China’s overseas lending and debt sustainability in Africa - Seen through the lens of the FOCAC

Criticism of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is misleading and the country did not intentionally entrap BRI countries into debt distress.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has long been blamed for Africa’s debt sustainability. The accusation that the BRI, launched in 2013, is a deliberate ‘debt trap’ first emerged in 2017, and has been used to criticise China’s investment in Africa since.

However this criticism is misleading. China did not intentionally entrap BRI countries into debt distress, as the Sri Lanka case shows. It isn’t Chinese investment, but the model of the Chinese investment, that has contributed to debt distress in some African countries. Chinese lending accounted for only 12% of Africa’s total $696 billion external debts in 2020 and made up less than 15% of debt stock in more than half of the continent’s 22 low-income countries struggling with debt.

That said, Chinese lenders have accumulated a large portion of debt stock in Africa in the past decade. With a higher percentage of Chinese loans in their total external debt stock, debt distress has become a serious problem in countries such as Angola, Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Kenya. China’s state-driven overseas investment model, which is transplanted from its long-standing domestic practices, largely contributes to debt distress in these African countries.

Again, it’s the model, not the investment, that’s the problem.

Different from profit-oriented investment by the private sector, China’s state-backed overseas investment follows a top-down route driven by politics. It usually begins with high-level policy coordination through bilateral agreements or multilateral channels such as the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). Following this will be a project contract signed by state-owned enterprises (SOEs), project approval by government agencies overseeing outbound investment, financial support by state-owned policy banks and commercial banks, and SOE implementation.

It’s not Chinese investment, but the model of the Chinese investment, that has contributed to debt distress in some African countries

Following government guidance, these investments usually go to huge infrastructure projects for transport, energy, real estate, etc. They come in different forms including loans and grants, foreign direct investment (FDI), contracted projects, equity funds and so on.

The state-led investment model can typically lead to problems and risks such as non-transparency and corruption, lower economic efficiency, lower degrees of localisation, and a lack of participation by the private sector and other international investors.

How do these problems that accompany the Chinese outbound investment model contribute to Africa’s debt problems? A mini case study of lending through FOCAC could shed some light.

