The promise of more investment

Africa’s growth is constrained by limited capital and low domestic revenues, so what can more financial inflows bring to the continent?

In the early stages of development, economic growth is largely driven by the contribution of labour before capital, and eventually, technology increases in relative importance. That was also the case with the Asian tigers and China when they were poor, and reflects the progression in the drivers of growth as countries climb the ladder to prosperity.

For its 2025/26 financial year, the World Bank considers 22 African countries to be low-income, with a Gross National Income (GNI) per person equivalent to or below US$1 145. This means that in these countries, economic growth essentially comes from their better-educated, healthier and employed labour force.

Then, as countries develop and enter middle-income status, the availability and role of adequate capital to boost manufacturing start to dominate, eventually becoming more important for economic growth compared to labour and/or technology contribution. That generally applies to the 23 African countries that the Bank considers lower-middle-income. Fast forward, and as countries settle into upper-middle-income status (Africa has eight) and try to achieve sufficient velocity to graduate to high-income status, the contribution of technology to enhance high-value service output starts to dominate.

Only the island state of Seychelles has managed to escape Africa’s notorious middle-income trap, and much of the inability of lower-middle- and upper-middle-income countries to do similarly relates to inadequate access to capital for manufacturing and technology advancement, respectively.

Most African middle-income countries struggle to escape the development trap due to limited access to capital for manufacturing and technological advancement

Access to capital is vital for development. It enables countries to invest in health, infrastructure and education, diversify from commodities, and pursue a manufacturing-led growth path for sustained and rapid growth.

Hence, the ability of countries to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) at scale becomes crucial. To this end, governments compete with one another on tax incentives, Special Economic Zones, regulatory incentives, infrastructure development and governance reforms.

With above-average FDI, African countries such as Senegal, Uganda, Rwanda, Niger, Djibouti, Togo, Ethiopia, Benin and Côte d’Ivoire are projected to grow at rates exceeding 6%, well above global averages. In 2025, these are among the fastest-growing economies in the world. Nigeria, the continent’s largest economy, is, however, expected to grow at only 3.2% in 2025. With a population increase of 2.6% per year, its income per capita essentially remains stagnant. In addition to poor governance and insecurity, its notorious low levels of FDI (at around 0.5% of GDP) are an important driver of lacklustre growth.

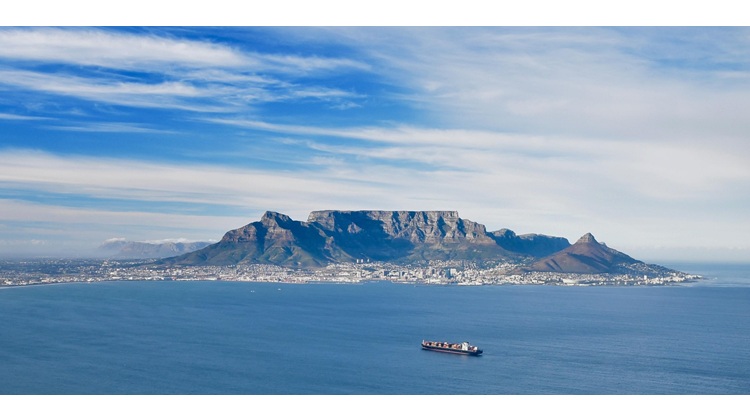

Other African countries struggle, including Equatorial Guinea, South Africa, Tunisia, Lesotho, Gabon, Angola and the Central African Republic. All grow particularly slowly at the moment and have low or negative FDI inflows, except Gabon, which continues to attract modest investment to its oil and gas sector despite the August 2023 coup and subsequent instability.

Gabon reflects the history of most FDI to Africa, which has been in the oil and gas sector, such as recently in Mozambique, Tanzania, Uganda and Namibia, with limited forward and backwards linkages to other sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing.

