Malawi

Malawi

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our About page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

Summary

- Current Path

- Malawi’s population has grown significantly from 3.6 million people in 1960 to an estimated 19.1 million in 2021. On the Current Path, Malawi’s population is expected to reach 24.2 million people by 2030, and by 2063 the country is likely to have a population of 38.8 million. Jump to Demographics

- Malawi’s score on the HDI increased from 0.34 in 1990 to 0.48 in 2019, ranking the country in 174th out of 189 countries globally. On the Current Path, Malawi's HDI score is forecast to improve and remains on par with the targets set out in MW2063 until 2050. Jump to Human Development

- The poverty rate at the national poverty line was estimated to be 51.5% in 2017, compared to 50.7% in 2011. The ambitious target of the government is to halve it by 2030. On the Current Path, the poverty rate is forecast to decline gradually to reach 52.6% by 2030, about 18 percentage points above the projected average of 34.5% for low-income Africa in the same year. Jump to Poverty and income inequality

- In 2020, only 18% of the country's total population had access to electricity, compared to 34% for the average for low-income Africa. On the Current Path, the national electricity access rate in Malawi does show improvements, reaching 26.5% of Malawi's population by 2030, but will remain far below the government's target of 50% by 2030. Jump to Infrastructure

- Across the forecast horizon, the maximum economic growth rate in Malawi is 8.3%. As a result, Malawi's GDP will substantially increase by about 62.8%, from US$12.01 billion in 2020 to US$19.56 billion in 2030. The size of the economy is forecast to be US$235.3 billion by 2063. Jump to Economy

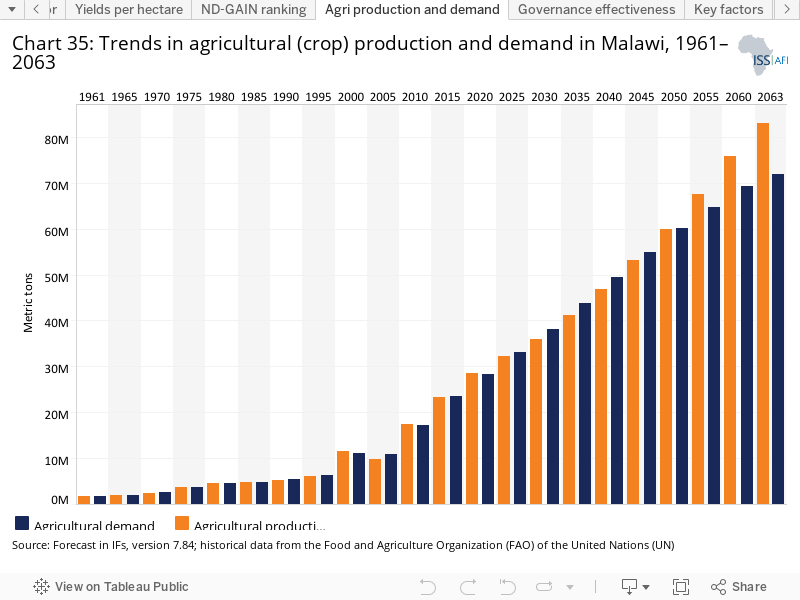

- In 2020, 27.7 million metric tons of crops were produced, a significant increase from the 5 million metric tons produced in 1990. In the Current Path forecast, crop production is forecast to increase to 34.4 million metric tons by 2030 and to an estimated 78 million metric tons by 2063. In the Current Path forecast, agricultural crop demand is set to increase from 27.4 million metric tons in 2020 to about 36.6 million metric tons by 2030 and to 67.2 million metric tons by 2063. Jump to Agriculture and climate change

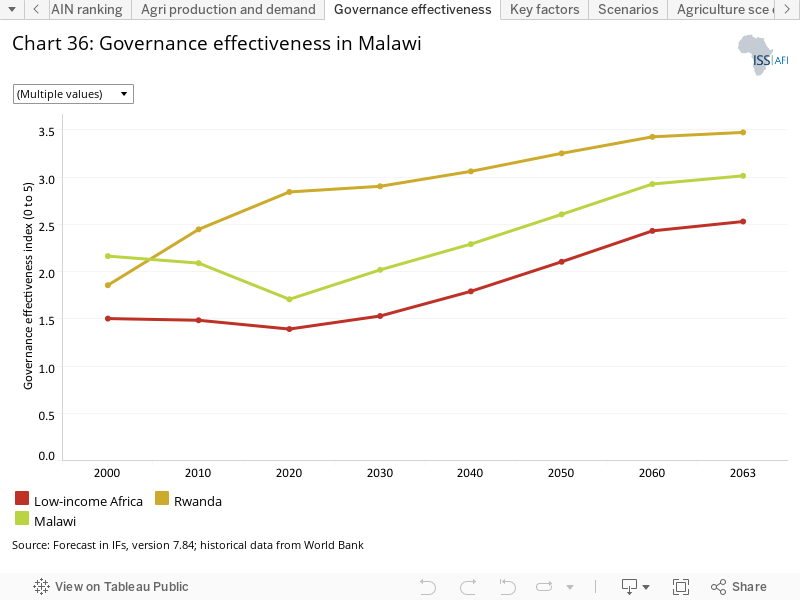

- Governance effectiveness in Malawi steadily declined over the last decade but remained above the average for its peers. In 2020, the governance effectiveness score for Malawi was 1.7 out of 5. On the Current Path, it is forecast to stay above the average for its peer income group in Africa. Jump to Governance development

- Scenarios

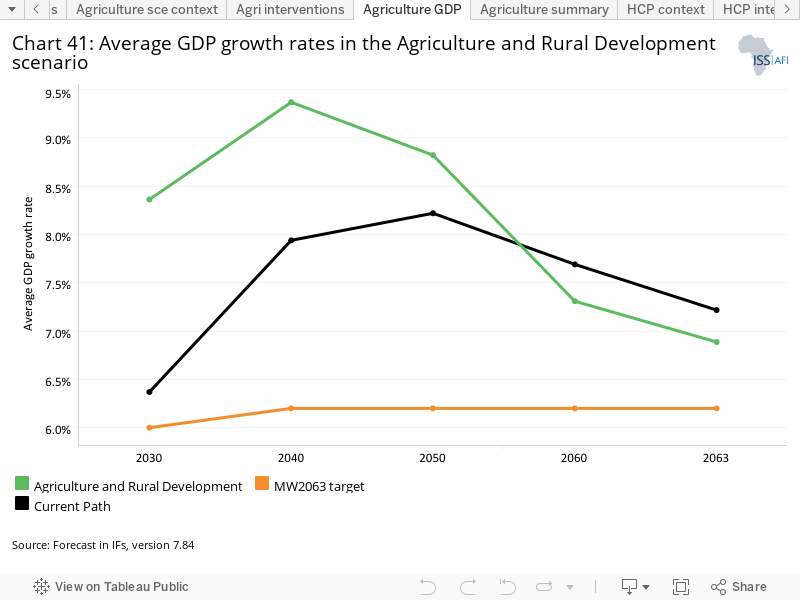

- The implementation of the Agriculture and Rural Development scenario is forecast to increase agricultural export to be 5.7 million metric tons by 2030 and 52.7 million metric tons by 2063, then about 41.5 million metric tons larger than the Current Path forecast. Malnourishment in the population is also halved by 2030 compared to the Current Path and the country becomes a net exporter of agricultural produce. Jump to Agriculture and Rural Development scenario

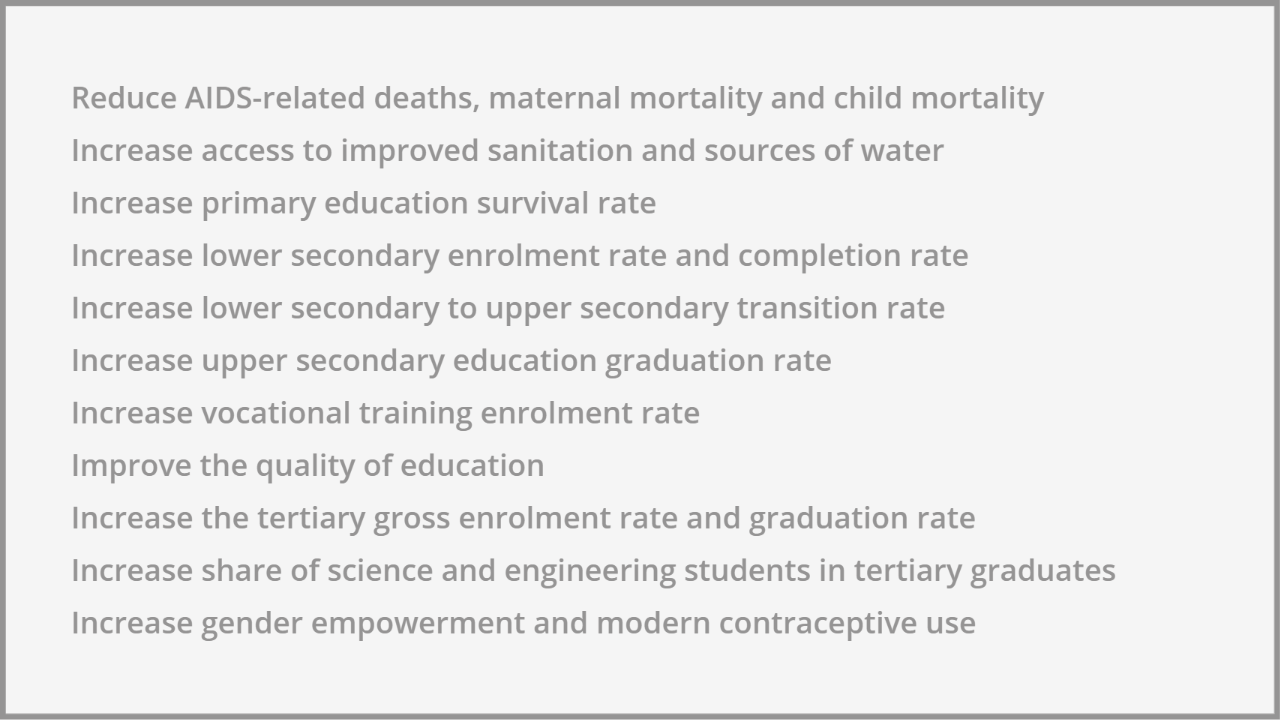

- In the Human Capital Push scenario, fertility rates are brought down to 2.3 births per woman by 2030, compared to 3.4 on the Current Path, reducing the population in 2030 to 23.5 million people instead of 24.2 million on the Current Path. This decline in the fertility rate could help Malawi start reaping its demographic dividend in 2033, eight years earlier than in the Current Path forecast. Jump to Human Capital Push scenario

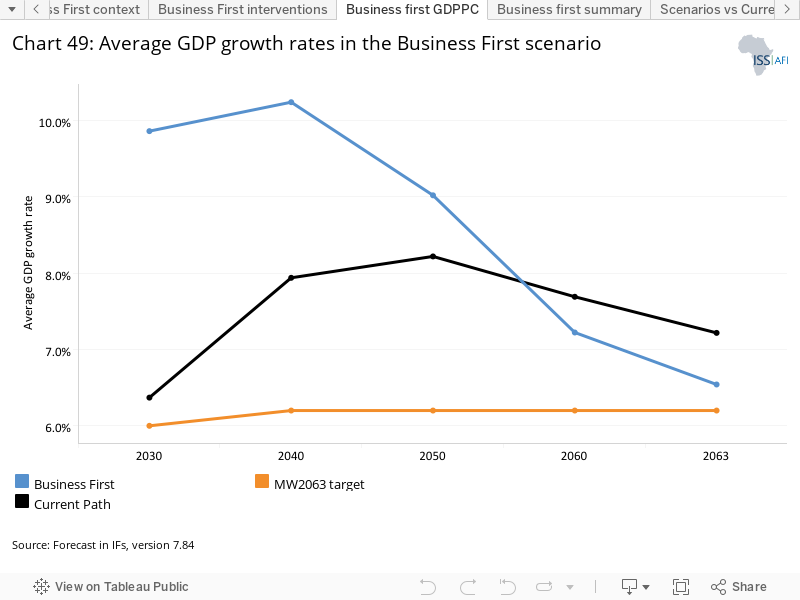

- As encapsulated in the Business First scenario, investment aimed at developing non-resources sectors such as manufacturing take time to yield expected results. This is typically associated with short- to medium-term costs relating to poverty or consumption and as such, household consumption will represent 66.7% of GDP by 2030 compared to 78.7% on the Current Path. However, in the long term, the Business First scenario generates inclusive wealth creation. The average growth rate between 2030 and 2040 is 10.2% compared with 7.3% on the Current Path. Jump to Business First scenario

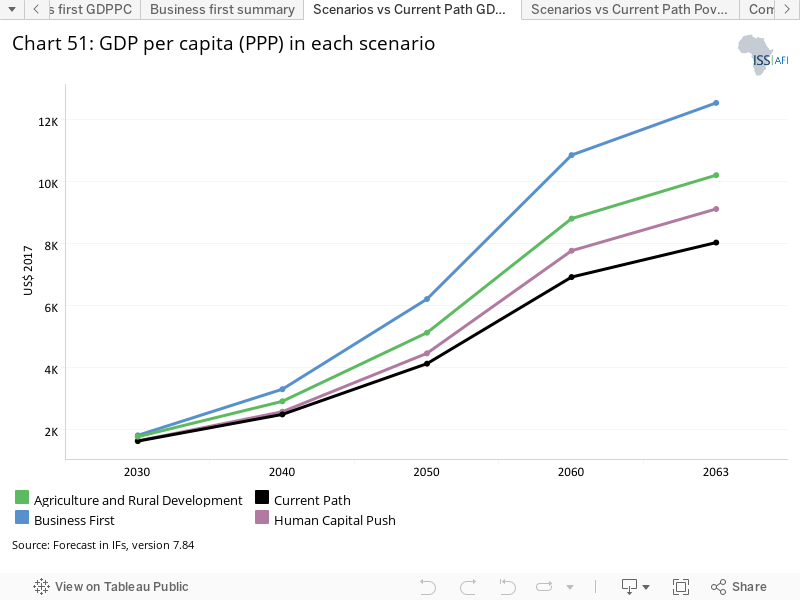

- Between the three scenarios, the Business First scenario has the biggest impact on GDP per capita by 2030 and by 2063 with GDP per capita equalling US$1 827 in 2030, and US$12 524 in 2063. Jump to Comparing scenario impact

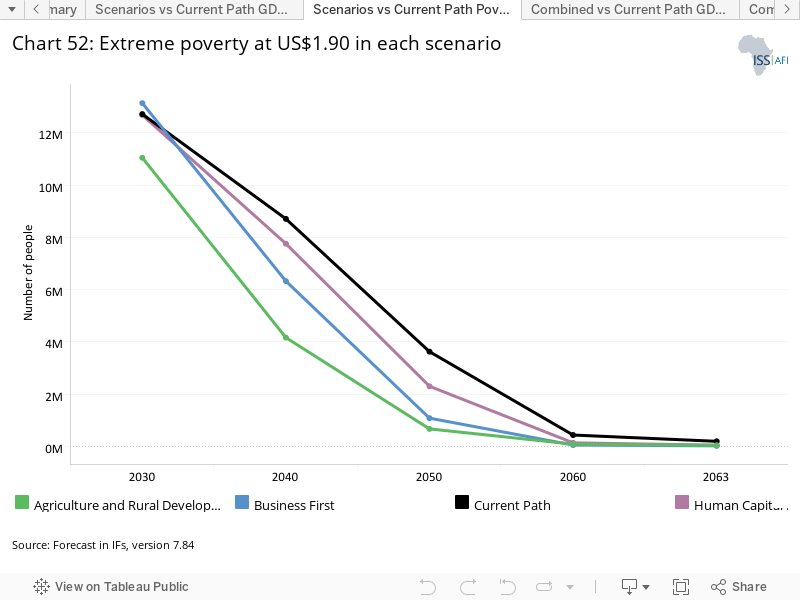

- All three scenarios lead to inclusive wealth creation as the poverty rate in each scenario is lower than the Current Path forecast, but, between 2023 and 2050, the Agriculture and Rural Development scenario leads to more inclusive wealth creation as it has the lowest number of people living in poverty. Jump to Comparing scenario impact

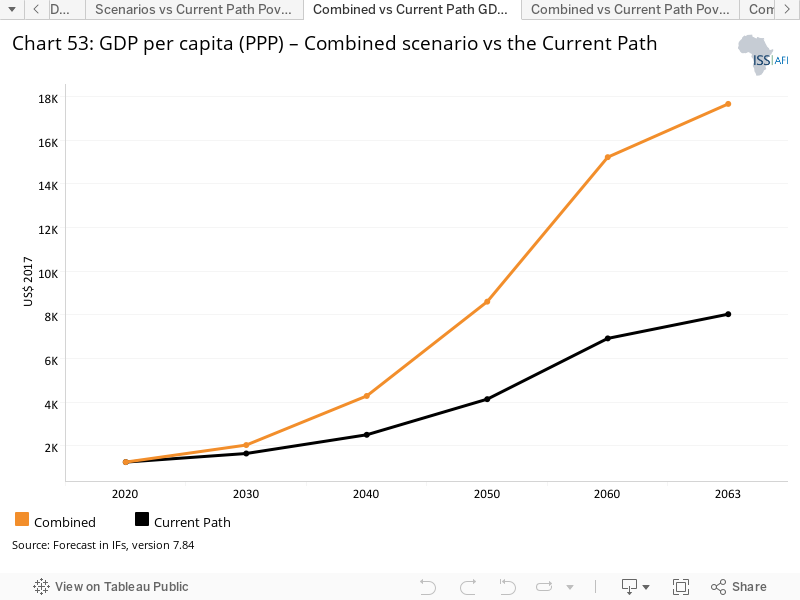

- The implementation of Combined scenario leads to an average growth rate of 8.5% between 2022 and 2030, 3.5 percentage points above the Current Path over the same period. Jump to The Combined scenario/MW2063 scenario

- In the Combined scenario, GDP per capita (PPP) is US$2 029 by 2030 (US$387 higher than the Current Path forecast) and US$17 669 by 2063 (US$9 639 more than the Current Path forecast). In the scenario, Malawi could graduate to lower middle-income status by 2032 and achieve upper middle-income status in 2058. Jump to The Combined scenario/MW2063 scenario

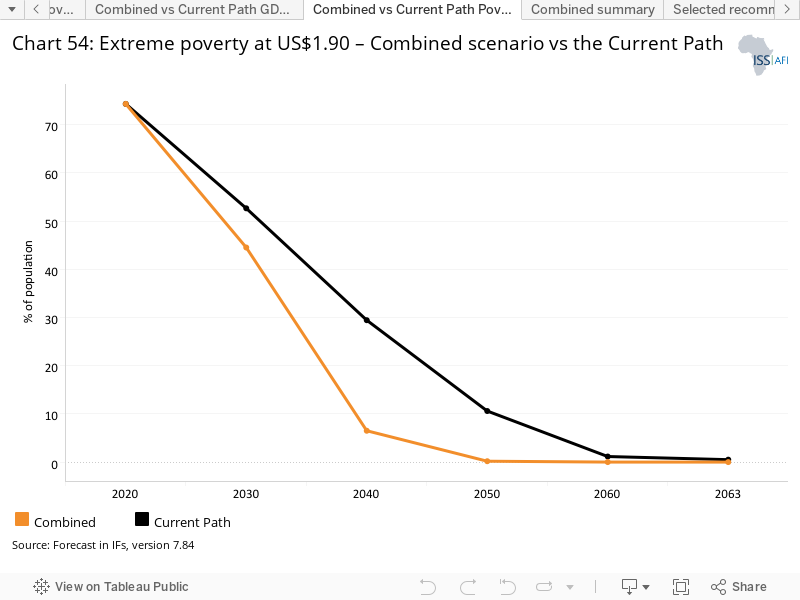

- The Combined scenario leads to more inclusive wealth creation, especially in the long term. Malawi achieves the elimination of extreme poverty (defined as the rate below 3% of the population) in 2043, 14 years earlier than the Current Path forecast. Jump to The Combined scenario/MW2063 scenario

- Conclusion and recommendations Jump to Conclusion and policy recommendations

- The starting point is to improve governance transparency and effectiveness, by improving the public financial management system, domestic revenue mobilisation and increase investigative journalism.

