What divides us? And the impact on democracy and stability

The growing divide between the Global North and Global South is driven by economic, political and environmental factors and has impacts on global governance and stability.

Our divided world

We know the storyline - the world is experiencing seismic shifts in power distribution, trade, influence and political cultures and the responses are insufficient. These changes, we are told, are more consequential even than the collapse of the Soviet Union some decades ago. The rise of China, economic growth in the Global South, the effects of climate change, political turmoil in the Global North and higher levels of conflict globally all have contributed to a period of exceptional volatility. As a result, expectations of the United Nations Summit of the Future at the end of September were low even as it was billed as a ‘once-in-a-generation opportunity to shape multilateral solutions for a better tomorrow’.

Gridlock, rather than collaboration, is the order of the day, given the polarisation between the United States and China, and increasingly between the G7 and BRICS+ groupings.

Gridlock, rather than collaboration, is the order of the day

The results are reflected in the divided opinions between the Global North and the Global South on Russia’s war on Ukraine and with respect to Israel's collective punishment of Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank, although there are also significant divergent views within each region.

This brief article starts by sketching out the extent of the growing gap between the Global North and the Global South. It then moves on to explore the impact on future democratisation and its relationship with capitalism and globalisation. The conclusion reflects on the required scale of meaningful pre-emptive action and African views on global developments.

The growing gap between the Global North and the Global South

Earlier this year, the Human Development Report 2023/2024 pointed to the gridlock that has developed from uneven development and lamented the lack of multilateralism amongst intensifying political polarisation. UN Secretary-General António Guterres is at the forefront of repeat warnings about the emerging global crises unfolding under his watch, and the price of inaction.

The extent of uneven development is evident when comparing measures such as GDP per capita (despite its well-known shortcomings). The accompanying chart presents the average GDP per capita from 1980 among eight global groups with a forecast from the International Futures forecasting platform to 2050. The groups comprise seven geographic regions constituting the Global South: sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and North Africa, Central Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, East Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean vs the Global North (the West). The latter group differs from the others because its membership is not geographically contiguous. It includes all larger industrialised, liberal democracies, including Canada, the US, all EU countries, the UK, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand.

Not unexpectedly, the average GDP per capita of the Global North is much higher than that of any other group. The GDP per capita of the poorest grouping, sub-Saharan Africa, is around 7% of the average for the Global North and remains at that portion into the future, reflecting no catch-up. In absolute terms, the gap increases from around US$47 000 per person in 2024 to more than US$72 000 per person by 2050.

Only East Asia is avoiding further backsliding in relation to the Global North. Its average GDP per capita is currently around 36% of the Global North, improving to an impressive 47% in 2050. The ratio is, however, a scant source of comfort since the absolute difference still increases from just below US$33 500 to more than US$41 000 by 2050.

It is difficult to envision a stable global future given these significant disparities when one considers the accelerated effects of climate change that will, by mid-century, have made large swaths of sub-Saharan Africa and Asia uninhabitable. Given these divergences and the power of social media, large-scale migration pressures on much of the Global North, Europe in particular, will follow. No amount of hard borders will be able to contain what will come particularly given Europe's declining population and its demand for labour. These flows will inevitably come with significant domestic political effects, some of which have started to unfold in recent years.

Only much more rapid development and investment in large-scale adaptation in critical regions of the Global South could moderate this situation.

At the African Futures & Innovation Program, we have invested considerable resources in modelling the future of Africa. The results should be a wake-up call to Europe, particularly given its proximity. In the most aggressive development scenario, the GDP per capita of sub-Saharan Africa increases by more than 30% above a business-as-usual forecast by mid-century. But it hardly dents the growing gap with the Global North, given the low levels from which it originates, although it could keep some Africans at home by mid-century. Africa then accounts for a quarter of humanity.

A fourth wave of democracy?

Wittingly or unwittingly, the West's approach to the Global South is deeply embedded in modernisation theory, which holds that, over time, societies become better educated, more prosperous, and eventually more inclusive and democratic. After all, the belief in China’s inevitable modernisation, on top of the attraction of its vast market, led the US and then Europe to include China in the World Trade Organisation and other multilateral institutions in the belief that it would, in time, evolve closer to the West's self-image.

