Lesotho

Lesotho

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

In this entry, we first describe the Current Path forecast for Lesotho as it is expected to unfold to 2043, the end of the third ten-year implementation plan of the African Union’s Agenda 2063 long-term vision for Africa. The Current Path in the International Futures (IFs) forecasting model initialises from country-level data that is drawn from a range of data providers. We prioritise data from national sources.

The Current Path forecast is divided into summaries on demographics, economics, poverty, health/WaSH and climate change/energy. A second section then presents a single positive scenario for potential improvements in stability, demographics, health/WaSH, agriculture, education, manufacturing/transfers, leapfrogging, free trade, financial flows, infrastructure, governance and the impact of various scenarios on carbon emissions. With the individual impact of these sectors and dimensions having been considered, a final section presents the impact of the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario.

We generally review the impact of each scenario and the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario on gross domestic product (GDP) per person and extreme poverty except for Health/WaSH that uses life expectancy and infant mortality.

The information is presented graphically and supported by brief interpretive text.

All US$ numbers are in 2017 values.

Summary

- Current Path forecast

- The Kingdom of Lesotho is a landlocked country surrounded by South Africa. It is a member of the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and is one of 23 lower middle-income countries according to the World Bank’s income classification. Jump to forecast: Current Path

- Lesotho’s population of 2.1 million in 2019 makes it the tenth smallest country in Africa. Prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019 the country was on the cusp of a demographic dividend window. It is expected that in the Current Path forecast the country is likely to reap the benefits of a demographic dividend by 2030 with the labour force increasing from 977 000 people in 2019 to 1.3 million by 2043. Jump to Demographics: Current Path

- In 2019, Lesotho’s small economy ranked fifth smallest among its income peers at US$3.5 billion. In the Current Path forecast, GDP will grow to US$7.6 billion by 2043, with a growth rate above 4% from 2035 onwards. Jump to Economics: Current Path

- Poverty is an endemic problem in Lesotho that has burdened communities, especially in rural areas, for decades. The continued stagnation of domestic food production together with a growing population, declines in remittances and revenue inflows and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic have resulted in worsening food insecurity in the country, and poverty is likely to continue the upward trends until at least 2025. Jump to Poverty: Current Path

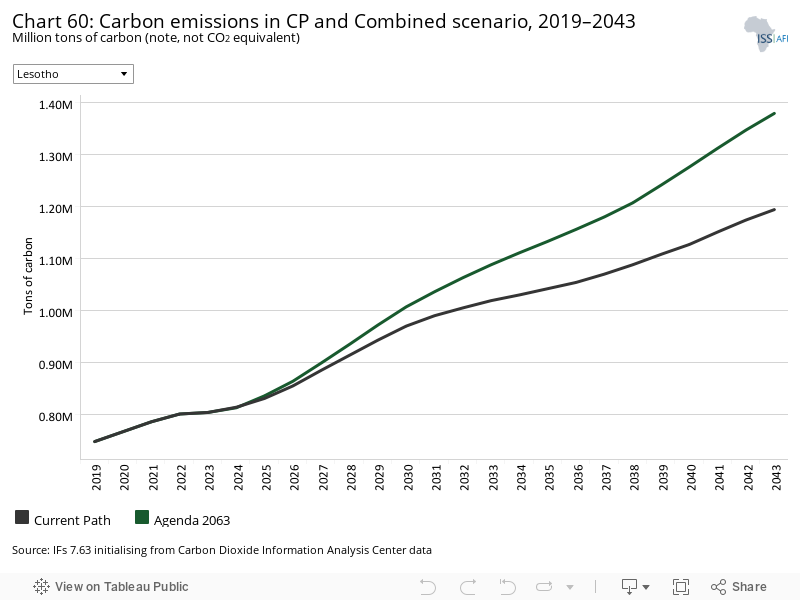

- In the Current Path forecast, carbon emissions are likely to increase to 1.2 million tons by 2043. The country has great hydro potential and wind and solar are additional viable options. Rural access will have to be addressed to break the dependence on fossil fuel burning for household needs. Jump to Carbon emissions/Energy: Current Path

- Sectoral scenarios

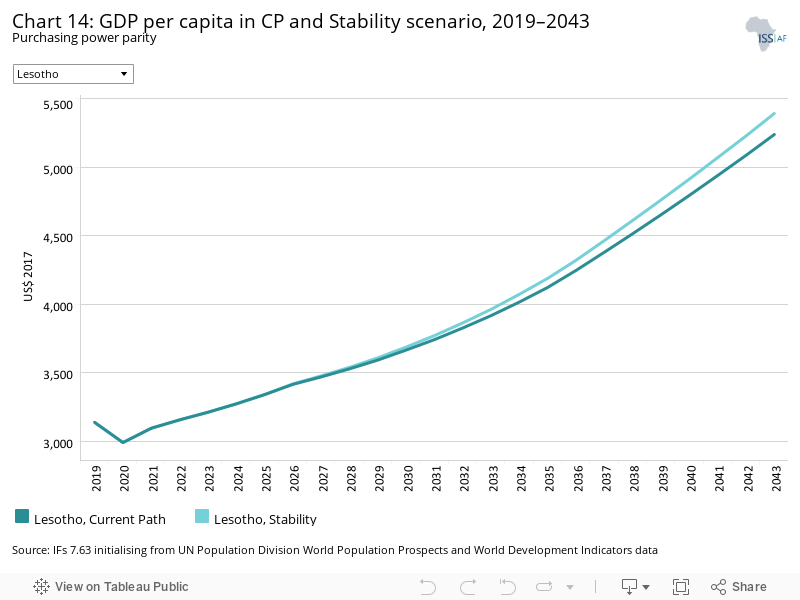

- Lesotho has had a turbulent history since gaining independence in 1966. A more stable environment will see Lesotho’s GDP per capita grow from US$3 136 in 2019 to US$5 393 in 2043, US$154 more than in the Current Path forecast for the same year. Jump to Stability scenario

- Lesotho has a high ratio of working-age population to dependants, exceeded by only nine other African countries. In the Demographic scenario, it is expected that Lesotho will enter its demographic dividend window in 2027. Jump to Demographic scenario

- In 2019, life expectancy stood at 51.9 years, 14 years below the African average and more than 15 years below the average for low middle-income countries in Africa. In the Current Path forecast, this figure is expected to improve to 60.2 years by 2043, 11.9 years below the average for African countries and 13.1 years below the average for low middle-income countries in Africa. Jump to Health/WaSH

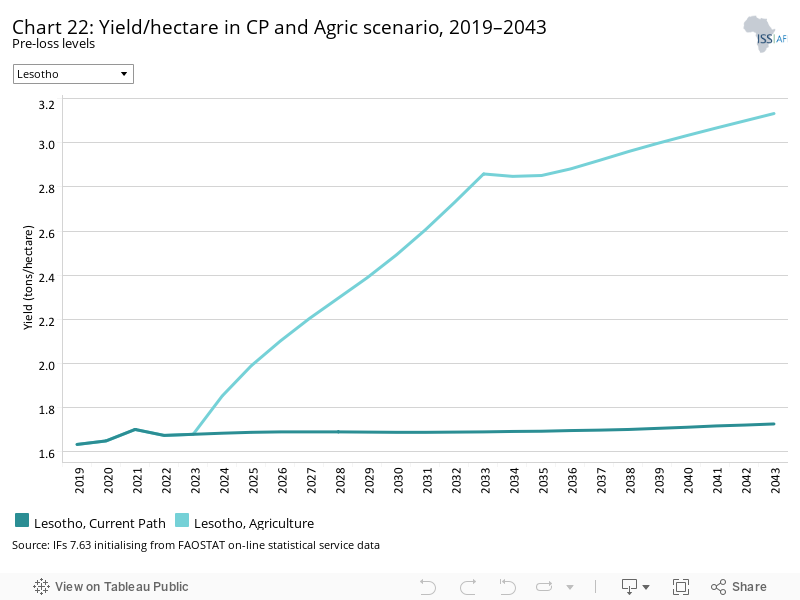

- In the Agriculture scenario, it is forecast that yields will increase to 3.1 metric tons per hectare by 2043. The Agriculture scenario will improve yields with 1.4 metric tons per hectare compared to the Current Path forecast in 2043. Jump to Agriculture scenario

- By 2043, GDP per capita in Lesotho is expected to increase by US$151 to US$5 391 in the Education scenario, compared to US$5 240 in the Current Path forecast. GDP per capita for Lesotho is expected to continue to lag behind its income peers throughout the forecast horizon to 2043. Jump to Education scenario

- In the Manufacturing/Transfers scenario, the service sectors will continue to be the largest contributor to the economy; it will contribute an additional US$400 million to the GDP by 2043, representing a 1.1 percentage point improvement compared to the Current Path forecast. Jump to Manufacturing/Transfers scenario

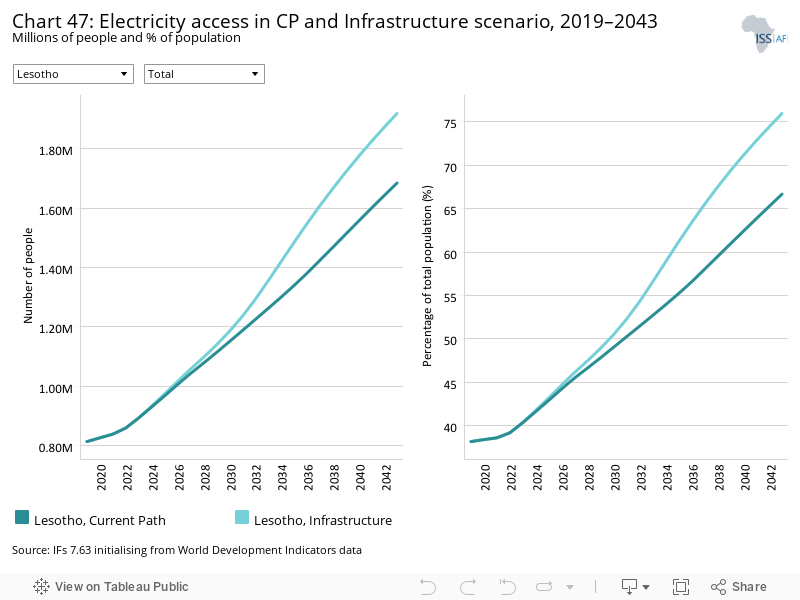

- Electricity access in Lesotho is critically low and lower than the average for Africa and lower middle-income Africa. In the Current Path forecast, it is projected that 66.7% of Lesotho’s population (1.7 million people) will have access to electricity by 2043. In the Leapfrogging scenario, electricity access is projected to reach 79.8% by 2043. Jump to Leapfrogging scenario

- By 2043, GDP per capita in Lesotho is expected to increase to US$5 653 in the Free Trade scenario, compared to US$5 240 in the Current Path forecast — an increase of US$413. Jump to Free Trade scenario

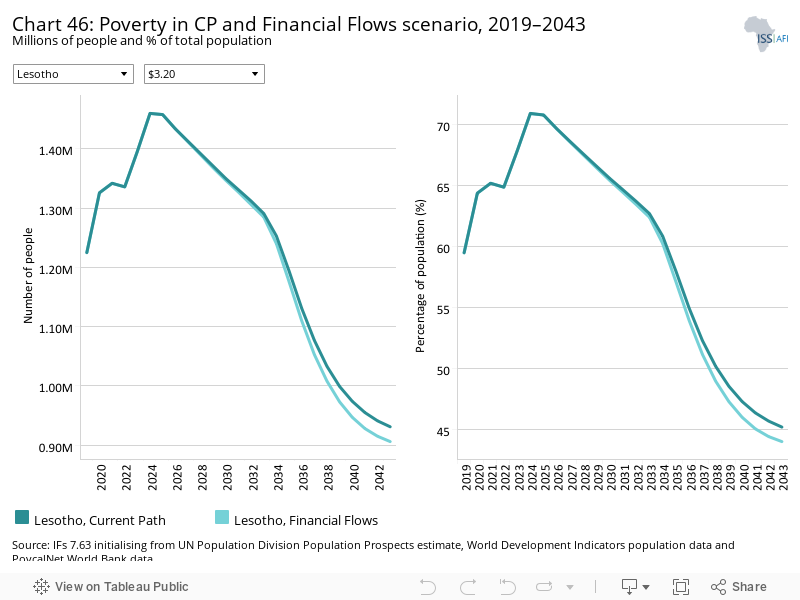

- By 2043, the poverty rate will drop marginally from 45.2% in the Current Path forecast to 44% in the Financial Flows scenario. This scenario therefore reduces the poverty rate by 1.2 percentage point compared to the Current Path forecast. Jump to Financial Flows

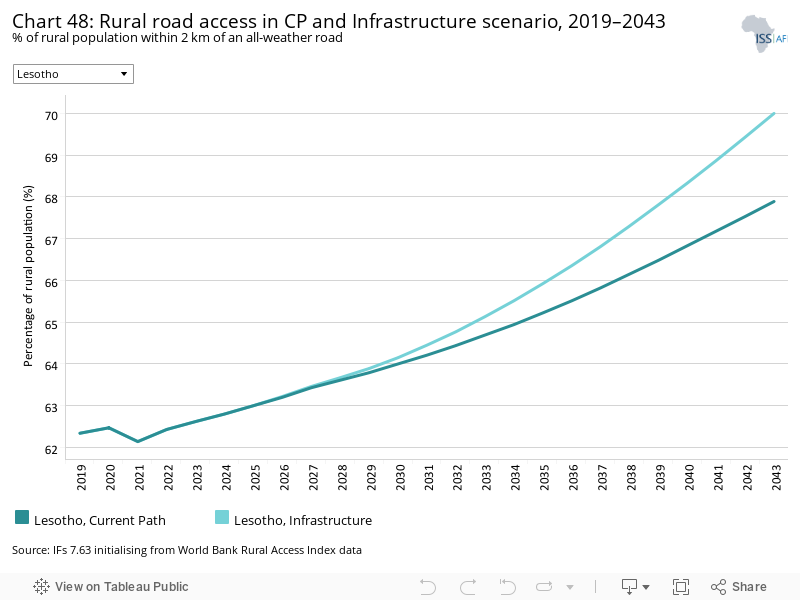

- The Infrastructure scenario stands to benefit Lesotho by increasing electricity access to 76% in 2043, 9.3 percentage points above the Current Path forecast. It will also address the vast rural access inequality and increase access to 71.3% by 2043, 11.8 percentage points above the Current Path forecast. Jump to Infrastructure scenario

- By 2043, the GDP per capita in Lesotho is expected to increase to US$5 367 in the improved Governance scenario, compared to US$5 240 in the Current Path forecast — an increase of US$127 per capita. Jump to Governance scenario

- Lesotho’s carbon emissions are projected to increase most in the Free Trade scenario, emitting an additional 0.4 million tons of carbon by 2043 compared to 2019, and a trivial 0.05 million tons of carbon more than the Current Path forecast for 2043. Jump to Impact of scenarios on carbon emissions

- Combined Agenda 2063 scenario

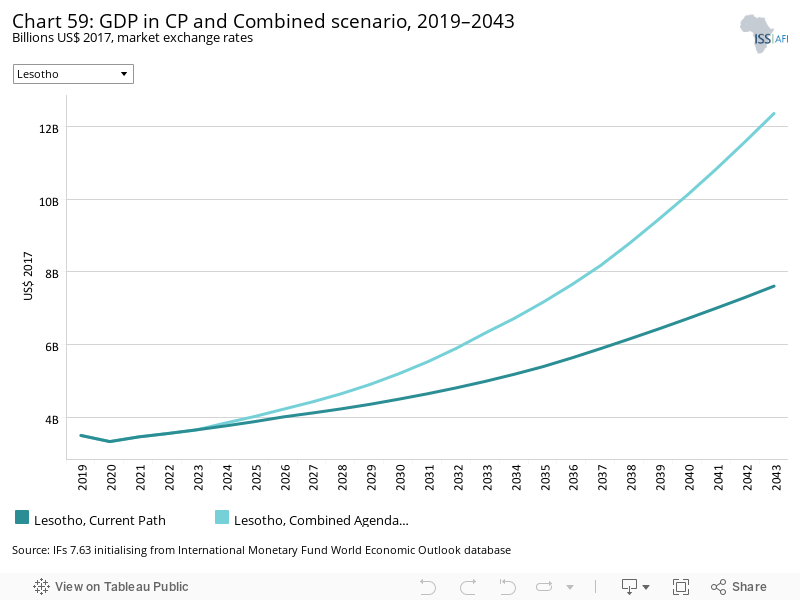

- The Free Trade scenario will raise GDP per capita most by 2043 with an additional US$413 above the Current Path forecast. The Combined Agenda 2063 scenario has the potential to raise GDP per capita in Lesotho to US$7 375 by 2043 — a significant US$2 135 above the Current Path forecast for the same year. Lesotho’s GDP is forecast to grow to US$12.4 billion by 2043 in the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario, compared to US$7.6 billion in the Current Path forecast — an increase of 62%. Jump to Combined Agenda 2063 scenario

