Republic of the Congo

Republic of the Congo

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

In this entry, we first describe the Current Path (CP) forecast for the Republic of the Congo as it is expected to unfold to 2043, the end of the third ten-year implementation plan of the African Union’s Agenda 2063 long-term vision for Africa. The Current Path in the International Futures (IFs) forecasting model initialises from country-level data that is drawn from a range of data providers. We prioritise data from national sources.

The Current Path forecast is divided into summaries on demographics, economics, poverty, health/WaSH and climate change/energy. A second section then presents a single positive scenario for potential improvements in stability, demographics, health/WaSH, agriculture, education, manufacturing/transfers, leapfrogging, free trade, financial flows, infrastructure, governance and the impact of various scenarios on carbon emissions. With the individual impact of these sectors and dimensions having been considered, a final section presents the impact of the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario.

We generally review the impact of each scenario and the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario on gross domestic product (GDP) per person and extreme poverty except for Health/WaSH that uses life expectancy and infant mortality.

The information is presented graphically and supported by brief interpretive text.

All US$ numbers are in 2017 values.

Summary

- Current Path forecast

- The Republic of the Congo is a lower middle-income country located in Central Africa and has the only deepwater port in the region, making it an important trans-shipment port for surrounding countries. Jump to Current Path forecast

- The country is highly urbanised: in 2019, 67.4% of the population was already living in urban areas, and by 2043 nearly 75% of the population will live in urban areas. Jump to Demographics: Current Path

- The economy of the Republic of the Congo is anchored by an industrial sector based on the extraction of oil and related support services. The manufacturing sector also constitutes a healthy portion of the economy, reaching 17.1% of GDP in 2019, with its share growing to 22.9% by 2043. Jump to Economics: Current Path

- The Republic of the Congo had one of the highest poverty rates in Africa in 2019 at 66.2%. The poverty rate will rise until 2025, reaching a peak of 71.5%, before falling substantially to 43.8% by 2043. Jump to Poverty: Current Path

- The Congolese economy is heavily dependent on oil exports and the majority of its industrial sector is geared towards the extraction of oil. This is reflected in the resource’s dominance of the country’s energy production: in 2019, 97.2% of all energy produced in the country stemmed from oil. Jump to Carbon emissions/Energy: Current Path

- Sectoral scenarios

- The Stability scenario will be effective in accelerating the Republic of the Congo’s projected decrease in poverty in the Current Path forecast: by 2043, the poverty rate will have dropped to 41.5% in the scenario, 2.3 percentage points below the Current Path forecast. Jump to Stability scenario

- In the Demographic scenario, the Republic of the Congo will enter its demographic dividend earlier than in the Current Path forecast, reaching the required minimum ratio of working-age population to dependants of 1.7 to 1 by 2042. Jump to Demographic scenario

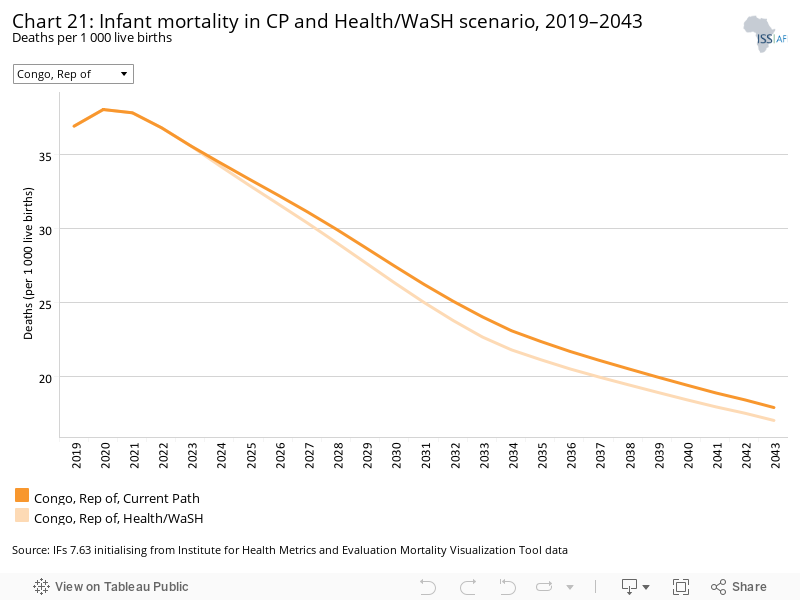

- The Republic of the Congo has seen sustained progress in reducing its infant mortality rate since its independence, and although still high, the rate will continue to decline over the forecast horizon, reaching a rate of 17 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2043 in the Health/WaSH scenario. Jump to Health/WaSH scenario

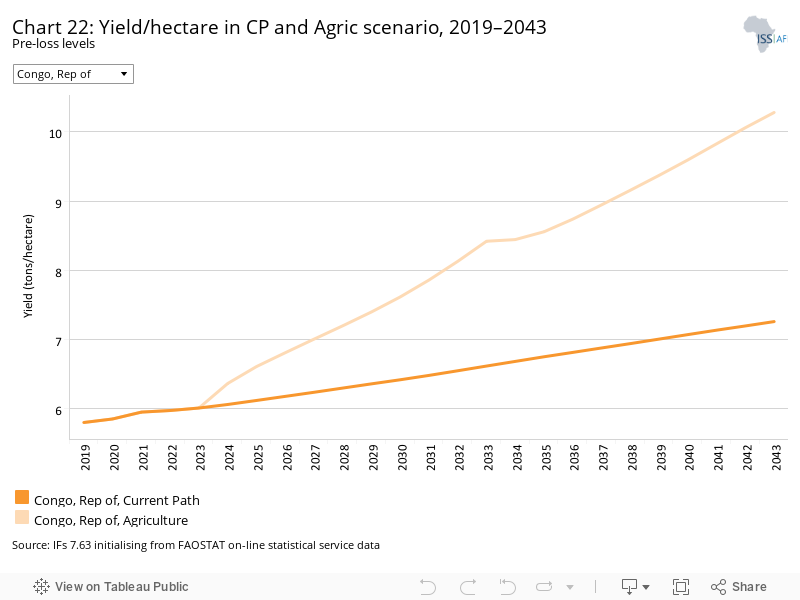

- The Agriculture scenario will boost the Republic of the Congo’s average crop yields to 10.3 tons per hectare by 2043, an increase of 3 tons per hectare compared to the Current Path forecast. The rise in agricultural productivity will reduce the country’s food insecurity and need for food imports. Jump to Agriculture scenario

- The Republic of the Congo’s mean years of education in 2019 stood at 6.5 years, which was slightly better than Africa’s average of 6.2 years, but below the average of 7.2 years for lower middle-income Africa. In the Education scenario, the country will erase that gap by 2043 and reach 8.8 mean years of education. Jump to Education scenario

- The Manufacturing/Transfers scenario will accelerate the growth of the service and manufacturing sectors, moving the economy away from its dependence on the energy sector. By 2043, manufacturing will add an additional US$1.6 billion to the economy, while the service sector will be US$3.4 billion larger. Jump to Manufacturing/Transfers scenario

- The Republic of the Congo’s poor electricity transmission and distribution facilities disproportionately affects its rural population: in 2019, only 18.3% of the rural population had access to electricity. The Leapfrogging scenario will raise rural access rates to 75% by 2043 — a 13.3 percentage point increase compared to the Current Path forecast. Jump to Leapfrogging scenario

- The Free Trade scenario will be very effective in raising the Republic of the Congo’s GDP per capita, performing the best out of all 11 scenarios. The country will see its average income rise from US$8 449 in the Current Path forecast, to US$9 131 in the Free Trade scenario by 2043. Jump to Free Trade scenario

- The Republic of the Congo is not heavily dependent on foreign aid and ranked 38th on the continent for foreign aid as a percentage of GDP in 2019 at 2.1%. In absolute terms, foreign aid will increase until 2031 in the Financial Flows scenario, reaching US$0.48 billion, before declining to US$0.3 billion by 2043. Jump to Financial Flows scenario

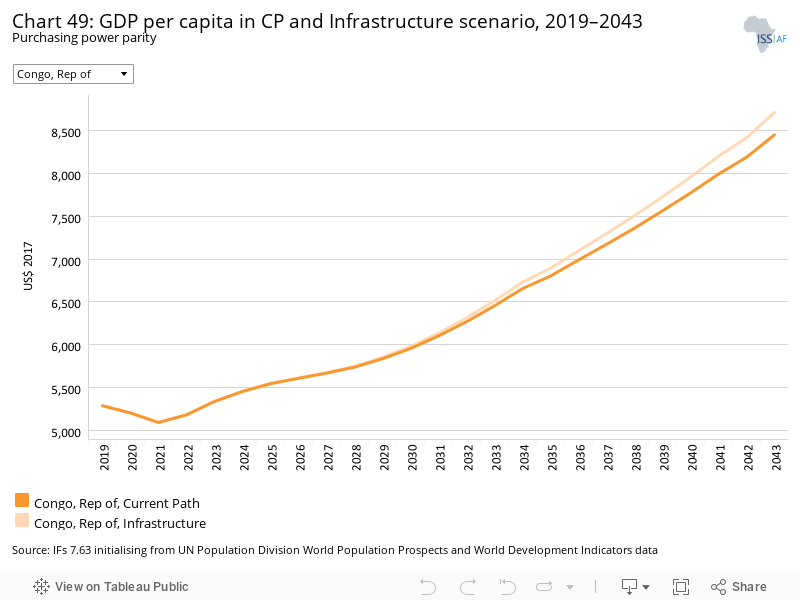

- The Infrastructure scenario will lift the Republic of the Congo’s average income from US$8 449 in the Current Path forecast to US$8 709 by 2043 — an increase of US$260. The scenario will move the country closer to lower middle-income Africa’s Current Path forecast, closing the gap to US$433 by 2043. Jump to Infrastructure scenario

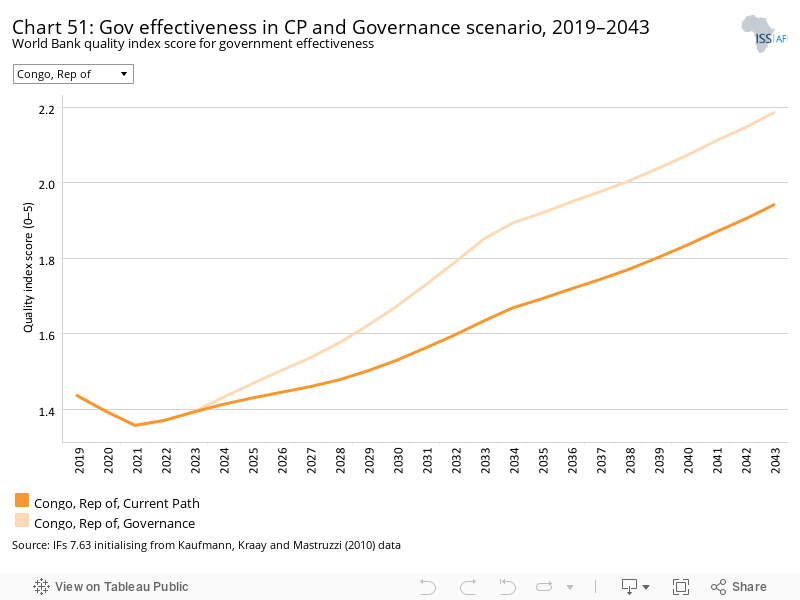

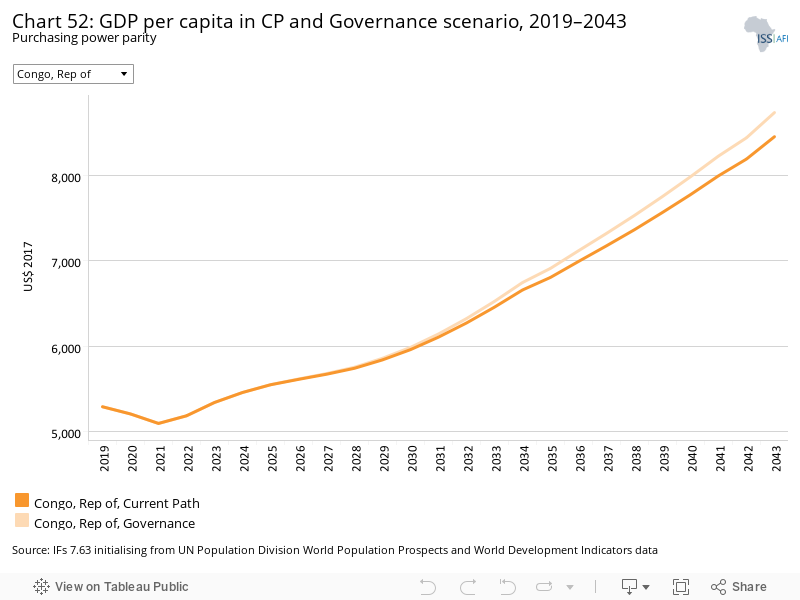

- The Republic of the Congo’s level of government effectiveness is low due to endemic corruption. In 2019, the Congo ranked 36th out of 54 African countries for government effectiveness, with a score of 1.4 out of 5. The Governance scenario will raise its score to 2.2 out of 5 by 2043 — 0.3 points higher than in the Current Path forecast. Jump to Governance scenario

- The projected increase in carbon emissions for the Republic of the Congo will see the country emit 4.07 million tons of carbon by 2043 in the Current Path forecast — an increase of 2.87 million tons compared to 2019. The Free Trade and Manufacturing/Transfers scenarios both increase GDP per capita appreciably but both cause emissions to rise to 4.3 million tons of carbon by 2043. Jump to Impact of scenarios on carbon emissions

- Combined Agenda 2063 scenario

- The combined impact of implementing the interventions of all 11 scenario, as encapsulated by the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario, is the Republic of the Congo’s GDP per capita rising to US$12 917 by 2043, an increase of 52.9% compared to the Current Path forecast. The effect of the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario on the country’s economy will be transformative: by 2043, GDP will equate to US$83 billion, an increase of 65% compared to the Current Path forecast for that year. Jump to Combined Agenda 2063 scenario

