South Sudan

South Sudan

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

In this entry, we first describe the Current Path forecast for South Sudan as it is expected to unfold to 2043, the end of the third ten-year implementation plan of the African Union's Agenda 2063 long-term vision for Africa. The Current Path in the International Futures (IFs) forecasting model initialises from country-level data that is drawn from a range of data providers. We prioritise data from national sources.

The Current Path forecast is divided into summaries on demographics, economics, poverty, health/WaSH and climate change/energy. A second section then presents a single positive scenario for potential improvements in stability, demographics, health/WaSH, agriculture, education, manufacturing/transfers, leapfrogging, free trade, financial flows, infrastructure, governance and the impact of various scenarios on carbon emissions. With the individual impact of these sectors and dimensions having been considered, a final section presents the impact of the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario.

We generally review the impact of each scenario and the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario on gross domestic product per person and extreme poverty except for Health/WaSH that uses life expectancy and infant mortality.

The information is presented graphically and supported by brief interpretive text.

All US$ numbers are in 2017 values.

Summary

- Current Path forecast

- South Sudan is a landlocked country of 644 329 km² in East Africa. It gained independence from Sudan on 9 July 2011 and is classified as a low-income country. Jump to forecast: Current path

- The population of South Sudan was 11.1 million in 2019. It is forecast to increase to 13.6 million by 2043 on the Current Path, representing an increase of 23% over the next 24 years. The country will experience slow urbanisation, with the urban population constituting 26.4% of the total population by 2043. Jump to Demographics: Current Path

- In 2019, GDP per capita for South Sudan was US$1 486. It is projected to grow to US$2 478 billion by 2043. This is US$1 312 lower than the projected average for low-income countries in Africa by then. Jump to Economy: Current Path

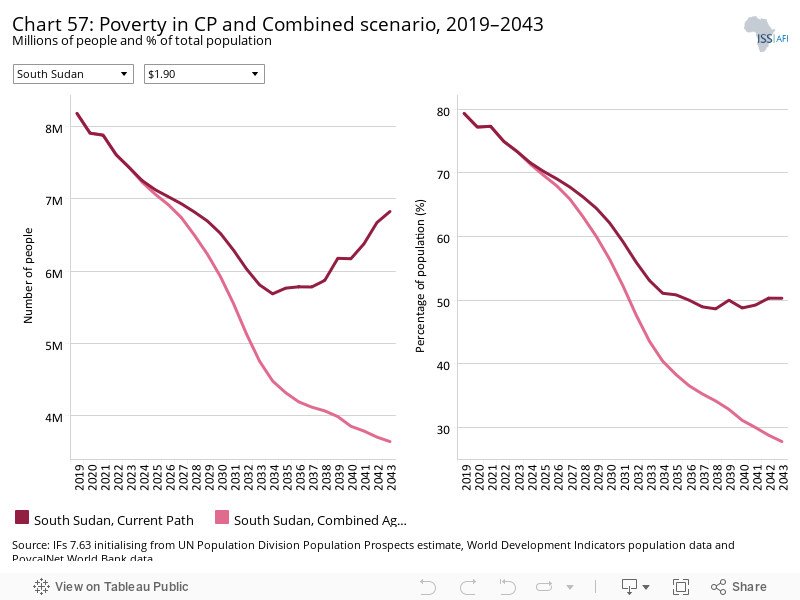

- Based on the US$1.90 poverty line, 79.4% of South Sudan’s population lived in extreme poverty in 2019, equivalent to 8.2 million people. The extreme poverty rate is forecast to decline to 50.3% (6.8 million people) by 2043, but remains above the average for low-income countries in Africa (25.1%). Jump to Poverty: Current Path

- Oil is the only type of energy produced by South Sudan. In 2019, the country produced an estimated 106 million barrels of oil equivalent. By 2043, oil will account for 91.6% of the country’s total energy production and will be complemented by renewable energies. In 2019, South Sudan produced 0.43 million tons of carbon, and by 2043 emissions are expected to have risen to 2.4 million tons. This represents an increase of 500%, but comes off a very low base. Jump to Carbon emissions/Energy: Current Path

- Sectoral scenarios

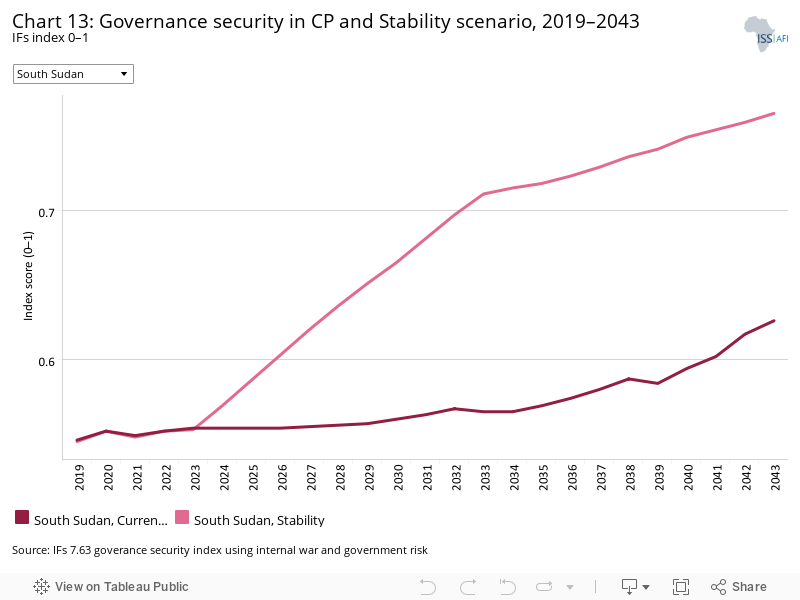

- The Stability scenario improves security and stability in South Sudan, with its score on IFs’ governance security index being 0.77 by 2043, about 22% higher than in the Current Path forecast and 8.5 % higher than the projected average of 0.71 for low-income countries in Africa. Jump to Stability scenario

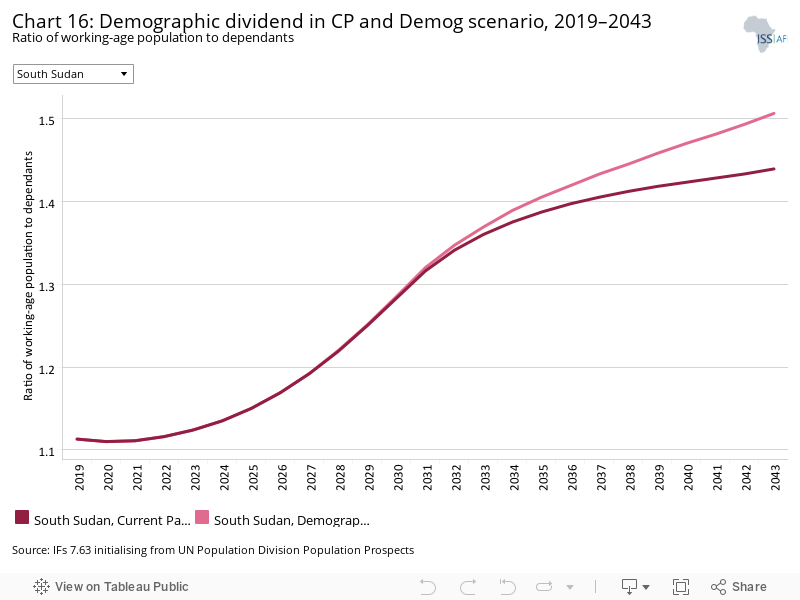

- In 2019, the ratio of the working-age population to dependants stood at 1.1. On the Current Path, it is forecast to reach 1.4 by 2043. In the Demographic scenario, the ratio of working-age population to dependants is 1.5 by 2043. The infant mortality rate is expected to decline from 78 deaths per 1 000 live births to 31 in the Demographic scenario. Jump to Demographic scenario

- The Health/WaSH scenario improves life expectancy at birth to 67.2 years by 2043, compared with 65.9 years in the Current Path forecast. This is more than three years less than the projected average (70.8 years) for low-income countries in Africa by then. The scenario further reduces the infant mortality rate to 33.5 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2043. Jump to Health/WaSH scenario

- The Agriculture scenario improves crop yields from about 3.2 tons per hectare in 2019 to 9.2 tons per hectare in 2043, compared with 4.6 tons in the Current Path forecast. Jump to Agriculture scenario

- In 2019, adults aged 15 years and older had received 3.8 years of education. In the Education scenario, it is projected to improve to 5.7 years by 2043, compared with 5.2 years in the Current Path forecast. Jump to Education scenario

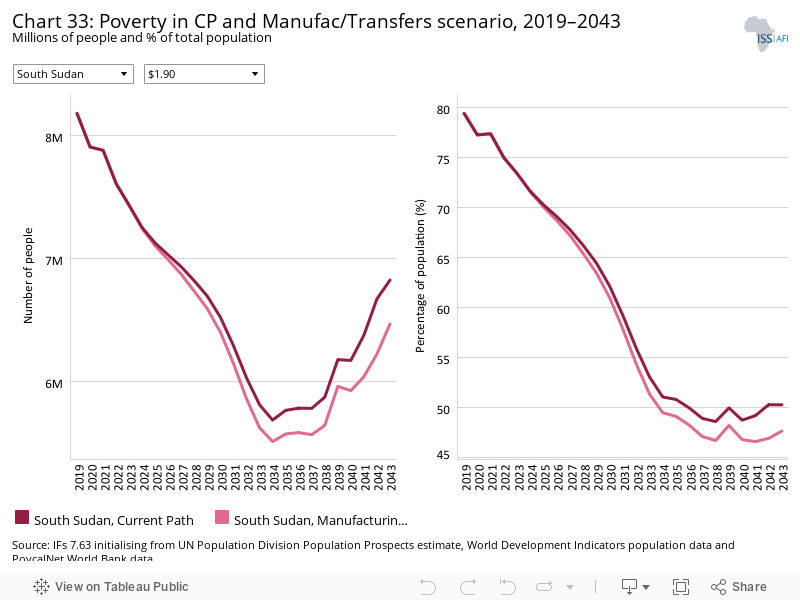

- The Manufacturing/Transfer scenario will increase household transfers by 67.2% over the Current Path forecast of US$580 million by 2043. By then, 47.6% of South Sudan’s population will be living in poverty (6.5 million people), compared with 6.8 million people (50.3%) in the Current Path forecast for that year. Jump to Manufacturing/Transfer scenario

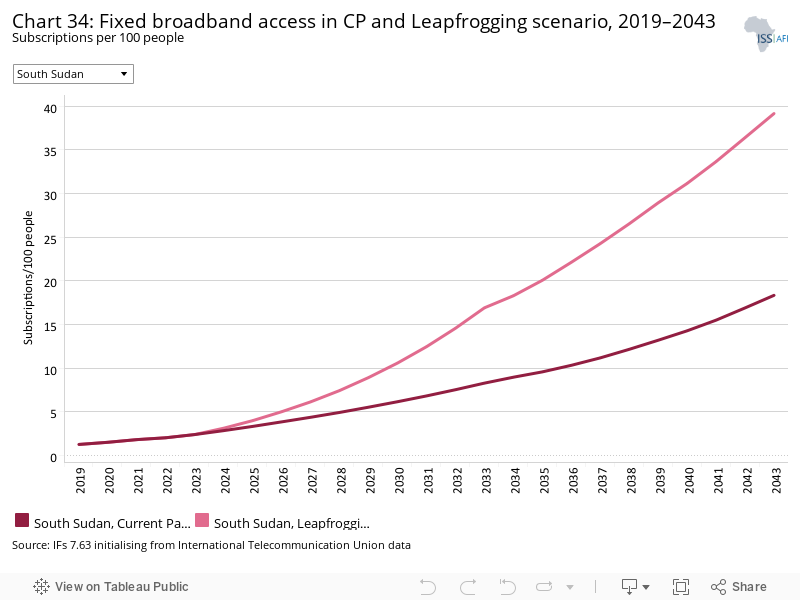

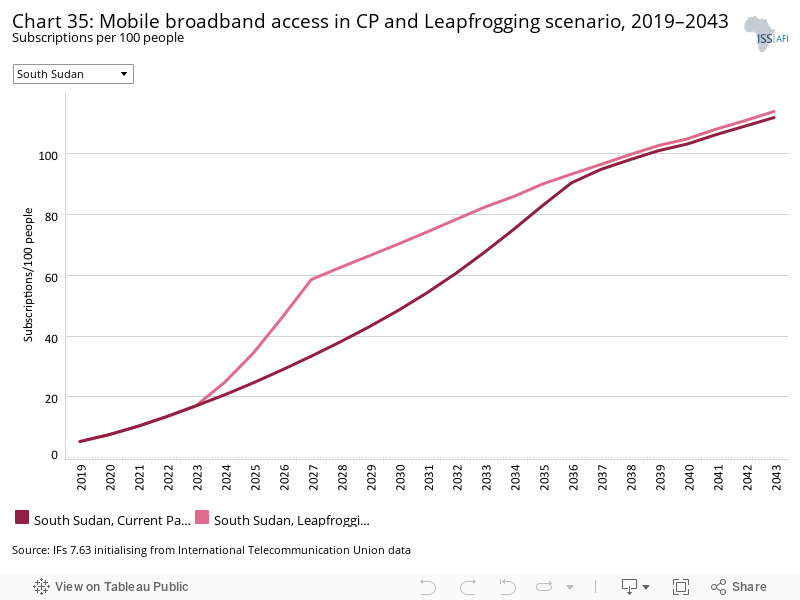

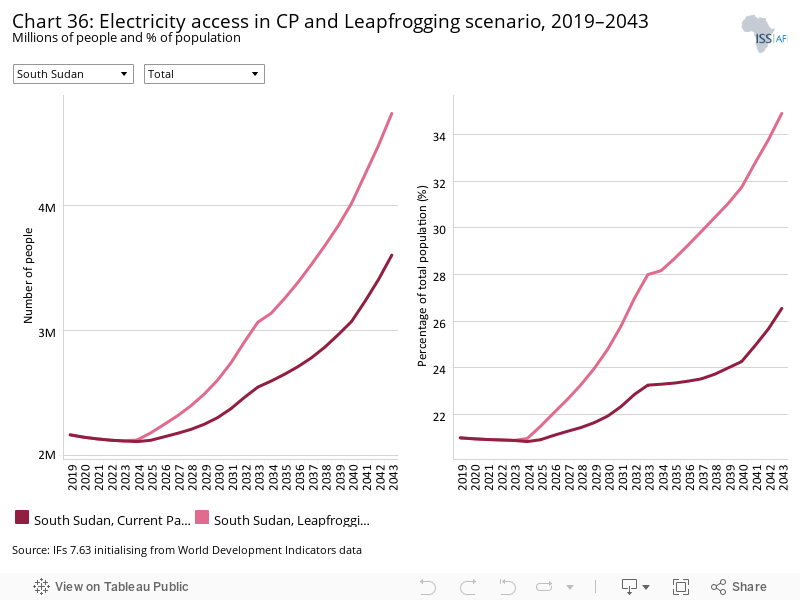

- In 2019, South Sudan had only 1.3 fixed broadband subscriptions per 100 people, below the average of 2.3 for low-income countries in Africa. In the Leapfrogging scenario, fixed broadband subscriptions increase to 39 per 100 people by 2043, higher than the Current Path forecast of 25.2 in the same year. The scenario further increases mobile broadband subscriptions from 5.3 per 100 people in 2019 to 113.9 per 100 people in 2043. Electricity access increases from 21% to 34.9% in the same period. Jump to Leapfrogging scenario

- In the Free Trade scenario, South Sudan's trade deficit increases to a peak of 36.4% of GDP in 2039, before slightly declining to 30% by 2043. Jump to Free Trade scenario

- In the Financial Flows scenario, foreign direct investment flows to South Sudan will grow from 0.16% of GDP in 2019 to 0.8% of GDP by 2043. However, as a percentage of GDP, aid will decline from 19.5% in 2019 to 13.1% in 2043 in this scenario Jump to Financial Flows scenario

- The Infrastructure scenario increases the rural population living within 2 km of an all-weather road by 2043 to 54.7%, slightly above the Current Path’s forecast. Jump to Infrastructure scenario

- The projected score for government effectiveness in the Governance scenario is 0.56 (out of 5) by 2043. This is 0.26 points higher than the projected score of 0.3 in the Current Path forecast for that year. Jump to Governance scenario

- The Agriculture scenario has the most significant impact on carbon emissions. Jump to the Impact of scenarios on carbon emissions

- Combined Agenda 2063 scenario Jump to Combined Agenda 2063 scenario

- By 2043, the GDP of South Sudan is US$13.3 billion larger than in the Current Path forecast.

- By 2043, GDP per capita is US$3 805, which is US$1 327 more than on the Current Path.

- The scenario will reduce extreme poverty from 79.4% in 2019 to 27.7% in 2043, translating to 3.2 million fewer people than in the Current Path forecast.