All charts for Lesotho

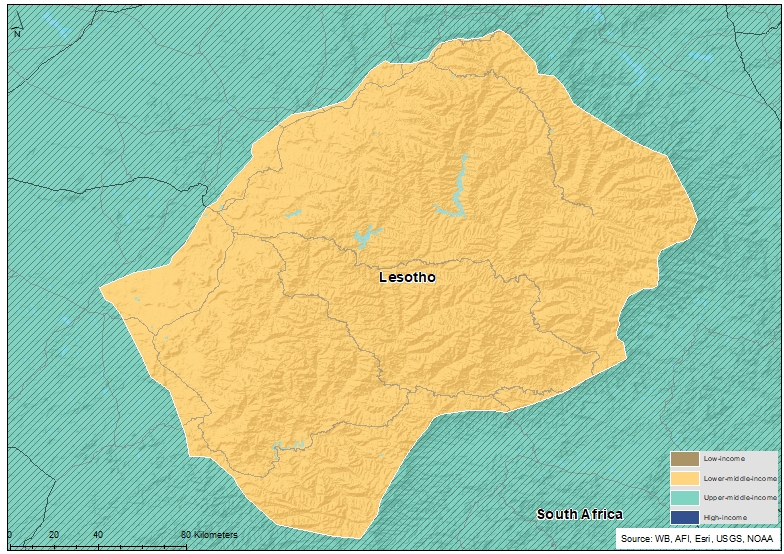

- Chart 1: Political map of Lesotho

- Chart 2: Population structure in CP, 1990–2043

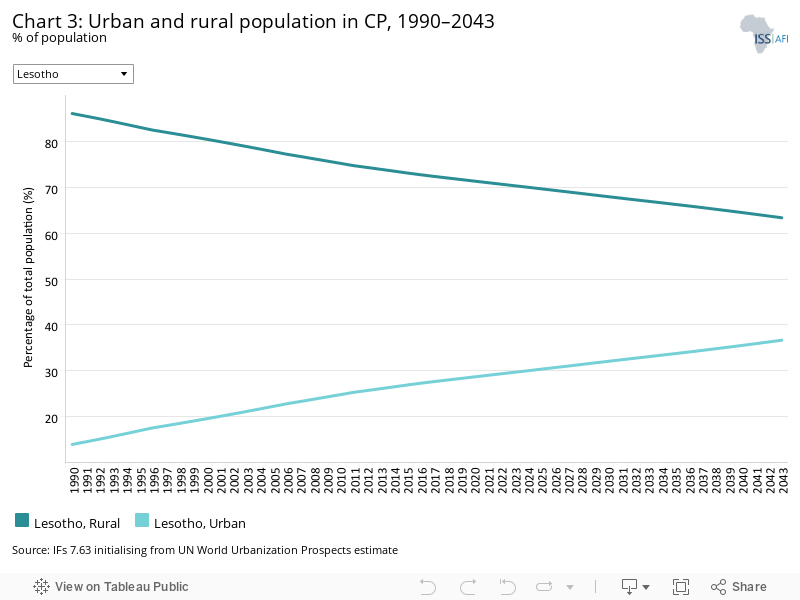

- Chart 3: Urban and rural population in CP, 1990–2043

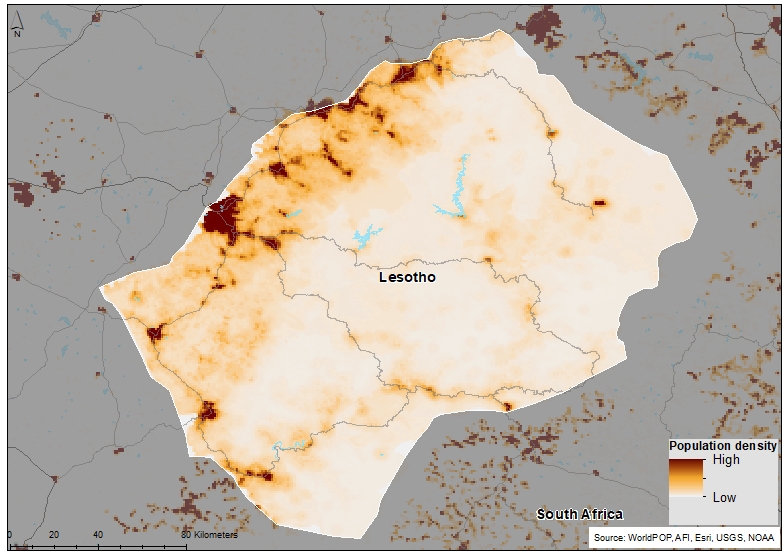

- Chart 4: Population density map for 2019

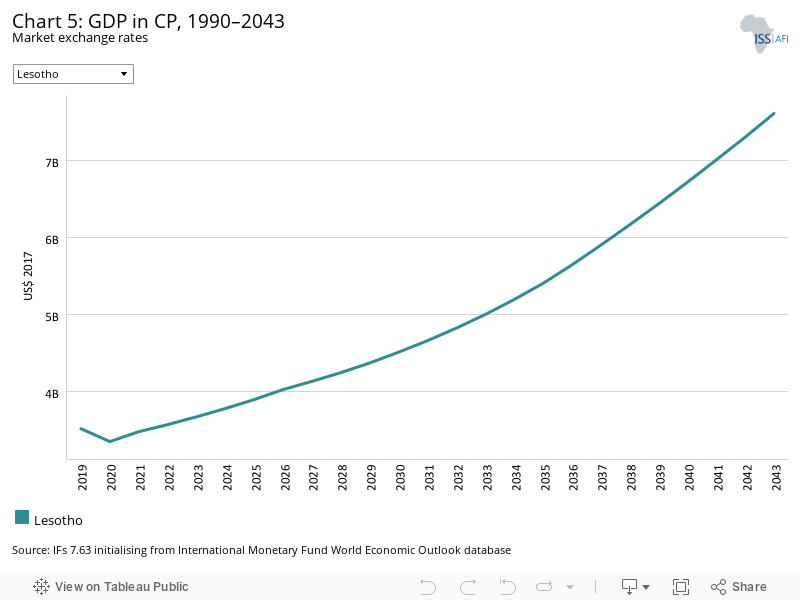

- Chart 5: GDP in CP, 1990–2043

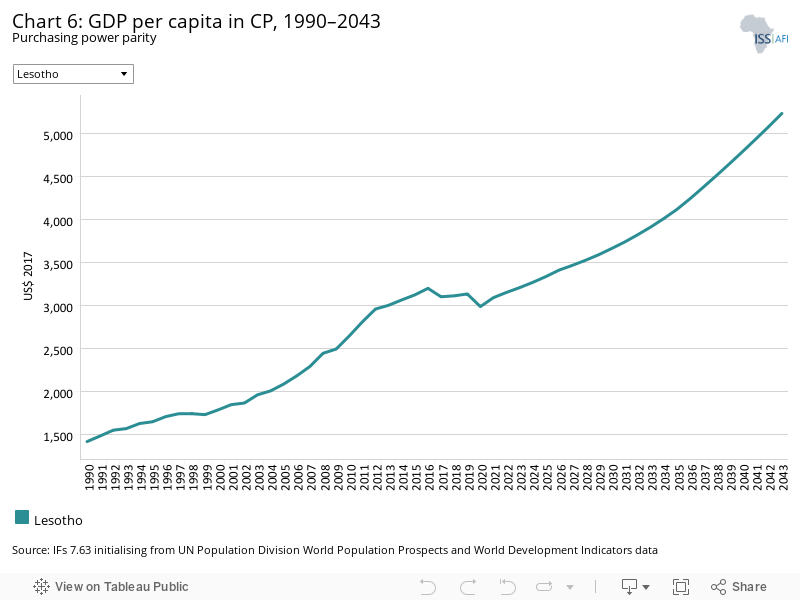

- Chart 6: GDP per capita in CP, 1990–2043

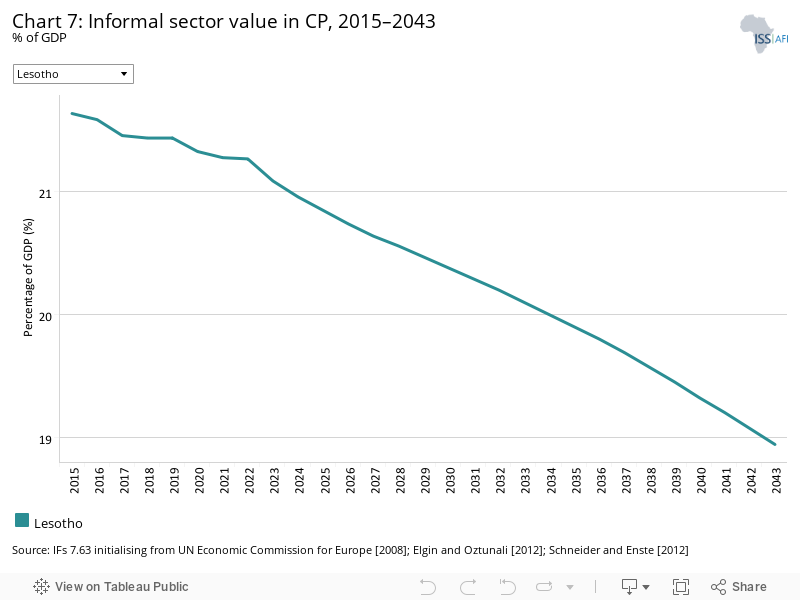

- Chart 7: Informal sector value in CP, 2015–2043

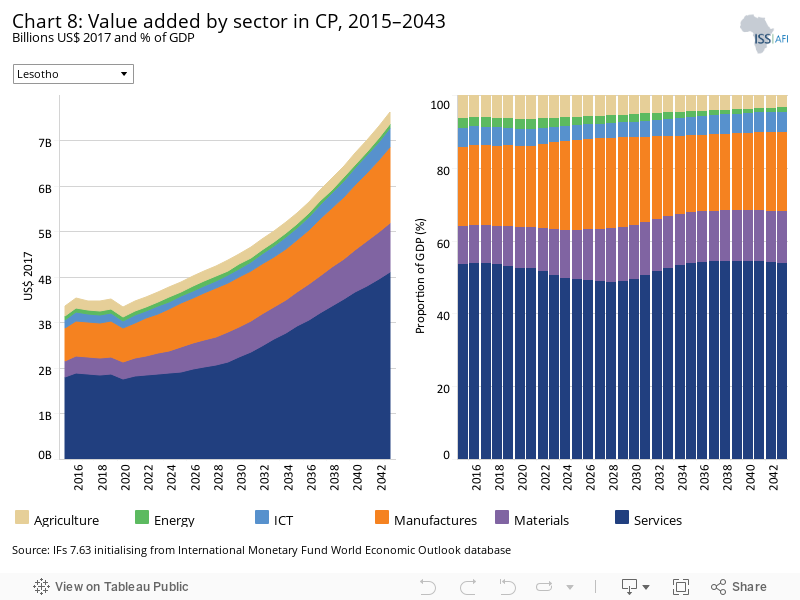

- Chart 8: Value added by sector in CP, 2015–2043

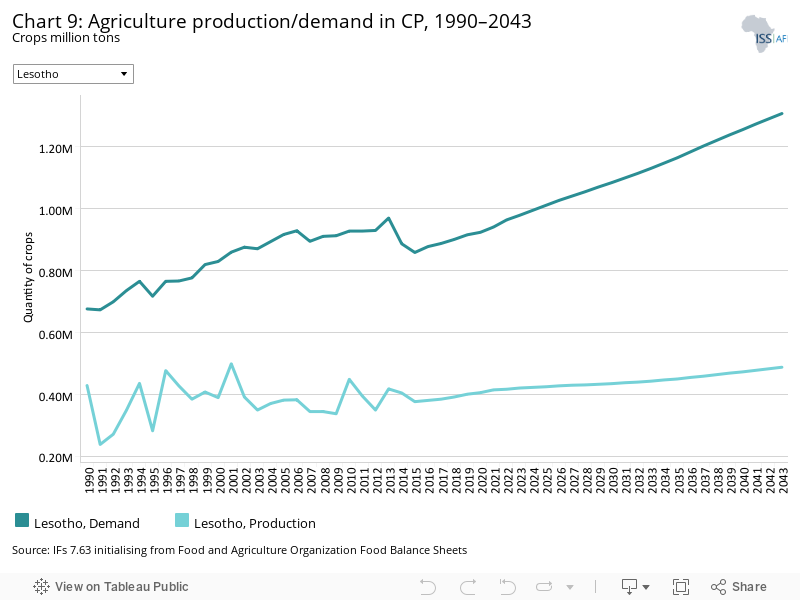

- Chart 9: Agriculture production/demand in CP, 1990–2043

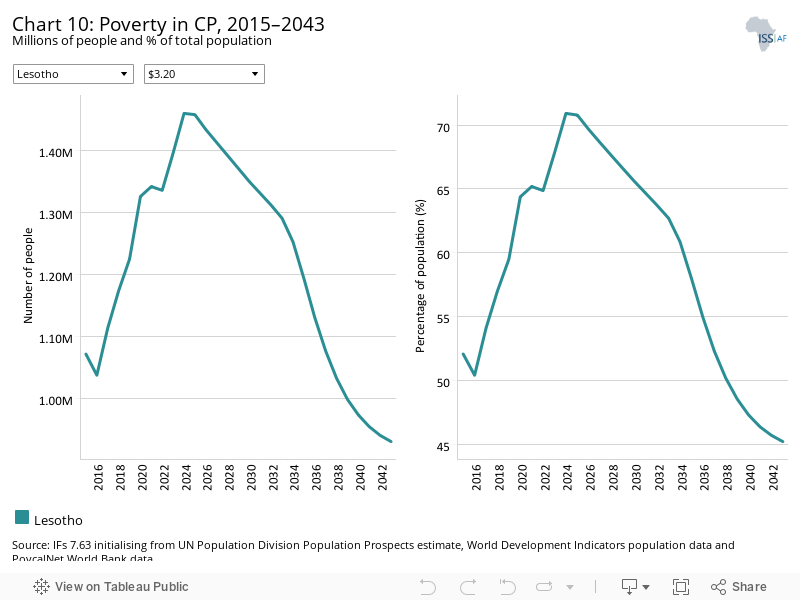

- Chart 10: Poverty in CP, 2015–2043

- Chart 11: Energy production by type in CP, 1990–2043

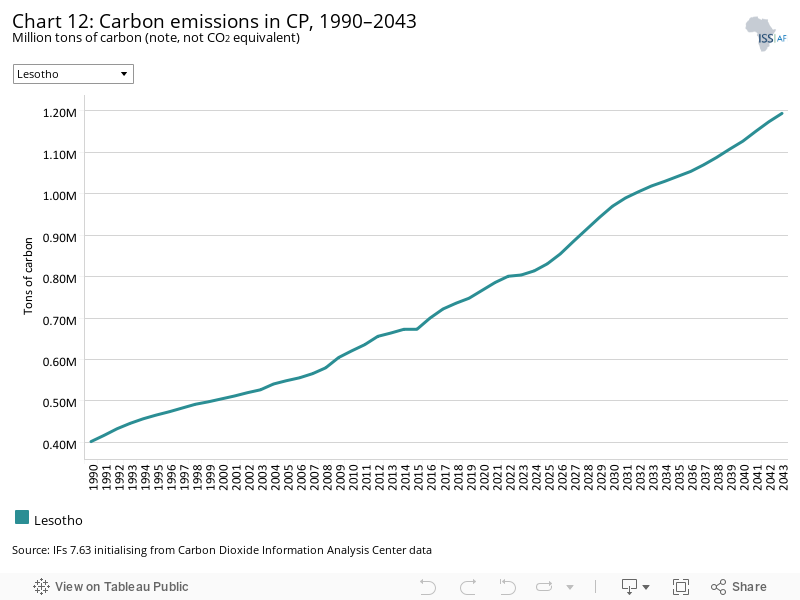

- Chart 12: Carbon emissions in CP, 1990–2043

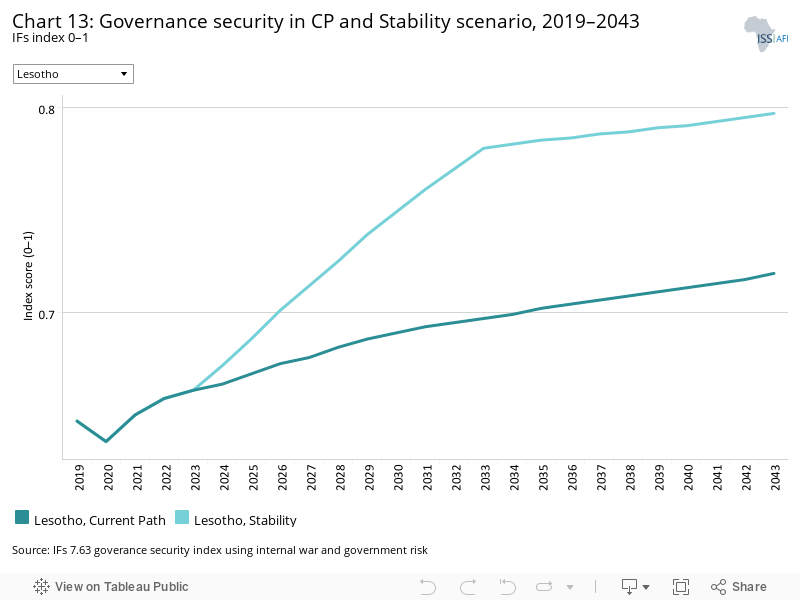

- Chart 13: Governance security in CP and Stability scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 14: GDP per capita in CP and Stability scenario, 2019–2043