All charts for Republic of the Congo

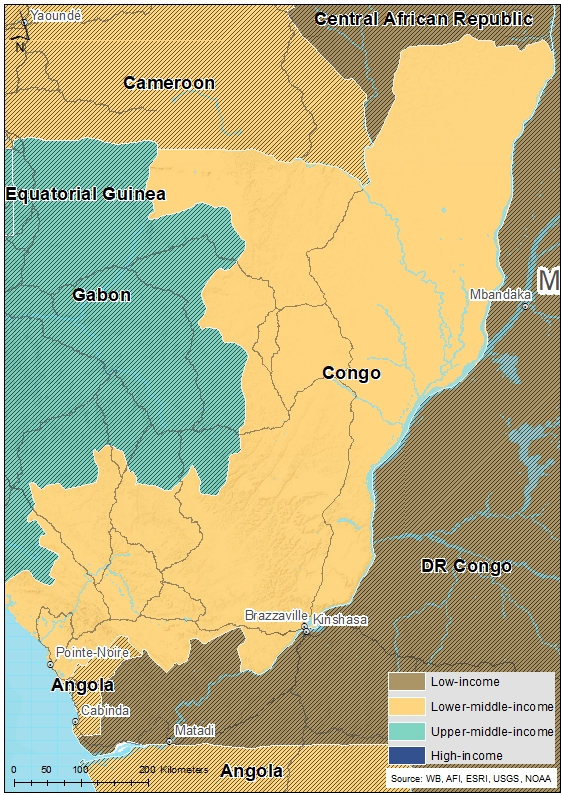

- Chart 1: Political Map of the Republic of the Congo

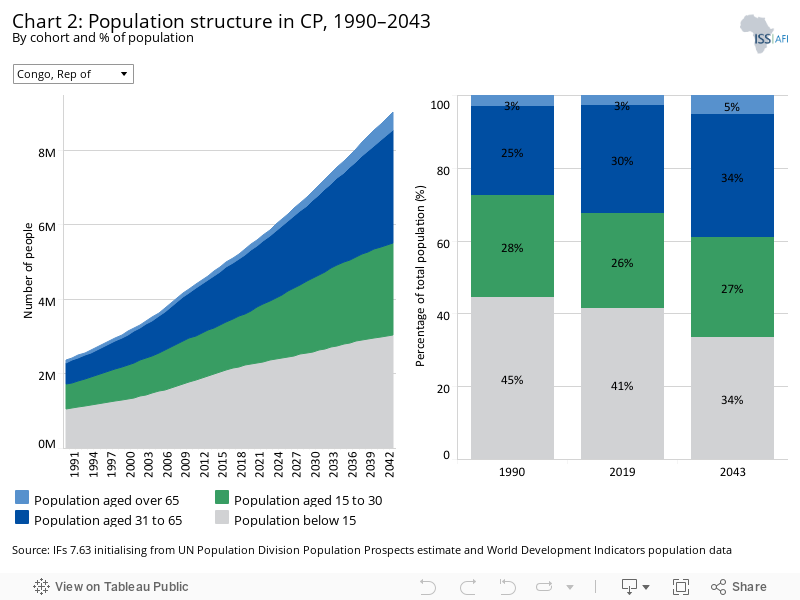

- Chart 2: Population structure in CP, 1990–2043

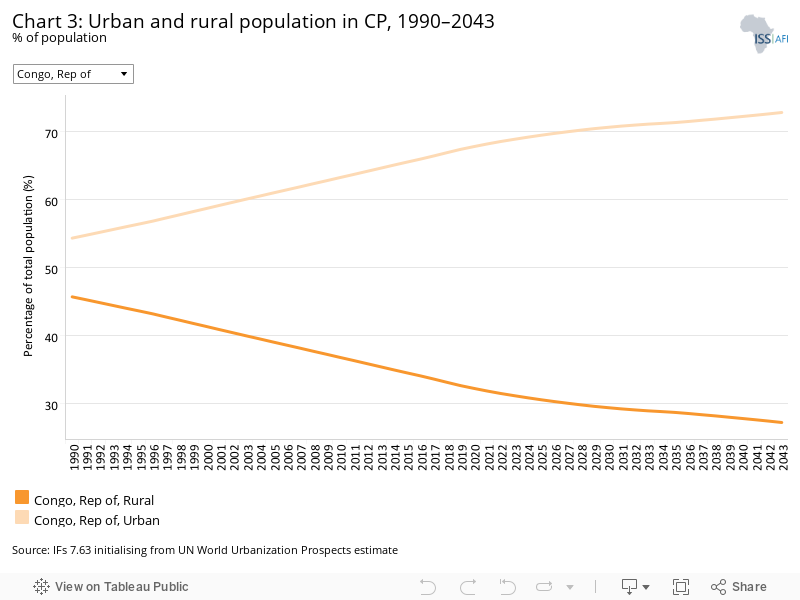

- Chart 3: Urban and rural population in CP, 1990–2043

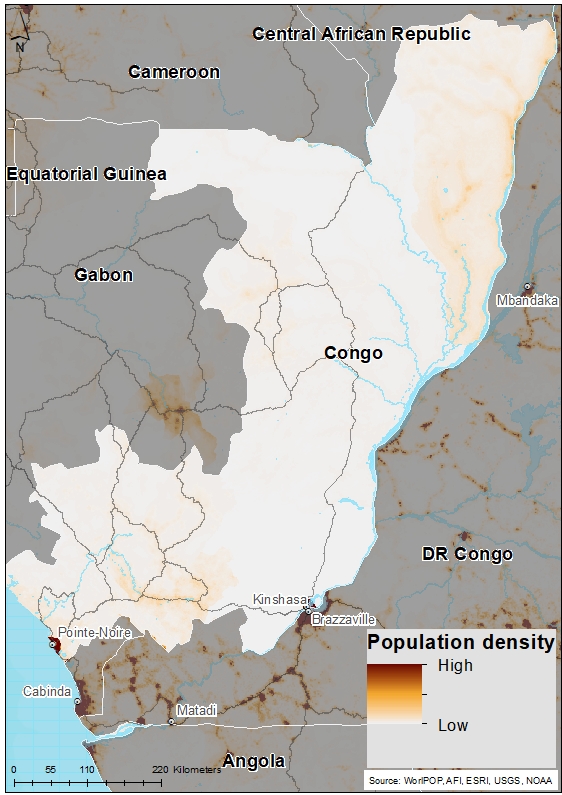

- Chart 4: Population density map for 2019

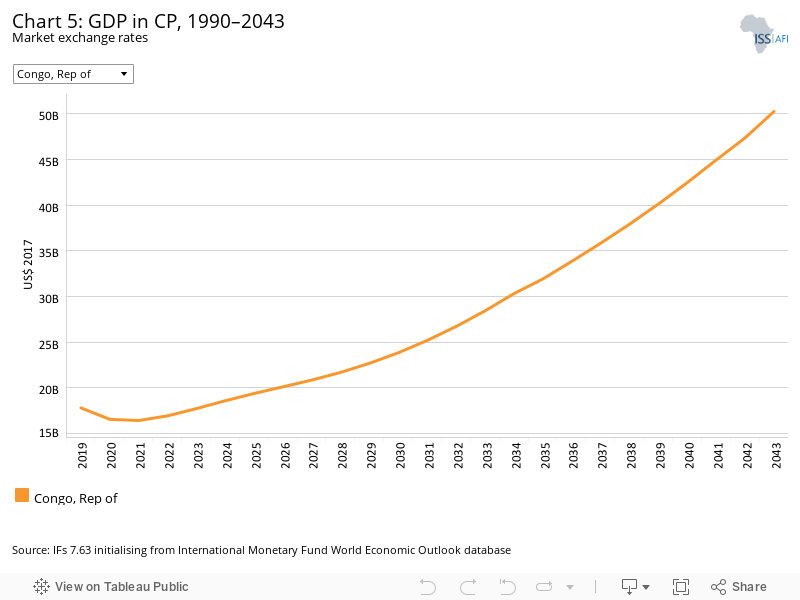

- Chart 5: GDP in CP, 1990–2043

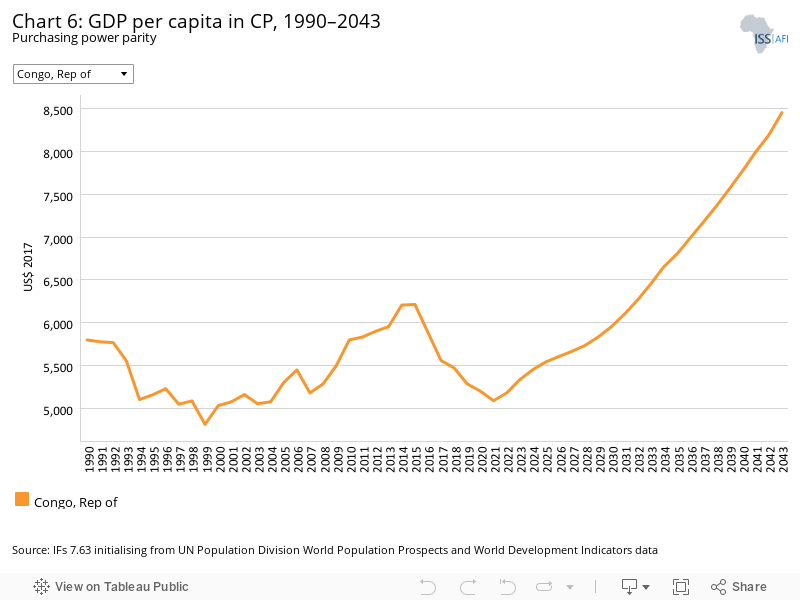

- Chart 6: GDP per capita in CP, 1990–2043

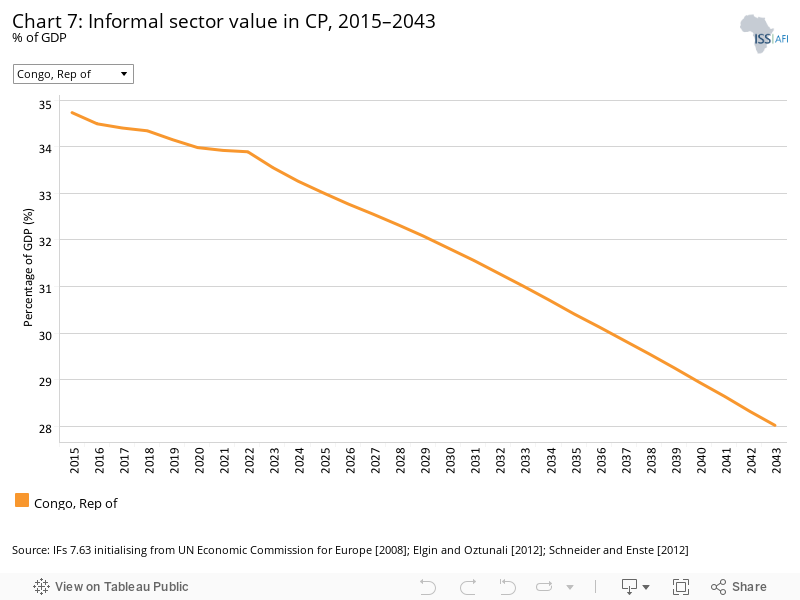

- Chart 7: Informal sector value in CP, 2015–2043

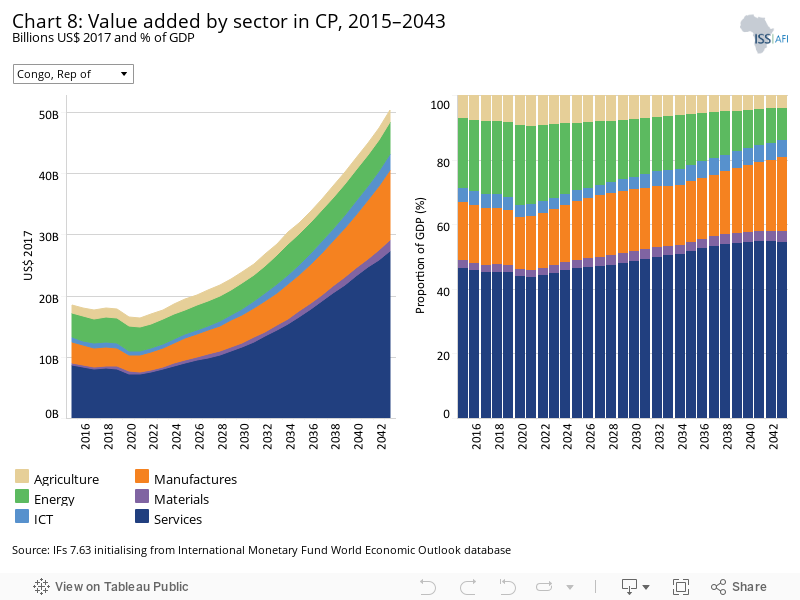

- Chart 8: Value added by sector in CP, 2015–2043

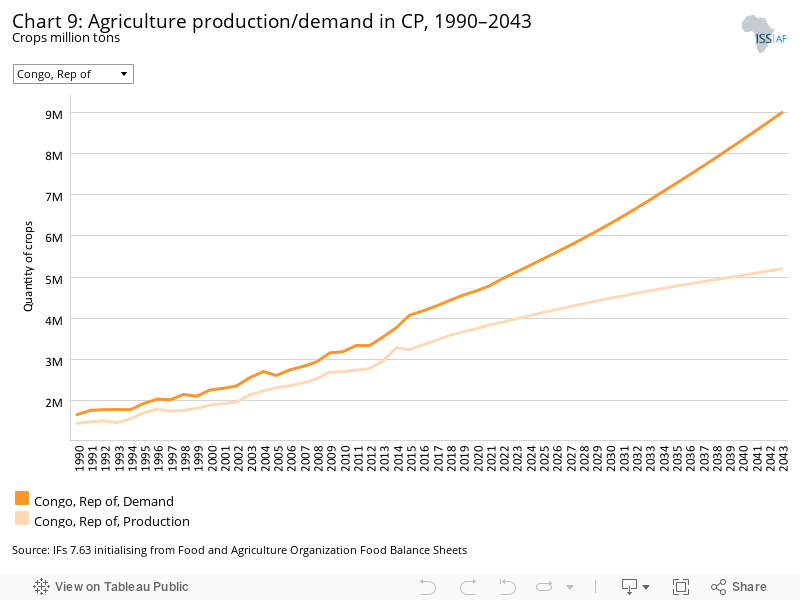

- Chart 9: Agriculture production/demand in CP, 1990–2043

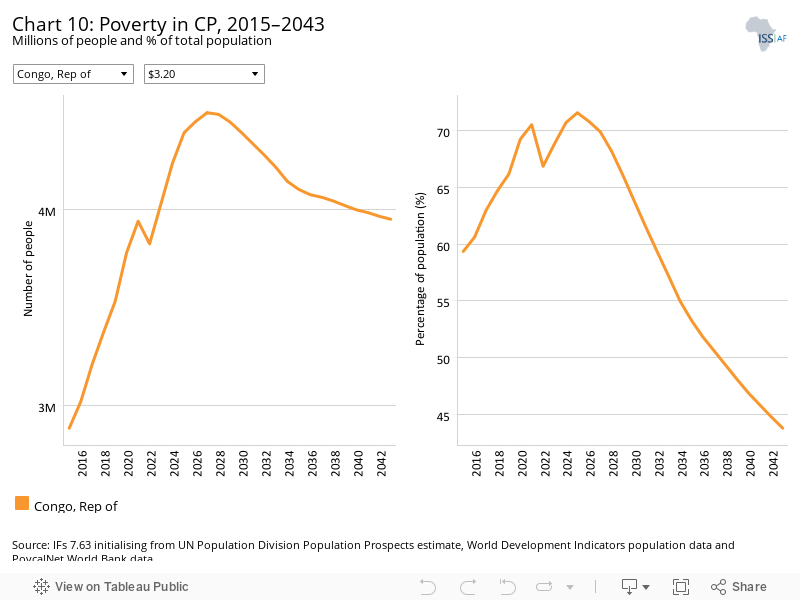

- Chart 10: Poverty in CP, 2015–2043

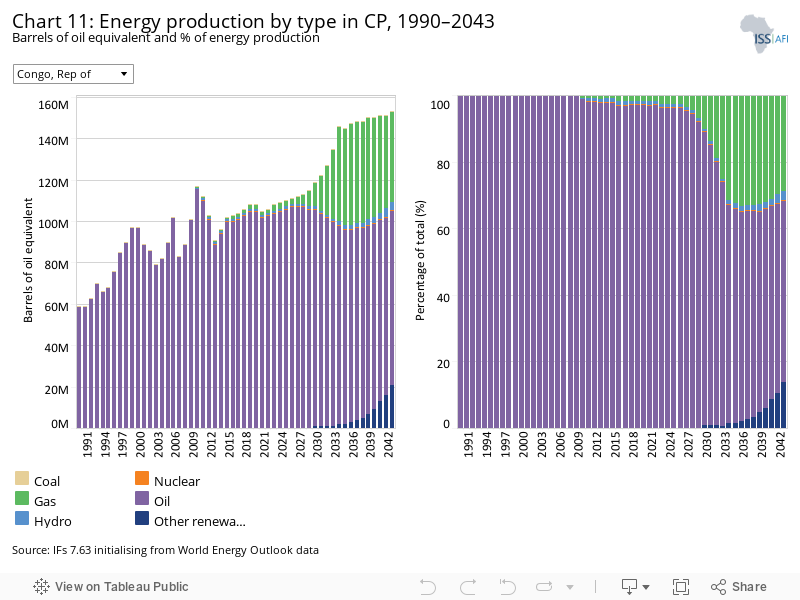

- Chart 11: Energy production by type in CP, 1990–2043

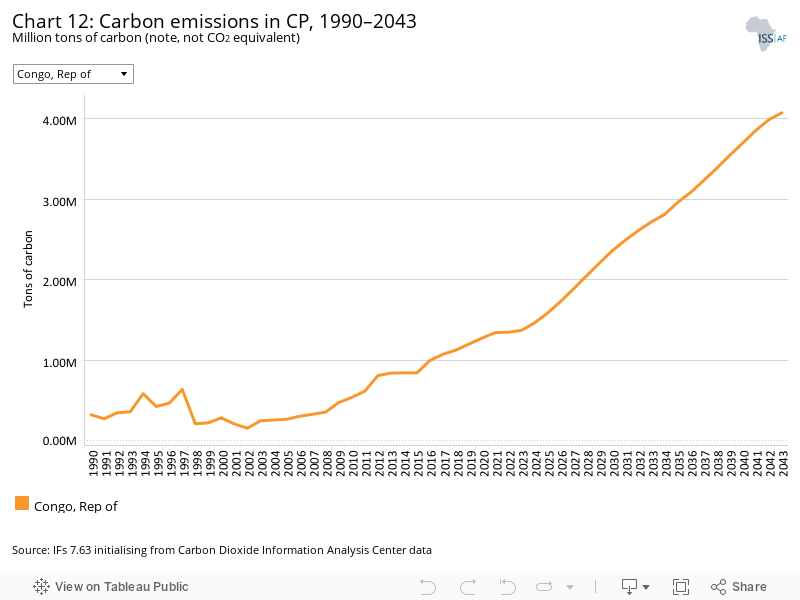

