Madagascar

Madagascar

Feedback welcome

Our aim is to use the best data to inform our analysis. See our Technical page for information on the IFs forecasting platform. We appreciate your help and references for improvements via our feedback form.

This page presents a comprehensive analysis of Madagascar. The analysis outlines the nation’s socio-economic challenges and opportunities, examining various developmental paths through 2043. It explores eight sectoral scenarios, including demographic, governance, economic and infrastructure-related outcomes. The analysis aims to provide policymakers and researchers with insights to guide Madagascar towards a more prosperous future for all.

For more information about the International Futures modelling platform we use to develop the various scenarios, please see the Technical page.

Summary

We begin this page with an introductory assessment of the country’s context by looking at current population distribution, social structure, climate and topography.

- The Republic of Madagascar is a low-income country, situated in the Indian Ocean off the coast of southern Africa. It is the world’s fifth-largest island, endowed with considerable natural resources and unparalleled biodiversity. It comprises the main island of Madagascar as well as multiple smaller peripheral islands. Neighbouring islands include the French territory of Réunion and the country of Mauritius to the east, as well as Comoros and the French territory of Mayotte to the north-west. The nearest mainland state is Mozambique, located to the west.

- Since 1992, Madagascar has officially been governed as a constitutional democracy, but repeated political crises have destabilised the country, compromised economic growth and development and undermined investor confidence. In December 2023, Andry Rajoelina was re-elected President of Madagascar. In 2023, the country had a population of about 31.3 million people. Its capital and largest city is Antananarivo, with approximately 3 million inhabitants. The country’s economy is based primarily on agriculture, mining, tourism and textiles. Madagascar has the highest poverty burden on the continent, with 80.5% of its population living in extreme poverty in 2023.

This section is followed by an analysis of the Current Path for Madagascar which informs the country’s likely current development trajectory to 2043. It is based on current geopolitical trends and assumes that no major shocks would occur in a ‘business-as-usual’ future.

- The population of Madagascar is growing rapidly at about 2.6% a year. In 2023, the country's population was estimated at 31.3 million people, and on the Current Path, it will expand to approximately 48.7 million people by 2043. Madagascar’s age structure is maturing slowly, and on the Current Path, the country will reach replacement-level fertility of 2.1 births per woman only by around 2060. More than 60% of the population lives in rural areas.

- Between 1990 and 2023, Madagascar’s GDP more than doubled from US$7 billion to just over US$15.1 billion. The country ranks ninth out of 23 African low-income economies, with Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda being the lead economies. In 2043, Madagascar’s GDP will be US$38.4 billion, more than two and a half times as large as in 2023. However, the expected average annual growth of under 5% over the coming two decades, combined with historically high levels of inequality, such expansion is insufficient to allow for meaningful progress in poverty reduction and human development more generally.

- In 2023, Madagascar’s GDP per capita ranked 13th out of 23 for Africa’s low-income economies, at a value of US$1 500. This is US$350 below the group average for Africa’s low-income economies (US$1 850). In the Current Path, the country’s per capita income will increase to US$2 200 per capita by 2043, maintaining its current regional rank. Madagascar’s GDP per capita will remain below the average of its low-income peer group, which will be US$3 006 by 2043. This points to the structural factors that undermine inclusive economic growth in Madagascar.

- As a low-income country, Madagascar uses the US$2.15 benchmark to define extreme poverty. The country has the highest poverty burden on the continent, with 80.5% of its population living in extreme poverty in 2023, followed by South Sudan, Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Unlike Madagascar, those three countries experience high levels of violent conflict. The average poverty rate for Madagascar’s low-income peers was more than 80% lower, standing at 44.6% in 2023 and a predicted 26.7% in 2043. A combination of political instability, geographic challenges, underinvestment in people and environmental fragility has led to such high and persistent levels of poverty.

- Madagascar has a long-term vision called Fasandratana 2030 - Vision pour le développement de Madagascar. This plan aims to raise Madagascar's GDP per capita by US$1 000 by 2030, reduce the poverty rate to less than 25% and improve the country’s Human Development Index (HDI) ranking to between 70th and 80th place by 2033. In addition, Madagascar has a national development plan known as Plan Émergence Madagascar, covering the period from 2019 to 2023. It emphasises sustainable development, inclusive growth and environmental stewardship with good governance as the backbone.

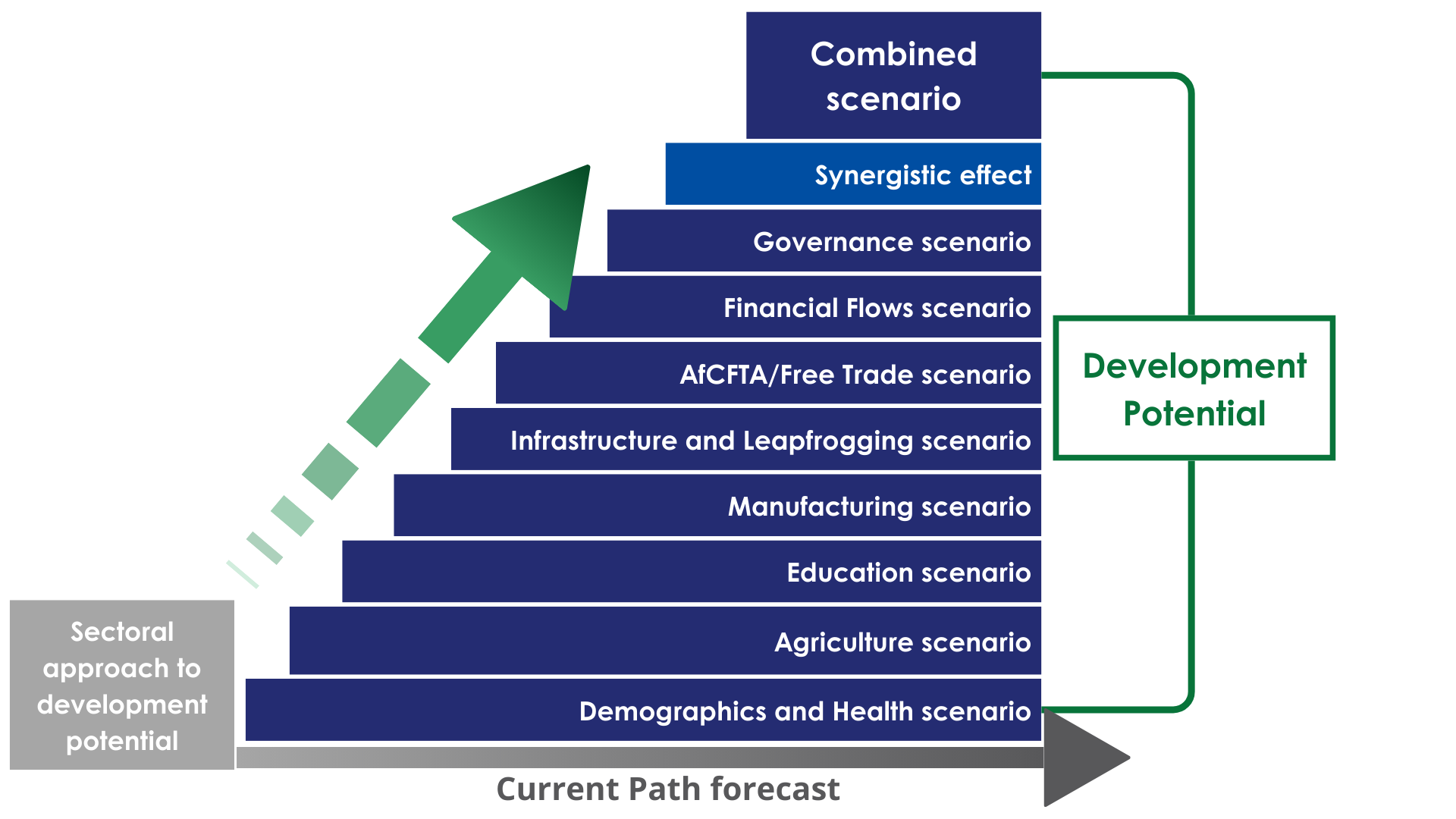

The next section compares progress on the Current Path with eight sectoral scenarios. These are Demographics and Health; Agriculture; Education; Manufacturing; the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA); Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging; Financial Flows; and Governance. Each scenario is benchmarked to present an ambitious but reasonable aspiration in that sector compared to the historical progress made by other countries at similar levels of development.

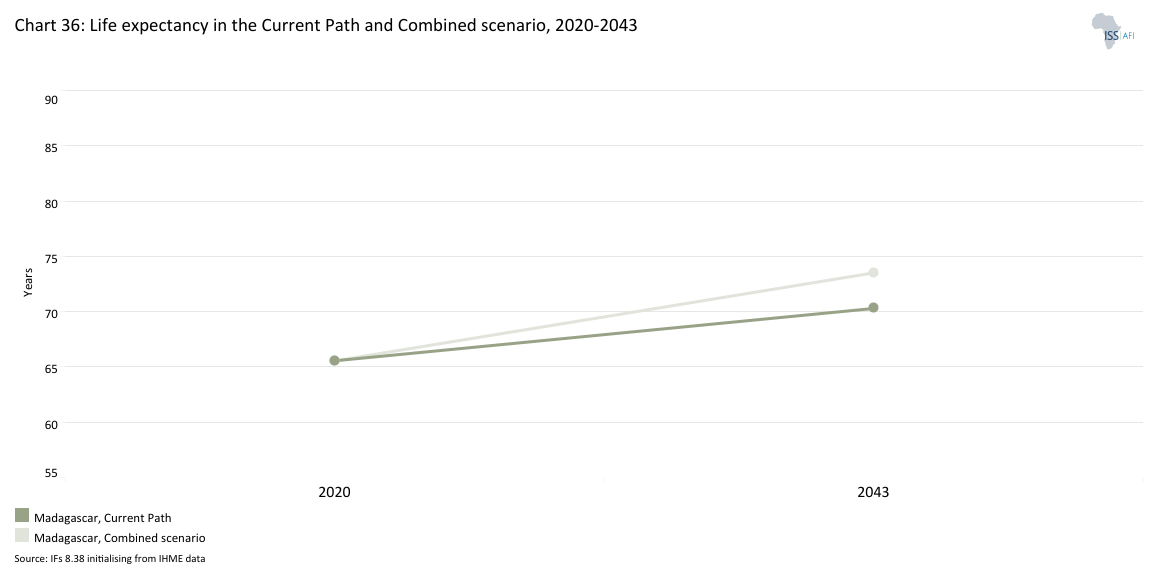

- The implementation of the Demographics and Health scenario will accelerate Madagascar’s demographic transition. In this scenario, the ratio between working-age and dependent population will change more quickly and allow Madagascar to enter the demographic “sweet spot” by 2038, with the potential to benefit from the large contribution that labour makes to economic growth. This is seven years earlier than on the Current Path. Moreover, the population will see several health benefits flowing from the scenario. Infant mortality will drop by roughly a third to 15.9 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2043, compared to 24 in the Current Path. Life expectancy will increase by 2.6 years to 72.9 years, compared to 70.3 years in the Current Path by 2043.

- The Agriculture scenario vitally increases total agricultural production in the face of growing demand. Crop production, coming from a base of 15.8 million metric tons in 2032, will hit 29.2 million metric tons in 2043, 7.5 million metric tons above the expected production level in the Current Path. Increased production will reduce Madagascar’s import dependence. By 2043, food imports will account for 10.8% of agricultural demand versus 32% on the Current Path. Further, the scenario promotes economic diversification by increasing the added value of the agricultural sector to 14.8% of GDP compared to 12.4% of GDP in the Current Path.

- The interventions in the Education scenario will improve human capital outcomes in Madagascar, a key driver of economic growth. The impact on mean years of education is significant, given that Madagascar comes from a low base. Mean years of education will increase by 2.4 years, from 4.8 years in 2023 to 7.2 years in the Education scenario, compared to 6.1 years in the Current Path. The share of science and engineering students among tertiary graduates will increase from 16.2% in 2023 to 21.5%, compared to 16.4% in the Current Path.

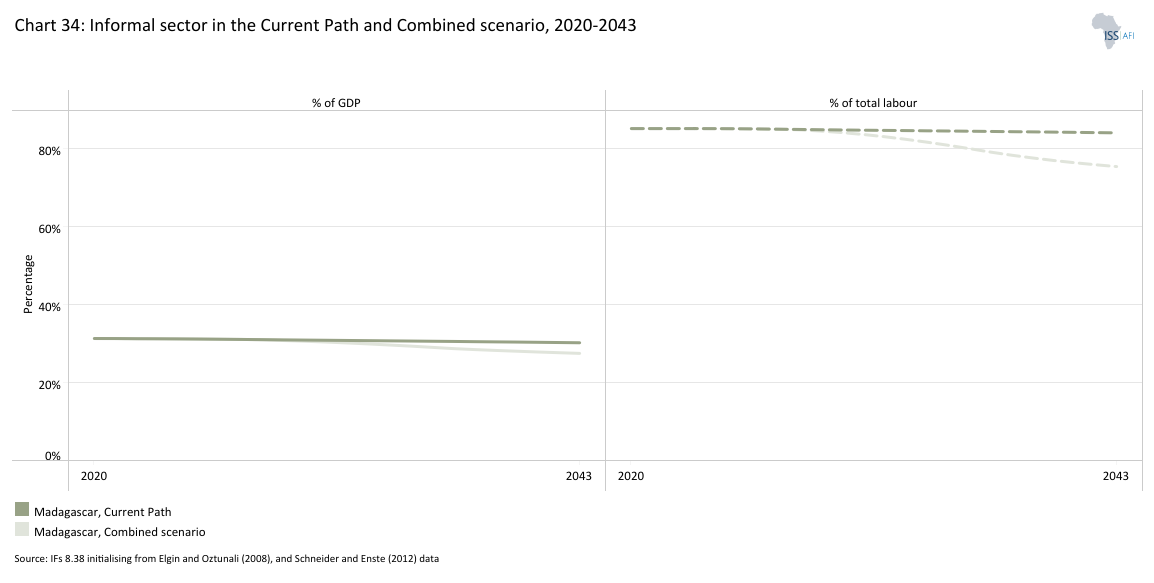

- In the Manufacturing scenario, efforts at boosting industrial development pay off. In this scenario, the sector’s share will account for 14.6% of GDP compared to 13.7% in the Current Path. This will put Madagascar above the group average of its African peer economies, which will be 10.8%. The Manufacturing scenario also has by far the greatest impact on reducing informal labour. As a share of total labour, informal labour will drop to 78.2% by 2043, compared to 83.9% in the Current Path.

- In the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) scenario, GDP (MER) will reach US$42.3 billion compared to US$38.4 billion in the Current Path. The impact of the interventions strengthens when extending the forecasting horizon by another two decades. The scenario will increase Madagascar’s total exports from US$16.9 billion in the Current Path to US$19 billion in 2043. Total trade to and from the country, this is exports plus imports, will rise from US$9.2 billion in 2023 to US$40.2 billion in 2043, versus US$36.2 billion in the Current Path.

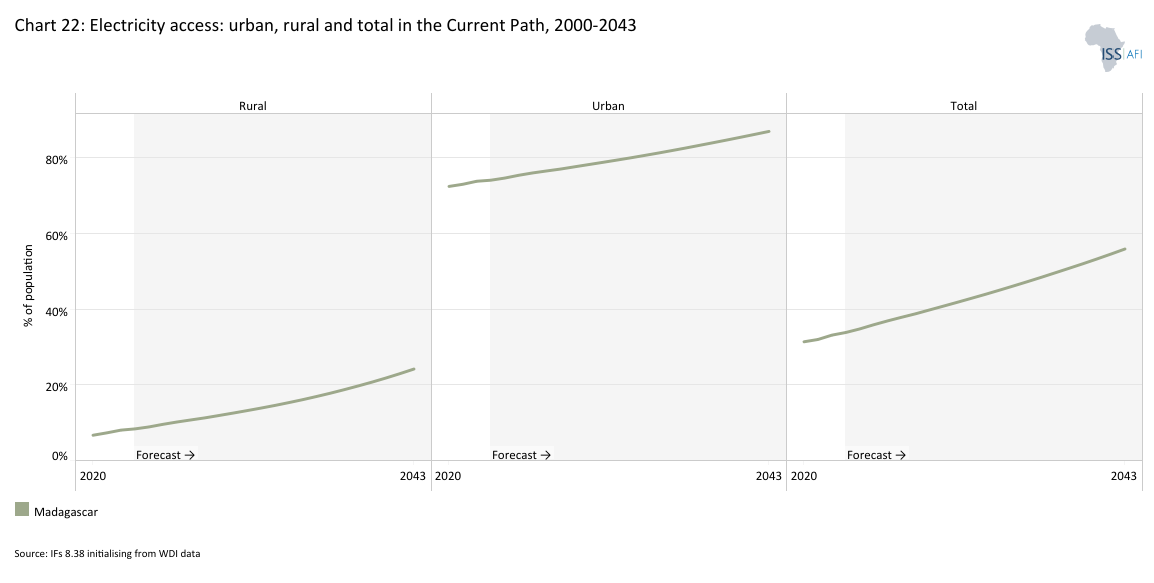

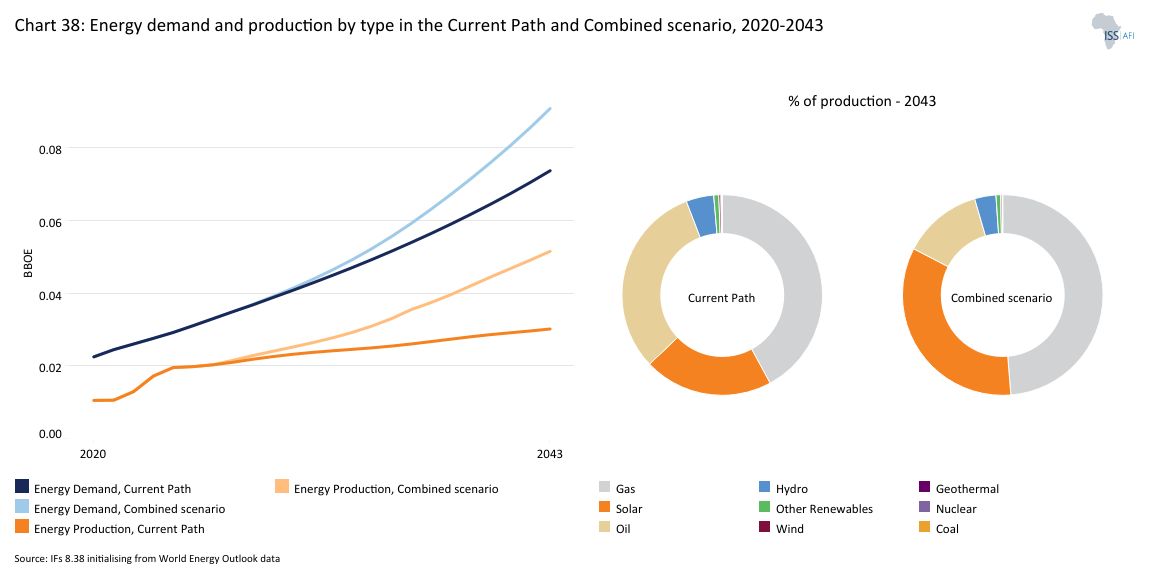

- In the Large Infrastructure and Leapfrogging scenario, the share of energy production from renewables will increase significantly, from accounting for 10.1% of total energy production in 2023 to 37.3% in 2043. In the Current Path, energy production from renewables will only increase to 26.5% of total energy production. Electricity access rates in rural areas will improve from 8.4% in 2023 to 29.8% in 2043, versus 24.2% in the Current Path.

