13 Work/Jobs

13 Work/Jobs

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

This theme explores Africa’s evolving employment landscape by analysing current trends and the projected outcomes of eight sector-specific scenarios—Demographics and Health, Agriculture, Education, Manufacturing, the AfCFTA (Free Trade), Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging, Financial Flows, and Governance—as well as their combined impact.

Under the Current Path (business-as-usual forecast), job creation lags significantly behind the continent’s fast-growing labour force, leaving many Africans reliant on informal, low-quality work for survival.

A central question is whether digitisation and technological innovation, as seen in countries like Ghana, can accelerate economic formalisation and employment growth across Africa. Achieving this will require a fundamental shift in policy and mindset, moving beyond incremental gains, toward bold, transformative strategies that expand opportunity.

The Combined scenario, representing the coordinated implementation of all eight positive sectoral interventions, offers a significantly more optimistic outlook. However, addressing persistent deficits in education and healthcare remains critical to developing a skilled, productive workforce. Even with these advances, many African nations will likely need to implement public employment programmes and social safety nets to reduce poverty and support those excluded from formal labour markets.

For more information about the International Futures (IFs) modelling platform used for the forecasts and scenarios, please visit the Technical page.

Summary

This theme begins with an introductory overview of the historical and current context of work in Africa. The report explores and assesses the concept of employment and informality, as well as the structure of African economies.

- According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), much of Africa’s workforce—despite being classified as “employed”—is engaged in informal, low-productivity activities. As a result, the average unemployment rate in Africa in 2024 stood at 6.7% with an estimated 85% of employment in Africa being informal. National disparities are stark, with South Africa (33.2%), Djibouti (25.9%) and Botswana (23.1%) reporting among the highest rates on the continent.

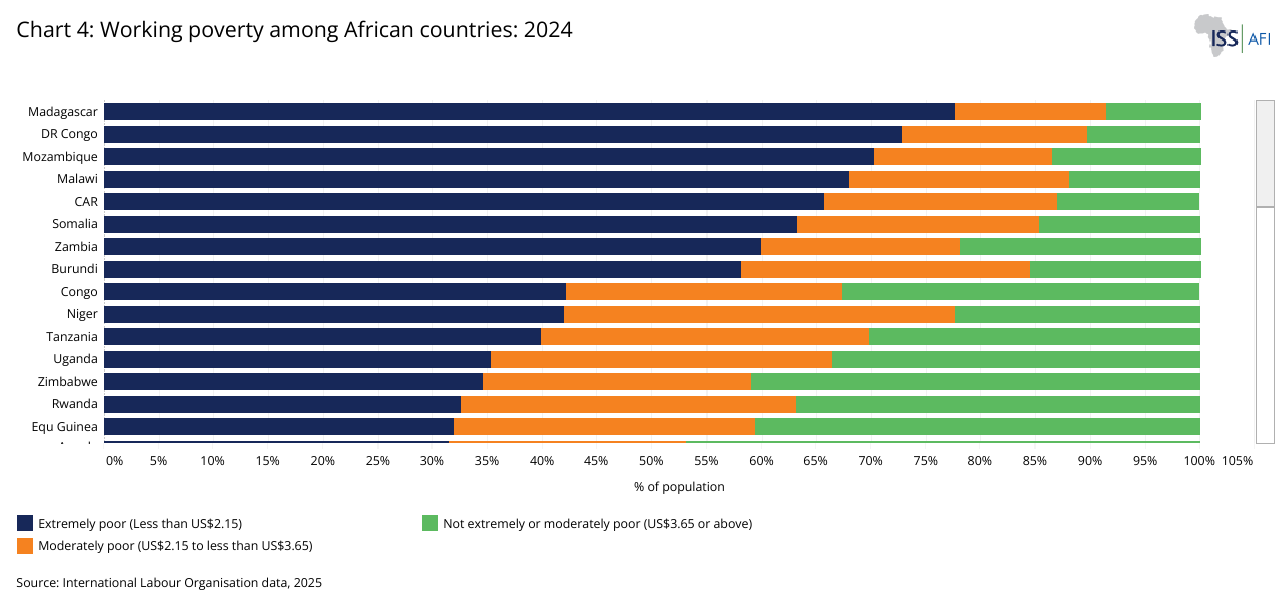

- In addition to the lack of formal employment is the prevalence of working poverty. In 2024, approximately 29.3% of employed Africans were classified as “working poor”—living on less than US$2.15 per day (at PPP). This burden is especially severe in low-income countries, where the informal economy is the dominant source of employment.

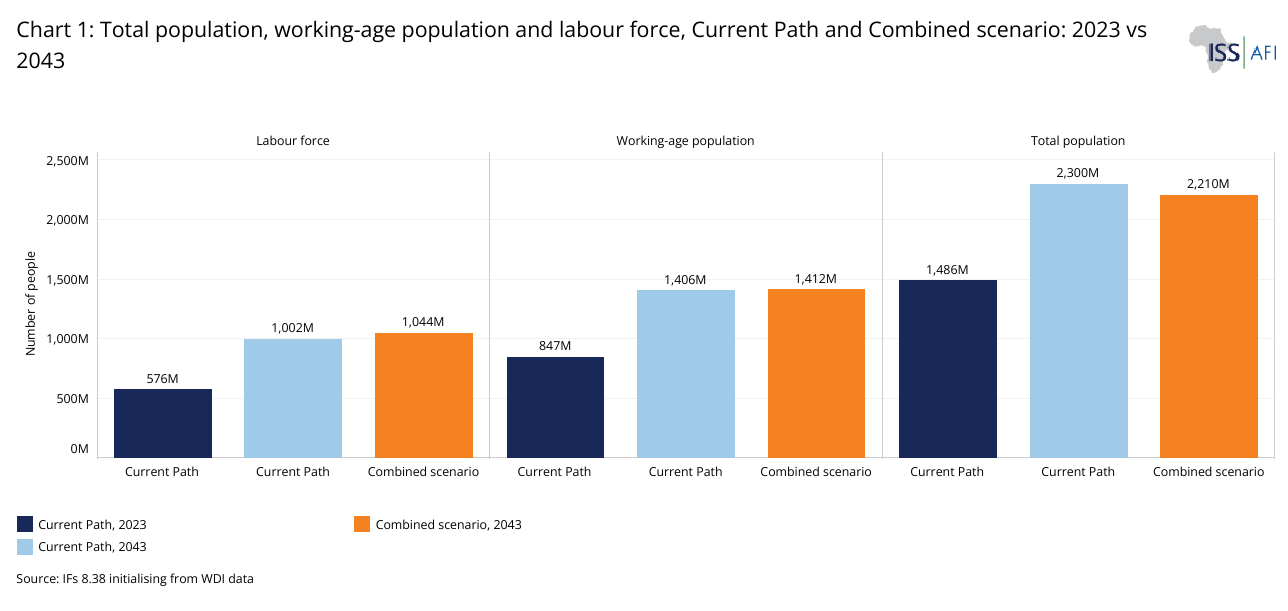

- Africa’s labour force is growing at an unprecedented pace. By 2023, it had reached 576 million, surpassing India’s 534 million, a milestone that it crossed in 2020. Projections suggest Africa will overtake China’s labour force in size by 2034, and exceed one billion by 2043. However, job creation has not kept pace: from 2005 to 2023, formal employment grew at a mere 6% annually, in stark contrast to a 2.9% annual increase in the labour force. This imbalance underscores the urgent need for structural economic transformation.

The subsequent sections then discuss possible future dynamics of employment as well as key sectors and key drivers. The report analyses the implications of a Combined scenario on Africa’s landscape of work and informality.

- Agriculture remains the largest employer across Africa (although the size of the services sector is much lager), followed by employment in the services and manufacturing sectors. Yet sectoral employment patterns are shifting as economies urbanise and modernise. The service sector’s share of GDP is expanding, though much of this growth is rooted in informal and low-wage activities. Meanwhile, the manufacturing sector, while crucial for structural transformation, has yet to generate sufficient employment at scale.

- Technological change offers both promise and challenge. Digitisation and the Fourth Industrial Revolution could accelerate the formalisation of Africa’s informal economies and enable a leap toward higher productivity. Yet, this shift requires significant investment in education and skills development to equip Africans for increasingly semi-skilled and skilled roles in emerging sectors.

- Under the Combined scenario, which integrates improvements across eight development sectors, the continent’s labour force participation rate is projected to reach 68% by 2043—a 39 percentage point increase over the Current Path. While this growth includes both formal and informal employment, it signals enhanced engagement in economic activity across the continent.

- Nonetheless, even in optimistic scenarios, job creation will not be enough to fully absorb Africa’s expanding labour force. Many African countries will likely need to adopt public employment programs, social grants and other redistributive measures to combat poverty and support vulnerable populations. The effectiveness of these interventions will depend on governance, institutional capacity and innovative policy design.

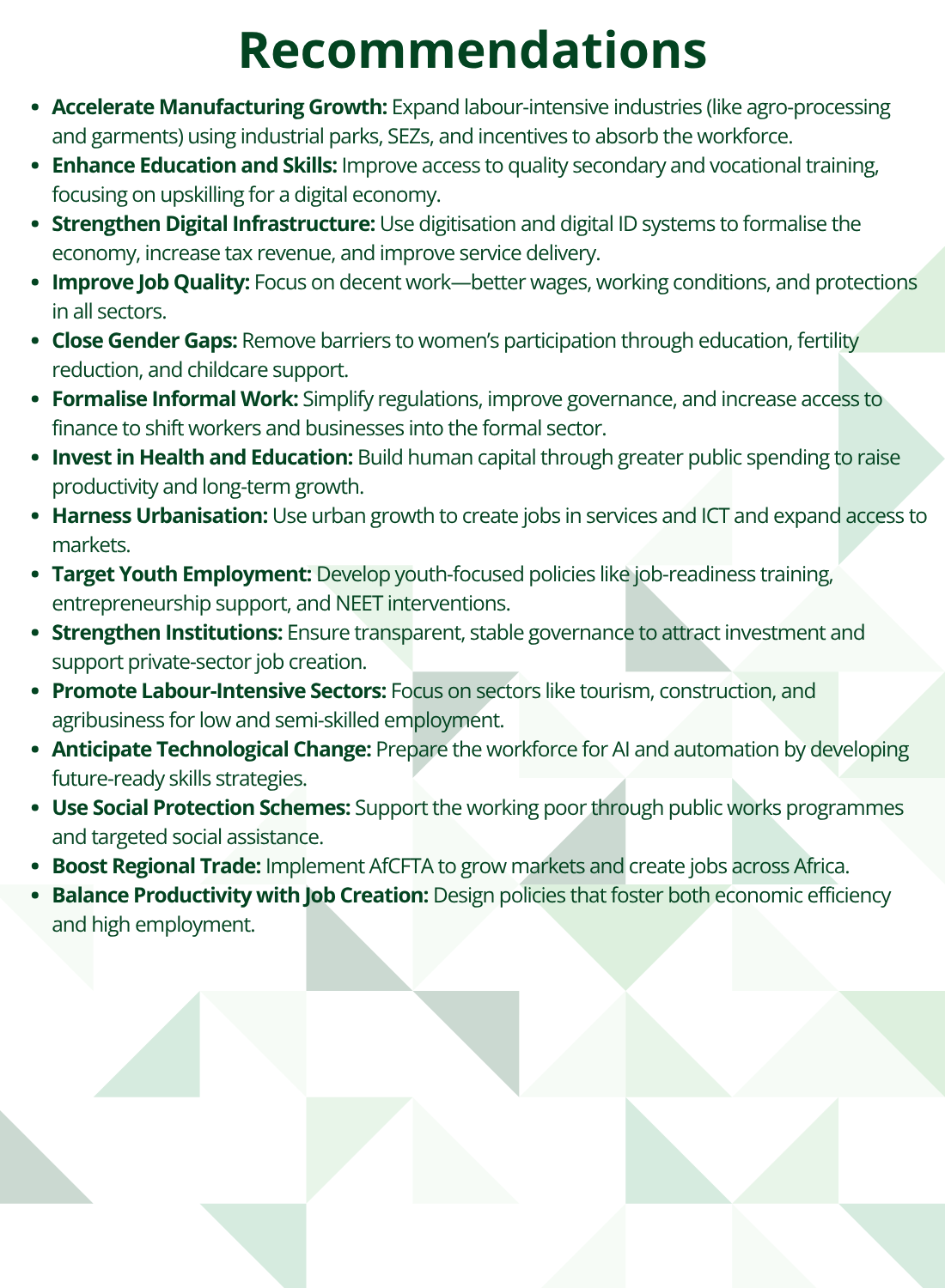

The theme ends with a concluding discussion offering key recommendations for addressing the challenges of employment across the continent.

