What are the low-hanging fruits for President Tinubu to accelerate Nigeria’s economic economy?

Nigeria is in a challenging and deteriorating economic position and unless important structural reforms are made, post-election recovery will stall.

Nigeria is the most populous country and has the largest economy in Africa with an estimated GDP of US$582.6 billion in 2022. With its high population growth, Nigeria is set to have a larger population than the US in 2040, making it the third most populated country in the world, behind only China and India.

Despite its economic size, the country struggles to improve the standard of living of its citizens and reduce poverty. A lower middle-income country, Nigeria’s GDP per capita of US$4 982 ranks as only the 17th highest in Africa. Extreme poverty (at US $1.90) is still rife at 44%. Although 22 other African countries have a larger share of extremely poor people, Nigeria will have the largest number of extremely poor people globally (100 million) in 2024 as poverty numbers in India plummet to below that of Nigeria earning it the dubious title of global poverty capital.

After the presidential elections in February, the new leadership now faces the difficult task of rebuilding the economy. The average population growth in Nigeria is high, at 2.9% meaning the economy needs to grow at least at double that number on a sustained basis for many years if it is to improve incomes. It has briefly done that in the past. From 2002 to 2010 growth accelerated, but has slowed down in recent years. The Nigerian economy contracted by 1.8% in 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic and the associated restrictions in economic activity but rebounded to 3.6% the following year. The rebound was supported by the easing of COVID-19 restrictions, a boost in the non-oil sectors and an uptick in private and public consumption. However, this recovery path has been tempered with slow output growth in 2022 of 3.1% as oil output continues to shrink and non-oil output growth slows. The latest IMF projections indicate that the Nigeria economy will grow by 3.2% in 2023 before slowing down to 2.9 % in 2024.

Despite its economic size, the country struggles to improve the standard of living of its citizens and reduce poverty.

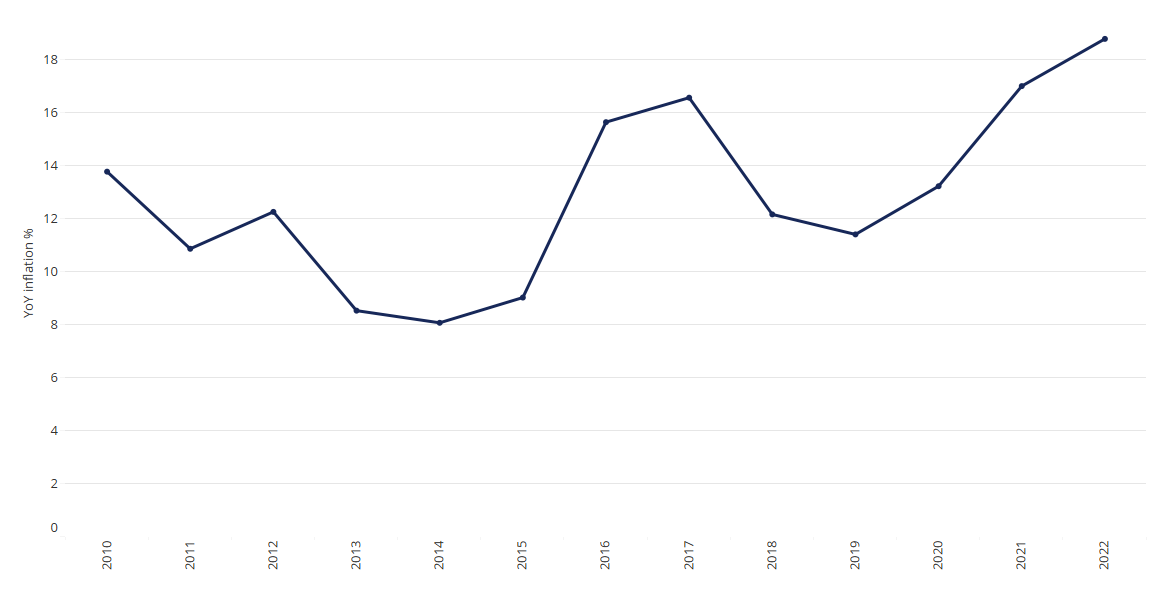

In addition to the shrinking oil output, macroeconomic instability is also holding back the growth recovery. The inflation rate in Nigeria stood at 18.7% in 2022 up from 11.4 % in 2019. This year, year-on-year inflation rate rose to 22.04 in March from 21.91 in February and 21.82 in January. The upsurge in inflation since 2019 has been driven by domestic factors such as a depreciating Naira, intensified trade restrictions and federal government borrowings from the central bank. External factors such as the increase in global energy and food prices, the war in Ukraine, and a strong international dollar have also contributed to rising prices.

While the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) responded by increasing the interest rate by 500 basis points (bps) and cash reserve requirement by 500bps since 2020, this has not helped much due to the continued financing of the federal government’s deficit, subsidized credit provisions to the agriculture and manufacturing sectors and unfavourable external conditions. A study by Ajide and Olukemi revealed that an inflation rate above 9% is harmful to economic growth in Nigeria, yet it has been above that since 2015 (chart 1).

With its high population growth, Nigeria is set to have a larger population than the US in 2040, making it the third most populated country in the world, behind only China and India.