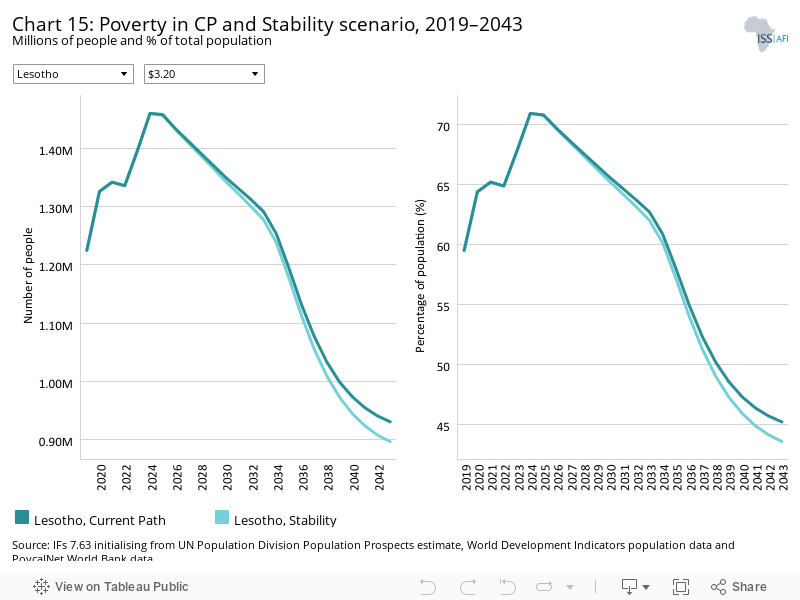

- Chart 15: Poverty in CP and Stability scenario, 2019–2043

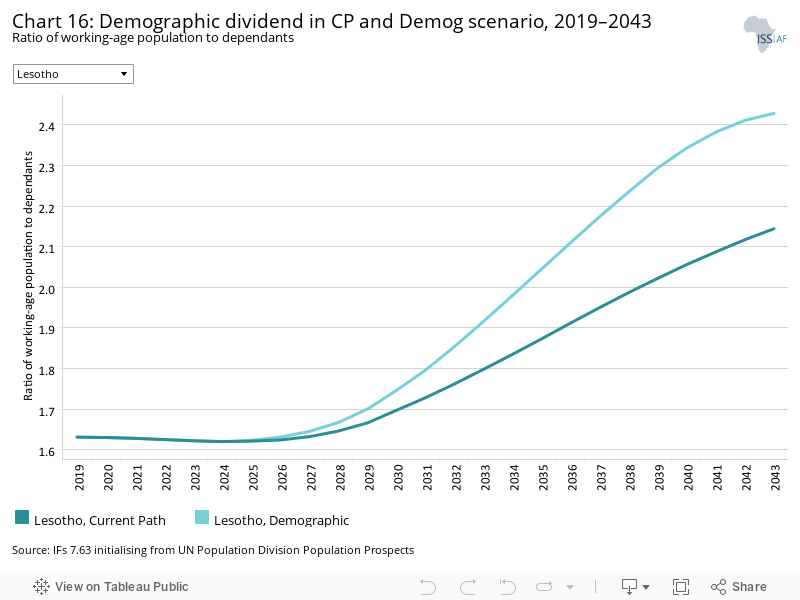

- Chart 16: Demographic dividend in CP and Demog scenario, 2019–2043

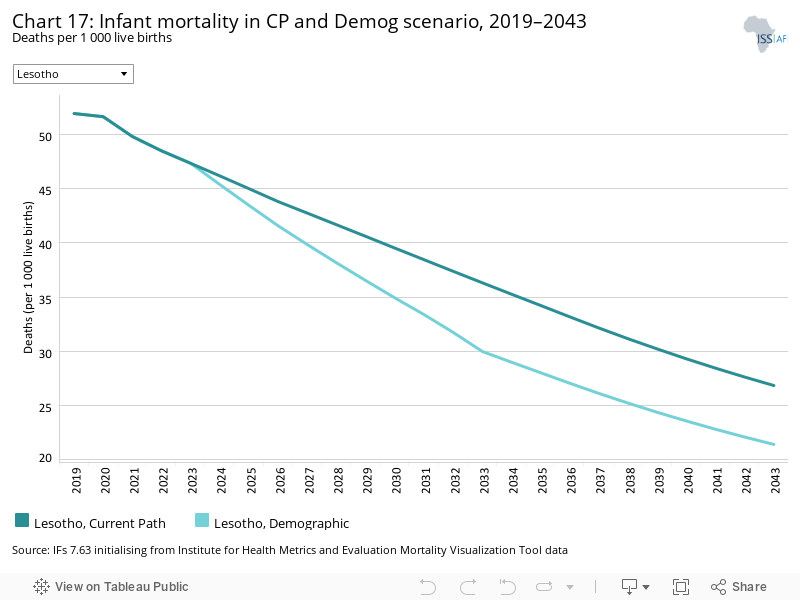

- Chart 17: Infant mortality in CP and Demog scenario, 2019–2043

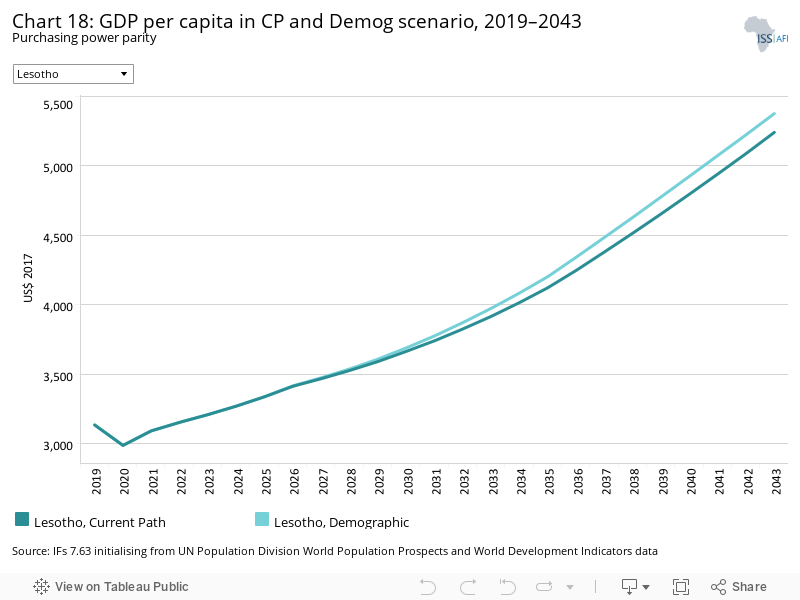

- Chart 18: GDP per capita in CP and Demog scenario, 2019–2043

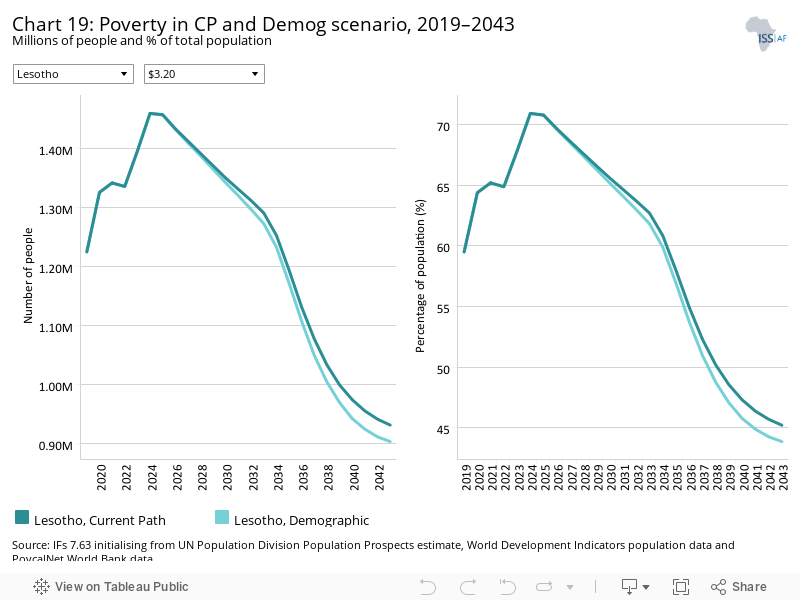

- Chart 19: Poverty in CP and Demog scenario, 2019–2043

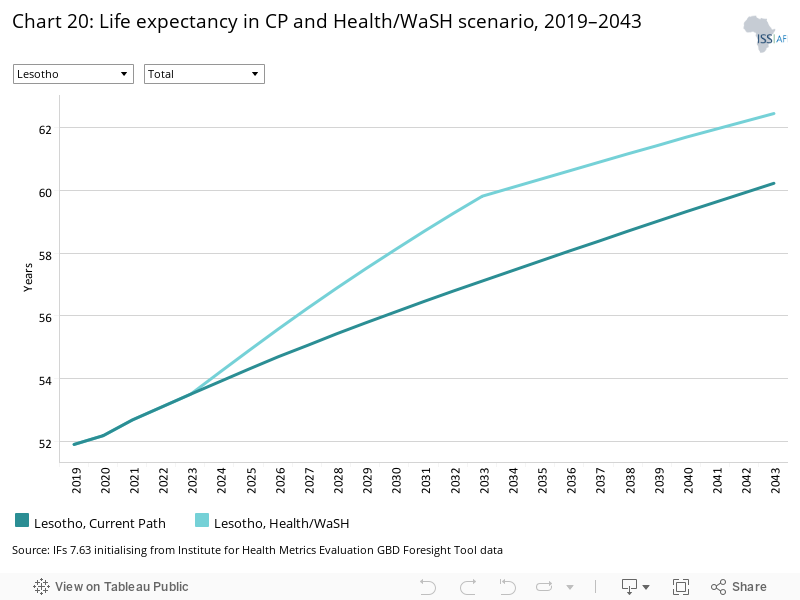

- Chart 20: Life expectancy in CP and Health/WaSH scenario, 2019–2043

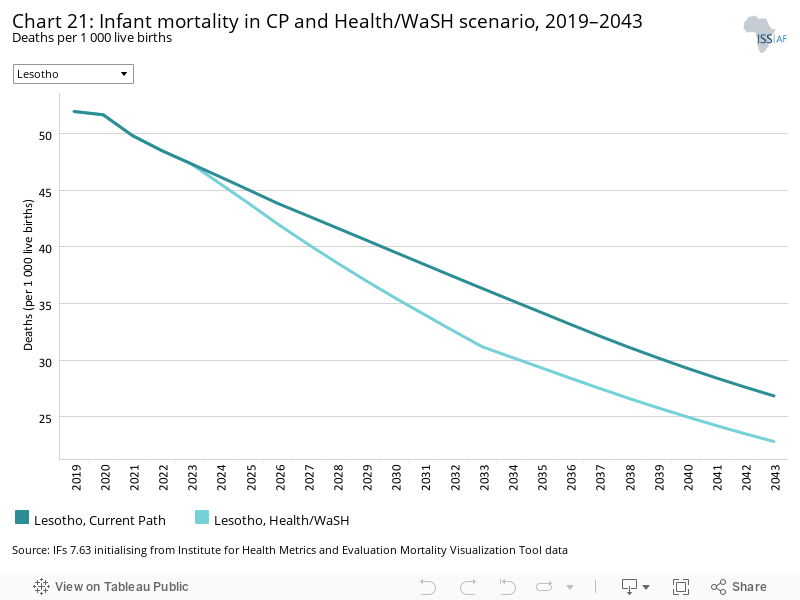

- Chart 21: Infant mortality in CP and Health/WaSH scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 22: Yield/hectare in CP and Agric scenario, 2019–2043