All charts for Work/Jobs

- Chart 1: Total population, working-age population and labour force, Current Path and Combined scenario: 2023 vs 2043

- Chart 2: GDP (MER) in Current Path and Combined scenario: 2020-2043

- Chart 3: Value added by economic sector, Current Path and Combined scenario: 2023 vs 2043

- Chart 4: Working poverty among African countries, 2024

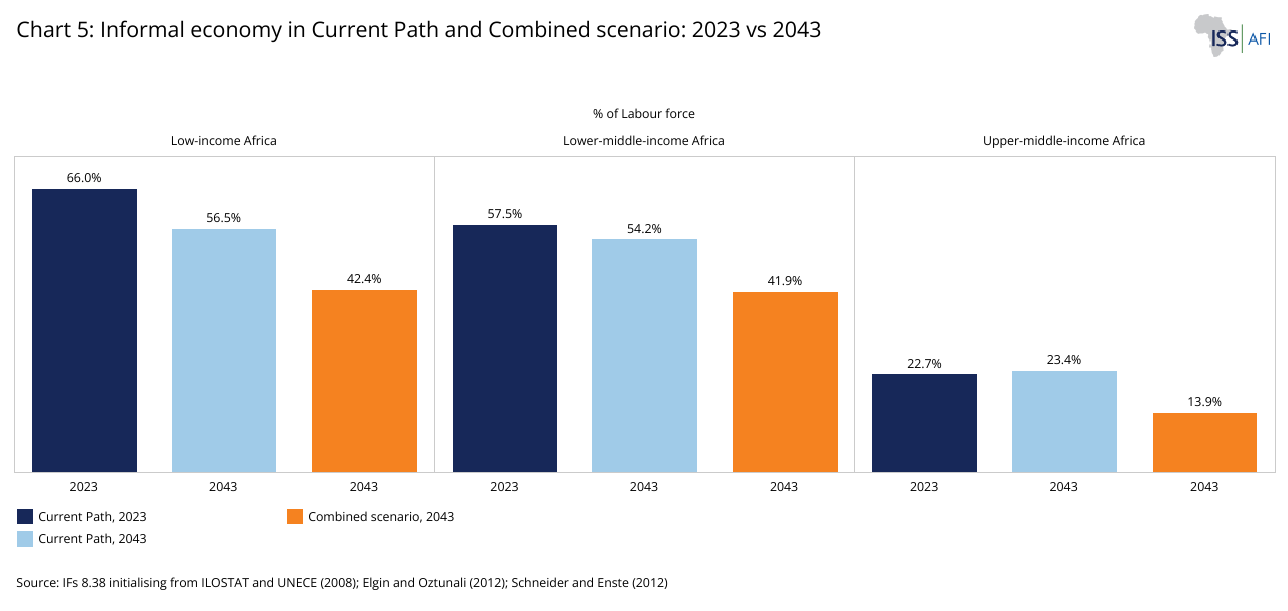

- Chart 5: Informal economy in Current Path and Combine scenario: 2023 vs 2043

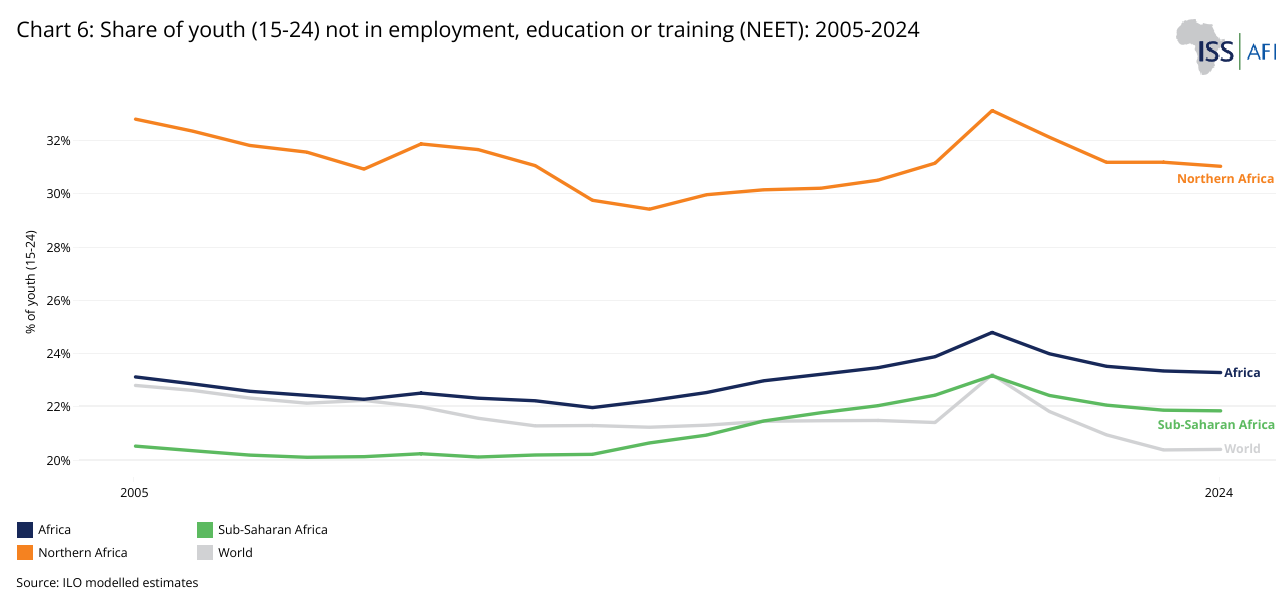

- Chart 6: Share of youth (15-24) not in employment, education or training (NEET): 2005-2024

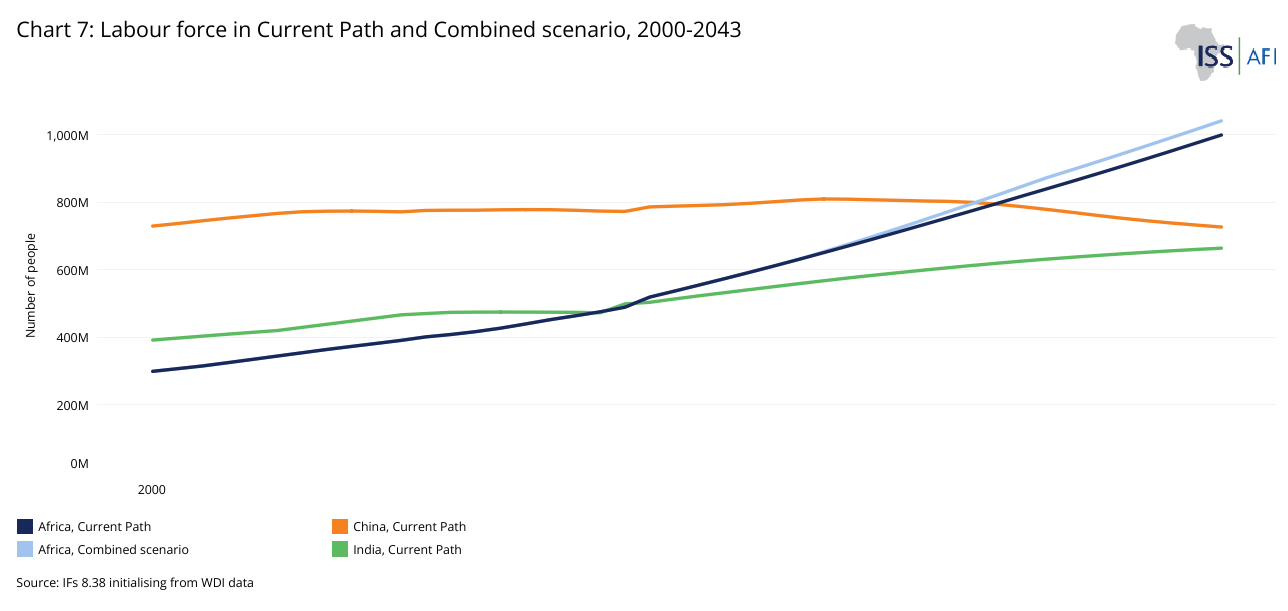

- Chart 7: Labour force in Current Path and Combined scenario, 2000-2043

- Chart 8: Education by age, sex, and level for China: 2023 vs 2043

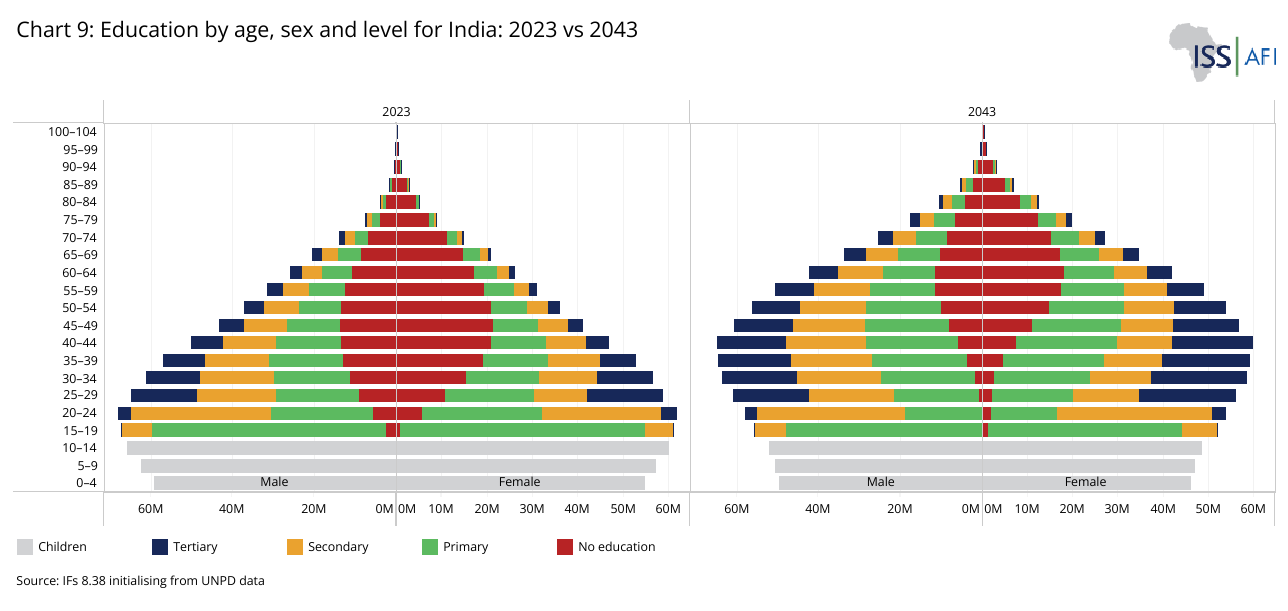

- Chart 9: Education by age, sex, and level for India: 2023 vs 2043

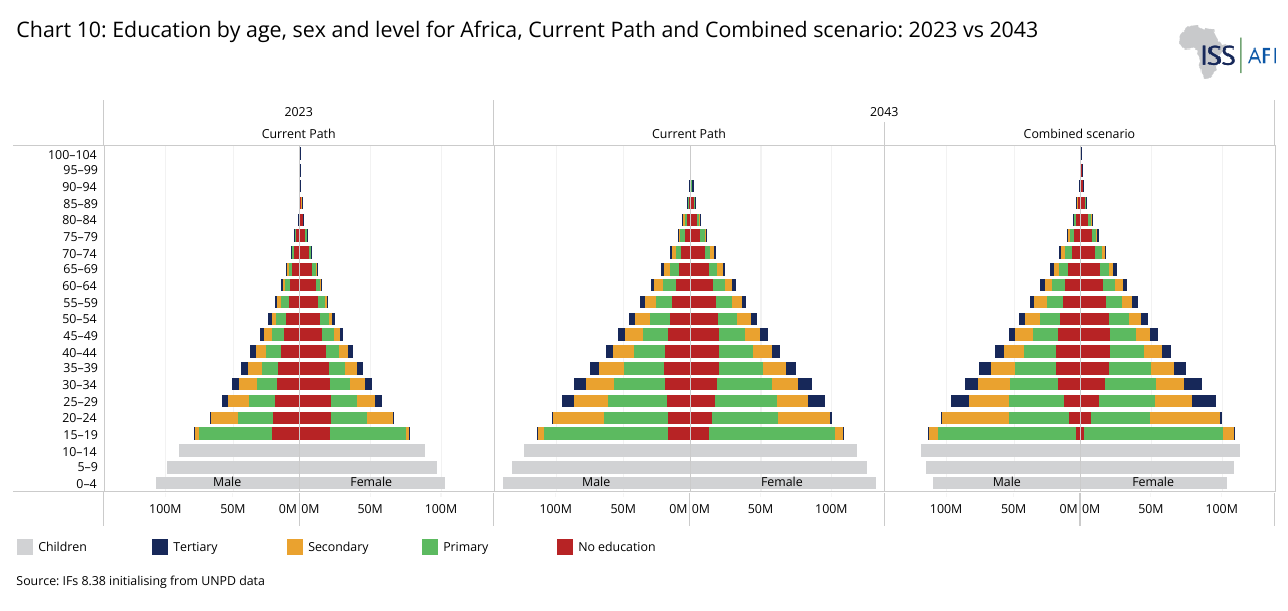

- Chart 10: Education by age, sex, and level for Africa, Current Path and Combined scenario: 2023 vs 2043