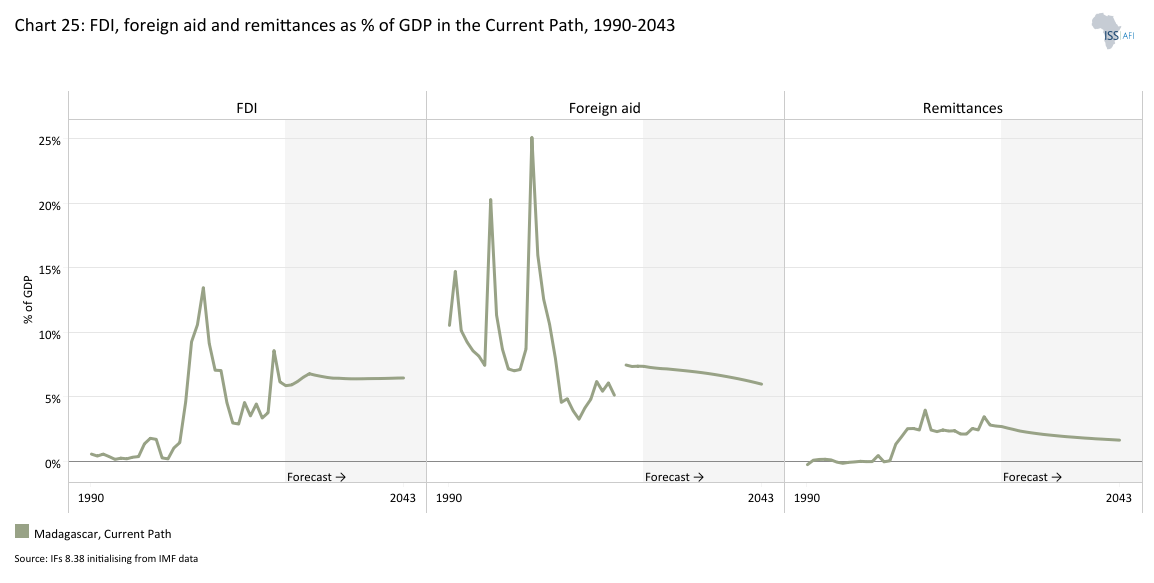

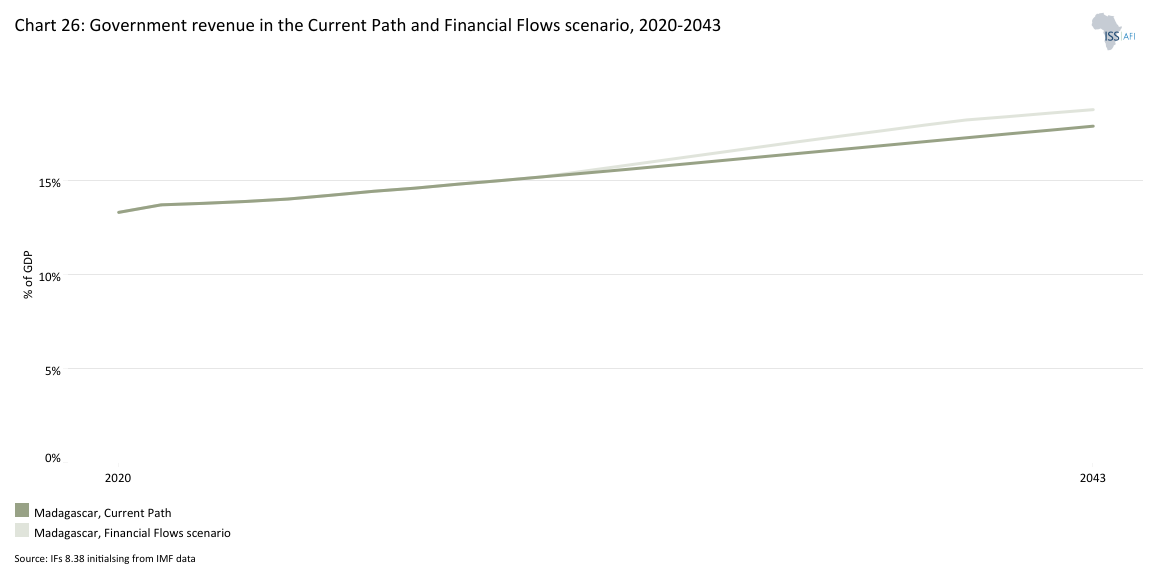

- In the Financial Flows scenario, foreign direct investment (FDI) as a share of GDP will account for 8.8% of Madagascar’s GDP in 2043, compared to 6.5% in the Current Path, almost two percentage points above the expected group average for Africa’s low-income economies. In 2024, FDI experienced an uptick, mostly fuelled by new legislation, a revision of the mining code and the liberalisation of the telecommunications sector.

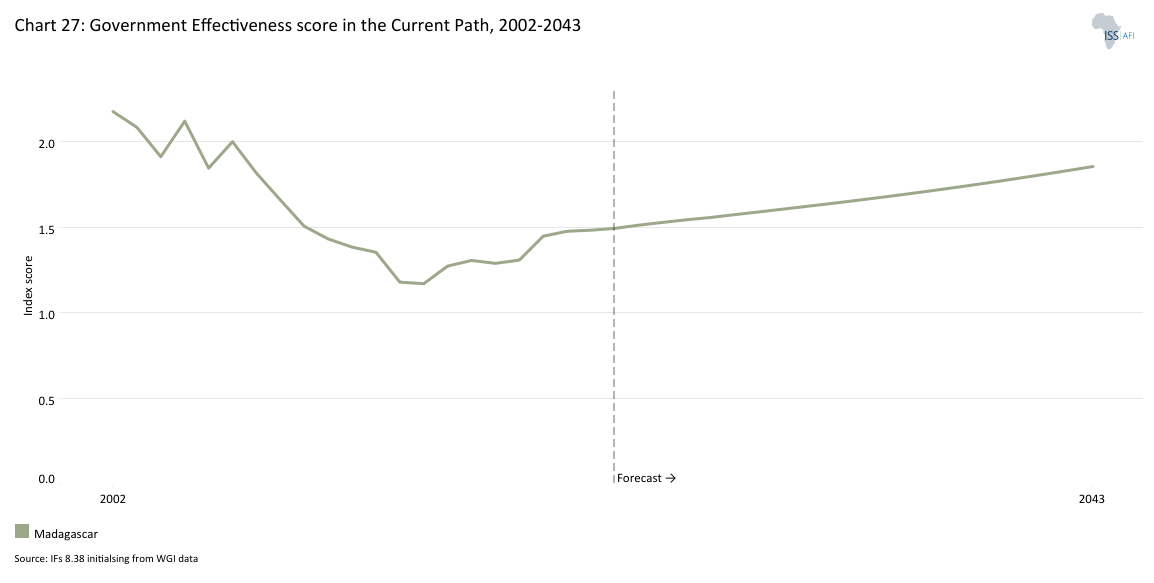

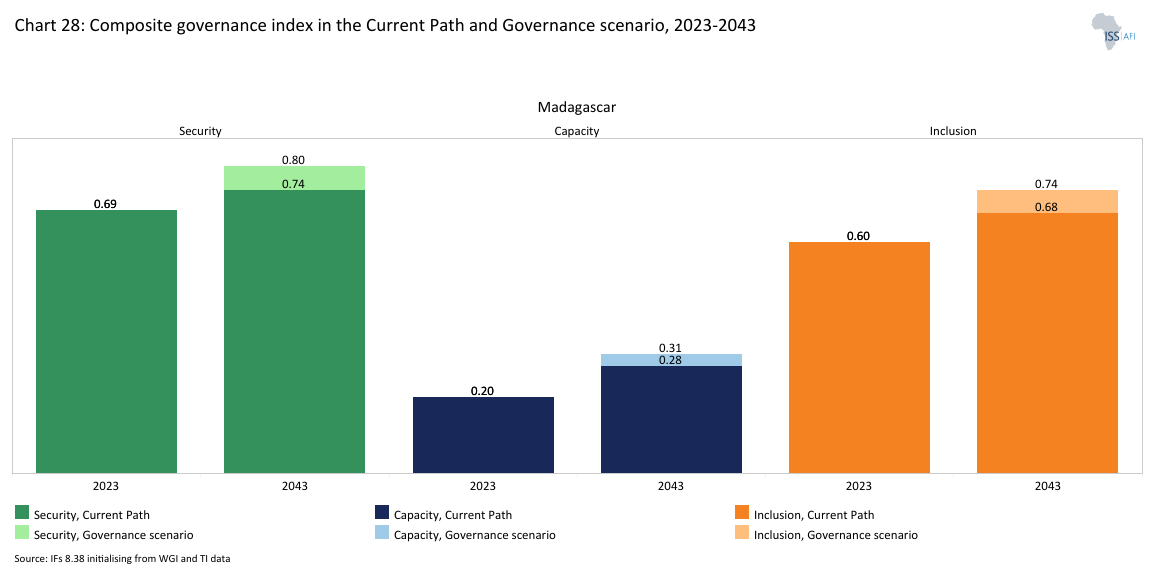

- In the Governance scenario, Madagascar’s government effectiveness quality score will improve to 2.1 by 2043, versus 1.85 in the Current Path. This is lower than Rwanda’s current score at 2.8, the country that performs the best among Africa’s low-income economies. Governance in Madagascar will improve across the three dimensions of security, inclusion and capacity, with the latter showing the least progress. If fully implemented, the Governance scenario will set the foundations for Madagascar to transition to more inclusive economic growth and sustainable development.

In the fourth section, we compare the impact of each of these eight sectoral scenarios with one another and subsequently with a Combined scenario (the integrated effect of all eight scenarios). In our forecasts, we measure progress on various dimensions such as economic size (in market exchange rates), gross domestic product per capita (in purchasing power parity), extreme poverty, carbon emissions, the changes in the structure of the economy, and selected sectoral dimensions such as progress with mean years of education, life expectancy, the Gini coefficient or reductions in mortality rates.

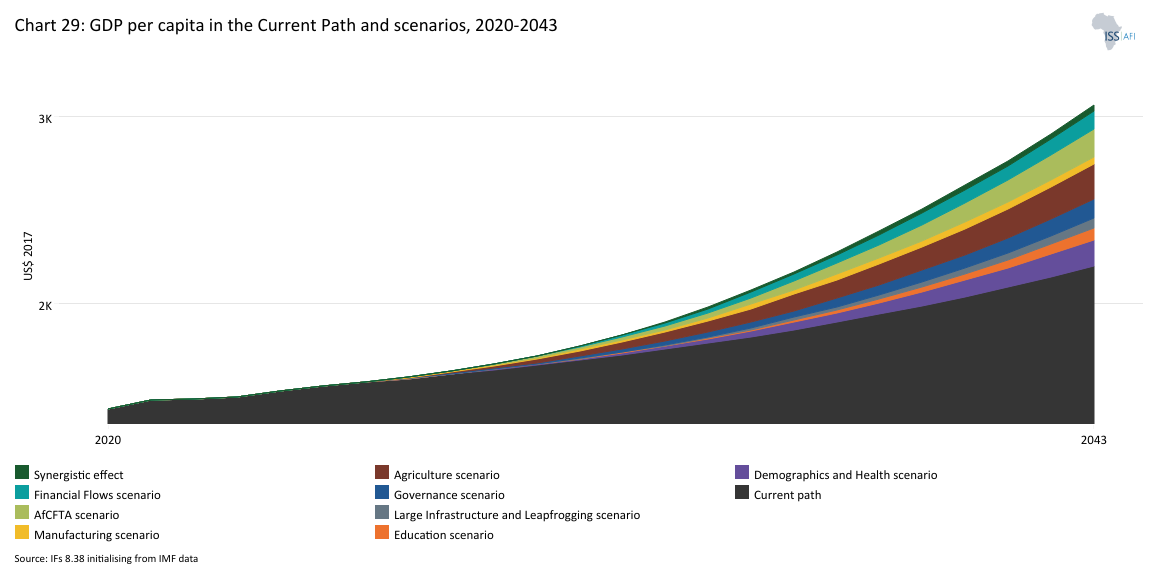

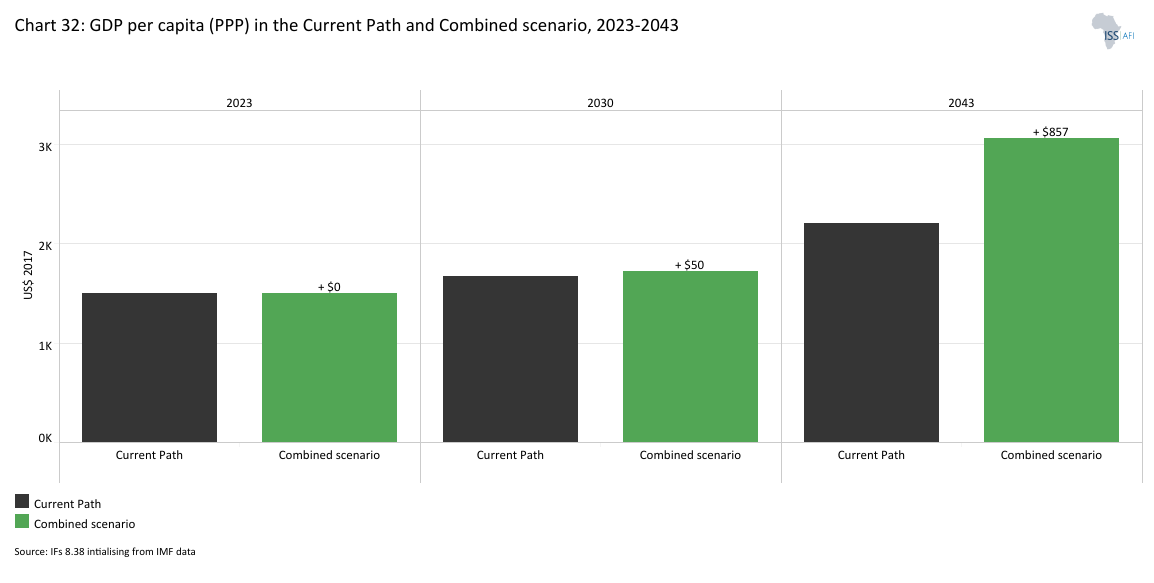

- Madagascar experiences a boost to its GDP per capita in all eight sectoral scenarios. Naturally, the Combined scenario has a greater impact on GDP per capita compared to the individual scenarios. By 2043, the GDP per capita of Madagascar (PPP) will be US$856.8 larger than in the Current Path. This indicates that an integrated push across all sectors could significantly improve the living standard of the people of Madagascar. Among the sectoral scenarios, the Agriculture and the AfCFTA scenarios will increase GDP per capita the most, with US$186.9 and US$150.5 above the Current Path in 2043, respectively. The third most significant impact on Madagascar’s GDP per capita is achieved in the Demographics and Health scenario, underlining the need to invest heavily in human capital, followed by the Governance scenario.