- Chart 12: Carbon emissions in CP, 1990–2043

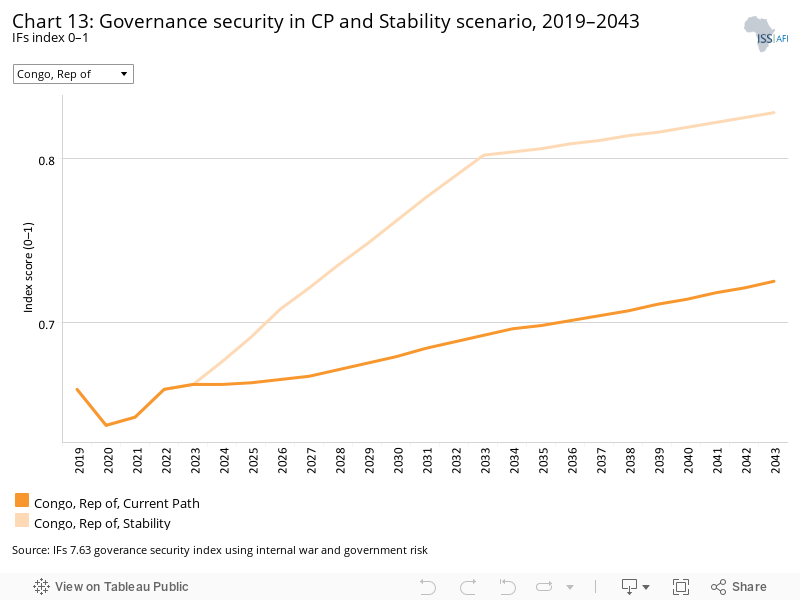

- Chart 13: Governance security in CP and Stability scenario, 2019–2043

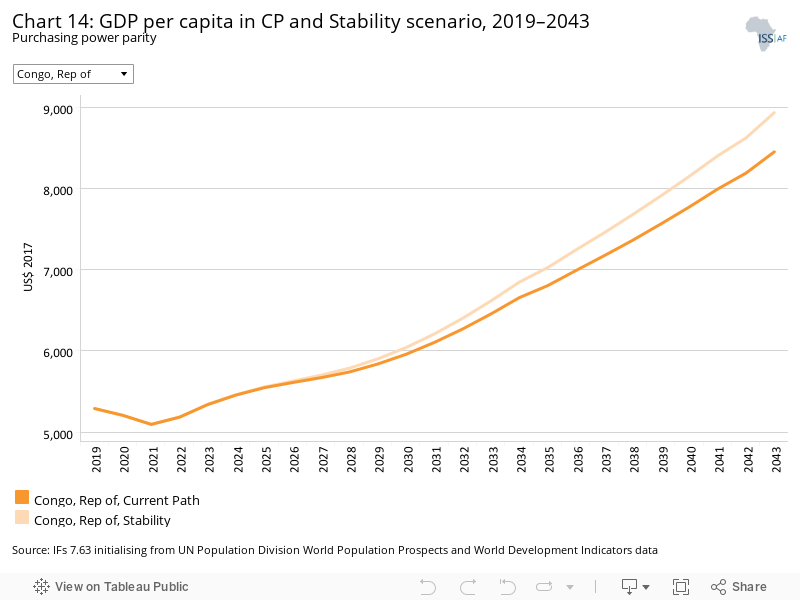

- Chart 14: GDP per capita in CP and Stability scenario, 2019–2043

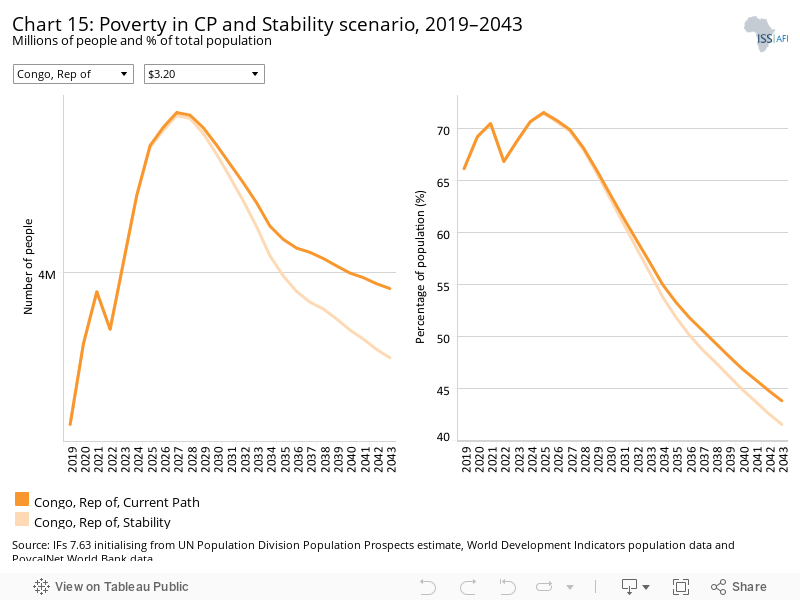

- Chart 15: Poverty in CP and Stability scenario, 2019–2043

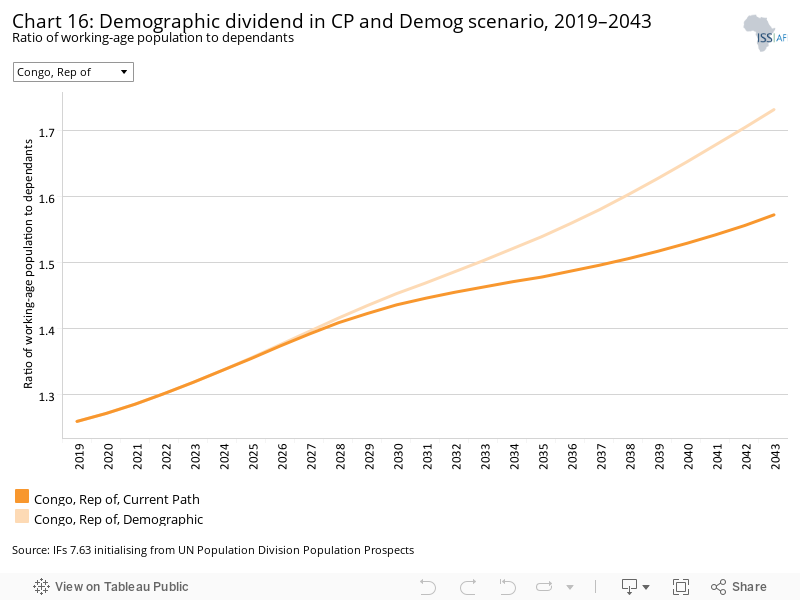

- Chart 16: Demographic dividend in CP and Demog scenario, 2019–2043

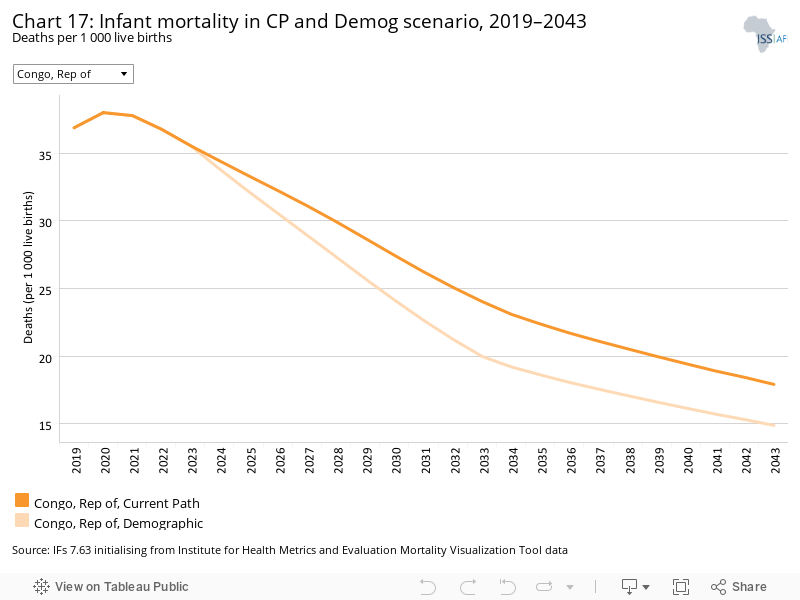

- Chart 17: Infant mortality in CP and Demog scenario, 2019–2043

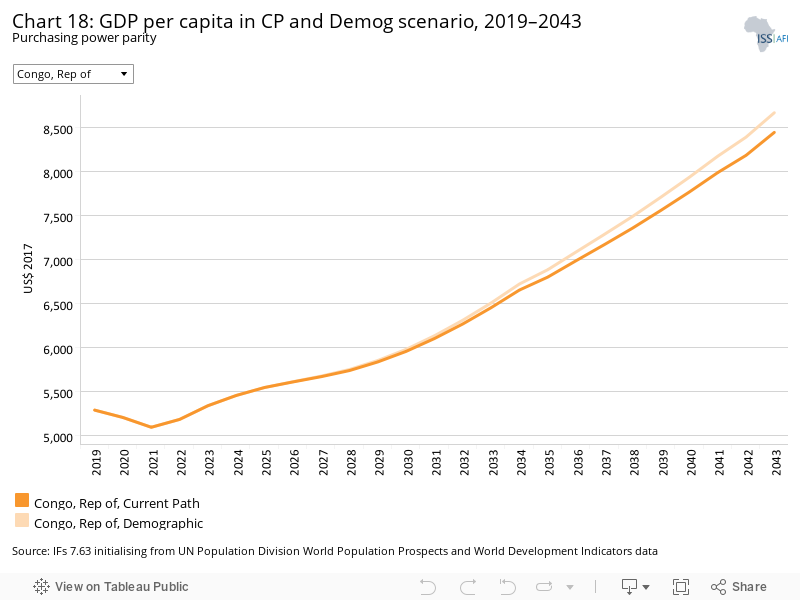

- Chart 18: GDP per capita in CP and Demog scenario, 2019–2043

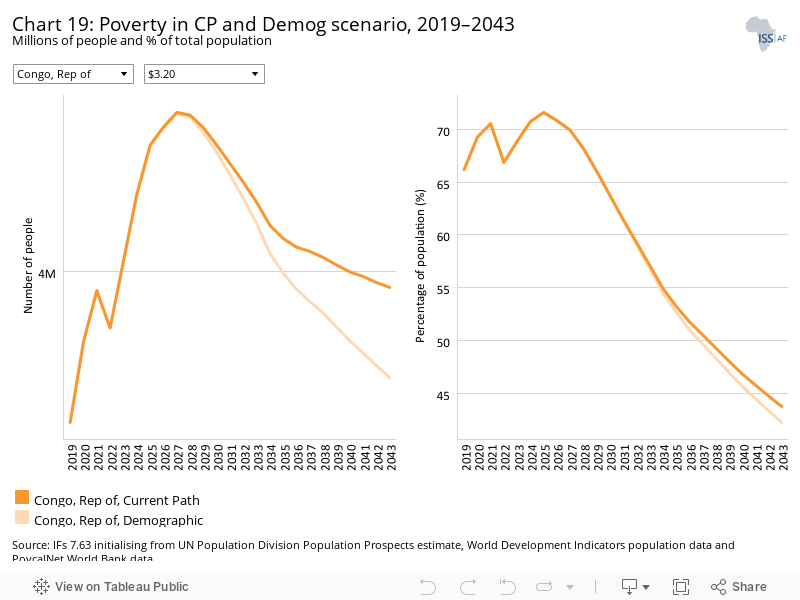

- Chart 19: Poverty in CP and Demog scenario, 2019–2043

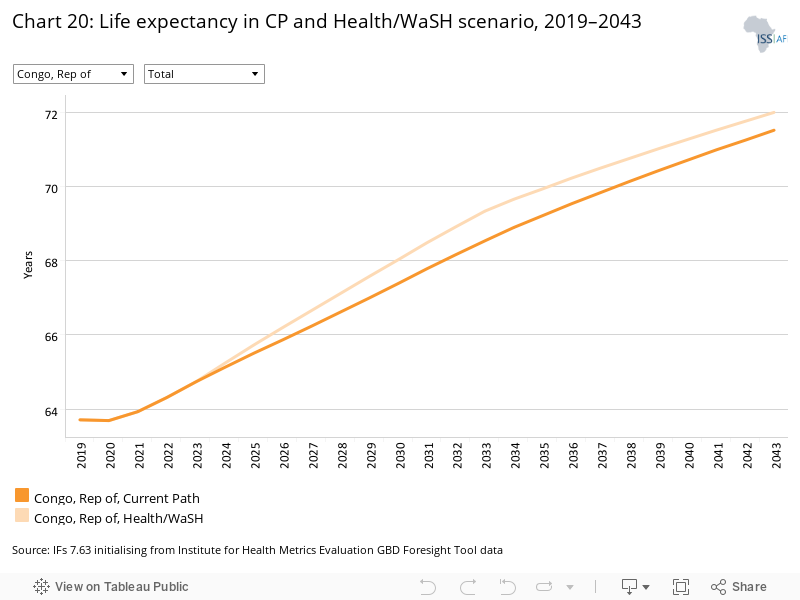

- Chart 20: Life expectancy in CP and Health/WaSH scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 21: Infant mortality in CP and Health/WaSH scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 22: Yield/hectare in CP and Agric scenario, 2019–2043