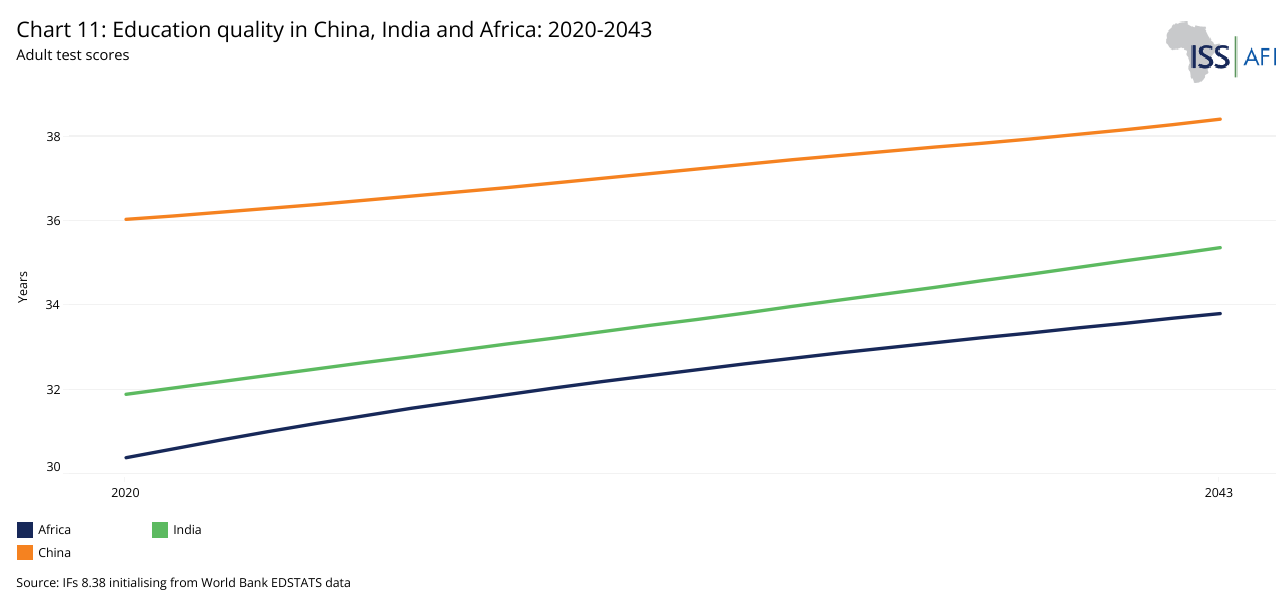

- Chart 11: Adult test scores on Education quality in China, India and Africa, 2020-2043

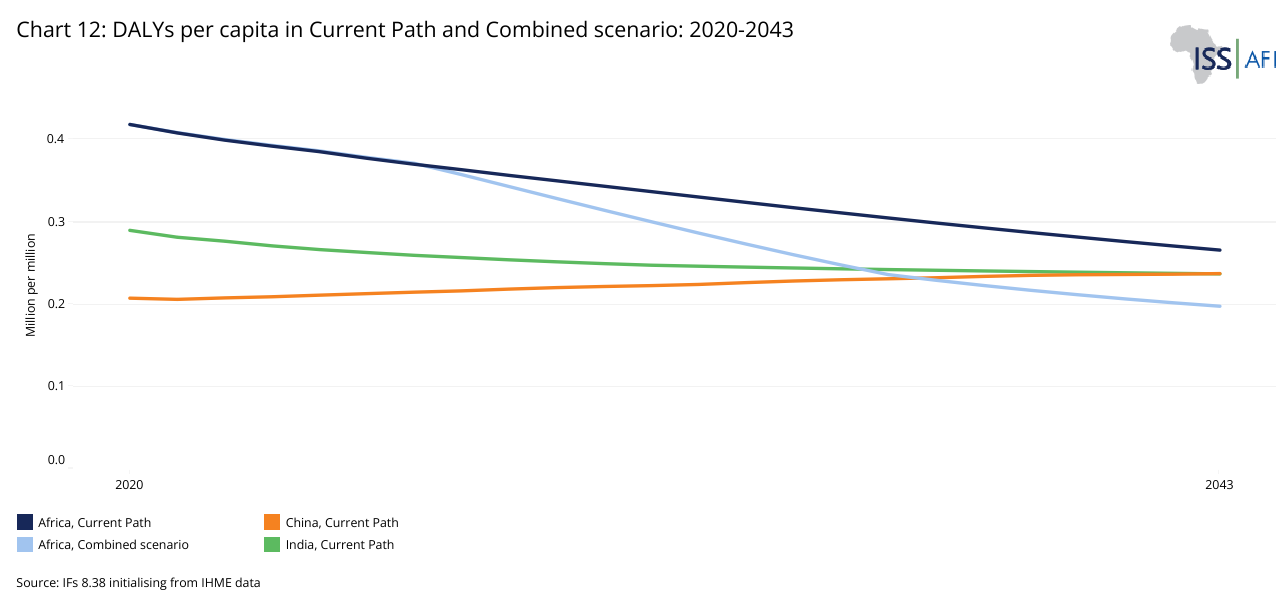

- Chart 12: DALYs per Capita in Current Path and Combined scenario: 2020-2043

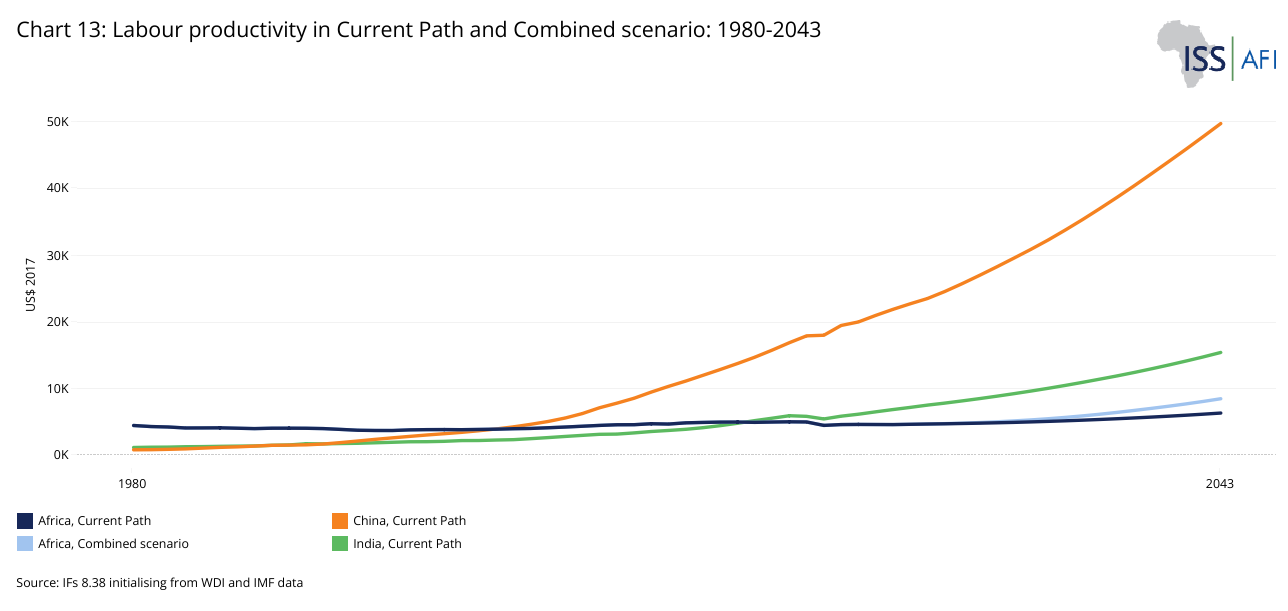

- Chart 13: Labour productivity in Current Path and Combined scenario: 1980-2043

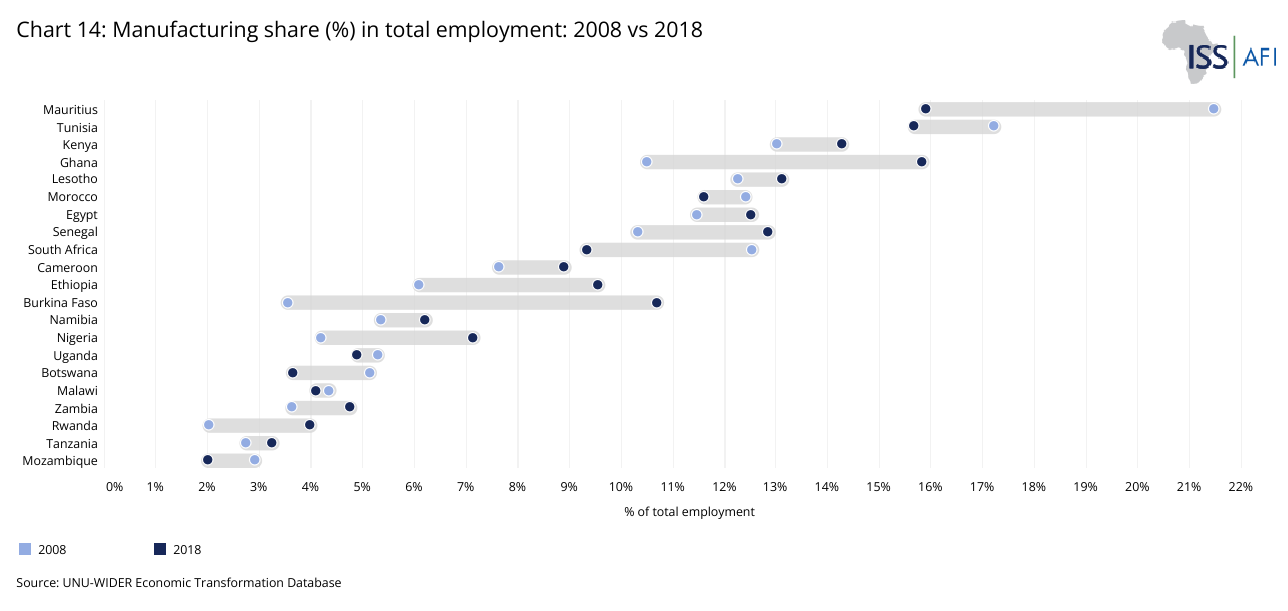

- Chart 14: Manufacturing share (%) in total employment, 2008 vs 2018

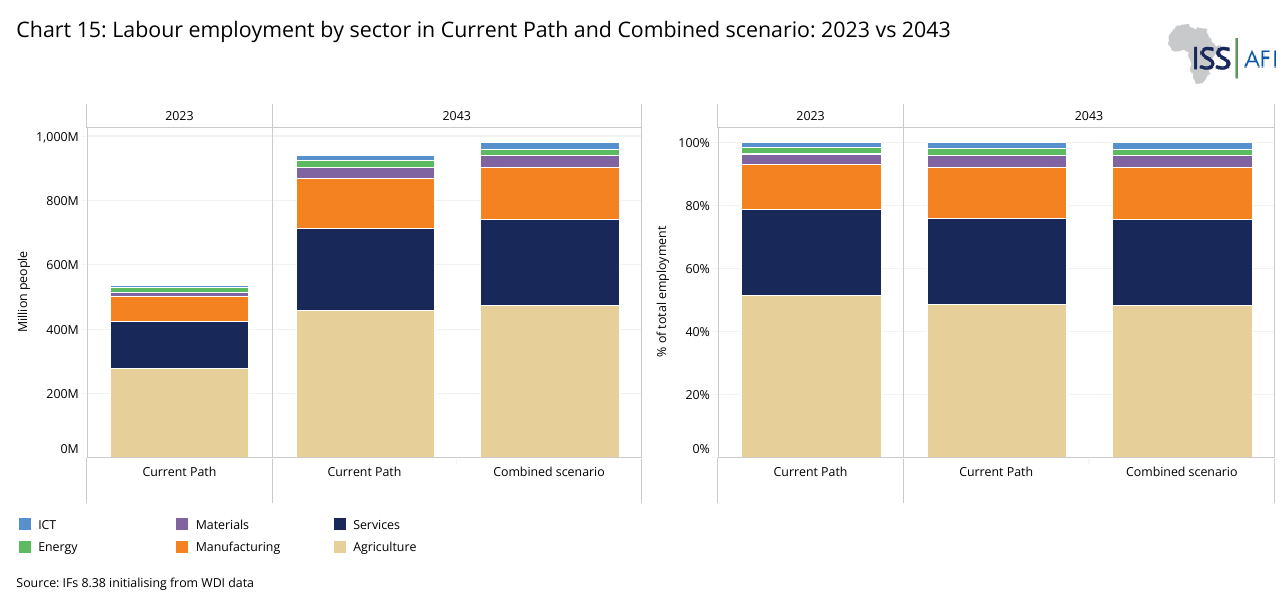

- Chart 15: Labour employment by sector in Current Path and Combined scenario: 2023 vs 2043

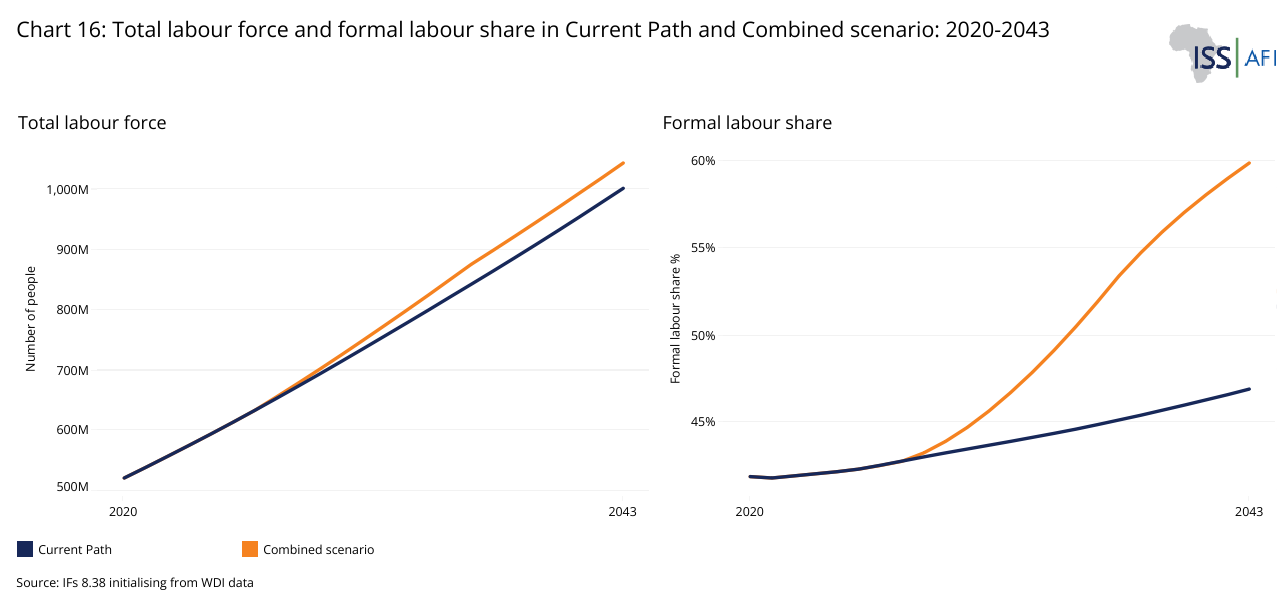

- Chart 16: Total labour force and formal labour share in Africa - Current Path vs Combined scenario, 2020-2043

