Risks and rewards of Africa’s access to international capital markets

International bond markets offer a ready funding stream but could increase debt vulnerabilities if not properly managed.

Africa needs roughly US$130 billion to US$170 billion a year for infrastructure investment. But countries lack the capacity to generate domestic revenues and don’t attract much global foreign direct investment flows either.

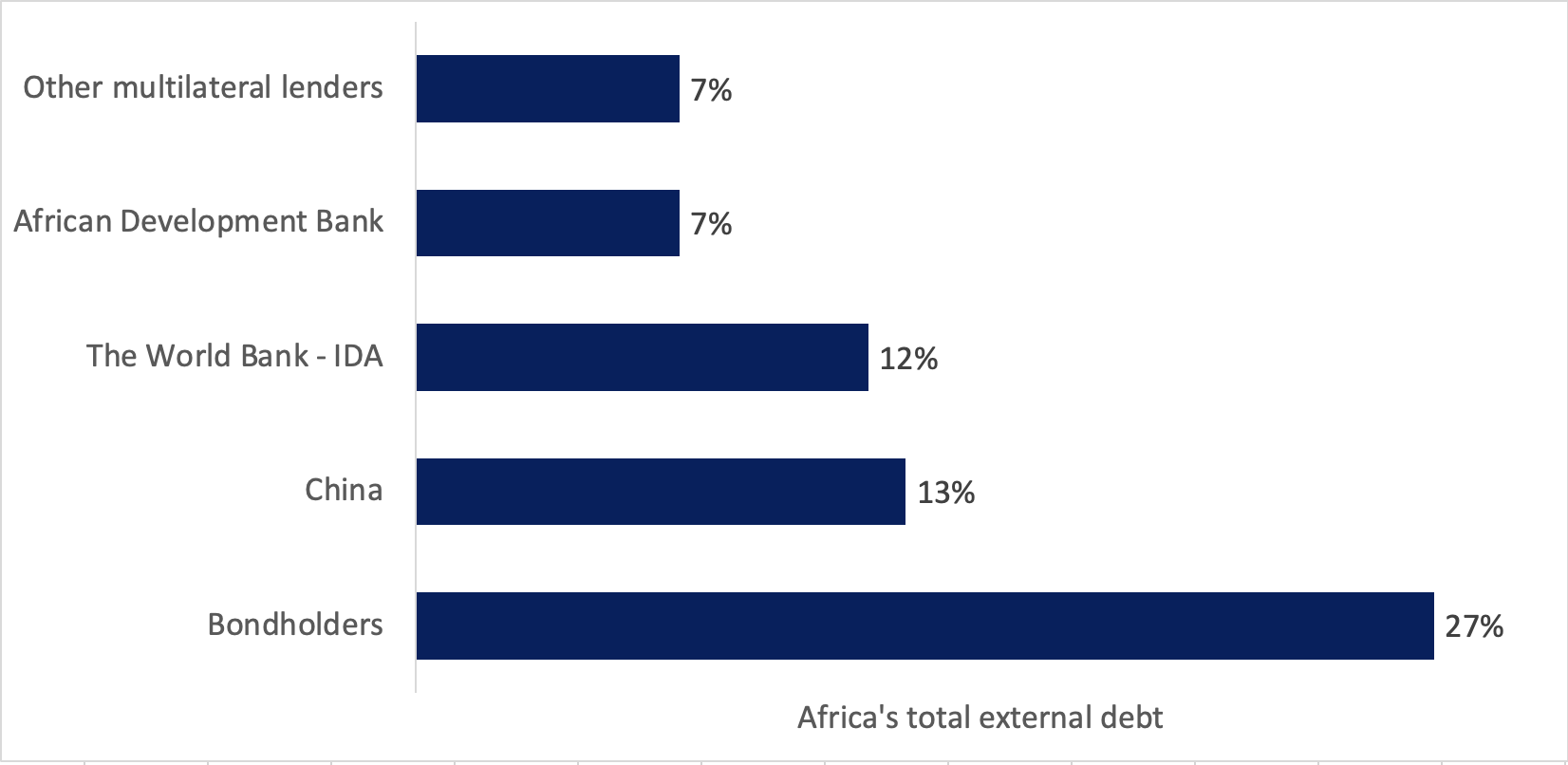

To meet their funding needs, states have relied mainly on aid and loans from multilateral institutions like the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) and bilateral creditors forming the Paris Club. But the composition of Africa’s debt is changing. Today a considerable share is held by private banks, bondholders and official lenders who are non-Paris Club members, such as China.