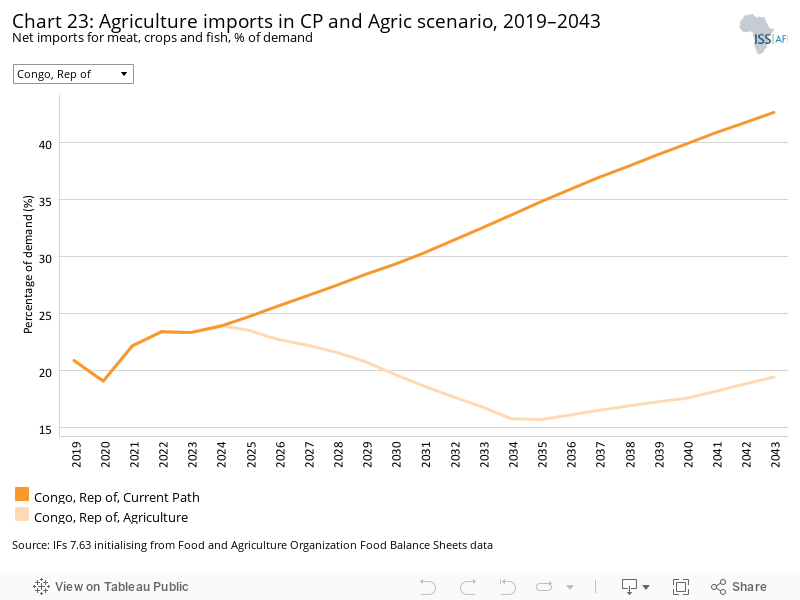

- Chart 23: Agriculture imports in CP and Agric scenario, 2019–2043

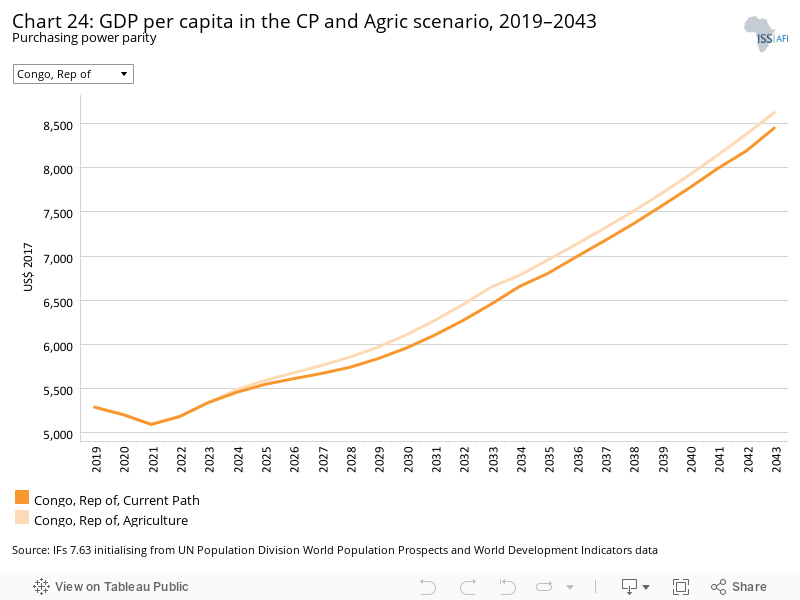

- Chart 24: GDP per capita in the CP and Agric scenario, 2019–2043

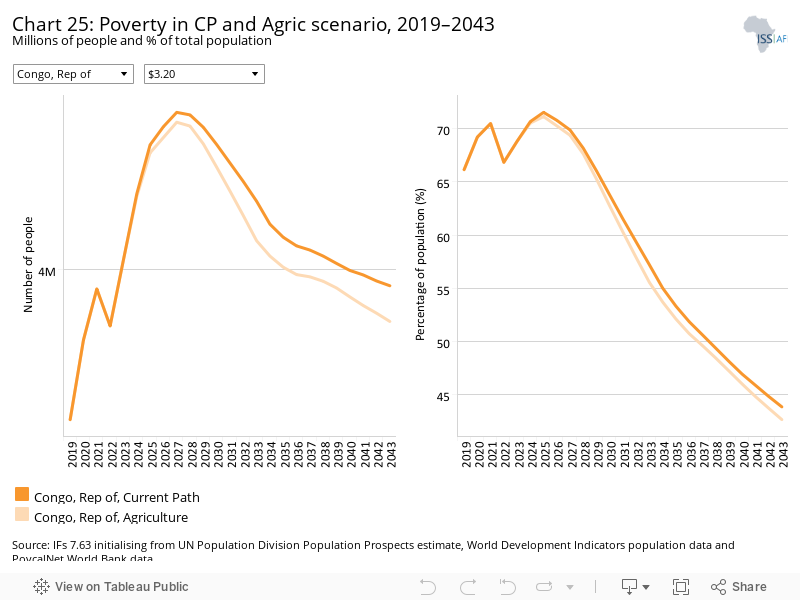

- Chart 25: Poverty in CP and Agric scenario, 2019–2043

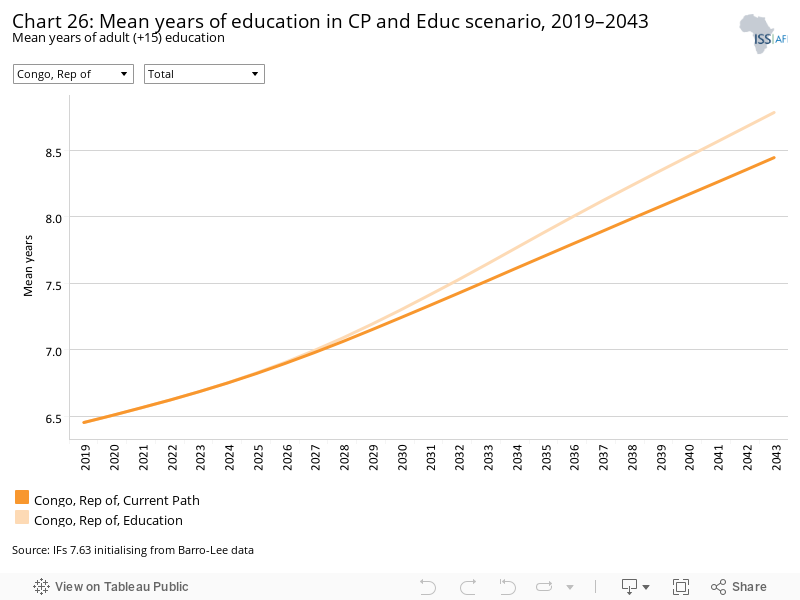

- Chart 26: Mean years of education in CP and Educ scenario, 2019–2043

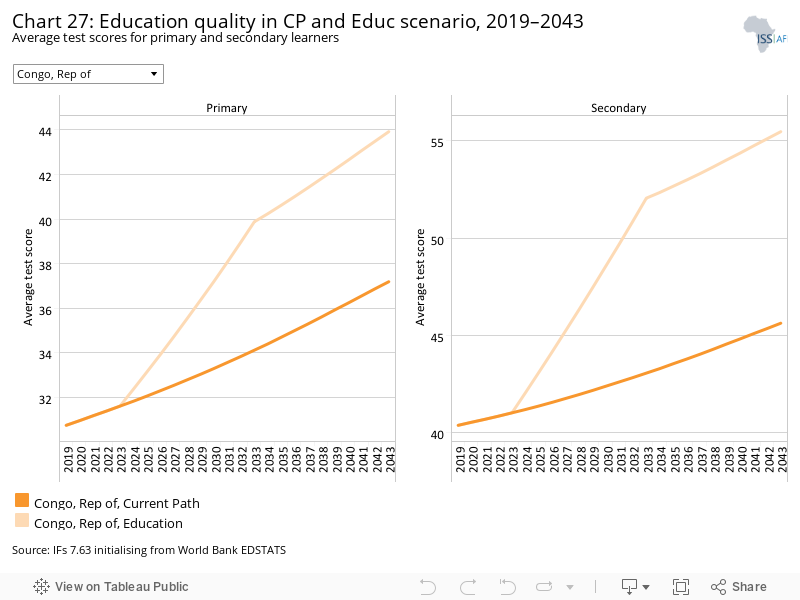

- Chart 27: Education quality in CP and Educ scenario, 2019–2043

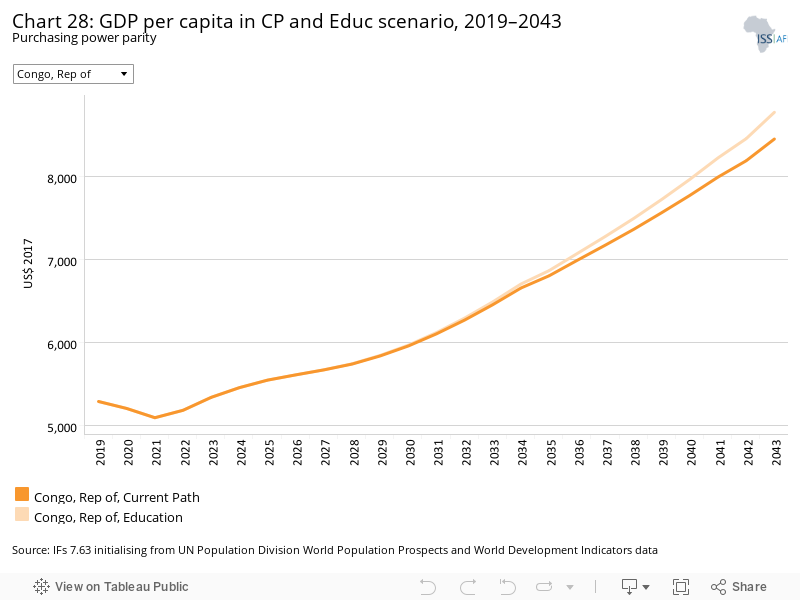

- Chart 28: GDP per capita in CP and Educ scenario, 2019–2043

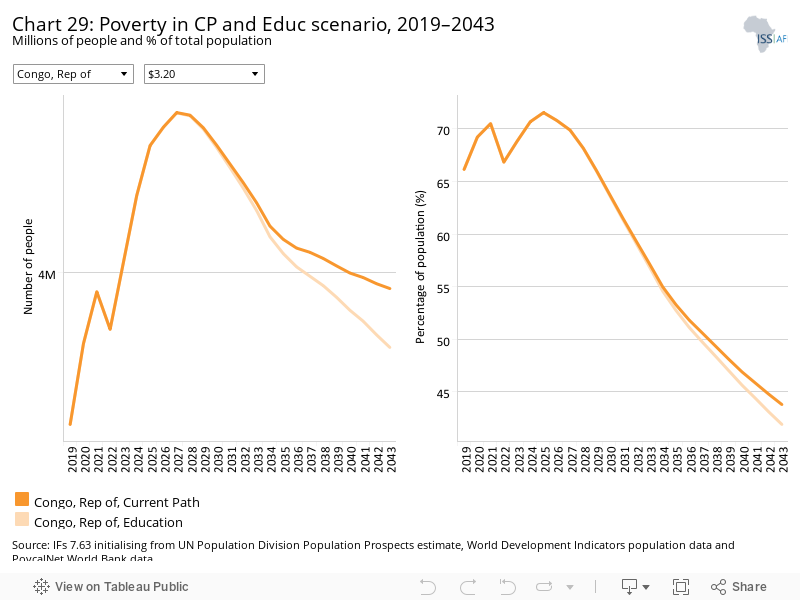

- Chart 29: Poverty in CP and Educ scenario, 2019–2043

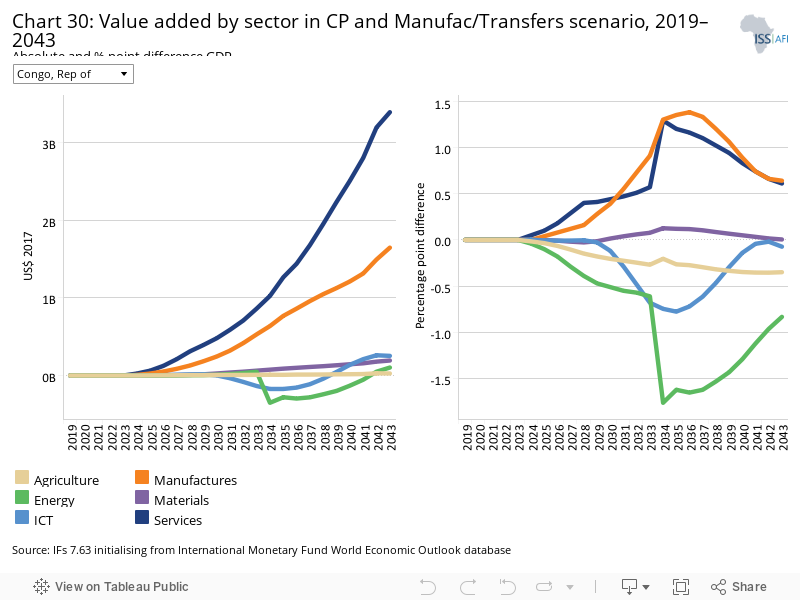

- Chart 30: Value added by sector in CP and Manufac/Transfers scenario, 2019–2043

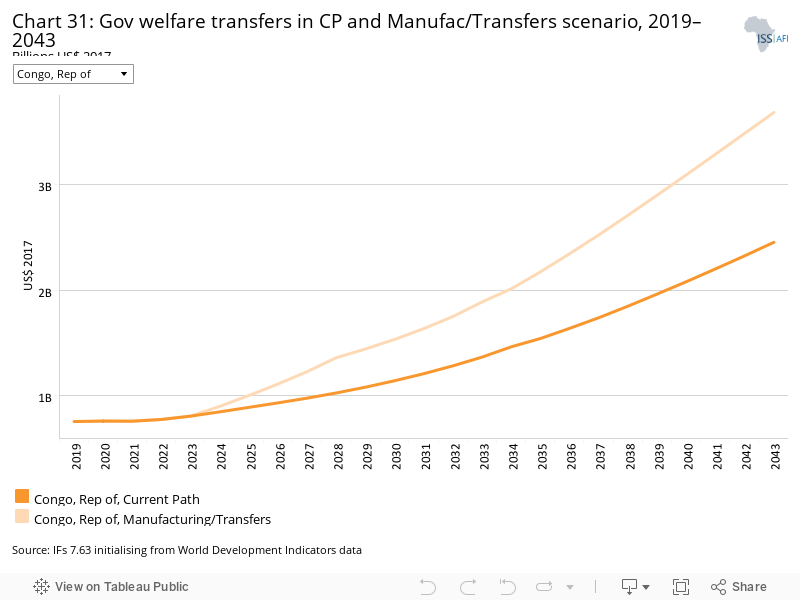

- Chart 31: Gov welfare transfers in CP and Manufac/Transfers scenario, 2019–2043

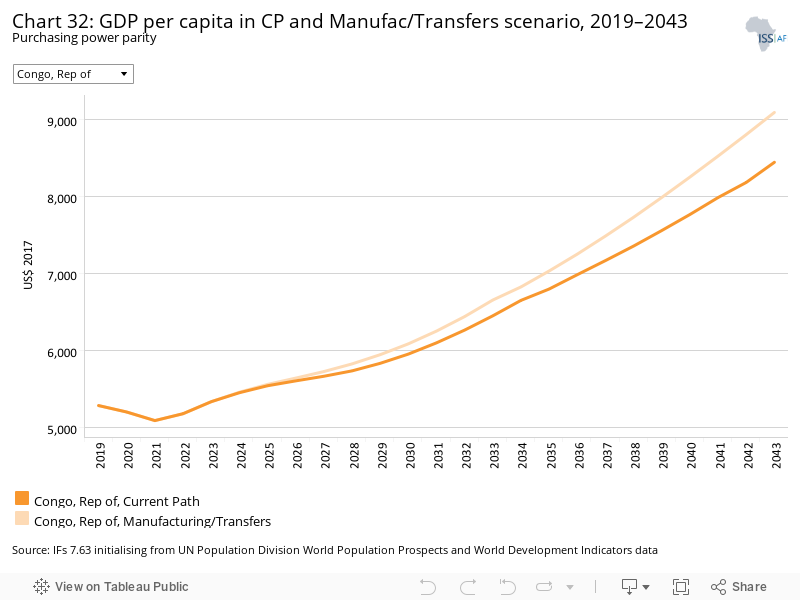

- Chart 32: GDP per capita in CP and Manufac/Transfers scenario, 2019–2043

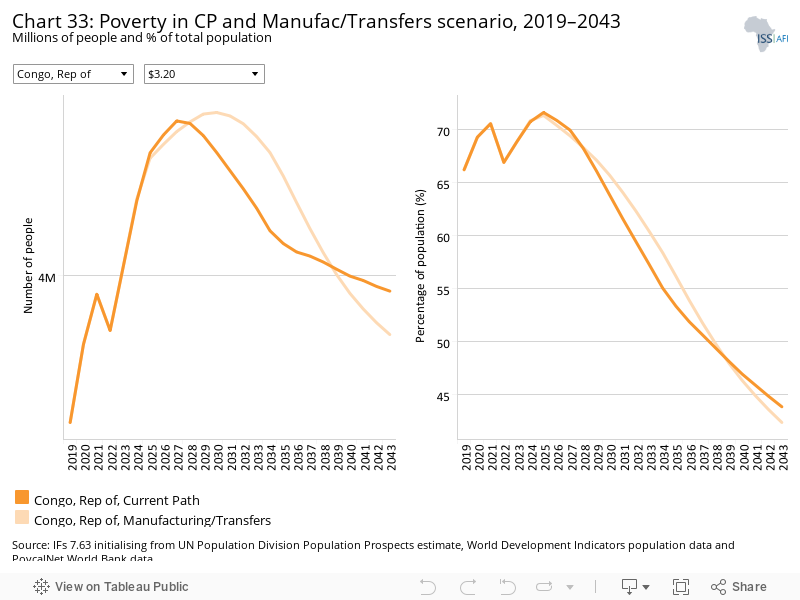

- Chart 33: Poverty in CP and Manufac/Transfers scenario, 2019–2043

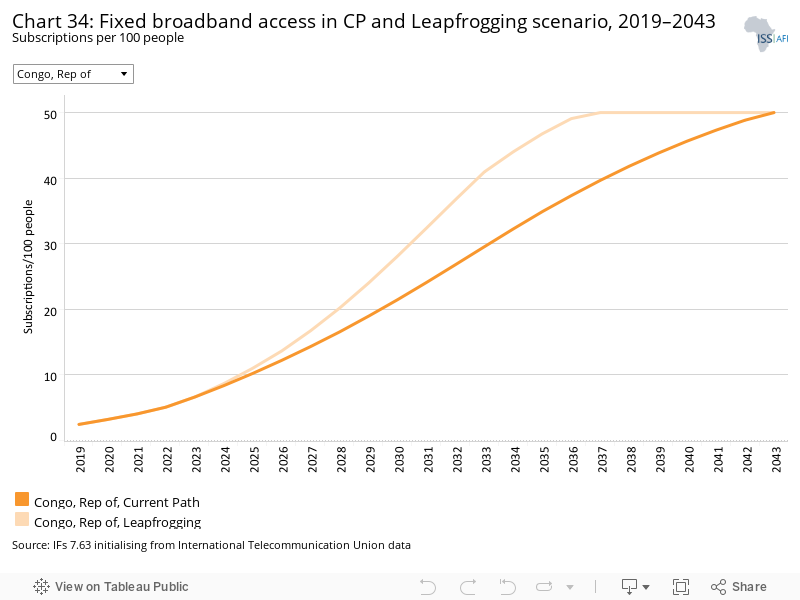

- Chart 34: Fixed broadband access in CP and Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

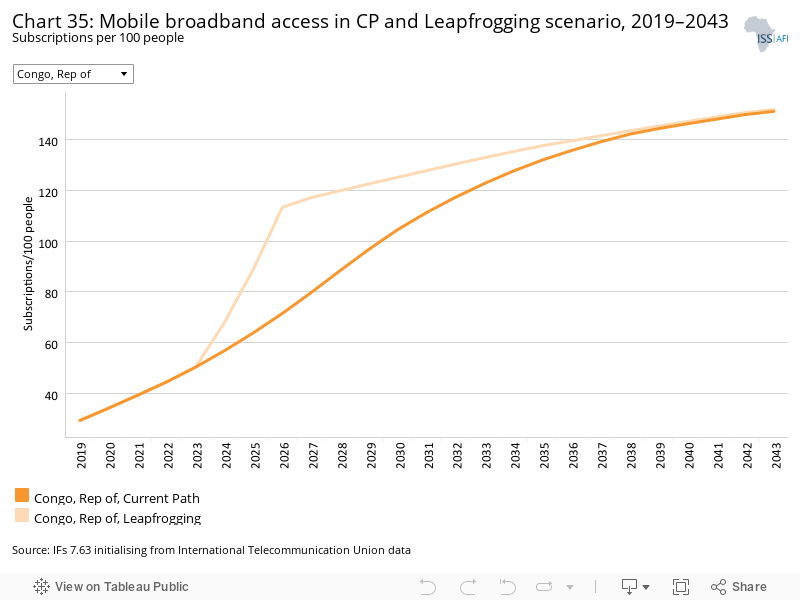

- Chart 35: Mobile broadband access in CP and Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

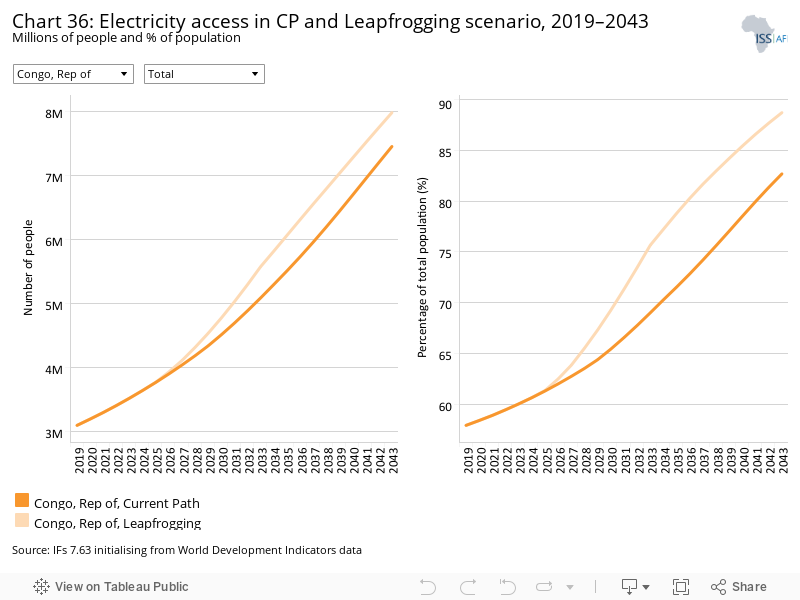

- Chart 36: Electricity access in CP and Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

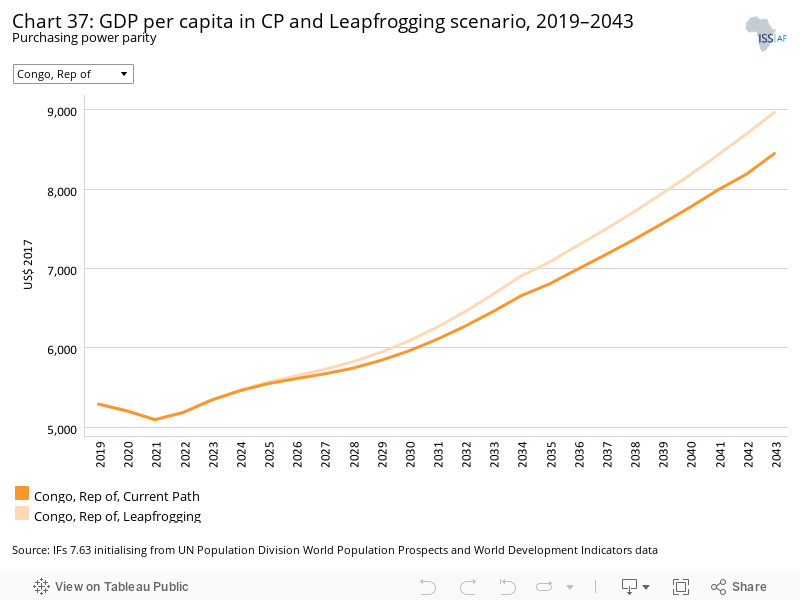

- Chart 37: GDP per capita in CP and Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

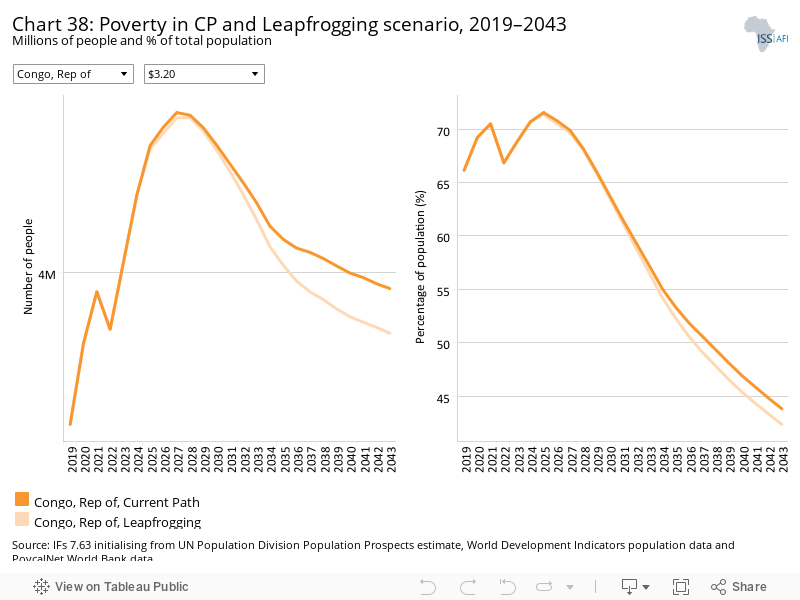

- Chart 38: Poverty in CP and Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

