Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

This page explores the current and projected future development of Burkina Faso, examining various sectoral scenarios and their potential impacts on the country's growth. It explores eight sectors, including demographic, economic and infrastructure-related outcomes for Burkina Faso up to 2043. The analysis also considers the implications of the Agenda 2063 goals, aiming to offer insights into policy actions that could enhance the country's developmental trajectory.

Burkina Faso by DuToit McLachlan

Summary

We begin this page with an introductory assessment of the Burkina Faso context, looking at the current population distribution and structure, climate and topography.

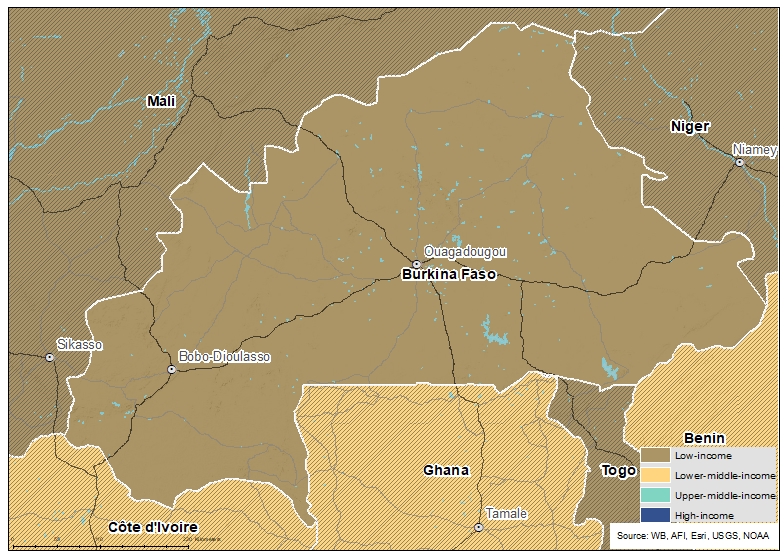

- Burkina Faso is a low-income and landlocked Sahelian country with limited natural resources. It is a former French colony that borders Mali to the northwest, Niger to the northeast, Benin to the southeast, Togo and Ghana to the south, and Côte d’Ivoire to the southwest. Since gaining independence in 1960, Burkina Faso has endured a turbulent history characterised by military coups and intermittent elections.

This section is followed by an analysis of the Current Path for Burkina Faso which informs the country's likely development trajectory to 2043. It is based on current geopolitical trends and assumes that no major shocks would occur in a 'business-as-usual' scenario.

- The population of Burkina Faso is growing rapidly at about 3 per cent per year. In 2023, the country’s population was estimated at 23 million, and on the Current Path (business-as-usual scenario), it will reach 27 million by 2030 and 35.3 million by 2043. This represents about 12 million more people over the next 20 years.

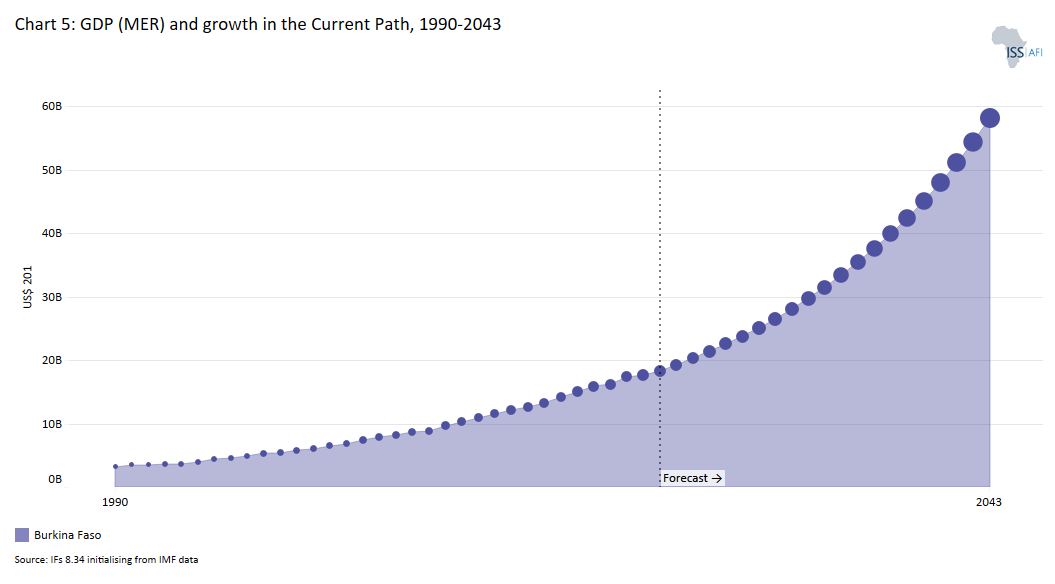

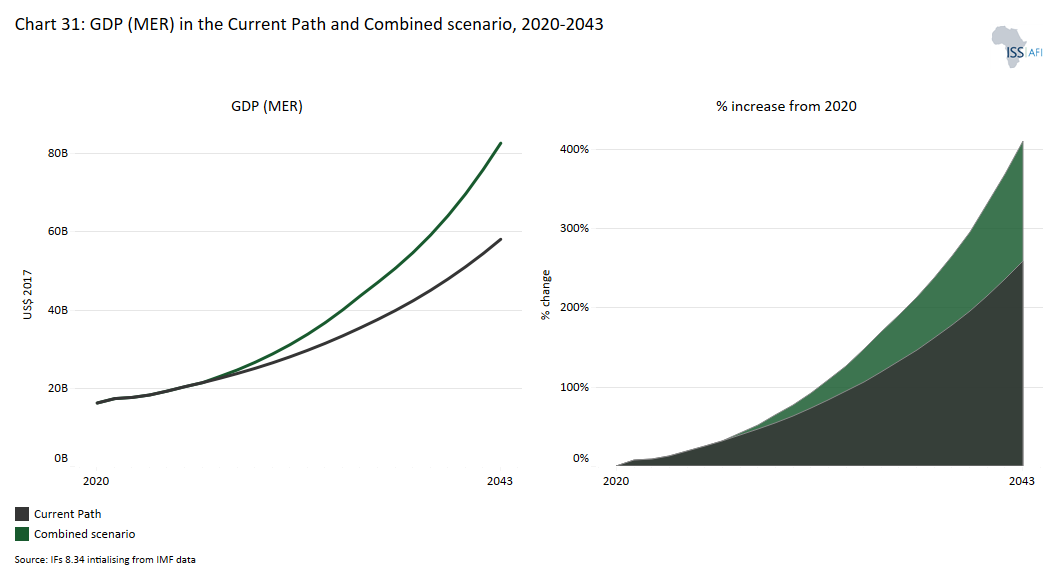

- Between 1990 and 2023, Burkina Faso’s GDP increased about sixfold from US$3.2 billion in 1990 to US$18.3 billion in 2023. On the Current Path, it will be US$26.5 billion in 2030, and US$58 billion by 2043. This is equivalent to an average annual growth rate of about 5.8% between 2023 and 2043. However, this optimistic economic growth forecast is contingent upon the ability to effectively respond to persistently high levels of political and security instability and climatic shocks.

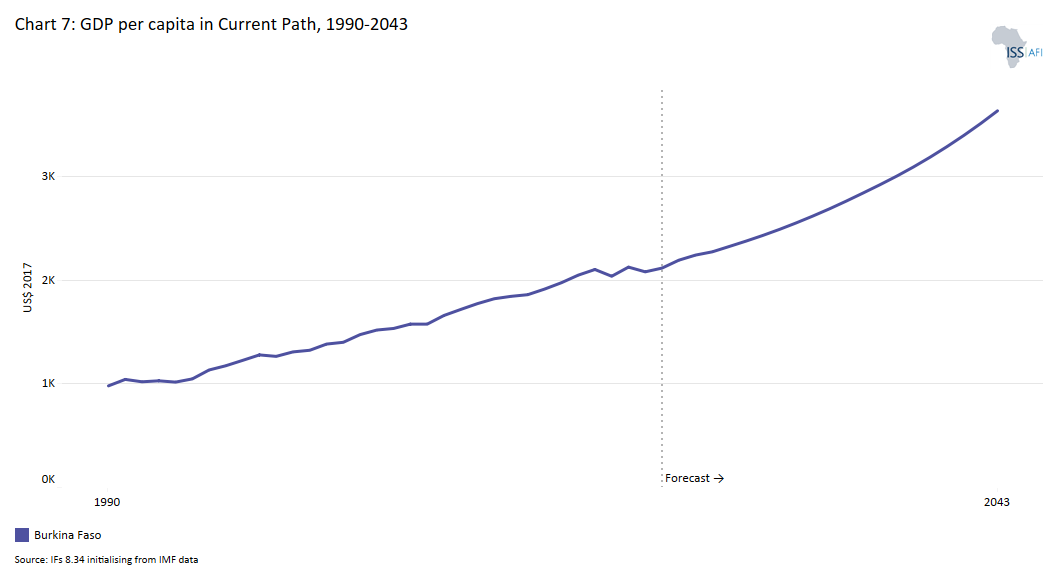

- The GDP per capita (PPP constant 2017) of Burkina Faso increased from US$1 266 in 2000 to US$2 119 in 2023, compared to the average of US$1 814 for low-income Africa in 2023. In the Current Path, the country will reach a GDP per capita of US$2 493 by 2030 and US$3 639 by 2043, above the projected average of US$2 985 for low-income Africa in 2043.

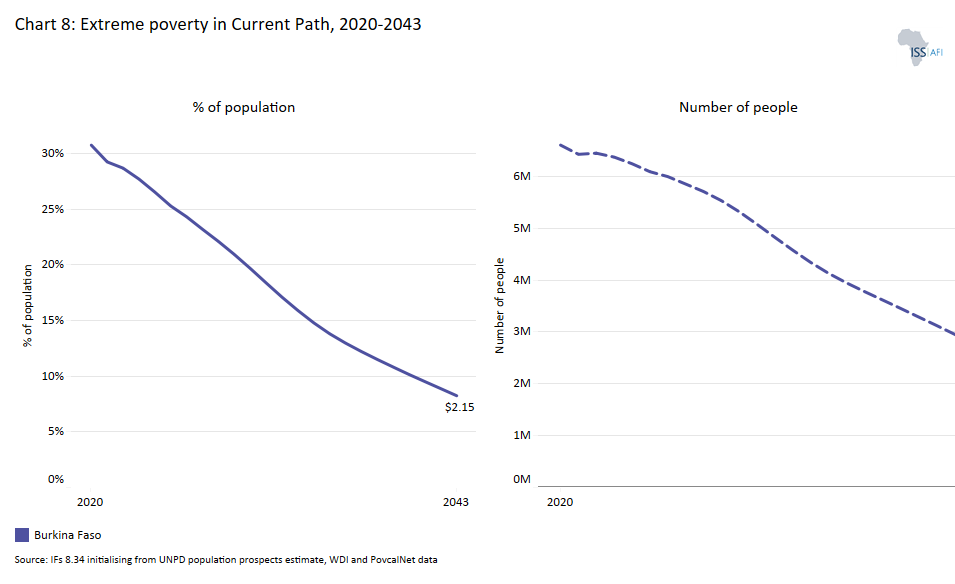

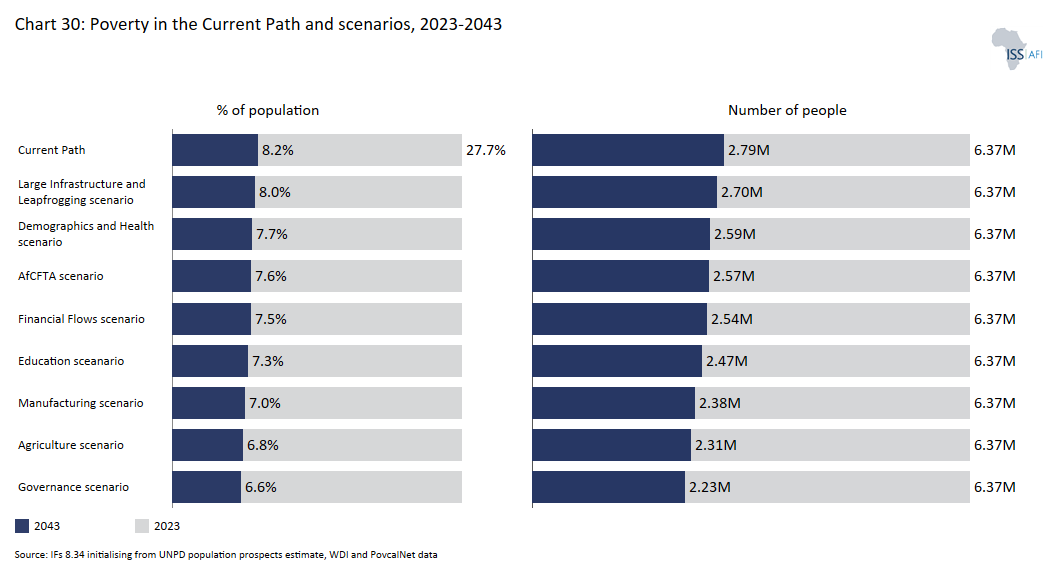

- The poverty rate, measured at the international extreme poverty line of US$2.15/day (per capita, 2017 PPP$), declined from 83% in 1990 to about 30.7% in 2019 (before the Covid-19 pandemic). In 2023, the poverty rate was at about 27.7% (6.4 million people). This is about 13 percentage points lower than the average of 41.5% for African low-income countries. On the Current Path, Burkina Faso's poverty rate will steadily decline to 19.6% in 2030 and to 7.9% (2.8 million people) by 2043, compared with the projected average of 24% for low-income Africa in the same year.

- In its quest to improve the living conditions of its population, Burkina Faso has developed and implemented a series of five-year development plans. The most recent ones are the National Economic and Social Development Plan (PNDES-I) 2016-2020 and the National Economic and Social Development Plan (PNDES-II) 2021-2025. The overall objective of the PNDES-II is to restore security and peace, strengthen the nation's resilience, and structurally transform Burkina Faso's economy for strong, inclusive and sustainable growth. It is unclear if the military government that took power in 2022 will release its own development plan.

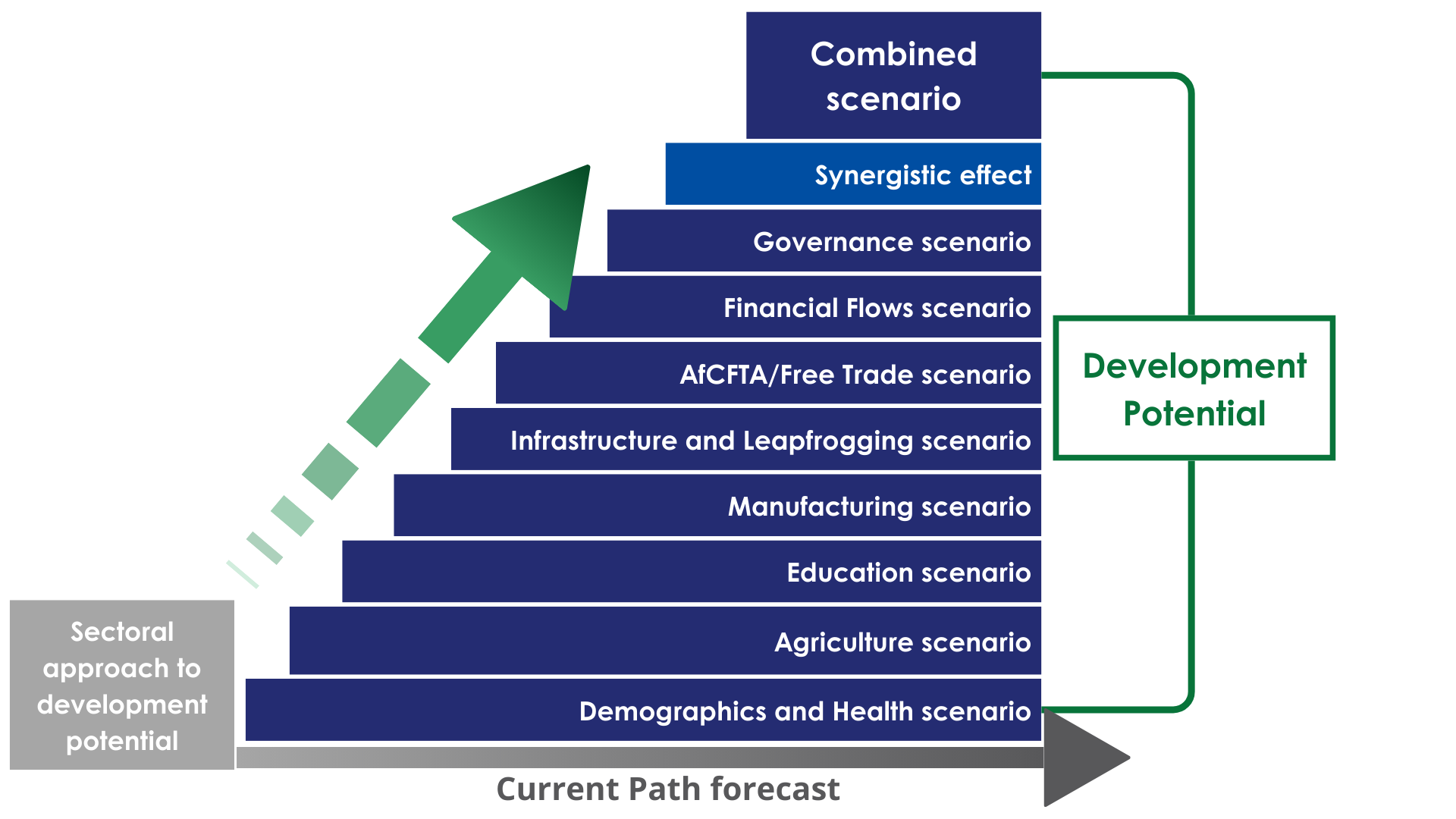

The next section compares progress on the Current Path with eight sectoral scenarios. These are Demographics and Health, Agriculture, Education, Manufacturing, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging, Financial Flows and Governance. Each scenario is benchmarked to present an ambitious but reasonable aspiration in that sector compared to other countries at similar levels of development.