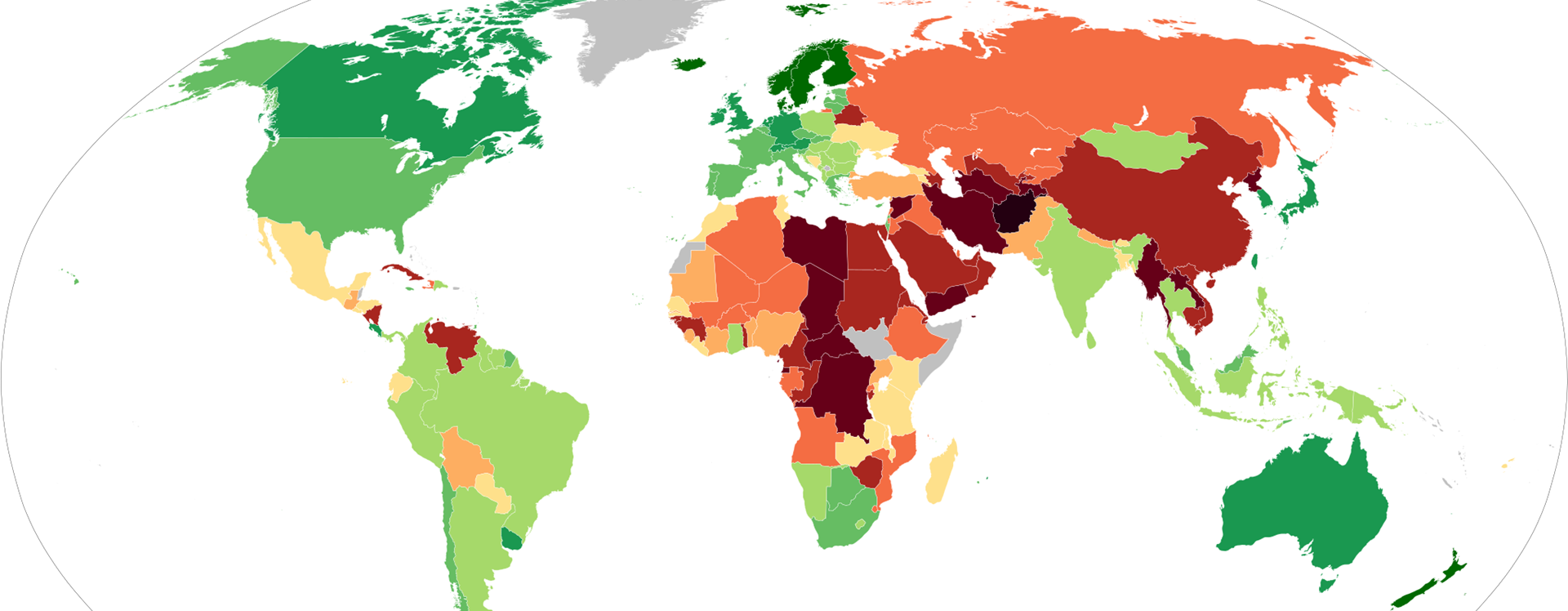

Relative to their development indicators, two regions can be considered to be more democratic than would otherwise be expected: Latin America and the Caribbean, and sub-Saharan Africa. Generally, this is the result of proximity and engagement from the US and Europe respectively. History, military intervention and conditional development aid from the US and Europe have left an indelible footprint on each.

South Asia too, does better than expected, largely because it has a democratic India at its core, in spite of the decline in the quality of democracy in recent years.

Yet, recent years have seen considerable evidence of a democratic retreat globally — an authoritarian resurgence — including in the Global North. The headline findings from the 2024 Democracy Report from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project show that the average level of democracy enjoyed by the average person in the world in 2023 has declined to be equivalent to 1985. Country-based averages, the authors find, are back to 1998.

Recent years have seen considerable evidence of a democratic retreat globally — an authoritarian resurgence

The four regions that do worse with levels of democracy are Central Asia, Southeast Asia, the MENA region, and East Asia, which include China, Hong Kong, North Korea, and Mongolia. To a degree, rapid development can offset the demand for individual self-actualisation, which is characteristic of various oil-rich countries in the Middle East and North Africa but it may also be that a democratic retreat in some of these regions is due to the rise of authoritarian China and the eminent success that is has achieved in delivering improved livelihoods.

