Mali

Mali

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our About page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

This page presents a comprehensive analysis of Mali. The analysis outlines the nation's extensive socio-economic challenges and opportunities, examining various developmental paths through 2043. It highlights Mali’s significant economic growth potential rooted in its rich natural resources, while also noting enduring development challenges related to inequality, governance, and a continued reliance on commodity exports, particularly gold and cotton. Various scenarios consider the impacts of improvements in sectors like governance, agriculture, education and manufacturing. The analysis aims to provide policymakers and researchers insights to guide Mali towards a more prosperous future.

For more information about the International Futures modelling platform we use to develop the various scenarios, please see About this Site.

Summary

We begin this page with an introduction and context to Mali.

Mali is a low-income country in north-west Africa. The country has been a member of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) since 1975 but decided in January 2024 to withdraw from the organisation, together with Burkina Faso and Niger, with whom it formed the Confederation of Sahel States in August 2024.

- The desert nation of Mali is characterised by its Sahelian climate — a transitional zone between the arid Sahara desert in the north of Africa and savannas to the south. The country is divided into three natural zones: the cultivated Sudanese zone in the south, the semi-arid Sahelian zone in the centre, and the arid Saharan zone in the north. The desert covers 30% of the country, and 59% of the country is classified as having annual rainfall of less than 400 mm. The result is a challenging environment with the country characterised by drought, desertification and the overexploitation of natural resources under the pressure of a rapidly growing population.

The introductory section is followed by an analysis of the Current Path for Mali which informs the region’s likely current development trajectory to 2043, mostly comparing Mali with its low-income peers in Africa. It is based on current developmental trends and assumes that no major shocks would occur in a ‘business-as-usual’ future.

- Mali is the fifth most populous country in West Africa and the 19th most populous in Africa. The total population increased from 9.2 million in 1990 to 23.8 million in 2023 and by 2043, it will be 41.5 million. In terms of population structure, Mali has a youthful and dependent population. In 2023, 46.2% of Malians were under the age of 15, 51.1% of whom were in the 15–64 age group (working age), and 2.6% were 65 years and older.

- Mali has urbanised more rapidly over the years such that the urban population stood at 45.2% in 2023, making it the ninth most urbanised country among low-income African countries instead of the 13th in 1990. On the Current Path, Mali will achieve parity in urban–rural settlement by 2030; and by 2043, 24.0 million Malians, constituting almost 57.8% of the population, will live in urban areas.

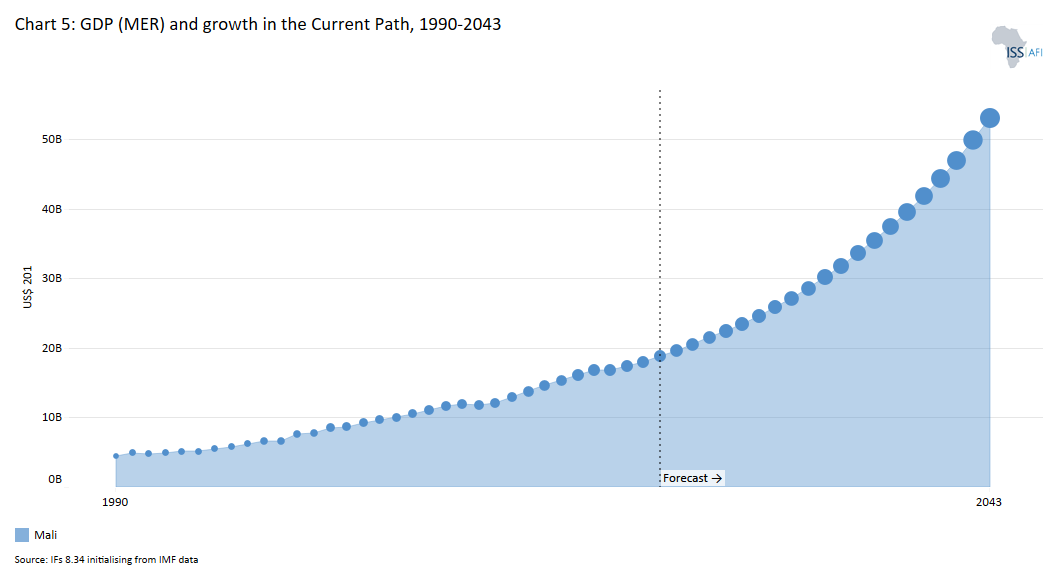

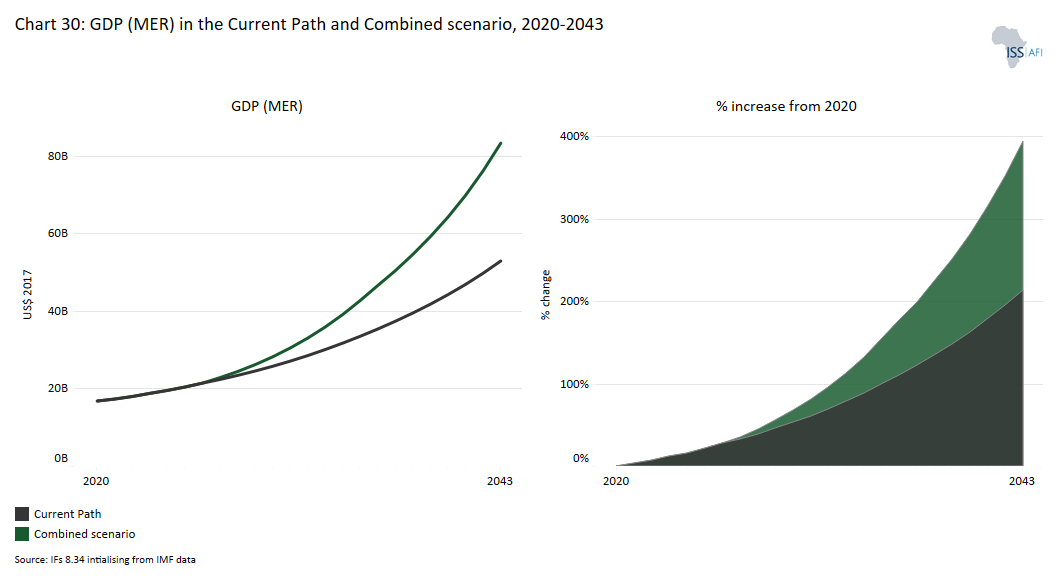

- The Malian economy revolves around the export of major traditional raw materials such as cotton and gold. The country’s GDP, measured in market exchange rates (MER), grew from US$4.5 billion in 1990 to US$18.6 billion in 2023, making it the fifth largest in West Africa after Nigeria, Ghana, Côte d'Ivoire and Senegal. The average GDP growth rate during this period stood at 4.3% per annum, above the average of 3.9% for low-income countries in Africa. By 2043, GDP will more than triple to US$53.0 billion with an average growth of 5.4% between 2024 to 2043.

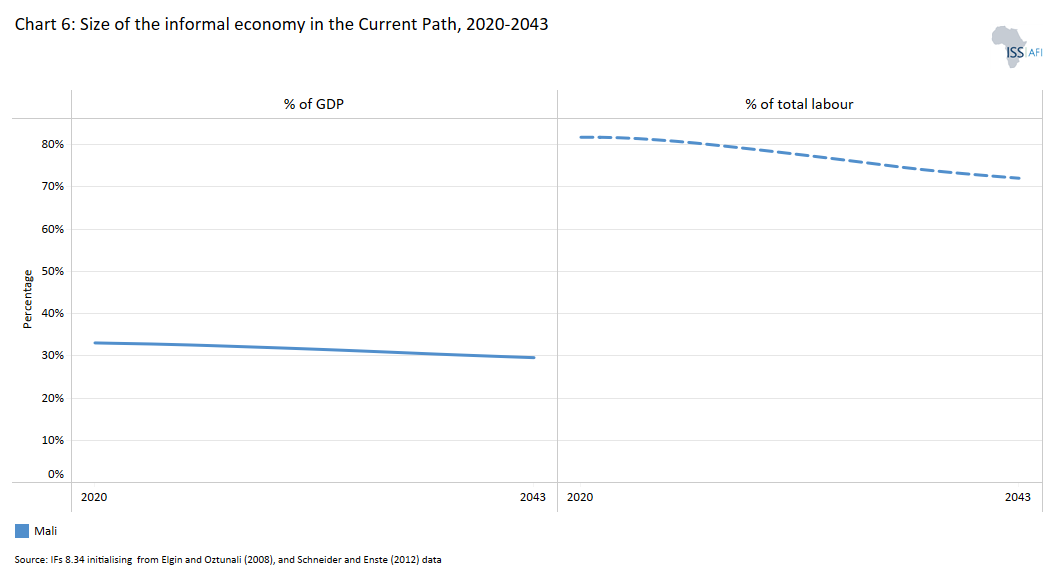

- Mali has a large informal sector that is vital to its economy. In 2023, the size of the informal sector was approximately 33% of GDP, which is above the average of 29.3% for its income peers in Africa reflecting the extent of poverty and a challenging development context. In the Current Path, the size of the informal sector will decline slightly to 29.3% of GDP by 2043.

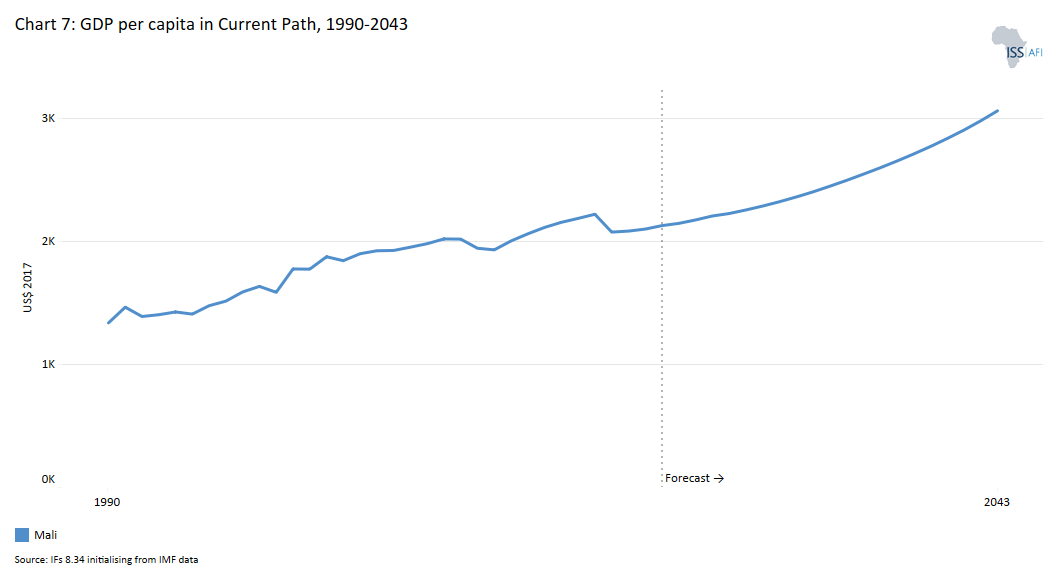

- Mali has the sixth-highest GDP per capita among the low-income countries in Africa. Its GDP per capita of US$2 127 in 2023 (in purchasing power parity) was 17% lower than the group average of US$1 814. By 2043, Mali’s GDP per capita will rise to US$3 059, indicative of a slower growth in GDP per capita.

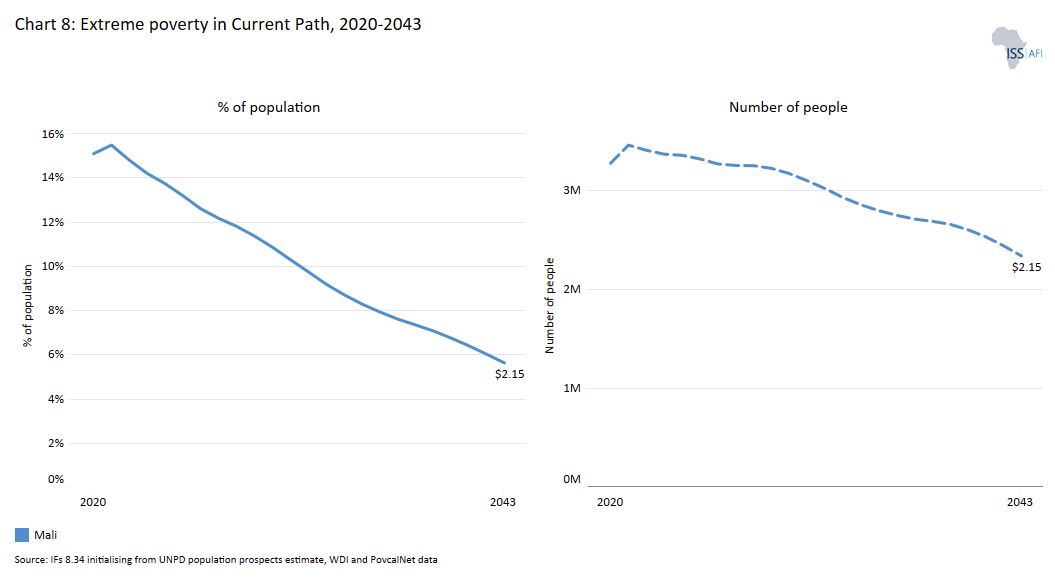

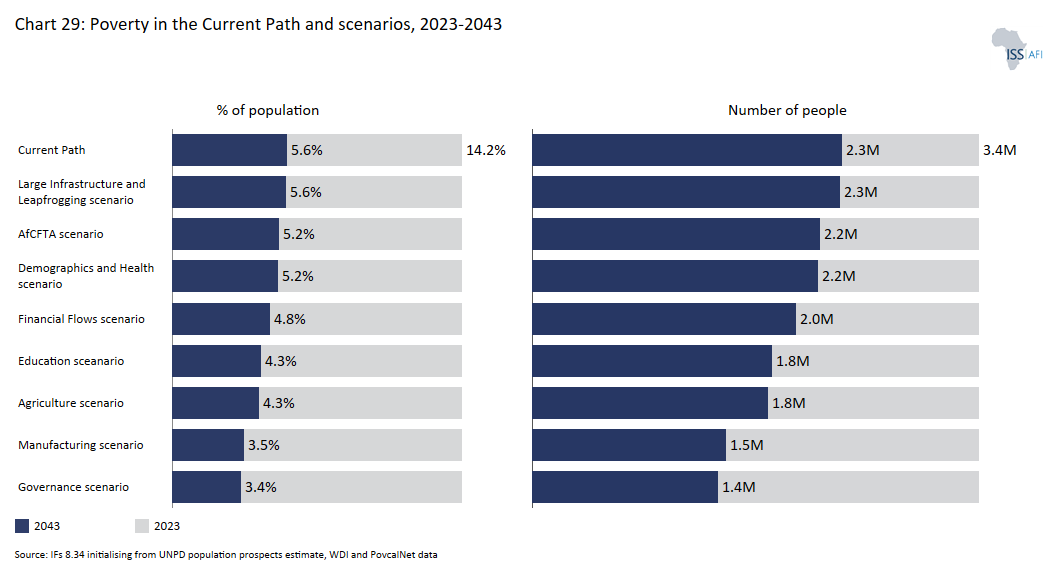

- Mali currently ranks 188th on the United Nations World Human Development Index with a score of 0.410. In 2023, 3.4 million Malians, representing 14.2% of the population, lived below the poverty line of US$2.15 per day, far below the average of 41.5% for low-income countries in Africa. By 2043, the poverty rate of 5.6% (equivalent to 3.2 million Maliians) means that Mali will miss the Sustainable Development Goal 1 target, which can only be met in 2051.

