11 Large Infrastructure

11 Large Infrastructure

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

This theme explores Africa’s current economic infrastructure deficit and its impact on the continent’s development outlook. Whereas the themes on Health/WaSH, Education, Agriculture and Leapfrogging cover sector-specific infrastructure, the focus here is on road, rail, port and other economic infrastructure. We then present a Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario showing how infrastructure type and quality affect development outcomes. Details on leapfrogging and its impact are explained in a separate and complementary theme. The Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario shows the significant development benefits that can be achieved in Africa by investing in both basic and advanced infrastructure projects and the potential benefits of modern technology.

Summary

- Infrastructure development has the potential to significantly contribute to the attainment of African Union Agenda 2063 long-term vision for the continent.

- With the end of colonialism, Africa was left with a legacy of fragmented infrastructure and subsequently invested little in maintenance or new build. As a result, Africa is lagging behind the rest of the world.

- Access to electricity, transport, and Internet services is generally limited across Africa and is lower than in other comparable, developing regions.

- The type of infrastructure, how it is financed and how quickly it is rolled out, together with levels of development, determine the extent to which infrastructure spending benefits development.

- Africa is not short of ambition for infrastructure and financing is available, but projects need to be appropriate to the requirements given levels of development, overcome numerous hurdles and ensure that financing is attractive.

- The Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario shows that investing in infrastructure projects, both basic and advanced, results in substantial improvement in economic growth, employment and poverty and boosts Africa’s trade.

All charts for Large Infrastructure

- Chart 1: History and forecast of infrastructure by regions, 2009, 2019 & 2043

- Chart 2: Comparison of infrastructure access in sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa, South Asia and South America in the Current Path forecast

- Chart 3: Access to electricity: total, urban & rural in Africa by income groups, 2009, 2019 & 2043

- Chart 4: Electricity generation capacity per capita in Africa compared with South America and South Asia, 1980–2043

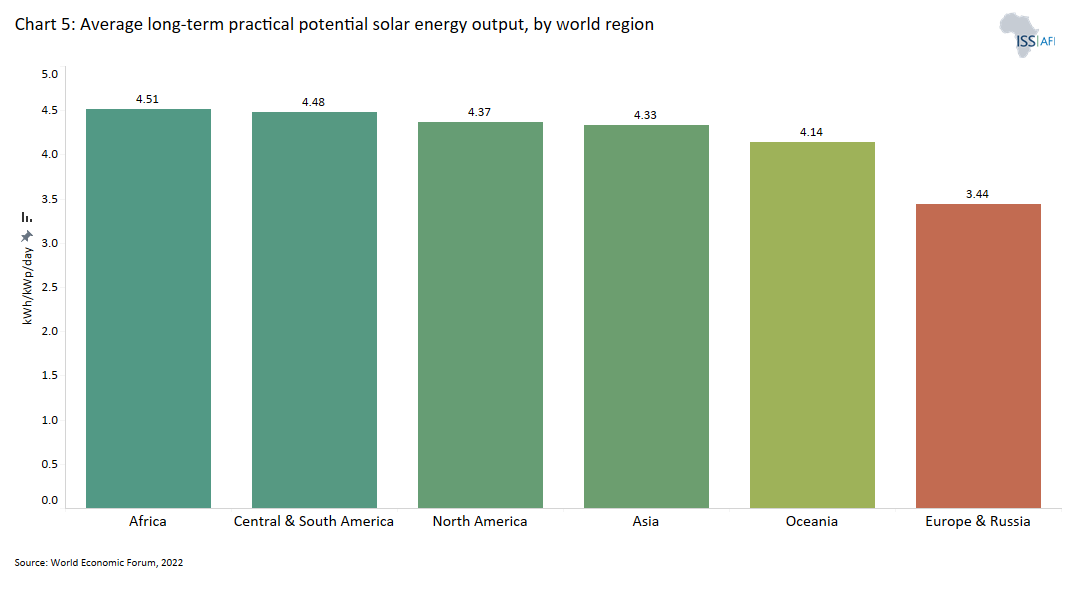

- Chart 5: Average long-term practical potential solar energy output, by world region

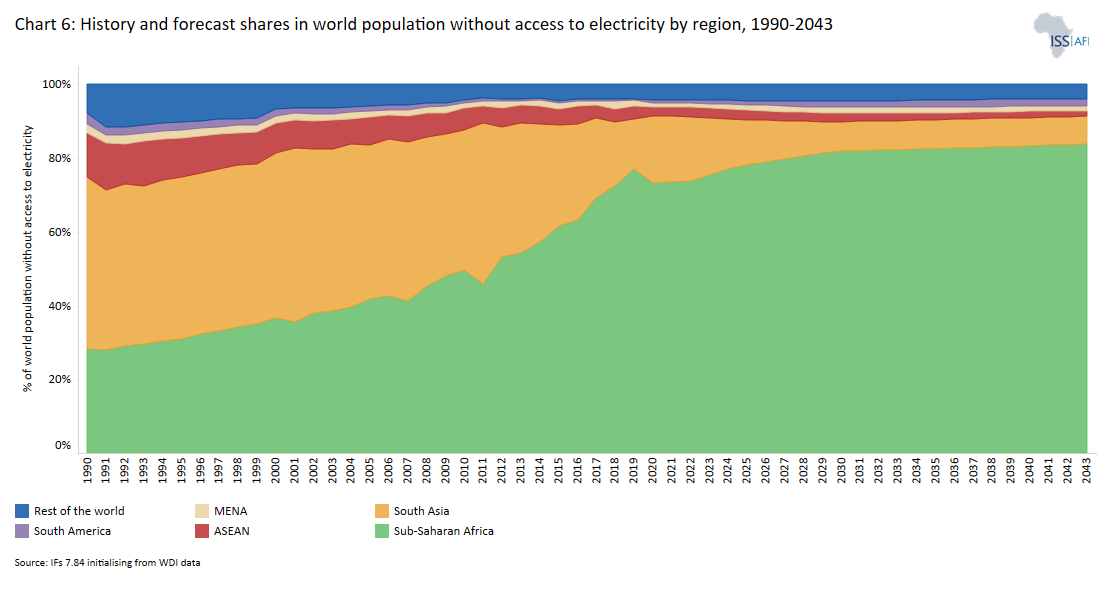

- Chart 6: History and forecast shares in world population without access to electricity by region, 1990–2043

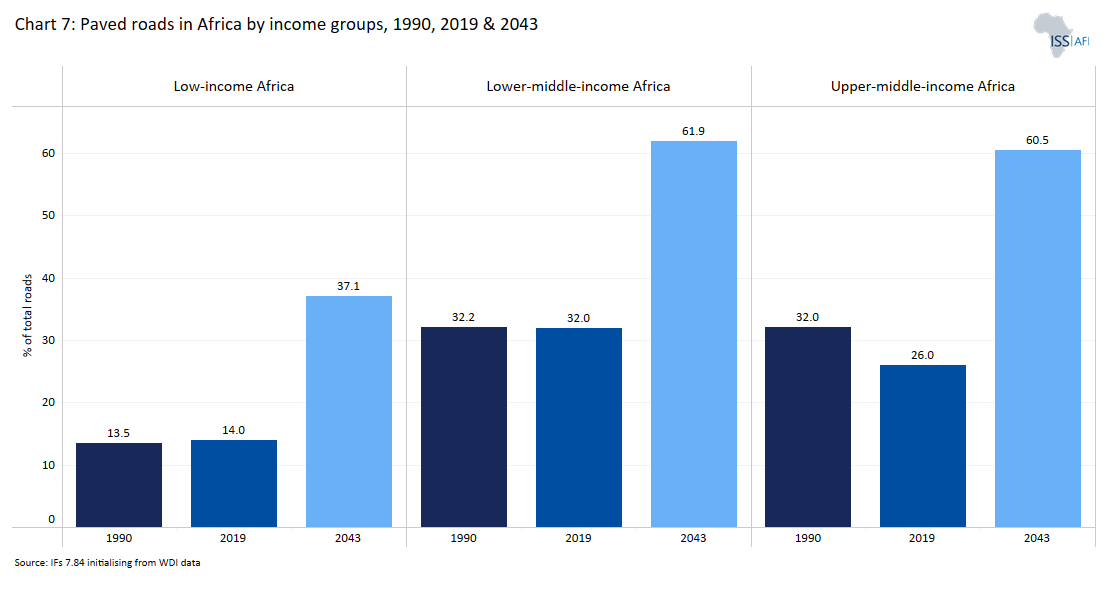

- Chart 7: Paved roads in Africa by income groups, 1990, 2019 & 2043

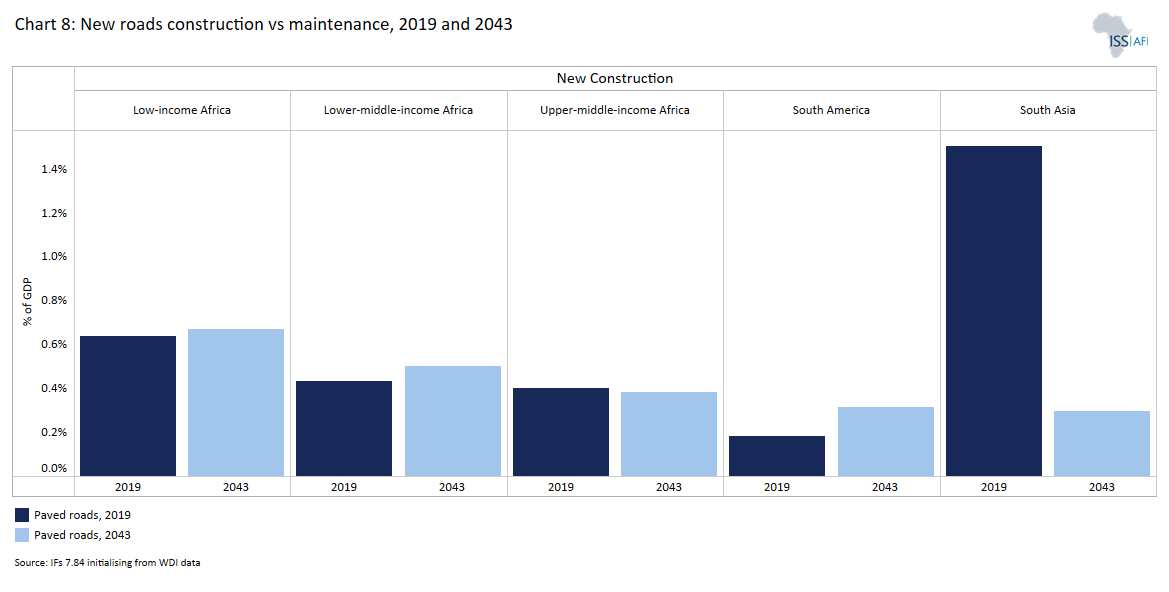

- Chart 8: New roads construction vs maintenance, 2019 and 2043

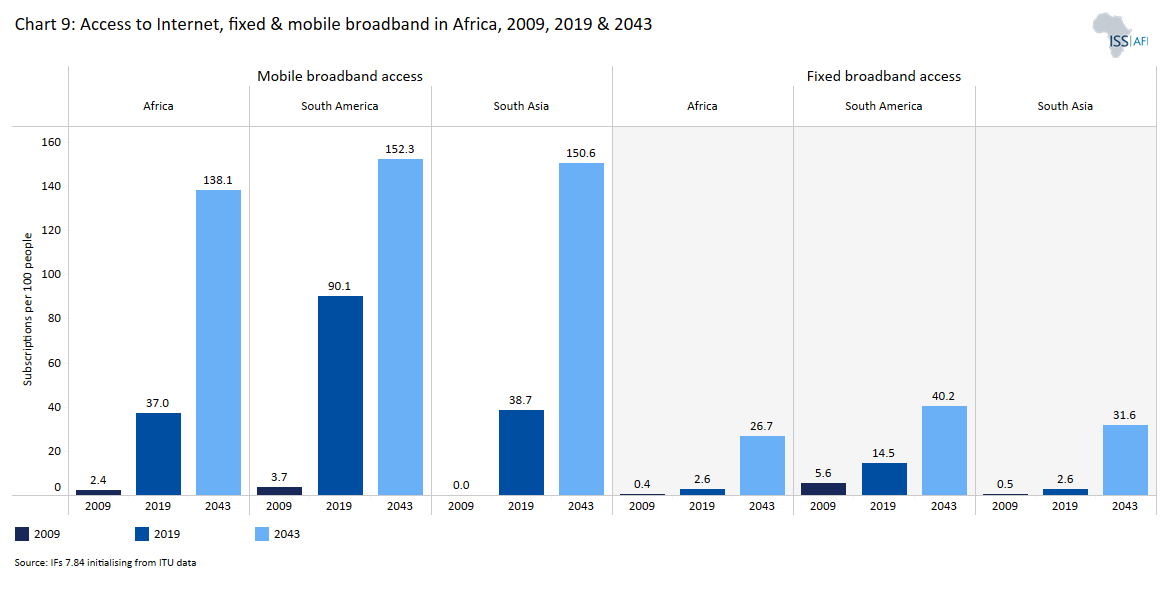

- Chart 9: Access to Internet, fixed & mobile broadband in Africa, 2009, 2019 & 2043

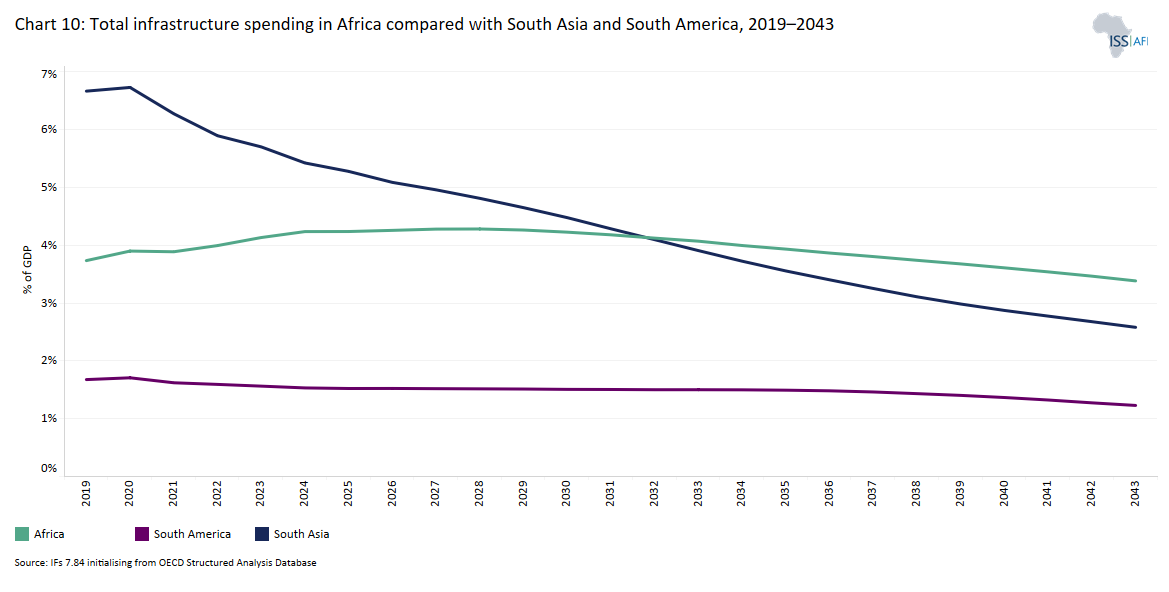

- Chart 10: Total infrastructure spending in Africa compared with South Asia and South America, 2017–2043