All charts for South Sudan

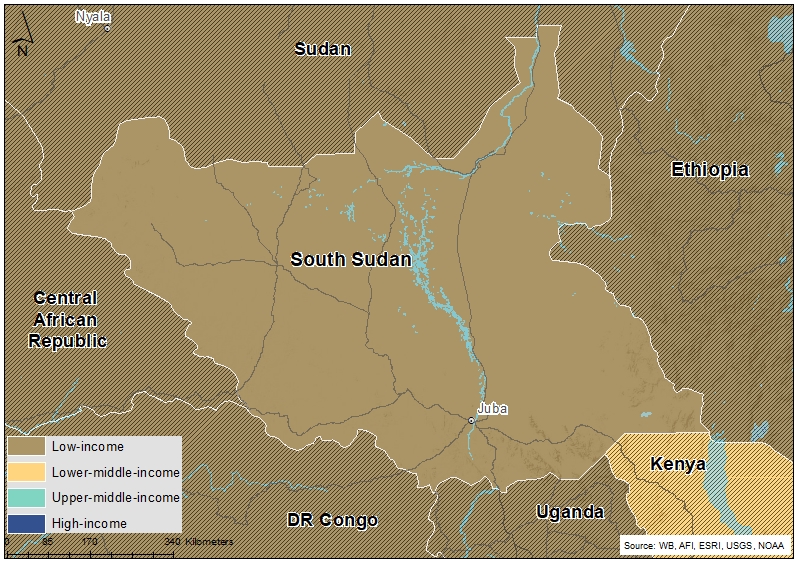

- Chart 1: Political map of South Sudan

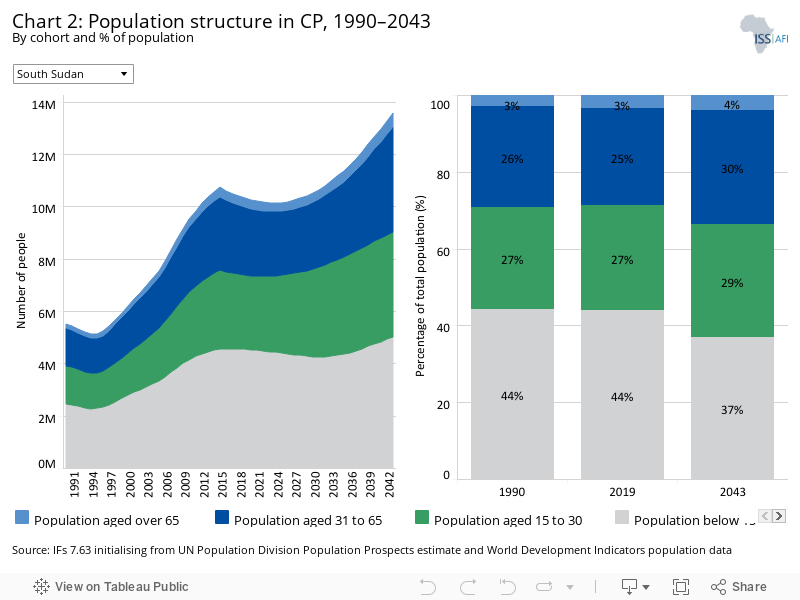

- Chart 2: Population structure in CP, 1990–2043

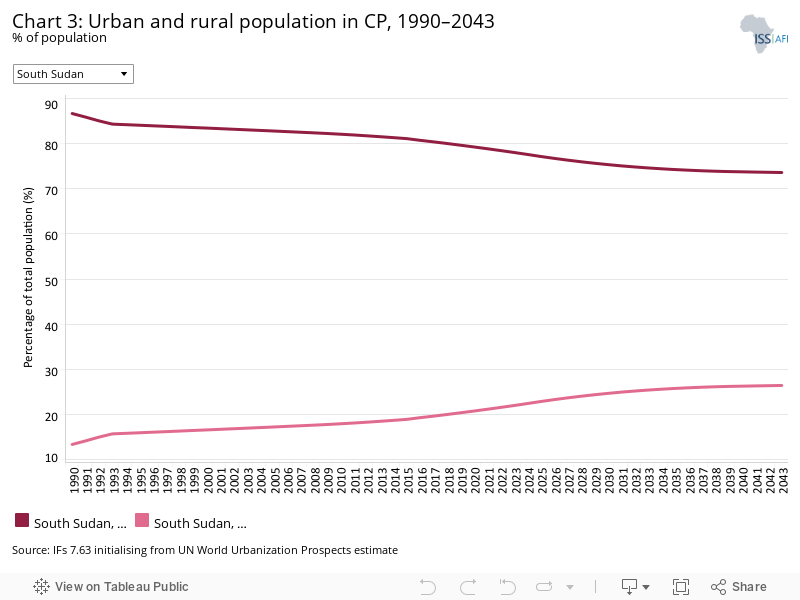

- Chart 3: Urban and rural population in CP, 1990–2043

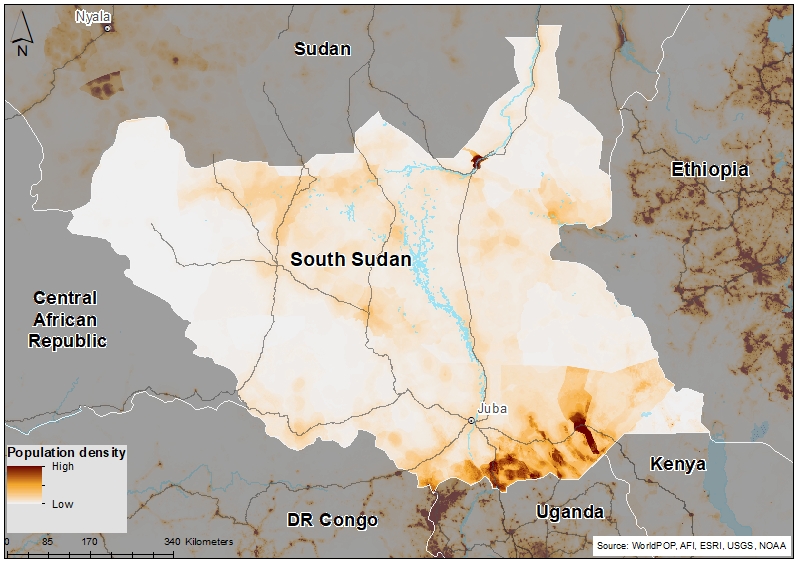

- Chart 4: Population density map for 2019

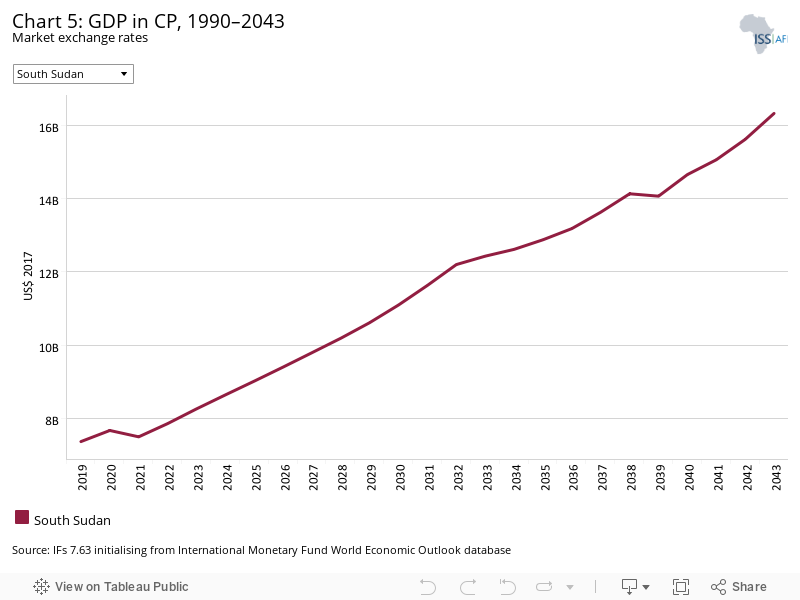

- Chart 5: GDP in CP, 1990–2043

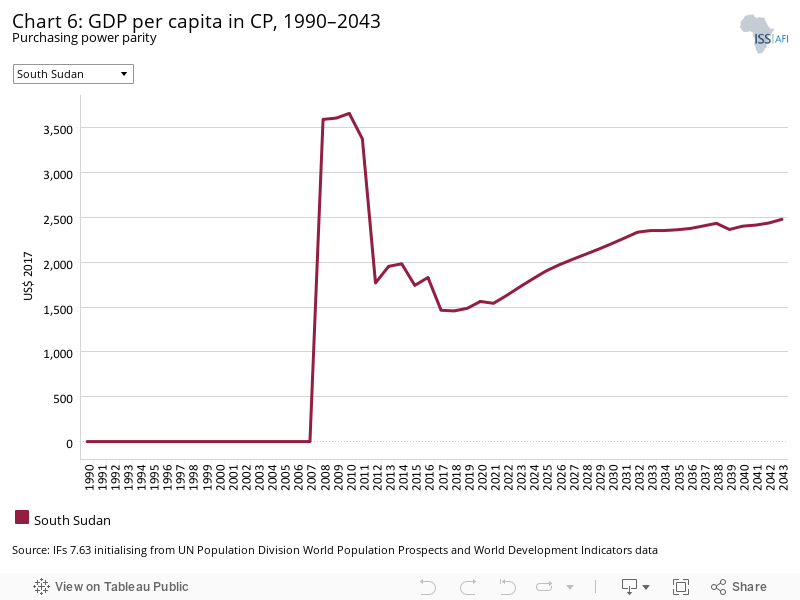

- Chart 6: GDP per capita in CP, 1990–2043

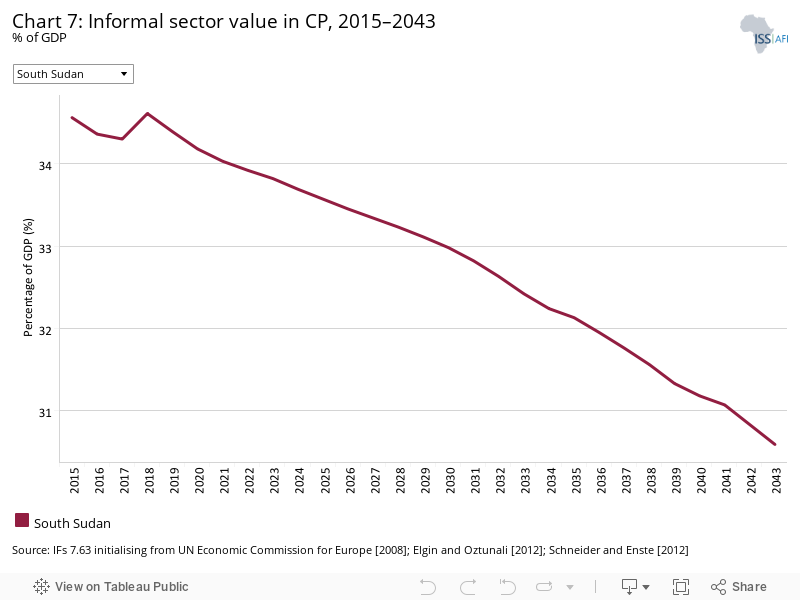

- Chart 7: Informal sector value in CP, 2015–2043

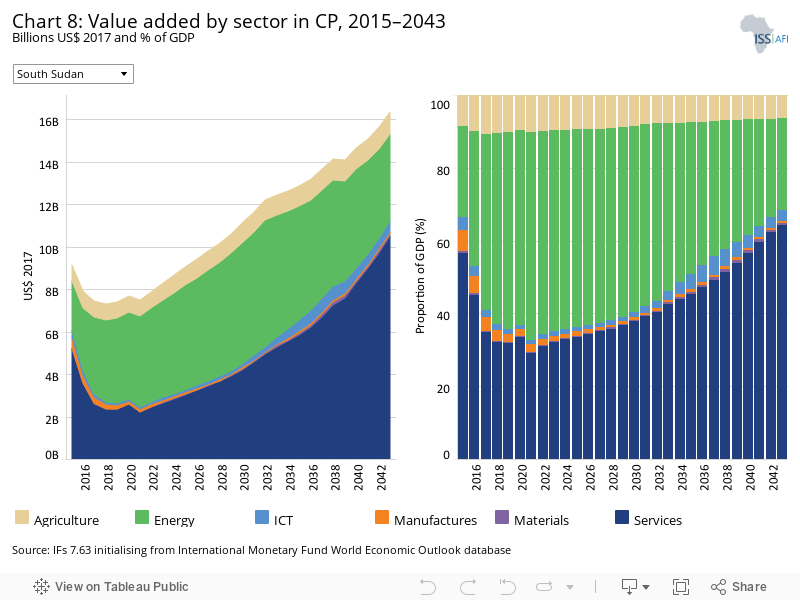

- Chart 8: Value added by sector in CP, 2015–2043

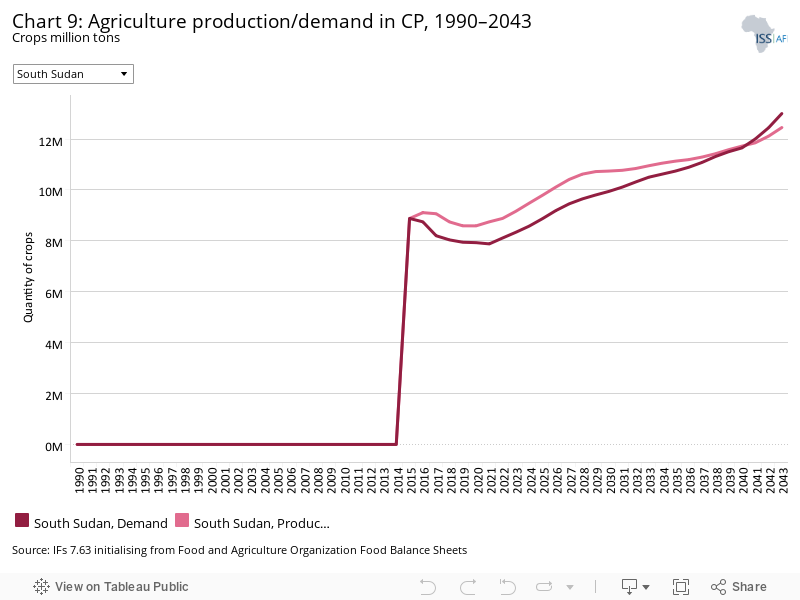

- Chart 9: Agriculture production/demand in CP, 1990–2043

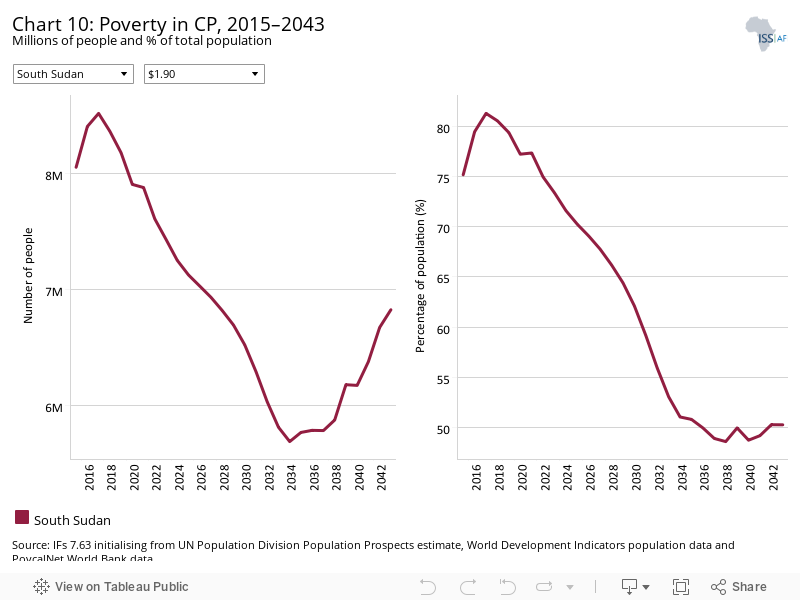

- Chart 10: Poverty in CP, 2015–2043

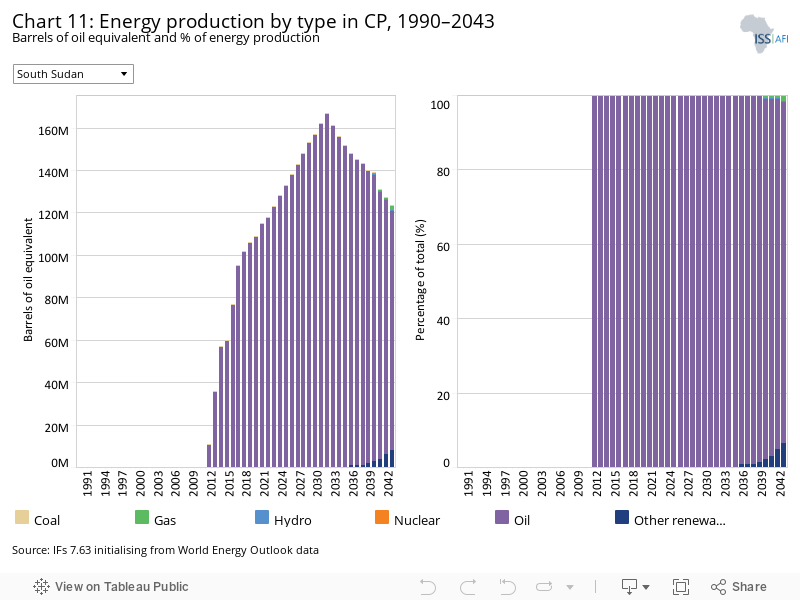

- Chart 11: Energy production by type in CP, 1990–2043

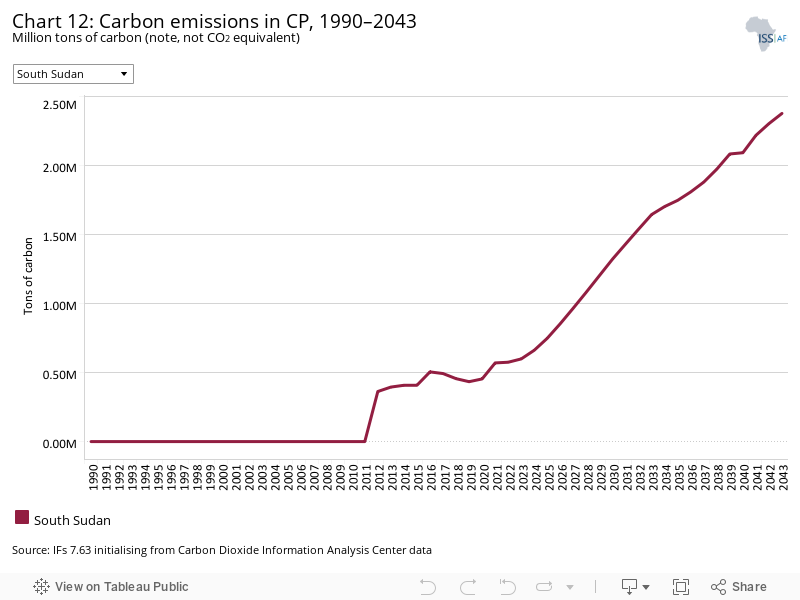

- Chart 12: Carbon emissions in CP, 1990–2043

- Chart 13: Governance security in CP and Stability scenario, 2019–2043

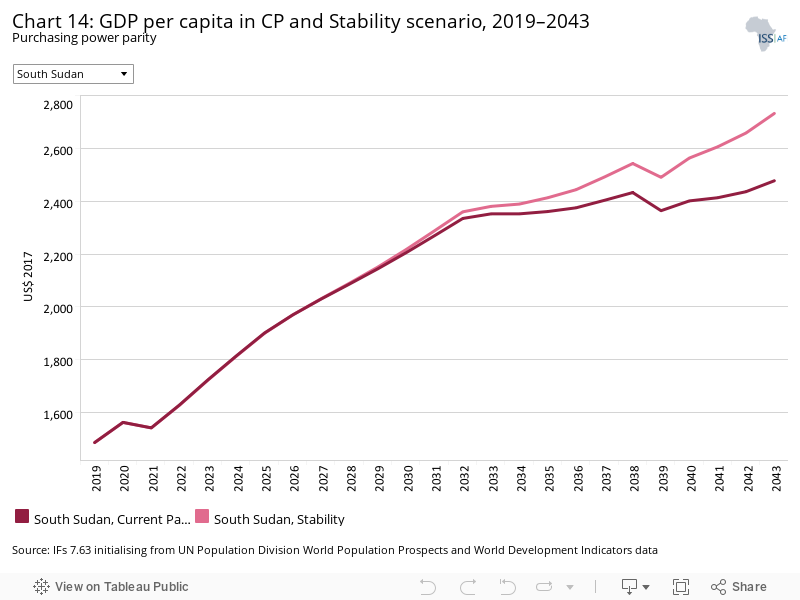

- Chart 14: GDP per capita in CP and Stability scenario, 2019–2043

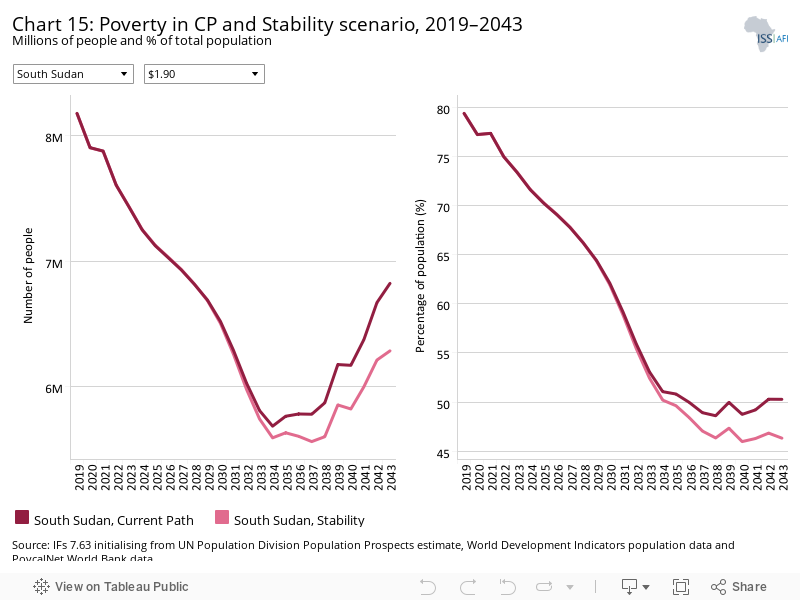

- Chart 15: Poverty in CP and Stability scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 16: Demographic dividend in CP and Demog scenario, 2019–2043