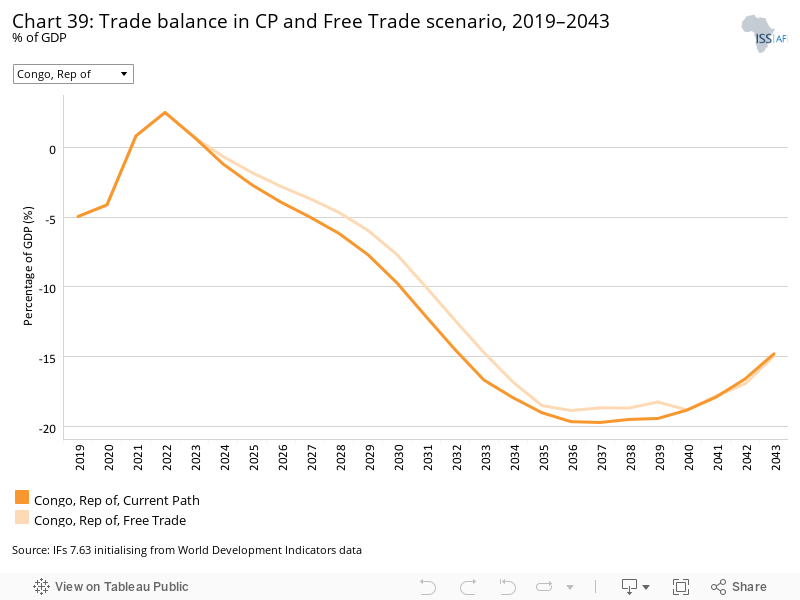

- Chart 39: Trade balance in CP and Free Trade scenario, 2019–2043

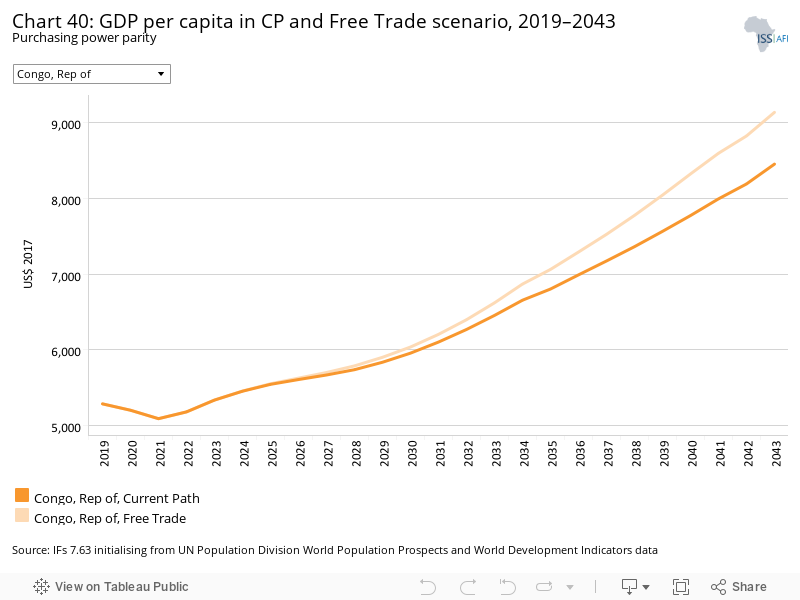

- Chart 40: GDP per capita in CP and Free Trade scenario, 2019–2043

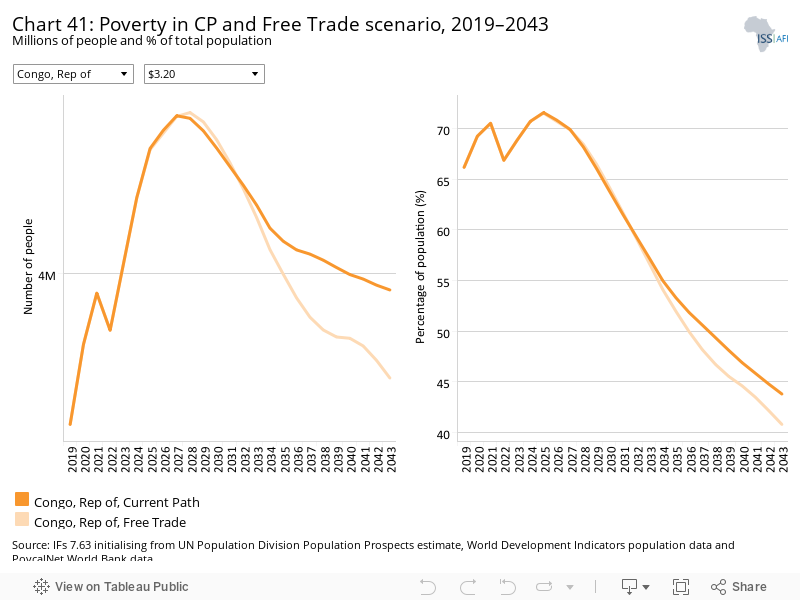

- Chart 41: Poverty in CP and Free Trade scenario, 2019–2043

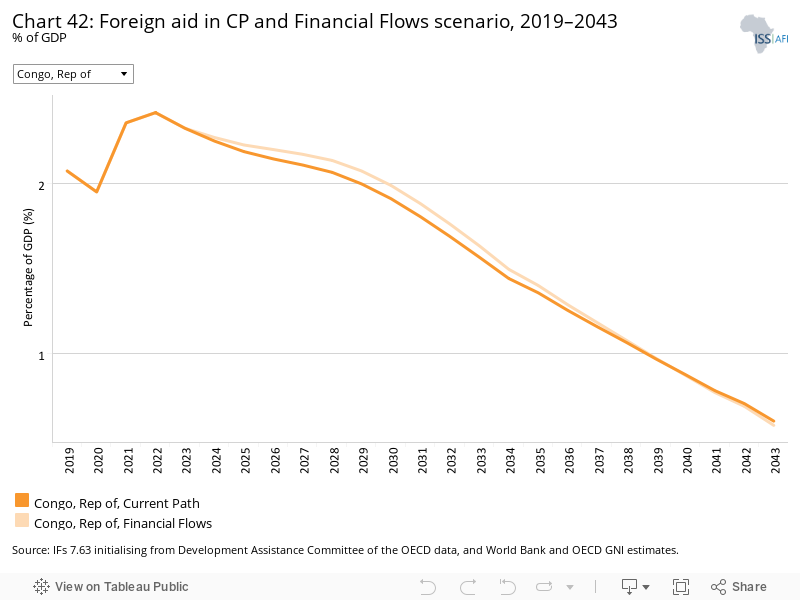

- Chart 42: Foreign aid in CP and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

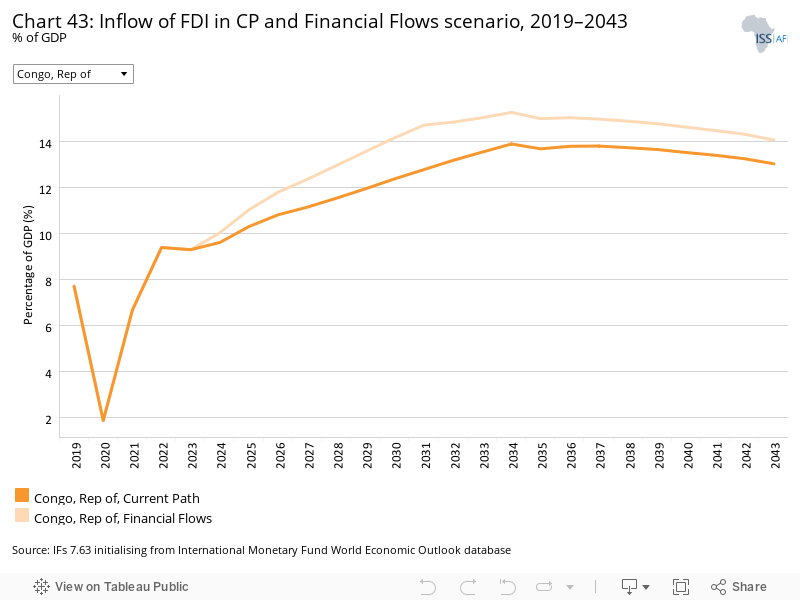

- Chart 43: Inflow of FDI in CP and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

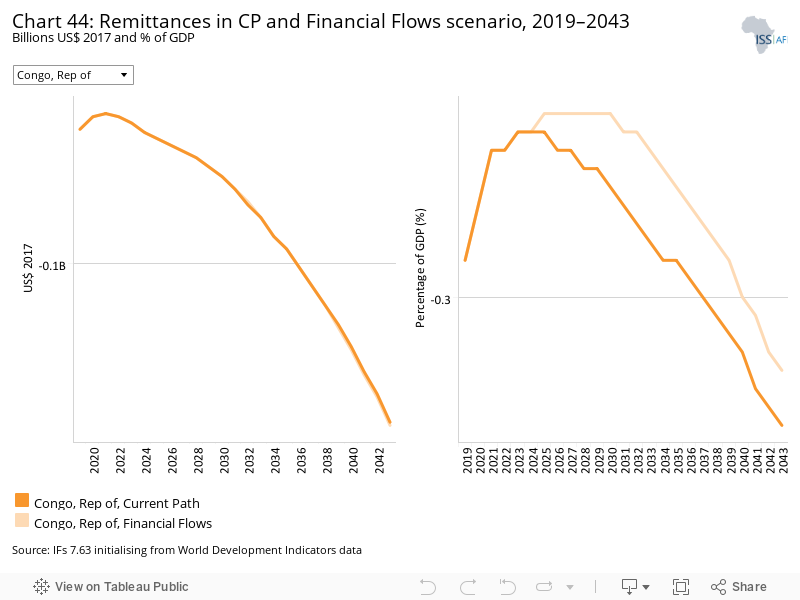

- Chart 44: Remittances in CP and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

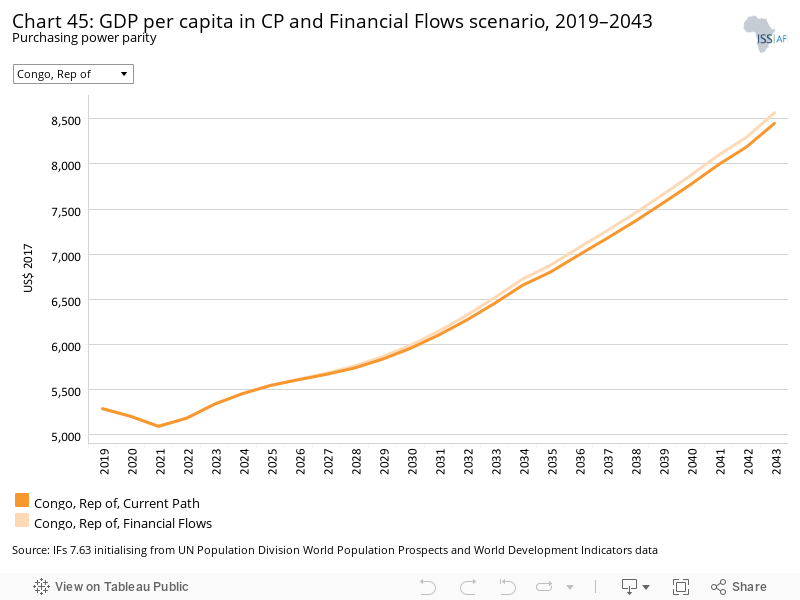

- Chart 45: GDP per capita in CP and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

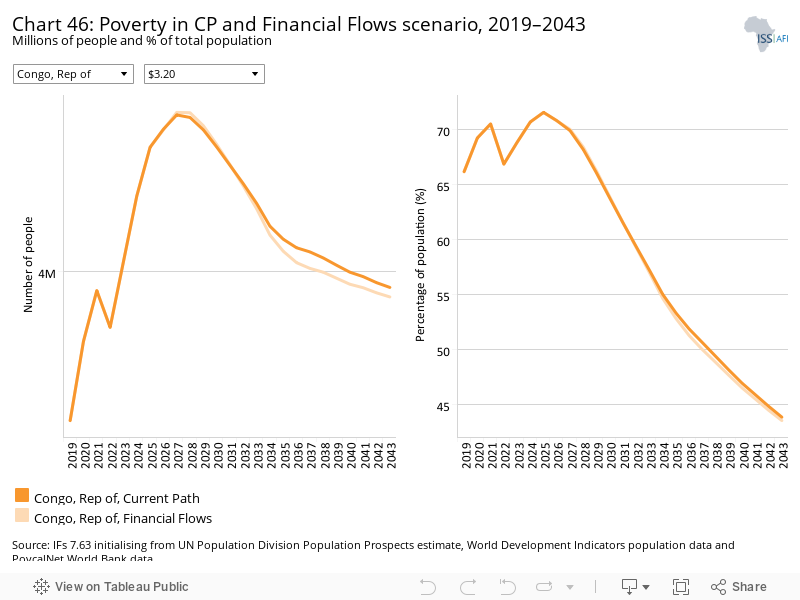

- Chart 46: Poverty in CP and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

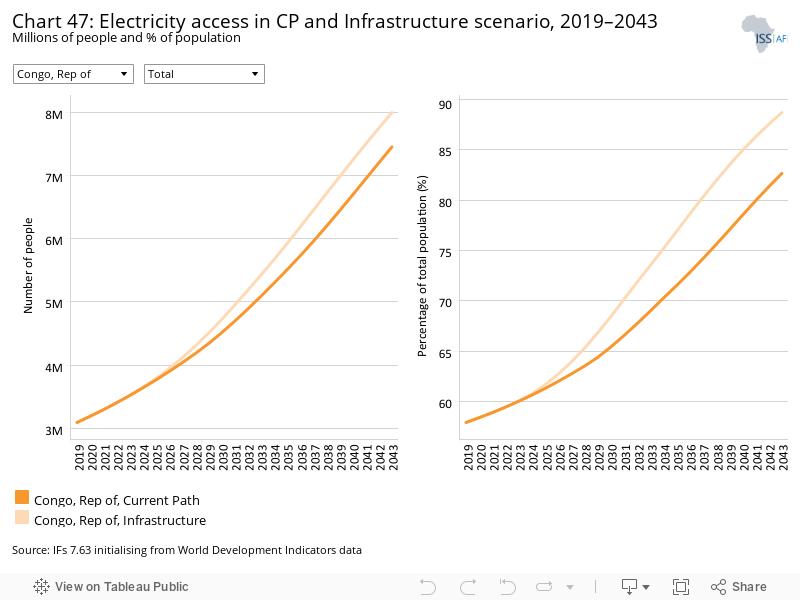

- Chart 47: Electricity access in CP and Infrastructure scenario, 2019–2043

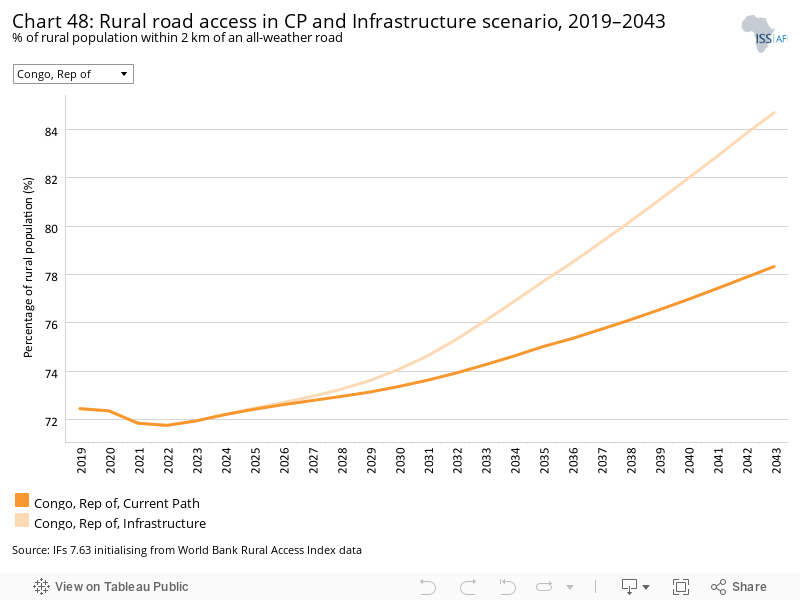

- Chart 48: Rural road access in CP and Infrastructure scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 49: GDP per capita in CP and Infrastructure scenario, 2019–2043

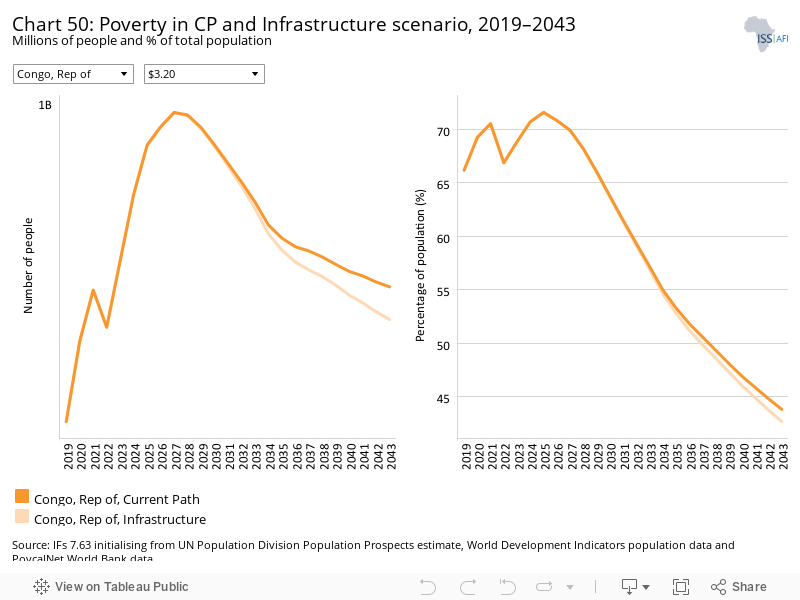

- Chart 50: Poverty in CP and Infrastructure scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 51: Gov effectiveness in CP and Governance scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 52: GDP per capita in CP and Governance scenario, 2019–2043

