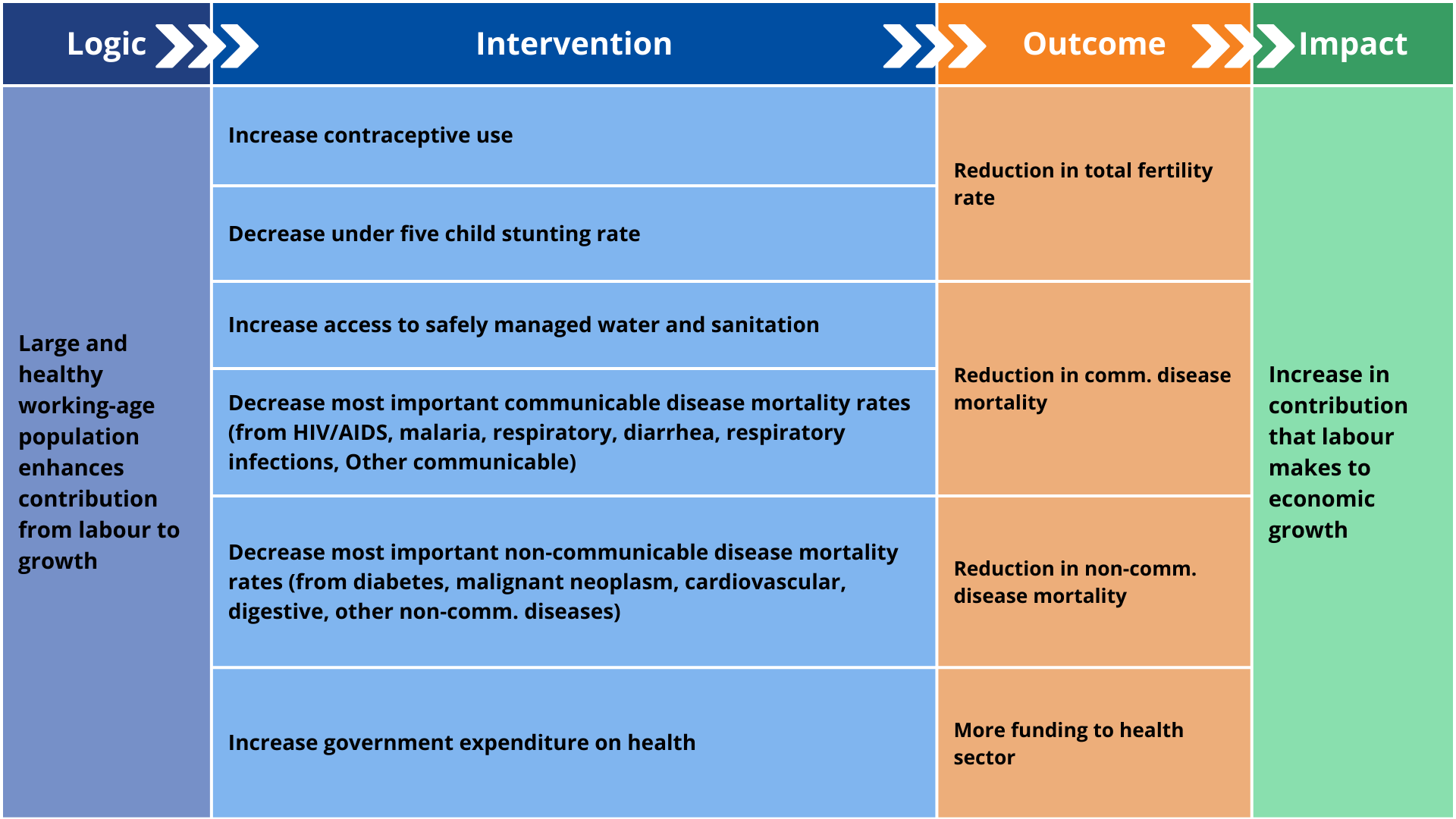

This section explains the structure of the Demographics and Health scenario that would accelerate the continent's demographic transition, and potentially advance and enhance its demographic dividend compared to the Current Path presented in preceding sections. A separate theme provides more detail on demographics, using the same scenario.

Africa’s demographic and health outlook can improve significantly through targeted interventions addressing fertility, mortality and WaSH infrastructure.

