Nigeria

Nigeria

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our About page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

Summary

- Nigeria has made socio-economic progress, but faces serious social, economic and security challenges. Insurgency, banditry, separatist agitations, policy discontinuity, corruption and mismanagement threaten Nigeria’s development prospects. Jump to Introduction

- Nigeria is not on track to achieve most of the SDGs by 2030 and is forecast to have the highest number of poor people globally by 2050. Jump to Poverty and inequality

- There is a poverty polarity between Northern and Southern Nigeria, with rates in the north significantly above the national average. Jump to Poverty and inequality

- Nigeria has one of the world’s lowest tax-revenue-to-GDP ratios, leaving little fiscal space for productive expenditure. Jump to Economy

- The public health and education sectors are incapacitated by mismanagement, corruption and inadequate funding. Jump to Health. Jump to Education

- Nigeria’s population is forecast to increase to over 450 million by 2050, by which time it will be the third most populous country globally. Jump to Demographics

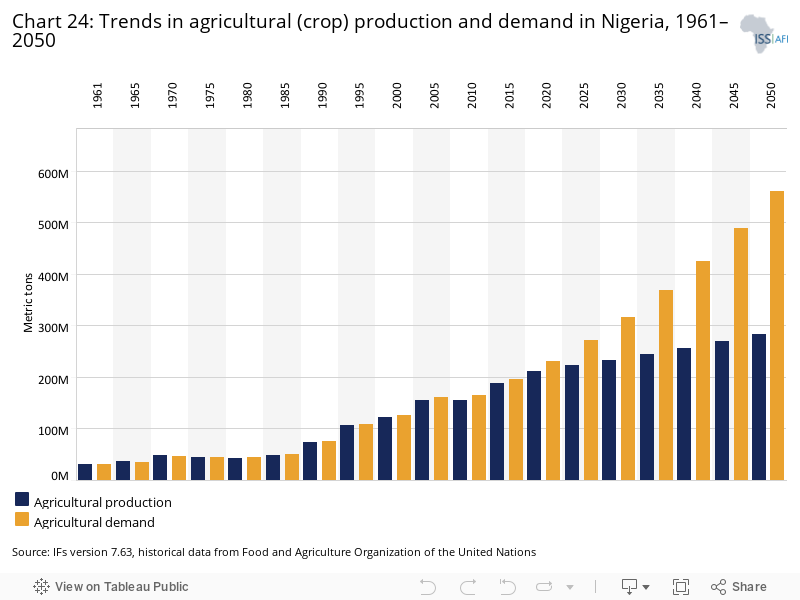

- Although Nigeria has great agricultural potential, the sector is unable to meet the nutritional demands of a rapidly growing population. Jump to Agriculture and climate change

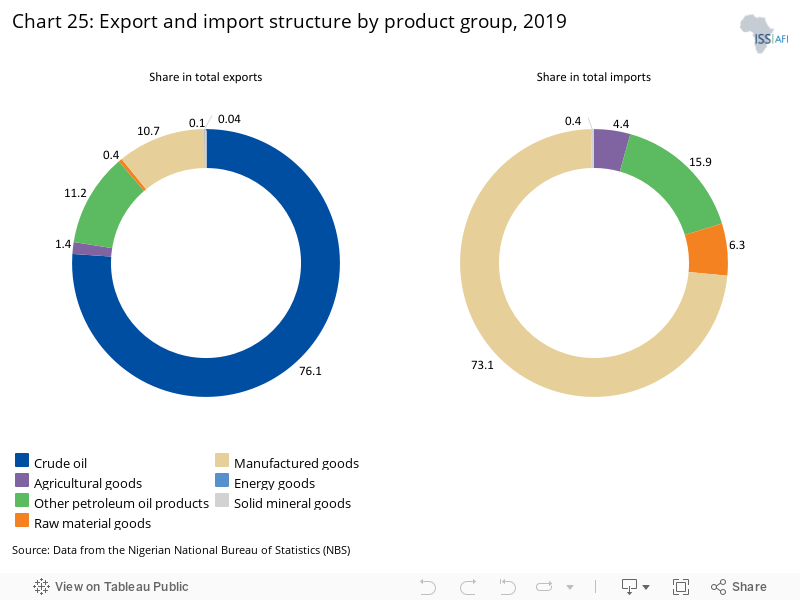

- Nigeria has made little progress in export diversification. The oil and gas sector determines economic growth and contributes to the bulk of export earnings and government revenue. Jump to Economy

- Macroeconomic instability, a skills shortage, an unfriendly business environment and infrastructure deficits constrain productivity and growth in the non-oil sector. Jump to Economy

- With aggressive but reasonable policy interventions, Nigeria could have a significantly brighter future. Jump to Scenario analysis

Recommendations Jump to Conclusion

The authorities should:

- address security challenges by upgrading the capability of the defence and security sector through adequate funding to respond promptly to armed groups’ attacks.

- promote national cohesion and social inclusion by ensuring a fair distribution of socio-economic amenities across the states.

- set up a national social protection programme to support the poorest and most vulnerable to reduce poverty and inequalities.

- intensify the fight against corruption, improve public financial management and domestic revenue mobilisation by accelerating digitalisation to enhance tax efficiency.

- address the infrastructure gap by creating an enabling environment for private-sector-led infrastructure development.

- continue rehabilitating oil-refining facilities to boost local refining capacity for self-sufficiency to permanently remove the petrol subsidy.

- involve religious leaders in family planning programmes and improve females’ education and job opportunities to reduce fertility.

- improve health and educational outcomes to enhance human capital and address skills shortages in line with the economy’s needs.

- invest in the agriculture sector to increase productivity, ensure food security, reduce poverty and enable a peaceful coexistence between farmers and herders.

- implement reforms to deepen economic and export diversification, focusing on manufacturing, starting with improving the business climate and macroeconomic stability.

All charts for Nigeria

- Chart 1: Political map for Nigeria

- Chart 2: National development plan of Nigeria

- Chart 3: Imagine Nigeria report

- Chart 4: Trends in government effectiveness in Nigeria and other groups, 1996–2050

- Chart 5: Trends in Nigeria’s population growth, 1960–2050

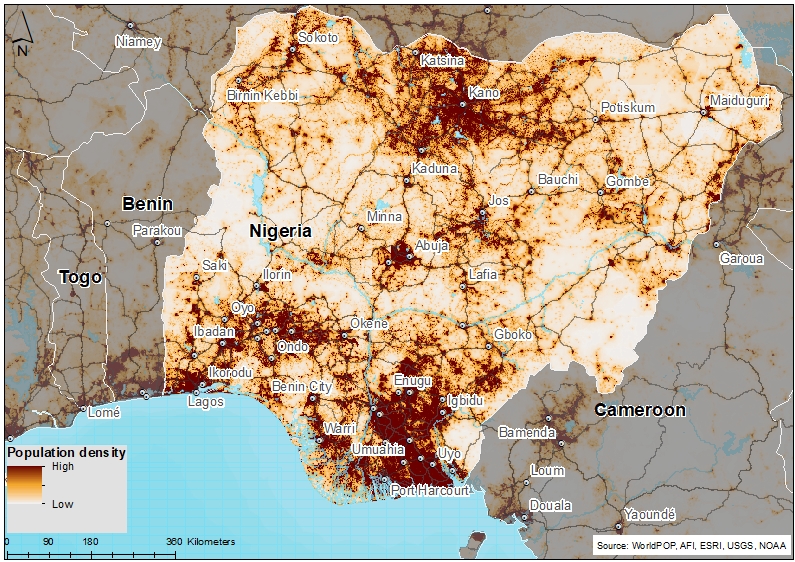

- Chart 6: Geographical distribution of Nigerian population, 2020

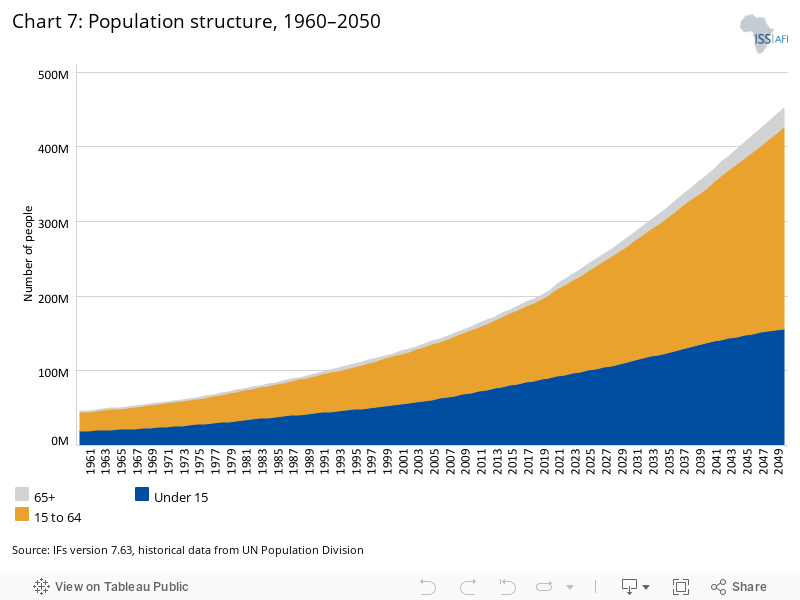

- Chart 7: Population structure, 1960–2050

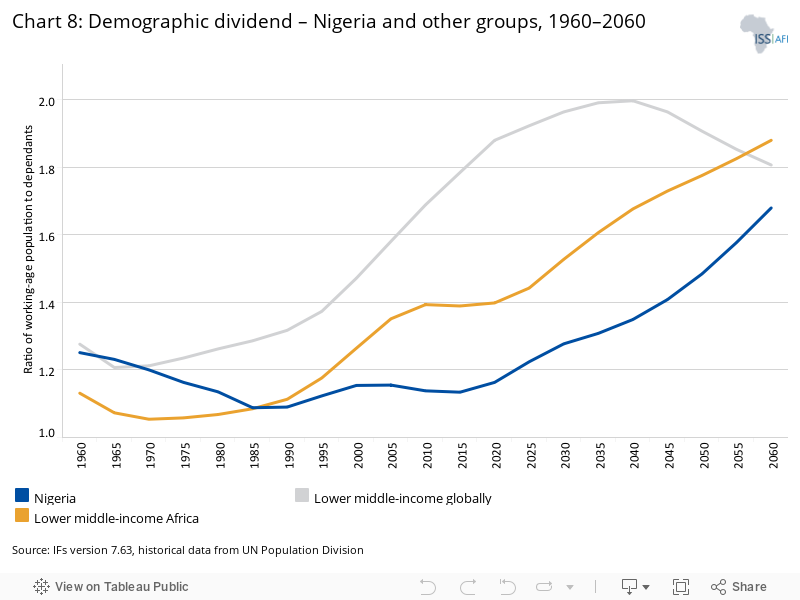

- Chart 8: Demographic dividend – Nigeria and other groups, 1960–2060

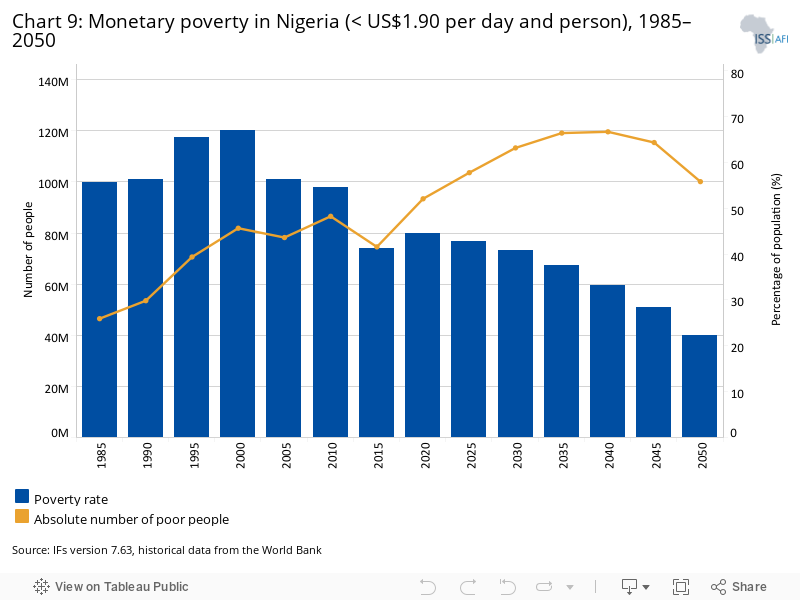

- Chart 9: Monetary poverty in Nigeria (< US$1.90 per day and person), 1985–2050

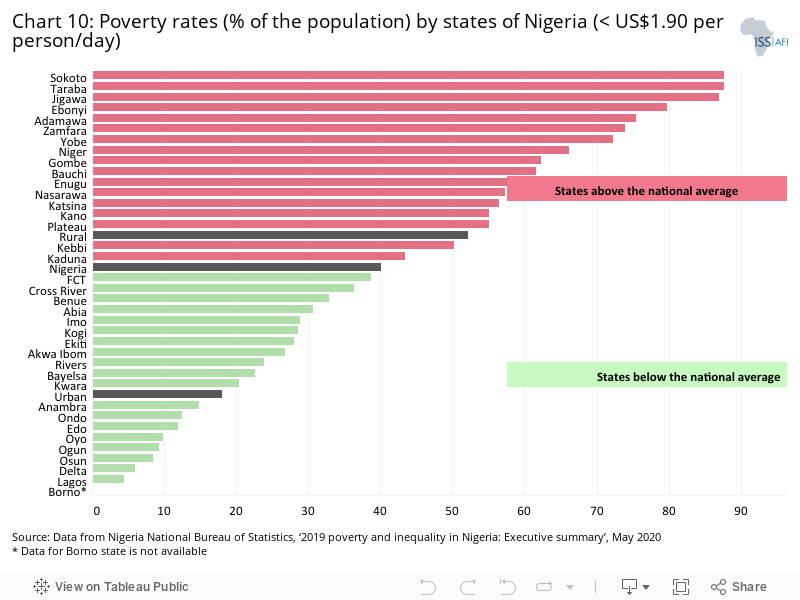

- Chart 10: Poverty rates (% of the population) by states of Nigeria (< US$1.90 per person/day)

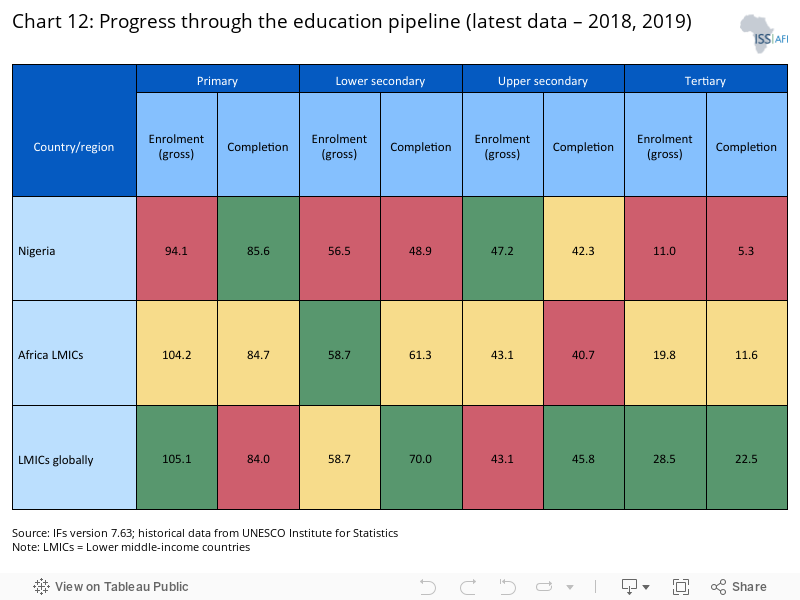

- Chart 11: Selected educational indicators

- Chart 12: Progress through the education pipeline (latest data – 2018, 2019)

