Nigeria

Nigeria

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

This page explores Nigeria's current and projected future development, examining various sectoral scenarios and their potential impacts on the country's growth. It explores eight sectors, including demographic, economic, and infrastructure-related outcomes for Nigeria up to 2043. The analysis also considers the implications of the Agenda 2063 goals, aiming to offer insights into policy actions that could enhance the country's developmental trajectory.

For more information about the International Futures modelling platform we use to develop the various scenarios, please see the Technical page.

Summary

We begin this page with an introductory assessment of Nigeria’s context, looking at the current population distribution and structure, climate and topography.

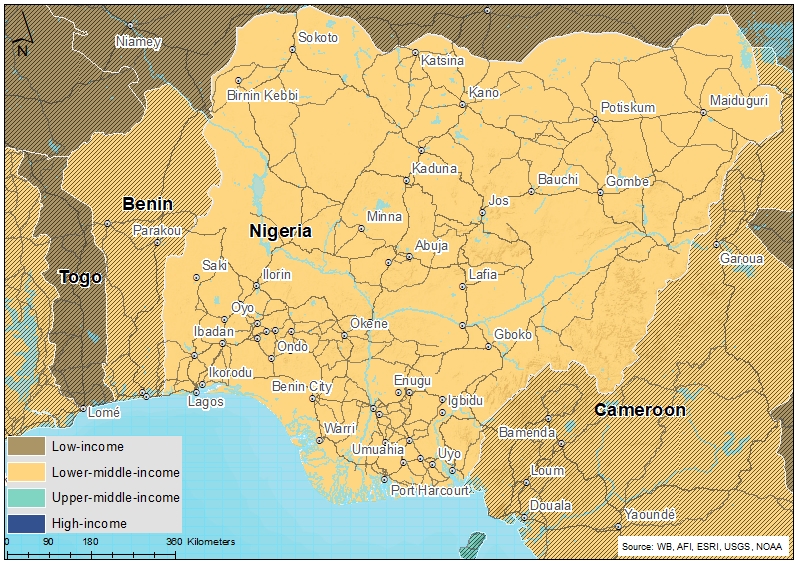

- Nigeria is a lower-middle-income country located in West Africa, the most populous country in Africa and a key regional player in West Africa. The country is a multi-ethnic and culturally diverse federation made up of 36 states and the Abuja Federal Capital Territory (FCT) grouped into six geo-political zones (North-West, North-Central, North-East, South-West, South-East and South-South). For nearly four decades, following its independence in 1960, Nigeria was predominantly under military rule. The transition to democracy only began in 1999.

The following section on Nigeria’s Current Path informs the country's likely development trajectory to 2043. It is based on current policy and geopolitical trends and assumes that no major shocks would occur in a 'business-as-usual' scenario.

- Nigeria is experiencing rapid population growth. It is currently the sixth most populous nation in the world. If the current demographic trends persist, Nigeria’s population will grow from 228 million in 2023 to around 380 million by 2043, making it the third most populous nation after India and China.

- Between 1990 and 2023, Nigeria’s GDP increased from US$118 billion to US$423 billion. On its current development trajectory, GDP is projected to reach US$888 billion in 2043, maintaining its position as Africa’s largest economy, with an average annual growth rate of 3.7%. However, this positive growth outlook is contingent upon tackling longstanding and potentially binding constraints to growth, including inadequate infrastructure, particularly unreliable power supply, trade barriers, an unfriendly business environment and insecurity, among other structural issues.

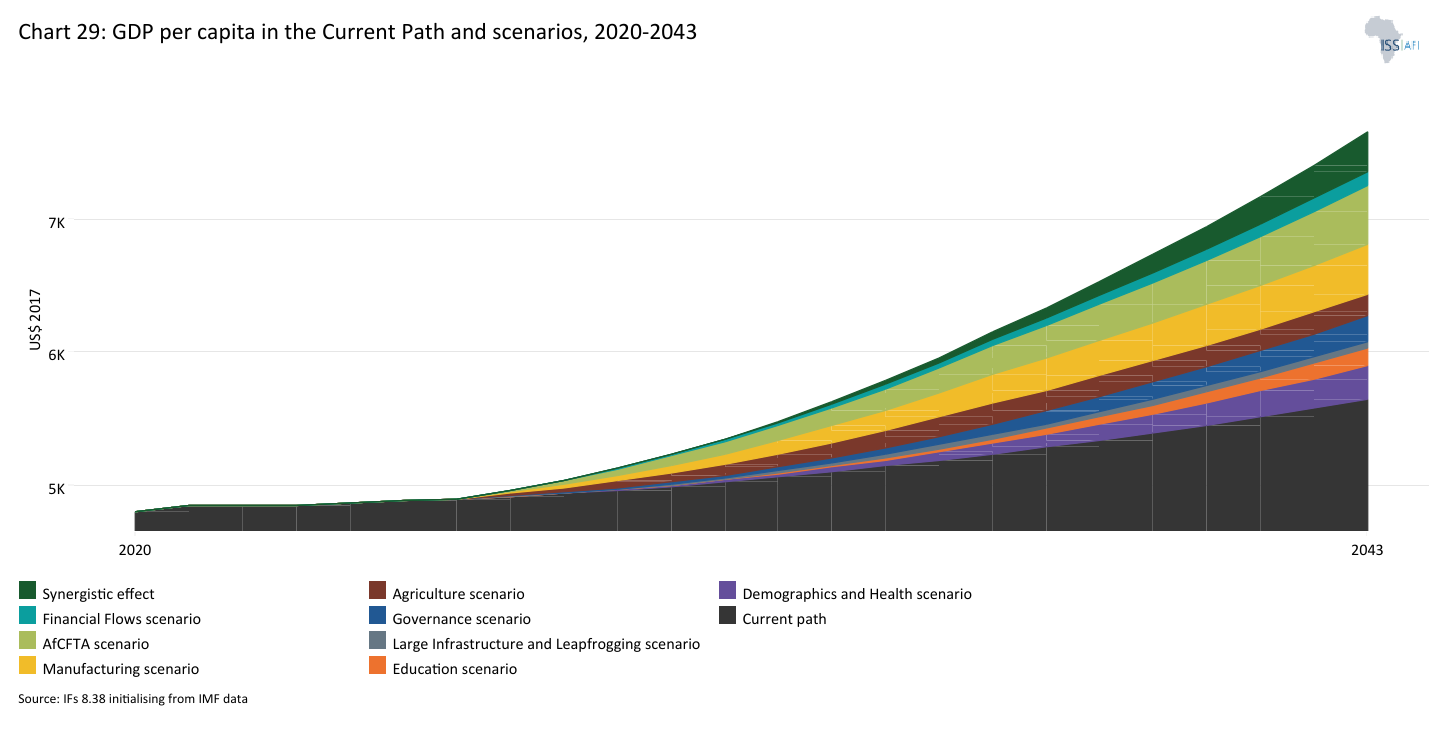

- Economic growth has not proceeded smoothly and Nigeria's inability to sustain its growth and the rapid population growth dilute its per capita income growth. On the Current Path, the GDP per capita (PPP constant 2017) will increase from about US$5 000 in 2023 to only US$5 650 by 2043, below the projected average of US$7 800 for lower-middle-income Africa in the same year.

- The COVID-19 pandemic, sluggish economic growth and high inflation have pushed millions more into poverty in Nigeria. As a result, the extreme poverty rate at US$2.15 increased from 31% in 2019 to 38.9% in 2023. The lower-middle-income poverty rate (US$3.65 in 2017 PPP) rose from 63.5% to around 70% over the same period. Projections suggest that on the current trajectory, extreme poverty (at US$2.15) in Nigeria will gradually decline to about 23.5% by 2043, well above the projected average of 13.8% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa.

- Nigeria Agenda 2050 outlines policies to position the country as a regional and global economic power. It focuses on three pillars: governance reform with strong institutions, inclusive and private sector-driven economic growth and empowering citizens by balancing economic progress with social welfare.

The next section compares progress on the Current Path with eight sectoral scenarios. These are Demographics and Health, Agriculture, Education, Manufacturing, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging, Financial Flows, and Governance. Each scenario is benchmarked to present an ambitious but reasonable aspiration in that sector compared to other countries at similar levels of development.

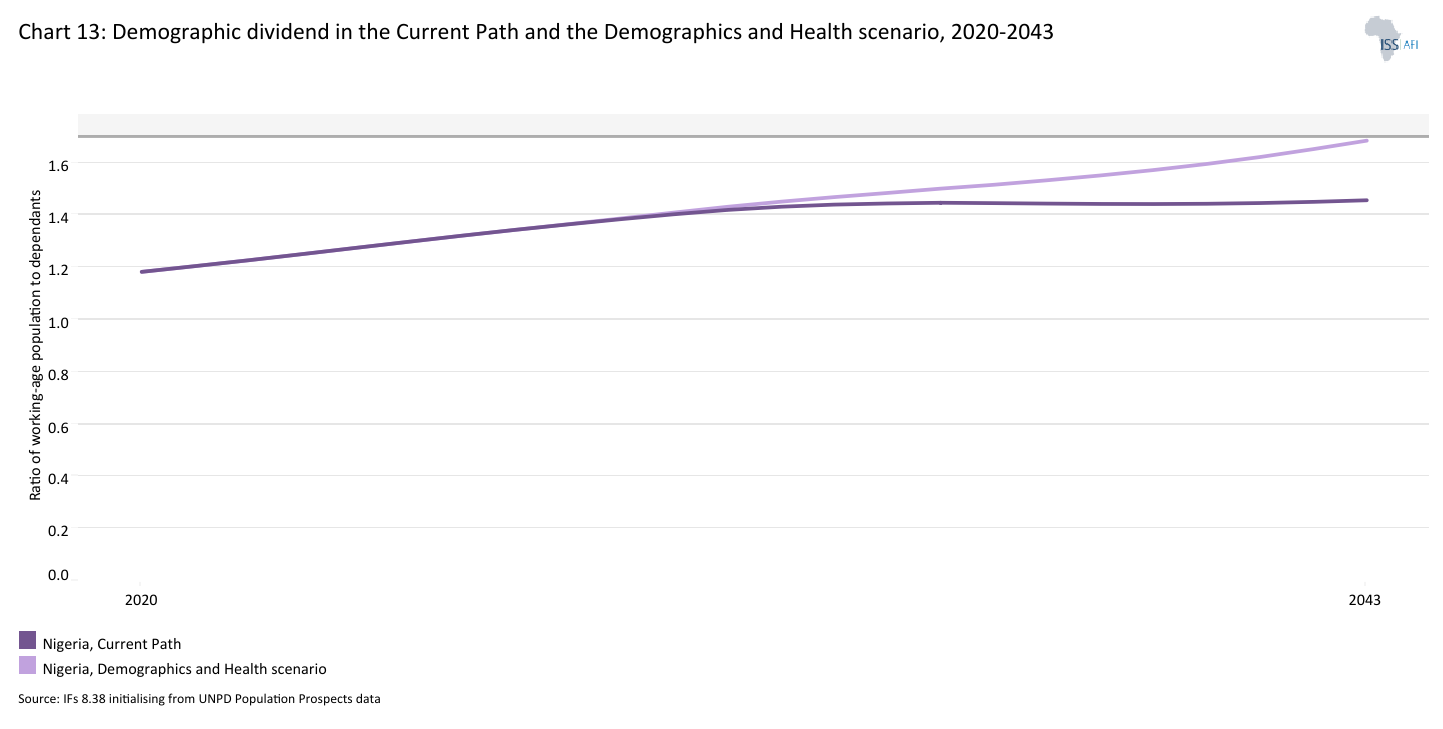

- The implementation of the Demographics and Health scenario will accelerate the demographic transition in Nigeria. In this scenario, the ratio of the working-age population to dependants will be at 1.7 by 2044, at which point the country will enter a potential demographic window of opportunity, provided other supporting conditions are in place. On the Current Path, this minimum ratio will only be achieved in 2061.

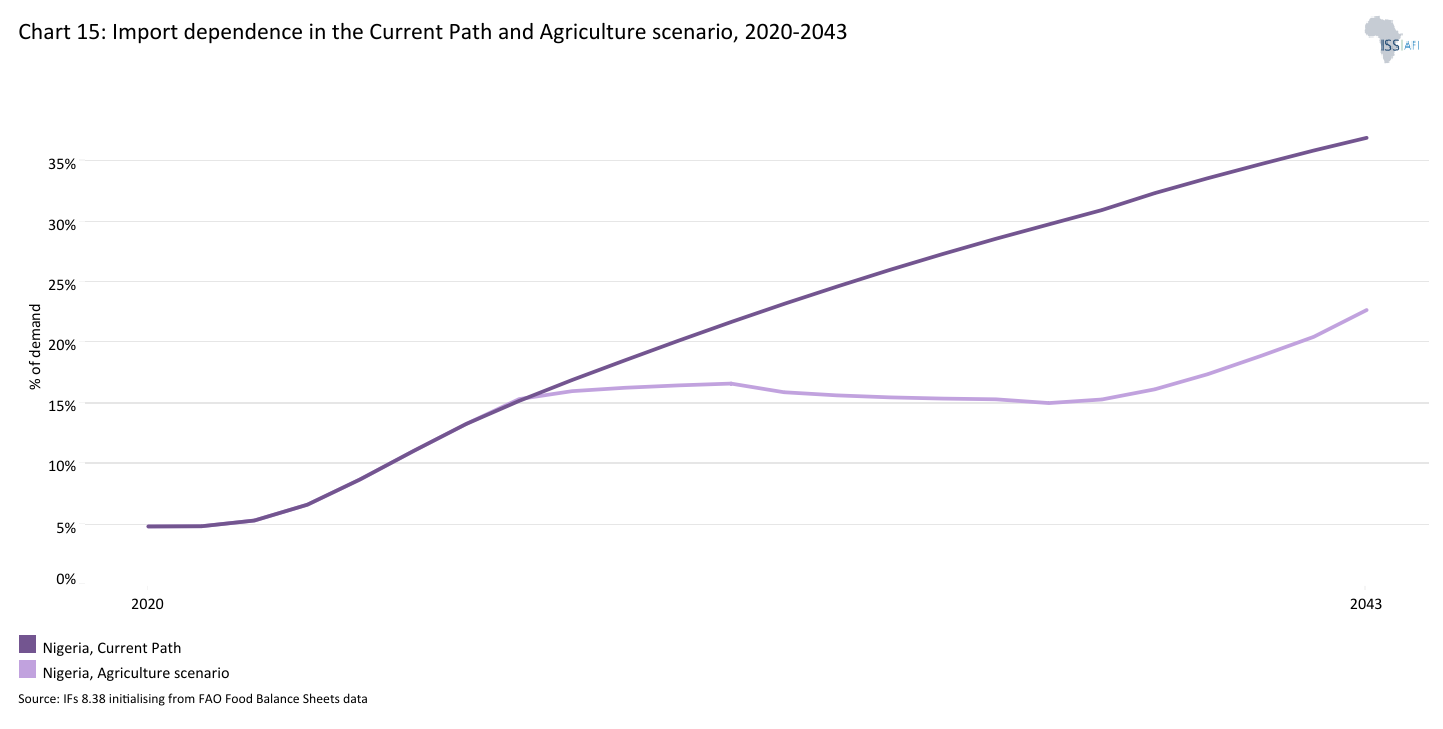

- In the Agriculture scenario, average crop yields increase to 8.4 metric tons per hectare in 2043, compared with 6.5 tons on the Current Path. As a result, crop production will be 9.2 million metric tons more by 2043 than in the Current Path. This will result in a lower import dependency of 22% of total demand in 2043, compared with 36.7% in the Current Path and below the projected average of 24% for lower-middle-income Africa in 2043.

- The implementation of the Education scenario would improve the mean years of education for adults aged 15 to 24 in the country to about 8.2 years by 2043, compared with about 7.2 years in 2043 in the Current Path.

- The continued reliance on hydrocarbons (oil and gas) means the Nigerian economy is undiversified and vulnerable to exogenous shocks. The manufacturing sector's contribution to Nigeria's GDP fell from a peak of approximately 20% in the 1980s to just 6.5% in 2010, before gradually rising to 13.5% in 2023—aligning with the average for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. The share of the manufacturing sector in Nigeria’s GDP will likely be 20% by 2043, above the projected average of 17% for lower-middle-income Africa. In the Manufacturing scenario the sector is, 22% larger in 2043 than on the Current Path forecast.

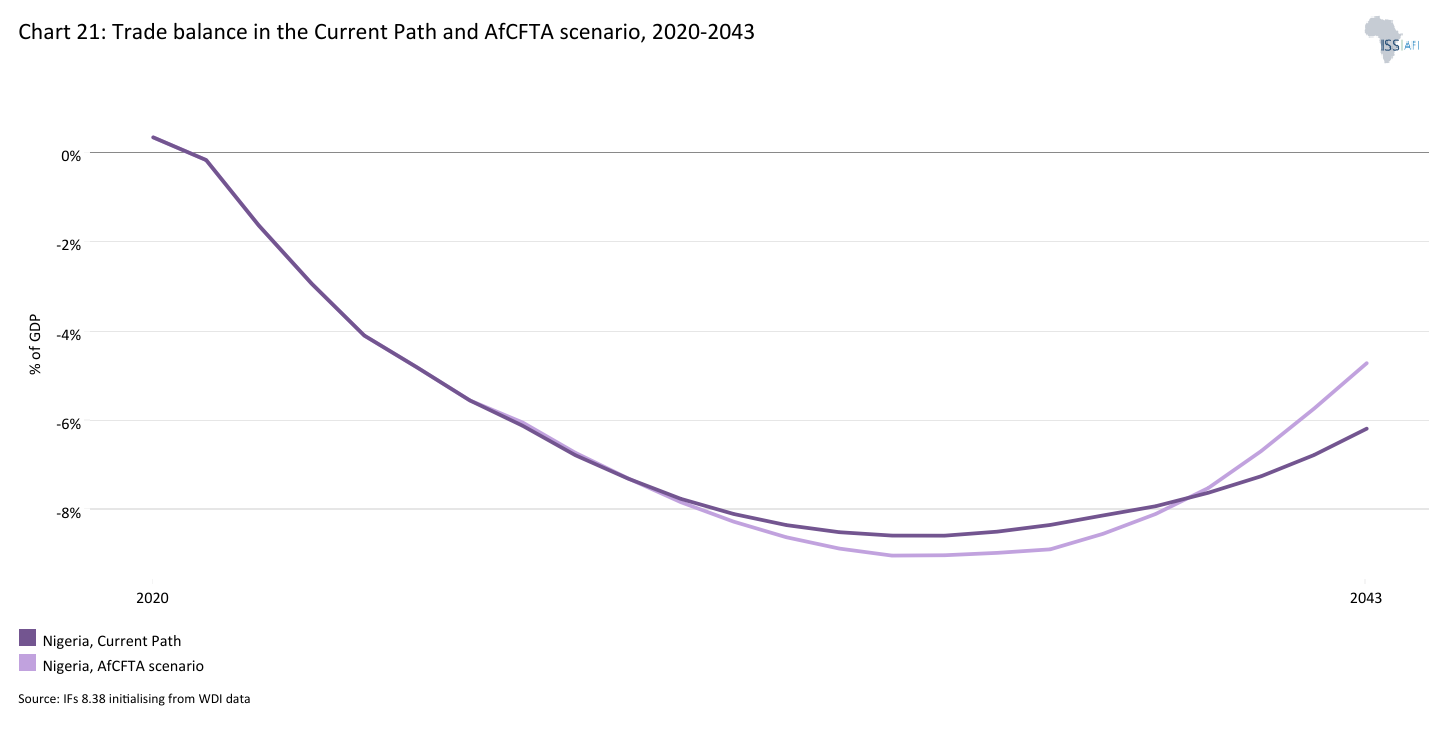

- The trade pattern of Nigeria is similar to that of many other African countries that rely on a few key commodity exports while importing higher-value manufactured goods, consumer items and foodstuffs. As a result, the country’s trade balance is structurally in deficit—a trend which is likely to persist over the forecast horizon. On the Current Path, the trade deficit will be equivalent to 6.2% of GDP in 2043. In the AfCFTA scenario, Nigeria would not record a trade surplus or be a net exporter, however, its trade deficit would reduce to 4.7% of GDP in 2043.