The scenario consists of the following individual country-level interventions, benchmarked to reflect reasonable but ambitious targets for countries at similar levels of development and continentally compared to South America and South Asia, the other regions with development indicators most similar to Africa:

- The first intervention is the large-scale rollout of modern contraceptives. Since total fertility rates in North Africa are already low, the increases in sub-Saharan Africa are more aggressive. In 2025, only 33% of fertile women in sub-Saharan Africa were using modern contraceptives, ranging from 85% in Seychelles to 1% in South Sudan. The average rate in North Africa was 59%. By 2050, the scenario is expected to increase average usage to 75% in sub-Saharan Africa, 24 percentage points above the Current Path, and 85% in North Africa. Rates in South America were 79% in 2025 and 64% in South Asia, increasing to 93% and 83%, respectively, by 2050.

- The next intervention is a reduction in the incidence of mortality from AIDS, diabetes, malignant neoplasm, diarrhoea, respiratory infections, respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, digestive diseases, malaria, other communicable diseases and other non-communicable diseases in the most highly affected countries. The interventions reduce mortality rates for the top five disease types in each African country by 20 percentage points below the Current Path. Deaths from respiratory infections (which include COVID-19) and cardiovascular disease are among the top five causes of death in all African countries, followed by other communicable diseases, malignant neoplasms and other non-communicable diseases. Chart 12 summarises the number of African countries in which the disease type ranked among the top 5 in 2022 (the last year of data coverage), which was used as a benchmark for the intervention. The high prevalence of non-communicable diseases, cardiovascular in particular, reflects the extent to which Africa is experiencing a double burden of disease.

- A separate intervention is done in the nine countries where the HIV infection rate is above 1% of the population, also reducing the rate by 20% below the Current Path.

- The next intervention involves the more rapid provision of safely managed water and sanitation, which addresses the drivers of Africa’s high communicable disease burden, as well as indirectly improving productivity through the benefits of a generally healthier workforce. In the scenario, average urban access rates in sub-Saharan Africa increase from 45% in 2025 to 74% in 2050, almost nine percentage points above the Current Path. Rural rates increase from 17% in 2050 to 45%, compared with 35% on the Current Path. Taken together, the average access rate for sub-Saharan Africa increases from 29% in 2025 to 61%, rather than 51%. Total access rates in North Africa (i.e. including both rural and urban areas) are already at 78% in 2025, and are projected to increase to 92% by 2050.

- The final health-related intervention reduces under-five stunting rates by 20% below the 2050 Current Path in the 39 African countries where the rate was above 20% in 2021, the latest year of data available. The intervention accelerates the decline in the Current Path. Whereas Africa had 30 million stunted children in 2025, that number declines to only 12.8 million in 2050, some 3.2 million below the Current Path forecast for the year. Burundi, Eritrea, Niger and the DR Congo had the largest rate of stunted children in 2025. By 2050, Burundi will still have the highest rate, now followed by Lesotho, Malawi and the CAR, but all with significantly lower rates than in the Current Path.

- Improvements in health care are not free. To this end, a final intervention increases health spending by 5%, resulting in an additional US$18.9 billion continentwide. Additional infrastructure spending peaks at US$4.7 billion per annum in 2037.

Each intervention ramps up over 10 years, starting in 2027, and is then maintained at that level.

The pace and scale of impact of the scenario vary across countries and subregions. North Africa, already at an advanced stage of its demographic transition, experiences modest additional gains as fertility stabilises near or below replacement level. Central and West Africa achieve the largest improvement in the ratio of working-age persons to dependants.

While the scenario is ambitious, it is grounded in real-world interventions that have proven feasible in several countries, particularly in key areas such as family planning and infrastructure expansion. The scenario assumptions, therefore, are not abstract targets, but are built on empirical benchmarks drawn from best-performing countries at similar income levels. For instance, the projected increase in contraceptive use is based on the progress seen in countries like Ethiopia and Malawi. Access to safely managed water and sanitation reflects progress in Ghana and Kenya. These comparisons suggest that while ambitious, the modelled trajectory is grounded in what has been done before—under challenging but comparable conditions.

The subsequent progress mirrors historical improvements in South America and South Asia. While strides have been made, particularly in AIDS-related mortality, Africa will likely fall short of global health benchmarks, highlighting the need for sustained investment and policy focus.The subsequent progress mirrors historical improvements in South America and South Asia. While strides have been made, particularly in AIDS-related mortality, Africa will likely fall short of global health benchmarks, highlighting the need for sustained investment and policy focus.