- Malawi has made progress in improving agriculture productivity but much more needs to be done through investments in productivity enhancing technologies, improvements in agricultural subsidy programme and by improving the rural transport network.

- Malawi needs to expand economic diversification and industrialisation for inclusive wealth creation and should do so by improving the quality of business regulation, encouraging a entrepreneurial mindset and investing in human capital and skills development.

- In sum, a dedicated implementation of these policies centred around the three pillars of MW2063 could help Malawi achieve its development objectives

All charts for Malawi

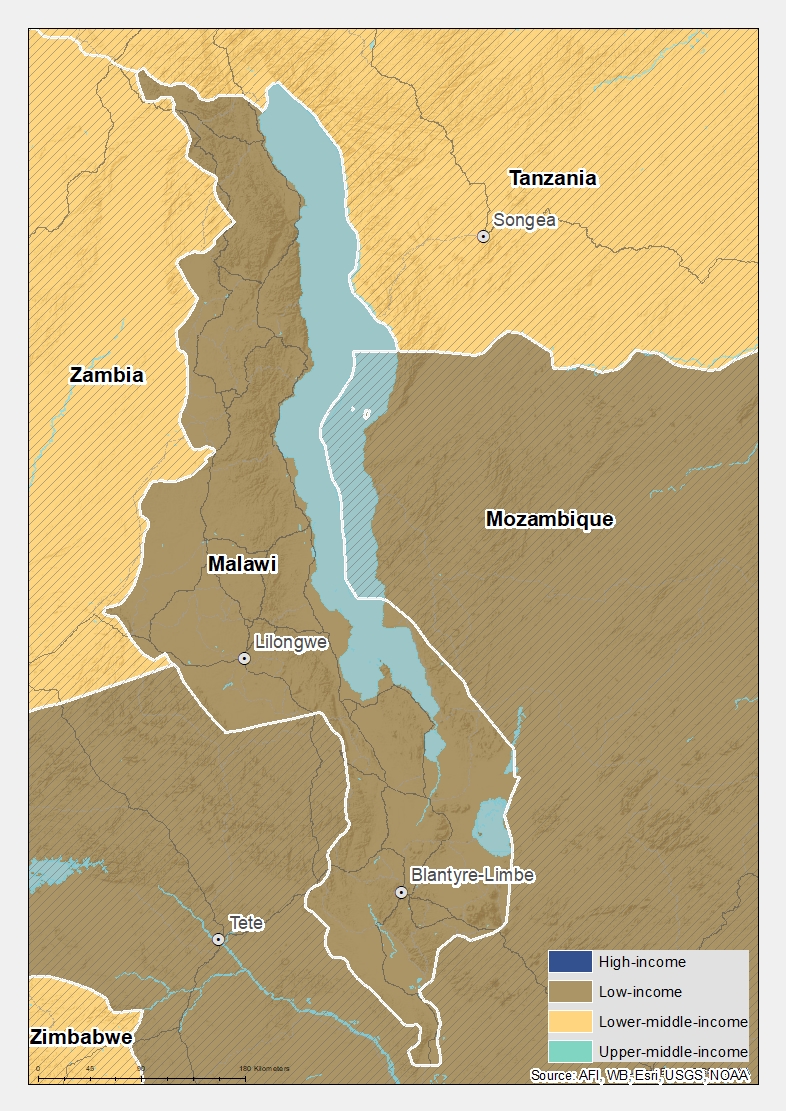

- Chart 1: Political map of Malawi

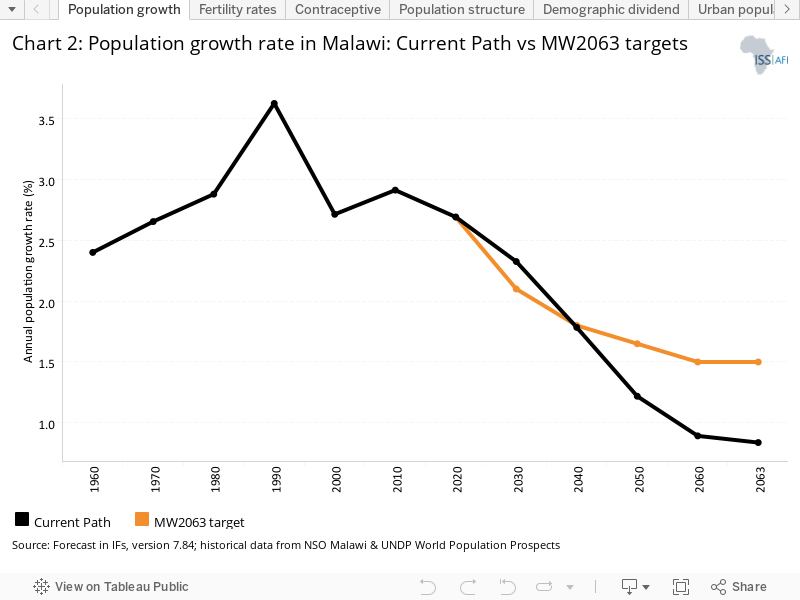

- Chart 2: Population growth rate in Malawi: Current Path vs MW2063 targets

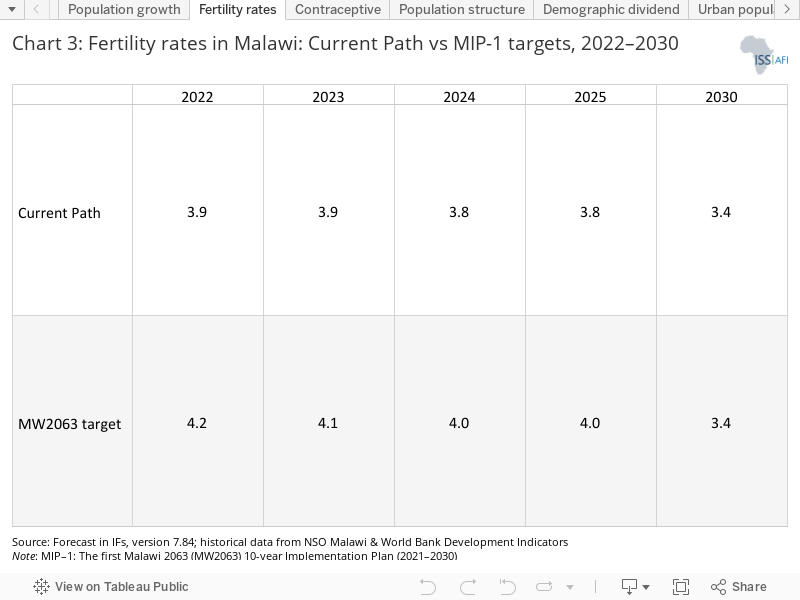

- Chart 3: Fertility rates in Malawi: Current Path vs MIP-1 targets, 2022–2030

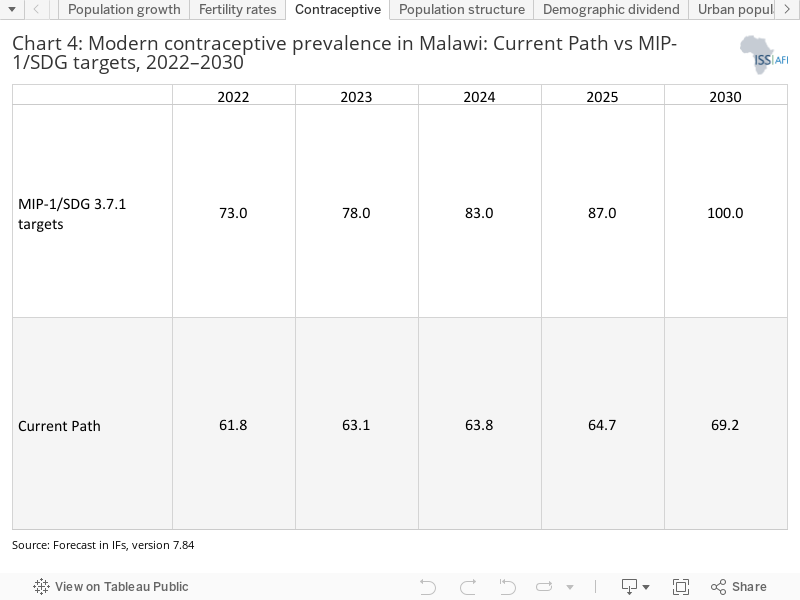

- Chart 4: Modern contraceptive prevalence in Malawi: Current Path vs MIP-1/SDG targets, 2022–2030

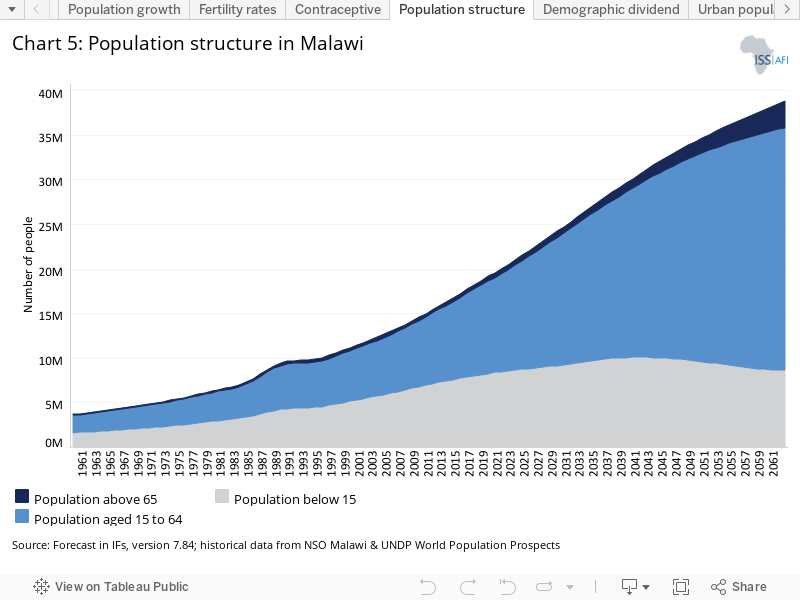

- Chart 5: Population structure in Malawi

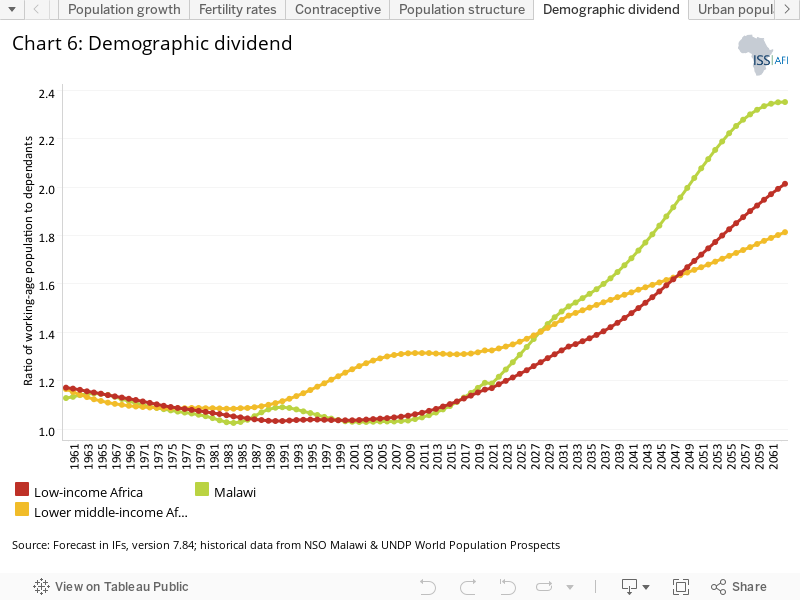

- Chart 6: Demographic dividend

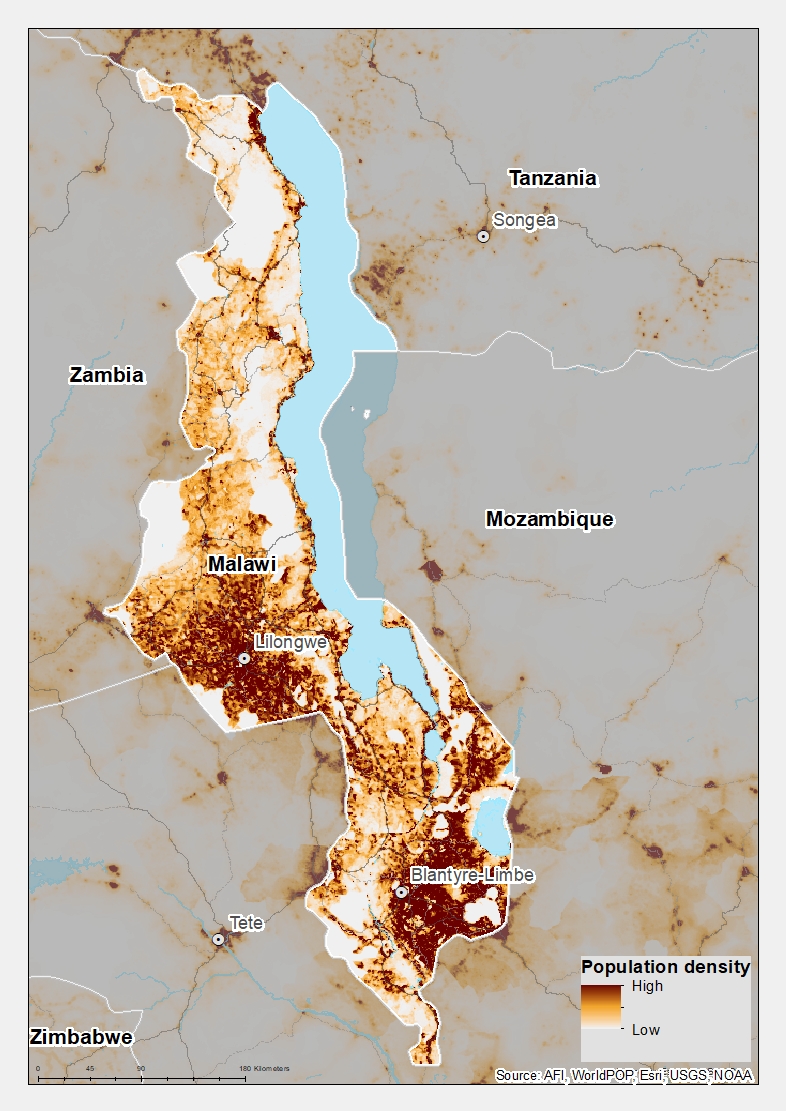

- Chart 7: Geographic distribution of Malawian population, 2020

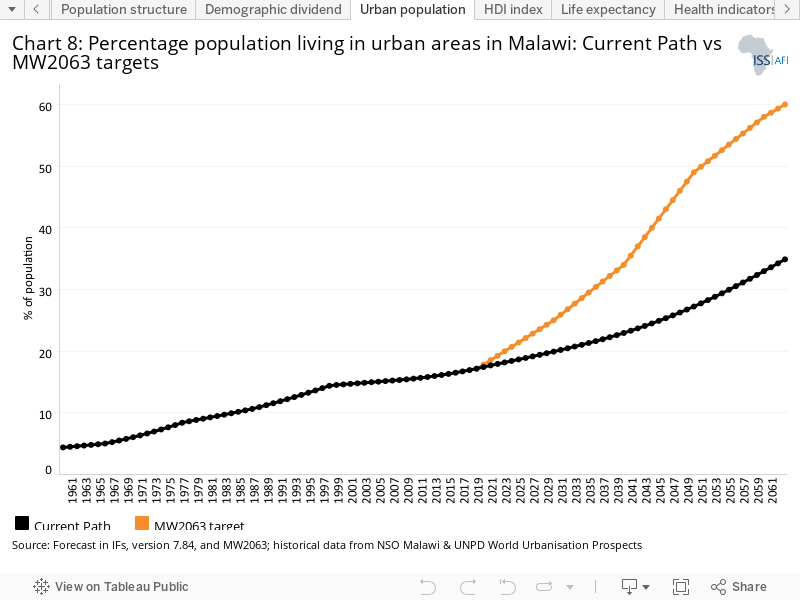

- Chart 8: Percentage population living in urban areas in Malawi: Current Path vs MW2063 targets