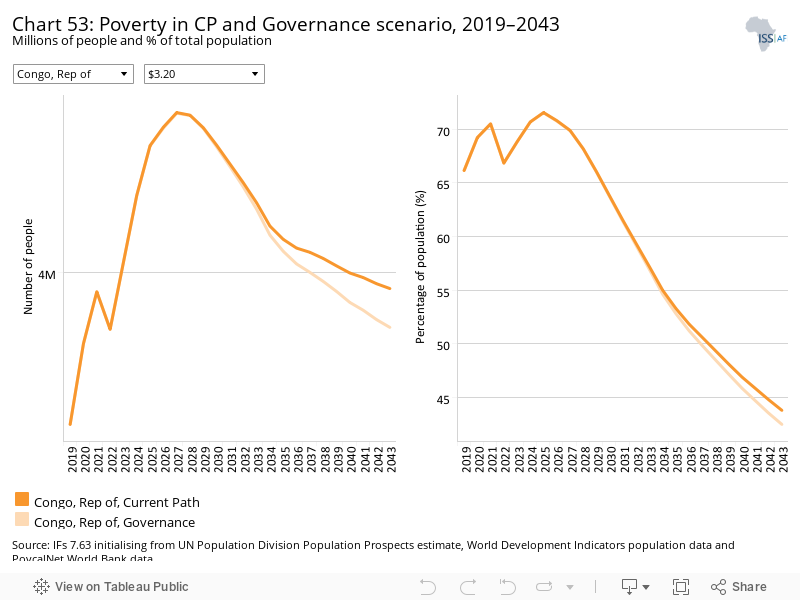

- Chart 53: Poverty in CP and Governance scenario, 2019–2043

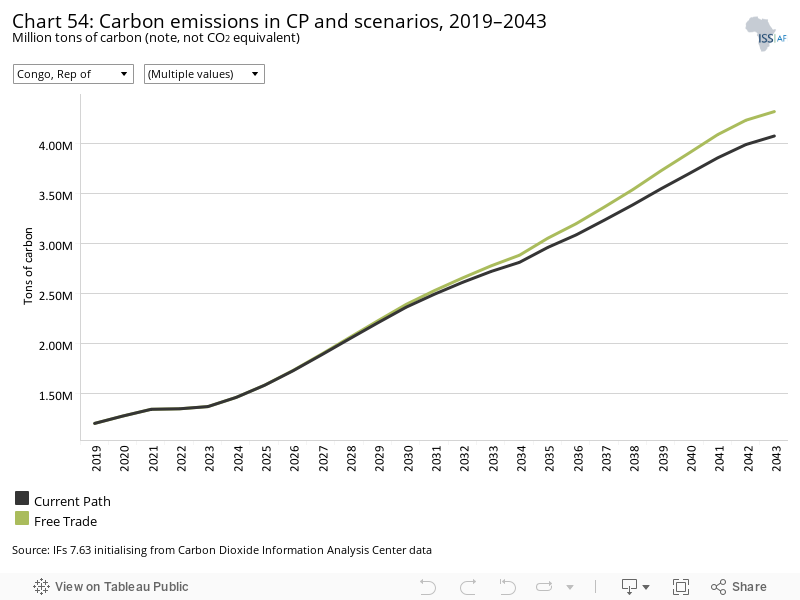

- Chart 54: Carbon emissions in CP and scenarios, 2019–2043

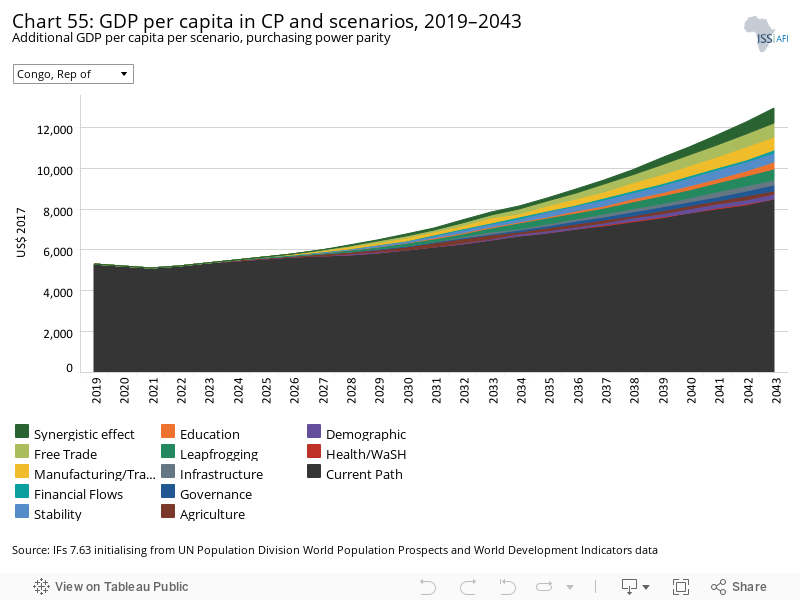

- Chart 55: GDP per capita in CP and scenarios, 2019–2043

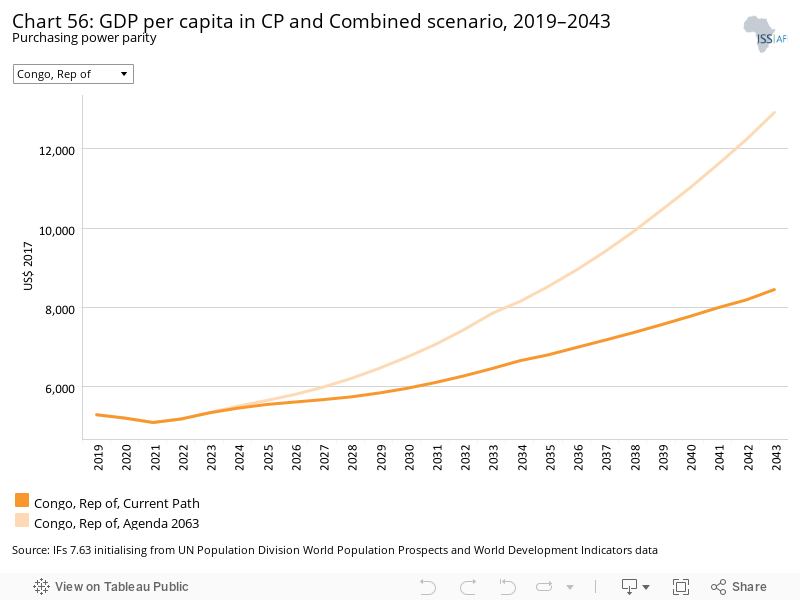

- Chart 56: GDP per capita in CP and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

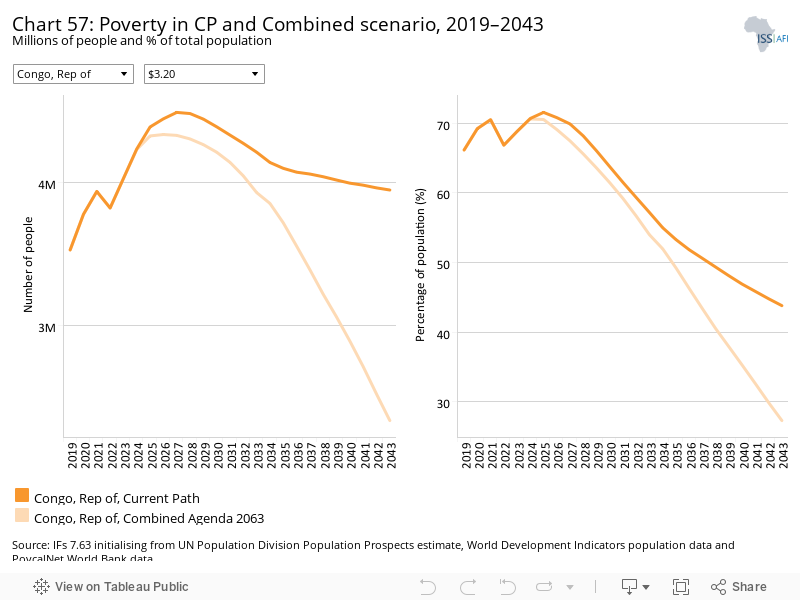

- Chart 57: Poverty in CP and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

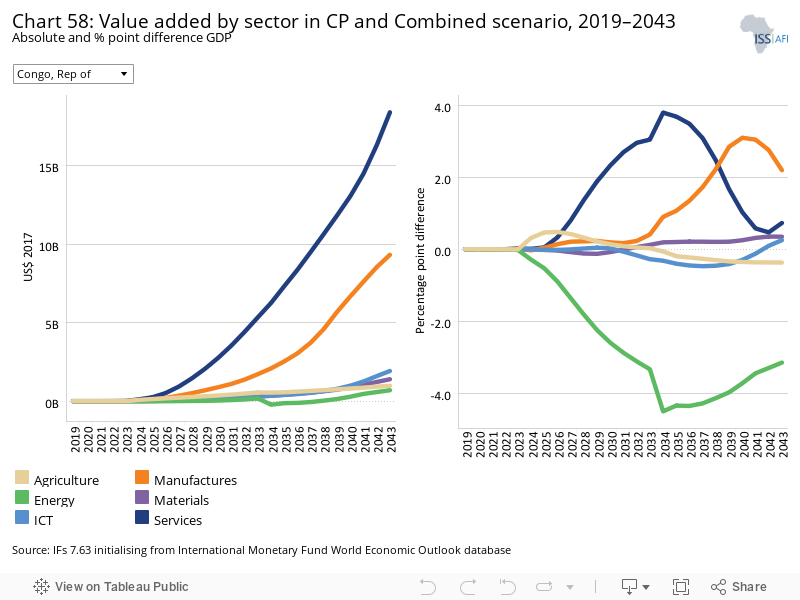

- Chart 58: Value added by sector in CP and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

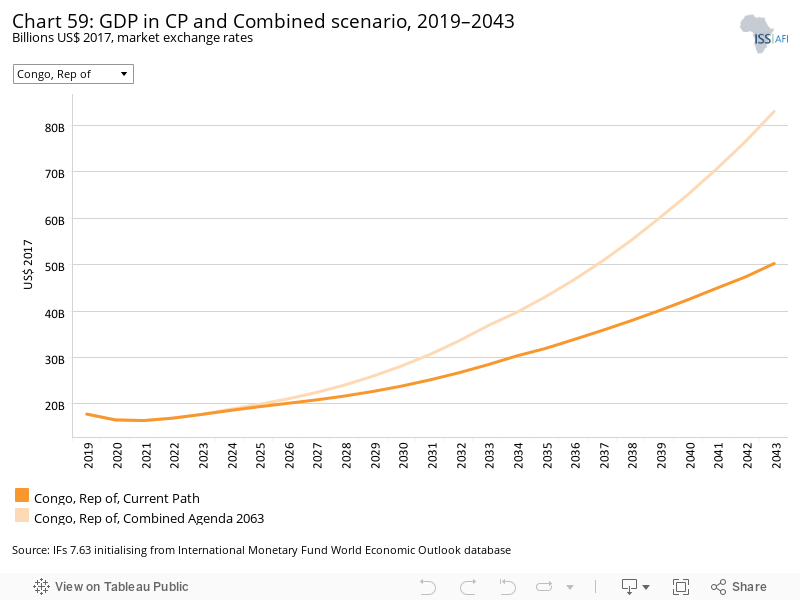

- Chart 59: GDP in CP and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

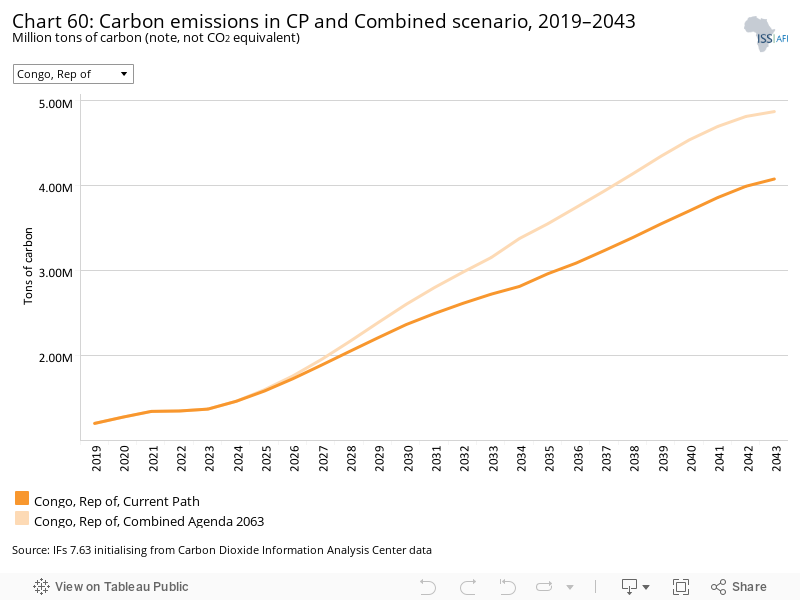

- Chart 60: Carbon emissions in CP and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

This page provides an overview of the key characteristics of the Republic of the Congo along its likely (or Current Path) development trajectory. The Current Path forecast from the International Futures forecasting (IFs) platform is a dynamic scenario that imitates the continuation of current policies and environmental conditions. The Current Path is therefore in congruence with historical patterns and produces a series of dynamic forecasts endogenised in relationships across crucial global systems. We use 2019 as a standard reference year and the forecasts generally extend to 2043 to coincide with the end of the third ten-year implementation plan of the African Union’s Agenda 2063 long-term development vision.

The Republic of the Congo is a lower middle-income country located in the Central Africa region and borders the Central African Republic, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Angola, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo). The country is a one of the five founding members of the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) regional economic community, and does not hold membership with any of the other seven regional economic communities recognised by the African Union — a rarity on the continent. The country’s capital city, Brazzaville, is located in the south-eastern part of the country on the banks of the Ubangi river, a tributary of the Congo, directly across from the DR Congo’s capital of Kinshasa. The country’s second largest city, Pointe-Noire, is situated on the coast and is vital to the country’s economy. The city is key to the Congo’s petroleum sector, which is a major source of government revenue, and is connected by rail to the capital, easing the transport of goods. Furthermore, Pointe-Noire is the only deepwater port in Central Africa, and acts as an important trans-shipment port for other ports situated in Angola and the DR Congo.

The Congo has a tropical climate and experiences year-long humidity and high temperatures due to its proximity to the Equator. The northern regions of the country consist mostly of sparsely populated rainforest, which covers nearly 66% of the country’s land area. Of the remaining 34%, permanent pasture takes up the most space, meaning the area available for other forms of agriculture is greatly reduced.

The negative effects of climate change have been keenly felt in the Congo, with floods in late 2021 adding to the list of extreme weather events the country has had to endure in recent times. The country ranked 109th on the Global Climate Risk Index in 2021, which indicates a moderate to high level of exposure and vulnerability to these extreme events, and warns of possible increases in the frequency of such events. Worryingly, the country also ranks low on the Notre Dame GAIN index, which ranks the ability of country’s to adapt to the effects of climate change.

The population of the Republic of the Congo has been growing rapidly in the period from 1990 to 2019, growing from 2.5 million people to 5.3 million people in that time — an increase of 112%. The rate will lessen over the forecast horizon: by 2043 the total population will equate to 9 million people, an increase of 69.8%. The structure of the population will also change in that time: those of working age will constitute 61% of the population in 2043, compared to 56% in 2019. The gradual maturation of the populace will reduce the dependency ratio and afford the country developmental benefits, provided the growing labour force is properly educated and can find employment opportunities.

The Congo is one of the most urbanised countries in Africa. In 1990, 54.3% of the population was already living in urban areas, and by 2019, the urban population accounted for 67.4% of the total population, meaning that less than a third of the Congolese population lived in rural areas. Poorly managed urbanisation due to a lack of resources and institutional capacity at both local and national level has resulted in the living environment in urban areas slowly deteriorating. The majority of the populace are clustered in Brazzaville, Pointe-Noire and the railway between the two cities, while the north-eastern reaches are sparsely populated. These areas will become more densely populated over the forecast horizon, with 72.9% of population centred in urban areas by 2043. These areas are ill-prepared for the growing threat of extreme weather events related to climate change, as previous occurrences have either destroyed or weakened key infrastructure. Restoration of infrastructure and adequate planning for the projected increase in urban dwellers is needed to guard against increasing fatalities and costs.

The highly urbanised population of the Congo is highly clustered around the country’s two biggest cities of Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire. The country had the seventh lowest population density in Africa in 2021, with the vast majority of the population clustered around these two cities, due to the country's northern region of tropical jungle being very sparsely populated. Indeed, in 2019, 64.8% of the country was covered by forests and jungle, while only 1.9% was available for crops but 30% for grazing. The areas outside of the urban centres are not utilised for economic activity as the country has moved away from forestry towards oil extraction and does not have a well-developed agriculture sector.

The Republic of the Congo’s economy has been hampered at various points by civil conflict and downturns in oil prices, the country’s main export, leading to lacklustre growth and periods of economic downturn from 1990 to 2019. The 1990s saw the GDP only rise from US$8.4 billion in 1990 to US$9 billion by 1999 as the country endured multiple episodes of internal conflict and violence, which culminated in a two-year civil war at the end of the decade. After the signing of a truce and the drafting of a new constitution, the country could focus on growing the economy and did so effectively: GDP doubled to US$18.5 billion by 2015, before a drop in oil prices meant the economy contracted to reach US$17.8 billion by 2019. Crude oil accounts for more than 80% of the country’s exports, making it one of the top 10 producers in Africa. This heavy dependency on oil exports puts the economy at the mercy of volatile international oil prices. An economic recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated oil price collapse necessitated an IMF loan of US$455 million at the start of 2022 to assist the Congo’s post pandemic recovery. One crucial aspect of future growth is the effective management of the country’s debt, mostly incurred by the state-owned oil company Société Nationale des Pétroles du Congo, which needed to be restructured to secure the loan.

Encouragingly, oil output is forecast to increase by 1% in the near term as large producers resume their investment in the economy. In the long term however, the country would fare better if the economy were more diversified, meaning fluctuations in oil prices would have less effect on the economy. To this end, the new national development plan which was adopted in early 2022 aims at greater economic diversification and will focus on improving six key sectors, namely agriculture, tourism, the digital economy, real estate, industrial development and the creation of free economic zones. In the Current Path forecast, the country’s GDP will see robust growth, growing by 183% from 2019 to 2043 to reach US$50.3 billion.

Although many of the charts in the sectoral scenarios also include GDP per capita, this overview is an essential point of departure for interpreting the general economic outlook of the Republic of the Congo.

The Congo has seen its GDP per capita fluctuate considerably between 1990 and 2019, reaching a low of US$4 819 in 1999 and a high of US$6 215 in 2015, before rapidly declining to US$5 290 by 2019. The country’s heavy dependence on oil exports explain the variance: when the price of oil declined sharply in 2015 and 2016 due to increased production from the US, the Congo’s GDP per capita tumbled to below its 1990 level of US$5 802. In the Current Path forecast, the country will only surpass this level again in 2029, before reaching a GDP per capita of US$8 449 by 2043. Despite the slow recovery from shocks in oil prices, the Congo will continue to outperform both its Central Africa peers and Africa’s average GDP per capita. Compared to its lower middle-income peers, the Congo will continue to trail over the forecast horizon, but the gap will close from US$1 699 in 2019 to US$693 by 2043.

The informal sector of the Congo is large, and its value as a percentage of GDP was 34.2% in 2019 was higher than the average for both low- and lower middle-income economies in Africa, and 8.3 percentage points above Africa’s average. The informal sector serves as a means of survival for poor people, and the size of the informal sector correlates with the country’s high poverty rate of 66.2% in 2019.

The advantages of formalisation for a country are myriad: the labour employed in the formal sector is more productive, they are better protected, and the government benefits from increased revenue due to a broad tax base. The Congolese government in particular will benefit, as fluctuating global oil prices often lead to budget deficits which impinge on planned spending and attempts at development. Encouragingly, the country will see the value of its informal sector drop to 28% by 2043, closing the gap to lower middle-income Africa to 1.6 percentage points, down from 5 percentage points in 2019.

The IFs platform uses data from the Global Trade and Analysis Project (GTAP) to classify economic activity into six sectors: agriculture, energy, materials (including mining), manufacturing, services and information and communication technologies (ICT). Most other sources use a threefold distinction between only agriculture, industry and services with the result that data may differ.

The Congo’s economy is anchored by an industrial sector based on the extraction of oil and related support services. The agriculture sector is not well developed and consists mostly of subsistence farming, which translates to the small role that the sector plays in overall GDP: in 2019, agriculture accounted for 8.4% of GDP. In contrast, the energy sector’s contribution stood at 23% of GDP in 2019, while the service sector accounted for 45.3% at that time. A positive development in the energy sector is the increased conversion of natural gas into electricity instead of being flared after extraction, a shift which will positively affect electricity access in the country.

The manufacturing sector also constitutes a healthy portion of the economy, reaching 17.1% of GDP in 2019, with its share growing to 22.9% by 2043. The potential of the sector is constrained by a lack of skilled labour and small domestic markets, which if addressed could unlock sustained economic growth for the Congo.

The data on agricultural production and demand in the IFs forecasting platform initialises from data provided on food balances by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). IFs contains data on numerous types of agriculture but aggregates its forecast into crops, meat and fish, presented in million metric tons. Chart 9 shows agricultural production and demand as a total of all three categories.

The gap between agricultural production and demand in the Congo has been growing since 1990. Demand outpaced supply by 300 000 tons of crops in 1990, a margin which grew to 900 000 tons by 2019. In the Current Path forecast, the gap will continue to widen and reach 3.8 million tons of crops by 2043. The robust population growth over the forecast horizon coupled with low agricultural productivity explains the growing gap. To avoid a situation where a majority of the population is dependent on food imports, interventions are needed to increase food production.