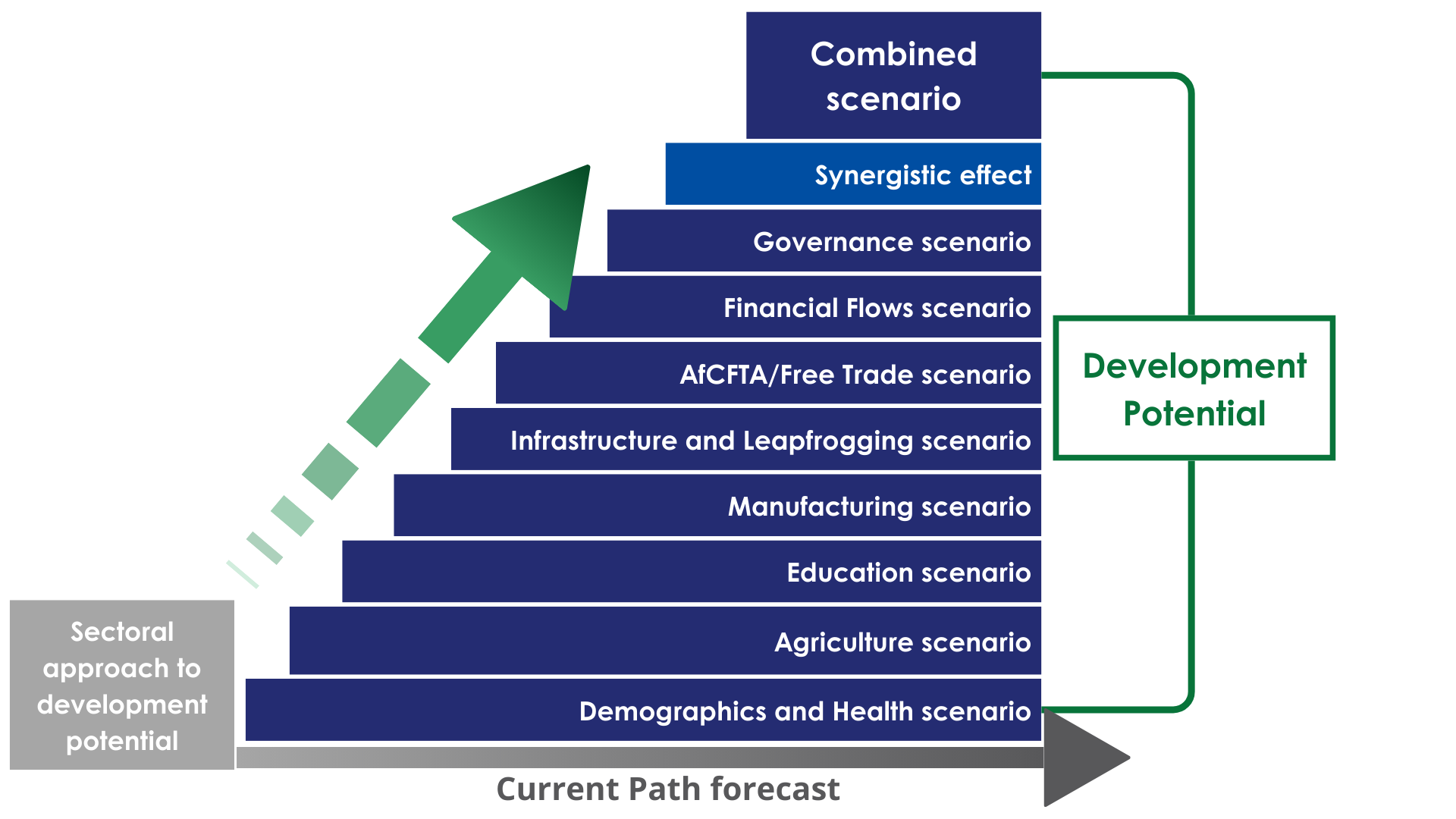

The next section compares progress on the Current Path with eight sectoral scenarios. These are Demographics and Health; Agriculture; Education; Manufacturing; the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA); Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging; Financial Flows; and Governance. Each scenario is benchmarked to present an ambitious but reasonable aspiration in that sector.

- Mali’s rapidly growing population constrains potential improvements in income. The Demographics and Health scenario will reduce the infant mortality rate from 64.1 deaths per 1 000 births in 2023 to 21.5 deaths by 2043, 7 deaths fewer than in the Current Path. The scenario pushes the ratio of the working-age population from its current ratio of 1.3 working-age persons to one dependants to 1.5 to one by 2043, close to the ratio of 1.7 to one that is required to enter a potential demographic window of opportunity.

- In 2023, Mali’s net import of crops stood at 1.4% of total crop demand, which was less than the average of 9.1% for low-income countries in Africa. Mali will reduce its import dependency on crops so that by 2043, the net import of crops will reach 10.2% in the Agriculture scenario.

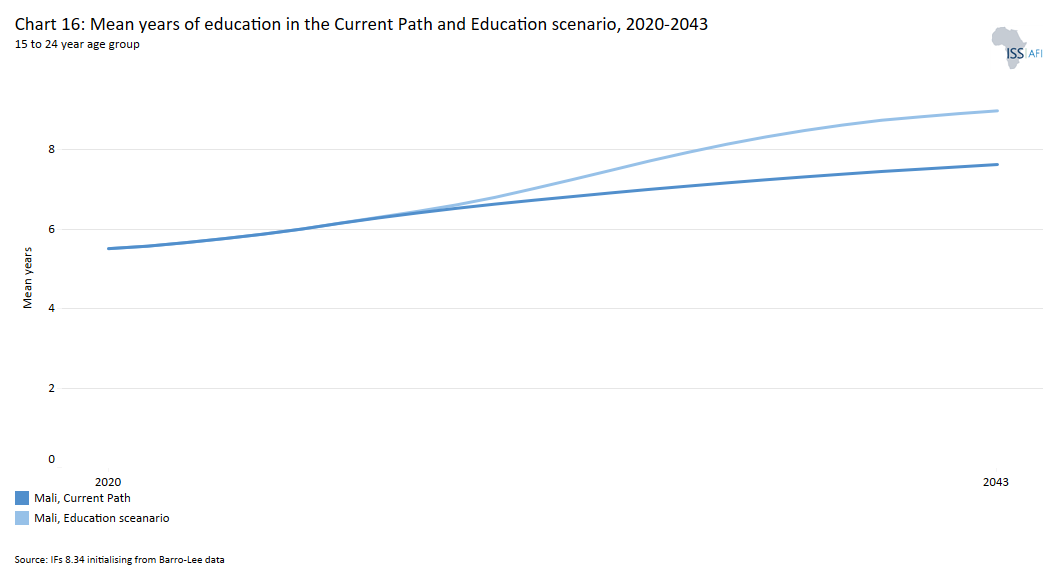

- In 2023, the mean years of education attained by adults between 15 and 24 years in Mali stood at 5.8 years — slightly below the average of 5.9 years for low-income countries on the continent. In the Education scenario, the mean years of adult education will rise to 9.0 years by 2043, 1.9 years more than the Current Path. By 2043, the scenario further increases average test scores for primary and secondary school students by 34.4% and 42.5%, respectively significantly closing the gap with its income peers.

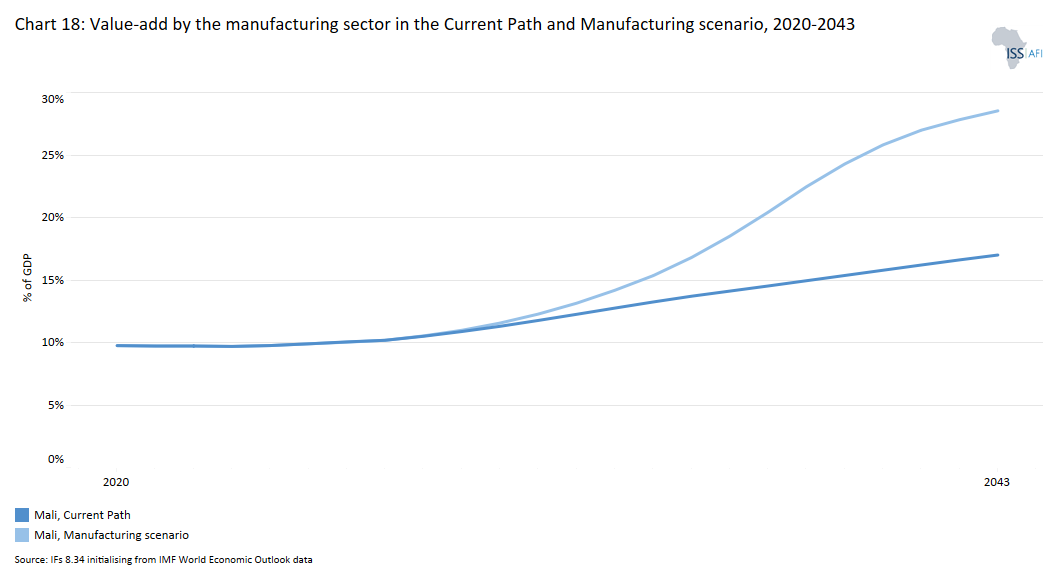

- In the Manufacturing scenario, Mali makes substantial progress in industrialisation such that, by 2043, the share of the manufacturing sector in GDP is about 29% equivalent to US$16.5 billion. This will be about 11 percentage points of GDP above the Current Path valued at US$7.5 billion. As a result, the manufacturing sector will become the second-largest contributor to GDP, surpassing the contribution of agriculture.

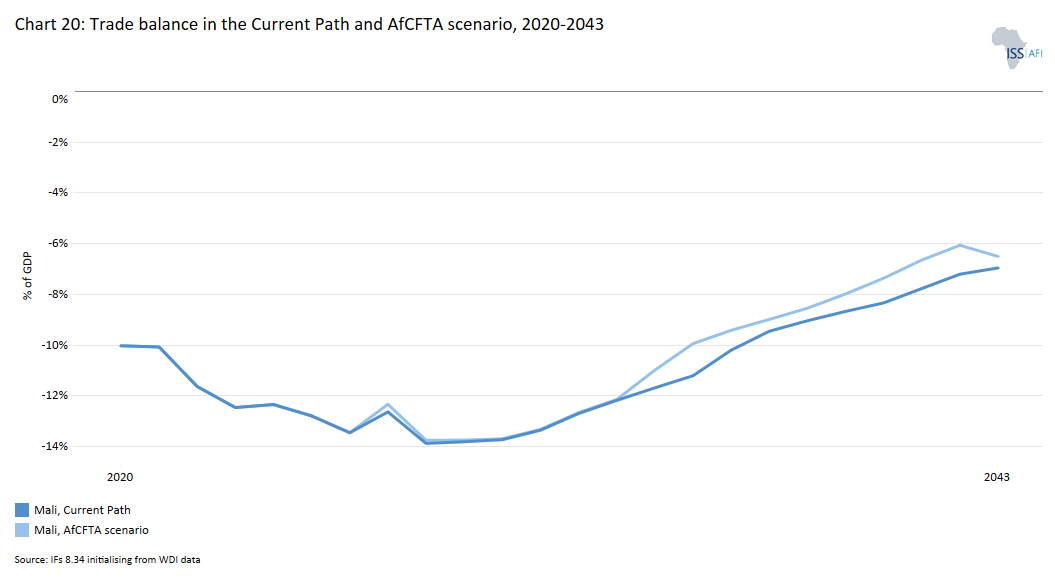

- In the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) scenario, Mali’s trade deficit will constitute about 6.5% of GDP by 2043 instead of the 6.9% of GDP on the Current Path. Also, the sum of Mali's exports and imports as a percentage of GDP will reach 123.3% by 2043.

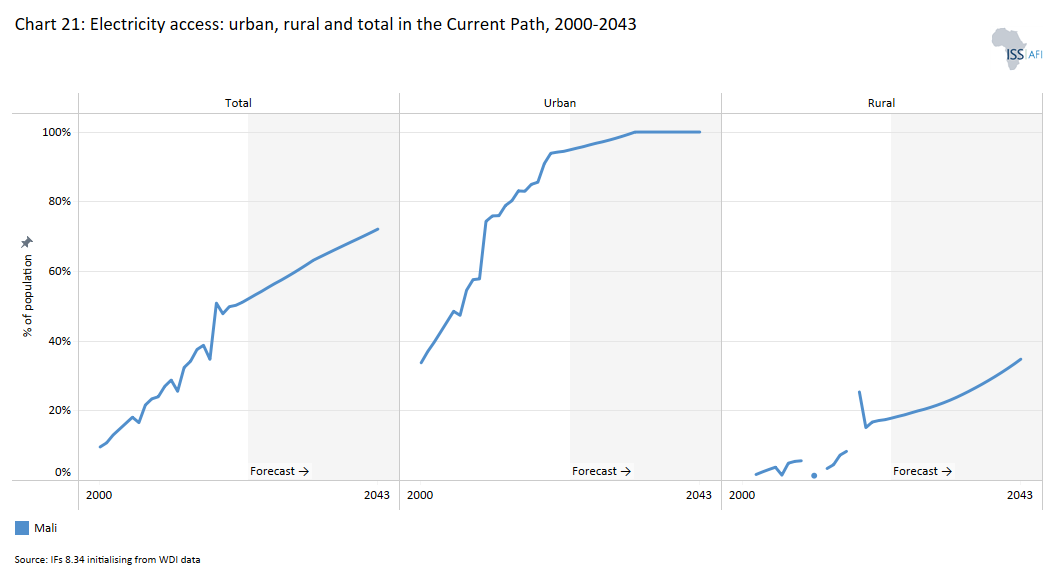

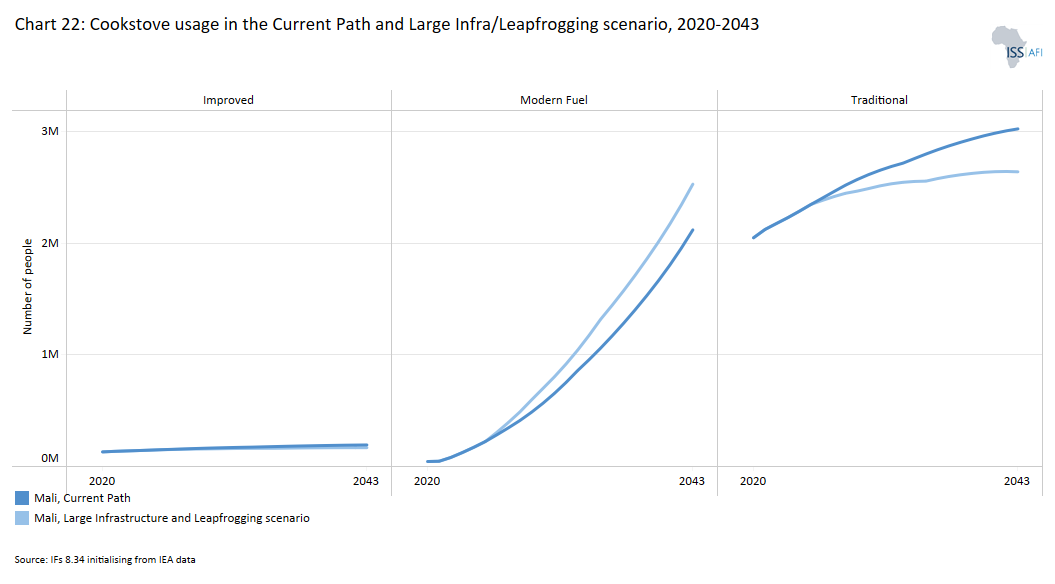

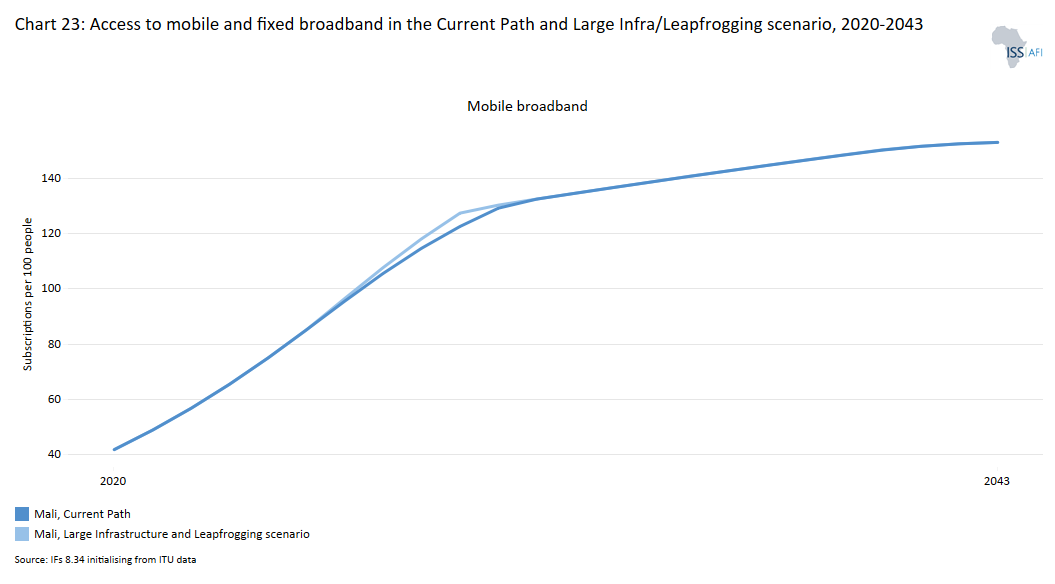

- Based on the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario, 80% of Malians will have access to electricity by 2043. As a result, 47.3% of households in Mali will use modern fuel for cooking in the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario. The scenario will further lead to a larger increase in fixed broadband access, so that, by 2043, subscriptions will likely be at 24 per 100 people compared to 5.6 subscriptions on the Current Path.