- The implementation of the Demographics and Health scenario will accelerate the demographic transition in Burkina Faso. In this scenario, the ratio of the working-age population to dependants will be at 1.71 by 2038, at which point the country will enter a potential demographic window of opportunity, provided other supporting conditions are in place. On the Current Path, this minimum ratio will only be achieved in 2044.

- In the Agriculture scenario, average crop yields could increase to 4.1 metric tons per hectare in 2043 compared with 2.6 tons on the Current Path in the same year. As a result, crop production will be 8.2 million metric tons more by 2043 than in the Current Path. This will result in a lower import dependency of 5.6% and 13% of total demand in 2030 and 2043, respectively, compared with 27.7% in the Current Path and below the projected average of 34% for low-income Africa in 2043.

- The implementation of the Education scenario would improve the mean years of education for adults aged 15 to 24 in the country to 7 years in 2030 and 8.6 years by 2043 compared with 6.8 years in 2030 and 7.8 years in 2043 in the Current Path.

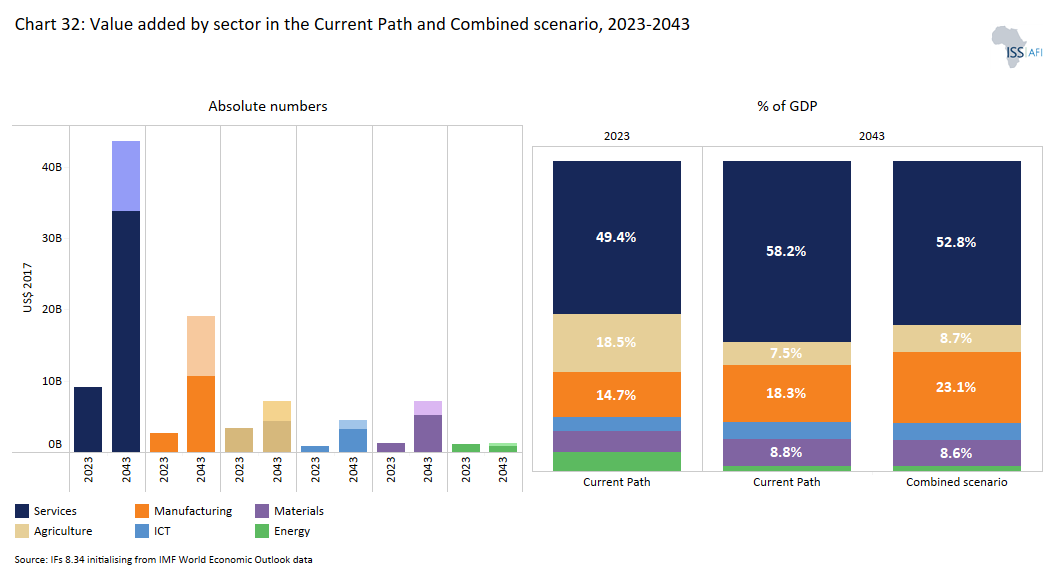

- The continued reliance on agriculture and mining has led Burkina Faso’s economy to being undiversified and vulnerable to exogenous shocks. Manufacturing forms only a small part of the economy. The contribution of the manufacturing sector to GDP has been declining from its peak of 19% in 1973 to 10% in 2019 and 9.6% in 2022 (the latest available data), on par with the average of 9.4% for low-income Africa. On the Current Path, the share of the manufacturing sector in Burkina Faso’s GDP will likely increase to 16% in 2030 and 18.3% by 2043, above the projected average of 16.2% for low-income Africa in 2043. The implementation of the Manufacturing scenario could further push the share of the manufacturing sector in GDP to 16.2% in 2030 and 22.4% by 2043, above the projected average of 16.2% for low-income Africa in 2043.

- The trade pattern of Burkina Faso is similar to that of many other African countries that rely on a few key commodity exports while importing higher-value manufactured goods, consumer items and foodstuffs. As a result, the country’s trade balance is structurally in deficit—a trend which is likely to persist over the forecast horizon. On the Current Path, the trade deficit will worsen, reaching 6.6% of GDP in 2030 and 6.7% in 2043. In the AfCFTA scenario, Burkina Faso would not record a trade surplus or be a net exporter, however, its trade deficit would reduce to only -5.4% of GDP in 2043.

- Infrastructure deficit, especially poor access to electricity and the lack of a good road network, poses a major obstacle to Burkina Faso’s economic development. Due to limited electricity access, especially in rural areas, the bulk of the households continue to rely on inefficient energy sources for cooking. It is estimated that around 81% of the population continue to depend on firewood and charcoal (used in traditional cookstoves). In the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario, the percentage of households that use traditional cookstoves could decline from 88.7% in 2023 to 79.7% in 2030 and 43% in 2043, compared to 58.7% in the Current Path for 2043.

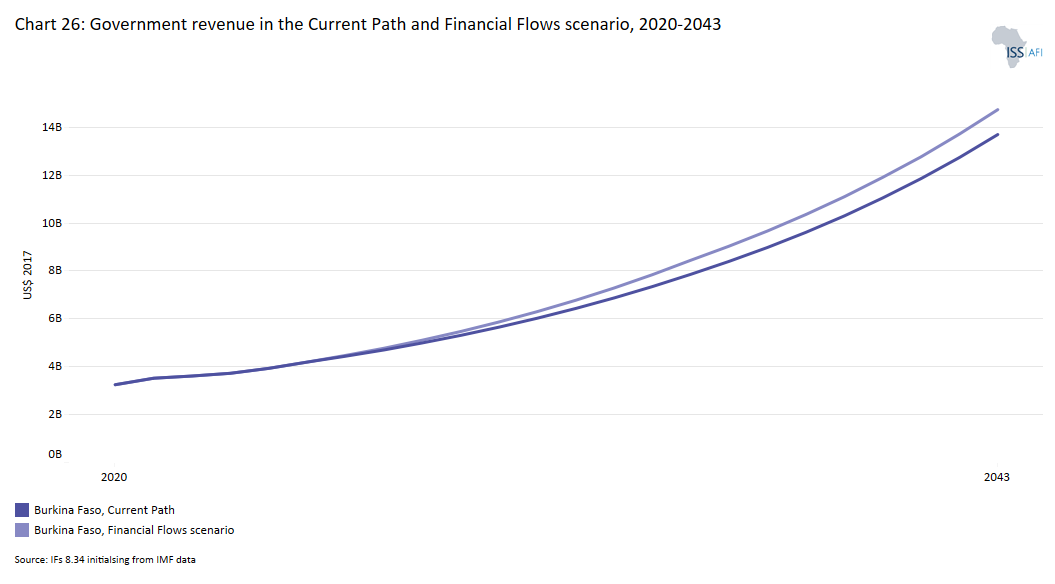

- Burkina Faso does not attract optimal international capital flows, even though foreign aid played a significant role in the country’s economic and social development historically, given its limited financial resources and significant poverty. In the Financial Flows scenario, government revenue increases to 24.7% of GDP by 2043, up from 20% in 2023. This is 1.14 percentage points of GDP above the Current Path in 2043, equivalent to US$1.06 billion. However, without meaningful political reforms or assurances of stability, the resumption of substantial foreign aid and direct investment unlikely.

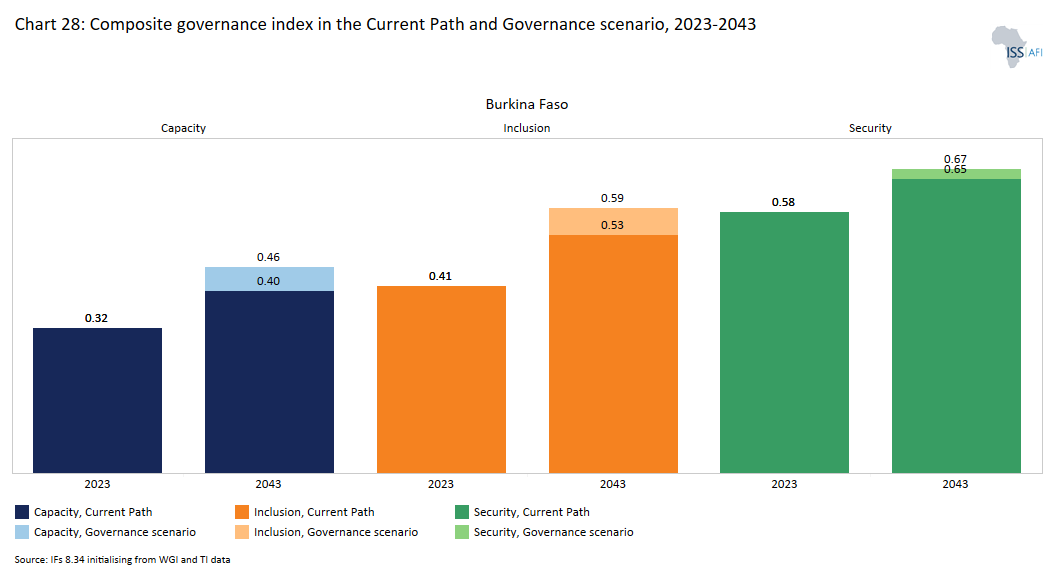

- Burkina Faso faces several governance challenges that have impacted its development. These include political instability, insecurity and extremism and weak institutions. In the Governance scenario, the overall governance performance of Burkina is about 9% higher than the Current Path in 2043.

In the third section, we compare the impact of each of these eight sectoral scenarios with one another and subsequently with a Combined scenario (the integrated effect of all eight scenarios). In our forecasts, we measure progress on various dimensions such as economic size (in market exchange rates), gross domestic product per capita (in purchasing power parity), extreme poverty, carbon emissions, the changes in the structure of the economy, and selected sectoral dimensions such as progress with mean years of education, life expectancy, the Gini coefficient or reductions in mortality rates.

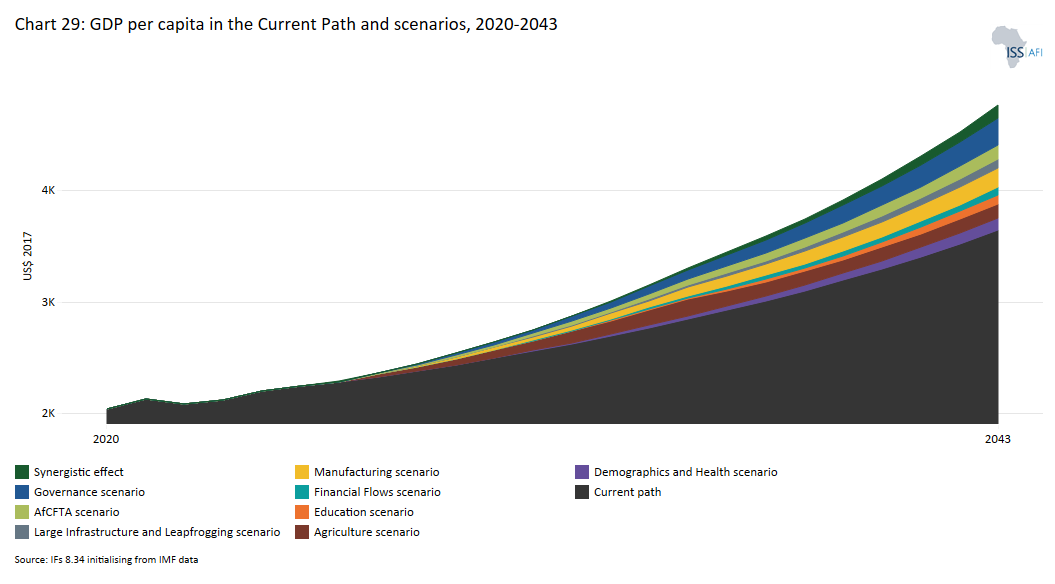

- Burkina Faso gets a boost to its GDP per capita in all eight sectoral scenarios. However, the Combined scenario has a much greater impact on GDP per capita compared to the individual scenarios. By 2030, the GDP per capita of Burkina Faso (PPP) is US$145, larger than in the Current Path. In 2043, it will be US$1 120, larger than in the Current Path, indicating that an integrated push across all the development sectors could significantly improve the living standard of the people of Burkina Faso. Among the sectoral scenarios, the Governance scenario has the most significant positive impact on GDP per capita with an increase of US$240 above the Current Path in 2043. The second, third and fourth most significant impact of the GDP per capita is achieved in the Manufacturing, the AfCFTA, and the Agriculture scenarios.

- All scenario interventions reduce poverty levels in Burkina Faso, however, the Governance scenario contributes most significantly to reducing the extreme poverty rate by 2043, followed by the Agriculture scenario. In the Combined scenario, by 2030, 16.4% of the population will be living in extreme poverty compared to 19.6% in the Current Path. Even under the Combined scenario, Burkina Faso's poverty rate will remain high at 16.4% by 2030. This suggests that without decisive action, the country risks significantly falling short of achieving the poverty-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). By 2043, the extreme poverty rate at the US$2.15 poverty line will decline to roughly 2.6% (1.1 million people) compared to 7.9% (3.5 million people) in the Current Path in the same year.

- The Combined scenario significantly improves Burkina Faso’s growth prospects. In this scenario, the average growth rate between 2025 and 2043 is 8% compared with 5.9% on the Current Path over the same period. The size of the economy measured in GDP at the market exchange rate (MER) is US$2.2 billion and US$24.5 billion larger than the Current Path in 2030 and 2043, respectively.

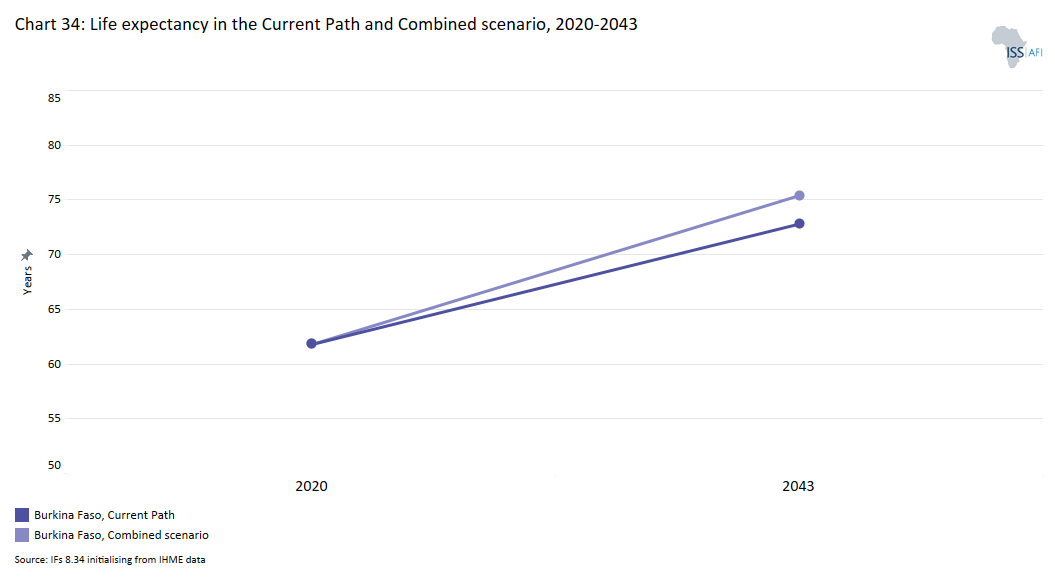

- In the Combined scenario, the average Burkinabé could expect to live about 2.6 years longer at 75.4 years in 2043, compared with the Current Path for the same year.