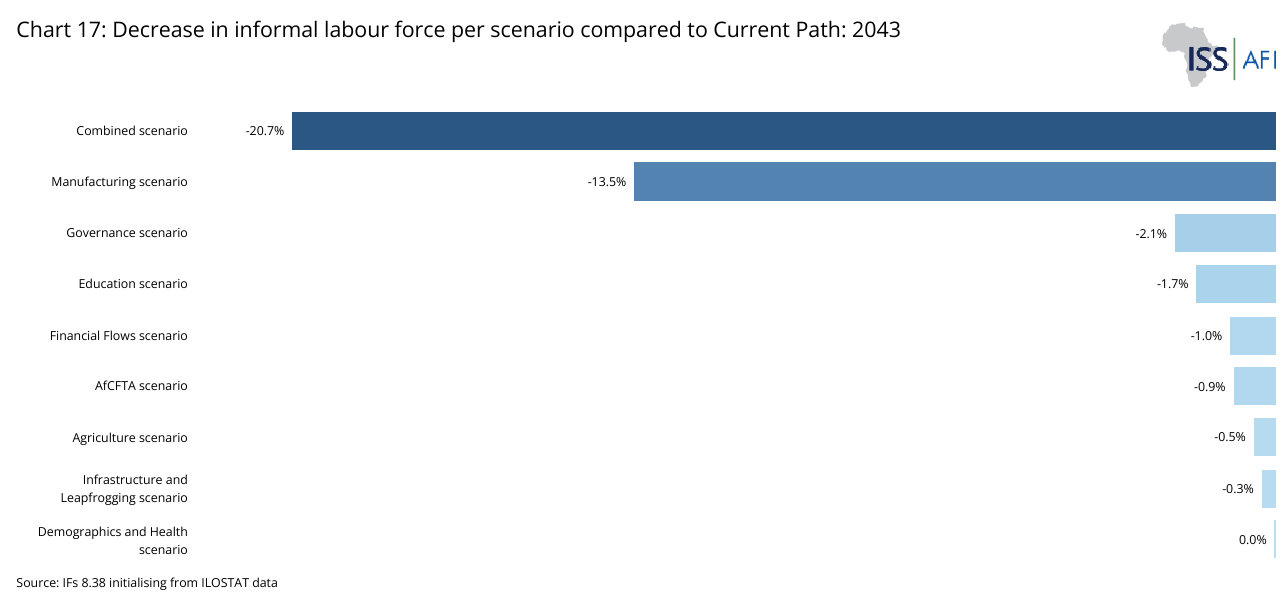

- Chart 17: Decrease in informal labour force per scenario compared to Current Path: 2043

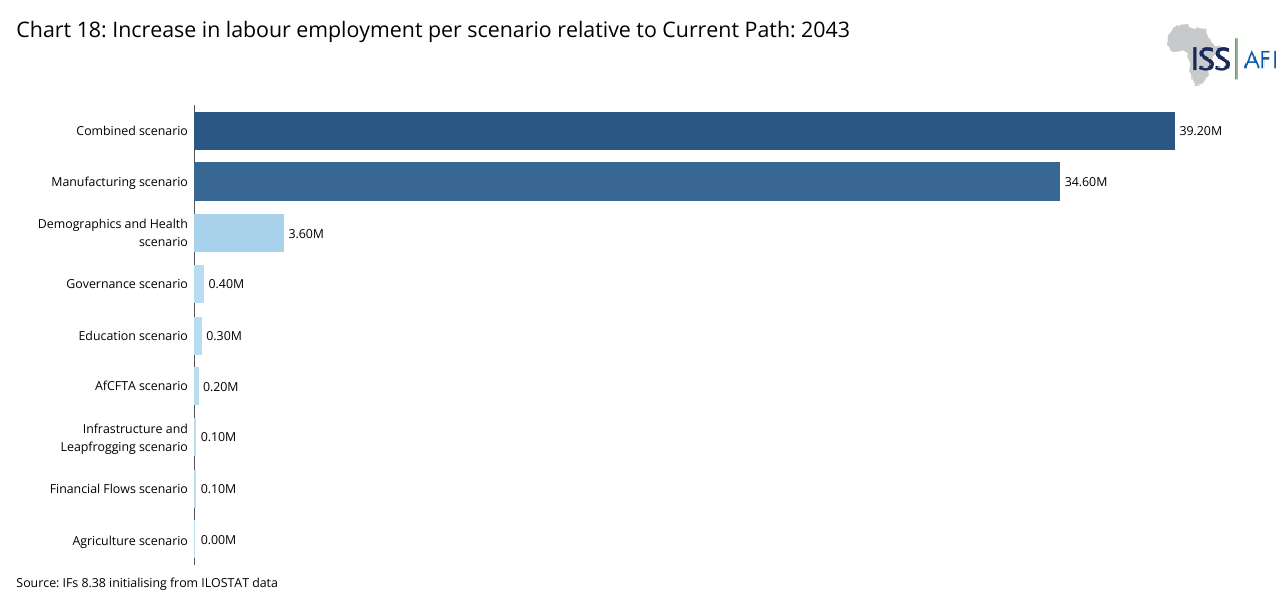

- Chart 18: Increase in labour employment per scenario relative to Current Path: 2043

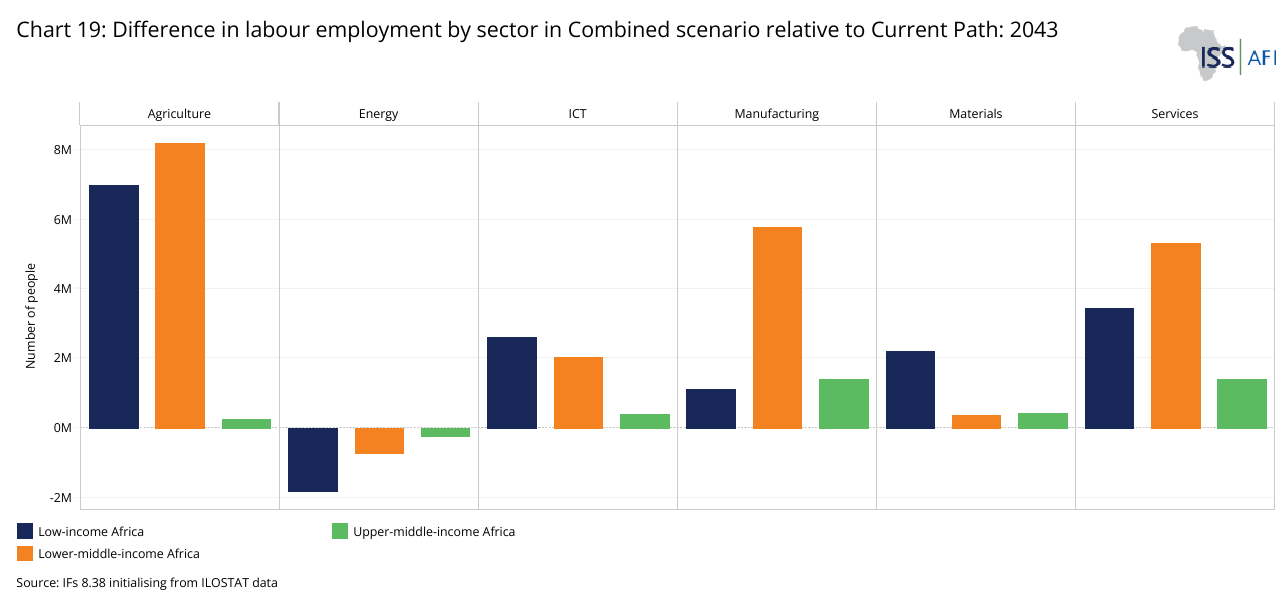

- Chart 19: Difference in 2043 Labour Employment by Sector and Country Income Group in millions and per cent: Current Path vs Combined scenario

- Chart 20: Summary of key recommendations

Africa faces significant challenges in creating adequate, decent employment. As the continent with the world's youngest population, enhancing employment opportunities is crucial to escape poverty by securing more and better jobs.

Chart 1 shows the total population, working-age population and labour force of Africa in 2023 and 2043, comparing the Current Path and Combined scenario. Africa had a total population of 1.486 billion people in 2023, of which 847 million (about 57%) were of working age (15-64 years). Africa’s labour force by definition, includes both employed and unemployed workers in search of a job. The labour force is therefore the total pool available to engage in the production of goods and services. In 2023, this amounted to 576 million Africans and will almost double by 2043.

Rapid population growth, driven by some of the highest fertility rates globally, is leading to a surge in the working-age population and labour force that is vastly out of kilter with the current ability of the African economy to produce decent job opportunities. Whereas, in 2023, the number of working-age Africans (15 to 64 years of age) increased by 24 million, by 2043 the number will be 31 million annually. Similarly, in 2023, Africa’s labour force increased by 18.4 million people and by 2043, it would be 23.5 million per year with marginal differences between the Combined scenario and the Current Path given the associated different fertility rates. Labour supply is growing significantly faster than demand if one considers that only about 2.6 to 3 million formal jobs are currently created each year in Africa. As a result, most employment growth occurs within the informal sector.

By 2043, nearly a quarter of all entrants into the global labour force will come from Africa.

In the time period to 2043, the reduction in fertility associated with the Combined scenario will produce a larger working-age population and labour force relative to population size given Africa’s more rapid demographic transition. This is the same labour dynamics that, in combination with pro-growth government policies, contributed to the rapid productivity growth of countries such as China and the Asian Tigers, though unfolding slowly.

The pace of job creation in the Current Path falls short of this large supply, leading to significant levels of un- and underemployment, particularly among youth.

The labour force participation rate, an important labour metric, is calculated as the number of people employed as a percentage of the total working-age population (typically 15-64 years of age) and is generally used to indicate the ratio of active workers in an economy, encompassing both formal and informal employment.

In Africa, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, the labour force participation rate tends to be relatively high compared to the global average, largely because of the youthful population structure and high levels of participation in the informal sector. In 2023, Africa's labour force participation rate stood at 64.5% and sub-Saharan Africa's at 67.7%, both above the global average of 60.5%.

Given rapid population growth, future employment in Africa depends upon the rate and nature of the continent's economic growth.

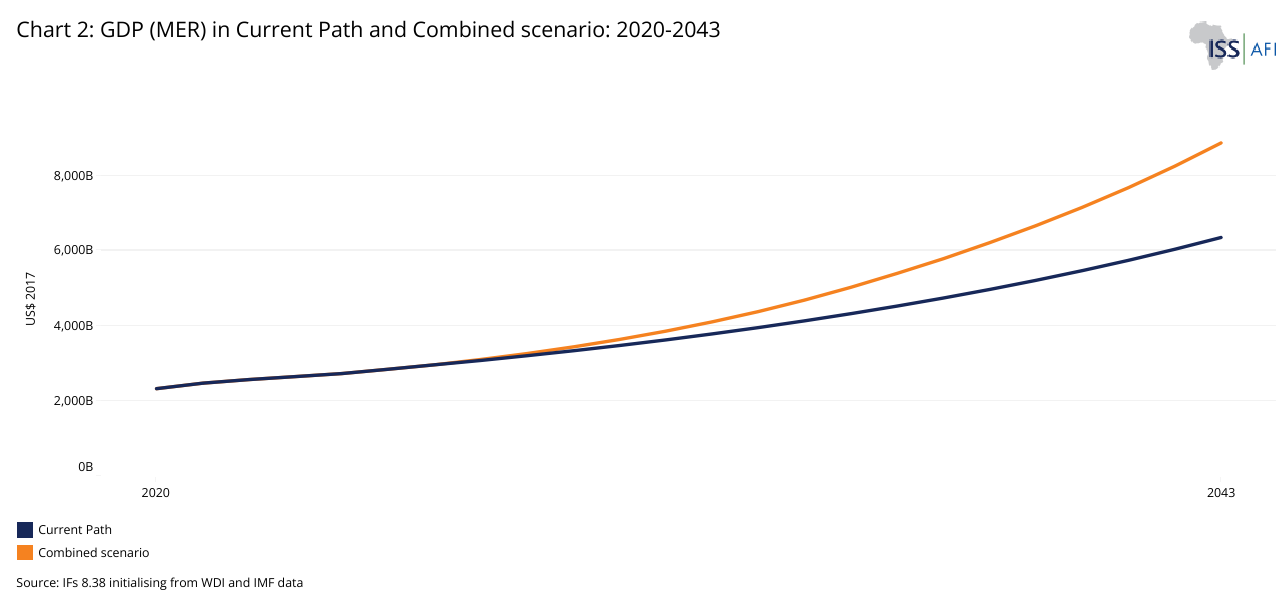

Chart 2 shows Africa’s GDP at market exchange rates from 2020 to 2043 under the Current Path and Combined scenario. In 2023, the size of the African economy was estimated at US$2.7 trillion and on the Current Path, it is forecast to increase to US$6.4 trillion by 2043. In the Combined scenario, the continent’s GDP could reach US$8.9 trillion, representing a 39.5% increase compared to the Current Path. Clearly employment and economic structure will be quite different in these two scenarios given that the Combined scenario includes pro-growth policies modelled in eight separate sectors.

