Accelerate, Extend, or Abandon? Africa’s SDG Dilemma

Africa is likely to miss most UN SDG targets — should we extend the 2030 deadline, abandon it, or accelerate action on key priorities?

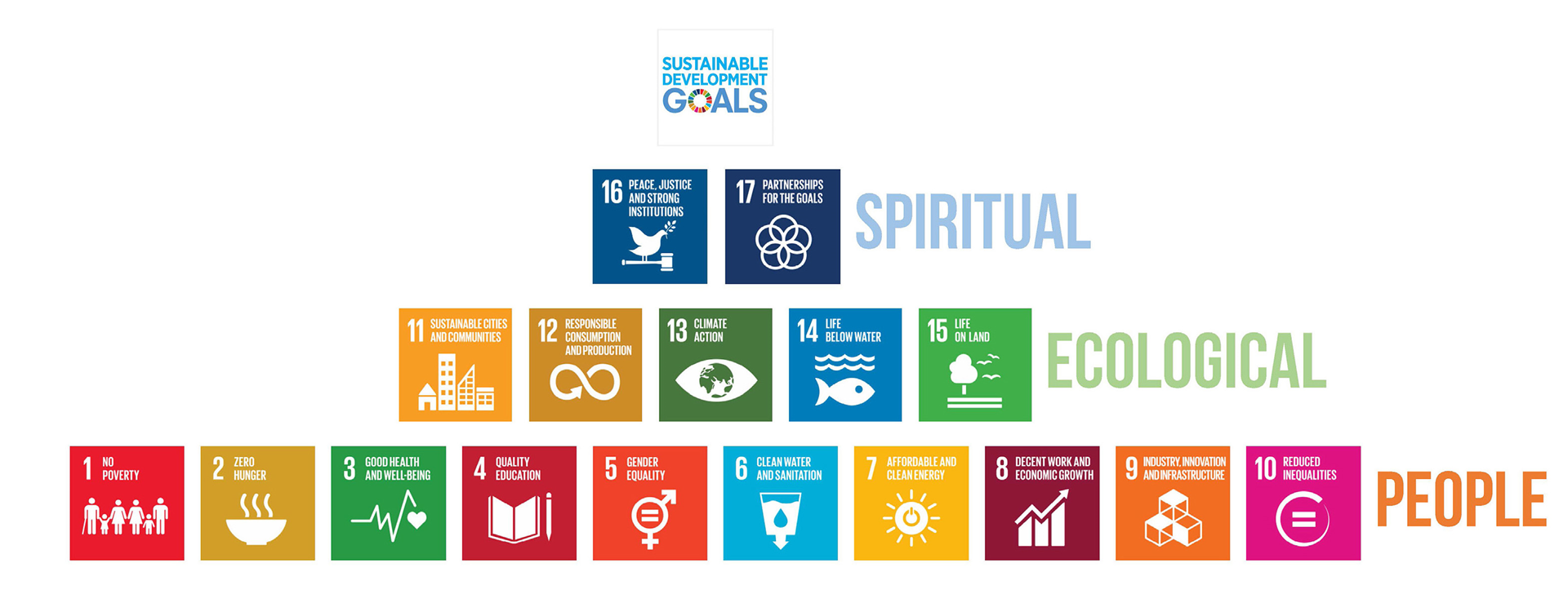

As the world prepares for the 2024 United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) and the Summit of the Future next month, Africa stands at a critical juncture. With just six years left until the 2030 deadline for the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), it is becoming increasingly evident that the continent is unlikely to meet most of these ambitious targets. This stark reality forces Africa to grapple with a difficult decision: Should it double down and accelerate its efforts, reconsider the 2030 deadline by extending it, or even contemplate abandoning certain goals altogether – channelling resources into much-needed critical areas that are more aligned with the specific priorities of individual countries?

The numbers present a sobering reality: out of the 144 measurable SDG targets, Africa is on track to achieve only 10 by 2030. An overwhelming 106 targets require accelerated action to be met, while 28 indicators are moving in the wrong direction. While Africa has made promising progress on SDG 9 (specifically mobile network coverage) and SDG 4 (specifically school enrollment rate), many critical goals are unlikely to be met.On its current trajectory, Africa is projected to have over 23% of its population still living in absolute poverty by 2030 (SDG 1), while the rest of the world is expected to have dipped below the desired 3% mark. Only Tunisia, Algeria, Mauritius, Gabon, Egypt, Seychelles and Morocco have achieved this target, with Libya and Cabo Verde well on track to meet this target by 2030. Countries like Cote d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Senegal and Equatorial Guinea can still meet this goal if accelerated action is prioritised. However, Madagascar, Mozambique, Malawi, Central African Republic, Burundi, Lesotho and the Democratic Republic of Congo are likely to have more than 50% of their population still living in absolute poverty, with Madagascar, Mozambique and Malawi having poverty rates above 70%.

In Africa, an overwhelming 106 targets require accelerated action to be met, while 28 indicators are moving in the wrong direction

This challenge is not unique to Africa; globally, the UN's 2023 SDG Progress Report highlights that only 15% of the SDGs are on track, with nearly half of them either moderately or severely off course. However, Africa’s performance is particularly concerning, raising critical questions about the viability of the 2030 deadline.