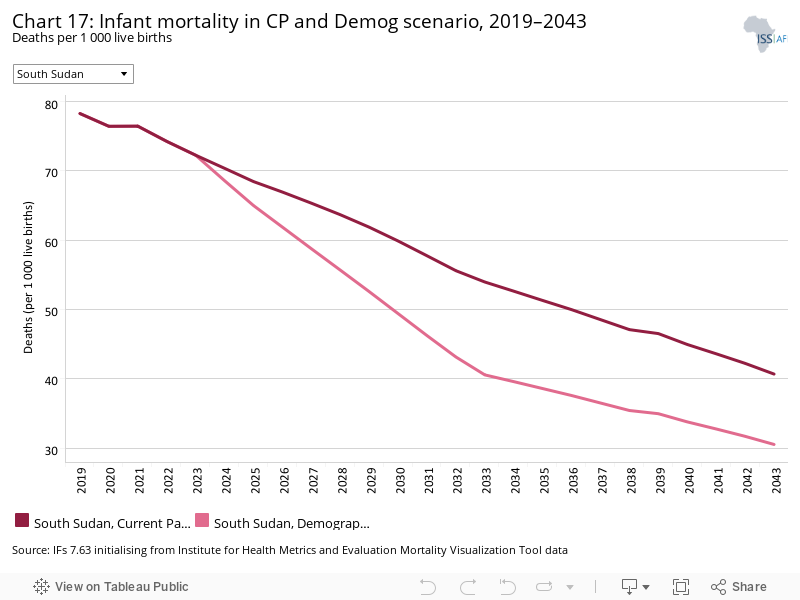

- Chart 17: Infant mortality in CP and Demog scenario, 2019–2043

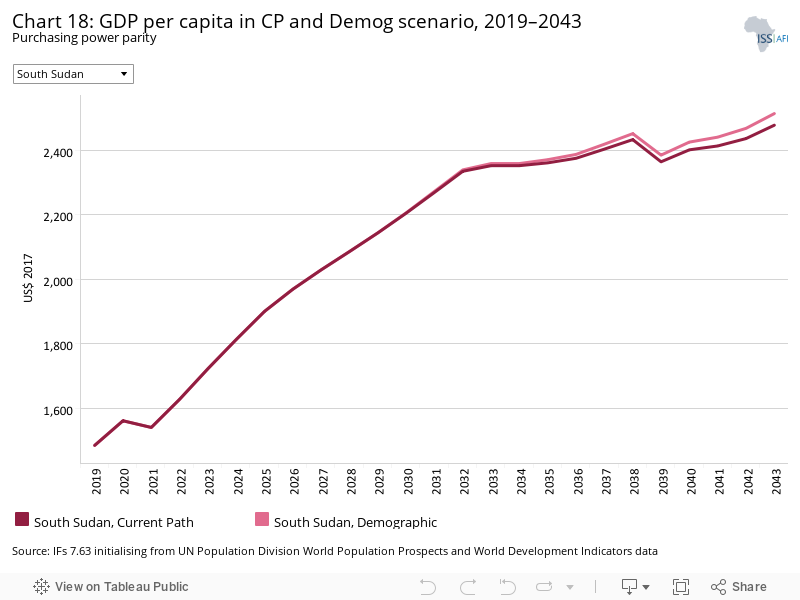

- Chart 18: GDP per capita in CP and Demog scenario, 2019–2043

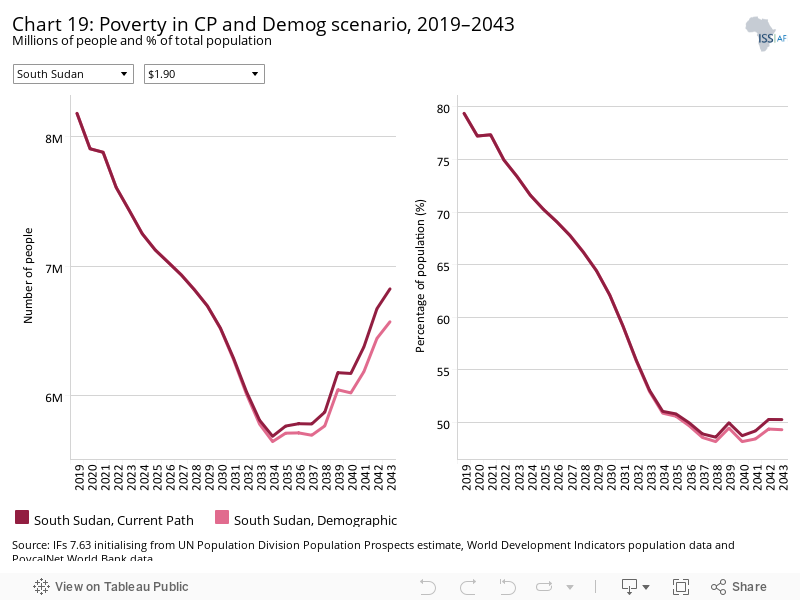

- Chart 19: Poverty in CP and Demog scenario, 2019–2043

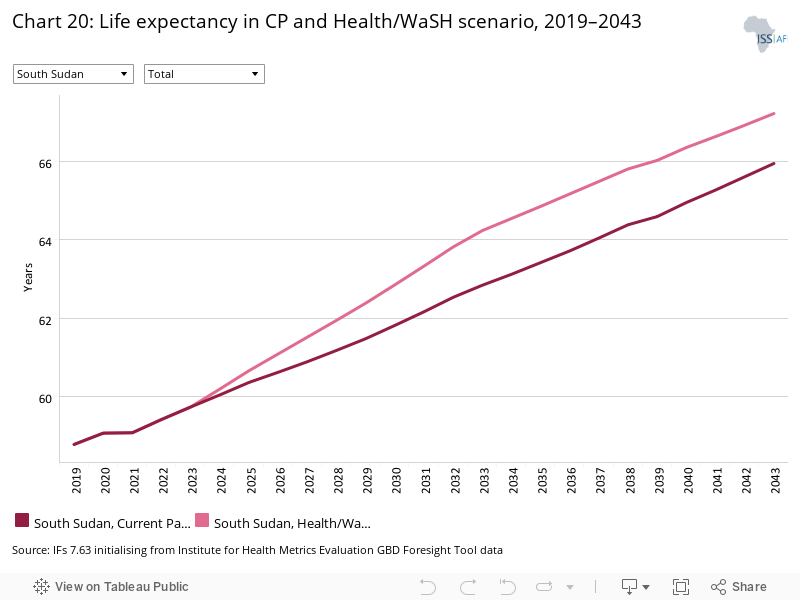

- Chart 20: Life expectancy in CP and Health/WaSH scenario, 2019–2043

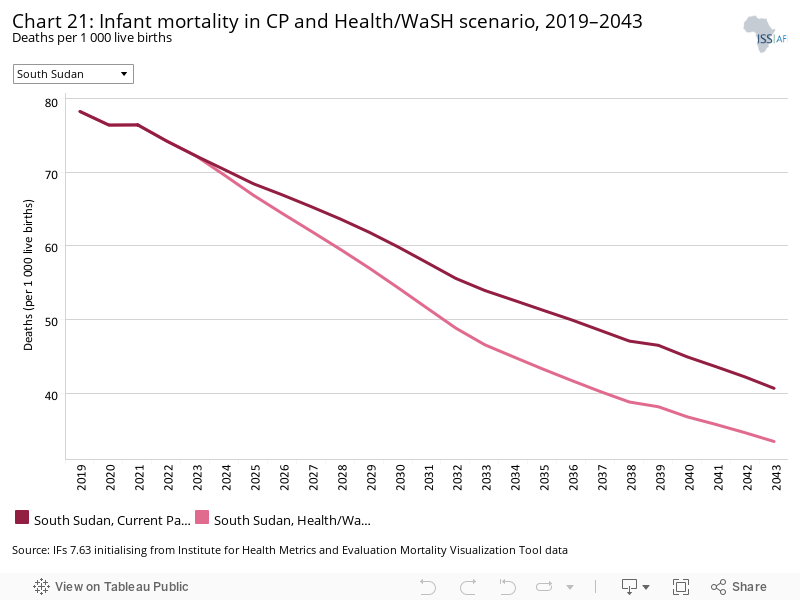

- Chart 21: Infant mortality in CP and Health/WaSH scenario, 2019–2043

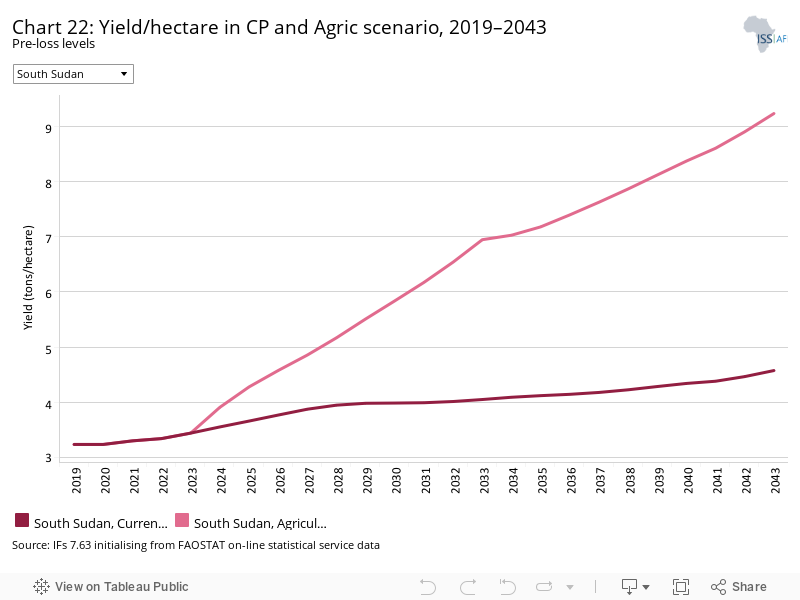

- Chart 22: Yield/hectare in CP and Agric scenario, 2019–2043

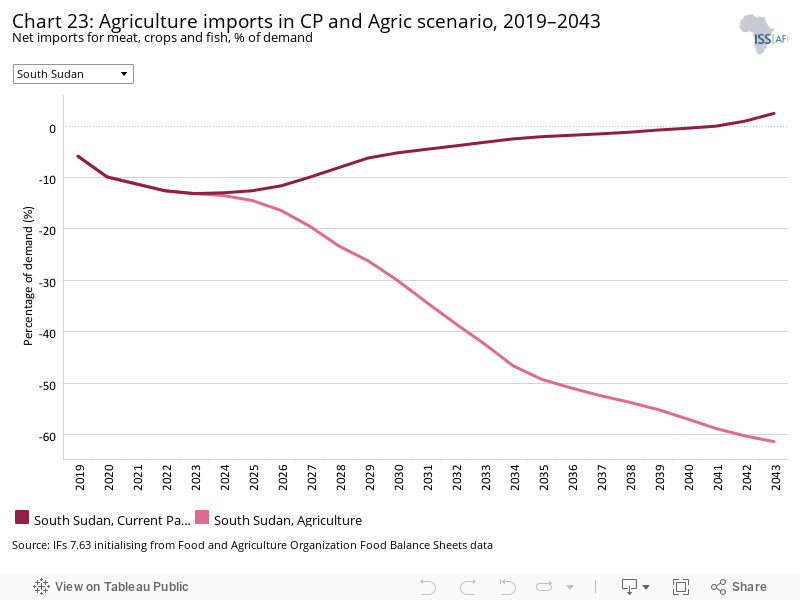

- Chart 23: Agriculture imports in CP and Agric scenario, 2019–2043

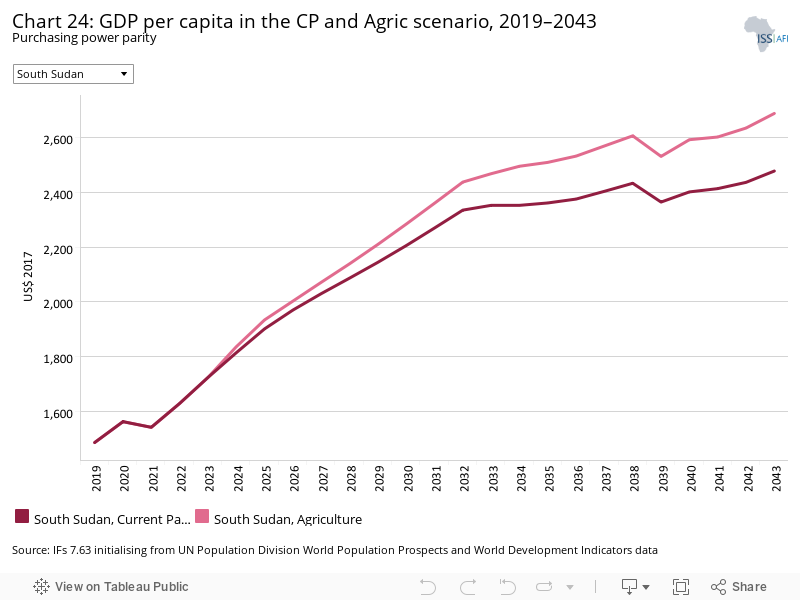

- Chart 24: GDP per capita in the CP and Agric scenario, 2019–2043

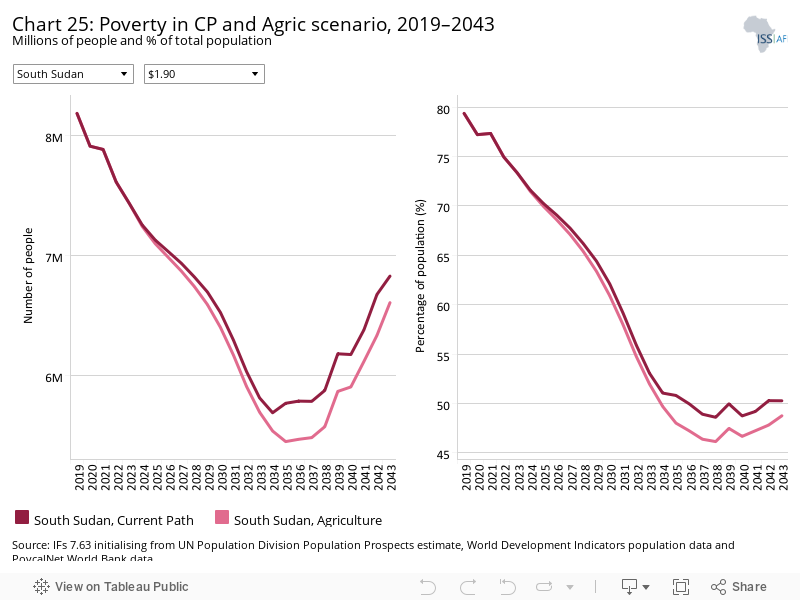

- Chart 25: Poverty in CP and Agric scenario, 2019–2043

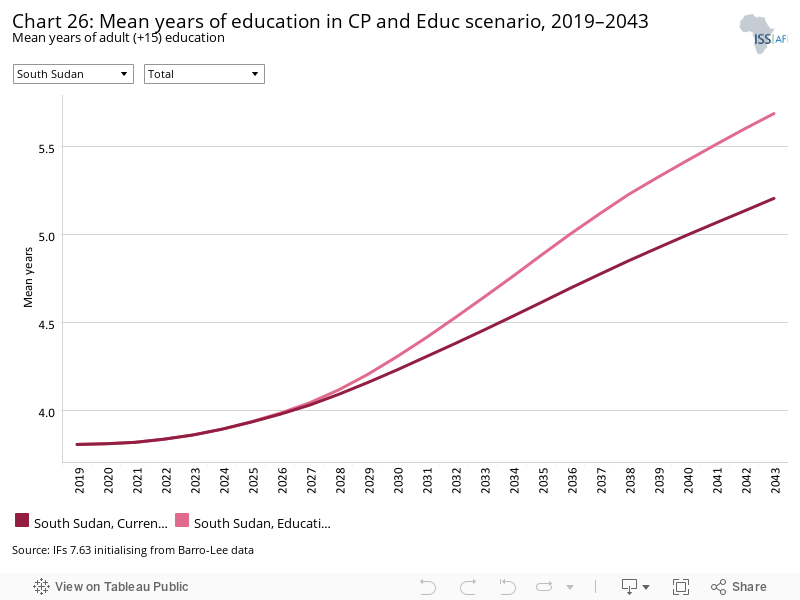

- Chart 26: Mean years of education in CP and Educ scenario, 2019–2043

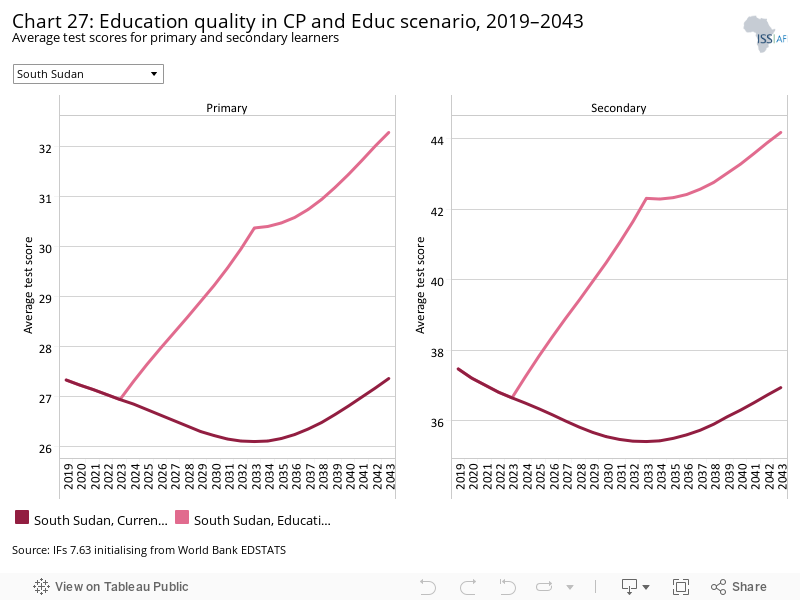

- Chart 27: Education quality in CP and Educ scenario, 2019–2043

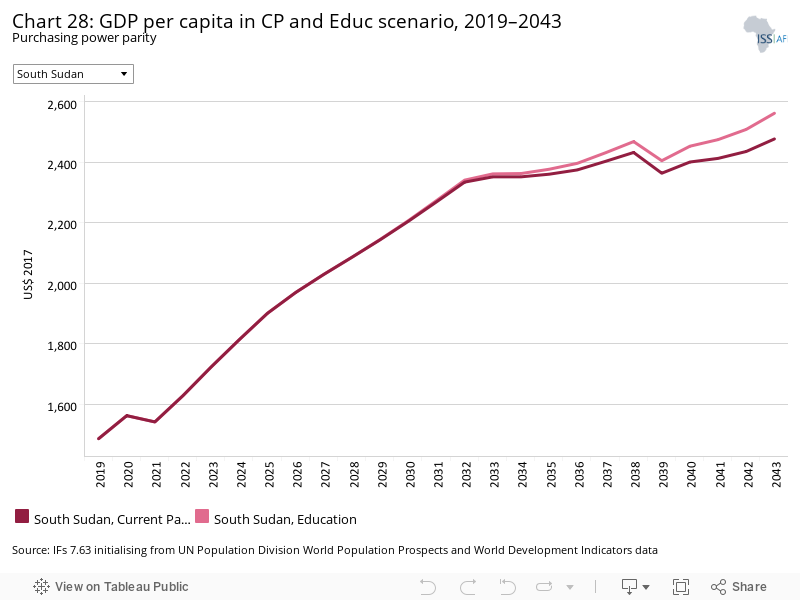

- Chart 28: GDP per capita in CP and Educ scenario, 2019–2043

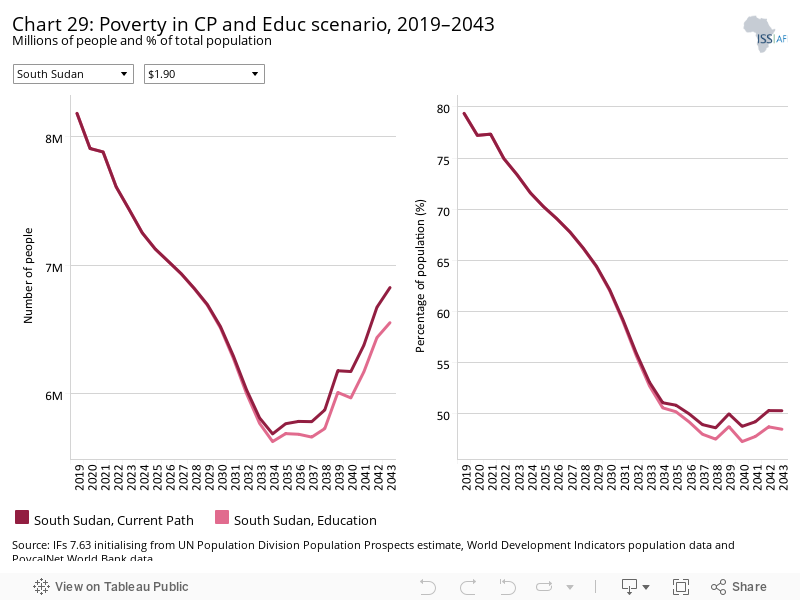

- Chart 29: Poverty in CP and Educ scenario, 2019–2043

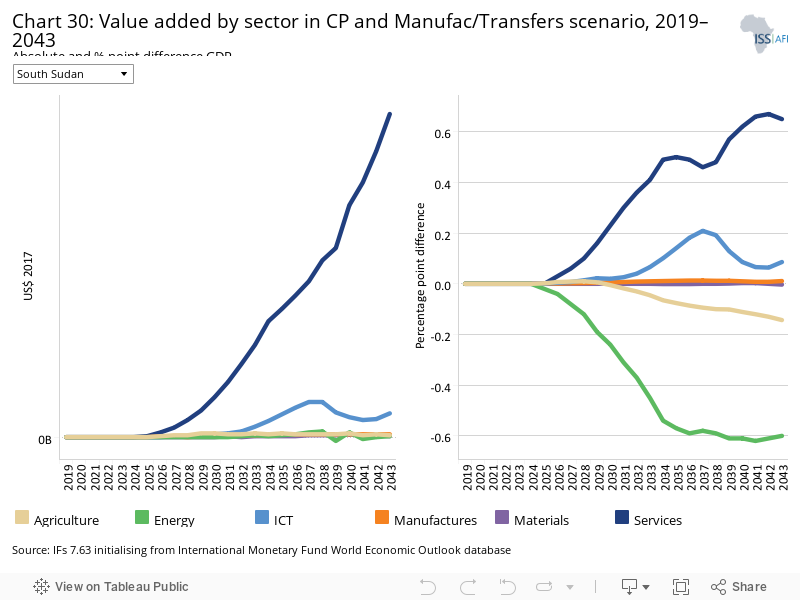