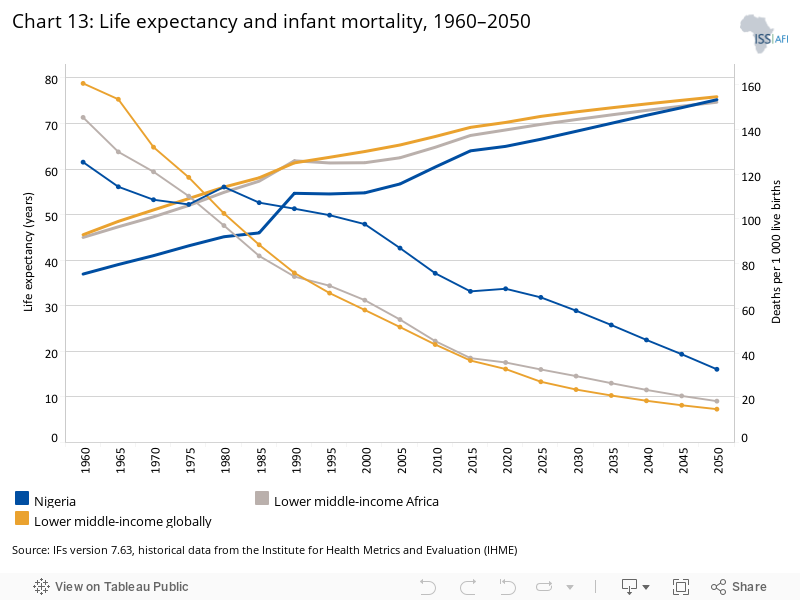

- Chart 13: Life expectancy and infant mortality, 1960–2050

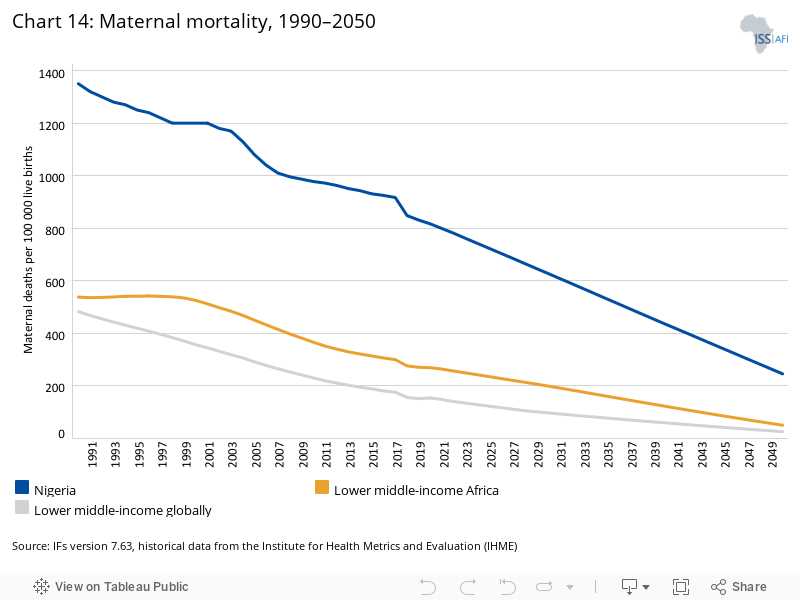

- Chart 14: Maternal mortality ratio, 1990–2050

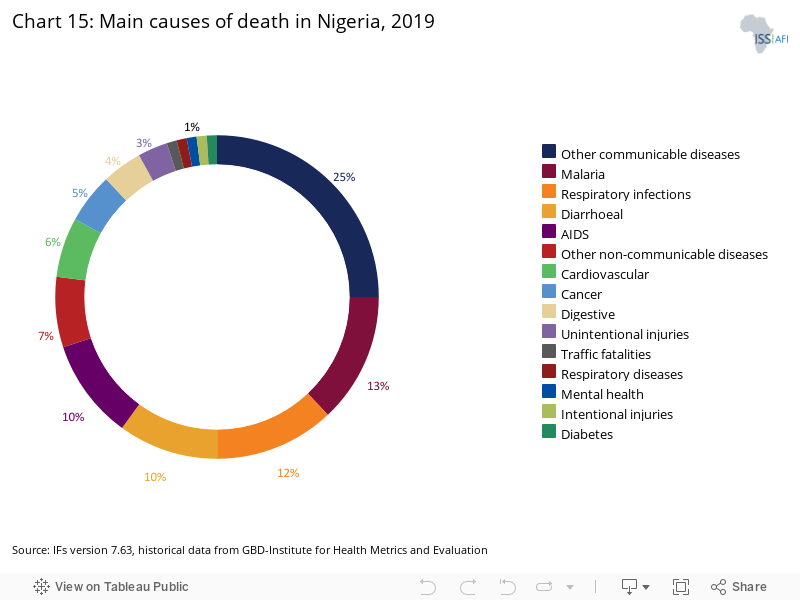

- Chart 15: Main causes of death in Nigeria, 2019

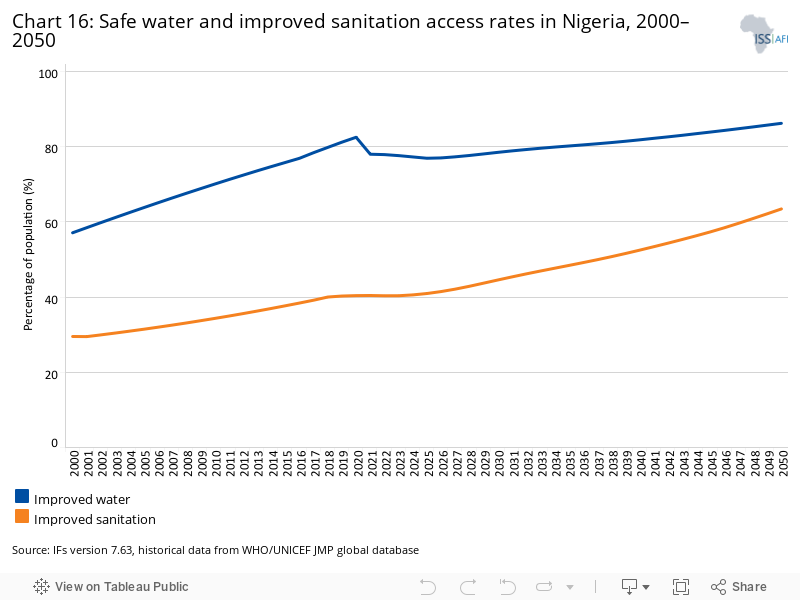

- Chart 16: Safe water and improved sanitation access rates in Nigeria, 2000–2050

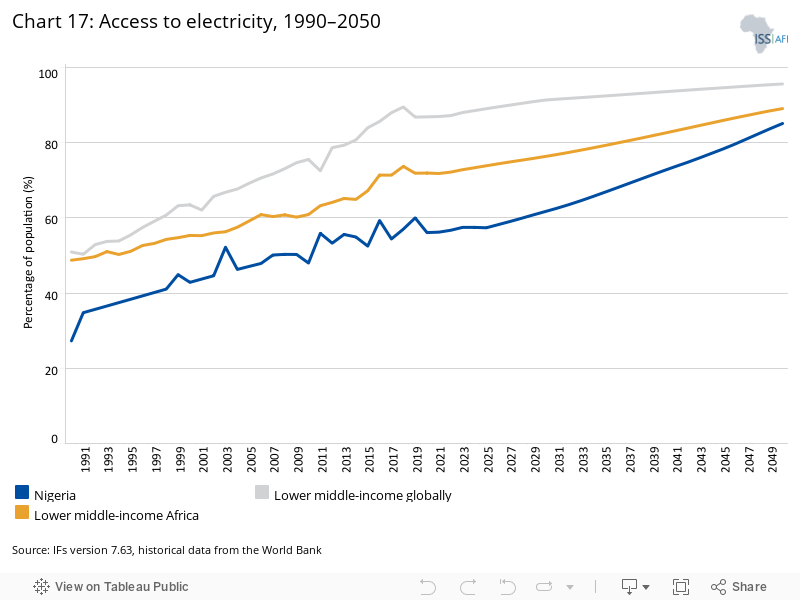

- Chart 17: Access to electricity, 1990–2050

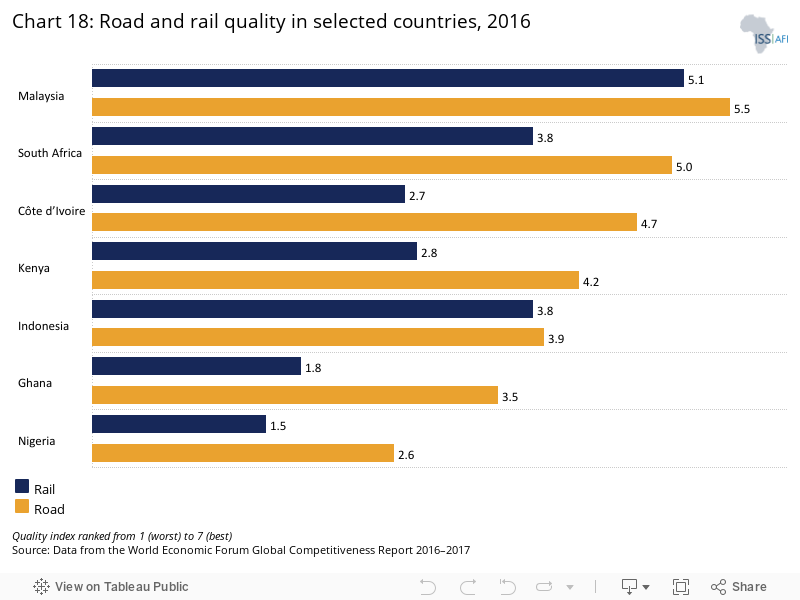

- Chart 18: Road and rail quality in selected countries, 2016

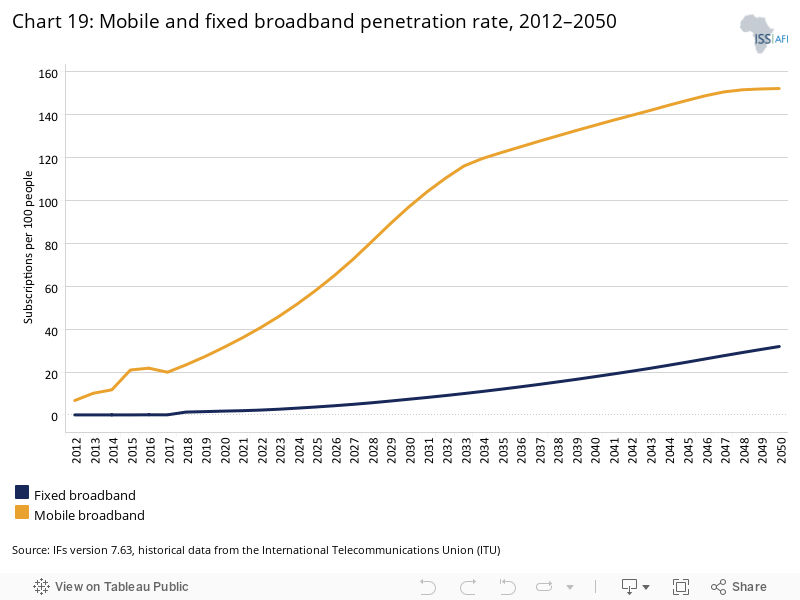

- Chart 19: Mobile and fixed broadband penetration rate, 2012–2050

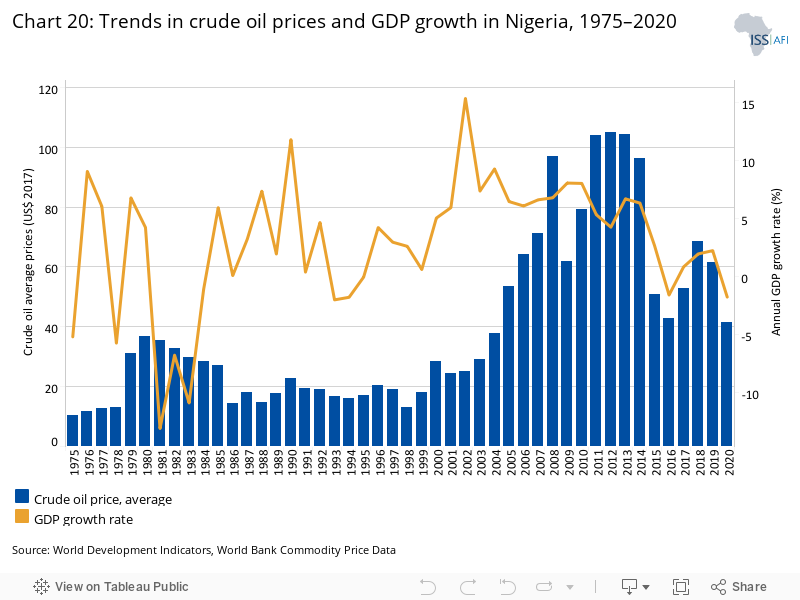

- Chart 20: Trends in crude oil prices and GDP growth in Nigeria, 1975–2020

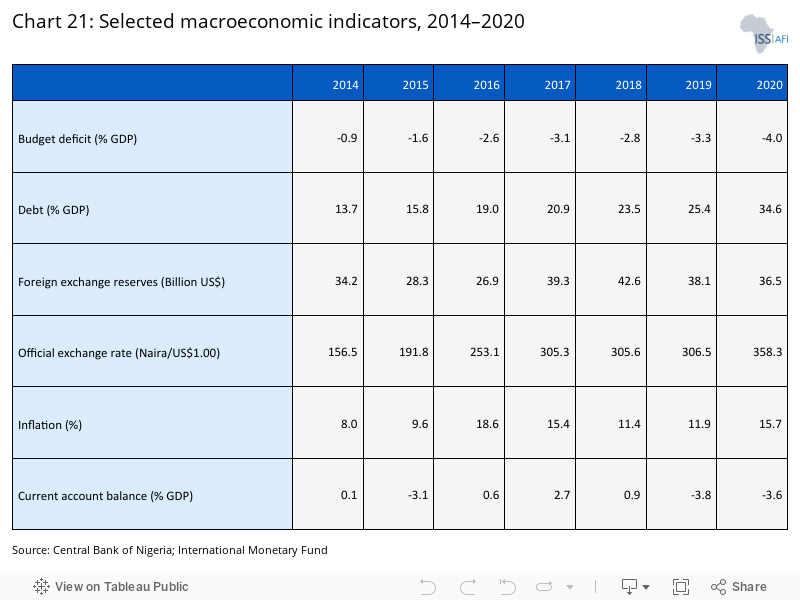

- Chart 21: Selected macroeconomic indicators, 2014–2020

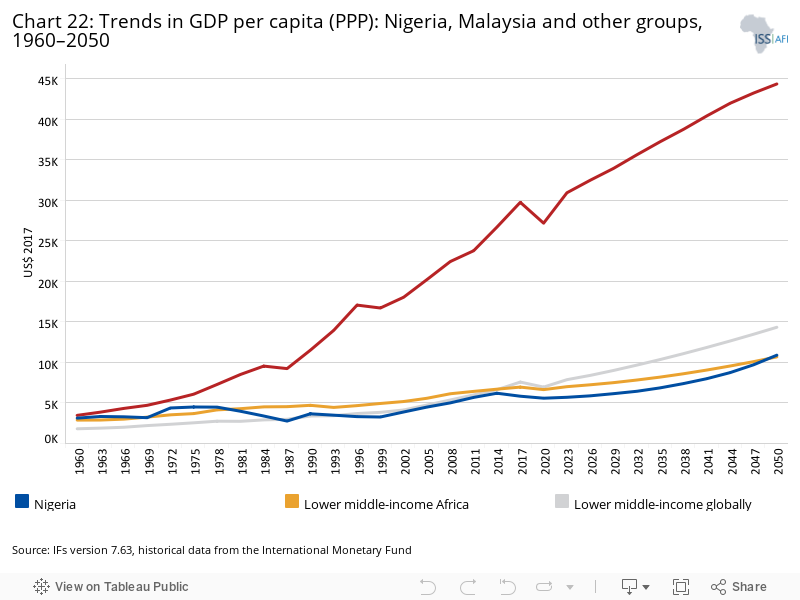

- Chart 22: Trends in GDP per capita (PPP): Nigeria, Malaysia and other groups, 1960–2050