Impact of the Demographics and Health Scenario

Download to pdfWhere to find the impact of the Demographics and Health scenario

The separate sections below discuss the combined impact of the Demographics and Health scenario on infant mortality and life expectancy, the disease burden, sanitation and water access, GDP per capita, and poverty.

The theme on Africa’s Demographic Dividend presents the combined impact of the Demographics and Health scenario on fertility rates, population structure, the African economy, and global and African population forecasts.

Aboutt 1 034 million Africans (47% of the total population) will be connected to safely managed sanitation services by 2043, compared to 904 million on the Current Path (39%), with 169 million still practising open defecation compared to 203 million on the Current Path. Although the continent will not achieve the 2030 SDG target, a push to combat communicable and non-communicable diseases and improve WaSH infrastructure would significantly benefit human and economic development.

Despite the significant push on WaSH infrastructure in this scenario, many Africans will not have reliable access to a safely managed water supply by 2043.

The aggressive improvements in the Demographics and Health scenario mean that although only nine countries will achieve 50% access to safely managed sanitation by 2030, that number will increase to 22 by 2043.

Chart 13 depicts improved access to safely managed water services for Africa in the scenario versus Current Path. 57% of Africa’s total population will be connected to safely managed water services in 2043 in the Demographics and Health scenario, instead of 48% on the Current Path.

Technological advances will drive the development of improved basic infrastructure at a lower cost. For example, since 2011, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has invested over US$200 million in the ‘Reinvent the Toilet’ challenge. Among the early successes was the Tiger Toilet, which costs about US$350 to install and requires no traditional sewer system. Instead, it uses Tiger worms (Eisenia fetida), which feed on human faeces. Once people have used the toilet, they flush their waste into the worm-filled compartment below using a small bucket of water. The process removes 99% of pathogens and leaves no more than 15% of the waste by weight, which performs much better than a septic tank. The leftover product is also an excellent fertiliser. After five years, the first Tiger Toilets have yet to require maintenance.

Another way of measuring the impact of the Demographics and Health scenario is to use disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), a standard metric for capturing a country or region’s disease burden. DALYs offers a way of accounting for the difference between a current and ideal situation, where everyone lives up to the life expectancy in Japan (the country with the longest life expectancy globally), free of disease and disability. Early death translates to years of life lost, and sickness translates to years lost due to disability. One DALY represents the loss of the equivalent of one year of whole health.

Chart 14 shows years of life lost by main International Classification of Diseases (ICD) categories disability-adjusted life years in Africa. For example, in 2023, sub-Saharan Africa is estimated to have lost around 294 million years of life mostly due to its high communicable disease burden and 122 million years due to its non-communicable disease burden. By 2043, that number will have changeddeclined to 145 million years and 157 million years respectively as life expectancy improves in the Demographics and Health scenario, also reflecting the ongoing shift from communicable to non-communicable diseases as well as the fact that Africa’s 2043 population is much larger than in 2023. These numbers can be compared to 216 million and 180 million years in the 2043 Current Path forecast for communicable and non-communicable diseases respectively.

The infant mortality rate is the number of deaths of infants under one year old per 1 000 live births in a given year. It reflects health system performance, maternal and child health, nutrition, disease burden, and broader socio-economic conditions. Rates in Africa have fallen steadily and steeply over successive decades, signifying significant improvements in health care and public health measures. However, Sub-Saharan Africa continues to experience the highest rates globally, significantly above North Africa and other regions.

On the Current Path, Africa is, therefore, already on its way to further reducing infant mortality from its 2023 average: from almost 42 deaths per 1 000 live births to 36 by 2030 and 25 by 2043. The Demographics and Health scenario reduces those rates to 34 in 2030 and 20 in 2043. Chart 15 presents the reduction in country-level rates of infant mortality. Because it already does well, Morocco will gain the least by 2043, and the Central African Republic will gain the most, followed by South Sudan and Lesotho. The scenario reflects intensified efforts in neonatal care and maternal health, as well as reducing disparities, especially in rural and underserved regions. It also requires integrated management of child illness, malaria prevention, and clean water initiatives.

Chart 16 shows the life expectancy for North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa and the EU in the Current Path and the Demographics and Health scenario from 2020 to 2043. By 2043, life expectancy in sub-Saharan Africa will be 73.3 years (instead of 71.3 years in the baseline scenario) compared to 83.4 years in the EU.

