Africa’s challenges in context

It is time to take free and fair elections and good governance seriously

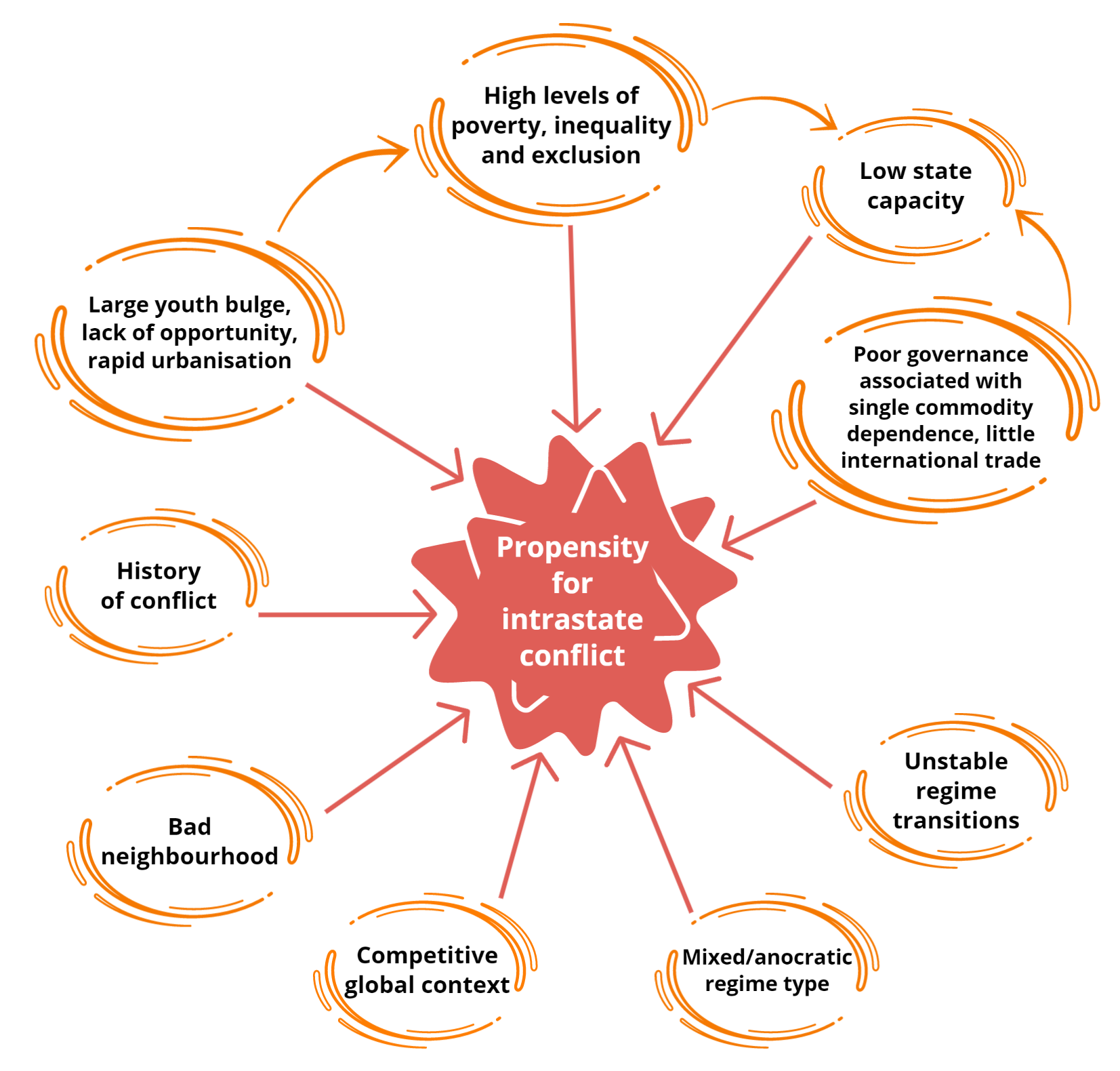

How do we understand the developmental and governance reversals recently haunting Africa? The reasons for the apparent collapse of security are complex (see schematic). However, the common theme among radical insurgencies, coups, and instability is slow development, poor or bad governance, and the nature of Africa’s demographic and other transitions. This at a time when geopolitics is marked by increasing competition, making for an unfavourable international environment for the continent.

Reasons for Africa’s apparent collapse of security

Conflict in Africa is influenced by the global context, although it is a history of conflict that is the largest indicator of future dissension. Previously, conflict in Africa peaked at the height of the Cold War, and today, power is shifting eastward globally. The traditional partners of the African Union (AU), the European Union and the United States (US), are distracted and losing ground. China has not stepped in to fill the gap despite Beijing’s Global Security Initiative.

At the same time, various Gulf countries active in the Horn of Africa do not conform to established international norms and have little associated experience. The result is a proliferation of bilateral, regional, international and other initiatives that allow for forum shopping by belligerents.

