Africa

Africa

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

This report analyses Africa’s current development path and prospects, examining how various sectoral interventions could shape the continent’s economic and social landscape through to 2043, the end of the third ten-year implementation plan of the African Union's Agenda 2063. The analysis is grounded in scenario modelling using the International Futures (IFs) modelling platform. It explores eight key sectors: Demographics and Health, Agriculture, Education, Manufacturing, Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), Financial Flows and Governance. In addition to evaluating the effects of each sectoral scenario individually, the report assesses the combined impact of these interventions on Africa’s long-term growth and development trajectory. The report summarises the key findings and offers policy insights to support Africa in pursuing a more inclusive, resilient and sustainable development path. It underscores the importance of coordinated, multi-sectoral reforms to unlock the continent’s long-term economic and social potential.

Visit the Technical section for additional information on the International Futures (IFs) modelling platform, which serves as the analytical foundation for this report's scenario simulations.

Summary

This report begins with an introductory assessment of the continent’s context, examining current population distribution, social structure, climate and topography.

- Africa, the world’s second-largest continent, spans 30.4 million km² and was home to 1.5 billion people in 2024. Demographically, it is the world’s youngest continent, with a median age of 19.7 years. Geographically diverse and politically varied, Africa is shaped by its semi-arid and tropical landscapes, colonial legacies and post-independence state-building, with 54 sovereign states organised into broad administrative divisions and rich cultural, linguistic and ethnic diversity that underpin both its development challenges and opportunities.

The introduction is followed by an analysis of Africa’s Current Path, which informs the continent’s likely development trajectory to 2043. It is based on current geopolitical trends and assumes that no major shocks would occur in a ‘business-as-usual’ or baseline scenario.

- Africa’s population will grow to 2.3 billion by 2043, with the working-age share rising steadily and laying the foundations for a potential demographic dividend. Realising this dividend, however, will depend on sustained investments in health, education and job creation to absorb Africa’s fast-growing youth population.

- Africa’s urban population share rose from 31% in 1990 to 44% in 2023, and will reach 52% by 2043 under the Current Path, with low-income countries urbanising the fastest. This rapid shift underscores the urgent need for inclusive urban planning, investment in affordable housing and infrastructure and strategies to address the growing rural-urban divide.

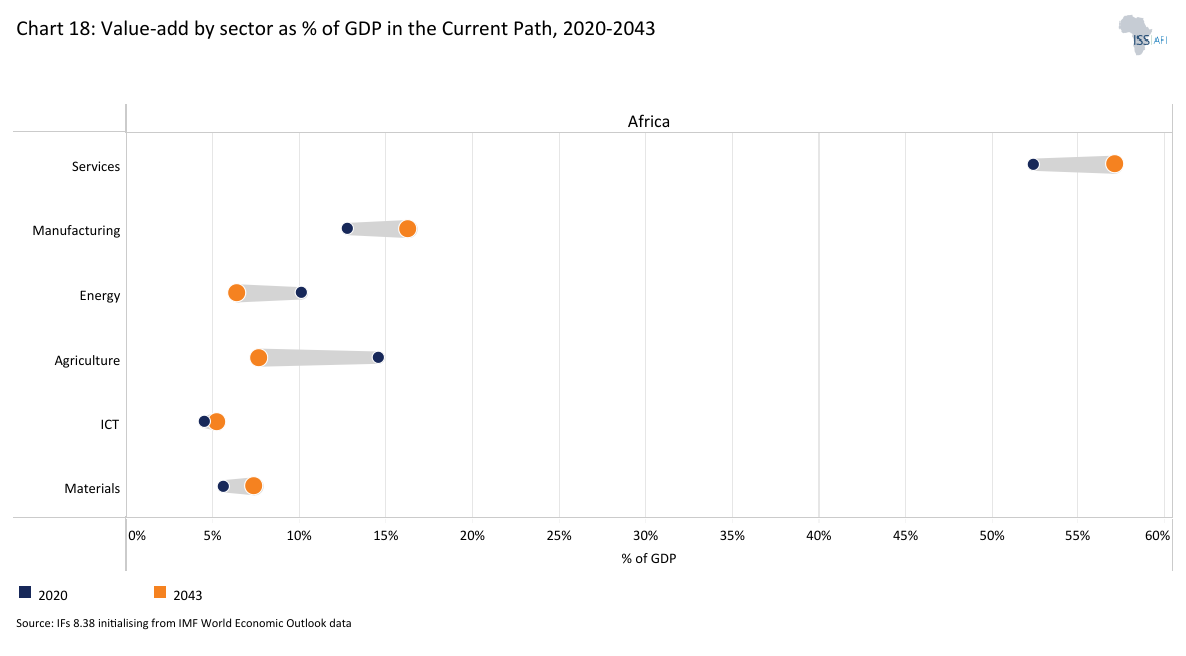

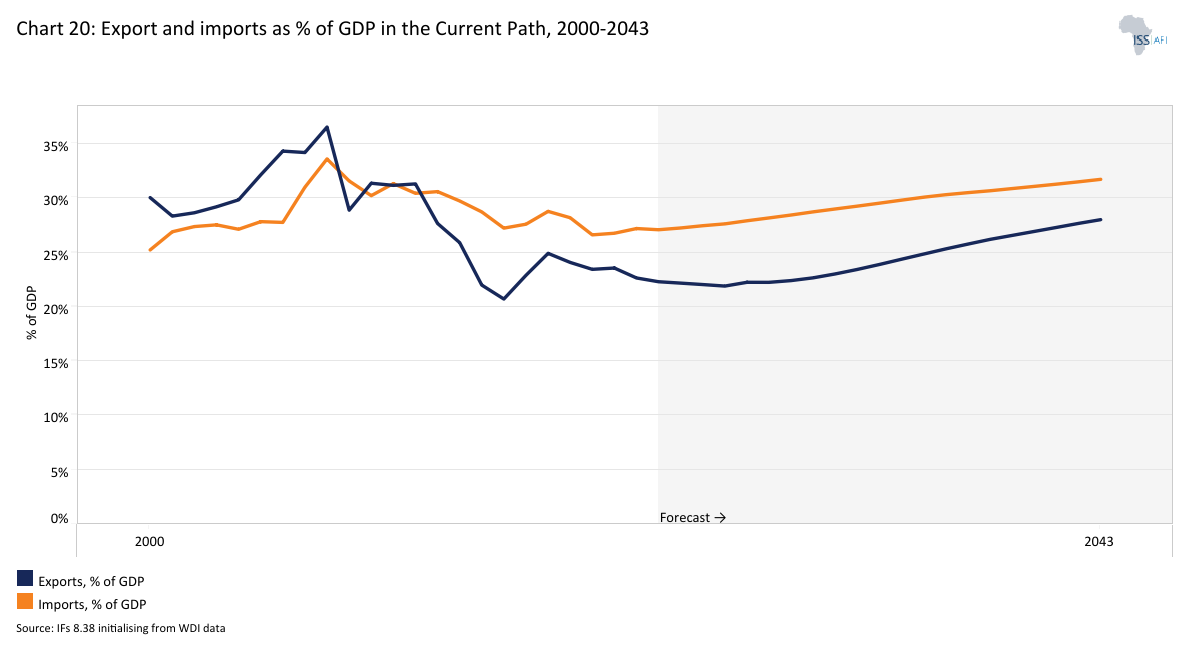

- In the Current Path, Africa’s GDP at market exchange rates (MER) will rise from US$2.66 trillion in 2023 to US$6.36 trillion by 2043, reflecting a moderate average growth of 4.6% annually, slower than South Asia but faster than South America. While services and domestic consumption remain the main drivers, structural transformation into industry and trade-led growth is essential if Africa is to align with Agenda 2063 targets and avoid vulnerability to commodity cycles.

- Africa’s GDP per capita in purchasing power parity (PPP) will rise from US$4 850 in 2023 to US$6 210 by 2043 under the Current Path, reflecting gradual improvements in living standards but still lagging behind peer regions, underscoring the urgency of structural reforms to avoid the middle-income trap and meet Agenda 2063 aspirations.

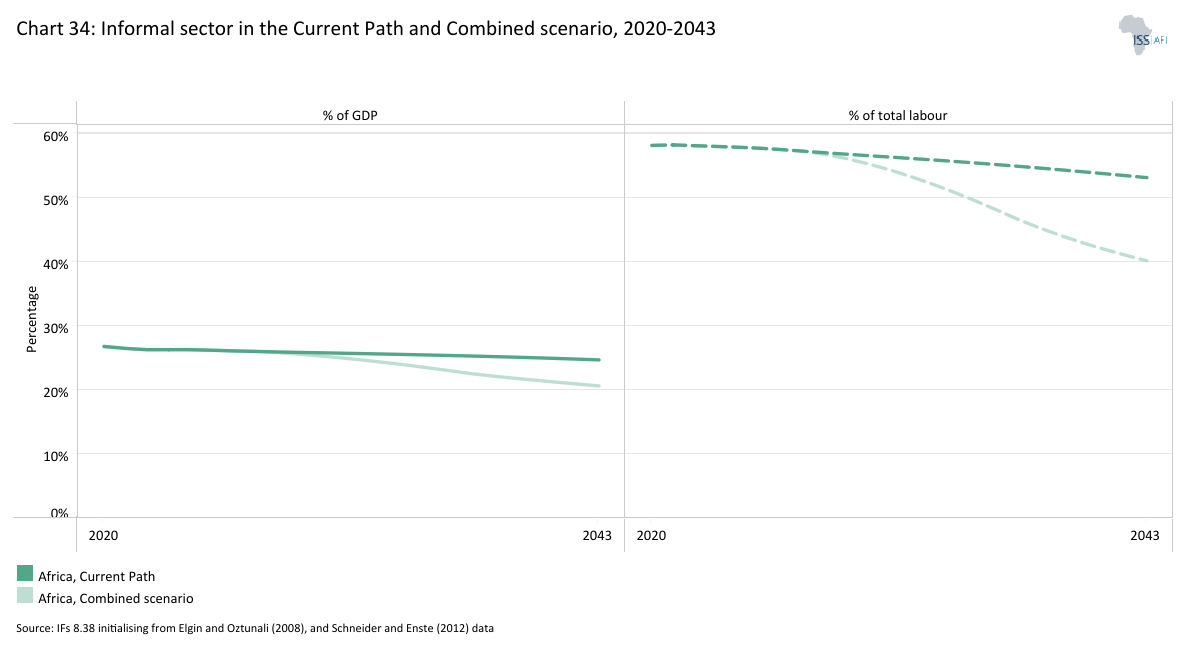

- Africa’s informal sector will remain pervasive, with its share of GDP above 27% and informal employment above 53% by 2043, reflecting structural rigidities in labour markets and limited progress toward formalisation, industrialisation and inclusive job creation. Low-income countries will continue to experience the highest levels of informality.

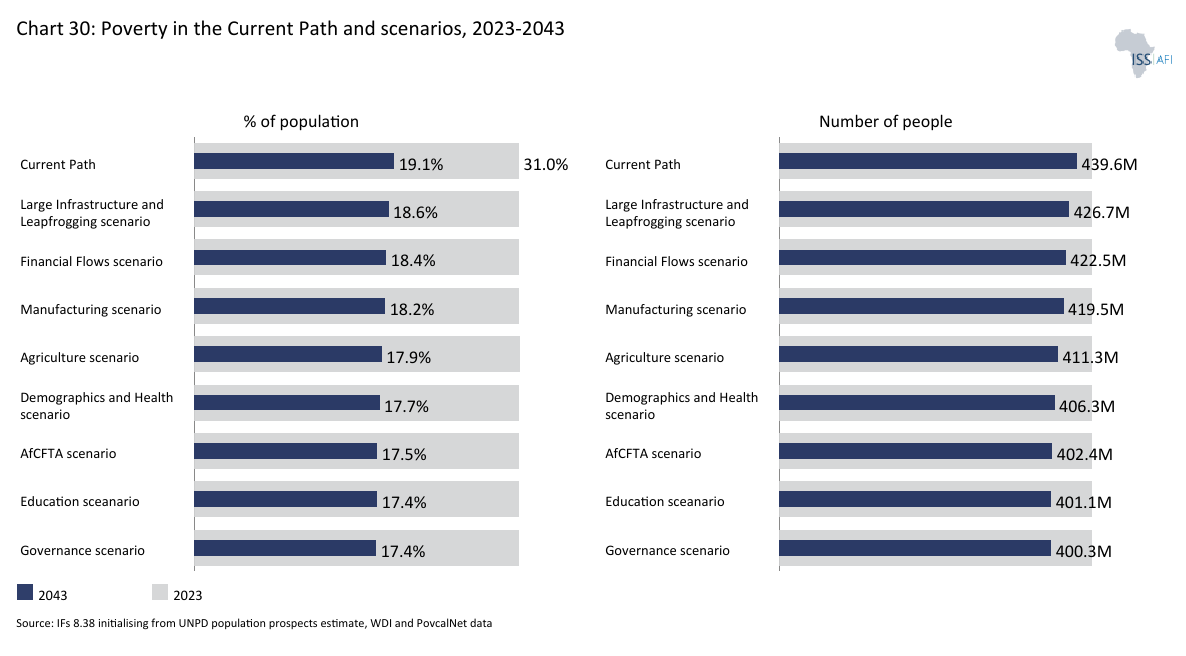

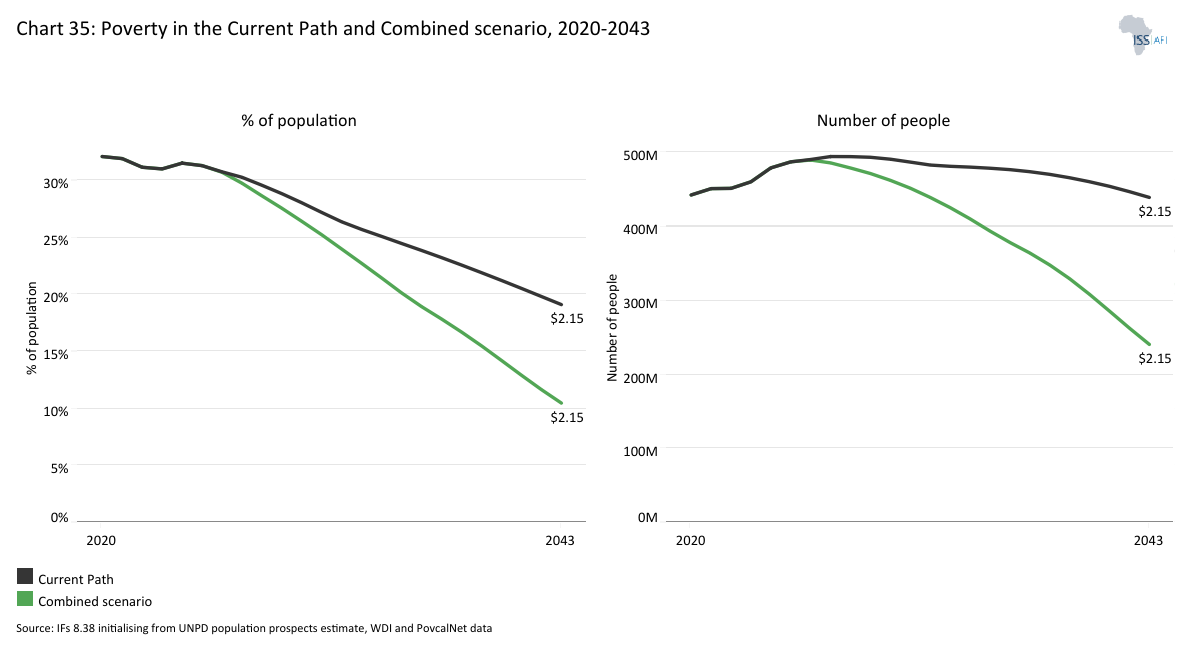

- Extreme poverty in Africa will decline from 31% in 2023 to 19.1% by 2043 under the Current Path, marking progress but leaving nearly half a billion people below the US$2.15/day line. This trajectory reflects modest improvements in income distribution and access to services. Yet, it lags far behind poverty reduction in South Asia and South America, underscoring that without accelerated structural transformation and inclusive policies, Africa will miss continental poverty reduction goals.

- Africa’s development ambitions are currently guided by the Second Ten-Year Implementation Plan (TYIP, 2024–2033) of Agenda 2063, which prioritises industrialisation, digital transformation and intra-African trade to consolidate early gains while tackling persistent poverty and inequality. Looking ahead, the Third TYIP (2034–2043) will focus on deepening structural transformation, embedding resilience against climate and geopolitical shocks, and driving Africa closer to its long-term vision of inclusive and sustainable prosperity.

The next section compares progress on the Current Path with eight sectoral scenarios. These are Demographics and Health; Agriculture; Education; Manufacturing; the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA); Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging; Financial Flows; and Governance. Each scenario is benchmarked to present an ambitious but reasonable aspiration in that sector, comparing Africa with other regions at similar levels of development and characteristics.