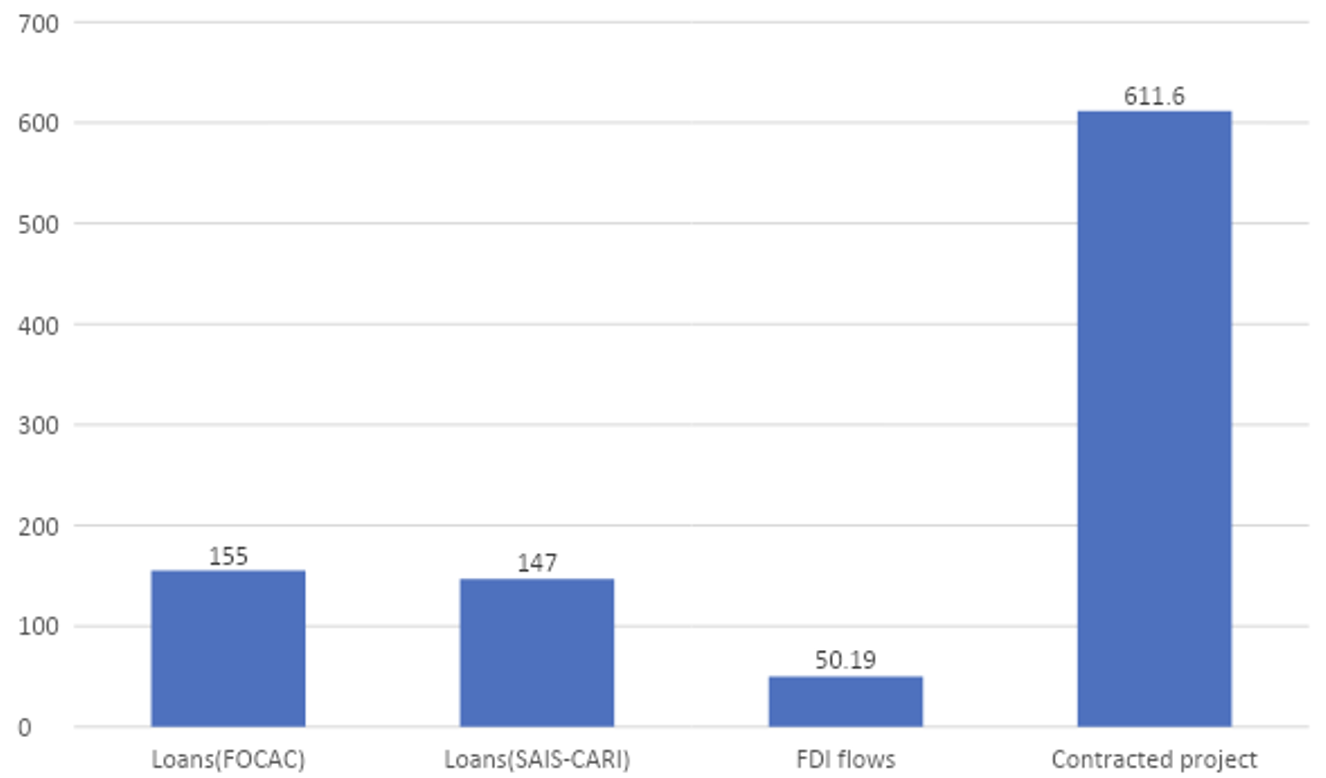

Established in 2000, FOCAC is the primary uni-multilateral mechanism for major policy coordination between China and African countries. The institutionalised forum is held every three years and has become the main platform channelling Chinese loans to Africa since 2006. Total promised lending through FOCAC between 2006 and 2021 was US$191 billion, with about $155 billion of this implemented by 2021 (Chart 1). A comparison of this number with data on China’s FDI and contracted projects (Chart 2) illustrates the significance of the loans financed through FOCAC.

Following the same financing model as China’s state-driven FDI and contracted projects in Africa, lending through FOCAC puts political agendas first, and economic agendas, including loans and investment programmes, must accommodate this. Commitments will be delivered at a preceding FOCAC within the three-year interval. These show China’s consistency in keeping its promise to African countries.

The state-led investment model can typically lead to problems and risks such as non-transparency and corruption

The established mechanisms for implementing FOCAC’s commitments guarantee that the financing arrangements will be fulfilled in three years. China’s official records show that all the loans promised at each forum since 2006 have been implemented in that time (Chart 1).

This seemingly efficient financing arrangement comes at the expense of economic returns for China and recipient countries, and debt sustainability for recipient countries; these are not prioritised goals in China’s state-led lending model. In practice, it isn’t possible for most big investment plans to be implemented in three years. Loans driven by political will under FOCAC are approved and provided in a short time, and can lead to reckless investment and contribute to debt distress.

With the guaranteed government bailout triggered by soft budget constraints, China’s state-owned policy and commercial banks, notably the Export-Import Bank of China and China Development Bank, ensure that providing the loans in three years is the priority. Economic efficiency or avoiding causing debt distress in recipient countries are not priorities.

Africa’s debt distress could be intensified by the small size of its economies compared to China’s, and these rapidly built loan stocks in such short periods. For example, the massive amounts lent to Zambia for a single project (US$337.6 million) under the 2015 FOCAC commitments added hugely to the country’s external debt.

Non-transparency is a big problem associated with the state-backed lending model. Under this model there’s a lack of public scrutiny of loan agreements. This could see African governments who are already cash-strapped borrowing excessively and landing in more debt. Chinese lenders are in a dominant position in these loan agreements. The agreements usually contain complicated guaranteed debt repayment measures and other controls such as confidentiality and ‘no Paris Club’ clauses for debt restructure to secure the creditors’ interests.

In practice, it isn’t possible for most big investment plans to be implemented in three years China’s Belt and Road Initiative has long been blamed for Africa’s debt sustainability

Political achievements, economic interests and bureaucratic gains for China obtained through FOCAC financing explain further why the country sticks to the bilateral lending model. The concession loans, grants and interest-free loans and equity funds made available through FOCAC help strengthen political ties, boost rapport, and realise China’s foreign policy goals.

The BRI, comprising hundreds of bilateral agreements between China and recipient countries, is President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy. Only nine African countries signed up to join the BRI before FOCAC in 2018. Twenty-eight African countries and the African Union Commission signed the BRI agreements during the 2018 FOCAC, helping China to grow the initiative.

Political priority in lending via FOCAC doesn’t mean China cares less about its economic interest – it still benefits with this state-led investment model. Chinese loans usually require state guarantees for repayment from recipient countries. The Chinese concessional loans for infrastructure projects typically come with Chinese SOEs as the main contractors, and a requirement for purchasing equipment and materials from China. This helps reduce its risk of loan defaults and promotes the export of Chinese industrial capacity and equipment.

When African states face financial difficulty, China typically tries to restructure existing debts and postpones the problems with the aim of finding a future solution rather than granting total debt forgiveness.

Bureaucracies in charge of financing through FOCAC and the BRI also benefit. There are many stakeholders under the lending model who can all claim multiple credits from the same loans and projects under FOCAC and the BRI. These include the Export-Import Bank of China, China Development Bank, commercial banks, and SOEs and their supervisor agencies. Government agencies overseeing outbound investment such as the foreign affairs, commerce and finance ministries, the China International Development Cooperation Agency, and the National Development and Reform Commission also all benefit.

Loans driven by political will under FOCAC are approved and provided in a short time

China is Africa’s biggest bilateral creditor. It tends to solve debt problems bilaterally or provide debt relief via FOCAC. Facing strict regulations and responsibility for maintaining the balance sheet and appreciating the value of state assets, Chinese state financiers are eager to assure the loans and investments are repayable and profitable.