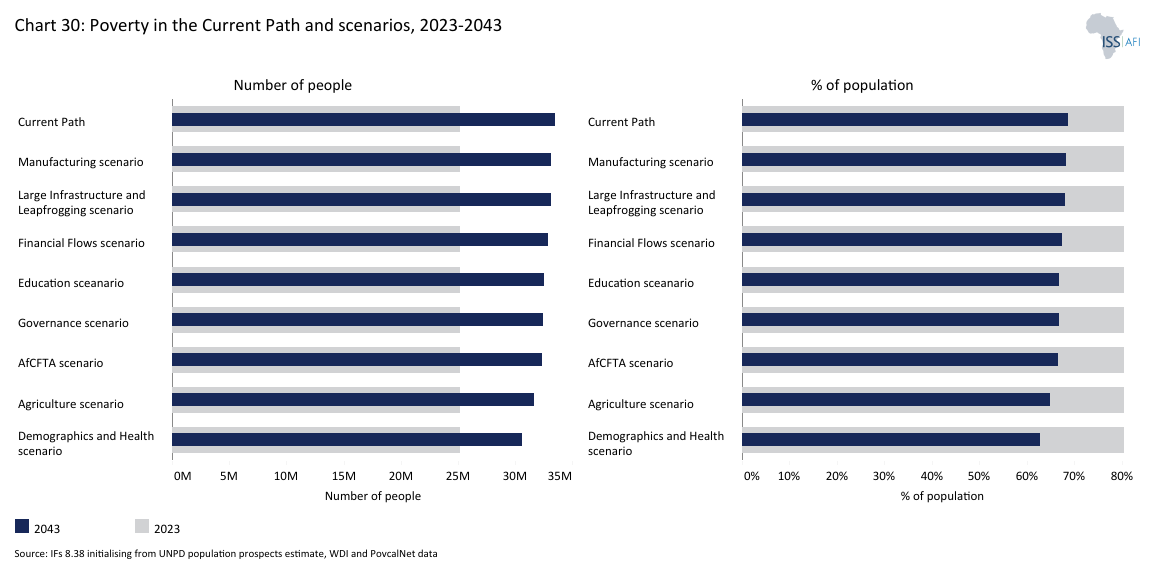

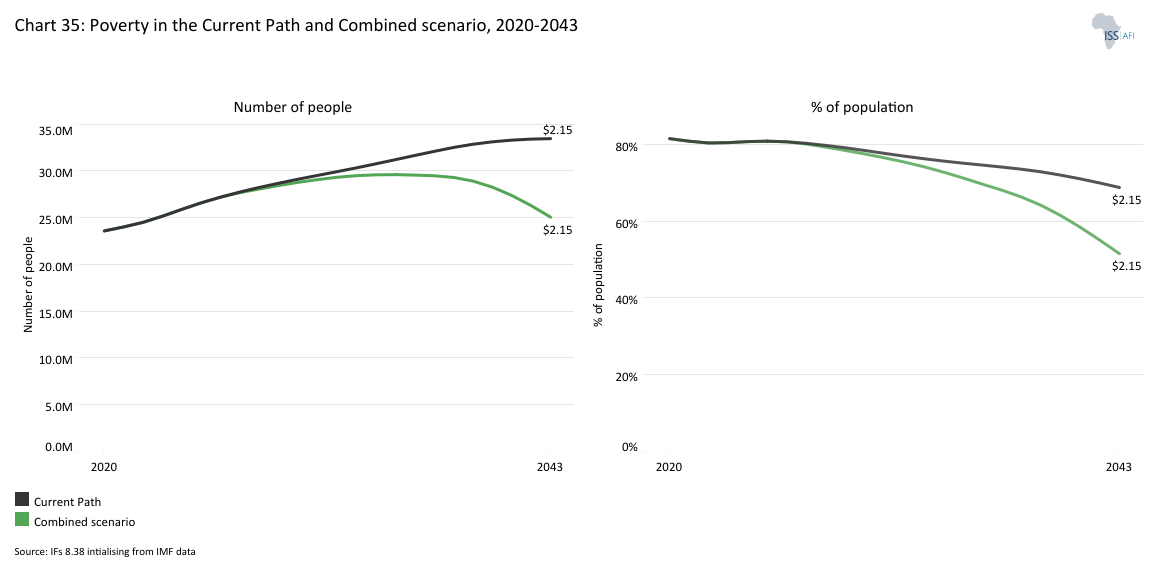

- Similarly, all scenario interventions contribute to poverty reduction in Madagascar. The Agriculture scenario is the most powerful in reducing the extreme poverty rate by 2043, followed by the AfCFTA, Demographics and Health, and Governance scenarios. In the Combined scenario, by 2043, 55.2% of the population will be living in poverty compared to 68.8% in the Current Path. The results illustrate that poverty reduction in Madagascar is best achieved via an integrated push across sectors, with boosting agriculture and trade and targeted investments in health and governance playing a key role. In light of the country’s extremely high poverty burden, such an integrated push is in fact vital to set Madagascar on a path of more sustainable development.

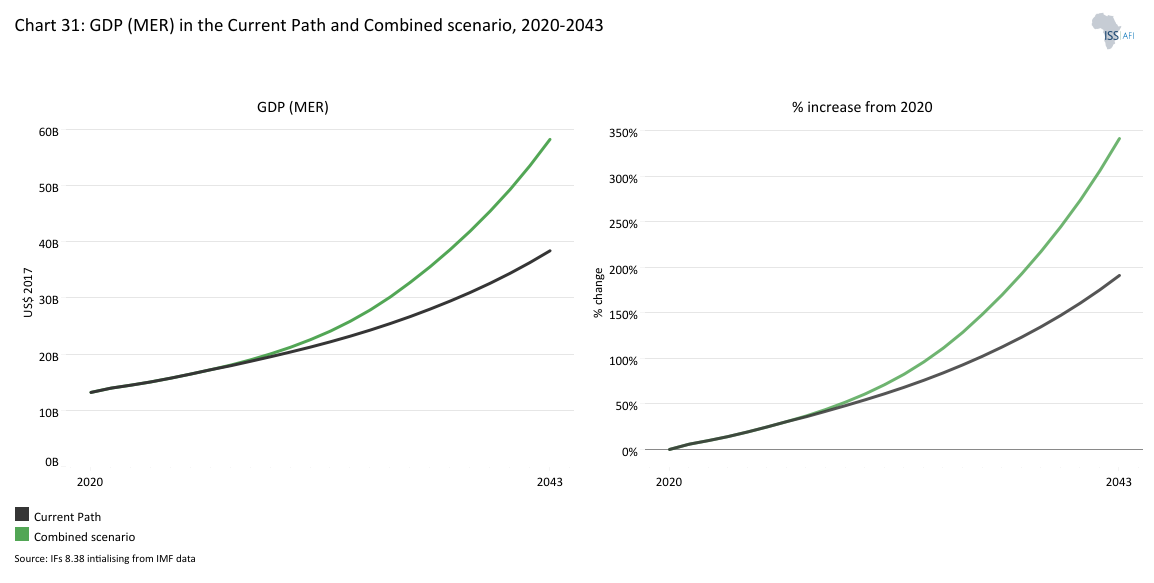

- The Combined scenario significantly improves Madagascar’s economic growth outlook. In this scenario, the economy will expand from US$15.1 billion in 2023 to US$58.2 billion in 2043, US$19.8 billion more than on the Current Path. In other words, in the Combined scenario, Madagascar's economy in 2043 would be more than 50% larger than in the Current Path. In the latter, GDP will expand by 155% while in the Combined scenario, the economy will grow by 288%. In this scenario, the average growth rate between 2025 and 2043 is 6.9% versus 4.6% in the Current Path over the same period.

- In the Combined scenario, the average Malagasi can expect to live more than three years longer at 73.5 years in 2043, compared with the Current Path for the same year (70.3 years). Infant mortality will stand at 13 deaths per 1 000 live births, compared to 24 deaths in the Current Path in 2043.

We end this page with a summarising conclusion offering key recommendations for decision-making. Madagascar is standing at a critical juncture to turn the tide on political instability, economic crisis and chronic poverty that affects more than 80% of the population. Political stability is key to improving governance and stimulating sustainable economic growth. The return to democracy in 2014 set the foundation to engage in evidence-based planning and policy-making across sectors that can put Madagascar on a path to sustainable development. Addressing governance challenges is critical, with a focus on transparency, inclusive decision-making and institutional strengthening to establish legitimacy and ensure effective policy implementation. Investing in agriculture is key to reducing poverty, import dependence and food insecurity. Leveraging AfCFTA opportunities can boost exports, reduce the trade deficit and drive growth. Investments to overcome the infrastructure bottlenecks are imperative, and so is gaining investor confidence to attract foreign direct investment. The government needs to encourage competition and foster a healthy fiscal climate. While maintaining public debt sustainability, pro-poor and pro-growth spending needs to increase, particularly in the areas of social protection, education and healthcare, with special attention to rural areas. Human capital development must optimise resource allocation, focus on reducing drop-out and pushing completion rates, improve the gender balance, as well as enhance the quality and accessibility of education overall. Efforts to accelerate the country's demographic transition through improved healthcare and family planning will alleviate the pressure on service delivery and increase the economic growth potential. Boosting investment in environmental protection and climate change mitigation is crucial to increasing Madagascar’s resilience in the face of external vulnerabilities.