According to African Development Bank statistics, bilateral debt – mostly owned by Paris Club lenders – accounted for 52% of Africa’s total external debt stock in 2000. By 2019 it had dropped to 27%. Over the same timeframe, the share of commercial creditors, namely bondholders and commercial banks, more than doubled – from 17% in 2000 to 40% in 2019.

By 2020, about 21 African countries had issued eurobonds worth more than US$155 billion, while only three borrowed commercially in 2001. This reflects the increasing access of African countries to international capital markets. Chart 1 shows the top five external creditors to Africa as of 2019.

Chart 1: Top five external creditors to Africa, 2019 Source: Author, using African Development Bank data

Source: Author, using African Development Bank data

Low debt levels following the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) debt relief programme of the mid-2000s improved states’ macroeconomic management. And continued high economic growth might have given some African countries confidence to explore new funding sources. The search for high yields by foreign investors following the historic low returns in advanced countries might also have played a role.

Access to international capital markets presents many opportunities for Africa. It helps diversify funding sources and makes countries less dependent on aid and multilateral and bilateral loans to finance investment and expenditure. While stringent conditions come with multilateral and bilateral loans, they generally don’t with commercial debt.

World Bank and IMF critics argue that the policy conditions attached to their financing often result in increased unemployment, poverty and income inequality, which undermines sustainable development. Bilateral loans, especially from China, are also often collateralised, requiring the surrender of strategic assets when countries default.

Bilateral debt has shrunk while the share of commercial creditors more than doubled from 2000 to 2019

Another advantage of access to international capital markets is that governments can use the money according to their development priorities. Successful participation in the global bond markets can also positively affect other capital flows to Africa, such as foreign direct investment, as it provides a benchmark of country risk.

But borrowing from international financial markets isn’t without risk. First, these debts are denominated in foreign currencies, mainly the euro and US dollar, exposing African countries to exchange rate risk. The IMF warns that capital flow reversals could coincide with the initial wave of eurobonds reaching maturity. Capital reversals could lead to a significant depreciation in the domestic currency and increase the external debt burden.

Second, interest rates paid by African countries on eurobonds or commercial debts are too high. African governments pay 5% to 16% on 10-year government bonds, compared to near-zero to negative rates for American and European governments. Africa continues, disappointingly, to suffer from a bad image as a place for investment, and this penalises countries through a high-risk premium.

Credit rating agencies, which play a pivotal role in determining these interest rates, are not fair with Africa. Generally there’s a strong positive correlation between economic strength and creditworthiness, but high economic growth hasn’t typically translated into better sovereign ratings in Africa. The combination of exchange rate risk and high borrowing costs can lead to large-scale defaults.