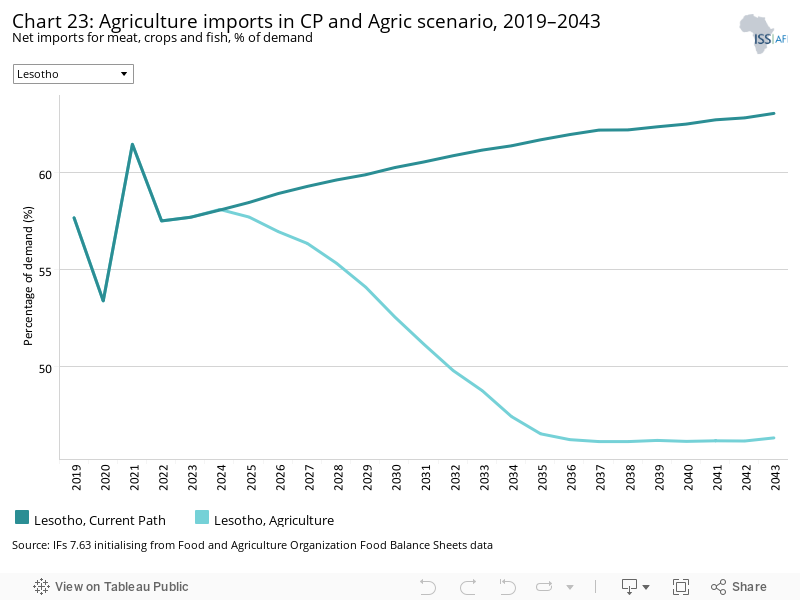

- Chart 23: Agriculture imports in CP and Agric scenario, 2019–2043

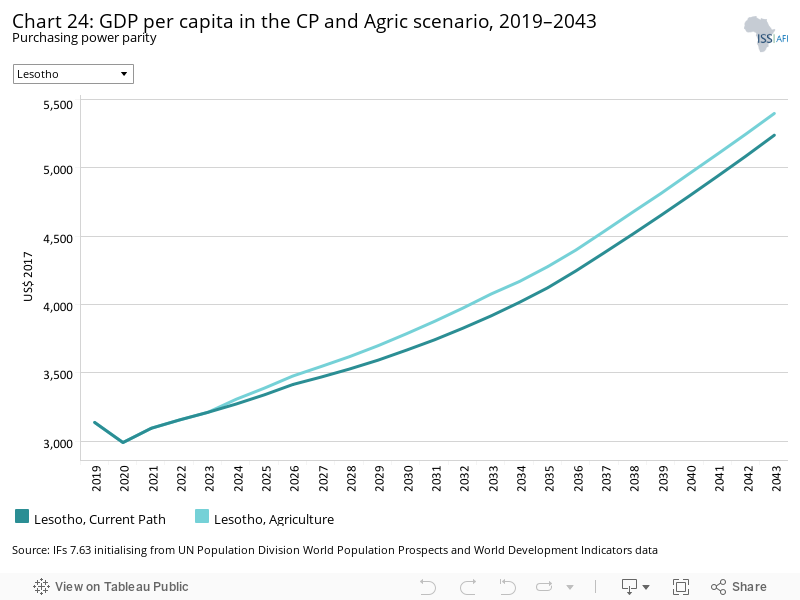

- Chart 24: GDP per capita in the CP and Agric scenario, 2019–2043

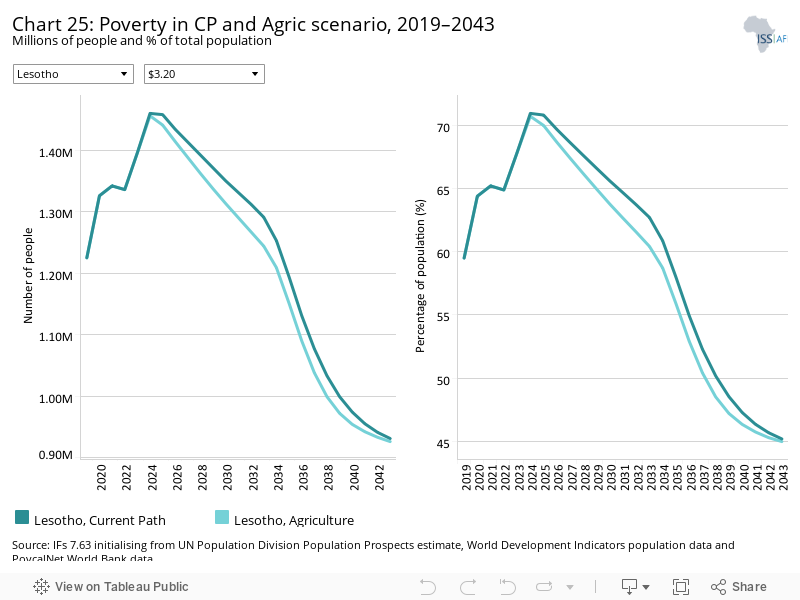

- Chart 25: Poverty in CP and Agric scenario, 2019–2043

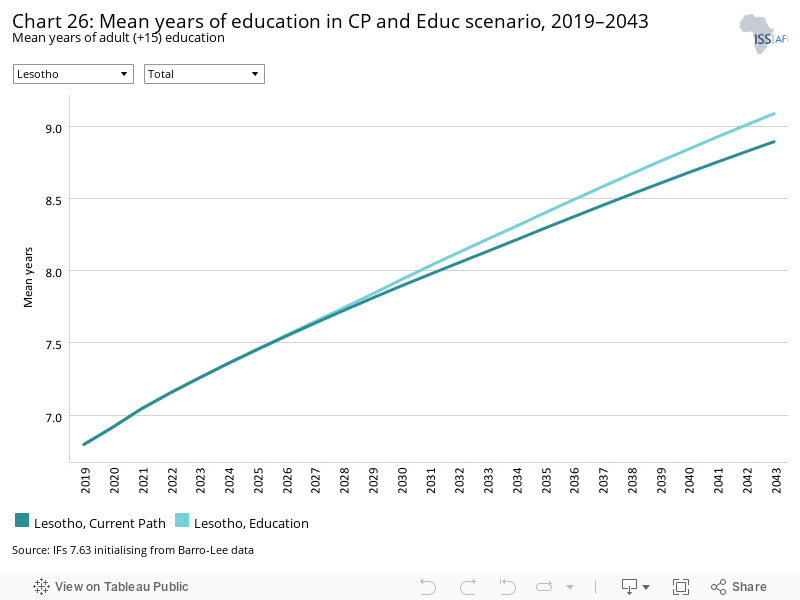

- Chart 26: Mean years of education in CP and Educ scenario, 2019–2043

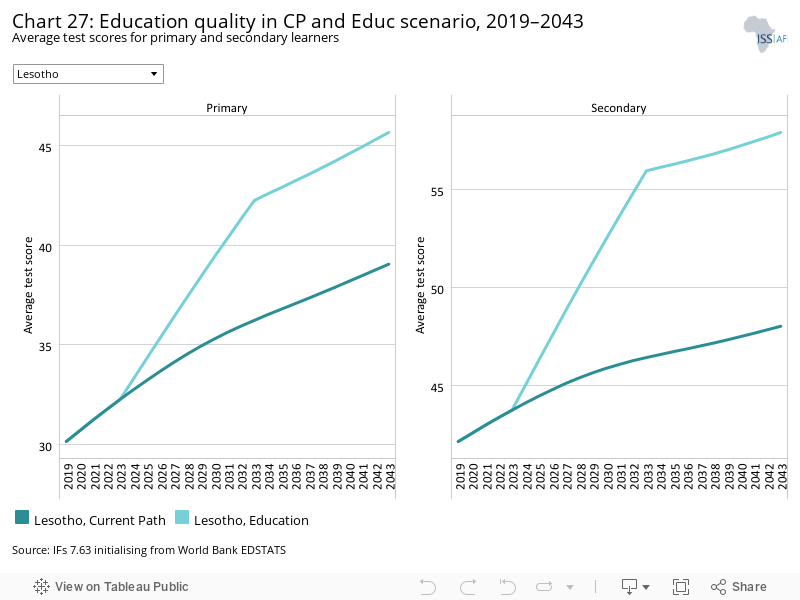

- Chart 27: Education quality in CP and Educ scenario, 2019–2043

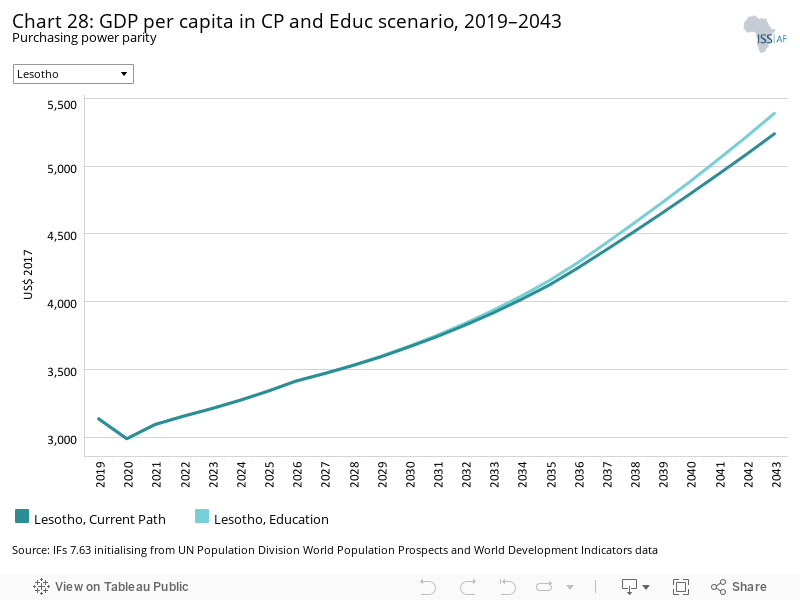

- Chart 28: GDP per capita in CP and Educ scenario, 2019–2043

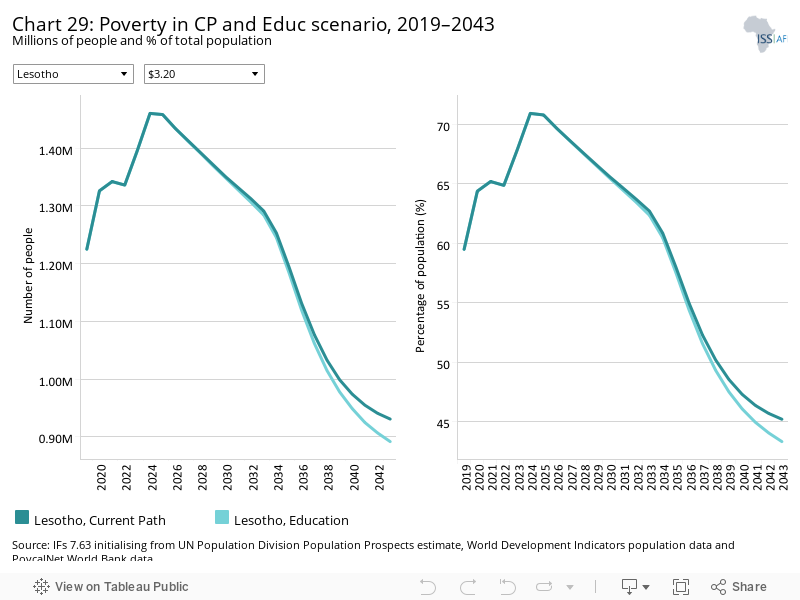

- Chart 29: Poverty in CP and Educ scenario, 2019–2043

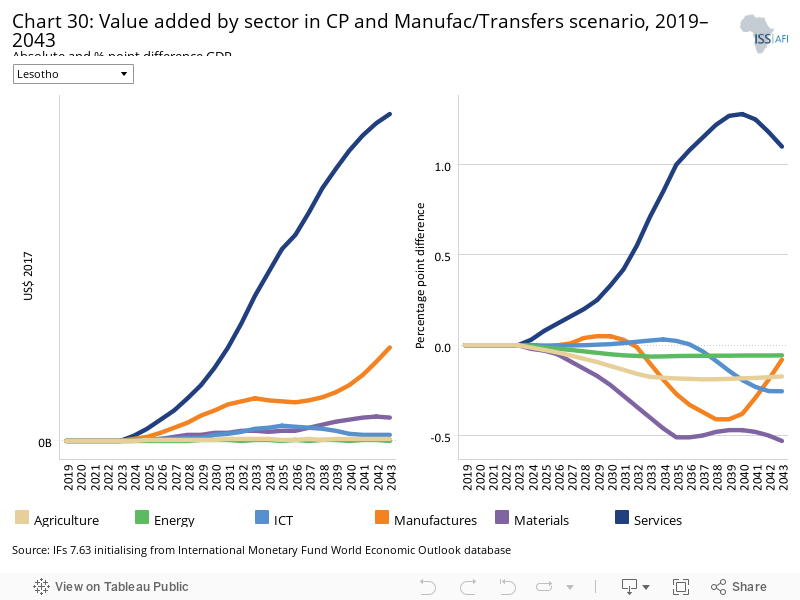

- Chart 30: Value added by sector in CP and Manufac/Transfers scenario, 2019–2043

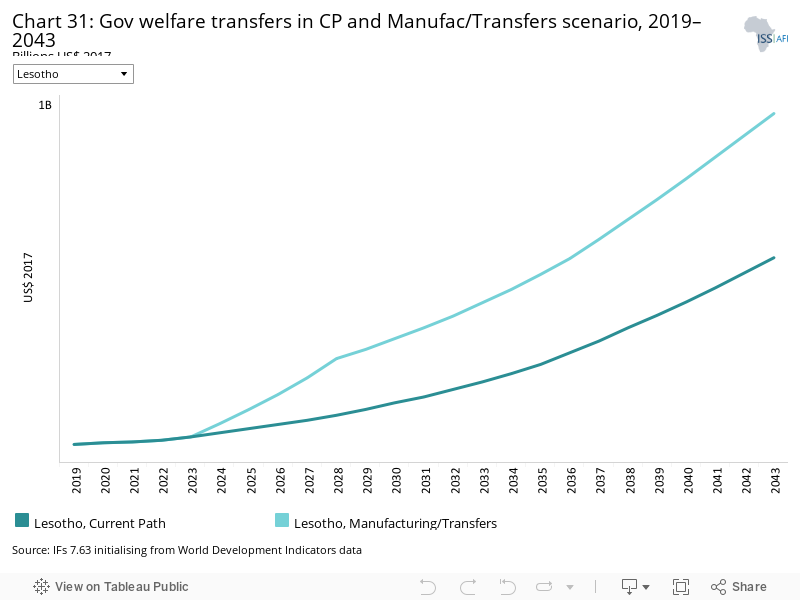

- Chart 31: Gov welfare transfers in CP and Manufac/Transfers scenario, 2019–2043

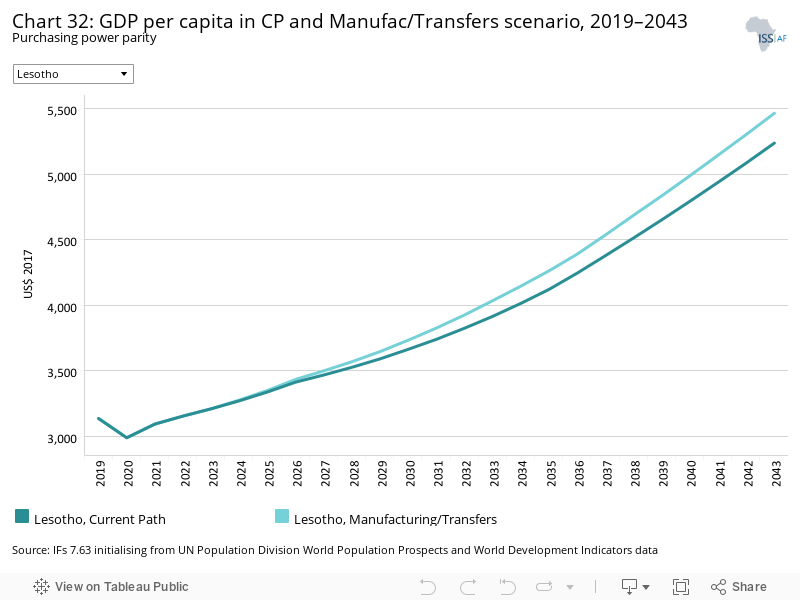

- Chart 32: GDP per capita in CP and Manufac/Transfers scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 33: Poverty in CP and Manufac/Transfers scenario, 2019–2043

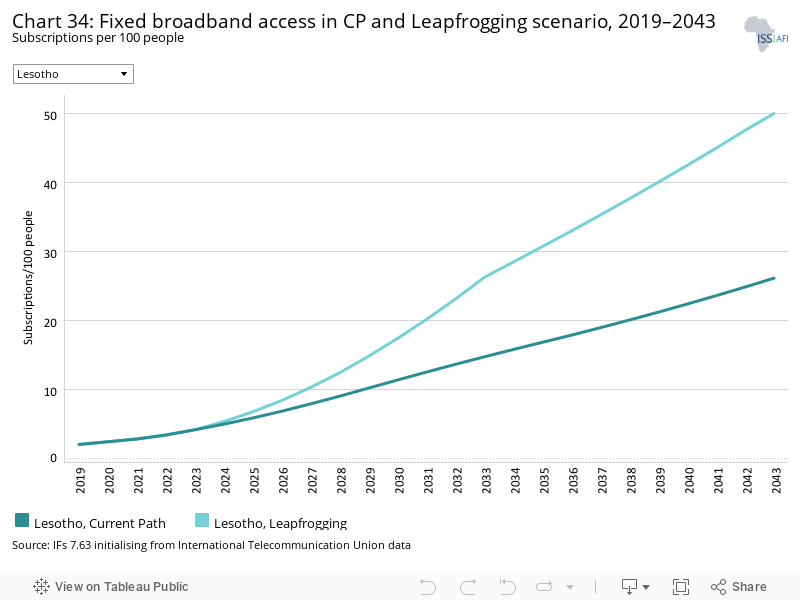

- Chart 34: Fixed broadband access in CP and Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

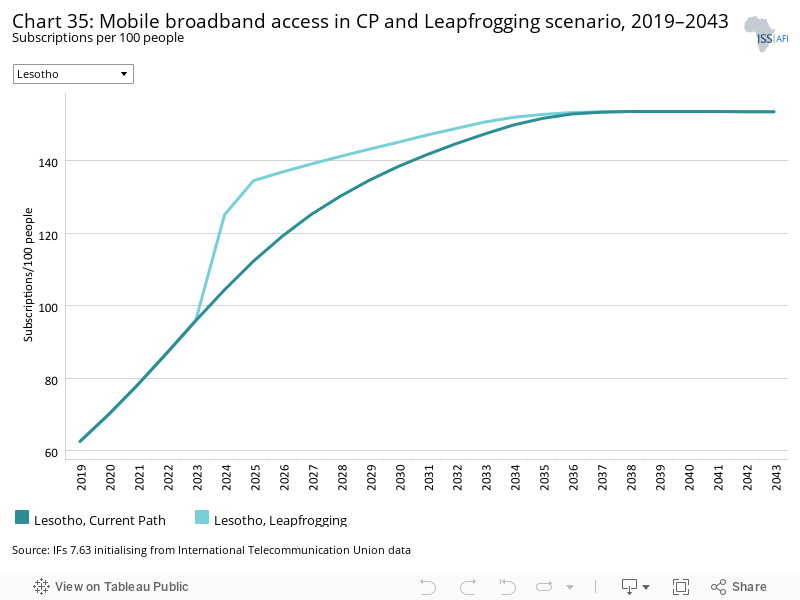

- Chart 35: Mobile broadband access in CP and Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

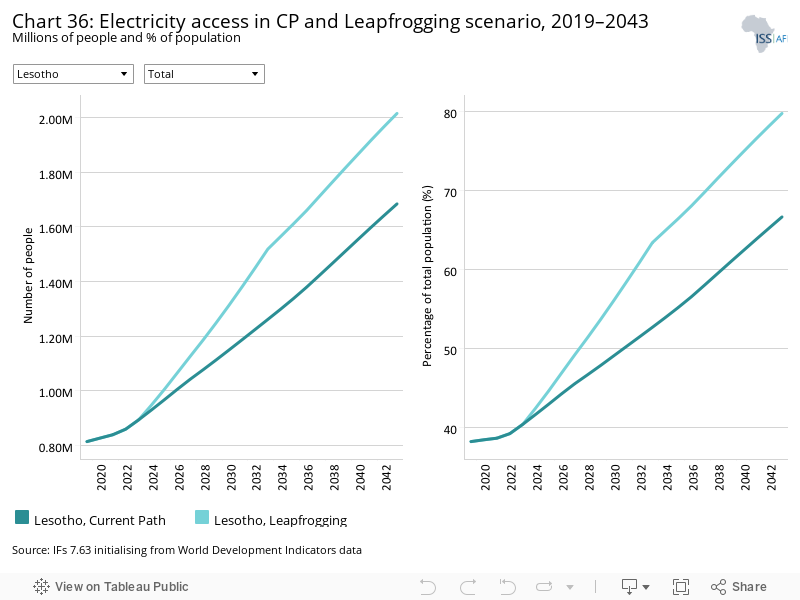

- Chart 36: Electricity access in CP and Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

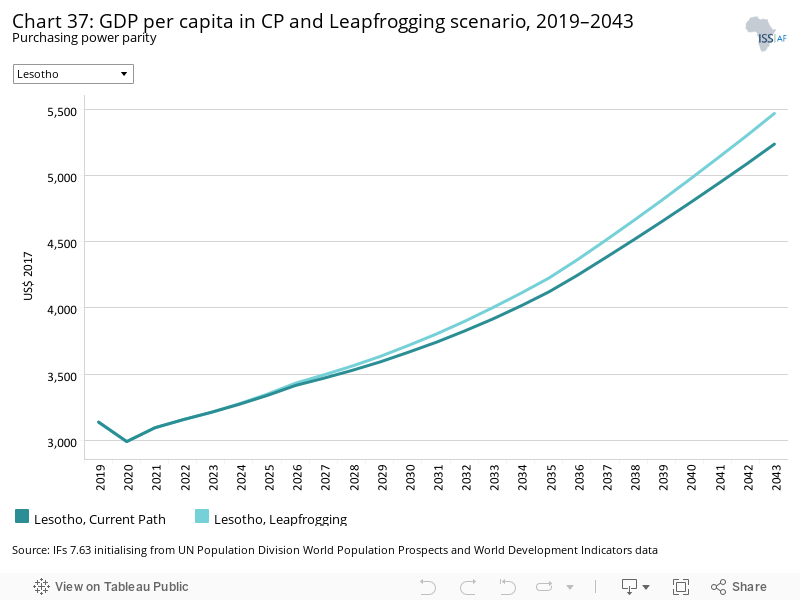

- Chart 37: GDP per capita in CP and Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

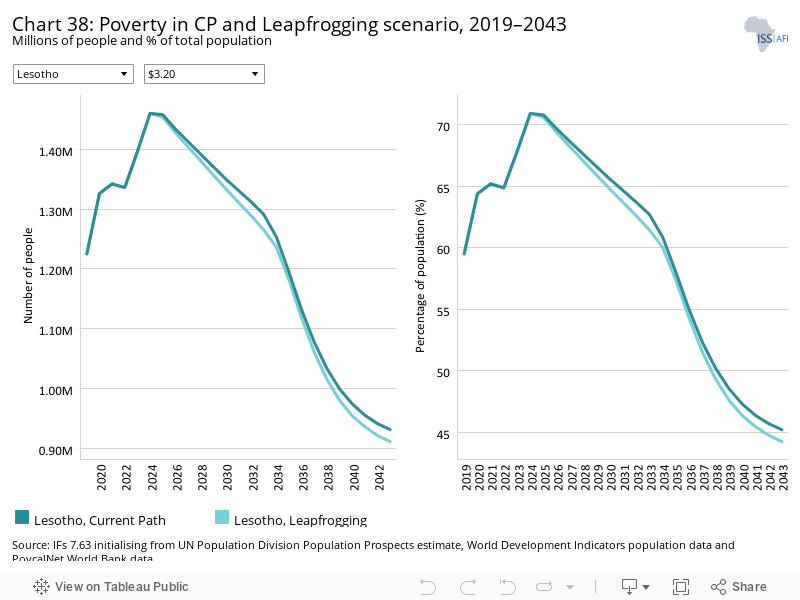

- Chart 38: Poverty in CP and Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