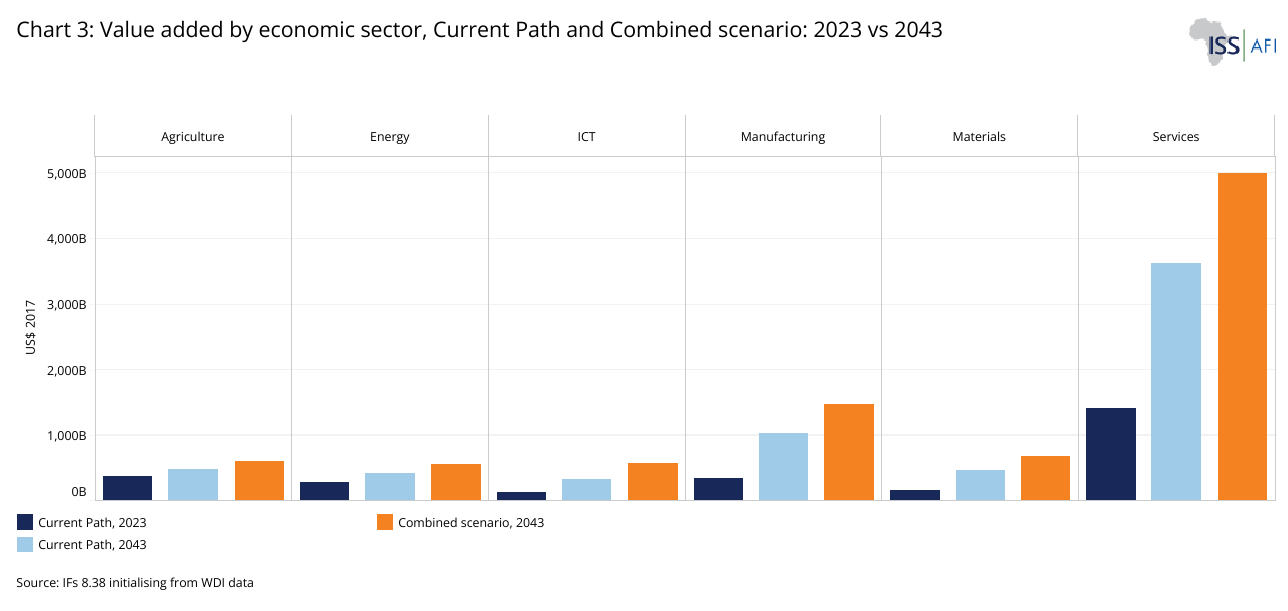

In 2023, the services sector accounted for about 53% of total output (or contribution to GDP), while the agriculture sector accounted for 14% and manufactures 13%. In recent decades, the continent has witnessed a significant shift in its economic composition, marked by a steady decline in agriculture's relative share and a growing prominence of the services sector, with more modest growth in the manufacturing sector. The Current Path reflects a continuation of these trends such that, by 2043, services will account for 57%, agriculture less than 8% and the contribution of manufactures for 16%.

Expected changes in the future structure of Africa’s economy are reflected in Chart 3, which compares sectoral sizes in 2023 with the forecast for 2043 on the Current Path and Combined scenario. The data is in per cent contribution to GDP and billion US$. Because the total African economy in 2043 will be significantly larger in the Combined scenario compared to the Current Path, all sectors are larger in absolute terms. In the Current Path, the contribution from the services sector to Africa’s economy will steadily increase from 53% in 2023 to 56.5% by 2043, while that of agriculture will decline from 14% to 7.6%. In line with the global trend towards more service-orientated economies, the services sector already dominates as a contribution to GDP. In the Combined scenario the contribution of the services sector (as a per cent of GDP) declines marginally, although still growing in absolute size.

According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), an employed person is anyone aged 15 or older who has worked at least one hour for pay within a given week or is temporarily absent from work due to reasons such as annual leave, illness or maternity, within a specified period. The definition covers all forms of employment, both formal and informal, regardless of whether the employment is declared or not.

In this context, the actual meaning of employment–having paid work–means earning something. But it is seldom a living wage. Employment data, therefore, would include an executive of a company, who may be earning a million dollars a year, and a teacher in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo), who earns US$100 per month. It also includes a street vendor in Soweto, South Africa, who sells packets of peanuts and may be earning 80 cents or a dollar per day in the informal sector. Hence, it is no surprise that over 238 million persons (6.9%) in employment globally survived in extreme poverty at less than US$2.15 per day, in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) in 2024, with the portion in Africa higher than in other regions.

Generally, people employed in the formal sector are assumed to enjoy better job quality, including higher earnings, job security, social protections and safer working conditions, while those in the informal sector tend to be characterised by lower wages, job insecurity, lack of benefits and poor working conditions. However, the reality is more complex, with many in the formal sector classified as extremely poor, despite being employed. In many cases, minimum wages are often too low to cover basic living costs. The ILO refers to these people as the working poor–employed population living in extreme poverty. This means their employment-related incomes are not sufficient to lift them and their families out of extreme poverty and ensure decent living conditions.

The phenomenon of the working poor is driven by several key factors, including low wages, a high cost of living, underemployment and high dependency ratios. People living on less than US$2.15 per day are considered extremely poor, while those living on US$3.65 per day in lower-middle-income countries and below US$6.85 in upper-middle-income countries are considered moderately poor.

Chart 4 depicts the share of employed people living in extreme poverty across African countries in 2024. The percentage of working poor living below US$2.15 per day in 2024 as a share of total employment in Africa was estimated at 29.3%, and the percentage was even higher in low-income countries. Chart 4 shows that the percentage of workers who are extremely poor in Madagascar and DR Congo is more than 70% of the employed labour force.

Because the ILO includes participation in the informal economy as part of employment, a larger portion of Africa’s labour force is classified as employed than one would expect. In 2024, Africa's unemployment rate was estimated at only 6.7%, thus just slightly above the global average of 5%. Among young Africans aged 15 to 35, approximately one in 22 (4.5%) were unemployed, with a forecast indicating an increase to 5.2% by 2030. To observers, Africa often presents the picture of a dual economy: a relatively small formal sector that includes government, certain services and a limited amount of industry, alongside a large informal sector where underemployment is prevalent and which is characterised by survival, poverty and low productivity.

Although many unskilled and undereducated individuals are employed in the informal sector, employment in this context cannot be classified as ‘decent work’, which the ILO defines as one that is productive and delivers a fair income, security in the workplace and social protection for all, better prospects for personal development and social integration, freedom for people to express their concerns, organise and participate in the decisions that affect their lives and equality of opportunity and treatment for all women and men.

In recognition of these challenges, the ILO recently updated the statistical standards for measuring work and economic activity in the informal economy. In October 2023, during the 21st International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS), new standards were adopted to improve the accuracy and consistency of measuring informality. The revised statistical standards on the informal economy expand the scope of informality statistics by incorporating the concept of informal productive activities alongside the broader definition of the informal economy. This approach recognises that informality is not limited to employment but also includes own-use production, unpaid trainee work, volunteer work and other labour activities. Furthermore, it integrates informality from both the perspective of economic units and individual work, ensuring the framework applies to both economic and labour statistics.

Economic transformation enables an increase in labour earnings and drives employment transformation—a shift in the share of employment from informal to formal. The majority of the labour force generally prefers formal employment due to lower income volatility, job security, associated legal and social protection, and the career prospects that come with formal compared to informal jobs. Formal job opportunities are particularly desirable among African youth upon completing their education because employment in the informal economy is predominantly associated with low wages and job insecurity, contributing to the persistently high poverty rates across the region.

The portion of Africa’s labour force employed in the formal part of the economy is forecast to grow from 242 million people, representing 42% of the total labour force in 2023, to 470 million people (47%) by 2043.

Many formal jobs in Africa, particularly in sectors like agriculture and retail, offer wages that often fall below the poverty line, limiting economic progress and deepening inequality. As a result, extreme and moderate poverty are also widely prevalent in the formal sector.

Underemployment is a key indicator of the poor quality of most jobs in Africa and is characterised by low work hours and low labour productivity. Inadequate work hours occur when a worker’s hours fall below the standard and are less than desired, resulting in visible underemployment. Low labour productivity occurs when the work performed does not align with the worker’s qualifications or provide the expected income, leading to invisible underemployment. The different forms of underemployment are not mutually exclusive; a worker may experience underemployment due to work hours, qualifications and income.

Many people in the informal sector live below or just above rates of extreme and moderate poverty, which explains the challenges in interpreting ILO employment data. Inevitably, the rate of the working poor in the informal sector is much higher than that in the formal sector. In the absence of a social net, employment in the informal sector is, of course, better than no employment or income. But by its nature, informal work does not offer benefits such as health insurance, unemployment insurance or paid leave. The majority of informal workers—many of them self-employed—must work daily to earn a living and cover basic household needs. Their livelihoods are often unstable, leaving them highly vulnerable and with limited capacity to withstand shocks, such as the lockdowns experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Among Africa’s regions, Southern Africa registered the highest unemployment rate globally at 31.8% in 2024. A key contributing factor is the region’s relatively smaller informal sector, which provides less of a cushion against unemployment compared to other parts of the continent. The region's low employment levels are also linked to generally high levels of inequality. The reason is rooted in historically extractive policies based on cheap labour and minerals in much of Southern Africa—a region that achieved the transition to majority rule quite recently and with ruling parties heavily infused with socialist ideological models from several decades ago, most prominently the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. In addition to the skewed economic structures inherited at the time of the transition to majority rule, all are stuck in a mindset of economic centralism and top-down control that offers little room for self-help. As a result, economic emancipation has not yet taken place. Governments promise to provide for their citizens, but rarely do.

Nominally, West Africa does much better than other African regions on employment statistics because of the large size of its informal sector, but the poor quality of work means that working poverty is significantly higher at 23.4% in 2024. Unemployment in West Africa was at 2.9%, whereas Central, East Africa and North Africa experienced rates that were more than three times higher.

At the country level, South Africa (33.2%), Djibouti (25.9%) and Botswana (23.1%) had the highest unemployment rates compared with 4.6% and 4.2% in China and India, respectively. In South Africa, the most recent country in the region to transition to majority rule, the previous system of mining, education and business was premised on the extraction of maximum profits and burdened the country with huge inequalities. With poor-quality education and limited entrepreneurship, employment is particularly low, and inequality is exceptionally high. In fact, on both these counts, South Africa fares the worst globally.

In our modelling, South Africa is forecast to deviate from the broader trend of declining informality. While other regions are projected to see a gradual reduction in the informal sector, both as a share of GDP and in terms of labour force participation, South Africa is likely to experience an increase. This is largely driven by a slow rate of economic growth and jobless growth. Notably, in 2023, the informal labour in South Africa accounted for just 17.5% of the labour force, significantly lower than the continental average of 58%.

At low levels of development, the informal sector is generally much less productive than the formal sector, but the gap typically reduces as countries move up the income ladder. At higher levels of development, a large informal sector often reflects a determined effort to avoid regulation because informality is often more nefarious at higher levels of income compared with being survival-oriented at low levels of development. In high-income countries, productivity in the informal sector could, in select examples, be similar to that in the formal sector, as the primary orientation is often not survival but regulatory avoidance. Therefore, productivity in the informal sector in a country such as Russia, Italy or Greece, where the illicit economy is large, is not likely to differ from that in the formal sector.

Against this background, it is possible to argue that the primary employment challenge in Africa lies more in the quality of available jobs than in the overall lack of employment. The reality is that employment in Africa is characterised by multiple dimensions: too few well-paying jobs, low average earnings, irregular and casual work arrangements, unpredictable daily and monthly working hours and a lack of labour regulations or workplace protections. The net effect of all these challenges faced by African workers in the labour market is low-wage earnings.

Generally, the share of informal employment tends to decline as GDP per capita increases, which means that countries with a high GDP per capita tend to have low informality rates. Between 2004 and 2024, the share of informal employment in Africa declined by around 2% while GDP per capita grew by about 16% during the same period. Typically, poor countries have a larger informal sector compared to rich countries, and many more people are employed in the informal sector in poorer countries than in wealthier ones.

Whereas the informal sector accounts for only around 2.5% of the GDP of the 38 members of the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and informal labour accounts for a mere 11% of the labour force, the ratio for Africa’s country income groups is much higher at about 26%. Chart 5 presents the size of the informal economy in Africa in 2023 and 2043 in the Current Path and Combined scenario.

Irrespective of the level of development, a large informal sector is costly for society and constrains sustainable development. Workers active in the informal sector do not contribute to direct taxes (as they are not registered to pay personal or company tax), but the informal sector still requires infrastructure and services. A large informal sector, therefore, puts an additional burden on service delivery and congests public infrastructure without contributing substantially to either, except through indirect taxes such as value-added and service taxes. However, this drag is balanced by the extent to which it absorbs people who would otherwise not have any employment or opportunity.

The ILO data on unemployment in Africa described above is therefore quite misleading without appropriate context, as poignantly revealed across 39 countries surveyed during Afrobarometer’s Round 9 (2022-2021) that identified unemployment as the leading policy priority for youth aged 18 to 35, significantly more than concerns about economic management and health.