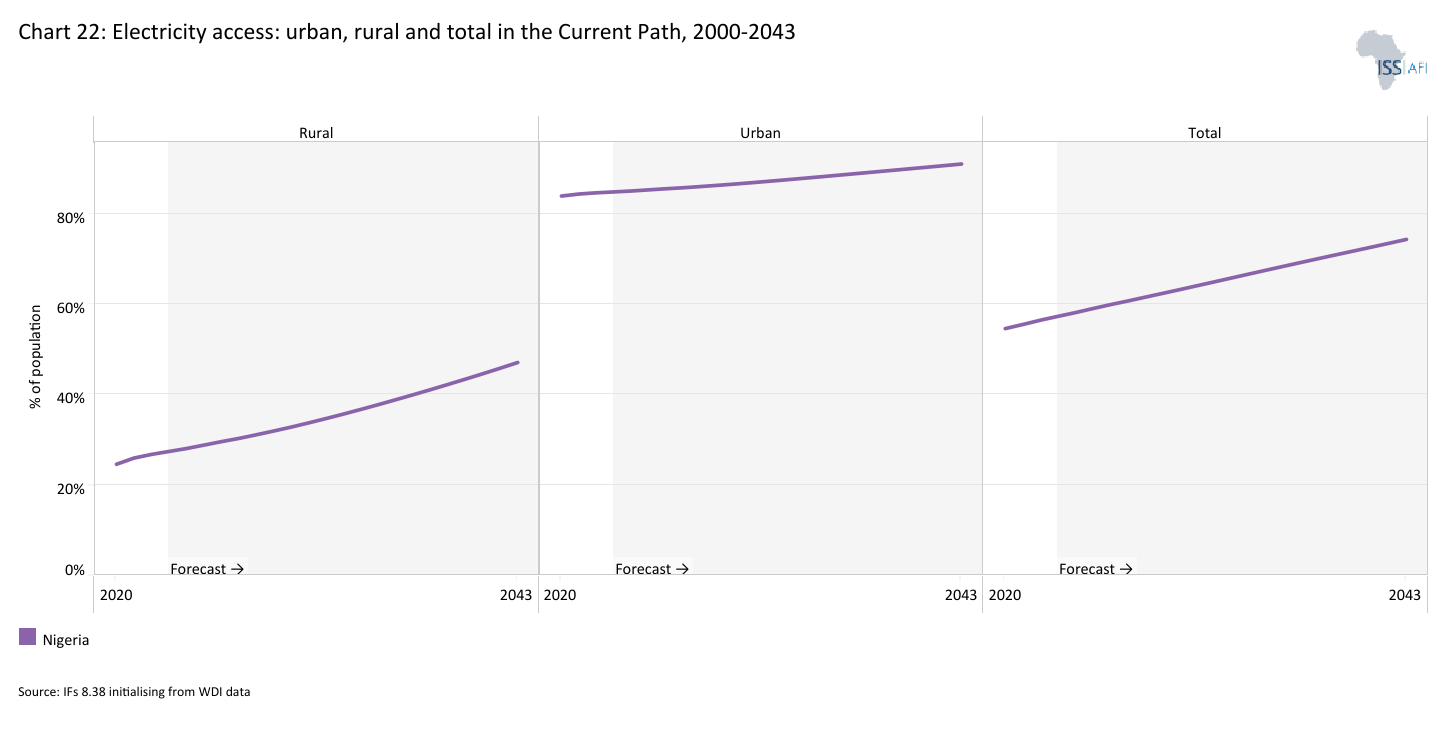

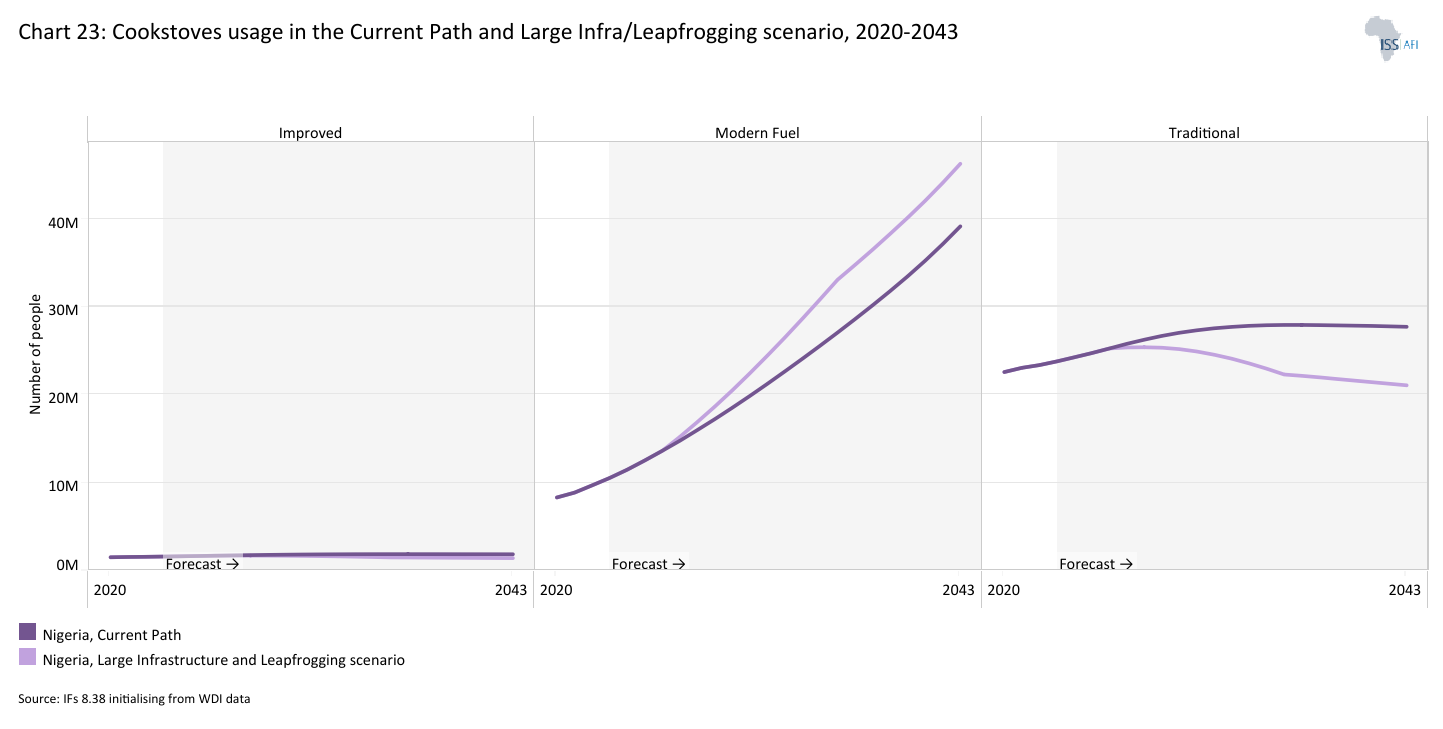

- The infrastructure gap has long been a drain on productivity, growth and competitiveness, especially in the manufacturing sector in Nigeria. Due to limited electricity access, especially in rural areas, the bulk of the households continue to rely on inefficient energy sources for cooking. In the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario, which models ambitious but realistic investment in renewable energy, the percentage of households that use traditional cookstoves could decline from 66% in 2023 to 30.6% in 2043, compared to the projected 40.3% in the Current Path.

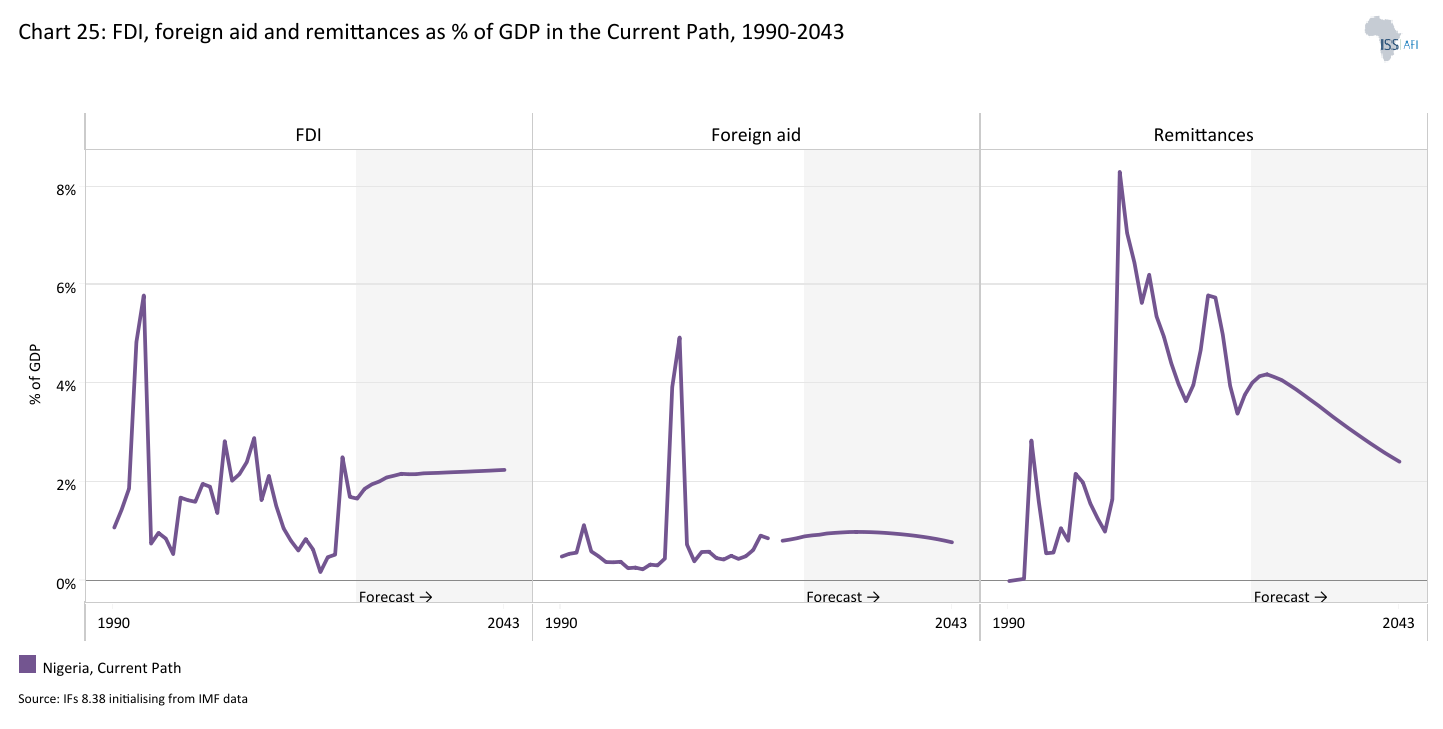

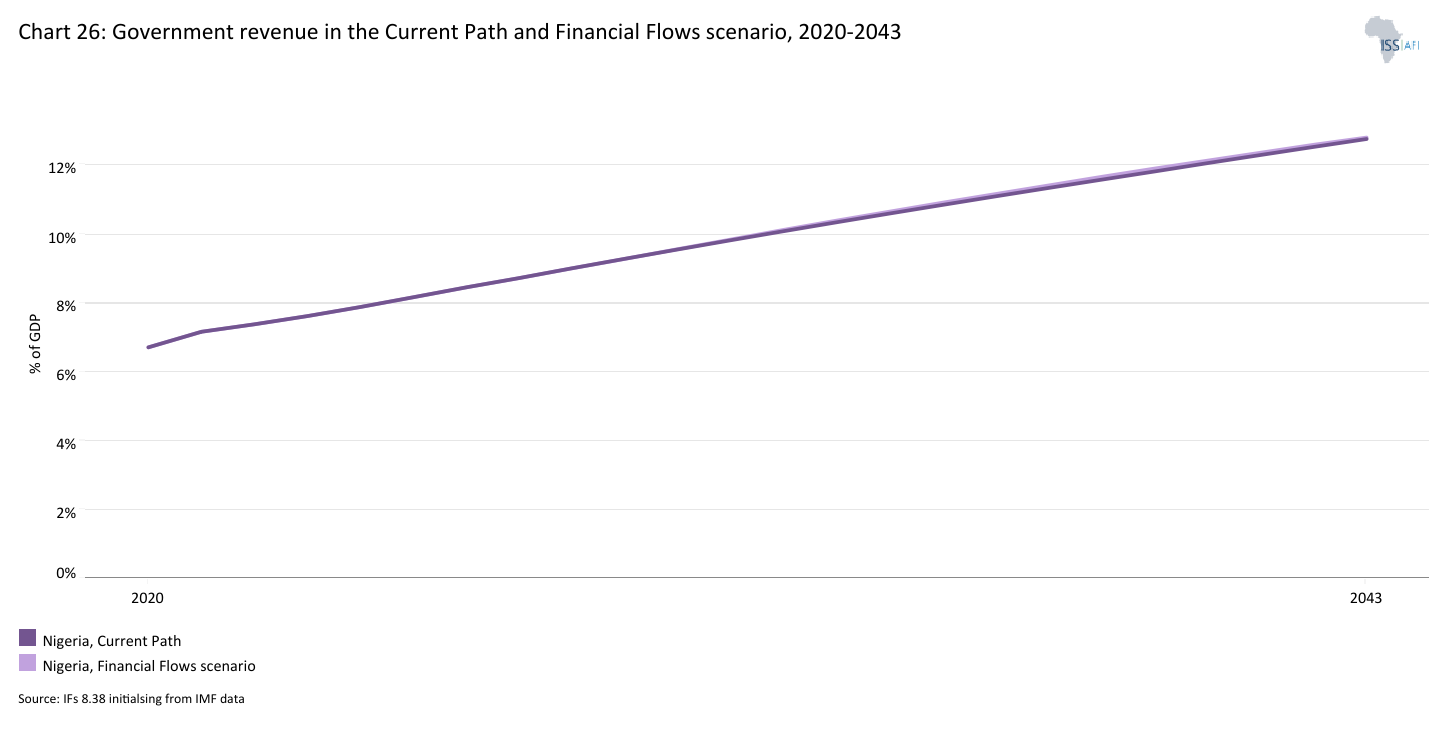

- Nigeria is an important destination of international capital flows in Africa, especially FDI and remittances, given its abundant natural resources and its large diaspora. In the Financial Flows scenario, government revenues increase to 12.8% of GDP by 2043, up from 7.6% in 2023. This is equivalent to US$3.7 billion above the Current Path forecast in 2043.

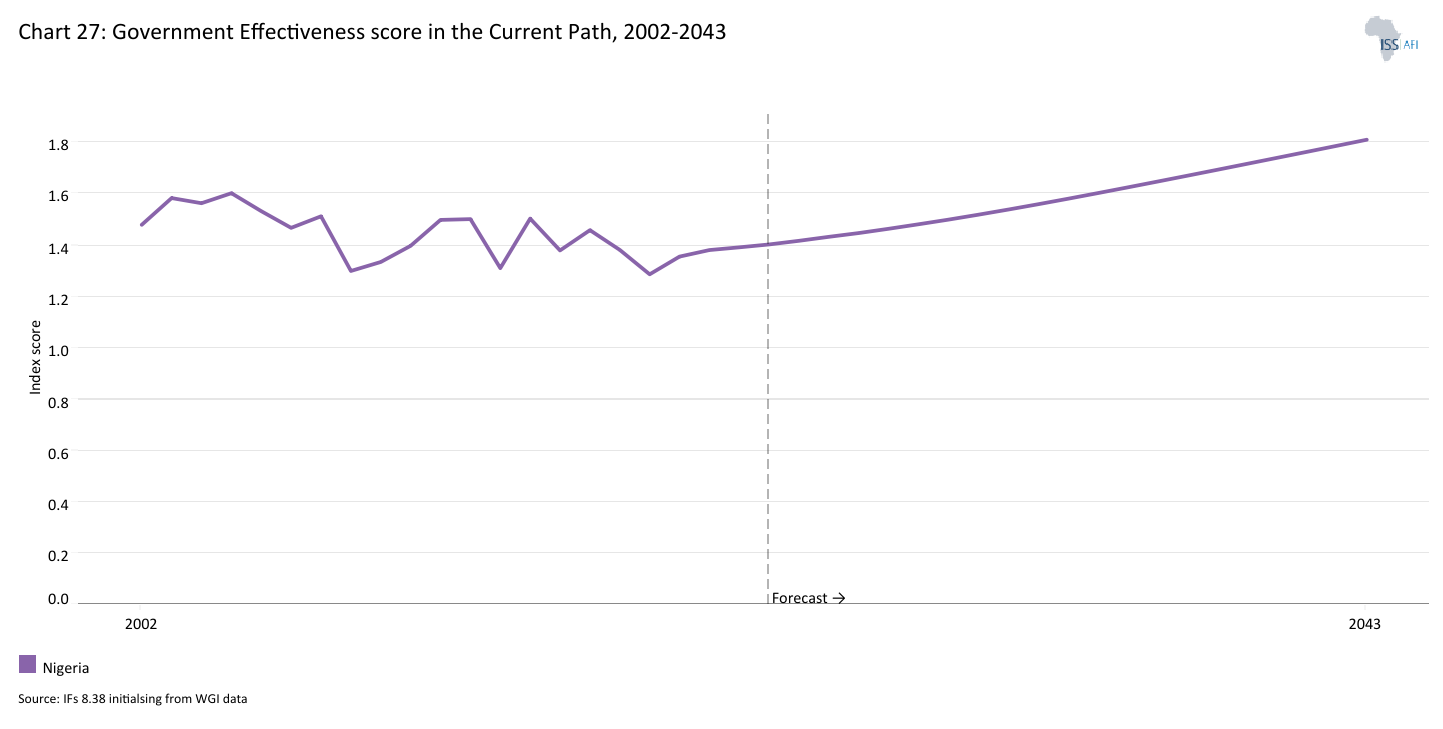

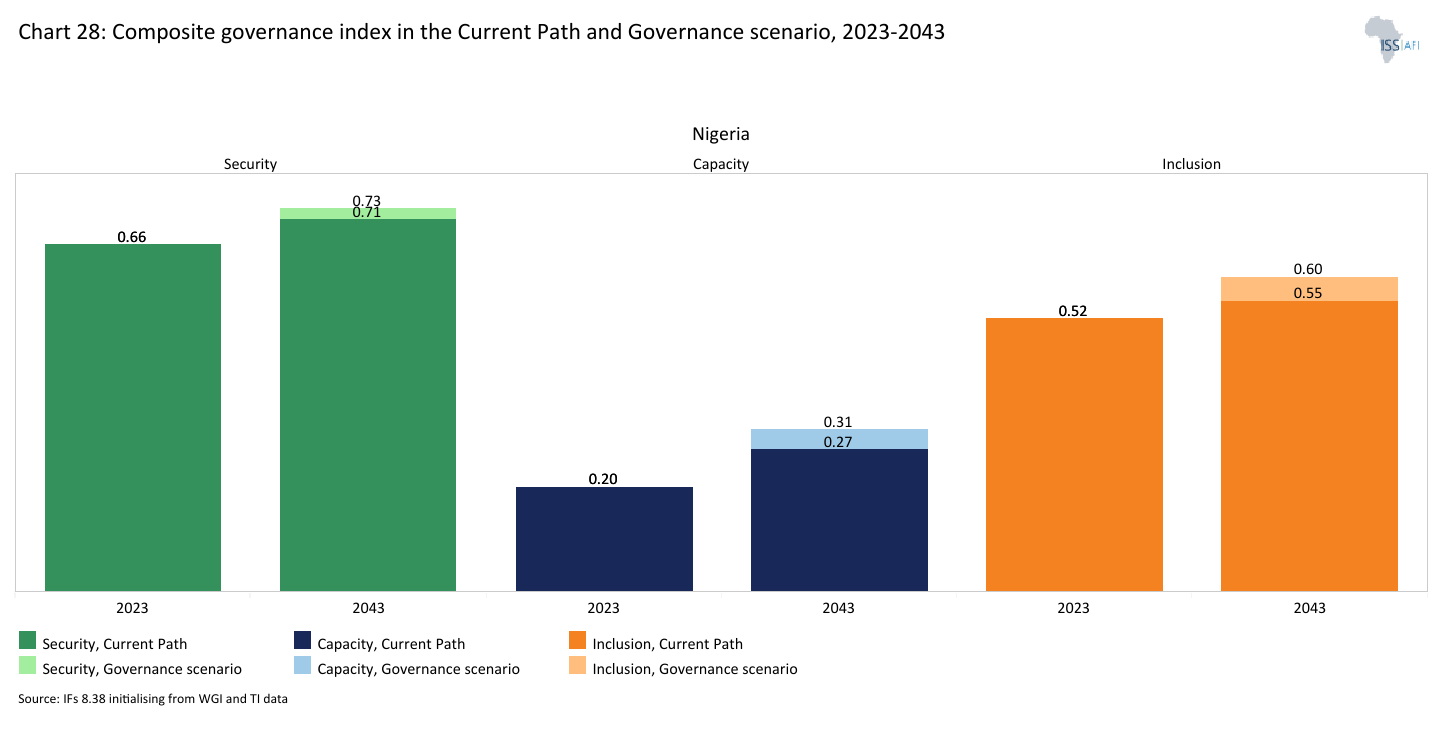

- Nigeria faces several governance challenges that have impacted its development. Governance in Nigeria is often marked by poor capacity, mismanagement and corruption. In the Governance scenario, Nigeria's overall governance performance is about 9% higher than the Current Path in 2043.