We end this page with a summarising conclusion offering key recommendations for decision-making.

Burkina Faso faces complex, interlinked challenges that have contributed to its economic fragility, impeding inclusive growth and development. The country's main growth constraints include insecurity, limited economic diversification, climate change and variability, low agricultural productivity, a difficult business environment, infrastructure shortages and limited human capital. Tackling these issues is crucial to set the country on a path of sustained growth and shared prosperity. The government should prioritise integrated policy reforms and investments that improve governance, address infrastructure shortage, facilitate private sector development, improve agriculture productivity, diversify the economy, and build quality human capital stock.

All charts for Burkina Faso

- Chart 1: Political map of Burkina Faso

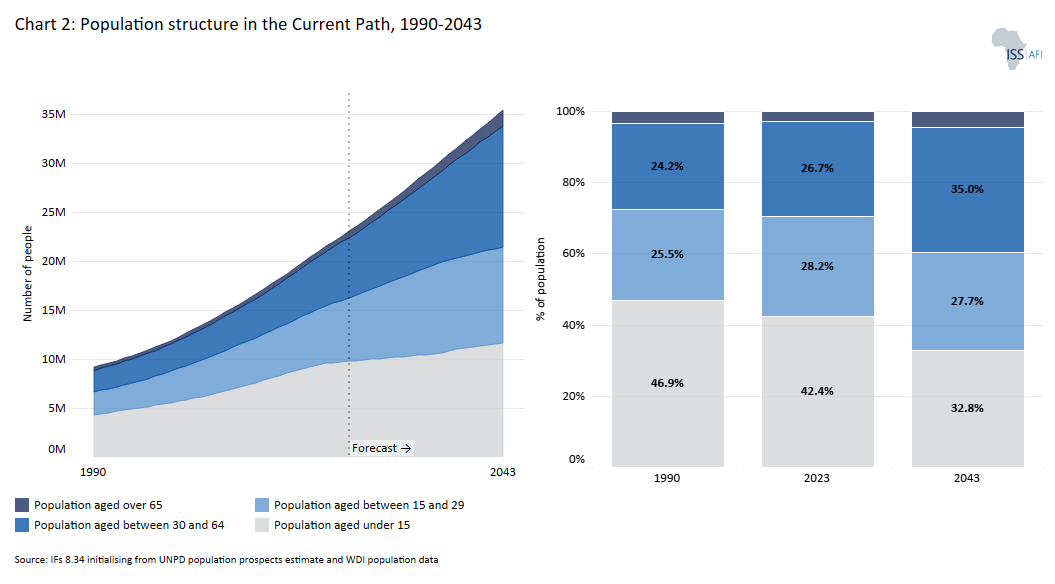

- Chart 2: Population structure in Current Path, 2019–2043

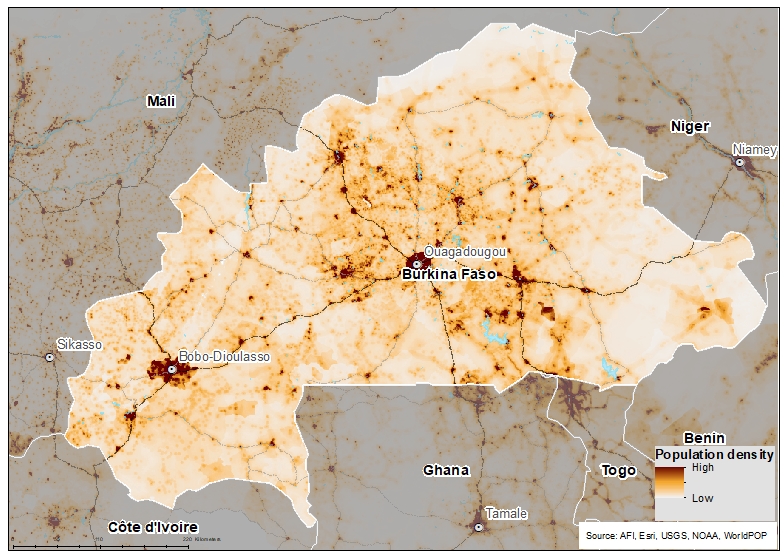

- Chart 3: Population distribution map, 2023

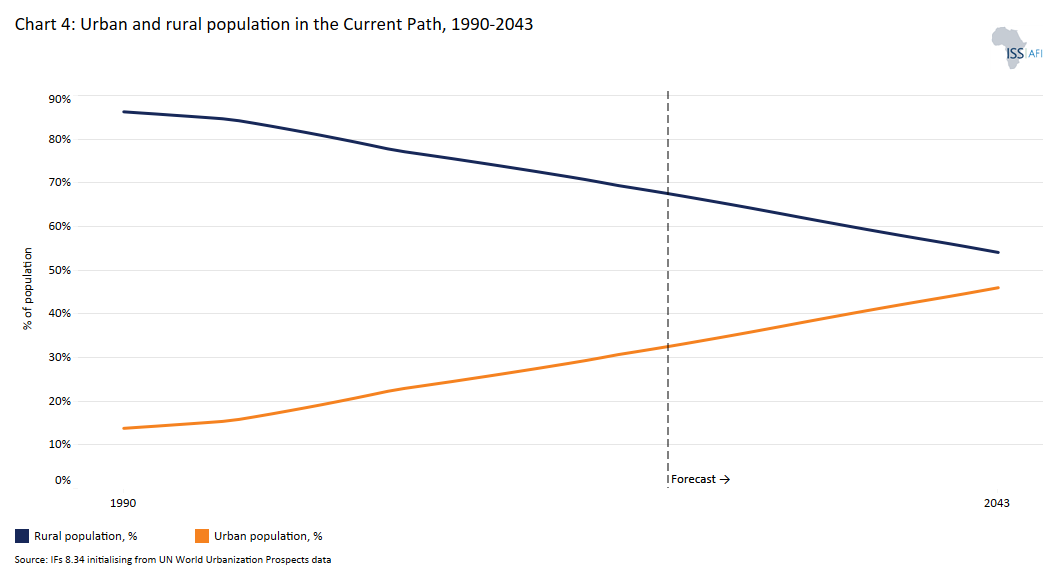

- Chart 4: Urban and rural population in the Current Path, 1990-2043

- Chart 5: GDP (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, 1990–2043

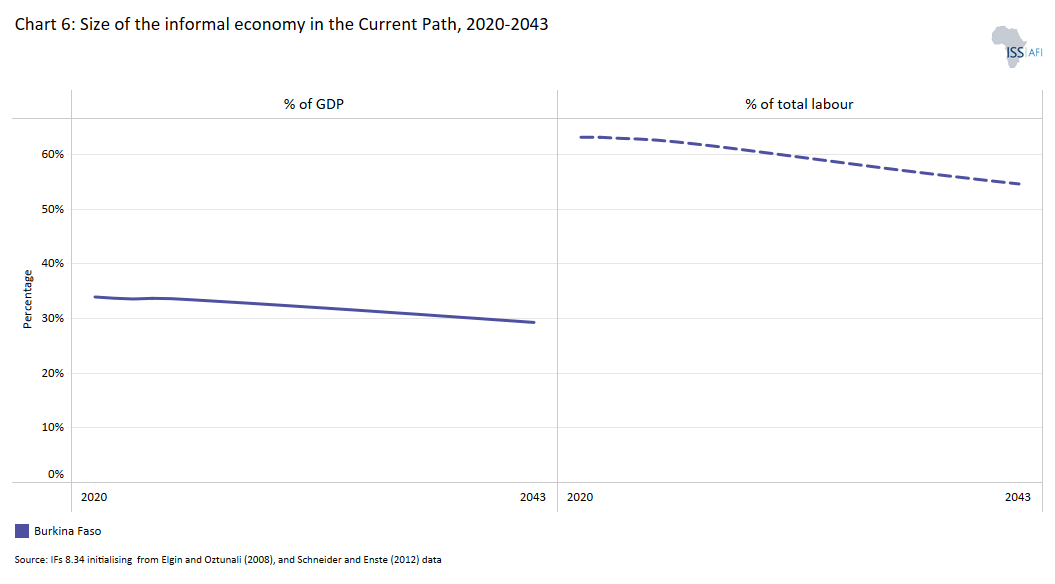

- Chart 6: Size of the informal economy in the Current Path, 2019-2043

- Chart 7: GDP per capita in Current Path, 1990–2043

- Chart 8: Extreme poverty in the Current Path, 2019–2043

- Chart 9: National Development Plan of Burkina Faso

- Chart 10: Relationship between Current Path and scenarios

- Chart 11: Mortality distribution in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 12: Infant mortality rate in Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 13: Demographic dividend in the Current Path and the Demographics and Health scenario, 2019–2043

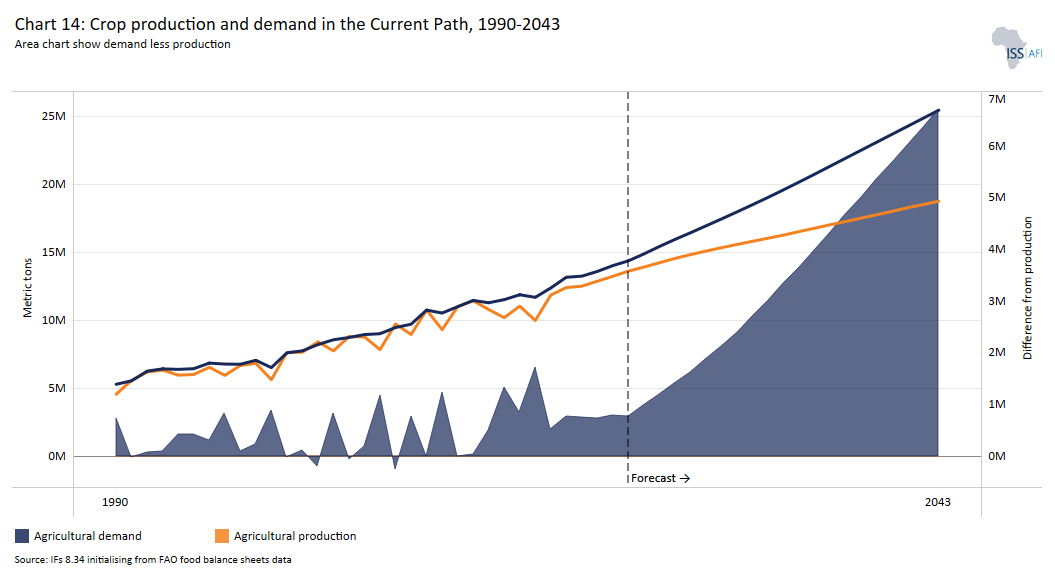

- Chart 14: Crop production and demand in the Current Path, 1990-2043

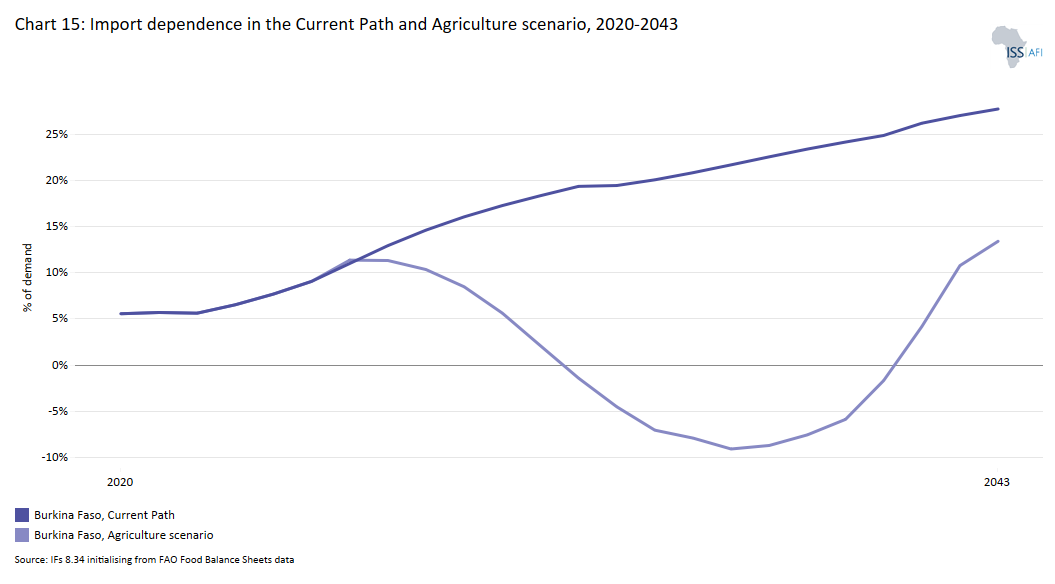

- Chart 15: Import dependence in the Current Path and Agriculture scenario, 2019–2043

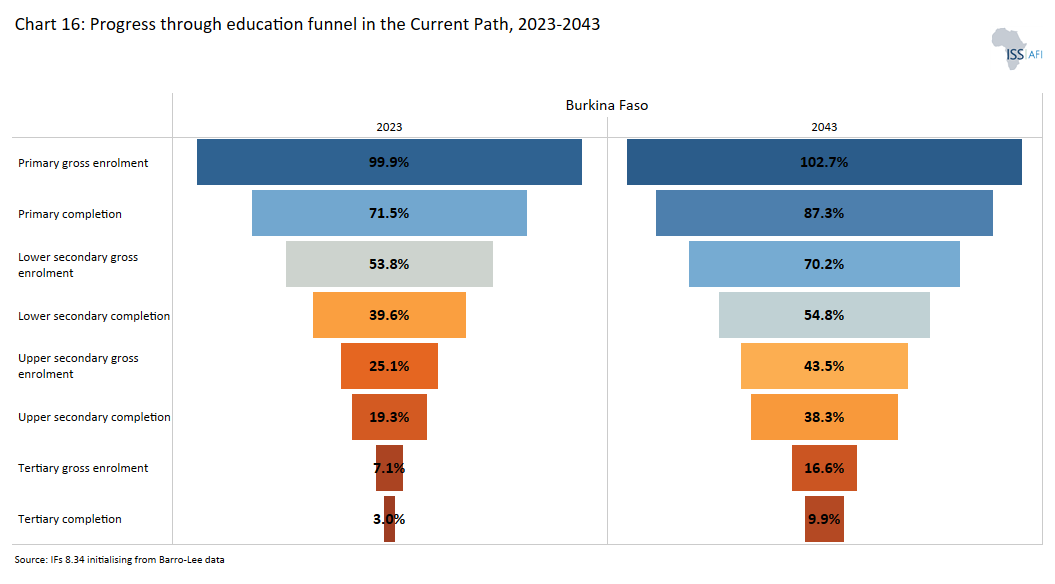

- Chart 16: Progress through the education funnel in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

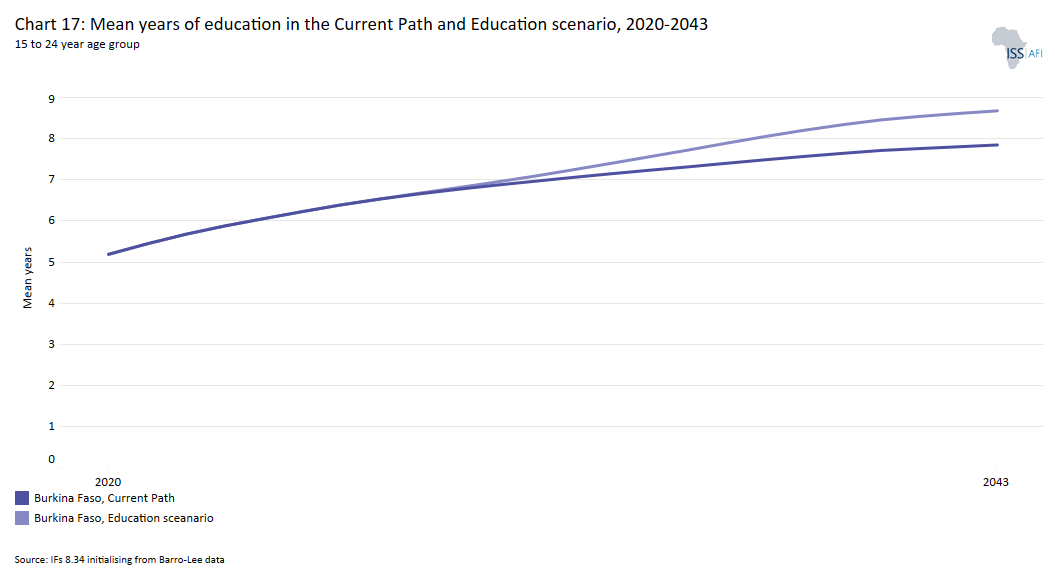

- Chart 17: Mean years of Education in Current Path and Education scenario, 2019–2043