All charts for Madagascar

- Chart 1: Political map of Madagascar

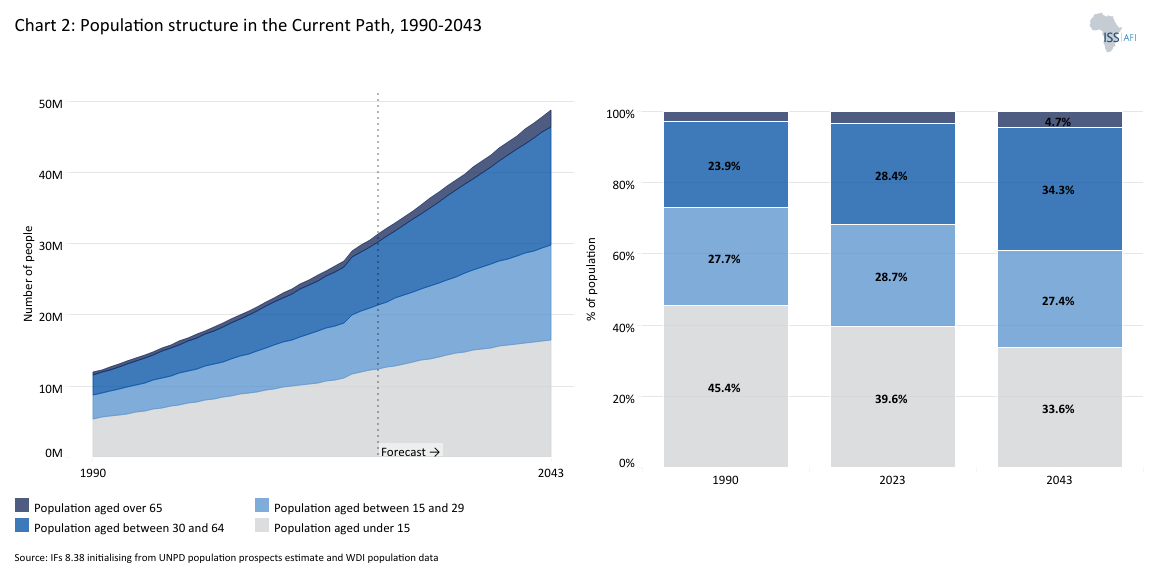

- Chart 2: Population structure in the Current Path, 1990–2043

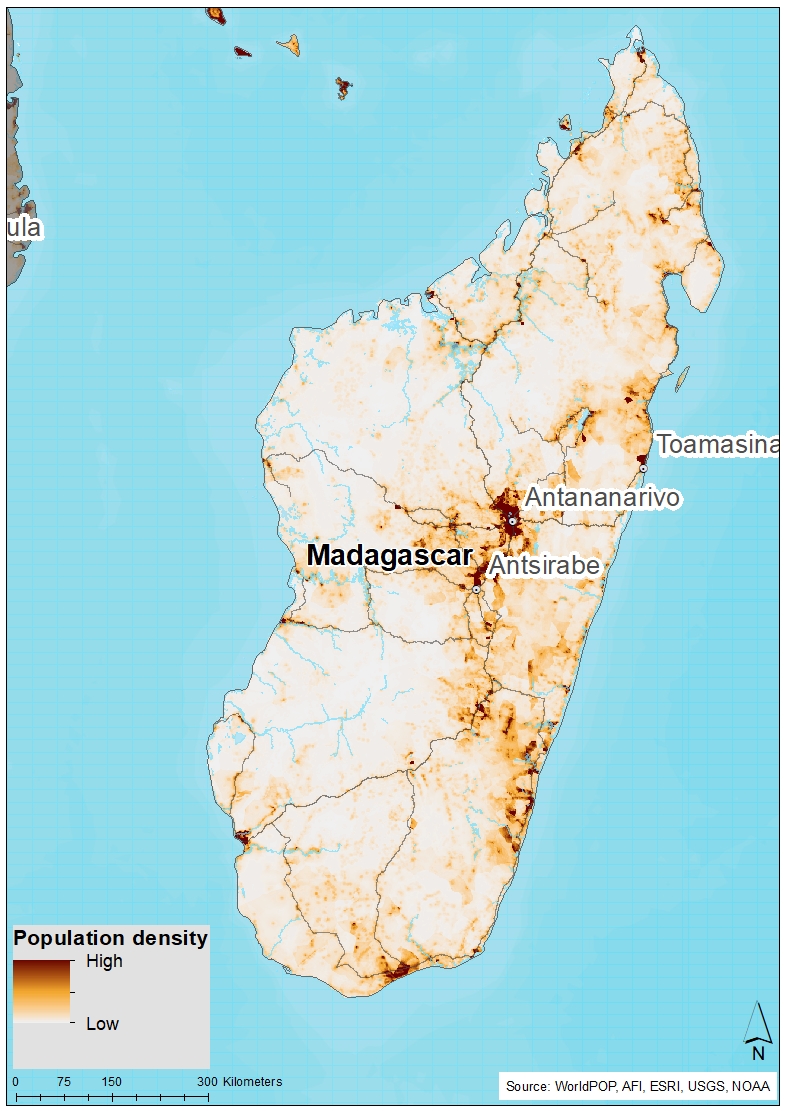

- Chart 3: Population distribution map, 2023

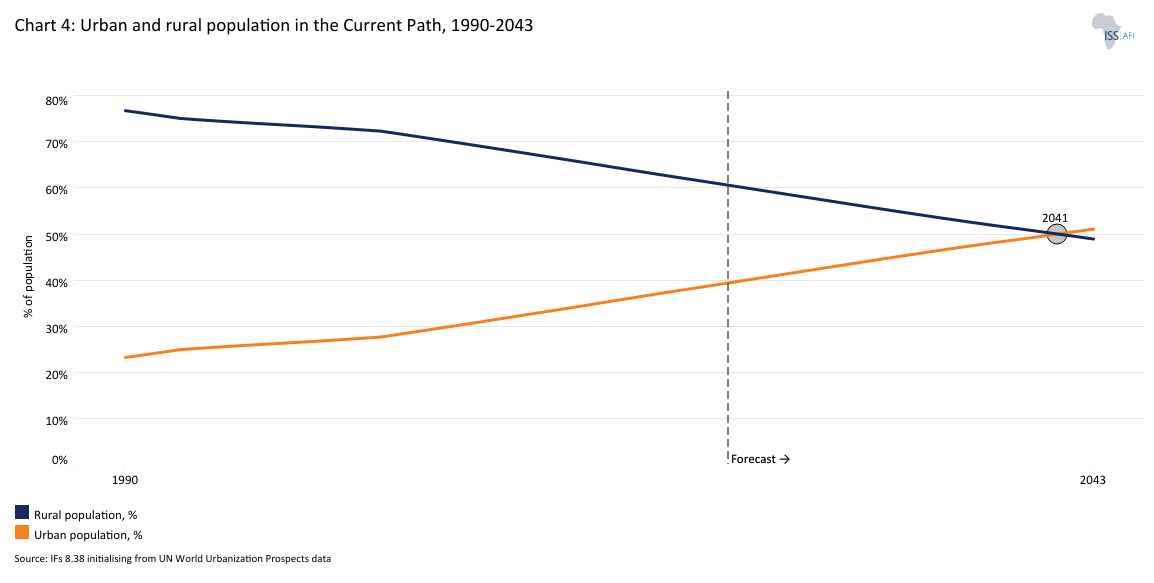

- Chart 4: Urban and rural population in the Current Path, 1990-2043

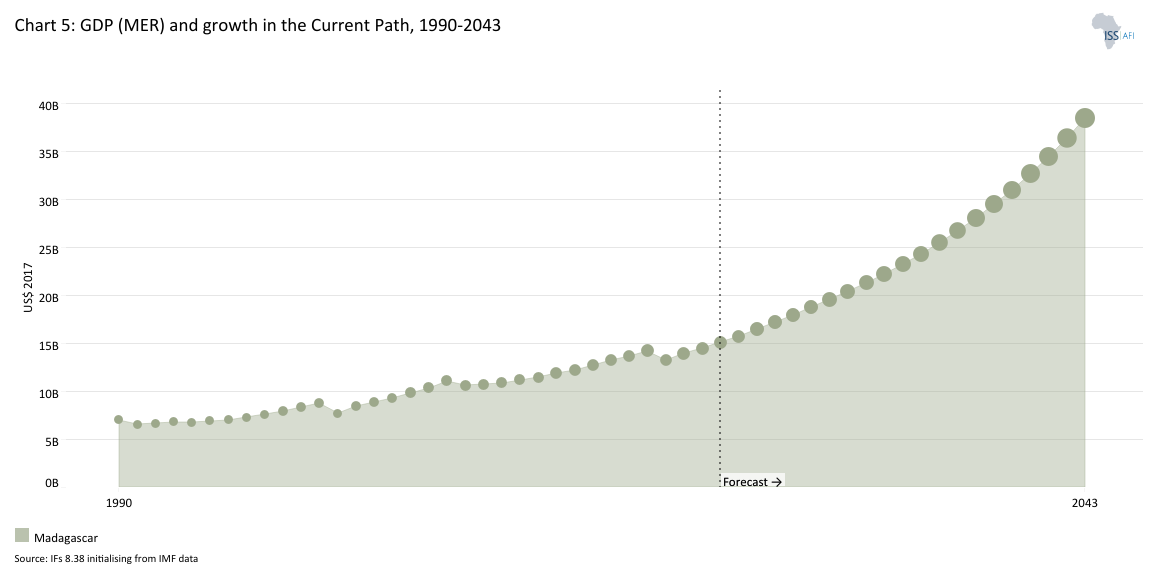

- Chart 5: GDP (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, 1990–2043

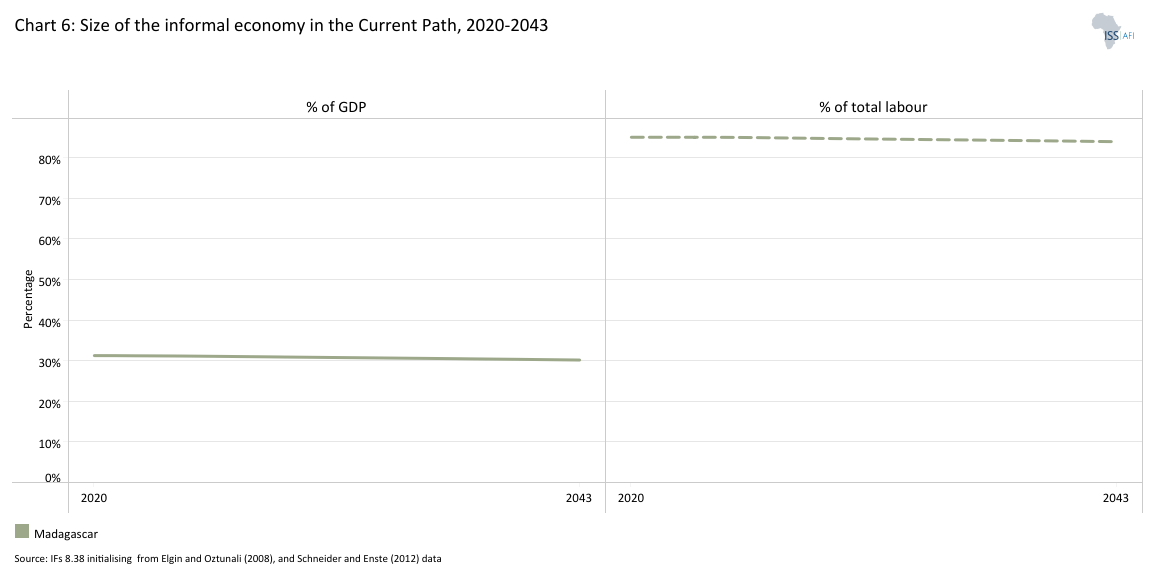

- Chart 6: Size of the informal economy in the Current Path, 2020-2043

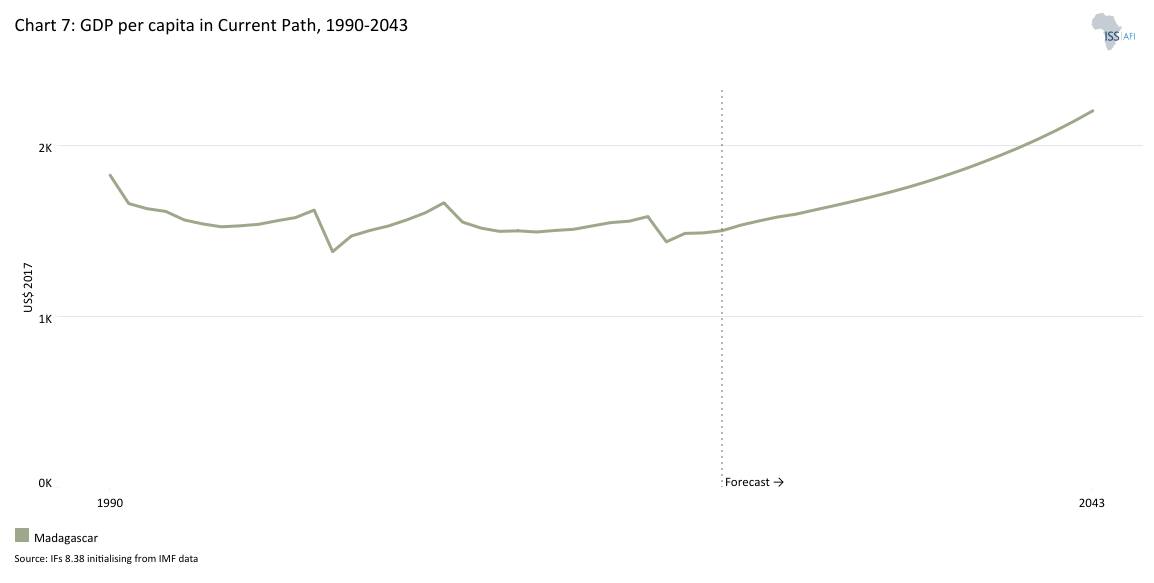

- Chart 7: GDP per capita in Current Path, 1990–2043

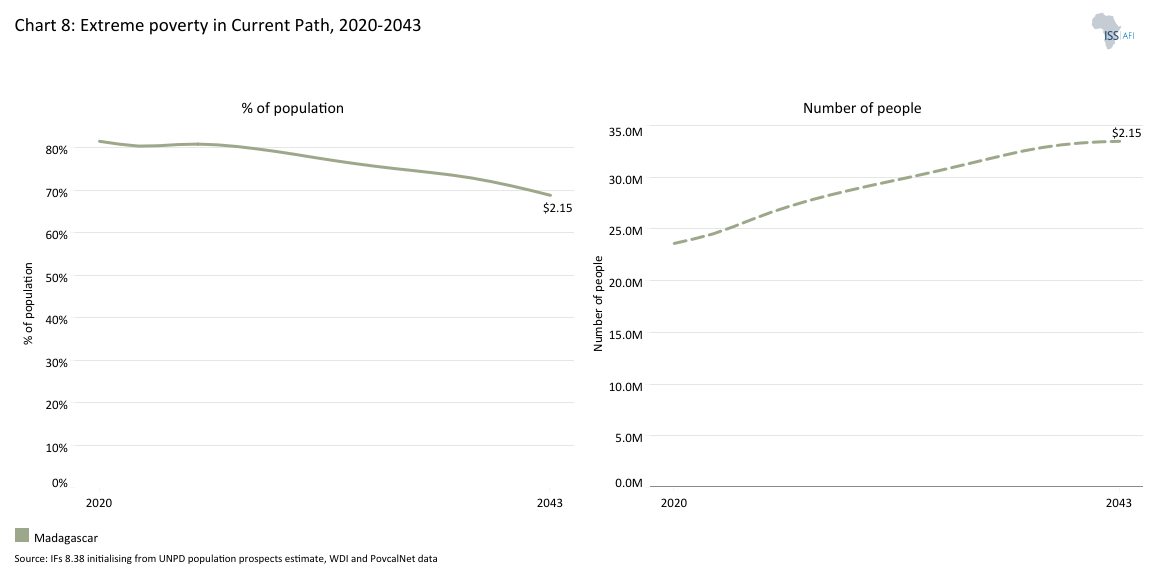

- Chart 8: Extreme poverty in the Current Path, 2020–2043

- Chart 9: National Development Plan of Madagascar

- Chart 10: Relationship between Current Path and scenarios

- Chart 11: Mortality distribution in the Current Path, 2023-2043

- Chart 12: Infant mortality rate in Current Path and Demographics and Health scenario, 2020-2043

- Chart 13: Demographic dividend in the Current Path and the Demographics and Health scenario, 2020-2043

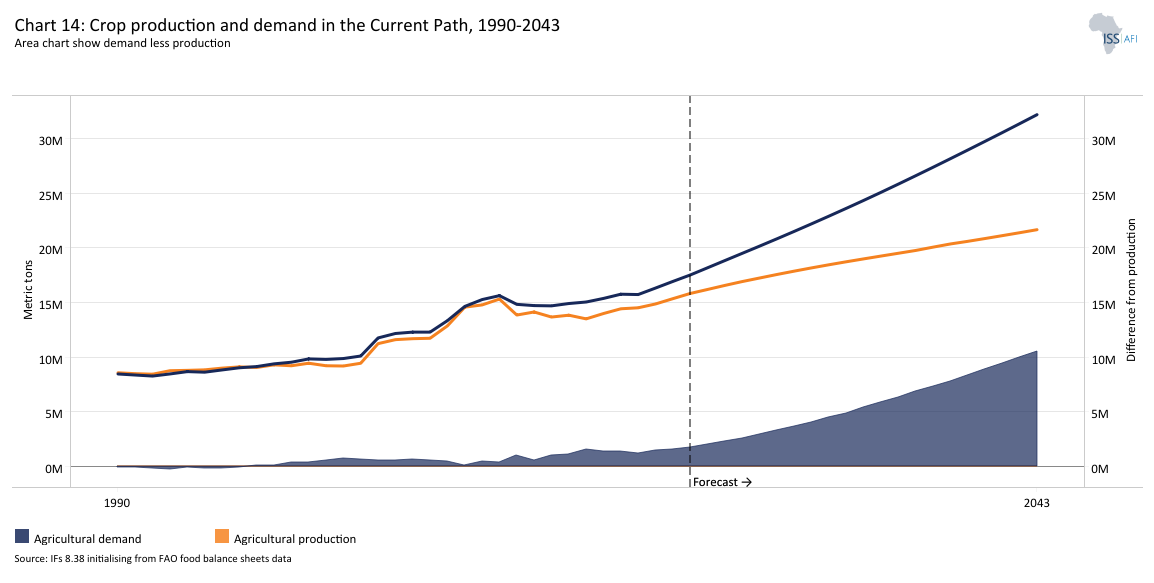

- Chart 14: Crop production and demand in the Current Path, 1990-2043

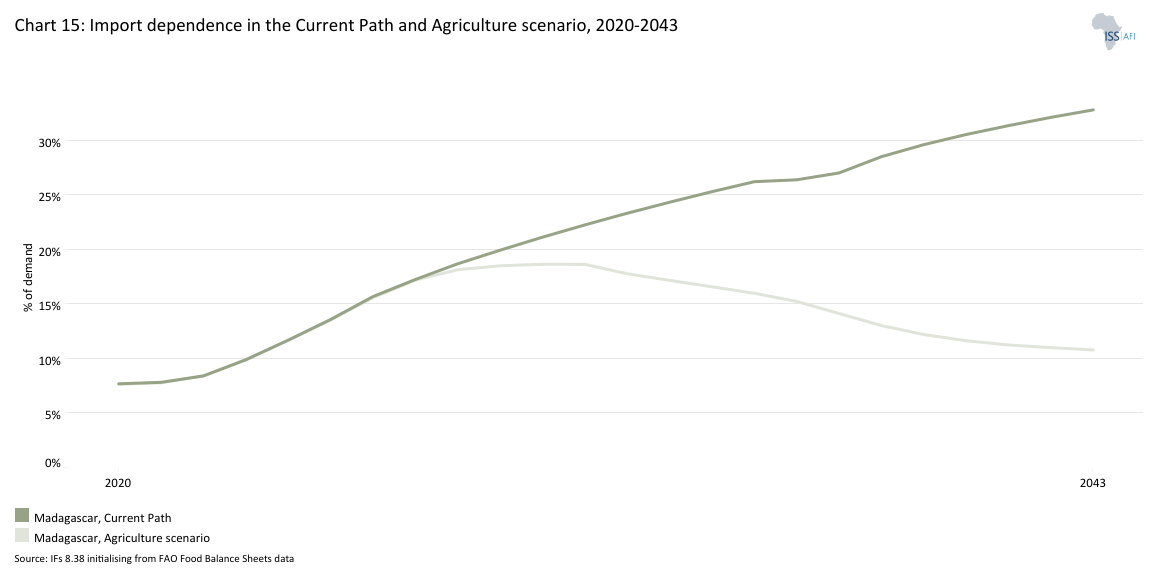

- Chart 15: Import dependence in the Current Path and Agriculture scenario, 2020–2043

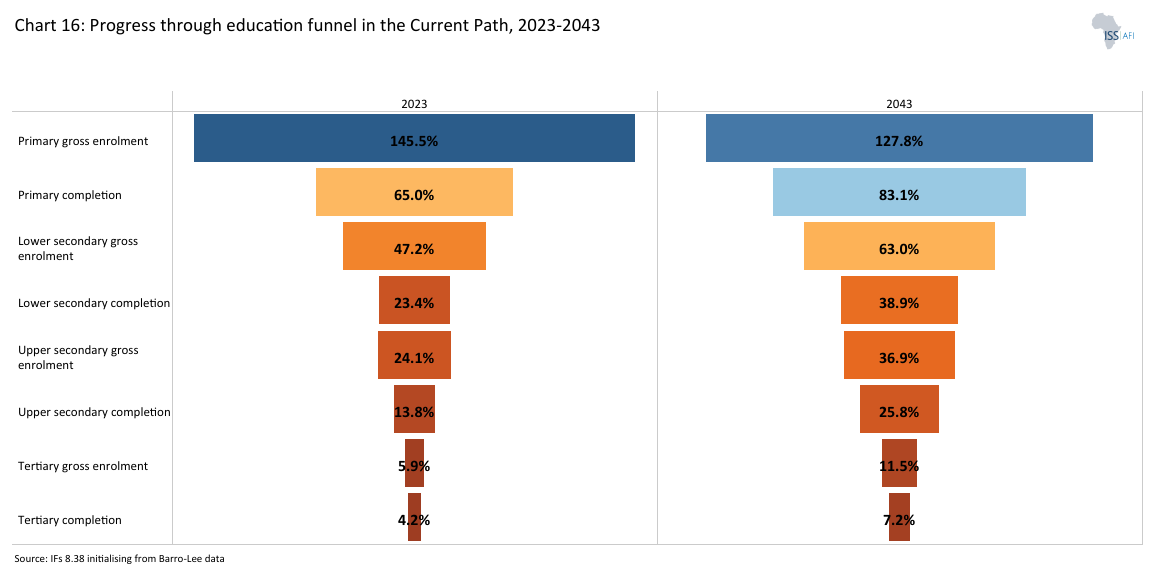

- Chart 16: Progress through the education funnel in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

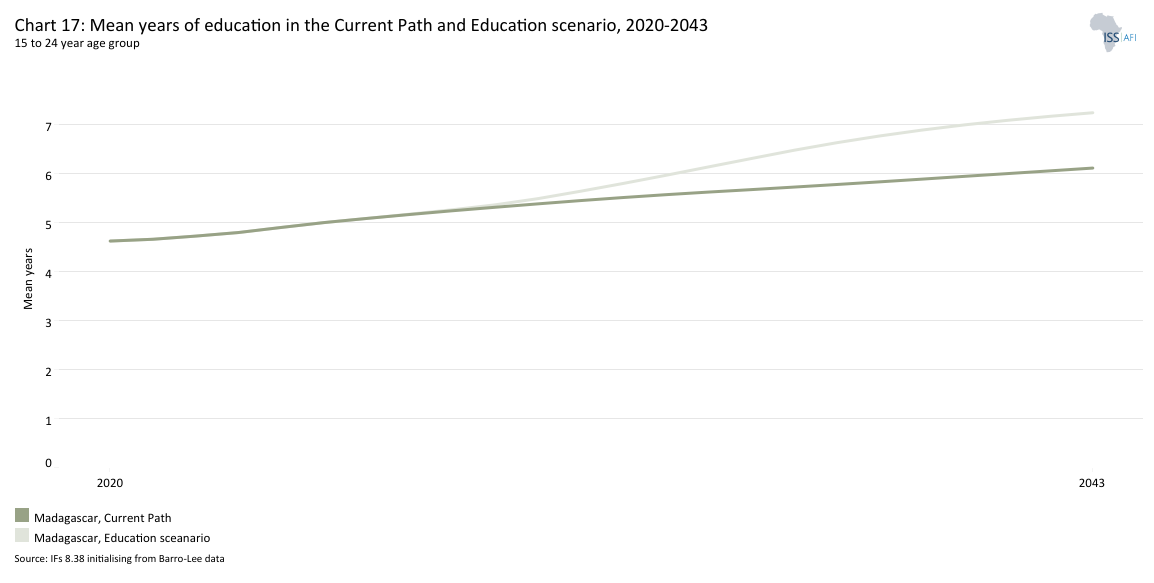

- Chart 17: Mean years of education in the Current Path and Education scenario, 2020–2043

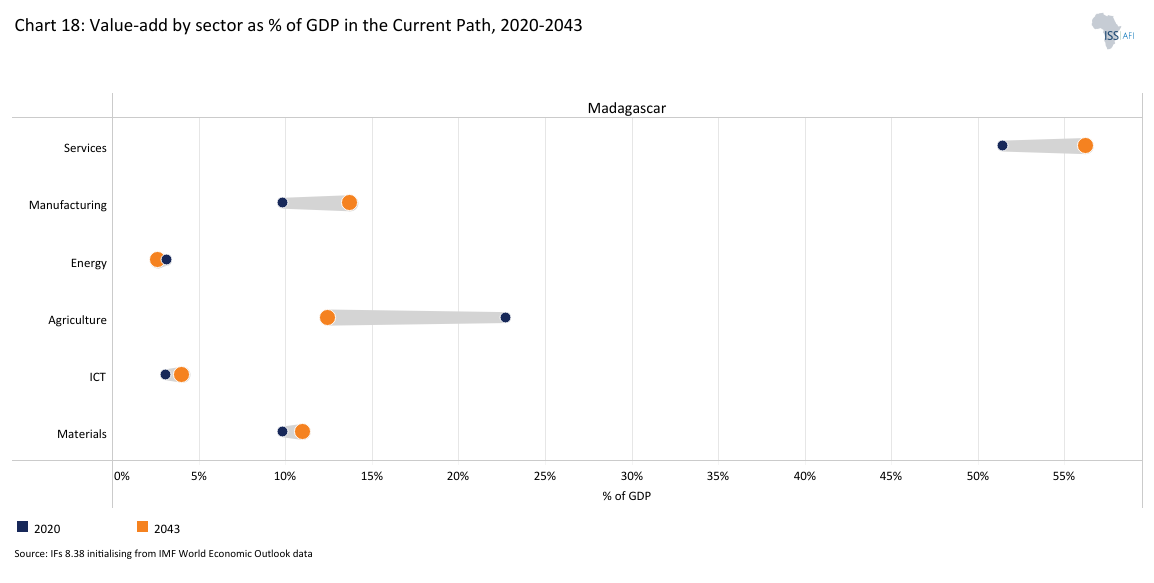

- Chart 18: Value-add by sector as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2023 and 2043