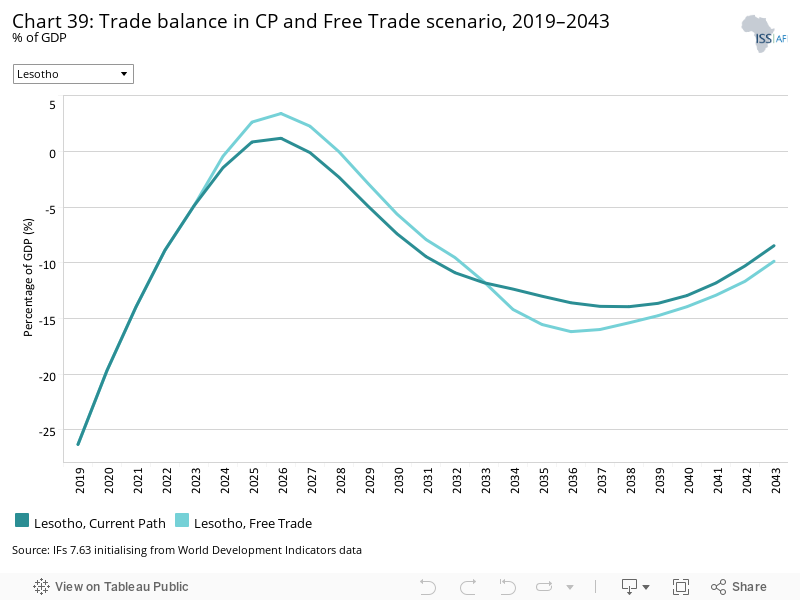

- Chart 39: Trade balance in CP and Free Trade scenario, 2019–2043

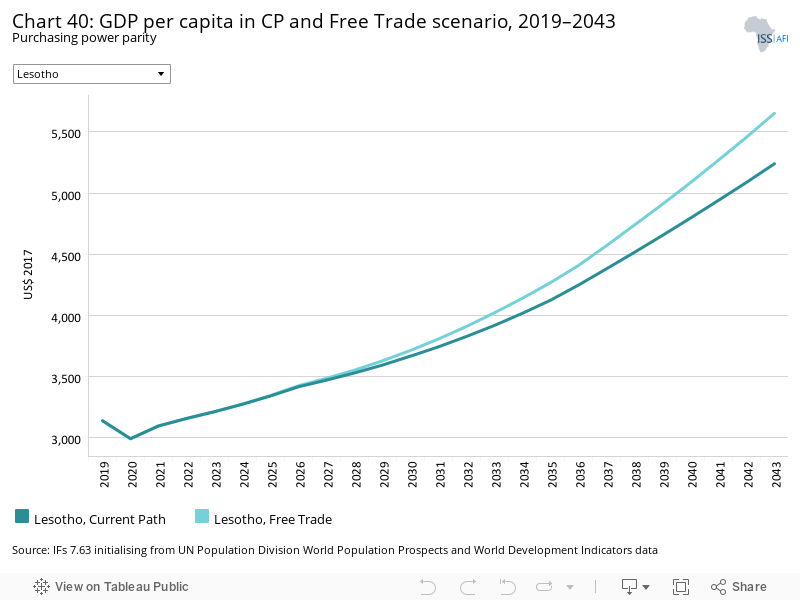

- Chart 40: GDP per capita in CP and Free Trade scenario, 2019–2043

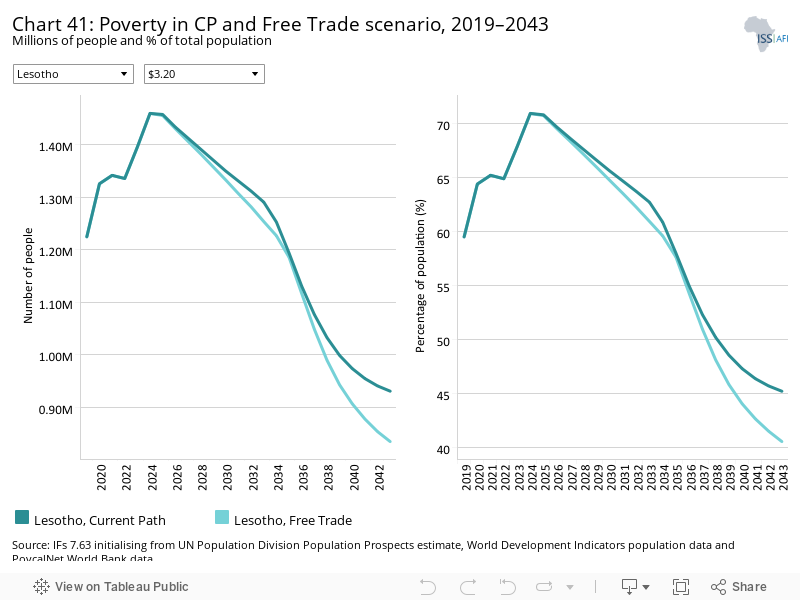

- Chart 41: Poverty in CP and Free Trade scenario, 2019–2043

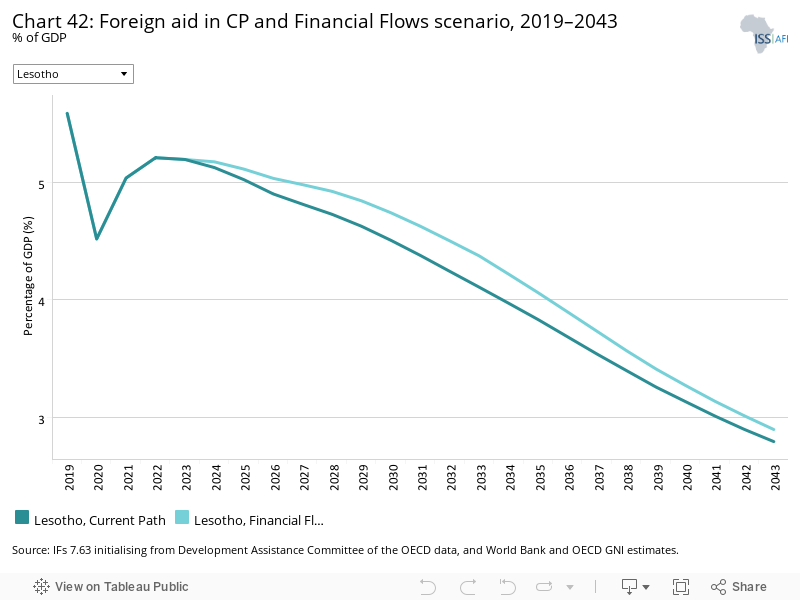

- Chart 42: Foreign aid in CP and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

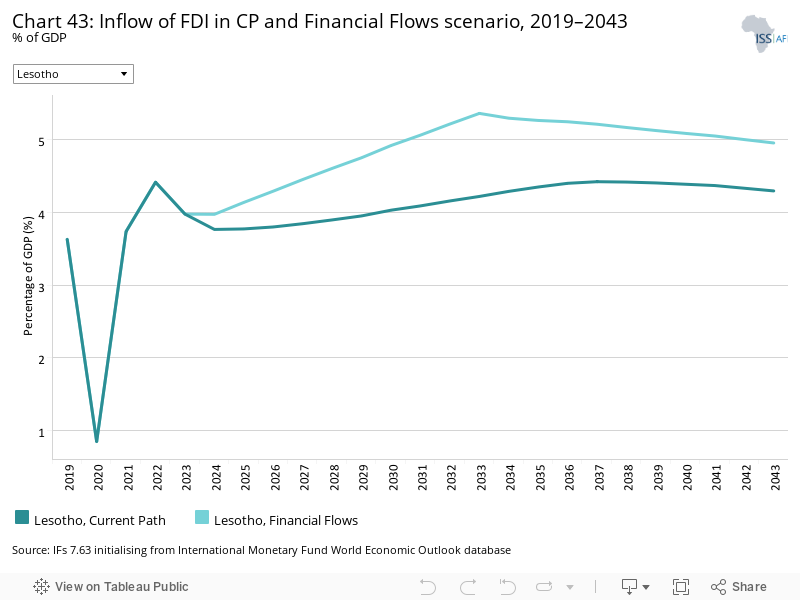

- Chart 43: Inflow of FDI in CP and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

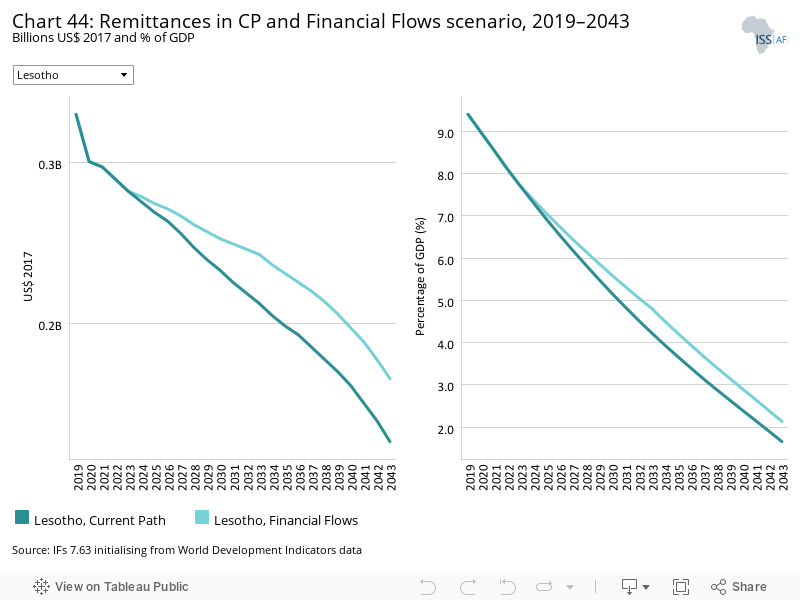

- Chart 44: Remittances in CP and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

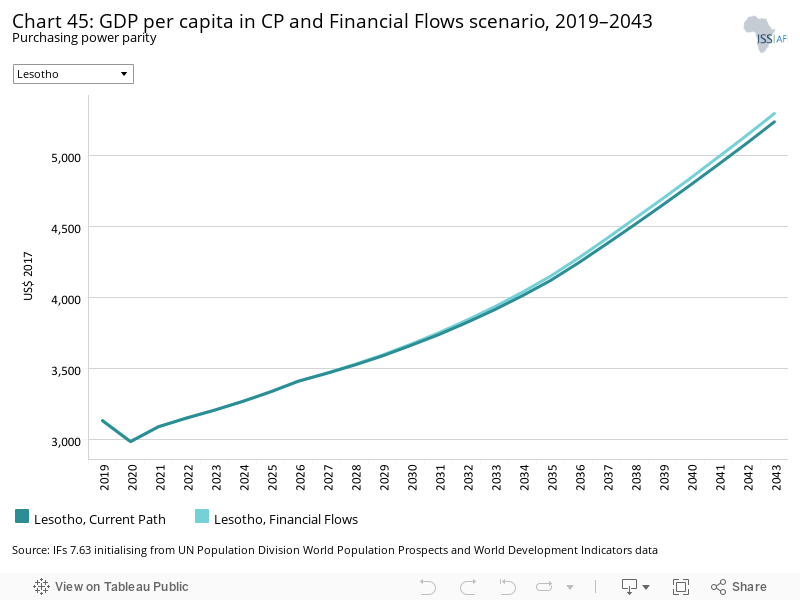

- Chart 45: GDP per capita in CP and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 46: Poverty in CP and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 47: Electricity access in CP and Infrastructure scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 48: Rural road access in CP and Infrastructure scenario, 2019–2043