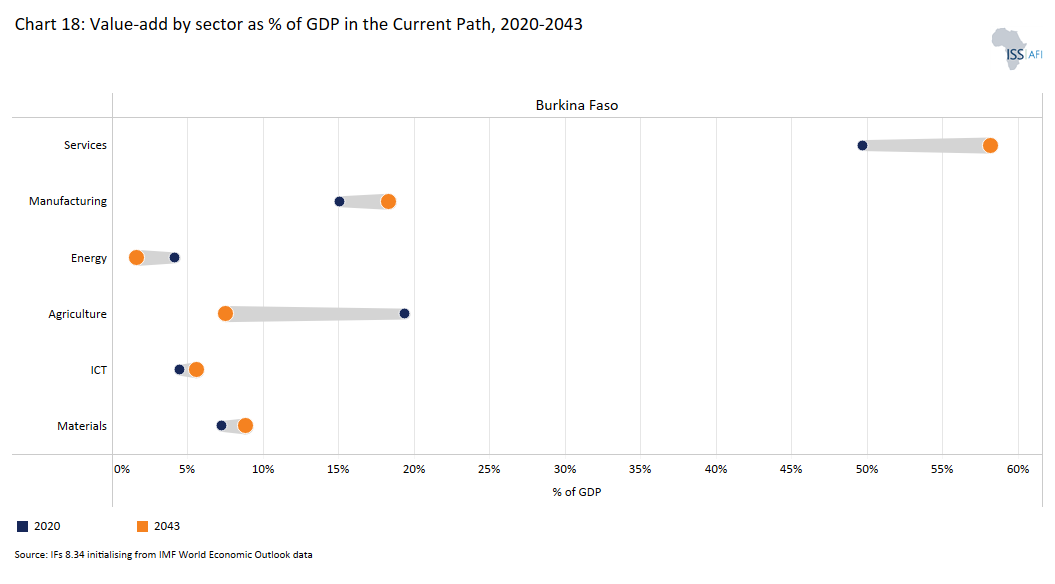

- Chart 18: Value-add by sector as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

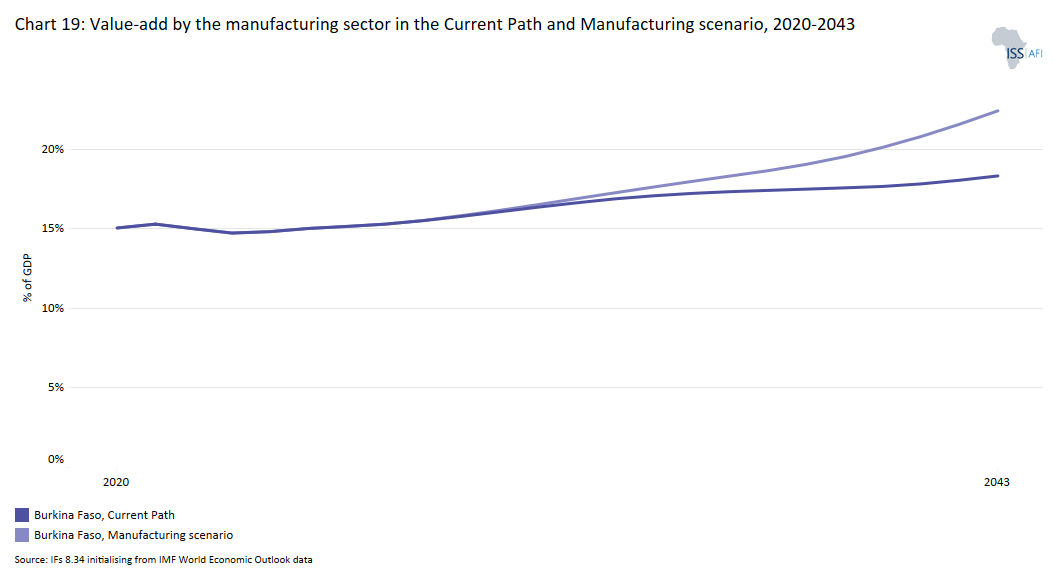

- Chart 19: Value-add of the manufacturing sector in Current Path and Manufacturing scenario, 2019–2023

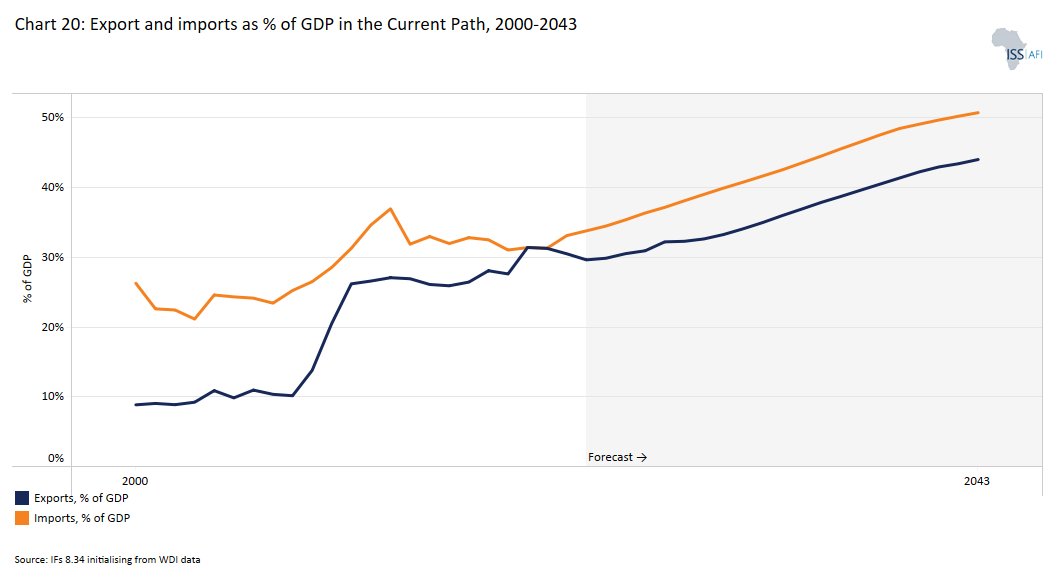

- Chart 20: Exports and imports as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2000-2043

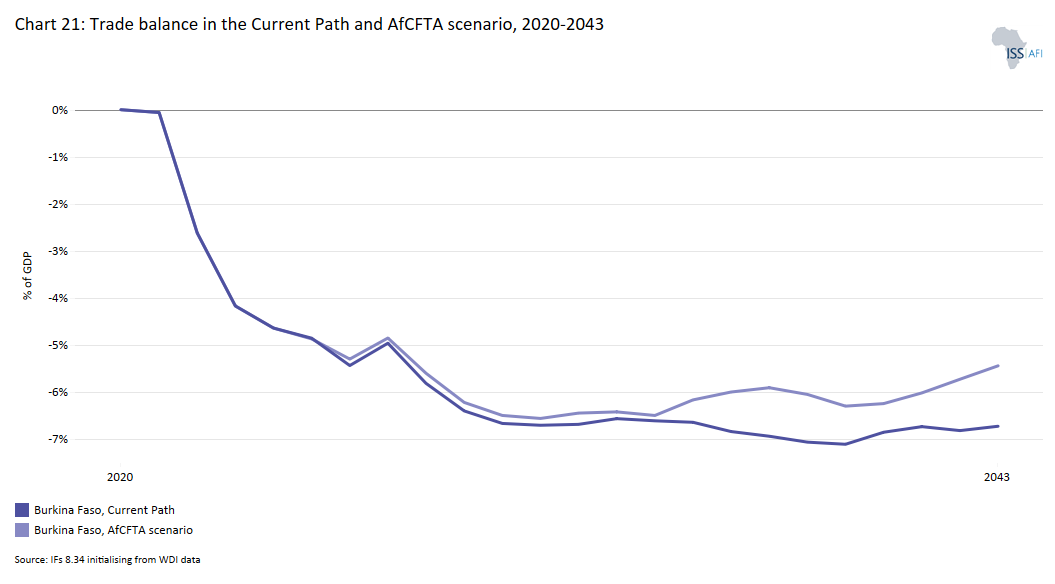

- Chart 21: Trade balance in the Current Path and AfCFTA scenario, 2019–2043

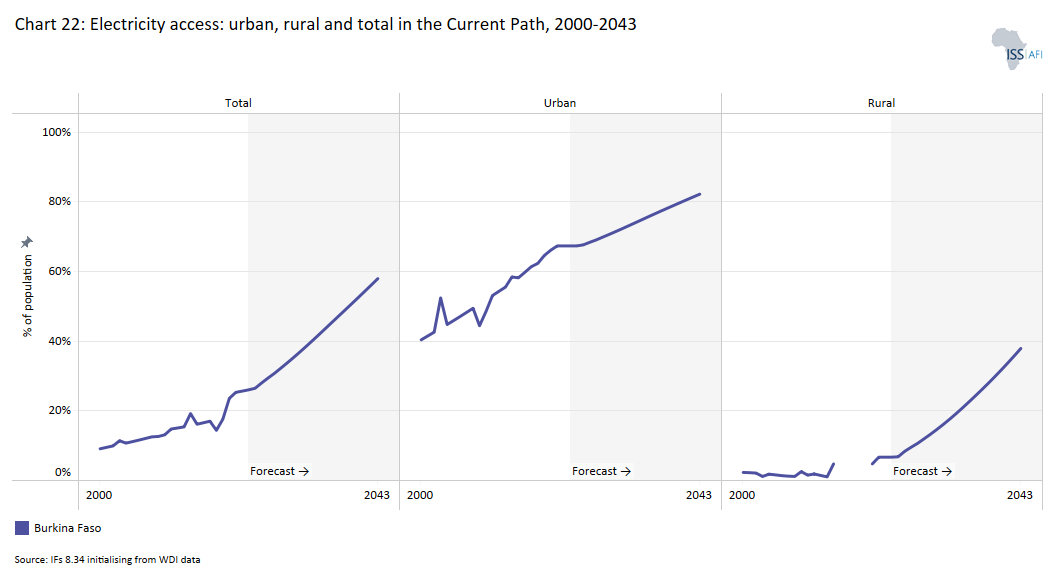

- Chart 22: Electricity access: urban, rural and total in the Current Path, 2000-2043

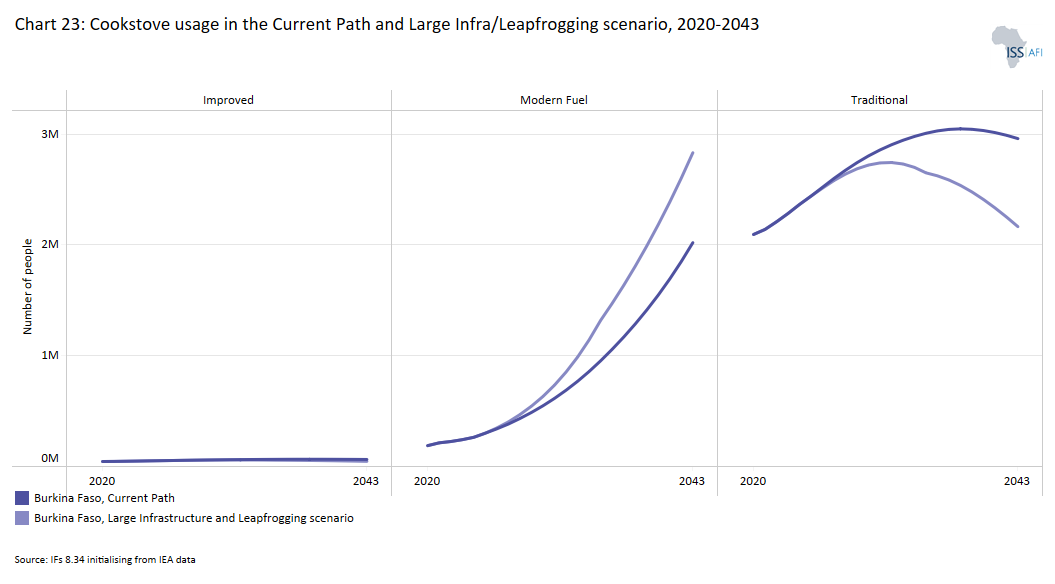

- Chart 23: Cookstove usage in the Current Path and Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

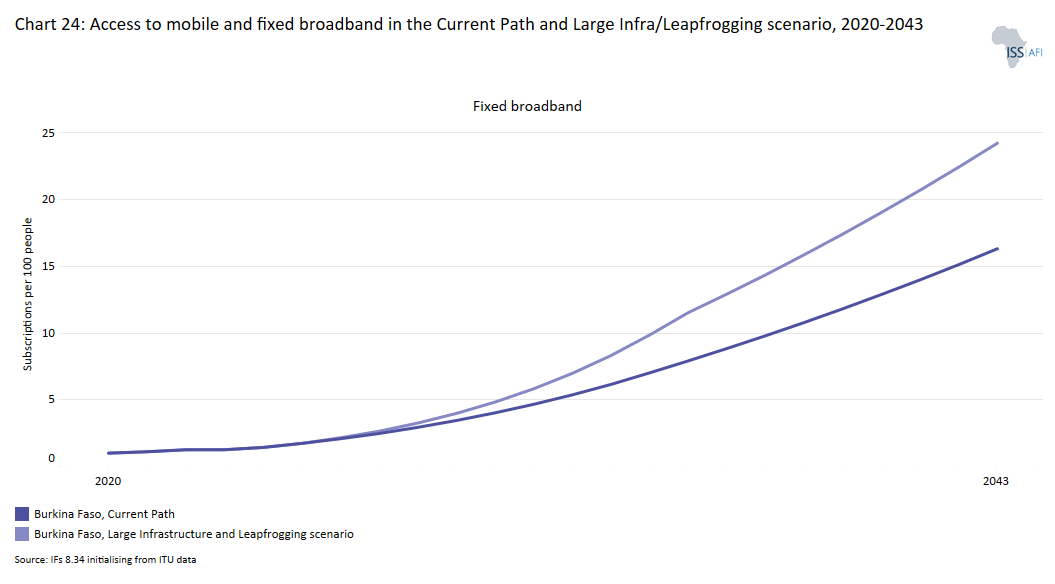

- Chart 24: Access to mobile and fixed broadband in Current Path and the Large Infra and Leapfrogging scenario, 2019–2043

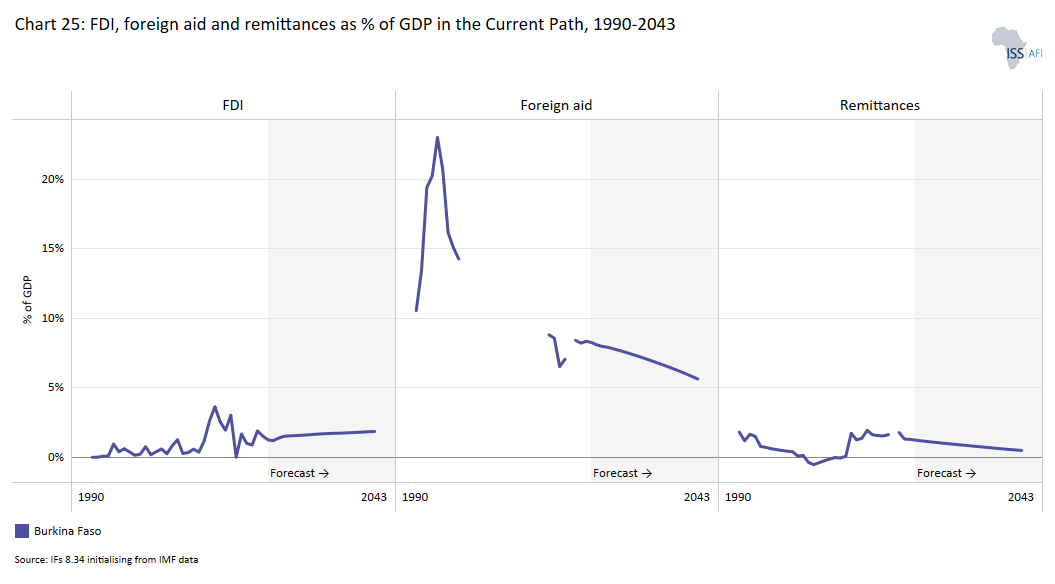

- Chart 25: FDI, foreign aid and remittances as % of GDP in the Current Path and in the Financial Flows scenario, 1990-2043