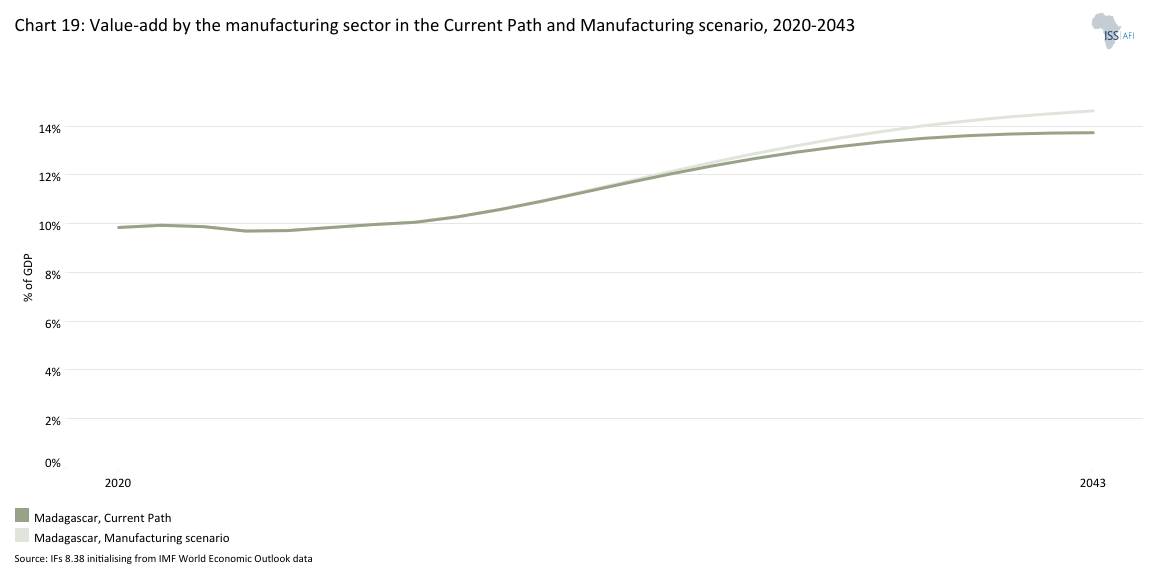

- Chart 19: Value-add by the manufacturing sector in the Current Path and Manufacturing scenario, 2020–2043

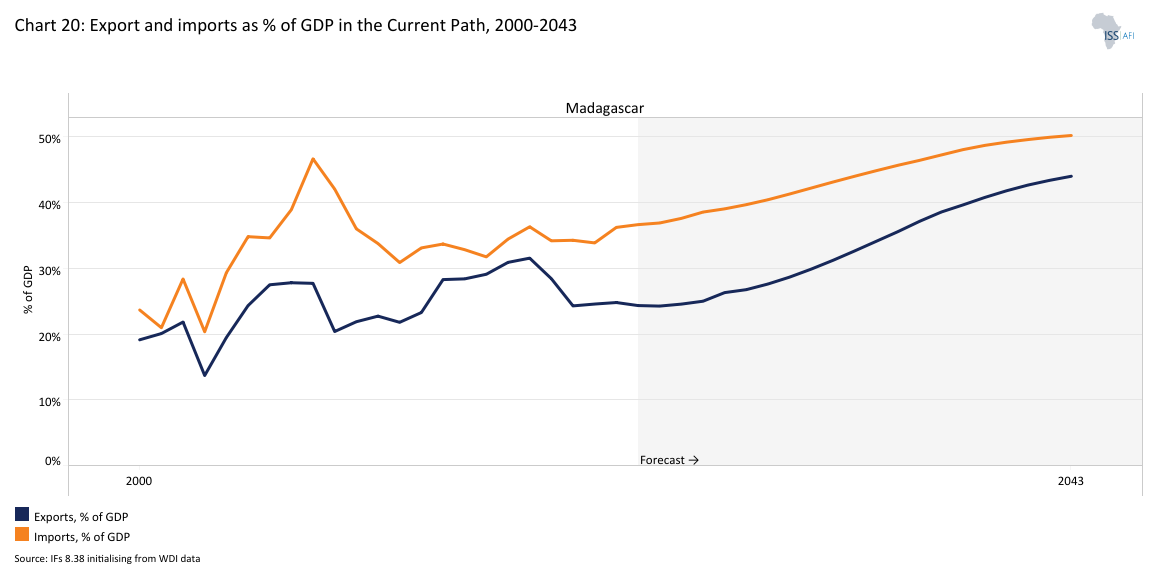

- Chart 20: Exports and imports as % of GDP in the Current Path, 2000-2043

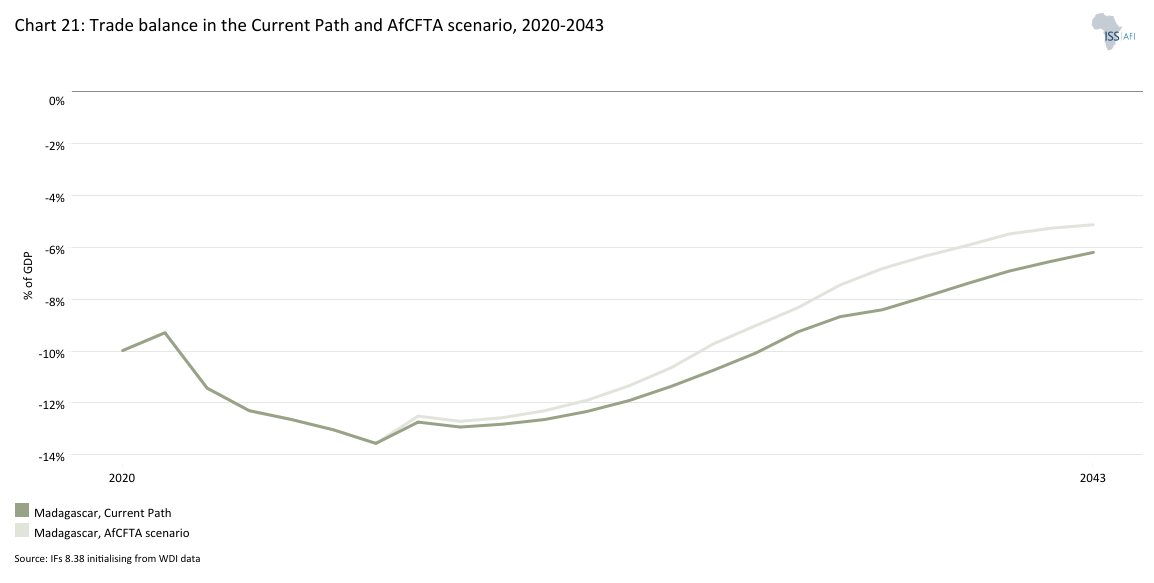

- Chart 21: Trade balance in the Current Path and AfCFTA scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 22: Electricity access: urban, rural and total in the Current Path, 2000-2043

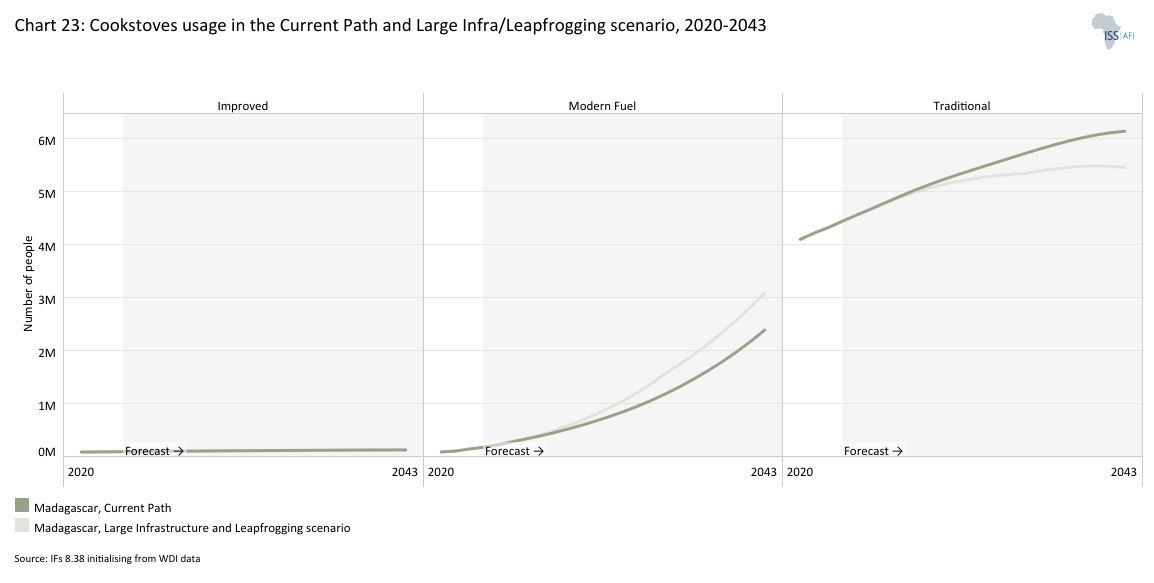

- Chart 23: Cookstove usage in the Current Path and Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2020–2043

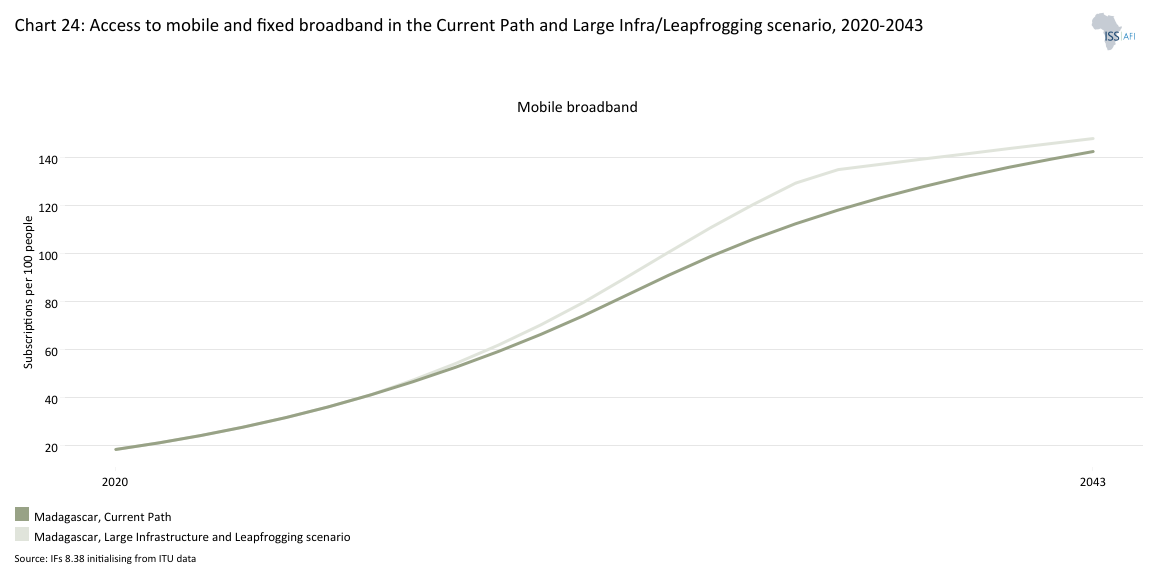

- Chart 24: Access to mobile and fixed broadband in the Current Path and the Large Infra/Leapfrogging scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 25: FDI, foreign aid and remittances as % of GDP in the Current Path and in the Financial Flows scenario, 1990-2043

- Chart 26: Government revenue in the Current Path and Financial Flows scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 27: Government effectiveness score in the Current Path, 2002-2043

- Chart 28: Composite governance index in the Current Path and Governance scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 29: GDP per capita in the Current Path and scenarios, 2020–2043

- Chart 30: Poverty in the Current Path and scenarios, 2020–2043

- Chart 31: GDP (MER) in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 32: GDP per capita in the Current Path and the Combined scenario, 2020-2043

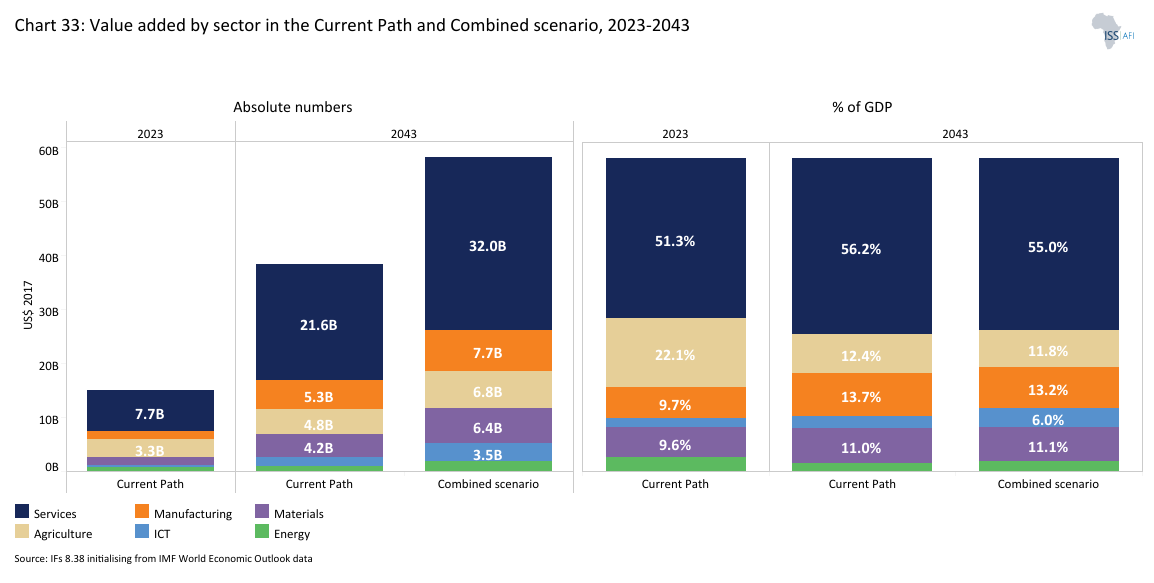

- Chart 33: Value added by sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 34: Informal sector in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 35: Poverty in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2023 and 2043

- Chart 36: Life expectancy in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

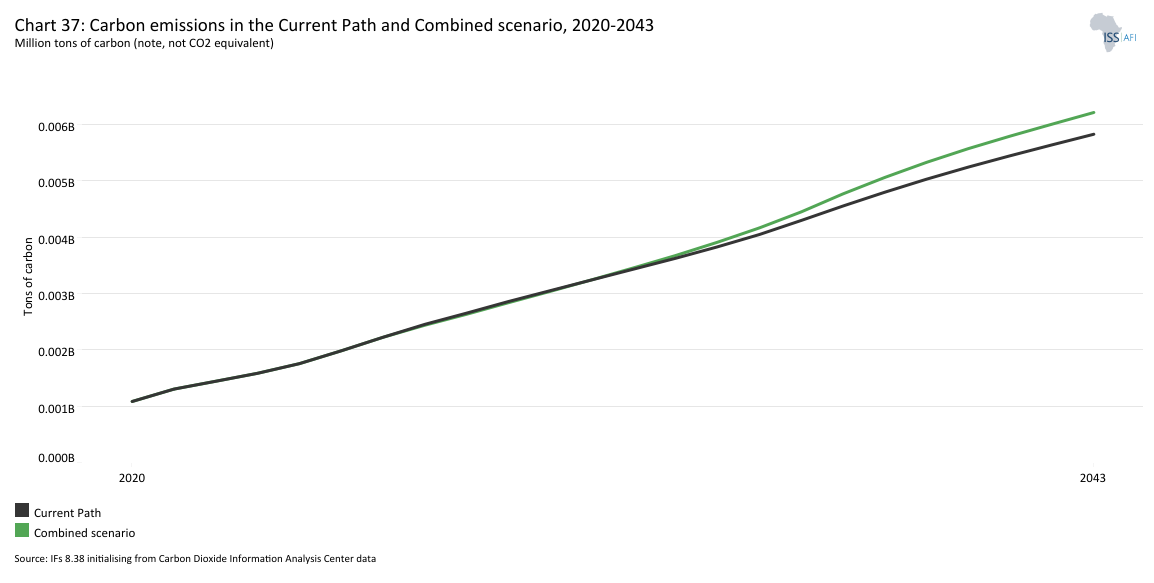

- Chart 37: Carbon emissions in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020–2043

- Chart 38: Energy demand and production by type in the Current Path and Combined scenario, 2020-2043

- Chart 39: Policy recommendations

Chart 1 is a political map of Madagascar.