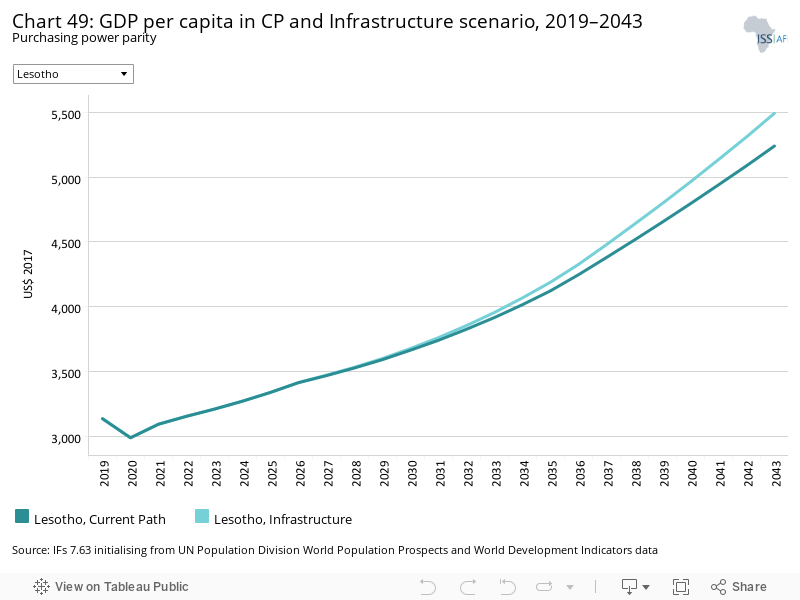

- Chart 49: GDP per capita in CP and Infrastructure scenario, 2019–2043

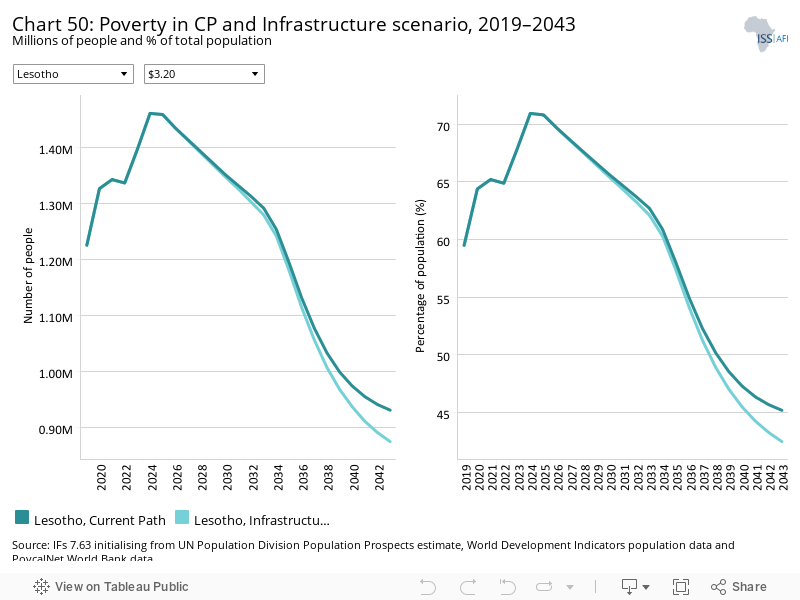

- Chart 50: Poverty in CP and Infrastructure scenario, 2019–2043

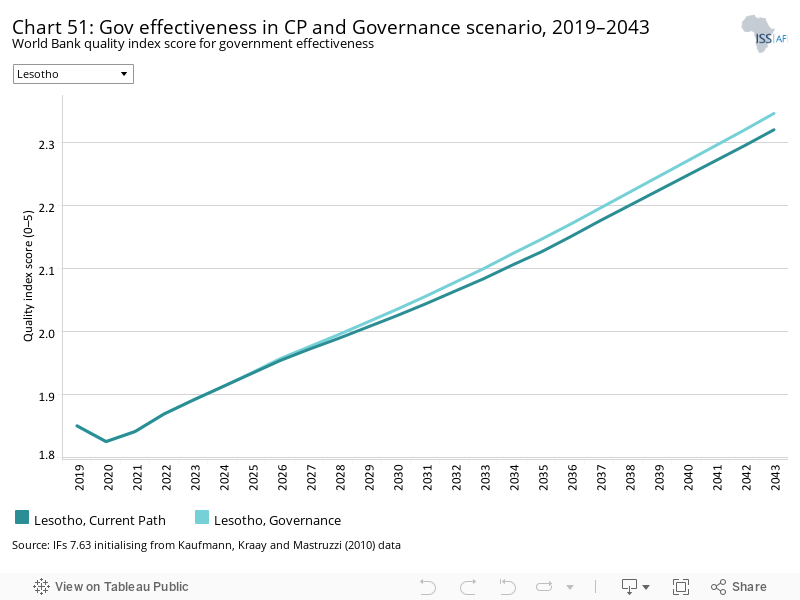

- Chart 51: Gov effectiveness in CP and Governance scenario, 2019–2043

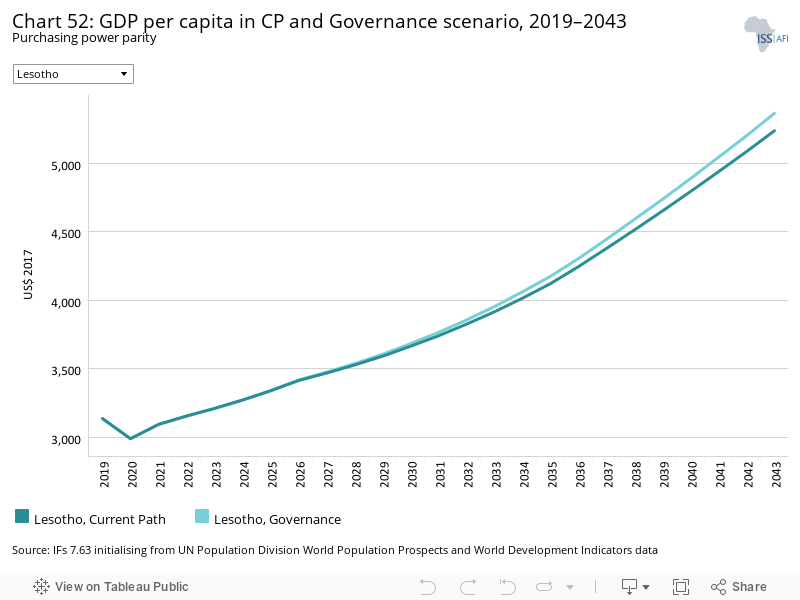

- Chart 52: GDP per capita in CP and Governance scenario, 2019–2043

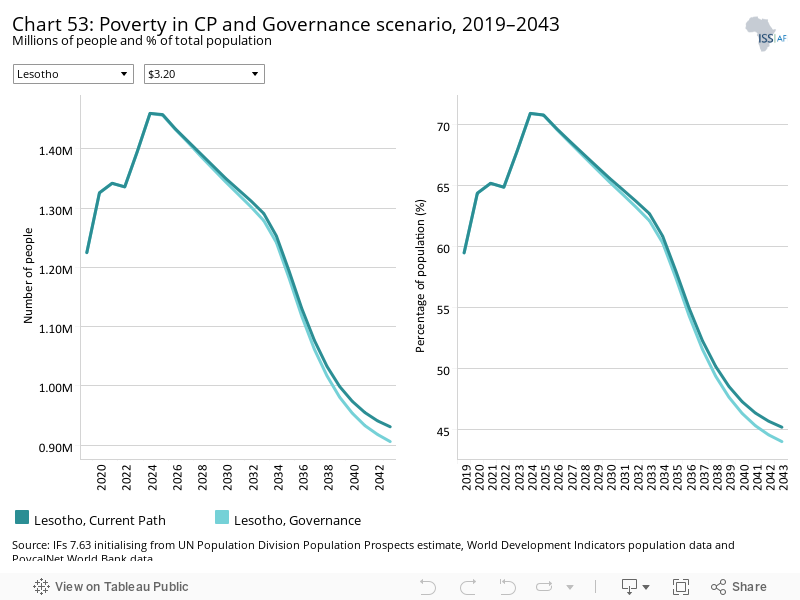

- Chart 53: Poverty in CP and Governance scenario, 2019–2043

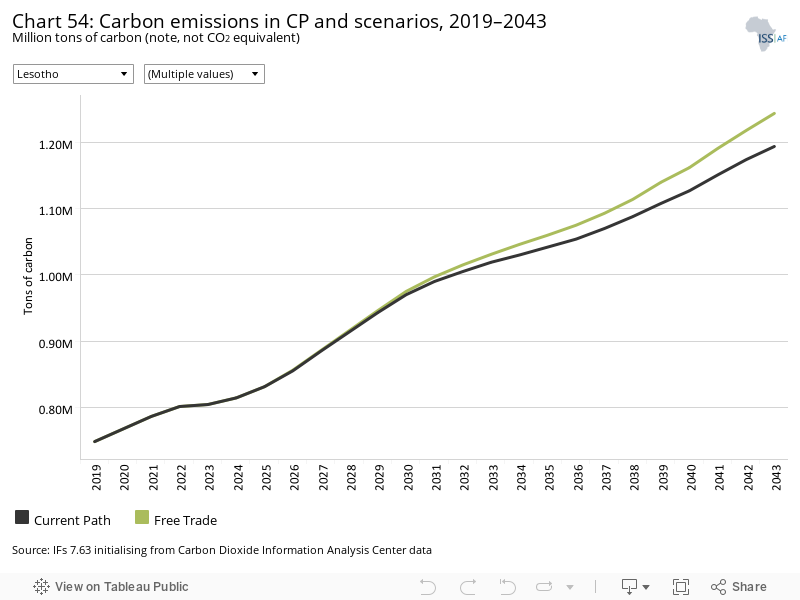

- Chart 54: Carbon emissions in CP and scenarios, 2019–2043

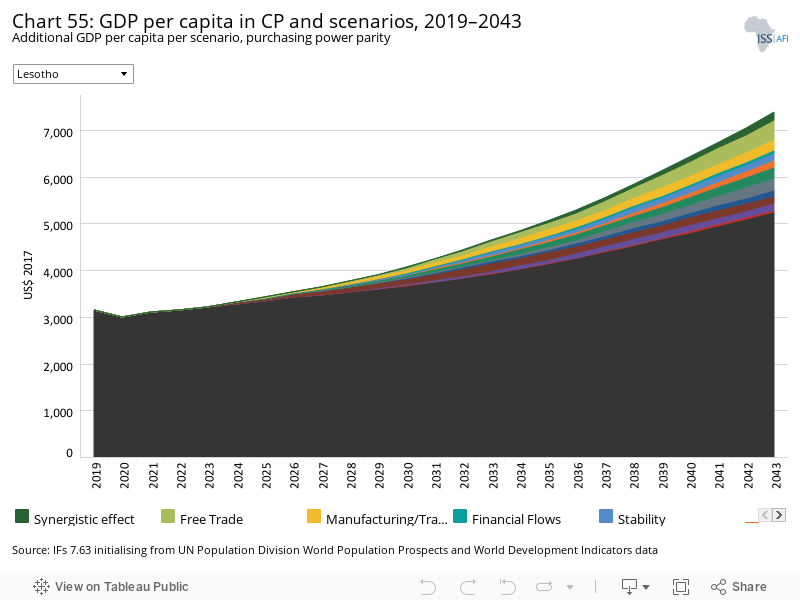

- Chart 55: GDP per capita in CP and scenarios, 2019–2043

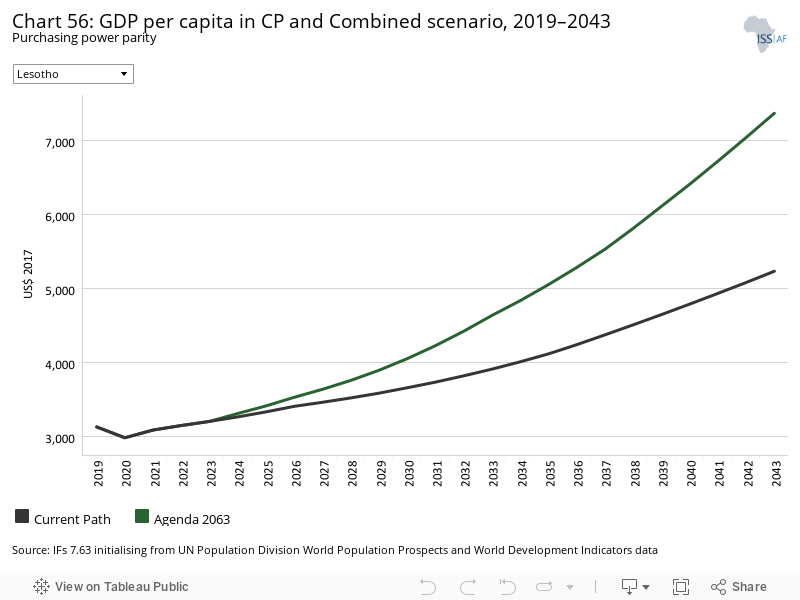

- Chart 56: GDP per capita in CP and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

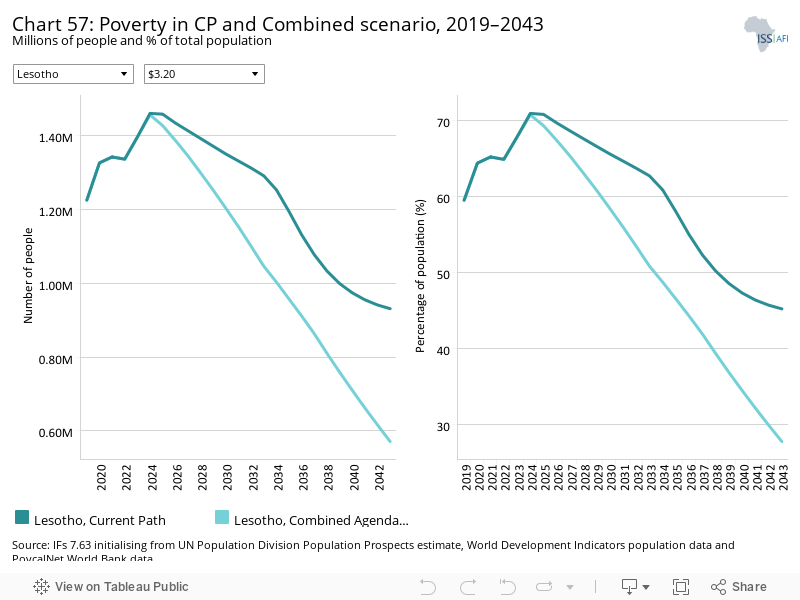

- Chart 57: Poverty in CP and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

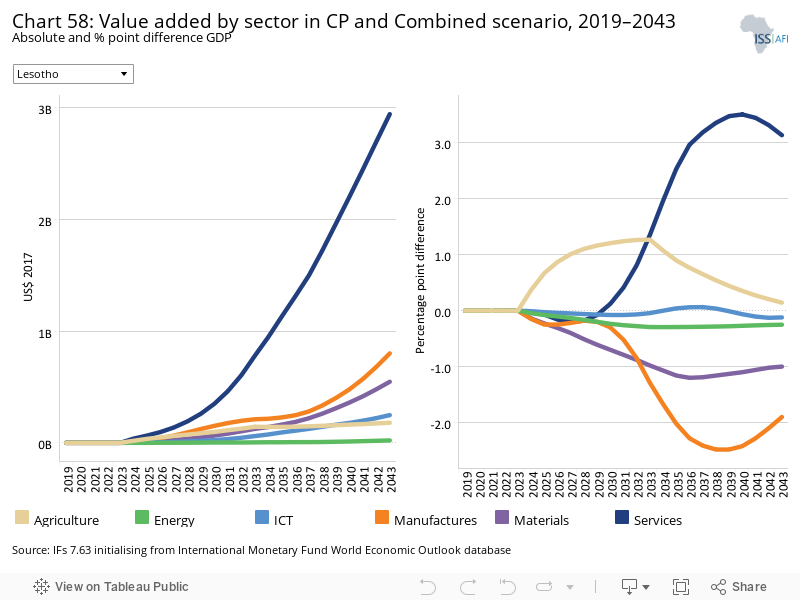

- Chart 58: Value added by sector in CP and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 59: GDP in CP and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 60: Carbon emissions in CP and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

This page provides an overview of the key characteristics of Lesotho along its likely (or Current Path) development trajectory. The Current Path forecast from the International Futures forecasting (IFs) platform is a dynamic scenario that imitates the continuation of current policies and environmental conditions. The Current Path is therefore in congruence with historical patterns and produces a series of dynamic forecasts endogenised in relationships across crucial global systems. We use 2019 as a standard reference year and the forecasts generally extend to 2043 to coincide with the end of the third ten-year implementation plan of the African Union’s Agenda 2063 long-term development vision.

The Kingdom of Lesotho is a landlocked country surrounded solely by South Africa. It is a member of the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and is one of 23 lower middle-income countries according to the World Bank’s income classification.

Even though it is located in the subtropical zone between the latitudes of 28° S and 30° S, its high altitude causes the country to experience cooler conditions, and it claims the spot as the coldest African country. Lesotho is home to the highest mountain ranges in Southern Africa and boasts mineral-rich soils. However, the rugged topography and subsistence farming practices subject the country to severe soil erosion.

Lesotho has abundant natural water resources and shares the Orange-Senqu River basin with South Africa. It therefore plays a critical role in the complex bulk water supply infrastructure system of South Africa. The bi-national Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) between Lesotho and South Africa significantly shaped Lesotho’s physical road infrastructure at the beginning of the century, opening up the highlands and making it much more accessible and reachable. The LHWP has also significantly altered the water storage landscape within the country, was the initial catalyst in decreasing the country’s energy dependency on South Africa, and has been pivotal in securing water for South Africa’s economic heartland, Gauteng.

Its troubled political history and current infighting however are likely to expose the country to ongoing and vast development challenges in the years ahead. Lesotho’s development prospects are unpacked in more detail in the subsequent charts.

Lesotho’s population of 2.1 million in 2019 makes it the tenth smallest country in Africa. The country’s ethnicity is homogenous with the vast majority of people belonging to the Basotho (Sotho) ethnic group. The total fertility rate has dropped significantly in the past three decades in Lesotho, down from 5 births per woman in 1990 to just over 3.1 in 2019. This has resulted in Lesotho’s population growing at a slower rate compared to the average for low middle-income African countries that had a fertility rate of 4.2 births per woman in 2019. In the Current Path forecast, the population is expected to reach only 2.5 million people by 2043, growth of about 19% in the population, equivalent to 400 000 people in the next 24 years.

This significant drop in fertility rates has and continues to alter the age structure of the country with the median age expected to increase from 23.2 years in 2019 to 27 years by 2043. The country has a small elderly population with fewer than 100 000 people in 2019 aged 65 and over representing 5% of the population. This figure will remain low with 129 000 elderly expected in 2043. The absolute number of young people (aged below 15 years) will decline in the Current Path forecast from 713 000 in 2019 to 675 000 by 2043. This will result in the percentage of the working-age population (aged 15–64) growing from 62% in 2019 to 68.2% in 2043.

Prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019, the country was on the cusp of a demographic dividend window. It is expected that in the Current Path forecast the country is likely to reap the benefits of a demographic dividend by 2030 with the labour force increasing from 977 000 people in 2019 to 1.3 million by 2043. To reap the benefits of this demographic window, Lesotho will have to create thorough social policies, grow employment opportunities in labour-intensive sectors and foster a sound economic investment environment.

Lesotho is a predominantly rural country with 72% of its population in 2019 living in rural spaces — the third highest rural percentage for low middle-income Africa. More than 50% of Lesotho’s 605 000 urban population lives in the capital of Maseru and the rest is located through a small network of towns and villages (see Chart 4). Even with a sustained urbanisation rate, the country will urbanise much slower than its income peers. In 2043, Lesotho will have an urbanisation rate of close to 37%, 22 percentage points below the average for lower middle-income African countries. It remains imperative, however, that the country addresses urbanisation sustainably to avoid and to tackle the growing informal housing trend in its capital, Maseru.

Lesotho’s population distribution reflects its mountainous geography. The vast majority of the population is located in the warmer western plains below the 2 000 m altitude mark. Small pockets of rural clusters can also be observed throughout the mountainous highlands but within the valleys next to the meandering rivers where altitudes drop below 2 000 m. The highlands and mountainous peaks are sparsely populated and much of the subsistence agricultural practices take part in the various valleys and river beds.

The country is just over 30 500 km2 with an average density of 0.7 people per hectare. The density however ranges from 36.7 in densely built up areas in Maseru to almost uninhabitable areas on the various mountain peaks. The western lowlands are characterised by more densely populated croplands with an average density of 9.7 people per hectare. In the Current Path forecast, population density is likely to increase to 0.8 people per hectare by 2043 with the croplands increasing densities to 11.2 people per hectare.

Lesotho’s enclaved nature within South Africa makes it inseparable from the economic landscape thereof. Its small economy is based on remittances from labour workers employed in South Africa, SACU revenue inflows, subsistence agriculture, diamond mining, small-scale industries (textiles), construction related to the various phases of the LHWP and limited tourism. South Africa also pays royalties to Lesotho for its water imports as part of the LHWP Phase 1. Aside from abundant water resources and diamond mining within the highlands, the country is poor in natural resources and depends heavily on imports of goods and foodstuffs.

The 1970s saw GDP growth rates reaching 8% due to SACU revenues, remittances from labour workers in South Africa, external aid inflows, a booming agriculture sector and increased diamond mining. In the 1980s and 1990s, GDP growth was sustained at around 4% with a boost from the construction sector as the LHWP took off. The early part of the century saw growth in manufacturing and a thriving textile export industry.

The country has however experienced a retraction in its economy since 2016, the result of turbulent political infighting, slow economic growth in South African, diminishing revenues from remittances from migrant workers and SACU inflows and the textile industry struggling to compete with Asia.

In 2019, Lesotho’s small economy ranked fifth smallest among its income peers at US$3.5 billion. In the Current Path forecast, GDP will grow to US$7.6 billion by 2043, with growth rates above 4% from 2035 onwards. Even with a sustained growth rate Lesotho will remain among the five smallest low middle-income economies in Africa in 2043.

Although many of the charts in the sectoral scenarios also include GDP per capita, this overview is an essential point of departure for interpreting the general economic outlook of Lesotho.

In 1990, Lesotho was the worst performing in regard to GDP per capita among the 23 lower middle-income African countries with an estimated GDP per capita of US$1 416. The country has improved this position, ranking 19th in 2019 with a value of US$3 136, but this is still US$1 819 below the average for Africa and less than half the average for lower middle-income Africa at US$6 989. Lesotho’s income gap to lower middle-income Africa has persistently increased from US$3 007 in 1990 to US$3 853 in 2019.

In the Current Path forecast, the country is expected to remain in 19th position by 2043 among lower middle-income countries in Africa with a GDP per capita of US$5 240. The gap to lower middle-income Africa will grow to US$4 102 in 2043.

Lesotho has a small informal sector compared to the rest of Africa and lower middle-income Africa. In 2019, the size of the informal economy was estimated at 21.4% of GDP, amounting to a value of US$692 million. This is 4.5 percentage points lower than the average for Africa and 7.8 percentage points lower than the average for lower middle-income economies in Africa.

In 2019, 34% of Lesotho’s labour force worked in the informal economy. In the Current Path forecast, this value is projected to decrease more, dropping to 29% by 2043. It is also forecast that the value of the informal sector as a per cent of GDP will decline to 18.9% by 2043. This will amount to an informal economy to a value of US$1.3 billion, 7.5 percentage points lower than its African income peers.

The IFs platform uses data from the Global Trade and Analysis Project (GTAP) to classify economic activity into six sectors: agriculture, energy, materials (including mining), manufacturing, service and information and communication technologies (ICT). Most other sources use a threefold distinction between only agriculture, industry and services with the result that data may differ.

Lesotho’s economic structure has changed from an economy dominated by agriculture, real estate and government services in the 1980s to one of manufacturing, retail and services. The country has a small economic base that is interwoven with that of South Africa and on the Current Path the structure is likely to remain the same throughout the forecast horizon.

At 53.1% (US$1.9 billion) in 2019, the service sector makes up the largest percentage of GDP contribution by sector, and it is projected to remain the dominant contributor at 53.9% (valued at US$4.1 billion) by 2043. The manufacturing sector is currently the second largest contributor to the economy at 22.2% (valued at US$800 million) in 2019 and is forecast to decline to 21.8% (valued at US$1.7 billion) by 2043.

The materials sector is expected to grow by 3.2 percentage point from 10.9% in 2019 to 14.1% by 2043, expanding the GDP contribution of this sector from US$400 million to US$1.1 billion. In the Current Path forecast, the agriculture sector is expected to continue declining to 2043, shrinking from 6.3% in 2019 to 3.4% in 2043.

The data on agricultural production and demand in the IFs forecasting platform initialises from data provided on food balances by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). IFs contains data on numerous types of agriculture but aggregates its forecast into crops, meat and fish, presented in million metric tons. Chart 9 shows agricultural production and demand as a total of all three categories.

Lesotho’s agriculture sector is dominated by subsistence rain-fed agriculture and animal husbandry, which serve as the main source of income to rural populations. Only 9% of land is deemed arable due to the mountainous and high-altitude nature of the country. The majority of croplands are located in the more densely populated western lowlands (below 2 000 m altitude) and limited land in the various river valleys on the highlands. The sector has seen a dramatic decline over the past few decades, with significant declines in crop production and productivity. This has resulted in food insecurity and a heavy importation bill from South Africa for basic foodstuffs.