- Chart 26: Government revenue in Current Path and Financial Flows scenario, 2019–2043

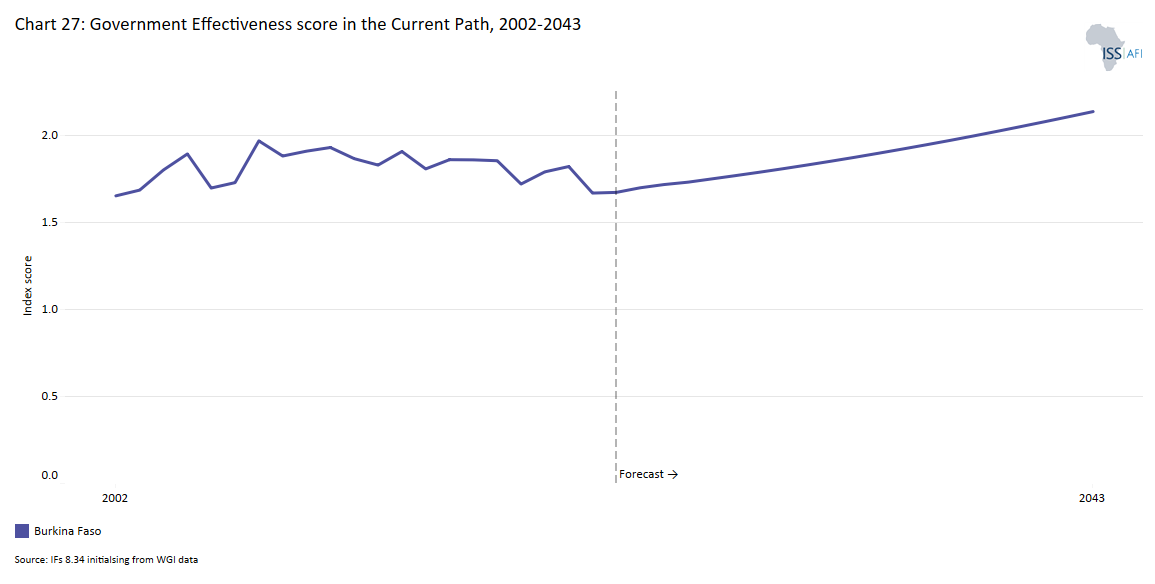

- Chart 27: Government effectiveness score in the Current Path, 2002-2043

- Chart 28: Composite governance index in the Current Path and Governance scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 29: GDP per capita in Current Path and scenarios, 2019–2043

- Chart 30: Poverty in Current Path and scenarios, 2023–2043

- Chart 31: GDP (MER) in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 32: Value added by sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

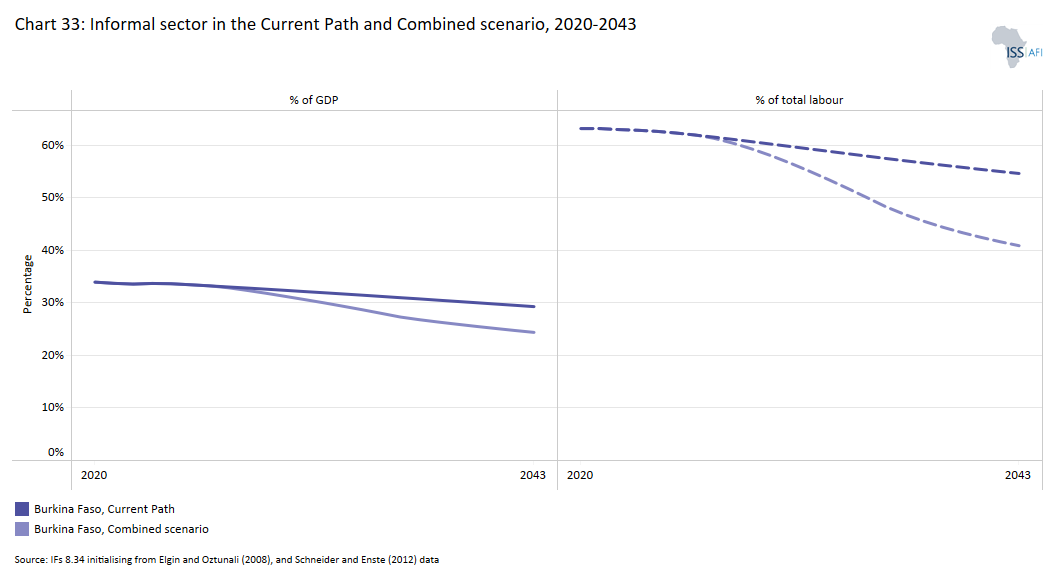

- Chart 33: Informal sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

- Chart 34: Life expectancy in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

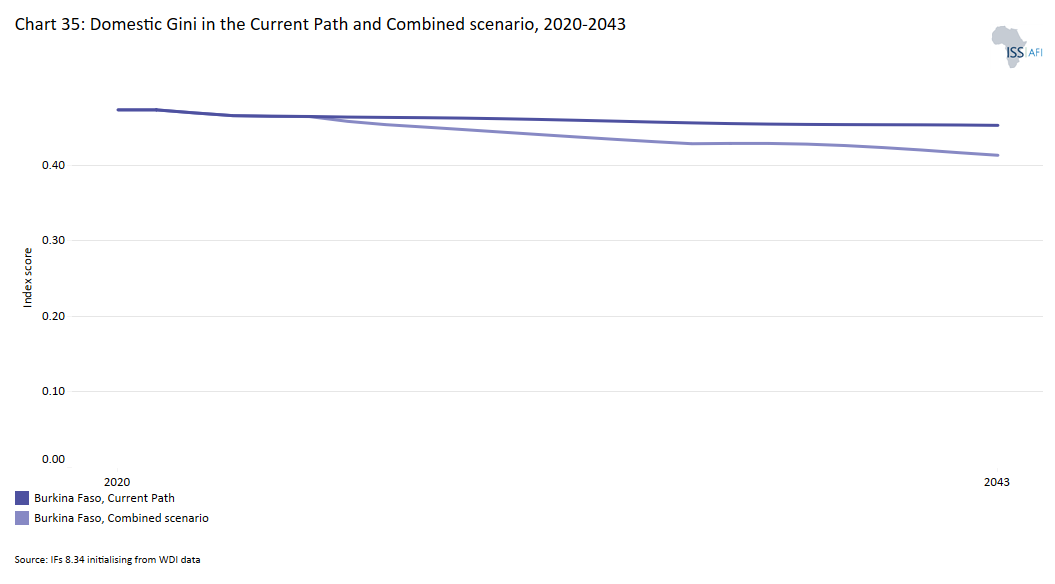

- Chart 35: Domestic Gini in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

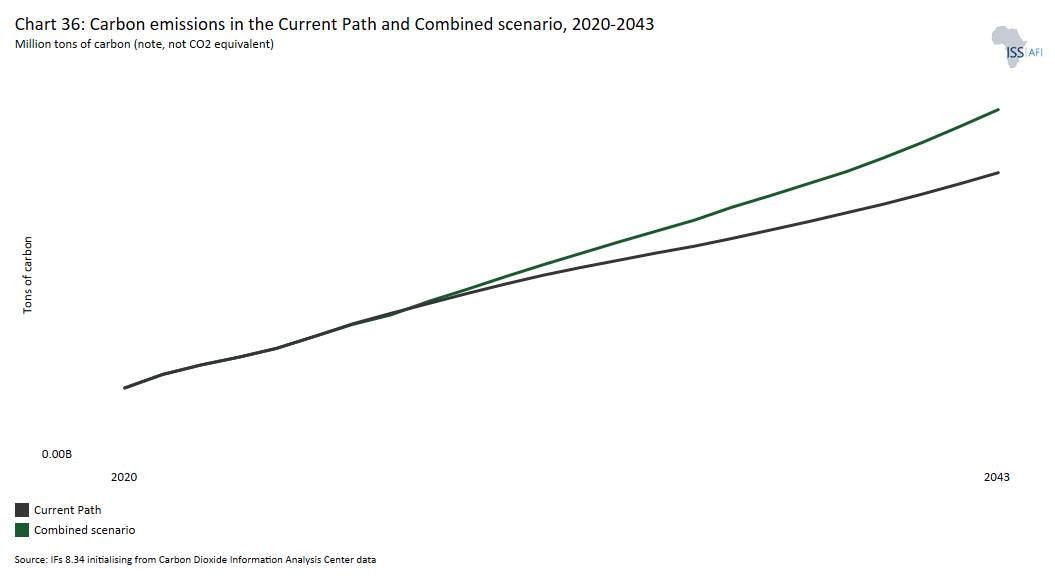

- Chart 36: Carbon emissions in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019–2043

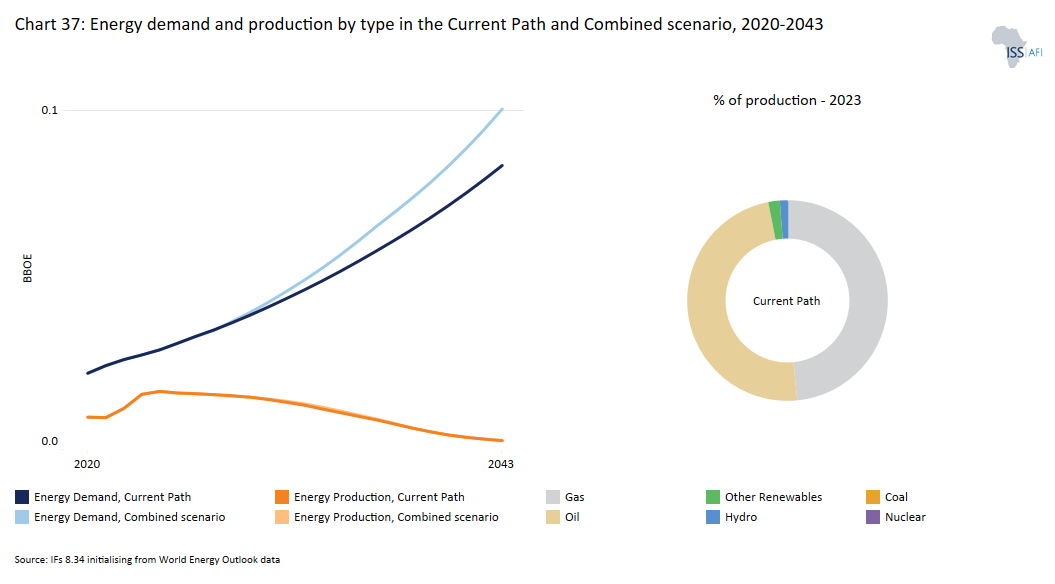

- Chart 37: Energy demand and production by type in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2019-2043

- Chart 38: Policy recommendations

Chart 1 is a political map of Burkina Faso.

Burkina Faso is a landlocked country located in the heart of West Africa with a land area of 274 200 km2. It lies between the Sahara Desert and the Gulf of Guinea, south of the loop of the Niger River. Burkina Faso borders Mali to the northwest, Niger to the northeast, Benin to the southeast, Togo and Ghana to the south, and Côte d’Ivoire to the southwest.

The country's post-colonial history is characterised by recurring political instability. It has experienced six coups (1966, 1980, 1982, 1983, 1987, and two coups in 2022), two attempted coups (1989, 2015), and one popular uprising in 2015.

Blaise Compaoré became president after the coup against charismatic leader Thomas Sankara in 1987, and ruled until his removal on 31 October 2014. After a one-year transition period (2014-2015) and two presidential elections (2015 and 2020), two coups occured in 2022, against the backdrop of dire jihadi violence carried out by groups affiliated with al-Qaeda and Islamic State groups. In September 2022, Captain Ibrahim Traoré, the current head of the state, took power from Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, who eight months earlier (January 2022) had ousted the re-elected president Christian-Roch Kaboré in 2020.

According to the 2024 Global Terrorism Index, Burkina was the country most affected by terrorism in the world in 2023. Fatalities from terrorism were up by 68% in 2023 since the start of the jihadi violence in 2014. While there were fewer than 50 000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) in January 2019, the country had 2.01 million IDPs by 30 March 2023 (the latest census to date), according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

The crisis has severely impacted the health and education sectors. As of December 2023, 20% of healthcare facilities (413 in total) have been affected, restricting access to care for approximately 3.8 million people. Similarly, 5 330 primary and secondary schools—20% of the country's educational infrastructure—are closed, disrupting education for 820 865 students, including 396 716 girls.

Under Traoré, Burkina Faso drastically overhauled its external relations, breaking off the country's security cooperation with France and moving closer to Russia. The country used to be a member of the G5 Sahel alliance until it withdrew in December 2023. Similarly, Burkina Faso, which had been a member of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) since its founding in 1975, announced its decision to withdraw from the organisation in January 2024, and formally exited on 29 January 2025. In August 2024, it established the Confederation of Sahel States (CSS) together with Mali and Niger. The Confederation originated as a mutual defense pact signed on 16th September 2023, following the 2023 coup in Niger. The confederation aims to promote cooperation and integration among its member states, particularly in areas such as security, defense, and economic development. Although the CSS is still part of WAEMU and uses the West African Franc (CFA), it has stated its intention to create a common currency to end the use of the CFA.

Burkina Faso is classified as a low-income country with an economy primarily reliant on subsistence farming and livestock raising. Persistent challenges include highly variable rainfall, poor soil quality, and inadequate communication networks and infrastructure. The country also depends heavily on mining, particularly gold, which accounts for approximately 16% of its GDP and 80% of its exports.

The country is classified among nations with low human development. According to the 2023/2024 Human Development Report, it ranked 185th out of 193 countries on the Human Development Index (HDI). Additionally, it placed 149th out of 167 countries on the 2024 SDG Index, which assesses performance across the 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

Burkina Faso’s development outlook hinges on the security situation and the expected impacts of a full ECOWAS withdrawal: lower trade with non-WAEMU (West African Economic and Monetary Union) ECOWAS states, and the associated higher investors’ risk premiums, and increased regional financing costs.

Chart 2 presents the Current Path of the population structure, from 2019 to 2043.

The characteristics of a country's population can shape its long-term social, economic and political foundations; thus, understanding a nation's demographic profile indicates its development prospects.

Citizens of Burkina Faso, regardless of their ethnic origin, are collectively known as Burkinabé. The major ethnolinguistic group of Burkina Faso is the Mossi. French is the official language, and Moore, the language of the Mossi, is spoken by a large majority of the population.

The population of Burkina Faso is growing rapidly at about 3 per cent per year. In 2023, the country’s population was estimated at 23 million, and on the Current Path, it will reach 27.1 million by 2030 and 35.3 million by 2043. This represents about 12 million more people over the next 20 years.

Exercising family planning was estimated at 31.2% of women in the country in 2023. On the Current development trajectory, it will increase to 36.7% by 2030.

With a total fertility rate estimated at 4.2 children per woman in 2023, Burkina Faso has the 12th-highest fertility rate in Africa and slightly below the average of 4.8 children per woman for low-income countries in Africa in the same year. On the Current Path, Burkina Faso’s fertility rate will decline slightly to 3.7 children per woman in 2030 and about 2.8 children per woman by 2043.

Burkina Faso's population is very youthful. With a median age of about 18 years in 2023, Burkina Faso has the 12th-youngest population in Africa, and its median age will modestly increase to 20 years in 2030 and 24 years by 2043.

Due to this youthful age structure, the dependency ratio is high, as a large portion of the population depends on a small workforce to provide for its needs—which constrains savings and investment in human and physical capital.

As of 2023, about 42.4% of the country's population was under 15 years of age. On the Current Path, the population below 15 will decline but will still constitute about 37.7% in 2030 and 32.7% in 2043. The share of the elderly (65 and above) has been stable over time—at about 2.7% in 2023—and will reach 3.2% in 2030 and 4.4% in 2043.