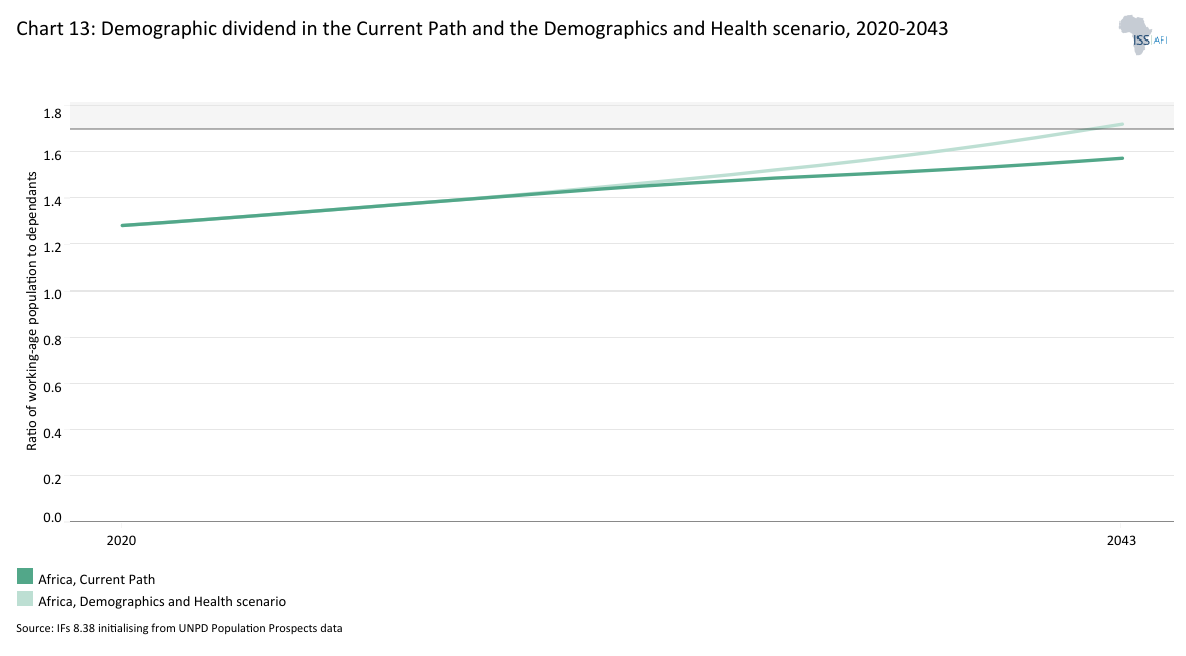

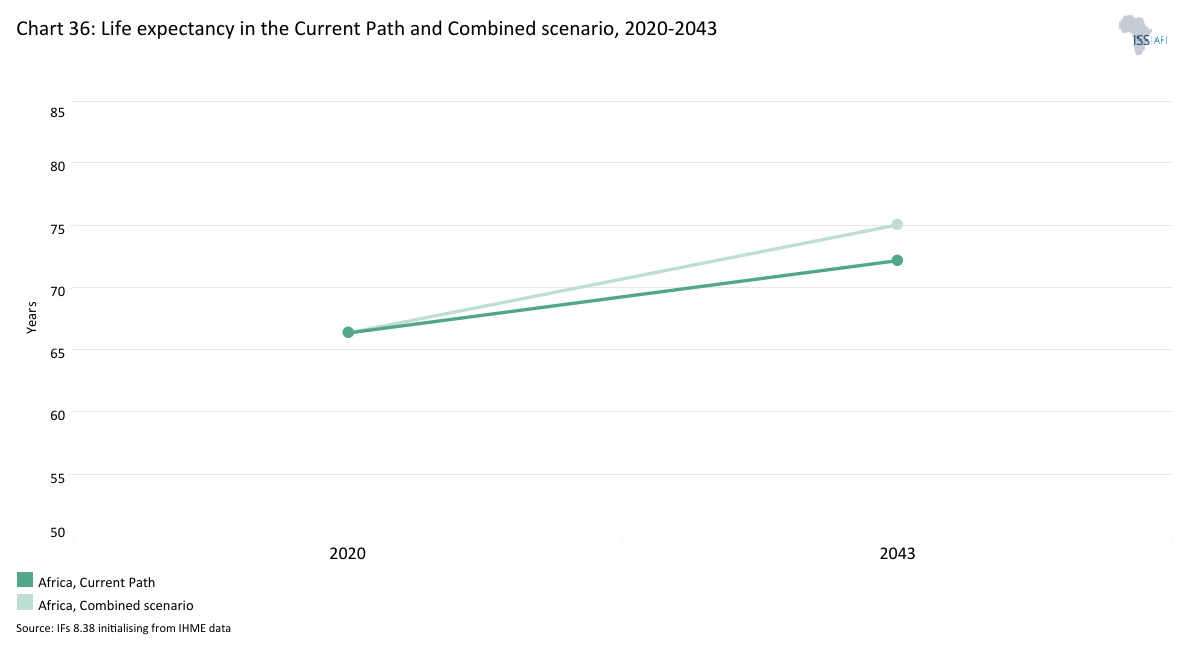

- The Demographics and Health scenario accelerates Africa’s demographic transition, with the dividend ratio improving to 1.72 by 2043 compared to 1.57 under the Current Path, marking the continent’s delayed but eventual entry into its demographic window. It also places Africa on track to meet the Agenda 2063 health target of a 75-year life expectancy, reaching 74.3 years by 2043, reflecting sustained investment in non-communicable diseases (NCDs) prevention, maternal and child health and universal healthcare access that underpins productivity and inclusive growth.

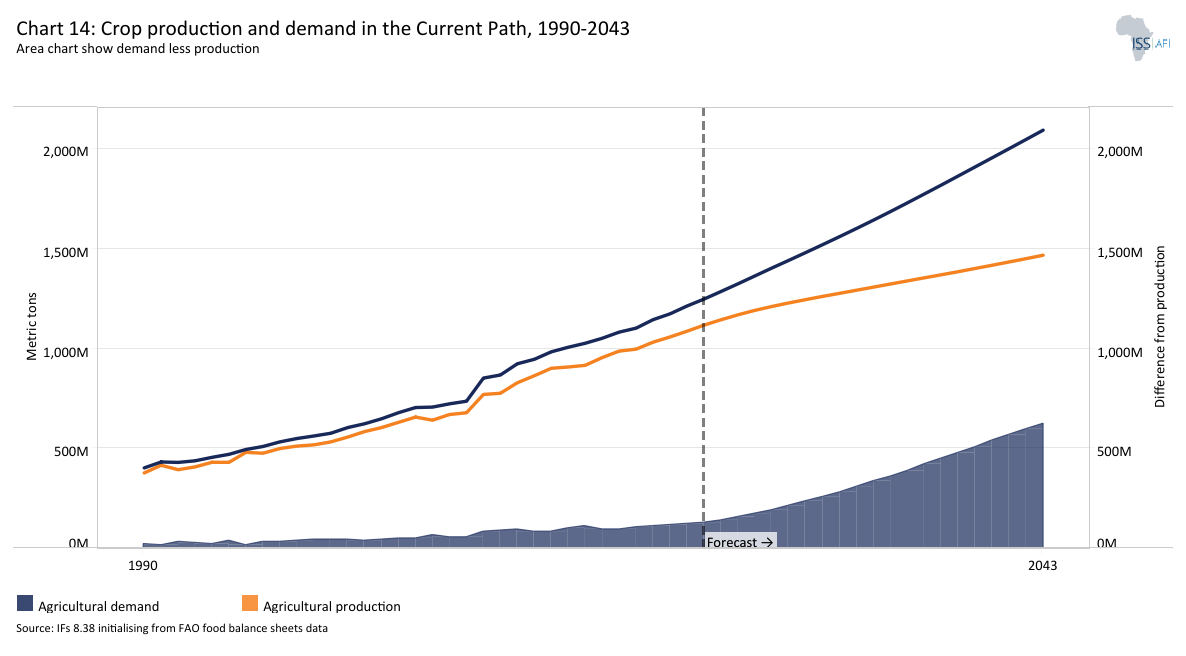

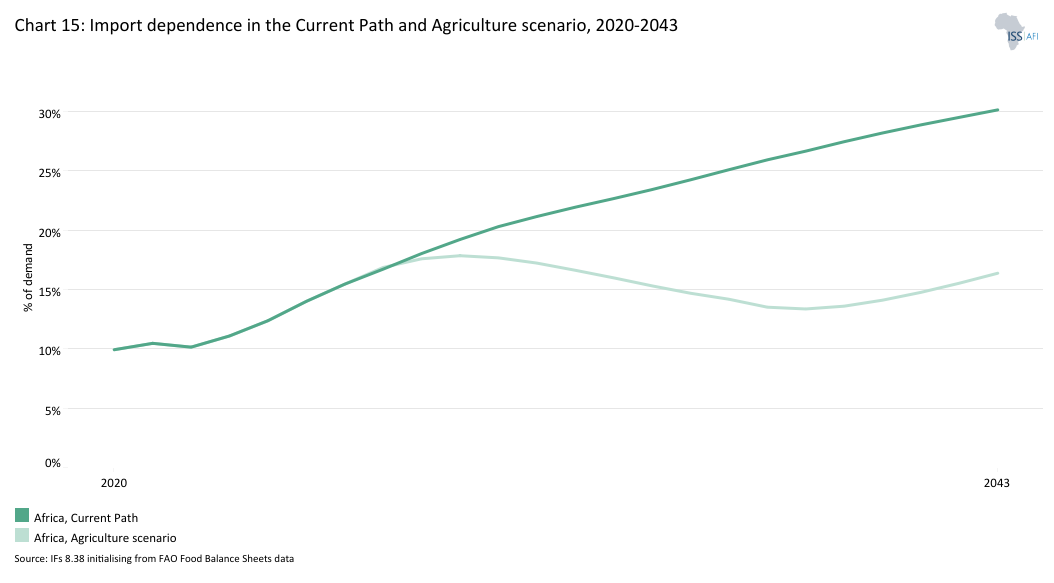

- The Agriculture scenario moderates Africa’s crop import dependence to 16.2% of total demand by 2043, compared to almost 31% baseline forecast, highlighting important gains in domestic production, trade balance and food system resilience. However, the transformative impact on poverty and livelihoods will hinge on integrating smallholder farmers into value chains, scaling agro-processing industries and strengthening climate adaptation strategies, particularly in low-income countries where vulnerability to food insecurity remains highest.

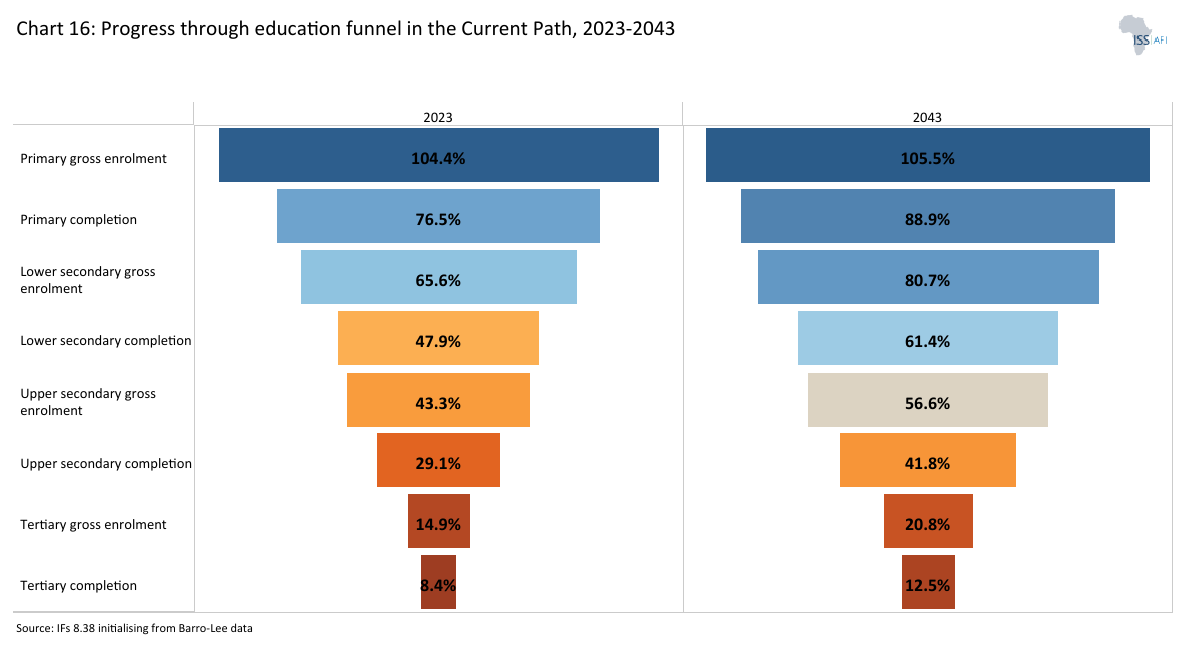

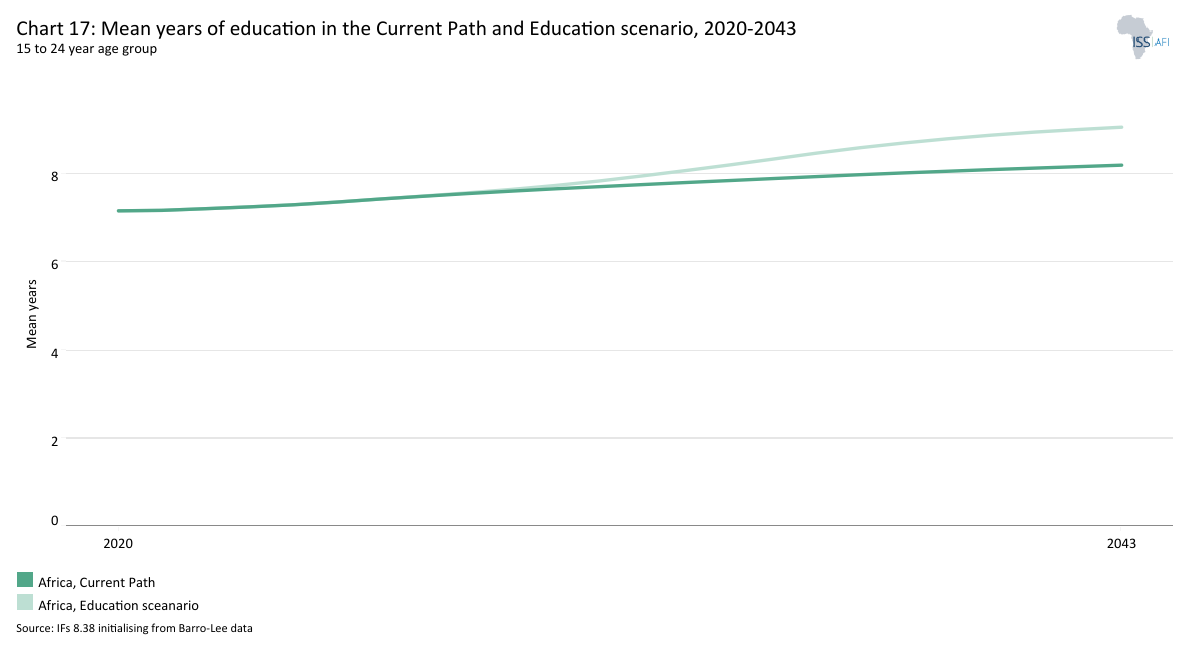

- Under the Education scenario, Africa’s youth aged 14-24 achieve an average of 9.1 years of schooling by 2043, nearly a year higher than the Current Path forecast, with narrowing gender gaps and improved learning outcomes. These developments strengthen human capital formation and labour productivity, while contributing to moderate poverty reduction, underscoring the pivotal role of education reform, vocational training and digital inclusion in sustaining long-term growth and preparing Africa’s workforce for the demands of the 21st-century economy.

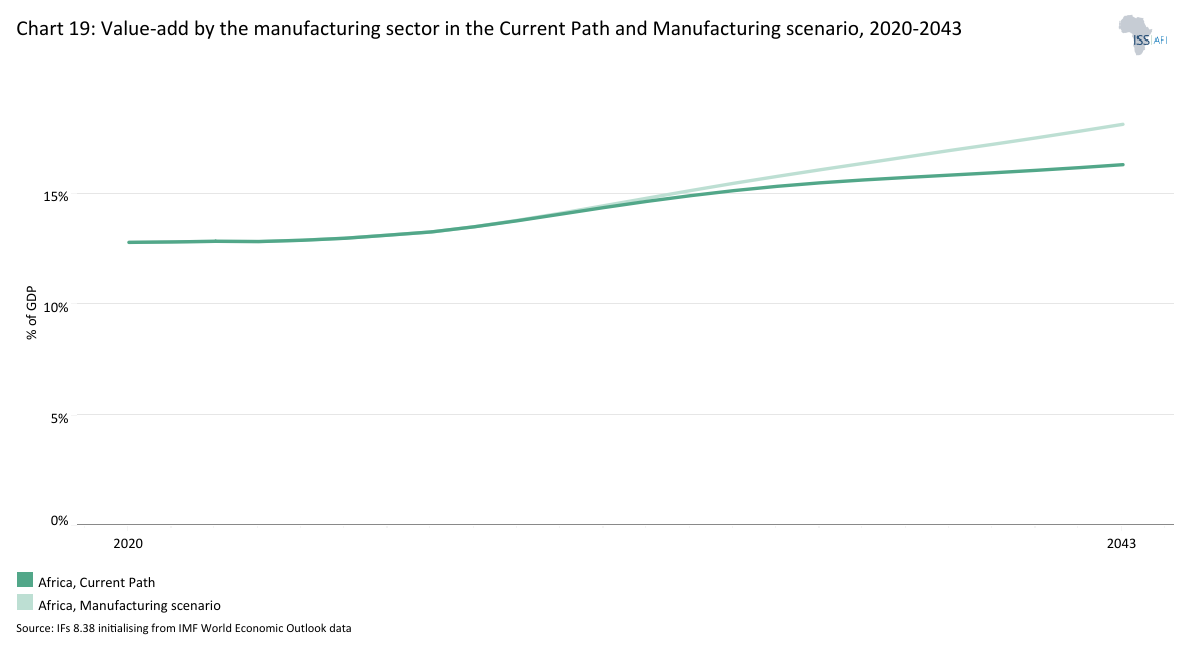

- The Manufacturing scenario revitalises Africa’s industrial base, raising manufacturing value-added to over 18% of GDP by 2043, and catalysing job creation, income growth and productivity gains, especially in the medium term. It underscores the centrality of industrial policy, infrastructure development and small to medium enterprise (SME) support in driving structural transformation, reducing dependence on primary commodities and positioning Africa to compete more effectively in global value chains.

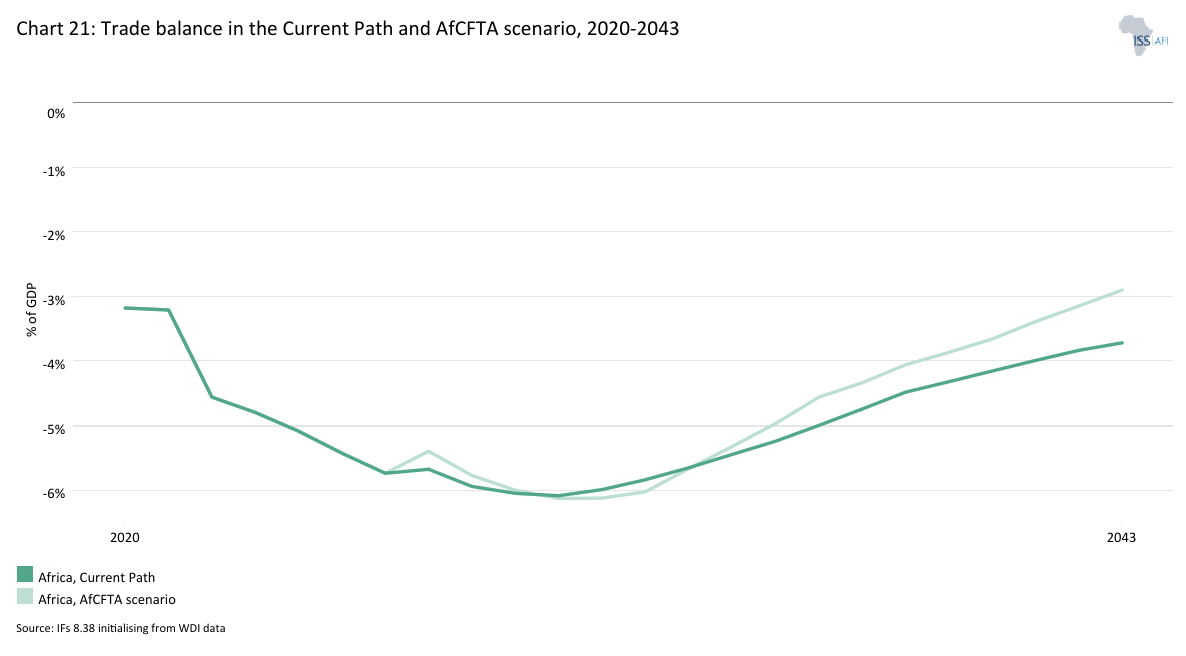

- Under the AfCFTA scenario, Africa’s trade deficit narrows from 4.8% of GDP in 2023 to 2.9% by 2043, compared to 3.7% under the Current Path. This reflects gains from greater intra-African trade, export diversification and market integration. By driving the highest gains in per capita income and accelerating export diversification, AfCFTA confirms regional integration as a decisive lever for Africa’s long-term transformation and global positioning.