All of this comes when the AU is floundering. It has stepped back from the 2000 Lomé Convention and its commitment to condemn coups by, for example, allowing the repackaging of the 2017 coup in Zimbabwe to avoid the suspension of Emmerson Mnangagwa’s regime from the AU. It repeated the mistake with the 2021 coup in Chad. Then, in 2019, in Sudan, the AU agreed that the coup plotters could participate in the subsequent process to re-establish civilian control.

The AU should comprehensively review the challenges it now faces to enable a coherent response

These examples have incentivised militaries elsewhere who now believe they can be part of the subsequent transitional arrangement without respecting timelines or removing themselves from the political scene. Flawed elections and constitutional manipulation to allow regime survival now occur regularly.

The AU has effectively stepped back from the comprehensive African Peace and Security Architecture established in terms of its Peace and Security Council (PSC) Protocol meant to Silence the Guns. Even its early warning unit has been disbanded. Apart from several training institutions, little has come of the five regional standby forces constituting the African Standby Force, including the associated logistics capacities. Even then, its peacekeeping conceptualisation is out of sync with current security challenges.

The Panel of the Wise, supposedly the AU’s most crucial conflict mediation tool, is not called in to mediate, whereas the demand is evident and needed more than ever. Nor are the underfunded offices of Special Envoys put to good use. The Peace Fund is now better funded with around US$400 million. Still, disbursement is complex, and the monies are inadequate to fund even the most modest peacekeeping operation, while the United Nations (UN) dithers about assuming financial responsibility for AU peacekeeping operations, which now outnumber its own.

Instead of strengthening the AU, the reforms led by Rwandan President Paul Kagame and various consulting companies have seen it regress by merging its Department of Political Affairs with Peace and Security, reverting to the architecture of its predecessor, the Organisation of African Unity. The potential of the African Peer Review Mechanism to provide a mechanism for self and peer review on good governance practices has also come to nought.

Like China, African leaders appear to want the right to abuse their citizens without comment or sanction by others

The AU is labouring with divisions and inefficiencies within its Bureau and Permanent Representative Committee, which undertake the political oversight and implementation of the decisions taken by the Executive Committee and the Assembly of Heads of State and Government.

Sitting at the apex of the AU’s Peace and Security Architecture, the PSC averts its eyes from instability in larger countries such as Ethiopia and Sudan. It does not effectively monitor elections or pronounce unconstitutional transitions of power and rigged elections. The cautious remarks of the Southern African Development Community to break from its tradition of unquestioned support to governing liberation parties and comment on Zimbabwe’s fraudulent elections were perhaps the only recent bright spark.

The PSC seems overwhelmed. It defers decisions, such as on Niger, to the regions, in this case, the Economic Community of West African States. The AU and its security and governance architecture react rather than lead at a time when Africa is now a member of the G20, which will require heavy lifting on policy input on various complex issues.

In summary, national, regional and international governance is weakening instead of strengthening.

At first blush, democracy has failed Africa. The reality is that Africans continue to believe in the promise of democracy – but want elections to be free and fair, and so should the AU and regional economic communities (RECs). If Africans insist that foreigners not criticise domestic abuse, they should have the decency to call it out themselves. Instead, the AU and its various RECs look the other way when incumbents extend their stay in power by manipulating the constitution and stealing elections.

Africans continue to believe in the promise of democracy – but want elections to be free and fair

Like China, African leaders appear to want the right to abuse their citizens without comment or sanction by others – a situation where national sovereignty is absolute. The result is that elections and the subsequent governments have limited legitimacy. In response, citizens rebel or simply do their own thing.

Turning these trends around will take time, and the impending choice of new leadership at the AU will distract attention from the situation in the Sahel, Sudan, Ethiopia, and other crises.

Among other reforms, the AU and RECs should clarify and revisit the subsidiary model (i.e. the relations between the RECs and the AU), including the relationship of the RECs with the UN. Some RECs are responding without real engagement by the AU, and the mantra of African solutions is not always helpful as it appears to allow interference by neighbours.

Most importantly, the AU needs to refocus on the tenets of good governance, including regular free and fair elections.

National, regional and international governance is weakening instead of strengthening

It will take a long time to recover from the current reversals. And even then, recovery is vitally dependent on inclusive economic growth and good governance, as our analysis on the African Futures website highlights.

The AU should comprehensively review the challenges it now faces to enable a coherent response. It did it previously with the 1990 Declaration on the Political and Socio-Economic Situation in Africa and the Fundamental Changes Taking Place in the World, which, in turn, led to the 1993 Cairo Declaration on the establishment of its Mechanism for Conflict Prevention, Management and Resolution. The Cairo Declaration eventually gave birth to the AU’s comprehensive Peace and Security Architecture in 2002 when the associated protocol was adopted.

It’s time to reinvigorate and recommit to the PSC Protocol and to comprehensively revise and implement the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance.

Image: Majority World CIC / Alamy Stock Photo