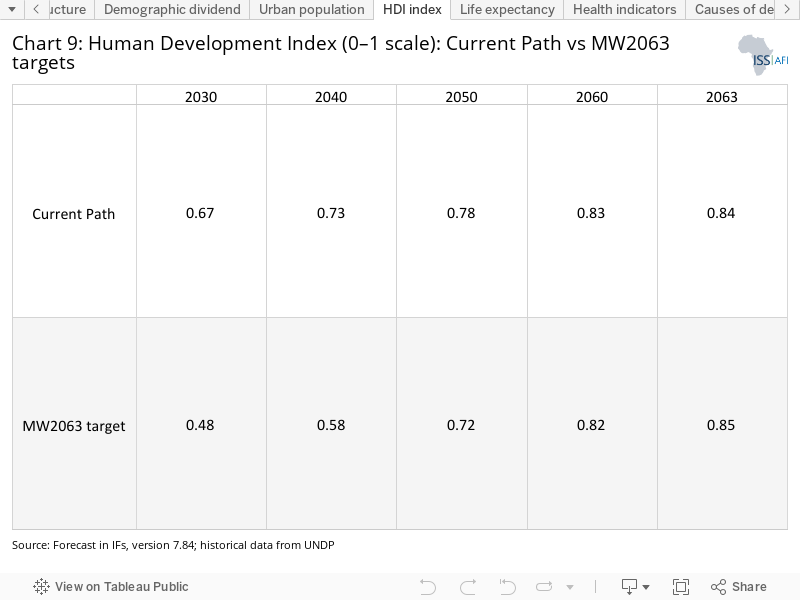

- Chart 9: Human Development Index (0–1 scale): Current Path vs MW2063 targets

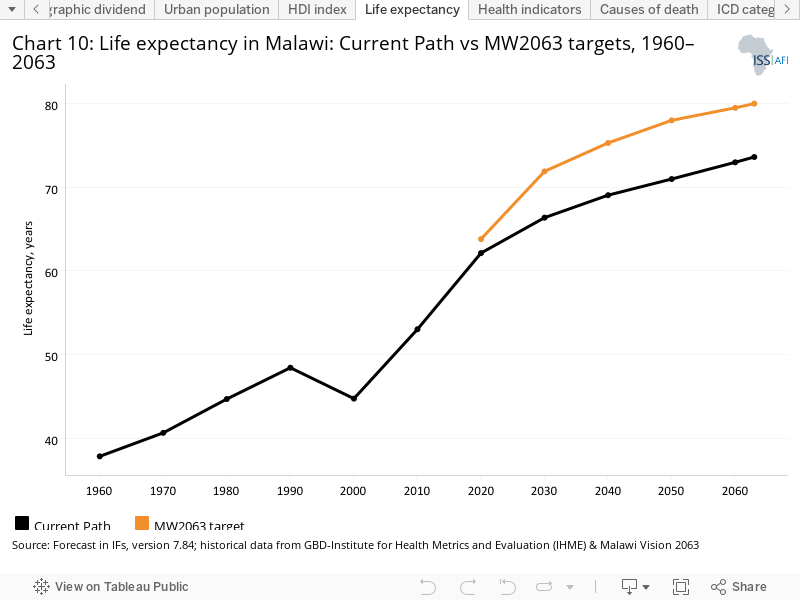

- Chart 10: Life expectancy in Malawi: Current Path vs MW2063 targets, 1960–2063

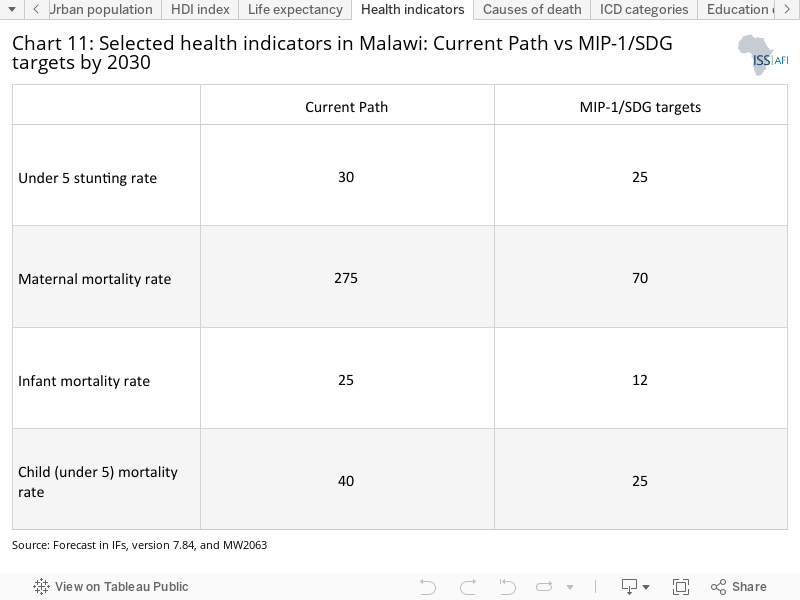

- Chart 11: Selected health indicators in Malawi: Current Path vs MIP-1/SDG targets by 2030

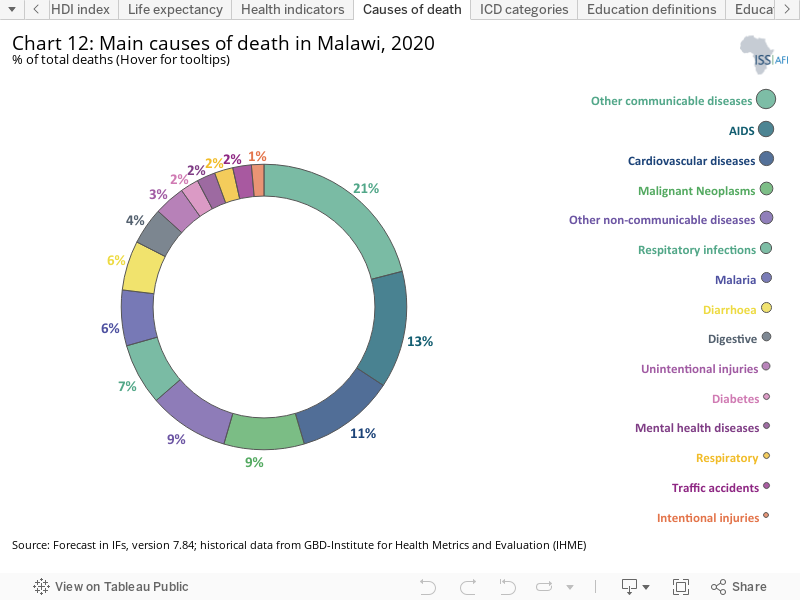

- Chart 12: Main causes of death in Malawi, 2020

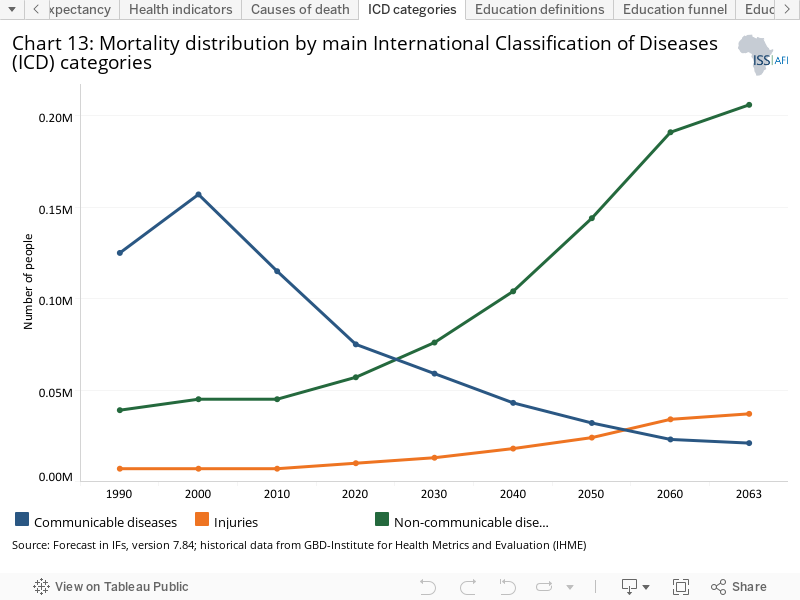

- Chart 13: Mortality distribution by main International Classification of Diseases (ICD) categories

- Chart 14: Definitions in education

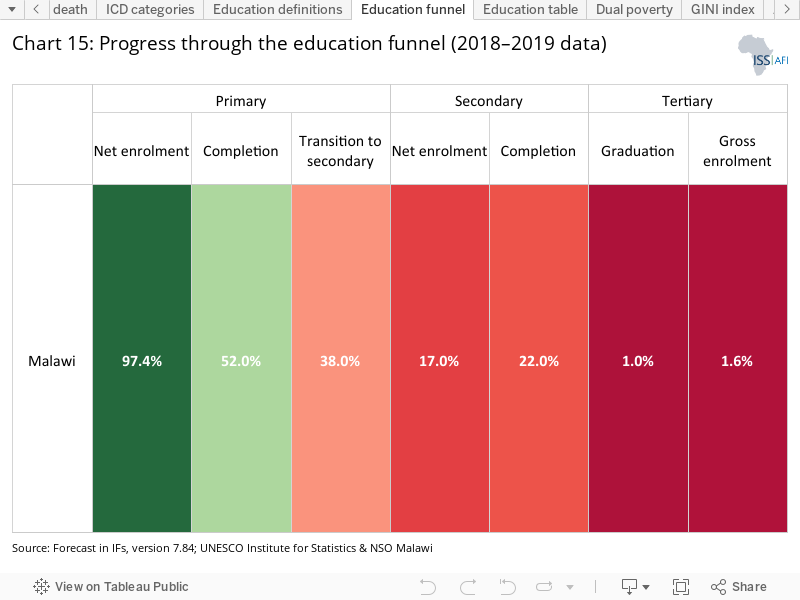

- Chart 15: Progress through the education funnel (2018–2019 data)

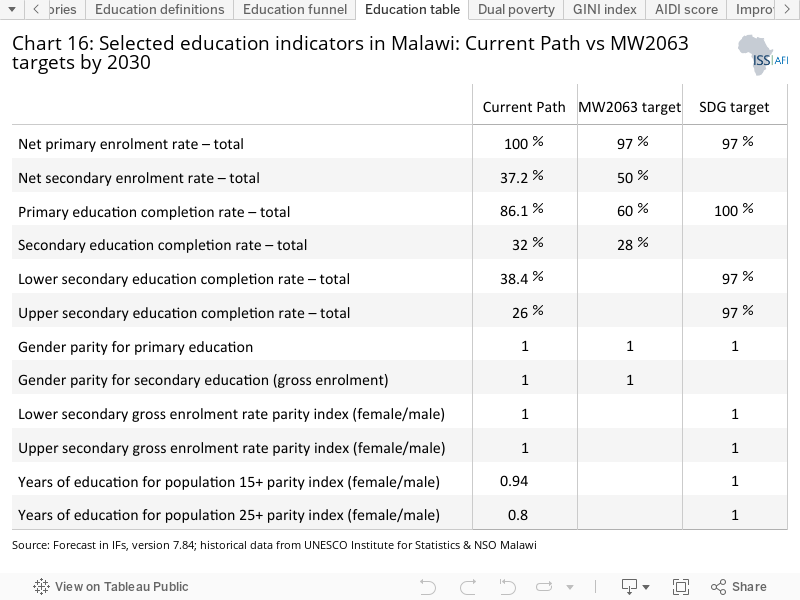

- Chart 16: Selected education indicators in Malawi: Current Path vs MW2063 targets by 2030

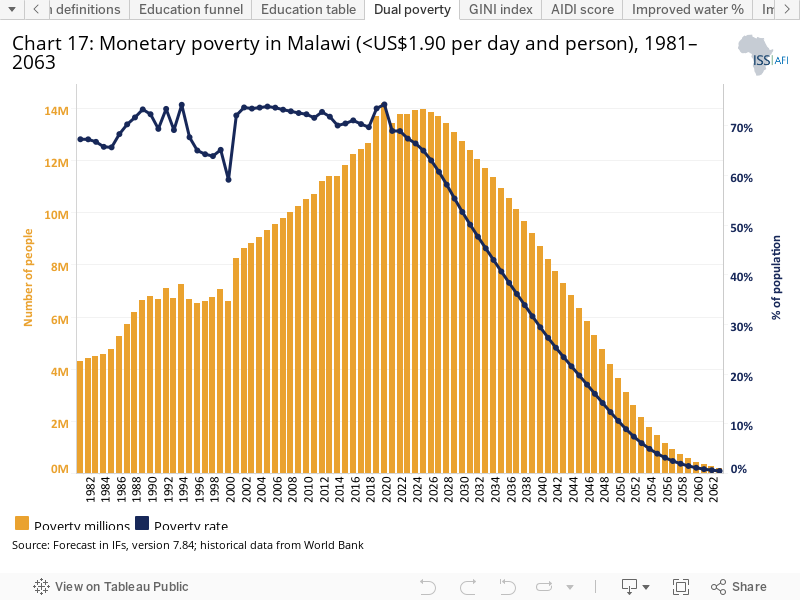

- Chart 17: Monetary poverty in Malawi (<US$1.90 per day and person), 1981–2063

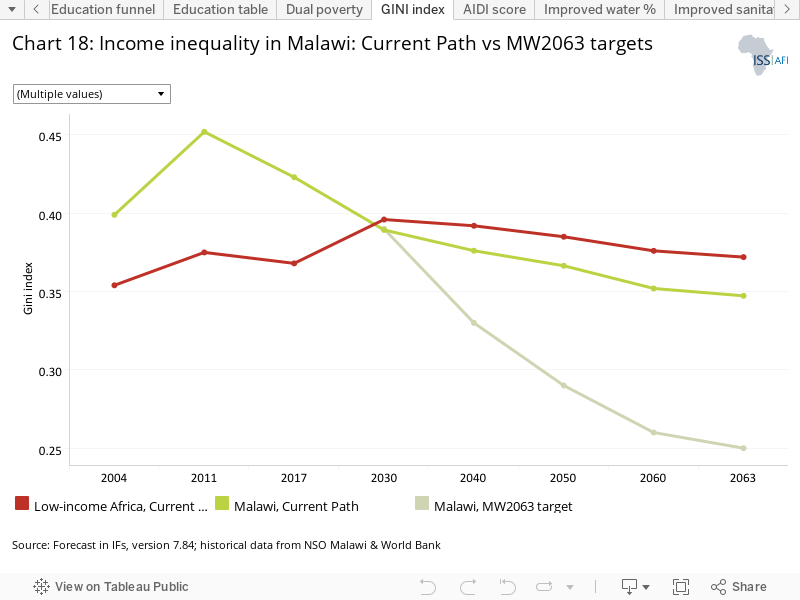

- Chart 18: Income inequality in Malawi: Current Path vs MW2063 targets

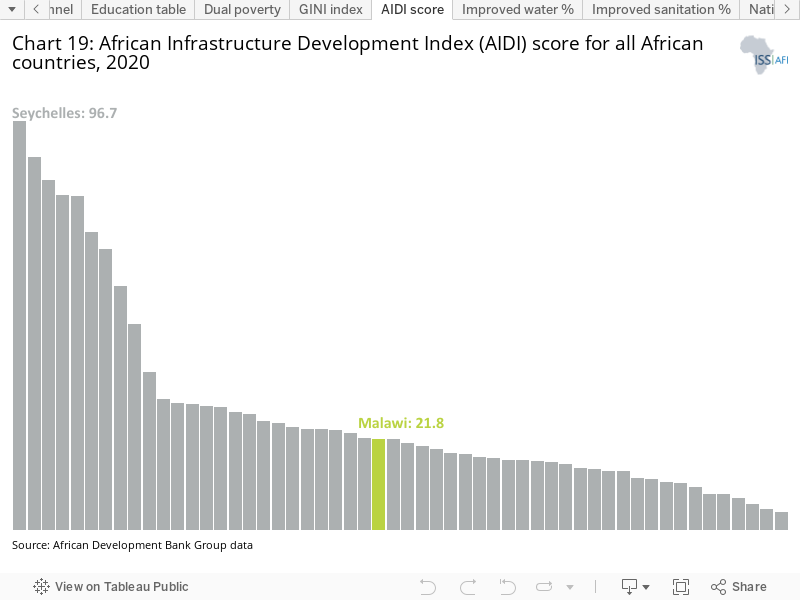

- Chart 19: African Infrastructure Development Index (AIDI) score for all African countries