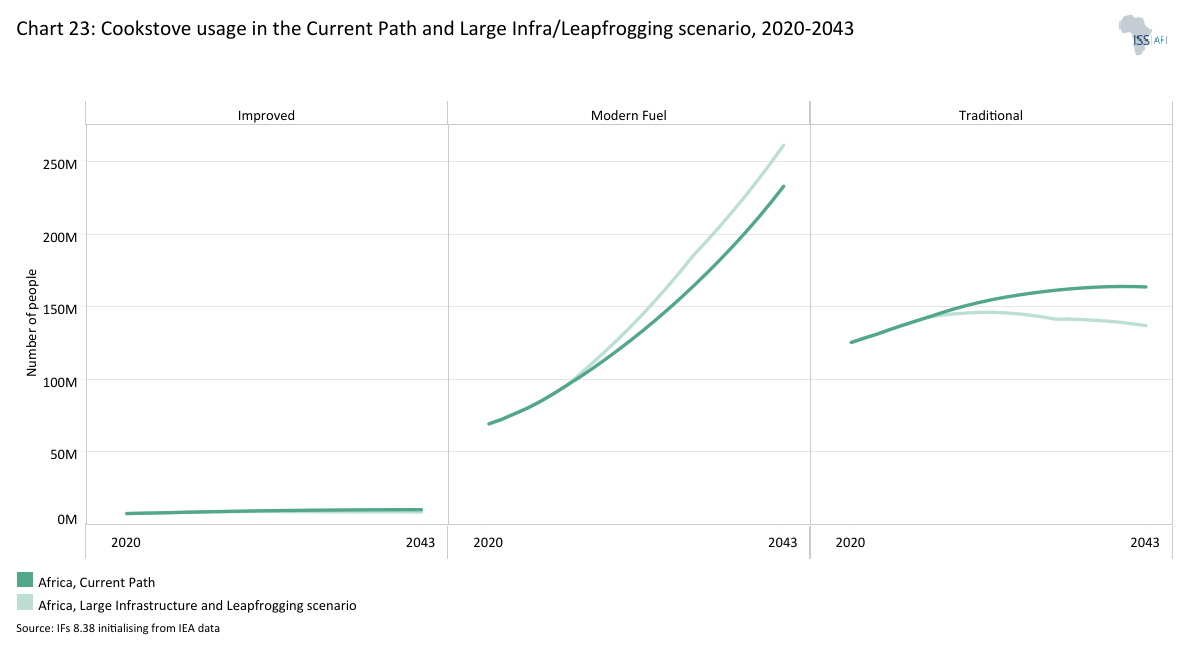

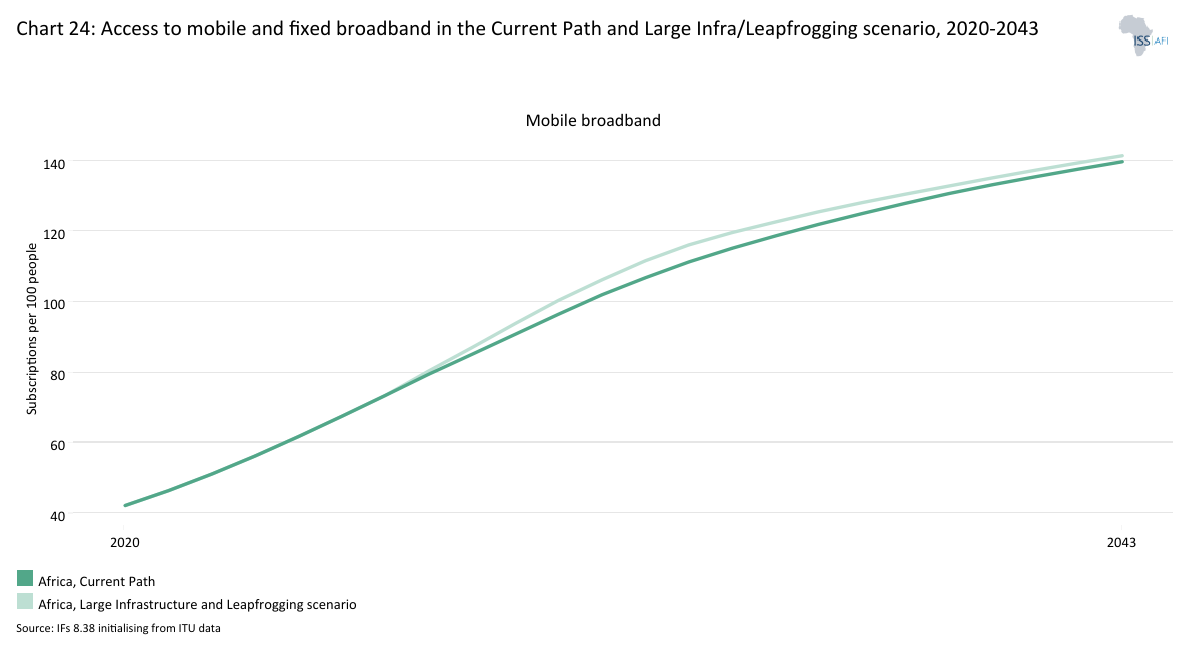

- The Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario accelerates Africa’s clean energy and digital transitions, with modern fuel cookstove adoption reaching 64% of households by 2043 compared to 57% under the Current Path, significantly expanding renewable energy production, especially solar. It also stimulates growth in digital services. However, persistent rural access gaps underline the need for targeted investment in infrastructure, affordability measures and inclusive energy planning to ensure no communities are left behind.

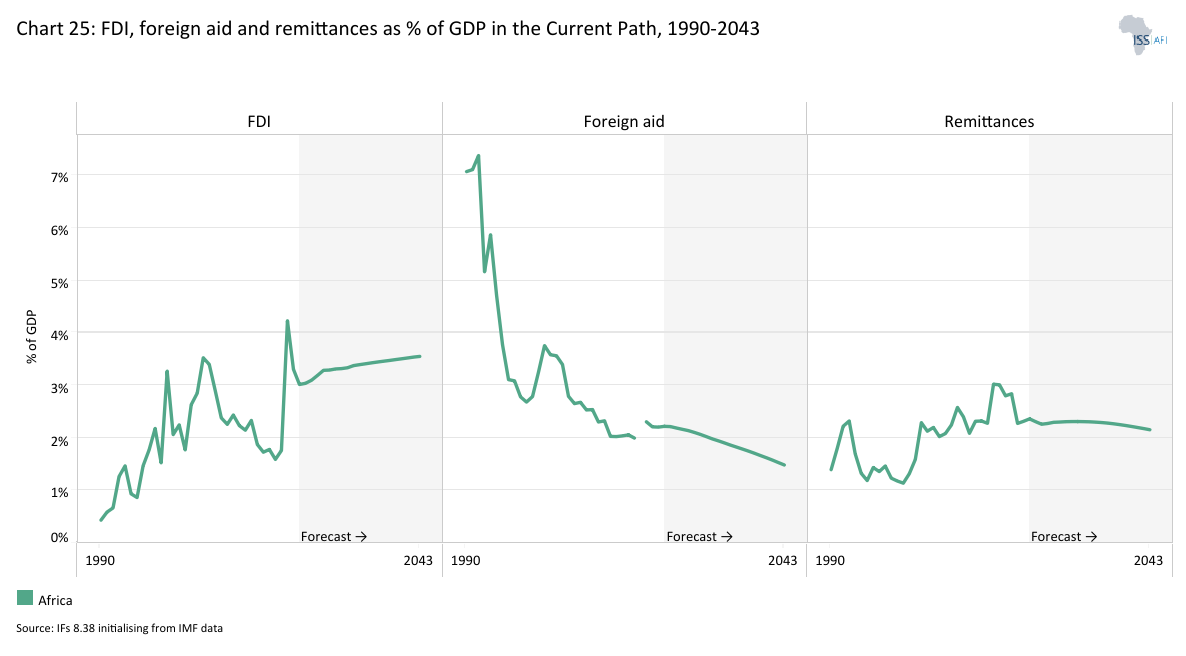

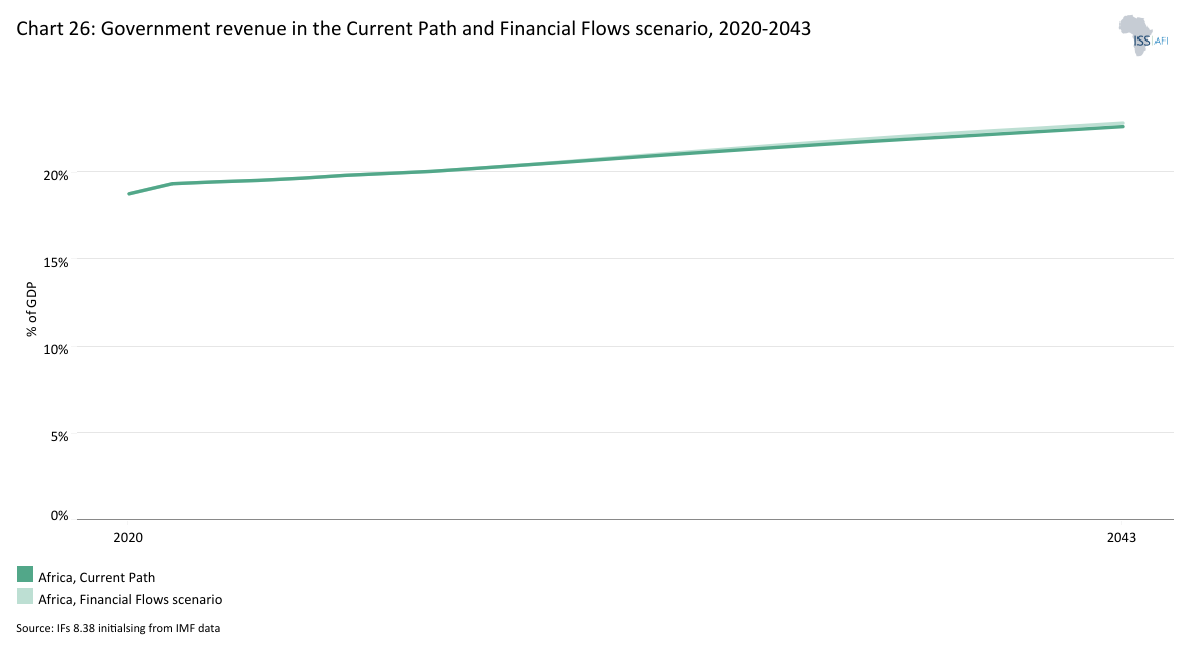

- The Financial Flows scenario boosts Africa’s external financing by raising FDI inflows to over 5% of GDP by 2043 and stabilising remittances, while moderating aid dependence to under 2% of GDP. However, without stronger domestic enterprise development and inclusive employment strategies, these flows risk reinforcing structural inequalities rather than driving broad-based growth.

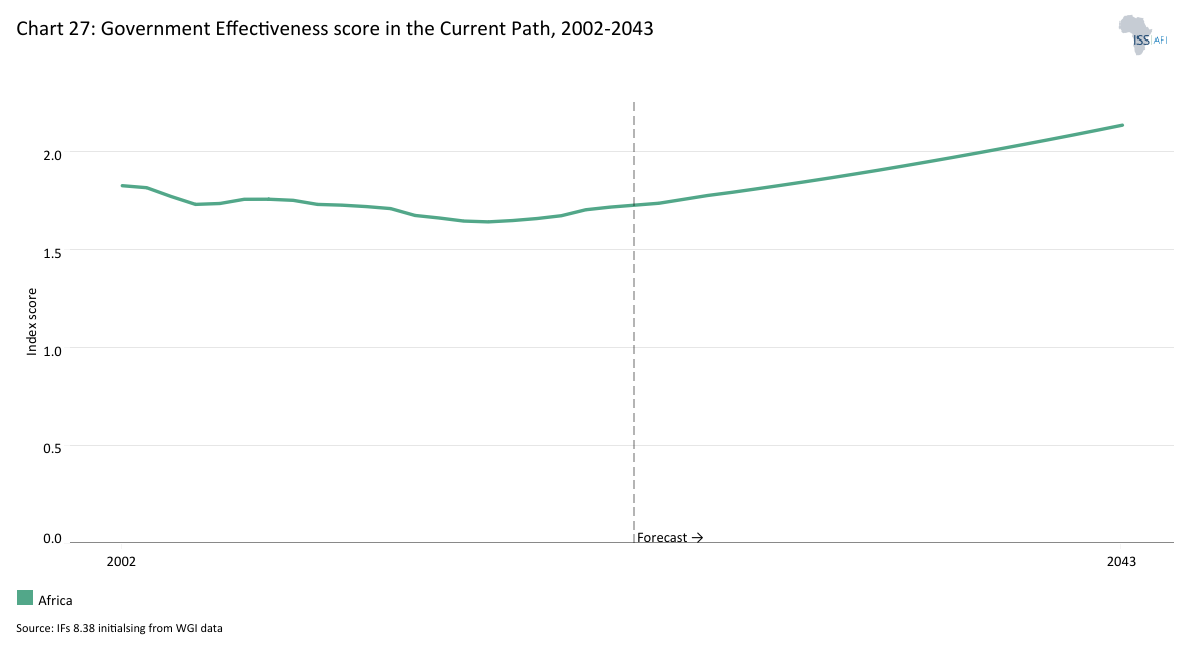

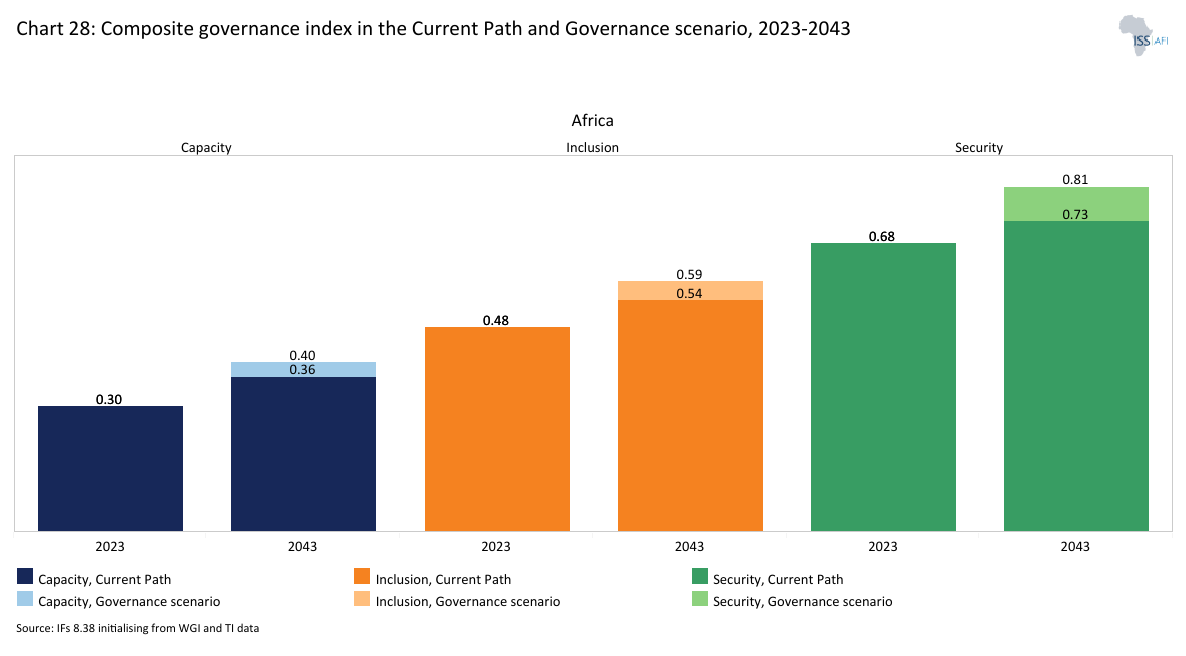

- The Governance scenario demonstrates that strengthening institutional effectiveness across all income groups enhances investor confidence, improves fiscal efficiency and expands welfare transfers, positioning governance reform as a decisive lever for inclusive growth, poverty reduction and sustainable development.

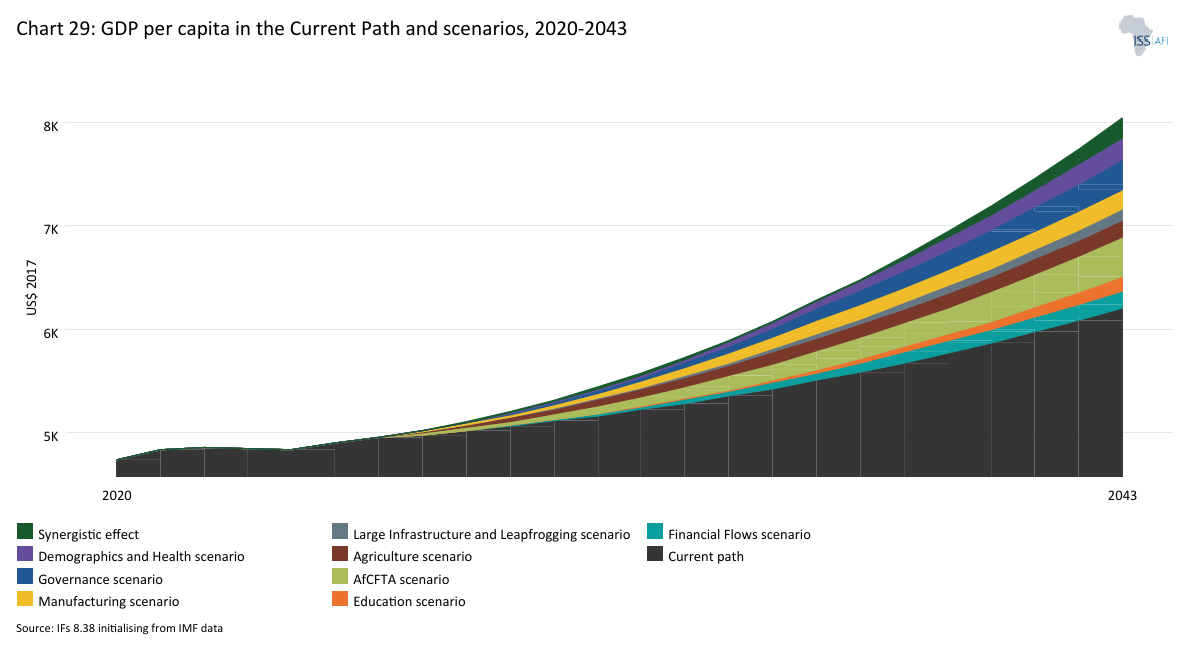

The fourth section compares the impact of each of these eight sectoral scenarios with one another and subsequently with a Combined scenario (the integrated effect of all eight scenarios). The forecasts measure progress on various dimensions such as economic size (in market exchange rates), gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (in purchasing power parity), extreme poverty, carbon emissions, the changes in the structure of the economy, and selected sectoral dimensions such as progress with mean years of education, life expectancy, the Gini coefficient or reductions in mortality rates.