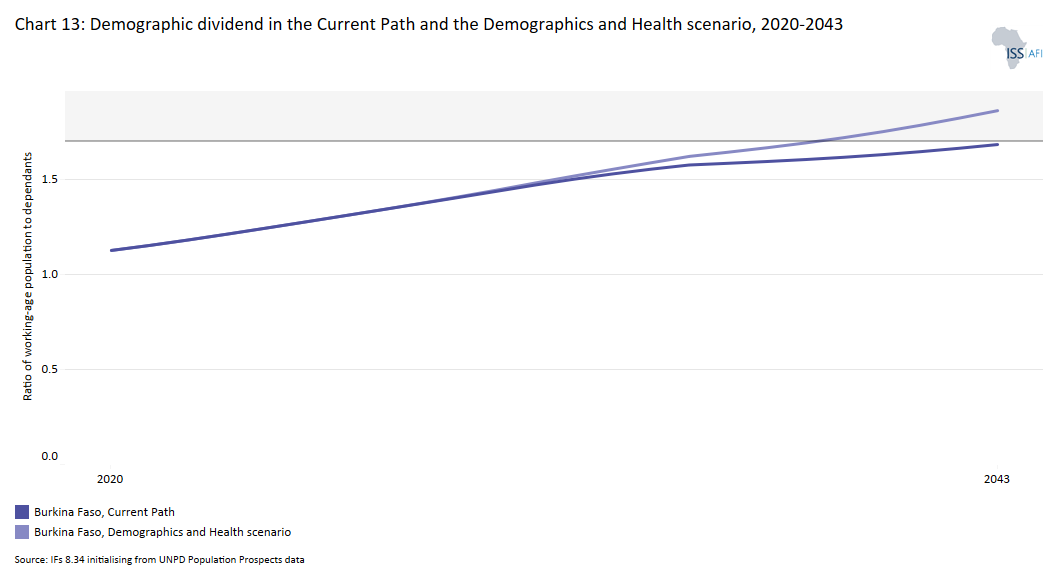

When the ratio of the working-age population to dependant is 1.7 or more, countries often experience more rapid economic growth, known as the demographic dividend, provided the workforce is appropriately skilled and absorbed in the labour market. Currently, the private sector's limited capacity makes it challenging to accommodate the large number of generally unskilled young job seekers in the country.

Burkina Faso is unlikely to reap its demographic dividend across the Current Path forecast horizon. The ratio of the working-age population to dependants stood at 1.2 in 2023--almost one working-age person for each dependant. It will only be at 1.4 in 2030 and 1.68 in 2043, slightly above the average of 1.5 for African low-income countries but still below the threshold of 1.7 that a country needs to enter a potential demographic window of opportunity. Burkina Faso only gets to this positive ratio at around 2044. However, Burkina Faso will enter this potential sweet spot almost a decade earlier than the average for low-income Africa.

Burkina Faso has a large youth bulge at 48.9%. Youth bulge is the percentage of the population between 15 and 29 years old relative to those aged 15 and above. It will get to 48.4% in 2030 and reach 41.2% by 2043. In addition to the requirement for more spending on education, health services and job creation, large numbers of young adults can lead to positive political change in a country through youth activism, but they can also carry the seeds for socio-political instability in the absence of economic opportunities.

Chart 3 presents a population distribution map for 2023.

Burkina Faso has an average population density of about 0.8 persons per hectare in 2023. Population density is unevenly distributed, with higher concentrations in and around urban areas such as the capital, Ouagadougou, and Bobo-Dioulasso that also evidence more agricultural activity. Rural areas, especially in the northern and eastern regions (the Sahel region), have lower population densities. These areas are semi-arid, making them less suitable for agriculture and currently impacted by insecurity. On the Current Path, Burkina Faso’s population density will be about 1.0 and 1.3 people per hectare in 2030 and 2043, respectively.

Chart 4 presents the urban and rural population in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

Burkina Faso experienced urbanisation later than similar countries in the region. The population is largely rural at about 67.5% in 2023, on par with the average of 67.3% for low-income Africa. On the Current Path, the rural population will reduce by about 13 percentage points to reach 54% by 2043. This means the urbanisation rate increases from about 32.5% in 2023 to 36.8% in 2030, and 45.9% by 2043.

If well planned, urbanisation can be critical to economic growth and development, as it fosters entrepreneurship and increases productivity. However, limited supply of energy, infrastructure deficit, limited skills, poor business regulation systems and low access to finance impede the productivity potential of Burkina Faso's urban areas. The current government needs to address these shortfalls while curbing unplanned informal sector development to reduce flood risks in urban areas. Burkina Faso, despite its generally arid and semi-arid climate, does experience flooding, particularly during the rainy season.

Chart 5 presents GDP in market exchange rates (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

Burkina Faso has limited natural resources. Its economy relies on agriculture and mining, particularly gold production. The agriculture sector entails primarily cotton cultivation, despite its low productivity and dependence on government subsidies, challenging climatic conditions, and an underdeveloped agro-industry.

Burkina Faso's economy is hindered by its faulty infrastructure, including limited electrical infrastructure, and vulnerability to the volatility of oil import prices as well as international commodity prices for gold and cotton. The structural challenges of the economy are the over-reliance on agriculture and mining, limited access to financial services, and low levels of human capital development.

Over the previous decade, Burkina Faso experienced relatively rapid economic growth, averaging 6% per annum between 2010 and 2019, driven by gold and cotton production. However, this growth trajectory was disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, followed by political and security challenges, with negative impact on growth.

After a slowdown in 2022 (+1.7%), economic growth bounced back to 3.6% in 2023, largely driven by the agriculture and services sectors. Cotton production, which had been affected by insect infestations in 2022, played a key role in revitalising agriculture. The resurgence of gold production, which accounted for 78% of exports in 2021, along with the reopening of previously closed mines due to security concerns and the government's renewal and issuance of new operating licenses, holds the potential to drive growth.

Regarding public finances, the country began fiscal consolidation in 2023, reducing the budget deficit to 6.5% of GDP. This consolidation was largely driven by expenditure cuts, primarily through reduced capital investment and subsidies, aided by lower international oil prices. However, military and humanitarian spending remained elevated. As bilateral donor grants decreased, efforts were intensified to sustain domestic revenue mobilisation. Despite these efforts, the fiscal deficit remained high, with public debt surpassing 60% of GDP in 2023.

Between 1990 and 2023, Burkina Faso’s GDP increased almost sixfold from US$3.2 billion in 1990 to US$18.3 billion in 2023. It will reach US$26.5 in 2030 and US$58 billion in 2043. In the Current Path, the average annual growth rate between 2023 and 2043 is expected to be about 5.8%. However, this optimistic economic growth forecast is contingent upon persistently high levels of political and security instability, climatic shocks, terms of trade shocks, and the full withdrawal from ECOWAS, which could lead to a significant increase in supply costs due to the reintroduction of customs barriers, particularly with Ghana. Going forward, Burkina Faso will have to revitalise its public affairs management, readjust public finances, reform the financial system, and create a better business climate to attract greater investment for development.

Chart 6 presents the size of the informal economy as per cent of GDP and per cent of total labour (non-agriculture), from 2019 to 2043. The data in our modelling are largely estimates and therefore may differ from other sources.

An informal economy (informal sector or shadow economy) is the part of any economy that is neither officially taxed nor monitored. Countries with high informality confront development challenges such as low revenue mobilisation. and economic growth tends to be sub-optimal.

Informality in lower-income countries arises not only from burdensome regulations or weak enforcement but also as a consequence of underdevelopment. In wealthier countries, where advanced production technologies and favourable economic conditions prevail, workers prefer formal wage employment because of higher wages. Similarly, managers are more likely to register and operate formal businesses, as the greater income potential in developed markets makes formality more profitable, even with the associated costs of taxes and regulations. As countries advance economically, the size of the informal sector typically shrinks. A World Bank study found that about 30% of the increase in aggregate output driven by higher productivity is linked to a roughly 25% reduction in the average size of informal enterprises.

With limited formal sector opportunities, most of Burkina Faso's workforce is employed in the low-value-add informal sector. The size of the country's informal economy was estimated at 33.6% of GDP in 2023, above the average of 29.3% for low-income Africa. On the Current Path, the size of the informal sector will decline to 32.3% of GDP in 2030 and 29.3% by 2043. However, this figure will still remain above the forecast of 27% for such low-income African countries in 2043.

Chart 7 presents GDP per capita in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

Despite being among the least developed countries globally, Burkina Faso's GDP per capita has almost doubled from 2000 and 2023 due to strong economic growth and decline in fertility rate. This helped the country reduce the large income gap with its peers. Since 2000, Burkina Faso’s GDP per capita has been above the average for low-income Africa. For the preceding 40 years it was below the average.

The GDP per capita (PPP, and constant 2017 US$) increased from US$1 266 in 2000 to US$2 119 in 2023, compared to the average of US$1 814 for such countries in 2023.

In the Current Path, the country will reach a GDP per capita of US$2 493 in 2030 and US$3 638 by 2043, above the projected average of US$2 984 for low-income Africa in the same year.

Chart 8 presents the rate and numbers of extremely poor people in the Current Path from 2019 to 2043.

In 2022, the World Bank updated the monetary poverty lines to 2017 constant dollar values as follows:

- The previous International/PPP $1.90 extreme poverty line is now set at US$2.15, also for use with low-income countries.

- US$3.20 for lower-middle-income countries, now US$3.65 in 2017 values.

- US$5.50 for upper-middle-income countries, now US$6.85 in 2017 values.

- US$22.70 for high-income countries. The Bank has not yet announced the new poverty line in 2017 US$prices for high-income countries.

Since gaining independence in 1960, Burkina Faso has pursued economic growth as a strategy to reduce poverty and inequality. Over the years, poverty reduction efforts have evolved through four distinct periods of policy development.

From 1990 to 1999, the focus was on implementing five-year development plans and structural adjustment policies, along with other initiatives aimed at fostering growth. The period from 2000 to 2010 marked a renewed emphasis on planning, highlighted by the introduction of the Strategic Framework for Poverty Reduction. This framework prioritised equity, improved access to basic social services for the poor, social advancement, and the creation of job opportunities.

The period from 2011 to 2015 focused on developing strategies to accelerate economic growth and promote sustainable development. This was followed by the implementation of the Economic and Social Development Plan (PNDES-I) (2016–2020). Currently, Burkina Faso is executing the Economic and Social Development Plan for 2021–2025 (PNDES-II).

These policies have contributed to poverty reduction (at least as measured using the monetary poverty line) even though a significant portion of the population still faces extreme poverty. Indeed, the poverty rate measured at the international extreme poverty line of US$2.15/day per person declined from 83% in 1990 to about 30.7% in 2019 (i.e. before the COVID-19 pandemic). In 2023, the poverty rate was estimated at about 27.7% (6.4 million people). This is 13 percentage points lower than the average of 41.5% for African low-income countries. Extreme poverty in Burkina Faso is primarily concentrated in rural areas, highlighting significant regional disparities, and the need to better target economic and social policy measures toward rural areas and regions for a greater impact on improving the well-being of the population.

In the Current Path, Burkina Faso's poverty rate will steadily decline to reach 19.6% in 2030, and about 7.9% (2.8 million people) in 2043 compared with the projected average of 24.1% for low-income Africa in the same year.

However, monetary poverty only tells part of the story. The global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) measures acute multidimensional poverty by measuring each person's overlapping deprivations across 10 indicators in three equally weighted dimensions: health, education and standard of living.

On the Multidimensional Poverty Index, 64.5% of the population in Burkina Faso is multidimensionally poor, about 37 percentage points higher than the monetary poverty rate. An additional 15.8% of the population is also classified as vulnerable to multidimensional poverty. Multidimensional poverty is primarily concentrated in rural areas (79.4% ) compared with 25.5% in urban areas.

The binding constraints to poverty reduction and shared prosperity in Burkina Faso are weak access to infrastructure, low agricultural productivity, limited access to education and health, increasing insecurity, climate change issues, low inclusion of women in the economy, weak public administration, political instability, and geographical challenges due to being landlocked.

Chart 9 depicts the National Development Plan of Burkina Faso.

In its quest to improve the living conditions of its population, Burkina Faso has developed and implemented several development plans. The most recent ones are its medium term plans, the National Economic and Social Development Plan (PNDES-I) 2016-2020 and the National Economic and Social Development Plan (PNDES-II) 2021-2025. It is unclear whether or not the military government that took power in 2022 will release a new development plan.

The overall objective of the current National Economic and Social Development Plan (PNDES-II) is to restore security and peace, strengthen the nation's resilience, and structurally transform Burkina Faso's economy to achieve strong, inclusive and sustainable growth.

The PNDES-II is built around the following four strategic pillars:

- Pillar 1: Consolidate resilience, security, social cohesion, and peace;

- Pillar 2: Deepen institutional reforms and modernise public administration;

- Pillar 3: Strengthen human capital development and national solidarity;

- Pillar 4: Boost key sectors for the economy and job creation.

The plan aims to strengthen security, prevent conflict, and consolidate peace and social cohesion. In this regard, it seeks to better integrate security into planning and implementation and to increase the involvement of the population in development processes by further promoting tools for endogenous development. Based on this, it aims to enhance the transformation of the economy by leveraging the following:

- Increasing productivity in the agro-sylvo-pastoral, fisheries, and wildlife sectors;

- Developing small and medium-sized manufacturing industries, focusing on the processing of local products;

- Diversifying exports;

- Accelerating the demographic transition to quickly benefit from the demographic dividend.

The expected impacts of the National Economic and Social Development Plan (PNDES-II) 2021-2025 are:

- Strengthening peace, security, social cohesion, and the country's resilience.

- Consolidating democracy and improving the efficiency of political, administrative, economic, financial, local, and environmental governance.

- Raising the level of education and training to better align with economic needs, while increasing the enrolment in technical and vocational training by an average of 8% per year.

- Creating an average of 50 000 decent jobs per year for young people and women.

- Modernising, diversifying, and energising the production system, generating an average annual GDP growth rate of 7.1%.

The eight sectoral scenarios as well as their relationship to the Current Path and the Combined scenario are explained in the About Page. Chart 10 summarises the approach.

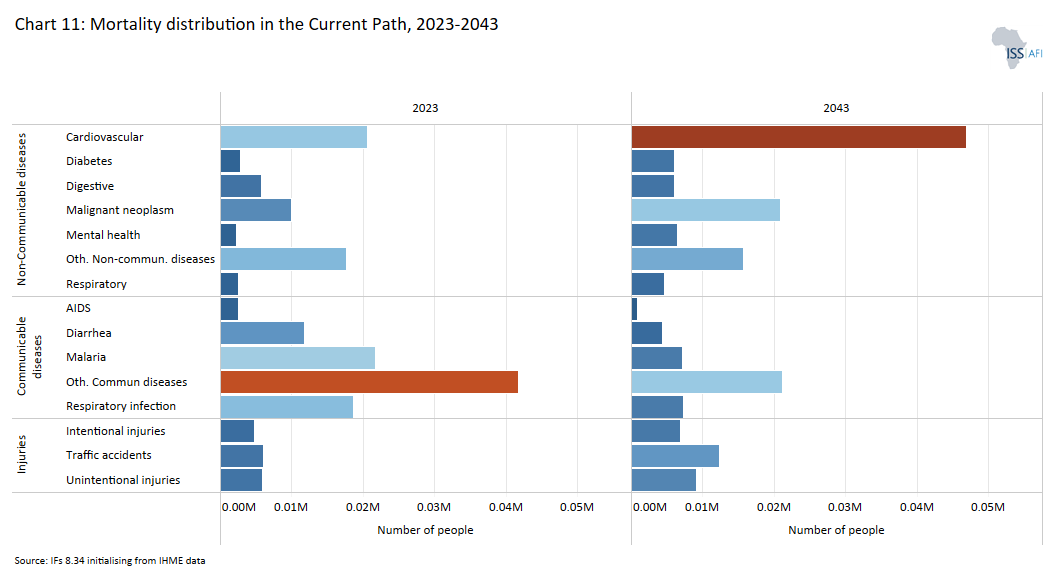

Chart 11 presents the mortality distribution in the Current Path for 2023 and 2043.

There are strong interactions between population size and health. The status of a country's health influences levels of fertility, mortality and morbidity. At the same time, high population growth contributes to an increased need for basic necessities for life, such as nutrition and health.

Burkina Faso made progress in healthcare delivery through the construction and equipping of healthcare facilities, the provision of healthcare personnel to these facilities, and the reduction of maternal and child healthcare costs through the introduction of free care for certain services. Yet, the health system in Burkina Faso is generally insufficient and faces persistent challenges. These include (i) weak disease prevention mechanisms; (ii) limited physical and financial access to healthcare centers for a large portion of the population; (iii) insufficient numbers and quality of healthcare personnel and their uneven geographic distribution; (iv) shortcomings in the management of free healthcare for pregnant women and children under five; (v) persistently high levels of maternal, neonatal and infant mortality; (vi) high in-hospital mortality rates; and (vii) malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies among children.