Chart 1: Inflation in Nigeria

Source: Central Bank of Nigeria, 2023

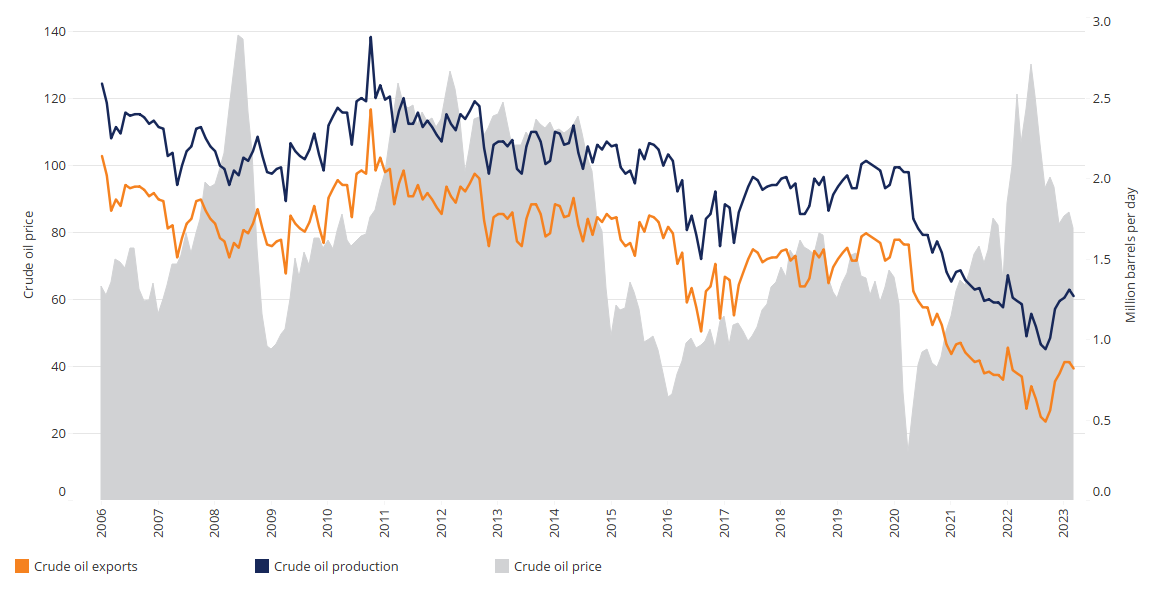

Despite a 150% increase in oil prices between 2020 and 2022, Nigeria’s economic performance is poor and its fiscal space has shrunk. The fiscal deficit has increased to 5.7% of GDP in 2022, up from 2.9% in 2019. Oil price increases have not helped Nigeria weather its economic problems because, since 2020, production levels continue to fall (chart 2) with ballooning costs associated with the government's petrol subsidy. Though Nigeria’s debt has not reached unsustainable levels yet and remains within the self-imposed limit of 40 percent of GDP, it continues to rise; and debt servicing costs are expected to reach 123% of 2023 revenues. Though the Strategic Revenue Growth Initiative (SRGI) has improved non-oil revenues since 2020, this has fallen short of a turnaround in government finances.

Chart 2: Nigeria’s crude oil production, export and prices

Source: Central Bank of Nigeria, 2023

The external reserves have only minimally changed despite a rapid increase in IMF SDR (special drawing rights) allocation and some Eurobond issuance. Foreign reserves declined from US$48.1 billion in October 2021 to US$35.3 billion as of 1st May 2023. The exchange rate policy of allowing only a slow, insufficient adjustment in the official exchange rate as forex shortage worsens is stifling business activity, hampering private investment and economic growth. Foreign exchange shortages to import essential commodities has become a common problem leading to Nigeria’s downgrading by international rating agencies. Moody’s downgraded Nigeria from B3 to a non-investment grade of Caa1 citing its deteriorating fiscal and debt position, while Flitch downgraded the country from B to B- in November 2022.

Despite a 150% increase in oil prices between 2020 and 2022, Nigeria’s economic performance is poor and its fiscal space has shrunk

On this pathway, Nigeria is poised to only achieve low growth and stalled development outcomes. To turn things around and solidify its macroeconomic recovery path, President Bola Tinubu needs to undertake a number of urgent interventions.

The structural bottlenecks that strangle the Nigerian economy must be removed. Reforms in the foreign exchange market should be prioritized. Transitioning the country away from multiple rates, where the Central Bank of Nigeria’s official rates and parallel market rates differ, regime to a single, market-responsive rate is crucial to restoring macroeconomic stability and charting a course to a sound recovery path.

To tackle the inflation and rising cost of living, more than monetary policy measures are required. Trade restrictions in the form of land border closures and restrictions on foreign exchange sales should be completely removed, while the federal government’s appetite for easy money should be curtailed.

In addition, more efforts should be geared towards increasing both oil and non-oil revenues through improved governance, better security and lowered production costs

In addition, more efforts should be geared towards increasing both oil and non-oil revenues through improved governance, better security and lowered production costs. In this context, the non-oil revenue gains made through the SRGI (1.0 and 2.0) should be solidified. Furthermore, phasing out the petrol subsidy worth N 400 billion (US$870 million) monthly is a crucial reform choice facing President Tinubu to reverse the revenue loss, improve fiscal space and put the country’s external position on a firm footing.

Of course, these reforms including addressing rising insecurity, won’t be a panacea to Nigeria’s economic development but a good starting point to address the structural development challenges facing the country.

Image: Chatham House/WikiMedia