Other large data projects concur. Freedom House’s 2023 report concludes: ‘Global freedom declined for the 18th consecutive year in 2023.’ The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA), another large data provider on the evolution of democracy globally, agrees. Their Global State of Democracy 2023 report finds that ‘Across every region of the world, democracy has continued to contract, with declines in at least one indicator of democratic performance [out of four] in half of the countries covered… and that net declines outnumber net advances for the sixth consecutive year.’

It is particularly glaring that the advance of democracy in much of the Global South has not delivered on the promise of better governance and more rapid development. Latin America and the Caribbean countries, together with sub-Saharan Africa, all have relatively high average levels of democracy when considering various indicators of development such as rates of infant mortality and life expectancy. Instead, the regions generally doing better, Southeast Asia and East Asia, have managed to improve government effectiveness (as measured by the World Bank as part of its World Governance Indicators) without much change to democratic accountability. Southeast Asia has grown more rapidly than any other region in recent years, but levels of democracy are barely above the averages for MENA and Central Asia.

What explains this remarkable shift in outcomes since Francis Fukuyama and others confidently wrote about the inexorable rise of liberal democracy some years previously? And what are the implications for Europe?

We posit two general explanations that allow some exploration of the future while acknowledging the large disparities in each region.

Giantism

The first is simply the spill-over effect of democracy or authoritarianism from a dominant core into its surrounding region. The balance of power between the core and the periphery will continue to play an important role in the future.

The Chinese economy is already larger than the US in purchasing power parity terms. It will be larger in market exchange rates at around 2038, at which point it will constitute more than 21% of the world’s economy. As China rises, its authoritarian model will continue to inspire and serve as an example in much of Asia and, inevitably, in other regions such as sub-Saharan Africa and even Latin America and the Caribbean as its trade and influence expand. China is already a much larger trading nation than any other.

There are limits to this line of thinking. The Chinese development and governance model is unique1 and probably not replicable outside the country and, different to the West of the late 20th Century, China does not wish to act as a global policeman or -women. It simply wants to be acknowledged as the most powerful (typically referred to as a Sinocentric world) and left to its sovereign devices without being judged or characterised by former imperial powers that subjected China to a “century of humiliation”. Still, it will shift the focus away from individual rights and democracy and towards authoritarian development models in those regions most intimately tied to it and embolden others in more distant regions to do the same. Southeast Asia has the most intimate connection with China due to its geographic proximity, centuries of migration, culture, trade and, recently, the impact of the Belt and Road project.

The extent to which democracy advances or retreats in South Asia, including in countries such as Bangladesh and Pakistan, will be influenced by what happens in India, and between India and China given the mutual animosity and rivalry. India is nominally the world's largest democracy when using population as a criterion and it is rising - but India is more than a generation away from great power status.

What happens in the West is also important since it will still account for half of global GDP by mid-century, having declined around five percentage points from its current contribution. However, whereas the West currently constitutes 14% of the world’s population, by 2050, it will be down to 11%. The US too will remain important. By 2050 it will still constitute one-fifth of global economic output, only three percentage points below China, then the largest economy globally.

The difference and potential dominance of groups will be determined by their partnerships and alliances, which currently favour the West rather than China. However, as the latter increases in size and influence, any number of countries in the region will shift into its economic and political orbit.

The difference and potential dominance of groups will be determined by their partnerships and alliances

Democracy and capitalism

We believe a second reason relates to the relationship between democracy and capitalism.

For Fukuyama and colleagues, the Western origins of democracy determine its future - embedded in capitalism as an economic theology - that political freedom requires economic freedom in the form of the free market and globalisation. ‘We are taught to think our democracies are held together by values, ’ writes Edward Luce2, ‘but liberal democracy’s strongest glue is economic growth.’ Instead of rapid growth, the years after the 2007/8 financial crisis have been characterised by slow growth then compounded by the COVID-19 crisis and today, trade nationalism as Western countries try and limit trade with China through reshoring, friendshoring and suchlike. The era of “slowbalisation” has arrived with slower growth in most regions.