Communicable diseases remain the leading cause of illness and death in Burkina Faso, with malaria being a major contributor. In 2020, the country recorded an estimated 8.1 million malaria cases and about 20 000 related deaths, making it the top cause of mortality among children under five. According to the Ministry of Health, malaria accounts for 43% of healthcare consultations and 22% of deaths.

A significant level of illness is caused by limited access to safe drinking water and insufficient hygiene and sanitation, especially children, in the country. As of 2023, only 30% of the population has access to piped water while 24% of the population has access to improved sanitation. On the Current Path, 35% of the population will likely have access to improved sanitation by 2030 while 82.9% will have access to improved water, below the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target of 98% in the same year.

Non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular and malignant neoplasm remain the leading causes of death among the elderly.

However, Burkina Faso has also made progress in improving key health outcomes in recent years. The stunting rate among children under the age of five has significantly declined from 34.7% in 2010 to 22% in 2023, about 13 percentage points below the average of 34.7% for low-income Africa. Burkina Faso has already achieved the SDG target of 25% by 2030. On the Current Path, the stunting rate among children below five will decline to 18.3% by 2030 and 12.3% by 2043.

Maternal mortality has declined from 727 deaths per 100 000 live births in 1990 to 232 in 2023, compared with an average of 383 for low-income Africa.

Child (under five) mortality has also declined from 198 deaths per 1 000 live births in 1990 to about 100 deaths in 2023, while life expectancy has increased from 50.7 years to 64.3 years over the same period.

Despite this progress, Burkina Faso is not on track to meet all the SDG targets related to infant and maternal mortality. On the Current Path, the maternal mortality rate will likely decline to 169 deaths per 100 000 live births by 2030, significantly above the SDG targets of less than 70 per 100 000 live births. This target will probably only be reached in 2043.

Infant mortality (under five) will also decline to 69 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2030 and 39 deaths by 2043, falling significantly short of the SDG target of 25 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2030.

The Government and development partners should strengthen their support for improving the health system. In this regard, USAID’s health initiatives across Burkina Faso aim to improve the country’s healthcare system. In collaboration with the Government of Burkina Faso, USAID focuses on reducing malaria-related morbidity and mortality, particularly among children under five and pregnant women.

However, as Western countries and international institutions often condition aid on political stability and democratic governance, the resumption of such aid is unlikely without meaningful political reforms or assurances of stability. In 2023, USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA) provided approximately US$111 million in funding to Burkina Faso, down from US$121 million in 2022. It remains unclear whether this decrease is linked to the military takeover.

Without foreign aid, health outcomes in Burkina Faso could significantly deteriorate unless the government enhances its capacity to mobilise domestic resources and manage priorities.

The Demographics and Health scenario therefore envisions ambitious improvements in child and maternal mortality rates, enhanced access to family planning, and decreased mortality from communicable diseases (e.g., AIDS, diarrhoea, malaria, respiratory infections) and non-communicable diseases (e.g., diabetes), alongside advancements in safe water access and sanitation. This scenario assumes a swift demographic transition supported by heightened investments in health and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WaSH) infrastructure.

Visit the themes on Demographics and Health/WaSH for more detail on the scenario structure and interventions.

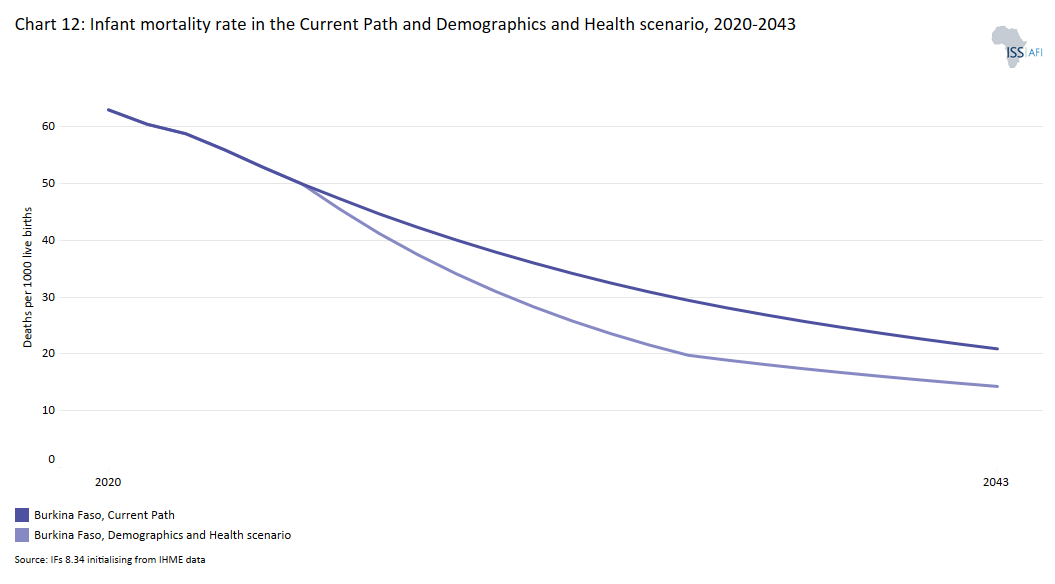

Chart 12 presents the infant mortality rate in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2019 to 2043.

The infant mortality rate is the probability of a child born in a specific year losing their life before reaching the age of one. It measures the child-born survival rate and reflects the social, economic and environmental conditions in which children live, including their health care. It is measured as the number of infant deaths per 1 000 live births and is an important marker of the overall quality of the health system in a country.

Infant mortality has declined from 109 deaths per 1 000 live births in 1990 to 56 deaths in 2023. On the Current Path, infant mortality will continue to decline to about 38 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2030 (above the SDG target of 25), and 21 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2043.

The interventions in the Demographics and Health scenario will see Burkina Faso's infant mortality rate drop to 31 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2030 and 14 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2043, below the projected average of 24 deaths for low-income Africa in 2043.

Chart 13 presents the demographic dividend in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2019 to 2043.

The demographic dividend is the economic growth generated by change in a country’s demographic structure. A potential demographic window of opportunity opens when the ratio of working-age persons to dependents (children and elderly) increases to at least 1.7 to one.

The implementation of the Demographics and Health scenario will accelerate the demographic transition in Burkina Faso. In this scenario, the ratio of the working-age population to dependents will reach the 1.7 threshold by 2038. On the Current Path, this minimum ratio will only be achieved in 2044. The materialisation of the demographic dividend (growth generated by change in a country’s population structure) is not straightforward; the growing labour force needs to be properly skilled and productively integrated into the economy.

Chart 14 presents crop production and demand in the Current Path from 1990 to 2043.

Agriculture plays a crucial role in Burkina Faso's economy and the livelihoods of its people. Although its contribution to the national economy has declined over time, it still accounts for about a quarter of the country’s GDP, and employs 71% of people facing poverty.

The sector is primarily made up of small-scale farms, each typically less than five hectares in size, producing key crops like sorghum, millet and maize (the highest in volume) as well as cotton (the most valuable). Before the rise of gold mining, cotton was the country’s leading export, and Burkina Faso is a top cotton producer and exporter in Africa. Traditional cereals, such as sorghum and millet, form the dietary staples of rural households, while urban residents favour rice and maize.

Agricultural production in Burkina Faso is generally characterised by low yields in both crops and livestock, mainly sustaining subsistence-level livelihoods. Although progress in the agricultural sector has reduced the threat of recurring famine, food insecurity remains a serious issue, affecting over 3.5 million people—about 20% of the population. In 2023, about 13% of the population faced malnourishment. On the current trajectory, the share of malnourished in the population will decrease to 12% by 2030 (still above the SDG target of 3%) and to 8.8% by 2043.

Burkina Faso is one of the few African countries to meet the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) target of allocating at least 10% of the national budget to agriculture. Yet, the country experiences one of the lowest average crop yields per hectare on the continent. In 2023, the country’s yield was estimated at 2.2 tons per hectare, ranking it 40th out of 54 African nations. While this represents a 57% increase from 1.4 tons per hectare in 1990, it remains low. Burkina Faso’s crop yields will rise only slightly to 2.3 and 2.6 tons per hectare in 2030 and 2043, respectively, still falling short of the 3.5 tons per hectare average projected for low-income African countries in 2043.

The country's low agricultural productivity is driven by several challenges, including limited access to quality inputs and services, high costs of inputs and equipment, insecure land tenure, lack of access to profitable markets, insufficient financial services, limited producer knowledge and capacity, poor transportation infrastructure, and inadequate irrigation systems. These challenges are compounded by the effects of climate change and growing insecurity, which further threaten an already vulnerable agricultural sector.

Going forward, providing food security to the growing population under such conditions will be one of the country's biggest challenges. In 2023, an estimated 13.2 million metric tons of crops were produced, a significant increase from the 5.3 million metric tons produced in 1990. On the Current Path, crop production will increase to about 15.6 million and 18.8 million metric tons by 2030 and 2043, respectively, while crop demand is set to increase from 14.4 million metric tons in 2023 to about 18 million and 25.5 million metric tons by 2030 and 2043, respectively. This leads to a deficit of 8 million metric tons in 2043. The Current Path paints a picture of a growing gap between domestic food production and demand, a situation that will exacerbate the country’s agricultural trade deficit with agricultural import dependency of 17.3% of total demand in 2030 and 27.7% of total demand by 2043 compared to 6.5% in 2023.

The Agriculture scenario envisions an agricultural revolution that ensures food security through ambitious yet feasible increases in yields per hectare, thanks to improved management, seed, fertiliser technology, and expanded irrigation and equipped land. Efforts to reduce food loss and waste are emphasised, with increased calorie consumption as an indicator of self-sufficiency and prioritising it over food exports. Additionally, the scenario includes enhanced forest protection signifying a commitment to sustainable land use practices.

Visit the theme on Agriculture for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions

Chart 15 presents the import dependence in the Current Path and the Agriculture scenario, from 2019 to 2043.

The Agriculture scenario will benefit Burkina Faso by increasing yields, reducing vulnerable rain-fed crops through irrigation schemes, reducing post-harvest losses and tapping into the country’s agricultural potential. In the Agriculture scenario, average crop yields could increase to 4.1 metric tons per hectare in 2043 compared with 2.6 tons on the Current Path in the same year. As a result, crop production will be 8.2 million metric tons more by 2043 than in the Current Path. This will result in a lower import dependency of 5.6% and 13% of total demand in 2030 and 2043, respectively, compared with 27.7% in the Current Path and below the average of 34% for low-income Africa in 2043.

Chart 16 depicts the progress through the educational system in the Current Path, for 2023 and 2043.

The Burkinabé educational system is structured into primary, secondary and higher education. It is generalist in nature, and does not meet the needs of the job market. Despite numerous reforms, the quality of basic education is deteriorating, while technical and vocational education and training (TVET) remains underdeveloped—both in quality and quantity—and suffers from poor coordination, with significant regional and gender disparities, as well as persistent challenges in access, quality and retention across all levels.

Burkina Faso has one of the lowest literacy rates in Africa. In 2023, the adult literacy rate (population aged 15 years and older) was estimated at 43.6%; the country ranks 47 of 54 countries in Africa. A higher literacy rate is important to improve employment prospects for the poor, and hence, an opportunity to escape from extreme poverty. On the Current Path, the literacy rate in Burkina Faso will likely increase to 54.7% in 2030 and 80% by 2043.

The country has made progress in primary gross enrolment, which stood at 99.8% in 2023, slightly below the average of 108% for Africa’s low-income countries. This high percentage, however, reflects the continued presence of over-aged learners at the primary level as the net primary school enrolment was 97% in 2023, reflecting challenges in getting all school-age children into classrooms.

While enrolment has improved, completion rates remain low even though above the average for low-income Africa (65.9% in 2019, the last year of available data), compared with an average of 54.3% for low-income countries.

On the Current Path, primary school completion rate will be 79.4% by 2030, still below the SDG target of 97%. High dropout rates, especially among girls, and disparities between urban and rural areas are major concerns.

Because of low completion and transition rates right from the primary level, fewer students are eligible for subsequent education levels and the resultant outcomes get poorer (Chart 16), which in turn reduces human capital accumulation.

Enrolment rates drop significantly after primary school, with a sharp decline in both lower- and upper-secondary levels. Many students do not transition from primary to secondary education, and those who do often face overcrowded classrooms and insufficient resources. In 2023, gross lower-secondary school enrolment stood at 53.7% while gross upper-secondary school enrolment was only 25%. On the Current Path, gross lower- and upper-secondary school enrolment will likely reach 60.9% and 31.8% in 2030, and 70% and 43.4% in 2043, respectively.

The lower-secondary education completion rate stood at 39.5% in 2023 while the upper-secondary education completion rate was only 19.3%. On the Current Path, lower- and upper-secondary education completion rates will increase but the country will likely miss the SDG target of 97% in 2030 by a substantial margin. Indeed, lower- and upper-secondary school completion rates will likely reach 44.4% and 26.2% in 2030, and 54.77% and 38.3% in 2043, respectively.

At the tertiary level, universities and other higher education institutions offer undergraduate, graduate and vocational programs. The Université Ouaga I Pr Joseph Ki-Zerbo, located in the capital Ouagadougou, is one of the largest and most prominent institutions in the country. The higher education sector faces constraints related to limited capacity, outdated curricula and inadequate infrastructure. The gross tertiary enrolment rate was just 7.1% in 2023, above the average of 8.7% for low income Africa. On the Current Path, it could get to 16.6% in 2043.

While Burkina Faso has made progress in closing the gender gap, significant disparities remain. Girls are less likely than boys to attend school, and the dropout rate for girls is higher, particularly in rural areas. Early marriage, pregnancy and discriminatory social norms contribute to lower education attainment among girls. For instance, the parity ratio at the tertiary level stood at 0.64 in 2023 (1 is full parity). Also, the upper-secondary education gross enrolment rate parity ratio (female/male) is forecast to be 0.85 in 2030 (below the SDG target of 1) and 0.94 in 2043.

Although the country has made some progress in getting more children into school, the quality of education they receive is poor. This remains one of the major challenges facing the education system. Similar to many other African countries, Burkina Faso is facing a learning crisis. Learning poverty, defined as the share of children not able to read and understand an age-appropriate text by age 10, is estimated by the World Bank, UNESCO, and other organisations at 74% in Burkina Faso. It is imperative to improve the quality of education provided in schools.

Overall, Burkina Faso has made progress in improving access to education, particularly at the primary level, however significant challenges remain in ensuring quality, reducing dropout rates, and expanding access to secondary and higher education. Efforts to address gender disparities, improve infrastructure and enhance teacher training will be critical for the future development of the country’s education system.

The Education scenario represents reasonable but ambitious improved intake, transition and graduation rates from primary to tertiary levels, with a particular focus on both lower- and upper-secondary levels and better quality of education. It also models substantive progress towards gender parity at all levels, additional vocational training at the secondary school level and increases in the share of science and engineering graduates.

Visit the theme on Education for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Chart 17 presents the mean years of education in the Current Path and in the Education scenario, from 2019 to 2043, for the 15 to 24 age group.

The average years of education in the adult population aged 15 to 24 is a good first indicator of the stock of human capital in a country, but Burkina Faso faces one of the lowest in Africa, at 5.8 years in 2023. The country ranked 38th in Africa (out of 54). The implementation of the Education scenario would improve the mean years of education for adults aged 15 to 24 in the country to about 7 years in 2030 and 8.6 years by 2043 compared with 6.8 years in 2030 and 7.8 years in 2043 in the Current Path (Chart 17).

Low-skilled and poorly educated workers make up most of the labour force in Burkina Faso. Due to the low economic complexity, the labour market tends to require more unskilled labour, but over time, as the economic complexity increases, there will be a growing demand for more skilled labour, particularly in the formal sector. Given the current weak education system, the country is ill-prepared to produce relevant skills for the job market, which could hamper competitiveness and productivity.

The Education scenario could contribute to addressing these challenges. In this scenario the share of science and engineering students in tertiary graduates in Burkina Faso will increase to 20.4% by 2043, five percentage points higher than the 15.4 % projected on the Current Path in 2043.