In the fourth section, we compare the impact of each of these eight sectoral scenarios with one another and subsequently with a Combined scenario (the integrated effect of all eight scenarios). In our forecasts, we measure progress on various dimensions such as economic size (in market exchange rates), gross domestic product per capita (in purchasing power parity), extreme poverty, carbon emissions, the changes in the structure of the economy, and selected sectoral dimensions such as progress with mean years of education, life expectancy, the Gini coefficient and reductions in mortality rates.

- Nigeria gets a boost to its GDP per capita in all eight sectoral scenarios. By 2043, the GDP per capita of Nigeria (PPP) is about US$2 000, larger than in the Current Path, indicating that an integrated push across all the development sectors (in the Combined scenario) could significantly improve the living standard of the Nigerians. Among the sectoral scenarios, the AfCFTA scenario has the most significant positive impact on GDP per capita, with an increase of US$435 above the Current Path in 2043. The second, third and fourth most significant impact on the GDP per capita is achieved in the Manufacturing scenario, the Demographics and Health scenario, and the Governance scenario.

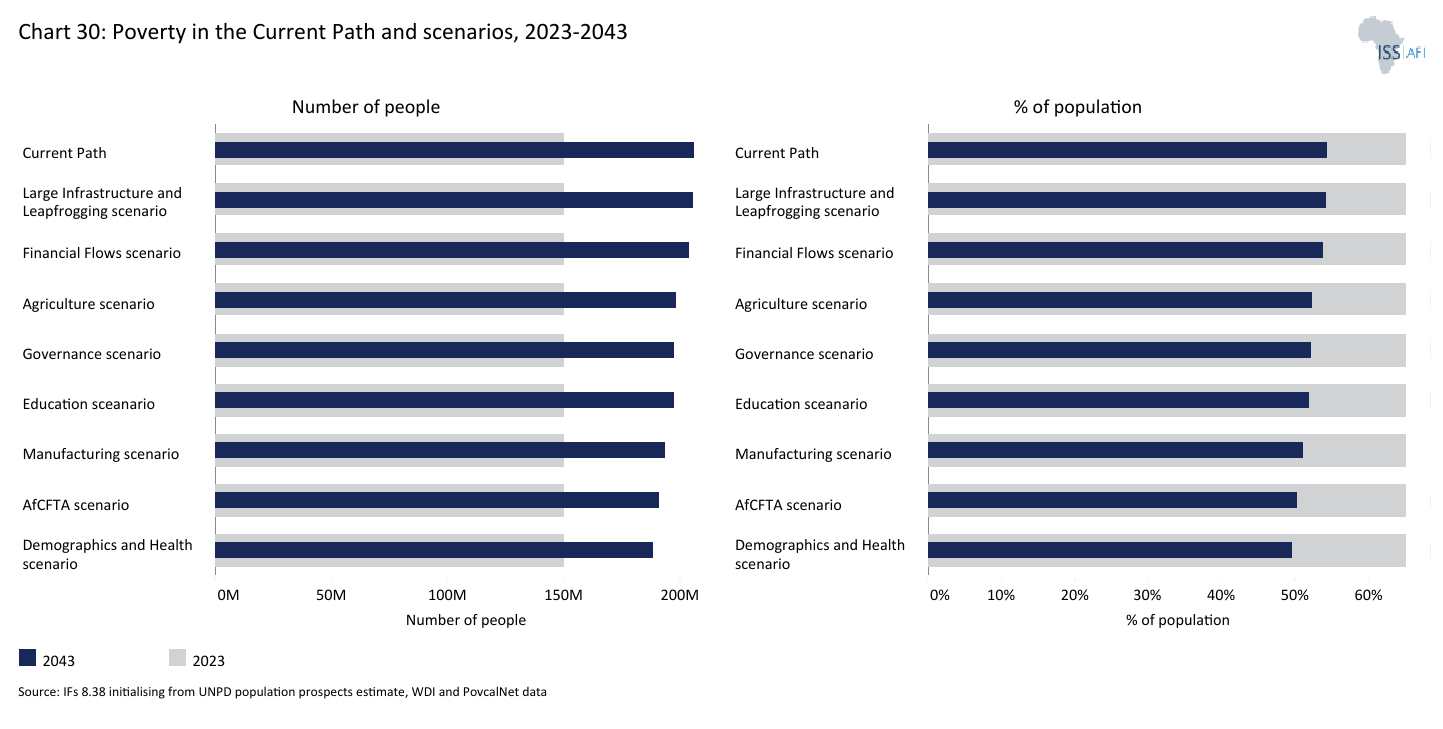

- All scenario interventions contribute to poverty reduction in Nigeria. However, the AfCFTA scenario has the largest impact by 2043, leading to the most substantial decline in extreme poverty, followed by the Manufacturing scenario. In the short term (up to 2035), the Agriculture scenario has the most significant effect on poverty reduction. Under the Combined scenario, the proportion of people living in extreme poverty falls to 11% by 2043, compared to 23.5% in the Current Path for the same year. Even inthe Combined scenario, extreme poverty in Nigeria will remain high at 25.6% by 2030.

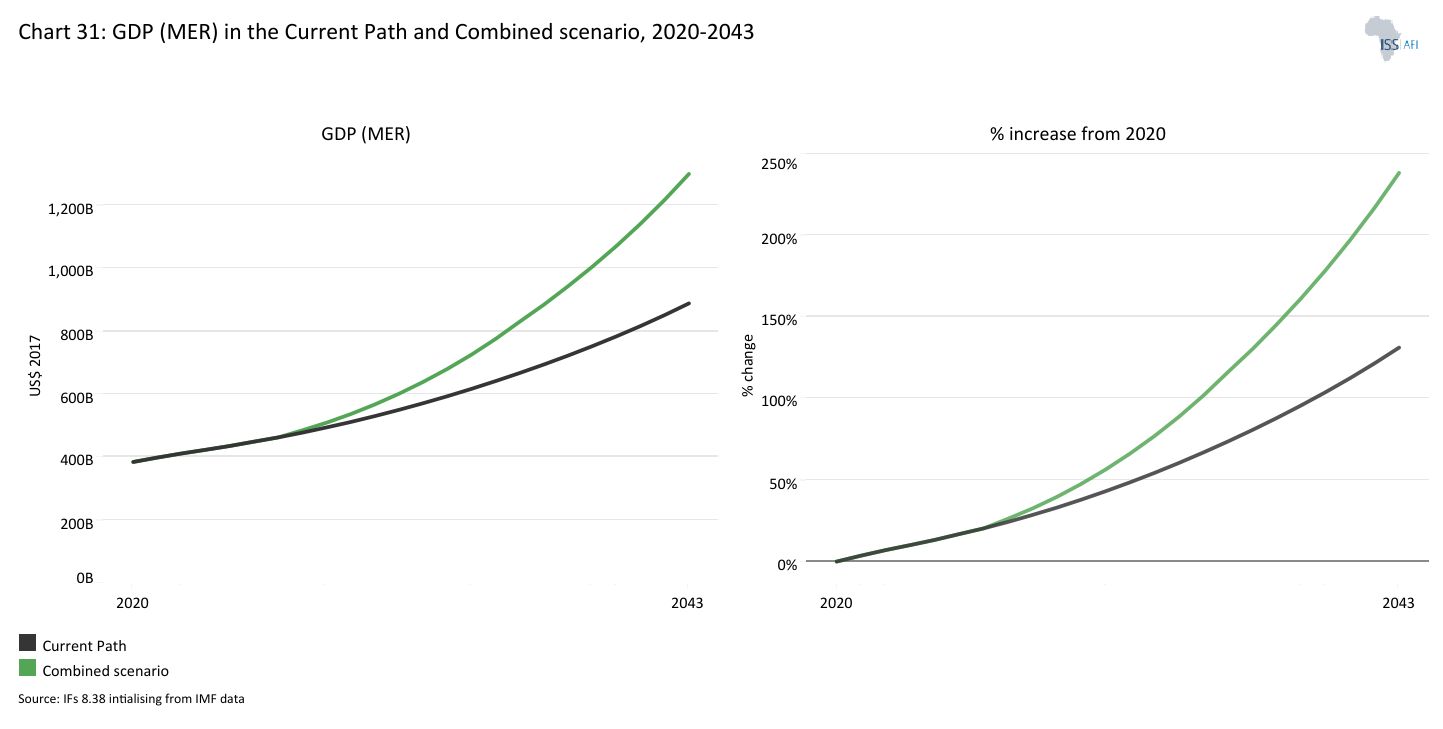

- The Combined scenario significantly improves Nigeria’s growth prospects. In this scenario, the average growth rate between 2025 and 2043 is about 6%, compared with 3.8% on the Current Path over the same period. The size of the economy measured in GDP at the market exchange rate (MER) is US$412 billion larger than the Current Path in 2043.

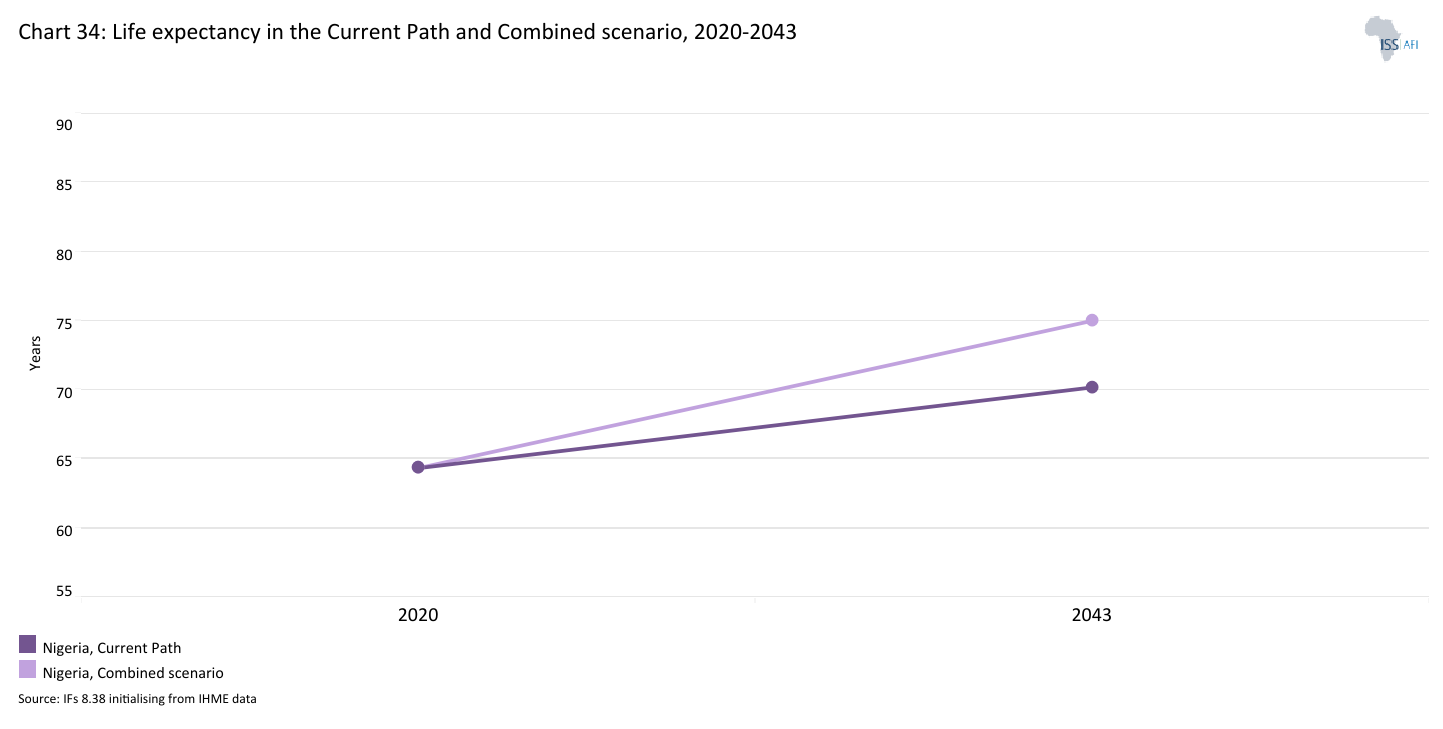

- In the Combined scenario, the average Nigerian could expect to live about five years longer at 75 years in 2043, compared with the Current Path for the same year.

We end this page with a summarising conclusion offering key recommendations for decision-making.

Nigeria faces a complex web of interconnected challenges that hinder inclusive growth and sustainable development. Key obstacles include weak governance, pervasive corruption, insecurity, rapid population growth, inadequate infrastructure, a mismatch between skills and labour market needs and limited economic diversification. These factors significantly constrain the country’s development trajectory.

Addressing these challenges is essential to place Nigeria on a path toward long-term growth and shared prosperity. While macroeconomic stabilisation reforms are important, the government must also prioritise comprehensive policy reforms and targeted investments. These should focus on strengthening governance, bridging infrastructure gaps, enhancing private sector development, boosting agricultural productivity and accelerating economic diversification. Equally important is investing in high-quality human capital and ensuring that economic growth benefits the poor and economically vulnerable by improving labour market outcomes, particularly through the creation of productive, private sector-driven employment that supports sustainable poverty reduction.