- Chart 30: Value added by sector in CP and Manufac/Transfers scenario, 2019–2043

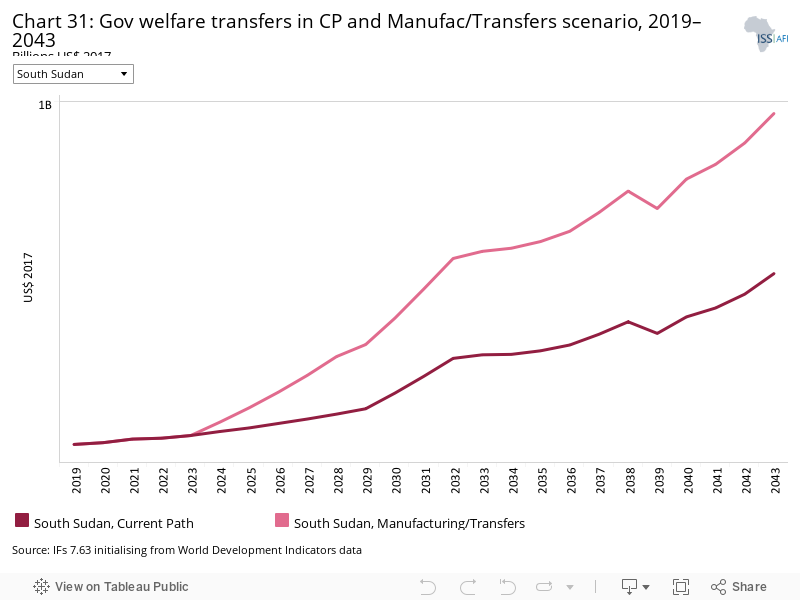

- Chart 31: Gov welfare transfers in CP and Manufac/Transfers scenario, 2019–2043

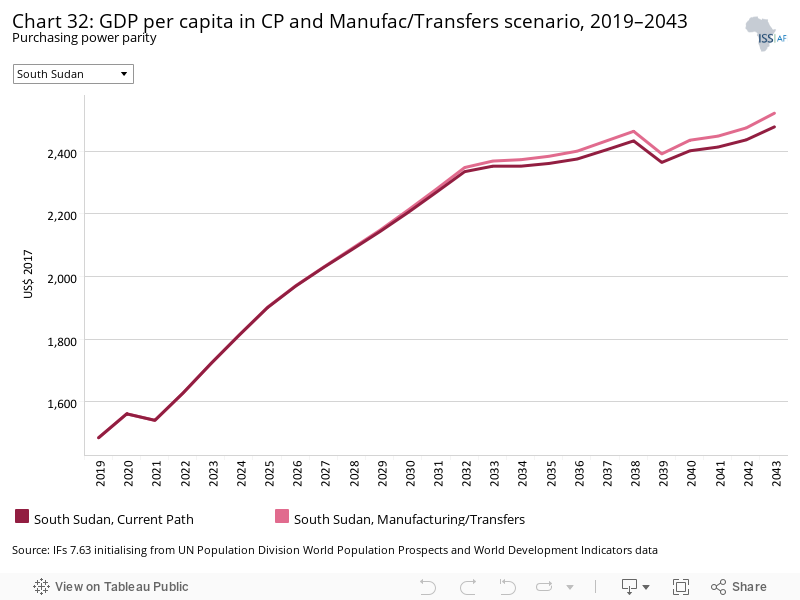

- Chart 32: GDP per capita in CP and Manufac/Transfers scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 33: Poverty in CP and Manufac/Transfers scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 34: Fixed broadband access in CP and Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 35: Mobile broadband access in CP and Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 36: Electricity access in CP and Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

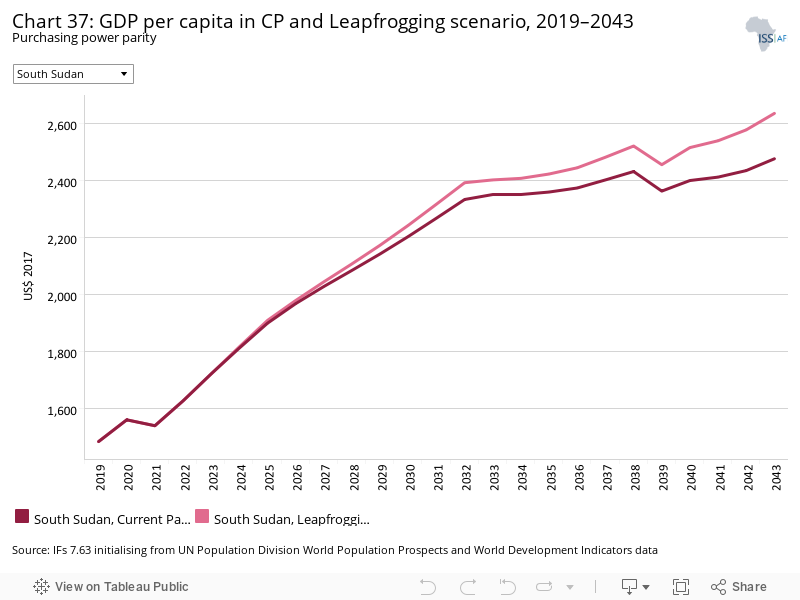

- Chart 37: GDP per capita in CP and Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

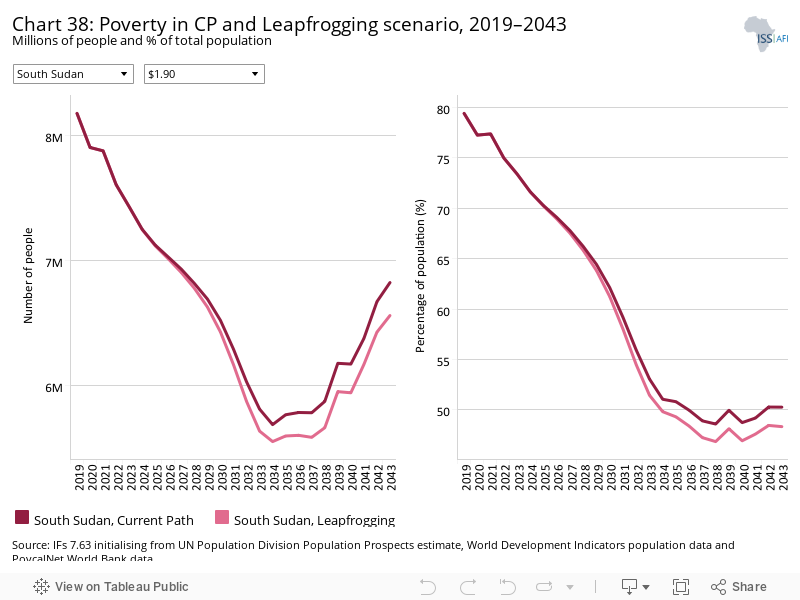

- Chart 38: Poverty in CP and Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

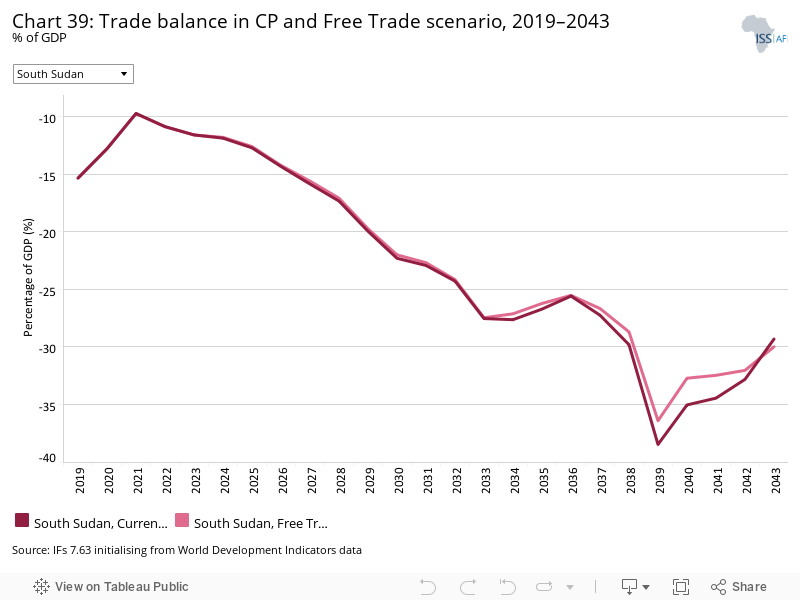

- Chart 39: Trade balance in CP and Free Trade scenario, 2019–2043

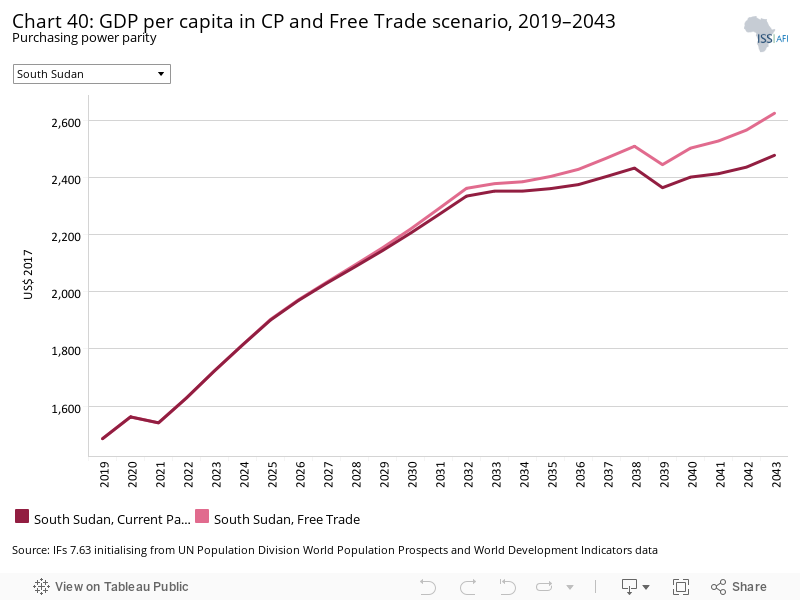

- Chart 40: GDP per capita in CP and Free Trade scenario, 2019–2043

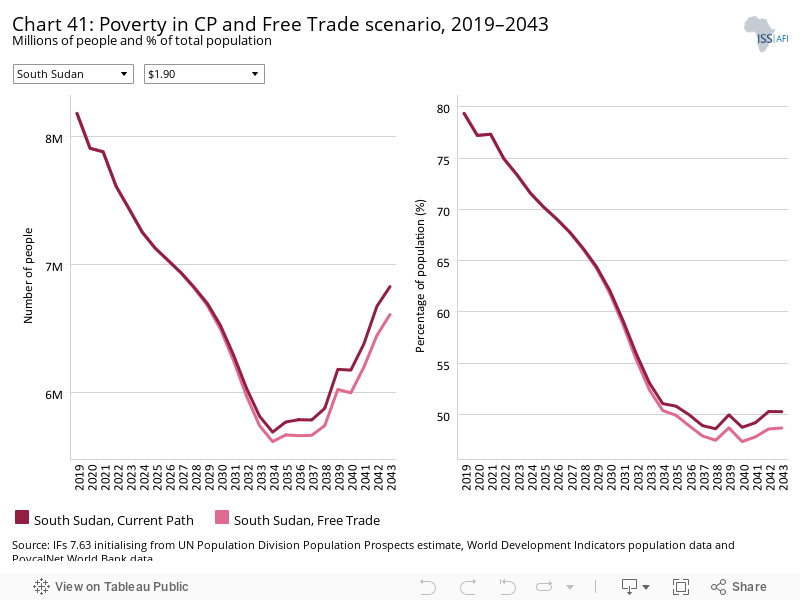

- Chart 41: Poverty in CP and Free Trade scenario, 2019–2043

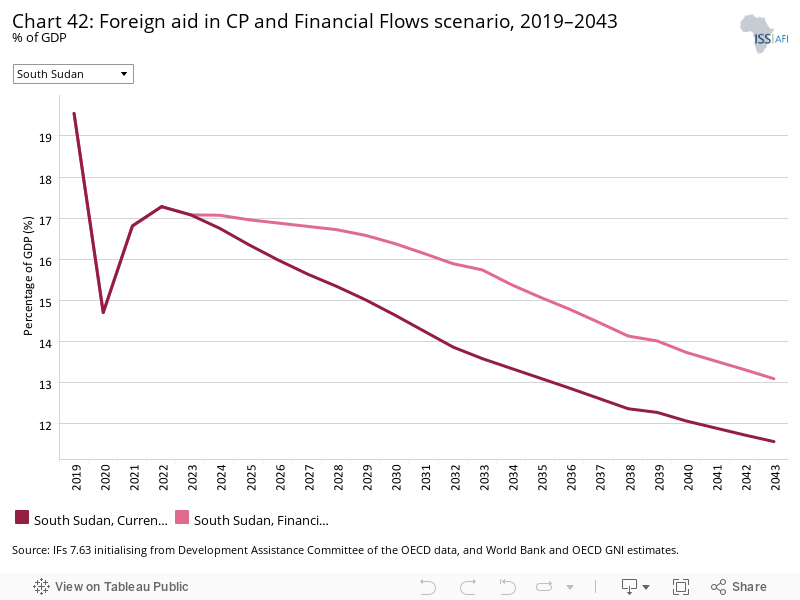

- Chart 42: Foreign aid in CP and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