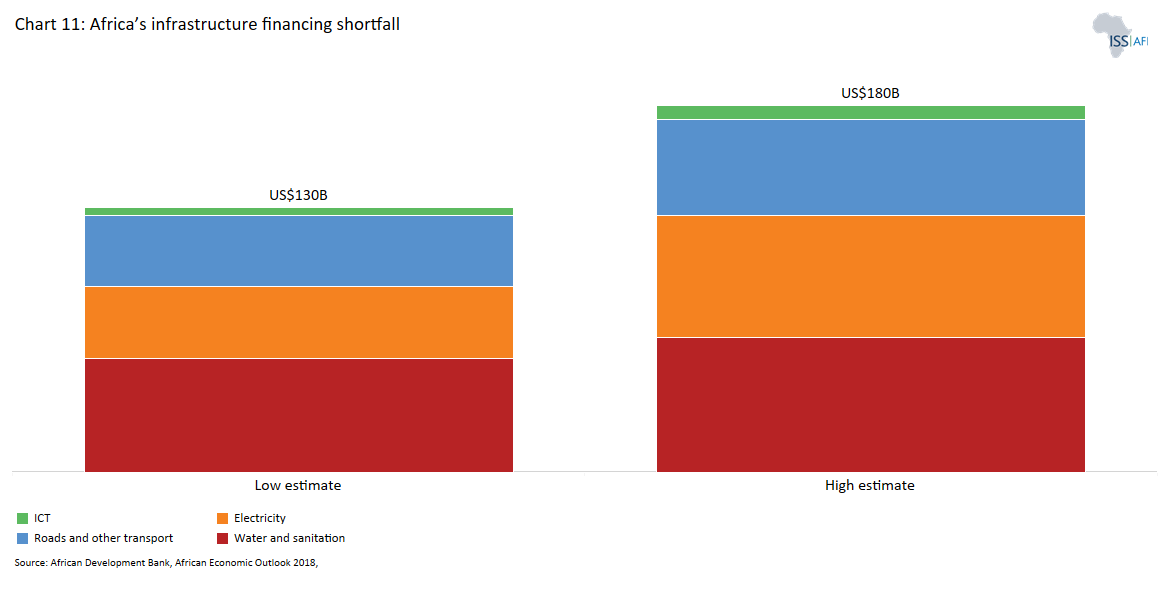

- Chart 11: Africa’s infrastructure financing shortfall

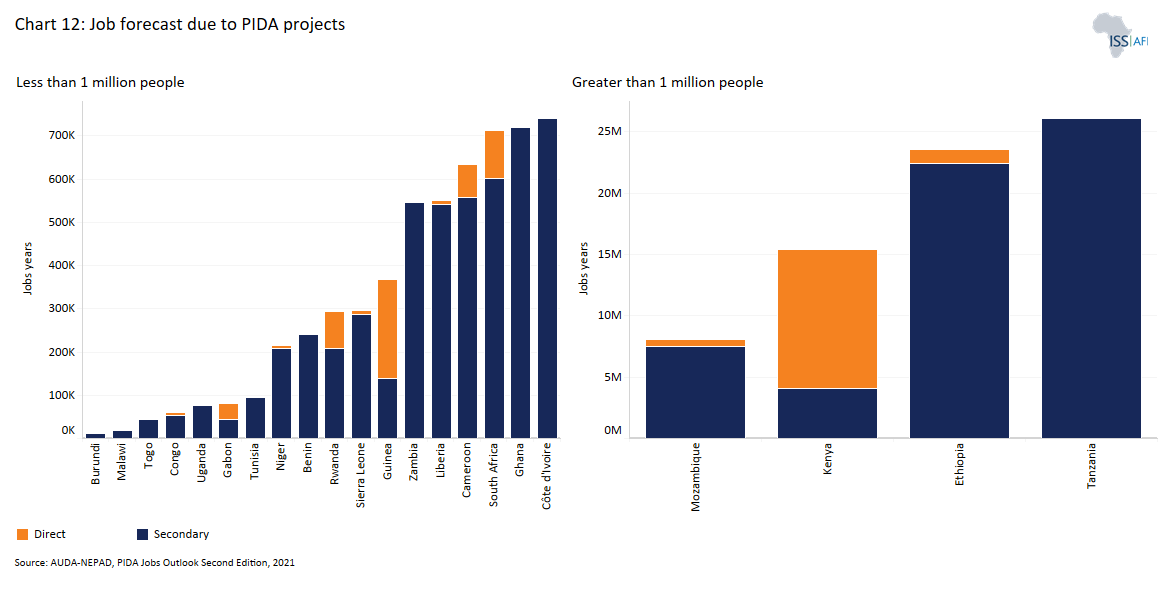

- Chart 12: Job forecast due to PIDA projects

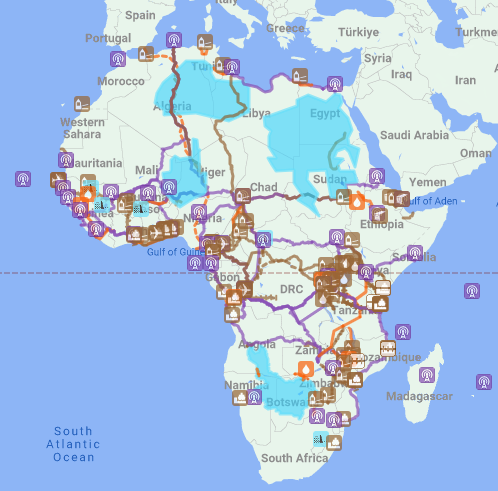

- Chart 13: PIDA projects across Africa

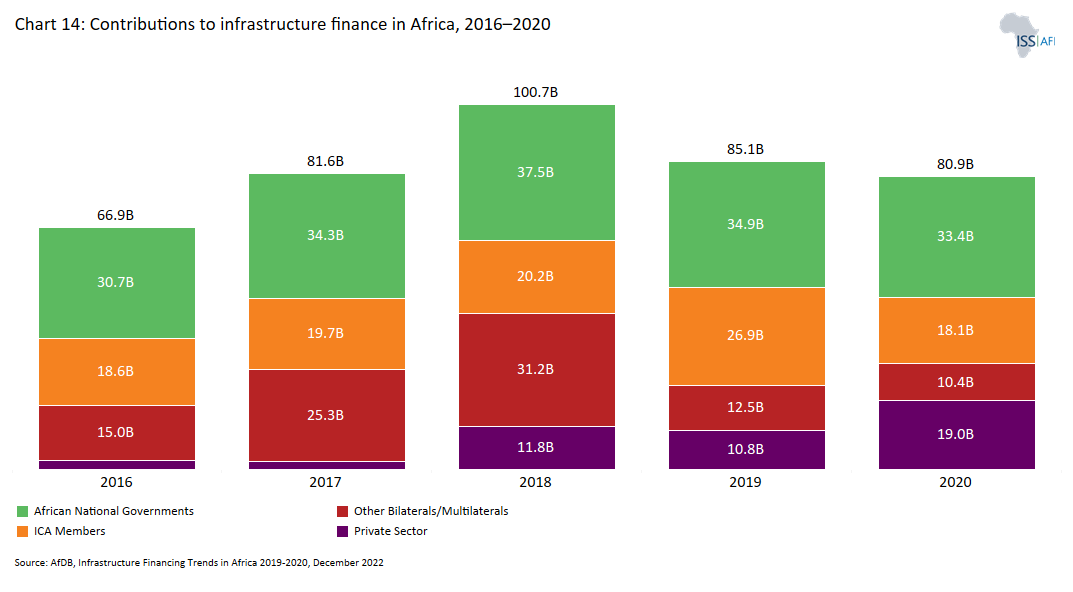

- Chart 14: Contributions to infrastructure finance in Africa, 2016–2020

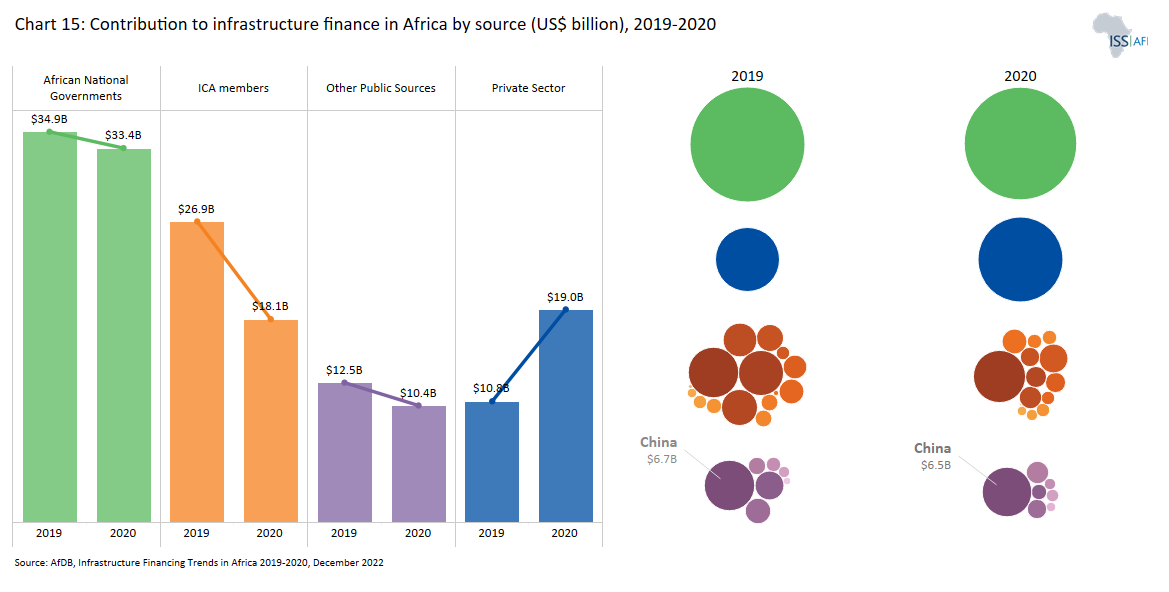

- Chart 15: Contribution to infrastructure finance in Africa by source (US$ billion), 2019–2020

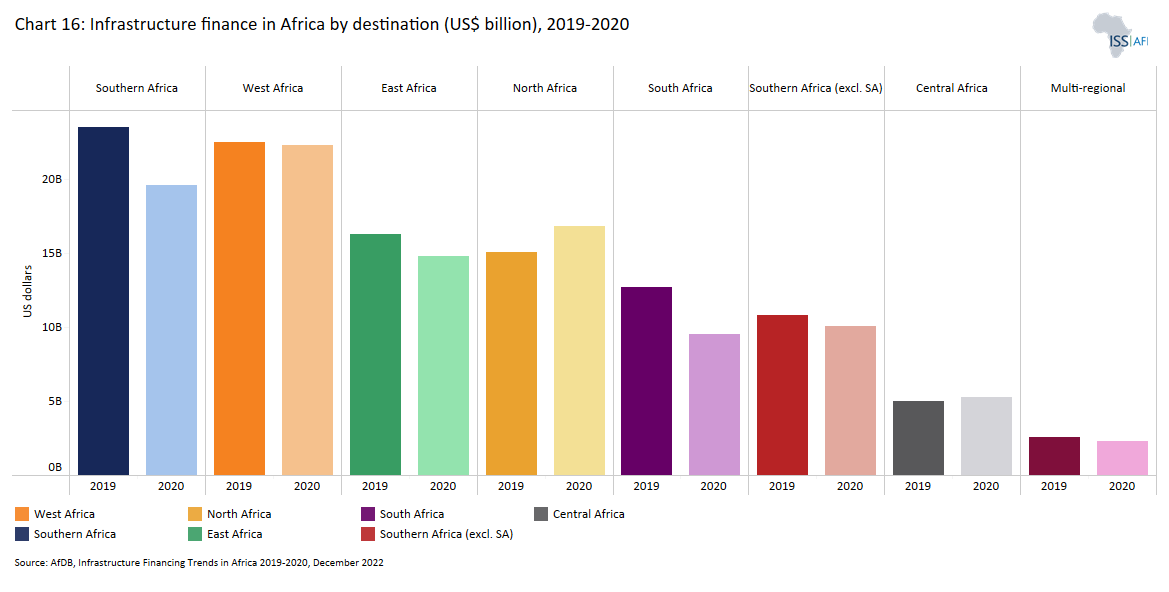

- Chart 16: Infrastructure finance in Africa by destination (US$ billion), 2019–2020

- Chart 17: Africa’s infrastructure pipeline

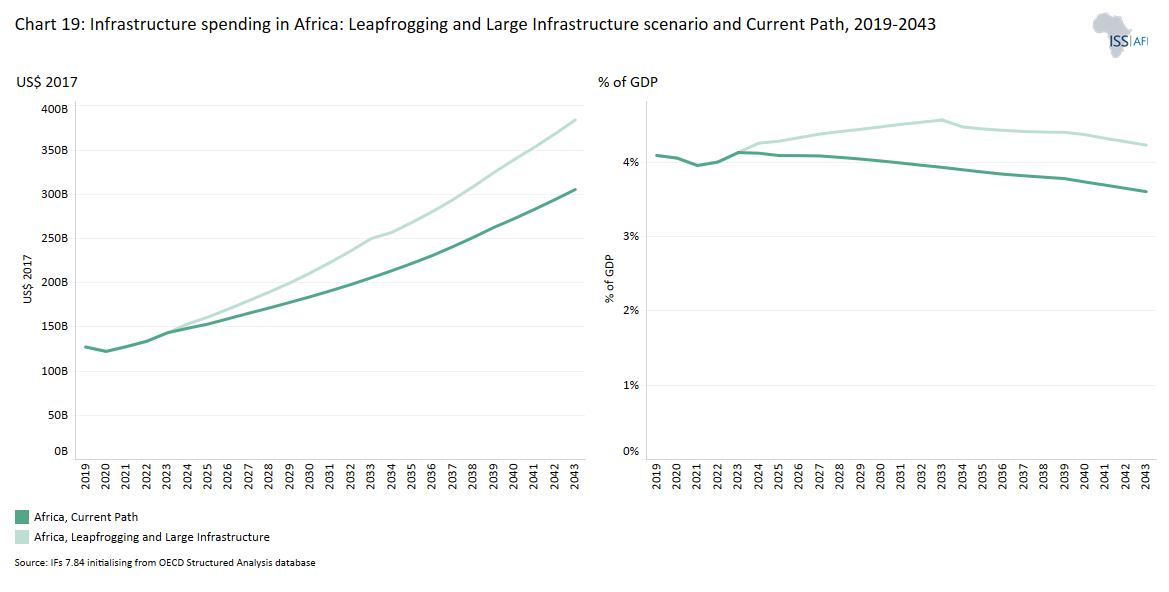

- Chart 18: Schematic of the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario

- Chart 19: Infrastructure spending in Africa: Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario and Current Path, 2019–2043