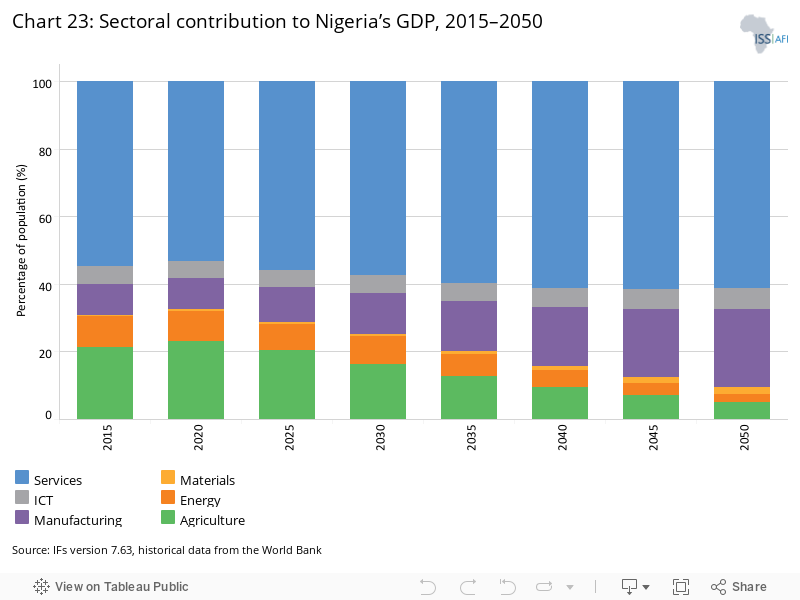

- Chart 23: Sectoral contribution to Nigeria’s GDP, 2015–2050

- Chart 24: Trends in agricultural (crop) production and demand in Nigeria, 1961–2050