Once investments in fossil fuels are excluded, it becomes clear that most FDI flows to upper-middle African countries, which is why development-oriented aid is so important for low- and lower-middle-income Africa. With the dissolution of USAID, which previously provided around 26% of aid to Africa, the significance of FDI and remittances has greatly increased, alongside enhanced domestic revenue mobilisation.

Much can be done to improve domestic revenue generation, particularly in utilising modern technology. Yet, Africa’s average tax-to-GDP ratio is only 16% (with a large spread when comparing rates per country), compared to 19.1% in Asia-Pacific, 21.5% in Latin America and the Caribbean, and 34% across OECD nations.

Using the International Futures forecasting platform (University of Denver), the updated theme on Financial Flows examines the effect of increased FDI, remittances and a resumption of aid in a post-Trump world on Africa, compared to a business-as-usual forecast.

In 2023, FDI inflows into Africa represented 3% of GDP. On a business-as-usual forecast, this figure will increase but modestly to 3.6% of GDP by 2043 as the growth of the African population and market steadily attracts more investment. Under the Financial Flows scenario, inward FDI is modelled to increase more aggressively to 5.3% of GDP (US$351 vs US$230 bn).

To place that in context: although inflows in the Financial Flows scenario are much larger, Africa’s stock of FDI in 2043 is still significantly below that of South America in absolute terms, and slightly less than half if expressed as a percentage of GDP.

In the scenario, Africa’s GDP would be US$243.5 billion larger in 2043 when compared with the business-as-usual forecast, and average GDP per capita will increase by US$160, with Seychelles and several upper-middle- and lower-middle-income countries doing exceptionally well.

Among the types of inward financial flows that were modelled, FDI outperforms aid and remittances in improving productivity, especially in countries with skilled labour, strong institutions and deeper financial markets. Because FDI generally advantages skilled (as opposed to unskilled) labour, its impact on extreme poverty in the Financial Flows scenario is limited to a one percentage point decline below the business-as-usual forecast. Upper-middle-income countries simply gain more from FDI than poorer African countries. Furthermore, most FDI in Africa still goes to extractives such as minerals, gas and oil, although that is changing.

However, it is the full implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) that generally does best when comparing the eight sectors that are modelled on the African Futures website, which, in addition to larger inward financial flows, also include better education and health, a manufacturing transition and more.

Except for aid, positive signs on larger inward financial flows abound. Intra-African investment is rising, especially from Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa, in areas such as IT, finance and manufacturing. This trend is likely to accelerate with the implementation of the AfCFTA, which the World Bank estimates has the potential to boost FDI by up to 120%, with intra-African investment also rising by about 85%.

Emerging economies, such as China, the Gulf states and India, are all growing their investments in Africa’s energy, infrastructure and logistics, reshaping the continent’s economic and geopolitical landscape.

As global competition intensifies, African countries have more opportunities to negotiate investment terms that serve their long-term goals. Investment in sectors like agro-processing, renewable energies, manufacturing and digital infrastructure tends to enable technology transfer, generate more jobs and build economic resilience.

As global competition intensifies, African countries have more opportunities to negotiate investment terms that serve their long-term goals

African governments must improve conditions to absorb and retain capital, most obviously by offering a favourable investment climate, policy stability and improving the ease of doing business. They must target investments that align with national priorities and structural transformation goals, following the East Asian example of leveraging FDI for technological upgrading and industrialisation. Some countries, such as Egypt, Senegal, Morocco, Ethiopia and Zambia, are doing well, but many still struggle.

FDI can be a powerful tool when managed strategically and in tandem with robust domestic reform.

Africa’s development trajectory is both promising and precarious. With the contribution of labour to economic growth now steadily improving, Africans need to turn their attention to mobilising more inward financial flows, particularly FDI, also reducing the costs of remittances and agitating for aid to poor countries, which typically struggle to attract FDI.

Image: Mohamed_hassan/Pixabay

Read the full recently updated theme report on Financial Flows here.

Republication of our Africa Tomorrow articles only with permission. Contact us for any enquiries.