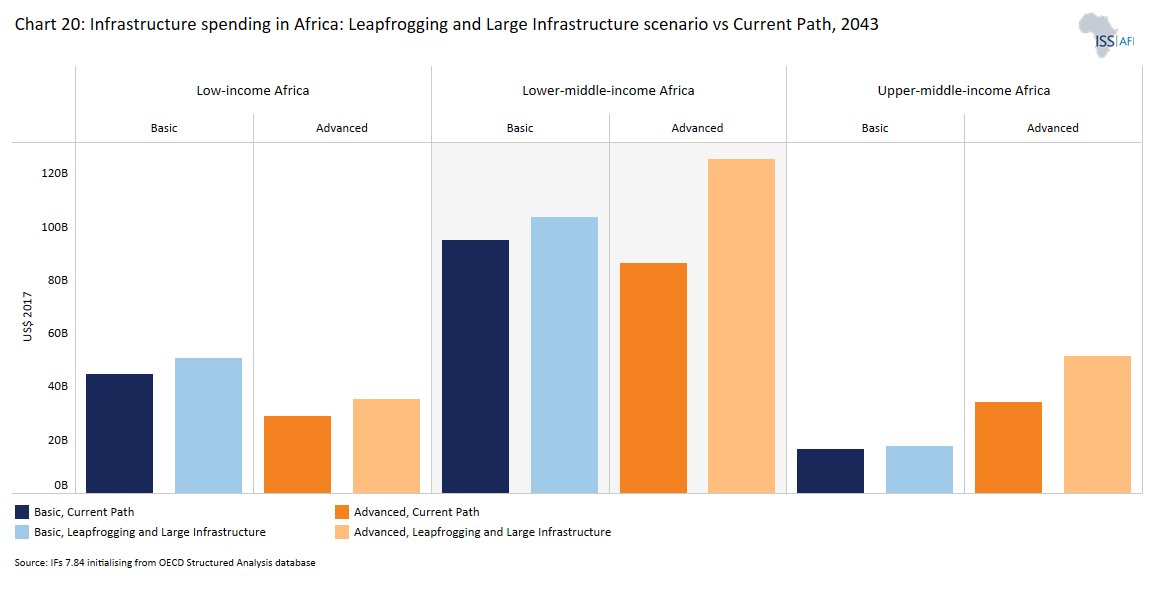

- Chart 20 Infrastructure spending in Africa: Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario vs Current Path, 2043

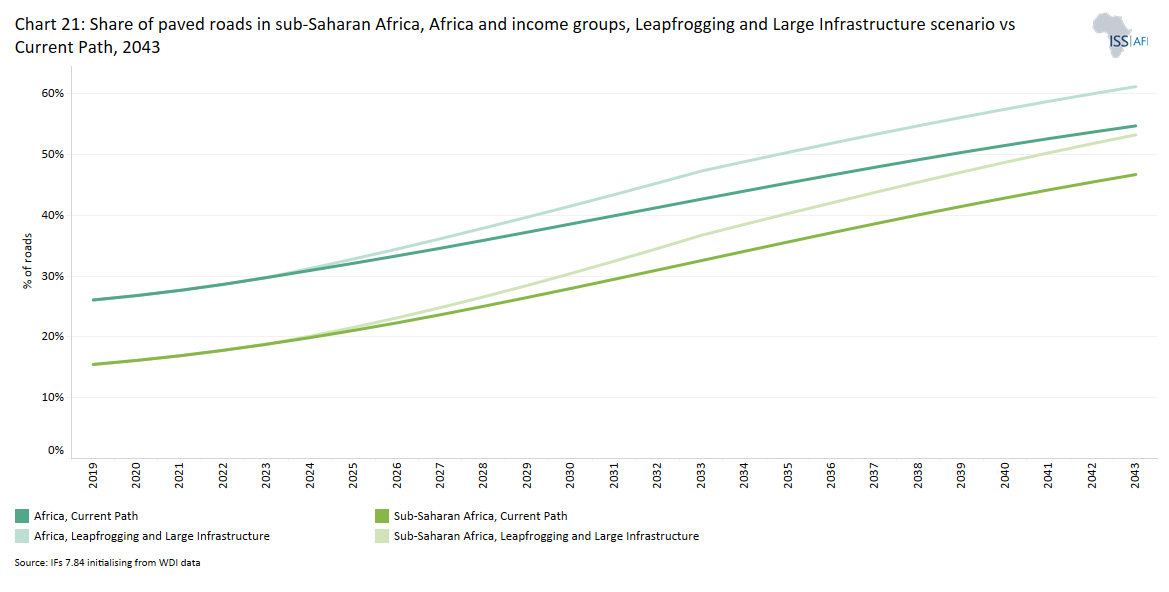

- Chart 21: Share of paved roads in sub-Saharan Africa, Africa and income groups, Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario vs Current Path, 2043

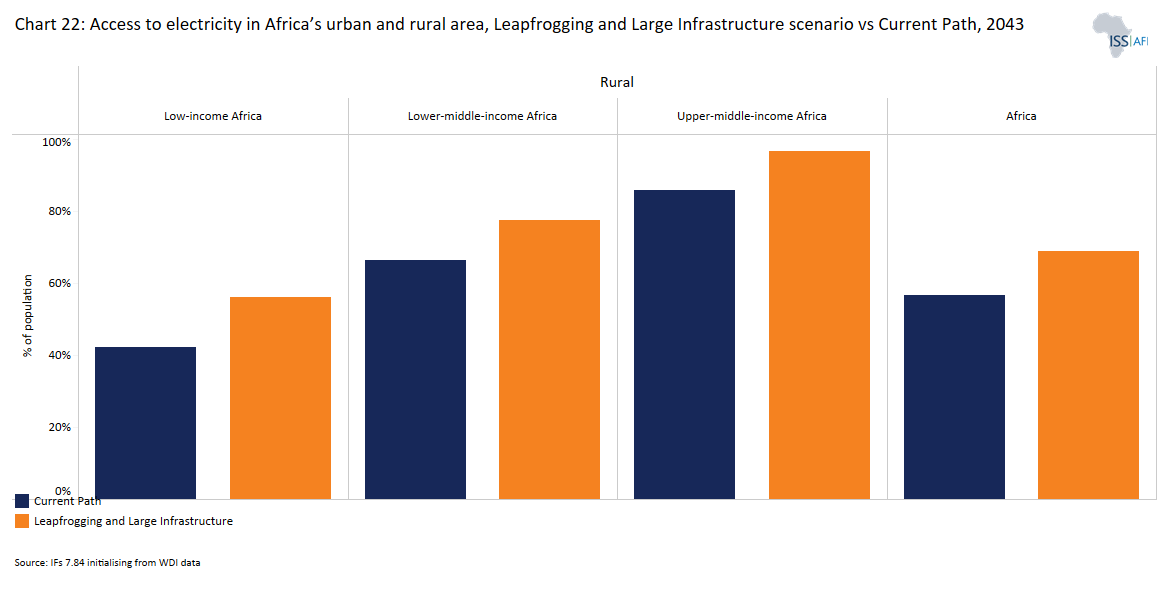

- Chart 22: Access to electricity in Africa’s urban and rural area, Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario vs Current Path, 2043

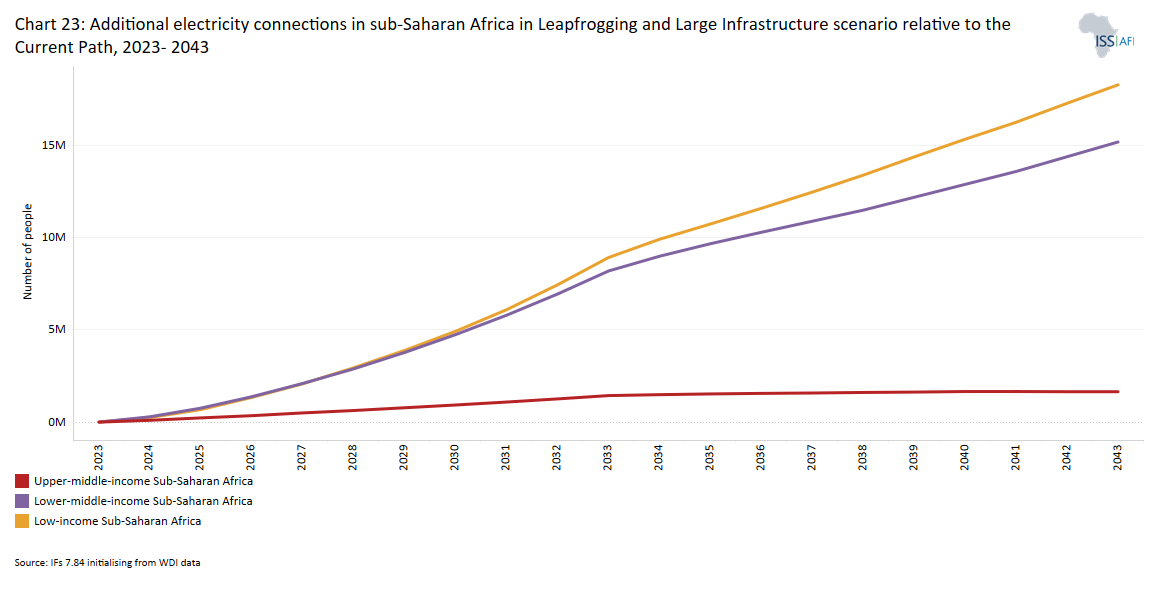

- Chart 23: Additional electricity connections in sub-Saharan Africa in Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario relative to the Current Path, 2023–2043

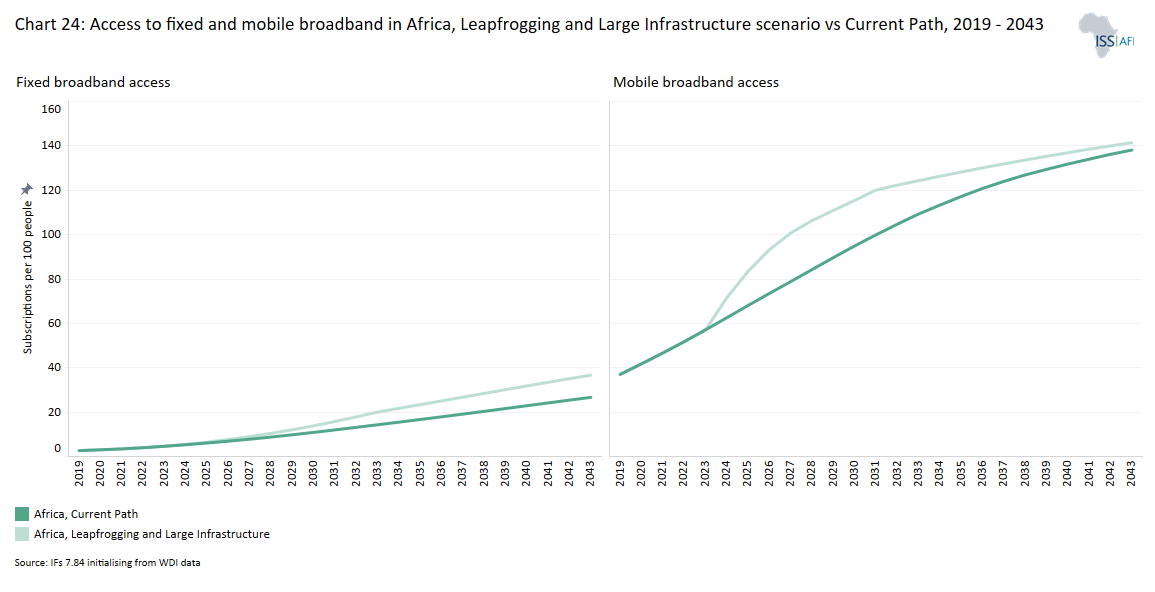

- Chart 24: Access to fixed and mobile broadband in Africa, Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario vs Current Path, 2019–2043

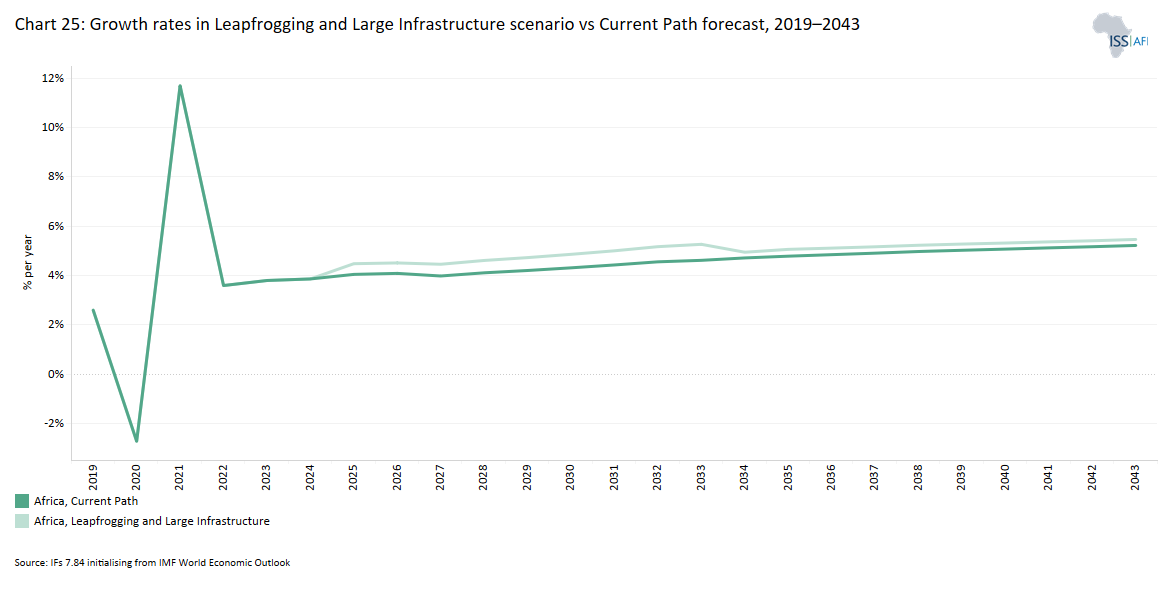

- Chart 25: Growth rates in Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario vs Current Path forecast, 2019–2043

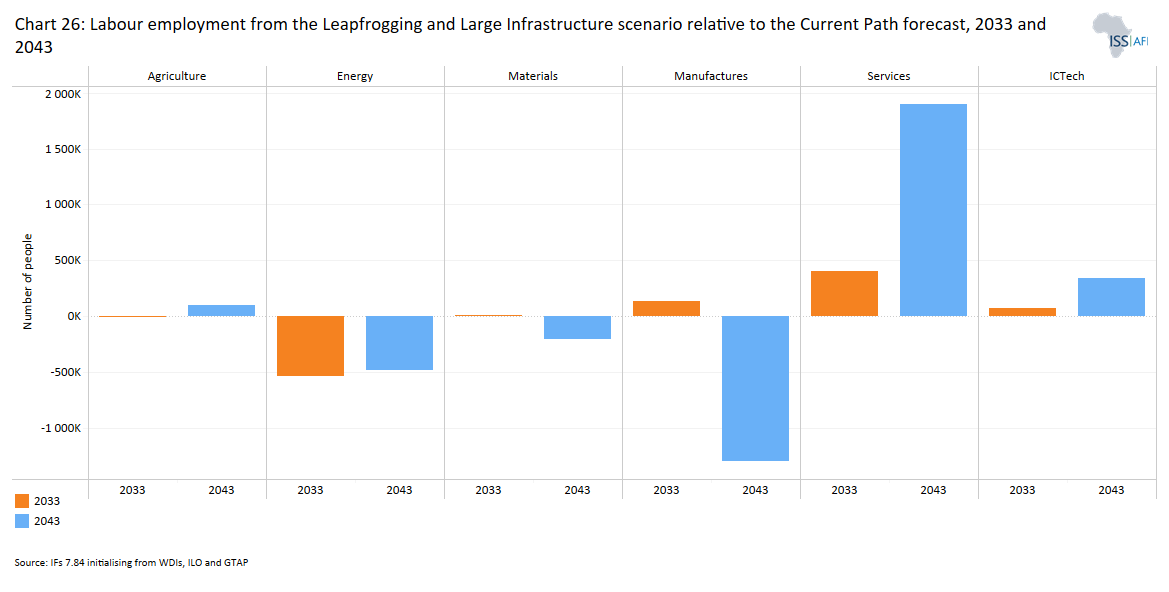

- Chart 26: Labour employment from the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario relative to the Current Path forecast, 2033 and 2043