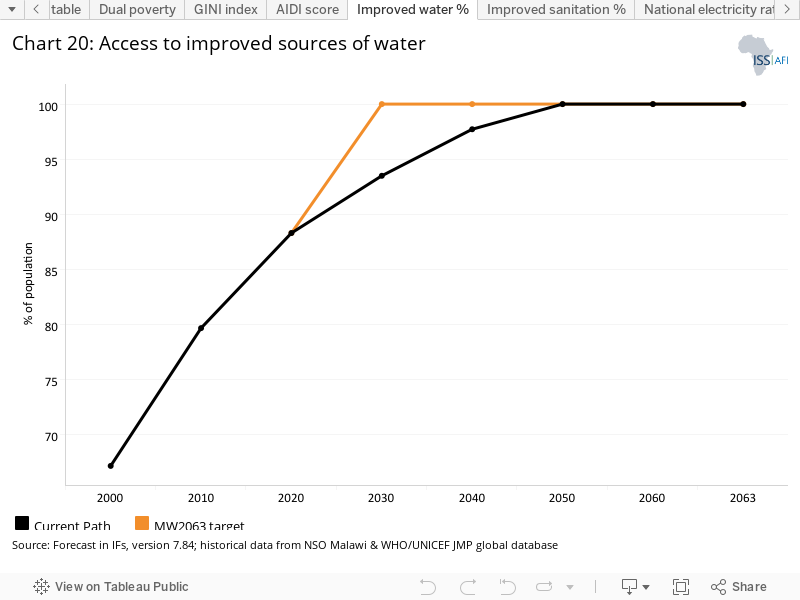

- Chart 20: Access to improved sources of water

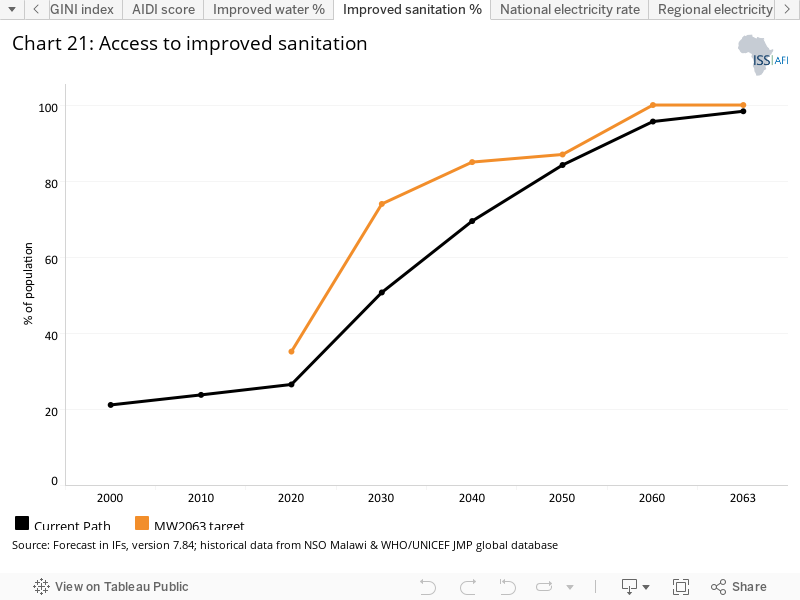

- Chart 21: Access to improved sanitation

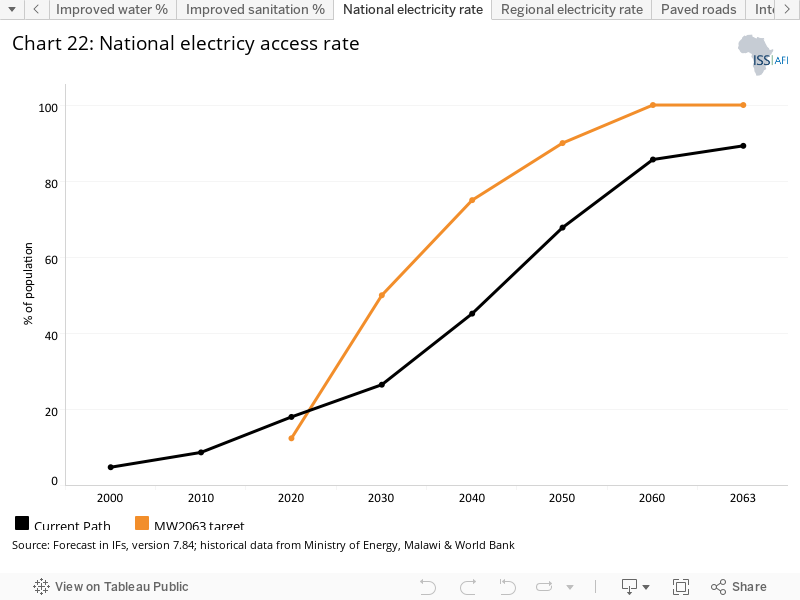

- Chart 22: National electricity access rate

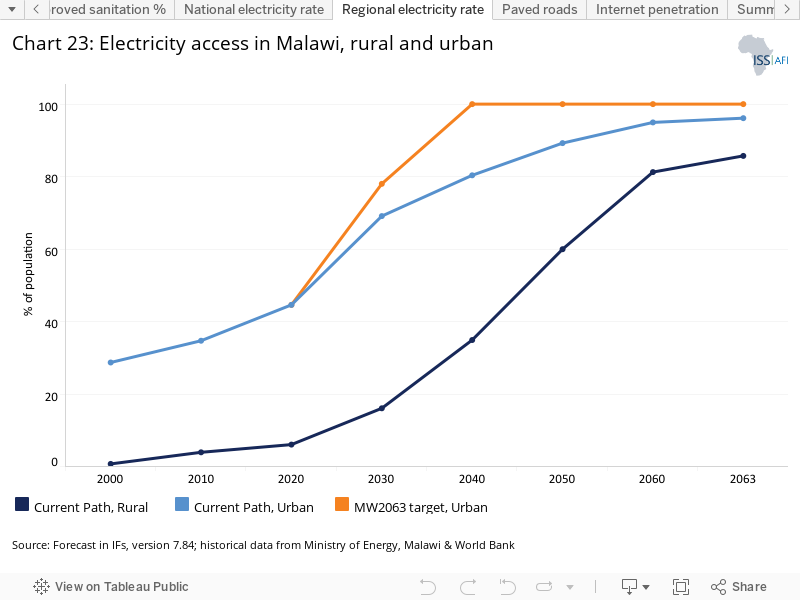

- Chart 23: Electricity access in Malawi, rural and urban

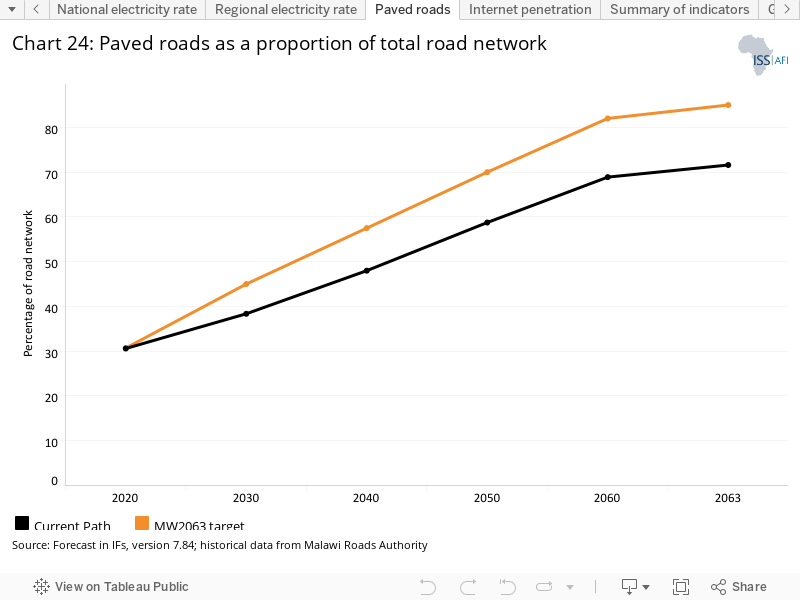

- Chart 24: Paved roads as a proportion of total road network

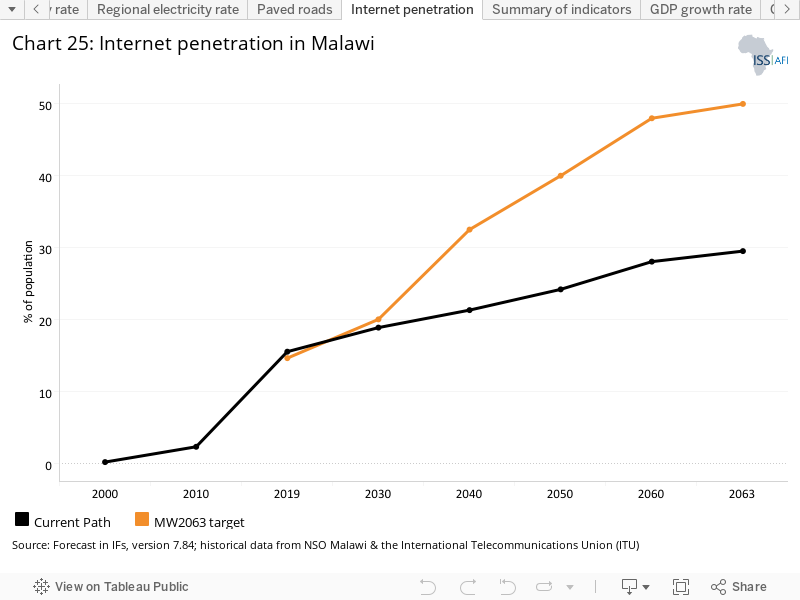

- Chart 25: Internet penetration in Malawi

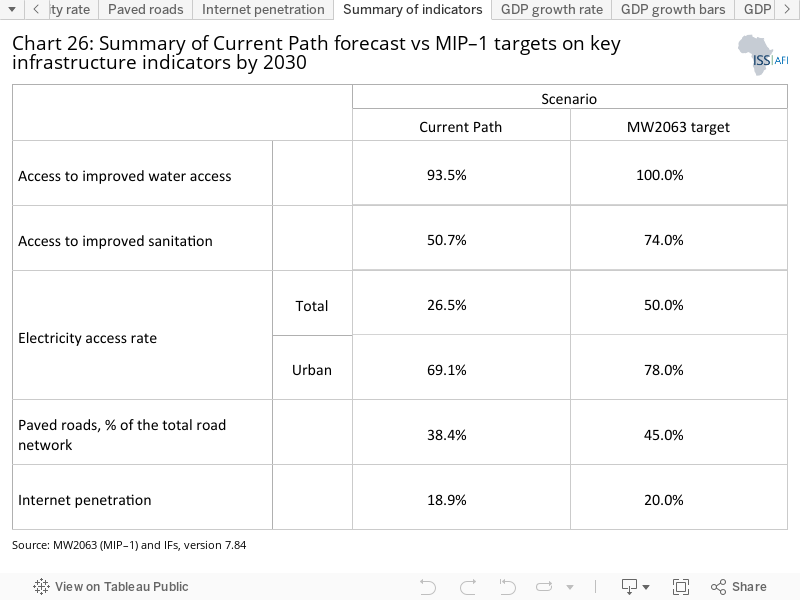

- Chart 26: Summary of Current Path forecast vs MIP-1 targets on key infrastructure indicators by 2030