But bad loans and debt distress have cost China’s government economically and politically both at home and abroad, and have made Beijing realise that the bilateral approach isn’t enough. In 2017 the country turned to a multilateral approach to mitigate the negative impact that comes with the BRI’s bilateral financing.

Post-COVID-19, China has been under pressure to apply multilateral approaches to Africa’s debt distress. Although reluctantly, Beijing has participated in debt relief initiatives under the Debt Service Suspension Initiative and the G20’s Common Framework, significantly contributing to debt relief. However the amount of debt relief China has promised accounts only for 1% of its total lending to the continent from 2000-20.

China’s preferred state-backed bilateral lending has contributed to debt distress in certain African countries while providing needed loans for development on the continent. The lending model won’t change in a significant way in the foreseeable future. The more important issue is to improve domestic governance and keep a stable political environment for investors in the recipient African countries that can put them in a better position to grow their economies.

Furthermore, the United States and European Union’s counter-measures to China’s BRI, the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment and the Global Gateway, have enabled African countries to more wisely use the investment from both China and the West to improve domestic governance for future development.

Chart 1: Financing through the FOCAC (2006-2021, US$)

|

FOCAC Ministerial Conference |

Total promised loans |

Amounts and forms of financing |

Follow-ups and implementation |

|

|

Form |

Amount |

|||

|

3rd Conference, 2006 (Beijing Summit) |

$10 billion |

Preferential loans |

$3 billion |

Implemented by September 2009, with 54 projects in 28 countries. |

|

Preferential export buyers’ credit (PEBC) |

$2 billion |

Implemented by September 2009, with 11 projects in 10 countries. |

||

|

Establishment of China-Africa Development Fund (CADF) |

$5bn (Raising $1 bn in Phase I, $2bn in Phase II and $2bn in Phase III) |

Invested more than $500 million for 27 projects by 2009. |

||

|

4th Conference, 2009 |

$11 billion |

Preferential loans and PEBC |

$10 billion |

Approved loans worth $11.3 billion for 92 projects by May 2012. |

|

CADF |

Raising $2 billion for Phase II |

Investment increased to $716 million for 30 projects by November 2011. |

||

|

Special loans to support small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) |

$1 billion provided by the CDB |

Promised loans worth $966 million for 38 projects by May 2012. |

||

|

5th Conference, 2012 |

$20 billion credit line |

Preferential loans and commercial loans |

A little more than $10 billion is preferential loans and the rest of it is commercial loans |

An extra $10 billion credit line promised and $2 billion for final phase of CADF increased, making it $5 billion in May 2014 when Premier Li Keqiang visited Africa. |

|

6th Conference, 2015 (Johannesburg Summit) |

$60 billion |

Preferential loans and PEBC |

$35 billion |

Foreign Minister Wang Yi declared at the 7th Ministerial Conference in September 2018 that all measures at the 6th Conference have been implemented. |

|

Grants and interest-free loans |

$5 billion |

|||

|

CADF |

$5 billion added |

|||

|

Special loans for SMEs |

$5 billion added |

|||

|

Initial loans for the China-Africa production capacity cooperation fund |

$10 billion |

|||

|

7th Conference, 2018 (Beijing Summit) |

$60 billion |

Grants and interest-free loans, preferential loans |

$15 billion |

90% of promised $60 billion ($54 billion) has been implemented, except for the portion of preferential loans, according to Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s speech at the 8th Conference in October 2021. |

|

credit line |

$20 billion |

|||

|

Special fund for China-Africa development finance |

$10 billion |

|||

|

Special fund for trade financing (export from Africa) |

$5 billion |

|||

|

Promoting investment from Chinese enterprises |

$10 billion |

|||

|

8th Conference, 2021 |

$30 billion |

Credit line |

$10 billion |

|

|

Promoting investment from Chinese enterprises |

$10 billion |

|||

|

Redirect its IMF Special Drawing Rights reserves |

$10 billion |

|||

|

Sum |

$191 billion |

About $155 billion implemented by October 2021. |

||

Chart 2: Chinese loans, FDI flows, gross revenues of contracted projects to African countries (2006-2021, US$ billion)

Sources: Loans (FOCAC): See Chart 1; Loans (SAIS-CARI): http://www.sais-cari.org/data; FDI flows: http://fec.mofcom.gov.cn/article/tjsj/tjgb/; Contracted Project: National Bureau of Statistic of China: https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01

Notes: There exist overlapping parts between loans and contracted projects or the FDI flows. Loans (SAIS-CARI) refer to data of the Chinese loans to African countries (2006-2019) cited from the Global Development Policy Center of Boston University and China Africa Research Initiative at Johns Hopkins University.

Image: © Oleg Elkov / Alamy Stock Photo