- Chart 25: Export and import structure by product group, 2019

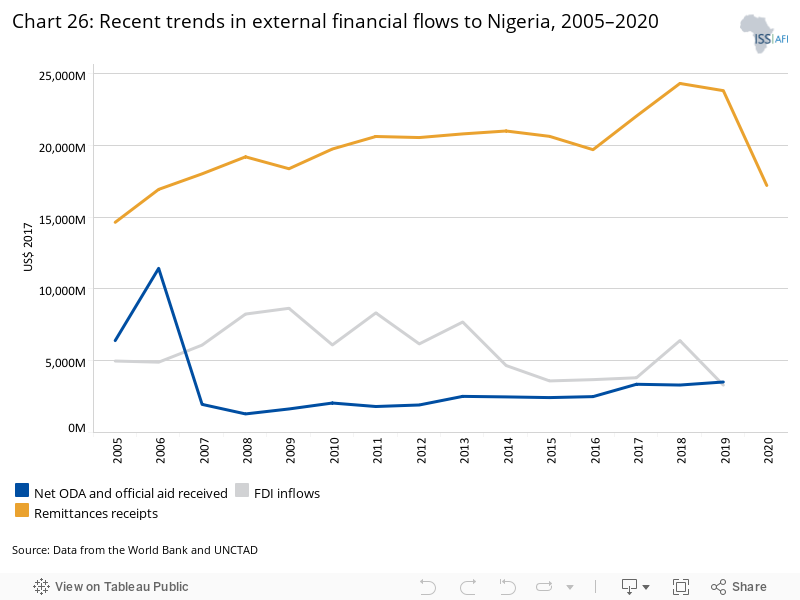

- Chart 26: Recent trends in external financial flows to Nigeria, 2005–2020

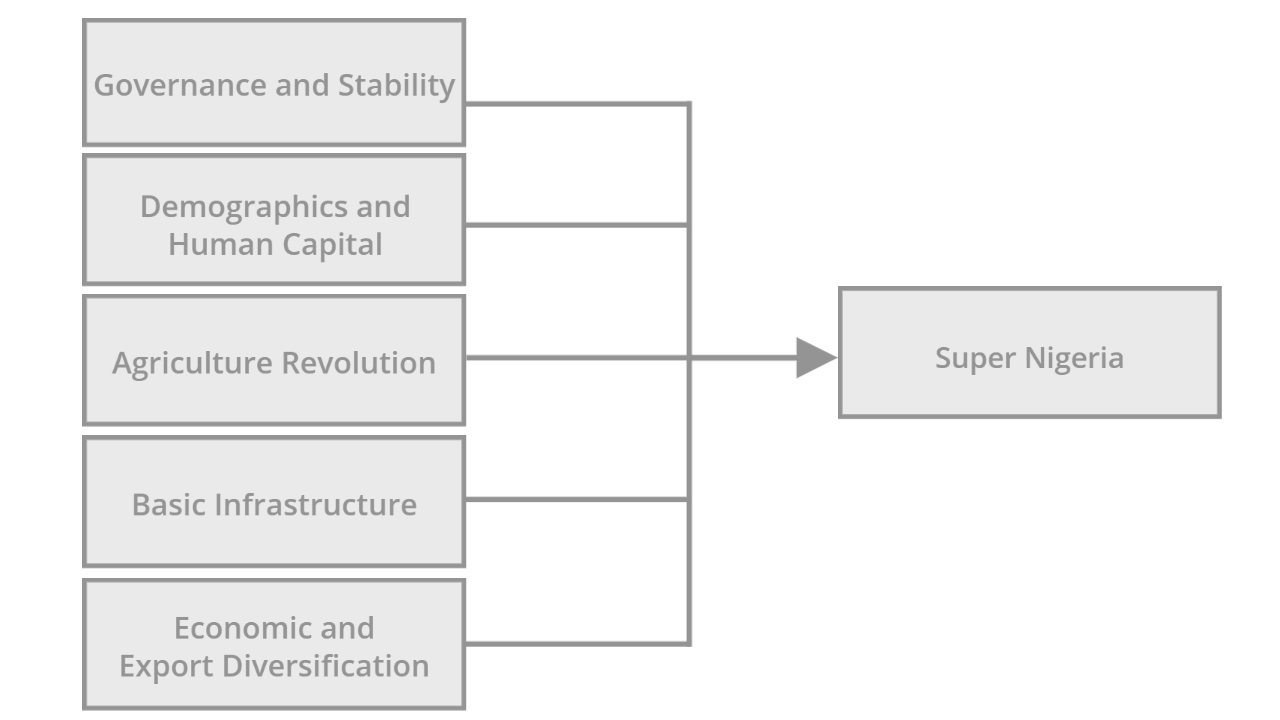

- Chart 27: Intervention clusters/Scenario components

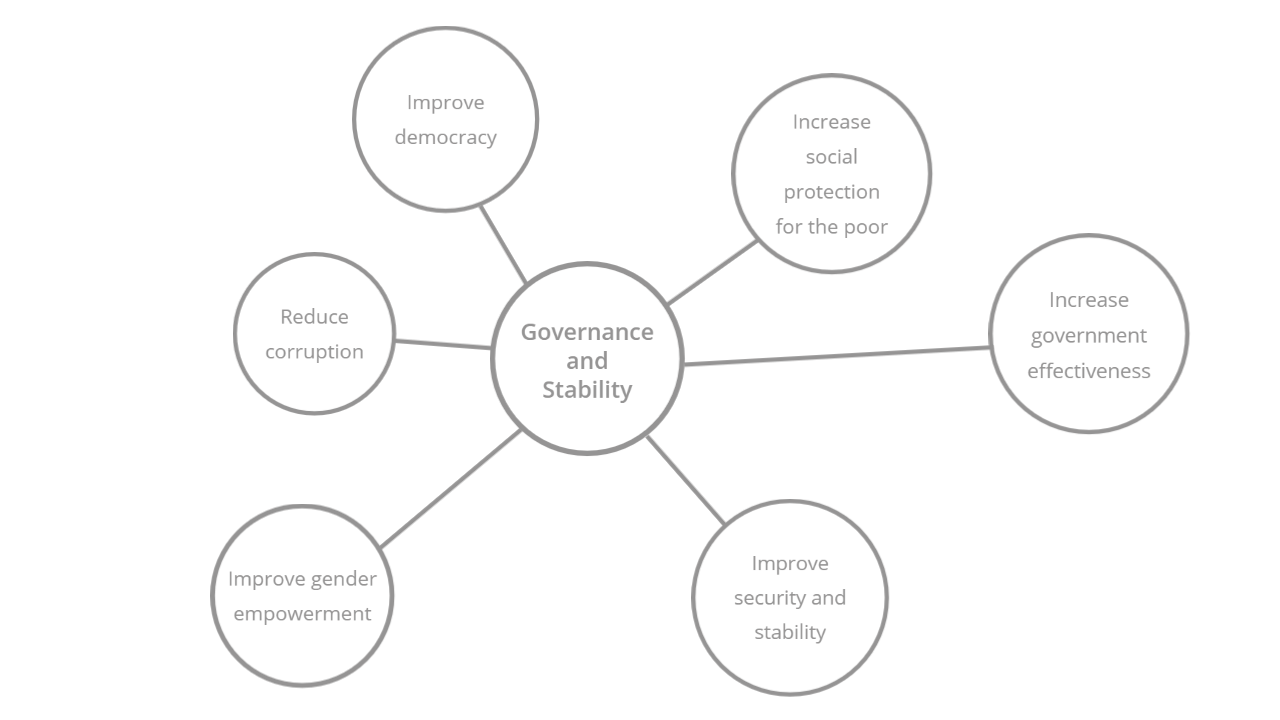

- Chart 28: Governance and Stability scenario

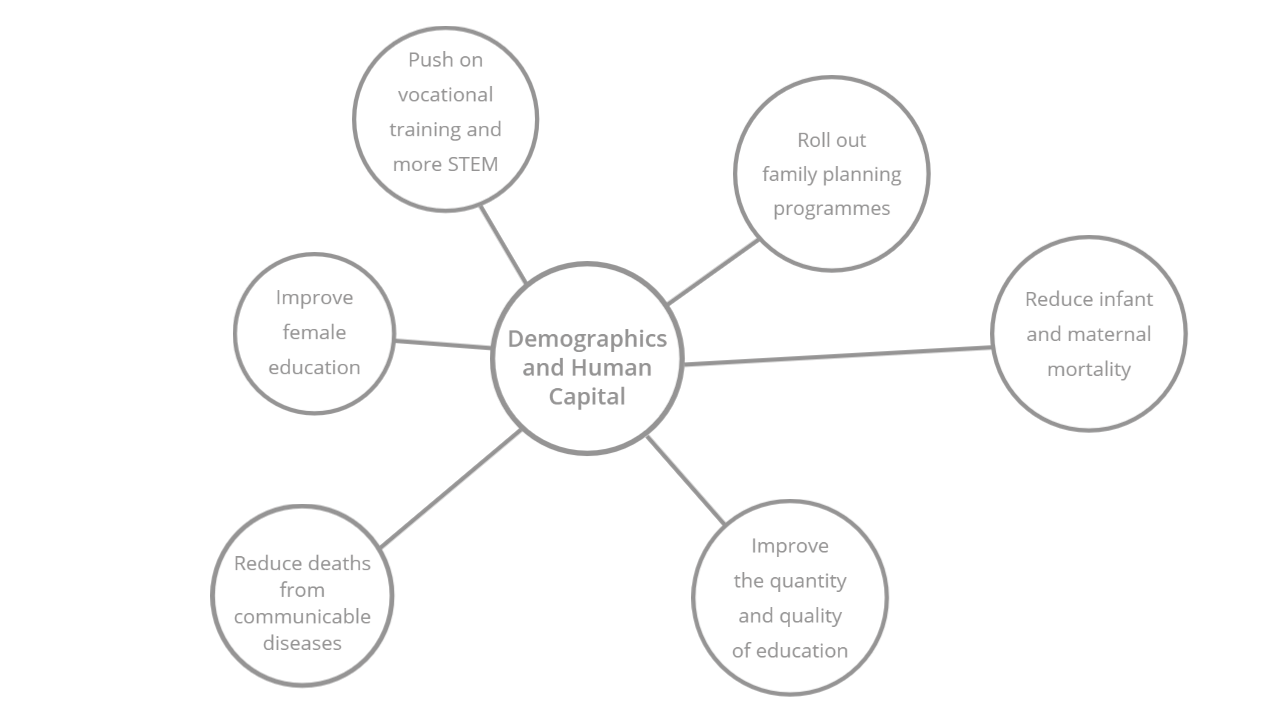

- Chart 29: Demographics and Human capital scenario

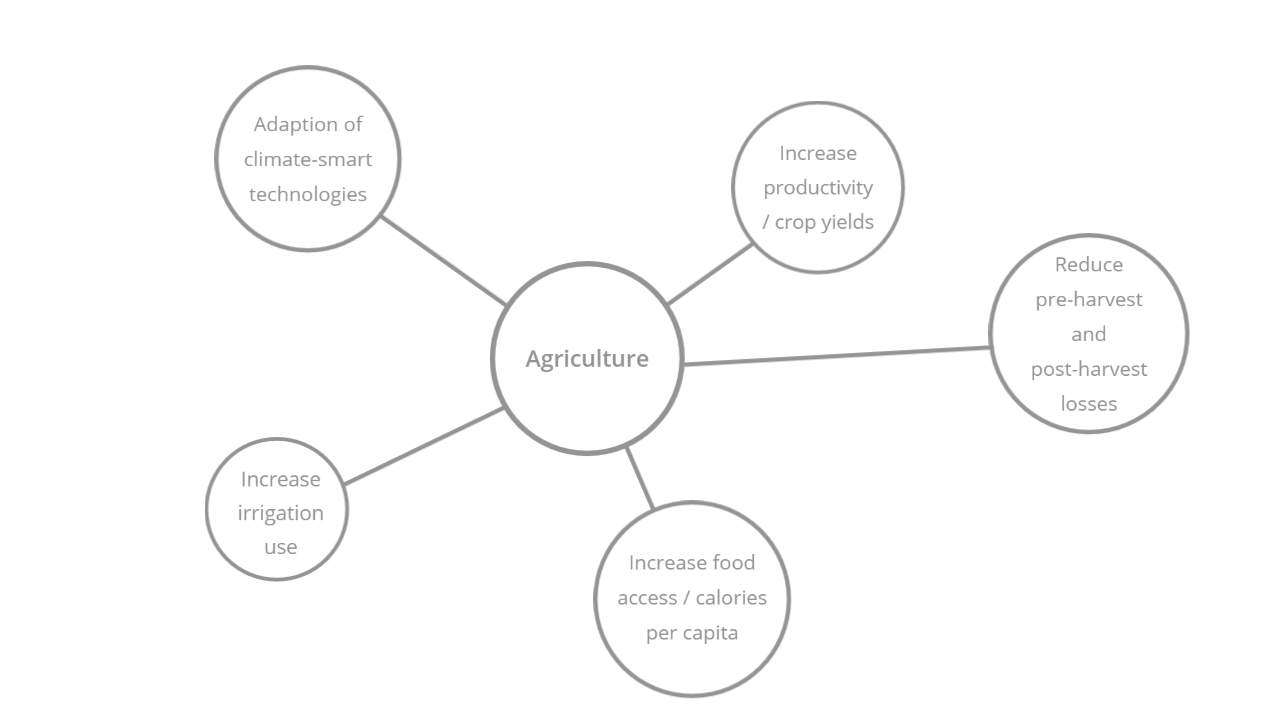

- Chart 30: Agricultural revolution scenario

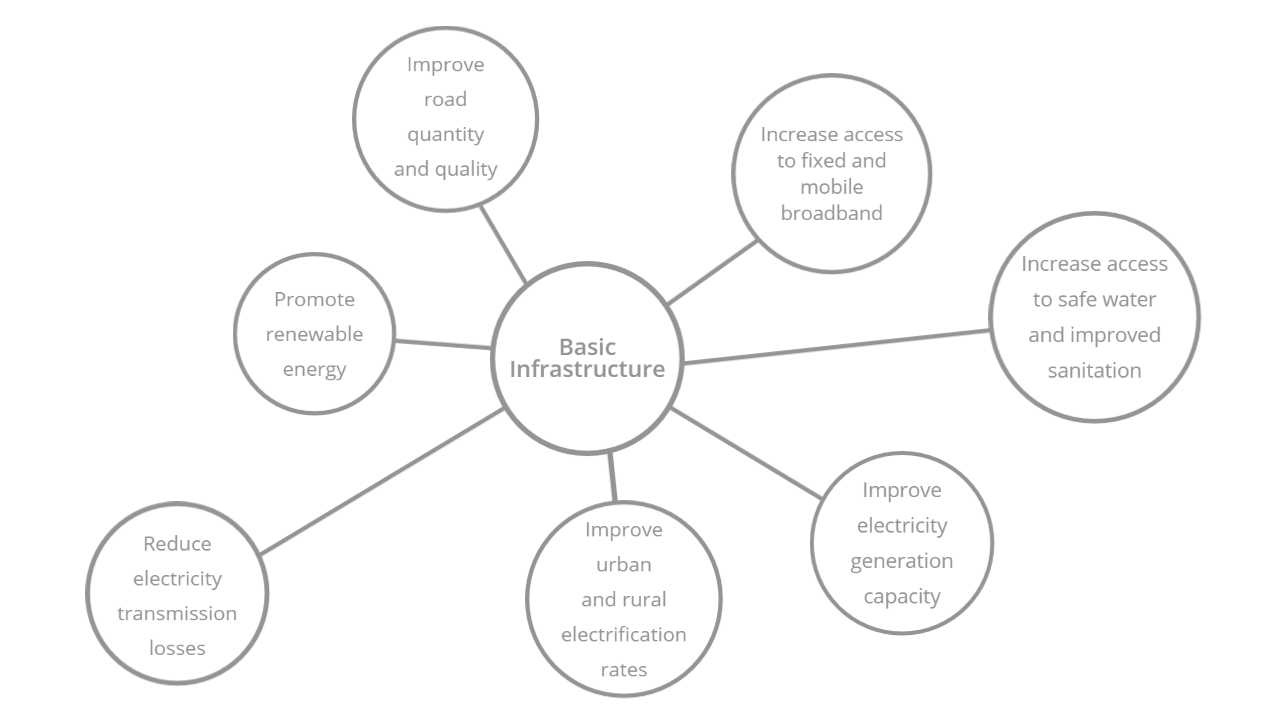

- Chart 31: Basic infrastructure scenario

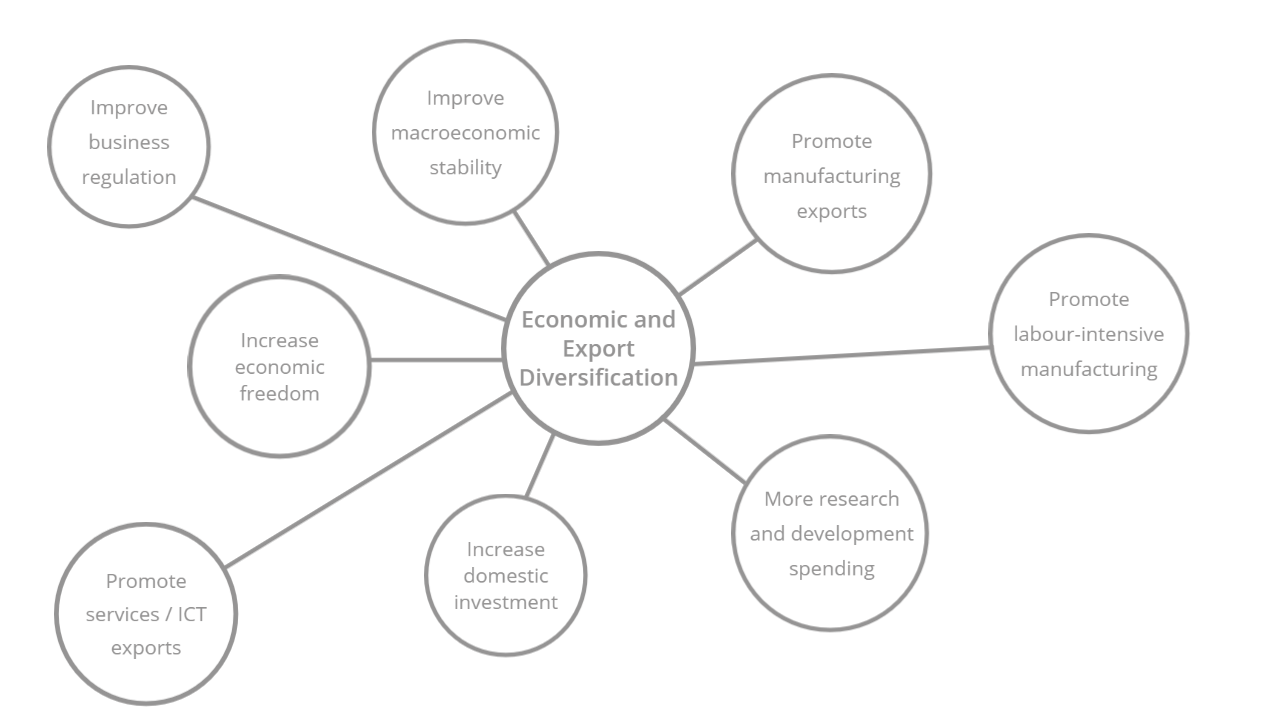

- Chart 32: Economic and export diversification scenario

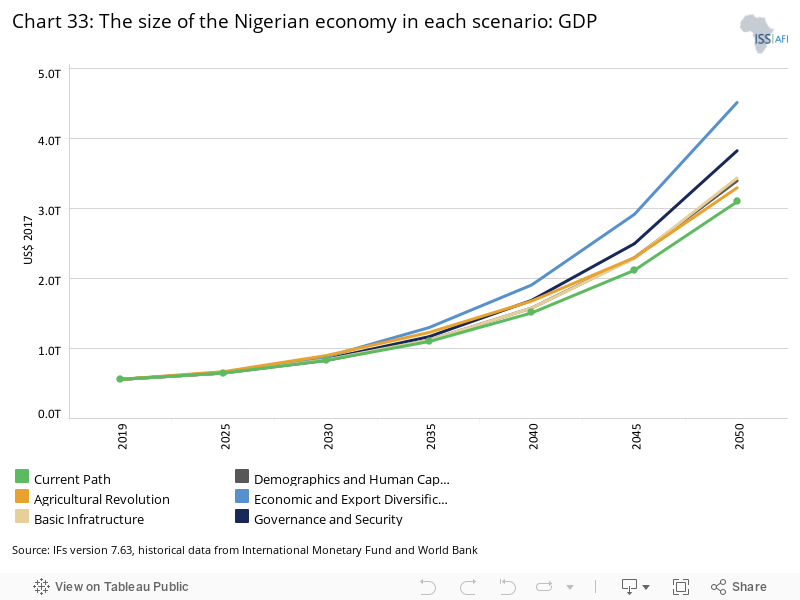

- Chart 33: The size of the Nigerian economy in each scenario: GDP

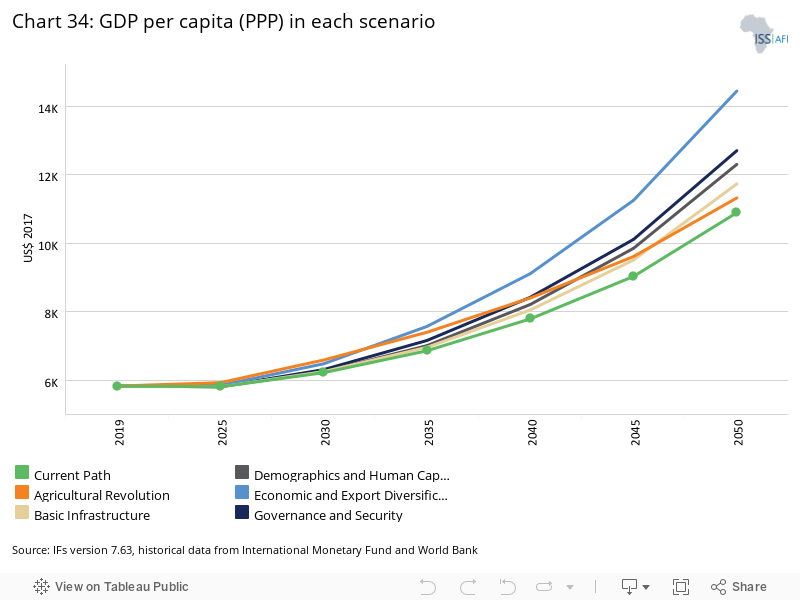

- Chart 34: GDP per capita (PPP) in each scenario

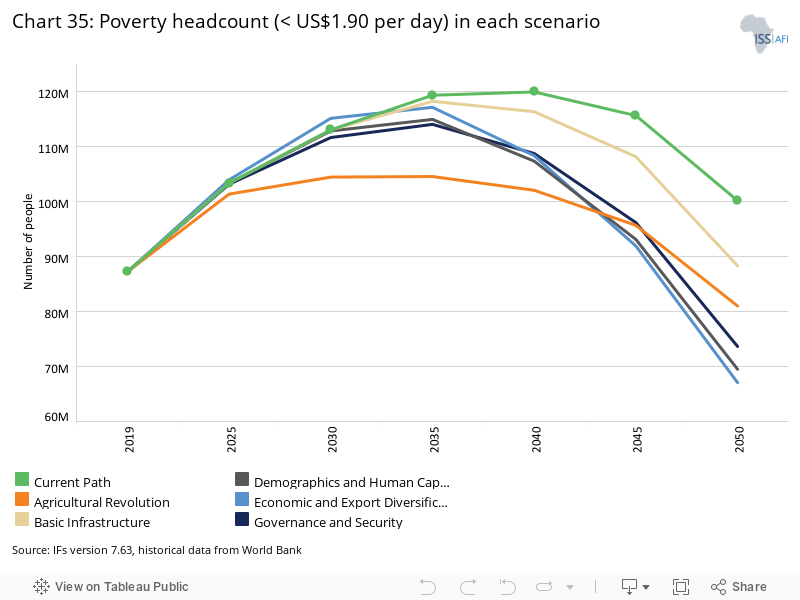

- Chart 35: Poverty headcount (< US$1.90 per day) in each scenario

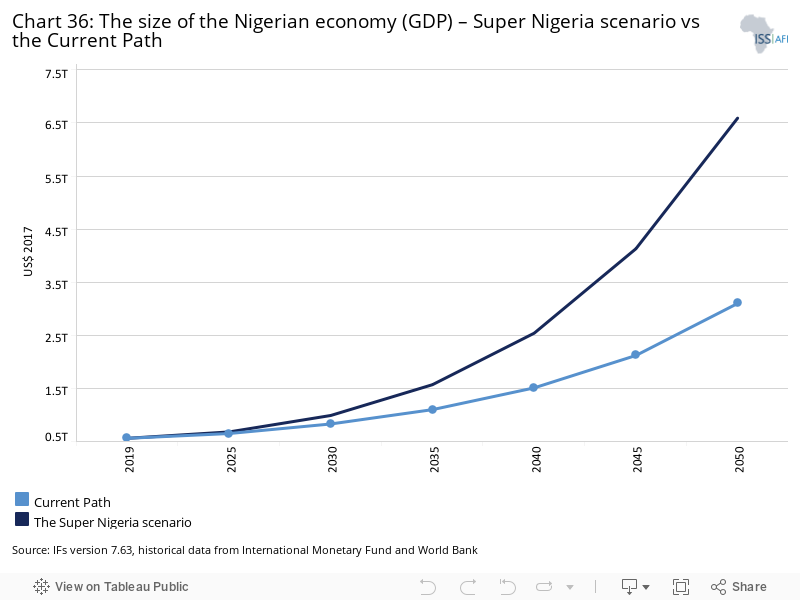

- Chart 36: The size of the Nigerian economy (GDP) – Super Nigeria scenario vs the Current Path

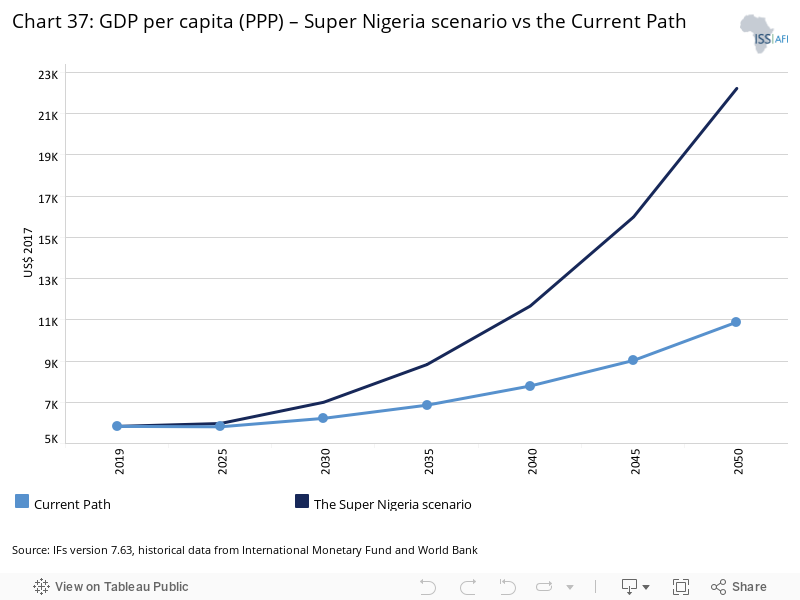

- Chart 37: GDP per capita (PPP) – Super Nigeria scenario vs the Current Path

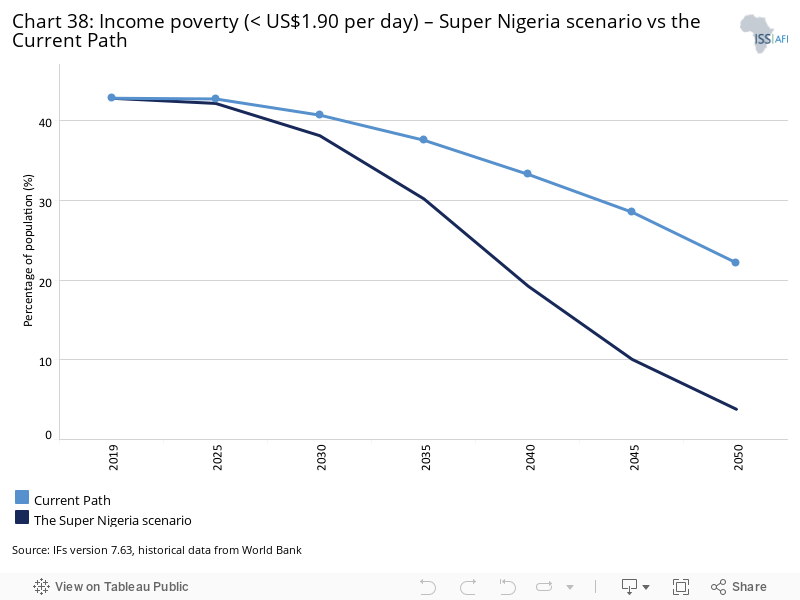

- Chart 38: Income poverty (< US$1.90 per day) – Super Nigeria scenario vs the Current Path

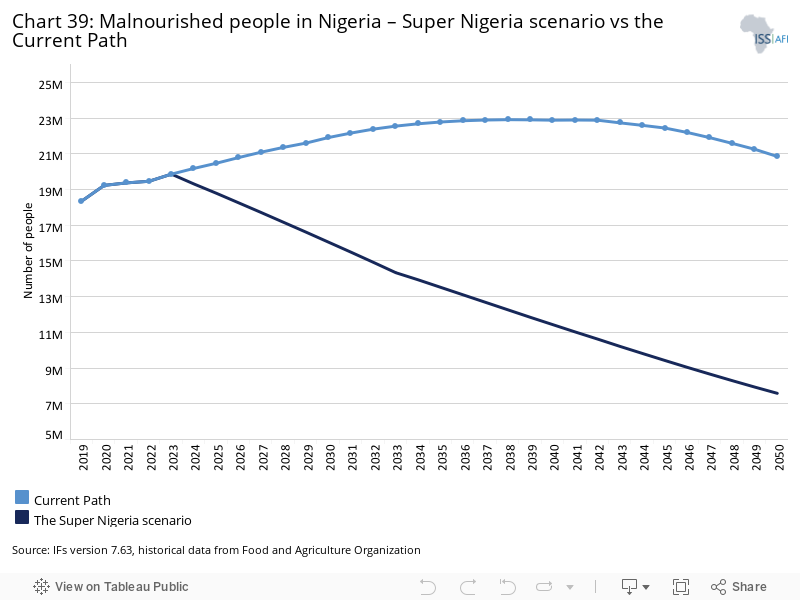

- Chart 39: Malnourished people in Nigeria – Super Nigeria scenario vs the Current Path

- Chart 40: Selected recommendations

Located in West Africa with a population of over 200 million in 2020, Nigeria is by far the most populous country in Africa and a key regional player in West Africa. The country is a multi-ethnic and culturally diverse federation made up of 36 states and the Abuja Federal Capital Territory (FCT) grouped into six geopolitical zones (north-west, north-central, north-east, south-west, south-east and south-south). Recognised as one of Africa’s largest economies, together with South Africa and Egypt, Nigeria is its largest crude oil exporter and has the largest natural gas reserve on the continent.