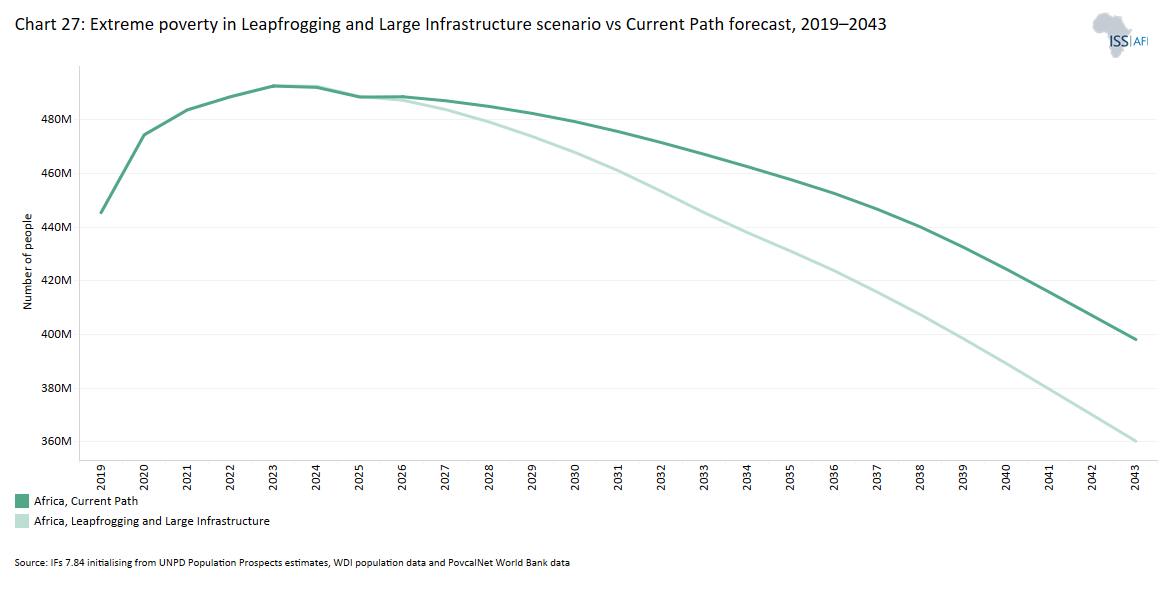

- Chart 27: Extreme poverty in Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario vs Current Path forecast, 2019–2043

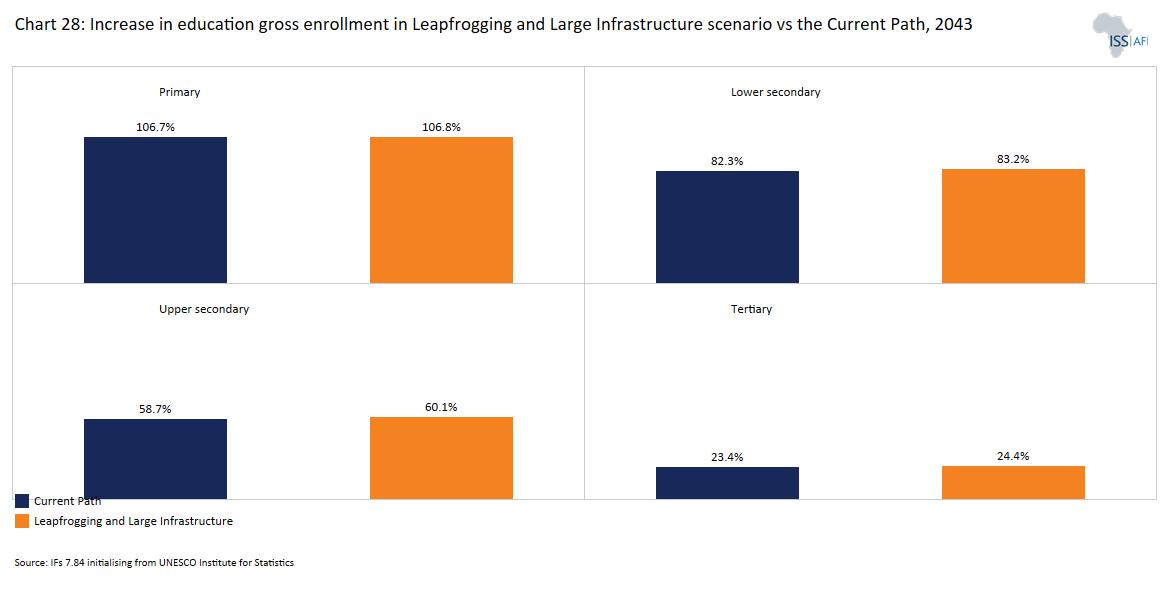

- Chart 28: Increase in education gross enrollment in Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario vs the Current Path, 2043

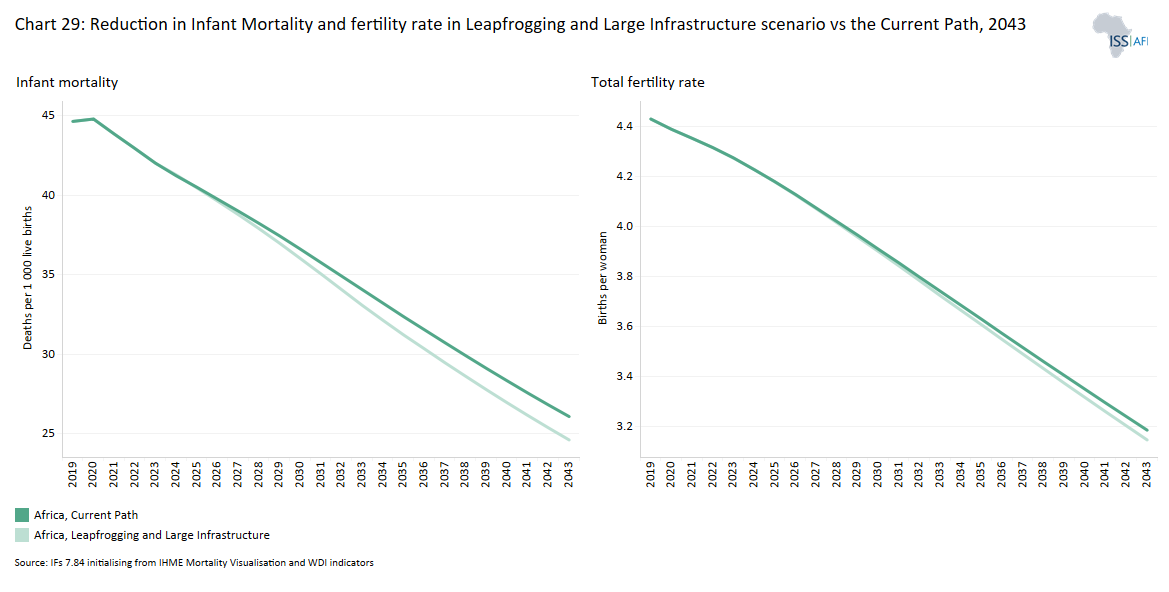

- Chart 29: Reduction in infant mortality and fertility rate in Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario vs the Current Path, 2043

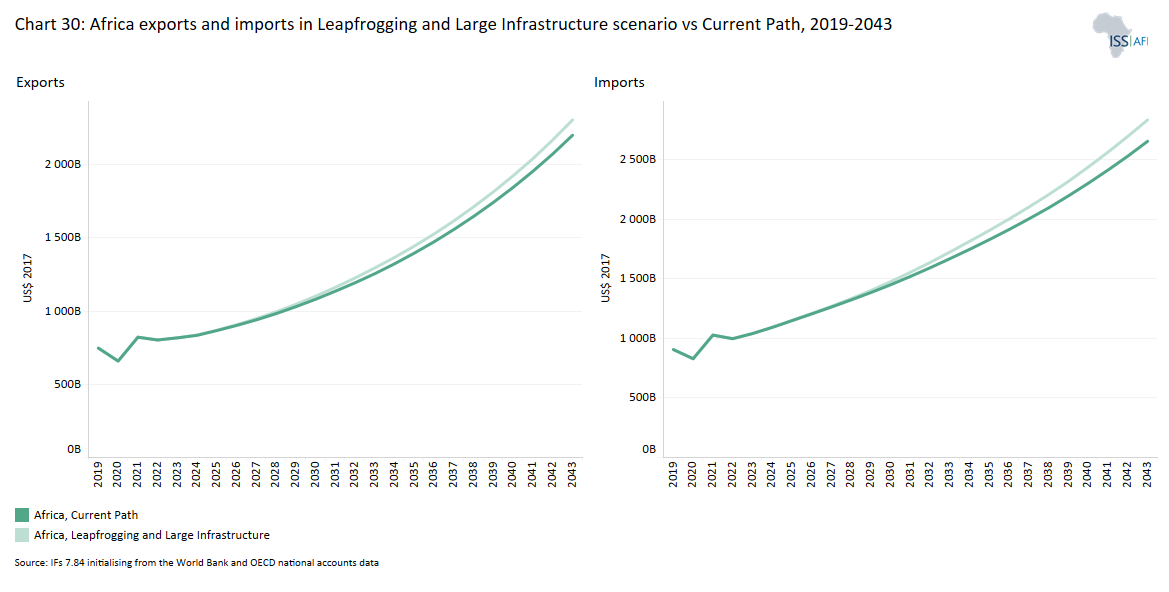

- Chart 30: Africa exports and imports in Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario vs Current Path, 2019–2043

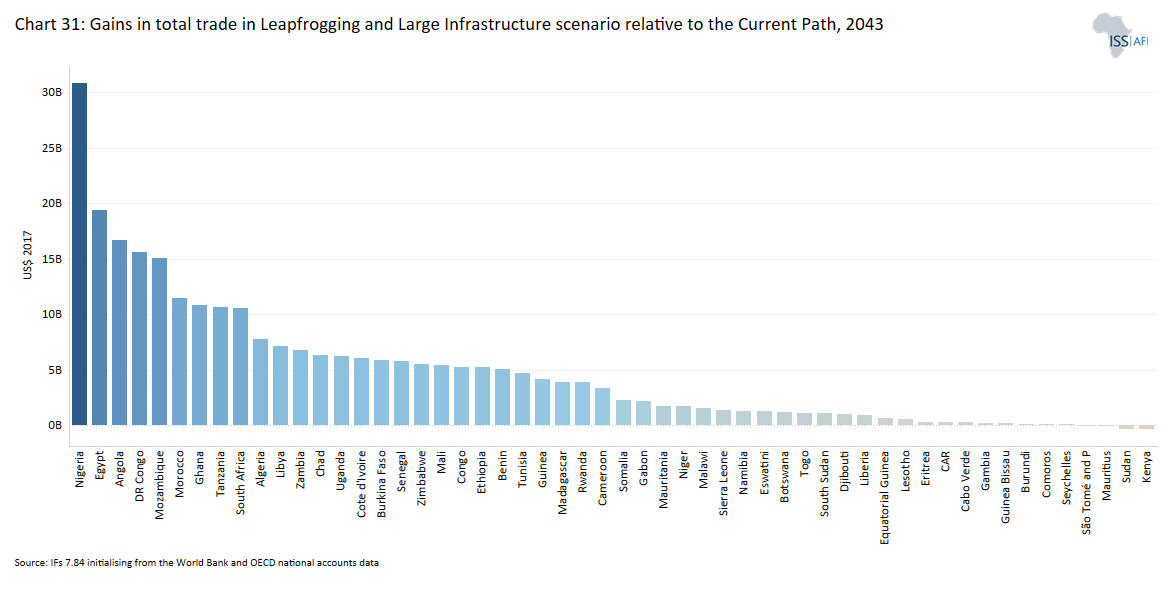

- Chart 31: Gains in total trade in Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario relative to the Current Path, 2043

- Chart 32: Key recommendations

Infrastructure is a crucial driver of economic growth and social progress and a critical enabler of productivity and sustainable economic growth. It contributes significantly to human development, poverty reduction and the attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The role of infrastructure in economic growth and development goes back to Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, which listed the duty of erecting and maintaining certain public infrastructure.[1A Smith, The wealth of nations [1776] (Vol. 11937), 1937.] In the production process, public infrastructure is seen as an intermediate input, even though it is a product of its own industry. When infrastructure is available in sufficient quantity and quality, it helps lower input costs and increase profitability.

For Africa, infrastructure development is central to its future. According to the African Development Bank (AfDB) it accounts for over 50% of the recent improvement in economic growth and has the potential to achieve even more. It can significantly contribute to achieving Africa’s Agenda 2063 ambitions. However, despite the importance of infrastructure development in Africa, the stock of infrastructure in most African economies is far below what is needed to support their required levels of economic growth and development.

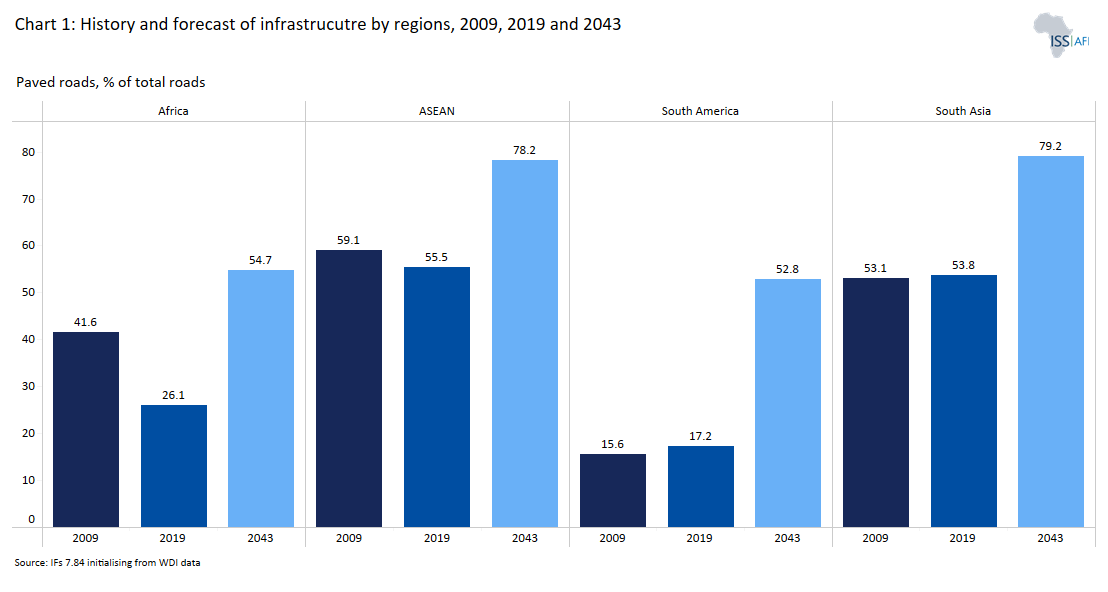

To put Africa’s infrastructure deficit into perspective, Chart 1 shows a comparative evolution of infrastructure endowments and forecasts for Africa relative to other developing regions. Compared to its peers (i.e. South Asia, South America and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations), the chart shows that Africa trails in key metrics of electricity generation capacity, Internet access, mobile broadband access and paved roads.