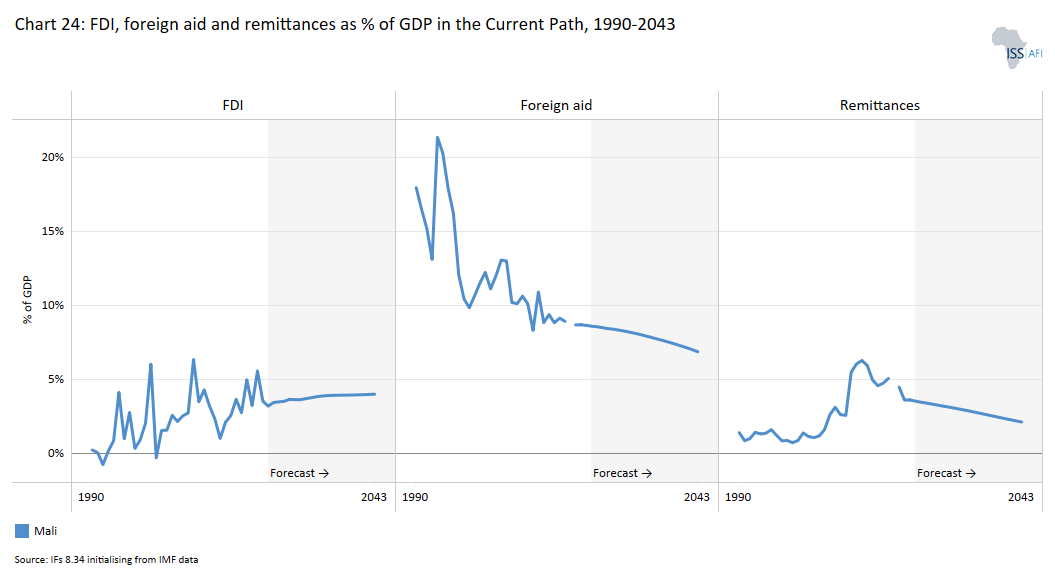

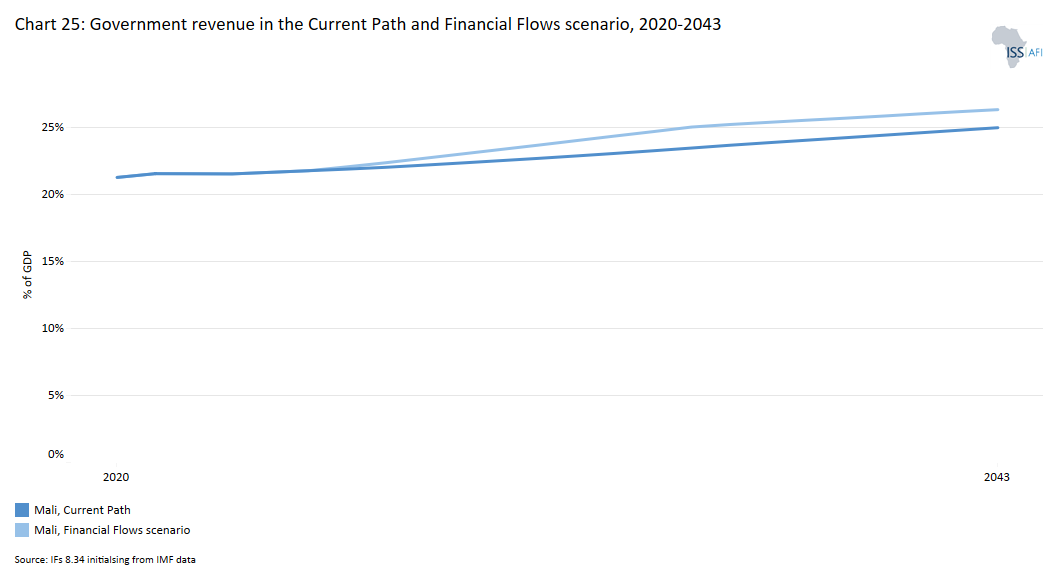

- In 2023, the government’s total revenue in Mali amounted to US$4.1 billion, equivalent to 22% of GDP — higher than the average of its income-group peers in Africa. Compared to the Current Path, the Financial Flows scenario will improve government revenue in Mali by an additional US$1.4 billion by 2043.

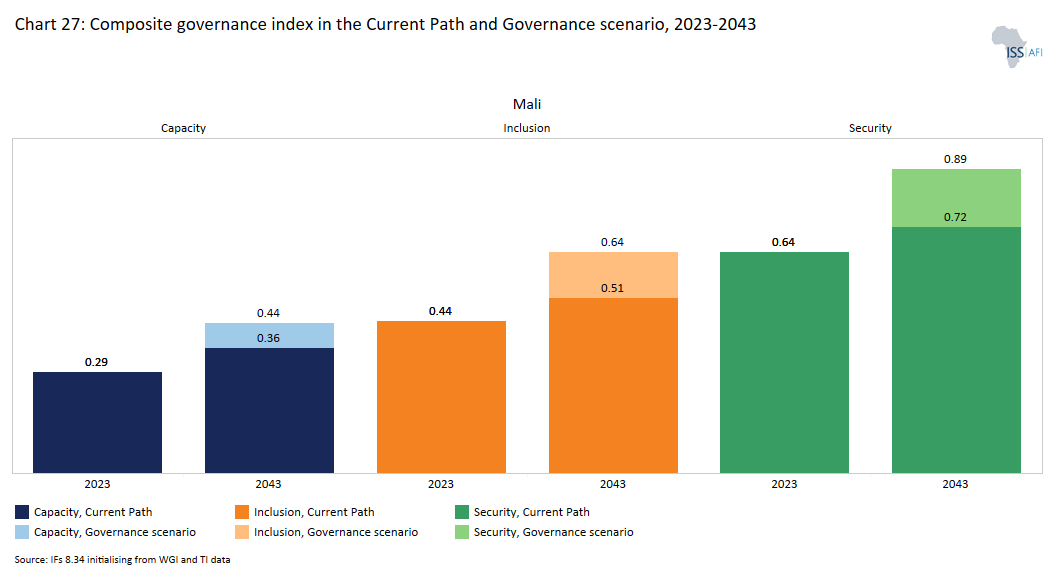

- Generally, Mali performs better on governance indices than its income peers in Africa. Mali’s score on the composite governance index of 0.46 in 2023 was 5.3% higher than the average for its income peers in Africa. In the Governance scenario, Mali's score on the composite governance index will improve to 0.65, which is about 23.3% above the Current Path by 2043.

In the third section, we compare the impact of each of these eight sectoral scenarios with one another and subsequently with a Combined scenario (the integrated effect of all eight scenarios). In our forecasts, we measure progress on various dimensions such as economic size (in market exchange rates), gross domestic product per capita (in purchasing power parity), extreme poverty, carbon emissions, the changes in the structure of the economy, and selected sectoral dimensions such as progress with mean years of education, life expectancy, the Gini coefficient or reductions in mortality rates.

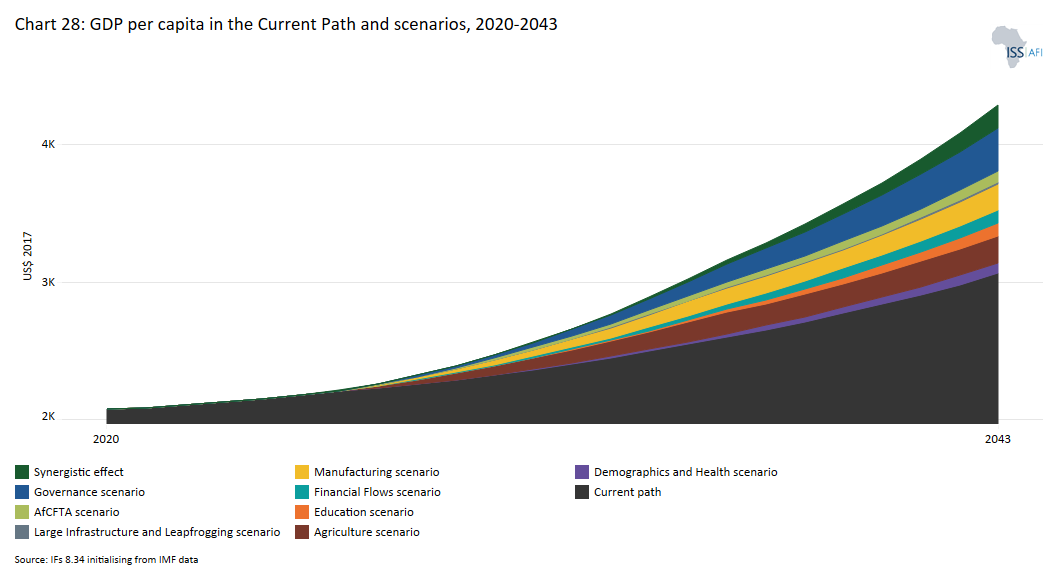

- The scenario with the greatest impact on GDP per capita in Mali by 2043 is the Governance scenario, followed by the Agriculture and Manufacturing scenarios. In the Governance scenario, Mali’s GDP per capita will witness an increase of US$312 or 10.2% more than the Current Path. The AfCFTA and Manufacturing scenarios further raise GDP per capita by an additional US$196 and US$190 by 2043.

- The Governance scenario also has the largest potential to reduce extreme poverty, followed by the Agriculture and Manufacturing scenarios. The Governance scenario has the potential to reduce extreme poverty in Mali by an additional 940 000 people compared to the 2043 Current Path. Similarly, the Manufacturing and Agriculture scenarios can lift about 880 000 and 570 000 people out of extreme poverty, respectively.

- In the Combined scenario, Mali’s GDP will rise to US$83.3 billion exceeding the Current Path of US$53 billion. Similarly, in the Combined scenario, GDP per capita will increase to US$4 284 by 2043. This will be US$1 225 more than the Current Path.

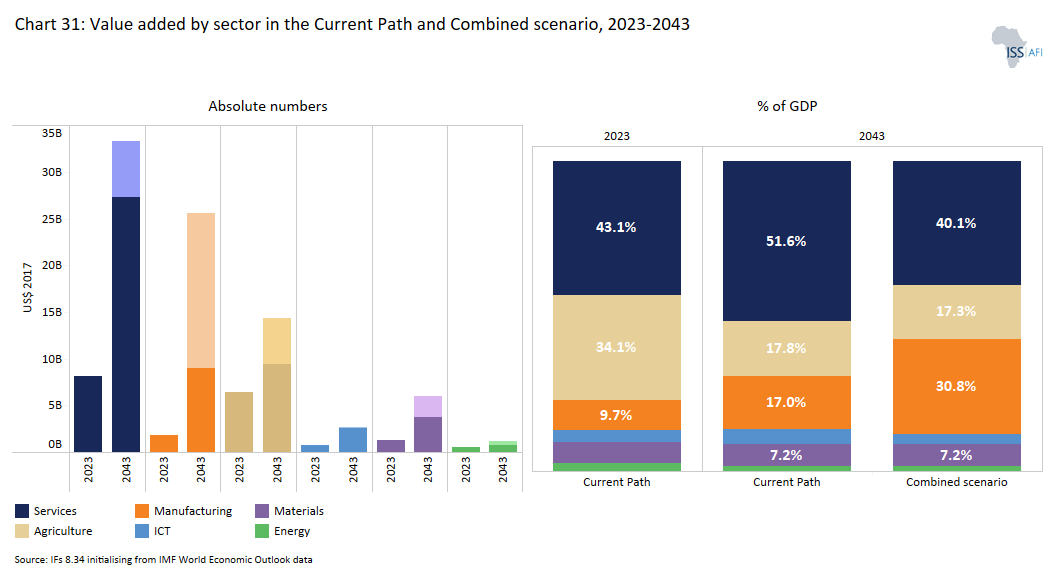

- By 2043, the services sector will still be the largest contributor to GDP at 40.1%. The manufacturing sector will be the second-largest contributor to GDP in the scenario by 2043 with a share of 30.8%. The share of the agriculture sector will decline to 17.2%.

- By 2043, the size of the informal sector in Mali will decline to 23.3% of GDP, valued at US$19.4 billion. At this rate, the contribution of the informal economy will be lower than the Current Path at 29.6% (valued at US$15.7 billion). Likewise, the size of the informal labour sector will constitute 51.4% of the total labour force instead of 72.1% in the Current Path by 2043.

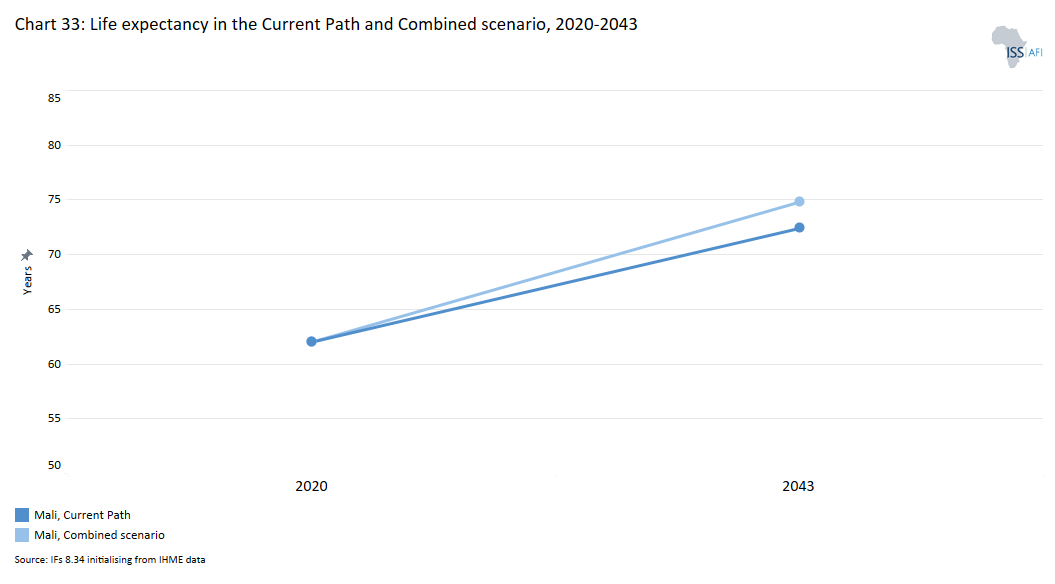

- In 2023, the average life expectancy at birth in Mali was 63.7 years, which was about 2.6 years lower than the average for the country’s income-group peers in Africa. In the Combined scenario, life expectancy will increase to 68.7 years in 2030 and 74.8 years by 2043, which will be 2.4 years more than the country’s Current Path in the same year.

- In the Combined scenario, both the number and portion of people facing poverty will significantly decline. By 2043, only about 0.4% of Malians equivalent to 150 000 people will be living in extreme poverty, meaning 2.2 million more people could be lifted out of poverty.

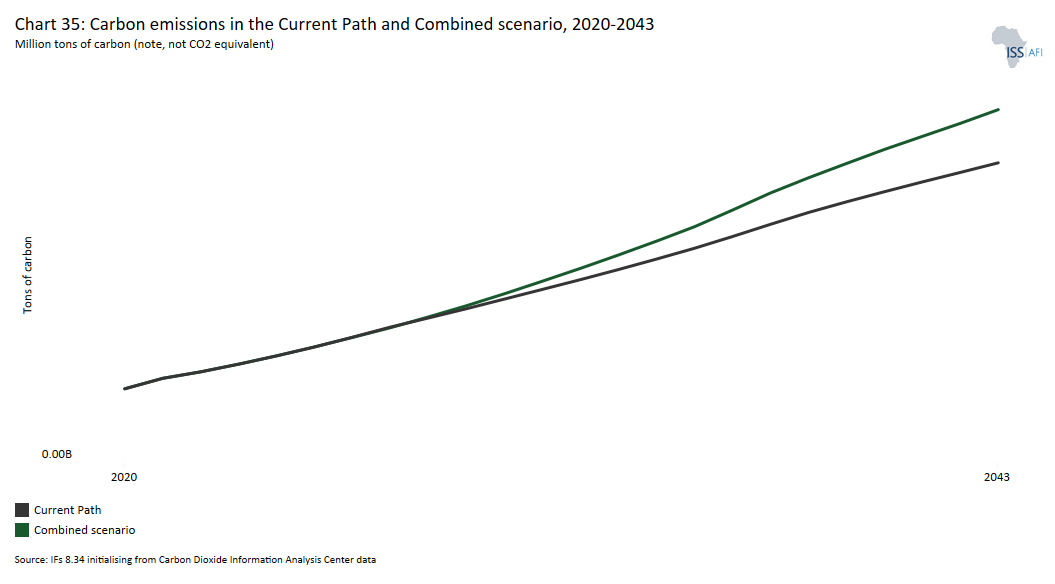

- Given its small economy, Mali releases little greenhouse gases. In 2023, Mali released about 2.4 million tons of carbon from fossil fuel use. In the Combined scenario, Mali’s total carbon emissions will rise to 8.4 million tons — 17.7% higher than what is estimated in the Current Path in the same year.