All charts for Nigeria

- Chart 1: Political map for Nigeria

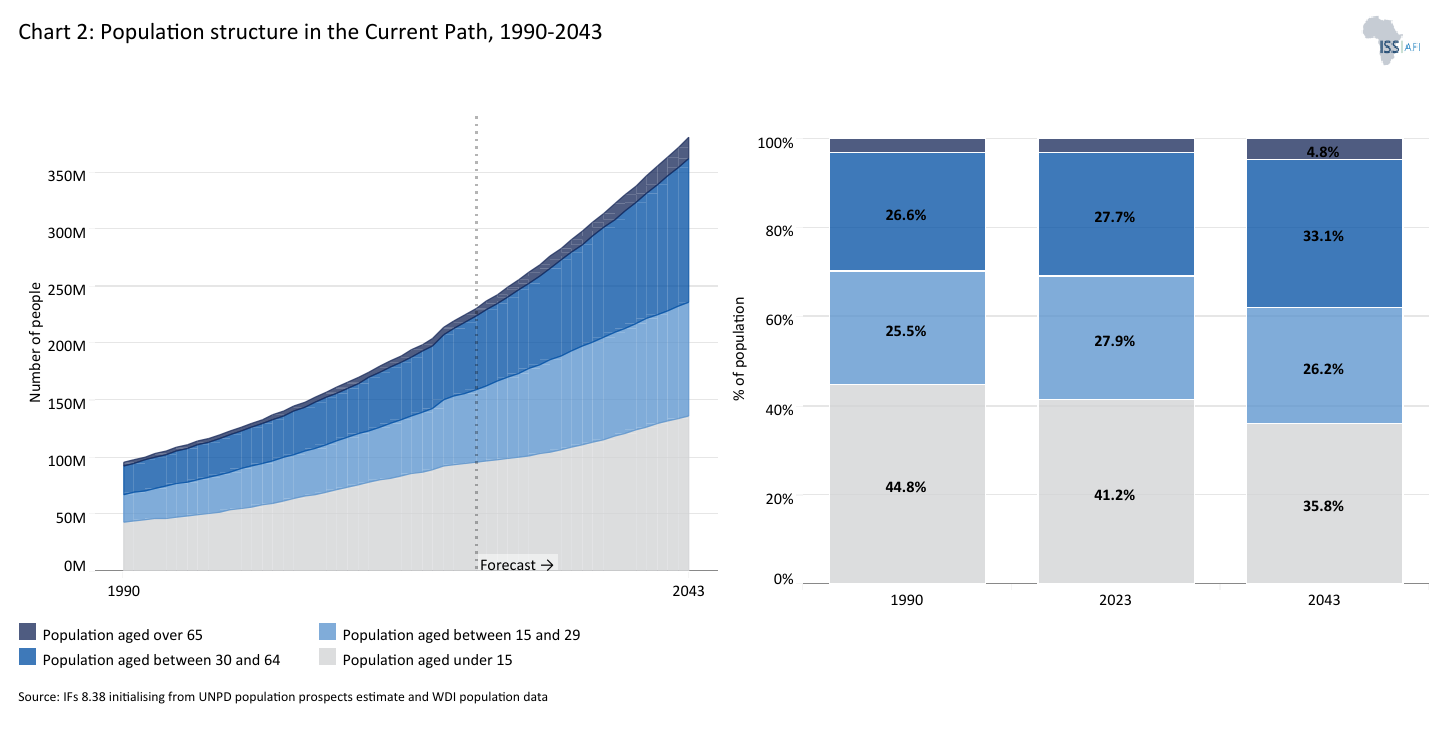

- Chart 2: Population structure in Current Path, 1990–2043

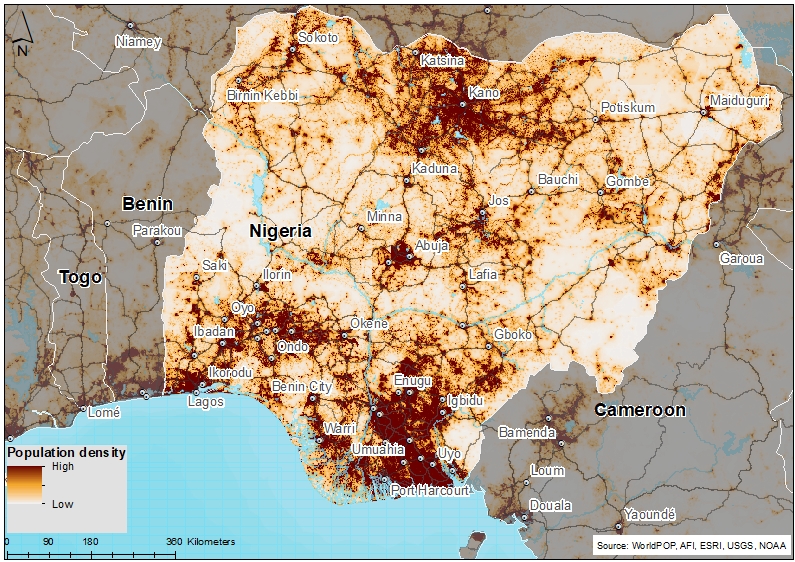

- Chart 3: Population distribution map, 2023

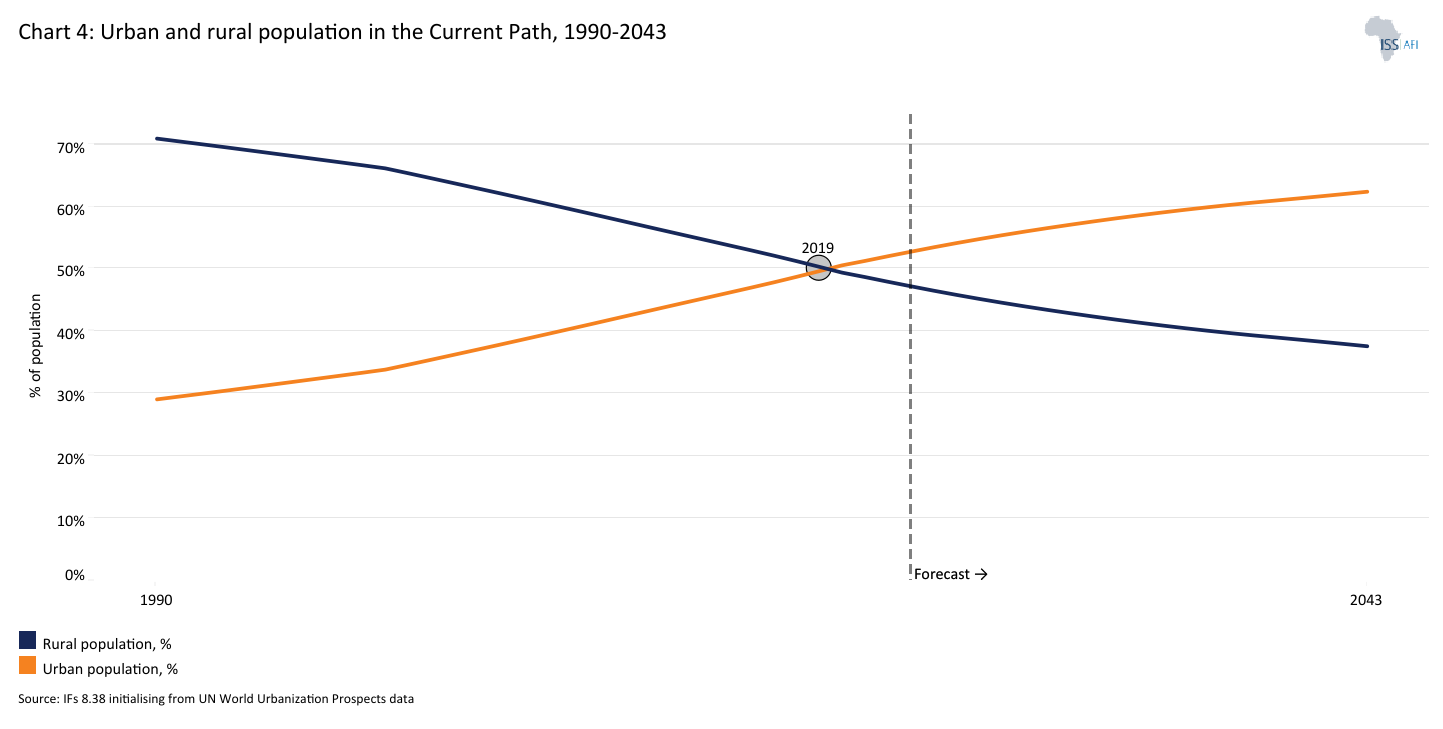

- Chart 4: Urban and rural population in the Current Path, 1990-2043

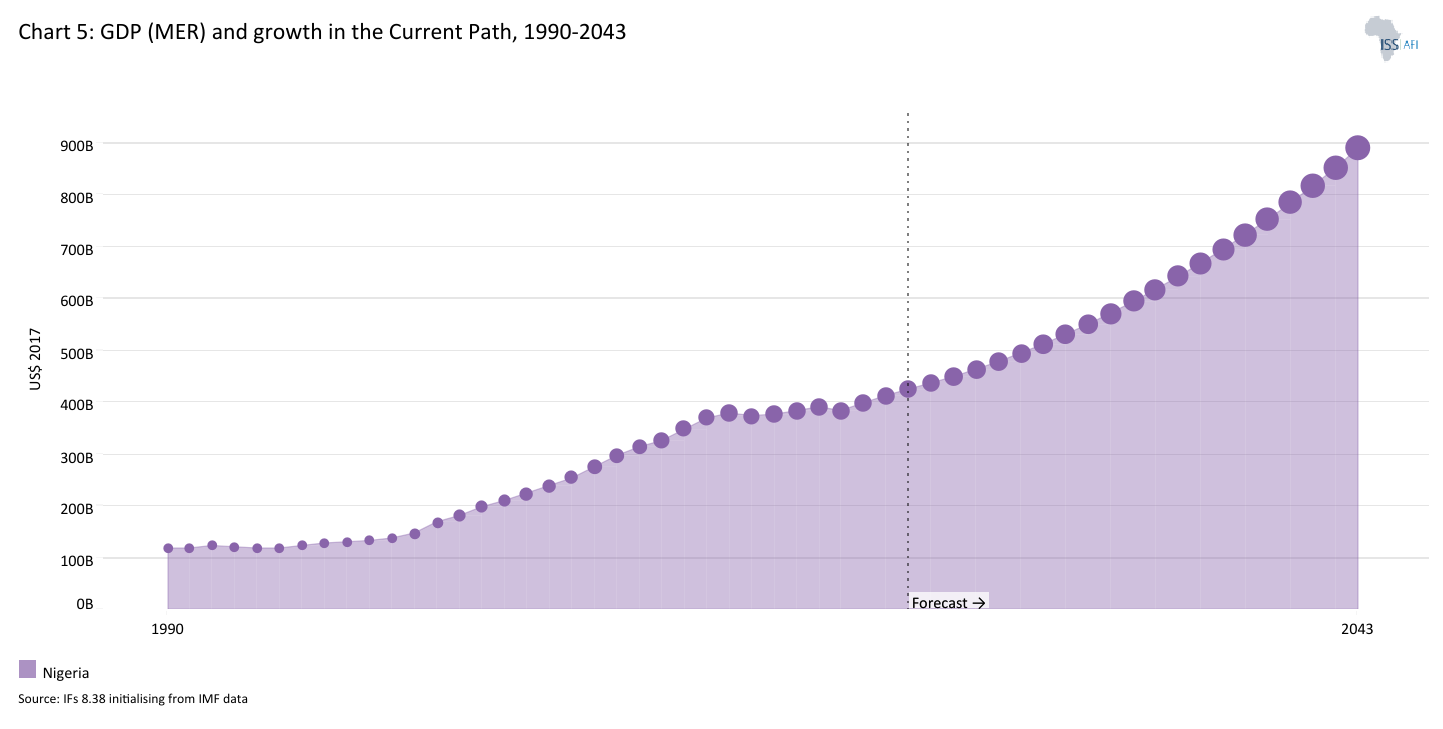

- Chart 5: GDP (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, 1990–2043

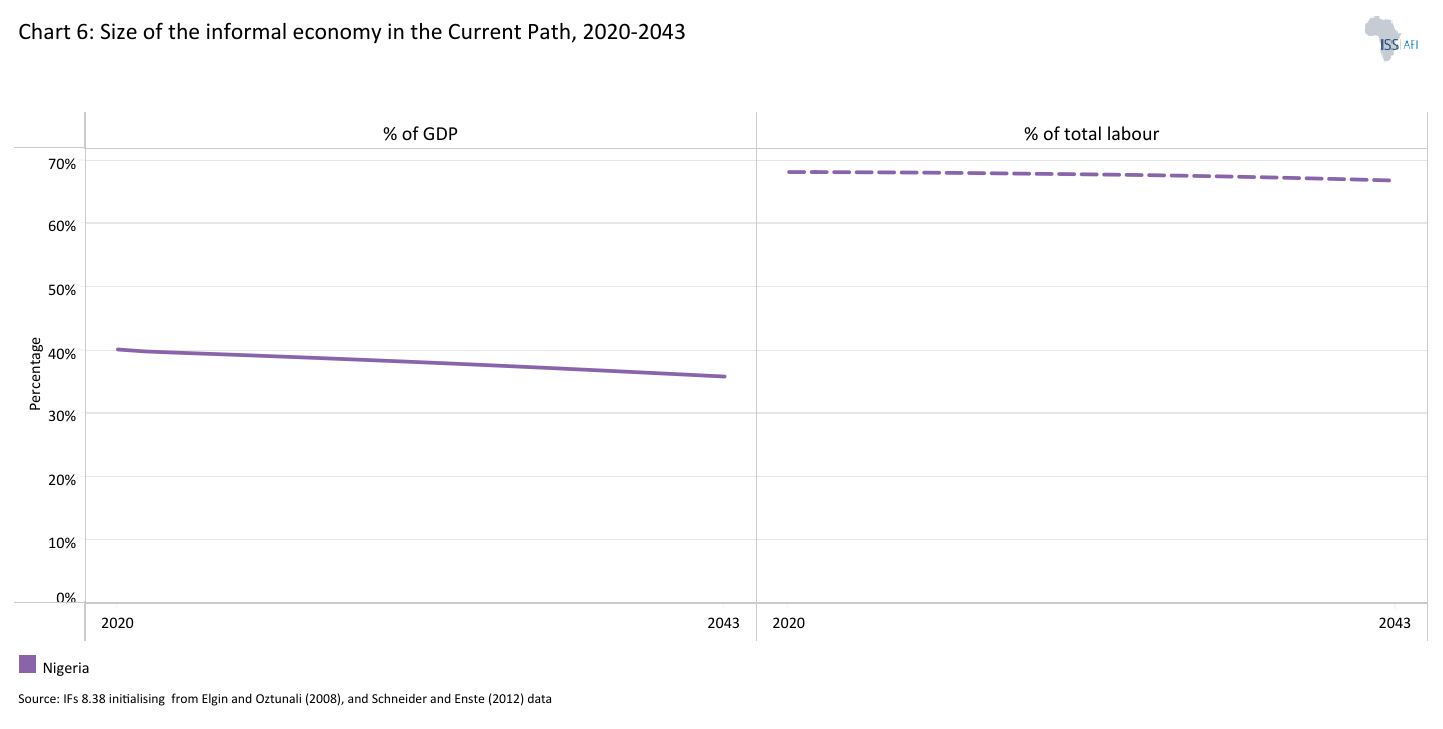

- Chart 6: Size of the informal economy in the Current Path, 2020-2043

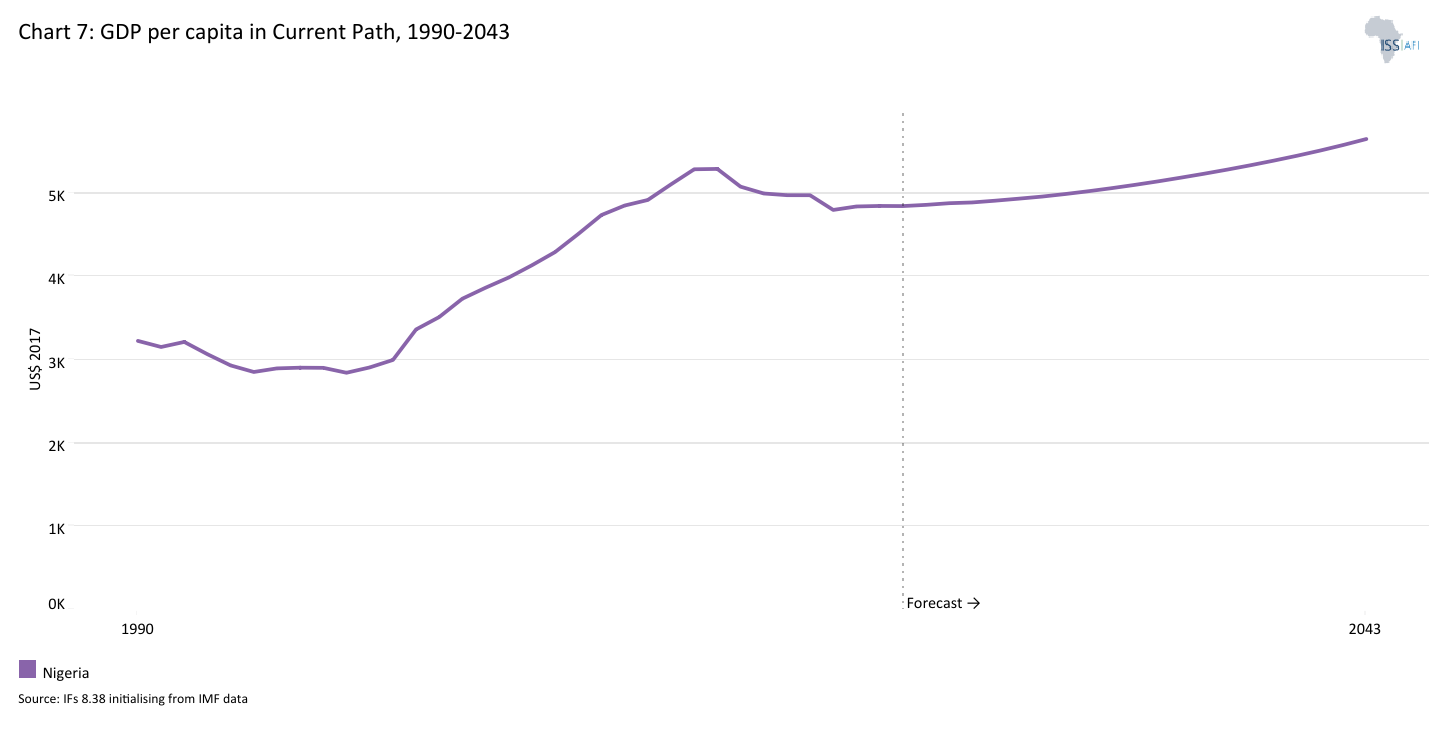

- Chart 7: GDP per capita in Current Path, 1990–2043

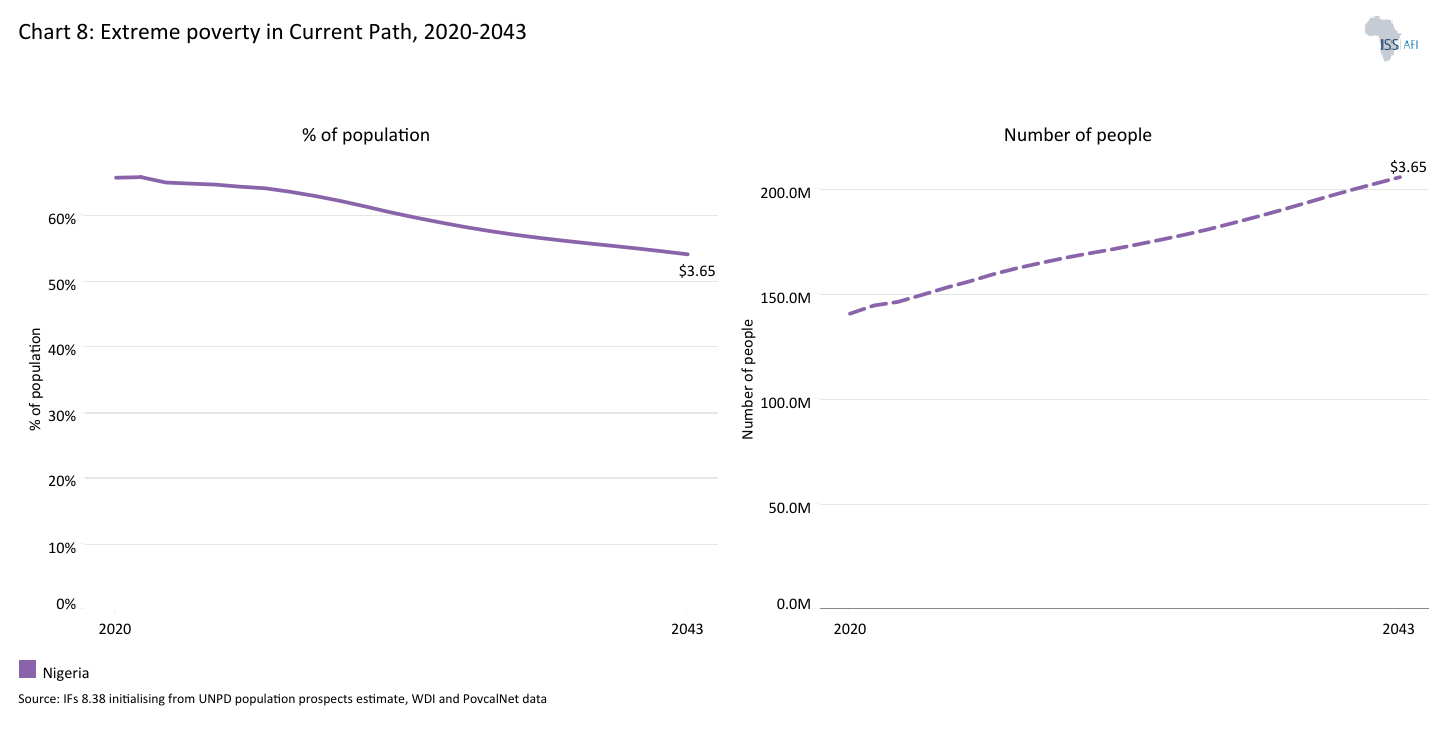

- Chart 8: Extreme poverty in the Current Path, 2020–2043

- Chart 9: National Development Plan of Nigeria

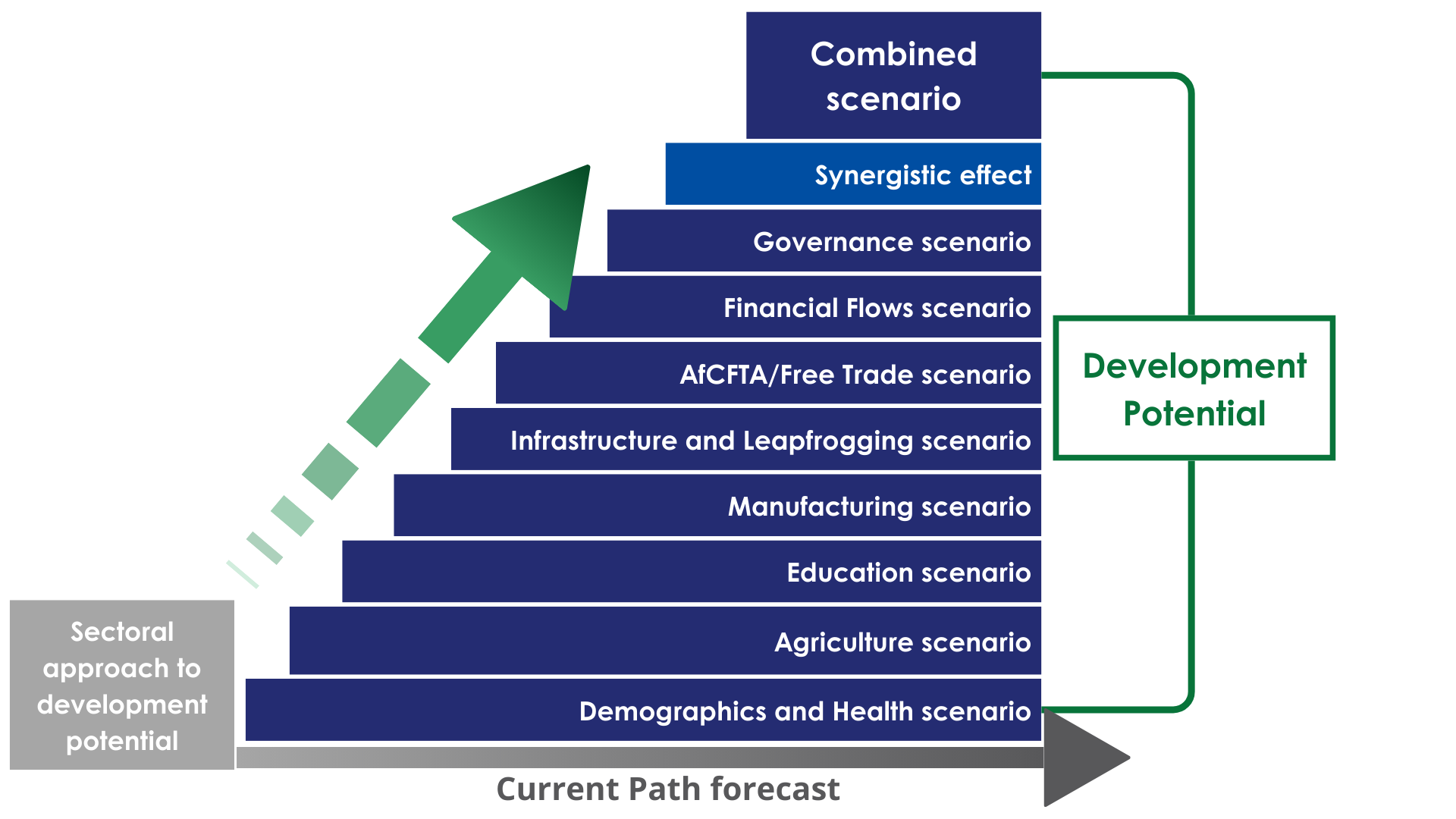

- Chart 10: Relationship between Current Path and scenarios

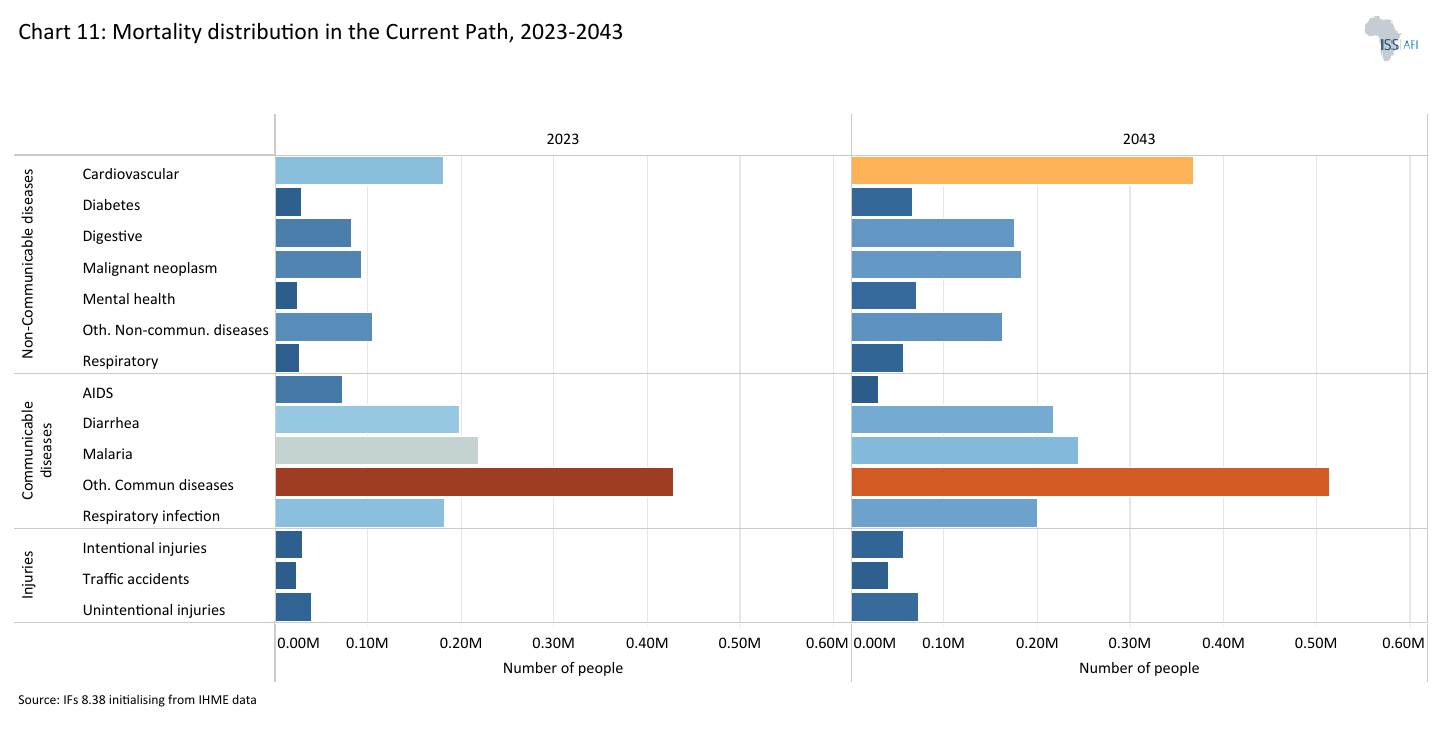

- Chart 11: Mortality distribution in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