While some progress has been made in socio-economic terms in recent years, Nigeria faces serious social, economic and security challenges. Indeed, the country has one of the highest numbers of people living in extreme poverty in the world and high youth unemployment. More than 80 million[1IFs database.] people survive on less than US$1.90 a day, the international measure for extreme poverty. An overdependence on oil exports, deplorable infrastructure, human capital bottlenecks, low tax revenue mobilisation, deeply embedded corruption and decades of mismanagement have stymied investment, growth and the diversification of the economy.

In addition, the chaos caused by rising banditry-related attacks, kidnapping and communal clashes in the country threaten food security as it hinders access to farms and food production. Furthermore, Nigeria has been facing terrorism threats from the Islamist group Boko Haram since 2009.

Violence perpetrated by this armed group is estimated to have resulted in the deaths of 350 000 people, with 314 000 of these attributable to indirect physical and economic causes. Also, criminal gangs and farmer–herder violence, most notably in the states of Zamfara, Katsina and Kaduna, have killed more than 8 000 people since 2011 and forced more than 200 000 people to flee their homes, according to a report by the International Crisis Group (ICG). Consequently, a severe humanitarian crisis persists in north-east, north-west and north-central regions of Nigeria.

These challenges, in addition to poor governance and massive income and wealth inequality, have manifested in many people having poor health, nutrition and education, and the country fares badly on socio-economic indicators. Nigeria finds itself at the lower end of the United Nations (UN) Human Development Index (HDI). According to the 2020 Human Development Report, the country ranks 161 out of 189 countries. As Africa’s largest economy and most populous country, a stable and prosperous Nigeria is crucial for regional stability and faster poverty reduction in West Africa. Concrete steps therefore need to be taken to overcome Nigeria’s monumental developmental challenges.

This report looks at the recent history and the likely human and economic development trajectory in Nigeria (referred to as the Current Path). The report explores a series of policy interventions aimed at laying the foundations for long-term inclusive growth and development. We use the International Futures (IFs) modelling platform (see the About section) hosted and developed by the Frederick S Pardee Center for International Futures at the University of Denver for much of the analysis and forecast.

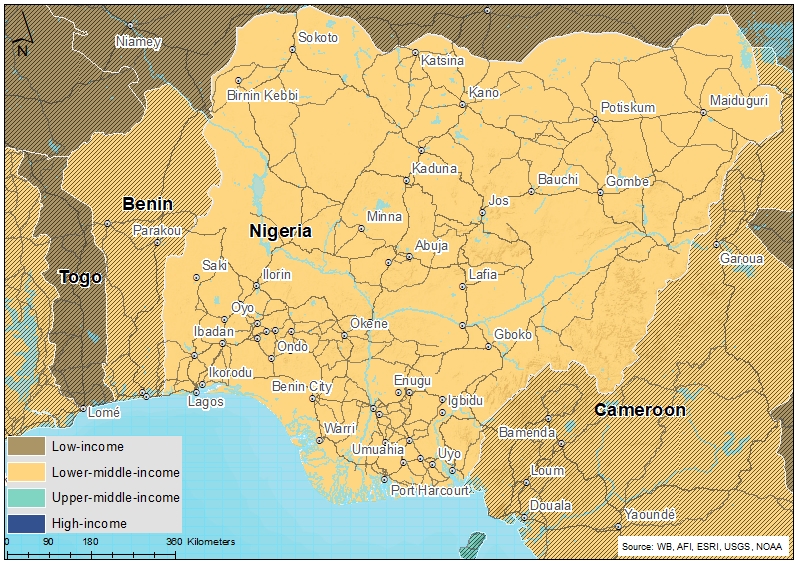

Two country groups, low-middle-income Africa and low-middle-income countries globally are used as benchmarks for gauging Nigeria’s historical and future progress. Both draw on the World Bank’s 2021/22 country income-grouping classifications. Nigeria is excluded from the groups for comparative purposes.

Nigeria’s long term development plan, Nigeria Agenda 2050, is available here and the associated first five year National Development Plan 2021-2025 is available here. In addition, the 2022 report Imagine Nigeria – Exploring the Future of Nigeria that includes various long-term scenarios on the future of the country is shown in Chart 3 and is available here.

For much of the four decades following independence in 1960, Nigeria was ruled by the military. The country only began its democratic transition in 1999.

Except for two short periods of civilian rule (1960–1966 and 1979–1983), the period 1960–1999 was marked by a succession of several military regimes that ruled the country after coming to power through coups d’état. The first two coups d’état in January and July of 1966 led to the Biafra War (1967–1970), which claimed more than one million lives, mostly from starvation.

In 1979, the army, led by General Olusegun Obasanjo, transferred power to an elected government. However, the second attempt at a democratic political system failed and the military returned to power. The worsened economic failures of the civil government under President Shehu Shagari ushered in a military coup led by Major General Muhammadu Buhari in December 1983. Nearly two years later, General Buhari’s regime was, in turn, overthrown by a coup led by General Ibrahim Babangida.

Babangida engaged in tightly controlled economic reforms under the auspices of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to facilitate the repayment of crushing external debt. The Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP), which was in effect between 1986 and 1993, was highly controversial and incited intense public unrest. For instance, between 1986 and 1993, the number of strikes in the country tripled even as the military government intensified its survivalist strategies by banning labour unions and arresting unionists.[2A Danladi and P Naankiel, Structural Adjustment Programme in Nigeria and Its Implication on Socio-Economic Development, 1980–1995, The Calabar Historical Journal, 6:2, 2016.]

After the controversial annulment of the nationwide election results in mid-1993, Babangida, under the pressure of continued civil unrest, ceded power to a caretaker government. But this interim arrangement was short-lived and was toppled by General Sani Abacha in November 1993. Nigeria experienced its most oppressive period of dictatorship under the Abacha regime, and the military lost much of its remaining legitimacy to rule the country.[3A Danladi and P Naankiel, Structural Adjustment Programme in Nigeria and Its Implication on Socio-Economic Development, 1980–1995, The Calabar Historical Journal, 6:2, 2016.] General Abdulsalami Abubakar, who took over after the death of Sani Abacha in 1998, freed all political prisoners and paved the way for early elections, which were won by the former head of the junta, Olusegun Obasanjo, in 1999.

The economic and social effects of these successive military regimes were disastrous. For example, in the 1980s, about 45% of foreign exchange earnings went into debt servicing, and there was very little growth and a rise in poverty and crime.[4M Siollun, Oil, Politics and Violence: Nigeria’s Military Coup Culture (1966–1976), New York: Algora Publishing, 2009.] Political leadership also became self-serving and driven by ethnicity and patron–client politics.[5D Yagboyaju and O Akinola, Nigerian State and the Crisis of Governance: A Critical Exposition, SAGE Open, 2019, doi: 10.1177/2158244019865810]

President Olusegun Obasanjo was re-elected in 2003, though the election was marred by electoral fraud and violence. Four years later, he was succeeded by Umaru Yar’Adua, who won the April 2007 presidential elections. However, health concerns dogged his presidency and prevented Yar'Adua from fully exercising his powers and, shortly before his death in May 2010, the National Assembly passed a resolution that allowed then vice president, Goodluck Jonathan, to serve as president. Immediately after Yar’Adua’s death, Jonathan was sworn in as executive president and later won the 2011 presidential elections.

In 2015, the All Progressives Congress (APC) party led by Muhammadu Buhari won the elections by promising to crack down on terrorism and corruption, modernise the economy and reduce poverty. Buhari secured a second term at the 2019 presidential elections, despite the fact that the results were contested by the main opposition party, the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). The presidential elections of February 2023 were won by vice president Bola Tinuba, a former governor of Lagos State and the nominee of the APC with 36.6% of the vote.

Nigeria’s economic and political transformation process since independence has been marked by progress and setbacks. However, there are reasons to be optimistic about the future of the country. The transition from authoritarian military regimes to democratic civilian rule and the entrenchment of regular elections provides the legitimacy to embark upon structural change and set the country on a much higher developmen trajectory.

Current development trajectory of Nigeria

Download to pdfThis section answers the following questions: What are the trends that have shaped modern Nigeria and how do they compare with trends for other countries at similar levels of development? Given the current policies and environmental conditions, what will the situation likely be in 2050, in line with Nigeria Agenda 2050? To answer these questions, the following sections highlight the recent past, current state of development and the possible future of Nigeria along the Current Path forecast within IFs, namely in terms of governance, demographics, education, health, poverty, economy, infrastructure and agriculture.

Despite a well-educated elite, entrepreneurial verve and abundant natural resources, leadership failure, weak institutions and policy missteps have made Nigeria symbolic of unfulfilled potential. The ruling elite have failed to transform the country’s potential into prosperity. As a result, six decades after independence, petroleum-rich Nigeria is still grappling with a high level of poverty, ailing infrastructure, socio-economic instability and underdevelopment.

Mismanagement, nepotism and favouritism characterise governance dynamics in Nigeria. The elite view politics as an avenue for wealth accumulation. Public office holders generally award contracts to cronies and personally held companies. As a result, governance and political leadership in Nigeria have been mainly driven by self-interest instead of collective well-being or national development.[6D Yagboyaju and O Akinola, Nigerian State and the Crisis of Governance: A Critical Exposition, SAGE Open, 2019, doi: 10.1177/2158244019865810.] Nigeria finds itself in the bottom half of the Mo Ibrahim African Governance Index, with a score of 43.6 out of 100, ranked 32 out of 54 countries in Africa in 2019.

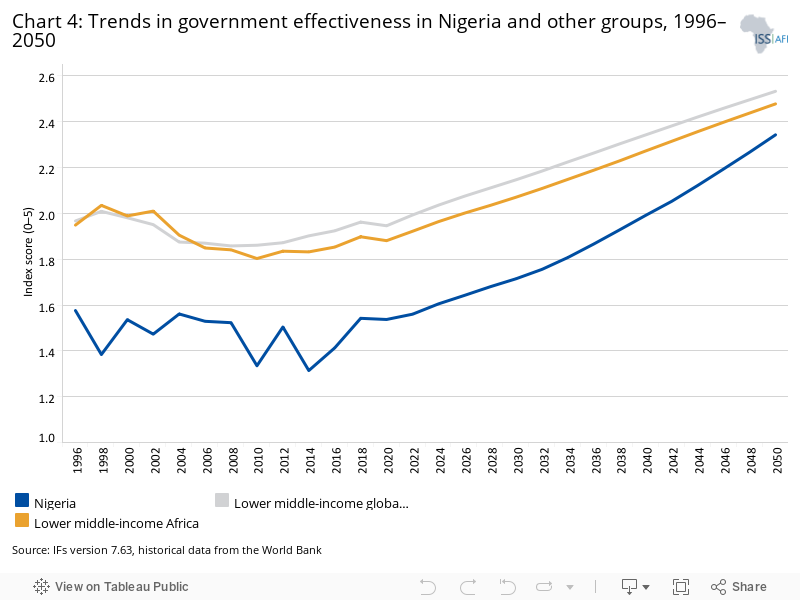

Chart 4 shows Nigeria’s government effectiveness score compared with the average for African and global income-group peers and includes a forecast to 2050. With a score of 1.5 out of a maximum of 5 in 2019, government effectiveness in Nigeria is very low and remains below the average for its peers. This implies that the Nigerian government’s performance in public services delivery and policy formulation and implementation is lower than the average for its income group. Although the forecast is that government effectiveness will improve, it will likely continue to remain below the average for its peer income groups across the forecast horizon.

Weak government capacity and corruption have undermined government effectiveness in service delivery. For instance, the tax-to-GDP ratio in Nigeria is about 6%, compared to 16% in Egypt, 18% in Ghana and Kenya, 29% in South Africa and 20% on average in sub-Saharan Africa. This low domestic revenue mobilisation limits the government’s ability to fund public goods and services to improve the dire social service delivery outcomes in the country. The structural corruption also compounds the inefficiencies in raising tax revenue.

Corruption is perhaps the Achilles heel of economic and human development in Nigeria. A study by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace cites corruption as ‘the single greatest obstacle preventing Nigeria from achieving its enormous potential. It drains billions of dollars a year from the country’s economy, stymies development, and weakens the social contract between the government and its people’.

The endemic corruption has led to the phenomenon of ‘ghost workers’ and ‘ghost pensioners’, terms used to describe people who do not actually exist but who are added to the payroll system, with their salaries and pension payments disappearing into the pockets of public officials. This has a knock-on effect on the government budget and limits government capacity to invest in badly needed socio-economic infrastructure.

Successive Nigerian governments have made efforts to fight corruption in the country. These measures have included reform of public procurement and anti-corruption enforcement agencies such as the recent Economic and Financial Crime Commission, the Independent Corruption and Other Practices Commission and the Code of Conduct Bureau.

However, progress has been slow. Profound political and institutional challenges, as well as inadequate funding, have undermined the credibility and effectiveness of these anti-corruption agencies.[7OG Igiebor, Political corruption in Nigeria: Implications for Economic Development in the Fourth Republic, Journal of Developing Societies, 35:4, 2019, 493–513.] As a result, corruption remains stubbornly high in the country. According to the global Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) 2020 by Transparency International, Nigeria occupies 149th position out of the 180 countries surveyed, with a score of 25 out of 100. The twin problems of corruption and bad governance have made Nigeria a ‘giant with clay feet’, the largest economy with the largest number of poor people in Africa.