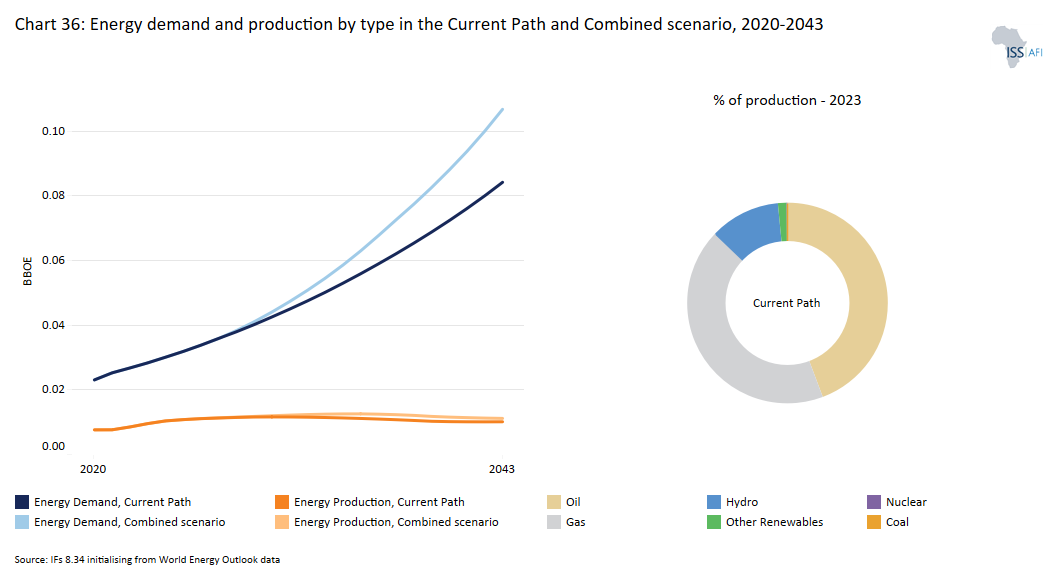

- The Combined scenario shows an increase in energy demand, creating a larger energy deficit, with solar energy becoming the dominant energy source, surpassing oil and gas. By 2043, the excess demand for energy in the scenario of 18.3 million barrels of oil equivalent (BOE) will be twice the Current Path. The share of solar energy in total energy production in the country will rise significantly to constitute 61% and become the leading contributor.

We end this page with a summarising conclusion, offering key recommendations for decision-making.

Mali has made significant progress in advancing human development and its economic growth prospect is higher than many of its African income-peers, but offset by its rapidly growing population. Widespread poverty and inequality persist, public debt is increasing and the unemployment rate, particularly among the youth, remains high, while average incomes are growing at a slower pace. The informal sector dominates a significant portion of the economy, depriving the government of potential revenue. The macroeconomic fundamentals of the Malian economy remain fragile, with an economic structure that is still largely agrarian and untransformed, relying heavily on the export of traditional raw materials like gold and cotton. As a result, economic growth is highly volatile, driven by weather conditions, fluctuations in international commodity prices and external shocks. Therefore, a comprehensive and targeted set of socio-economic policy interventions across demographics, health, education, agriculture, infrastructure, manufacturing, trade, financial flows and governance is necessary to redirect the country’s current development trajectory towards a more sustainable and inclusive path. At the core of this multisectoral approach is the need to strengthen governance systems, with a particular focus on revitalising agriculture and manufacturing. Development assistance continues to play a key role in supporting progress and improving livelihoods, calling for strong partnerships with international development actors.

All charts for Mali

- Chart 1: Political map of Mali

- Chart 2: Population structure in the Current Path, 2020–2043

- Chart 3: Population distribution map, 2022

- Chart 4: Urban and rural population in the Current Path, 1990-2043

- Chart 5: GDP (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, 1990–2043

- Chart 6: Size of the informal economy in the Current Path, 2020-2043

- Chart 7: GDP per capita in Current Path, 1990–2043

- Chart 8: Extreme poverty in the Current Path, 2020–2043

- Chart 9: Relationship between Current Path and scenarios

- Chart 10: Mortality distribution in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 11: Infant mortality rate in Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 12: Demographic dividend in the Current Path and the Demographics and Health scenario, 2020–2043

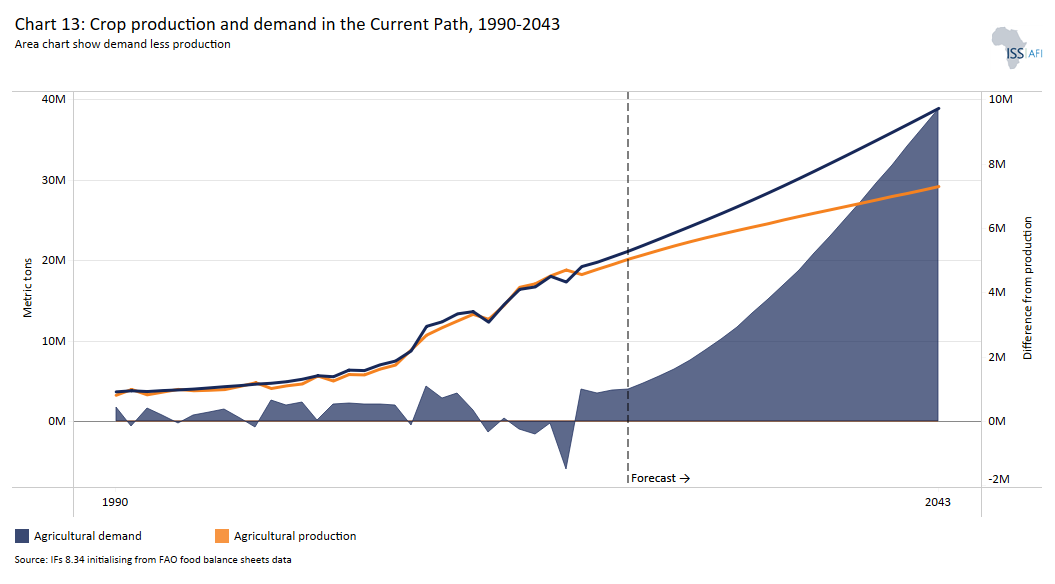

- Chart 13: Crop production and demand in the Current Path, 1990-2043

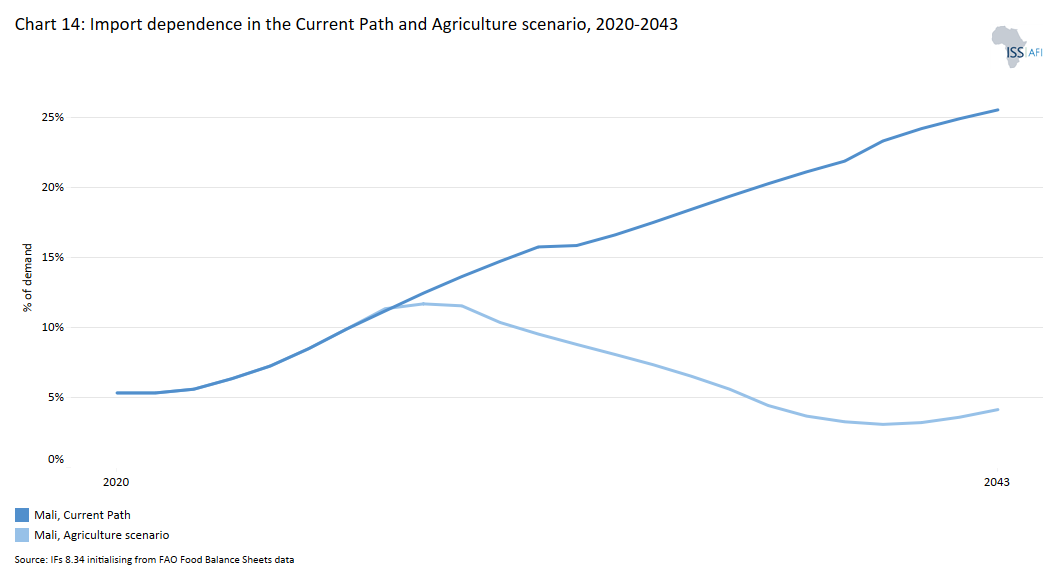

- Chart 14: Import dependence in the Current Path and Agriculture scenario, 2020–2043

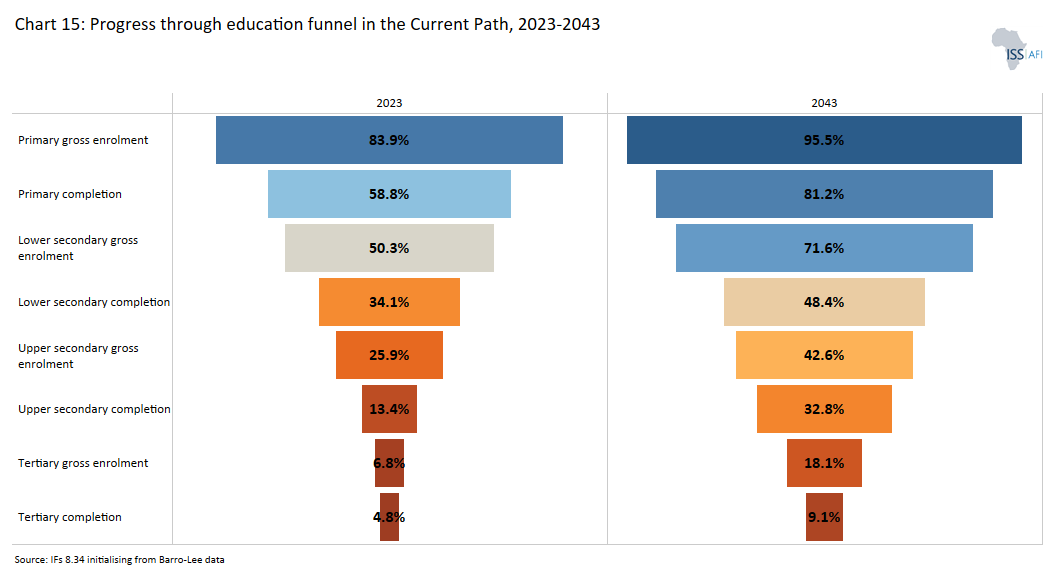

- Chart 15: Progress through the education funnel in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 16: Mean years of education in the Current Path and Education scenario, 2020–2043

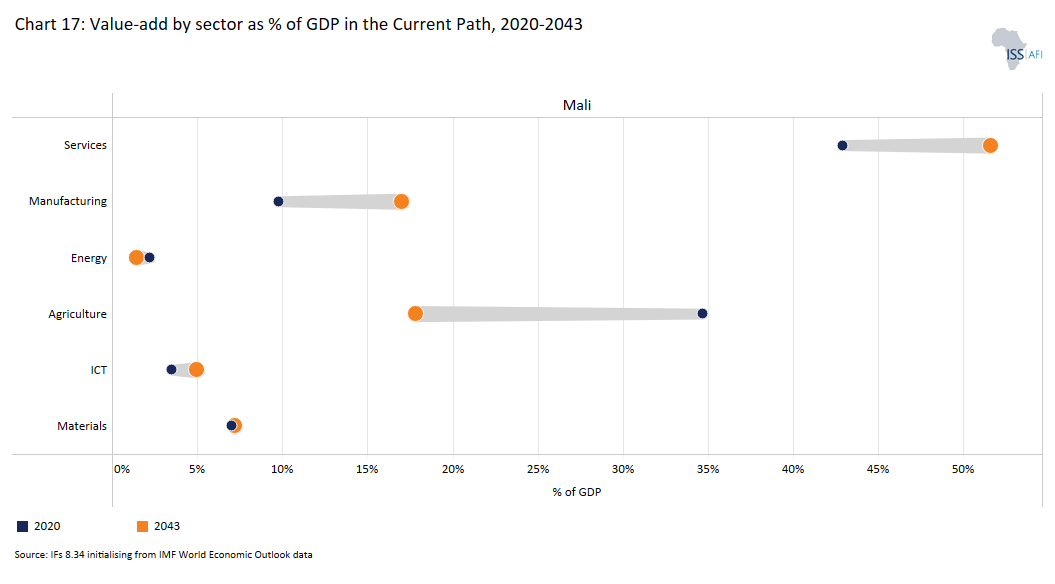

- Chart 17: Value-add by sector as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 18: Value-add by the manufacturing sector in the Current Path and Manufacturing scenario, 2020–2043

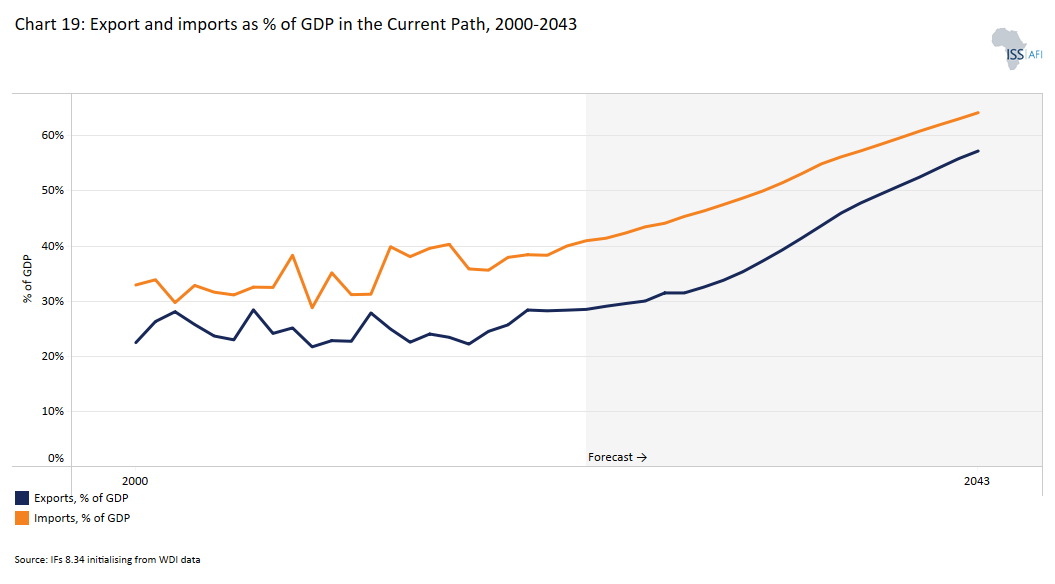

- Chart 19: Exports and imports as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2000-2043

- Chart 20: Trade balance in the Current Path and AfCFTA scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 21: Electricity access: urban, rural and total in the Current Path, 2000-2043

- Chart 22: Cookstove usage in the Current Path and Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 23: Access to mobile and fixed broadband in the Current Path and the Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 24: FDI, foreign aid and remittances as % of GDP in the Current Path and in the Financial Flows scenario, 1990-2043

- Chart 25: Government revenue in the Current Path and Financial Flows scenario, 2020–2043