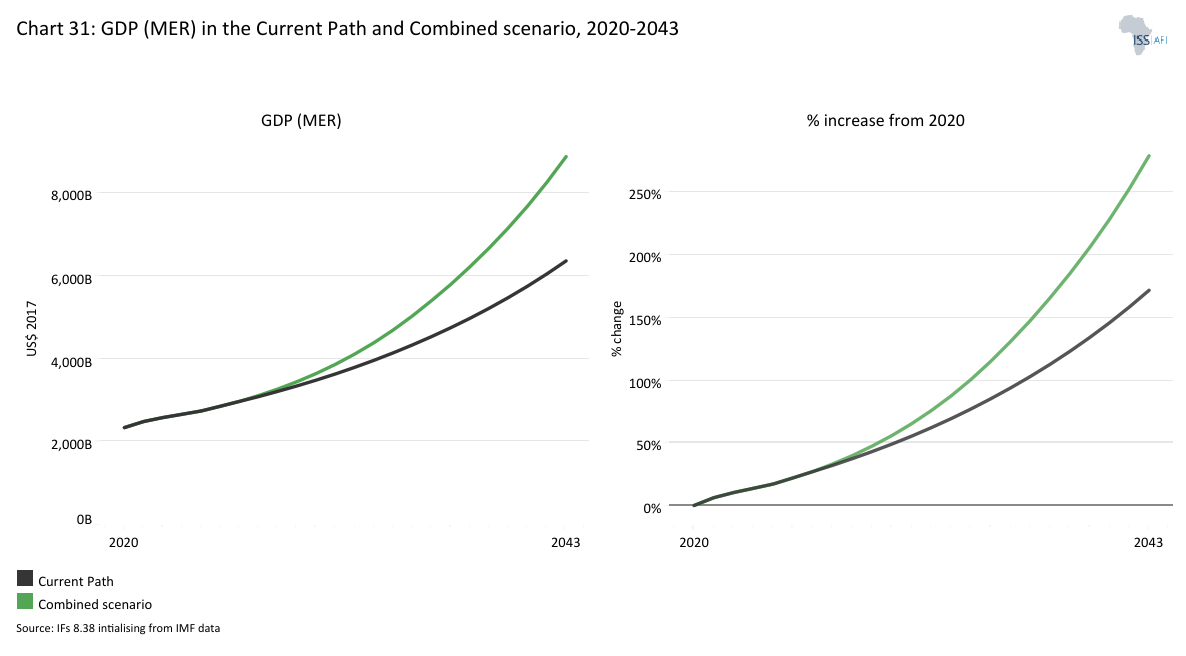

- Under the Combined scenario, Africa’s GDP (MER) will reach US$8.87 trillion by 2043, compared to US$6.36 trillion under the Current Path, reflecting accelerated growth from coordinated reforms across governance, intra-Africa trade, education and infrastructure. The average annual growth rate rises to 6.2% for the period 2024-2043 compared to 4.6% on the baseline, highlighting the compounding impact of coordinated, cross-sectoral reforms.

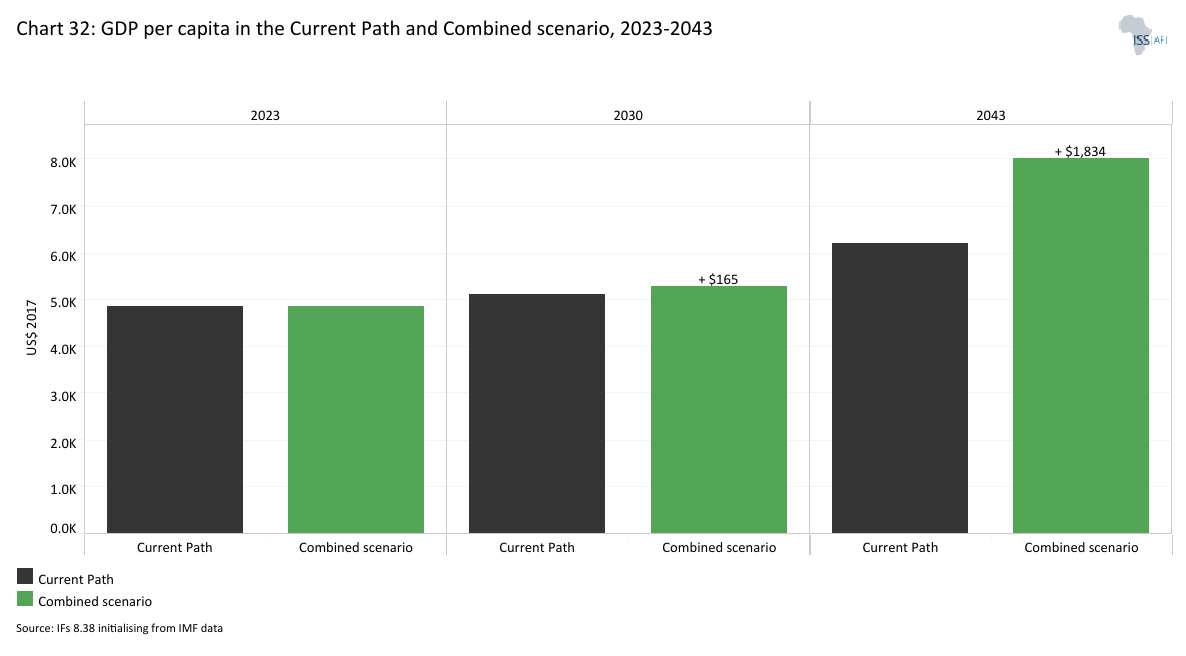

- GDP per capita increases to US$8 040 by 2043, approximately US$1 830 higher than the baseline forecast, reflecting more inclusive and sustained improvements in living standards. These gains are driven by stronger labour market performance, enhanced export competitiveness and expanded human capital development, underscoring the transformative potential of coordinated reforms.

- In the Combined scenario, Africa’s extreme poverty rate (measured at less than US$2.15/day per person) falls to about 11% by 2043, which is about 8.2 percentage points lower than the Current Path, lifting nearly 200 million more people out of poverty. These gains reflect faster income growth and more equitable distribution of development outcomes, highlighting the power of integrated, cross-sectoral reforms in breaking persistent poverty traps.

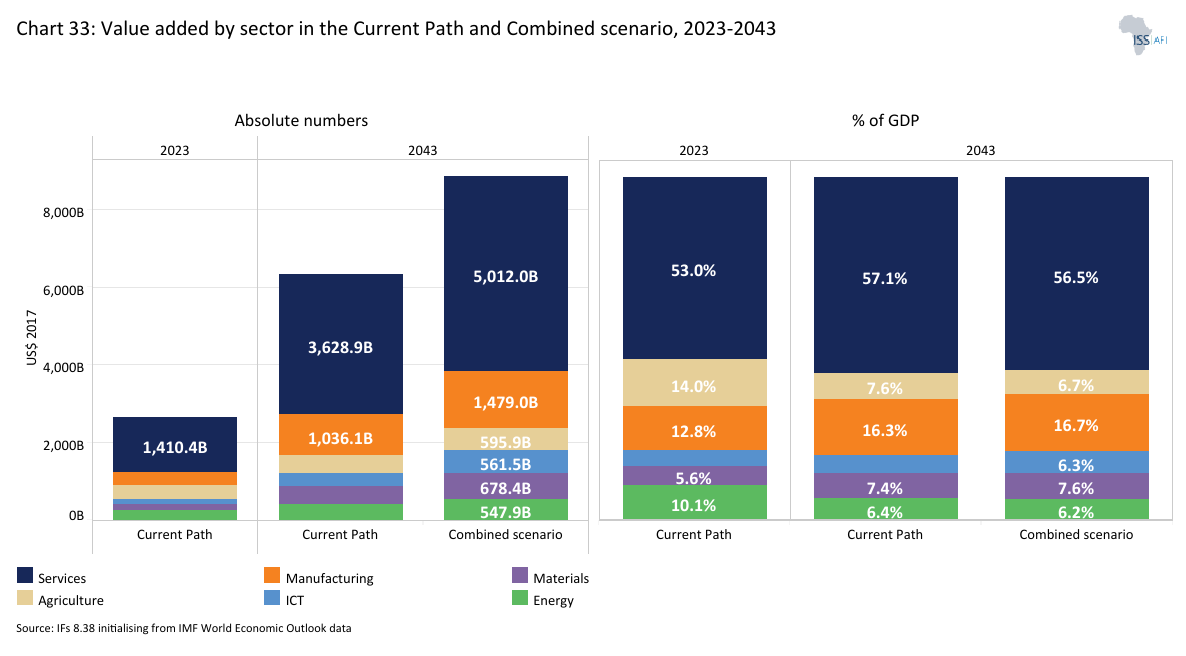

- The Combined scenario accelerates Africa’s structural transformation, with ICT, manufacturing and materials gaining the largest value-added shares of GDP by 2043, while agriculture and services contract slightly in relative terms. However, all sectors expand in absolute size, underscoring how industrialisation and digitalisation drive economy-wide spillovers, boosting productivity, technological diffusion and fiscal space across income groups.

- Informality declines considerably, with the informal sector’s GDP share falling to about 21% and informal employment dropping to 40% by 2043, compared to over 25% and 53% in the Current Path. These changes reflect progress in labour market formalisation, skills upgrading and SME integration into formal value chains.

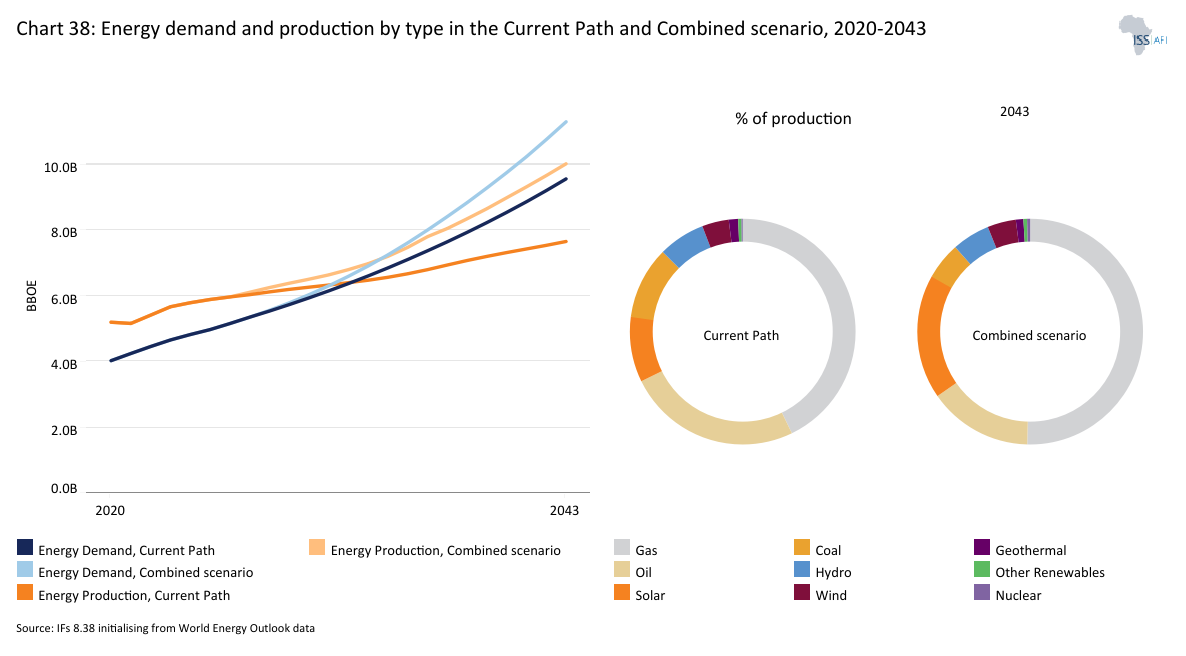

- Under the Combined scenario, Africa’s energy production rises to over 10 billion barrels of oil equivalent (BOE) by 2043, compared to 7.7 billion under the Current Path, with solar emerging as the main driver of growth. While the scenario narrows the continent’s energy deficit through renewables expansion, demand will still outpace supply, highlighting the urgency of scaling investments in solar, wind and regional power integration to sustain industrialisation and universal access goals.

The analysis concludes with a summarising section offering recommendations. The Current Path allows steady but insufficient progress, while the Combined scenario demonstrates that coordinated sectoral reforms can unlock transformative growth. Achieving this potential demands bold, integrated policies that drive structural transformation, inclusive development and sustainable energy systems, lifting hundreds of millions out of poverty and positioning Africa as a competitive global growth pole. Among the individual scenarios, AfCFTA and Governance emerge as pivotal levers, underpinning stronger economic growth, poverty reduction and more equitable income distribution.