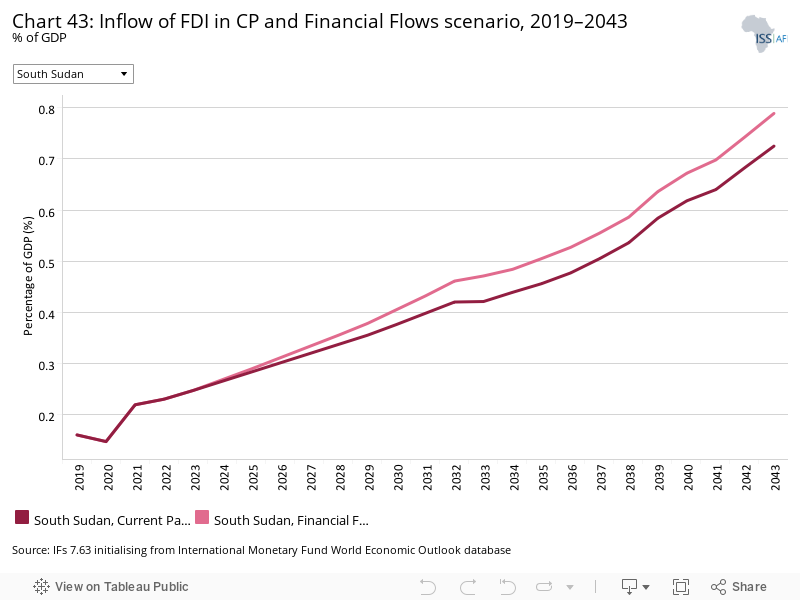

- Chart 43: Inflow of FDI in CP and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

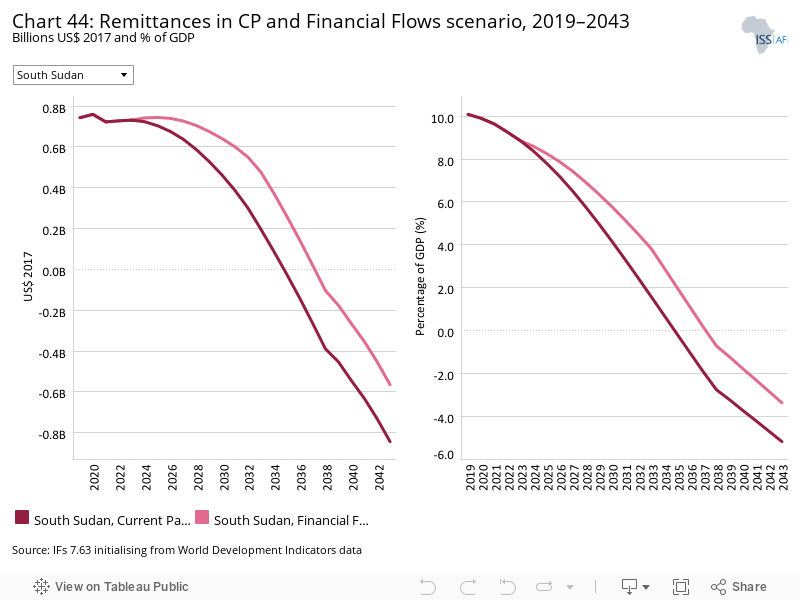

- Chart 44: Remittances in CP and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

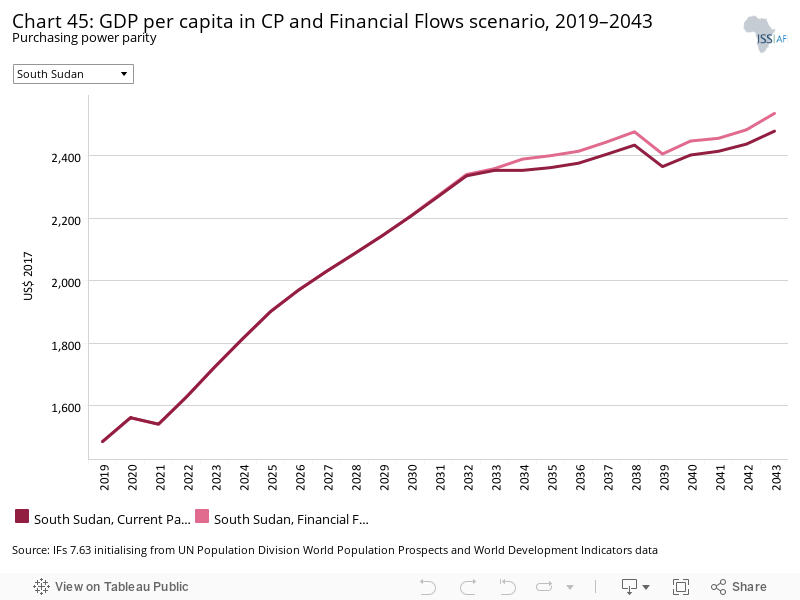

- Chart 45: GDP per capita in CP and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

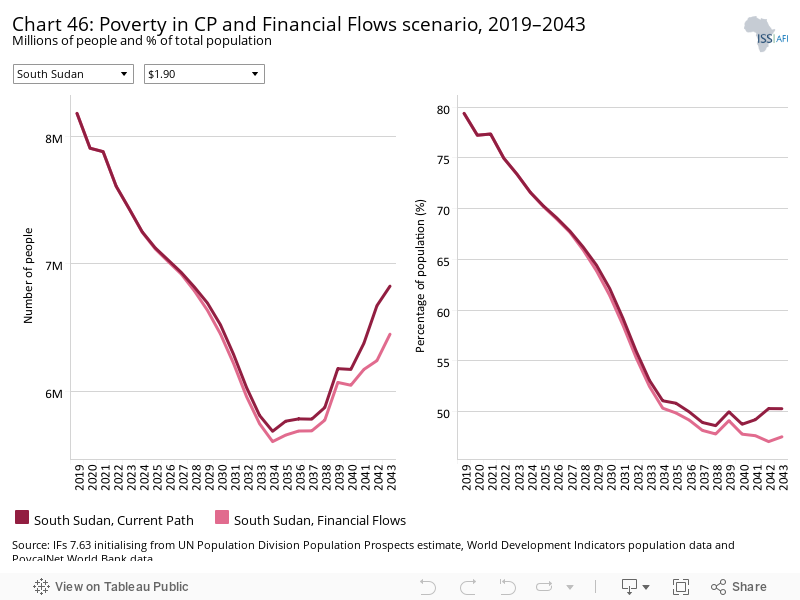

- Chart 46: Poverty in CP and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