Nigeria is also facing multidimensional security threats, including insurgencies, terror acts, kidnappings, armed robberies and communal clashes, particularly between farmers and herders. Boko Haram and an Islamic State-affiliated splinter faction, the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), have spread terror in their strongholds in the north-eastern part of the country by increasing attacks and kidnappings. This violence has left more than 36 000 dead and more than two million displaced to date. Since 2018, Boko Haram has strengthened and increased its deadly attacks, targeting Nigerian military bases in particular. As a result, Nigeria is ranked third out of 135 countries on the 2020 Global Terrorism Index (GTI).

In addition to Boko Haram in the north-east, criminal gangs and other armed organisations are mushrooming in north-west and north-central Nigeria. Violence in north-west Nigeria has three dimensions. The first layer includes violence from competition between Fulani herders with their associated militias, known as yan-bindiga (gun owners), and Hausa farmers with their vigilantes, referred to as yan sa kai (volunteer guards), over land and water resources. Farmer–herder conflicts in Northern Nigeria have gained momentum in recent years due to rising population pressures and diminishing water resources, as well as desertification caused by climate change.

The second dimension is comprised of violence perpetrated by criminal gangs seeking to enrich themselves amid the proliferation of small arms in the region. These criminal gangs generate revenue by rustling cattle, pillaging villages and kidnapping people for ransom. At least US$11 million was paid in ransom between 2016 and 2020. The third dimension of violence in Nigeria’s north-west involves the infiltration of jihadist groups seeking to take advantage of the security crisis. Women and girls are paying a heavy price in these attacks by different armed groups in the region as they are also subjected to sexual violence, often abducted or gang-raped in the presence of family members.

In addition to this multidimensional violence, a new separatist rebellion is emerging in the south-east, where a past secessionist attempt to create the republic of Biafra sparked a civil war between 1967 and 1970. Operations by Nigeria’s security forces to dismantle these armed groups also have unintended consequences, as they push some of them to other regions in the country, further exacerbating insecurity countrywide.

In sum, corruption, bad governance and insecurity are threatening Nigeria’s development prospects. Good leadership is needed to attain effective governance capable of addressing corruption, security and resource mobilisation for inclusive and sustainable development.

According to the 2018 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey, Nigeria’s population is 46% Christian (broken down between 10% Catholics and 36% Protestants) and 53.5% Muslim, with the remaining 0.5% being followers of traditional animist religions or not declared (atheists, agnostics).[8Data on religious affiliations of Nigeria’s population are limited, unreliable and contested; questions concerning religion are not integrated into the national census.] The country is home to over 250 different ethnic groups. This ethnic and religious diversity is often the source of tension, and religious affiliation plays a role in shaping political and power dynamics in Nigeria.

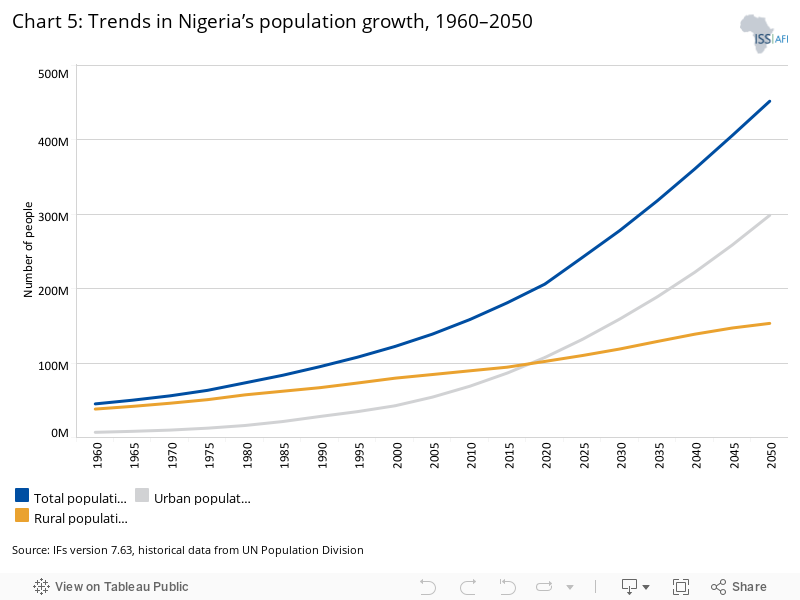

Nigeria is facing a significant population boom. According to IFs, from an estimated 45 million people at independence in 1960, Nigeria’s population has more than quadrupled to 200 million people, making it the seventh most populous country globally. On the current development trajectory (Current Path), Nigeria’s population is likely to increase from about 200 million in 2019 to about 452 million by 2050 (Chart 5). At that point, Nigeria will be the third most populous country globally, after India and China.

The fertility rate in Nigeria was 5.4 children per woman in 2020, a slight decline from 6.6 in 1990, making it currently ranked eighth globally. The Current Path forecast is that Nigeria’s fertility rate will decline to 3.4 children per woman by 2050, making it the fourth highest globally. The population of the northern states is growing faster than that of the southern states. For instance, the average fertility rate in the south-west is about 3.9 children per woman while it is about 6.6 in the north-west. By state, the fertility rate ranges from 3.4 children per woman in Lagos to 7.3 children per woman in Katsina.

As evident in Chart 5, the high population growth in Nigeria goes hand in hand with rapid urbanisation. In 2019, about half of Nigerians, or 100 million people, lived in cities. The population of Lagos itself has grown from 300 000 inhabitants in 1950 to 15 million in 2018. The urbanisation rate in Nigeria is one of the fastest in the world — the Nigerian urban population is growing at a rate of 4.2% per year, that is to say, twice the world rate, and is significantly higher than the Nigerian population growth rate of 3%.

On the Current Path, 66% of the population will be urban by 2050; this is equivalent to nearly 300 million people. The increasing size of the urban population is also associated with unemployment, poverty, inadequate healthcare, poor sanitation, urban slums and environmental degradation. It is estimated that more than half of the Nigerian urban population lives in slums.

The population is unevenly distributed across the country, concentrating along trade routes and natural resource locations. Average density ranges from five people per hectare in rural areas to 45 people per hectare in urban spaces. The highest rural densities are found in the south-west, while the highest urban densities are located in the cities of Lagos, Kano, Ibadan, Kaduna, Port Harcourt, Benin City and Maiduguri (Chart 6).

Successive Nigerian governments have recognised the necessity of reducing the rapid population growth, but efforts to implement a comprehensive demographic policy have often been met with religious objections. Family planning policies are a topic of fractious debate among religious leaders in the country. Nigeria’s modern contraceptive prevalence rate is 12% among women aged 15–49; this is significantly lower than the average for its region (28%).

A country’s population age structure plays a vital role in social, economic and political development. Nigeria is among the countries with the most youthful age structure, with a median age of 18. This means that half of the Nigerian population is younger than 18.

About 43.5% of the population is in the below 15 years of age dependency age group, while 2.7% are in the 65 and above dependency age group. On the Current Path, the share of these two dependency age groups is projected to be, respectively, 34.4% and 5.8% by 2050. About 54% of the Nigerian population is in the 15–64 working-age group, and this is forecast to increase to 59.7% by 2050. The structure of Nigeria’s population is typical of countries with a low life expectancy and high fertility rates.

The large cohort of children below 15 requires more investment in education, healthcare and infrastructure. An increase in the working-age population relative to dependent children and elders can generate economic growth known as the demographic dividend.

Generally, the demographic dividend materialises when a country reaches a ratio of at least 1.7 people of working age for each dependant. When there are fewer dependants to take care of, it frees up resources for investment in both physical and human capital formation, and eventually increases female labour force participation. Studies have shown that about one-third of economic growth during the East Asia economic miracle can be attributed to the large worker bulge and a relatively small number of dependants.[9D Canning, S Raja and AS Yazbeck (eds.), Africa’s Demographic Transition: Dividend or Disaster? Africa Development Forum Series, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2015.]

However, the growth in the working-age population relative to dependants does not automatically translate into rapid economic growth unless the labour force acquires the needed skills and is absorbed by the labour market. Without sufficient education and employment generation to successfully harness their productive power, the growing labour force could turn into a demographic ‘bomb’ instead of a demographic dividend, as many people of working age may remain in poverty, potentially creating frustration, social tension and conflict.

On the Current Path, the ratio of working-age people to dependants will improve slowly from its current level of 1.1 to about 1.5 by 2050, below the minimum threshold of 1.7 that a country should reach to expect the demographic dividend. Nigeria only gets to this positive ratio around 2060, implying that it will experience its demographic dividend almost two decades later than the average for lower middle-income Africa and five decades later than the average for lower middle-income globally (Chart 8).

Also, the youth bulge, defined as the ratio of the population between the ages of 15 and 29 to the total adult population, is currently about 47% for Nigeria, and it will remain above 40% across the Current Path forecast horizon. While this large youth bulge can usher in youth activism and positive political changes in a country, it can also increase the likelihood of criminal violence, conflicts and instability, mainly when the needs of the youth, such as employment, cannot be met. Nigeria has one of the highest youth unemployment rates: two-thirds of the youth are either jobless or under-employed, while one-third of the country’s working-age population is unemployed. Recently, the EndSARS protests which were initially against police brutality became a platform for the youth to express their anger with the leaders of the country, and demand change.

Better management of population growth is key to the development of a nation. Policymakers in Nigeria need to take much more urgent action to address the high population growth in order to speed up the country’s demographic transition. A decline in the below-15 dependency age group helps governments and parents to invest more in each child in terms of education and health,[10R Cincotta, Does demographic change set the pace of development? Guest contributor, Wilson Center, Environmental Change and Security Program, 2018.] with positive implications for human capital formation.

Like in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo) and many other sub-Saharan African countries, poverty in Nigeria presents a paradox: the country is resource rich, but most people are poor. Chart 9 reveals that the rate of poverty and the number of people living in extreme poverty have been very high in Nigeria over time. The poverty rate in the country reached its highest levels over the period 1995–2000 (66.1% on average) before taking a downward trend to 40.1% in 2018 — its lowest level since independence in 1960. The average poverty rates for lower middle-income Africa and globally were 22.4% and 9.7%, respectively, in 2018.

According to the IMF, poverty rates have declined more slowly in Nigeria than in other sub-Saharan African countries with similar GDP per capita growth because the ineffectuality of the various poverty-alleviation programmes, in part due to corruption.[11OC Iheonu and NE Urama, Addressing Poverty Challenges in Nigeria, AfriHeritage Policy Brief No. 21, July 2019.] Corruption can undermine the effectiveness of government poverty-alleviation programmes by diverting public social spending away from its targets, such as education and health.

On the Current Path, the poverty rate in Nigeria is forecast to increase from 42.8% in 2019 to 44% in 2021 before declining gradually across the forecast horizon. This is mainly due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated economic crisis, which has plunged millions more people into poverty. According to the World Bank, the COVID-19 crisis is expected to push an additional 10.9 million people into poverty by 2022 in Nigeria. On the Current Path, the poverty rate in Nigeria is forecast to decline gradually to reach 22.1% by 2050, versus 9.1% and 2.5% for the projected averages for, respectively, lower middle-income Africa and lower middle-income globally in the same year.

However, the absolute number of poor people will continue to increase due to the rapid population growth. The number of poor people is projected to increase from 87.3 million in 2019 to peak at about 120 million in 2038 before slowly declining to 100 million by 2050. Therefore, unless the Nigerian government takes proactive measures in confronting poverty, the country will miss the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of eliminating extreme poverty by 2030 by a substantial margin. Indeed, on the Current Path, the extreme poverty rate in Nigeria is projected to be about 41% by 2030, while Goal 1 of the SDGs requires that less than 3% of every country’s population should be living in extreme poverty by 2030.

Also, Nigeria shows a characteristic pattern of poverty polarity between Northern and Southern Nigeria. Poverty in the country is more concentrated in the northern states. As shown in Chart 10, poverty rates in most northern states are above the national average. For instance, more than 87% of the population in the northern states of Sokoto, Taraba and Jigawa live in extreme poverty compared to only 6% and 4.5% of the population, respectively, in the southern states of Delta and Lagos.

The northern region performs poorly on almost all human development indicators when compared to the south. According to the World Bank, 87% of Nigeria’s poor live in the northern region, with about half of them in the north-west. The conflict between farmers and herders has contributed to the high level of poverty in Northern Nigeria. The violence has deeply affected the economy of the region. Agriculture, on which about 80% of the population of the region depends for livelihoods, has been particularly hit. Thousands of hectares of farmland have been either destroyed or rendered inaccessible, a situation that has resulted in poverty and aggravated malnutrition.

Chart 10 also reveals that Nigerian poverty is predominantly a rural phenomenon; the average poverty rate in rural areas is 52.1% versus 18% in urban areas. This indicates significant challenges with access and opportunities for Nigerians that live in rural areas of the country. For instance, about 78% of financially excluded adults in the country live in rural areas, compared to nearly 22% in urban areas.

The above analysis of extreme poverty in Nigeria is based purely on a monetary measure. However, poverty is not only about money; it is increasingly being understood as a multidimensional phenomenon. Even households that are not monetarily poor may find it difficult to access food, clean water, housing, security and health and education services.

The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) complements monetary measures of poverty by taking into account the multiple deprivations faced by people in a country. Multidimensional poverty is more widespread in Nigeria and has been compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the 2020 global MPI, 46.4% of Nigerians are multidimensionally poor. This is equivalent to about 95 million people living in multidimensional poverty. This is more than the entire population of the DR Congo. According to the World Bank, Nigeria is the largest contributor to multidimensional poverty in sub-Saharan Africa. This implies that meeting regional targets on monetary and non-monetary poverty hinges on Nigeria.

In addition to corruption and unemployment, inequality is another key driver of poverty in Nigeria. The wealth of the nation is concentrated in the hands of a few. For instance, about one-third of billionaires in sub-Saharan Africa are Nigerians, and there are 194 Nigerian multimillionaires whose fortune exceeds US$30 million, with 93% of them living in Lagos state. According to Oxfam International, the combined wealth of the five richest Nigerians, US$29.9 billion, could end extreme poverty in the country. Oxfam International revealed that a few wealthy elites had exploited the benefits of the nation’s economic growth to the detriment of ordinary Nigerians.

Also, Nigerian women are subject to unequal treatment in terms of labour, education and property. The patriarchal society and deep-rooted traditions make life difficult for many women in Nigeria. For example, low-skilled and low-wage jobs are predominantly occupied by women. In addition, they are five times less likely to own land than men. Widowhood is often a source of discrimination and can lead to losing property, land and any money saved before a husband’s death.

According to the IFs database, the income inequality level measured by the Gini index was 0.42 in 2019 in Nigeria versus 0.39 for lower middle-income Africa and 0.37 for lower middle-income globally. Although Nigeria has the largest number of poor people among its lower middle-income peers, it has the lowest public spending on social protection (0.3% of GDP), which is also poorly targeted.[12World Bank Group, Nigeria biannual economic update, Fall 2018: Investing in human capital for Nigeria’s future, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2018.] As a result, Nigeria ranked second to last among 158 countries assessed on Oxfam’s 2020 Commitment to Reducing Inequality (CRI) Index, which captures governments’ actions concerning social spending, tax and labour rights.

A high level of inequality reduces the elasticity of poverty to economic growth and can cause socio-political instability in a country. The growing social discontent and the surge in criminal gangs involved in kidnappings for ransom in Nigeria in recent years are partly linked to unemployment, poverty, limited economic opportunity, social inequality, and unequal allocation and distribution of state resources.

Frustrated by living in abject poverty with no prospect of a job, some Nigerians may sympathise with the armed groups or get involved in criminal activities. According to the ICG, some girls and women living mainly in the north-east part of Nigeria chose to join Boko Haram voluntarily in the hope of a better life. Also, an empirical study by Adekoya and Abdul-Razak revealed a strong relationship between crime and poverty in Nigeria.[13A Adekoya and N Abdul-Razak, Effect of Crime on Poverty in Nigeria, Romanian Economic and Business Review, 11:2, 2016, 29–42.]