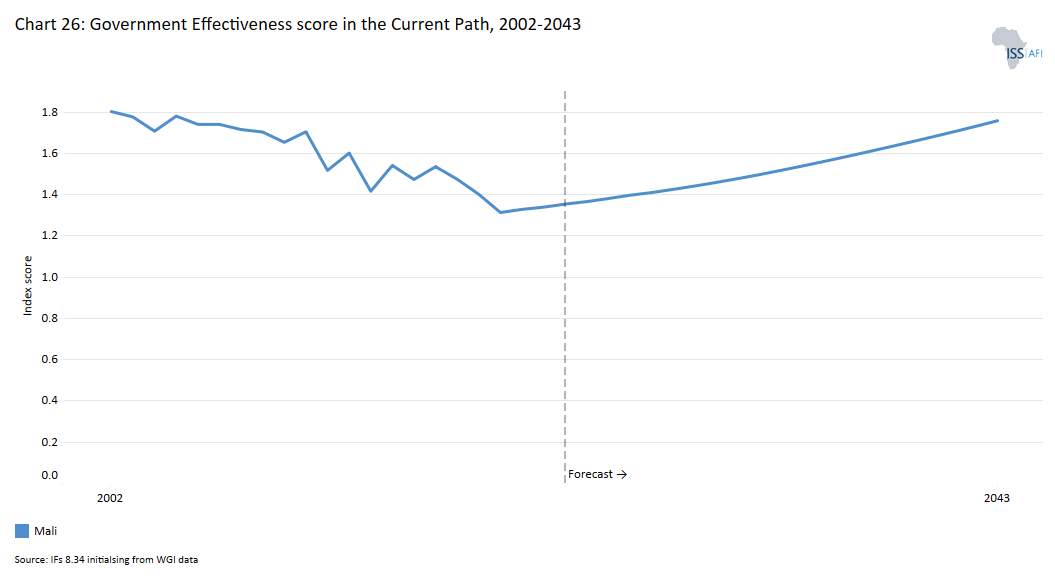

- Chart 26: Government effectiveness score in the Current Path, 2002-2043

- Chart 27: Composite governance index in the Current Path and Governance scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 28: GDP per capita in the Current Path and scenarios, 2020–2043

- Chart 29: Poverty in the Current Path and scenarios, 2020–2043

- Chart 30: GDP (MER) in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 31: Value added by sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 32: Informal sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 33: Life expectancy in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

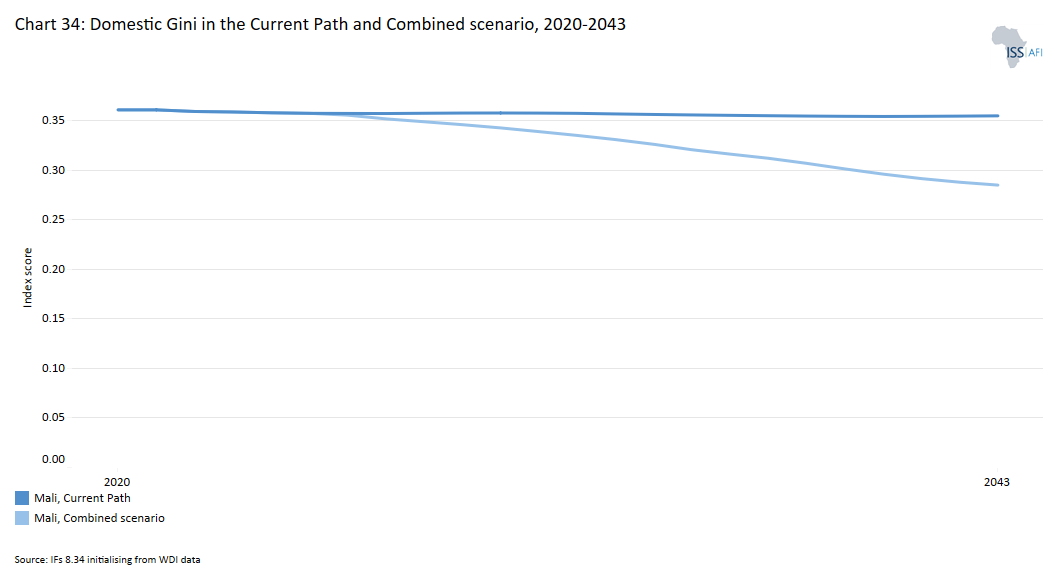

- Chart 34: Domestic Gini in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 35: Carbon emissions in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 36: Energy demand and production by type in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020-2043

- Chart 37: Policy recommendations

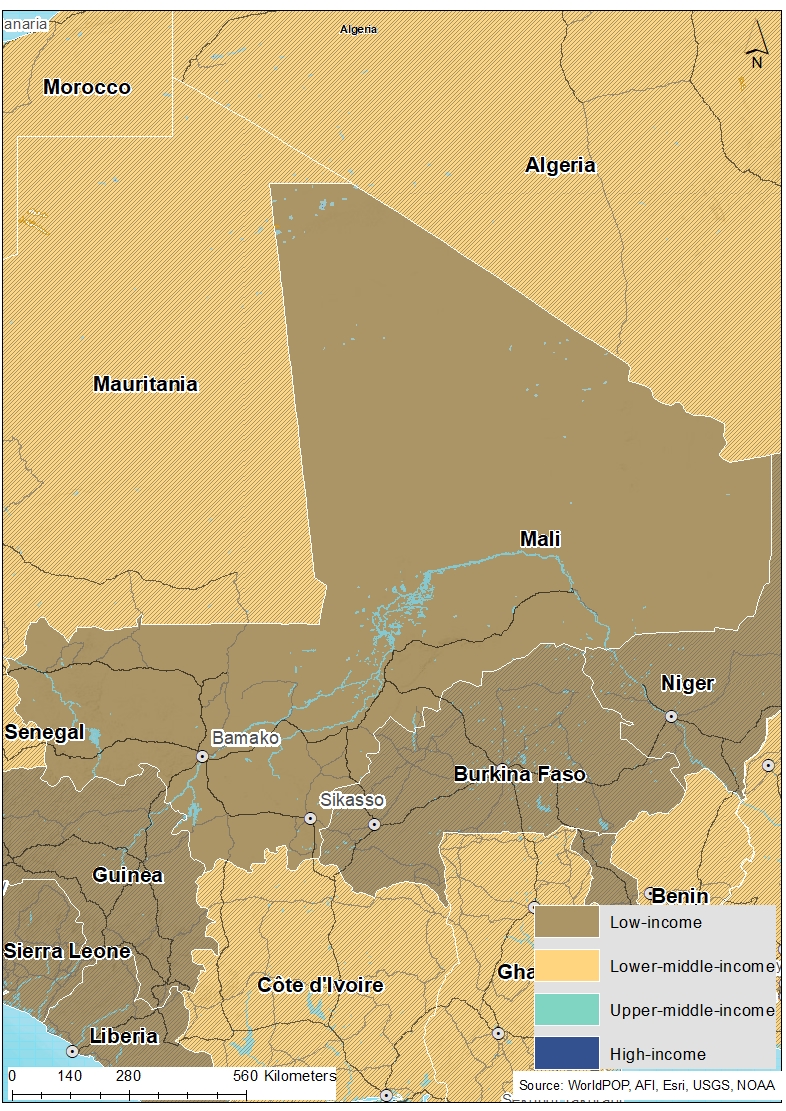

Chart 1 is a political map of Mali.

Mali is a low-income country in north-west Africa. The country has been a member of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) since 1975, but its military leadership following the 2020 coup decided in January 2024 to withdraw from the organisation, together with Burkina Faso and Niger, with whom it formed the Confederation of Sahel States in August 2024. The country however remains a member of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU, or UEMOA in French). Mali is also a member of the Community of Sahel–Saharan States (CEN-SAD), which has had minimal activity following the turmoil in Libya, where its secretariat was initially based, although it has now been relocated to Chad.

The desert nation of Mali is characterised by its Sahelian climate — a transitional zone between the arid Sahara desert in the north of Africa and savannas to the south. The country is divided into three natural zones: the cultivated Sudanese zone in the south, the semi-arid Sahelian zone in the centre, and the arid Saharan zone in the north. The desert covers 30% of the country, and 59% of the country is classified as having annual rainfall of less than 400 mm. As a result, the country is characterised by drought, desertification and the overexploitation of natural resources that are under the pressure of a rapidly growing population.

The Sahel region has historically been highly porous. Ancient trans-Saharan trade routes facilitated cross-border trade and a transhumance lifestyle for hundreds of years, predating the French colonial period. This way of life is now under dire threat. Climate change is having a devastating impact on the Sahel countries. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) notes that the Sahel has ‘experienced the most substantial and sustained decline in rainfall recorded anywhere in the world within the period of instrumental measurements during the 1980s.’ Environmental degradation and violent conflict have displaced millions of people and will continue to worsen the environmental crisis in the area. Furthermore, the Sahel countries will experience some of the most severe climate change impacts globally as early as 2030. These impacts range from increasingly variable rainfall, rising temperatures and more frequent droughts to prolonged heatwaves.

Mali gained independence in 1960, with President Modibo Keïta as the first president of a socialist one-party state. However, the 1968 military coup led by Lieutenant Moussa Traoré truncated Keïta’s presidency. A new constitution in 1979 paved the way for a fresh election, which was won by President Moussa Traoré and ushered the country into its second republic. A military coup in March 1991 ousted the Traoré administration and replaced it with a transitional committee led by Amadou Toumani Touré who organised the country’s first democratic elections in 1992. These elections saw the victory of Alpha Oumar Konaré, who was re-elected for a second term in 1997. Touré, the author of the 1991 putsch, would return to power, winning presidential elections in 2002 and re-election in 2007.

In January 2012, the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) started the fifth rebellion in the country’s history, taking control of two-thirds of the country's territory. Since its independence, the country has been struggling against irredentist movements from the Tuareg communities in the north, who periodically re-emerge (1963, 1986, 1990, 2006, 2012) and call for autonomy.

The fifth rebellion prompted military officers in Bamako to overthrow President Touré’s government in March 2012, citing his inability to deal with the Tuareg rebellion.

Under pressure from ECOWAS, the coup leaders ceded power the following month to an interim civilian government led by then President of the National Assembly Dioncounda Traoré as leader.

However, the crisis in the north provided an opportunist context for the occupation of these regions by violent extremist groups (Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa, Ansar Dine), who ousted the MNLA rebels in June 2012. Despite the intervention of French operation Serval/Barkhane, ECOWAS and the deployment of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) from 2013 onwards to tackle the jihadist threat, terrorist attacks expanded from 2015 onwards to central Mali, then towards Burkina, Niger and the coastal countries of West Africa.

The signing of a preliminary agreement between the government and MNLA rebels in June 2013 paved the way for the organisation of general elections in September 2013, with the support of MINUSMA. Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta won the election and Keïta was re-elected in June 2018. However, rising violence and insecurity in northern and central Mali and poorly organised 2020 parliamentary election results triggered nationwide protests, ultimately leading to Keïta's ouster as military officers removed him from power in August 2020.

A transitional government has since ruled over Mali, with Colonel Assimi Goïta declared Head of State by the Constitutional Court in May 2021. Also, the National Transition Council replaced the National Assembly until the country returned to constitutional rule. The military regime drastically overhauled Mali’s external relations, ending its longstanding bilateral cooperation with France in 2022 and moving closer to Russia. The French military, which had been supporting Mali’s counterterrorism efforts since 2013 through operations Serval and Barkhane, was requested to depart and, in 2023, Mali also requested the withdrawal of the MINUSMA.

Meanwhile, various efforts and consultations have occurred between the government, political parties and civil society organisations to return to constitutional rule. A new constitution, approved through a referendum in June 2023, paved the way for the announcement of general elections to restore constitutional rule. Under a timetable agreed upon with ECOWAS, national legislative elections were tentatively scheduled for October and November 2023, while presidential elections were scheduled for February 2024. However, the elections were indefinitely suspended by the military government junta in September 2023, citing technical difficulties. After it was sanctioned by ECOWAS in response to the coup, Mali announced its withdrawal from ECOWAS and formally exited the Community on 29 January 2025. Together with Burkina Faso and Niger, it formed the Confederation of Sahel States (CSS) in August 2024. Although the CSS is still part of WAEMU and uses the West African Franc (CFA), it has announced its intention to create a common currency to end the use of the CFA.

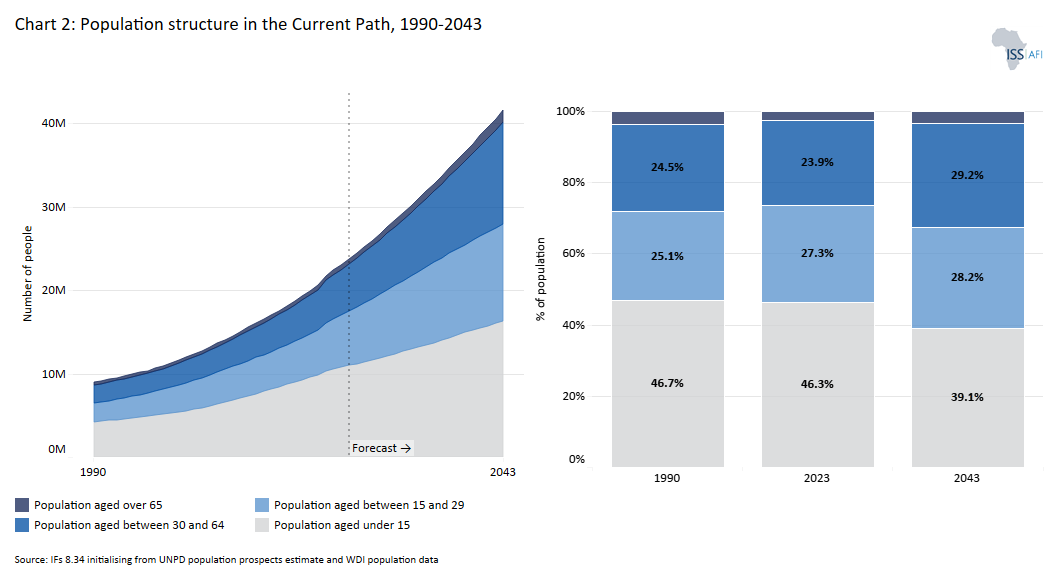

Chart 2 presents the Current Path of the population structure, from 2020 to 2043.

Mali’s population has more than doubled between 1990 and 2023, growing from 9.2 million to 23.8 million people. This makes Mali the fifth most populous country in West Africa and the 19th most populous in Africa. In 2023, the country had the seventh-highest population growth rate in Africa at 3.3%, up from 2.6% in 1990. This rapid population growth places significant pressure on government finances, as the government must increase its spending on essential social services, including education, healthcare and other amenities, to accommodate the growing population.

Mali’s fertility rate fell from 7.1 children per woman in 1987 to 6.3 in 2018, and further to 5.5 children per woman in 2022. Despite this decline, it remains the fourth-highest rate in the world. Several factors contribute to this, including the widespread occurrence of early childbearing, limited levels of women's education and empowerment, persistent poverty, reliance on informal and subsistence lifestyles, low urbanisation and extremely limited family planning. As a result of this high fertility rate, 46.2% of Malians were below the age of 15 years in 2023 while 51.1% were in the age group 15–64 years (working age) and 2.6% were 65 years and older. Comparing this with the structure in the 1990s reveals that Mali’s population structure has not fundamentally changed over the past three decades. The high dependency ratio significantly affects the government's ability to generate the necessary revenue for development, as there are fewer individuals in the working-age population. On a household level, families with more dependants can typically save less, which reduces overall domestic savings. This, in turn, limits the capital available for investment, impeding economic growth.

Mali has the 7th-largest youth bulge (the ratio of its population aged between 15 and 29 to the total adult population) in Africa and the second highest in West Africa, after Niger. The country’s youth bulge stood at about 50.8% in 2023 — a rise from 47.2% in 1990 and above the average of 45.3% for Africa and 47.5% for West Africa. Likewise, the median age for Mali in 2023 was 16.6 years — a slight increase from 15.4 years recorded in 1990 and lower than West Africa and Africa’s median ages of 18.8 and 20.6 years, respectively. This makes Mali the country with the second-lowest median age in West Africa after Niger and 5th lowest in Africa after Niger, Central African Republic, Somalia and Chad.

The large youth population in Mali presents both opportunities and challenges. On one hand, it can lead to youth activism and drive positive political change in the country. On the other hand, if the needs of the youth are not adequately addressed, it can increase the risk of criminal violence, conflict and instability. A major concern is the rising youth unemployment and underemployment, as the government struggles to provide employment for the growing youth population. For example, youth unemployment in Bamako is 32%, well above the national average of 12%. With over 300 000 young Malians entering the labour market each year, the security crisis could worsen if sufficient job opportunities are not created. However, the country can harness the potential of its youthful population by making substantial investments in education and training, equipping young people with the skills they need, and creating opportunities through both government initiatives and private sector involvement.