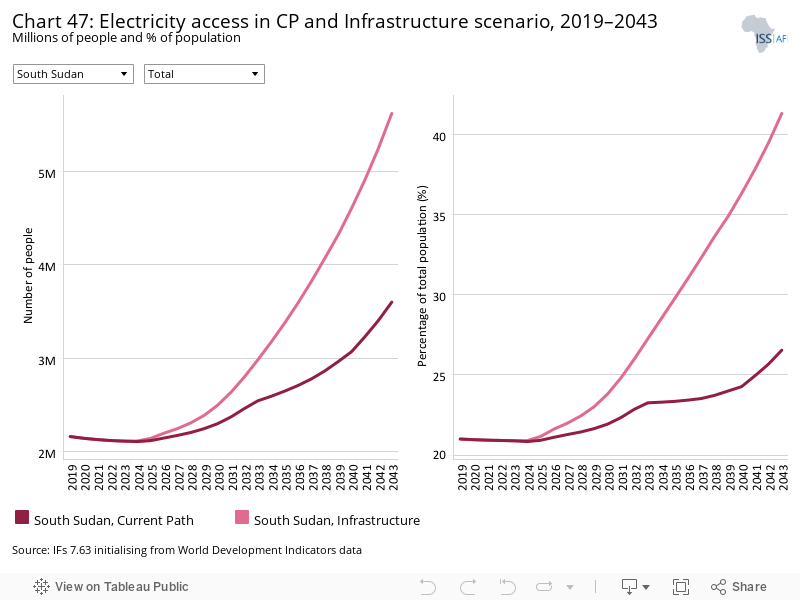

- Chart 47: Electricity access in CP and Infrastructure scenario, 2019–2043

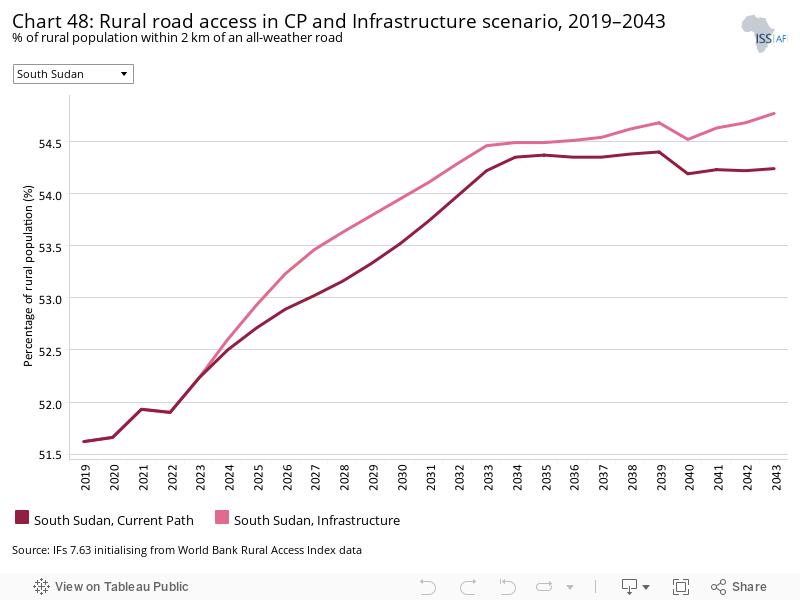

- Chart 48: Rural road access in CP and Infrastructure scenario, 2019–2043

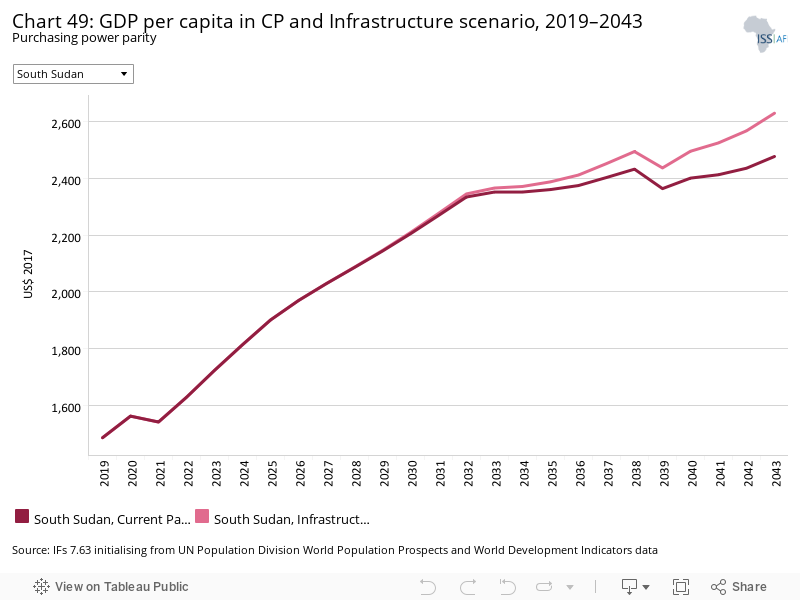

- Chart 49: GDP per capita in CP and Infrastructure scenario, 2019–2043

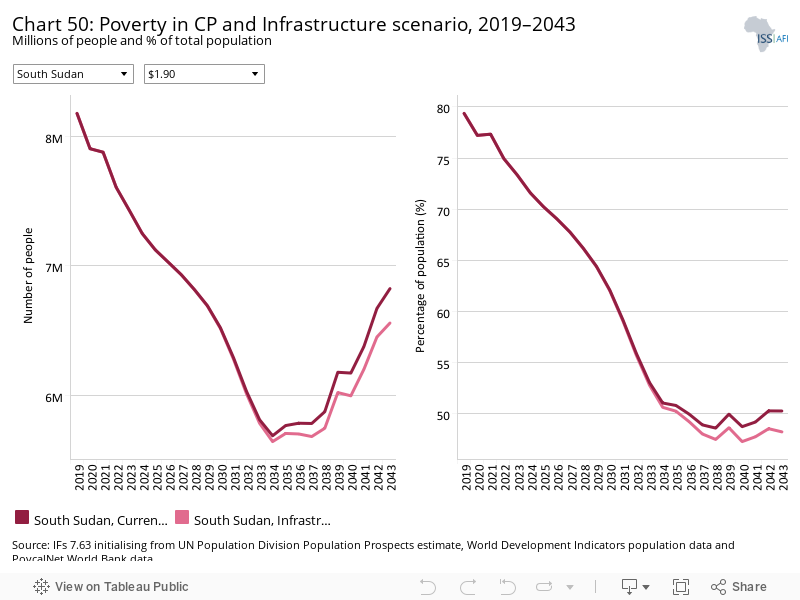

- Chart 50: Poverty in CP and Infrastructure scenario, 2019–2043

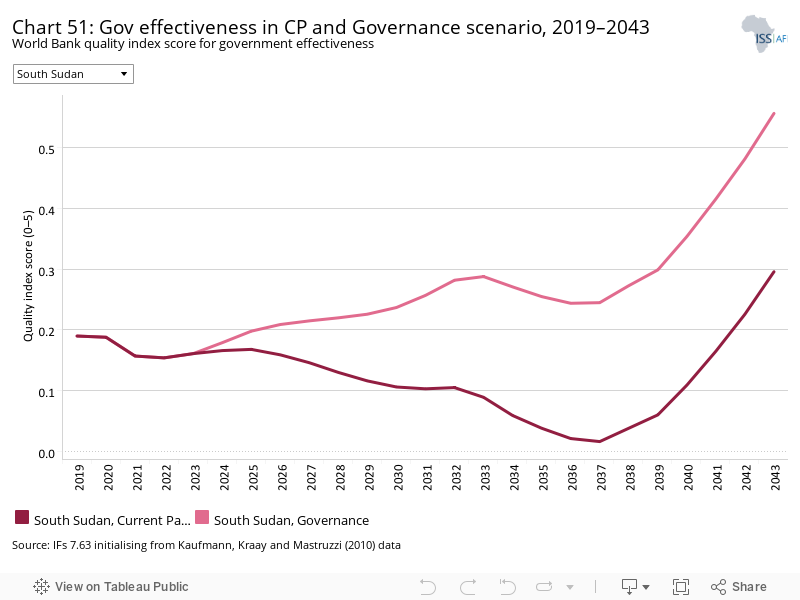

- Chart 51: Gov effectiveness in CP and Governance scenario, 2019–2043

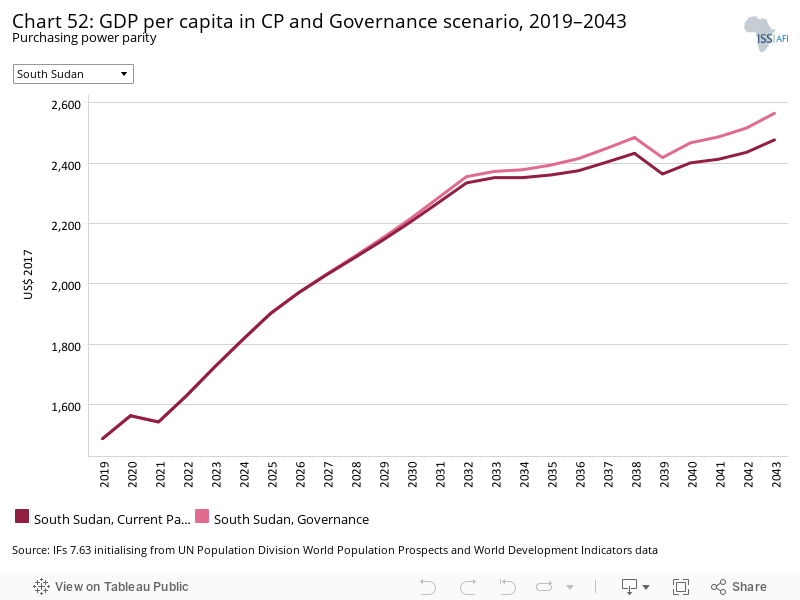

- Chart 52: GDP per capita in CP and Governance scenario, 2019–2043

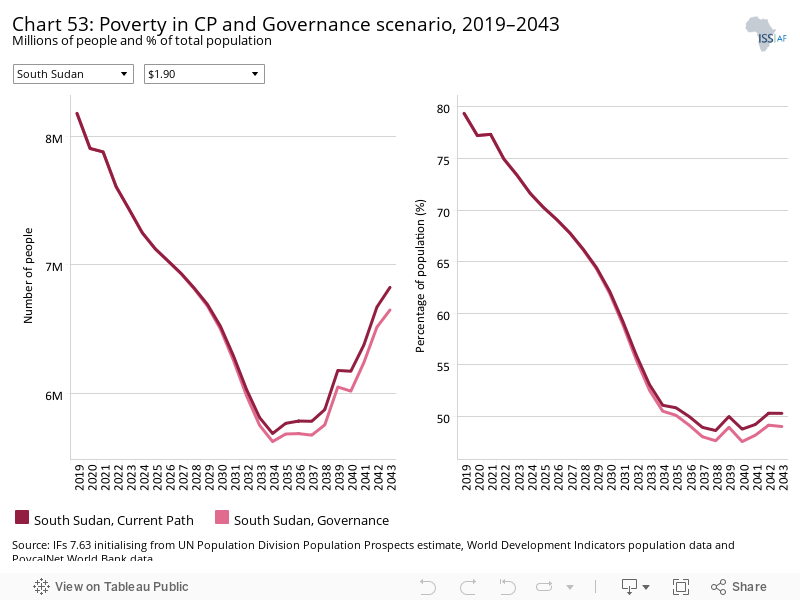

- Chart 53: Poverty in CP and Governance scenario, 2019–2043

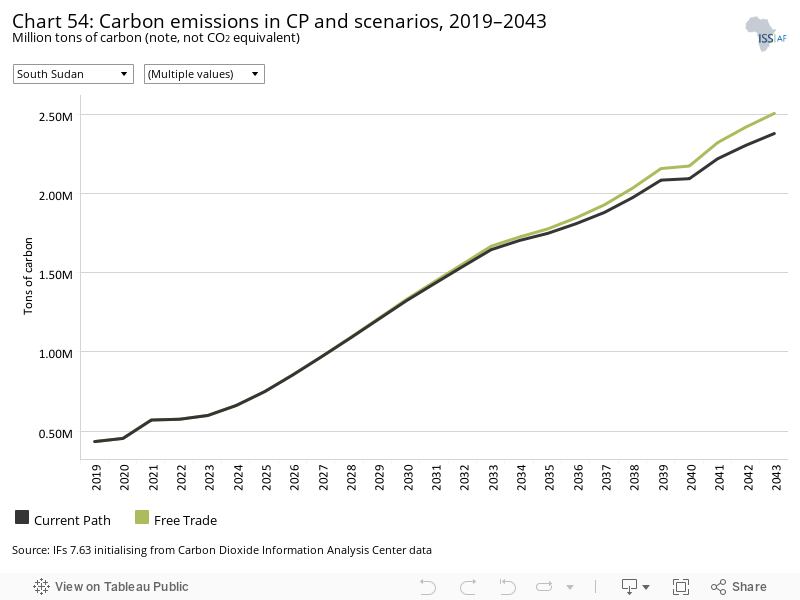

- Chart 54: Carbon emissions in CP and scenarios, 2019–2043

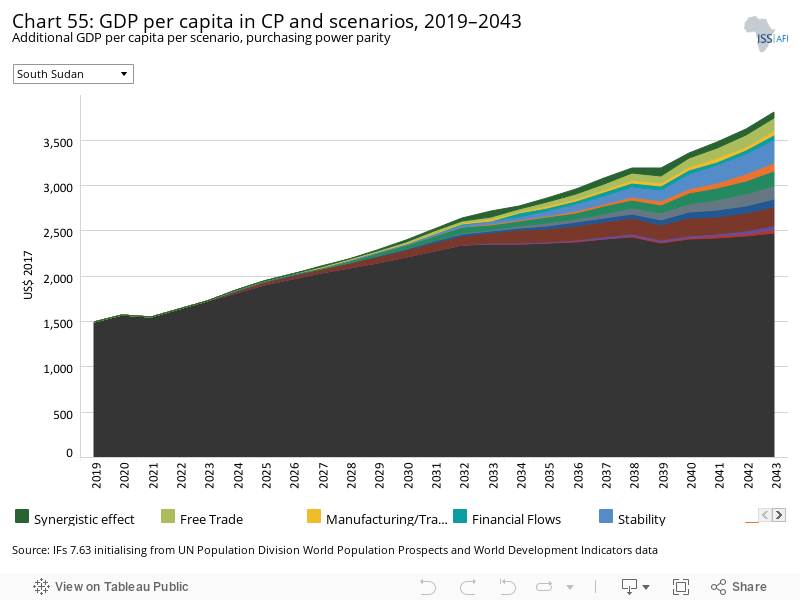

- Chart 55: GDP per capita in CP and scenarios, 2019–2043

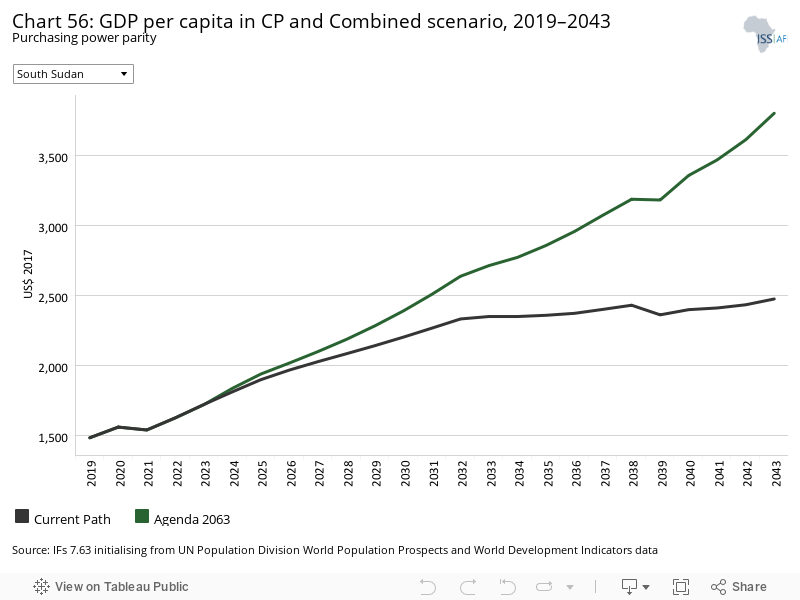

- Chart 56: GDP per capita in CP and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 57: Poverty in CP and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

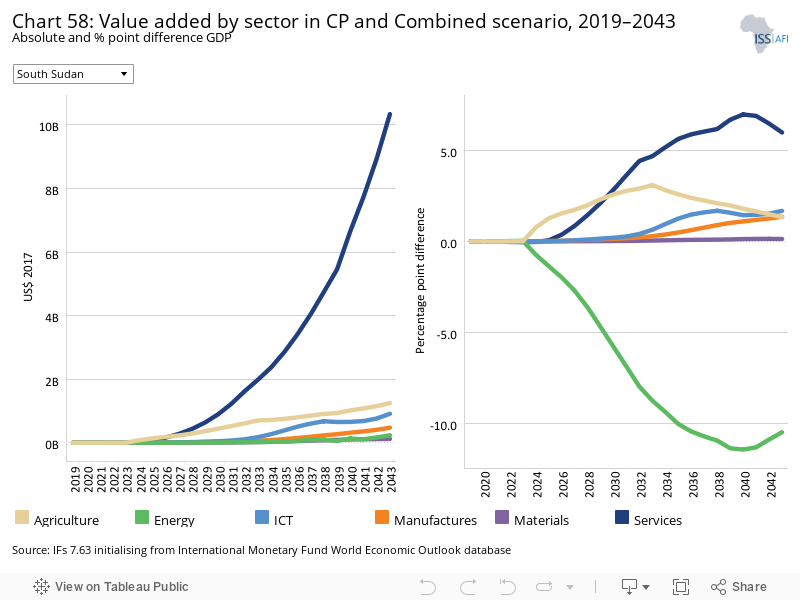

- Chart 58: Value added by sector in CP and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

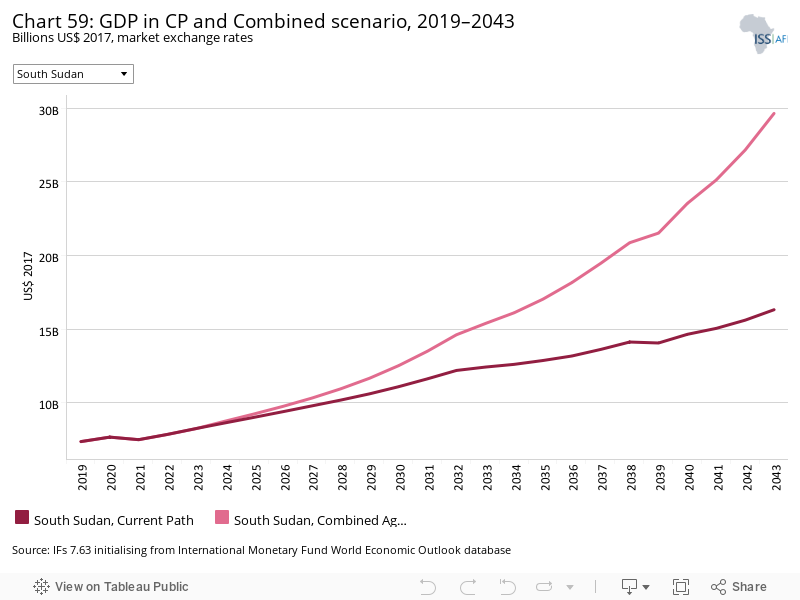

- Chart 59: GDP in CP and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

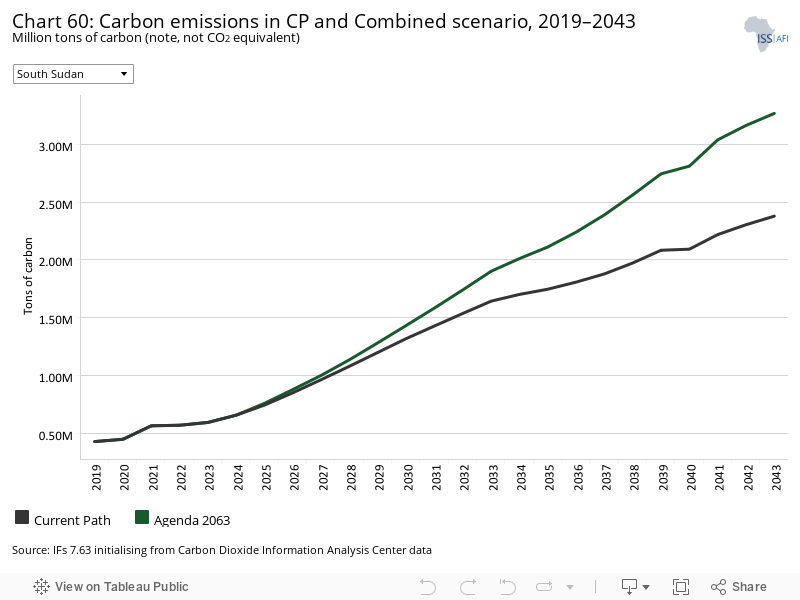

- Chart 60: Carbon emissions in CP and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

This page provides an overview of the key characteristics of South Sudan along its likely (or Current Path) development trajectory. The Current Path forecast from the International Futures forecasting (IFs) platform is a dynamic scenario that imitates the continuation of current policies and environmental conditions. The Current Path is therefore in congruence with historical patterns and produces a series of dynamic forecasts endogenised in relationships across crucial global systems. We use 2019 as a standard reference year. The forecasts generally extend to 2043 to coincide with the end of the third ten-year implementation plan of the African Union's Agenda 2063 long-term development vision.

South Sudan is a landlocked country in East Africa, bordered by Ethiopia, Sudan, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda and Kenya.

South Sudan gained its independence from Sudan on 9 July 2011, following 98.83% support for the split in a referendum in January 2011, and so became the world's newest nation and Africa's 54th country. It has a surface area of 644 329 km² and, by 2019, had a population of more than 10 million. The country is also a member of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), an eight-country regional bloc in Africa with ambitions to embark on regional integration.

South Sudan is classified as a low-income country, relying largely on oil for revenue (oil accounts for more than 90% of the country's total exports).

Despite its abundant natural resources, South Sudan ranks near the bottom in various human and economic development indicators. For most of its recent history, the country has been plagued by persistent political instability, violent conflicts, corruption and poor governance.

Thanks to a peace treaty negotiated in 2018, the devastating civil war experienced by the country between 2013 and 2018 has subsided. The main protagonists, Salva Kiir Mayardit and Riek Machar, agreed to form a unity government, but the situation remains fragile and the pact could, as before, crumble again. Aside from a recent ceasefire, little else has been achieved, and mistrust among the various parties persists. Insecurity, lack of basic services, and unresolved housing, land and property issues prevented many people from returning home in large numbers. Some 8.3 million people in South Sudan are estimated to have needed humanitarian assistance in 2021. In sum, South Sudan faces many development challenges, which require decisive action.

The characteristics of a country's population can shape its long-term social, economic and political foundations; thus, understanding a nation's demographic profile indicates its development prospects.

The South Sudan government's negligible provision of medical care, along with poverty, violence and endemic disease, has limited life expectancy, which is far below the global average for both men and women.

At 4.7 children per woman, South Sudan had the 17th highest total fertility rate in Africa in 2020.

The population of South Sudan was 11.1 million in 2019, and on the Current Path it is forecast to be roughly 13.6 million by 2043, a 23% increase over a period of 24 years.

South Sudan also has an overwhelmingly young population. The median age in 2019 was 17.6 years and the country had a youth bulge of about 49% in the same year. As of 2019, about 44% of the country's population is under the age of 15, and 27.4% is under 30. This means that a large portion of the population is dependent on the workforce to provide for its needs. The population under 15 years is expected to decline, but will still constitute about 37% of the population by 2043. The share of the elderly (65 and older) has been stable at 3.4% over time and it is projected to increase slightly across the forecast horizon to reach 4% by 2043.

In 2019, 55.3% of South Sudan’s population was in the 15–64-year age group, which is forecast to increase to 59% by 2043. The working-age group constitutes the largest share of the population, and this can be a potential source of growth provided the labour force is well trained and sufficient jobs are created.

As of 2019, only 20.3% of South Sudan’s population lived in urban areas, which makes the country one of the least urbanised in the Horn, East and Central Africa (HECA) region. This is nearly 11 percentage points below the average of 31% for low-income countries in Africa. On the Current Path, the rate of urbanisation in South Sudan is projected to increase to 26.4% by 2043, while the rural population will have dropped from 79.7% in 2019 to 73.6%. South Sudan will therefore remain largely rural across the Current Path forecast horizon.

In addition to forced urban migration driven by armed conflict and its effects, rural-to-urban migration is driven by the search for employment opportunities and education, as well as 'push factors' such as poverty, food insecurity, crop failure, land shortage and lack of cattle.

If not well managed, urbanisation could lead to problems such as unemployment, poverty, inadequate health, poor sanitation, urban slums and environmental degradation. Nearly the entire number of urban residents (91%) in South Sudan live in slums.

Good urban planning could foster an inclusive economy by improving service delivery and reducing urban poverty. In addition, adequate and appropriate urban planning is essential to mitigate the impacts of climate change such as flooding.

As of 2019, only 20.3% of South Sudan’s population lived in urban areas, which makes the country one of the least urbanised in the Horn, East and Central Africa (HECA) region. This is nearly 11 percentage points below the average of 31% for low-income countries in Africa. On the Current Path, the rate of urbanisation in South Sudan is projected to increase to 26.4% by 2043, while the rural population will have dropped from 79.7% in 2019 to 73.6%. South Sudan will therefore remain largely rural across the Current Path forecast horizon.

In addition to forced urban migration driven by armed conflict and its effects, rural-to-urban migration is driven by the search for employment opportunities and education, as well as 'push factors' such as poverty, food insecurity, crop failure, land shortage and lack of cattle.

If not well managed, urbanisation could lead to problems such as unemployment, poverty, inadequate health, poor sanitation, urban slums and environmental degradation. Nearly the entire number of urban residents (91%) in South Sudan live in slums.

Good urban planning could foster an inclusive economy by improving service delivery and reducing urban poverty. In addition, adequate and appropriate urban planning is essential to mitigate the impacts of climate change such as flooding.

The South Sudanese economy is especially vulnerable to weather fluctuations, oil price volatility and conflict-related shocks. The civil war that began in late 2013 severely disrupted the economy of South Sudan.

Oil extraction continues to be the backbone of the economy, accounting for nearly 90% of government revenue and more than 30% of the country’s GDP. Outside the oil sector, economic activities are concentrated in rudimentary agriculture and pastoral farming.

In 2019, the size of the South Sudanese economy was US$7.4 billion. The economy is projected to grow to US$16.3 billion by 2043, which will make it the 40th largest economy in Africa under the Current Path assumptions for other countries.

The current growth model of South Sudan, which is based on the oil sector, is fragile and holds little promise for improving livelihoods. Without significant structural transformation of the economy, growth will continue to be at the mercy of international commodity price shocks.

Therefore, sustainable economic recovery in South Sudan will require addressing the underlying causes of the conflicts. Comprehensive macroeconomic reforms and policy changes will be needed to combat inflation, address foreign exchange distortions and diversify the economy away from oil.

Although many of the charts in the sectoral scenarios also include GDP per capita, this overview is an essential point of departure for interpreting the general economic outlook of South Sudan.

The South Sudanese economy has been particularly hard hit by the violent conflict that raged between 2013 and 2018. For example, in 2017 the GDP per capita was about 17% lower than its level in 2012. The GDP per capita (PPP) was US$1 486 in 2019, and on the Current Path it is forecast to increase to US$2 478 by 2043. This will be US$1 312 lower than the projected average of US$3 790 for low-income countries in Africa in the same year.

The informal economy comprises activities with market value and that would add to tax revenue and GDP if they were recorded. The informal sector is a lifeline for many people in South Sudan and, in 2019, represented 66% of the total labour force.

In 2019, the size of the informal economy was equivalent to 34.4% of the country's GDP. It is projected to decline modestly — to 30.6% — by 2043, which will be above the average of 25.8% for low-income countries in Africa.

Although the informal economy provides a safety net for the country's large and growing working-age population, it impedes economic growth and hinders improved economic policies. Reducing informality will allow more people to benefit from better wages and redistributive measures. Therefore, South Sudan needs to reduce the size of its informal economy with the least friction possible, by removing obstacles to business registration, tackling corruption and improving access to education and finance.

The IFs platform uses data from the Global Trade and Analysis Project (GTAP) to classify economic activity into six sectors: agriculture, energy, materials (including mining), manufacturing, service and information and communications technology (ICT). Most other sources use a threefold distinction between only agriculture, industry and services, with the result that data may differ.

Oil extraction is the backbone of the South Sudanese economy, making the energy sector dominant in the economy. In 2019, energy accounted for 54.2% of the country's GDP (US$4 billion), while the service sector, the second largest contributor to GDP, represented 32% (US$2.3 billion). Agriculture has the third largest contribution to the country's GDP, representing 10.1% of GDP in 2019 (US$750 million).

On the Current Path, the service sector will overtake the energy sector to become the largest contributor to GDP by 2034. Thus, the share of the service sector in GDP is projected to reach 64.3% (US$10.5 billion) by 2043 compared with 25.1% (US$4.1 billion) for the energy sector.

As a result of the structural transformation of the economy, the share of agriculture in GDP is forecast to decline to 6.4% (US$1.04 billion) by 2043. ICT and materials contribute marginally to the country’s GDP.

The manufacturing sector historically has been small, its development being hindered by factors such as the long-running civil war and severe shortages of trained labour. The manufacturing sector’s contribution to GDP in 2019 was 2.2%, and is forecast to decline to 0.5% by 2043. In order words, South Sudan will deindustrialise while it is still poor (premature deindustrialisation). This is not good for the country’s development prospects, as it will make it difficult to sustain growth, create jobs and reduce poverty.

The data on agricultural production and demand in the IFs forecasting platform initialises from data provided on food balances by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). IFs contains data on numerous types of agriculture, but aggregates its forecast into crops, meat and fish, presented in million metric tons. Chart 9 shows agricultural production and demand as a total of all three categories.

South Sudan has considerable agricultural potential. Favourable soil, water and climatic conditions make 75% of its total land area suitable for agriculture. However, only 4% of the total land area is cultivated continually. Limited use of productivity-enhancing technologies, capacity constraints, poor infrastructure and protracted conflict have constrained agricultural production and the country continues to face recurrent episodes of acute food insecurity.

As South Sudan became independent from Sudan only in 2011, there is no historical data regarding agricultural production and demand for the country. The IFs model therefore initialises from 2015. According to the forecast, South Sudan will have an agricultural surplus until 2040. This seems unrealistic, given the country's recurrent food insecurity and widespread malnutrition.

According to a study by the African Development Bank, South Sudan is a net importer of food, and it imports 40% of its cereals from neighbouring countries, particularly Uganda and Kenya. IFs forecast on this issue will improve over time as data becomes available. By 2043, agricultural demand is forecast to be 0.55 million metric tons higher than agricultural production.

There are numerous methodologies and approaches to defining poverty. We measure income poverty and use GDP per capita as a proxy. In 2015, the World Bank adopted the measure of US$1.90 per person a day (in 2011 international prices), also used to measure progress towards the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 1 of eradicating extreme poverty. To account for extreme poverty in richer countries occurring at slightly higher levels of income than in poor countries, the World Bank introduced three additional poverty lines in 2017:

- US$3.20 for lower middle-income countries

- US$5.50 for upper middle-income countries

- US$22.70 for high-income countries.

Although South Sudan is rich in oil, the citizens are yet to fully benefit from it. Expenditures on key social sectors, including health, education, water and sanitation, and agricultural and rural development, which could significantly reduce poverty, are limited. The government prioritises defence and security expenditures over basic service delivery. For example, military expenditure increased from about 6% of GDP in 2011 to nearly 21% in 2018, and the security payroll represents 58% of South Sudan's total government expenditure. As a result, poverty is ubiquitous in the country and reinforced by intercommunal conflict, displacement and external shocks.

Based on the $1.90 threshold, the poverty rate in South Sudan was 79.4% in 2019, equivalent to 8.2 million people. The rate is almost twice the average of 47.7% for low-income countries in Africa, and the highest in the Horn of Africa.