The Demographics and Health scenario would result in a total fertility rate of about 2.6 children per fertile woman in Sub-Saharan Africa by 2043 (as opposed to 3.3 children in the Current Path). Rates in North Africa would also marginally decline. By comparison, the average fertility rate in the EU will average 1.5 by 2043.

The impact of the Demographics and Health scenario is a smaller, healthier, wealthier and better-educated population. Chart 17 shows GDP per capita in the scenario and the Current Path. In 2043, Africa's average GDP per capita would be US$252 higher than the Current Path. The impact is most evident among Africa’s low-income countries, which see a 4% improvement in GDP per capita, compared to 3% for lower-middle-income and 1% for upper-middle-income countries. Given its youthful population and high fertility rates, Mozambique, Liberia and the DR Congo will gain the most (calculated per cent increase above the Current Path) by 2043. With their more mature population structures, Morocco, Tunisia and Cabo Verde are likely to gain the least.

Healthier individuals are more productive—able to work more, learn longer and contribute more economically. This dynamic is not one-way: better health boosts income, and higher income often improves health in a positive feedback loop known as the Preston Curve. The relationship is powerful at low per capita income levels and flattens out at high income levels; thus, it is vital for Africa, with its many developing countries.

According to Economist Impact, every US$1 invested in climate-resilient WaSH returns at least US$7 to African economies. Sub‑Saharan Africa could gain over 5 % of GDP (roughly US$200 billion/year) with sufficient WaSH investment. The UN estimates that inadequate WaSH costs Sub-Saharan Africa approximately 5% of GDP annually, more than what the continent received in aid.

Although Africans would spend more on health and WaSH infrastructure in this scenario, these expenses are eventually offset by more rapid growth, to the extent that the African economy will be US$79 billion larger in 2043 despite the fact that the population would be 84 million smaller.

With less children to clothe, feed and education, a healthier population, and an increase in the number of working-age persons relative to dependents, 41 million fewer Africans would be considered extremely poor, in 2043 with the most significant reductions in the number of extremely poor Africans in Mozambique, Nigeria and the DR Congo—a remarkable testament to the contribution that family planning and better healthcare can make to Africa’s fortunes.

Chart 18 shows the decline in extreme poverty in millions per year Africa (using US$3 per person), which would follow the Demographics and Health scenario compared with the Current Path.

A complex interplay of structural, social, environmental and geopolitical forces will shape Africa’s health and WaSH future. Among the most influential is the continent’s demographic trajectory.

A growing and youthful population—with persistently high fertility rates in many regions and significant rural-urban and cross-border migration—continues to exert immense pressure on basic services. Yet, this demographic shift also presents an opportunity: if countries invest strategically in health, education and employment, they could harness a demographic dividend that boosts long-term development. A blend of political will, sound strategies, enhanced implementation capacity and adequate financing can reap that dividend.

There are also risks. Climate change is already amplifying health and WaSH challenges. Rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns and more frequent extreme weather events are intensifying water stress, altering the distribution of disease vectors and increasing climate-related displacement. These disruptions are straining fragile systems and undermining progress, particularly in drought- and flood-prone regions. Whether African institutions can anticipate, absorb and adapt to these shocks remains a critical uncertainty, with implications for health security and economic stability.

At the same time, technological innovation is unlocking new solutions. From mobile health platforms and digital diagnostics to off-grid sanitation systems and real-time disease surveillance, African countries are increasingly piloting tools that leapfrog traditional infrastructure constraints. However, the ability to scale such innovations inclusively is a considerable challenge. Rural and marginalised communities still face digital infrastructure gaps, limited connectivity and insufficient governance frameworks—raising the risk that new technologies could widen existing inequalities if equity is not built into their design and deployment.

Governance and financing dynamics also play a defining role. Many African health systems remain underfunded, with substantial reliance on external aid to deliver essential services such as HIV treatment and immunisation. The degree of decentralisation varies widely, influencing how services are planned and delivered—and how responsive they are to local needs. Strengthening public financial management, increasing domestic budget allocations and reducing aid dependency are vital to improving resilience and sustainability.

Social norms and inequalities further shape outcomes. Gender disparities, stigma and entrenched behavioural norms affect how communities engage with health services—from vaccine acceptance and menstrual hygiene practices to care-seeking behaviour and facility use. These factors interact with broader systemic constraints, particularly in informal urban settlements, creating unequal health and sanitation access.