The structure of Mali’s population will not change much across the forecast horizon to 2043. Although the country’s population growth rate will decline to 3.0% in 2030 and 2.4% by 2043, the total population will rise to 29.2 million in 2030 and double to 41.5 million by 2043 on the Current Path. By then, the median age will increase to 17.8 years in 2030 and 20.3 years in 2043, while the youth bulge will rise to 51.3% in 2030 before eventually declining to 46.3% by 2043. The proportion of people under the age of 15 will slightly decline to 43.3% in 2030 and 39.1% in 2043. Consequently, the share of the working-age population and the population aged 65 and older will increase to 54.0% and 2.7% in 2030 and 57.4% and 3.5%, respectively, by 2043. Despite these shifts, the rapid population growth will continue to place pressure on development and limit improvements in average income, as the government will face significant challenges in addressing the needs of its rapidly expanding, youthful population.

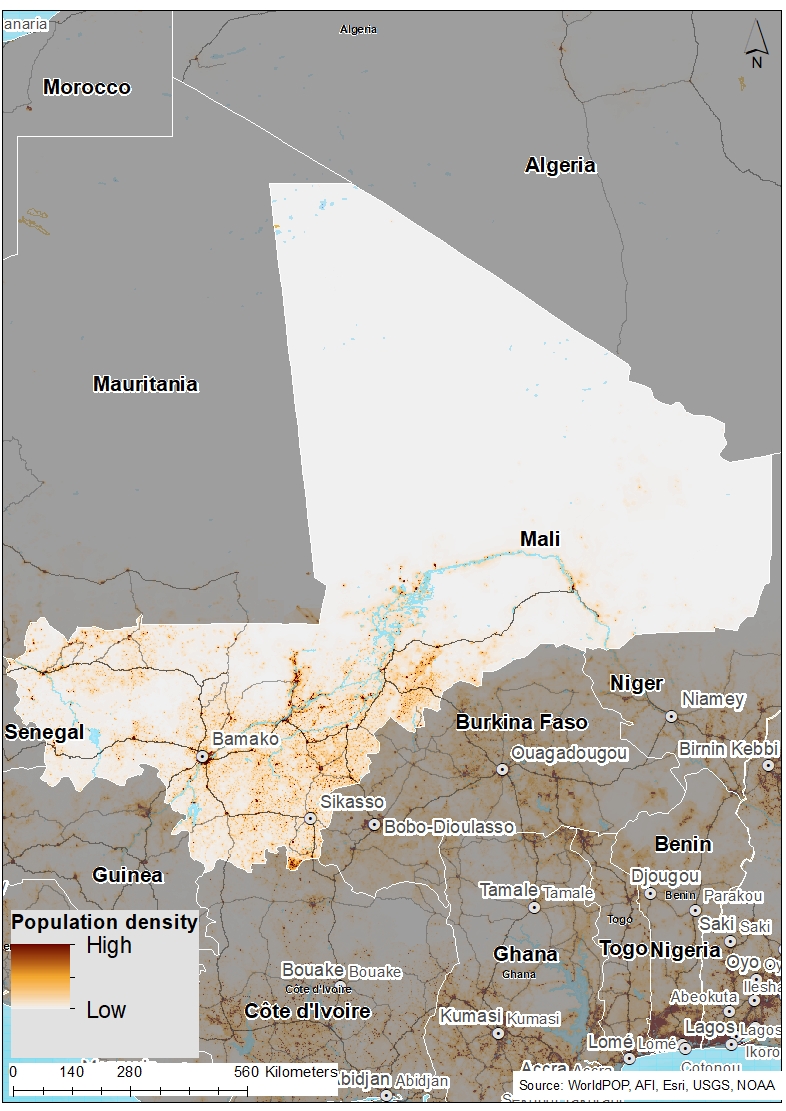

Chart 3 presents a population distribution map for 2023.

Spanning 1.24 million km2, Mali is the eighth-largest country in Africa, comparable to the sizes of Angola and South Africa. This, coupled with its small total population makes it technically one of the most sparsely populated countries in Africa. In 2023, Mali was the most sparsely populated country in West Africa and the 11th most sparsely populated country in Africa. Mali's population density is estimated to be about 0.2 people per hectare, which is about 2.5 times lower than the average of 0.5 people per hectare for Africa and 4 times lower than West Africa’s average of 0.88 people per hectare.

The majority of Malians live in the less arid southern half of the country, which is more suitable for agriculture thanks to the Niger River and is home to nearly all of Mali’s sizable cities. This includes cities like Sikasso with over 445 000 people, Mopti with 200 000 people and Koutiala with over 160 000 people. Conversely, the north of the country has faced continuous depopulation fuelled by desertification, insecurity, instability and the attraction of urban life in the south.

In the Current Path, Mali’s population density will reach 0.24 people per hectare, less than half the average of 0.60 for Africa in 2030. By 2043, this will increase to 0.34 people per hectare, although that will still be significantly lower than the average of 0.78 and 1.4 people per hectare for Africa and West Africa, respectively.

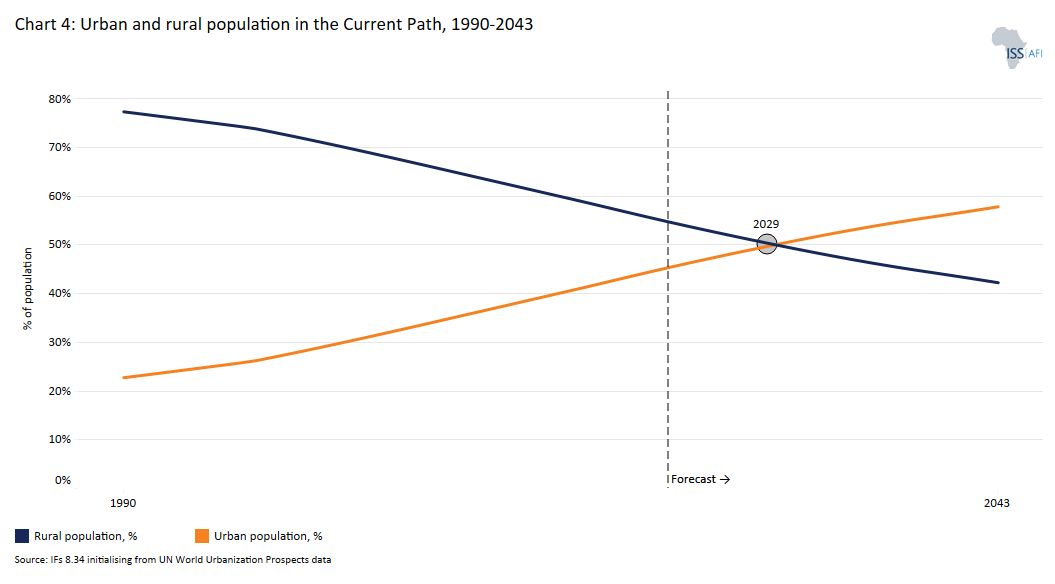

Chart 4 presents the urban and rural population in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

Mali’s population is predominantly rural. In 1990, over two-thirds of Malians lived in rural areas — slightly below the average for low-income countries in Africa. However, Mali has urbanised more rapidly than its income peer group in Africa over the years. As a result, by 2023, 13.0 million Malians, equivalent to 54.8% of the population, lived in rural areas. This was below the 67.4% average of low-income countries in Africa. Consequently, the urban population stood at 45.2% in 2023, making Mali the ninth most urbanised country among low-income African countries, instead of the 13th in 1990.

Urban growth is the result of population increases of people already living in urban areas as well as rural-urban migration. In the case of Mali, rural-to-urban migration is a significant driver of urbanisation. Many rural residents are moving to urban areas in search of better employment opportunities, improved housing and access to essential services such as healthcare, security and education. Bamako, the capital city, is the largest urban centre with over three million inhabitants and is considered one of Africa’s fastest-growing cities. Other factors influencing urbanisation in Mali include the commercialisation and transformation of agriculture. As the economy shifts from subsistence farming to commercial agriculture, there is a growing demand for labour in urban areas like Koulikoro, particularly in agro-industries and processing plants, which further encourages rural residents to migrate to cities.

On the Current Path, Mali will achieve parity in urban-rural settlement by 2030; and by 2043, 24.0 million Malians, constituting almost 57.8% of the population, will live in urban areas. This will be far above the average of 41.4% projected for low-income countries in Africa.

The rapid urbanisation in Mali, particularly in Bamako, has several significant implications. It places considerable strain on public infrastructure, resulting in overcrowded roads, inadequate public transportation and limited access to essential services like healthcare and education. The growing urban population can also lead to increased demand for housing, driving up housing costs and contributing to the development of slums with poor living conditions. Additionally, rapid urbanisation raises environmental concerns, including heightened pollution in urban areas. It thus requires careful planning and investment in sustainable development to ensure positive outcomes.

Chart 5 presents GDP in market exchange rates (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

The Malian economy is the fifth largest in West Africa (after Nigeria, Ghana, Côte d'Ivoire and Senegal) and among the low-income countries in Africa (after Ethiopia, Sudan, DR Congo and Uganda). Its GDP measured in market exchange rates (MER) more than quadrupled from US$4.5 billion in 1990 to US$18.6 billion in 2023. Within this period (between 1990 and 2023), Mali’s GDP grew at an average of 4.3% per annum, above the average of 3.9% for low-income countries in Africa. The relatively stronger performance compared to its income peers can be attributed to rapid population growth in addition to the implementation of several medium-term plans, such as the Strategic Plan for Economic Recovery and Sustainable Development (CREDD 2019-2023). Additionally, various internationally supported economic reform programs have contributed by promoting economic development and improving quality of life. These include initiatives like the Structural Adjustment Programmes, the Aid Effectiveness, the Highly Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) initiative, the Poverty Reduction Strategies, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and the African Union Agenda 2063.

Despite this relatively strong performance above its income peers, the fundamentals of the Malian economy remain weak and the economic structure is still agrarian and untransformed. Mali’s economy is centred on the export of traditional raw materials such as cotton and gold, while much of its processed and finished goods are imported. Efforts to promote more value-added industrialisation remain at an early stage. For instance, in 2020, gold accounted for 82.9% and cotton for 6.7% of exports. The implication of this is that economic growth is highly volatile and mainly driven by weather patterns, international commodity price fluctuations and external shocks. For instance, its exceptional growth of 15% in 2001 was largely driven by the global commodity boom or supercycle in the early 2000s (1999 to 2001) due to high demands from then-emerging economies like China. Similarly, the country’s strong economic growth in recent years, averaging about 5.7% from 2014 to 2019 before COVID-19 has mainly been driven by the large commodity exports of gold and agriculture (mainly cotton) within the period.

On the other hand, in periods where the country had experienced severe drought such as in the early 2000s and in 2010/2011, the economy contracted. For instance, the negative growth rate of 0.8% recorded in 2012 was due to the severe drought in previous years. Aside from this, global or external shocks also significantly worsen domestic vulnerability and lead to adverse economic conditions. Key among them is the 2007 global financial crisis which caused economic growth to dip in those years. In recent years, Mali’s economic growth was further disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The restrictive measures and protocols instituted to control the virus curtailed economic activities, resulting in the GDP shrinking by 1.2% in 2020 — the largest drop since 1992. The economic contraction was accentuated by political instability in the country arising from the 2020 coup. However, the GDP recovered and grew by 3.1% in 2021, mainly due to the recovery of the services and agriculture sectors. GDP growth dropped to 1.8% in 2022 as a result of the combined effect of ECOWAS sanctions, high food inflation and parasite infestations affecting cotton production as well as the negative impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on commodity prices. Such volatility in economic growth further hinders development, job creation and poverty reduction.

Annual inflation reached an all-time high of 13.9% in August 2022, mainly driven by high food inflation. This was due to the displacement of farmers arising from the persistent insecurity, ECOWAS sanctions and increased global food prices. Huge public spending is also resulting in a large fiscal deficit and public debt largely financed by external borrowing. Public debt stood at about 55.9% of GDP by the end of 2023, with external debt constituting about 25.9% of total debt in 2022. This is 37.3% larger than the 40.7% recorded in 2019 prior to COVID-19. The increase in expenditure within this period is accounted for by the large COVID-19 expenditure, high wage bills and security spending.

Regardless, the economy has began to show signs of recovery, with economic growth in 2024 estimated at 3.5% and annual average inflation estimated at 2.1% in the same period.

To build a resilient economy, Mali needs to address its structural long-term economic vulnerabilities. These include its undiversified export basket dominated by gold and cotton, which exposes the economy to commodity price and climatic shocks, rising foreign debt and a large informal sector. Also, over-reliance on the agriculture sector, in addition to its low-productivity informal service sector and a limited manufacturing sector concentrated in agro-industries and cotton ginning, remains a structural weakness in the economy.

However, in the medium term, insecurity and the ongoing political transition present potential risks to the economy, as the military has yet to transfer power to civilian rule and restore the country to multiparty democracy and constitutional governance. This is particularly important given that the country’s recurring insecurity and political instability have historically worsened economic conditions. Also, an ECOWAS withdrawal that is not properly negotiated could disrupt the free movement of goods and people and thereby trade with non-WAEMU countries (Nigeria, Ghana and Sierra Leone, for example).

With the removal of the ECOWAS sanctions in July 2022, the economy is expected to bounce back as Mali still has strong growth potential. The country faces an optimistic future with economic growth projected to rebound to 4.0% in 2024 and 4.9% by 2026. Inflation is projected to fall to 1.2% due to reduced import costs and increased agricultural production. The government now faces the difficult job of reviving its economic growth record and translating such gains into poverty and inequality reductions as well as addressing long-term development needs. Achieving sustainable development requires Mali to build a resilient economy that is less dependent on external volatility or shocks, particularly the global commodity cycle.

On the Current Path, Mali’s GDP will reach US$25.8 billion and 2030 and more than triple to US$53.0 billion by 2043. The average growth rate within this period is estimated at 5.4%, meaning that the economy of Mali has the potential to grow quicker than it has in the past, although its high population growth will impede income growth. In the long term, the country needs to rethink its economic development strategy to focus on economic diversification and value-addition to its main commodities. Its huge natural resource deposits, together with its agricultural and renewable energy potential, are opportunities that can be used to grow and transform the economy.

Chart 6 presents the size of the informal economy as per cent of GDP and per cent of total labour (non-agriculture), from 2020 to 2043. The data in our modelling are largely estimates and therefore may differ from other sources.

The informal sector serves as a lifeline to many people, especially unskilled labourers, who cannot secure employment in the formal sector. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), informal employment is often associated with income insecurity, unsafe work conditions, and limited access to the rights and benefits accorded to the formal sector. The lack of workplace safeguards can impact workforce participation rates and limit the contribution to the economy by lower-waged workers.

The informal sector in Mali, like in many African countries, is large, serving as a source of livelihood for the majority of the population, especially women and young people. Informal enterprises in Mali are typically small-scale businesses, including artisans, shopkeepers and service providers, which are often unregistered and lack access to formal credit and markets. The sector offers a more flexible entry point for individuals, allowing them to engage in economic activities without the formal requirements of registration and taxation.

According to the ILO, 73% of the economically active population in Mali works in the informal sector, with about one-third of these workers being young people between the ages of 15 and 35 years. Women, also account for 79.6% of non-agricultural employment, compared to 62.9% for men. In 2023, about 81.5% of total labour in Mali works in the informal sector, making it the fifth largest among the low-income countries in Africa. A significant proportion of informal workers are employed in the agriculture sector. In the Current Path, the proportion of informal labour share will decline to 78.4% in 2030 and 72.1% in 2043 far above the average for its income peers in Africa.

Over the years, the share of the informal sector to GDP has grown rapidly compared to the formal sector. The contribution of the informal sector to total value added by the service sector increased from less than 40% in 1980 to over 60% in 2015. It currently contributes about 98% of all value added in the primary sector, mainly agriculture. In 2023, the size of the informal sector in Mali was approximately 33% of GDP above the average of 29.3% for its income peers in Africa. Despite this large contribution to GDP, the informal sector in Mali faces numerous challenges that hinder the growth of businesses in the sector. Many businesses are reluctant to transition to the formal economy due to the complexity, cost and burdensome compliance with tax regulations and bureaucratic procedures. Additionally, many informal workers lack formal education or business training, which limits their productivity and makes it difficult for them to move into formal employment. Poor infrastructure further hampers business operations, creating obstacles for informal enterprises to thrive or expand.