For instance, Africa had an electricity generation capacity of only 0.2 kilowatts per person in 2019, whereas South Asia had 0.3 per person and South America had 0.8 electricity generation capacity per person. In addition, compared to its peers, Africa has a significantly lower proportion of paved roads. The length of paved roads in Africa was less than one-fourth of the paved road length in South Asia in 2019.

The AfDB regards Africa’s infrastructure deficit as a sign of untapped productive potential, which is also a huge investment opportunity. In early 2022, the AfDB estimated Africa’s infrastructure investment gap to be more than US$100 billion per year, affecting the living conditions of Africans and the continent’s global competitiveness.

This infrastructure deficit has made it difficult for the continent to attract foreign direct investment (FDI), develop significant regional value chains (RVCs), expand trade and fully participate in the global economy. One of the continent’s biggest projects, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), will not succeed without supporting infrastructure, especially regarding transportation, electricity provision, information and communication technology (ICT) services, education and healthcare infrastructure projects.

In 2009, the World Bank conducted a study on Africa's infrastructure and found that the continent's inadequate infrastructure decreases annual economic growth by two percentage points and reduces business productivity by up to 40%. Similarly, a AfDB report estimates that inadequate water and sanitation infrastructure is costing the continent about 5% of GDP and high transport costs add 75% to the price of Africa’s goods.

One of the main reasons for the infrastructure deficit in Africa particularly in the sub-Saharan African region is the historical underinvestment in infrastructure by both governments and the private sector. Many African countries have limited financial resources, which makes it difficult for them to finance the necessary infrastructure development. In 2020, only 42.2% of infrastructure investment in African countries was financed by national governments.

In addition, poor governance, corruption and conflict have contributed to a lack of effective planning and implementation of infrastructure projects. However, there have been efforts to address the infrastructure deficit in Africa. International organisations such as the AfDB and the World Bank have provided financing and technical assistance for infrastructure development.

Colonial powers were not concerned about connecting Africa’s people and promoting regional trade. Infrastructure that could serve military purposes, provide access to mineral deposits and connect agriculturally rich areas with the coast were prioritised. This resulted in sub-Saharan Africa’s pre-independence railroads being built primarily to provide the shortest and cheapest route from extraction points to ports for shipping cargo to Europe, rather than connecting towns.[2For example, the so-called Lunatic Express, from Kisumu (Lake Victoria) to the port of Mombasa, built between 1886 and 1901, literally bypassed all the highly populated areas.] Only places with a significant and permanent European settlement, particularly South Africa, saw any meaningful roll-out of infrastructure designed to improve the welfare of the local population, and then only for the colonist minority.

After independence, most railroads fell into disuse because they were often not suited to new development priorities owing to conflict, mismanagement and changes in national priorities. Generally, attention shifted from rail to roads. This shift was accompanied by a lack of attention to basic infrastructure such as sanitation that could facilitate human development or cross-border connecting infrastructure to advance regional integration. With advances in medicine keeping communicable diseases at bay, instead of effective sanitation, water and health (WaSH) infrastructure, urbanisation proceeded in much of Africa with limited additional basic infrastructure, discussed in the theme on health/WaSH.

Yet the impact of colonial railways persisted, with locations along these routes becoming more developed and urbanised than towns not close to rails. In summary, the ‘railroads built during the colonial period strongly predicted the current location of cities.’ Similarly, many African cities still depend on creaking water, electricity and sanitation infrastructure, which often predate independence more than half a century ago.

Post-colonial Africa has subsequently also had its fair share of so-called white elephant projects, where a large development (such as a factory or power station) was constructed as the political pet project of an incumbent leader. This was a particular problem during the 1980s after the (ultimately overly) ambitious Lagos Plan of Action was adopted. Projects were often initiated without proper economic analysis or consideration of potential synergies or regional cooperation. This approach resulted in inappropriate or an oversupply of infrastructure, saddling governments with unsustainable debt levels.

The situation eventually led to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank imposing various structural adjustment programmes in the 1980s, which sought to adjust a country’s economic structure, improve international competitiveness and restore its balance of payments. The latter intention inevitably discouraged government expenditure, including on infrastructure, with the result that Africa actually regressed from already low rates of access to key indicators (such as WaSH).

Africa’s general low population density has, until quite recently, largely precluded the development of economies of scale. Infrastructure development was also primarily considered and planned on a project-by-project basis and so has generally lacked the integrated, systemic approach evident in more developed regions.

Spending on infrastructure began rising again with the commodity boom in the first decade of the 2000s, with many of Africa’s development ambitions consisting of grandiose urban projects driven by local politicians and global investors. The visions typically reflect images of Dubai, Singapore or Shanghai, with glass skyscrapers and landscaped freeways that suggest fashionable smart cities. For example, the Nairobi 2030 Metro Strategy, which was unveiled by the Kenyan government in 2008, aimed to make Nairobi a world-class African metropolis. Another is Hope City in Ghana — a US$10 billion IT hub to be built outside Accra. Launched by President John Mahama in 2013, the project proposed to build Africa’s tallest building within three years.

Rapid population growth in Africa increases the demand for more infrastructure such as roads, railways and ports while the continent simultaneously also faces major expenditure requirements in education and health. The challenge is less serious in North Africa, which boasts the best infrastructure regarding both quantity and quality on the continent.

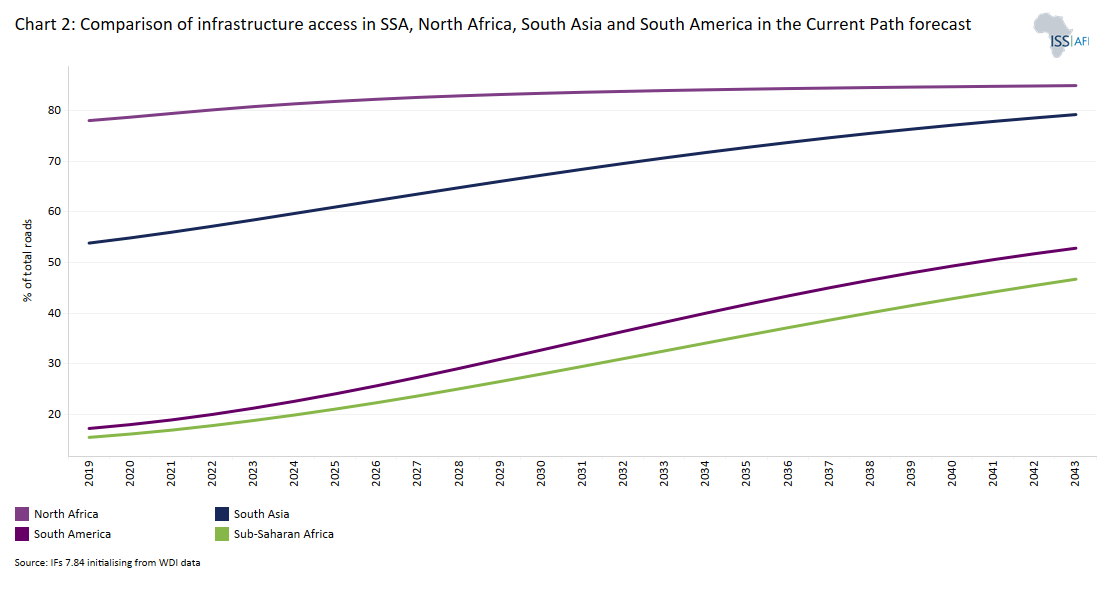

Chart 2 provides a snapshot of infrastructure in sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa in a comparative context. Sub-Saharan Africa is expected to make significant improvements in the coming decades. However, in 2019, it lagged behind North Africa, South Asia, and South America in all four categories, and the lag is projected to continue until 2043. This is also not simply a case of watching sub-Saharan Africa catch up, as Africa’s stock of infrastructure is much smaller than that of China and India when they were at similar levels of development.

In recent years, infrastructure development has been driven by Chinese interest in Africa, as examined in the themes on the AfCFTA and Financial Flows, culminating in the Belt and Road Initiative. As a result, China has become Africa’s single biggest trade partner, investor and lender and is driving the expansion of trade-catalysing infrastructure such as ports and railways, particularly on the eastern seaboard. In the process, Chinese state lending practices closely resemble that of Western private banks, with punitive conditionalities and secrecy compared but are often much more expensive than the concessional terms that Africans can obtain from the (Western) international financial institutions such as the World Bank and the IMF.

Chinese-funded projects initially led to the displacement of local communities in Zambia and elsewhere and many of the jobs created by these projects went to imported Chinese nationals and not to local people. However, China has adapted and recent practices do not differ substantially from those of Western countries that have steadily adopted more of a capacity building and local training approach.

The African Union Development Agency New Partnership for Africa’s Development (AUDA-NEPAD) Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA) intends to pull in foreign state and private funding while centring on pan-African interests. PIDA has already facilitated hundreds of projects across the continent, although it remains to be seen whether Africa has turned the corner on closing its infrastructure deficit.

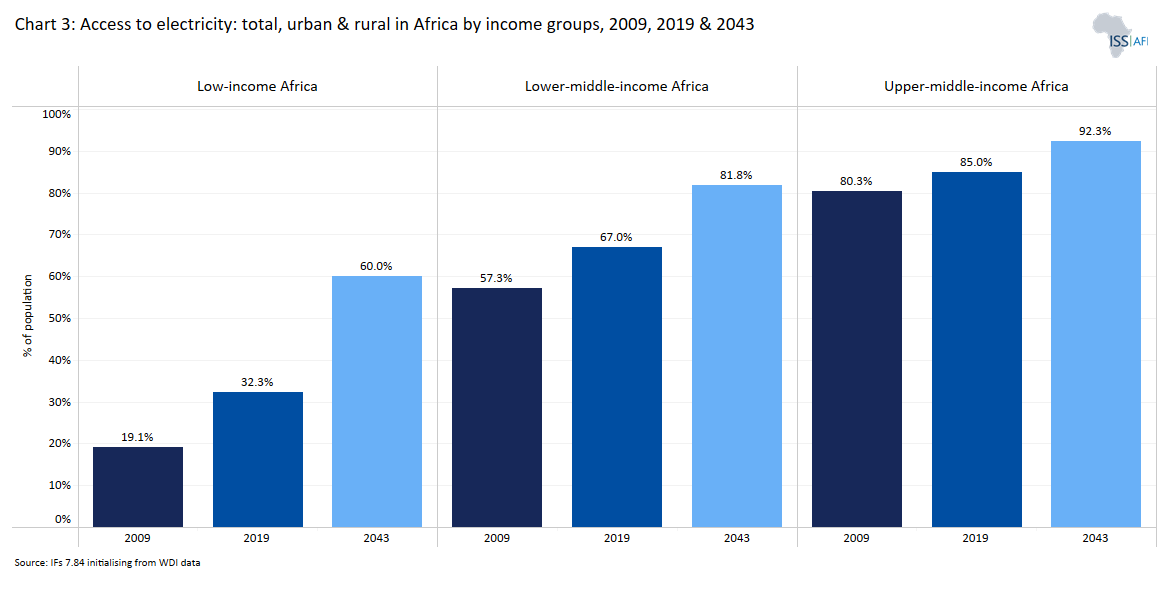

Electricity infrastructure is lacking in Africa, with the disparities between urban and rural access rates continuing to persist. About 45.4% of Africa’s population had no access to grid electricity in 2019, and only four African countries (Egypt, Mauritius, Seychelles and Tunisia) had universal access. The situation in rural areas is much worse. Only 19.6% of low-income Africans residing in rural areas had access to electricity in 2019. In rural lower-middle-income Africa, this figure was approximately 52.2%, while in rural upper-middle-income Africa, it reached nearly 73% (see Chart 3). Fourteen African countries have less than 10% rural electricity access and some, such as the Central African Republic, Sierra Leone and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo), do not even reach 2%.

Limited access to and insufficient supply of electricity in Africa, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, create substantial limitations for modern economic activities, public service provision, quality of life and the adoption of new technologies. These constraints affect various sectors including education, health, trade and finance. Approximately 1.75 million public health centres and schools lack reliable electricity supply in Africa, while one healthcare facility in four lacks electricity and three in four lack reliable power. About 80% of businesses in Africa (except in North Africa and, until recently, South Africa) experience outages, compared to 66% in South Asia and 38% in Europe. Furthermore, electricity load-shedding durations tend to be far longer in Africa than in Asia and Europe.

In the Current Path forecast, rates of access will increase but progress will likely be slow. In fact, the absolute number of Africans without access to electricity in both low- and low- middle-income countries will either remain static or increase modestly beyond 2030 as investment in infrastructure lags behind rapid population growth.

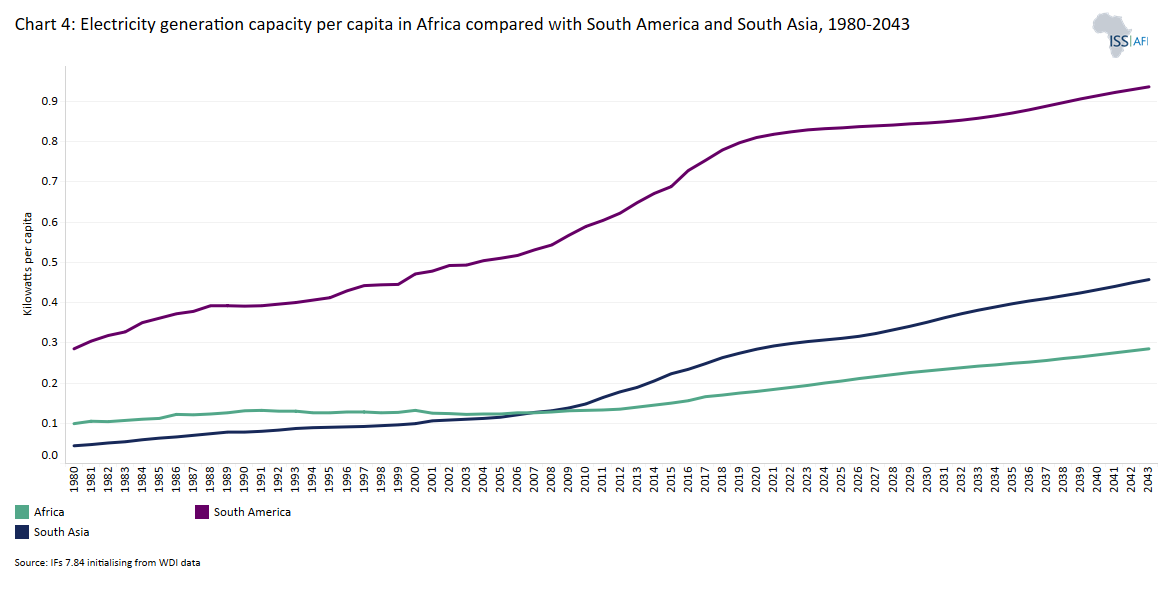

By 2043, electricity generation capacity in Africa (0.3 kW per capita) will also be lower than in South America and South Asia (see Chart 4). So, instead of catching up, Africa is falling further behind.

Little progress has been made in per capita electricity generating capacity in the past decades, although the continent has the potential to generate 4.51 kWh/kWp/day, the highest in the world (see Chart 5). This is more than double the average use now.

Furthermore, Africa has the potential to generate 350 GW of hydroelectricity, 110 GW of wind power and 15 GW of geothermal power. However, about 592.3 million Africans had no access to electricity in 2019 — accounting for nearly 77.8% of the world population without access to electricity, with the larger percentage being in sub-Saharan Africa (see Chart 6).

In sub-Saharan Africa, the number of people without electricity has risen due to population growth outpacing electrification progress. In 2019, sub-Saharan Africa had the highest number of people without access to electricity in Africa, 587.4 million people — accounting for about 99.2% of Africa’s population without access to electricity. At the same time, South America had only 1.6 million and South Asia had 102.8 million people without access.