The view of David Buckham, Robyn Wilkinson and Christiaan Staeuli ring true in that ‘democracy peaked in the 1990s following which the capitalist system has run amok, socially elevating greed and hubris to inevitably destructive outcomes.’3 The associated rise in inequality, particularly the stagnant incomes of the bottom 90% of the population, has provided a fertile ground for populists in the Global North and authoritarian leaders in the Global South.

Whereas the free-market system previously underpinned the ideology of liberal capitalism, in its modern, extreme neoliberal guise that accompanies populism in the West, it now threatens to destroy it. Capitalism is no longer rooted in democratic values but has escaped from the bonds of liberal democracy. In much of the Global North, democracy is now an economic model that benefits the ultra-rich through the concentrated economic and narrative power of social media and related companies that set the political agenda. A handful of social technology companies with business models that encourage dissent (social media in particular) have become extraordinarily large and powerful globally and spread the myth that technology such as generative artificial intelligence benefits all whilst the natural effect, without corrective action by government, is that it entrenches privilege4. The spread of information and communication due to unregulated social media has led to polarised, populist leaders and social movements harnessing democratic institutions for illiberal ends.

In much of the Global North, democracy is now an economic model that benefits the ultra-rich through the concentrated economic and narrative power of social media and related companies that set the political agenda

Interpretation

Democracy is not a panacea for development, and we expect frustration with democracy and the growing gap between the Global North and the Global South to undermine its appeal. In an era of slow global growth and a growing gap between the Global North presented previously on top of the shift of economic heft towards China, we probably need to revisit our expectations about a fourth wave of democracy and the resumption of democratic advancement in much of the Global South.

Eventually, democracy, capitalism, and globalisation must be unlinked from one another. Leaders in the Global North need to be dissuaded from propagating the view that markets generally work well and governments poorly. ‘Free and unfettered markets’, writes Joseph Stiglitz5, ‘are more about the right to exploit than the right to choose’. There is no such thing as a free market, wrote Ha-Joon Chang in his 2010 best-seller 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism6 before proceeding to point out that companies should not be run in the interest of their shareholders, that most people in rich countries are paid more than they should be and that free-market policies rarely make poor countries rich. The pursuit of these beliefs has directly contributed to the current turbulent times where cost-benefit analysis dominates policy in the Global North.

Indirectly, democracy does contribute to more rapid and equitable development for upper-middle and high-income countries, but there is little evidence that rapid and early democratisation at low development levels unlocks improved livelihood outcomes while unregulated capitalism in high-income countries undermines democracy.

What is to be done?

The UNDP’s Global Development Report 2024-2025 notes, ' We are at an unfortunate crossroads. Polarization and distrust are on a collision course with an ailing planet.’ Its subsequent recommendations are politically palatable but provide no meaningful guide. It proposes that we ‘build a 21st-century architecture for global public goods … dial down temperatures and push back polarization …narrow agency gaps’ - none of which capture the imagination or reflect the dedication required to avert or manage the emerging global crises. Rather it seems more likely that the World is heading towards a global tipping point. Then it could, of course, be too late but that is what happened at the end of the Second World War, after the crisis that followed the First World War.

There has seldom been sufficient consensus about an impending global disaster to spur pre-emptive action at scale. Disaster-spurring action is, therefore, more likely than early prevention. To this end, we developed a series of illustrative, long-term global scenarios: a Sustainable World, a Divided World, a World at War, and a Growth World and modelled their effects on Africa (see box). In line with the historical precedent of crisis leading to response, the potential pathway to a Sustainable World only emerges from a World at War scenario.

|

In the alternative global futures scenarios modelled by our team, the current trajectory most closely aligns with the Divided World scenario that reflects disaffection with the Western rules-based system. This scenario reflects the acceleration of the current trends towards a more fragmented global order, an associated retreat from the Western rules-based system, and the more rapid rise of China to become globally dominant towards the end of the forecast horizon. The World at War scenario is the worst case for everyone, as overall gains are below any other. War in Europe and the Middle East is followed by wars in Asia. The scenario could escalate from the war in Ukraine to conflict in the Middle East or Asia as China and India come to blows. Military expenditures and inequality increase. Africa still grows, but very slowly. Neoliberal, trickle-down economics and increased corporate concentration characterise the Growth World scenario, which leads to better economic results but to the detriment of equality and efforts to contain global greenhouse gases, resulting in negative climate change impacts. The Sustainable World scenario maximises Africa's economic potential, such as income and poverty reduction improvements. The international community acts in concert to balance growth and distribution by reducing overall consumption and constraining greenhouse gas emissions. However, it is the most difficult scenario to attain and most likely to emerge from a crisis such as the World at War scenario. See our theme page: Africa in the World |