All charts for Africa

- Chart 1: Political map of Africa

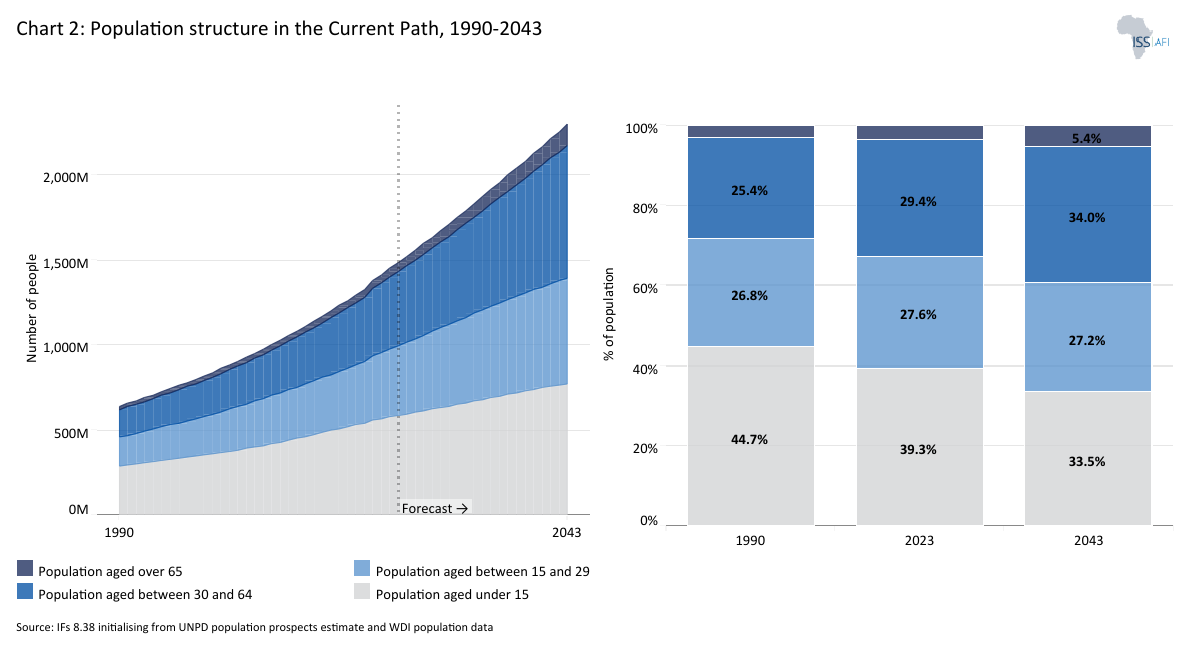

- Chart 2: Population structure in Current Path, 2020–2043

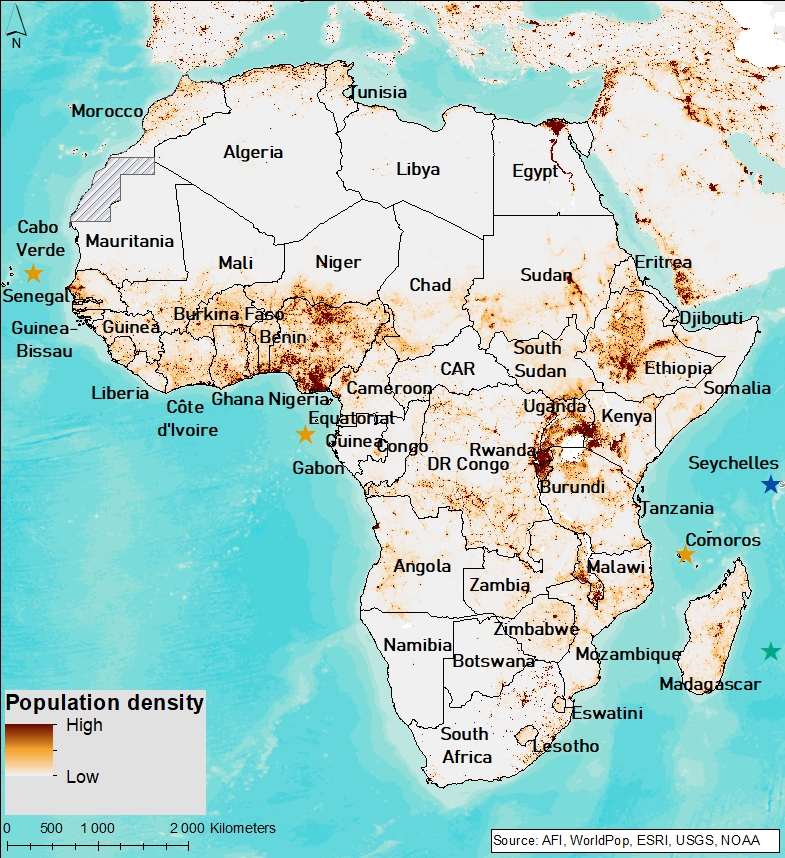

- Chart 3: Population distribution map, 2023

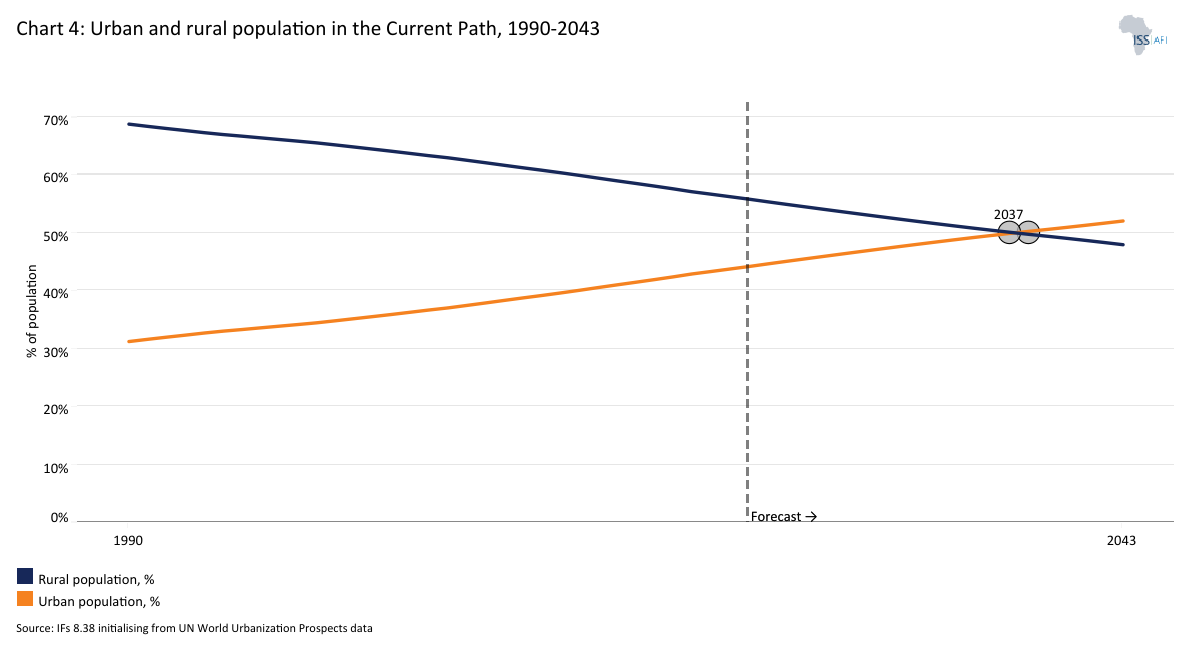

- Chart 4: Urban and rural population in the Current Path, 1990-2043

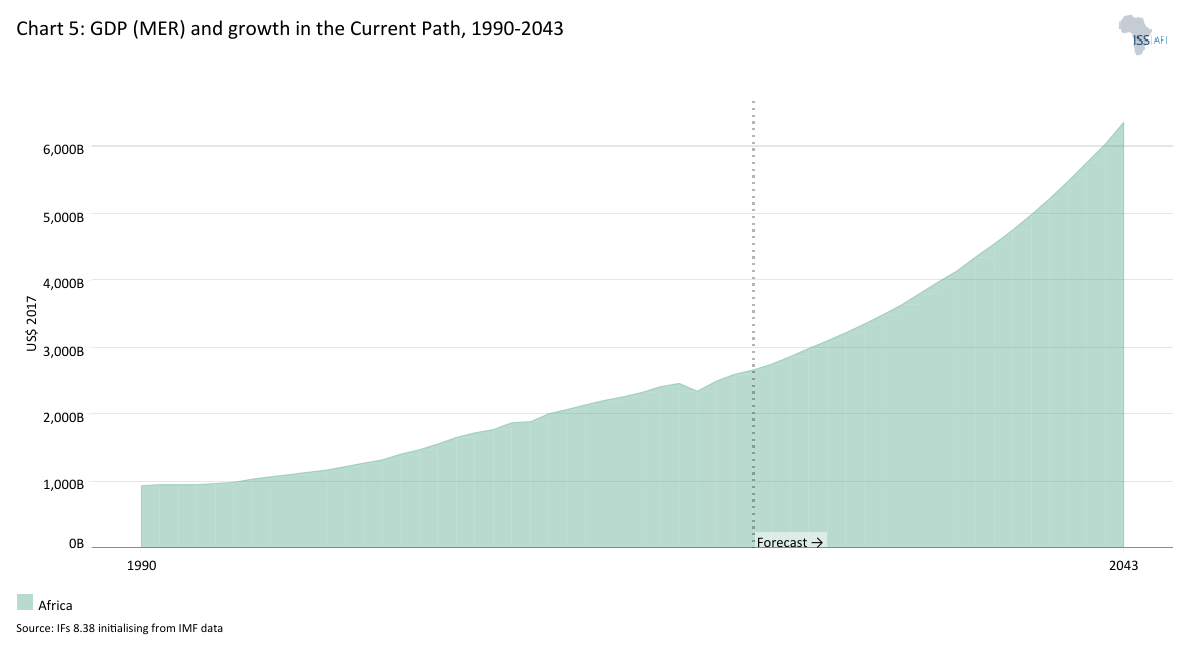

- Chart 5: GDP (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, 1990–2043

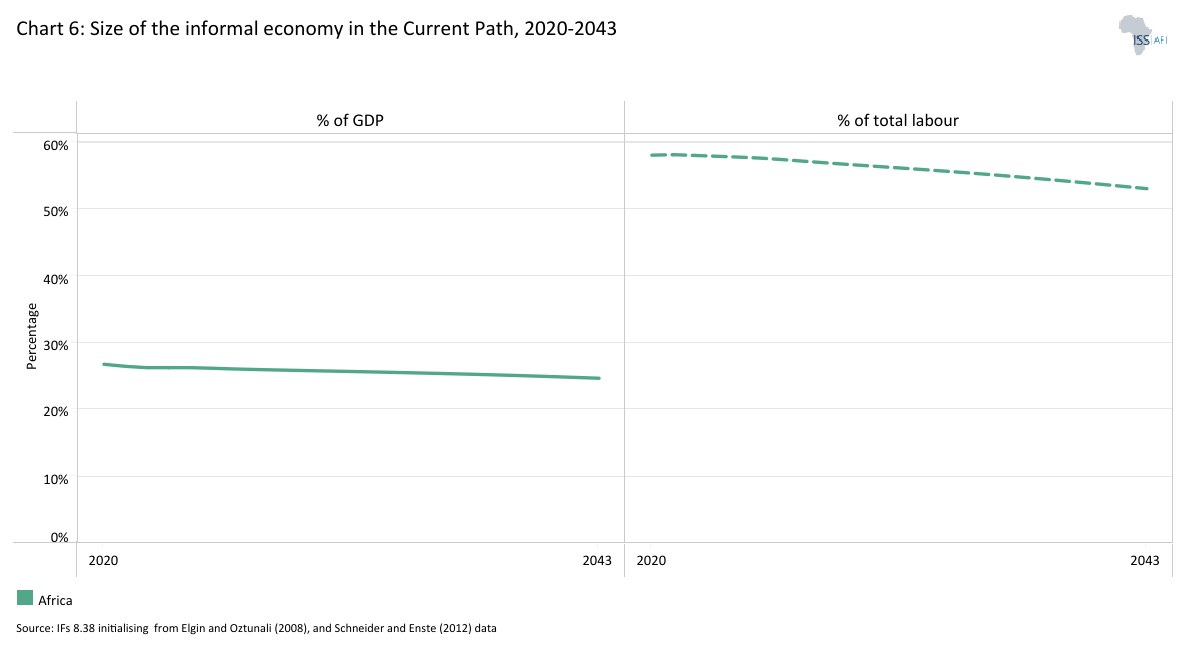

- Chart 6: Size of the informal economy in the Current Path, 2020-2043

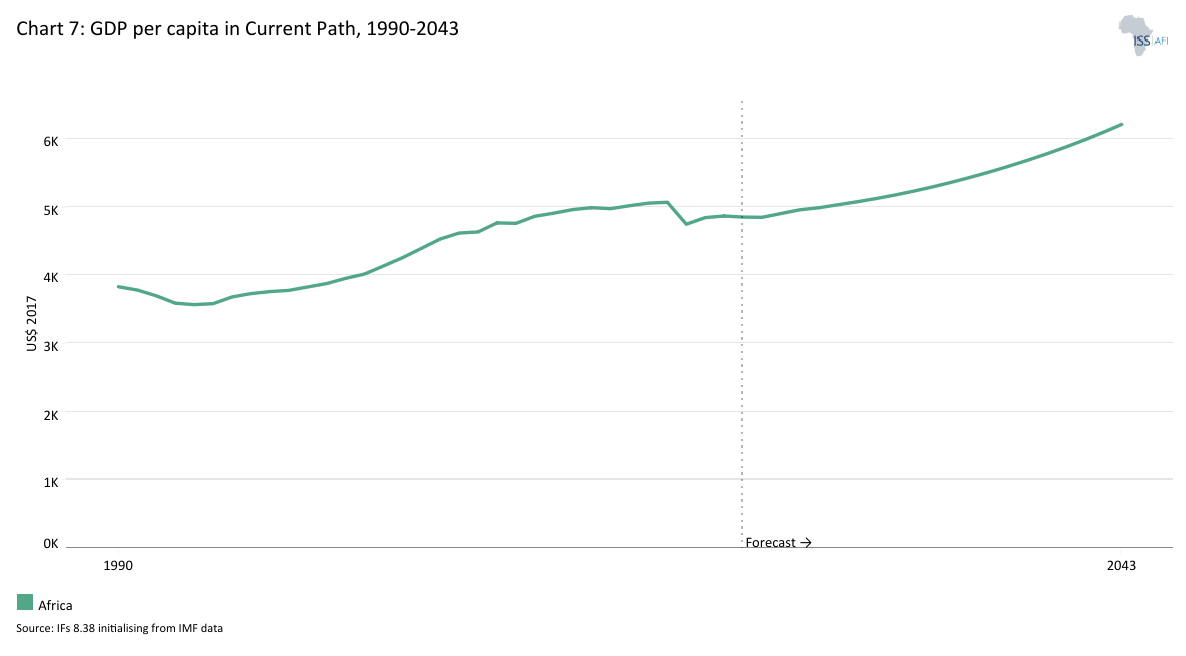

- Chart 7: GDP per capita in Current Path, 1990–2043

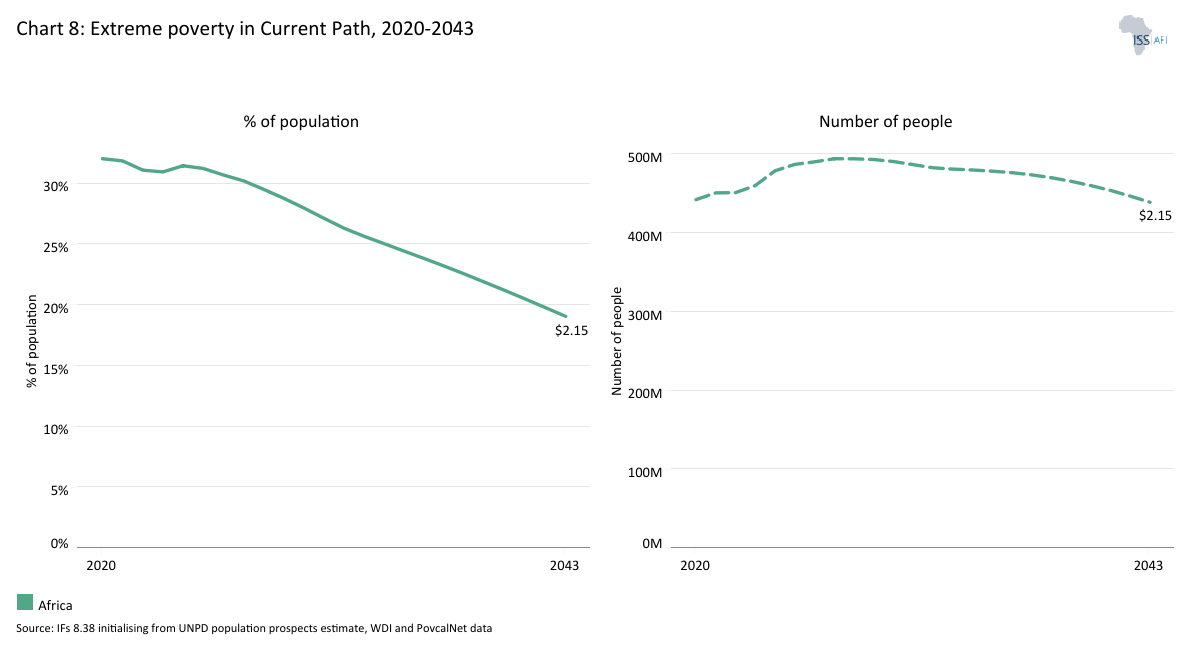

- Chart 8: Extreme poverty in Current Path 2020–2043

- Chart 9: Regional Development Plan of AFRICA

- Chart 10: Relationship between Current Path and Scenarios

- Chart 11: Mortality distribution in the Current Path, 2023

- Chart 12: Infant mortality rate in Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 13: Demographic dividend in the Current Path and the Demographics and Health scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 14: Crop production and demand in the Current Path, 1990-2043

- Chart 15: Import dependence in the Current Path and Agriculture scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 16: Progress through the education funnel in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 17: Mean years of education in Current Path and Education scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 18: Value-add by sector as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 19: Value-add by the manufacturing sector in the Current Path and Manufacturing scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 20: Exports and imports as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2000-2043

- Chart 21: Trade balance in Current Path and AfCFTA scenario, 2020–2043

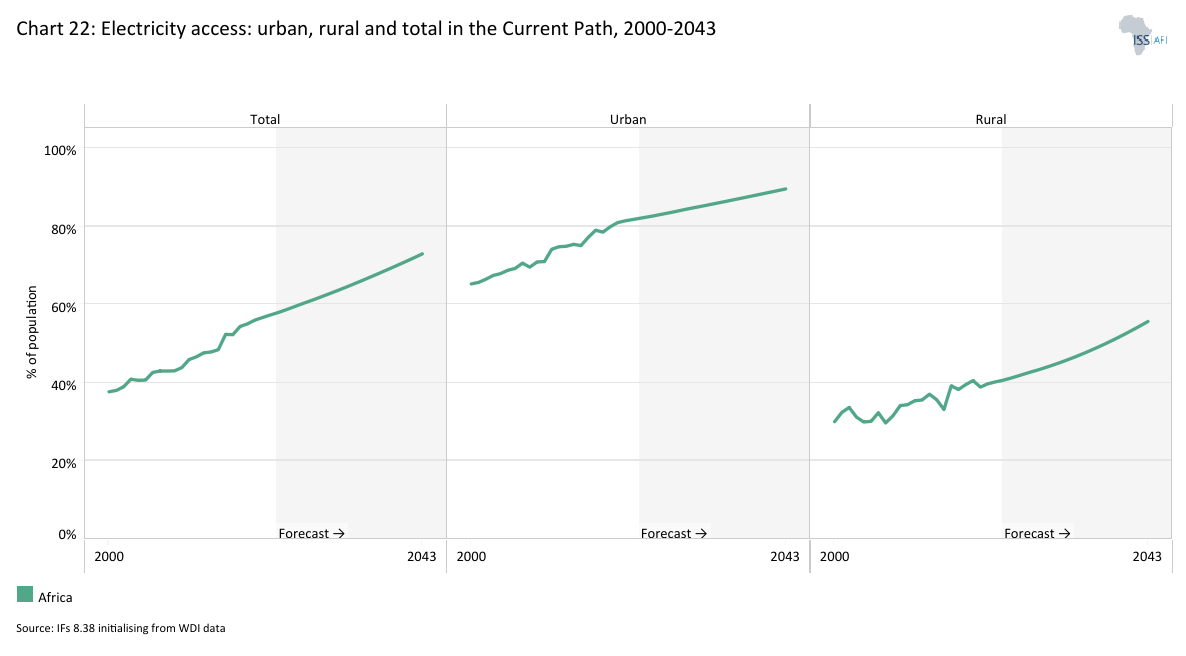

- Chart 22: Current Path access to electricity: urban, rural and total, 1990 to 2043

- Chart 23: Cookstove usage in Current Path and Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 24: Access to mobile and fixed broadband in Current Path and Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 25: Trends in FDI, aid and remittances as a % of GDP, 1990 to 2043

- Chart 26: Government revenue in Current Path and Financial Flows scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 27: Current Path of Government Effectiveness, 1990 to 2043

- Chart 28: Composite governance index in Current Path vs Governance scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 29: GDP per capita in Current Path and sectoral scenarios, 2020–2043

- Chart 30: Poverty in Current Path and sectoral scenarios, 2020–2043

- Chart 31: GDP (MER) in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 32: GDP per capita in the Current Path and the Combined scenario, 2020-2043

- Chart 33: Value added by sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 34: Informal sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 35: Poverty in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 36: Life expectancy in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

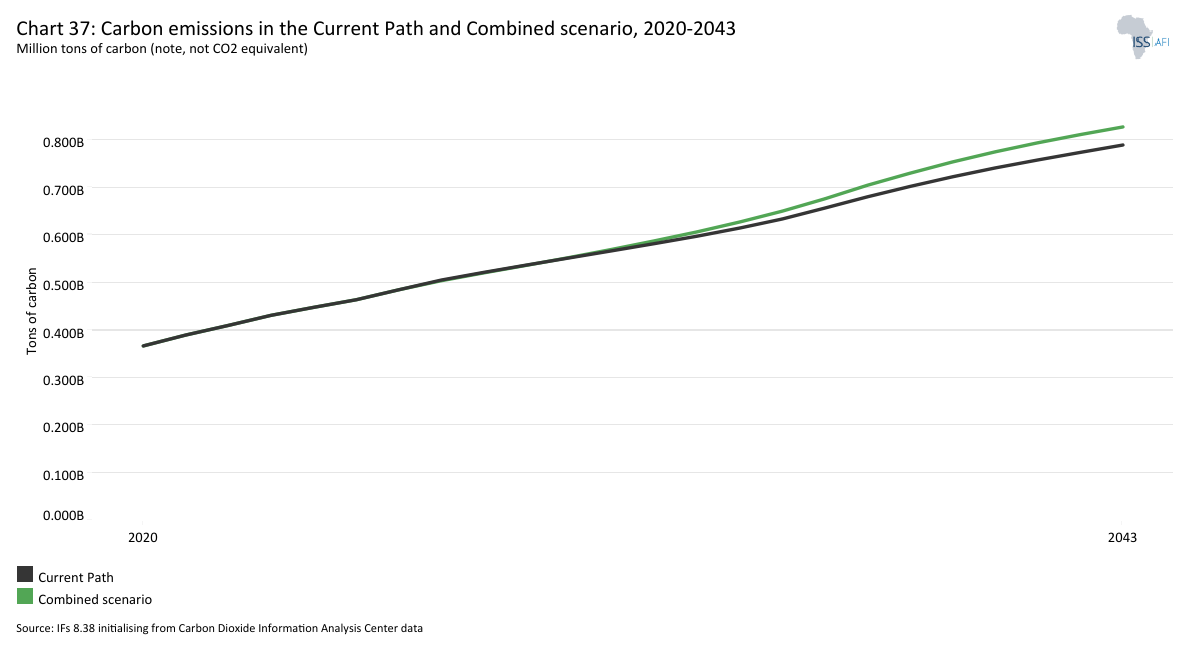

- Chart 37: Carbon emissions in Current Path and in Combined Agenda 2063 scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 38: Energy production by type in Current Path and Combined Agenda 2063 scenario, 2020-2043

- Chart 39: Policy recommendations

Chart 1 is a political map of Africa.

Africa is the world’s second-largest continent after Asia, spanning about 30.37 million km² or roughly 20% of Earth’s land area. Geographically, it straddles the Equator and is bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, the Red Sea and Indian Ocean to the east, and the Atlantic Ocean to the west. The continent stretches about 8 000 km north-south and 7 400 km east-west.