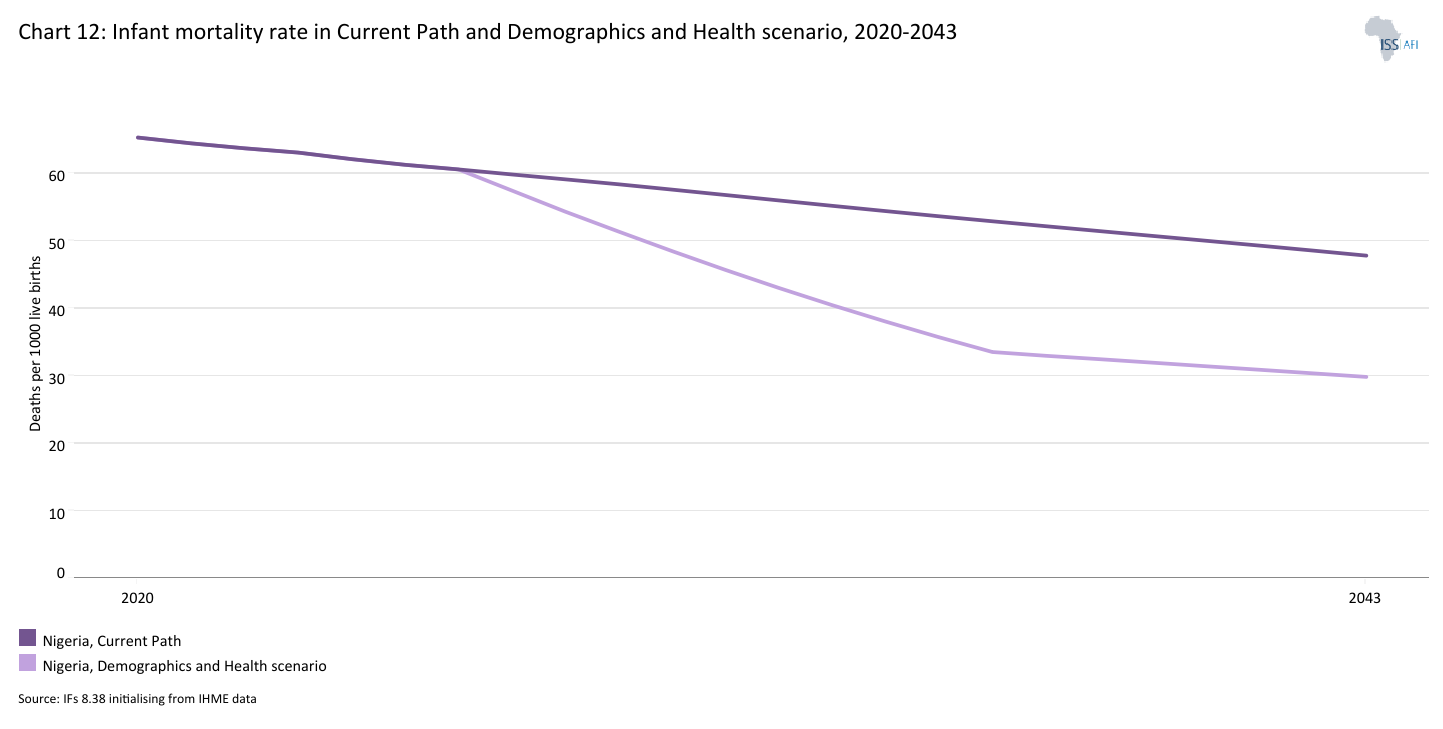

- Chart 12: Infant mortality rate in Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 13: Demographic dividend in the Current Path and the Demographics and Health scenario, 2020–2043

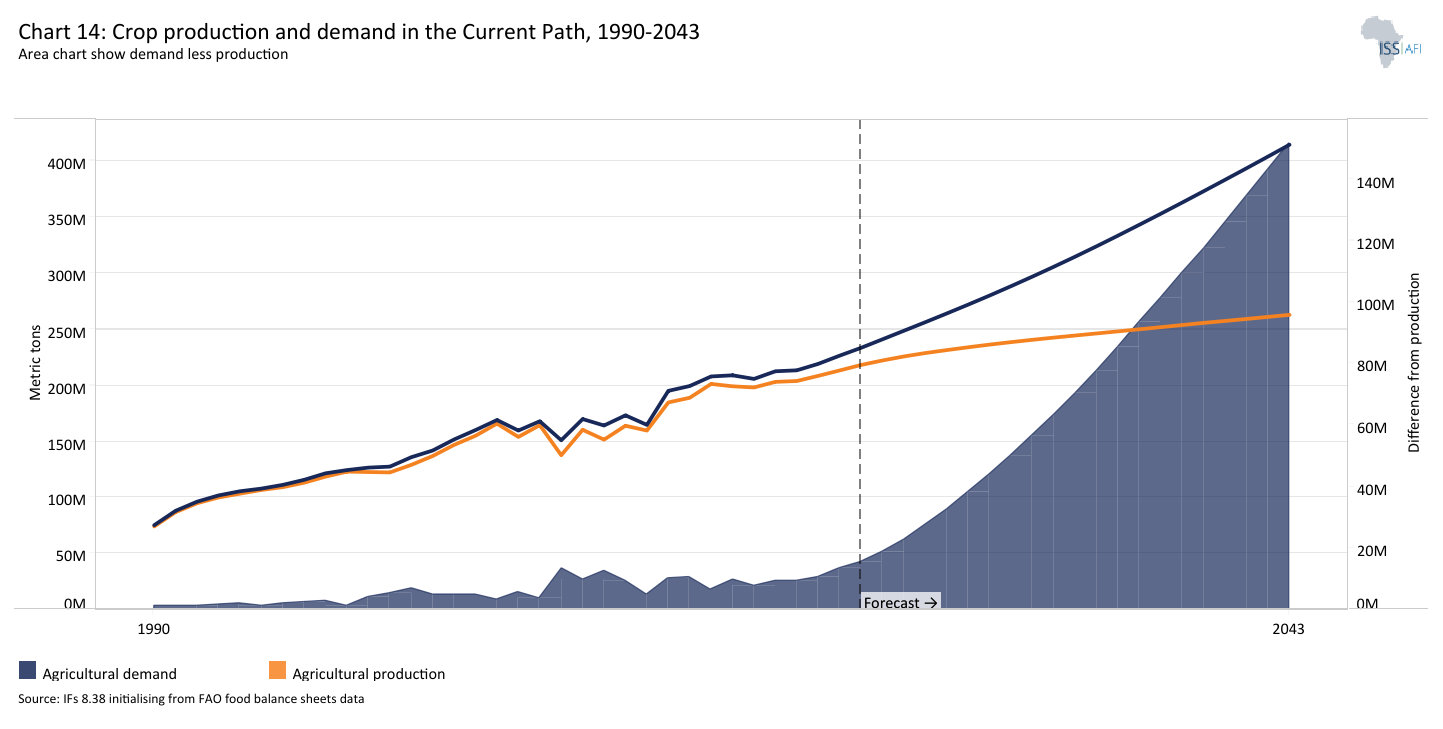

- Chart 14: Crop production and demand in the Current Path, 1990-2043

- Chart 15: Import dependence in the Current Path and Agriculture scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 16: Progress through the education funnel in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 17: Mean years of education in the Current Path and Education scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 18: Value-add by sector as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 19: Value-add by the manufacturing sector in the Current Path and Manufacturing scenario, 2020–2043

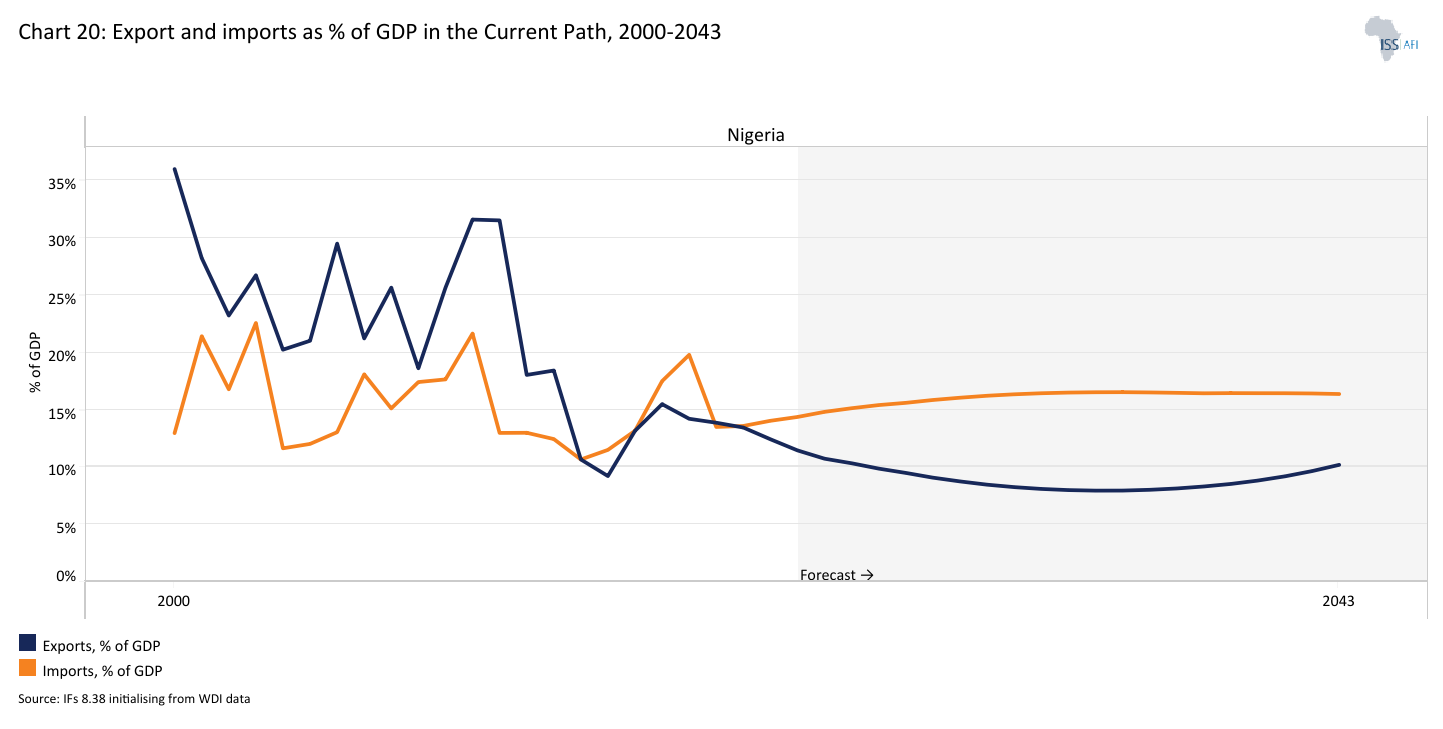

- Chart 20: Exports and imports as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2000-2043

- Chart 21: Trade balance in the Current Path and AfCFTA scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 22: Electricity access: urban, rural and total in the Current Path, 2000-2043

- Chart 23: Cookstove usage in the Current Path and Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2020–2043

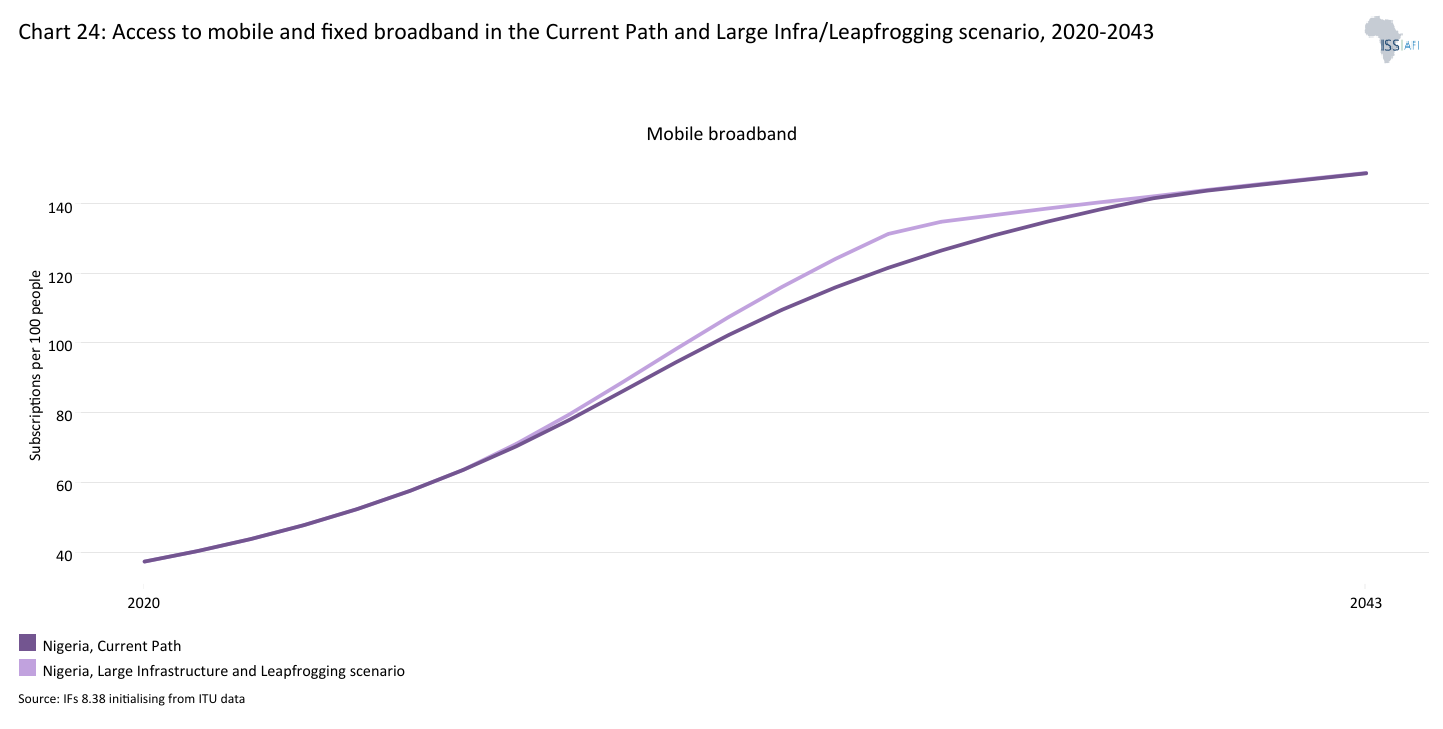

- Chart 24: Access to mobile and fixed broadband in the Current Path and the Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 25: FDI, foreign aid and remittances as % of GDP in the Current Path and in the Financial Flows scenario, 1990-2043

- Chart 26: Government revenue in the Current Path and Financial Flows scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 27: Government effectiveness score in the Current Path, 2002-2043

- Chart 28: Composite governance index in the Current Path and Governance scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 29: GDP per capita in the Current Path and scenarios, 2020–2043

- Chart 30: Poverty in Current Path and scenarios, 2023–2043

- Chart 31: GDP (MER) in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

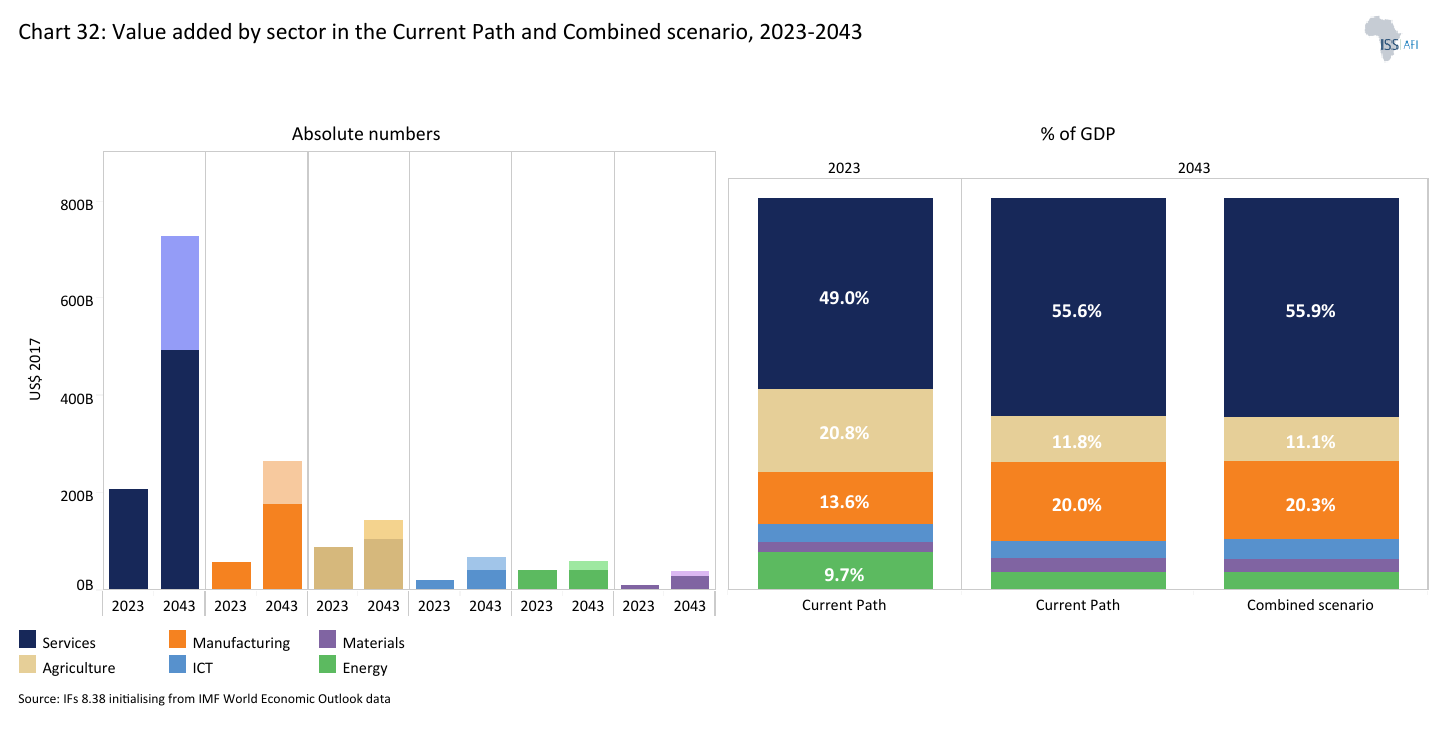

- Chart 32: Value added by sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