There are numerous methodologies for and approaches to defining poverty. We measure income poverty and use GDP per capita as a proxy. In 2015, the World Bank adopted the measure of US$1.90 per person per day (in 2011 international prices), also used to measure progress towards the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 1 of eradicating extreme poverty. To account for extreme poverty in richer countries occurring at slightly higher levels of income than in poor countries, the World Bank introduced three additional poverty lines in 2017:

- US$3.20 for lower middle-income countries

- US$5.50 for upper middle-income countries

- US$22.70 for high-income countries.

The Republic of the Congo had one of the highest poverty rates in Africa in 2019 at 66.2%. The rate translates to 2.9 million poor people in 2019, which will rise rapidly to 4.5 million by 2027 due to high levels of population growth. The poverty rate will in turn rise up until 2025, reaching a peak of 71.5%, before falling gradually to 43.8% by 2043.

The country trailed behind Africa’s other lower middle-income countries in 2019, and will continue to do so over the forecast horizon: the Congo’s poverty rate was 16.1 percentage points higher than the average for lower middle-income Africa in 2019, a gap which will fall to 5.5 percentage points by 2043. The large gap is due to the Congo underperforming in a number of social indicators, such as inequality, access to WaSH infrastructure and education, and higher unemployment than its income peers.

The IFs platform forecasts six types of energy, namely oil, gas, coal, hydro, nuclear and other renewables. To allow comparisons between different types of energy, the data is converted into billion barrels of oil equivalent (BBOE). The energy contained in a barrel of oil is approximately 5.8 million British thermal units (MBTUs) or 1 700 kilowatt-hours (kWh) of energy.

The Congolese economy is heavily dependent on oil exports and the majority of its industrial sector is geared towards the extraction of oil. This is reflected in the resource’s dominance of the Congo’s energy production: in 2019, 97.2% of all energy produced in the country stemmed from oil. As discussed in Chart 8 , natural gas is being used more in electricity generation and its increased importance will result in gas accounting for 28.7% of energy production by 2043 in the Current Path forecast. Other renewables will also gain ground and constitute 13.7% of total energy production by 2043, a large increase given that it did not contribute at all in 2019. The economy will require increased diversification in the medium term as oil production will plateau over the forecast horizon in the Current Path forecast: by 2043, the country will produce 84 million barrels of oil, down from 105 million in 2019. However, this forecast could be turned around as oil output could increase in the near future as investments by large oil producers are predicted to resume.

Carbon is released in many ways, but the three most important contributors to greenhouse gases are carbon dioxide (CO2), carbon monoxide (CO) and methane (CH4). Since each has a different molecular weight, IFs uses carbon. Many other sites and calculations use CO2 equivalent.

The lack of industrialisation and growth in the manufacturing sector means the Congo was a low carbon emitter from 1990 to 2019, with emissions only rising by 900 000 tons in that time. Total carbon emissions will steadily increase as the economy grows in the Current Path forecast, reaching 4.1 million tons of carbon by 2043.

The Congo will however remain a small emitter on the continent. In 2019, the country ranked 29th for emissions and will fall two places to 31st by 2043. In fact, carbon emissions in Africa are heavily skewed towards a select number of countries: in 2019, the top three emitters in Africa, South Africa, Egypt and Algeria, emitted more tons of carbon than the rest of Africa’s countries combined, and by 2043 four countries will emit more than the other 50 countries combined. Although not a large emitter, the Congo will continue to face the consequences of climate change, and the country is ill-prepared, as discussed in Chart 1.

Sectoral Scenarios for Republic of the Congo

Download to pdfThe Stability scenario represents reasonable but ambitious reductions in the risk of regime instability and lower levels of internal conflict. Stability is generally a prerequisite for other aspects of development and this would encourage inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) and improve business confidence. Better governance through the accountability that follows substantive democracy is modelled separately.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

The Republic of the Congo’s score of 0.66 out of 1 on the governance security index was below both Africa and lower middle-income Africa’s average in 2019. The country experienced unrest and violence in the late 1990s during a civil war and continued upheaval persisted through the early part of the 21st century as the country battled to instil an electoral democracy. Although this goal was realised, subsequent elections have been tainted with suspicion of the integrity of the results. Coupled with weak economic performance due to the pandemic and other external shocks, renewed unrest remains a possibility.

The Stability scenario improves the Congo’s governance security index score to 0.83 by 2043, 0.1 points above the Current Path forecast, in the process surpassing Africa and lower middle-income Africa’s Current Path forecast score of 0.74 and 0.76, respectively. The added stability should lead to increasing FDI inflows and economic growth.

The projected increase in stability produced by the Stability scenario results in the Congo’s GDP per capita rising to US$8 931 by 2043, an increase of US$482, or 5.7%, compared to the Current Path forecast in the same year. The country will close the gap to lower middle-income Africa’s Current Path forecast level of US$9 142 by 2043.

The Stability scenario will be effective in accelerating the Congo’s projected decrease in poverty in the Current Path forecast: by 2043, the poverty will have dropped to 41.5% in the scenario, 2.3 percentage points below the Current Path forecast. Compared to 2019, this is robust progress, as the poverty rate then stood at 66.2%. The scenario will also lift an additional 210 000 people out of poverty in 2043 compared to the Current Path forecast.

This section presents the impact of a Demographic scenario that aims to hasten and increase the demographic dividend through reasonable but ambitious reductions in the communicable-disease burden for children under five, the maternal mortality ratio and increased access to modern contraception.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

Demographers typically differentiate between a first, second and even a third demographic dividend. We focus here on the contribution of the size of the labour force (between 15 and 64 years of age) relative to dependants (children and the elderly) as part of the first dividend. A window of opportunity opens when the ratio of the working-age population to dependants is equal to or surpasses 1.7.

The Republic of the Congo will gradually see its ratio of working-age population to dependants move towards the 1.7 to 1 mark in the Current Path forecast, but fail to enter a period of demographic dividend before the end of the forecast horizon. The progress, albeit slow, is a consequence of the total fertility rate dropping from a high of 6.3 births per woman in 1975 to 4.5 by 2019. The rate will continue falling over the forecast horizon and reach 3 births per woman by 2043. The Demographic scenario accelerates this decrease and by 2043 the total fertility rate will have fallen to 2.5 births per woman. As a result, the country will enter its demographic sweet spot earlier, reaching the required minimum ratio of working-age population to dependants of 1.7 by 2042.

The infant mortality rate is the number of infant deaths per 1 000 live births and is an important marker of the overall quality of the health system in a country.

The Congo has seen a rapid fall in its infant mortality rate since gaining independence in 1960, when the rate of infant deaths per 1 000 live births stood at 125.9. By the turn of the century, as the country was starting the process of recovering from a civil war, the rate had dropped to 61.7 deaths per 1 000 live births. The subsequent years of relative peace and shift towards rebuilding the economy resulted in the infant mortality decreasing to 36.9 by 2019.

The Congo outperformed both Africa and lower middle-income Africa’s averages and will continue to do so in the Current Path forecast. The Demographic scenario will enable the Congo to widen this gap, reaching an infant mortality rate of 14.9 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2043, 3 deaths lower than in the Current Path forecast.

The Demographic scenario will speed up the Congo’s transition into a period of demographic dividend sooner than in the Current Path forecast. The benefit for growth plays out in the increase in GDP per capita: by 2043, the Congo’s average income will rise to US$8 672, US$223 higher than in the Current Path forecast.

The Congo will see its poverty rate fall from 66.2% in 2019 to 43.8% by 2043 in the Current Path forecast, a reduction of 22.4 percentage points. The Demographic scenario adds to this positive trend, lowering the poverty rate by an additional 1.6 percentage points by 2043. As the scenario decreases the total fertility rate, a smaller population in the scenario translates to an additional 280 000 people moving above the poverty line of US$3.20 by 2043.

This section presents reasonable but ambitious improvements in the Health/WaSH scenario, which include reductions in the mortality rate associated with both communicable diseases (e.g. AIDS, diarrhoea, malaria and respiratory infections) and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) (e.g. diabetes), as well as improvements in access to safe water and better sanitation. The acronym WaSH stands for water, sanitation and hygiene.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

A key intervention for improving the health of a country’s population is increasing access to WaSH infrastructure. The resulting improvement in cleanliness and safe drinking water helps to reduce the spread of communicable diseases such as diarrhoea and respiratory infections. The Republic of the Congo has done well in providing its population with access to the safe drinking water: in 2019, 83.2% of the population had access to an improved form of water sources, and the rate will reach 100% in both the Current Path forecast and the Health/WaSH scenario by 2034. Access to improved sanitation has however lagged far behind, with an access rate of 23.2% in 2019.

The country does however have space to improve in its investment in the healthcare sector. In fact, the country ranked the third lowest for health expenditure (percentage of GDP) in the world and lowest in Africa in 2019, at 2.1% of GDP. The level of investment has remained low since 2000, when health expenditure equated to 1.5% of GDP. As the country transitions to a higher non-communicable disease burden relative to communicable diseases, increased investment will be needed to care for a population faced with longer-term illnesses and conditions, such as cancer and obesity.

As discussed in Chart 17, the Congo has seen sustained progress in reducing its infant mortality rate since independence and performed better than Africa and lower middle-income Africa in 2019. Although still high, the rate will continue to decline over the forecast horizon, reaching a rate of 17 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2043 in the Health/WaSH scenario, marginally below the 17.9 deaths per 1 000 live births in the Current Path forecast.

The Congo also performs better than the two groupings in terms of maternal mortality: in 2019, the country had a rate of 349.9 deaths per 100 000 live births, 94.6 deaths below Africa’s average, and will see its rate drop to 121.8 deaths in the Health/WaSH scenario, 53 deaths below Africa’s Current Path forecast average.

The Agriculture scenario represents reasonable but ambitious increases in yields per hectare (reflecting better management and seed and fertiliser technology), increased land under irrigation and reduced loss and waste. Where appropriate, it includes an increase in calorie consumption, reflecting the prioritisation of food self-sufficiency above food exports as a desirable policy objective.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

The data on yield per hectare (in metric tons) is for crops but does not distinguish between different categories of crops.

The agriculture sector in the Republic of the Congo is characterised by small-scale subsistence farming which limits commercial farming practices and delivers low yields due to poor soil quality and the insufficient use of fertiliser. More than a third of the labour force is employed in the agriculture sector, meaning increased levels of investment in agriculture would help significantly in alleviating poverty in the Congo. As discussed in Chart 1 , the land area not covered by forest is mainly used for pastures and grazing, limiting the space available for crops and the food needed to feed the population. Indeed, in 2018, the FAO estimated that only 1.84% of the country’s total land area was either arable or already under permanent crops. This combination of a large labour force employed in the sector, available land and high demand means the sector lends itself to investment opportunities.

The Congo recorded a yield of 5.8 ton per hectare in 2019, and will reach 7.3 tons per hectare by 2043 in the Current Path forecast. The Agriculture scenario will boost output to 10.3 tons per hectare by 2043, an increase of 3 tons per hectare compared to the Current Path forecast. The rise in output will alleviate the Congo’s food shortage and need for food imports.

The Congo performs better than both lower middle-income Africa and Africa as a whole, and will widen its gap over the forecast horizon. This positive gap does not mean however that the Congo is realising its potential, rather that given the limited arable land area available, the country is producing higher levels of output. Higher crop production could be achieved if more of the ample available land were converted into cropland, and larger scale farming practices were employed.

The unfulfilled potential in the Congo’s agriculture sector and the inadequate amount of food produced by agricultural activities, as discussed in Chart 22, are highlighted when considering agricultural imports as a percentage of agricultural demand. Although the country outperforms both lower middle-income Africa and Africa for yields per hectare, the Congo’s dependency on food imports is much higher.

The lack of overall production is thus the problem for the Congo’s agriculture sector: in 2019, 20.9% of agricultural demand was met through imports, 7.6 percentage points higher than lower middle-income Africa. The rate will rise sharply over the forecast horizon in the Current Path forecast, but in the Agriculture scenario, import dependency will fall to 15.7% by 2035, before increasing again to 19.4% by 2043.

The Congo will not see a large improvement in GDP per capita in the Agriculture scenario: by 2043, the country’s average income per person will have increased to US$8 623, US$174 more than in the Current Path forecast. The Congo will continue to close the gap to the Current Path forecast average for lower middle-income Africa and increase its margin over Africa’s average GDP per capita.

The poverty rate for Congo is not significantly reduced in the Agriculture scenario, decreasing from 43.8% to 42.6% by 2043. The country will continue to trail behind lower middle-income Africa Current Path forecast rate, which will stand at 38.3% by 2043.

The Education scenario represents reasonable but ambitious improved intake, transition and graduation rates from primary to tertiary levels and better quality of education. It also models substantive progress towards gender parity at all levels, additional vocational training at secondary school level and increases in the share of science and engineering graduates.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

Government expenditure on education in the Republic of the Congo (percentage of total expenditure) ranks among the highest in Africa, but educational quality remains an issue as educational outcomes fail to align with labour market demands. In 2019, 22% of total government expenditure was spent on education and is expected to rise slightly to 24.4% by 2043. The country performs relatively well in terms of literacy rates, ranking 16th in Africa in 2019 with a rate of 81.6%. The Congo will, however, lose ground going forward, slipping to 29th place on the continent with a rate of 91%.

Despite the levels of spending, the Congo’s score on the human capital index is 0.42, meaning the country has made little progress in the areas of health and education. The education system faces challenges, such as a lack of pre-primary education, high levels of repetition and overcrowding of classrooms. In addition, dropout rates after primary school are high, while educational attainment varies widely between regions and ethnicity. High levels of corruption in the public sector dilutes the impact of government expenditure on education and leads to inefficient outcomes.

The Congo’s mean years of education in 2019 stood at 6.5 years, which was slightly better than Africa’s average of 6.2 years, but below the average of 7.2 years for lower middle-income Africa. In the Education scenario, the Congo will erase that gap by 2043 and reach 8.8 mean years of education.

When broken down by gender however, a wide gap in education attainment appears in 2019, mean years of male education was 1.1 years higher than female mean years of education in the Congo. The gap will shrink to 0.5 years by 2043 in the Education scenario, a positive trend which must be reinforced and accelerated to reach parity as soon as possible.

As discussed in Chart 26, the quality of education in the Congo remains inadequate for labour market demands, despite relatively high levels of government spending and education being free to all citizens. The average primary school learner in the Congo achieved a test score of 30.8 in 2019, marginally lower than Africa’s average of 31.4 and a distance behind lower middle-income Africa’s score of 33.6. At a secondary level, the Congo’s average score was 40.4 in 2019, higher than Africa’s average score of 39.1 but below lower middle-income Africa’s of 41.7.

In the Education scenario, the Congo will see its primary score rise to 43.9 by 2043, erasing the gap to lower middle-income Africa, whose score will equate to 41.1. The same holds for the secondary school level, where the Congo’s score will reach 55.5 by 2043, compared to 49.4 for lower middle-income Africa.

The Education scenario improves the country’s GDP per capita by US$321 by 2043 compared to the Current Path forecast. Average income will reach US$8 770 by 2043, closing the gap to Africa’s lower middle-income countries and their Current Path forecast GDP per capita.

The Congo’s poverty rate at the US$3.20 line will fall significantly over the forecast horizon, and the Education scenario will accelerate this progress. By 2043, the poverty rate will be 1.9 percentage points lower than in the Current Path forecast at 41.9%, while the country will close the gap to lower middle-income Africa’s Current Path forecast poverty rate to 3.1 percentage points.

The Manufacturing/Transfers scenario represents reasonable but ambitious manufacturing growth through greater investment in the economy, investments in research and development, and promotion of the export of manufactured goods. It is accompanied by an increase in welfare transfers (social grants) to moderate the initial increases in inequality that are typically associated with a manufacturing transition. To this end, the scenario improves tax administration and increases government revenues.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

Chart 30 should be read with Chart 8 that presents a stacked area graph on the contribution to GDP and size, in billion US$, of the Current Path economy for each of the sectors.

The Republic of the Congo is heavily dependent on its oil sector for GDP growth and foreign currency earnings, and the most recent national development plan has emphasised the growth of alternative sectors to decrease the exposure of the country to international oil price shocks. The Manufacturing/Transfers scenario will accelerate the growth of the services and manufacturing sectors, moving the economy away from the energy sector. By 2043, manufacturing will add an additional US$1.6 billion to the economy, while the service sector will be US$3.4 billion larger. As a percentage of GDP, the manufacturing and service sectors will see an increase of 0.6 percentage points, while the energy sector will see its contribution decline by 0.8 percentage points. The agriculture sector will remain a small part of the economy, as will the ICT sector.

The Manufacturing/Transfers scenario increases the amount of welfare transfers by 48% compared to the Current Path forecast by 2043 to US$3.7 billion. This represents an increase of over 300% compared to the US$0.8 billion in welfare transfers in 2019. These welfare transfers will be needed to address the initial increase in poverty often associated with investment in the manufacturing sector. Industrialisation is often funded by an initial decrease in consumption, increasing poverty in the short term. However, these efforts stimulate inclusive growth with a greater impact on poverty alleviation in the long term.

The Manufacturing/Transfers scenario will significantly increase the Congo’s GDP per capita and propel the country towards the average income for Africa’s other lower middle-income countries. Indeed, by 2043 the Congo’s GDP per capita will be US$9 042, only US$146 behind lower middle-income Africa’s Current Path forecast. In 2019, the gap was much larger at US$1 699.

In the short term, the Congo’s poverty rate is expected to rise above the Current Path forecast, before falling below the Current Path by 2038. The scenario shows how a transition towards an industrialised economy may often cause short term increases in poverty as massive investment in industrialisation leads to initial reductions in consumption and consumer spending. By 2043, the poverty rate will however be 1.5 percentage points below the Current Path forecast at 42.3%.

The Leapfrogging scenario represents a reasonable but ambitious adoption of and investment in renewable energy technologies, resulting in better access to electricity in urban and rural areas. The scenario includes accelerated access to mobile and fixed broadband and the adoption of modern technology that improves government efficiency and allows for the more rapid formalisation of the informal sector.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

Fixed broadband includes cable modem Internet connections, DSL Internet connections of at least 256 KB/s, fibre and other fixed broadband technology connections (such as satellite broadband Internet, ethernet local area networks, fixed-wireless access, wireless local area networks, WiMAX, etc.).

The telecommunication systems in the Republic of the Congo face a number of challenges: the use of microwave radio relay and coaxial cables are not suitable even for government use, intercity telephone lines are out of order constantly, and large inequalities exist in Internet access between rich and poor people, with most teenagers accessing the Internet at Internet cafes. Low levels of electricity access in rural areas also negatively affect those populations in accessing the Internet.