Africa’s northern extremity reaches into the temperate zone, but most of the landmass lies in tropical latitudes, giving rise to generally warm climates. The Sahara Desert dominates northern Africa, at around 8.6-9 million km², it is the world’s largest hot desert, spanning from the Atlantic coast to the Red Sea. In contrast, equatorial Africa is home to lush rainforests; the Congo Basin rainforest is the planet’s second-largest after the Amazon, covering roughly 300 million hectares (3 million km²).

Between these extremes lie the Sahel (a semi-arid belt south of the Sahara) and vast savanna grasslands. Major mountain highlands punctuate the continent, especially along the Great Rift Valley in the east. Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania rises to 5 895 m, the highest point in Africa, while the Atlas Mountains of the northwest and Ethiopia’s highlands are other prominent uplands. Africa’s longest rivers have been cradles of civilisation: the Nile River (6 650 km) is the longest in the world, flowing northward through 11 countries to the Mediterranean, and the Congo River (about 4 700 km) is the second-longest in Africa and by far the most voluminous, draining the continent’s largest basin into the Atlantic. Other major rivers include West Africa’s Niger (approximately 4 180 km) and Southern Africa’s Zambezi (approximately 2 574 km, featuring Victoria Falls).

Africa’s diverse terrain also encompasses the Kalahari and Namib Deserts in the south, the volcanic Great Lakes region (with Lake Victoria as Africa’s largest lake), and a generally elevated plateau that gives the continent an average altitude higher than that of Europe. This rich physical geography underpins Africa’s biodiversity, from rainforests teeming with species to savannas supporting the continent’s iconic megafauna, while also posing challenges such as arid expanses and limited natural harbours (Africa’s coastline, though long, has relatively few deep indentations).

Administratively, Africa is divided into 54 internationally recognised sovereign countries (all members of the United Nations), along with a handful of territories or disputed areas (the African Union, a continental body, counts 55 member states, including the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic/Western Sahara). These modern states are largely a legacy of colonial history. By the late 19th century, the “Scramble for Africa,” European powers partitioned nearly the entire continent into colonies. All but two African countries, Liberia and Ethiopia, were under colonial rule in the early 20th century.

After World War II, decolonisation swept the continent: beginning in the 1950s, dozens of nations attained independence (the 1960 “Year of Africa” saw 17 new countries). By the late 1970s, most of today’s African states were sovereign. The newest African country is South Sudan, which gained independence in 2011. Crucially, the post-colonial leaders upheld the colonial borders to avoid endless territorial disputes, despite those borders often cutting across ethnic or historical lines. This has left Africa with a patchwork of states varying greatly in size and shape, from Algeria (the largest by area, 2.38 million km²) and the DR Congo to island microstates like Seychelles (455 km²). Population distribution is likewise uneven: Nigeria, for example, has over 220 million people (Africa’s most populous nation), whereas several Saharan countries and small islands have under 2 million each.

Today, all African states (including the contested Western Sahara) are members of the African Union (AU), which was founded (as the OAU) in 1963 to promote unity and development. Many countries also cooperate through regional blocs. For instance, 12 West African nations form ECOWAS, and 16 Southern African nations comprise the Southern African Development Community (SADC). These and other Regional Economic Communities (East African Community, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), etc.) facilitate economic and political coordination across sub-regions.

Regarding internal governance, most African countries are unitary states with central governments subdividing the country into provinces or regions for administration. A few are federations, notably Nigeria’s 36 states and Ethiopia’s ethnically based regions, granting substantial autonomy to subnational units. Capital cities and major administrative centres are spread throughout the continent, with Cairo, Lagos, Kinshasa and Johannesburg among the largest urban agglomerations. Politically, Africa’s nations exhibit a range of systems from long-standing multiparty democracies (e.g. Ghana, Senegal) to authoritarian regimes or fragile states, often reflecting the varied post-independence trajectories. Nonetheless, Africa has seen an expansion of democratic institutions since the 1990s, alongside efforts to resolve conflicts and improve governance through AU initiatives.

Africa’s countries span the full spectrum of development levels, but overall, the continent remains the least economically affluent major region. A majority of the world’s low-income countries are in Africa. The World Bank classified 22 African countries as low-income in 2023. This accounts for almost 41% of Africa’s states and over 80% of all low-income states globally. By contrast, South Asia, a region of eight countries often compared to Africa, has reduced its share of low-income economies from 100% in 1987 to just 13% in 2023. Twenty-three African nations were in the lower-middle-income bracket, while only eight (Algeria, Botswana, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Libya, Mauritius, Namibia and South Africa) were upper-middle-income. Only Seychelles qualified as a high-income economy by World Bank criteria. This means Africa has the fewest high-income countries of any continent. Overall, Africa’s GDP per capita remains well below the global average, reflecting challenges such as limited industrialisation, infrastructure gaps, financial constraints and historical inequalities. However, there is significant variation: for example, small resource-rich states (like Gabon or Botswana) enjoy per capita incomes far above those of large, impoverished countries (like Burundi or Niger).

Africa’s cultural and linguistic diversity is unparalleled. The continent is home to an estimated 1 500 to 3 000 languages, roughly one-third of all languages on Earth. These fall into four major language families: Afro-Asiatic (around 200 languages across North Africa and the Horn, including Arabic, Amharic, Somali, Hausa), Niger-Congo (the largest group, over 1 000 languages widespread in West, Central and Southern Africa, notably the Bantu languages like Swahili, Yoruba, Igbo, Zulu), Nilo-Saharan (around 140 languages in pockets of the Sahara and East-Central Africa, e.g. Dinka, Kanuri) and Khoisan (a few dozen click-based languages in Southern Africa).

In addition, due to colonisation, European languages serve as official tongues in many countries. English is an official language in 23 African countries, French in 21, Arabic in 13, Portuguese in 6, Spanish in one and Swahili in at least 4. Most African states are multilingual, often recognising an indigenous lingua franca alongside a colonial language for government and education. For example, Swahili (Kiswahili), an indigenous pan-African lingua franca, is widely spoken in East Africa and was recently added as an official language of the African Union.

Other widely spoken African languages include Arabic (in North Africa and the Sahel), Amharic (Ethiopia), Yoruba and Igbo (Nigeria), Fulani (across the Sahel), Oromo (Horn of Africa) and many others, each with tens of millions of speakers. This mosaic of languages can be a developmental challenge (for instance, less than 20% of students in Francophone Africa are taught in their mother tongue). Still, it is also a rich cultural heritage. Efforts are underway to promote bilingual education and preserve endangered African languages.

Parallel to its linguistic variety, Africa’s ethnic composition is extraordinarily diverse. There are over 3 000 distinct ethnic groups across the continent. By comparison, no African country (except possibly Somalia or Swaziland) is ethnically homogeneous. Most nations comprise dozens of ethnic communities; Nigeria alone has over 250 ethnic groups, DR Congo over 200, while Tanzania has more than 100 distinct groups. These groups range in size from millions-strong peoples like the Arabs of North Africa, Hausa of West Africa, Yoruba and Igbo of Nigeria, Oromo and Amhara of Ethiopia, or Bantu clusters (e.g. Shona, Zulu, Luba), to small indigenous communities numbering only a few thousand. Ethnicity, defined by shared language, culture and ancestry, remains a key identity marker for most Africans, alongside nationality.

This enormous diversity is a source of cultural richness (manifested in Africa’s variety of traditions, music, art and social structures) but also a source of social complexity and potential tension. Colonial-era borders often grouped disparate peoples into one state or split the same ethnic group across countries, sometimes contributing to ethno-political rivalries. Several of Africa’s post-independence conflicts have had ethnic dimensions, from Nigeria’s Biafra war in the 1960s to inter-ethnic violence in Rwanda, Sudan, the Ivory Coast and others. That said, most African countries have also seen long periods of peaceful coexistence among their ethnic groups, and national identities have strengthened over time. Many governments maintain a delicate balance of power among major communities, and regional organisations like the AU emphasise non-discrimination and inclusivity.

Religiously, Africa is also diverse but largely dominated by Christianity and Islam, with roughly 45% of Africans Christian and 40% Muslim, plus sizable adherents of indigenous traditional beliefs. The religious mix often correlates with geography (for example, North Africa and the Sahel are predominantly Muslim, and sub-Saharan Africa is predominantly Christian except in the Horn and parts of West Africa). Importantly, religious and ethnic identities sometimes overlap; for example, Arab and Berber populations in the north are mostly Muslim, while many Bantu groups in southern Africa are Christian, but in other cases they cut across each other (Nigeria has both Christian and Muslim Yoruba and other groups). This pluralistic tapestry of ethnicities, languages and faiths makes Africa a continent of immense cultural complexity. Pan-African institutions often celebrate this diversity as a strength, even as they acknowledge its practical challenges for unity and development.

In summary, Africa’s political map, with its intricate blend of geographical features, colonial legacies, socio-economic disparities and cultural pluralism, provides the essential context for understanding the continent’s current development path and prospects.

Chart 2 presents the population structure from 2020 to 2043 in the Current Path.

Africa’s population has been growing faster than that of any other region, rising from about 644 million people in 1990 to roughly 1.5 billion in 2024. This represents nearly 18% of the world’s population, up from just 12% in 1990. The Current Path indicates that Africa’s population will continue to expand rapidly, reaching approximately 2.3 billion by 2043. By comparison, South Asia’s population (currently about 2.0 billion) is slightly larger today but growing more slowly. Africa is on course to overtake South Asia in total population around the middle of the century due to its higher growth rate. The United Nations forecasts that more than a quarter of the world’s people will be African by 2050, underscoring Africa’s demographic weight in the coming decades.

Africa is demographically the world’s youngest continent, with a median age of less than 20 years, far lower than that of any other region. In 2019, the median age in Africa was 19.7 years, compared to 31 years in South America and about 27 years in Southern Asia. This youthful age structure is reflected in the very large share of children in Africa’s population. As of 2023, an estimated 40% of Africans were under the age of 15, compared to about 25% of the global population being under 15 years. South Asia’s population is also youthful but somewhat older, with a median age in the late 20s and a smaller proportion of children due to faster fertility decline. Latin America’s demographic transition is even more advanced: its median age is now 31.7 years, up from 18 years in 1950, and only about 22% of Latin Americans are under 15. These comparisons highlight that Africa stands out for its youthful demographic profile, which brings opportunities and challenges. On one hand, a young population can energise a continent’s workforce and consumer base; on the other, it creates immense demand for basic services like education, healthcare and jobs for the growing ranks of youth.

Africa’s age structure is gradually evolving as the continent undergoes a slow demographic transition. Under the Current Path, the share of children will decline over time, even as absolute numbers still increase. By 2043, children under 15 will make up roughly one-third of Africa’s population, indicating a slowly narrowing base of the population pyramid. This decline is driven by falling fertility rates and improved child survival. Africa’s total fertility rate (TFR), which is the average number of children per woman, has begun to decrease from very high levels. It fell from about 6.6 in 1960 to 3.8 in 2024, and will drop to about 3.2 by 2043 under the Current Path. Nevertheless, African fertility remains high compared to other regions. For example, South Asia’s TFR is around 2.2 (near the replacement level) and in Latin America it is even lower at about 1.8.

Africa’s higher birth rates mean its population will continue growing faster and longer than elsewhere. In fact, five of the eight countries expected to account for over half of global population growth through 2050 are in Africa. In short, Africa’s demographic transition is in progress but lags behind peer regions: fertility is declining gradually and more children are surviving to adulthood, which will slowly reduce the youth dependency burden in the decades ahead. However, until fertility falls further, the continent’s population momentum will remain strong and will keep adding large numbers of people each year, even as growth slows modestly.

The share of the working-age population (15–64 years) is rising due to these trends. In 2023, about 56% of Africans were of working age, up from roughly 50% in the 1980s. In other words, the dependency ratio (the ratio of children and elderly to working-age adults) will improve over the next two decades. This is a positive development because a higher working-age share creates the potential for a demographic dividend, boosting economic growth when more people are in the labour force relative to dependants. By 2043, Africa’s working-age bracket will reach about 61% of the population under the Current Path, which is equivalent to roughly 1.6 working-age persons per dependant, inching closer to the threshold of 1.7 workers per dependant often seen as necessary to decisively reap a first demographic dividend. For context, the global average today is about 67% working-age (around two workers per dependant), a level that East Asia and Latin America have already surpassed. Africa is moving in the same direction: the number of dependants per adult is slowly falling. The labour force is set to expand substantially. Africa’s working-age population is projected to roughly double by 2050, which could fuel faster economic growth if those people can be productively employed.

Africa will also see growth in its elderly population. Though the share of elders remains small, the proportion of people aged 65 and above will rise from about 3.7% in 2023 to around 5.4% by 2043. Life expectancy on the continent will rise from 66 years in 2024 to 72.2 years by 2043 under the Current Path. This greying of the population is modest compared to other regions; Europe and East Asia have over 15% of their population above 65 years, but it signals an emerging need for policies and programs to support an ageing cohort. Healthcare systems and social services in Africa will increasingly need to cater to the elderly even as they continue to focus on the young. Improving pension systems, elderly healthcare and social safety nets will become more important as the absolute number of African seniors grows.

Overall, Africa’s evolving population structure presents a two-sided dynamic for policymakers. On one side is the promise of a massive working-age cohort that, if equipped with skills and jobs, can significantly boost productivity and development, the so-called demographic dividend. On the other side is the sobering reality that this dividend is not automatic. The swelling ranks of youth and young adults will put tremendous pressure on job creation, education and health services in the near term. Many African economies already struggle with high youth unemployment and underemployment, challenges that could intensify if economic growth and job creation do not keep pace with labour force growth.

The next 20 years are thus a critical period to implement policies that accelerate the demographic transition and harness its benefits. These include investing in girls’ education, expanding access to family planning, improving child survival and health, and stimulating economic sectors that can absorb young workers. Such measures can help to speed up the decline in fertility and enhance the productivity of the future workforce. Without sufficient investment in human capital and economic opportunities, the demographic dividend could be deferred or missed, leaving a large youth population frustrated by a lack of prospects.

Chart 3 presents a population density map of Africa for 2023.

Africa’s population distribution reflects a complex interplay of geography, economic opportunity and historical settlement patterns. The continent’s 1.5 billion people are unevenly spread, with significant concentrations in the fertile river basins, coastal zones, megacities and highland regions. The Nile Valley, the West African coastal belt and the Great Lakes region are among the most densely populated areas. At the same time, vast expanses such as the Sahara Desert, the Kalahari Desert and parts of the Sahel remain sparsely inhabited due to harsh climatic conditions.

Urbanisation continues to reshape Africa’s demographic landscape, with megacities such as Lagos, Cairo, Kinshasa, Johannesburg and Nairobi emerging as critical hubs of economic activity and migration. In 2023, the continent’s average urbanisation rate was about 45%, but this masks sharp contrasts across income groups and regions. North Africa is the most urbanised while upper-middle-income countries, such as those in Southern Africa, generally also record higher urbanisation levels, often above 65%, while low-income, primarily agrarian economies in Central and East Africa remain predominantly rural.

Regional differences are pronounced. North Africa exhibits dense populations along Mediterranean coasts and river valleys. At the same time, West Africa has large rural populations and rapidly growing urban clusters along trade corridors from Abidjan to Lagos. East Africa shows high rural density in fertile highlands, particularly in Ethiopia, Rwanda and Uganda. At the same time, Southern Africa is more urbanised, with population spread influenced by mining, industry and service hubs.

Compared with South Asia, Africa has a lower overall population density, around 52 people per square kilometre versus South Asia’s 308. However, its urban centres are growing faster in relative terms, reflecting accelerating rural-to-urban migration. Similarly, South America shows a more even spread of urbanisation across its territory. In contrast, Africa’s population distribution remains heavily concentrated in specific ecological and economic zones, leaving large areas sparsely populated.

From a policy perspective, the population distribution and rapid urbanisation rates underscore the need for spatial planning, infrastructure investment and regional economic integration to balance development between densely populated urban areas and underserved rural and semi-arid regions. This requires targeted investments in urban planning, transport corridors, energy access and digital connectivity to bridge geographic divides and unlock the full economic potential of both urban growth poles and rural economies.

Chart 4 presents the proportion of the population living in urban and rural areas between 1990 and 2043 in the Current Path.

Africa has undergone a steady and transformative urbanisation process over the past three decades. The proportion of people living in urban areas has risen from approximately 31% in 1990 to 45% in May 2025, driven by rural-to-urban migration, natural urban population growth and the expansion of secondary cities. This trend will continue under the Current Path, with the level of urbanisation surpassing 50% around 2037/38 and reaching 52.1% by 2043. From a comparative perspective, Africa’s levels of urbanisation are lower than South America’s, which is currently over 80%, but is converging toward Asia’s, which is currently 53% (albeit with greater variation between countries and regions).

Africa’s urbanisation will advance across all income groups, but at different speeds and from different baselines. Upper-middle-income African countries will remain the most urbanised, increasing from nearly 70% in 2023 to 76.5% in 2043, reflecting both their mature urban systems and continued economic pull of metropolitan centres. Lower-middle-income countries will see urbanisation rise from 49.2% to almost 58% over the same period, driven by industrialisation corridors, agricultural transformation and expanding services sectors. Low-income countries, although starting from a low base, will also experience a notable shift, from 32.5% in 2023 to 41.6% in 2043, as demographic pressures, infrastructure investment and climate-related livelihood changes accelerate migration to towns and cities.

Despite these trends, rural populations will continue to grow in absolute terms in many parts of Africa, especially in low-income countries where agriculture remains the primary livelihood, keeping pressure on rural services and livelihoods. This dual growth of urban and rural populations poses a spatial planning challenge. Urban centres require large-scale infrastructure upgrades, affordable housing and job creation strategies. At the same time, rural regions will need sustained investment in connectivity, agricultural value chains and essential services to prevent uneven development and rising inequality.

Harnessing the economic potential of this urban transition, while avoiding the pitfalls of unplanned growth, will be central to achieving Agenda 2063 targets for inclusive and sustainable development and SDG 11 on sustainable cities. However, as rapid urbanisation coexists with expanding absolute rural populations in many low-income countries, policy priorities therefore need to balance city-region investments (mass transit, affordable housing, resilient infrastructure, serviced land and municipal finance reforms) with rural connectivity and basic services (all-weather roads, digital links, electricity, water and sanitation) to avoid widening spatial inequality. This is consistent with the AfDB’s High 5s (“Improve the quality of life,” “Integrate Africa,” “Industrialise Africa”, “Feed Africa” and “Light up and Power Africa”) and with removing logistics bottlenecks to unlock the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) market access for firms in both metropolitan and hinterland locations.

Chart 5 presents a stacked area graph that includes each country in Africa’s economy from 1990 with a forecast to 2043, including the associated growth rate.

Africa’s economy has expanded substantially over the past three decades, with GDP at market exchange rates (MER) rising from almost US$1 trillion in 1990 to US$2.66 trillion in 2023, representing an average annual growth rate of 3.3%. Under the Current Path, GDP (MER) will more than double, reaching US$6.36 trillion by 2043, with average annual growth accelerating to 4.6% between 2024 and 2043. While this trajectory reflects steady progress, it remains below the 7% annual growth target envisioned in the African Union’s Agenda 2063 for achieving inclusive and sustainable prosperity.