This page provides an overview of the key characteristics of Madagascar along its likely (or Current Path) development trajectory. The Current Path is a dynamic scenario that imitates the continuation of current policies and environmental conditions. The Current Path is therefore in congruence with historical patterns and produces a series of dynamic forecasts endogenised in relationships across crucial global systems. We use 2023 as a standard reference year and the forecasts generally extend to 2043, to coincide with the end of the third ten-year implementation plan of the African Union’s Agenda 2063 long-term development vision.

The Republic of Madagascar is the world’s fifth-largest island, situated in the Indian Ocean off the coast of southern Africa. The country falls into the low-income category even though it is endowed with considerable natural resources and unparalleled biodiversity. It comprises the main island of Madagascar as well as multiple smaller peripheral islands. Neighbouring islands include the French territory of Réunion and the country of Mauritius to the east, as well as Comoros and the French territory of Mayotte to the north-west. The nearest mainland state is Mozambique, located to the west.

Madagascar has a diverse precipitation pattern due to its large size, varied topography and location in the southwestern Indian Ocean. Rainfall is highly seasonal and varies dramatically from east to west and north to south. Rainfall on the east coast can reach up to 3 500-4 000 mm per year, compared to the central highlands with much more moderate rainfall between 1 200-1 500 mm per year. The west coast is drier with around 800-1 200 mm per year, and the south and southwest are characterised by semi-arid to arid conditions. The northwest is seasonally wet, affected by monsoons and cyclones.

Madagascar faces severe climate risks. Due to its location, topography and socioeconomic conditions, the country is very vulnerable to extreme weather events, especially cyclones, flooding and drought.

From the early 19th century, most of the island was united and ruled as the Kingdom of Madagascar. The monarchy ended in 1897 when the French colonised the island. Madagascar gained independence in 1960, and since 1992, it has officially been governed as a constitutional democracy. In 2023, Madagascar had a population of about 31.3 million people. Its capital and largest city is Antananarivo, with approximately 3 million inhabitants. The country’s economy is based primarily on (subsistence) agriculture, mining, tourism and textiles.

Madagascar is ethnically diverse with at least 18 different ethnic groups. The two main groups are the Merina people, who predominantly live in the central, more urban highlands and the Côtier people, the nominal grouping of the country’s coastal ethnic groups. The Merina ruled Madagascar in the period immediately preceding French annexation in 1896. They were heavily represented within the small Malagasy elite that was favoured under colonial rule and continues to be well represented in government functions.

In 2001, a disputed presidential election between Didier Ratsiraka (incumbent) and Marc Ravalomanana led to a severe political standoff. Both candidates declared themselves president, leading to two rival governments and widespread civil unrest throughout 2002. In 2009, growing dissatisfaction with President Marc Ravalomanana over authoritarian tendencies and controversial decisions sparked opposition led by the then mayor of Antananarivo, Andry Rajoelina. In March 2009, with the backing of the military, Rajoelina ousted Ravalomanana in a coup d’état.

Rajoelina assumed power as head of a transitional government, despite international condemnation and suspension of foreign aid. The African Union’s (AU) Peace and Security Council declared it an unconstitutional change of government and suspended Madagascar from participating in all AU organs and activities. As a consequence of the coup, Madagascar faced economic hardship, diplomatic isolation and years of political uncertainty until elections were eventually held in 2013. Hery Rajaonarimampianina, backed by Rajoelina, won the run-off, and Madagascar was readmitted to the AU and international financial institutions—marking the official return to democracy. The country restored constitutional order in January 2014.

In December 2023, Andry Rajoelina was re-elected President of Madagascar. Christian Ntsay was reappointed as Prime Minister. In the legislative elections held in May 2024, the presidential party secured an absolute majority in the National Assembly, with 84 out of 163 deputies belonging to the presidential platform. In the communal and municipal elections held in December 2024, the presidential coalition won over 960 out of 1 695 mayoral seats nationwide.

Madagascar is a member of the United Nations, the AU, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie.

Chart 2 presents the Current Path of the population structure, from 1990 to 2043.

The demographic profile of a country is key in shaping its long-term social, economic and political path. It is hence a useful predictor for a nation’s development prospects.

Madagascar has a young and relatively fast-growing population with an average annual growth rate of 2.6% in 2023, which is roughly in line with the average for Africa’s low-income economies. Coming from a baseline of about 12.1 million people in 1990, the population has since grown close to threefold to 31.3 million people. By 2043, it will reach over 48 million people. In 2023, 40% of the population was under 15 years old. The current median age is 19.9 years compared to the average of 18.3 years for Africa’s low-income economies. On the Current Path, Madagascar is expected to experience demographic change, but rather slowly.

In 2023, average total fertility stood at four births per woman, high but somewhat below the average of 4.8 births for Madagascar’s low-income peer group. By 2043, the country’s fertility rate is expected to drop to 3 births per woman. It is only in 2060 that the country will reach replacement level fertility of 2.1 births per woman. As a consequence, Madagascar’s population will continue to grow relatively fast, and by 2043, the median age will only increase to 23.4 years. Rwanda’s anticipated median age, for example, is 26.5 years, the highest among Africa’s low-income economies by then.

A maturing age structure will benefit Madagascar’s workforce. By 2043, people of working age are expected to account for about 62% of the population compared to 57% in 2023. This means that the ratio between the working age and the dependent population is improving, but not fast enough to significantly boost economic growth. On the Current Path, Madagascar will reach the peak of its “demographic sweet spot” only in 2076. By 2043, for every dependent there will be 1.6 workers, up from 1.3 in 2023.

In 2023, the average life expectancy in Madagascar was 66.2 years, with that for women (67.4) being almost 2.5 years higher than for men (65 years). On the Current Path, the average life expectancy of Madagascar’s citizens will increase to 70.3 years over the next two decades, 1.5 years below the expected average of 71.8 years for Africa’s low-income economies in 2043. Madagascar’s gender gap in life expectancy will grow, reaching 2.9 years compared to 2.4 years in 2023.

Chart 3 presents a population distribution map for 2023.

Most of Madagascar’s population is concentrated in the central highlands and around major cities like Antananarivo. Much of the country is rural, with significant areas of forest, mountains and sparsely inhabited land.

Madagascar has an overall population density of approximately 0.54 people per hectare, just above the African average of 0.5 in 2023. However, density varies across the territory as the country’s population is unevenly distributed, with the centre and the east coast being more densely populated compared to the west coast where population is sparse.

Antananarivo, located roughly in the centre of the island, is Madagascar’s capital and by far its largest city with an estimated population of more than 3 million people in its metropolitan area. The city is the political, economic and cultural centre of the country. Other larger cities include Toamasina, Antsirabe and Mahajanga with between 250 000 and 300 000 inhabitants each. Toamasina is the main port and industrial hub. Mahajanga, Toliara and Antsiranana are important regional hubs. These secondary cities are growing, but not as fast as the capital.

Chart 4 presents the urban and rural population in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

Madagascar is more urbanised than the average African low-income economy. This is consistent with the pattern that Island economies are typically more urbanised than their non-island counterparts in similar income categories. In 2023, close to 40% of Madagascar’s population lived in urban areas, versus just over 60% who were living in rural areas. Africa’s low-income countries had a rural-urban split of 32.5% versus 67.5% in 2023. On the Current Path, Madagascar is becoming more urbanised. By 2043, 51% of the population will be living in urban areas versus 49% living in rural areas. The anticipated ratio for Africa’s low-income economies is 41.6% urban versus 58.4% rural by 2043.

Urbanisation in Madagascar is driven by natural population growth as well as rural to urban migration. Extremely high levels of rural poverty push people towards cities in search of work as well as better access to services. Young people are especially drawn to migrate to cities for education or employment opportunities. When it comes to access to services, such as hospitals, housing and schools, the rural-urban disparity is significant, with urban areas and the capital city especially providing better access, despite the majority of the population residing in rural areas.

Chart 5 presents GDP in market exchange rates (MER) and growth rate in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043.

Between 1990 and 2023, Madagascar’s GDP more than doubled from US$7 billion to just over US$15.1 billion. The country ranks ninth out of 23 African low-income economies, with Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda being the lead economies. In 2043, Madagascar’s GDP will be US$38.4 billion, more than two and a half times as large as in 2023. The economy will expand, but the expected average annual growth of under 5% over the coming two decades, combined with historically high levels of inequality, will be insufficient to allow for meaningful progress in poverty reduction and human development more generally.

Madagascar’s economy is vulnerable to external climate shocks (cyclones and droughts) as well as global market fluctuations that affect supply chains and inputs. This is why the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the war in Ukraine, was significant, causing a recession. Moreover, the economy lacks diversification in terms of export markets, such as the United States and the EU.

The country`s economy is mostly based on services and has a poorly developed industrial sector that generates little value added. According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation, despite the country’s vast potential, the agriculture sector is dominated by subsistence farming. In principle, its varied climate allows for the cultivation of tropical crops such as rice, cassava, beans and bananas. Rice accounts for the largest share of total crop acreage. Other valuable export-oriented agricultural products include cloves, vanilla, cacao, sugar, pepper and coffee. Even though the agricultural sector has seen little to no reforms over the past 15 years, it provides employment for the majority of people, accounting for close to 80% of Madagascar’s workforce.

In 2024, growth was estimated at 4.2%. According to the World Bank, the service sector, in particular tourism and telecommunications, has been driving growth, including through increased international air traffic, new airlines and a new telecom licensing regime. The Bank predicts growth to average 4.7% from 2025 to 2027, with industrial production (including textiles and mining) and services expected to continue to lead the expansion. Tourism is expected to maintain its growth momentum, supported by new infrastructure development. The growth projection is equally based on the assumption that the government will implement structural reforms to enhance market competitiveness in critical sectors and improve the investment climate.

Madagascar faces significant challenges, including frequent power outages and climate change-induced risks that can potentially disrupt manufacturing and agricultural productivity as well as tourism. Macroeconomic stability has also been difficult to ensure. Annual inflation averaged 7.5% in 2024, and the current account deficit worsened to an estimated 5% of GDP in 2024, mostly due to declining exports of key commodities like vanilla, cloves, cobalt and nickel. According to the World Bank, ‘the fiscal deficit has been gradually narrowing,’ and Madagascar’s economic resilience depends on ‘maintaining reform momentum, diversifying exports, and addressing infrastructure constraints.’

Chart 6 presents the size of the informal economy as per cent of GDP and per cent of total labour (non-agriculture), from 2020 to 2043. The data in our modelling are largely estimates and therefore may differ from other sources.

Countries with high informality typically encounter multiple development challenges connected to low revenue mobilisation. Further, high levels of informality tend to hold back economic growth.

Informality in Madagascar is exceptionally high, even for African standards. The formal economy has not grown fast or inclusively enough to offer better alternatives. At the same time, structural barriers—like poor infrastructure, education and financial access—keep people trapped in informal, low-productivity work.

In 2023, Madagascar’s informal sector was equivalent to approximately 31.2% of GDP. This is just slightly below the average share of 31.7% in Africa’s low-income economies. The informal sector is a burden on the formal economy because of low contributions to tax revenues and the subsequent negative impact on expenditure on public services. By 2043, Madagascar’s informal sector will still account for 30.2% of GDP. This represents rather limited progress that likely reflects slow improvements in overall state capacity, including for taxation. In the average African low-income economy, the informal economy will account for 28.2% by 2043.

In the absence of formal sector opportunities, 85% of Madagascar’s labour force works in the informal sector, the highest share on the continent, followed by Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The informal sector adds little value to the economy overall and typically offers precarious employment conditions. In the Current Path, informal labour will still account for 83.9% by 2043, pointing to stagnation rather than improvement. In comparison, in the average African low-income economy, informal labour will account for 46.5% of the overall workforce by 2043. The three low-income countries with the smallest share of informal labour in 2043 are Sudan, Togo and Niger with 21.8%, 42% and 44.8%, respectively.

Addressing informality constructively is essential to promote inclusive wealth creation in Madagascar and reduce inequalities. The sector is the only source of income for most people of working age. Improving access to quality education, job creation and financial inclusion are some policies that can reduce informality.

Chart 7 presents GDP per capita in the Current Path, from 1990 to 2043, compared with the average for the Africa income group.

In 2023, Madagascar’s GDP per capita ranked 13th out of 23 for Africa’s low-income economies, at a value of US$1 499. This is US$353 below the group average for Africa’s low-income economies (US$1 852). Between 1990 and 2023, Madagascar’s GDP per capita fell from around US$1 800 to US$1 500. This long-term decline reflects decades of weak productivity growth, limited industrialisation and recurring political instability that undermined investment. Rather than converging with regional peers, Madagascar has fallen further behind in income terms. The sharp contraction between 2001 and 2002 was largely the result of the disputed presidential election, which triggered a prolonged political crisis. The standoff between rival governments led to blockades at ports, disruption of trade and transport and undermined investor confidence.

In the Current Path, the country’s per capita income will increase to US$2 200 by 2043, maintaining its current regional rank. Madagascar’s GDP per capita will stay below the average of its low-income peer group, which will be US$3 061 by 2043, with the gap growing to US$861. This points to the structural factors that undermine inclusive economic growth in Madagascar.

On the Human Development Report 2023/2024, Madagascar scored 0.487 based on data from 2022 (higher scores mean higher human development). The country ranked 177 out of 191 countries. The scores in the low human development category range from 0.380 (Somalia, lowest) to 0.548 (Nigeria, highest).

Chart 8 presents the rate and numbers of extremely poor people in the Current Path from 2020 to 2043.

In 2022, the World Bank updated the poverty lines to 2017 constant dollar values as follows:

- The previous US$1.90 extreme poverty line is now set at US$2.15, also for use with low-income countries.

- US$3.20 for lower-middle-income countries, now US$3.65 in 2017 values.

- US$5.50 for upper-middle-income countries, now US$6.85 in 2017 values.

- US$22.70 for high-income countries. The Bank has not yet announced the new poverty line in 2017 US$ prices for high-income countries.

As a low-income country, Madagascar uses the US$2.15 benchmark to define extreme poverty. The country has the highest poverty burden on the continent, with 80.5% of its population living in extreme poverty in 2023, followed by South Sudan, Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of Congo with rates of 76%, 75% and 74.9%, respectively. Unlike Madagascar, those three countries experience high levels of violent conflict. The average poverty rate for Madagascar’s low-income peers is much lower, standing at 44.6% in 2023. By 2043, the burden will shrink to 26.7%.

In absolute numbers, 25.2 million people lived in extreme poverty in 2023 in Madagascar. On the Current Path, the number of people living in extreme poverty will increase by one-third to 33.5 million people in 2043, due to high rates of population growth. The poverty rate, however, is projected to decline to 68.8%, and South Sudan will have Africa’s highest poverty burden by 2043 (77.8%). A combination of political instability, geographic challenges, underinvestment in people and environmental fragility has led to such high and persistent levels of poverty. Incipient economic development has repeatedly been interrupted by political instability.

Monetary poverty only tells part of the story, however. Therefore, the global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) assesses acute multidimensional poverty by measuring each person’s overlapping deprivations across 10 indicators in three equally weighted dimensions: health, education and standard of living. The MPI complements the respective international monetary poverty thresholds by identifying who is multidimensionally poor and also shows the composition of multidimensional poverty. The headcount or incidence of multidimensional poverty is often several percentage points higher than that of monetary poverty. This implies that individuals living above the monetary poverty line may still suffer deprivations in health, education and/or standard of living.[x] Madagascar scores 0.386 on the Multidimensional Poverty Index 2024 with 68.4%, of the population considered multidimensionally poor and with sanitation and cooking fuel being the most critical dimensions, followed by housing. This is much higher than the average score for sub-Saharan Africa at 0.254.

Chart 9 depicts the National Development Plan of Madagascar.

Madagascar has a long-term vision called Fasandratana 2030 – Vision pour le développement de Madagascar. This plan aims to elevate Madagascar's GDP per capita US$1 000 by 2030, reduce the poverty rate to less than 25% and improve the country’s Human Development Index (HDI) ranking to between 70th and 80th by 2033.

In addition, Madagascar has a national development plan known as Plan Émergence Madagascar. This framework, covering the period from 2019 to 2023, envisions transforming Madagascar into an emerging country where future generations can live better together, sharing prosperity and collective happiness. The plan emphasises sustainable development, inclusive growth and environmental stewardship.

It features the core priority of good governance, which is the backbone of the plan and three fundamental pillars. The plan focuses on ensuring political stability and security, promoting access to justice for all and strengthening public administration, transparency and anti‑corruption efforts. Pillar one targets social and human capital and aims at improving people’s well‑being and opportunities via

- quality education for all (especially girls),

- universal healthcare access and reproductive health,

- decent employment and professional training, and

- social cohesion via cultural and sporting initiatives.

The second pillar focuses on accelerated economy and growth and the transformation of the economy via legislative reforms and upgrading infrastructure, boosting agriculture, industrial processing and a circular blue economy. It equally aims to develop the mineral sector and expand tourism.

Pillar three focuses on the environment and the living environment and includes a commitment to sustainable development, including aligning economic growth with environmental standards, conserving natural resources and biodiversity, massive reforestation and climate resilience measures.

The plan also serves to attract investments related to the construction of new road infrastructure, the development of water supply and the energy and mining sectors.

The different plans are aligned with broader frameworks such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the African Union's Agenda 2063. They serve as guiding documents for various international partners and organisations, including the World Food Programme (WFP) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), to align their country strategies and programs with Madagascar's development priorities.

Moreover, in January 2023, the Malagasy Government together with the United Nations published a Vision prospective 2030 2040 2063 de Madagascar, a holistic vision that identified four priorities of intervention to set Madagascar on a more sustainable development trajectory: governance ( resilience to environmental risks, humanitarian action and social protection, security), human capital development (youth, gender equality and social wellbeing, technological innovation), macroeconomic stability and private sector development, and lastly land use and planning and infrastructure development.