Agricultural production has not increased in the past three decades. In 1990, agricultural production stood at 430 000 metric tons and by 2019 this had declined to 400 000 metric tons, while demand increased from 680 000 metric tons to 920 000 metric tons. As a result, the food import dependency in the country more than doubled from 250 000 metric tons in 1990 to 520 000 metric tons in 2019. Contributing to this decline are a growing population, later than normal onset rains (brought about by a shifting climate), frequent droughts within the region, and soil erosion due to poor land practices and overgrazing.

This production and demand gap is expected to increase in the Current Path forecast. By 2043, agricultural production is forecast to be 490 000 metric tons and demand would exceed 1.3 million metric tons, translating to a food import dependency valued at 820 000 metric tons. This paints a picture of growing food insecurity in a country already experiencing the devastating effects thereof.

There are numerous methodologies for and approaches to defining poverty. We measure income poverty and use GDP per capita as a proxy. In 2015, the World Bank adopted the measure of US$1.90 per person per day (in 2011 international prices), also used to measure progress towards the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 1 of eradicating extreme poverty. To account for extreme poverty in richer countries occurring at slightly higher levels of income than in poor countries, the World Bank introduced three additional poverty lines in 2017:

- US$3.20 for lower middle-income countries

- US$5.50 for upper middle-income countries

- US$22.70 for high-income countries.

Poverty is an endemic problem in Lesotho that has burdened communities, especially in rural areas, for decades. More recently, a growing urban poor population has emerged as those migrating to cities and towns have been met with severe lack of housing and employment opportunities. Poverty declined in the early part of the century when Lesotho’s economy was growing, especially in the labour-intensive textile industry, and the country received inflows of aid and remittances from labour workers in South Africa.

However, since 2016 poverty has started increasing again, the result of slower economic growth in South Africa, increased unemployment, political infighting and turbulence in its political structures, unmet urbanisation needs, declining food production and a struggling agriculture sector. Lesotho has a high poverty burden at 59.5%, equivalent to 1.2 million people, in 2019, almost 10 percentage points above the average for lower middle-income economies in Africa (using the US$3.20 poverty measure).

The continued stagnation of domestic food production together with a growing population, declines in remittances and revenue inflows and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic have resulted in worsening food insecurity in the country. On the Current Path, the extreme poverty rate is projected to continue an upward trend peaking at 70.8% in 2025. Afterwards, poverty rates are forecast to decline as the country recovers and reach 45.2% in 2043, still 7 percentage points above the average for its African income peers.

The IFs platform forecasts six types of energy, namely oil, gas, coal, hydro, nuclear and other renewables. To allow comparisons between different types of energy, the data is converted into billion barrels of oil equivalent (BBOE). The energy contained in a barrel of oil is approximately 5.8 million British thermal units (MBTUs) or 1 700 kilowatt-hours (kWh) of energy.

Lesotho has great renewable energy potential but is poor in fossil fuel reserves and is a net importer of electricity from South Africa and Mozambique. Since the construction of the LHWP Phase 1, the country has been able to generate 72 MW (around 50% of peak energy demand) through the Muela hydropower station located at Katse dam.

Even with the installed hydropower capacity the country still relies very heavily on imported energy from its neighbours to meet demand. Much of the rural communities are still disconnected from the electricity grid and low access rates force many rural households to utilise biomass fuels in the forms of wood, animal dung, imported coal and petroleum to meet their household heating and cooking needs.

While energy demand has steadily increased, local generation supply has been consistent at 72 MW with a slow uptake of other renewable energy production methods. For economic growth to take off the country needs to urgently address the supply gap together with the access rates to rural households in particular.

Carbon is released in many ways, but the three most important contributors to greenhouse gases are carbon dioxide (CO2), carbon monoxide (CO) and methane (CH4). Since each has a different molecular weight, IFs uses carbon. Many other sites and calculations use CO2 equivalent.

Lesotho is a low carbon emitter with carbon emissions of 700 000 tons in 2019. It is dwarfed by carbon emissions from South Africa yet reliant on energy export thereof to meet its needs. In 2019, Lesotho’s emissions placed it in 35th position in Africa and 144th in the world, and among lower middle-income countries in Africa it ranked sixth lowest.

In the Current Path forecast, carbon emissions are likely to increase to 1.2 million tons by 2043. The country has great hydro potential and wind and solar are additional viable options. Rural access to sustainable electricity will have to be addressed to break the dependence on fossil fuel burning for household needs.

Sectoral Scenarios for Lesotho

Download to pdfThe Stability scenario represents reasonable but ambitious reductions in risk of regime instability and lower levels of internal conflict. Stability is generally a prerequisite for other aspects of development and this would encourage inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) and improve business confidence. Better governance through the accountability that follows substantive democracy is modelled separately.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

Lesotho has had a turbulent history since gaining independence in 1966. The country has experienced three successful coups d'état and in 2014 a failed attempt that exposed the infighting and turmoil within the top structures.

Lesotho has a low level of governance security estimated at 0.65 in 2019 compared to the average for Africa and lower middle-income countries. It also falls below the average for SADC and in 2019 was on par with the situation in Eswatini. Lesotho however enjoys more civil and political freedoms than the average lower middle-income country in Africa but has a history of military involvement in politics.

The country stands to benefit greatly from a more stable political environment, and in the Stability scenario, governance security would improve considerably by 2043 to 0.80 which will be higher than the Current Path forecast of 0.72 in the same year.

Stability stimulates economic growth as it attracts foreign investment and creates an enabling environment for businesses to thrive. A more stable environment will see Lesotho’s GDP per capita grow from US$3 136 in 2019 to US$5 393 in 2043, US$154 more than in the Current Path forecast for the same year. In both the Current Path forecast and the Stability scenario, GDP per capita remains significantly below the average for lower middle-income African countries throughout the forecast horizon to 2043.

Improving stability within the country’s leadership and avoiding the same turbulent military interventions as the past couple of decades can go a long way in raising investor confidence and lowering the perception of risks within Lesotho. It will also shift the focus to much needed investments in basic and critical services and will lift rural as well as urban populations out of poverty. The troubling food security crises and endemic nature of poverty however still dominate the poverty picture.

The Stability scenario therefore has a positive but small impact on poverty rate reduction and will only benefit the country from 2030 onwards. Poverty rates in this scenario are likely to reach 43.6% by 2043, 1.6 percentage points lower compared to the Current Path forecast. Poverty rates will also remain above the average for lower middle-income Africa.

This section presents the impact of a Demographic scenario that aims to hasten and increase the demographic dividend through reasonable but ambitious reductions in the communicable-disease burden for children under five, the maternal mortality ratio and increased access to modern contraception.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

Demographers typically differentiate between a first, second and even a third demographic dividend. We focus here on the contribution of the size of the labour force (between 15 and 64 years of age) relative to dependants (children and the elderly) as part of the first dividend. A window of opportunity opens when the ratio of the working-age population to dependants is equal to or surpasses 1.7.

Lesotho has a high ratio of working-age population to dependants, exceeded by only nine other African countries. In 2019, this ratio was 1.6, on the cusp of the desired 1.7 value needed to reap the benefits of a demographic dividend. This is substantially above the 1.3 average for Africa and lower middle-income Africa.

The COVID-19 pandemic has set back the transition in Lesotho by almost a decade. As such, Lesotho achieves the desired ratio of 1.7 by 2029 in the Demographic scenario and by 2030 on the Current Path forecast. By 2043, the ratio of working-age population to dependants is projected to reach 2.4 in the Demographic scenario and 2.1 on the Current Path forecast.

The Demographic scenario will also impact the population growth of Lesotho, resulting in a population of 2.4 million in 2043, 100 000 fewer than in the Current Path forecast.

The infant mortality rate is the number of infant deaths per 1 000 live births and is an important marker of the overall quality of the health system in a country.

Infant mortality in lower middle-income Africa has substantially and consistently dropped over the past couple of decades and is less than half the figures recorded in the 1980s. Lesotho’s infant mortality rates have also declined but at a much slower pace. In the 1980s, infant mortality in Lesotho was lower than the average for lower middle-income Africa but at the turn of the century increased and surpassed that of its income peers. By 2019, infant mortality rates in Lesotho stood at 51.9 deaths per 1 000 live births compared to 46.4 for lower middle-income Africa.

Many of the most severe challenges have received attention, and Lesotho’s downward trend is expected to accelerate in the Demographic scenario reaching an infant mortality rate of 21.4 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2043, compared to 26.9 in the Current Path forecast. This means that the Demographic scenario can reduce infant mortality rates in Lesotho by 5.5 deaths.

The Demographic scenario marginally increases the GDP per capita. By 2043, Lesotho’s GDP per capita is expected to increase with US$135 above the Current Path forecast resulting in a per capita income of US$5 375. The GDP per capita gap between the Current Path average for lower middle-income countries and Lesotho is forecast to remain persistent throughout the forecast horizon to 2043 reaching US$3 767 in 2043.

The Demographic scenario will have a positive impact on the poverty rate of Lesotho but only by a small margin of 1.3 percentage points. The Demographic scenario reduces the poverty rate to 43.9% in 2043 (using the US$3.20 per day threshold), compared to 45.2% in the Current Path forecast. It means that compared to the Current Path forecast, the Demographic scenario could move an additional 30 000 people out of extreme poverty by 2043.

This section presents reasonable but ambitious improvements in the Health/WaSH scenario, which include reductions in the mortality rate associated with both communicable diseases (e.g. AIDS, diarrhoea, malaria and respiratory infections) and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) (e.g. diabetes), as well as improvements in access to safe water and better sanitation. The acronym WaSH stands for water, sanitation and hygiene.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

Lesotho suffers the worst life expectancy among its African income peers and is the second lowest in the world. This misfortune is the result of extremely high prevalence of HIV/AIDS, high infant and maternal mortality rates and a lack of access to basic and critical services.

In 2019, life expectancy stood at 51.9 years, 14 years below the African average and more than 15 years below the average for low middle-income countries in Africa. On average, women in Lesotho live longer than men by about 6 years.

In the Current Path forecast, this figure is expected to improve to 60.2 years by 2043, 11.9 years below the average for African countries and 13.1 years below the average for lower middle-income countries in Africa. By 2043, women are projected to live at least 8 additional years more than men in both the Current Path forecast and the Health/WaSH scenario.

Even though basic sanitation and infrastructure improvements as suggested in the Health/WaSH scenario will impact life expectancy positively, their impact would be limited with life expectancy improving to 62.2 years by 2043. This still falls more than 10 years short of lower middle-income Africa.

The Health/WaSH scenario will reduce infant deaths more quickly than the Current Path forecast, lowering the figure to 22.8 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2043. It means that the Demographic scenario reduces infant mortality quicker than the Health/WaSH scenario. Compared to the Current Path, this constitutes a reduction in infant mortality by 4.1 deaths.

The Agriculture scenario represents reasonable but ambitious increases in yields per hectare (reflecting better management and seed and fertiliser technology), increased land under irrigation and reduced loss and waste. Where appropriate, it includes an increase in calorie consumption, reflecting the prioritisation of food self-sufficiency above food exports as a desirable policy objective.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

The data on yield per hectare (in metric tons) is for crops but does not distinguish between different categories of crops.

Lesotho does not boast great agricultural potential. The country only has 9% of arable land available most of which is located on the western plains below 2 000 m altitude. Much of the agricultural land in the highlands is inaccessible due to the mountainous topography of the country making the land not suitable for large-scale commercial farming.

In 1966, the contribution of agriculture to GDP stood at 55%; by 2019 the sector's contribution had dropped to 6.3%. While this is a reflection on the structural transformation of the Lesotho economy, it also reflects the poor performance of the sector and its reluctance to innovate and become more resilient towards climate shocks.

In 2019, yields in Lesotho stood at 1.6 metric tons per hectare, 3.5 tons per hectare less than the average for lower middle-income countries in Africa.

In the Agriculture scenario, it is forecast that yields will increase to 3.1 metric tons per hectare by 2043. The Agriculture scenario will improve yields with 1.4 additional metric tons per hectare compared to the Current Path forecast in 2043. The projected yield per hectare of 3.1 metric tons in the Agriculture scenario will still be below the Current Path average of 6.1 for lower middle-income African countries.

Lesotho remains extremely vulnerable to food insecurity. The country relies heavily on South Africa for food imports with an importation bill from South Africa estimated at US$1.06 billion in 2020. In 2019, total agricultural demand exceeded production by 0.5 million metric tons, accounting for a 57.7% import dependency. On the Current Path, demand is forecast to exceed production in 2043 by 0.8 million metric tons, a significant import dependency of 63%.

The Agriculture scenario will benefit Lesotho through increasing yields and reducing post-harvest losses. In this scenario, Lesotho can lower its import dependency to 46.3%, down from 63% in the Current Path forecast. This however still paints a picture of a food insecure country with heavy dependency on the importation of foodstuffs.

By 2043, the Agriculture scenario will have a modest impact on GDP per capita, increasing income by US$159 over the Current Path forecast. This will result in a GDP per capita income of US$5 399 in 2043. Income will remain below the average for lower middle-income countries in Africa in both scenarios.

The Agriculture scenario will have a negligible impact on poverty reduction in the country by 2043. The scenario does however have a more immediate impact on reducing poverty in the short term and will reduce poverty by 1.8 percentage points compared to the Current Path forecast in 2030. By 2043, the Agriculture scenario will result in an extreme poverty rate of 45% compared to the Current Path forecast at 45.2%, below the average for lower middle-income countries in Africa. The minimal impact on poverty of the Agriculture scenario can be attributed to the low agriculture sector in the country that accounts for 8.4% of total employment in the country in 2020.

The Education scenario represents reasonable but ambitious improved intake, transition and graduation rates from primary to tertiary levels and better quality of education. It also models substantive progress towards gender parity at all levels, additional vocational training at secondary school level and increases in the share of science and engineering graduates.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

Lesotho spends 6.3% of GDP on Education, the seventh highest among lower middle-income countries in Africa. Literacy rates are high, measuring 80.8% and are expected to reach 93% by 2043 in the Current Path forecast. Primary education is compulsory and the government has used education funding as a major lever in achieving their socio-economic development goals.

The mean years of education in Lesotho (measuring 6.8 in 2019) is lower than the 7.2 average for lower middle-income Africa but higher than the 6.2 average for Africa. Mean years of education among the female population group is however very high in comparison to the average for Africa and lower middle-income Africa and is 1.2 years higher than male attendance. This makes Lesotho one of the few countries in Africa where females obtained relatively higher education than males. Lesotho’s investment in education remains high and by 2043 mean years of education will be above the average for lower middle-income countries in Africa. In the Education scenario, Lesotho will reach a mean of 9.1 years in 2043 — 0.2 years above the Current Path forecast.

Lesotho’s primary test score in 2019 was 30.2, and by 2043, it is expected to increase to 39.1 in the Current Path forecast. The country is expected to benefit from the Education scenario and is forecast to attain average test scores for primary learners of 45.7 by 2043, 6.6 percentage points higher than the Current Path forecast. In 2019, average test scores for primary learners was lower than the average for Africa and lower middle-income countries in Africa but by 2043 the Education scenario will elevate Lesotho above the average for Africa and lower middle-income Africa.

In the Education scenario, the test score for Lesotho at the secondary level is 57.9 in 2043, up from 42.1 in 2019. This means that, on average, learners in Lesotho perform relatively better at the secondary level compared to primary level. The Education scenario is expected to result in test scores for secondary learners to be nearly 10 percentage points higher by 2043 than the Current Path forecast at 48. Average test scores for secondary learners were above the average for lower middle-income countries in Africa in 2019, and will remain significantly above by 2043 in the Education scenario.

By 2043, GDP per capita in Lesotho is expected to increase to US$5 391 in the Education scenario, compared to US$5 240 in the Current Path forecast. It means that the Education scenario can improve average GDP per capita in Lesotho by an additional US$151. Education improves the human capital of a country which ultimately leads to economic growth although it takes time. GDP per capita for Lesotho is expected to continue to lag behind its income peers throughout the forecast horizon to 2043.

In the Education scenario, it is expected that poverty in Lesotho will decrease to 43.3% by 2043 down from 59.5% in 2019. This is a 1.9 percentage point improvement to the Current Path forecast that is expected to be 45.2% by 2043 but below the Current Path average of 38.3% for lower middle-income African countries. It means that the Education scenario can lift 40 000 people out of extreme poverty in Lesotho. Although education is a powerful tool for poverty reduction as it equips individuals to obtain livelihoods, its effect takes long before they manifest.

The Manufacturing/Transfers scenario represents reasonable but ambitious manufacturing growth through greater investment in the economy, investments in research and development, and promotion of the export of manufactured goods. It is accompanied by an increase in welfare transfers (social grants) to moderate the initial increases in inequality that are typically associated with a manufacturing transition. To this end, the scenario improves tax administration and increases government revenues.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

Chart 30 should be read with Chart 8 that presents a stacked area graph on the contribution to GDP and size, in billion US$, of the Current Path economy for each of the sectors.

In the Manufacturing/Transfers scenario, the service sectors will continue to be the largest contributor to the economy, contributing an additional US$400 million to the GDP by 2043, representing a 1.1 percentage points above the Current Path forecast.

The Manufacturing/Transfers scenario will not improve the contribution of the other sectors above the Current Path forecast. In fact, the scenario forecasts a decline in contributions compared to the Current Path forecast for the energy, manufacturing, agriculture, ICT and materials sectors. The manufacturing sector will however contribute US$100 million more to the economy than in the Current Path forecast.

In 2019, social welfare spending (government welfare transfers to unskilled workers) equated to US$200 million. In the Manufacturing/Transfers scenario, social welfare expenditure will increase to US$600 million — US$190 million higher than in the Current Path forecast. This means that compared to the Current Path forecast, the Manufacturing/Transfers scenario will increase government welfare transfers by nearly 50%.