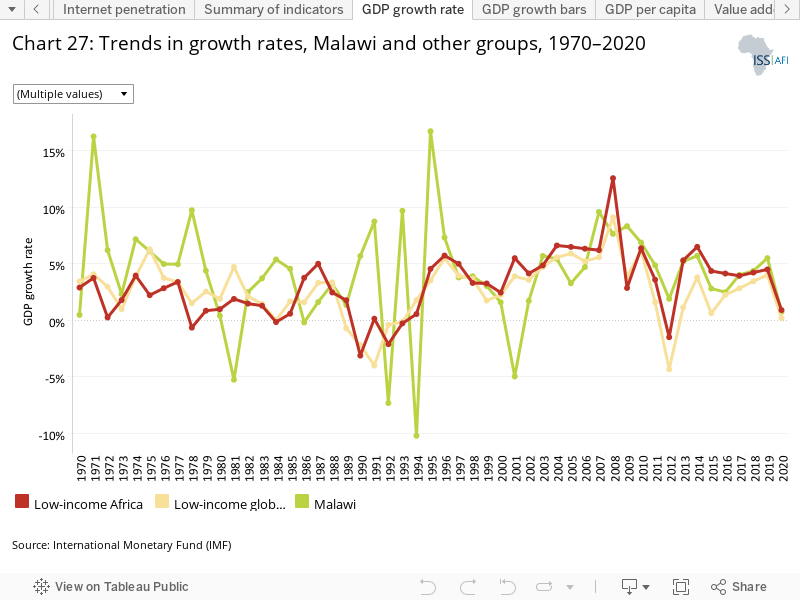

- Chart 27: Trends in growth rates, Malawi and other groups, 1970–2020

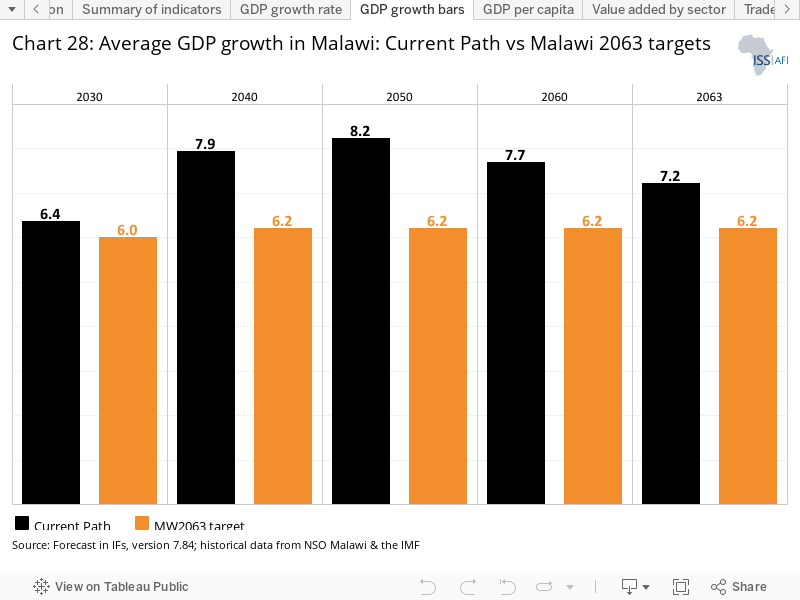

- Chart 28: Average GDP growth in Malawi: Current Path vs Malawi 2063 targets

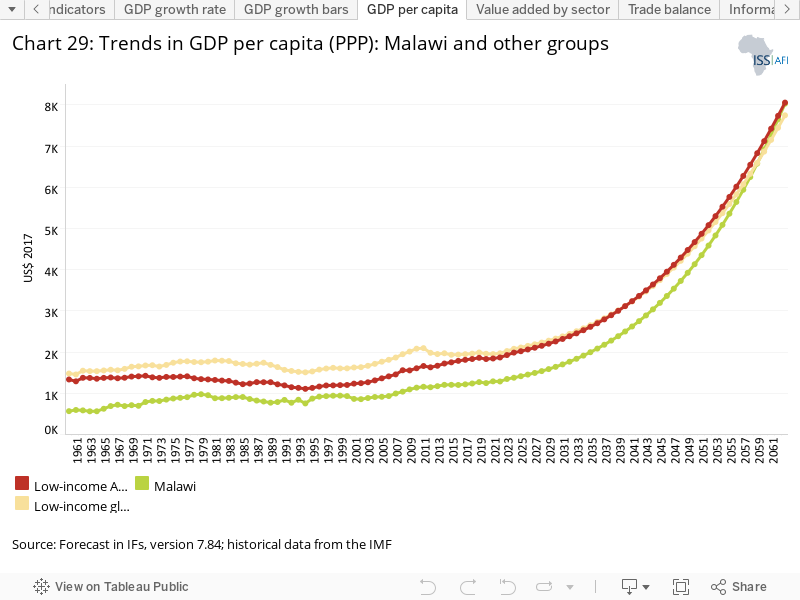

- Chart 29: Trends in GDP per capita (PPP): Malawi and other groups

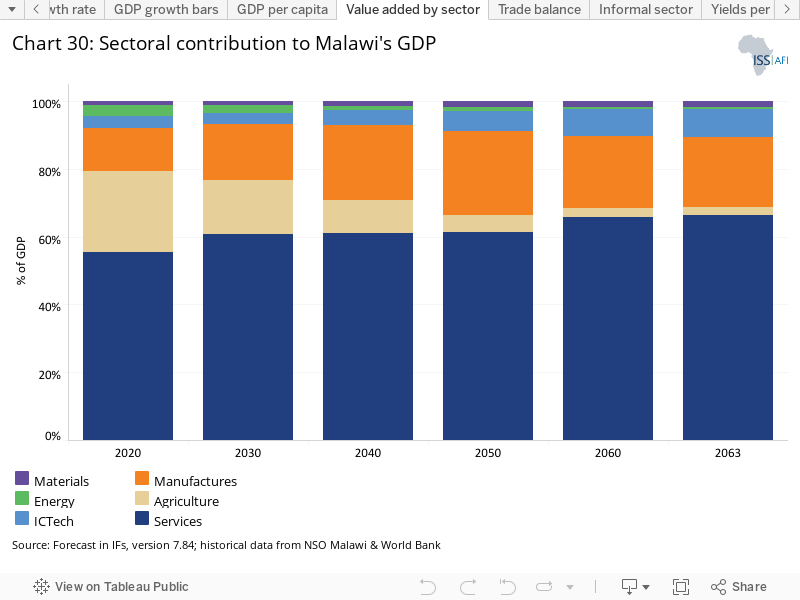

- Chart 30: Sectoral contribution to Malawi's GDP

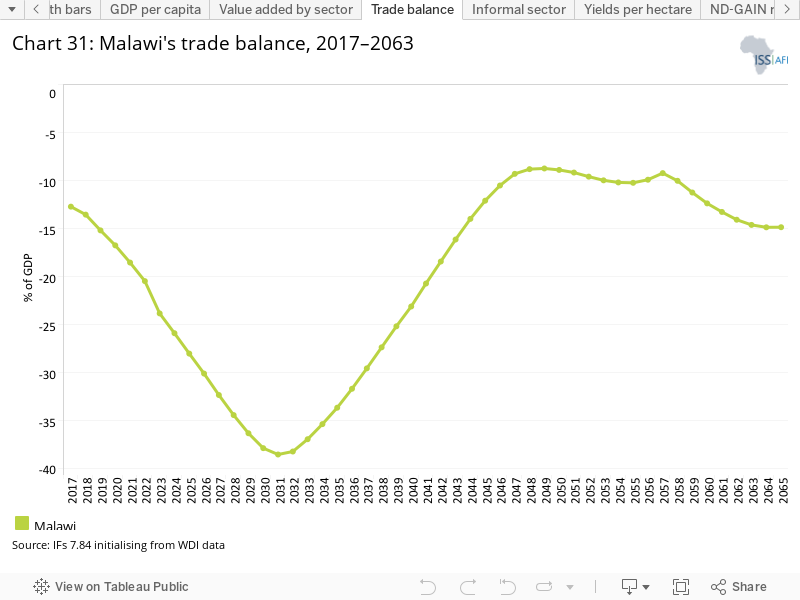

- Chart 31: Malawi's trade balance, 2017–2063

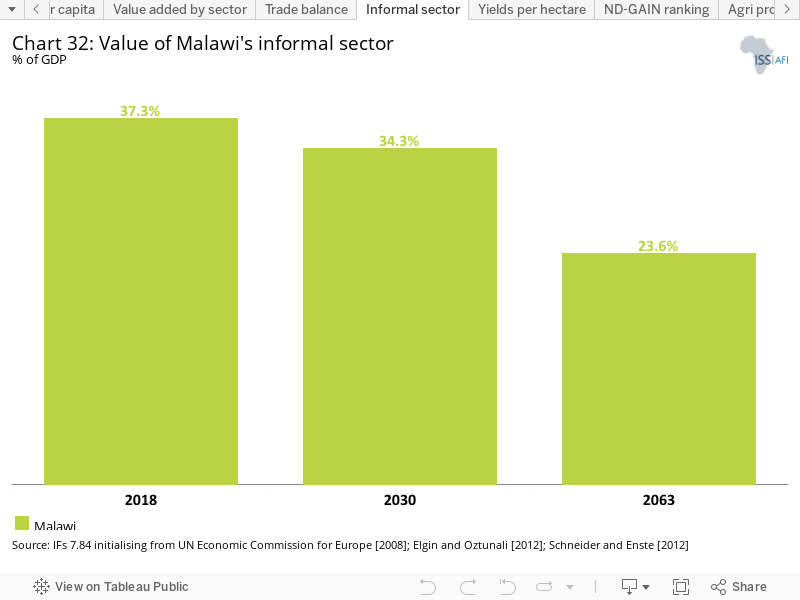

- Chart 32: Value of Malawi's informal sector

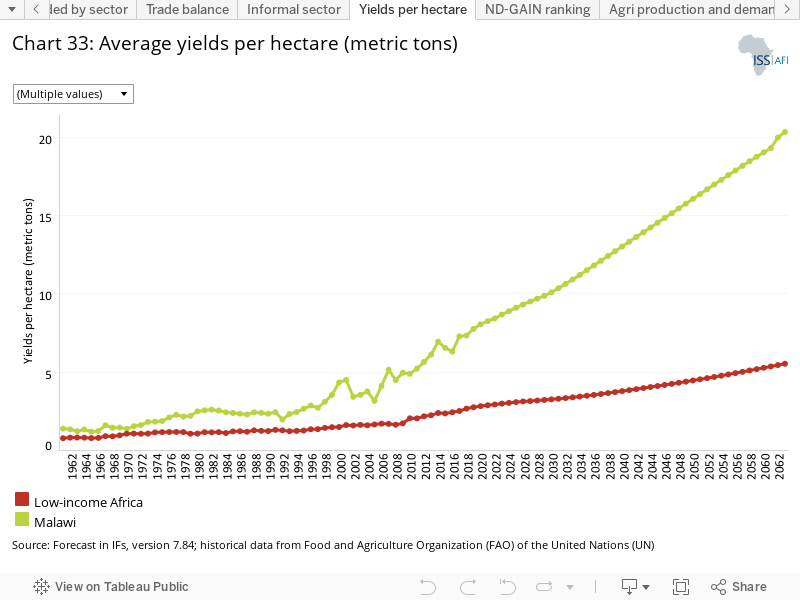

- Chart 33: Average yields per hectare (metric tons)

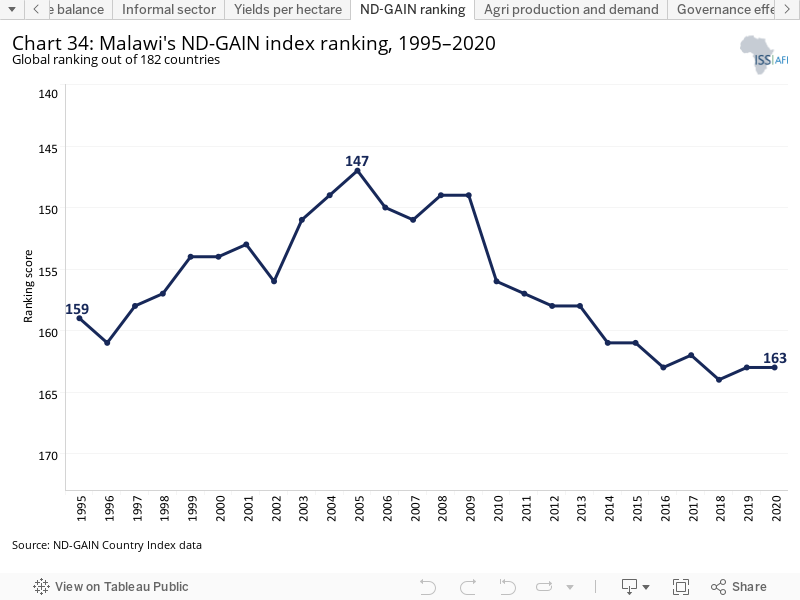

- Chart 34: Malawi's ND-GAIN index score, 1995–2020

- Chart 35: Trends in agricultural (crop) production and demand in Malawi, 1961–2063

- Chart 36: Governance effectiveness in Malawi

- Chart 37: Key factors impeding development progress

- Chart 38: Scenarios

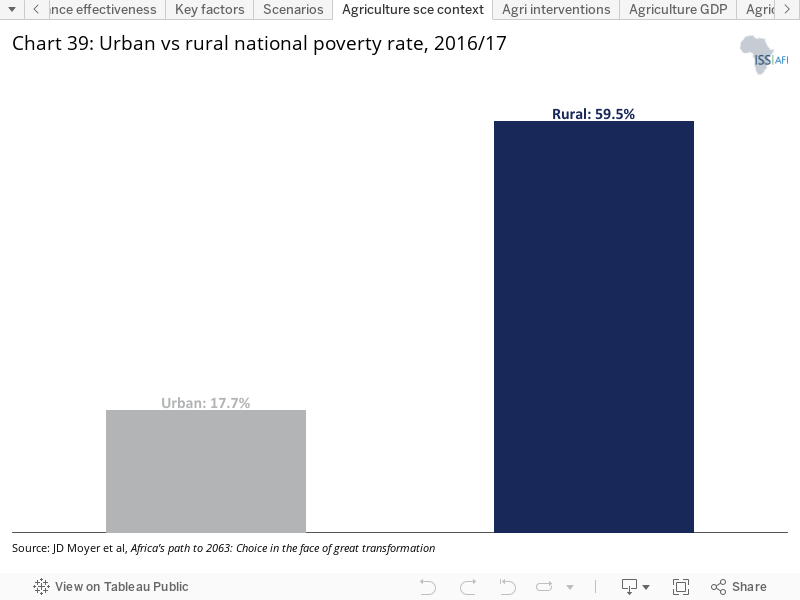

- Chart 39: Urban vs rural national poverty rate, 2016/17

- Chart 40: Summary of the Agriculture and Rural Development scenario interventions

- Chart 41: Average GDP growth rates in the Agriculture and Rural Development scenario

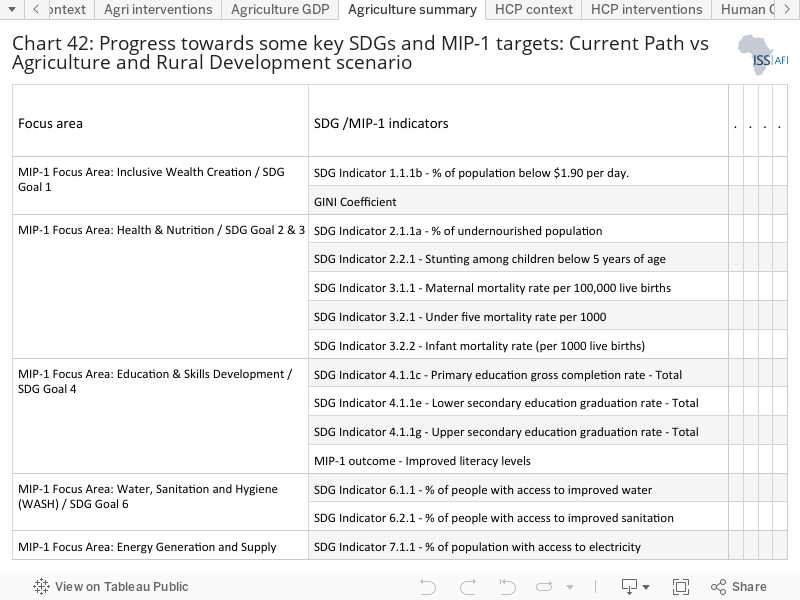

- Chart 42: Progress towards some key SDGs and MIP-1 targets: Current Path vs Agriculture and Rural Development scenario

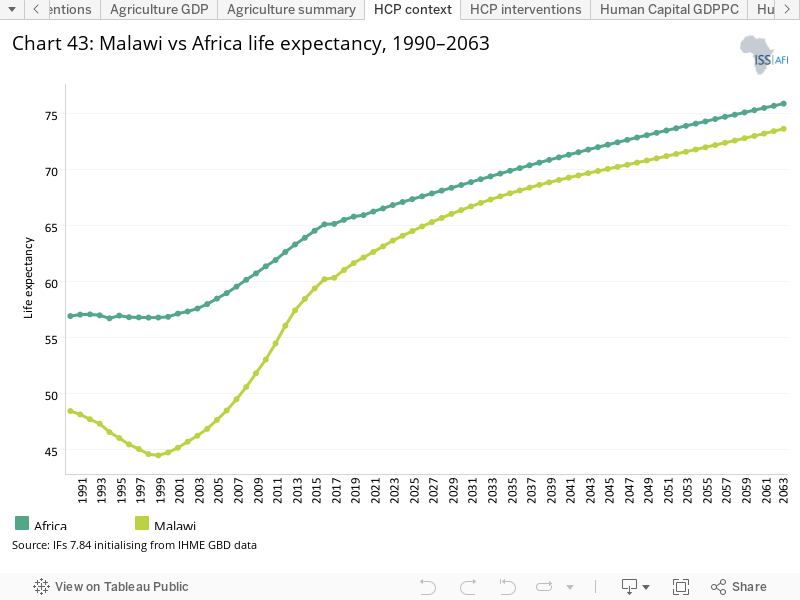

- Chart 43: Malawi vs Africa life expectancy, 1990–2063

- Chart 44: Summary of the Human Capital Push scenario interventions

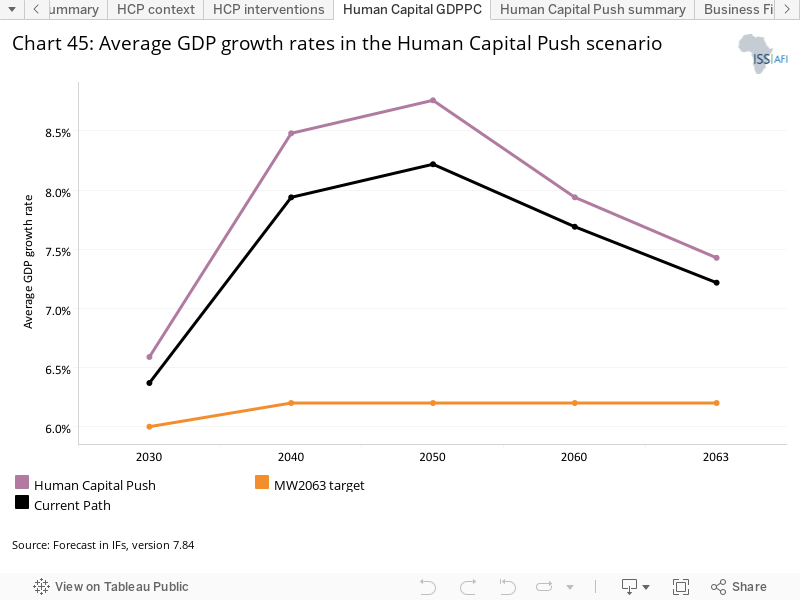

- Chart 45: Average GDP growth rates in the Human Capital Push scenario

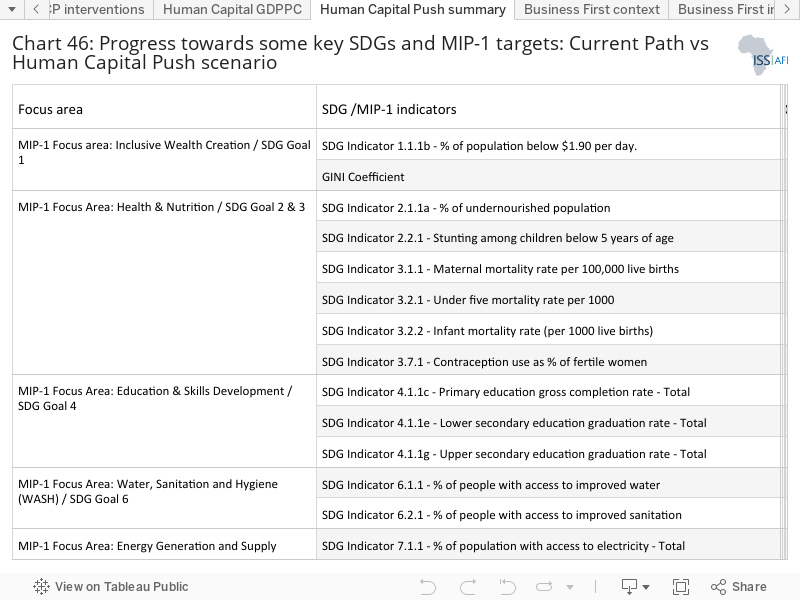

- Chart 46: Progress towards some key SDGs and MIP-1 targets: Current Path vs Human Capital Push scenario

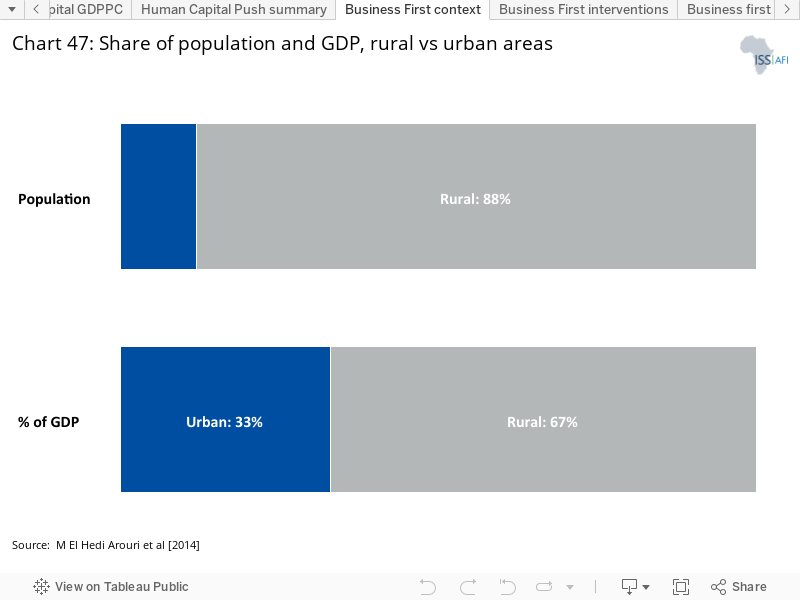

- Chart 47: Share of population and GDP, rural vs urban areas

- Chart 48: Summary of the Human Capital Push scenario interventions

- Chart 49: Average GDP growth rates in the Business First scenario

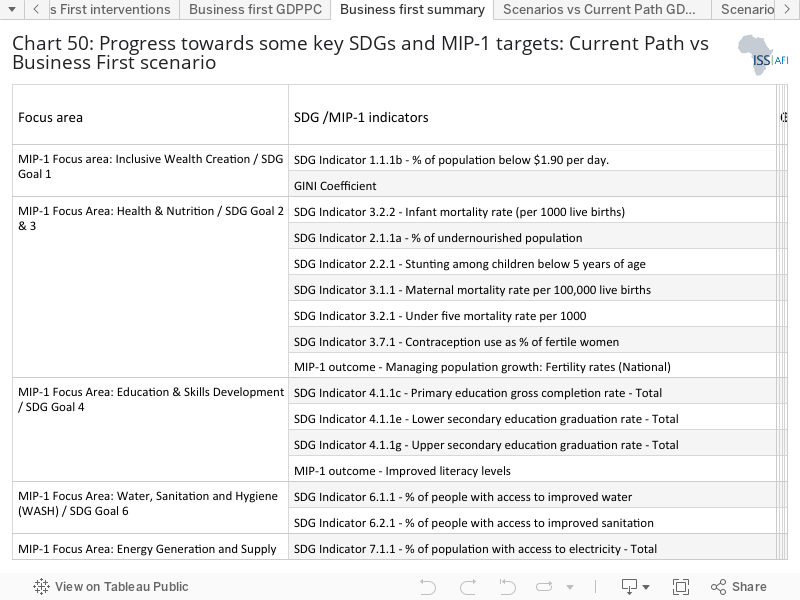

- Chart 50: Progress towards some key SDGs and MIP-1 targets: Current Path vs Business First scenario

- Chart 51: GDP per capita (PPP) in each scenario

- Chart 52: Extreme poverty at US$1.90 in each scenario

- Chart 53: GDP per capita (PPP) - Combined scenario vs the Current Path

- Chart 54: Extreme poverty at US$1.90 - Combined scenario vs the Current Path

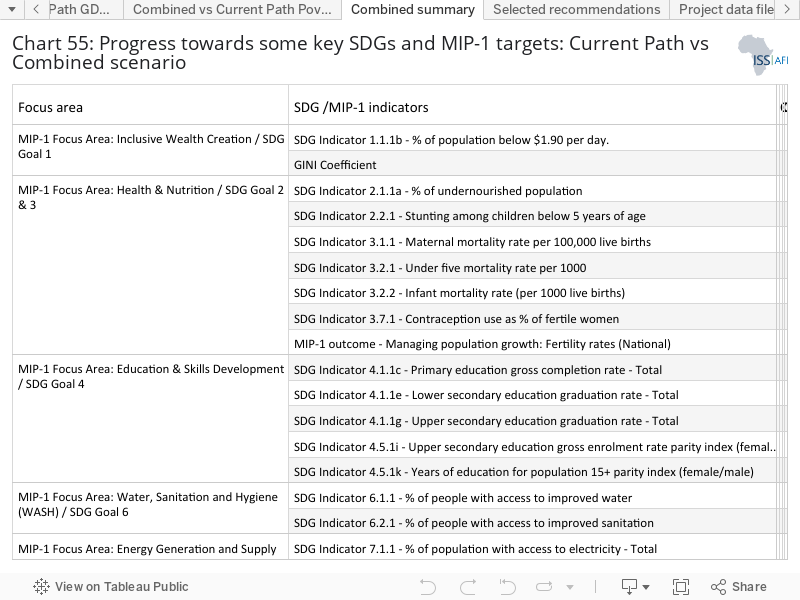

- Chart 55: Progress towards some key SDGs and MIP-1 targets: Current Path vs Combined scenario

- Chart 56: Selected recommendations

- Chart 57: Creation of project data file

- Chart 58: Agriculture and Rural Development interventions

- Chart 59: Human Capital Push scenario interventions

- Chart 60: Business First scenario interventions

Located in Southern Africa, landlocked Malawi is nestled between Mozambique, Zambia and Tanzania. It is one of the 23 low-income countries in Africa and had an estimated population of 19.1 million in 2020. The country is a member of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA).