The eight sectoral scenarios as well as their relationship to the Current Path and the Combined scenario are explained in the About Page. Chart 10 summarises the approach.

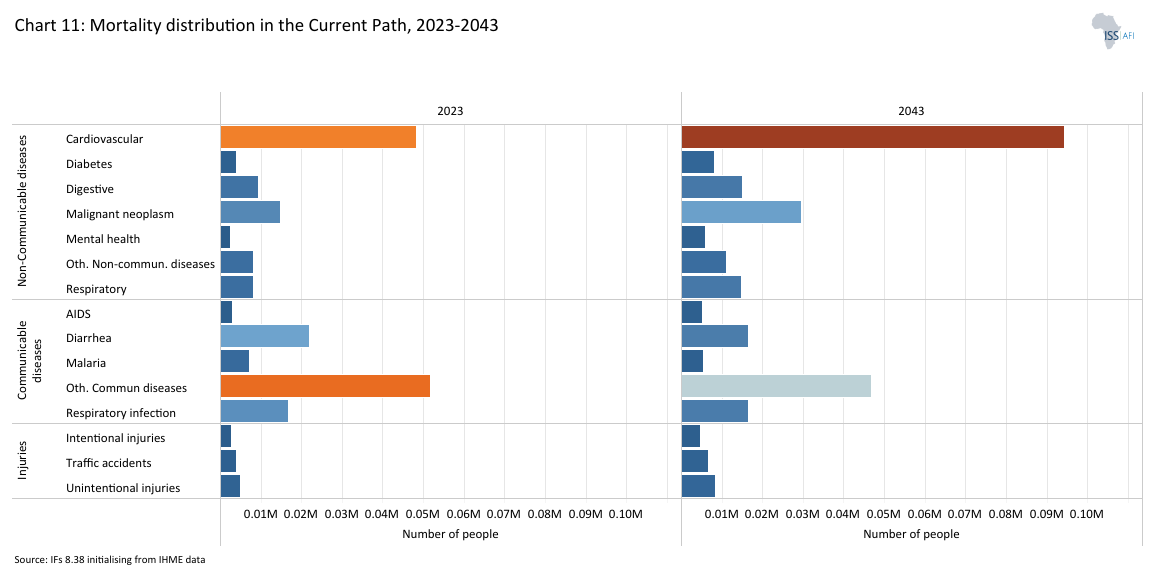

Chart 11 presents the mortality distribution in the Current Path for 2023 and 2043.

The Demographics and Health scenario envisions ambitious improvements in child and maternal mortality rates, enhanced access to modern contraception, and decreased mortality from communicable diseases (e.g., AIDS, diarrhoea, malaria, respiratory infections) and non-communicable diseases (e.g., diabetes), alongside advancements in safe water access and sanitation. This scenario assumes a swift demographic transition supported by heightened investments in health and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WaSH) infrastructure.

Visit the themes on Demographics and Health/WaSH for more detail on the scenario structure and interventions.

Demographics and health constitute two intimately connected systems. Madagascar’s population structure is maturing only slowly. Relatively high levels of fertility and above-average life expectancy are driving natural population growth. This youthful and rapidly expanding population places significant strain on the health system: high fertility increases demand for maternal and child health services, while a growing cohort of young people requires immunisation, nutrition and primary healthcare. Such pressure can undermine service quality and compound longstanding challenges, such as malnutrition, high child mortality and uneven access to care.

In 2023, the average total fertility stood at four births per woman of childbearing age. The Current Path, the fertility rate will drop to 3 births per woman by 2043. It is only in 2060 that the country will reach replacement level fertility of 2.1 births. As a consequence, Madagascar’s population will continue to grow relatively fast, and by 2043 the median age will only increase to 23.4 years, up from 19.9 in 2023. Rwanda’s anticipated median age, for example, is 26.5 years, the highest among Africa’s low-income economies by then.

The Demographics and Health scenario accelerates Madagascar’s demographic transition by almost two decades, opening up opportunities for economic growth. Average total fertility is set to drop to 2.1 births per woman by 2043. This means that Madagascar would reach replacement fertility level 17 years earlier than in the Current Path. A gradual rise in median age and decline in fertility are key drivers of economic growth, as they reduce the dependency ratio and allow a larger share of the population to enter the labour force. This so-called ‘demographic dividend’ can boost productivity and savings, but only if accompanied by investments in education, job creation and health.

In 2023, the average life expectancy in Madagascar was 66.2 years. On the Current Path, it will increase to 70.3 versus 72.9 in the Demographics and Health scenario in 2043; a gain of 2.6 years. In this scenario, Madagascar will perform above the average life expectancy of Africa´s low-income economies at 71.8 years and get close to the average of 72.4 years for the continent’s lower-middle-income economies. Ethiopia, the top performer among the low-income peers, will have a life expectancy of 76.2 years in 2043 in the Current Path, followed by Rwanda at 75 years.

Between 1990 and 2023, Madagascar notably improved its child survival rates, increasing overall life expectancy. The under-five mortality rate dropped from 159.5 deaths to 51.5 deaths per 1 000 births, and infant mortality fell from 88.1 deaths per 1 000 live births in 1990 to 39.2 deaths in 2023. By 2043, the under-five mortality will drop to 30.7 deaths per 1 000 births.

However, chronic malnutrition remains a significant concern, with 38.6% of children under five experiencing stunting in 2023. In the Demographics and Health scenario, the under-five mortality will drop to around 25 deaths per 1 000 births before 2036, catching up with the Sustainable Development target with a delay of 6 years. By 2043, the under-five mortality will have dropped to 20 deaths per 1 000 live births. The under-five stunting rate will have dropped 20.1% compared to 26% on the Current Path. These improvements not only save lives but also improve cognitive development, school readiness and long-term productivity, laying the foundation for a healthier, more skilled workforce. Over time, reduced child mortality and malnutrition also ease pressure on households, enabling greater investments in education and income-generating activities.

Madagascar is undergoing an epidemiological transition, which is characterised by a double burden of disease. This means that the burden from infectious diseases persists alongside the rising prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). In 2023, there are nearly as many deaths from NCDs as there are from communicable diseases (CDs) (0.09 million versus 0.1 million). In 2023, other communicable diseases were the leading cause of death in Madagascar. Diarrhoea and respiratory infections are ranked 3rd and 4th. Already by 2025, NCDs will be the leading cause of death in Madagascar. By 2043, twice as many Malagasy will die from NCDs as from communicable diseases, placing additional strain on its health sector as NCDs are more expensive to treat.

Among the former, cardiovascular diseases are the most prevalent, followed by malign neoplasms, which relate to deaths caused by cancers. Currently, cardiovascular diseases are already the second leading cause of death in the country.

The coexistence of communicable and non-communicable diseases requires a comprehensive health strategy that addresses both ends of the disease spectrum with increasing attention to non-communicable diseases.

Madagascar’s health sector has a dual structure. Health services are provided by the government, non-governmental organisations as well as some private clinics. The public sector comprises basic health centres (Centres de Santé de Base), district hospitals and regional as well as university hospitals. However, health expenditure is far too low and relies heavily on foreign aid, which has seen severe cuts recently, with implications for poverty and health outcomes on the continent. Generally, the sector suffers from important infrastructure deficits, a shortage of doctors and nurses and lacks essential supplies. In 2022, according to World Bank data, health expenditure in Madagascar only accounted for 3.3% of GDP, almost 2 percentage points below the average for sub-Saharan Africa excluding high-income economies at 5.1%.

Access to healthcare is limited, and more so in rural areas. Private facilities, more common in urban areas, offer better services but are unaffordable for most people. The government has committed to universal health care for children under five, pregnant women and people over 65, but implementation is slow.

According to the latest available data (2019) from the Global Burden of Disease, Madagascar scored 40 on the Universal Healthcare effective coverage index (index from 0-100, higher is better); a below-average performance (the sub-Saharan African average was 46.2 in 2023), showing the greatest deficiencies in the area of cancer treatment. This underscores that the country needs to be more proactive about its growing non-communicable disease burden. At the same time, significant challenges in the areas of antenatal, peripartum and postnatal care for newborn babies and antenatal, postpartum and postnatal care for mothers still exist.

Strengthening healthcare infrastructure, improving access to services and addressing underlying socioeconomic factors are key steps toward improving the country's health outcomes.

In the Demographics and Health scenario, the poverty rate drops to 66.6% compared to 68.8% in the Current Path. This scenario has the third-strongest impact on poverty reduction, following the Agriculture and AfCTA scenarios.

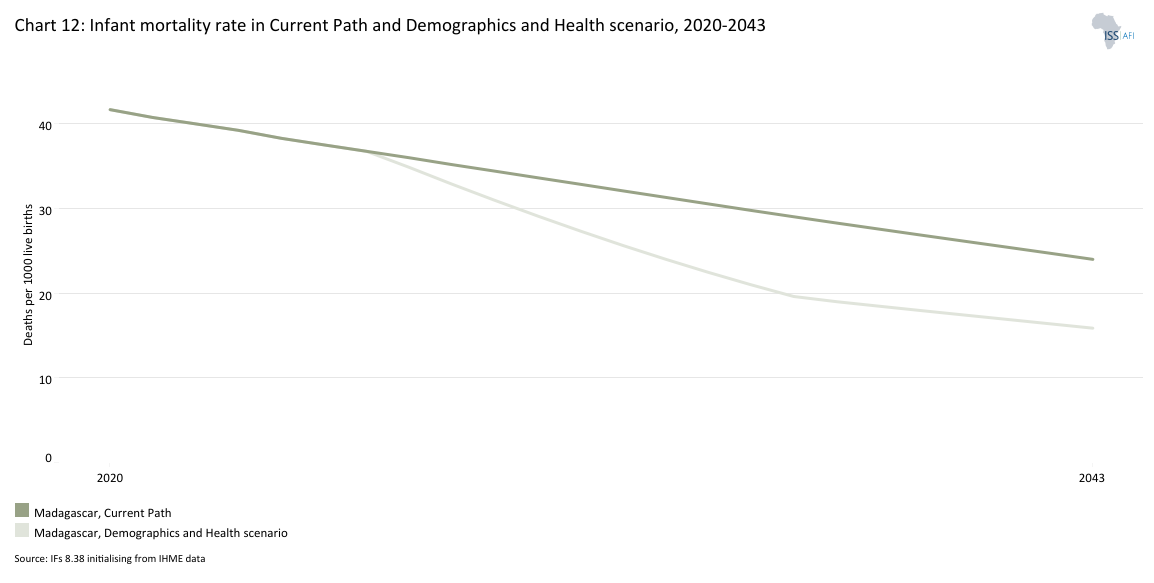

Chart 12 presents the infant mortality rate in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

The infant mortality rate is the probability of a child born in a specific year dying before reaching the age of one. It measures the child-born survival rate and reflects the social, economic and environmental conditions in which children live, including their health care. It is measured as the number of infant deaths per 1 000 live births.

The infant mortality rate is an important marker of the overall quality of a country’s health system. Madagascar significantly reduced its infant mortality rate over the past decades from 88.1 deaths per 1 000 live births in 1990 to 39.2 deaths in 2023. On this indicator, the country performs above the group average of its low-income peers, which is 43.3 deaths per 1 000 live births. Gambia, the best performer, had an infant mortality rate of 25.1 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2023. The Central African Republic, on the other hand, with 80.6 deaths per 1 000 live births, had the highest infant mortality rate among Africa’s low-income economies. Madagascar ranked eighth in 2023.

Access to safe water and improved sanitation, in particular in Madagascar, is suboptimal. Both are key drivers of health outcomes. In 2023, 58.3% of the population had access to safe water, and only 14.3% were in a position to access improved sanitation. Madagascar performs the worst among its African low-income peers. The Demographics and Health sector aims to improve access to water, sanitation and hygiene (WaSH) infrastructure.

As a result of these interventions, in the Demographics and Health scenario, infant mortality in Madagascar will reduce by more than 50% dropping to 15.9 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2043. The Current Path forecasts 23.4 deaths per 1 000 live births in 2043. The scenario interventions set Madagascar on a path to come much closer to the SDG infant mortality goal of 12 deaths per 1 000 live births, albeit with a significant delay.

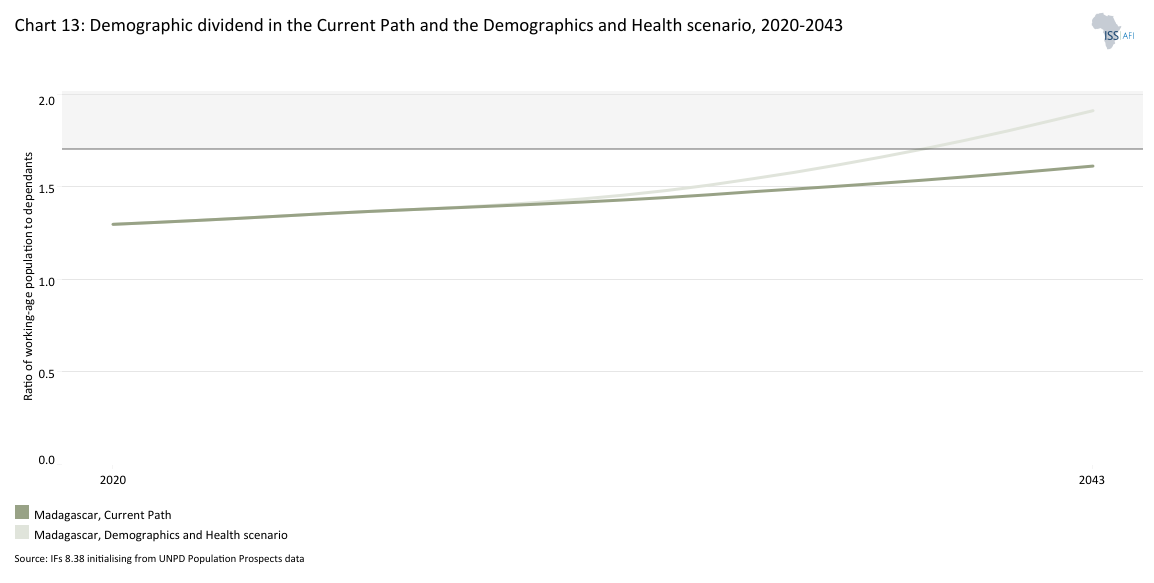

Chart 13 presents the demographic dividend in the Current Path and in the Demographics and Health scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

The dividend is the window of economic growth opportunity that opens when the ratio of working-age persons to dependants increases to 1.7 to 1 and higher.

A maturing age structure will benefit Madagascar’s workforce. By 2043, people of working age will account for about 62% of the population compared to 57% in 2019. This means that the ratio between the working age and the dependent population is improving, but not fast enough to significantly boost economic growth. On the Current Path, Madagascar is expected to reach the peak of its “demographic sweet spot” only in 2076. By 2043, for every dependant there will be 1.6 workers, up from 1.3 in 2023. In the Demographics and Health scenario, Madagascar’s demographic dividend is fast-tracked by nearly two decades, with 2.4 workers for every dependant in 2058.

A lower dependency burden would allow households to save and invest more, while a larger share of the population contributes to the labour force. This accelerates economic growth, broadens the domestic tax base and creates fiscal space for greater investment in health, education and infrastructure. If paired with job creation and skills development, the earlier demographic shift can generate a substantial ‘demographic dividend’.

Chart 14 presents crop production and demand in the Current Path from 1990 to 2043.

The Agriculture scenario envisions an agricultural revolution that ensures food security through ambitious yet feasible increases in yields per hectare, thanks to improved management, seed, fertiliser technology, and expanded irrigation. Efforts to reduce food loss and waste are emphasised, with increased calorie consumption as an indicator of self-sufficiency and prioritising it over food exports. Additionally, enhanced forest protection signifies a commitment to sustainable land use practices.

Visit the theme on Agriculture for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

The data on agricultural production and demand in our modelling initialises from data provided on food balances by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Our model contains data on numerous types of agriculture but aggregates its forecast into crops, meat and fish, presented in million metric tons.

Madagascar is endowed with abundant natural resources and has exceptional potential for agricultural development, which remains, however, largely unexploited. The country’s agricultural sector, including fishing and forestry, is the backbone of the economy, although it contributes less than half of what the service sector contributes to GDP. In 2023, agriculture accounted for close to one-fourth (22.8%) of GDP, but employed roughly 80% of the working population, often in subsistence farming or informal work. Rice production is the leading economic activity. Value added from the services sector accounted for 51.3% of GDP, including retail, tourism, public administration, education and health, many of which are urban and informal. Manufacturing accounted for 9.7% of GDP.

In the Current Path, the contribution of agriculture to GDP will drop to 12.9% in 2043, with services gaining importance (56.2% of GDP in 2043). In absolute terms, however, value added from agriculture is expected to increase from US$3.3 billion to US§4.8 billion. The agricultural sector is extremely vulnerable in that it faces a series of challenges, including deforestation and erosion, aggravated by bushfires, slash-and-burn clearing techniques, as well as the use of firewood as the primary source of fuel.

Rice is the primary crop, followed by other subsistence crops like cassava, corn and sweet potato. Cash crops such as vanilla, coffee, cloves and cocoa are cultivated for the export market.

According to the International Fund for Agricultural Development, the rice sector’s annual average growth rate is only 1.5 per cent, a key driver of rural poverty. Other drivers include fragmented production, low productivity, rural insecurity, overuse of natural resources, vulnerability to natural disasters, limited access to economic and commercial opportunities, poor infrastructure and limited access to agricultural markets and rural finance.