The Manufacturing/Transfers scenario will have a modest impact on the GDP per capita of Lesotho in 2043, increasing it by US$227 above the Current Path forecast. This translates to GDP per capita of US$5 467 in this scenario compared to US$5 240 in the Current Path forecast. The GDP per capita in both the Current Path forecast and the Manufacturing/Transfers scenario will still be significantly below the average for lower middle-income countries in Africa by 2043. The Manufacturing/Transfers scenario also has a smaller impact on Lesotho compared to the impact it has on lower middle-income countries as a whole.

The impact of the Manufacturing/Transfers scenario on poverty reduction in Lesotho is not straight forward. In the short term (between 2025 to 2035), the Manufacturing/Transfers scenario leads to a quicker reduction in extreme poverty rates compared to the Current Path, peaking at 2.5 percentage points above the Current Path in 2033. However, the situation reverses after 2035 so that by 2043, extreme poverty rates on the Current Path forecast will be slightly below the projections of the Manufacturing/Transfers scenario.

The Leapfrogging scenario represents a reasonable but ambitious adoption of and investment in renewable energy technologies, resulting in better access to electricity in urban and rural areas. The scenario includes accelerated access to mobile and fixed broadband and the adoption of modern technology that improves government efficiency and allows for the more rapid formalisation of the informal sector.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

Fixed broadband includes cable modem Internet connections, DSL Internet connections of at least 256 KB/s, fibre and other fixed broadband technology connections (such as satellite broadband Internet, ethernet local area networks, fixed-wireless access, wireless local area networks, WiMAX, etc.).

Lesotho’s fixed broadband subscriptions at 2.1 per 100 people in 2019 was slightly lower than the average for lower middle-income countries in Africa and for Africa as a whole. In the Leapfrogging scenario, fixed broadband subscriptions increase to 50 subscriptions per 100 people by 2043. This is 23.8 subscriptions more than in the Current Path forecast and higher than the average for Africa and lower middle-income African countries.

Mobile broadband refers to wireless Internet access delivered through cellular towers to computers and other digital devices.

Compared to fixed broadband, mobile broadband has expanded rapidly in Africa. At 62.5 subscriptions, Lesotho had more mobile broadband subscriptions per 100 people in 2019 than the average for lower middle-income countries in Africa and for Africa as a whole. In the short term (between 2024 to 2035), the Leapfrogging scenario leads to a greater improvement in mobile broadband than in the Current Path forecast. Eventually, both projections converge so that by 2043, mobile broadband subscriptions will increase to 153.5 subscriptions per 100 people in both scenarios.

Electricity access in Lesotho is critically low and lower than the average for Africa and lower middle-income Africa. In total, only 38.2% of the country’s population had access to electricity in 2019, the third lowest among lower middle-income Africa. This is the result of ageing infrastructure, inadequate investment in transmission and distribution lines, and a very mountainous and inaccessible topography.

In the Current Path forecast, it is projected that 66.7% of Lesotho’s population, translating to 1.7 million people, will have access to electricity by 2043. In the Leapfrogging scenario, electricity access is projected to reach 79.8% by 2043.

The projection indicates that in the Leapfrogging scenario rural electricity access will increase from 31% in 2019 to 77.7% by 2043 — 18.2 percentage points higher than in the Current Path forecast. For populations living in urban spaces, it is projected that in the Leapfrogging scenario, electricity access will increase from 56.5% in 2019 to 83.5% by 2043. In 2019, average electricity access for lower middle-income African countries was 28.1% percentage points higher than Lesotho. In the Leapfrogging scenario, this gap will narrow significantly by 2043. Without energy the socio-economic development of the country will remain constrained.

The effect of technology on economic growth is not in doubt as it enhances the productivity of labour. By 2043, GDP per capita in Lesotho is expected to increase to US$5 472 in the Leapfrogging scenario, compared to US$5 240 in the Current Path forecast. It means that compared to the Current Path, the scenario could improve GDP capita by US$232. However, GDP per capita for Lesotho is expected to continue to lag behind its income peers.

The Leapfrogging scenario improves the extreme poverty rates of US$3.20 only slightly, lowering it by 1 percentage point compared to the Current Path forecast. By 2043, poverty will have dropped from 45.2% in the Current Path forecast to 44.2% in the Leapfrogging scenario meaning that the Leapfrogging scenario will lift 20 000 additional people out of extreme poverty in Lesotho.

The Free Trade scenario represents the impact of the full implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) by 2034 through increases in exports, improved productivity and increased trade and economic freedom.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

The trade balance is the difference between the value of a country's exports and its imports. A country that imports more goods and services than it exports in terms of value has a trade deficit, while a country that exports more goods and services than it imports has a trade surplus.

The full implementation of the AfCFTA not only enables countries to export more easily but also opens them up to increased imports, endangering those sectors where they lack competitive advantage.

Lesotho’s trade deficit in 2019 stood at 26.3% of GDP. This is expected to improve significantly in the near future, peaking in 2026 at a surplus of 3.4% and 1.2% of GDP in the Free Trade scenario and the Current Path forecast, respectively. The longer-term forecast shows a growing import dependency and declining exports with a trade deficit peaking in 2036 at 16.2% before improving to a deficit of 9.9% in 2043 in the Free Trade scenario, higher than the Current Path forecast of 8.5% in the same year.

Trade enables countries to export comparatively advantageous products while importing goods that they have less advantage in producing. This eventually results in higher growth due to increased income from export and reduced expenditure on cheaper imported commodities. From all the interventions introduced in the scenarios, it is the Free Trade scenario that has the biggest positive impact on per capita income in Lesotho. By 2043, GDP per capita in Lesotho is expected to increase to US$5 653 in the Free Trade scenario, compared to US$5 240 in the Current Path forecast, an increase of US$413. However, the GDP per capita for Lesotho is expected to continue to lag behind its income peers.

By 2043, poverty will drop from 45.2% in the Current Path forecast to 40.5% in the Free Trade scenario — the biggest impact on poverty from the various intervention scenarios. This scenario therefore contributes a 4.7 percentage point reduction in the poverty rate compared to the Current Path forecast meaning that the Free Trade scenario can lift an additional 90 000 people out of extreme poverty by 2043. The huge impact of trade on poverty reduction can be as a result of large proportion of the country’s labour force employed in the industrial sector (41.9% in 2020), which means promoting intra-Africa trade can improve the livelihood of these people through increased sales and incomes.

The Financial Flows scenario represents a reasonable but ambitious increase in worker remittances and aid flows to poor countries, and an increase in the stock of foreign direct investment (FDI) and additional portfolio investment inflows to middle-income countries. We also reduced outward financial flows to emulate a reduction in illicit financial outflows.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

The Lesotho economy benefited significantly from foreign aid inflows, and in 2019 foreign aid contributed 5.6% to the country’s GDP, equivalent to US$180 million. Lesotho’s reliance on foreign aid is significantly above the average for lower middle-income countries in Africa (at 1.7% of GDP in 2019). Historically, the country’s economy has been very dependent on aid inflows peaking at 18.4% of GDP in the mid-1980s. Foreign aid flows are projected to decrease in both scenarios, equating to 2.9% in the Financial Flows scenario, compared to 2.8% for the Current Path forecast by 2043.

In 2019, foreign investment as a percentage of GDP in Lesotho measured above the average for lower middle-income Africa by 1 percentage point. In the Financial Flows scenario, FDI inflows increase to 5% of GDP by 2043, 0.7 percentage points higher than the Current Path forecast.

Lesotho’s economy is heavily dependent on remittances received from labour workers working in South Africa. The decline in employment opportunities in South Africa has impacted Lesotho's economy significantly and remittance income has declined sharply in recent years. Lesotho receives large amounts of remittances and is a net receiver of remittance money. In 2019, net remittances were US$330 million (9.4% of Lesotho’s GDP). The downward trend in remittance earnings is expected to continue and in the Current Path forecast is expected to contribute 1.7% to Lesotho’s economy (valued at US$100 million) in 2043. The Financial Flows scenario will only improve this projection with slightly increasing remittance inflows to 2.1% of GDP in 2043 valued at US$200 million.

By 2043, the GDP per capita is expected to increase to US$5 298 in the Financial Flows scenario, compared to US$5 240 in the Current Path forecast, an increase of only US$58 per capita. The GDP per capita for Lesotho is expected to continue to lag significantly behind its income peers.

Trade openness will reduce poverty in the long term after initially increasing it due to the redistributive effects of trade. Most African countries export primary commodities and low-tech manufacturing products, and therefore a continental free trade agreement (AfCFTA) that reduces tariffs and non-tariff barriers across Africa will increase competition among countries in primary commodities and low-tech manufacturing exports. Countries with inefficient, high-cost manufacturing sectors might be displaced as the AfCFTA is implemented, thereby pushing up poverty rates. In the long term, as the economy adjusts and produces and exports its comparatively advantaged (lower relative cost) goods and services, poverty rates will decline.

By 2043, the poverty rate will drop marginally from 45.2% in the Current Path forecast to 44% in the Financial Flows scenario. This scenario therefore reduces the poverty rate by 1.2 percentage points, equivalent to 20 000 people, compared to the Current Path forecast.

The Infrastructure scenario represents a reasonable but ambitious increase in infrastructure spending across Africa, focusing on basic infrastructure (roads, water, sanitation, electricity access and ICT) in low-income countries and increasing emphasis on advanced infrastructure (such as ports, airports, railway and electricity generation) in higher-income countries.

Note that health and sanitation infrastructure is included as part of the Health/WaSH scenario and that ICT infrastructure and more rapid uptake of renewables are part of the Leapfrogging scenario. The interventions there push directly on outcomes, whereas those modelled in this scenario increase infrastructure spending, indirectly boosting other forms of infrastructure, including those supporting health, sanitation and ICT.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

Prior to the LHWP, the country had very low access to electricity. In 2000, less than 2% of the rural population and less than 14% of the urban population had access to electricity, with a very high dependence on electricity importation. The hydro capacity and distribution grid installed as part of the revenue earned from the LHWP have improved this picture dramatically. In 2019, 56.5% of urban and 31% of rural populations had access to electricity. However, the national grid remains sparse and the current electricity access rates still fall short of the average for Africa and lower middle-income Africa.

The Infrastructure scenario stands to benefit Lesotho by increasing electricity access from 38.2% in 2019 to 76% in 2043, 9.3 percentage points above the Current Path forecast for 2043. It will also address the vast rural access inequality and raise access to 71.3% by 2043, 11.8 percentage points above the Current Path forecast. The Infrastructure scenario will benefit urban areas by increasing access with 4.9 percentage points above the Current Path forecast of 79.2% by 2043.

Indicator 9.1.1 in the Sustainable Development Goals refers to the proportion of the rural population who live within 2 km of an all-season road and is captured in the Rural Access Index.

Measuring rural accessibility is a very important development indicator. There is a strong link between investing in rural access roads and positive socio-economic impacts, such as improving rural income, reducing poverty, reducing maternal deaths, improving paediatric health and increased agricultural productivity.

Lesotho has a fair overall road network density, owing to the vast expansion of the road network as part of the various phases of the LHWP. In 2019, 62% of Lesotho’s rural population had access to an all-weather road, compared to an average of 61.4% for lower middle-income countries in Africa and 53% for the average of Africa. The Infrastructure scenario will positively influence rural accessibility and by 2043 it is projected that 70% of the rural population will have access to an all-weather road, compared to 67.9% for the Current Path forecast.

By 2043, the GDP per capita in Lesotho is expected to increase to US$5 493 in the Infrastructure scenario, compared to US$5 240 in the Current Path forecast. It means that the Infrastructure scenario will lead to an increase of US$253 in GDP per capita relative to the Current Path forecast; however, the GDP per capita for Lesotho is expected to continue to lag behind its income peers and that of Africa as a whole.

By 2043, poverty will drop from 45.2% in the Current Path forecast to 42.5% in the Infrastructure scenario, a 3 percentage point improvement using the US$3.20 poverty rate. It means that the Infrastructure scenario can help lift 50 000 people out of extreme poverty.

The Governance scenario represents a reasonable but ambitious improvement in accountability and reduces corruption, and hence improves the quality of service delivery by government.

The intervention is explained here in the thematic part of the website.

As defined by the World Bank, government effectiveness ‘captures perceptions of the quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to such policies’.

Chart 51 presents the impact of the interventions in the Governance scenario on government effectiveness.

Lesotho's score of 1.9 on the government effectiveness index in 2019 was higher than the average for Africa but lower than the average for lower middle-income countries in Africa. In the Governance scenario, Lesotho’s score is projected to increase to 2.4 by 2043, compared to 2.3 in the Current Path forecast.

By 2043, the GDP per capita in Lesotho is expected to increase to US$5 367 in the Governance scenario, compared to US$5 240 in the Current Path forecast, representing an additional gain of US$127 per capita. The GDP per capita for Lesotho is expected to continue to lag behind its income peers and that of Africa as a whole.

The Governance scenario will have a small impact on alleviating poverty in Lesotho by 2043, reducing poverty by 1.2 percentage points, translating to 20 000 people, compared to the Current Path forecast. The poverty rate will remain very high at 44% and Lesotho will continue to suffer endemic poverty throughout the forecast horizon.

This section presents projections for carbon emissions in the Current Path for Lesotho and the 11 scenarios. Note that IFs uses carbon equivalents rather than CO2 equivalents.

Lesotho’s carbon emissions are projected to increase most in the Free Trade scenario, emitting an additional 0.4 million tons of carbon by 2043 compared to 2019, and a trivial 0.05 million tons of carbon more than the Current Path forecast for 2043.

In the Demographic scenario, emissions are forecast to be the lowest. In 2043, emissions in the Demographic scenario are likely to be 0.01 million metric tons less than emissions in the Current Path forecast for the same year. This is largely the result of the population being smaller in the Demographic scenario compared to the Current Path forecast. The most carbon intensive intervention is the Free Trade scenario mainly because it is the intervention that results in the greatest increase in GDP per capita as a result of economic growth.

The Combined Agenda 2063 scenario consists of the combination of all 11 sectoral scenarios presented above, namely the Stability, Demographic, Health/WaSH, Agriculture, Education, Manufacturing/Transfers, Leapfrogging, Free Trade, Financial Flows, Infrastructure and Governance scenarios. The cumulative impact of better education, health, infrastructure, etc. means that countries get an additional benefit in the integrated IFs forecasting platform that we refer to as the synergistic effect. Chart 55 presents the contribution of each of these 12 components to GDP per capita in the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario as a stacked area graph.

Although Lesotho faces economic challenges as outlined in the previous sections, there are plenty of opportunities to improve the future of the country. Improving intra-Africa trade (as captured in the Free Trade scenario) will raise GDP per capita most by 2043 by an additional US$413 above the Current Path forecast. Increasing stability and subsequent investment inflows (as captured in the Stability scenario) will raise GDP per capita by 2043 by US$154 above the Current Path forecast while investment in infrastructure could raise income by US$253 in 2043 above the Current Path forecast. The synergistic effect of a Combined Agenda 2063 scenario that assumes improvements are made in all 11 broad intervention areas could add an additional US$170 in 2043 on top of the combined per capita income. The Health/WaSH and Financial Flows scenarios are the interventions that will lead to the least improvement in GDP per capita by 2043 valued at US$53.4 and US$58.9, respectively.

Whereas Chart 55 presents a stacked area graph on the contribution of each scenario to GDP per capita as well as the additional benefit or synergistic effect, Chart 56 presents only the GDP per capita in the Current Path forecast and the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario.

The Combined Agenda 2063 scenario has the potential to raise GDP per capita in Lesotho to US$7 375 by 2043, a significant US$2 135 above the Current Path forecast for the same year. The Combined Agenda 2063 scenario shows that a policy push across all the development sectors is necessary to achieve greater economic growth and development in Lesotho.

Without economic growth, Lesotho’s poverty will remain largely unchanged. The Combined Agenda 2063 interventions can significantly benefit the economy of the country reducing the poverty burden thereof. If Lesotho can effectively implement measures as outlined in the Combined Agenda 2063, poverty can be reduced from 59.5% in 2019 to 27.7% in 2043. The scenario therefore has the potential to reduce poverty in 2043 by 17.5 percentage points compared to the Current Path forecast meaning that the scenario can reduce extreme poverty in Lesotho by an additional 360 000 people by 2043.

See Chart 8 to view the Current Path forecast of the sectoral composition of the economy.

The service sector will contribute 3 percentage points more to GDP in the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario compared to the Current Path forecast, equivalent to a difference of US$2.9 billion by 2043. Agriculture will contribute 0.1 percentage points more, which will translate to a value of US$180 million by 2043. Although the manufacturing sector is projected to make an absolute contribution of US$800 million by 2043, this will correspond to 1.9 percentage points below the Current Path. Likewise contribution of materials and energy will also be 0.1 and 0.3 percentage points below the Current Path.

Lesotho’s GDP is forecast to grow to US$12.3 billion by 2043 in the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario, compared to US$7.6 in the Current Path forecast. It means that in the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario, the size of the Lesotho economy will grow by an additional 62%. This shows the value that the interventions in the 11 sectoral scenarios could have on economic growth.

In 2019, Lesotho’s carbon emissions were 0.7 million tons and they are projected to increase to 1.4 million tons of carbon by 2043 in the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario, 0.2 million tons above the Current Path forecast for 2043. The higher carbon emissions in the Combined Agenda 2063 scenario reflect the ambitious economic growth that is projected to occur in this scenario.

Page information

Contact at AFI team is Alize le Roux

This entry was last updated on 14 August 2025 using IFs v7.63.

Reuse our work

- All visualizations, data, and text produced by African Futures are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

- The data produced by third parties and made available by African Futures is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

- All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Cite this research

Alize le Roux (2026) Lesotho. Published online at futures.issafrica.org. Retrieved from https://futures.issafrica.org/geographic/countries/lesotho/ [Online Resource] Updated 14 August 2025.