The SDGs were conceived as successors to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which aimed to address the most pressing global challenges between 2000 and 2015. While the MDGs achieved notable successes, such as halving extreme poverty and improving access to clean drinking water (mostly making progress in China and to some extent in India), they also faced significant shortcomings, particularly in areas like maternal health and environmental sustainability. The SDGs were designed to build on these achievements and address the gaps left by the MDGs, expanding the scope to include goals such as reducing inequality, combating climate change and promoting sustainable economic growth. Yet, the current trajectory suggests that, without a significant shift in strategy, the SDGs will fall short of their ambitious aims, just as the MDGs did in certain areas.

There are overwhelming calls for accelerated action to achieve the SDGs. Last month, President Nana Akufo-Addo of Ghana emphasised the need for a significant push to mobilise the resources and political will required to meet these goals. He highlighted reforms that could help unlock the estimated US$1.3 trillion needed annually, through stronger domestic revenue mobilisation, public-private partnerships and innovative financial mechanisms like blended finance. However, the challenges to acceleration are formidable. The required financial mobilisation is unprecedented, and it is unclear whether the political will exists across the continent to push through the necessary reforms. Many African countries are also facing severe challenges that may leave them without the capacity to meaningfully address the SDG goals. Additionally, the remaining gaps are immense, particularly for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) in Africa, where insufficient financing remains a major barrier, exacerbated by debt burdens, reduced fiscal space and limited access to global financial markets.

The African Futures and Innovation (AFI) team at the ISS has modelled various reforms and development strategies aimed at achieving meaningful and sustainable development in Africa. Even under its most optimistic scenario, the Combined scenario — one assuming significant improvements in governance, financial reforms, integrated trade and domestic manufacturing (amongst others) — many 2030 targets remain unattainable.

Given these challenges, extending the 2030 deadline seems like a pragmatic option. A more flexible timeline could align with Africa’s unique socio-economic and environmental contexts, allowing for a more measured pace of development. Aligning the SDG timeline with Africa’s Agenda 2063 could provide a coherent framework, offering a longer-term vision more in tune with the continent's realities setting progressive goals and intermediate timelines. This extension could also enhance the relevance and impact of the SDGs by integrating regional goals tailored to diverse contexts across the continent, overall enhancing the impact, relevance and impact of the SDGs.

However, extending the SDG timeline beyond 2030 risks undermining global development efforts. It could dilute the urgency to tackle pressing challenges, leading to complacency and reduced political will. This delay may worsen inequalities, leaving vulnerable populations further behind. For instance, sidelining goals related to poverty reduction (SDG 1) could mean that around 1 in 3 people in sub-Saharan Africa will continue to live in extreme poverty, perpetuating cycles of deprivation and hopelessness. This, in turn, could exacerbate inequality (SDG 10), leading to heightened social unrest and potential conflicts. Moreover, postponing critical climate actions could cause irreversible environmental damage, eroding trust in global commitments and setting a troubling precedent for future international development agendas.

It is also useful to ask whether the SDGs are fully aligned with Africa’s unique development trajectories. Some goals may be unattainable within the current framework due to deep-rooted structural issues, such as economic dependence on a narrow range of exports, inadequate infrastructure, and limited access to essential services like energy, healthcare and education. In such cases, abandoning or significantly redefining certain SDGs could allow Africa to concentrate its efforts on more attainable objectives that prioritise country-specific targets. This strategic reallocation of resources might lead to more significant overall development outcomes for individual countries, though it risks fragmenting global efforts and undermining the momentum needed to tackle global challenges like poverty, inequality and climate change.

Given the significant external and internal challenges facing Africa, an Africa-specific approach is needed. This would involve a strategic combination of efforts to accelerate progress where feasible, extend deadlines where necessary, and, in some cases, abandon or redefine goals that are clearly unattainable within the current framework.

For instance, focusing on sectors where Africa holds a strategic advantage, such as renewable energy and digital innovation, could lead to significant socio-economic benefits. According to projections by the AFI team, in the pursuit of rapid development, Africa may need to depend on natural gas as a temporary energy solution in addition to renewables and nuclear, especially in the next decade or two, until alternative sources become more viable. Strictly applying the United Nations Environment Programme’s fossil fuel reduction guidelines across Africa could lead to an energy shortfall that hinders the continent’s growth.

Additionally, efforts to boost local processing of extracted minerals are expected to elevate carbon emissions in the short term, complicating Africa's climate commitments. Thus, while progress in these sectors could spur economic growth, alleviate poverty, expand electricity access, create jobs and promote development, these advantages must be carefully balanced against the environmental consequences and the broader implications for global climate objectives. Consequently, the international community may need to intensify its climate mitigation efforts to allow Africa the flexibility it requires to achieve rapid growth. This could include providing financial and technical support for clean technologies, facilitating knowledge transfer for sustainable practices, and enhancing global cooperation on climate adaptation and mitigation strategies.

The upcoming Summit of the Future must serve as a catalyst for prioritisation around bold, strategic decisions that speak to the core challenges at hand

The upcoming Summit of the Future must serve as a decisive turning point, compelling leaders to confront the critical choices that will shape Africa’s developmental future. The summit should be more than just a discussion forum or a call for finances. It must be a catalyst for prioritisation around bold, strategic decisions that speak to the core challenges at hand. African leaders, in partnership with the global community, must rigorously evaluate the pathways of acceleration, extension, or abandonment of specific SDG targets, all while deeply considering the continent’s unique challenges and opportunities. Failure to make these difficult but necessary trade-offs risks entrenching the same fragmented and inconsistent approaches that have hindered progress in the past.

Image: United in Diversity/WikimediaCommons