In the Current Path forecast, the rate of extreme poverty is projected to decline to its lowest point (48.6%) by 2038, before slightly increasing to 50.3% (6.8 million people) by 2043. This rate is twice the projected average of 25.1% for low-income countries in Africa in the same year.

However, poverty goes beyond income, as it also impacts individuals' access to basic nutrition, health and education (multidimensional poverty). About 92% of the South Sudanese population is multidimensionally poor, with 74.3% of them in severe multidimensional poverty – the highest rate in the Horn of Africa.

Policymakers in South Sudan should make growth more inclusive by integrating the most vulnerable segments of the population, especially women, into the economy and enhancing human capital formation to meet the needs of the labour market and hence create more gainful jobs and accelerate poverty reduction. The government of South Sudan should prioritise investing in its people by allocating its income from oil into schools, hospitals, roads and agriculture to ensure sustainable, inclusive growth and poverty reduction.

The IFs platform forecasts six types of energy, namely oil, gas, coal, hydro, nuclear and other renewables. To allow for comparisons between different types of energy, the data is converted into billion barrels of oil equivalent. The energy contained in a barrel of oil is approximately 5.8 million British thermal units (MBTUs) or 1 700 kilowatt-hours (kWh) of energy.

Oil was the sole type of energy produced in South Sudan in 2019 (106 million barrels of oil). On the Current Path, oil will account for 91.6% of energy production by 2043.

Energy production from other renewable sources is currently at the embryonic stage. From a very low base, other renewable energy will account for 6.5% of total energy production (8 million barrels of oil equivalent) by 2043, despite South Sudan’s vast potential for renewable energy. For instance, the country has about 8 hours of sunshine per day, with a solar potential 436 W/m2/year. Wind power density is between 285 and 380 W/m2, which implies good resources for wind power generation.

Carbon is released in many ways, but the three most important contributors to greenhouse gases are carbon dioxide (CO2), carbon monoxide (CO) and methane (CH4). Since each has a different molecular weight, IFs uses carbon. Many other sites and calculations use CO2 equivalent.

Annual carbon emissions, which were 0.4 million tons in 2019, are forecast to reach 2.4 million tons by 2043, an increase of 500% between 2019 and 2043. However, this increase comes from a very low base and South Sudan's total emissions in 2043 will only constitute about 0.02% of global carbon emissions.

Developed economies must help South Sudan and the many other developing African countries deal with the impact of climate change, which will disproportionately affect them.

Sectoral Scenarios for South Sudan

Download to pdfThe Stability scenario represents reasonable but ambitious reductions in risk of regime instability and lower levels of internal conflict. Stability is generally a prerequisite for other aspects of development and this would encourage inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) and improve business confidence. Better governance through the accountability that follows substantive democracy is modelled separately.

The intervention is explained in here in the thematic part of the website.

South Sudan remains caught in a web of fragility, economic stagnation and instability a decade after independence. Insecurity is widespread as the state's monopoly over power is challenged with only a semblance of government control evident in small parts of the country. The country's political space is dominated by the military owing to its long history of armed liberation struggle. In addition to its limited capacity, the government is unable to protect the civilian population as its national police, security forces and other armed actors are themselves involved in infighting and large-scale abuses of human rights. Overall, South Sudan's governance institutions are dysfunctional. The lack of elite consensus among the political and military leaders (at both national and local levels), who prioritise their own interests instead of the population's needs, threatens the country's stability and security and development.

IFs' governance security index ranges from 0 (low security) to 1 (high security). The Current Path forecast shows lower stability in South Sudan than the average for low-income Africa. South Sudan’s score on the government security index was 0.55 in 2019, compared with 0.64 for low-income African countries.

This scenario improves security and stability in South Sudan. By 2043, the score in the Stability scenario is 0.77, about 22% higher than in the Current Path forecast and 8.5% higher than the projected average of 0.71 on the Current Path for low-income African countries.

A state's capacity to maintain order is one of the most important conditions for development. Thus, the government and policymakers in South Sudan should take proactive measures for more social and political stability.

Increased stability would promote peace and political consensus in the country, which will attract greater domestic and foreign investment, positively affecting per capita income growth.

Thus, by 2033, South Sudan's GDP per capita would be US$29 higher in the Stability scenario than in the Current Path forecast for that year. In 2043, the difference is expected to increase to US$255, with South Sudan likely recording GDP per capita at US$2 733, 10.3% higher than the Current Path’s US$2 478. However, GDP per capita in the Stability scenario would still be below the projected average for low-income African countries in 2043.

Stability is an essential condition for economic growth and poverty reduction. Measured at the threshold of US$1.90, 8.2 million South Sudanese (79.4% of the population) were considered to be extremely poor in 2019.

In the Stability scenario, the number of poor people will stand at 6.3 million (46.3% of the population) in 2043 compared with 6.8 million (50.3% of the population) in the Current Path forecast for that year, translating to 0.5 million fewer people living in extreme poverty. In 2043, the poverty rate in the Stability scenario (at US$1.90 per day) is almost twice the projected average of 25.2% for low-income African countries in the Current Path forecast.

This section presents the impact of a Demographic scenario that aims to hasten and increase the demographic dividend through reasonable but ambitious reductions in the communicable-disease burden for children under five, the maternal mortality ratio and increased access to modern contraception.

The intervention is explained in here in the thematic part of the website.

Demographers typically differentiate between a first, second and even a third demographic dividend. We focus here on the first dividend, namely the contribution of the size and quality of the labour force to incomes. It refers to a window of opportunity that opens when the ratio of the working-age population (between 15 and 64 years of age) to dependants (children and the elderly) reaches 1.7.

In 2019, the ratio of the working-age population to dependants was 1.1, meaning that there was almost one person of working age for every dependant. On the Current Path, it is forecast to be 1.4 by 2043. In the Demographic scenario, the ratio of the working-age population to dependants will reach 1.5 by 2043. The minimum ratio of 1.7 will only be reached in 2055, five years later than the average for low-income countries in Africa.

The increasing size of the working-age population in South Sudan can be a catalyst for growth if sufficient education and employment are generated to successfully harness their productive power. However, without sufficient education and employment opportunities, the situation could turn into a demographic 'bomb', as many people of working age may remain unemployed and in poverty, potentially creating frustration, social tension and conflict.

The infant mortality rate is the number of infant deaths per 1 000 live births and is an important marker of the overall quality of the health system in a country.

As of 2019, the infant mortality rate in South Sudan was 78 deaths per 1 000 live births, above the average of 48.5 for Africa's low-income countries.

The Demographic scenario reduces infant mortality to 40.6 per 1 000 live births by 2033, compared with 54 in the Current Path forecast. By 2043, the infant mortality rate will be 31 in the Demographic scenario, compared with 41 in the Current Path forecast.

At 21.2 deaths per 1 000 live births, the infant mortality rate in the Demographic scenario will be about 10 percentage points above the average for low-income countries in Africa by 2043. Nearly 75% of all child deaths in South Sudan are caused by preventable conditions such as diarrhoea, malaria and pneumonia. Almost 90% of South Sudan's population has no access to improved sanitation, and only 17% of schools have suitable latrines. The risk of contracting waterborne diseases such as diarrhoea, cholera, hepatitis, typhoid or Guinea worm disease is one of the world's highest.

Continuing conflicts, instability and bad governance have resulted in limited access to clean water, which often leads to tensions between communities.

The Demographic scenario's impact on per capita income is marginal: only US$7 above the Current Path’s forecast of US$2 352 in 2033. By 2043, the average South Sudanese will have about US$36 more than the Current Path’s forecast of US$2 514, an improvement of 1.5%.

However, this is US$1 276 less than the average projected by 2043 for Africa’s low-income countries in the Current Path forecast.

Measured at the threshold of US$1.90, 8.2 million people in South Sudan (79.4% of the population) were considered to be extremely poor in 2019. In the Demographic scenario, the number of poor people will be 6.6 million by 2043, representing 49.3% of the population, compared with 6.8 million, equivalent to 50.3%, in the Current Path forecast for that year. This is 200 000 fewer people living in extreme poverty by 2043.

The poverty rate in the Demographic scenario in 2043 is almost twice the Current Path forecast’s average of 25.1% for low-income countries in Africa.

South Sudanese authorities should try to accelerate the demographic transition, which can be another source of growth and contribute to poverty reduction.

This section presents reasonable but ambitious improvements in the Health/WaSH scenario, which include reductions in the mortality rate associated with both communicable diseases (e.g. AIDS, diarrhoea, malaria and respiratory infections) and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) (e.g. diabetes), as well as improvements in access to safe water and better sanitation. The acronym WaSH stands for water, sanitation and hygiene.

The intervention is explained in here in the thematic part of the website.

The quality of a nation's health system can be gauged through indicators such as life expectancy, maternal mortality and infant mortality, among others. South Sudan lags behind its low-income peers on several health indicators. The civil war created health personnel shortages and destroyed health infrastructure. South Sudan has only one physician per 65 574 people and one midwife per 39 088. As a result, access to healthcare in South Sudan remains dangerously low, with a negative effect on life expectancy.

Life expectancy in South Sudan was 58.8 years in 2019, below the average of 63.8 years for low-income countries in Africa.

Based on the Health/WaSH scenario, life expectancy is estimated to increase to 67.2 years by 2043, compared with 66 years in the Current Path forecast. Even in the Health/WaSH scenario, life expectancy in South Sudan is more than three years below the projected average for low-income countries in Africa (70.9 years) in 2043.

On average, women had a higher life expectancy at birth (60 years) than men (57.6 years) in 2019. In the Health/WaSH scenario, life expectancy at birth for women is projected to be 68.8 years by 2043 compared with 65.8 years for men.

About 75% of all child deaths in South Sudan are due to preventable conditions such as diarrhoea, malaria and pneumonia. Nearly 90% of South Sudan's population has no access to improved sanitation, and only 17% of schools have suitable latrines. The risk of contracting waterborne diseases such as diarrhoea, cholera, hepatitis, typhoid or Guinea worm disease is one of the world's highest.

Continuing conflicts, instability and bad governance have results in limited access to clean water, which often leads to tensions between communities.

The infant mortality rate in South Sudan was 78.2 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2019.

The Health/WaSH scenario reduces the infant mortality rate to 46.6 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2033, compared with 54 in the Current Path forecast. By 2043, this rate is set to decline to 33.5 deaths per 1 000 in this scenario, compared with 40.7 in the Current Path forecast.

The infant mortality rate in the Health/WaSH scenario is still above the 2043 projected average of 21.2 for low-income countries in Africa.

The Agriculture scenario represents reasonable but ambitious increases in yields per hectare (reflecting better management and seed and fertiliser technology), increased land under irrigation and reduced loss and waste. Where appropriate, it includes an increase in calorie consumption, reflecting the prioritisation of food self-sufficiency above food exports as a desirable policy objective.

The intervention is explained in here in the thematic part of the website.

The data on yields per hectare (in metric tons) is for crops, but does not distinguish between different categories of crops.

A thriving agriculture sector is crucial to long-term peace and development in South Sudan. Up to 95% of the country's population depends on farming, fishing or herding for their livelihoods. However, levels of crop and vegetable production in the country remain low. As is the case in much of East Africa, farmers rely heavily on rain-fed crop production, meaning erratic or delayed rains can result in poor harvests. Limited access to quality seeds and planting materials constrain yields.

In the Agriculture scenario, crop yields in South Sudan improve from 3.2 tons per hectare in 2019 to 9.2 tons per hectare in 2043, which is twice the value forecast on the Current Path (4.6 tons) by 2043. By 2043, average crop yields in the Agriculture scenario are above the projected Current Path average for low-income Africa (3.5 tons per hectare) for that year.

Without significant efforts to improve agricultural production, the current low crop yield will keep South Sudan a net food importer (the country imports as much as 50% of its food needs). Total food imports are estimated to be US$200–300 million a year. This points to major underperformance given the country's huge agricultural potential, and is unsustainable in the long run.

On the Current Path, the food import dependence will be about 2.5% of total agricultural demand by 2043. However, in the Agriculture scenario, the food import dependence will be completely eliminated, with agricultural surplus representing 61.4% of total demand in 2043.

The Agriculture scenario significantly impacts GDP per capita in South Sudan (Chart 24).

By 2043, the Agriculture scenario improves GDP per capita by about US$210 compared with the Current Path forecast, meaning the average South Sudanese will be earning US$2 688 at that stage. However, this is US$1 102 less than the projected average for low-income countries in Africa in 2043.

The agriculture sector is a lifeline for millions of people in South Sudan, as 95% of the country's population depends on the sector to meet their food and income needs.

Measured at the US$1.90 threshold, the poverty rate in the Agriculture scenario will be 48.8% by 2043, compared with 50.3% in the Current Path forecast for the same year. This is equivalent to 200 000 fewer people living in extreme poverty. In the agriculture scenario, the number of poor people declines to a minimum (5.5 million) in 2035, before increasing to 6.6 million by 2043; the reason may be linked to population growth.

Further development in the agriculture sector is a viable option to reduce poverty in South Sudan. More investment in the sector will increase consumption and income, and pave the way for an agri-industry, positively affecting growth and poverty reduction.

The Education scenario represents reasonable but ambitious improved intake, transition and graduation rates from primary to tertiary levels and better quality of education. It also models substantive progress towards gender parity at all levels, additional vocational training at secondary school level and increases in the share of science and engineering graduates.

The intervention is explained in here in the thematic part of the website.

Years of conflict, displacement and economic collapse continue to deprive children of education, harming the country's future. According to UNESCO, at least 2.2 million children in South Sudan are not in school, representing one of the highest rates of out-of-school children in the world. The majority of these children are girls, child soldiers, children with disabilities and children who are just too hungry, too busy working to help their families, or too afraid of the journey to school.

The average years of education in the adult population (aged 15 years and older) is a good indicator of the stock of education in a country. School life expectancy in South Sudan is among the lowest in the world. The mean years of education for adults aged 15 years and over stood at 3.8 years in 2019, below the average of 4.4 years for low-income countries in Africa. On the Current Path, it is projected to improve to 5.2 years by 2043, which will just be a year below the average for low-income countries in Africa. Technically, this means that most people in South Sudan will not have primary education by 2043. However, in the Education scenario, the mean years of education improves by about six months above the Current Path forecast for 2043.

The situation facing girls at all ages is particularly alarming in South Sudan. About 60% of 7-year-old girls are not in school. The gender gap widens with age: while 10.6% of boys were in secondary school at age 16 in 2018, this was the case for only 1.3% of 16-year-old girls.

In 2019, the mean years of education for men was 4.4 compared with 3.2 for women. In the Education scenario, the mean number of years of education for men reaches 6.1 by 2043, versus 5.2 for women.

The legacy of the civil war, combined with the cumulative effects of years of conflict, political instability and extreme poverty, has taken a toll on the quality of the education system in South Sudan. With a new peace agreement in place, development partners are making efforts to support the government’s effort in bringing children back to school and providing them with a quality education. However, the road to quality education for all children in South Sudan is still long.

In the Education scenario, the score for the quality of primary education improves from 27.3 in 2019 to 32.3 in 2043, an increase of 18% increase compared with the Current Path forecast of 27.4 and about 6% higher than the average of 30.6 for low-income African countries in the same year.

The score for the quality of secondary education goes from 37.5 in 2019 to 44.2 in 2043 in the Education scenario, an improvement of 20% compared to the Current Path forecast of 36.9 and the average of 37.8 for low-income African countries by then.

Quality education is crucial for economic development. It allows the country to increase its current added value and create tomorrow's technological innovations. Thus, authorities in South Sudan should accelerate reforms to improve the quality of education in the country.

By 2043, the Education scenario will increase GDP per capita by about US$85 above the value of US$2 478 forecast on the Current Path, representing an increase of 3.4%.

Investment in education significantly impacts economic growth, but it takes time to materialise. For instance, it will take more than a decade for a child enrolled in primary school to contribute meaningfully to the economy.

Education is an important tool to reduce poverty, as it improves people’s employment and income prospects. By 2043, South Sudan will record a poverty rate of 48.5% (6.5 million people) in the Education scenario, compared with 50.3% (6.8 million people) in the Current Path forecast. This means 300 000 fewer people will live in extreme poverty by 2043 than in the Current Path forecast. The number of poor people in the Education scenario declines to its minimum (5.6 million) in 2034, before increasing to 6.5 million by 2043, probably due to population growth.

The Manufacturing/Transfers scenario represents reasonable but ambitious manufacturing growth through greater investment in the economy, investments in research and development, and promotion of the export of manufactured goods. It is accompanied by an increase in welfare transfers (social grants) to moderate the initial increases in inequality that are typically associated with a manufacturing transition. To this end, the scenario improves tax administration and increases government revenues.

The intervention is explained in here in the thematic part of the website.

Chart 30 should be read with Chart 8, which presents a stacked area graph of the contribution to GDP and size, in billion US$, of the Current Path economy for each of the sectors.

In absolute terms, the service sector’s contribution to GDP represents the biggest improvement compared with the Current Path forecast for 2043 and is forecast to be US$400 million larger than in the Current Path. The service sector is followed by ICT, with its contribution of US$30 million above the Current Path in 2043.

As a percentage of GDP, the share of the service sector is 0.65 percentage points larger than in the Current Path forecast in 2043. ICT follows, being 0.09 percentage points above the Current Path forecast. The contribution of Manufacturing improves slightly (0.01 percentage points) above the Current Path forecast by 2043, while the share of energy declines by 0.6 percentage points compared with the Current Path forecast.

The current growth model of South Sudan, driven by the oil sector, is fragile and holds little promise for improvements in livelihoods. Authorities should make efforts to diversify the economy and focus on the manufacturing and agricultural sectors to create jobs and, ultimately, reduce poverty.

In 2019, the value of household welfare transfers in South Sudan was about US$200 million. Compared with the Current Path forecast, the Manufacturing/Transfers scenario increases household transfers by 67.2% in 2043. This is US$390 million more than in the Current Path forecast (US$580 million). These transfers will be needed to address the initial increase in poverty associated with investment in the manufacturing sector. Industrialisation is funded by an initial crunch in consumption, which increases poverty in the first few years. However, in the long term, these efforts stimulate inclusive growth, with a greater impact on poverty alleviation.

To make the social safety net programmes more effective at reducing poverty, better targeting and efficient approaches are critical.

In the Manufacturing/Transfers scenario, GDP per capita is US$43 higher by 2043 than the US$2 478 of the Current Path forecast, an increase of 1.7%.

Manufacturing is important for economic growth owing to its backward and forward linkages with other sectors and its ability to transform the productive structures across an economy. Thus, a robust manufacturing sector is crucial for sustained growth and improves the population's living standard.

At the poverty threshold of US$1.90, 8.2 million people in South Sudan (79.4% of the population) were considered to be extremely poor in 2019. In the Manufacturing/Transfers scenario, the number of poor people will reduce to 6.5 million (47.7% of the population) by 2043, compared with 6.8 million (50.3% of the population) in the Current Path forecast for that year. This is a difference of 300 000 people. In 2043, the poverty rate in the Manufacturing/Transfers scenario is 22.5 percentage points above the average in the Current Path forecast for low-income countries in Africa.