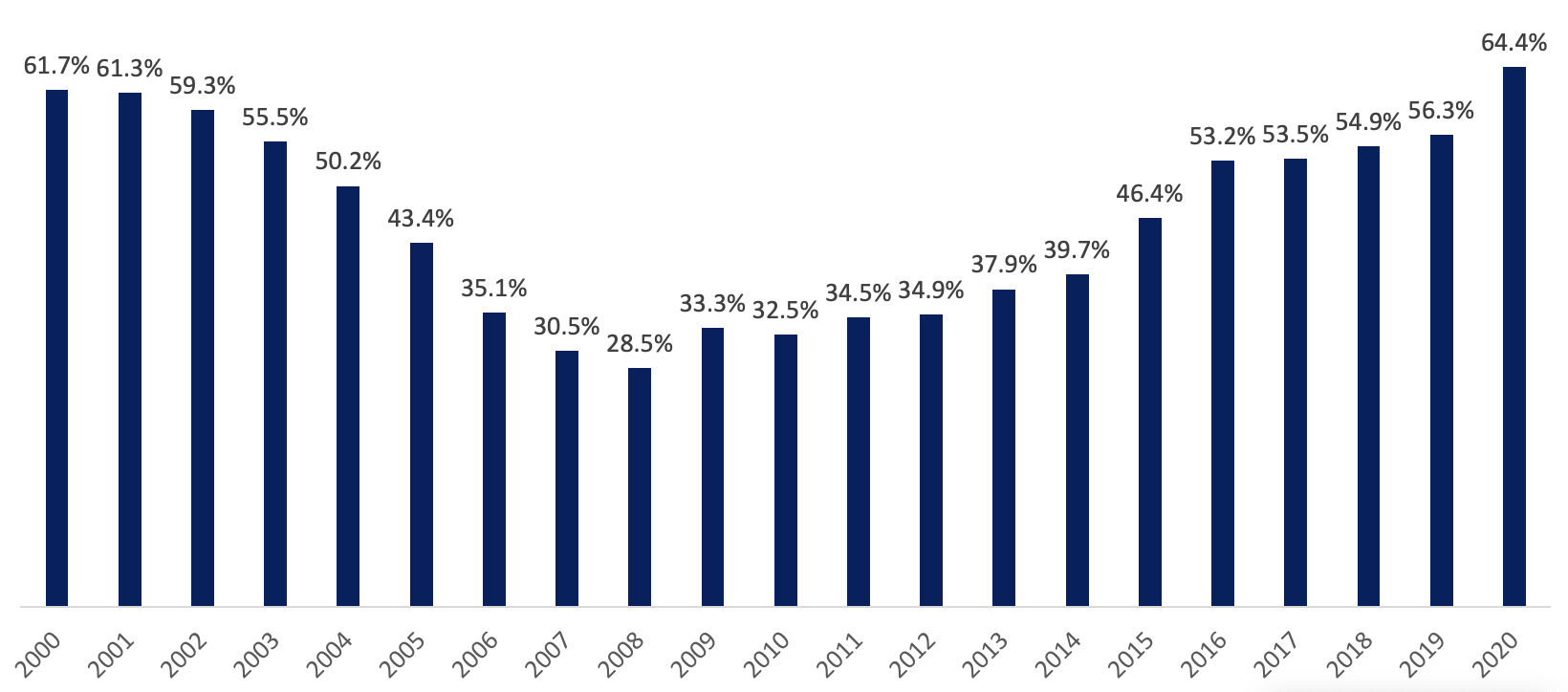

Spurred by increased access to international financial markets and bilateral loans from non-Paris Club members such as China, Africa’s total general government debt has been rising from a low of 28.5% of GDP in 2008 (Chart 2). Even before the impact of COVID-19, many African countries were already struggling to meet their debt commitments. As of December 2020, six were in debt distress, and 14 others were at high risk.

Chart 2: African total government debt (% of GDP), 2000-2020

Source: Author, using IMF data

Source: Author, using IMF data

If properly managed, borrowing money can help a country boost its development. But much African debt ends up in the pockets of the governing elite instead of fuelling economic growth for its repayment. Governments should use borrowed money for productive investments and manage proceeds from international bonds more prudently, with integrity and transparency.

This will require a significant effort to improve public financial management, governance and political stability in general. Commercial creditors are not philanthropic – they look at countries’ economic, political, social and climate risks to fix the risk premium. So the recent wave of military coups in Africa doesn’t help.

For their part, investors should not apply the same risk premium to all African countries. Those that manage their debt well and show more political stability should be rewarded with lower-risk premiums.

The combination of exchange rate risk and high borrowing cost can lead to large-scale defaults

While access to international bond markets offers a ready stream of funding, investors’ loyalty cannot be taken for granted. This means African countries must accelerate the development of their domestic financial markets. The starting point should be a strong regulatory framework and judicial system. Strong domestic financial markets would provide a stable and less expensive funding source in the local currency and reduce countries’ exposure to foreign exchange volatility.

African governments should also improve domestic revenue through digitised tax collection and administrative systems and anti-corruption reforms. More substantial tax revenue would allow authorities to provide better public services without adding to debt burdens.

International capital markets can be a useful source of financing for Africa to accelerate industrialisation and development. But the continent’s ability to increase its access and remain in these markets will depend on how it uses these loans.

This article was first published by ISS Today.