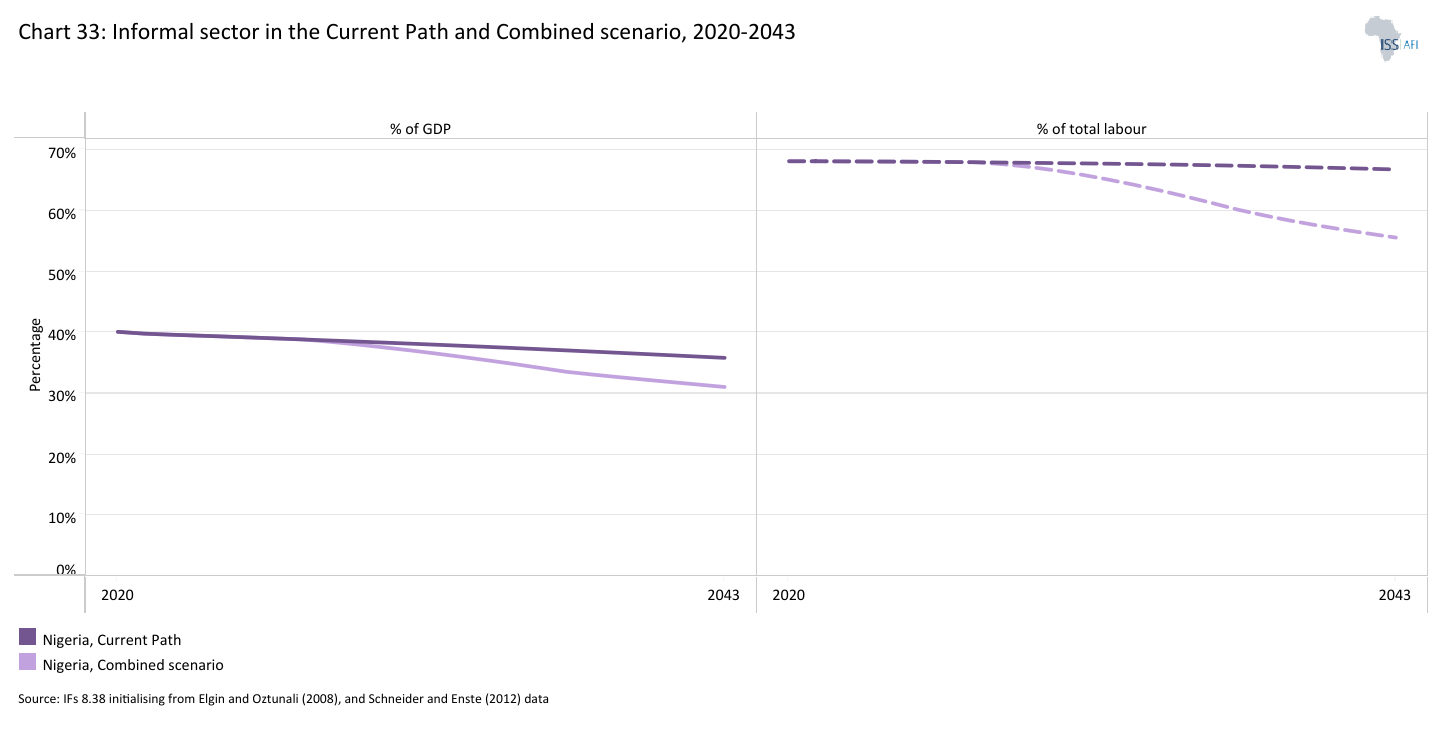

- Chart 33: Informal sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 34: Life expectancy in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

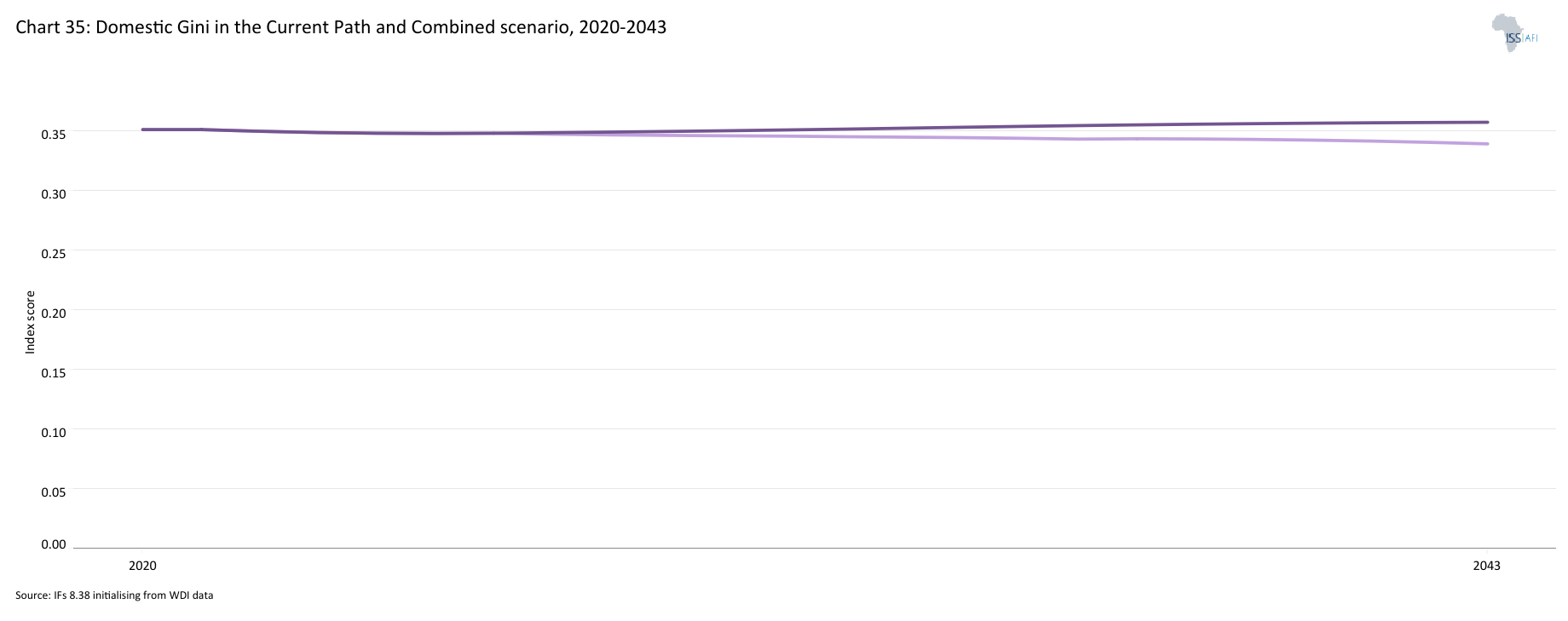

- Chart 35: Domestic Gini in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

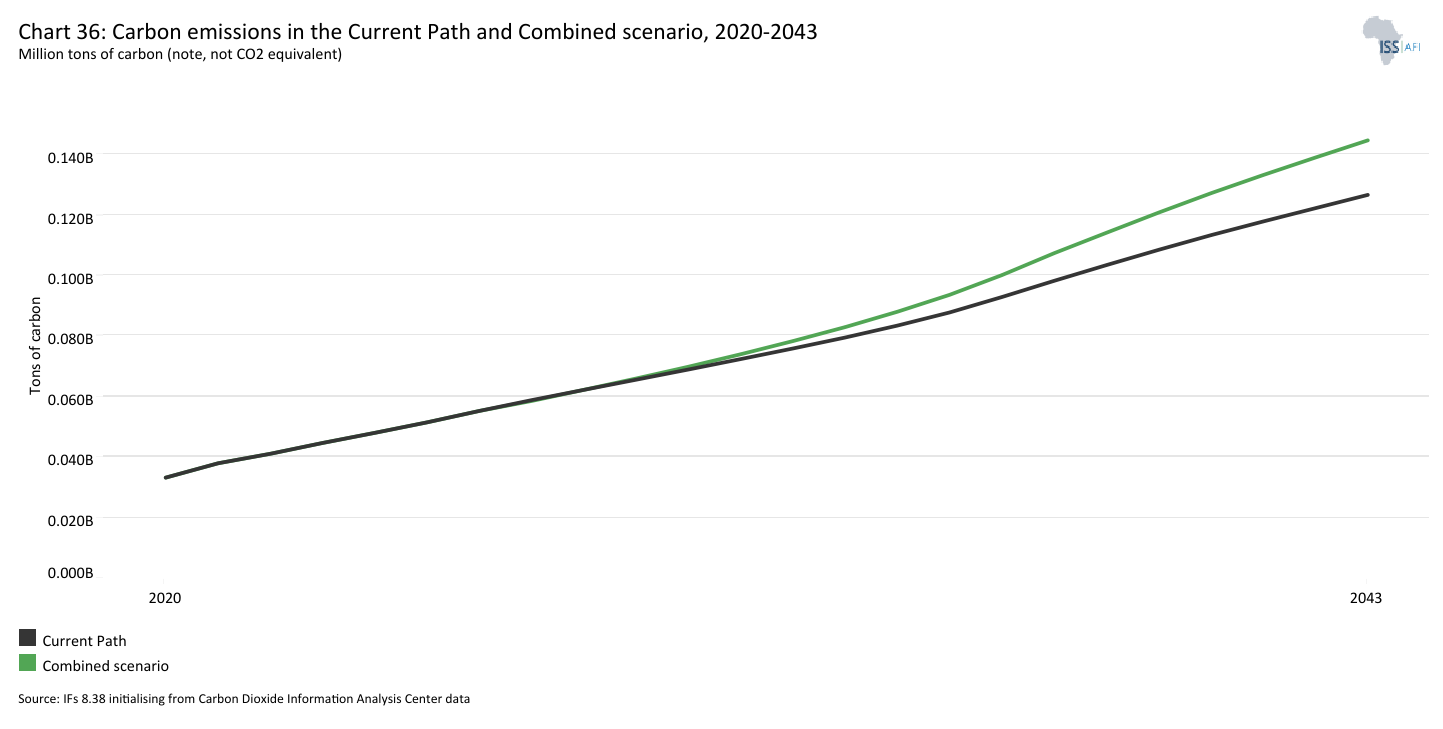

- Chart 36: Carbon emissions in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

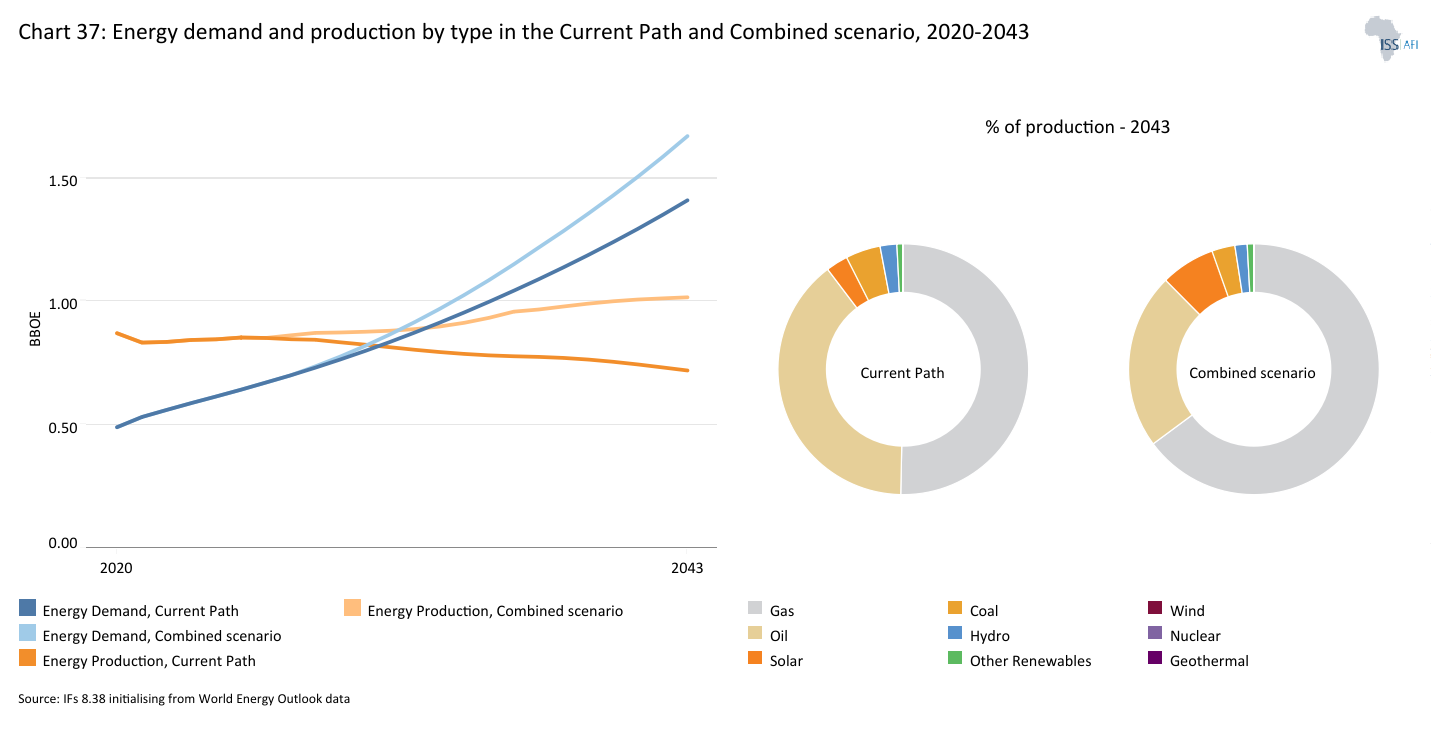

- Chart 37: Energy demand and production by type in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020-2043

- Chart 38: Policy recommendations

Chart 1 is a political map of Nigeria.

Located in West Africa, Nigeria is by far the most populous country in Africa and a key regional player in West Africa. The country is a multi-ethnic and culturally diverse federation made up of 36 states and the Abuja Federal Capital Territory (FCT) grouped into six geo-political zones (North-West, North-Central, North-East, South-West, South-East and South-South).

For nearly four decades, following its independence in 1960, Nigeria was under military rule, with only brief periods of civilian governance (1960–1966 and 1979–1983). The transition to democracy only began in 1999.

The first military coups in January and July of 1966 triggered the Biafra War (1967–1970), which resulted in over a million deaths, mostly due to starvation. In 1979, General Olusegun Obasanjo's military government handed over power to an elected civilian administration. However, economic mismanagement under President Shehu Shagari led to a military coup in 1983, bringing Major General Muhammadu Buhari to power. Two years later, he was overthrown by General Ibrahim Babangida.

In 1993, Babangida annulled the results of nationwide elections, prompting widespread unrest. Under pressure, he handed over power to an interim civilian government, which was quickly overthrown by General Sani Abacha. His regime, marked by extreme repression, became Nigeria’s most brutal dictatorship. Following Abacha’s death in 1998, General Abdulsalami Abubakar took over, released political prisoners and initiated democratic reforms. In 1999, elections were held, and former military ruler Olusegun Obasanjo was elected president, marking Nigeria’s return to civilian rule.

The legacy of military rule left deep economic and social scars. By the 1980s, nearly 45% of foreign exchange earnings were allocated to debt servicing, while poverty and crime surged. Political leadership was increasingly characterised by ethnic divisions and patronage.

Obasanjo was re-elected in 2003, though the election was marred by irregularities and violence. In 2007, he was succeeded by Umaru Yar'Adua, whose ill health led to Vice President Goodluck Jonathan assuming office shortly before Yar'Adua’s death in 2010. Jonathan later won the 2011 elections.

In 2015, Muhammadu Buhari returned to power, this time through democratic elections under the All-Progressives Congress (APC), promising to combat terrorism, corruption and economic instability. He secured a second term in 2019, despite opposition parties contesting the results.

Bola Ahmed Tinubu succeeded Muhammadu Buhari as Nigeria's president on 29 May 2023, following his victory in the February 2023 presidential election. Tinubu, representing the APC, won the election amidst allegations of electoral fraud from opposition parties. Despite these challenges, he was inaugurated as the nation's leader, marking a continuation of APC's governance. The transition from Buhari to Tinubu represents a significant moment in Nigeria's political landscape, reflecting both continuity and change within the nation's leadership.

Nigeria is also the largest crude oil exporter in Africa and holds the continent’s largest natural gas reserves. However, despite some socioeconomic progress in recent years, the country continues to face serious economic, social and security challenges. Nigeria has the third-largest number of people living in extreme poverty in the world, and high youth unemployment. Overdependence on oil exports, leadership failure and weak institutions, deplorable infrastructure, human capital bottlenecks, low tax revenue mobilisation, deeply embedded corruption and decades of mismanagement have impeded economic development and made Nigeria symbolic of unfulfilled potential. In addition, security concerns, including banditry, kidnappings, terrorism, communal clashes and separatist agitations in the south-east further threaten economic stability and limit foreign investment inflows. These issues, coupled with vast income inequality, have resulted in low socioeconomic indicators. Many Nigerians lack adequate healthcare, nutrition and education. As a result, Nigeria ranks 161 out of 193 countries in the UN Human Development Index 2024.

However, there are reasons to be optimistic about the future of Nigeria. President Tinubu has continuously pledged to turn around the economy and ensure security across the country. Since assuming office, he has introduced key socioeconomic reforms in an attempt to address these challenges and revitalise the economy. One of his first major policy decisions was the removal of the longstanding fuel subsidy, aimed at reallocating resources to critical sectors such as infrastructure and education. His administration has also unified exchange rates to stabilise the currency and attract foreign investment. These reforms are part of a broader strategy to foster economic resilience and sustainable growth, positioning Nigeria for long-term development.

Chart 2 presents the Current Path of the population structure from 1990 to 2043.

The composition of a country's population plays a crucial role in shaping its long-term social, economic and political landscape. Therefore, analysing a nation’s demographic profile provides valuable insights into its development prospects.

Nigeria is experiencing rapid population growth. At the time of its independence in 1960, the country had an estimated population of 45 million. Today, that number has surpassed 200 million, making Nigeria the sixth most populous nation in the world. If the current demographic trends persist, Nigeria’s population will grow from 228 million in 2023 to around 380 million by 2043. This would position Nigeria as the third most populous country globally, behind only India and China.

Nigeria's fertility rate was about 4.5 children per woman in 2023, a decline from 6.45 in 1990, currently ranked 15th highest globally. The Current Path is that Nigeria's fertility rate will decline to 3.7 children per woman by 2043, making it the 8th highest globally.

Fertility is much higher in rural areas than in urban areas and regionally. On average, women in rural areas give birth to 5.6 children over their lifetime, while urban women give birth to 3.9 children. The population of the northern states is also growing much faster than that of the southern states.

Nigeria is among the countries with the most youthful age structure, with a median age of about 19. This means that half of the Nigerian population is younger than 19. On the Current Path, the median age will modestly increase to 23 years by 2043.

Due to this youthful age structure, the dependency ratio is high, as a large portion of the population depends on the small workforce to provide for its needs—this constrains savings and investment in human and physical capital.

As of 2023, about 41% of the population is in the below 15 years of age dependency age group, while 3% are in the 65 and above dependency age group. On the Current Path, the share of these two dependency age groups is projected to be, respectively, 35.8% and 4.8% by 2043. About 56% of the Nigerian population is in the 15-64 working-age group, and this will increase to 59 % by 2043. The structure of Nigeria’s population is typical of countries with a low life expectancy and high fertility rates.

The large cohort of children below 15 requires more investment in education, health and infrastructure. An increase in the working-age population relative to dependent children and elders can generate income growth, known as the demographic dividend. Generally, the demographic dividend materialises when a country reaches a ratio of at least 1.7 people of working age for each dependant. When there are fewer dependants to take care of, it frees up resources for investment in both physical and human capital formation, and eventually increases female labour force participation.

However, the growth in the working-age population relative to dependants does not automatically translate into rapid economic growth unless the labour force acquires the needed skills and is absorbed by the labour market. Without sufficient education and employment generation to successfully harness their productive power, the growing labour force could turn into a demographic ‘bomb’ instead of a demographic dividend, as many people of working age may remain in poverty, potentially creating frustration, social tension and conflict. Currently, the private sector's limited capacity makes it challenging to accommodate the large number of young job seekers in the country.

Nigeria is unlikely to fully benefit from its demographic dividend within the Current Path forecast horizon. In 2023, the ratio of working-age individuals to dependants was just 1.2—meaning nearly one working-age person for every dependant. This ratio will rise slowly, reaching only 1.45 by 2043—still below the average of 1.6 for African lower-middle-income countries and short of the 1.7 threshold needed to enter the demographic window of opportunity. On the Current Path, Nigeria is not expected to cross this critical threshold until around 2061, nearly a decade later than the average for its income group on the continent.

Nigeria also has a large youth bulge at 47%. Youth bulge is the percentage of the population between 15 and 29 years old relative to its total adult population. It will get to 40.9% by 2043. In addition to the requirement for more spending on education, health services and job creation, large numbers of young adults can lead to positive political change in a country through youth activism, but they can also increase the likelihood of criminal violence, conflicts and instability, mainly when the needs of the youth, such as employment, cannot be met. Nigeria has one of the highest youth unemployment rates; two-thirds of the youth are either jobless or underemployed, while one-third of the country's working-age population is unemployed.