There are ways in which pre-emptive action at scale can avoid such an apocalyptic pathway - ways in which leaders and civic action can alleviate the global divide, none of which are easy and will be accompanied by considerable pain. Most obvious is the potential with the steady expansion of development to countries currently considered on the periphery of the West. Examples are found in North Africa and countries such as Turkey that are turning away from Europe, as well as in Central America. Extending the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and the European Union southward into Central America and North Africa has the most potential, as complex as that would be. The benefit of expanding from a solid base has always proven to be a strategy with the most likely positive outcome.

Other considerations are also important. For example, countries in the MENA region evidence general declines in development indicators and democracy, and their future will likely be determined by the extent to which Islam is evolving, rather than other factors.

The future is inherently unknowable, and any number of events could disrupt these scenarios and pathways, such as the death of a key leader such as Xi Jinping or Vladimir Putin - just consider what could have occurred in the US if the attempted assassination of Donald Trump had succeeded! China may democratise, inevitably a violent process with huge ramifications internationally, or we could see the dramatic expansion or contraction of the European Union - the only global actor able to moderate the drift towards extremism. But we cannot bank on the unexpected.

Privilege and resources translate into leadership, and for the time being, only the West has the power to unlock the pathway towards a more prosperous and stable global future. That is a long shot in the best of times. It will be determined by the results of the presidential elections in the US in November, an end to Russia’s war on Ukraine, and the intensifying competition between the US and China, each of which could go disastrously wrong.

These three matters are closely related. Should Donald Trump become president it will weaken the West, embolden Russia in Ukraine and possibly ignite a global trade war with considerable collateral damage. From the perspective of the West divergence between its two main blocks, the US and Europe, as well as political decline in each (populism) will detract from the appeal of democracy, globalisation and capitalism. Instead, what is necessary is for the West to come to terms with the evolving global order. As we wrote elsewhere:

There is, simply put, no strategic profit to be gained by the ongoing demonisation of China in the US and Europe and vice versa. The Chinese Communist Party will not abandon its collectivist views on politics and development as much as democratic countries will not abandon a belief in individual freedoms and political rights. Nor can the West constrain China’s momentum towards great power status. What is needed is a determined effort to rebuild relations between the West and China to one of mutual respect and acknowledgement of the differences in approaches to development and governance.

Such an approach would lead to a sigh of relief in the Global South, particularly in Africa, which faces the most intractable development challenges. Instead of pawns in a great global game, African leadership's priority is to focus laser-like on every obstacle to maximise its sustainable development prospects. That includes a next-generation rules-based global system that will facilitate poverty reduction, economic growth, stability, and investment in the Global South. In that context, choosing to side with China, the US or Europe on matters not directly concerned with Africa or playing the one-off against the other serves no purpose.

Image: Wikipedia/Wikimedia Commons

This guest paper was written in anticipation of the second The Hague Strategic Foresight Forum Talks ‘Global Perspectives on Future Security Trends’, a closed-door event on 23 September 2024.

This paper was originally published by The Hague Center for Strategic Studies, Netherlands on 19 September 2024 and can also be downloaded as a PDF version here.

The paper draws on ongoing work for the International Development Research Centre conducted by the AFI team.

References:

1. See, for example, the excellent book David Daokui Li, China’s World View, WW Norton & Company, New York, 2024

2. Edward Luce, The Retreat of Western Liberalism, Little, Brown, London, 2017, p. 13

3. David Buckham, Robyn Wilkinson and Christiaan Staeuli, Unequal, Ad Lib, London, 2023, p 18

4. Joseph E Stiglitz, The Road to Freedom - Economics and the Good Society, Allen Lane, London, 2024, p 206

5. Joseph E Stiglitz, The Road to Freedom - Economics and the Good Society, Allen Lane, London, 2024, p 10

6. Ha-Joon Chang, 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, Penguin, 2011, pp 1-10