In 2023, Madagascar’s total crop yield was approximately 15.8 million metric tons. Crop yields will increase by 37% to 21.7 million metric tons in 2043. However, crop production is outpaced by demand, increasing the risk for excessive food import dependence. In 2023, 15.8 million metric tons were not enough to meet domestic demand, which stood at 17.52 million metric tons.

Fast population growth is rapidly fuelling agricultural demand, and in combination with low productivity, it fuels the widening gap between demand and production. The gap of almost 1.7 million metric tons observed in 2023 will reach 10.4 million metric tons by 2043. A growing gap automatically translates into growing import dependence for food items, which in turn affects the current account balance.

Further, environmental degradation and high exposure to climate change-related risks heighten Madagascar’s risk for food insecurity. Southern Madagascar is particularly vulnerable to droughts, with the one in 2021 being especially severe, and the southeast is prone to recurrent cyclones and flooding. According to the World Food Programme, in these regions, more than 1.3 million people face high levels of acute food insecurity.

In 2023, Madagascar’s service sector accounted for more than half of the country’s GDP (51.3%), followed by the value added from agriculture, which represented 22.1%, and manufacturing at 9.8%. In the Current Path, the service sector is expected to remain the most important contributor to Madagascar’s GDP. Its share is set to increase to 56.2% by 2043. At the same time, the contribution of the agriculture sector will drop to 12.9%. Manufacturing, on the other hand, will increase by close to four percentage points to 13.7% in 2043.

Madagascar’s expected trajectory roughly mirrors that of its low-income peer group, with services continuing to represent the largest share of GDP, with manufacturing experiencing modest growth and the contribution of agriculture declining.

In 2023, Madagascar’s crop production stood at 15.8 million metric tons. In the Current Path, it will increase by 37% to 21.7 million metric tons in 2043. Interventions in the Agriculture scenario create momentum and push crop production to 29.2 million metric tons, an 84% increase.

This level of crop production is still not enough to meet the increasing demand of a growing population, but it helps to gradually reduce the gap. In 2023, demand for crops was estimated at 17.5 million metric tons. By 2043, it will have grown to 21.7 million metric tons. In 2023, the gap between production and demand was 1.7 million metric tons.

In 2043, in the Current Path, production will fall 10.4 million metric tons short of demand in 2043. In the Agriculture scenario, the expected gap will be 3 million metric tons; smaller than on the projected Current Path trajectory yet larger than in 2023. This result illustrates that systems are interconnected and, more importantly, the need for holistic development planning.

Chart 15 presents the import dependence in the Current Path and the Agriculture scenario, from 2020 to 2043.

In the Agriculture scenario, total agricultural production will increase from 16.8 million metric tons in 2023 to about 31.9 million metric tons in 2043, 7.6 million metric tons more than in the Current Path. This allows for curbing the growing level of import dependence that Madagascar will experience on the Current Path as demand continues to grow due to population growth. In 2023, imports accounted for 9.9% of agricultural demand. With increased agricultural production in the Agriculture scenario, by 2043, imports will account for 10.8% of agricultural demand compared to 32% in the Current Path. This reflects curbing Madagascar’s growing import dependence.

Reduced import dependence strengthens food security, lowers vulnerability to global price shocks and improves the balance of payments. It also supports rural livelihoods by expanding domestic agricultural markets and reducing the outflow of foreign exchange, resources that can instead be invested in infrastructure, health and education.

Chart 16 depicts the progress through the educational system in the Current Path, for 2023 and 2043.

The Education scenario represents reasonable but ambitious improvements in intake, transition, and graduation rates from primary to tertiary levels and better quality of education at primary and secondary levels. It also models substantive progress towards gender parity at all levels, additional vocational training at the secondary school level, and increases in the share of science and engineering graduates.

Visit the theme on Education for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Madagascar’s education system faces significant challenges across access, quality and inequality when it comes to gender as well as the rural-urban divide. The system is largely based on the French model, and the colonial legacy is still visible in the structure, language, curriculum and assessment methods. The school calendar, for example, is an obstacle to children completing primary education, especially in rural areas.

The calendar mirrors the European school calendar and is misaligned with the country’s agricultural and cyclonic seasons. Many children drop out of school at harvest time, teachers are absent and schools are forced to close during cyclones and heavy rains. However, Madagascar has made efforts to include Malagasy language and culture in the curriculum, decentralise some education policies and adapt the system to local realities.

Primary education is officially free and compulsory for children aged 6 to 11. This was reinforced by the 2004 Madagascar Education Law and the country’s commitments to the UN Sustainable Development Goals. However, in practice, families often need to pay for uniforms, supplies and books. School fees, especially informal contributions to teachers or school operations more generally, and transportation or boarding in rural areas. Schools are generally underfunded and often rely on community fees, making access unequal.

Primary net enrollment is high (over 95%), but completion is still a challenge, although above the average for Africa’s low-income economies. In 2023, only about 65% of primary students successfully finished primary school. Barriers include long distances to travel to school, poor infrastructure, school fees, early marriage (especially for girls) and poverty. Political instability also impacts educational outcomes. World Bank and UNICEF data show that, in the years following the 2009 crisis, roughly 500 000 primary-age children were not enrolled in school, reflecting a sharp disruption in educational access. Meanwhile, in some regions, child stunting reached 50-60% by 2018, among the highest in the world.

Madagascar’s general expenditure on education as a share of GDP is low. In 2022, education expenditure was estimated to account for 3.1% of GDP, almost a full percentage point below the regional average of just under 4% of GDP. Rwanda, for example, allocated 4.7% of GDP to education in 2022.

Generally, learning outcomes are suboptimal. According to the World Bank, 94% of students are “learning poor”, i.e. do not achieve the minimum reading proficiency level at the end of primary school (2019 data). This is 11 percentage points higher (higher is worse) than the continental average and six percentage points higher than the average for low-income countries globally. A recent study concludes that the education system does not equip students with the necessary skills for productive employment later on.

According to the Global Education Policy Dashboard, only 3.8 per cent of students in the fourth year of primary school participating in the assessments achieve 80% of the minimum required reading, writing and mathematics skills.

Further, repetition and dropout rates remain high. In primary education, the repetition rate increased from 23 per cent in 2018/19 to 31 per cent in 2019/20, far exceeding the Ministry of Education’s target of 11 per cent for 2022.

Currently, the literacy rate among the Malagasy population older than 15 years old is 78.2%, the third highest among its African income peers, following Eritrea and the Democratic Republic of Congo. For Malagasy women, the literacy rate is somewhat lower than for their male counterparts (76% versus 79%). A recent study conducted by the World Bank highlights the correlation between levels of poverty and levels of education. The research says that illiterate individuals have a poverty rate of 97%, while those who have completed primary education have a poverty rate of 83.5%. Those who have completed secondary education have a significantly lower poverty rate of 46% and those with higher education of just 17%.

Gross primary enrolment rates in Madagascar stood at 145.5% in 2023. About 86.1% of girls and 89.6% of boys successfully transition to secondary school. On the Current Path, gross primary enrolment rates will reach 127.8% by 2030 and continue to drop thereafter. In lower-secondary education, enrolment was 47.2% in 2023 and will increase to 63% in 2043. Enrolment rates in upper-secondary education stood at 24.1% in 2023 and will increase to 37% by 2043 on the Current Path. Tertiary education sees the lowest enrolment rate, with 6% in 2023, projected to increase to 11.5% by 2043.

Completion rates follow the same trend as gross enrolment rates, with the highest rates recorded at the primary level, followed by a sharp decline as students progress to higher education levels. In 2023, the primary completion rate was 65.1%, while lower-secondary rates saw a massive drop to 23.4%. Upper-secondary completion stood at 13.8%, with tertiary education having the lowest rate at just 1.5%.

In 2023, the ratio of girls to boys for primary enrolment was 0.97, which reflects the expected trend where more boys than girls are enrolled in schooling. However, the ratio temporarily changes in favour of girls at the lower-secondary education level when it increases to 1.06 before it drops again to 0.99 at the upper-secondary level and to 0.96 at the tertiary level. This is not in line with the global trend, as in many countries, secondary and even more so tertiary enrolment rates for females surpass those of their male peers.

In the Education scenario, the gender gap in tertiary education closes. Both female and male students will reach enrolment rates of 22% versus 12.3% (female) and 10.8% (male) in the Current Path. For primary education, the scenario interventions accelerate achieving full gender parity by roughly a decade. As for secondary education, the Education scenario results in a ratio of girls to boys of 1.03 by 2043 versus 0.98 in the Current Path.

In Madagascar, the labour force participation rate among females is lower than among males (83.3% versus 88.8%), pointing to systemic barriers and gender inequalities. Since 1990, female labour force participation has remained roughly the same. However, compared with labour force participation in the low-income group, the gender gap is smaller in Madagascar. As in the health sector, many of these reforms are still heavily reliant on external aid, although recent government budgets have signalled a gradual increase in domestic investment.

Chart 17 presents the mean years of education in the Current Path and in the Education scenario, from 2020 to 2043, for the 15 to 24-age group.

The average years of education in the adult population aged 15 to 24 is a good first indicator of how the stock of knowledge in society is changing.

With a mean of 4.8 years of education among the adult population aged 15 to 24 years in 2023, Madagascar’s educational outcomes are more than one year below the group average of Africa’s low-income economies, which is 5.9 years. With a mean of 4.3 years, female education lags behind male education with a mean of 5.3 years, highlighting a gender disparity in favour of male educational attainment. Given Madagascar’s poor performance on educational attainment, the implementation of the Education scenario yields significant improvements. The scenario has the potential to increase Madagascar’s mean years of education by 2.4 years to 7.2 years by 2043. This represents an improvement of 1.1 years compared to the Current Path forecast of 6.1 years in 2043. Female education outcomes will continue to lag behind outcomes for males (6.7 versus 7.8 mean years of education, respectively). Globally, Madagascar has the 6th-worst educational performance measured in mean years of education, and the 5th worst in sub-Saharan Africa.

Primary completion rates will reach 106.8% versus 83.1% in the Current Path. Lower and upper-secondary completion rates will rise to 43.7% and 30.9%, versus 38.9% and 25.8%, respectively, in the Current Path.

In 2023, Madagascar’s average primary test score was 34. According to the Current Path, it will increase to 34.8. The Education scenario is expected to improve the country’s average test scores for primary learners to 41.2 by 2043—an increase of 6.4 points compared to the Current Path for 2043. In the Education scenario, the test score at the secondary level could increase by 5.1 points from 37.5 in 2023 to 43 in 2043, versus 37.9 on the Current Path.

In 2023, science and engineering students accounted for 16.2% of tertiary graduates in Madagascar. On the Current Path, this share will remain almost unchanged by 2043 (16.4%). However, the Education scenario offers a more optimistic outlook, with the share of science and engineering students expected to increase to 21.5% by 2043.

Such improvements would have long-term benefits for Madagascar by raising the quality of its human capital. Higher test scores and a greater share of science and engineering graduates improve workforce skills, potentially allowing for greater economic diversification beyond low-productivity agriculture and extractives. This could also help address the schooling system’s current weak alignment with labour market needs. Despite relatively high enrolment rates, many young people struggle to find work; youth unemployment stood at around 13% in 2022, and underemployment is widespread. Strengthening education quality and relevance is therefore essential to reduce unemployment, boost productivity and lay the foundation for sustained economic growth.

Chart 18 presents the value-add by sector as share of GDP in the Current Path, for 2020 and 2043.

In the Manufacturing scenario, reasonable but ambitious growth in manufacturing is envisaged through increased investment in the sector, research and development (R&D), and improved government regulation of businesses. This aims to enhance total labour

Visit the theme on Manufacturing for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Madagascar’s key industries are centred around its natural resources (nickel, cobalt, gold, gems), agriculture (vanilla, cloves, coffee, rice) and fisheries (tuna, shrimp, crab), as well as low-cost labour, with some potential in tourism and services. Manufacturing is heavily concentrated in textiles and garments (especially under AGOA and EPZ schemes). The textile sector is particularly vulnerable to the ending of AGOA and rising US tariffs, which could undermine competitiveness and employment. There is little downstream processing of raw materials like vanilla, cloves or minerals, and limited domestic demand constraints scaling.

The most important constraints to a prospering manufacturing sector include poor infrastructure (especially electricity supply and transport networks), limited access to finance, trade and customs bottlenecks, as well as skills gaps and labour challenges, and lastly regulatory and governance issues. These constraints limit local value addition, product diversification and competitiveness. The government has taken steps through its Plan Emergence Madagascar and donor-supported programs to improve infrastructure and energy supply, streamline customs, expand SME finance and strengthen vocational training. However, implementation lags behind and the impact remains very limited.

In 2023, manufacturing accounted for about 9.7% of Madagascar’s GDP (US$1.5 billion). The services sector accounted for 51.2% of GDP, the equivalent of US$7.7 billion, followed by agriculture which represented 22.1% of GDP (US$3.32 billion). In the future, services will continue to be the most important contributor to Madagascar’s GDP, forecast to account for 56.2% of GDP by 2043 at a value of US$21.6 billion, followed by the manufacturing sector that will account for 13.7% of GDP (US$5.3 billion). The contribution of agriculture will decline and account for 12.4% of GDP (the equivalent of US$4.8 billion).

Chart 19 presents the contribution of the manufacturing sector to GDP in the Current Path and in the Manufacturing scenario, from 2020 to 2043. The data is in US$ and % of GDP.

In 2023, the value added by Madagascar’s manufacturing sector accounted for 9.7% of GDP. This is below the average of Africa’s low-income economies (10.8%). In the world´s low-income economies, in 2023, manufacturing accounted for an average of 12% of GDP. On the Current Path, the value added to GDP by Madagascar´s manufacturing sector will increase to 13.7% by 2043, again performing below the expected average of its income peer group at 16.2%.

In the Manufacturing scenario, the value added by Madagascar’s manufacturing sector will account for 14.6% of GDP in 2043, an increase of almost 1 percentage points compared to the Current Path, but still below the expected average of its peer group (16.2%). Added value by manufacturing as per cent of GDP will increase by more than 50% relative to the 2023 baseline.

According to the Economic Complexity Index, during the last 20 years, Madagascar’s economy has become relatively less complex or less sophisticated, moving from the 95th to the 113th position in the Economic Complexity Index (ECI) rank. This decline reflects Madagascar’s reliance on a narrow range of low-complexity exports, limited industrialisation and poor value addition, which in turn constrain job creation, skills development and resilience to external shocks.

The ECI measures an economy's capacity, which can be inferred from data connecting locations to the activities that are present in them. It is a holistic measure of the productive capabilities of large economic systems, such as countries, cities or regions. Productive capabilities are all the inputs, technologies and ideas that, in combination, determine the frontiers of what an economy can produce. They include infrastructure, land, laws, machines, people, collective knowledge and more. Typically, economies with higher economic complexity exhibit faster economic growth.

Chart 20 depicts exports and imports as a percentage of GDP, from 2000 to 2043, in the Current Path.

The AfCFTA scenario represents the impact of fully implementing the African Continental Free Trade Agreement by 2034. The scenario increases exports in manufacturing, agriculture, services, ICT, materials and energy exports. It also includes improved multifactor productivity growth from trade and reduced tariffs for all sectors.

Visit the theme on AfCFTA for our conceptualisation and details on the scenario structure and interventions.

Madagascar’s trade is concentrated in a few key sectors and countries, making it vulnerable to external shocks. The country’s top exports are raw nickel, vanilla, cloves, gold and non-knit men's suits. The top export destinations include the United States, France, Japan, China and South Korea. In 2023, Madagascar was by far the world’s largest exporter of vanilla, accounting for around 54% of global vanilla exports, valued at about USD$271 million. At the continental level, Madagascar’s major export partners in 2022 were South Africa, Mauritius, Kenya, Ethiopia and Tanzania.

In 2000, Madagascar via the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) gained non-reciprocal duty-free access to the US market. Exports of apparel boomed thereafter. However, the 2009 coup led to a termination of that access in January 2010, followed by a sharp fall in textile production, a loss of more than 100 000 jobs and a GDP drop of nearly 11%.

Under the second Trump administration, Madagascar remained AGOA eligible. However, AGOA benefits were effectively erased due to steep tariffs of 47% although those were reduced to 10% during a 90-day period. The textile sector was hardest hit (180 000 jobs threatened), and vanilla exports were severely disrupted. In response, Madagascar entered into diplomatic negotiations with its US counterparts and joined regional coordination efforts with other affected AGOA beneficiaries.

As of June 2025, Prime Minister Christian Ntsay engaged in a strategic dialogue with US officials in Luanda, Angola. The talks focused on reforming AGOA to reflect evolving trade realities and foster industrial development in Madagascar. These high-level discussions reflect positive diplomatic momentum, but no definitive policy reversal or tariff relief has been formally agreed to date.

Key imports of Madagascar are refined petroleum, rice, light rubberised knitted fabric, wheat and palm oil. The top import partners include China, Oman, France, India and South Africa. On the continent, other than South Africa, the most important trading partners are Mauritius, Tunisia, Kenya and Morocco.

Madagascar is part of the Southern African Development Community (SADC), a regional economic bloc focused on regional integration and development. Intra-regional trade, however, is hampered by non-tariff barriers, weak institutional enforcement and divergent national agendas. For Madagascar, these challenges exacerbate its reliance on external markets and limit its ability to fully benefit from regional trade opportunities.

Madagascar is also a member of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the largest regional economic organisation on the continent with 19 member states and a population of about 390 million. COMESA has a free trade area, with 19 member states, and launched a customs union in 2009. Moreover, it is also part of the Indian Ocean Commission (IOC), which includes other island nations in the region. Additionally, Madagascar has its own Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), which extends 200 nautical miles from its coastline.