While Burkina Faso faces significant educational challenges, particularly in terms of low average years of schooling and a predominance of low-skilled workers, targeted improvements in the education sector could foster substantial progress. By enhancing the quality and relevance of education through increased support for science, engineering and vocational training, the achievement of the outcomes modelled in the Education scenario would equip the country with a more skilled labour force by 2043. Improved education outcomes would also support broader socio-economic growth, enabling the country to take advantage of future opportunities in the regional and global labour markets.

Chart 18 presents the value-add by sector as share of GDP in the Current Path, for 2023 and 2043.

The economy of Burkina Faso depends heavily on agriculture, particularly livestock farming, and the exploitation of mineral resources.

Agro-processing is the most prominent part of Burkina Faso’s small manufacturing sector, and it includes the processing of agricultural products like cotton, grains, fruits and nuts. Cotton processing is particularly important, as Burkina Faso is one of Africa's largest cotton producers. Other agro-processing activities include the production of flour, edible oils, sugar, beverages and dairy products.

The textile industry, linked to the cotton sector, includes activities such as spinning, weaving and garment production. However, the industry has not fully capitalised on Burkina Faso’s strong cotton production due to infrastructure and technological constraints.

The production of cement, bricks and other construction materials is an important part of the manufacturing sector. This is largely driven by domestic demand from the construction and infrastructure industries.

Several small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are also involved in the production of packaged foods, drinks (such as beer and soft drinks), and processed food items. This sub-sector is growing as urbanisation and a rising middle class create higher demand for consumer goods.

The country also has a modest pharmaceutical industry that produces medicines for domestic consumption. There are also companies involved in producing soaps, detergents and chemical products.

Burkina Faso, like many African nations, has been de-industrialising while still facing poverty (premature de-industrialisation), raising the worrying prospect that it could miss out on the chance to increase incomes by shifting workers from subsistence farming to higher-paying factory jobs.

The contribution of the manufacturing sector to GDP has been declining from its peak of 19% in 1973 to 10% in 2019 and about 9.6% in 2022 (the latest available data), on par with the average of 9.4% for low-income Africa. Burkina Faso is currently one of the least-industrialised countries in Africa. In 2022, it ranked 36 of 52 countries on the African Development Bank's African Industrialisation Index, which measures African progress on industrialisation. On the Current Path, the share of the manufacturing sector in Burkina Faso’s GDP will likely be 16% in 2030 and 18% by 2043, above the projected average of 16% for low-income Africa (Chart 18).

The manufacturing sector faces significant challenges. One is the lack of adequate infrastructure, particularly in energy and transportation. Frequent power outages and expensive electricity make manufacturing costs high, limiting competitiveness. Also, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which form the backbone of the manufacturing sector, often struggle with limited access to affordable financing. Banks in Burkina Faso tend to have high lending rates, and there is limited venture capital for industrial investment.

Manufacturing firms in Burkina Faso generally operate with outdated technologies and lack the advanced machinery needed for efficient production. Additionally, there is a shortage of skilled labour and technical expertise, which hinders productivity and innovation.

Ongoing political instability and security threats from terrorism have also deterred both domestic and foreign investment in the manufacturing sector. Uncertainty reduces long-term planning and investment in industrial projects. In sum, though there have been great strides in improving the regulatory environment for doing business in Burkina Faso, an unskilled and uneducated workforce, poor transportation infrastructure, periodic shortages of water and electricity, high energy costs, a deteriorating security environment, and a weak judicial system are still undermining growth of the manufacturing sector in Burkina Faso.

Many people experiencing poverty in Burkina Faso find themselves trapped in subsistence agriculture and informal service-based activities. Boosting the manufacturing sector will generate inclusive growth by facilitating the transition of low-income individuals from these sectors to higher-productivity areas. This structural shift not only boosts incomes but fosters a positive cycle wherein the growth of productive employment, capacities and earnings mutually reinforce one another, propelling economic expansion and poverty reduction.

The Manufacturing scenario models the impact of a manufacturing push in Burkina Faso. A reasonable but ambitious growth in manufacturing is envisaged through increased investment in the sector, research and development (R&D), and improved government regulation of businesses. This aims to enhance labour intensive manufacturing to create more jobs, particularly among females.

Visit the theme on Manufacturing for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Chart 19 presents the contribution of the manufacturing sector to GDP in the Current Path and in the Manufacturing scenario, from 2019 to 2023. The data is in US$ and % of GDP.

The manufacturing sector in Burkina Faso is still in its early stages of development, but it holds potential as a driver of economic diversification and job creation. Key areas for growth include agro-processing, textiles and renewable energy integration. Addressing challenges related to infrastructure, finance and skills development will be crucial for unlocking the sector’s full potential and making Burkina Faso more competitive in regional and global markets.

On the Current Path, the share of the manufacturing sector in Burkina Faso’s GDP will likely increase to 16% in 2030 and 18.3% by 2043, above the projected average of 16.2% for low-income Africa in 2043. The implementation of the Manufacturing scenario could further push the share of the manufacturing sector in GDP to 16.2% in 2030 and 22.4% by 2043 (Chart 19), above the projected average of 16.2% for low-income Africa in 2043.

However, industrialisation is a long-term process. It requires constructive relationships between the state that encourages and supports the private sector. Firms need a state that has strong capabilities in advancing an overall economic vision and strategy, efficiently providing supportive infrastructure and services, maintaining a regulatory environment conducive to entrepreneurial activity, and making it easier to acquire skilled labour and new technology and enter new economic activities and markets.

Chart 20 depicts exports and imports as a percentage of GDP, from 2000 to 2043, in the Current Path and in the AfCFTA scenario.

Burkina Faso has an economy largely dependent on cotton and gold exports, making it vulnerable to terms-of-trade shocks, which can have an outsized impact on its impoverished population.

The trade pattern of Burkina Faso is similar to that of many other African countries that rely on a few key commodity exports while importing higher-value manufactured goods, consumer items and foodstuffs.

Burkina Faso's top exports are gold and raw cotton. In 2022, gold accounted for 82.2% of Burkina Faso's total export value, while raw cotton accounted for 6.12%. Other exports are oily seeds (2.06%), coconuts, brazil nuts, cashews (2.05%) and zinc ore (1.97%). The most common destinations for the exports of Burkina Faso are Switzerland (74.2% of total exports in 2022), United Arab Emirates (6.56%), Mali (3.71%), Singapore (2.11%) and Côte d'Ivoire (2.09%). On the Current Path, total export value will be equivalent to 29.5% of GDP in 2030 and 38.8% of GDP by 2043.

Burkina Faso's top imports are refined petroleum (22.6%), electricity (3.14%), packaged medicaments (3.1%), petroleum gas (2.38%) and cement (2.35%). The most common import partners for Burkina Faso are Côte d'Ivoire (16% of Burkina’s total imports), China (11%), Russia (7.41%), France (7.28%) and Ghana (5.41%).

Outside of ECOWAS and the Community of Sahel–Saharan States (CEN-SAD), Burkina Faso has limited trade with other non-member African countries. Intra-Africa trade exports (imports) remain very low at 11% (9%) which is less than the continental average of 18%.

In 2023, the total import value was estimated at 33.8% of GDP while the total export represented 29.6%, leading to a trade deficit equivalent to 4% of GDP. On the Current Path, the value of imports is expected to continue to remain above Burkina’s exports reaching 39.9% in 2030. By 2043, Burkina’s import value will represent 50.7% of GDP against 44% for its exports in the same year (Chart 20).

The AfCFTA scenario models the impact of fully implementing the African Continental Free Trade Agreement by 2034. The scenario increases exports in manufacturing, agriculture, services, ICT, materials and energy exports. It also includes improved multifactor productivity growth from trade and reduced tariffs for all sectors.

Visit the theme on AfCFTA for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Chart 21 presents the trade balance in the Current Path and in the AfCFTA scenario, from 2019 to 2043 as a percentage of GDP.

Burkina Faso’s trade balance is structurally in deficit— a trend which is likely to persist over the forecast horizon. On the Current Path, the trade deficit will worsen reaching 6.6% of GDP in 2030 and 6.7% in 2043.

In the AfCFTA scenario, where trade restrictions are loosened and productivity is increased through competition and technology diffusion, Burkina Faso would not record a trade surplus by becoming a net exporter; however, its trade deficit could improve from a projected deficit equivalent to -6.7% of GDP in the baseline scenario (Current Path) by 2043 to -5.4% of GDP.

The AfCFTA represents a major opportunity for African countries, including Burkina Faso, to overcome the constraints of narrow domestic markets to boost exports. The full implementation of the AfCFTA will also enable the country to avoid high tariffs on its exports to ECOWAS countries if its withdrawal from the regional bloc is finalised.

Chart 22 presents the Current Path of access to electricity for urban, rural and the total population from 2000 to 2043.

Burkina Faso faces significant infrastructure challenges that have hindered its economic development and growth. The country, like many in West Africa, has been constrained by insufficient infrastructure in key sectors such as transportation, energy, telecommunications and water supply.

In 2024, Burkina Faso ranked 29 out of 54 African countries on the African Infrastructure Development Index (AIDI) produced by the African Development Bank. Poor infrastructure coverage and low quality in Burkina Faso increase transaction costs and lower the return on capital and work, discouraging domestic and foreign investment and constraining economic growth.

Burkina Faso imports nearly 70% of its electricity from neighbouring Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire and faces unreliable and expensive electricity access. As of 2021, only 18.9% of the country's total population had access to electricity compared to about 37% for the average for low-income Africa. Access to electricity for rural populations is woefully low at 6.6% in 2021 compared with 67.6% in urban areas. Most rural communities rely on biomass (wood and charcoal) for their energy needs.

Even for those connected to the power grid, supply is often unreliable. This increases operational costs for industries and hampers manufacturing, which is already constrained by other infrastructure challenges.

Solar and wind energy offer Burkina Faso a pathway to expand energy access, reduce reliance on imported energy, and enable economic growth. Solar power is particularly advantageous for remote areas without access to the national grid. With abundant solar resources—averaging around 2 800 hours of sunshine and 5.5 kWh/m² of solar irradiance daily—Burkina Faso has the potential to develop up to 95.9 gigawatts (GW) of solar capacity. The country has already initiated projects like the Zagtouli solar power plant, the largest in the Sahel, and aims to source 30% of its electricity from solar by 2030. Additionally, Burkina Faso could harness up to 1.96 GW of wind energy, with numerous regions identified as suitable for wind power development.

On the Current Path, the national electricity access rate will improve to 35% in 2030 (still below the SDG target of 98%) and about 58% by 2043, with 37.9% in rural areas and 82.2% in urban areas (Chart 22).

The road network in Burkina Faso is underdeveloped, with many rural areas poorly connected to urban centers. Only a small percentage (26% in 2023) of roads are paved, and those that are paved often suffer from poor maintenance. This limits the movement of goods and people and increases the cost of transportation. During the rainy season, many unpaved roads become impassable, further isolating rural communities and affecting the transportation of agricultural products to markets. On the Current Path, 33% and 48% of the total road network will likely be paved by 2030 and 2043, respectively.

Limited access to and poor quality of digital connectivity also limits Burkina Faso's growth potential. The mobile broadband subscriptions per 100 people were at about 61 in 2021, against an average of 27 for low-income Africa. On the Current Path, it will be 143.7 in 2030 and 154 by 2043.

Fixed broadband provides faster internet access speeds with more secure connections and is important for higher value-add service sectors. However, fixed broadband penetration in Burkina Faso is strikingly low, with a subscription rate of 0.07 per 100 people, below the average of 0.2 for African low-income. On the Current Path, fixed broadband subscriptions will be 4 and 16 per 100 people by 2030 and 2043, respectively.

In sum, the infrastructure deficit, especially poor access to electricity and the lack of a good road network are cited as some of the most significant obstacles to expanding the small private sector in the country. The Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario, therefore, addresses these issues. It involves ambitious investments in road and renewable energy infrastructure, improved electricity access and accelerated broadband connectivity. It emphasises adopting new technologies to enhance government efficiency and the rapid formalisation of the informal sector, incorporating significant investments in major infrastructure projects like rail, ports, and airports while highlighting the positive impacts of renewables and ICT.

The interventions in the scenario bring the national access to electricity rate to 39% in 2030 and 74% in 2043, compared with 33.8% and 57.9% on the Current Path in 2030 and 2043, respectively. The share of paved roads in the total road network is 36% in 2030 and 57.8% in 2043 compared with 32.9% and 48% on the Current Path in 2030 and 2043, respectively. Fixed broadband subscriptions will be 4.8 and 24 per 100 people by 2030 and 2043, respectively compared with 4 and 16 per 100 people in the Current Path forecast.

Visit the themes on Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Chart 23 presents the number of people using cookstoves in the Current Path and in the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario, from 2019 to 2043.

Due to limited electricity access, especially in rural areas, the bulk (81%) of Burkinabé households rely on inefficient energy sources for cooking such as firewood and charcoal (used in traditional cookstoves). In rural areas, nearly all energy consumption is biomass-based.

As a result, the national average firewood consumption stands at 0.69 kg per person per day. This poses a risk to the environment with the acceleration of deforestation and affects the health of infants and children by causing respiratory problems. Also, the daily collection of firewood (unpaid domestic work), which involves more women and young girls, limits their time for paid work and reduces study hours for girls, depriving them of opportunities to focus on education.

In the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario, the percentage of households that use traditional cookstoves would decline from 88.7% in 2023 to 79.7% in 2030 and about 43% in 2043 compared to 58.7% in the Current Path for 2043.

The share of households using modern fuel cookstoves is 56% by 2043 in the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario, compared to the Current Path of 40% in the same year. These findings imply that increasing access to modern energy, including electricity and off-grid renewable solutions, particularly in rural areas, can play a key role in reducing carbon emissions and mitigating climate change. By transitioning households from traditional cooking methods to modern alternatives, these measures lower emissions and reduce the burden of unpaid domestic work for women and girls. This shift can free up valuable time, enabling them to engage in paid work and study as well as leisure and personal care. For instance, rural electrification led to a 9% increase in female labour force participation through a reduction in the time women spent on housework in South Africa.

Chart 24 presents the percentage of the population and number of people with access to mobile and fixed broadband in the Current Path and in the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario, from 2019 to 2043. The user can toggle between mobile and fixed broadband.

The mobile broadband subscriptions per 100 people will be 154.4 by 2043 in the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario. Because the mobile broadband subscriptions are already approaching saturation levels on the Current Path, the intervention does not improve mobile broadband subscriptions above the Current Path.

In the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario, fixed broadband subscriptions will reach 4.8 and 24 per 100 people by 2030 and 2043, respectively, compared with 16.3 in the Current Path for 2043.

Chart 25 presents the trends in FDI, aid and remittances in the Current Path and in the Financial Flows scenario as a percentage of GDP, from 1990 to 2043.

Burkina Faso is not an important destination of international capital flows in Africa even though foreign aid plays a significant role in the country’s economic and social development, given its limited financial resources and high levels of poverty. Aid from international donors and development partners is crucial in supporting sectors such as education, healthcare, infrastructure, governance and security. Grants—non-repayable funds from international organisations, and development partners to support specific projects, programs or general budget needs—represented the largest share of non-tax revenues in Burkina Faso in 2021, amounting to 2.5% of GDP and 57% of non-tax revenues.

Development partners have traditionally supported Burkina Faso in addressing key development challenges, including strengthening agricultural markets and production, improving maternal and child health, adapting to climate change, enhancing governance and human rights, reducing malaria rates and responding to complex crises.

For instance, in 2021, USAID allocated over US$5.5 million toward agriculture and food security, targeting vulnerable communities, with a focus on women and youth. In 2024, the EU allocated €45 million for humanitarian aid in the country, a slight increase compared with €44 million in 2023. These funds support actions on (i) food insecurity and malnutrition, (ii) protection, (iii) health, (iv) nutrition, (v) shelter, (vi) water, sanitation and hygiene, (vii) education, (viii) disaster preparedness activities, and (ix) a rapid response to displacements.

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Aid (OCHA) humanitarian response plan was allocated US$316.1 million in 2020 compared to only US$148 million in 2024 – only 16 percent of Burkina Faso’s growing humanitarian aid needs.

Foreign aid represented about 8% of GDP in 2023. On the Current Path, aid flows to Burkina Faso as a percentage of GDP will likely decline to reach 7.5% of GDP in 2030 and 5.6% in 2043 (see Chart 25).

In addition to aid, Burkina Faso actively welcomes foreign investment and seeks to attract international partners to support its development. The country has made partial progress in establishing the legal and regulatory framework needed to ensure fair treatment of foreign investors, including creating mechanisms for resolving commercial disputes and simplifying the processes for obtaining permits and registering businesses.