As part of efforts to address these challenges, Mali has introduced a new registration system for micro and small enterprises to streamline the transition of informal workers into the formal economy. Additionally, initiatives like the National Fund for Youth Employment aim to integrate young workers into the labour market through targeted programs that provide training and support. Efforts are also being made to improve access to credit for informal businesses, which could encourage them to formalise their operations if they see clear benefits. Furthermore, programmes focusing on enhancing skills development among informal workers, particularly through vocational training that meets market demands, are essential for improving employability and productivity.

In the Current Path, the size of the informal sector will decline slightly to 31.8% of GDP in 2030 and 29.3% of GDP by 2043.

While the large informal sector in Mali provides employment and income opportunities, particularly for the poor and vulnerable, its activities can also hinder economic growth. The widespread informality deprives the government of essential revenue, as many businesses in this sector do not pay taxes. Most individuals employed in the informal sector are in vulnerable positions, lacking job security and social protection (such as pensions and health insurance), and often receiving lower wages. Given these challenges, it is in the country’s best interest for the government to implement incentives that encourage businesses in the informal sector to formalise their operations. This can be achieved through measures such as tax education, tax incentives, simplified business registration requirements, and creating a more enabling business regulatory environment.

Chart 7 presents GDP per capita in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043, compared with the average for the Africa income group.

Despite its limitations, GDP per capita is generally used to measure the standard of living and is the most widely used and accepted indicator to compare welfare among countries. Using the purchasing power parity (PPP) measure for this analysis, Mali’s GDP per capita of US$2 127 in 2023 is the sixth-highest GDP per capita among the low-income countries in Africa, and it is 17% higher than the group average of US$1 814 for low-income countries in Africa. This figure represents a tremendous improvement of about 59.1% from the US$1 337 it recorded in 1990 when it was the eighth highest among the low-income countries group in Africa. However, this growth is insufficient to drive a faster transformation in livelihoods. The slow pace of GDP per capita growth is primarily attributed to high population growth, which hampers progress in reducing poverty and improving human development indicators.

By 2030, Mali’s GDP per capita will rise to US$2 320 above the average of US$2 084 for low-income countries in Africa. In the long run, Mali will lose ground on its income-group peers as GDP per capita will reach US$3 059 by 2043, placing it eleventh among low-income African countries. At this rate, the country’s GDP per capita will be slightly higher than the average of US$2 986 for its income-group peers in Africa.

Slower growth in GDP per capita can have several implications. First, it can lead to slower poverty reduction and limited improvements in living standards in Mali. Additionally, slow GDP per capita growth may imply that the benefits of economic growth are not evenly distributed or broadly shared which can worsen inequality in the country. It may also constrain government revenue, limiting the ability to invest in critical areas such as education, healthcare and infrastructure.

Chart 8 presents the rate and numbers of extremely poor people in the Current Path from 2020 to 2043.

In 2022, the World Bank updated the poverty lines to 2017 constant dollar values as follows:

- The previous US$1.90 extreme poverty line is now set at US$2.15, also for use with low-income countries.

- US$3.20 for lower-middle-income countries, now US$3.65 in 2017 values.

- US$5.50 for upper-middle-income countries, now US$6.85 in 2017 values.

- US$22.70 for high-income countries. The Bank has not yet announced the new poverty line in 2017 US$ prices for high-income countries.

Like many low-income countries in Africa, poverty in Mali is widespread. As a low-income country, Mali uses the US$2.15 benchmark for extreme poverty. In 1990, 7.9 million Malians, representing 86.3% of the population, lived below the poverty line of US$2.15, far above the average of 66.6% for low-income countries in Africa. Over the past three decades, the country’s effort at poverty eradication has yielded some results as the poverty rate declined to 14.2% in 2023 — far below the average of 41.5% for low-income countries in Africa — but still corresponds to 3.4 million Malians living below the poverty line of US$2.15 in 2023.

Efforts to combat poverty in Mali have been diverse, encompassing national strategies, international collaborations and community-level initiatives. The Malian government has developed several Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs) to guide its poverty alleviation efforts, with the most recent one focusing on increasing public spending on programmes aimed at reducing poverty and improving access to essential services such as education and healthcare as long-term solutions to poverty. Additionally, since the early 1990s, Mali has implemented governance reforms to decentralise administration, allowing local governments to take a more active role in addressing poverty. This approach empowers communities to identify specific needs and develop context-sensitive solutions.

Mali has also forged partnerships with international organisations such as the World Bank and the IMF, securing funding and technical support for poverty reduction initiatives, which are vital for sustainable development. Furthermore, collaborations with organisations such as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) have focussed on improving youth social and economic behaviours, increasing agricultural productivity and fostering community-based organisations, creating synergies across the health, education and economic sectors. Access to microfinance is another key initiative aimed at empowering poor families, enabling them to invest in small businesses and improve their livelihoods. This provides a crucial safety net during periods of economic hardship.

Despite these efforts, Mali faces significant challenges in poverty alleviation as poverty still persists. To appreciate the full incidence of poverty, one must look beyond monetary poverty as it only tells part of the story. The Human Development Index (HDI), which measures the average achievement of countries in three main areas: health, knowledge and standard of living, is one such measure. Mali’s HDI score of 0.410 in 2022 ranks 188 out of 193 countries globally, constituting a drop compared to the 0.434 it recorded in 2019. The global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) also measures acute multidimensional poverty by measuring each person’s overlapping deprivations across 10 indicators in three equally weighted dimensions: health, education and standard of living.

The MPI complements the international US$2.15 a day poverty rate by identifying who is multidimensionally poor and also shows the composition of multidimensional poverty. The headcount or incidence of multidimensional poverty is often several percentage points higher than that of monetary poverty. This implies that individuals living above the monetary poverty line may still suffer deprivations in health, education and/or standard of living. According to the 2023 UNDP Multimensional Poverty Index, about 68.3% of Malians were considered to be multidimensionally poor with an intensity of deprivation estimated to be 55%. An extra 15.3% of the population was considered to be vulnerable to multidimensional poverty. Aside from these, inequality is also prevalent in Mali with more poor people in the rural areas. Also, about 90% of the poor people in the country are concentrated in the densely populated areas of the southern part of Mali.

The cause of poverty in Mali is multifaceted. It includes lack of education, poor governance, malnutrition and widespread conflict due to terrorism and political instability. Also, the ypically large family size (average household size in 2019 was 8.2 people), coupled with increased drought, food shocks and outdated agricultural practices, has severely raised the cost of living in the country. In recent years, the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic in addition to the security crisis has increased poverty levels particularly from 2020 to 2022. These issues intensify pressure on resources and public services, hindering effective poverty reduction.

On the Current Path, Mali’s progress in reducing poverty rates will be slower so that by 2030, 10.9% of the population, equivalent to 3.2 million people will be living in extreme poverty. This means that Mali will require significant policy shifts in order to meet SDG 1, of eliminating extreme poverty. Projections indicate that by 2043, Mali is still likely to fall short of achieving SDG 1, with an estimated 5.6% of the population expected to remain below the international extreme poverty threshold of US$2.15 per day.

The eight sectoral scenarios as well as their relationship to the Current Path and the Combined scenario are explained in the About Page. Chart 9 summarises the approach.

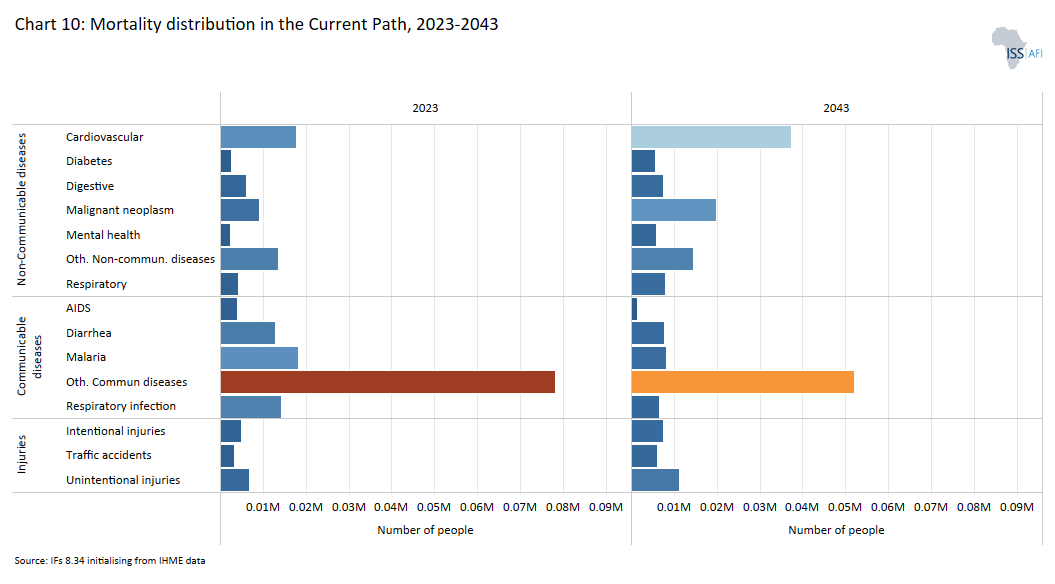

Chart 10 presents the mortality distribution in the Current Path for 2023 and 2043.

The Demographics and Health scenario envisions ambitious improvements in child and maternal mortality rates, enhanced access to family planning, and decreased mortality from communicable diseases (e.g., AIDS, diarrhoea, malaria, respiratory infections) and non-communicable diseases (e.g., diabetes), alongside advancements in safe water access and sanitation. This scenario assumes a swift demographic transition supported by heightened investments in health and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WaSH) infrastructure.

Visit the themes on Demographics and Health/WaSH for more detail on the scenario structure and interventions.

Mali's health sector has made significant progress in recent years, although several challenges remain. For instance, expanding the healthcare infrastructure and placing medical personnel in rural regions have increased access to high-quality healthcare services in Mali. The Malian National Statistics Office (INSTAT) and ICF (2019) report notes improvements in maternal and child health outcomes, including decreased maternal mortality rates and increased vaccine coverage. A 2020 World Health Organization study emphasised the need to strengthen disease surveillance and response systems to effectively manage and prevent outbreaks. It also stressed the importance of improving healthcare infrastructure, expanding access to hygienic conditions, and ensuring clean water to prevent the spread of infectious diseases.

The country faces various health challenges due to its inadequate healthcare infrastructure, however. Malnutrition, exacerbated by the security crisis, is widespread, particularly among children, with around 21% of children under five years old classified as underweight. Mali's infant, child and maternal mortality rates continue to be among the highest in sub-Saharan Africa. This is mainly due to the poor availability and uptake of family planning in the country, early childbearing, high rates of female genital mutilation, infrequent use of skilled birth attendants and a paucity of emergency obstetrical and neonatal care. Furthermore, the country also has one of the lowest densities of healthcare workers, especially in the rural areas, limiting its capacity to provide essential health services. Like many African countries, Mali has historically experienced high mortality rates from communicable diseases. Persistent challenges include high maternal and child mortality, the world’s highest adolescent fertility rate, low child immunisation coverage and widespread malnutrition. The country also faces a significant burden from infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, malaria and diarrhoea, while the prevalence of non-communicable diseases is on the rise which are typically more expensive to treat.

Our modelling uses the International Classification of Disease (ICD) to differentiate between three broad categories of diseases: communicable, non-communicable and injuries, as well as 15 subcategories of mortality and morbidity. In 1990, communicable diseases caused about 121 000 deaths — representing about 75% of total deaths in that year. This was followed by non-communicable diseases that caused 32 600 deaths (20.2% of total deaths) and injuries that caused 7 710 deaths (4.8% of total deaths). By 2023, deaths from communicable diseases had steadily declined to 127 360, although this was still 64.4% of all deaths. Deaths from non-communicable diseases and injuries rose to 55 500 (equivalent to 28.1% of all deaths) and 14 800 (equivalent to 7.5% of all deaths), respectively. According to the WHO, the leading causes of death in Mali include malaria, lower respiratory infections, diarrhoeal diseases, preterm birth complications, birth asphyxia and birth trauma, stroke and Ischaemic heart disease. Indeed, malaria alone caused 88 500 deaths in 2021 followed by lower respiratory infections with 83 800 deaths.

On the Current Path, this trajectory will continue till about 2039 when Mali is projected to achieve its epidemiological transition: the point where deaths from non-communicable diseases outweigh deaths from communicable diseases. By 2043, non-communicable diseases will be the highest cause of death in Mali causing 98 750 deaths in the country (about 49.5% of all deaths). The transition to deaths from non-communicable diseases as the main cause of mortality will inevitably increase health sector costs as they are more expensive to treat. By then, deaths from communicable diseases will rapidly decline to 75 980, constituting 38.1% of all deaths, while deaths from injuries will constitute the remaining 12.4%.

Access to improved, safe and treated water, such as piped water, and proper sanitation is crucial in preventing the spread of communicable diseases. Poor water sources and inadequate sanitation are linked to diseases such as diarrhoea, which disproportionately affect children. It is estimated that over 20% of deaths in Mali are attributed to poor water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) conditions. Many wells remain uncovered and untreated, posing contamination and health risks.

Mali has implemented various initiatives to ensure access to hygienic facilities and clean water, particularly in urban areas. Organisations like World Vision are actively working to address Mali’s water and sanitation challenges. Their efforts include drilling new boreholes to ensure reliable access to clean water, conducting community programs that raise awareness about good hygiene practices. Despite these efforts, Mali continues to face significant challenges in water supply and sanitation due to the uneven distribution of water resources across the country, making access difficult, particularly for rural populations. This situation negatively impacts public health, especially among vulnerable groups such as children.

Mali has made significant advancements towards the attainment of SDG 6.1 of universal access to safe drinking water. In 2023, 20.7 million Malians (constituting 86.9% of the population) had access to improved water supply. Out of this, 12.1 million people (about 50.8% of the population) had access to a piped water supply in the country. On the Current Path, Mali’s progress will lag as the population with access to improved water will be 87.1% in 2030, meaning that the country will miss the SDG target in this area. By 2043, access to improved water will increase to about 90.5%, of which piped water will constitute almost 55% of connections.

Regarding sanitation, about 5.9 million Malians (47.9% of the population) had access to improved sanitation in 2023, twice the average for its income-group peers in Africa. At 16.7%, the share of the population with access to shared sanitation is slightly above the average of Africa’s low-income group of 15.%. This means that more than one-third of the Malians resort to unimproved sanitation including inadequate waste management and the absence of proper toilet facilities, which poses major health and environmental risk to the country. On the Current Path, the proportion of the population with improved access to sanitation will rise to 50.3% in 2030 and 60.1% by 2043. This means that Mali will lag behind in achieving SDG target 6.2 of ensuring access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and an end to open defecation. Consequently, the share of the population with unimproved sanitation access will fall to 32.9% in 2030 and 24.4% in 2043 while the use of shared sanitation will constitute 16.8% of the population in 2030 and 15.5% by 2043.

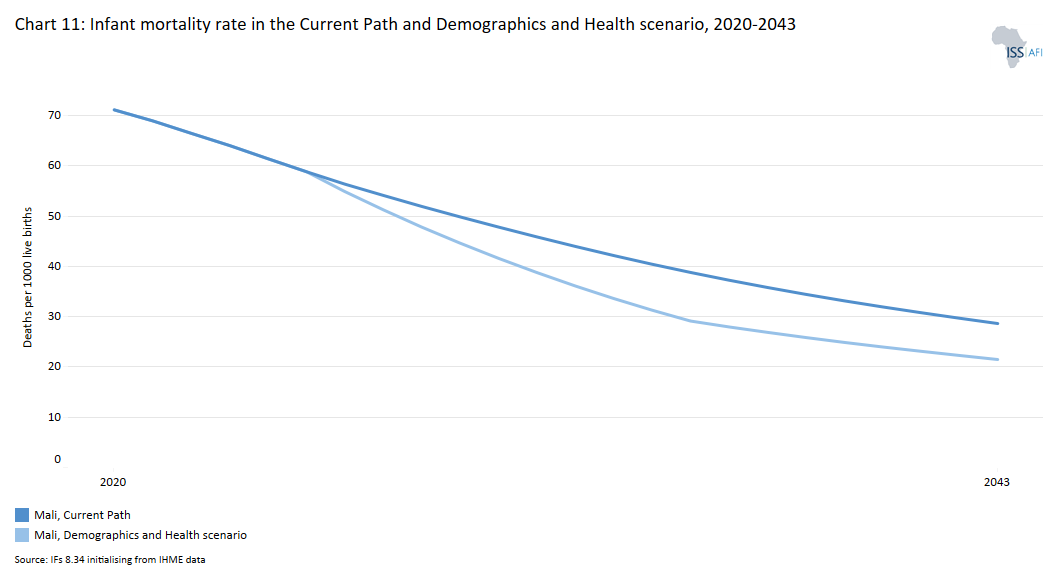

Chart 11 presents the infant mortality rate in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

The infant mortality rate refers to the probability that a child born in a specific year will not survive to their first birthday. It measures the child-born survival rate and reflects the social, economic and environmental conditions in which children live, including their health care. It is measured as the number of infant deaths per 1 000 live births and is an important marker of the overall quality of the health system in a country.

