Africa’s prospects for 2024

Africa looks set for a year of sluggish economic growth but lively politics.

With an increasingly volatile and divided world, Africa’s weak economic and political integration makes it vulnerable to external influences. Persistent divisions create the risk of further political turmoil and continuing conflicts, which some external actors may exploit. But Africa’s weight and influence are growing in areas like mining, fintech and creative industries.

Africa’s economic potential remains good. Human resources and abundant physical resources, including raw materials, offer huge potential. Renewable energy and farming all show promise. But both internal and external headwinds obstruct rapid sustainable growth.

At the end of 2023, the IMF predicted that sub-Saharan Africa’s GDP would grow marginally by 4% in 2024, against 3.3% in 2023.

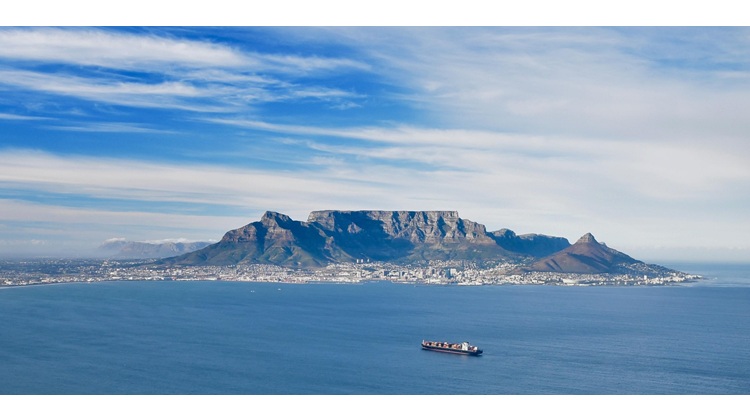

A few countries could top 6%, including Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, The Gambia, Rwanda, Senegal and Tanzania. Several more, like Kenya and the Democratic Republic of Congo, are on track for 5%. But Africa’s biggest economies – Nigeria, South Africa, Angola and Egypt – will struggle to exceed 3%. Still, Africa is set to grow faster than any region in the world except Asia. This indicates its resilience despite multiple global shocks.

With population growth averaging over 2%, extreme poverty will persist and possibly even increase due to conflict and displacement. The World Bank reported that 500 million Africans were food insecure in 2023, and northern Ethiopia already suffers famine conditions this year.

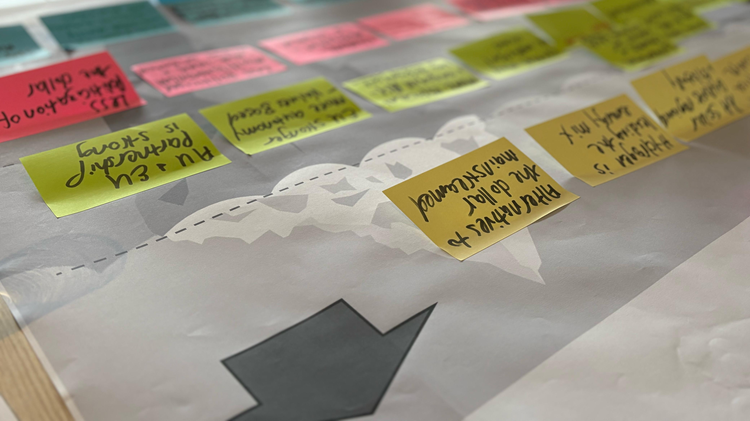

Africa’s weight and influence are growing in areas like mining, fintech and creative industries

Debt levels remain a brake on growth. In 2023, Ethiopia, Ghana and Zambia all defaulted on debt repayments. China is less generous these days, and higher global interest rates have increased the cost of borrowing. As 2024 opens, nine African countries are in debt distress, 15 more are at high risk of it, and a further 14 are at moderate risk. Falling interest rates would help, but political instability discourages private investment. Development funding is stagnant. Only remittances are holding up. Côte d'Ivoire nevertheless raised $2.6 billion in Eurobonds on 24 January 2024. For stable countries, money can be found.