The infrastructure gap in sub-Saharan Africa cuts national economic growth by two percentage points every year and reduces productivity by as much as 40%. Despite efforts to narrow this gap, sub-Saharan Africa still falls behind. For example, India connected an additional 29.2 million people to grid electricity between 2017 and 2022, compared to just 19.1 million achieved by the whole of sub-Saharan Africa. This has led to electricity generation capacity per person in Togo, Malawi, Uganda, Rwanda, Burkina Faso, Sierra Leone, Niger and Lesotho being less than 10% of that of South Asia and less than 4% of that of South America average in 2019. Furthermore, in the Current Path forecast, the unmet electricity demand in sub-Saharan Africa countries will increase by 5.5% between 2022 and 2033.

It is not only that access to electricity in Africa is low, but electricity is also much more expensive than in other regions. The AfDB estimates that electricity costs in Africa are three times more than in other developing regions, and most manufacturing firms operating in East and West Africa heavily rely on expensive backup generators as their primary energy source, which negatively affects their productivity and profit margins.

High electricity costs in Africa is largely driven by the lack of investment in generation capacity and in the associated distribution networks. Ironically, several African countries export substantial quantities of energy, including coal, and unrefined oil and gas, but they end up importing refined fuels. Citizens and businesses in many countries in sub-Saharan Africanthen often have to rely on generators to supplement their electricity supply due to frequent outages.

The continuous increase in demand for electricity in Africa is expected to be four times higher in 2040 than it was in 2010. Improving the supply and distribution of electricity infrastructure is a priority, considering Africa’s vast and environmentally friendly electricity generation potential. Africa has numerous sites for generating wind, solar and hydropower, though it currently uses less than 10% of its hydroelectric capacity. As Africa seeks both to grow and to industrialise, green energy should enable it to leapfrog past a heavy and environmentally catastrophic dependence on fossil fuels into a future of renewable energy. See the theme on energy and climate change.

The transport infrastructure in all four subsectors (road, railways, air and ports) is a major bottleneck for development across much of Africa, particularly for landlocked countries. Reliable transport infrastructure is crucial for firms in Africa to import and export goods, fill orders and obtain supplies.

Road networks are the predominant model of transport in Africa as they carry at least 80% of goods and 90% of passengers. In 2019, nearly 74% of Africa’s road network was unpaved, isolating the population from basic education, healthcare services, transport corridors, trade hubs and economic opportunities. Moreover, access to road networks is uneven, particularly in rural areas where the rate of access is low. This unequal access makes the flow of goods and services from and to rural areas difficult and expensive. In addition, poorly constructed rural roads that wash away during rainy seasons can make rural areas inaccessible and travel dangerous. However, rural transport is an essential facilitator for achieving SDGs, particularly within the agriculture sector.

Maintenance of road networks is also inadequate and, when done, is often inefficient. Road networks in many African countries suffer from vehicle overloading, which causes road surfaces to prematurely degrade and results in reduced construction lifespan and high maintenance costs. Despite the continent having fewer vehicles on its roads than other world regions, the road infrastructure deficit has resulted in traffic congestion. Poor road infrastructure contributes to traumatic injuries through avoidable road accidents, further stressing Africa’s health system, which is already overburdened by its high communicable disease and increasing non-communicable disease burdens. An empirical study on Africa by the World Bank in 2021 finds that investments in roads alone have a larger impact on sectoral change — moving workers from agriculture to manufacturing and service.

Chart 7 shows the historical and forecast trends for paved roads in Africa by income group. The progress in expanding paved roads in Africa is limited, particularly in low-income and lower-middle-income regions. By 2043, it is projected that low-income Africa will have reached only 37.1% of paved roads, while lower-middle-income Africa will have reached 61.9%.

Chart 8 shows the relationship between new road investments and maintenance of existing roads as a portion of GDP across African countries’ income groups compared to South Asia and South America, based on data for 2019 and the forecast for 2043. A general increase in spending on new paved construction is apparent in Africa and South America. Chart 8 also shows that low-income African countries invest more in the construction of new, unpaved roads, while at the same time spending larger amounts on their maintenance than South Asia, South America and other African income groups.

There is also a significant shortage of deep-water ports able to handle large vessels, which increases transport costs and leaves some regions deprived of the benefits of trade. However, considerable investment in ports and associated infrastructure has been seen over the past few years (e.g. Tanger Med in Morocco, Port Said in Egypt, Durban in South Africa, Djen Djen in Algeria, Mombasa in Kenya and Lagos in Nigeria). Sustained and substantial investment is required to clear the deficit.

ICT infrastructure is becoming easier and cheaper to expand across the continent, which explains why the roll-out of mobile broadband is accelerating, even in the Current Path forecast. The availability and adoption of broadband services plays an important role in connecting people on the continent, fostering economic development and enabling access to information and social development. Africa is expected to have at least one mobile broadband subscription per person by 2043. Gabon and Algeria are the only two African countries that reached this goal by 2019.

However, fixed broadband subscriptions lag far behind. Chart 9 shows that the low number of fixed broadband subscriptions in Africa has been mitigated by expanded mobile broadband coverage, which is expected to surpass that of South Asia and South America by 2043.

Although access to mobile broadband is improving in Africa, data remains prohibitively expensive for most. In Africa, 1 GB of data costs nearly 18% of the average income, whereas the same amount of data costs only 3% of the average income in Asia. The gap in ICT infrastructure and the potential to catch up are discussed in the theme on Leapfrogging.

Wagner’s Law asserts that as countries develop, governments require more revenue (as a share of GDP) to invest in the provision of services such as health, education and infrastructure. As a result, state spending steadily increases as a portion of GDP (along with higher GDP per capita) and outpaces improvements in average income. This indicates a significant connection between the capacity of governance and income levels. The relationship is also evident in Africa, where government expenditure in Africa’s low-income countries was, on average, 18.3% of GDP, compared to 24.2% in lower-middle-income countries and 33.6% in upper-middle-income countries.

Major transformations in improving infrastructure often consist of layering new or additional systems over existing ones. In wealthy countries, this layering has occurred over successive centuries and reduces the costs of improvements, whereas in much of Africa, the infrastructure challenge is to build from scratch in mere decades although modern technology does allow for leapfrogging.

Chart 10 compares spending on infrastructure (all types and including maintenance) in Africa with that in South America and South Asia. Africa spends significantly more on infrastructure than South America (using the portion of GDP as yardstick), but much less than South Asia. This gap will largely close by 2032 as South Asia’s spending diminishes at a higher rate than Africa’s. Spending on infrastructure is also set to remain quite robust across the forecast horizon, despite a slight reduction over time. However, because of rapid population growth, Africa needs to spend significantly more on infrastructure than other regions, now and in the future. In 2019, Africa spent 3.7% of GDP on all aspects of infrastructure (core and maintenance, public and private), compared to 4.4% in South America and 9.1% in South Asia.

According to the AfDB, it will cost US$130 billion to US$180 billion a year to eventually eliminate Africa’s infrastructure gap (see Chart 11). Although considerable funding is flowing into Africa to address this need, the AfDB estimates that a shortfall of between US$68 billion and US$108 billion remains annually. The gap is due mostly to a backlog in water and sanitation infrastructure (approximately 41% of the gap), followed by electricity supply and transport access (about 28% each). ICT infrastructure makes up the remainder.

Closing the infrastructure gap in Africa is not a simple task and requires governments to overcome major obstacles, such as financing, government capacity and corruption. Given limited domestic sources of revenue, Africa generally looks to financial institutions such as the World Bank and the AfDB or state-backed lending from a country with deep pockets, such as China, to fund its infrastructure deficit.

China’s building of large infrastructure projects in Africa is advantageous because it largely operates on a government-to-government basis (instead of private sector entities dealing with each other). China also has significant finances to invest due to its consistent trade surplus from the 1990s until recently. In addition, China has an excess of resources and extensive expertise in constructing infrastructure within its own country. None of these advantages are readily available from the US or Europe, and the result is that China dominates building African infrastructure, although some smaller countries, such as Turkey, are gaining a foothold.

The more developed a country is, the higher its infrastructure stock is. Consequently, there is lower return from additional infrastructure investment unless the infrastructure investment aims at addressing a major challenge or introducing new technology. For example, a village without a road connecting it to the capital city may benefit greatly from the first single-lane paved road making such a connection, whereas a major city such as Cairo or Johannesburg could add many kilometres of additional road with a barely measurable impact on the fortunes of the city. This is true not only for cities but for entire economies, and infrastructure spending is far more potent, dollar for dollar, in less developed economies. Increasing infrastructure when stocks are low (such as in low-income Africa) will likely have a greater impact on economic development than the same proportional increase in an upper-middle-income country that has a much larger stock of infrastructure.

ICT and energy infrastructure tend to show the greatest impacts on development indicators, but ultimately, the prioritisation of infrastructure depends greatly on country-specific bottlenecks and opportunities.

Investing in infrastructure can stimulate economic growth by increasing capital accumulation and facilitating the transition of workers to higher-productivity jobs. Trade and economic integration, in general, can contribute significantly to productivity improvements. An IMF study of infrastructure spending in several countries from 1985 to 2014 found that an unanticipated 1% increase in public infrastructure boosted GDP by 0.4% the following year and by 1.5% four years later. The Economic Policy Institute agrees, noting that ‘infrastructure investments can boost even private-sector productivity growth.’

In general, the positive relationship between infrastructure and development is uncontroversial, but the benefits of investment in different types of infrastructure over shorter horizons are heavily debated. The type of infrastructure, how it is financed and how quickly it is rolled out, together with levels of development, all matter:

- In the short term (i.e. during the construction phase), goods and services are consumed in building the infrastructure and additional workers are hired. This temporary fiscal stimulus precedes a more lasting improvement in productivity, as completed roads and railways open new markets and make product delivery and worker commutes more efficient. Power plants also produce more energy more cheaply, which, in turn, supports power-heavy secondary industries.

- Long-term benefits depend substantially on the kind of infrastructure. Core infrastructure such as roads, ports and utilities have the largest economic effects as they unlock more economic activity than other investments. The productivity impact of the new infrastructure improves the competitiveness of firms, which allows them to expand and increase employment.

Provided that poor people are not priced out of access, expanding basic infrastructure such as roads, ICT, electricity access and water and sanitation can reduce inequality by improving equal access to essential services. The impact of freight rail, port and airport developments may be more indirect, reducing inequality by raising employment, for example. However, such investments may also disproportionately benefit wealthy holders of capital, increasing inequality and poverty in the short term.

Chart 12 shows the AUDA-NEPAD forecast of job creation by implementing PIDA. The forecast distinguishes between direct, indirect, induced and secondary job years:

- Direct jobs are created in the construction, maintenance and operation of a project.

- Indirect jobs are created through the suppliers of goods and services needed for a project.

- Induced jobs are created by the multiplier effect associated with the spending of income acquired through direct and indirect employment.

Secondary jobs are created by the improved infrastructure itself (such as new businesses and factories opening in response to cheaper, more reliable electricity, or better road access to an underdeveloped district).

Infrastructure development can, of course, have short-lived negative effects, particularly for local communities, if it is implemented without careful consultation and good planning. For example, a freeway could cut through a poor community that still largely commutes by foot or bicycle and thus reduces people’s mobility. Infrastructure developments could lead to increased conflict over land as projects increase land value around them, or detract from value. In many poor African countries, large, prestigious projects such as railways and airports have distracted from potentially more helpful but unglamorous projects such as investing in rural roads and water and sanitation infrastructure.

Both the amount and quality of infrastructure are positively correlated with growth in income, although not equally so: the impact depends on the relative development stage of the country and the period over which impact is assessed.

A World Bank study showed that in Africa the amount of infrastructure contributed almost nine times as much to per capita income growth as the quality thereof. However, this effect is region specific, with the potency of increasing quantity over quality appearing to be particularly strong for sub-Saharan Africa. In contrast, in North Africa, where the infrastructure deficit is smaller, improving the quality of infrastructure, specifically roads, had the greatest potential impact on income.

Although increasing the amount of infrastructure in sub-Saharan Africa remains the most decisive factor in infrastructure development in the region, a commensurate increase in quality would make the impact of infrastructure on economic growth far more potent.

The demand for infrastructure in Africa is rising as its population continues to grow and become increasingly more urban, putting immense pressure on existing networks. Africa’s dependence on trade is also large, with a disproportionate reliance on commodity exports. Yet poor logistical infrastructure makes trade expensive or difficult, undercutting Africa’s ability to engage and compete in global markets. Non-tariff barriers such as inaccessibility to markets are a significant hindrance. Better rail, road and port infrastructure would allow Africa to better tap into global markets and maximise growth.

Major infrastructure projects are expensive and often unaffordable for Africa’s many low-income countries. Even upper-middle-income and high-income countries can rarely pay for an infrastructure project directly from an annual budget and often face high debt-to-GDP ratios, which make lending for such projects unaffordable and unwise. The estimated infrastructure financing gap of US$68 billion to US$108 billion per year for the continent cannot be solved by governments alone. However, a key problem with funding projects via private capital is finding bankable (commercially viable) projects in an environment where perceived risk requires large returns on investment.

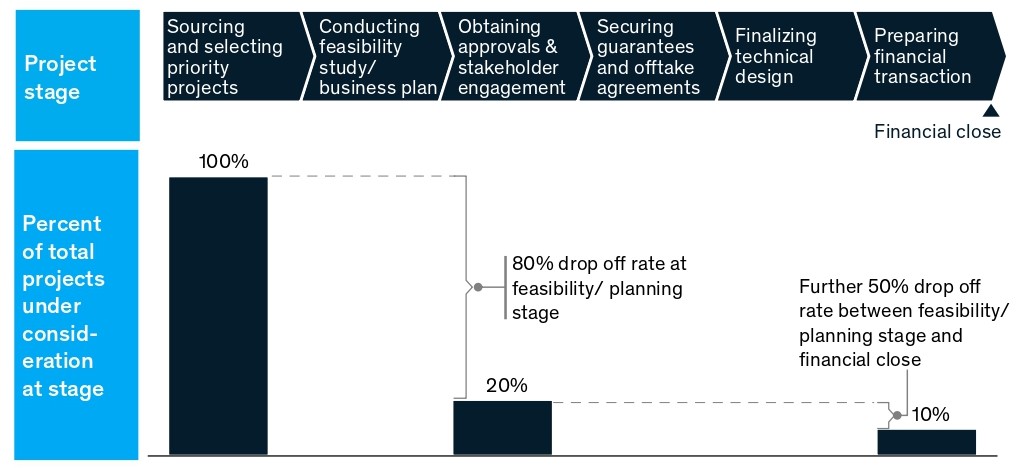

Analysts estimate that several hundred billion dollars worth of financing is available through institutional investors, such as major pension funds, investment corporations and government agencies seeking better returns in the context of historically low interest rates in the developed world. Also, Africa is not short of ambition for infrastructure. There are up to US$2.5 trillion worth of infrastructure projects in the pipeline by 2025, but a large number of these projects are likely to fail: 50% of them are in the feasibility phase and only 10% of projects at this phase ever make it to financial close. Half of these projects are found in only six African countries, with 17% in Nigeria alone, suggesting that while some countries are pulling ahead, others are falling behind.

AUDA-NEPAD emphasises the importance of corridor-type infrastructure projects in Africa, which are often multi-country projects (such as the Lamu Port South Sudan–Ethiopia Transport Corridor) that incorporate road, rail and ICT links to facilitate regional integration. Such an approach brings hope of fewer non-tariff barriers to trade, greater economic linkages between African nations and integrated approaches to cross-border issues such as water management.