Malawi is a generally peaceful country and has experienced stable governments since independence in 1964. The one-party rule ended in 1993, and since then, multiparty presidential and parliamentary elections have been held every five years. The new democratic dispensation coincided with the second phase of the structural adjustment programme which saw the liberalisation of markets such as the labour and industrial markets.

The country has achieved improvements in a number of socio-economic indicators, including health, education, and child and maternal mortality. According to the Malawi 2022 Voluntary National Review Report for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Malawi has made significant progress towards goals 2 (zero hunger), 3 (good health and well-being), 4 (quality education), and 6 (clean water and sanitation).[1Malawi 2022 Voluntary national review report for sustainable development goals (SDGs), June 2022]

However, Malawi faces significant development challenges and has made little progress in goal 1 (no poverty) and goal 10 (reduced inequality). In 2019, more than 70% of Malawians lived below the international poverty line of US$1.90 per day.[2Malawi 2022 Voluntary national review report for sustainable development goals (SDGs), June 2022] The gross domestic product (GDP) per capita remains low, averaging US$550 (market exchange rate) over the past decade. In its 2020 report, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) classified Malawi as a country with low human development, with a score of 0.483 in the Human Development Index (HDI).[3UNDP, Human Development Report 2020] Malawi ranks 174th globally, a few places below its neighbours Tanzania (at 163) and Zambia (at 146), although it does better than Mozambique (at 181).

Persistent structural factors such as corruption,[4MW Kateta, How corruption derails development in Malawi, Foreign Policy, 21 May 2021] poor infrastructure, weak human capital, policy inconsistency and a poor business environment[5S Bhoojedhur and T Isbell, Almost half of Malawians consider emigration; most-educated are most likely to look overseas, Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 281, 6 March 2019] limit growth and economic diversification. The economy continues to rely heavily on a low-productivity agriculture sector, which contributes about one-quarter of the country's GDP and employs 64% of the labour force.[6 The Malawi 2063 First 10-year Implementation Plan (MIP–1), 2021–2030] This sector is extremely vulnerable to weather shocks, climate change and global economic shocks.

Vision 2020, launched in 2000, had the aim of Malawi becoming a technologically driven middle-income country by the year 2020. However, by 2020, Malawi failed to realise its development aspiration. In January 2021, the government launched a new long-term development blueprint called Malawi 2063 (MW2063). MW2063 builds on the lessons learnt from the challenges that marred the successful implementation of Vision 2020. MW2063 strives to transform Malawi into an inclusive, wealthy and self-reliant industrialised upper middle-income country by the year 2063. Vision 2020 was critiqued[7 W Kumwembe, ‘Vision 2020 lacked focus’, The Times, 2 December 2019] for its lack of mid-term targets to measure progress and was void of specific short-term goals. The operationalisation of MW2063 was therefore phased in 10-year periods and captured in the implementation plan (MIP–1), the first of which runs from 2021 to 2030, and aims to graduate Malawi to a lower middle-income country by 2030 and meet most of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) by the same period.

Recent global geopolitical and economic events as well as a noticeable increase in weather-related disasters have impacted Malawi’s likely development pathway and necessitate a relook at the growth paths and interventions that Malawi needs to prioritise. The COVID-19 pandemic and other natural disasters such as floods and droughts have contributed to soaring fiscal deficits, which have been largely funded by domestic borrowing and have resulted in a high public debt. The December 2021 Debt Sustainability Analysis by the World Bank indicates that Malawi’s external and public debt are both at high risk of debt distress and that the debt is unsustainable. Malawi’s total public debt stock as of end-June 2021 stood at 59% of GDP, up from 27% in 2011.[8 Malawi Annual Public Debt Report 2020/2021, Ministry of Finance] The costly debt service reduces the fiscal space for productive expenditure to materialise the country’s development vision.

Foresight planning and modelling are therefore critical in the implementation process of MIP–1 to ensure that interventions towards realising MW2063 and the medium-term goals (MIP–1) are guided with a careful analysis of the development terrain, with trajectories/scenarios which point to optimal expected outcomes. This foresight modelling therefore assesses whether Malawi is on track to meet key goals of MW2063 on its current development trajectory (Current Path or business-as-usual scenario). Specifically, this report presents the recent past, current state of development and the likely future of Malawi along the Current Path forecast in terms of demographics, education, health, poverty and inequality, economy, infrastructure, agriculture and climate change, and governance. The Current Path is a future without any substantial changes in Malawi’s current policy and implementation path. It does not assume any seismic policy changes or transformative events such as global war, pandemics, cataclysmic climate change or technological shocks.

Malawi’s population has grown significantly from 3.6 million people in 1960 to an estimated 19.1 million in 2021. The country’s population size relative to the geographic size of the country makes it one of the ten most densely populated countries in Africa. Throughout much of the 1970s, Malawi’s annual growth rates were well above the average for African countries, and in the latter half of the 1980s, growth rates in Malawi were among the highest rates globally. In the first half of the 1990s, growth rates plummeted as HIV/AIDS-related deaths coincided with mass repatriation of refugees back to Mozambique after the civil war ended.[9 NSO, Malawi, 2018 Malawi Population and Housing Census] Since 2000, sustained annual high population growth rates have been recorded ranging from lows of 2.4% to highs of 2.9%.

On the Current Path, a future without any substantial changes in Malawi’s current policy and implementation path, Malawi’s population is expected to reach 24.2 million people by 2030, as annual population growth rates decline to 2.3%. By mid-century it's likely that Malawi will be home to 34.3 million people and by 2063 the country is likely to have a population of 38.8 million. Population growth rates are expected to be aligned with the indicators as set out in MW2063 (Chart 2) until at least 2040 after which the Current Path forecast shows a much larger reduction in population growth rates. Even with this sustained reduction in growth rates, the country will see population densities double within the next four decades, undoubtedly placing a significant strain on land use planning and resource management.

The total fertility rate peaked in 1980 when the country recorded 7.8 births per woman — the third highest in Africa. Since then, the government of Malawi has made significant strides in reducing fertility rates and the decline in fertility rates between 2010 and 2019 was among the three fastest reductions globally.[10National Planning Commission, Cost-benefit analysis of increasing contraceptive use through post-partum counselling and free improved access to contraception in Malawi, Malawi Priorities, National Planning Commission (Malawi), Copenhagen Consensus Center (USA) and African Institute for Development Policy (Malawi), 2021] This decline in part can be attributed to a significant push in providing access to modern contraceptives, with numerous government and donor plans and programmes active within the family planning domain. Significant attention to this sector has led to an estimated 61% prevalence rate of modern contraception use in 2020 among women aged 15 to 49 years. This is the second highest prevalence rate among low-income Africa and is well above the rate of 35% estimated for Africa.[11IFs database]

Despite this promising trend, the current fertility rate of 4.1 births per woman in 2020, while below the average for Africa and its low and lower middle-income countries, remains unfavourably high. The government has reiterated that population growth management remains a critical priority in order to meet the country’s social and economic development goals. This is currently prioritised as a focus area in the first MW2063 10-year Implementation Plan (MIP–1). The targets, as set out in the outcomes indicators, are to improve family planning and access to modern contraceptives to reduce fertility rates further to 3.4 births per woman by 2030.

The Current Path forecast shows that while Malawi is well on track to meet its fertility rate targets (Chart 3), it will fall significantly short of reaching its SDG target on contraceptive use (SDG 3.7.1) (Chart 4). Several studies[12J Forty, SD Rakgoasi, and M Keetile, Patterns and determinants of modern contraceptive use and intention to use contraceptives among Malawian women of reproductive ages (15–49 years), Contracept Reprod Med 6:21, 2021] show that the prevalence rate of contraceptive use is lowest among the younger and poorer population cohorts. Political and community leadership and raising awareness among this population cohort is required to address this challenge and meet the MIP–1 target. Interventions targeting the youth specifically must be mainstreamed within the current policies and programmes.[13B Franklin, R Naik, S Pappa and S Sacher, Accelerating Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals of Malawi: The role of population and family planning, Policy Brief, 2017]

These historical high fertility rates coupled with persistent low life expectancies resulted in Malawi having one of the most youthful age structures in Africa at the turn of the century. The median age in 2000 was 16.4 years, the seventh lowest in Africa, a figure that stagnated for years. The past decade, however, has seen the start of a slow transition in Malawi’s age structures with the median age climbing to 17.8 years by 2020.[14 IFs database. Original data source: UN Department of Economics and Social Affairs] This is on par with the average for low-income African countries, with half of the population below the age of 18. The Current Path forecast shows that the median age in 2030 is likely to be 20.3 years and by 2063 will have improved to 31.6 years, 3.5 years more than the average for low-income Africa. This gradual ageing of the population is most noticeable in the decline in the population below 15 years, with associated growth in the economically active age groups (Chart 5).

In 2020, 43% of the population was below the age of 15 years. This large cohort of children below 15 years of age requires huge investment in education and healthcare infrastructure. With an expected drop in fertility rates, it is forecast that by 2030, 37.8% of the population will be below 15 years, and 22.2% by 2063. The increase in life expectancy is also evident in the growing elderly dependant population group that is expected to increase from 2.6% in 2020 to 2.9% in 2030 and to 7.6% by 2063.

The working-age population cohort (between 15 and 64 years) is expected to increase from 54.4% in 2020 to 59.4% in 2030 and to 70.2% by 2063. This growing workforce could allow Malawi to reach its demographic dividend by 2041 (Chart 6). An increase in the working-age population relative to dependants (children and elderly people) can generate economic growth due to the resultant demographic dividend. Generally, the demographic dividend materialises when a country reaches a ratio of at least 1.7 people of working age for each dependant (children and elderly people).[15 Berlin Institute for Population and Development, Demographic dividend]

When there are fewer dependants to take care of, it frees up resources for investment in both physical and human capital formation, and eventually increases female labour force participation. Studies have shown that about one-third of economic growth during the East Asia economic miracle can be attributed to the large worker bulge and the relatively small number of dependants.[16D Canning, S Raja and AS Yazbeck (eds.), Africa’s demographic transition: Dividend or disaster? Africa Development Forum Series, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2015] However, the growth in the working-age population relative to dependants does not automatically translate into rapid economic growth unless the labour force acquires the needed skills and is absorbed by the labour market. Without sufficient education and employment generation to successfully harness their productive power, the growing labour force (very likely in urban areas) could result in the emergence of civil instability as many people of working age may remain unemployed and in poverty, potentially creating frustration, social tension and conflict.

Malawi needs to sustain its momentum on the reduction in fertility rates and invest in education to empower this future workforce with appropriate skills. Without sufficient employment opportunities and a responsive governance system, Malawi’s large youth bulge could threaten stability. The youth bulge, defined as the ratio of the population between the ages of 15 and 29 to the total adult population, is currently about 51% for Malawi. It will slightly decline to 49% by 2030 and to 32% by 2063 as the population ages. Around 29% of Malawi’s working-age population was estimated as economically inactive in 2019.[17Danish Trade Union Development Agency, Labour Market Profile Malawi – 2022/2023]

Together with population growth and structural demographic changes, Malawi is also expected to see a dramatic shift towards urban areas. Malawi is a predominantly rural country and one of the least urbanised in the world, hence it is at the very early stages of the urban transition. Globally, only Papua New Guinea, Burundi and Niger have higher percentages of populations living in rural areas.

In 1970, 6% of the Malawian population lived in urban spaces. The 1970s and 1980s saw urbanisation increasing rapidly with an average annual rate bordering on 7%. By 1990, almost 12% of the population lived in urban areas, equivalent to just more than one million people. From 1990 to 2020, the annual urbanisation rate slowed down to an average of 3.8% and, in 2020, just over 17% of the population resided in urban areas, accounting for 3.3 million people.

This slower urbanisation trend is the result of pro-rural policies such as the very aggressive integrated rural development plan contained in the 2006 Malawi Growth and Development Strategy.[18Government of Malawi, Malawi growth and development strategy 2006–2011] Malawi’s densely populated rural areas (Chart 7) also reflect an economy dependent on subsistence agriculture that has been very slow to diversify. Prior to the Malawi National Urban Policy (NUP), approved in 2019, there was an absence of urban policies. This resulted in a lack of urban investment and, in turn, growing urban poverty and vast informality. More than 75% of Malawi’s urban populations live in the four major cities of Blantyre, Lilongwe, Mzuzu and Zomba. Pressure to provide basic services and housing within these urban areas is immense and in 2018 nearly 67% of Malawi’s urban populations lived in slums.[19UN Habitat, Housing, slums and informal settlements] MW2063 has set an ambitious target of reducing informality to 50% by 2030 and to 10% by 2063, but achieving this will require a significant effort.

Urbanisation is critical to economic growth and development as it fosters entrepreneurship and increases productivity. Cities in Africa generate between 55% and 60% of the continent’s GDP.[20M El Hedi Arouri et al, Effects of Urbanization on Economic Growth and Human Capital Formation in Africa, PGDA Working Paper, Harvard University, 2014] In 2018, 12% of the Malawian population resided in only the four major urban areas yet was responsible for contributing 33% to the national GDP. When urbanisation is managed sustainably, it reduces poverty and provides several social and economic benefits.

The government of Malawi has recognised the important role that cities will play in getting Malawi to middle-income status. Urban development has gained traction with the government and the need to accelerate urbanisation is supported as pillar 3 in MW2063. The government launched the Malawi Secondary Cities Plan (MSCP)[21Government of Malawi, Malawi Secondary Cities Plan (MSCP), National Planning Commission, Lilongwe, Malawi, 2022] in 2022 — a new spatial master plan that aims to decongest the existing cities through the development of eight additional secondary cities. These catalytic locations aim to be centres of government, industry, agriculture, tourism, and mining activities and investment. The secondary cities are expected to provide economic opportunities, easy commuting and close connectivity to social amenities while playing a vital role in the decongestion of current cities.

On the Current Path, urbanisation rates are expected to continue to increase but at a much lower rate compared to the objectives as set out by the government of Malawi. The Current Path forecast is that the urbanisation rate for Malawi will be 19.9% in 2030, below the government’s desired target of 25%. By 2063, in the Current Path forecast, Malawi’s cities and towns will be home to 35% of the population, significantly below the 60% target of MW2063 (Chart 8). This is very likely the result of the urbanisation lag that followed historical pro-rural policies and underinvestment in urban spaces. While new plans such as the MSCP will support the transition, it will take some time for urbanisation to gain critical momentum.

Urbanisation has gained policy traction in Malawi and the new MSCP envisages a more rapid urban transition, but the historical pro-rural development focus is still engraved in the country’s landscape and land use practices. If the MSCP is successfully implemented and investment in the provision of infrastructure, schools and other efforts continues to be prioritised, this could increase the urbanisation rate above the Current Path forecast.

Accommodating the rural–urban migration and growth within cities in a safe and sustainable manner will be a challenge but managing the transition sustainably will be key to unlocking Malawi’s development future. Expanding infrastructure and education access in urban areas is easier and costs less than expanding it in rural areas. People in urban areas have greater access to technology. For instance, while Internet penetration in Africa is at 16%, in cities that number was about 50%.[22J Manyika et al, Lions Go Digital: The Internet’s Transformative Potential in Africa, McKinsey Global Institute, 2013]

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a useful composite indicator for exploring trends in human development across time and countries. The three pillars of HDI include: health (as measured by life expectancy), education (as measured by mean years of schooling of the adult population and school life expectancy), and a decent standard of living (as measured by gross national income per capita). This section focuses on health and education.

Malawi’s rapid population growth is challenging the country’s ability to meet its key and critical social and economic development goals. While Malawi has made steady progress on increasing life expectancy and mean years of schooling, it has fallen behind in per capita income and remains categorised in the low human development category. Malawi’s score on the HDI increased from 0.34 in 1990 to 0.48 in 2019, which placed the country in 174th position globally out of the 189 countries measured.[23UNDP, Human Development Reports 2020] In SADC, Malawi is only ahead of the Democratic Republic of Congo and Mozambique. On the Current Path, the human development level (measured through the HDI) in Malawi is forecast to improve and remains on par with the targets set out in MW2063 until 2050 (Chart 9). After 2050, improvement in human development in the country will likely be slower than expected in MW2063. This might be explained by inefficiencies in government spending on health and education or the increasing size of the population that eventually reduces public expenditure per capita in education and health. The Malawi authorities should improve spending efficiency in education and health and tackle the country’s high fertility rate.

Health and nutrition

Health is a critical pillar of human development. In MW2063, health and nutrition are two of the key enablers to achieve Malawi’s human capital development objectives towards a healthy population with improved life expectancy, quality, equitable and affordable healthcare, food security and adequate nutrition.[24National Planning Commission, Malawi's Vision 2063: An Inclusively Wealthy and Self-reliant Nation, 2020]

Malawi has invested significantly in its health sector and the country’s spending on the sector measured 4.8% of GDP in 2017,[25 Human Capital Index 2020, Malawi Human Capital Project, 2020] which was above the average for the region and low-income Africa. This investment is reflected in the significant progress that Malawi has made with reductions in infant, child and maternal mortality compared to its peers in Africa, but the country continues to suffer from poor health outcomes. In 2019 Malawi ranked 185th for overall health efficiency among 191 WHO member states,[26A Tandon et al, Measuring Overall Health Systems Performance for 191 Countries, World Health Organisation, GPE Discussion Paper Series, No. 30, 2019] a statistic that reflects the poor state, inequality and ineffectiveness of the sector.