The Leapfrogging scenario represents a reasonable but ambitious adoption of and investment in renewable energy technologies, resulting in better access to electricity in urban and rural areas. The scenario includes accelerated access to mobile and fixed broadband and the adoption of modern technology that improves government efficiency and allows for the more rapid formalisation of the informal sector.

The intervention is explained in here in the thematic part of the website.

Fixed broadband includes cable modem Internet connections, DSL Internet connections of at least 256 KB/s, fibre and other fixed broadband technology connections (such as satellite broadband Internet, ethernet local area networks, fixed wireless access, wireless local area networks, WiMAX, etc.).

Despite some improvements, the ICT sector in South Sudan is one of the world's least developed, while future growth of the sector is hindered by instability, insecurity, widespread poverty and low literacy rates.

Fixed broadband subscriptions stood at 1.3 per 100 people in 2019, compared with the average of 2.3 for low-income countries in Africa.

In the Leapfrogging scenario, fixed broadband subscriptions increase to 39.1 per 100 people by 2043, more than double the Current Path forecast of 18.3 subscriptions per 100 people and the average of 30 subscriptions per 100 people for low-income countries in Africa in the same year.

Mobile broadband refers to wireless Internet access delivered through cellular towers to computers and other digital devices.

Mobile broadband subscriptions stood at 5.3 per 100 people in South Sudan in 2019, significantly below the average of 22.9 for low-income Africa.

In the Leapfrogging scenario, mobile broadband subscriptions in South Sudan increases to 113.9 per 100 people by 2043, slightly above the Current Path forecast of 111.9 — in other words, only two subscriptions more per 100 people than in the Current Path forecast for 2043. Mobile broadband subscriptions in both the Leapfrogging and Current Path scenarios will be below the projected average of 133.9 subscriptions per 100 people in 2043 for low-income Africa.

In 2019, 2.2 million people had access to electricity in South Sudan, representing 21% of the total population. This is below the average of 32.2% for low-income countries in Africa.

In addition, access to electricity is skewed towards the urban population. In 2019, about 34.7% of the urban population had access to electricity, compared with only 17.6% in rural areas.

In the Leapfrogging scenario, 34.9% of the South Sudanese population (4.7 million people) will have access to electricity by 2043. This is far below the projected average of 60.5% in the Current Path forecast for low-income countries in Africa in the same year.

By 2043, 51.7% of the urban population will have access to electricity in the Leapfrogging scenario, compared with 44.9% in the Current Path forecast.

The Leapfrogging scenario projects that 28.9% of the rural population will have access to electricity by 2043, compared with 20% in the Current Path forecast for the same year.

Widespread access to high-speed Internet has the potential to improve a country's socio-economic outcomes. Broadband can increase productivity, reduce transaction costs and optimise supply chains, positively affecting economic growth.

By 2033, GDP per capita will be at US$2 403 in the Leapfrogging scenario, compared with US$2 352 in the Current Path forecast, a difference of US$51. In 2043, this difference will grow to US$159. GDP per capita in the Leapfrogging scenario is US$1 153 less than the projected average for low-income countries in Africa in 2043.

In the Leapfrogging scenario, the number of poor people is expected to be 6.6 million by 2043, representing 48.4% of the population. This is about 300 000 fewer poor people than in the Current Path forecast for that year. In the Leapfrogging scenario, the poverty rate is 23.2 percentage points above the average for Africa's low-income countries.

The Free Trade scenario represents the impact of the full implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) by 2034 through increases in exports, improved productivity and increased trade and economic freedom.

The intervention is explained in here in the thematic part of the website.

A trade balance is the difference between a country's exports and the value of its imports at a given time. A country that imports more goods and services than it exports in terms of value has a trade deficit, while a country that exports more goods and services than it imports has a trade surplus.

Since its independence in 2011, South Sudan has struggled to integrate into the international trade network. The external trade of South Sudan is dominated by its oil exports, which accounted for 98% of total exports in 2019, putting the country's trade balance at the mercy of international commodity prices volatility.

Like many African countries, the trade balance of South Sudan is structurally in deficit. In 2019, the country's trade deficit amounted to nearly 15.4% of GDP. In the Free Trade scenario, South Sudan's trade balance does not improve and the deficit increases to a peak of 36.4% of GDP in 2039, before declining slightly to about 30% in 2043, in line with the Current Path forecast.

With the removal of trade restrictions following trade liberalisation, it is easier to import goods, especially as the weak manufacturing sector of South Sudan faces intense competition on the export markets.

However, using only the trade balance is not a viable indicator to conclude that South Sudan will be a loser when the AfCFTA is implemented, as other indicators also need to be considered.

Generally, trade liberalisation improves productivity through competition and technology diffusion, stimulating growth and raising income levels.

In the Current Path forecast, GDP per capita increases from US$1 486 in 2019 to US$2 478 in 2043. In the Free Trade scenario, this is expected to be US$2 625, an increase of US$147 above the Current Path forecast for that year. This shows that the full implementation of the AfCFTA will enhance economic growth in South Sudan.

In the Free Trade scenario, the poverty rate (at $1.90) is 48.7% in 2043, compared with 50.3% in the Current Path forecast. This is equivalent to about 220 000 fewer people living in extreme poverty than on the Current Path. The full implementation of the AfCFTA will improve growth, raise incomes and reduce poverty in South Sudan.

However, the projected poverty rate in the Free trade scenario by 2043 (48.7%) will still be far above the average of 25.1% in the Current Path forecast for low-income Africa.

The Financial Flows scenario represents a reasonable but ambitious increase in worker remittances and aid flows to poor countries and an increase in the stock of FDI and additional portfolio investment inflows to middle-income countries. We also reduced outward financial flows to emulate a reduction in illicit financial outflows.

The intervention is explained in here in the thematic part of the website.

Many countries in sub-Saharan Africa are still heavily dependent on foreign aid to provide basic services such as education and health. This is also the case for South Sudan, despite its immense oil deposit. The European Commission estimates that nearly 8.7 million people, representing 75% of the South Sudanese population, will require humanitarian aid in 2022. This is as a result of the combined effect of conflict, climate change, economic crises and the COVID-19 pandemic.[1European Commission, South Sudan factsheet.] Aid constituted 19.5% of the country's GDP in 2019, significantly above the average of 8.5% for low-income Africa.

In the Financial Flows scenario, foreign aid flows to South Sudan will account for 13.1% of GDP by 2043, above the Current Path forecast of 11.5%, and the average of 3.8% for low -income countries in Africa.

The poor business climate, recurrent political instability and conflicts deter foreign investment inflows to South Sudan. In the World Bank’s 2020 Doing Business report, South Sudan ranked 185th out of 190 countries. South Sudan is ahead of only Somalia and Eritrea in terms of the business environment in the Horn of Africa.

In 2019, FDI inflows represented 0.16% of the country's GDP, significantly below the average of 4.3% for low-income African countries.

In the Financial Flows scenario, FDI inflows will represent about 0.8% of GDP by 2043, compared with 0.7% on the Current Path.

FDI can act as a catalyst for economic growth and development as it brings much-needed capital and technology to recipient countries. Authorities in South Sudan should improve stability and make the necessary reforms to attract more FDI, especially for manufacturing.

South Sudan is a net recipient of remittances, which amounted to US$700 million in 2019. This is equivalent to 10.1% of GDP for that year. the country remains a net recipient of remittances until 2034. In the Financial Flows scenario, the total net remittances to the rest of the world amounts to US$600 million (3.4% of GDP) by 2043, compared with US$800 million (5.2% of GDP) in the Current Path forecast.

It is worth mentioning that as South Sudan gained its independence from Sudan only in 2011, there is no historical data regarding remittance inflows for the young country. The IFs model therefore initialises from 2015. According to the forecast, South Sudan will be a net supplier of remittances from 2034. This is not realistic. IFs’ forecast on this issue will improve over time as historical data become available.

In the Financial Flows scenario, the GDP per capita of South Sudan increases from US$1 486 in 2019 to US$2 534 in 2043, which is US$56 higher than on the Current Path for the same year. Overall, the Financial Flows scenario has a modest impact on GDP per capita in South Sudan. FDI can boost growth and development through capital accumulation and technology transfer, but has not yet reached the level that would make it a game-changer in the country owing to continued instability .

Measured at the US$1.90 threshold, the Financial Flows scenario reduces the number of extremely poor people in South Sudan by only 400 000 by 2043 compared with the Current Path forecast. This is because FDI is concentrated in the oil sector, which does not have strong forward and backward linkages with other sectors of the economy. As a result, it does not substantially impact job creation, incomes or poverty reduction. Whereas 79.4% of South Sudan's population lived in extreme poverty in 2019, it would be 47.5% by 2043 in the Financial Flows scenario, compared with 50.3% in the Current Path forecast.

The Infrastructure scenario represents a reasonable but ambitious increase in infrastructure spending across Africa, focusing on basic infrastructure (roads, water, sanitation, electricity access and ICT) in low-income countries and increasing emphasis on advanced infrastructure (such as ports, airports, railway and electricity generation) in higher-income countries.

Note that health and sanitation infrastructure is included as part of the Health/WaSH scenario and that ICT infrastructure and more rapid uptake of renewables are part of the Leapfrogging scenario. The interventions there push directly on outcomes, whereas those modelled in this scenario increase infrastructure spending, indirectly boosting other forms of infrastructure, including that supporting health, sanitation and ICT.

The intervention is explained in here in the thematic part of the website.

Infrastructure, whether in transportation, telecommunications, electricity or water and sanitation, is severely lacking in South Sudan. Since the colonial era, there has never been a backbone for electricity transmission, and none was developed during Sudanese rule.

In 2019, about 2.2 million people had access to electricity in South Sudan, representing 21% of the population. This is below the average of 32.2% for low-income countries in Africa. The Infrastructure scenario increases the number to 5.6 million by 2043, constituting 41.3% of the population. This is above the projected number of 3.6 million (26.5% of the population) in the Current Path forecast.

In the Infrastructure scenario, it is projected that 55% of the urban population in South Sudan will have access to electricity by 2043, compared to 44.9% in the Current Path forecast. However, by 2043 only 36.4% of the rural population (3.6 million people) will have access to electricity in the described scenario, compared with 20% (2 million people) in the Current Path forecast. This points to the huge disparity in access to electricity between the urban and rural population in South Sudan.

Indicator 9.1.1 in the Sustainable Development Goals refers to the proportion of the rural population who live within 2 km of an all-season road and is captured in the Rural Access Index.

Accessibility to rural areas encourages socio-economic development and improves the rural population's living standards. Better rural roads facilitate trade between rural and urban areas and, for example, allow the rural population to enjoy products from nearby urban areas while giving the urban population easier access to agricultural products supplied by rural areas.

By 2019, 51.6% of the rural population in South Sudan resided within 2 km of an all-weather road, above the average of 43% for low-income African countries. In the Infrastructure scenario, it is projected to increase to 54.8% by 2043, slightly above what is projected on the Current Path (54.2%) for that year.

Quality infrastructure facilitates business and industry development and increases efficiency in the delivery of social services. Critical basic infrastructure such as roads and electricity play a vital role in achieving sustainable and inclusive economic growth. Lacking infrastructure impedes productivity and growth.

South Sudan's GDP per capita is forecast to rise to US$2 630 by 2043 in the Infrastructure scenario. This is US$152 more than on the Current Path for the same year but below the Current Path average of US$3 790 for low-income countries in Africa.

In the Infrastructure scenario, the extreme poverty rate is projected to decline from 79.4% in 2019 to 48.2% in 2043. This translates to 6.56 million people living in extreme poverty by 2043, compared with 6.8 million in the Current Path forecast. This is a decrease of 240 000 people. The extreme poverty rate for 2043 (48.2%) in the Infrastructure scenario is higher than the projected Current Path average of 25.1% for low-income countries in Africa.

The Governance scenario represents a reasonable but ambitious improvement in accountability and reduces corruption, and hence improves the quality of service delivery by Government.

The intervention is explained in here in the thematic part of the website.

As defined by the World Bank, government effectiveness 'captures perceptions of the quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government's commitment to such policies'.

Weak government effectiveness and the absence of strong institutional and legal mechanisms to ensure accountability hamper economic progress in South Sudan. According to the Ibrahim Index of African Governance, the country was the second worst performer in governance in Africa after Somalia and rates similarly with regard to corruption.

The government effectiveness score for South Sudan was 0.19 (out of a maximum of 5) in 2019, which is projected to increase in both the Current Path forecast and the Governance scenario by 2043 — to 0.3 and 0.56, respectively. The score in the Governance scenario is therefore 0.26 points higher than the projected score in the Current Path forecast for that year.

However, the score will still be lower than 2043 average in the Current Path forecast (1.9) for low-income countries in Africa.

In the Governance scenario, South Sudan's GDP per capita is projected to increase to US$2 566 by 2043, which is US$88 more than in the Current Path forecast. However, this Governance scenario’s forecast is lower than the Current Path average of US$3 790 for low-income countries in Africa for the same year.

Critical determinants of growth depend on governance and the institutional settings in a country. The governing elite in South Sudan should set aside their personal differences and focus on the national interest in order to promote good governance for sustainable development.

Measured at the US$1.90 threshold, the poverty rate in South Sudan is projected to decline to 49% by 2043 in the Governance scenario. This is almost twice the average for low-income countries in Africa (25.1%). South Sudan’s expected 2043 poverty rate in the Governance scenario translates to roughly 200 000 fewer people living in poverty by 2043 than in the Current Path forecast.

This section presents projections for carbon emissions in the Current Path for South Sudan and the 11 scenarios. Note that IFs uses carbon equivalents rather than CO2 equivalents.

In 2019, South Sudan released about 0.4 million tons of carbon, and on the Current Path it is expected to emit 2.4 million tons by 2043. This is an increase of 500%. Although carbon emissions are set to increase as economic activity increases, South Sudan's carbon emissions come from a very low base. Like many developing countries, the country will suffer disproportionately from climate change, which it has contributed very little to. Nonetheless, the country must reduce its carbon emissions and move towards using renewable energy for sustainable growth to mitigate climate change.

The Agriculture scenario has the most significant impact on carbon emissions. The Demographic scenario has the lowest level of carbon emissions. The reduction in population growth curtails pressure on resources and hence minimises environmental degradation. By 2043, the amount of carbon emissions is higher than in the Current Path forecast in all scenarios, except for the Demographic scenario. Carbon emissions range from 2.6 million tons (Agriculture scenario) to 2.3 million tons (Demographic scenario).

The Combined Agenda 2063 scenario consists of the combination of all 11 sectoral scenarios presented above, namely the Stability, Demographic, Health/WaSH, Agriculture, Education, Manufacturing/Transfers, Leapfrogging, Free Trade, Financial Flows, Infrastructure and Governance scenarios. The cumulative impact of better education, health, infrastructure, etc. means that countries get an additional benefit in the integrated IFs forecasting platform, which we refer to as the synergistic effect. Chart 55 presents the contribution of each of these 12 components to GDP per capita in the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario.

The synergistic effect of all the scenarios on GDP per capita is US$62.1 in 2043.

The scenario with the most significant impact on GDP per capita by 2043 is Stability, followed by Agriculture. Health/WaSH has the least impact on GDP per capita. This suggests that harnessing the country's agricultural potential and increasing internal stability is key to improving human and economic development in South Sudan.

Chart 55 presents a stacked area graph of the contribution of each scenario to GDP per capita, as well as the additional benefit or synergistic effect, whereas Chart 56 presents only GDP per capita in the Current Path forecast and the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario.

In the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario, it is expected that the government of Sudan will make a concerted effort to remove the binding constraints on growth and inclusive development.

The Combined Agenda 2063 scenario has a much greater impact on GDP per capita than the individual thematic scenarios.

By 2033, GDP per capita is US$364 more in the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario than in the Current Path forecast. By 2043 it is expected to increase to US$3 805, which is US$1 327 more than in the Current Path forecast for that year.

The Combined Agenda 2063 scenario shows that a policy push across all the development sectors is necessary to achieve sustained growth and development in South Sudan.

In the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario, 43.5% of the South Sudanese population will be living in extreme poverty by 2033, compared with 53.1% in the Current Path forecast. This represents about 1.1 million fewer people than in the Current Path forecast.

By 2043, the extreme poverty rate declines to 27.7% (3.6 million people), compared with 50.3% (6.8 million people) in the Current Path forecast, representing a reduction of 3.2 million people.

The Combined Agenda 2063 scenario shows that a concerted policy push across all the development sectors could significantly reduce poverty in South Sudan.

See Chart 8 to view the Current Path forecast of the sectoral composition of the economy.

As a percentage, the agriculture sector records the largest improvement in contribution to GDP compared with the Current Path forecast. This lasts until 2029, by when it will be overtaken by the service sector. By 2043, the contribution of the service sector in this scenario is nearly six percentage points larger than in the Current Path forecast. The contributions from the agriculture and manufacturing sectors are 1.3 and 1.4 percentage points above the respective Current Path forecasts. However, the share of the energy sector will be 10.5 percentage points below the Current Path forecast.

In absolute value, the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario results in the service sector representing the most significant improvement, with its value US$10.3 billion larger than in the Current Path forecast for 2043. The service sector is followed by the agriculture sector, with its 2043 value in the Agenda 2063 scenario being US$1.2 billion larger than in the Current Path forecast.

The contributions from materials, ICT and energy to GDP are US$100 million, US$900 million and US$200 million larger, respectively, than the Current Path’s forecasts for 2043. Going forward, services will become the dominant sector of the South Sudanese economy, although manufactures will grow appreciably in the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario.

The Combined Agenda 2063 scenario dramatically impacts South Sudan's economic expansion. In the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario, the size of the economy is projected to expand from US$7.4 billion in 2019 to US$29.6 billion in 2043, which represents a 300% increase over the period, compared with 120% on the Current Path.

By 2043, the GDP of South Sudan will be US$13.3 billion larger in the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario than on the Current Path.

The Combined Agenda 2063 scenario shows that a policy push across all development sectors is a viable approach to achieving sustained growth and development in South Sudan.

The Combined Agenda 2063 scenario significantly impacts carbon emissions, albeit from a very low base, owing to the increased economic activity.

In this scenario, carbon emissions increase from 0.43 million tons in 2019 to 3.3 million tons by 2043, an increase of 667.4%. In the Current Path forecast carbon emissions increase by 458% over the same period.

In 2043, the carbon emissions in the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario is 0.88 million tons higher than in the Current Path forecast.

If the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario materialises, it would stimulate high economic growth and reduce poverty significantly in South Sudan, but the cost in terms of environmental degradation will be relatively high.

To mitigate the environmental impact of the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario, its implementation should be accompanied by concrete steps to accelerate the green energy transition.

Endnotes

European Commission, South Sudan factsheet.

Page information

Contact at AFI team is Kouassi Yeboua

This entry was last updated on 14 August 2025 using IFs v7.63.

Reuse our work

- All visualizations, data, and text produced by African Futures are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

- The data produced by third parties and made available by African Futures is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

- All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Cite this research

Kouassi Yeboua (2026) South Sudan. Published online at futures.issafrica.org. Retrieved from https://futures.issafrica.org/geographic/countries/south-sudan/ [Online Resource] Updated 14 August 2025.