Overall, Nigeria’s poor are mostly rural, predominantly female, mostly illiterate and mainly in the informal sector.[14A Adekoya and N Abdul-Razak, Effect of Crime on Poverty in Nigeria, Romanian Economic and Business Review, 11:2, 2016, 29–42.] Nigeria was declared the ‘poverty capital’ of the world a while ago despite its abundant natural resources. To ensure peace and stability in the country, proactive measures need to be taken to break the cycle of poverty. The government should scale up social safety net transfers to a broader share of the poor, reduce corruption and improve employment and educational opportunities.

The education system in Nigeria is administered at federal, state and local government levels. The Federal Ministry of Education oversees overall policy formation and ensures quality control but is mainly involved with tertiary education. Basic and senior secondary education remain primarily under the jurisdiction of the state and local governments. The Nigerian education system can be described as a ‘1-6-3-3-4’ system: one pre-primary year (recently introduced) and six years of primary, followed by three years of junior secondary education, which together comprise the basic education. The next three years are senior secondary education, followed by four years of tertiary education for a basic degree.[15R Outhred and T Fergal, Prospective evaluation of GPE’s country-level support to education, Country level evaluation: Nigeria, Final Report – Year 2, 2020.]

According to Nigeria’s national policy on education, the language of instruction for the first three years of elementary school should be the ‘indigenous language of the child or the language of his/her immediate environment’, most commonly Hausa, Ibo or Yoruba. After that, English is used from Grade 4. This policy, however, is not always followed and instruction is often delivered in English.

The education sector has not received enough attention in Nigeria, and this manifests in the chronically low public funding, decaying educational infrastructure, deteriorating teaching capabilities and high illiteracy, among other issues.

The national literacy rate improved modestly from 55% in 2003 to about 65% in 2019, 10 percentage points below the average for lower middle-income Africa and 20 percentage points below the world average. However, despite the progress made, more than 30% of Nigeria’s population aged 15 years and older can neither read nor write. Moreover, the literacy rate is even lower in most of the northern states of the country. For instance, the literacy rate in north-west Nigeria is estimated to be about half the national rate.

These distressing statistics imply that a significant proportion of Nigeria’s working-age population is not employable in an economic environment where manual labour is becoming less important. The absence of appropriate knowledge and skills leads to poverty.

The mean years of education of adults is a good indicator of the general level of education or the stock of education in a country. In Nigeria, the average number of years of schooling for adults aged 15 years and over, according to 2019 data in IFs, is about eight years. However, when disaggregated by gender, males have about nine years and females seven years of schooling. This means that most adults in the country have barely completed basic education.

However, Nigeria performs slightly better than the average for its income group in Africa, which is about seven years. By 2050, the average years of education for adults 15+ will only be about nine years, nearly one year higher than the projected average for African lower middle-income.

Primary school enrolment in Nigeria has improved in recent years but remains below the average for its Africa income group. UNICEF reports that the net attendance at the primary level is only 70%. Also, the net primary enrolment rate (not shown in the table) is only 67%, implying that many children who are supposed to be in school are not. This means that Nigeria still has a bottleneck at the primary enrolment stage, as the number of learners that can get into and through primary school determines the size of the pool available for secondary and tertiary.

Consequently, educational outcomes for secondary and tertiary levels are very low in Nigeria, with the situation at the tertiary level significantly worse. The low educational outcomes at the tertiary level are also explained by the low-carrying capacity or intake level of the tertiary institutions. Only about 10% of applicants seeking admission into tertiary institutions are placed.

Officially, primary education is free and compulsory in Nigeria, but the reality on the ground is quite different. According to UNICEF, Nigeria has the world’s highest number of out-of-school children — about 10.5 million children aged 5–14 are not in school, with 60% of them in Northern Nigeria. The rapid population growth and the youthfulness of Nigeria’s population have brought many challenges to the education system.

With children under 15 making up over 40% of the 200 million people, the education system is unable to cope. North-west Nigeria has the highest number of out-of-school children in the nation. In states like Kano, Katsina, Sokoto, Zamfara and Kebbi, more than 30% of school-age children are not in school. In addition to those who do not attend school, millions of children are in the poorly resourced and under-supervised Quranic school system (almajiranci), which is notorious for producing unskilled youth cohorts.[16Almajiranci is a Quranic school system which is common in Nigeria. Its students are called almajiri, which literally means a person who has left his dwelling place in search of Quranic knowledge. Under this system, mostly poor rural parents send their young children away from home to study the Quran under a Mallam (religious teacher). As the schools are poorly resourced, during lesson breaks, the children are sent out into the streets to beg for food and money.]

Furthermore, a gender imbalance in the education sector also affects enrolment and educational outcomes. While the gender parity index for primary school and secondary school has improved to 1.00 and 0.97 respectively, UNICEF reports that about 60% of out-of-school children in the country are girls. Many girls are not in school due to stereotypes about education for girls, financial constraints and early marriages.

However, the situation of female education varies by state or region. For instance, in the north-east and north-west states, girls’ primary net attendance rate is 47.7% and 47.3%, respectively, implying that more than half of the young girls in these states are not in school.

Girls in the southern regions have more than twice the chance to attend school than their peers in the north, where jihadist insurgency and poverty are rampant. Education in Northern Nigeria has become one of the casualties of jihadist insurgency and banditry as learners are frequently taken from schools in mass abductions. More than 1 000 learners have been abducted since December 2020 and the group Boko Haram, for instance, kidnapped over 270 schoolgirls from Chibok in 2014.

On top of the alarming number of out-of-school children, the quality of education received by those who have the opportunity to be in school has slipped significantly. Getting more children into school is essential but ensuring that they actually learn is more important. Many empirical studies have reported that educational quality impacts economic growth more than educational quantity. The quality of education is usually tracked using Harmonized Test Scores. According to the 2020 World Bank Human Capital Project report, learners in Nigeria score 309 on a scale where 625 represents advanced attainment and 300 represents minimum attainment.

Dilapidated school infrastructure, obsolete educational materials, insufficiency of qualified teachers, limited STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) training, and lack of high-quality technical and vocational education and training programmes affect the quality of education and create a disconnect between graduates’ skills and labour market needs. The end result is the low employability of the labour force and high youth unemployment in the country.

Chronically inadequate public funding, corruption and bad governance are some of the key factors underlying the deterioration in public education outcomes across all levels in Nigeria. The resources allocated to the education sector have increased only modestly despite the exploding number of learners. The education budget increased from 6.4% of the national budget in 2003 to 8.2% in 2013 and 10.7% in 2014 before dipping below 10%.

In 2018, only about 7% of the national budget was allocated to the education sector while the ‘Education 2030 Agenda’ (Incheon Declaration) requires states to allocate at least 15% to 20% of total public expenditure to education. As a result of insufficient funding, some public schools are highly dilapidated or have collapsed and learner-to-teacher ratios have significantly increased. It is common to see 100 learners for one teacher or learners learning under trees due to the lack of classrooms in some areas. As parents seek better education than they find in the public schools, private education has mushroomed over the years in the country. In Lagos state alone, more than 18 000 private schools were operating in 2018.

Corruption is another factor hindering the growth of the education sector and, in consequence, the development of a skilled labour force in Nigeria. Often, school funds meant for salaries, equipment and maintenance are diverted or mismanaged. This pushes teachers to strike in protest of low wages and late payments, which negatively affects their productivity and the quality of teaching they deliver.

In 2017, for instance, the University of Ibadan ranked at 801 and was the only Nigerian university listed among the top 1 000 in international university rankings, while universities from other African countries such as South Africa, Ghana and Uganda were ranked much higher. Nigeria’s deteriorating tertiary education condition has pushed many secondary school graduates to migrate, searching for quality education abroad. Nigeria’s outbound tertiary students were estimated at about 85 000 in 2017, making Nigeria the largest African country of origin of international students.

There are, however, promising efforts to improve the quantity and quality of education in the country. The number of recognised universities grew almost tenfold from 16 in 1980 to 152 in 2017, and the federal government has announced plans to build more classroom blocks and federal universities across the country and improve the teacher recruitment process. There are also many reform projects to enhance vocational training to provide employment-geared education in the private sector.

The public health sector in Nigeria is incapacitated by a cocktail of mismanagement, corruption and poor resources. As a result, Nigeria has very poor health outcomes, with some of the worst healthcare statistics in the world. In 2019, the country ranked 187th for overall health efficiency among 191 WHO member states.[17A Tandon, CJL Murray, JA Lauer and DB Evans, Measuring overall health systems performance for 191 countries, World Health Organisation, GPE Discussion Paper Series No. 30, 2019. ]

The efficacy of a country’s health system can be assessed through several indicators such as infant mortality, maternal mortality and life expectancy. In 2019, Nigeria’s infant mortality ranked as the highest among lower middle-income countries in Africa, with 67 deaths per 1 000 live births, and the under-five mortality rate of 23 deaths per 1 000 live births ranked as the third highest in the world, and the highest among all lower middle-income economies.

The SDG target regarding the infant mortality rate is below 25 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2030. On the Current Path, Nigeria is not on track to achieve this target as it is forecast to have an infant mortality rate of 59 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2030 and 33 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2050, significantly above the projected average of 15 deaths per 1 000 live births for global lower-income countries in the same year (Chart 13). Life expectancy climbed from 55 years in 1990 to 65 years in 2019, and in the Current Path forecast is likely to reach 75 years by 2050, on a par with the projected average for its income peers.

Nigeria has the highest maternal mortality ratio among lower middle-income African countries, with 831 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births. The SDG target for maternal mortality (SDG 3.1) is a ratio of less than 70 deaths per 100 000 by 2030, a target that will be unattainable on the Current Path trajectory of the country. In the Current Path forecast, Nigeria is forecast to reach a ratio of 246 deaths per 100 000 live births by 2050, well above the projected averages of 50 deaths per 100 000 live births and 26 deaths per 100 000 live births for lower middle-income Africa and global lower middle-income countries, respectively (Chart 14).

Nigeria is also battling with the highest incidences and prevalence of severe acute malnutrition on the African continent and an estimated two million children are affected.[18World Bank Group, Nigeria Biannual Economic Update, 2018: Investing in Human Capital for Nigeria’s Future, Washington, DC: World Bank, 201] Children in Nigeria are exposed to chronic malnutrition, with 44% of children,[19World Bank Group, Nigeria Biannual Economic Update, 2018: Investing in Human Capital for Nigeria’s Future, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2018.] the second highest burden in the world, considered stunted. Stunting prevalence in children has only marginally improved in the past three decades, dropping from a rate of 48.7% in 1990 to 36.5% in 2019. Most of the gains towards lowering stunting rates have been made in the southern states of Nigeria but of concern is a consistent increase observed between 2008 and 2015 in the north-western states.[19World Bank Group, Nigeria Biannual Economic Update, 2018: Investing in Human Capital for Nigeria’s Future, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2018.]

Nigerian children are experiencing a nutritional crisis.[20World Bank Group, Nigeria Biannual Economic Update, 2018: Investing in Human Capital for Nigeria’s Future, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2018.] A study by the World Bank found that only 23.7% of children had the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding during their first six months of life, while 30% had a vitamin A deficiency and 76% were anaemic.[21World Bank, An Investment Framework for Nutrition: Reaching the Global Targets for Stunting, Anemia, Breastfeeding, and Wasting. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2017.] These worrisome figures are the result of poor-quality food, unhygienic environments, a lack of education around child nutrition, inadequate access to health services and information and a lack of access to community-based programmes.[22World Bank, An Investment Framework for Nutrition: Reaching the Global Targets for Stunting, Anemia, Breastfeeding, and Wasting. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2017.]

The most predominant causes of adult mortality are preventable, treatable and curable (Chart 15) and 13% of deaths in the under-five age category could have been prevented through vaccines that target diseases such as measles, pertussis and meningitis.[23A verbal/social autopsy study to improve estimates of the causes and determinants of neonatal and child mortality in Nigeria, Johns Hopkins University, 2016.] Vaccination coverage, however, remains low and has not changed much in the past 25 years.[24A verbal/social autopsy study to improve estimates of the causes and determinants of neonatal and child mortality in Nigeria, Johns Hopkins University, 2016.] Vaccine rates also vary significantly across states, with the highest vaccination rates in the southern and north-central states and the lowest observed in the north-east and north-west. The under-five mortality rate also remains highest in the northern states due to the lower vaccination rates.[25A verbal/social autopsy study to improve estimates of the causes and determinants of neonatal and child mortality in Nigeria, Johns Hopkins University, 2016.]

Nigeria has the highest malaria prevalence and mortality headcount in Africa, placing a huge economic burden on the country. The direct and indirect economic burden of malaria is estimated at about 13% of Nigeria’s GDP. Nigeria has, however, made significant strides in combating malaria and has seen death rates drop since 2008. Insecticide-treated net access increased from 1% in 2003 to 47% in 2016 and other interventions in the form of rapid diagnostic tests and treatment courses have all contributed to lower mortality rates.

The new malaria vaccine approved by the WHO is viewed as a ‘game-changer’ in combating the disease in Africa, which accounted for 94% of the world’s cases in 2019. The Nigerian government needs to get ready in terms of the infrastructure and logistics required to roll out the vaccine when it becomes available.

The past three decades have also seen the country battling close to 60 epidemics. Diseases such as Lassa fever were responsible for epidemics in 1989, 2012, 2016 and 2018. Yellow fever caused epidemics in 1991 and as recently as 2019, and a devastating (and completely preventable) measles outbreak affected nearly 22 000 people in 2019. Cholera alone has been responsible for 20 epidemics in the country, a direct result of poor water, sanitation and hygiene (WaSH).

Poor environmental health also directly affects the health and well-being of citizens. Nigeria’s delta region has seen significant air, soil and water pollution as a direct result of oil spillage and gas flaring, with the latter leading to increased respiratory and dermal illnesses. High rates of deforestation coupled with population increases pose an increased risk to the emergence and re-emergence of infectious diseases, while overexploitation of resources, such as the mining in the north-western states, has caused devastating and fatal lead toxicity in communities.[26S Morand and C Lajaunie, Outbreaks of Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases Are Associated with Changes in Forest Cover and Oil Palm Expansion at Global Scale, Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8, 2021]

Overall, communicable diseases are the leading causes of deaths in Nigeria (Chart 15). On the Current Path, this trend is forecast to change from 2044, when non-communicable diseases will become the leading causes of deaths. This will occur much later than the average for global lower middle-income countries. This has implications for Nigeria’s healthcare system, which will need to invest in the required capacity as the treatment of non-communicable diseases is difficult and costly.

Nigeria is chronically underinvesting in its health sector, with health expenditure in 2019 at a mere 3.6% of GDP, the fourth lowest among low middle-income economies in Africa. The private health sector is responsible for about 60% of healthcare service delivery in the country.[27BS Aregbeshola and SM Khan, Out-of-Pocket Payments, Catastrophic Health Expenditure and Poverty among Households in Nigeria 2010, International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 7:9, 2018, 798–806.] About 67% of Nigerians can reach a health facility within a 30-minute walking distance.[28MI Amedari and IC Ejidike, Improving Access, Quality and Efficiency in Health Care Delivery in Nigeria: A Perspective, PAMJ - One Health, 5:3, 2021, doi: 10.11604/pamj-oh.2021.5.3.28204.] However, households and individuals are unable to access quality and equitable services due to limited human resource capacities; poor equipment; poor coordination between the local, state and federal governments responsible for primary, secondary and tertiary levels of care, respectively; and excessive healthcare fees, among others.[29MI Amedari and IC Ejidike, Improving Access, Quality and Efficiency in Health Care Delivery in Nigeria: A Perspective, PAMJ - One Health, 5:3, 2021, doi: 10.11604/pamj-oh.2021.5.3.28204.]