Finally, global dynamics are shifting. Africa’s experience with pandemics, debates over vaccine equity and growing involvement in global health diplomacy are expanding its role in the international health landscape. The evolving roles of the African Union, Africa CDC and the WHO in coordinating pandemic response and strengthening health security are signs of progress. However, geopolitical rivalry, fractured multilateralism and donor fatigue cast uncertainty over future global cooperation. Whether the coming decade brings renewed solidarity or increasing fragmentation will significantly affect Africa’s ability to access vaccines, shape global norms and secure health financing.

In sum, while the drivers of health and WaSH transformation are well understood, the uncertainties around political commitment, climate resilience, equitable innovation and international cooperation will decisively shape Africa’s health trajectory. Strategic foresight and adaptive policymaking will be essential to navigate this unpredictable terrain.

Africa’s trajectory in Health and WaSH will reverberate far beyond its borders, shaping global development, security and sustainability. As the world’s fastest-growing population and home to the largest share of children and youth, the continent’s ability to improve health outcomes and expand access to clean water and sanitation will directly affect global human capital, economic demand and labour mobility. A healthier, better-nourished, and better-educated African population can be a demographic dividend for the continent and the global economy, providing a dynamic workforce, consumer base, and innovation partner in a rapidly ageing world.

Conversely, failure to strengthen health and WaSH systems could amplify global risks. Epidemics do not respect borders: Africa’s high burden of infectious diseases, fragile health infrastructure and growing urban density make it a hotspot for potential future outbreaks. The lessons from HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 have shown that delayed responses, under-investment and vaccine inequity can allow diseases to spread globally, disrupting trade, travel and livelihoods. Ensuring robust surveillance, laboratory capacity and pandemic preparedness in Africa is a global public good. Global resilience will increasingly depend on Africa’s ability to anticipate and manage systemic health risks, supported by stronger regional coordination, data systems and local manufacturing capacity.

Climate-linked health vulnerabilities in Africa will also increasingly intersect with global stability. Water stress, food insecurity and health-related displacement are already contributing to migration pressures and regional instability. These dynamics could intensify without action, with ripple effects on neighbouring regions and beyond. In particular, deteriorating WaSH conditions and inadequate healthcare in fragile and conflict-affected areas will likely drive cross-border movements within Africa and toward Europe and the Middle East. Such mobility patterns are already evident in the Sahel, the Horn of Africa and North Africa. Integrating health and WaSH priorities into emerging climate and peacebuilding agendas offers a pragmatic way to address displacement, food insecurity and disease together.

Economically, Africa’s Health and WaSH gaps also shape global supply chains and investment strategies. Interruptions in access to clean water or workforce health can undermine industrial productivity, agricultural outputs and trade reliability. For international businesses, supporting resilient infrastructure in Africa is part of future-proofing value chains. At the same time, health technology, diagnostics, and WaSH solutions tailored to Africa’s needs offer emerging markets for global innovation partnerships, with African-led enterprises increasingly contributing to these ecosystems. Early examples—such as vaccine manufacturing in South Africa and Senegal, or the spread of drone-based medical logistics—point to areas of comparative advantage that could expand with the right investment climate.

Digital innovation will be equally critical for Africa’s health future. Expanding digital health and data ecosystems can enhance disease surveillance, service delivery and early-warning capacities across borders. Strengthening data governance, interoperability and local analytics capacity will improve national decision-making and make Africa an integral part of global health intelligence networks. Investments in digital infrastructure, from electronic health records to AI-driven outbreak prediction, represent one of the most cost-effective ways to build resilience and close the global health information gap.

Finally, Africa’s experience will continue to shape the future of global health governance. The continent’s growing diplomatic weight and practical experience in managing pandemics are shifting international health narratives toward equity and regional leadership. Africa’s engagement with the WHO, Africa CDC, GAVI and other platforms is already influencing how global priorities are set and financed. Its collective voice is increasingly present in global health financing, technology transfer and data governance debates. How the global community supports—or fails to support—Africa’s health ambitions will determine progress toward the SDGs and the credibility of international solidarity in an era of overlapping crises.

The Demographics and Health scenario illustrates how strategic investment in health and WaSH can transform Africa’s development trajectory. Countries can substantially reduce communicable diseases, extend life expectancy and improve productivity by accelerating access to clean water, sanitation, and quality healthcare by accelerating access to clean water, sanitation and quality healthcare. The findings highlight that progress in health is a social imperative and a macroeconomic driver: healthier, better-educated populations contribute to higher growth, lower poverty and greater demographic dividends.