Malawi scored very low in life expectancy and ranked 40th in Africa in 2020. Life expectancy improved from 37.8 years in 1960 to 48.4 years in 1990, but the onset of the HIV/AIDS pandemic in the 1990s impacted the country severely and by the turn of the century life expectancy had fallen to 44.7 years. Life expectancy has slowly recovered since and in 2020 the average Malawian could expect to live to 62.1 years, though this figure is still below the average for low-income Africa at 63.8 years. In the Current Path forecast, life expectancy is likely to reach 66.3 years by 2030 and 73.6 years by 2063. However, Malawi is expected to perform below the MW2063 target throughout the forecast horizon. Malawi authorities, with the support of the development partners, should reduce HIV/AIDS-related death rates through the roll-out of lifesaving antiretrovirals (ARVs) and aggressive information campaigns about the disease. There is also a need to improve access to clean water and sanitation to reduce communicable diseases. Such actions could increase life expectancy.

Chronic food insecurity is a persistent threat to Malawi’s population. A recent food insecurity report[27Malawi IPC Chronic Food Insecurity Report 2022] indicates that in 2021, 33% of Malawians who live in rural areas were classified as moderately to severely food insecure and only 36% of the population faced no or minimal food insecurity. The highest levels of severe food insecurity occur in the southern regions, driven by high poverty rates, the dependency on rain-fed agriculture, recurrent flooding and droughts, low resilience to climate shocks, and subsistence farming practices.[28Malawi IPC Chronic Food Insecurity Report 2022]

Together with food insecurity, the country’s population also battles poor nutrition. Lack of access to a nutritious and diverse diet has contributed to severe malnutrition. In 2018, UNICEF[29UNICEF, Nutrition statistics in Malawi, 2018] estimated that 64% of children below the age of five had some form of anaemia and that 23% of child deaths were related to undernutrition. Likewise, only 61% of infants below five months were exclusively breastfed and 4% of children suffered from acute malnutrition. In 2020, the prevalence of stunting among children under five years of age was just below 40%, while this is a significant drop from the 55% recorded in 2000, it is the seventh highest prevalence rate in Africa.

Malnutrition therefore remains a public health concern in Malawi, especially among women and children, contributing to the high stunting rates among children. This high number is being addressed by the government as part of the MIP–1 implementation plan of MW2063. Within the plan, the government adopted the SDG targets of ending all forms of malnutrition and achieving a reduction in stunting rates among children through the provision of improved nutrition. The Current Path forecast shows that Malawi will likely fall short of achieving this critical SDG target (SDG 2.2.1) and that the stunting rate would likely still be close to 30% by 2030, against a target of 25% (Chart 11). A significant number of Malawian children will therefore continue to be at risk of cognitive and physical limitations, impacting the future productivity and labour force of the country.

Despite the high malnutrition and stunting rates, the government of Malawi has made great strides in reducing infant and child mortality, currently below the average for low-income Africa. The government has achieved this feat through the roll-out of antenatal and delivery care, distribution of insecticide-treated nets, the preventative and curative treatment of common infectious diseases, field vaccinations programmes and the availability of community-based education programmes.[30UNICEF, Malawi making positive strides in saving newborn lives, but more needs to be done, 20 February 2018][31 JM Thornton, Child malnutrition in Malawi, The Borgen Project, 20 June 2015]

In 1990, infant mortality rates stood at 136 deaths per 1 000 live births, and the under-five mortality rate at 232. By 2020, infant mortality had dropped to 37 deaths per 1 000 live births, while the under-five death rate had dropped to 58. Infant mortality rates are nine deaths fewer than the average for low-income Africa, and under-five mortality rates are nearly 15 deaths fewer. While the reduction in infant deaths has shown much progress in the Current Path forecast, it will still not meet the SDG target. On the Current Path, infant deaths would likely be just above 25 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2030, more than double the SDG target of 12. The Current Path forecast shows (Chart 11) that Malawi will only achieve this target in 2050. Likewise, the Current Path forecast also shows that Malawi will not reach its under-five mortality rate targets of 25 deaths by 2030 and will likely only achieve this target by 2044. While the progress in reducing death rates among children, infants and maternal women has been promising, these figures are very high. One in eight Malawian children dies each year from preventable conditions such as malaria, HIV-related diseases and neonatal defects.[32JM Thornton, Child malnutrition in Malawi, The Borgen Project, 20 June 2015]

Malawi’s maternal mortality rates have also dropped significantly from 1 123 deaths per 100 000 live births in 2000 to 396 in 2020, below the average of 435 for low-income African countries. The SDG target for maternal mortality (SDG 3.1.1) is a ratio of fewer than 70 deaths per 100 000 by 2030. In the Current Path forecast (Chart 11), Malawi is estimated to reach a ratio of 275 deaths by 2030. On the Current Path, this target will likely be achieved in 2050.

Malawi has a very high disease burden, as evident in its low life expectancy. The main causes of mortality in Malawi are mostly preventable and treatable. Malaria and HIV/AIDS-related deaths accounted for 19% of deaths in 2020 (Chart 12) and communicable diseases made up a sizable portion of related deaths. A preventable measles outbreak in 2009 affected more than 11 000 people and poor water, sanitation and hygiene (WaSH) and municipal infrastructure has been responsible for severe cholera outbreaks. Cholera alone has been responsible for 63% of all epidemics experienced the past four decades in Malawi.[33Data source: EM-DAT, CRED / UCLouvain, Brussels, Belgium, www.emdat.be (D. Guha-Sapir), Version 2021-08]

Malawi is forecast to experience its epidemiological transition, a point at which death rates from non-communicable diseases exceed that of communicable diseases, in 2027 (Chart 13). It is roughly two years later than the average for low-income countries globally. This has implications for Malawi’s healthcare system which will need to invest in the capacities for dealing with this double burden of disease.

In spite of the progress made, Malawi’s health system still faces many challenges, including limited access to health services, poor management system in healthcare delivery, ineffective spending of funding and weak linkages with traditional medicine.[34 Malawi SDNP, Human resource development and management (social sector development)]Good health is a critical factor in human development and human capital formation. The Malawi authorities should therefore improve the quality of the healthcare system, enhance the quality of health workers’ training, improve the accessibility and affordability of healthcare, and roll out a national health insurance scheme across the entire country. This should go hand in hand with efforts to improve access to safe WaSH facilities to prevent the spread of communicable diseases. Such actions could fast-track attainment of the 2030 targets relative to infant and maternal mortality rates, as well as stunting rates.

Education and skills development

Education is a key pillar of human development and productivity. In the MW2063 vision, education is recognised as a crucial enabler to achieving Malawi's development objectives. Malawi's education system is guided by the 1993 Malawi Constitution in which education is a human right.[35Danish Trade Union Development Agency, Labour Market Profile – Malawi 2022/2023] The country’s formal education system comprises three levels: primary, secondary and higher education. At the end of eight years in primary education, the Malawi Primary School Leaving Certificate of Education (PSLCE) makes learners eligible for four years of secondary education.[36Danish Trade Union Development Agency, Labour Market Profile – Malawi 2022/2023]After obtaining the Malawi School Certificate of Education (MSCE) from secondary education, learners have the option of joining the Teachers Training Colleges, TEVET institutions, agriculture, forestry and natural resources training institutions, health services training, and universities to attain tertiary education.[37Danish Trade Union Development Agency, Labour Market Profile – Malawi 2022/2023] Non-formal education consists of Early Child Development and Adult Education, Out of school Youth and Functional Literacy, and Complementary Basic Education.[38Danish Trade Union Development Agency, Labour Market Profile – Malawi 2022/2023]

The government of Malawi has made efforts to expand access to education. Over the last decade, education expenditure has ranged from 13% to more than 20% of total government expenditure.[39Danish Trade Union Development Agency, Labour Market Profile – Malawi 2022/2023] In the 2020/21 national budget, the education sector got the lion's share, equivalent to 21.6% of the total budget, representing 5.4% of GDP.[40 W Chiuta, Malawi: Education Gets Lion’s Share in Malawi 2020/21 Budget, Nyasa Times, 11 September 2020] This places Malawi above the average of 3.7% for low-income countries in Africa. Education expenditure (% GDP) in Malawi is within the level recommended by the Incheon Declaration on Inclusive Education, which proposes that governments allocate between 4% and 6% of their GDPs to education if they are to achieve the SDG 4.[41UNESCO, What you need to know about the right to education, 2020]

As a result, Malawi has achieved notable improvements in some indicators related to education, especially primary education. The gross primary school enrolment rate has been above 100% since 1994 and stood at 142.5% in 2018 (the last year of available data), well above the average of 113.6% for low-income countries in Africa. This high percentage, however, reflects the continued presence of over-aged learners at the primary level as the net primary school enrolment was 97.4% in 2018. Also, the adult literacy rate (population aged 15 years and older) has increased from 61.3% in 2010 to 76.7% in 2018.[42 National Statistical Office (NSO) Malawi] This is almost 20 percentage points above the average of 56.4% for low-income Africa in 2018. Higher literacy rates improve employment prospects for poor people and provide an opportunity for formal sector employment and to escape extreme poverty. The Current Path shows that the country is progressing and on track to achieve the target of 81% in MW2063 by 2030. The national literacy rate is forecast to be 87.7% on the Current Path by 2030, almost seven percentage points above the MW2063 target of 81% in the same year.

Despite this progress, Malawi still experiences several challenges in its education sector, with negative implications for national development. Chart 15 presents the performance of various education indicators (Box 1) from one level to another for Malawi. The chart is colour-coded to show the country's performance, ranging from good (green) to bad (red). It shows that access to secondary and tertiary education remains a huge challenge in Malawi. While the primary school net enrolment rate remains high and stood at about 97.4% in 2018 (the last year of available data), secondary school net enrolment and completion rates are extremely low at 17% and 22%, respectively. This means that Malawi has among the lowest secondary completion rates of the countries in the East Africa and Southern Africa regions. Malawi's gross enrolment ratio for tertiary education, at about 1.6%, is also one of the lowest in the world, and far below the average for low-income African countries at 6.3%.

The education system can be conceived as a long funnel where completion or attainment of one level gives access to the next. The more learners who enrol and complete primary school, the greater the pool of learners that can proceed to secondary and tertiary levels. Malawi has a very low transition rate from primary to secondary school (38%) (Chart 14), and this bottleneck together with a limited number of secondary schools are some of the key underlying factors of the low educational outcomes for secondary and tertiary levels. Such poor educational outcomes at secondary and tertiary levels impede progress in poverty and inequality reduction. Evidence suggests that children who complete secondary school are more likely to participate in formal and paid employment. For instance, a study in 2009[43E Chirwa and M Matita, The Rates of Return on Education in Malawi, University of Malawi, Chancellor College, 2009] revealed that attaining secondary education in Malawi improved earning potential by 15.4%, compared to 5.1% for primary school education.

The mean years of education for adults — a good indicator of the stock of human capital in a country — is low in Malawi. In 2015 (the last year of available data), the average number of years of schooling for adults aged 15 years and older was 4.6 years, below its neighbours Zambia (7.6 years), Zimbabwe (7.8 years) and Tanzania (6.1 years), however, above Mozambique (3.1 years).[44BarroLee Data Set, Barro-Lee estimates of educational attainment for the population aged 15–64 from 1950 to 2015] When disaggregated by gender, males have, on average, about five years of schooling, whereas females have 4.4 years. This means that most adults in Malawi have barely completed primary education. However, Malawi performs slightly better than the average of 4.1 years for low-income countries in Africa. On the Current Path, the average years of education for adults 15 years and older will likely be 5.9 years by 2030 and 8.4 years by 2063.

Despite the progress made, women still face challenges to accessing education in Malawi, especially higher education. Malawi has achieved gender parity at primary level, but the gender parity ratio is 94% for secondary enrolment and 60% for tertiary enrolment. In 2021, less than 40% of all students that entered public universities and colleges were women, compared to 60% men, with training courses such as engineering dominated by men.[45PS Hettinger et al, Malawi Economic Monitor: Addressing Macro and Gender Imbalances, World Bank, 1 December 2021] On the Current Path, Malawi will maintain the gender parity at primary enrolment and achieve gender parity for secondary and tertiary enrolment by 2030. However, the country is not on track to achieve many of the other targets in MW2063 (MIP–1) and SDG related to education (Chart 16).

The above analyses refer mainly to the quantity of education. Getting more children into school is essential, but ensuring that they actually acquire the requisite knowledge and skills is even more important. Education quality is low in Malawi and there is a mismatch between the skills offered in schools and what the labour market requires. The quality of education is usually tracked using Harmonized Test Scores, which are averaged across grades and subjects for those tests covering multiple grades and programmes.[46HA Patrinos and N Angrist, A Global Dataset on Education Quality: A Review and Update (2000–2017), World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 8592, 2018] According to the 2020 World Bank Human Capital Project report, students in Malawi score 359 on a scale where 625 represents advanced attainment and 300 represents minimum attainment.[47World Bank, Malawi – Human Capital Index 2020, October 2020]

Skills gaps and shortages in Malawi have serious macroeconomic implications. For instance, labour productivity in Malawi is the lowest among its neighbouring countries.[48Danish Trade Union Development Agency, Labour Market Profile – Malawi 2022/2023] While a number of factors enter into short-term growth, the new growth models have shown that, in the long term, economic growth depends primarily on the skills of the people.[49EA Hanushek and L Woessmann, The Economic Impacts of Learning Losses, Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2020] On the Current Path, the quality of education in Malawi as measured by test scores is forecast to gradually improve across the forecast horizon. A study in 2020[50EA Hanushek and L Woessmann, The Economic Impacts of Learning Losses, Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2020] revealed that skill differences account for three-quarters of cross-country variations in long-term growth. Investing in quality education and skills development training programmes is therefore vital to sustain economic growth in Malawi.

The education systems must be oriented towards producing youth that have both strong foundational skills as well as specific skills for jobs. This will require more investment in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) education, and high-quality technical and vocational education and training (TVET) programmes. The current TVET system in the country is unable to supply trainees at all qualification levels, leaving firms with inadequate labour supplies. Only 0.5% of the total education expenditure is directed towards TVET.[51Danish Trade Union Development Agency, Labour Market Profile – Malawi 2022/2023] Malawi should put more resources into its TVET and STEM programmes to respond to the demands of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

The IFs forecasting platform relies on the international measures for extreme poverty. Thus, we use the US$1.90 a day poverty line (2011 purchasing power parity), unless otherwise specified, to remain consistent with international poverty analyses, and to track Malawi's progress towards the achievement of Goal 1 of the SDGs. As such, the poverty rates reported here differ from the poverty rates measured using the national poverty line, which was MWK137 428 per year or MWK376.5 per day as of 2017.[52National Statistical Office, Malawi Poverty Report 2018: Trends in Poverty, 2019, National Statistical Office (NSO), Malawi]

Using the poverty threshold of US$1.90, Malawi had the sixth highest poverty rate in Africa and globally in 2018. Chart 17 shows the past trends in poverty and projections in the Current Path scenario. It reveals that poverty is not a new phenomenon but a long-standing issue in Malawi. Using US$1.90 per day, Malawi experienced its lowest extreme poverty rates between 1996 and 2000, but the poverty rate has never been below 60%, except in 2000 when it declined to 59%. A deep economic contraction of −4.9% in 2001 increased the poverty rate to 72.1%, which slowly declined to 69.7% in 2018. The poverty rate in Malawi jumped to more than 70% in 2020 due to slow growth and increased unemployment caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, more than half of Malawi's population consistently lives in extreme poverty.

The poverty rate at the national poverty line was estimated to be 51.5% in 2017, compared to 50.7% in 2011.[53National Statistical Office (NSO), Fourth Integrated Household Survey (IHS4), 2018] The ambitious target of the government is to create inclusive wealth to halve it by 2030. Given Malawi’s past performance on poverty reduction, it will require significantly more rapid rates of inclusive economic growth, combined with additional measures such as expanded social transfers (grants) and/or employment schemes, to achieve this target. Over a 20-year period, poverty has declined only by about 14 percentage points from 65.3% in 1997 to 51.5% in 2017 using the national poverty line. Overall, little progress has been made in poverty alleviation in Malawi, and poverty still remains pervasive in the country regardless of the measures used (by national or international standards).

On the Current Path, the poverty rate in Malawi at US$1.90 is forecast to decline gradually to reach 52.6% by 2030, about 18 percentage points above the projected average of 34.5% for low-income Africa in the same year. The number of poor people is projected to peak at 13.9 million in 2025 due to population growth, before steadily declining to 12.7 million by 2030. Goal 1 of the SDGs requires that less than 3% of every country’s population should be living in extreme poverty by 2030. On the Current Path, Malawi will likely achieve this target only in 2057, meaning that on a business-as-usual pathway, the country will miss the SDG target of eliminating extreme poverty by 2030 by a substantial margin.

A key feature of Malawian poverty is its rural prevalence: the national poverty rate was 59.5% in rural areas compared to 17.7% in urban areas in 2016/17.[54 National Statistical Office (NSO), Fourth Integrated Household Survey (IHS4), 2018] The IFs platform currently does not disaggregate poverty by an urban–rural division to see how this massive disparity in poverty rate between rural areas and urban areas might evolve across the forecast horizon. But, given the pace of urbanisation and current forecasts for urban population growth, most of Malawi’s poor will likely still live in rural areas for many decades to come.

While urbanisation can drive innovation, productivity and growth and reduce poverty, if not well planned it can also lead to vicious cycles of poverty, inequality and social instability. A study[55M Ravallion, S Chen and P Sangraula, New Evidence on the Urbanization of Global Poverty, Population and Development Review 33:4, 2007, 667–701] found that urbanisation has been associated with falling overall poverty in all the regions of the developing world, except sub-Saharan Africa. This is because urbanisation in sub-Saharan Africa is generally not accompanied by significant economic opportunities, directly for rural–urban migrants and indirectly for people living in rural areas. Structural transformation of the economies, as well as infrastructure and service delivery, has not kept pace with the rate of urbanisation. For instance, over 50% of urban dwellers in sub-Saharan Africa live in slums, and only 40% of the urban population has access to improved sanitation facilities.[56J Barofsky, E Siba and J Grabinsky, Can rapid urbanization in Africa reduce poverty? Causes, opportunities, and policy recommendations, 7 September 2016] In sum, without additional measures, urbanisation is unlikely to reduce overall poverty in Malawi.