Fixed broadband access is thus low in the country, with a rate of 2.5 subscriptions per 100 people in 2019. Significant progress will occur over the forecast horizon in the Leapfrogging scenario, with access rates rising to 50 subscriptions per 100 people by 2037, before plateauing through to 2043. Greater access to the Internet for businesses and individuals holds developmental benefits as it increases knowledge transfer, access to international services and markets, and increases productivity.

Mobile broadband refers to wireless Internet access delivered through cellular towers to computers and other digital devices.

Low and lower middle-income countries have generally benefited from using mobile phones to access the Internet, as it costs much less than fixed-line infrastructure. The Congo’s level of mobile subscriptions are however below the average for both Africa and lower middle-income Africa, standing at 29.5 subscriptions per 100 people in 2019 compared to 40.5 for Africa and 49.1 for lower middle-income Africa. Mobile broadband access will increase rapidly both in the Leapfrogging scenario and in the Current Path forecast, surpassing 150 subscriptions per 100 people by 2043.

Electricity access in the Congo is constrained by the low quality of the distribution and transmission infrastructure currently in place. Furthermore, the national utility, Société Nationale d’Electricité, suffers from high electricity losses, low tariff rates and low collection rates. Recent investments aimed at increasing generation capacity by 330 MW, in addition to a shift towards converting natural gas into electricity instead of flaring it, will contribute to an increasing level of electricity access over the forecast horizon.

The country also has huge hydropower potential, of which only a small percentage is currently being utilised. The country has three hydropower plants, with a number of new plants planned but unlikely to contribute to electricity generation in the near future. Most of the country’s electricity is generated through fossil fuels, 63% of net generation capacity, while the rest is provided by hydroelectric power.

The Congo’s poor transmission and distribution facilities disproportionately affect its rural population: in 2019, only 18.3% of the rural population had access to electricity, while urban areas had an access rate of 77.5%. The shortfall is primarily met through the burning of biomass, which holds potential health risks to rural inhabitants. The Leapfrogging scenario will raise rural access rates to 75% by 2043 — a 13.3 percentage point increase compared to the Current Path forecast. Urban rates will see an increase of 3.2 percentage points compared to the Current Path forecast, reaching 93.8% by 2043.

The Congo’s GDP per capita will increase significantly in the Leapfrogging scenario, highlighting the value of increased electricity access and greater connectivity. In the scenario, GDP per capita will have risen to US$8 967 by 2043, US$518 above the Current Path forecast. This rise in GDP per capita will bring the country closer to the projected average for lower middle-income Africa and widen the margin to Africa’s average income of US$7 157 in the Current Path forecast by 2043.

The Leapfrogging scenario will accelerate the progress Congo will make in the Current Path forecast, decreasing the poverty to 42.3% by 2043. The decrease will translate to an additional 140 000 people moving out of poverty at the US$3.20 per day poverty level compared to the Current Path forecast for 2043.

The Free Trade scenario represents the impact of the full implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) by 2034 through increases in exports, improved productivity and increased trade and economic freedom.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

The trade balance is the difference between the value of a country's exports and its imports. A country that imports more goods and services than it exports in terms of value has a trade deficit, while a country that exports more goods and services than it imports has a trade surplus.

The Free Trade scenario’s focus on regional integration and increased exports due to the AfCFTA results in the Congolese economy running a trade deficit from 2024 until it reaches a low point of 18.7% in 2040 as its economy, based mainly on oil extraction and its support services, will be forced to compete with other countries and the products they produce at comparatively cheaper rates. The Republic of the Congo’s trade deficit will gradually improve to 2043 as the country readjusts and produces goods in which it holds a cost advantage over its regional partners. By 2043, the trade deficit will reach 14.8% of GDP both in the Current Path forecast and in the Free Trade scenario, 10.9 percentage points below Africa’s trade deficit of 3.9% of GDP.

The Free Trade scenario will be very effective in raising the Congo’s GDP per capita, performing the best out of all 11 scenarios. The country will see its average income rise from US$8 449 by 2043 in the Current Path forecast to US$9 131 in the scenario, an increase which will put it nearly level with the projected average for lower middle-income Africa in the Current Path forecast.

Trade openness will reduce poverty in the long term after initially increasing it due to the redistributive effects of trade. Most African countries export primary commodities and low-tech manufacturing products, and therefore a continental free trade agreement (AfCFTA) that reduces tariffs and non-tariff barriers across Africa will increase competition among countries in primary commodities and low-tech manufacturing exports. Countries with inefficient, high-cost manufacturing sectors might be displaced as the AfCFTA is implemented, thereby pushing up poverty rates. In the long term, as the economy adjusts and produces and exports its comparatively advantaged (lower relative cost) goods and services, poverty rates will decline.

The Congo will not immediately benefit from the Free Trade scenario in terms of poverty reduction, but once the full effect of the AfCFTA is felt on the economy, the scenario will effectively reduce the poverty rate and by 2043 translate to a decrease of 3 percentage points compared to the Current Path forecast. The decrease in the Free Trade scenario is the largest out of all 11 scenarios and will close the gap to lower middle-income Africa’s Current Path forecast poverty rate to 2.5 percentage points.

The Financial Flows scenario represents a reasonable but ambitious increase in worker remittances and aid flows to poor countries, and an increase in the stock of foreign direct investment (FDI) and additional portfolio investment inflows to middle-income countries. We also reduced outward financial flows to emulate a reduction in illicit financial outflows.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

The Republic of the Congo is not heavily dependent on foreign aid, and it ranked 38th on the continent for foreign aid as a percentage of GDP in 2019 at 2.1%. The average for Africa was 2.4% and lower middle-income Africa’s average was 1.7% in 2019. As the Congolese economy continues to grow strongly in the Current Path forecast, foreign aid as a percentage of GDP will decline, reaching 0.6% by 2043, compared to 0.5% for lower middle-income Africa and 1.3% for Africa. In absolute terms, foreign aid will increase until 2031 in the Financial Flows scenario, reaching US$0.48 billion, before declining to US$0.3 billion by 2043.

The flow of inward FDI to the Congo has increased in recent years, as international companies aim to benefit from the country’s natural resources, especially oil and timber. The concentration of investment in oil specifically hinders progress towards diversifying the economy and becoming less dependent on oil exports and less vulnerable to international price shocks.

Multiple factors hindering investment include weak infrastructure, especially inconsistent electricity supply, a poor business environment, high risks of corruption and a lack of transparency. Those notwithstanding, the country’s potential for increased agricultural output and related agro-processing, coupled with a highly urbanised population and the possibility of new special economic zones being created in the near future, mean the country could be successful in attracting the investment it needs to diversify the economy. Indeed, if the government focuses on attracting investment to the agriculture sector in a sustainable and inclusive manner, the country could make progress in fighting against food insecurity and lessen its dependence on food imports.

Foreign direct investment statistics differ between the IFs model and recent World Bank data. The latter shows FDI equalling 38.3% of GDP in 2020, despite the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The IFs model in contrast predicted these flows to decrease to just 1.9% of GDP, and as such the forecast until 2043 will be adjusted downwards. By 2043, the inward flow of FDI will equate to 14.1% of GDP in the Financial Flows scenario, a rate far above both Africa and lower middle-income Africa.

The Congo has seen its net migration rate vary considerably in the past two decades, from 25 800 in 2000 to −5 600 in 2012. The rate has been negative since 2012, indicating a steady outflow of Congolese in the last decade. The previous nine years all saw a positive net migration rate however, possibly due to the Congo’s inhabitants returning to the country following the end of the civil war at the end of the 20th century. In total, the country has seen more immigration than emigration since the 1970s, with the total number of emigrants below 300 000.

The Congo thus does not have a large diaspora, which is reflected in the country being a net sender of remittances. In 2019, the country sent US$0.05 billion in remittances to other countries, a figure which will grow to US$0.16 billion by 2043 in the Financial Flows scenario.

The Financial Flows scenario will have a limited impact on the Congo’s average incomes over the forecast horizon: by 2043, GDP per capita will have risen to US$8 566, US$117 above the Current Path forecast. The increase will only marginally close the gap to lower middle-income Africa, whose GDP per capita will equate to US$9 142 by 2043 in the Current Path forecast.

The Financial Flows scenario will marginally decrease the Congo’s poverty rate, with the rate dropping by 0.3 percentage points to 43.5% by 2043. This translates to 30 000 fewer poor people compared to the Current Path forecast in 2043.

The Infrastructure scenario represents a reasonable but ambitious increase in infrastructure spending across Africa, focusing on basic infrastructure (roads, water, sanitation, electricity access and ICT) in low-income countries and increasing emphasis on advanced infrastructure (such as ports, airports, railway and electricity generation) in higher-income countries.

Note that health and sanitation infrastructure is included as part of the Health/WaSH scenario and that ICT infrastructure and more rapid uptake of renewables are part of the Leapfrogging scenario. The interventions there push directly on outcomes, whereas those modelled in this scenario increase infrastructure spending, indirectly boosting other forms of infrastructure, including those supporting health, sanitation and ICT.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

The Republic of the Congo’s problems with electricity distribution and transmission and reasons for low utilisation of hydroelectric potential were explored in Chart 36. The country would benefit greatly from capitalising on its hydroelectric potential, but new projects will not be fully operational for the next few years due to continued deliberation and them being in the early phases of development. The country will however see a sharp rise in rural electricity access rates over the forecast horizon, coming from the low base of 18.3% in 2019 to reach 61.7% by 2043 in the Current Path forecast.

The Infrastructure scenario will boost this progress further and result in an increase of 12.8 percentage points by 2043 as the Congo reaches a rural access rate of 74.5% — above both Africa and lower middle-income Africa’s averages. Urban access rates will also surpass these two groupings’ averages in the Infrastructure scenario, reaching 94% by 2043 — nearly two percentage points above its lower middle-income peers.

Indicator 9.1.1 in the Sustainable Development Goals refers to the proportion of the rural population who live within 2 km of an all-season road and is captured in the Rural Access Index.

Indicator 9.1.1 falls under Goal 9 and Target 9.1 of the Sustainable Development Goals. The goal strives for resilient infrastructure that crosses borders to aid economic development and improve human well-being. Increased access to roads improves access to services for those living in rural areas and reduces transport costs.

The proportion of the population living in rural areas is small and decreasing, meaning the rural population is becoming more dispersed and harder to service. Nevertheless, the Congo had a score of 72.5% in 2019, which will rise to 84.7% by 2043 in the Infrastructure scenario, 6.4 percentage points above the Current Path forecast. These figures could however be inflated and must be treated with caution.[1The manner in which the metric is calculated has changed from its initial conception in 2006 when surveys were used to estimate access. Since 2012, the World Bank has started to move towards spatial data on population distribution and road networks, including their condition, to compile the Rural Access Index. IFs v7.63 still uses the old methodology, and thus some of its estimates are higher than current data.] The majority of the Congo’s roads are not paved, and most routes are either small, local roads or rural roads, which are more susceptible to damage caused by heavy rains during the country’s two wet seasons.[2World Food Programme, Republic of the Congo Road Network] These factors decrease the usefulness of the road network and negatively affect accessibility.

The Infrastructure scenario will lift the Congo’s average income from US$8 449 in the Current Path forecast to US$8 709 by 2043, an increase of US$260. The scenario will move the country closer to lower middle-income Africa’s Current Path forecast, closing the gap to US$433 by 2043.

The Congo’s poverty rate will drop from 43.8% in the Current Path to 42.7% in the Infrastructure scenario by 2043. The drop translates to an additional 200 000 people not living below the US$3.20 poverty line by 2043.

The Governance scenario represents a reasonable but ambitious improvement in accountability and reduces corruption, and hence improves the quality of service delivery by government.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

As defined by the World Bank, government effectiveness ‘captures perceptions of the quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to such policies’.

Government effectiveness is one of six indicators that the World Bank uses to measure governance. The bank investigates three dimensions of governance, i.e. political, economic and institutional respect, with two indicators detailed under each dimension. Together these indicators are used to gauge the quality of governance in a country.

The Republic of the Congo’s level of government effectiveness is low due to corruption being endemic in the country, affecting all spheres of life. Although a law specifically aimed at combating corruption by public officials exists, the implementation of the law is severely lacking. Prosecution of corrupt officials is usually politically motivated, and entrenched patronage systems in multiple sectors of the economy and government mean efforts to curb corruption will likely prove unsuccessful.

In 2019, the Congo ranked 36th out 54 African countries for government effectiveness, with a score of 1.4 out of 5. The 2021 Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index ranked the Congo 162nd out 180 countries for public sector corruption, with its score deteriorating from 26 out of 100 in 2012 to 21 out of 100 by 2021. The country will see an increase in governance effectiveness in the Governance scenario, with its score rising to 2.2 out of 5 by 2043, 0.3 points higher than in the Current Path forecast.

The Congo will see its GDP per capita rise from US$8 449 to US$8 731 by 2043 in the Governance scenario — a rise of 3.3%. Increased accountability and transparency means the Congo will continue to close the gap to lower middle-income Africa’s Current Path forecast of US$9 142 for 2043.

The poverty rate in the Congo will decrease from 43.8% to 42.5% by 2043 in the Governance scenario — a 1.3 percentage point drop which translates to an additional 200 000 people living above the US$3.20 poverty line. The decrease in the rate means Congo continues to close the gap to lower middle-income Africa’s Current Path forecast, which will be 38.3% by 2043.

This section presents projections for carbon emissions in the Current Path for the Republic of the Congo and the 11 scenarios. Note that IFs uses carbon equivalents rather than CO2 equivalents.

The projected increase in carbon emissions for the Republic of the Congo will see the country emit 4.07 million tons of carbon by 2043 in the Current Path forecast — an increase of 2.87 million tons compared to 2019. The 11 scenarios discussed in this report all have an effect on this forecast, with the increase in average incomes leading to higher emissions. The Leapfrogging scenario is an outlier, however, as the rise in GDP per capita it engenders does not come at the cost of rising emissions but rather sees emissions drop to 4.05 million tons of carbon by 2043. The Free Trade and Manufacturing/Transfers scenarios both increase GDP per capita appreciably, but both cause emissions to rise to 4.3 million tons of carbon by 2043. The Demographic scenario sees emissions fall to 4.01 million tons of carbon by 2043 due to the scenario’s effect on slowing down population growth.

The Combined Agenda 2063 scenario consists of the combination of all 11 sectoral scenarios presented above, namely the Stability, Demographic, Health/WaSH, Agriculture, Education, Manufacturing/Transfers, Leapfrogging, Free Trade, Financial Flows, Infrastructure and Governance scenarios. The cumulative impact of better education, health, infrastructure, etc. means that countries get an additional benefit in the integrated IFs forecasting platform that we refer to as the synergistic effect. Chart 55 presents the contribution of each of these 12 components to GDP per capita in the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario as a stacked area graph.

The Republic of the Congo will benefit most from the Free Trade scenario, which increases the country’s GDP per capita by US$682 in 2043 compared to the Current Path forecast. The Manufacturing/Transfers scenario has a slightly smaller impact, raising average incomes by US$647, while the Leapfrogging scenario is the third most effective with an increase of US$519. The Leapfrogging scenario does, however, have the advantage of increasing GDP per capita in an environmentally conscious manner, as shown in Chart 54. The Agriculture scenario has the third lowest impact on GDP per capita out of all 11 scenarios, highlighting the extent to which the agriculture sector is underperforming despite its considerable potential.

Whereas Chart 55 presents a stacked area graph on the contribution of each scenario to GDP per capita as well as the additional benefit or synergistic effect, Chart 56 presents only the GDP per capita in the Current Path forecast and the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario.

The combined impact of implementing all 11 scenarios’ interventions, as encapsulated by the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario, is the Congo’s GDP per capita rising to US$12 917 by 2043 — an increase of 52.9% compared to the Current Path forecast. The country will also see remarkable progress over the forecast horizon as GDP per capita will increase by 144.2% from 2019 to 2043.

The broad, integrated nature of the scenarios’ interventions mean the Congo will surpass the Current Path forecast for lower middle-income Africa by US$3 775 in 2043.

The Combined Agenda 2063 scenario will decrease the Congo’s poverty rate by 16.5 percentage points by 2043, compared to the Current Path forecast, resulting in a rate of 27.3%. A decrease of this magnitude will mean that an additional 1.7 million people are lifted out of poverty in the scenario by 2043. The country will also gain significant ground on lower middle-income Africa: in 2019, the gap between the Congo and Africa lower middle-income countries was 16.1 percentage points. In the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario, the gap will have decreased to 8.6 percentage points, nearly half the original difference.

See Chart 8 to view the Current Path forecast of the sectoral composition of the economy.

The Combined Agenda 2063 scenario will accelerate progress towards the Congo’s goal of diversifying the economy and moving away from its overdependence on the oil extraction sector. The growth of both the manufacturing and service sectors will be impressive, as the former will add additional US$9.3 billion to the economy by 2043, while the latter will nearly double this to reach an increase of US$18.4 billion. As a percentage of GDP, the manufacturing sector will add 2.2 percentage points more to the economy by 2043 compared to the Current Path forecast. The service sector will add an additional 0.7 percentage points to the economy by 2043, down from 3.8 percentage points in 2034. The shift away from the energy sector is also pronounced, as its contribution to GDP will decline by 3.2 percentage points of GDP compared to the Current Path by 2043.

The effect of the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario on the Congo’s economy will be transformative as by 2043 GDP will equate to US$83 billion, an increase of 65% compared to the Current Path forecast for that year. The significant increase showcases the powerful effect an integrated and holistic approach to development could have on the country, as opposed to a narrower focus on the extractive sector and its related services.

The Combined Agenda 2063 scenario will spur on significant gains in economic growth, which will necessarily lead to an increase in carbon emissions. The scenario will result in the Congo’s emissions rising by 800 000 tons of carbon compared to the 2043 level in the Current Path forecast. The increase is low when taking into account the increase in GDP: whereas the GDP will rise by 65% by 2043 compared to the Current Path forecast, emissions will only grow by 19.5% in the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario.

Endnotes

The manner in which the metric is calculated has changed from its initial conception in 2006 when surveys were used to estimate access. Since 2012, the World Bank has started to move towards spatial data on population distribution and road networks, including their condition, to compile the Rural Access Index. IFs v7.63 still uses the old methodology, and thus some of its estimates are higher than current data.

World Food Programme, Republic of the Congo Road Network

Page information

Contact at AFI team is Du Toit McLachlan

This entry was last updated on 14 August 2025 using IFs v7.63.

Reuse our work

- All visualizations, data, and text produced by African Futures are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

- The data produced by third parties and made available by African Futures is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

- All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Cite this research

Du Toit McLachlan (2026) Republic of the Congo. Published online at futures.issafrica.org. Retrieved from https://futures.issafrica.org/geographic/countries/republic-of-the-congo/ [Online Resource] Updated 14 August 2025.