PIDA is spearheading this regional integration through its Priority Action Plans (PAP), which are a kind of infrastructure master plan for Africa. Although it regurgitates many previous ambitions, some of which date from colonial times, it has seen some implementation.

The concept note for a recent (November 2018) PIDA-PAP workshop at Victoria Falls revealed that the capital cost of delivering the plan was estimated at US$68 billion, requiring the expenditure of US$7.5 billion annually. This was a relatively modest ambition compared with the infrastructure funding gap calculated by the AfDB. Of the more than 400 projects, the conference heard, 26% were moving from concept to pre-feasibility or feasibility phases; 16% were being structured for tendering; and 32% were either under construction or already operational, reflecting steady progress.

A map of PIDA projects across the continent (Chart 13) shows the prioritisation of regional integration in infrastructure development, as corridor projects criss-cross the continent, and port and border investments dot the perimeters.

PIDA currently oversees and facilitates 409 projects across the continent, with the following major focuses:

- Transport sector: 237 projects related to airports, seaports, border posts, rail and road infrastructure.[3Airports: 13; border post upgrades: 38; bridges: 5; port-related projects: 45; rail lines: 23; road projects: 113.]

- ICT: 114 projects, of which most (71) relate to cross-country and cross-border fibre optic links.

- Energy: 54 projects, including some (but very few) focused on renewable energy generation,[4Although eight of these projects are major hydroelectric dams, PIDA does not oversee any solar, wind or other renewable energy projects.] the rest relate to cross-border power connections and gas or petroleum pipelines.

- Water management: nine projects, including reservoirs and regional river basin and aquifer management programmes, particularly in the Sahara in North Africa and the Kalahari Desert in the south.

Chart 14 shows the relative contribution to infrastructure finance in Africa from 2016 to 2020, and the extent to which the COVID-19 pandemic has negatively impacted Africa’s infrastructure investment inflows, affecting the progress in reducing the annual financing gap for infrastructure. The average 2019-2020 funding of US$83 billion was below the 2017-2018 average of US$91.2 billion, and significantly lower than the US$100.8 billion in 2018.

Total commitments in 2020 were 10% lower than in 2019, largely because of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The financing gap increased from a range of US$53 billion to US$93 billion to a range of US$59 billion to US$96 billion in 2020. This was primarily due to the shift in resources to the needs of the pandemic, setting back the target for the achievement of basic public infrastructure for the continent as a result.

African governments continue to provide the lion’s share of funds, with donors from the Infrastructure Consortium for Africa (ICA) and China as the next two biggest sources of finance. Several bilateral and multilateral organisations became ICA members in 2019, which resulted in a significant increase in the commitment level for that group in that year. China’s contribution decreased significantly from US$25.7 billion in 2018 to US$6.7 billion in 2019 and further to US$6.5 billion in 2020. This reduction reflects the decision by China’s government to reduce their investments in Africa because of concerns about the external debt position of African countries. There was a sizeable resurgence in private sector investment in 2020 — contributing about 23.5%, an increase from 12.7% in 2019.

In response to Western concerns about the role being played by China with its Belt and Road Initiative the G7 countries launched the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) in 2022 at Elmau with a goal to mobilise US$700 billion by 2027, mostly from the private sector. The flagship project in Africa is the Lobito Corridor that would provide a 1 300km railway link for the DR Congo and Zambia to the port of Lobito in Angola. According to Boston University’s Chinese Loans to Africa Database, China provided more than $170 billion to African countries and regional organizations from 2000 through 2022.

The share of infrastructure financing allocated to transport has increased over the past few years, from 32% (US$33.8 billion) of the total infrastructure financing in 2018 to 42% (US$34.4 billion) in 2020. It is the only sector with an increase in 2020 and reflects a recognition of the contribution that improved connectivity makes to productivity, especially the interest in improvements in intra-continental trade. It also reflects the relative maturity of the transport sector in Africa and the relative success in capacity building in the transport sector.

Given Africa’s rising debt levels (also see Current Path ), together with China’s declining appetite for additional loans, it is likely that government financing (using taxpayers’ money) for infrastructure will necessarily expand, particularly for projects that have a larger economic than social role.

Public–private partnerships will likely also become more common in the future, with a country granting concessions to a company using a build-operate-transfer (BOT) model. Public–private partnership projects are relatively new in Africa but could allow access to more private sector finance, based on a ‘user pays’ principle. A port, for example, is funded by charging berthing and storage fees and a road can be funded by charging toll fees (although larger toll roads are currently limited to South Africa, Morocco and Senegal). However, the challenge is to prevent the usage fee from prohibiting access to poor people and the wisdom of embarking on large projects that have little chance of becoming commercially viable or that require considerable profits to be guaranteed to attract investment has been questioned.

Some projects serve as examples of these concerns:

- The Chinese-held loans for the US$3.6 billion Mombasa–Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway, originally intended to run from Mombasa to Nairobi and then on to Naivasha and Kampala, were granted at commercial rather than concessional rates (in 2014). Secrecy surrounded the associated agreements. The project has put Kenya massively in debt to China and construction was halted at Naivasha, despite repeated pleas for better terms and the continuation of the project. Much of the construction was also undertaken by Chinese (not African) contractors.

- The Nairobi Expressway is a six-lane 27 km highway that cuts through the heart of Kenya’s notoriously congested capital city. The expressway connects Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in the east of the city to the Nairobi–Nakuru highway in the west. Although a substantial portion of the work was undertaken by local companies using local labour, some of the associated arrangements have raised eyebrows. The project grants the China Road and Bridge Corporation, which is building and will operate the highway in a 27-year concession, a guaranteed US$988 million in profit by charging toll fees (US$2–US$3 per vehicle), implying that many poor Kenyans will be precluded from usage.

Major obstacles to infrastructure development, not unique to Africa, are the corruption and politics often associated with large projects.

In South Africa, the Medupi and Kusile projects involved the construction of two 4.8 GW coal-fired, direct dry-cooled power stations. When the contracts were signed in 2007, with completion at the end of 2015, the estimated costs for Medupi were R80 billion. By 2018, it had increased threefold and completion was repeatedly delayed. Some of the primary reasons for the cost escalation included a fluctuating rand exchange rate affecting imports of components, substantial redesigns having to be done midway through the project, labour disputes and standing time. A week after Medupi was eventually finished, in August 2021, one of its units exploded, with a repair bill estimated at R1.5 billion required over the next two years. Construction of the equally large Kusile Power Station started in 2008 and was supposed to have been finished by 2014. The initial budget of around R81 billion had doubled by 2020, with completion now expected in 2024/25.

Both projects have been mired in controversy and corruption, particularly the manipulation of the associated contracts to provide coal at excessive costs and have landed the public electricity company, Eskom, with an unsustainable debt burden. Ironically, in 2001, Eskom was named power company of the year at the Financial Times Global Energy Awards in New York. At this time, South Africa had cheap surplus electricity; 15 years later South Africa was experiencing continued intermittent blackouts owing to insufficient electricity supply. In addition to self-enrichment by members of the governing party, the African National Congress, decisions about the procurement of additional electricity supply were delayed for several years. In the run-up to and during the hosting of the soccer World Cup in 2010, South Africa literally ran its power stations into the ground in an effort to keep the lights on. Due to delayed maintenance and insufficient new power generation, the country began facing shortages that resulted in blackouts occurring every third day of the year by 2015. The situation has worsened since then and is projected to last until 2027.

Even disregarding the seemingly ever-present disease of corruption, gearing infrastructure projects to the private sector is no easy task. Project development at the preparatory stages can amount to 5–12% of the project’s total value and take up to seven years to complete. For large projects (involving millions or billions of dollars), this is a substantial cost, particularly if the result could conclude that the project is not commercially viable. Even when project preparation is done, the quality of the preparation and planning is often low, representing a large and expensive risk for private sector investors.

Up to 90% of infrastructure projects in Africa fail at the preparatory stages and before financial close; 80% of projects fail at the feasibility stage when preliminary studies determine that the project is not financially or practically viable.

Closely connected to project preparation are the institutions and legal frameworks that should support these processes. Legal frameworks for public–private partnerships are poorly developed in much of Africa, and major potential institutional investors, such as pension funds, are often barred from investment in the sector owing to the high risk associated with countries that are considered below investment grade.

Financial feasibility can also be undermined by inefficient use of revenues or the inability to collect them. Poor delivery of infrastructure for utilities such as electricity and water can lead to up to 50% of wastage, while illegal connections to these utilities can also contribute to costs without contributing revenue. Furthermore, 70–90% of utility bills go uncollected across Africa, representing a major loss of expected revenues. These inefficiencies can turn potential profit-making enterprises into loss-making assets, scaring off potential funders.

Many of these challenges are reflected in the ambitions of the Grand Inga Hydropower Project in the DR Congo. Electricity supply in rural parts of the country is almost non-existent, with an average rate of around 1% compared to 42% in urban areas. The power supply is unstable and characterised by recurring outages even in urban areas. For example, it is estimated that in Kinshasa about 21% of those who have access to electricity receive fewer than four hours of power per day, and on average, electricity shortages occur 10 days per month in the country. Owing to this unreliable electricity supply, about 60% of firms in the DR Congo have backup generators, compared to 43%, on average, in sub-Saharan Africa. These frequent electricity shortages penalise the productive sectors of the economy and hamper productivity and growth.

In addition, the state power utility, Société Nationale d'Électricité (SNEL) is highly inefficient. Almost half of the electricity produced is lost during transmission and distribution owing to the equipment being outdated or not maintained.[5There are some mini-grids, albeit very limited. For example, Synoki, Hydroforce and Virunga operate mini-grid hydroelectric projects and their market share of the electricity sector is estimated at 6%. Only 3.66 MW of solar photovoltaics had been installed by the end of 2017.]

Of the country’s 100 GW hydroelectric potential, less than 2.7 GW has been installed and only 1.1 GW is being exploited. This power is mainly generated by the Inga I and Inga II dams, which operate at around 50% of their capacity due to a lack of maintenance. The World Bank has been leading efforts to rehabilitate turbines at Inga I and II, but the project is incomplete.

Against this backdrop, the Grand Inga hydropower scheme has an expected capacity of 44 GW of electricity and could meet the entire need of the country, with large amounts exported elsewhere. The project is estimated to cost US$80 billion.

Inga III, which is estimated to cost US$14 billion, will generate 4.8 GW of electricity, and its entry into service was initially scheduled for 2024 or 2025. However, the implementation of the project, which has been on the cards for several decades, was recently again significantly delayed. In 2016, the World Bank suspended its funding because the then-president, Joseph Kabila, decided to bring the project oversight committee into his presidency, and it lacked transparency as a result. The project is still ongoing, albeit at a very slow pace. The Inga III project is now estimated to come on stream in 2030 at the earliest, dependent on a partnership with South Africa.

A 2020 McKinsey study proposes a number of solutions to make infrastructure projects less risky and thus more attractive to private capital. According to the authors, governments, international financial institutions and private investors can all play a part:

- Governments should minimise risks for investors by reducing regulatory, currency, and political uncertainties. This includes safeguarding investments from arbitrary decision-making, expropriation or delays in obtaining necessary regulatory approvals to ensure profitability. (A tax system that incentivises investment but is also fair to local citizens may be difficult to achieve but is an important objective nevertheless.)

- International financial institutions should offer risk-sharing instruments to private investors, such as guarantees.

- Private investors should invest more in early feasibility studies (with the assistance of international financial institutions as necessary).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the study recommends that governments take on low-return projects, such as basic water and sanitation and transport projects, and set aside high-return projects for the private sector. This is an important caveat, as the primary goal of governments in their infrastructure strategy is to develop the economy and improve citizen well-being. This goal must be balanced by the need to attract private investment in the sector.

AUDA-NEPAD is attempting to address some of these concerns by: providing greater financing and technical assistance for feasibility studies; implementing the PIDA quality label (for projects that perform well during feasibility assessment) as a measure of bankability for infrastructure projects; and providing risk-sharing arrangements such as the African Infrastructure Guarantee Facility. However, much work remains to be done, and these facilities require development and fine-tuning. A great deal more cooperation between national governments, international financial institutions (and even among the various organs of these institutions) and the private sector will be needed to make the financing of major infrastructure projects more efficient.

The Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario

Download to pdfThis section explains the structure of the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario, which could set the continent on a more positive human development trajectory than the Current Path forecast. The same scenario is used for the theme on Leapfrogging .

Although they are discussed separately the two themes, large infrastructure (this theme) and leapfrogging necessarily overlap and complement one another, particularly with regard to the impact of large-scale renewables and the introduction of off-grid and micro-grid systems on electricity access. That and the multiplier effect of ICT have the impact of lowering the entry point for private capital as well as more rapidly crowding in the informal sector into the formal.

The IFs forecasting platform distinguishes between traditional infrastructure (water, roads, electricity, sanitation and wastewater), ICT infrastructure (mobile phones, fixed broadband and mobile broadband) and a residual called ‘other infrastructure’ (facilities such as ports, airports, railways etc.). Rather than focusing on a specific type of infrastructure (e.g. for water and sanitation or education), the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario increases investments in both. It allows the algorithms in the forecasting platform to ‘allocate’ the additional spending and then to forecast the associated impact.[6The allocation is to: paved roads; unpaved roads; electricity generation; rural and urban electricity access; irrigation; safe water for households; improved water access; household sanitation; improved sanitation; wastewater; telephones; mobile broadband and fixed broadband.] IFs consider both public and private spending on core infrastructure and public spending on other infrastructure, but do not provide for infrastructure that is explicitly funded through public–private partnerships (one could argue that is captured through domestic and FDI in the economy). It also models and forecasts the construction and maintenance of public and private infrastructure.

In general, the intervention that increases infrastructure spending pushes harder on ‘core’ infrastructure in lower-income countries than in higher-income countries. The inverse applies in the case of advanced or ‘other’ infrastructure.