Africa particularly needs finance to manage climate change. Erratic rainfall threatens both farming and urban infrastructure. Governments must encourage climate adaptation in rural water management, urban drainage and construction. Energy infrastructure needs to prepare for renewables. Domestic funding isn’t enough.

Intra-African trade needs to grow

Raw materials still dominate African exports, with imports mainly of manufactured goods. Tourists are another key source of foreign revenue. Taken together, that means global inflation hits Africa hard, weakening currencies and making people feel poorer. Intra-African trade is still only 15% of the total, though more in East and Southern Africa. Accelerating implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) will will help Africa generate more autonomous growth.

Still, there are bright spots: mining, if Africa can negotiate better contracts to meet the global demand; fintech, where Africa’s ability to innovate remains impressive; and creative industries, where its global impact is growing.

In 2024, conflict in Africa’s ‘belt of instability’ from Mali to Somalia looks set to get worse. A number of elections will show if Africa’s democracies can retain popular support

Politically, 2023 looked more like a 1970s rerun, with coups in Niger and Gabon, war in Sudan, and continuing instability in Ethiopia, Somalia, Nigeria and the Sahel. At least elections in Nigeria and the DRC passed off peacefully, with outcomes that, while contested, have been broadly accepted.

In 2024, conflict in Africa’s ‘belt of instability’ from Mali to Somalia looks likely to worsen. Forthcoming elections will show whether Africa’s democracies can retain popular support.

Presidents are likely to retain their seats in Chad, Mauritania, Rwanda and Tunisia. In Mozambique, the tarnished President Filipe Nyusi will step down, though FRELIMO will almost certainly win in October.

But other elections are uncertain. Both Senegal and Ghana will see new presidents as incumbents stand down. In South Africa, the African National Congress will probably lose its majority but seek a coalition with the most pliable partners.

A half dozen countries could experience less voluntary regime change. On the watch list for potential coups are Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, the Republic of Congo, Chad, Togo and Sierra Leone.

The military juntas in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger are all doubling down on their determination to avoid early elections. In January they announced their split with ECOWAS, showing their preference for a military response to jihadist rebellions. So instability will continue.

Despite its political and economic woes, Africa’s profile in the world is rising

The civil war in Sudan, fuelled by outside actors, looks likely to wreak havoc until one side wins a decisive victory. Ethiopia continues to wrestle rebels in Oromia and Amhara, while destabilising Somalia through its new partnership with Somaliland. In all these cases, regional bodies, including the AU, struggle to achieve meaningful negotiation, let alone peace. But they try.

All this means Africa will remain a forum for geo-political contestation. Increasingly, Russia explicitly supports the Sahelian juntas and with China, Russia offers membership of the BRICS group of countries as an incentive for Africans to support them both at the United Nations. Algeria, Angola and Nigeria are in the queue to join the club of emerging markets. Their narrative of helping the Global South resist the influence of the ‘neo-colonialist West’ is gaining traction, helped along by the Gaza conflict. France will continue to be vilified, and the EU and other Europeans are struggling to retain influence.

The current UK government gives little attention to Africa – except Rwanda, for immigration policy reasons. The United States is working hard to retain its own influence, as Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s visit in January showed. Much will depend on the outcome of the US election later this year. Furthermore, Western countries need to accelerate the reform of multilateral institutions if they are to compete for influence.

Despite its political and economic woes, Africa’s profile in the world is rising. The African Cup of Nations (AFCON 2024) is putting Côte d’Ivoire on the world map. African music, arts and culture are having a global impact in the West, especially Europe and the US. Africa’s ever-growing and prospering diaspora is an increasingly significant market and a global influence to Africa’s benefit – if it chooses to be. Watch this space.

Image: Blue Ox Studio/Pexels