The scenario underscores that incremental change will not be enough. Without a decisive shift toward domestic investment, institutional reform and innovation, the continent will fall short of its potential. The future of Africa’s health and WaSH systems depends on governance that links evidence to policy, strengthens local capacity and ensures that gains are resilient to climate, economic and geopolitical shocks.

Africa has a unique opportunity to reshape its health and WaSH systems, turning structural challenges into platforms for innovation and equity. At the frontline are community health systems, the most cost-effective and trusted means of reaching underserved populations. Scaling and professionalising these systems through training, fair remuneration, and digital tools can improve maternal health, child immunisation, and disease surveillance.

Decentralised and context-specific WaSH solutions also show promise. Boreholes that use solar-powered pumps to provide water, off-grid filtration units and nature-based sanitation systems can bypass costly centralised infrastructure, particularly in rural and peri-urban areas. Innovation: Africa claims to have built over 1 000 solar water-pumping systems across Africa, drilling wells up to ~250 m deep and installing solar panels, pumps, tanks and tap-stations for entire villages (e.g., a village of ~3 000 people).

Financing remains the most critical lever. With traditional donor flows declining, blended finance, pooled funding and diaspora bonds offer new ways to mobilise capital and align resources with long-term priorities. Integrating health and WaSH within national climate strategies can further unlock climate finance and strengthen adaptation.

Continental institutions such as the Africa CDC, the African Union and regional economic communities (RECs) can accelerate coordination, innovation sharing and preparedness. The AfCFTA adds an economic dimension by fostering regional supply chains for pharmaceuticals, diagnostics and hygiene products.

Africa’s health and WaSH priorities will differ widely across contexts. The typology used in this report (fragile and conflict-affected states, middle-income reformers, resource-rich but underperforming countries and small high-performing states) illustrates how diverse starting points require tailored approaches rather than one reform model. In fragile contexts, immediate priorities often lie in stabilising essential services, preventing disease outbreaks and coordinating humanitarian and development responses. Over time, linking emergency mechanisms to local institutions and community systems can help rebuild trust and capacity. For middle-income reformers, consolidating gains and expanding access through digital systems, universal coverage, and climate-resilient infrastructure will be key, alongside investment in innovation and regional knowledge exchange. Resource-rich countries may focus on translating revenue into sustainable human development by redirecting public spending toward preventive health, water and sanitation, and strengthening accountability in resource allocation. Small high-performing states can continue refining service quality and efficiency while sharing expertise regionally through the AfCFTA, Africa CDC and other continental platforms.

While each group faces distinct challenges, they share a common opportunity: reimagining health and WaSH as catalysts for human capital, resilience and inclusive growth. Tailored, evidence-based strategies adapted to these differing contexts will be essential for translating Africa’s demographic and health potential into sustained development gains.

Going forward, three priorities will determine success. First, invest in resilient community systems by strengthening frontline health and sanitation workforces, integrating digital tools and embedding climate adaptation in infrastructure design. Second, accelerate regional self-reliance by expanding local production, building data and surveillance systems and mobilising innovative finance to reduce dependency. Third, health and WaSH strategies should be aligned with Africa’s green and demographic transitions, ensuring the continent’s growing youth population becomes a source of innovation, resilience, and shared prosperity.

If pursued together, these shifts can transform Africa’s health and WaSH sectors from chronic vulnerabilities into dynamic foundations of inclusive growth, human security, and sustainable development.

Endnotes

J Reader, Africa: A Biography of the Continent, New York: Penguin, 1998, 234

Spanish influenza killed 40 million to 50 million people in 1918, Asian flu killed 2 million people in 1957, and Hong Kong influenza killed 1 million people in 1968.

Includes HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis together with maternal deaths, neonatal deaths and deaths from malnutrition.

These are often chronic, long-term illnesses and include cardiovascular diseases (including stroke), cancers, diabetes and chronic respiratory diseases (such as chronic pulmonary disease and asthma, but excluding infectious respiratory diseases such as tuberculosis and influenza).

Injuries are caused by road accidents, homicides, conflict deaths, drowning, fire-related accidents, natural disasters and suicides.

Infant mortality is the death of an infant before its first birthday. Rates are typically expressed as the number of infant deaths for every 1 000 live births.

Page information

Contact at AFI team is Jakkie Cilliers

This entry was last updated on 11 February 2026 using IFs 7.84.

Reuse our work

- All visualizations, data, and text produced by African Futures are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

- The data produced by third parties and made available by African Futures is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

- All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Cite this research