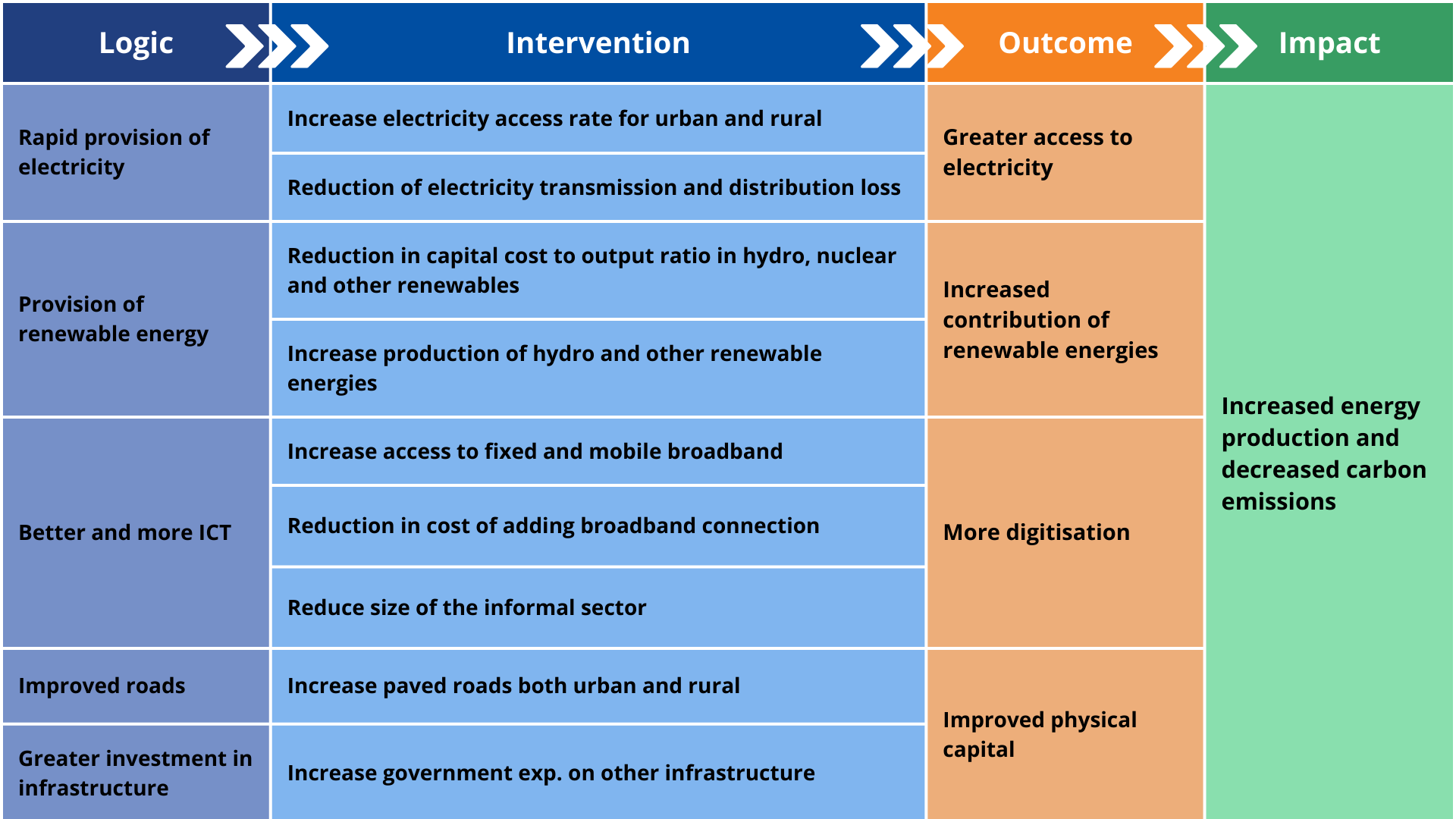

The interventions for the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario are presented schematically in Chart 18. This theme subsequently discusses the greater investments in ‘core’ and ‘other’ infrastructure that lead to improvements in physical capital and subsequently improve the contribution of multifactor productivity (MFP) to economic growth. In addition to physical capital, MFP in IFs consists of contributions from human, social and knowledge capital (the other interventions are discussed in the theme on Leapfrogging).

The Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario models an increase in government spending on infrastructure to 4.2% of GDP by 2043, instead of 3.6% in the Current Path forecast, reflected in Chart 19.

In the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario, Africa is expected to spend US$77.9 billion (US$ 2017) more on infrastructure by 2043 than on its Current Path — an increase of 25.5%. Cumulatively, the difference amounts to an additional spend of US$813.5 billion from 2024 to 2043. Low-income Africa increases expenditure on infrastructure (basic plus advanced infrastructure) by 16.4% above the Current Path forecast in 2043, with 26.2% in lower-middle-income Africa and 36.1% in upper-middle-income Africa (see Chart 20). Investments in advanced (other) infrastructure increase relative to the Current Path forecast in low-income Africa (21.5%) compared to low-middle-income (45.1%) and upper-middle-income Africa (50.5%) in 2043. This follows the logic that lower-income countries should focus on basic infrastructure (even at the expense of more prestigious projects), while higher-income countries should be looking to invest in more advanced infrastructure as their economies become more complex.

A 25.5% increase in Africa’s infrastructure spending relative to the Current Path forecast in 2043 will result in an increase in the share of paved roads (as a percent of total roads) by 6.5 percentage points. In sub-Saharan Africa, the share of paved roads will increase from 46.7% to 53.2% (see Chart 21). However, with such an increase in infrastructure spending, the continent’s share of paved roads will remain significantly below the percentage share of paved roads in South Asia’s forecast at 79.2% in 2043.

Chart 21 also disaggregates Africa’s share of paved roads data by Africa income groups. In 2043, low-middle-income Africa will have the largest share of paved roads relative to low-income and upper-middle-income Africa. The share of paved roads in low-middle-income Africa will increase from 61.9% in the Current Path forecast to 67.6% in the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario, whereas the share for upper-middle-income Africa will increase by 6.3 percentage points to 66.8%. High-income Africa (Seychelles), which is not included in Chart 22, will have universal paved roads in 2043. Low-income countries in Africa will further decrease the overall proportion of paved roads in the global economy.

The percentage share patterns of paved roads in sub-Saharan Africa compared to North Africa are also shown in Chart 22. In the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario, road networks in sub-Saharan Africa remain below average compared to other developing subregions. Consequently, the significant gap in road infrastructure provision between sub-Saharan Africa and other developing subregions persists. North Africa’s share of paved roads will increase by 6.3 percentage points to 91.1% in the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario in 2043.

The result of the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario is an African economy with 179.9 million (or 8%) more people with access to electricity than expected in the Current Path forecast in 2043. Chart 22 presents the increase in access to electricity that will occur in urban and rural areas in Africa as a result of the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario. The disparities between urban and rural access to electricity rates will continue to persist by 2043, however.

By 2043, the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario projects a 3.2% increase in access to grid electricity in urban areas of Africa, benefiting an additional 37.7 million people. In the scenario, in rural areas there is a rise from the current 56.6% access to 68.9%, providing grid electricity to approximately 132.8 million more people in Africa by 2043.

Sub-Saharan Africa has the largest proportion of population without access to grid electricity in the world. In the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario, 35.2 million more people in the region are expected to be connected to grid electricity in 2043 than in the Current Path forecast.

Low-income sub-Saharan African countries will have the largest additional number of people on the continent connected to grid electricity in the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario relative to the Current Path forecast in 2043. An additional 18.1 million people will be connected to grid electricity in low-income sub-Saharan Africa relative to the Current Path forecast in 2043.

Chart 23 also displays how this pushes the percentage of the population with access to electricity in sub-Saharan Africa low-income countries from about 60% (Current Path forecast) to nearly 70% (Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario). Overall, sub-Saharan Africa is expected to have 78.2% of its population connected to grid electricity in the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario compared to 69.1% in the Current Path forecast in 2043 — an increase of 9.1%.

Chart 24 shows the impact of the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario on fixed and mobile broadband infrastructure in Africa. In 2043, fixed broadband will remain below one subscription per person in 2043, whereas mobile broadband will increase from 1.38 subscriptions per person on the Current Path to 1.41 subscriptions per person in this scenario.

Even Africa's low-income group is expected to have at least one mobile broadband subscription per person by 2043. Mobile broadband in low-income African countries will increase from 1.29 subscriptions per person to 1.34 subscriptions per person in 2043.

The Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario makes a significant dent in the World Bank’s estimation of Africa’s infrastructure shortfall. As economic growth rates accelerate, the influence of other scenarios becomes more significant. In the absence of such growth, these scenarios can undermine government spending priorities like education and health, resulting in undesirable outcomes. This demonstrates the importance of other measures to increase rates of economic growth, such as through more regional trade and through the intensification of agriculture examined in the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario.

Infrastructure investment is a primary factor of economic growth and rising income per capita over time. This is a lesson that has been well learned and applied in Asian countries over the last several decades, where large infrastructure investments have contributed to high economic growth. However, government expenditure is believed to be consumptive and leads to crowding out of private investments if financed with public debt. Government borrowing or raising taxes could have negative effects on economic activity, which might offset the gains of public sector capital spending.

In the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario, Africa’s economy will grow by about 5.6% in 2043 — a growth rate of around 0.2 percentage points above the Current Path forecast. Across the entire forecasting period (2024–2043), the average growth rate for the continent will just be approximately 0.4 percentage points above the Current Path forecast.

The result is that the African economy will be US$600 billion (at market exchange rates), or 7.1%, larger in 2043 than expected in the Current Path forecast. The growth rate translates to GDP per capita (at purchasing power parity) of about US$377 (or nearly 4.9%) higher than expected on the Current Path.

The Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario will create 310 000 more jobs relative to the Current Path forecast in 2043. The increase in jobs in the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario is expected to come from the service sector, with a shift more towards the service economy (see Chart 26). In contrast, the size of the labour force in the energy, materials and manufacturing sectors is projected to decrease in 2043, with the manufacturing sector having the largest reduction. Labour employment gains from the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario will be mainly driven by increases in Africa’s low-middle-income countries (184 000 jobs) and low-income countries (117 000 jobs).

Poverty reduction requires inclusive economic growth. The growth rate in the scenario, shown in Chart 27, translates into 37.8 million fewer people living in extreme poverty (using the benchmark of US$1.90 per day) in 2043. About 50.8% of the people lifted out of extreme poverty will be from low-income Africa, 48.4% from low-middle-income Africa and just 0.8% from upper-middle-income Africa.

Chart 27 also illustrates the reduction in extreme poverty at country level. Nigeria is projected to have the largest number of people (nearly 9.4 million) lifted out of extreme poverty relative to the Current Path forecast in 2043, followed by DR Congo (3.4 million) and Tanzania (2.6 million). Extreme poverty will worsen in Equatorial Guinea and the Republic of the Congo. About 100 more people will fall into the extreme poverty bracket in Equatorial Guinea and around 25 000 more people will experience extreme poverty in Congo compared to the Current Path forecast in 2043.

An increase in government spending on infrastructure has a significant impact on human capital development, in addition to the positive effects of increased infrastructure spending on growth and poverty reduction. For instance, increased access to ICT, clean water, roads and electricity may lead to improved education and strengthen the population’s health.

The Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario shows that an increase in government infrastructure investment from 3.6% to 4.2% of GDP will improve education gross enrollment and completion rates. It also reduces infant mortality and fertility rates in Africa.

Chart 28 presents the increase in education enrollment and completion rates in Africa. An increase of 0.6% of GDP in government infrastructure investment will have a larger impact on upper secondary education in 2043. The upper secondary education enrollment rate will increase by 1.4 percentage points relative to the Current Path forecast, while the completion rate will increase by 1.6 percentage points in 2043.

The Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario has the least impact on the primary education enrollment rate and the tertiary education completion rate. The former will increase by just 0.1 percentage points, while the latter will increase by only 0.3 percentage points relative to the Current Path forecast in 2043.

Women (or parents) with less education tend to have a higher number of children compared to those who have more education. A woman’s education level has a positive impact on the well-being and survival of her children as educated mothers often follow safer hygiene practices, which contribute to better health and increased chances of surviving children. In addition, improved access to infrastructure can allow women to dedicate more time to economic activities, which promotes greater economic growth.

This scenario will lead to a reduction in both infant mortality and fertility rates in 2043. An increase in infrastructure investment of 0.6% of GDP in Africa will result in a reduction of infant mortality by 24.6 deaths per 1 000 children born. This represents a 5.2% decrease (equivalent to 1.4 fewer deaths per 1 000 children born) compared to the Current Path forecast in 2043. The total fertility rate will drop by about 1.2% relative to the Current Path in 2043, from about 3.2 births per woman (Current Path forecast) to nearly 3.1 births per woman (scenario) (see Chart 29).

The Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario will boost trade (both exports and imports) in Africa. In 2043, total trade gains (exports plus imports) from this scenario will increase by US$272.5 billion (or 5.6%) relative to the Current Path forecast. Africa’s total exports will increase by US$100.6 billion (or 4.6%), while total imports increase by US$172 billion (or 6.5%) relative to the Current Path forecast, as shown in Chart 30.

The majority of Africa’s trade benefits, with regard to total trade value, are anticipated to come from Nigeria in the Leapfrogging and Large Infrastructure scenario (see Chart 31). Relative to the Current Path forecast, Nigeria’s trade value will increase by nearly US$35.4 billion.

At the low end, however, the total trade values of Sudan and Kenya are expected to decrease relative to the Current Path. Sudan’s total trade will decrease by US$306.5 million and Kenya’s total trade will fall by US$723.5 million relative to the Current Path in 2043.

Much of Africa’s current infrastructure endowment reflects the patterns first established under colonialism. Subsequently, low levels of investment and little maintenance have resulted in significant deficits in infrastructure, which are essential for improving human well-being, promoting industrial development and advancing regional integration.

Closing this gap requires more spending on infrastructure, but it must inevitably balance with other priorities such as education and health. The good news is that much of this is happening. Infrastructure investment in Africa has been steadily increasing over the past 15 years, predominantly funded by national governments, although others (China in particular) have an important role. The challenge is to move more projects in the large infrastructure pipeline to financial close. To this end, the international community can play an important role by:

- funding and supporting feasibility studies

- providing insurance against risk

- reducing the risk premium charged by private banks (based on the negative views through which rating agencies view the continent), and

- assisting African governments in managing and overseeing complex projects.

Transforming projects into bankable, sustainable assets requires appropriate procurement and investment reform, including investment in subsidising and properly capacitating feasibility studies, will be essential to attract this capital.

In some places (particularly the US and Europe), generous fiscal stimulus during the COVID-19 pandemic has unlocked large amounts of capital for additional infrastructure spending. Low interest rates have also made borrowing for large projects more affordable than in the past. The shift to remote work by office workers is driving demand for improved ICT infrastructure, and the urgent fight against climate change continues to drive demand for investment in renewable energy.

Mobilising the private sector is clearly part of the solution to Africa’s infrastructure backlog, but government resources will remain essential, particularly for basic infrastructure. Proper prioritisation of projects is key. Although major power plants and highways may be appropriate in many contexts, the resources invested in these high-profile projects are often better spent on the basics.

If African governments can properly prioritise projects, and implement the reforms necessary to close the funding gap, infrastructure development across the continent could be transformative. Even a partial closing of the gap, as demonstrated in the scenario presented here, could lead to a significant increase in incomes. Eventually, the development of proper infrastructure is likely an essential prerequisite for the implementation of other major development programmes, such as those examined in our scenarios on industrialisation and trade presented on this site.

Endnotes

A Smith, The wealth of nations [1776] (Vol. 11937), 1937.

For example, the so-called Lunatic Express, from Kisumu (Lake Victoria) to the port of Mombasa, built between 1886 and 1901, literally bypassed all the highly populated areas.

Airports: 13; border post upgrades: 38; bridges: 5; port-related projects: 45; rail lines: 23; road projects: 113.

Although eight of these projects are major hydroelectric dams, PIDA does not oversee any solar, wind or other renewable energy projects.

There are some mini-grids, albeit very limited. For example, Synoki, Hydroforce and Virunga operate mini-grid hydroelectric projects and their market share of the electricity sector is estimated at 6%. Only 3.66 MW of solar photovoltaics had been installed by the end of 2017.

The allocation is to: paved roads; unpaved roads; electricity generation; rural and urban electricity access; irrigation; safe water for households; improved water access; household sanitation; improved sanitation; wastewater; telephones; mobile broadband and fixed broadband.

Page information

Contact at AFI team is Jakkie Cilliers and Blessing Chipanda

This entry was last updated on 14 January 2025 using IFs v7.64.

Reuse our work

- All visualizations, data, and text produced by African Futures are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

- The data produced by third parties and made available by African Futures is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

- All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Cite this research

Jakkie Cilliers and Blessing Chipanda (2026) Large Infrastructure. Published online at futures.issafrica.org. Retrieved from https://futures.issafrica.org/thematic/11-large-infrastructure/ [Online Resource] Updated 14 January 2025.