Growth patterns differ markedly across income groups. The Current Path suggests that low-income countries will outpace all others, expanding at an average rate of 6.31% annually between 2024 and 2043, a reflection of the catch-up effect, rapid urbanisation and demographic momentum, followed by lower-middle-income economies at 4.65%, and upper-middle-income countries at 2.57%. The catch-up dynamic is consistent with Agenda 2063 and AfDB’s High 5 priorities, which emphasise accelerated growth in the least-developed economies through industrialisation, agricultural transformation and infrastructure-led integration.

Africa’s average growth has often trailed developing Asia, particularly South Asia, which the World Bank and IMF forecast to maintain the highest growth rates globally, about 5.8% in 2025 and averaging 6.2% in 2026-27, driven by strong private investment, large domestic markets and diversified exports. In contrast, Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) are forecasted to grow by a modest 2.3-2.5%, constrained by low productivity growth, political uncertainty and structural rigidities. This positioning leaves Africa between a high-performing Asia and a slower-growing LAC, but with much greater volatility due to commodity dependence and recurrent shocks.

Africa’s growth trajectory is shaped by a complex interplay of structural drivers and persistent constraints. The continent’s youthful demographics and rapid urbanisation are expanding domestic markets and labour supply, offering the potential for a demographic dividend similar to that once leveraged in parts of East and South Asia. However, unlike South Asia, which is further along in its fertility transition, Africa’s demographic window will only open fully with substantial investments in education, healthcare and job creation.

Economic performance is further constrained by heavy commodity dependence, with over half of African economies classified as commodity-dependent by UNCTAD, exposing them to price volatility and external shocks, a stark contrast to South Asia’s manufacturing- and services-led model and parts of Latin America with more diversified export baskets. Infrastructure and investment gaps, particularly in energy, transport and digital connectivity remain significant, keeping productivity low and trade costs high.

While Africa leads globally in mobile-money penetration, according to Global Findex, access to long-term credit and capital, particularly for small to medium enterprises (SMEs) and infrastructure, remains limited compared to South Asia and LAC. The AfCFTA offers a unique opportunity to reshape the continent’s growth model by boosting intra-African trade and building regional value chains. However, realising this potential requires accelerated investment in connecting infrastructure, industrial capacity, harmonised standards and stronger trade facilitation.

Africa’s growth potential is high, but its trajectory remains volatile. To match South Asia’s pace and structurally outpace LAC, the continent must diversify exports, strengthen governance, deepen regional integration, accelerate infrastructure development, mobilise private capital and invest in human capital at scale. These priorities are central to policy frameworks such as the Agenda 2063 First and Second Ten-Year Implementation Plans (FTYIP and STYIP, the AfCFTA, the Programme Infrastructure Development for Africa (PIDA), and strategies of regional economic communities. Implementing these measures would help unlock the demographic dividend, raise productivity and sustain higher growth rates. Without decisive action, Africa risks falling short of its potential, particularly when compared to peer regions that have successfully harnessed structural transformation to achieve rapid and sustained development.

Chart 6 presents the size of the informal economy as a per cent of GDP and in absolute terms, as well as the per cent of total non-agriculture labour involved in the informal economy, from 2020 to 2043.

In 2023, Africa’s informal sector accounted for 26.3% of GDP, nearly double the share observed in South Asia (approximately 14%) and South America (about 13%), and employed almost 58% of the labour force, a rate between that of South America (approximately 44.7%) and South Asia (almost 78%). Under the Current Path, this contribution will decline modestly to 24.7% of GDP and 53.1% of employment by 2043, signalling gradual structural transformation but leaving informality entrenched as a dominant labour market feature.

Informality is more pronounced across Africa’s income groups in lower-middle-income and low-income countries. In 2023, informal GDP shares stood at 30.6% and 31.7% for these groups, respectively, compared with just 14.7% for upper-middle-income countries. Under the Current Path, these figures will fall to approximately 27% for lower-middle-income, 28.2% for low-income and 13.8% for upper-middle-income economies by 2043. Employment patterns follow a similar trend: upper-middle-income countries’ informal employment will remain relatively low, inching up from 22.7% in 2023 to 23.4% in 2043, while lower-middle-income and low-income countries will see declines from 57.5% to 54.2% and approximately 66% to 56.5%, respectively.

Africa’s slower pace of economic formalisation reflects a combination of labour market informality traps, weak industrial absorption capacity and the persistence of subsistence and low-productivity service activities. While South America has reduced informality through stronger social protection, tax reform and industrial upgrading, and South Asia is benefiting from export-oriented manufacturing, Africa’s path has been constrained by low levels of human capacity development, poor infrastructure, underdeveloped manufacturing bases, inadequate SME financing and regulatory burdens.

Upper-middle-income African countries are best positioned to reach South American informality levels (less than 13% GDP share) before 2043, provided they expand SME formalisation incentives, digitise business registration systems and implement targeted tax reforms. Lower-middle-income countries could make substantial gains if they integrate regional value chains, supported by targeted skills development, export-oriented industrial policy and the digitalisation of microfinance. For low-income countries, foundational reforms, such as investing in agro-processing hubs, expanding basic infrastructure and strengthening social safety nets, are essential to shift large informal agricultural labour pools into semi-formal manufacturing and services.

Across all income groups, aligning formalisation strategies with Agenda 2063’s industrialisation and inclusive growth targets will be critical to maximising fiscal revenue, boosting productivity and sustaining poverty reduction. Key policy guidance can be drawn from the AU’s Labour Migration Governance Framework, which supports cross-border labour mobility and formal sector opportunities, and the ILO’s Recommendation No. 204 on transitioning from the informal to the formal economy, which provides direction on legal, institutional and social protection reforms. Together, these frameworks emphasise the need for labour-intensive manufacturing, targeted skills upgrading, digitalisation of microenterprises and expanded social protection coverage. These interventions can reduce vulnerability, increase productivity and create stronger incentives for formal participation across Africa’s diverse economies.

Chart 7 depicts GDP per capita in the Current Path from 1990 to 2043.

Africa’s GDP per capita, measured in purchasing power parity (PPP), increased from US$3 790 in 1990 to US$4 850 in 2023, reflecting an average annual growth rate of just 0.8%. This rate is significantly lower than that of peer regions, 3.7% in South Asia and 1.1% in South America over the same period. Africa now has the lowest GDP per capita of the three regions, having been overtaken by South Asia in 2014. In 2023, South Asia’s GDP per capita reached US$6 560, while South America’s was US$14 780. Under the Current Path, Africa’s per capita income will grow slowly, at 1.2% annually, to US$6 210 by 2043, still trailing its peers, South Asia at 2.8% and South America at 1.5% over the 2024-2043 period because of rapid population growth, modest economic growth rates and relatively high levels of inequality.

The average GDP per capita for upper-middle-income African countries will expand from US$13 000 in 2023 to US$14 870 by 2043 at just 0.68% annually, roughly matching South America’s current average. The average for lower-middle-income countries will grow from US$5 880 to US$7 650 at 1.4% annually. In contrast, that for low-income countries will expand fastest, from US$1 850 to US$3 060 at 2.5% annually, reflecting catch-up effects from a low base, a pattern consistent with the convergence hypothesis in growth theory.

This modest per capita income growth is shaped by enabling factors and structural bottlenecks. On the positive side, Africa’s demographic profile, resource endowments and rapid urbanisation create a foundation for market expansion, industrialisation and agglomeration economies. Regional integration through the AfCFTA and the spread of digital innovation, especially mobile financial services, offer potential productivity gains and inclusion benefits, echoing McMillan and Rodrik’s findings on structural change as a growth driver.

However, these merits are offset by deep-seated constraints: low productivity in agriculture and manufacturing, overreliance on volatile commodity exports, infrastructure deficits in energy, transport and logistics, and acute skills mismatches. Persistent governance challenges, political instability and climate vulnerabilities further undermine resilience and deter investment, reflecting the institutional quality-growth nexus highlighted in Robinson and Acemoglu’s work.

The Current Path trajectory falls short of the African Union’s Agenda 2063 and the African Development Bank’s High 5s, aiming for sustained, inclusive and high-growth pathways that would elevate most African countries to upper-middle- or high-income status by mid-century. Achieving these ambitions requires accelerating structural transformation through industrial policy and value addition, strengthening human capital via universal education and healthcare (SDGs 3 and 4), investing in renewable energy and digital infrastructure to lower costs and increase competitiveness, and mainstreaming climate resilience into economic planning. Without these interventions, Africa risks maintaining a growth path that narrows, but does not close, the per capita income gap with South Asia and South America.

Chart 8 presents extreme poverty as per cent and total numbers of the population for the Current Path, from 2020 to 2043.

In 2022, the World Bank updated the poverty lines to 2017 constant dollar values as follows:

- The previous US$1.90 extreme poverty line is now set at US$2.15, also for use with low-income countries.

- US$3.20 for lower-middle-income countries, now US$3.65 in 2017 values.

- US$5.50 for upper-middle-income countries, now US$6.85 in 2017 values.

- US$22.70 for high-income countries. The Bank has not yet announced the new poverty line in 2017 US$ prices for high-income countries.

Monetary poverty only tells part of the story, however. In addition, the global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) measures acute multidimensional poverty by measuring each person’s overlapping deprivations across ten indicators in three equally weighted dimensions: health, education and standard of living. The MPI complements the international US$2.15 a day poverty rate by identifying who is multidimensionally poor and also shows the composition of multidimensional poverty. The headcount or incidence of multidimensional poverty is often several percentage points higher than that of monetary poverty. This implies that individuals living above the monetary poverty line may still suffer deprivations in health, education and/or standard of living.[x]

Africa has made notable progress in reducing income poverty since the 1990s. The share of people living in extreme poverty, defined as living on less than US$2.15 per day, fell from 45.5% (293 million people) in 1990 to around 31% (461 million people) in 2023. This is a substantial improvement, but still lags behind peer regions. South Asia, for example, reduced extreme poverty from 50% in 1990 to just 9% in 2023, while South America cut its rate from 16.3% to about 3% over the same period. The Current Path suggests that Africa’s extreme poverty rate will fall to 19.1% (440 million people) by 2043, yet this will remain far above South Asia’s 2.5% and South America’s 2%, converging towards minimal rates.

The persistence of high absolute numbers, forecasted at nearly double the 1990 figure by 2043, is driven by rapid population growth, insufficient pro-poor growth strategies, relatively high levels of inequality and structural constraints in labour absorption. While most large South Asian economies have transitioned into middle-income status, many African states, especially in the Sahel and parts of Central Africa, remain trapped in cycles of low productivity, vulnerability to commodity shocks and fragility. This gap underscores the urgency for inclusive economic transformation as articulated in the African Union’s Agenda 2063 and AfDB’s High 5s, which prioritise industrialisation, economic diversification and job creation as levers for poverty eradication.

Disaggregating by income group shows the scale of the challenge. In low-income African countries, extreme poverty will decline from 44.6% in 2023 to 26.8% in 2043, but absolute numbers will stagnate at around 271 million people, peaking at 304 million around 2029–2030. In lower-middle-income countries, the extreme poverty rate will fall from 23.4% to 13.6%, with the number of poor decreasing from 175 million to 154 million. In upper-middle-income countries, poverty will drop from 11.3% to 9.3%, though numbers will edge up slightly from 14.5 million to 14.8 million. These differences highlight the asymmetric capacity of African economies to translate growth into broad-based welfare improvements.

However, monetary poverty alone does not capture the full extent of deprivation in Africa. The 2024 Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) reveals that around 52% of the population in sub-Saharan Africa lives in multidimensional poverty, far above the global average and more than double the region’s income poverty rate. This translates to roughly 544 million people deprived of health, education and living standards across 46 countries. Africa accounts for nearly half of the 1.1 billion people worldwide in acute multidimensional poverty, and more than half are children. Conflict-affected areas, such as parts of the Sahel, Sudan and the DR Congo, have the highest deprivation levels, where progress has stalled or reversed. By 2030, almost 60% of the world’s extreme poor are expected to live in conflict-affected economies, up from just over half now.

Children bear a disproportionate share of the burden; 317 million in sub-Saharan Africa are multidimensionally poor, and almost 27% of children under five suffer from severe food poverty. These overlapping deprivations create intergenerational poverty traps, where lack of nutrition, education and health care reinforce low productivity and limited economic mobility.

Multidimensional poverty remains significant even in relatively wealthier African economies. Namibia, an upper-middle-income country, has 40.9% of its population living in multidimensional poverty and another 19.2% vulnerable. In Ethiopia, despite its projected transition to middle-income status by 2025, 68.7% of the population was multidimensionally poor as of 2019. In the DR Congo, conflict and infrastructure collapse have left 3.9 million in emergency hunger and 23.8 million in crisis levels, figures that reveal poverty well beyond income measures.

Tackling poverty in Africa, therefore, requires a dual-track strategy that addresses both income and multidimensional poverty. On the income side, accelerating structural transformation through labour-intensive industrialisation, agricultural modernisation and intra-African trade via the AfCFTA is key. On the multidimensional front, investments must target universal access to healthcare, quality education, safe water, sanitation and affordable housing. In fragile contexts, this must be coupled with peacebuilding, governance reforms and climate resilience. Child-focused nutrition and social protection are critical to break intergenerational poverty traps. Aligning these interventions with Agenda 2063’s Aspiration 1 (A Prosperous Africa) and SDGs 1, 3, 4 and 8 will ensure that poverty reduction is embedded within a broader economic transformation agenda, narrowing the gap with South Asia and South America and reducing the risk of a permanent low-income equilibrium.

Chart 9 shows the Continental Development Plan.

Agenda 2063 is the continental umbrella. It sets the long-term vision, “The Africa We Want”, and is executed through successive Ten-Year Implementation Plans. The Second Ten-Year Implementation Plan (STYIP, 2024–2033) reframes this decade as one of acceleration, translating lessons from the first plan into tighter results frameworks, clearer institutional responsibilities and stronger financing and monitoring arrangements. In practice, the STYIP is the hinge: it links the high-level aspirations of Agenda 2063 to the sectoral and regional plans that actually move projects, money and regulations on the ground.

Market integration and industrialisation anchor the economic transformation agenda, and here the AfCFTA is the flagship. AfCFTA is explicitly branded by the AU as an Agenda 2063 project because dismantling tariff and non-tariff barriers, opening services markets and enabling movement of persons are the levers that turn a fragmented continent into a single production and demand base. The AU’s 2023 theme, “Acceleration of AfCFTA implementation”, underlined that linkage. Operational instruments such as the Pan-African Payments and Settlement System (PAPSS) reduce currency-conversion frictions and aim to make cross-border trade settle in local currencies. At the same time, the Single African Air Transport Market (SAATM) connects people and freight by liberalising skies, conceived as Agenda 2063 flagships that make AfCFTA tradeable in practice.

Infrastructure is the connective tissue that allows integration to translate into growth. The Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa - Priority Action Plan (PIDA-PAP 2 for 2021–2030) curates a portfolio of regional energy, transport, digital and transboundary water projects selected to reflect Agenda 2063 priorities, using an integrated corridor approach to crowd-in private capital and lift bankability. In other words, PIDA-PAP2 is the hard-asset pathway through which Agenda 2063’s aspirations for an integrated, competitive Africa become investable projects.

Productive transformation in food systems sits under the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) and the Malabo Declaration (2014–2025), which AU leaders designed to push agricultural productivity, resilience and trade as the foundation for inclusive growth. The Malabo era culminates in 2025 and is being succeeded by a Post-Malabo roadmap; both are deliberately aligned to Agenda 2063 because raising on-farm productivity, cutting food import dependence and scaling agro-processing are preconditions for broad-based industrialisation, poverty reduction and export diversification in the 2063 horizon.

Human capital, science and digital are the capability stack of Agenda 2063. The AU’s Science, Technology and Innovation Strategy for Africa 2034 (STISA-2034) is the updated science agenda meant to drive innovation-led growth and support industrial upgrading, health security and climate resilience; it is framed explicitly as a delivery instrument for Agenda 2063. In parallel, the Digital Transformation Strategy for Africa (2020–2030) provides the policy scaffolding for connectivity, data governance and digital trade, again positioned by the AU as aligned with Agenda 2063 and the SDGs, with the goal of an integrated and inclusive digital society and economy. Together, STISA-2034 and the digital strategy equip countries to exploit AfCFTA scale effects, adopt standards and build regional value chains in knowledge- and data-intensive sectors.

Climate and health security are the resilience pillars that keep growth durable along the 2063 path. The AU Climate Change and Resilient Development Strategy & Action Plan (2022–2032) is deliberately framed as an Agenda 2063 support instrument, aligning adaptation, mitigation and finance to protect development gains and open access to climate capital. On health, the Africa CDC Strategic Plan (2023–2027) operationalises the “New Public Health Order,” linking surveillance, manufacturing, workforce and regulation (via the African Medicines Agency) to Agenda 2063’s prosperity and human-development aspirations. In both domains, the message is the same: resilience is not peripheral to Agenda 2063; it is a core enabler of its macro-objectives.

Regional Economic Communities (RECs) translate Agenda 2063 into regional delivery compacts. SADC’s Vision 2050 and its Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan (RISDP) 2020-2030 were explicitly aligned to Agenda 2063 by ministerial directive and now prioritise industrialisation, infrastructure, human capital and cross-cutting climate goals in a way that mirrors the continental plan. ECOWAS Vision 2050 likewise states its linkage to Agenda 2063 and Agenda 2030, and the EAC’s Vision 2050 and Sixth Development Strategy anchor targets in both Agenda 2063 and the SDGs while pushing trade, industrialisation and digital transformation. The net effect is a cascading architecture: from continental goals to regional strategies to national plans, improving coherence and measurability.

What does this integrated architecture imply for implementation? First, Agenda 2063 is no longer abstract: it is operationalised through AfCFTA, PIDA-PAP2, CAADP/Post-Malabo, STISA-2034, the Digital Strategy, the AU Climate Strategy and the Africa CDC plan, each with defined institutions and scorecards under the STYIP. Second, delivery depends on knitting these plans together at the point of execution, for example, using AfCFTA rules and PAPSS to make regional agro-processing investments (PIDA corridors) bankable, while STISA-2034 and the Digital Strategy build the skills and data pipes that firms need, and the Climate Strategy de-risks projects for concessional finance. Third, RECs act as the last-mile orchestrators, aligning regional regulations, logistics and standards so that national reforms add up to continental outcomes. The through-line is clear: Agenda 2063 provides the compass; the sectoral and regional plans provide the routes; and the STYIP is the dashboard that keeps the convoy on schedule.