Malawi’s structural poverty can be explained by several factors, including low productivity in the agriculture sector, volatile economic growth, rapid population growth, poor human capital, limited access to financial services, recurrent natural shocks, and limited coverage of safety net programmes and targeting challenges.[57 Malawi 2020 Voluntary National Review Report for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), 2020] The current high debt burden also may hinder poverty alleviation efforts in Malawi, as it would reduce public investment, income growth and fiscal space for social spending due to the high debt service costs.

The government of Malawi, in collaboration with development partners, should implement policies and programmes that will likely produce inclusive wealth creation and reduce poverty. Such policies may include improving market and road infrastructure, and promoting irrigation to boost agricultural production and income.

The poverty rates discussed above show the share of the population below the poverty line, however they fail to reveal any information about the distribution of income above or below the threshold. Even though it has slightly decreased, the level of income inequality still remains high in Malawi (above the average for low-income Africa) and hinders progress in poverty reduction. The Gini coefficient is a standard measure of the level of inequality. In 2017, the national Gini coefficient was 0.42 compared to 0.45 in 2011.[58National Statistical Office (NSO), Fourth Integrated Household Survey (IHS4), 2018] Often, the implicit assumption in poverty reduction strategies is that poverty reduction will come through growth, i.e. the benefits of more rapid economic growth will trickle down to reduce poverty. However, while economic growth is necessary, it is not sufficient for poverty reduction as levels of inequality also matter. Higher levels of inequality have been shown to undermine the poverty-reducing effect of economic growth.[59AK Fosu, Growth, Inequality and Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa: Recent Progress in a Global Context, Oxford Development Studies, 43:1, 2015, 44–59; M Ravallion and S Chen, What Can New Survey Data Tell Us about Recent Changes in Poverty and Distribution? World Bank Economic Review, 11:2, 1997, 357–82] This is because an initial maldistribution of physical, human and financial resources make it much harder for poor people to participate in, and therefore gain from, the proceeds of economic growth.

Without tackling inequality, economic growth will have little effect on poverty reduction in Malawi. MW2063 identified inequality as a challenge, and the target is to reach a Gini coefficient (Gini index) of 0.39 by 2030 and of 0.25 by 2063. Chart 18 shows how income inequality might evolve going forward on the Current Path.

On the Current Path, the Gini coefficient for Malawi by 2030 is 0.39, in line with the target of 0.39 set out in MW2063 (Chart 18). However, after 2030 the Current Path forecast shows a much slower reduction in income inequality than expected in MW2063, likely to be about 0.35 by 2063, 39% higher than the 0.25 desired. To achieve the objective of inclusive wealth creation, the government must commit to policies that redistribute the benefits of economic growth to all. To this end, Malawi will need to tackle corruption, scale up social safety nets and address the targeting challenges, employment creation and gender equality, among others. Promoting gender equality is a central development agenda in Malawi, but progress has been slow. Gender gaps across several economic dimensions persist in the country. In 2021, Malawi poorly ranked 115th out of 156 countries on the Global Gender Gap Index.[60World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Report 2021, March 2021] Closing the huge gender gap in agricultural productivity could contribute to inclusive wealth creation by lifting more than 238 000 people out of poverty and increasing the country’s total GDP by 1.85%.[61PS Hettinger et al, Malawi Economic Monitor: Addressing Macro and Gender Imbalances, World Bank, 1 December 2021]

The IFs model focuses on basic infrastructure such as water and sanitation, energy/electricity, roads and information and communication technology (ICT). Infrastructure development has widespread benefits to productivity and human well-being and has many direct linkages to poverty and inequality reduction.[62A Brenneman and M Kerf, Infrastructure and Poverty Linkages: A Literature Review, World Bank, 2002] MW2063 identifies economic infrastructure such as energy, ICT, roads, railway, water and airports as key enablers to the inclusive wealth creation agenda.

Infrastructure is generally poor in Malawi, and the fact that most Malawians reside in rural locations complicates the provision of infrastructure since it is usually much more cost-effective and easier to provide infrastructure to people in urban areas than in remote rural settings. In 2020, Malawi ranked 26th out of 54 African countries on the African Infrastructure Development Index (AIDI), with a score of 21.8 out of 100.[63African Development Bank Group, Economic brief – The Africa Infrastructure Development Index (AIDI) 2020, 17 September 2020] The AIDI is developed by the African Development Bank, and is based on four major components: water and sanitation, energy/electricity, transport and ICT. Each is briefly discussed below.

Water and sanitation

Access to improved water and sanitation infrastructure is critical to preventing deaths and illnesses from preventable communicable diseases, thus directly improving human well-being and leading to many indirect socio-economic benefits. Chart 20 shows the trends in access to improved water sources in Malawi. In 2000, 67% of the population had access to improved water sources; it increased to 88.3% in 2020, however about two million people still lack access to safe water.

Access to improved sources of drinking water is skewed towards urban areas. According to the Malawi Integrated Household Survey (2020), 97.1% of the population living in urban areas have access to improved sources of drinking water compared to 86.5% in rural areas. Most of the population (64.5%) access safe drinking water through boreholes, 17.8% have access to piped water into a yard/plot/communal standpipe, and only 2.4% have access to piped water into their dwelling.[64National Statistical Office (NSO), Integrated Household Survey 2020, 2020]

On the Current Path, the access rate of improved sources of water is forecast to be 93.5% by 2030, an improvement of 4.9 percentage points between 2020 and 2030. The target in MW2063 is 100% by 2030; however, in the Current Path forecast universal access (100%) is reached only in 2050 (Chart 20). The large portion of the rural population, compounded by the rapid population growth, might explain this slow growth in clean water access.

Access to improved sanitation rate in Malawi increased modestly from 21.2% in 2000 to 35.2% in 2020, compared to 21.8% for the average for low-income Africa and 29.4% for the average for Malawi's global low-income peers (Chart 21). In rural Malawi, only 29% of the population has access to improved toilet facilities compared to 65.5% in the urban areas.[65National Statistical Office (NSO), Integrated Household Survey 2020, 2020] Poor sanitation practices commonly increase the communicable diseases burden, which leads to more infant and child deaths.

The Current Path forecast is that access to improved sanitation in Malawi will continue to improve to reach 50.7% of the population by 2030, below the Malawi government target of 65%. After 2040, the gap between the Current Path forecast for access to improved sanitation and the targets in MW2063 will significantly narrow. Overall the sector of water and sanitation in Malawi has experienced significant achievements. However, the sector is beset with a number of challenges ranging from vandalism of water infrastructure, ageing infrastructure and funding shortages to dwindling sources of water. To achieve the goal of safe water and sanitation for all, a number of projects aimed at extending, upgrading and rehabilitating rural gravity water supply systems but also development and rehabilitation of boreholes across the country are being implemented. These projects include the Sustainable Rural Water Project and the Malawi Drought and Resilience and Recovery Project.[66Government of Malawi, Malawi Annual Economic Report 2021, Ministry of Finance, Economic Planning and Development and Public Sector Reforms, 2021]

Energy/electricity

Malawi is fortunate to have a range of energy sources such as hydro, fossil fuels, biomass, solar and wind, among others. However, energy shortage is one of the country's major problems and limits its socio-economic and industrial development.

Malawi has the lowest national electricity access rate in SADC and one of the lowest in the world. In 2020, only 18% of the country's total population had access to electricity, compared to 34% for the average for low-income Africa and 42% for the average for its global low-income peers. And for those connected to grid power, supply remains largely unreliable. Malawi’s power generation is heavily dependent on weather conditions as about 98% of electricity is generated by hydroelectric power stations. Thus, low water levels during drought periods and silting during the rainy season disrupt electricity generation. This overreliance on hydropower for energy provision further increases the country’s vulnerability to climate changes.

On the Current Path, the national electricity access rate in Malawi does show improvements, reaching 26.5% of Malawi's population by 2030, but will remain far below the government's target of 50% by 2030. With a projected national electricity access rate of 89.3% by 2063, Malawi remains below the targets captured in MW2063 across the forecast horizon (Chart 22). The Malawi government should prioritise decentralised mini- and off-grid schemes, using renewable energy to improve the electrification rate.

Like other infrastructure types, electricity access has a strong rural–urban dimension in Malawi. In 2019, 45.5% of the population in urban areas had access to electricity, while only 5% of the population in rural areas had access. The lack of equity between the rich and the poor is also stark, with the poorest 20% reporting 1% access to electricity and the wealthiest 20% reporting 31%.[67M Kojima et al, Who Uses Electricity in Sub-Saharan Africa – Findings from Household Surveys, Policy Research Working Paper No. 7789, Washington, D.C.: World Bank, 2016]

On the Current Path, access to electricity in urban areas is forecast to be 69% by 2030, nine percentage points below the target of 78% in MW2063. In rural Malawi, many households rely on biomass (firewood and charcoal), which accounts for 89% of the energy used in the country.[68Malawi Growth and Development Strategy (MGDS) III] Biomass contributes to environmental degradation such as deforestation. Also, the use of wood and charcoal leads to indoor air pollution, which causes respiratory-related illnesses. Moreover, in rural areas, the time-consuming task of gathering firewood is borne by women and girls, who are then diverted from education that could eventually have improved their productivity and lives.

The Current Path forecast is that the electricity access rate in rural Malawi will increase by about 10 percentage points from 6% in 2020 to 16.1% by 2030. Going forward, the gap between rural and urban electricity access rates will narrow (Chart 23). This forecast aligns with the Malawi government's effort to enhance electricity access in rural areas. The Ministry of Energy is implementing the Malawi Rural Electrification Programme (MAREP) to increase access to electricity for rural and peri-urban communities to transform rural economies and to reduce poverty among the rural population.[69Government of Malawi, Malawi Annual Economic Report 2021, Ministry of Finance, Economic Planning and Development and Public Sector Reforms, 2021]

On the Current Path, the gap between total energy production and demand is forecast to widen due to economic and population growth. The Current Path forecast is that the proportion of energy production to energy demand will be 61.5% by 2030 — below the Malawi government target of 100% in the same year.

Energy is the lifeblood of every modern economy. The availability of reliable electricity access is essential to companies’ decisions to adopt new technology. Hence, reliable, affordable and sustainable energy will be crucial in achieving the MW2063 development targets. The government of Malawi recognises the importance of energy in socio-economic development and is already making reforms in the power sector to address the energy deficit. The reforms have led to the entry of independent power producers (IPPs) for new generation capacity. A number of potential developers (more than 30) have been in contact with the government of Malawi to develop independent power projects. Most of the interested IPPs focus on solar PV, while some coal, heavy fuel oil (HFO) and small hydropower projects are also among the candidates.[70Privacy Shield Framework, Malawi – Energy]

Roads/transport

Good transport infrastructure is crucial for economic growth and development as it cuts across all the sectors of a country's economy. Roads improve accessibility to and mobility of goods, services and people, with positive effects on internal and external market integration, employment and productivity in rural and urban areas.[71S Asher and P Novosad, Rural Roads and Local Economic Development, American Economic Review, 110:3, 2020, 797–823]

Malawi has a multi-modal but underdeveloped transportation system consisting of road, rail, air and inland water transport. The country has a road network of 15 415 km, comprising main (21.7%), secondary (20.2%), tertiary (26.7%), district (22.7%) and urban (8.7%) roads.[72Ministry of Transport and Public Works, Malawi National Transport Master Plan, 2017] Road transport remains the major mode of transportation in the country, accounting for more than 70% of the internal freight traffic and over 90% of international freight traffic, mainly due to the inadequacy of other forms of transportation and the country being landlocked.[73Ministry of Transport and Public Works, Malawi National Transport Master Plan, 2017]

In 2020, about 30% of Malawi's road network was paved, compared to the average of 17.5% for low-income countries in Africa. According to the IFs forecast, 38.4% of Malawi's total road network will be paved by 2030, 6.6 percentage points below the target of 45% in the same year in MW2063. Across the forecast horizon, paved roads as a proportion of the total road network remain below the targets captured in MW2063 (Chart 24).

Malawi’s rural road network plays a vital role in the country’s economy, especially given the large rural population and their agricultural dependency. The Rural Access Index (RAI)[74ReCAP, Rural Access Index (RAI)] was measured at 63% in 2019, meaning that 37% of the rural population does not have access within 2 km to an all-season road. This makes it especially difficult for these communities to partake in economic activities.

The road condition surveys of 2011, 2014 and 2017 revealed deterioration in the condition of the road network in Malawi, mainly due to inadequate financing for rehabilitation and maintenance activities. For instance, the target for the 2020/21 financial year was to rehabilitate 5 km of the paved road network, but only 1 km was rehabilitated by 31 December 2020 (mid-year 2020/21) due to funding limitations.[75Government of Malawi, Malawi Annual Economic Report 2021, Ministry of Finance, Economic Planning and Development and Public Sector Reforms, 2021] Poor road conditions imply higher transport costs that reduce the competitiveness of Malawi's exports. Malawi authorities need to enhance transport infrastructure to reduce transport costs and to increase the competitiveness of Malawi's produce in domestic, regional and global markets. MW2063 identifies transport infrastructure development as key to reducing transport costs, which is in line with the National Transport Master Plan (NTMP).

The NTMP provides an opportunity for transport infrastructure development if it is implemented. It aims to provide strategies and a range of projects for urban transport designed to reduce costs and move towards high capacity mass transit in the main cities. The plan fosters a shift from road transport to rail for imports and exports along the major corridors and looks forward to meeting the transport needs of a changed economy in which growth sectors such as mining, oil and tourism will be fostered through improved transport links by implementing a major programme of rural roads upgrading. In addition, the NTMP takes into account the risk that climate change poses to transport infrastructure and services and includes proposals for both mitigation and adaptation measures.[76Ministry of Transport and Public Works, Malawi National Transport Master Plan, 2017]

Information and communication technology

Information and communication technology (ICT) is another critical enabler to achieving Malawi's development objectives. Efforts to expand access to broadband and ICT services could provide a new avenue for economic diversification, reduce distance barriers, improve efficiency in public service delivery and improve productivity with a positive effect on growth and poverty reduction.

Malawi has made progress in expanding digital infrastructure coverage. As of 2020, 83%, 82% and 65% of Malawi's population were covered by 2G, 3G and 4G mobile networks, respectively.[77National Statistical Office (NSO), 2019 National Household Survey on Access and Usage of ICT Services in Malawi, August 2020] Yet high Internet prices, the high cost of smart devices, low electricity access and a shortage of digitally skilled labour, among other reasons, hamper the uptake of ICT services in Malawi.[78World Bank, Malawi Economic Monitor: Investing in Digital Transformation, 23 June 2021] There are currently two mobile networks in the country: Airtel Malawi and TMN. The lack of market competition and an unfavourable tax regime for the ICT sector has resulted in some of Africa's highest prices for telecom services in Malawi.[79BuddeComm, Malawi Telecoms Market Report, June 2022]

Mobile cellular subscriptions are low in Malawi compared to the average for its income peers. Mobile phone subscriptions stood at about 42 per 100 people in 2017, below the average of 49.5 for low-income Africa and far below SADC's average of 74. The Current Path forecast is that mobile phone subscriptions in Malawi will stand at 88 per 100 people by 2030, which is above the Malawi government target of 80 in the same year.

In 2017, mobile broadband subscriptions per 100 people in Malawi stood at 25, compared to an average of 13 for low-income Africa and 26 for SADC. IFs estimated the subscription rate per 100 people at 37 in 2019, in line with the data from Malawi authorities. By 2030, mobile broadband subscriptions per 100 people are projected to reach 88, which is well above the Malawi government target of 60 in the same year. Fixed broadband provides faster Internet access speeds with more secure connections and is important for the high value-add service sector. However, fixed broadband penetration in Malawi is strikingly low, with a subscription rate of 0.05 per 100 people, below the SADC average of 1.3 and 0.2 for low-income countries in Africa. On the Current Path, fixed broadband subscriptions are forecast to be 13 per 100 people by 2030.

According to the 2019 National Survey on ICT Access and Usage, only 14.6% of Malawians use the Internet and connectivity is unpredictable. Malawi lags behind its immediate neighbours such as Tanzania (20%) and Zambia (19%), and is almost on par with Mozambique (15%). Internet connections are mostly via mobile networks. The Current Path forecast is that mobile broadband will continue to be the most common and popular way people in Malawi access the Internet. Internet penetration in Malawi will increase to about 19% by 2030, one percentage point below the expected 20% in the same year in the MW2063 development plan (Chart 25).

The gap between the Current Path forecast and the expected targets is projected to widen after 2030 probably due to the increasing size of the population relative to the ICT infrastructure, as well as poverty. To increase Internet penetration and achieve the target set in MW2063, efforts should be made to expand the provision of LTE infrastructure (wireless broadband communication for mobile devices) in poorer areas, accelerate electricity access, and reduce high Internet prices and the high cost of smartphones.

Enhancing ICT infrastructure and access to ICT services in Malawi will diversify and strengthen economic growth, increase government revenue, and lead to more job creation and innovation. Studies have shown that an additional 10% increase in mobile broadband penetration in Malawi could increase the GDP by US$189 million and tax revenue by US$33 million annually.[80World Bank, Malawi Economic Monitor: Investing in Digital Transformation, 23 June 2021] To this effect, the government of Malawi has developed several strategies, including the adoption of a national broadband and cyber security strategy in 2019. The Digital Economy Strategy 2021–2026 aims to support the growing ICT sector that provides goods and services which spur economic growth and create employment opportunities.

Agriculture is the backbone of Malawi’s small economy but the sector consists of subsistence, rain-fed agriculture, which limits its growth potential and increases its vulnerability to weather shocks. Malawi has experienced slow economic growth over the last decade due to a number of economic, political and climate-related shocks. Economic growth in 2020 was strongly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, falling to 0.8%, four percentage points below the pre-pandemic projections of 4.8%, and the lowest registered growth rate since the 2001 recession. In 2021, favourable weather and agricultural input subsidies contributed to increases in the maize harvest and tobacco production. As a result, the economic growth rose to 3.9% from 0.8% in 2020.