Successive Nigerian governments have recognised the necessity of reducing the rapid population growth, but efforts to implement a comprehensive demographic policy have often been met with religious objections. Family planning policies are a topic of fractious debate among religious leaders in the country. According to the country’s latest Demographic and Health Survey 2023–2024, the contraceptive prevalence rate is only 20% among currently married women and 50% among sexually active unmarried women aged 15-49.

Better management of population growth is key to a nation's development. The decline in the below-15 dependency age group helps governments and parents invest more in each child in terms of education and health, which has positive implications for human capital formation and long-run economic growth.

Chart 3 presents a population distribution map for 2023.

Nigeria’s population is unevenly distributed across the country, concentrating along trade routes and natural resource locations. The highest rural densities are found in the South-West region, known for its agricultural productivity and strategic trade routes. Urban population densities are notably high in major cities such as Lagos, Kano, Ibadan, Kaduna, Port Harcourt, Benin City, and Maiduguri. These cities function as economic hubs, drawing in migrants from rural areas in search of employment opportunities, better living standards, and improved access to services. On the Current Path, Nigeria’s population density will be about four people per hectare in 2043, compared with an average of 2.5 people per hectare in 2023.

Lagos, with its status as Nigeria's largest city and commercial center, exemplifies this urban concentration. The city's strategic location along the coast and its infrastructure supporting trade and industry attract a diverse population, contributing to its high density. Similarly, Kano serves as the economic and cultural heartbeat of Northern Nigeria, with its rich history as a trade center and its current role in manufacturing and agriculture. These urban centers, while contributing significantly to Nigeria's GDP, also face challenges such as congestion, inadequate infrastructure, and environmental degradation due to their burgeoning populations.

Comparatively, Nigeria's population density is higher than many lower-middle-income African countries. This is partly due to its large population base, currently the largest in Africa, and the rapid urbanization rate driven by both natural population growth and rural-to-urban migration. The demographic trend in Nigeria aligns with the broader African experience, where urban areas are expanding rapidly, creating both opportunities and challenges for sustainable development.

The projection for 2043 indicates a population density increase to about four people per hectare. This anticipated growth underscores the urgent need for comprehensive urban planning and policy interventions to manage the pressures of urbanization. As Nigeria continues on its demographic path, the potential to harness a demographic dividend exists, given the increasing proportion of the working-age population. However, realizing this potential depends on strategic investments in education, healthcare, and infrastructure to enhance productivity and economic growth.

The concept of a demographic dividend emphasizes the economic benefit arising when a country's working-age population is larger than the non-working-age share. For Nigeria, capitalizing on this demographic transition could significantly boost economic development, provided the labor force is adequately skilled and employed. However, the challenge remains in ensuring that the benefits of growth are equitably distributed across regions, particularly in addressing the rural-urban divide.

Policy implications of Nigeria's population distribution are profound. Government and policymakers must prioritize investments in infrastructure, such as transportation and housing, to accommodate the growing urban populations. Additionally, enhancing rural development through improved agricultural practices and rural industrialization can help balance the population distribution, reducing excessive pressure on urban centers.

Chart 4 presents the urban and rural population in the Current Path from 1990 to 2043.

Nigeria’s rapid population growth is closely tied to accelerated urbanisation with the portion of urbanites exceeding 50% as from 2020. As of 2023, 53.4% of the country’s population—approximately 122 million people—lived in urban areas. Lagos, for example, has experienced a dramatic increase in population, rising from 300 000 in 1950 to 16.5 million in 2024. With an annual urban population growth rate of about 4%—twice the global average and higher than Nigeria’s overall population growth rate of 3%—the country ranks among the fastest urbanising nations in the world.

If current trends continue, an estimated 63% of Nigeria’s population—around 237 million people—will reside in urban areas by 2043. However, this rapid urban expansion presents significant challenges, including rising unemployment, poverty, inadequate healthcare, poor sanitation, the spread of urban slums and environmental degradation. Currently, it is estimated that between half and two-thirds of Nigeria’s urban population lives in slum conditions.

Historically, cities have been key drivers of economic growth, industry and commerce worldwide. When well-managed, they provide opportunities for social and technological advancement and facilitate the exchange of ideas through cultural interaction. Cities have also served as hubs for political activities, governance systems and employment generation, reinforcing their critical role in national development.

Chart 5 presents GDP in market exchange rates (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

At the time of Nigeria's independence, its economy showed significant potential, with agriculture serving as its backbone. The country embraced an import substitution industrialisation policy, aiming to produce locally most of the goods it previously imported. However, the discovery of crude oil in commercial quantities marked a turning point in Nigeria's economic trajectory. As oil prices surged and demand increased, crude oil extraction and export became the dominant economic activity. The influx of petrodollars made it easier to import a variety of goods and services, which led to the neglect of agriculture and manufacturing. Over time, these sectors have become less competitive.

Today, Nigeria's exports remain heavily reliant on crude oil, which accounts for more than 80% of total exports, half of government revenues and the majority of foreign currency earnings. Since the late 1960s, when the country shifted focus from agriculture and light manufacturing bases in favour of an unhealthy dependence on crude oil and gas, Nigeria's economic growth has been marked by volatile boom-bust cycles driven by fluctuations in oil prices. As a result, the country has experienced volatile and low average growth.

Between 2000 and 2014, Nigeria recorded an average growth rate of 7%. However, a sharp drop in oil prices from mid-2014 to 2016 plunged the economy into a recession. Growth fell from 6.3% in 2014 to -1.6% in 2016, leading to a budgetary crisis. The subsequent recovery was slow and the collapse of commodity prices during the COVID-19 crisis led to a contraction of -1.8% in 2020. This was Nigeria's deepest recession in four decades, although resumed in 2021 at 3.6% as pandemic restrictions were eased and oil prices recovered. By 2023, growth rates had recovered to 2.9%, now constrained by high inflation and sluggish growth in the global economy. Domestic shocks, such as the disruptive demonetisation policy in early 2023 and the devastating floods of October 2022, further exacerbated the situation.

Since the elections in May 2023, the administration of President Tinubu has launched ambitious reforms to restore economic stability and growth. Key actions include removing most gasoline subsidies, unifying the exchange rate to reflect market conditions and tightening monetary policy. These steps have improved fiscal performance and reduced economic distortions. The Central Bank of Nigeria has also refocused on its price stability mandate, facilitated by the authorities’ commitment to end budget deficit monetisation (deficit financing through money printing). Despite progress, inflation and poverty remain high. To cushion the impact on vulnerable groups, the government is providing temporary cash transfers to 15 million households. These ongoing macroeconomic reforms enhance Nigeria’s global competitiveness, attracting both domestic and foreign investment, and begin to ease fiscal pressures linked to debt, creating more budgetary space. If sustained and expanded, they could lay a solid foundation for renewed growth and set Nigeria on a better development path.

Between 1990 and 2023, Nigeria’s GDP more than tripled, rising from US$118 billion to US$423 billion. On the current development trajectory, it will reach US$530 billion in 2030 and US$888 billion in 2043, maintaining its position as Africa’s largest economy. In the Current Path, the average annual growth rate between 2023 and 2043 is expected to be 3.7%. However, this positive growth outlook is contingent upon tackling longstanding and potentially binding constraints to growth, including inadequate infrastructure, particularly unreliable power supply, trade barriers, an unfriendly business environment and insecurity, among other structural issues.

In this regard, the African Development Bank Group has a new five-year Country Strategy Paper (2025-2030) for Nigeria, committing about US$650 million annually to drive economic transformation, build resilience and foster broad-based prosperity across the country.

Under the new strategy, the Bank will provide US$2.95 billion over the first four years, complemented by an estimated US$3.21 billion in co-financing from development partners. The strategy focuses on two key priority areas: promoting sustainable, climate-smart infrastructure to enhance competitiveness and industrial development; and advancing gender and youth-inclusive green growth through industrialisation.

The new strategy aligns with Nigeria’s long-term development plan (Agenda 2050) and supports Nigeria’s efforts to capitalise on opportunities offered by the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) by boosting energy access, improving transportation networks and enhancing market access for farmers, agro-entrepreneurs and businesses.

Chart 6 presents the size of the informal economy as per cent of GDP and per cent of total labour (non-agriculture), from 2020 to 2043. The data in our modelling are largely estimates and therefore may differ from other sources.

An informal economy (informal sector or shadow economy) typically consider as neither officially taxed or monitored. Countries with high informality have a whole host of development challenges, such as low revenue mobilisation and economic growth tends to be below potential.

Informality in poorer countries arises not only from burdensome regulations or weak enforcement but also as a consequence of underdevelopment. In wealthier countries, where advanced production technologies and favourable economic conditions prevail, workers prefer formal wage employment because of higher wages. Similarly, managers are more likely to register and operate formal businesses, as the greater income potential in developed markets makes formality more profitable, even with the associated costs of taxes and regulations. As countries advance economically, the size of the informal sector typically shrinks. A recent World Bank study found that about 30% of the increase in aggregate output driven by higher productivity is linked to a roughly 25% reduction in the average size of informal enterprises.

Nigeria’s crude oil-dependent economy makes it unable to achieve inclusive growth. According to the World Bank, a one per cent increase in economic growth leads to only a 0.1% increase in employment in Nigeria. This low elasticity of employment to economic growth shows the extent to which the Nigerian oil-driven growth path is jobless. The informal sector has therefore become the lifeblood of millions of Nigerians. Estimates by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) show that 93% of all employment in Nigeria is informal, with 95% of women working in the informal sector compared to 90% of men.

While the informal sector contributes a significant portion of GDP, its productivity is markedly lower than that of the formal sector. The large number of individuals employed informally, juxtaposed with their relatively smaller economic output, underscores the low productivity and precarious nature of these jobs. Such employment is often characterized by a lack of job security, absence of legal protection, and insufficient earnings, which overall contribute to social and economic vulnerabilities.

The persistence of informality in Nigeria can be attributed to several structural challenges. Rapid population growth, coupled with inadequate formal job creation, exacerbates the reliance on the informal sector. Regulatory complexity and the high cost of compliance deter small businesses from entering the formal economy. Additionally, limited access to finance and inadequate education systems restrict opportunities for formal employment and entrepreneurship. Gender disparities also play a role, as women are often overrepresented in the informal sector, engaging in lower-paid and less secure forms of employment.

The implications of a dominant informal sector are profound. The low productivity associated with informal employment constrains economic growth and reduces potential fiscal revenues, as these activities are largely untaxed. Moreover, the lack of formal employment opportunities limits economic resilience and exacerbates socio-economic inequalities. For Nigeria to foster a more dynamic and inclusive economy, targeted policy interventions are necessary. Improving governance, simplifying regulatory frameworks, and expanding access to education and financial services are crucial steps toward facilitating the transition to formal employment.

The size of the country's informal economy was estimated at 39.5% of GDP in 2023, above the average of 30.5% for lower-middle-income Africa. On the Current Path, the size of the informal sector is expected to slowly decline to 35.8% by 2043. However, this figure will still remain above the forecast of 27% for lower-middle-income African countries in 2043.

Chart 7 presents GDP per capita in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

Nigeria boasts the largest GDP in Africa; however, in 2023, it ranked only 20th among the continent’s 54 countries in terms of GDP per capita (PPP). Between 2015 and 2023, Nigeria’s population grew at an average annual rate of 2.3%, outpacing the country’s average economic growth of 1.5% during the same period. As a result, GDP per capita has declined, returning to nearly the same level as in 2010. Projections along the Current Path suggest that Nigeria’s GDP per capita will remain below its 2015 level until at least 2040.

The country's inability to sustain economic growth and the rapid population growth dilute per capita income growth. On the Current Path, the GDP per capita of Nigeria will increase from about US$5 000 in 2023 to US$5 650 by 2043, below the projected average of US$7 800 for lower-middle-income Africa in the same year.

Nigeria’s economic development has been hindered by an over-reliance on crude oil, policy missteps, corruption and poor governance. For instance, Malaysia, once as poor as Nigeria in the 1960s, now has a GDP per capita nearly six times higher. From 1960 to 1975, the two countries had comparable GDP per capita levels. However, Malaysia pulled ahead significantly after it began diversifying its economy to reduce dependence on volatile commodity prices. In 1957, tin and rubber made up 85% of Malaysia’s exports, but starting in the 1970s, the country pursued a robust diversification strategy centred on commodity-based manufacturing. As a result, crude oil’s share in Malaysia’s petroleum exports fell from 95% to 20%, while processed palm oil exports rose from 0% in 1974 to 99% by 1994. Nigeria, by contrast, has remained heavily dependent on crude oil exports, leaving its economy vulnerable to external shocks and limiting growth in GDP per capita.

Chart 8 presents the rate and number of extremely poor people in the Current Path from 2020 to 2043.

In 2022, the World Bank updated the monetary poverty lines to 2017 constant dollar values, with the previous International/PPP $1.90 extreme poverty line now set at US$2.15, also for use with low-income countries. The US$3.20 for lower-middle-income countries such as Nigeria, is now US$3.65 in 2017 values.

Like many sub-Saharan African countries, poverty in Nigeria presents a paradox: despite being rich in natural resources, the majority of the population lives in poverty. Over time, both the poverty rate and the number of people living in extreme poverty have remained high. At the international poverty line of US$2.15 per day, Nigeria's poverty rate peaked between 1995 and 2000, at 58% of its population, before declining steadily to 31% in 2018–2019—its lowest level since gaining independence in 1960.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Nigeria has experienced a slower reduction in poverty rates compared to other sub-Saharan African countries with similar GDP per capita growth. This is partly due to the ineffectiveness of successive poverty alleviation programmes, often undermined by corruption and poor governance. Corruption diverts public spending from critical sectors such as education and healthcare, limiting the impact of these initiatives on vulnerable populations.

Since 2019, poverty and hardship levels have worsened. The COVID-19 pandemic, sluggish economic growth and high inflation have pushed millions more into poverty. As a result, the poverty rate at US$2.15 increased from 31% in 2019 to 38.9% in 2023. The lower-middle-income poverty rate (US$3.65 in 2017 PPP) rose from 63.5% to around 70% over the same period.

To support the poorest and most economically vulnerable households, the Nigerian government is implementing targeted, temporary cash transfer programs. However, these efforts need to be significantly scaled up and sustained to make a meaningful impact.

Projections suggest that on the current trajectory, the extreme poverty rate (US$2.15) will gradually decline to 23.5% by 2043. Yet, this remains well above the projected average of 13.8% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. Similarly, the lower-middle-income poverty rate (US$3.65) will decline to 54% by 2043, compared to an average of 35% for Nigeria’s peer group.

On the Current Path, the number of Nigerians living in extreme poverty is projected to remain alarmingly high, increasing slightly from 88.6 million in 2023 to 89 million by 2043—positioning Nigeria as the country with the largest population of extremely poor people globally. Without bold and proactive policy action, the country is set to fall far short of achieving the Sustainable Development Goal of eradicating extreme poverty by 2030.

Poverty in Nigeria also follows a stark regional pattern, with a disproportionate concentration in the northern part of the country. States such as Sokoto, Taraba and Jigawa report poverty rates well above the national average. Overall, the northern region lags behind the south across almost all human development indicators. According to the World Bank, 87% of Nigeria’s poor reside in the northern region, with nearly half located in the North-West.

Ongoing conflicts between farmers and herders have further deepened poverty in the North. The violence has severely disrupted agricultural activity, which provides livelihoods for about 80% of the region’s population. Farmlands have been destroyed or rendered inaccessible, contributing to increased food insecurity, poverty and malnutrition.

Moreover, poverty in Nigeria is predominantly rural. Access to infrastructure, financial services and economic opportunities remains limited in rural communities. For example, approximately 78% of financially excluded adults live in rural areas, compared to 22% in urban settings.

While this analysis has primarily focused on monetary measures of poverty, it is increasingly recognised that poverty is multidimensional. Even those who do not fall below the income poverty line may still lack access to essentials such as nutritious food, clean water, healthcare, housing, security and education.

The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) captures these deprivations. According to the 2024 global MPI, 41% of Nigerians—approximately 81 million people—are multidimensionally poor. This figure makes Nigeria the largest contributor to multidimensional poverty in sub-Saharan Africa. It underscores Nigeria’s central role in achieving regional targets for both monetary and non-monetary poverty reduction.

In summary, the face of poverty in Nigeria is largely rural, predominantly female, mostly illiterate and deeply entrenched in the informal sector. Addressing this complex challenge is crucial not only for national development but also for ensuring peace and stability.

Chart 9 depicts the National Development Plan of Nigeria.

The Nigeria Agenda 2050 (NA 2050) is a long- and medium-term development plan designed to tackle the country’s persistent economic and social challenges. By 2050, Nigeria aspires to become a dynamic, industrialised and knowledge-based economy that generates inclusive and sustainable development.

To this end, Nigeria Agenda 2050 espouses policies, strategies and initiatives that will be implemented to position Nigeria as an African regional power and global economic force. The plan envisages an annual average of 7% GDP growth rate during 2021-2050 and a per capita income of US$33 328 by 2050. Nigeria Agenda 2050 is premised upon three key factors that are critical to realising the nation’s potential:

- Reforming governance structure with strong institutions and administrative machinery capable of responding to the needs of the people;

- Inclusive and sustainable growth of a private sector-driven economy through the concentric diversification of the economy; and

- Empowerment of the Nigerian people by ensuring a balance between economic growth and social welfare.

The Technical Page explains the eight sectoral scenarios and their relationship to the Current Path and the Combined scenario. Chart 10 summarises the approach.

Chart 11 presents the mortality distribution in the Current Path for 2023 and 2043.

Access to quality healthcare is necessary for citizens to live socially and economically productive lives and contribute to sustainable development. Over the years, the federal and state governments of Nigeria have devoted significant amounts of resources to the development and implementation of numerous health plans and strategies to achieve a modern, efficient and effective healthcare delivery system. Despite these investments and some improvements that follow, Nigeria’s health indices remain below expectations.

The health sector in Nigeria faces significant challenges that hinder its effectiveness and accessibility, particularly for vulnerable populations. It is plagued by mismanagement, corruption and inadequate resources, all of which contribute to poor health outcomes. A major issue is insufficient health care financing, compounded by the limited reach of the universal health insurance program, which leaves many Nigerians without adequate medical coverage. Currently, only about 4% of Nigeria’s annual budget is allocated to the health sector, far below the 15% target set by African leaders in the 2001 Abuja Declaration.

The high out-of-pocket health expenditures in Nigeria significantly limit the ability of poor households to access and utilise basic healthcare services. It is estimated that over half of the country’s total health spending is out-of-pocket, which disproportionately affects millions of Nigerians, particularly those who are multidimensionally poor, by depriving them of access to modern healthcare facilities.

Also, the health sector suffers from a high rate of brain drain, with skilled professionals leaving the country in search of better work conditions and pay abroad.

Communicable diseases remain the leading cause of illness and death, with malaria being a major contributor, while non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular and respiratory infections, remain the leading causes of death among the elderly. Malaria is a major public health concern in Nigeria; the country has the highest burden of malaria globally, accounting for nearly 27% of the global malaria burden. According to the 2023 World Malaria Report, nearly 200 000 deaths from malaria occurred in Nigeria. Children under five and pregnant women are the most affected, with a national malaria prevalence rate of 22% in children aged 6-59 months.

Despite these challenges, Nigeria’s weak health indices have slightly improved. For instance, the country ranked 157 of 191 countries in the WHO health system ranking in 2024, an improvement from its previous ranking at 163rd in 2021.

The stunting rate among children under the age of five has also significantly declined from 43.6% in 2016 to 30% in 2023, about four percentage points above the average of 26% for Africa lower-middle-income countries. Nigeria is on track to achieve the SDG target of 25% by 2030.

Maternal mortality has declined from 1 350 deaths per 100 000 live births in 1990 to 957 in 2023, almost double the average of 494 for lower-middle-income Africa. On the Current Path, the maternal mortality rate will likely decline to 810 deaths per 100 000 live births by 2030, significantly above the SDG target of less than 70 per 100 000 live births. By 2043, Nigeria will have a maternal death rate of 535 deaths per 100 000 live births.

Child (under five) mortality has also declined from 213 deaths per 1 000 live births in 1990 to about 104 deaths in 2023, while life expectancy has increased from 54.7 years to 65 years over the same period. On the Current Path, under five infant mortality will decline to 96 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2030 and 78 deaths by 2043, a far cry from the SDG target of 25 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2030.

The Demographics and Health scenario, therefore, envisions ambitious improvements in child and maternal mortality rates, enhanced access to modern contraception, and decreased mortality from communicable diseases (e.g., malaria) and non-communicable diseases (e.g., cardiovascular), alongside advancements in safe water access and sanitation. This scenario assumes a swift demographic transition supported by heightened investments in health and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WaSH) infrastructure.