The share of informal employment in total employment, including both casual informal wage employment and non-wage household production activities, was estimated at 85.3% for Africa in 2024, compared to the world average of 57.8% during the same year. Africa's upper-middle-income countries, which are much more developed, have the lowest share of informal employment than Africa's low-income countries. The share of informal employment in Africa also varies by region; Central and West Africa have the highest shares, estimated at 92.5% and 91.8% respectively, in 2024. While females are more likely to work in informal employment in sub-Saharan Africa (91.4%), but less likely to do so in North Africa (53%), particularly in non-agricultural informal jobs. Overall, Africa’s female informal employment share accounted for 89.4% compared to 82.2% for males in 2024.

Employment in Africa also differs by age group. Chart 6 shows the share of youth aged 15-24 not in employment, education or training (NEET) in Africa from 2005 to 2022. Unemployment among younger adults (below 25) is higher than among adults (25+ years) and is higher in rural areas than in urban areas, particularly in young women. More than 25% of Africa’s youth—an estimated 72 million individuals—are not in employment, education or training (NEET), with two-thirds of them being young women. Africa’s youthful and fast-growing population positions the continent for tremendous opportunity, though it also brings challenges that must be addressed. With the right investments, this demographic trend could drive innovation, growth and prosperity.

The labour force participation rate in Africa’s low-income countries (which typically have the largest informal sector) is typically higher than in lower-middle- and upper-middle-income African countries because workers in low-income countries tend to take any job to earn a living, regardless of the quality of that employment, and also because low-income countries generally have younger populations. In 2023, the low-income African countries' average labour participation rate was 72%, significantly above the average of 61% and 51% for lower-middle- and upper-middle-income African countries.

Typically, labour participation is higher among men than women, and cultural factors also play a role. Despite accounting for over 50% of Africa’s population, women’s labour force participation has remained below 60%, while male participation has consistently exceeded 70% over the past three decades. The trend is positive; however, female participation is gradually rising across African countries.

Maximising women’s contribution to economic growth requires increasing their labour force participation. However, various factors influence participation rates, such as cultural and religious perceptions of women’s roles, policy frameworks and structural challenges, including limited job opportunities and industry-specific constraints that hinder women’s involvement. Also see the separate theme on gender in this regard.

Sub-Saharan Africa has witnessed notable growth in female labour force participation, from around 40% in the 1980s to about 60% in the 2000s, spurred by declining fertility rates and a reduction in gender disparities in education. Sub-Saharan Africa has also experienced significant growth in the services sector, which accounts for a large share of female employment. In 2023, the sub-Saharan Africa female labour participation rate was estimated at 62.7% compared to 22.5% in North Africa. While agriculture and extractive industries (like oil and mining) historically dominated the productive portions of many sub-Saharan African economies, services have increasingly become a major driver of growth.

In 2023, North Africa showed a significant gender gap in labour force participation, with a difference of approximately 47 percentage points between men and women, far greater than the 10 percentage point gap observed in sub-Saharan Africa. Since the 2000s, female labour force participation in North Africa has remained stagnant at around 20%. Women in the region face considerable challenges in accessing employment, largely due to societal norms and structural barriers prevalent in many Muslim-majority countries, where traditional roles often cast women as primary caregivers and men as breadwinners. As a result, female labour underutilisation is especially pronounced in North Africa and the Arab States more broadly.

To better understand Africa’s labour force challenges, it is useful to compare its size and quality with those of India and China.

The size of Africa’s large and rapidly growing labour force is illustrated in Chart 4, comparing Africa with India and China. In 2023, it was estimated at 576 million, nearly matching India’s 534 million, which it had already surpassed in 2020. By 2034, Africa’s labour force is forecast to exceed China’s, and by 2043, it is expected to surpass 1 billion with no significant differences in the Current Path and Combined scenario.

Labour plays a crucial role in driving growth at the early stages of development, reflecting Africa’s significant potential. As wages in China and India rise due to economic advancement and a shift toward higher-value industries, global labour-intensive manufacturers and investors are increasingly likely to view Africa as a prime destination for affordable labour, provided the continent is also able to unlock larger markets through trade integration. With its large, youthful and rapidly expanding workforce, the continent presents positive prospects for labour-intensive industries seeking to remain globally competitive. Africa's comparatively low wage levels, along with a growing labour supply and gradual improvements in the business environment across many countries, make it an increasingly attractive option for companies looking to reduce labour costs and diversify their supply chains.

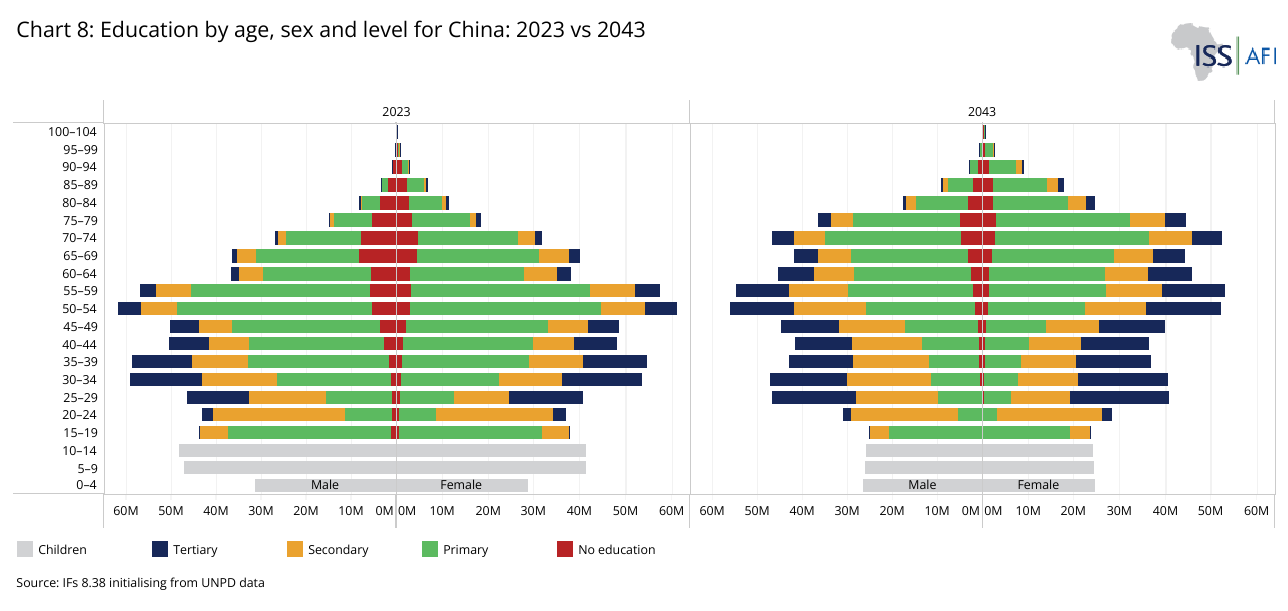

However, relying solely on Africa’s size and low labour costs presents a misleading picture of its potential without significant advancements in education and healthcare. Moreover, the growing role of labour-saving technology is gradually diminishing the traditional importance of labour costs on economic growth. Two critical indicators of workforce productivity—education levels and overall health—are illustrated in Charts 8 to 10, which compare the current state and a 2043 forecast for China, India and Africa on the Current Path.

The following differences are evident in Charts 8 to 10:

- Africa’s population pyramid retains its broad base to 2043 on the Current Path, reflecting its youthful population structure and its large cohort of child dependants, whereas that of India increasingly takes on the image of the Taj Mahal, a fat, rounded belly of working-age persons who are increasingly well educated. In the Combined scenario, the shape of the African pyramid starts to change towards the end of the forecast horizon, with the number of children starting to contract sharply with the promise of more funds available for those already in school and attendant educational improvements. China, in contrast, has a large elderly population that needs to be supported by a shrinking working class, but is on track to provide secondary education to the majority of its younger population by the end of the forecast horizon, a target that India is only likely to achieve several decades later. The impact of the one-child policy on China’s population structure is evident in the jagged age cohorts compared to the smooth progression in the evolution of India’s population age structure, which did not suffer the same government efforts at population control.

- Africa lags significantly behind both India and China in providing education at primary, secondary and tertiary levels. Whereas the mean years of education in Africa for adults (15 years and older) was 6.8 years in 2023 and is expected to increase to 7.8 years by 2043 in the Current Path, it was 8.9 years in China in 2023 and is forecast to increase to 10.4 years by 2043. The mean years of adult education in India will increase from 7.6 years to 9.2 years over this period. Although the amount of education adults receive in Africa is improving, the continent will slowly fall further behind China and India over the next two decades when considering the mean years of adult education. In the Combined scenario Africa’s mean years of education increases to 8.3 years in 2043 and the continent starts closing the gap with India although catch-up will take several additional decades.

- Men typically are better educated than women. In 2023, Chinese men had about 0.7 years more education than women, doing better than in India and Africa. The difference in India was 1.6 years, and in Africa, it was 1.3 years. In all instances, the Current Path forecast is for the male-female gap to decline by 2043 as female empowerment proceeds, although slowly. In the Combined scenario, African women have 0.7 years less education than men in 2043, having almost halved the gap compared to the Current Path.

Africa also trails with regard to the quality of education measured by adult test scores, both currently and likely in the future, as shown in Chart 11. On this important measure, the forecast presents poor progress compared to China and India. In the Combined scenario, Africa’s adult educational quality converges with India by 2043, still significantly below the forecast for China.

A second key indicator of the ability of a workforce to be productive is its general health. To compare countries and regions, the modelling turns to a combined indicator of premature mortality and the years lived with a disability owing to prevalent cases of the disease or health condition. The two are combined in disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). One DALY represents the loss of the equivalent of one year of full health.

Chart 12 presents the DALYs per capita for China, India and Africa and shows positive convergence over time on the Current Path. In 2023, DALYs in Africa were 392 000 years lost per million of its population, compared with 271 000 in India and 209 000 in China. In other words, the burden of ill health in Africa was almost double that of China. Coming from such a high level, rapid progress is possible, but it takes time.

Chart 12 also shows the aggresive impact of the Combined scenario on DALYs in Africa. Since the Combined scenario is a best-of-best combination of improvements in heatlh, education and various other sectors, Africa does significantly better than India and China in this scenario. DALYs in Africa will reduce to 198 000 years lost per million people compared to 266 000 in the Current Path, equivalent to a 25% improvement.

Labour productivity indicates the economic value generated by each worker and reflects how effectively a country empowers its people to succeed. Higher productivity leads to greater output of goods and services per worker, resulting in higher incomes, better living standards and stronger economies. In addition to a lack of infrastructure and other enabling factors, the combined effect of poor education and poor health is that China’s average labour productivity overtook the average for Africa in 2001, and India overtook Africa in 2016. On the Current Path, Chinese and Indian labour productivity is significantly better than Africa’s, as illustrated in Chart 13. In the Combined scenario, Africa’s labour productivity improves by 34% in 2043 in the Combined scenario but is still significantly below that of India, which is more than three times lower than that of China.

In 2023, Africa’s average labour productivity was less than one-quarter of China's and about US$1 900 below that of India. By 2043, the gap will have widened significantly, with labour productivity in Africa being less than half of that in India and only about 13% of that in China. The Current Path forecast is for slow improvements in Africa and even in the Combined scenario, in spite of significant improvements in health, eduction, infrastructure and other enablers, African productivity is still below that of India, although less so.

Having described the size and quality of Africa’s labour force and compared that to India and China, as well as explored changes in the African economy in the Combined scenario compared to the Current Path, a next step is to define and discuss employment in more detail.

Between 2005 and 2023, formal employment in Africa expanded by an average of about 0.6% per year, while the labour force expanded by 2.9% during the same period. Even at the robust average annual economic growth rate of 4.8% during this period, it could not create enough formal-sector jobs.

Despite more than two decades of steady economic growth in Africa (except 2020), averaging around 3.6% yearly between 2000 and 2023, formal employment has remained relatively stagnant at around 15%, with many engaged in the informal sector. Internal and external shocks, including domestic conflicts and the COVID-19 pandemic, have dealt significant blows to local economies.

African governments face a number of challenges in bridging the gap between economic growth and employment growth. A key factor behind this is the region's limited competitiveness as a result of low productivity relative to other developing regions such as South Asia and South America, which is, in part, due to the dominance of low-end services in the economy and the quality of labour translating into low productivity. Many job seekers, particularly young people, face significant employability challenges due to inadequate training and limited skill development.

It is ironic, given Africa’s large working-age population and labour force, that economic growth in the continent is not job-rich, meaning that the employment elasticity of growth is low, with fewer jobs created per unit of growth than in South America, for example. The reasons are that growth in sub-Saharan Africa is still heavily reliant on commodities from agriculture and mining, which have limited spillover effects on the broader economy. Since it is more industrialised with a large public sector, North African countries such as Morocco, Tunisia and Egypt typically have higher elasticities. Given the dominance of subsistence agriculture, productivity is low in much of sub-Saharan Africa, while the enclaves of mining and mineral industries are capital-intensive, generating few local jobs and retaining only a small share of their revenues within domestic markets. Often, the expansion of other formal industries is constrained by an unfriendly business environment characterised by high operational costs, excessive bureaucracy and widespread corruption.