In 2023, the infant mortality rate in Mali was 64.1 deaths per 1 000 live births — a drop by more than half of the rate in 1990. However, this was 47.6% higher than the average of 43.4 deaths for low-income countries in Africa. The major causes of infant mortality in Mali include preterm birth which constitutes 30% of all deaths, neonatal asphyxia constitutes 28% of deaths and sepsis/tetanus constitutes 21% of deaths. Other causes include acute respiratory infections and congenital anomalies.

There is a disparity in infant mortality in Mali as babies born in rural areas and poorer households are less likely to survive. For instance, the UNICEF estimates show that Mali records 38 deaths per 1 000 live births for babies born in rural areas compared to 27 deaths per 1 000 live births for babies born in urban centres. Similarly, poorer households record 39 deaths per 1 000 live births of babies compared to richer households that record 30 deaths. The disparity largely reflects access to improved healthcare services for richer and urban households which are usually not available to poorer and rural households. Another important factor explaining the disparity in infant mortality is the educational attainment of the mother. Estimates show that children born to less educated mothers in Mali are 2.1 times less likely to survive during their first month compared to those born to educated mothers. This highlights the urgent need for Mali to invest in girls' education to help reduce these preventable deaths.

On the Current Path, the infant mortality rate will decline further, reaching 47.8 and 28.6 deaths per 1 000 live births by 2030 and 2043, respectively. It means that Mali will fall short of achieving the SDG target of 12 deaths per 1 000 live births even by 2043 and is only lieklety to achieve this by 2066 in the Current Path.

The Demographics and Health scenario will reduce Mali’s infant mortality rate to 41 deaths per 1 000 births in 2030 and 21.5 deaths per 1 000 births by 2043. This is seven deaths fewer than in the Current Path and two fewer deaths than the Current Path average of low-income countries in Africa in 2043. Although this does not meet the SDG target, it pushes Mali close to the SDG target emphasising the need for the country to invest in access to improve healthcare service.

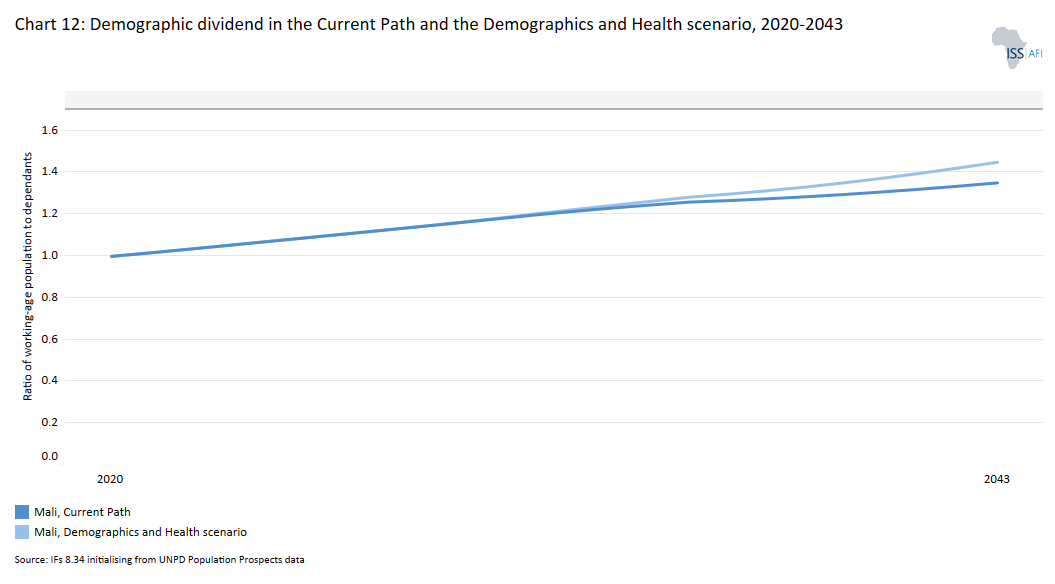

Chart 12 presents the demographic dividend in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

The dividend is the window of economic growth opportunity that opens when the ratio of working-age persons to dependents increases to 1.7 to 1 and higher.

We explain the different conceptualisations relating to a demographic dividend in a separate theme.

The demographic dividend is the economic growth generated by changes in the population structure. It generally materialises when the ratio of the working-age population to dependants is at least 1.7 to one, meaning that for every dependant, there are 1.7 persons of working age. When there are fewer dependants to take care of, it frees up resources for investment in both physical and human capital formation. Studies have shown that about one-third of economic growth during the East Asia economic ‘miracle’ can be attributed to the large worker bulge and a relatively small number of dependants. However, the growth in the working-age population relative to dependants does not automatically translate into rapid economic growth unless the labour force acquires the needed skills and is absorbed by the labour market. Without sufficient education and employment generation to successfully harness their productive power, the growing labour force (especially those in urban areas) could increasingly become frustrated with the lack of job opportunities leading to social tension and even the emergence of civil instability.

In 2023, the ratio of the working-age population to dependants in Mali was one to one, which means that on average, for every dependant in Mali, there was only one person of working age (15–64 years of age). This is lower than the 1.2 to one average for low-income countries in Africa. The high dependency rate in Mali can be attributed to the high fertility rate as discussed previously. On the Current Path, Mali will likely not achieve the minimum ratio of 1.7 working-age persons for each dependant required for the materialisation of the demographic dividend, or demographic gift, even by 2043. Indeed, based on the Current Path, Mali is likely only to achieve this minimum ratio by 2059.

The Demographics and Health scenario pushes the country close to this target such that by 2043, the ratio of the working-age population to dependants will be 1.5 to one in the scenario instead of the 1.3 to one as in the Current Path (on par with the average for its income-group peers in Africa by 2043). This underscores the importance of investing in education and expanding decent opportunities for Mali’s growing population, to ensure that demographic trends contribute positively to inclusive and sustained growth.

Chart 13 presents crop production and demand in the Current Path from 1990 to 2043.

The Agriculture scenario envisions an agricultural revolution that ensures food security through ambitious yet feasible increases in yields per hectare, thanks to improved management, seed, fertiliser technology, and expanded irrigation and equipped land. Efforts to reduce food loss and waste are emphasised, with increased calorie consumption as an indicator of self-sufficiency and prioritising it over food exports. Additionally, enhanced forest protection signifies a commitment to sustainable land use practices.

Visit the theme on Agriculture for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Mali has ideal circumstances for agricultural development as it has a sizable area of arable land and an abundance of water supplies from the Niger and Senegal rivers. Agriculture and agro-pastoralism are the main economic pillars of Mali: nearly 80% of Malians work in the agriculture sector. According to the International Trade Administration (ITA), the Malian government dedicates about 12% of its national budget to the agricultural sector and subsidises cotton. Cotton is one of Mali's essential agricultural products, accounting for a significant portion of its exports. Other agricultural commodities, such as rice, corn, millet, sorghum and wheat, make up the majority of Mali's agricultural output.

Over the years, the government has made efforts to improve agricultural productivity by encouraging foreign and national private investors to undertake agricultural activities in the lands of the Office du Niger (an irrigation scheme). In addition, the government has been investing in irrigation infrastructure, aiming to enhance water accessibility and to minimise the impact of climate change. Government and NGO training programmes and extension services connect farmers to contemporary agricultural methods, enhanced seed varieties, effective water management strategies and financial access. Also, through funding, rural infrastructure and fostering integration with regional and global markets, efforts are being undertaken to increase market access.

Nonetheless, the sector is confronted with numerous challenges. Although the country has important and underexploited agricultural potential, especially in the southern and central regions, climate change and vulnerability to droughts and desertification pose significant threats to agricultural productivity and food security. The sector's potential for growth is also hampered by a lack of infrastructure, including storage facilities, irrigation systems and transportation, making it difficult for farmers to access markets and avoid post-harvest losses. Furthermore, traditional farming practices and a lack of access to modern technology and high-quality inputs like seeds and fertiliser continue to result in low output.

In 1990, Mali’s average crop yield of 1.7 metric tons per hectare was 36% higher than the average of 1.3 tons for its income-group peers in Africa. However, by 1996, the average yield per hectare in Mali had fallen below its income-group peers in Africa. The decline can be attributed to changing weather patterns, especially since agriculture production in the country is rainfed and, thus, susceptible to climate change. This trend continued except for 2016 and 2017 when Mali overtook its income-group peers in Africa. By 2023, the average crop yield per hectare of 2.6 metric tons in Mali was 8.9% lower than the average of low-income countries in Africa. This ranks Mali 13th in the low-income group but equates to less than half the yield per hectare in Rwanda and Malawi. On the Current Path, yield per hectare will rise to 2.9 and 4 metric tons per hectare by 2030 and 2043 respectively—still below the average of low-income African countries.

Total agriculture production[1The data on agricultural production and demand in the IFs forecasting platform initialises from data provided on food balances by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). IFs contains data on numerous types of agriculture but aggregate its forecast into crops, meat and fish, presented in million metric tons.] in 1990 stood at about 4 million metric tons. Of this, 3.3 million metric tons, representing 82.5%, were crops, with the remainder constituting meat production. By 2023, total agricultural production had grown to 21.7 million metric tons. Of this, crop production constituted about 93%, equivalent to 20.2 million metric tons, meat production 6.5%, and fish production constituted the remainder of the total production. Mali faces also huge agriculture loss and waste estimated at 30.3% of total production. This is largely due to post-harvest losses for crops, estimated at 10.3% of production. Such losses are a result of pest and disease infections, spoilage and the lack of adequate and effective storage facilities. Transmission losses for crops, which are mainly due to poor transportation networks also accounts for 16.6% of production.

In terms of demand, the total demand for agricultural products in Mali has always been more than the total production. Total demand stood at about 4.5 million metric tons in 1990, of which 3.7 million metric tons, equivalent to 83% of total demand, were for crops. The remaining demand was for meat (685 000 tons) and for fish (73 000 tons). Comparing this to the total production (about 4 million metric tons) in the same year reveals that Mali had excess demand for agricultural products in that year of about 490 450 metric tons. Since then, domestic demand has rapidly outgrown production, and by 2023, agricultural demand exceeded domestic production by 1.2 million metric tons, despite the increase in production. Of the total demand of 22.9 million tons, 92.4% is for crops (21.2 million tons). The remaining demand is mainly for meat (1.5 million tons), and the lowest demand is for fish (240 000 tons).

Despite the projected increase in domestic production, reaching 25.9 million metric tons in 2030 and 33.3 million metric tons in 2043, it will not be enough to meet domestic demand that will rapidly grow to 29.2 million metric tons and 37.6 million metric tons in the same period, respectively. As a result, excess demand for agricultural products will reach 3.2 million metric tons in 2030 and 10.4 million by 2043. This highlights the need for strengthened efforts to enhance domestic agricultural production, as Mali may face growing pressure on food security in the future if current trends continue. The World Bank estimates that about 1.4 million people faced severe food insecurity between June and August 2024. Notwithstanding this expected rising food insecurity, many agricultural subsectors, including biofuels, shea butter, mangoes, peanuts and cashews, are still entirely untapped and present a unique opportunity for investors. Modernising Mali's poultry and cattle production and transformation industries also serve as potential avenues for improvement and growth.

Chart 14 presents the import dependence in the Current Path and the Agriculture scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

With total agricultural demand outgrowing domestic production, Mali is likely to rely on imports to meet its domestic demand. In 2023, Mali’s net import of crops stood at 1.4% of total crop demand, which was less than the average of 9.1% for low-income countries in Africa. In the Current Path, net crop imports will grow rapidly in Mali to 14.8% and 26.2% of total crop demand by 2030 and 2043, respectively. This suggests a growing level of national food insecurity; however, it can also be as a result of changes in dietary preferences among Malians.

In the Agriculture scenario, yield per hectare will increase to 5.4 metric tons by 2043 — a 35% improvement compared to the projections of the Current Path and the average of low-income countries in Africa. The improvement in yields will lead to an improvement in total agricultural production. In the Agriculture scenario, total crop production will increase to 26.2 million tons, almost 2.5 million metric tons, or 10.5%, more than the Current Path by 2043. By 2043, crop production in Mali will rise by 32.2% over the Current Path to 38.6 million tons in the Agriculture scenario by 2043. The projected increases in crop production in the Agriculture scenario reduce the import dependency of crops in the country compared to the Current Path. By 2030, the net import of crops will decline to 10.2 in the Agriculture scenario instead of 14.8% in the Current Path. This reduction in import dependence will continue so that by 2043 net crop import will be 3.4% of total demand far below the projected Current Path average of 26.2%. This implies that Mali has the potential to reduce its food import and become food-sufficient if significant steps are taken to revamp the agricultural sector.

Efforts towards improving yield per hectare such as the adoption of modern technology, improved seed, fertiliser and expanded irrigation facilities as well as provision of storage facilities can improve agriculture potential of the country.

Chart 15 depicts the progress through the educational system in the Current Path, for 2023 and 2043.

The Education scenario represents reasonable but ambitious improvements in intake, transition, and graduation rates from primary to tertiary levels and better quality of education at primary and secondary levels. It also models substantive progress towards gender parity at all levels, additional vocational training at the secondary school level, and increases in the share of science and engineering graduates.

Visit the theme on Education for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Mali has a 6-3-3 education system, which consists of six years of elementary education, three years of lower-secondary school and three years of upper-secondary education. Like many countries in the region, Mali allocates a significant share of its resources to education. However, outcomes remain uneven, in part due to systemic inefficiencies and challenges related to governance and accountability within the sector. The Malian government’s spending on education is boosted by support from non-governmental and international organisations. For example, the Global Partnership for Education provides the country with financial assistance and technical support to improve its education system.

The education system can be viewed as a long funnel where children enter at the primary level and exit after completing tertiary-level education. However, the education funnel in Mali, like many sub-Saharan African countries, is leaky with various cracks along the way. Many children enter the system at the mouth of the funnel, but few complete the entire journey — from primary to secondary school and then university — to eventually graduate with a tertiary or equivalent education at the other end. In 2023, the gross enrolment rate for primary school students in Mali was 83.9%, a remarkable increase from 27.3% in 1990 but still far lower than the average of 108.3% of low-income countries in Africa. Comparing this to the net enrolment rate of 63.9% in the same period leads to two important conclusions. First, a significant number of children in Mali who are of school-going age are not in school (reflected in the low net number). Secondly, many classrooms in Mali are likely to be crowded by older students (reflected in the high gross number).

In the Current Path, Mali's gross enrolment rates will reach 88.9% and 95.5% in 2030 and 2043, respectively. In the same period, the net enrolment rate will be 68.5% in 2030 and 75.7% by 2043. At this rate of progress, the country will still lag behind the average of its income-group peers in Africa. The gross primary completion rate stood at almost 58.8% in 2023, indicating that a sizable number of children who enrolled did not complete the last grade of primary school in Mali. Although this rate is low, it is close to the average of the country’s African income-group peers at 61%. On the Current Path, Mali’s progress in ensuring more children complete primary school will be slower as it will reach 71.4% in 2030 slightly below the average of 73.8% for its income peers in Africa. By 2043, the primary completion rate in Mali will rise to 81.2% — this is almost on par with the average of African low-income countries at 83.6%.

Of those who complete primary-level education, it is expected that some will transition immediately to the lower-secondary level, some will enrol in the lower-secondary level after some years out of school and some will never enter the lower-secondary level, to, thereafter, potentially progress through to the upper secondary and tertiary levels. In Mali, more students transition from primary level to lower-secondary level than they do from lower-secondary level to upper-secondary level. In both cases, the rates are lower than Mali’s income-group peers in Africa: gross enrolment for lower- and upper-secondary levels in the country stood at 50.3% and 25.9%, respectively, in 2023, compared to 65.3% and 29.7%. In the Current Path, Mali's progress in gross enrolment for lower and upper secondary will rise to 61.9% and 32.8%, respectively, in 2030. By 2043, gross enrolment for the lower-secondary level will rise to 71.6%, while that of the upper-secondary level will rise to 42.6%. This indicates a significant drop in student retention from lower to upper secondary education.