Africa’s health sovereignty can build more equitable and prosperous societies

Strong institutional COVID-19 responses prepare the continent for future health emergencies.

While COVID-19 vaccines were rolled out in under a year in much of the developed world, this was not the case for Africa. The coverage for those fully vaccinated on the continent stood at 21.2% in August 2022, which represents steady progress but is far from reaching all those who are most vulnerable.

Africa faced costly delays and shortfalls with insufficient access to doses as international support faltered, with countries imposing restrictions on the export of essential diagnostic equipment and medical materials. Nine countries still have vaccination rates below 10%.

Africa’s health sector typically deals with communicable diseases and has the double burden of facing increasing levels of non-communicable diseases. COVID-19 emerged as yet another challenge, but in a far younger demographic than elsewhere. This shielded it from the worst projections being realised.

Africa’s regional institutions rose to the challenge in their response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This was seen across many fronts. African countries had experience in fighting the HIV/AIDS pandemic, which meant they were better geared to fight infectious diseases.

In the wake of the 2014-16 Ebola outbreak, the AU established the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC). This organisation played a seminal role, together with support from the AU Ministers of Health, in managing a pandemic strategy, which was underpinned by a ‘commitment to coordinate, collaborate, cooperate, and communicate.’

The strategy was a remarkable response and exemplary in the way it sought to introduce strong coordination between a range of actors through its clear goals and objectives ‘to ensure synergy and minimize duplication.’ The strategy further sought to advance an evidence-based approach to public health for enhanced prevention, monitoring and treatment of COVID-19.

In 2020, the AU and Africa CDC launched the Partnership to Accelerate COVID-19 Testing. Africa’s low rate of ‘seeding events’ – the result of a less connected continent – highlighted the lack of access and provision to testing facilities. As of August 2022, more than 121 million tests had been carried out and more than two million cases of COVID-19 had been detected in AU Member States, representing 2.1% of all cases globally. Testing capacity has been strengthened in 43 countries, which is cause for optimism.

Another innovative approach saw a joint partnership emerge between the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, the AU, Africa CDC, and the African Export-Import Bank to launch an Africa Medical Supplies Platform to help fight the COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. This initiative had strong backing from South Africa’s president, demonstrating solid political leadership and support for stronger action in response to the pandemic. This enables AU Member States to buy certified medical equipment such as diagnostic kits, personal protective equipment and clinical management devices cheaper and more transparently.

In a powerful move to transform vaccine access, the first tech transfer hub was established by a South African consortium comprising Biovac, Afrigen Biologics and Vaccines, a network of universities, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Africa CDC. There was significant political will around these types of initiatives.

This shift set the stage for knowledge sharing of patents, by four major manufacturing players, that enable the transfer of technology and an expanded opportunity to build vaccine development and manufacturing capability in other African countries. The ability of these countries to strengthen their health infrastructure will fill critical gaps and extend opportunities for greater health science advances. This will only be further enabled if technology is offered to more countries and is extended to intellectual property and goes beyond vaccines to include treatments and diagnostics.

The strong institutional responses to COVID-19 will stand Africa in good stead in the years ahead as other health emergencies, including pandemics, emerge. The hallmarks of the successful response centre around policy innovation, a strong partnership approach, including a display of continental unity, political backing, and will that is not seen enough. All these improvements in testing ability and vaccine development, through mRNA technology, provide Africa with the tools to better address current and future health challenges.

Mariana Mazzucato and Vera Songwe in their article A New Model for African Health frame health as a ‘public good’, where policy should be oriented towards promoting a ‘health for all’ policy agenda. They argue that the public sector, and strong partnerships with public health actors, including African multilaterals, should take the lead in activities often pursued by organisations seeking profits at the expense of strengthening public health systems. This approach calls for a more capacitated, capable state that can take advantage of promoting research and development alongside appropriate policy responses.