Visit the themes on Demographics and Health/WaSH themes for more details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Chart 12 presents the infant mortality rate in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

The infant mortality rate is the probability of a child born in a specific year dying before reaching the age of one. It measures the child-born survival rate and reflects the social, economic and environmental conditions in which children live, including their health care. It is measured as the number of infant deaths per 1 000 live births and is an important marker of the overall quality of the health system in a country.

Infant mortality in Nigeria has declined from 103 deaths per 1 000 live births in 1990 to 63 deaths in 2023. On the Current Path, infant mortality will continue to decline to about 58 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2030 (above the SDG target of 25), and 48 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2043.

The interventions in the Demographics and Health scenario will see Nigeria's infant mortality rate drop to 48 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2030 and 30 deaths in 2043, on par with the projected average of 30 deaths for lower-middle-income Africa in 2043.

Chart 13 presents the demographic dividend in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

The dividend is the window of economic growth opportunity that opens when the ratio of working-age persons to dependants increases to 1.7 to 1 and higher.

The implementation of the Demographics and Health scenario will accelerate the demographic transition in Nigeria. In this scenario, the ratio of the working-age population to dependants will reach the 1.7 threshold by 2044. On the Current Path, this minimum ratio will only be achieved in 2061.

Chart 14 presents crop production and demand in the Current Path from 1990 to 2043.

Nigeria has immense agricultural potential, yet the sector continues to underperform due to a range of persistent challenges. These include the use of low-quality and inefficient technologies and inputs, poor distribution systems and low yields in both arable crops and forest products. Traditional livestock practices and artisanal fishing remain largely inefficient, while limited financing and inadequate government budgetary allocations constrain growth.

High post-harvest losses, minimal value-added processing, insufficient storage facilities and poor market access also weaken the sector. According to the FAO, Nigeria loses up to 50% of its agricultural produce along the food supply chain, posing serious threats to food security, economic growth and environmental sustainability. Key challenges contributing to these losses include technological limitations, inefficient harvesting methods, pest infestations and limited access to modern farming equipment. Post-harvest losses are further exacerbated by inadequate storage facilities, poor handling practices and weak transportation infrastructure.

Additionally, environmental issues such as desertification and farmers' limited access to climate information compound these challenges, leaving agriculture unable to meet the nutritional needs of Nigeria’s rapidly growing population.

The sector continues to suffer from low productivity, relying heavily on rainfall and therefore remaining highly vulnerable to fluctuations in precipitation. The country’s irrigation potential remains largely underutilised.

The sector is dominated by crop production, which accounts for around 87% of its output. Other subsectors like livestock (9%), fishing (2.2%) and forestry (1.4%) account for lower shares of the sector’s output. Major crops are maize, cassava, guinea corn, yam beans, millet and rice.

The current crop yields of about 5.5 metric tons per hectare place Nigeria in 13th position on the continent, and it is unable to meet the growing domestic demand. On the Current Path, the average crop yields will be 6.5 metric tons per hectare by 2043, slightly above the projected average of 6.3 metric tons per hectare for lower-middle-income countries on the continent.

Although its contribution to the economy is steadily declining, the agricultural sector remains vital for the Nigerian economy and its people. It is the main source of livelihood for the majority of rural Nigerians; it employs approximately 65% of the labour force and contributed 17% to the GDP in 2022.

Going forward, the large and rapidly growing population will undoubtedly place enormous pressure on food production and land administration. For the Nigerian agricultural sector to meet the food and fibre needs of the population and industries, it needs to grow faster than the population growth rate.

In the Current Path, agricultural demand is set to increase from 233 million metric tons in 2023 to about 415 million metric tons by 2043, while agricultural production is likely to reach only 263 million metric tons by 2043. This will result in a significant unmet demand of nearly 50% of total demand by 2043. This huge deficit will substantially increase the import bill, further putting pressure on foreign reserves and the exchange rate.

Enhancing agricultural productivity through the adaptation of new technologies and innovations, as well as climate-smart agriculture, is crucial to ensure food security and nutrition in Nigeria. In this regard, the US$2.5 billion fertiliser plant owned by Africa’s richest man, Aliko Dangote, which is expected to produce 3 million metric tons of urea fertiliser per annum, will help Nigeria meet the domestic demand for fertiliser, a critical component of achieving food sufficiency for the country.

The Agriculture scenario envisions an agricultural revolution that ensures food security through ambitious yet feasible increases in yields per hectare, thanks to improved management, seed, fertiliser technology and expanded irrigation and equipped land. Efforts to reduce food loss and waste are emphasised, with increased calorie consumption as an indicator of self-sufficiency and prioritising it over food exports. Additionally, the scenario includes enhanced forest protection, signifying a commitment to sustainable land use practices.

Visit the theme on Agriculture theme for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Chart 15 presents the import dependence in the Current Path and the Agriculture scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

The Agriculture scenario will benefit Nigeria by increasing yields, reducing vulnerable rain-fed crops through irrigation schemes, reducing post-harvest losses and tapping into the country’s agricultural potential. In the Agriculture scenario, average crop yields could increase to 8.4 metric tons per hectare in 2043, compared with 6.5 tons on the Current Path in the same year. As a result, crop production will be 9.2 million metric tons more by 2043 than in the Current Path. This will result in a lower import dependency of 22% of total demand in 2043, compared with 36.7% in the Current Path and below the projected average of 24% for lower-middle-income Africa in 2043.

Chart 16 depicts the progress through the educational system in the Current Path, for 2023 and 2043.

The education system in Nigeria is administered at different levels. The Federal Ministry of Education oversees overall policy formation and ensures quality control but is mainly involved with tertiary education. Basic and senior secondary education remain primarily under the jurisdiction of the state and local governments. The Nigerian education system can be described as a ‘1-6-3-3-4’ system: one pre-primary year (recently introduced) and six years of primary, followed by three years of junior secondary education, which together comprise basic education. The next three years are senior or secondary education, followed by four years of tertiary education for a basic degree.

According to Nigeria’s national policy on education, the language of instruction for the first three years of elementary school should be the “indigenous language of the child or the language of his/her immediate environment,” most commonly Hausa, Igbo or Yoruba. After that, English is used from Grade 4. This policy, however, is not always followed and instruction at lower grades is often delivered in English.

The education sector has not received enough attention in Nigeria, as reflected in chronically low public funding, decaying educational infrastructure, deteriorating teaching capabilities and high illiteracy, among other things.

The national literacy rate has modestly improved from 54.7% in 2003 to about 63.8% in 2023, eight percentage points below the average for lower-middle-income Africa. However, despite the progress made, more than 30% of Nigeria's population aged 15 years and older can neither read nor write, many of whom are in the Northern states of the country. For instance, the literacy rate in North West Nigeria is estimated to be about half of the national rate. These distressing statistics imply that a significant proportion of Nigeria’s working-age population is only employable in an economic environment that requires manual labour. The absence of appropriate knowledge and skills leads to poverty. On the Current Path, the literacy rate in Nigeria will likely increase to 71% in 2030 and 89% by 2043, slightly below the projected average of 90% for lower-middle-income Africa.

The country has made progress in primary school enrolment, with gross enrolment at 103% in 2023, slightly below the average of 108% for Africa’s lower-middle-income countries. This high percentage, however, reflects the continued presence of over-aged learners at the primary level, as the net primary school enrolment was 76% in 2023, reflecting challenges in getting all school-age children into classrooms. The out-of-school children, which were 6.56 million in 2000, now stood at more than 10 million, with 60% of them in northern Nigeria. In addition to those who do not attend school, millions of children are in the poorly resourced and under-supervised Quranic school system, which is notorious for producing unskilled youth cohorts.

While primary enrolment has improved, completion rates remain relatively low (73% in 2021, the last year of available data), even though they are on par with the average for lower-middle-income Africa. On the Current Path, primary school completion rate will be 87.7% by 2030 and 85.9% by 2043, still below the SDG target of 97%. High dropout rates, especially among girls, and disparities between urban and rural areas are major concerns.

The education system can be viewed as a pipeline where completion or attainment of one level gives access to the next. The more students are allowed to enrol and complete primary school, the greater the pool of students that can proceed to secondary and tertiary levels. Because of relatively low completion and transition rates right from the primary level, fewer students are eligible for subsequent education levels, and the resultant outcomes get poorer (Chart 16), which in turn reduces human capital accumulation.

Enrolment rates drop significantly after primary school, with a sharp decline in both lower- and upper-secondary levels. Many students do not transition from primary to secondary education, and those who do often face overcrowded classrooms and insufficient resources. In 2023, gross lower-secondary school enrolment stood at 52.9% while gross upper-secondary school enrolment was only 43%. On the Current Path, gross lower- and upper-secondary school enrolment will likely reach 75% and 45.5% in 2030, and 76% and 58.6% in 2043, respectively.

The lower-secondary education completion rate stood at 30.5% in 2023 (50.8% for lower-middle-income Africa) while the upper-secondary education completion rate was only 26.8% (34.5% for lower-middle-income Africa). On the Current Path, lower- and upper-secondary education completion rates will improve, but the country will likely miss the SDG target of 97% in 2030 by a substantial margin. Indeed, lower- and upper-secondary school completion rates will likely reach only 42.6% and 26% in 2030, and 57.5% and 39.4% in 2043, respectively.

At the tertiary level, universities and other higher education institutions offer undergraduate, graduate and vocational programs. The higher education sector faces issues related to limited capacity, outdated curricula and inadequate infrastructure. Nigeria's deteriorating tertiary education condition has pushed many secondary school graduates to migrate, searching for quality education abroad.

The gross tertiary enrolment rate was just 11% in 2023, above the average of 16% for lower-middle-income Africa. On the Current Path, it could get to 15% in 2043 compared with the projected average of 22.5% for lower-middle-income Africa.

Furthermore, gender imbalance in the education sector also affects enrolment and educational outcomes. While the gender parity index (ratio of females to males) for primary school and secondary school has improved to 1.00 and 0.98, respectively, UNICEF reports that about 60% of out-of-school children in the country are girls. Many girls are not in school due to stereotypes about education for girls, financial constraints, early marriages and teenage pregnancy, among others. However, the situation of female education varies by state or region. Girls in the southern regions have more than twice the chance to attend school than their peers in the north, where jihadist insurgency and poverty are rampant.

On top of the alarming number of out-of-school children, the quality of education received by those who have the opportunity to be in school has significantly declined. Getting more children into school is essential, but ensuring that they actually learn is even more important. Many empirical studies have reported that educational quality impacts economic growth more than educational quantity. The quality of education is usually tracked using Harmonised Test Scores. According to the World Bank Human Capital Project report, students in Nigeria score 308 on a scale where 625 represents advanced attainment and 300 represents minimum attainment.

Dilapidated school infrastructure, obsolete educational materials, insufficiency of qualified teachers, limited STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) training, lack of high-quality Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) programs, among others, affect the quality of education and create a disconnect between graduates' skills and labour market’s needs. The end result is a low employability of the labour force and high youth unemployment in the country.

Overall, Nigeria has made progress in improving access to education, particularly at the primary level. However, significant challenges remain in ensuring quality, reducing dropout rates and expanding access to secondary and higher education. Efforts to address gender disparities, improve infrastructure and enhance teacher training are critical for the future development of the country’s education system.

Investing in people and ensuring that every Nigerian has access to quality education is crucial for promoting equity, sustaining economic growth and unlocking new opportunities for disadvantaged populations.

The Education scenario, therefore, aims at building quality human capital in Nigeria. It represents reasonable but ambitious improved intake, transition and graduation rates from primary to tertiary levels, with a particular focus on both lower- and upper-secondary levels and better quality of education. It also models substantive progress towards gender parity at all levels, additional vocational training at the secondary school level and increases in the share of science and engineering graduates.

Visit the theme on Education for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Chart 17 presents the mean years of education in the Current Path and in the Education scenario, from 2020 to 2043, for the 15 to 24 age group.

The average years of education in the adult population aged 15 to 24 is a good first indicator of how the stock of knowledge in society is changing. Nigeria has one of the lowest in Africa, at 6.5 years in 2023 compared with an average of 7.8 years for its income group in Africa. The country ranked 35th in Africa (out of 54). The implementation of the Education scenario would improve the mean years of education for adults aged 15 to 24 in the country to 8.2 years by 2043, compared with 7.2 years in 2043 in the Current Path (Chart 17).

While higher levels of education enable Nigerians to pursue high-skilled jobs, such opportunities remain limited, even for those with secondary or post-secondary qualifications. Currently, only 8.7% of employed Nigerians occupy high-skilled positions, which typically require skills associated with at least secondary education. Among those with post-secondary education, the majority are still not employed in high-skilled roles. For individuals with only secondary education, the figure drops to just 7.2%.

This gap highlights not only a potential mismatch between available skills and job opportunities but also a fundamental shortage of high-skilled jobs in the economy. Nigeria’s low economic complexity contributes to a labour market dominated by demand for low-skilled workers. However, as the economy becomes more complex, the demand for skilled labour, especially within the formal sector, is expected to increase. To remain competitive and boost productivity, Nigeria must proactively equip its workforce with relevant skills aligned with future labour market demands.

The Education scenario emulates the effect of such a pathway in addressing these challenges. Under this scenario, the share of science and engineering graduates among tertiary education graduates in Nigeria will rise to 23.4% by 2043, five percentage points higher than the 18.4% anticipated under the Current Path.

Despite the country’s significant educational hurdles, targeted reforms could yield meaningful progress. Strengthening the quality and relevance of education, particularly through expanded support for science, engineering and vocational training, will help Nigeria cultivate a more skilled workforce. Achieving the outcomes envisioned in the Education scenario would not only improve individual employment prospects but also drive broader socioeconomic development, positioning Nigeria to capitalise on emerging opportunities in both regional and global labour markets.

Chart 18 presents the value-add by sector as share of GDP in the Current Path, for 2023 and 2043.

The manufacturing sector in Nigeria plays a critical role in the country’s aspirations for economic growth, diversification and industrialisation. It encompasses a wide range of industries such as food and beverages, cement, textiles, chemicals, pharmaceuticals and automobile assembly, among others. Notably, the food and beverage, tobacco, cement, textile, apparel and footwear industries contribute over 70% of the sector’s total GDP, underscoring their significant role in the country's industrial landscape. Lagos, Ogun, Kano and Kaduna are some of the key industrial hubs, hosting a variety of manufacturing companies that serve both local and regional markets.

Nigeria's manufacturing sector’s competitive advantages include a large and growing domestic market, the availability of raw materials, low labour costs and the potential to serve as a manufacturing hub for the ECOWAS region.

However, despite various policy efforts and development programs, the sector continues to face deep-rooted structural challenges. Key among these is infrastructure deficit, including unreliable energy supply and limited transport options, which result in high production costs, policy inconsistencies, lower product quality and reduced global competitiveness. Additionally, an unstable macroeconomic environment—marked by high inflation, volatile exchange rates, multiple taxation and limited access to affordable financing—has further constrained the sector’s ability to thrive. Furthermore, insecurity in some regions of the country disrupts supply chains and discourages investment in the sector.

The manufacturing sector's contribution to Nigeria's GDP fell from a peak of approximately 20% in the 1980s to just 6.5% in 2010, before gradually rising to 13.5% in 2023, aligning with the average for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. In 2022, Nigeria ranked 8th of 52 countries on the African Development Bank's African Industrialisation Index, which measures African progress on industrialisation. On the Current Path, the share of the manufacturing sector in Nigeria’s GDP will likely be 20% by 2043, above the projected average of 17% for lower-middle-income Africa.

The services sector will continue to dominate Nigeria's economy, with its share of GDP expected to rise from the current 44% to 55.6% by 2043. In contrast, the agriculture sector’s contribution will decline from 23.7% to 11.8% over the same period, reflecting the ongoing structural transformation of the economy.

Strengthening the manufacturing sector can drive inclusive growth by creating more wage-paying jobs that enable workers to lift themselves out of poverty. While a large share of Nigeria’s working-age population—about 75.8%—is employed (either for pay or profit), many still live in poverty. This is because many Nigerians are engaged in low-productivity jobs that offer insufficient income to ensure a decent standard of living. Expanding and enhancing the manufacturing sector can help address this issue by generating more productive and better-paying jobs. This, in turn, can create a virtuous cycle: as employment becomes more productive, incomes rise, capacities are strengthened, and broader economic growth is stimulated, ultimately contributing to sustainable poverty reduction.

The Manufacturing scenario models the impact of a manufacturing push in Nigeria. A reasonable but ambitious growth in manufacturing is envisaged through increased investment in the sector, research and development (R&D), and improved government regulation of businesses that increases employment, particularly among females.

Visit the theme on Manufacturing for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Chart 19 presents the contribution of the manufacturing sector to GDP in the Current Path and in the Manufacturing scenario, from 2020 to 2043. The data is in US$ and % of GDP.

Nigeria’s manufacturing sector presents significant potential to drive economic diversification and job creation. Priority growth areas include agro-processing, petrochemicals and plastics (leveraging the country’s oil and gas resources), textiles and garments, building materials (like cement and steel) and consumer goods and packaging. To fully unlock this potential and enhance Nigeria’s competitiveness in regional and global markets, it will be essential to address key challenges related to infrastructure, access to finance and workforce skills development.

On the Current Path, the manufacturing sector’s share of Nigeria’s GDP will rise to 20% by 2043, surpassing the estimated average of 17.2% for lower-middle-income countries in Africa. However, under the Manufacturing scenario, this share could increase even further, reaching 22.25% by 2043, two percentage points higher than the projection on the Current Path (see Chart 19).

Industrialisation is a long-term process. It requires constructive relationships between the state and the private sector that encourage and support the private sector. Firms need a state that has strong capabilities in setting an overall economic vision and strategy, efficiently providing supportive infrastructure and services, maintaining a regulatory environment conducive to entrepreneurial activity, and making it easier to acquire skilled labour and new technology and enter new economic activities and markets.

Chart 20 depicts exports and imports as a percentage of GDP, from 2000 to 2043, in the Current Path.

Nigeria’s trade regime remains protectionist in key areas. High tariffs and prohibitions on many other imports aim to spur domestic agricultural and manufacturing sector growth, but they have not done so.

The country’s export basket is heavily dominated by hydrocarbons—primarily oil and gas—leaving the economy highly exposed to fluctuations in global commodity prices. Like many African nations, Nigeria mainly exports primary commodities while relying on imports for manufactured goods and refined petroleum products. Due to the weak domestic refining capacity, Nigeria relies on imported petroleum products despite being the continent’s largest oil producer. The launch of the Dangote Refinery, with an estimated daily production capacity of 650 000 barrels, is expected to help Nigeria meet its domestic fuel demands, reduce reliance on imported petroleum products and address fuel shortages, especially in the context of fuel subsidy removal.

Already Bloomberg reported that from 1 to 24 January 2025, fuel shipments into Nigeria stood at only about 110 000 barrels a day, compared to more than 200 000 barrels per day in 2017.

In 2023, Nigeria’s top exports were Crude Petroleum (US$43.5 billion), Petroleum Gas (US$8.38 billion), Gold (US$1.54 billion), Nitrogenous Fertilisers (US$1.05 billion) and Cocoa Beans (US$763 million). As a percentage of total exports, Crude Petroleum accounted for 71.3%, while Petroleum Gas accounted for 13.7%. Gold (2.5%), Nitrogenous fertiliser (1.7%) and Cocoa beans (1.25%).

The manufacturing sector in Nigeria underperforms in its contribution to exports, accounting for only about 6% of total exports compared to other countries such as Malaysia, where manufacturing accounts for over 70% of exports.

Most of Nigeria’s exports are to the United States (10.3% of total exports in 2023), Spain (9.4%), Netherlands (7.1%), India (5.9%), Côte d'Ivoire (3.9%) and South Africa (3.8%). On the Current Path, total export value will be equivalent to 10.2% of GDP by 2043.

Nigeria's top imports are Refined Petroleum (26.6%), Tanks and Armoured vehicles (13.4%), Wheat (4.3%), Cars (2.3%) and Raw sugar (1.1%). The most common import partners for Nigeria are China (US$18 billion), Singapore (US$9.35 billion), Belgium (US$5.34 billion), India (US$4.06 billion) and the United States (US$3 billion).

In 2023, the total import value was estimated at 14.4% of GDP, while the total export represented 11.4%, leading to a trade deficit equivalent to 3% of GDP. On the Current Path, the value of imports will remain above Nigeria’s exports, reaching 16.4% of GDP in 2043 against 10.2% for its exports in the same year (Chart 20).

The AfCFTA scenario models the impact of fully implementing the African Continental Free Trade Agreement by 2034. It increases exports in manufacturing, agriculture, services, ICT, materials and energy. It also includes improved multifactor productivity growth from trade and reduced tariffs for all sectors.