Due to poor working conditions, Nigeria is experiencing a medical ‘brain drain’. It is estimated that about 2 000 doctors have left the country over the past few years to seek better work conditions and pay abroad, a situation which, combined with inadequate funding, has led to a chronically under-resourced health system. High out-of-pocket health payments also limit the ability of poor households to access and utilise basic healthcare services in the country. Private healthcare expenditure accounts for 76% of total health expenditure, while out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure represents 73% of total health expenditure, the highest compared to other African countries.

A well-fed and healthy population will aid in national development and productivity. It is therefore critical that the country addresses its poor healthcare outcomes. Corrupt practices should be eliminated through accountability measures. Investing in primary health facilities and community programmes will significantly reduce the nutritional risks faced by children. Ramping up vaccinations for preventable diseases and expanding basic WaSH infrastructure can also significantly reduce mortality rates.

The role of basic infrastructure such as roads, electricity, information and communication technology (ICT) and improved water and sanitation in boosting productivity, growth and human development is well documented. The adequate provision of basic infrastructure affects inequalities by allowing the poor segment of the society to access core economic activities and services in a country. Nigeria’s infrastructure gap has long been a drain on productivity, growth and competitiveness, especially in the non-oil sector.

The provision of infrastructure in Nigeria has not kept pace with the continued rapid population growth. Nigeria’s core infrastructure stock is estimated at 20% to 25% of GDP compared to the international benchmark of 70%. In 2020, Nigeria ranked 24 out of 54 African countries on the African Development Bank’s Infrastructure Development Index, with a score of 23.2 out of 100. The relatively good ranking of Nigeria despite its poor score reveals the extent to which infrastructure development is low in Africa.

Water, sanitation and hygiene

Improved water and sanitation infrastructure improves the human capital stock in a country through its positive impact on health outcomes. Better provision of clean water and improved sanitation will help to prevent the spread of communicable diseases, which is the leading cause of death in Nigeria. As stated by UNICEF, in Nigeria: ‘The use of contaminated drinking water and poor sanitary conditions result in increased vulnerability to water-borne diseases, including diarrhoea which leads to deaths of over 70 000 children under five annually. 73% of the diarrhoeal and enteric disease burden is associated with poor access to adequate WASH. Frequent episodes of WASH related ill-health in children, contribute to absenteeism in school, and malnutrition.’

Nigeria has, however, made significant progress in providing clean water to its population over the past 20 years. According to IFs, in 2000, only 57.1% of Nigerians had access to safe water, while the averages for lower middle-income Africa and global lower middle-income were, respectively, 73.5% and 83%. As of 2020, 82.5% of the Nigerian population had access to clean water against 83.8% for the average for African income peers. In other words, the absolute number of people with access to improved water sources increased from nearly 70 million in 2000 to 163 million in 2020, a 133% increase over 20 years.

Although the improvement is impressive, more needs to be done as nearly 43 million people still do not have access to improved water sources. This implies that 43 million people rely on unsafe water sources for their needs, thereby exposing them to malnutrition and communicable diseases such as cholera.

Access to drinking water is skewed towards urban areas, where 95.3% of the population has access to improved sources of water, against 68.8% in rural areas. This discrepancy between urban and rural areas can also be observed regarding access to basic hand-washing facilities. In 2020, only 25% of the rural population had access to a basic hand-washing facility compared to nearly 41% in urban areas. Overall, nearly 138 million people are without access to a basic hand-washing facility in Nigeria.

On the Current Path, the access rate to safe water is forecast to decline in the short to medium term; it will only recover its 2020 level around 2042 before increasing to 86.2% by 2050 (Chart 16). This implies that nearly 60 million people will still be without access to clean water sources by 2050 in Nigeria. The slow growth associated with the long-term impact of COVID-19, compounded by the rapid population growth, might explain this slowdown in the water access rate. By 2050, the water access rate is forecast to be, respectively, 91.5% and 97% for Africa lower middle-income and global lower middle-income.

The access to improved sanitation in Nigeria increased modestly from 29.5% in 2000 to 42.5% in 2020, against 57.8% for the average for lower middle-income Africa, and 66.3% for the average for Nigeria’s global lower middle-income peers. In rural Nigeria, only 33% of the population has access to improved sanitation compared to over 50% of the population in urban areas. Nearly 30% of the population in rural areas practise open defecation, a fraction that has changed marginally since 2000. The Current Path forecast is that access to improved sanitation will improve slightly to reach about 64% of the population by 2050 compared to nearly 75% and 89%, respectively, for Nigeria’s Africa income peers and global income peers.

This overall low level of access to WaSH services is linked to Nigeria’s high burden of communicable disease and malnutrition. With the support of the World Bank, the government of Nigeria has recently strengthened its commitment to improve access to WaSH to catch up with regional peers and ensure universal access by 2030 in line with the SDGs. In May 2020, the World Bank approved a loan of US$700 million for Nigeria to support its National Action Plan (NAP) for the Revitalization of the Water Supply, Sanitation, and Hygiene Sector.

Energy/Electricity access

Nigeria is endowed with large oil, gas, hydro, solar, geothermal and biomass resources. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), currently, Nigeria has, respectively, 15% and 16% of Africa’s oil and gas reserves. However, Nigeria has one of the highest rates of energy poverty in the world and is unable to meet the energy demand of the population. While Nigeria’s oil-refining capacity is estimated at 445 000 barrels per day (bpd), the actual output is only about 45 000 bpd, which is far below the domestic demand.

As of 2019, about 60% of Nigerians (roughly 120 million people) had access to electricity in Nigeria (Chart 17). In other words, nearly 80 million people were without electricity in the country. The current electricity access rate in Nigeria is more than 15 percentage points below the average for lower middle-income Africa (71.8%), and nearly 30 percentage points below the average for Nigeria’s global lower middle-income peers (86.1%).

After 2035, Nigeria will gradually narrow the electricity access gap with the average of its Africa income peers and show convergence beyond the 2050 time horizon. The electricity access rate in Nigeria is forecast to reach nearly 85% (or 384 million people) by 2050 compared to, respectively, 89% and 95.6% for the averages for Africa lower middle-income and global lower middle-income groups in the same time period. Over the next 30 years, an additional 274 million people will gain access to electricity in Nigeria.

Electricity provision is also skewed in favour of urban areas. According to IFs, in 2019, 86% of the urban population had access to electricity against only 34% in rural areas. In rural areas, many households rely on biomass (coal and firewood), which causes harmful indoor air pollution and deforestation. This causes respiratory-related illness and affects girls’ education outcomes as they are generally tasked with domestic chores like collecting firewood, which limits their study time. IFs estimates that about 69% of households use traditional cookstoves, and it is forecast to steadily decline to 18% by 2050.

Access to reliable electricity is critical to economic growth and improvements in livelihoods. However, in Nigeria, getting connected to the national grid does not necessarily mean access to reliable electricity supply. Power cuts are the key feature of electricity supply in Nigeria. Currently, Nigeria has about 16 384 MW of installed generation capacity which mostly depends on thermal and hydro (11 972 MW of gas; 2 062 MW of hydro; 10 MW of wind; 7 MW of solar, and 2.3 MW of other/diesel).

However, due to inefficiencies in the power sector, only 4 000 MW are eventually distributed to the end users, which is hugely insufficient for a country of over 200 million people. Poorly maintained or dysfunctional plants, deteriorating transmission lines, corruption and power theft are some of the key factors explaining this huge gap between installed capacity and capacity distributed. To remedy this situation, parts of the country’s power sector were privatised in 2013 but this has not led to significant improvements in electricity provision in the country.[30J Bello-Schunemann and A Porter, Building the future: Infrastructure in Nigeria until 2040, ISS West Africa Report 21, 2017.]

As a result, households and businesses continue to constantly experience power outages with a negative impact on productivity. Nigeria’s per capita annual consumption of electricity, estimated at 136 kWh, is one of the lowest in Africa.[31J Bello-Schunemann and A Porter, Building the future: Infrastructure in Nigeria until 2040, ISS West Africa Report 21, 2017.] In 2018, the typical Nigerian firm experienced more than 32 power cuts and these repeated power cuts have led to a heavy reliance on fossil fuel back-up generators across the country.

The result is that Nigeria is the largest importer of electric generators in Africa, and among the global top six countries (Nigeria, India, Iraq, Pakistan, Venezuela and Bangladesh) that generate electricity through back-up generators. According to a report by the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the amount spent every year in Nigeria on buying and operating small generators is about US$12 billion, and the collective installed capacity of generators is eight times more than the entire national grid.

The operations of back-up generators come with high financial costs, often double that of grid electricity, and this is a huge burden on the small and medium scale enterprises (SMEs), which account for about 90% of businesses and over 80% of employment in Nigeria. Also, these generators emit carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide that may pose serious risks to health and the environment.

In sum, Nigeria’s power sector situation requires significant investment and capability building for a reliable electricity supply. It is estimated that the country needs investment worth US$100 billion in the power sector over the next 20 years to provide electricity to its rapidly growing population.

With the support of international organisations, the government is trying to boost power generation in the country. For instance, the African Development Bank (AfDB), which is already working with the Nigerian government on a US$410 million transmission project, is pledging to invest an additional US$200 million through the Rural Electrification Agency (REA) to improve access to electricity in the country. Also, the World Bank has approved a US$750 million Power Sector Recovery Operation (PSRO) loan for Nigeria to ensure the supply of 4 500 MW/h of electricity to the grid by 2022.

The Nigerian National Integrated Infrastructure Master Plan (NIIMP) emphasises improving energy supply to meet the rapidly growing demand for energy in the country. In the plan, the government’s ambitious energy sector targets by 2043 are: 350 GW of electricity generation; increase oil production to four million bpd; gas production to 30 000 thousand cubic feet per day (mcfpd); and oil-refining capacity to four million bpd.

Roads and rail

Adequate transport infrastructure in good condition is an important requirement of economic growth and development as it cuts across all the sectors of a nation’s economy. With a total road network of about 195 000 km in 2017, Nigeria has the largest road network in West Africa.

According to the NIIMP, federal roads account for 18% of the total road network but carry about 70% of the national vehicular and freight traffic. State roads make up about 15% while local government roads represent 67% of the total road network. The road sector accounts for nearly 90% of all freight and passenger movement in the country, mainly due to the inadequacy of other forms of transportation, especially rail. For instance, in 2018, there were only six operational locomotives in Nigeria and most of the rail lines of 3 798 km are in a severe state of disrepair and need to be replaced.

Nigeria lags behind its global income peers in terms of percentage of roads paved and road density. In 2019, about 31% (60 000 km) of Nigeria’s road network was paved compared to the averages of 35.4% and 54.3% for Africa lower middle-income and global lower middle-income, respectively. As for road density, Nigeria has about 2.1 km of roads per 1 000 hectares of land area, ahead of Africa’s lower middle-income average, but behind the average for global lower middle-income countries, which is estimated at around 4.1 km per 1 000 hectares.

As shown in Chart 18, most of Nigeria’s roads are in poor condition and are often mentioned as a cause of the country’s high rate of road fatalities. In the rainy season, travelling becomes very difficult, and sometimes almost impossible on many secondary roads. According to the NIIMP, in 2012, around 40% of the federal road network was in poor condition, requiring rehabilitation; 30% was in fair condition, hence in need of periodic maintenance; and 27% was in good condition, requiring only routine maintenance. The rest (3%) is unpaved trunk roads. As for the state roads and local government roads network, 78% and 87%, respectively, are in poor condition.

There are, however, ongoing efforts to revamp and extend the road network to improve connectivity. For instance, in the 2018 federal government budget, 295 billion naira (nearly US$1 billion) were allocated for road capital works and maintenance. On the Current Path, IFs estimates that the share of paved roads as a per cent of the total road network will be around 80% in 2050, on a par with the projected average for global lower middle-income countries.

Information and communication technology

ICT connectivity has been growing in recent years with continued effort to promote competition in the sector. Thus, Nigeria has the largest mobile telecom market in Africa, although it is subject to erratic electricity supply and vandalism of infrastructure.

As of 2017, mobile phone subscriptions per 100 people were about 76 compared to 97 and 99.8 respectively for the averages for lower middle-income Africa and lower middle-income globally. Currently, there are four GSM (Global System for Mobile Communications) operators in the country: AIRTEL, a subsidiary of the Indian mobile group; MTN, a subsidiary of the South African MTN Group; 9mobile, a subsidiary of ETISALAT of the United Arab Emirates; and GLOBACOM, owned by a privately held Nigerian group. There are also two operators using Code Division Multiple Access (CDMA) technology, Visafone and Multilinks, but their market share is quite small.

In 2017, mobile broadband subscriptions per 100 people in Nigeria were at 19.9. IFs estimates it at 27 in 2019, against 43 for lower middle-income Africa. Fixed broadband penetration in the country is very low, with a penetration rate of 0.04%, below the African average of 0.6% and well below the world average of 13.6%.

Overall, about 42% of Nigerians use the Internet and the connections are mostly via mobile networks. In absolute terms, Nigeria has the largest number of Internet users in Africa due to its large population; the country accounts for more than 30% of Internet users on the continent, with most of them in the urban areas. The Current Path forecast is that mobile broadband will continue to be the most common and popular way through which people in Nigeria access the Internet (Chart 19). By 2050, mobile broadband subscriptions per 100 people are projected to reach 152, on a par with the average for global lower middle-income countries.

Nigeria scores better on ICT skills than the sub-Saharan African average but falls well below the global average. The country is home to several high-growth digital companies. Lagos is a thriving digital hub in Africa and the centre of digital developments in Nigeria. It was the only city in Africa that featured in the 2019 Global Startup Ecosystem Report as a start-up ecosystem that could challenge the 30 leading global ecosystems led by Silicon Valley. Digital entrepreneurship ecosystems are also growing in the cities of Abuja and Port Harcourt.

Also, Nigeria has the largest e-commerce market in Africa. In 2018, the e-commerce spending in the country was estimated at US$12 billion and was projected to increase to US$75 billion in revenues by 2025, with big homegrown players like Jumia and Kong. According to the World Bank, there are 87 digital platforms operating in Nigeria and 66 of them are homegrown (76%); the remaining are from the US, Europe and the rest of Africa.

However, Nigeria still has a long way to go to achieve widespread use of the Internet (broadband) due to infrastructural bottlenecks, particularly in rural areas. In 2017, Nigeria ranked 143rd out of 176 countries on the International Telecommunication Union’s (ITU) ICT Development Index (IDI). It is a composite index that is used to monitor and compare ICT development in countries. Nigeria’s poor ranking reflects its low broadband subscriptions (fixed and mobile).

Widespread access to high-speed Internet has the potential to improve the country’s socio-economic outcomes. Broadband can increase productivity, reduce transaction costs and optimise supply chains, with a positive effect on economic growth. A study by the World Bank revealed that a 10% increase in broadband penetration in developing countries leads to a 1.4% increase in GDP.[32CZ Qiang and CM Rossotto, Economic Impacts of Broadband, in Information and Communications for Development 2009: Extending Reach and Increasing Impact, 35–50, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2009.] Cognisant of this economic growth opportunity offered by broadband technologies, the Nigerian government has designed a National Broadband Plan 2020–2025 to deliver data download speeds of about 25 Mbps (megabytes per second) in urban areas and 10 Mbps in rural areas; the target by 2025 is a penetration rate of at least 70%.

Nigeria’s economy at independence showed great promise, with agriculture as its backbone. The country adopted import substitution as an industrialisation policy to produce most imported goods locally. The discovery of crude oil in commercial quantities changed the course of Nigeria’s economy, however. With rising oil prices and increasing demand, extracting and exporting crude oil became the dominant economic activity. The abundance of petrodollars made it easier to import various goods and services. As a result, advances made in agriculture and manufacturing were neglected and these sectors have become less competitive over time. Today, Nigerian exports remain undiversified; it is highly dependent on crude oil, which accounts for more than 80% of total exports, half of government revenues and the bulk of hard currency earnings.

Economic growth and sectoral contribution to GDP