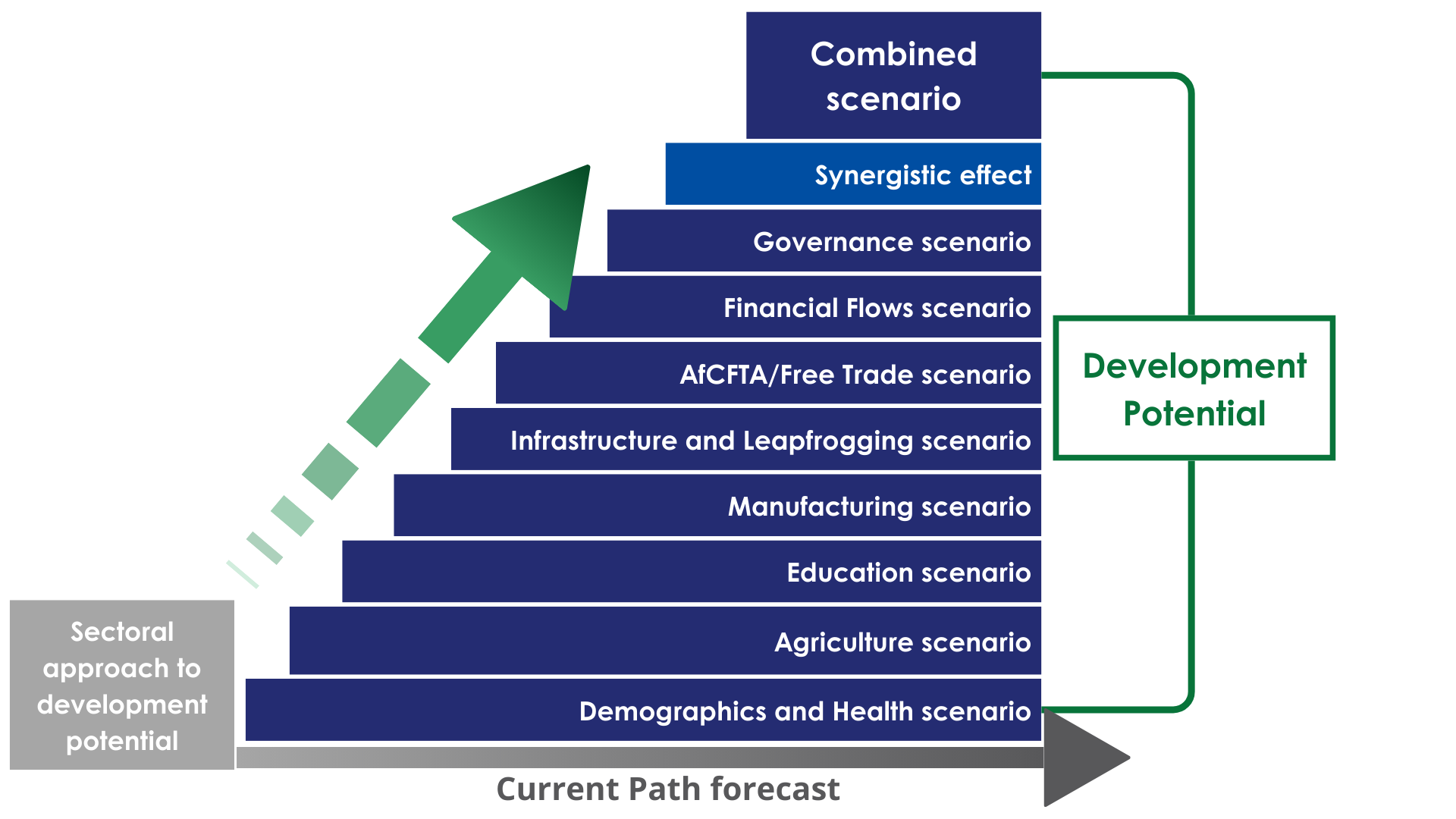

The eight sectoral scenarios, as well as their relationship to the Current Path and the Combined scenario, are explained in the Technical page. Chart 10 summarises the approach.

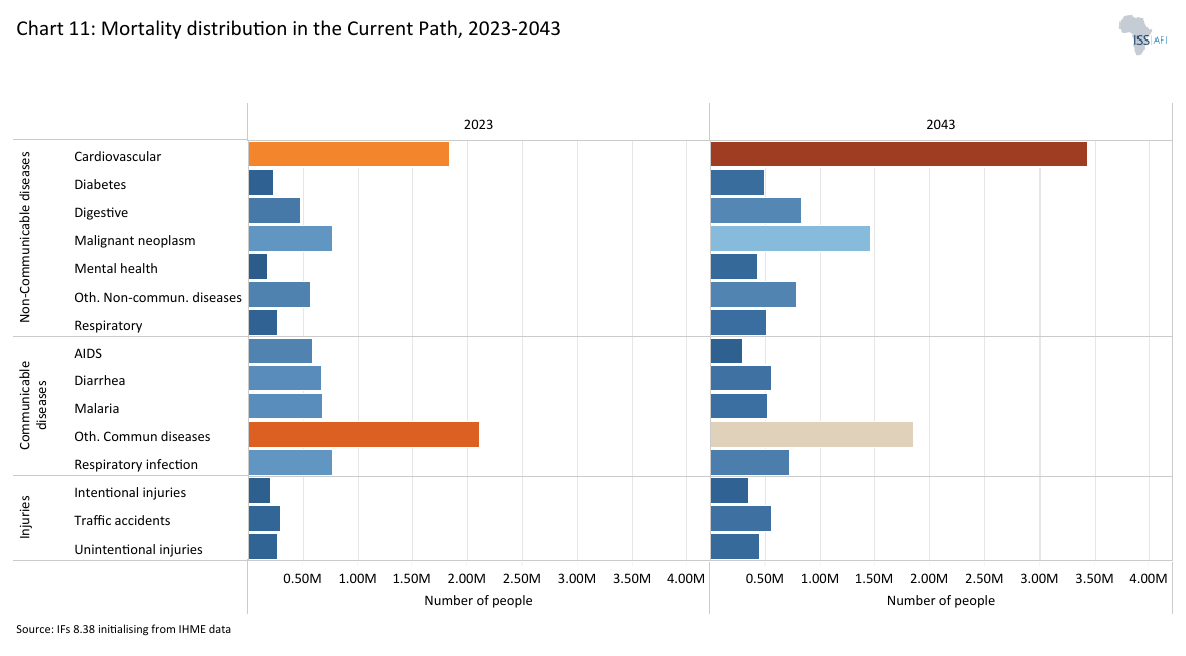

Chart 11 presents the mortality distribution in 2023.

The Demographics and Health scenario envisions ambitious improvements in child and maternal mortality rates, enhanced access to modern contraception, and decreased mortality from communicable diseases (e.g., AIDS, diarrhoea, malaria, respiratory infections) and non-communicable diseases (e.g., diabetes), alongside advancements in safe water access and sanitation. This scenario assumes a swift demographic transition supported by heightened health and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WaSH) infrastructure investments.

Visit the themes on Demographics and Health/WaSH for more details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Africa’s health profile reflects a double burden of disease, persisting communicable, maternal, neonatal and nutritional conditions alongside a rapidly rising tide of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). Between 2000 and 2019, deaths from communicable, maternal, perinatal and nutritional causes declined by about 31%, from 5.9 million to 4.1 million, reflecting progress in expanding immunisation, improved child survival and better access to basic health interventions. Yet these conditions remain dominant, with neonatal disorders (11.3%), lower respiratory infections (9.9%), diarrhoeal diseases (6.4%), HIV/AIDS (5.6%) and malaria (5.5%) ranking among the top causes of death in 2019. While malaria had dropped to 7th place by 2019, by 2021 it again ranked among the top five, underscoring the fragility of recent gains and the risks of climate change, weak health systems and conflict in reversing progress.

Looking forward, the Current Path suggests a continued decline in deaths from infectious causes, but not enough to erase them as major killers. Respiratory infection- and malaria-related deaths will drop modestly, from 771 050 and 677 290 in 2023 to around 716 550 and 527 330 by 2043, respectively. Mortality from other communicable diseases will drop from 2.12 million to 1.86 million over the same period.

Communicable mortality trends vary by income group. AIDS remains more prevalent in upper-middle-income countries, while malaria, respiratory infections and diarrhoeal diseases dominate in low-income and lower-middle-income countries, where poor sanitation and limited health infrastructure compound vulnerabilities. HIV/AIDS-related deaths in upper-middle-income African countries will fall from about 149 000 in 2023 to 101 170 by 2043, reflecting greater access to antiretroviral treatment. However, inequalities in rural areas remain a concern.

Low-income countries carry the heaviest malaria, respiratory infections and diarrhoeal diseases burden. In 2023, they accounted for approximately 287 000 malaria deaths, 323 000 respiratory infection deaths and 316 000 diarrhoeal deaths. While these figures will decline to roughly 176 000, 286 000 and 220 000 by 2043, respectively, they will remain high, highlighting persistent gaps in water, sanitation and universal health coverage. In lower-middle-income countries, malaria- and respiratory infection-related deaths will also drop slightly from about 386 000 and 402 000 to 348 000 and 395 000, respectively.

In contrast, Africa faces a sharp rise in NCDs. Between 2000 and 2019, NCD-related deaths increased by almost 38%, from 2.10 million (24.1% of total deaths) to 2.89 million (37.1%). In 2019, ischaemic heart disease (5.5%), stroke (5.5%), road injuries (3.8%) and liver cirrhosis (2.5%) emerged as major killers, reflecting Africa’s epidemiological transition alongside rapid urbanisation, dietary changes and rising obesity. By 2021, stroke had surged to the third leading cause of death, highlighting the growing burden of cardiovascular disease.

The Current Path indicates a steep rise in NCD mortality. Deaths from cardiovascular diseases will grow from 1.84 million in 2023 to 3.44 million by 2043, while deaths from malignant neoplasms will rise from 770 000 to 1.45 million. Other NCD-related deaths will also increase, from approximately 580 000 to 790 000 over the same period.

This burden will be felt universally across income groups. In upper-middle-income countries, cardiovascular disease and malignant neoplasm deaths will rise from 231 000 and 106 000 in 2023 to 409 000 and 176 000 by 2043. In lower-middle-income countries, they will expand from 1 million and 392 000 to 1.8 million and 710 000, while in low-income countries, they will climb from about 600 000 and 273 000 to 1.3 million and 566 000, respectively.

Thus, this dual challenge shapes Africa’s health outlook: while communicable diseases remain widespread, NCDs are rising rapidly due to urbanisation, dietary changes, sedentary lifestyles, and ageing populations. The consequence is a growing strain on already under-resourced health systems, which must simultaneously invest in infectious disease control and prevention and treatment of chronic conditions.

To navigate this epidemiological transition, Africa must scale up integrated health strategies that strengthen primary healthcare systems, expand access to universal health coverage and invest in disease surveillance and epidemiological capacity. Expanding prevention programs for NCDs, such as tobacco and alcohol regulation, nutrition policies and road safety campaigns, will be critical, alongside ongoing malaria, diarrhoea and HIV/AIDS control efforts. Furthermore, health sector reforms should be linked to broader continental initiatives like the Africa CDC’s New Public Health Order, Agenda 2063’s health priorities and the SDGs, ensuring health security and resilience are at the centre of Africa’s development trajectory.

Africa’s Agenda 2063 and the Africa Health Strategy (2016–2030) emphasise the dual challenge of finishing the unfinished agenda on communicable disease control while addressing the surge of NCDs through prevention, early detection and health system strengthening. Comparatively, the health burden in South Asia has shifted decisively toward NCDs, with India and Bangladesh reducing child mortality and infectious disease deaths to levels far below Africa’s. South America has also transitioned more rapidly, benefiting from stronger social protection and universal health care systems.

In sum, the continent’s progress in mortality reduction remains fragile and uneven, with low-income countries at risk of being trapped with a double disease penalty. Without scaled-up investment in universal health coverage, resilient primary health care and climate-sensitive disease surveillance, the continent risks falling short of Agenda 2063 health targets and SDG 3, particularly in reducing neonatal mortality, ending preventable deaths from communicable diseases and tackling NCDs.

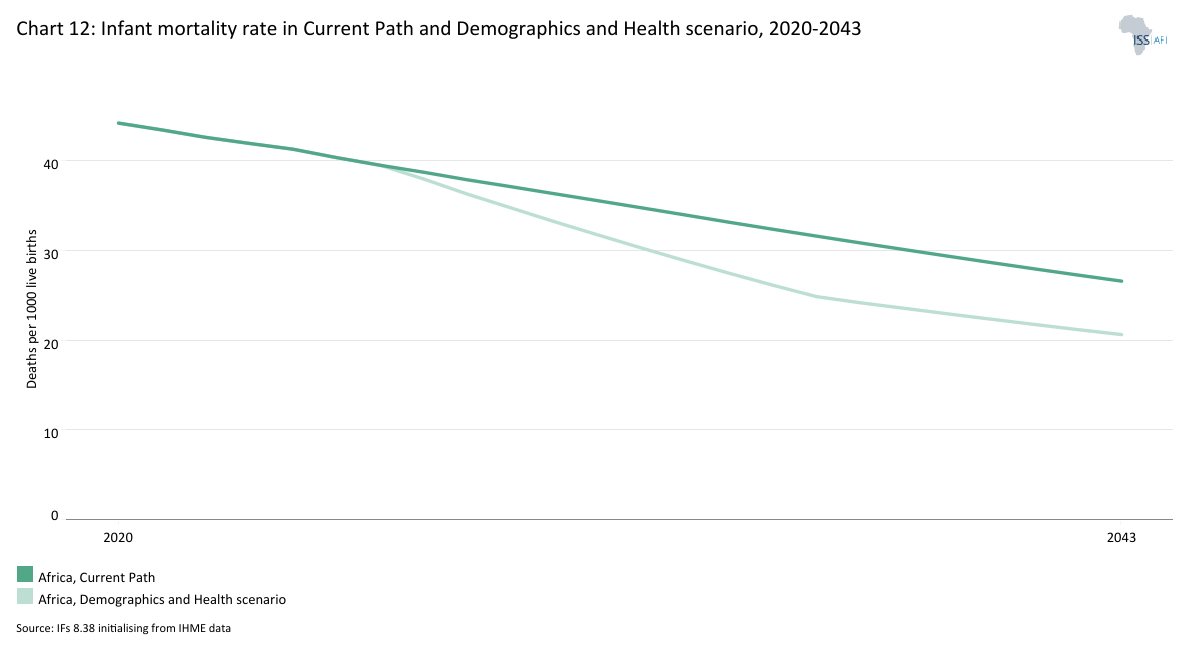

Chart 12 depicts the infant mortality rate in the Current Path versus the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

The infant mortality rate is the probability of a child born in a specific year dying before reaching the age of one. It measures the child-born survival rate and reflects the social, economic and environmental conditions in which children live, including their health care. It is measured as the number of infant deaths per 1 000 live births and is an important marker of the overall quality of the health system in a country.

Africa has recorded significant improvements in child survival over the past three decades. In 2024, the continent’s infant mortality rate (IMR) stood at 41 deaths per 1 000 live births, representing a 60% decline from 1990 levels. The Current Path suggests further progress to approximately 27 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2043. However, income-group disparities will persist. Low-income countries will see the largest improvements, with infant mortality declining from 43.3 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2023 to 23.7 by 2043, surpassing lower-middle-income country performance by around 2025/26. This trajectory reflects progress in maternal and child health interventions among African low-income countries. In lower-middle-income countries, IMR will decrease by about 12 deaths, from 42.8 to 30.9, during the same period. Upper-middle-income countries will experience slower gains, with rates dropping by only four deaths per 1 000 live births, from 24 in 2023 to about 20 in 2043.

Lower-middle-income countries lag behind low-income peers in achieving sharper improvements, despite relatively stronger economies, a paradox that reflects structural health system challenges. Lower-middle-income countries often face widening inequalities between urban and rural populations, with healthcare investments disproportionately concentrated in cities. Moreover, these countries experience a middle-income trap in health financing, external donor support declines as incomes rise, but domestic fiscal space for healthcare remains constrained, leading to underfunded primary care and child health services. By contrast, low-income countries continue to attract targeted donor programs for child survival (for example, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and Global Fund support for HIV, TB and malaria), which directly improve child mortality outcomes. This divergence underscores the importance of equitable health financing, prioritisation of rural healthcare delivery, and better integration of maternal and child health services into universal health coverage frameworks.

Despite the overall progress under the Current Path, Africa’s infant mortality rates remain relatively high compared to peer regions. In 2022, sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 57% of global under-five deaths (about 2.8 million) while representing only 30% of global live births. The region also recorded the highest neonatal mortality rate in the world (27 deaths per 1 000 live births), well above central and southern Asia (21 per 1 000). These figures highlight both the progress made and the urgent need for accelerated interventions in maternal and child health.

Alternative policy pathways show even greater potential. Under the Demographics and Health scenario, which envisions faster investments in healthcare access, immunisation and maternal health, Africa’s IMR will fall to 21 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2043, six deaths lower than the Current Path forecast. Disaggregated by income groups, upper-middle-income countries would reduce IMR to about 16 per 1 000 live births (four deaths below the Current Path), while lower-middle-income countries would achieve the largest additional gains, reaching 23 per 1 000 (seven deaths lower). In low-income countries, IMR could decline to 19 per 1 000 (five deaths below the baseline), marking a dramatic improvement compared to historical performance.

To sustain and accelerate progress in reducing infant mortality, Africa must prioritise short-term, high-impact interventions, particularly in low-income and lower-middle-income countries where child survival remains most precarious. Central to this effort is the strengthening of primary healthcare systems, ensuring they are adequately staffed, financed and equipped to deliver essential maternal and child health services. Expanding immunisation programs, improving maternal and child nutrition and guaranteeing universal access to skilled birth attendants will directly address the leading causes of infant and neonatal deaths. These must be complemented by investments in clean water, sanitation and reliable electricity access, which are vital for reducing infection risks and ensuring safe deliveries, especially in fragile and conflict-affected contexts.

If scaled effectively, such interventions would enable Africa to narrow its gap with South Asia and advance towards Agenda 2063’s Aspiration 1, which envisions a “healthy and well-nourished Africa.” They would also bring the continent closer to achieving SDG 3.2, which commits to reducing neonatal mortality to at least 12 deaths per 1 000 live births and under-five mortality to at least 25 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2030. Achieving these targets will require increased domestic resource mobilisation and sustained international support. Still, the payoff is clear: accelerated reductions in infant mortality not only save lives but also strengthen human capital foundations critical for Africa’s long-term development.

Chart 13 presents the demographic dividend in the Current Path compared to the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

The dividend is the window of economic growth opportunity that opens when the ratio of working-age persons to dependents increases to 1.7 to 1 and higher.

The concept of the demographic dividend refers to the accelerated economic growth potential that arises when a country’s working-age population grows larger relative to its dependent population (children and elderly). This shift can unlock higher savings, greater labour supply, and enhanced productivity. However, as highlighted by Bloom, Canning and Sevilla, these benefits are not automatic but require deliberate investments in education, health, employment creation, and governance.

Africa’s age structure has been shifting gradually over the past three decades, but the transition remains slow compared to peer regions. The continent’s working-age to dependant population ratio (demographic dividend ratio) improved modestly from 1.1 working-age persons to every dependant in 1990 to 1.32 in 2023. This lags behind South Asia and South America, which entered their demographic windows in 2011 and 2000, respectively, and are now benefiting from higher savings, productivity and accelerated growth. The Current Path suggests that Africa’s dividend ratio will reach 1.57 by 2043, still below the benchmark of 1.7 working age persons to every dependant that marks the onset of the first demographic dividend.