The availability of better employment opportunities is closely linked to the degree of structural economic transformation, which is the shift of labour and resources from low-productivity, low-income sectors such as traditional agriculture into higher-productivity sectors, typically associated with the manufacturing or formal services sector. The shift could be as a result of the more rapid entry and growth of firms in the higher-productivity sectors; and sectoral transformation - the increase in productivity within individual sectors such agriculture, such as from informal subsistence farming to small-scale farms and later commercial agriculture..

Wealthier countries tend to offer decent jobs because they create productive employment opportunities. However, in low- and lower-middle-income countries, limited progress in economic transformation has resulted in an insufficient formal jobs to absorb the expanding labour supply, with the result that most employment occurs in the informal sector. ICTech offers a promising pathway for youth employment in Africa, but realising this potential requires investment in digital skills, smart regulation to support innovation, regional integration to scale startups and closing the urban-rural digital divide.

Economic transformation can reflect the use of new technology to lower the costs of production, follow more diversity and sophistication of what is produced, as well as be a result of improvements (and increases) in the efficient allocation of resources (land, labour and capital). Progress in economic transformation depends on: (i) gains in labour productivity within sectors; (ii) the structural shift of employment and output toward sectors with higher productivity levels; (iii) enhanced export diversification, increased domestic value addition in exported goods and progression along global value chains (GVC); and (iv) convergence in labour productivity across sectors at the national level.

The ICTech sector (typically contributing three to four per cent of GDP in Africa) is generally considered one of the most dynamic sectors with significant potential, but tends to be highly urbanised and regionally concentrated, even within countries. Whereas mobile-based, basic connectivity is typically the characteristic in low-income countries, often informal and microenterprise-oriented (such as phone shops and mobile money agents), upper-middle-income countries such as South Africa would have diversified ICT and technology services, global outsourcing and have various innovation hubs with significant research and development capacity. In between several emerging tech startup ecosystems (of which M-Pesa is best known) are evident in lower-middle-income country capitals such as Nairobi, Lagos, Accra and Dakar.

Africa is often associated with agriculture, yet African economies have been dominated by the services sector since independence, with the average contribution hovering at around 50% of GDP. Most job seekers in Africa have found employment in the services sector (particularly in informal jobs). While these sectors have provided livelihoods, they often yield low productivity and income.

The Current Path suggests a modest increase in the contribution of the sector in line with the general trend towards servicification evident globally. In low- and lower-middle-income Africa, the services sector is dominated by low-productivity informal services such as street vending, small retail and wholesale trade, personal services such as haircuts and repairs, and transport in the form of motorcycles, taxis and informal minibuses. These are all highly informal, precarious employment with low wages and weak linkages to the higher-productivity sector. The picture changes somewhat in lower-middle-income countries such as Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria and Senegal, which see a larger formal sector. Here, services include urban retail, ICT and financial services. Most services are, however, still non-tradeable; in other words, they meet local demand. Upper-middle-income countries such as South Africa, Mauritius and Botswana have a much larger and more diversified services economy, including developed ICT and telecom sectors. Much of the associated employment is formal and more skill-intensive. This situation raises concerns about job quality and the sustainability of growth.

Because the services sector is larger than any other economic sector it is also the largest employer in Africa, estimated to account for 36-38% of labour force employment according to the ILO, compared to the 32-35% in the agricultural and 27-30% in industry/manufacturing sectors, although, in some low-income and rural countries such as Burkina Faso and Ethiopia, agriculture still accounts for over 50% of employment.

The contribution of agriculture has been steadily declining from around 20% of GDP to around 14% in 2023, and the trend is likely to continue. Again, there are large differences in the structure, productivity, employment, value chains and integration of the agricultural sector when comparing country income groups. Agriculture in low-income African countries such as Malawi, Chad, Burkina Faso and the DR Congo is low-productivity, subsistence-focused. In most of these countries, agriculture consists of labour-intensive smallholder, subsistence farming, growing staple foods and using little, if any, modern inputs such as fertiliser and better seeds. In these countries, agriculture is a survivalist safety net, but is trapped in low productivity.

In lower-middle-income countries such as Senegal, Zambia and Ghana, an expanding base of commercial agriculture complements the large base of smallholder farmers, engaged in horticulture, cocoa, oil palm, cotton, tobacco and tea. These farmers make irregular use of inputs such as irrigation and mechanisation, but it is uneven. Thus, agriculture is a mix of subsistence and dynamic niches. By contrast, upper-middle-income countries such as South Africa, Botswana and Namibia have a largely commercialised, market-oriented agricultural sector that uses lots of mechanisation, irrigation and scientific inputs, and crops are typically high-value, such as wine, fruit, vegetables and beef. Employment in the agricultural sector is typically much smaller, and this is often a globally competitive sector, commercialised and integrated with value addition.

Across all income groups, agro-processing is often the entry point for industrialisation, with potential for exports and to benefit from regional trade agreements. The associated strategies, examined in the manufacturing theme, are often Special Economic Zones (SEZs) and industrial parks, but with mixed success. Regional integration such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) offers an opportunity to scale manufacturing markets beyond small domestic bases.

The nature of Africa’s manufacturing sector differs across African countries depending on income level, structural transformation and integration with global markets. Whereas manufacturing in low-income countries such as Chad, Malawi, Burundi and the DR Congo is basic, small-scale and informal, it includes a mix of informal and emerging formal sectors in lower-middle-income countries and is more diversified and globally connected in upper-middle-income Africa. Thus, in low-income Africa, manufacturing is small, informal and micro-enterprises, often family-based enterprises in the informal sector that make furniture, textiles and garments, process food and beverages and handicrafts with no or limited capital investment and using outdated technology. In lower-middle-income countries such as Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal, agro-processing of cocoa, coffee, cashew, maize, oil palm, as well as production of construction material, is rampant. Growth in manufacturing in these countries is often constrained by high energy costs, unreliable energy supply, infrastructure deficit, skills shortages and import competition compared to the more mature and globally integrated sectors such as automotive and component manufacturing, chemicals and petrochemicals, metals and machinery found in upper-middle-income African countries such as South Africa, Mauritus, Botswana and Nambiia which face intense competition from Asia.

Traditionally, manufacturing has been viewed as a labour-absorbing sector that can convert a growing population in low-income countries into an economic dividend and middle-income status. As manufacturing industries with higher productivity emerge, labour moves from farms into factories and factory-related jobs in urban areas. This process not only increases overall productivity (since workers shift from low-output agriculture to higher-output industry), but also tends to raise wages and incomes, creating a middle class. No example illustrates this better than China: its formal manufacturing sector employed around 105 million workers by 2023, up from only 30 million in the 1990s. Mass industrial employment was a pillar of China’s rapid growth and poverty reduction.

Africa’s manufacturing sector is, however, not creating jobs fast enough to absorb the continent’s burgeoning workforce. The ILO estimates that manufacturing employs only around 10% of Africa’s formal sector workforce on average, a low figure even compared to other developing regions. Over the past few decades, the share of manufacturing employment in total employment has stagnated or even declined in many African countries. For example, while employment in South Africa’s manufacturing sector peaked at around 23% of total employment in 1981, by 2023 it was down to around 11%. A similar or worse trend is seen in a number of other countries, where the relative and absolute number of manufacturing jobs have not kept up with population growth. Chart 14 shows the manufacturing sector’s share of total employment in 2008 and 2018.

There are several reasons for the weak employment performance of Africa’s manufacturing sector. One factor is the nature of technologies and firm capabilities in African manufacturing. An important recent study suggests that when manufacturing firms in Africa do exist, they tend to be either very small and informal (employing few workers), or if they are larger and formal, they often employ surprisingly capital-intensive methods given the labour-abundance of their countries.

In other words, African manufacturers may be adopting modern machines and processes that do not require many workers, perhaps because they compete on cost with global firms and need to be efficient, or because skilled labour is scarce, so they automate where possible. Studies in Tanzania and Ethiopia showed that some of the relatively large manufacturing firms were far more capital-intensive than one would expect at those low-income levels. This premature automation or high capital intensity means that even when manufacturing output grows, it does not generate as much employment as it could.

Another issue is competition from imports and the difficulty of breaking into export markets. Many would-be industries in Africa are out-competed by cheaper imported goods (whether second-hand clothing, cheap electronics or even basic consumer goods) before they scale up enough to be job engines. The result is that manufacturing activities remain small and often confined to niches (e.g., food processing for local markets) with limited job creation. Additionally, poor infrastructure and unreliable power supply in many countries raise costs and reduce the competitiveness of labour-intensive manufacturing. Frequent electricity outages in countries like Nigeria, Zimbabwe or Zambia, or severe load-shedding in South Africa, make it hard to sustain factories running multiple shifts.

If factories cannot operate efficiently, they hire fewer workers. In some cases, manufacturers resort to expensive generators or backup systems, which again incentivise keeping the workforce smaller and more skilled rather than expanding employment.

Across all country income groups, the share of employment in services (the largest economic sector in most countries) is growing, and the share of employment in both agriculture and manufacturing is declining. This applies as much to Africa as to the rest of the world. But will services-led growth provide sufficient jobs?

Historically, technology-driven shifts in employment, for example, following the introduction of the personal computer, have created more jobs than they have destroyed. In this future, as in the past, the demand for skilled and semi-skilled workers is steadily increasing, and that for unskilled labour (of which Africa has a large supply) will decrease. In the themes on Agriculture and Manufacturing, we note that African workers are moving from employment in subsistence agriculture in rural areas and into low-end services in the urban informal sector. Working conditions are generally worse in the service sector than in the manufacturing sector and only marginally better than in the subsistence agriculture sector.

Currently, most Africans are employed in the agricultural sector, which accounts for roughly double the employment in the service sector, although the contribution of the service sector to GDP is substantially larger than the agricultural sector. Services, in turn, employ more than double the number of Africans employed in the manufacturing sector. Other sectors, such as energy, materials and ICT, employ significantly fewer people. Much of Africa’s agriculture consists of subsistence farming, and most services are low-end services in informal settlements in urban areas, characteristics that translate into low levels of productivity. It is therefore no surprise that Africa grows slowly. Chart 15 shows employment by economic sector in Africa in 2023 and 2043 under the Current Path and Combined scenario.

Employment patterns across African countries and income groups vary significantly, influenced by a range of factors including economic structure, development stage, resource availability, government policies, education levels and historical context. In low-income countries, agriculture remains the dominant source of employment, although not in the contribution that it makes to GDP, especially in rural areas. Conversely, middle- and high-income countries tend to have more diversified economies, with growing industrial and service sectors that drive urban employment. As economies develop, they generally shift from agriculture to industry and then to services, though this transition occurs at different rates across the continent. For instance, Ethiopia and Malawi still rely heavily on agricultural employment, whereas countries like South Africa and Mauritius have more advanced industrial and service-based labour markets.

Countries endowed with natural resources such as oil and minerals often exhibit stronger industrial or extractive sectors. However, they tend to be capital-intensive and create relatively few direct employment opportunities. In Nigeria, for example, the oil sector dominates the economy but employs far fewer people than agriculture or informal services. Similarly, countries with higher levels of urbanisation typically experience greater employment in services and manufacturing, while those with predominantly rural populations continue to rely heavily on agriculture for livelihoods.

In summary, employment in the agricultural sector dominates in low- and lower-middle-income countries (accounting for 46 of the 54 states in Africa), but the contribution of agriculture to GDP is quite low. Generally, the service sector dominates in its contribution to GDP for all country income groups, particularly for upper-middle- and high-income countries, and employment in this sector is growing, but currently reflecting low-productive structural transformation.

The employment per sector versus contribution to GDP per sector could be seen as a broad indication of productivity in each sector. The relationship is complex. For example, owing to the large surplus of labour on the continent, economic growth in Africa is more employment-intensive than it would otherwise be (although not in middle-income manufacturing), but does not translate into productivity improvements. It is often cheaper to employ more labour than to invest in better systems, technology or even in training for current employees.

Meagre investments in health and education lead to a skills gap, which, in turn, results in low labour productivity, as also reflected in the World Bank’s Human Capital Index, which ranks sub-Saharan Africa lowest globally in respect of lost productivity of the next generation of workers.

Previous sections have indicated the changes to Africa’s labour force, shaped by demographic trends, shifting economic dynamics and the implementation of policy reforms. Chart 16 shows the total labour force and formal labour share in Africa from 2020 to 2043 under the Current Path and Combined scenario.

In the Combined scenario, consisting of the combination of all eight sectors positively modelled for all African countries, the continents total labour force in 2043 will increase by 4.2% in size compared to the Current Path, as the working age portion of Africa’s total population increases in size relative to dependants. The share of the informal labour force as a percentage of the total labour force will decline by 13 percentage points, increasing the portion of the formal labour force to 60% of the total labour force by 2043. As the continent progresses and shifts from an agrarian economy to industrial and service-based structures, new formal job opportunities are created in sectors such as manufacturing, finance and information technology (IT). Additionally, the Combined scenario will boost Africa’s urbanisation by 0.7 percentage points above the Current Path, reaching approximately 53% as the labour force transitions from informal rural employment to formal jobs in urban areas.

Chart 17 depicts the projected decrease in the informal labour force by 2043 under each scenario, compared to the Current Path. In interpreting this chart, it is important to remember that a portion of informal labour is also employed in the formal sector which is not included in the depiction.

The Manufacturing scenario has the most significant impact on reducing the informal labour force, by about nine percentage points by 2043, highlighting the transformative potential of industrial expansion in creating more formal job opportunities.

For Africa to take advantage of its demographic dividend rather than face a demographic burden, expanding productive employment is essential. Manufacturing can play a vital role in this effort because it has the potential to provide jobs for a large number of semi-skilled workers, particularly in areas like agro-processing, garment production and assembly work. Additionally, manufacturing has multiplier effects on job creation in supporting sectors such as logistics, distribution and maintenance.