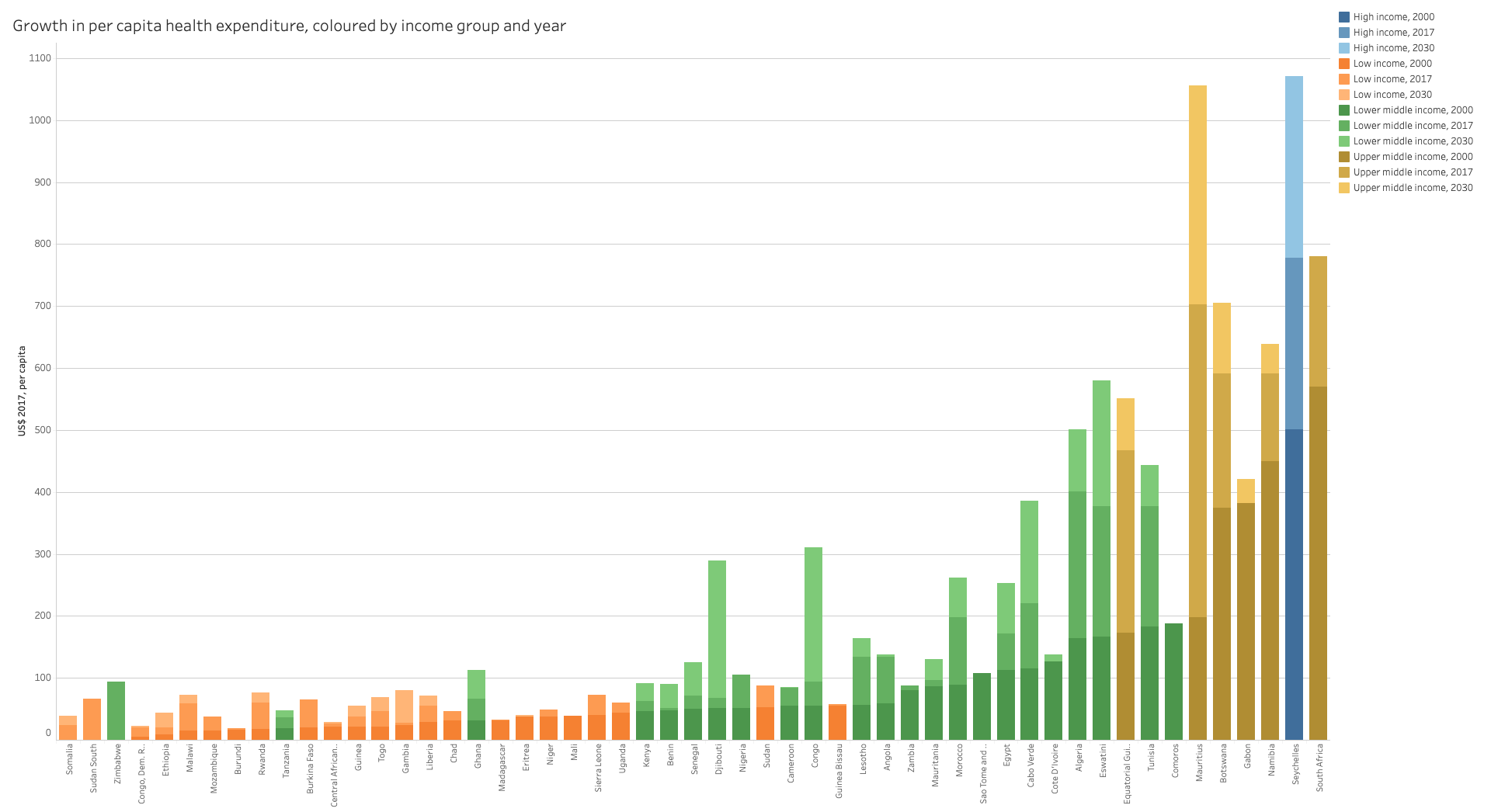

The authors note that a key piece of the puzzle is ensuring there is sufficient economic scope to make the necessary long-term investments in health and pandemic preparedness and response. Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa generally spend significantly less on health, as a percentage of gross domestic product, than other regions globally, save that of South Asia.

Low- and lower-middle-income governments have less revenue to spend on health than upper-middle- and high-income countries. This will need to change and significant expenditure will be required, largely from outside Africa, to address the shortcomings that threaten future responses to what many regard as inevitable future health crises, including pandemics. African government spending on health hovers at around 3% of their overall budgets. Experts believe 15% is required.

Poverty and communal access to water, sanitation and hygiene must be a focus of government expenditure. This is integral to health emergency resilience building. African governments, international financial institutions and ratings agencies will need to see health as fundamental to building more stable societies, underpinning educational and productivity outcomes that improve and lay the basis for future progress towards sustainable development and resilience. More effective governance and efficient systems will further consolidate progress.

African heads of state have recognised the need to strengthen African health institutions, giving more authority and autonomy to the Africa CDC and creating a pandemic preparedness and response authority, an epidemic fund, and a health workforce task team. National health systems must also be a focus of African governments and efforts to strengthen them must be prioritised.

Mazzucato and Songwe argue that health needs to be seen as an integral part of a country’s future stability and prosperity, and not as a discretionary annual expenditure. It should be part of a long-term strategic and developmental response. African finance ministers, they say, ‘should see themselves not only as guarantors of stability but as supporters of healthy and equitable societies.’ Alongside fiscal and monetary policy responsibilities, investments in health and well-being must be guaranteed.

African countries must further deepen and consolidate the strong health sector institutional gains made. This can boost greater sovereignty in an area that is fundamental to ensuring the stability and prosperity of its people.

Working from continental to national health system level and national to continental level to share lessons and best practices and strengthen regional approaches through the RECs could bolster support where it’s most needed. Strengthening early warning systems and testing capacity, including investments in overall hygiene, could deliver the health gains and resilience required to address future health crises.

Image: Yasuyoshi CHIBA / AFP