There are encouraging examples of the associated potential: for example, the establishment of industrial parks in Ethiopia created tens of thousands of jobs for youth, particularly women, in apparel factories before the the Tigray War disrupted progress from November 2020. New industries such as automotive assembly in countries like Morocco and Egypt are generating manufacturing employment that was virtually non-existent a decade ago.

However, to truly move the needle, these examples need to be scaled up and replicated widely. African governments need to address the constraints by improving infrastructure (reducing outages and transport costs), offering targeted incentives for labour-intensive industries, investing in technical training and managing competition (through smart use of tariffs or local content policies where feasible under trade rules). They will also need to encourage linkages between large and small firms so that the growth of big factories stimulates job creation in small to medium enterprises (SMEs) that supply inputs or services.

Without significantly more manufacturing (and modern agribusiness) jobs, countries risk high unemployment or merely growing informal employment as millions of young people entering the job market each year. Industrial expansion should seek to crowd informal manufacturing into the formal sector, particularly those involved in low-productivity or subsistence-level activities. Following the positive effect of the Manufacturing scenario in reduction of informal labour are the Governance and Education scenarios. Better governance fosters a conducive environment for business growth and formal sector development, while improved education equips workers with the skills needed for formal employment.

Together, these scenarios underscore the importance of targeted interventions in industrial policy, governance reform, regional trade, human, physical and financial capital development to address the challenge of informality in Africa’s labour markets.

Given the dominance of the service sector in both the Current Path and Combined scenario, most future formal employment growth on the African continent is set to come from tourism, retail, trade, transportation, finance and other service-related activities. This is in contrast to the African growth experience over the last 35 years, which, in general, relied on growth in capital-intensive resource and energy-based industries that did not generate jobs at scale. Instead, most of the new jobs that emerged were necessarily in the informal sectors, with its low productivity levels, such as subsistence agriculture and its low-value-added contribution to the economy. Self-employment has continued to be predominant.

Against the background presented in the previous section, improvements in each of the eight development scenarios discussed on this website will boost employment, with the largest increase expected in the Manufacturing scenario, followed at some distance by the Demographics and Health scenario. However, these increases will not be sufficient to keep pace with the increase in the size of the working-age population.

Chart 18 shows the increase in labour employment by 2043 in each scenario relative to the Current Path.

The themes dealing with the Current Path and Manufacturing briefly commented on the phenomenon of Africa’s premature deindustrialisation from already low levels. Middle-income countries are experiencing declining shares of industry as a contribution to GDP and, hence, declining shares of employment in this sector. This is happening at an earlier stage of development than it did in today’s developed countries. But because manufacturing is important in changing the productive structures in the entire economy (i.e. also in the agriculture and service sectors), African countries need to pursue industrialisation aggressively where this is possible. Politically and socially Africa cannot emulate the exploitative manufacturing labour practices through which countries such as China and the Asian Tiger economies initially developed. It is inherently more difficult for low-income democracies (of which Africa has many) to institute the measures required for rapid economic growth than it is for authoritarian states, reflected in the exceptional growth rates of Rwanda and Ethiopia, amongst others, compared to more democratic African states.

The trend of premature deindustrialisation complicates the potential impact of structural transformation towards more formal and less vulnerable employment in many African countries. In effect, the opportunity for industrialisation in Africa as a pathway to provide employment and productivity improvements seems to be slipping away. As manufacturing is the single most important vehicle through which economies transition to higher productivity, the long-term impact of premature deindustrialisation could be debilitating. The conclusion, presented by many, is that African countries need to additionally look elsewhere for growth, primarily tourism, agriculture, natural resource extraction and IT services.

The problem is that few of these sectors offer particularly exciting employment or productivity prospects. Africa is already overly dependent on natural resource extraction and very vulnerable to the associated swings in commodity prices. Commodity dependence can provide growth, but it is often linked to political dysfunction and may trap a country at the low end of the value chain. Tourism is employment-intensive, but not all countries have the offerings to provide attractive packages or destinations. Nor does tourism offer the kind of learning-driven productivity improvements generally common to manufacturing. Agriculture, where Africa has significant potential, automates even faster than industry, meaning that additional employment is dependent upon expansion of the sector rather than higher productivity. While agriculture remains vital to Africa’s economy and for food security, its potential for large-scale, sustainable job creation within the sector is therefore limited. Rather, growth in the agricultural sector enables development more broadly and creates jobs in other sectors, manufacturing in particular.

Improvements in productivity in agriculture reduce employment intensity as it introduces modern technology into the sector, although a growing agricultural sector would increase the total number of jobs even as employment intensity declines. In other words, the agricultural sector will only provide the jobs that Africa so desperately needs if it grows significantly more rapidly.

Chart 19 presents the difference in labour employment by sector and country income group in millions and percentage terms in 2043, comparing the Current Path and Combined scenario. Total employment does not change much between the various scenarios by 2043, but there is a shift of employment between sectors—thus, some more, but different, jobs. This is most noticeable in the Agriculture scenario, which sees a large decline in employment, although a roughly similar number of jobs are created in the service, ICT and other sectors.

The findings appear to reinforce the view that a larger manufacturing sector has important enabling spillover effects and that it has greater promise in changing the productive structures of African economies, i.e. it unlocks more rapid growth. For example, it incentivises high-end services such as financial intermediation, which is crucial for the development of the private sector, and also encourages a more productive agricultural sector and, consequently, the transition into agro-processing and agribusiness. These changes eventually produce higher growth rates and a more rapidly growing economy, which, in turn, creates more jobs (although only in the medium to long term). The implementation of the AfCFTA will play an important role in this regard, given the potential that regional trade offers in terms of value addition.

Also important, although less explicit, are the limits of Africa’s higher-than-expected levels of democratisation in affecting a manufacturing-led growth path. Whereas authoritarian countries such as Ethiopia and Rwanda can pursue exploitative manufacturing labour practices that enable them to compete on cost with emerging Asia, it is doubtful whether that is replicable in countries where democratic accountability is more deeply entrenched.

The African Center for Economic Transformation (ACET) in Ghana is one of many institutions that advocates that both agriculture and light manufacturing are key requirements for the future, and argues for a dual track to industrialisation, where one route leverages the relative abundance of workers for labour-intensive and export-oriented light manufacturing, while the other leverages advantages in agriculture for globally competitive agriculturally based manufacturing. Although an agricultural growth path is appropriate for low-income countries, a manufacturing growth path generally becomes more important as countries transition towards middle-income status.

The preceding analysis implies that Africa would have to consider additional means, such as public work programs and an extensive system of social grants, to alleviate extreme poverty, as discussed below. Even then, the majority of job growth is likely to be in the informal rather than the formal sector.

Given the size of the informal sector and the nature of work in Africa, the key question when looking at the future of work is whether digitisation and the use of modern technology can more rapidly formalise African economies and accelerate employment growth, with all the associated benefits.

These employment trends will be increasingly shaped by emerging technologies—especially digitisation, automation and artificial intelligence.

Estimates about the impact of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and, more recently, Artificial Intelligence differ significantly and include alarmist forecasts predicting the destruction of up to 30% of all jobs globally by 2030. Not unexpectedly, the Economist argues that artificial intelligence, robotics and automation will not change what it refers to as the historical trend that saw technological revolutions create more jobs than they destroy. Wealthy regions, it argues, such as Europe and North America, are enjoying an unprecedented bonanza of jobs, with low-end workers being upskilled with a concomitant rise in wages. Research findings by the IMF are more cautious, as it notes that:

Artificial Intelligence (AI) can potentially reshape the global economy, especially in the realm of labour markets. Advanced economies will experience the benefits and pitfalls of AI sooner than emerging markets and developing economies, largely due to their employment structure focused on cognitive-intensive roles. There are some consistent patterns concerning AI exposure, with women and college-educated individuals more exposed but also better poised to reap AI benefits, and older workers potentially less able to adapt to the new technology. Labour income inequality may increase if the complementarity between AI and high-income workers is strong, while capital returns will increase wealth inequality.

More philosophically, Daren Acemoglu and Simon Johnson argue that the belief that technological progress automatically translates into higher productivity and higher wages, eventually reducing inequality and welfare through the bandwagon effect, is mistaken. They argue that technology often does not result in more productivity, or only does so in the very long term. Where it does, it has not increased wages, although it has increased corporate profits and return on investment to shareholders. Instead, it has resulted in a decline in employment and stagnant or decreasing wages as employers reduce labour input costs. That trend, the authors argue, is particularly evident when considering the impact of automation and offshoring. It is in this domain that democracy has proved wanting in the US, with the intensifying relationship between money and politics. Instead of holding entrepreneurs and technology leaders to account, pushing production methods and innovation in a more worker-friendly direction, the association between capitalism, limited government and democracy has translated into increased inequality and populism. Thus, ‘blind optimism’ about technological progress is ‘again enriching a small group of entrepreneurs and investors, whereas most people are disempowered and benefit little.’ Huge resources are behind this global movement in favour of more open markets, deregulation and the free flow of capital, most prominently advanced by powerful pro-business media and tech billionaires.

The impact of robots and artificial intelligence will, therefore, likely widen the gap between rich and poor countries by shifting more investment to advanced economies where automation is already established and the means to access AI, such as reliable and rapid broadband, are widely available. Developing economies will tend to specialise in sectors that rely more on unskilled labour, and the impact could result in a permanent decline in the terms of trade of poorer countries. In that way, robots may still end up stealing jobs in developing countries.

The question is whether the current crop of low-skilled workers in low- and lower-middle-income countries will be able to reskill and upskill to benefit from these technologies. Even upper-middle-income countries will struggle. For example, as South Africa transitions from coal to renewables as the dominant source of energy, thousands of coal miners in places such as the coal-rich province of Mpumalanga will lose their jobs. Although many more jobs will be created across the country as distributed wind, solar and biomass energy sources come online, that shift is only possible if accompanied by a drastic effort to rapidly improve and transform skills and will penalise Mpumalanga even whilst benefiting other provinces.

The largest potential for robot-based automation and artificial intelligence is in countries with large and well-paying manufacturing sectors, such as Germany, Japan, South Korea, the US and increasingly China. The automation of low-wage and light manufacturing jobs, such as those generally found in Africa, seems much less likely in the foreseeable future. Both the AfDB and the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) suggest that robot-based automation has had a relatively small effect in developing countries to date, which is likely to remain given their lack of technological diversification. The impact of robotisation is mostly concentrated in countries with a large manufacturing sector dominated by industries such as automotives and electronics.

The current views on automation and artificial intelligence are that jobs will increase in vocations that require non-routine cognitive skills, such as managing teams, nursing and cleaning. Care work that requires empathy and judgement (such as nurses and elderly care) is harder to automate and is likely to increase as populations outside of Africa age. So, people will have to transition from one set of skills that may be replaced by automation to another, where that threat is not as acute. This is less of a challenge in Africa, where employment is less formal and structured than elsewhere.

With the advent of AI, the demand for routine, job-specific skills, such as those required for processing payroll, bookkeeping or assembling goods, will decrease, and jobs that combine different skill sets will increase. As a result, global value chains (GVCs) are becoming more knowledge-intensive, and low-skilled labour is becoming less important as a factor of contribution compared to capital and technology. The demand for labour is increasingly away from low-skilled to semi-skilled and skilled labour, and it is for this reason that more and better education is so important for Africa.

Recently, the AfDB projected that by 2030, approximately 100 million African youth may struggle to find employment, with technological advancements, including automation, being significant contributing factors. In South Africa, Accenture estimated that 35% of all jobs were at risk of total automation, meaning that machines could perform at least 75% of the tasks associated with these jobs. A recent report by the country’s Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) estimates that up to 30% of manufacturing jobs in South Africa could be automated by 2030, highlighting the urgency for skills development and diversification within the sector.

Technology and the job market will differ hugely between countries at different levels of development. In Japan and Germany, countries with highly paid and scarce workers, many of whom work in the automotive industry, a higher percentage of additional work could be automated. However, in many parts of Africa, new jobs could be created at much lower start-up costs owing to the reductions in the capital costs and lower barriers to entry. These findings underline the importance of providing the basics for empowerment, such as household electricity and low-cost global Internet coverage, which will unlock access to education, trade and other means of self-help.

So, will future jobs also come to Africa or will most still be created in Asia? In considering this question, it is important to bear in mind that the capital and labour intensity of manufacturing is declining and that technology (or knowledge) is globalising.

Given these considerations, and contrary to the trepidation with which the Fourth Industrial Revolution and AI is viewed in Europe and North America, the view from Africa is positive. In a recent research survey in Africa, less than a fifth of respondents thought the Fourth Industrial Revolution would hurt jobs. As progress comes from a low base, it offers prospects for a degree of catch-up, with the expectation that it will create more jobs in both the formal and informal sectors.

In this vein, a report prepared for the European Commission concluded that the nature of work is part of the changing economy and ‘no longer a static concept but an umbrella term for roles performed in a different manner and under different legal arrangements.’ Instead of workers being replaced completely by machines, the more likely future is one in which people work alongside highly productive machines. This is already evident in the way in which ICT and artificial intelligence are penetrating modern life through the use of smartphone applications to augment or ease the completion of everyday tasks.

Therefore, the impact of the digital economy in high-income OECD countries will include a trend towards short-term contracts and part-time work. In addition, the European Commission believes that automation will reduce routine job opportunities, such as those on a typical assembly line, in the formal sector.